Política Monetaria

Monetary Policy Report (IPOM)

Third quarter

2021

Publication that aims to explain in a transparent manner the reasons of the BCRA for its monetary policy decisions.

Table of Contents

Chapters

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlook

2. International context

3. Economic Activity and Employment

4. External Sector

5. Public Finance

6. Prices

7. Monetary Policy

Sections

1. Towards the definition of a new international

tax scheme 2. The OECD monitors economic

activity on a weekly basis 3. Main features of the labour

market recovery 4. Recent performance of agricultural

exports 5. Solidarity and Extraordinary Contribution to help mitigate the effects of the pandemic

6. The importance of variety in savings instruments

For inquiries, write to politica.monetaria@bcra.gob.ar

Summary

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlook

The global economy continued to navigate the COVID-19 health crisis, with the emergence of a new wave attributed to the Delta variant, which is more contagious and possibly more aggressive than the other strains in circulation. However, the economic recovery continued its course, with marked differences between countries due to inequalities in the pace of vaccination and in the monetary and fiscal space available to continue implementing stimulus measures. In this context, during the second quarter, inflation accelerated globally, driven by the increase in the price of raw materials and the reopening of activities. The potential actions of the central banks of advanced economies in the face of this inflationary outbreak could affect global financial conditions, with negative implications for emerging countries.

In Argentina, economic activity showed signs of recovery in June, after the slowdown observed during April and May due to the arrival of the second wave of COVID-19 infections. In mid-March, the National Government, in coordination with the provincial authorities, adopted measures to contain the outbreak, individually calibrated for each region of the country according to its epidemiological situation. This time the measures had a shorter duration, thanks to the advances in the vaccination process and the improvements made in the health system. To contain the economic and social effects of this second wave, the Central Bank and the National Government focused their stimulus measures on the most vulnerable social strata and on assistance to companies in the affected jurisdictions. Economic normalization is expected to continue in the coming months, although it cannot be ruled out that, as observed in other countries, the circulation of new variants of the virus may delay this process.

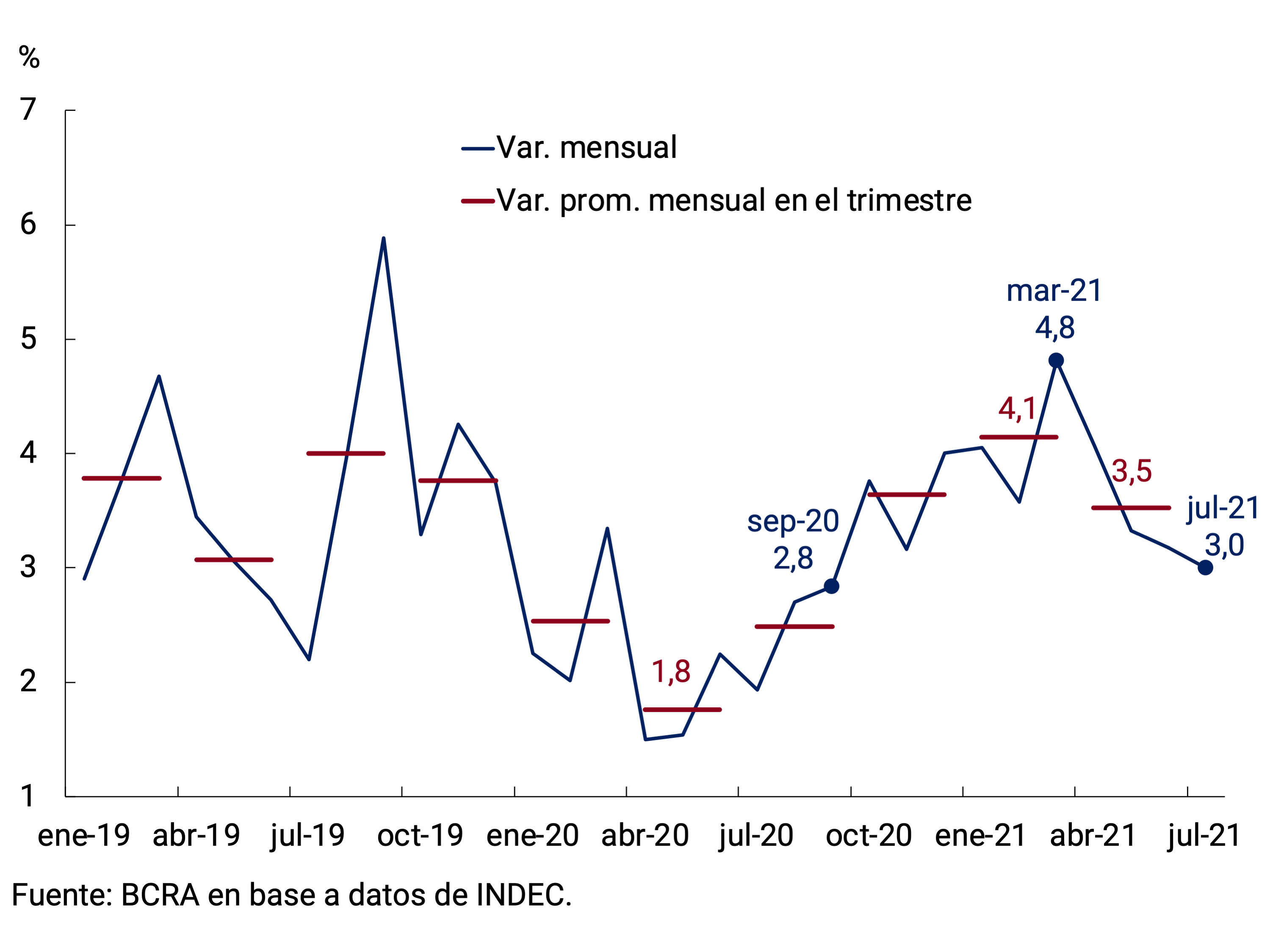

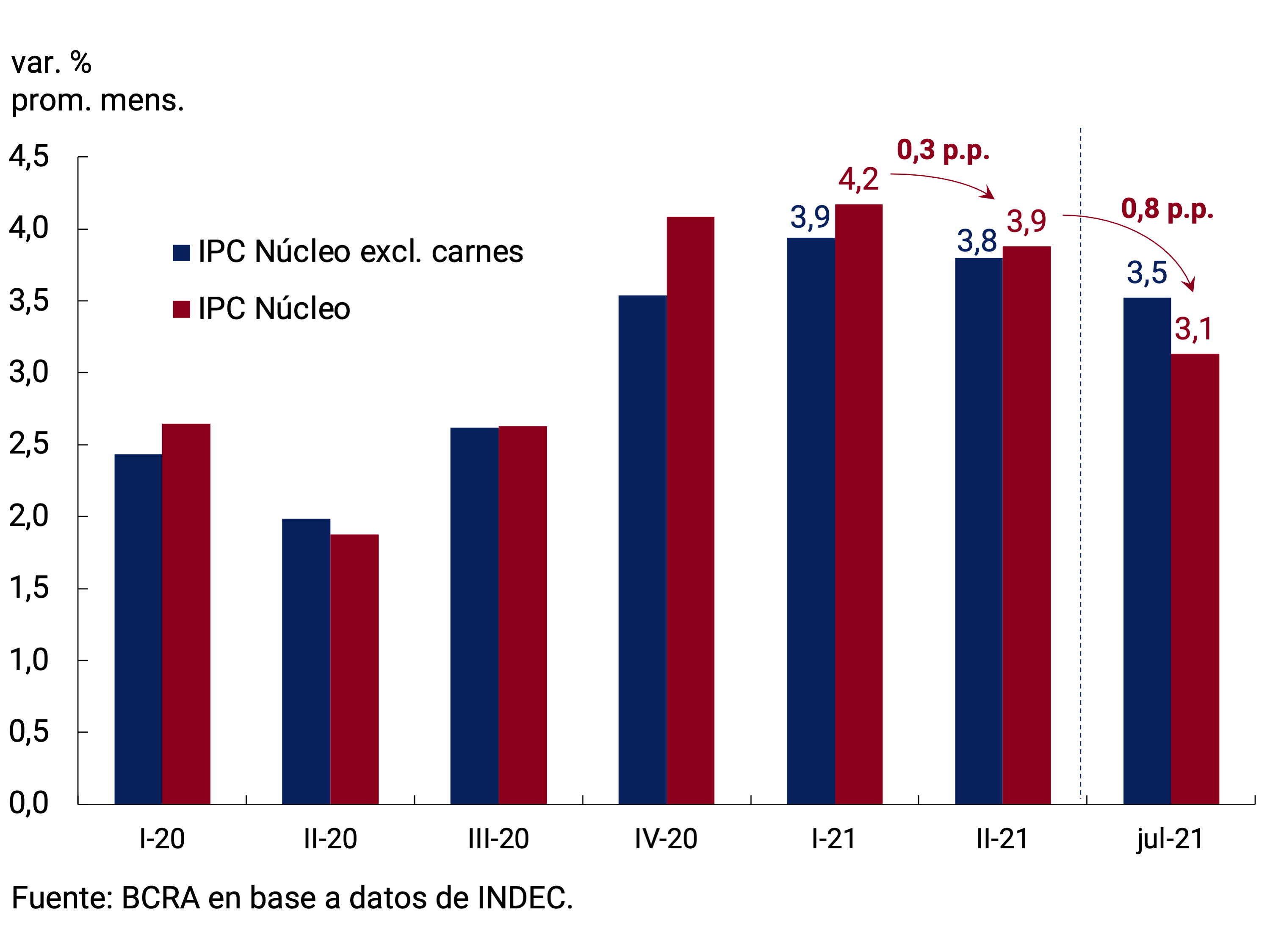

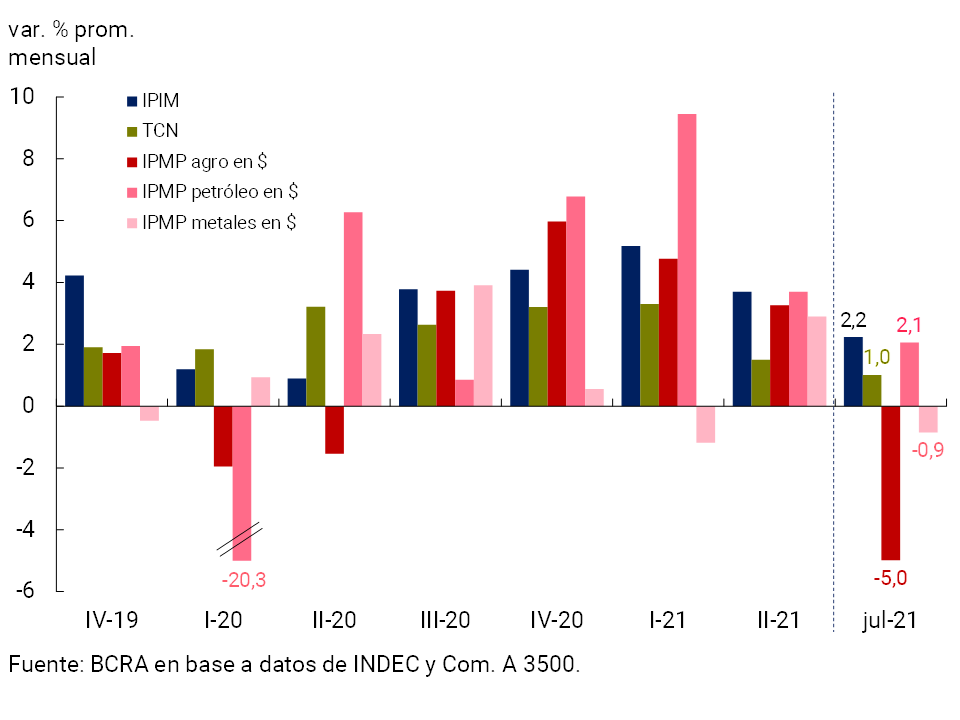

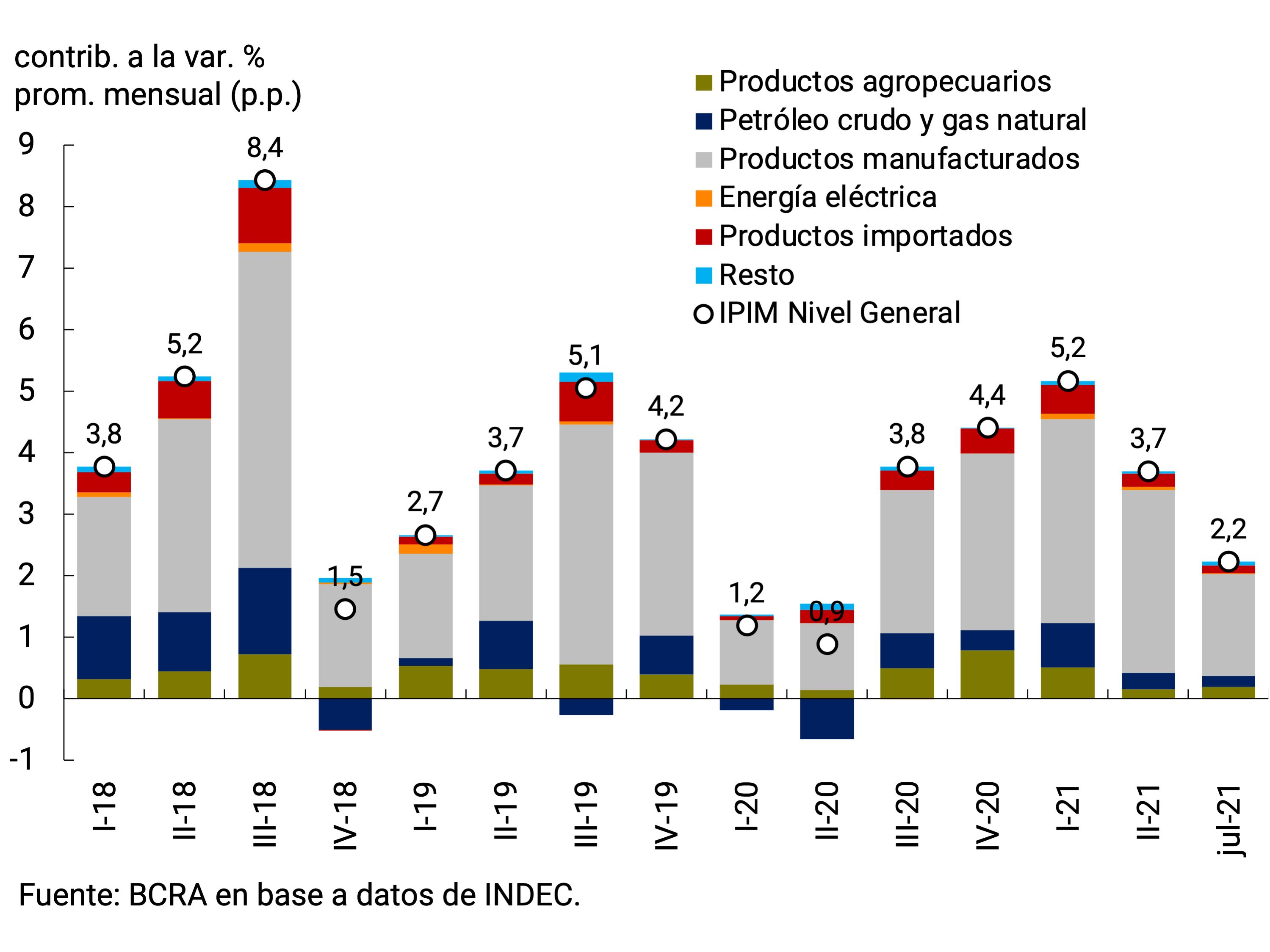

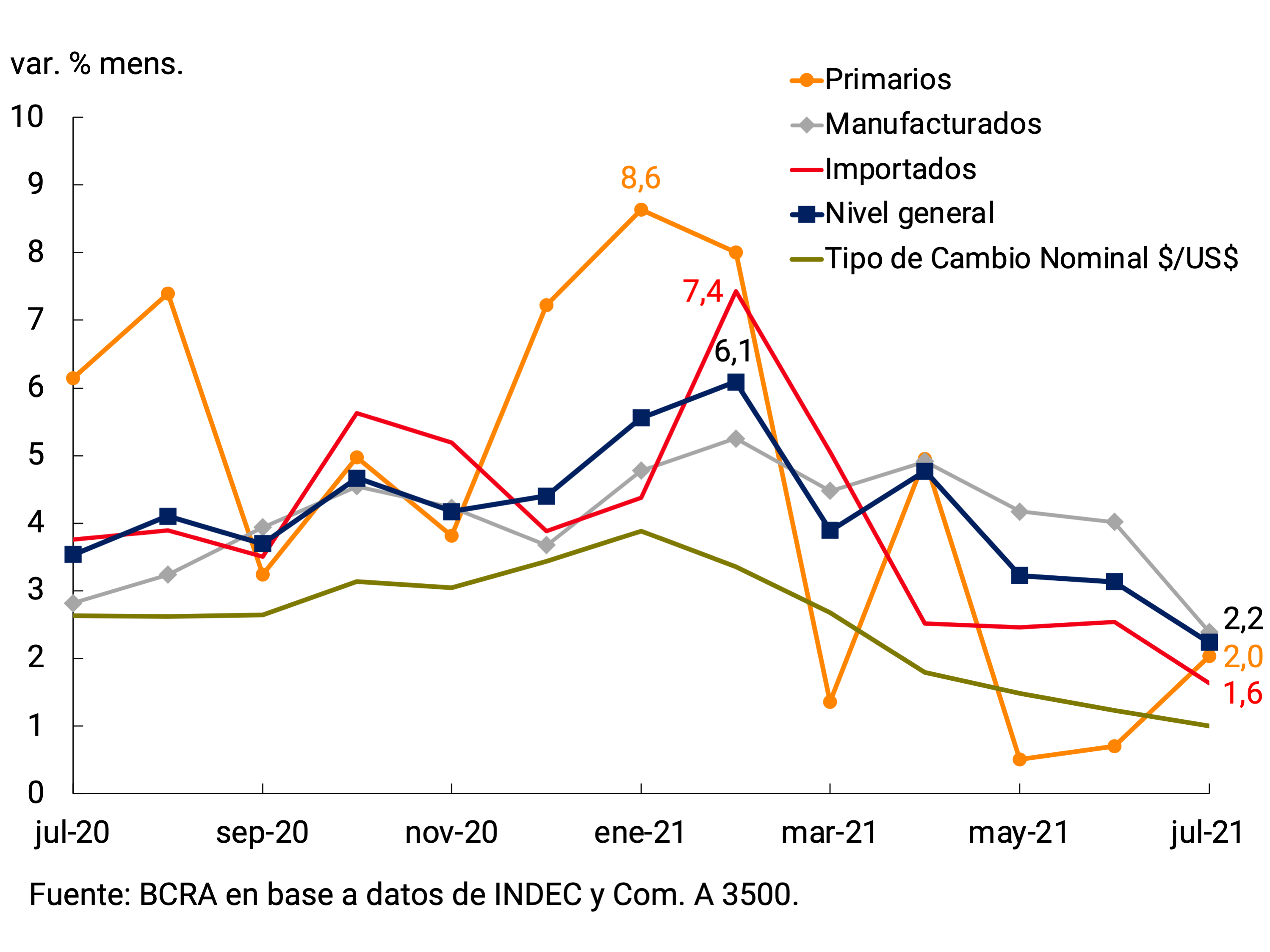

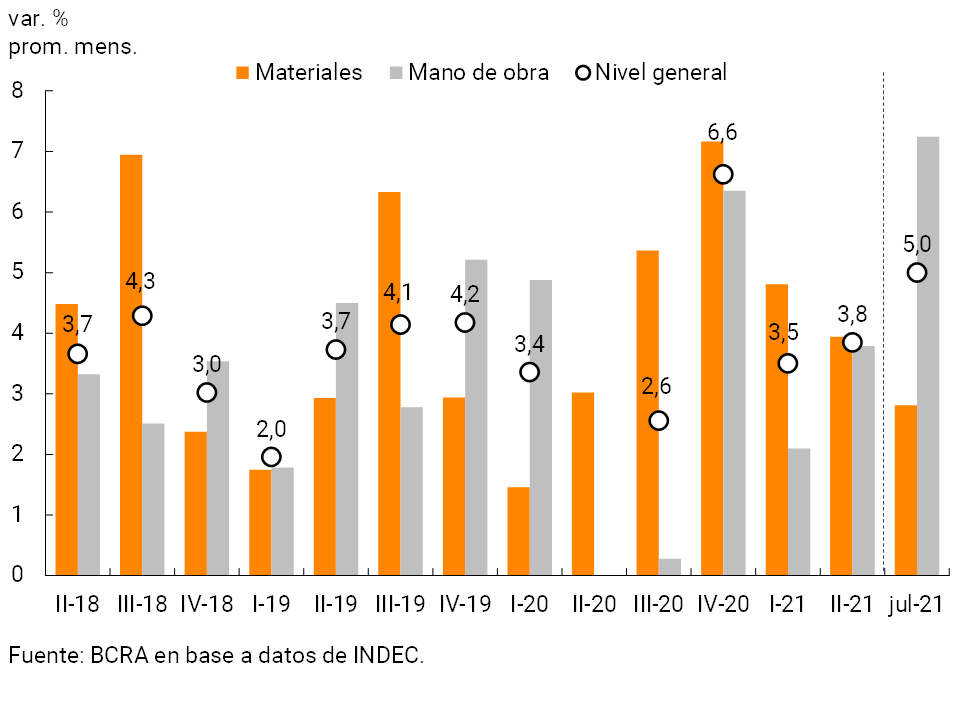

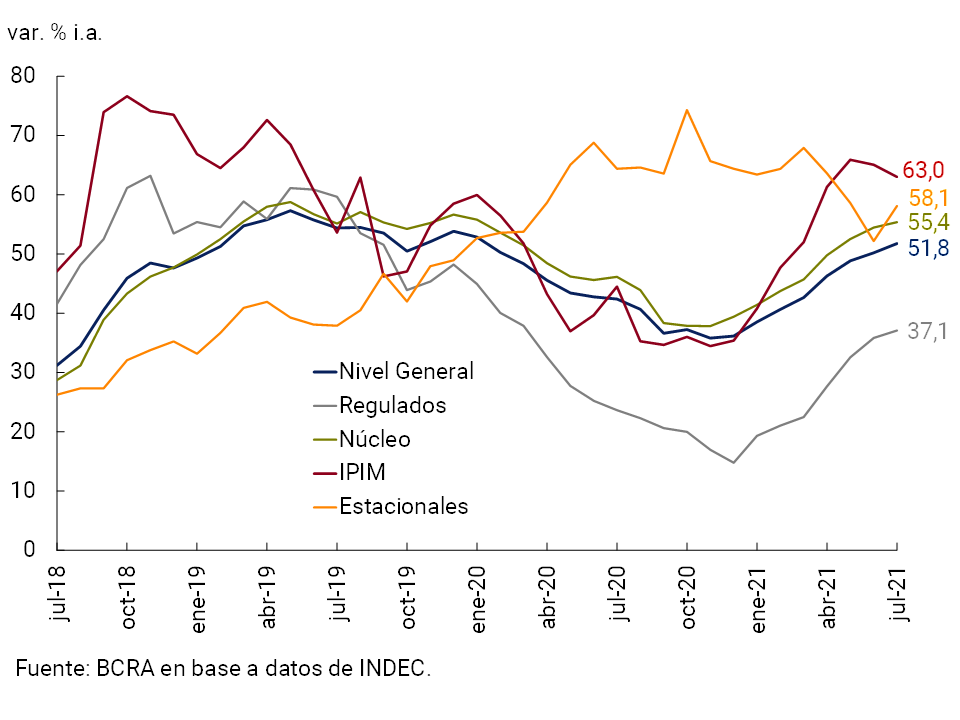

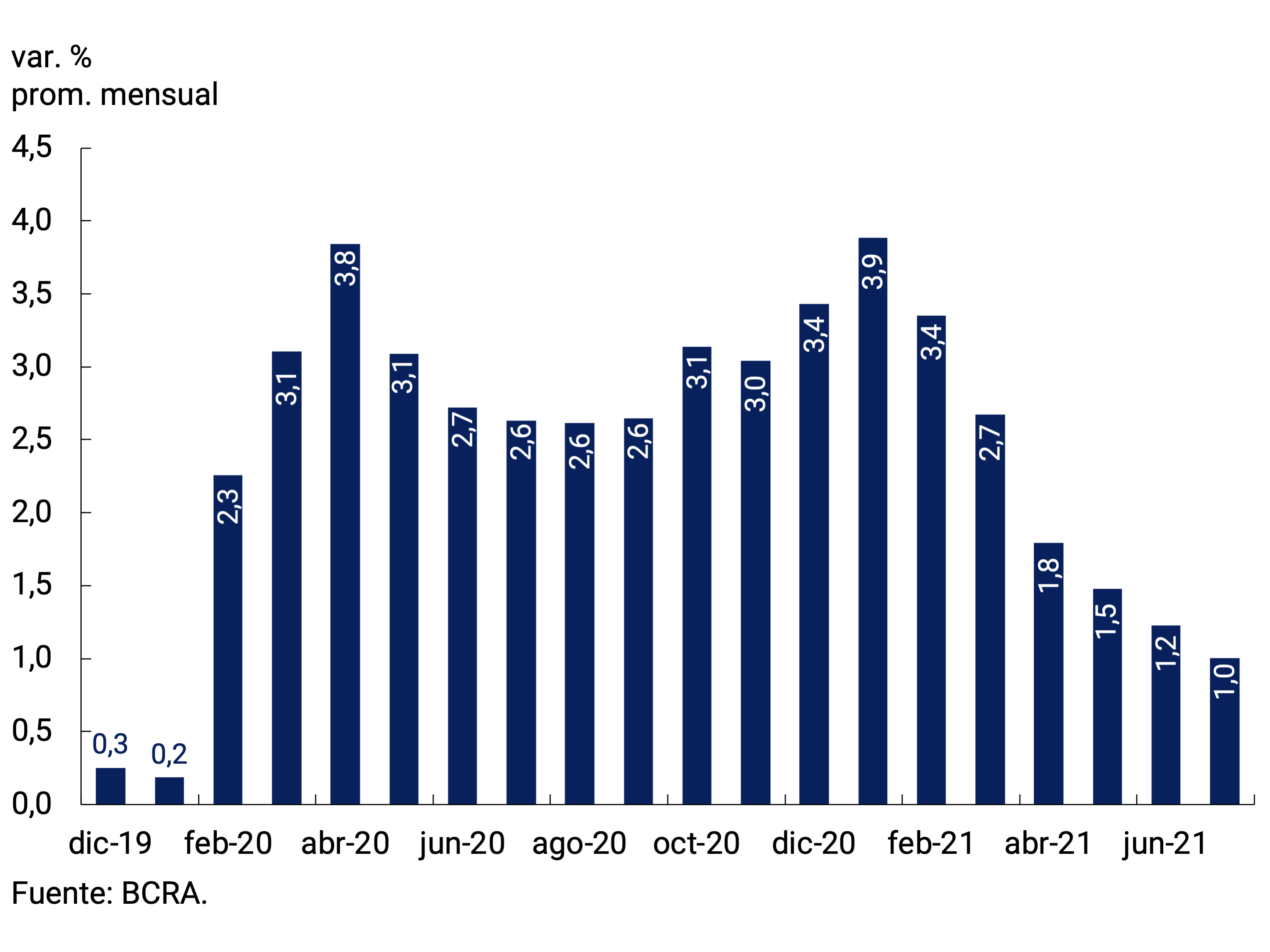

In terms of prices, as we anticipated in the previous IPOM, the monthly inflation rate began to decelerate gradually, given the lesser influence of the transitory factors that drove an increase in the rate of price increases towards the end of last year. Among the latter, the increase in the international price of food and key inputs in manufacturing value chains, the dynamism of the price of meat and certain seasonal goods, and the recomposition of profitability margins, especially in those sectors most affected by the pandemic, stood out. once the economy began to reactivate. This trend of gradual and sustained decline in inflation continued in July, with a 3% increase in the general level of the CPI and a 3.1% increase in core inflation, these being the smallest monthly increases since September 2020. For its part, the Domestic Wholesale Price Index (IPIM), which had cut its average monthly expansion rate in the second quarter to 3.7% (-1.5 p.p. compared to the first quarter), deepened its slowdown in July, with an increase of 2.2% compared to June. The monthly slowdown in prices compared to the previous quarter is expected to continue in the coming months, contributing to a decline in year-on-year growth rates towards the end of the year.

In this regard, the BCRA will continue with its exchange rate management policy, ensuring that the exchange rate dynamics continue to contribute to consolidating the drop in inflation. In addition, monetary policy will continue to focus on absorbing countercyclical efforts in order to preserve monetary and financial balances, ensuring the necessary conditions for the gradual process of reducing the inflation rate to continue. These macroeconomic policies will continue to be accompanied by other more specific policies promoted by the National Government, both in the area of income policies and in the regulation of certain markets with non-competitive price formation.

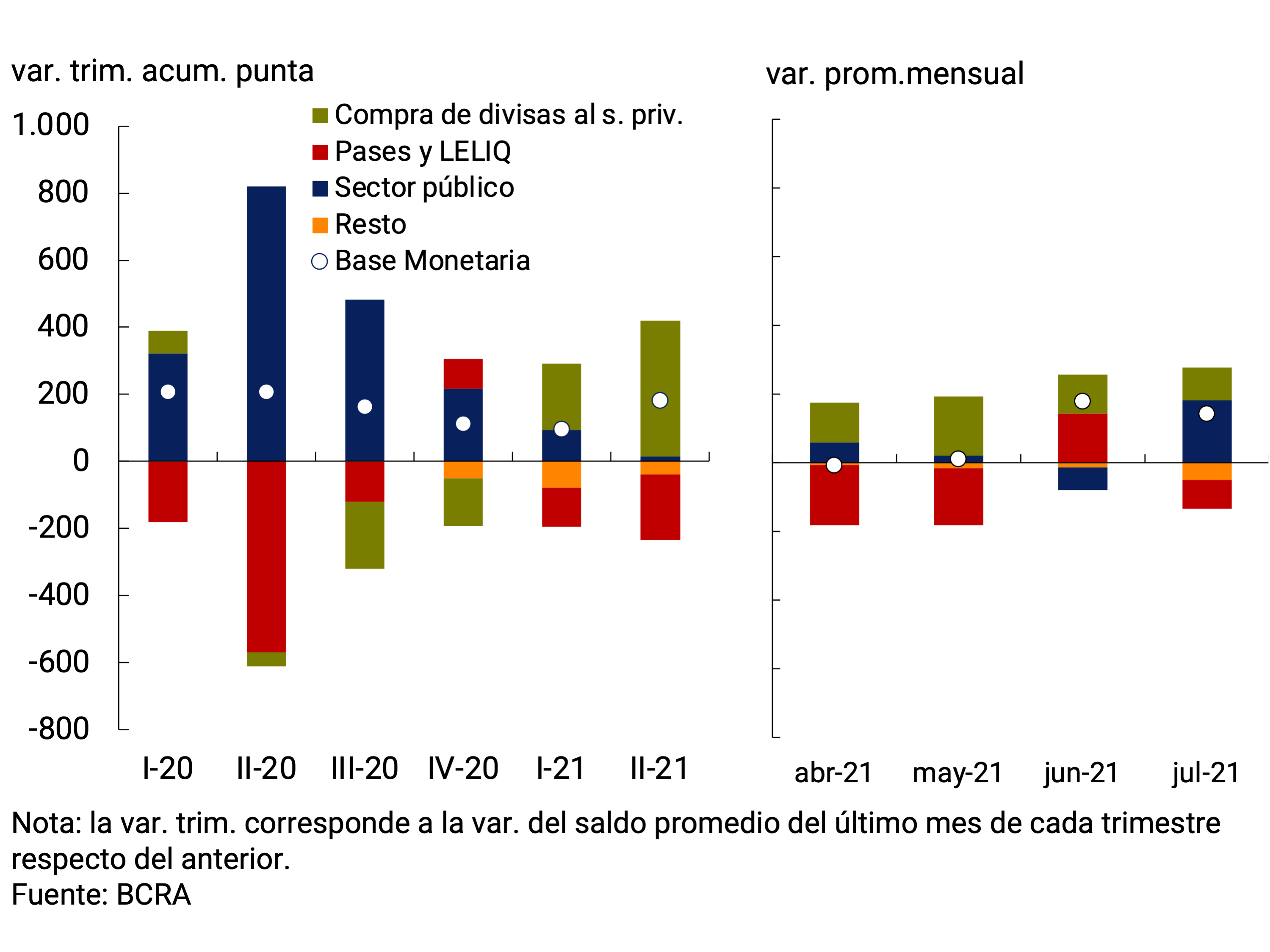

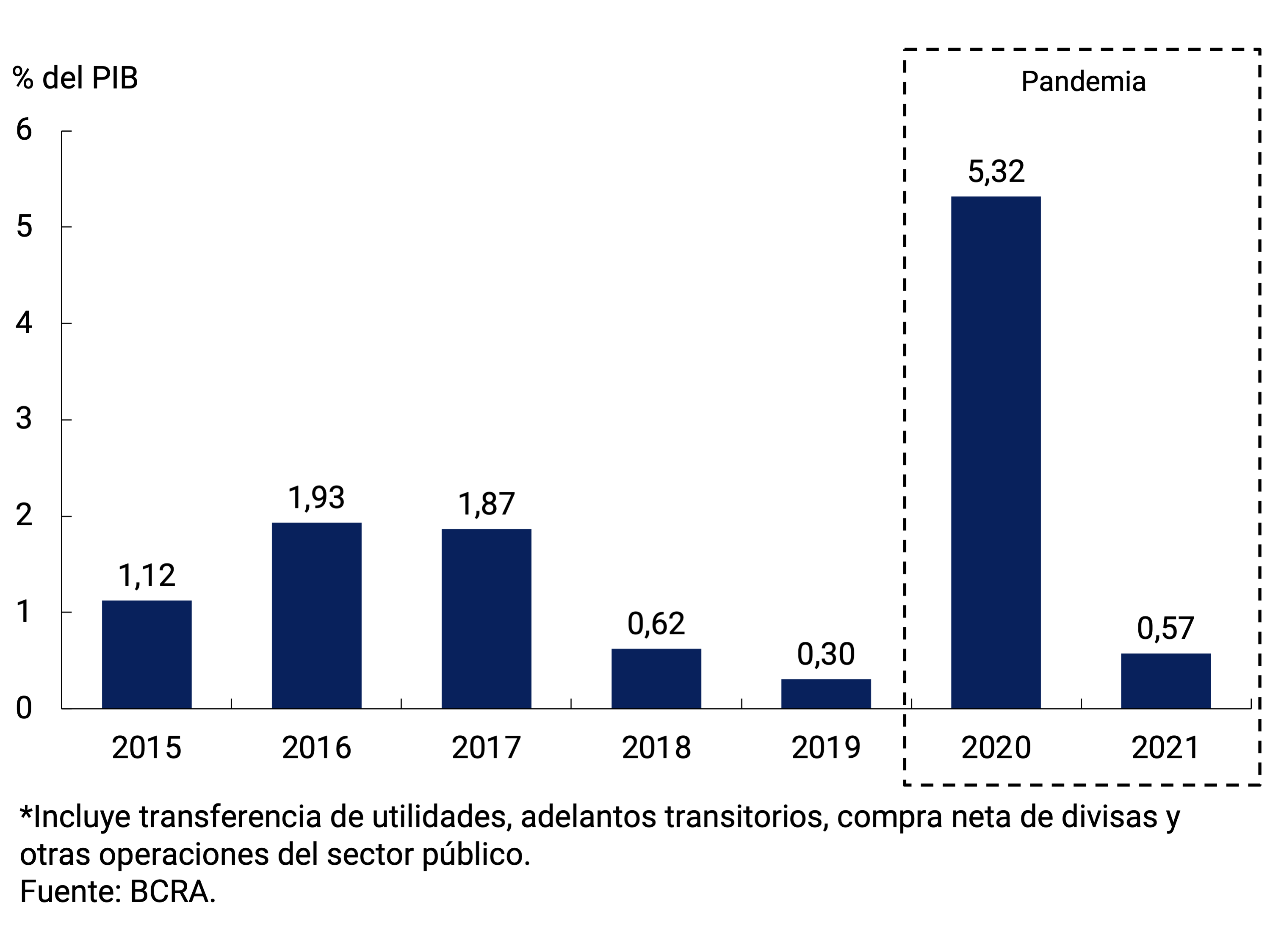

With a more limited fiscal deficit and financed in a greater proportion by the market, the primary monetary expansion linked to the public sector in the first seven months of the year was at levels similar to those of previous years, excluding 2020. In order to continue contributing to the development of the local capital market, in June financial institutions were enabled to integrate the fraction of reserve requirements that until May were remunerated with LELIQ through Treasury bonds in pesos. This regulatory modification led to a change in the composition of bank liquidity: approximately 20% of the requirement previously integrated into LELIQ was integrated into National Treasury Bonds. In the same sense of deepening liquidity in the capital market, the Central Bank began to operate in the public securities futures market.

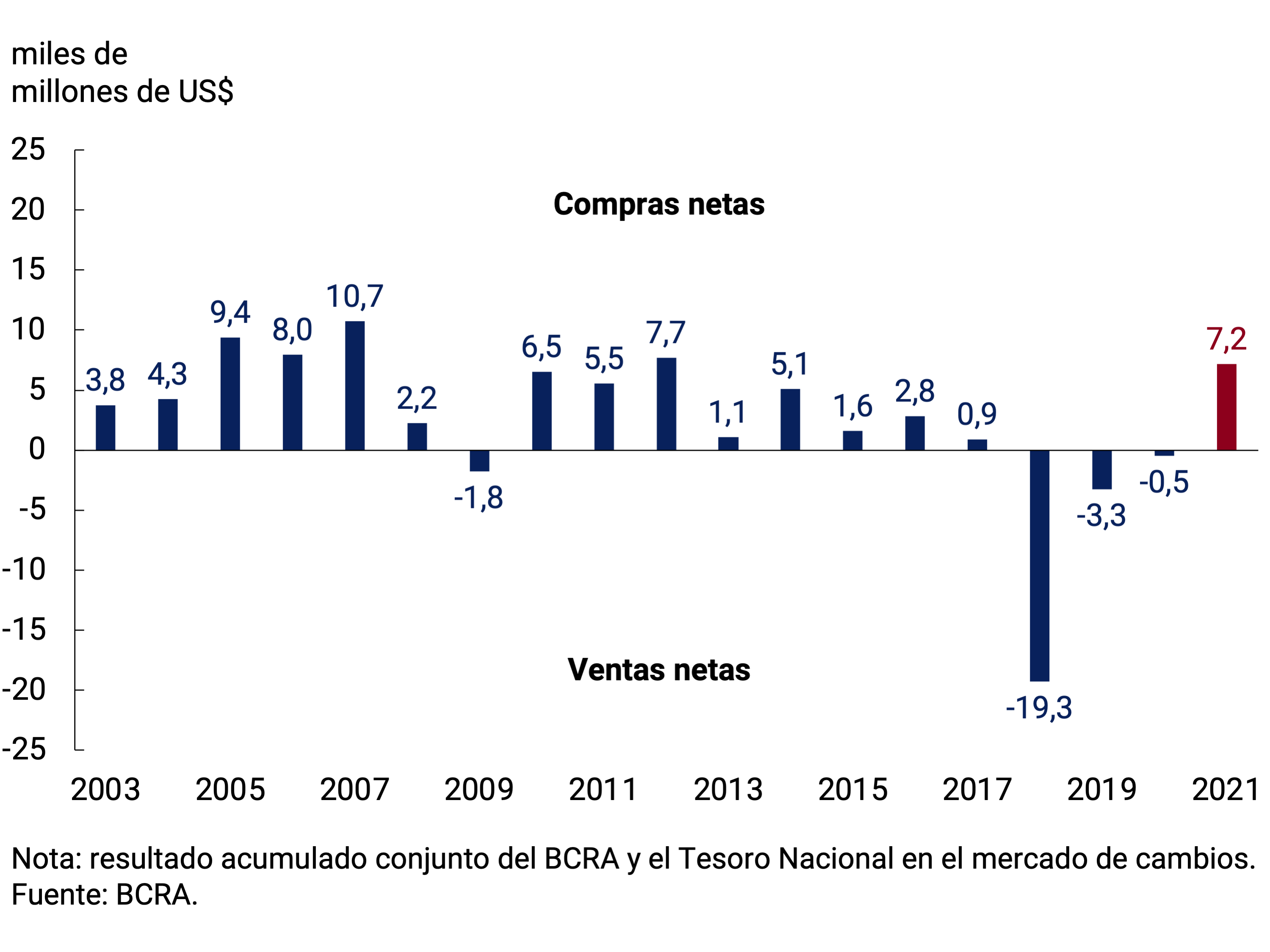

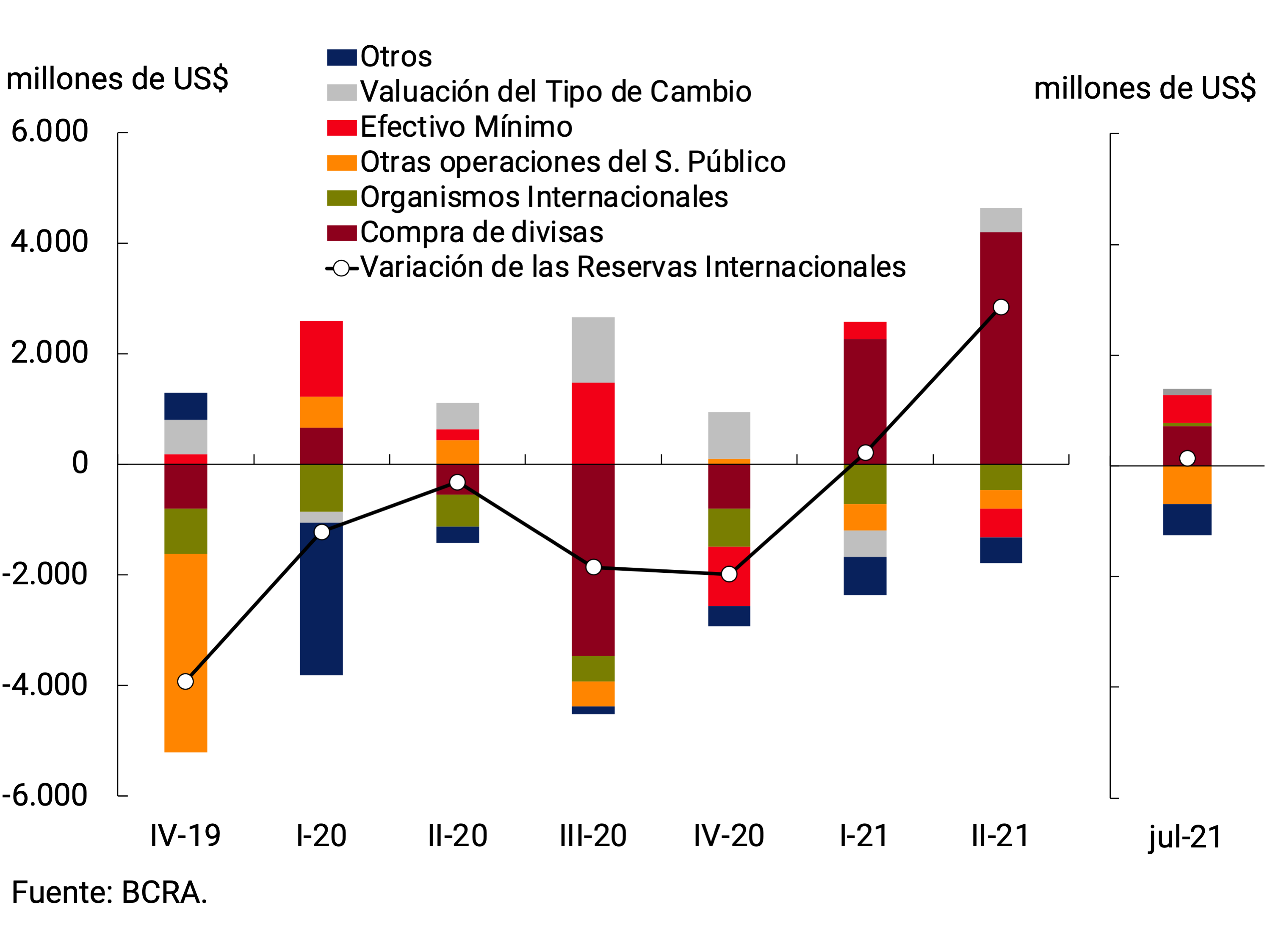

The main factor in the expansion of the monetary base during the first half of the year was the purchase of foreign currency by the BCRA in the foreign exchange market. The administration of the foreign exchange market made it possible to strengthen the balance of International Reserves. Between December 2020 and August 2021 (with data as of August 19), net purchases of US$8.0 billion were recorded. The greater external slack simultaneously made it possible to adjust the pace of adjustment of the exchange rate with the aim of contributing to the slowdown in the rate of increase in domestic prices.

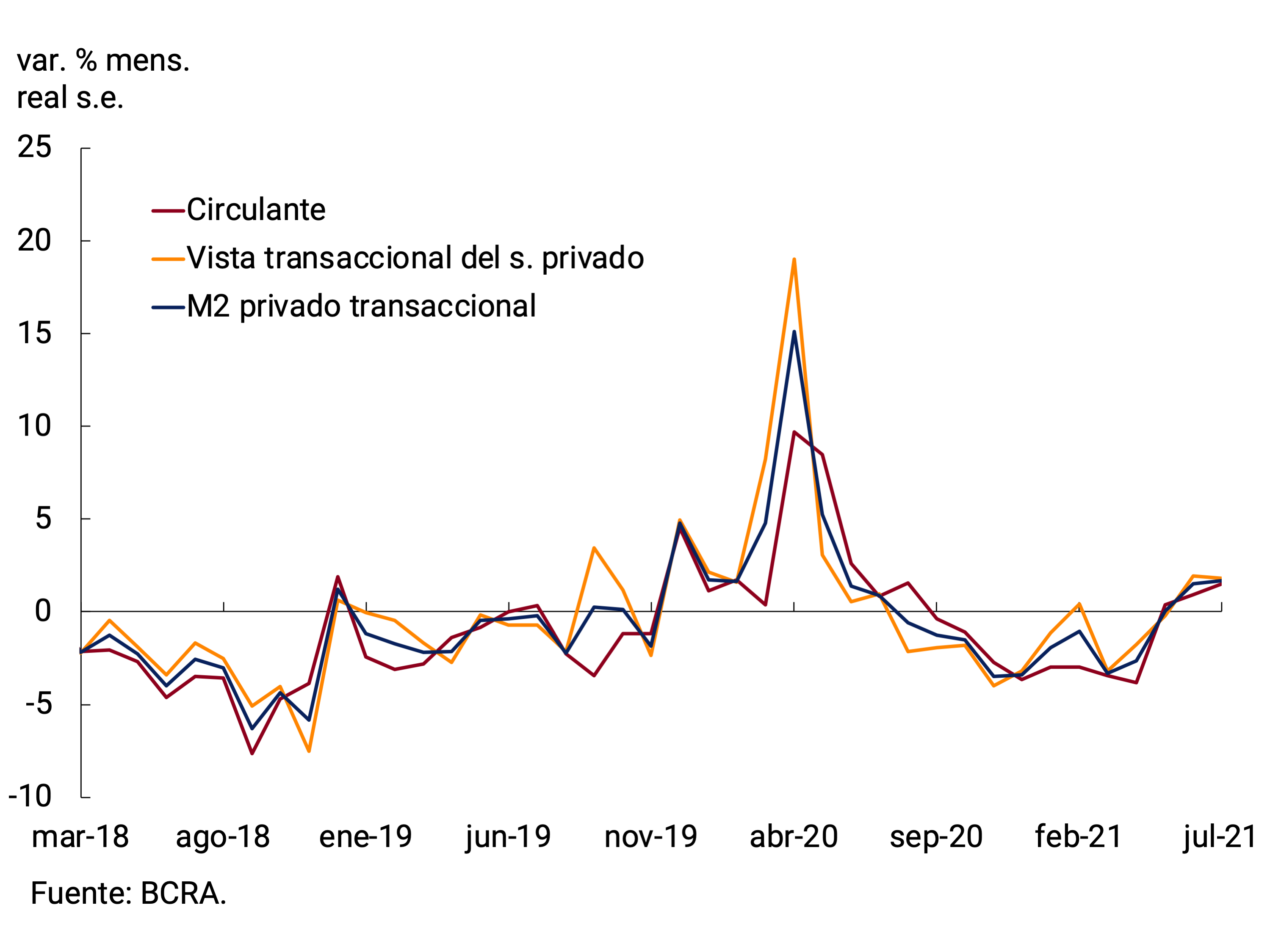

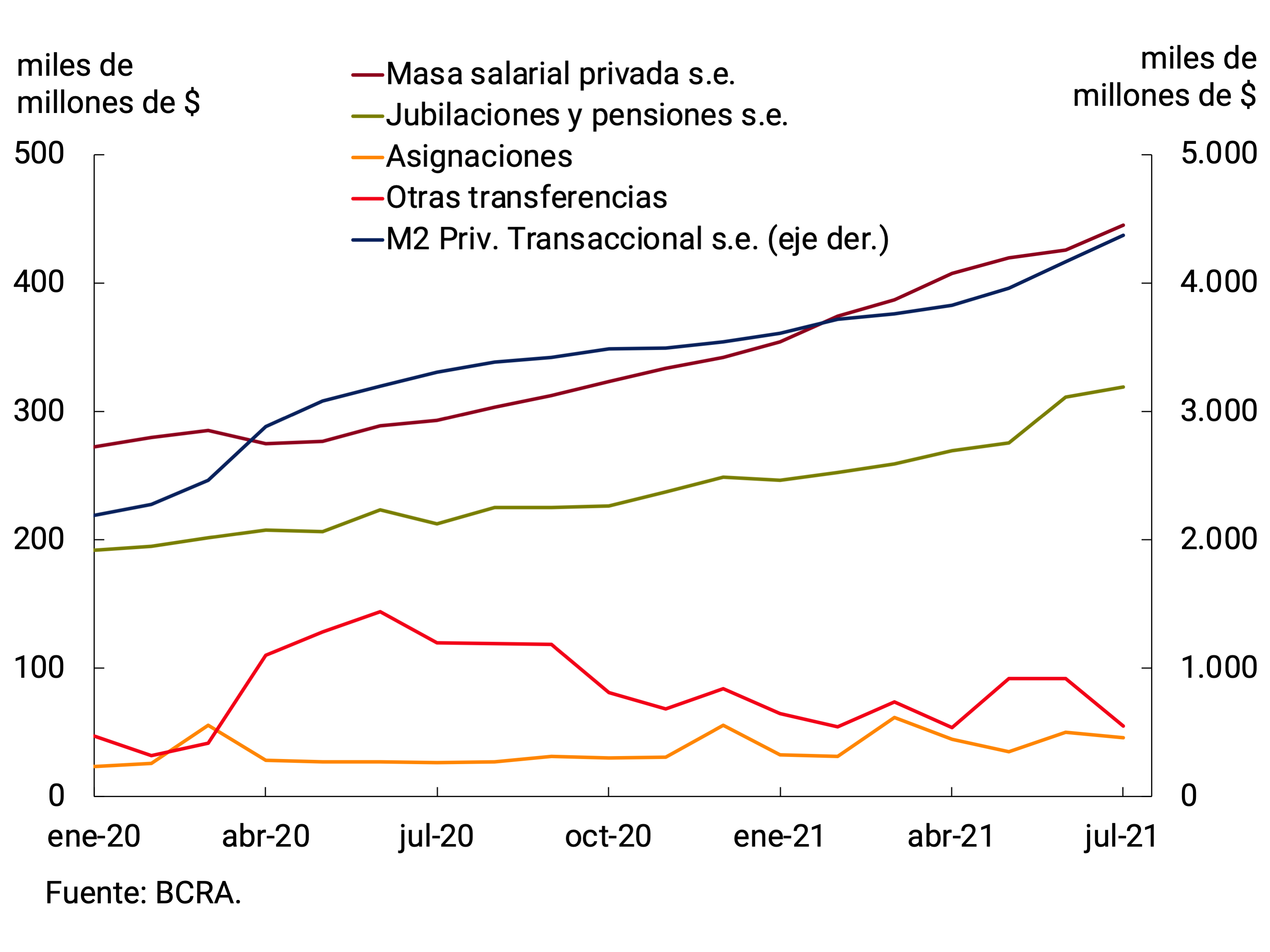

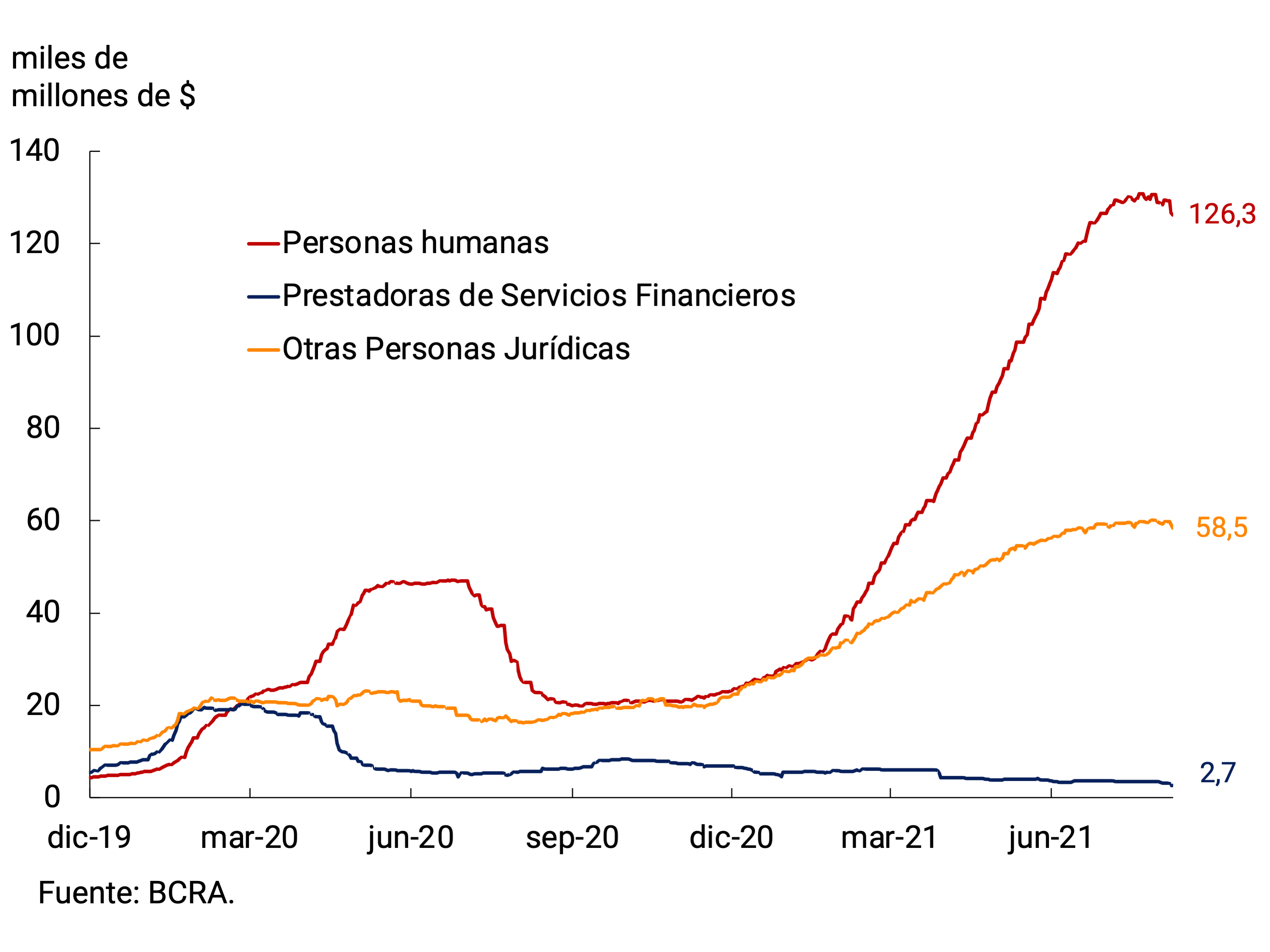

In this context, towards the end of the second quarter of the year, the means of payment expanded again in real terms. This dynamic was influenced by transfers from the public sector to vulnerable sectors and the recomposition of real wages. To cope with a higher level of salary expenses and the payment of tax obligations, legal entities reduced their position in investment assets in pesos. All this contributed to an increase in the demand for liquidity.

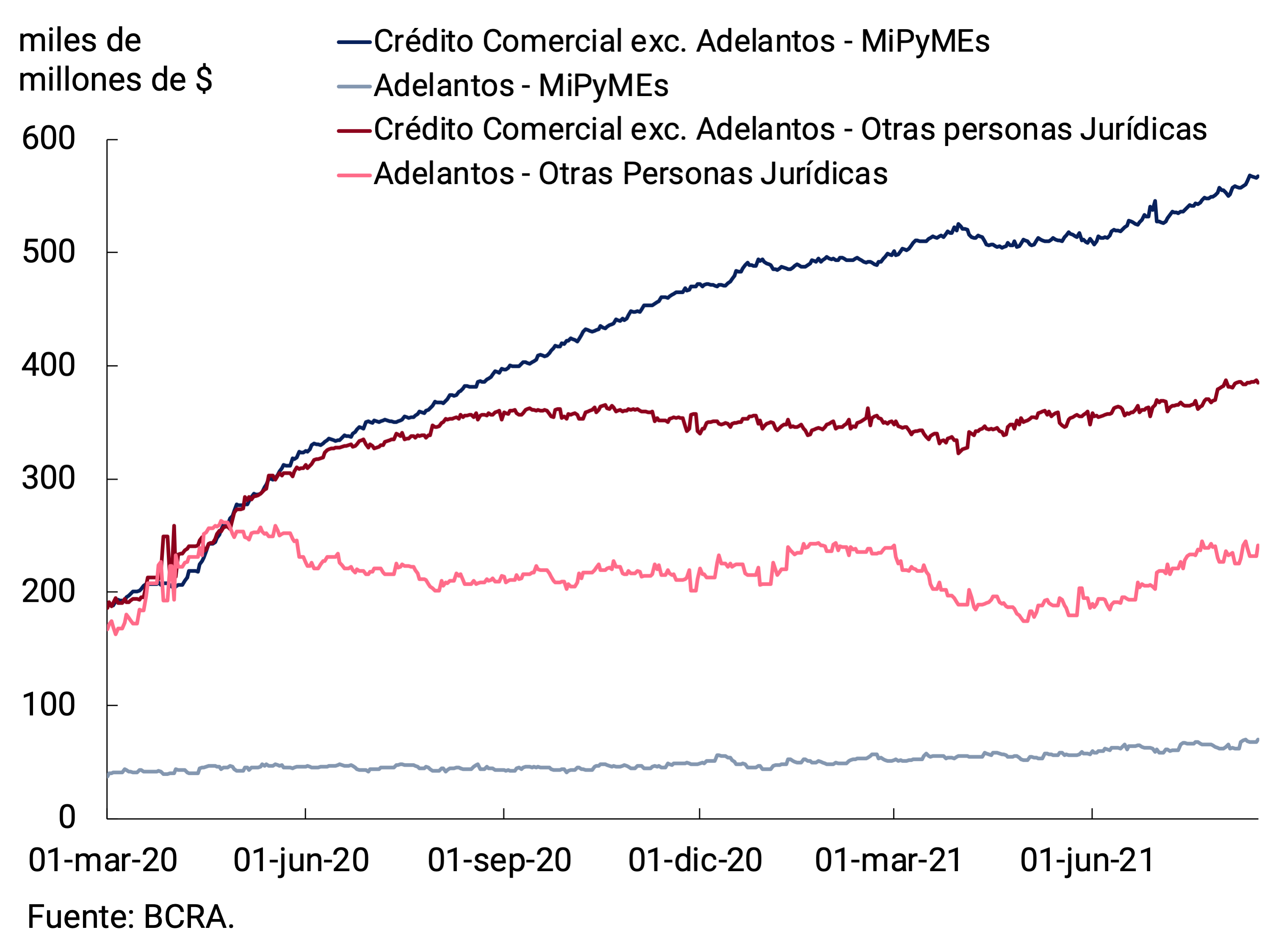

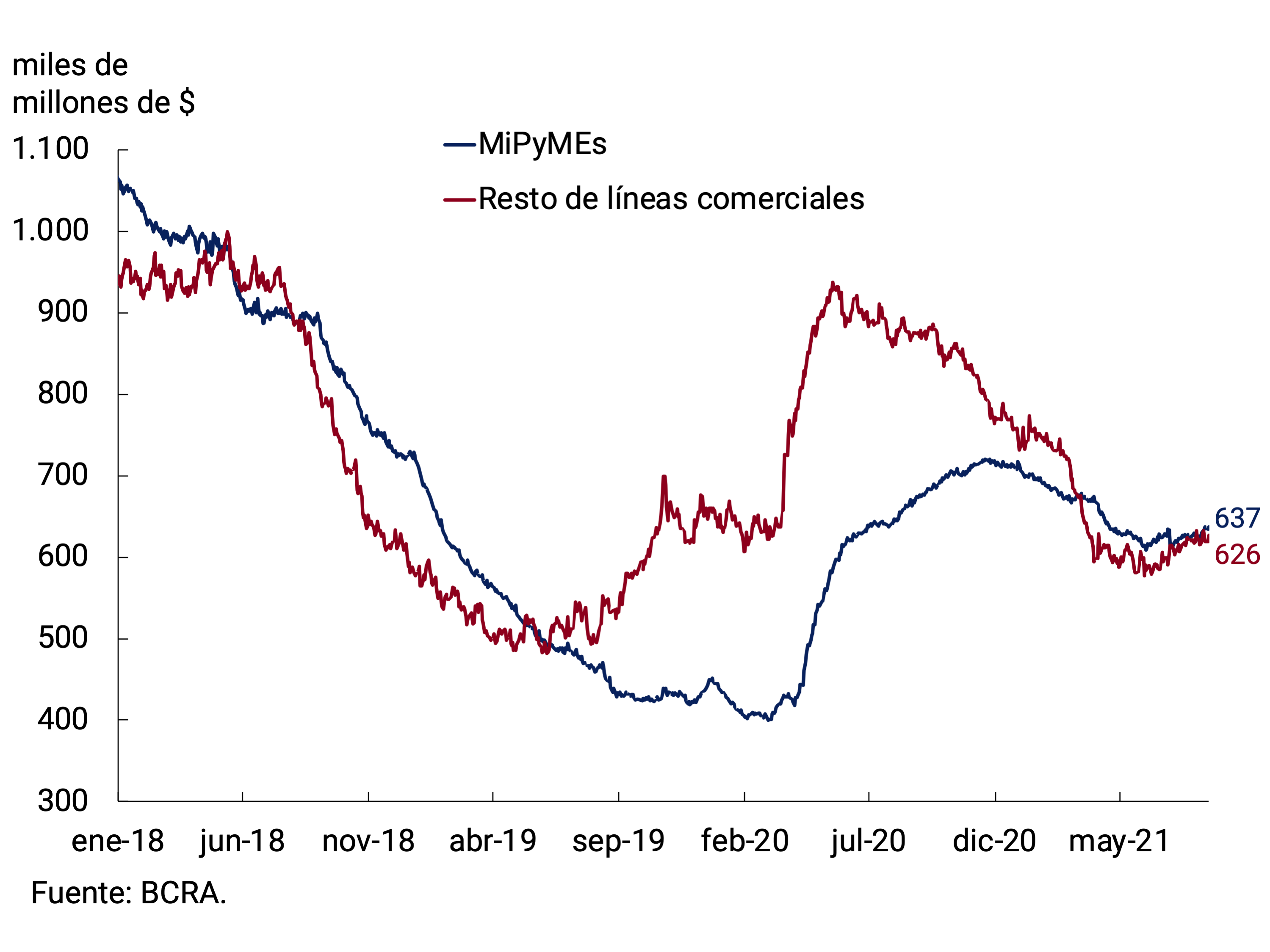

Credit policy continued to focus on the sectors most affected by the pandemic and on leveraging investment projects. The main instrument used by the BCRA was the Productive Investment Financing Line (LFIP), designed to channel productive credit to MSMEs under favorable conditions. Since its implementation, and with data as of July 31, the accumulated disbursements through the LFIP totaled $801,000 million. Thus, in the second quarter of the year, the average monthly nominal growth of these placements was 19%. Recently, the BCRA decided to extend the line “Financing of investment projects”, which contemplates an interest rate of 30% n.a., to all companies, regardless of their size, that make investments aimed at increasing the production capacity of poultry and pork. These sectors have a potential margin to increase their production and contribute both to the diversification of the meat consumption basket and to the increase in net exports.

In addition, measures were taken to increase the level of bank financing to the private sector. The deferral of unpaid installments (with the exception of credit card financing) was granted to beneficiaries of the Productive Recovery Program II. The National Government extended the “Ahora 12” program until January 31, 2022, with some modifications to encourage consumption and boost credit card financing. Finally, the National Government announced that as of the end of August, credits will be available for more than one million single-tax people, who will be able to request an amount of up to $150,000, depending on their category, and repay it in 12 interest-free installments after a six-month grace period.

The BCRA has a robust position to face possible episodes of greater financial volatility, which in Argentina have typically coincided with electoral periods. In the last 9 months, the monetary authority has rebuilt its stocks and perfected exchange rate regulation, increasing its firepower to preserve exchange rate stability. In fact, since the beginning of December 2020, when international reserves reached a minimum of US$38.6 billion, the BCRA has accumulated reserves in the amount of US$3.4 billion. This dynamic of recomposition of balances, together with the entry of the allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) by the IMF to mitigate the effects of the pandemic for a total of US$4.3 billion, allowed the stock of international reserves to currently stand at around US$46 billion.

Likewise, the BCRA has a wide margin of intervention in the dollar futures market, which makes it possible to contain any distortion that could be generated in the depreciation expectations and interest rates that arise from these contracts. Finally, the improvement of foreign exchange regulations ensures the normal functioning of the foreign exchange market, avoiding a repeat of certain exchange rate tensions that took place during 2020 in the midst of the pandemic.

In a context still marked by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the BCRA will carry out a monetary policy that, in addition to preserving monetary and financial stability, will lay the foundations for a path of economic development with social equity.

2. International context

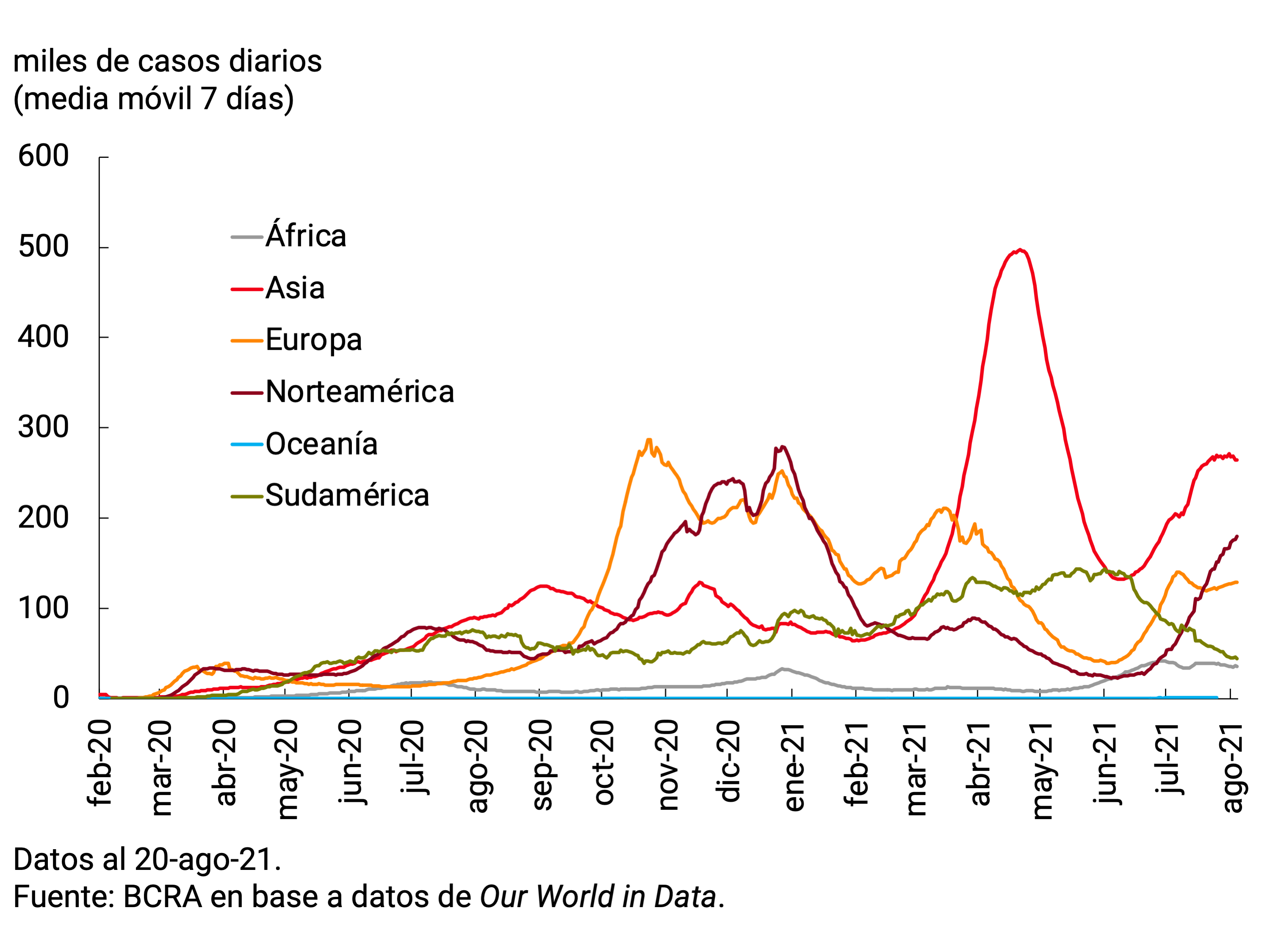

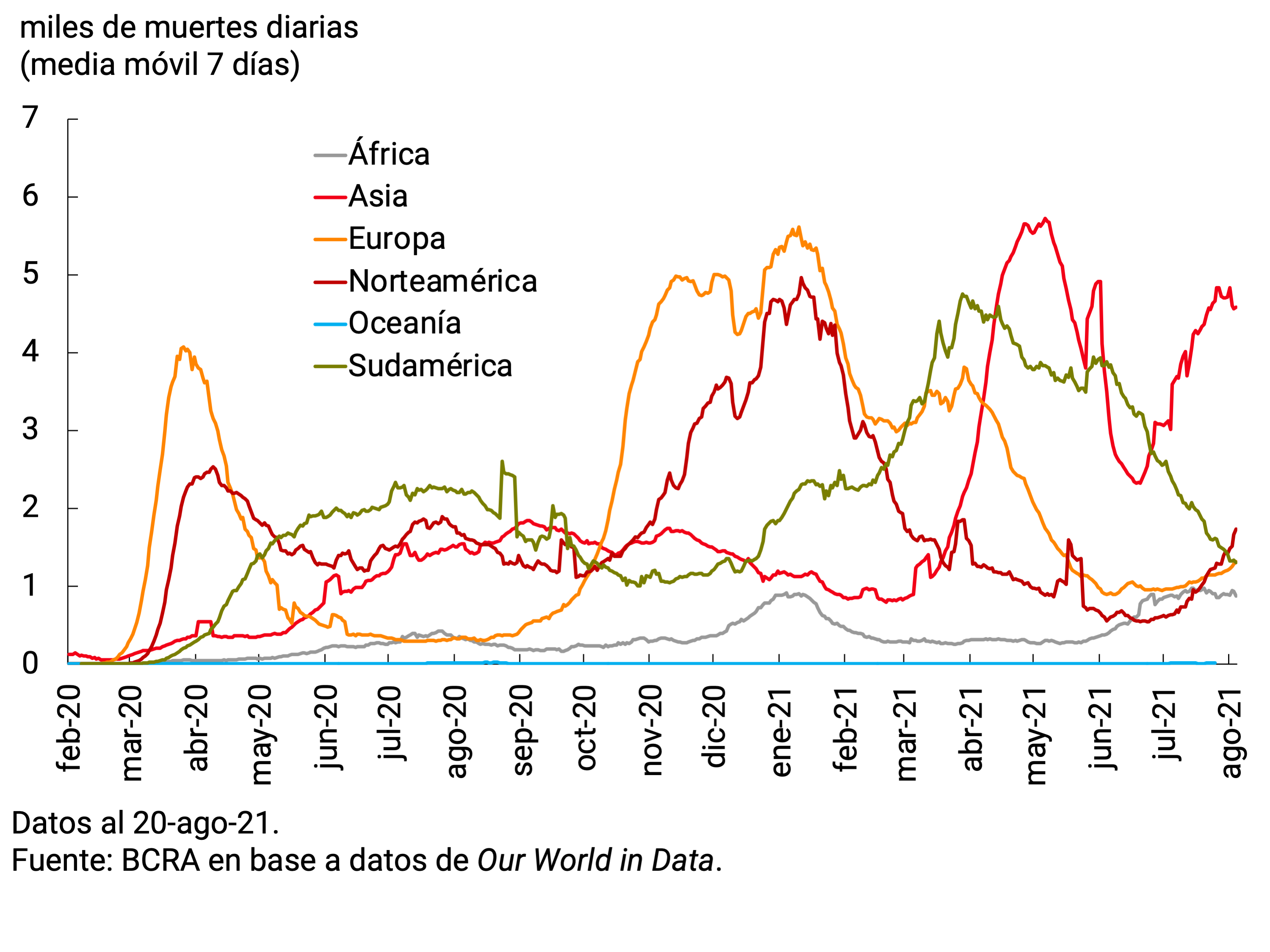

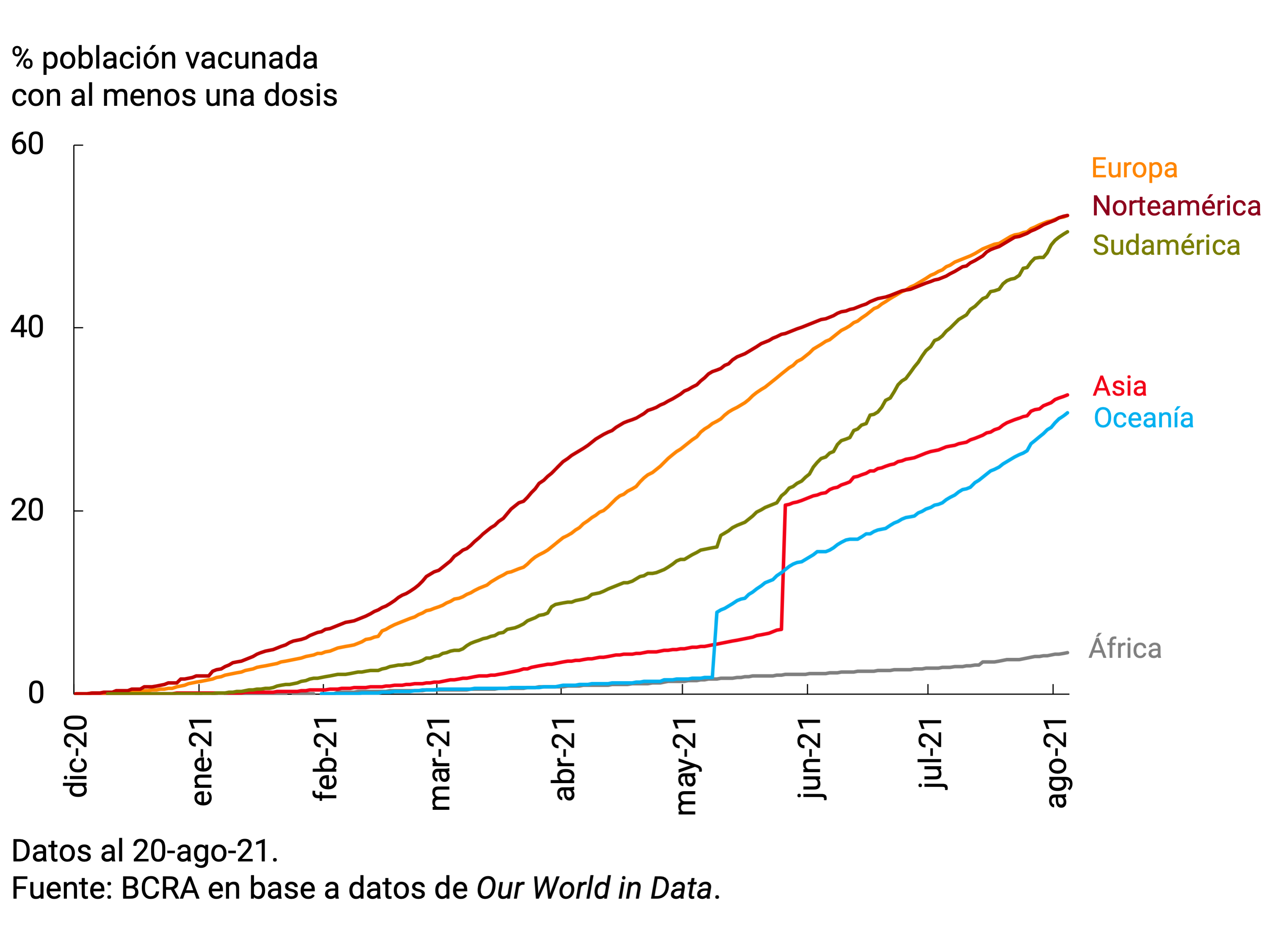

Since the previous IPOM, there has been a sharp rise in COVID-19 cases in Europe, North America and Asia, which would be due to the spread of the more contagious Delta variant. However, unlike previous waves of the pandemic, deaths have increased by a smaller amount, possibly due to the positive effect of vaccines. The vaccination process has accelerated globally, but the gap between countries in the percentages of the population fully vaccinated is still notorious.

The global economic recovery continued, especially after several countries left behind the impact of the “second wave” during the first quarter of the year. The divergence between advanced and developing countries was also accentuated, based on the former’s greater fiscal and monetary space, as well as their faster progress in vaccination.

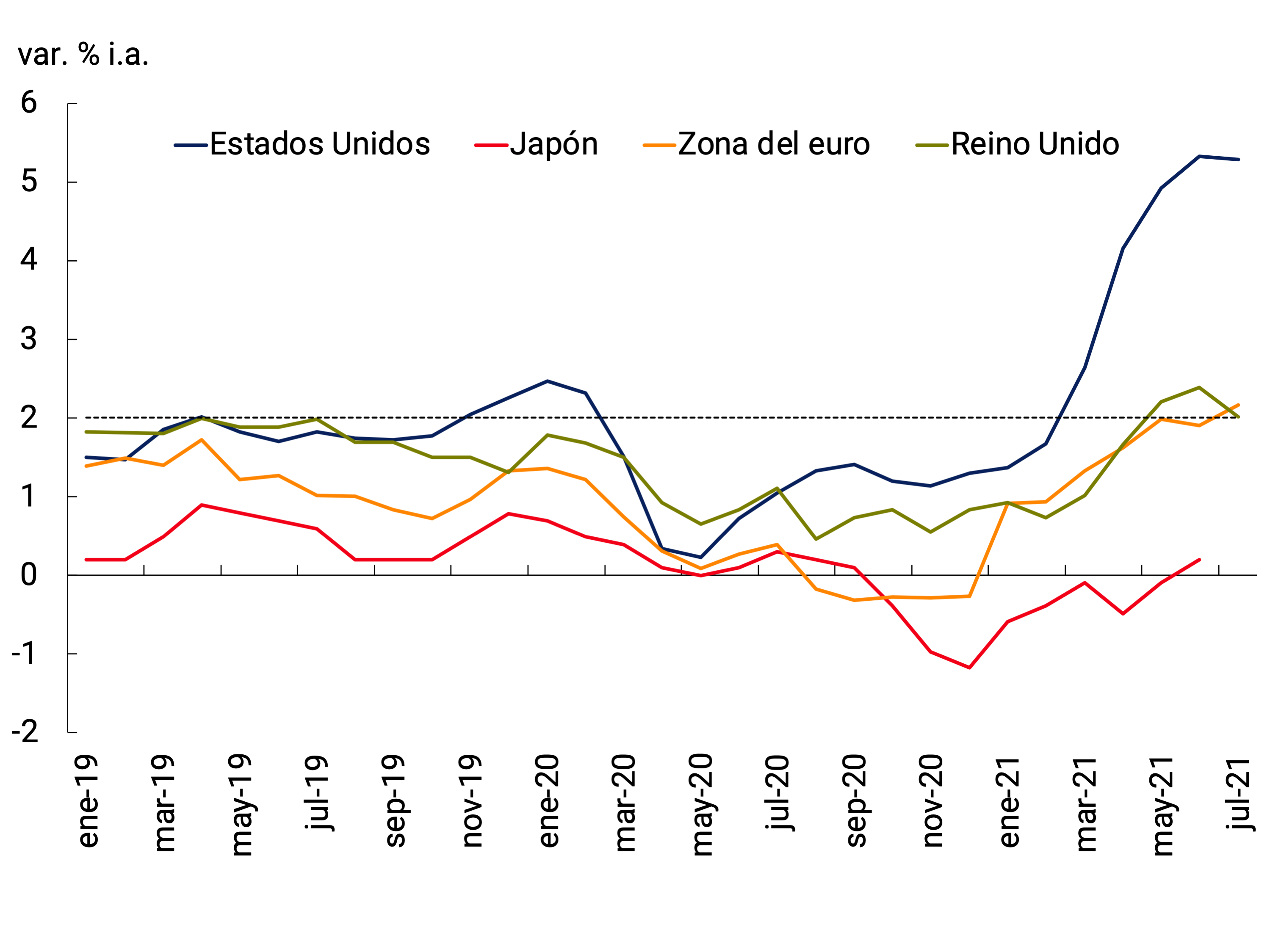

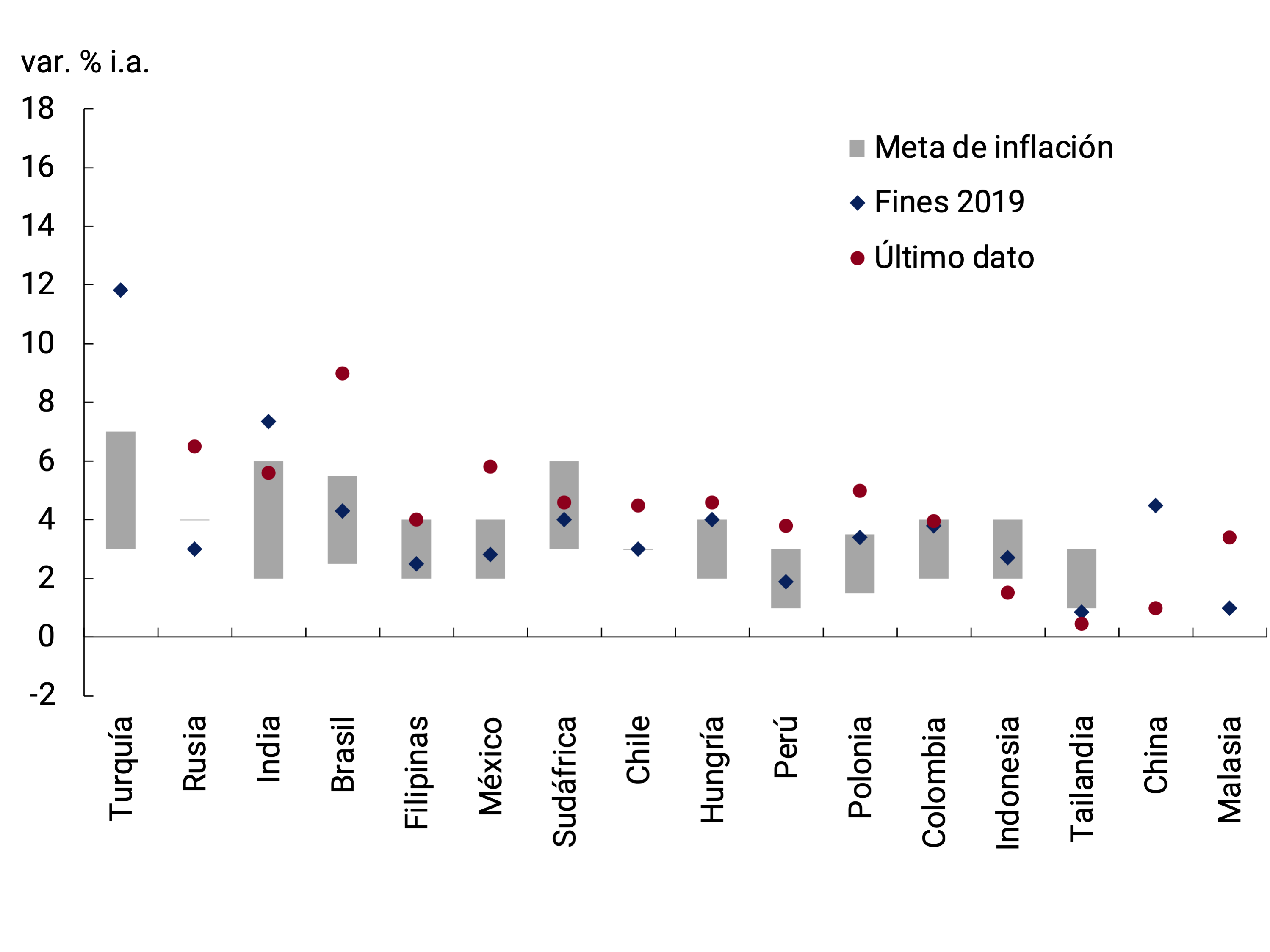

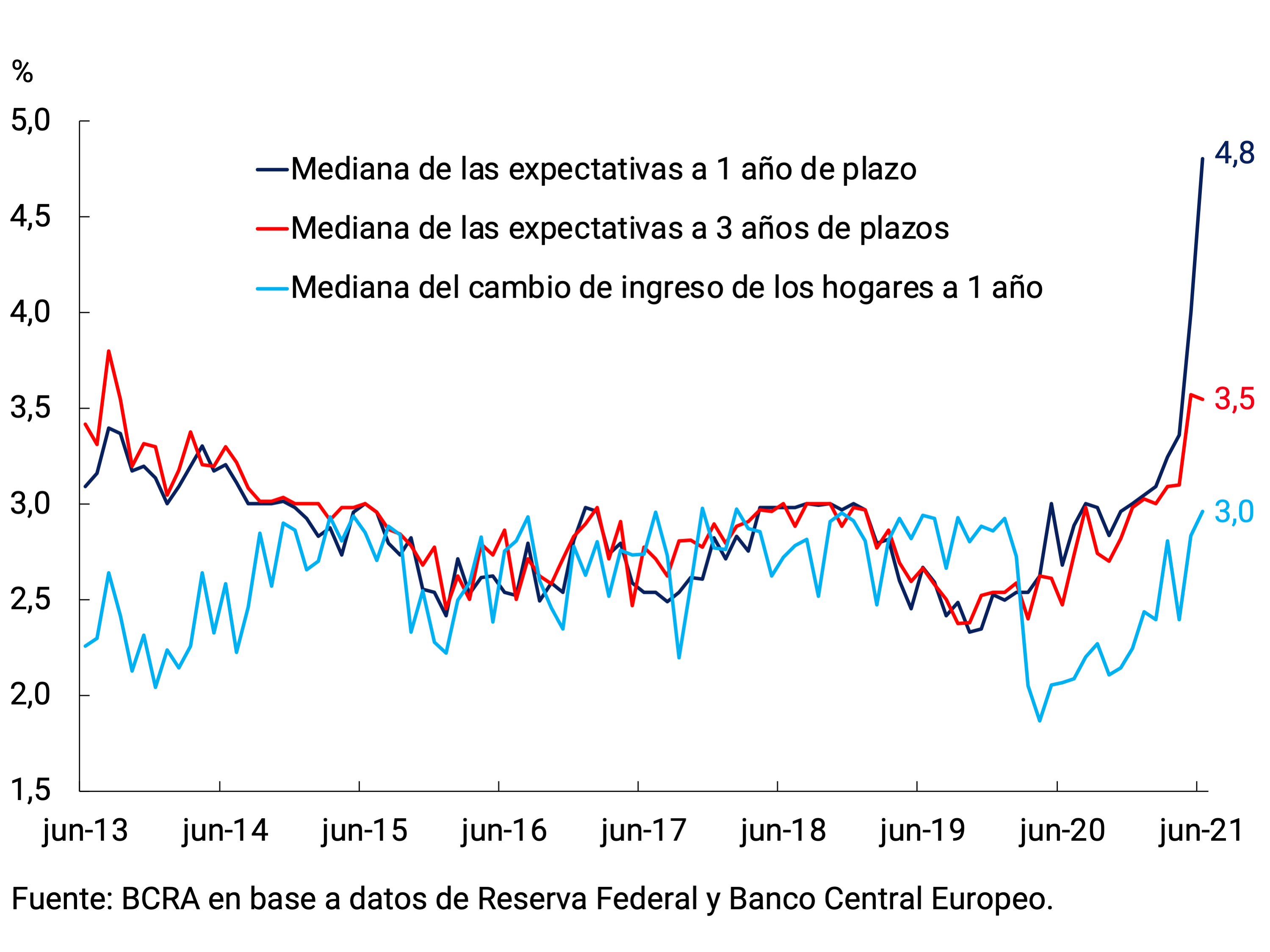

Along with expansionary policies and the recovery, inflation accelerated in many countries: “base of comparison” effects and increases in certain goods and services affected by the pandemic would account for much of this acceleration. In emerging countries, inflationary pressures were accentuated by higher commodity prices and exchange rate depreciation in response to the crisis. The consensus so far is that this acceleration would be transitory (it is not reflected in expectations of higher inflation more than a year into the future).

Going forward, the global recovery continues to face a set of health, economic and financial risks. Inequality in vaccination would translate into recoveries of dissimilar pace. Shrinking policy space—especially in developing countries—makes it difficult to contain the economy in the face of new waves of the pandemic. Finally, the strong pace of increase in the prices of financial assets continues to present a certain disconnect from the real economy, and with it the risk of a correction. It could materialize, for example, if inflation in advanced countries led to a higher or sooner than expected rise in interest rates, with the consequent volatility in the financial conditions faced by emerging countries.

2.1. Pandemic: daily cases on the rise and uneven vaccination progress

New COVID-19 cases fell from peaks of 5.7 million per week recorded in the previous IPOM to a floor of 2.5 million per week towards the end of June. Since then, there has been a resurgence in Europe, North America and Asia (in the latter case, with an epicentre in the Southeast; see Figure 2.1). On the other hand, cases fell in South America. As of the date of publication of this report, new cases exceeded 4.5 million per week globally.

The resurgence may have been due to the spread of the Delta variant, which is more contagious and became dominant in most countries for which information is available, with the exception of South America. The studies known so far found that the vaccines are still effective (although somewhat less effective than against the other variants), especially in preventing hospitalization1.

Figure 2.1 | Evolution of confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths by continent

Unlike in previous waves, daily deaths increased less than cases in countries in Europe and North America, the continents with the highest percentage of the population vaccinated with two doses. By contrast, deaths have risen in tandem with the increase in cases in Asia (see Figure 2.1). Between February and June, the pace of application of doses in the world accelerated, but the gap between countries persists.

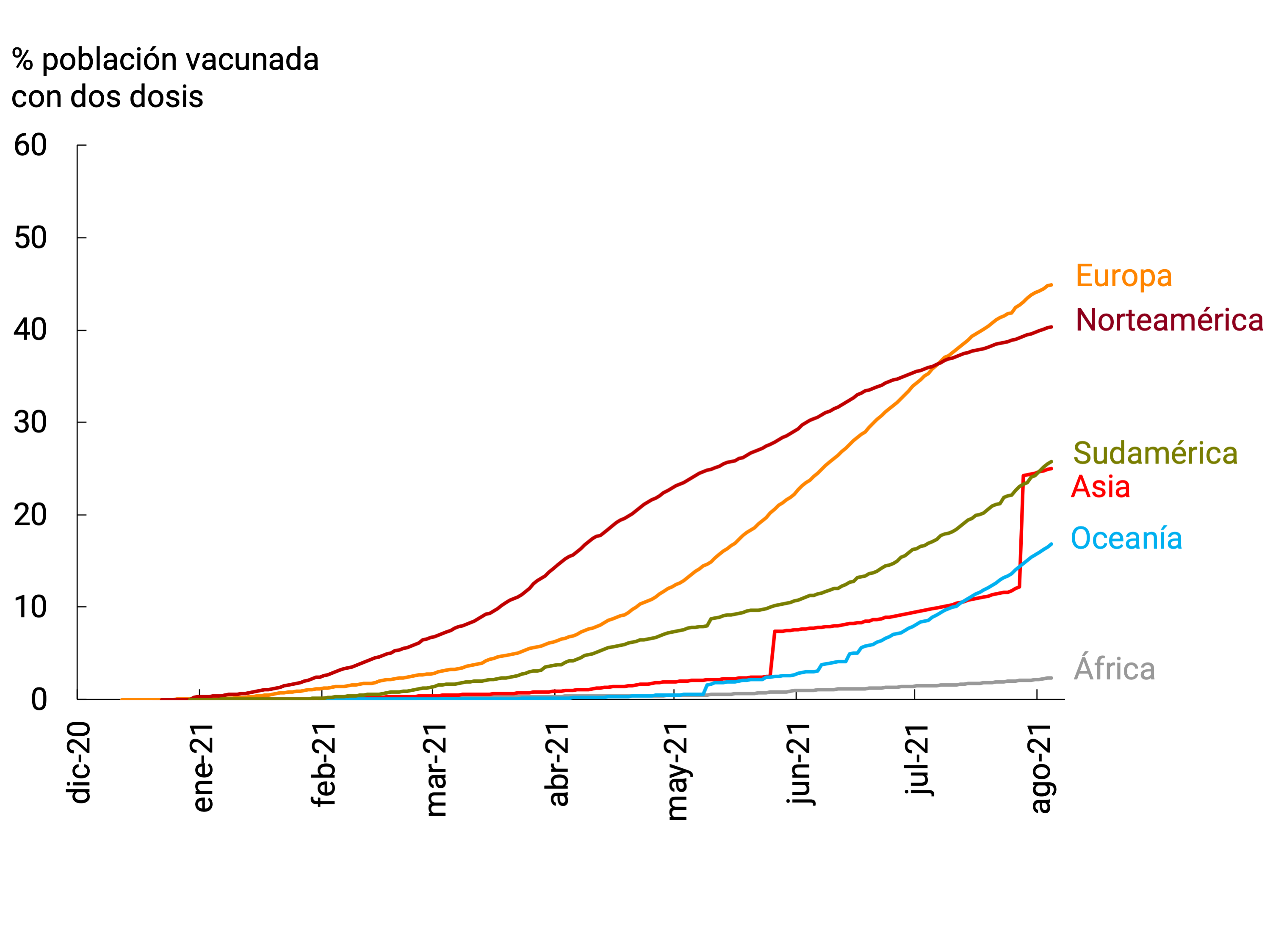

Figure 2.2 | Vaccination evolution by continent

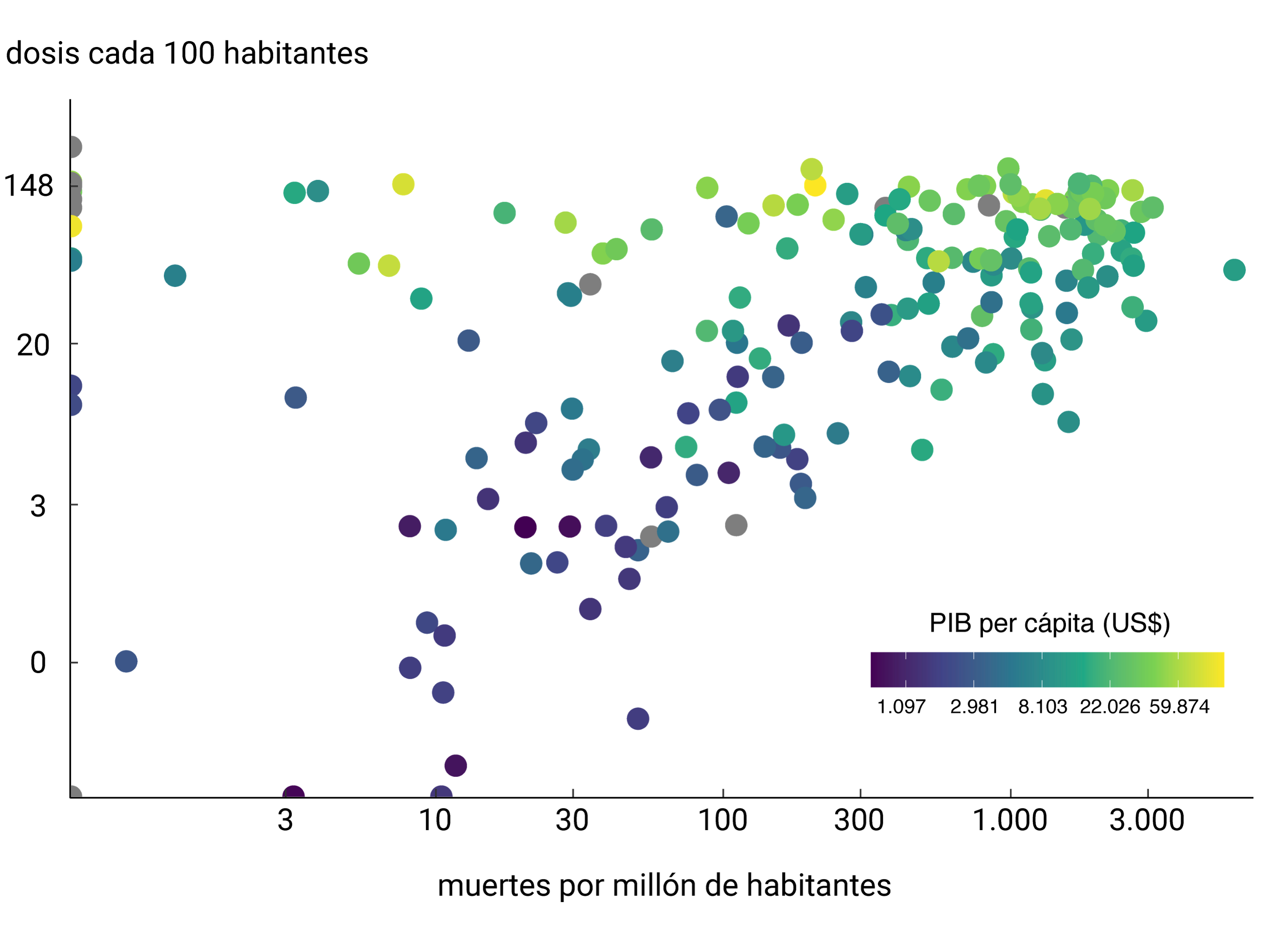

The intensity of vaccination not only depends on the severity of the pandemic, but at the same level of deaths per million, lower-income countries vaccinated much less (see Figure 2.3). Between continents, the gap narrowed in the application of first doses, but continued to be noticeable in the proportion of the population vaccinated with two doses (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.3 | Vaccination (doses applied per capita) and deaths from COVID-19 according to GDP per capita

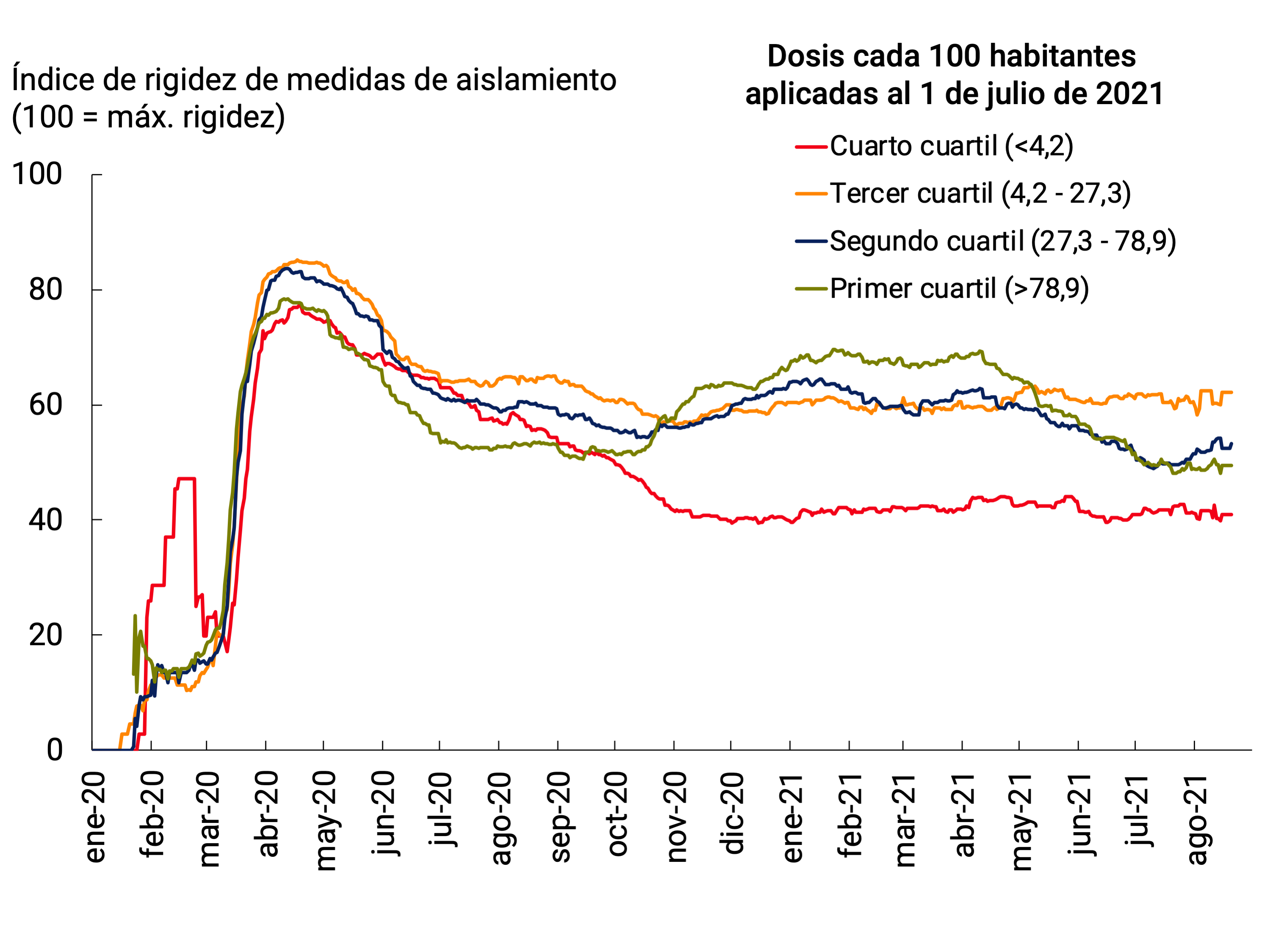

Figure 2.4 | Variation in the rigidity index of social distancing measures according to vaccination progress

Since May there has been a general increase in mobility. The countries that made the most progress in vaccination removed the most restrictions in recent weeks (see Figure 2.4)2. The inequitable distribution of vaccines, then, is relevant for at least two reasons: the emergence of new, potentially more aggressive variants in areas of high viral circulation; and because it could accentuate an uneven recovery in activity.

2.2. Global economic recovery continues, but divergence between groups of countries is accentuated

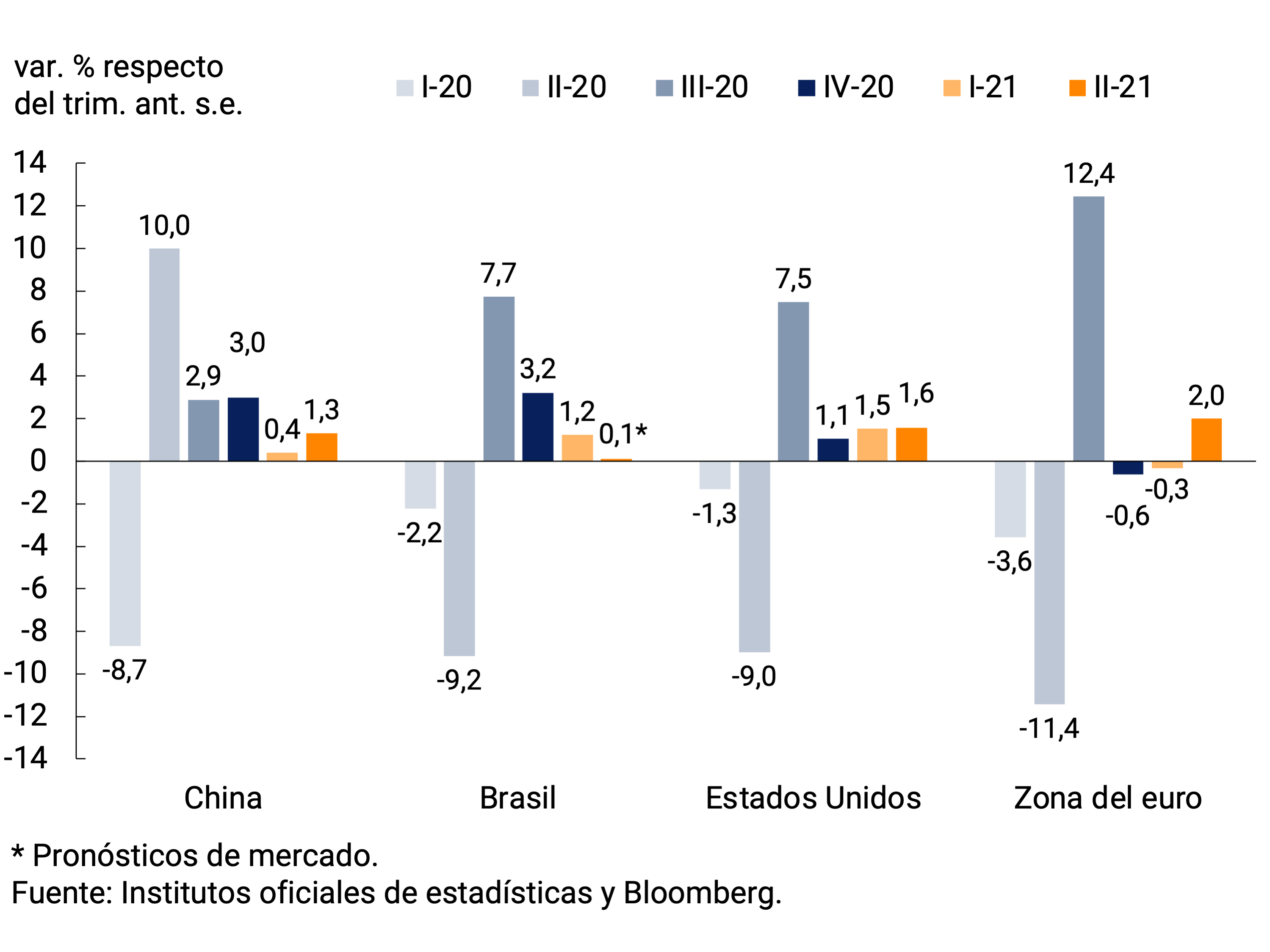

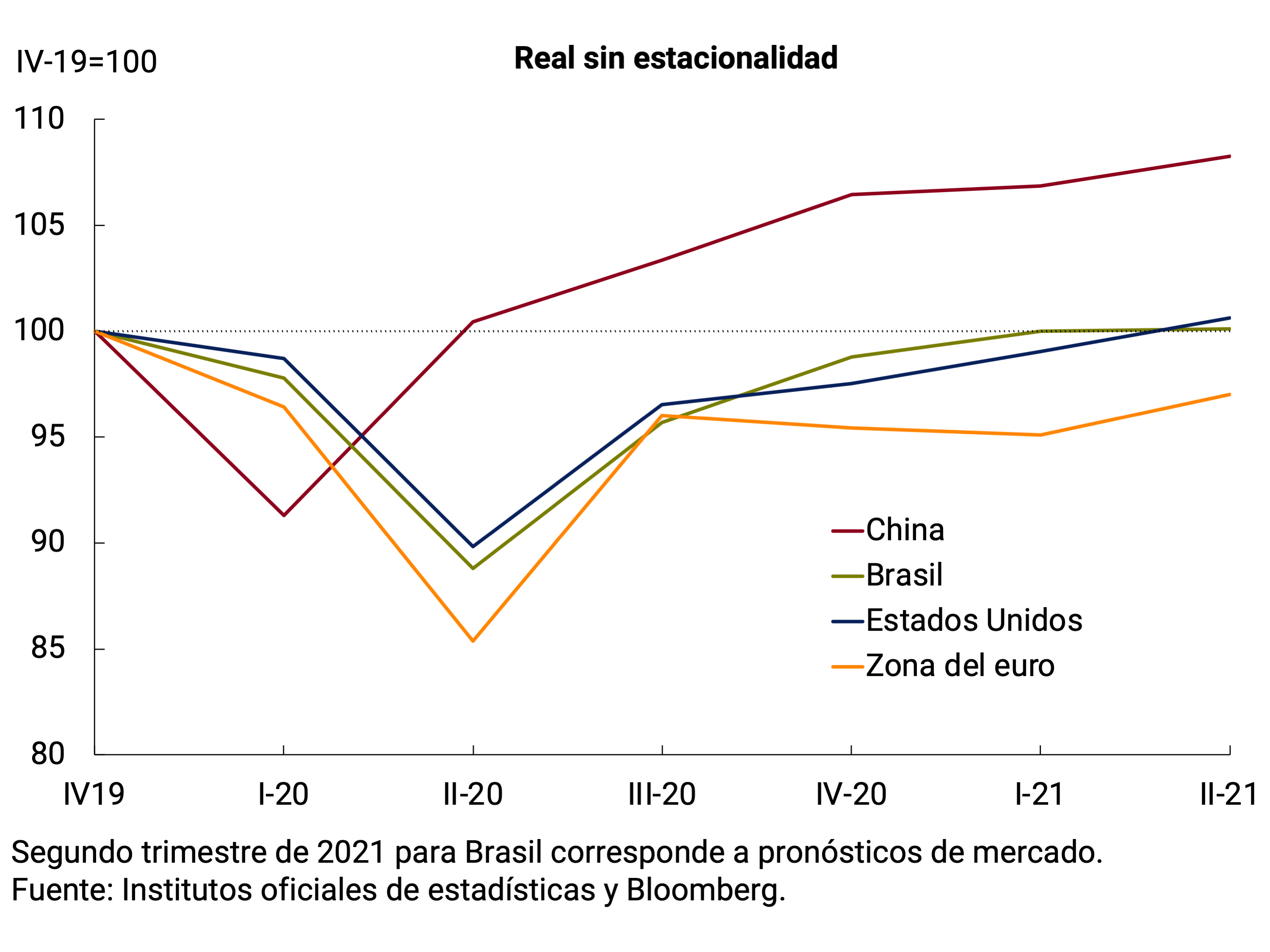

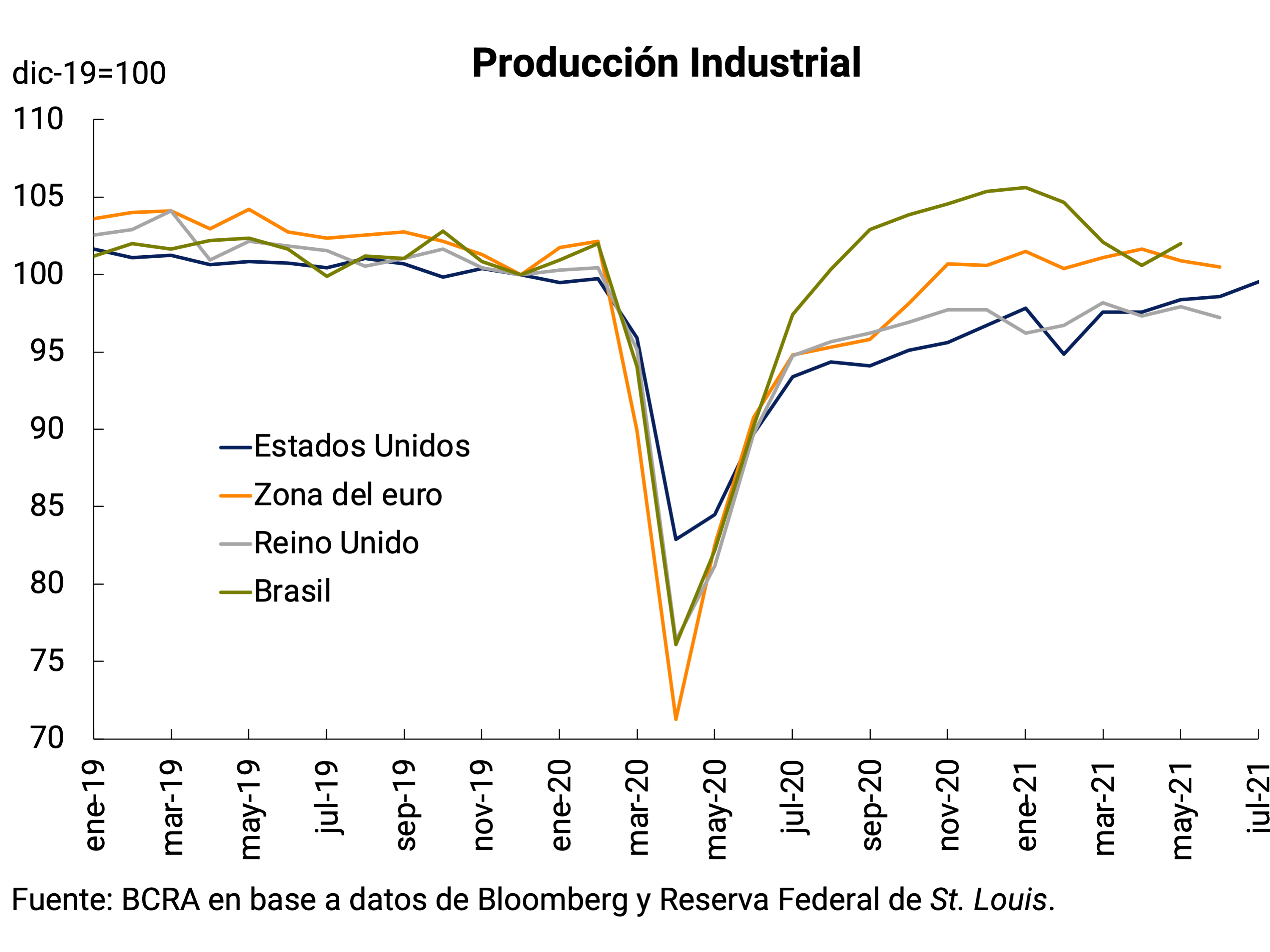

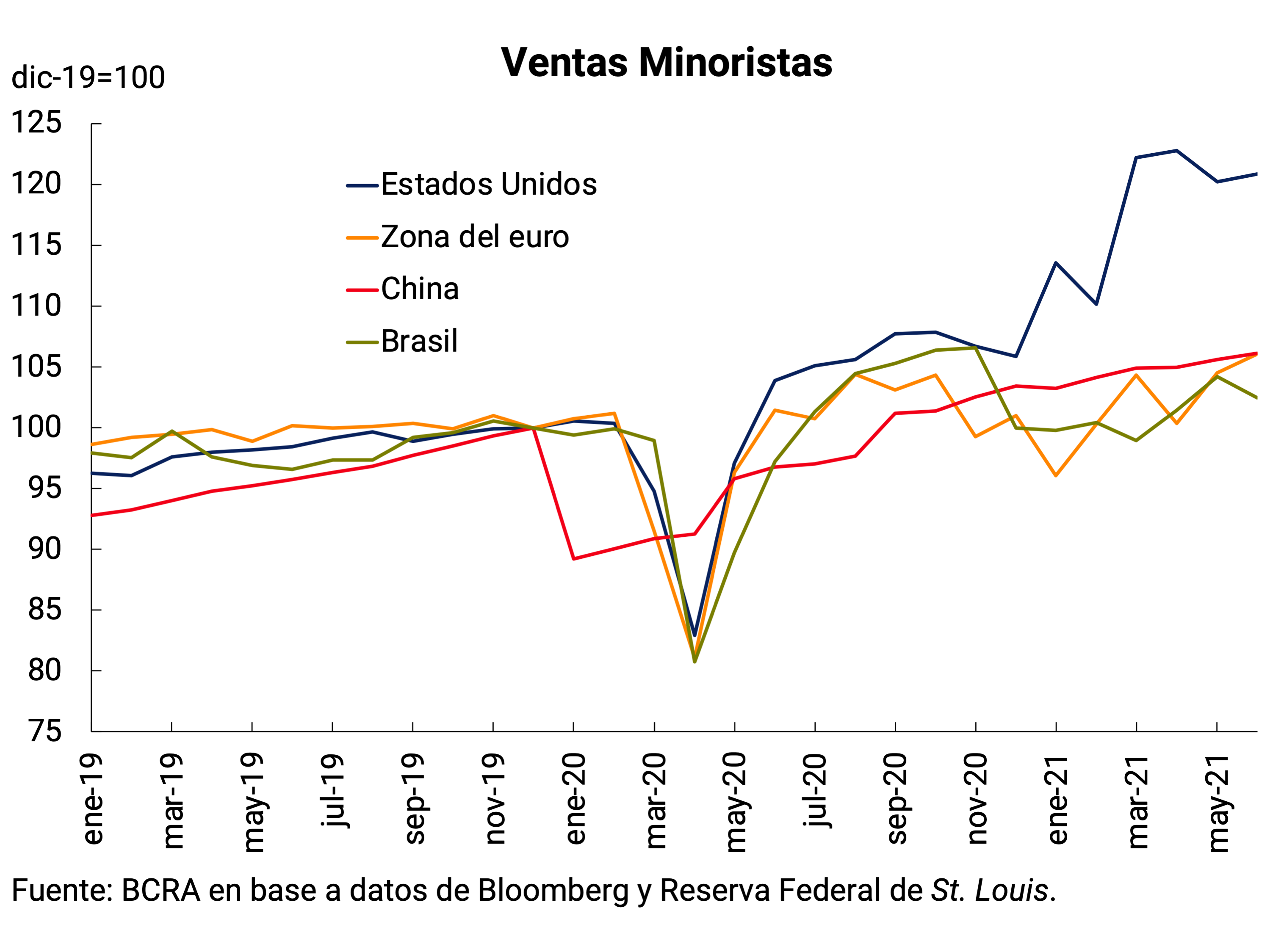

The global economy continued to recover in the second quarter of the year (see Figure 2.5). With regard to Argentina’s main partners, in the United States, economic activity accelerated in the first two quarters compared to the last quarter of last year, due to the progress of vaccination and greater fiscal stimulus. In the euro area, after the fall in the economy in the first quarter due to the impact of the second wave, activity grew again in the second quarter thanks to the reopenings and also a greater fiscal boost in some countries. In Brazil, the second wave reduced the economy’s growth rate in the second quarter, while in China it accelerated, after a first quarter of more moderate expansion. Thus, at the end of the first half of the year, activity levels in China, the United States and Brazil were above or close to pre-pandemic levels, while in the euro area they were still 3% below.

Figure 2.5 | Evolution of the GDP of Argentina’s main trading partners

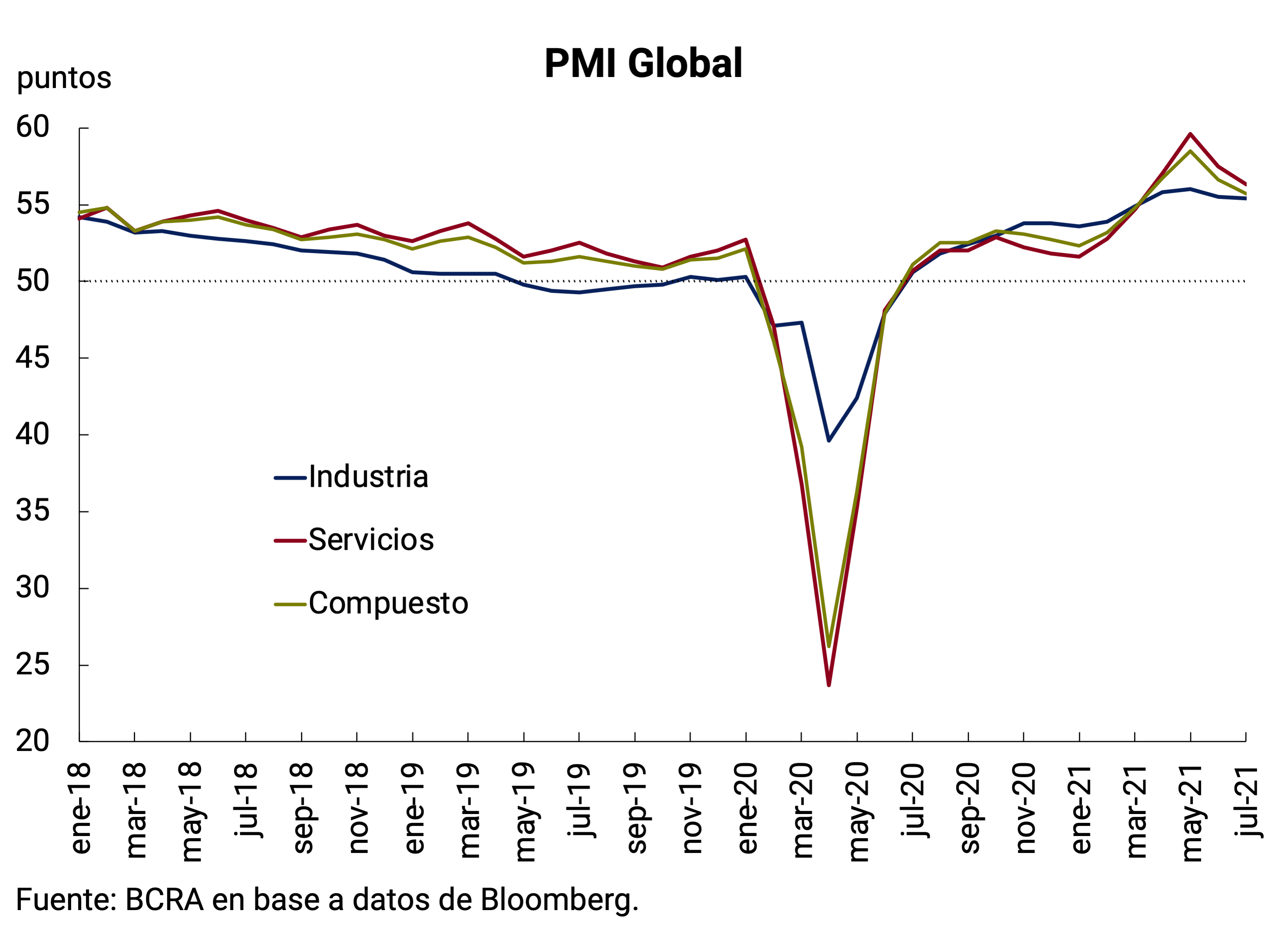

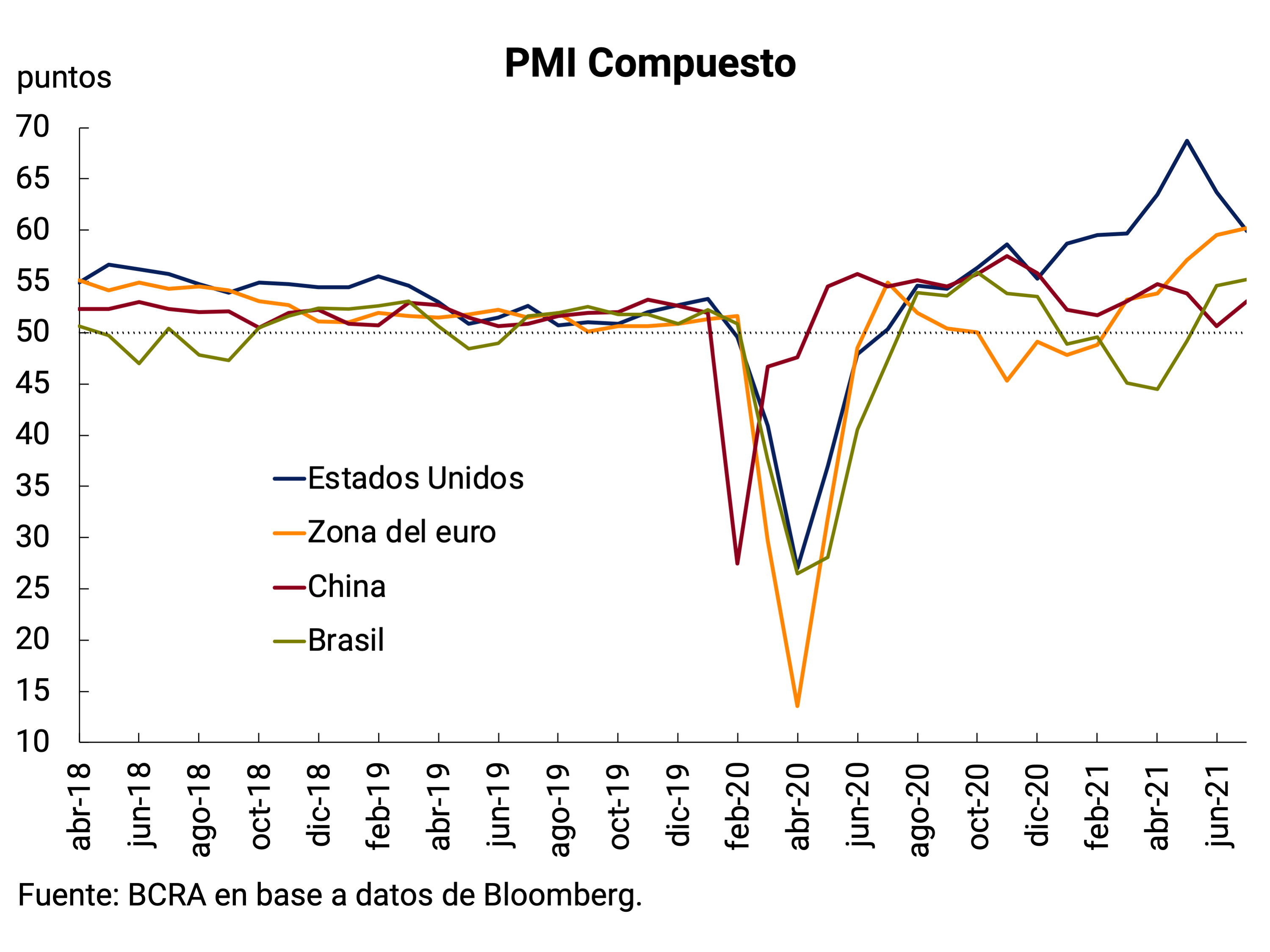

High-frequency data and some forward-looking indicators point to a continued recovery in global activity. In May and June, the global purchasing managers’ indicator (PMI) marked twelve consecutive months in expansionary territory (above 50) and was at the highest levels in the last fifteen years. The services sector showed a better performance than manufacturing in recent months in the face of the reopenings that were registered in several countries, and which allowed the recovery of close contact services (linked to tourism and leisure, for example). The United States and Europe showed greater dynamism in recent months with higher PMI levels compared to emerging economies. The continuation of the global recovery in recent months could also be seen in the indicators of industrial production and retail sales (see Figure 2.6).

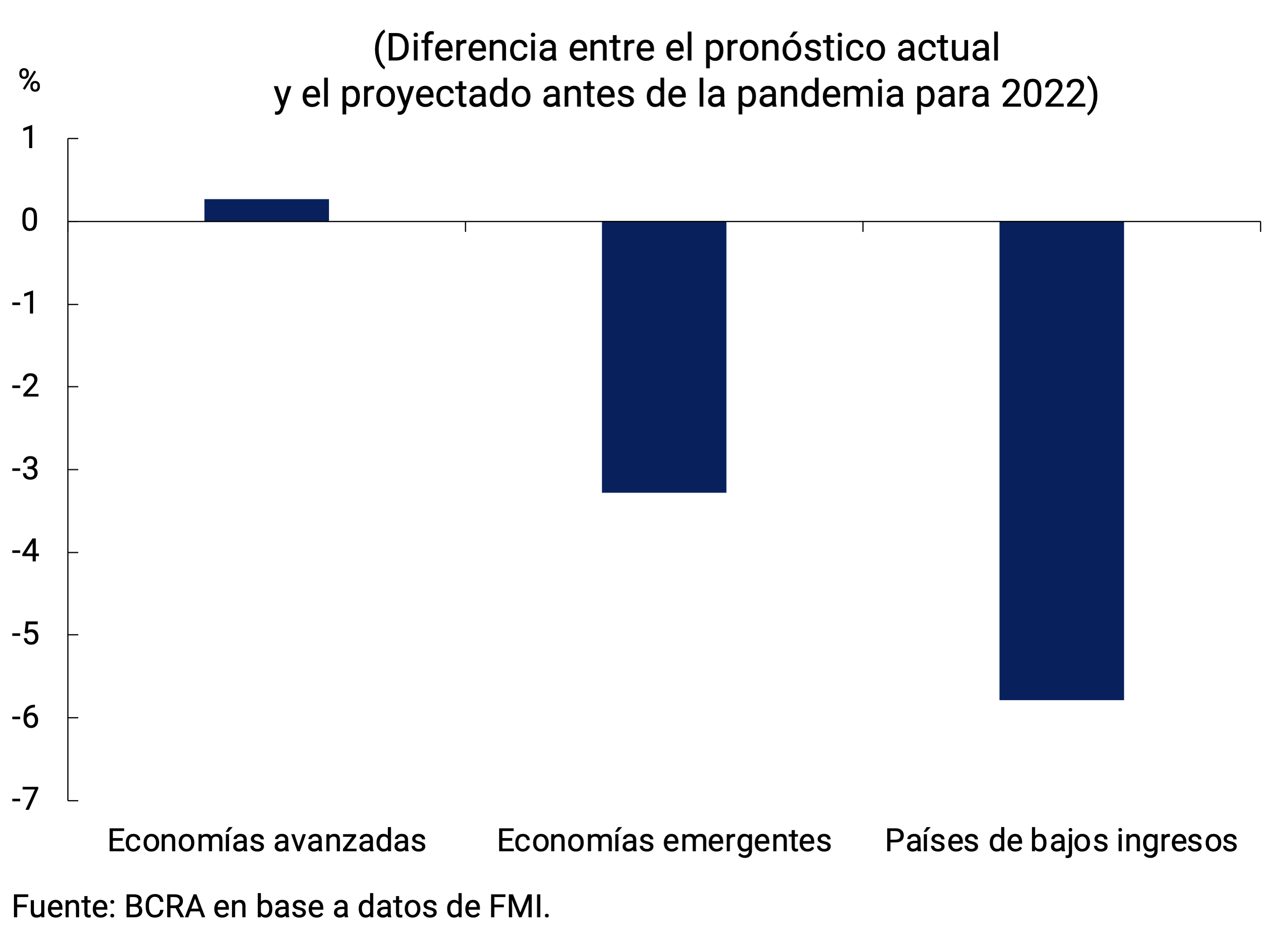

Figure 2.6 | Activity indicators

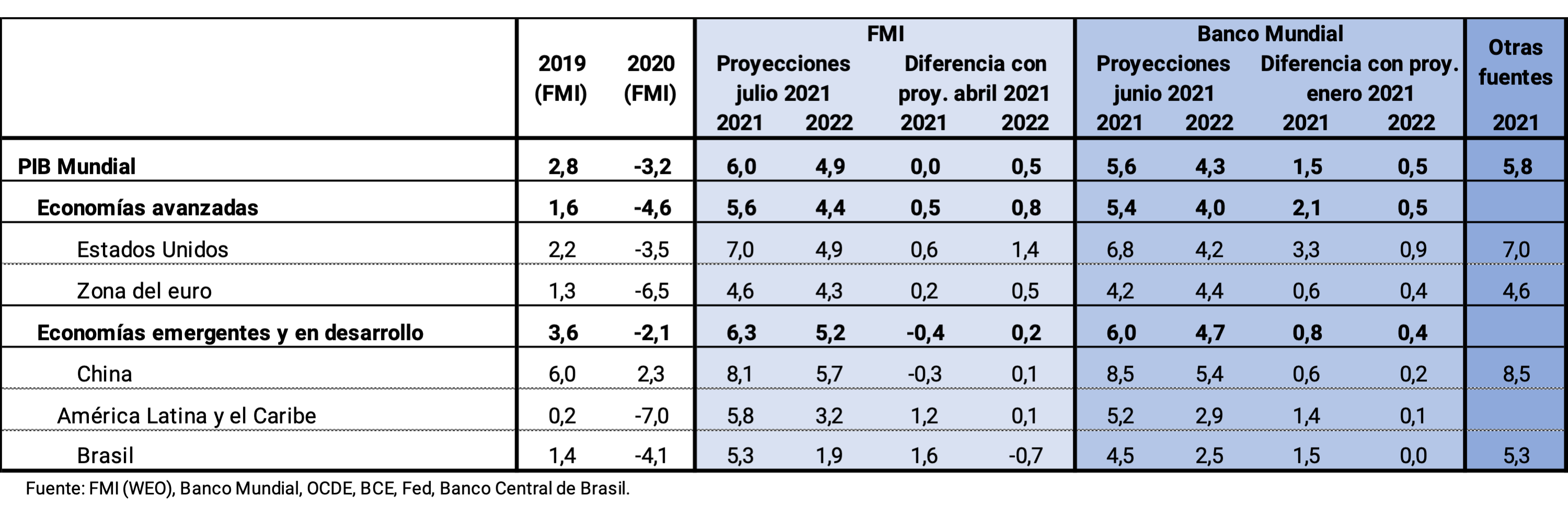

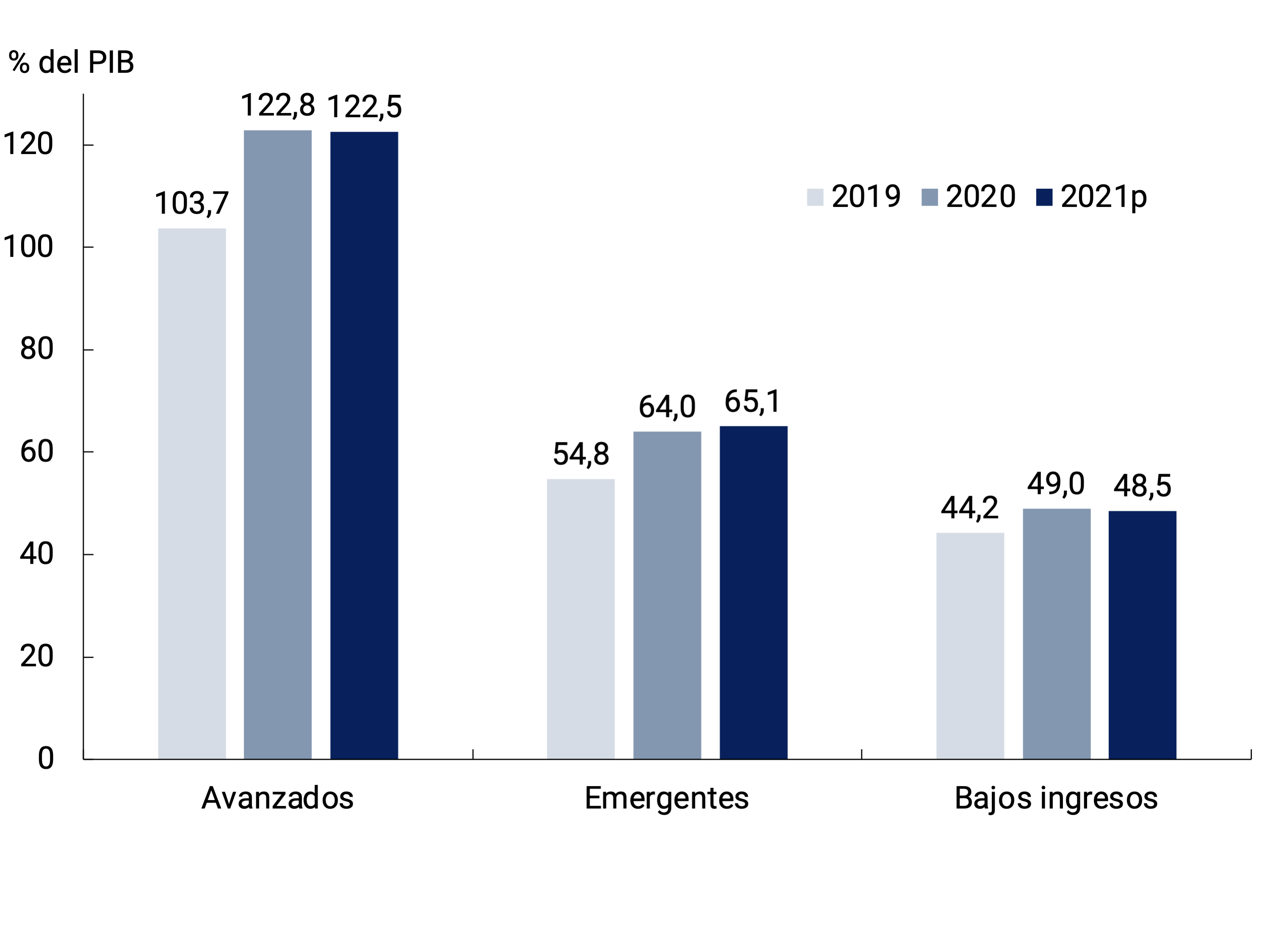

The latest forecasts also agree that the recovery would continue (see Table 2.1). The International Monetary Fund expects the world economy to grow 6% in 2021 and raised growth in 2022 to 4.9%. However, the divergence in recovery between groups of countries would be accentuated. On the one hand, the GDP growth projection was increased for advanced economies (+0.5 p.p. for 2021 and +0.8 p.p. for 2022). In this group, the performance of the United States stands out, with an expected growth of 7% for this year and 4.9% for next year. The sharp upward revision (+0.6 p.p. and +1.4 p.p., respectively) responds to the new medium-term fiscal stimulus plans promoted by the U.S. government. However, for developing economies (emerging and low-income countries) the growth forecast was lowered in 2021 and revised slightly upwards in 2022 (-0.4 p.p. and +0.2 p.p., respectively), mainly due to a lower expected performance for the economies of Asia (China, India and Southeast Asia). Developing economies would generally take longer than advanced economies to reach the growth path projected before the pandemic, due to less policy space and greater difficulties in accessing vaccines, which would create wider gaps between these countries’ living standards (see Figure 2.7).

Table 2.1 | Economic projections

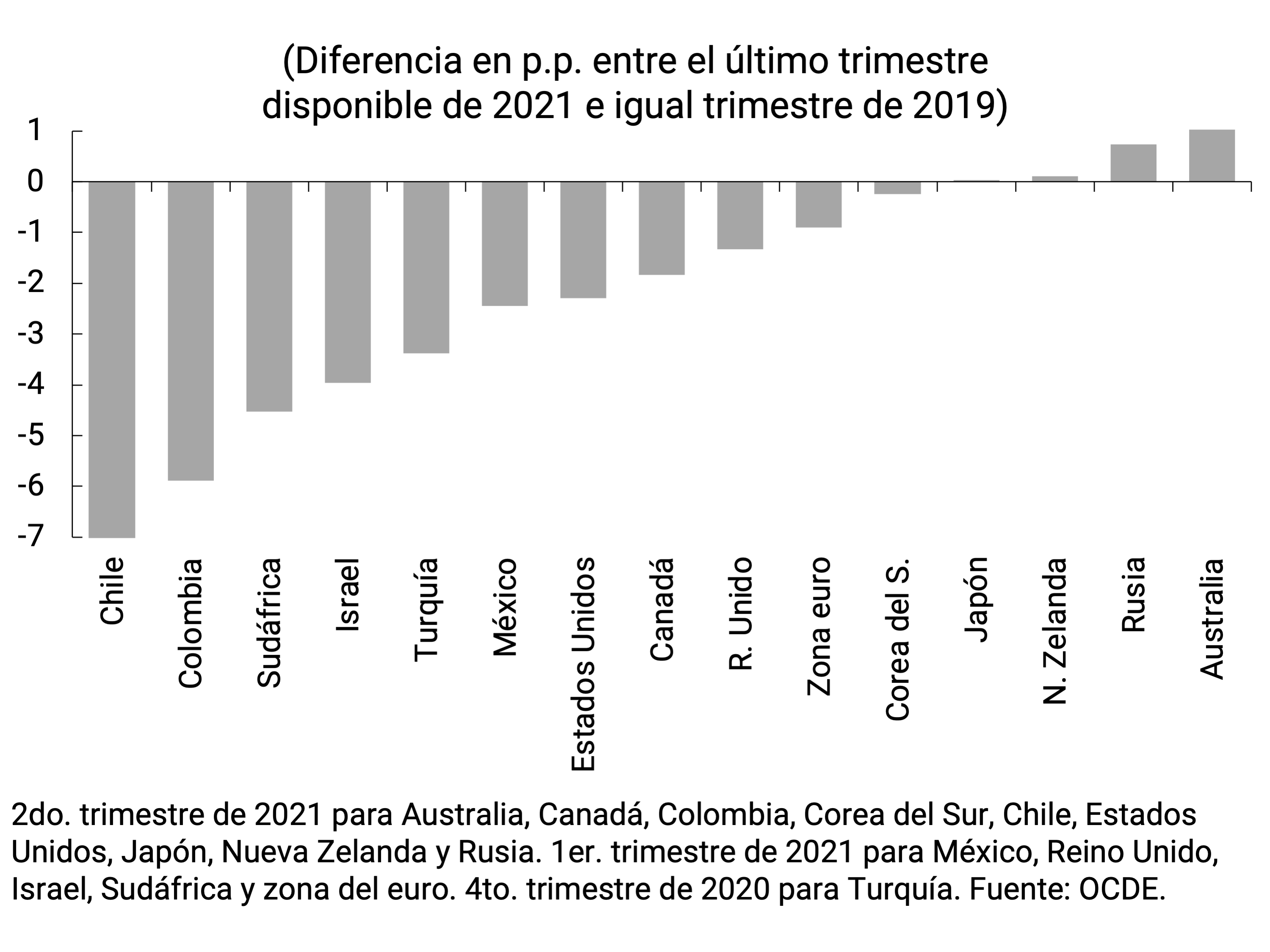

The labour market shows less dynamism in the recovery. The improvement in employment is far from complete, even in places where the level of activity has returned or would be close to reaching pre-pandemic levels. Employment has increased since the peak of the second and third quarters of 2020 but generally remained below pre-pandemic rates (see Figure 2.8).

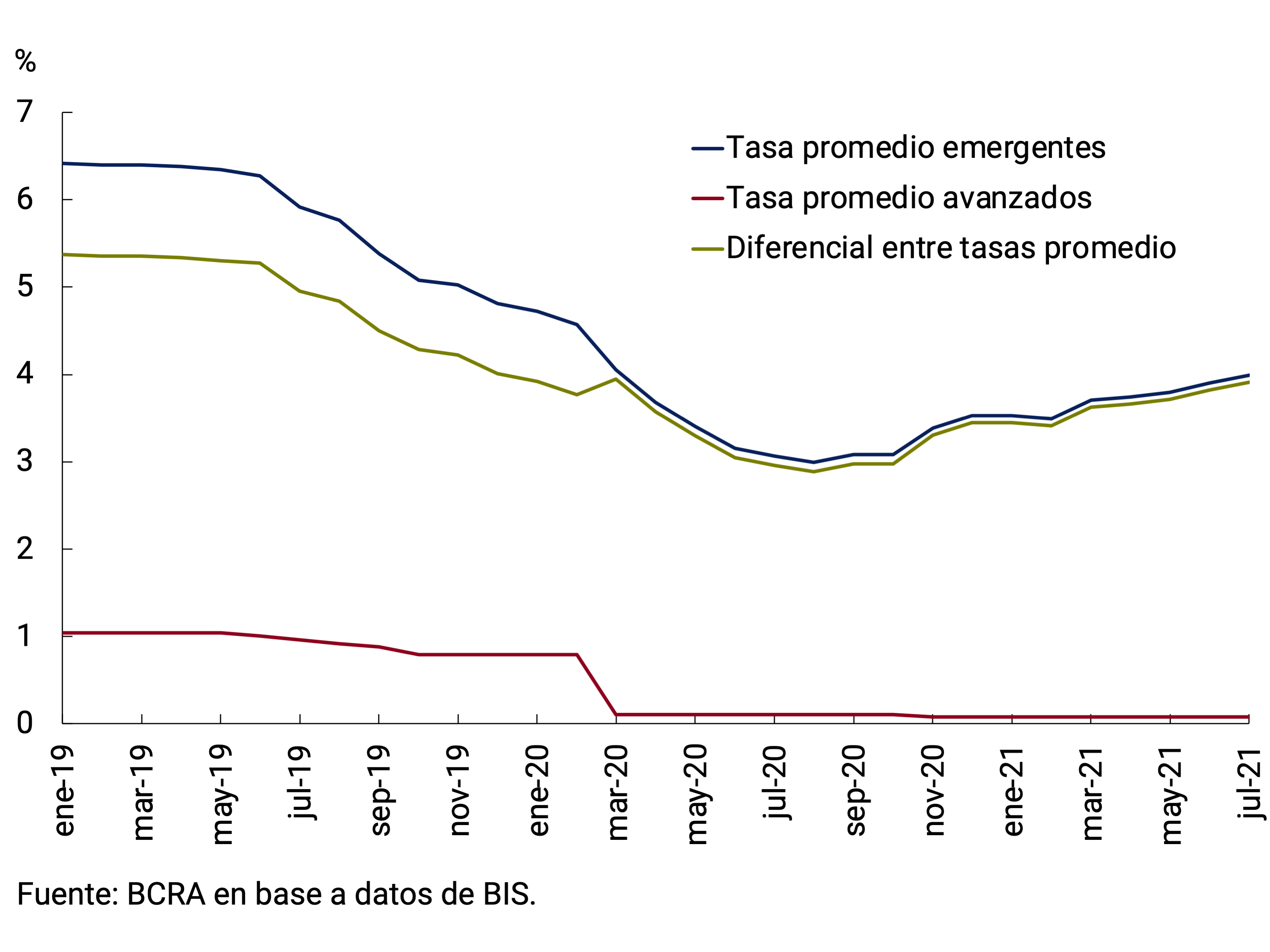

2.3. Monetary and fiscal policies: the expansionary bias continues, although stimuli are beginning to be withdrawn, especially in developing countries

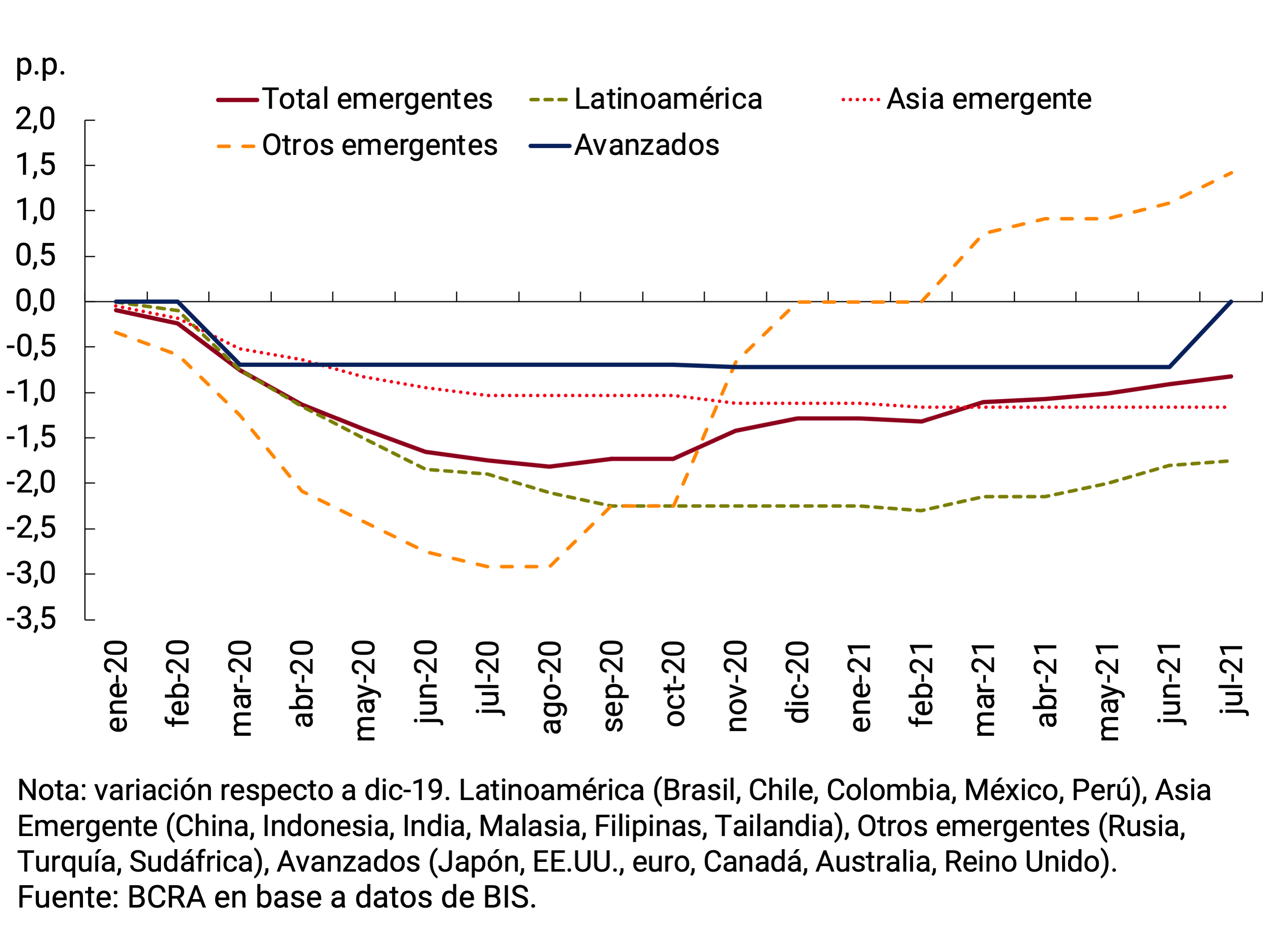

Monetary policy in advanced countries continued to be expansionary in the last three months, although in some cases “unconventional” measures were reduced. As we anticipated in the previous IPOM, some emerging countries began to take contractionary monetary policy measures (see Figure 2.9). In all cases, inflation has had a clear upward trend, in some cases exceeding the inflation target. In most of the countries analyzed, the monetary authorities estimate that the rise in inflation would be transitory, as reflected in the expectations surveys.

Figure 2.9 | Monetary policy indicators

Central banks in advanced economies have kept their benchmark interest rates unchanged in recent months. The largest economies (the United States, the euro area, Japan, and the United Kingdom) also did not change their unconventional monetary policy programs, while countries such as Australia and Canada began to reduce them. In particular, the Federal Reserve of the United States (Fed) would announce in the second half of 2021 the reduction of its asset purchase program of US$120,000 thousand per month, which would become effective by the end of the year. (according to the minutes of the last meeting of the Open Market Committee, FOMC). In addition, FOMC members’ projections anticipated the likely date of its benchmark interest rate hike to 2023 (from 2024). For its part, within the framework of its new monetary policy strategy3 , the European Central Bank (ECB) would keep its quantitative easing program unchanged at least during 2021.

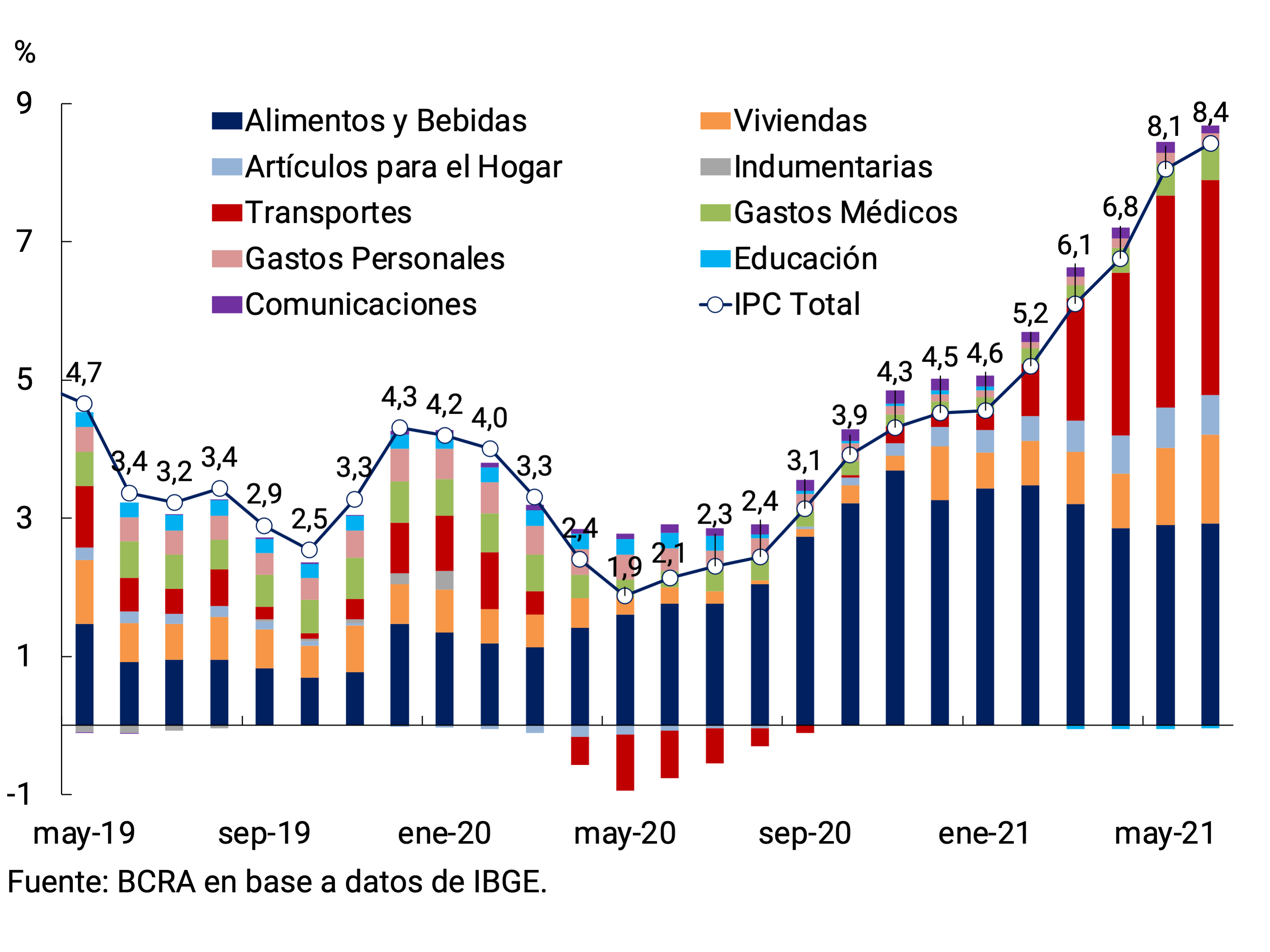

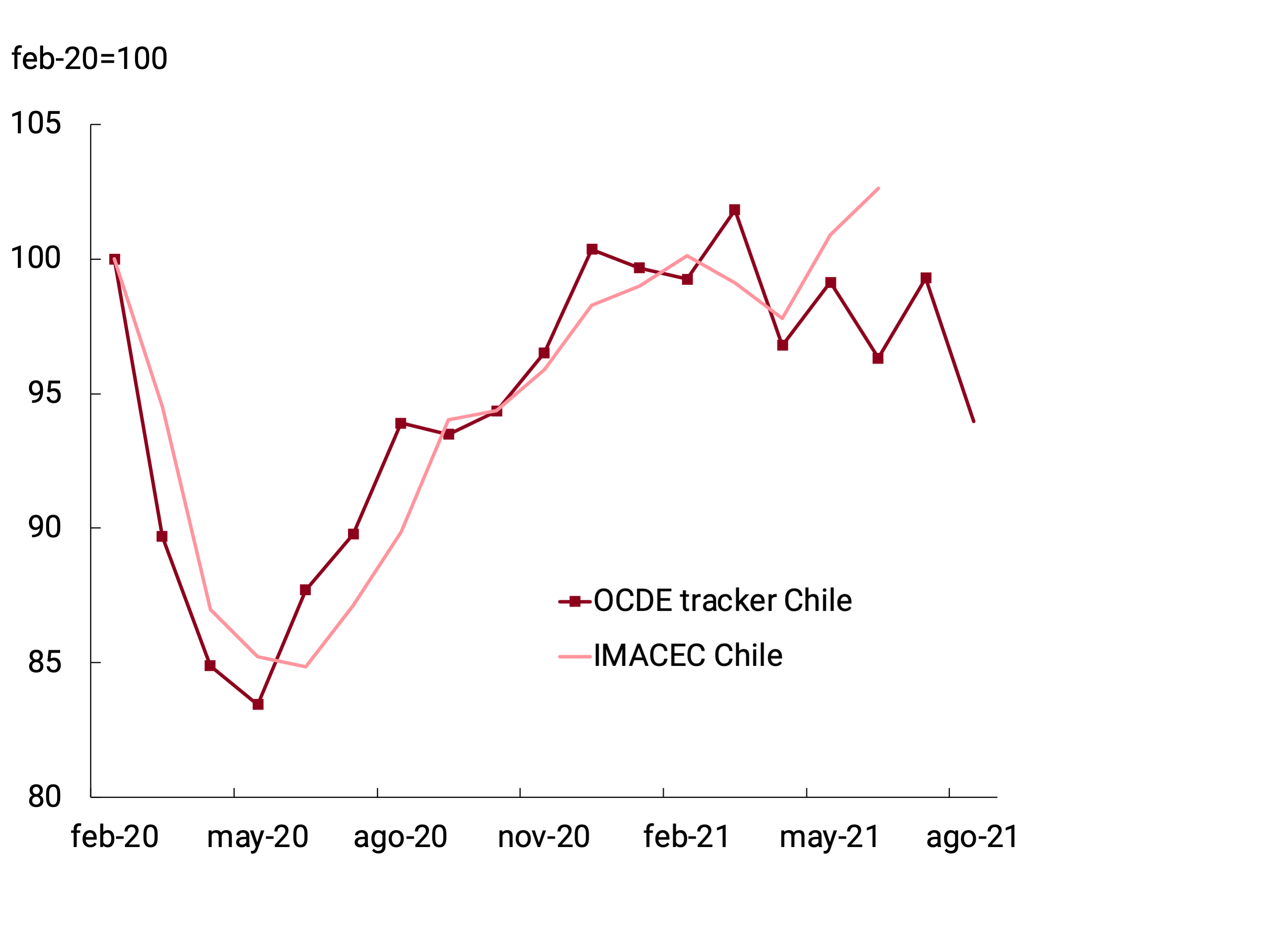

Some emerging countries began to raise their monetary policy interest rates. Brazil increased it by +1.75 p.p. since the last IPOM) due, among other factors, to the fact that inflation accelerated to 9% y.o.y. in July after several months of increase, above the target (2.25-5.25%). Chile’s monetary authority also took contractionary measures through the interest rate (+0.25 p.p. since the last IPOM), due to an inflation rate above the target (4.5% YoY in July and a target of 3%). Other central banks that increased their benchmark interest rates due to inflation above their targets were Mexico and Russia (increases of 0.25 p.p. and 1.5 p.p. since the last IPOM, respectively), while Turkey’s kept it at double-digit levels due to high inflation (see Figure 2.10).

Figure 2.11 |

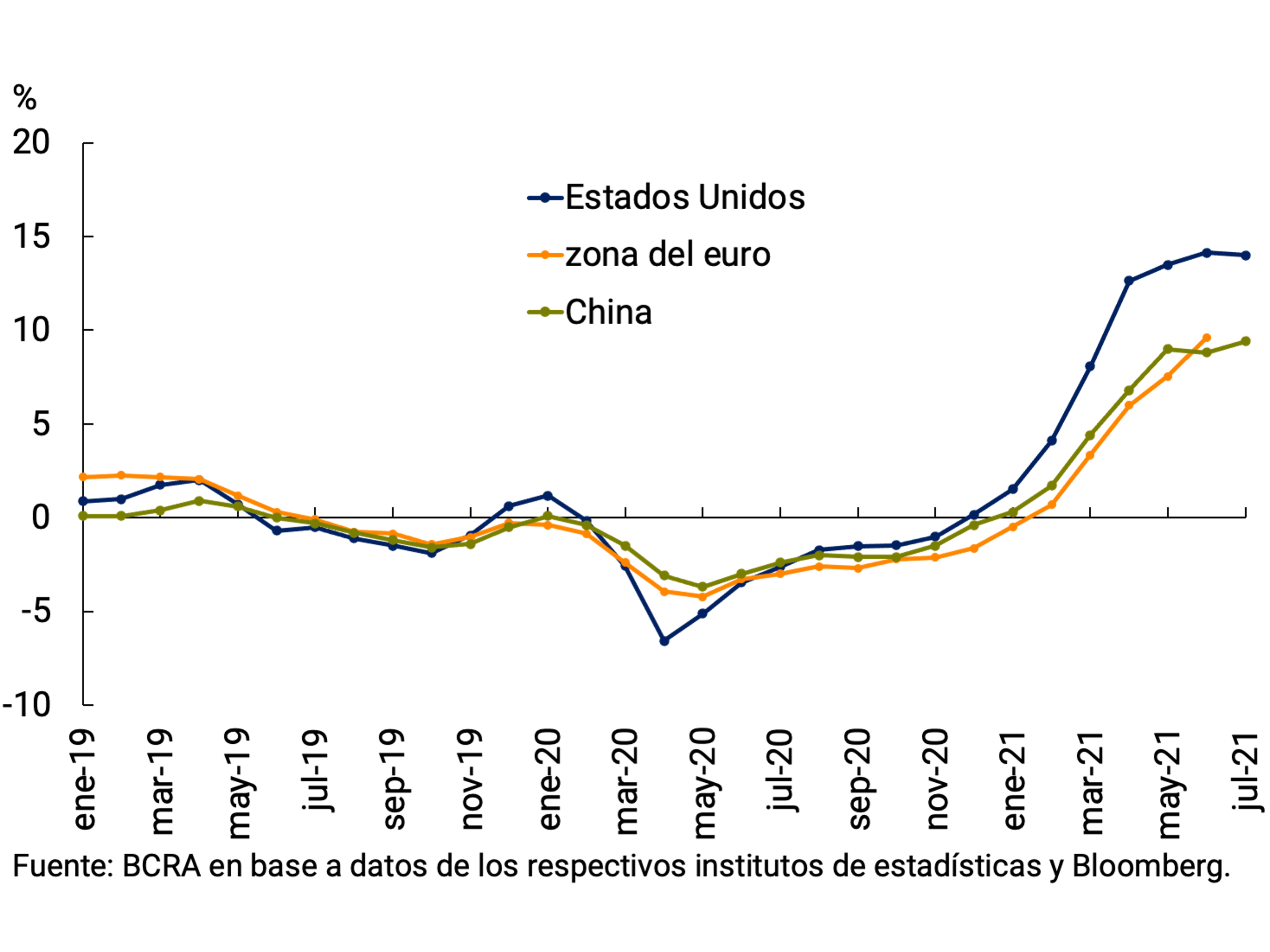

Different factors underlie the inflationary acceleration, such as the global economic recovery and the “bottlenecks” in many sectors (shortage of microchips with an impact on different industries, including the automotive industry), together with higher energy prices, “base of comparison” effects and increases in certain goods affected by the pandemic (see, for example, a recent report by the Bank for International Settlements). Wholesale inflation has also accelerated in many countries (see Figure 2.11); this affected Argentina’s import prices (see Chapter 4. External Sector).

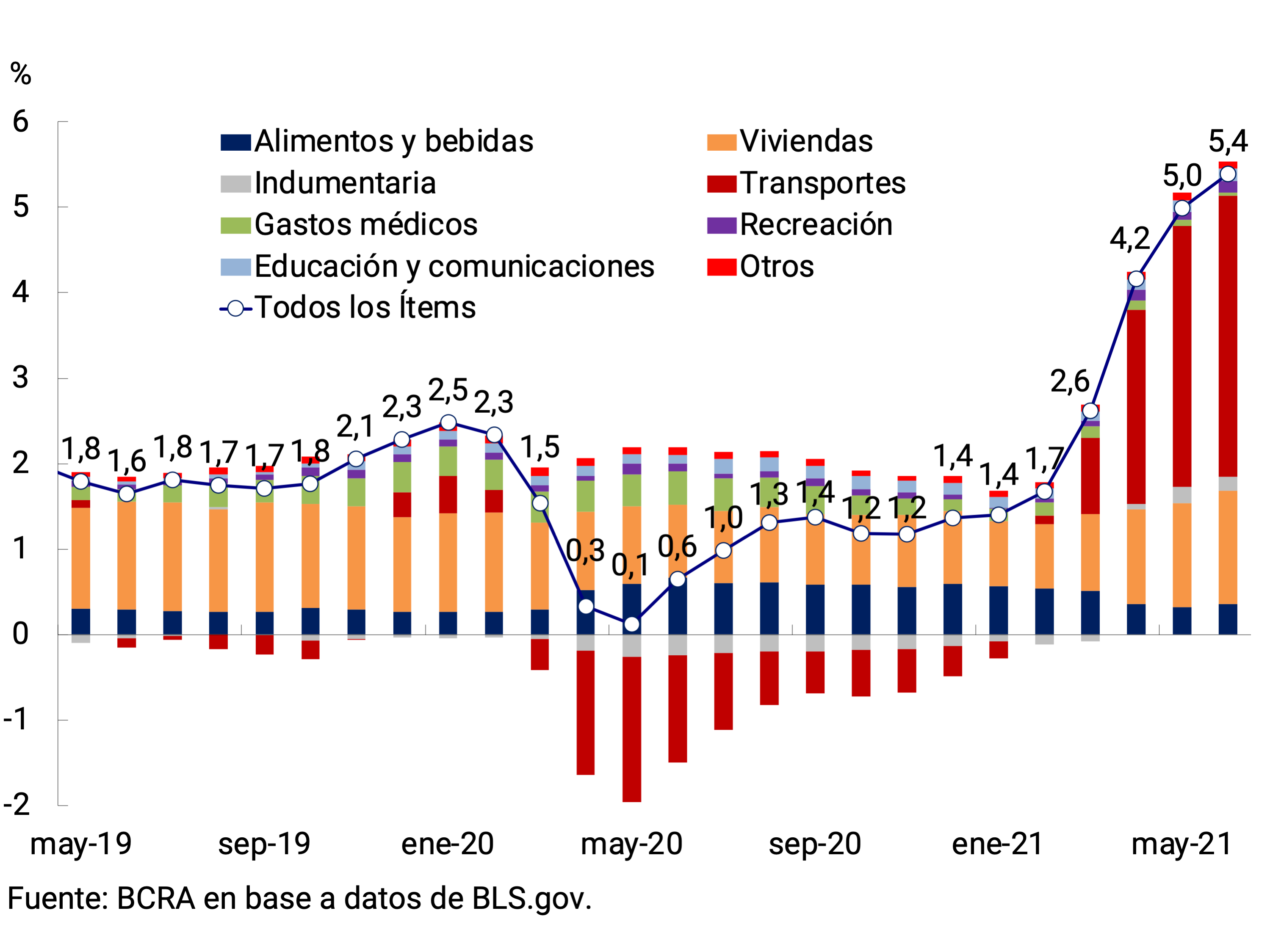

From a breakdown of the inflation rate of different countries among their main items, it emerges that those that contributed the most to the increase in prices were the items linked to the price of oil, such as transport and housing (the latter includes increases in electricity and gas). Another factor that would have been influencing part of the transport sector is the increase in the price of vehicles due to the shortage of some of their inputs. In developing countries, this dynamic has been enhanced by exchange rate depreciation in response to the crisis and higher commodity prices. For example, the two items that had the greatest impact on the increase in inflation in Brazil were food and beverages and transport, linked to the factors mentioned above (see Figure 2.12).

Despite higher inflation, expectations remain relatively stable over the medium term (see Figure 2.13). This is evident in advanced countries, but also in some developing economies such as Brazil. This supports the notion that the recent increase is perceived as transitory.

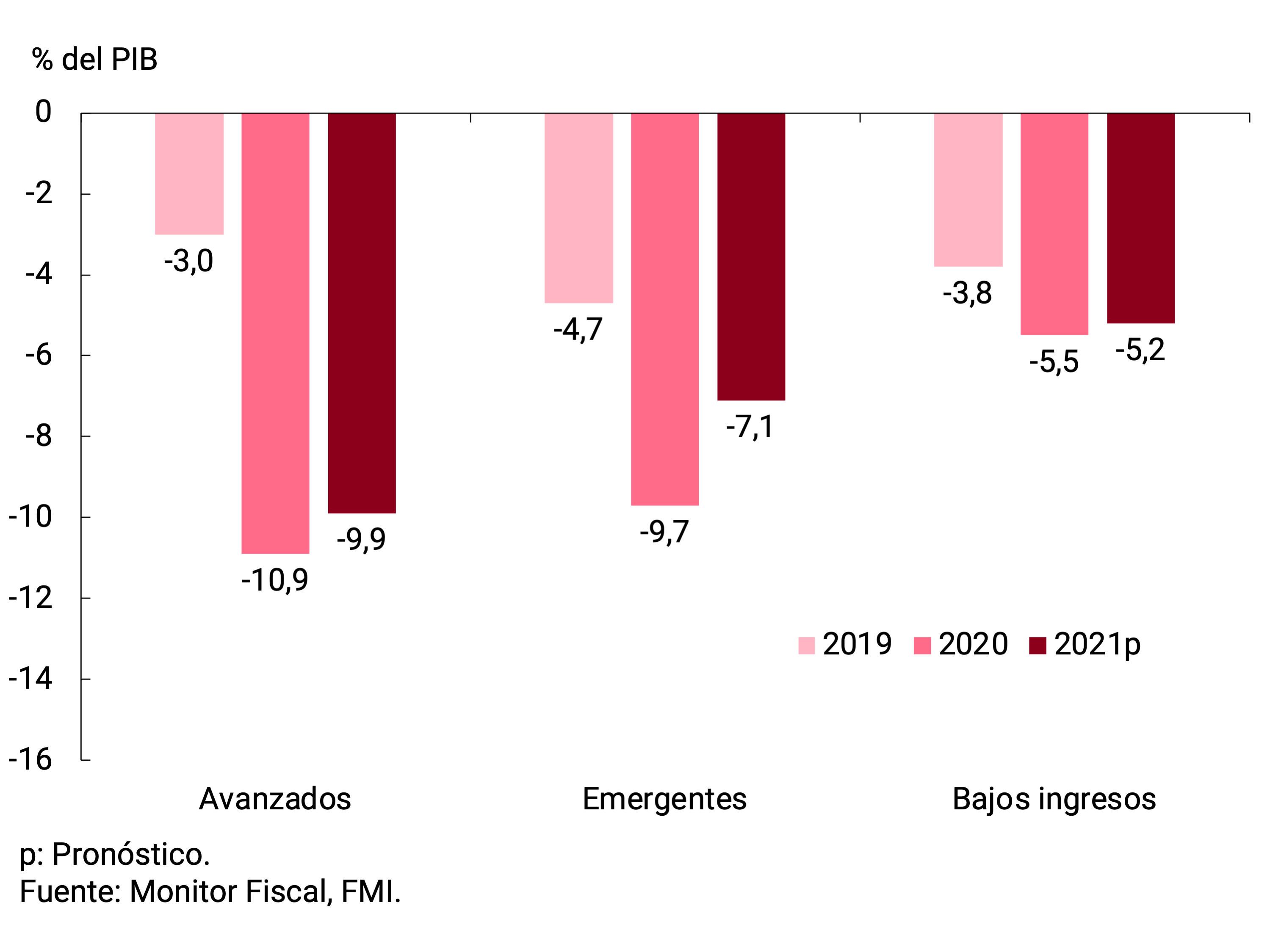

In the second quarter of the year, the fiscal policy response to the pandemic increased by US$500 billion globally, reaching 16% of global GDP (+0.6% of GDP), according to IMF data. Most of this new support was provided in advanced countries (euro area, the United Kingdom, Japan, Canada and Australia) to deal with the outbreaks at the beginning of the year, while many developing economies sought to rebuild their fiscal positions. For the coming years, with the promotion of the Employment Plan and the Family Plan in the United States and the advance of the “New Generation” plan in the European Union, the differences in fiscal stimulus could remain, which would further complicate the possibilities of convergence between advanced and developing countries.

Most countries would register smaller deficits in their public accounts in the year than in 2020, although still high. The largest imbalances would be registered in advanced countries, which would close the year with an average fiscal deficit of 9.9% of GDP, while emerging economies and lower-income economies would end up with imbalances of -7.1% of GDP and -5.2% of GDP, respectively. This fiscal dynamic, together with the expected recovery in economic activity, would lead to a moderation in the evolution of debt-to-GDP ratios at the global level this year, even with slight declines in advanced and lower-income countries (see Figure 2.14). However, for some middle-income and low-income countries, financing large deficits remained a challenge, given limited market access and limited scope for tax collection in the short term.

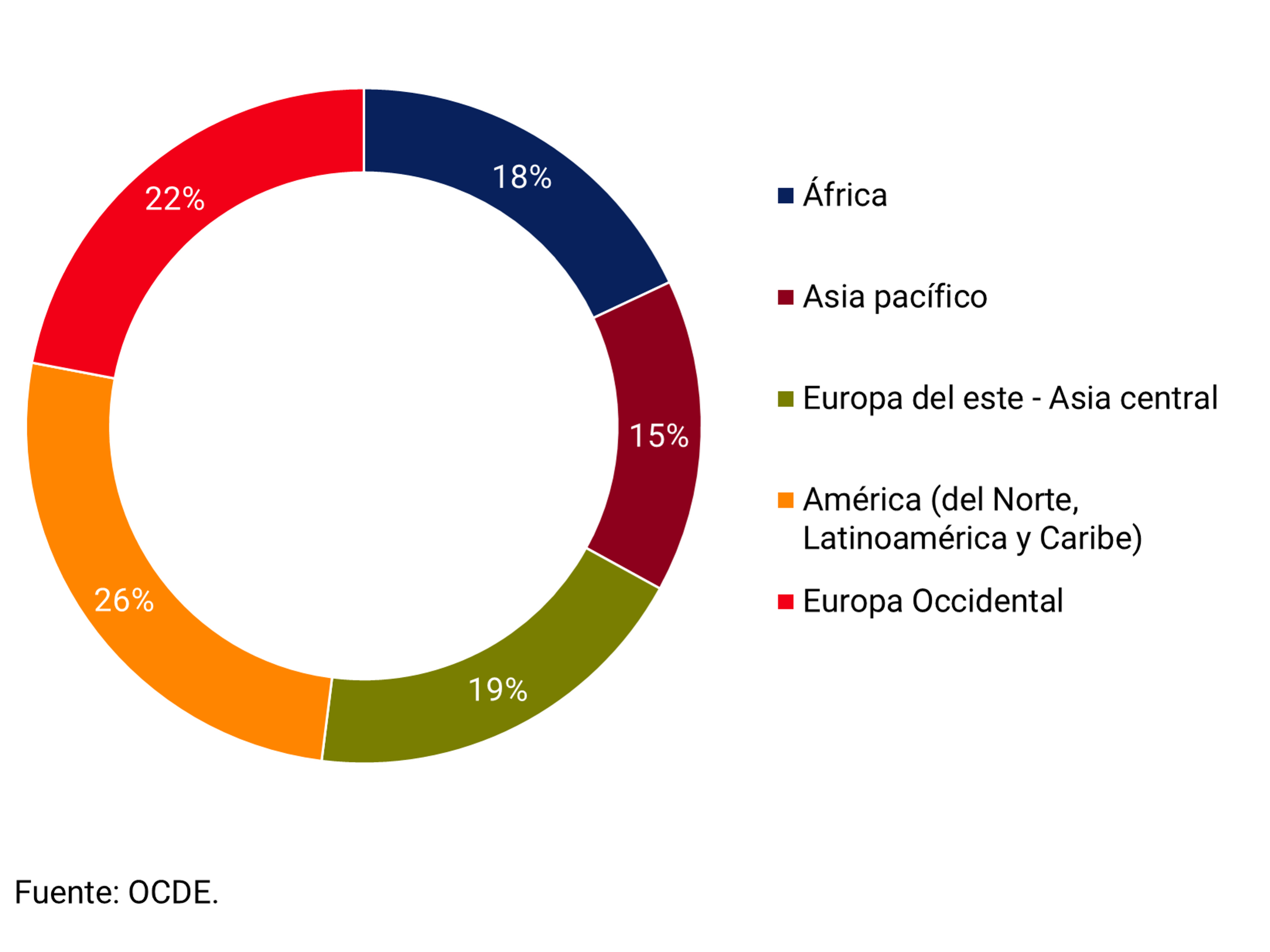

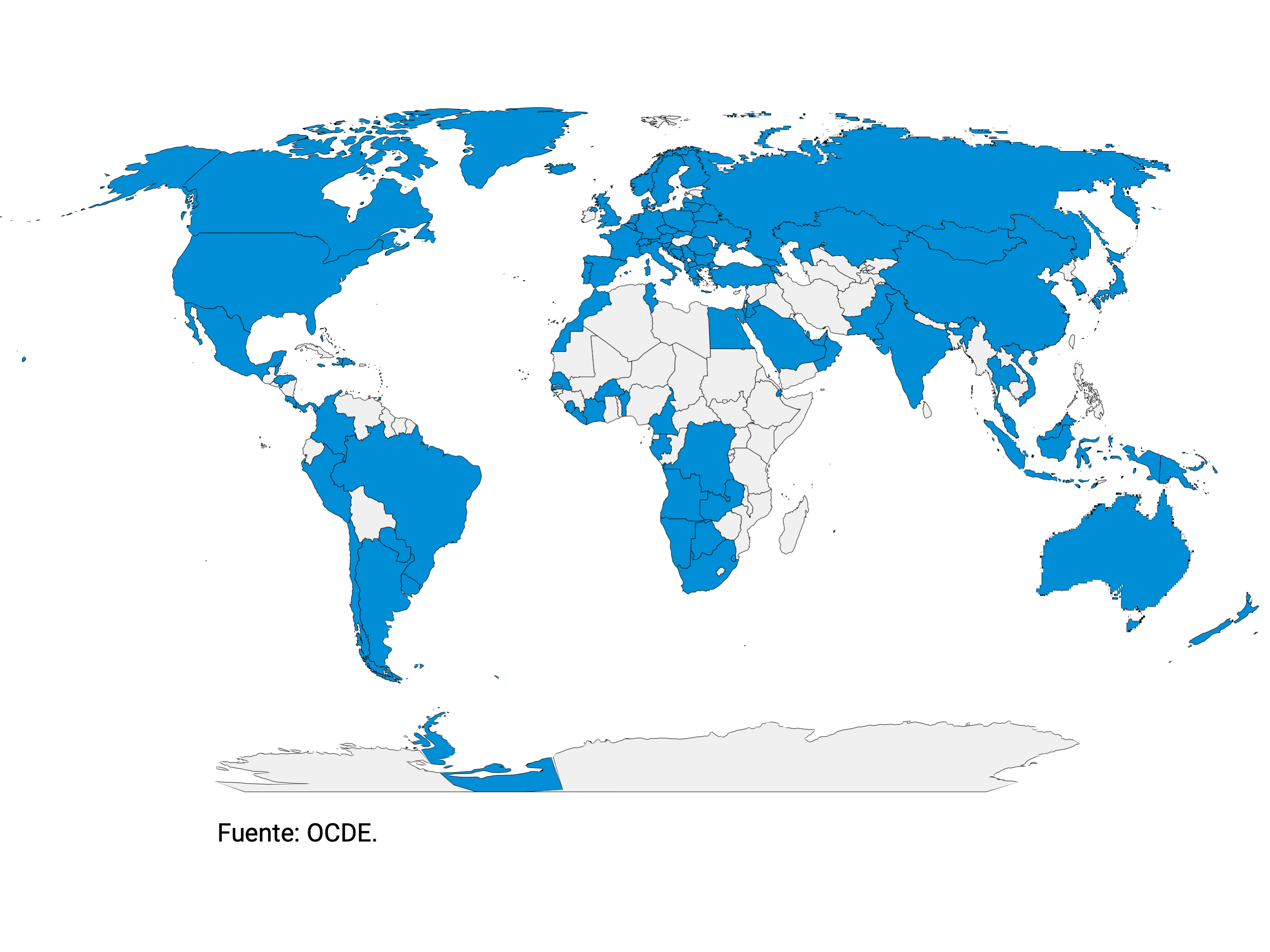

In the context of multilateral economic measures to address the crisis, the progress of the new allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) for US$650 billion was highlighted, which, after being approved by the IMF Board of Governors, was implemented on August 23 (Argentina received the equivalent of about US$4,350 million)5. In addition, at the last meeting of G20 ministers and central bank governors, the agency was tasked with exploring options for the recirculation of surplus SDRs from countries with strong external positions to vulnerable economies, which could include the creation of a new multilateral fund that also serves middle-income countries6. Another relevant event of international coordination was the approval of a tax agreement proposed by the OECD by 130 countries, which seeks to implement a global minimum income tax rate for multinationals and that the profits of large multinational companies are taxed in part by the countries where they sell products and services. rather than just those that host their headquarters or intellectual property (see Section 1 / Towards the definition of a new international tax scheme).

2.4. Markets: Declines in Long-Term Interest Rates and Stock Market Rises

Since the beginning of the year, there have been a couple of events of long-term interest rate hikes in advanced countries (with peaks in early April and mid-May) that generated concern and capital outflows from emerging countries. In recent times, the panorama seemed to have changed. While global growth expectations remained elevated, long-term inflation expectations in the United States, as measured by the difference between inflation-indexed bonds (TIPS) and Treasuries, declined and appeared to stabilize.

The market seemed to adhere to the thesis that the highest inflation in these months is a transitory phenomenon. Thus, despite the possibility of the Fed’s first rate hike for 2023 having been brought forward, the rate on the 10-year bond fell from the peak of 1.77 at the end of March and is already below 1.30 (see Figure 2.15). In addition, the differentials between long-term interest rates and short- and medium-term interest rates are falling, making the yield curve less steep. This is relevant because the increases in long rates and the steepening of the curve tend to be detrimental to capital flows to emerging markets. Meanwhile, the U.S. dollar hit a low in late May and from there began to appreciate against a basket of currencies. Finally, in Europe there was also a reversal of the rise at the beginning of the year, with the 10-year bond rates of the most relevant countries falling between 35 and 50 basis points since the close of the previous IPOM (see Figure 2.15).

Figure 2.15 |

Global stocks continued to rise, although at a slower pace than in the first months of the year. The U.S. S&P 500 was up 17 percent for the year, while Europe’s Stoxx 50 rose 16 percent over the same period. Stock markets surpassed pre-pandemic levels: for example, the S&P 500 was 36% above the end of 2019. This was in addition to some indications of “irrational exuberance” or disconnection of prices from their fundamentals, such as the prices of cryptoassets, euphoria with some particular stocks or, more recently, the rise in property prices in advanced countries. The outlook raised doubts about the sustainability of the quotations.

Capital flows to emerging countries did not have large movements. Net revenues were recorded between the end of May and mid-June, and have turned negative since then, to end with a neutral accumulated balance since the close of the previous IPOM. Compared to previous months, less volatility was noted in flows.

2.5. In summary

The evolution of the pandemic continues to represent the main risk to the global economy: in the face of the spread of the Delta variant of COVID-19, fewer hospitalizations and deaths have been recorded so far in the countries with the greatest progress in vaccination. The disparities in the vaccination process are reflected in the prospects for global economic recovery, which continues but is becoming more unequal between advanced and developing countries. The latter is also due to the smaller fiscal and monetary policy space available to the latter. Faced with higher global inflation, developing countries tend to react faster by raising interest rates, limiting the use of countercyclical monetary policy.

Finally, although global interest rates reversed the increases at the beginning of the year, there is a risk that, for example, in the face of higher inflation, there will be new increases in long-term interest rates that will generate financial turbulence and capital outflows from emerging countries. The quotes of various asset groups, including cryptocurrencies, also pose a significant risk, as the real fundamentals behind their quotes are not very clear.

3. Economic Activity and Employment

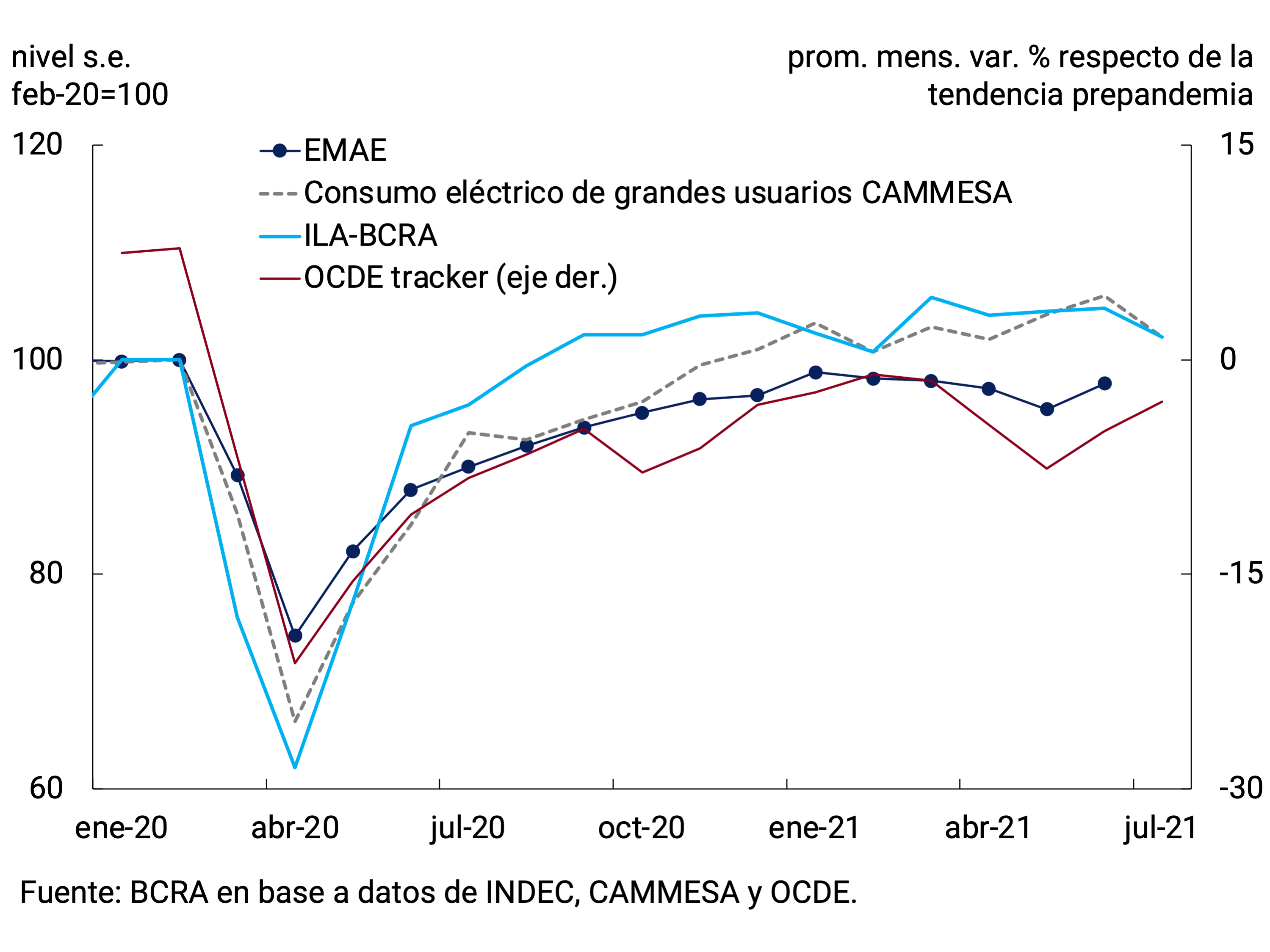

Economic activity fell in the second quarter of the year as a result of the outbreak in the country of the second wave of COVID-19 infections since the end of March. This interrupted an economic recovery that had begun in the third quarter of 2020, but only temporarily. The available data from the EMAE for June allow us to infer that a level of activity similar to that of last March has already been recovered, while, according to the evolution of various leading indicators, in July activity would have sustained its recovery.

The second wave led to the implementation of new restrictions on movement until the end of May. These measures had a greater impact on the sectors most affected by the limitations on mobility and health protocols. In line with the progress made in the vaccination process and the improvements made in the health system, the restrictions applied had a much shorter duration and impact compared to the first wave of infections that had begun in March last year, which allowed activity levels to recover more quickly. At the same time, in order to limit the impact of the new context on the social and productive fabric, the National Government maintained support policies focused on the productive sectors and social assistance to the most affected families.

Going forward, the greater coverage of the population with the application of the first dose and the expected progress in the vaccination process with complete schemes would significantly reduce the possible impact of the circulation of new strains of the virus on the level of activity. In any case, as observed in other countries, it cannot be ruled out that the circulation of new variants of the virus could postpone the conclusion of the economic normalization process.

3.1. In the third quarter, activity showed signs of continuing on the path of recovery, interrupted during April and May by the second wave of COVID-19 infections

The accelerated increase in COVID-19 cases and deaths from the end of March led to the partial and temporary tightening of health restrictions7, with a negative impact on economic activity in April and May. In order to mitigate the impact of this second wave, the National Government continued to implement support policies during the second quarter focused on productive sectors8 andhouseholds 9 most affected by the pandemic and others aimed at promoting strategic sectors in order to foster a sustainable and inclusive economic recovery. For its part, the BCRA contributed to the economic recovery process by sustaining and expanding credit lines for both productive and consumer purposes (see Chapter 7. Monetary Policy).

In line with the progress made in the vaccination process, the curves of infections and deaths began to fall at an accelerated and sustained pace starting at the end of May (see Figure 3.1). As a consequence, and as anticipated in the previous IPOM, the limitations on movement and trade had a much shorter duration and impact compared to the first wave of infections in March last year, which allowed activity levels to recover more quickly.

Figure 3.1 | Vaccination process. New cases and deaths from COVID-19

Per 100 thousand inhabitants.- last moving average 7 days

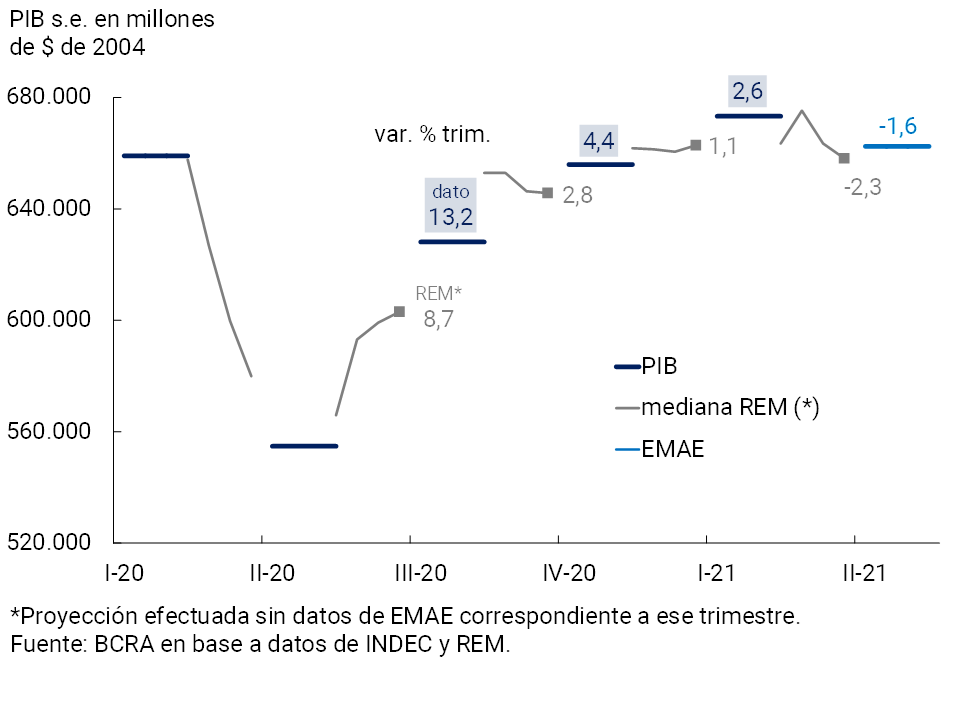

The Monthly Estimator of Economic Activity (EMAE) adjusted for seasonal factors (s.e.) accumulated a contraction of 2.7% s.e. between April and May and in June it recovered 2.5% monthly s.e. Thus, after registering an increase of 2.6% s.e. in the first quarter, the Product would register a transitory fall of 1.6% quarterly s.e. in the second, lower than initially forecast by market analysts10.

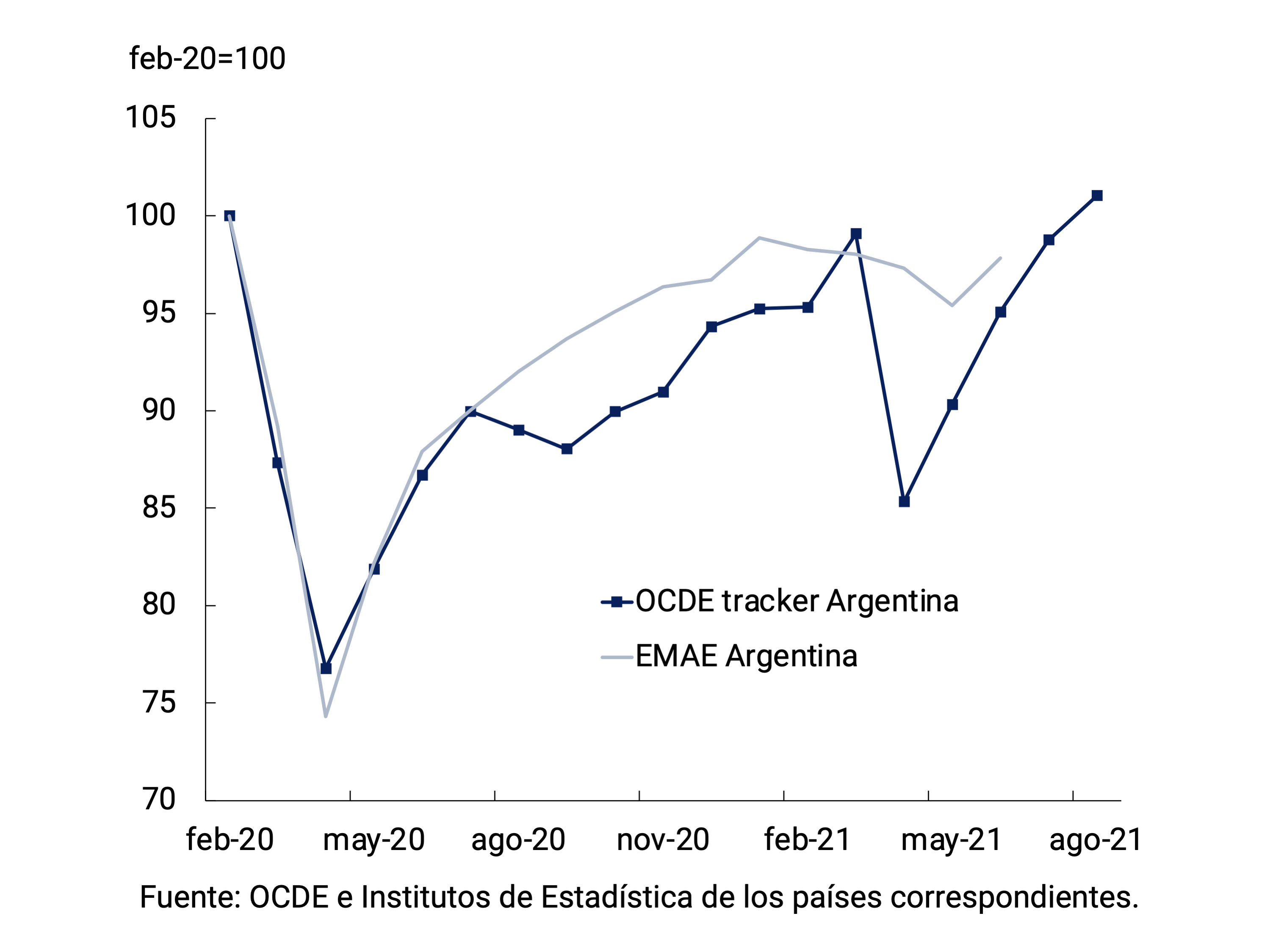

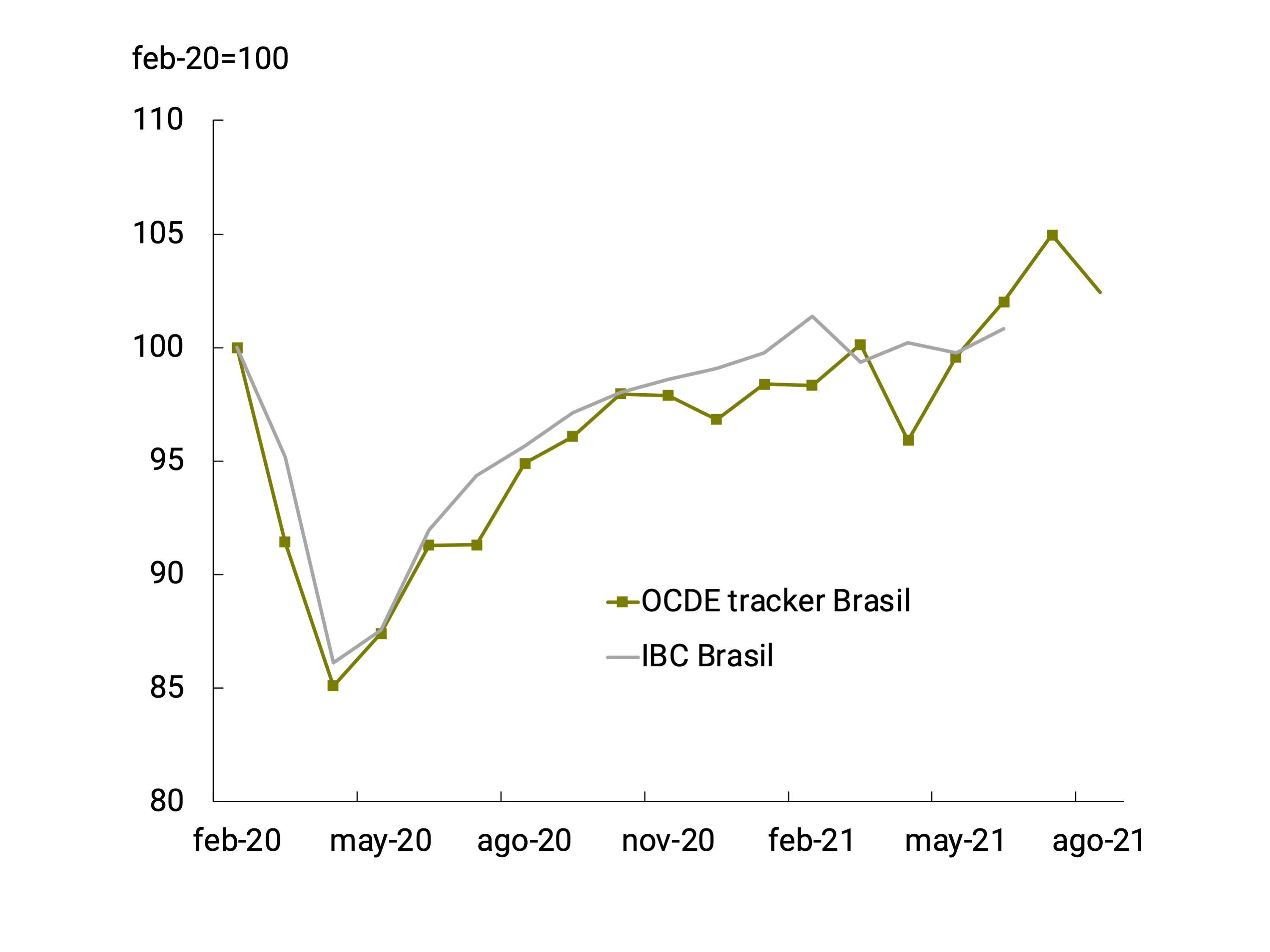

The high-frequency data available for the third quarter anticipate a recovery in economic activity linked to the decline in infections in the face of the acceleration of the vaccination process throughout the country. The Leading Indicator of Economic Activity (ILA-BCRA) remained in the recovery phase11 (see Figure 3.2). For its part, the OECD indicator registered a strong rise in June and continued to increase in July (See Section 2 / The OECD monitors economic activity on a weekly basis).

3.1.1. The impact of the second wave of infections on private consumption was limited

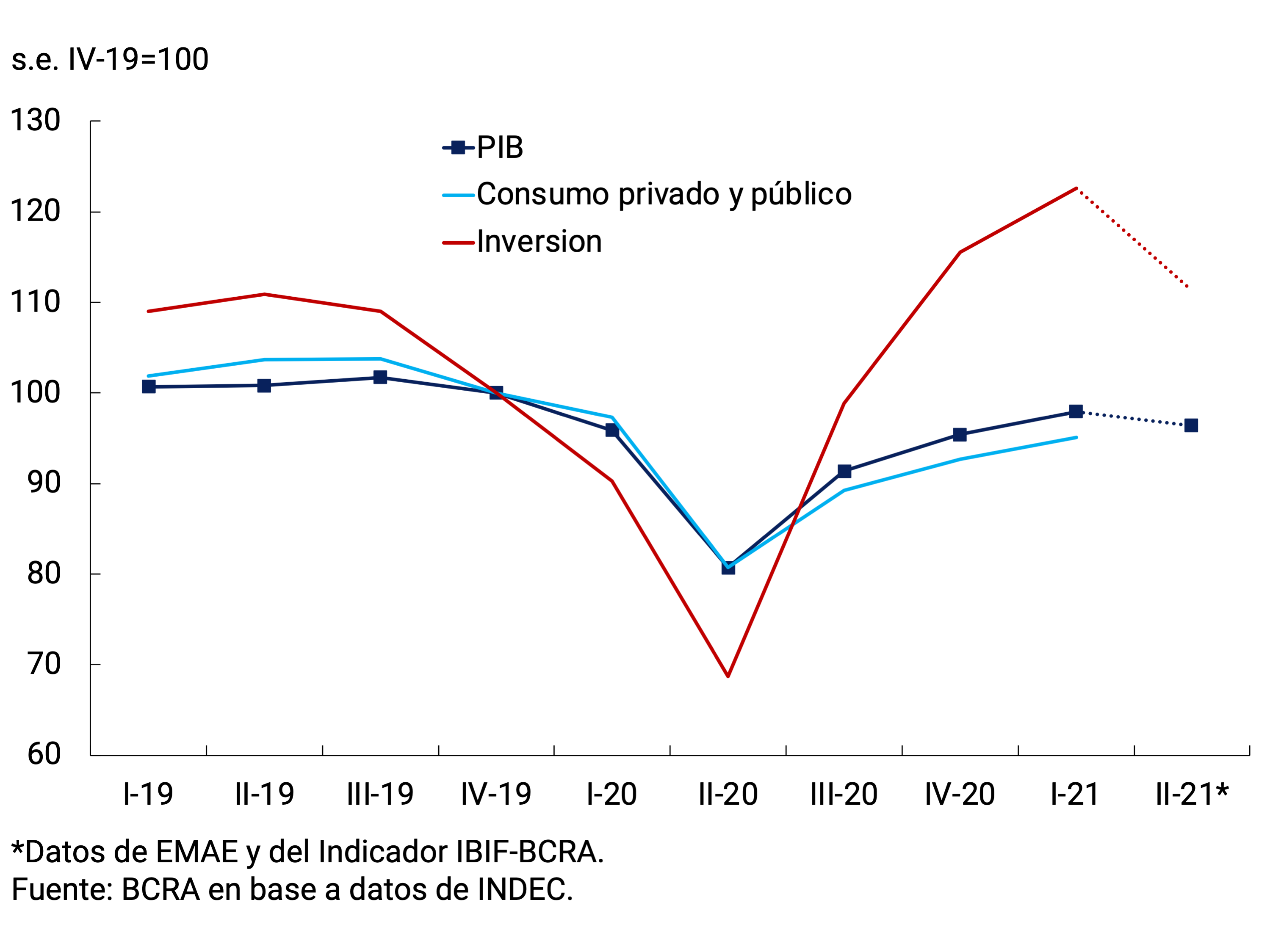

In the first quarter of 2021, GDP recovered 2.6% quarter-on-quarter and was 2.1% below its level in the last quarter of 2019. Domestic demand – total domestic expenditure on consumption and investment – recovered again at a faster pace (3.3% quarterly s.e.), bringing it closer to its pre-pandemic level (-0.4% s.e.). Private consumption grew 2.9% qoq s.e. (-0.7% y.o.y.), public consumption increased 1.4% s.e. (-0.5% y.o.y.) and investment12 by 6.1% qoq s.e. (38.4% y.o.y., see Figure 3.3). Exports of goods and services increased 19.2% qoq s.e. (1.2% y.o.y.) and imports, 13.5% qoq s.e. (18.8% y.o.y.).

Advance data for the second quarter of 2021 indicate that the component of demand most affected by the second wave of the pandemic was investment, although the magnitude of the fall was a third of that observed in the second quarter of 2020. The IBIF-BCRA indicator showed a quarterly contraction of 9.2% s.e. with decreases in all its components13. The available statistics for the third quarter allow us to estimate a rapid recovery. Firstly, due to the high statistical drag left by the good performance of the different indicators in the month of June: cement shipments in the domestic market increased 2.4% s.e., the national production of capital goods rose 14.2% monthly s.e. according to FIEL14 and the imported quantities of capital goods grew 3.6% s.e. in the month.

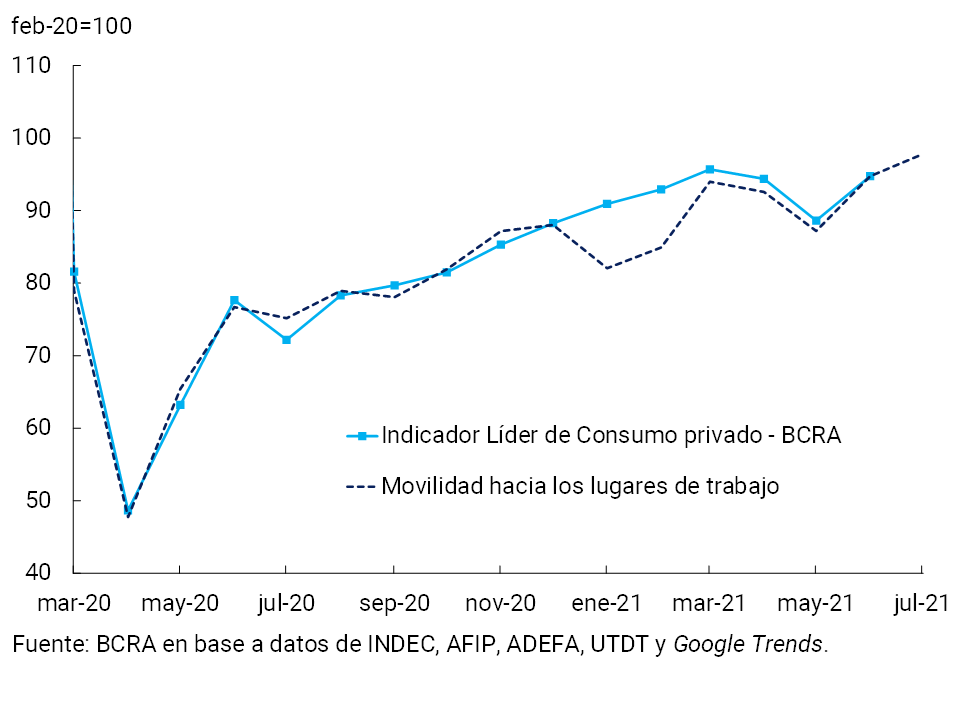

As for private consumption, the BCRA Leading Indicator15 shows two consecutive monthly falls in April-May and then a recovery in June, approaching the seasonally adjusted levels of April. The magnitude of the contraction in private consumption in May-21 is comparable to that observed in Jul-20, when social mobility had been restricted and the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area had returned to phase 1 for fifteen days (see Figure 3.4). The gradual recovery in private consumption – although still below pre-pandemic levels – also reflected the sustained recovery in employment and the evolution of real wages.

With respect to the external sector and according to the information referring to the Commercial Exchange of Goods of INDEC, in the second quarter the contribution of net exports of goods and services to the quarterly variation of the Product would have been negative. Exported quantities of goods registered a quarterly fall of 1.1% s.e. while imports increased 1.2% s.e. in the same period (see Chapter 4. External Sector).

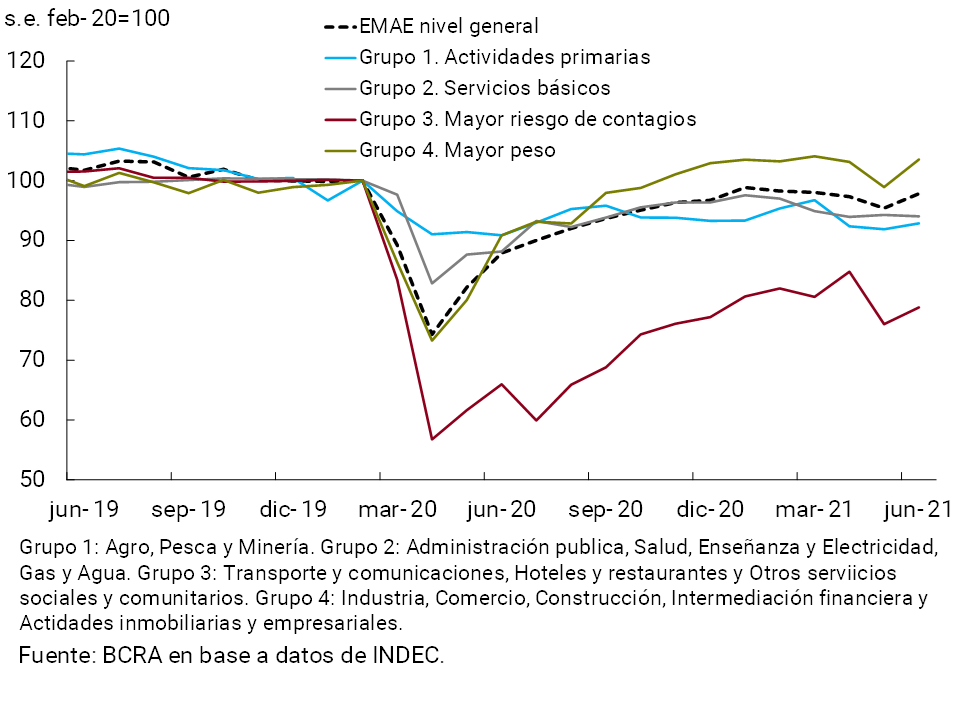

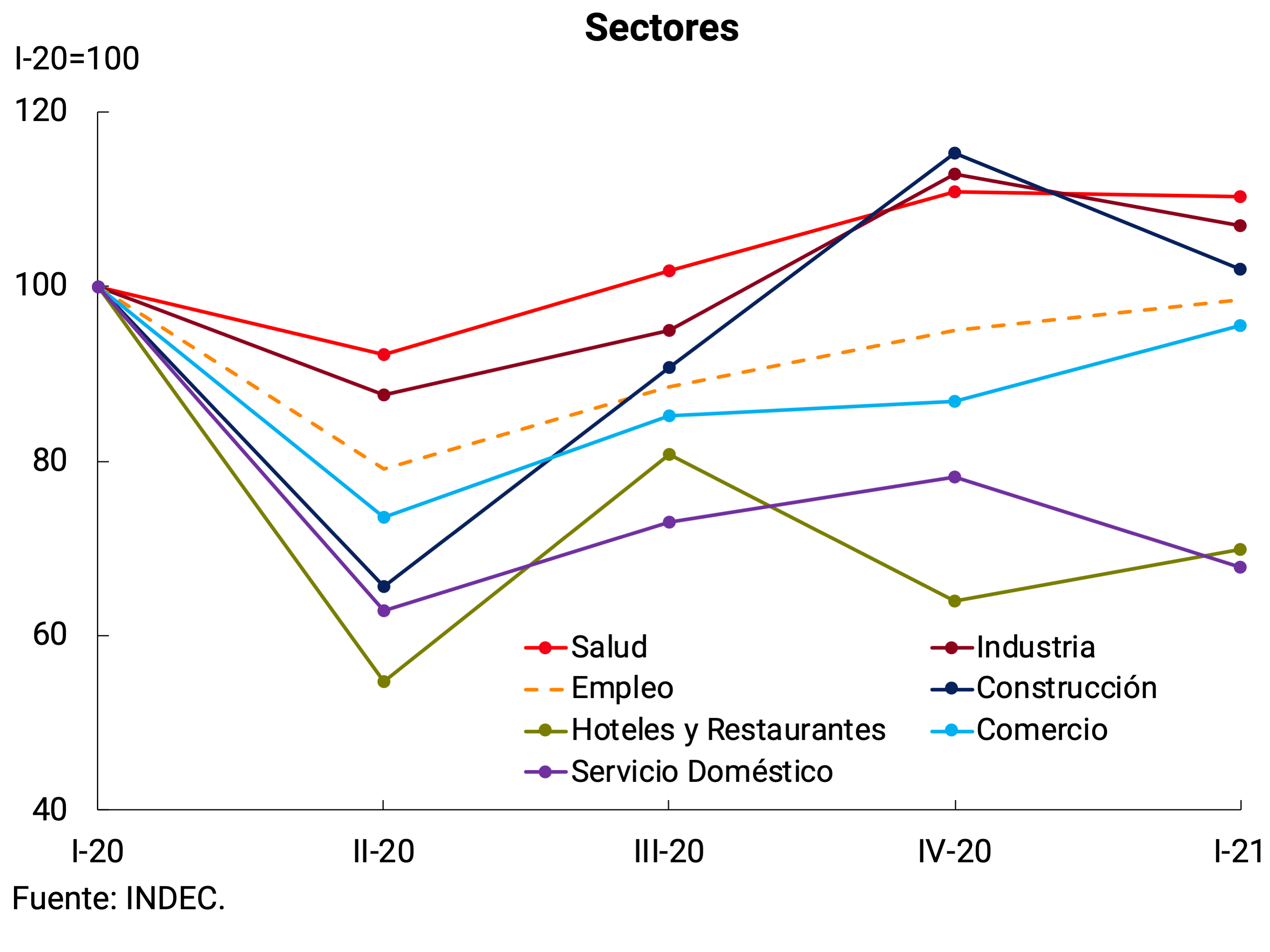

3.1.2. The second wave of infections temporarily accentuated the sectoral disparity in activity

In the first quarter of 2021, the recovery in economic activity was widespread among the different productive sectors. Of the 16 blocks that make up GDP, 14 registered seasonally adjusted increases in relation to the previous quarter, highlighting the performance of those services that had been most affected by the pandemic: Hotels and restaurants (30.7% quarterly s.e.) and Other community service activities, including social and recreational activities (10.7% quarterly s.e.) and Transport and communications (4% quarterly s.e.). In any case, those sectors with the highest risk of contagion were unable to recompose their previous levels of activity16.

The group made up of the sectors with the greatest weight in GDP – due to their production chains and employmentlevels 17 – showed a joint growth of 2.6% quarterly s.e. in the first quarter, thus exceeding the level of activity recorded in the fourth quarter of 2019 by 4.6%. The rest of the sectors can be categorized as primary activities (Agriculture, Fishing and Mining and Quarrying) and basic services (Health, Education, Public Administration and Electricity, Gas and Water). The activity of these two groups also increased in the first quarter of the year (1.6% and 0.4% quarter-on-quarter s.e., respectively), standing around 5% below the pre-pandemic level.

The reestablishment of restrictions on social mobility between April and May, initially at night and then longer, had an unequal impact on the different productive groupings in the April-May two-month period. As could be anticipated, the group with the highest risk of contagion suffered the greatest impact, accumulating a 5.6% s.e. contraction in those two months. Industry, included within the group with the greatest weight in GDP that fell by 5% s.e. in the April-May two-month period, was affected in addition to health restrictions and absenteeism due to COVID-19, by the limitation of the use of oxygen, prioritized for medical use (which would also have caused shortages of supplies for construction) and also by the measure of force to cease the marketing of livestock products in the last weeks of the month.

The acceleration in the vaccination process and the strengthening of the health system made it possible to apply social isolation measures that were much lighter in intensity and duration compared to those in force in March and April 2020. Thus, in June, the health situation allowed the gradual lifting of restrictions and sectoral activity regained dynamism (see Figure 3.5).

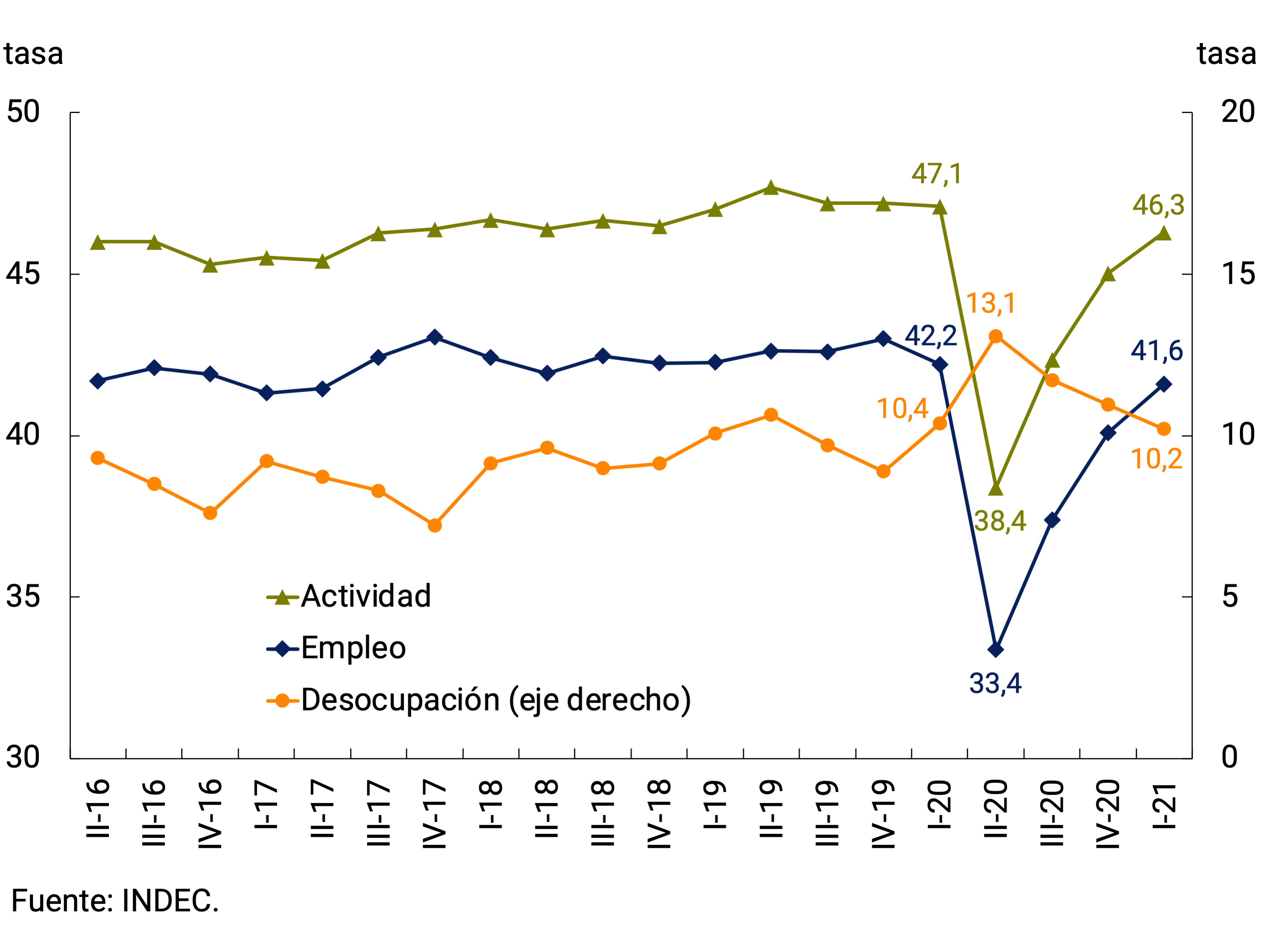

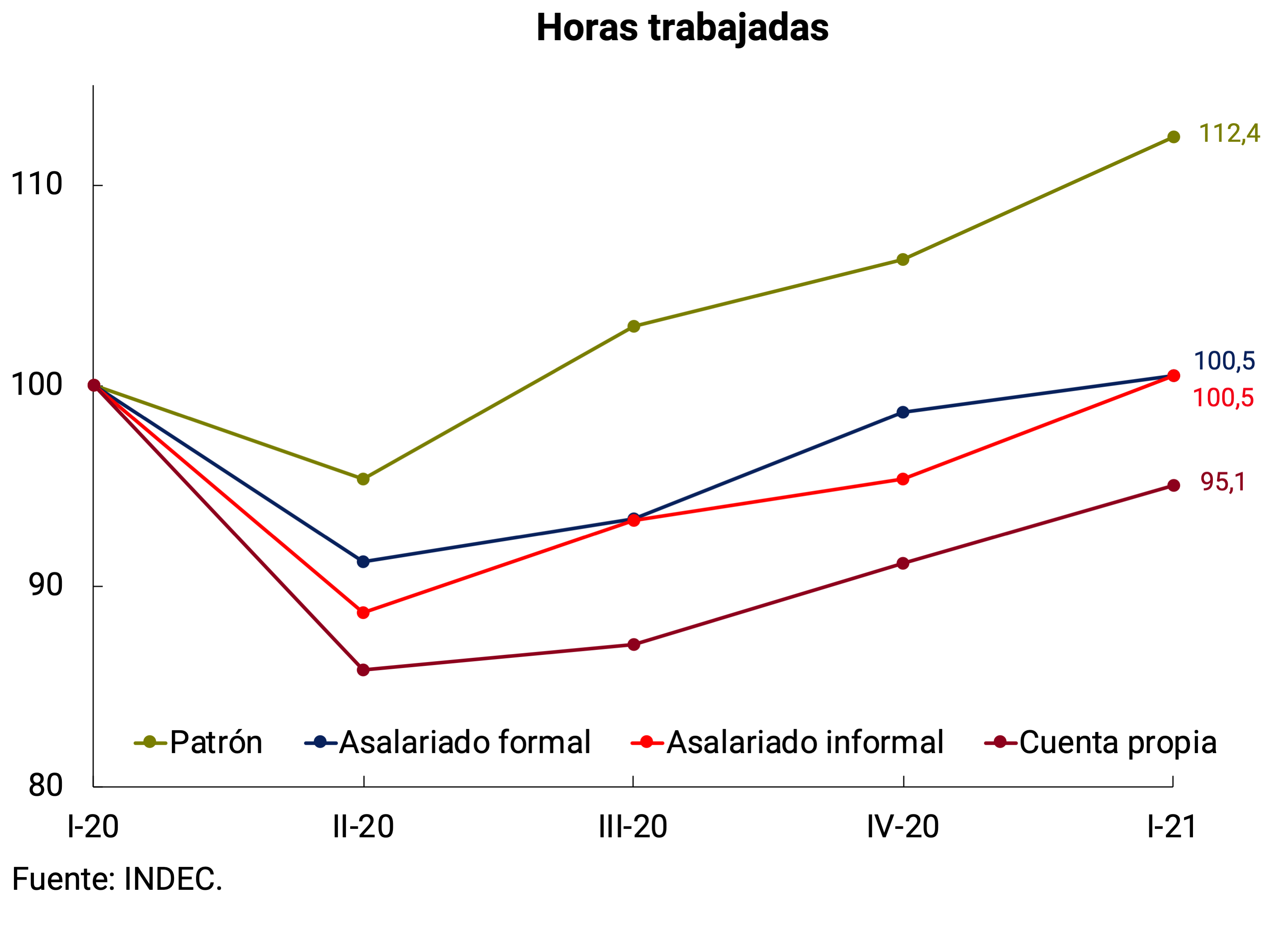

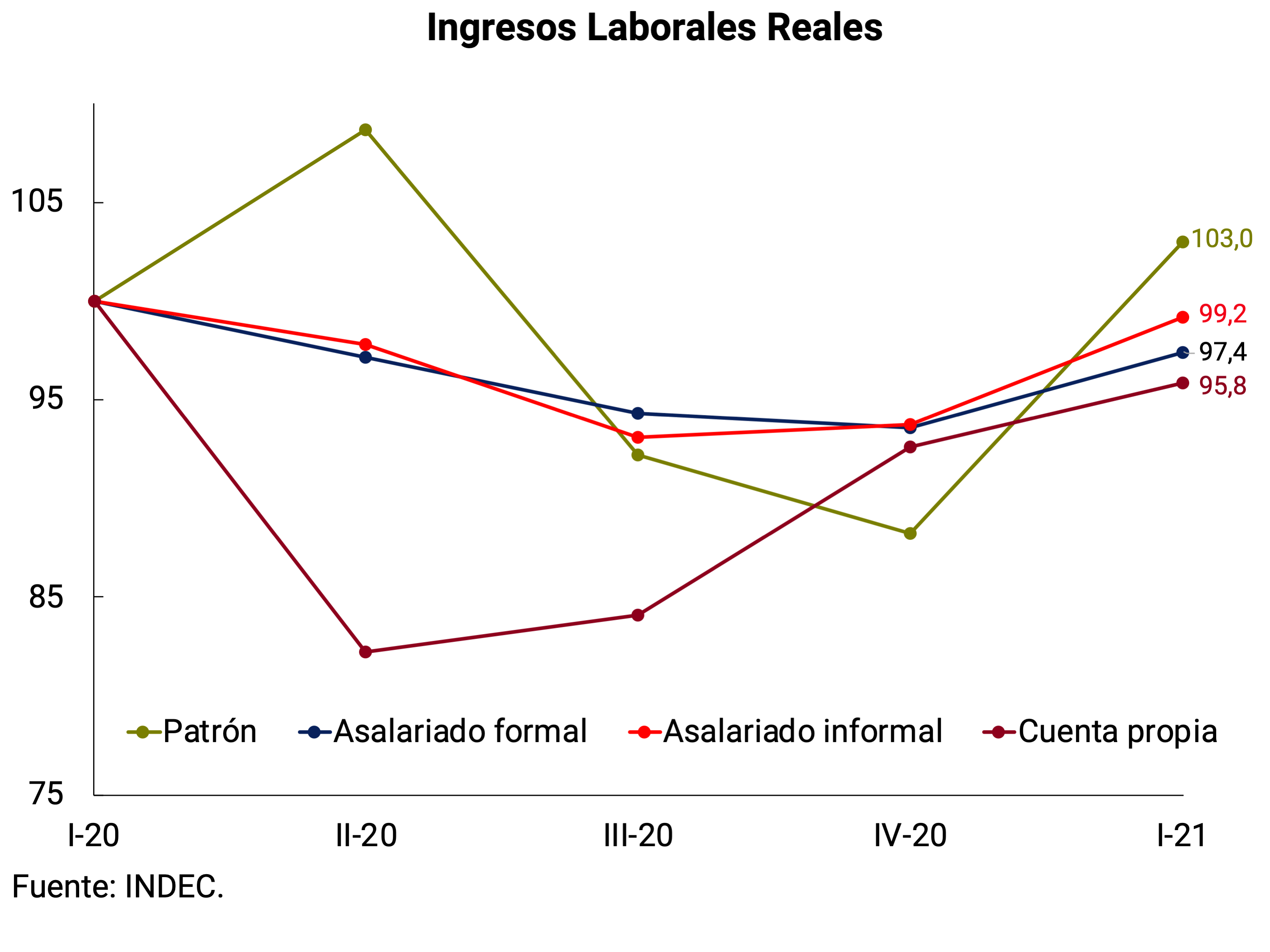

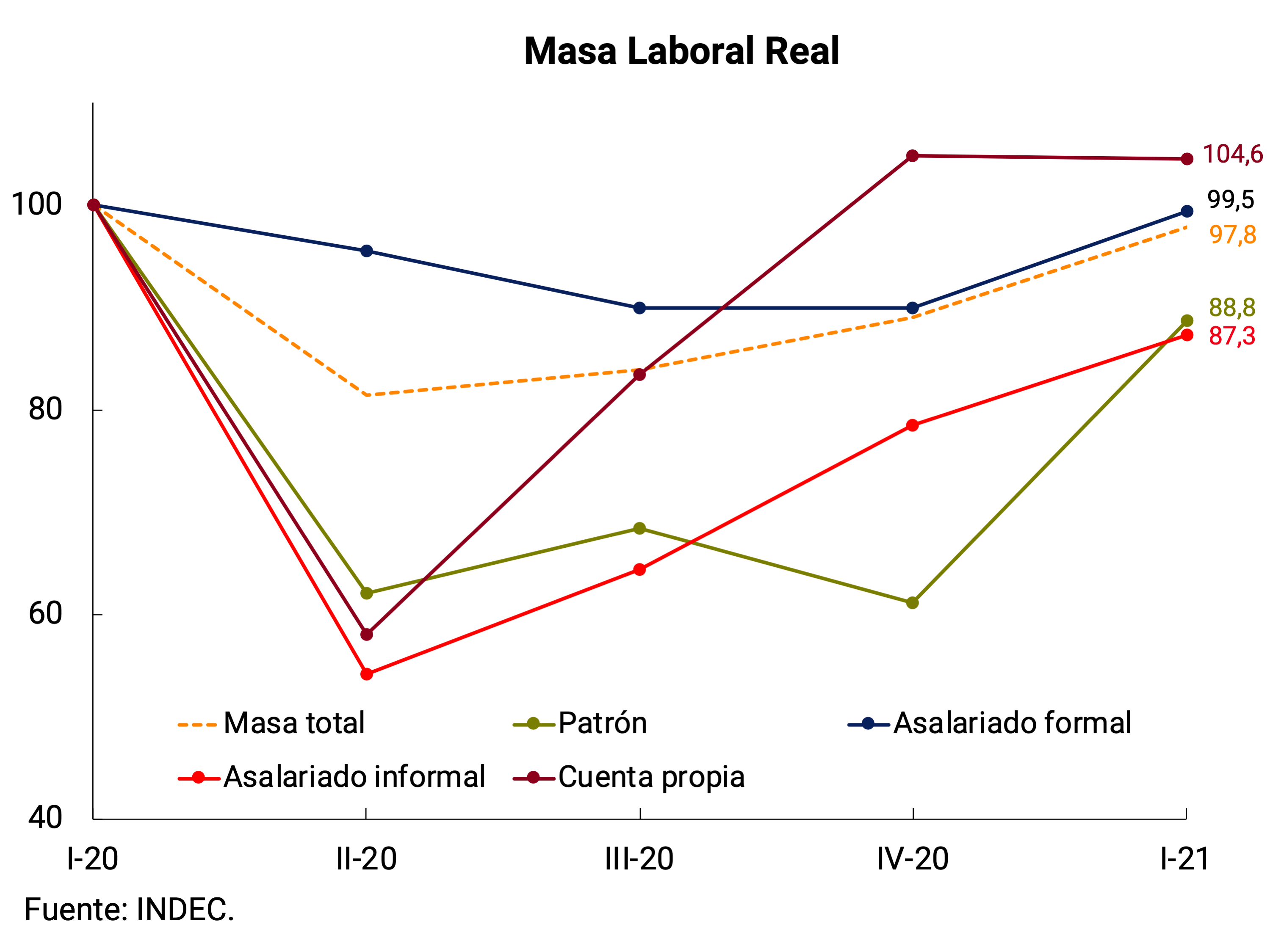

3.1.3. The labour market continued its recovery, approaching pre-pandemic levels

During the first quarter of 2021, the labour market extended the recovery seen in the previous two quarters. The Employment and Economically Active Population (EAP) rates were slightly below the levels in force in the first quarter of 2020 (-0.6 p.p. and -0.8 p.p. respectively). The open unemployment rate stood at 10.2% and showed a reduction of 0.2 p.p. compared to that of the first quarter of 2020 (see Figure 3.6).

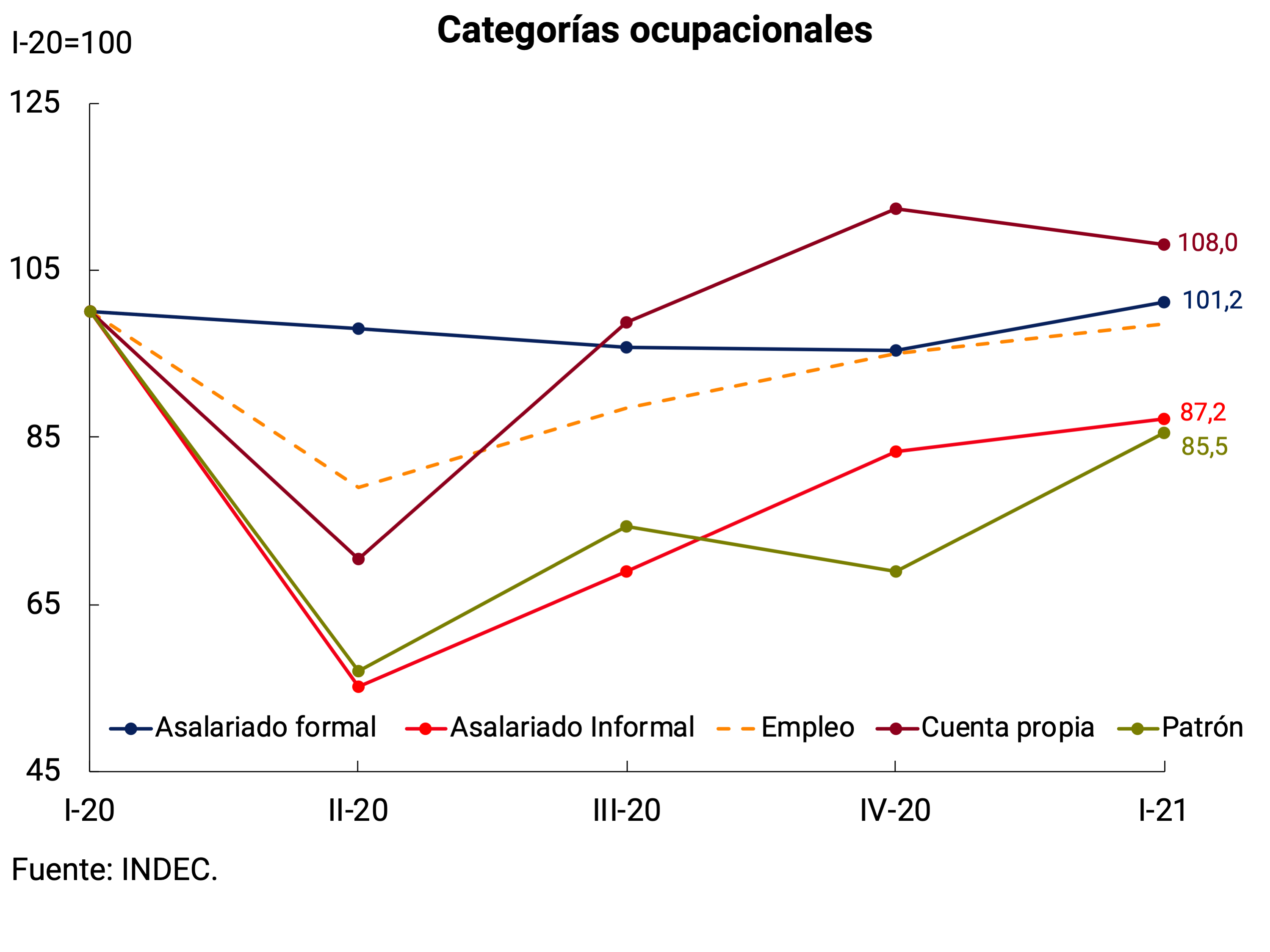

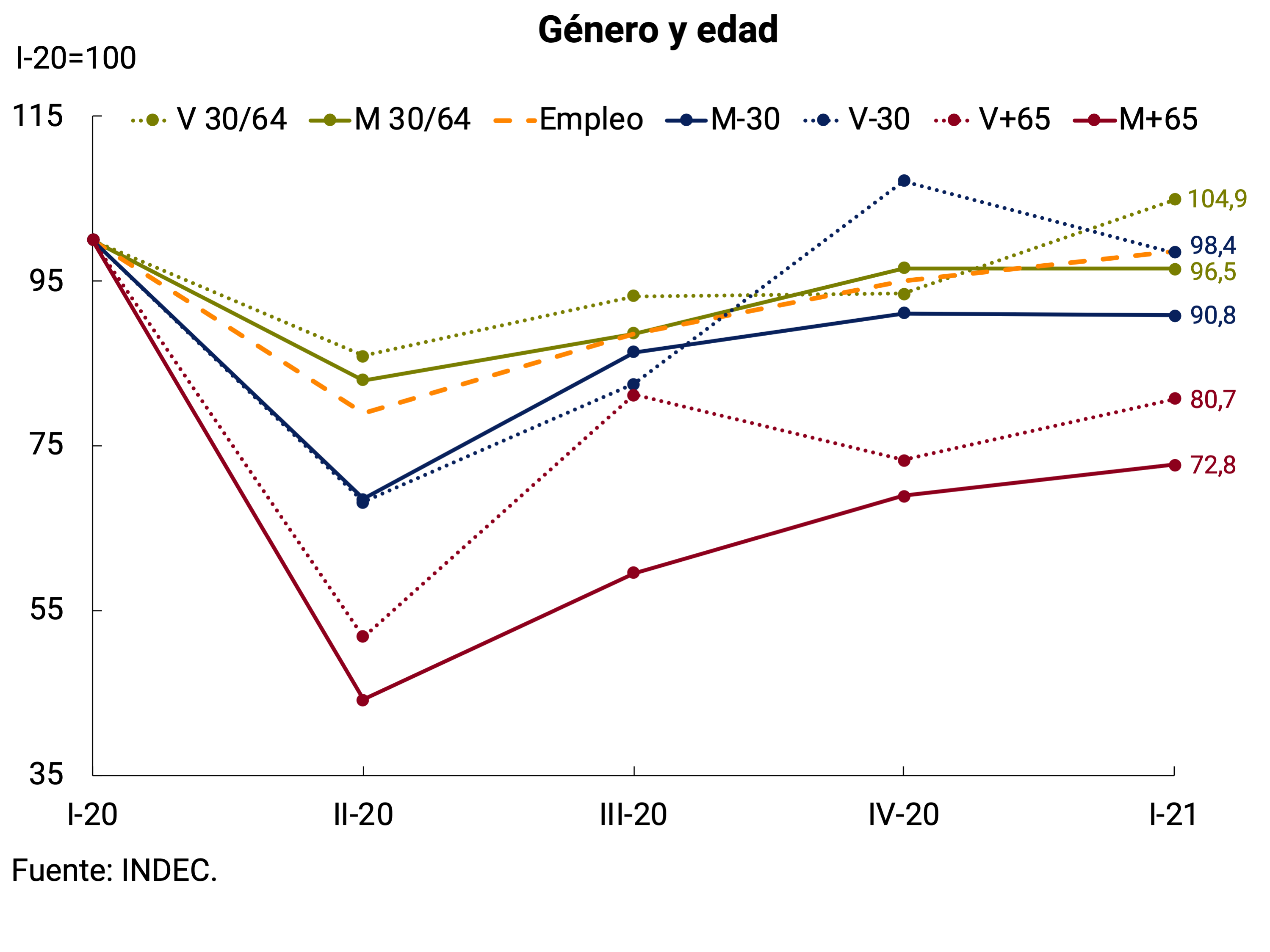

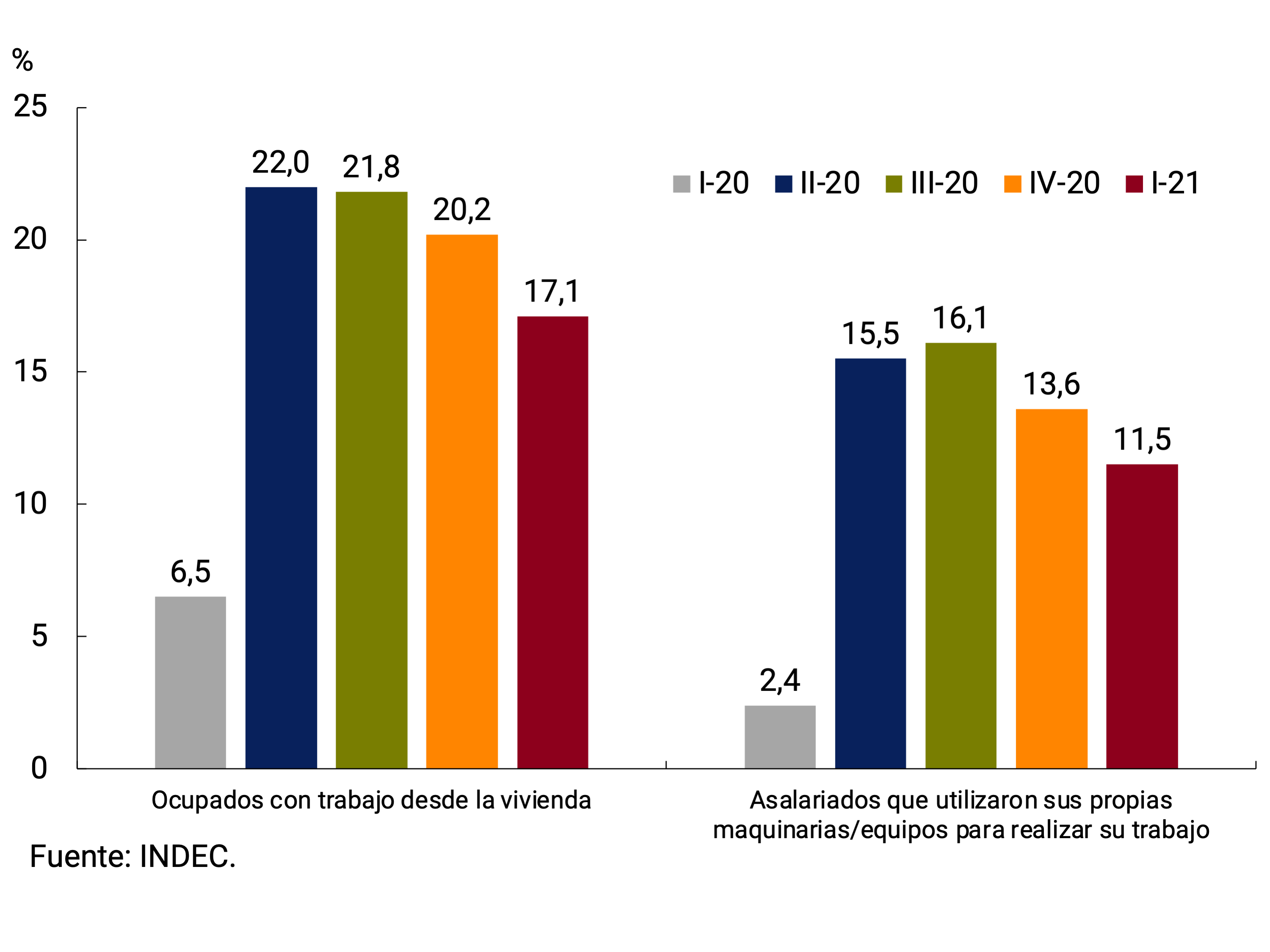

In terms of labor transitions, the labor market normalization process presented, at the beginning of 2021, the same trend observed during the fourth quarter of 2020. The increase in the number of employed people (862 thousand) was fueled by both the inactive (553 thousand) and the unemployed (309 thousand)18. Although the labor market has been normalizing, some particularities can be observed, both at the sectoral level, age range, gender and occupational categories, related to the effects of the pandemic that still persist (see Section 3 / Main characteristics of the labor market recovery).

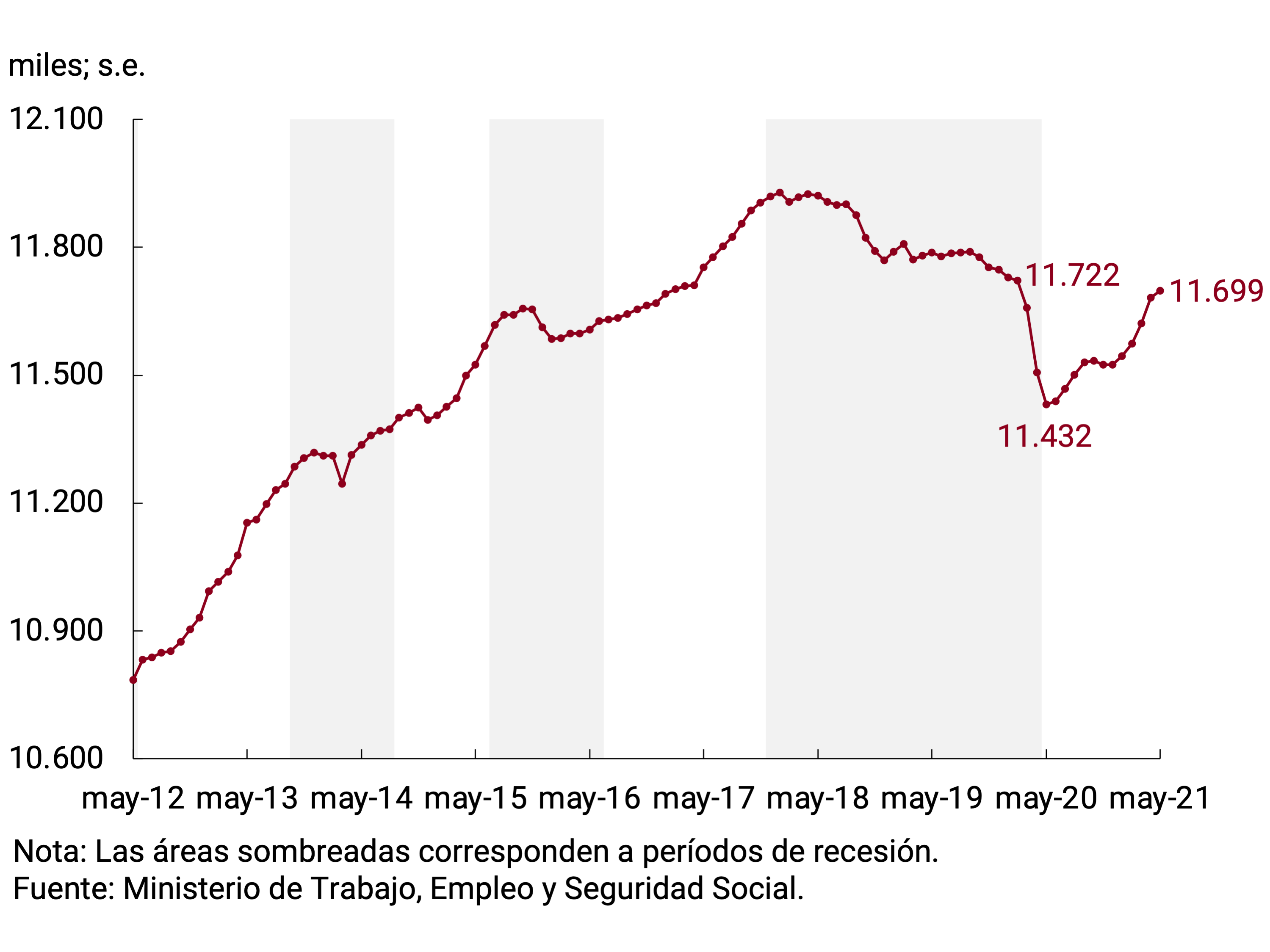

According to the Ministry of Labor, Employment and Social Security, total registered employment maintained the positive trend in April and May, accumulating a 1.5% s.e. increase in the first five months of1919 and reaching an improvement of 2.3% s.e. from the pandemic floor (May 2020; see Figure 3.7).

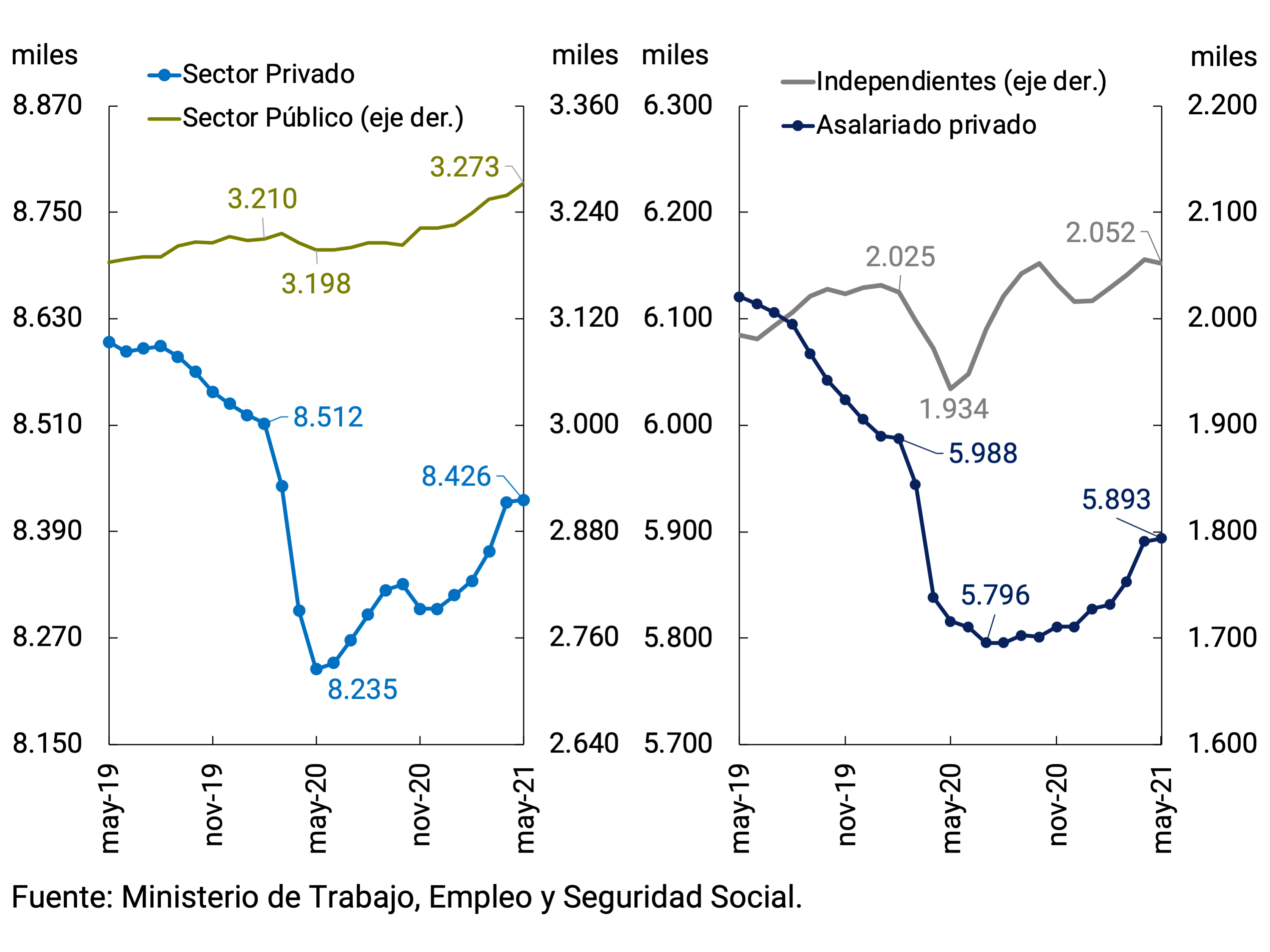

This recovery in total registered employment is related to a positive dynamic of registered salaried employees since the beginning of the year. In particular, public wage earners grew 1.6% s.e. since December 2020 while the private sector showed a cumulative increase of 1.5% s.e. since the same period. This growth was complemented by the sustained rise in registered self-employment (single-tax and self-employed persons; 1.8% s.e. since December 2020) despite a slight drop in the margin (see Figure 3.8).

The behaviour of private salaried employment allows us to distinguish at the sectoral level a greater dynamism in sectors such as Real estate, business and rental activity, Manufacturing industry and Construction since June 2020. On the other hand, the branches economically most affected by the pandemic (Transport and Hotels and restaurants) continued with the process of falling in the level of employment in the same period.

The Labor Indicators Survey (EIL) as of June 2021 shows a positive trend in net hiring expectations, added to the stability in suspensions and in the dismissal rate. Net expectations for hiring personnel three months ahead remained in positive territory between February and June, with values ranging between 0.5 p.p. and 2.4 p.p. The suspensions, after a persistent drop from their peak in May 2020, stabilized. For its part, despite the validity of decree 413/202120 , the dismissal rate showed increases in April, May and June, approaching the historical average.

3.2. Perspectives

Based on a wide level of coverage of the population vaccinated with first doses, a large part of the at-risk population and strategic personnel inoculated with complete schemes21, and given the expected availability of vaccines from both international and local suppliers for the rest of the year, it is expected that economic activity will continue to travel the path of recovery towards a new normal. The National Government recently provided the Recovery Plan for Sustained and Progressive Activities, which includes new openings and flexibilizations of activities such as domestic group and international tourism in the coming months. The enabling of the most lagging economic activities, together with the progressive return to face-to-face work of various sectors in both the public and private sectors, would contribute to concluding the process of recovery of activity in the coming months and consolidating a new normality.

However, the activity scenario presents several risks, among which is mainly an eventual and still uncertain impact of the circulation of the Delta variant of the virus in the country, which could temporarily slow down the process of economic normalization, as is the case in other countries. It should be noted that the emergence of new strains of the virus also represents a downside risk in the global recovery scenario. Conversely, greater international cooperation on vaccines could end the health crisis sooner than expected and allow for a faster normalisation of activity in emerging and developing countries.

The upward revision of the prospects for economic growth on a global scale and the terms of trade at levels close to the maximum will continue to favor our country’s exportable balances. Thus, the international context continues to be favourable, although it is not without risks (see Chapter 2. International Context).

In the coming months, the BCRA will continue to deploy an exchange rate policy that favors monetary stability and allows for the efficient management of international reserves, while continuing to promote productive credit (see Chapter 7. Monetary policy). The National Government will continue to carry out the necessary policies to sustain the incomes of the families that need it most, assisting the strategic productive sectors or those that were left behind by the characteristics of the economic recovery22 and stimulating public and private investment, without neglecting the sustainability of the public accounts (see Chapter 5. Public Finance).

The seasonally adjusted data from the EMAE for June left a statistical drag of 1 p.p. of growth for the third quarter and 6.9 p.p. for 2021. The economic growth expectations of the main market analysts, compiled by this Central Bank through the Market Expectations Survey (REM), were successively corrected upwards and underestimated the magnitude of the economic recovery from the third quarter of 2020 onwards. This bias on the evolution of economic activity is observed even in the second quarter of 2021 (see Figure 3.9).

The latest available edition of the REM, corresponding to July 2021, indicates an expectation of GDP recovery of 0.5% quarterly s.e. for the third quarter and 6.8% annually in 2021 (+0.5 p.p. compared to the previous month). The International Monetary Fund (IMF) also improved our country’s growth projections for 2021 in July to 6.4% year-on-year (+0.4 p.p. compared to the world economic evolution report published in April), while the Ministry of Economy forecasts a 7% annual increase in GDP.

4. External Sector

As a result of a high trade balance of goods, the economy would have sustained the current account surplus during the second quarter of 2021. Exports of goods reached the highest quarterly record since the second quarter of 2014, driven mainly by the high prices of raw materials exported by the country. On the other hand, imports of goods grew for the fourth consecutive quarter with a notable dynamism of those directly linked to the domestic production of goods, as well as fuels. Data for July suggest that this dynamic of the trade balance of goods continues in the third quarter.

This recovery of exports, added to the evolution of the commercial debt for exports and imports of goods, resulted in a net result for goods in the foreign exchange market of US$12,041 million in the first 7 months of the year. This allowed the BCRA to accumulate net purchases in the foreign exchange market until July for US$7,165 million, a record for this period since 2012. Meanwhile, on August 23, the allocation of Special Drawing Rights by the IMF to mitigate the effects of the pandemic was accounted for around US$4,333 million, which brought the level of international reserves to US$46,306 million.

Going forward, the current account is expected to continue to exhibit balanced records, supported by the trade surplus of goods. The main risk factors for the external sector of the Argentine economy are an eventual resurgence of the pandemic due to the expansion of new strains of COVID-19 and potentially a sharp correction in global financial markets that negatively impacts commodity prices or the activity of the main trading partners.

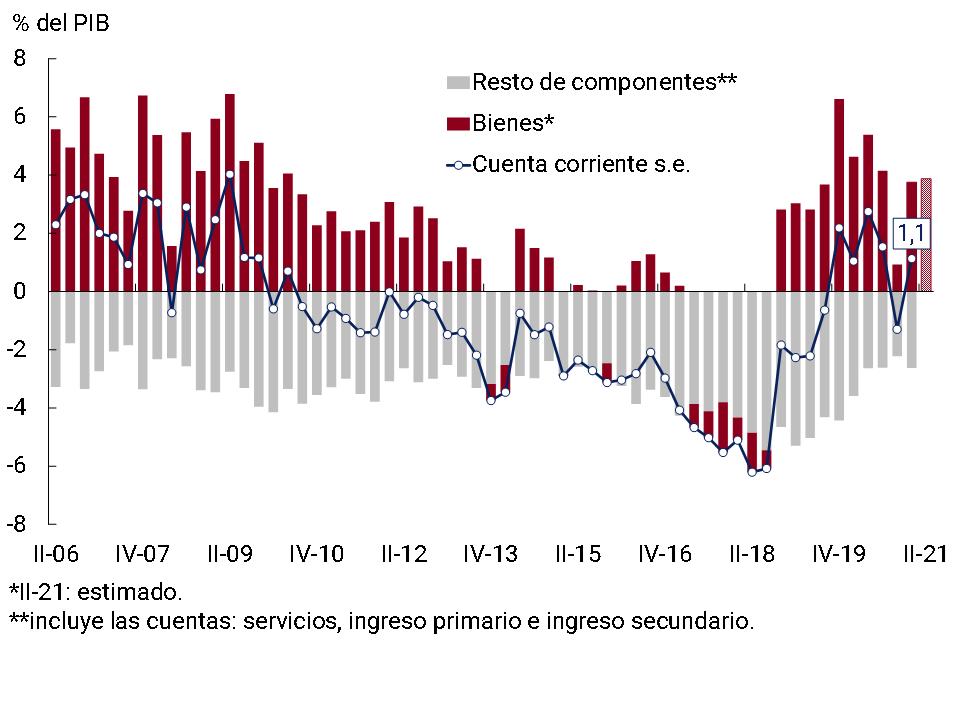

4.1. In the second quarter of 2021, the economy would have sustained the current account surplus

In the first quarter of 2021 (latest official data available) the Argentine economy recorded a current account surplus of US$690 million – equivalent to 1.1% of GDP in seasonally adjusted and annualized terms. The normalization of shipments of grains and derivatives, after they were interrupted for most of December as a result of a union conflict in the port, favored this result.

In the second quarter of 2021, the improvement in international prices of the main agricultural commodities exported by Argentina allowed the trade balance of goods to be maintained. In this context, the current account is expected to return to a positive balance of around 1% of GDP (see Figure 4.1).

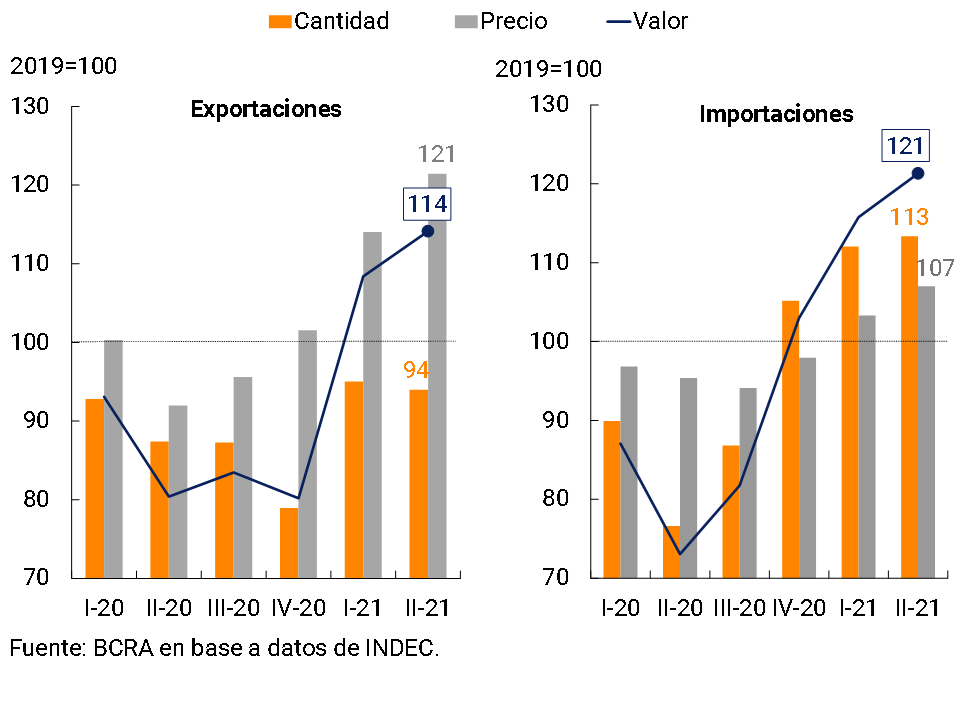

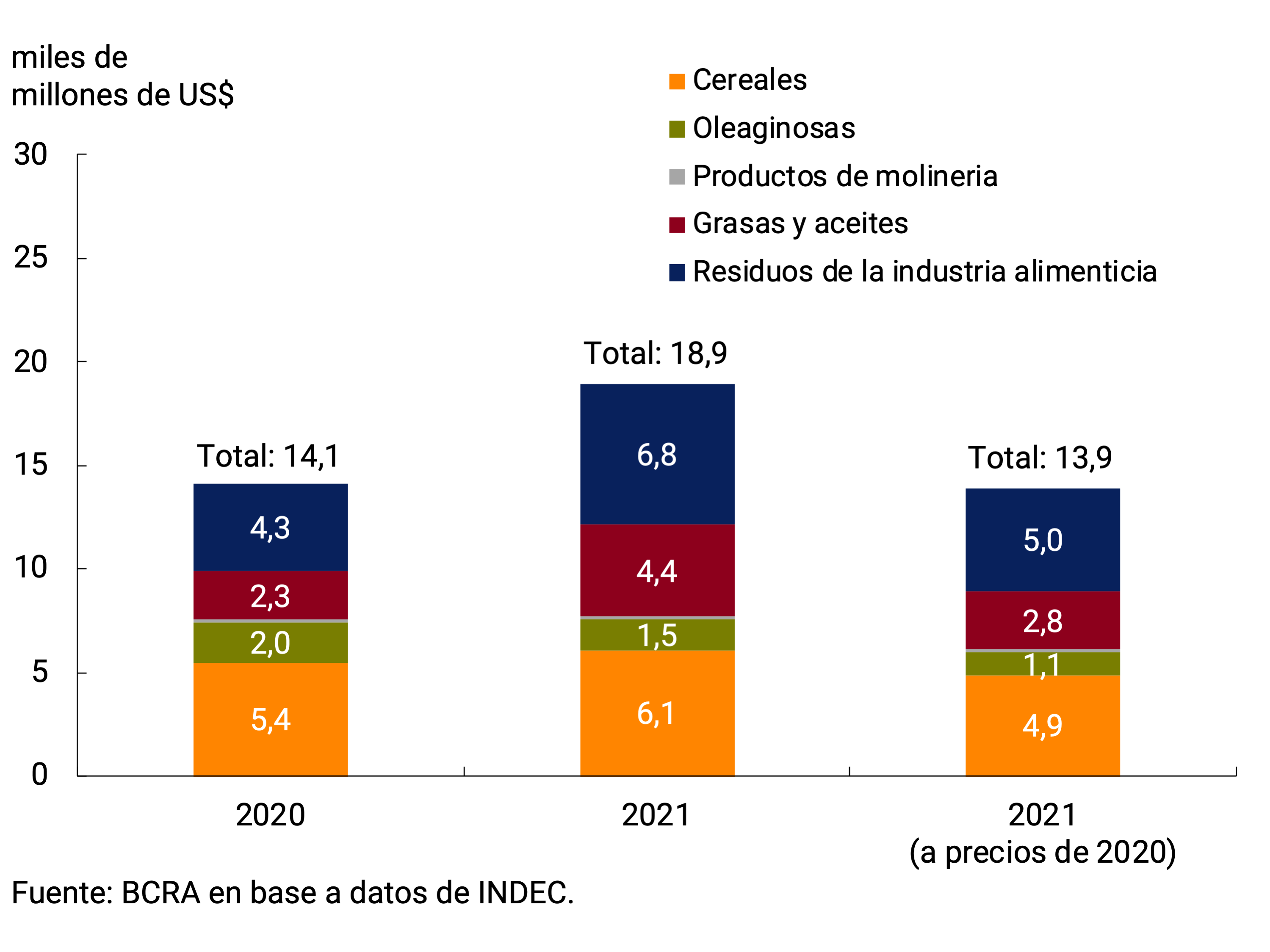

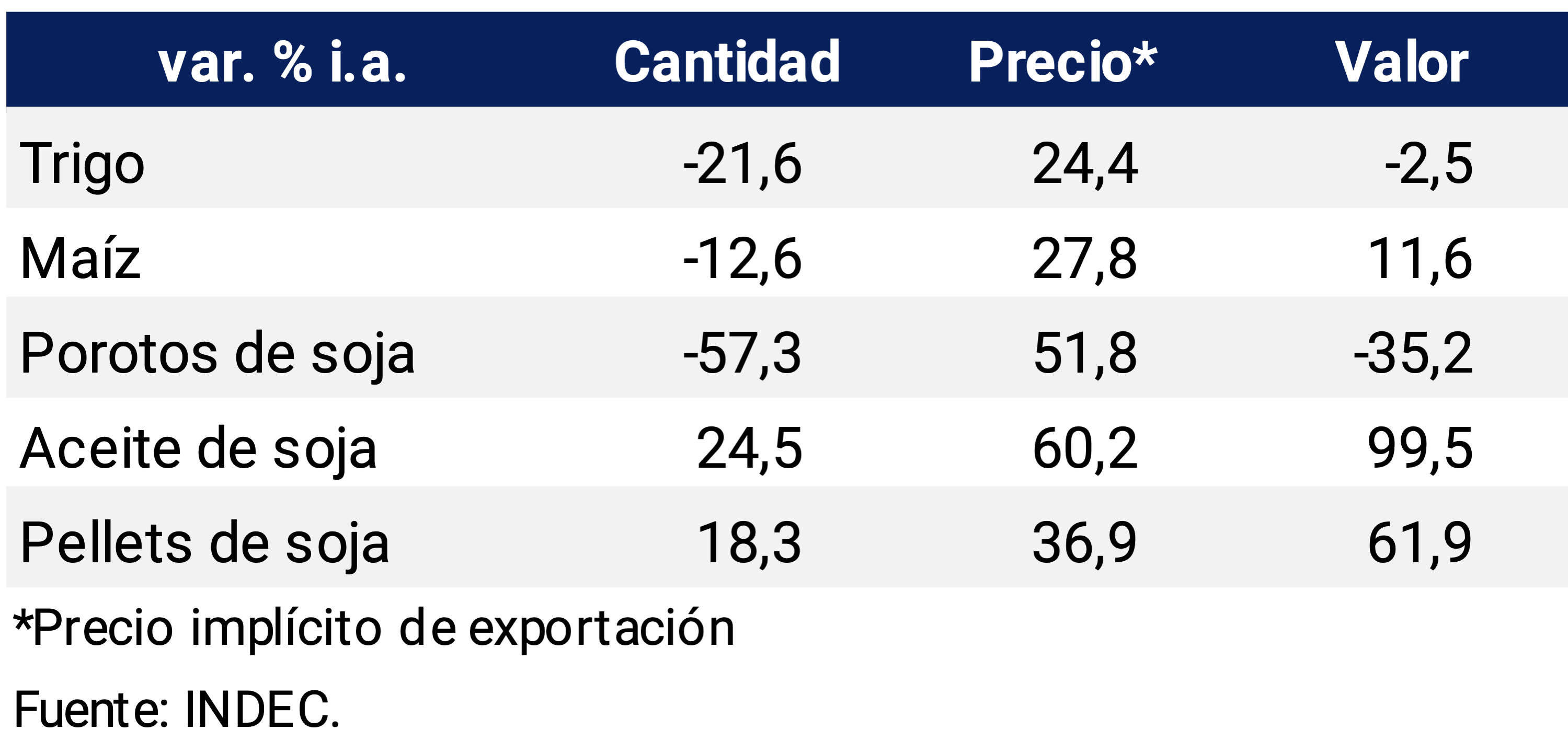

In that period, the exported values of seasonally adjusted goods reached US$18,579 million (FOB), the highest record since the second quarter of 2014. This favorable evolution of exports of goods was mainly due to the performance of export prices, which grew 6% quarter-on-quarter and were comfortably above pre-pandemic levels (see Section 4. Recent performance of agricultural exports). For their part, the exported quantities of goods had a slight drop (1% quarterly s.e.) and are still 6% below the level of 2019. In July, exports in value maintained their upward trajectory (+2% monthly s.e.) again driven by an increase in foreign sales prices.

At the disaggregated level, exported volumes continued to exhibit heterogeneous behaviors in the second quarter. Shipments of Manufactures of Industrial Origin (MOI) grew 7% QoQ. s.e. driven by higher exports of base metals, precious metals and chemicals. On the other hand, foreign sales of Primary Products registered a slight increase (1% QoQ, s.e.), which was explained by the positive drag left by the March-April two-month period. At the grouping level, the increases in cereals and fishing and the fall in oilseeds stood out. On the contrary, the exported quantities of Manufactures of Agricultural Origin (MOA) fell 10% quarter-on-quarter. s.e. negatively affected by the delay in shipments of Argentina’s main export product (soybean meal) derived from the downspout of the Paraná River. Finally, fuel exports fell by 6% quarter-on-quarter. s.e.—due to a negative carry-over effect—, although they showed signs of recovery at the margin.

For its part, between April and June 2021, seasonally adjusted imports of goods totaled US$14,899 million (CIF), 34% above the quarterly average recorded in 2020 and 21% higher than the average for 2019. In the case of external purchases, both higher prices and volumes contributed to the increase in imported values (see Figure 4.2). In July, imports registered a decrease (-3% monthly s.e.) that reflected the performance of imported quantities. In any case, the July data leaves a positive carryover of 4 p.p. of imported values for the third quarter.

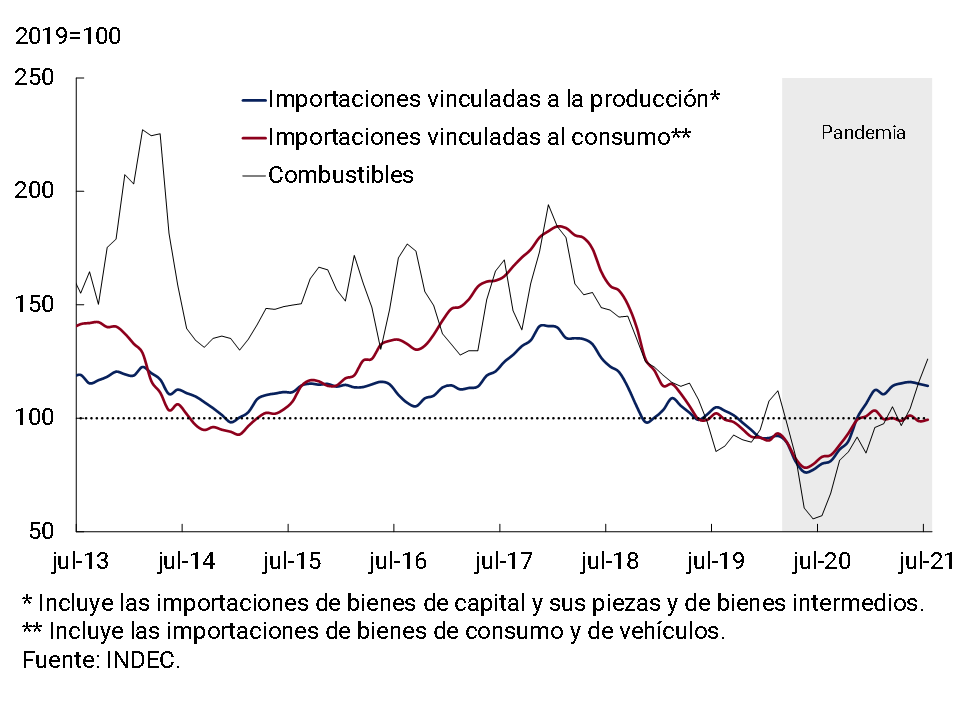

A differentiated behavior was also observed within imports of goods so far this year. In the second quarter of 2021, the quantities imported of uses directly linked to production (capital goods and their parts and intermediate goods) were 8% higher than those of the fourth quarter of 2020 and 15% higher than the average for 2019, which again suggests a good performance of the production of goods (see Chapter 3. Economic Activity and Employment). At the disaggregated level, the increases in the imported volumes of parts and accessories for capital goods (18%), parts and accessories for transport equipment (27%), chemical products – where vaccine purchases are recorded – (13%) and base metals (12%) stood out in this period.

On the other hand, imports directly linked to private consumption have been stagnant since the beginning of the year. Higher purchases of consumer durables, non-durables, and non-industrial transportation equipment were offset by a sharp drop in passenger vehicle imports.

Finally, it is worth noting the sharp increase in imported fuel volumes (+11% QoQ, s.e. in II-21 and +37% compared to IV-20), driven by higher domestic energy demand in a context of lower local gas supply.

Data for July anticipate a similar dynamic for the third quarter of the year (see Figure 4.3).

Box. Foreign trade prices of goods and terms of trade

In II-21, prices in dollars of exports of goods grew for the fourth consecutive quarter and were at the highest level since the third quarter of 2014. At the disaggregated level, the quarterly increases in the prices of cereals (+15%), oilseeds (+13%), fats and oils (+16%) and crude oil (20%) stood out.

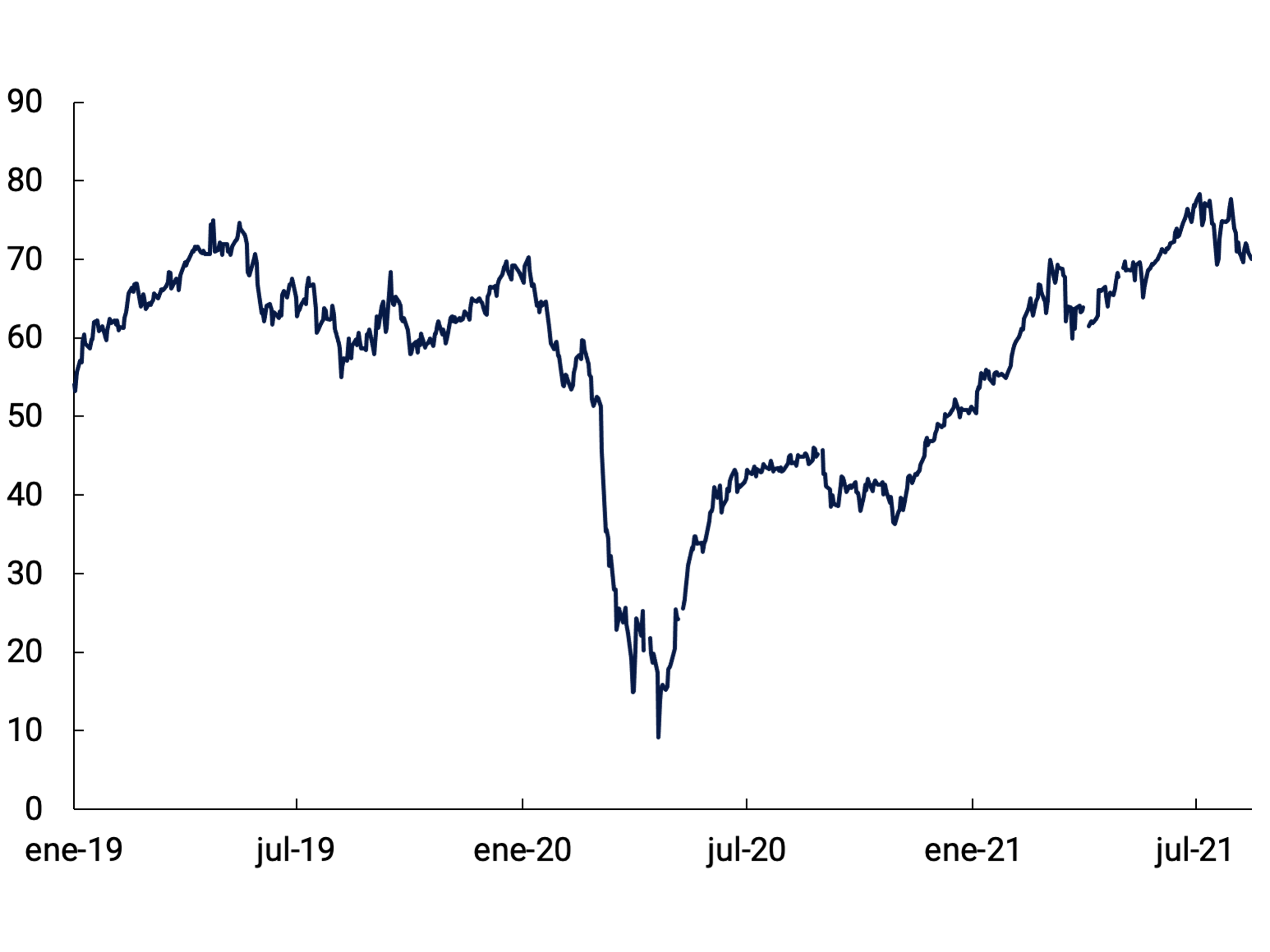

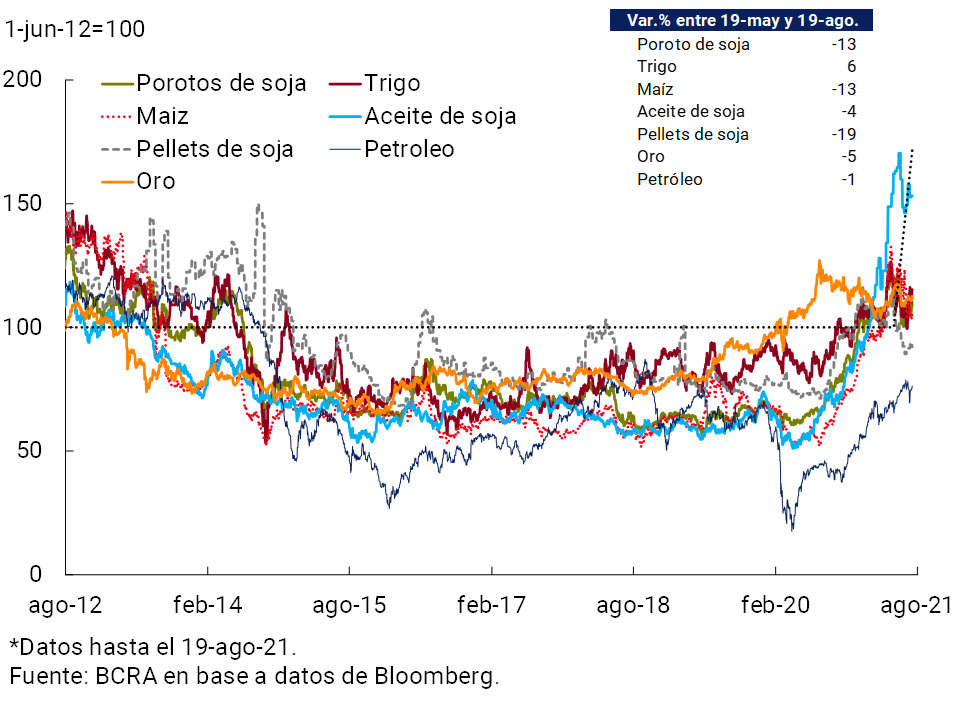

As mentioned in previous editions of IPOM, the trajectory of Argentina’s export prices is associated with the dynamics of commodity prices in the world’s reference markets. In fact, the Commodity Price Index prepared and published daily by the BCRA (IPMP), had an average quarterly growth of 11% in II-21, spread among its 3 components (agriculture, metals and oil).

In any case, it should be noted that, with the exception of oil and wheat, the international prices of the main raw materials exported by Argentina have fallen across the board since mid-May. Since the publication of the last IPOM, the products of the soybean complex have accumulated a decrease of between 4% and 19%, and corn a decrease of 13%. Despite this evolution at the margin, prices are still at historically high levels (see Figure 4.4)

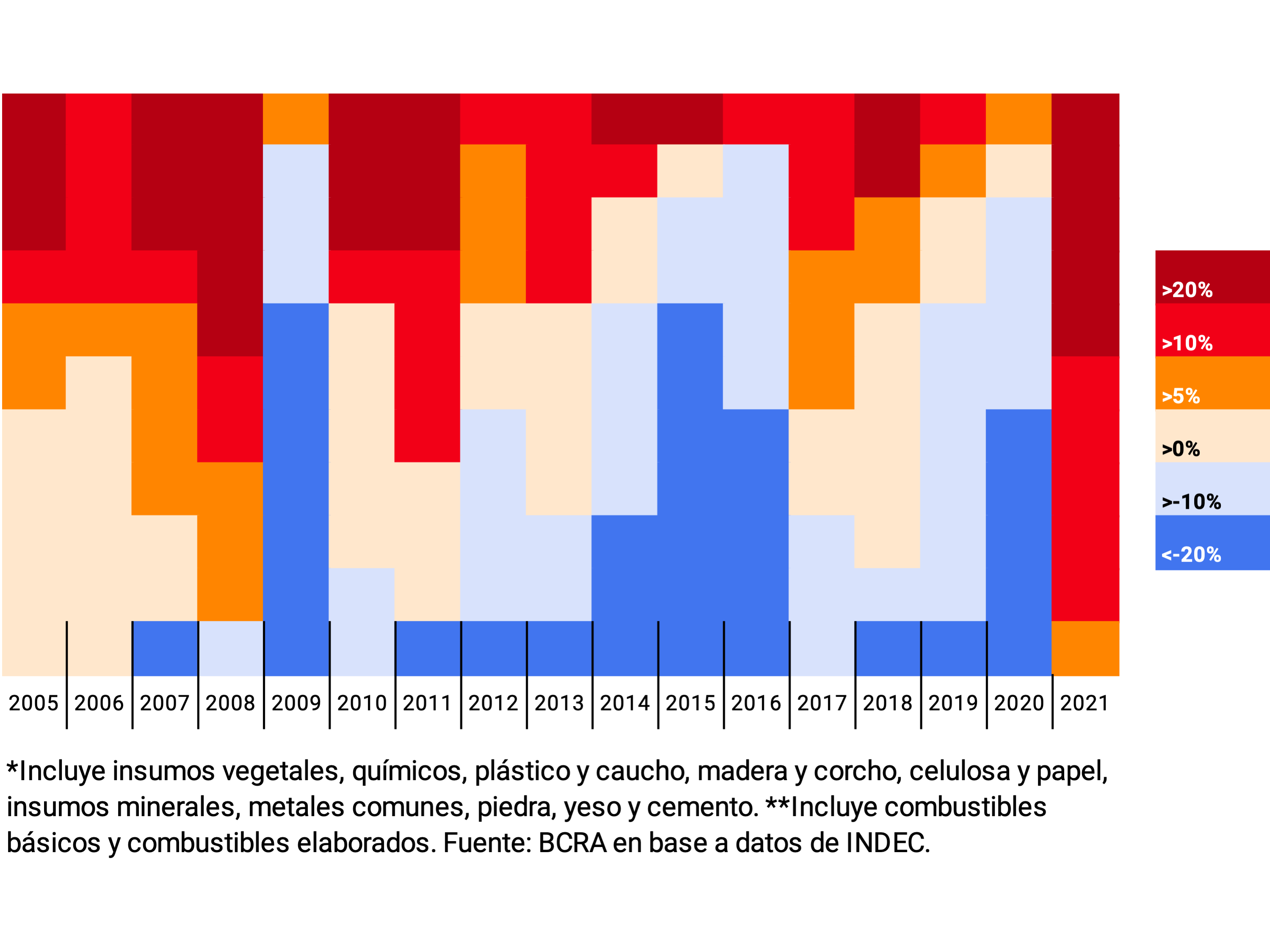

On the other hand, the prices of imports of goods measured in current dollars also showed great dynamism recently. Until July, they accumulated a 21% increase compared to the level of December 2020. This rise was particularly marked among intermediate goods and fuels. Of the 11 categories that make up both import uses – most of them being inputs disseminated for the domestic production of goods – 10 presented increases of more than 10% in current dollars in the first half of 2021, an unprecedented situation in the last 15 years. This evolution of international prices contributed, together with other factors, to partially explain the domestic price dynamics (see Chapter 6. Prices). The six-month increases in the prices of imports of processed fuels (59%), mineral inputs (33%), chemical products (28%) and plastic and rubber (28%) stood out for their magnitude; see Figure 4.5.

Figure 4.5 | Import prices of intermediate goods* and fuels**

Var. % acum. in the first half of each year

Thus, as a result of the faster growth in import prices, the terms of trade – the ratio between export and import prices – deteriorated by 2.3% in the second quarter of 2021. However, they continue to be favorable in historical terms

4.2. In the second quarter, the ITCRM was around the average of the last 24 years

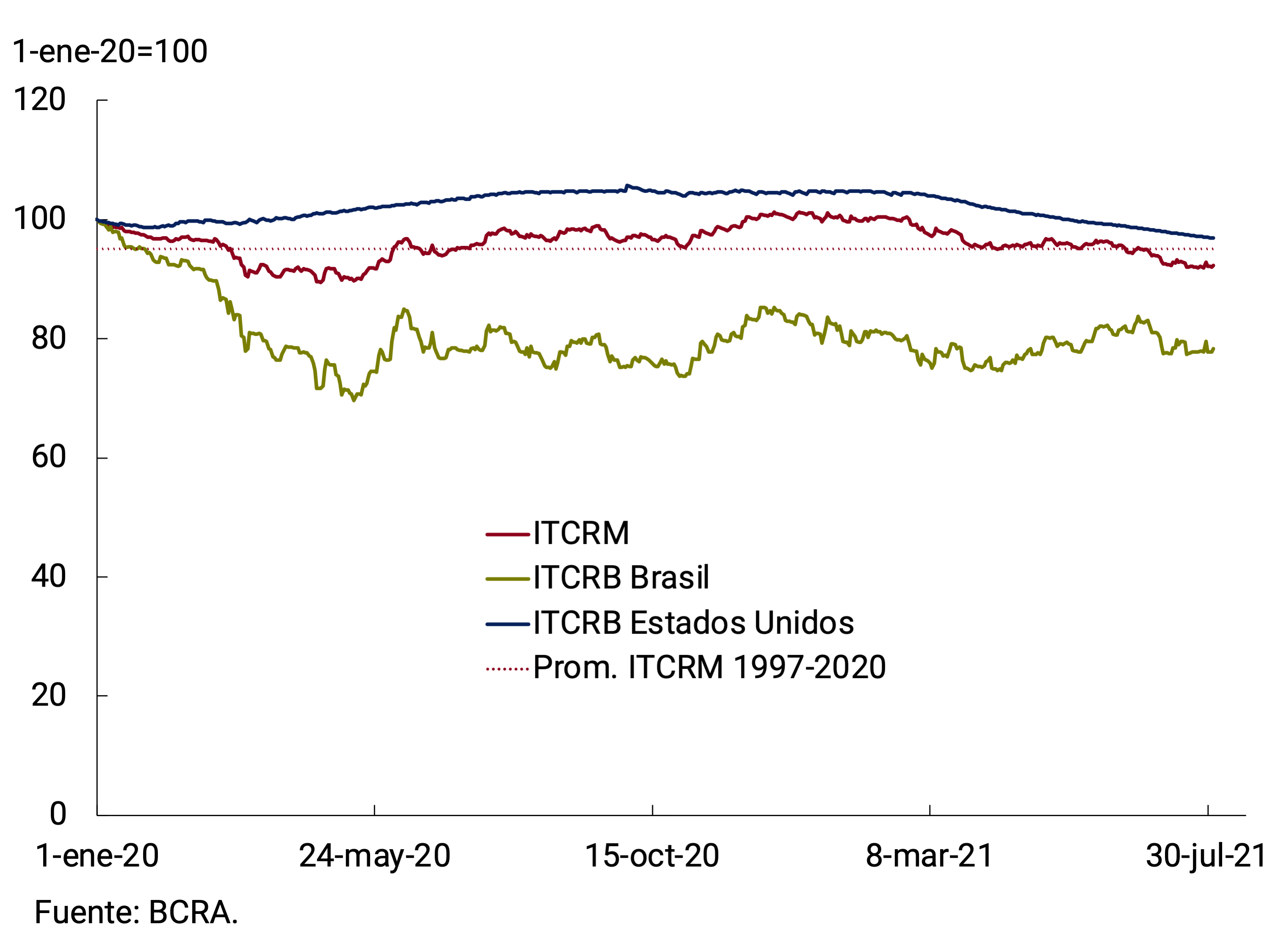

In the second quarter, the multilateral real exchange rate index (ITCRM) fell by an average of 3.7% compared to the first quarter of the year. In real terms, the peso appreciated bilaterally against the currencies of the 13 economies that make up the index, and was generally more marked against the currencies of advanced economies (Japan, Switzerland, the euro area and the United States). In the case of the bilateral real exchange rate with Brazil (our main trading partner), the drop in the index was very slight (0.7%), as a result of the greater volatility to which the currency of the neighboring country was subjected. Despite this decline, the ITCRM was around the average of the last 24 years throughout the second quarter. In July and so far in August, the currencies of emerging economies depreciated against the dollar, accelerating the peso’s multilateral real appreciation (see Figure 4.6).

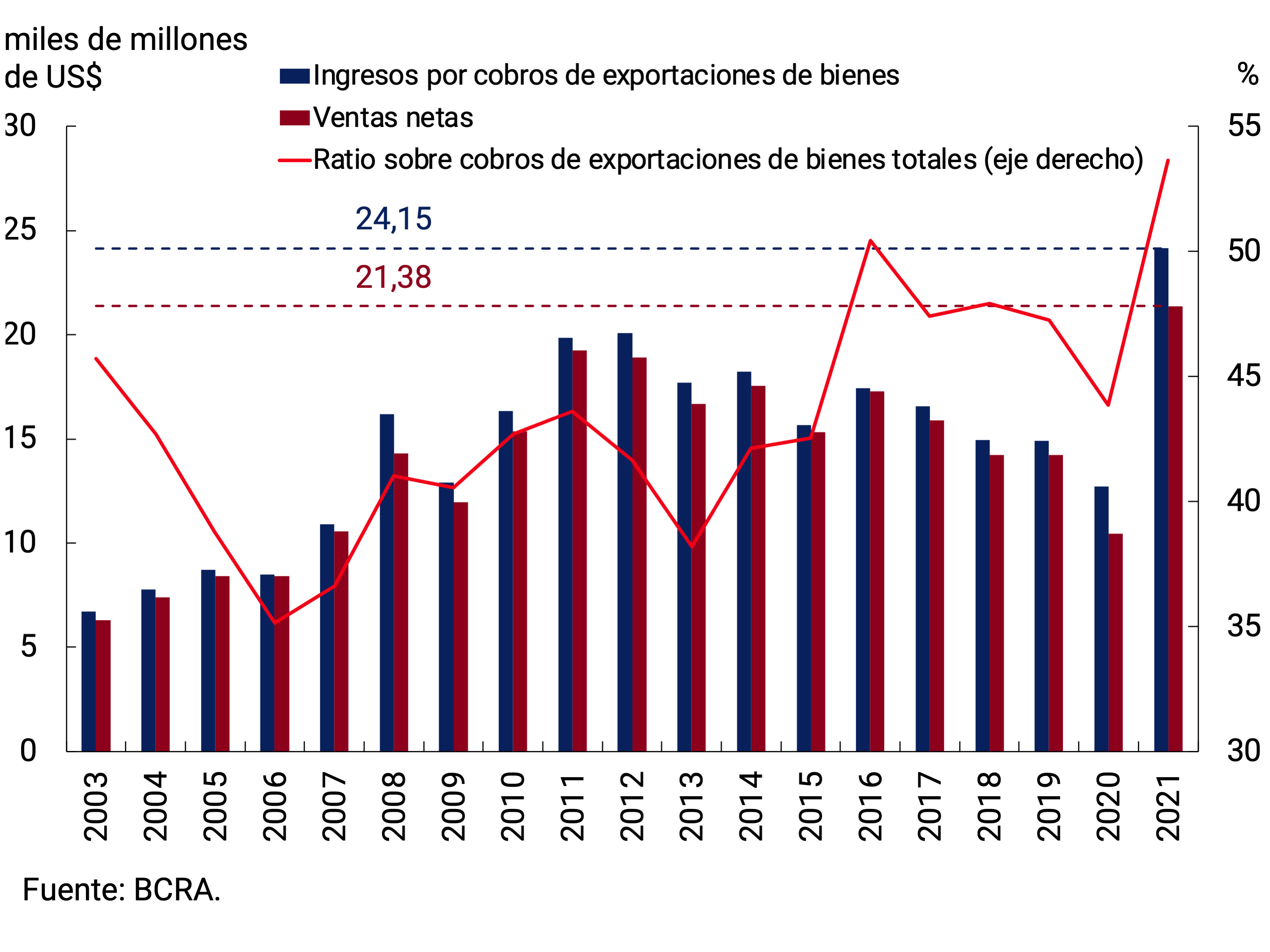

4.3. So far this year, the BCRA has recorded the largest net purchases of foreign currency in the foreign exchange market since 2012

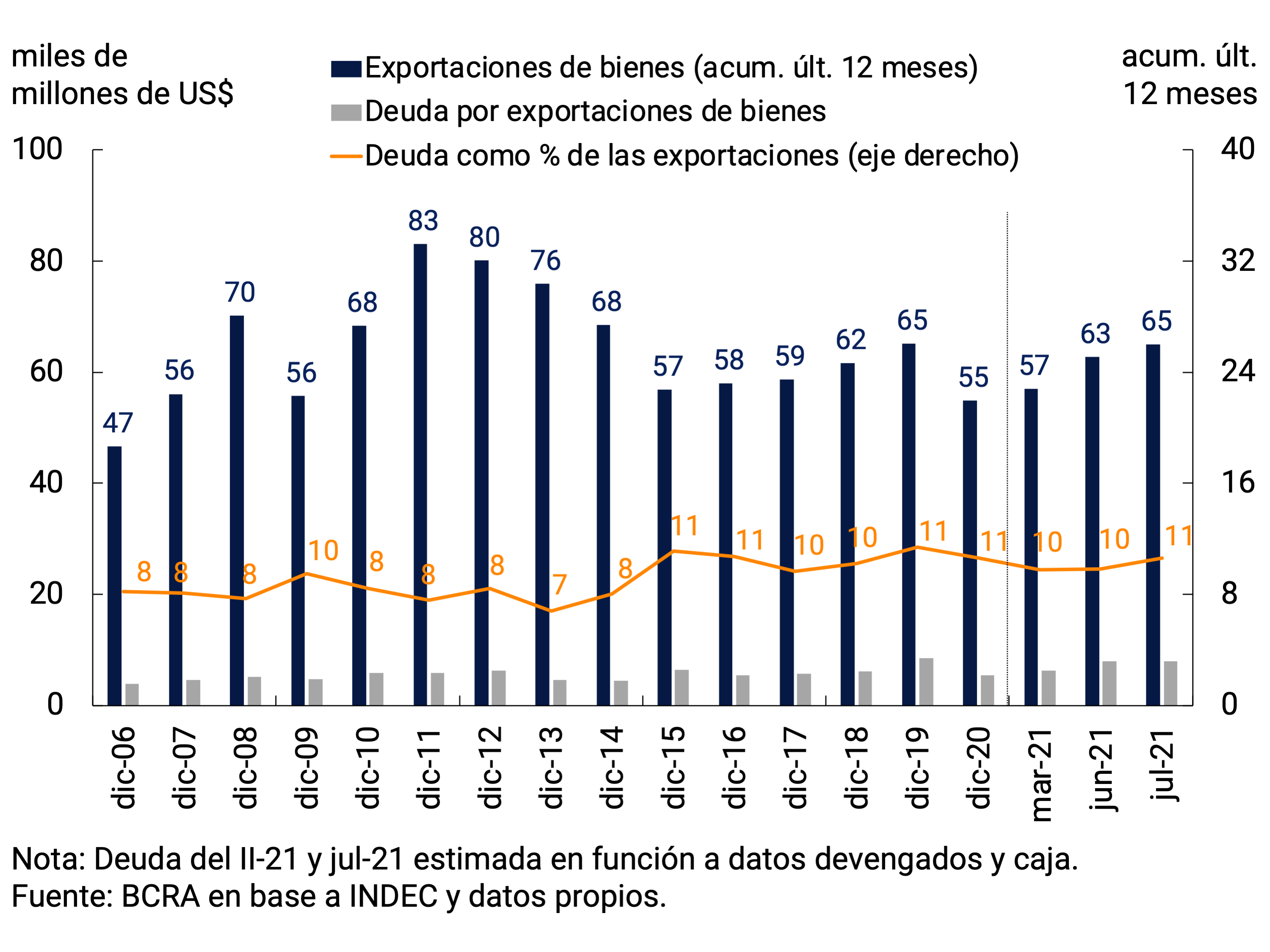

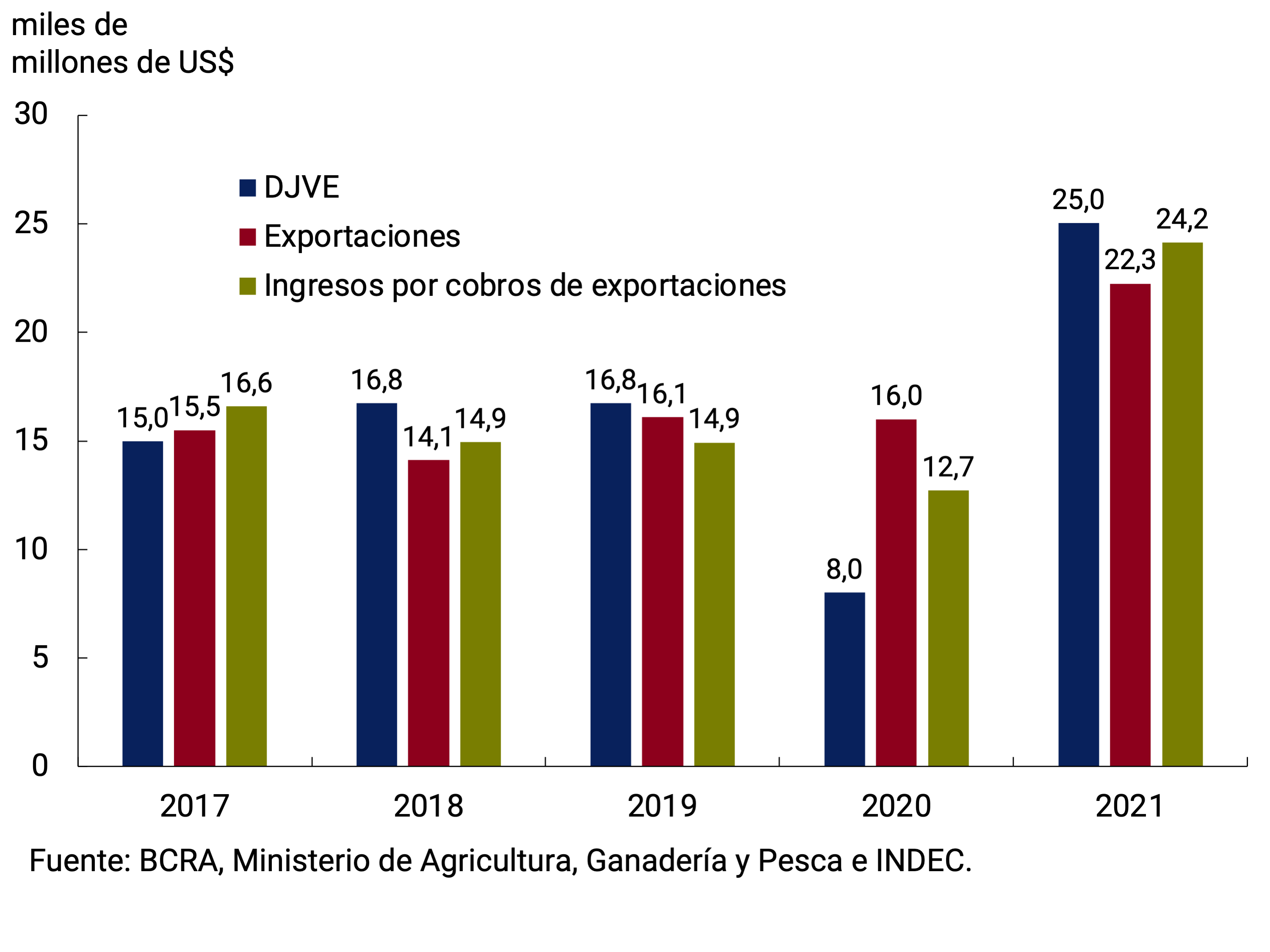

During the second quarter of 2021, exporters recorded revenues from the collection of exports of goods through the foreign exchange market for US$21,700 million. Given that exports of goods stood at about US$20,000 million, an increase in external debt for advances and pre-financing of about US$1,700 million is estimated. In July, collections for exports of goods were at a level similar to that of exports, with no variations in debt for advances and pre-financing from abroad. Thus, the ratio of this type of indebtedness to exported values stood at 11%, remaining at the levels observed in recent years (see Figure 4.7).

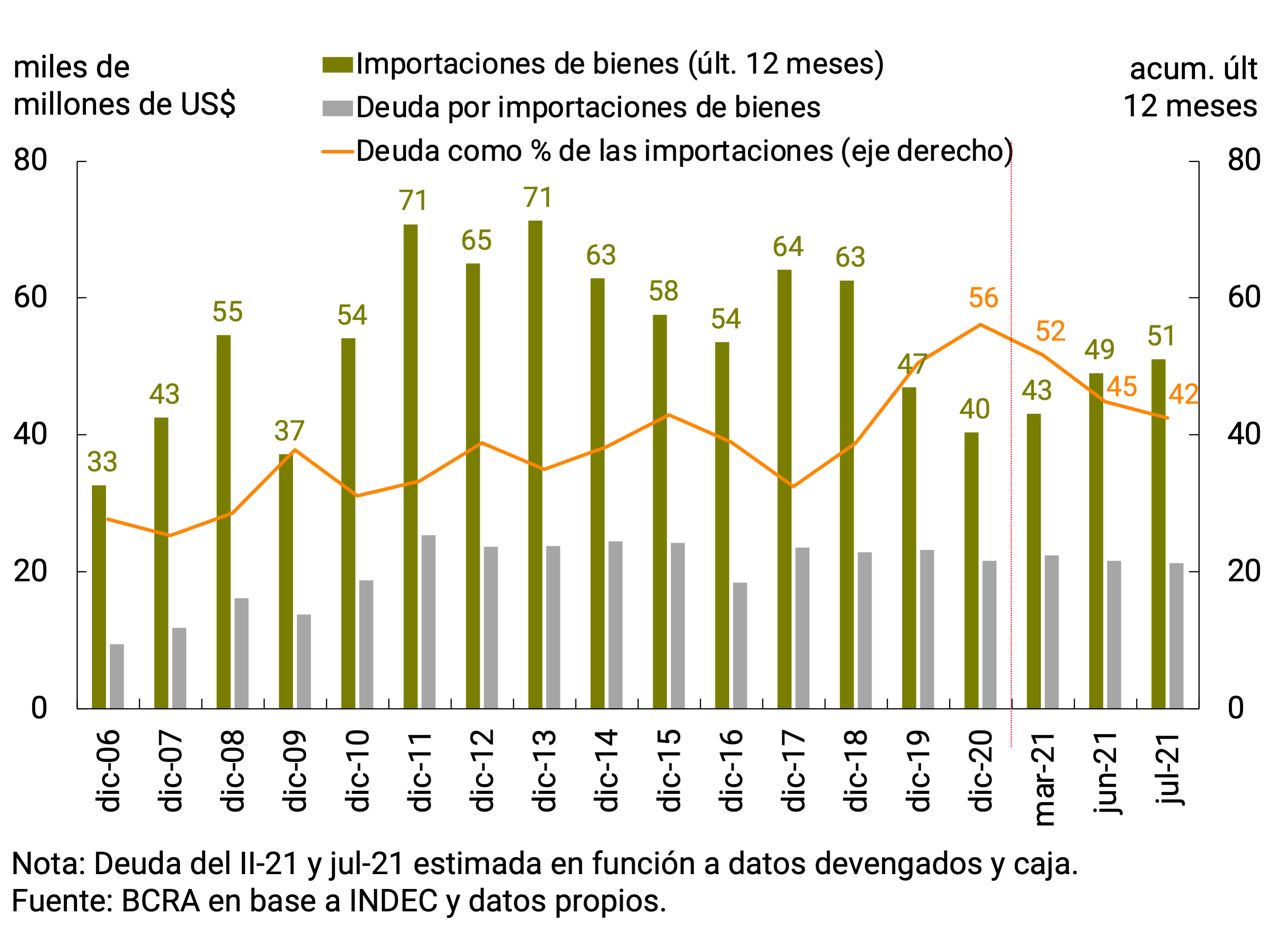

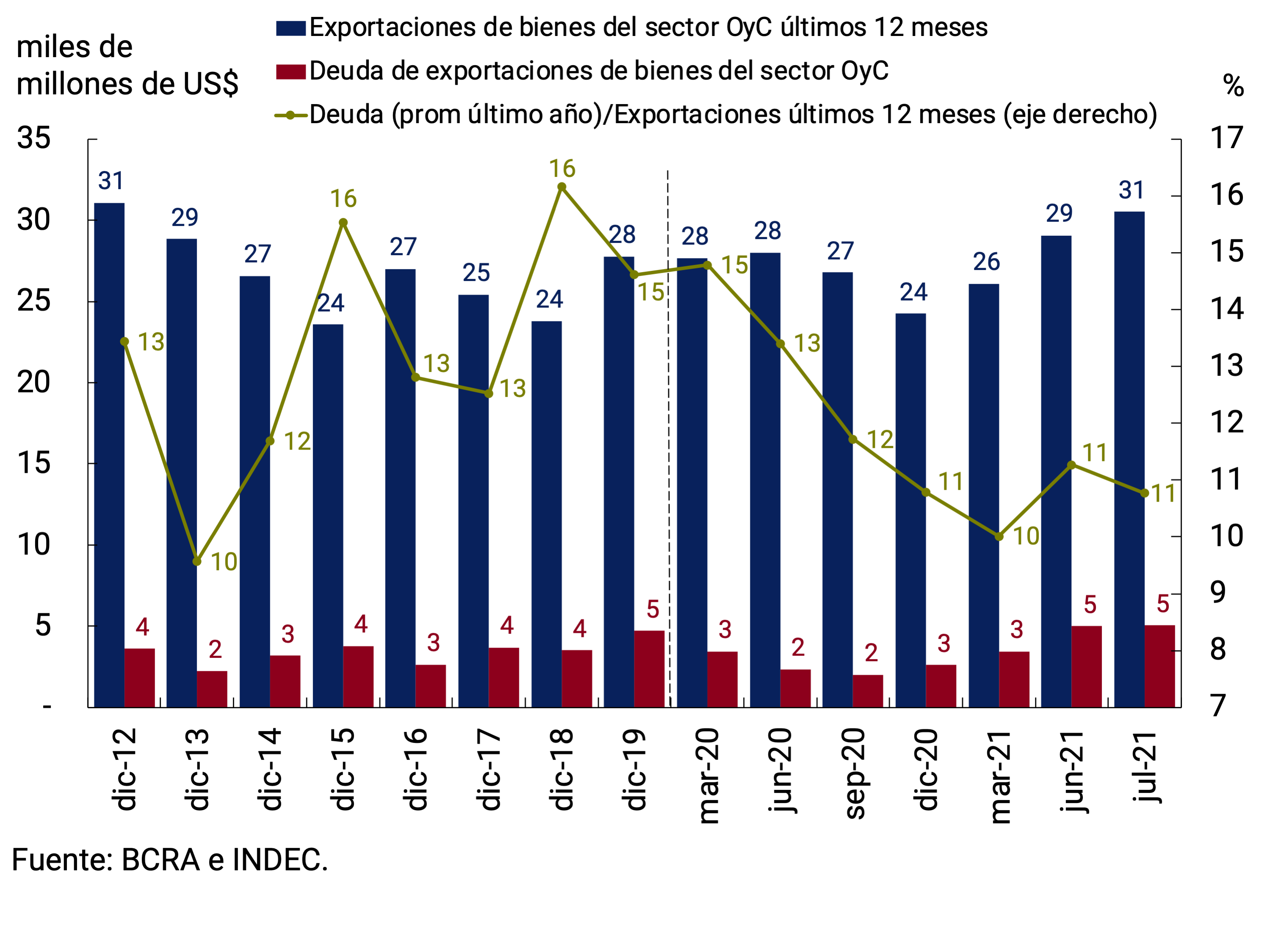

During 2020, the BCRA issued a series of regulations, aimed at promoting a more efficient allocation of foreign currency, which affected both the evolution of private commercial and financial debt, and are still in force1. In this context, during the second quarter of 2021, payments for imports of goods through the foreign exchange market for US$15,600 million were about US$780 million above FOB imports for the period, which would imply a fall in foreign indebtedness for this concept (or an increase in foreign assets due to early payments). During the month of July, this behavior was maintained, with payments for imports of goods through the foreign exchange market for US$5,740 million, surpassing FOB imports by about US$400 million. If the increase in imports in recent months is added to this situation, the ratio between external debt and the level of imports registered a fall of 10 percentage points compared to the first quarter and 14 p.p. compared to the end of 2020 (see Figure 4.8).

Finally, with regard to financial debt, and as part of the current regulatory framework mentioned above, in September 2020 the guidelines were established under which private sector companies could initiate a process of refinancing their respective external liabilities, which would allow their maturity profile to be adapted to the guidelines required for the normal functioning of the foreign exchange market31. This regulation, which reached certain capital maturities between 15.10.2020 and 31.03.2021, was extended covering maturities from then until the end of 202132.

In this context, the renegotiations registered during the second quarter of 2021 of some 33 companies had an impact on them demanding in net terms US$900 million less in the Foreign Exchange Market compared to what the original maturities implied for that same period, accumulating lower net payments of more than US$1,300 million in the year. During the month of July, some 13 companies renegotiated debts, resulting in a lower net demand in the market of about US$100 million (of the US$160 million of maturities originally registered for that month).

The aforementioned recovery of exports, added to the evolution of the commercial debt for exports and imports of goods, resulted in a net result for goods in the foreign exchange market of US$12,040 million in the first 7 months of the year, higher by about US$1,800 million than the result of the FOB trade balance of the same period. and exhibiting a strong improvement compared to the same period of the previous year (80%).

This result allowed the BCRA to accumulate net purchases in the foreign exchange market until July for US$7,165 million, a record for the first 7 months of the year since 2012 (See Chart 4.9), while international reserves increased by US$3,194 million in the same period. This difference was mainly explained by the net cancellations of principal and interest on foreign currency debt of the National Government with a direct impact on international reserves of about US$2,300 million and by payments for operations carried out through the Local Currency Systems with Brazil, Uruguay and Paraguay and ALADI for about US$400 million. Meanwhile, on August 23, the allocation of Special Drawing Rights by the IMF to mitigate the effects of the pandemic was accounted for around US$4,333 million.

4.4. Perspectives

For the remainder of the year, the current account is expected to remain balanced, oscillating in terms of output around the levels of recent quarters. Exports of goods would be boosted by the strengthening of demand from our main trading partners, in particular Brazil, while imports will accompany the performance of domestic economic activity. A resurgence of the pandemic due to the expansion of new strains of COVID-19 and/or a sharp correction in global financial markets that negatively impacts commodity prices or the activity of our main trading partners are the main risk factors for the external sector of the Argentine economy.

The regulatory framework in force in the Foreign Exchange Market will allow the BCRA to continue to efficiently manage foreign currency originating in commercial and financial transactions, in order to preserve monetary and exchange rate stability.

5. Public Finance

During the second quarter of 2021, national public finances continued to strengthen due to higher public revenues, a trend that continued during July. The recovery of domestic demand, taxes related to foreign trade – in a context of increases in international commodity prices – and non-tax revenues, associated with the Solidarity and Extraordinary Contribution, fundamentally determined its favorable evolution. Likewise, the regulatory modifications on taxes provided for in the Social Solidarity and Productive Reactivation Law of the end of 2019 and in the National Budget Law 2021 continued to have a positive impact.

The dynamism of social spending was maintained – within the framework of the social and economic emergency that has been in force since the end of 2019 – and a significant increase in capital expenditure was promoted in line with the provisions of the 2021 National Budget with the aim of supporting the recovery process of economic activity. In the opposite direction, there was a more limited trajectory of extraordinary expenditures associated with the evolution of the pandemic. Due to the high base of comparison due to the unprecedented and extensive package of mass assistance associated with alleviating the consequences of COVID-19 during the same period in 2020, year-on-year primary expenditure fell in real terms.

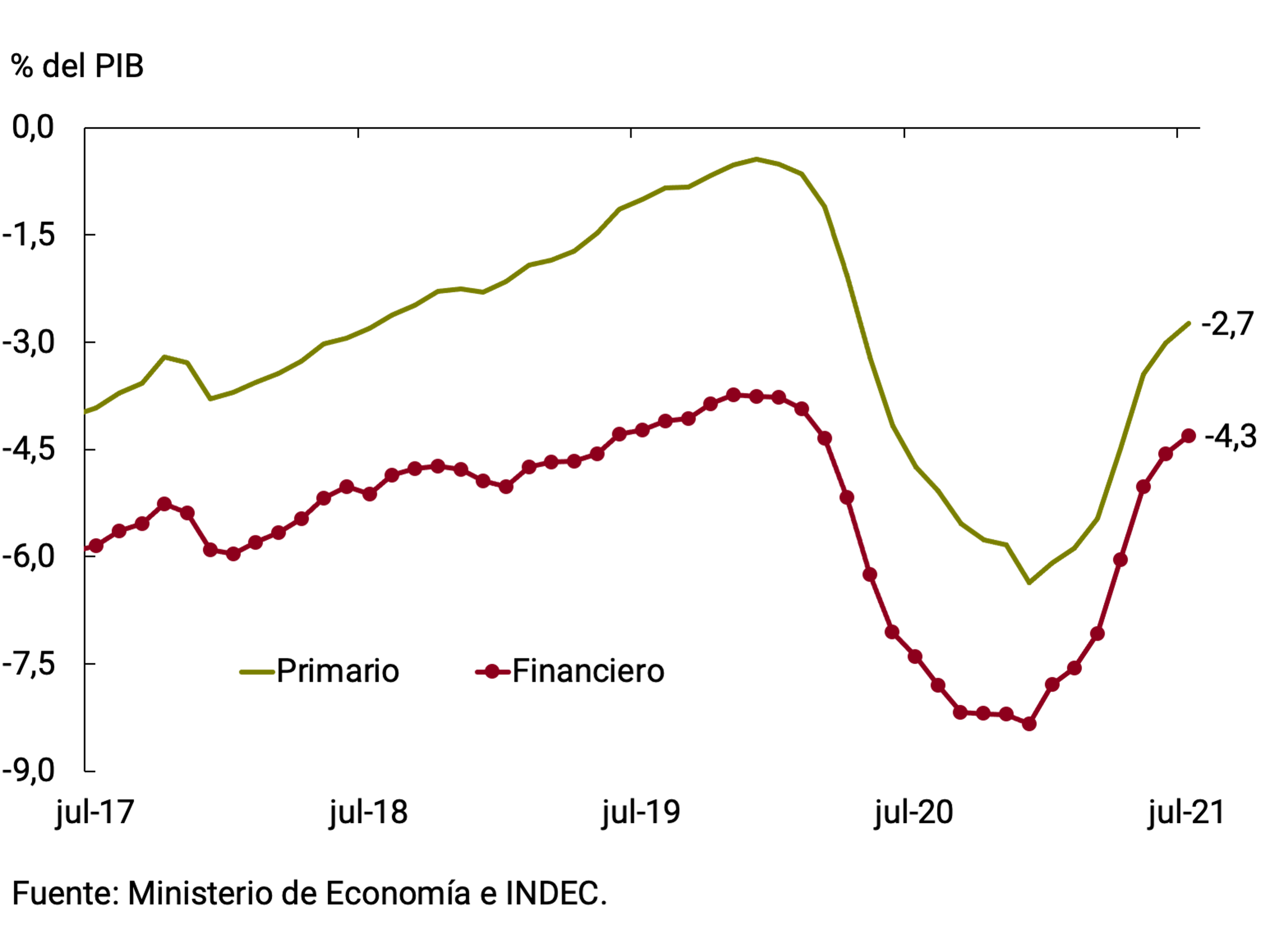

Given the trajectory of revenues and expenditures, a reduction in the fiscal deficit continued to be observed. In the last 12 months to July 2021, the primary deficit on a cash basis accumulated a balance equivalent to 2.7% of GDP, significantly lower than that observed during 2020 (-6.4% of GDP). This trajectory is consistent with what was established in the 2021 National Budget, which foresees a primary deficit of NFPS of 4.2% of GDP during this year.

Regarding financing from the National Treasury, during the second quarter the local market continued to play a greater role, allowing less financial assistance from the BCRA. The National Government continues negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and reached a bridge agreement with the creditor countries grouped in the Paris Club to extend the debt repayment terms by around US$2,500 million. For its part, the extraordinary allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) by the IMF was effective, benefiting Argentina by approximately US$4,333 million. Among the risks faced in the fiscal scenario, an eventual resurgence of the pandemic stands out, which could require intensifying assistance policies and negatively affecting tax revenues. Likewise, challenges persist to continue developing a financing policy with greater prominence of the local debt market.

5.1. Tax revenues showed a marked dynamism and strengthened the public accounts

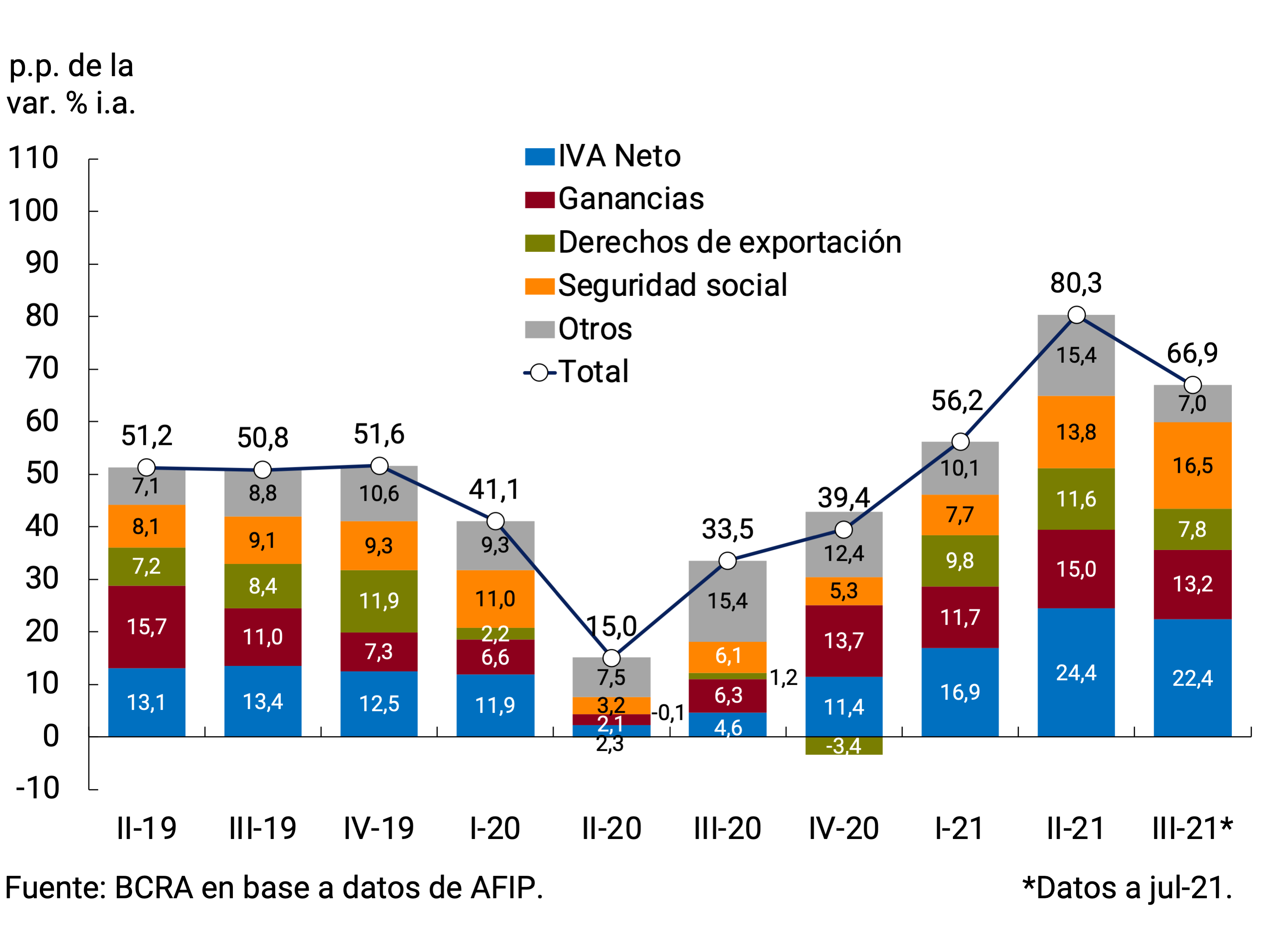

National tax collection increased 80.3% YoY in the second quarter of 2021 (see Figure 5.1). This behavior was explained by the consolidation of the economic recovery, the low base of comparison due to the full impact of the pandemic during the second quarter of 2020 and the higher values exported. In real terms, this performance implied an increase of 22% YoY (11 p.p. higher than the real year-on-year variation recorded during the first quarter). In July, the nominal increase was 66.9% YoY (+10% YoY in real terms).

Taxes associated with foreign trade continued to show high dynamism. In a context of high international commodity prices, export duties registered a year-on-year growth of 139% in July, after expanding 189% YoY between April and June, maintaining an advance similar to that of the first quarter (190.4% YoY between January and March). Taxes linked to foreign purchases36 also showed a strong increase during the period: 100.6% YoY in July and 113.4% YoY in the second quarter. This behavior was basically explained by the high dynamism of imports (see Chapter 4. External Sector).

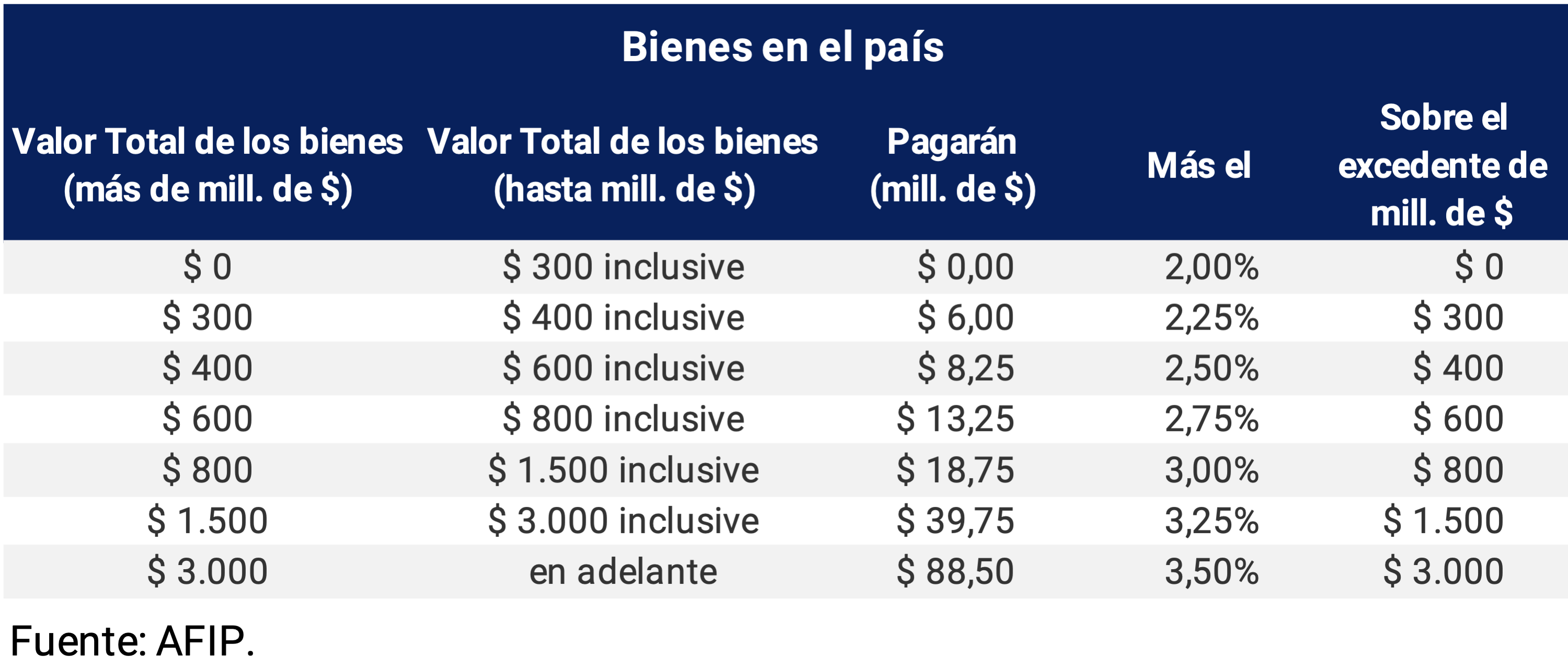

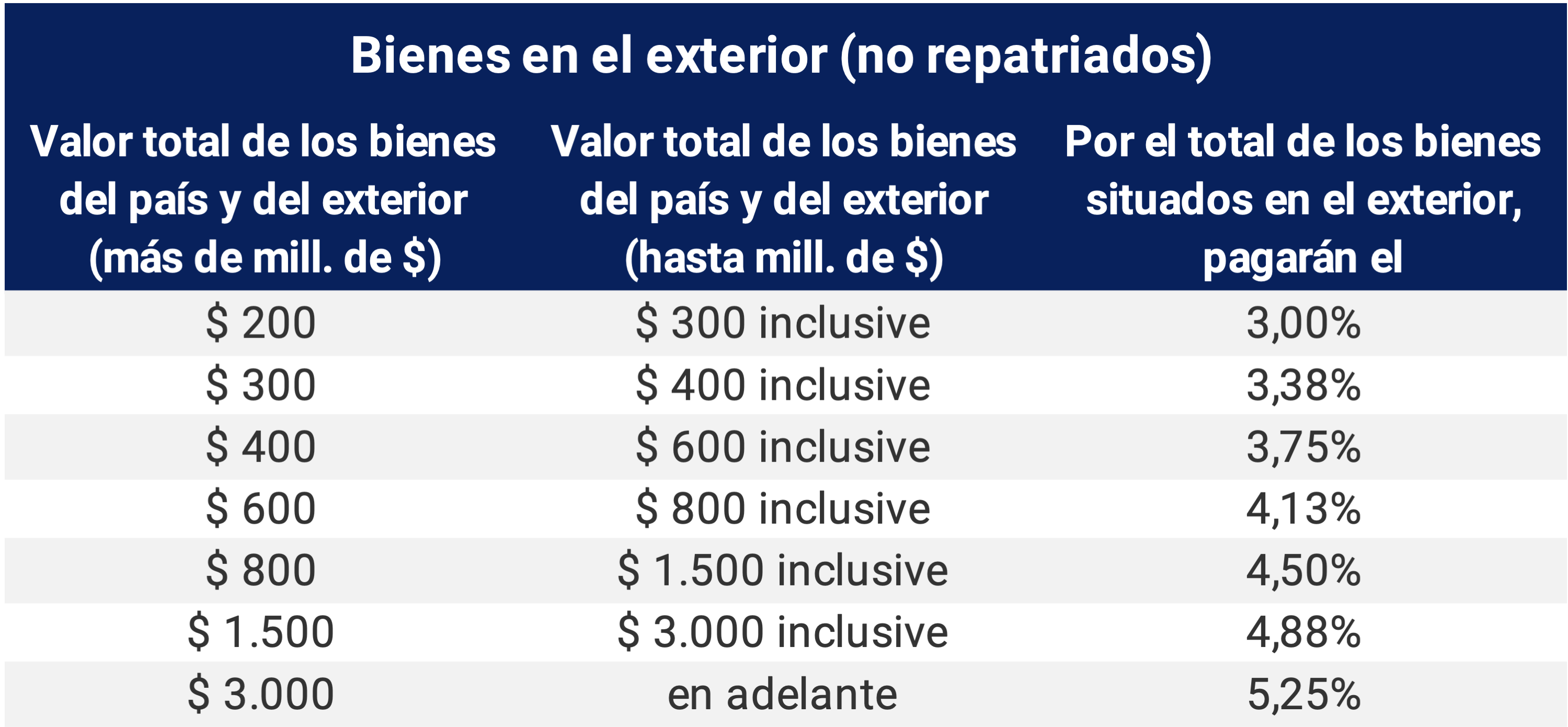

Taxes related to the domestic market (Value Added Tax (VAT), Profits, Fuels, among others) showed a better year-on-year performance between April and June in relation to previous quarters, due to the recovery of economic activity and the low base of comparison —the period of greatest intensity of the harmful impact of the pandemic—. Income Tax rose 68.5% YoY in July and 59.4% between April and June 63% YoY, in line with what was observed in the first quarter of the year. This tax is still affected upwards by the regulatory change of September 2020 on the withholding on purchases of dollars and expenses in foreign currency through credit cards. In addition, it is negatively impacted by the increase in personal deductions on the income of employees and by refunds for differences owed to these taxpayers in past months37. Net VAT grew 88.5% YoY in the second quarter of 2021 compared to the 54.2% YoY increase recorded in the previous quarter. For its part, the set of taxes modified by the Law of Social Solidarity and Productive Reactivation (such as Personal Property, Internal, PAIS) and by the National Budget Law 2021, maintained a good performance. In the opposite direction, the extensions of the payment dates of the balances of the Income Tax, Personal Property Tax and Cedular Tax affidavits operated.

Finally, social security resources showed a sustained recovery, mainly explained by the evolution of wages and employment: they grew 63.3% YoY between April and June (influenced by the low base of comparison due to the impact of the pandemic in 2020), 35 p.p. above the increase observed between January and March and maintained the year-on-year dynamism in July (+62.6% YoY). This set of taxes is still negatively impacted by the measures taken by the National Government to address situations in sectors critically affected by COVID-19, also reducing employer contributions in the health sector, the critical sectors contemplated in the REPRO II program and in the provinces of the Norte Grande.

The evolution of tax revenues allowed the total revenues of the National Non-Financial Public Sector (NFPS) to increase in nominal terms by 73.7% YoY in July and 99% YoY (34% real) between April and June, after having increased by 61% YoY during the first quarter of the year. Non-tax revenues increased by 202% YoY in July and 493% YoY in the second quarter due to the allocation of resources associated with the Solidarity and Extraordinary Contribution to Help Mitigate the Impact of the pandemic (between May and June, almost $170,000 million were recorded for this concept; Law 27605). Property rents increased 269% y.o.y. between April and June, explained by the collection of services of loans granted by the National Social Security Administration (ANSeS) – which was suspended in the same period last year – a trend that continued into the seventh month. Meanwhile, capital resources decreased in year-on-year terms in July and in the second quarter, affected by the provisions of Law No. 27574 on the defense of the assets of the Sustainability Guarantee Fund (FGS), which stipulates the suspension of financing to the ANSES by the FGS to meet the disbursements of the Historical Reparation program.

Meanwhile, the tax collection of the provinces as a whole exhibited a behavior consistent with what was observed at the national level. According to the partial information available for the main districts, in the second quarter of the year the nominal advance of own tax resources would have accelerated compared to the first quarter, with variations of around 80% y.o.y. due to the low base of comparison of the same quarter of 2020.

5.2. Within public spending, capital spending was prioritized to contribute to economic recovery

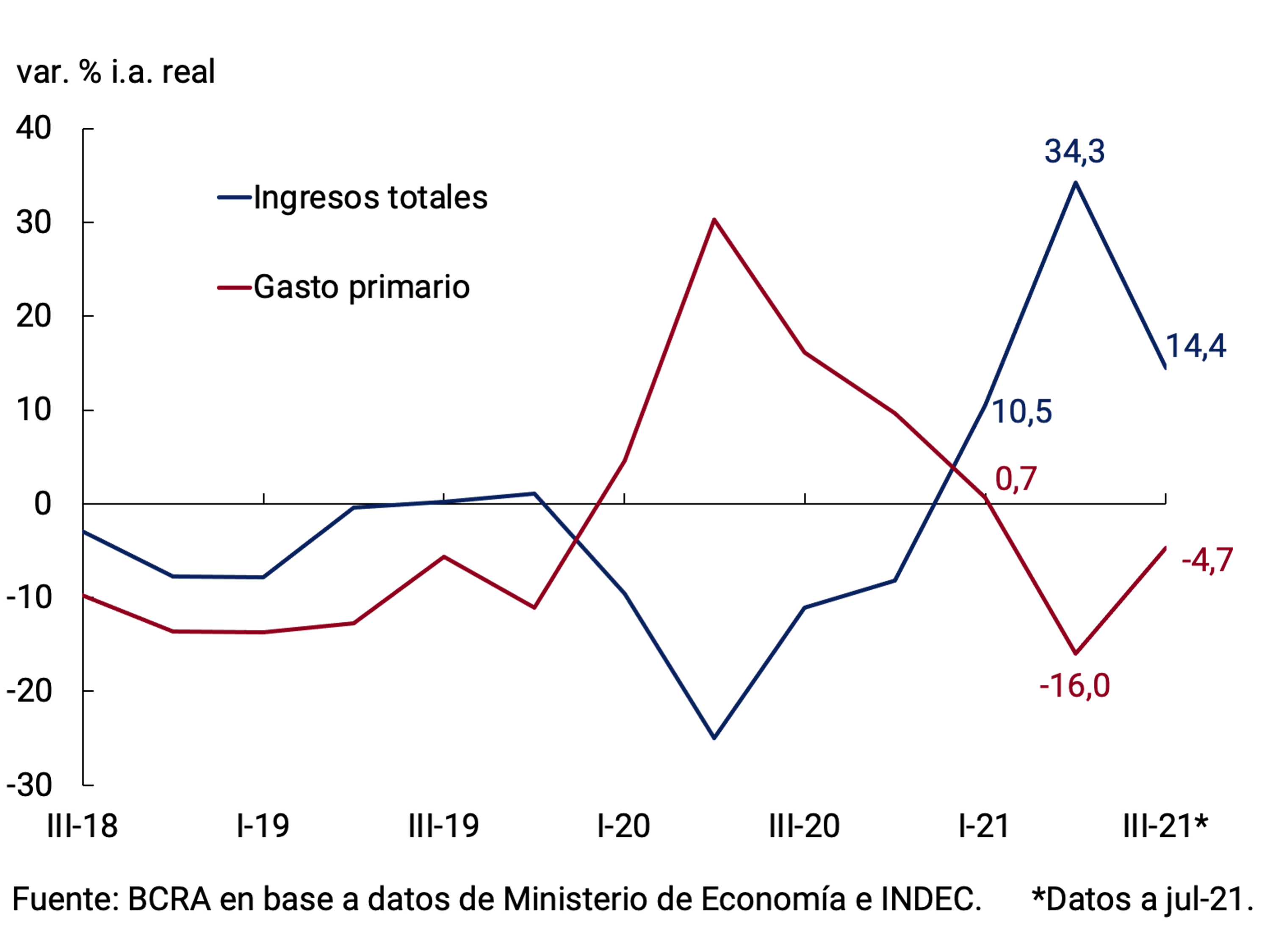

NFPS primary expenditure showed a nominal increase of 44.7% YoY in July and 25% YoY in the second quarter of the year, 74 p.p. below the nominal increase in revenues. In real terms, expenditures decreased by 4.7% YoY in July and by 16% YoY between April and June, while revenues increased by 14.4% and 34.3% YoY, respectively (see Figure 5.2).

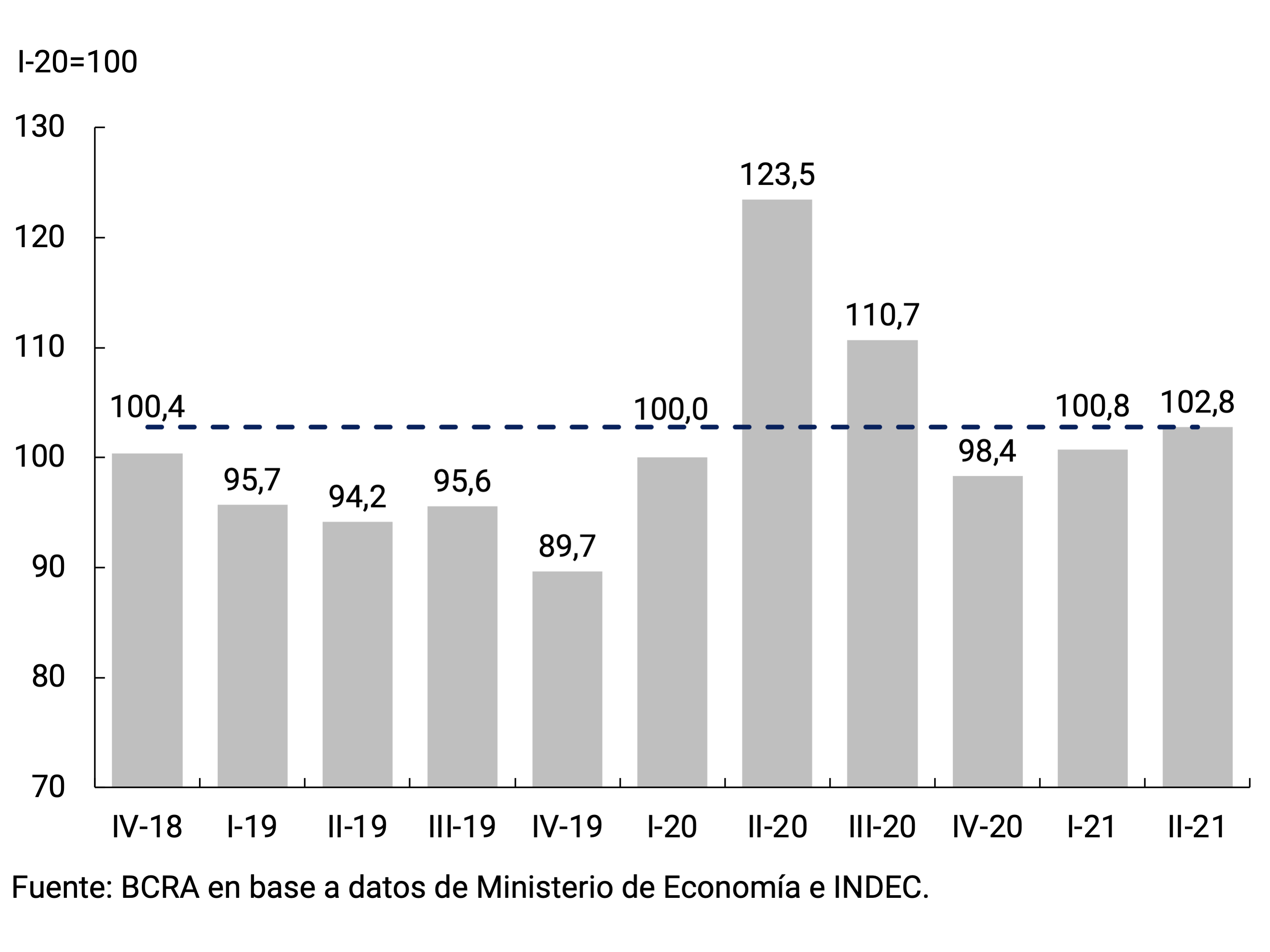

It should be borne in mind that for most of the current year, the public accounts will be affected by a basis of comparison that includes the effects of the pandemic, the greatest deployment of which was concentrated in the second quarter of 2020. In this sense, if real seasonally adjusted primary expenditure is observed, it was 2.8% above the pre-pandemic level (I-20; see Figure 5.3) in the second quarter of 2021 and even higher than in 2019.

During the second quarter of 2021, social security benefits accounted for most of the increase in primary spending: they grew by 35% YoY (vs. +29% YoY in the first quarter)38, within the framework of the provisions of the new Social Security Mobility Law39. Regarding social programs, the expenditures of the Food Policies program were highlighted due to the increase in the allocation of 50% as of February 2021 and the expansion of the universe of beneficiaries up to 14 years of age, inclusive, and the Empower Work program due to the increase in both the number of people and the Minimum Living and Mobile Wage. In turn, payments from the Employment Actions program – mainly REPRO II – registered a significant increase in order to assist the productive sectors critically affected by the pandemic40. For its part, the ANSES paid a one-time reinforcement of $15,000 in April to holders of Universal Child Allowances for Social Protection (AUH) and Universal Pregnancy Allowance (AUE), and to the lowest category single-payers residing in the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires (AMBA)41. In order to sustain the purchasing power of the most vulnerable older adults, ANSES also ordered the payment in April and May of an extraordinary sum of $1,500 to more than 4 million retirees and pensioners with assets of up to 1.5 minimum salaries, while promoting in August the payment of a bonus of $5,000 for beneficiaries who receive up to two minimum salaries.

In a context in which the national government promoted a policy of containing the rates of public services – electricity, gas, water and transport – economic subsidies accounted for a significant portion of the year-on-year increase in spending: they grew 125.3% YoY in July and 65% YoY during the second quarter compared to 77% YoY in the first three months of the year. The increase was disseminated among the main destinations associated with energy and public passenger transport.

Items associated with salaries (including transfers to universities) grew 50.4% in July and 52% between April and June, while other current expenditures grew by 134.3% YoY and 99% YoY, respectively. It should be noted that in this last item the purchases of goods and services (including expenditures associated with the purchase of vaccines) and the deficit of public companies, among others, are recorded. For their part, current transfers to the provinces moderated significantly compared to the same period in 2020, when the National Government had extraordinarily assisted the districts in the face of the abrupt decrease in collection. This performance was verified despite the fact that since the beginning of 2021, the transfers associated with the creation of the Fund for the Fiscal Strengthening of the Province of Buenos Aires42 began to be recorded in the budget.

Capital expenditure continued to be the most dynamic item, in line with the definition of priorities set out in the 2021 National Budget to promote the recovery of economic activity. In fact, Real Direct Investment (IRD) grew 159% YoY during the second quarter, while transfers for capital expenditures increased 68% YoY in the43rd quarter. In July, capital expenditure increased 91.6% YoY.

It is important to note that the reduction in interest payments on public debt, achieved after the successful restructuring of liabilities denominated in foreign currency last year, and the reconstruction of the local debt market generated fiscal space to sustain the dynamism of NFPS primary expenditure aimed at financing public policies that mitigated the health and economic effects of the pandemic and promoted economic recovery. Interest on public debt, net of intra-public sector payments, went from representing 3.4% of GDP in 2019 to around 2% of GDP in 2020 and around 1.6% of GDP in the accumulated of the last 12 months to July 2021.

Thus, the primary deficit of the NFPS accumulated in the last 12 months to July represented approximately 2.7% of GDP, 3.6 p.p. less than in December 2020 (see Figure 5.4). This evolution is in line with the 2021 National Budget, which forecasts that the primary deficit result will be reduced to 4.2% of GDP for the accumulated to December. For its part, the financial deficit of the NFPS accumulated in the same period stood at 4.3% of GDP, 4 p.p. below the total deficit of 2020.

5.3. The National Government met its needs to a greater extent through the placement of debt instruments in the local market

During the second quarter of 2021, the National Treasury (TN) achieved a refinancing of 136% of principal and interest services (112% in July), which implied a net financing of approximately $266,000 million (about $35,000 million in July)44. The issuances of public debt instruments were made mostly with securities adjustable by CER, followed by discount instruments and finally by fixed-rate government securities. Additionally, in the first auction in August, securities adjusted to the evolution of the dollar were awarded.

Since the beginning of the National Government’s administration at the end of December 2019, a process of extending the terms of the instruments issued was consolidated, while the cost of financing in pesos remained relatively stable. For its part, during the month of June and July 2021, voluntary debt conversion operations were carried out, which made it possible to significantly decompress the maturity profile. Going forward, a continuity of the TN financing strategy is expected with the aim of developing the local peso debt market. In this sense, in mid-July, the new guidelines for the implementation of the Market Makers Program 2021 were established, registering in August a total of 13 entities interested in the role of45 applicants. In addition, in order to deepen liquidity in the capital market, the Central Bank began to operate in the public securities futures market.

So far in 2021, and in contrast to the same period last year, the greater role of the market in financing the needs of the NT stands out, which led to a reduction in the BCRA’s financial assistance, which was consolidated in the second quarter, remaining in line with the budget. So far this year, $520,000 million have been transferred as a transfer of profits from the BCRA to the TN and $190,000 million in net transitory advances46.

A bridge agreement was negotiated with the creditor countries grouped in the Paris Club on the maturity of around US$2,500 million, achieving an extension of negotiation terms with a maturity of March 31, 2022. In return, in the period between May 2021 and March 2022, around US$430 million will have been paid in capital payments47.

Finally, the National Government continues with negotiations with the IMF, having as next capital maturities with it, those scheduled for September and December. Meanwhile, the extraordinary general allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) by the agency was confirmed, which represented for Argentina a financial source of around US$4,333 million to meet its needs in foreign currency.

6. Pricing

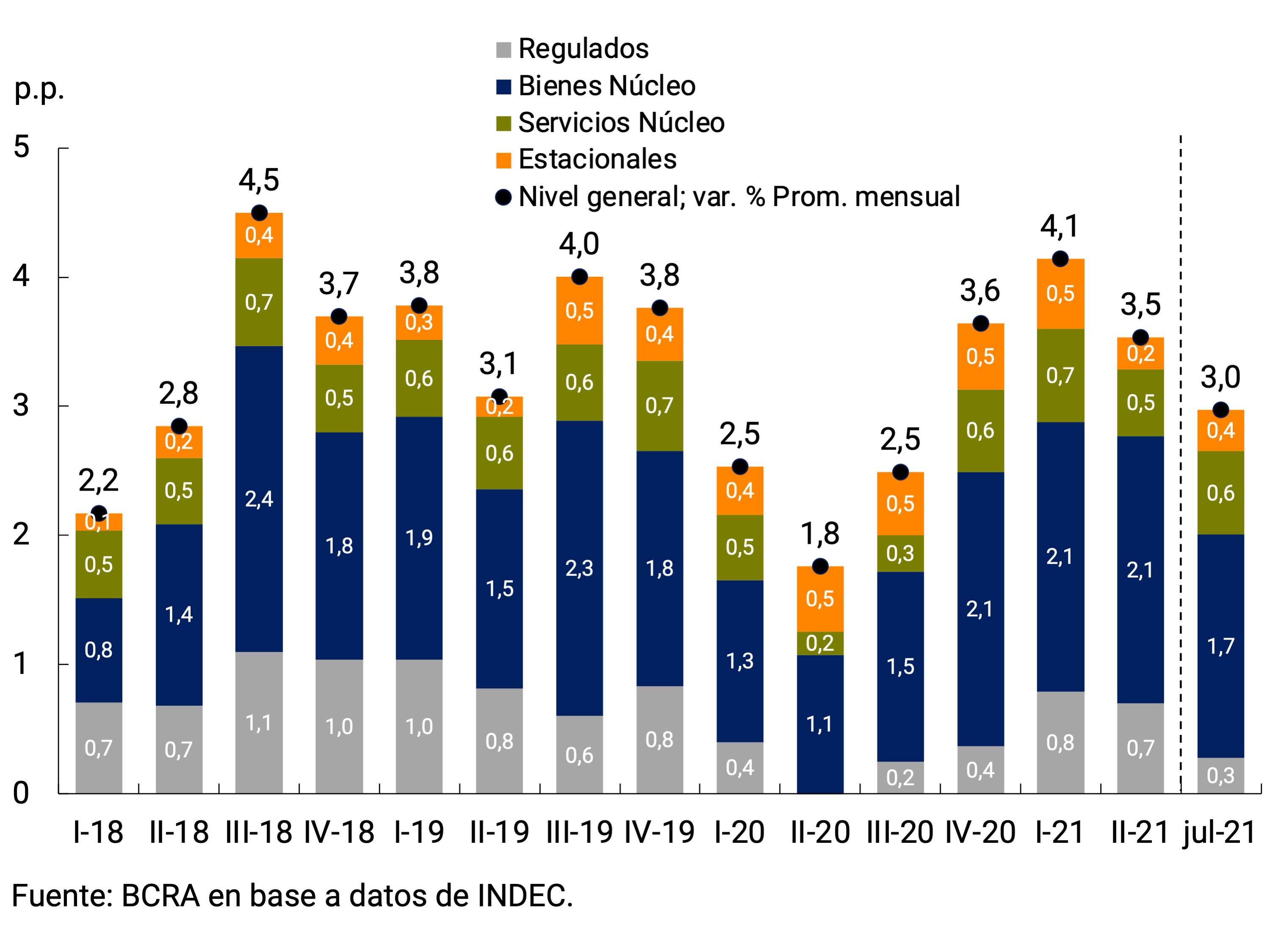

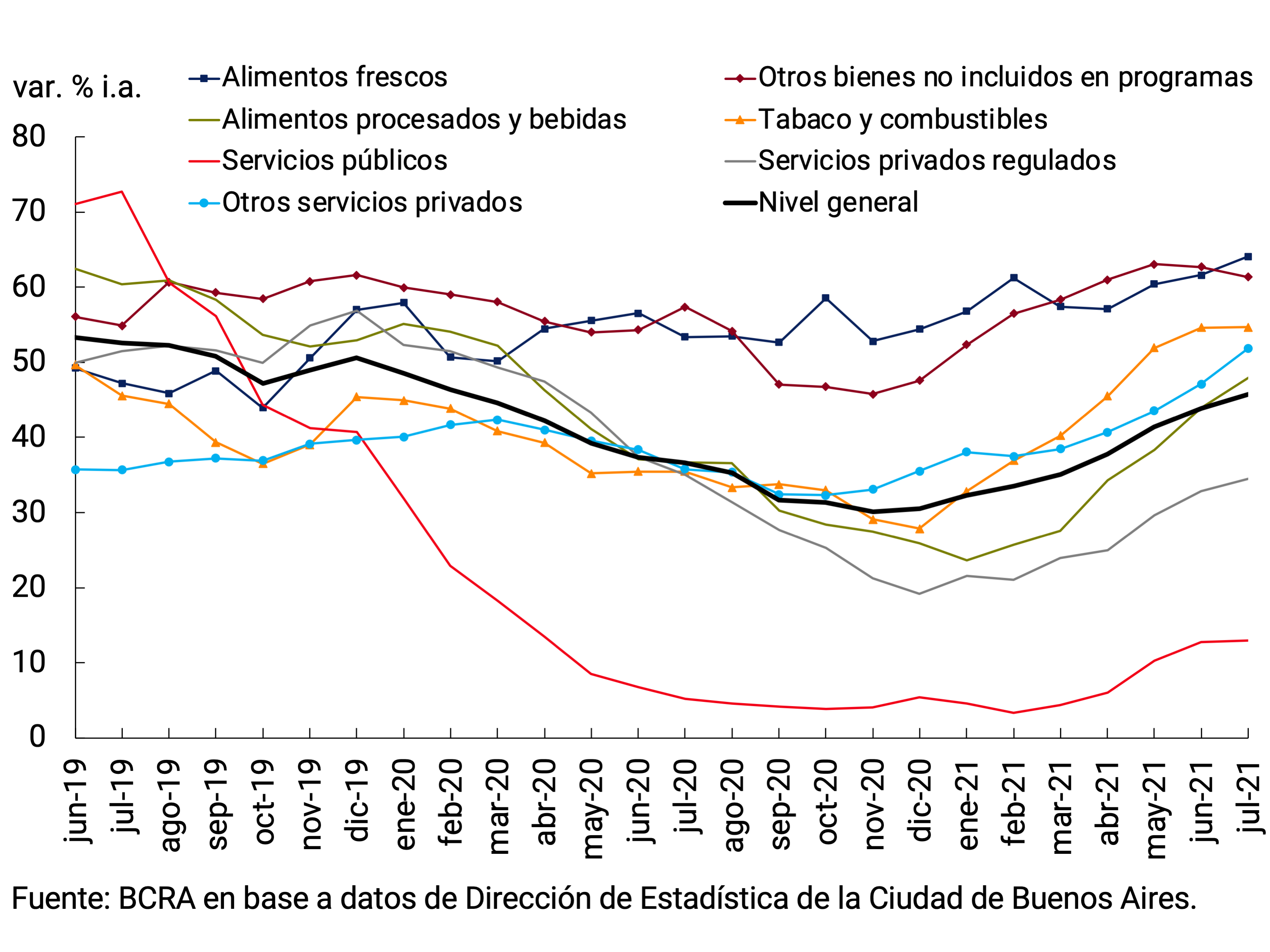

Average monthly inflation in the second quarter was down from the previous quarter. This gradual deceleration in prices was widespread among categories, being more pronounced in seasonal ones. This trend continued in July, with the lowest monthly increase in the General Level since September 2020 (3.0%).

Prices of goods continued to grow at a faster rate than services during the second quarter of the year. In a period with limited variations in the nominal exchange rate, this dynamic was partially explained by the sharp increase in international prices that has been verified since mid-2020. The moderation of services with respect to goods is associated with their lower relative demand since the pandemic began and the national government’s policy of containing public service rates.

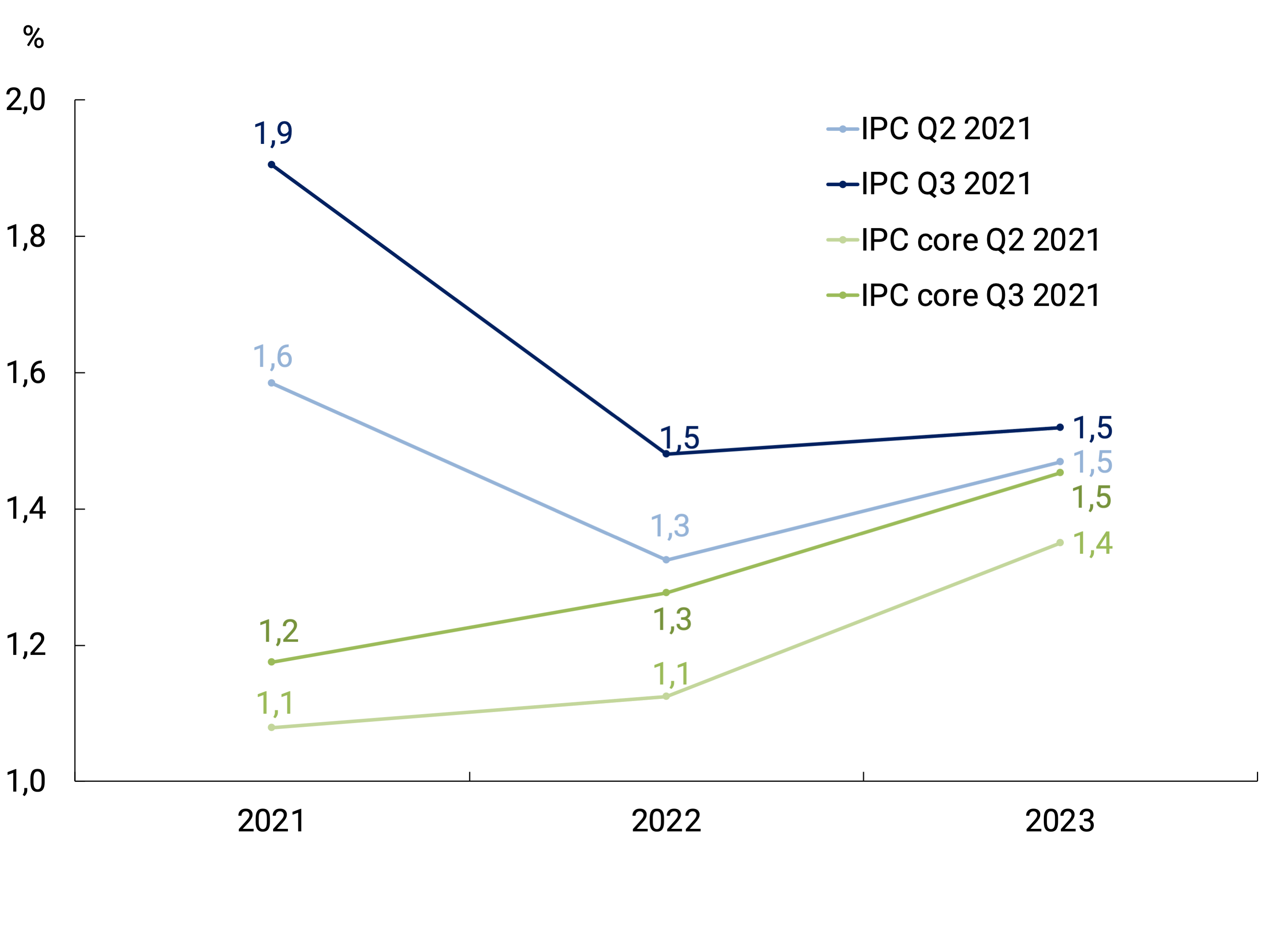

Year-on-year inflation continued to rise to 48.5% in the second quarter and to 51.8% in July, despite the monthly slowdown in prices. This divergence is explained by the low base of comparison of the same period in 2020 when, in the context of the greatest impact of the pandemic on the economy, monthly records were on average 1.9%.

The slowdown during the second quarter was more pronounced in wholesale prices, a trend that continued in July. The domestic wholesale price index (IPIM) rose during the quarter at a higher rate than the exchange rate, influenced by international prices, but lower than that recorded by retail goods.

The gradual decline in monthly inflation rates is expected to continue for the remainder of the year from a reduction in the pace of growth in regulated services and goods. For their part, the updates of the wage parity and the gradual recovery of demand would generate a recomposition of the relative prices of private services. As a result of the low base of comparison, the monthly deceleration of prices would be reflected in a stabilization of the year-on-year inflation rate in the coming months that would begin to fall only towards the end of the year. In this context, the BCRA will continue to guide its monetary and exchange rate policy to help consolidate the process of gradual reduction of inflation.

6.1. Retail prices slowed during the second quarter

During the second quarter of 2021, retail prices registered an average monthly increase of 3.5%, slowing down 0.6 p.p. compared to the previous quarter (see Figure 6.1). The reduction in monthly registrations, which began in April, continued in July with a price increase of 3.0%, the lowest since September 2020.

The slower pace of increase in the second quarter was generalized for all categories of the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Seasonal products averaged a monthly increase of 1.4% (-3.0 p.p. compared to the first quarter), being the category that contributed the most to the slowdown in the general level. The Core category expanded at an average monthly rate of 3.9% (-0.3 p.p. compared to the previous quarter), with a marked decrease in monthly registrations starting in May. For their part, the prices of Regulated items also slowed the pace of increase, averaging a monthly increase of 3.5% in the first quarter (0.4 p.p. below the first quarter of 2021; see Chart 6.2).

In the second quarter of the year, goods continued to grow at a faster rate than services, accentuating the pattern observed since the beginning of the pandemic, although both slowed down, averaging increases of 3.9% and 2.7% respectively (-0.6 p.p. and -0.9 p.p. compared to I-21, in each case). In July, the monthly variation of services (3.1%) exceeded that of goods (2.9%), which meant an incipient recomposition of their relative prices.

In a period with limited variations in the nominal exchange rate, the higher rate of increase in the prices of goods compared to that of services was partially explained by the sharp increase in international prices that began in mid-2020. Regarding the slowdown in goods during the second quarter compared to the first, it was mainly explained by the lower dynamism in the Food and non-alcoholic beverages division (3.6% monthly average, -0.9 p.p. compared to I-21). The slowdown in Clothing and footwear also had an impact, explained by seasonal effects linked to the change in the autumn/winter season, present in the previous quarter (3.8% monthly average, -1.1 p.p. compared to I-21). To a lesser extent, the reduction in the average monthly increase of the Alcoholic Beverages and Tobacco division (3.6%, -1.3 p.p. compared to I-21) also contributed, mainly due to the evolution of tobacco (2.2% monthly average, -2.7 p.p. compared to I-21). On the other hand, with a higher level of disaggregation, certain goods, such as fuels and lubricants for home vehicles and medicines, increased the rate of increase compared to the first quarter of the year.