Política Monetaria

Monthly Monetary Report

April

2023

Monthly report on the evolution of the monetary base, international reserves and foreign exchange market.

Table of Contents

Contents

1. Executive Summary

2. Payment Methods

3. Savings instruments in pesos

4. Monetary base

5. Loans in pesos to the private sector

6. Liquidity in pesos of financial institutions

7. Foreign currency

The statistical closing of this report was January 8, 2024. All figures are provisional and subject to revision.

Inquiries and/or comments should be directed to analisis.monetario@bcra.gob.ar

The content of this report may be freely cited as long as the source is clarified: Monetary Report – BCRA.

1. Executive Summary

The BCRA raised the monetary policy interest rate (LELIQ 28 days) twice during the month by a total of 13 percentage points (p.p.), bringing it to 91% n.a. (141.0% y.a.). It also raised interest rates on the rest of the monetary regulation instruments and the minimum regulated interest rates on deposits.

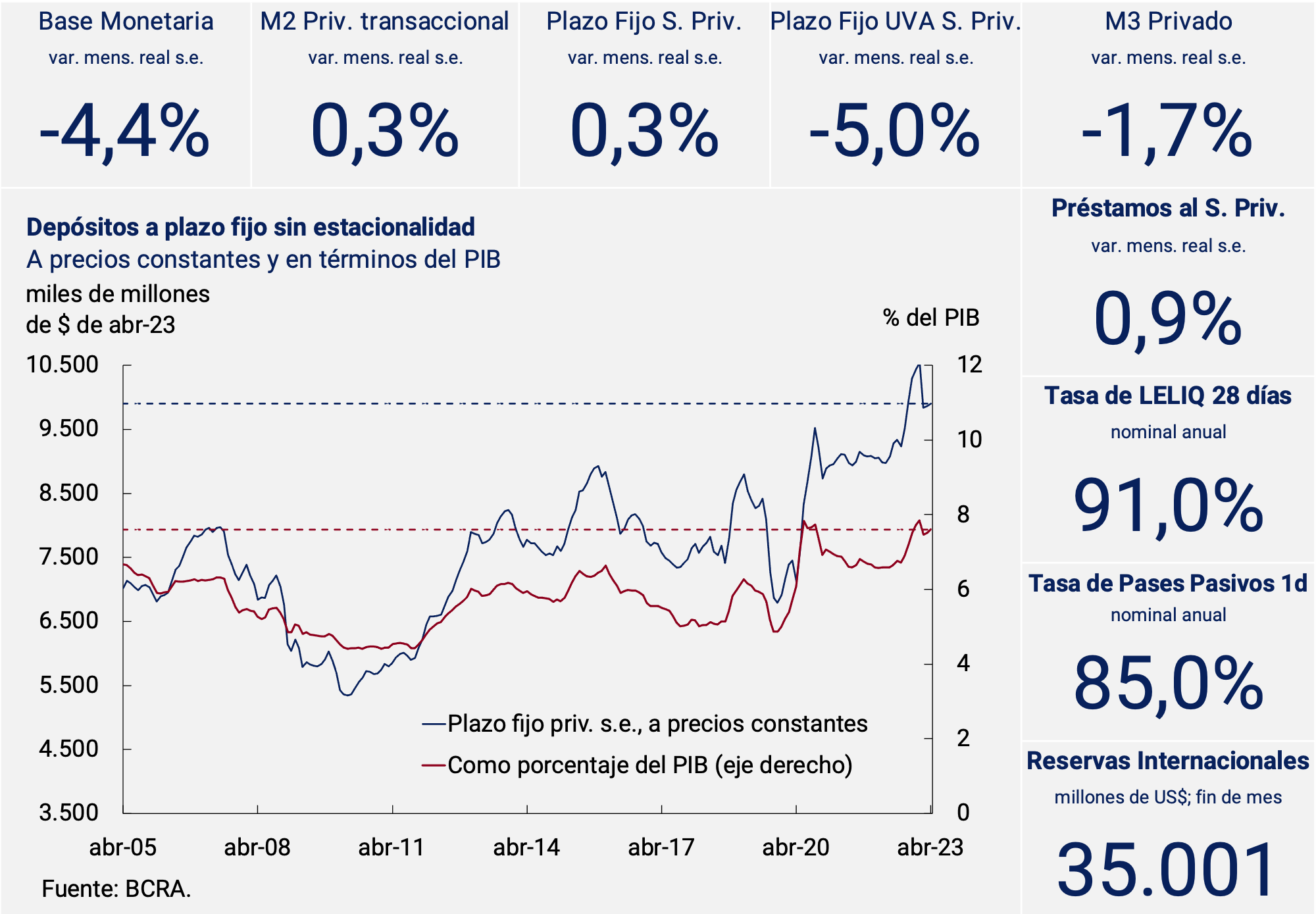

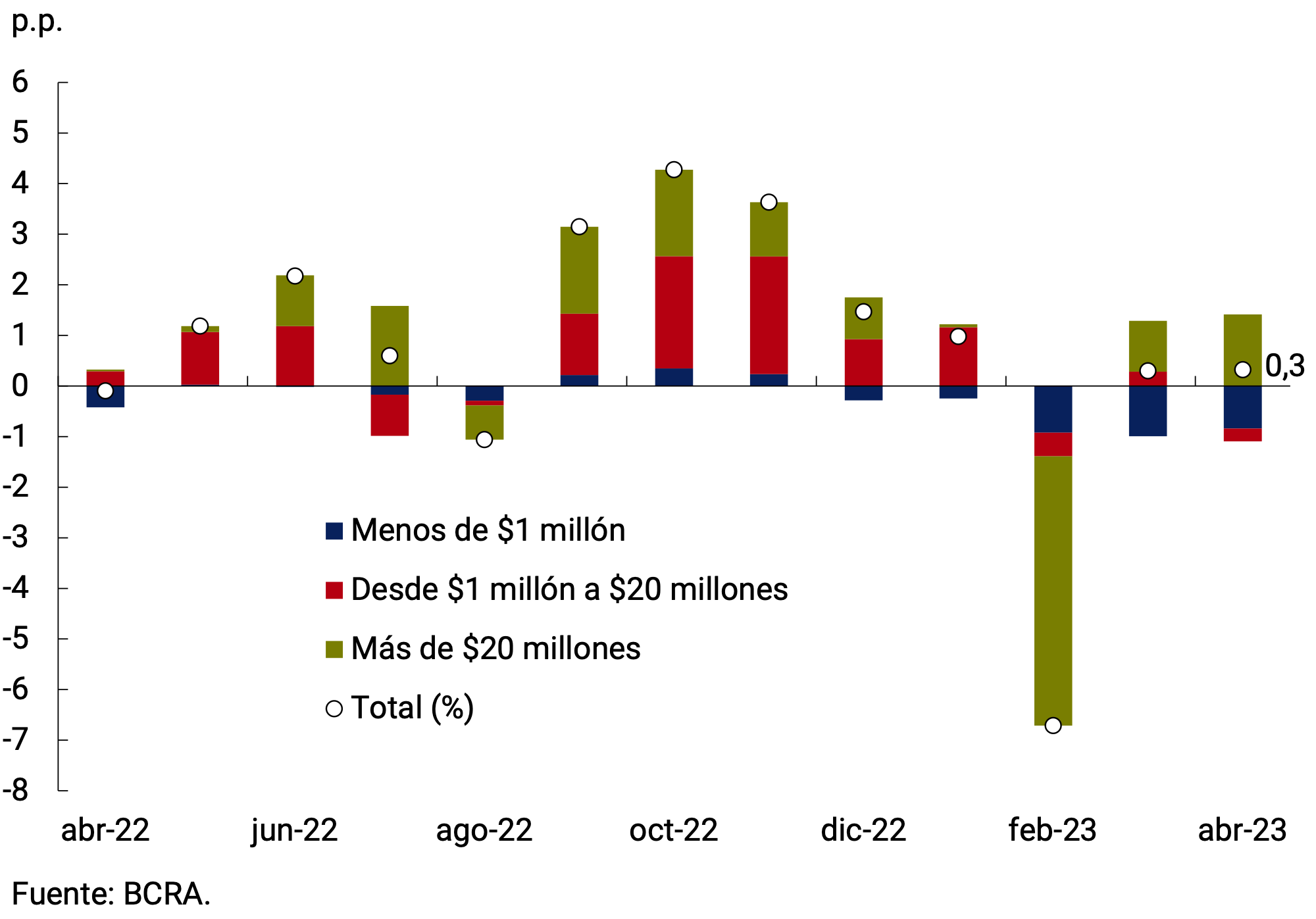

Given that the largest increase in the rate occurred towards the end of April, the private sector’s fixed-term deposits in pesos did not yet show significant variations in real terms and persisted around the highest values in recent decades, both at constant prices and as a percentage of GDP. By strata of amount, the wholesale segment (more than $20 million) registered an expansion, which was offset by the dynamics of the rest of the placements.

However, the broad monetary aggregate (private M3) at constant prices and without seasonality would have registered a contraction in the fourth month of the year. This dynamic was mainly explained by the behavior of interest-bearing demand deposits, which fell at constant prices in the period under analysis.

On the other hand, loans to the private sector at constant prices and without seasonality would have grown in the month, breaking with a period of nine consecutive months of declines. Commercial lines were the ones that led the rise, with increases in financing to MSMEs and large companies.

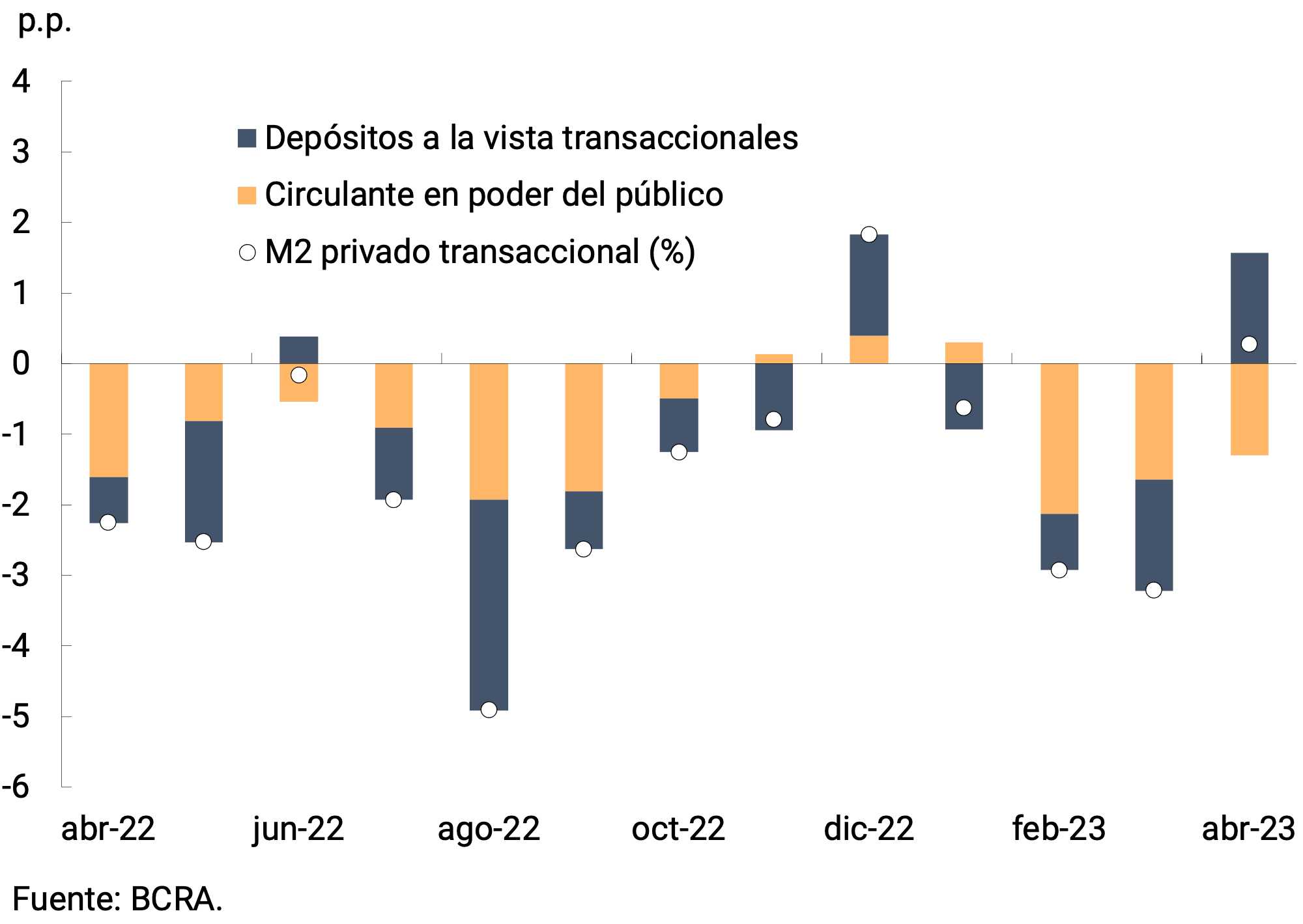

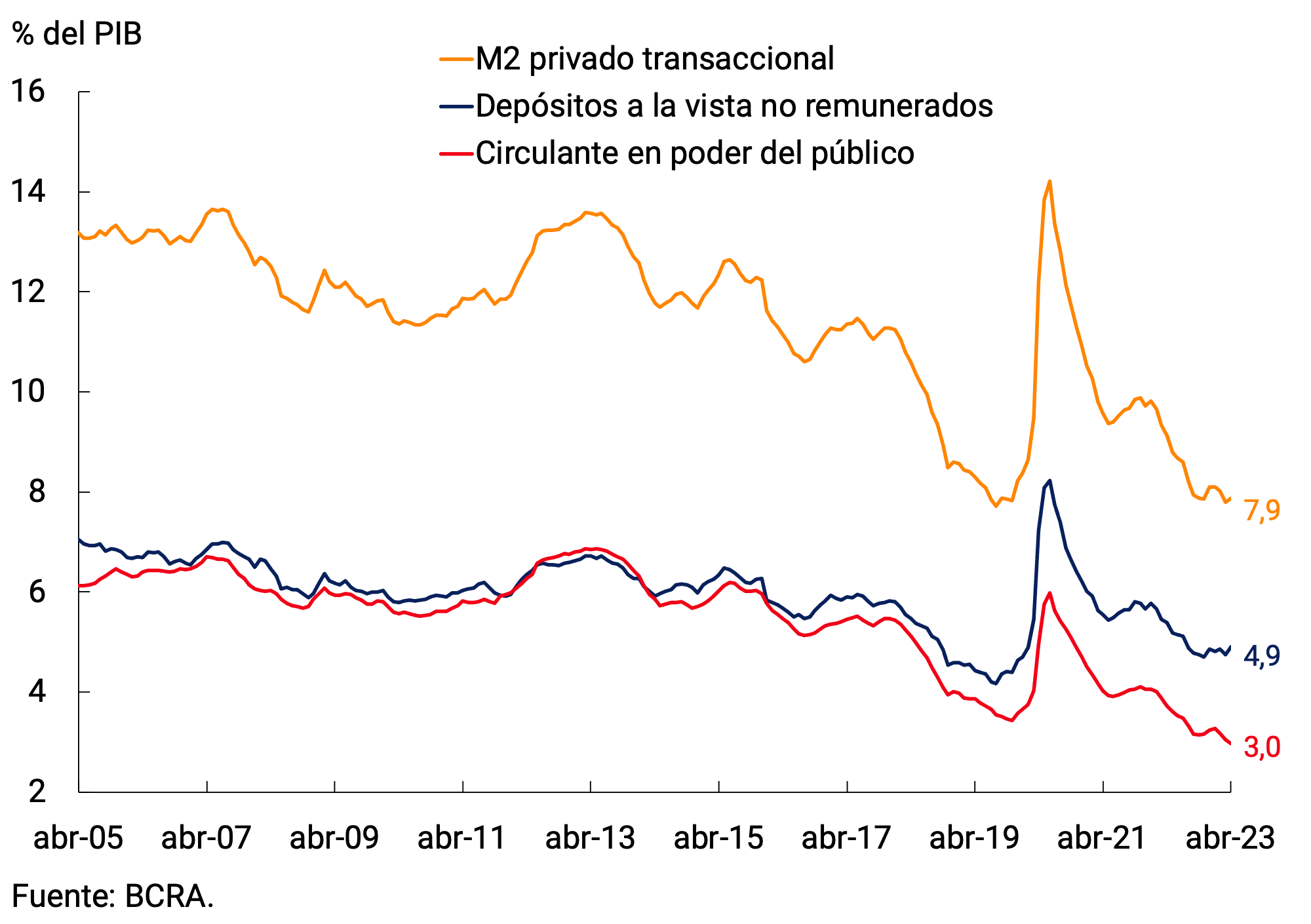

2. Payment methods

Means of payment (transactional private M21), in real terms and adjusted for seasonality (s.e), would have experienced an expansion of 0.3% in April. This increase was mainly due to the behavior of non-interest-bearing demand deposits, while the working capital held by the public registered a negative contribution to the variation for the month (see Chart 2.1). In the year-on-year comparison, and at constant prices, the transactional private M2 would be 18.2% below the level of April 2022. As a Product ratio, means of payment would have represented 7.9%, showing a slight increase (0.1 p.p.) in relation to the previous month and around their lowest values of the last 20 years (see Graph 2.2).

Figure 2.1 | Private transactional M2 at constant

prices Contribution by component to the monthly vari. s.e.

3. Savings instruments in pesos

The Board of Directors of the BCRA decided to increase the minimum guaranteed interest rates on fixed-term deposits on two occasions throughout the month, with the aim of maintaining the incentive to save in domestic currency and contributing to the financial and exchange rate balance2. Specifically, the monetary authority raised the minimum guaranteed interest rate for fixed terms for individuals from 78% n.a. to 91% n.a. (140.5% e.a.) and tripled the maximum taxable amount, setting it at $30 million. Meanwhile, for the rest of the depositors in the financial system, the minimum guaranteed interest rate rose from 69.5% n.a. to 85.5% n.a. (128.53)

Seasonally adjusted and at constant prices, the private sector’s fixed-term deposits in pesos would have registered a slight expansion (0.3% s.e. real). In this way, they remain in real terms close to the highest records of recent decades. As a percentage of GDP, this type of deposit would have stood at 7.6% in April.

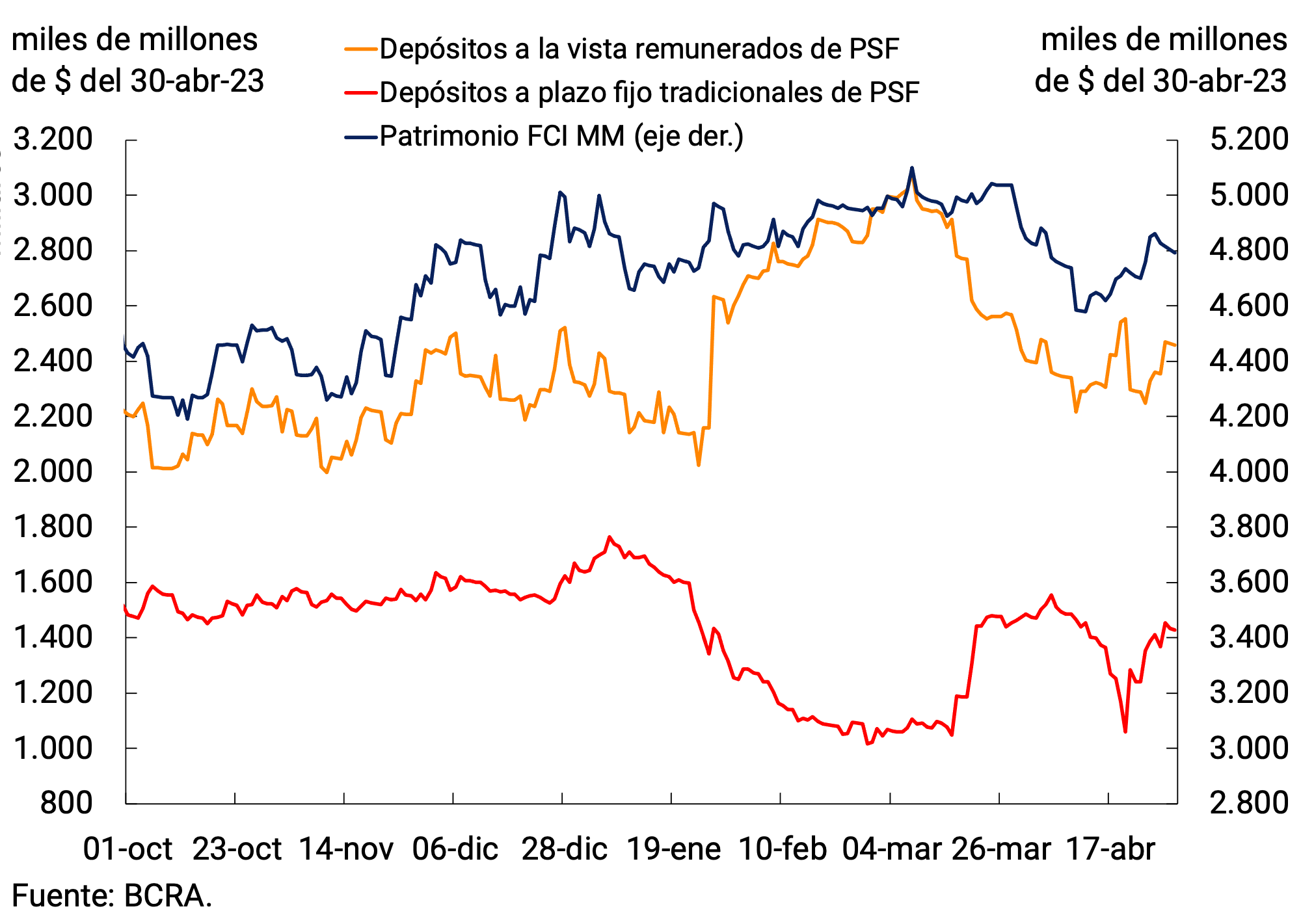

Analyzing time placements by strata of amount, wholesale deposits (more than $20 million) grew on average, favored by the carry-over effect of the previous month (see Figure 3.1). Its evolution throughout the month was not homogeneous, which was due to the behavior of Financial Services Providers (FSPs), whose main agents are the Money Market Mutual Funds (FCI MM). In this sense, the equity of the FCI MM presented a fall during the first days of the month, a trend that was reversed with the beginning of the “Export Increase Program”, since part of the liquidity generated by these operations was channeled to FCI MM. In this context of greater availability of funds, a portfolio rebalancing was observed in the first instance in favor of interest-bearing sight and to the detriment of fixed-term placements, a movement that was reversed after the rise in the interest rate paid on these investments (see Figure 3.2). The dynamics of the wholesale segment were offset by the behavior of retail deposits (up to $1 million) and those from $1 to $20 million, which experienced declines in real terms. With regard to the interest-bearing view, the improvement observed since the middle of the month was not enough to reverse the carry-over effect left by March, when the FCIs of MM rotated their portfolio towards time deposits, causing the interest-bearing view to register a contraction of 13.7% at constant prices and without seasonality on average.

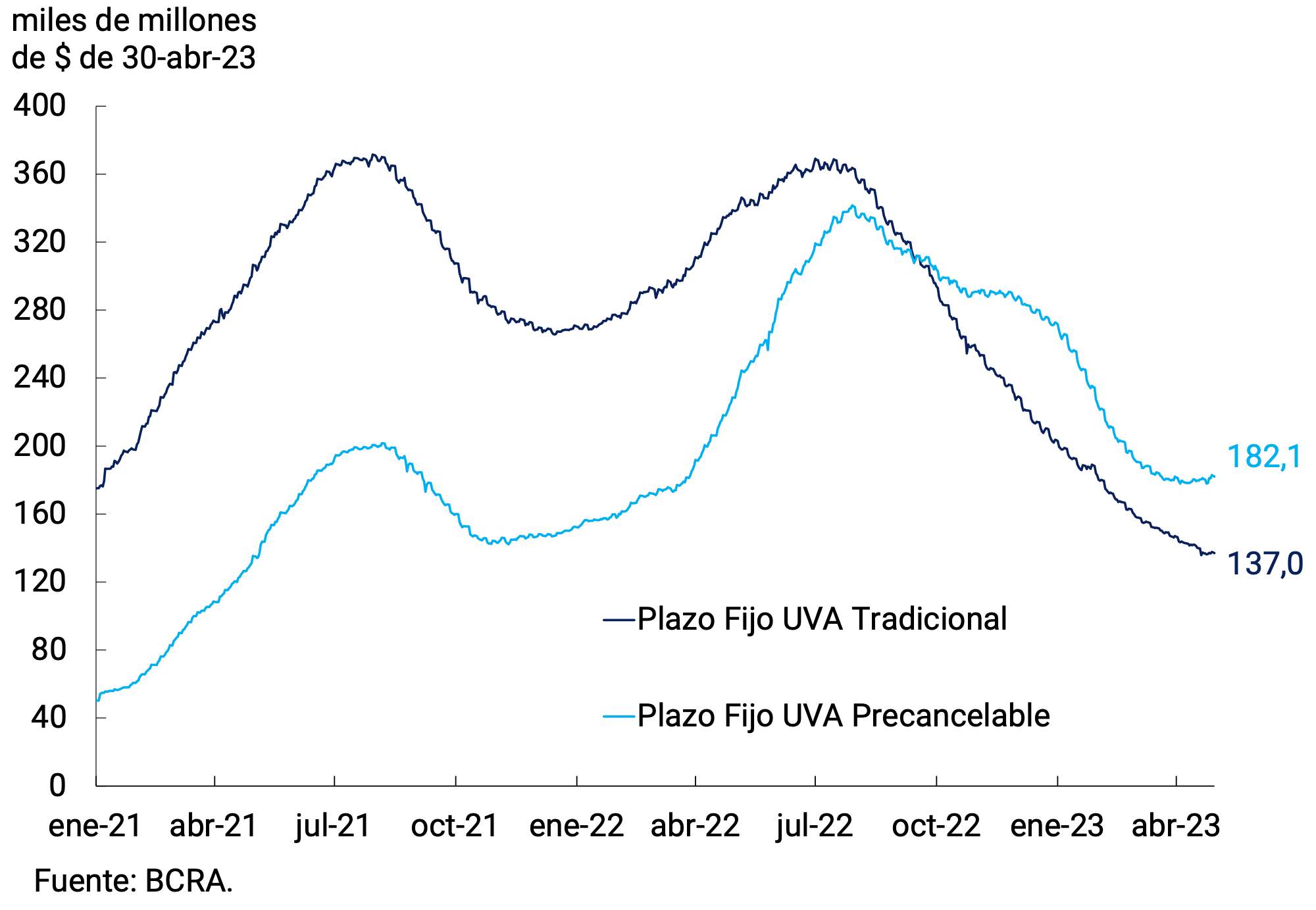

The segment of fixed-term deposits adjustable by CER continued to experience a contraction in real terms, accumulating nine consecutive months of decline. Although this reduction was observed in both traditional and pre-cancelable UVA placements, the latter began to stabilize in April. Thus, the monthly rate of change of traditional UVA placements would have stood at -7.8% s.e. at constant prices, compared to -2.6% s.e. in the case of UVA deposits with an early cancellation option (see Figure 3.3). Distinguishing by type of holder, it can be seen that the decrease is largely due to the dynamics of placements by individuals, which represent approximately 85% of the total. As a result, the balance of UVA deposits reached $319,100 million at the end of April, which is equivalent to 3.1% of the total of term instruments denominated in domestic currency.

Figure 3.3 | Fixed-term deposits in UVA of the private

sector Balance at constant prices by type of instrument

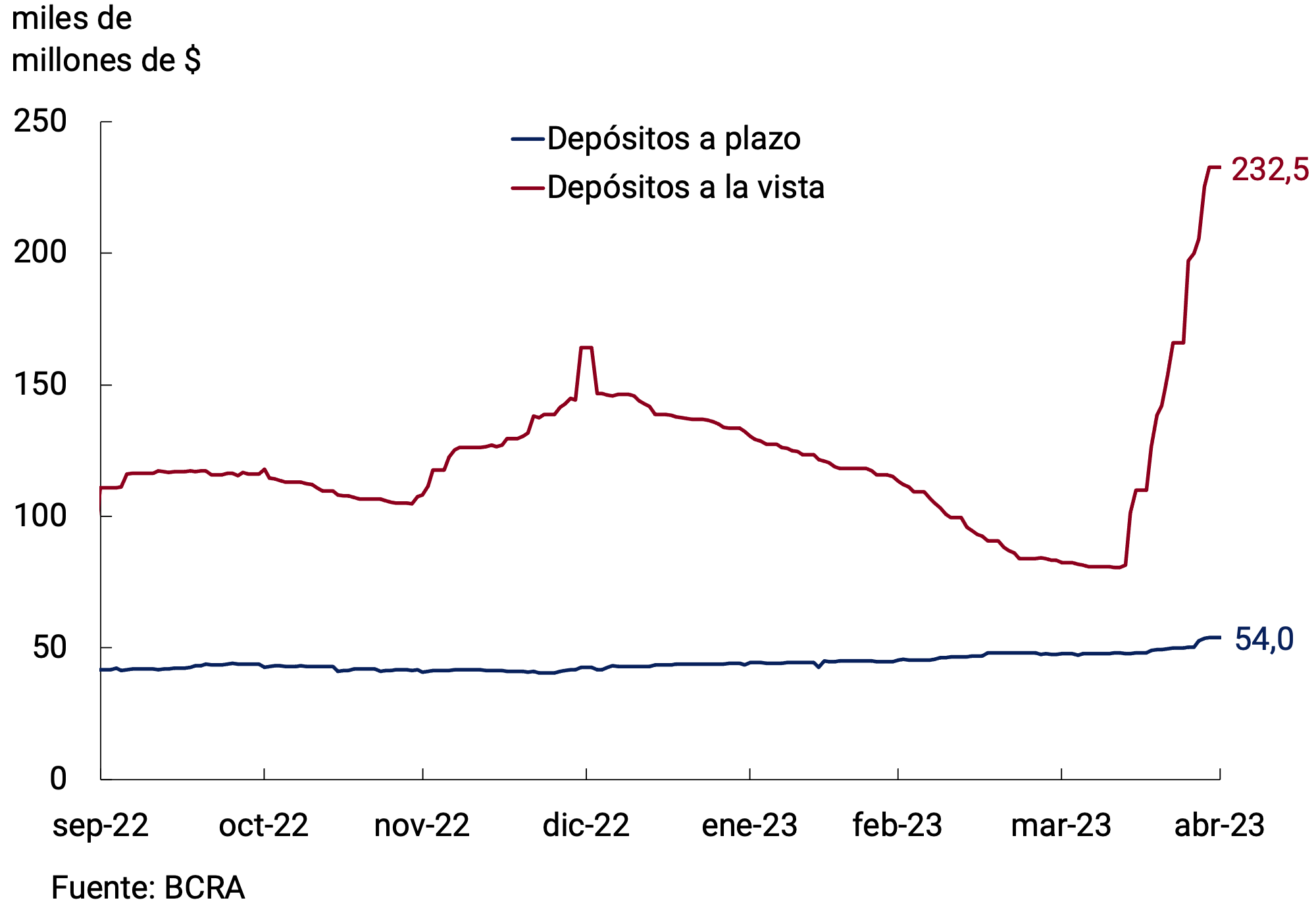

On the other hand, deposits adjusted for the value of the reference exchange rate registered an increase in the fourth month of the year. Currently, there are two types of deposits with exchange rate hedging: a demand account and term investments, the latter called DIVA dollar4. Demand deposits adjusted for exchange rates experienced a variation at the end of the month of 182.2% at current prices, reaching a balance of $232,500 million at the end of April. It should be noted that the origin of these funds were the operations carried out under the “Export Increase Program”. Meanwhile, the DIVA dollar reached a balance of $54,000 million at the end of the month, which implied an average monthly expansion of 5.1% at current prices (see Figure 3.4). To cover the exchange rate risk of these deposits, financial institutions have at their disposal the Bills with adjustment according to the value of the dollar (LEDIV).

All in all, the broad monetary aggregate private M3 would have exhibited a monthly fall of 1.7% in real and seasonally adjusted termsin April 5. In the year-on-year comparison, this aggregate would have experienced a decrease of 1.9%. As a proportion of GDP, it would have stood at 17.6%, exhibiting a decrease (0.2 p.p.) compared to last month and persisting in line with the average for the 2010-2019 period.

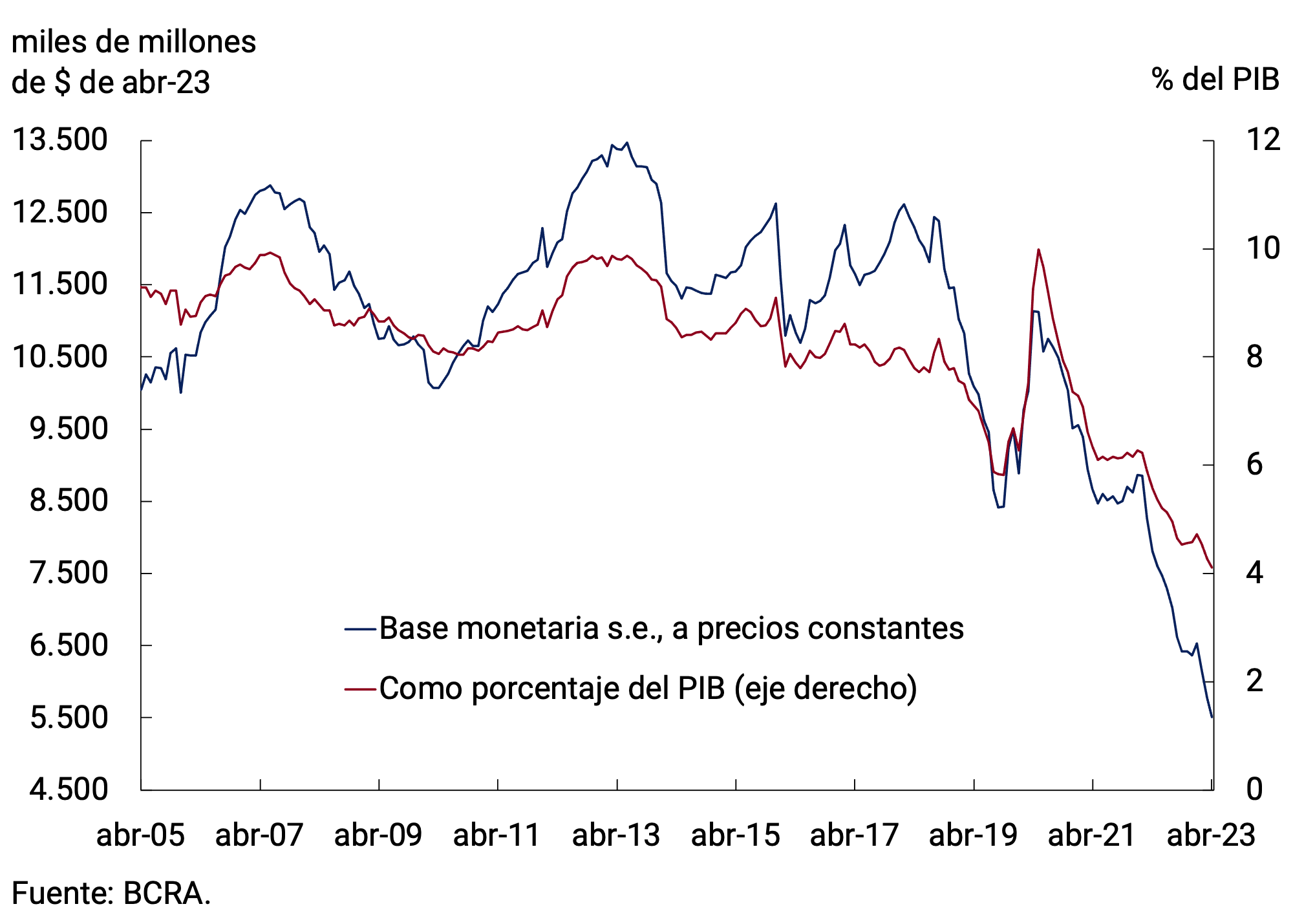

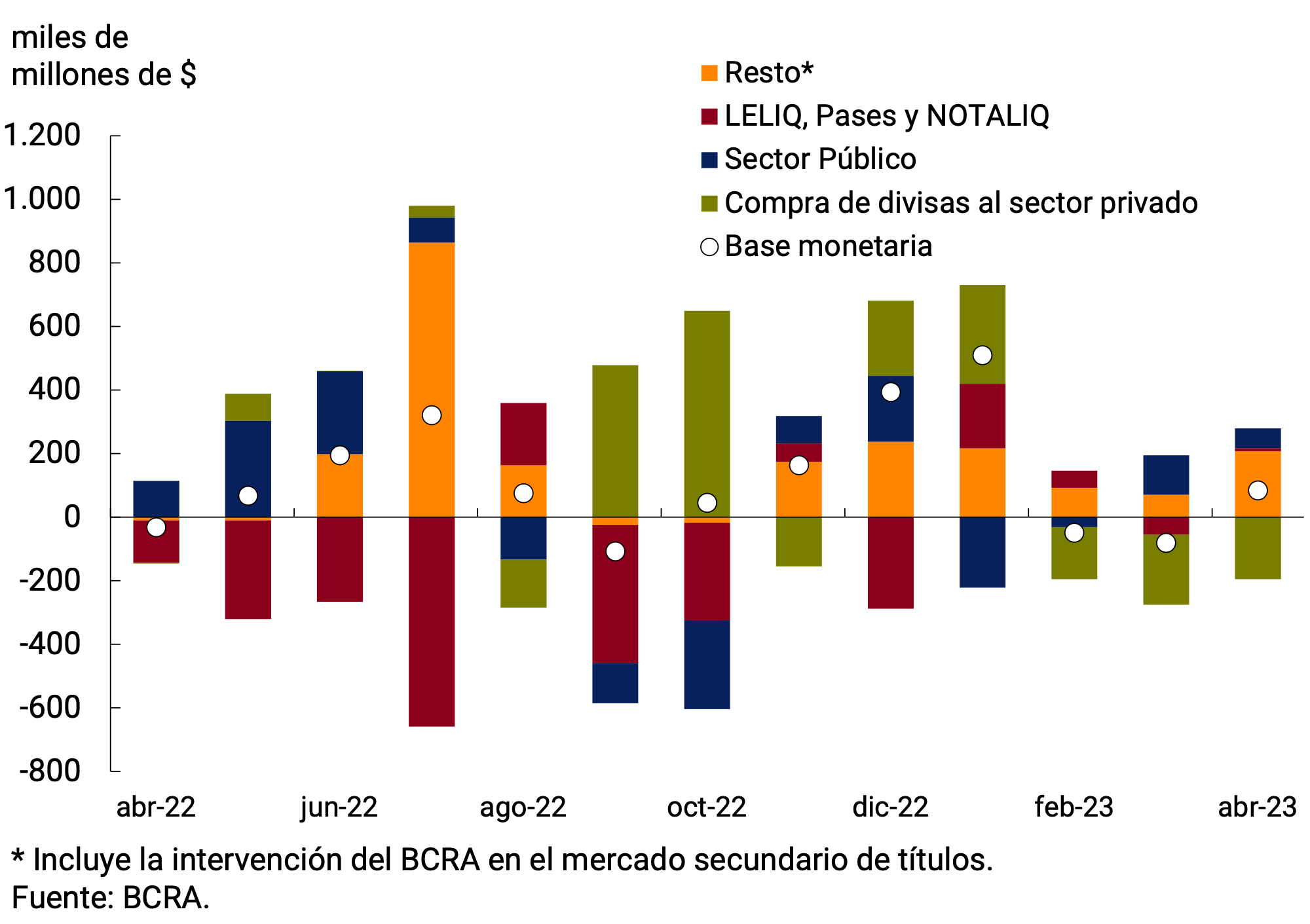

4. Monetary base

In April, the average of the Monetary Base reached $5,245.4 billion, experiencing a monthly increase of 1.6% (+$84,095 million) at current prices. Seasonally adjusted and at constant prices, it would have exhibited a decrease of 4.4%, accumulating a fall of 29.3% in the last twelve months. As a GDP ratio, the Monetary Base would stand at 4.1%, a figure 0.2 p.p. lower than that of the previous month and close to the lowest values since the exit from convertibility (see Chart 4.1).

In order to limit excessive volatility in the secondary market for public securities, the BCRA continued to participate in that market. This generated, from the supply side, an expansion of liquidity. Although to a lesser extent, public sector operations also led to an expansion of liquidity. Taken together, these effects were partially offset by the net sale of foreign currency to the private sector (see Figure 4.2).

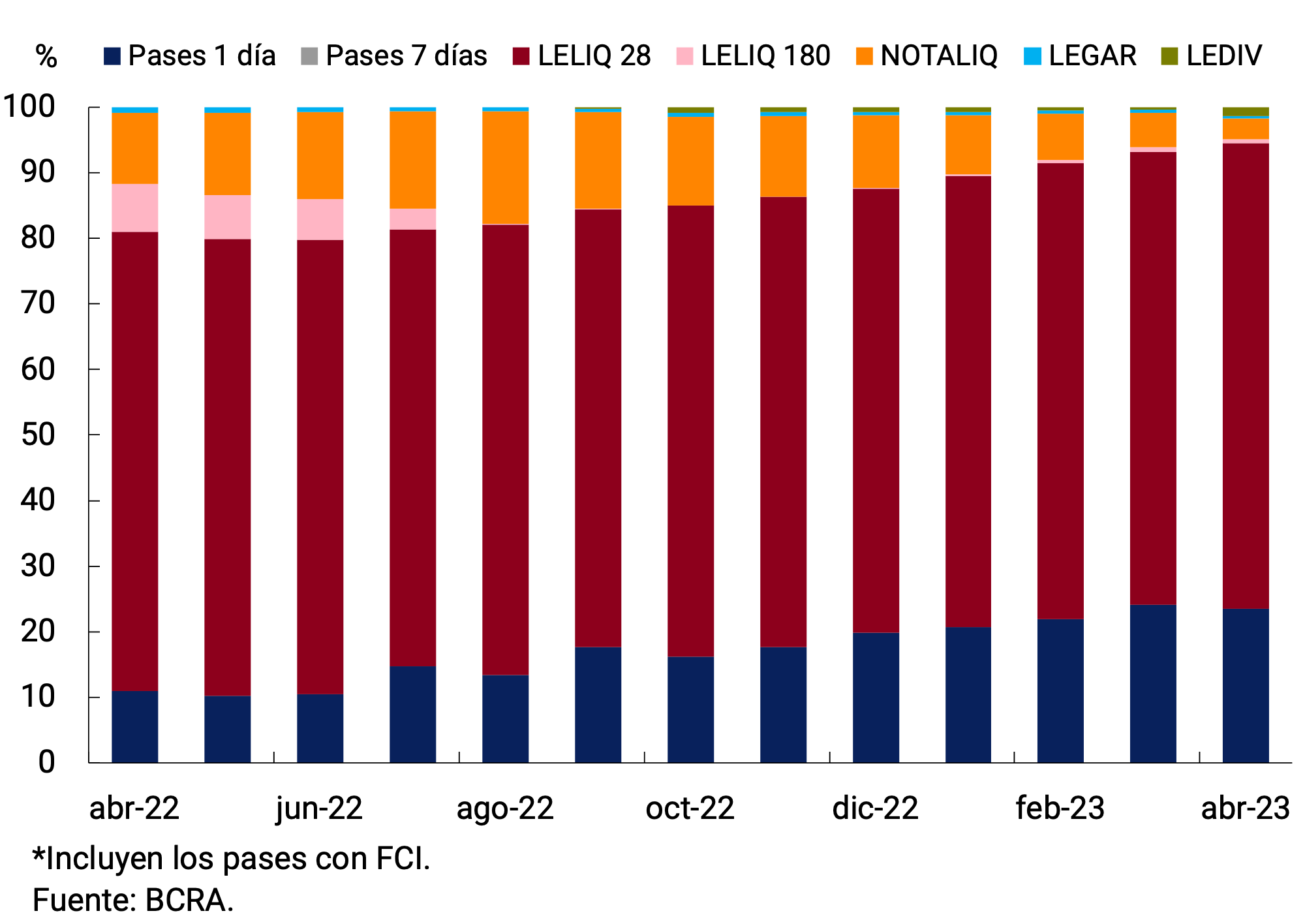

The BCRA accelerated the pace of raising reference interest rates, raising them twice in the month by a total of 13 p.p. Thus, the interest rate of the 28-day LELIQ stood at 91.0% n.a. (141.0% y.a.) and that of the 180-day LELIQ stood at 99.5% n.a. (124.7% y.a.). As for shorter-term instruments, the interest rate on 1-day pass-by-passes increased from 72% n.a. to 85% n.a. (133.7% y.a.); Meanwhile, the interest rate on 1-day active passes was set at 110% n.a. (199.9% e.a.). Finally, the spread of the NOTALIQ was 8.5 p.p. in the last auction, the same value it has registered since September last year. The decision to raise benchmark rates at the end of the month was based on recent developments and short-term expectations of inflation and the foreign exchange market. In this way, the Central Bank of the Argentine Republic (BCRA) aims to tend towards positive real returns on investments in local currency, which contributes to preserving financial and exchange rate stability.

With the current availability of instruments, in April the remunerated liabilities were conformed, on average, to 70.9% by LELIQ with a 28-day term. The longer-term species accounted for 3.8% of the total, mainly concentrated in NOTALIQ. Meanwhile, 1-day pass-by-passes decreased their share of total instruments, representing 23.6% of the total. The rest was made up of LEDIV and LEGAR, increasing their participation by 1.8 p.p. compared to March (see Figure 4.3).

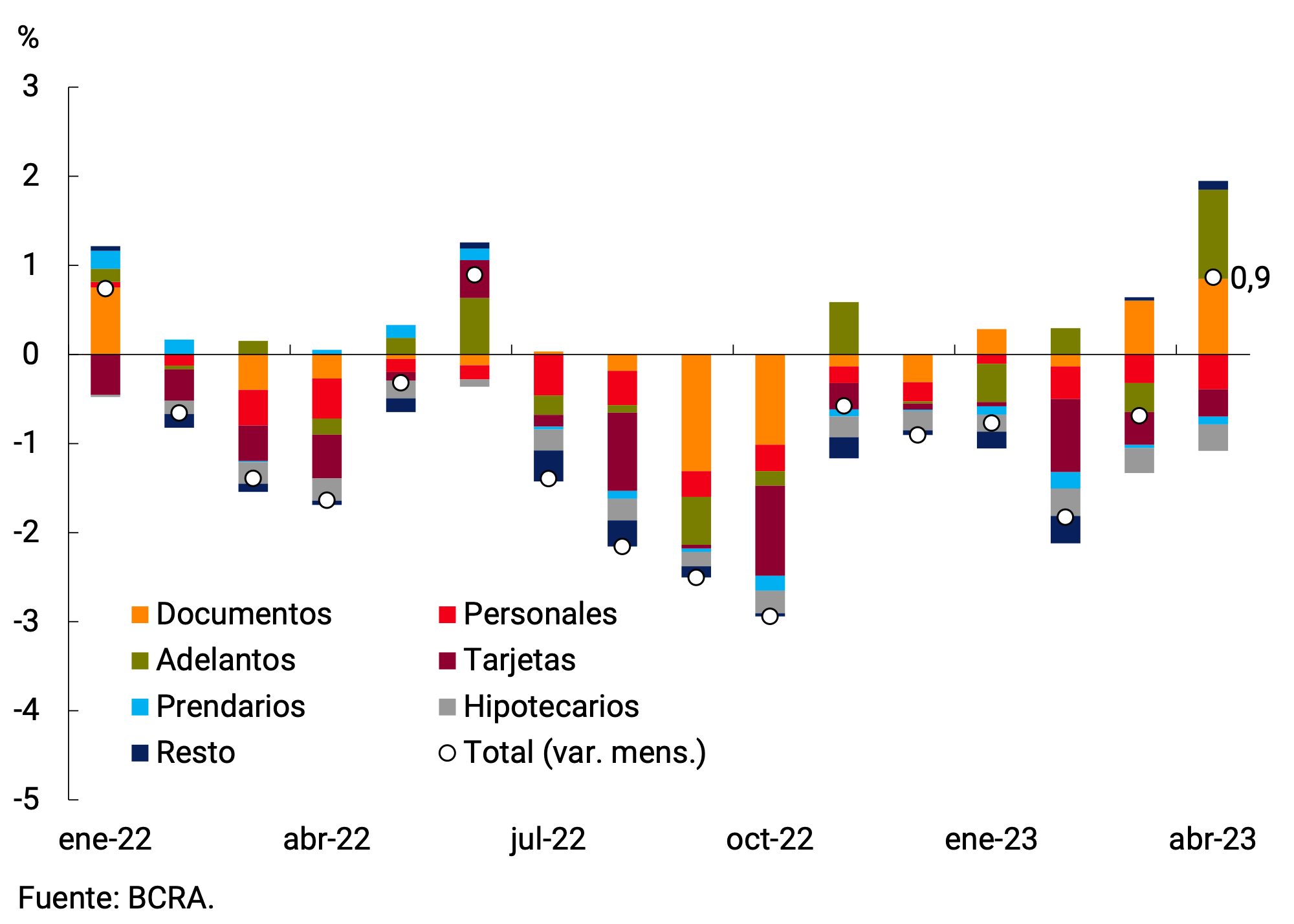

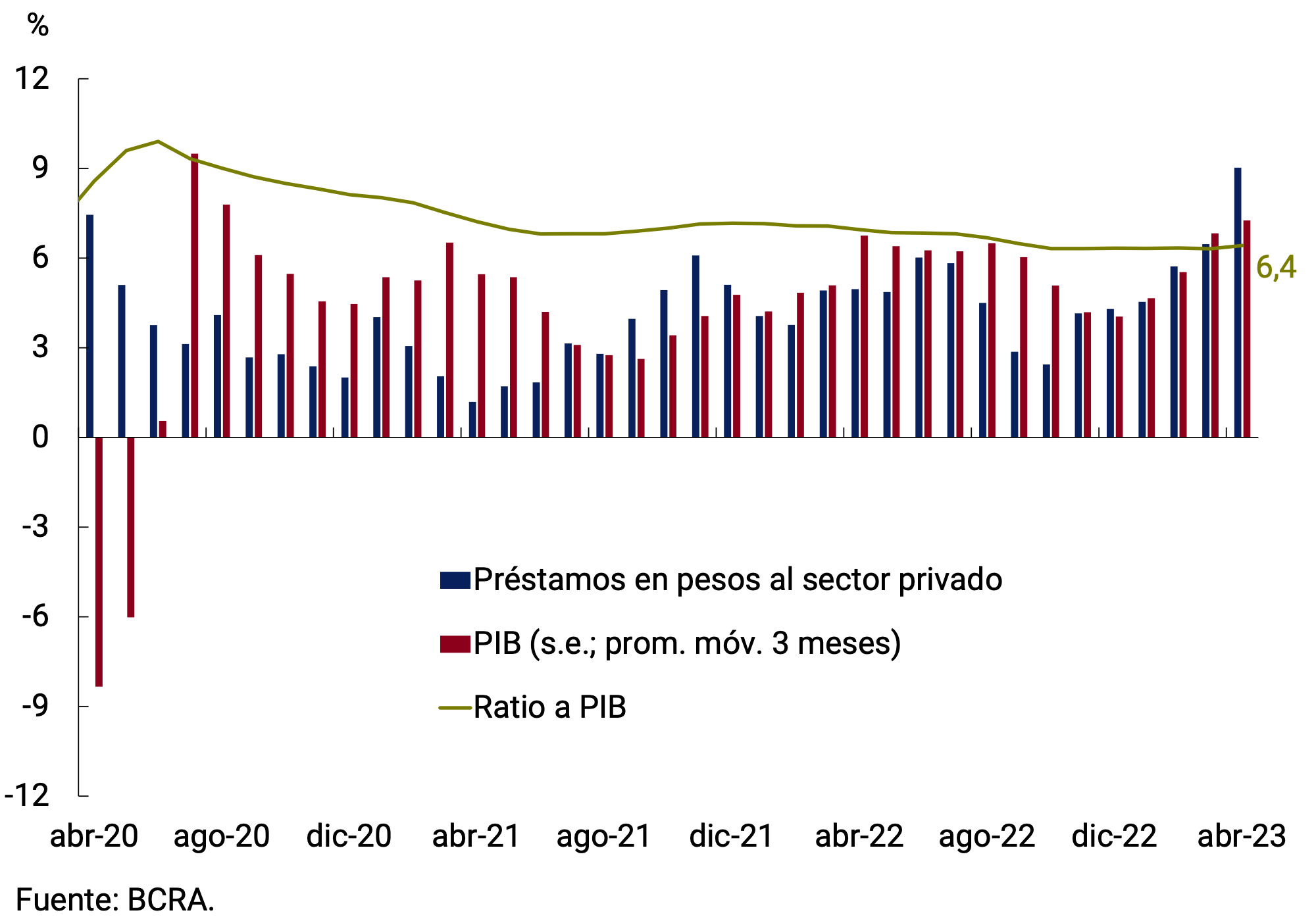

5. Loans to the private sector

In April, loans in pesos to the private sector in real terms and without seasonality would have registered an expansion (0.9%), breaking with a period of nine consecutive months of declines. At the level of the large lines of credit, the behavior was heterogeneous. Commercial lines showed a strong increase in the month, which was partially offset by the dynamics of other financing (see Figure 5.1). In the last 12 months, credit would have accumulated a fall of 11.7% in real terms. Measured as a percentage of GDP, loans in pesos to the private sector remained stable in the month and stood at 6.4% (see Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.1 | Loans in pesos to the private

sector Real without seasonality; contribution to monthly growth

Lines with essentially commercial destinations would have registered a monthly expansion of 4.5% s.e. at constant prices and thus cut their year-on-year fall to -5.3%. Among these lines, advances would have registered a real monthly expansion of 8.6% s.e., the highest since July 2021, standing 8.4% above the level of a year ago. On the other hand, loans granted through documents would have exhibited an increase in the month of 3.2% s.e. in real terms, driven by both discounted documents and documents with a single signature. However, they are about 6% below the April 2022 level.

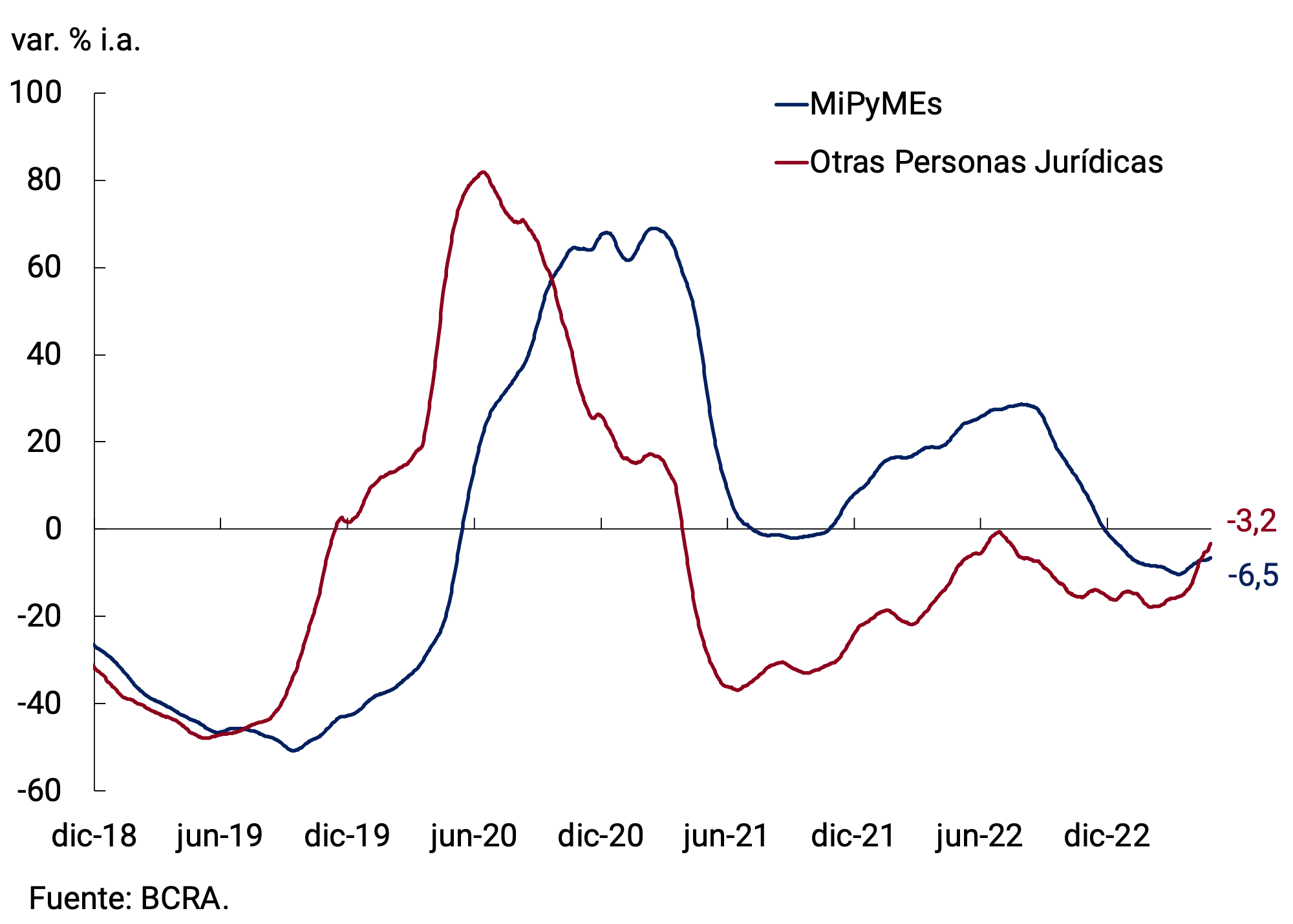

By type of debtor, the expansion of commercial credit was reflected in financing to MSMEs and, to a greater extent, in credit to large companies, with monthly increases in real terms of 1.1% s.e. and 9.6% s.e., respectively. In this way, they cut their year-on-year rate of decline in both cases (see Figure 5.3).

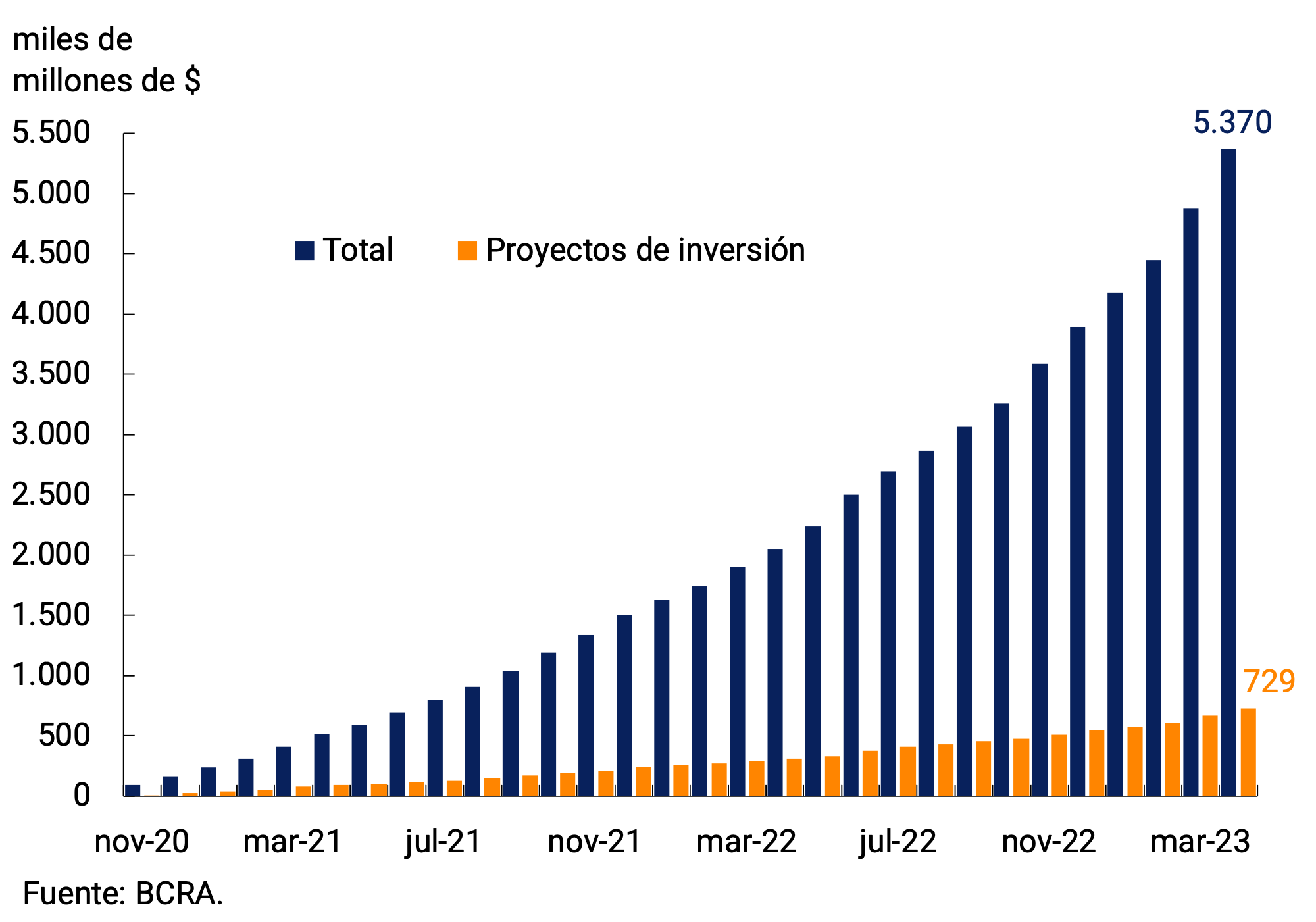

The Financing Line for Productive Investment (LFIP) continued to be the main tool used to channel productive credit to MSMEs. At the end of April, loans granted under the LFIP accumulated approximately $5.37 billion since its launch, an increase of 10% compared to last month (see Figure 5.4). It should be noted that the average balance of financing granted through the LFIP reached approximately $1,370 billion in March (latest available information), which represents about 18.1% of total loans and 42.6% of total commercial loans. Of the average balance in March, 43.7% corresponded to investment projects, exceeding the minimum quota of 30% established in the regulations.

Consumer loans would have contracted in April 1.6% s.e. at constant prices, accumulating a reduction of 14.4% in the last 12 months. Within these lines, credit card financing would have shown a decrease of 1.0% s.e. (-11.6% y.o.y.), while personal loans would have contracted 2.5% s.e. in the month and would be 19.0% below the level recorded a year ago.

With regard to secured lines, in real terms, collateral loans would have registered a decrease of 1.3% s.e. and are 7.7% below the level of a year ago. For its part, the balance of mortgage loans would have shown a decrease of 5.8% s.e. in April at constant prices, accumulating a contraction of 37.6% in the last twelve months.

6. Liquidity in pesos of financial institutions

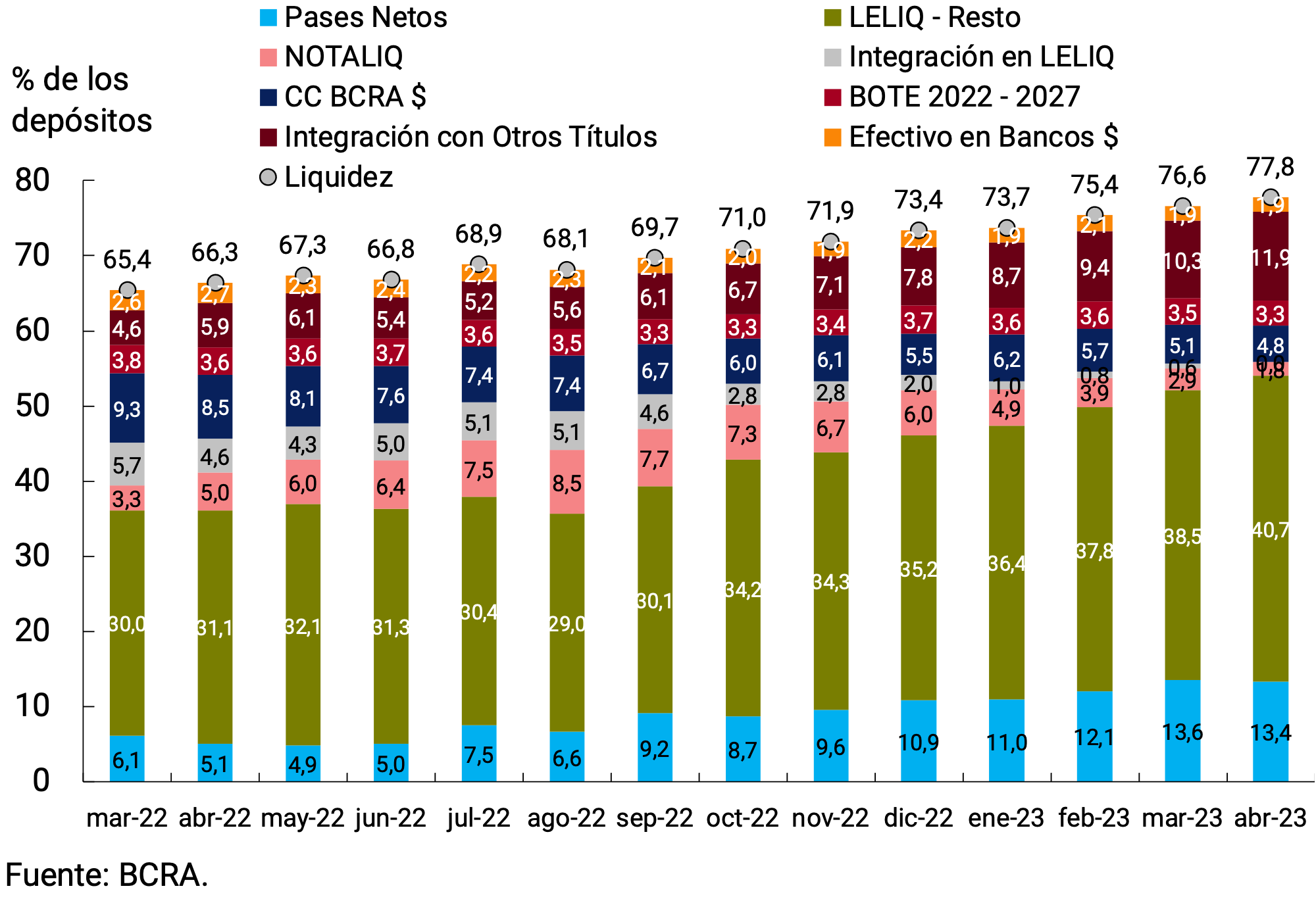

In April, ample bank liquidity in local currency6 showed an increase of 1.2 p.p. compared to March, averaging 77.8% of deposits (see Figure 6.1). In this way, it remained at historically high levels. The increase was mainly explained by the LELIQ and the integration with public securities, partially offset by the NOTALIQ, the passive passes and the current accounts at the Central Bank.

7. Foreign currency

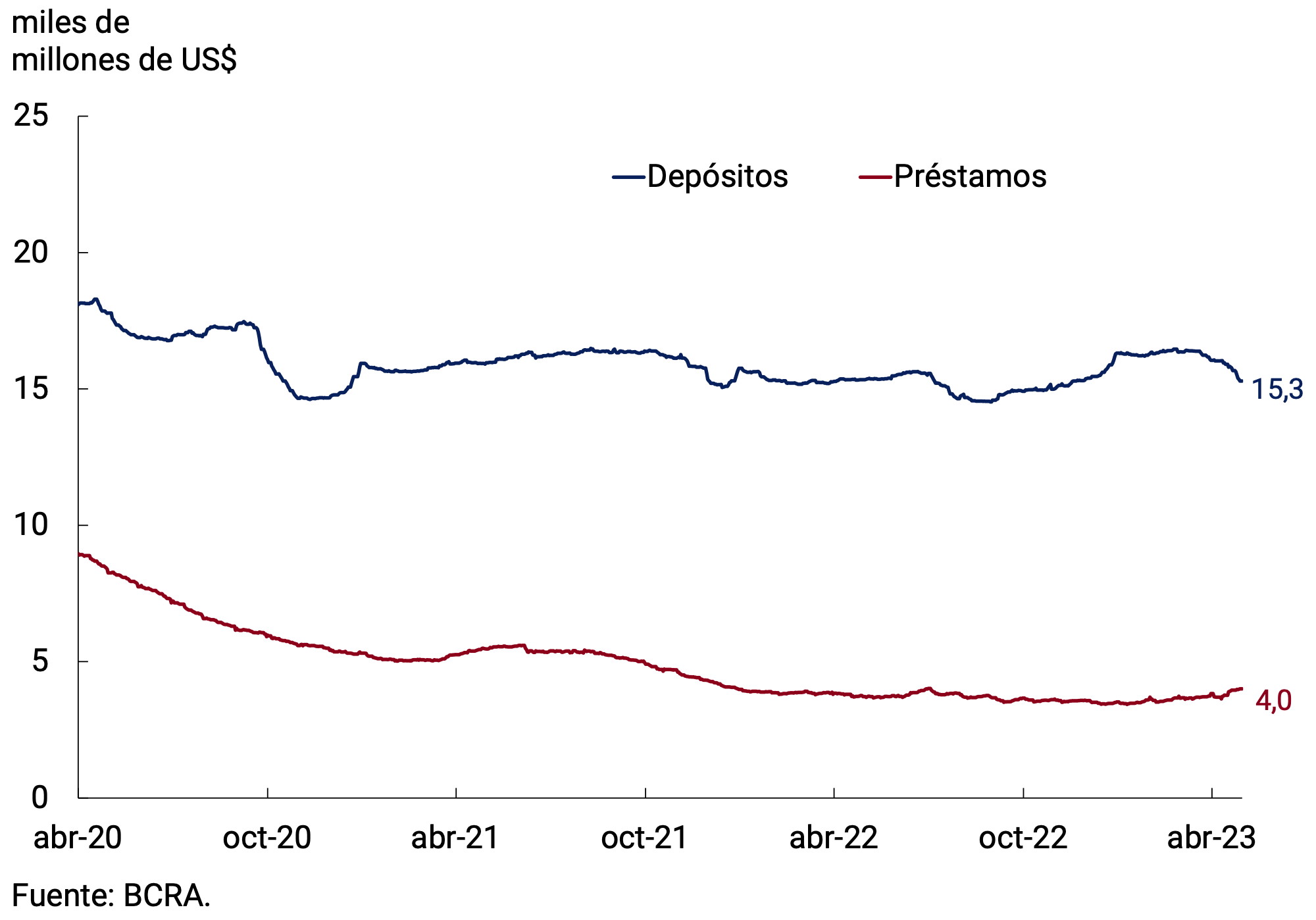

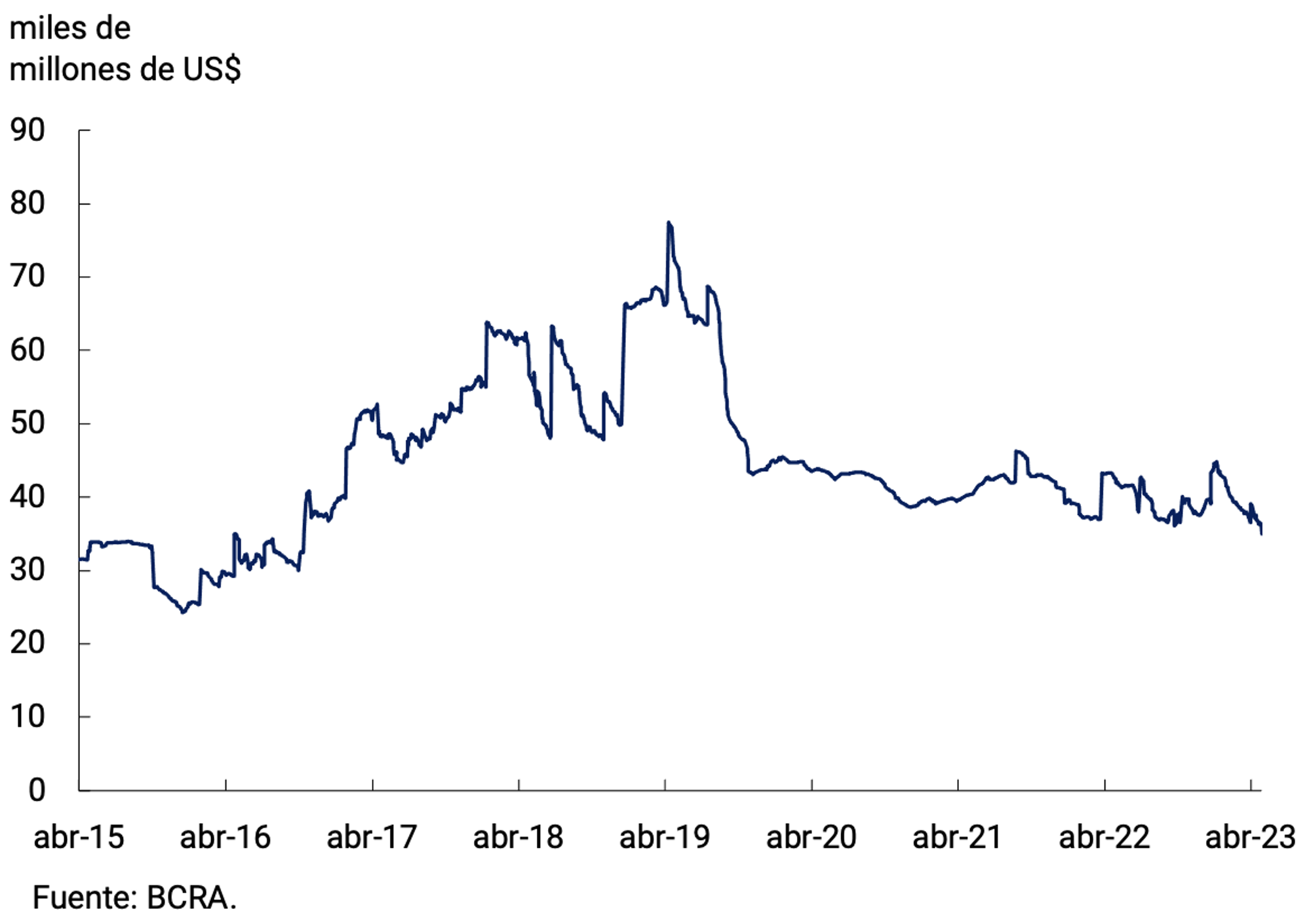

In the foreign currency segment, the main assets and liabilities of financial institutions had a mixed performance. On the one hand, at the end of the month, the balance of private sector deposits was US$15,289 million, registering a fall of US$757 million compared to the end of March, which was mainly explained by demand deposits of individuals and, to a lesser extent, of legal entities of more than US$1 million. On the other hand, the balance of loans to the private sector increased by US$175 million, mainly due to the contribution of documents with a single signature, and ended the month at US$4,004 million (see Figure 7.1).

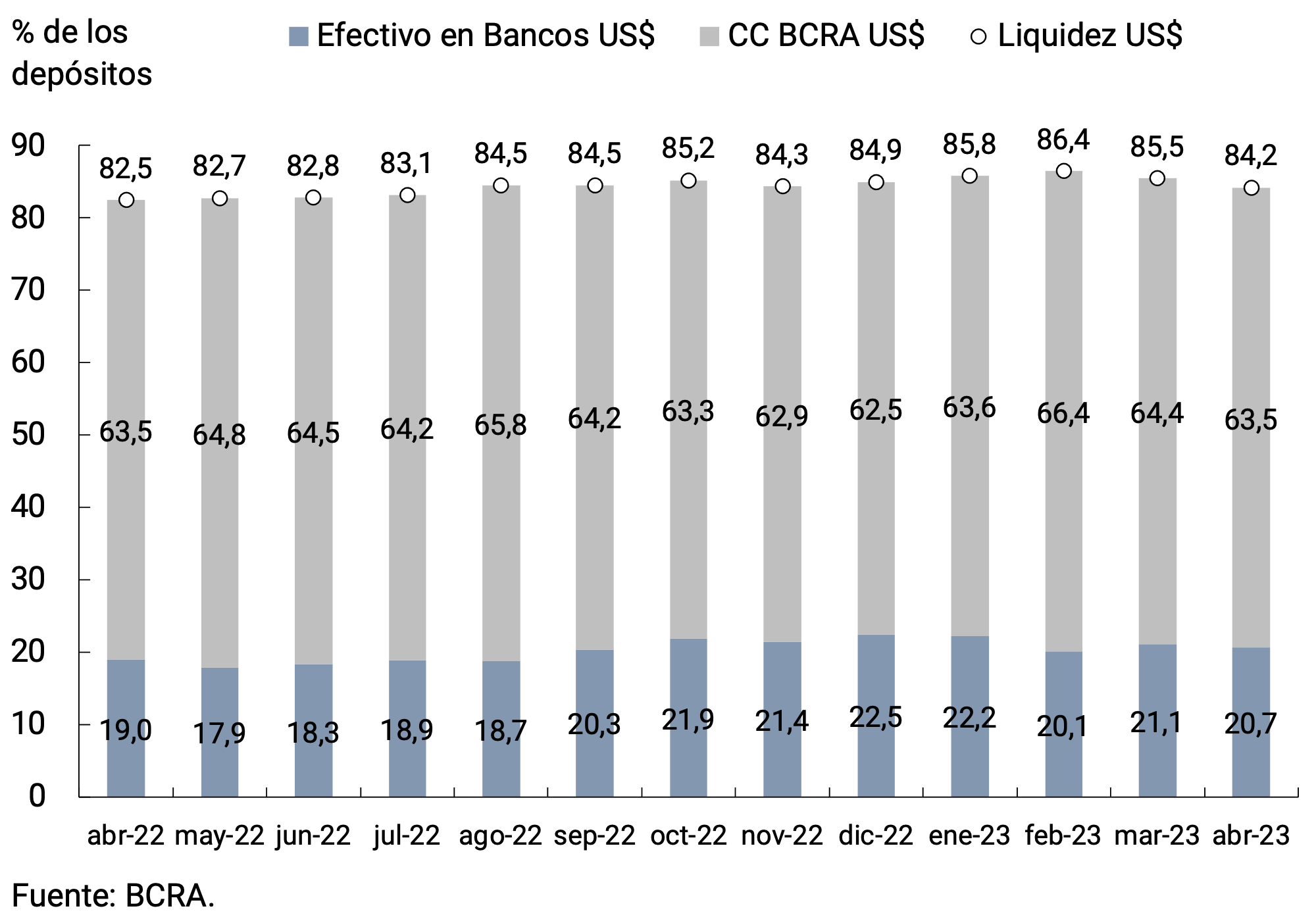

The liquidity of financial institutions in the foreign currency segment experienced a fall of 1.3 p.p. compared to the March average, standing at 84.2% of deposits and remaining at historically high levels. The movement was explained both by the current accounts in foreign currency at the BCRA and by the cash banks (see Figure 7.2).

During April, a series of regulatory modifications were made in foreign exchange matters, which were aimed at increasing the supply of foreign currency and reducing pressures on International Reserves. First, measures were taken to finance the payment of the import of professional services and freight between related companies and prior authorization was provided for the payment of interest on intra-company debt7. In addition, the deadline for entering and settling foreign currency corresponding to advances, pre-financing and post-financing of foreign exports was extended to 180 days8. On the other hand, with the aim of increasing the supply of foreign currency through the establishment of export incentives, the “Export Increase Program” was reestablished9. On this occasion, a transitory differential exchange rate of $300/US$ is contemplated for the settlement of foreign currency for exports of soybeans and by-products until May 31. In this edition, in order to counteract the negative impact of adverse weather conditions, it was decided to extend it to Regional Economies, if they meet a series of requirements, which will have this benefit available until August 31, 10.

The BCRA’s International Reserves ended April with a balance of US$35,001 million, registering a decrease of US$4,059 million compared to the end of March. This drop was mainly explained by payments to international organizations, among which the capital payments to the International Monetary Fund for US$2,667.6 million stood out. The rest of the factors of variation in reserves also had a negative impact, with the exception of foreign currency purchases under the Export Increase Program, which totaled US$1,613 million in the month (see Figure 7.3).

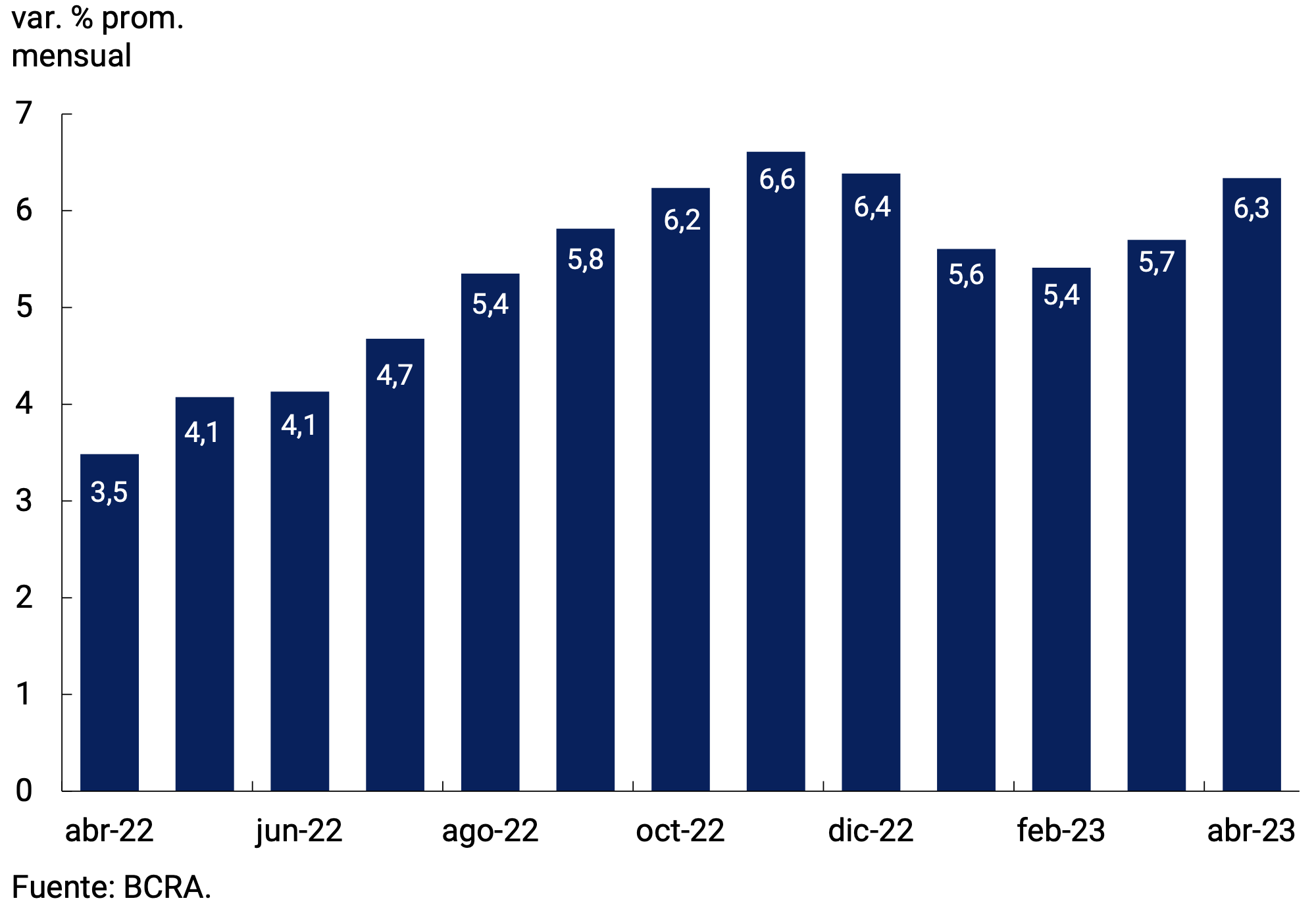

Finally, the bilateral nominal exchange rate (TCN) against the U.S. dollar increased 6.3% in April, a higher increase than in the previous month (see Figure 7.4). Thus, it was located, on average, at $215.78/US$.

Glossary

ANSES: National Social Security Administration.

AFIP: Federal Administration of Public Revenues.

BADLAR: Interest rate on fixed-term deposits for amounts greater than one million pesos and a term of 30 to 35 days.

BCRA: Central Bank of the Argentine Republic.

BM: Monetary Base, includes monetary circulation plus deposits in pesos in current account at the BCRA.

CC BCRA: Current account deposits at the BCRA.

CER: Reference Stabilization Coefficient.

NVC: National Securities Commission.

SDR: Special Drawing Rights.

EFNB: Non-Banking Financial Institutions.

EM: Minimum Cash.

FCI: Common Investment Fund.

A.I.: Year-on-year .

IAMC: Argentine Institute of Capital Markets

CPI: Consumer Price Index.

ITCNM: Multilateral Nominal Exchange Rate Index

ITCRM: Multilateral Real Exchange Rate Index

LEBAC: Central Bank bills.

LELIQ: Liquidity Bills of the BCRA.

LFIP: Financing Line for Productive Investment.

M2 Total: Means of payment, which includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and demand deposits in pesos from the public and non-financial private sector.

Private M2: Means of payment, includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and demand deposits in pesos from the non-financial private sector.

Private transactional M2: Means of payment, includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and non-remunerated demand deposits in pesos from the non-financial private sector.

M3 Total: Broad aggregate in pesos, includes the current currency held by the public, cancelling checks in pesos and the total deposits in pesos of the public and non-financial private sector.

Private M3: Broad aggregate in pesos, includes the working capital held by the public, cancelling checks in pesos and the total deposits in pesos of the non-financial private sector.

MERVAL: Buenos Aires Stock Market.

MM: Money Market.

N.A.: Annual nominal.

E.A.: Effective Annual.

NOCOM: Cash Clearing Notes.

ON: Negotiable Obligation.

GDP: Gross Domestic Product.

P.B.: basis points.

PSP.: Payment Service Provider.

p.p.: percentage points.

MSMEs: Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises.

ROFEX: Rosario Term Market.

S.E.: No seasonality

SISCEN: Centralized System of Information Requirements of the BCRA.

SIMPES: Comprehensive System for Monitoring Payments of Services Abroad.

TCN: Nominal Exchange Rate

IRR: Internal Rate of Return.

TM20: Interest rate on fixed-term deposits for amounts greater than 20 million pesos and a term of 30 to 35 days.

TNA: Annual Nominal Rate.

UVA: Unit of Purchasing Value

References

1 Corresponds to private M2 excluding interest-bearing demand deposits from companies and financial service providers. This component was excluded since it is more similar to a savings instrument than to a means of payment.

2 The interest rates currently in force are those established by communication “A” 7726.

3 The rest of the depositors are made up of Legal Entities and Individuals with deposits of more than $10 million.

4 Demand accounts with adjustment for exchange rates are available for: 1) special accounts for holders with agricultural activity (PIE and incorporates exporters from regional economies) and 2) special accounts for exporters. This includes exporters of goods under certain requirements and entities that receive financial assistance and/or non-refundable contributions from international organizations. On the other hand, time deposits with adjustment by exchange rate only for agents with agricultural activity.

5 The private M3 includes the working capital held by the public and the deposits in pesos of the non-financial private sector (demand, time and others).

6 Includes current accounts at the BCRA, cash in banks, balances of net passes arranged with the BCRA, holdings of LELIQ and NOTALIQ, and public bonds eligible for reserve requirements.

7 Communication “A” 7746.

8 Communication “A” 7740.

9 Decree 194/2023 of the National Executive Branch.

10 Communication “A” 7743 regulated the use of the accounts to which the funds credited under Decree No. 194/23 are allocated.