Política Monetaria

Monetary Policy Report (IPOM)

Second Quarter

2018

Quarterly report presenting the macroeconomic analysis and monetary policy guidelines of the BCRA.

Table of Contents

Chapters

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlook

2. International context

3. Economic Activity and Employment

4. Pricing

5. Monetary Policy

Sections

1.

2. Evaluation of the performance of the BCRA’s Contemporary Output Forecast

3. The Impact of the Drought

4. Foreign exchange intervention in inflation targeting regimes

5.

For inquiries, write to analisismacro@bcra.gob.ar

Summary

As indicated in its Organic Charter, the Central Bank of the Argentine Republic “aims to promote, to the extent of its powers and within the framework of the policies established by the National Government, monetary stability, financial stability, employment and economic development with social equity”.

Without prejudice to the use of other more specific instruments for the fulfillment of the other mandates – such as financial regulation and supervision, exchange rate regulation, and innovation in savings, credit and means of payment instruments – the main contribution that monetary policy can make

for the monetary authority to fulfill all its mandates is to focus on price stability.

With low and stable inflation, financial institutions can better estimate their risks, which ensures greater financial stability. With low and stable inflation, producers and employers have more predictability to invent, undertake, produce and hire, which promotes investment and employment. With low and stable inflation, families with lower purchasing power can preserve the value of their income and savings, which makes economic development with social equity possible.

The contribution of low and stable inflation to these objectives is never more evident than when it does not exist: the flight of the local currency can destabilize the financial system and lead to crises, the destruction of the price system complicates productivity and the generation of genuine employment, the inflationary tax hits the most vulnerable families and leads to redistributions of wealth in favor of the wealthiest. Low and stable inflation prevents all this.

In line with this vision, the BCRA formally adopted an Inflation Targeting regime that came into effect as of January 2017. As part of this new regime, the institution publishes its Monetary Policy Report on a quarterly basis. Its main objectives are to communicate to society how the Central Bank perceives recent inflationary dynamics and how it anticipates the evolution of prices, and to explain in a transparent manner the reasons for its monetary policy decisions.

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlook

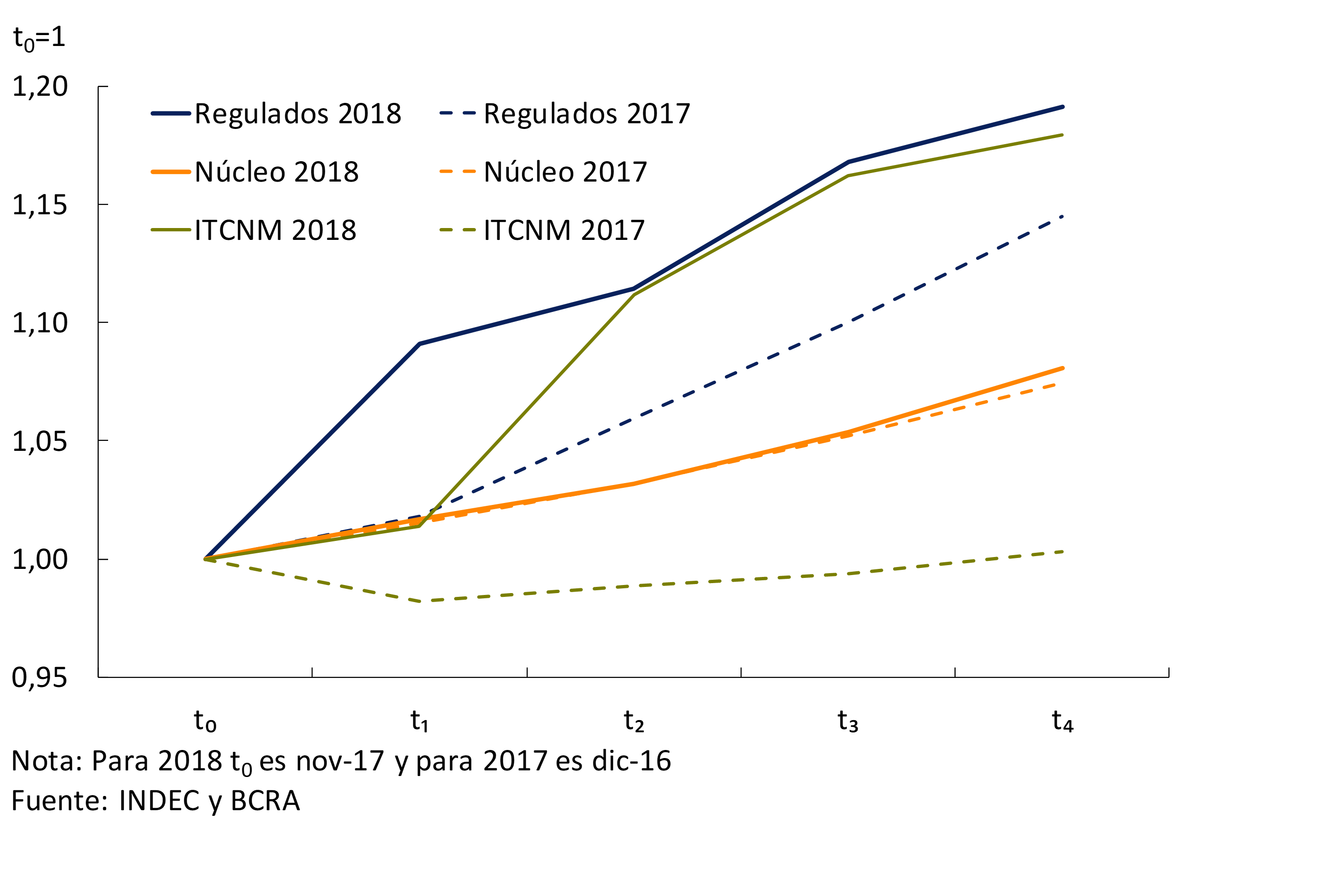

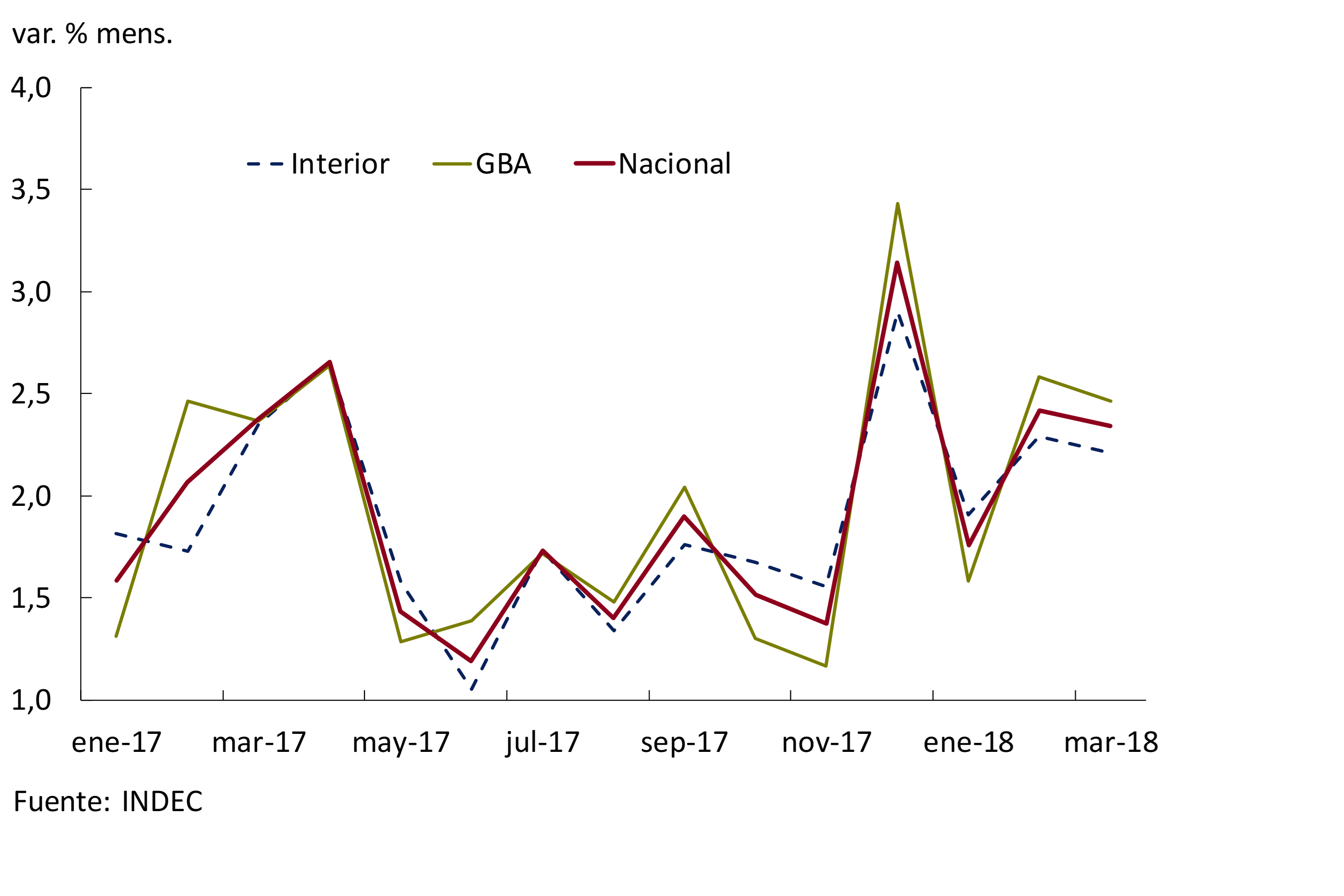

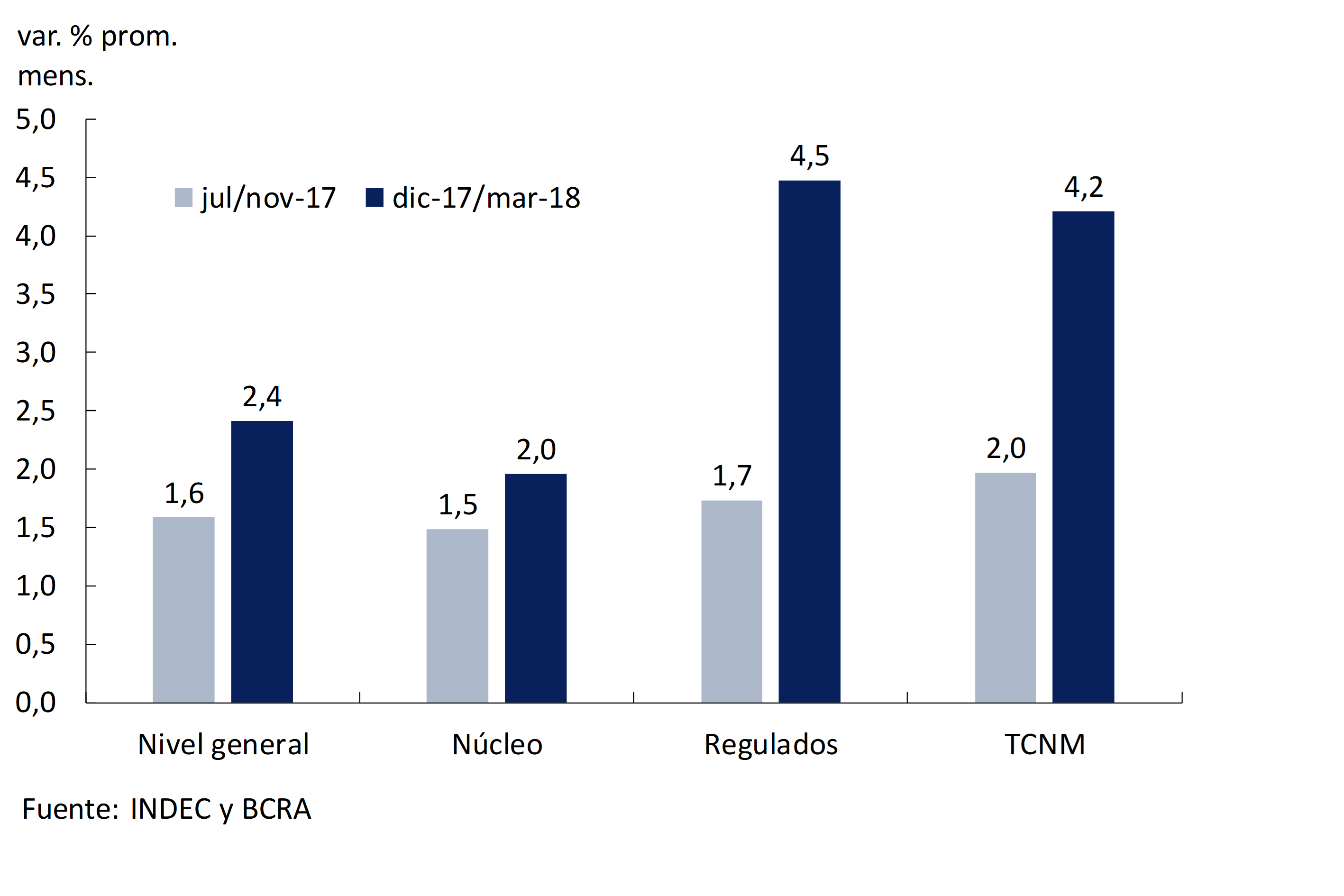

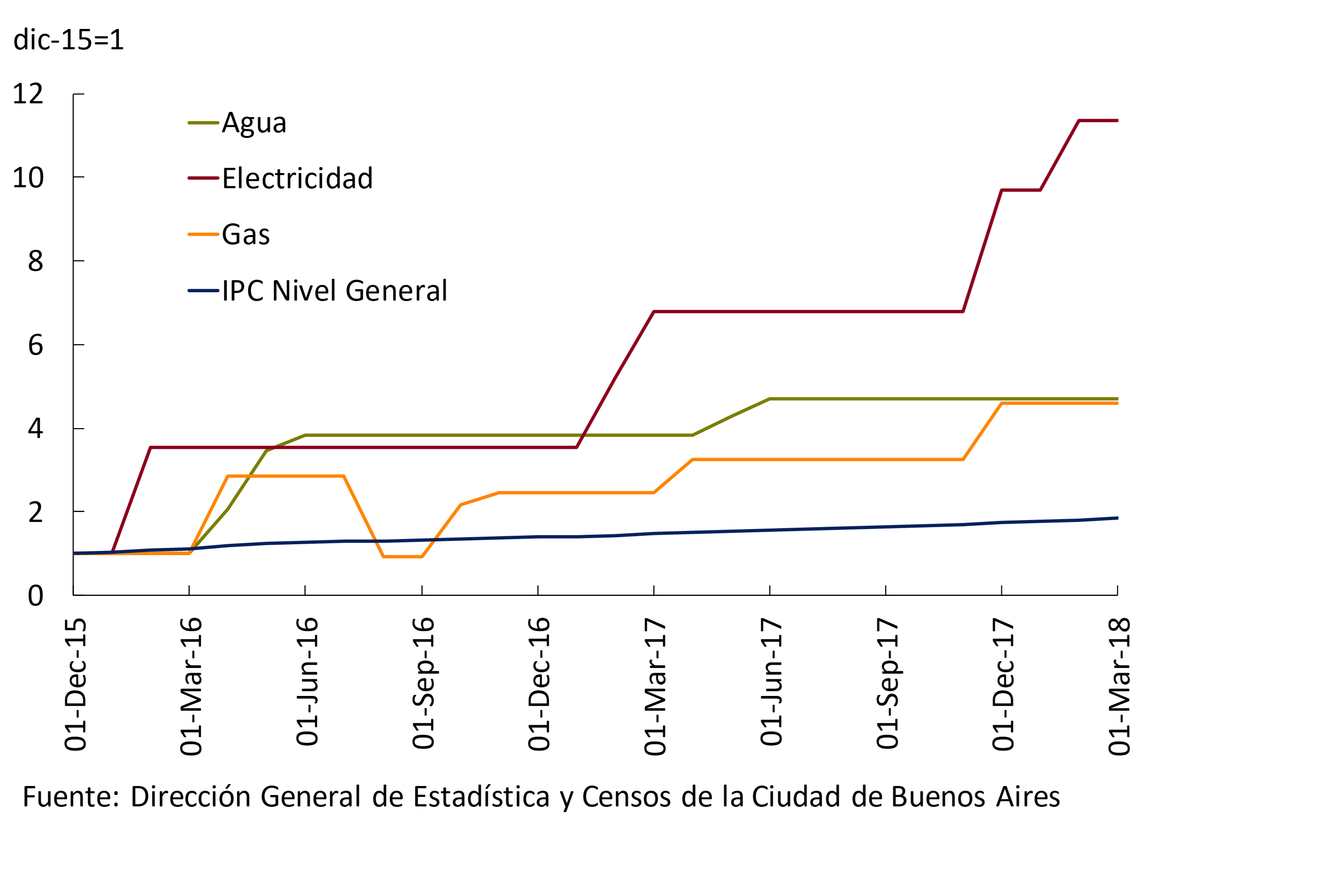

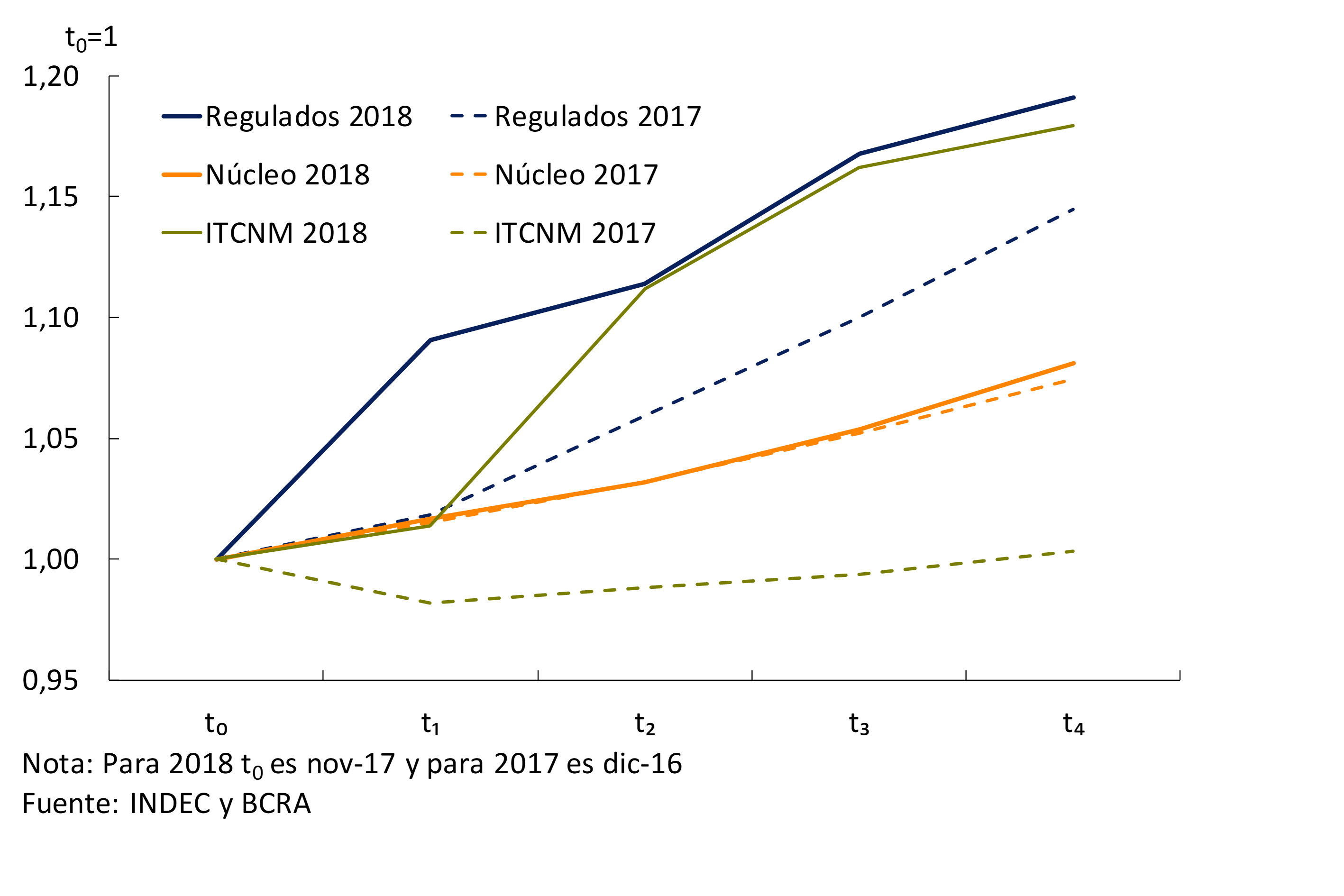

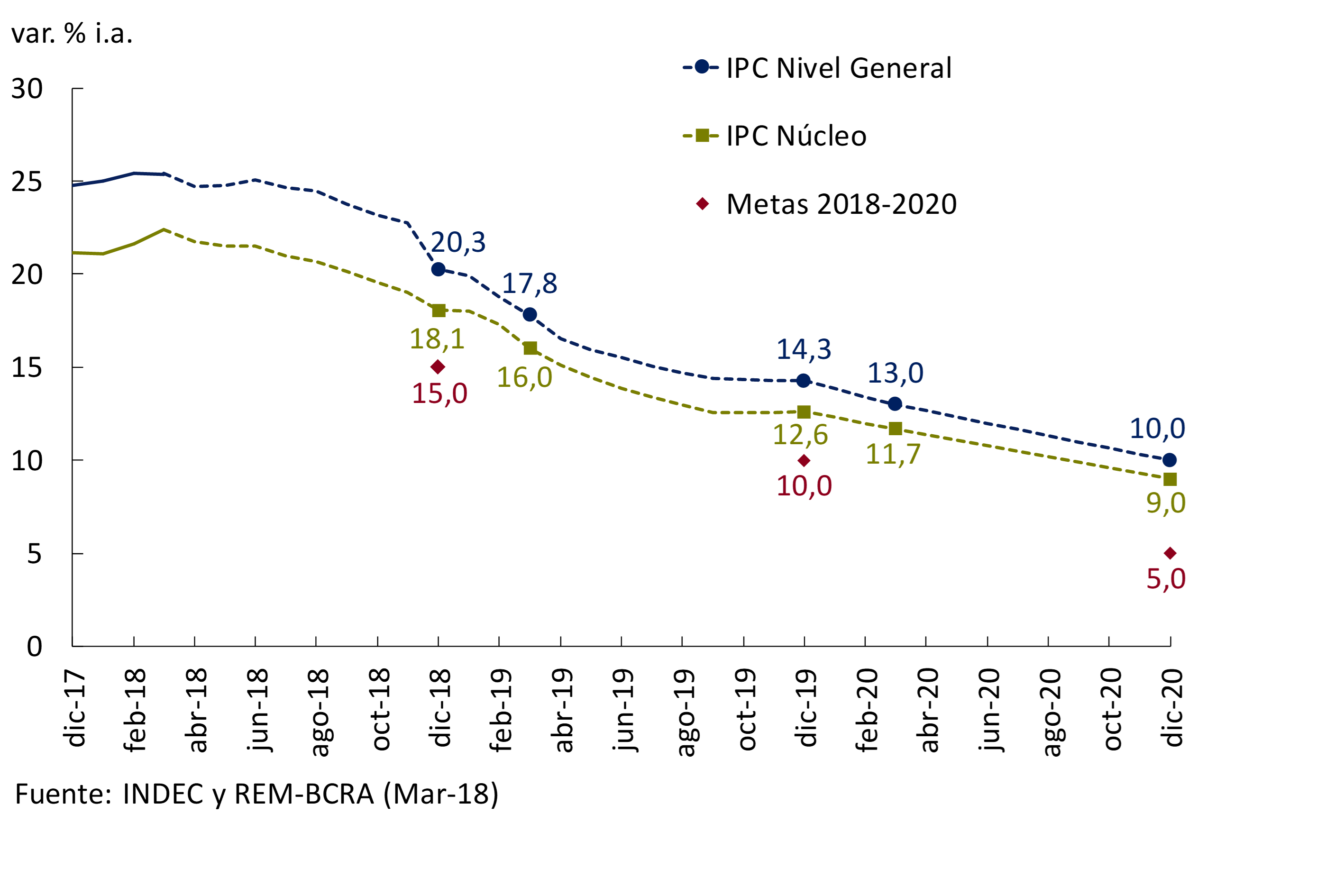

Inflation accelerated in the first quarter of 2018 compared to the last quarter of 2017, reaching a monthly average of 2.2%. The rise in inflation responded to the impact of the increase in public service rates and, to a lesser extent, to the depreciation of the peso observed between December 2017 and February 2018. Core inflation showed similar trajectories in the summers of 2017 and 2018, even though significantly higher increases in regulated prices and exchange rates were recorded this year (see Figure 1.1).

The BCRA considers that this higher inflation is transitory and that, once the aforementioned factors have been overcome, it will consolidate its downward trend and monthly inflation will be at values that the Argentine economy has not recorded since the global financial crisis. This favorable outlook is based on the fact that: a) monetary policy shows a more contractionary bias than that observed in the first half of last year; b) the process of adjustment of regulated prices is less than that of 2017 and, as it is concentrated in the first four months, it will decelerate sharply after April; c) no significant depreciation of the peso is expected due to macroeconomic fundamentals and the Central Bank’s own action, and d) wage negotiations in the public and private sectors are being agreed around the 15% guideline.

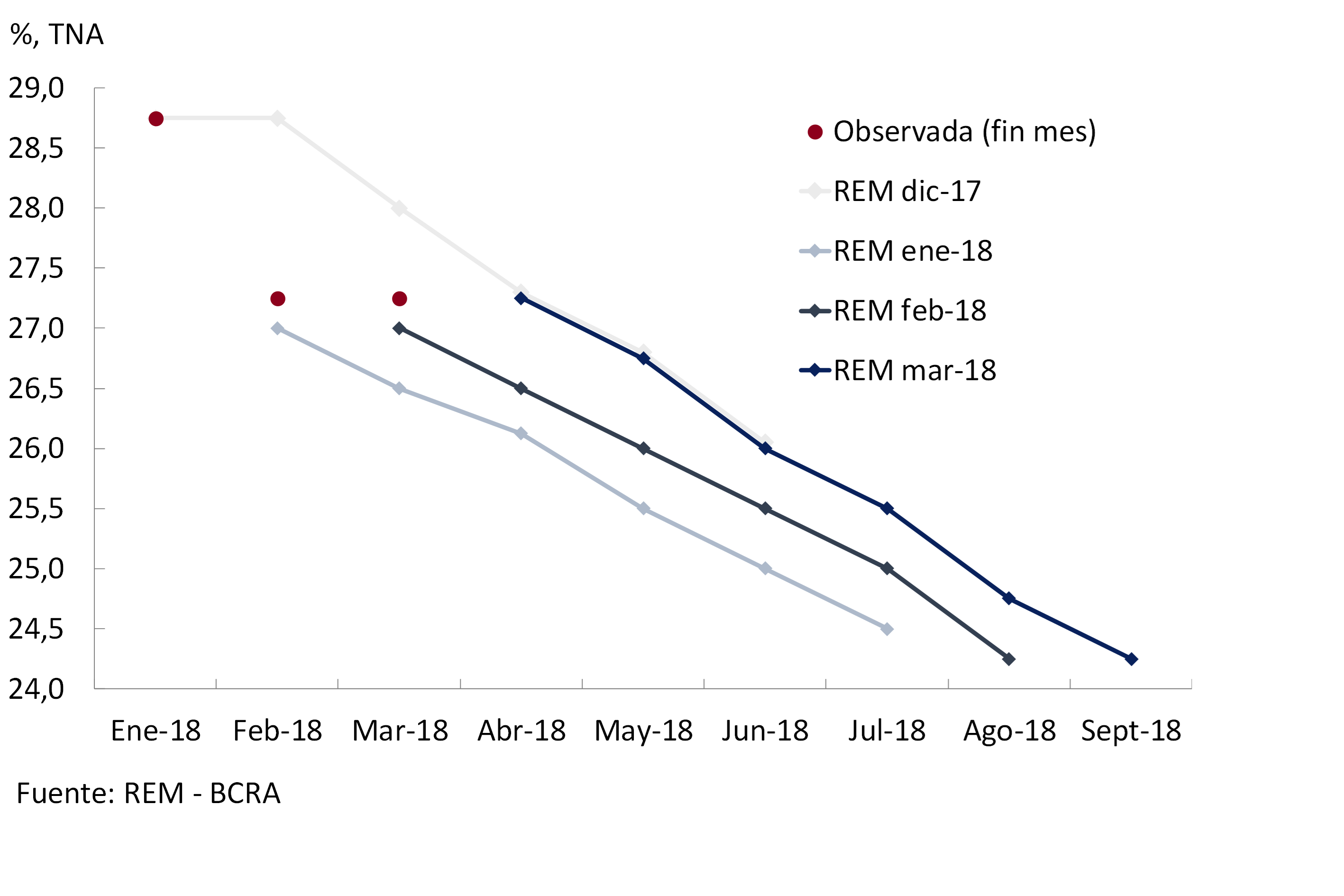

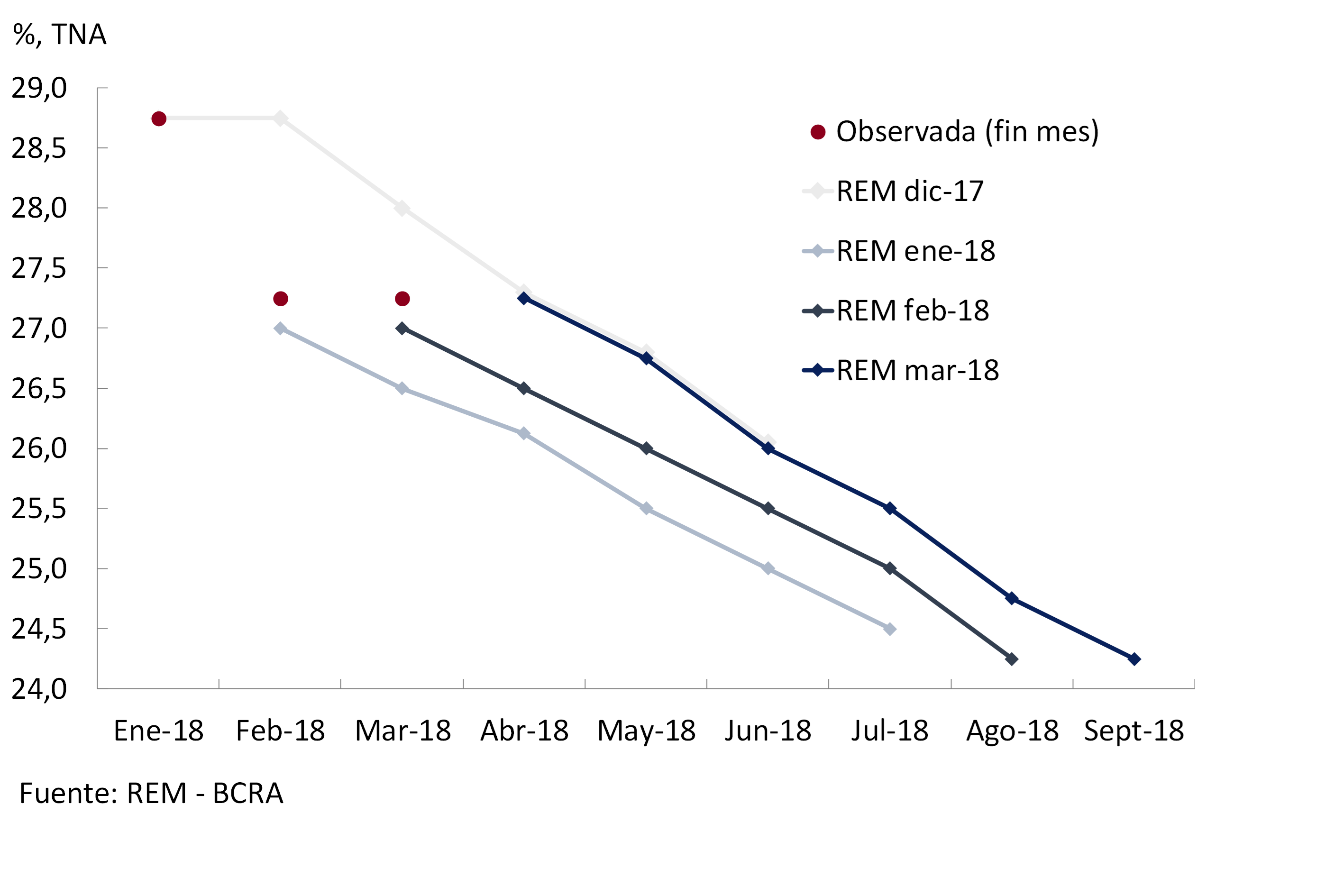

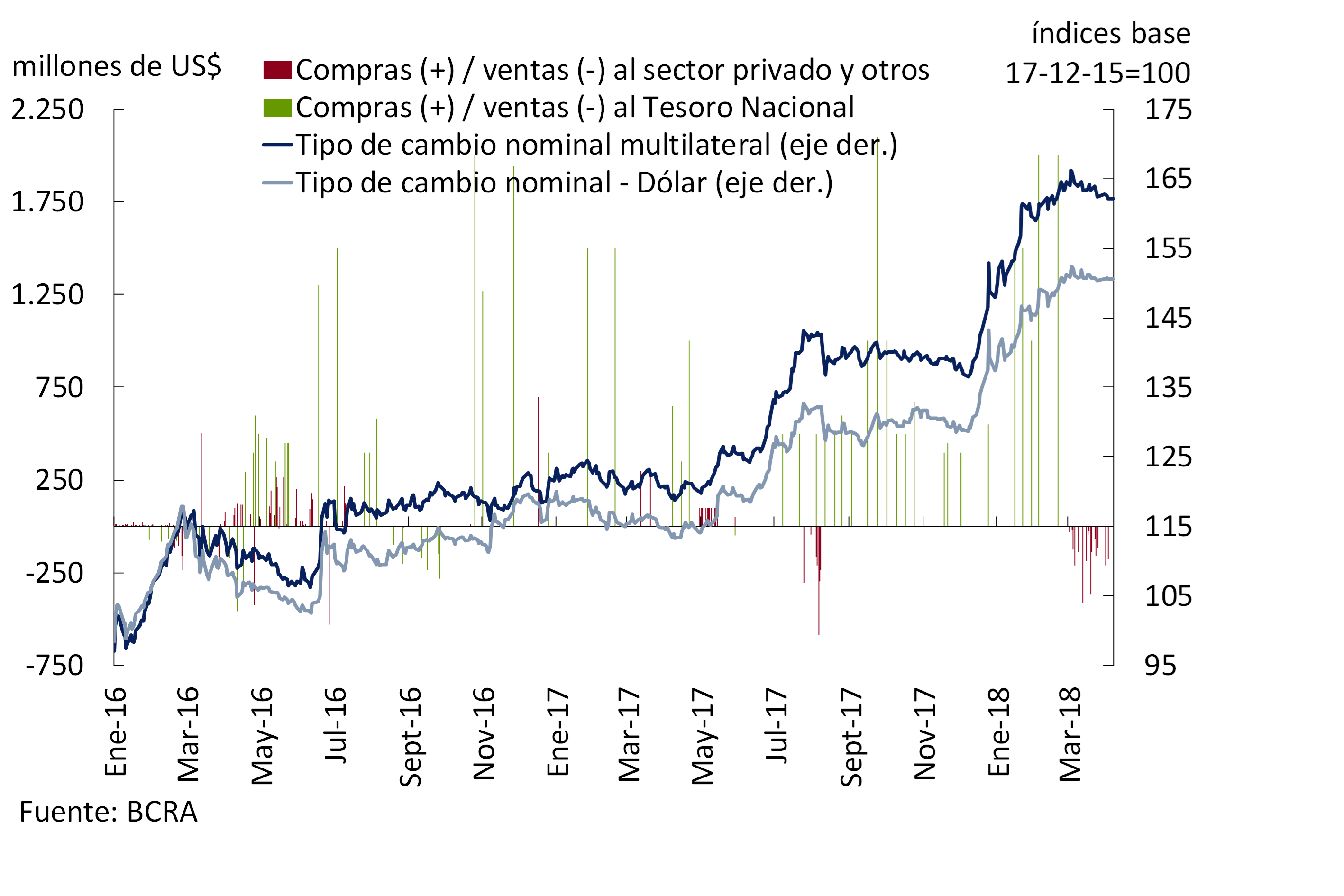

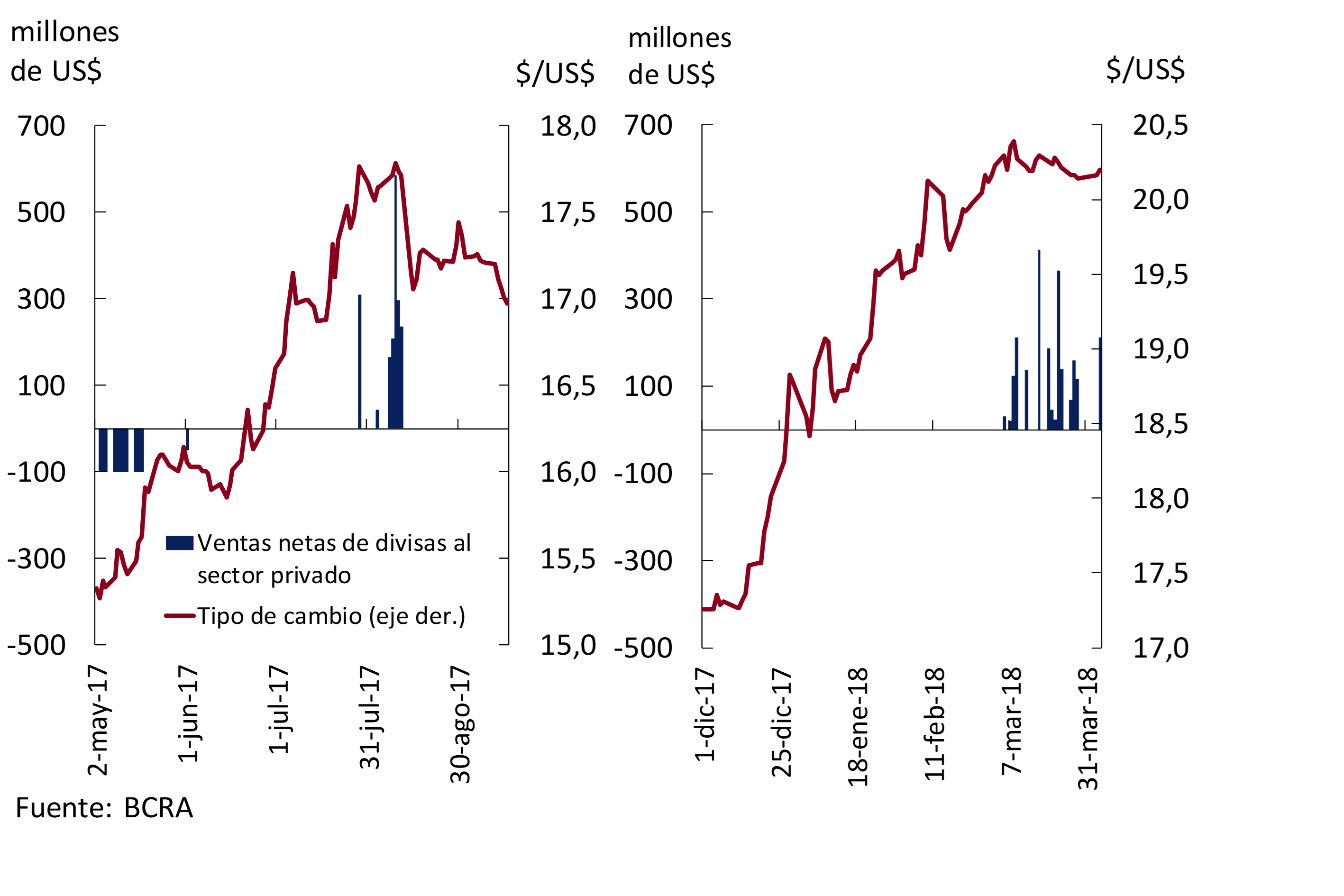

Considering that the pressures on prices responded to temporary factors, the Central Bank kept the policy interest rate unchanged after the reduction that had been decided in January to make it compatible with the lower disinflation required by the new intermediate target. However, the one-year shift in the inflation target of 5%, the reconfiguration of the interim targets for 2018 and 2019, and the reduction in the policy interest rate at the beginning of the year were interpreted by the market as the prelude to an excessive easing of monetary policy (see Figure 1.2). This led to a dynamic of depreciation of the peso that reflected a market view of the future of monetary policy that did not correspond to the Central Bank’s vision. In this context, and in a complementary way to the management of the interest rate, the Central Bank intervened in the foreign exchange market since the beginning of March. A depreciation of the peso greater than that recorded up to that point was not justified by real economic factors or by the expected course of its monetary policy and, if not avoided, could affect the disinflation process. Analysts have begun to incorporate a more contractionary behavior of the BCRA than they expected at the end of January, and monetary policy rate expectations are already at the level of those expected in December 2017 (see Figure 1.2).

The economy continues to grow at a sustained pace and with low volatility. In line with what was anticipated in January’s IPOM, the gross domestic product (GDP) had a non-seasonalized growth of 4% annualized in the fourth quarter of 2017, maintaining a similar pace to the rest of last year. During the first quarter of 2018 the economy continued to expand, completing seven quarters of uninterrupted growth for the first time since 2011. The latest BCRA Contemporary GDP Prediction (PCP-BCRA) indicates a quarterly increase of 0.73% without seasonality for the first quarter of 2018. Investment closed 2017 with strong growth, reaching an all-time high in spending on durable production equipment; and it is expected to continue to lead the expansion of aggregate spending in 2018.

The BCRA’s view is that the inflation rate will fall once the transitory factors mentioned above are left behind. To consolidate this scenario, the monetary authority will be extremely cautious with which the monetary policy rate will accompany the fall in inflation, will remain attentive to the foreign exchange market to avoid movements inconsistent with its vision of monetary policy and its commitment to disinflation and will be ready to act by adjusting its monetary policy rate upwards if the disinflation process does not follow the expected path. The contractionary bias of monetary policy will thus be used to achieve the intermediate targets of 15% inflation in 2018, 10% in 2019 and a target of 5% in 2020. In this way, it will continue to promote monetary stability, financial stability, employment and economic development with social equity.

2. International context

Global economic activity continued to improve in recent months, both in advanced and emerging countries. A positive performance of international financial markets continued to be observed, although with some deterioration in the margin. Credit conditions for Argentina continue to be relatively favorable, both for the public sector and for companies. On the other hand, the prices of Argentina’s main export raw materials increased in the last three months.

Fears of a steeper rise in the U.S. policy rate, coupled with the growing number of protectionist measures adopted by some countries, have increased volatility in international financial markets. These measures have not yet impacted global growth projections but, if deepened, would affect growth prospects and financial markets.

2.1 A higher level of activity is expected in 2018 from Argentina’s trading partners

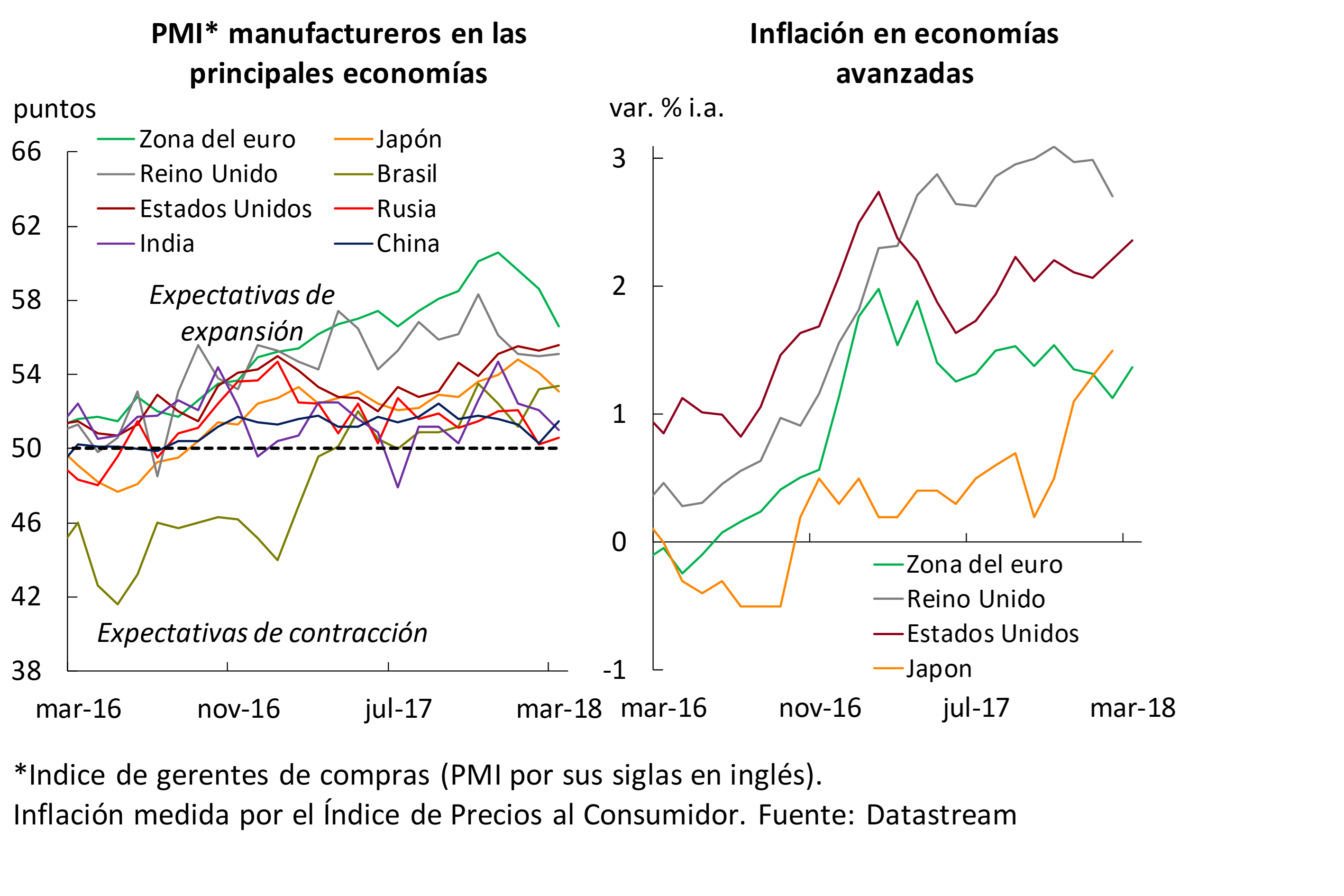

The leading indicators of activity of the main economies are in all cases in the expansion zone, although they show a certain slowdown in the margin that would be momentary according to the growth projections for 2018 and 2019 of the IMF (International Monetary Fund). On the other hand, according to the most recent data, inflation continued to rise. More specifically, inflation in the United States is around target, the United Kingdom’s inflation is 0.7 p.p. above (albeit on a downward trend), and in the euro area and Japan it is below, albeit upward (see Figure 2.1).

The most recent indicators confirm that Brazil, our main trading partner and leading player in the region’s economic performance, continues to grow steadily. The latest projections of the Focus survey – carried out by the country’s central bank, BCB, among market analysts – foresee GDP growth of 2.8% for 2018. This figure is slightly above the 2.7% projected at the time of publication of the previous IPOM, and is markedly higher than the growth recorded in 2017, around 1%. The first data for 2018 confirm this trend, as the Economic Activity Index prepared by the BCB increased by 3% YoY in January.

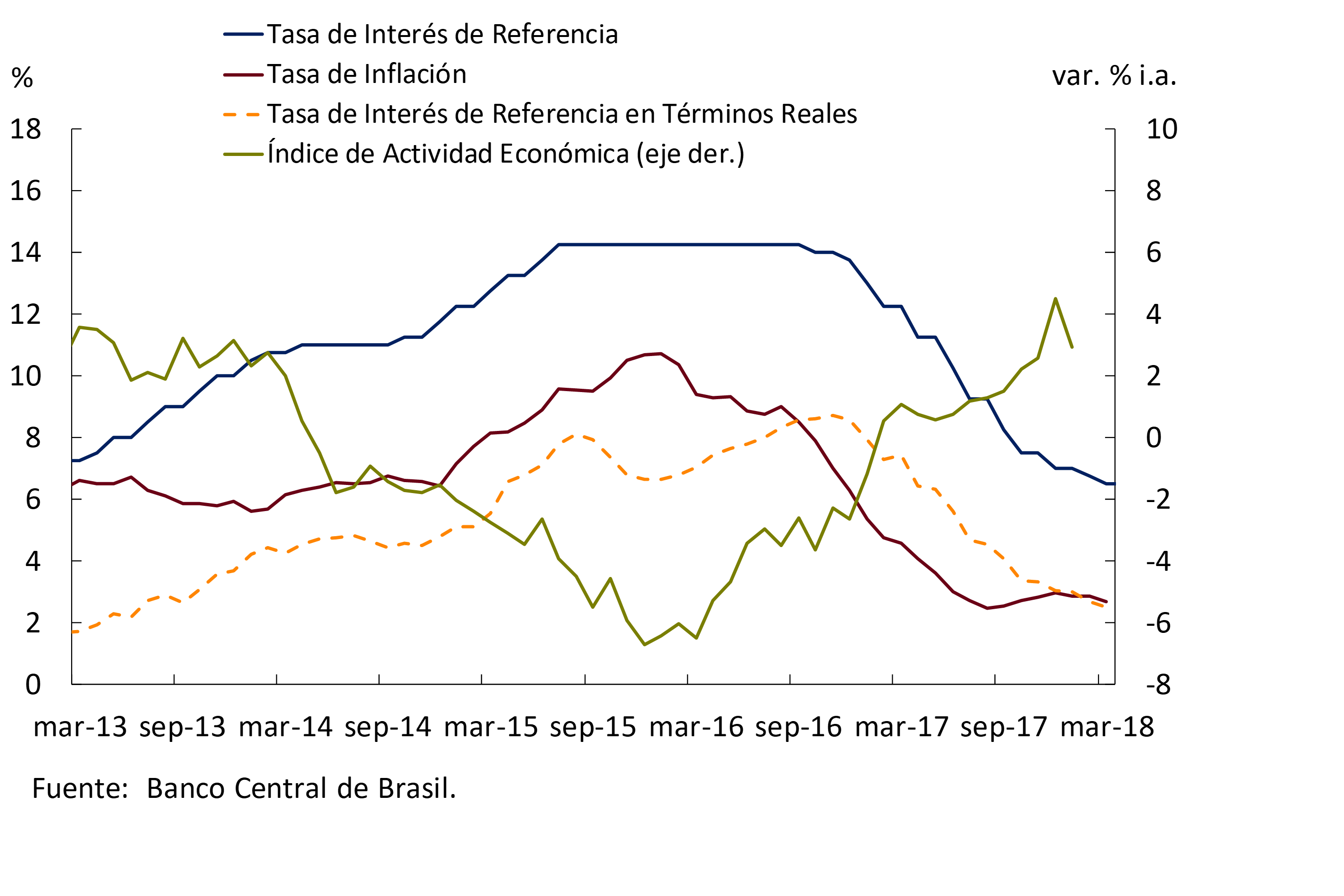

For its part, the BCB continued to reduce the monetary policy interest rate (the target on the Selic rate) in the face of declining inflation rates. Inflation in 2017 (2.95%) was below the target of 4.5% ± 1.5% set by the BCB. In addition, according to the projections of the Focus survey, inflation would be in the lower range of the target in 2018. For all these reasons, the same survey foresees a new reduction in the Selic rate of 0.25 p.p., unlike the previous IPOM where this was not foreseen. The policy rate in real terms continued to decline (see Figure 2.2).

The euro area, the second destination for Argentine exports, maintains a sustained pace of growth, according to data for the fourth quarter of 2017 and the leading indicators for the first quarter of 2018 (although with a slight slowdown in the margin in the latter case). GDP grew 2.7% in year-on-year terms in 2017, and 0.6% during the last three months of 2017. The latest projections of the European Central Bank (ECB) indicate growth of 2.4% and 1.9% for 2018 and 2019 respectively, (0.1 p.p more than in the previous projection for 2018, unchanged for 2019). Finally, the most recent labor market data in February show an unemployment rate of 8.5%, the lowest value since December 2008.

At the March meeting, the ECB kept its monetary policy interest rate at a record low of 0%. In turn, it did not modify the rate corridor, leaving the interest rate of the credit facility at 0.25% and the interest rate of the deposit facility at -0.4%1. Finally, the ECB maintained the inflation projected for 2018, at 1.4%, 0.1 p.p. below inflation in 2017.

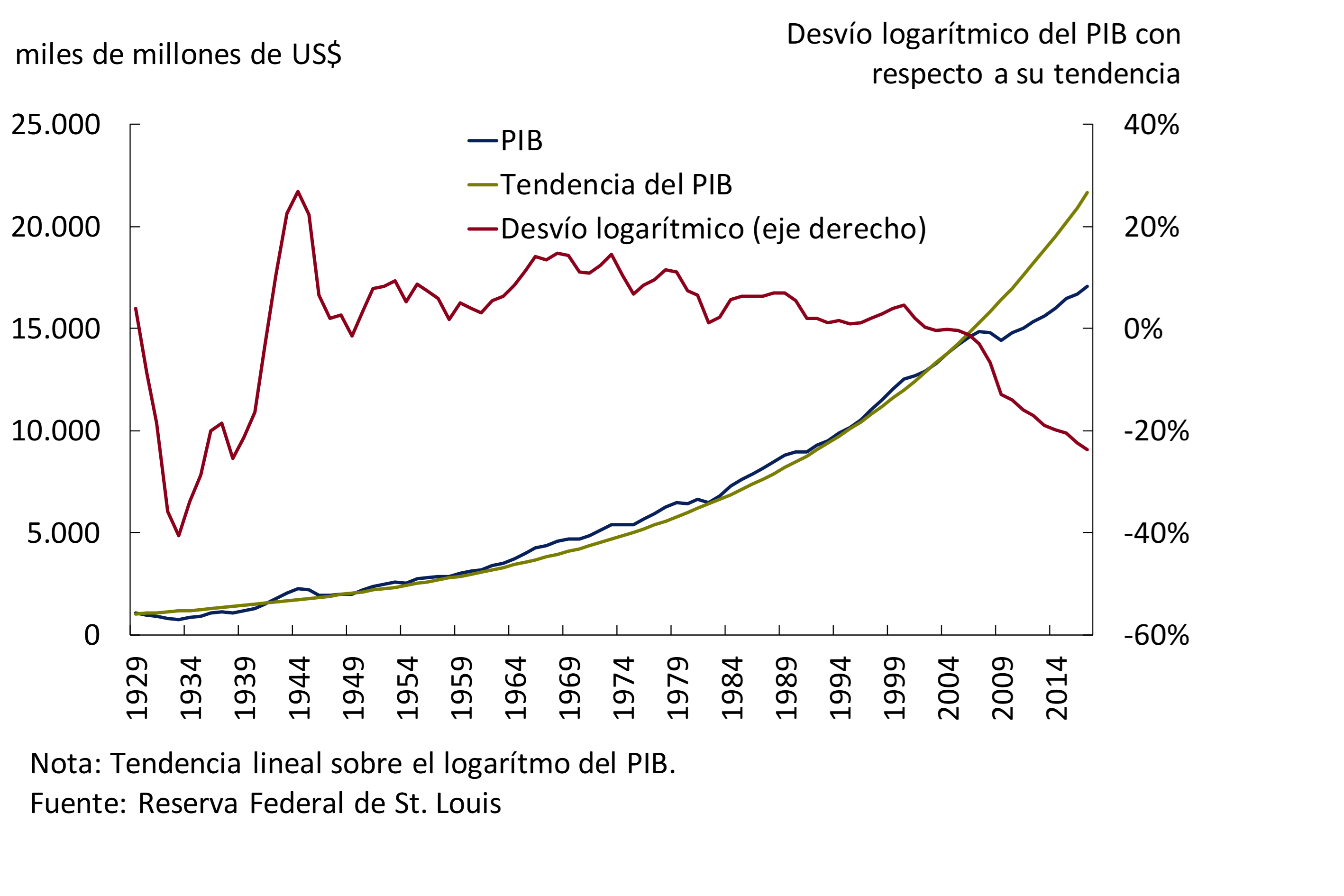

The United States – the third destination for Argentine exports – grew 2.3% in 2017. For its part, the Federal Reserve (Fed) increased its growth projections for both 2018 and 2019, to 2.7% and 2.4% respectively (0.2 p.p. and 0.3 p.p. more than in the current projection in the previous IPOM). This increase in growth projections is partly linked to the fiscal stimulus resulting from the recently approved tax reform. The unemployment rate (4.1% in March) remains at its lowest value since late 2000, and below the levels estimated not to accelerate inflation (NAIRU). Although the participation rate of the EAP increased, so did the employment rate. On the other hand, the analysis of other indicators such as the difference between GDP and the trend of GDP in the United States shows that there is room to continue with positive growth rates, without necessarily implying an acceleration of inflation (see Figure 2.3)2.

As was widely expected by the market, the Fed’s Monetary Policy Committee (FOMC) increased the benchmark interest rate again at its March meeting to the 1.5-1.75% range. The Fed projects further increases of 0.5 p.p. during 2018, while by the end of 2019 the FOMC projects a monetary policy rate 1.5 p.p. above that of the end of 2017. At the same time, the Fed continues with the process of normalizing its balance sheet.

Finally, China, the main destination for Argentina’s exports of primary products, had a GDP growth of 6.9% in 2017, mainly driven by consumption and investment. During 2017, the process of rebalancing its economy continued with a growing weight of consumption in aggregate demand, and a decreasing weight of investment (which, however, is still at high levels); At the same time, the levels of indebtedness that finance these investments were reduced. The most recent projections for 2018 show lower GDP growth at around 6.6%, mainly due to lower expected export growth.

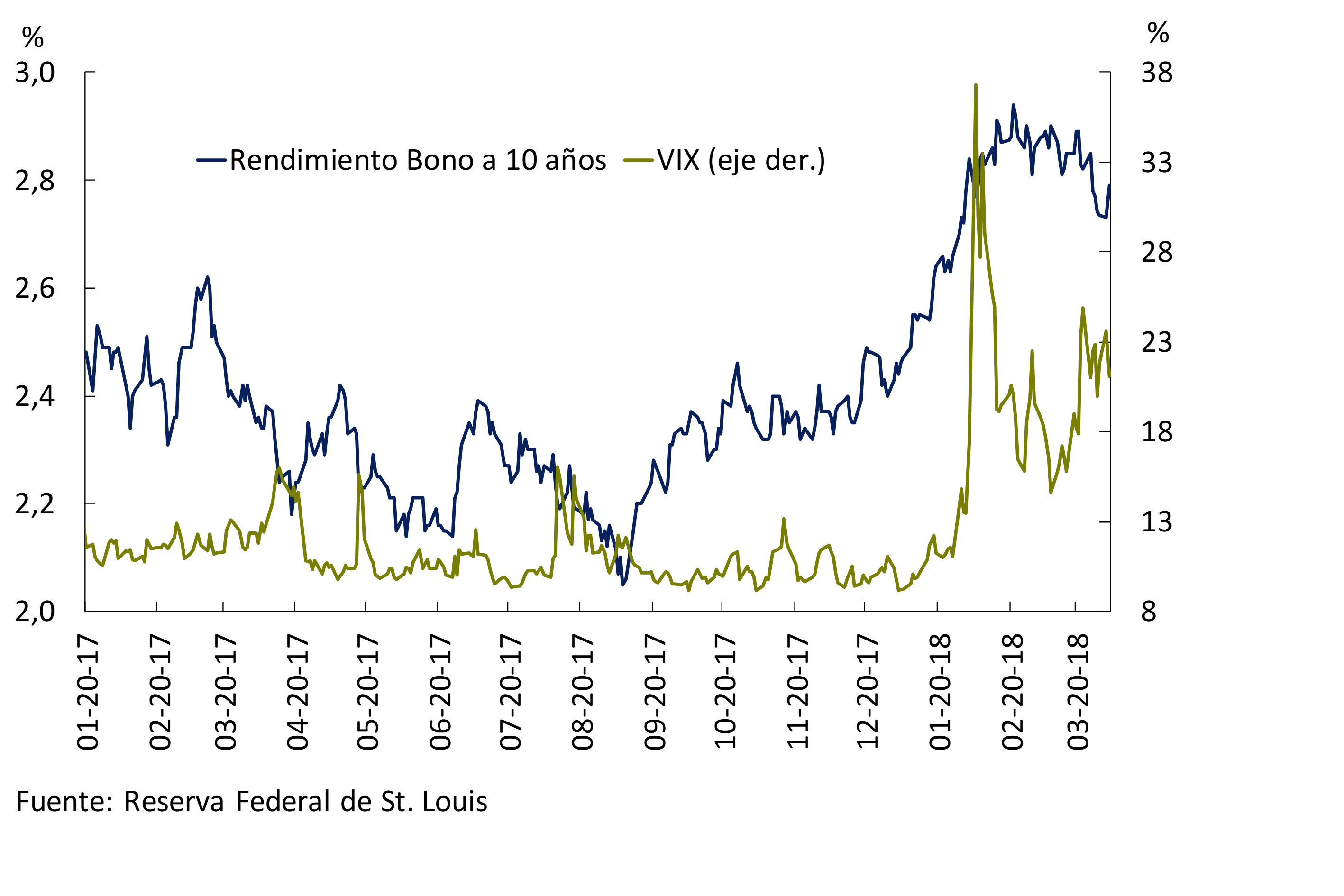

2.2 The external financial scenario remains favourable, although with some warning signs

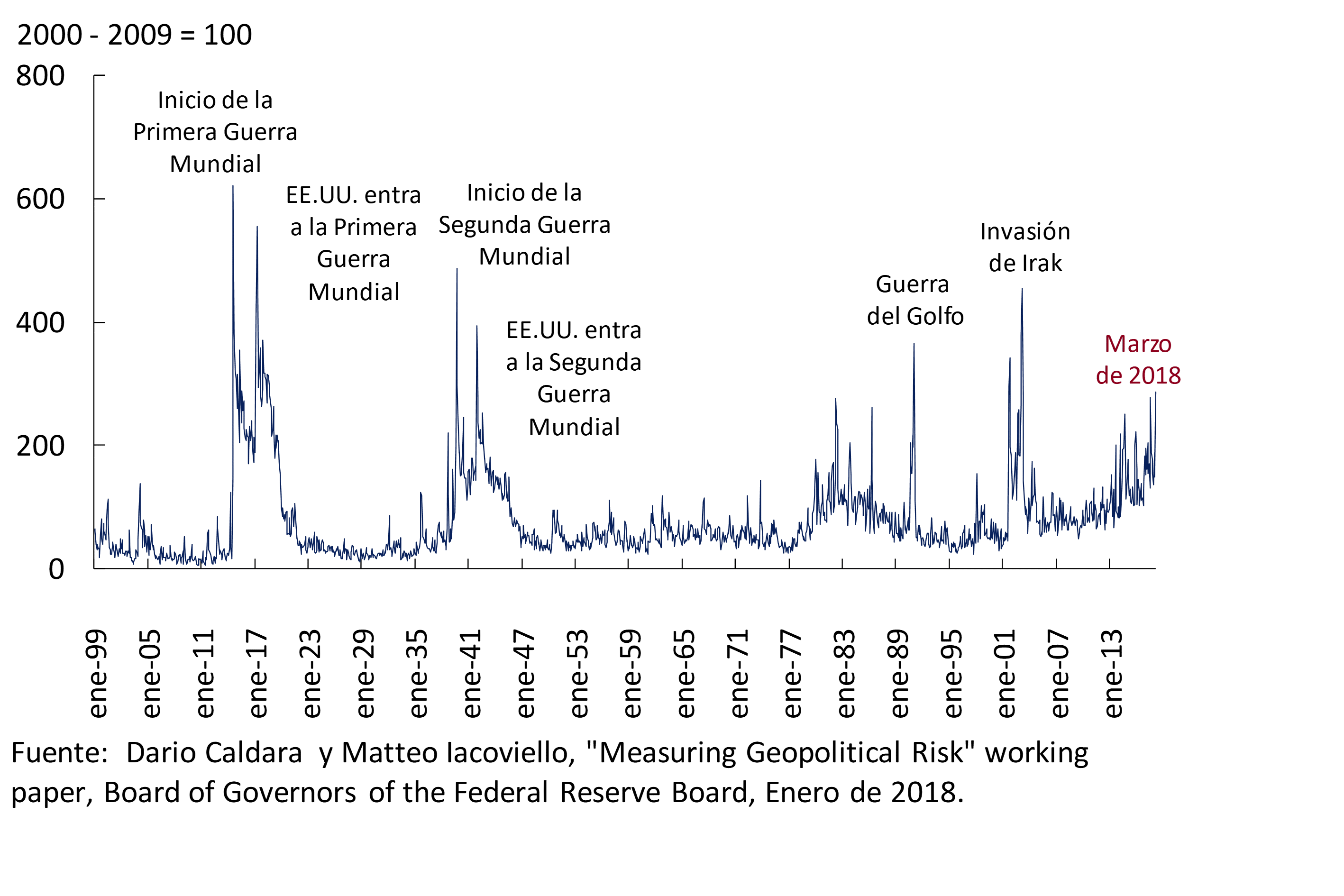

Global liquidity conditions remain accommodated for emerging countries in general and for Argentina in particular, although they worsened at the margin. During February and March, there was a significant increase in market volatility, along with higher yields on U.S. government bonds (see Figure 2.4). This was related to U.S. labor market data (which made a faster pace of increases in the Fed’s benchmark interest rate more likely), growing fears of a U.S.-China trade war, along with geopolitical tensions (see Figure 2.5), and the possible creation of new taxes on “digital companies.” among other factors.

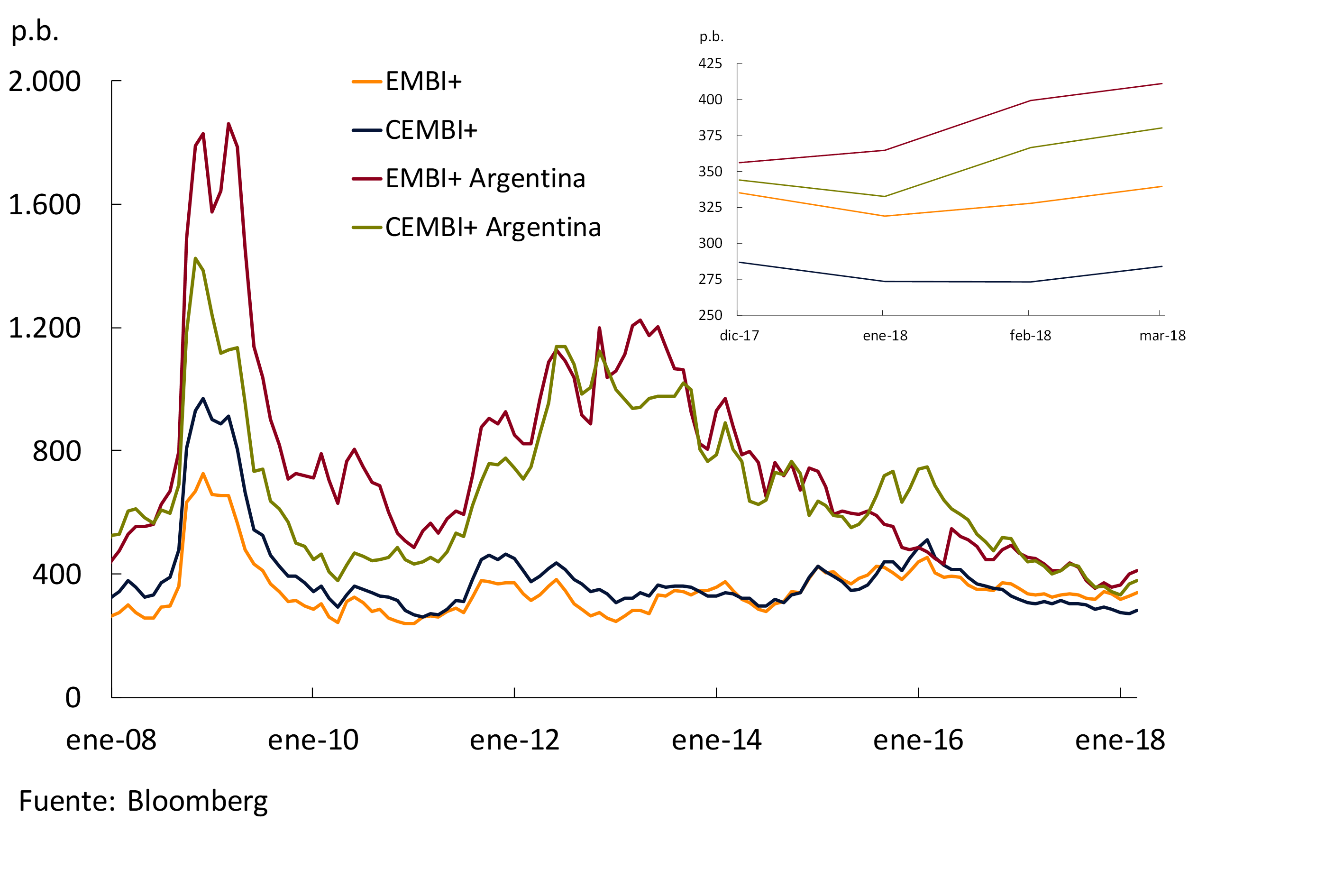

During the first quarter of 2018, emerging countries faced sovereign risk premiums similar to those recorded in recent years, reaching a minimum in early February and registering a slight upward correction in the margin. Corporate risk premiums exhibited a similar behavior, highlighting that they are still around the minimum levels of 2017.

For Argentina, external credit conditions have deteriorated somewhat so far in 2018. At the beginning of April, the cost of sovereign external financing was around 60 bps above the average for the last quarter of 2017. This increase was mainly determined by the rise in the risk-free external financing rate, in line with the monetary policies of the world’s main central banks3. Meanwhile, throughout 2018 the corporate risk premium (CEMBI+ Argentina) reflected a similar trajectory to the sovereign risk premium, although with a smaller increase (see Figure 2.6).

The amount of gross issuances of sovereign and corporate debt of emerging countries in international markets slowed down in the first quarter of the year. After growing 38% annually in 2017 (with an increase in the share of private sector placements), in the first quarter of 2018 there was a 7% year-on-year growth in corporate placements and a stagnation of sovereign ones. In the case of Argentina, the amount of gross debt issuances in international markets grew 5% in the first months of 2018 (total sovereign and corporate placements). Argentine sovereign issuances went from US$7 billion in the first quarter of 2017 to US$9 billion in the same quarter of 2018, while corporate issuances fell from almost US$2.3 billion to US$750 million in the same period.

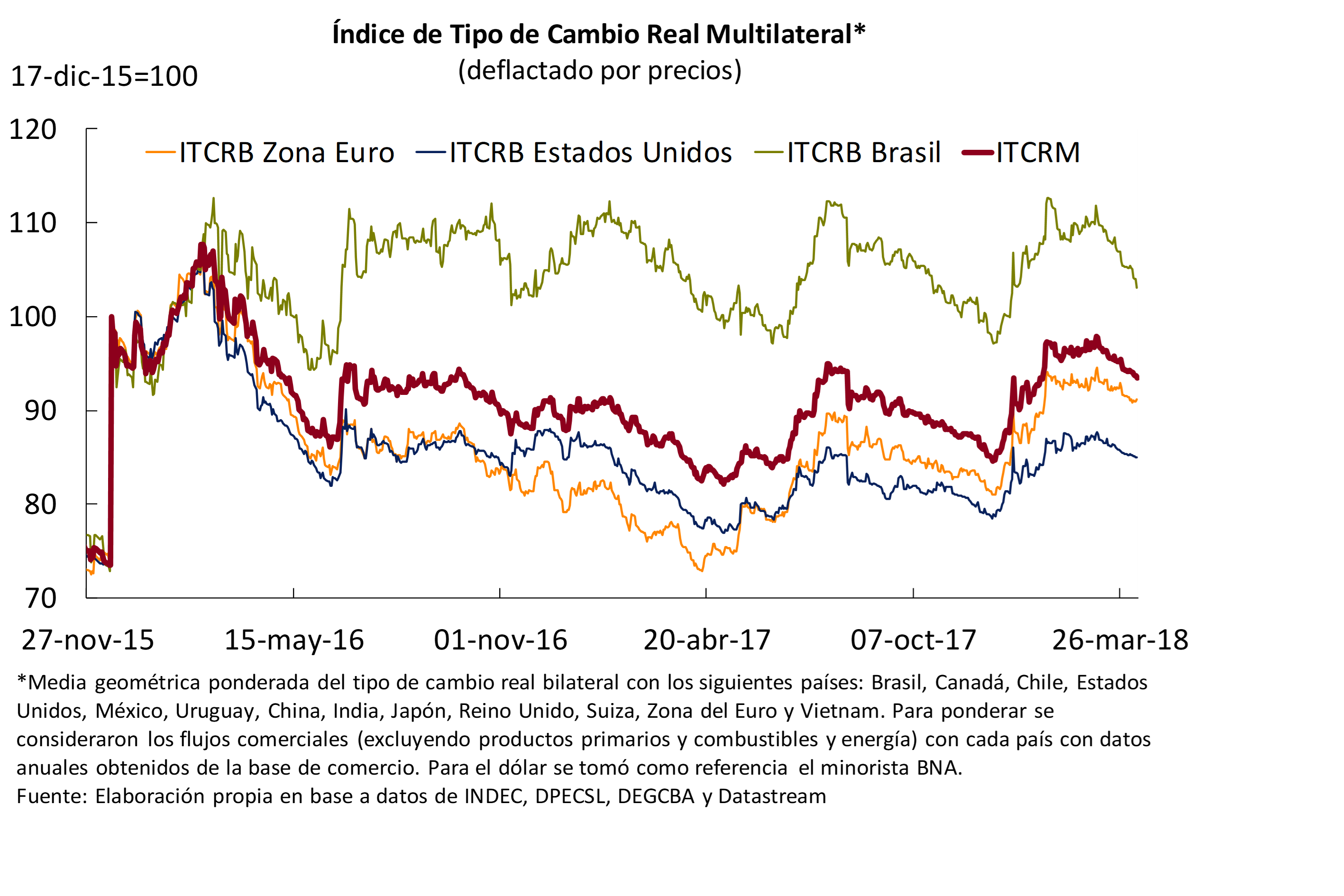

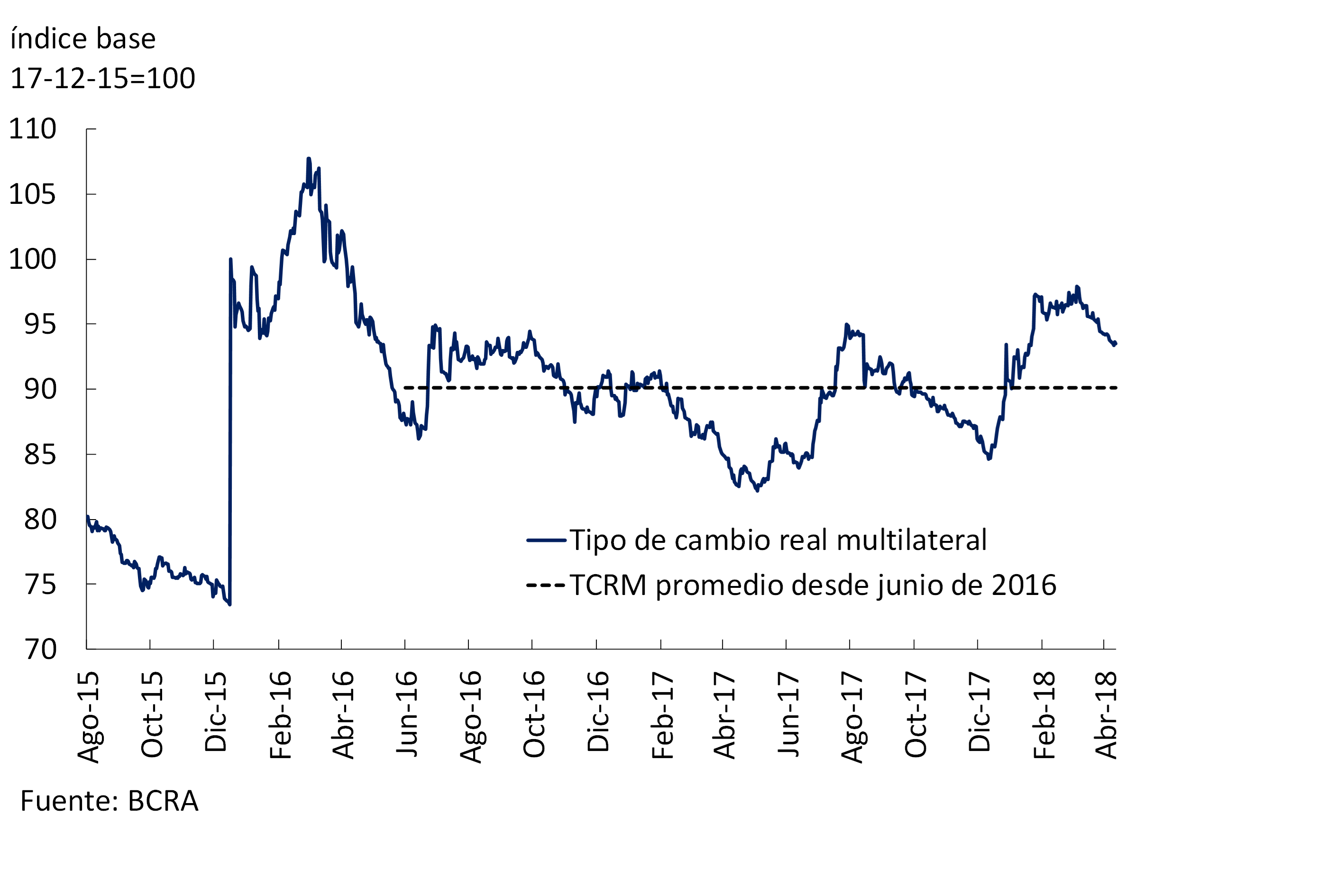

The combination of a less favourable external scenario and the drought affecting exportable balances led to a depreciation of Argentina’s multilateral real exchange rate, which nevertheless remained around the levels recorded after the adoption of the floating exchange rate regime. The Multilateral Real Exchange Rate Index (ITCRM) rose 8.2% in the first quarter of 2018, as a result of a nominal depreciation of the peso against the dollar at the same time as an appreciation against the dollar of the currencies of the country’s main trading partners. Higher relative inflation in the domestic economy partially dampened nominal depreciation. The volatility exhibited by Argentina’s real exchange rate is similar to that of other countries in the region with similar exchange rate regimes (see Figure 2.7).

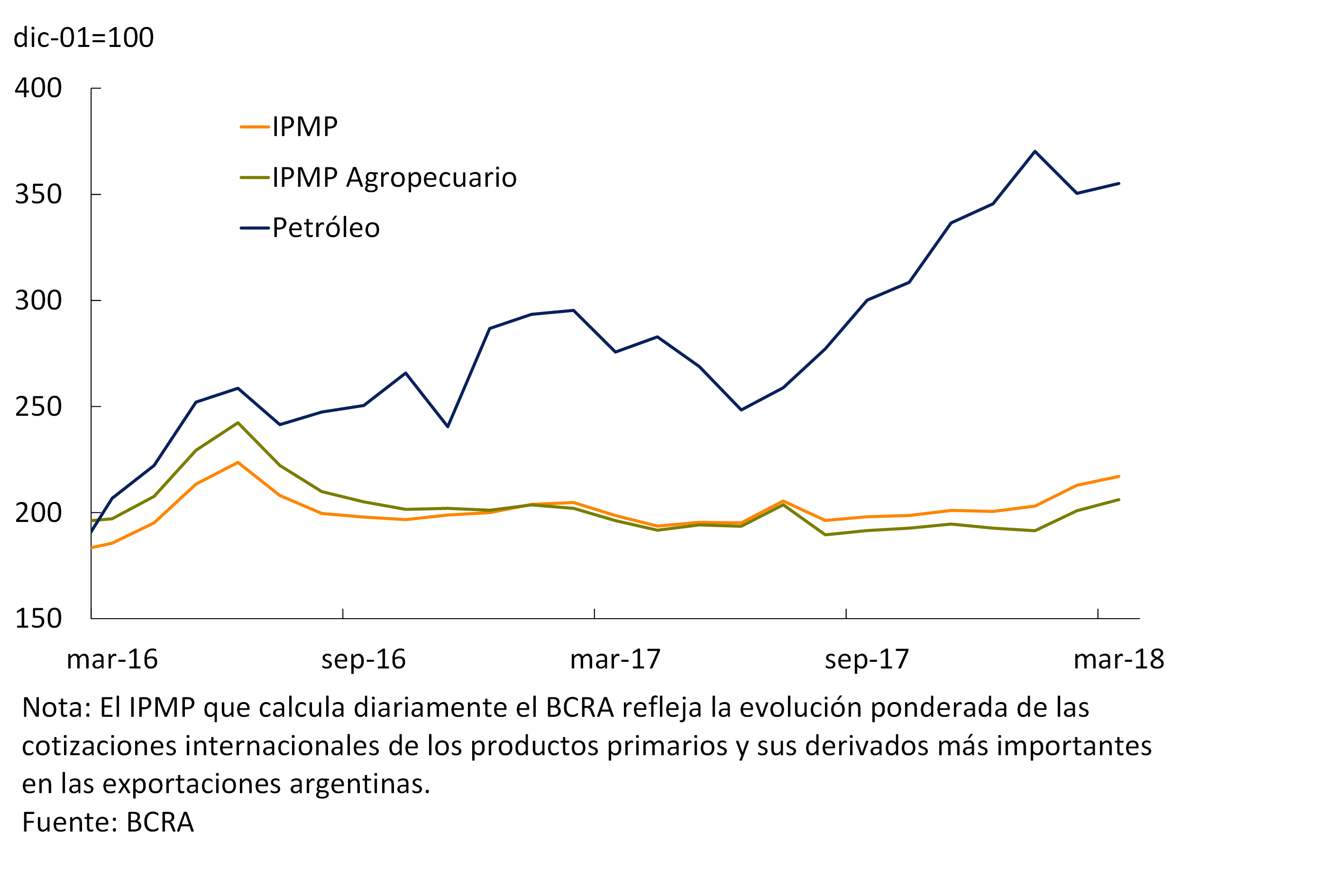

On the other hand, international prices of primary goods measured indollars 4 rose 7% in the last 3 months, driven by the 7% increase in agricultural products – with price increases in products of the soybean complex of 11% since December 2017 (17% y.o.y.), due to the drought that affected the coarse harvest in Argentina. To a lesser extent, the 3% increase in the international value of crude oil had an impact. In year-on-year terms, they grew 9%, with a marked increase of 29% YoY in the case of oil and increases of 5% YoY and 10% YoY in the case of agricultural products and metals, respectively (see Figure 2.8).

Recently, China announced the imposition of a 25% tariff on soybean imports from the United States5. Immediately after the announcement, the price declined accumulating a 3% drop (later reversed the decline). This can be understood through the model of Gardner and Kimbrough (1990)6. Because there is no other soybean producer globally capable of completely replacing U.S. supply, the price of soybeans for Chinese importers should increase, so the quantity consumed by Chinese importers should decrease. Since China is one of the main demanders of this product, the market price of soybeans could fall in world markets in the coming months. However, for Argentine producers, on whom no tariff has been imposed, the price of soybeans actually charged should not fall and could even improve from the conditions prior to China’s measure7. They could take advantage of the gap caused by such a tariff, selling at a price higher than that received by U.S. producers.

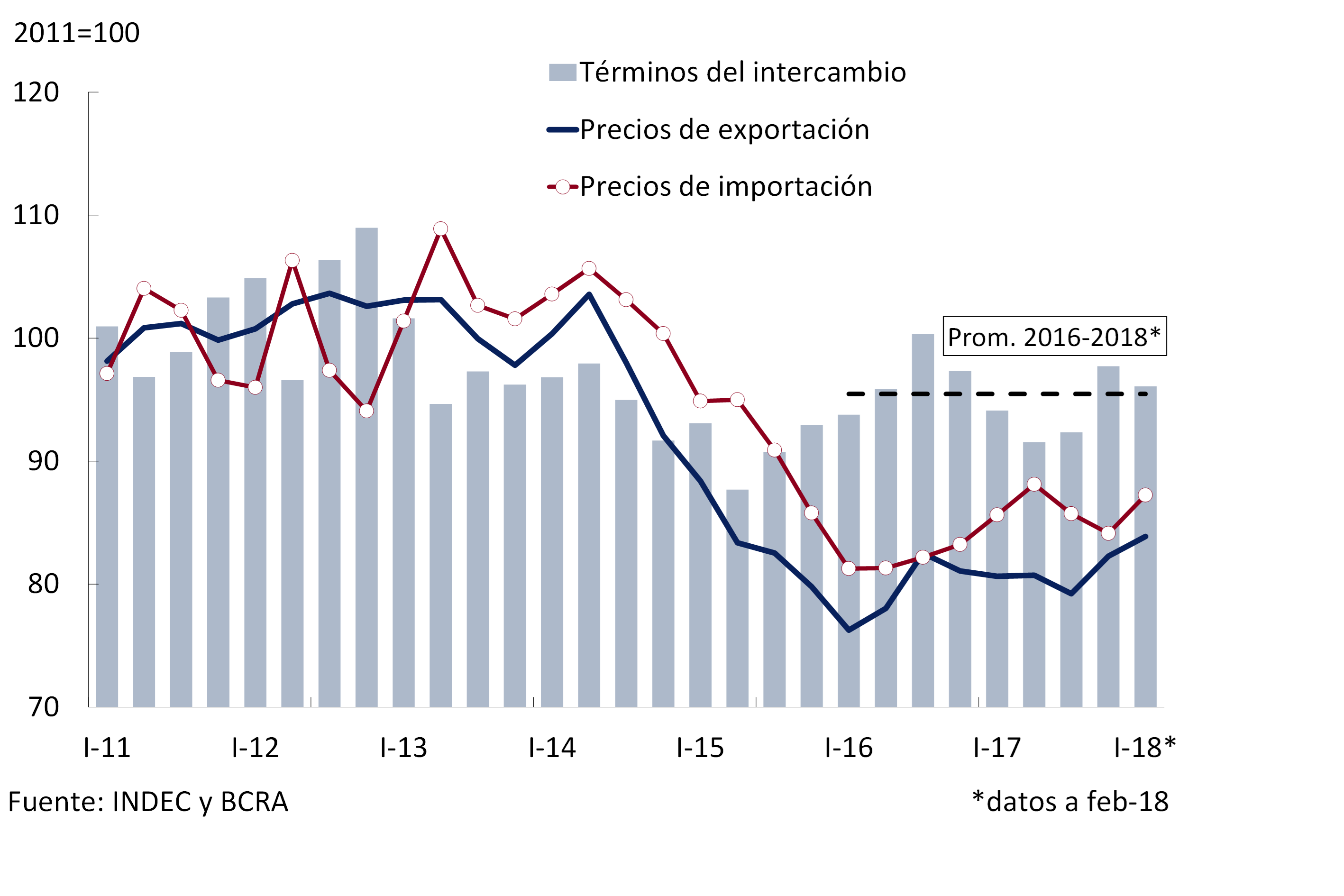

Finally, the terms of trade (quotient between Argentine export and import prices)8 fell slightly in the first quarter of 2018, as a result of a greater rise in import prices than in export prices. In any case, they are at a level similar to the average of the last 2 years, around which they have been oscillating in recent quarters (see Figure 2.9).

In summary, an improvement in the level of global activity is expected, especially in Argentina’s main trading partners, with a positive impact on exports. Financing conditions for emerging markets remain favorable, albeit with some red flags on the sidelines. However, this scenario could deteriorate if the Fed’s withdrawal of monetary stimulus is accelerated, or if protectionist measures are deepened.

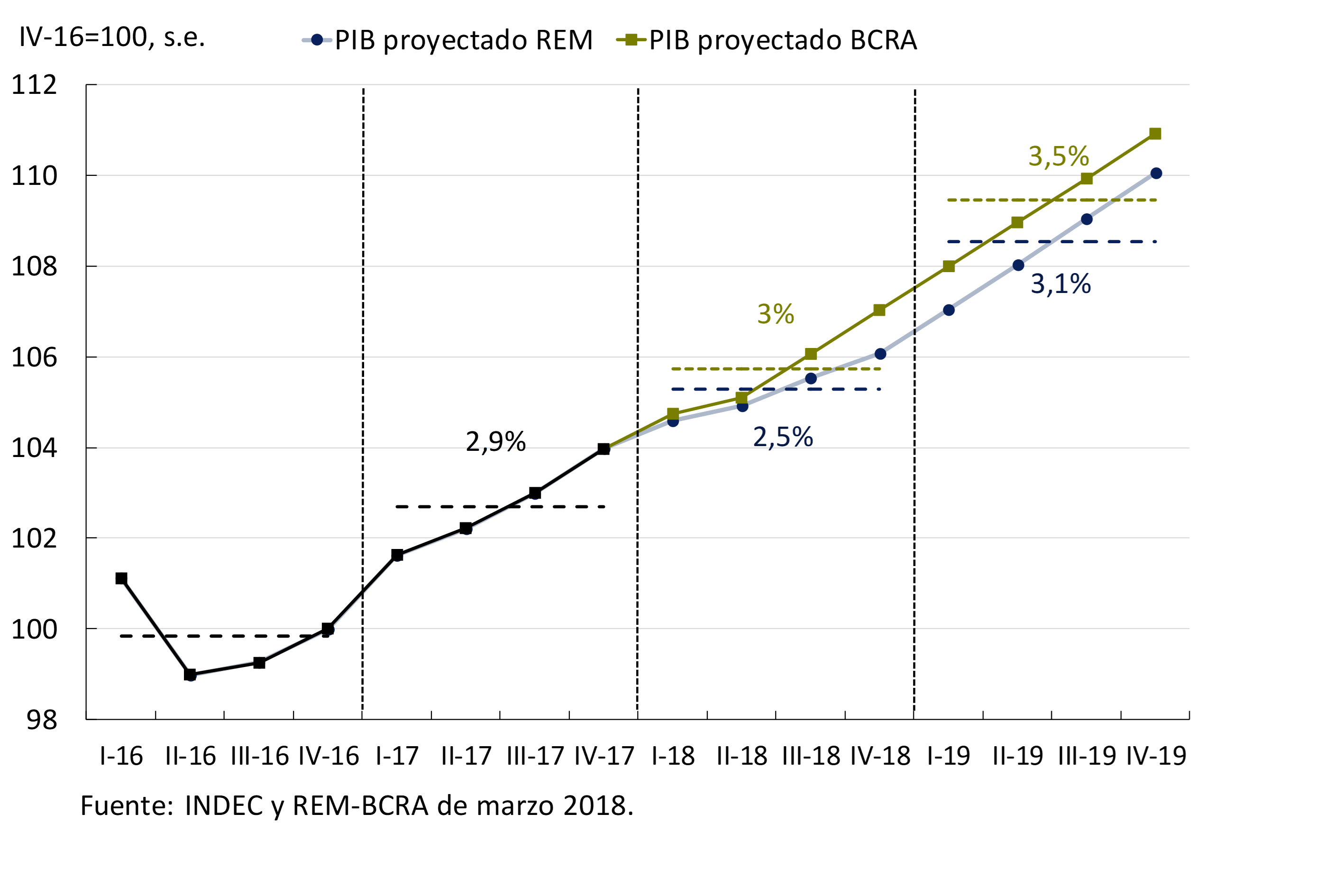

3. Economic activity

The economy continues in a phase of expansion, growing at a sustained pace. Investment closed 2017 with a strong increase and is expected to continue leading the expansion of aggregate spending in 2018. Private consumption will grow due to the favorable prospects of increasing employment and credit. In contrast, public consumption grew below the rest of the components, in line with the expected fiscal consolidation. Exports would contribute positively, driven by the higher growth of our trading partners, in particular the recovery of the Brazilian economy, rather than offsetting the impact of the drought on the quantities exported. At the sectoral level, the expansion phase is widespread and accompanied by increases in productivity in most sectors. The BCRA forecasts a negative impact of the drought on GDP in the second quarter of 2018, although several factors suggest that this effect will be cushioned without affecting medium-term growth prospects. This view is shared by the participants of the Market Expectations Survey (REM), who project that growth will slow down in 2018 (2.5%) and then return to growth of 3.1% and 3.0% in 2019 and 2020, respectively.

3.1 The economy continues to expand after surpassing the previous high

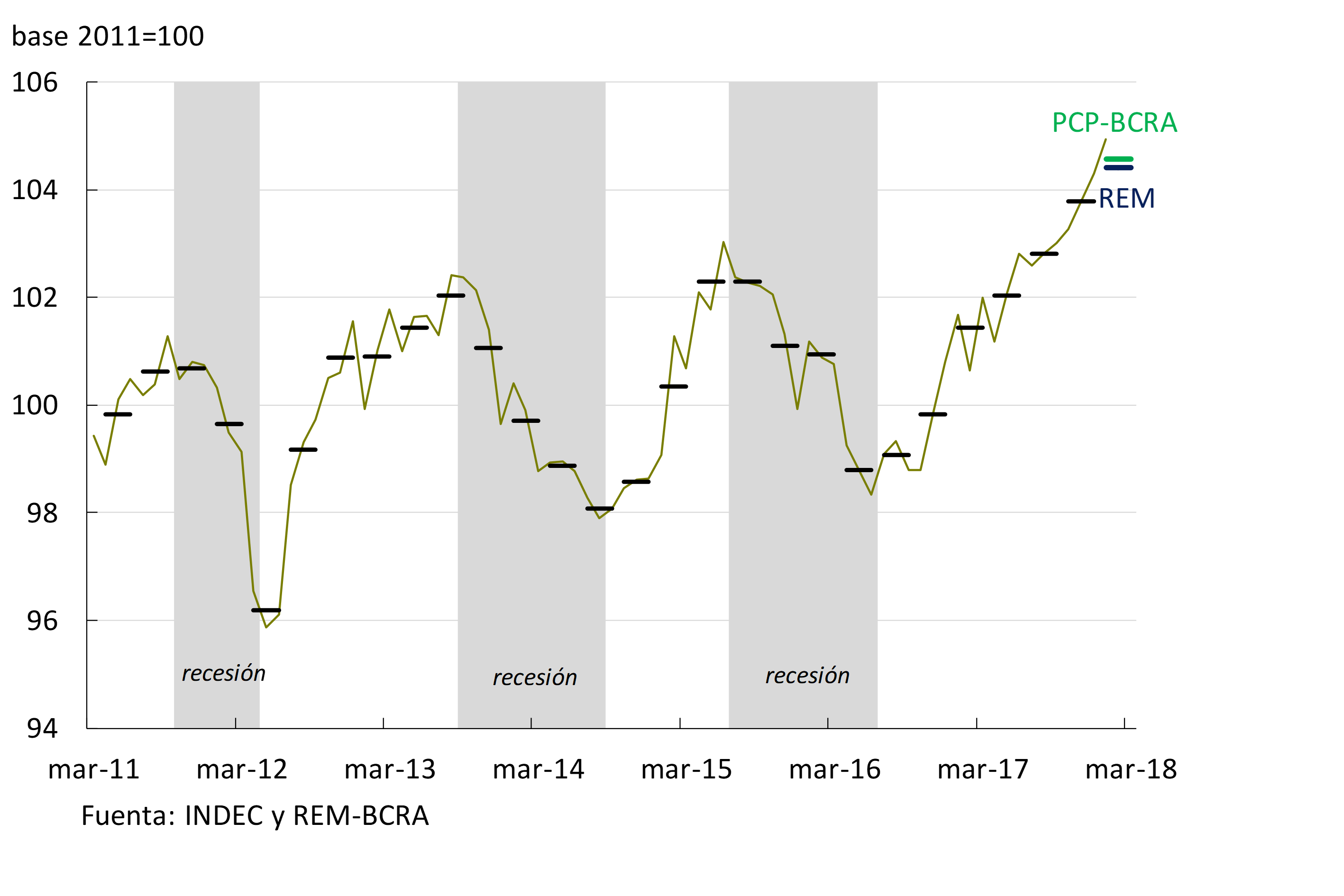

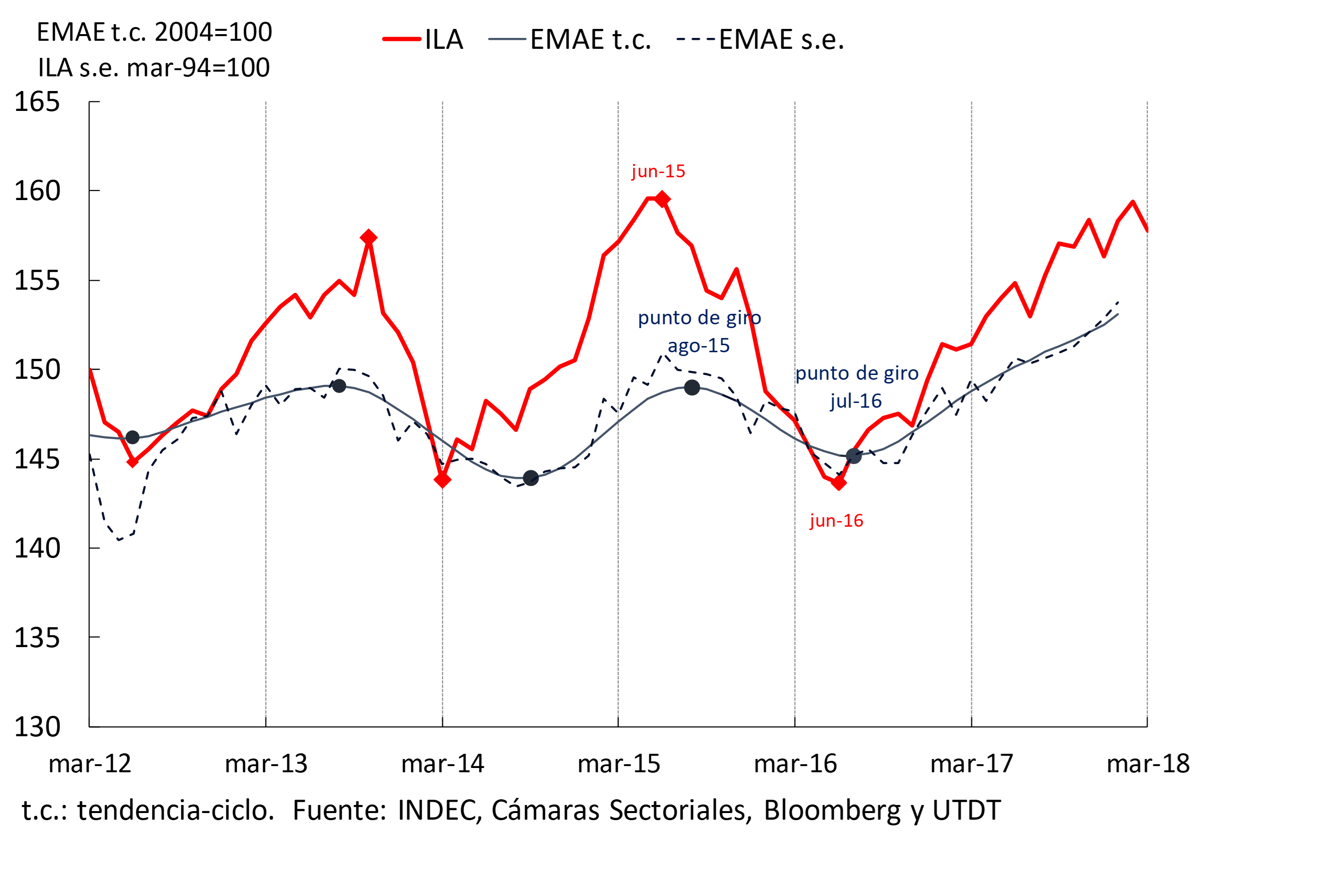

In line with what was anticipated in the January IPOM, GDP grew 4% s.e. annualized in the fourth quarter of 2017, maintaining a similar rate of expansion during 2017 (see Section 2. Performance Assessment of the BCRA’s Contemporary Output Forecast). During the first quarter of 2018 the economy continued to expand, completing seven quarters of uninterrupted growth for the first time since 2011. The latest Contemporary BCRA GDP Prediction (PCP-BCRA) indicates a quarterly increase of 0.73% without seasonality (s.e.). The level of economic activity would be 2% above the peak reached in 2013 and 2015 at the end of the first quarter. In those years, the peak of activity was followed by recessions that implied cumulative falls in GDP of 3.9% and 3.4% respectively, highlighting restrictions on productive supply (see Figure 3.1). The current expansion phase stands out both for its longer duration compared to the last three recoveries and for its low volatility.

The BCRA’s Leading Indicator of Activity (ILA) shows no signs that the economic recovery that began in the third quarter of 2016 is running out of steam9 (see Figure 3.2). Although the drought that affected much of the country’s main agricultural areas will have a negative impact on economic activity in the second quarter, this adverse shock is expected to be transitory.

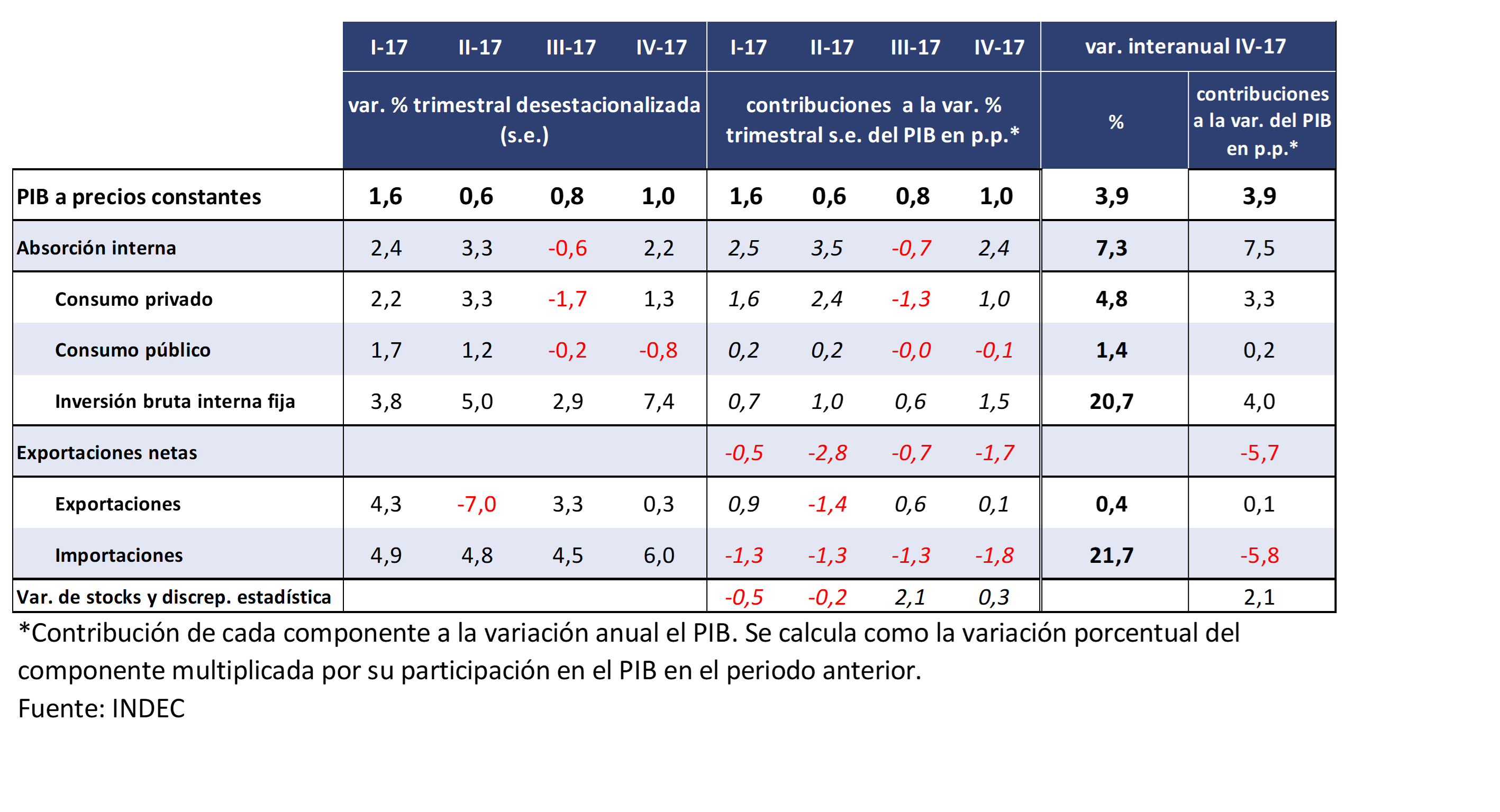

3.1.1 Investment is the component of demand with the greatest impact on growth

In the fourth quarter of 2017, domestic demand grew 2.2% s.e., highlighting the strong rise in investment (gross fixed capital formation; 7.4% quarterly s.e.). Compared to a year ago, local demand grew by 7.3%, with an incidence of 4 percentage points (p.p.) of investment (see Table 3.1). Private consumption increased 1.3% s.e. (4.8% y.o.y.) in the last quarter of the year, while public consumption fell 0.8% s.e. (grew 1.4% y.o.y.).

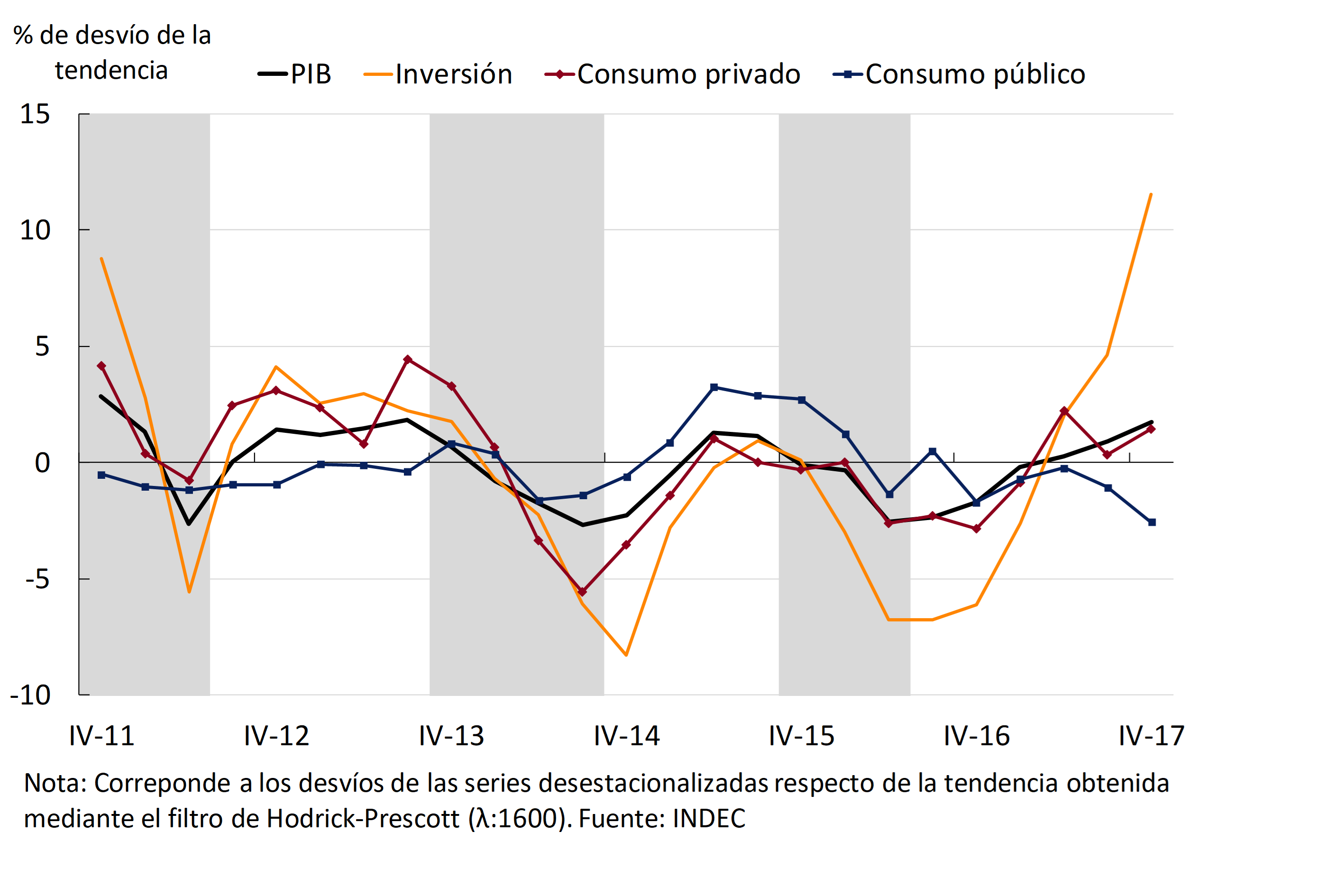

Thus, the expansionary phase that began in the second half of 2016 is characterized by a strong dynamism of investment, with a performance higher than that observed in previous recoveries. In the fourth quarter of 2017, after six consecutive quarters of growth, investment was 11.5% above its medium-term trend (see Figure 3.3).

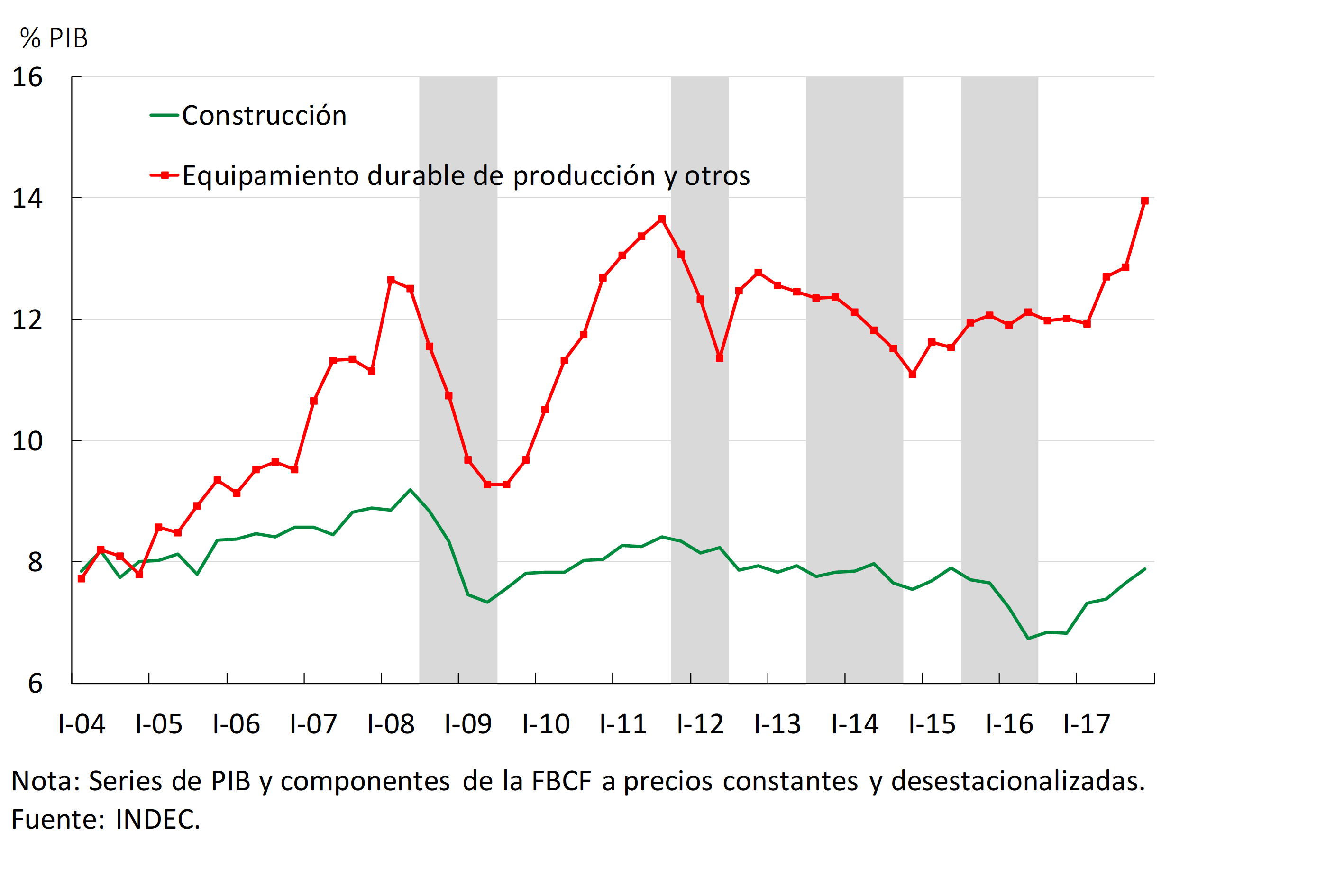

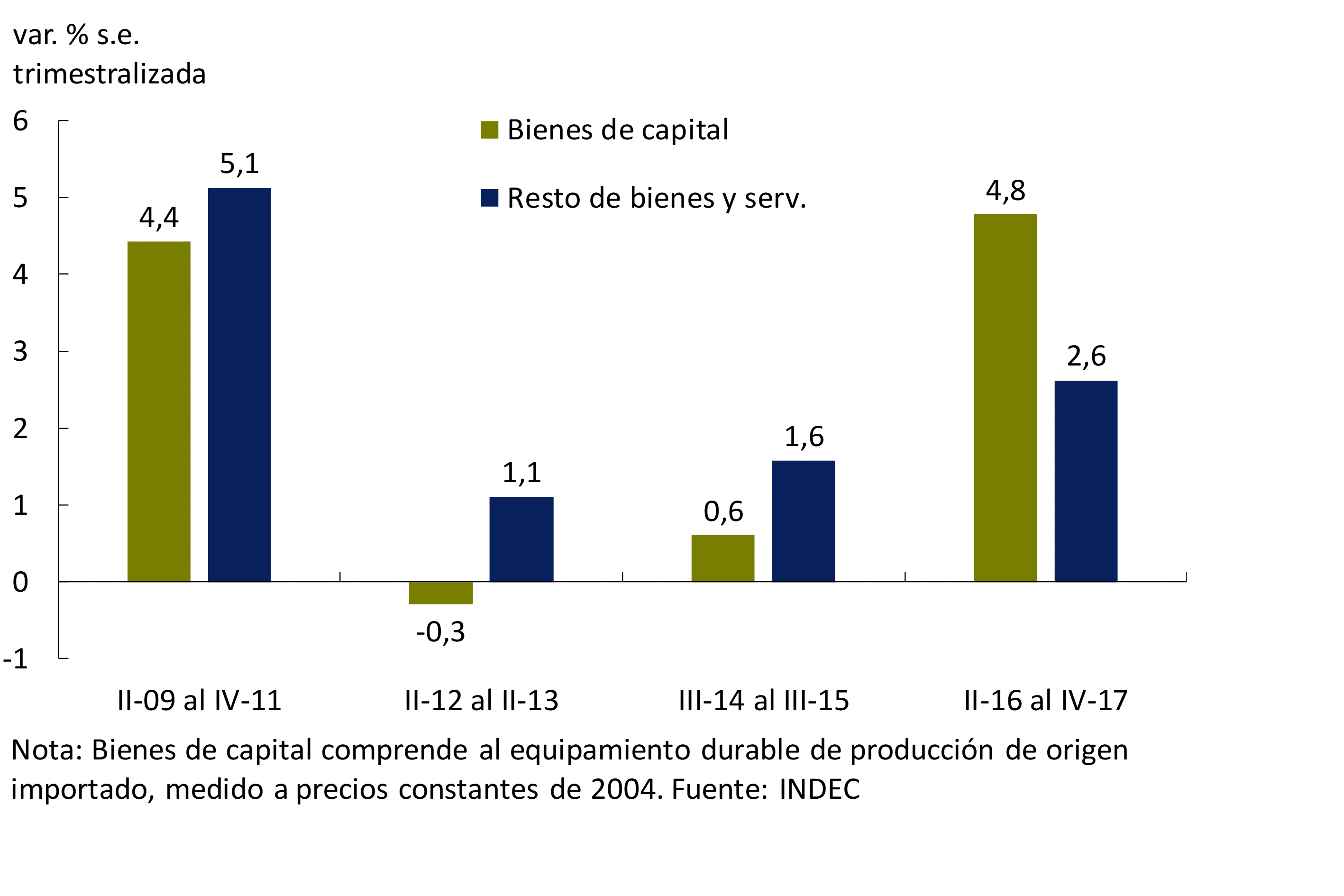

The growth in investment in the fourth quarter of 2017 was due to the combined increase in real spending on construction (3.9% quarter-on-quarter) and durable production equipment (8.5% s.e.), with a notable relative improvement in equipment of national origin (11.7% s.e.). On average in 2017, investment increased 11.3% YoY, the largest increase since 2011.

The investment rate10 stood at 21.8% at the end of 2017, very close to the maximum recorded in the third quarter of 2011 (22.1%) and with a greater share of spending on durable equipment11, which reached an all-time high (13.9% of GDP). Construction has also gained share of output since mid-2016, although it is below the 2011 level (see Figure 3.4).

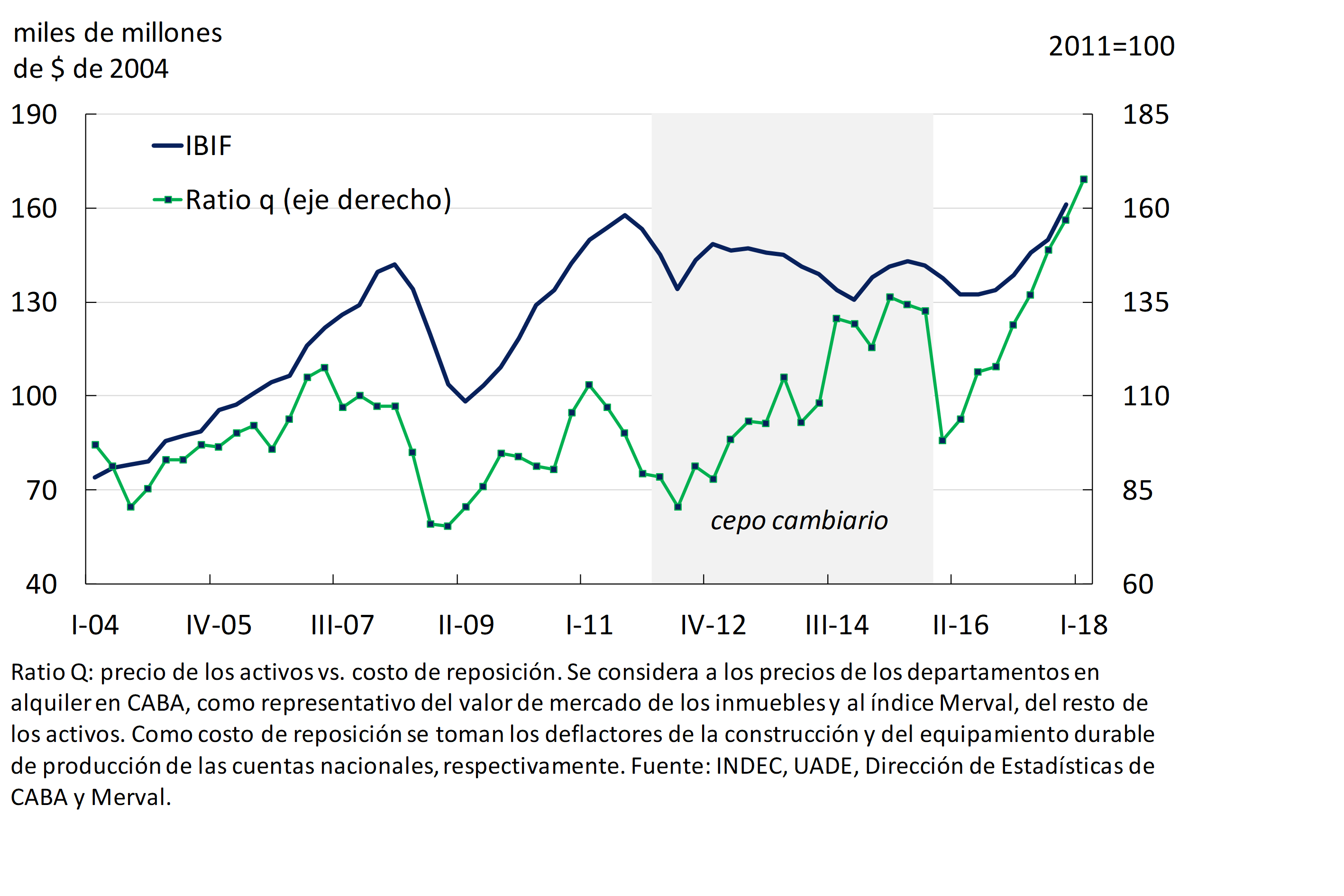

In the first quarter of 2018, leading indicators suggest that domestic demand continued to rise, driven by investment in a context of favorable relative prices. The Q ratio, which relates the market value of the invested assets to their “real” replacement cost, maintained its positive trend at the beginning of 2018. When this ratio rises, investment responds positively, with the exception of the 2013-2015 period, which is atypical, evidencing the impact of exchange restrictions (stocks) and the expectation of economic reforms that would improve the business climate. This market optimism did not translate into an increase in investment until the macroeconomic reorganization took place. The strong increase in the Q-ratio during 2017 and early 2018 suggests that investment will continue to show positive dynamics in the coming months (see Figure 3.5).

Imported quantities of capital goods rose 2.5% s.e. in the first two months of 2018 compared to the last quarter of 2017. With data as of February, the IBIF-BCRA12 indicator, whose variation is a weighted average of the variations in the leading indicators, increased 0.2% s.e. compared to the previous quarter (11.3% y.o.y.). In the same sense, the Coincident Investment Index prepared by the Ministry of Finance registered a rise of 13.7% y.o.y.

3.1.2 Private consumption continues to rise, with a greater inclination towards durable goods

Private consumption increased by 1.3% quarter-on-quarter in the fourth quarter of 2017 (4.8% y.o.y.) in a context of rising wage bills in real terms and expanding credit to households. On average for the year, private consumption increased 3.6% compared to 2016.

Different indicators indicate that this growing trajectory would have been sustained at the beginning of 2018. With data from February, the BCRA13’s Leading Indicator of Private Consumption showed an increase of 0.9% s.e. compared to the last quarter of 2017 (see Figure 3.6). For its part, the Coincident Consumption Index of the Ministry of Finance increased 0.5% s.e. in the first two months. Personal and credit card loans grew 3.2% s.e. in the first quarter compared to the previous quarter in real terms.

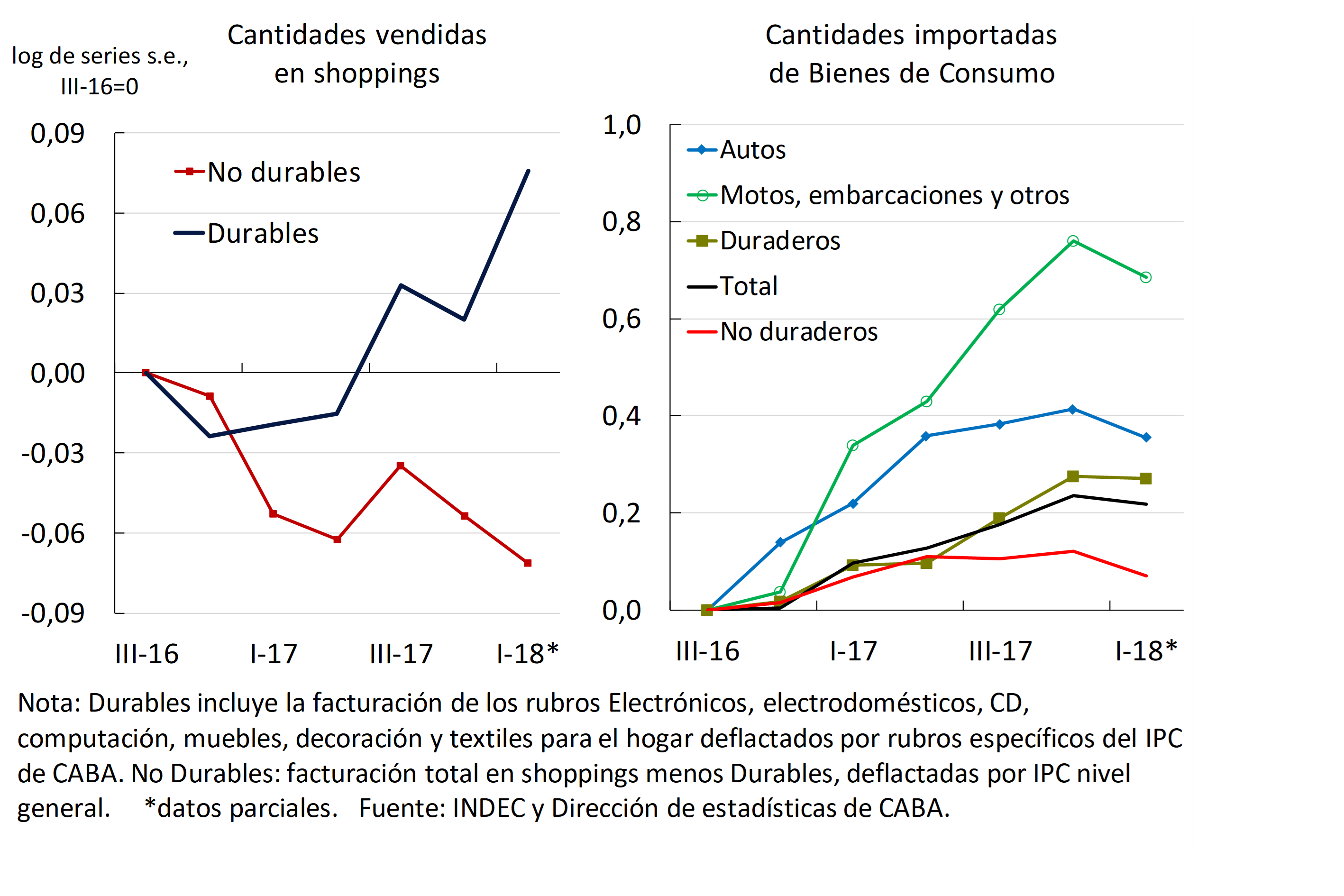

Partial indicators point to a higher relative consumer preference for durable goods. From the beginning of the economic recovery in the third quarter of 2016 until the latest available data, the units sold of automobiles in the domestic market accumulated an increase of 31% s.e. and those of household appliances and household goods of 22.6% s.e. In the same period, in the purchasing centers of Greater Buenos Aires, real sales of durable goods grew 7.6% s.e. while the rest of sales fell 7.1% s.e.14. Sales of used cars and motorcycles also showed increases. For its part, the Argentine Chamber of Electronic Commerce (CACE) pointed out that during 2017 more than 60 million purchase orders were placed, 28% more than in 2016. Among the most purchased categories, in addition to tickets and tourism, are Electro and air conditioning, Electronics, audio and video, Home and garden furniture and Computing.

The higher relative demand for durable goods compared to non-durable goods is also verified in imports of consumer goods. Between the third quarter of 2016 and February 2018, the quantities imported accumulated an increase of 21.8% s.e., which is made up of a strong increase in cars (68.5% s.e.), passenger transport equipment (35.5% s.e.), other durable goods (27% s.e.), while non-durable goods had a smaller increase (7% s.e.; Figure 3.7).

3.1.3 Current account reflects expansion in domestic demand

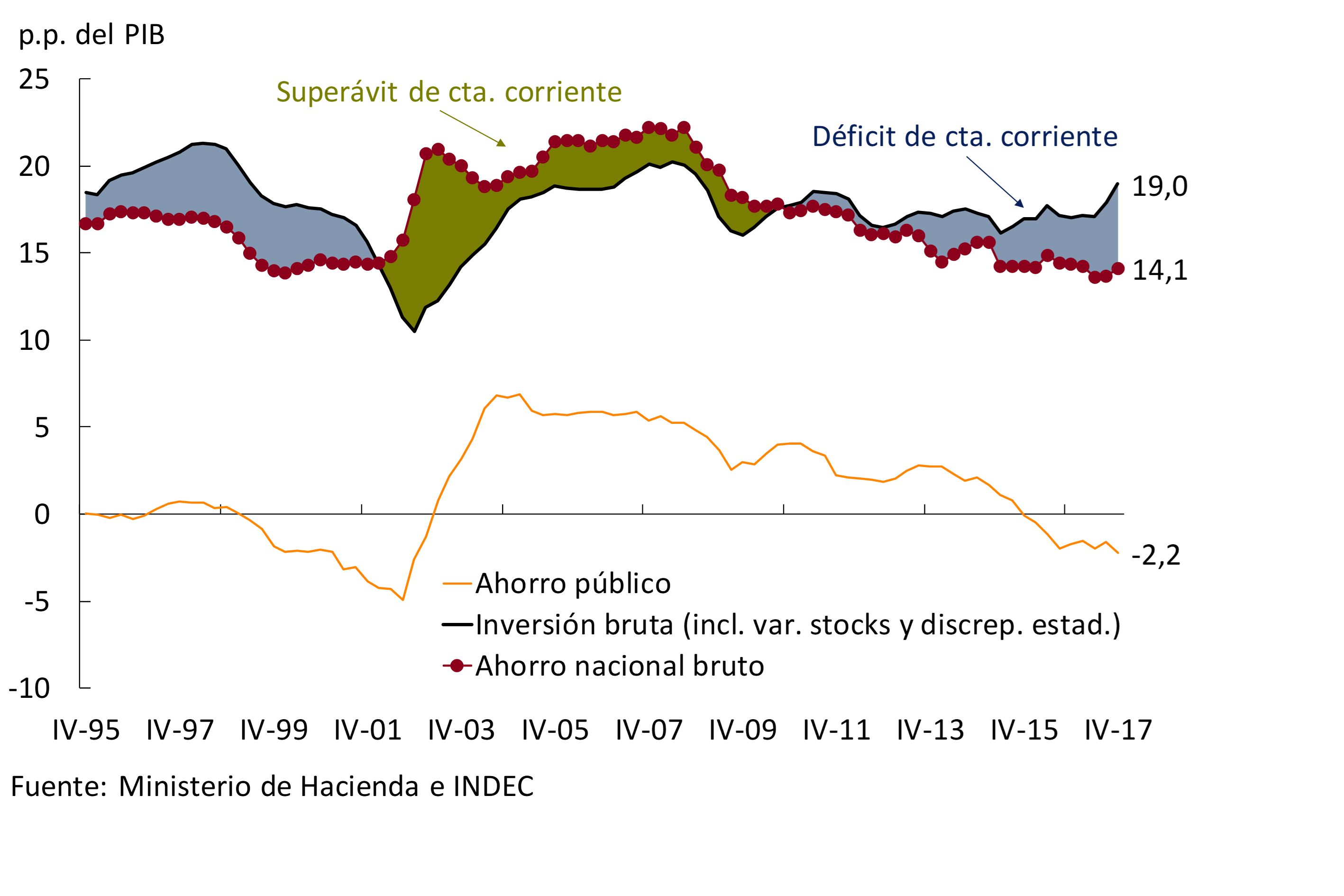

In 2017, the current account reflected the greater dynamism of absorption in relation to GDP, due to the strong rebound in investment that required greater financing from the rest of the world. Public dissavings remained significant but would gradually stabilize, in line with the achievement of fiscal targets (see Figure 3.8; Box Current Account, Savings and Investment).

Box. Current account, savings and investment

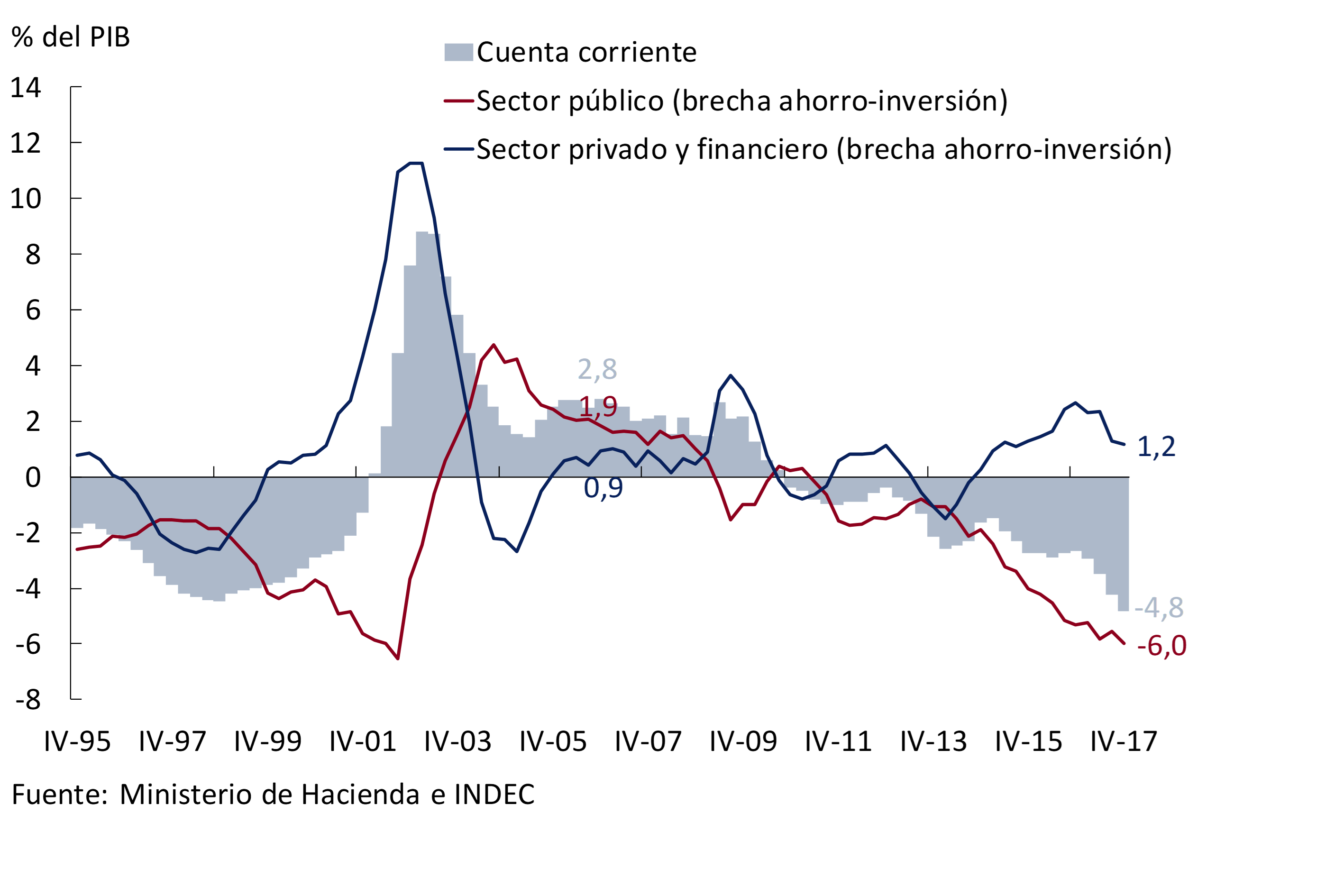

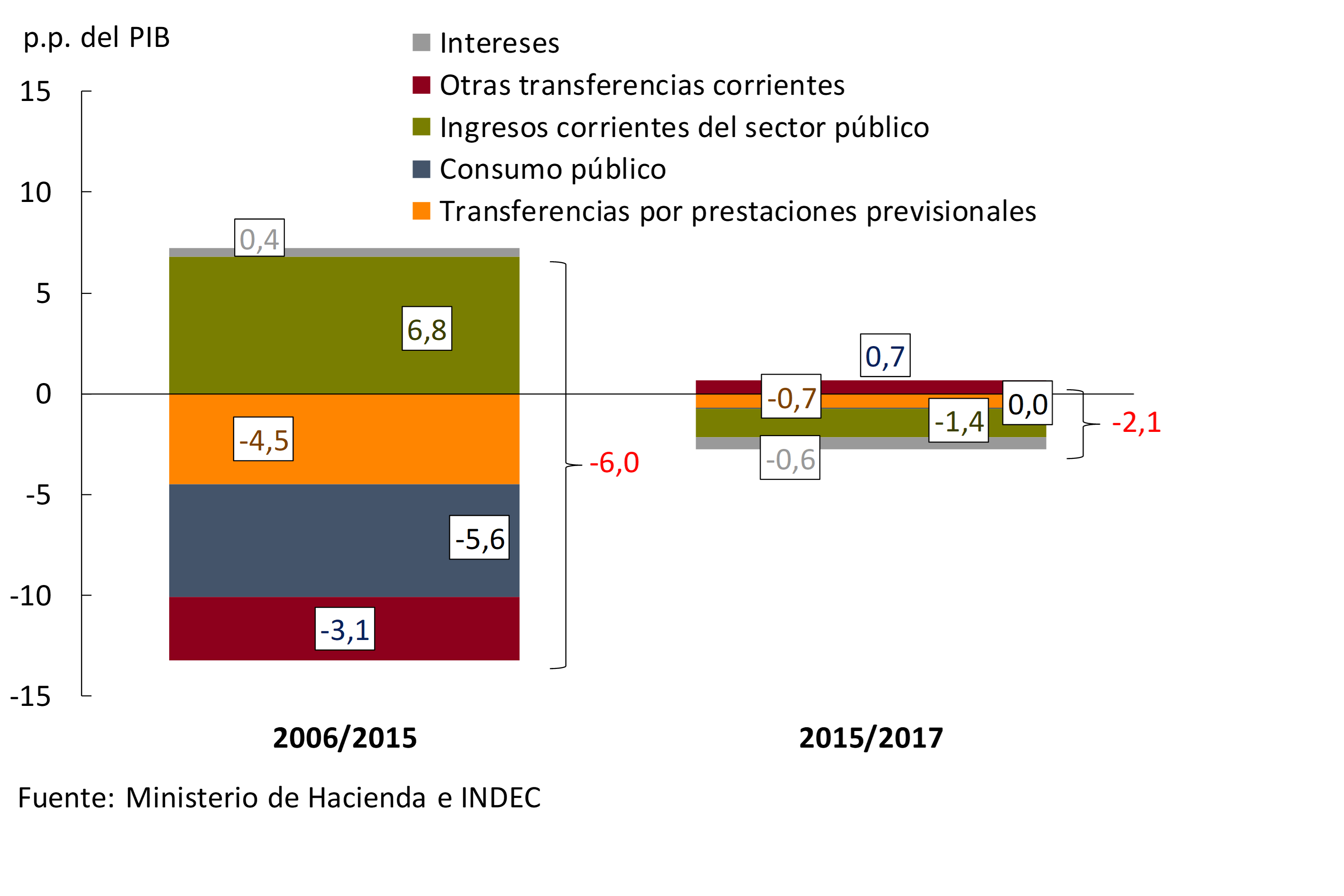

The increase in the current account deficit of the international balance of payments over the last twelve years is largely explained by the deterioration of the public accounts.

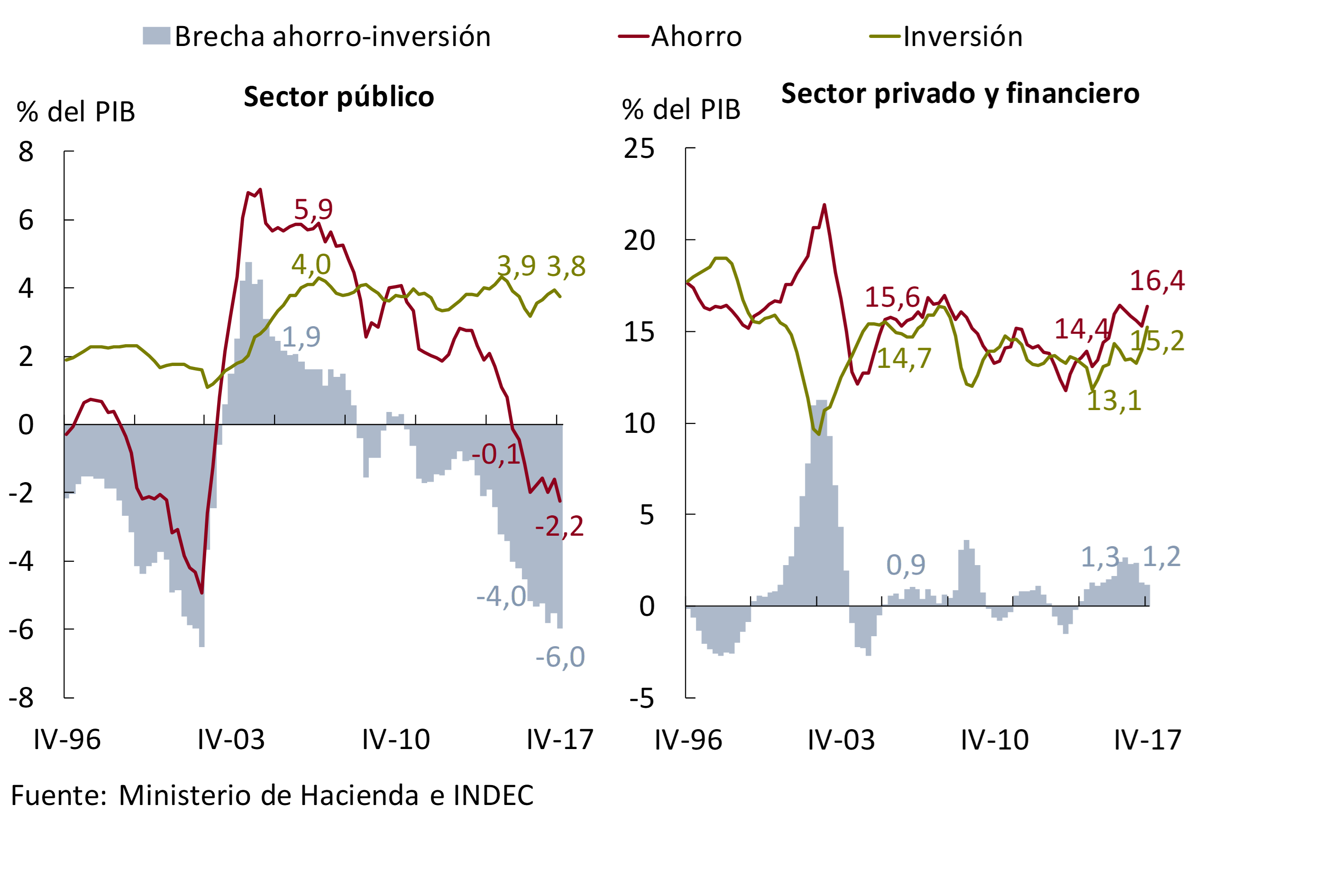

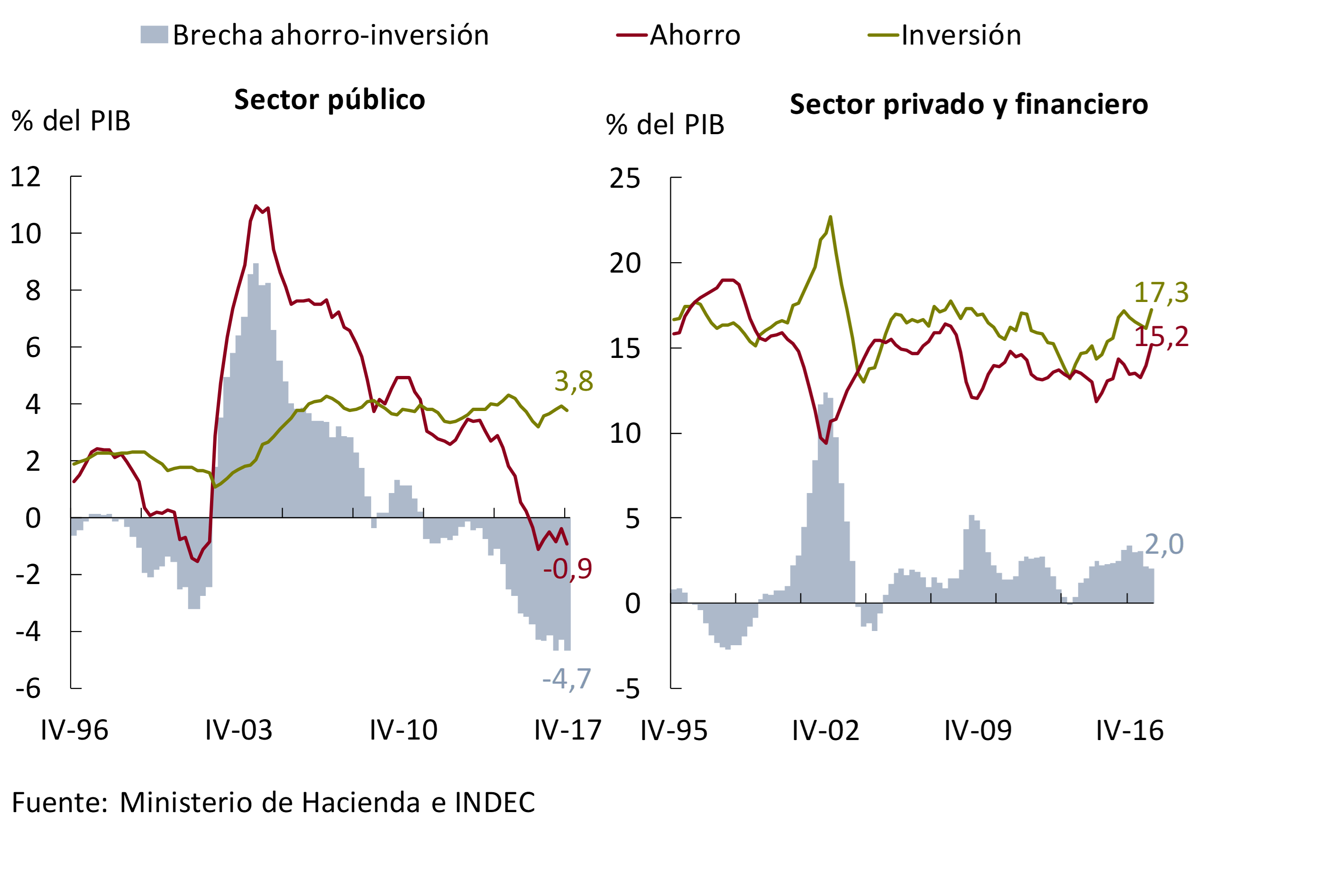

To carry out the analysis, a calculation of the gap between national savings and domestic investment was made. The public sector gap15 reflected a deterioration of about 8 percentage points of GDP between 2006 and 2017, a period in which the current account balance contracted by a similar magnitude. Meanwhile, the gap between the private and financial sectors oscillated around 1 p.p. of GDP (see Figure 3.9).

Figure 3.9 | Current account of the balance of payments (at current prices; rolling average 4 quarter)

Two periods can be distinguished depending on the dynamics of savings and investment in the sectors: between 2006 and 2015 and the last two years. The first period is characterized by a fall in private savings, public savings and private investment. Between 2006 and 2015, public savings fell by 6 p.p. of GDP due to increases in public consumption and transfers to private companies, despite an increase in the tax burden of 7 p.p. of GDP. On the other hand, between 2016 and 2017 the private sector transitioned towards higher savings and investment rates, in the context of a lower tax burden and higher rents paid to the private sector, which implied that public savings fell by an additional 2 p.p. of GDP (see Figures 3.10 and 3.11).

Figure 3.10 | Current account and gap between national savings and investment (at current prices; rolling average 4 quarter)

The relevance of net income payments to foreign factors is evident when, by excluding them from the calculation of savings and investment (i.e. only considering trade transactions with the rest of the world), both public and private savings show improvements. The gap in the public sector narrowed by 1.3 p.p. of GDP, while that of the private sector improved by almost 1 p.p. of GDP (see Figure 3.12).

Figure 3.12 | Trade balance and gap between domestic savings and investment (at current prices; rolling average 4 quarter)

In 2017, the private sector contributed a greater proportion to the financing of the current account deficit than in 2016, when net capital inflows of the public sector had played a preponderant role. The sum of income from direct investment and portfolio instruments issued by the private sector is at an all-time high. This development is to be expected in a context of greater financial integration following the resolution of the conflict with external creditors in 2016 (see Figure 3.13).

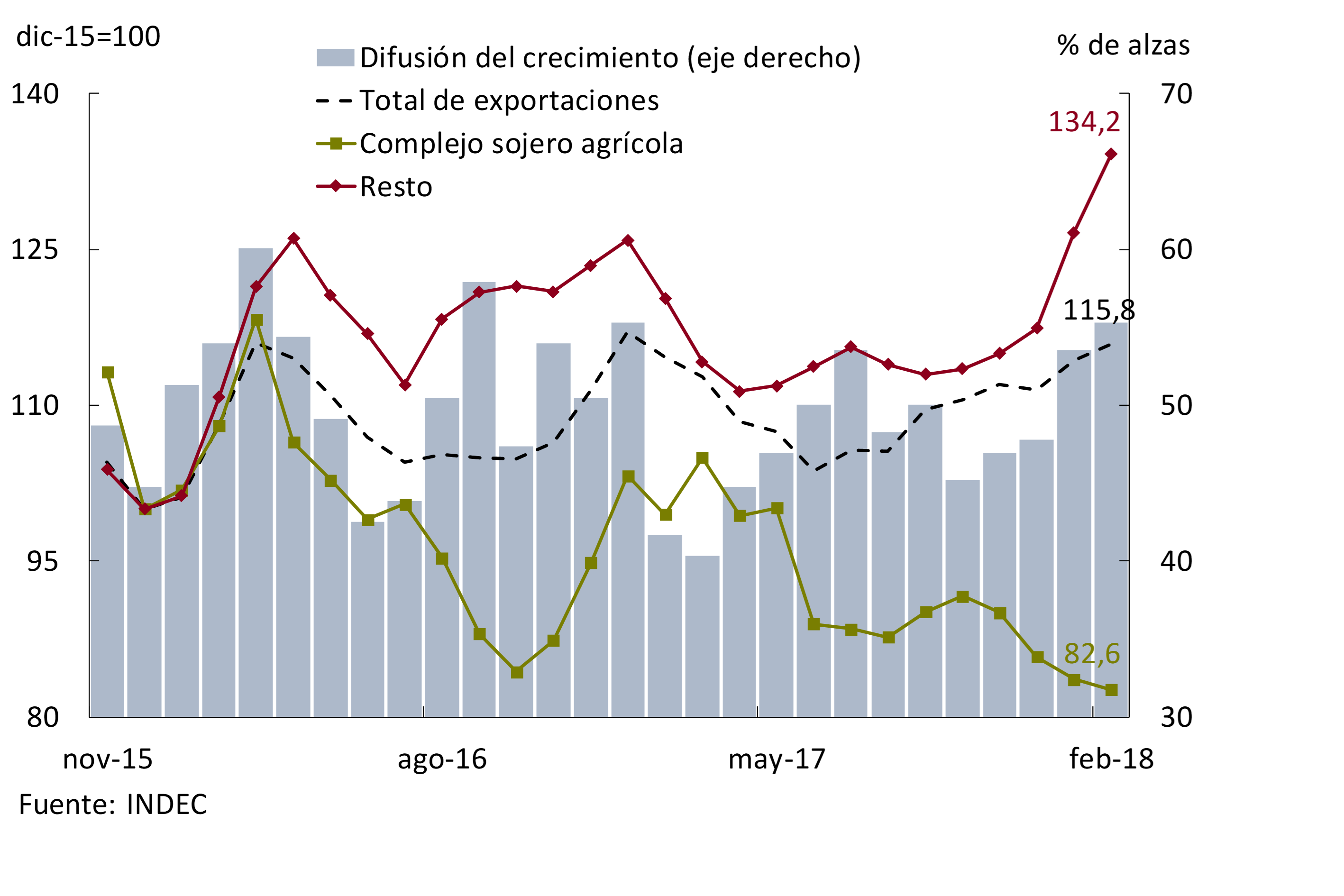

In the first months of 2018, certain changes in the dynamics of the external sector were observed: the quantities exported of goods grew 8% s.e. compared to the fourth quarter of 2017 and accumulated 16% s.e. since June 2017. Throughout this period, shipments of cereals, meat, base metals and vehicles stood out. The diffusion of export growth expanded in the last six months, particularly in sales of manufactures of industrial origin, closely linked to the Brazilian economy. The increase in exports occurred despite the adverse performance of the agricultural soybean complex, affected by producers’ inventory management (see Figure 3.14).

Imported quantities are around all-time highs during the first quarter of 2018, showing a slowdown. Import growth is expected to accompany the business cycle with lower elasticity16.

The strong growth in imports observed between 2016 and 2017 reflects the greater role played by investment in the current recovery compared to previous ones. In fact, in the growth process that began in the second half of 2016, imports of capital goods accounted for 35% of the total increase in imports, a value higher than that recorded in previous recoveries (see Figure 3.15).

3.1.4 Growth was highly diffused among the productive sectors

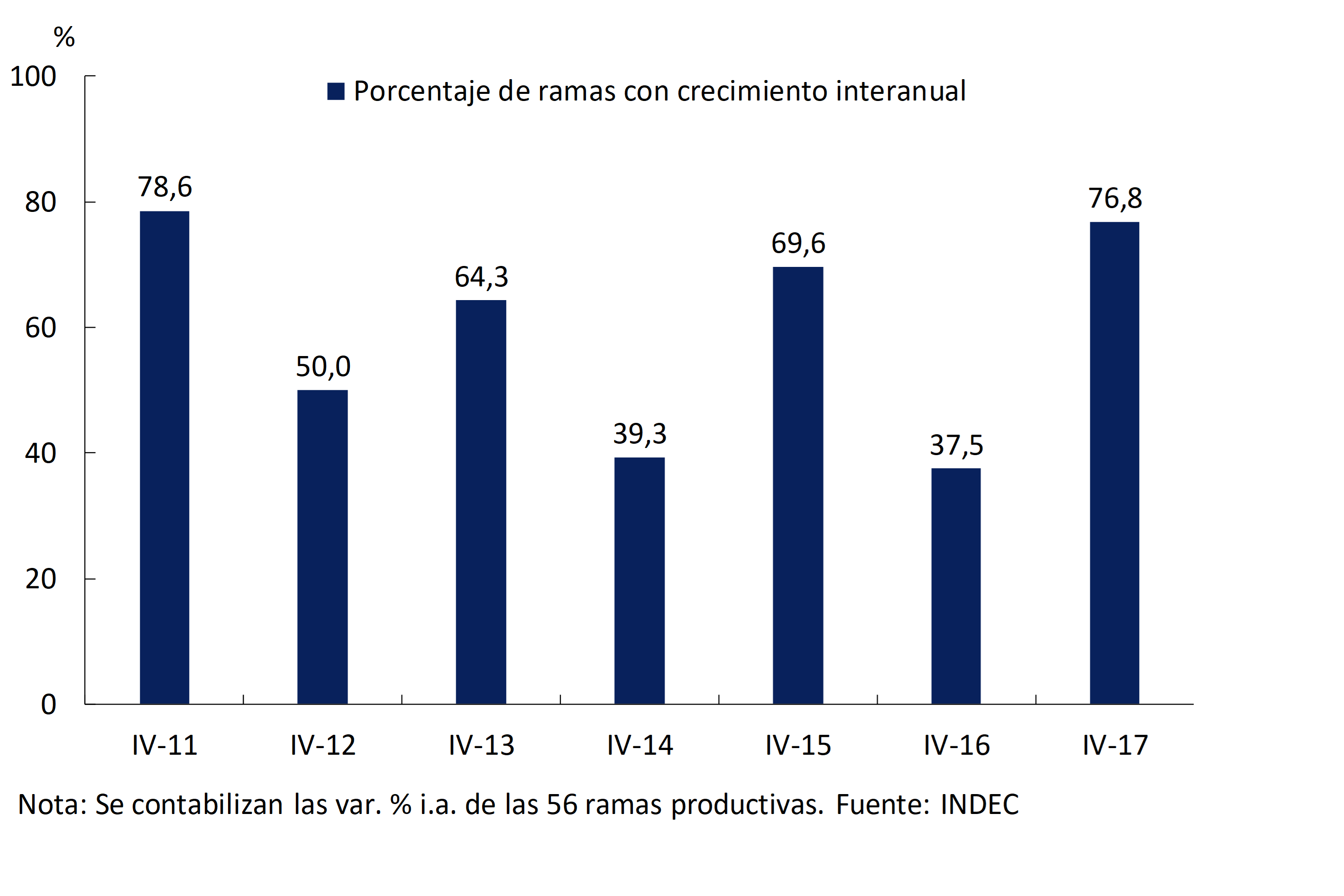

During 2017, most of the 56 branches of economic activity performed favorably. In the fourth quarter, the diffusion index that counts the percentage of branches that grew with respect to the same period of the previous year stood at 76.8%, the highest since 2011 (see Figure 3.16).

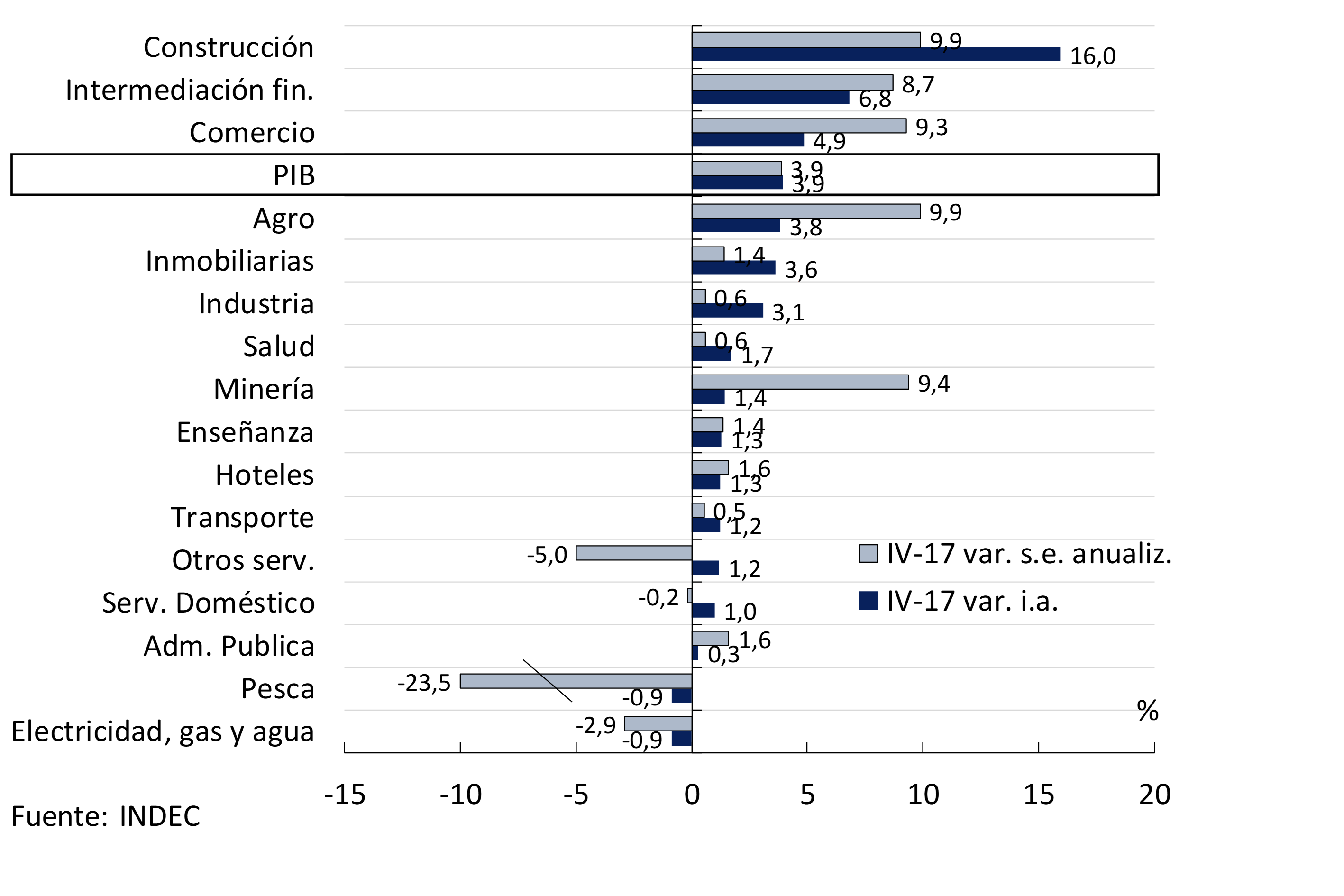

Policies aimed at favoring access to credit, improving infrastructure, and reducing distortions to foreign trade had a positive impact on different activities that led growth in 2017. Construction (+16% YoY), financial intermediation (+6.8% YoY), real estate activity (+3.6% YoY) and agriculture (+3.8% YoY) grew well above the average17. The improvement in these sectors boosted other activities such as trade (+4.9% YoY), transport (+5.5% YoY) and the extraction of metallic minerals (2.7% YoY). The latter, together with the extraction of coal, gas and oil (1.2% YoY), constituted an increase of 1.4% YoY in mining as a whole (see Figure 3.17).

Industrial activity registered a heterogeneous evolution. Branches linked to investment (machinery, equipment and construction), durable consumption (automotive and furniture) and exports (automotive and metal products) led industrial growth. The production of food and beverages decreased 1.6% y.o.y., affected by low dairy production and lower milling.

The service sectors most dissociated from the economic cycle slowed down, growing at rates below 2%: education (+1.3%), health (+1.7%), public administration (+0.3%) and domestic service (+1%).

The only sectors that contracted in the fourth quarter of 2017 compared to the same period of the previous year were electricity, gas and water (-0.9%) and fishing activity (-0.9%). In the first case, the sector was affected by the fall in residential demand and the reduction of subsidies. Fishing registers a high volatility, while in the fourth quarter it fell slightly, the average for 2017 exhibits a strong growth of 14% y.o.y.

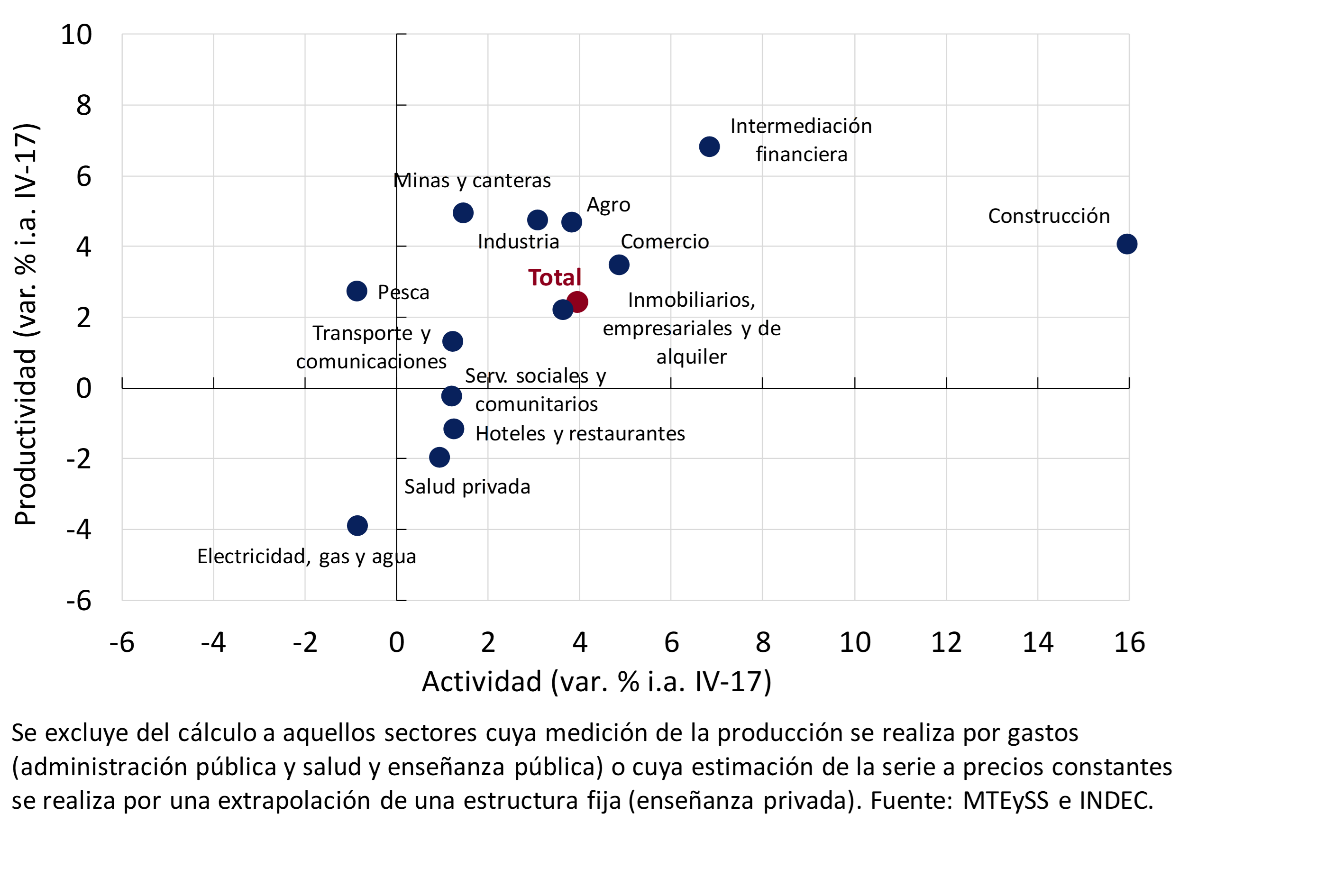

Economic growth in 2017 was based on increases in both employment and productivity per registered worker. Total registered employment increased reaching a level 2% higher than in 2016 in the fourth quarter of 2017, while informal employment grew 4.6% YoY. In particular, private formal salaried employment rose at a rate of 1.3% YoY. This made it possible to reduce the unemployment rate to 7.2%, 0.4 p.p. less than the same quarter of 2016, in a context of greater labor supply.

Productivity per registered employee rose 2.4% YoY and was generalized at the sectoral level, with improvements in industry, agriculture, commerce, and real estate and business activities standing out (see Figure 3.18).

At the end of the fourth quarter of 2017, an improvement in the distribution of per capita income was observed18. This improvement occurred in the context of a recovery of real private wages and a fall in poverty. In particular, the salaries of registered private wage earners rose 2% y.o.y. in real terms in the fourth quarter of 201719 and poverty fell by 4.6 p.p. to 25.7% of the population during the second half of the year.

3.2 A positive balance for 2017 and consolidated growth prospects for the next two years

During 2017 the economy grew uninterruptedly at an average rate of 4% annualized and in the first quarter of 2018 it completed seven consecutive quarters of growth. This expansion phase has the particularity of being led by investment (growing 21% year-on-year in the fourth quarter of 2017 and representing 22% of GDP).

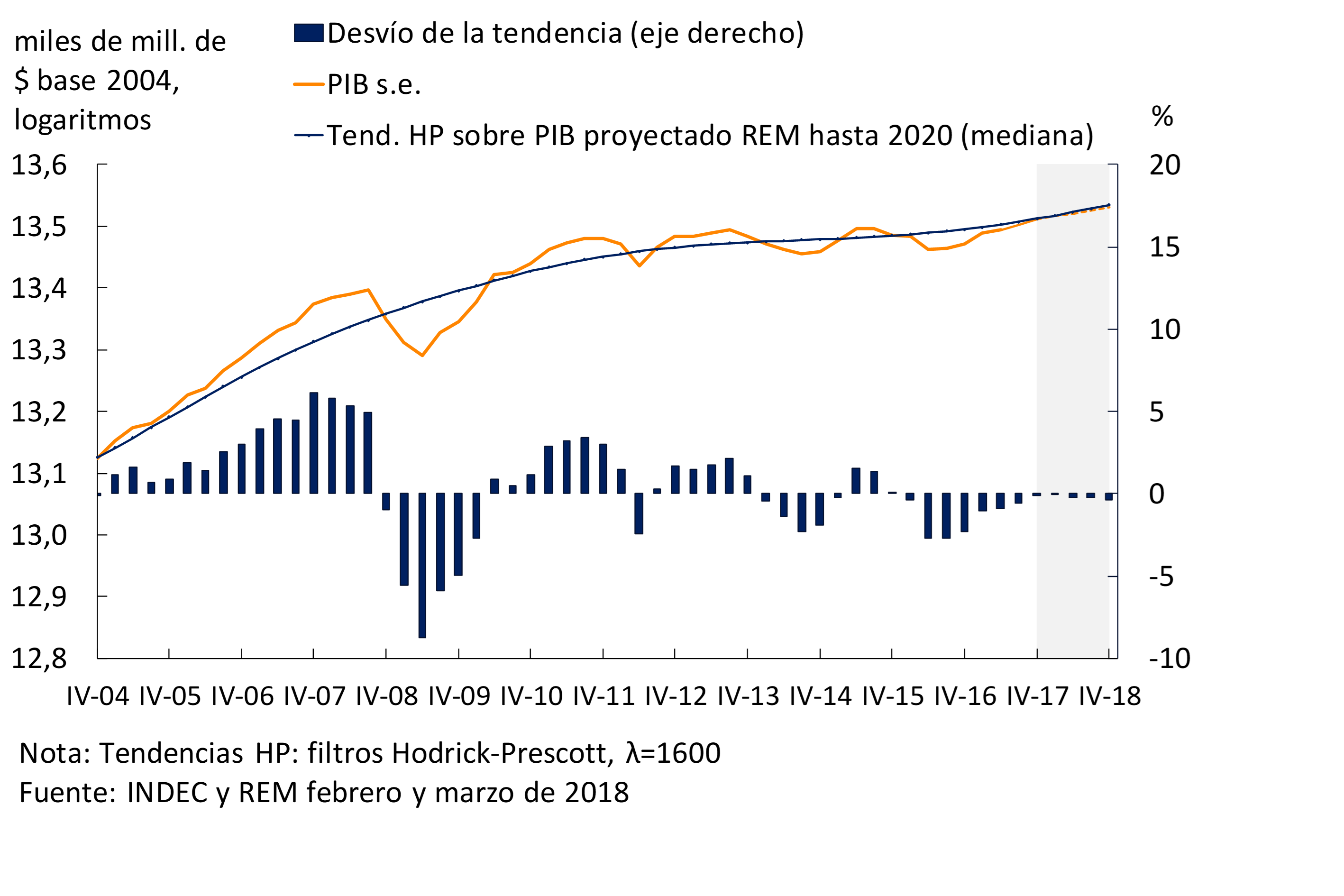

The BCRA expects the economy to continue in a growth phase that began in the second quarter of 2016, characterized by a sharp reduction in the volatility of output as a distinctive feature, which made it possible to leave behind the trend stagnation of the product typical of the 2011-2015 period.

Infrastructure will continue to be a key factor in investment, mainly through the development of PPP20, which will improve competitiveness by lowering costs associated with logistics while simultaneously increasing productivity. The ART law, the gradual reduction of distortionary taxes and the productive financing law21 will promote the development of the capital market and local financing and will allow the strong expansion of credit22 that increased 21% in real terms during 2017 to continue.

Although transitory shocks such as drought (see Section 3. Direct impact of drought) reduce the growth rate of the economy expected for 2018, growth projections continue to be positive. This is the result of the reforms implemented since the end of 2015, the expansion of investment and the greater external demand (particularly from Brazil). In line with these assumptions, the Market Expectations Survey (REM) projects a slowdown for 2018 and then growth of 3.1% and 3.0% in 2019 and 2020 (see Figure 3.19).

This outlook implicitly contains a break in the trend of GDP growth since 2016 and the absence of inflationary pressures from the point of view of demand for 2018. The pace of growth projected by REM analysts would keep GDP below its medium-term trend throughout the year (see Figure 3.20).

4. Pricing

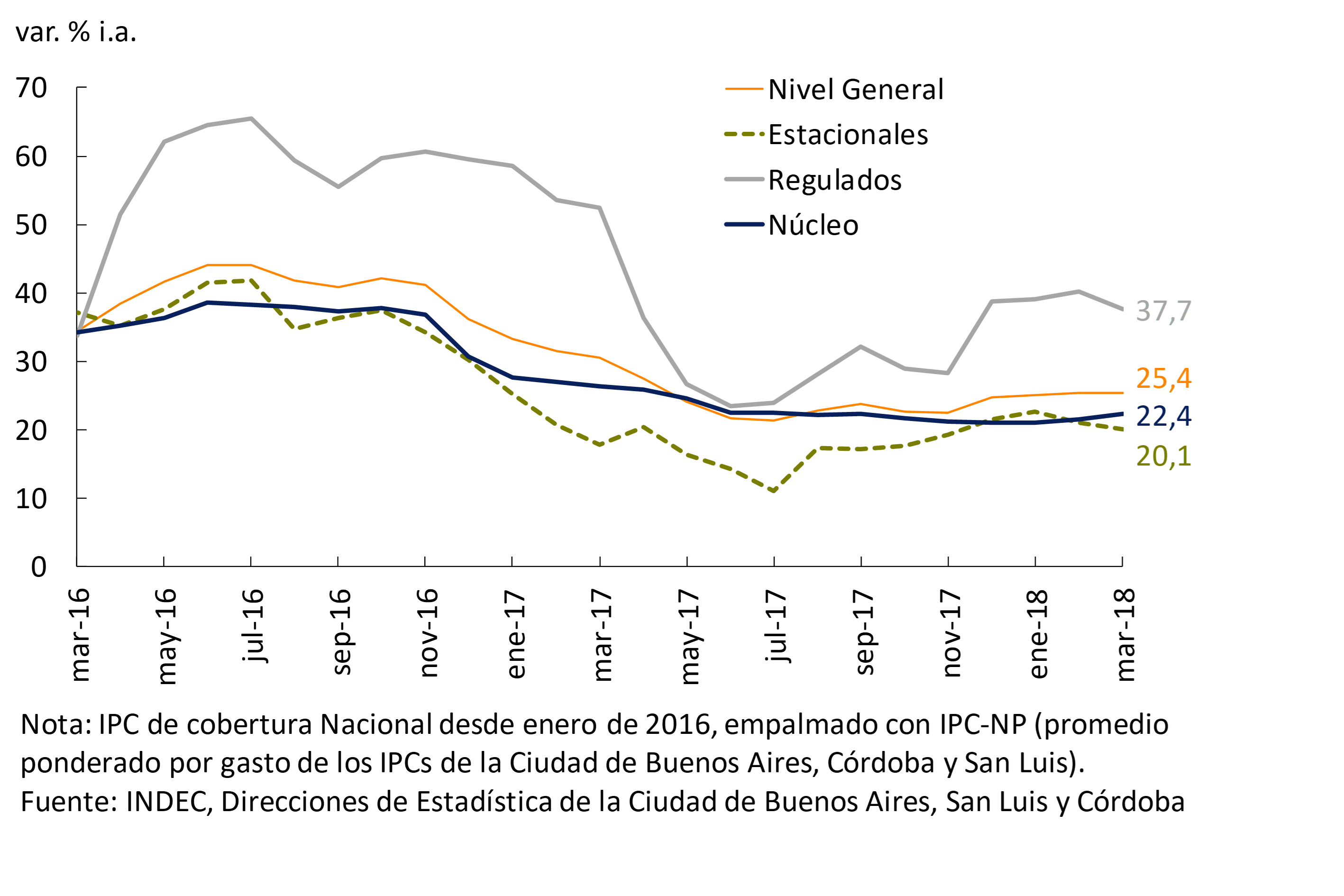

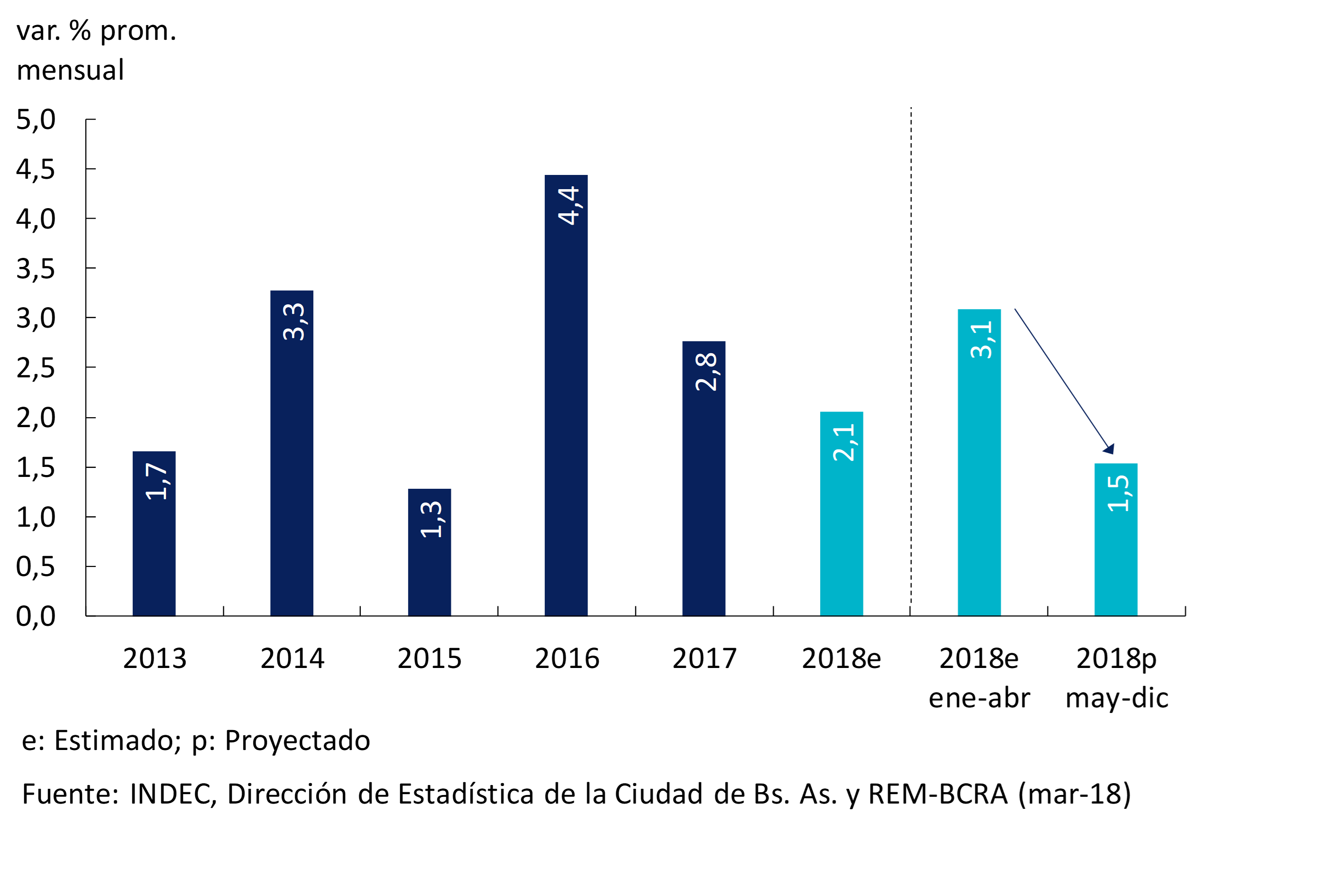

Since December of the previous year, inflation has accelerated, according to the CPI of national coverage, reaching an average increase of 2.2% in the first quarter of 2018. The rise in inflation responded to the direct and indirect impact of the increase in public service rates and, to a lesser extent, to the depreciation of the peso observed between December 2017 and February 2018. Core inflation reacted relatively less to the increases in regulated and exchange rates than in other episodes in the past. The BCRA considers that higher inflation is transitory and that it will fall significantly in the coming months. Wage negotiations are being agreed at around 15% and the process of adjusting regulated prices will slow down sharply from May. REM inflation expectations for 2018 increased compared to the December survey. However, they remain below the inflation observed in 2017. This upward revision was mainly due to the fact that the inflation observed during the first quarter was higher than expected, given that the implied forecast for the rest of the year remained practically unchanged. For 2019 and 2020, expectations were also raised, although they continue to indicate a marked disinflation.

4.1 Recent Acceleration in Inflation Is Transitory

During the first quarter, there was a transitory acceleration of inflation. This dynamic was linked to the relative price adjustments of regulated goods and services and the nominal depreciation of the domestic currency. The CPI for national coverage grew at an average monthly rate of 2.2% in the first quarter of 2018. All subnational consumer price indicators showed similar dynamics (see Figure 4.1).

The prices of regulated items had a preponderant impact on inflation in the period. In the first quarter of 2018, these goods and services adjusted at an average rate of close to 3% and 4.5% if we include the data for December last year (see Figure 4.2). This group reflected the increases in public passenger transport, both in the AMBA and in some urban centers in the interior of the country, increases in electricity, gas, cigarettes, prepaid, education, telephony, tolls and fuel for the automobile.

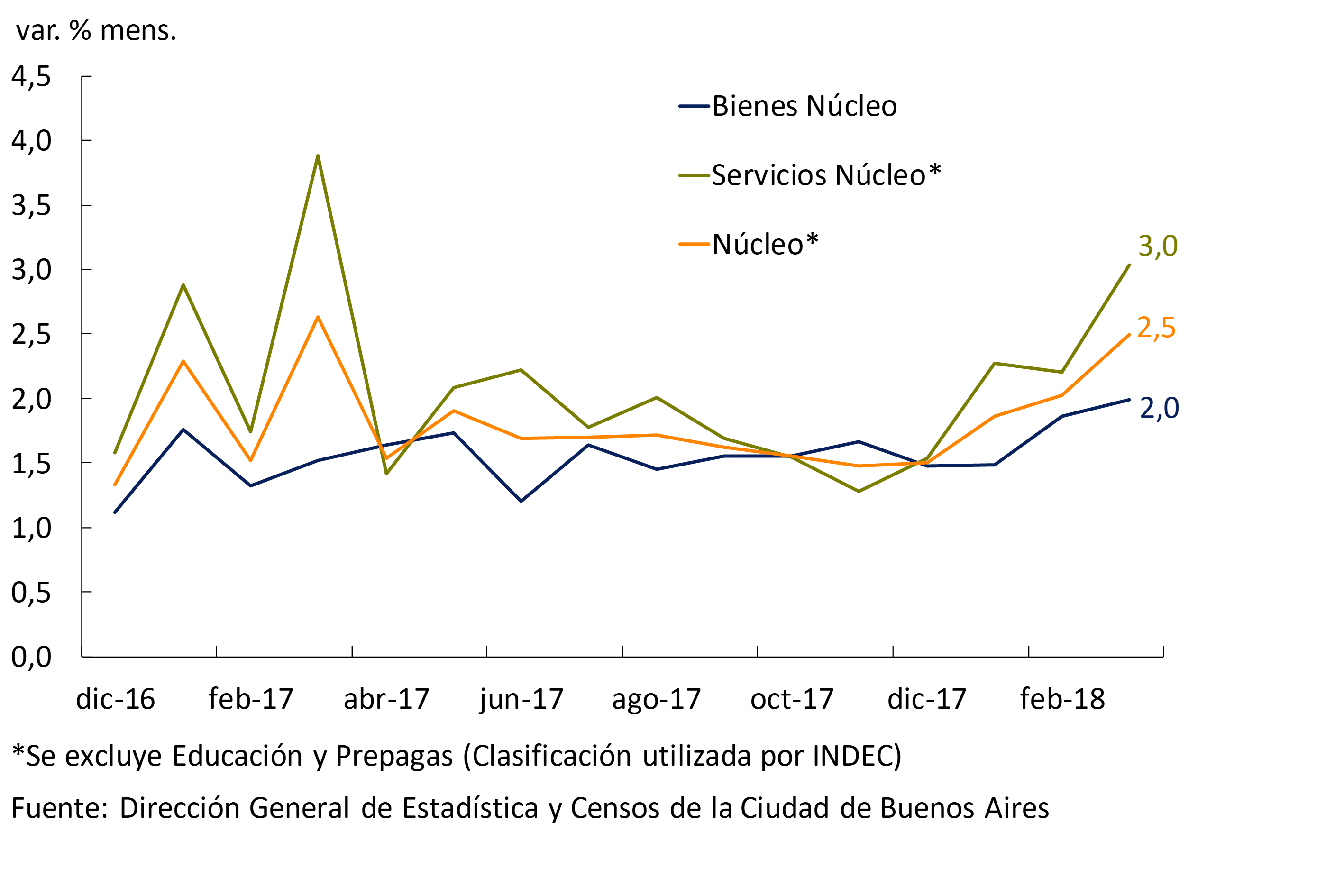

The adjustment in the relative prices of regulated services, and in particular that of public services, which registered increases well above the general level of inflation, also had a direct and indirect impact on core inflation (see Figure 4.3). Thus, core inflation accelerated by 0.6 p.p. compared to the second half of 2017 (2.1% monthly average in the first quarter and 2.0% if Dec-17 is added to the quarter).

Core inflation accelerated both for the goods and services that compose it. The behavior of goods would be more associated with the higher rates of depreciation of the domestic currency. In addition, the impact of the drought on the prices of agricultural raw materials contributed to the increase in the prices of some foodstuffs. Meanwhile, the acceleration of private services would be more closely linked to the direct and indirect impact of the increase in public services23 and to the evolution of wages (see Figure 4.4).

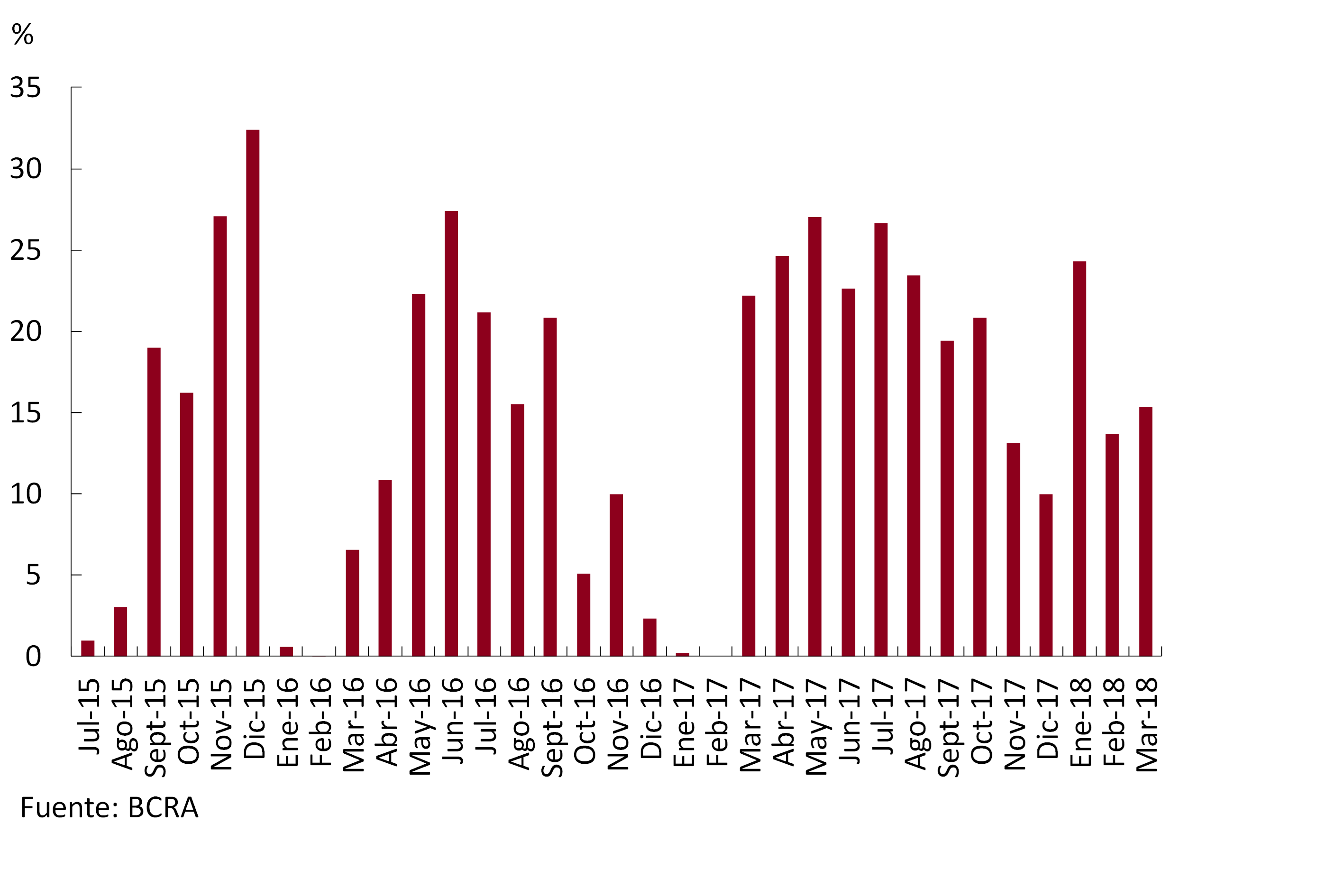

Since December 2017, core inflation has accumulated a rise of 8.1% (equivalent to a monthly average rate of 2%). This rate of increase is similar to that recorded in the first four months of 2017. However, this time the increases in regulated and exchange rates were significantly higher than those observed a year ago. Thus, with the information available so far, the response of core inflation this time was less than proportional than that observed at the beginning of the previous year (see Figure 4.5). The pass-through of the recent increases in regulated prices (between December and March) and the depreciation of the exchange rate has been more limited on this occasion than in previous periods.

The year-on-year change in the general level of the CPI remained relatively stable at around 25% during the first quarter of 2018. Regulated goods and services grew at rates close to 40%, continuing the process of adjusting relative prices. Core inflation, after a continuous downward trend since mid-2016, rose slightly to 22.4% YoY in March (see Figure 4.6).

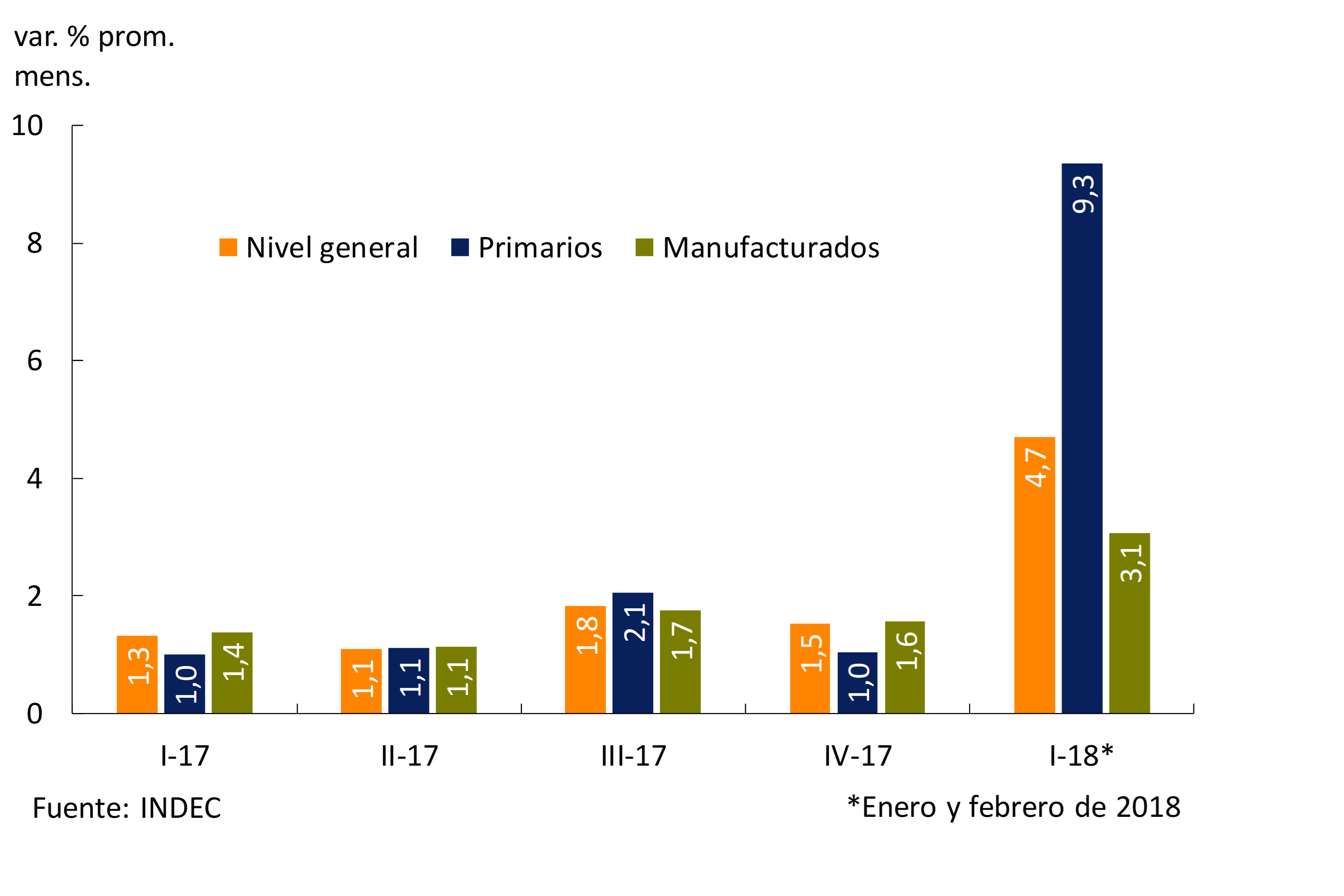

Wholesale prices registered an average increase of 4.7%, standing 3.2 percentage points above the records of the last quarter of 2017. The significantly higher rates of change than those of consumer prices were basically due to three factors. First, increases in the prices of regulated goods and services (mainly electricity and gas) had a significant impact on the increase in wholesale prices. Secondly, some prices of primary products (oil and agriculture) also rose due to the rise in their international quotations. Added to this was the depreciation of the peso, whose pass-through to wholesale prices is greater than to retail prices due to the greater participation of tradable goods in foreign markets in wholesale indices. For raw materials and imported goods, the pass-through is almost proportional to the change in the exchange rate (see Figure 4.7).

In the first two months of the year, wholesale electricity and gas prices accumulated increases of 13% and 76%, respectively, explaining 30% of the variation in wholesale prices in the period. Specifically, in gas, the survey includes the prices of gas at the wellhead reported by producers, regardless of their final destination of consumption. Thus, within this set of prices are included the prices of this input intended for small businesses, shops and also for residential consumption. In the latter case, in addition to the rise in gas prices in December, the regulatory changes in the social tariff24 had an impact, which were only reflected in the wholesale marketing prices of February.

International prices of raw materials of agricultural origin accumulated increases in dollars of approximately 4% in the first two months of the year. Meanwhile, WTI oil, which is the one used as a reference in the IPIM survey, rose 3% in the same period. These increases were boosted by the 12% average depreciation of the domestic currency against the U.S. dollar between December 2017 and February 2018. Other products whose prices were directly affected by the dynamics of the exchange rate were imports, which accumulated an increase of 11.6% in the IPIM. The monthly acceleration of wholesale prices in the first months of the year boosted the year-on-year rates of change, which rose to values close to 26% in February 2018.

4.2 Nominal wages moderated their growth rate

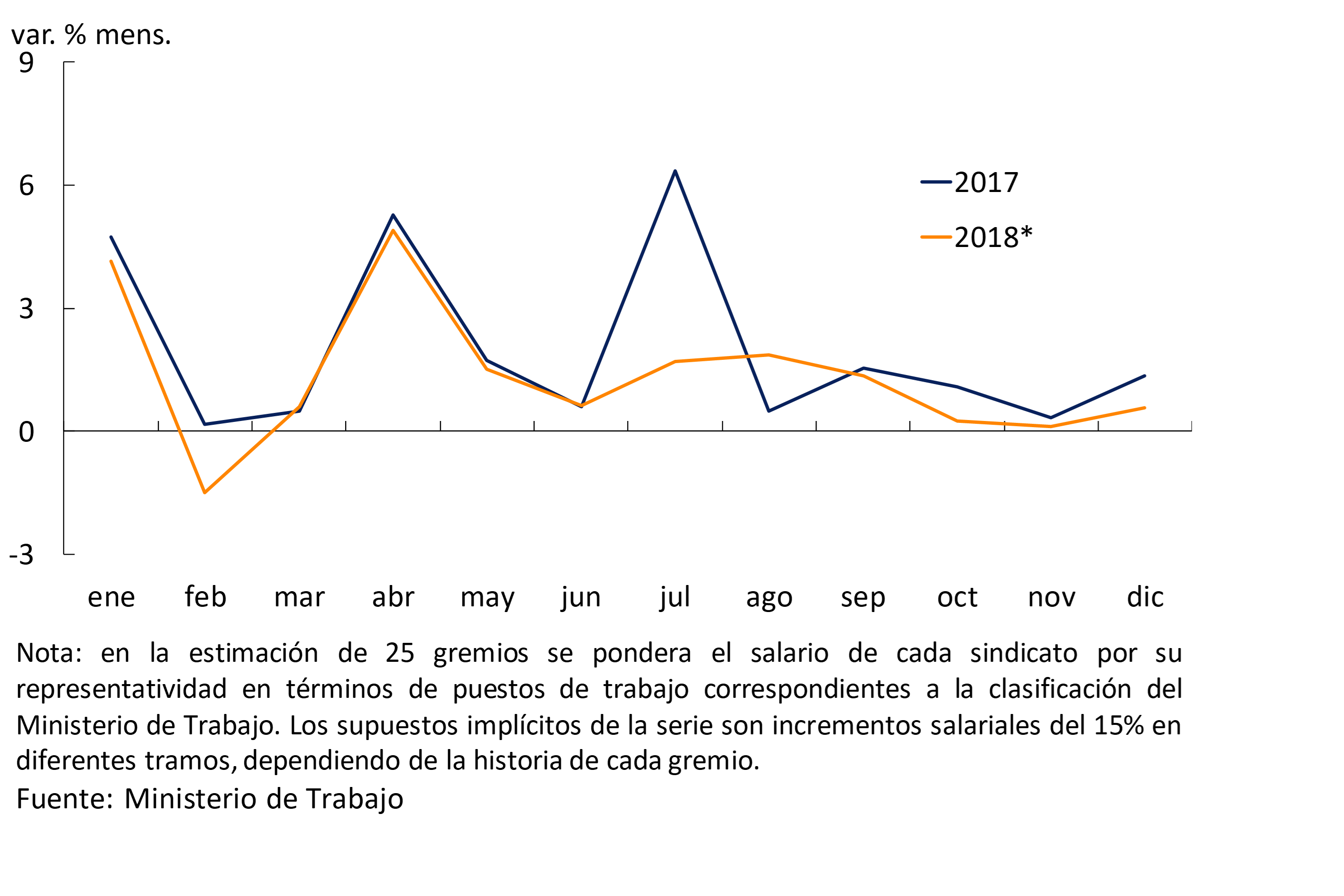

Nominal wages in the formal private sector ended 2017 with a rate of increase of 23.6% YoY and 29.7% annual average, in line with our forecasts. In the first months of the year, the dynamics of nominal wages reflected the entry into force of the last tranches of increases corresponding to the parity agreements of some unions and the application of some trigger clauses. The parity negotiations already closed during 2018, which represent half of the workers under the agreement, were agreed in line with the inflation target for the year (15%).

In addition to contemplating future inflation, the parity contracts for 2018 have a different intra-annual distribution than the previous year. In most agreements, the tranches in 2018 have a downward load during the year, while in 2017 the tranches had similar magnitudes. The lower nominal increases agreed together with the descending tranches will allow us to better accompany the disinflation process observed since the beginning of 2017 (see Figure 4.8).

4.3 The path of disinflation would continue in 2018

Although an acceleration of inflation was observed in the first months of the year, this dynamic would only be transitory. A number of factors suggest a marked reduction in inflation from May onwards. The highest concentration of increases in regulated goods and services is in the first four months of the year. For the rest of the year, significantly smaller adjustments than those recorded in the first part of the year in the prices of public services are expected. No significant depreciation of the peso is expected due to macroeconomic fundamentals and the Central Bank’s own action. Negotiating wage patterns in line with the inflation target would reduce labor cost pressures on prices. Finally, the current monetary policy is more contractionary than that observed during the first half of last year. Consistently, market analysts’ expectations have incorporated this inflation dynamic and foresee a reduction for the coming months. From the forecasts of the General Level and Core of the REM, an estimate of the evolution of the Regulated items can be obtained implicitly, considering that seasonal goods and services behave like the Core. According to these calculations, as of May the increases in this component would be significantly reduced (see Figure 4.9).

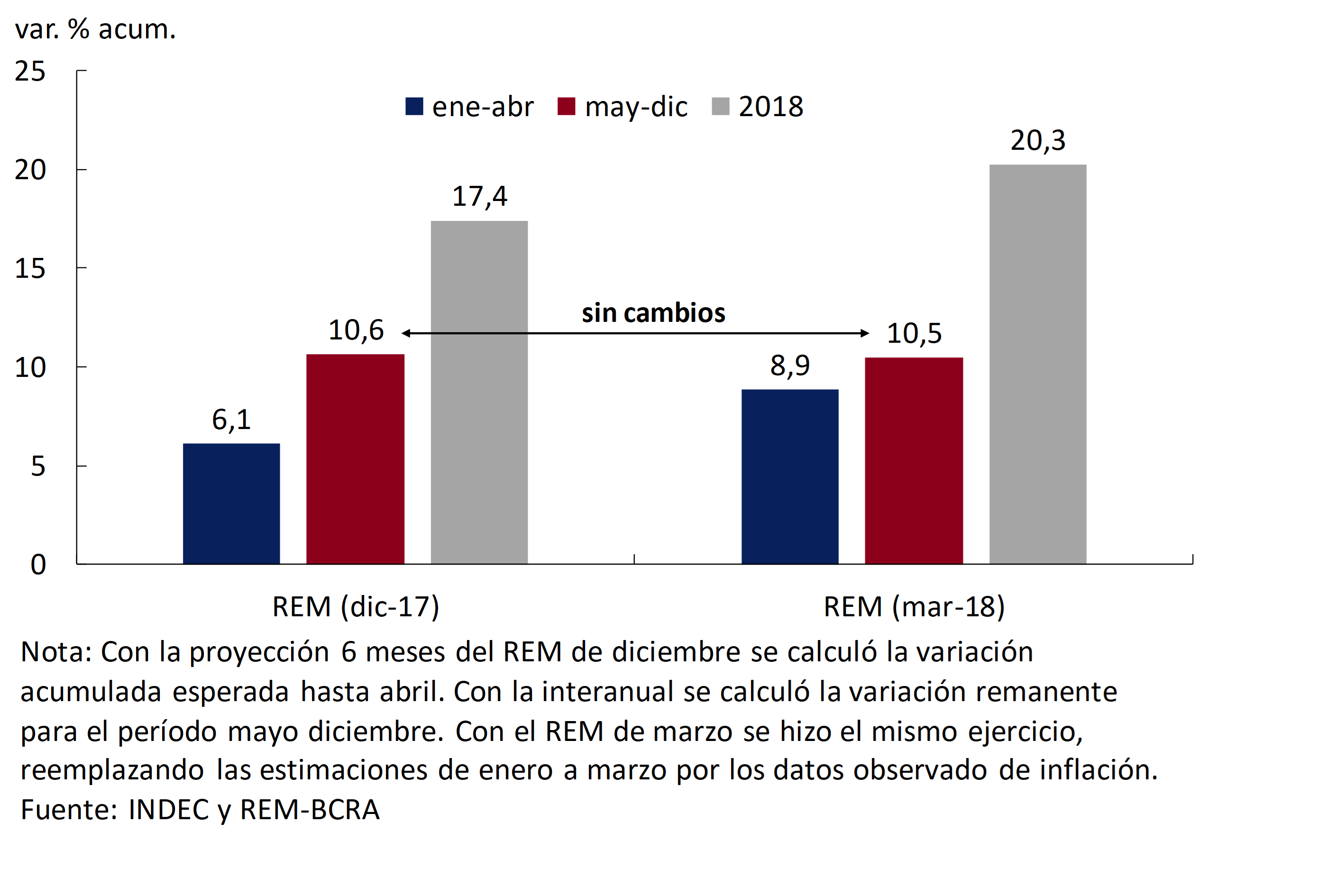

For December 2018, the REM estimates that inflation will stand at 20.3%, 4.5 p.p. below inflation in 2017 but 5.3 p.p. above the target. The increases in the REM’s inflation forecasts since December were due to the incorporation of higher-than-expected inflation rates during the first four months of the year, with estimated inflation remaining constant for the remainder of the year (see Figure 4.10).

Market analysts’ expectations anticipate that the disinflation process will continue over the next few years, although with rates higher than those contemplated in the inflation targets. Estimates for 2019 are 14.3% YoY and for 2020 at 10% YoY. In both cases, these forecasts were revised upwards and are almost 5 p.p. higher than the target set (see Figure 4.11).

5. Monetary policy

Starting in December of last year, higher monthly inflation rates began to be observed due to the impact of increases in regulated prices and the increase in some prices of tradable goods, the latter affected by the rise in international prices of oil and agricultural products and by the rise in the exchange rate (see Chapter 4. Prices).

Considering that these pressures on the general price level were mainly due to temporary factors, that monetary policy showed an adequate anti-inflationary bias and that it operates with lags, the Central Bank’s strategy consisted of keeping the policy interest rate unchanged (after the reduction decided in January of this year) pending clear signs of disinflation.

However, the change in the horizon of the inflation targets and the drop in the policy interest rate at the beginning of the year were interpreted by the market as the prelude to an excessive easing of monetary policy. This led to a dynamic of depreciation of the peso that reflected a market view of the future of monetary policy that did not correspond to the Central Bank’s vision.

In this context, and in a complementary way to the management of the interest rate, the Central Bank intervened in the foreign exchange market since the beginning of March. A depreciation of the peso greater than that recorded up to that point was not justified by real economic factors or by the expected course of its monetary policy and, if not avoided, could affect the disinflation process.

The recent acceleration in prices is expected to be temporary and that, once the transitory factors indicated have been overcome, inflation will consolidate its downward trend. This favorable outlook is based on the fact that: a) monetary policy shows a more contractionary bias than that observed in the first part of last year; b) the process of adjustment of regulated prices will slow down sharply after April; c) no significant depreciation of the peso is expected due to macroeconomic fundamentals and the Central Bank’s own action; d) Wage negotiations in the public and private sectors are being agreed around the 15% guideline.

As mentioned in recent monetary policy statements, the Central Bank will maintain the bias of monetary policy until signs of disinflation compatible with the planned path are confirmed; and it will be ready to act in case the trajectory of inflation deviates from the aforementioned scenario.

5.1 Monetary policy in the first quarter of 2018

5.1.1 Interest Rate Decisions: Deferral of Target and Transient Shocks to the Inflation Rate

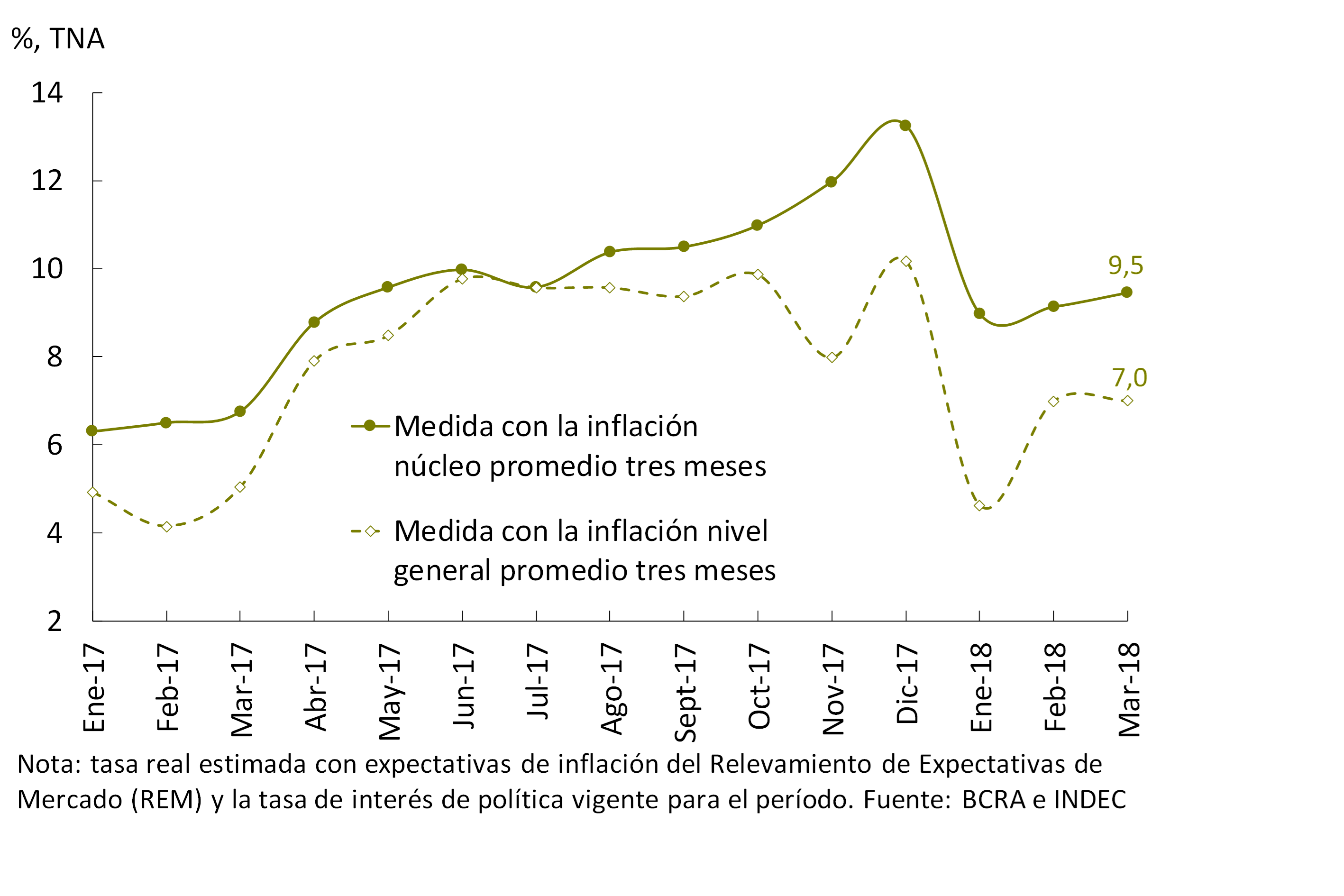

Following the deviation from the inflation target observed over the past year, the government announced at the end of December a deferral of the 5% target from the original path: 15% for this year, 10% for 2019, and 5% from 2020 onwards (see Figure 4.11). The bias of monetary policy up to that point was in line with the original objective of reaching inflation of 10% (±2%) during 2018, so a higher inflation target (15%) required a lower policy interest rate. At the same time, core inflation had reached a monthly average of 1.4% in the last quarter of last year, which in annualized terms was equivalent to 18.5%, the lowest record in the last six years. Thus, during January the Central Bank decided to reduce its monetary policy rate by 75 p.p. on two occasions to take it from 28.75% per year at the end of December to 27.25% per year at the end of that month. Although this led to a reduction in the real interest rate, it remained at levels consistent with the intended disinflation path and at values higher than those recorded in the first part of last year (see Figure 5.1). 25

On the other hand, as of December last year, higher monthly inflation rates were observed due to the impact of increases in regulated prices (mainly gas, electricity and transport) and the increase in some prices of tradable goods. The latter were affected by the rise in international prices of oil and agricultural products and by the rise in the exchange rate in recent months (see Chapter 4. Prices).

Considering that the pressures observed on the general price level were mainly due to temporary factors, that monetary policy showed an adequate anti-inflationary bias and that it operates with lags, the Central Bank kept the policy interest rate unchanged for the rest of the quarter pending clear signs of disinflation. The cautious management of the interest rate was intended to avoid the generation of unnecessary volatility in financial conditions and the sending of confusing signals to economic agents.

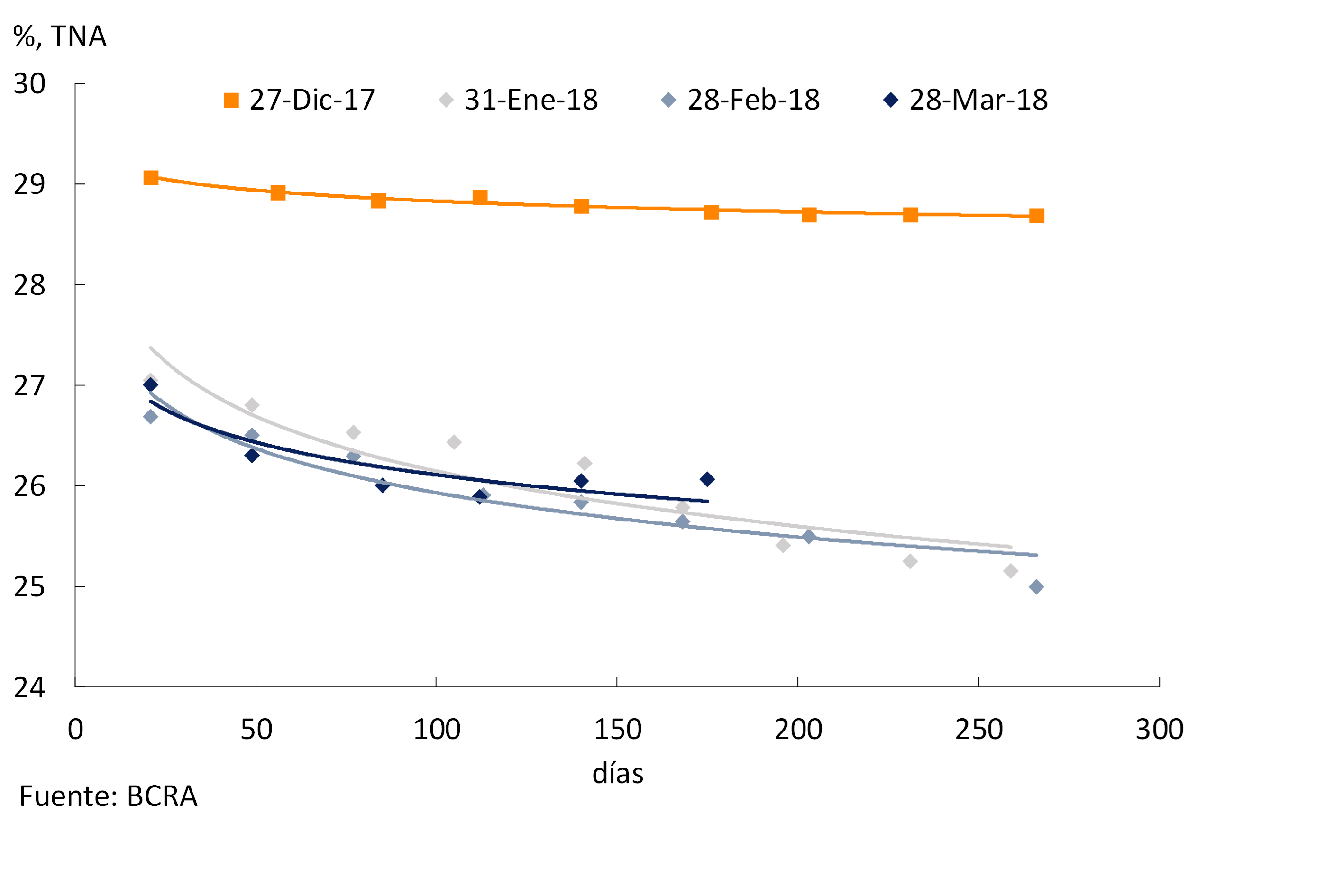

The change in the inflation target horizon and the reduction in the policy interest rate in January were interpreted by the market as the prelude to an excessive easing of monetary policy. This was reflected in the policy rate path foreseen in the January expectations survey, which showed a decline in the expected rates for all maturities surveyed in relation to the December survey (see Figure 5.2). However, the monetary authority’s interest rate decisions did not validate what the market expected; This contributed to raising the expected path of policy rates until reaching the same level in March as in December.

The recent acceleration in prices is expected to be temporary and that, once the transitory factors indicated have been overcome, inflation will consolidate its downward trend. This favourable outlook is based on the fact that: (a) monetary policy shows a more contractionary bias than that observed during the first part of last year; b) the process of adjustment of regulated prices will slow down sharply after April; c) no significant depreciation of the peso is expected due to macroeconomic fundamentals and the Central Bank’s own action; d) Wage negotiations in the public and private sectors are being agreed around the 15% guideline.

Likewise, a relevant factor for inflation in a long-term perspective is that the transfers that the Central Bank makes to the National Treasury will continue to decrease until they are limited to the real growth in the demand for money from 2020 onwards (see Figure 5.3). Last year, funds for $ 150,000 million (1.5% of GDP) were transferred as transitory advances and profits, according to the Budget law this year $ 140,000 million (1.1% of GDP) will be transferred, next year they will reach $ 70,000 million (0.5% of GDP) and from 2020 a figure equivalent to the real growth in the demand for money will be transferred. which will be put into practice through a seigniorage rule based on multiplying economic growth by the monetary base. Thus, assuming a monetary base stock of 10% of GDP and a growth of the economy of 3%, by 2020 the transfer of funds to the Treasury would reach 0.3% of GDP.

As mentioned in recent monetary policy statements, the Central Bank will not relax the bias of monetary policy until signs of disinflation compatible with the path sought to achieve the inflation target of 15% year-on-year at the end of the year, 10% in 2019 and 5% in 2020 are confirmed; and it will be ready to act in case the trajectory of inflation deviates from the aforementioned scenario.

5.1.2 Foreign Exchange Market Interventions: Complementing Policy Rate Management

The 150 basis point cut in the policy interest rate at the beginning of the year and the change in inflation targets were interpreted by the market as the prelude to an excessive easing of monetary policy. This led to an increase in inflation expectations (see Figure 4.10) and a depreciation of the peso that reflected a market view of the future of monetary policy that did not correspond to the Central Bank’s view.

In this context, and in addition to the management of the interest rate, the Central Bank intervened in the foreign exchange market since the beginning of March after considering that a greater depreciation than that recorded up to that point was not justified by real economic factors or by the expected course of its monetary policy and that, if not avoided, it would have the potential to affect the disinflation process. The objective of these interventions was to break expectations of depreciation and inflation and to point out that the Central Bank’s vision of future monetary policy differed from that of the market. Thus, between March 5 and April 10, the monetary authority sold international reserves on 16 occasions for a total amount of US$ 2,427 million (average of US$ 152 million per intervention), which represented 3.9% of international reserves (see Figure 5.4).

After having risen 18% between mid-December last year and early March of this year, the exchange rate in relation to the dollar slowed its upward trend. This rise in the value of the U.S. currency did not differ substantially from that observed between May and August of last year due to the episode of political uncertainty in Brazil and subsequent doubts about the result of the primary elections in Argentina, when the exchange rate had increased 15% and the Central Bank had sold foreign currency for US$ 1,837 million in the foreign exchange market. also with the aim of avoiding excessive volatility in the exchange rate (see Figure 5.5).

The increase in the nominal value of the exchange rate was reflected in a rise in the multilateral real exchange rate, similar to that recorded in last year’s bullish episode. Thus, at the beginning of April of this year, the real exchange rate was 27% above the level prior to the unification of the exchange rate in December 2015 and 4% above the average observed since June 2016 (see Figure 5.6).

The BCRA’s operations in the foreign exchange market are consistent with the flexible exchange rate regime in force since the beginning of 2016 and complementary to the management of the interest rate as the main monetary policy instrument to achieve a low and stable inflation rate. Thus, the occasional participation in the foreign exchange market by the Central Bank is justified in the face of disruptive dynamics capable of altering the course of inflation or generating negative effects on financial conditions, and is common in inflation targeting regimes in emerging countries (see Section 4 / Foreign Exchange Intervention in Inflation Targeting Regimes).

5.1.3 The policy of accumulating international reserves continues

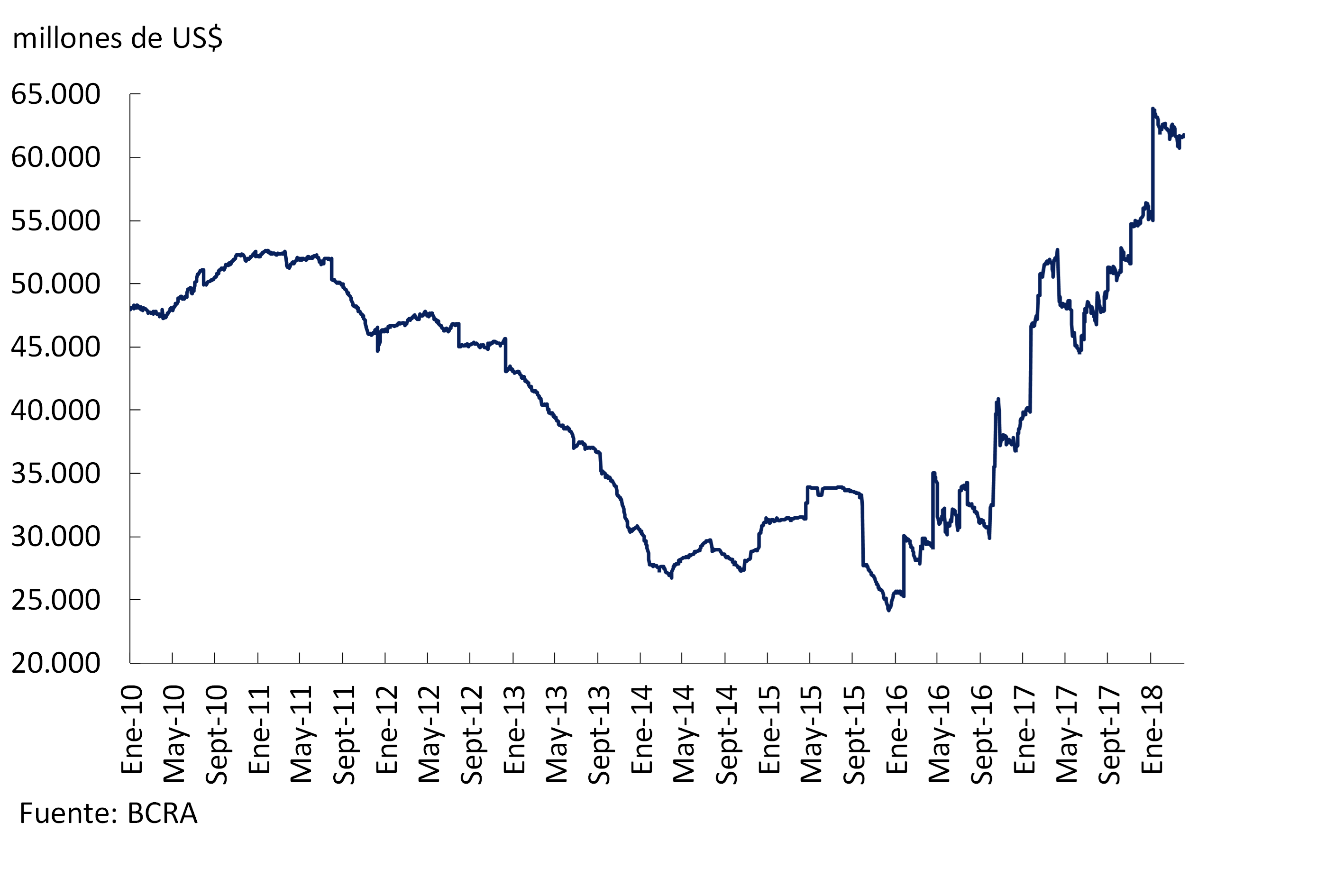

International reserves grew by US$ 6,714 million since the end of last year, reaching US$ 61,769 million at the beginning of April, representing 10% of GDP (see Figure 5.7). Despite the selling interventions in the foreign exchange market, the stock of international reserves increased due to the purchase of US$ 8,000 million directly from the National Treasury in the first two months of the year.

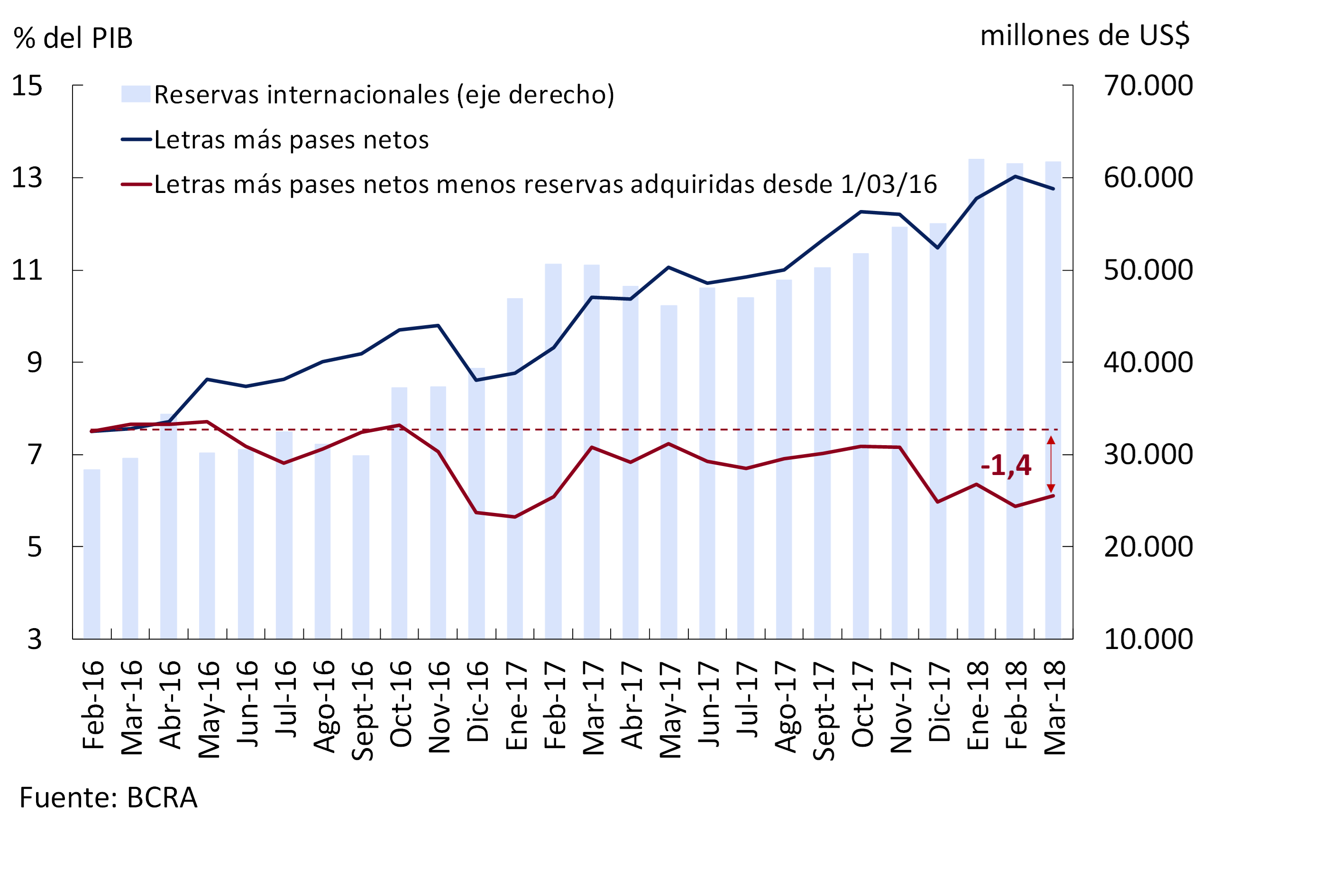

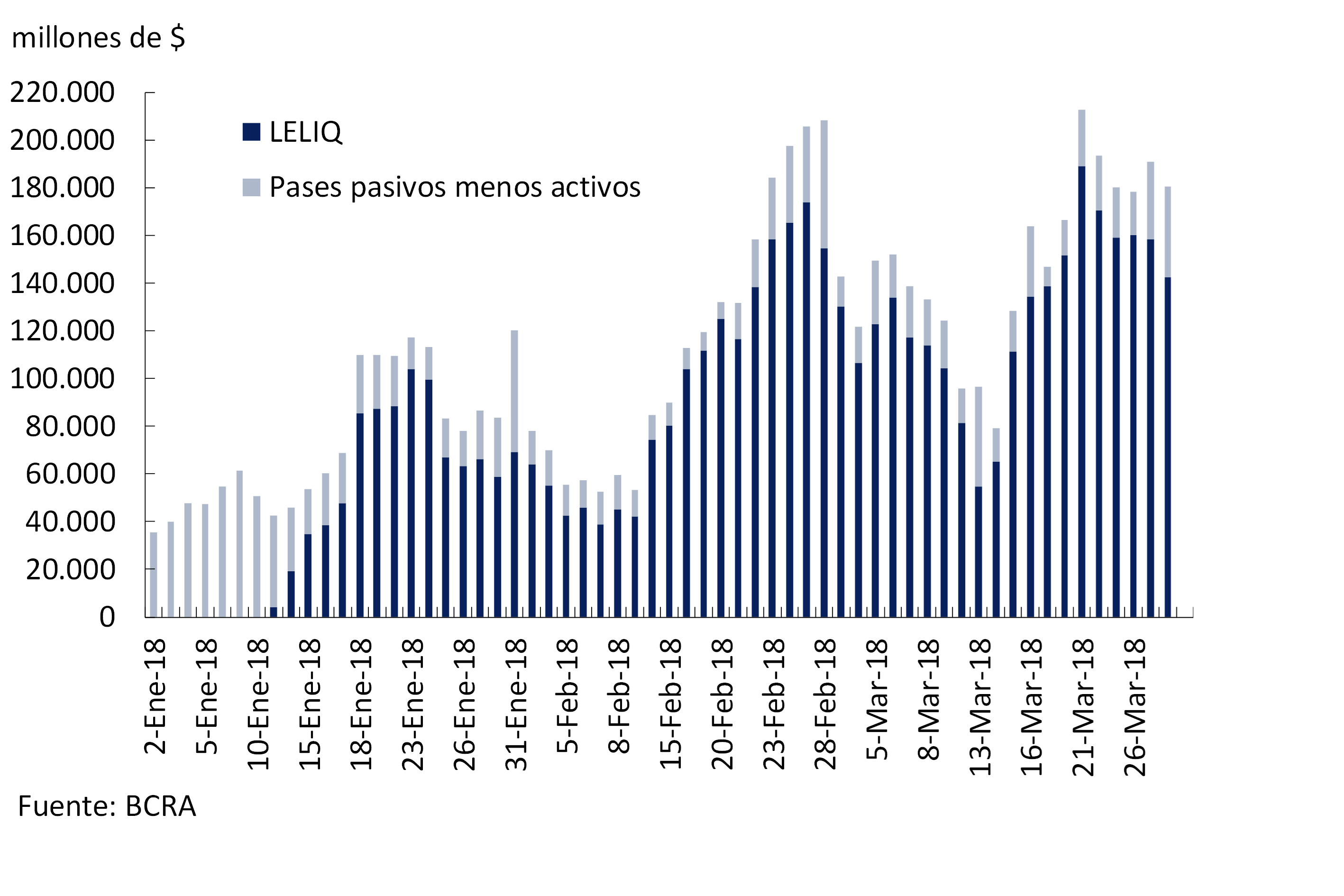

In this monetary policy framework, in which the Central Bank sets the short-term interest rate, increases in the monetary base derived from the purchase of foreign assets are automatically sterilized. An excess supply of money that places the interest rate below its desired level is automatically absorbed by a sale of bills or by passive pass operations. As a result, at the same time that foreign assets increase, the non-monetary liabilities of the Central Bank (LEBAC, LELIQ and net passes) increase. In this regard, although the stock of net bills and passes in terms of GDP went from 7.5% to 12.8% between the beginning of March 2016 and the end of March of this year, when the foreign currency acquired in that period is discounted, the stock of non-monetary liabilities showed a fall of 1.4 percentage points of GDP (see Figure 5.8).

5.2 Transmission mechanism to market interest rates

5.2.1 Money Market Interest Rates

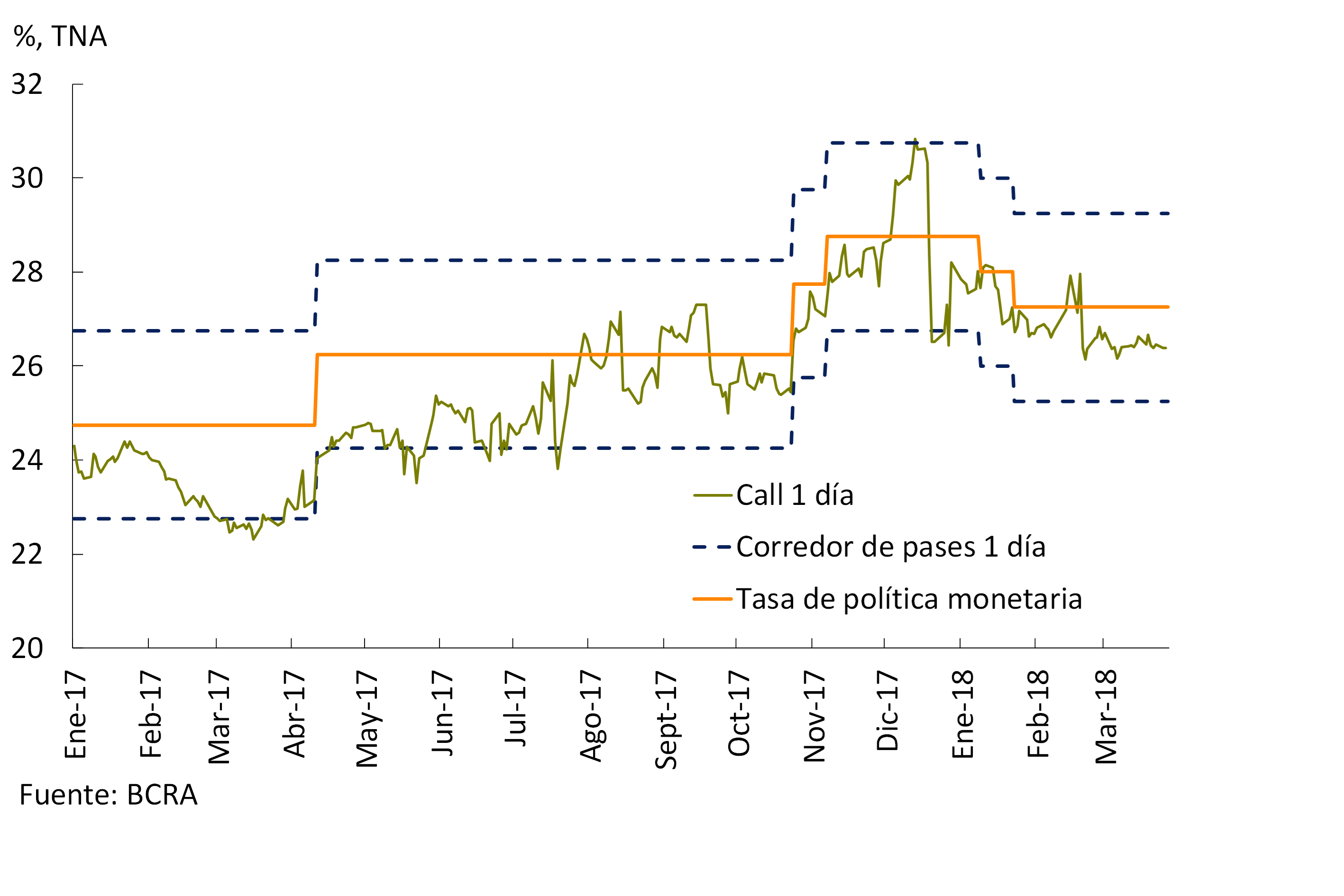

Money market interest rates followed the decline in the monetary policy rate at the beginning of the year and remained limited within the pass corridor throughout the quarter. Thus, the 1-day third-party pass rate fell 2.7 p.p. between December last year and March of this year to a monthly average of 25.0% per year, while the 1-day interbank call rate fell 2.3 p.p. in the same period to reach 26.5% annually (see Figure 5.9).

The interest rate on passive passes acts as a floor for money market interest rates. When the market rate is pressured to be below the floor, agents can place their excess funds by making passive passes with the Central Bank or buying Liquidity Bills (LELIQ). On the other hand, the interest rate on active passes functions as a ceiling for the rates at which banks finance themselves, i.e., when the market rate faces pressure to rise above the ceiling, financial institutions can cover their shortfall in funds with loans from the Central Bank through active passes. The LELIQ were launched by the Central Bank at the beginning of January of this year. They are zero-coupon securities with a term of 7 days that can be acquired only by financial institutions and that can be traded on the secondary market, which makes them more liquid than passes. So far these bills have been placed at the 7-day passive pass rate. Since its launch, they have been gaining participation in banks’ liquidity holdings against passive passes. While the stock of net passes (liabilities minus assets) fell from $100,175 million at the end of December last year to $38,161 million at the end of March, LELIQ’s holdings reached $142,524 million in the same period (see Figure 5.10).

In the first quarter of the year, the Central Bank continued to affect the liquidity conditions of the secondary LEBAC market through open market operations. Thus, the monetary authority made sales of securities for VN$ 334,924 million, which represented 18.1% of the total operations carried out in the secondary market of LEBAC, a participation slightly higher than the 14.5% recorded in the last quarter of last year (see Chart 5.11). Unlike what happened in the second half of last year, when paper operations with residual values of less than 90 days represented 45% of the amount traded, in the first quarter of the year they concentrated 87% of the operation, mainly in terms up to 30 days (24%) and between 31 and 60 days (44%).

At the beginning of the year, LEBAC rates in the secondary market were accommodated to the new monetary conditions, showing a fall of between 2 and 3 p.p., depending on the term, from the maximum levels of late December last year. After this initial decline, the yield curve showed only a change in slope compared to the end of January, with a slight reduction in yields on shorter stocks and a slight increase in longer ones (see Figure 5.12).

5.2.2 Deposit and Loan Interest Rates

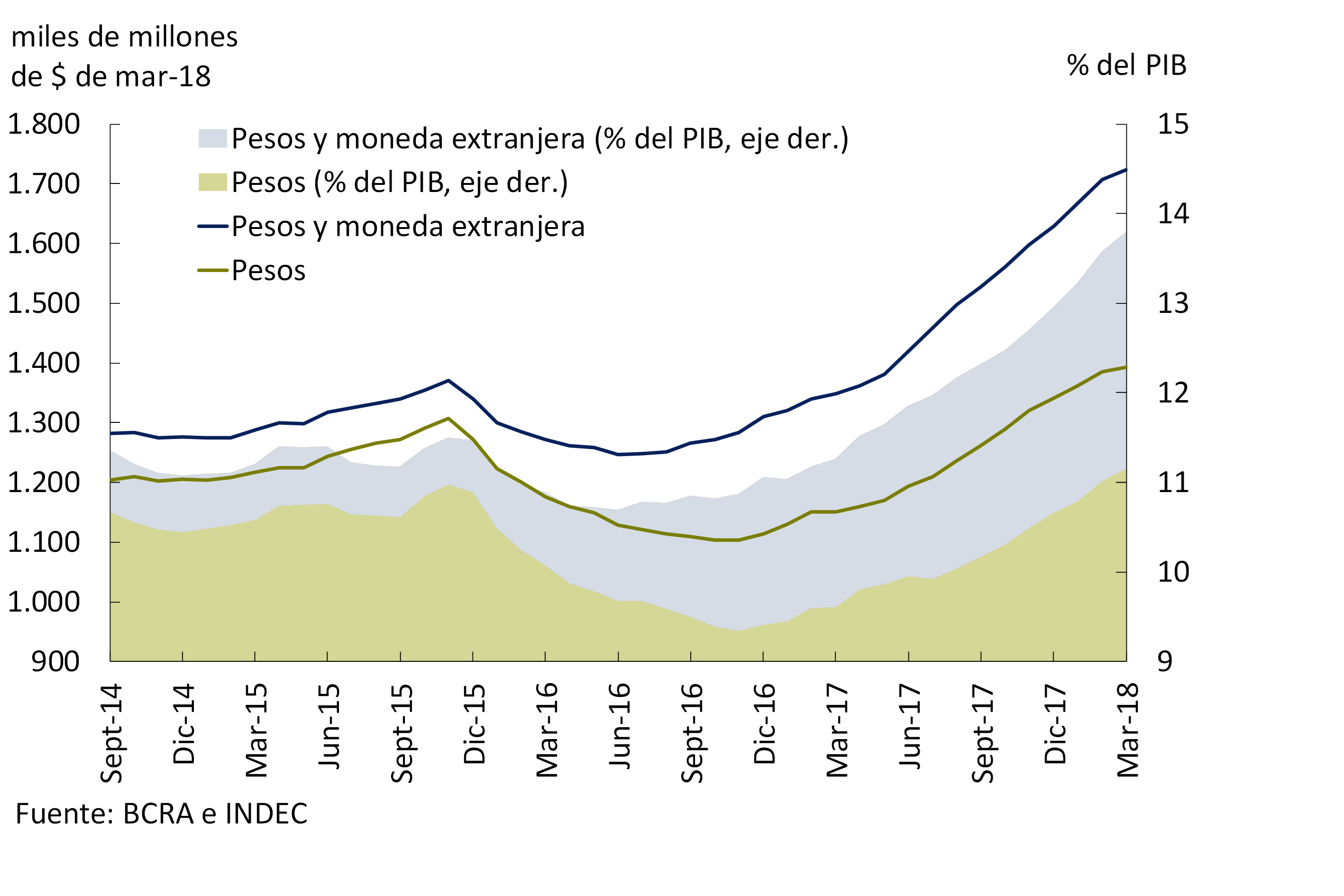

In the first quarter of the year, bank loans to the private sector in pesos continued to grow, although at a slower pace compared to that observed in the second half of 2017, with a real monthly variation without seasonality of 1.3%, and reaching an expansion of 21.1% real year-on-year in March (an increase of 27.9% real year-on-year if we consider, in addition, loans in foreign currency) (see Figure 5.13). Although increases were observed in most of the lines, the largest increases in the quarter were registered in mortgage credit, within which UVA loans, personal loans and advances in current accounts stood out. Despite this dynamic, the stock of loans to the private sector in terms of GDP is still at low levels both in historical terms and in relation to other emerging economies (March: 11.1% of GDP for financing in pesos and 13.8% of GDP when loans in foreign currency are also considered – data without seasonality).

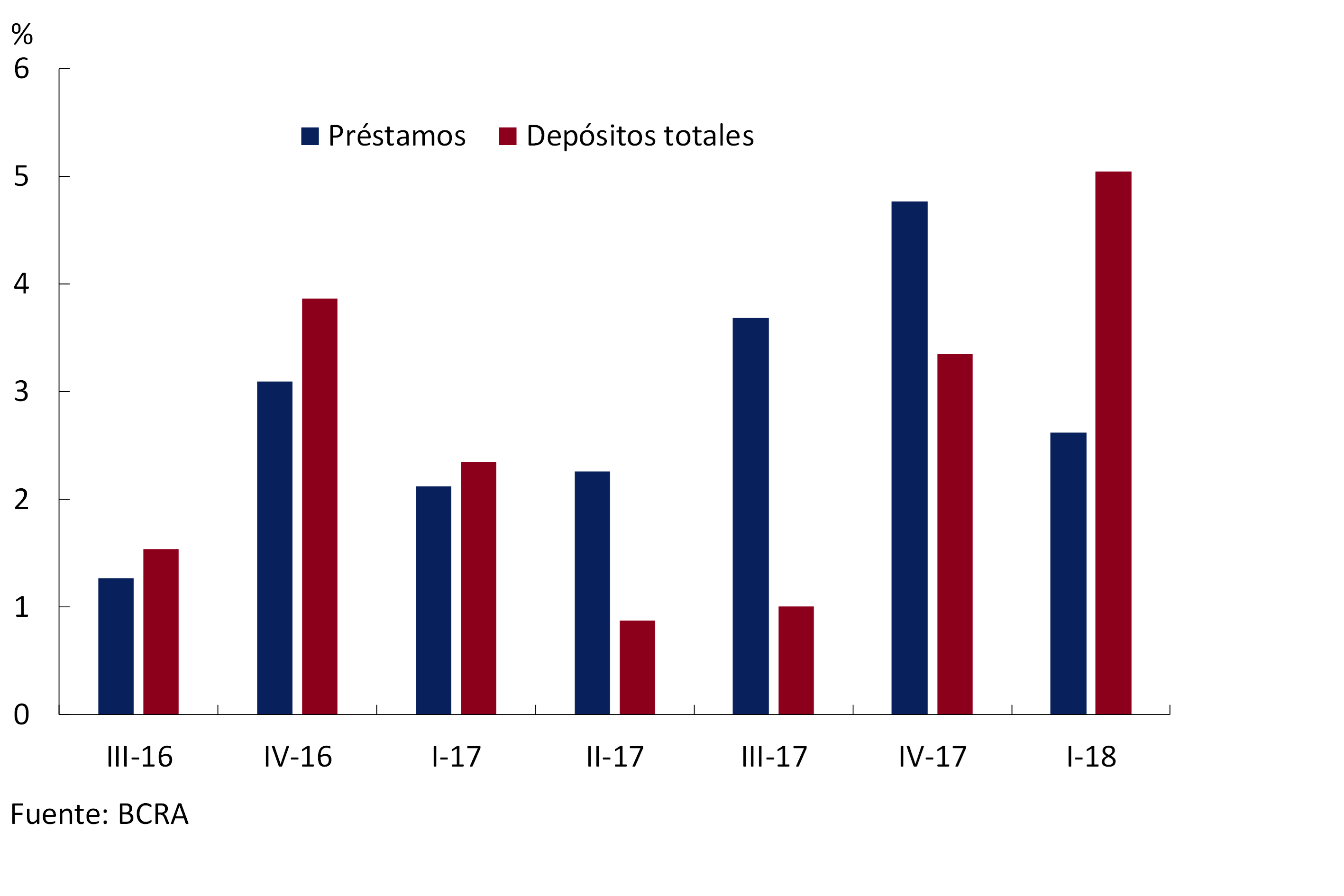

With regard to the main source of funding for banks, in the first quarter of the year the growth of deposits in pesos accelerated compared to what was observed in 2017, which increased at a rate of 3.4% per month in real terms, marking a year-on-year expansion of 11.8% in real terms in March. Time placements showed a better performance compared to demand deposits (current account and savings account deposits) in the first months of the year. In particular, the evolution of fixed-term deposits in the public sector was highlighted, growing at a rate of 30.6% in real terms per month during the quarter, due to the placement of funds from the National Treasury from the sale of foreign currency obtained from external debt (see Section 5.1.3). Private sector fixed-term deposits also increased in the quarter, but at a slower pace (1.9% real monthly), driven by seasonal factors and by the regulatory change that prevented insurance companies from renewing their LEBAC holdings. 26

Figure 5.14 | Evolution of loans to the private sector and total deposits in pesos (average monthly nominal growth)

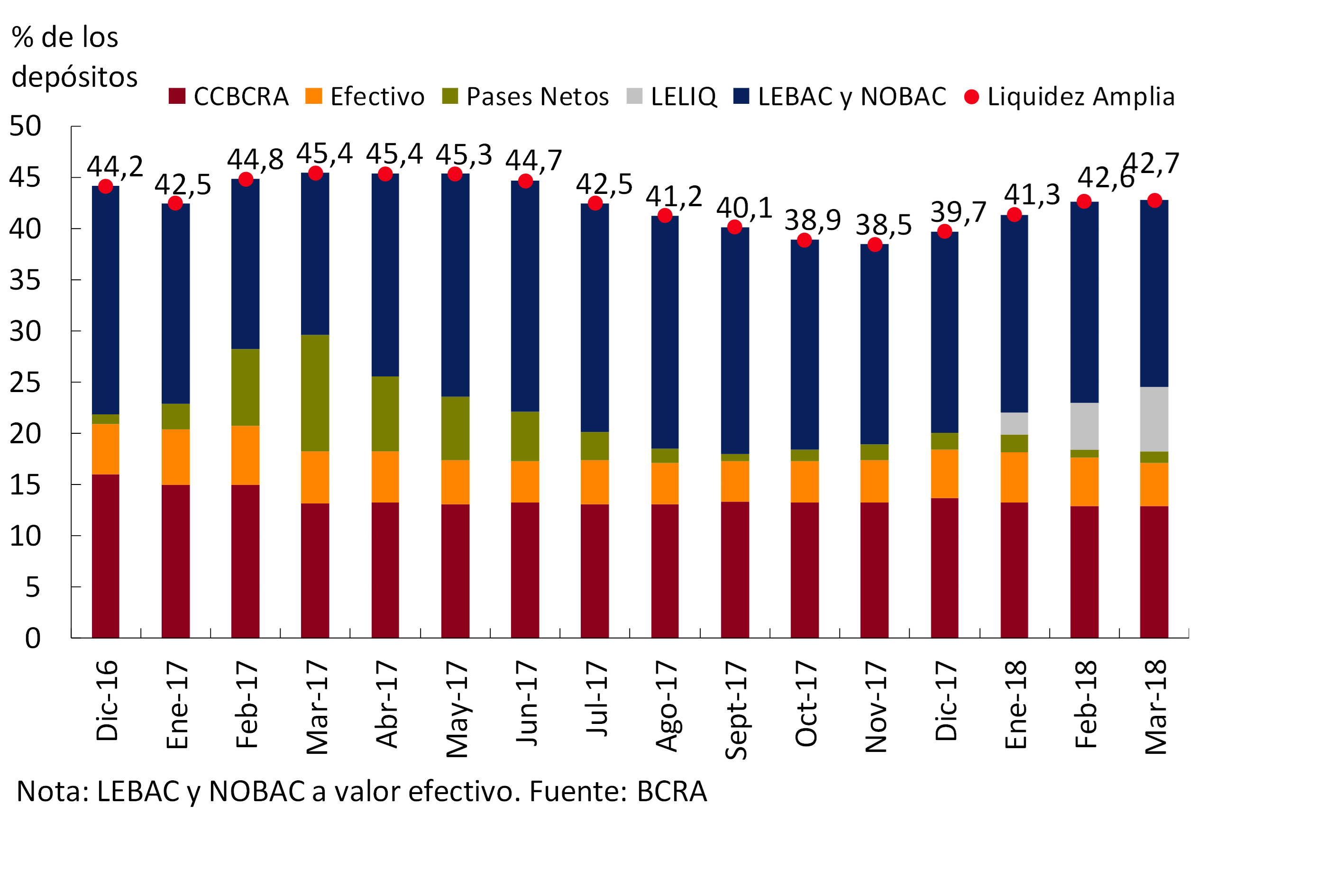

Unlike most of last year, and despite the expansion of lending, bank funding increased the most in the first three months of the year, particularly in January and February, which was reflected in an increase in bank liquidity (see Figure 5.14). Thus, the broad liquidity ratio (current account deposits at the BCRA, cash, net passes, LELIQ and LEBAC) in relation to total deposits went from 39.7% in December last year to 42.7% in March (see Figure 5.15). This increase in the liquid assets of financial institutions was concentrated in public banks due to the increase in public sector deposits that these entities ended up placing mainly in LELIQ (their liquidity ratio increased from 35.8% to 41.8% in the period). For its part, the liquidity ratio of private entities also rose, but to a lesser extent (from 43.2% to 43.7%).

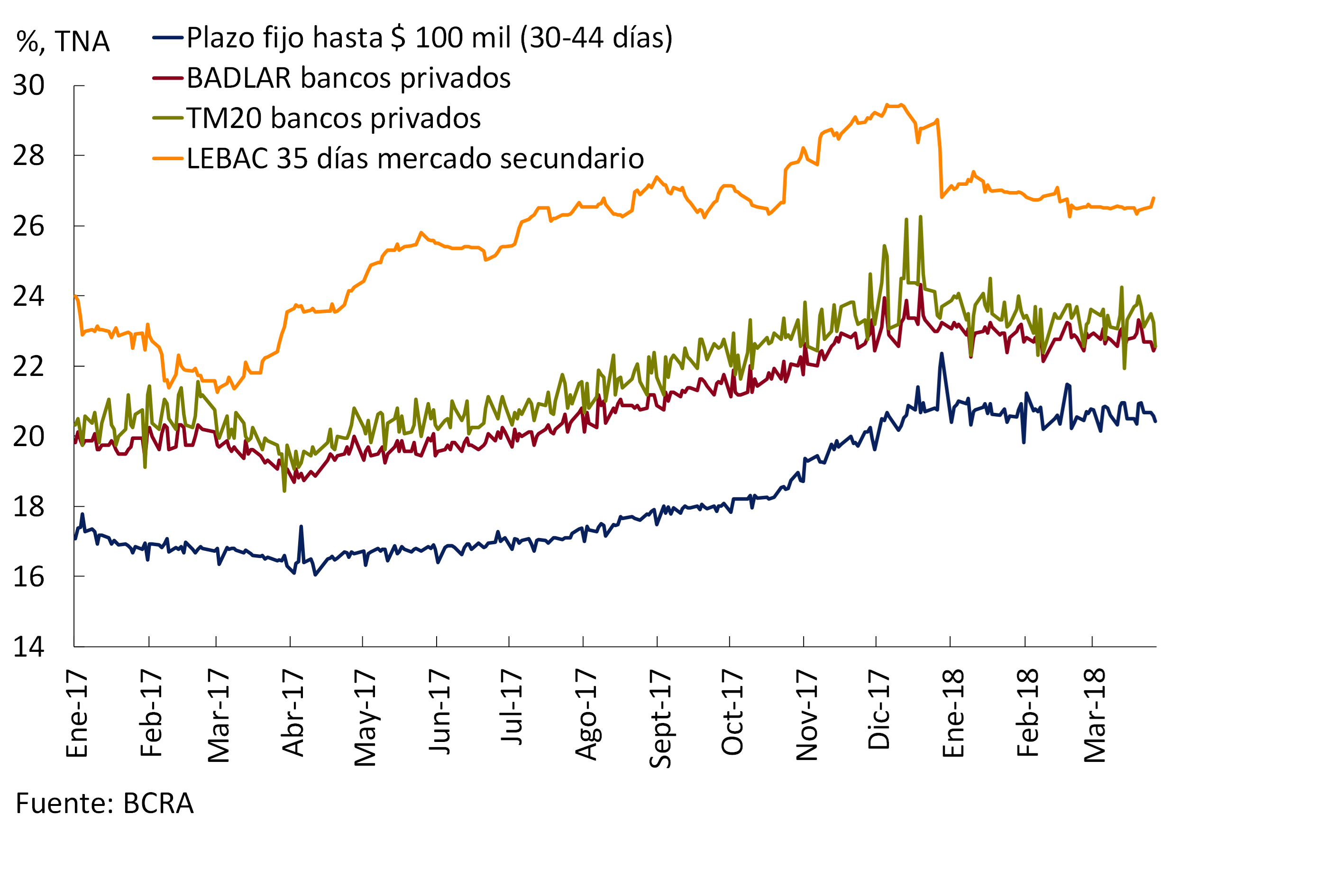

In this context, passive interest rates stopped rising at the beginning of the year to remain stable or show a slight decline throughout the first quarter. While the retail fixed-term rate remained stable at around 20.7% annually, the private bank TM20 and the BADLAR private banks fell 0.7 p.p. and 0.4 p.p. to reach a monthly average of 23.3% and 22.8%, respectively, in March (see Figure 5.16) 27. Interest rates on UVA-adjusted deposits also fell in the first three months of the year, with the monthly average falling from 5.1% annually in December last year to 4.4% annually in March this year.

In this way, the spread of the BADLAR rate (corrected for reserve requirements) against the shorter LEBAC was reduced by about three percentage points compared to the values recorded during most of last year, standing at around zero. This reduction in the spread would indicate that the system’s passive rates would be more sensitive to liquidity conditions, as banks need to react more decisively to attract funds from savers when they need to meet the growth in loan demand. It is expected that as financial intermediation deepens, the transmission of the monetary policy rate to the rest of the system’s rates will continue to strengthen.

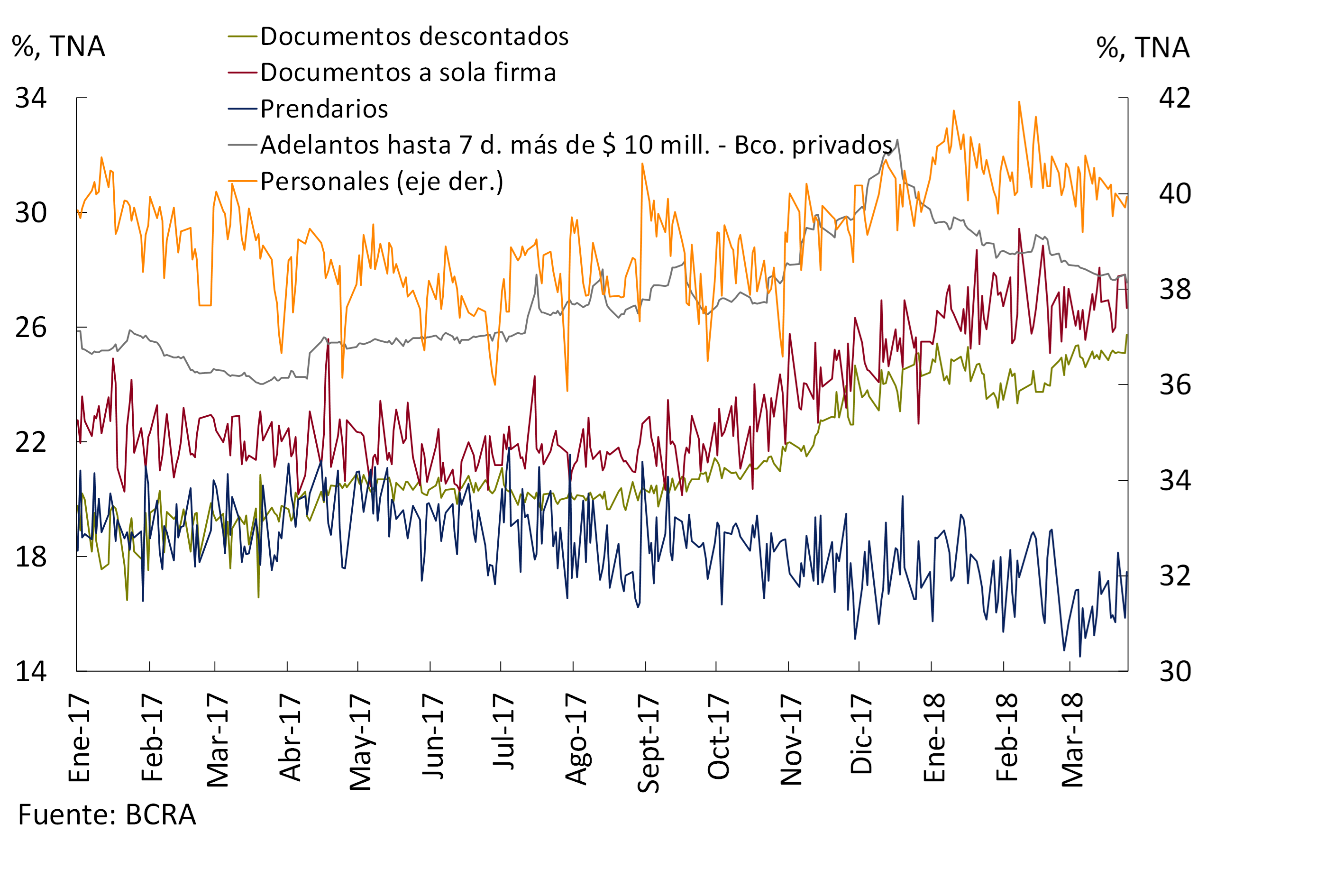

For their part, lending rates showed a mixed behavior in the first three months of the year. In the case of interest rates associated with loans in pesos to companies, while those of current account advances fell 1.1 p.p. in the first quarter of the year (reaching 33.0% annual average in March), those of discounted and single-signature documents rose 0.8 p.p. and 1.0 p.p. (to reach 25.0% and 26.3% annually, respectively). With regard to loans in pesos associated with household consumption, interest rates increased 0.3 p.p. in the case of personal loans and 2.8 p.p. in the case of credit cards in the same period (up to 40.2% annually and 45.0% annually in March, respectively). Finally, the cost of collateral loans continued to fall in the first quarter of the year, with a decline of 1.5 p.p. to reach 15.9% annually in March (see Figure 5.17). UVA-adjusted loan rates also showed heterogeneous behaviors, with the cost of mortgage loans practically unchanged between December last year and March of this year (around 4.8% annually) and personal loans rising 0.6 p.p. to reach 10.5% annually in March, respectively.

Section 1 / Complementarities of the Argentine economy with Brazil

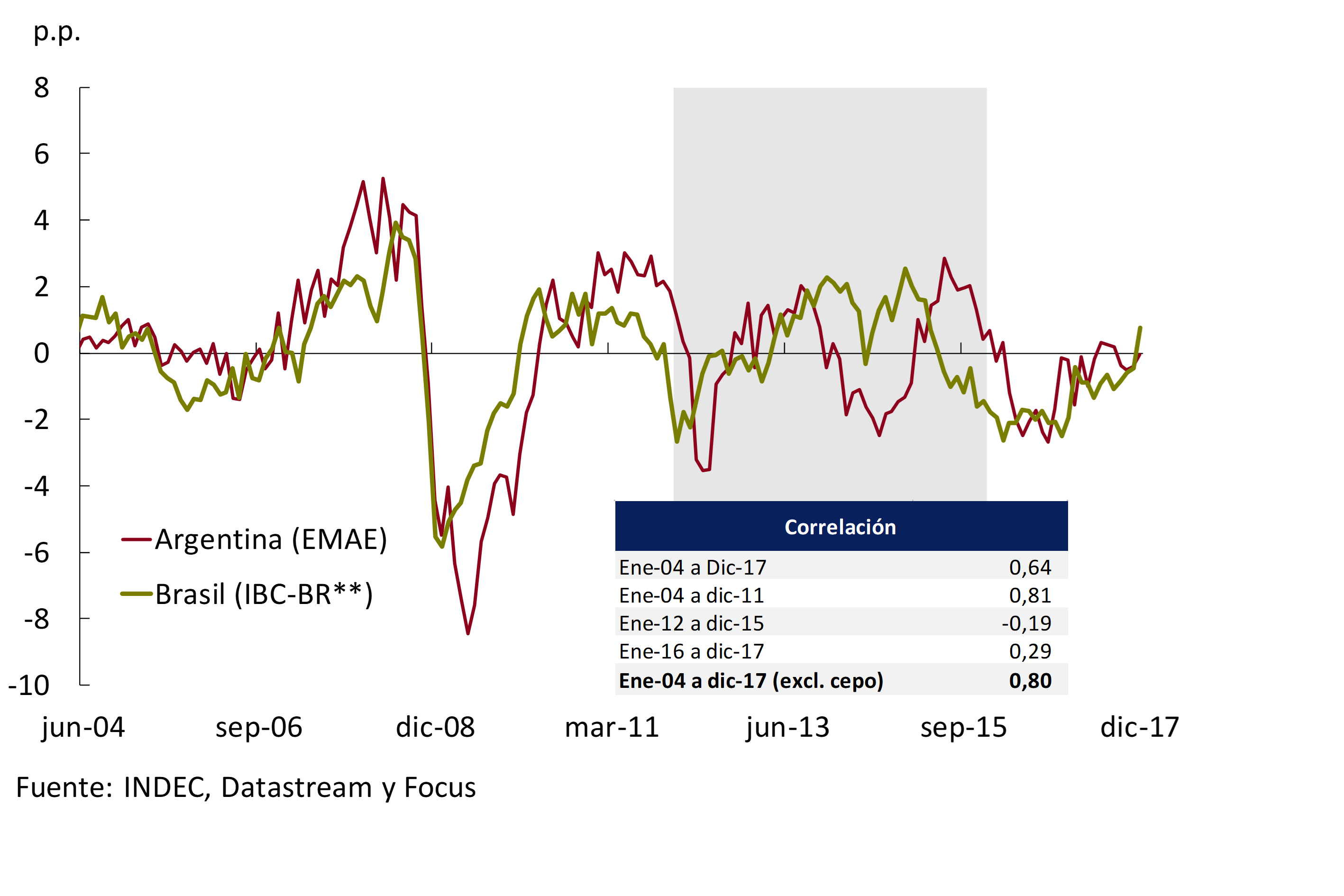

The recovery of the Brazilian economy has already been reflected in various indicators for 2017 and in the numbers projected for the end of this year: private consumption (+2.9%), investments (+4.9%) and output (+2.8%). Given the importance of Brazil’s economy for Mercosur in general and for Argentina in particular, it is interesting to analyze how and through which channels the economic reactivation of our trading partner impacts our economy and how the two countries are economically related. A preliminary analysis allows us to observe the strong correlation that exists between both economies (80% for the period 2004-2017) and how the establishment of the clamp even turned negative, tending to normalize from the end of 2015 to the present.

When analyzing bilateral trade with Brazil, the analysis tends to focus (almost) exclusively on the automotive sector, which is why other sectors that are important and relevant within the composition of the Manufactures of Industrial Origin (MOI) exported by Argentina and are integrated from the productive point of view with Brazil are left aside.

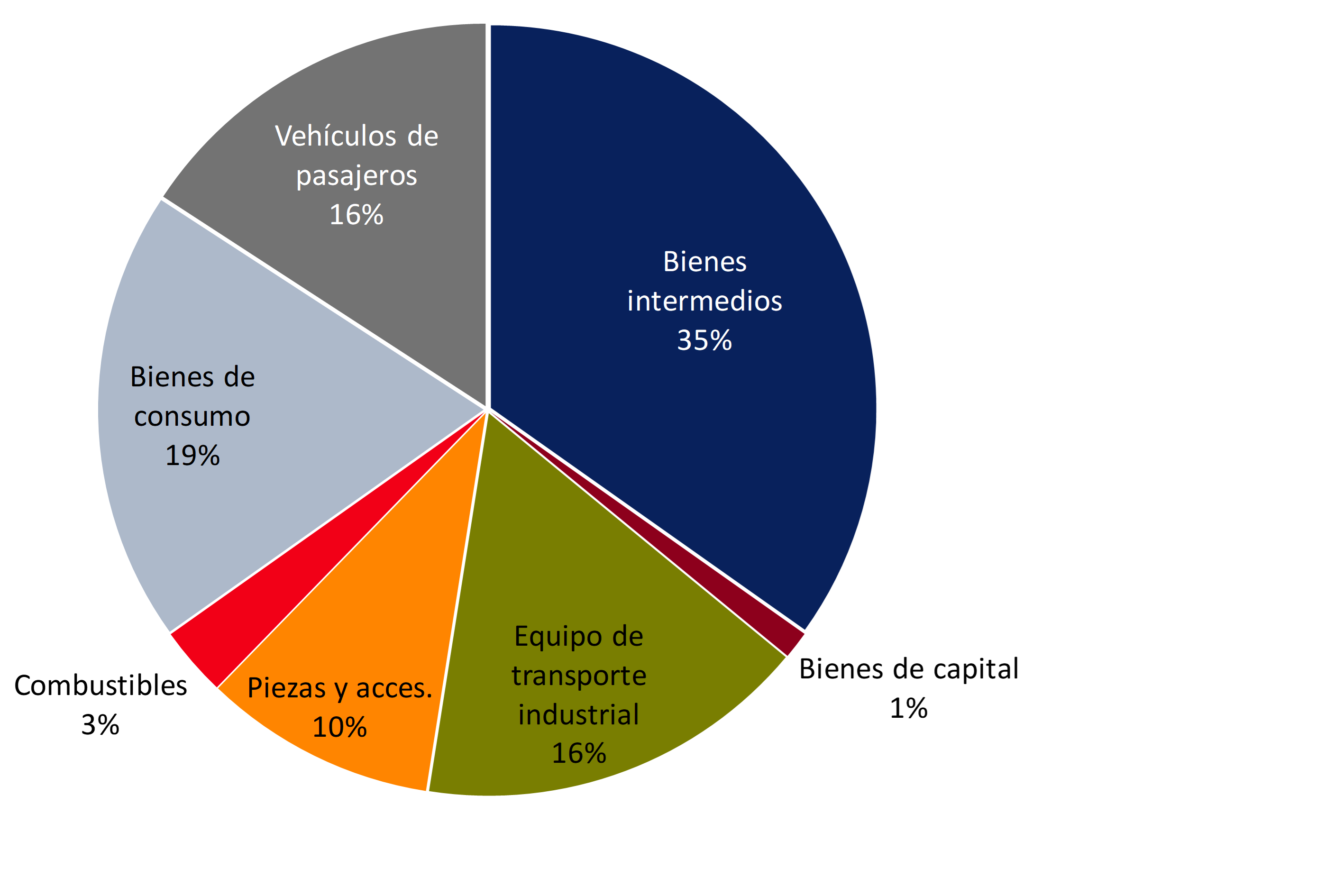

Argentina exports to Brazil a range of goods that is not clearly exhausted in the automotive sector, 62% of Argentine exports to Brazil are directly linked to the productive activity of that country. The main item is intermediate goods (see Graph 2), including electrical materials, plastic polymers and different agricultural raw materials to be processed in Brazil. In particular, there is some complementarity between Brazil’s food and beverage industry and agriculture in Argentina. Therefore, it is feasible to assume that an increase in Brazilian industry implies a greater demand for inputs used as intermediate goods that would then impact an increase in the demand for Argentina’s exports.

As can be seen in the following two graphs (see Graph 3.A and 3.B), since 2013 Brazil’s share of Argentine exports has decreased drastically in all sectors except plastics. In some cases, such as the automotive sector, there were regulatory changes in both countries that converged to the same result (the establishment of exchange restrictions in Argentina and the Innovar Autos plan in Brazil) that led to a sharp decrease in Brazil’s share of Argentina’s total exports.

Currently, the fall of the Innovar Auto program, a substantial drop in the federal tax on the sale of cars in Brazil (IPI28) and additionally the managed trade regime in force between the two economies29 augurs a strong increase in Argentine exports to that country during 2018 (different estimates place it in a range between 13% and 20%).

In conclusion, we can foresee that the improvement of the Brazilian economy that started at the beginning of 2017 and was consolidated at the end of last year, the reforms carried out in both countries and the reconfiguration of the trade relationship between the two countries, augurs an increase in Argentine exports to that destination, which will have a positive impact that will extend over the next few quarters (for a detailed analysis see the IPOM January 2017, Section 4 / On exports to Brazil and their effect on Argentina).

Section 2 / Evaluation of the performance of the BCRA’s Contemporary Output Prediction

Evaluating the predictive performance of a model is one of the most important tasks in the forecasting process. For several years now, the Central Bank has been monitoring activity in real time through its Nowcast30 or Contemporary Product Prediction (PCP-BCRA). In this box we make an evaluation of this prediction for the year 2017 taking 2 dimensions:

• Anticipation capacity, compared to other indicators available in the monthly frequency.

• Relative predictive performance in terms of a loss function commonly used in the forecasting literature, the mean square error (RMSE). In particular, we focus on comparing it with the survey of market expectations.

Temporal anticipation

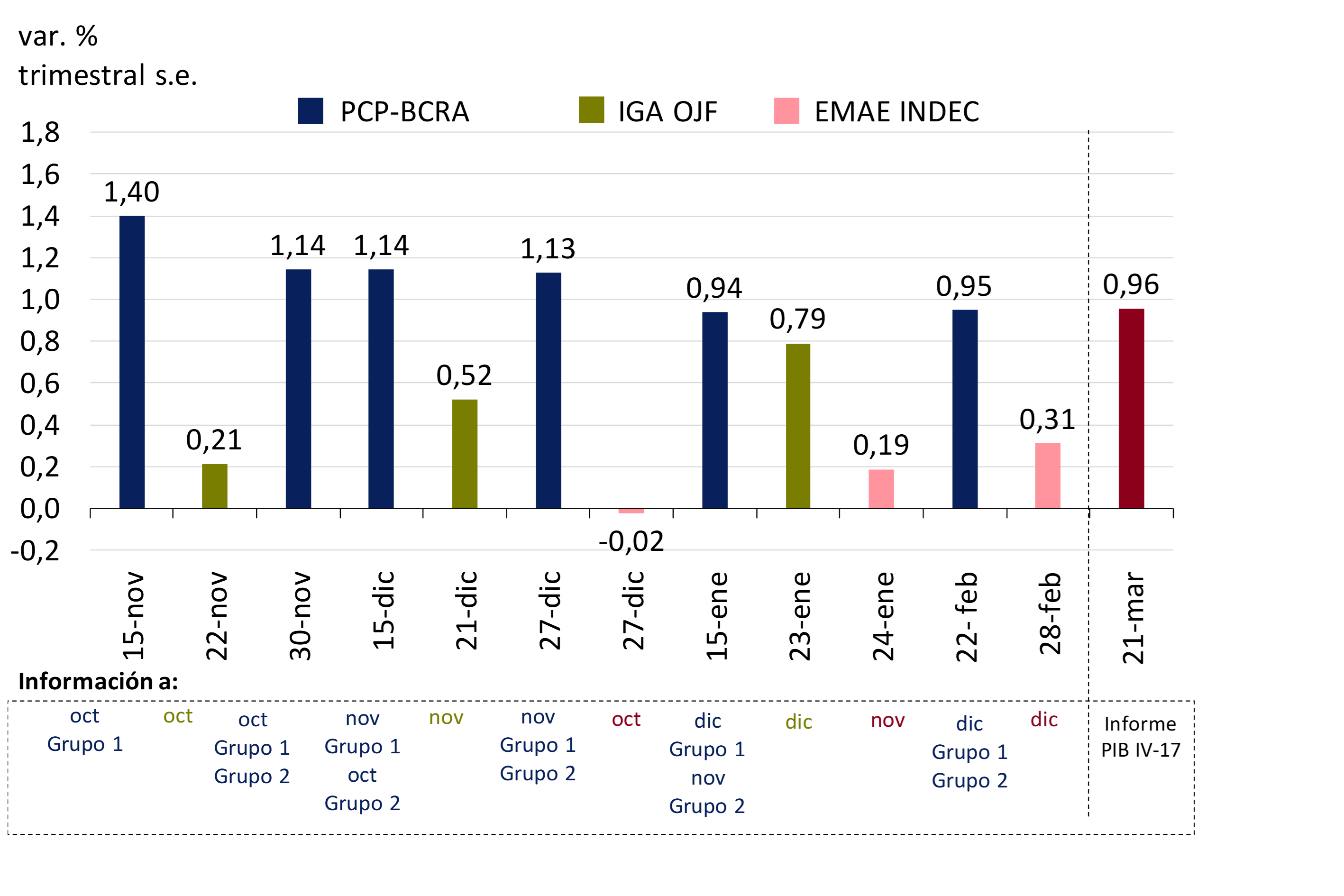

Policy decision-making requires tracking aggregate activity in real-time. The main source of information, national accounts, is quarterly and is published with a delay of approximately ten weeks after the end of the quarter. Therefore, having early information on the progress of the economy is a fundamental input for monetary policy. Chart 1 illustrates the PCP-BCRA’s ability to anticipate the fourth quarter of 2017. We compared the forecasts against the Monthly Estimator of Economic Activity (EMAE) of INDEC and the General Activity Index of Orlando J. Ferreres and associates (IGA OJF).

Through the PCP-BCRA it is possible to obtain an estimate 15 days after the end of the first month within a quarter. Then, following the update schedule of the series that are part of this model, it is possible to obtain 6 early estimates of activity for each quarter. It should be noted that the EMAE only provides partial information on the evolution of activity in the quarter, in the last month of the quarter (in the case of the fourth quarter, it provides information for October in December).

Performance of Predictive Capacity

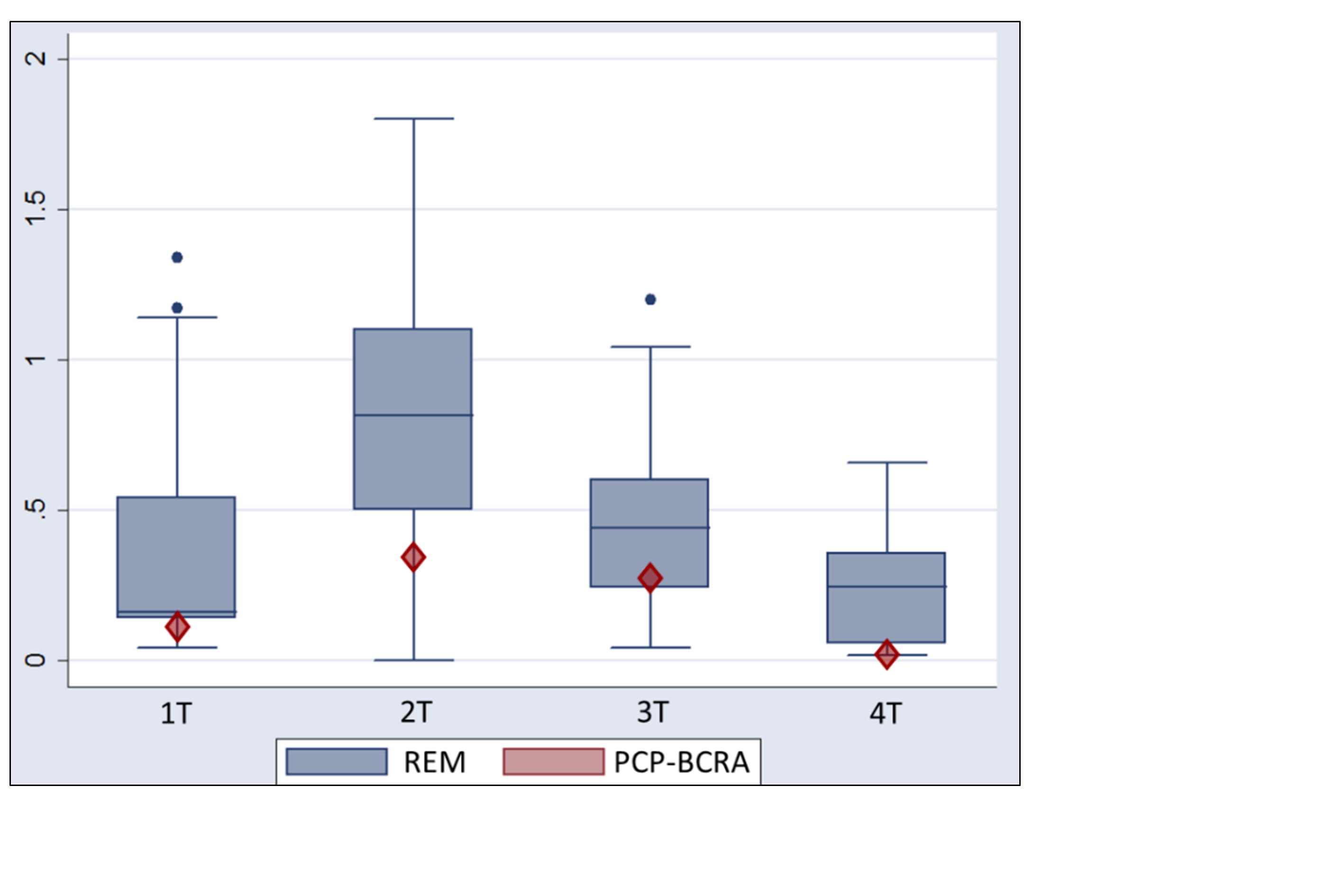

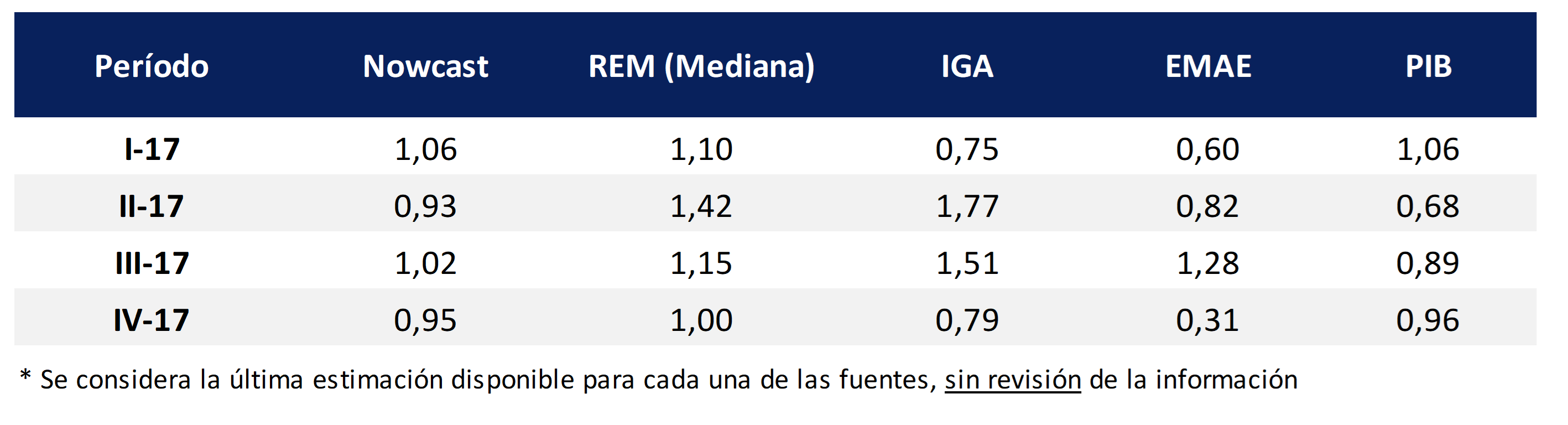

We evaluated the performance of the PCP-BCRA in terms of its relative forecast error. In this case, we compare the estimates with those of the Market ExpectationsSurvey 31. Graph 2 presents the box plots of the distribution of forecast errors in the REM throughout the different quarters of the year. The forecast error of the latest PCP-BCRA estimate available for each period is also included.

The box plot summarizes the most relevant information about the distribution of a variable – the RMSE of the REM forecasts in this case. In the graph, the box “contains” 50% of the core values of the RMSE distribution of the REM predictions during 2017. How compact the box is depends on how concentrated the RMSE values are around the median (the line inside the box). Observations (the points) beyond the lines that extend vertically up the box are considered outliers.

The noteworthy fact is that in all quarters of 2017, the RMSE of the PCP-BCRA is below the median of the RMSE of the REM. Moreover, in three of the four quarters, the RMSE of the PCP-BCRA is outside and below the cash register, which represents the central 50% of the distribution of the RMSE of the REM – in the remaining quarter it is at the lower limit of the fund. Finally, and by way of summary, Table 1 below presents the update of the growth estimates of activity, according to various sources considered.

As can be seen, the Nowcast predictions are not only available in advance of the rest of the estimates – both from public and private sources – but in general terms they also manage to surpass them in predictive capacity, even the high-frequency estimator (EMAE) published by the National Institute of Census and Statistics.

Section 3 / The direct impact of drought

The adverse weather conditions32 affecting the country’s main agricultural areas allow us to foresee a sharp drop in grain production in 2018, particularly soybeans and corn in the core zone. Although the current drought is more intense than the previous two (2008/09 and 2011/12), there are several buffers that would mitigate its macroeconomic impact33.

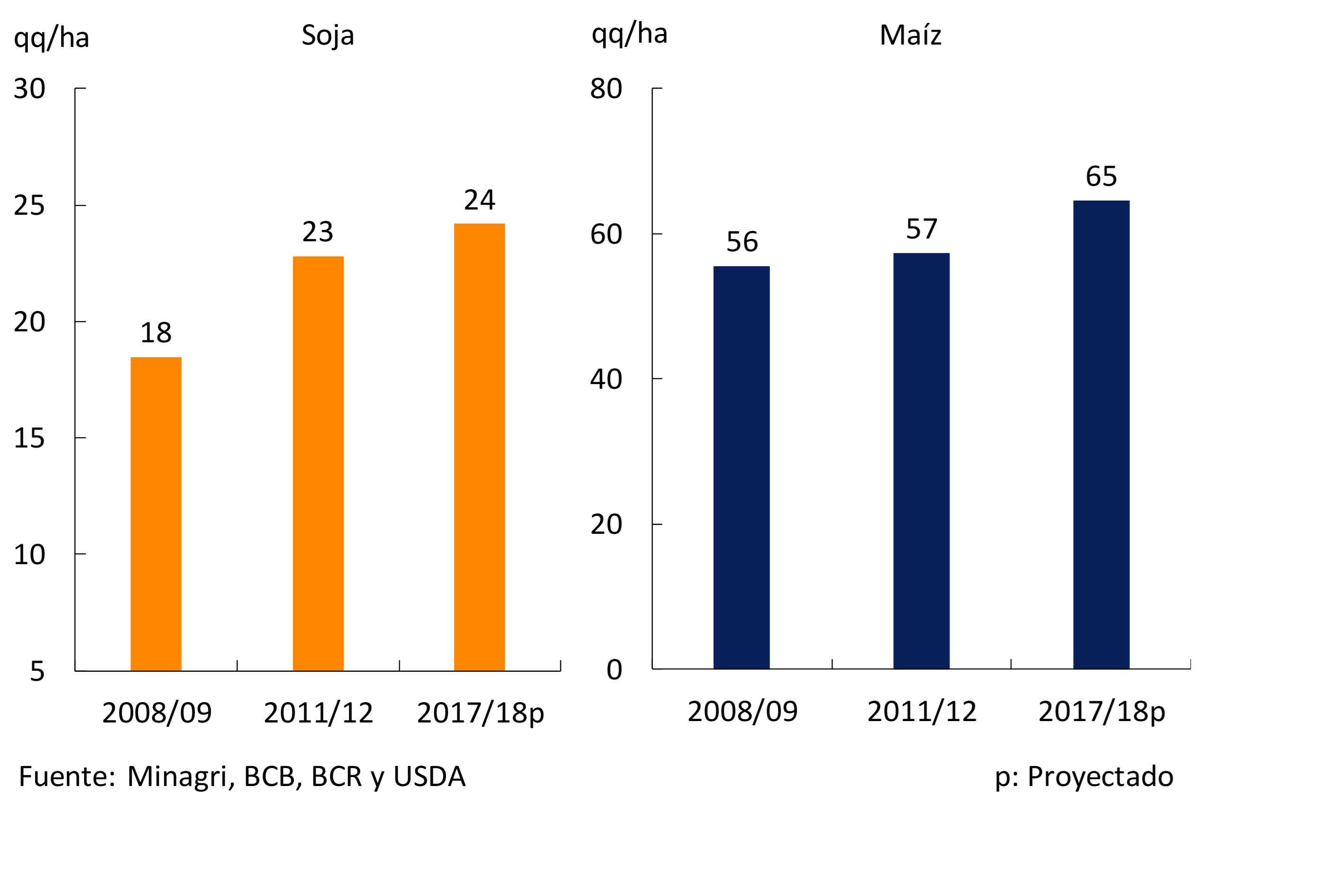

The first factor is that which allows the expected yields for the current campaign to be higher than those obtained in previous cycles that had a water deficit. The yield projections for the completion of the 2017/18 harvest tasks are around 24 quintals per hectare (qq/ha) for soybeans and 65 qq/ha for corn, which imply year-on-year drops in production of 31% and 14% respectively (see Graph 1).

The improvements in productivity (yields) per hectare are mainly due to:

1. The presence of shallow water tables in areas that had suffered floods: in some areas, the availability of water tables significantly reduced the adverse effects of water deficit. The first results34 of the coarse harvest in the core region show a very high disparity of situations, with yields ranging from 10 to 50 qq/ha for soybeans and from 60 to 100 qq/ha for corn depending on the influence of the groundwater.

2. Progress in the adoption of crop management technologies35 and the use of more defensive seeds with longer planting dates, which allowed for a more uniform implantation, with a higher incidence of late crops and less depressive yields in the face of drought events for the different areas; reflecting a learning process after the adverse results of the last two major droughts.

For the current season, losses of around 17 million tons of soybeans are estimated compared to the previous season and 7 million tons of corn (see Table 1).

The second factor that would cushion the impact of the drought is the increase in grain prices. On this occasion, the drop in expected production had a significant impact on international prices. In the case of soybeans, bean prices in Chicago were 3% above the same month a year ago in March 2018, while in 2009 they were 30% yoy on the same date, in the context of the international crisis (see Graph 2).

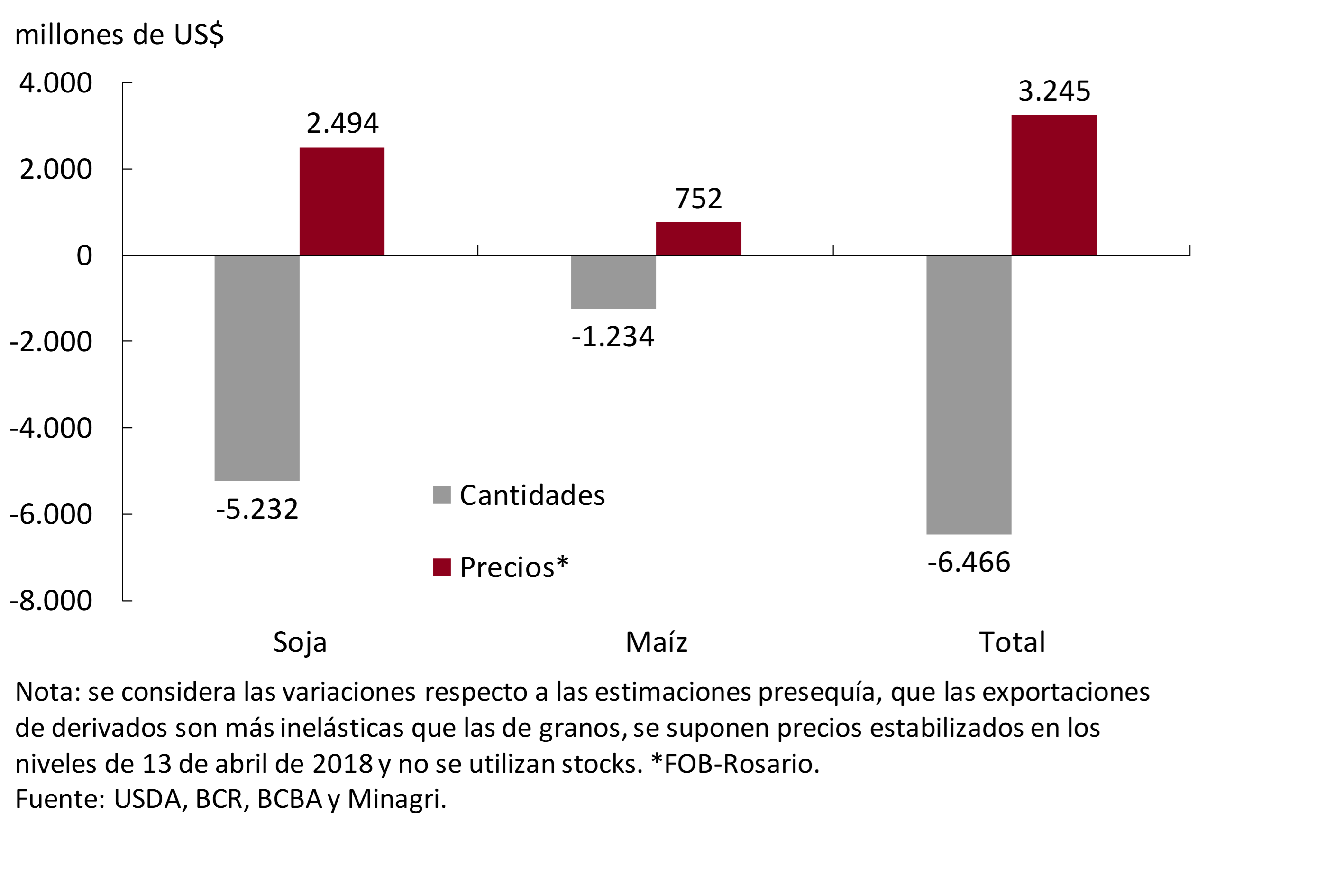

The rise in the prices of soybeans, corn and their derivatives would partially offset the macro impact generated by the projected fall in quantities36. The net effect is negative at US$3,044 million (see Graph 3) and would represent about 0.5% of GDP37. This result is sensitive to the prices that are actually traded in the market38.

Another additional factor that would make it possible to mitigate the negative macro impact would be the use of record stocks of soybeans and corn. The wealth effect of holders due to the appreciation of these inventories is positive between US$1,000 and US$1,500 million. The liquidation of such holdings depends on several factors. Stocks, particularly soybeans, continue to be a store of value, not only because of changes in crop prices but also because of the expected decline in soybean export duties for 2018-201939.

Finally, it is important to consider that these losses in income do not affect all the actors involved in a homogeneous way depending on the place they occupy in the chain: producers and regions affected by the drought, tenants with fixed rents or owners, small or large, producers or exporters, transporters, degree of productive integration, etc. In addition, the total macroeconomic result is more negative if we include the indirect effect on the rest of the productive framework, the so-called second and third round effects linked to the evolution of commercial activity in the affected areas, investment in agricultural machinery and other capital goods, the planning of the next campaign, etc.

Section 4 / Foreign exchange intervention in inflation-targeting regimes

The inflation targeting regime is a monetary policy framework in which a medium-term inflation target is announced to the public and in which the central bank uses the tools at its disposal to bring inflation as close to that target as possible. Typically, the main instrument of monetary policy in this regime is the interest rate since it is inversely correlated with the inflation rate. Foreign exchange intervention in these regimes complements the interest rate policy when there are disruptive movements in the exchange rate. This section reviews the international experience of foreign exchange interventions within the framework of the inflation targeting regime.

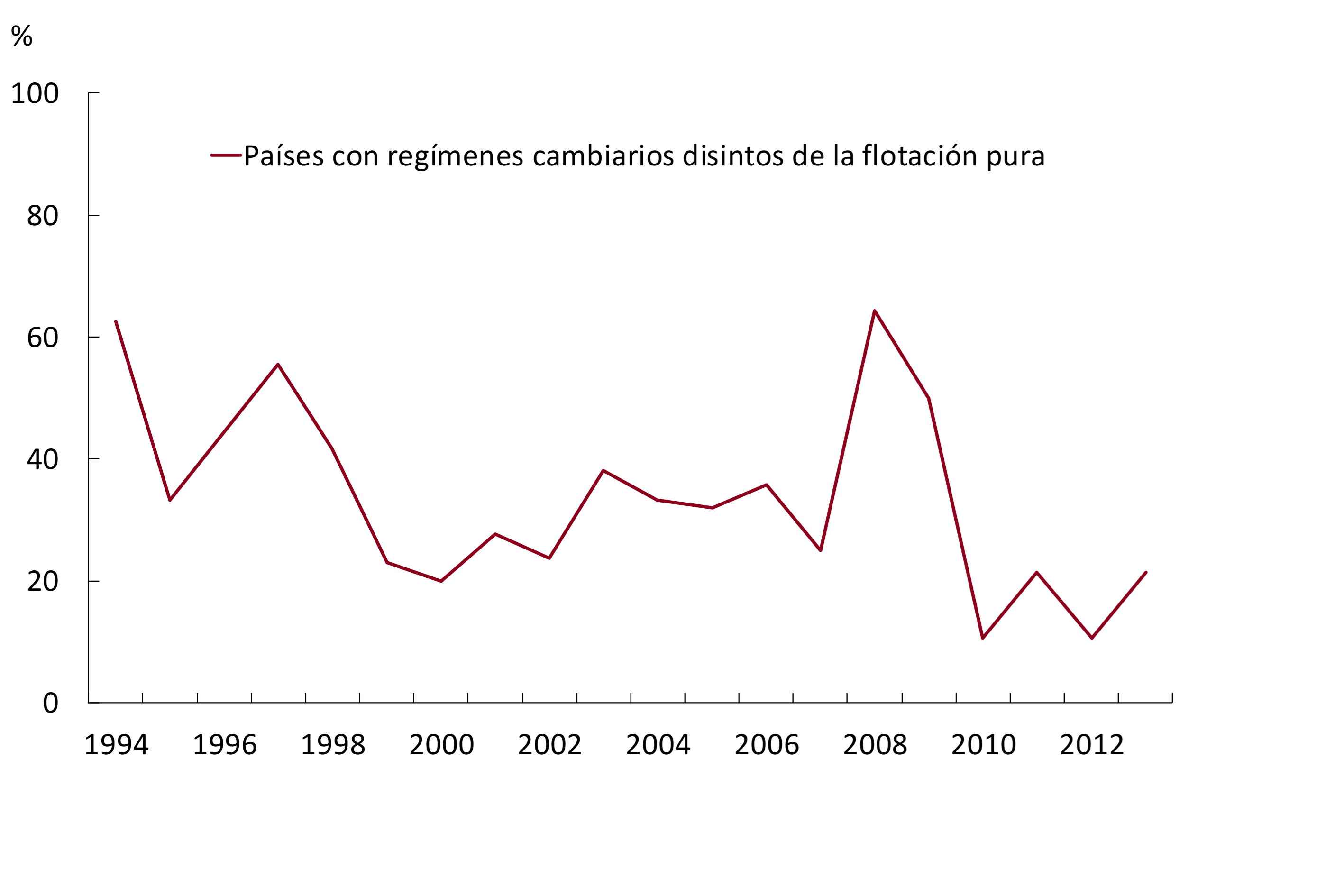

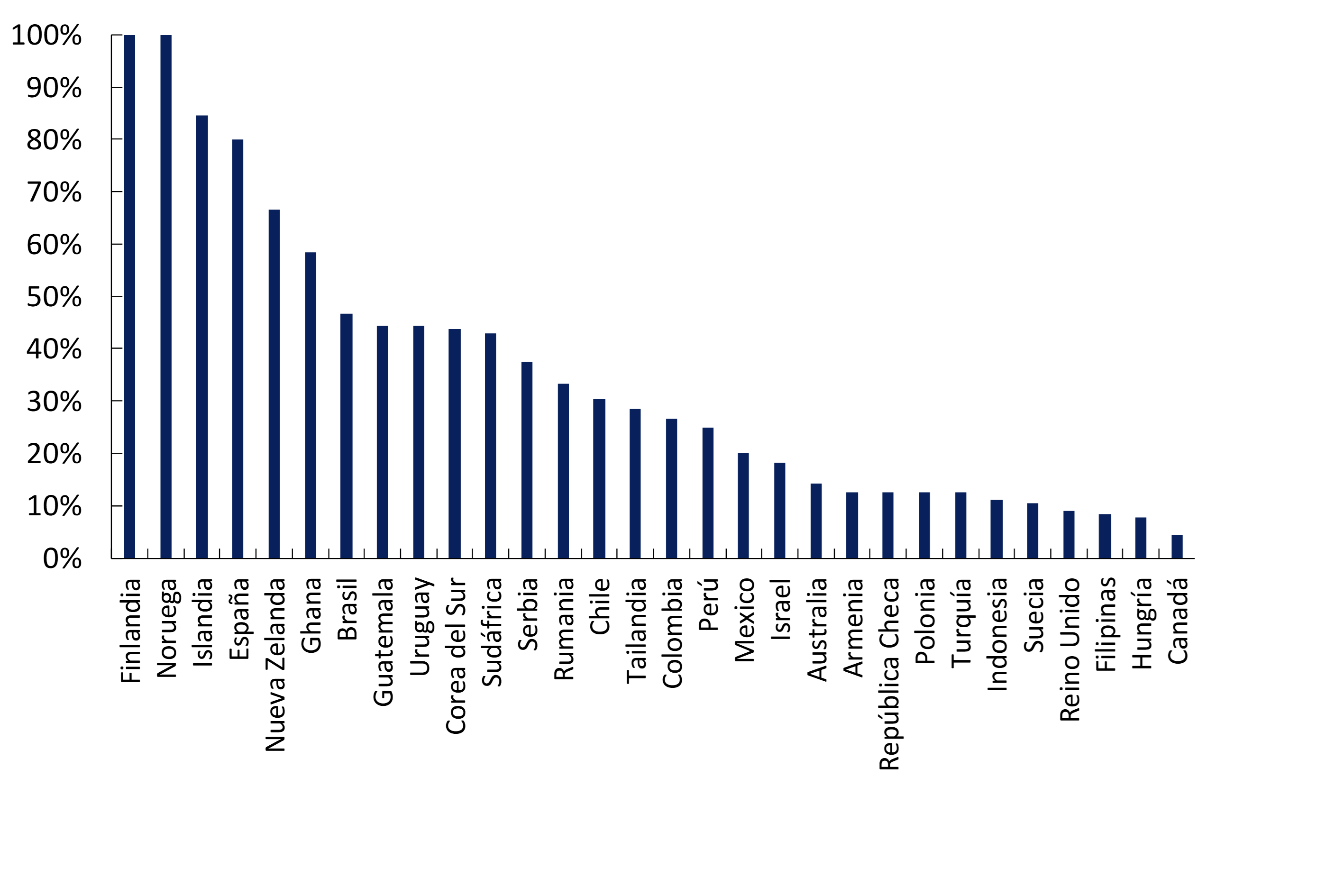

Some 20% of the countries that have inflation targets do so with a de facto exchange rate regime other than pure floating (see Chart 1; data for 2013, the latest available for the classification of exchange rate regimes by Levy Yeyati and Sturzenegger, 201640). This has changed over time, but there is another telling fact: none of the 28 countries that have implemented inflation targets since 1991 has always had a perfectly floating exchange rate (see Chart 2).

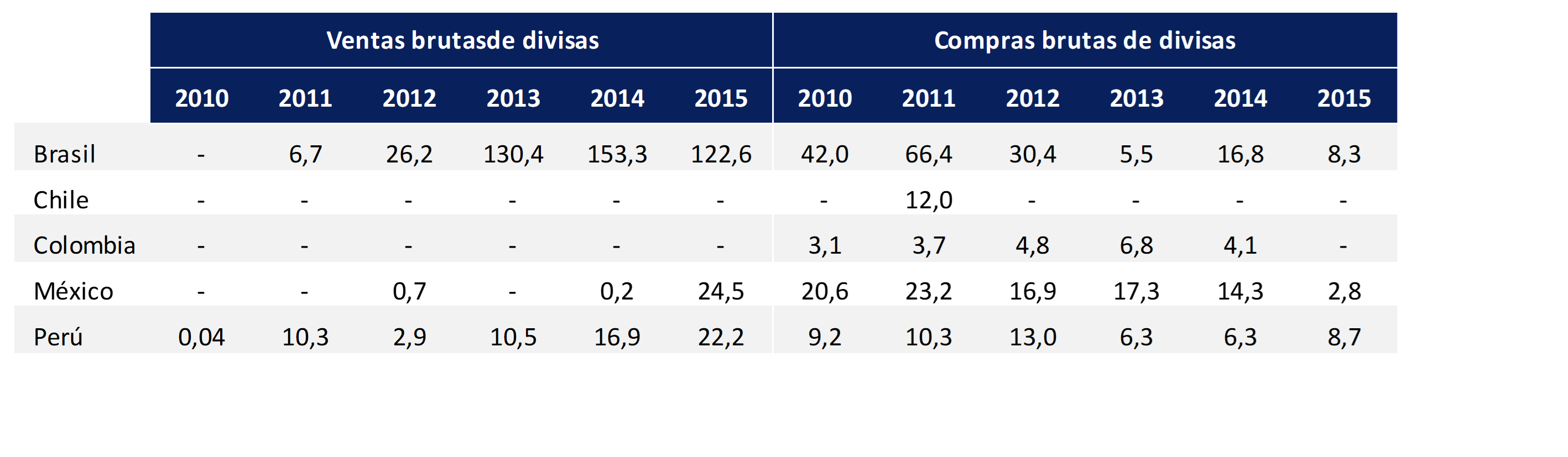

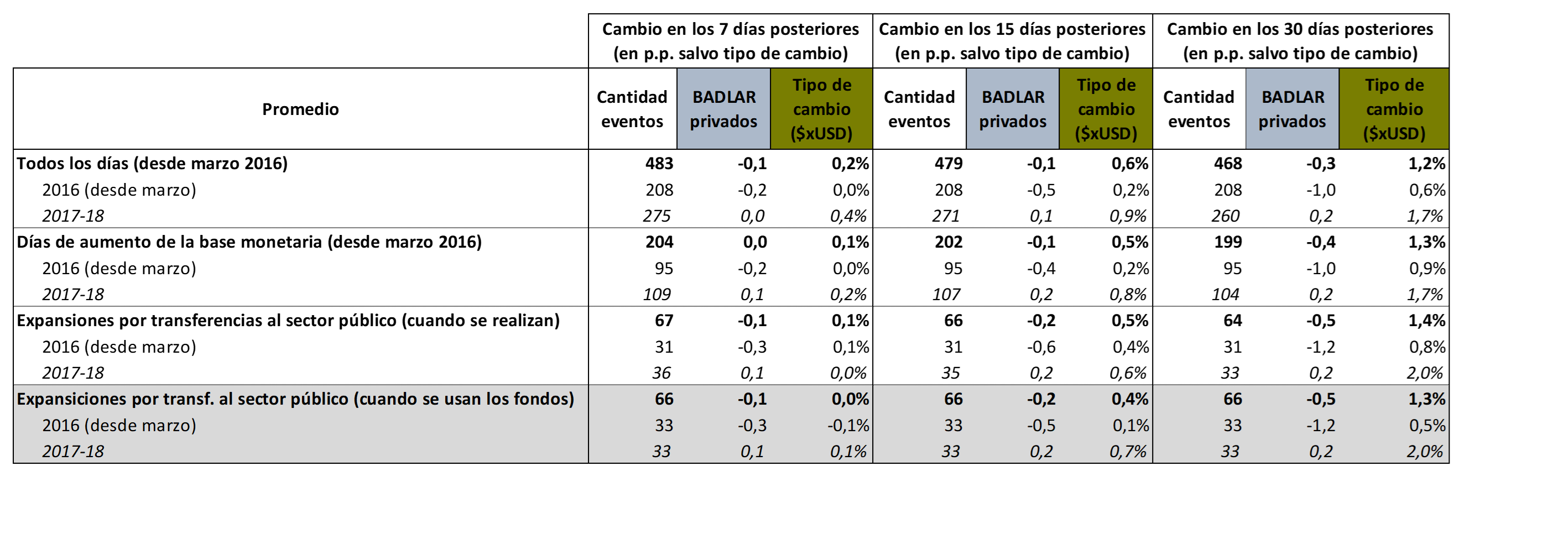

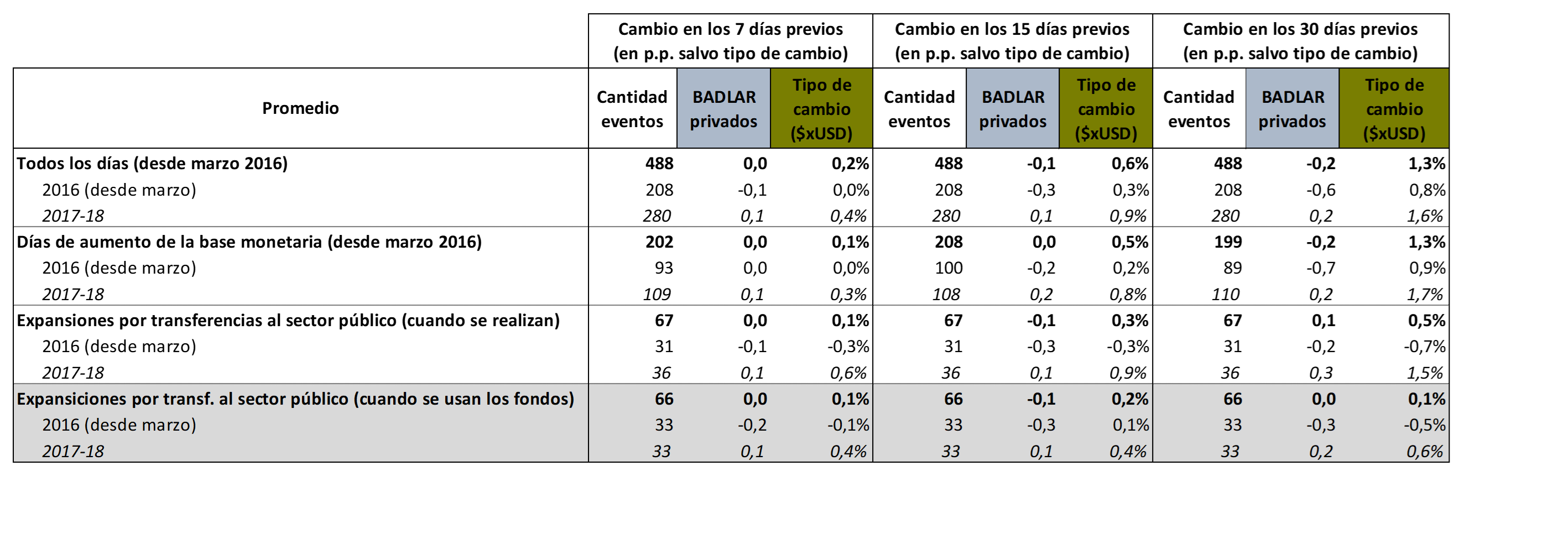

Figure 1 also highlights that periods when most inflation-targeting countries moved away from pure floating coincided with events of excessive volatility, not directly related to the fundamentals of their economies: the Asian crisis of 1996-97 and the onset of the international financial crisis in 2008. Latin America has not been the exception41: Chile adopted the pure floating exchange rate in 1999, leaving open the possibility of intervening occasionally, as it did in 2008 (when it announced the decision to increase its international reserves by almost half of the stock it held) and in 2011. Faced with the “taper tantrum” episode (when the market reacted strongly to the possible withdrawal of monetary stimulus by the Federal Reserve), the Central Bank of Brazil implemented interventions through daily auctions of up to 3 billion dollars per week since August 2013, focused on pre-announced swap and pass operations. In 2015, when the exchange rate depreciated sharply following the fall in oil prices, Colombia defined a rule specifying that when the daily volatility of the exchange rate exceeded a certain threshold, the central bank would intervene; The program ceased the following year. In Mexico, the central bank has intervened on several occasions; in 2017, and in the face of the uncertainty associated with the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), a futures auction program was launched for up to 20 billion dollars. In Peru, an economy with a high degree of financial dollarization, the central bank has intervened since the implementation of inflation targets. These are just a few examples of Latin American countries with inflation targets that have intervened in the face of exchange rate volatility that is detrimental to their objectives; Table 1 details the amount of these operations in recent years.

Graph 2 | Inflation-targeting countries (1991-2013): Years with non-pure floating exchange rate regime (in % of target years)