Política Monetaria

Monetary Policy Report (IPOM)

Third quarter

2023

This quarterly publication aims to analyze the national and international economic situation, assess the dynamics of inflation and its prospects, and explain in a transparent manner the fundamentals of monetary policy decisions.

Table of Contents

Chapters

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlook

2. International context

3. Economic Activity and Employment

4. External Sector

5. Public Finance

6. Pricing

7. Monetary Policy

Sections

1. Progress in the energy

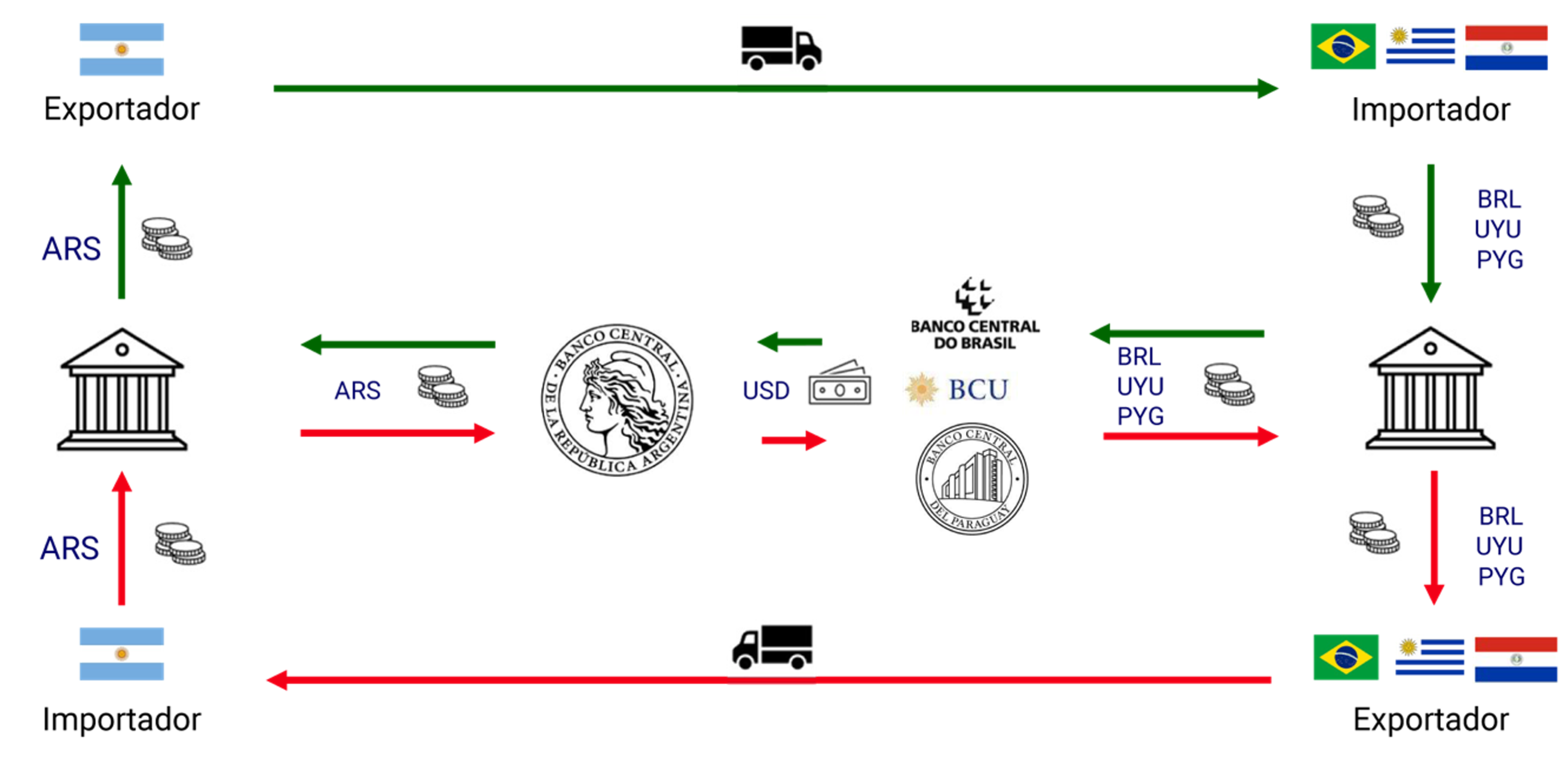

sector 1. Mercosur Local Currency Payment System (SML)

2. Real and Financial Determinants of Productive Investment at the Firm Level: Structural Trends and Post-Pandemic Changes in Latin America (1995-2022)

3. Recovery forecasts for the next crop season

4. The BCRA resumes the publication of the Foreign Direct Investment Report

5. Main aspects of the draft National Budget Law 2024

6. The impact of commodities and capital goods and inputs on inflation: a long-term analysis for Argentina

Summary

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlook

The global economy has tended to slow down in recent months. With core inflation persisting in many advanced economies and easing in much of the emerging economies, central banks in the former maintained, or even raised, benchmark interest rates; while those of the latter began to reduce them, especially in Latin America. This had an impact on capital flows to emerging economies, which lost dynamism, with its consequent impact on currencies. Likewise, the U.S. dollar has appreciated at the margin, putting downward pressure on agricultural commodity prices, while oil strengthens in the face of supply constraints.

In Argentina, economic activity contracted in the second quarter of the year, as a result of the severe drought that mainly affected the coarse harvest, as had been anticipated in the previous IPOM. For its part, the level of activity of the non-agricultural sectors as a whole remained stable compared to the first quarter and also in year-on-year terms, with the activities most linked to agriculture contracting and the rest growing. Formal employment in the non-agricultural sectors continued to increase. Domestic demand remained relatively stable compared to the first quarter, with some heterogeneity among its components. The contraction in net exports, falling inventories, both affected by the drought, and the decline in private consumption were partially offset by the increase in investment. Going forward, it is expected that the set of income reinforcement policies implemented by the National Government will contribute to sustaining domestic demand, in a context of high inflation and uncertainty associated with the electoral period.

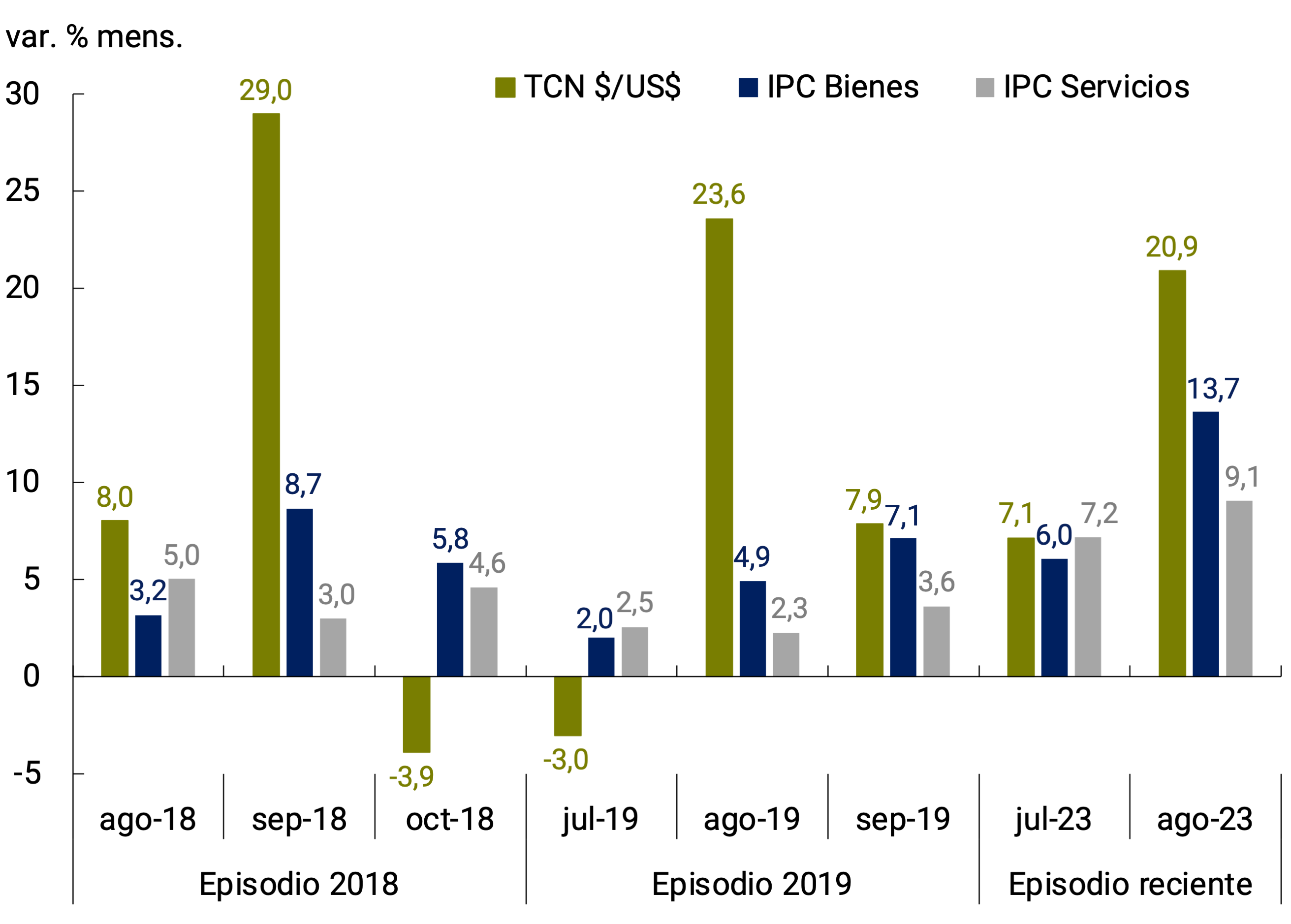

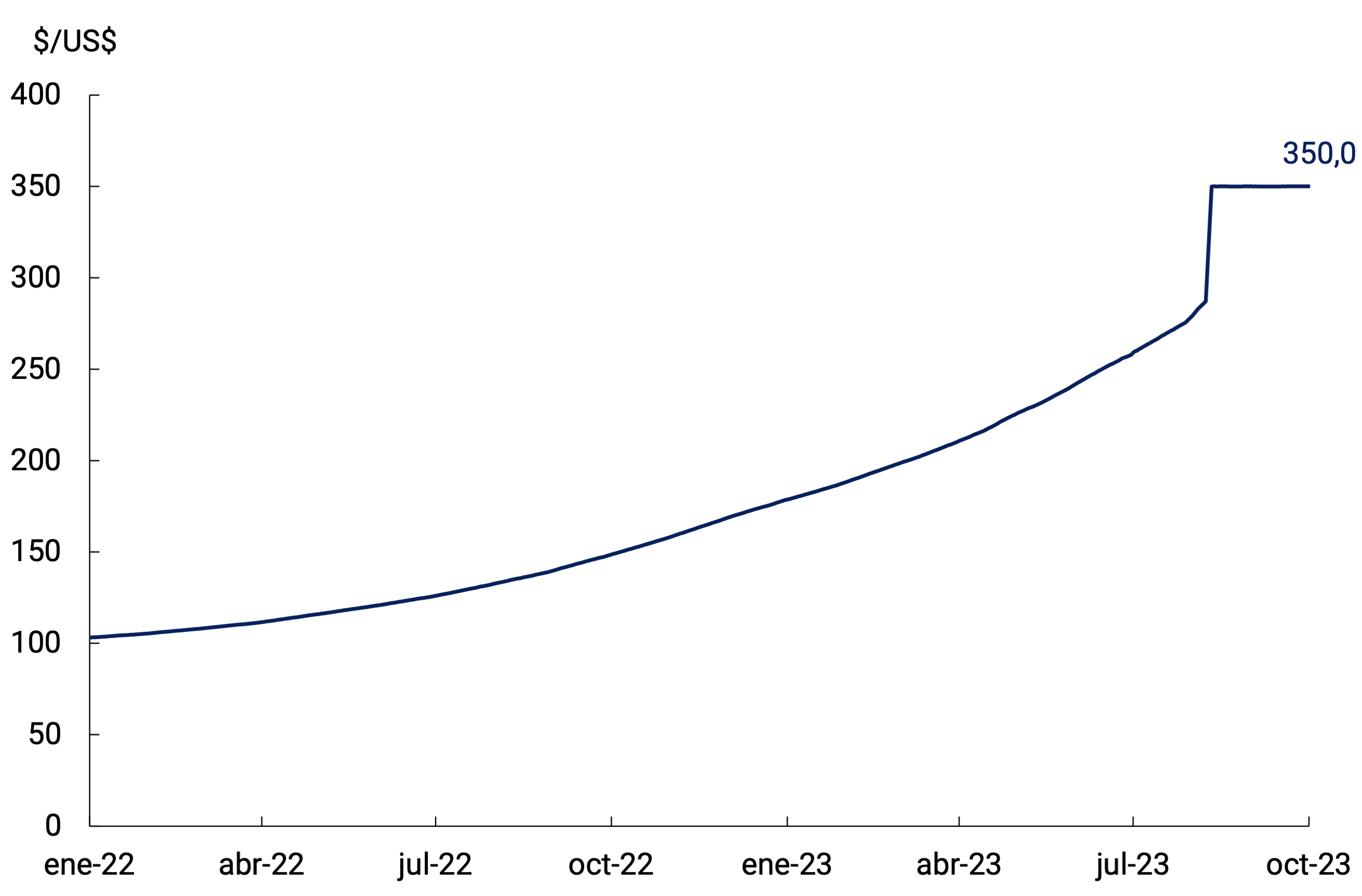

The drought also caused a sharp drop in foreign trade flows, with an estimated loss of around US$20 billion, and in export duty revenues, which fell by 0.6% of GDP. With the aim of contributing to an improvement in the trade balance and favoring the accumulation of international reserves, as well as strengthening fiscal resources, since mid-July the National Government and the BCRA promoted a set of tax and exchange measures. Among them were the recalibration of the official exchange rate to a value of $/US$350, the extension of the PAIS tax on the import of other goods and services and a series of modifications to the Export Increase Program (PIE).

In this context and in view of the need to timely meet the payments of debt services with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), given the delay in the disbursements corresponding to the fifth review of the Extended Facilities Program (PFE), the BCRA had to provide financial assistance to the National Treasury on a temporary and extraordinary basis. In addition, to meet the commitments of the end of July and the beginning of August, extraordinary sources of funding were used (the placement of a non-transferable bill to the BCRA, financing from CAF and a bilateral loan with the State of Qatar). These operations made it possible to comply in a timely manner with debt services with the multilateral credit agency until the joint approval of the fifth and sixth revisions of the PFE. In it, the international reserves target was adjusted, reflecting the impact of the drought and maintaining a high accumulation effort in the rest of the year. On the other hand, the limit of monetary financing to the Treasury was increased from 0.6% to 0.8% of GDP; while maintaining the primary fiscal deficit target of the Non-Financial Public Sector.

Following the approval of the PFE review, on August 23 the agency made a disbursement of 5.5 billion SDRs (about US$7.3 billion) and the aforementioned bridge financing mechanisms began to be reversed. That same day, $0.5 billion of net transitory advances were canceled. The loan with the State of Qatar was also canceled and the National Government decided to advance the September payment to the IMF for 687.5 million SDRs (about US$ 910 million).

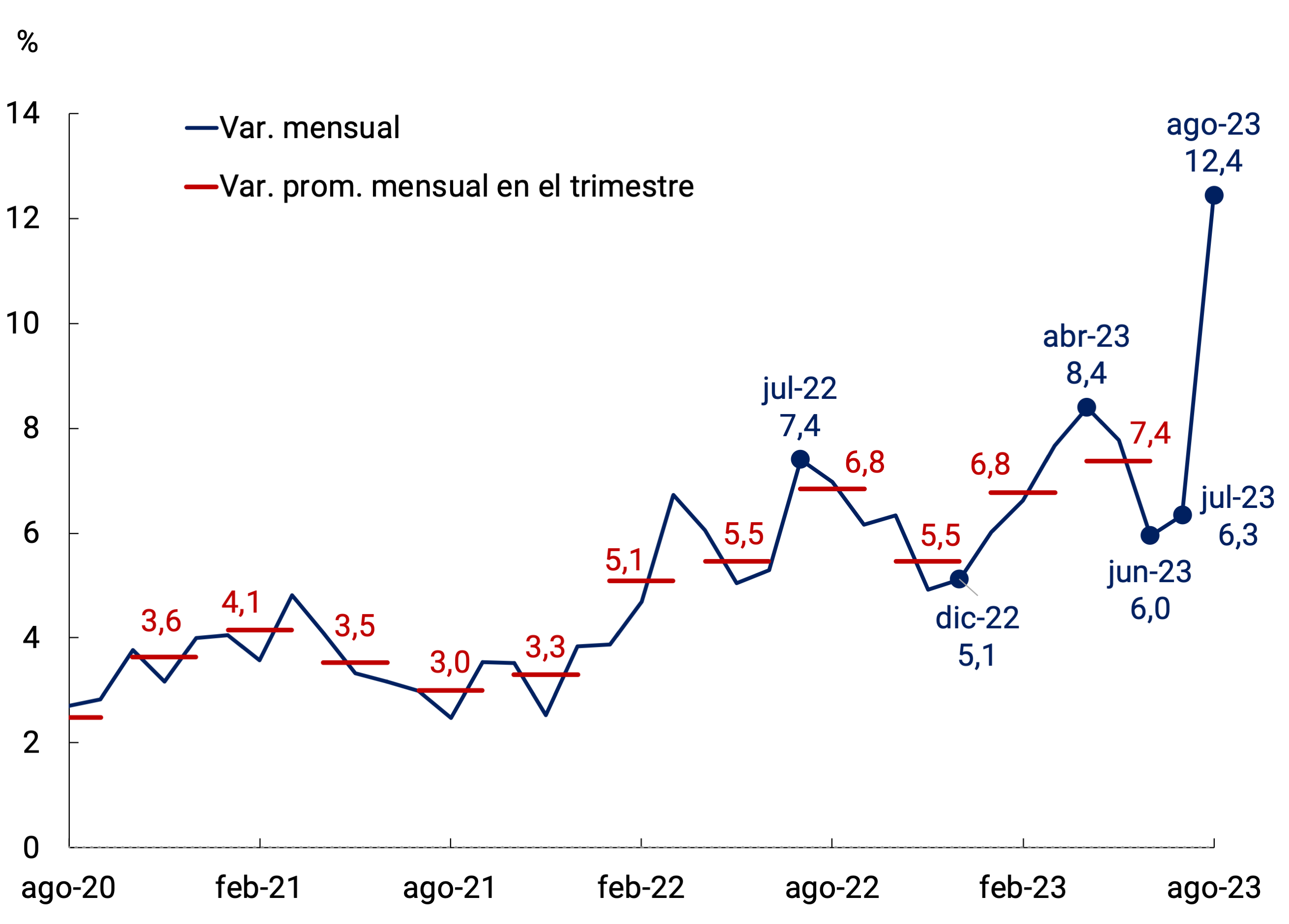

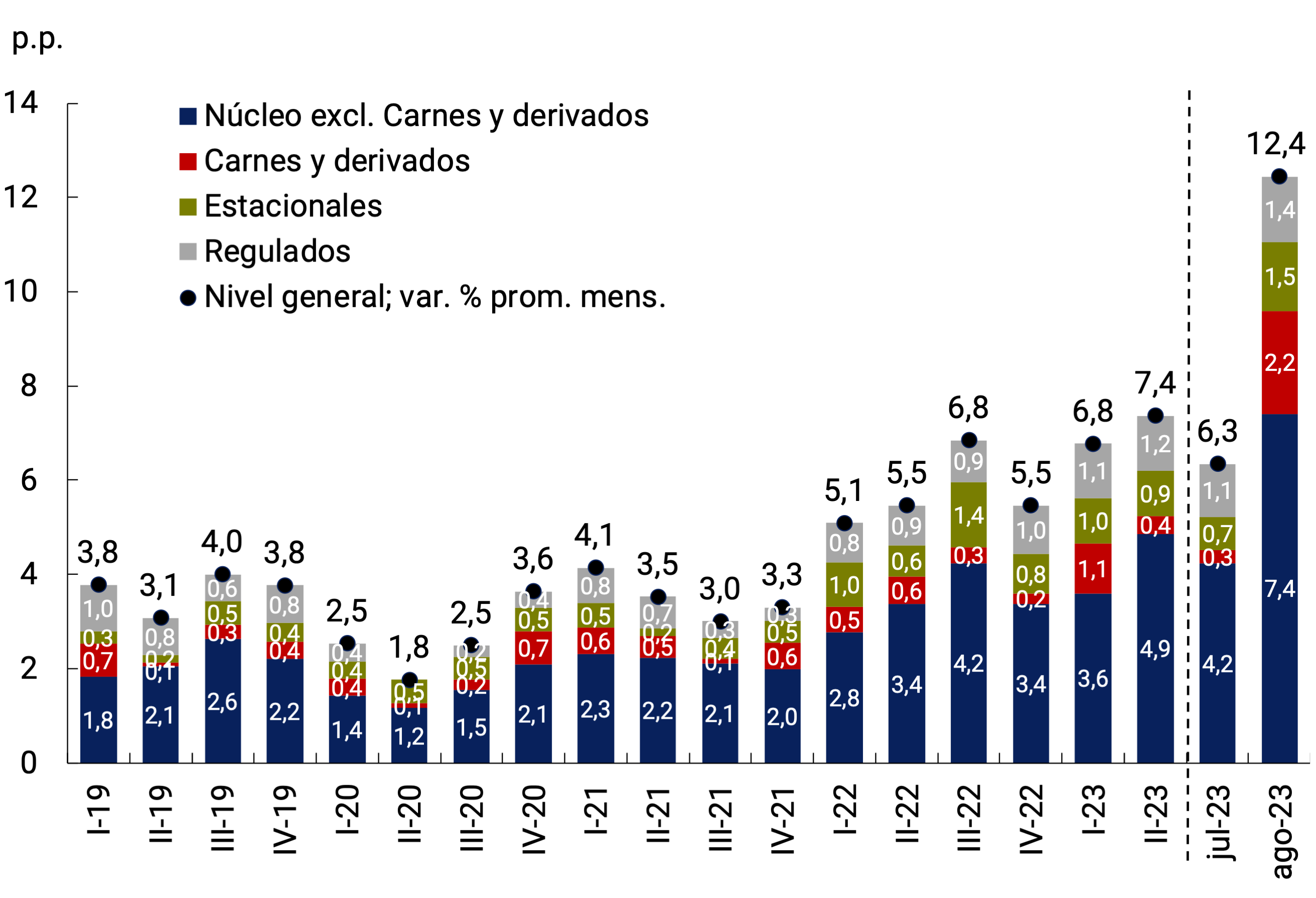

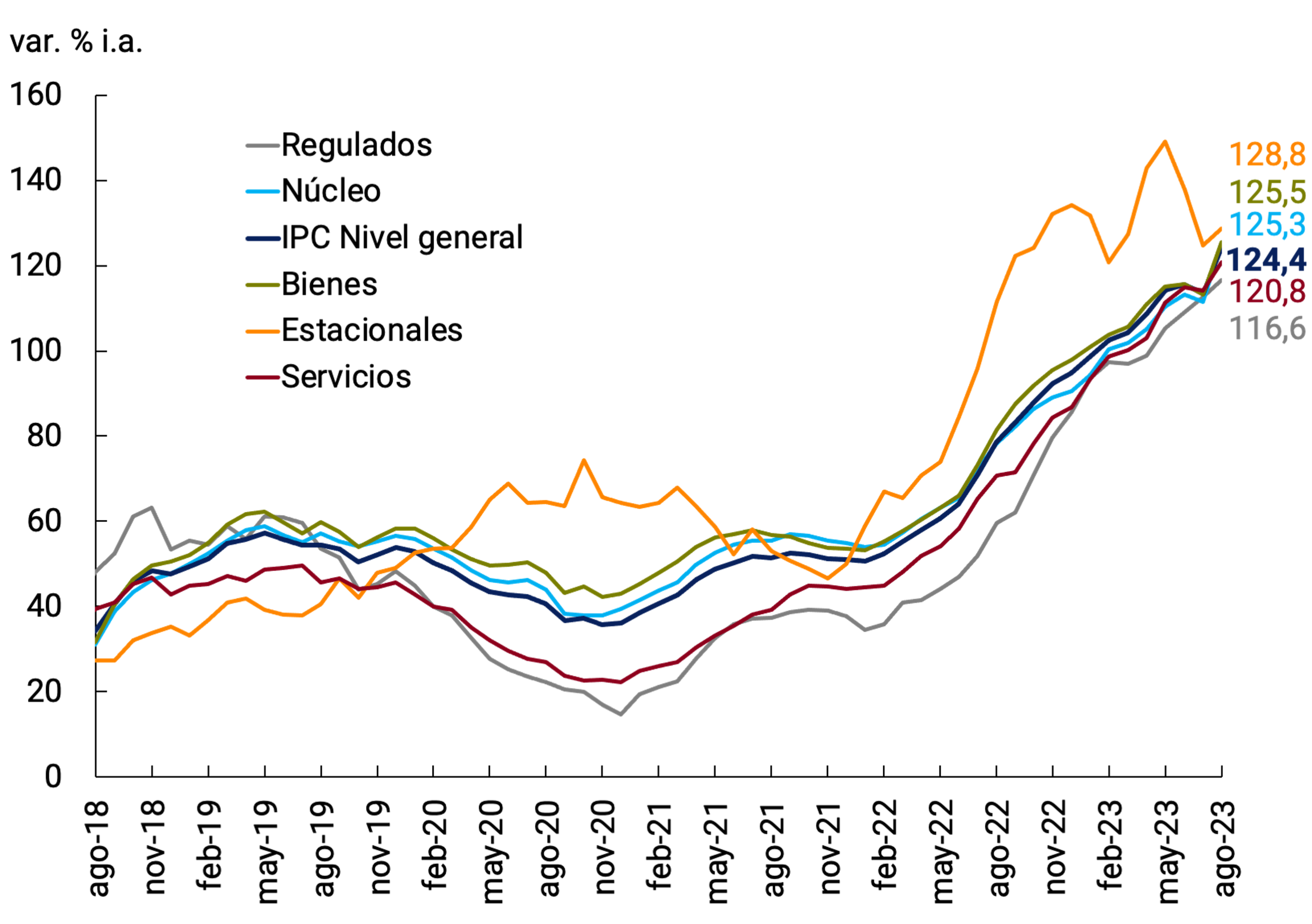

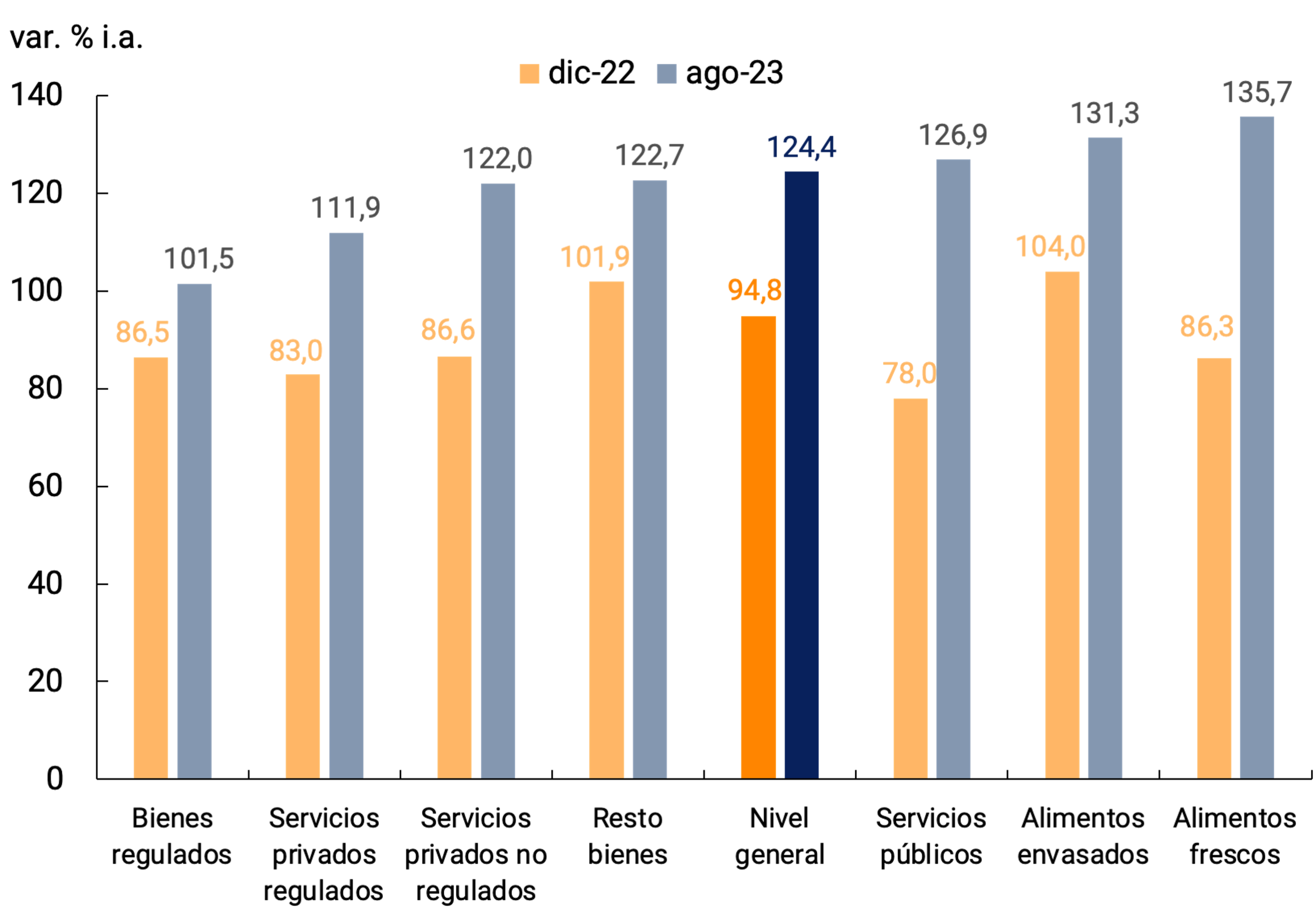

Inflation in recent months reflected the impact of greater financial volatility and the various measures aimed at offsetting the consequences of the drought on fiscal resources and international reserves, among which the recalibration of the official exchange rate stood out. The effect on prices would have been mainly concentrated in August and September, with average monthly inflation of around 12%. However, inflation showed a downward trend since the first week of September and a marked reduction in the monthly inflation rate is expected for October. The slowdown in inflation in recent weeks was mainly due to a series of measures implemented by the National Government and the BCRA.

The National Government renewed the price agreements within the framework of the Fair Prices program – limiting the rate of increase in products in the basic basket and stabilizing the prices of medicines. It also ordered the temporary freezing of prices of certain regulated products – such as gasoline and prepaid medicine fees – and postponed the increase in train, bus, gas and electricity fares.

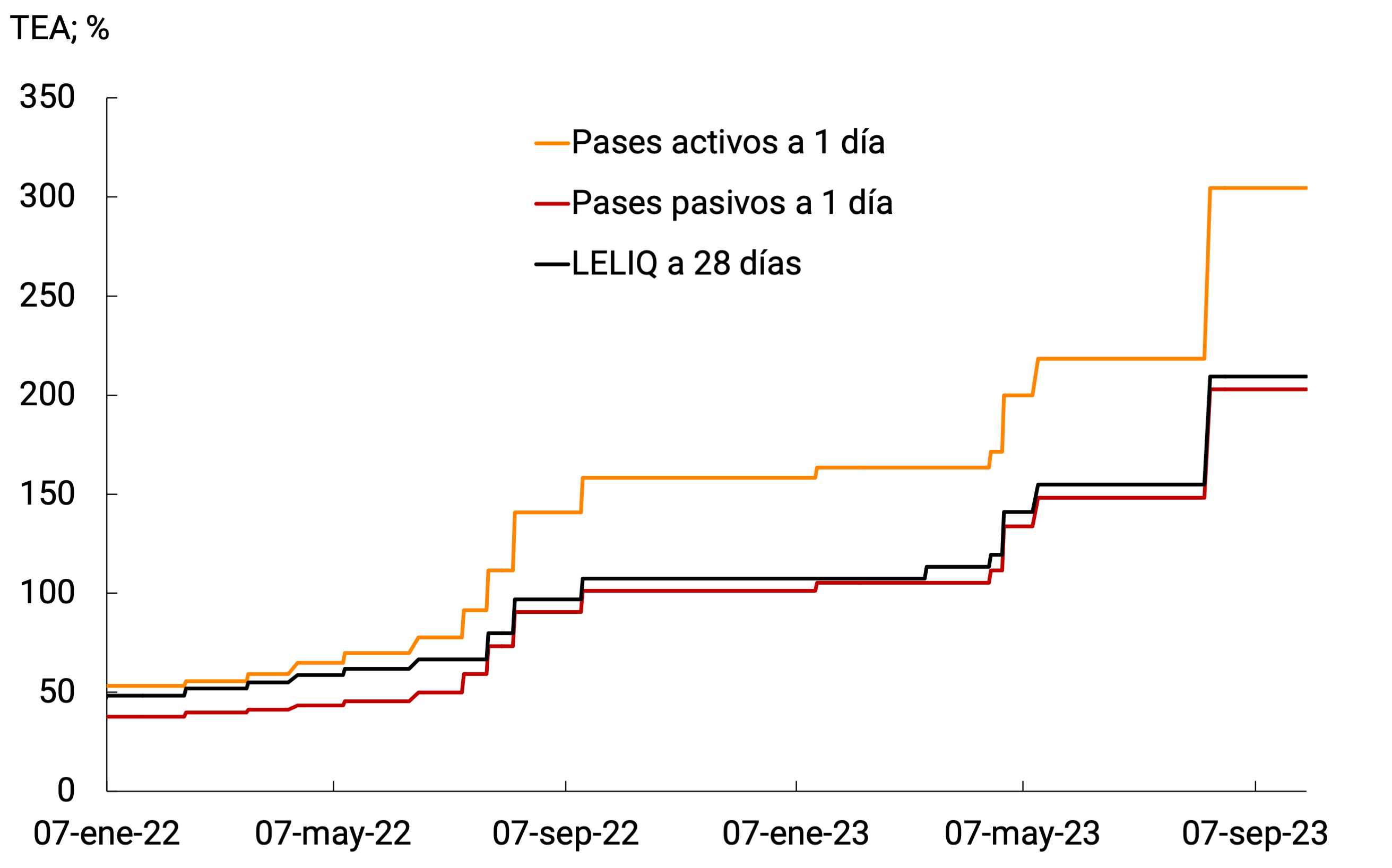

The BCRA, for its part, readjusted the monetary policy interest rate with the aim of mitigating the transfer to prices of the recalibration of the official exchange rate. Specifically, it ordered to raise the interest rate of the LELIQ by 21 p.p. to 28 days, bringing it to 118% n.a. (209.4% e.a.). It also raised the minimum guaranteed interest rate for placements by individuals to an effective monthly yield of 9.7%. In this way, the aim was to tend towards positive real returns on investments in local currency and to contribute to financial and exchange rate balance.

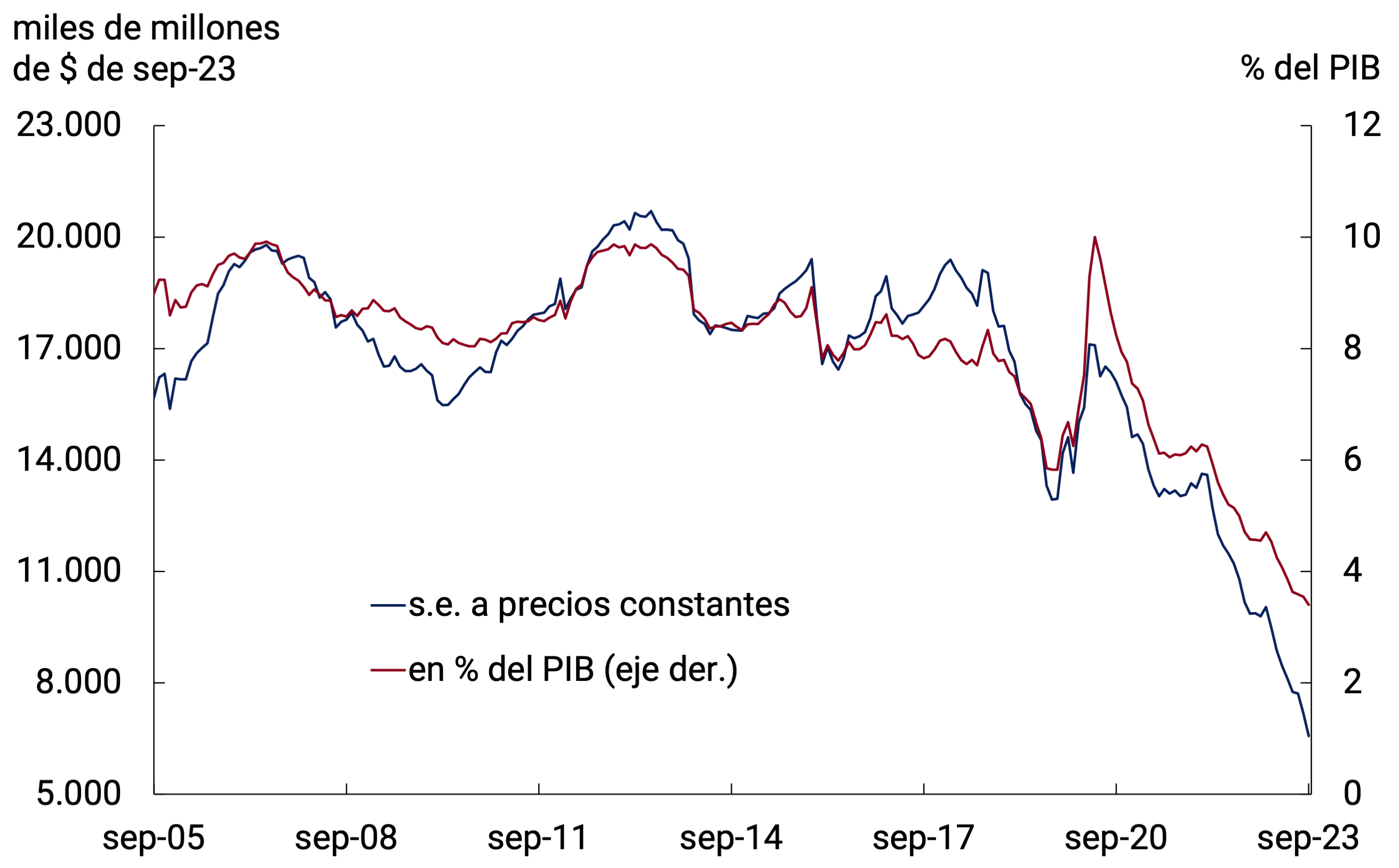

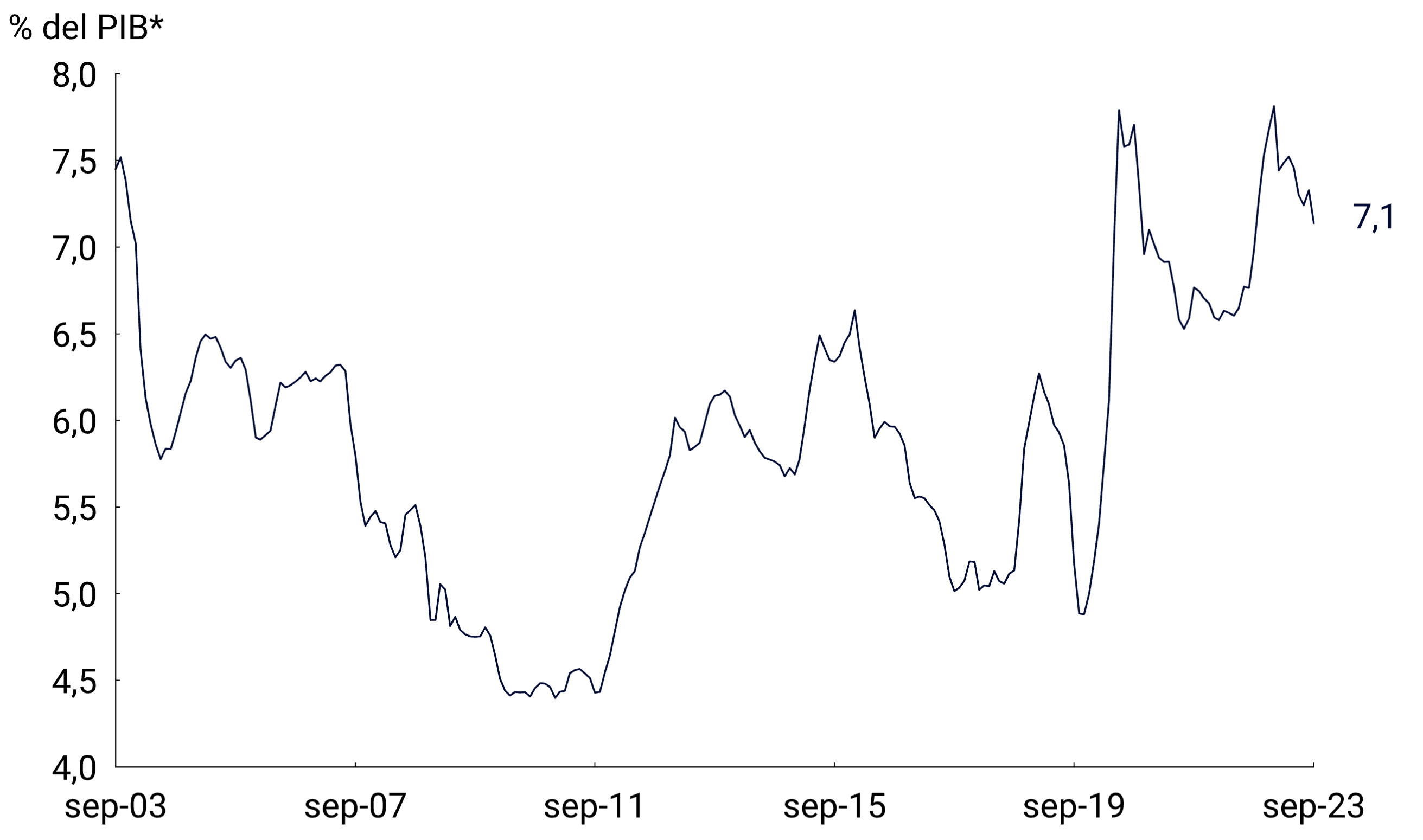

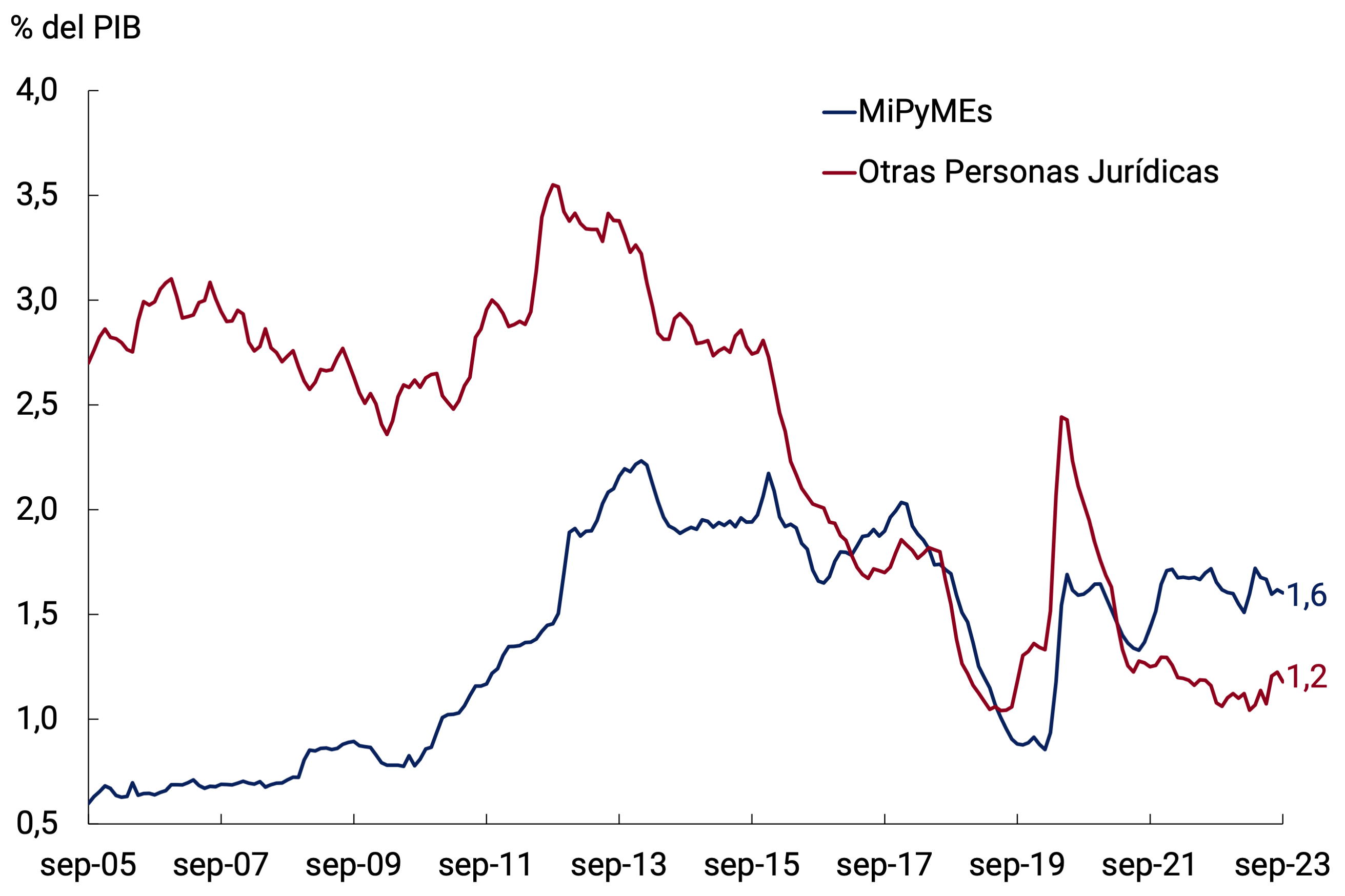

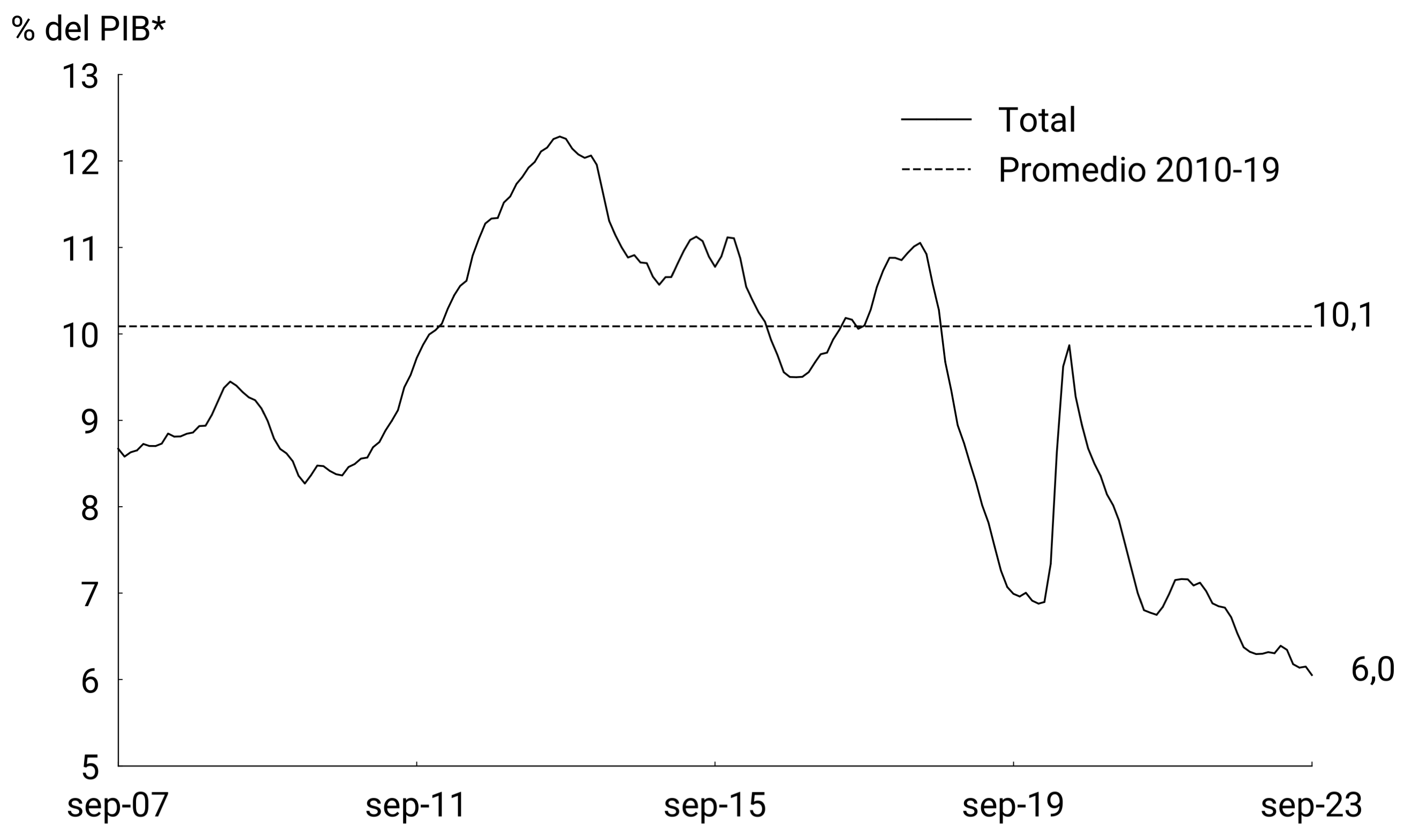

On the other hand, the BCRA continued to use its intervention capacity through open market operations, in order to limit volatility and promote greater liquidity, depth and transparency of the sovereign debt markets. Likewise, it maintained its credit policy focused on productive development through the Productive Investment Financing Line (LFIP). This tool allowed bank financing to relatively smaller companies to be above the pre-pandemic record and the historical average.

In the coming months, the BCRA will continue to calibrate its policies in a context of greater volatility in the financial markets associated with the electoral period. In terms of interest rates, it will act within its structural objective of tending towards positive real returns on investments in local currency and favoring the accumulation of reserves. Likewise, the BCRA will continue to intervene in the secondary markets of public debt in order to avoid excessive volatility that compromises financial and exchange stability, and will maintain a prudent administration of monetary aggregates, sterilizing any surplus liquidity, in order to preserve monetary balance. Finally, in order to continue supporting the expansion of economic activity, the BCRA will continue to stimulate credit, particularly that linked to productive development through the Financing Line for Productive Investment.

2. International context

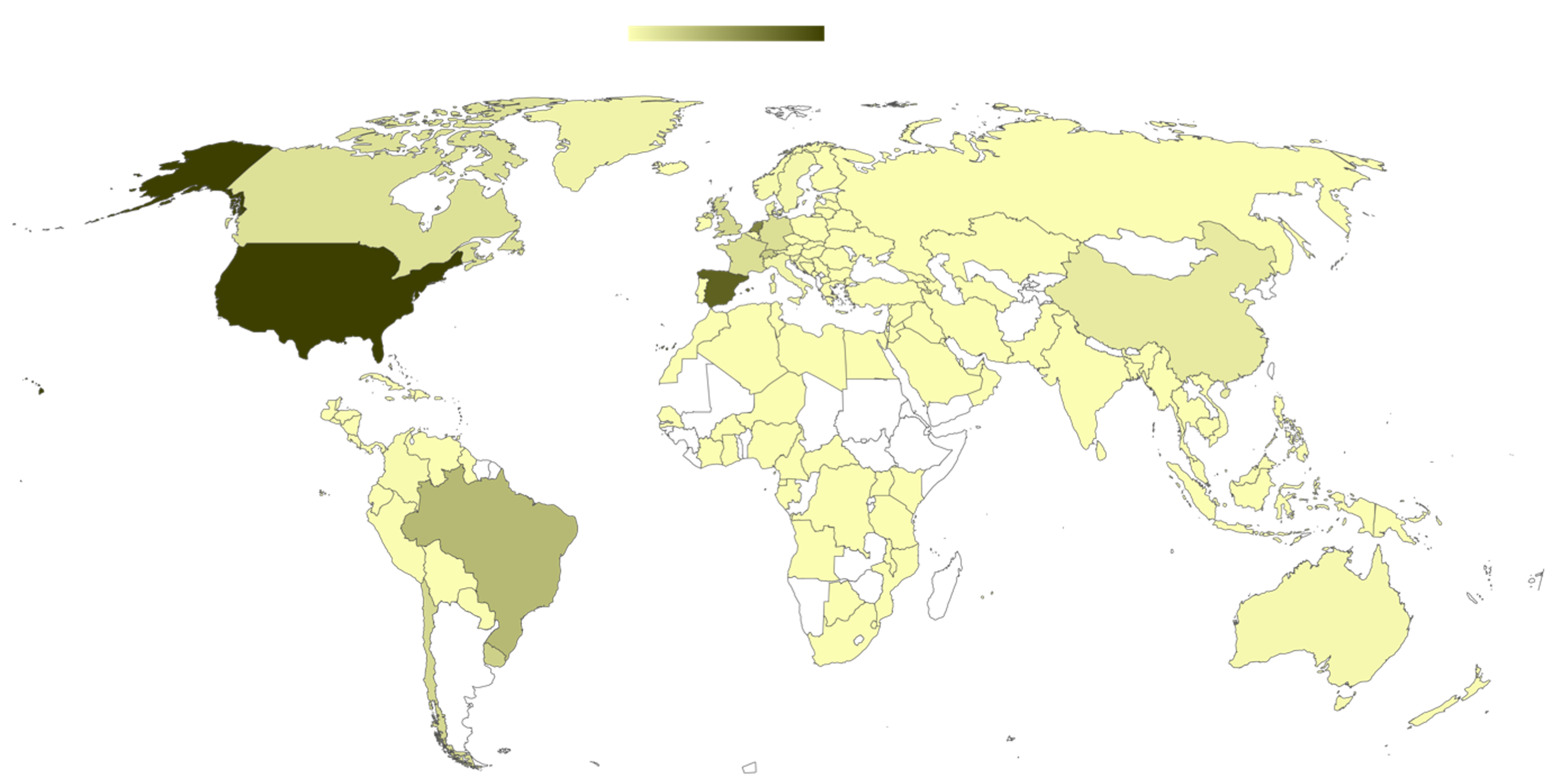

The global economy has tended to slow down in recent months. Of Argentina’s main trading partners, China is growing less than expected, while experiencing a real estate crisis. Brazil is also slowing, while the euro area and the United Kingdom are stagnating. Only growth in the United States shows signs of any strength.

With core inflation persisting in many advanced economies and easing in much of emerging and developing economies, central banks in the former maintain or even raise interest rates, while those in the latter have begun to reduce them (especially in Latin America). This has recently had an impact on currencies and capital flows to emerging economies.

A scenario of “higher rates for longer” is consolidating in the markets, with its impact on bonds and stocks, and currencies. The U.S. dollar, which had been depreciating so far this year, has appreciated at the margin; this is also reflected in the prices of raw materials. Agricultural commodities show some retraction, while oil strengthens in the face of supply constraints.

Risks to global activity remain skewed to the downside. In China, the financial impact of the real estate crisis is uncertain, and the economic policy response will be key. Meanwhile, the persistence of core inflation in some advanced economies could lead to additional interest rate hikes and eventual financial turbulence (banking or linked to situations of unsustainability of corporate and sovereign debts). Geopolitical tensions persist as sources of risk, and may imply greater trade fragmentation.

2.1. Lower global growth in a more uncertain context

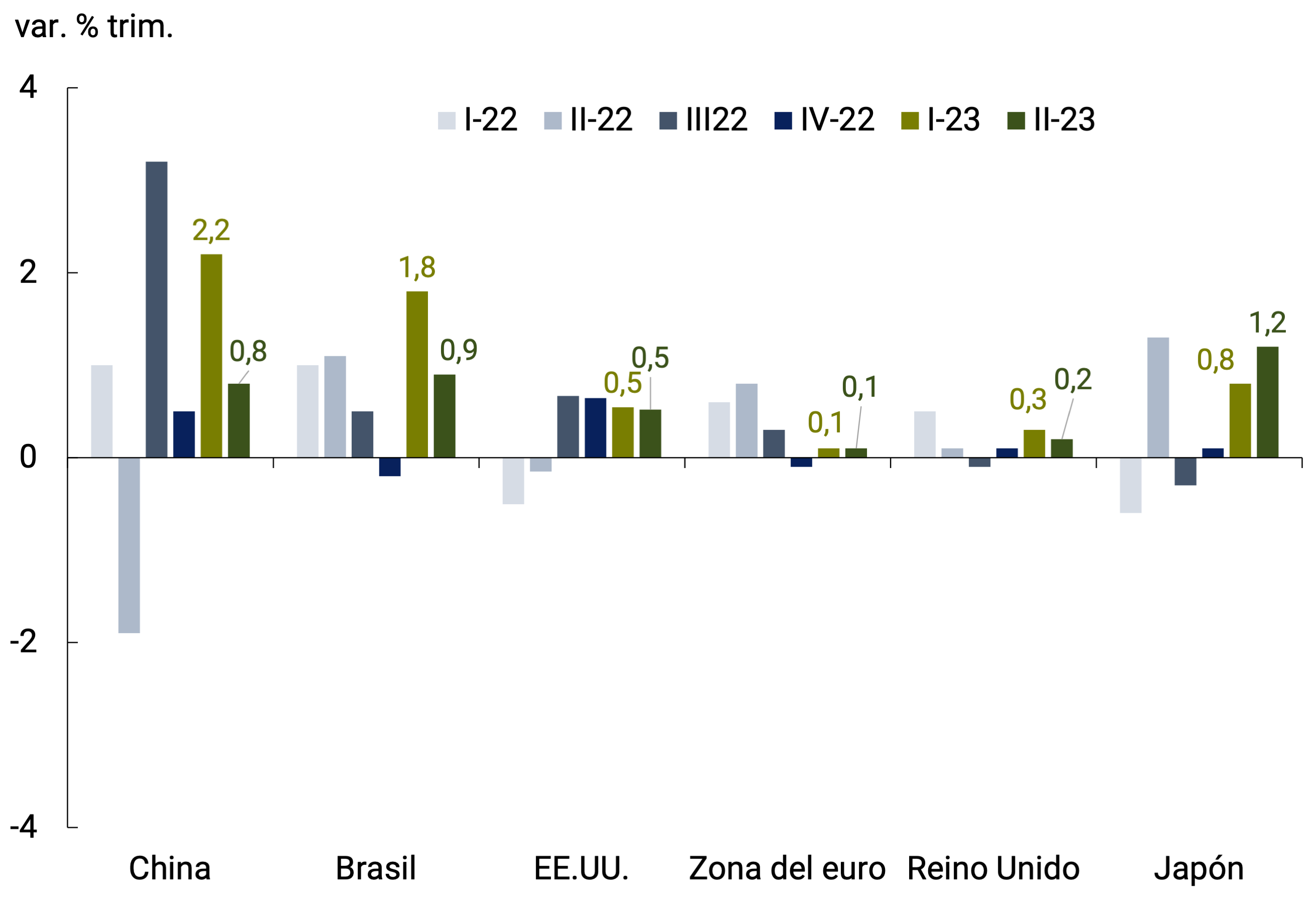

In the second quarter of the year, global economic activity tended to slow down. In advanced economies, the picture was mixed: the euro area and the United Kingdom remained stagnant, with quarterly growth of 0.1% and 0.2% (seasonally adequate), respectively. In the United States, the strength of the economy in the face of contractionary monetary policy was surprising, with a growth rate similar to that of the previous quarter (+0.5% quarter-on-quarter s.e.); while in Japan growth accelerated unexpectedly (from +0.8% to +1.2% qoq/s.). Emerging economies continued to perform better, but with signs of slowdown in some relevant cases. In China, a real estate crisis in residential investment combined with less dynamism in household consumption and lower external demand due to the global slowdown. This led to an expansion of only 0.8% quarter-on-quarter s.e. in the second quarter of the year, after the 2.2% increase in the previous quarter. Likewise, in Brazil, economic activity grew 0.9% quarter-on-quarter, after expanding 1.8% in the previous quarter (see Figure 2.1). Labor markets remain robust in both groups of countries, with job creation dynamics sustaining, albeit at a slower pace, and unemployment rates remaining at historically low levels, but with some signs of deteriorating working conditions at the margin in some cases.

Figure 2.1 | Evolution of GDP of selected economies (real GDP without seasonality)

Source: BCRA based on data from national statistics institutes.

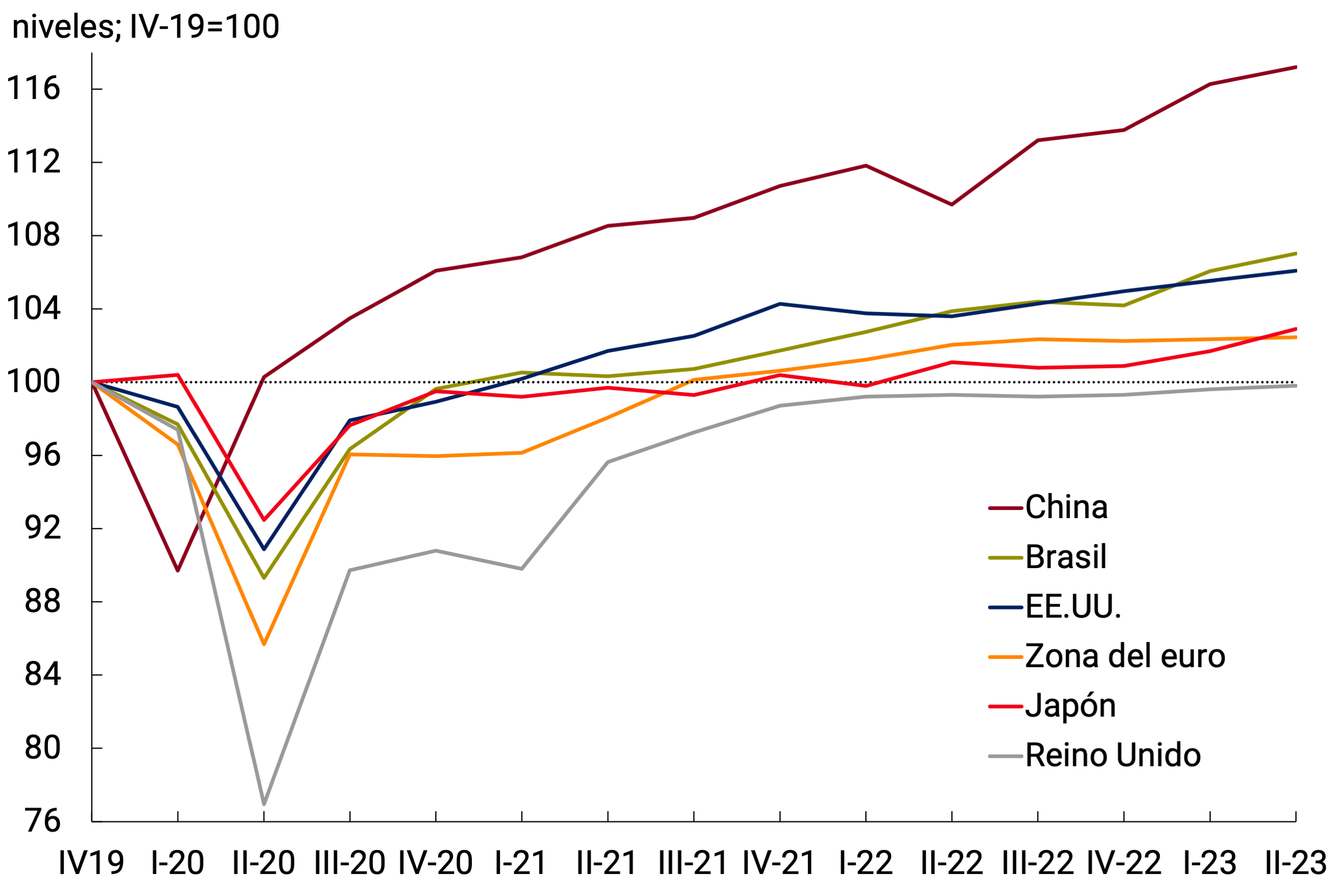

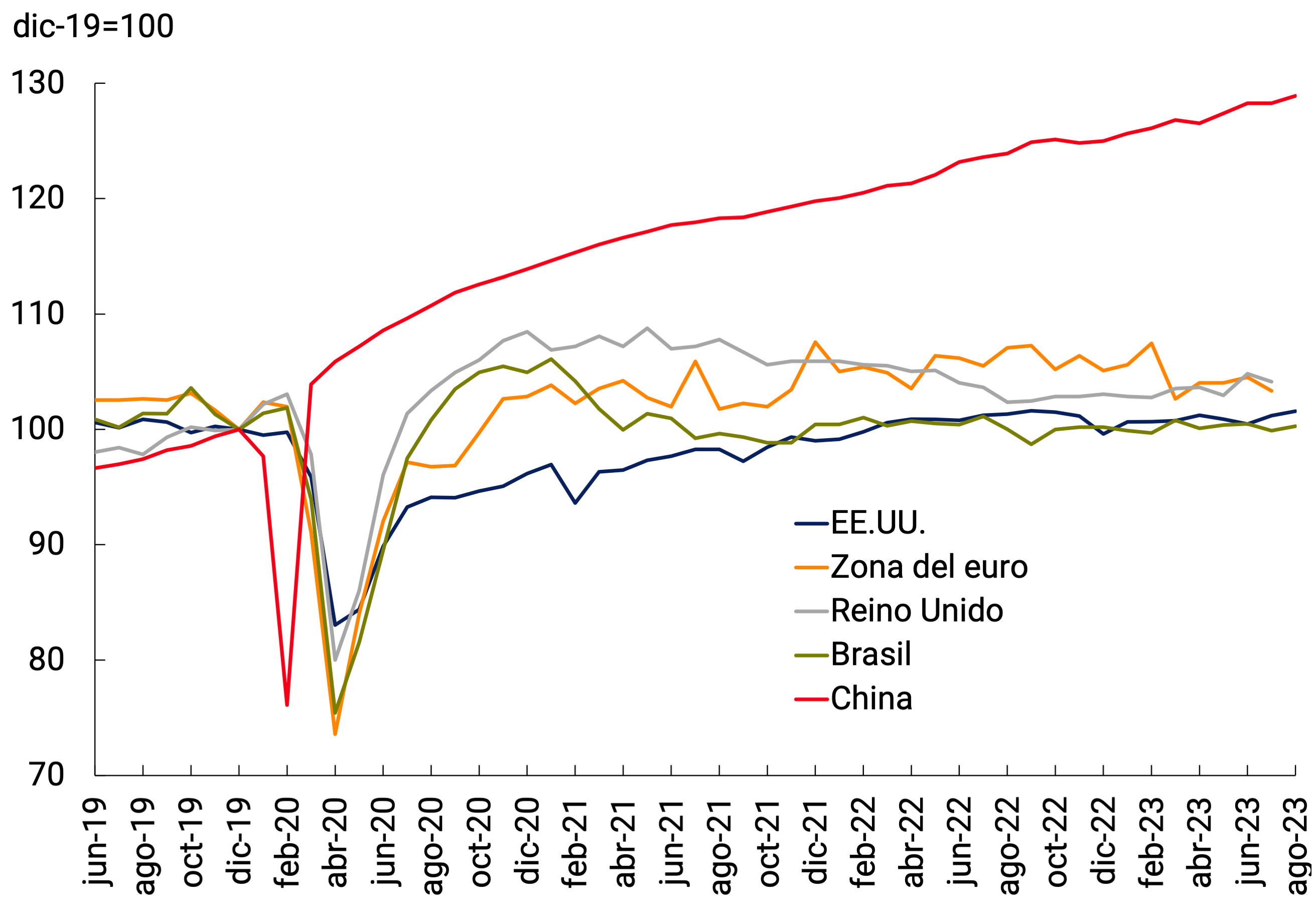

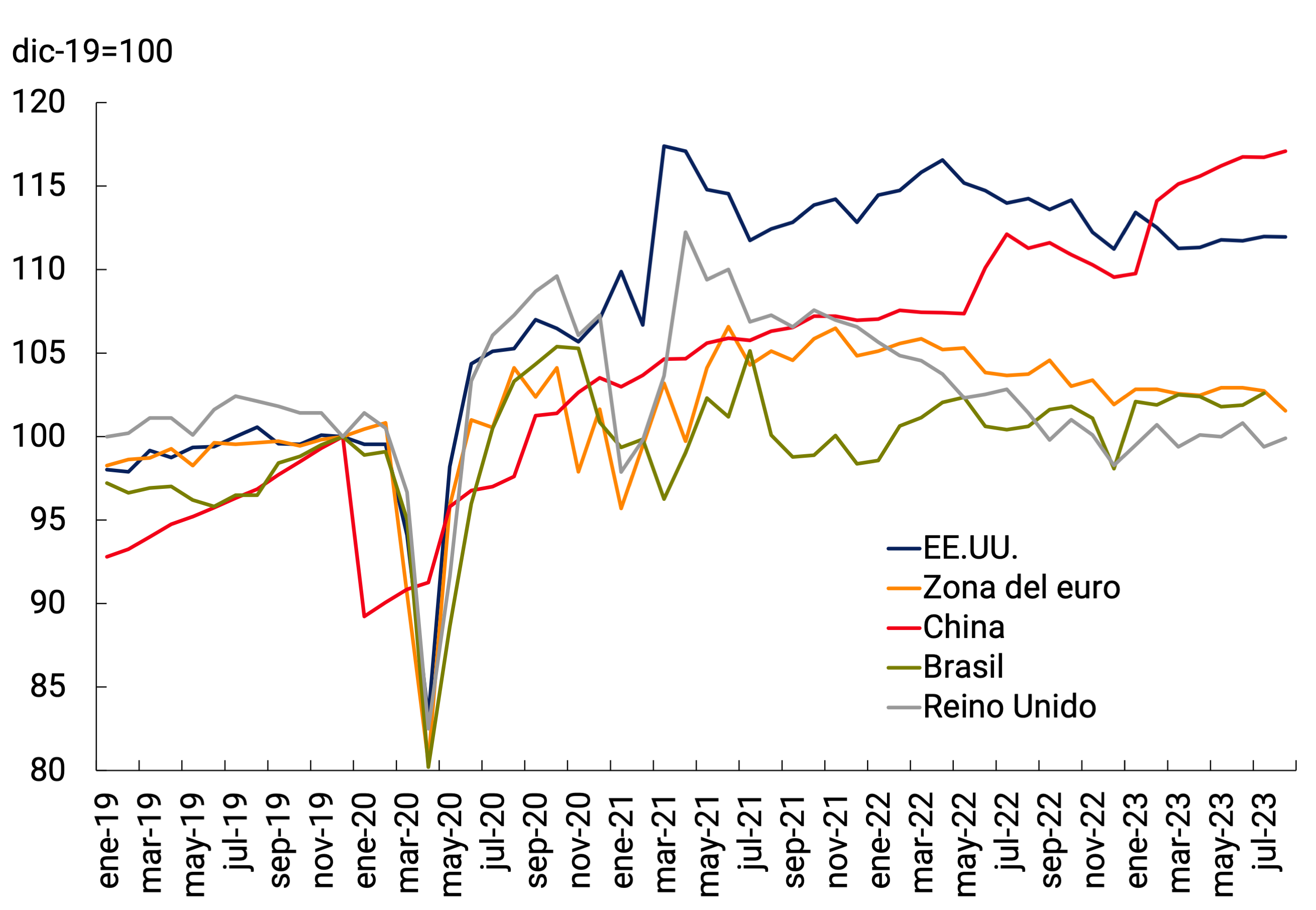

High-frequency indicators generally suggest a worse performance of economic activity in the third quarter in the euro area and the United Kingdom, with declines in industrial production and retail sales. In July, the bad signs for China remained, with retail sales and industrial production stagnating, but then recovering in August. The exception is the United States, where economic activity seems to be sustained, with monthly expansion of both variables in July and August (see Figure 2.2). On the other hand, world trade has been showing a slight recovery in recent months, in the context of a downward trend that began in mid-20211.

Figure 2.2 | Activity indicators

Source: BCRA based on data from the national statistical offices.

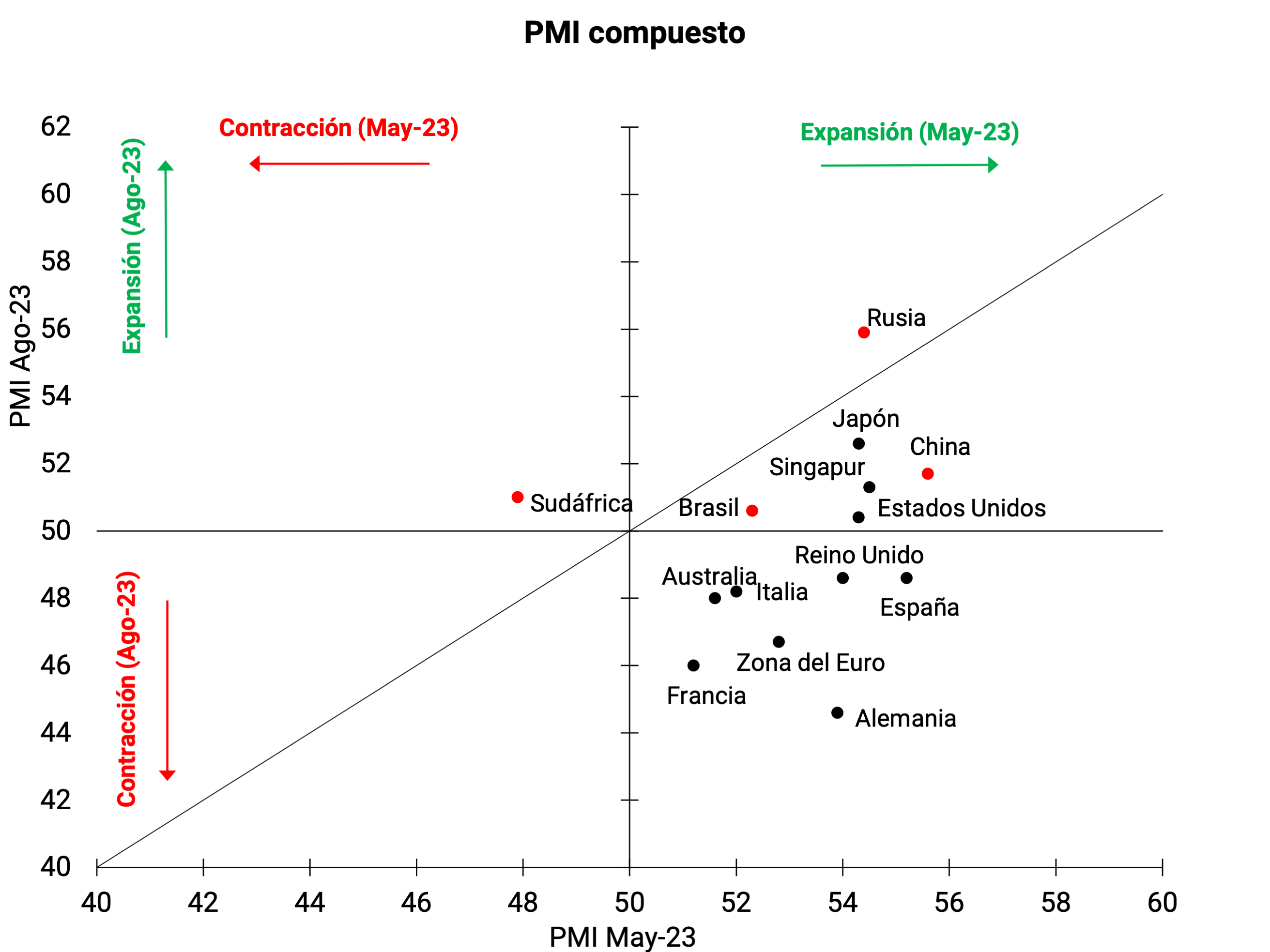

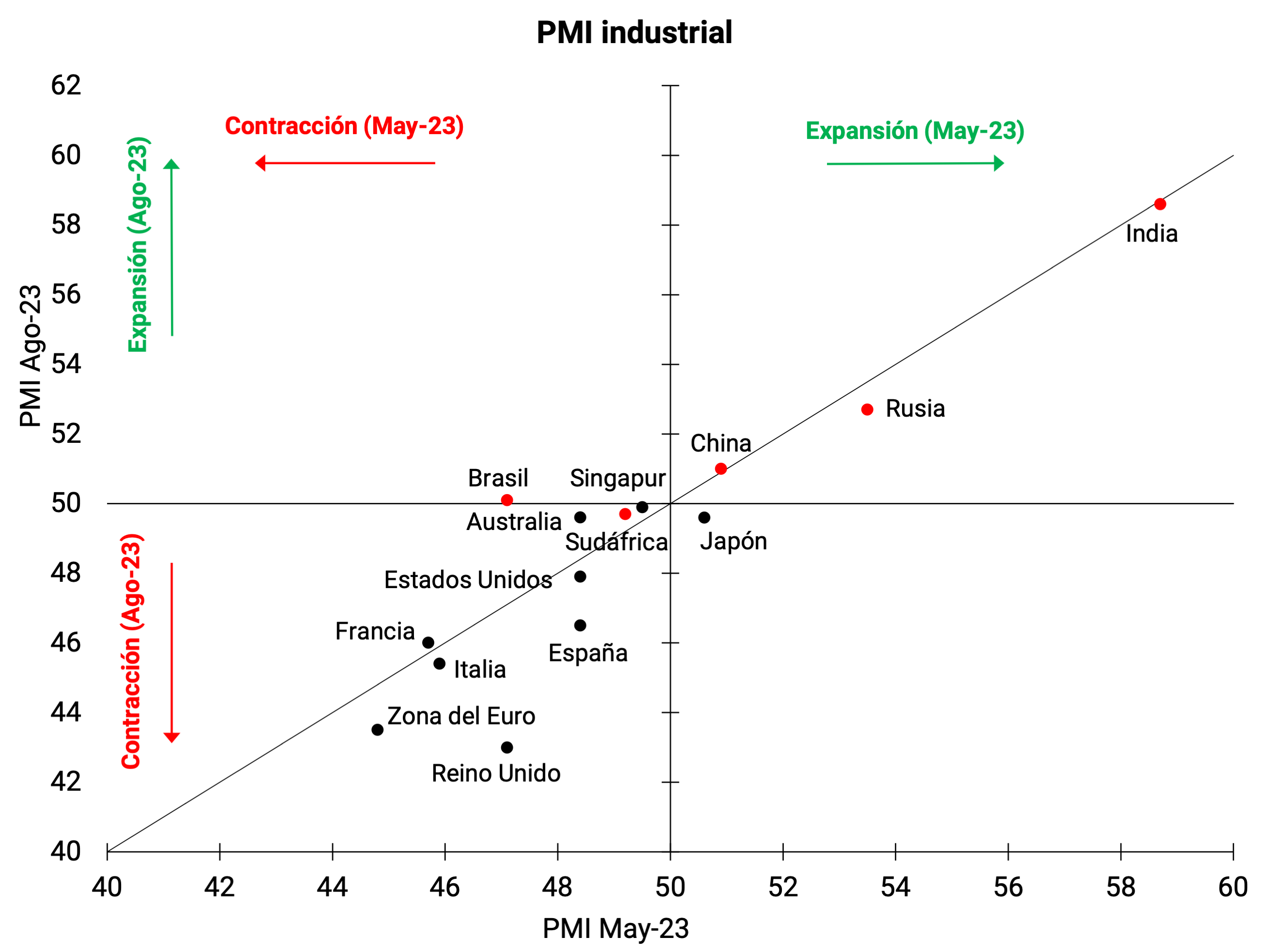

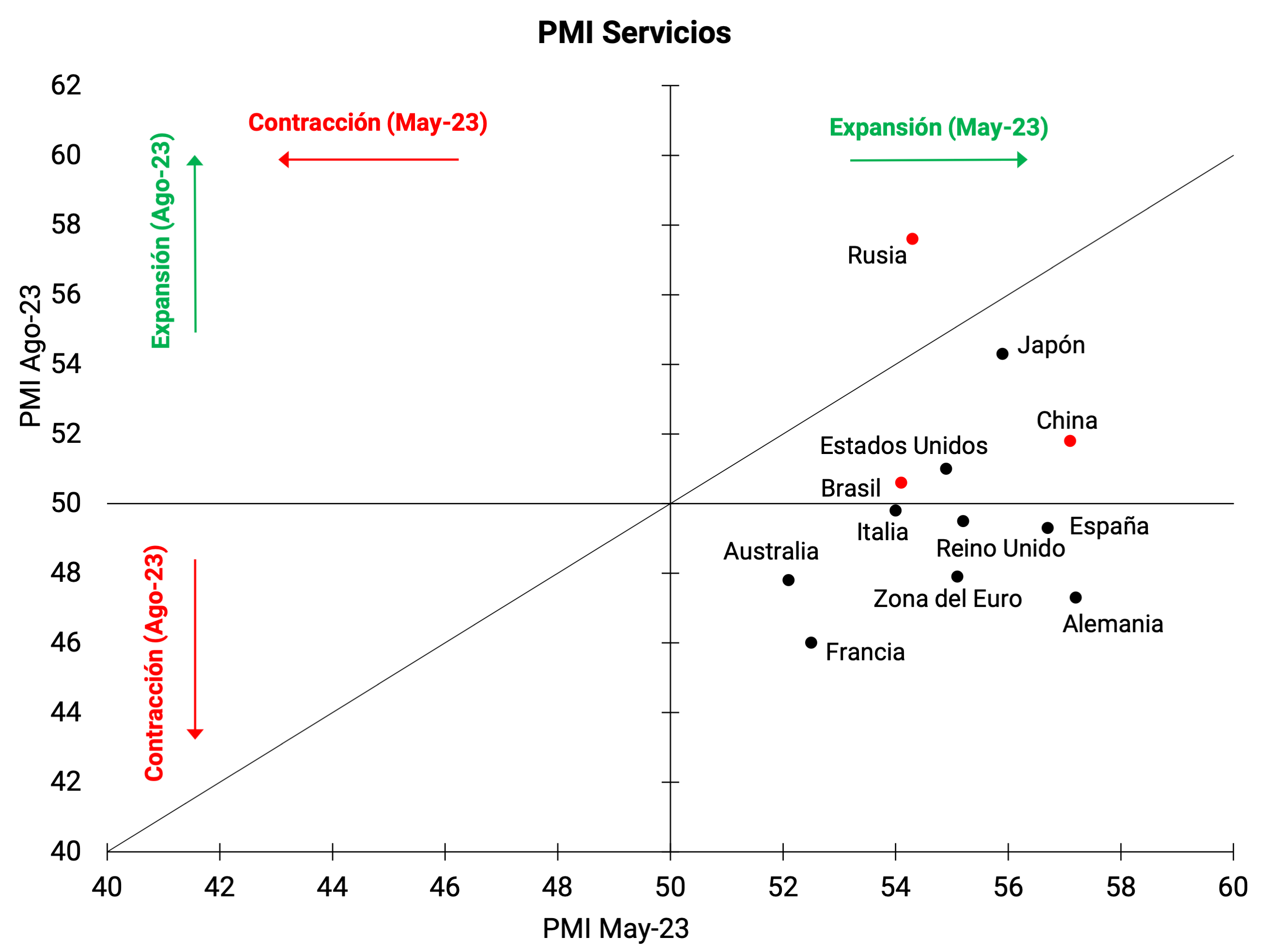

The forward-looking indicators also show the same dynamics of a deterioration in activity in the third quarter, with a reversal in its trend compared to the previous report. The composite index from purchasing managers’ surveys (PMIs) tended to decline in many countries (below the diagonal) and, in particular, moved into contraction zone in Europe (Figure 2.3a). The services sector, which was driving the expansion, experienced a significant decline (see Figure 2.3c) and the industrial sector, with the exception of the BRICS countries, remains in contraction (see Figure 2.3b).

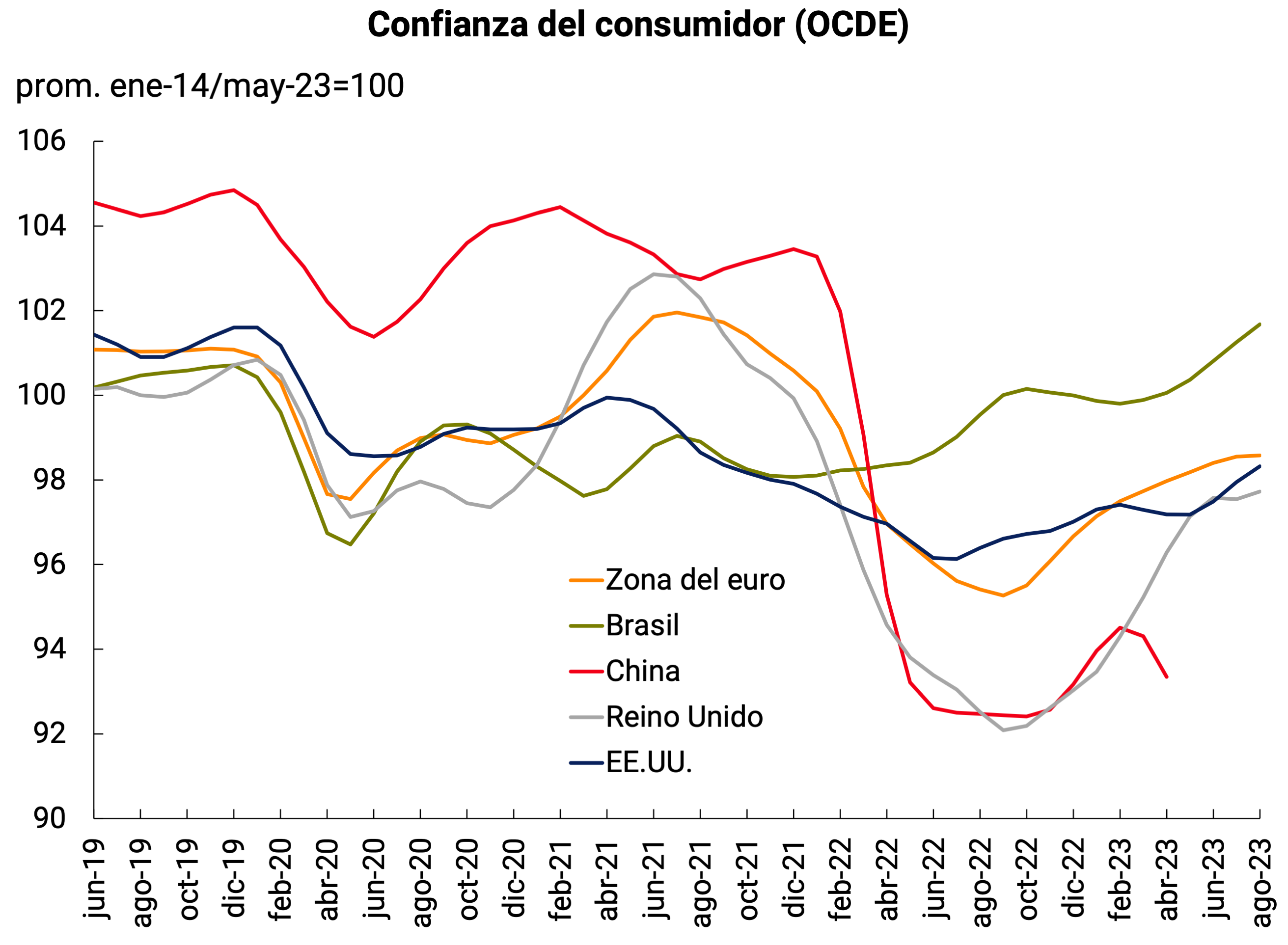

Consumer confidence continued its recovery in the May-August period in the euro area, the United Kingdom, the United States and Brazil, but remained below the average of the last five years (except in Brazil, which has exceeded it) (see Chart 2.3d). In China, the latest available measurement is from April and showed a deterioration of such magnitude that the reported value returned close to the levels of December 2022 when health restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic began to be lifted. Analysts agree that consumer confidence has continued to decline.

Figure 2.3 | Forward-Looking Activity Indicators

Source: BCRA based on data from IHS Markit, OECD and Trading Economics.

The outlook for economic activity continues to point to a slowdown in global growth this year, and a similar expansion for 2024, with persistent inflation, especially in advanced economies, and higher financial risks. Developing and emerging economies, particularly China and India, are expected to continue to show higher-than-advanced growth rates and lead the global expansion, albeit with greater downside risks (see Table 2.1). The latest forecasts, in general, have slightly increased the global growth projection for this year, although it remains below last year’s rate. Thus, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts that global growth will slow to 3% this year (after a 3.5% increase in 2022) and will also be 3% by 2024, while the consensus of analysts forecasts expansion rates of 2.7% for both years. On the other hand, forecasts also point to a gradual reduction in the global inflation rate, which will remain at high levels in 2023 and 2024. According to the IMF, headline inflation will fall from 8.7% in 2022 to 6.8% in 2023 and to 5.2% in 2024 (-0.2 p.p. and +0.3 p.p. compared to the previous forecast, respectively), but with core inflation (which excludes energy and food prices) more persistent.

Table 2.1 | Projections of economic activity 2022-2023

Source: IMF, World Bank and Reuters (market consensus). (1) July 2023 forecast.

Risks to global activity remain skewed to the downside. The risk of lower growth in China increased: the main factor of uncertainty lies in the impact of the real estate crisis on the financial system; And the economic policy response will be key, which, for the moment, the consensus of market analysts judges as modest. Another important factor is the persistence of core inflation, particularly in some advanced economies, in a context in which monetary policy cycles are lagging between advanced and emerging economies. This could lead to additional policy interest rate hikes and new financial turbulence, such as those recorded in the U.S. banking system in the first quarter or those linked to situations of unsustainability of corporate or sovereign debts. Public debt-to-GDP ratios remain above pre-pandemic levels in emerging countries and low-income countries. In the latter group, the situation is more delicate, with interest payments on the debt as a percentage of tax revenues growing in recent years. Geopolitical conflicts, such as an escalation of the war in Ukraine or an escalation of tensions between China and the United States, cannot be ruled out as additional sources of risk. In addition to the negative impact of these factors on international financial stability, they may imply greater trade fragmentation (see Box “Argentina in BRICS”).

2.2. Monetary policy: stable or rising interest rates in advanced countries, easing in developing countries

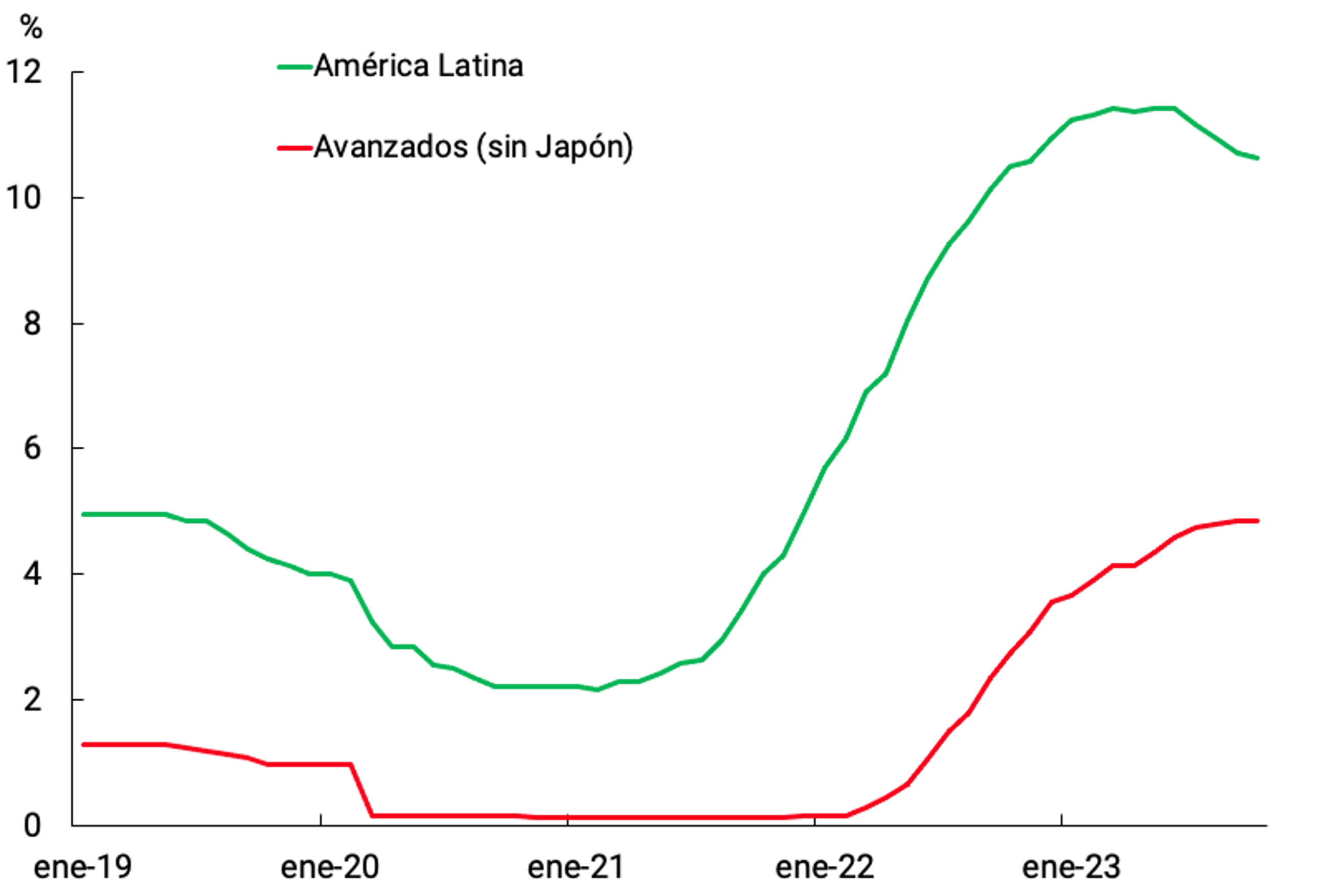

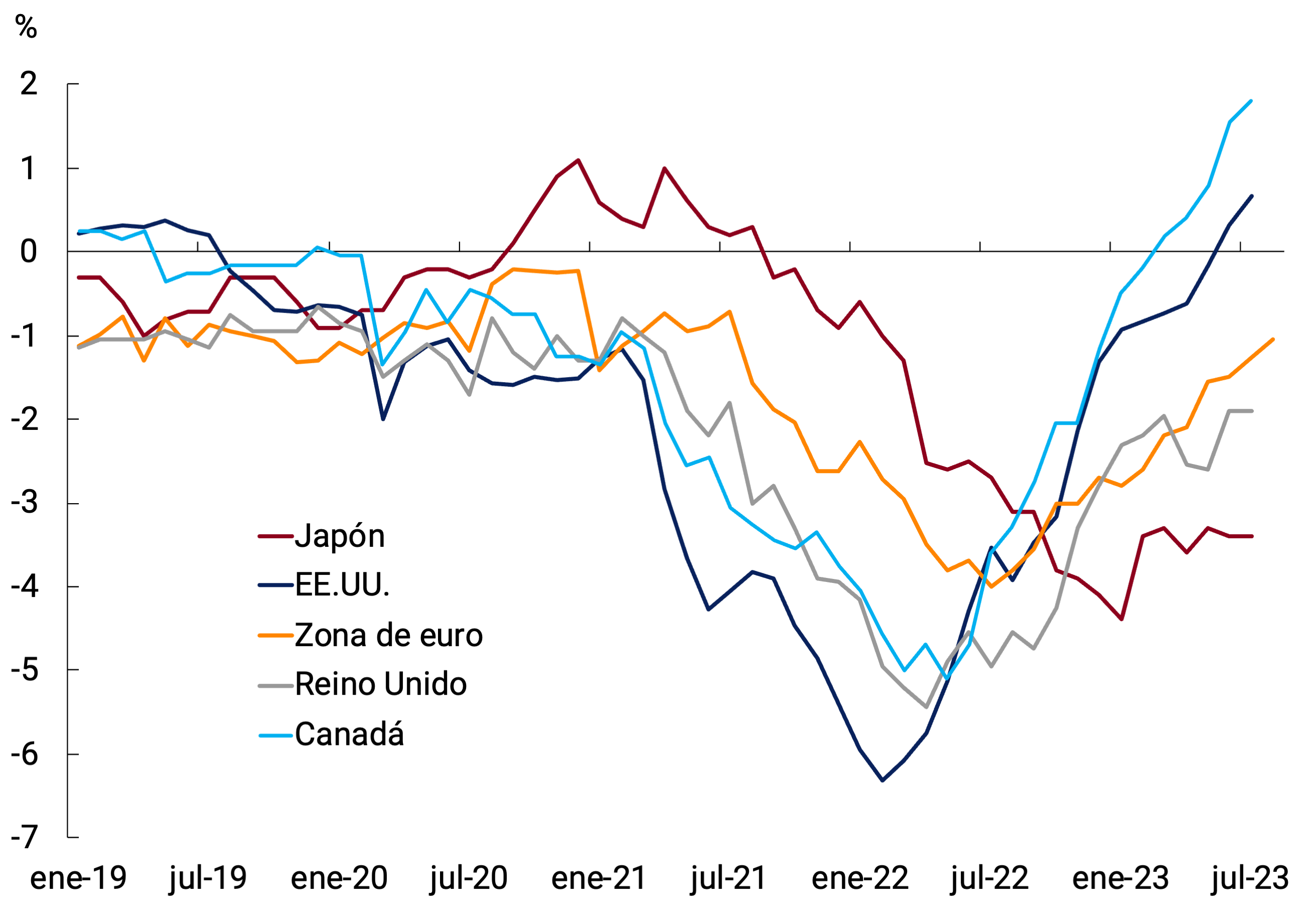

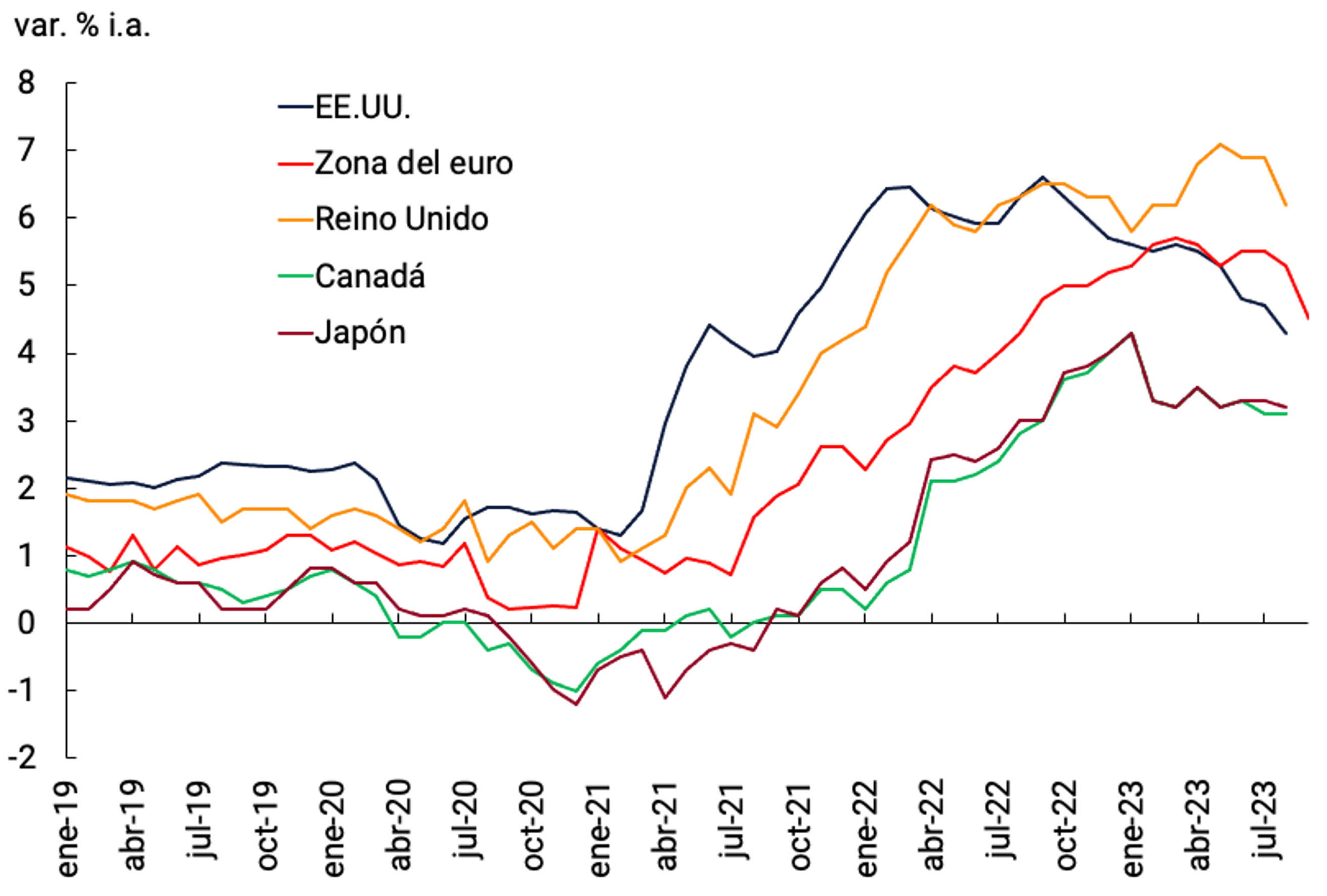

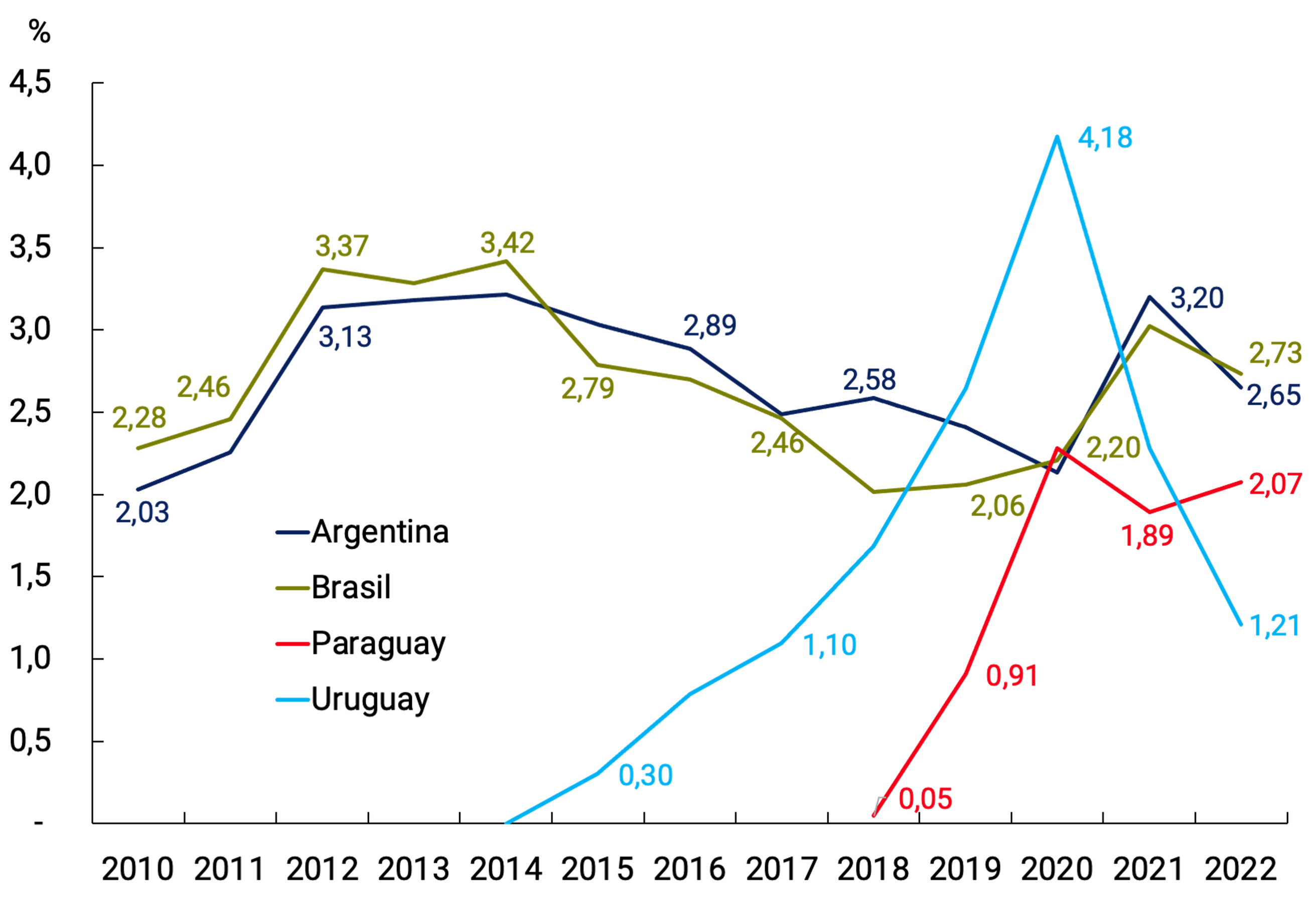

Monetary policy cycles remain outdated. Central banks in developed economies keep their policy interest rates (MPRs) “on pause” and could even raise them again (as the European Central Bank did in September); while those in developing countries have begun to lower them, particularly in Latin America. These monetary policy cycles are related to the evolution of inflation: Latin American central banks began to raise their MPRs earlier, and inflation in the region has begun to ease earlier (see Figures 2.4a and b).

Figure 2.4 | Monetary policy and inflation

Source: BCRA based on Reuters data.

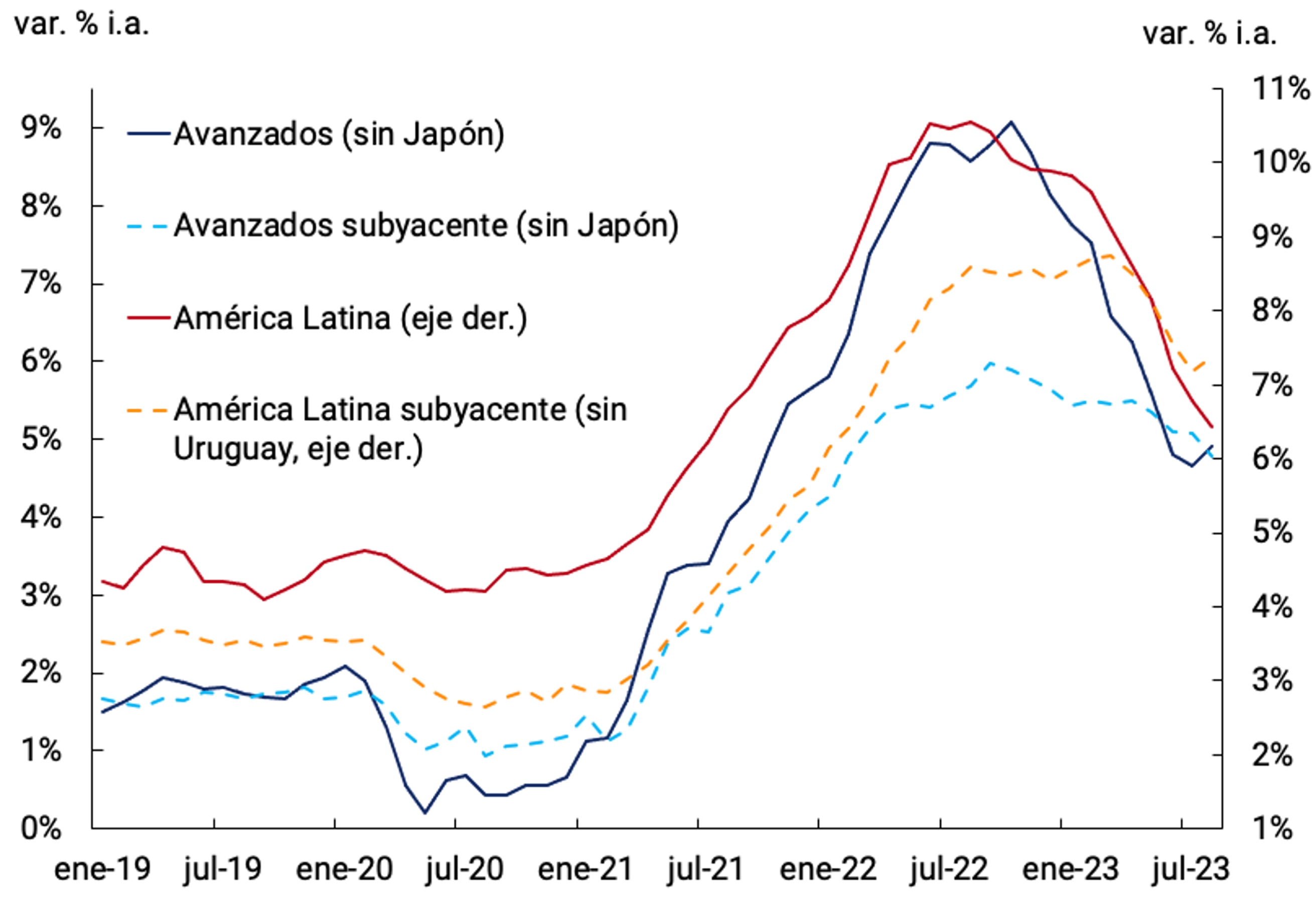

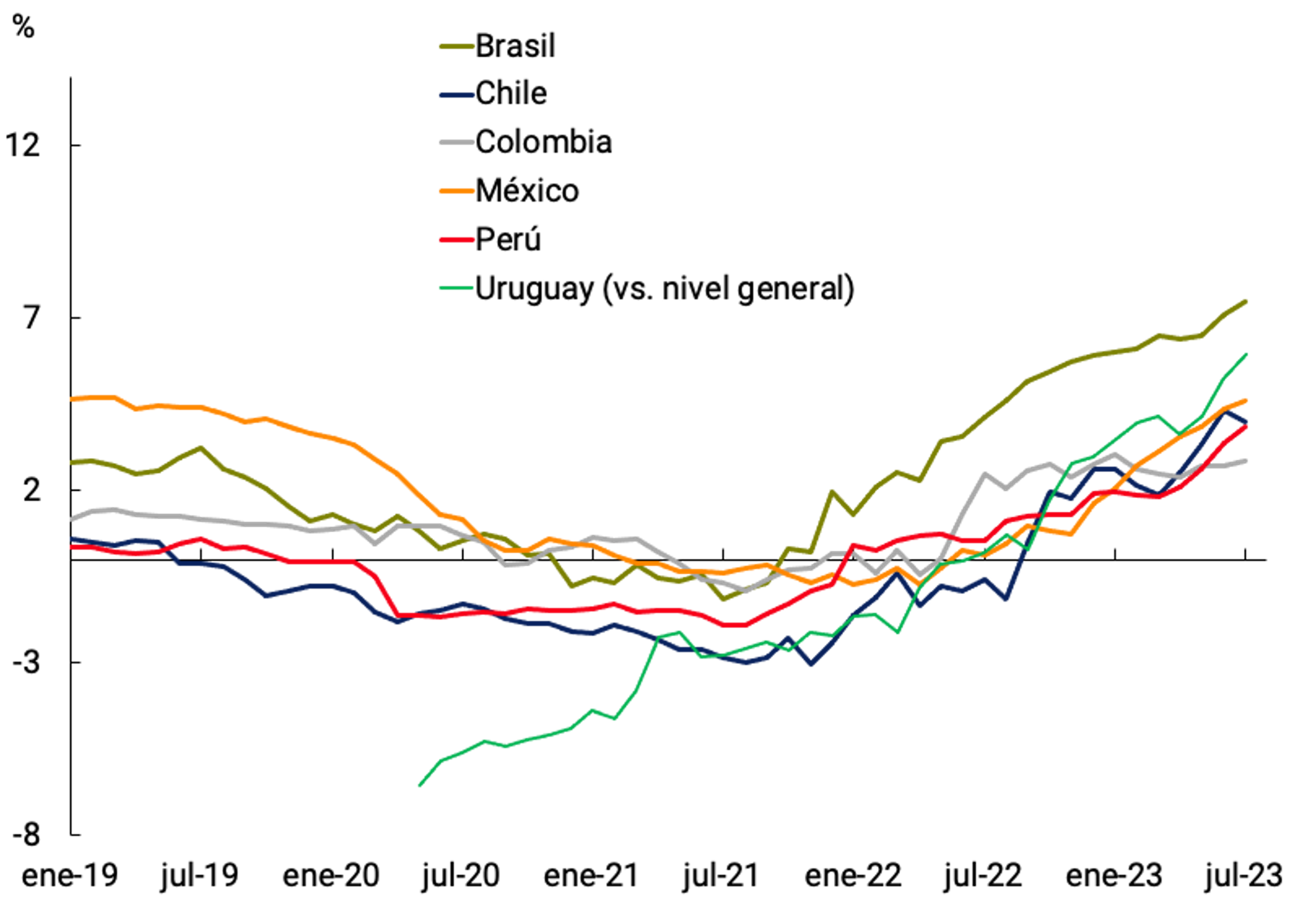

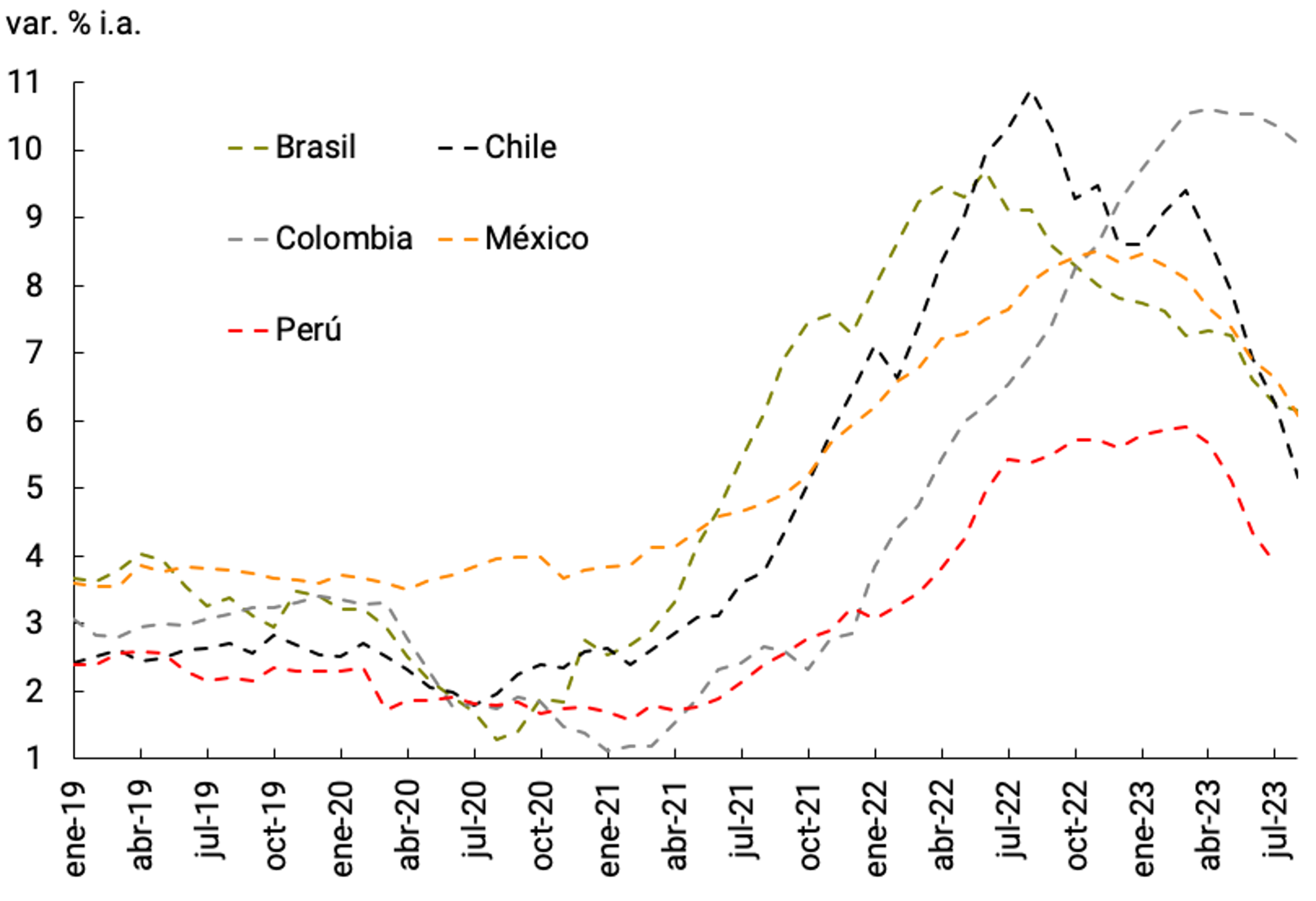

In Latin America, the Central Bank of Uruguay began reducing its MPR, followed by those of Brazil and Chile. In all cases, the MPR would have already passed its maximum level (perhaps with the exception of Colombia). The MPR in real terms (vs. core inflation) in all cases continued to increase, except in Chile. Core inflation is falling, except in Colombia (where, although it has stopped rising, it is constant at values close to 10.5%; see Figures 2.5a and b).

Figure 2.5 | Economies of Latin America

Source: BCRA based on Reuters data.

By contrast, while advanced economies are heading for the “terminal” rates of this cycle, there is no sign that they will begin to reduce them. Another difference with respect to Latin American economies is that in most of the developed countries in the sample, MPRs are projected at high levels for longer than expected so far; in part, because core inflation remains high and is slowly falling (see Figures 2.6a and b).

Figure 2.6 | Major advanced economies

Source: BCRA based on Reuters data.

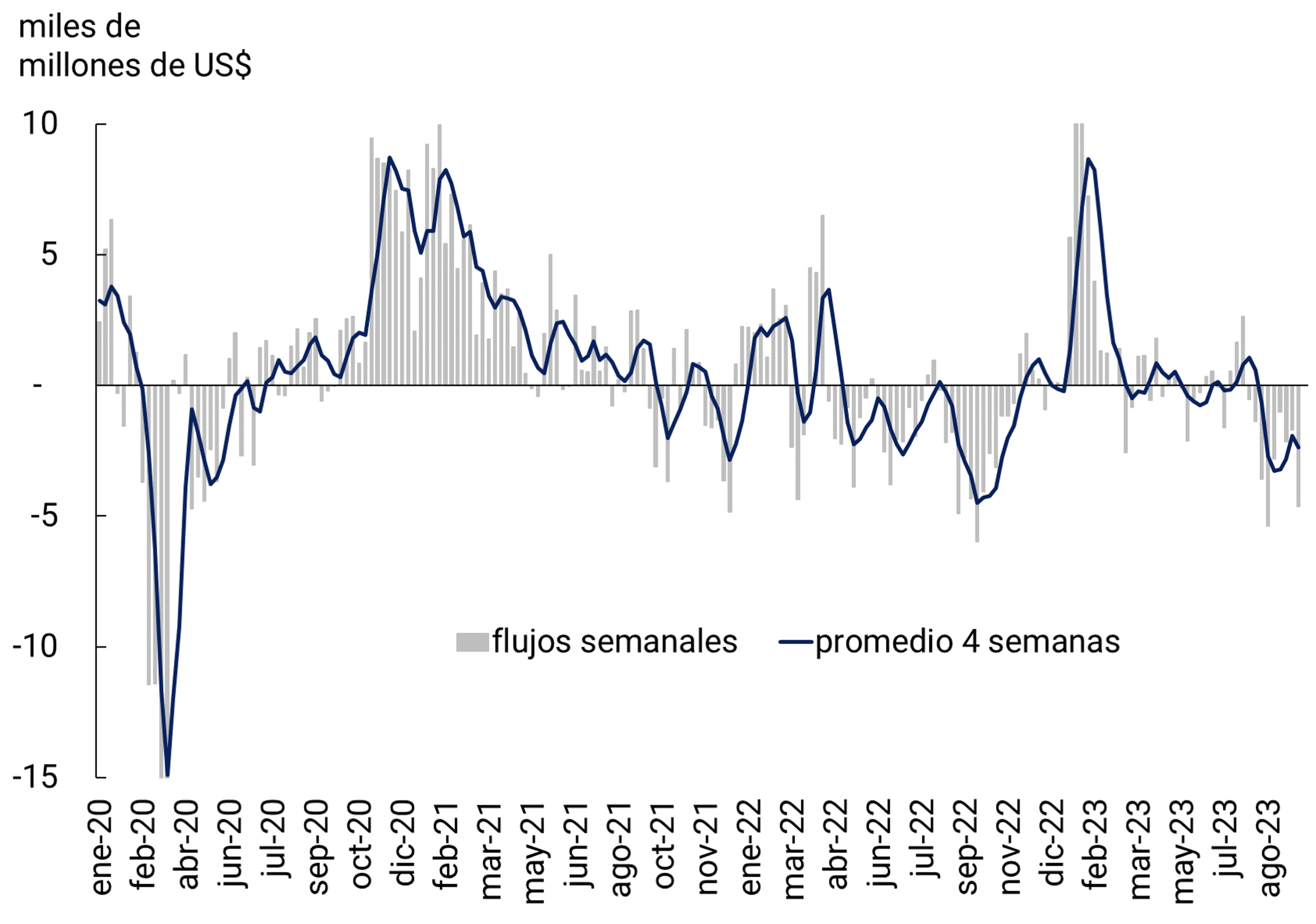

This interest rate dynamic has been reflected in the foreign exchange market. If for a good part of the year Latin American currencies had been appreciating -in part- driven by the rate differential, now this factor is reversed at the margin, and in fact depreciations of currencies are observed along with capital outflows in the main countries of the region.

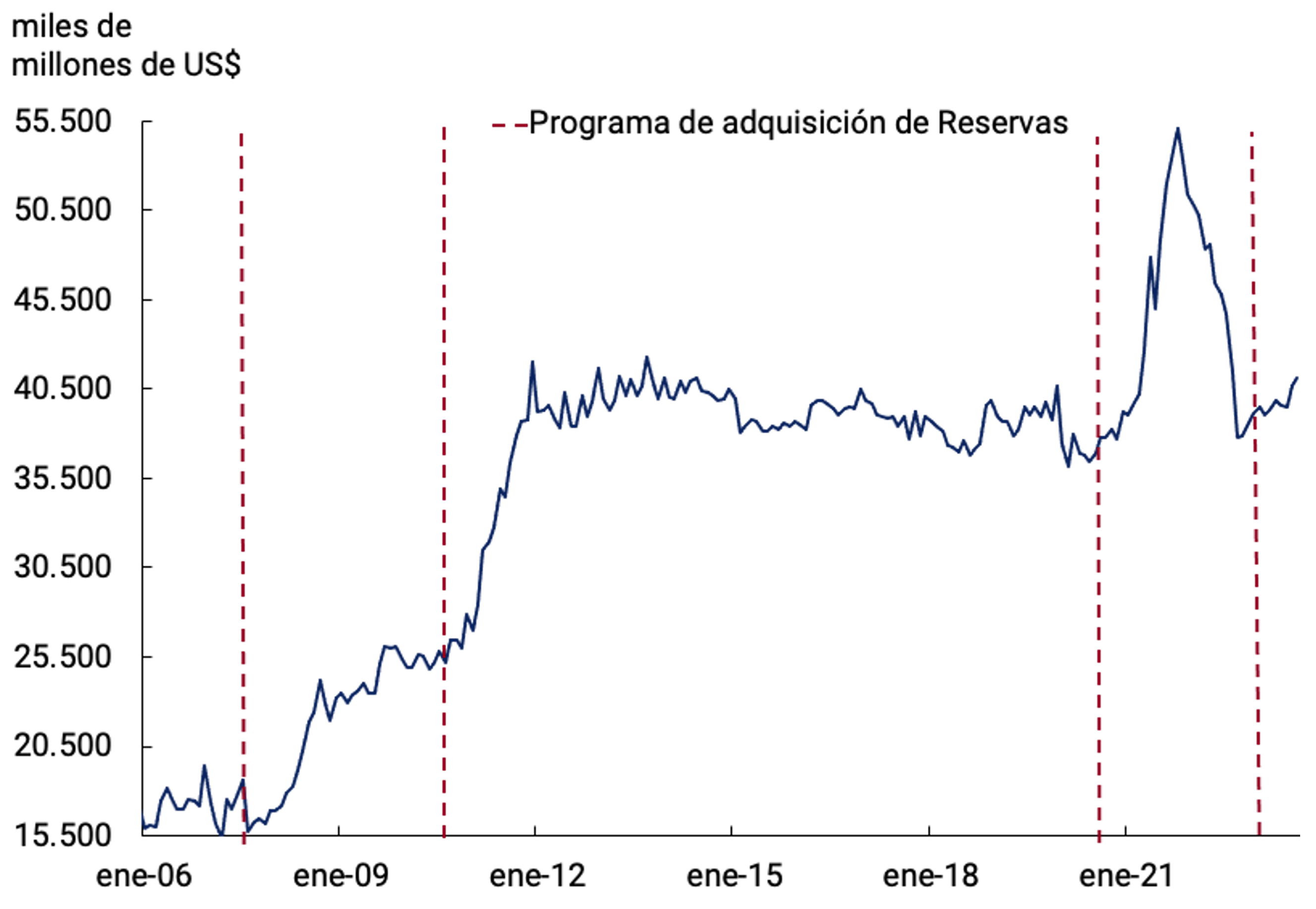

In addition, within the region, Chile’s monetary authority (BCCh) began a new process of accumulating international reserves. The BCCh initiated a program to replenish and expand international reserves for a total of US$10,000 million, to strengthen the country’s international liquidity position, purchases that will have a zero monetary effect when sterilized (see Figures 2.7a and b).

Figure 2.7 | Indicators of Chile’s external sector

Source: BCRA based on data from the Central Bank of Chile.

Meanwhile, the Fed’s quantitative tightening programs continued as announced, and without new impacts on the financial sector, after what happened with Silicon Valley Bank, among others. In addition, the risks of an exit from the Bank of Japan’s expansive monetary policy continue, which, if it fails to be orderly, could have disruptive effects both locally, especially in non-bank financial institutions, and internationally due to the dismantling of carry trade positions.

For the rest of the major monetary authorities, slight reductions in the MPR for Southeast Asia are expected. Its central banks are the ones that in relative terms had raised their MPRs the least since their inflation rate remained within or very close to the target. On the other hand, Turkey’s monetary authority drastically changed its monetary policy strategy, and began to sharply increase its MPR to combat inflation.

Box. Argentina in the BRICS

Last August, the presidents of the BRICS group (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) invited six countries to become full members from 2024: Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. The current members of the BRICS represent more than 42% of the world’s population, 30% of the territory, 23% of global GDP and 18% of international trade.

In 2001, a report by Goldman Sachs (“Building better global economic BRICs”) reported on the growth of these five emerging countries, stating that in the short term they would surpass those of the G-7 to become the future leaders of the world economy. The leaders of Brazil, Russia, India and China met informally for the first time in July 2006, and in September of that year, they agreed to incorporate the BRIC concept into foreign policy categories, stressing the need to strengthen mutual cooperation.

In 2008, the global financial crisis catalyzed the consolidation of the bloc within the G20: the BRIC Finance Ministers adopted joint declarations on global problems, making alternative proposals to deal with the crisis. In June 2009, the First BRIC Leaders’ Summit was finally held. They defined their fundamental mission: to promote the reform of the international financial institutions and cooperation on crucial issues of global development. They agreed to hold an annual Leaders’ Summit. South Africa was invited in 2010, and the group adopted the name BRICS.

Annually, the BRICS holds about 150 meetings on three pillars of cooperation: (i) political and security, (ii) financial and economic, and (iii) cultural and people-to-people. The signing of more than 30 agreements and memorandums of understanding provide the legal basis for cooperation in areas as diverse as the Contingent International Reserve Agreement, customs, taxation, banking, culture, science, technology and innovation, agricultural research, energy efficiency, competition policy and diplomatic academies.

The communiqué of this year’s Summit emphasizes that its members share the vision of BRICS as a group that defends the needs and concerns of the peoples of the Global South. These include the need for beneficial economic growth, sustainable development and reform of multilateral systems.

As has been made clear throughout Argentina’s participation in the G20, our country shares an agenda with the BRICS members on issues such as i) reform of the international financial architecture; (ii) food and energy insecurity; and (iii) climate change. For its part, it opens the possibility of accessing a new source of financing for infrastructure and sustainable development projects through the New Development Bank (NDB) established by BRICS members in 2015. At the end of 2022, the NDB had 96 approved projects for a total amount of US$32.8 billion.

Finally, the BRICS members have been promoting the use of their own currencies for trade within the bloc (see the section on Local Currency Payment System in Mercosur). This is of special interest for Argentina’s current situation since trade with members represents approximately 29% of exports and 43% of imports.

2.3. Markets: Higher interest rates for longer, with an impact on bonds, stocks and currencies

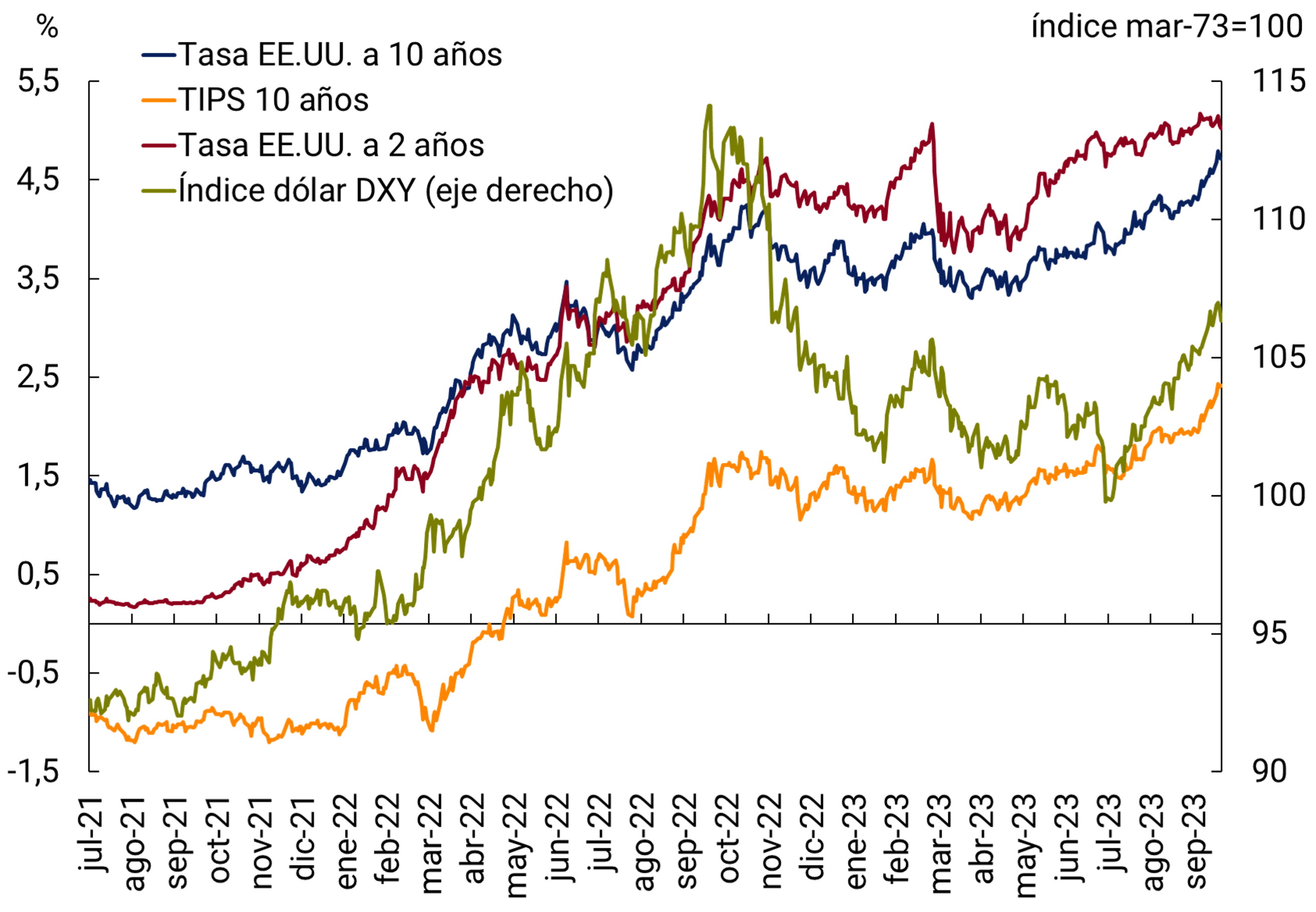

Despite the turbulence due to the banking crisis in the US at the beginning of the year, interest rates remained high and, with increases in the margin, they seem to stabilize in these values, which leads many analysts to propose a scenario of “higher rates for longer”, which would be a very relevant change for emerging countries.

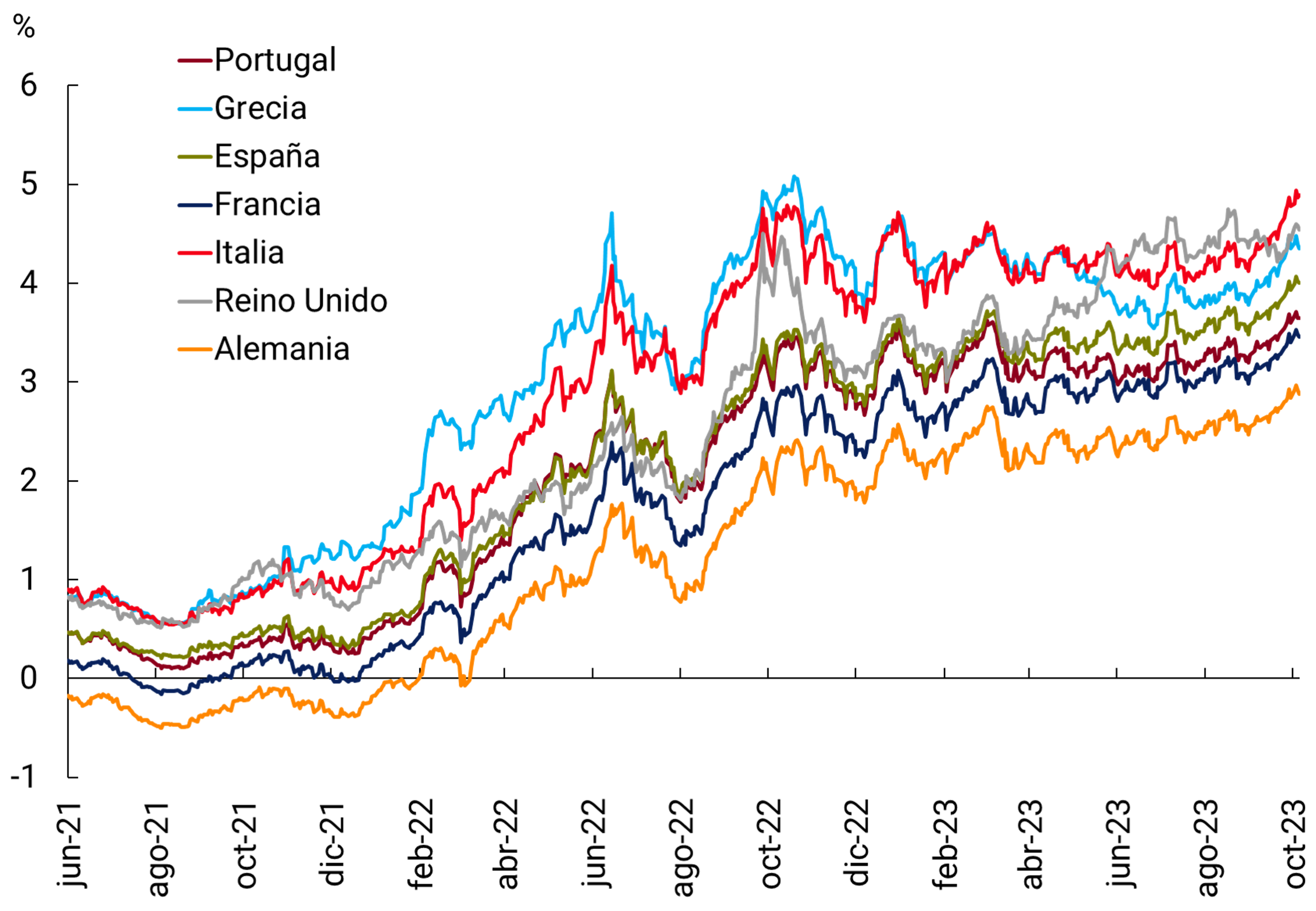

Since the close of the previous IPOM, the 10-year US Treasury rate rose 75 bps and has reached highs not seen since 2007. Real interest rates, as measured by 10-year inflation-indexed bond (TIPS) rates, are also very high, up 88 bps over the year (see Figure 2.8a.). This is not only seen in the United States; in Europe, rates also stabilized at high values and with increases in the margin (see Figure 2.8b).

These higher and longer interest rate levels have already begun to impact some sectors of the economy. On the one hand, there are beginning to be more restrictions on financing companies at a global level, for example, in the corporate bond sector. There are fears of the impact on the real estate markets, although for the moment the United States remains resilient to the new scenario. There are countries, such as Great Britain, that have a higher proportion of variable-rate mortgage loans and already show a cooling in the real estate market. Finally, China continues with its problems in the real estate sector that threaten the financial stability of banks and non-bank financial intermediaries, although the problems are idiosyncratic and unrelated to the global rate hike cycle.

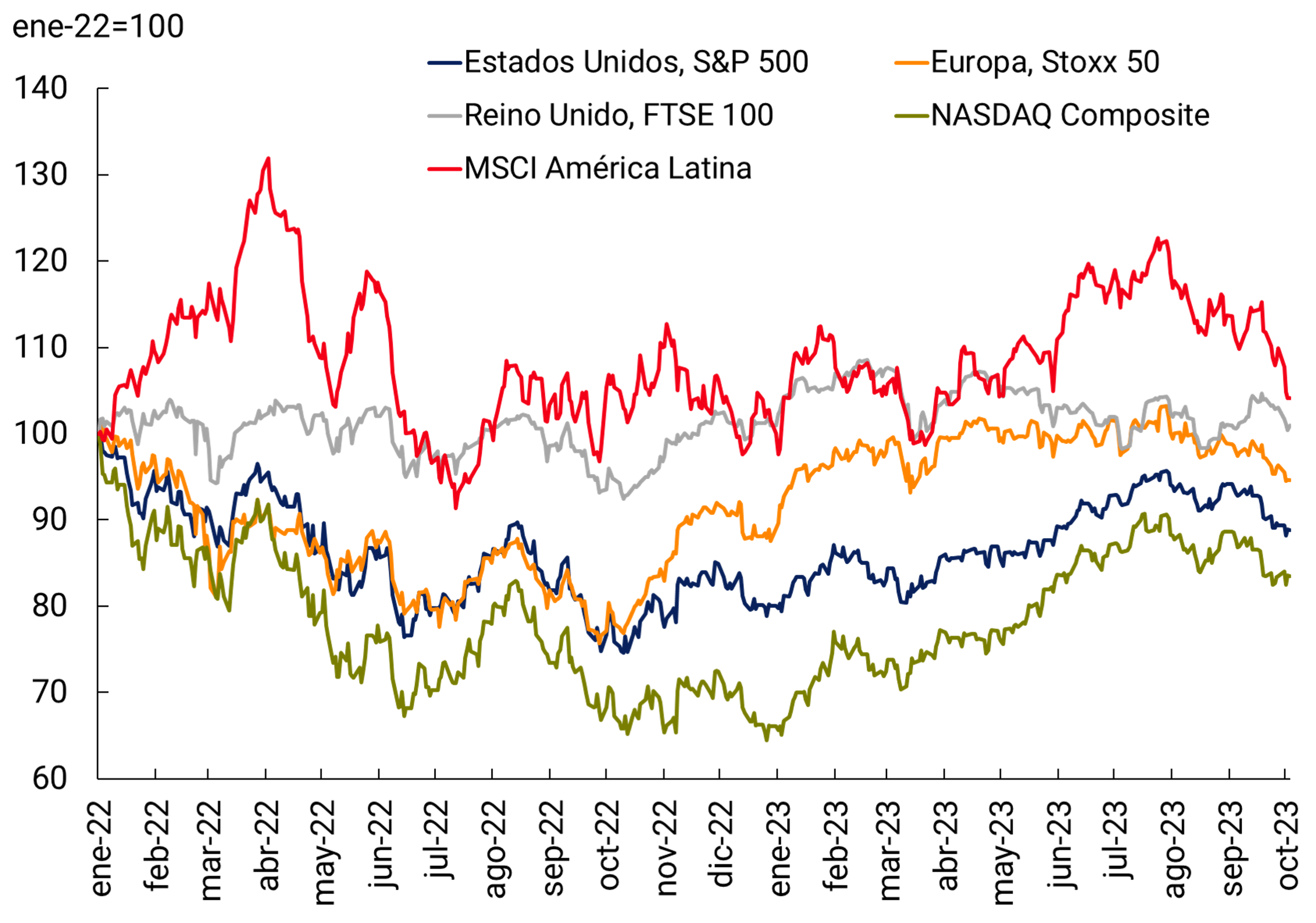

In this context, global stock markets moderated the increases in the year and fell by about 4% compared to the previous IPOM close. Since the beginning of the year, European stock markets have risen by about 8%, and in the United States the S&P 500 and Nasdaq rose 11% and 26%, respectively (see Figure 2.9a). Latin American equities, as measured by the MSCI index, have fallen 14.9% since the end of July, a period that coincides with capital outflows from emerging countries in line with the rate cycle reversal described in the previous section (see Figure 2.9b). Although capital outflows occurred throughout the emerging countries, they were much more important in the case of China.

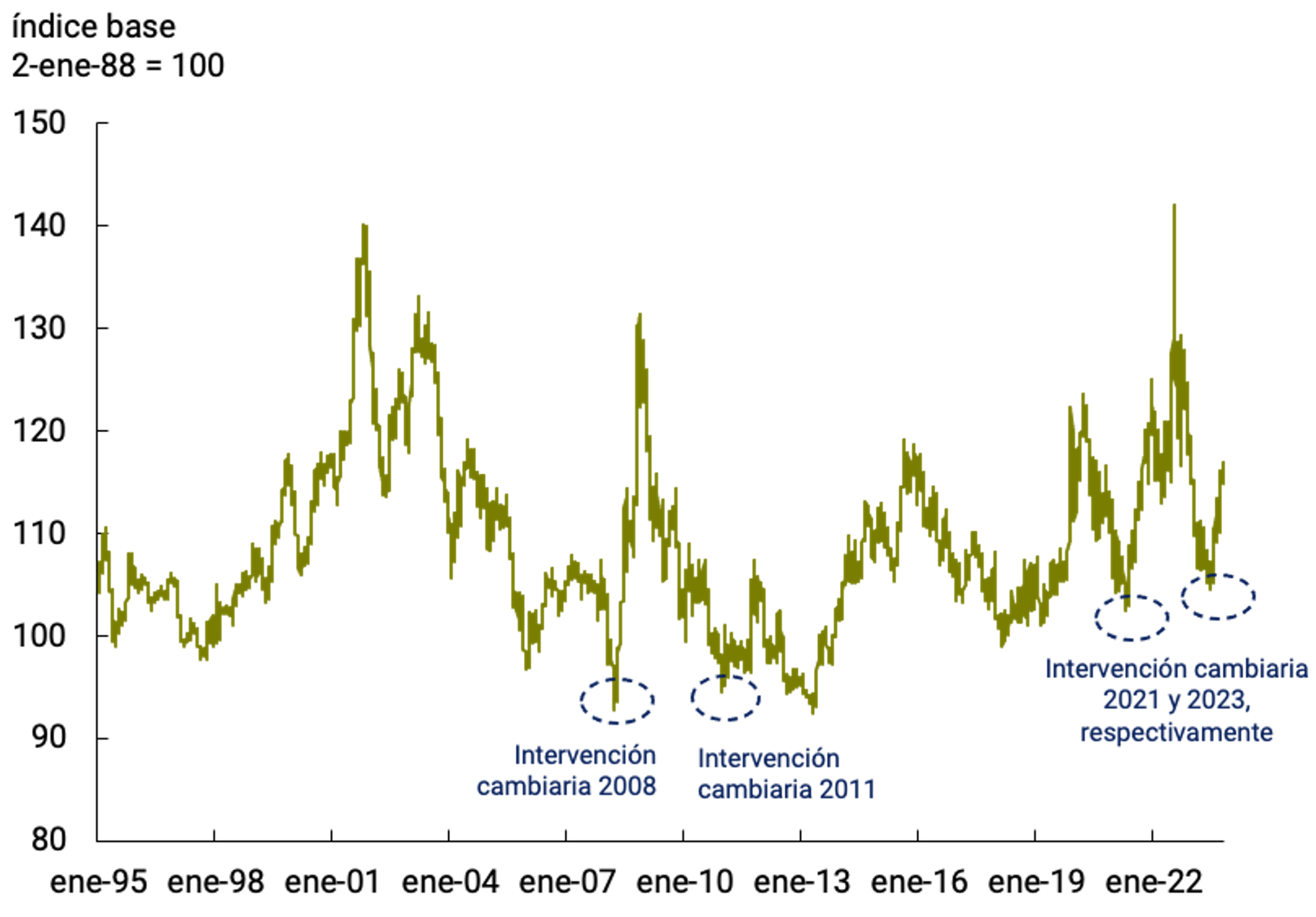

During the first half of 2023, the U.S. dollar in multilateral terms experienced a depreciation that began to reverse from mid-July for various reasons, the divergence in the speed of the implementation of monetary policies with other economies, with its impact on the interest rate differential, and the increase in the price of oil, among others.

In particular, during the third quarter of 2023, the prices of the main agricultural commodities such as soybeans, wheat and corn continued to fall, while energy such as crude oil and gas rose. OPEC+’s decision to cut production at different meetings had an impact on the increase in oil prices, although the rise in global interest rates and the greater risk of recession would be the opposite factors that would work as a counterweight to the fall in commodity prices.

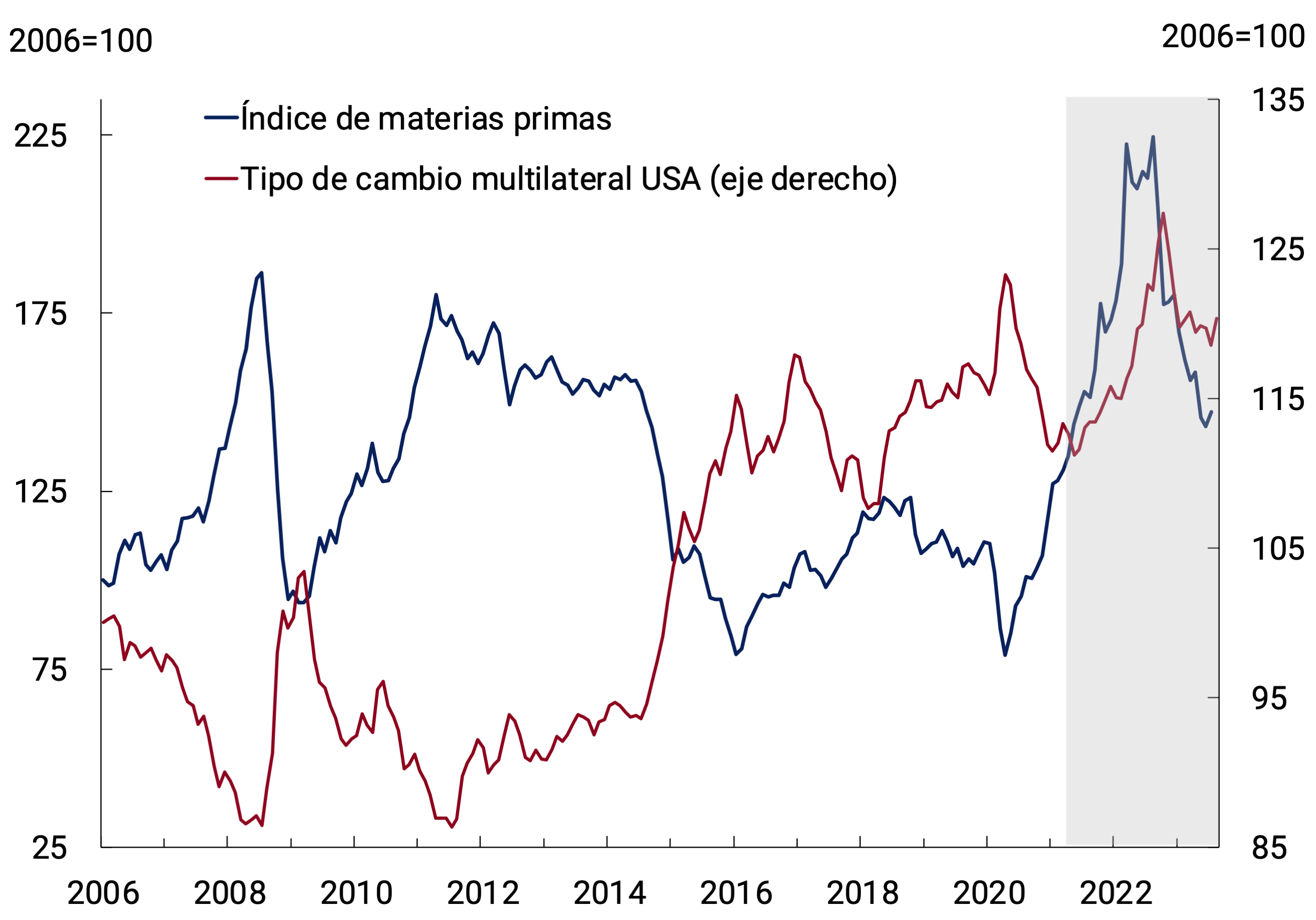

As noted in the June 2023 IPOM, commodity prices and the US dollar have moved in tandem recently, in contrast to their usual pattern of doing so in opposite directions (see Figure 2.10). The causes are partly temporary, such as the unusual combination of recent shocks, and partly structural, such as the emergence of the United States as a net exporterof energy.

Figure 2.10 | U.S. multilateral exchange rate and commodity

Source: BCRA based on data from FRED.

Brent oil began to rise from mid-June until reaching its highest value in the year in September as a result of the different cuts in production levels that the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC+) carried out, increasing its price by 25% during the third quarter3. The price of natural gas in Europe rose 30% this quarter, although starting from very low values due to the high levels of reserves reached in European deposits (see Figure 2.11a).

Figure 2.11 | Selected raw material prices

Source: Bloomberg.

2.4. In summary

Several sources of risk are opening up for the global economy. China’s developments and the financial repercussions of its real estate crisis will be key. On the other hand, if the scenario of a “soft landing” of the US economy is consolidated, this would support global activity, in contrast to other advanced economies that are almost not growing. But at the financial level, the scenario of “higher rates for longer” would imply a yield differential in favor of the bonds of advanced economies, also strengthening the US dollar and tightening international financial conditions in general. The balance of risks looks bearish for global activity and persistent for inflation, especially in advanced economies.

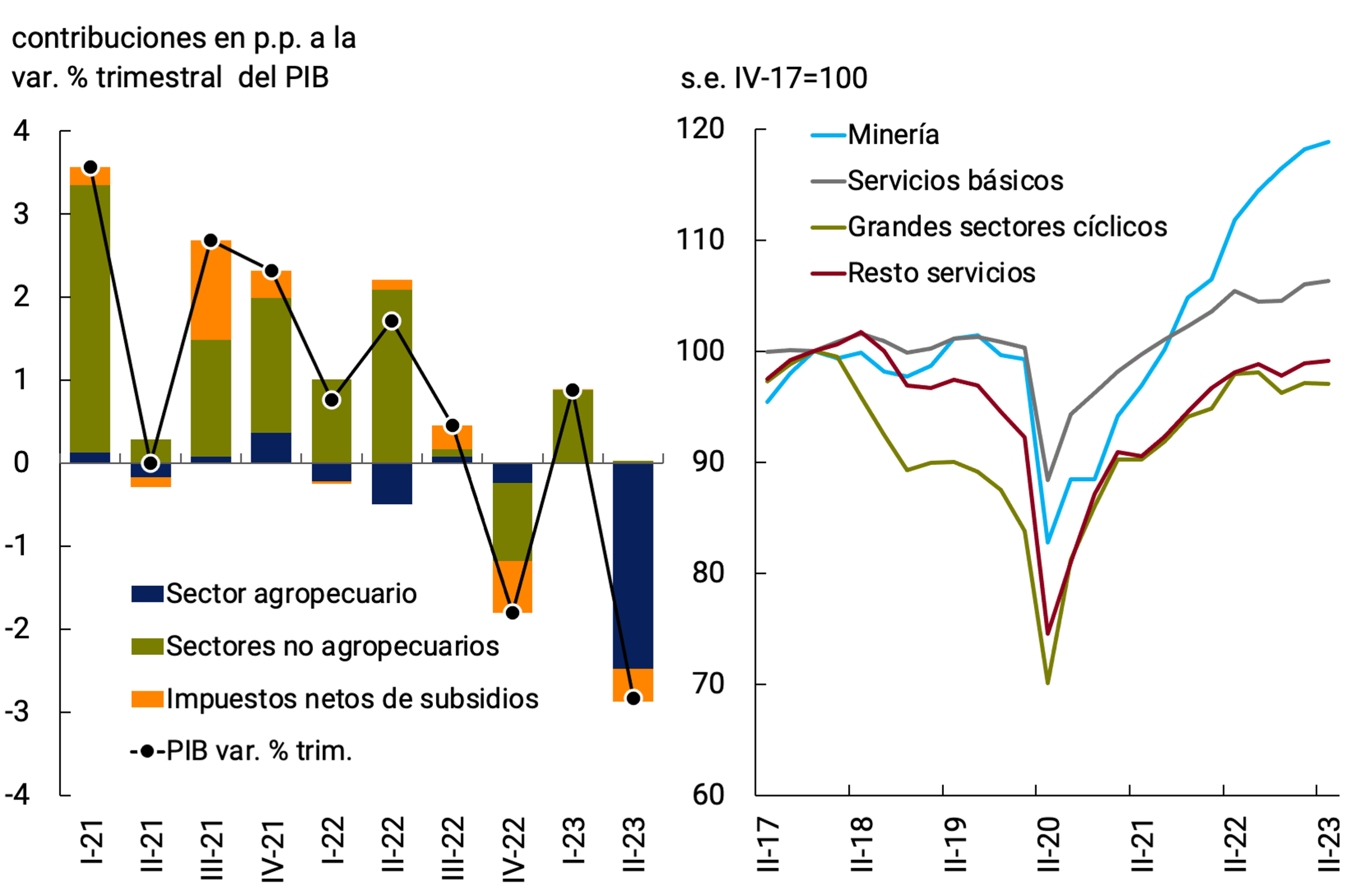

3. Economic Activity and Employment

GDP fell 2.8% qoq/s/a and 4.9% y/y (y.o.y.) in the second quarter of 2023, as a result of the severe drought, as anticipated in the previous IPOM. The level of activity in the non-agricultural sectors as a whole remained in similar ranges to those of the first quarter and also in year-on-year terms, although greater heterogeneity was observed. The activities most linked to agriculture contracted while the rest averaged a positive variation. As a result, the creation of formal employment in the non-agricultural sector sustained a growth rate of 3.7% y.o.y.

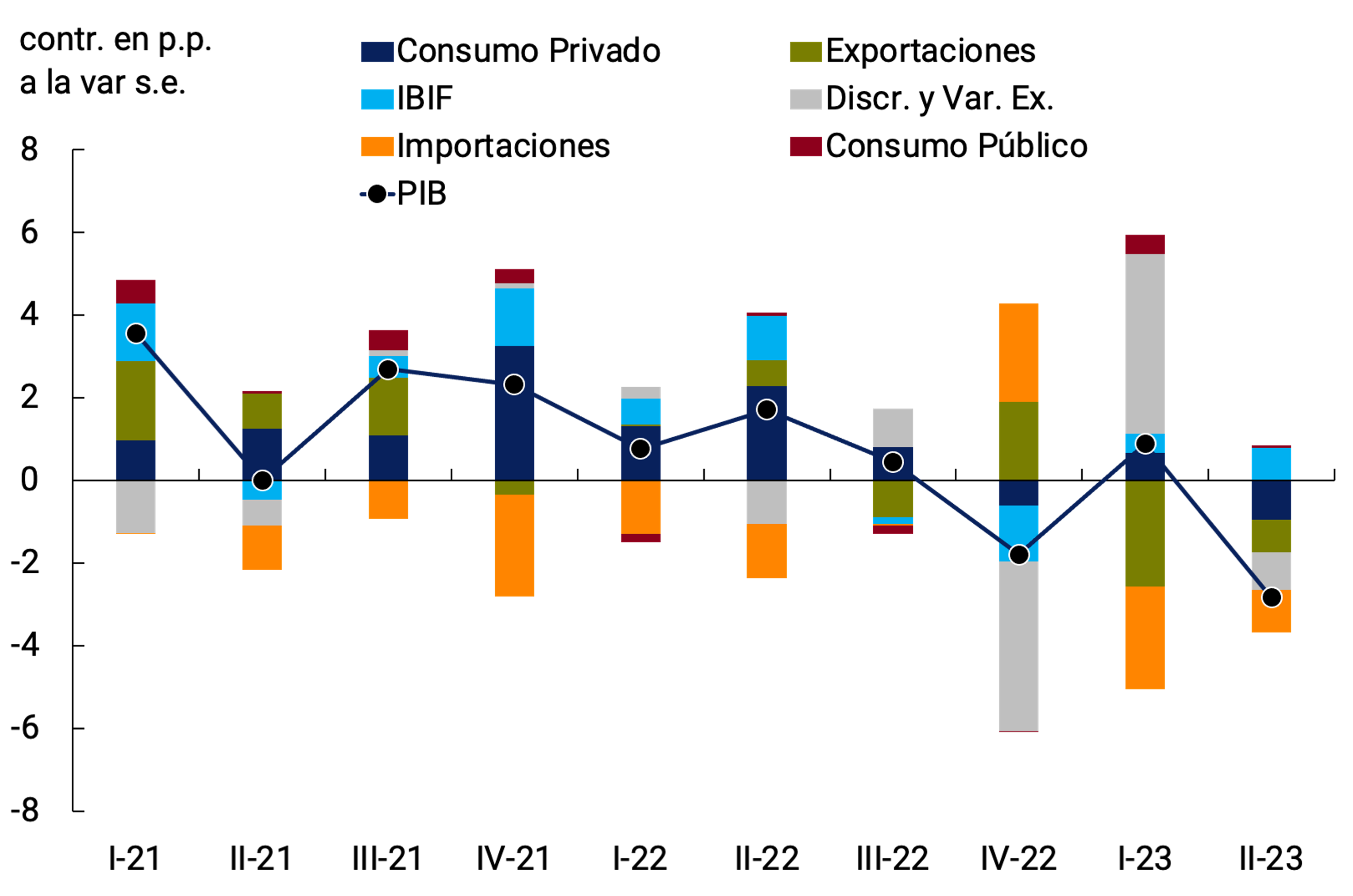

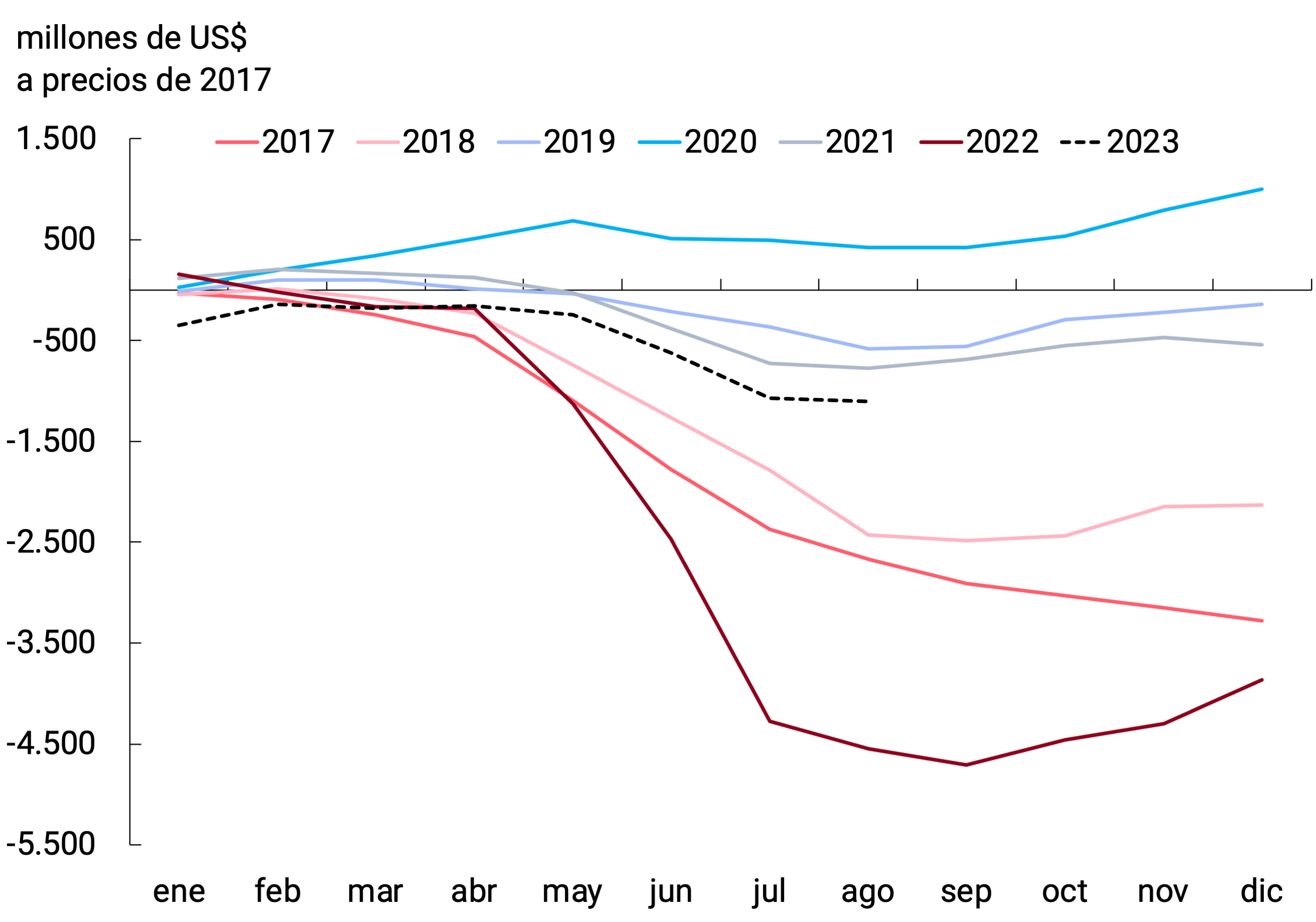

Domestic demand remained relatively stable compared to the first quarter (-0.1% s.e.) and registered slight growth compared to the previous year (0.7% y.o.y.), with a contraction in private consumption and growth in investment. The negative effects of the drought were reflected in a contraction in net exports and inventories, being, together with lower private consumption, the main factors that explained the fall in output in the second quarter from the demand side.

In the third quarter, opposite effects on economic activity were combined. On the one hand, the recalibration of the level of the official exchange rate and the increase in financial volatility after the PASO elections would have had a contractionary impact on domestic demand. This effect would be attenuated by the set of income policies recently implemented by the National Government. The recovery in agricultural production and related activities would allow seasonally adjusted output to increase compared to the second quarter. In the same sense, unconventional oil and gas production is expected to continue to grow, driven by the commissioning of the Néstor Kirchner gas pipeline and investment in pipelines.

During the last quarter of the year, the economy is expected to operate in an environment of greater volatility associated with the political cycle, which could negatively affect consumption and investment decisions. By 2024, the economy is expected to gradually resume the growth path boosted by the favorable prospects for the agricultural harvest and the energy sector.

3.1. The fall in activity during the second quarter was mostly concentrated in the agricultural sector

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fell 2.8% quarter-on-quarter s.e. and 4.9% y.o.y. in the second quarter of 2023 (II-23) due to the direct impact of the drought on agricultural activity. In fact, the contraction of agricultural output fully explained both the quarterly (-3.0% s.e.) and year-on-year (-5.1%) variations in GDP measured at basic prices (excluding taxes).

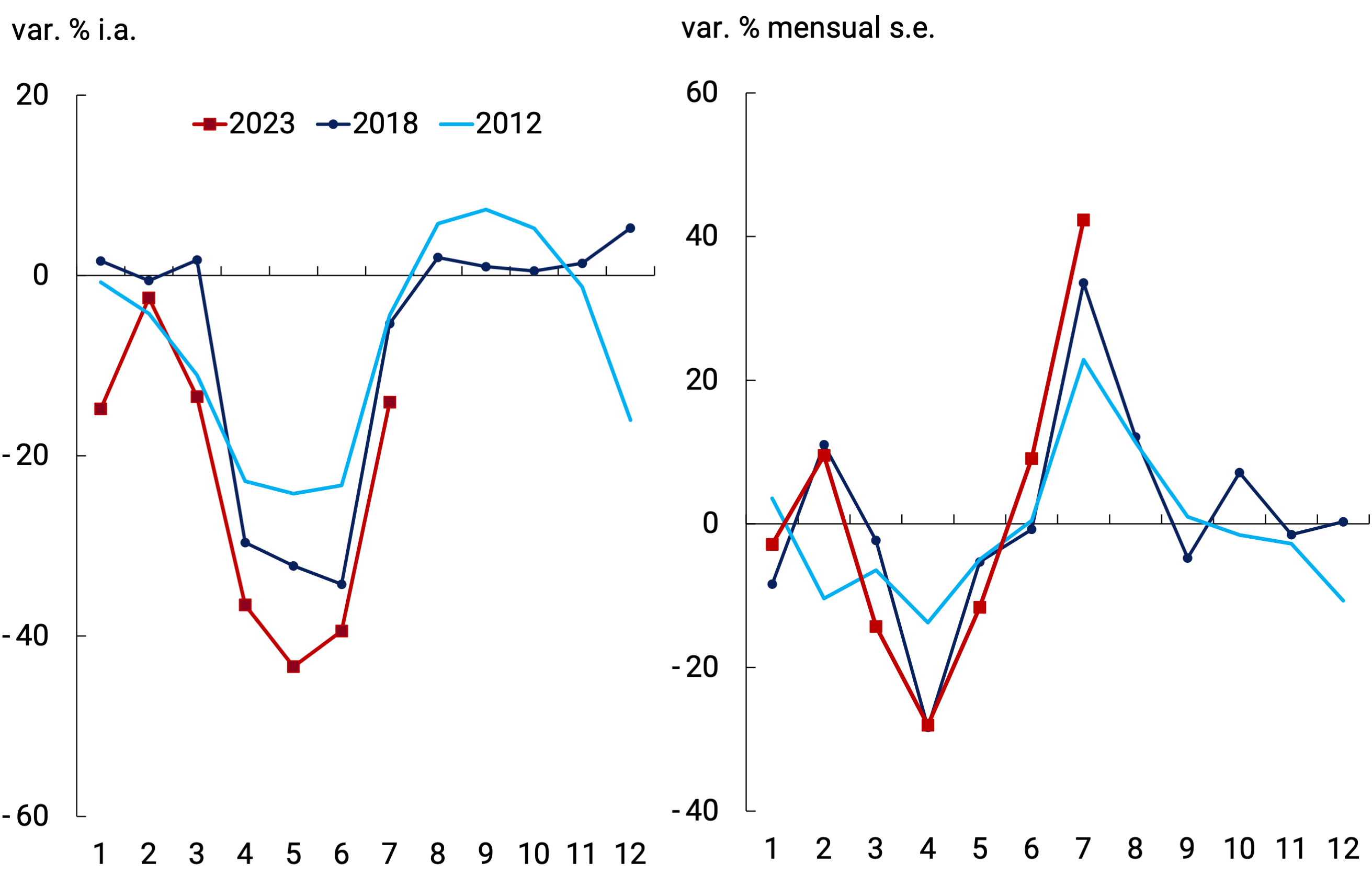

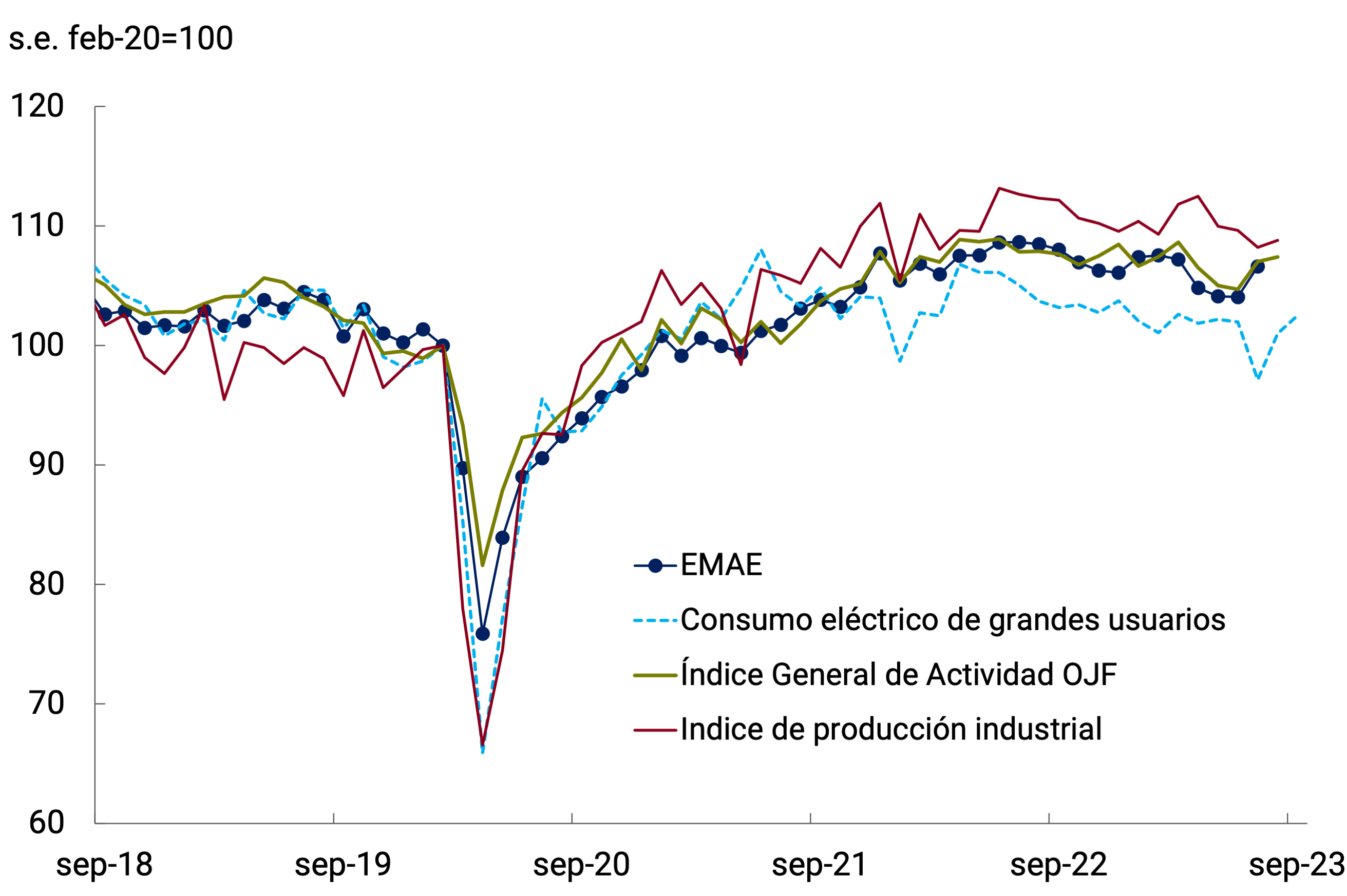

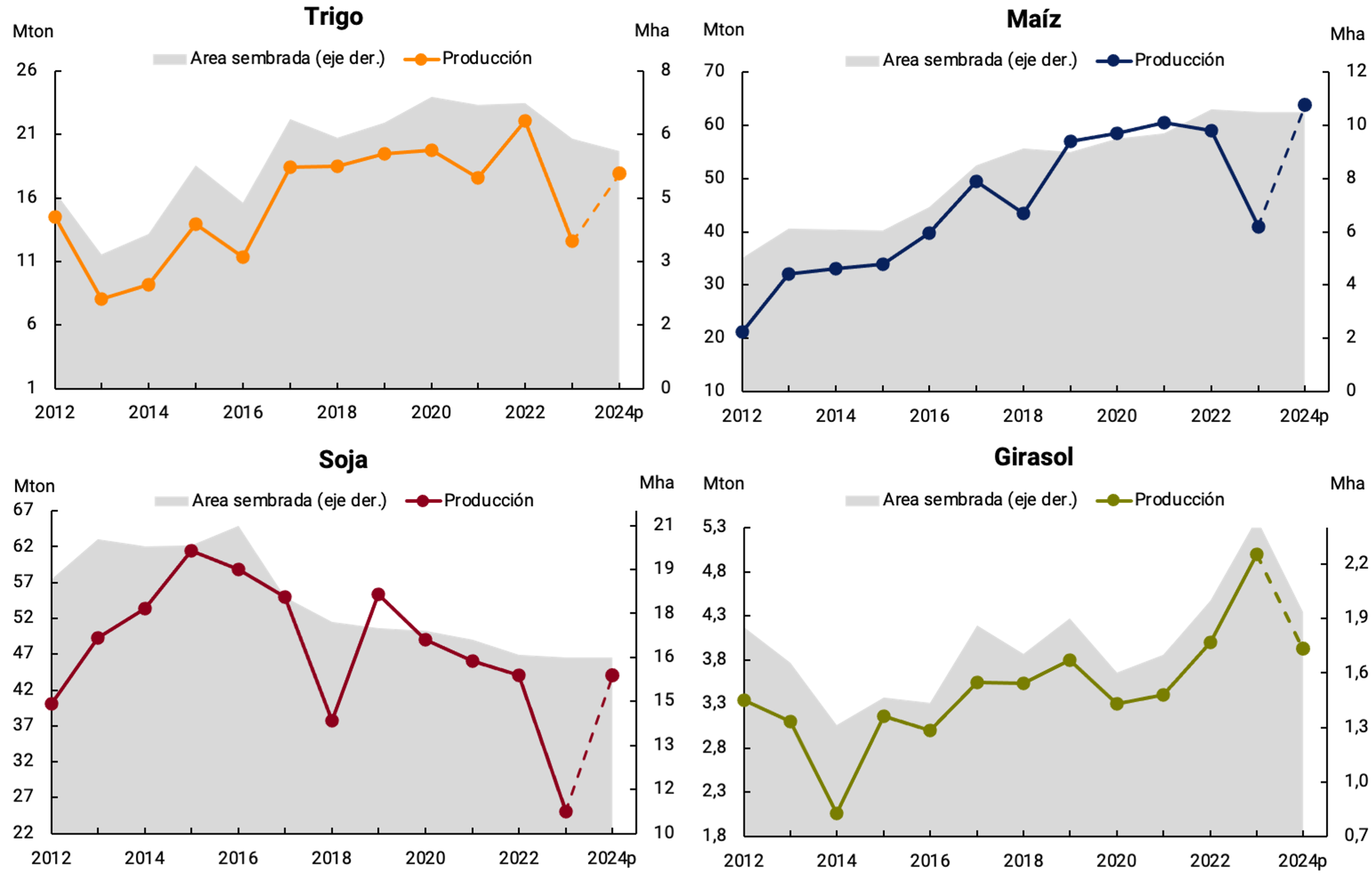

It should be noted that in the second quarter of each year, the product derived from the coarse harvest, mainly soybeans and corn, is counted in the GDP. These crops were the most affected by the drought, resulting in falls of 43% and 30% y.a., respectively12, thus explaining the severe contraction recorded in Output. Starting in June, and as expected based on what happened in previous episodes of drought, activity in the agricultural sector began to reverse the strong contractions recorded between March and May (see Figure 3.1). In fact, the Monthly Estimator of Economic Activity (EMAE) showed a monthly increase of 2.4% s.e. in July, which is made up of a strong increase in the agricultural sector (42.3% s.e.), which contributed approximately 1.8 p.p. to the monthly variation of the general level, while the rest of the sectors and taxes net of subsidies rose approximately 0.6% monthly s.e.

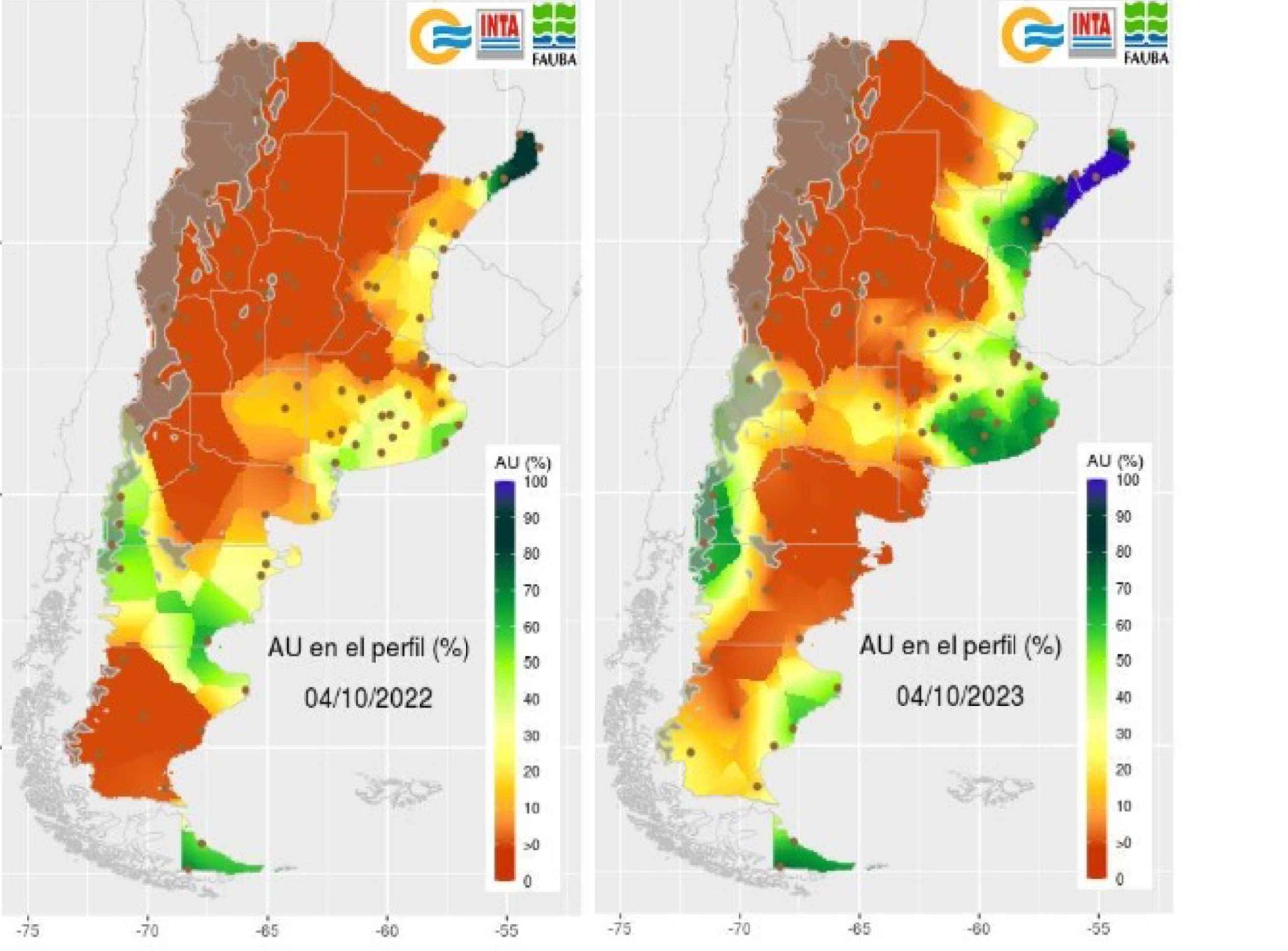

For the remainder of the year, agricultural output will reflect the evolution of the tasks carried out with a view to the next season13 and the result of the harvests of some crops, mainly wheat. The consolidation of the El Niño climate phenomenon with evident improvements in the water profiles of the soils in the core area of the country, would ensure the reversal of the climatic conditions that prevailed in the last three seasons. This allows us to foresee a substantial improvement in agricultural production corresponding to the 2023/2024 campaign (see Section 3 / Recovery forecasts for the next agricultural season).

3.1.1. Non-agricultural sectors lost momentum, registering a heterogeneous evolution

The non-agricultural sectors as a whole remained stable compared to the second quarter and also in year-on-year terms (0% quarter-on-quarter and 0.1% y.o.y.), with greater heterogeneity observed. This performance was the result of contractions in some sectors related to agriculture (Transport and communications and certain industrial blocks), the supply of electricity, gas and water (EGA) and financial intermediation, which were offset by the growth of the rest of the sectors.

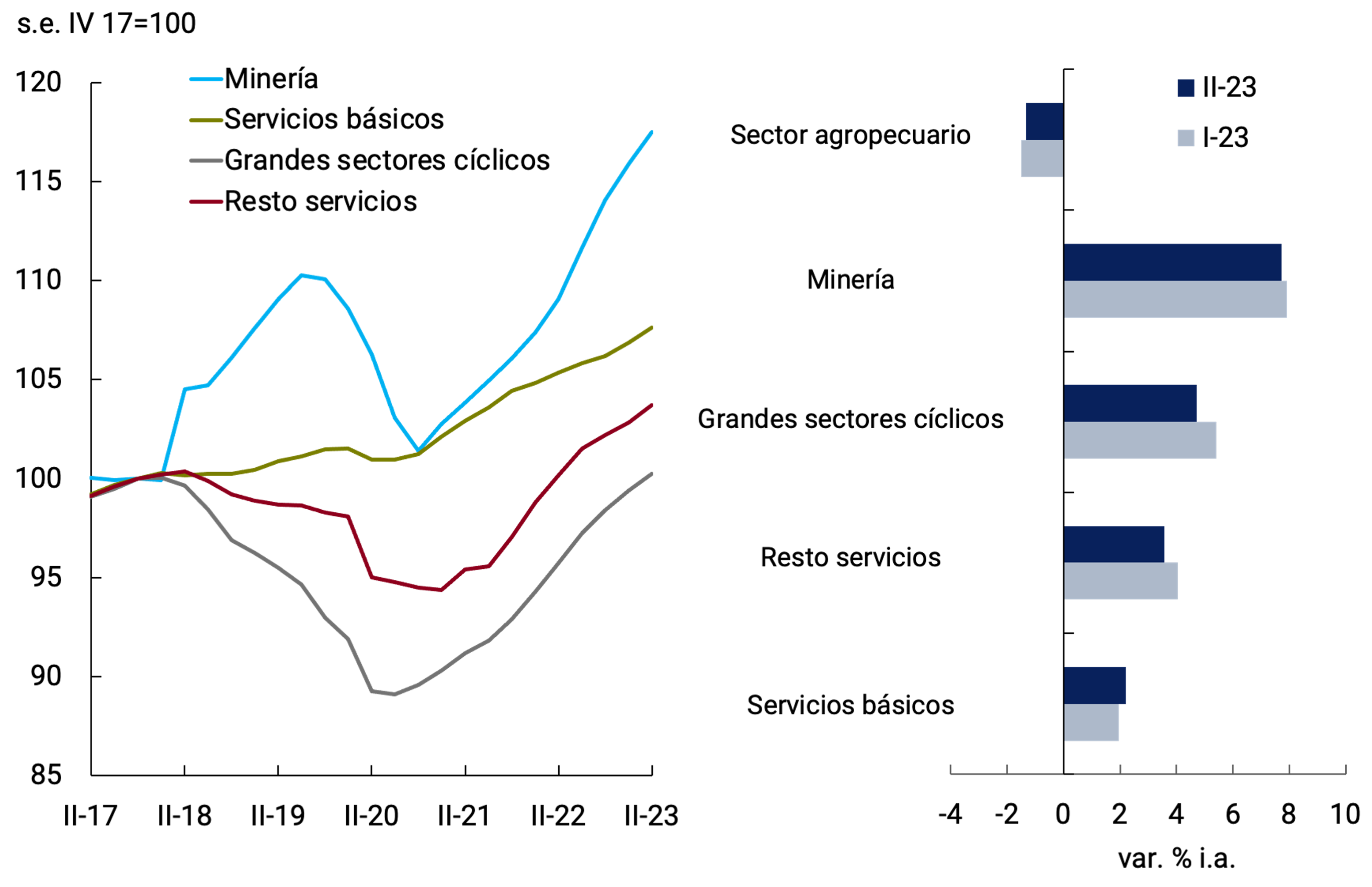

The most outstanding segment for its performance continued to be Mining and Quarrying (Mining) which, with an increase of 0.6% qoq s.e. and 6.3% y.o.y. during the second quarter of 2023, exceeded the level of the fourth quarter of 2017 by 18.8% s.e., a period in which GDP had reached the previous maximum (see Figure 3.2). The unconventional extraction of oil and gas, mainly developed in the Vaca Muerta field, is the main factor of expansion in this area. In fact, shale oil extraction increased 26.9% YoY in that quarter and represented 47% of national crude oil production, while in the case of natural gas, shale registered a growth of 7.8% YoY (40% of total production).

Source: BCRA based on INDEC data.

The activity of the group of sectors with the highest weighting in Output, due to their linkages, employment levels and procyclicality – Industry, Trade, Construction and Transport and communications – decreased compared to the first quarter of 2023 (-0.8% quarterly s.e.). This was mainly explained by the closer link between the agricultural sector and some segments of the agro-industrial chain, the transport of ships and trucks to ports and the trade in inputs for the countryside, among other segments, whose activity was indirectly affected by the lower harvest.

Finally, the other services averaged an increase in the second quarter, although they slowed the pace of increase. The set of the so-called basic products – Electricity, gas and water (EGA), Health, Education and Public Administration – rose 0.3% quarterly s.e. and 1% y.o.y. as a whole. The rest of the services—Hotels and restaurants, Financial intermediation, Real estate and business activities, and Other community services—showed a similar performance (0.3% quarterly s.e. and 1.1% y.o.y.) and exceeded the maximum level of 2022. However, it is relevant to note that, within these groups, both EGA (-7.6% s.e. and 6.3% y.o.y.) and Financial intermediation (-2.4% s.e. and -3.0% y.o.y.) contracted in the second quarter.

3.1.2. The level of formal employment continued to grow at a sustained rate in the non-agricultural sectors

The differentiated evolution between the levels of activity of the economic sectors during the second quarter of the year was reflected in the formal employment data of the Ministry of Labor, Employment and Social Security (MTEySS). In fact, in the non-agricultural sectorsas a whole14 employment grew by 3.4% YoY in the second quarter, while in the agricultural sector there was a fall of 1.3% YoY.

In line with the evolution of activity, Mining led the creation of formal employment in II-23, with an increase of 7.7% YoY and 17.5% s.e. accumulated since IV-17. Formal employment in the major cyclical sectors as a whole (Industry, Trade, Construction and Transport and Communications) increased significantly in the II-23 (4.7% YoY), with a higher rate than that experienced by “Other Services” (3.6% YoY). In the so-called “basic” services, formal job creation maintained its relatively stable trend at around 2.2% y.o.y. (see Figure 3.3).

Source: BCRA based on data from MTEySS.

It should be noted that within private employment, there was a significant growth in self-employed workers (self-employed and single-payers; 1.0% monthly average s.e.), while private salaried employment also rose, although to a lesser extent (0.3%). The growth of private salaried employment as of July 2023 has shown, in terms of sectoral diffusion, historically high values, continuing the positive dynamics that began in the post-pandemic period.

According to data from the Permanent Household Survey (EPH), in the second quarter of 2023 both the employment rate (44.6%, unchanged)15 and the activity rate (47.6%, -0.3 p.p. y.o.y.), continued at high values, while the open unemployment rate contracted to 6.2% (-0.7 p.p. y.o.y.), reaching historic lows at least since the beginning of the series. in 201616.

3.1.3. From the point of view of demand, the lower activity during the second quarter was explained by the fall in net exports, the deaccumulation of stocks and the reduction in private consumption

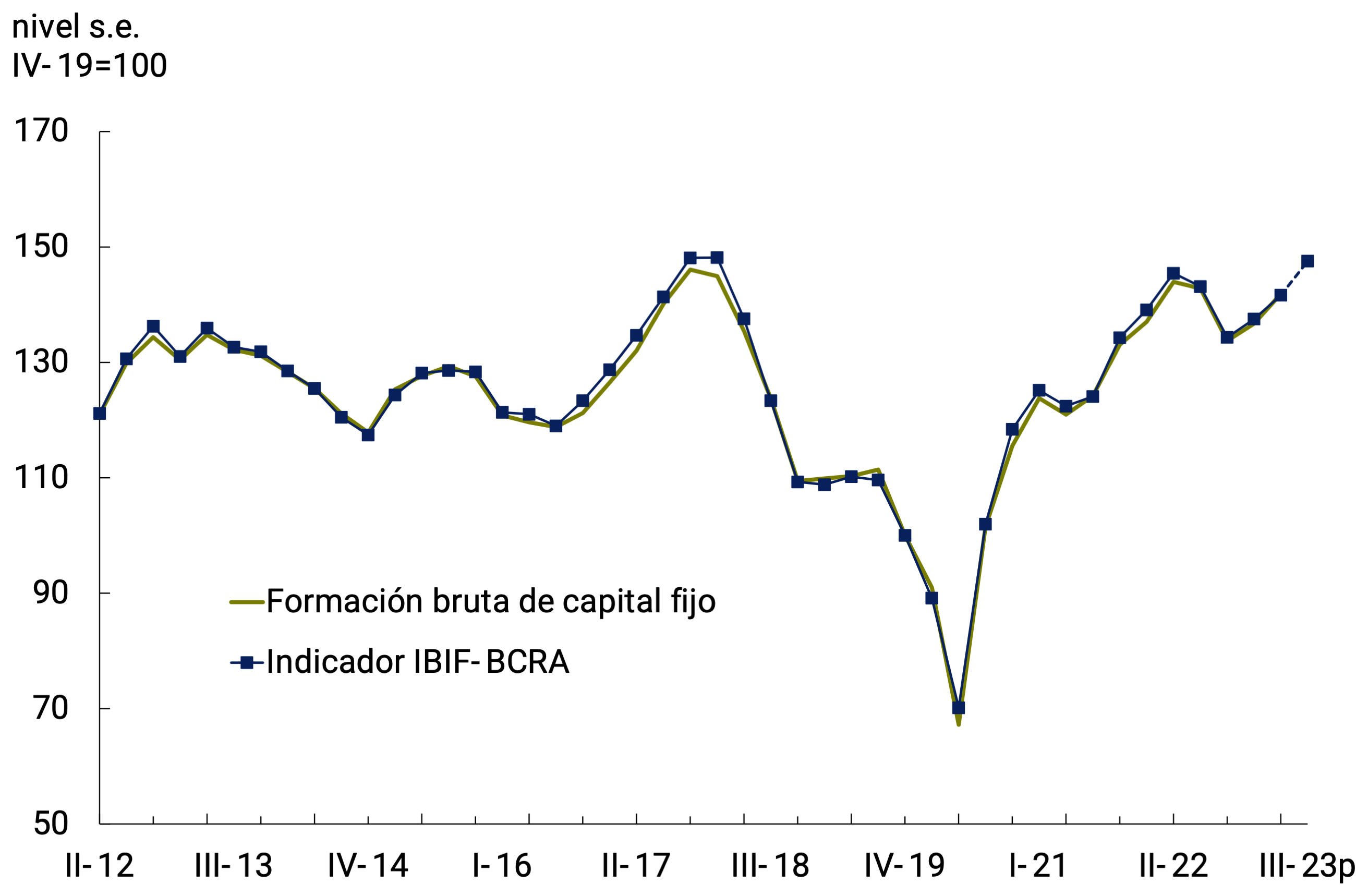

During the second quarter of 2023, domestic demand remained practically stable (-0.1% qoq s.e. and +0.7% y.o.y.), showing a differential behavior between Private Consumption, which fell 1.3% qoq s.e. (+0.8% y.o.y.), Public Consumption, which increased slightly (+0.4% qoq s.e. and 2.6% y.o.y.) and Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF), which showed a significant expansion of 3.8% qoq s.e. (-1.1% y.o.y.). The growth in gross investment was verified both in Durable Production Equipment, which showed a 4.6% quarter-on-quarter increase, and also in Construction (2.3% quarter-on-quarter). Regarding domestic consumption, a differentiated behavior was observed, with a contraction in the demand for non-durables and a rise in that of durables, probably as a hedging strategy against the increase in inflation. In this sense, there was a drop in supermarket sales, while sales in shopping malls, car and motorcycle patents and the marketing of some large appliances grew in the17th quarter. Another evolution to highlight during the period was the growth recorded by the Hotels and Restaurants sector (4.7% s.e.; 6.4% y.o.y.).

Given the stability of domestic demand, the fall in output was mainly explained by the decumulation of stocks, which could largely be attributed to the agricultural sector, and by the performance of the external sector. In fact, the variation in inventories, together with the statistical discrepancy, subtracted 0.9 p.p. s.e. from the quarterly variation of the Product, after the strong contribution it had had in the I-23. In addition, imports of goods and services increased 3.7% quarter-on-quarter, while exports fell 4.1% quarter-on-quarter, mostly linked to the agricultural sector (see Chapter 4. External Sector). In this way, the net external sector subtracted 1.8 p.p. from the quarterly variation of GDP (see Chart 3.4).

Figure 3.4 | Quarterly variations in GDP and contributions from demand

Source: BCRA based on INDEC data.

3.1.4. Partial data for the third quarter show a recovery from the previous quarter

In July, the EMAE increased significantly (2.4% monthly s.e.), due to both the strong recovery of the agricultural product and the rise in the rest of the sectors, which averaged 0.6% monthly s.e. In this way, the statistical carryover left by the data was positive for the third quarter (+2.2 p.p.), but it is still negative for the 2023 average.

With respect to other available indicators that are useful for estimating the evolution of activity at the aggregate level, during the third quarter there was a contraction in July-August and then a recovery in September in the electricity consumption of large companies18. The General Activity Index (IGA) prepared by O.J. Ferreres, whose correlation with the official activity data is high, rose in July and August by 2.2% and 0.4% monthly, respectively. Finally, the Nowcast-BCRA – which more accurately predicts non-agricultural GDP – anticipates a 0.5% quarterly fall s.e. during the third quarter.

Figure 3.5 | EMAE and leading indicators of economic activity

Source: BCRA based on data from INDEC, CAMMESA, OJF and Associates.

The industrial production statistics and construction indicators available for the third quarter19 anticipate a possible quarterly (s.e.) contraction in these sectors. On the other hand, the indicators show that services associated with tourism and leisure would remain in positive territory20.

Regarding private consumption, the available data suggest that the demand for durable goods showed a similar behavior in July and August to that observed in the first half of the year, with significant increases due to the same factors mentioned above. In the case of sales of domestic automobiles to the domestic market, they increased 1.2% quarter-on-quarter s.e. in the third quarter of 2023. Although since mid-August private consumption has been negatively affected by the increase in inflation and the greater electoral uncertainty after the PASO, the validity since September of a set of measures adopted by the National Government to shore up the real incomes of families and boost credit would have helped to offset its negative impact (see Chapter 5. Public Finance).

Gross investment is expected to increase again in the third quarter according to the IBIF-BCRA indicator (see Figure 3.6). Demand for imports of capital goods and industrial transport equipment would have explained the improvement, while domestic production of such goods and construction would have evolved in the opposite direction21.

Figure 3.6 | Gross

Note: The evolution of the IBIF-BCRA indicator is calculated using the variations in the index of industrial production in capital goods prepared by FIEL, the quantities imported of capital goods and the EMAE of construction. The III-23 was projected with the statistical carryovers of the respective series.

p: Projected.

Source: BCRA based on data from INDEC and FIEL.

In conclusion, although the indicators related to non-agricultural product show mixed signals, the expected recovery for agriculture would allow GDP growth compared to the second quarter in seasonally adjusted terms. Regarding domestic demand, although there are favorable indicators on durable consumption and investment in imported capital goods, it could be expected that during the third quarter it will have been affected by the increase in inflation in August and September. However, the negative effect on real incomes would have been attenuated by the maintenance of employment and by the set of compensatory measures adopted by the National Government. Regarding external demand, the data on the commercial exchange of goods for July and August showed an increase of 3.4% s.e. in the quantities exported compared to the previous quarter and a fall in imported volumes of 0.5% s.e. in the same period. Thus, estimating a behavior of the exchange of services similar to that of goods, the external sector would show a positive net contribution to the quarterly variation of GDP in the third quarter of 2023, after two strongly negative quarters (see Chapter 4. External Sector).

3.2. Perspectives

During the last quarter of the year, the economy will develop in an environment of greater volatility associated with the political cycle that could negatively affect consumption and investment decisions. In this context, domestic demand will continue to be underpinned by the broad set of income and social protection policies, implemented by the National Government since the third quarter with the aim of cushioning the possible contractionary effects of the recalibration of the level of the official exchange rate in mid-August. The labor market continued to create jobs until the third quarter and this trend is expected to continue in the last months of the year, according to the Survey of Labor Indicators (EIL).

From the sectoral point of view, it is expected that some items may exhibit a contraction in their activity levels as a result of the context summarized above, however, there are favorable determinants to sustain the good performance that some sectors showed during the first three quarters of the year. Among them, the growth recorded in recent years and the potential for development of the mining sector and, especially, the hydrocarbon sector enhanced by the recent commissioning of the Néstor Kirchner Gas Pipeline stand out. On the other hand, the agricultural product would also have a positive evolution, which, in the last quarter of the year, will mainly reflect the result of the wheat harvest, with an estimated growth of 30% compared to the previous season. In the short term, it is also expected that the increase in tourism, cultural and leisure services, favored by the PreViaje program, will continue.

By 2024, the economy is expected to gradually resume the growth path boosted by the favorable prospects for the agricultural harvest and the energy sector. This scenario is not without risks both locally and globally. In this context, the BCRA will intensify its actions to preserve exchange rate and financial stability and will continue to facilitate the financing of the productive sectors. In this way, it will seek to contribute to the sustainability of economic activity and the labor market.

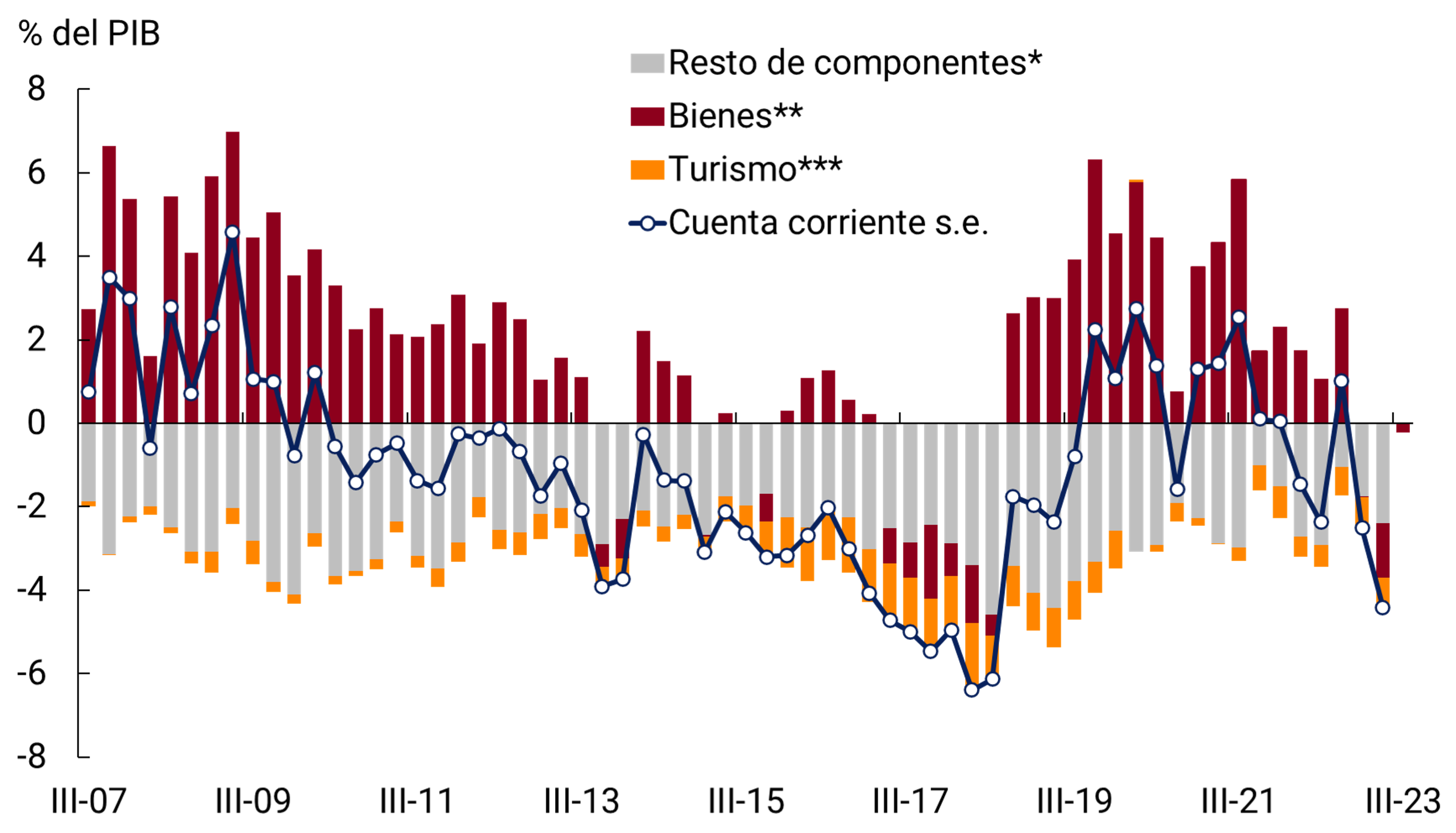

4. External Sector

In the second quarter of 2023, the economy operated with a current account deficit mainly due to a widespread fall in exports of goods, in which the lower shipments of grains and their derivatives strongly affected by the drought stood out for their weight, which would have impacted lower revenues of about US$20,000 million. At the same time, imports of goods showed a quarterly increase, although concentrated in a few import categories, among which capital goods and their parts and soybeans in the context of the drought stood out. In the third quarter, a reduction in the trade deficit of goods was observed, in a context in which the National Government and the BCRA promoted a set of measures aimed at achieving this objective.

Despite a negative trade balance, the dynamics of the trade debt for exports and imports allowed the accumulation of a positive net result for goods in the foreign exchange market of US$6,267 million during the first nine months of 2023, 65% less than what was observed in the same period of the previous year. In addition, net outflows were recorded through the foreign exchange market for services, interest and other financial transactions for US$9,026 million. In this way, the BCRA was a net seller in the foreign exchange market for US$1,990 million, added to the net payments by the Local Currency Payment System (SML) for US$771 million.

As of September 30, the BCRA’s international reserves reached a level of US$26,925 million, showing a fall of US$17,673 million throughout the year. This reduction was mainly explained by the net cancellation of principal and interest with international organizations (excluding the IMF) and other financial debt of the National Treasury for US$5,197, by the net cancellation of principal, interest and charges with the IMF for US$4,020 million, by the fall of the current accounts in foreign currency of the entities in the BCRA by US$2,517 million, by the BCRA’s net sales in the foreign exchange market, by the BCRA’s net payments through the SML and by the fall in the price in US dollars of the assets that make up the reserves for US$723 million.

As a result of the measures recently adopted, a slight contraction in the current account deficit of the international balance of payments is expected from the third quarter onwards. For the last quarter of the year, exports are expected to be boosted by the entry of fine harvest products (mainly wheat), although they will continue to be conditioned by the effects of the drought on the coarse harvest and by the uncertainty associated with the electoral context.

4.1. In the second quarter of 2023, the economy deepened the current account deficit

In the second quarter of 2023 (latest official data available) the Argentine economy recorded a current account deficit of US$6,351 million – equivalent to 4.4% of GDP in seasonally adjusted and annualized terms. This result occurred in the context of a fall in exports compared to the previous quarter and higher imports. In addition to the seasonally adjusted deficit from the exchange of goods (1.3% of annualized GDP), there are deficits caused by international tourism (0.7% of annualized GDP) and the rest of the current account items (2.4% of annualized GDP). With partial data for the third quarter, there was an improvement in the trade balance of goods, although a deficit result (0.2% of annualized GDP) is maintained.

This performance implied the year-on-year reversal of the trade balance of goods and services in the second quarter of the year of US$5,011 million, which was mainly due to a sharp fall in the values exported of goods by about US$7,400 million, partially offset by an approximate contraction of US$2,400 million in imports25.

On the other hand, rents continued to reflect the increase in international interest rates, while a high level of earnings from foreign direct investment would have been maintained. Thus, it is estimated that the seasonally adjusted current account would have yielded a new negative result in the third quarter of 2023 (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 | Seasonally adjusted current account. Annualized

* Includes accounts: primary income services and secondary income.

** II-23: Data as of August 2023.

Includes travel and ticket accounts.

Source: BCRA based on INDEC data.

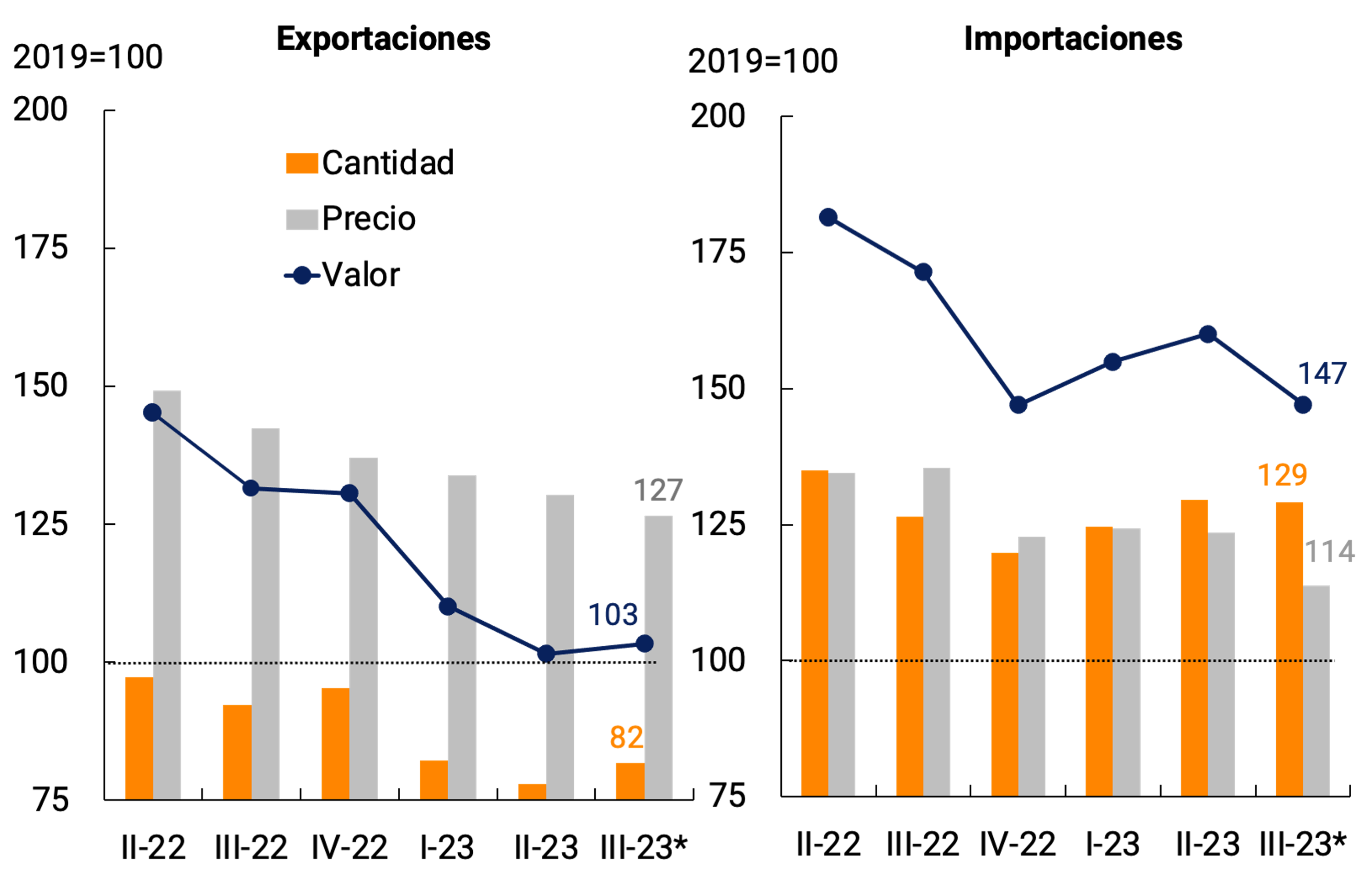

Between April and June 2023, the exported values of seasonally adjusted goods reached US$16,534 million (Free on Board (FOB)) at current prices, which represented a drop of 7.8% compared to the level recorded in the first quarter of 2023. This drop occurred as a result of a generalized decrease in quantities, which was enhanced by a slight fall in prices. In the July-August 2023 two-month period, exported values interrupted their downward trend mainly as a result of an increase in quantities sold, despite a further fall in export prices (see Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2 | Trade in goods. Seasonally

* Data up to August 2023.

Source: BCRA based on INDEC data.

On the other hand, in the second quarter of 2023, seasonally adjusted imports of goods totaled US$19,659 million (Cost, insurance and freight (CIF)) at current prices, 3.3% higher than the figure for the first quarter of the year. This performance of imported values was mainly explained by an increase in the quantities acquired (+4.0% s.e.). In the July-August two-month period, a fall in the securities acquired was observed as a result of a fall in prices and a stagnation in quantities. The leading indicators for September suggest that the third quarter would close with a pronounced decrease in imported values, in the context of the measures recently implemented by the National Government and the BCRA (generalization of the PAIS tax on imports of goods and services and recalibration of the official exchange rate) and the aforementioned fall in prices.

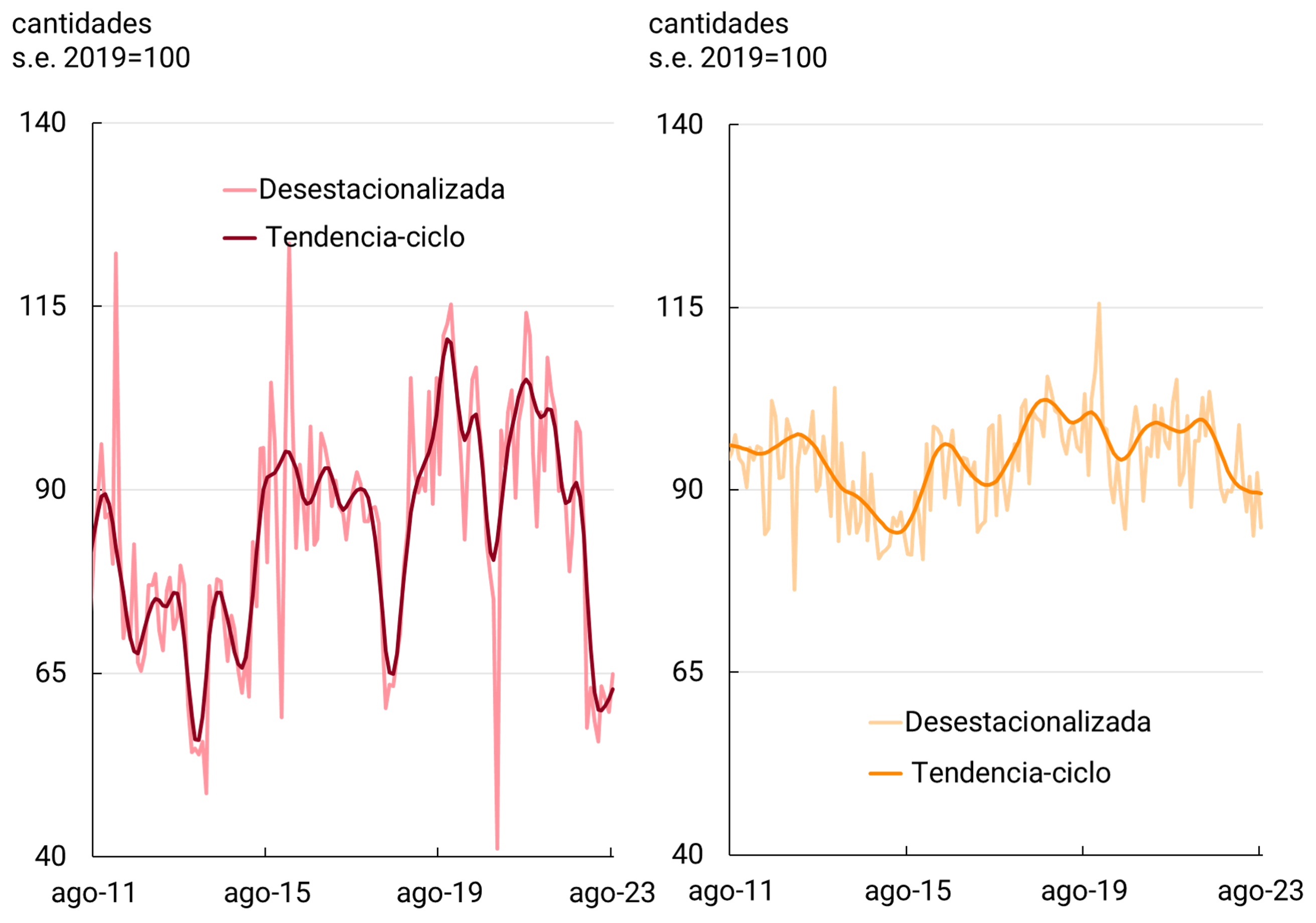

At the disaggregated level, the volumes exported largely replicated the trajectory of the general level. Foreign sales of agricultural crops (in grain and its derivatives —including biodiesel—) hit their bottom in the second quarter of 2023, reaching levels even lower than those observed in the drought episodes of 2018 and the months after the outbreak of the pandemic in 2020). The largest negative contributions in this group of exportable products were those of soybeans and corn. In the second quarter, falls were also observed in the rest of the Manufactures of Agricultural Origin (MOA) and Primary Products (PP) and Manufactures of Industrial Origin (MOI) – excluding biodiesel. In all cases, the decline in exports was widespread. Finally, between April and June, a brief interruption of the upward trend in external fuel sales was also observed.

On the other hand, in the July-August two-month period, the four product groupings contributed to the seasonally adjusted growth of exported volumes. The case of Fuels and Energy stands out, which, driven at the margin by gas shipments, resumed its upward trajectory (+10.4% s.e. compared to II-23) and remains at the highest levels in the last 12 years (see Chart 4.3).

Figure 4.3 | Quantities exported

Source: BCRA based on INDEC data.

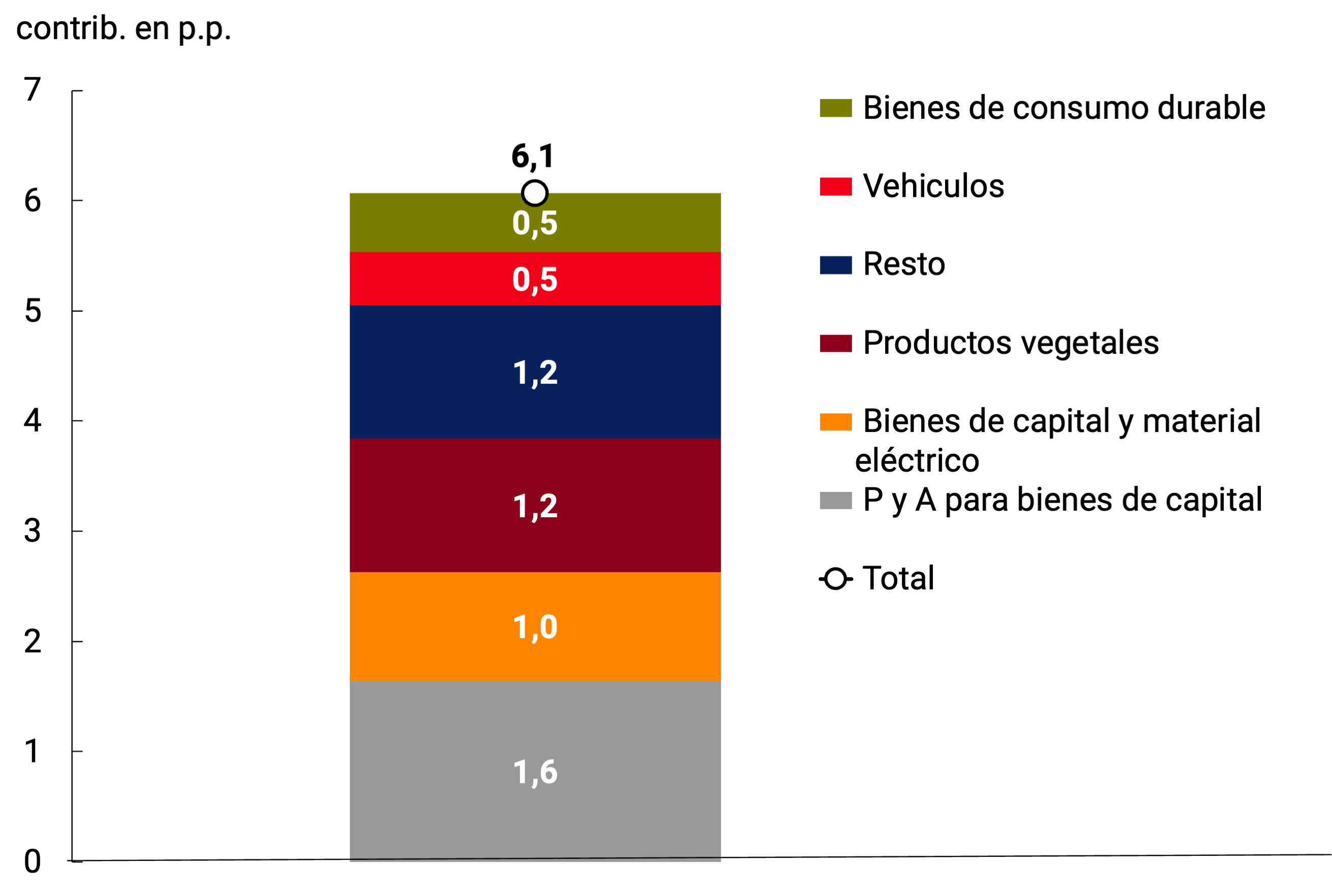

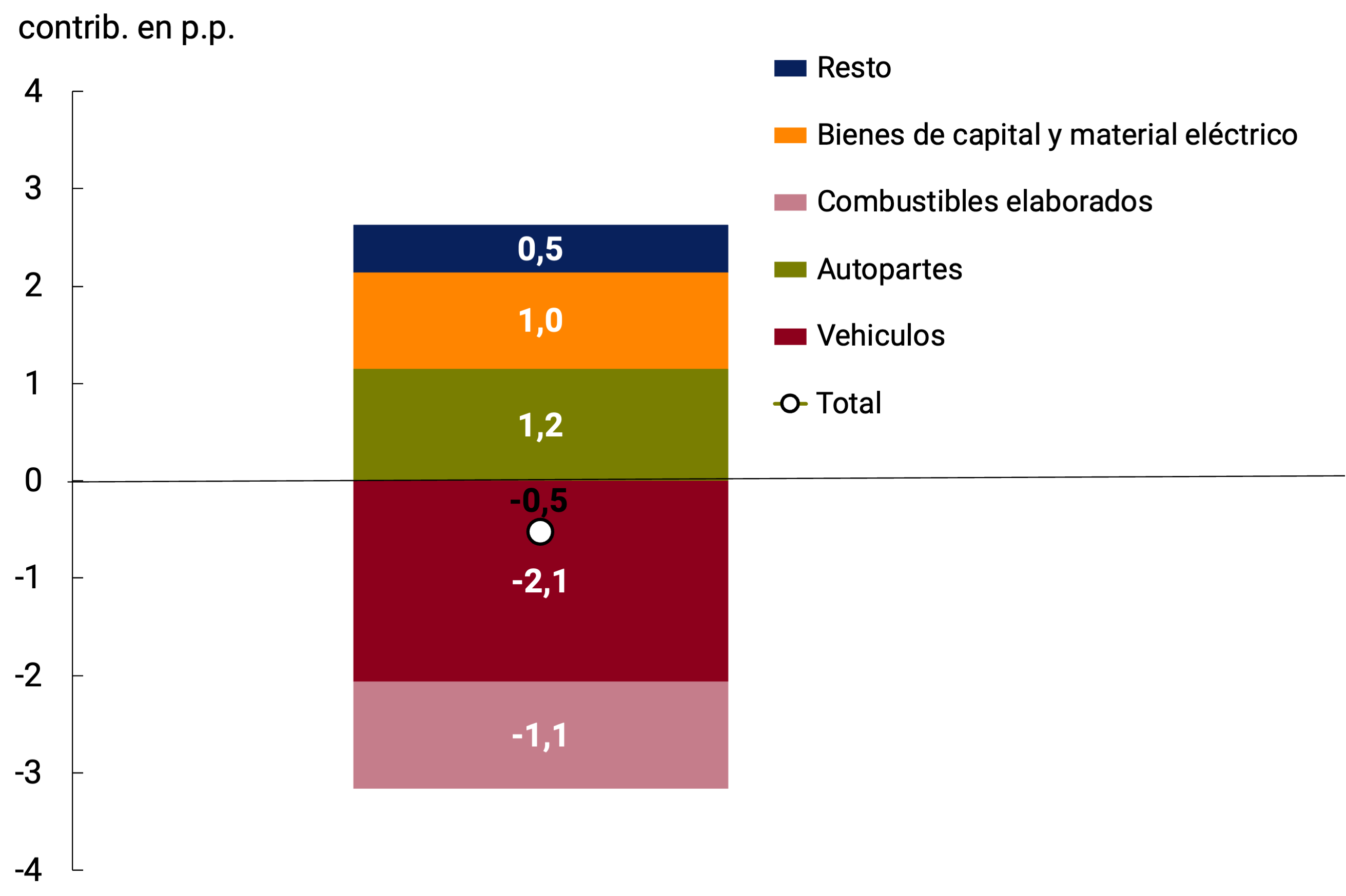

As for imports of goods, in the second quarter of 2023 the growth in quantities was concentrated in a few product categories: vegetable inputs (in the context of low availability of soybeans due to drought), capital goods and their parts, durable consumer goods, and vehicles (see Figure 4.4).

In the July-August two-month period, the quantities of goods imported showed a slight drop (0.5% s.e. compared to the previous quarter), with heterogeneous behaviors between product groups. The fall in purchases of vehicles and processed fuels stood out for its impact, which coincides with the commissioning of the Néstor Kirchner Gas Pipeline, partially offset by the increase in foreign purchases of capital goods and auto parts, accompanying the growth of gross investment (see Chapter 3. Economic Activity).

Figure 4.4 | Imported quantities by category. Seasonally adjusted series (var. % acum. s.e.)

* Data up to Aug-23.

The cumulative change in imports may differ from that obtained in Figure 4.2 because an indirect seasonally adjusted method was used on this occasion.

Source: BCRA based on INDEC data.

Box. Energy Trade Balance 2023

In the first eight months of 2022, a significant deterioration in the energy balance had been observed. This deterioration was mainly explained by the increase in imported energy values. The downspout of the rivers resulted in a lower contribution from hydroelectric sources that was replaced by imports of fuel oil and diesel for the thermal generation of electricity. In addition, Bolivia – our main supplier of natural gas – whose gas fields are in the declining phase, reduced the available supply, forcing Argentina to replace that energy source with greater imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) and liquid fuels such as fuel oil and diesel. In the context of the war between Russia and Ukraine, the largest quantities imported were made at extraordinarily high international energy prices.

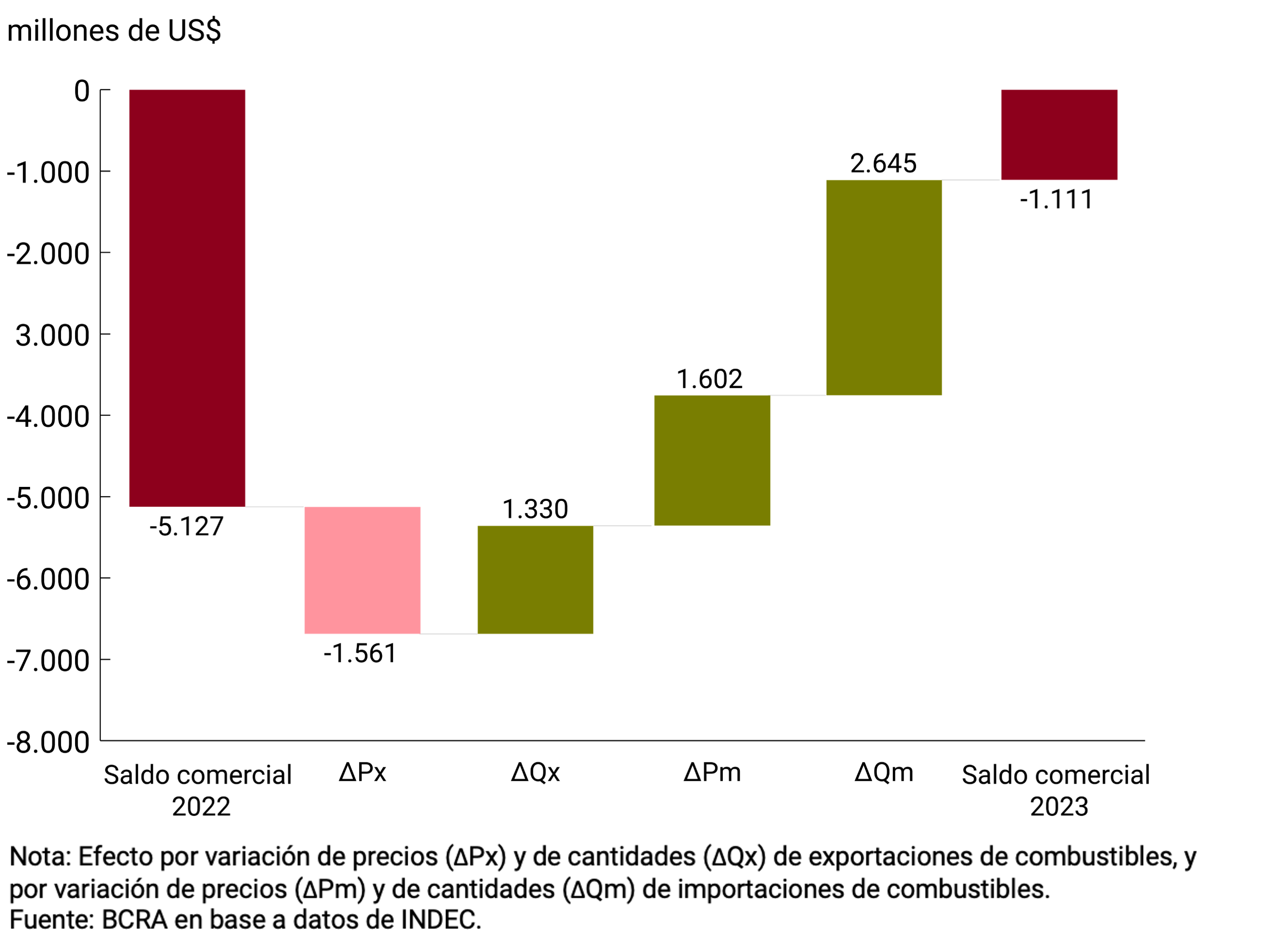

This situation was reversed this year. In the first eight months of 2023, the energy balance improved its result by US$4,016 million compared to the same period in 2022 (see Figure 4.5). Lower import prices meant savings of US$1,602 million, while lower imported quantities of energy accounted for savings of US$2,645 million. In addition, and despite the fact that lower energy export prices meant a deterioration of the energy balance by US$1,561 million, the higher quantities of energy exported added US$1,330 million to the improvement in the balance. In this way, the deficit was reduced from US$5,127 million to US$1,111 million.

Figure 4.5 |Factors of variation in the energy balance

Note: Price change effect (? Px) and quantities (? Qx) of fuel exports, and by price variation (? Pm) and quantities (? Qm) of fuel imports.

Source: BCRA based on INDEC data.

The fall in fuel imports was influenced by a number of factors. The increase in electricity generation by hydroelectric means -due to the increase observed in the flow of water in the main rivers-, renewable and nuclear allowed a reduction in the share of thermal generation. Due to this and other factors, such as lower fuel consumption by the agricultural sector in a context of drought and the increase in local fuel refining, lower quantities of diesel oil (-47.8% YoY) and fuel oil (-51.3% YoY) were observed. Given the fall in prices, the savings in imports of diesel (-57.7% YoY) and fuel oil (-59.9% YoY) was US$2,631 million in the period. Second, the fall in imported quantities of natural gas (-41.1% YoY) and lower unit prices of imports meant lower imported gas values of US$545 million. On the other hand, the higher imported quantities of LNG were more than offset by lower import prices (-27.2% YoY), implying an additional saving of US$794 million.

Accumulated exports in the first 8 months of 2023 also contributed to the improvement of the energy trade balance. The exported volumes of fuels and energy have been on a growth trend of almost 7 years, supported by the exploitation of the unconventional resources of Vaca Muerta. This export take-off in quantities meant that there was no further fall in the values exported as a result of the fall in international prices.

As a result, in the first 8 months of 2023, there was a notable improvement in the cumulative trade balance of the energy balance (see Figure 4.6). Prospectively, the improvement in the energy trade balance is expected to be significantly more noticeable in the second half of 2023. In this sense, the completion of the construction and recent commissioning of the Néstor Kirchner Gas Pipeline as of June will increase the exploitation of the Vaca Muerta gas resource, compensating for the expected lower imports of gas from Bolivia and eventually LNG ships.

Finally, the deterioration in the trade balance of goods so far in 2023 is not exclusively explained by the sharp drop in exported volumes and/or the recovery in imported quantities. The terms of trade also contributed negatively, although this effect was partially diluted in the margin as a result of lower import prices. This situation is different from what happened in other episodes of drought, such as 2009 or 2018, in which the improvement in the relationship of external prices was a buffer for the economy with respect to the harmful effects of losses in the agricultural harvest.

4.2. In the first nine months of 2023, the BCRA’s net sales in the foreign exchange market accumulated US$1,990 million

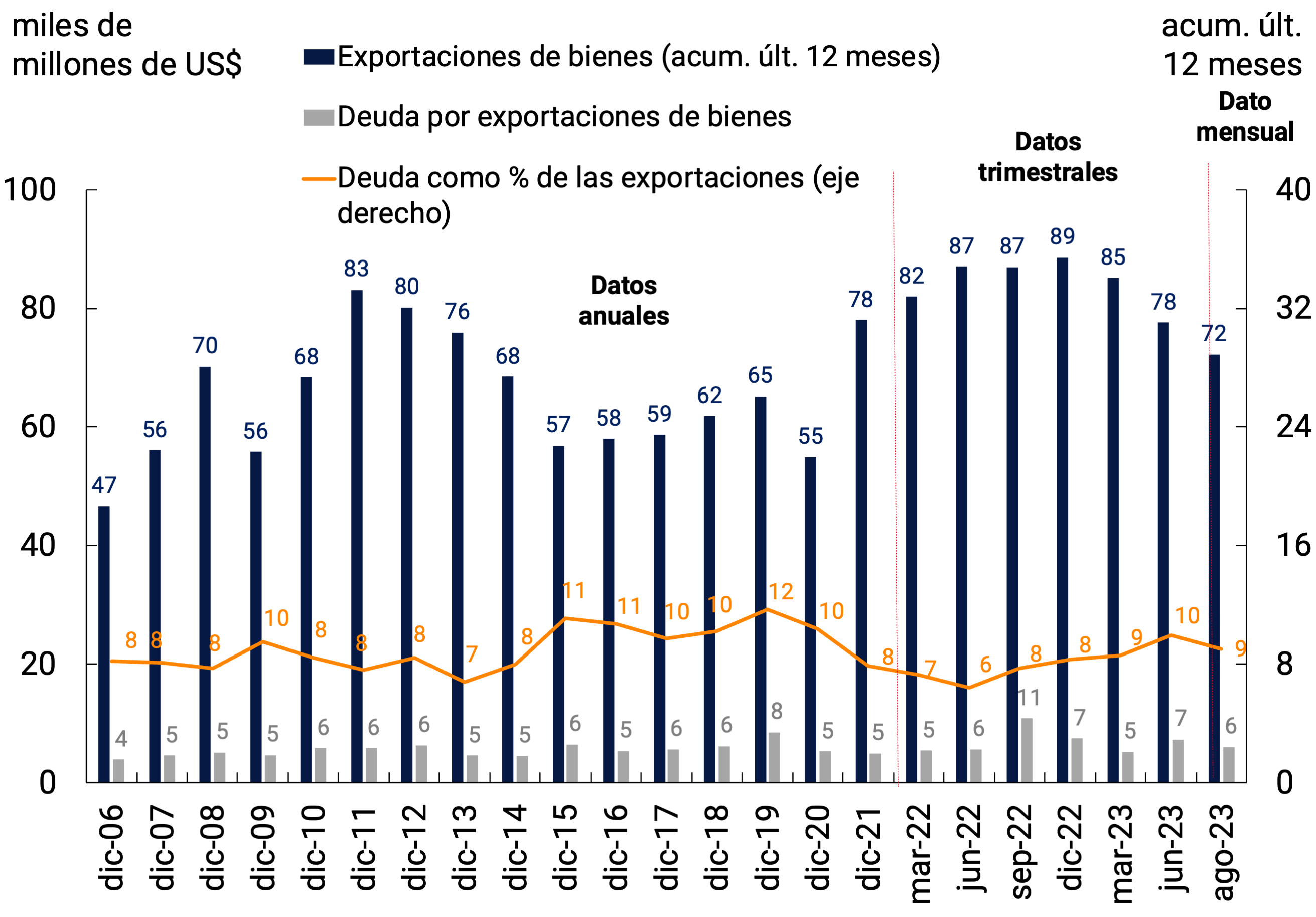

During the first nine months of 2023, exporters recorded revenues from collections of exports of goods of about US$50,400 million. For its part, exports of goods totaled about US$51,000 million, which would imply a reduction in external debt through advances and pre-financing of around US$600 million. Thus, the ratio of this type of indebtedness to exported securities was around 9%, with an increase of 0.7 p.p. compared to December 2022 (see Figure 4.7)26.

Figure 4.7 | Assets. Exports and external debt for exports

Note: II-23 debt subject to revision and debt of Jul-23, Aug-23 and Sep-23 estimated based on accrual data and cash.

Source: BCRA based on INDEC and own data.

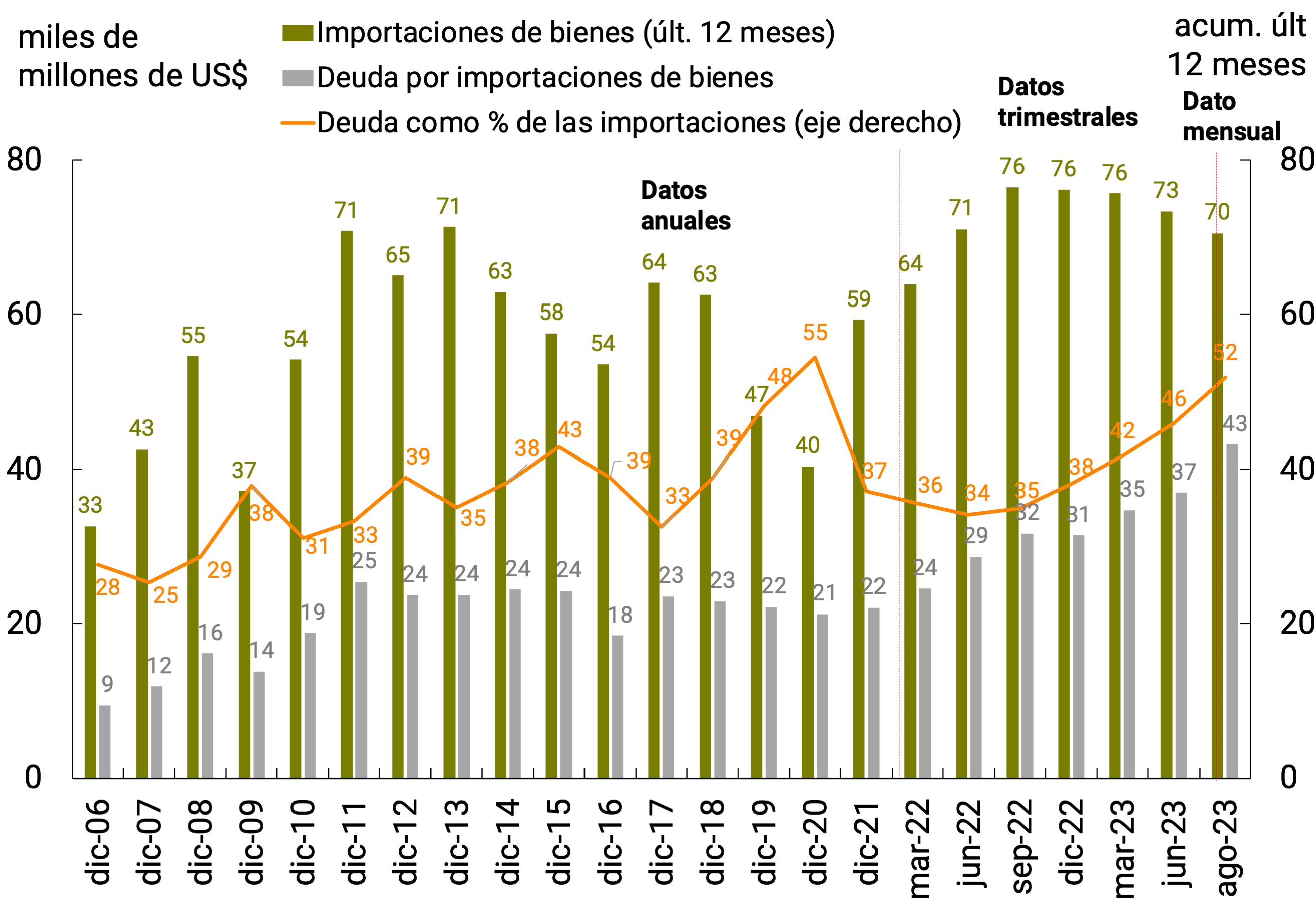

For its part, it is estimated that the debt for imports of goods would have registered an increase of about US$11,800 million27 in the first 9 months of the year. Thus, the ratio of external debt to the level of imports rose by 13.7 p.p., to 51.8% (see Figure 4.8).

This evolution of exports and imports of goods, added to the dynamics of commercial debt for these concepts, resulted in a positive net result for goods in the foreign exchange market of US$6,267 million in the first nine months of 2023.

Note: II-23 debt subject to revision and debt of Jul-23, Aug-23 and Sep-23 estimated based on accrual data and cash.

Source: BCRA based on INDEC and own data.

With regard to financial debt, and as part of the current regulatory framework mentioned above, in September 2020, Communication “A” 7106 established the guidelines under which private sector companies could initiate a process of refinancing their respective external liabilities, which would allow their maturity profile to be adapted to the guidelines required for the normal functioning of the foreign exchange market. This communication, which reached certain capital maturities between 15-Jan-20 and 31-Mar-21, was extended by Communication “A” 7230, covering maturities from then until the end of 2021. Likewise, Communication “A” 7422 extended the term of the maturities until 30-Jun-22 and Communication “A” 7466 did so until 31-Dec-22. In October of last year, Communication “A” 7621 extended the capital maturities until Dec 31, 23.

In this context, from the renegotiations registered from the beginning of the regulation until September 2023, net payments made through the foreign exchange market represented 40% of the original maturities, impacting on lower net purchases of about US$5,350 million.

As for the BCRA’s result in the foreign exchange market, in the first nine months of the year it agreed on net sales of US$1,990 million and transfers through the SML for US$771 million. These sales were explained by purchases by customers and entities for US$2,758 and US$3 million, respectively. The result of customers within this period was explained by the purchases of the sectors “Real excluding Oilseeds and Cereals”, “Individuals”, the own operations of the entities and “Institutional Investors and others”, for US$10,847 million, US$4,660 million, US$431 million and US$699 million, respectively, partially offset by the sales of the “Oilseeds and Cereals” sector and the “General Government” for US$13,548 million and US$330 million. respectively (see Figure 4.9 and Table 4.1).

Figure 4.9 and Table 4.1 | Exchange market. Result

*Data as of 29-Sep-23.

Note: joint cumulative result of the BCRA and the National Treasury in the Foreign Exchange Market.

Source: BCRA.

In particular, the net income of the “Oilseeds and Cereals” sector through the foreign exchange market was impacted both by lower export collections and by higher payments for imports of goods.

Collections for exports of goods from the “Oilseeds and Cereals” sector – the main foreign exchange selling sector in the foreign exchange market – during the first nine months of the year accumulated a total of US$18,490 million, while in the same period of 2022 they had amounted to US$37,512 million, so they received 51% less foreign currency compared to the previous year. This was mainly explained by the severe drought and frost suffered by the crops of the 2022/23 campaign.

Payments for imports of goods were increased by the increase in imports of raw materials by the oil industry, as explained above (see section 4.1). Thus, in the accumulated until September 2023, the sector made import payments for US$4,861 million, while in the same period of 2022 they had been US$3,775 million, showing a year-on-year increase of 29%.

Thus, as a result of lower export charges and higher import payments, net revenues from the “Oilseeds and Cereals” sector fell by approximately 43% compared to the previous year.

In this context, in order to encourage the marketing of soybeans, their derivatives and other exportable products produced by regional economies, the National Government instructed, through Decree 194/202328 of April 10, the reestablishment of the “Export Increase Program” (known as PIE III), where an exchange rate of $300 for every US$1 was provided for income through the foreign exchange market for exports of those products. The validity of the decree was extended until June 2 for soybeans29 and its derivatives and until August 31 for the rest of the products. Subsequently, the program was modified by Decree 378/202330 of July 24, providing an exchange rate of $340 for every US$1 for income through the foreign exchange market for exports of products from regional economies, maintaining the validity until August 31, giving rise to the “PIE IV”. Additionally, through Resolution 216/202331 published on July 24 by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries, new eligible products (among which corn stands out) were included within the group of regional economies32. In turn, on Tuesday, September 5, decree 443/202333 was published, starting the new “Export Increase Program”, in force until the end of September, in which exporters were allowed to settle 75% of the foreign currency from exports at the official exchange rate and that the other 25% be freely available. On October 2, through Decree 492/202334, this program was extended, this time with a duration until the 25th of the same month, but making it explicit that 25% of the income that is not settled in the foreign exchange market must be channeled through purchase and sale operations with negotiable securities acquired with settlement in foreign currency and sold with settlement in local currency.

Within the framework of the third edition of this Program, from April 10 to July 24, US$5,630 million were received, of which US$4,520 million corresponded to export receipts from the “Oilseeds and Cereals” sector (mostly linked to exports of products from the soybean complex; see Figure 4.10) and US$1,110 million associated with exports of products from regional economies outside the “Oilseeds and Cereals” sector. Likewise, revenues under the validity of PIE IV were US$2,125 million, linked entirely to products from regional economies (mainly associated with external sales of corn by companies within the “Oilseeds and Cereals” sector). On the other hand, income from export collections through the foreign exchange market under PIE V was US$1,027 million. It should be clarified that, due to the characteristics of the last edition of the program, a considerable part of the sector’s export collections did not enter through the foreign exchange market, but did so through the stock market.

Thus, as of September 30, 2023, the BCRA’s international reserves reached a level of US$26,925 million, showing a fall of US$17,673 million throughout the year. This reduction was mainly explained by the net cancellation of principal and interest with international organizations (excluding the IMF) and other financial debt of the National Treasury for US$5,197, by the net cancellation of principal, interest and charges with the IMF for US$4,020 million, by the fall of the current accounts in foreign currency of the entities in the BCRA by US$2,517 million, by the BCRA’s net sales in the foreign exchange market, by the BCRA’s net payments through the SML and by the fall in the price in US dollars of the assets that make up the reserves for US$723 million.

4.3. Perspectives

Recently, the National Government and the BCRA adopted policy measures that began to contain the growth of imports (in the face of the generalization of the PAIS tax on imports of goods and services and the recalibration of the official exchange rate in mid-August). Leading indicators for September suggest that the third quarter would close with a sharp decline in imported values. In any case, it is expected that the supply of imported products will continue to be prioritized to sustain local production. In this regard, import authorizations were recently approved within the framework of the SIRA (Import System of the Argentine Republic) for more than 7,400 SMEs for an amount of US$700 million for the provision of spare parts, intermediate goods for production and consumption.

In addition, these policies have provided a boost to the export sectors through the new exchange rate values, new lines of credit for pre-financing foreign sales, promotion of agricultural fertilization and the redefinition of the export increase program to include soybeans (during September and October), hydrocarbons and some derivatives (during October). the extension of the program for regional economies (until October) and the announcement of the incorporation of SME exports into this scheme. To boost exports from regional economies with high industrial value, withholdings on certain products (wine, must, rice, tobacco, forestry and citrus peel, among others) were reduced or eliminated. The improvement in the trade balance for the remainder of the year will be supported by the expected evolution of the energy trade balance. Indeed, a significant substitution of fuel imports is expected after the commissioning of the new Néstor Kirchner gas pipeline and a greater boost for oil exports after investments in pipelines.

As a result of the measures recently adopted, a slight contraction in the current account deficit of the international balance of payments is expected from the third quarter onwards. For the last quarter of the year, exports are expected to be boosted by the entry of fine harvest products (mainly wheat), although they will continue to be conditioned by the effects of the drought on the coarse harvest and by the uncertainty associated with the electoral context.

5. Public Finance

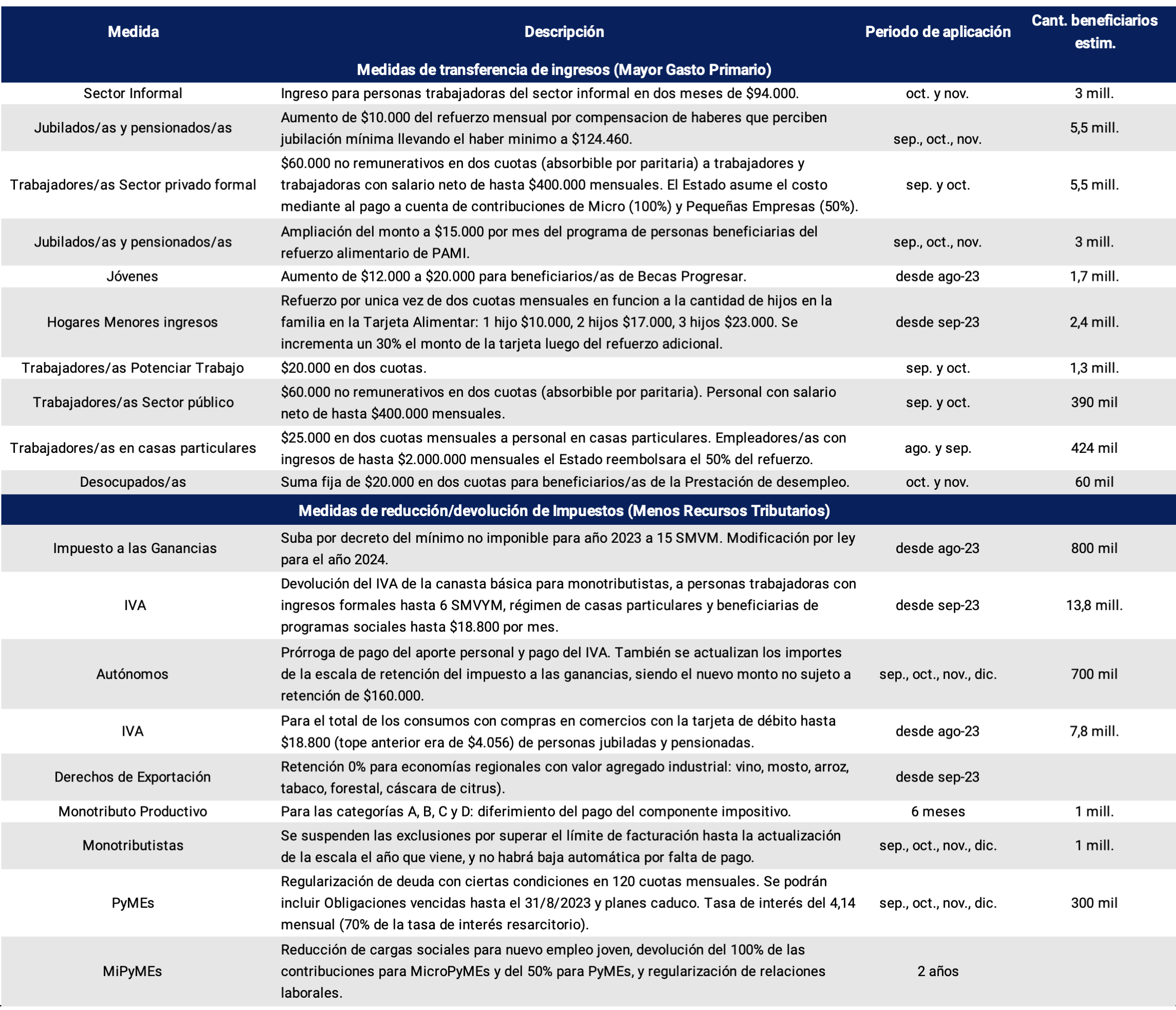

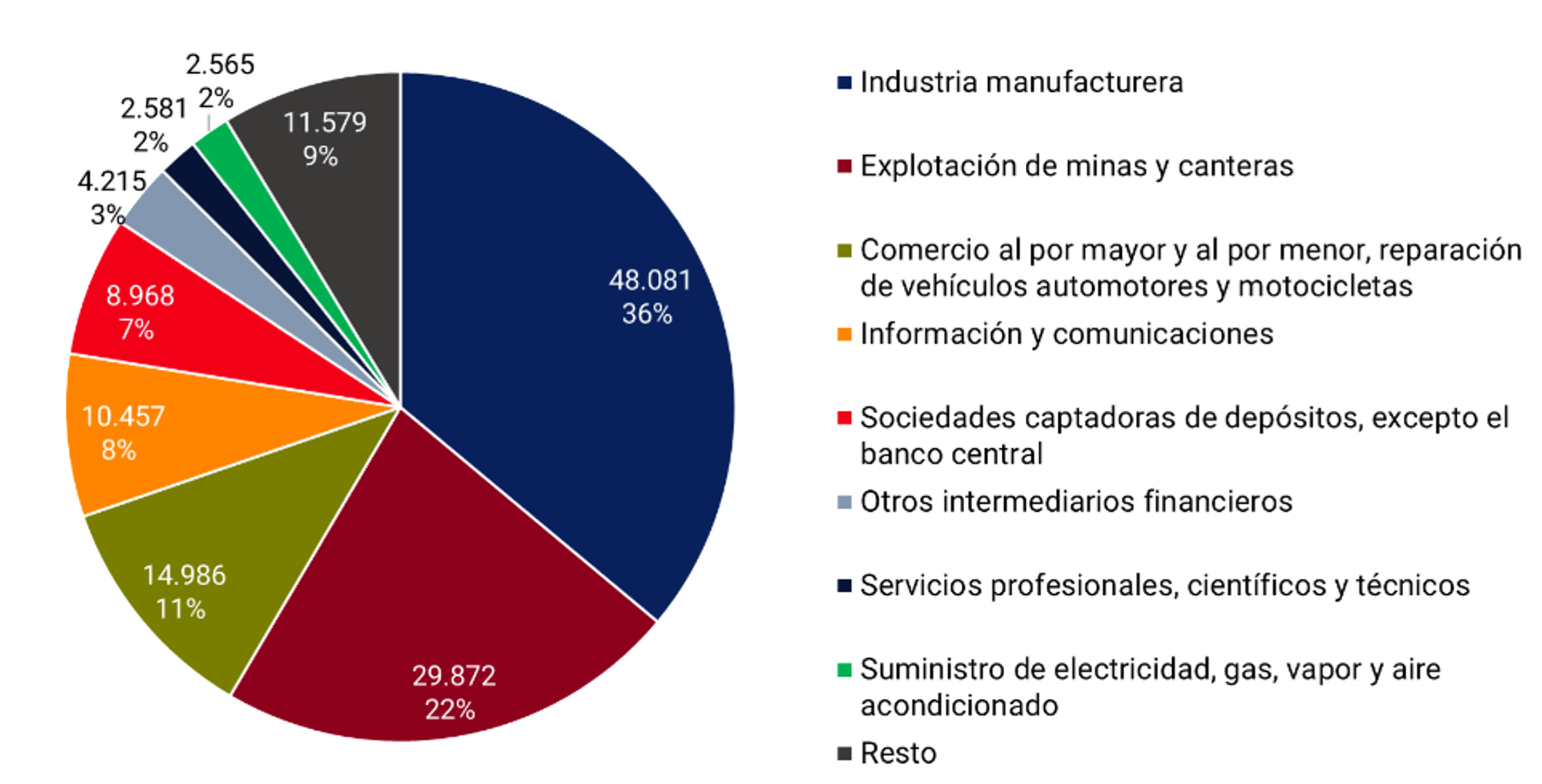

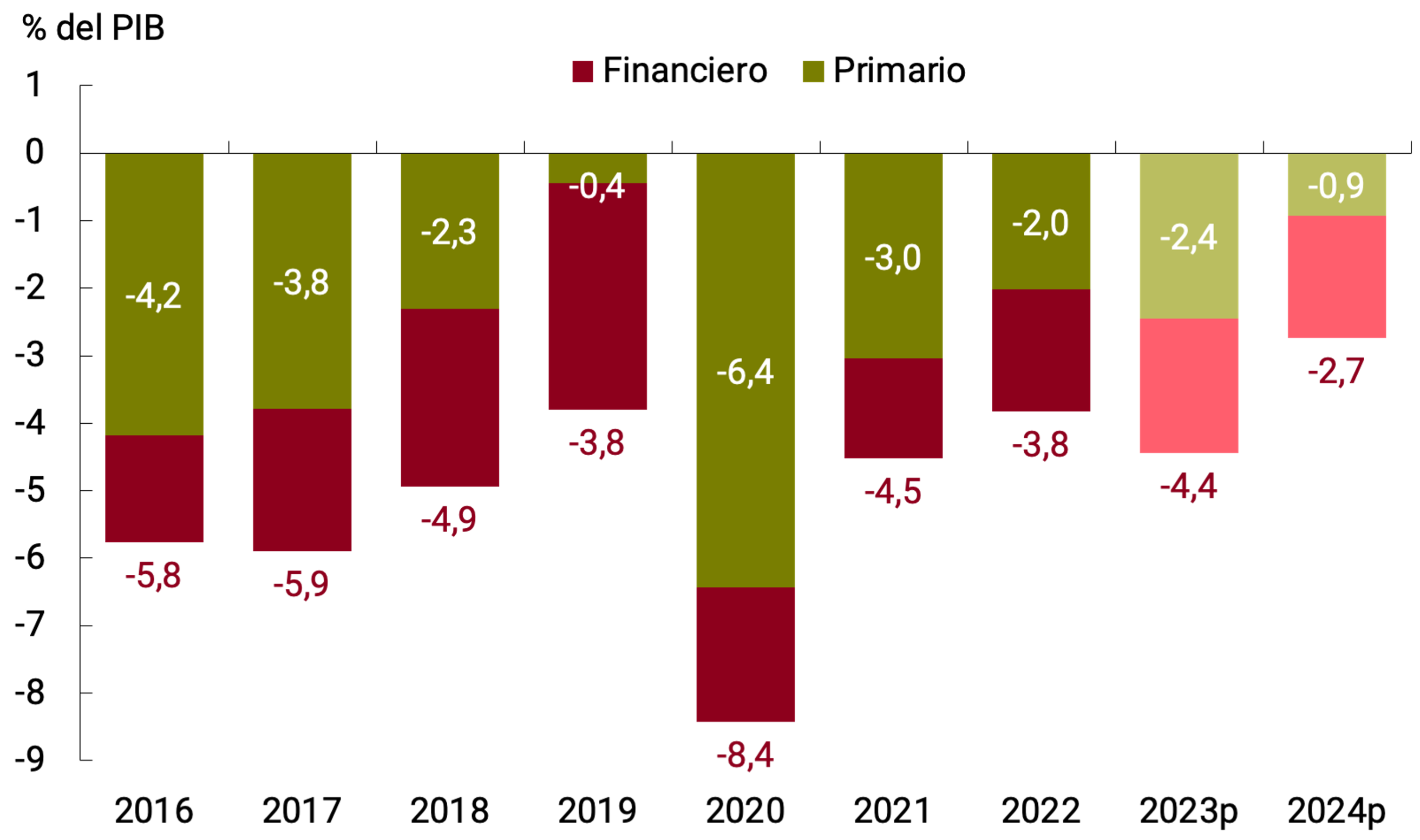

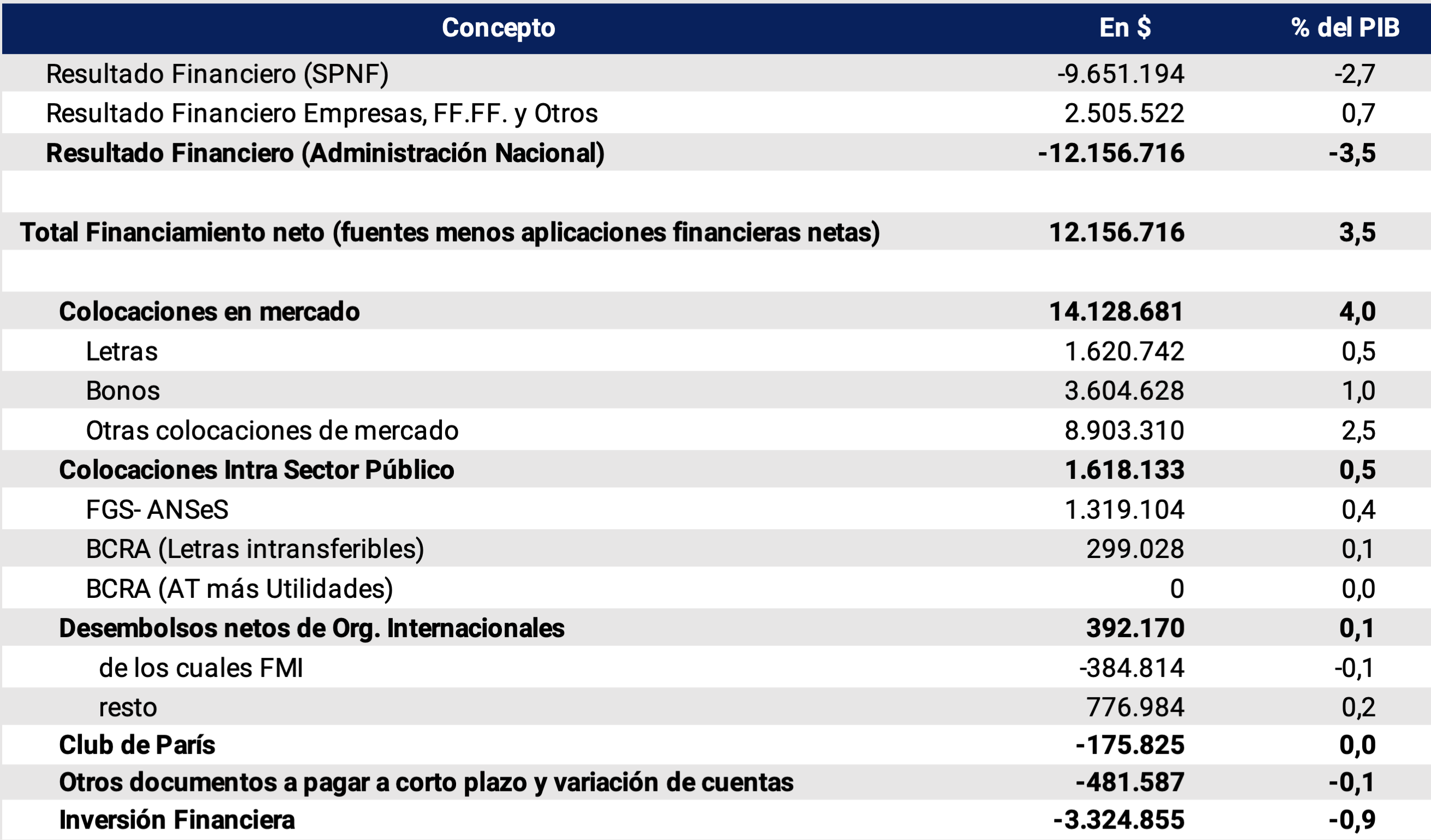

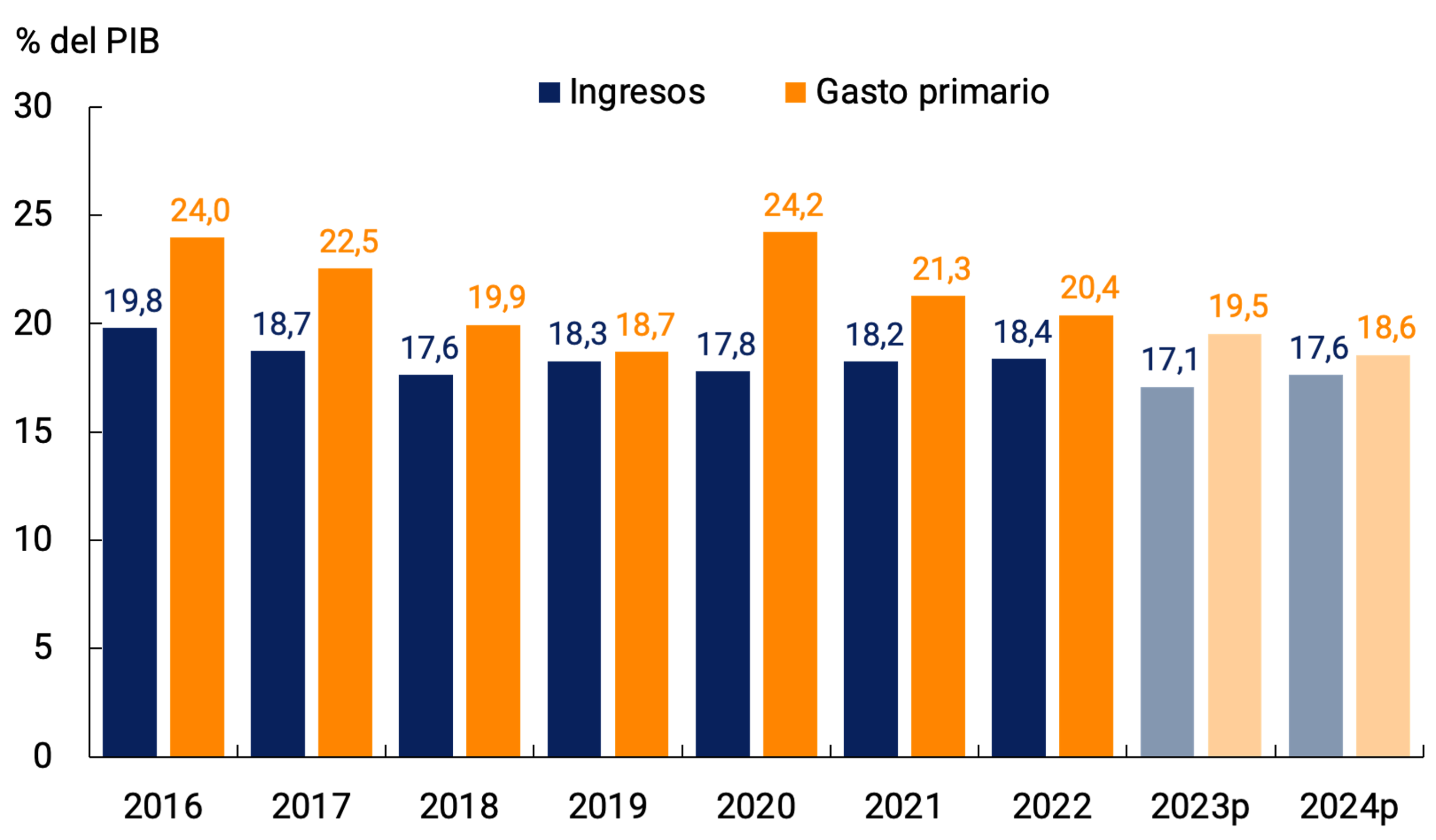

National tax revenues were mainly affected by the impact of the drought on agricultural production in the first three quarters of the year. In a context of normal development of the rest of the taxes, there were lower revenues from Export Duties – associated with the worst agricultural harvest in recent history – for an amount equivalent to about 0.6% of GDP. The National Government took a set of measures to strengthen public revenues: after modifying the system of withholdings on imports in the Value Added Tax (VAT) in April, since the end of July it imposed a generalized tax on imports of goods and services (PAIS tax) and in the last days of September the extraordinary payment of an advance of the income tax to banks was arranged. financial companies and insurance companies. Likewise, in mid-August, the direct impact of the higher official exchange rate on taxes associated with international trade was added.

Primary cash expenditure of the National Non-Financial Public Sector (NFPS) continued to decline in real terms, but the fall was less than the decrease in resources in the period and the June targets established in the agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) were not met. In this context, progress was made with the aforementioned reinforcements of tax revenues and new increases were applied in the rates of public services aimed at reducing the amount of economic subsidies.

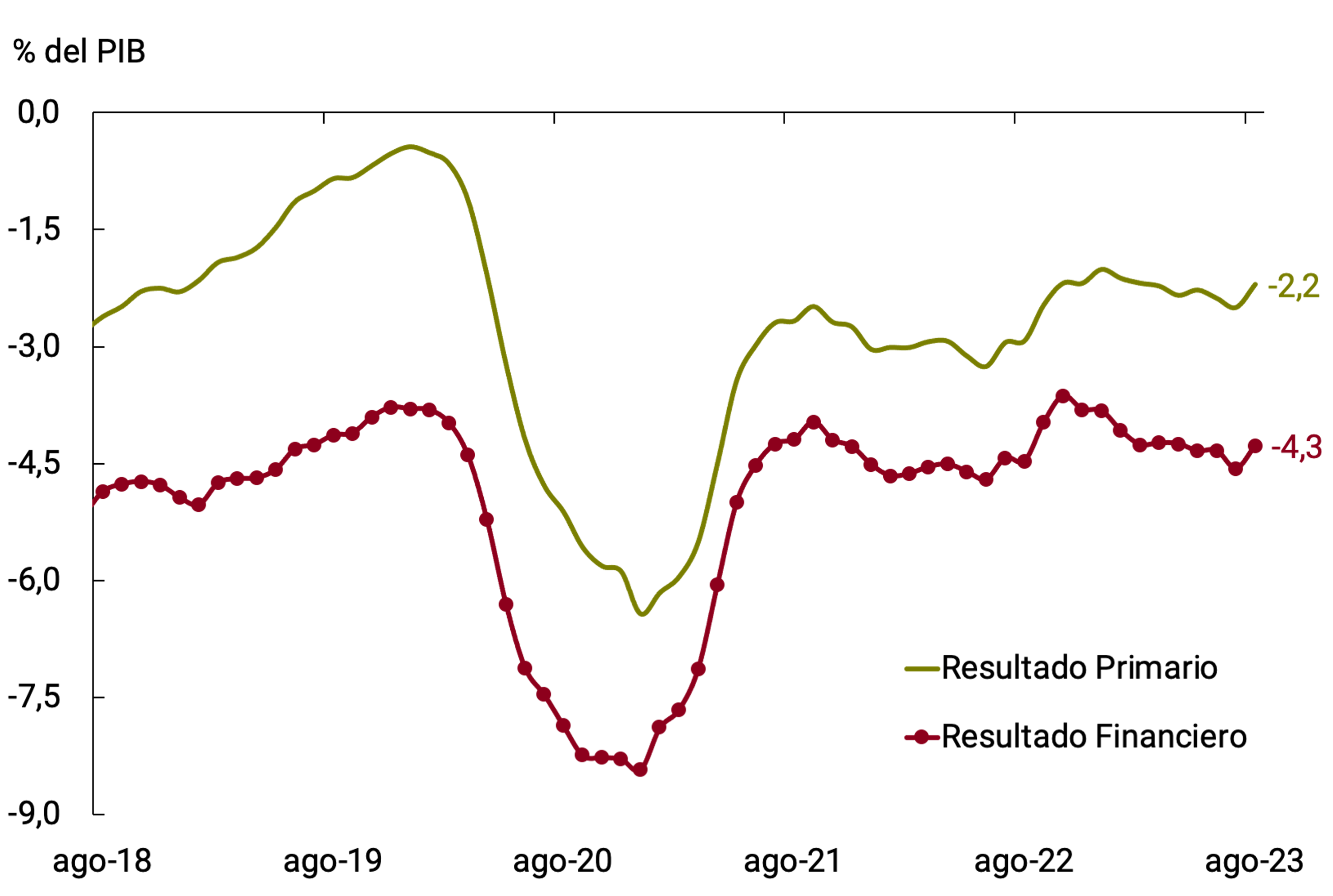

The primary deficit accumulated a balance equivalent to about 1.3% of annual GDP as of August 2023. Going forward, a fiscal impact is expected from the announcement of income reinforcement policies for the population in a situation of greater vulnerability to the transitory increase in inflation. Among the measures announced is the VAT refund scheme on the basic consumption basket for lower-income families and tax relief for formal salaried people, single-payers, self-employed and MSMEs. For the year 2023, both the 2024 National Budget Bill and the fifth and sixth revisions of the IMF’s Extended Facilities Program maintained the NFPS deficit target on a cash basis of 1.9% of GDP for 2023 and 0.9% of GDP for 2024, although it was recently announced that an addendum with modifications to the bill would be sent.

Finally, the greater needs derived from lower tax revenues were covered with net financing that the National Treasury obtained through auctions of instruments in the domestic market. However, during the months of June, July and August, the need to meet timely payments of services to the IMF in the face of the delay in the fifth review of the program with the IMF required extraordinary temporary financial assistance from the BCRA.

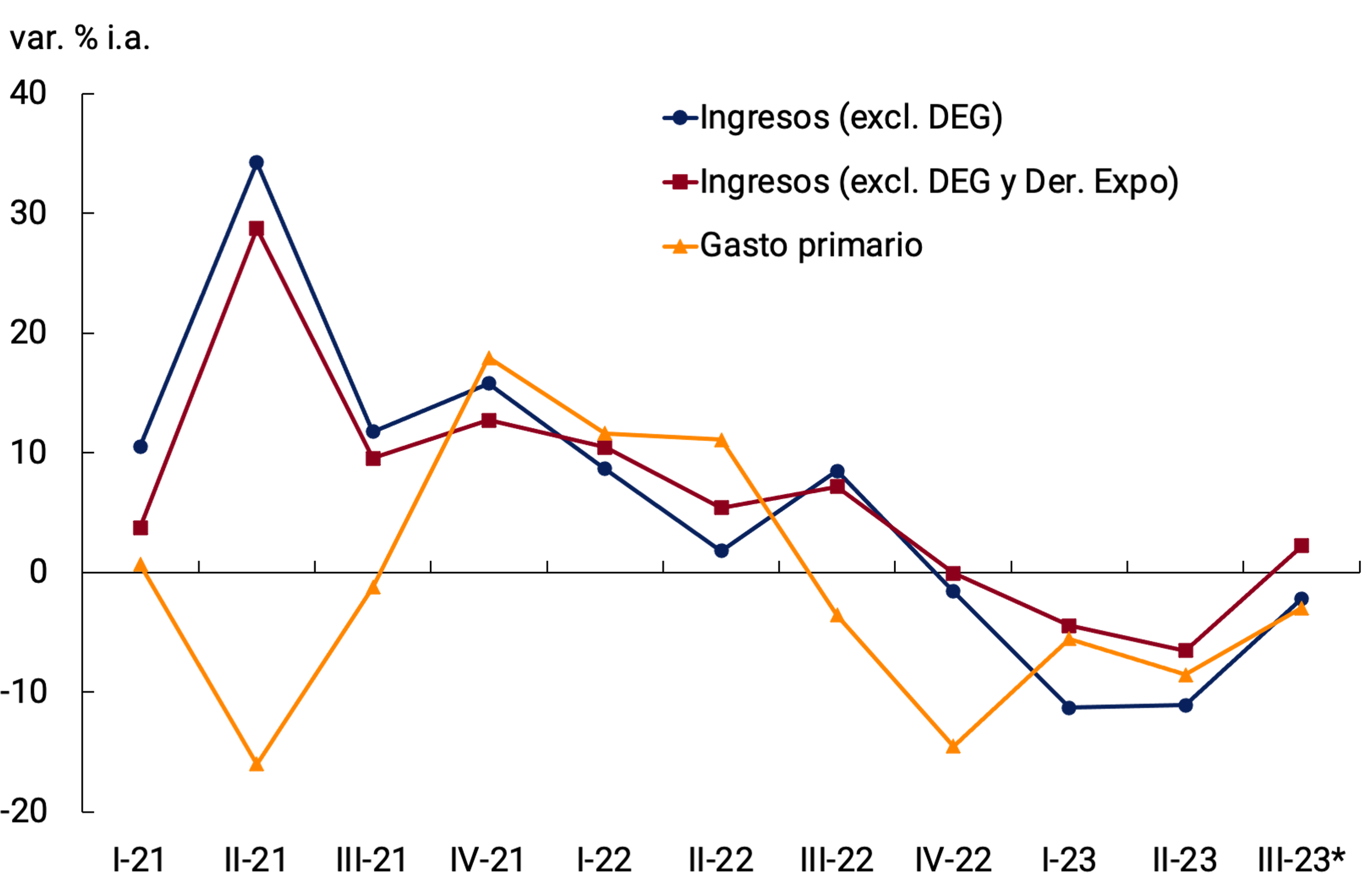

5.1.La total revenue fell year-on-year in real terms in the third quarter at a similar rate to that of the previous two quarters

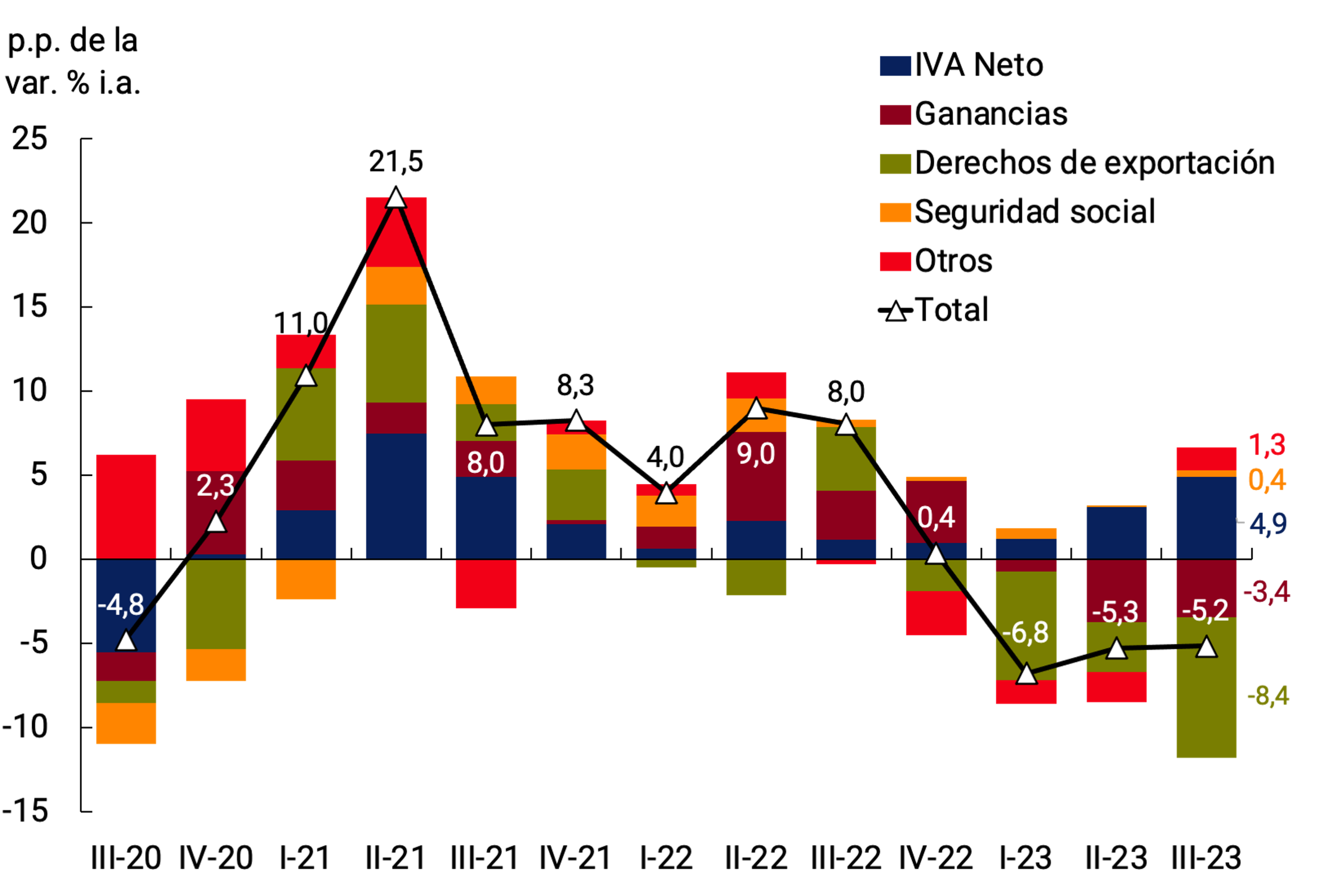

National tax collection increased by 113.0% YoY during the third quarter, which would have meant approximately a real drop of 5.2% YoY, similar to previous quarters (-6.8% YoY and -5.3% YoY in the first and second quarters of the year, respectively; see Figure 5.1). The performance of collection in the third quarter had dissimilar behaviors between taxes.

On the one hand, Export Duties continue to be negatively impacted by the drought, by the advancement of affidavits encouraged by the successive Export Increase Programs (PIE) of 2022 and by early frosts. Export Duties fell by 76.1% YoY in real terms between July and September (-74% YoY and -41.8% YoY in the first and second real quarters), despite the boost in foreign sales due to the fourth Export Increase Program40 aimed at encouraging exports from regional economies, including corn, and the higher nominal exchange rate since mid-August. In September, this right improved its performance due to the implementation of a new PIE41 focused on the soybean complex, but the record collection during September 2022 within the framework of the first PIE has a negative impact on the international comparison.

The Value Added Tax (VAT) maintained the good performance shown throughout the first half of the year, in line with the growth of domestic demand and, in particular, of the real consumption of durable goods (see Chapter 3. Economic Activity and Employment). The effect of tax administration measures (monitoring, payment facility plans) and regulatory changes (changes in the collection regime) continued to weigh positively on this tax42. Net VAT increased by 17.5% YoY in real terms between July and September (+4% YoY, +10.8% YoY in the first and second quarters). In mid-September, theimplementation 43 of the “Buy Without VAT” program was announced, which consists of the refund of 21% VAT for consumption with debit cards of the basic basket for approximately 12 million people with monthly incomes of up to $708,000, while continuing with the refund announced since August to approximately 7.8 million retired and pensioned people; and approximately 2.3 million single-payers are incorporated.

Other taxes linked to the domestic market had a more limited behavior at constant prices, such as the “check” tax and internal taxes (-0.3% y.o.y. and -0.6% y.o.y. in real terms in the third quarter, respectively). Social security resources increased by 1.9% real y.o.y. in the third quarter of 2023 (+0.6% y.o.y. in real terms in the second), basically responding to the improvement in formal employment (see Chapter 3. Economic Activity and Employment).

Figure 5.1 | Contribution to the growth of national tax collection, in constant

Source: BCRA based on data from AFIP and INDEC.

In the third quarter, income tax collection continued to show the impact of the effect of the extraordinary advance payment made by large companies during the last months of last year44, falling by 15.4% YoY in real terms in the period, a magnitude similar to that of the second quarter (-14.7% YoY). Likewise, the updates of the non-taxable minimum and the scale of the tax for individuals and the reduction, as of the second half of August, to 5% of the additional rate of 25% on travel and expenses abroad for certain subjects45. In addition, in mid-September, a modification was implemented by Decree46 that raises, for the second half of the 2023 fiscal period, the Minimum Non-Taxable Amount (MNI) of the Income Tax, up to a monthly sum equivalent —according to the amount in force on October 1, 2023—, to fifteen minimum wages (Minimum Living and Mobile Wage —SMVM—)47. As of this modification, workers in a relationship of dependency and retirees ceased to be covered by the tax, with the only exception of those with remuneration linked to managerial positions or very high incomes or retirements from special regimes. This measure will have an impact on tax collection in the last quarter of the year. On the other hand, the real fall in the tax was cushioned by the increase in the withholding on account of taxes on Income (and on Personal Property) for the consumption of foreign currency for travel and expenses abroad and other taxable operations48. At the end of September, the extraordinary payment of an advance on income tax to banks, financial companies and insurance companies was arranged.

Meanwhile, Import Duties and the Statistical Tax cut the reduction to 1.9% YoY in real terms in the third quarter (vs. -20.7% YoY and -12.4% YoY in the first and second quarters respectively), due, in part, to a higher nominal exchange rate since August. However, the contraction was again basically explained by lower imported values (see Chapter 4. External Sector).

Since the end of July, revenues have grown significantly due to the generalized imposition of the PAIS tax on imports of goods and services. The newrates 49 range from 7.5% to 25%. Thus, the collection of this tax in the months of August and September increased by about 270% compared to the monthly average of the previous50 months.

The evolution of tax revenues implied that the total revenues of the National Non-Financial Public Sector (NFPS) cut the fall in real terms to 2.2% y.o.y. in the third quarter of 2023 (with partial data as of August). The annual comparison was impacted by the decrease in Export Duties already described and lower revenues from non-tax resources, in particular Property Income related to primary emissions51. Net of Export Duties, funds would have shown a real increase of 2.2% YoY in the third quarter.

5.2. Primary expenditure decreased in real terms in the third quarter of the year

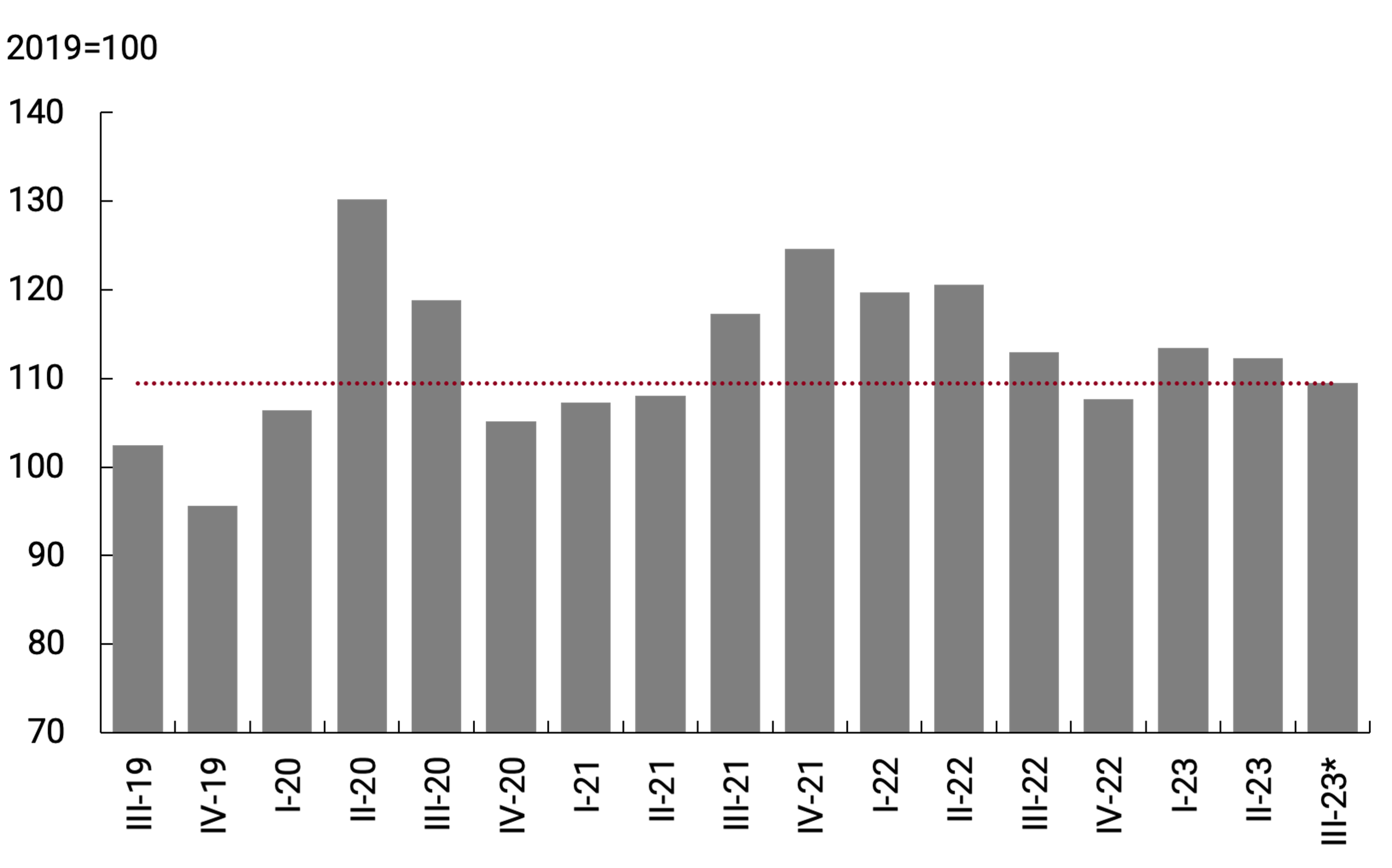

Primary expenditures accumulate 5 quarters (with partial data up to August) of real year-on-year reduction and would have cut the real fall to 3.0% y.o.y. in the third quarter of the year. In real and seasonally adjusted terms, real primary expenditure contracted by 2.5% s.e. compared to the second quarter (see Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2 | Primary expenditures in constant

currencySeasonally

*Data as of Aug-23.

Source: BCRA based on data from the Ministry of Economy and INDEC.

This decrease in spending was made without affecting capital expenditure (+14.1% YoY with data as of August), associated with road infrastructure, housing, transport and energy works, mainly highlighting the construction of the Néstor Kirchner Gas Pipeline, which, in fiscal matters, will reduce the cost of energy from the second half of the year and thus strengthen fiscal consolidation in the medium term.

Expenditure on social benefits increased 0.2% y.o.y. in real terms in the third quarter – with partial data as of August. Within this category, pension benefits fell by 5.8% YoY between July and August as they advanced at the pace imposed by the Retirement Mobility Law, which showed increases of 17.0% in March and 21.0% in June (89.2% YoY as of June). However, retirements and pensions, particularly those of those who receive the lowest benefits (up to two minimum salaries) were increased by the bonuses that were granted on a monthly basis since the end of 2022 to partially offset the inflation observed. Including these compensations, spending on pension benefits would have fallen by 2.5% in real y.o.y. in the third quarter. Among the measures announced in August and September, the amount of this bonus was increased again for the months of September, October and November, thus trying to make those who receive the lower salaries compensate for the increase in the general price level.

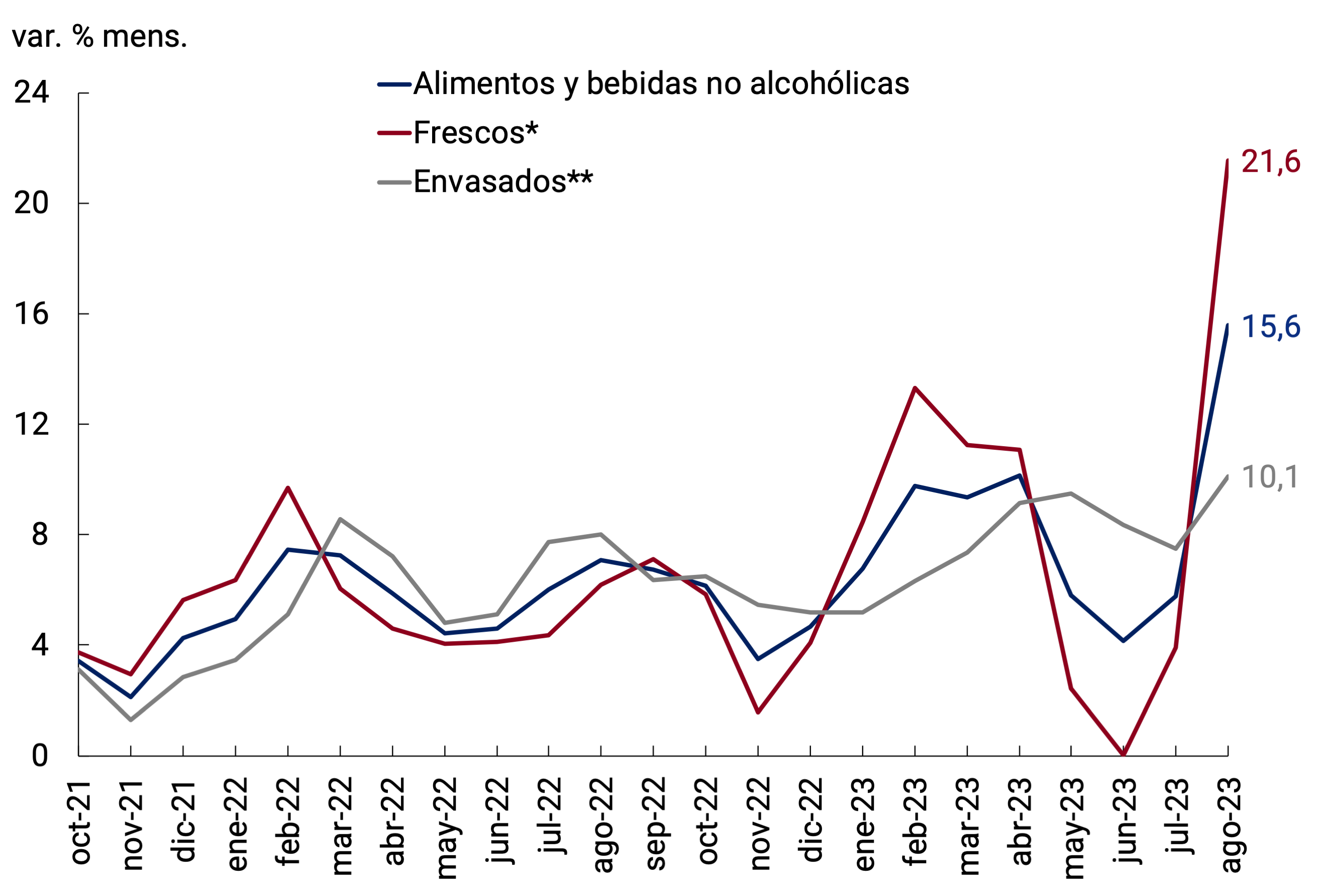

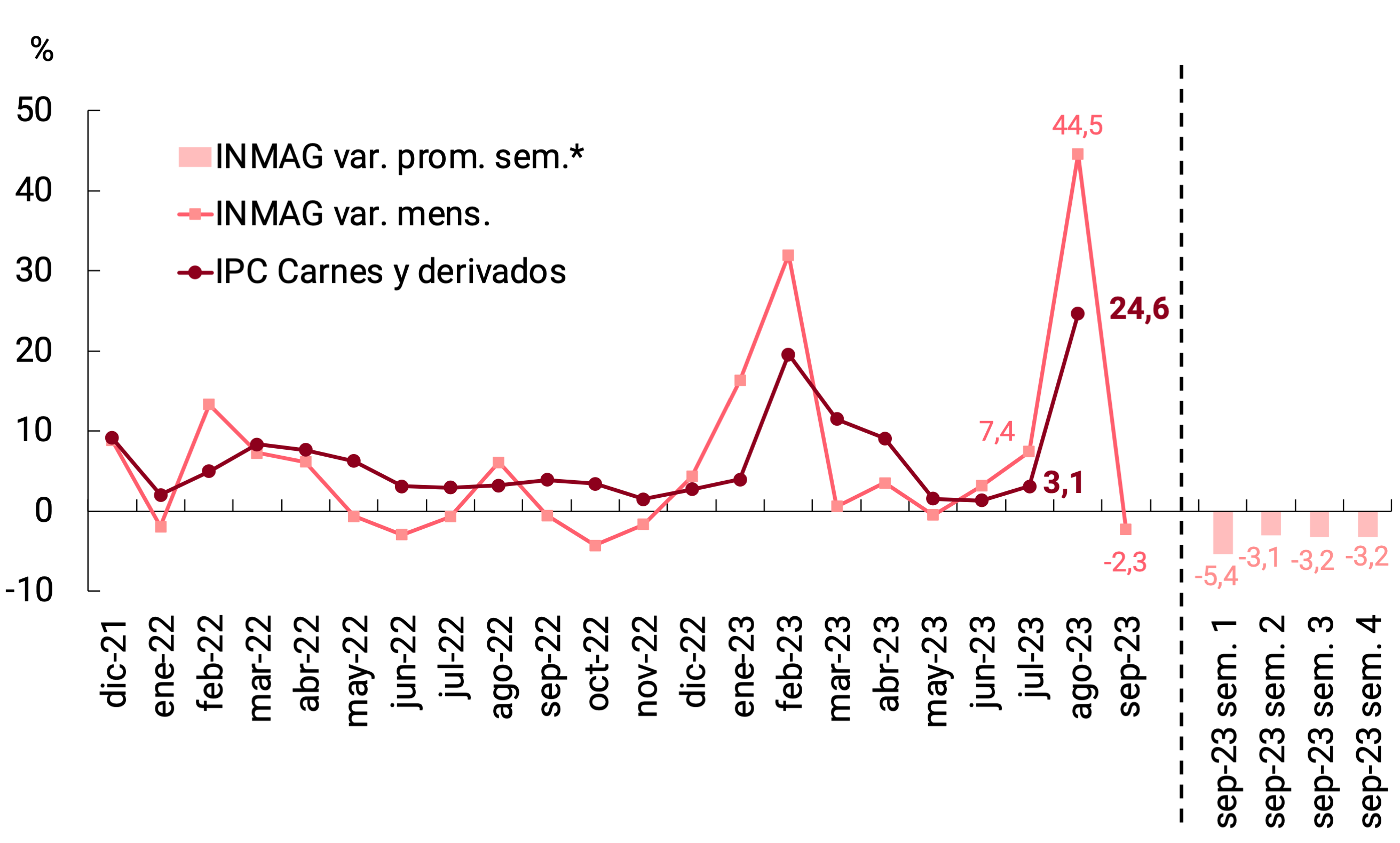

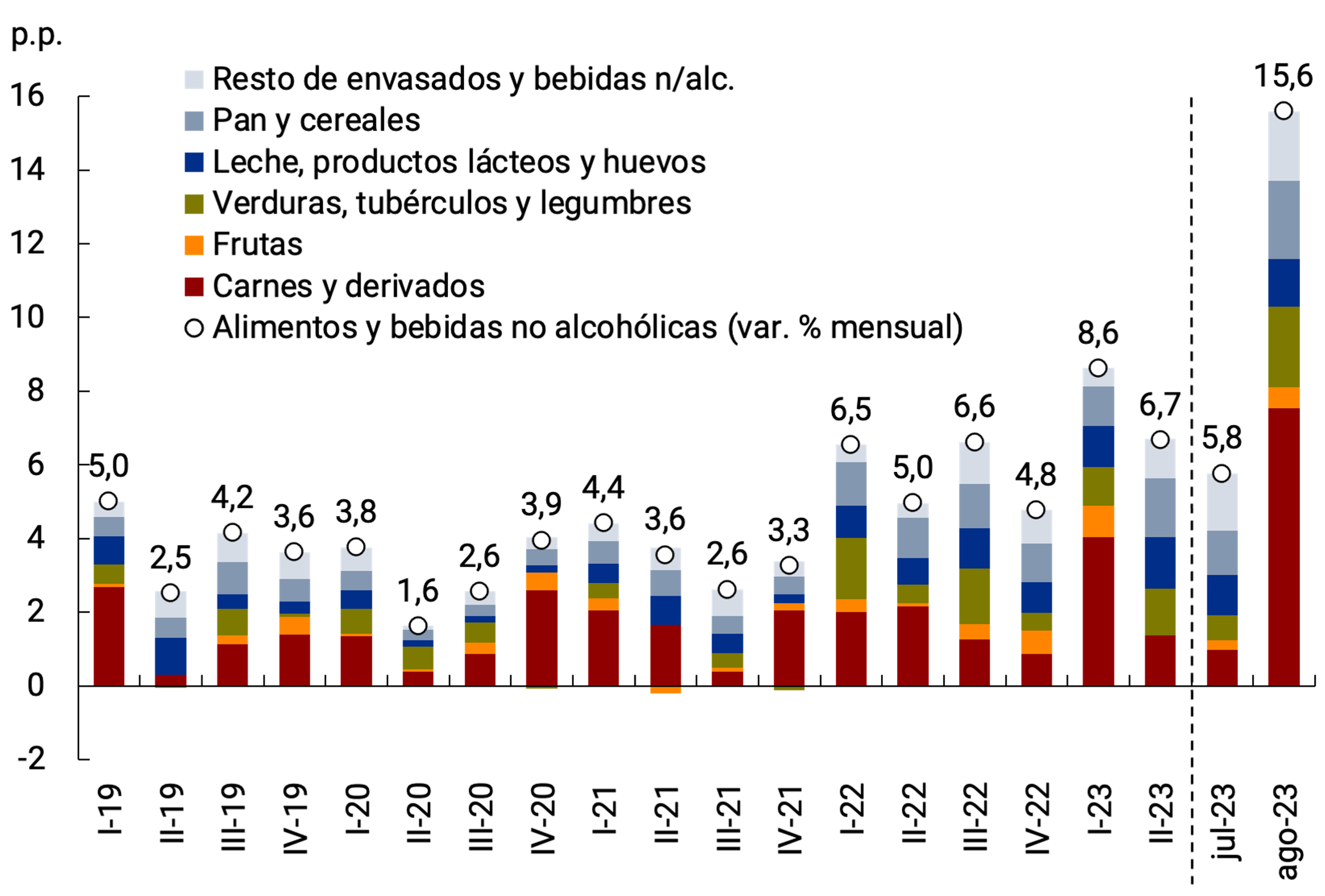

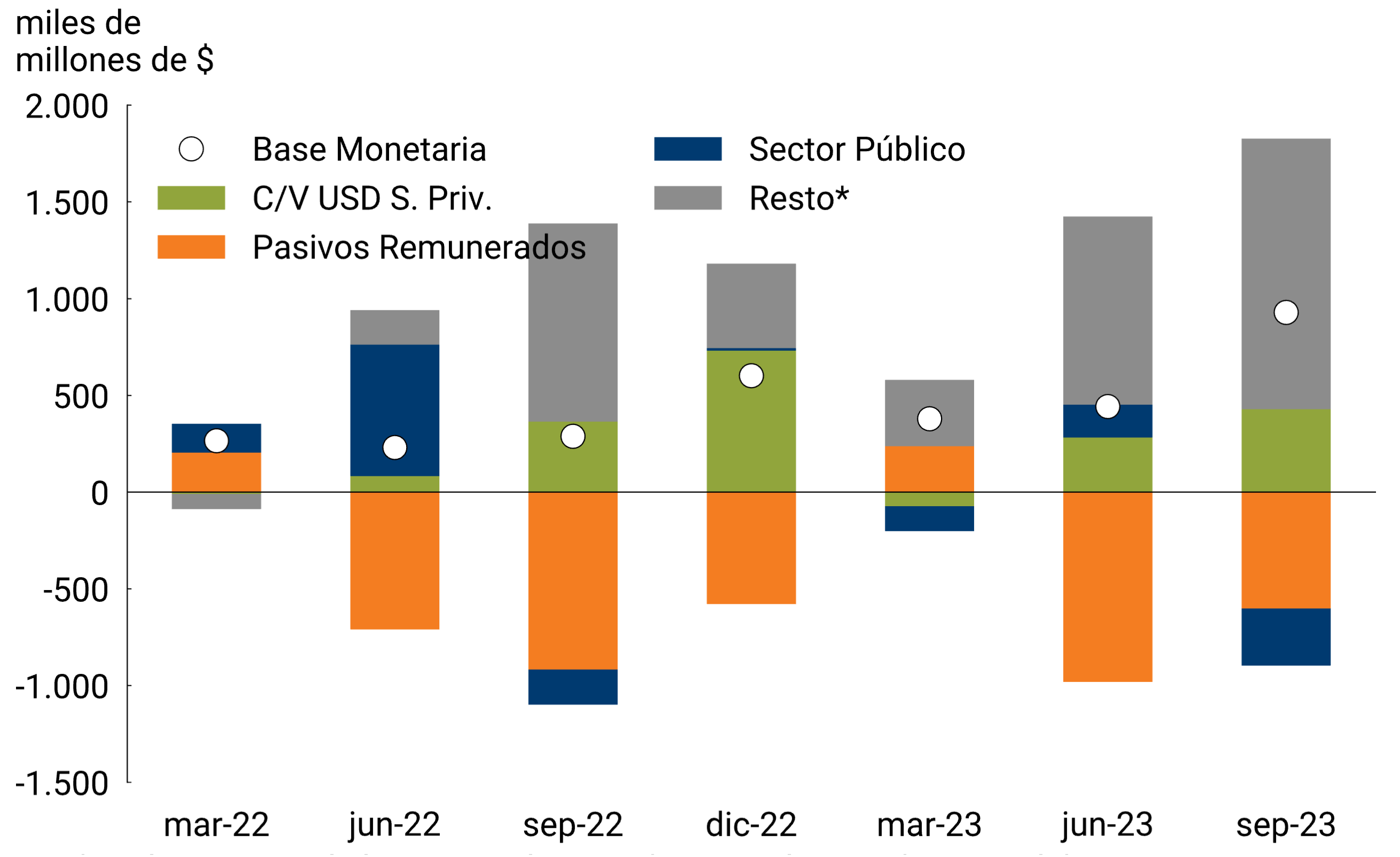

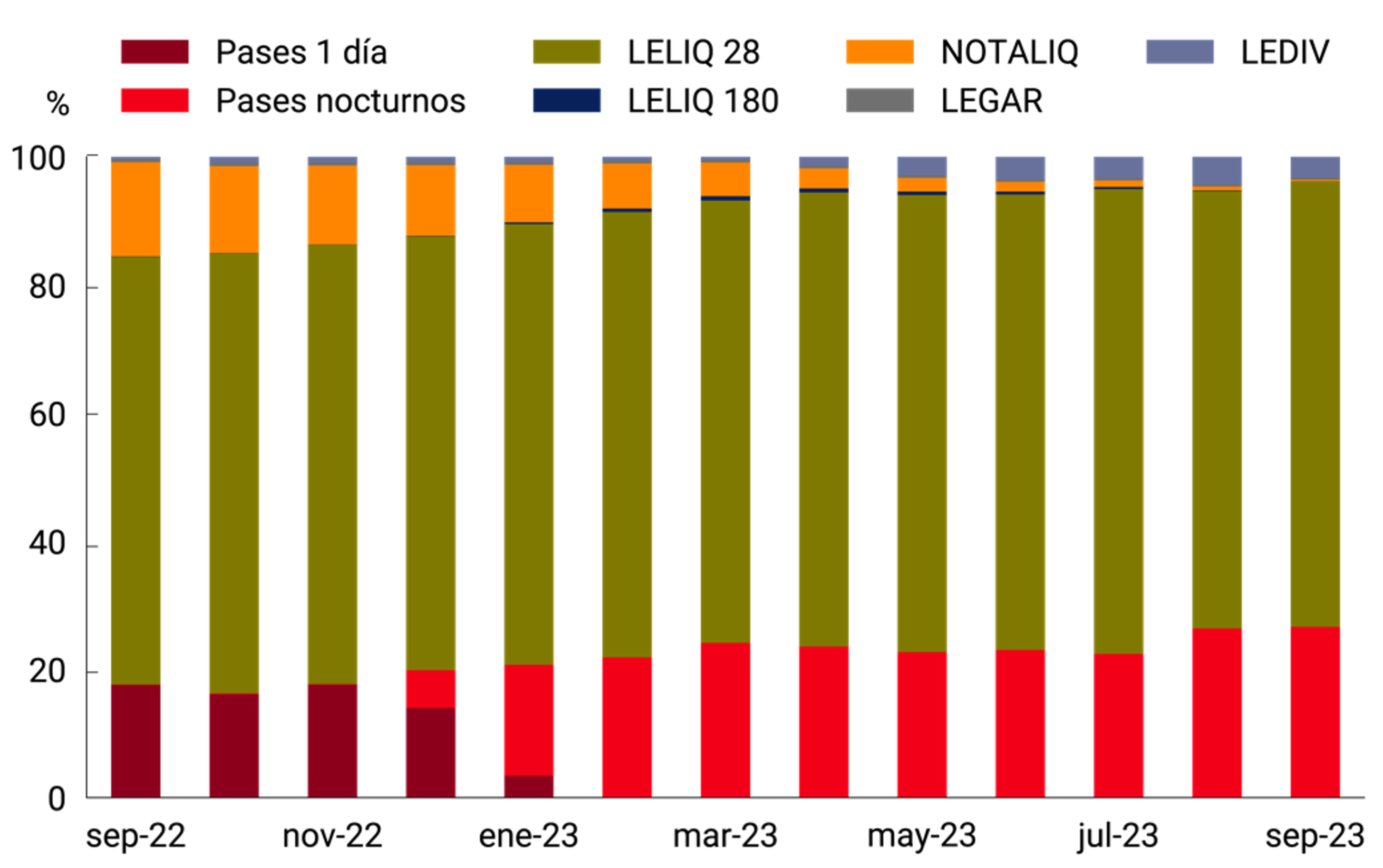

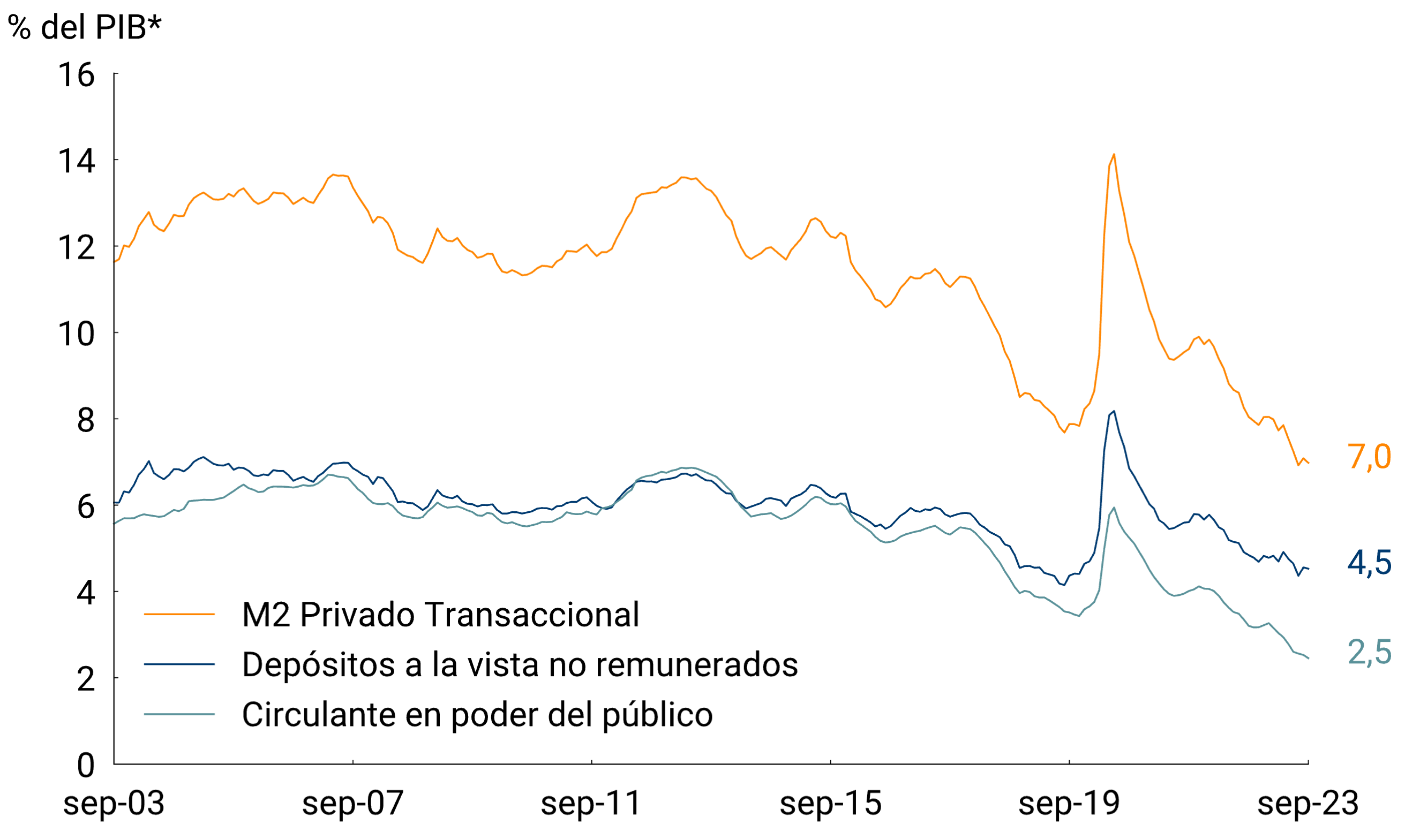

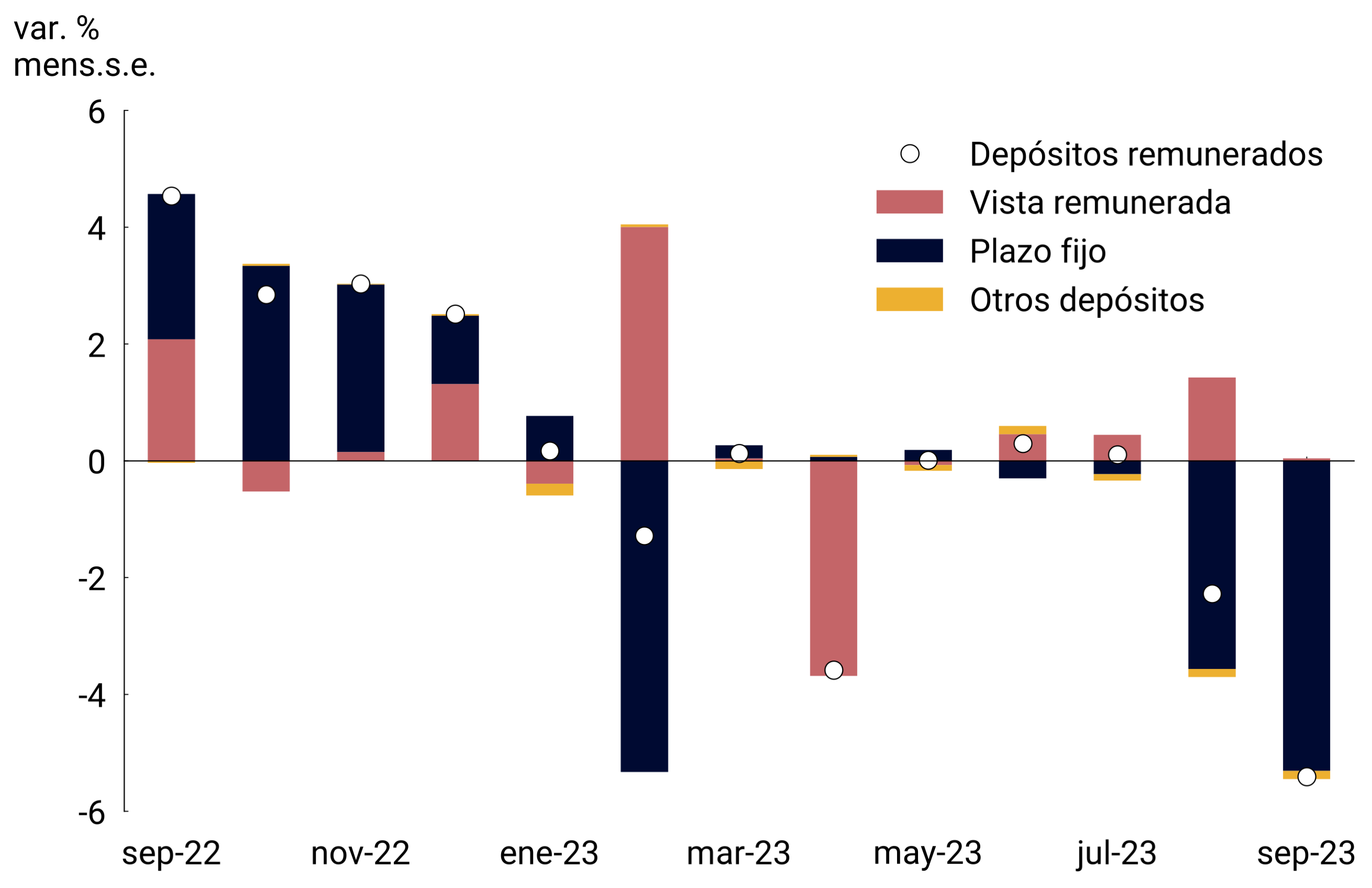

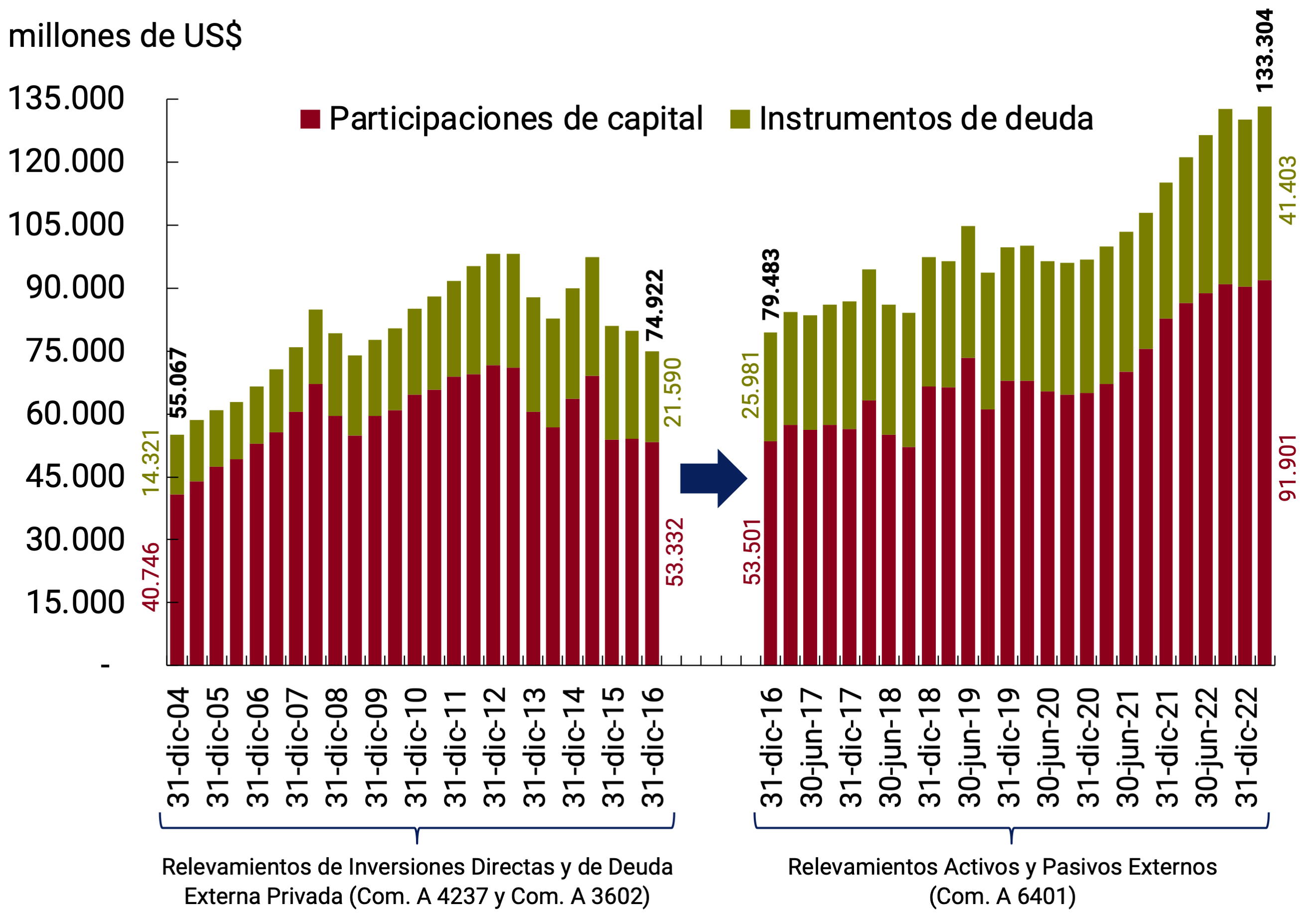

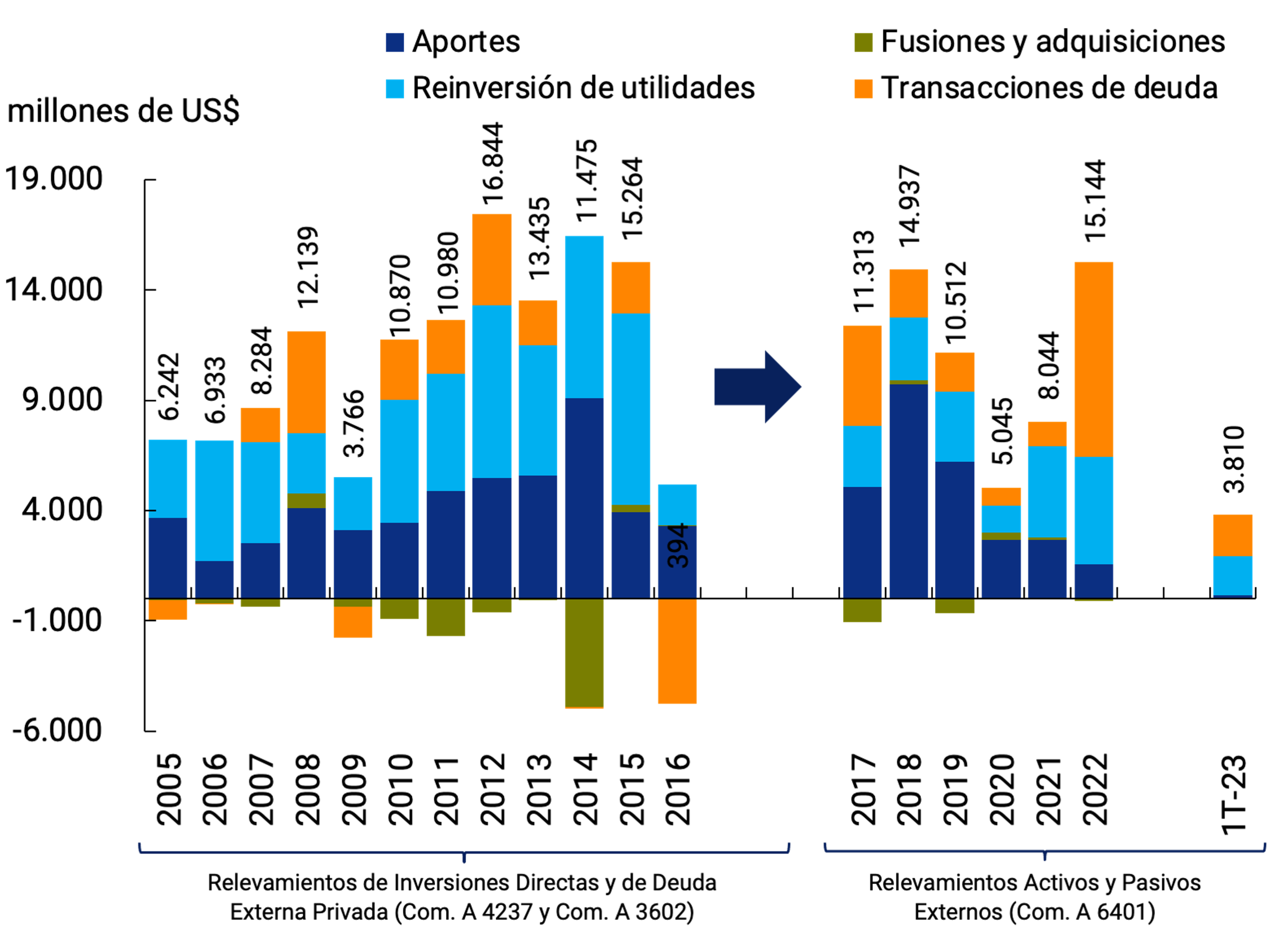

In general terms, the Government took a series of measures aimed at cushioning the effect of the exchange rate movement on the incomes of retired and unemployed people, workers in a relationship of dependence on lower wages, monotributistas and entrepreneurs, among others. In contrast, to compensate, an extraordinary income tax advance was provided to banks, financial companies, and insurance companies (see Table 5.1).