Política Monetaria

Monthly Monetary Report

January

2023

Monthly report on the evolution of the monetary base, international reserves and foreign exchange market.

Table of Contents

Contents

1. Executive Summary

2. Payment Methods

3. Savings instruments in pesos

4. Monetary base

5. Loans in pesos to the private sector

6. Liquidity in pesos of financial institutions

7. Foreign currency

The statistical closing of this report was February 7, 2023. All figures are provisional and subject to revision.

Inquiries and/or comments should be directed to analisis.monetario@bcra.gob.ar

The content of this report may be freely cited as long as the source is clarified: Monetary Report – BCRA.

1. Executive Summary

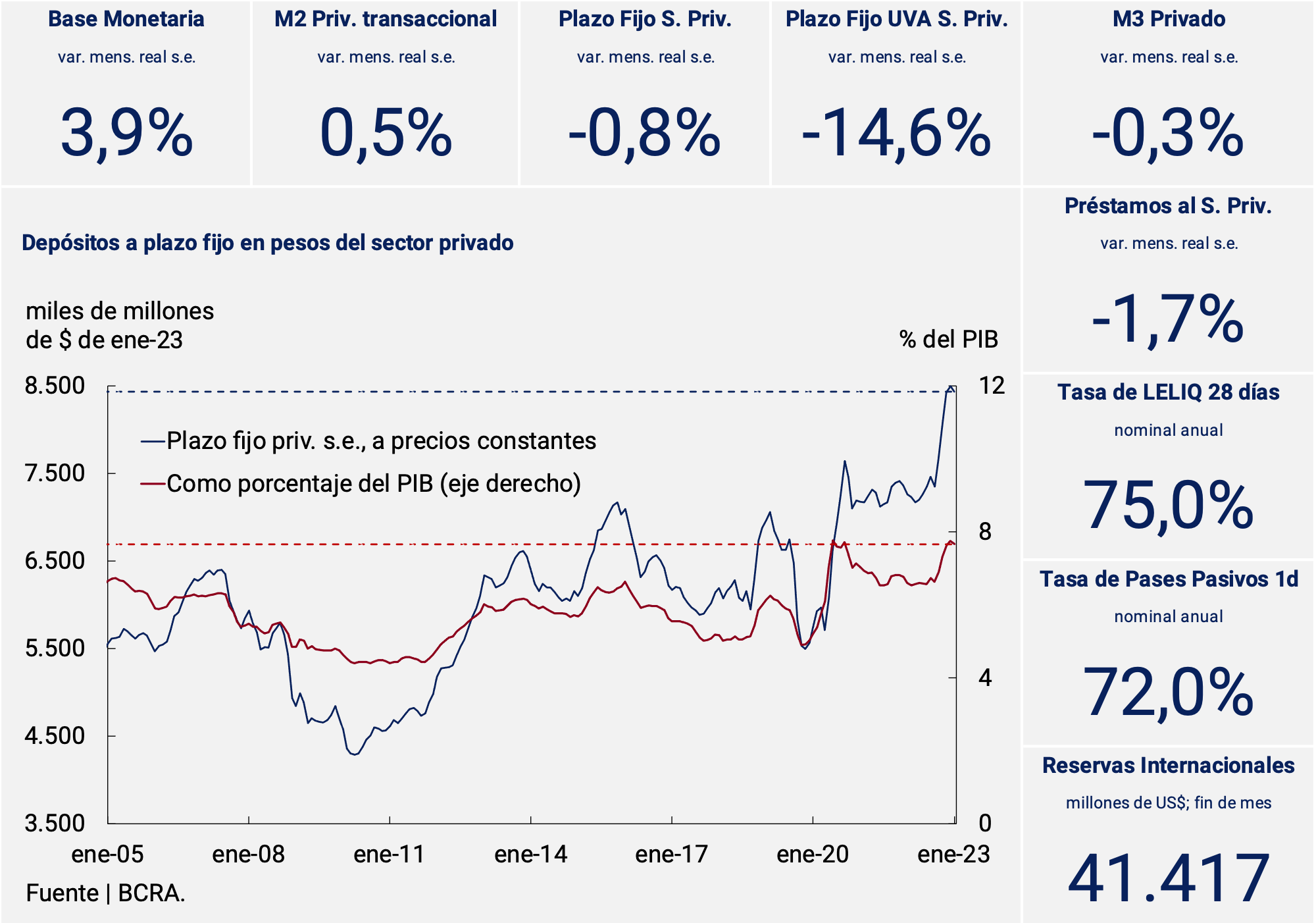

The broad monetary aggregate (private M3) at constant prices and without seasonality would have registered a slight contraction in the first month of the year. At the component level, the means of payment presented a rise that was more than offset by the fall in fixed-term deposits. However, savings instruments in pesos continue to be around the highest values of recent decades and in a record similar to the maximum of the pandemic in terms of Output.

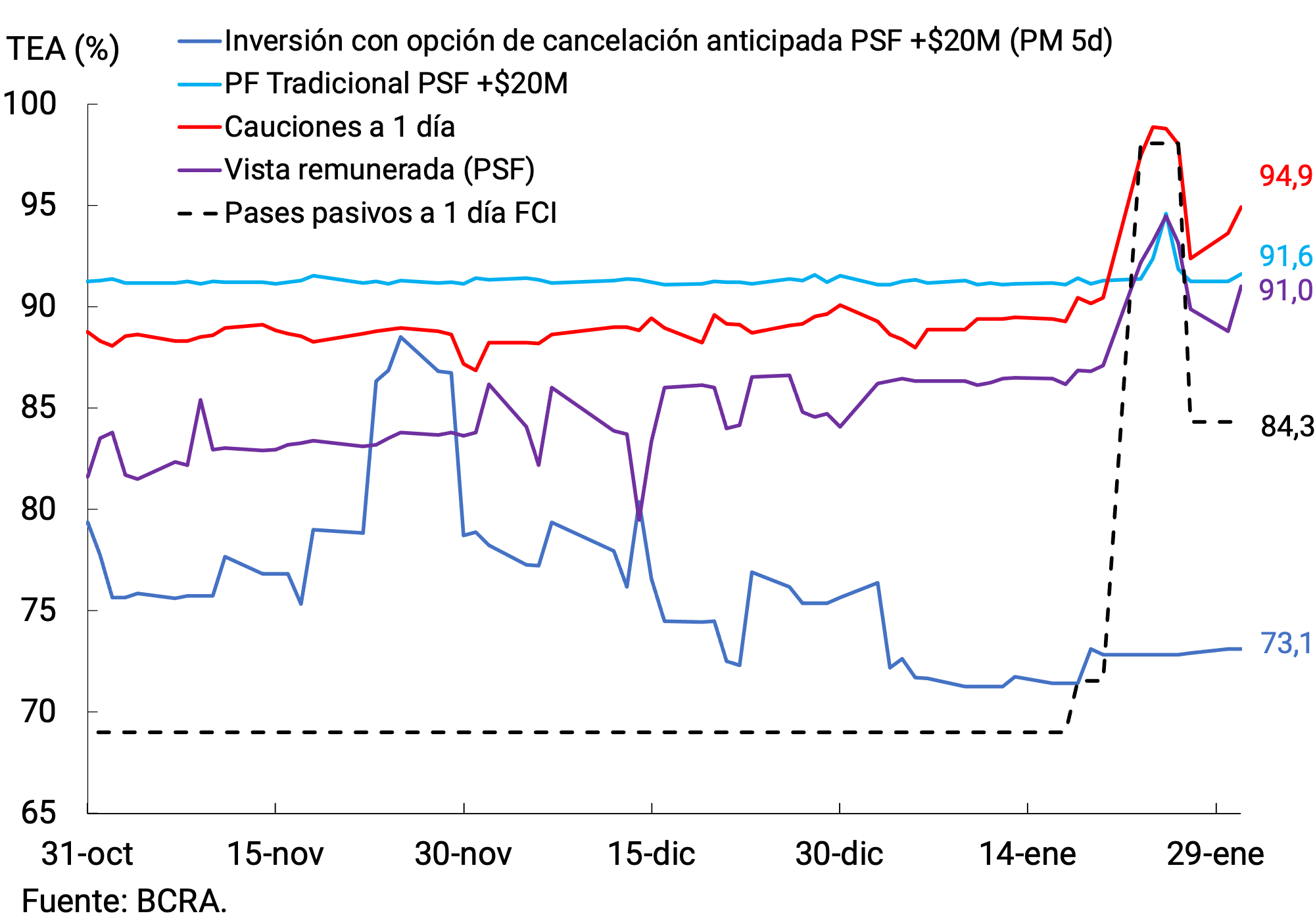

In the middle of the month, the BCRA decided to raise the remuneration of its shorter-term instruments, increasing the interest rate of the passes of financial institutions by 2 p.p. Likewise, with the aim of reinforcing the channel for transmitting monetary policy to the different segments of the financial system and the capital market, the BCRA decided to increase the rate of 1-day passive passes to FCI, which finally remained at the equivalent of 85% of the current rate for 1-day passive passes with financial institutions. Financial institutions were also authorized to carry out stock market surety operations (policyholders) in pesos.

Finally, loans to the private sector at constant prices and without seasonality would have registered a new monthly contraction, which was generalized at the level of the large lines of credit.

2. Payment methods

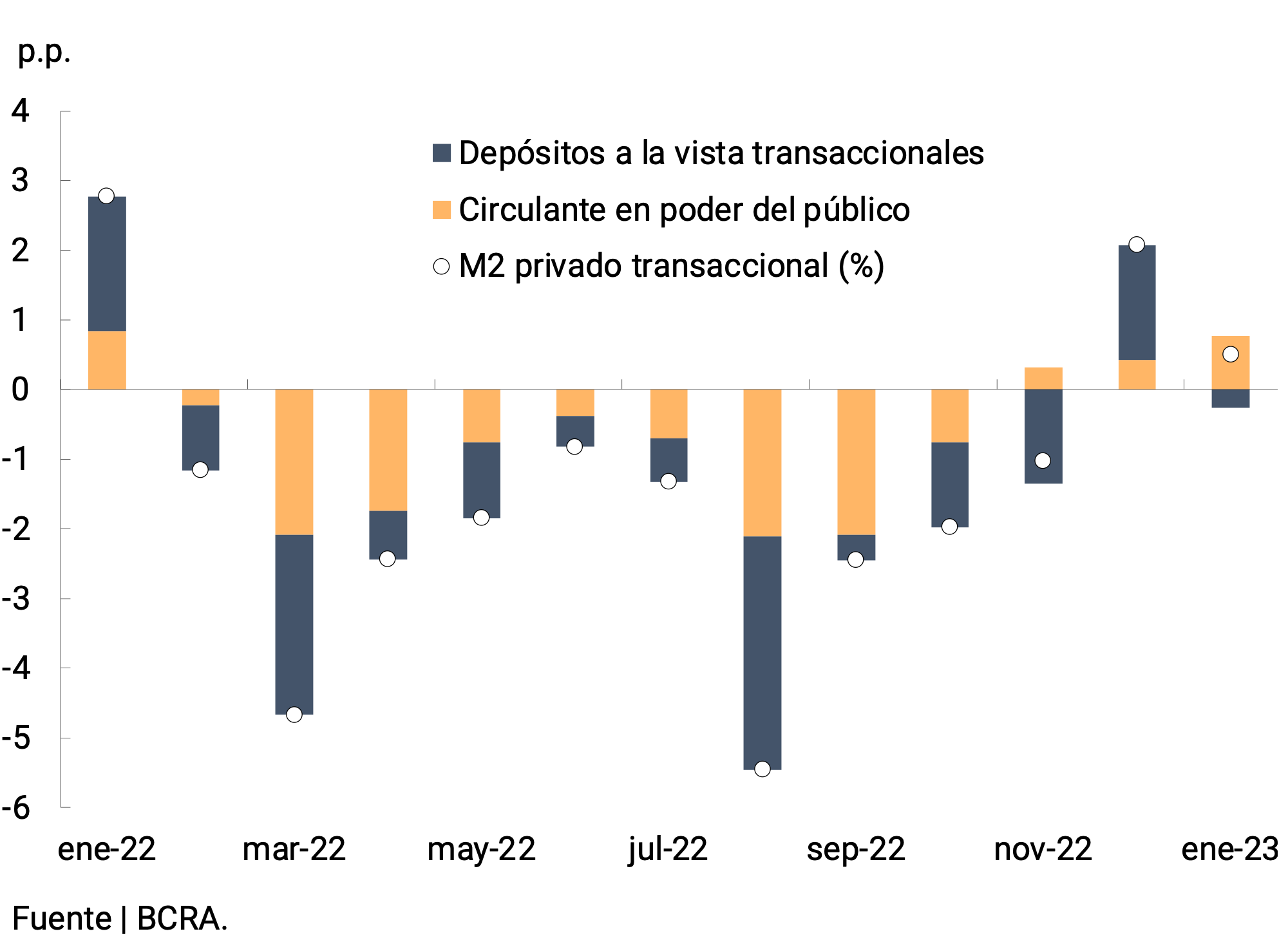

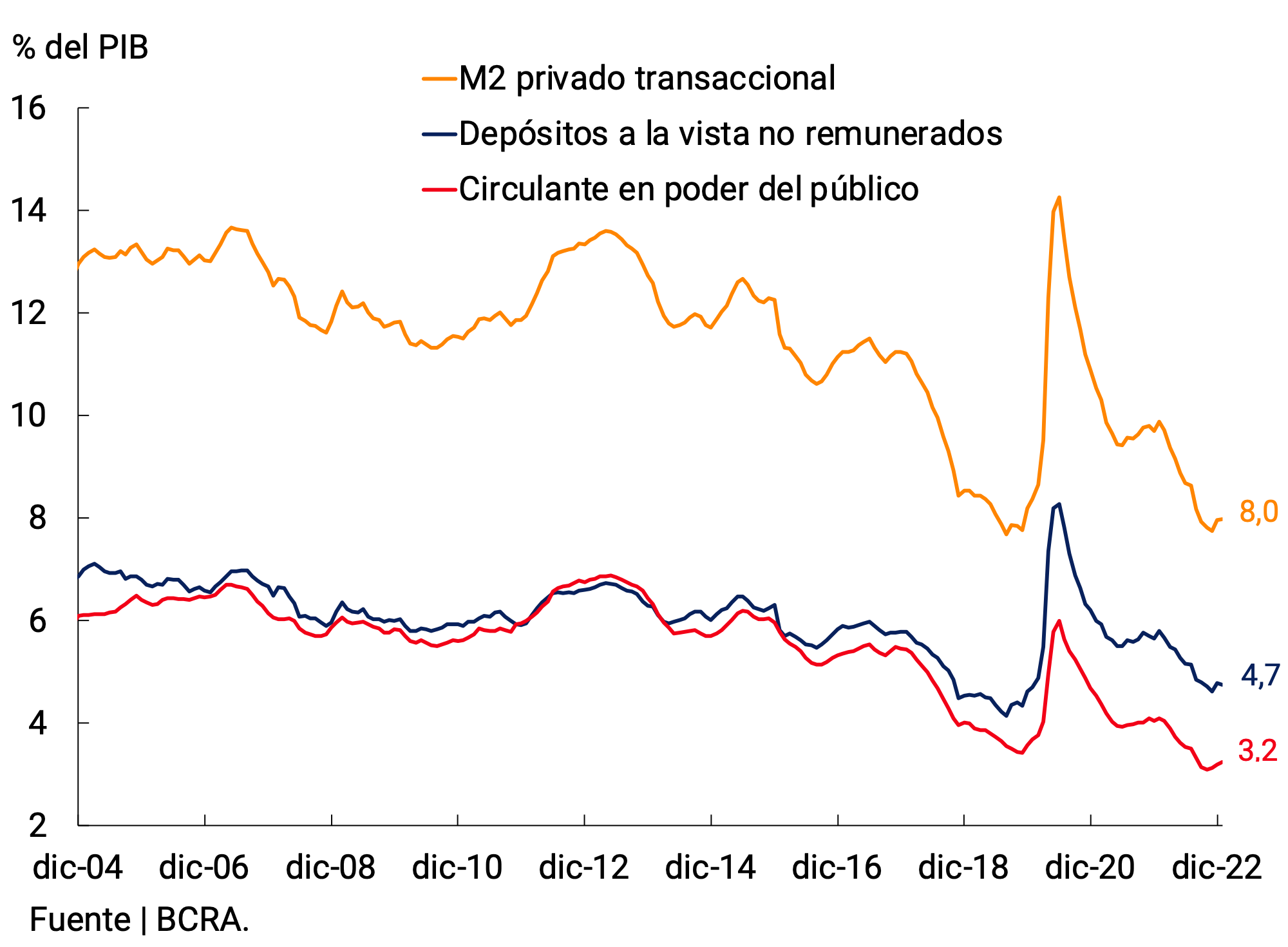

Means of payment (transactional private M21) in real and seasonally adjusted terms (s.e.) would have registered an increase of 0.5% in January, mainly explained by the positive statistical carry-over left by December (see Figure 2.1). Within its components, the growth was almost entirely explained by the circulating money held by the public. Thus, in year-on-year terms and at constant prices, means of payment would have presented a contraction of around 19.1%. In terms of Output, private transactional M2 would have stood at 8%, remaining practically unchanged from the previous month (see Chart 2.2). Both components of the means of payment remain in terms of GDP at around the lowest levels of the last 20 years.

Figure 2.1 | Private transactional M2 at constant

prices Contribution by component to the monthly vari. s.e.

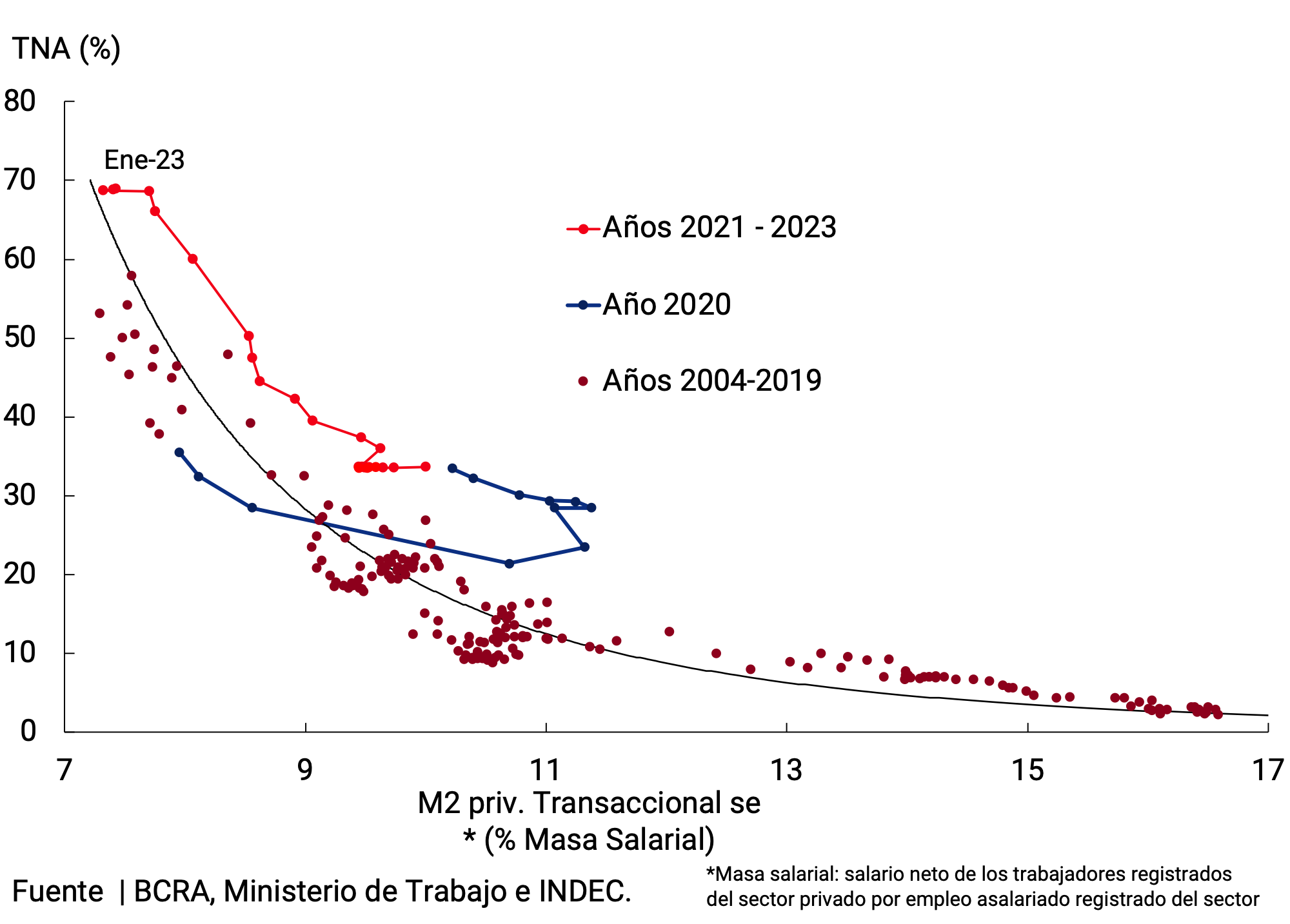

In a more structural view, when analyzing the relationship between the ratio of transactional means of payment to the wage bill and the interest rate, which represents the opportunity cost of money, it is verified that, after the significant increase in means of payment during the first year of the pandemic, the demand for real balances is in line with what was expected in a context of exchange restrictions and given the current level of interest rates of savings instruments. The fall in means of payment in real terms observed in recent months reflects the greater preference of agents for remunerated instruments (see Figure 2.3).

3. Savings instruments in pesos

The Board of Directors of the BCRA decided to maintain unchanged the minimum guaranteed interest rates on fixed-term deposits at the beginning of the year, noting 4 consecutive months without modification2. The decision was made considering that the real return on investments in local currency remains in positive territory. Thus, the minimum guaranteed rate for placements of individuals for up to an amount of $10 million remained at 75% n.a. (107.05% e.a.), while for the rest of the depositors of the financial system the interest rate persisted at 66.5% n.a. (91.07% e.a.)3.

Fixed-term deposits in pesos in the private sector would have registered a contraction of 0.8% s.e. at constant prices in the first month of the year, reversing the rise of the previous month. However, these placements remained around the highest levels in recent decades. As a percentage of GDP, these deposits would have stood at 7.7% in January, a figure similar to the maximum reached during the pandemic.

Analyzing the evolution of term placements by strata of amount, a heterogeneous behavior is observed. Deposits of $1 to $20 million, whose main holders are individuals, registered an increase on average in the month. This dynamic was offset by the fall experienced by retail deposits (less than $1 million) and wholesale deposits (more than $20 million).

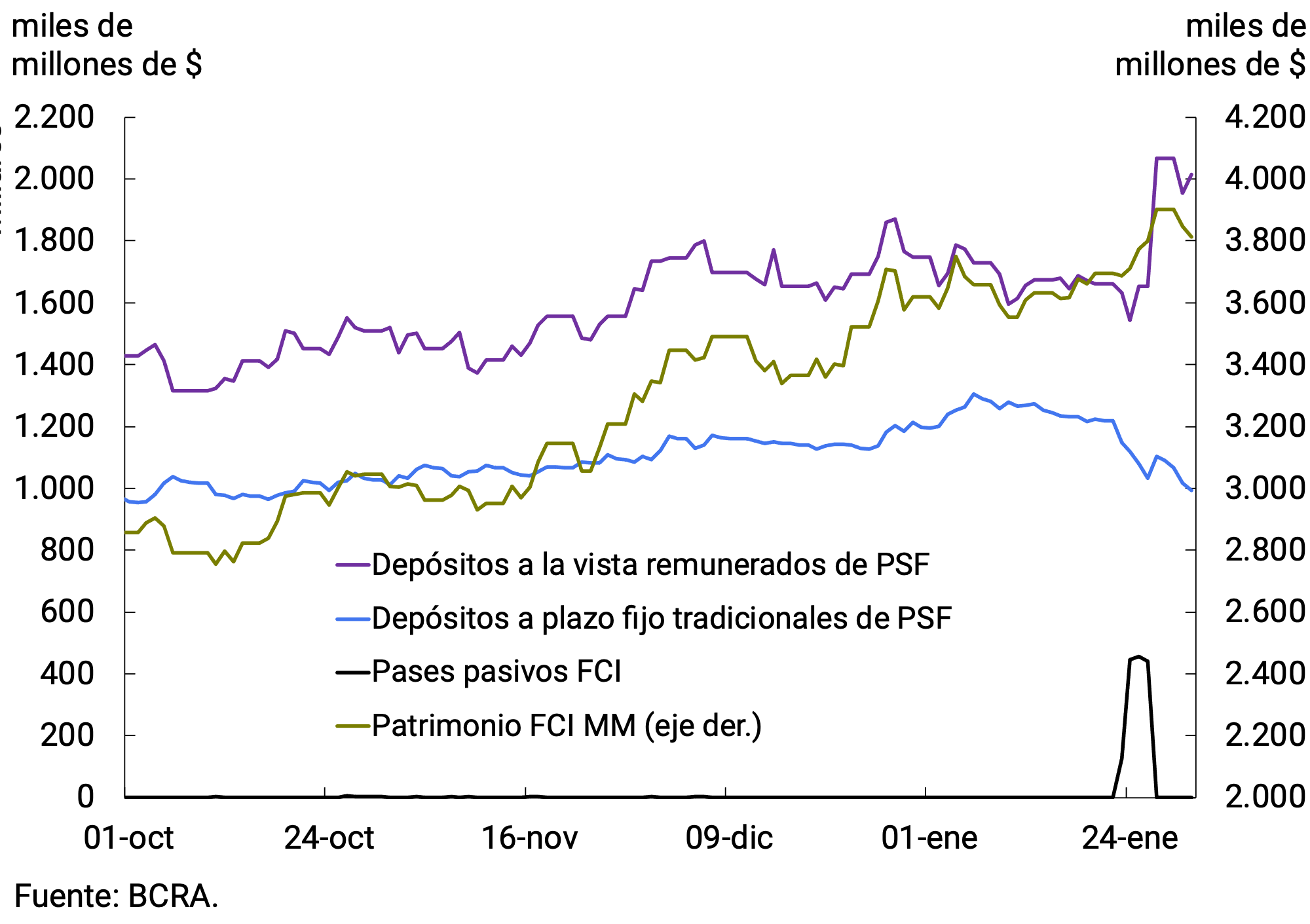

The decrease in placements in the wholesale segment was explained by the dismantling of positions of the Mutual Investment Funds (FCI MM), which are the main agents within the Financial Services Providers (FSPs). They temporarily rebalanced their portfolio in favor of passive passes with the BCRA to the detriment of fixed-term placements and also interest-bearing demand deposits (see Figure 3.1). This occurred during a period when the relative performance of FCI passes was almost on par with that of other investment alternatives (see Figure 3.2). Towards the end of the month, with the readjustment of the coefficient that determines the interest rate of FCI passes, the liquidity of the funds was channeled back to deposits (mainly interest-bearing sight), since the interest rate differential was once again turned in favor of this type of instrument.

Figure 3.1 | Equity of FCI from Money Market and main investment

instruments Balance at current prices

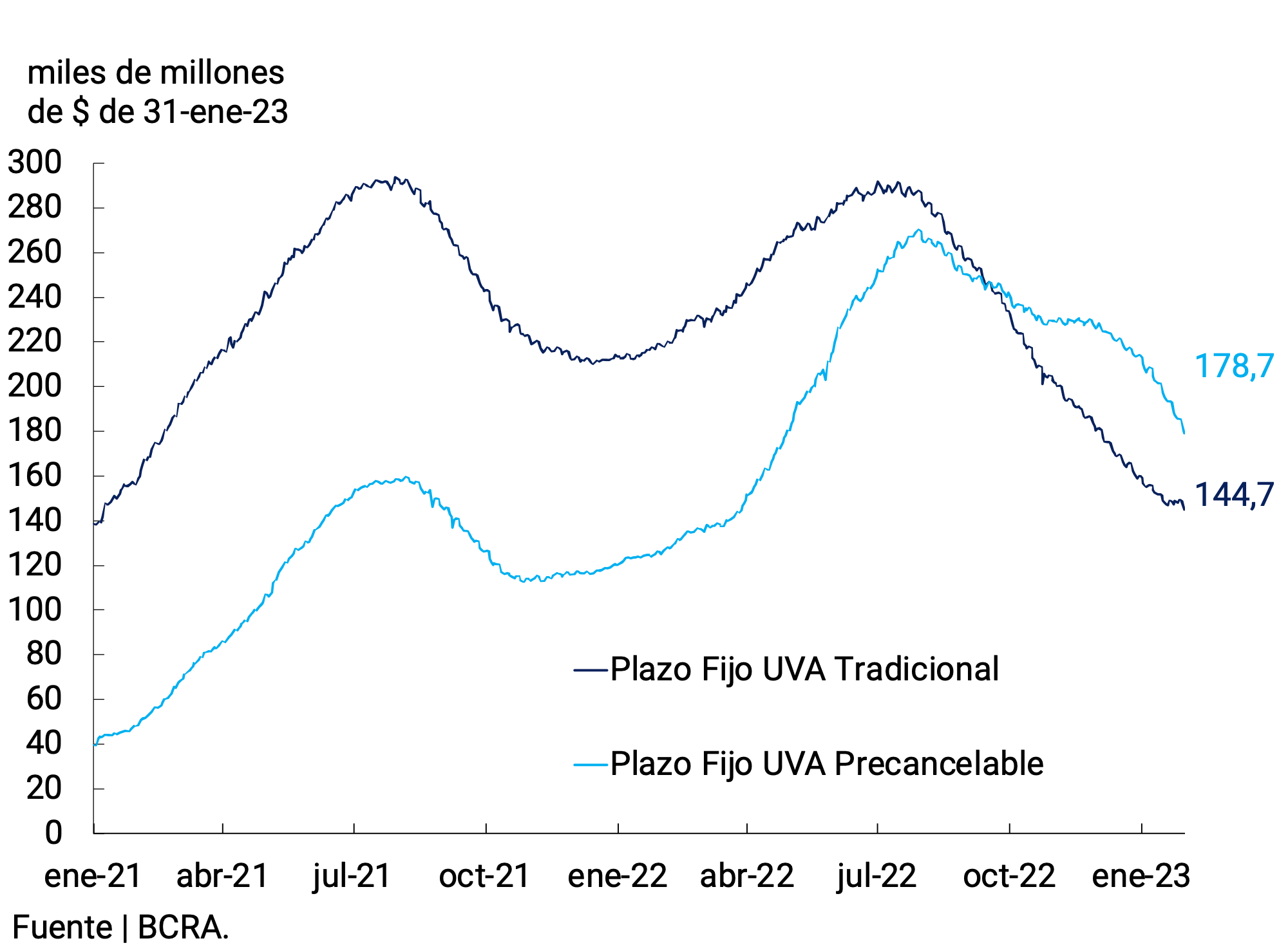

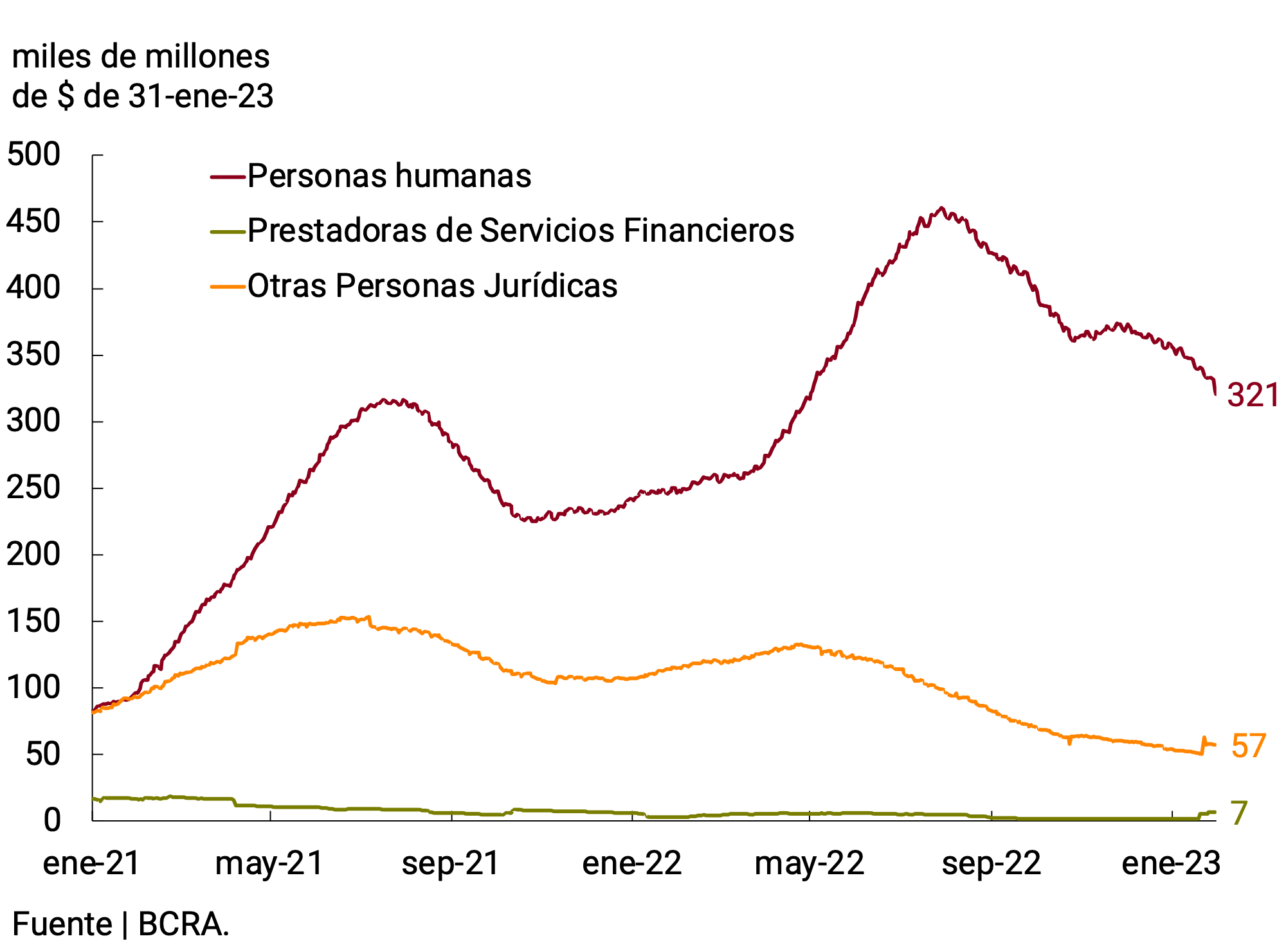

The segment of fixed-term deposits adjustable by CER exhibited a new contraction in real terms, accumulating 6 consecutive months of declines. The decrease was verified in both traditional and pre-cancellable UVA placements, whose monthly rates of change were -14.8% s.e. and -14.5% s.e., respectively (see Figure 3.3). Distinguishing by type of holder, it can be seen that the fall was mainly explained by the holdings of individuals, which account for about 85% of the total. Meanwhile, companies and FSPs increased their positions slightly in the month (see Figure 3.4). All in all, UVA deposits reached a balance of $323,500 million at the end of January, which represented 3.8% of the total of term instruments denominated in domestic currency.

Figure 3.3 | Fixed-term deposits in UVA from the private

sector Balance at constant prices by type of instrument

The BCRA approved the creation of an electronic fixed term: the Electronic Certificate for Time Deposits and Investments (CEDIP)4. Through the CEDIP, deposits and term investments constituted through Home Banking and mobile banking, both those made in pesos (including those expressed in UVA) and in dollars, can be transferred electronically in an easy and simple way, be divided into smaller placements and cleared, which will allow their use as a means of payment.

This new instrument will be in force as of July (with the exception of the functionalities of fractionation, transmission for trading in the stock market and the over-the-counter charge, which must be operational from November). In this way, the BCRA continues to promote the development of new instruments that expand the menu available to channel savings in domestic currency.

The broad monetary aggregate, private M3, at constant prices would have registered a monthly decrease of 0.3% s.e.5 in January. In year-on-year terms, this aggregate would have experienced a decrease of 3% and as a percentage of GDP it would have stood at 17.6%, 0.1 p.p. below the previous month’s record and at a level similar to the 2010-19 average.

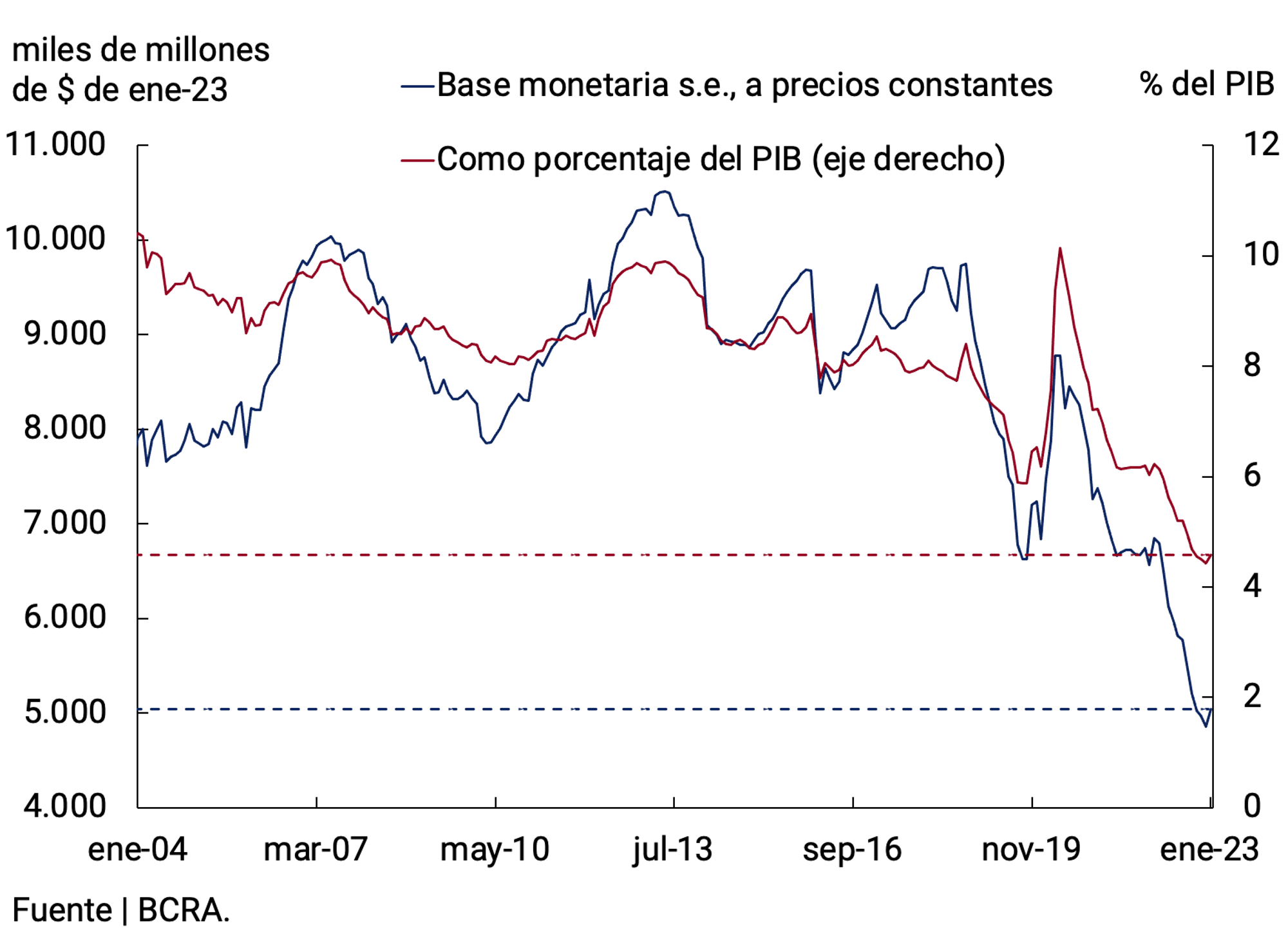

4. Monetary base

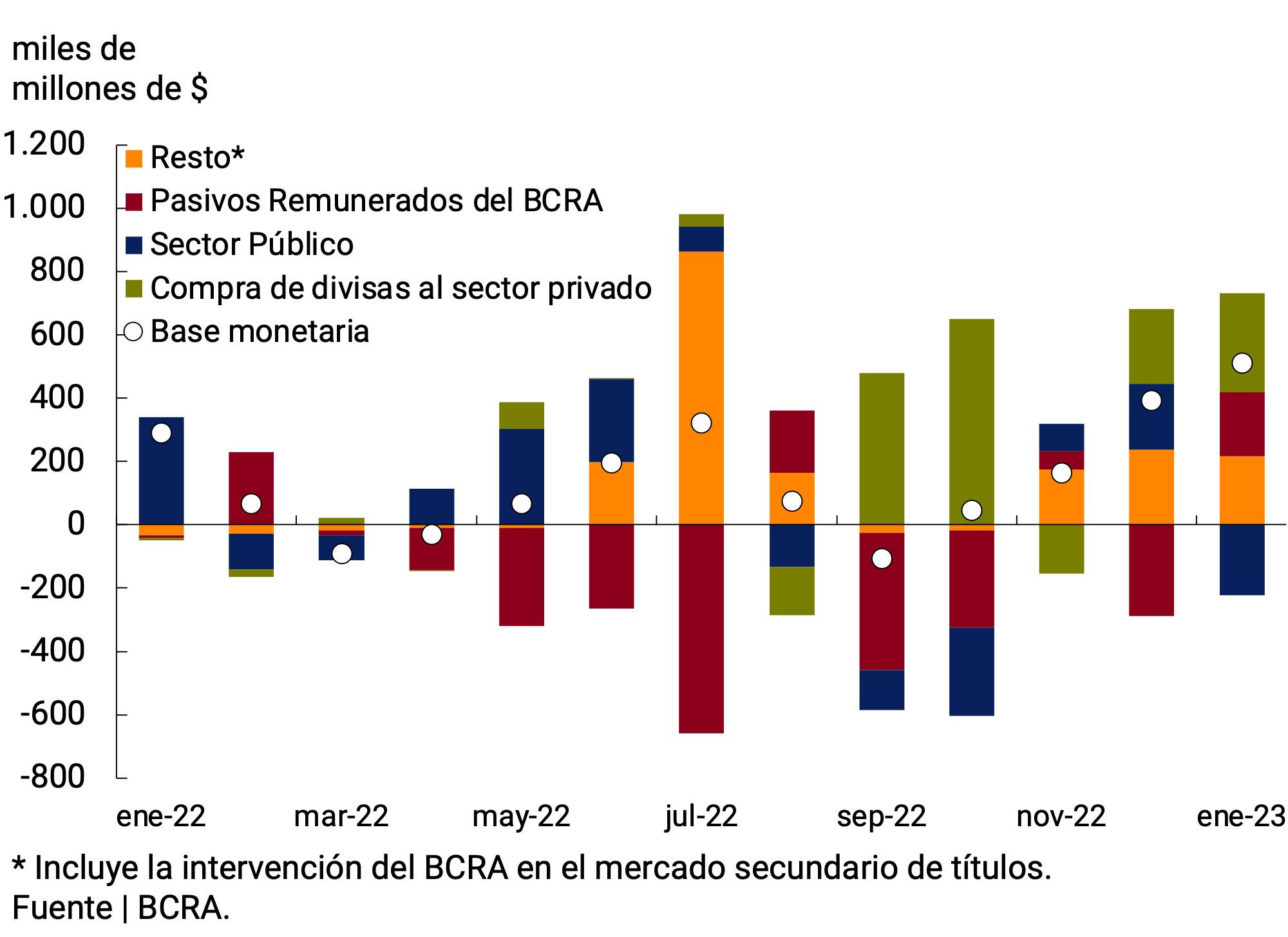

In January, the Monetary Base stood at $5,291.3 billion, which meant an average monthly nominal increase of 10.7% (+$509,352 million) in the original series. This rise was largely explained by the positive statistical carryover left by December, a month with strong positive seasonality. In fact, the variation between December 31 and January 31 was 2.2% (+$112,970 million). Adjusted for seasonality and inflation, the Monetary Base would have registered an increase of 3.9% and in year-on-year terms a contraction of around 26.3%. As a GDP ratio, the Monetary Base would stand at 4.6%, 0.2 p.p. above the value recorded the previous month and around the lowest values since the exit from convertibility (see Chart 4.1).

On the supply side, the average monthly expansion of the Monetary Base was largely explained by the statistical carryover left by the purchases of foreign currency made within the framework of the “Export Increase Program” during December. Other factors in the expansion of the monetary base were: the BCRA’s purchases in the secondary market of public securities, with the aim of limiting excessive price volatility, and the use of regulatory instruments by banks. These effects were partially offset by the contractionary effect of public sector operations (see Figure 4.2).

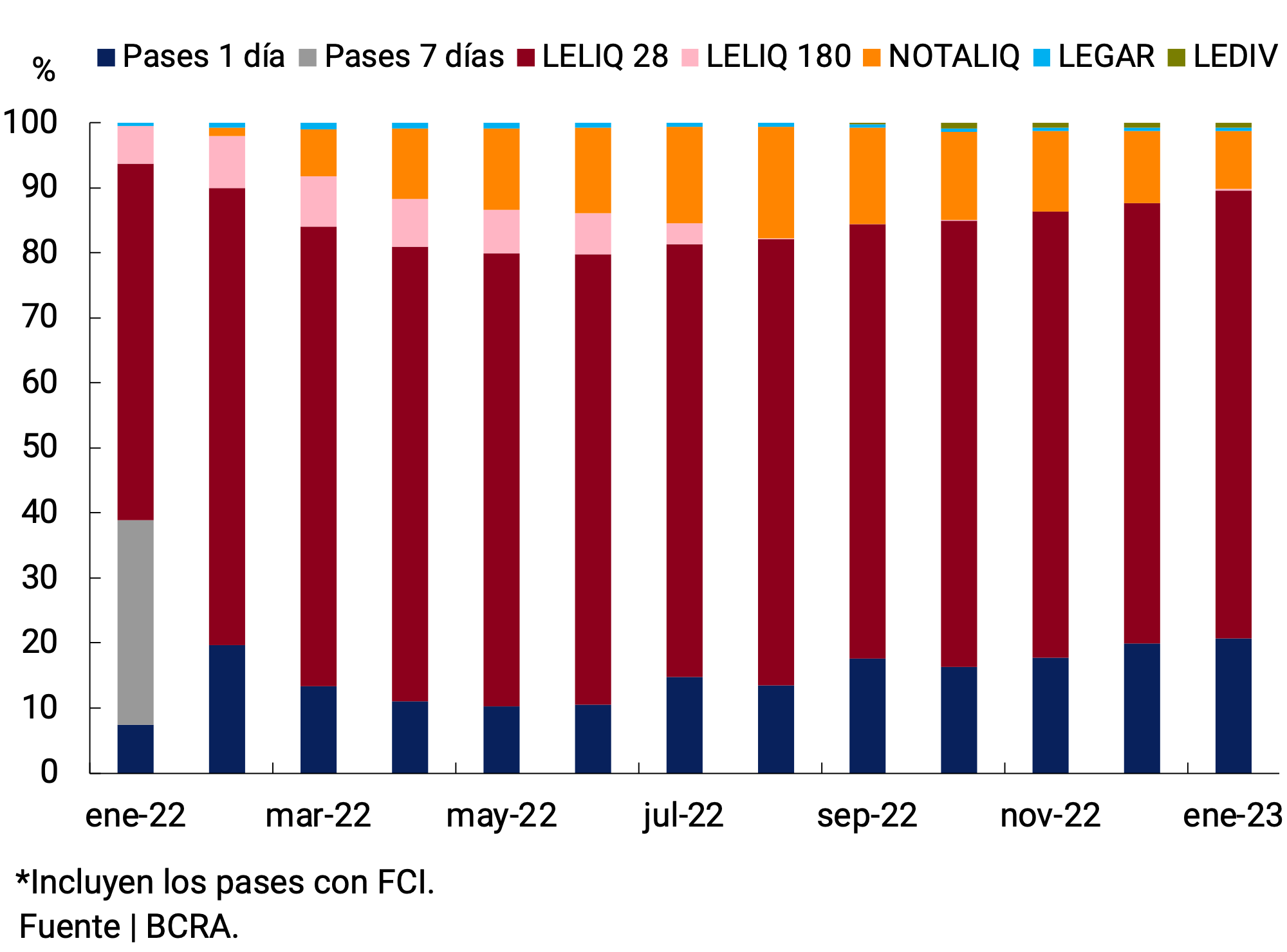

In mid-January, the Board of Directors of the BCRA decided to raise the interest rates corresponding to its shorter-term instruments. In this way, both the interest rate on 1-day passive passes and 1-day active passes increased by 2 p.p., which stood at 72% n.a. (105.3% e.a.) and 95% n.a. (163.5% e.a.) respectively.

In addition, in order to strengthen the channel for transmitting monetary policy to the different segments of the financial system and the capital market, the BCRA decided to raise the coefficient that determines the interest rate on FCI passive passes. Thus, on January 23, this coefficient went from 75% to 95% of the rate of passive passes of financial institutions (68.4% n.a.; 98.1% e.a.). Towards the end of the month, the FCI pass rate was readjusted, setting it at 85% of the pass rate of financial institutions (61.2% n.a.; 84.3% e.a.) and financial institutions were enabled to carry out stock exchange bond operations (policyholders) in pesos6.

For its part, the interest rate on the LELIQ with a 28-day term remained at 75% n.a. (107.35% y.a.), while the interest rate on the LELIQ with a 180-day term remained at 83.5% n.a. (101.23% y.a.). Finally, the spread of the NOTALIQ in the last auction of the month was set at 8.5 p.p.

With the current configuration of instruments, in the first month of the year the remunerated liabilities were conformed, on average, to 68.8% by LELIQ with a 28-day term. The longer-term species accounted for 9.3% of the total, almost entirely concentrated in NOTALIQ. Meanwhile, 1-day pass-by-passes increased their share of total instruments, representing 20.7% of the total (0.8 p.p. more than the previous month). Finally, the LEDIV, together with the LEGARs, accounted for the remaining 1.2%, remaining stable compared to December (see Figure 4.3).

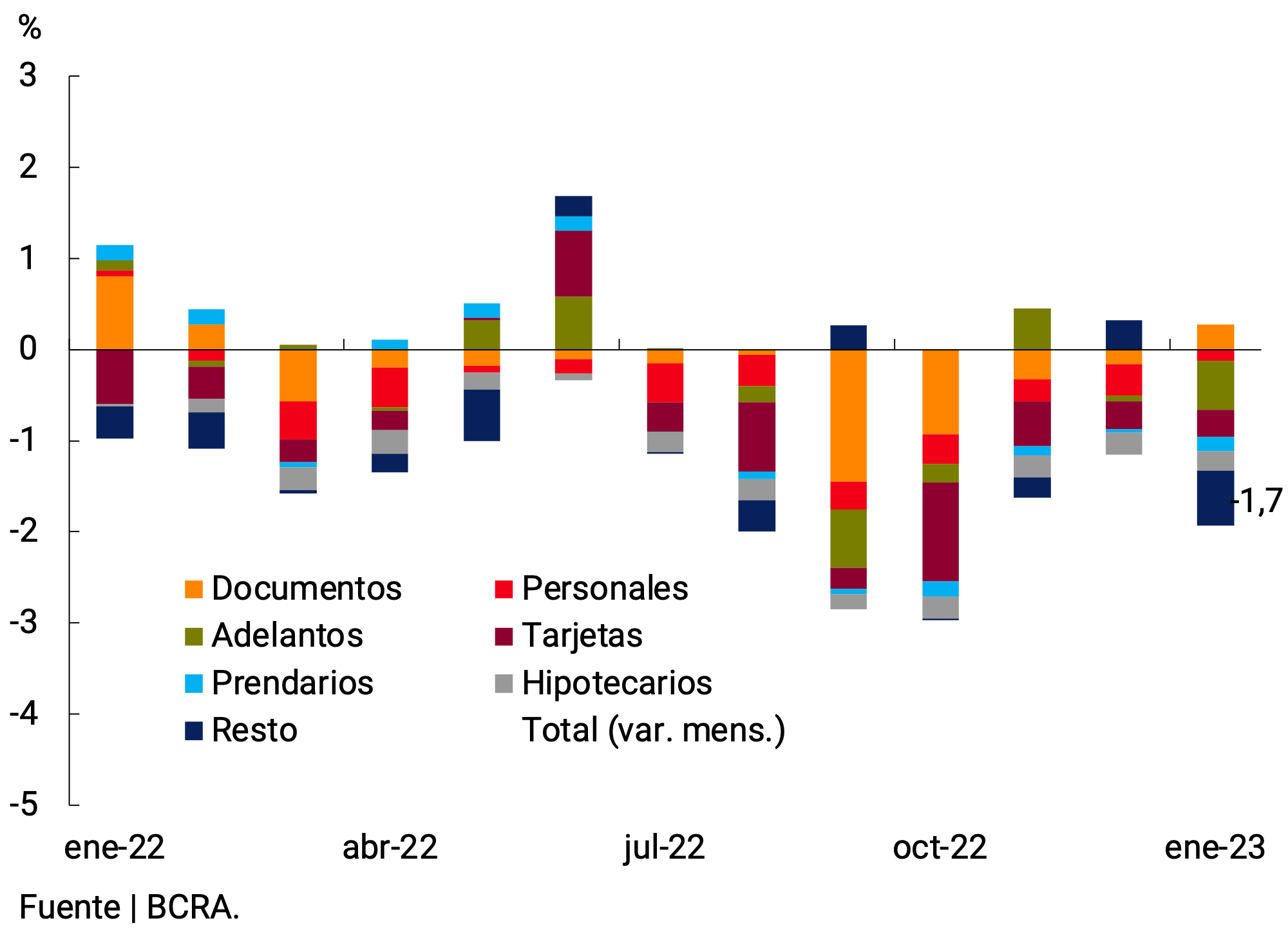

5. Loans to the private sector

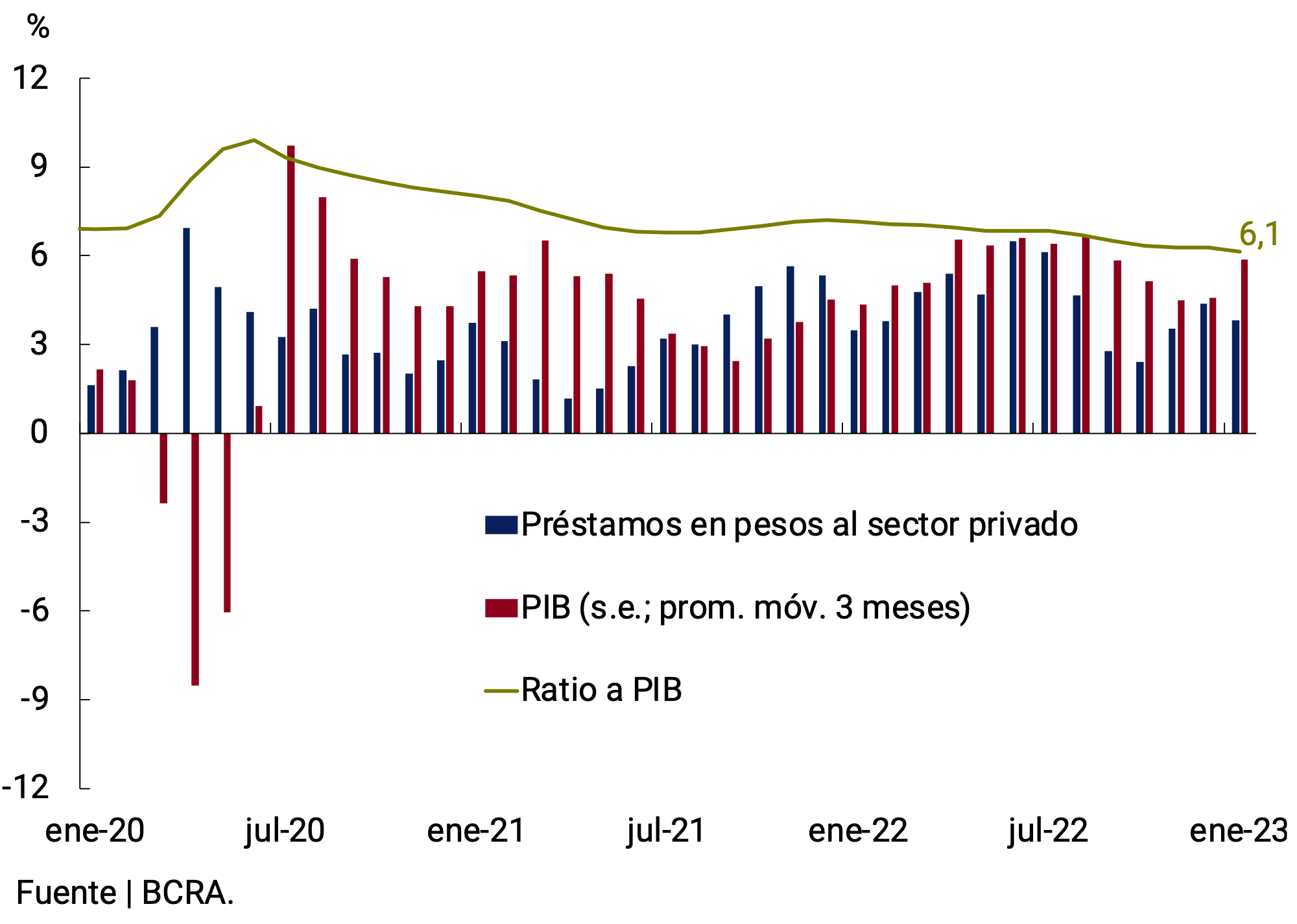

In the first month of the year, loans in pesos to the private sector measured in real terms and without seasonality would have registered a monthly fall of 1.7%, accumulating seven consecutive months of decline. The decrease occurred in virtually all funding lines with the exception of documents (see Figure 5.1). Thus, credit would have accumulated a fall of 13.9% y.o.y. in real terms. The ratio of peso loans to the private sector to current GDP fell slightly in the month to 6.1 percent (see Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.1 | Loans in pesos to the private

sector Real without seasonality; contribution to monthly growth

When looking at the evolution of loans by type of financing, lines with mainly commercial use were the ones that showed the best performance. Bonds would have registered a monthly growth of 1.1% s.e. at constant prices (-13.0% y.o.y.), driven by discounted documents. Meanwhile, single-signature documents, with a longer average life, would have fallen during January. On the other hand, financing granted through advances would have exhibited a decrease at constant prices of 4.6% s.e. (-2.5% y.o.y.). Overall, trade financing contracted 1.1% s.e. in the month and 12.6% year-on-year.

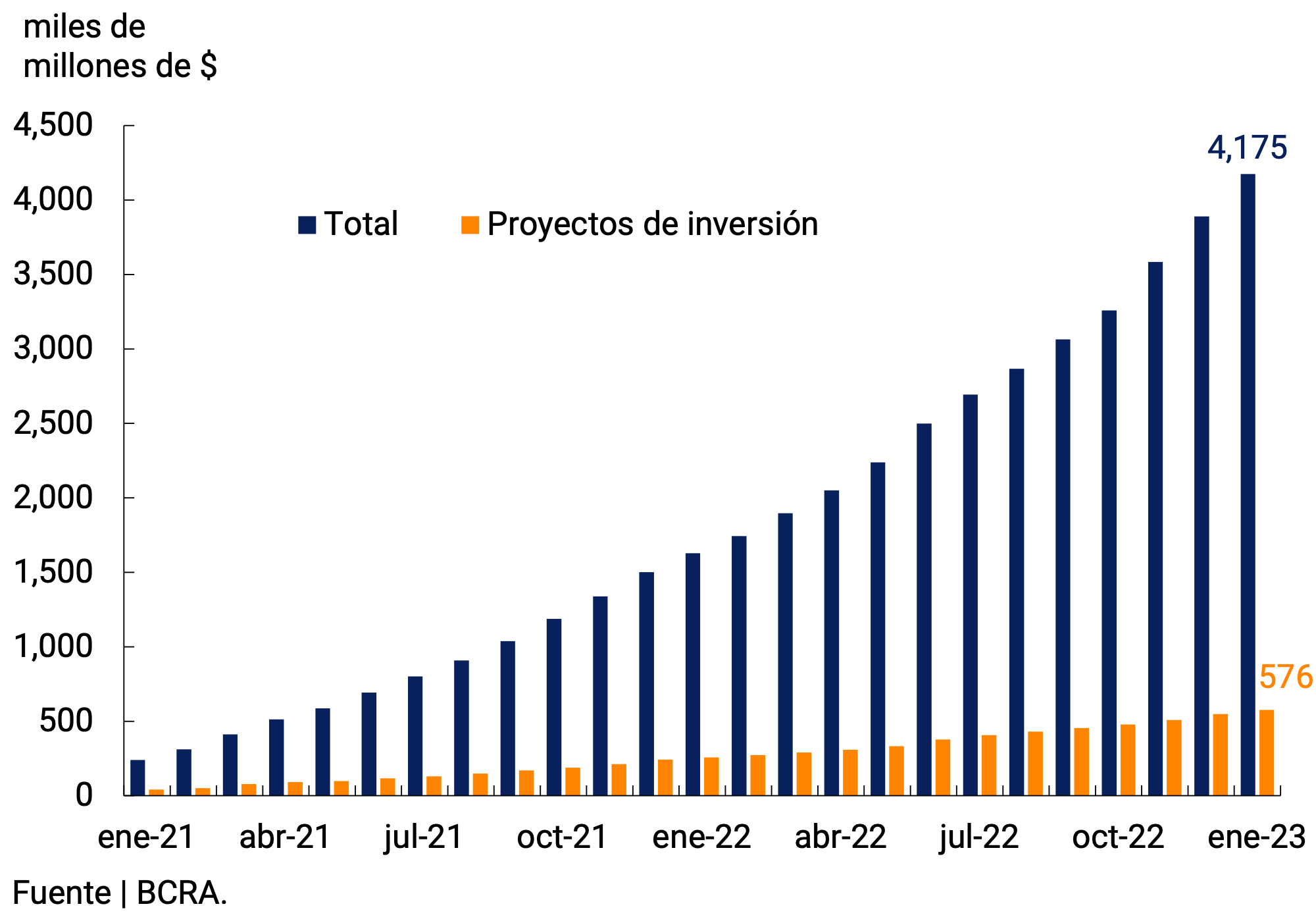

The Financing Line for Productive Investment (LFIP) continued to be the main tool used to channel productive credit to Micro, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (MSMEs). At the end of January, loans granted under the LFIP accumulated approximately $4.175 billion since its launch, an increase of 7.3% compared to last month (see Figure 5.3). On the other hand, of the total financing granted through the LFIP, 13.8% corresponds to investment projects and the rest to working capital. It should be noted that the average balance of financing granted through the LFIP reached approximately $1,254 million in December (latest available information), which represents about 18.7% of total loans and 44.5% of total commercial loans.

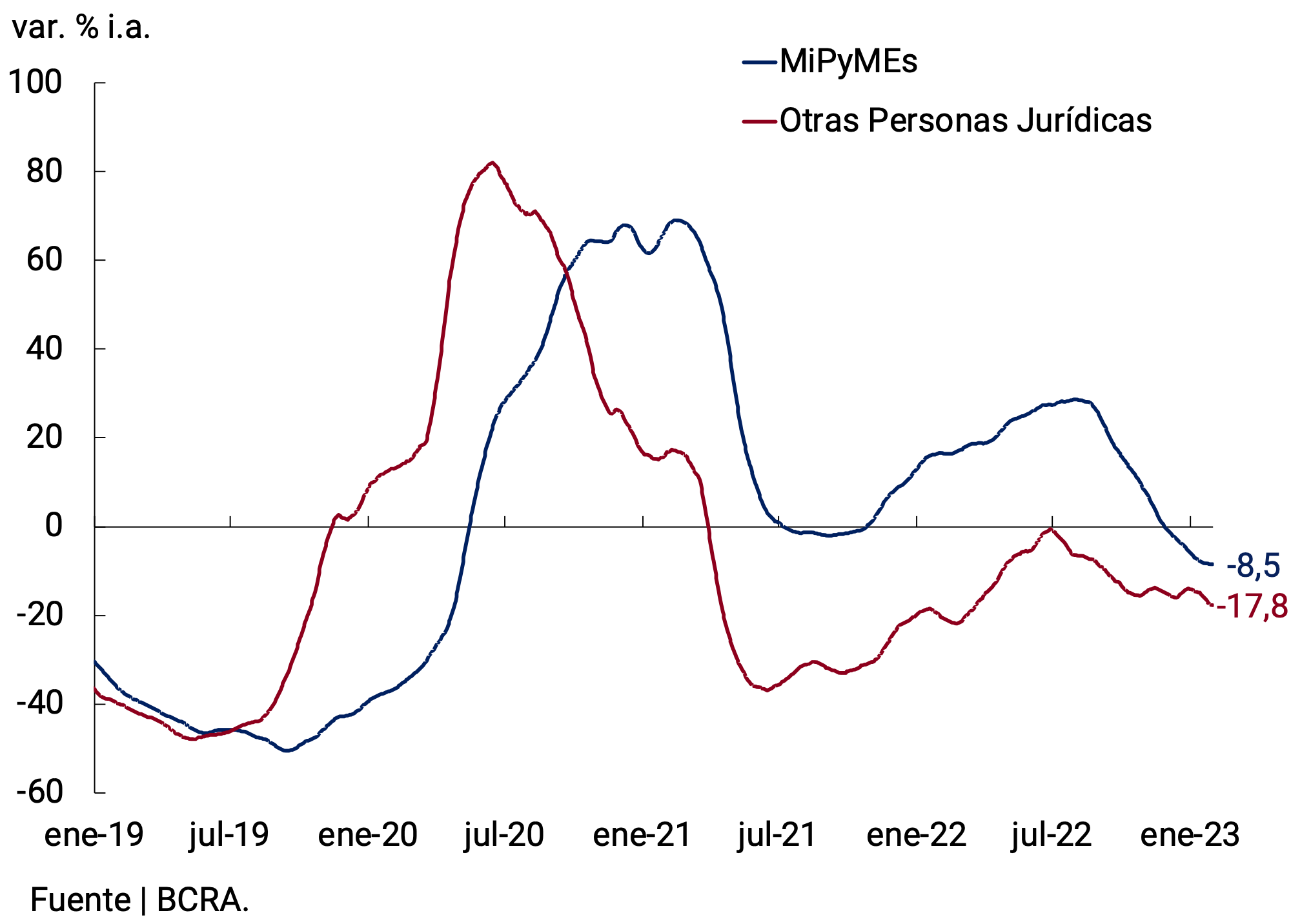

As for commercial credit by type of debtor, despite the imposition of the LFIP, credit to MSMEs continued to show a slowdown. In year-on-year terms, it would have contracted by about 8.5% at constant prices in the first month of 2023, while the one for large companies would have shown a greater contraction (17.8% y.o.y.; see Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.3 | Financing granted through the Productive Investment Financing Line (LFIP)

Accumulated disbursed amounts; data at the end of the month

Among loans associated with consumption, financing instrumented with credit cards would have shown a monthly decrease of 1.0% s.e. at constant prices (-11.5% y.o.y.). Likewise, personal loans would have exhibited a fall of 0.8% s.e. and would already be 18.4% below the level recorded a year ago. During January, the interest rate corresponding to personal loans stood at an average of 79.2% n.a. (115.5% y.a.), registering a decrease of 2.0 p.p. compared to the previous month.

With respect to secured lines, collateral loans would have registered a decrease in real terms of 2.3% s.e., remaining at levels similar to those of a year ago. For its part, the balance of mortgage loans would have shown a fall of 3.7% s.e. at constant prices in the month, accumulating a contraction of 32.7% in the last twelve months.

6. Liquidity in pesos of financial institutions

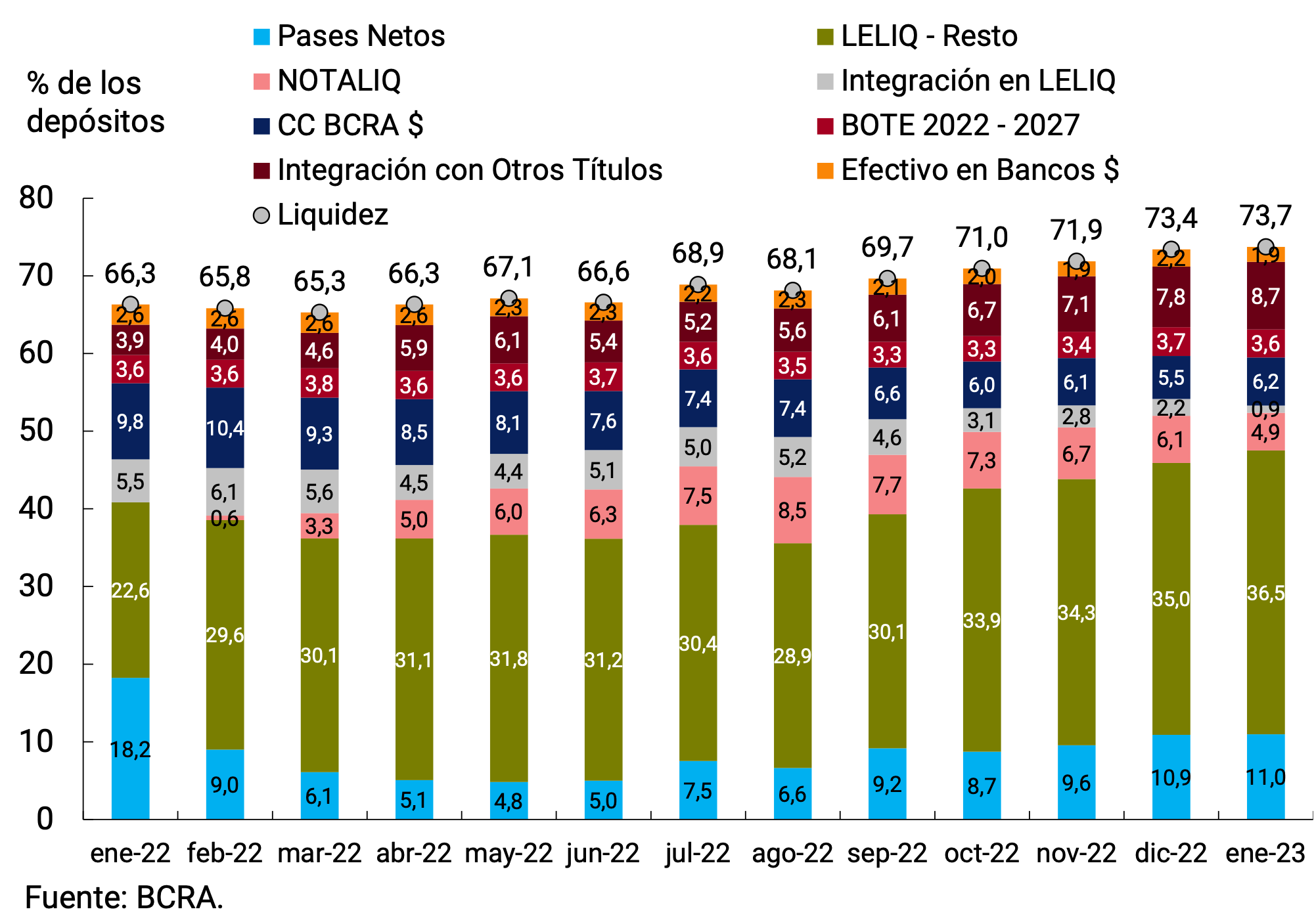

In January, ample bank liquidity in local currency7 showed an increase of 0.3 p.p. compared to December 2022, averaging 73.7% of deposits. Thus, it remained at historically high levels. The increase was mainly driven by the integration with public securities and current accounts in the BCRA, partially offset by a fall in interest-bearing liabilities.

Among the regulatory changes with an impact on bank liquidity, it is worth mentioning that it was provided that the borrowing stock guarantees are excluded from the obligations included for the determination of the minimum cash requirement8.

7. Foreign currency

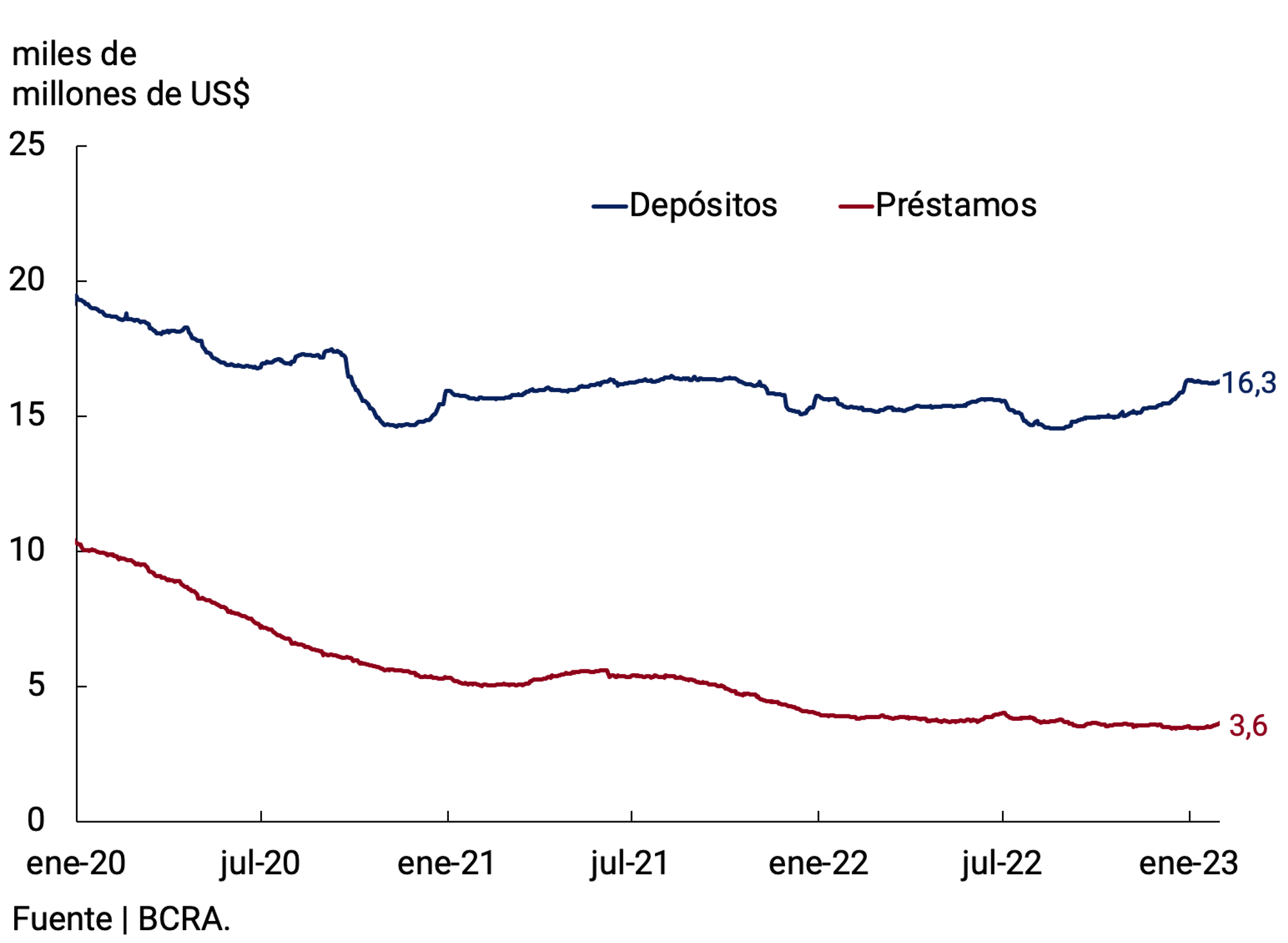

In the foreign currency segment, the main assets and liabilities of financial institutions had a mixed performance. On the one hand, the balance of private sector deposits increased for the fifth consecutive month averaging US$16,260 million in the month, which implied an increase of US$575 million compared to December. It should be noted that this increase was explained in its entirety by the statistical carryover of the previous month, impacted by the behavior of demand deposits of individuals that usually grow at the end of December as a result of the exemption from the payment of the personal property tax to this type of placement. In fact, the variation between balances at the end of the month resulted in a drop of US$28 million. On the other hand, the stock of foreign currency loans to the private sector remained broadly unchanged in the month (see Figure 7.1).

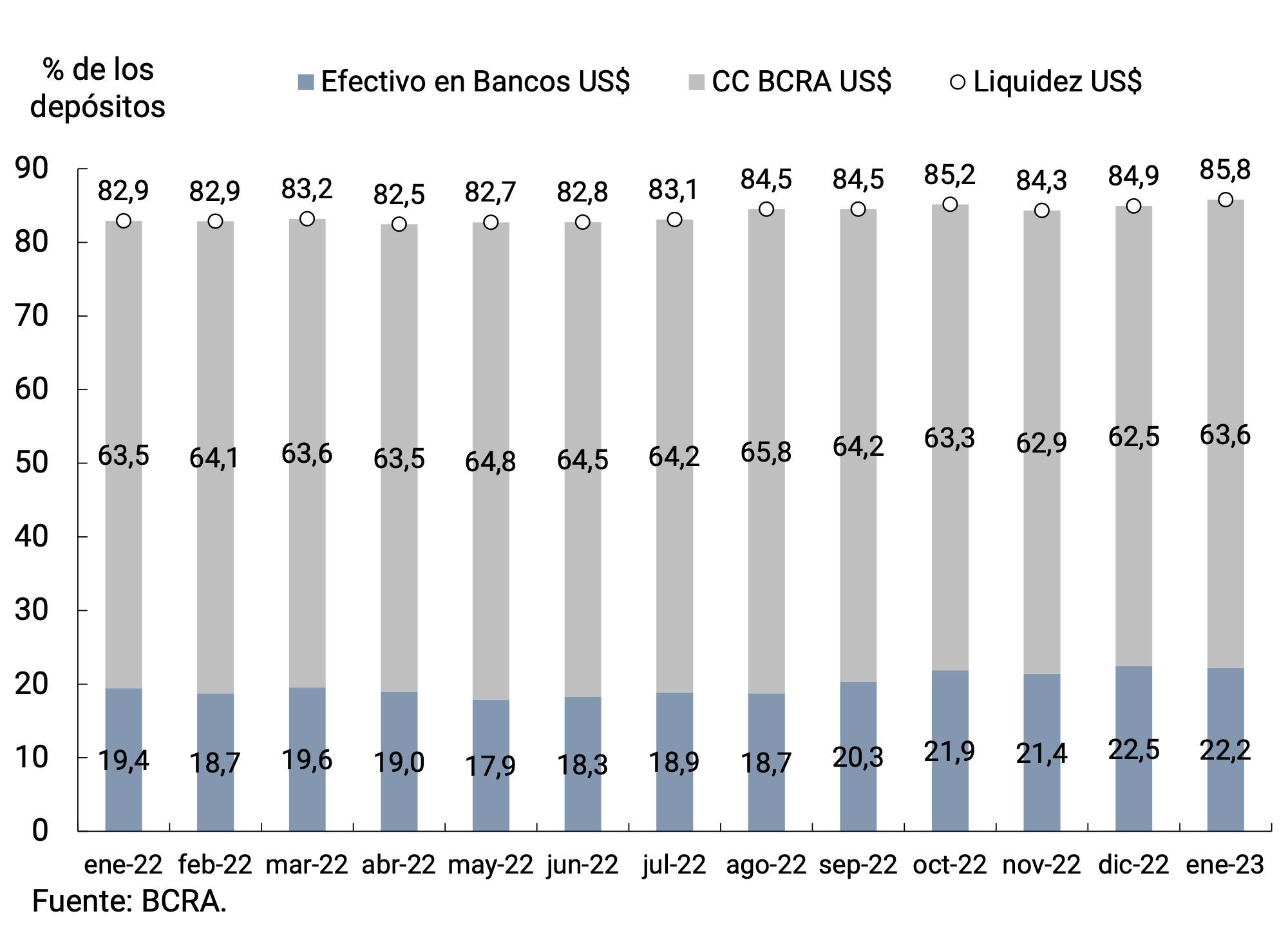

The liquidity of financial institutions in the foreign currency segment experienced an increase of 0.9 p.p. compared to the previous month, standing at 85.8% of deposits in January and remaining at historically high levels. The increase was explained by current accounts in foreign currency at the BCRA, and was only partially offset by cash in banks (see Figure 7.2).

During January, a series of regulatory modifications took place in exchange matters. Thus, seeking to allocate foreign currency more efficiently, the characteristics of the goods for which access to the foreign exchange market for the payment of imports is made more flexible, within the framework of the Import System of the Argentine Republic (SIRA)9, were detailed. At the same time, the accounts to which funds from the liquidation of financing and contributions from international organizations in foreign currency must be allocated10 and those from the voluntary declaration of the holding of foreign currency in the country11 were regulated.

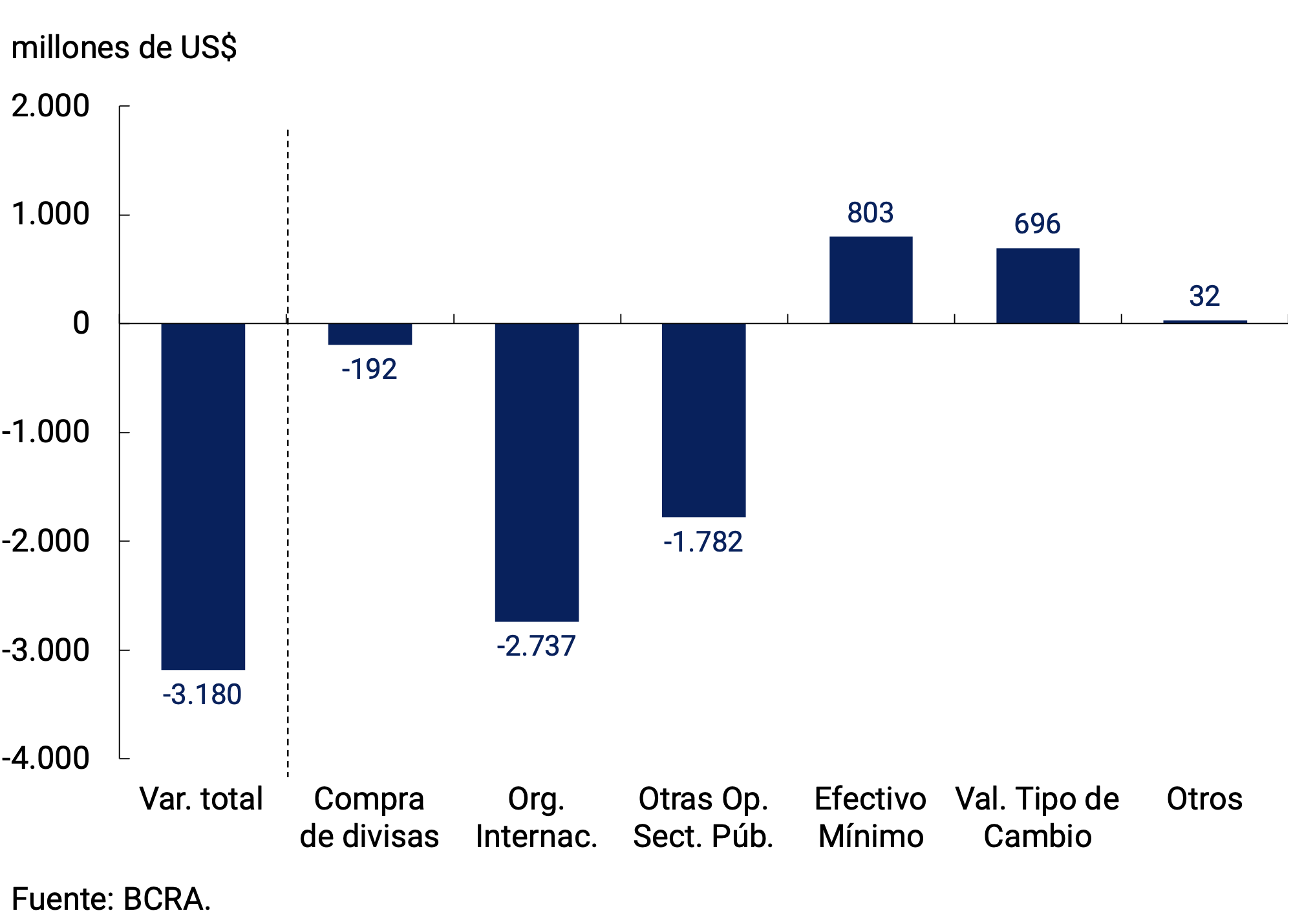

The BCRA’s International Reserves ended the month with a balance of US$41,417 million, registering a decrease of US$3,180 million as of December 31. This fall was mainly explained by capital payments to the International Monetary Fund for US$2,641 million and other public sector operations, including payments for cancellation of National Government debt and the repurchase of national public debt instruments denominated in foreign currency12. These effects were partially offset by the change in the current account balances in dollars at the BCRA and the gains on the valuation of net foreign assets (see Figure 7.3).

It should be noted that at the beginning of the month, the currency swap agreement in force between the Central Bank of the Argentine Republic (BCRA) and the Bank of the People’s Republic of China (PBC) was activated, which includes the exchange of currencies as a reinforcement of International Reserves for 130,000 million yuan and a special activation for 35,000 million yuan to compensate for foreign exchange market operations.

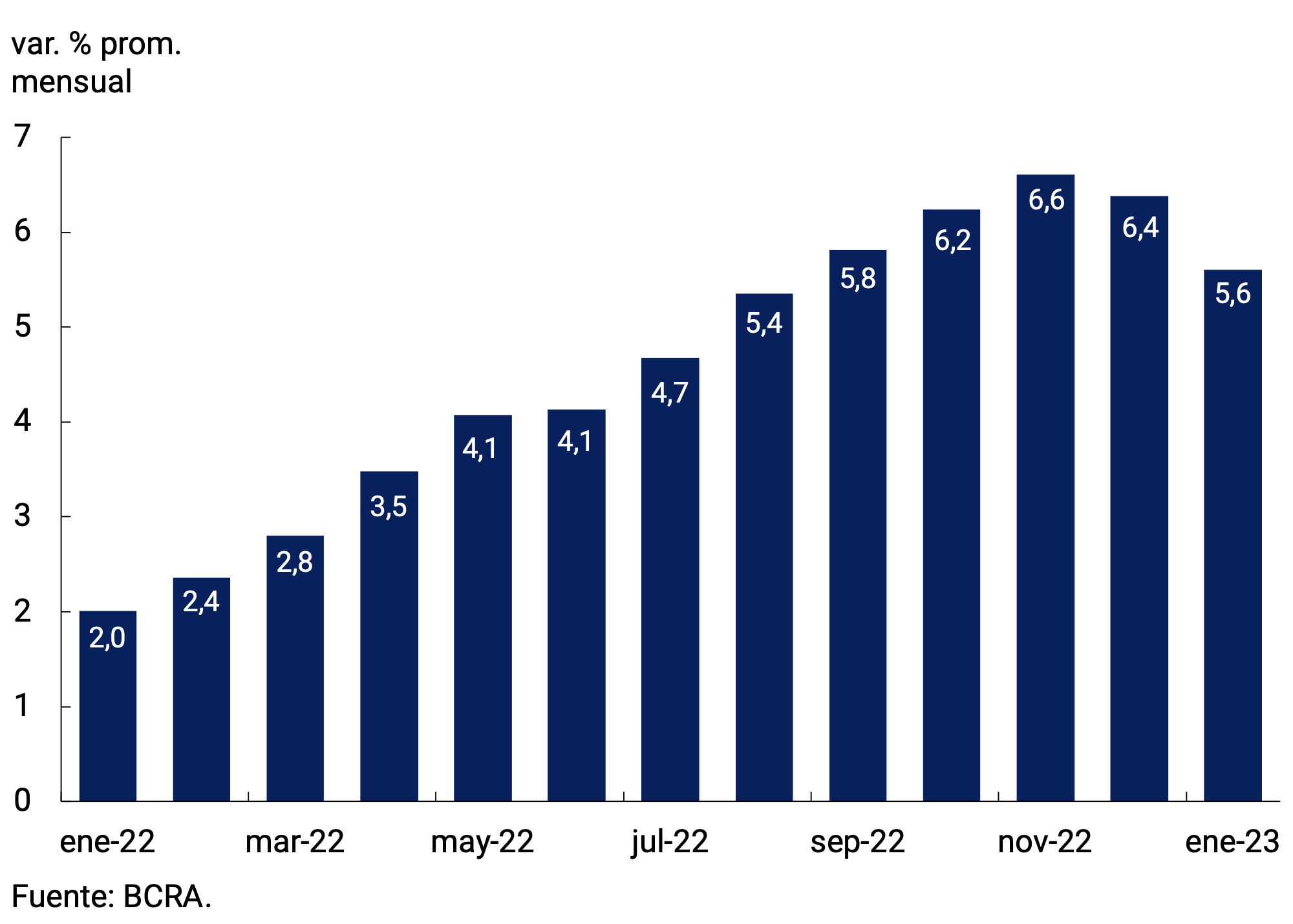

Finally, the bilateral nominal exchange rate (TCN) against the U.S. dollar increased 5.6% in January to settle, on average, at $182.12/US$ (see Figure 7.4). In this way, the BCRA has slowed down the pace of depreciation of the domestic currency in line with the moderation of inflation.

Figure 7.3 | Variation in the balance at the end of the month of International Reserves

: Explanation factors. December 2022

Glossary

ANSES: National Social Security Administration.

AFIP: Federal Administration of Public Revenues.

BADLAR: Interest rate on fixed-term deposits for amounts greater than one million pesos and a term of 30 to 35 days.

BCRA: Central Bank of the Argentine Republic.

BM: Monetary Base, includes monetary circulation plus deposits in pesos in current account at the BCRA.

CC BCRA: Current account deposits at the BCRA.

CER: Reference Stabilization Coefficient.

NVC: National Securities Commission.

SDR: Special Drawing Rights.

EFNB: Non-Banking Financial Institutions.

EM: Minimum Cash.

FCI: Common Investment Fund.

A.I.: Year-on-year .

IAMC: Argentine Institute of Capital Markets

CPI: Consumer Price Index.

ITCNM: Multilateral Nominal Exchange Rate Index

ITCRM: Multilateral Real Exchange Rate Index

LEBAC: Central Bank bills.

LELIQ: Liquidity Bills of the BCRA.

LFIP: Financing Line for Productive Investment.

M2 Total: Means of payment, which includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and demand deposits in pesos from the public and non-financial private sector.

Private M2: Means of payment, includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and demand deposits in pesos from the non-financial private sector.

Private transactional M2: Means of payment, includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and non-remunerated demand deposits in pesos from the non-financial private sector.

M3 Total: Broad aggregate in pesos, includes the current currency held by the public, cancelling checks in pesos and the total deposits in pesos of the public and non-financial private sector.

Private M3: Broad aggregate in pesos, includes the working capital held by the public, cancelling checks in pesos and the total deposits in pesos of the non-financial private sector.

MERVAL: Buenos Aires Stock Market.

MM: Money Market.

N.A.: Annual nominal.

E.A.: Effective Annual.

NOCOM: Cash Clearing Notes.

ON: Negotiable Obligation.

GDP: Gross Domestic Product.

P.B.: basis points.

PSP.: Payment Service Provider.

p.p.: percentage points.

MSMEs: Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises.

ROFEX: Rosario Term Market.

S.E.: No seasonality

SISCEN: Centralized System of Information Requirements of the BCRA.

SIMPES: Comprehensive System for Monitoring Payments of Services Abroad.

TCN: Nominal Exchange Rate

IRR: Internal Rate of Return.

TM20: Interest rate on fixed-term deposits for amounts greater than 20 million pesos and a term of 30 to 35 days.

TNA: Annual Nominal Rate.

UVA: Unit of Purchasing Value

References

1 Corresponds to private M2 excluding interest-bearing demand deposits from companies and financial service providers. This component was excluded since it is more similar to a savings instrument than to a means of payment.

2 The rates currently in force are those established by Communication “A” 7527.

3 The rest of the depositors are made up of Legal Entities and Individuals with deposits of more than $10 million.

5 The private M3 includes the working capital held by the public and the deposits in pesos of the non-financial private sector (demand, time and others).

7 Includes current accounts at the BCRA, cash in banks, balances of net passes arranged with the BCRA, holdings of LELIQ and NOTALIQ, and public bonds eligible for reserve requirements.

9 Communications “A” 7676 and Communications “A” 7682.

12 https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/recompra-de-instrumentos-de-deuda-publica-nacional-denominados-en-moneda-extranjera .