Política Monetaria

Monetary Policy Report (IPOM)

First trimester

2022

Publication that aims to explain in a transparent manner the reasons of the BCRA for its monetary policy decisions.

Table of Contents

Chapters

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlook

2. International context

3. Economic Activity and Employment

4. External Sector

5. Public Finance

6. Prices

7. Monetary Policy

Sections

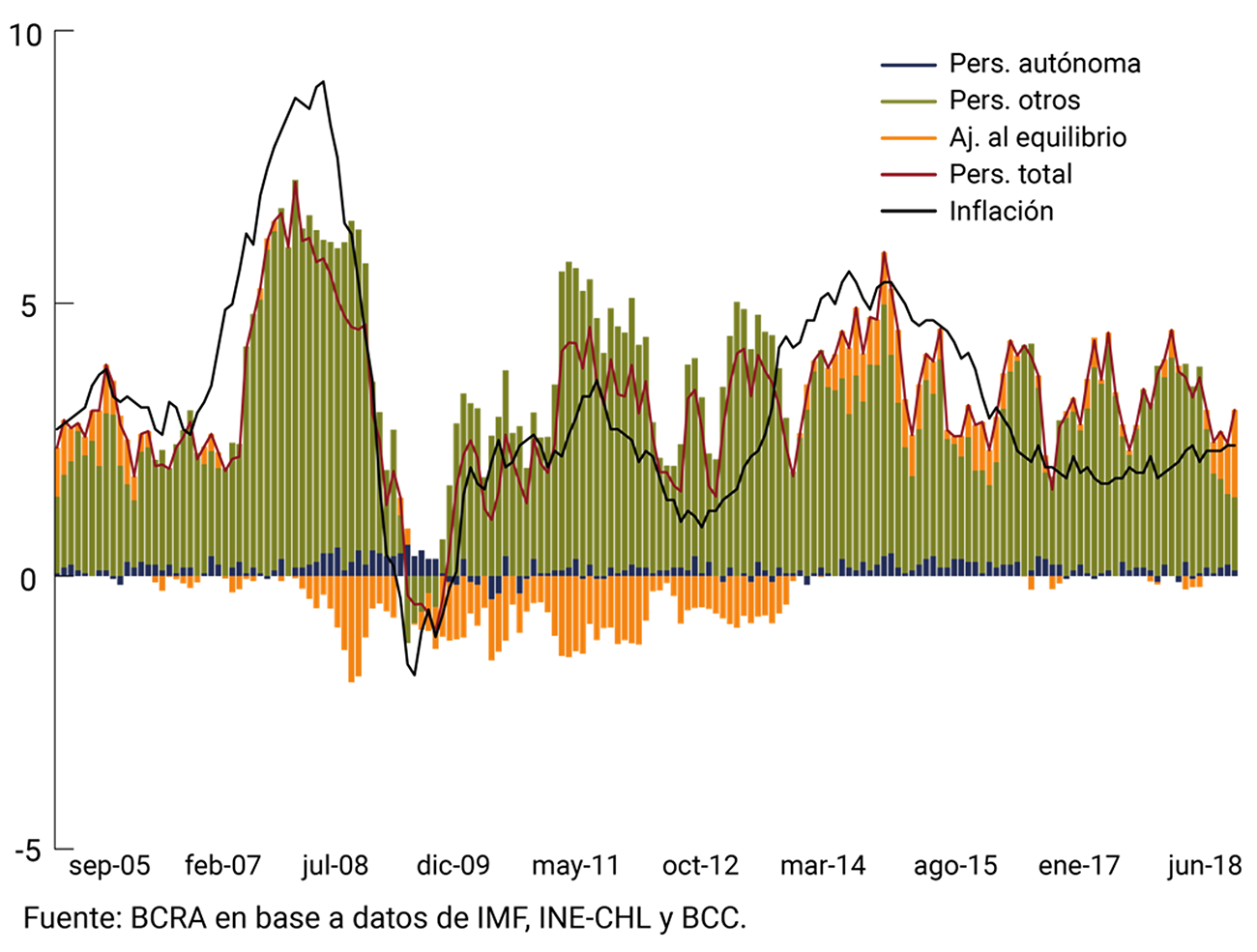

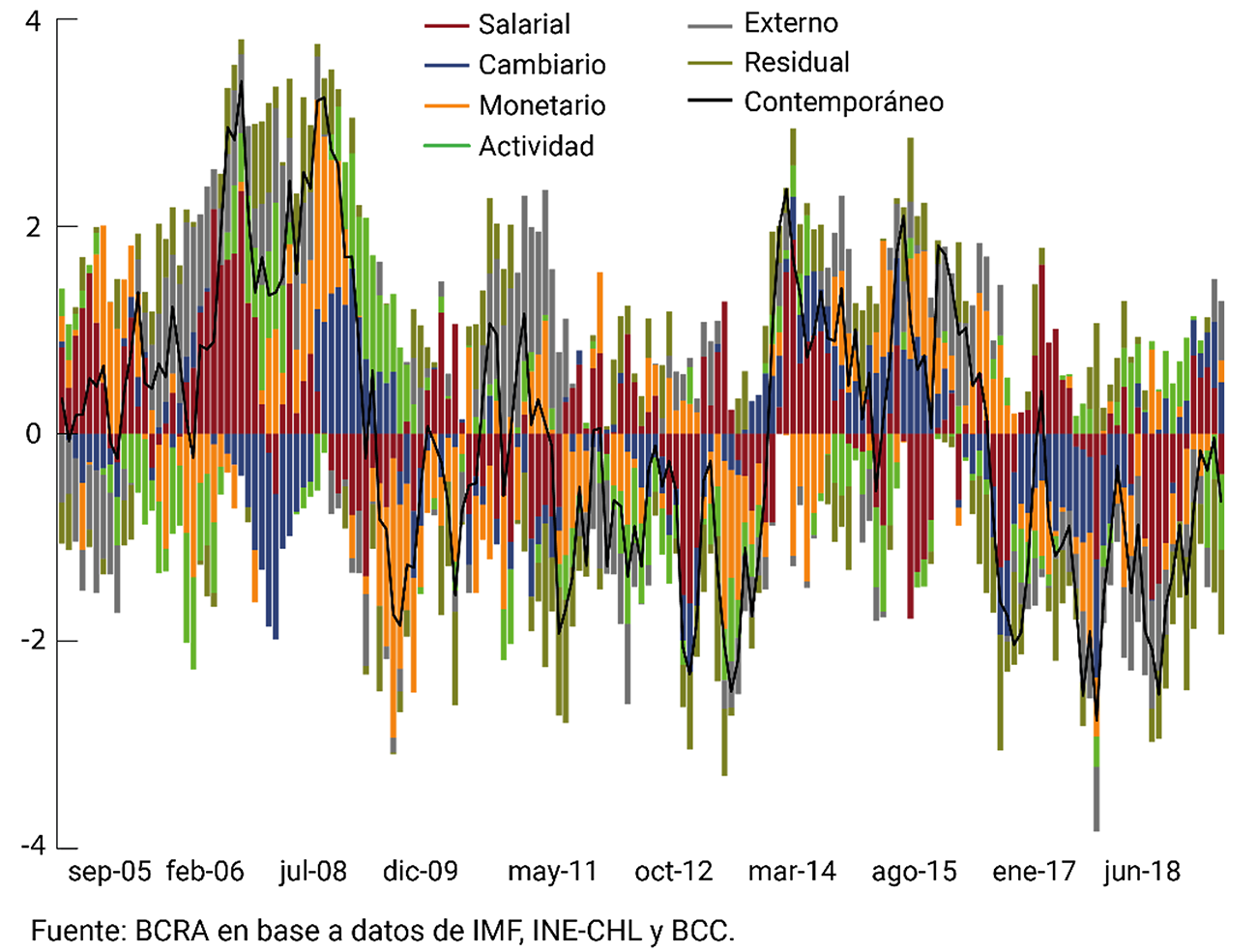

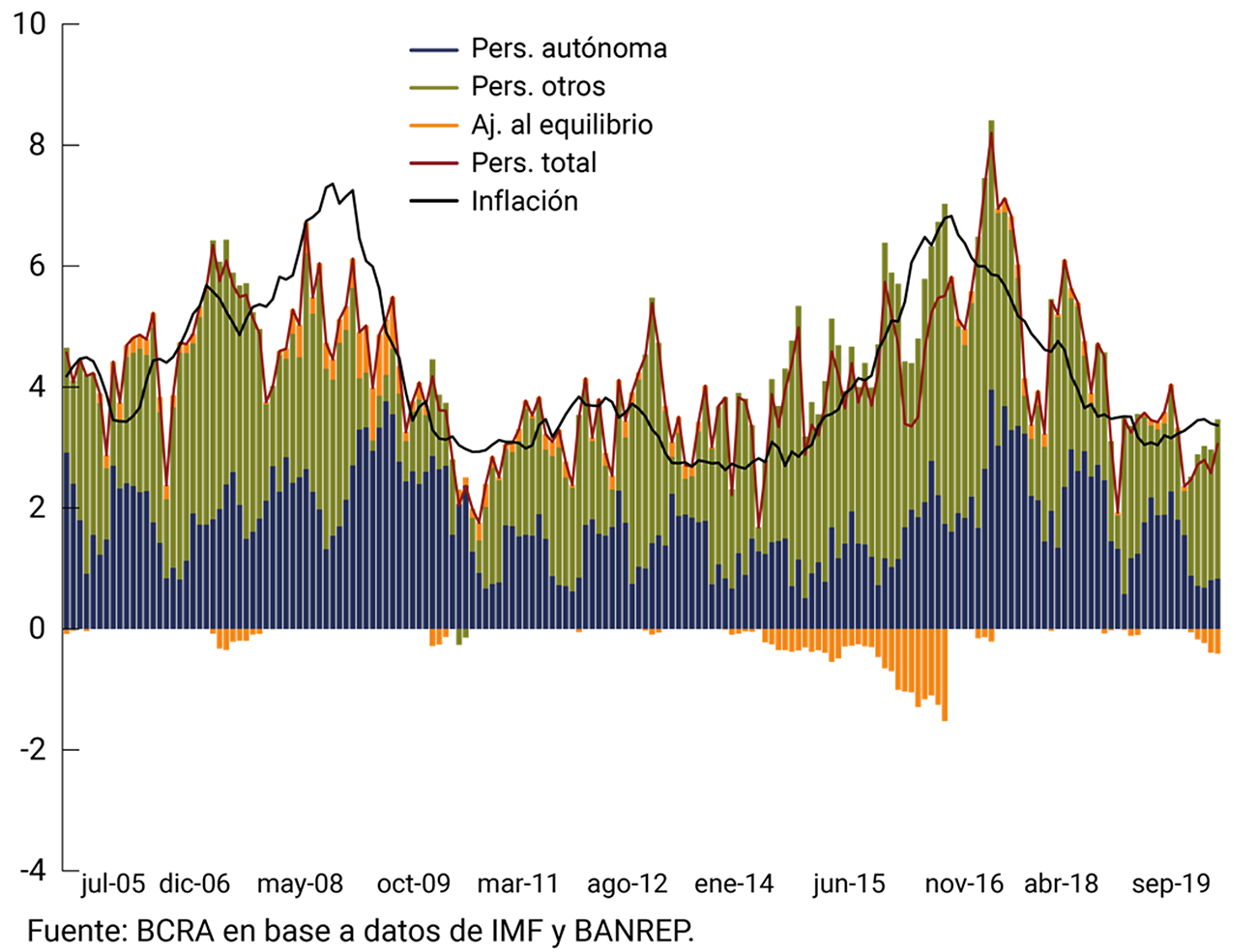

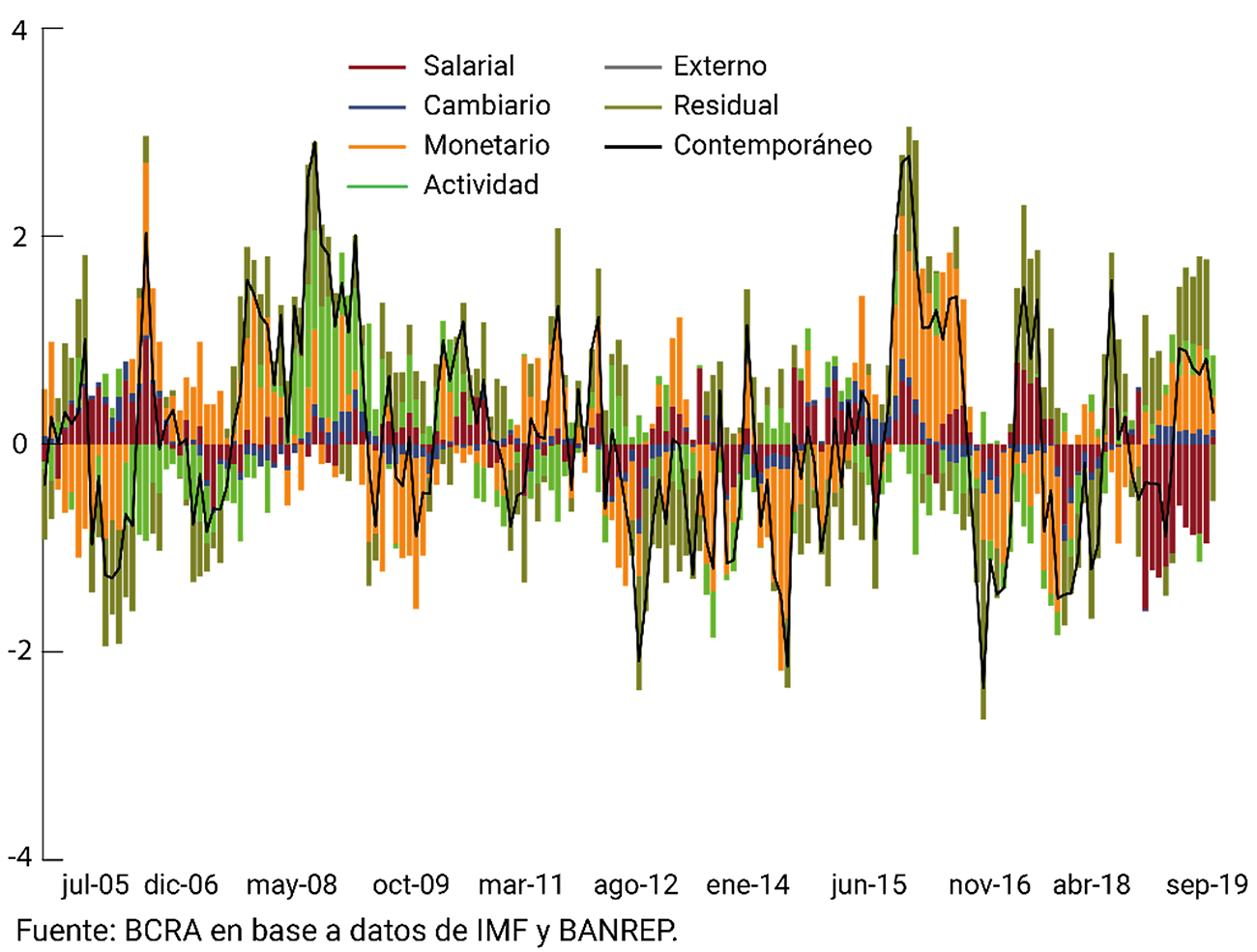

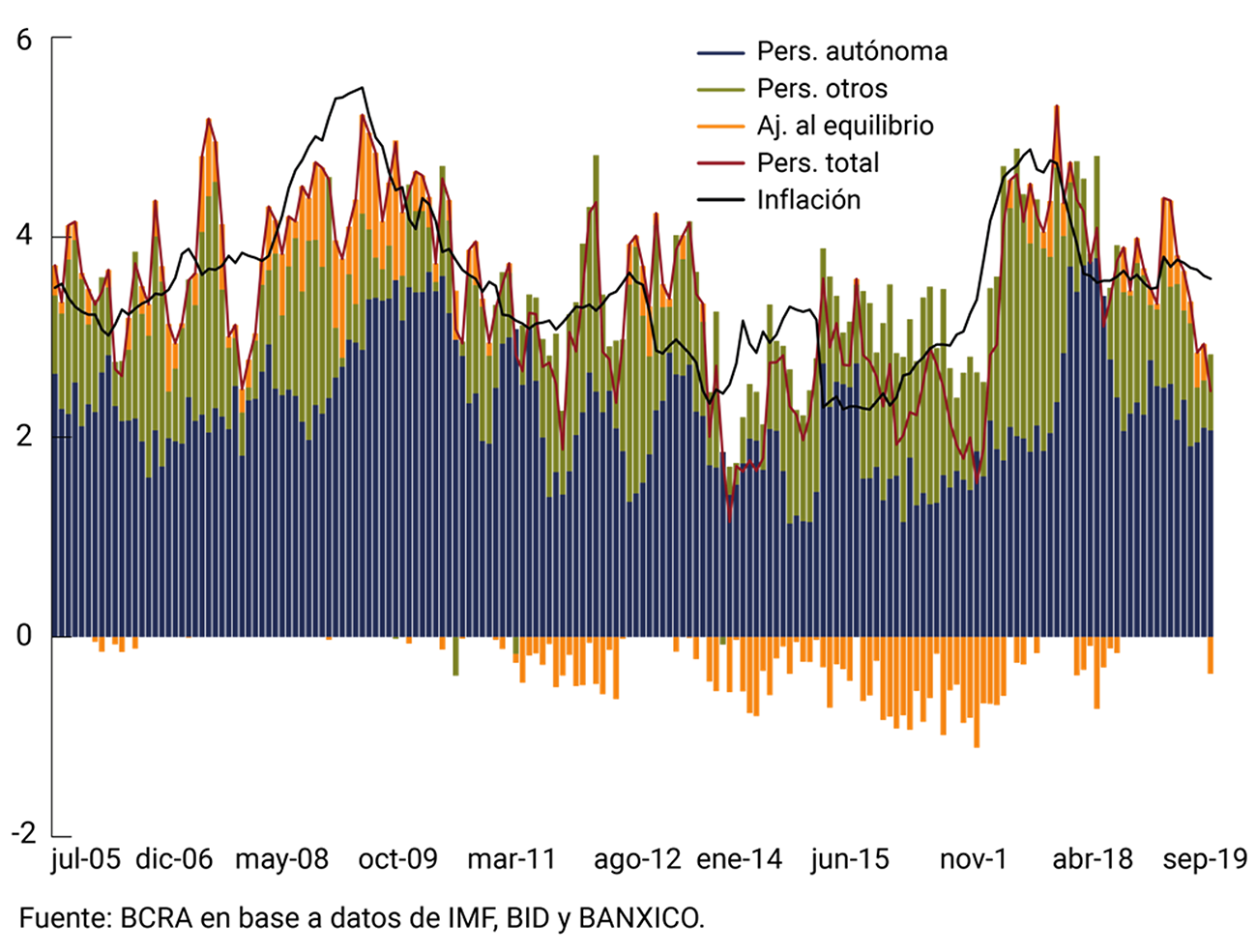

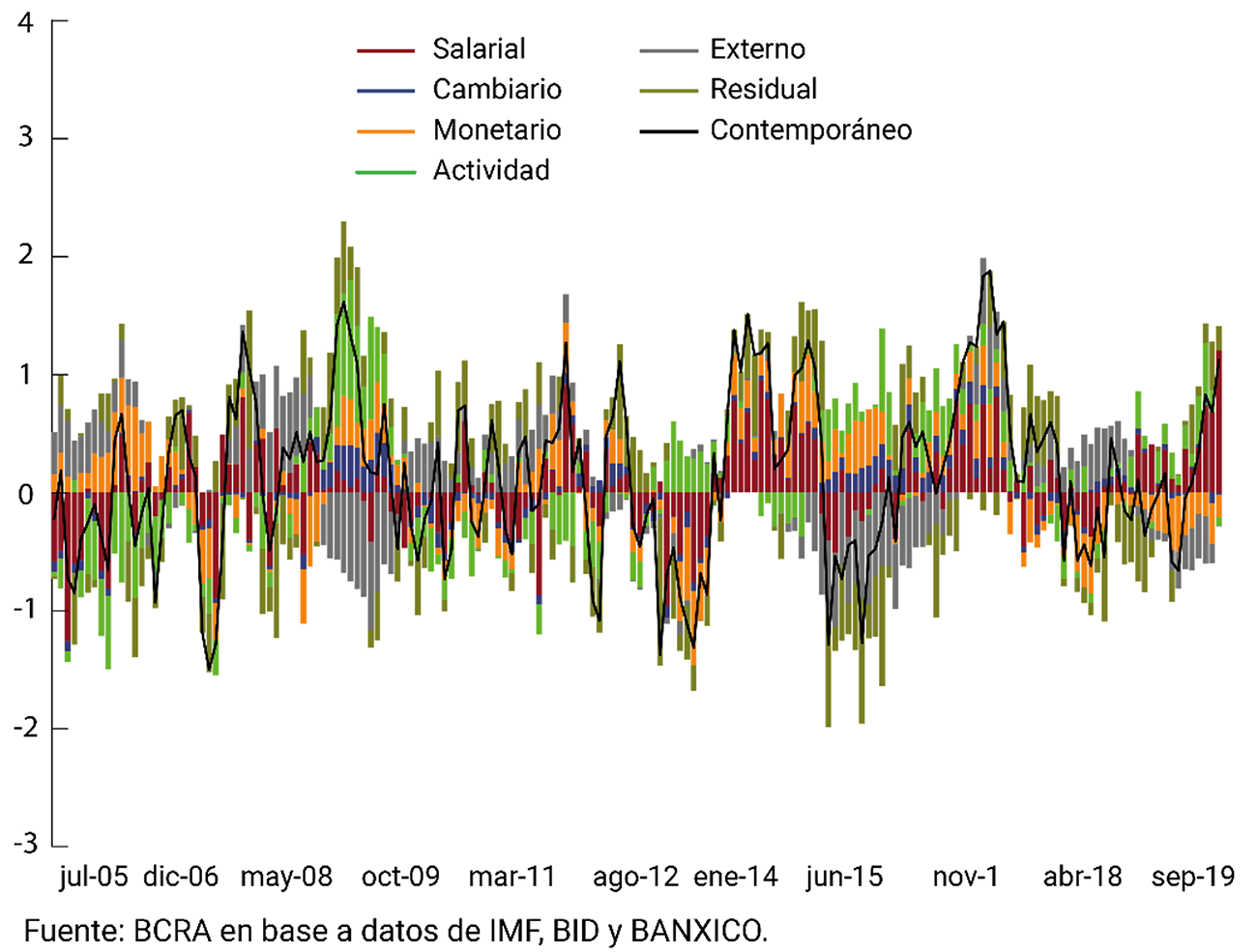

1. Decomposition of the short-term dynamics of inflation in Latin America

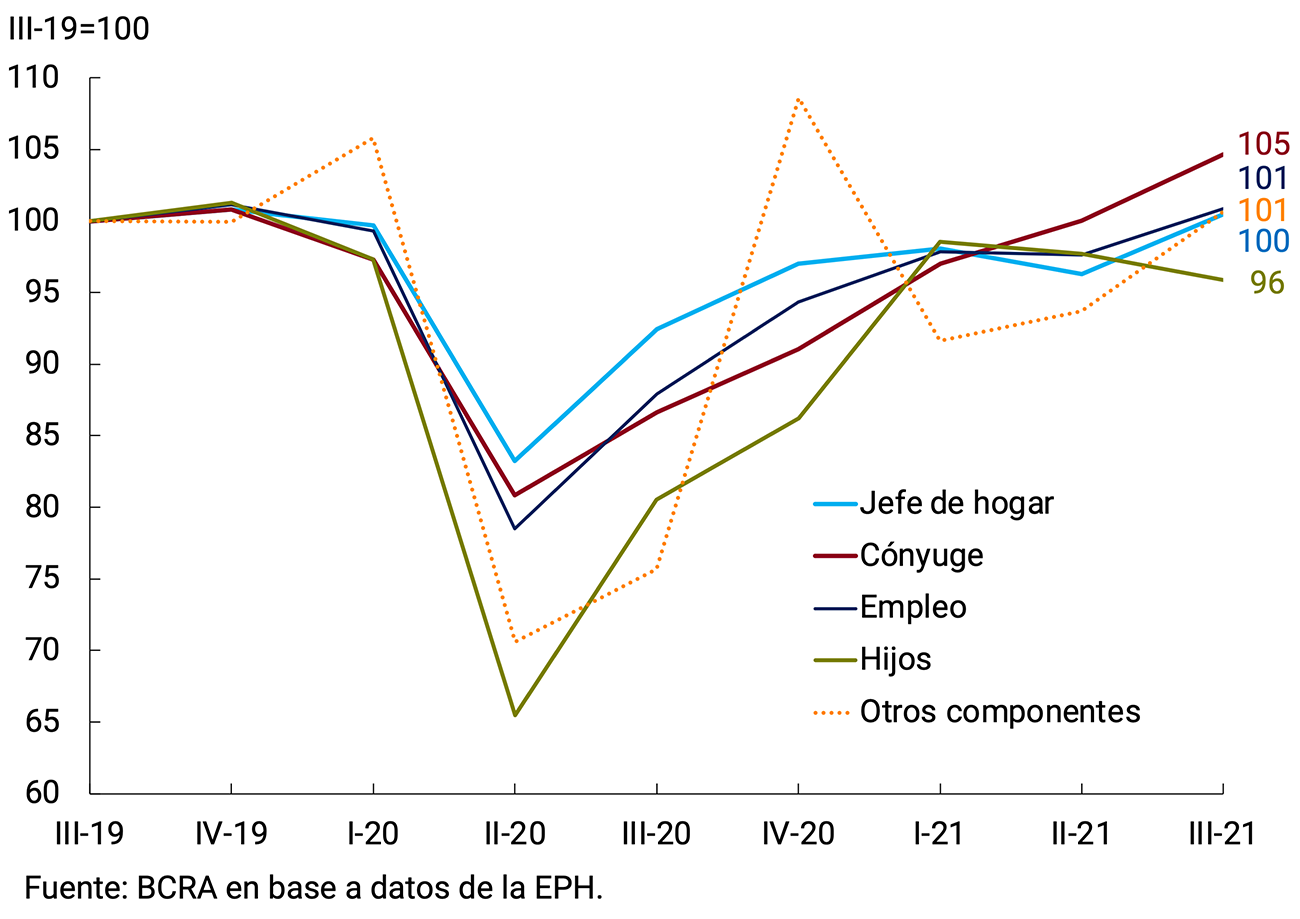

2. Asynchronicities in the labor

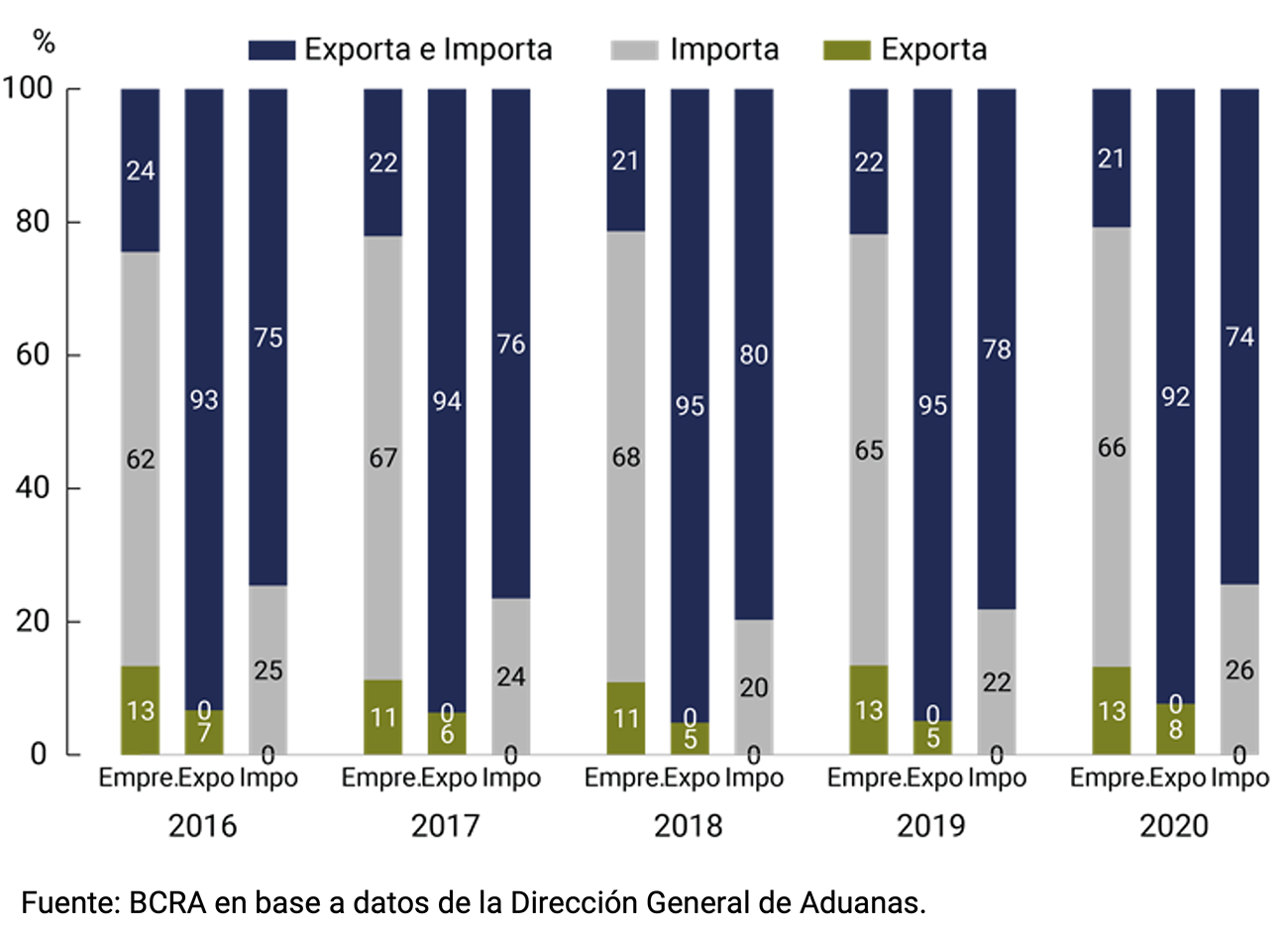

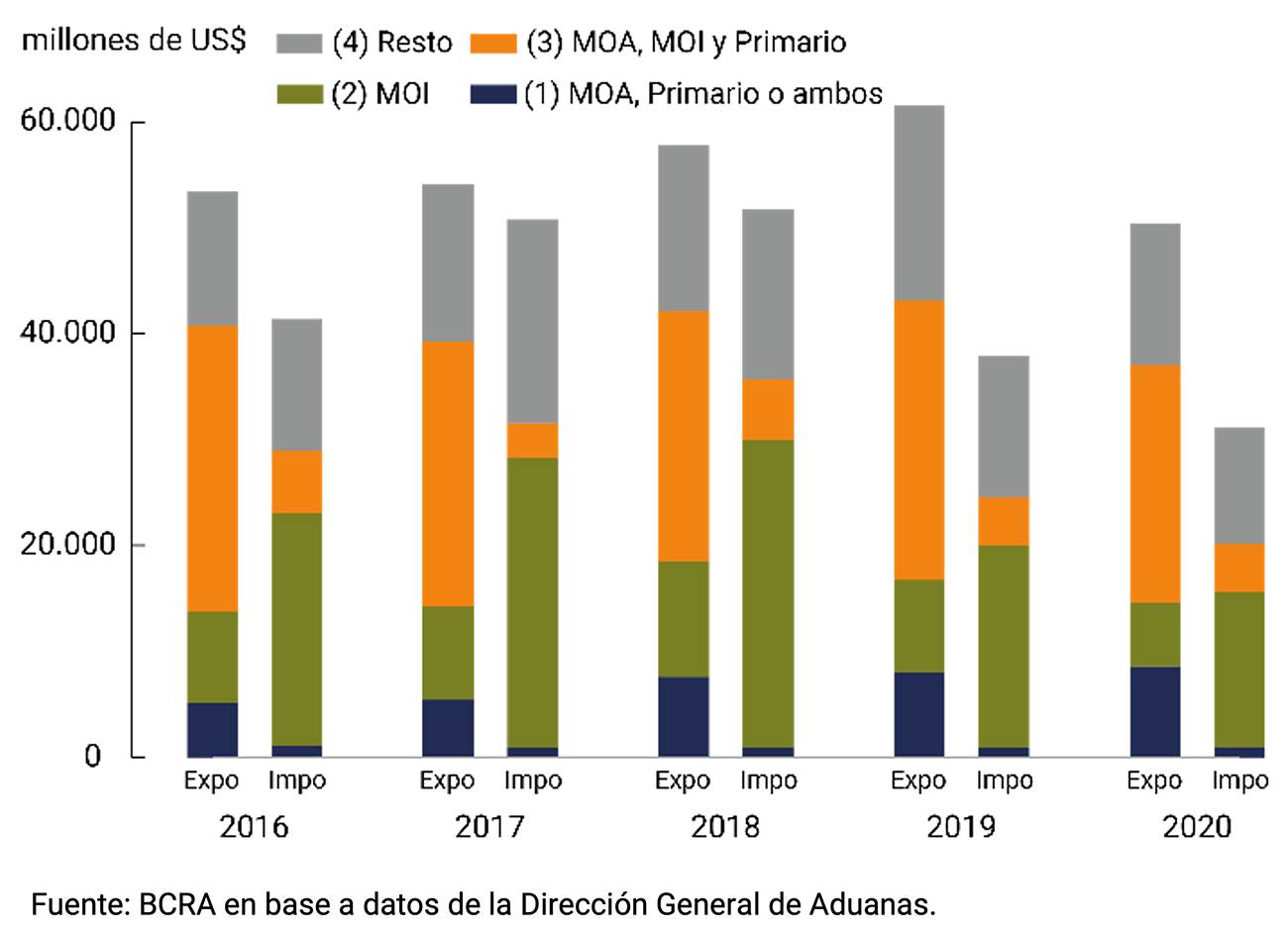

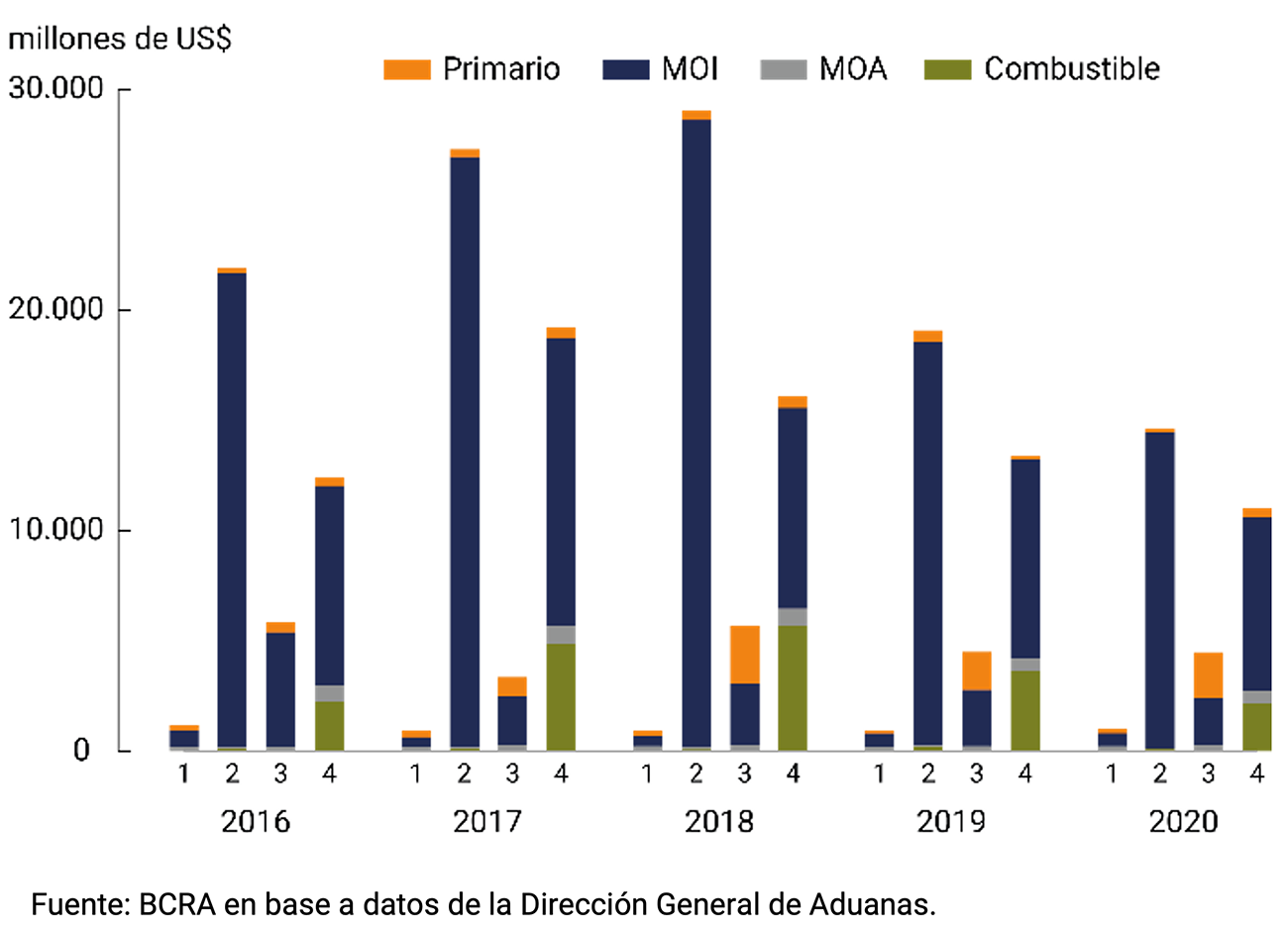

market 3. Foreign Trade Pattern in Argentina: A Firm-Level

Analysis 4. The Extended Facilities Agreement with the IMF

5. Recent evolution of the relative price structure of the CPI

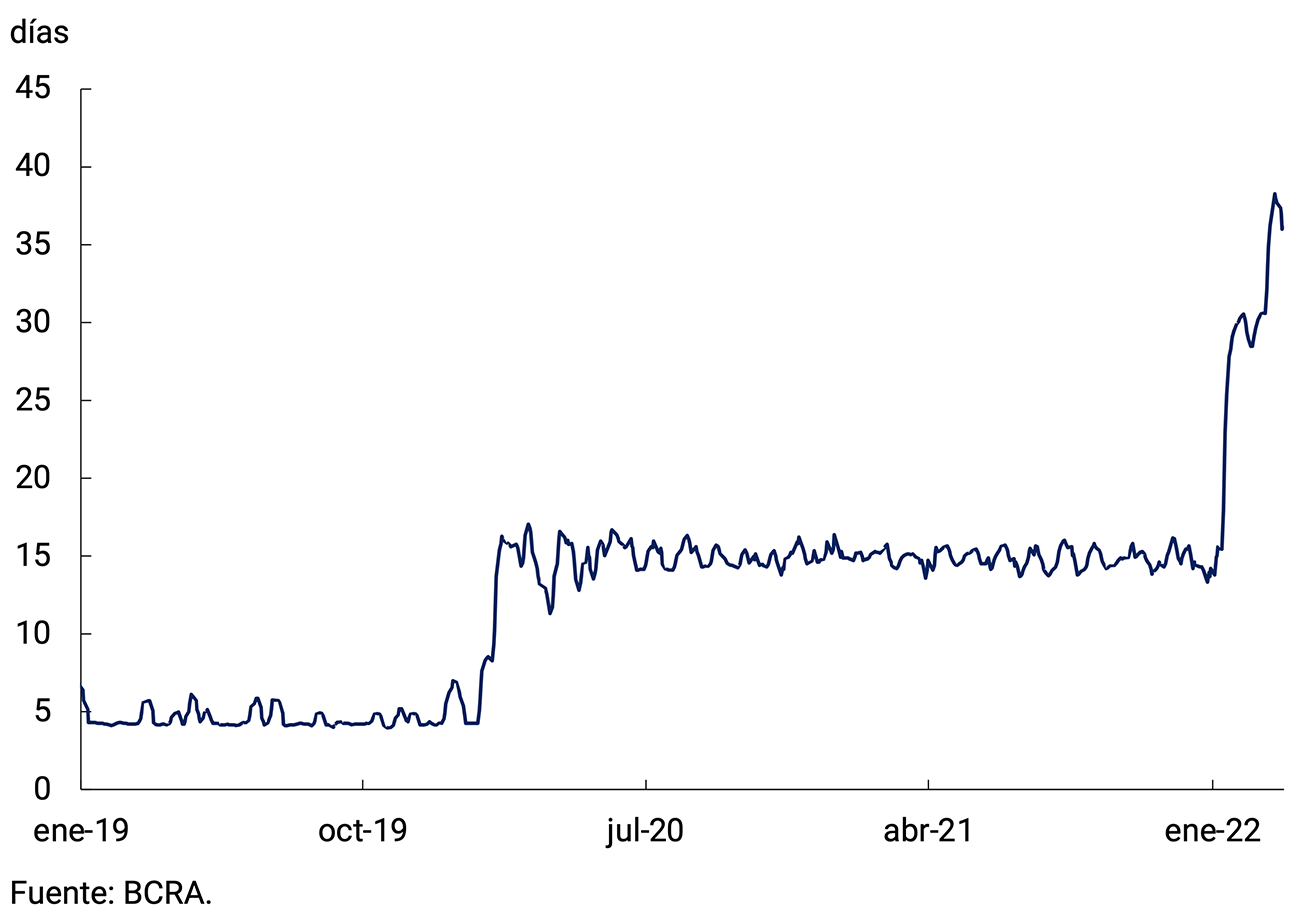

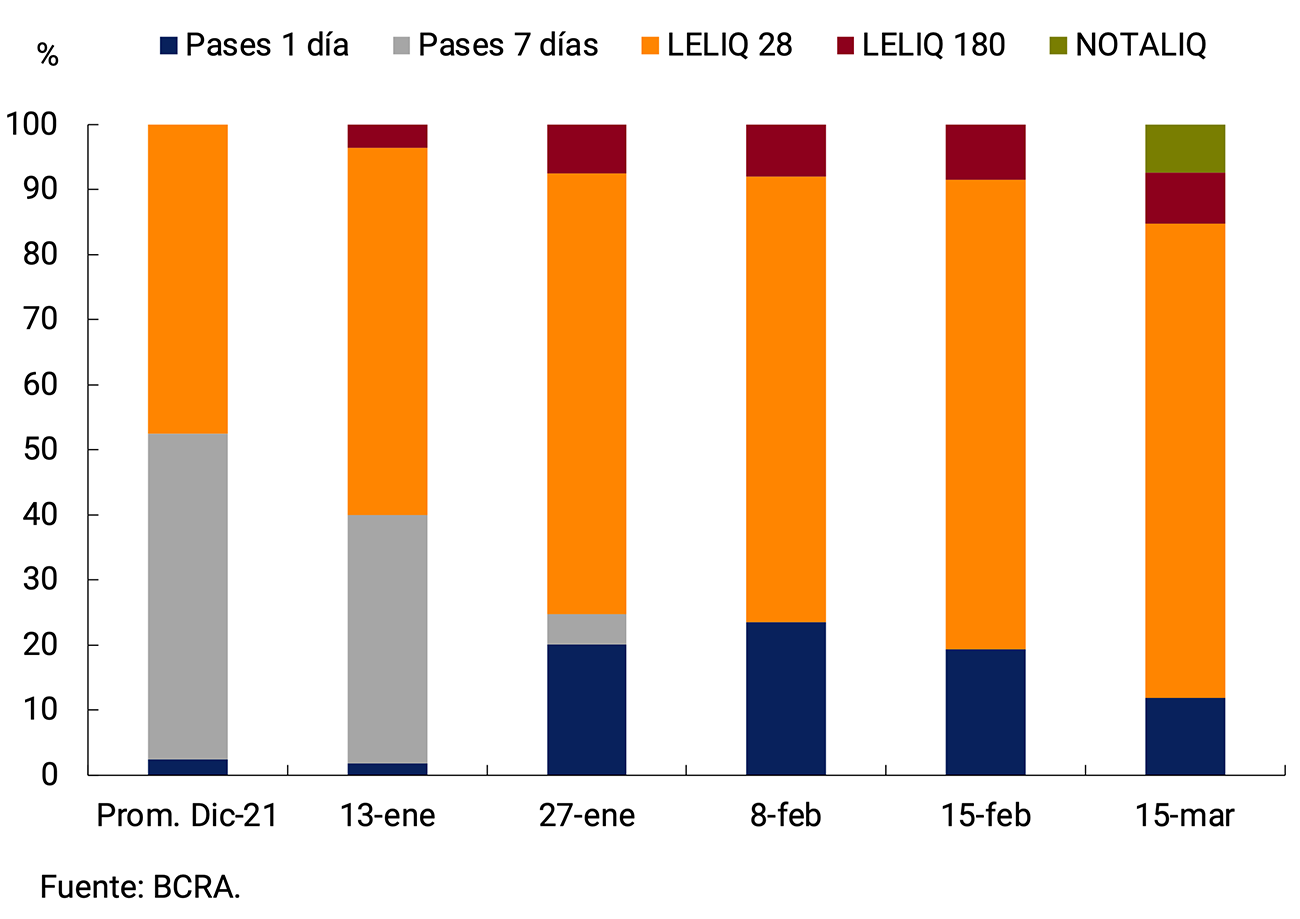

6. The reconfiguration of monetary policy instruments

For inquiries, write to analisismacro@bcra.gob.ar

Summary

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlook

The international scenario has become more uncertain in recent weeks. Although the global economy closed 2021 with an annual expansion of GDP of 5.7%, in the first months of 2022 a new wave of the pandemic and, more recently, the war between Russia and Ukraine had an impact on the dynamism of activity. This last event increased uncertainty regarding the future prospects of the prices of raw materials that our country exports and imports. So far, higher energy and other commodity prices have driven an acceleration in inflation in advanced economies, prompting central banks in these economies to consider a more contractionary bias in their monetary policy. A steeper monetary contraction would impact developing countries in the form of tighter financial conditions, capital outflows, and eventually lower growth.

In Argentina, in a more favorable health context based on greater coverage of the population with complete vaccination schedules, economic activity continued to improve in the fourth quarter of 2021 and continued to operate at levels higher than pre-pandemic levels. Thus, the year ended with a growth of 10.3%, significantly above that initially expected. The advance data on economic activity showed a progressive reduction in sectoral heterogeneity. For 2022, a continuity in the process of recovery of economic activity is expected, driven by greater dynamism in sectors that have not yet managed to operate at pre-pandemic levels, especially services.

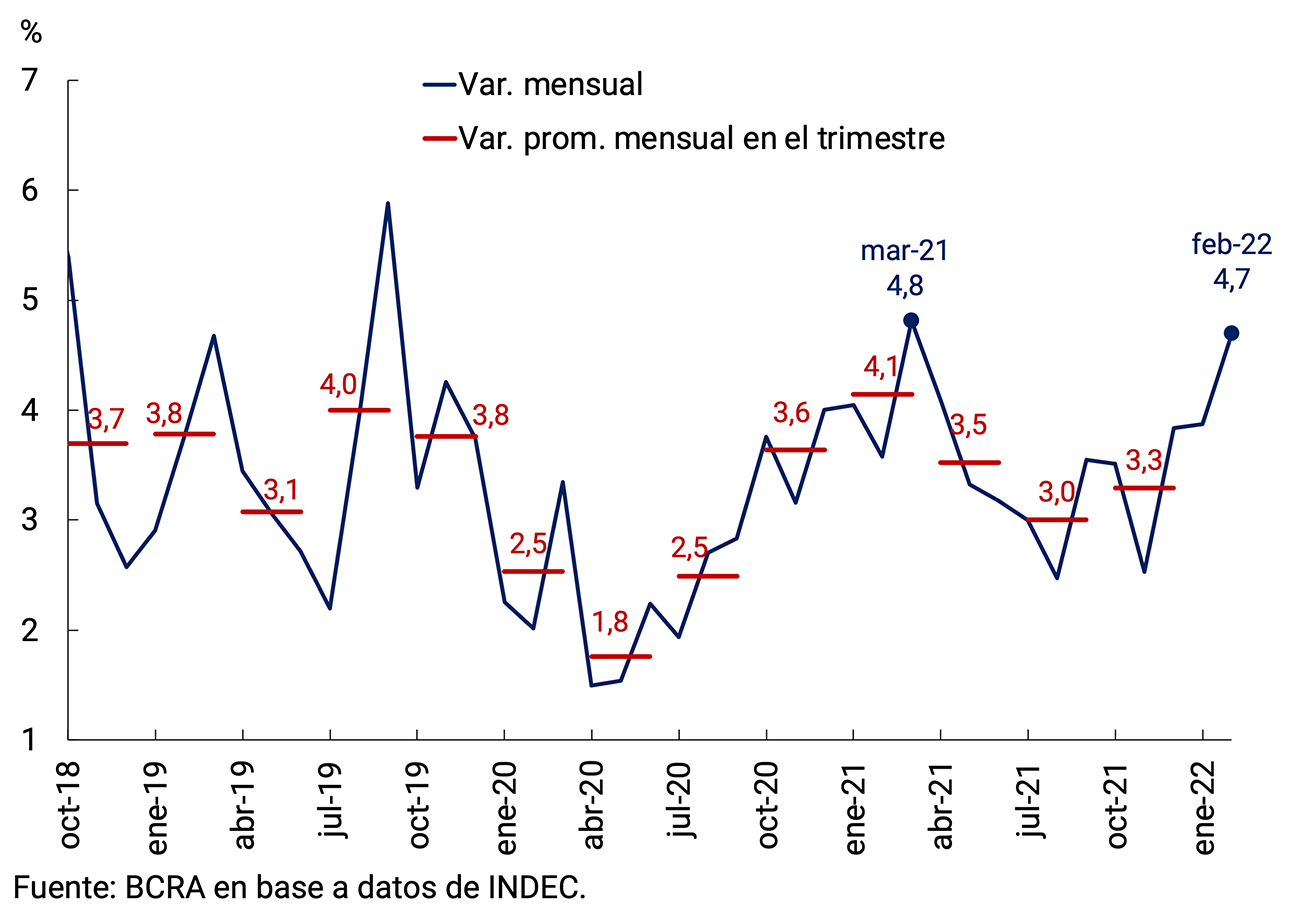

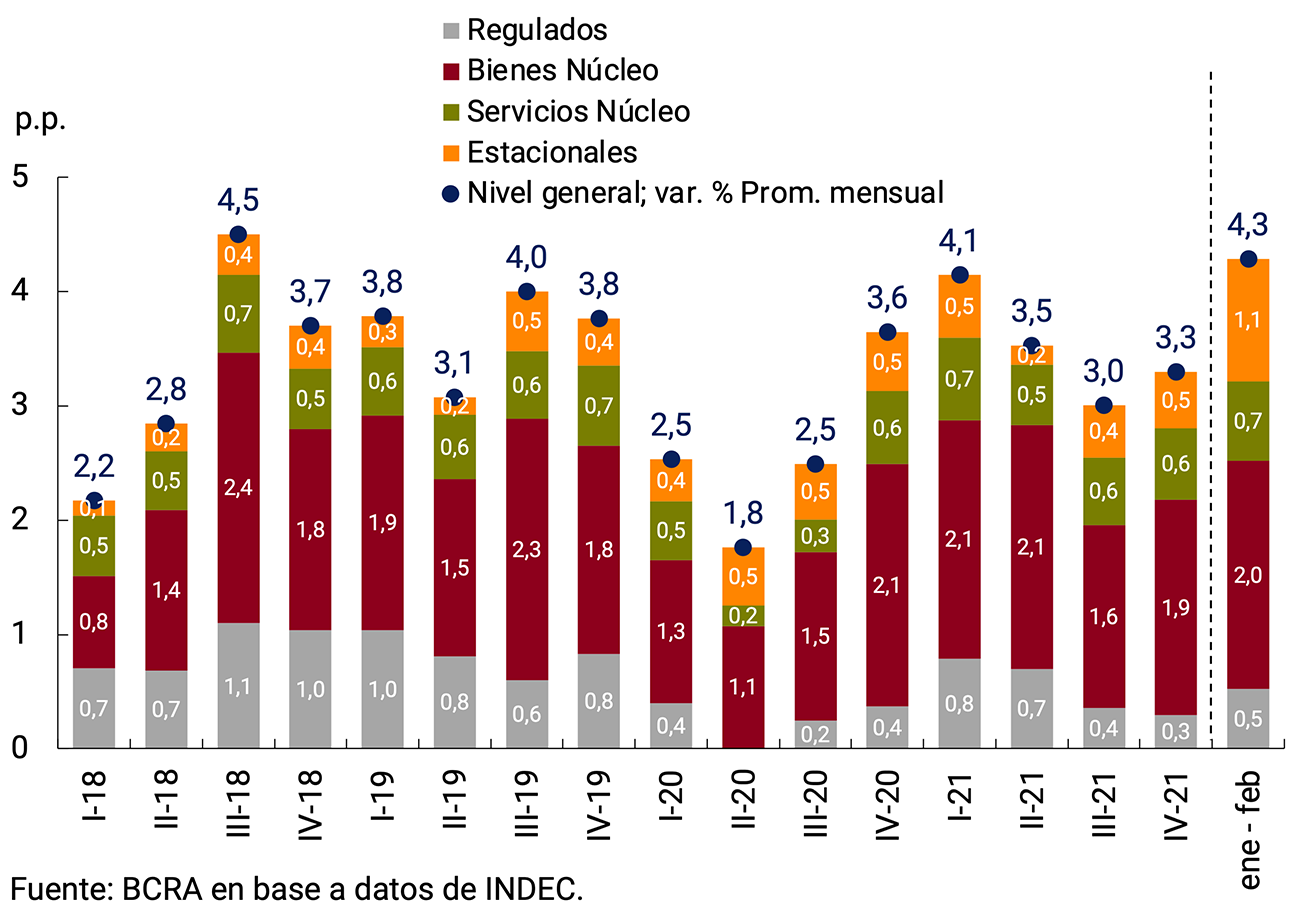

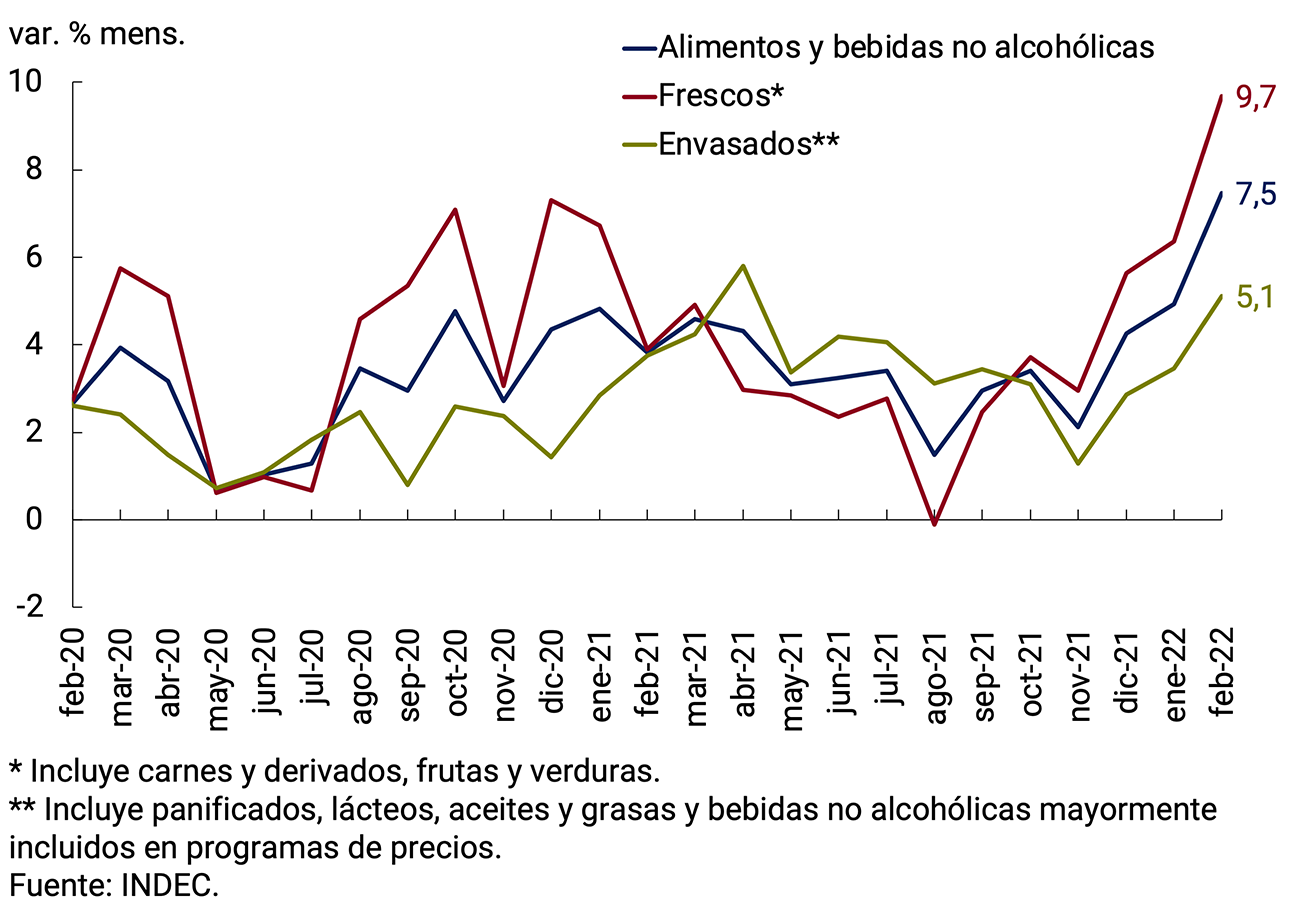

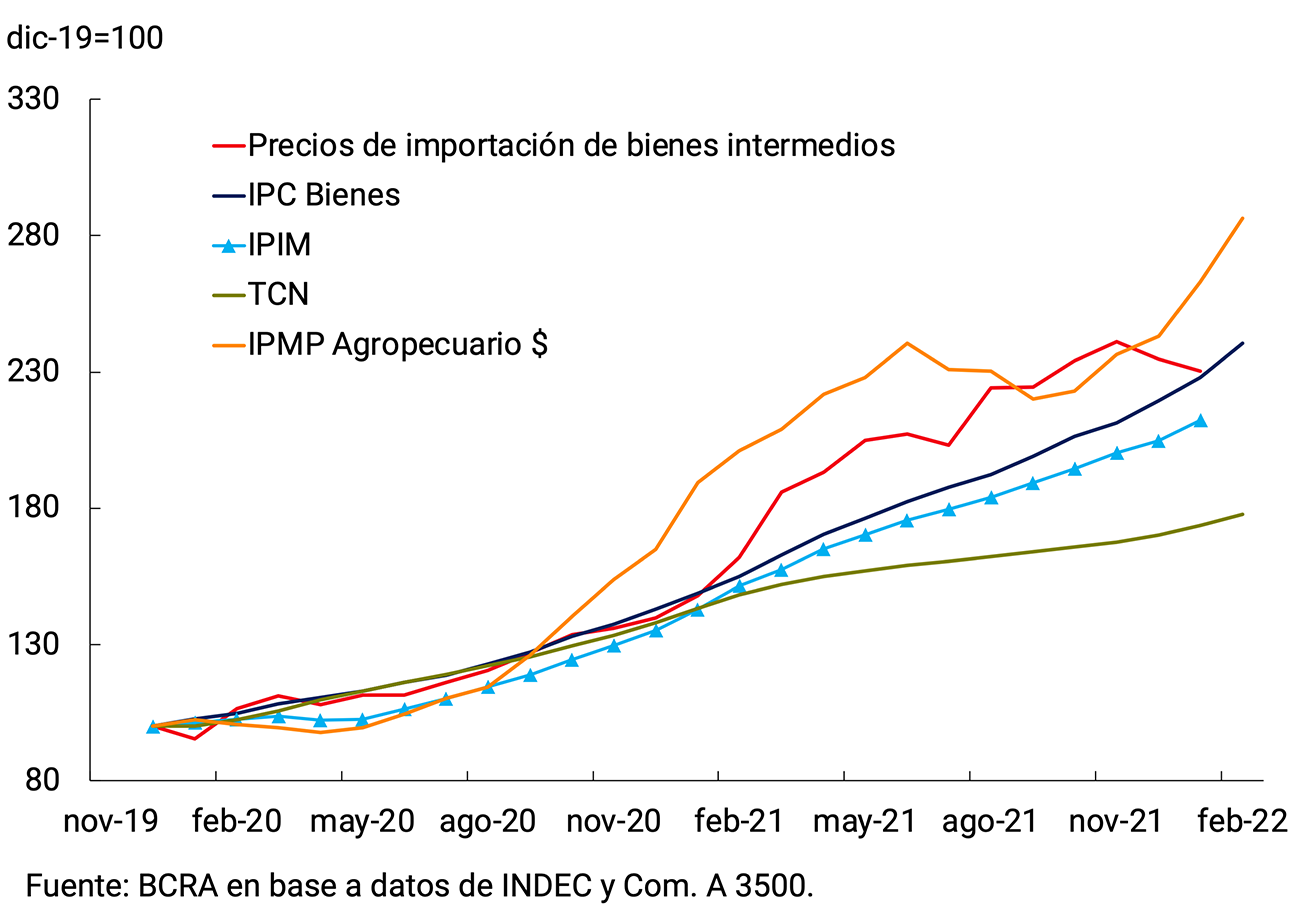

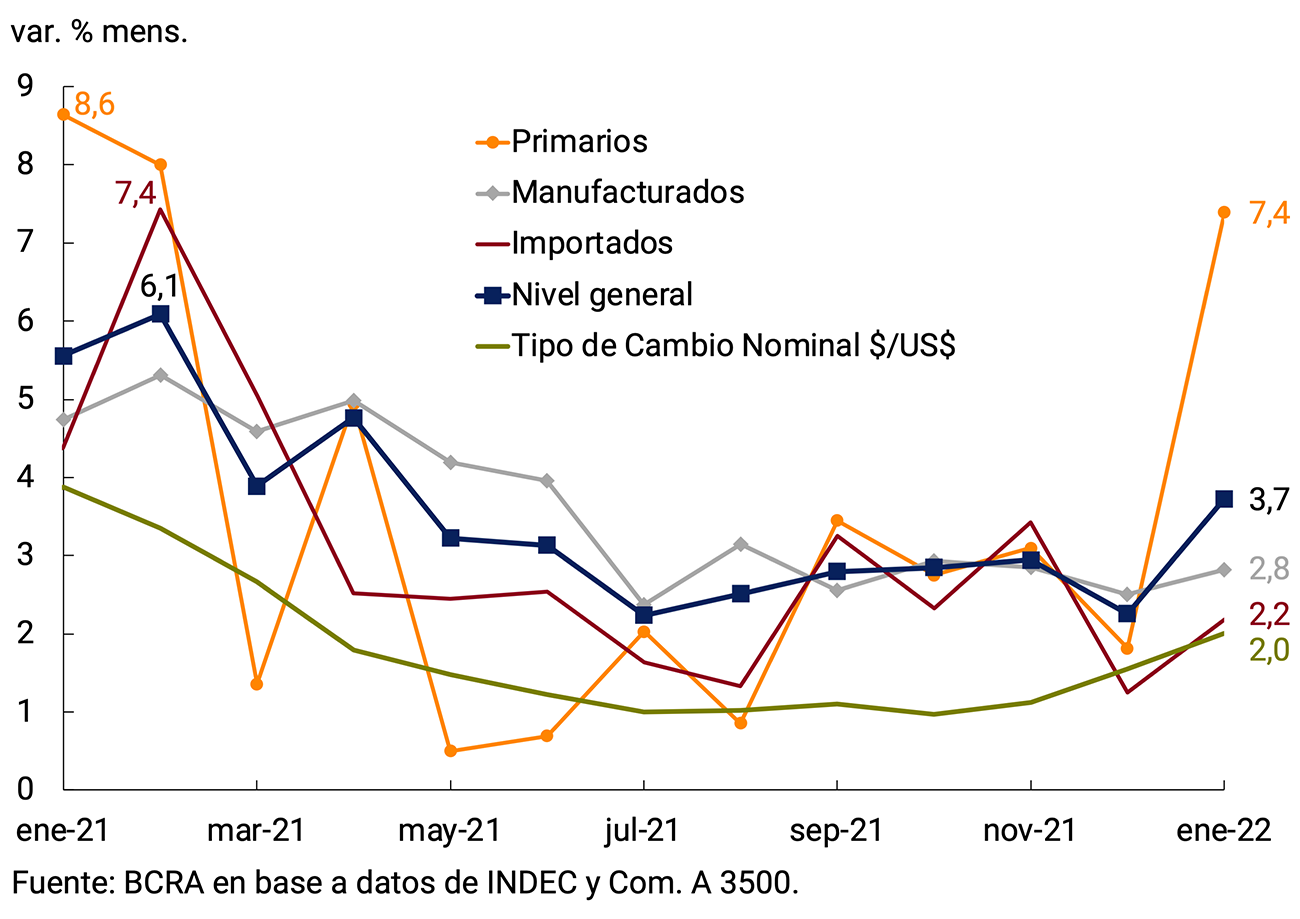

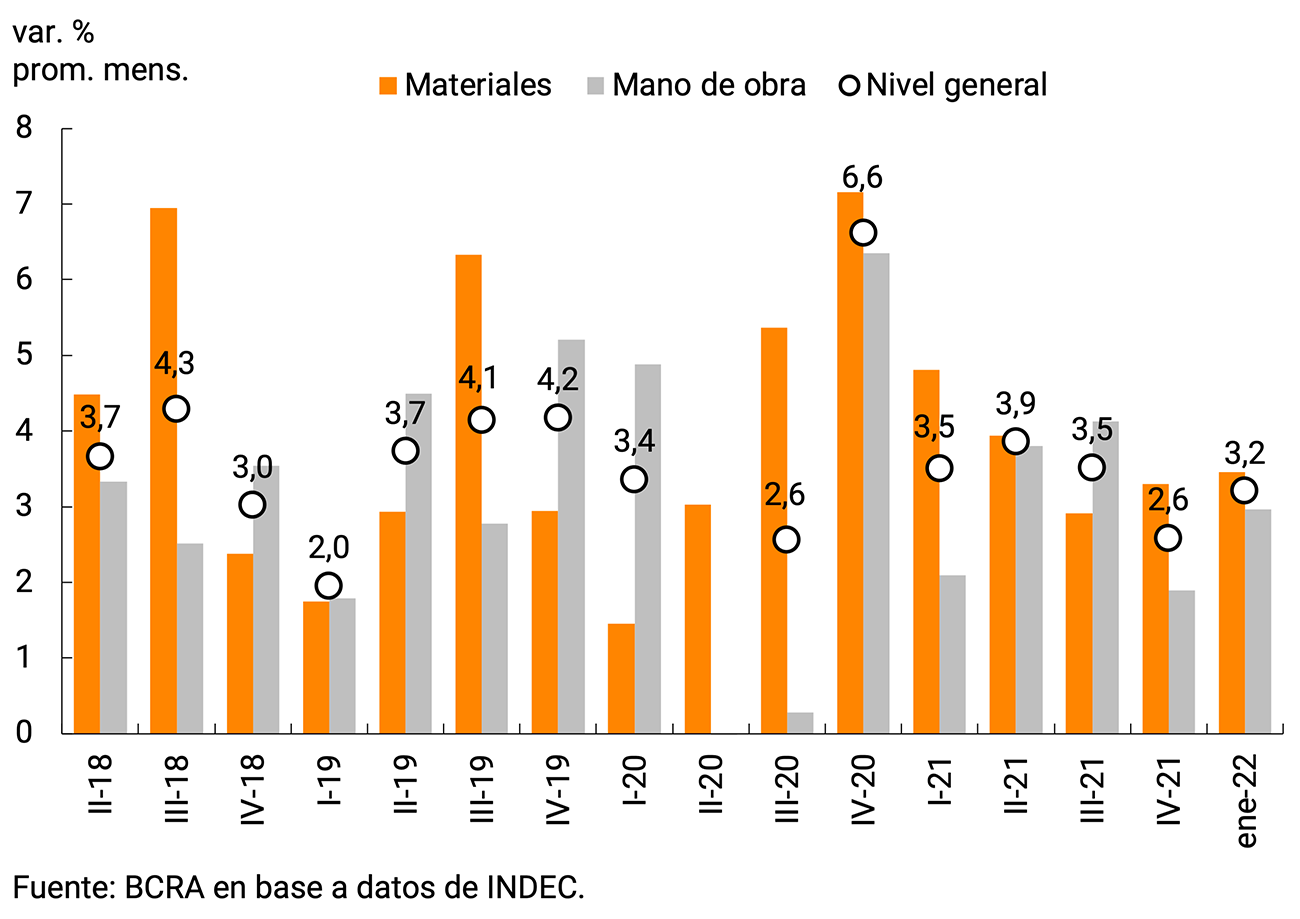

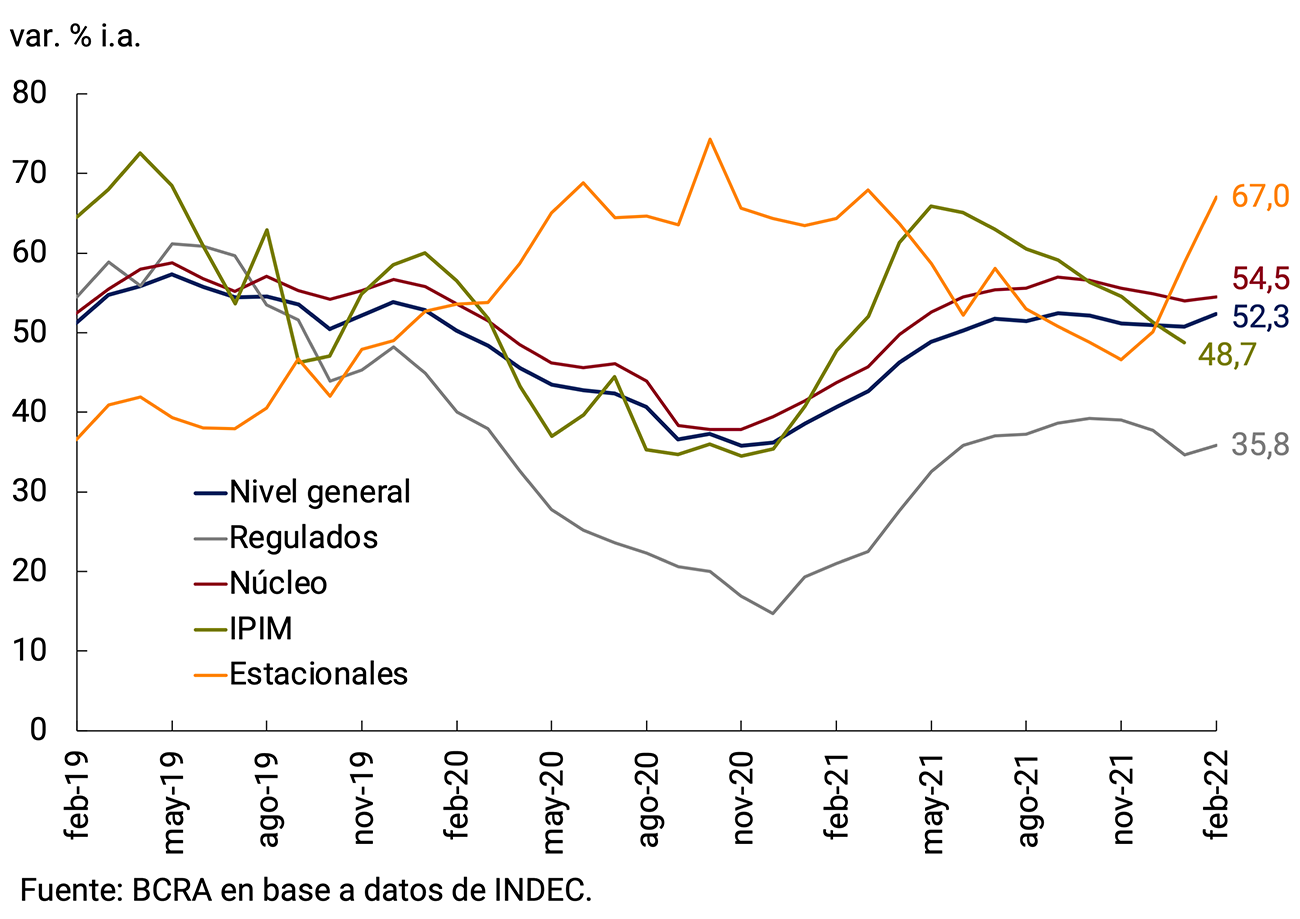

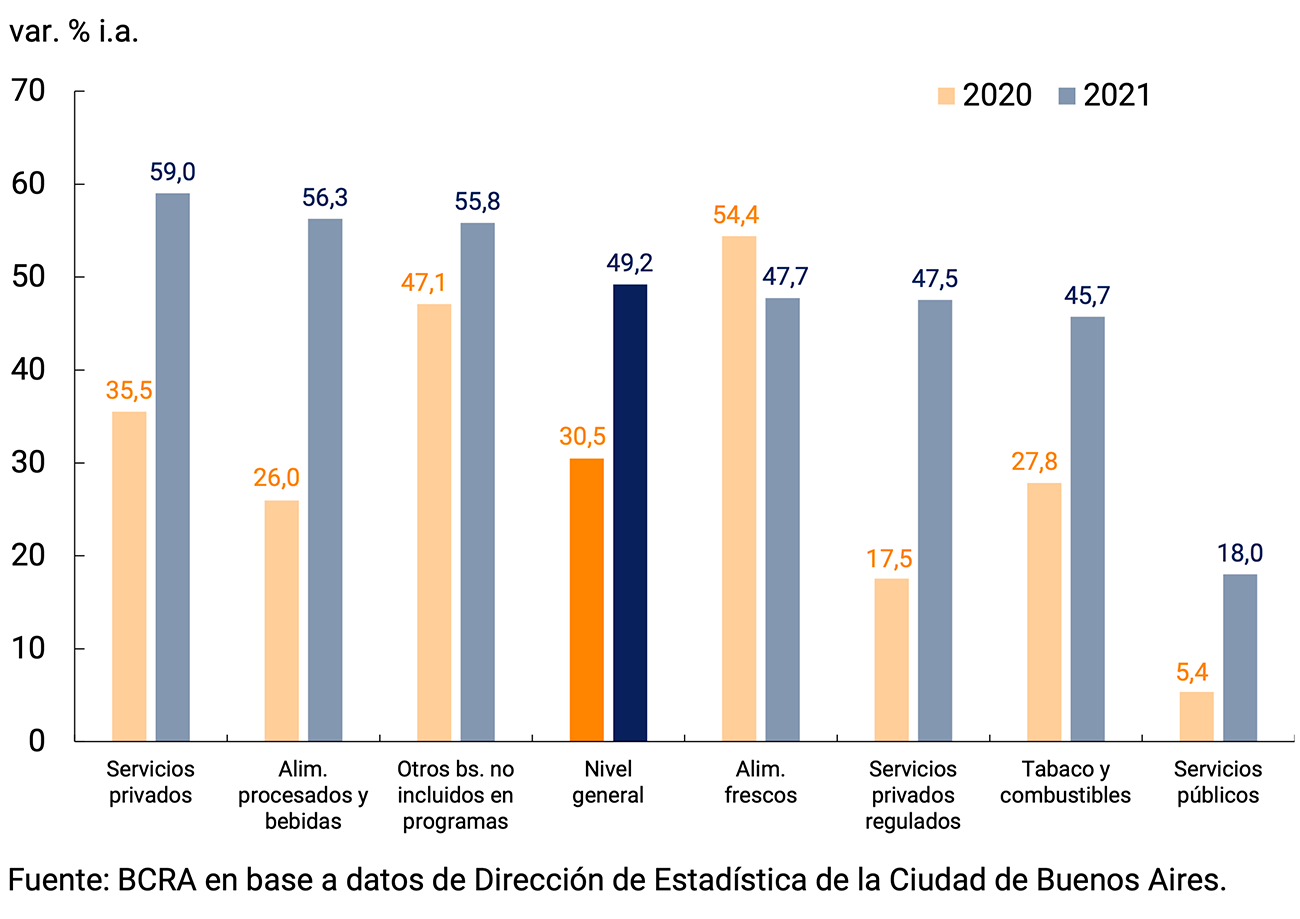

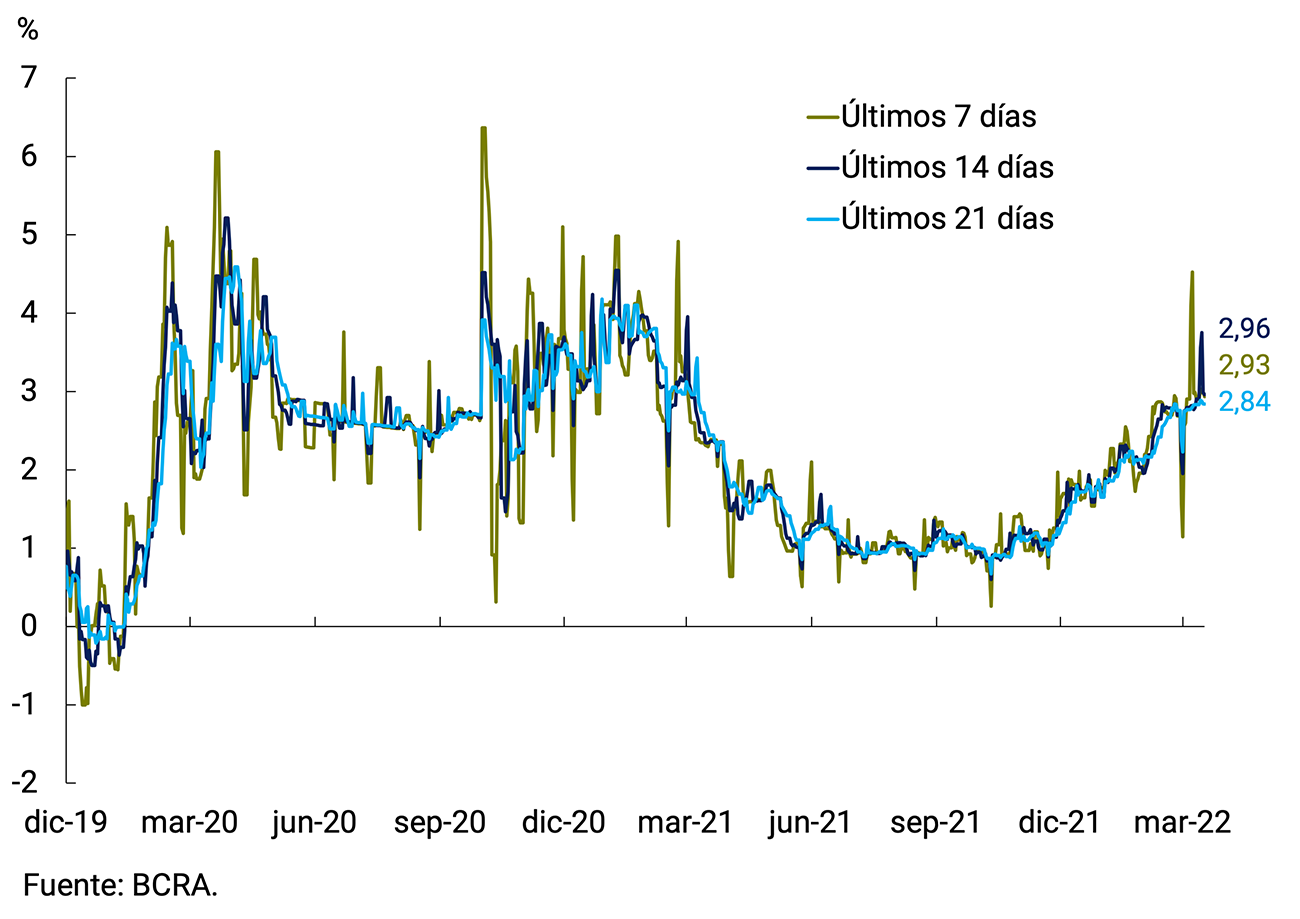

In this more dynamic macroeconomic environment, during the first two months of the year, inflation accelerated again and averaged 4.3% per month, above the 3.3% monthly average observed during the fourth quarter of 2021. The greater dynamism of prices since September 2021 was verified in a context of recomposition of the marketing margins of certain sectors, reopening of wage parity and higher inflation expectations as a result of the greater exchange rate pressures typically associated with electoral processes, where the private sector tends to accentuate its pattern of financial dollarization. to which was added the financial uncertainty generated by entering a stage of definition of the negotiation with the IMF for a new debt agreement with the organization. In addition to the scenario of high inflationary inertia, unfavorable domestic weather conditions and the significant increase in international prices of agricultural raw materials, energy and global manufactures have accelerated since January, which accelerated in the face of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, which poses a challenging scenario, especially for the next two months.

Having reached pre-pandemic levels of activity and without neglecting the growth process underway, the BCRA proposed to resume the policy guidelines enunciated at the beginning of 2020, which combine the consolidation of domestic market growth and exports with monetary and macro-financial stability. In this scenario, the BCRA defined and published in December 2021 its Objectives and Plans1 for the year 2022.

A necessary condition for reducing levels of inflationary inertia is to maintain a process of accumulation of reserves that dissipates the risks of balance of payments crises and abrupt jumps in the exchange rate, thus anchoring exchange rate expectations. Thus, with the aim of strengthening the position of international reserves, the rate of depreciation was modified to gradually bring it to levels more compatible with the domestic inflation rate. Thus, so far in 2022, a stabilization was observed in the Multilateral Real Exchange Rate Index (ITCRM), which is at levels that preserve external competitiveness and around the average of the last 24 years.

Likewise, since the first week of January, the BCRA has reconfigured its monetary policy instruments to accompany the economic recovery process and reinforce monetary, exchange rate and financial stability. Thus, the reference interest rate was raised on two occasions, taking it from 38.0% n.a. (45.4% e.a.) to 42.5% n.a. (51.9% e.a.), the limit on LELIQ holdings to 28 days was readjusted (focusing the policy interest rate signal on this instrument), new instruments were created in order to increase the average term of sterilization and the minimum interest rates for deposits were raised fixed-term. The increase in the monetary policy interest rate seeks to tend towards positive real returns on investments in local currency, in order to boost the demand for pesos. That is why, looking ahead, the developments in inflationary matters will be reflected in the calibration of interest rates by the monetary authority.

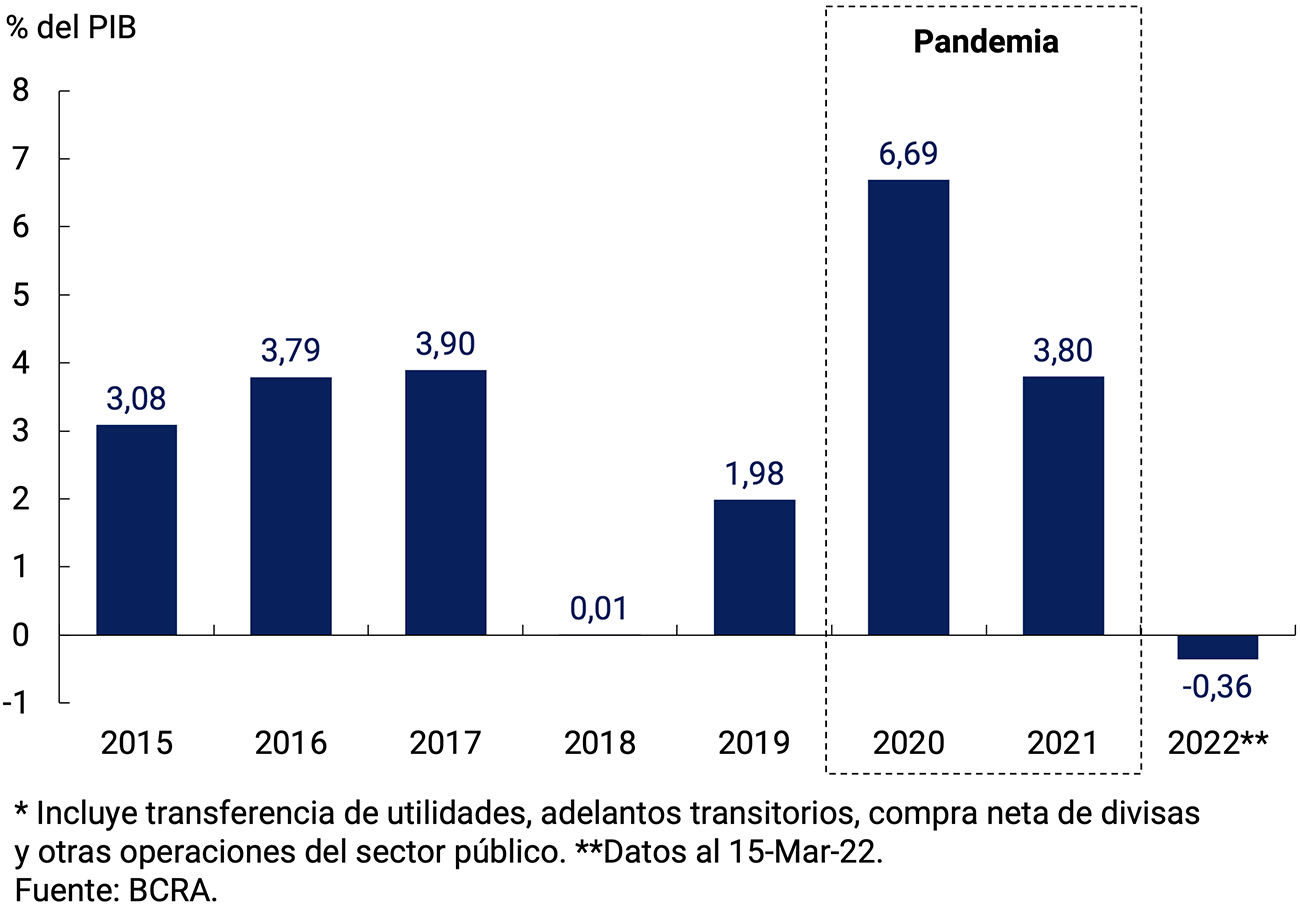

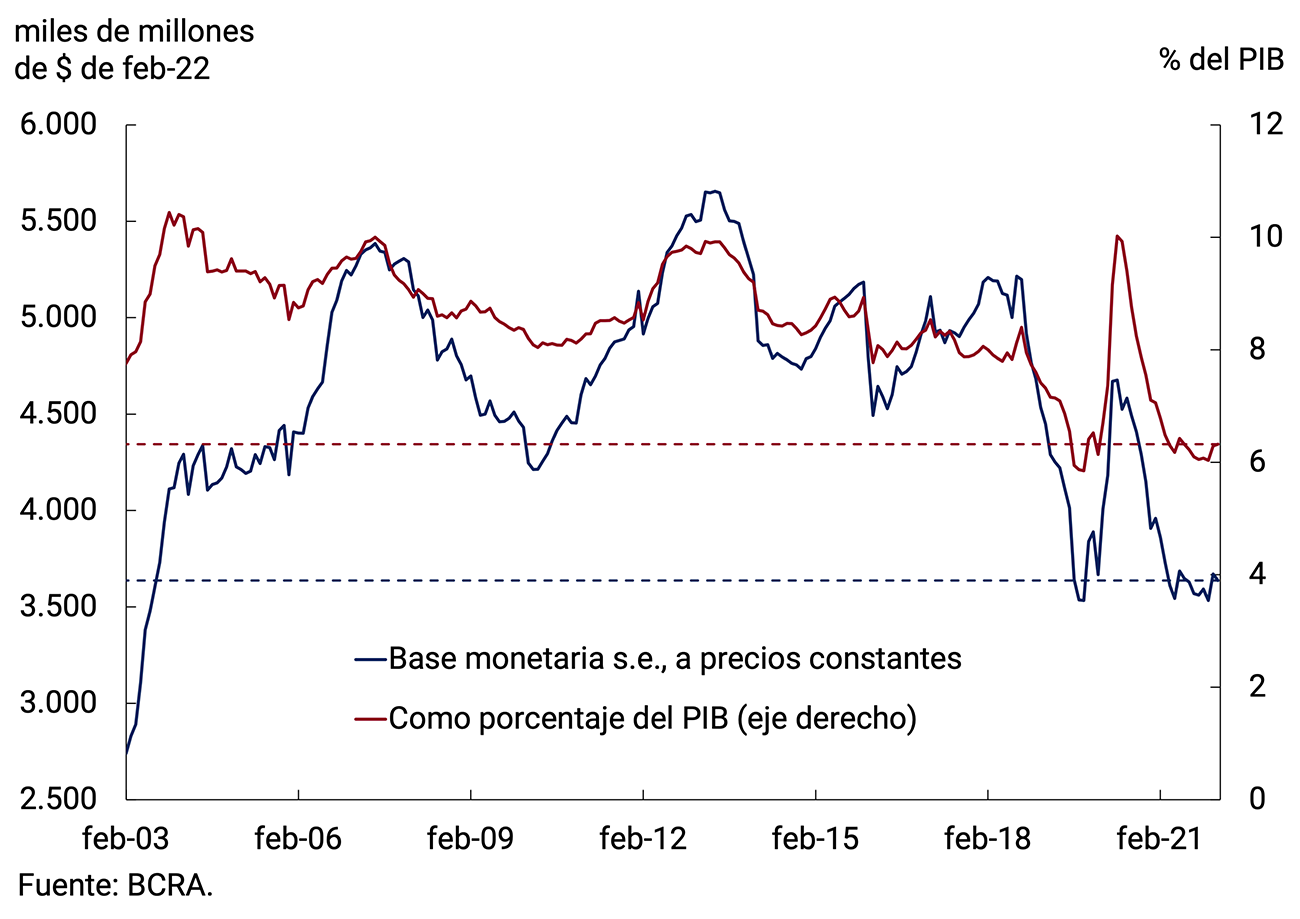

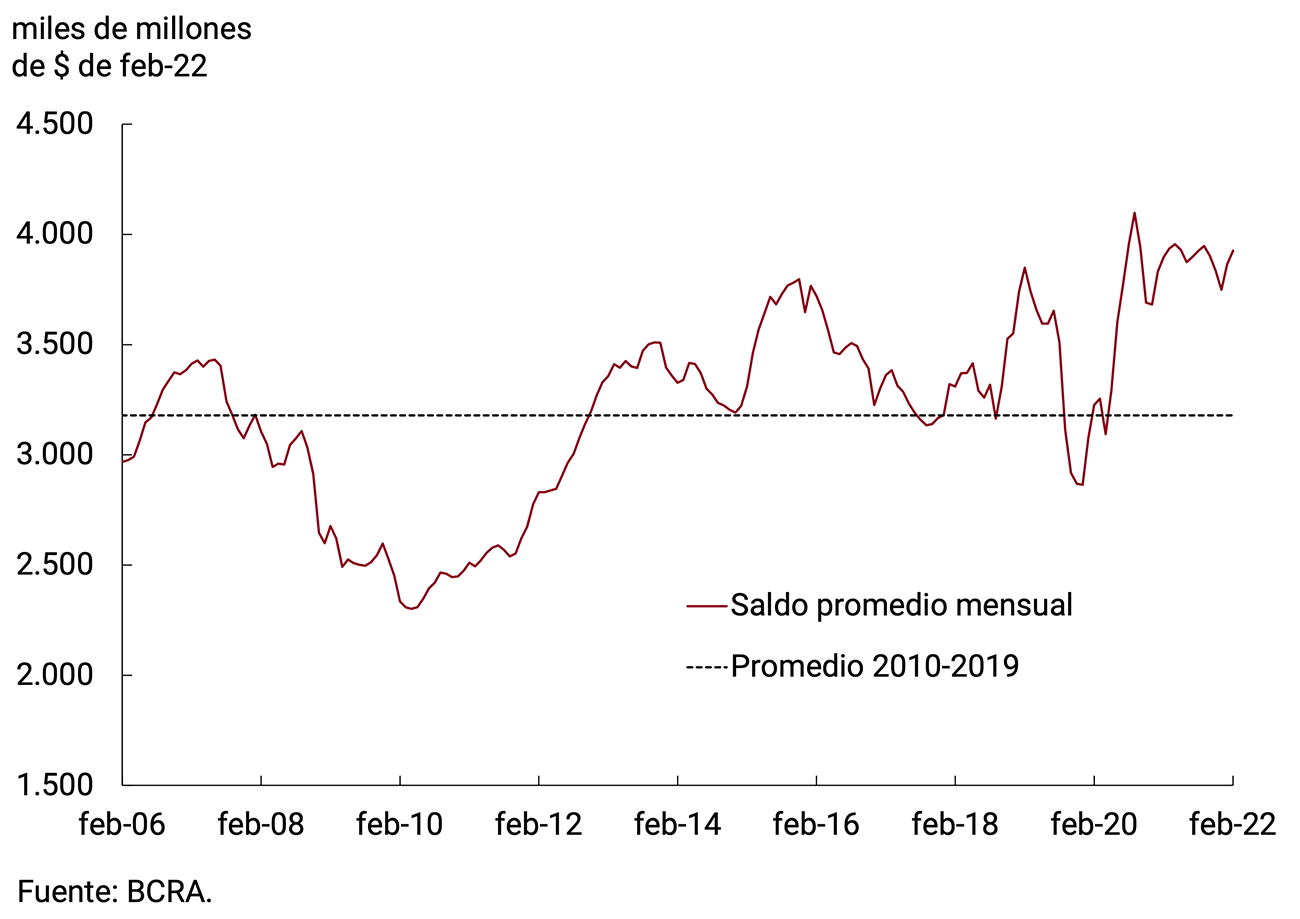

In turn, the BCRA will continue to calibrate the liquidity of the economy, sterilizing any surpluses, to help preserve monetary balance. In this regard, in 2021 primary expansion linked to the public sector was at levels significantly lower than those of 2020, reflecting values with respect to GDP similar to those of previous years, and so far this year it helped to contract liquidity in the market. The purchase of foreign currency from the private sector also contributed positively to the expansion of the Monetary Base during 2021 and in the first months of the current year. These factors were partially sterilized through monetary regulation instruments (passive passes and LELIQ). All in all, the Monetary Base ended the year with an expansion of 40.0%, which implied a contraction in real terms, and the balance of interest-bearing liabilities stood at around 9.7% of GDP. Given the projected growth in the demand for the monetary base, it is estimated that, for every 1 p.p. increase in monetary policy interest rates, interest-bearing liabilities would increase by 0.07 p.p. of GDP. Even considering this effect, in a context of lower sterilization needs, during 2022 interest-bearing liabilities will be reduced in relation to GDP.

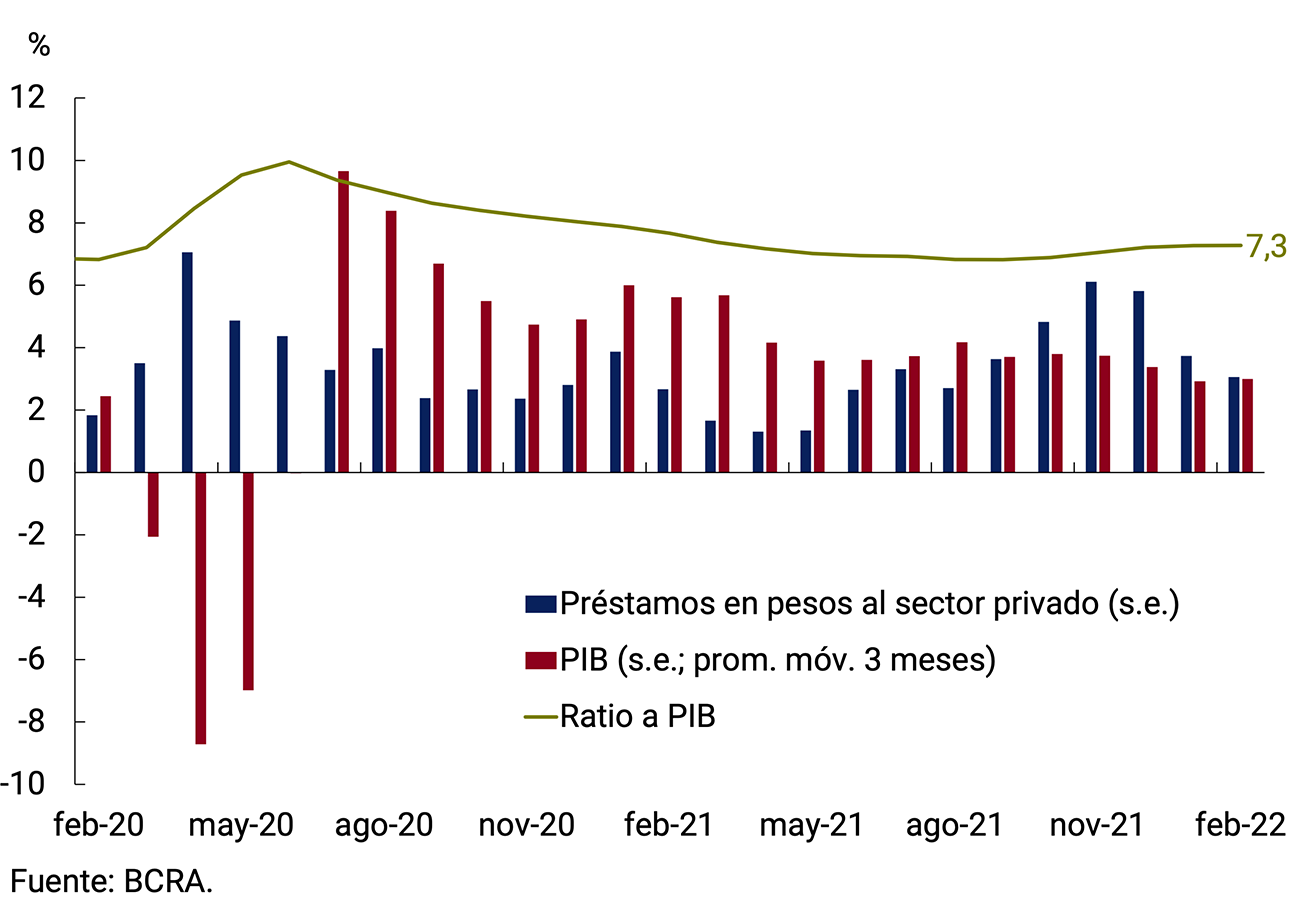

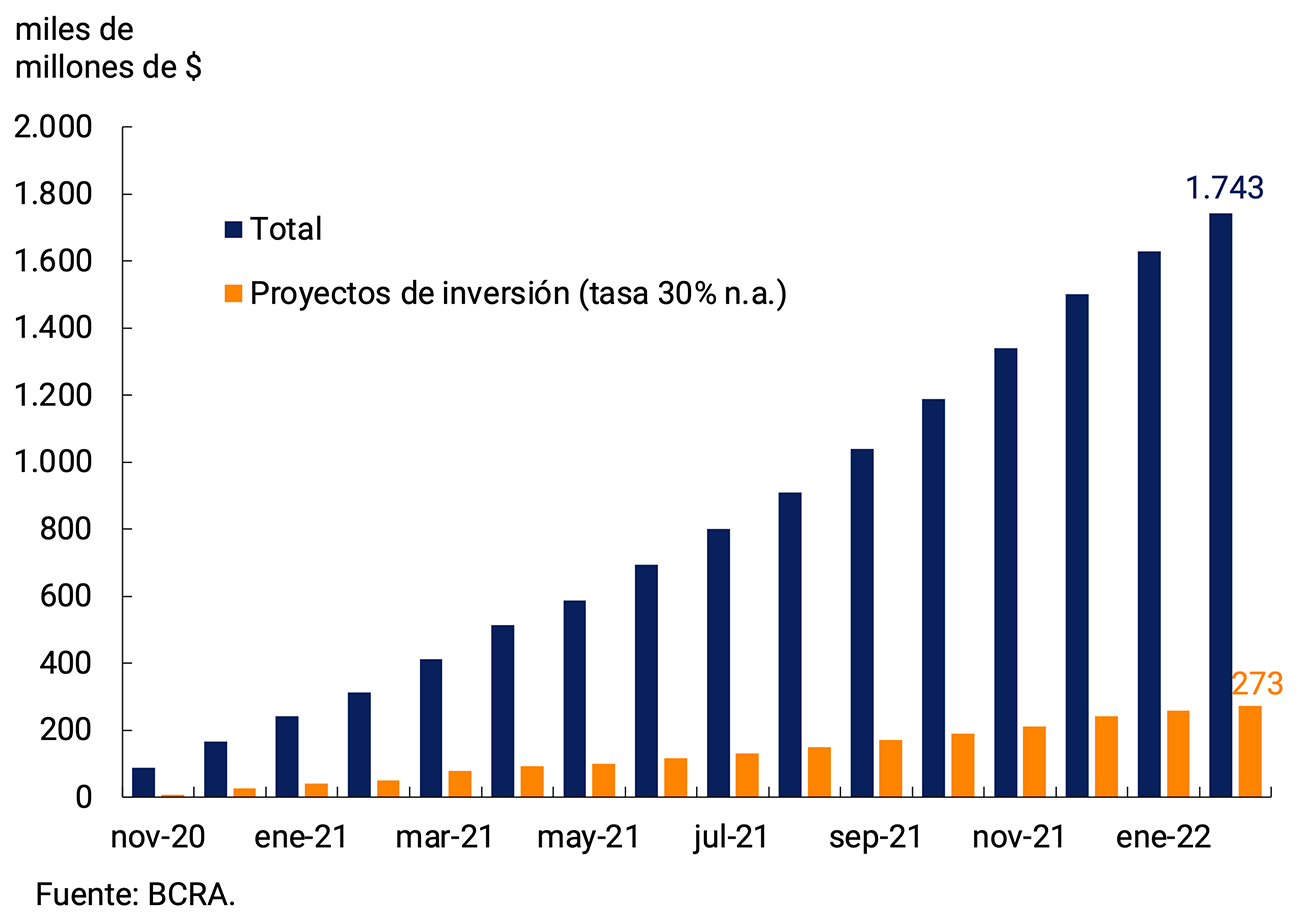

The continuity of the process of normalization of the activities of the productive sectors allowed the BCRA to continue with its credit policy focused on the most backward sectors and on the promotion of productive development. During 2022, the Central Bank will continue to stimulate the supply of credit to the private sector. The Productive Investment Financing Line (LFIP) will continue to be the main vehicle for channeling productive credit to MSMEs under favorable financial conditions.

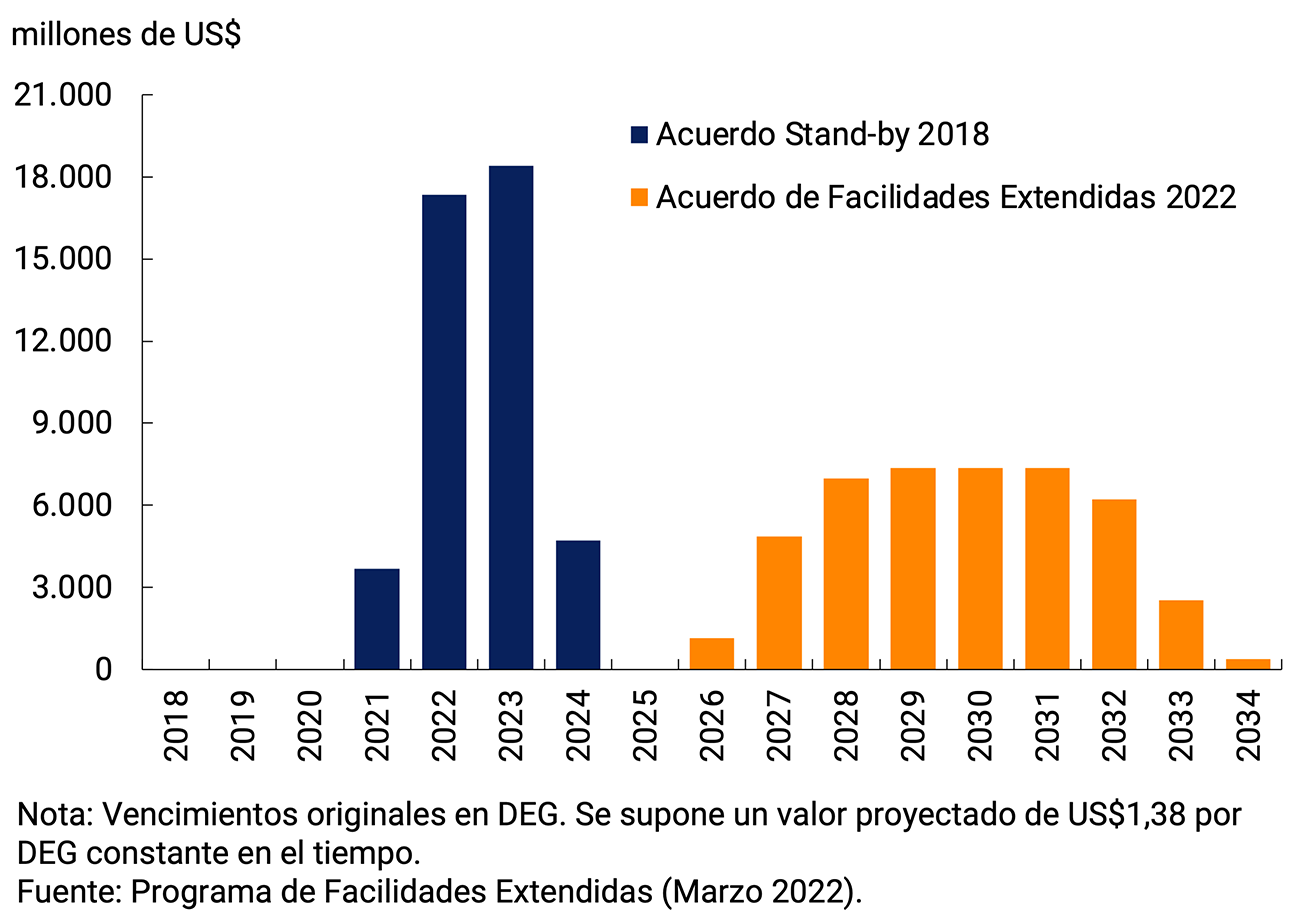

Within this monetary policy framework, the National Government recently reached an agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to implement an Extended Facilities Program (EFF), which will cover the maturities of the Stand-By Agreement (SBA) signed in 2018, obtain budgetary support to partially finance the needs of the National Treasury and strengthen the Central Bank’s reserves.

Under this agreement, repayments will be made from the middle of the fourth year after signing and will extend until the tenth year of the last disbursement, i.e. between 2026 and 2034. The agreed macroeconomic policy scheme stipulates a gradual reduction in the primary deficit of the Federal Government, without contracting public spending in real terms in order not to negatively affect the process of recovery of GDP underway. Likewise, monetary assistance to the Treasury in terms of GDP will be reduced from 1% in 2022 to zero by 2024. With regard to the rest of the policies implemented by the BCRA, the guidelines incorporated in the agreement are in line with the Objectives and Plans that were presented for the year. Mainly, it will seek to maintain the reference interest rate at a level that allows safeguarding the real value of Argentines’ savings and contributing to the depth of the domestic public debt market. On the external front, it was agreed to maintain the rate of depreciation of the domestic currency at a level that would allow progress in the process of accumulating International Reserves.

This macroeconomic policy scheme is projected to help sustain the ongoing economic recovery in an environment of lower inflation levels that will deepen the improvements in social and employment conditions. To this end, the policies of the National Government and the Central Bank will seek: to improve the sustainability of public finances and debt, without compromising growth or the reduction of social and infrastructure gaps; strengthening external sustainability through the accumulation of international reserves through policies that boost the trade surplus, promote exports and long-term capital inflows, and enable Argentina’s eventual access to international financial markets in the medium term; gradually and persistently reduce the rate of inflation through the coordination of monetary, fiscal, and income and price policies; and, finally, to create conditions to make the growth process sustainable while protecting the environment, by mobilizing domestic savings, strengthening investment in infrastructure and innovation, and promoting strategic tradable sectors.

2. International context

Since the previous IPOM, two issues dominated the international scene. First, the Omicron variant of COVID-19 affected mobility and activity level. More recently, the armed conflict between Ukraine and Russia impacted the financial and commodity markets.

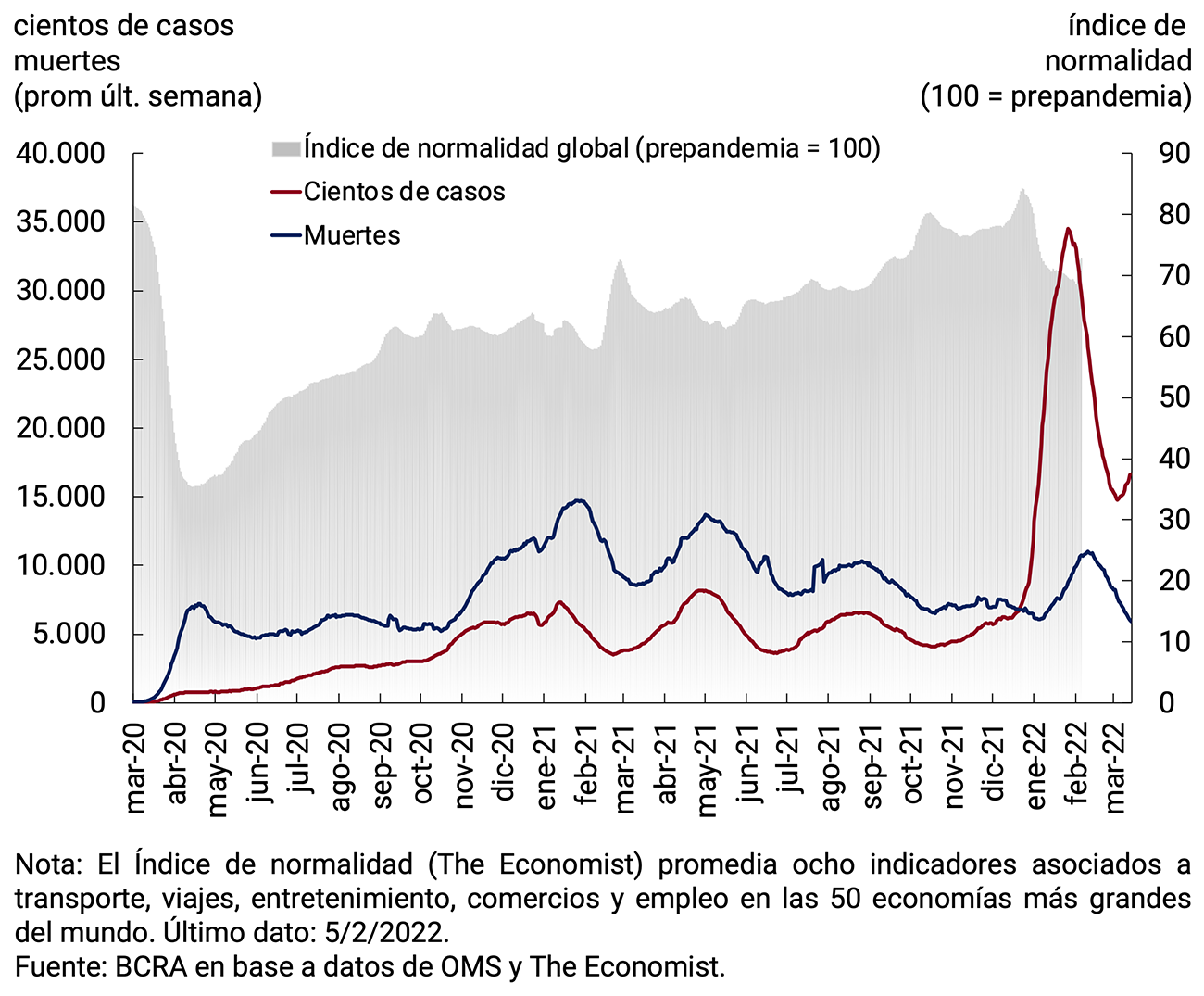

The spread of Omicron generated a global record number of cases, while deaths increased to a much lesser extent and were below the highs of previous waves. Vaccination has been intensified with booster doses, but the strong inequality between countries remains. This wave of infections has been shorter than previous ones; and it has implied an increase in restrictions and a drop in mobility comparable to those of the former, despite the fact that the increase in cases has been much greater.

The global economy continued to recover, but moderating its pace of expansion due to the impact of the new pandemic wave. Its estimated growth for this year has been reduced since the previous IPOM, which also considers the effect of a more contractionary monetary policy, the progressive withdrawal of fiscal expansion and the persistence of problems in global supply chains. The latter, together with higher prices for energy and other raw materials, has been behind much of the higher-than-expected global rise in inflation. Central banks in advanced economies have begun to reverse the expansionary bias of their policy; while those in developing countries, which had reacted earlier, continued to raise interest rates.

The armed conflict intensified two previous trends: higher energy and food prices and transportation costs, implying greater global inflationary pressures and lower levels of activity. Going forward, the dynamics of the conflict will determine the magnitude of that impact. Likewise, the evolution of the pandemic and the inequality in the pace of vaccination will continue to be decisive. The speed and amount of the withdrawal of monetary and fiscal stimuli in advanced countries and their potential “spillover” on the international economy will be risk factors of the first order; They would have an impact, at the very least, through global interest rates, the appreciation of the dollar and the reversal of capital flows to emerging countries (also affected by the conflict). High debt levels and the possible overvaluation of many assets would enhance the impact of a sudden “correction” in their prices on global financial conditions.

2.1. The Omicron variant caused a record number of global cases; lethality continued to be reduced

Since the end of November 2021, the Omicron variant has spread around the world: daily infections reached a record 24 million per week at the end of January 2022, quadrupling the previous high, and fell to 11 million per week in early March. After first manifesting itself in South Africa, cases of Omicron began to rise rapidly and reached peaks first in Europe and North America, and towards the end of December there were accelerated rises on all continents. The waves generated by this variant were generally shorter. At the close of this IPOM, there was a rise in cases in Asia (China, South Korea) and some European countries (such as Germany).

Despite the records in cases, deaths increased to a lesser extent: they reached about 75 thousand weekly, below the historical maximum of 103 thousand in January 2021. As a result, the death rate for cases 10 days ago reached a low of 0.45% (up from more than 2.5% in March 2021). Along with the increase in cases, global mobility was reduced on average to 70% of its pre-pandemic level (see Figure 2.1a).

Figure 2.1a | New Global Confirmed Cases and Deaths from COVID-19 (Last 7-Day Moving Average) and Mobility Normality Index

Figure 2.1b | New confirmed cases and deaths from COVID-19, in selected

countries Moving average last 7 days

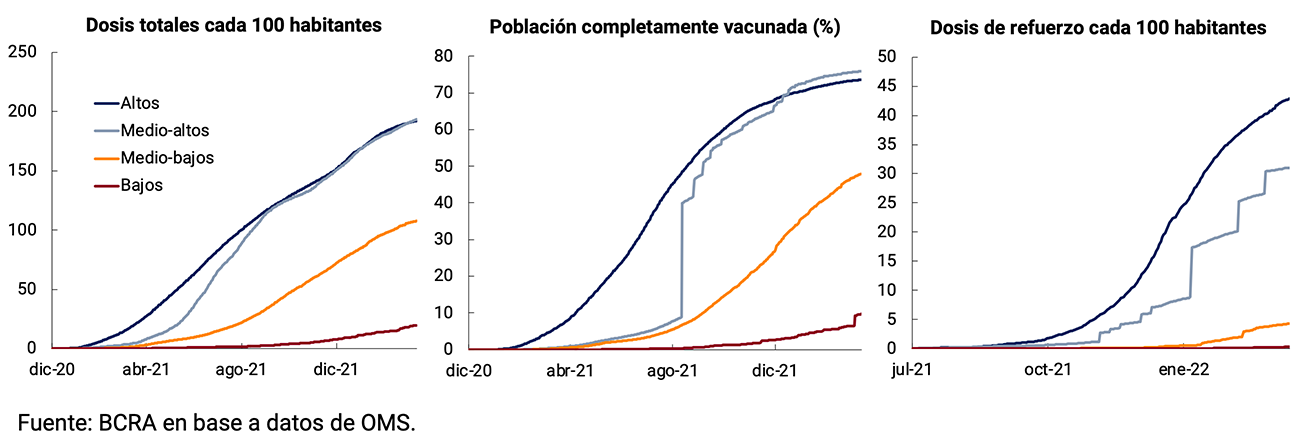

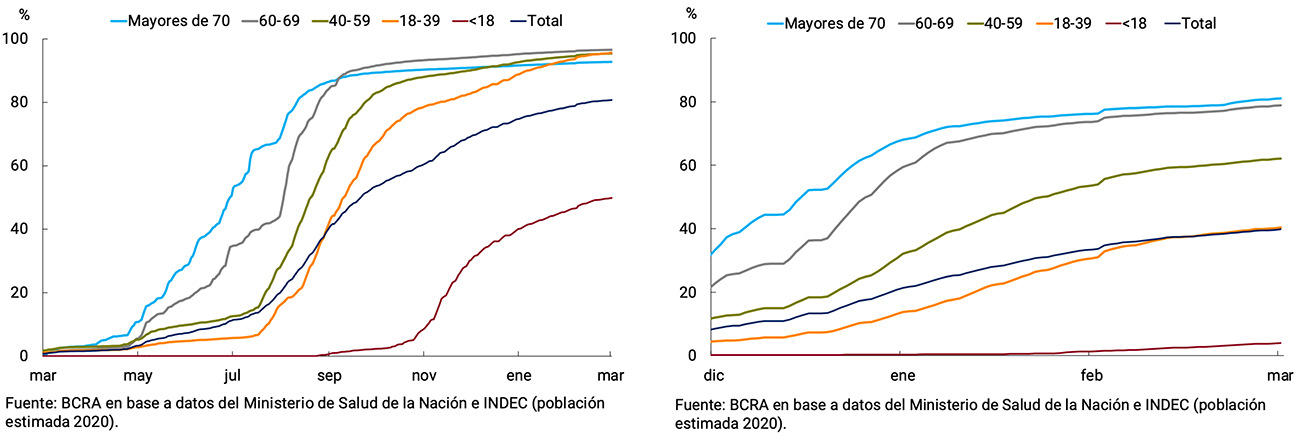

The lower lethality would be due to the characteristics of Omicron and the greater acquired immunity. The variant is more contagious and has a greater capacity for reinfection (infecting previously vaccinated or infected people), but it usually causes milder disease. The effectiveness of vaccines is lower in terms of antibodies, but a booster dose helps increase antibodies and maintain protection against severe disease. In fact, the main strategy of governments in the face of the increase in cases has been to reinforce vaccination campaigns, although the gap between higher- and lower-income countries remains. The percentage of the population fully vaccinated in low-income countries is more than 7 times lower than in high-income countries; and while high-income countries have more than 42 booster doses per 100 inhabitants, low-income countries have applied less than 0.3 (see Figure 2.2).

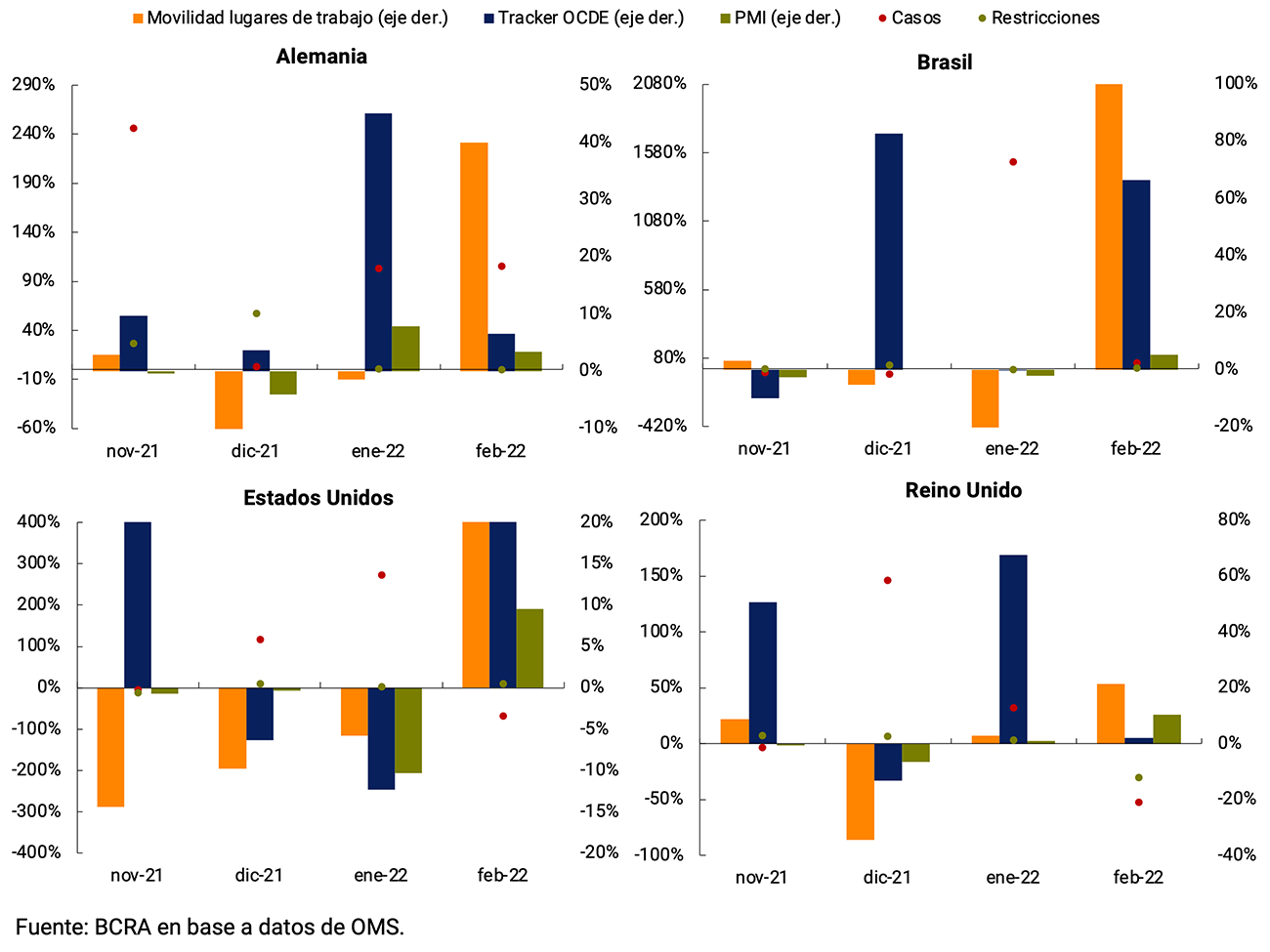

Several countries reintroduced restrictions, albeit with varying levels of rigidity, and there was a drop in mobility, with the consequent impact on the slowdown in the recovery, as detailed in the next section. With the drop in cases during February, mobility increased again and many restrictions began to be lifted (see Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 | Monthly change in cases, deaths, tightening of restrictions, mobility, OECD economic activity and PMI indices during the latest wave of Coronavirus

2.2. Due to the conflict, commodity prices rise and global financial conditions tighten

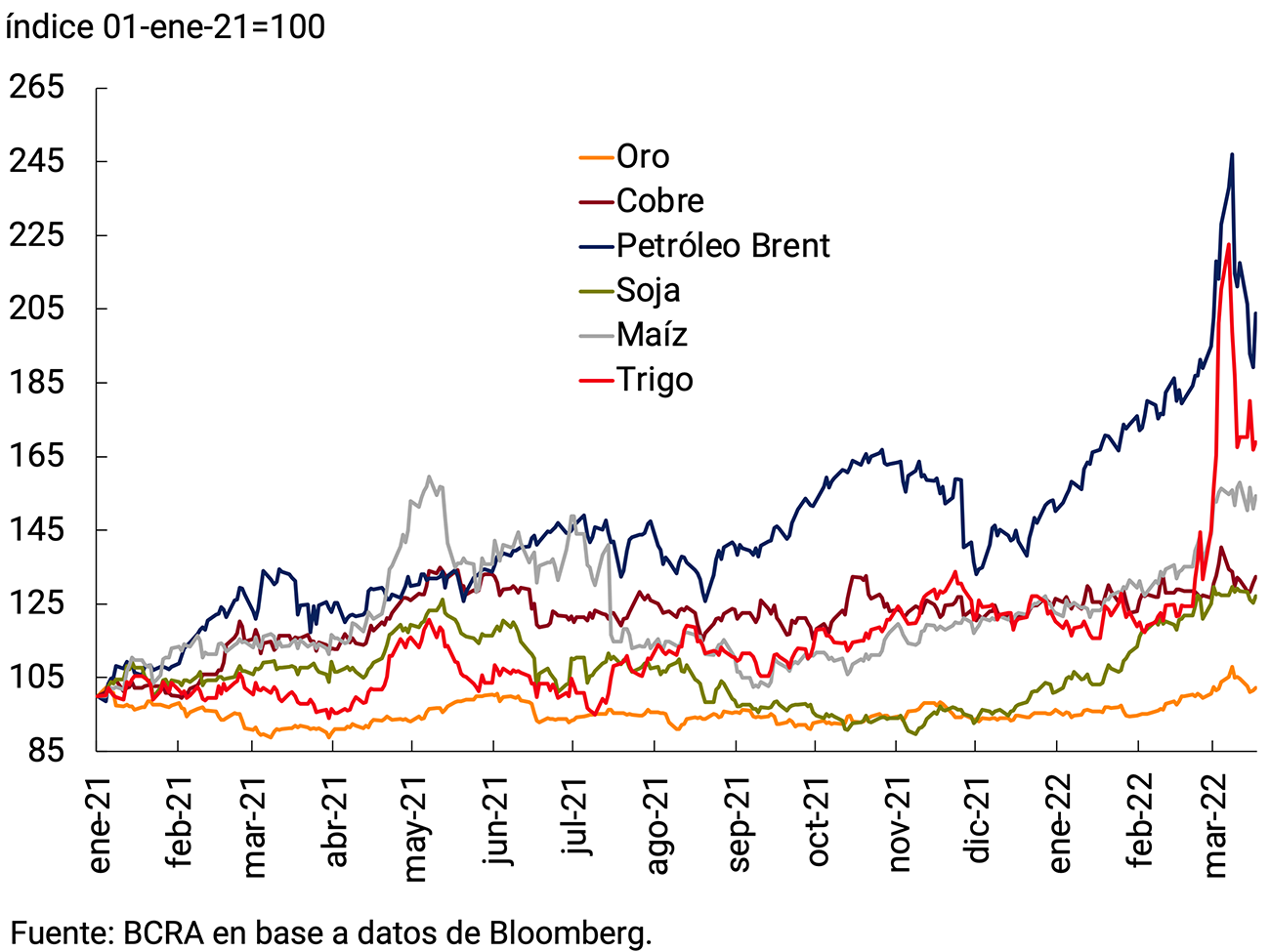

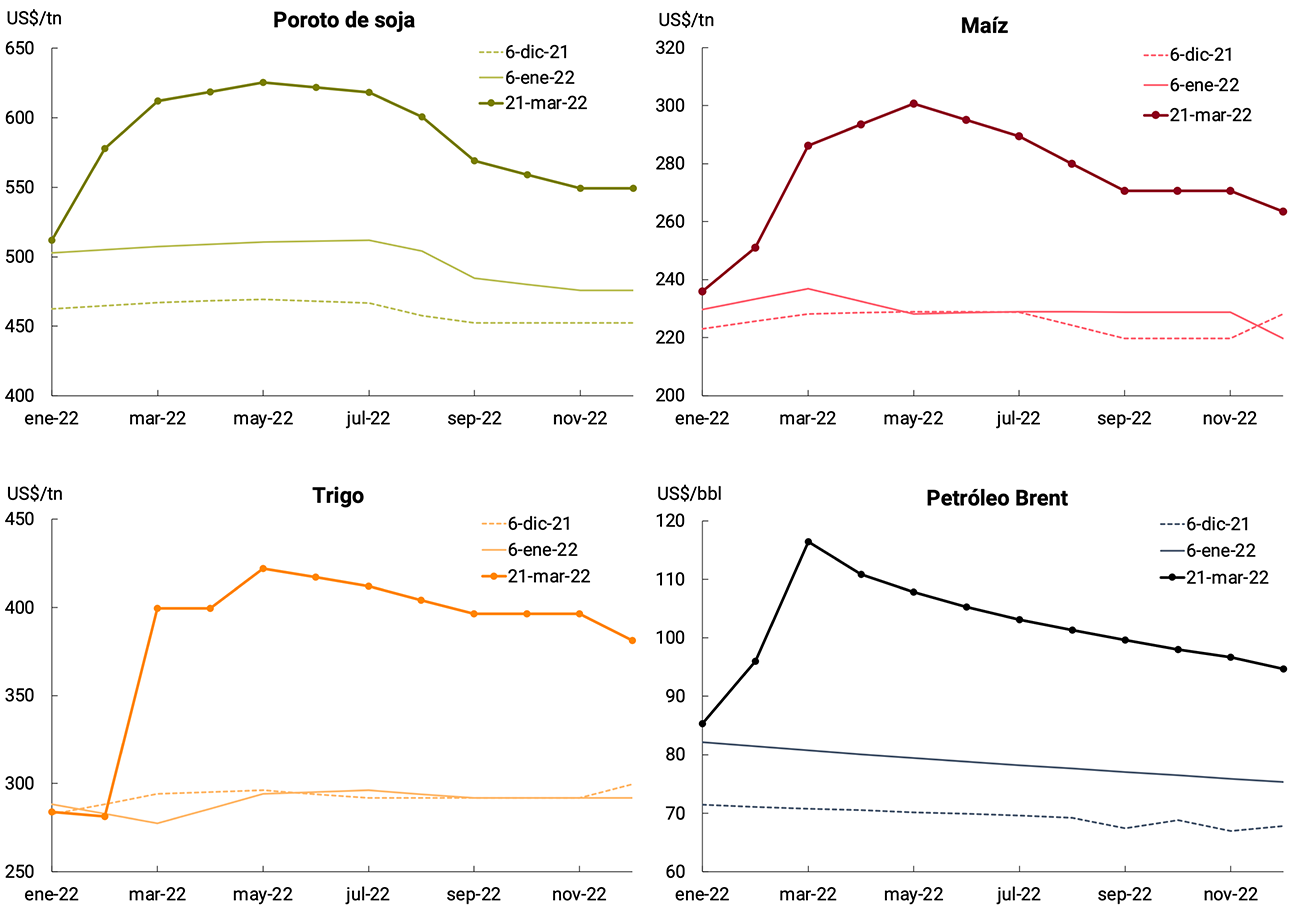

The price of oil had been rising since December due to the recovery in fuel demand and a supply that has been slow to respond. The sanctions imposed on Russia and the problems of oil transport had a strong impact on Brent, which reached US$139 per barrel on March 8, the highest since 2008; and fell to values close to US$100 a barrel during the following week (see Figure 2.4). In addition, Russia is the world’s leading exporter of natural gas, and Europe is heavily dependent on energy imports from that country. At the beginning of the crisis, gas was trading at 116 euros per MWh; and reached 212 euros per MWh on March 7, representing an increase of 83% in the reference market of the Netherlands.

At the same time, the prices of various food commodities rose because Russia and Ukraine are among the main global producers: among them, wheat and sunflower and, to a lesser extent, corn. Together, Ukraine and Russia account for approximately 25% of world wheat exports, 56% of sunflower oil and 10% of corn. The price of wheat hit a record high of US$523 per ton on March 7 before falling, accumulating an increase of 23% since the conflict began and 40% for the year at the time of writing (see Figure 2.4).

Prices of raw materials used as inputs for manufacturing production, in which Russia leads as a producer or exporter, also rose. The impact on palladium (it reached a record of US$2,994 per ounce), where Russia concentrates 40% of world production and is used in the manufacture of automobiles, was highlighted; but the prices of metals such as nickel also rose (after rising 92% since the beginning of the conflict, trading on the London market was suspended) and copper, which reached US$477 per pound. Gold, which is used as a store of value in situations of international stress, reached US$2,070 per ounce, partially reflecting geopolitical tensions (see Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4 |

Box. Energy consumption and imports in Europe

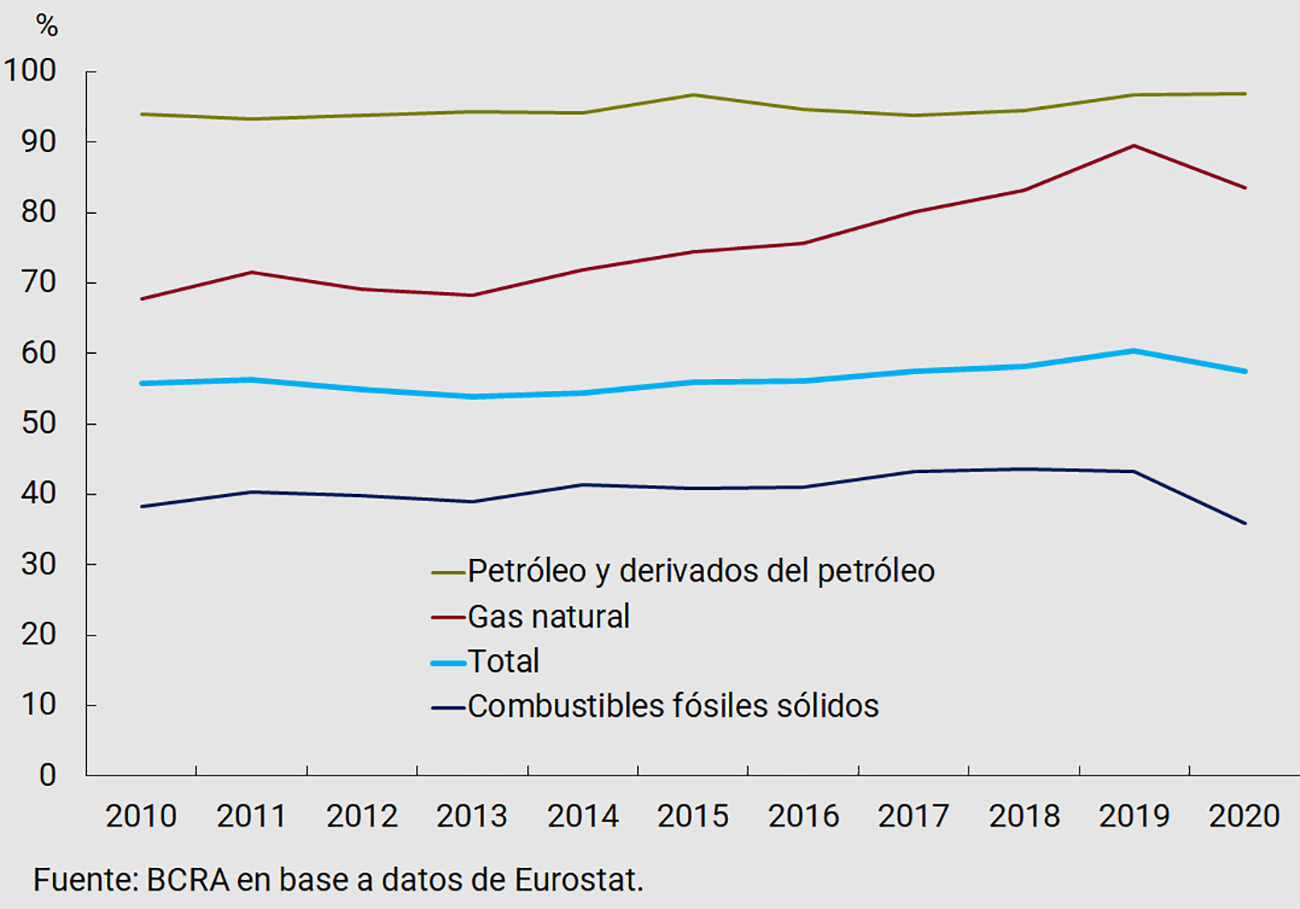

Between 2010 and 2020, more than half of the gross energy available in the European Union (EU) was covered by net imports: they ranged from 55.7% to 57.5%. In 2020, the highest rates of energy dependence were recorded for oil (97%) and natural gas (83.6%), while for solid fossil fuels it was 35.8% (see Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5 | Energy dependency ratio, EU-27, 2010-2020

Net imports of gross available energy, as % of total energy consumption

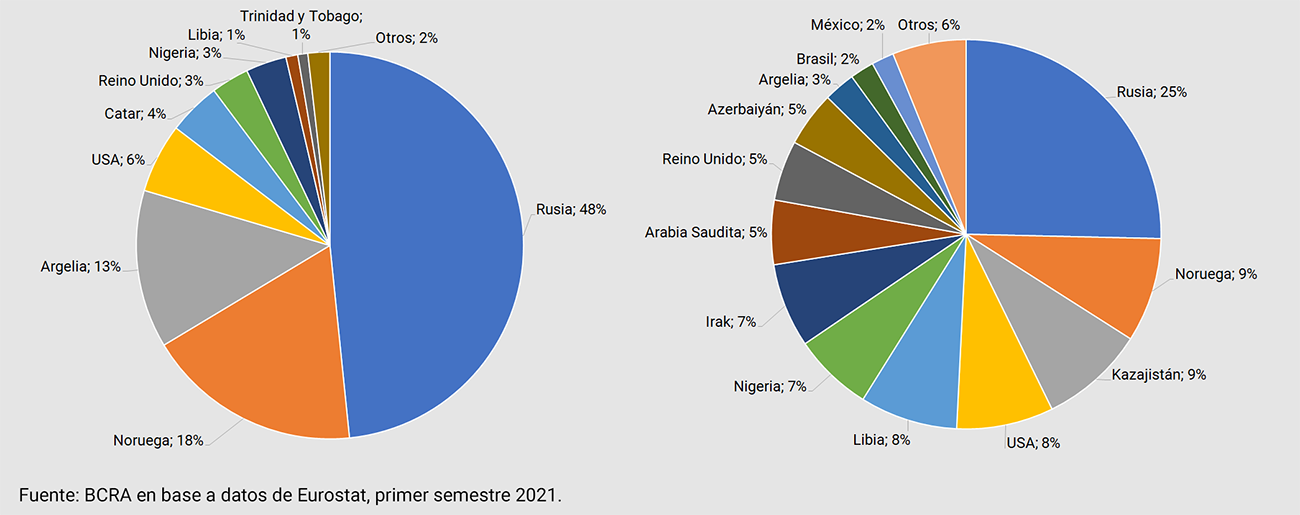

Among the different energy sources, the strong growth in gas consumption stands out. Between 2010 and 2020, the EU’s dependence on third countries for natural gas supplies increased by 15.8 p.p., much faster than dependence on crude oil during that decade (it increased by 3 p.p.). Much of the EU’s imported energy comes from Russia, which stands out as the main supplier of gas (48%) and oil (25%), as can be seen in Figure 2.6.

The war between Russia and Ukraine accentuated the tightening of global financial conditions that had been observed in recent months, also increasing volatility. As a result of the conflict, the interest rate on 10-year U.S. government bonds reversed part of the rise it registered. But in recent days and with the tightening of the monetary policy of the US Federal Reserve (Fed), it increased again, and as of March 16 it was 65 bps above its level at the close of the previous IPOM, reaching 2.17% (see Figure 2.4). Meanwhile, the 30-year rate rose 52 basis points in the same period, so the yield curve continued to flatten. In Germany, the 10-year government bond rate rose 65 basis points and turned positive again.

The U.S. dollar — measured against a basket of currencies — has appreciated since last May, a trend that has accelerated since the beginning of the war. For its part, the VIX indicator (which reflects the implied volatility on a set of market options) also rose, reaching more than 35 points at the beginning of March.

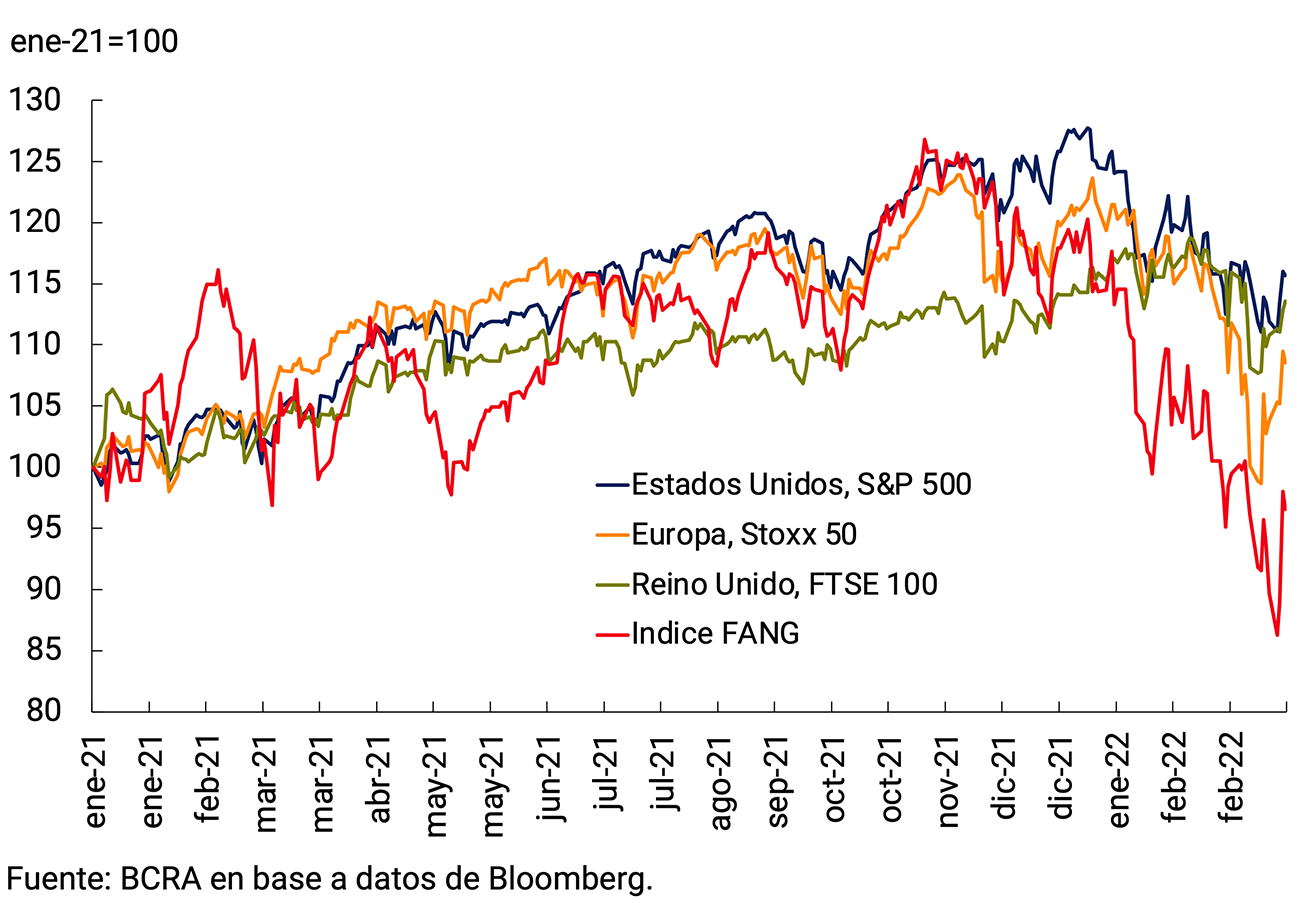

The rise in market interest rates and the war in Ukraine impacted stock prices; the most risky assets were the most affected, as warned in previous reports. While the S&P 500 fell 9% and the European Stoxx 50 fell 10% so far this year, the FANG index, with the largest share of technology companies, was down 17% over the same period and 22% since the previous IPOM close (see Figure 2.7). This dynamic has been accentuated since the beginning of February and if it continues, it would put at risk the performance of the digital “winners” of the last couple of years and the “support” they have meant for the market. Cryptoassets have also fallen substantially in price, and a further fall could have consequences that are not entirely foreseen in the global financial system. Bitcoin, which was once worth more than US$67,000, is now trading around US$40,800, depreciating by more than 40%.

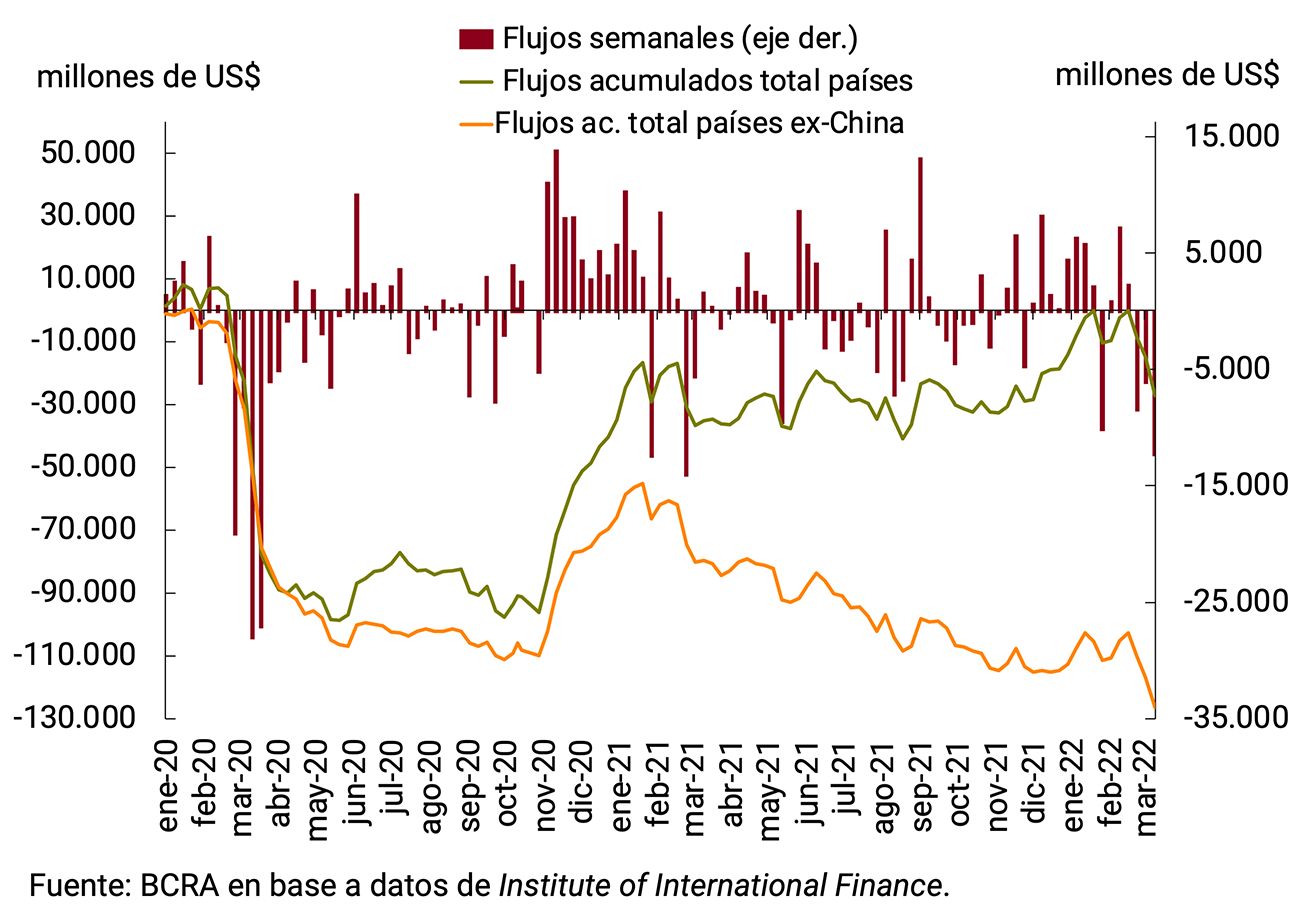

Capital flows to emerging countries, which had been positive and with low volatility, began to show outflows in recent weeks. Although the accumulated flows since the previous IPOM were slightly positive, since the beginning of the year they were negative by US$13 billion. However, its composition was very concentrated. Of a cumulative total of US$3.5 billion since the close of the previous IPOM, US$17.5 billion were flows to China, so flows to the rest of the emerging countries were negative. Since the recovery began, China has been absorbing a growing share of flows to emerging markets (see Figure 2.7).

2.3 The global economy is expected to expand in 2022, albeit at a slower pace and with the conflict in Ukraine as a new source of uncertainty

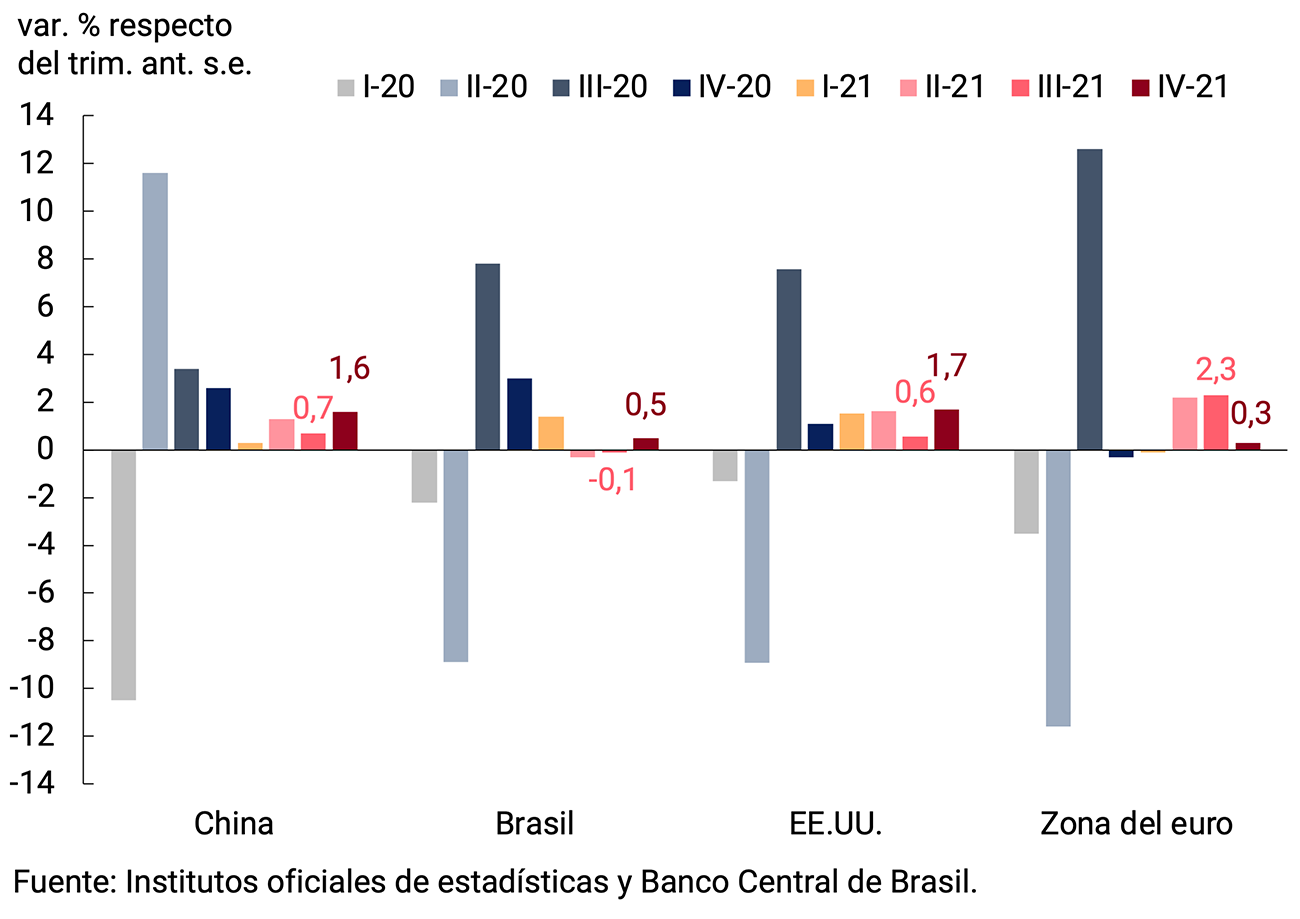

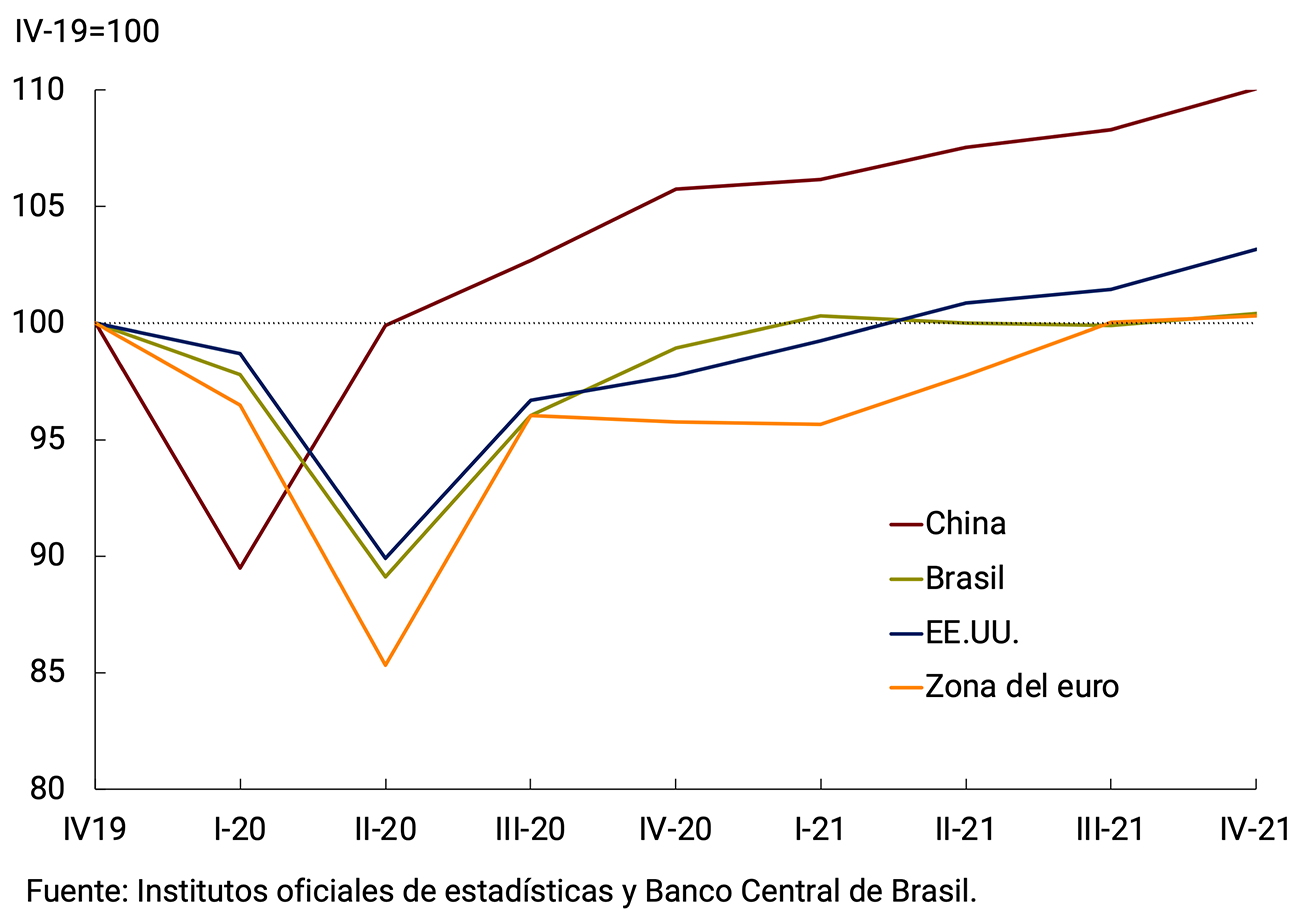

The global economy continued to grow in the fourth quarter of 2021, with heterogeneous dynamics among Argentina’s main trading partners (see Figure 2.8). The United States, China and Brazil accelerated their quarterly growth in that period, while the euro area grew less than in previous quarters, due to the impact of mobility restrictions due to COVID-19 outbreaks and bottlenecks. Thus, at the end of last year, activity levels in the United States and China were clearly above pre-pandemic levels, while the euro area and Brazil showed greater difficulties in overcoming them (see Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8 | Evolution of the GDP of Argentina’s main trading partners (real GDP without seasonality)

High-frequency data from December 2021 and January 2022 reflected the impact of the spread of the Omicron variant and reduced mobility on economic activity, particularly in advanced countries (see Figure 2.9). Purchasing managers’ surveys (PMIs) showed lower global economic activity, with composite indices falling in the United States, the euro area, the United Kingdom, and China in January (although still in the expansion zone, above 50). The services sector was the main affected. Retail sales also felt the impact, with declines in the United States, the euro area and the United Kingdom in December. In the same vein, the OECD’s economic activity indicator reflected lower activity in the United States and Europe in November, December and January.

From February onwards, the reduction in cases and fewer restrictions on mobility were reflected in a recovery in economic activity, with improvements in PMIs, the OECD economic activity indicator and retail sales (see Figure 2.9). For its part, the manufacturing industry showed a better performance with an increase in industrial production in January in the United States and the United Kingdom and the global manufacturing PMI in February; and some improvement in delay times and supply chain problems in the United Kingdom, the euro area and the United States. Activity indicators are expected to begin to reflect the impact of the war in Ukraine and the economic sanctions on Russia from March.

Before the outbreak of the war, forecasts for the global economy indicated that the world would grow again in 2022, although at a slower rate than the 5.7% recorded in 2021 (average of the IMF, World Bank and OECD). At the beginning of this year, the expected global expansion had been reduced due to the continuity of the pandemic and problems in global supply chains, increasingly contractionary monetary policy and a lower fiscal stimulus. Thus, in January of this year, the average growth forecasts for 2022 of the three aforementioned agencies was 4.3%, 0.3 p.p. below the previous projection (see Table 2.1).

The armed conflict implies lower projections of global growth. Its initial impact has reinforced previous trends of tightening global financial conditions and rising commodity prices. According to the European Central Bank, the expansion of the world economy would fall from 4.5% to 4.1% in 2022 and from 3.9% to 3.6% in 2023 and, in the euro area, from 4.3% to 3.7% in 2022 and from 2.9% to 2.8% in 2023. For its part, the Fed’s board also lowered its growth forecasts for this year, from 4.0% to 2.8%, but maintained next year’s at 2.2% (see Table 2.1).

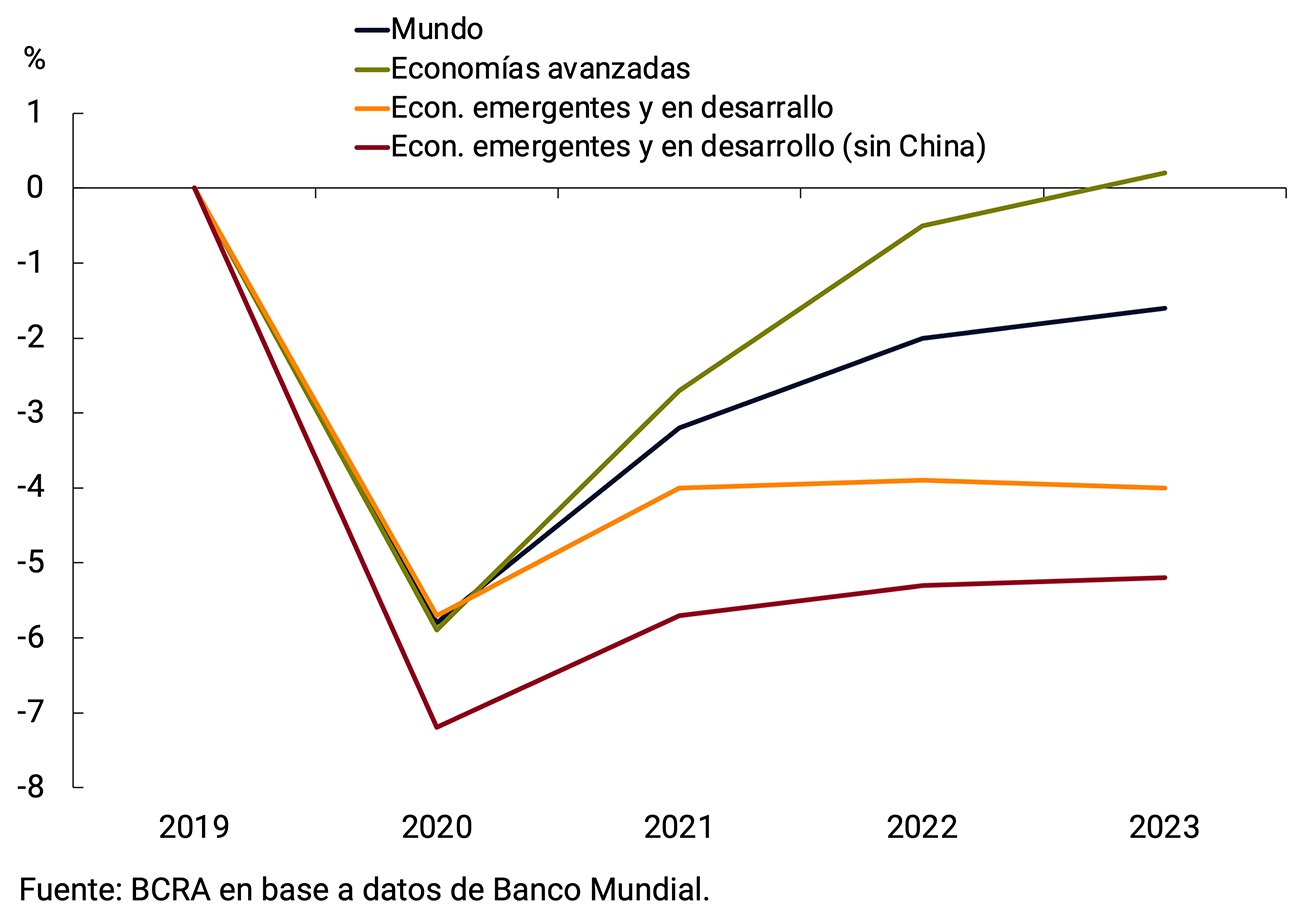

The recovery would continue to diverge between advanced and developing countries given differences in access to vaccines and policy space and the impact of the monetary cycle on both groups of countries. According to the World Bank, and considering pre-conflict forecasts, economic activity in advanced economies would exceed the trajectory forecast before the pandemic in 2023; while that of emerging and developing economies would remain 4 p.p. below the pre-pandemic trend, a difference that widens to 5.2 p.p. if China is excluded from the latter group (see Figure 2.10).

Unemployment rates have recovered from the highs recorded in the second and third quarters of 2020. In several cases, they have returned to their pre-pandemic levels or are close to reaching them, while labor participation rates are slowly returning to pre-COVID-19 levels (see Figure 2.11).

Figure 2.11 Unemployment and labour force participation rates in selected countries

Unemployment

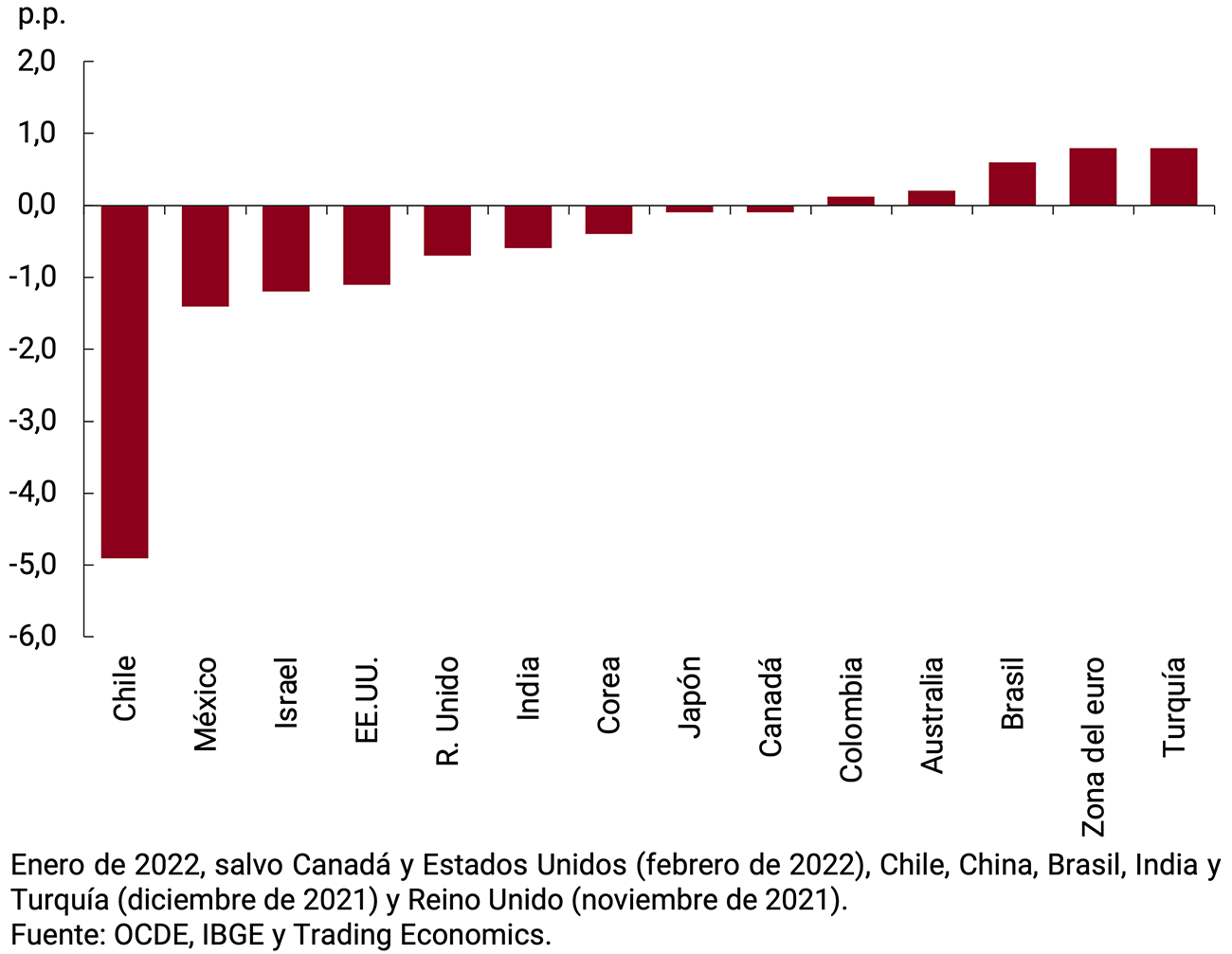

rateDifference in p.p. between the last available month and comparable pre-pandemic month

2.4. Central banks accelerate the reduction of monetary stimulus in the face of rising inflation, facing new dilemmas due to the conflict

In the face of higher global inflation, a risk highlighted in the previous IPOM materialized: central banks in developed countries began to withdraw monetary stimulus in recent months. Their peers in emerging countries continued to take contractionary measures and, in some cases, accelerated their pace. The conflict in Ukraine adds a supply shock (energy and other raw materials) to a scenario that had previous impacts in this regard. This accentuates the dilemma for central banks: let these relative price changes (which would be temporary) pass them by, or raise interest rates more aggressively.

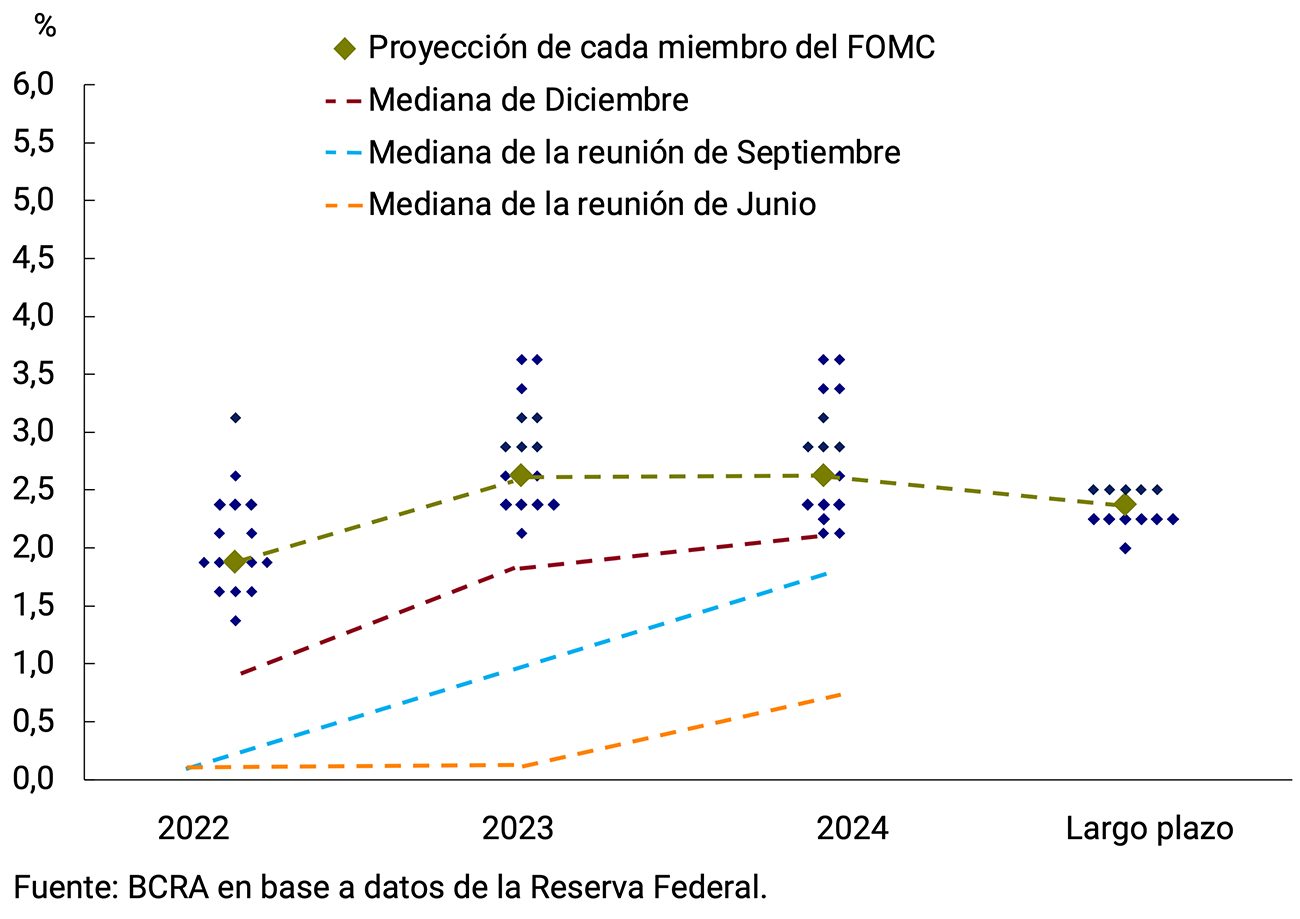

On March 16, the Fed announced the first increase in its benchmark interest rate since 2018 (TFF, +0.25 p.p.). In addition, it has ended the asset purchase program and at the next meeting in May it will announce how it plans to reduce its bond holdings. In just a few months, the Fed markedly accelerated the expected trajectory of TFF hikes: at its meeting in March of this year it revealed a forecast of seven TFF increases in 2022 (the first has already occurred); while in December 2021 it foresaw three increases in the TFF; in the previous meeting only two increases; in June 2021, none; and in the March 2021 census, it did not foresee increases until 2024 (see Figure 2.12).

The European Central Bank (ECB) will end its pandemic emergency asset purchase program (PEPP) in March 2022. In addition, the ECB decided to accelerate the withdrawal of the asset purchase program (APP); however, it gave mixed signals regarding when it will make the first increase in its benchmark interest rate. The Bank of Japan also announced the end of additional purchases of commercial paper and corporate bonds in March 2022. The Bank of England made similar announcements, while raising its interest rate for the third time in a row in March (to 0.75%).

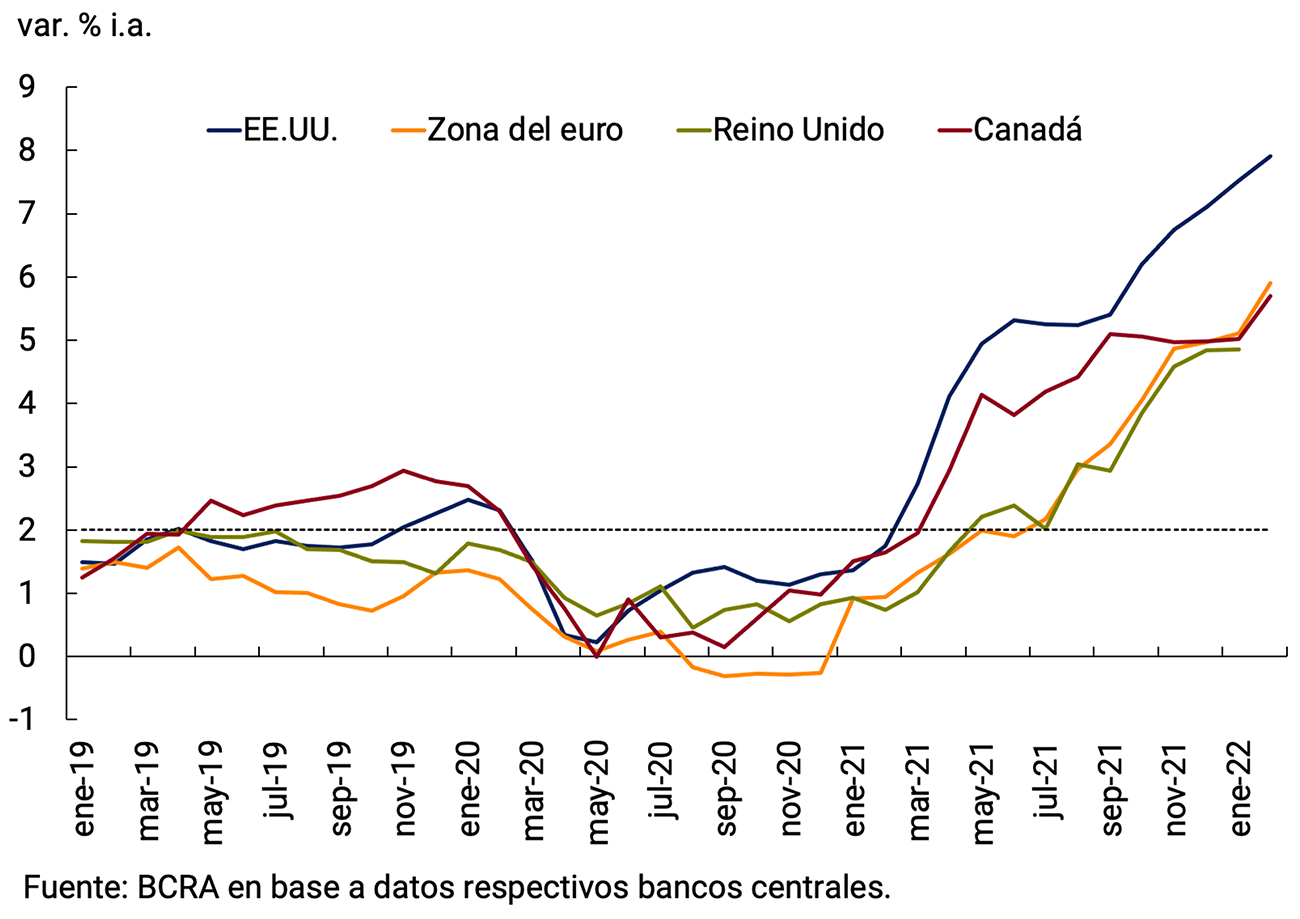

These decisions are due to the fact that inflation in developed countries reached record levels in recent decades, more than doubling the targets of their central banks (see Figure 2.13). In February, retail inflation was 7.9% YoY in the United States (highest since 1982), 5.9% YoY in the Euro Area (highest since 1991), 5.7% YoY in Canada (highest since 1991), while in January it reached 4.9% YoY in the United Kingdom (highest since 1992).

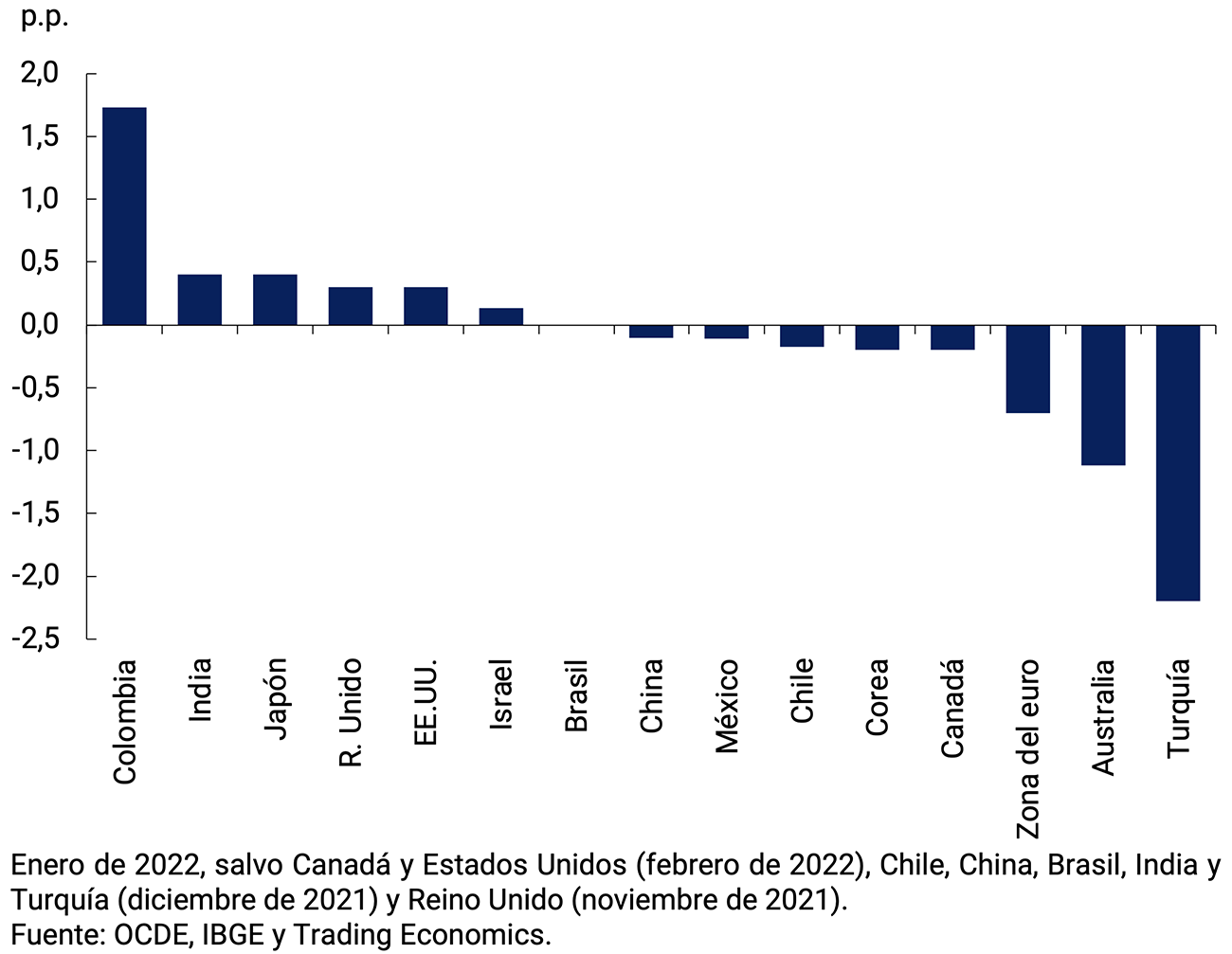

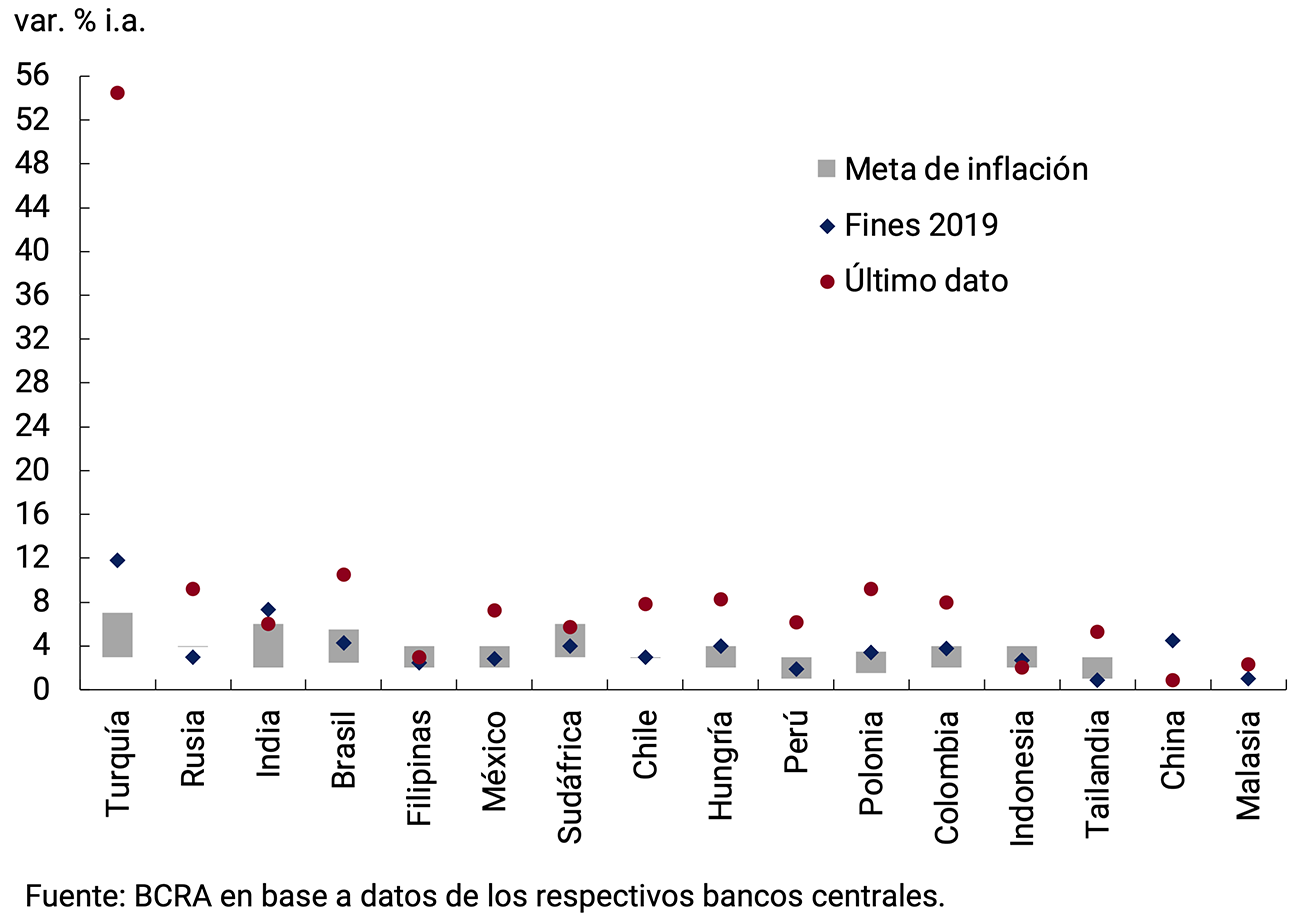

Meanwhile, the central banks of emerging countries continued to take contractionary measures in the face of inflationary pressures that manifested themselves earlier than in advanced countries and in greater amounts. The average interest rate of the group of countries surveyed touched a minimum of 2.98% in August 2020 and now stands at 6.1% (see Figure 2.14). In Latin America, there were record interest rate increases in two decades: 1.5 p.p. in Brazil (on three occasions) and 1.5 p.p. in Chile. Other emerging economies that raised their rates were South Africa and Russia (in the latter case also due to the recent impact of economic sanctions on their foreign exchange market). Central banks in Asia, where inflation has risen much less, kept them unchanged. The exception was Turkey, which reduced its rate, only to suffer a sharp depreciation and the consequent transfer to inflation (almost 11.1% monthly in January). The recent rise in energy and agricultural commodities is expected to reinforce the trend in inflation during March, in both advanced and emerging countries.

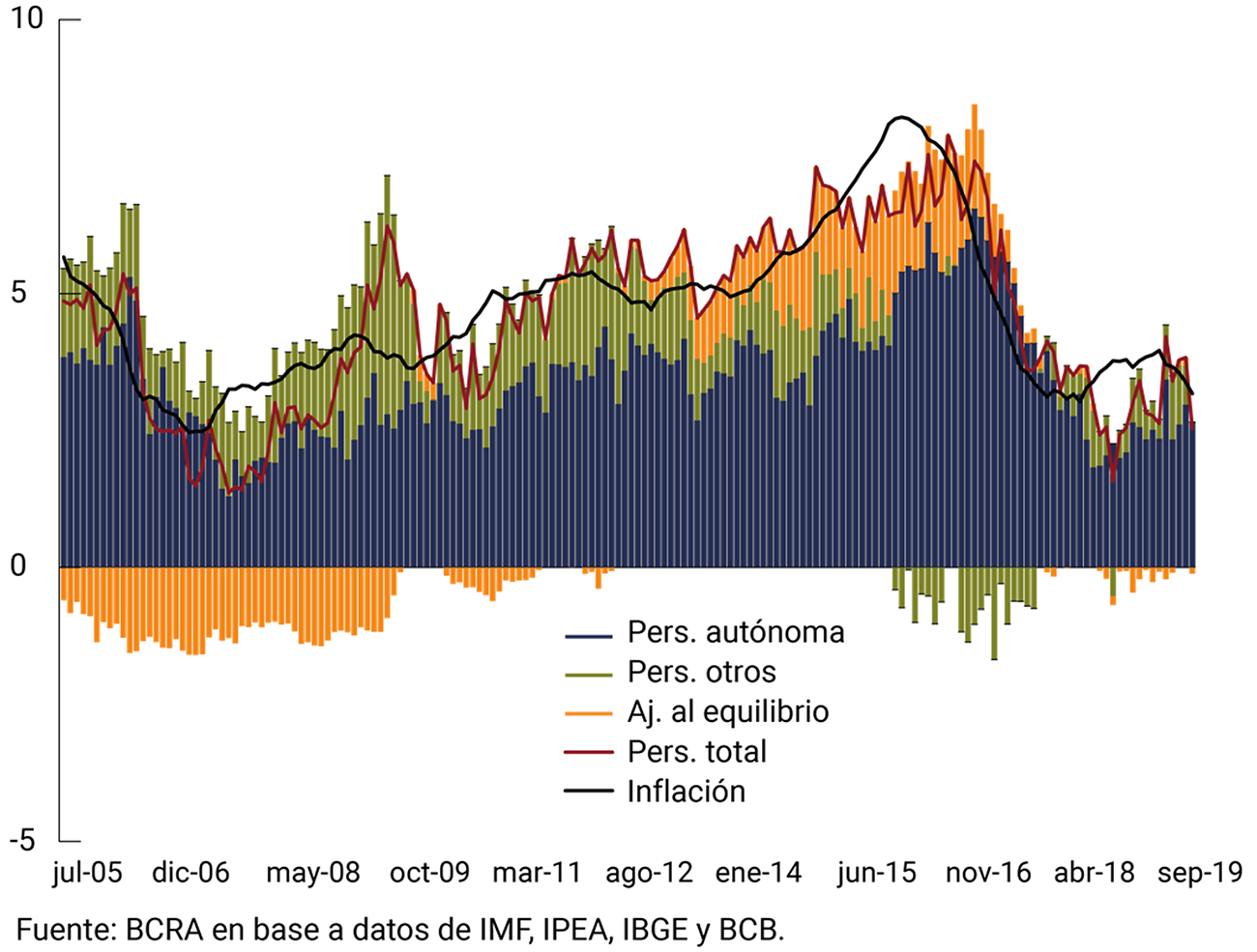

Box. Contractionary monetary policy in Brazil

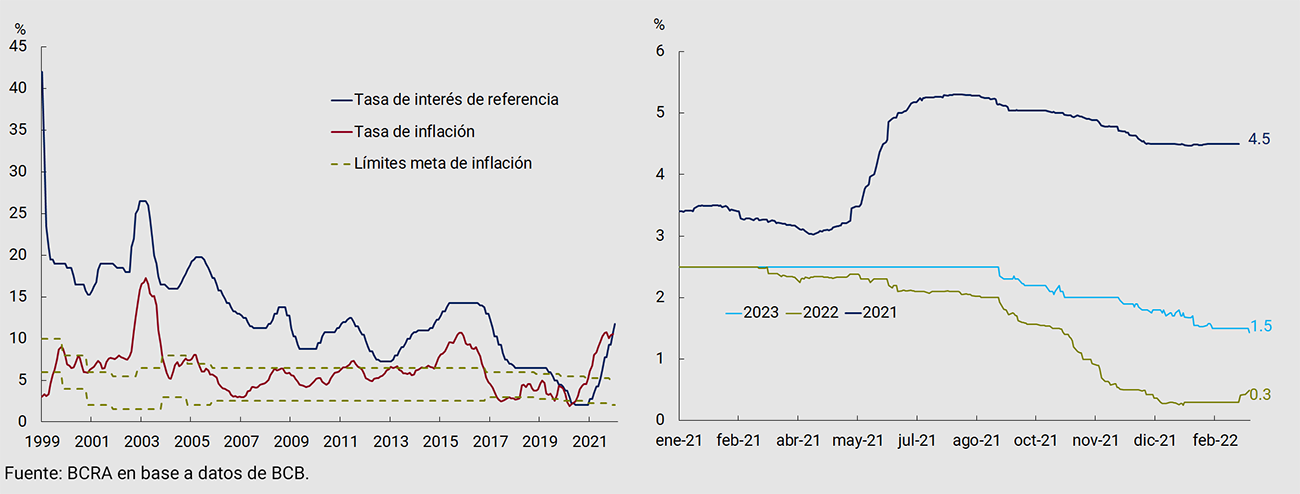

Brazil’s central bank (BCB) has raised its benchmark interest rate (Selic) nine consecutive times since March 2021, from record lows of 2% that month (see Figure 2.15).

Inflation rose to 10.5% YoY in February, more than 5 p.p. above the upper limit of the target, with expectations rising and with the BCB projecting it above the target this year. Part of the inflationary increase was driven by the depreciation of the real, which was reinforced by higher commodity prices.

The increases in the Selic have had a negative impact on growth expectations for 2022 and 2023 (see Figure 2.15). In addition, they will weigh on fiscal results since almost half of Brazil’s public debt is indexed to this rate. Each 1 p.p. increase in the target on the Selic rate implies an increase of approximately 0.5 p.p. in fiscal deficit. The BCB pointed out, after its latest decision, that Selic’s rate of hikes would be slower this year.

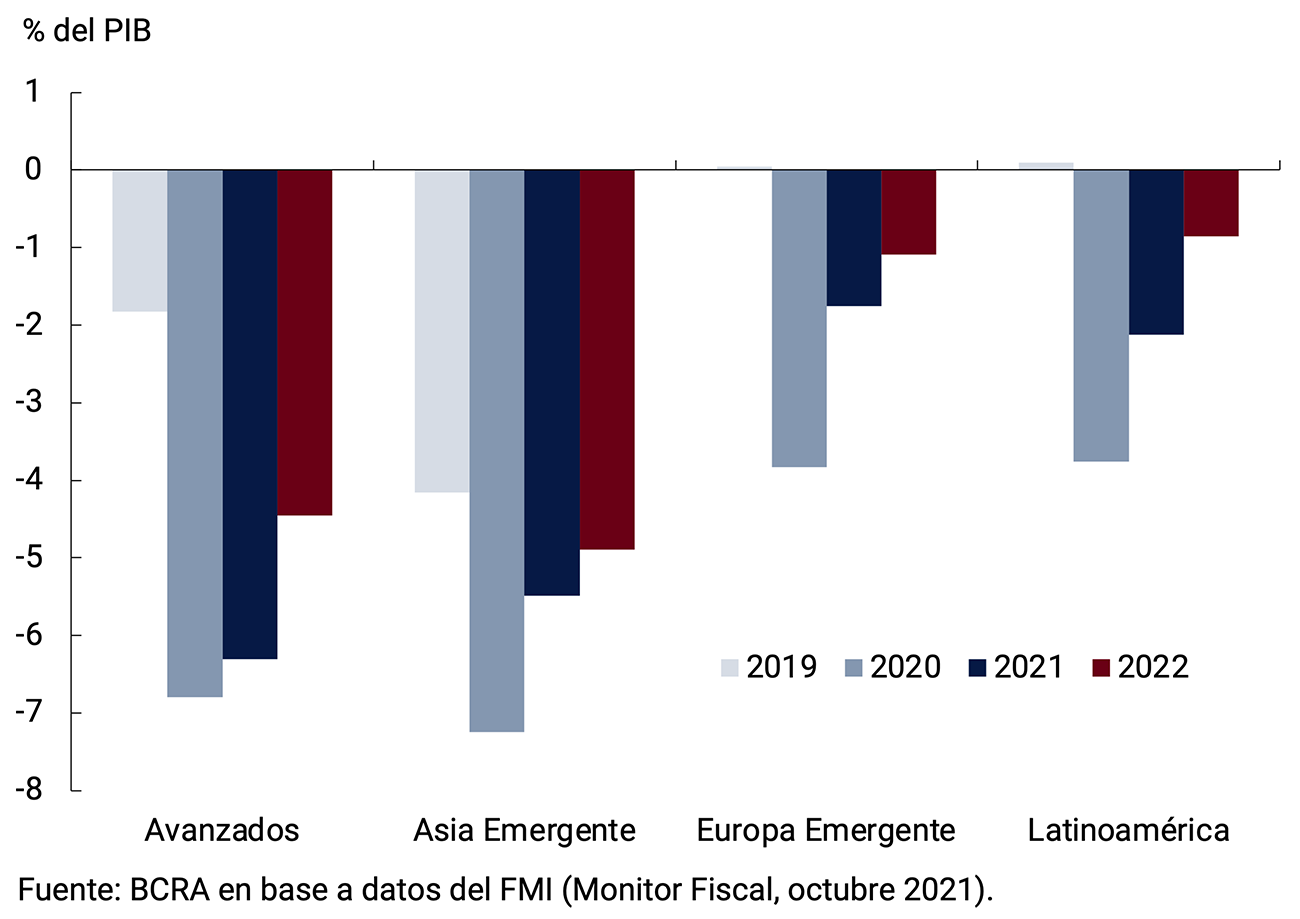

For its part, the fiscal stimulus tended to be withdrawn during 2021 as governments reduced spending to alleviate the effects of the pandemic, as shown by structural fiscal outcome measures. This contraction was more marked in emerging countries than in advanced ones, given the former’s lower capacity to finance large deficits. The withdrawal of the fiscal stimulus is expected to continue this year, with a larger reduction in advanced economies (see Figure 2.16).

2.5. In summary

The global recovery continues in a divergent manner (due to the unequal policy space and gaps in vaccination campaigns) and has slowed down (due to the expansion of Omicron and the withdrawal of monetary and fiscal stimulus). Rising inflation in advanced economies creates the risk of a steeper monetary contraction, which would “trickle down” to developing countries under higher international interest rates, dollar appreciation, capital outflows and, eventually, lower growth. A possible “correction” of high global asset valuations would enhance that risk. The armed conflict in Ukraine opened a new source of uncertainty for the global economy. It affected financial markets and intensified two previous trends: higher commodity prices and transportation costs, implying greater global inflationary pressures and lower levels of activity. Going forward, the dynamics of the conflict will determine the magnitude of that impact.

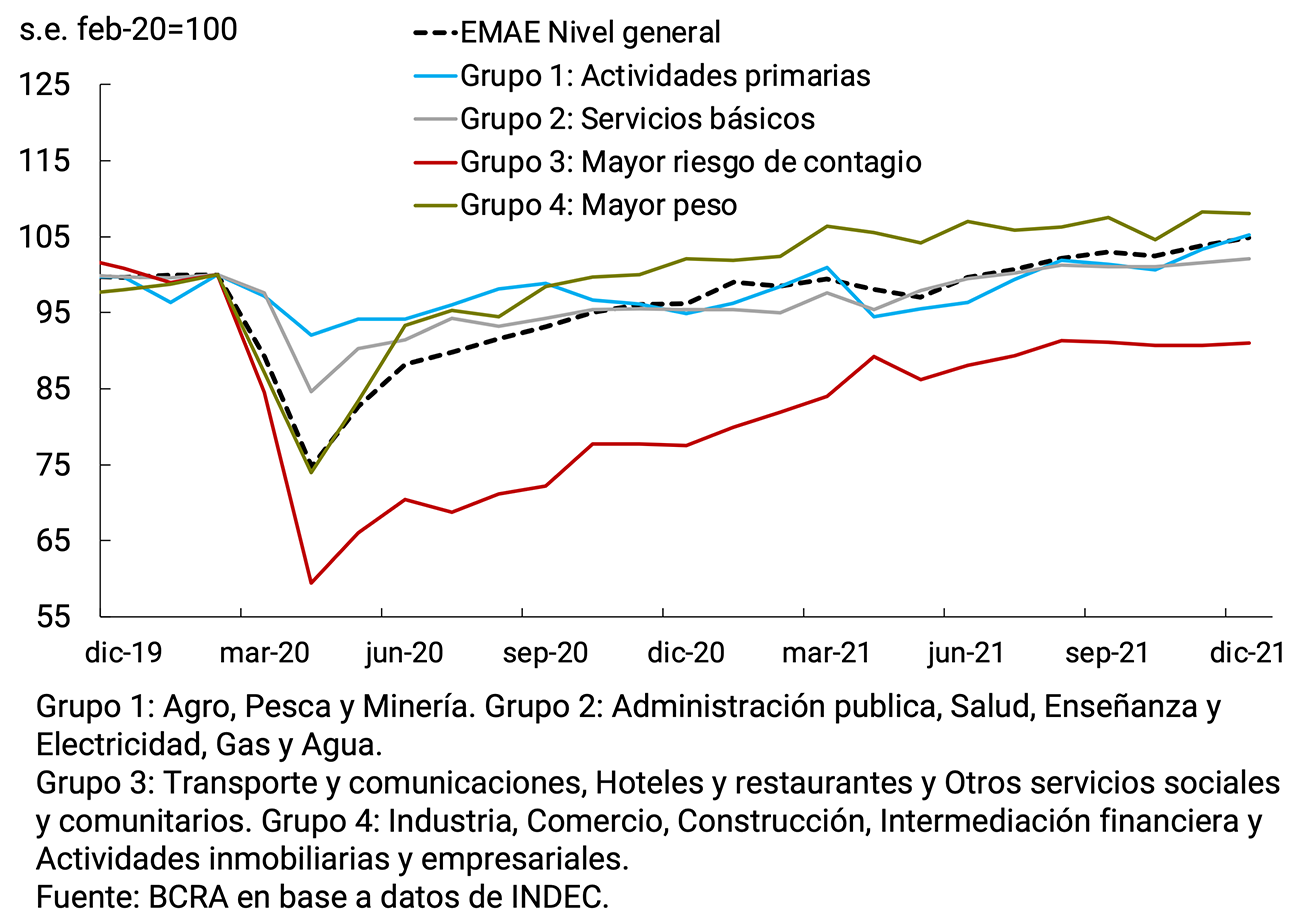

3. Economic Activity and Employment

Economic activity continued to improve in the fourth quarter of 2021 and continued to operate at levels above pre-pandemic levels, closing the year with greater dynamism than initially expected. The data available from the EMAE for December showed a progressive reduction in sectoral heterogeneity – with a recovery that had initially been led by industry, trade and construction. The sectors with the highest health risk began to operate at levels closer to those of pre-pandemic after the progressive normalization of social mobility.

The recovery of activity took place in a context of broad coverage of the population with complete vaccination schemes and the progressive progress in the application of booster doses that, in a context of circulation of a new strain of the virus with less lethality, made it possible to limit the impact of the third wave of COVID-19 cases at the beginning of the year. with fewer critical hospitalizations and deaths compared to previous outbreaks of the disease.

In this context, the National Government continued to implement policies aimed at sustainable and inclusive economic growth, while making progress in the promotion of strategic sectors, the promotion of the development of local suppliers, regional economies and the recovery of employment. It also temporarily extended targeted support measures on sectors severely affected by the pandemic. For its part, the BCRA continued to contribute to the recovery process through lines of credit linked to productive development, the continuity of measures to promote private consumption and benefits for investments aimed at expanding export capacity.

After recovering 10.3% during 2021 and with a very good performance in the last quarter, GDP has a statistical drag of 4.1 percentage points of growth for this year. With a greater degree of immunity of the population, the rapid progress of the application of booster doses of vaccines against COVID-19, the BCRA expects that the services that are still lagging behind will be able to recompose the levels of pre-pandemic activity, in an environment of great adaptation of households and firms to preventive care and a greater flow of international tourism. In the same sense, the stimulus policies implemented by the National Government and the BCRA will contribute. However, the evolution of activity in the short term is conditioned by the risks associated with a less favourable international scenario, with the deterioration of the financial context and tensions in the energy market, weather conditions and the circulation of new variants of the virus at a global level.

3.1. With greater dynamism than initially expected, economic activity registered an average increase of 10.3% in 2021

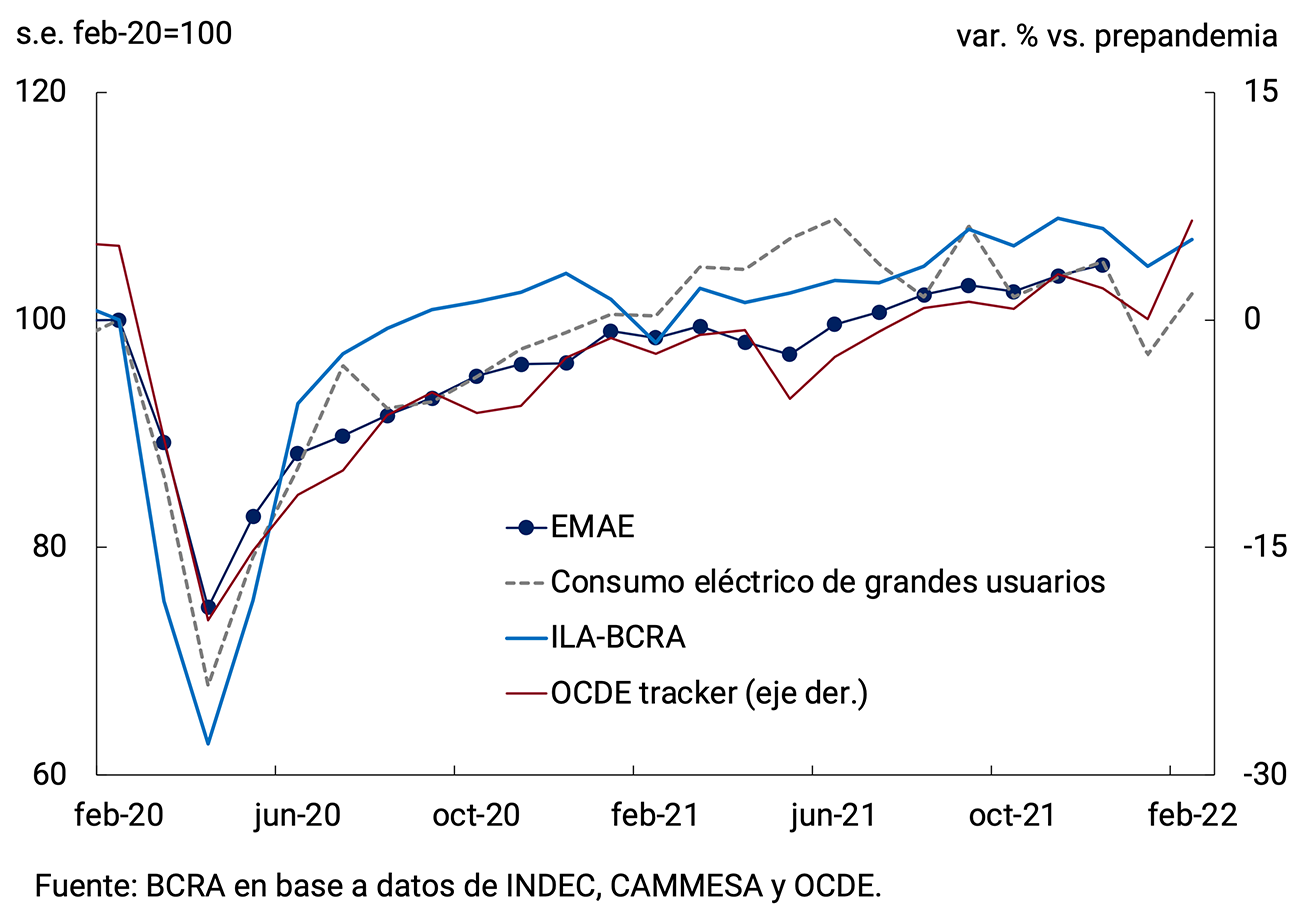

In a context of high social mobility with the gradual recomposition of sectoral activity, the seasonally adjusted Monthly Estimator of Economic Activity (EMAE) (s.e.) registered a 1.7% quarterly increase s.e. in the fourth quarter and a year-on-year variation (y.o.y.) of 10.3% on average for 2021.

The data available for January and February 2022 show heterogeneous performances. In January 2022, industrial production registered a monthly drop of 5.5% s.e., while the quantities sold of construction inputs (measured from the Synthetic Indicator of Construction Activity (ISAC)) fell by 3.9% s.e. in a context of abundant rainfall. The normalized and seasonally adjusted electricity consumption of CAMMESA’s large users fell in January and partially recovered in February, as did the OECD indicator based on Google searches and the ILA-BCRA4, after two consecutive months of declines (see Figure 3.1). All this shows that the impact of the resurgence of COVID-19 infections on economic activity was transitory, with a large number of companies that had difficulties operating normally due to the high absenteeism of their staff and some power cuts due to the record temperatures recorded in mid-January. On the other hand, during the month of January, some financial tensions were evident that moderated after the agreement in principle with the IMF staff was announced at the end of the month.

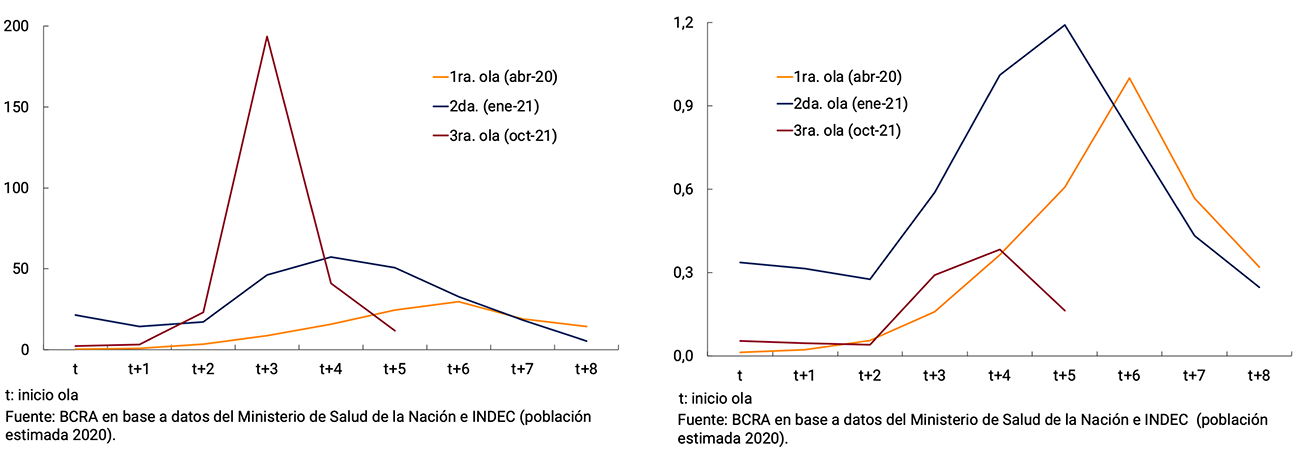

The exponential increase in COVID-19 infections at the end of 2021 and the beginning of this year — when the number of cases more than doubled last May’s peak with a strong prevalence of the strain called Omicron — revived uncertainty about the economic impact that this third wave of the pandemic could cause. Statistics from the Ministry of Health show that vaccination has been very effective in mitigating the severity of the disease in the face of the development of new variants of the coronavirus and, in line with international experience, the number of infections showed a rapid decline (see Chapter 2. International Context). The wide vaccination coverage with complete schedules of the total population and the highest risk with a booster dose5, resulted in a lower rate of hospitalization and deaths compared to previous peaks of infections (April 2020 and early 2021; see Figure 3.2). According to local health authorities, unprotected (unvaccinated) people, those who had only one dose and people at higher risk due to comorbidities, have accounted for a significant proportion of the most recent hospitalizations for COVID-19.

3.1.1. Private consumption would have recovered significantly towards the end of 2021

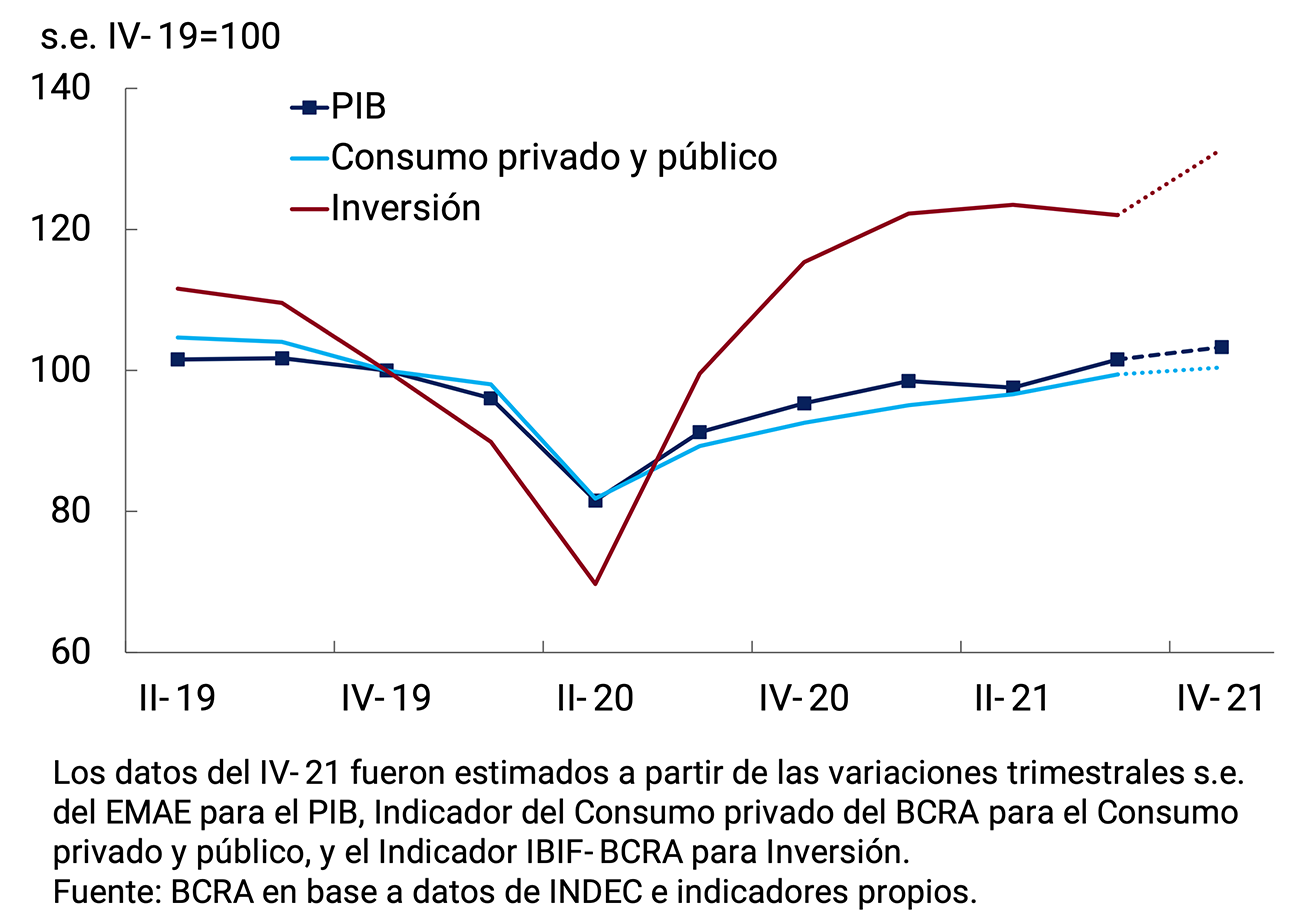

In the third quarter of 2021, GDP increased 4.1% quarter-on-quarter (11.9% y.o.y.) and was 1.6% s.e. above its level in the last quarter of 2019. Domestic demand – total domestic expenditure on consumption and investment – exceeded its pre-pandemic level by 3.1% s.e. and recovered 2.1% quarter-on-quarter s.e. basically due to the performance of consumption: private consumption recovered 2.8% quarter-on-quarter (12.1% y.o.y.) and public consumption increased 3.4% s.e. (11.5% y.o.y.). Investment6 was the only component of aggregate demand that contracted in relation to the previous quarter (-1.2% s.e.; 21.2% y.o.y.). External demand for goods and services increased 7.3% qoq s.e. (18.8% y.o.y.) and imports, 1.7% qoq s.e. (26.2% y.o.y.)7. The EMAE data for the fourth quarter anticipate a new rise in GDP, with increases in both consumption and investment.

For the fourth quarter, the BCRA Private Consumption Indicator8 anticipates a new recovery (see Figure 3.3). The rise in private consumption is explained by the evolution of the mass of household income. This includes improvements in employment levels, both formal and informal, in a context of progressive normalization of service activities, mainly those associated with tourism and leisure.

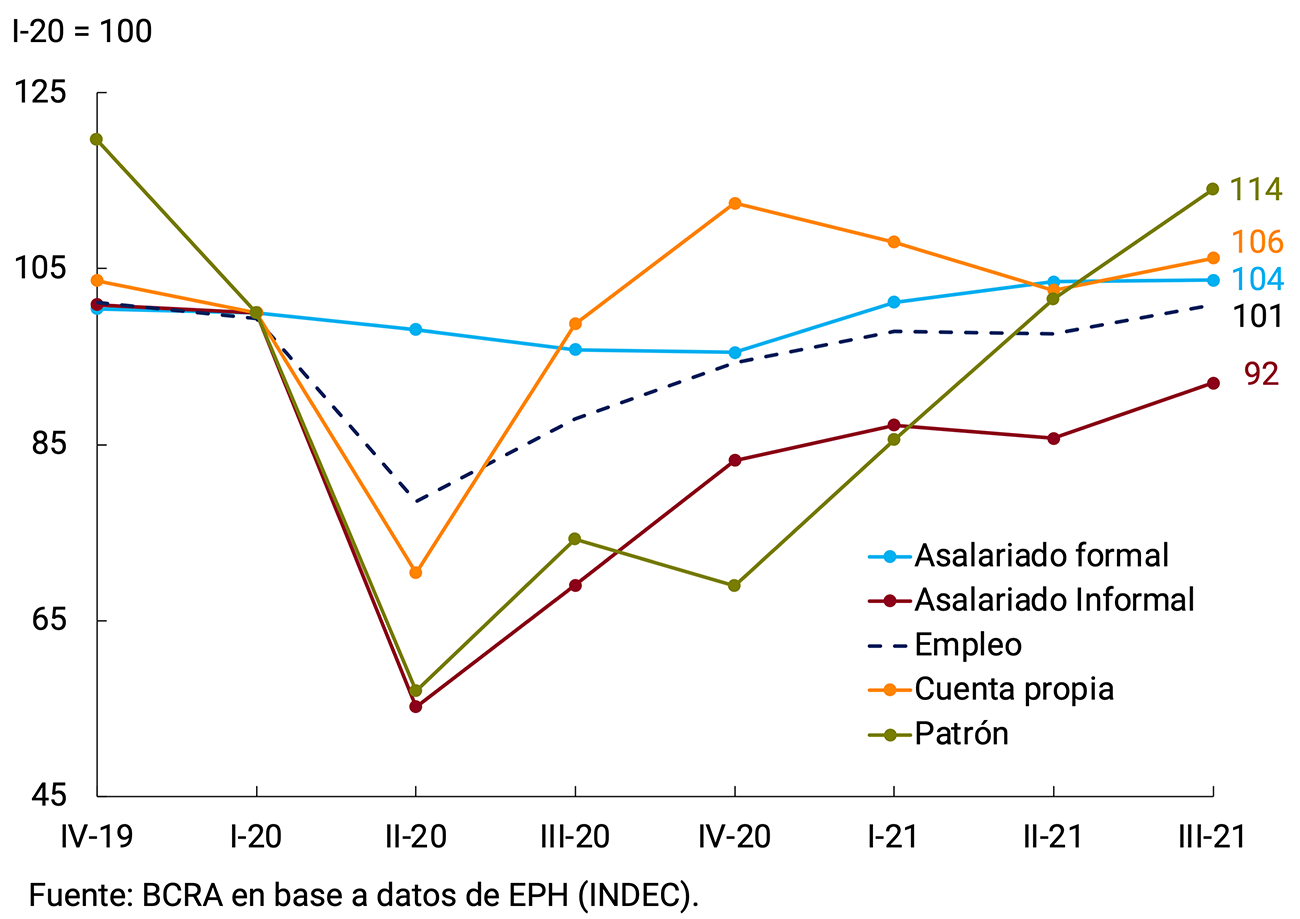

It should be noted that one of the characteristic features of the COVID-19 crisis in Argentina was the asymmetric recovery of activity in relation to quality jobs (formal and full-time), with greater job insecurity observed in relation to the pre-pandemic (see point 3.1.3 on the Labor Market). This slow recovery in registered private salaried employment mainly affected the population as a whole in the lower-income strata – with less qualified jobs – whose propensity to consume is relatively higher than the average. Labour-intensive sectors, such as services, were severely affected in 2020 and were unable to fully recover in 2021, with still high uncertainty regarding the end of the pandemic that slows down staff hiring decisions.

For its part, the IBIF-BCRA9 indicator recovered significantly and showed a quarterly improvement of 7.7% s.e. in the fourth quarter of 2021. This increase was due to an increase in investment in durable equipment of both imported and national origin and, to a lesser extent, in construction.

With respect to the external sector and in line with the information referring to the Commercial Exchange of Goods of INDEC, in the fourth quarter the contribution of net exports of goods and services to the quarterly variation of the Product would have been negative. Exported quantities of goods registered a quarterly fall (-9% s.e.), while imported volumes of goods increased 9.7% in seasonally adjusted terms (see Chapter 4. External Sector).

3.1.2. Among the productive sectors, services were the ones with the greatest contribution to the recovery in 2021

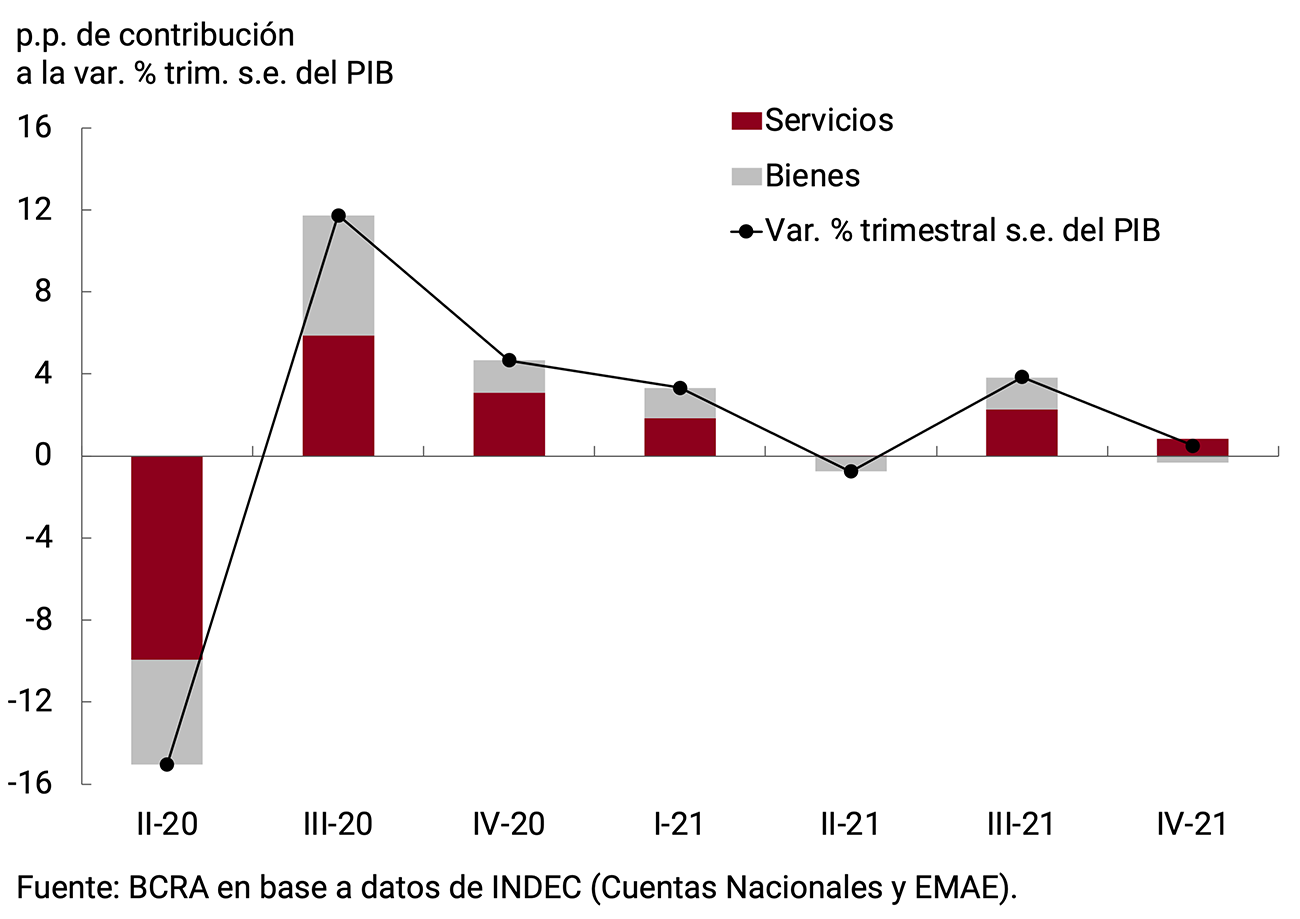

In line with what was anticipated in the previous IPOM, during the third quarter of 2021 services were the ones with the greatest contribution to the quarterly variation of GDP of 4.1% s.e., with which it was possible to recompose the level of economic activity observed before the outbreak of the pandemic in the country (see Figure 3.4). Among the services, those whose activity is closely linked to the increase in social mobility stand out, such as Commerce and Other social and community services, an area in which social, cultural, sports, personal and recreational activities are counted. In the fourth quarter, EMAE data indicate that services once again contributed to the growth of activity, highlighting the recovery of Transport.

The control of the health situation made it possible to implement new flexibilizations and measures to promote tourism in the last quarter of 2021, with the authorizations of group trips for tourism purposes, the opening of borders and foreign tourism without quota and the elimination of capacity for recreational activities and social events, among others. These measures were reflected in the first available indicators of tourist activity10 , anticipating a strong dynamism during the rest of the summer season.

This performance is expected to be reflected in the EMAE for the coming months, mainly in the activity of the group of services with “Most risk of contagion” – made up of Hotels and restaurants, Transport and communications and Other community services – which continued to lag behind the rest of the sectors that make up the EMAE. In December, the value added by this set of services – which account for 13% of GDP – was still 9% s.e. below its pre-pandemic level. Once these most affected sectors manage to fully recover from the COVID-19 crisis, they will have contributed more than 1 percentage point to the variation in Output (see Figure 3.5).

In the average of 2021, the EMAE recovered 10.3% compared to a year ago, with a very heterogeneous performance in terms of the dynamism of the productive sectors. Services were the ones with the greatest contribution to the annual recovery of the Product at basic prices (5.6 percentage points), with Trade standing out, which increased by an average of 13% and contributed 2 p.p., and Services most affected by the pandemic – led by Other Community Services – which contributed 1.6 p.p., recovering by 12.9% as a whole. Among the goods-producing sectors, Construction and Industry were the most dynamic, increasing 27.5% YoY and 15.7% YoY in that period, respectively, and jointly contributing 4.2 p.p. to the economic recovery of 2021 (see Figure 3.6)11.

3.1.3. The labour market, in line with economic activity, regained dynamism at the end of 2021

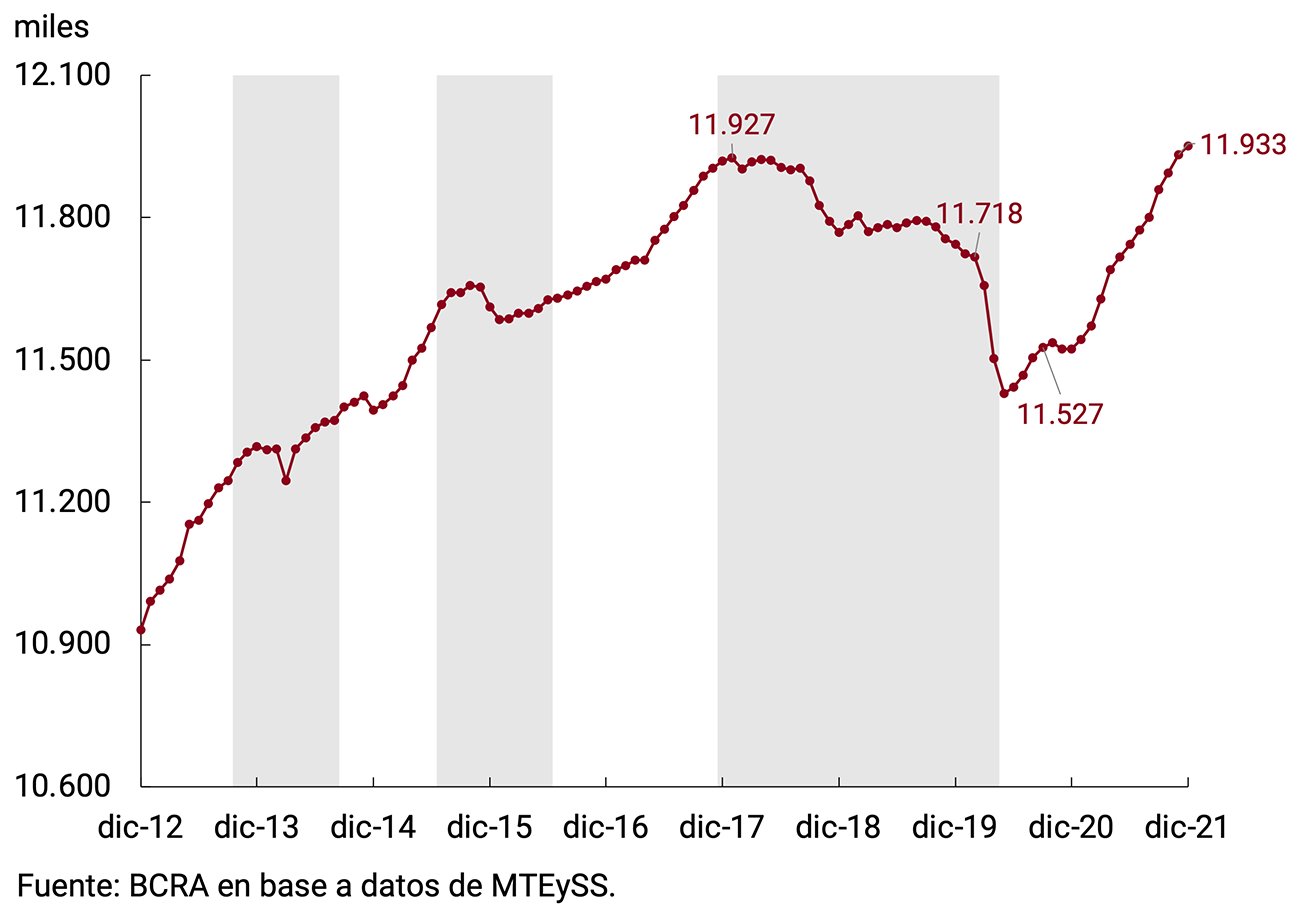

With data as of December 2021, according to the Ministry of Labor, Employment and Social Security (MTEySS), registered employment reached historic high levels of employment in seasonally adjusted terms, surpassing the previous maximum of January 2018 (see Figure 3.7). The pace of expansion during the fourth quarter maintained the dynamics evidenced since the beginning of 2021, growing at 0.3% per month on average.

Since June 2020, the recovery of total registered employment has been driven by a positive dynamic of self-employment and registered salaried workers in both the private and public sectors. In the months of September to December 2021, an increase in registered self-employment (1.6% s.e.), public employment (1.3% s.e.) and private salaried employment (1.3% s.e.) was observed. It should be noted that the latter category of employment had a pronounced acceleration (+0.3% in the period vs. +0.1% in the previous period), which allowed it to exceed pre-pandemic levels (see Figure 3.8).

The behavior of private salaried employment between September and December 2021 allows us to distinguish at the sectoral level a strong dynamism in branches such as Hotels and restaurants (6.7% s.e.), Construction (3.8% s.e.) and Mining (1.8% s.e.). However, taking into account pre-pandemic levels, the Hotels and Restaurants sector, as well as Community, Social and Personal Services and Transport, still have potential for recovery both in terms of activity and hiring (see Figure 3.9). On the other hand, it is observed that in the sectors that experienced the greatest recovery in activity, Trade and Construction, the growth of registered salaried employment has occurred in a lower proportion, moving away from the 45° line.

The Survey of Labor Indicators (EIL) as of January 2022 ratified the positive trend in net hiring expectations that began in February 2021, chaining 12 consecutive months of positive values. On the other hand, suspensions continued to reduce, reaching levels within the historical average and the rate of layoffs remains in a limited range.

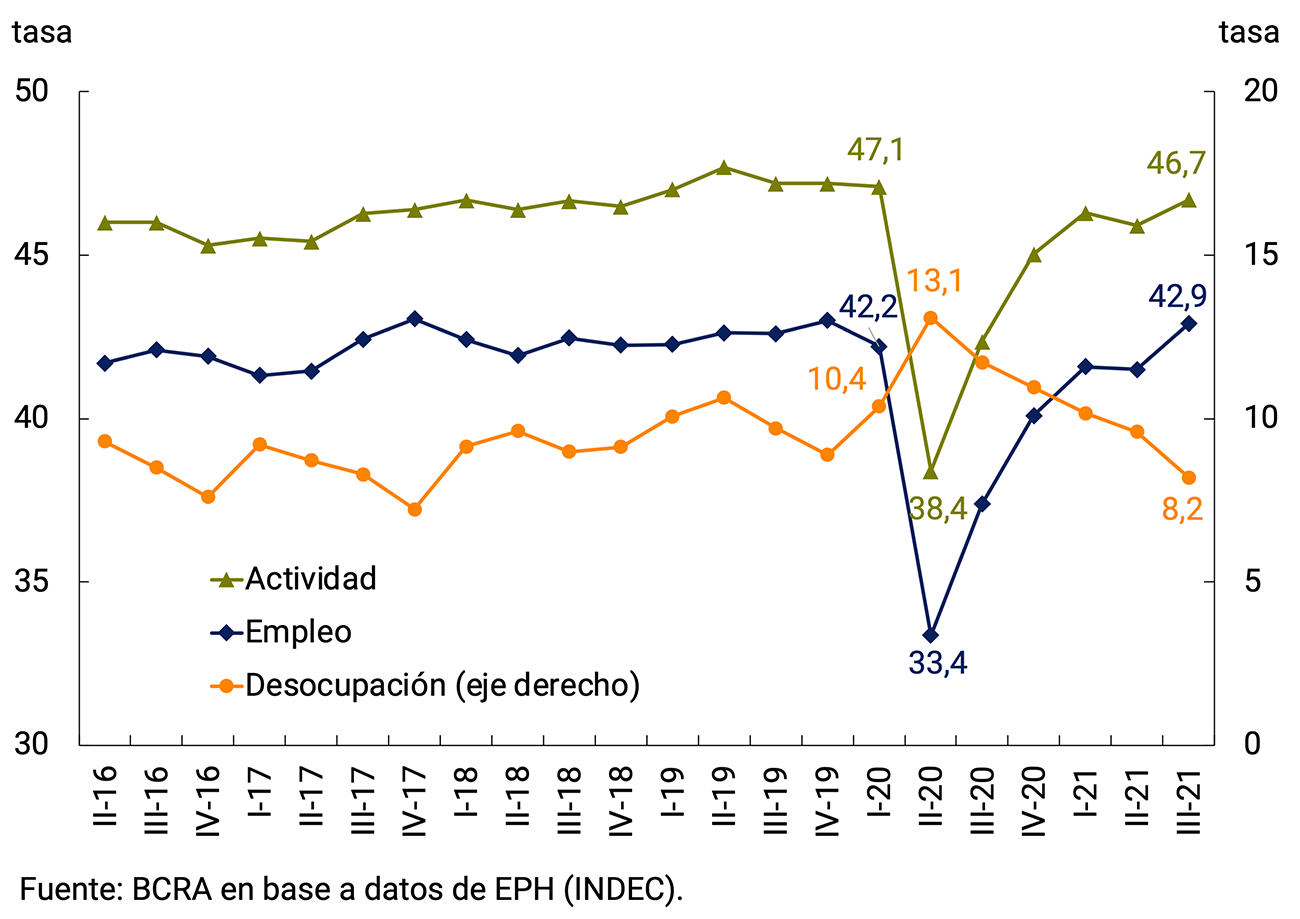

According to data from the Permanent Household Survey (EPH), in the third quarter of 2021 employment resumed its growth, registering a year-on-year increase of 5.5 p.p. in line with the improvement in economic activity. PEA12 also showed an increase compared to the previous quarter and stood at 46.7% (+4.4 p.p. y.o.y.). This effect was probably associated with the normalization of economic activities in the face of the easing of restrictions related to the second wave of the pandemic. Thus, it was job creation that drove this increase in the EAP, generating a drop in the unemployment rate, which stood at 8.2% (-3.5 p.p. y.a.; see Figure 3.10).

With regard to the evolution of the different occupational categories, it is observed that during the third quarter of 2021 self-employment presented a slight increase compared to the previous quarter and employers maintained sustained growth since IV-20. On the other hand, informal wage earners recovered, although they remain below pre-pandemic levels. Finally, the growth of salaried workers with a retirement discount lost dynamism, but, unlike what the registration data reflects, according to the survey they are above the pre-pandemic level.

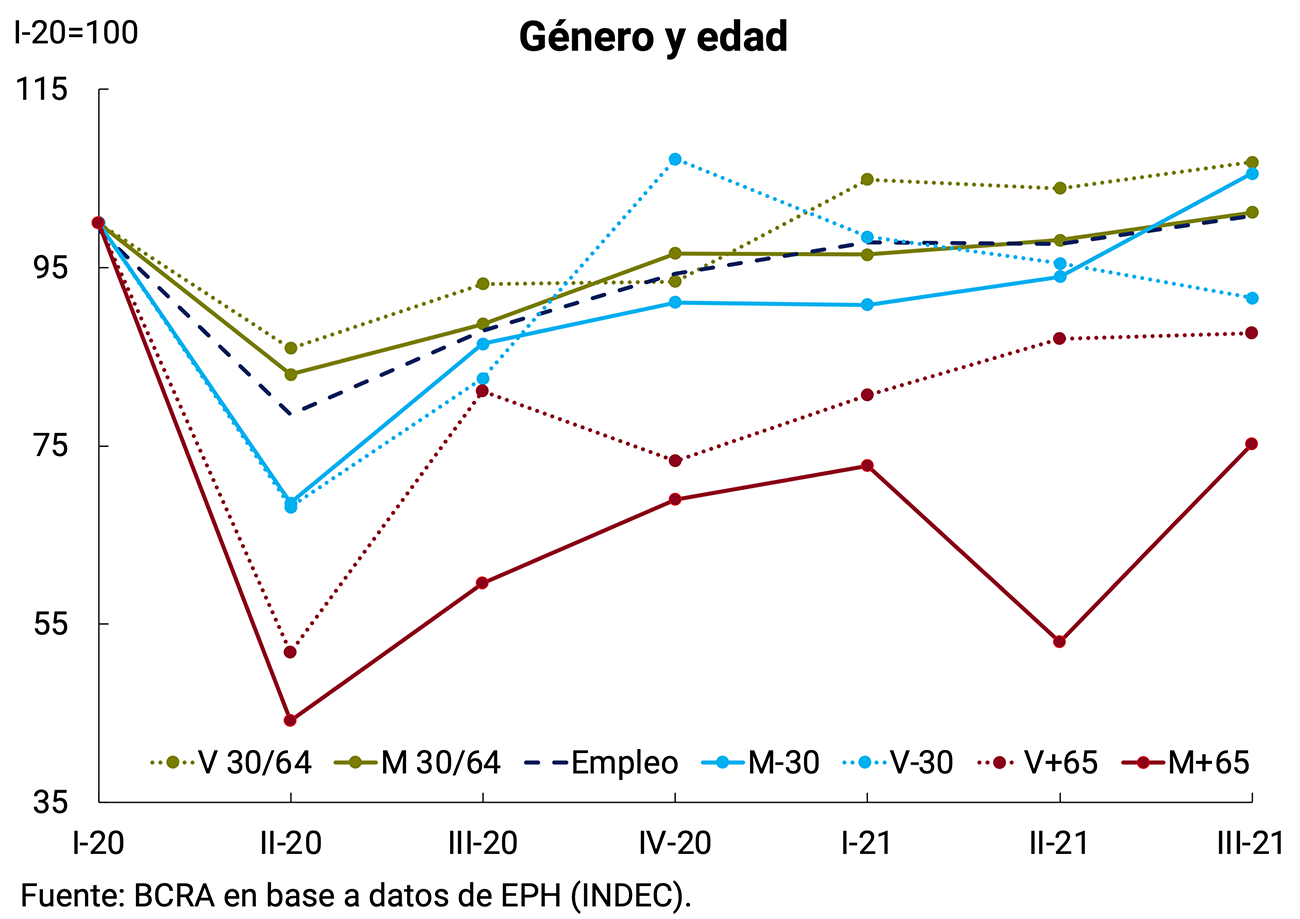

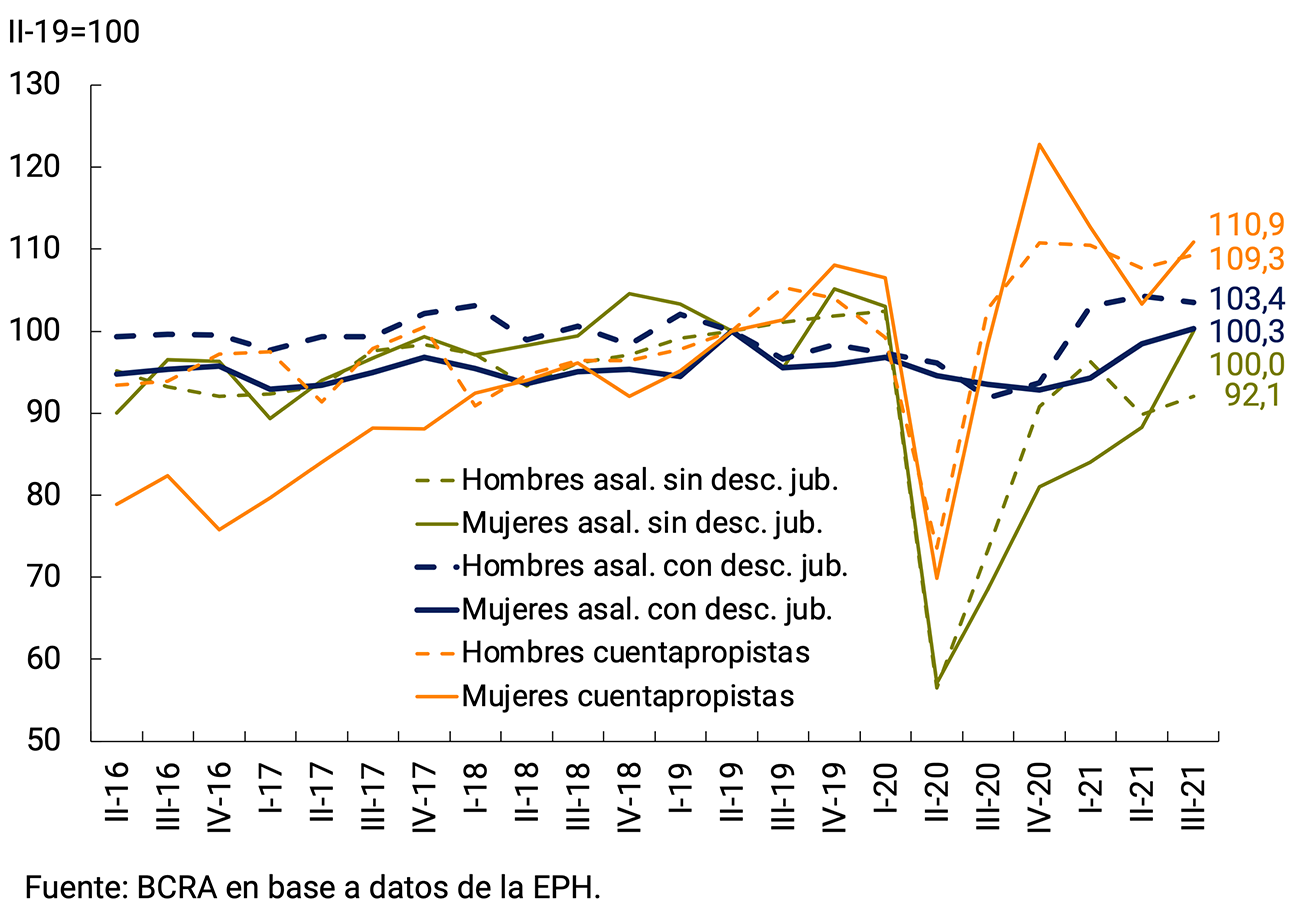

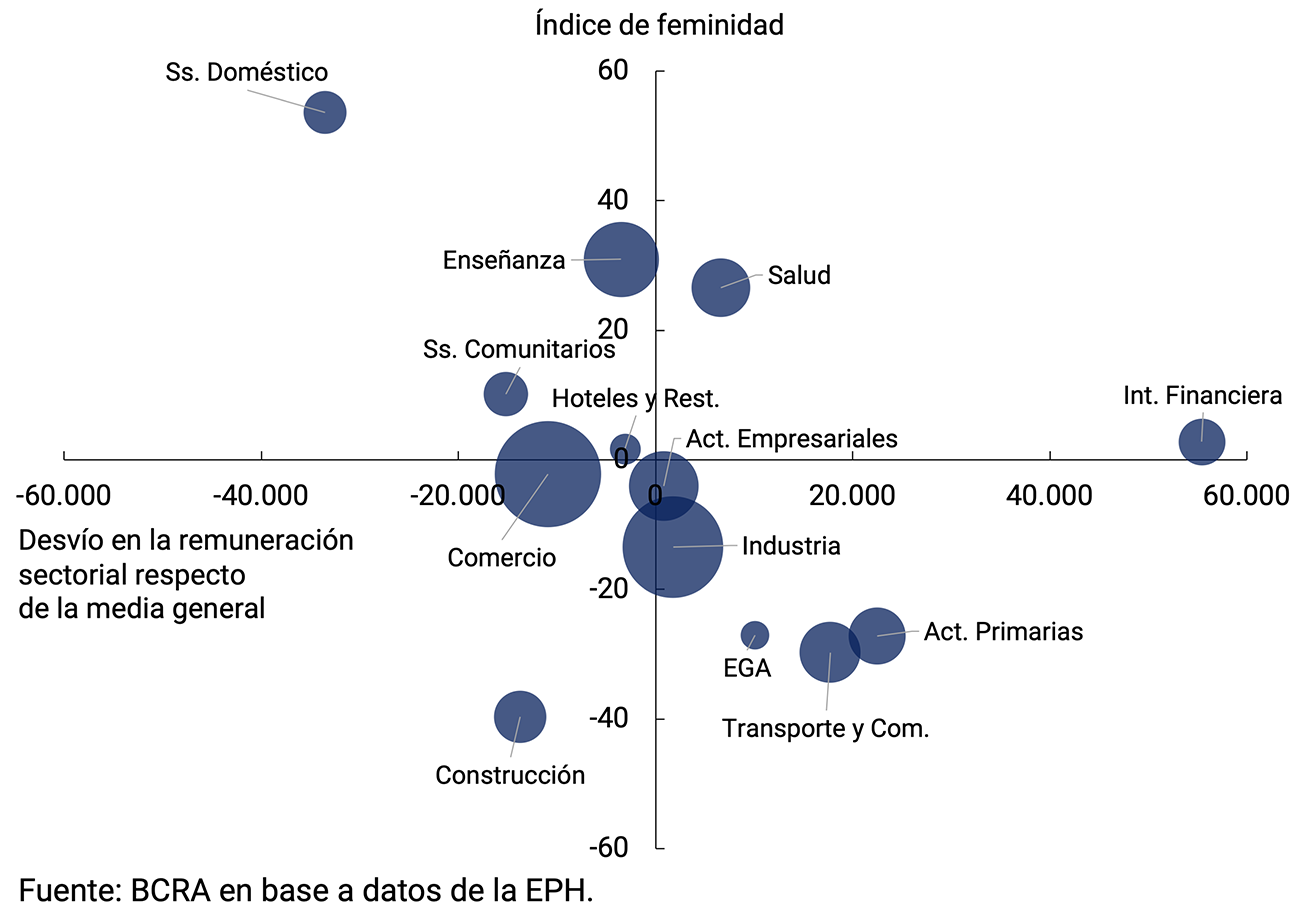

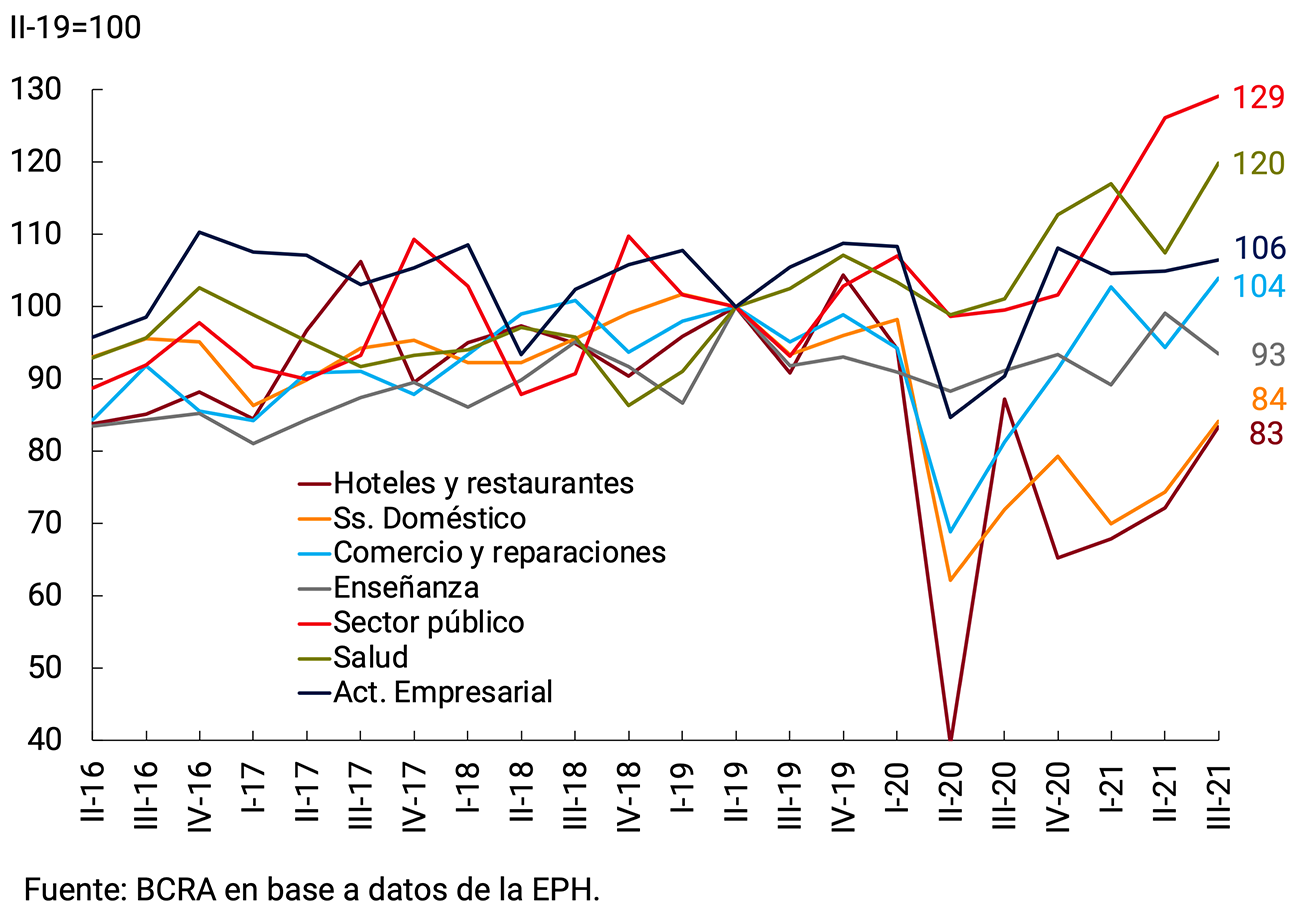

By age range and gender, it is worth highlighting the dynamics of employment among women under 30 years of age (see Figure 3.11 and Section 2 / Asynchronicities in the Labour Market) and women over 65 years of age. Both groups, which for different reasons had a moderate recovery after the initial impact of the pandemic, showed a strong increase in the third quarter of 2021.

3.2. Perspectives

In a context of progress in the application of vaccine boosters13 together with the progressive immunization of the lowest age ranges and in an environment of strong adaptation of the economy to operate in a pandemic, the BCRA expects that in the coming months activity will continue to strengthen the process of growth and economic recovery. The broad vaccination coverage achieved at the beginning of 2022 with complete schemes of the total population and the population at highest risk with a booster dose made it possible to transit, at the beginning of this year, a significant third wave of COVID-19 associated with the Omicron variant – more transmissible, although less lethal – with limited and transitory effects on the level of activity.

The BCRA expects an additional recovery of the sectors that have not yet managed to operate at pre-pandemic levels, through the extension of the targeted stimulus policies implemented by the National Government14 and the BCRA, and the continuity of the growth process of the rest of the sectors within the framework of policies aimed at the recovery of the domestic market and the productive transformation necessary for sustainable and inclusive growth.

This base scenario is not without risks. Among the main threats to the consolidation of the recovery in activity are the recent deterioration of the international financial context in the face of the sharp escalation of the war between Russia and Ukraine (see Chapter 2. International Context), the tensions in the international energy market and the lack of moisture in the soils in a large part of the productive areas of our country and its potential impact on the yields of the coarse harvest. In addition, there is still uncertainty associated with the circulation of new variants of the Coronavirus that could emerge and compromise the efficacy of the vaccines, truncating the health advances achieved so far.

The outlook for global growth contemplates a slowdown in the coming months, associated with the reduction of monetary stimuli by advanced economies in the face of high and more persistent levels of inflation, in addition to the continuity and deepening of bottlenecks in some supply chains due to geopolitical conflicts. This scenario poses a slowdown in global growth, including for our main trading partners, and higher external financing costs for emerging countries, with international commodity prices at historically high levels.

Argentina’s economic activity closed 2021 with an average recovery of 10.3% per year. The seasonally adjusted data from the EMAE for December left a statistical drag of 4.1 p.p. for this year’s average. The market outlook is below this level: according to the estimates of the Market Expectations Survey (REM) at the end of February 2022, specialized analysts expect a growth of 3.0% for economic activity during this year. The economic growth forecast contemplated in the agreement with the IMF contemplates a growth in economic activity between 3.5 and 4.5% for 2022.

In the medium term, the fulfillment of the goals set out in the agreement with the IMF, consistent with the ongoing economic growth process, together with a gradual but permanent reduction in inflation and an increase in exports and international reserves, will strengthen macroeconomic stability and improve the perception of risk of public debt and the economic expectations of domestic and external agents. This will contribute to the gradual recovery of access to external financing for both the public and private sectors.

4. External Sector

In the fourth quarter of 2021, the trade surplus of goods was reduced, both due to an increase in imported volumes (mainly fuels, capital goods and their parts) and a widespread fall in the quantities exported. In this context, the seasonally adjusted current account is expected to have shown a slight transitory deficit. In 2021, the annual trade surplus was around 1.2% of GDP.

In the foreign exchange market, the evolution of exports and imports of goods, added to the dynamics of commercial debt for exports and imports of goods, resulted in a net result in the exchange market for goods of US$2,318 million in the last quarter of 2021, remaining practically stable compared to the previous quarter. Additionally, net outflows were recorded through the foreign exchange market for services, interest and other financial transactions for US$4,028 million, while entities made sales for US$426 million. For its part, the BCRA made sales through the Local Currency System (SML) for US$227 million and directly in the foreign exchange market for US$1,057 million.

These net sales by the BCRA, together with the net outflows of financial debt from the general government and the BCRA for about US$900 million, brought the level of international reserves to US$39,663 million at the end of the year, slightly above its value at the end of 2020.

In the first month of 2022, customers made purchases in the foreign exchange market for US$289 million, while the BCRA and the entities sold US$161 and US$77 million, respectively.

For the year 2022, the economy is expected to register a trade surplus in goods for the fourth consecutive year, in a context of stability of the real exchange rate within the framework of a managed floating exchange rate policy. Total agricultural production, the economic activity of our trading partners and the evolution of the international price of fuels (in particular liquefied petroleum gas) will define the slack of the trade surplus, while the agreement reached with the IMF for the rescheduling of the maturities inherited from the Stand-by agreement signed in 2018 will have a positive impact on the dynamics of financial flows. The BCRA will prudently manage foreign exchange regulations in order to adapt them to the needs of the situation, favoring monetary and exchange rate stability.

4.1. In the fourth quarter of 2021, the economy would have operated with a transitory current account deficit

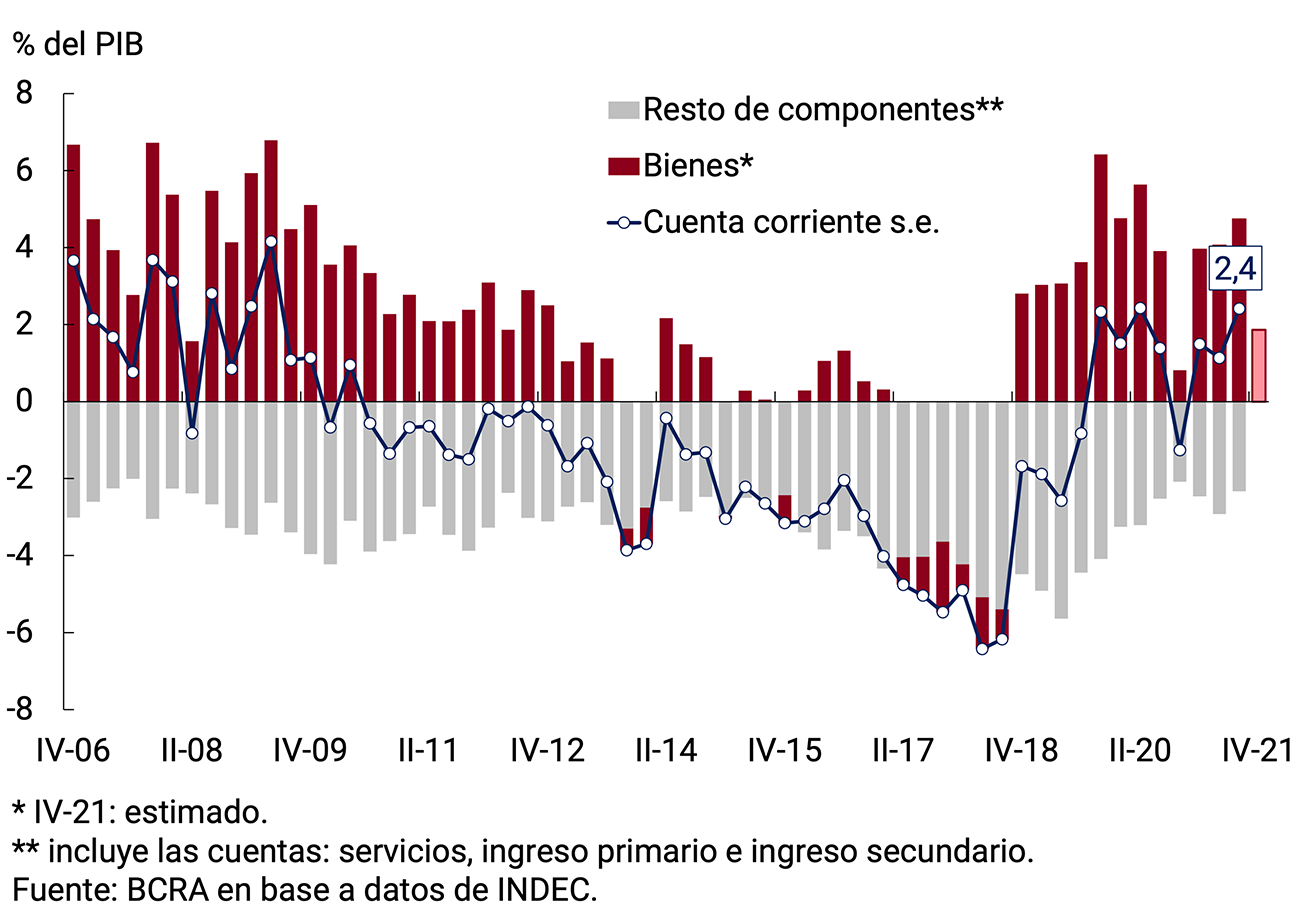

In the third quarter of 2021 (latest official data available) the Argentine economy recorded a current account surplus of US$3,287 million – equivalent to 2.4% of GDP in seasonally adjusted and annualized terms. The sharp increase in exported volumes of goods was the main factor behind this result.

In the fourth quarter of 2021, the trade surplus for goods was reduced, both due to an increase in imported volumes and a fall in exported quantities. In this context, the seasonally adjusted current account is expected to exhibit a slight transitory deficit (see Figure 4.1).

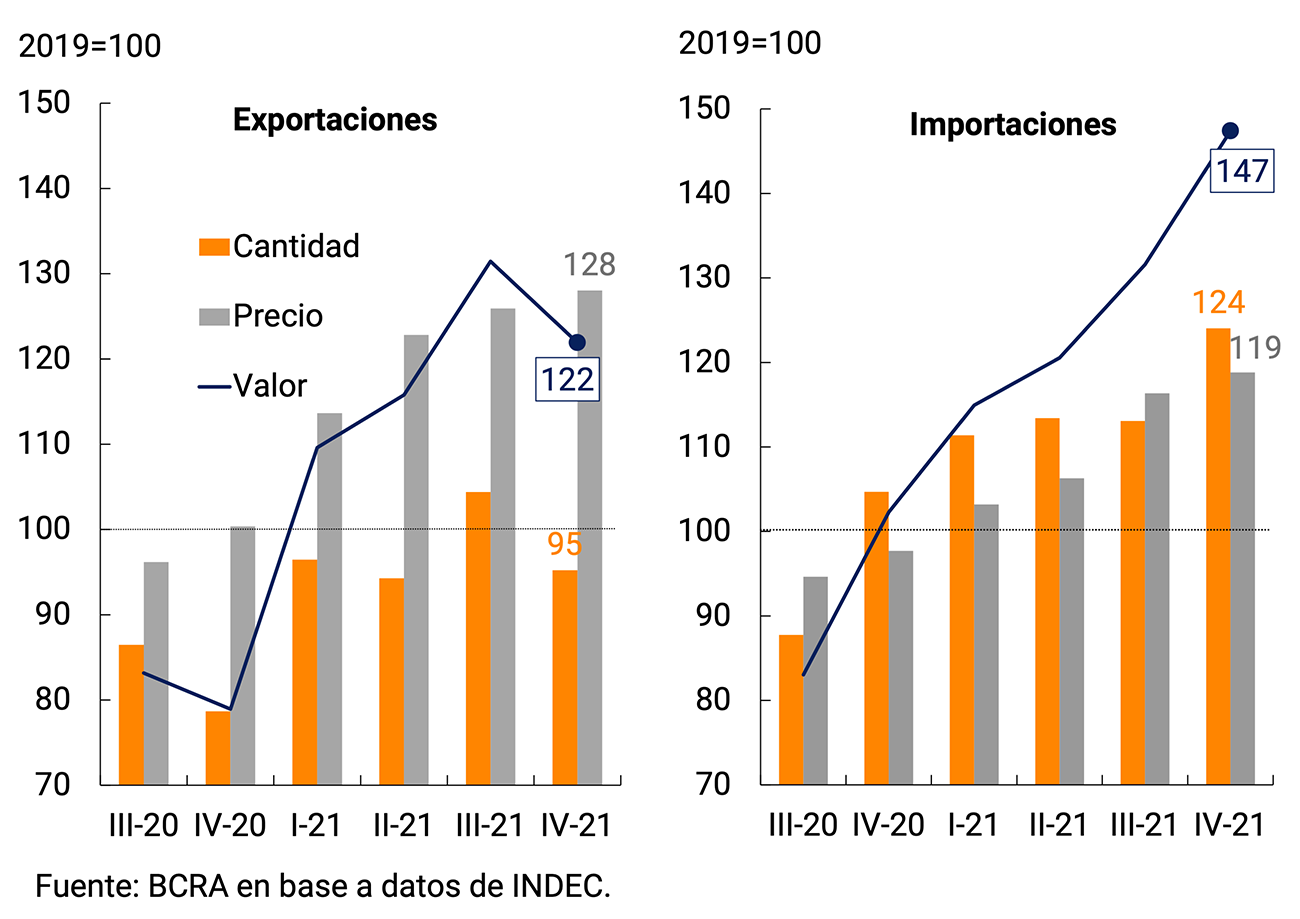

In that period, the exported values of seasonally adjusted goods reached US$19,846 million (Free on Board —FOB—) at current prices, which represented a drop of 7.2% compared to the high level recorded in the third quarter of 2021. This evolution was mainly due to the performance of the quantities exported, which decreased 9% quarter-on-quarter s.e. and fell back to the levels of the first half of 2021. Export prices grew for the sixth consecutive quarter and partially mitigated the effect of quantities.

On the other hand, between October and December 2021, seasonally adjusted imports of goods totaled US$18,108 million (CIF) at current prices, almost 50% above the 2019 average, close to the levels of the first quarter of 2018. This performance of imported values was explained to a greater extent by the rise in volumes, which grew 10% quarter. s.e. (see Figure 4.2).

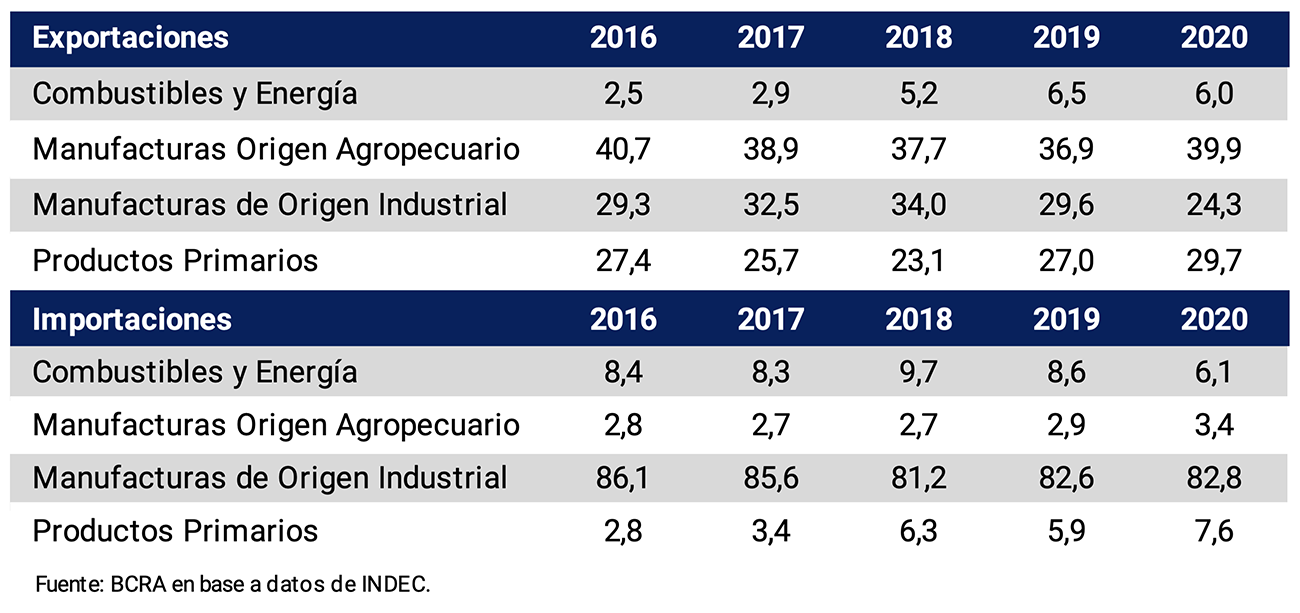

The four main export items had falls in exported volumes in the last quarter of 2021. In the case of Primary Products (PP, -9% qq. s.e.), although the decrease was widespread, the lower shipments of oilseeds and fishery products stood out for their incidence. The fall in Manufactures of Agricultural Origin (MOA, -5% qq. s,e,) was concentrated in three of its main categories: meat, fats and oils and residues from the food industry21. The exported quantities of Manufactures of Agricultural Origin (MOI) also decreased, although with mixed behaviors within the category. Shipments of land transport material continued with the upward trend they have exhibited since the third quarter of 2020 and reached levels not recorded since the end of 2018, mainly due to vehicle exports to Brazil. The performance of foreign sales of precious metals22 also contributed positively, gradually approaching pre-pandemic levels. On the contrary, decreases were recorded in the other two categories with the highest incidence of the item, chemical products and base metals. Finally, the exported volumes of Fuels and Energy (S) fell 34% s.e. compared to the third quarter of 2021, mainly due to the high base of comparison left by electricity shipments to Brazil in that period (see Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3 | Quantities exported. Seasonally

adjusted series Mobile Avg. 3 months

Source: BCRA based on INDEC data.

In the case of imported quantities of goods at the functional category level, increases predominated in the fourth quarter (12 increases and 7 falls). Notable for their impact were the increases in the imported volumes of processed fuels (+69% QoQ), final capital goods (+11% QoQ), parts and accessories for capital goods (+14% QoQ) and parts and accessories for transport equipment (+11% QoQ). Together, these four categories accounted for more than 90% of the increase in the overall level.

In January 2022, the seasonally adjusted trade surplus rose compared to December due to the fact that imported values fell at a higher rate than exports (-13% monthly and -1% monthly respectively). Declines were associated with widespread falls in traded volumes, with a sharp decrease in MOAs in exports and, in the case of imports, a decline in fuels (which had shown great dynamism in the last quarter of 2021).

Box. Rising freight transportation cost and import prices

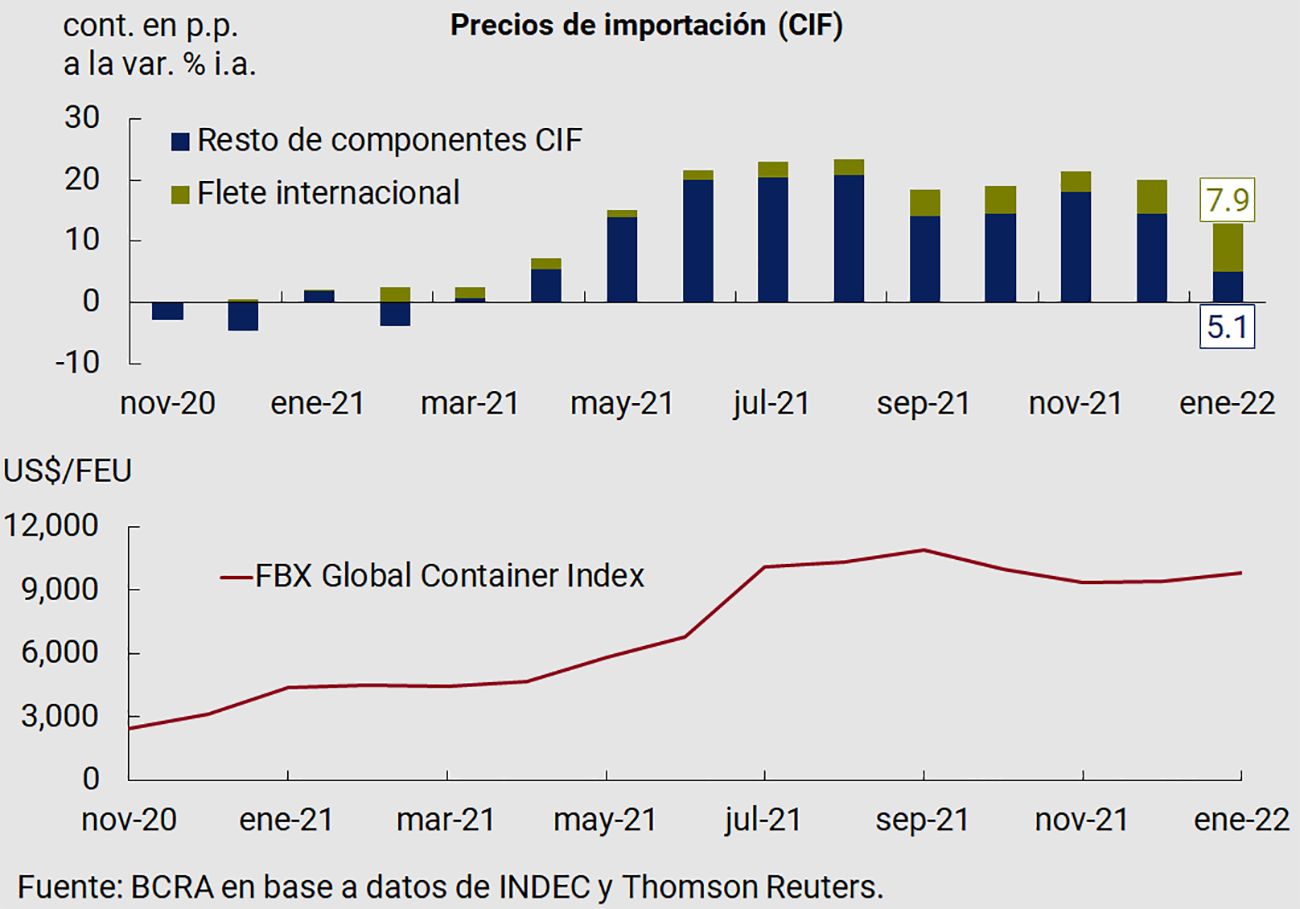

In the November 2021 IPOM, it had been commented that the rise in global manufacturing prices measured in dollars was behind the sharp increase in Argentina’s import prices since the beginning of 2021. Another factor that influenced this performance was the increase in the cost of cargo transport worldwide.

In the statement of Argentine Commercial Exchange prepared monthly by INDEC, data on imports of goods are reported at CIF (cost, freight and insurance) valuation. This means that the unit price reported for each imported good includes not only the “factory departure” price at origin, the costs of hauling, handling and shipping to the port of departure, but also the cost of international freight and insurance to the final destination port in Argentina. For this reason, the import price index (which represents the rolling basket of imported goods) is necessarily affected by the evolution of the cost of international freight.

From the second half of 2020, with the recovery of world trade, but, above all, during 2021, the logistics of international trade in goods at a global level was crossed by the existence of bottlenecks that notoriously limited cargo capacity. This transitory inability of the supply of logistics services to meet demand was reflected in a sharp increase in the cost of international freight, which more than quintupled in nominal terms in July 2021 compared to July 2020, as measured by the global benchmark index for containerized transport. the Freightos Baltic Index (FBX). This situation was reflected in Argentina’s foreign trade statistics as a widening gap between imports valued in CIF terms and those valued in terms (FOB23), which reached 7.8% in December 2021, when for almost the entire previous decade it was around 4.5%. According to a recent study prepared and published by INDEC24 , the incidence of freight costs on the import price index was increasing throughout 2021 and so far in 2022. In January 2022, more than half of the year-on-year increase in import prices in dollar terms was due exclusively to the direct impact of freight transport costs25 (see Figure 4.4).

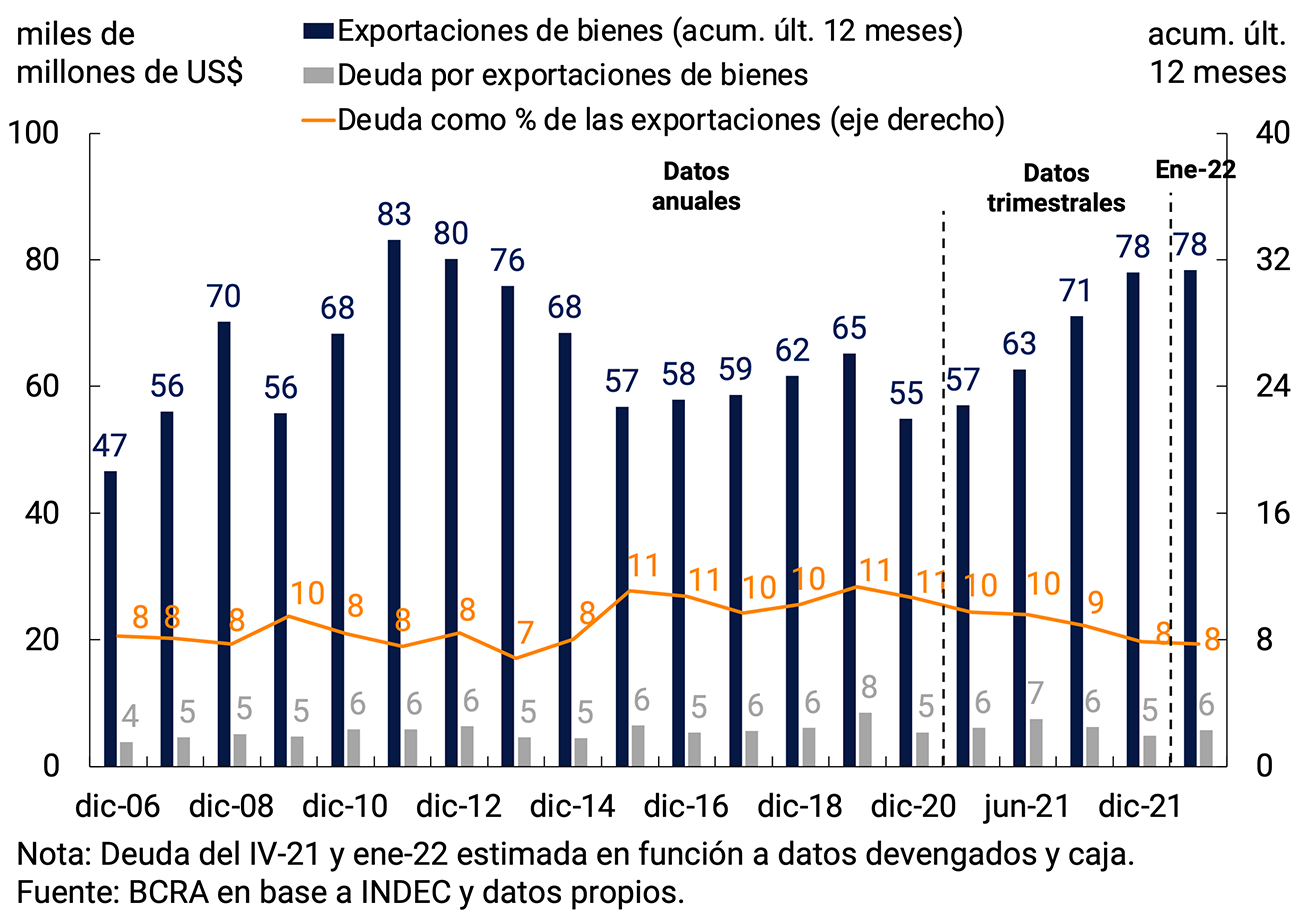

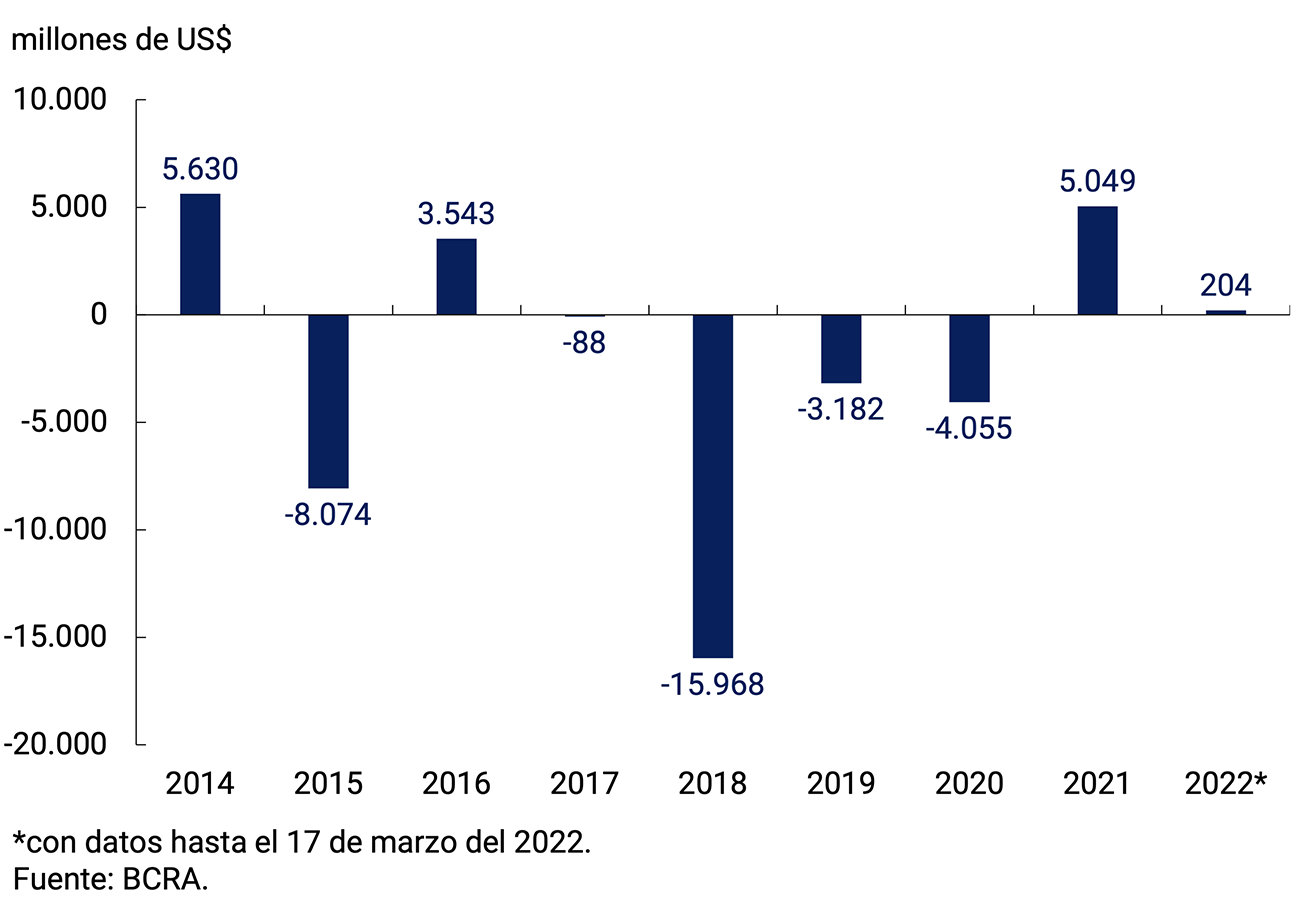

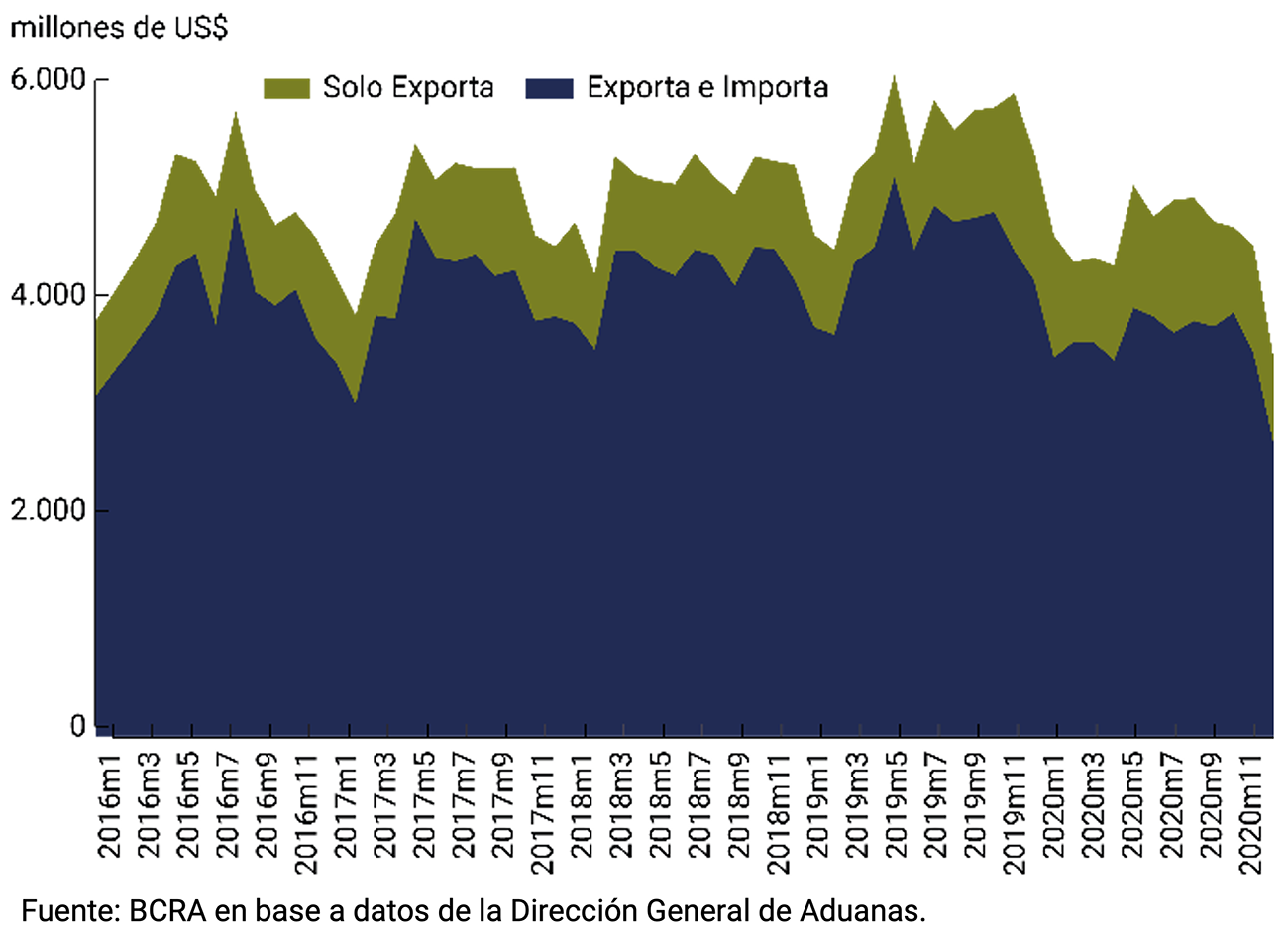

4.2. In 2021, the BCRA recorded the largest net purchases of foreign currency in the foreign exchange market since 2014

During the fourth quarter of 2021, exporters recorded receipts from exports of goods of about US$18,292 million. Given that exports of goods stood at about US$19,641 million, it is estimated that the external debt will be reduced by advances and pre-financing of about US$1,350 million. In this way, the ratio of this type of indebtedness with respect to the values exported is reduced to 8%. In January 2022, the same trend of this ratio continued to be verified, with an estimated debt of advances and pre-financing of about US$5,685 million. This level of the ratio represents the lowest level verified since December 2013 (see Figure 4.5).

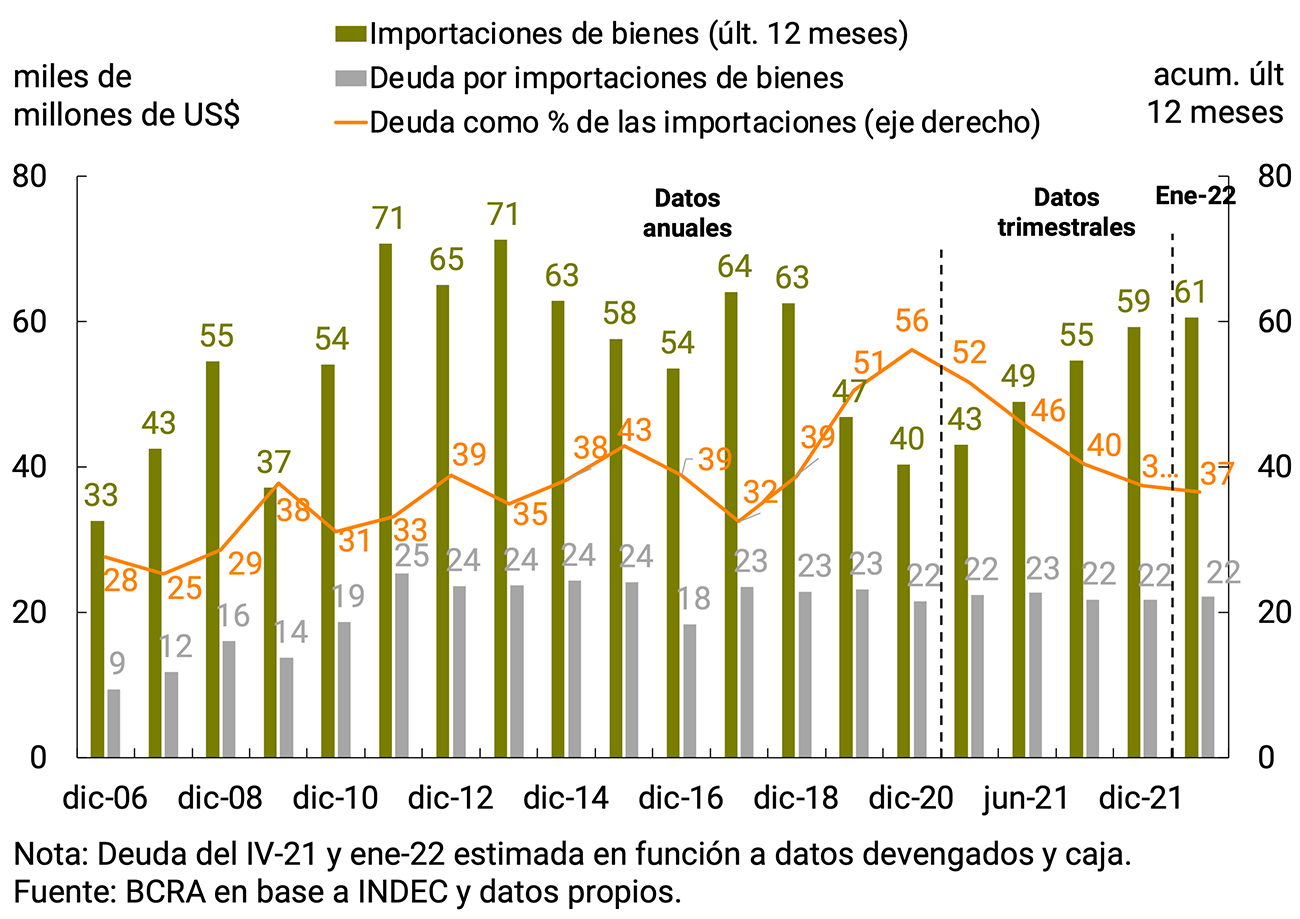

During 2020, the BCRA established a series of regulations that aim to promote the allocation of foreign currency more efficiently, with an impact on both the evolution of private commercial and financial debt. These rules were maintained throughout 2021 and remain in force for the year 202226. In this context, during the fourth quarter of 2021, payments for imports of goods through the foreign exchange market reached US$16,000 million, a value similar to that of FOB imports for the period, which would imply that the stock of foreign debt for this concept was maintained during the quarter, a trend that is estimated to continue in January 2022. In addition, due to the increase in shipments to the market in recent months, the relationship between external debt and the level of imports registered a new fall, which would imply almost 20 p.p. compared to the end of 2020 (see Chart 4.6).

Finally, with regard to financial debt, and as part of the current regulatory framework mentioned above, in September 2020, through Communication “A” 7106, the guidelines were established under which private sector companies could initiate a process of refinancing their respective external liabilities, which would allow their maturity profile to be adapted to the guidelines required for the normal functioning of the foreign exchange market. This communication, which reached certain capital maturities between 15-Jan-20 and 31-Mar-21, was extended by Communication “A” 7230, covering maturities from then until the end of 2021. Likewise, Communication “A” 7422 extended the term of the maturities until 30.06.22 and Communication “A”7466 did so until 31.12.22.

In this context, the renegotiations recorded during the fourth quarter of 2021 and January 2022 had an impact on lower net purchases in the foreign exchange market of about US$390 million compared to the original maturities for the same period, accumulating since December 2020 lower net payments of about US$2,160 million.

The aforementioned recovery of exports, added to the evolution of the commercial debt for exports and imports of goods, resulted in a net result for goods in the foreign exchange market of US$15,282 million in the year, about US$3,300 million lower than the result of the FOB trade balance for the same period, and exhibiting a strong improvement compared to the previous year (80% y.o.y.).

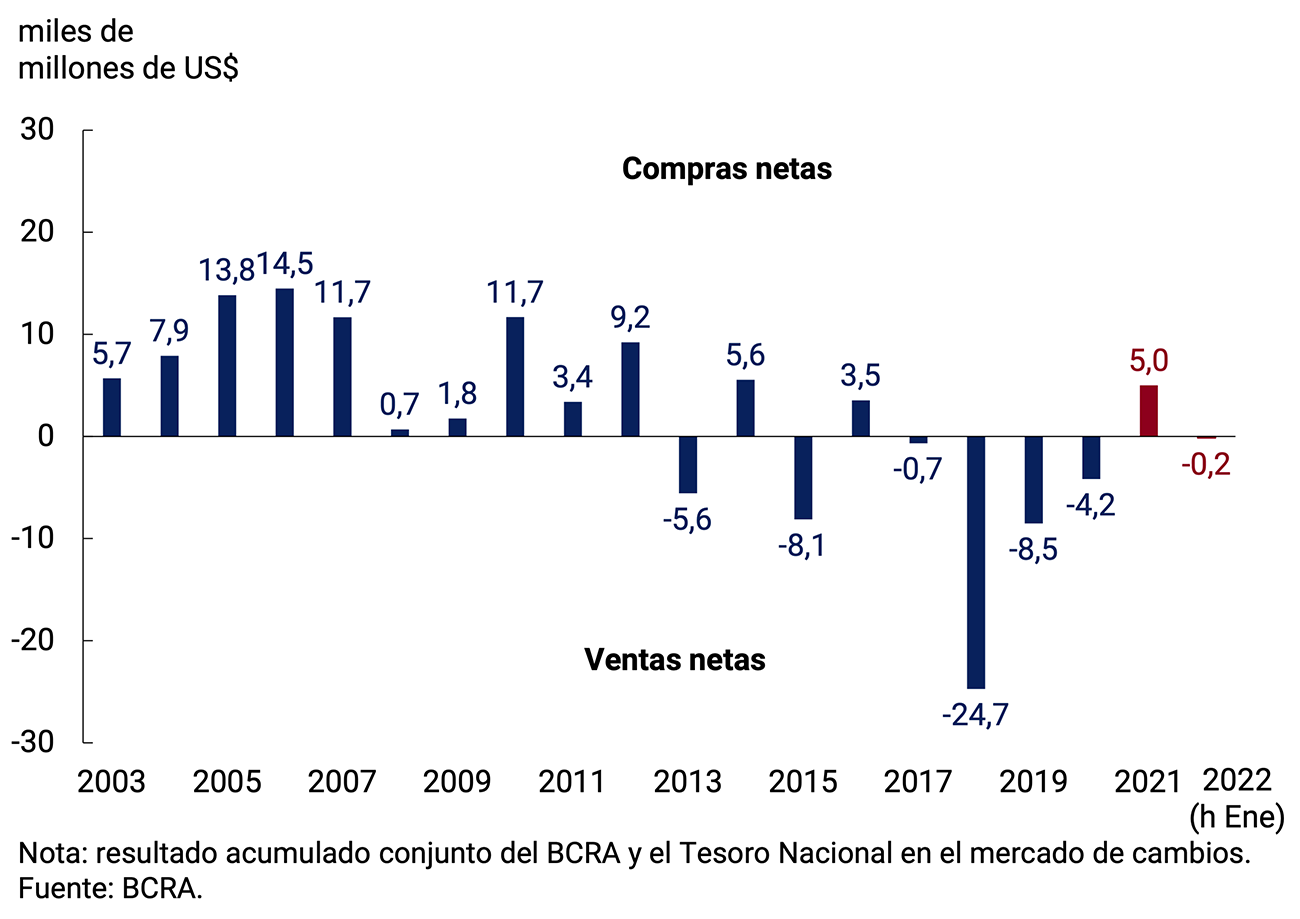

This result allowed the BCRA to accumulate net purchases in the foreign exchange market for US$5,000 million in the year, a record since 2014 (see Figure 4.7), while international reserves increased by US$275 million in the same period. This difference was mainly explained by the net cancellations of principal and interest on foreign currency debt of the National Government with a direct impact on international reserves of about US$5,500 million -of which around US$5,000 million corresponded to principal and interest payments to the International Monetary Fund-, due to the increase in payments for operations carried out through the Local Currency Systems with Brazil. Uruguay and Paraguay and ALADI for about US$800 million and for the increase in the balances held by the entities in BCRA current accounts for US$1,200 million and in the prices of the assets that make up the international reserves in relation to the currency of account (US dollar), which resulted in an increase in them by about US$400 million.

For its part, in January the BCRA made net sales in the foreign exchange market for US$161 million, in addition to the net payments through SML and ALADI for US$73 million. International Reserves decreased by US$2,074 million, mainly due to net payments of principal and interest on debt in foreign currency of the National Government for about US$1,600 million.

4.3. Perspectives

For the year 2022, the economy is expected to register a trade surplus in goods for the fourth consecutive year, in a context of stability of the real exchange rate within the framework of a managed floating exchange rate policy.

The slack in the trade balance will depend to a large extent on four factors about which there is a high level of uncertainty. First, the production of grains from the coarse harvest (soybeans and corn) on which there are forecasts of cuts compared to what was expected at the end of 2021, as a result of low rainfall in the main producing areas (see Chapter 3. Economic Activity and Employment). Second, the evolution of the economic activity of our trading partners, in particular Brazil, whose growth prospects have deteriorated since the publication of the Nov-21 IPOM and may be affected by the effects of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine (see Chapter 2. International Context). These two downside risks to exports could be offset by the recent rise in international prices of Argentina’s export commodities (see Figure 4.8). Finally, on the side of imports of goods, the main source of uncertainty is currently the import price of the fuels that the country will have to acquire during the winter, mainly liquefied natural gas, which, in the context of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, has risen significantly in recent months.

On the financial account side, the determining factor for 2022 and the years that follow will be the rescheduling of the contractual capital maturities assumed under the Stand-by Agreement signed in 2018. The agreement reached with the IMF will strengthen the external position of the Argentine economy, by providing for a significant accumulation of international reserves, which will contribute to the nominal stability of the economy. An improvement in the risk perception of external debt is expected, helping Argentina to gradually regain access to financing in international financial markets under more favorable conditions (lower interest rates and longer maturities), both for the public and private sectors.

The BCRA will prudently manage foreign exchange regulations in order to adapt them to the needs of the situation, favoring monetary and exchange rate stability. To the extent that macroeconomic conditions allow, regulations will be relaxed, with the aim of maintaining in the medium and long term a set of macroprudential regulations compatible with the dynamization of capital flows oriented to the real economy.

5. Public Finance

National public finances continued to strengthen in the fourth quarter of 2021 mainly on the basis of the improvement in government revenues. National tax collection increased by 66% during 2021 compared to the previous year, which meant a real growth of 11.9%. This increase was explained both by the consolidation of the economic recovery and by the low base of comparison due to the impact of the pandemic during 2020. In addition, the greater flow of foreign trade contributed positively to collection through withholdings and tariffs. In real terms, seasonally adjusted revenue grew 3% in the fourth quarter of 2021 and was 15.7% above the pre-pandemic level (first quarter of 2020).

During 2021, the level of real primary expenditure was maintained. In particular, capital expenditure aimed at strengthening the recovery of economic activity was boosted. In the opposite direction, there was a more limited trajectory of extraordinary expenditures associated with the evolution of the pandemic. However, excluding extraordinary expenditures in 2020 and 2021 aimed at mitigating the effects of the pandemic and accompanying the most affected sectors, real primary expenditure expanded by 15% YoY in the fourth quarter of 2021.

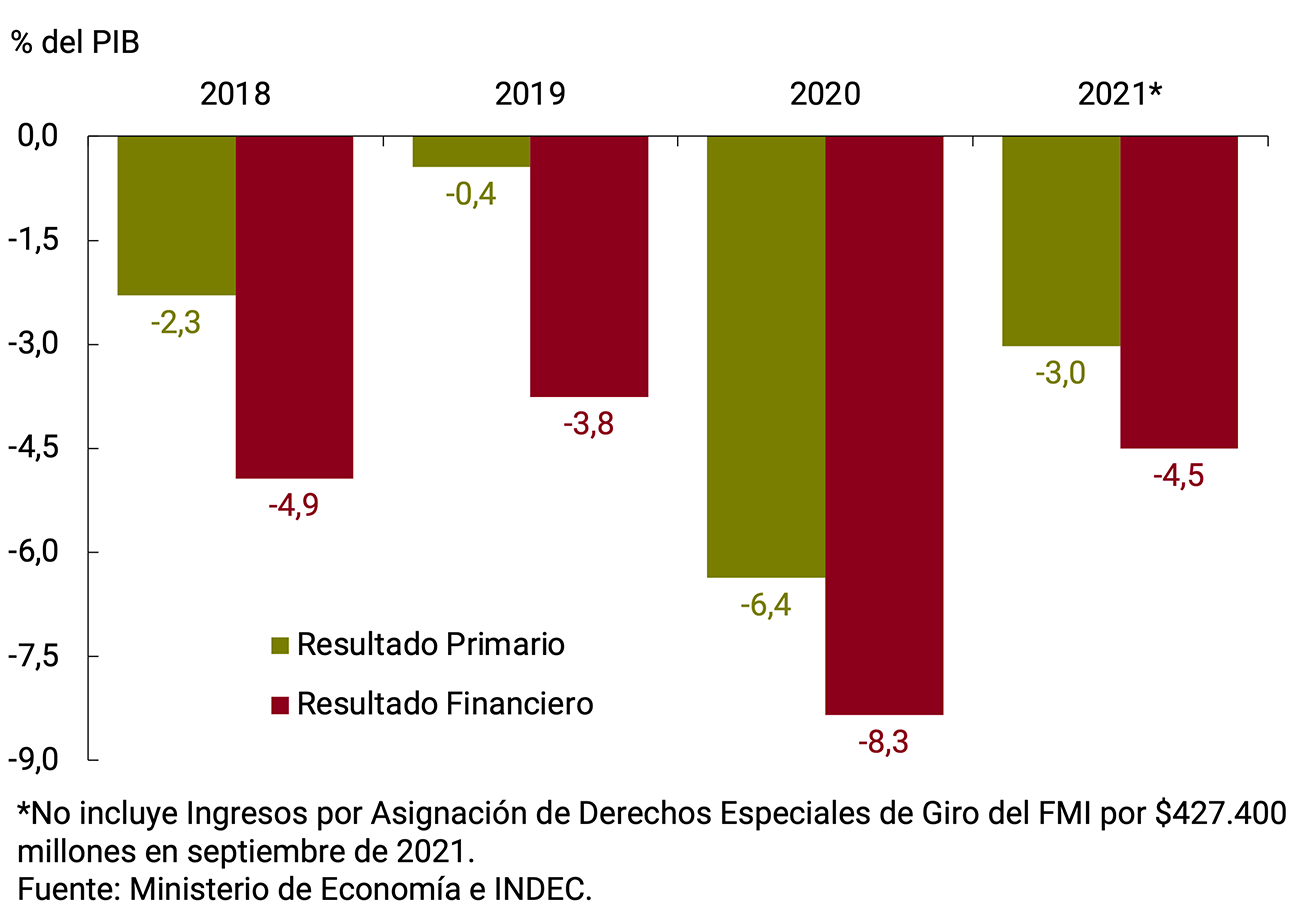

In 2021, primary expenditures grew below the increase in revenues, contributing to reducing the fiscal deficit. The primary deficit on a cash basis of the National Non-Financial Public Sector (NFPS) accumulated a balance equivalent to approximately 2.1% of GDP (which rises to 3% of GDP if it is not included among the transfer revenues from the extraordinary allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) distributed among member countries to deal with the impact of the COVID-19 crisis). This level of deficit was significantly lower than that observed during 2020 (6.4% of GDP).

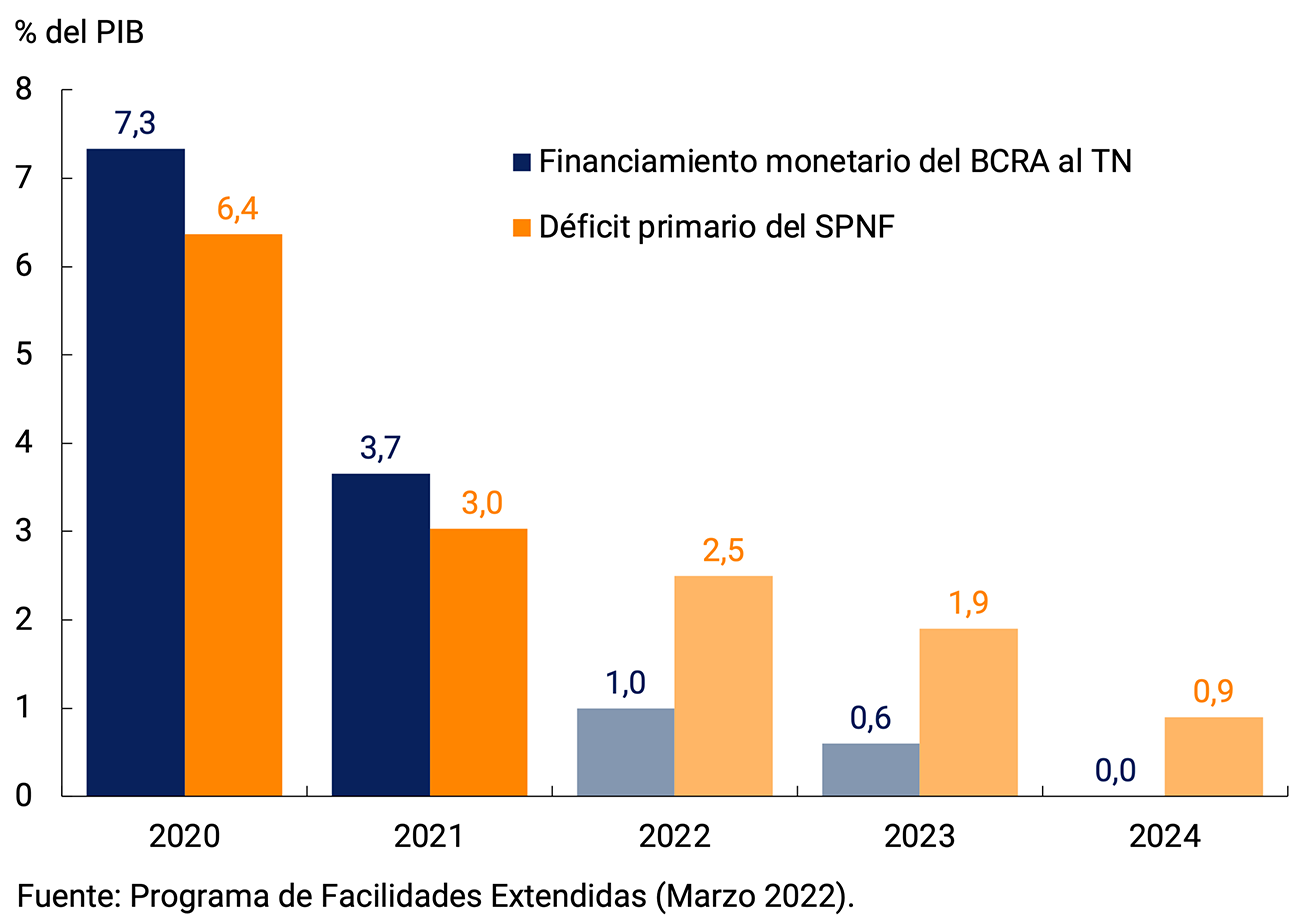

The agreement between the National Government and the IMF (See Section 4 / The Extended Facilities Agreement with the IMF) contemplates a path to reduce the primary deficit in terms of GDP for the coming years: in 2022 it would stand at 2.5%, and then be reduced to 1.9% in 2023 and 0.9% in 2024. Likewise, less monetary financing of the needs of the National Treasury (NT) is expected, with a cap of 1% of GDP in 2022, 0.6% in 2023 and zero in 2024. These paths are consistent with the guidelines that had been proposed in mid-September 2021 with the 2022 National Budget Bill (despite the fact that it did not have the approval of the National Congress, having to resort to what the legislation establishes in this case: an extension of the 2021 Budget for 2022, with certain adaptations). This project highlighted a reduction of a similar magnitude in the Product of the primary deficit of the NFPS for 2022 and a lower monetary financing of the needs of the National Treasury (TN).

Finally, although significant progress has been made, challenges remain to deepen the development of the local public debt market.

5.1. Tax revenues strengthened public accounts by growing above inflation during 2021

National tax collection increased 64% YoY in the third quarter of 2021 (see Figure 5.1). This increase is explained by the consolidation of the economic recovery and the low base of comparison due to the impact of the pandemic during the third quarter of 2020. In addition, the higher values of international trade flows that are taxed continued to contribute positively. In real terms, tax collection expanded 8% YoY between July and September. In October, the nominal increase was 58.7% YoY (+4.7% YoY in real terms).

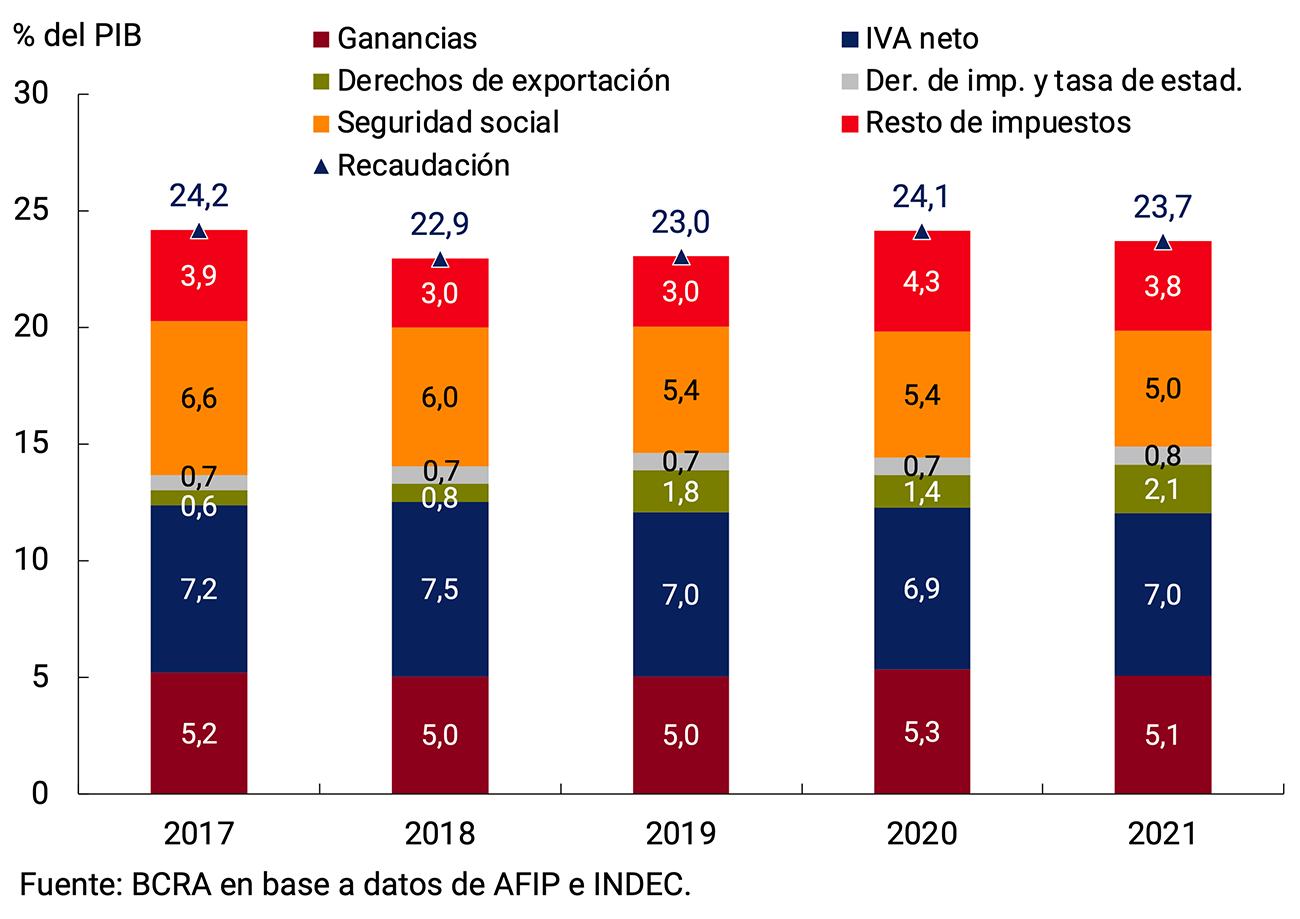

During 2021, national tax collection represented 23.7% of GDP, which was 0.4 percentage points (p.p.) less than in 2020 (see Figure 5.1). Among the taxes that explained this drop are social security resources (-0.4 p.p.), the PAIS tax (for lower taxed transactions; -0.3 p.p. of the Product), the Income Tax (-0.2 p.p.) and the tax on personal assets (-0.2 p.p.). On the other hand, there was a significant increase in duties on foreign trade.

In fact, export duties grew 148.5% yoy in 2021. The rise responded both to the favorable international context for the international prices of the main export products and to the recovery of external demand. In this way, export duties came to represent 2.1% of GDP in 2021 (+0.7 p.p. compared to 2020). Import Duties and Statistical Tax also showed a strong increase during the period, although a little more moderate: +85.4%. This behavior was explained by higher imported values (see Chapter 4. External Sector). Thus, revenues from tariffs and import taxes accumulated an amount equivalent to approximately 0.8% of GDP (+0.1 p.p. vs. 2020).

Taxes related to the domestic market (Value Added Tax (VAT), Profits, Fuels, among others) performed well throughout 2021 due to the recovery of economic activity. Net VAT remained highly dynamic throughout last year, growing by 70.2%, mainly due to the recovery in economic activity and household consumption. Net VAT accounted for 7% of GDP (+0.1 p.p. vs. 2020), remaining at a figure similar to that prior to the pandemic.

Income Tax rose 59.9% YoY in 2021. The performance of this tax was impacted by various factors throughout the year. The regulatory change of September 2020 associated with the withholding on purchases of dollars and expenses in foreign currency through credit cards had an upward effect. On the other hand, it was impacted by the increase in personal deductions on the income of workers in a relationship of dependency29. Towards the end of the year, the modification that incorporates new rates in a staggered manner for companies, setting the maximum rate at 35% and maintaining the tax on dividends at 7%30, had an upward impact. Thus, income tax contributed 5.1% of GDP in 2021 (-0.2 p.p. vs. 2020).

Social security resources increased by 55.1% in 2021. They were negatively impacted by the measures taken by the National Government, with reductions in employer contributions in the health sector, to the critical sectors contemplated in the REPRO program and to companies located in the provinces of the Norte Grande. However, in the last quarter of 2021 they showed a better performance: they grew 67.5% YoY vs. 63.2% YoY in the third. Thus, social security represented 5% of GDP during 2021, which implied a decrease of 0.4 p.p. compared to the previous year. Going forward, it is expected that the collection linked to social security will recover its share in line with the forecast of an increase in formal employment and real wages.

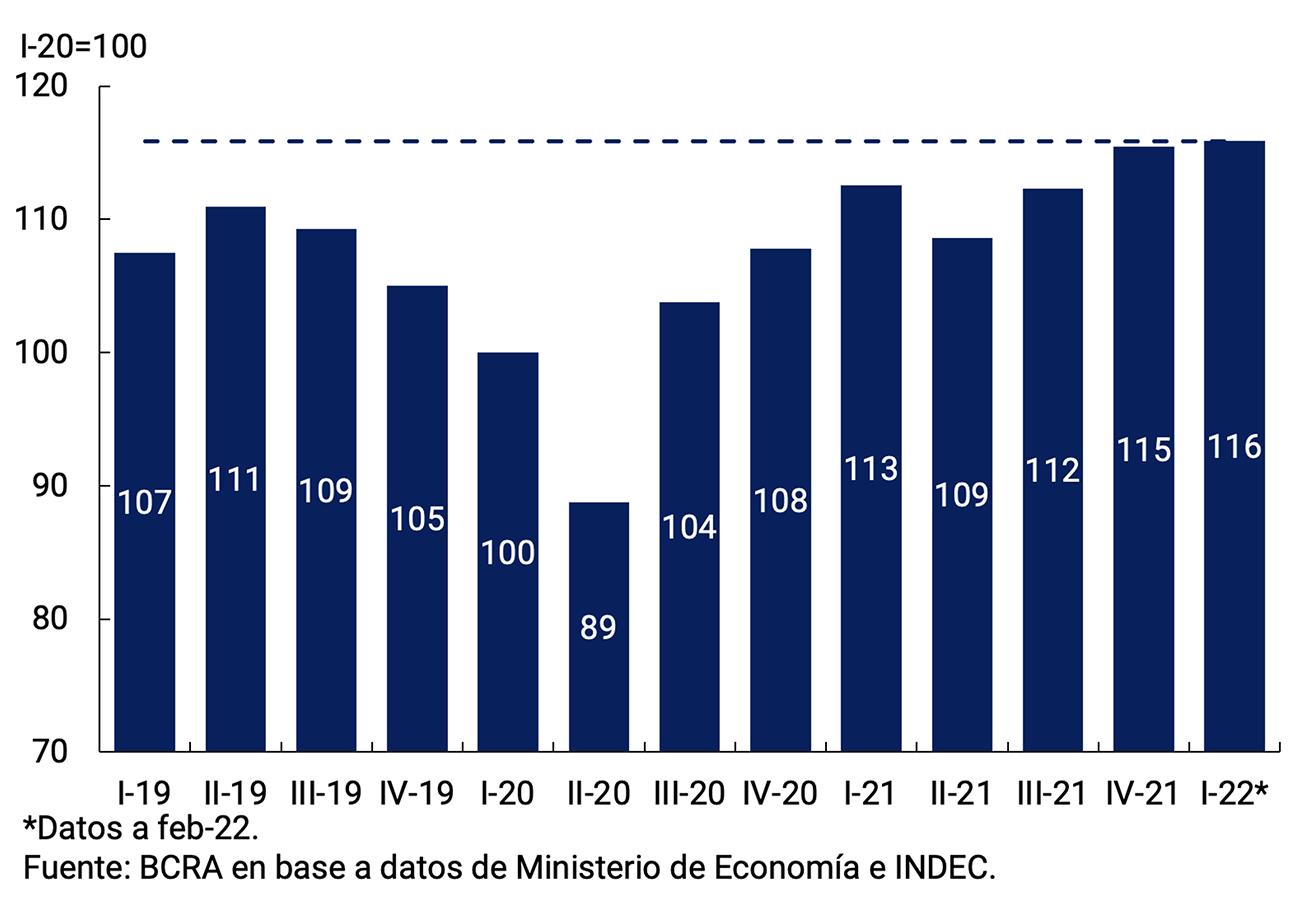

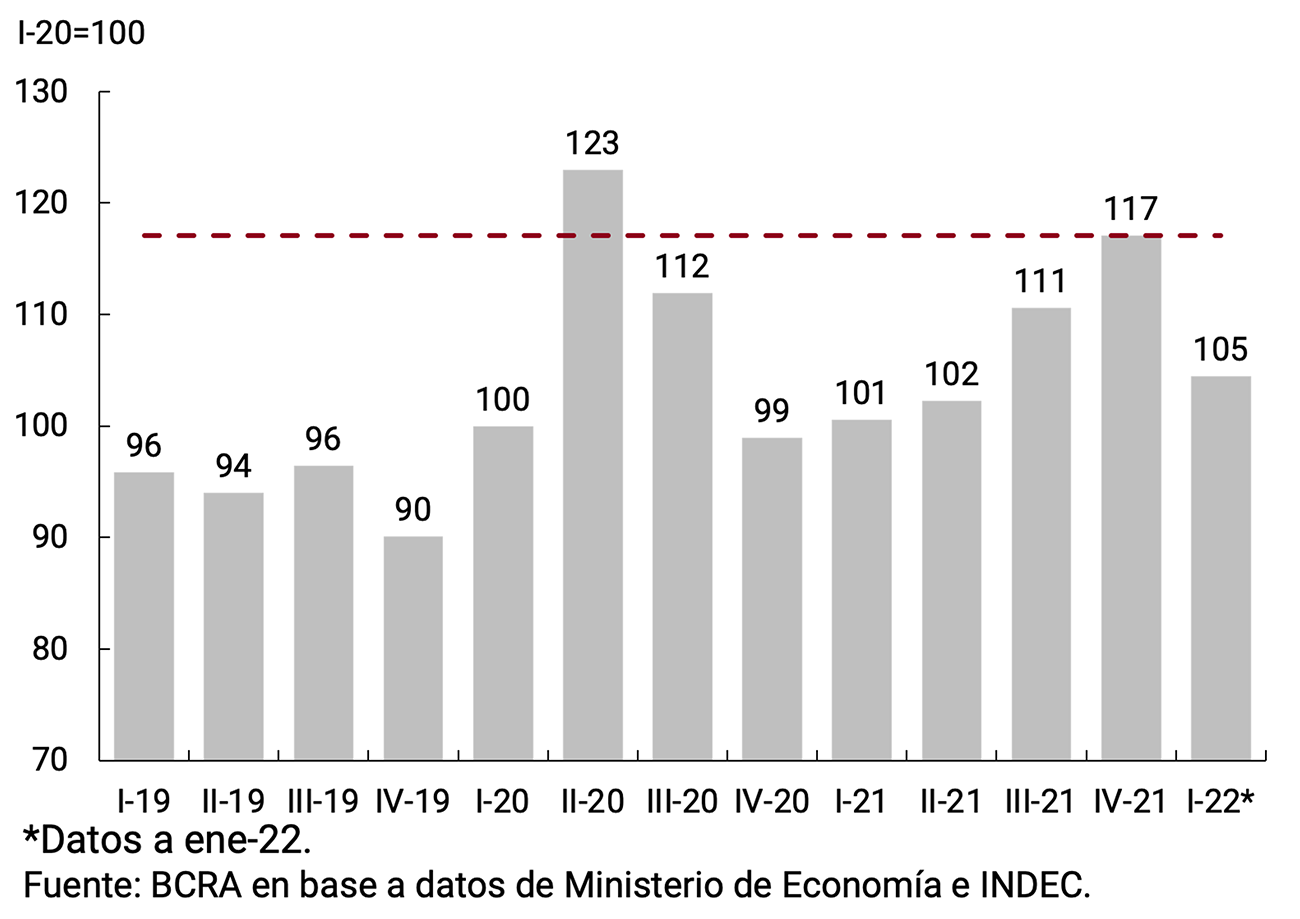

In real terms, seasonally adjusted national tax collection grew 3% in the fourth quarter of 2021 and was 15.4% above the pre-pandemic level (see Figure 5.2). This performance reflects the consolidation of the recovery in tax revenues after the harmful effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. With partial data as of February 2022, real revenue would have grown 0.4% s.e. in the first quarter of the current year. Thus, real seasonally adjusted revenue would still be 16.1% above the pre-pandemic level (I-20).

The evolution of tax revenues allowed total revenues of the National Non-Financial Public Sector (NFPS) to increase in nominal terms by 83.4% in 2021 (+23% in real terms). The annual comparison was impacted by the calculation in current transfers of the extraordinary allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) that the IMF made in the context of the global crisis due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Net of this effect, funds would have shown a nominal increase of 74.6% in the year. Non-tax revenues were also affected upwards during 2021 by the imputation of resources associated with Law 27605 on Solidarity and Extraordinary Contribution to Help Mitigate the Impact of the pandemic (between May and December 2021, $243,463 million were recorded for this concept; approximately 0.5% of GDP). Property rents advanced 118% in the year due to the collection of interest on loans granted by the National Social Security Administration (ANSeS) – which had been suspended for most of 2020. On the other hand, capital resources decreased throughout 2021 affected by the provisions of Law 27574 on the Defense of the Assets of the Sustainability Guarantee Fund (FGS), which stipulates the suspension of financing to the ANSES by the FGS to meet the disbursements of the Historical Reparation program.

Meanwhile, the tax collection of the provinces as a whole exhibited a behavior consistent with what was observed at the national level. According to the partial information available for the main districts, in the fourth quarter of the year the nominal advance of own tax resources would have shown an increase of close to 66% y.a., still impacted by the low base of comparison of the same quarter of 2020.

5.2. NFPS primary expenditure ended the year at values similar – in real terms – to the level shown during 2020

NFPS primary expenditure exhibited a nominal increase of 49.6% YoY in 2021, below the nominal increase in revenues. During 2021, real primary expenditures remained practically constant compared to 2020 (see Figure 5.3). It should be borne in mind that during the last two years the public accounts were affected by expenses associated with the effects of the pandemic, the greatest deployment of which was concentrated in the second and fourth quarters of 2020.

Indeed, excluding in 2020 and 2021 the extraordinary expenditures aimed at mitigating the effects of the pandemic and accompanying the most affected sectors, since March 2020, primary expenditure would have expanded at a nominal rate approximately 15 p.p. higher than that of primary expenditure without deductions for COVID-19 expenditure. This implies that net of the effect of the greater comparison base of 2020, due to COVID-19 spending, primary expenditures would have exhibited growth in real terms in 2021.

In this sense, if real seasonally adjusted primary expenditure is observed, it was 17.1% above the pre-pandemic level in the fourth quarter of 2021 (I-20; see Figure 5.4). Between October and December 2021, spending grew 5.8% s.e. compared to the previous quarter. With partial data from the first quarter (as of January), it can be seen that real seasonally adjusted primary expenditure fell 10.7% s.e. compared to the last quarter of 2021.

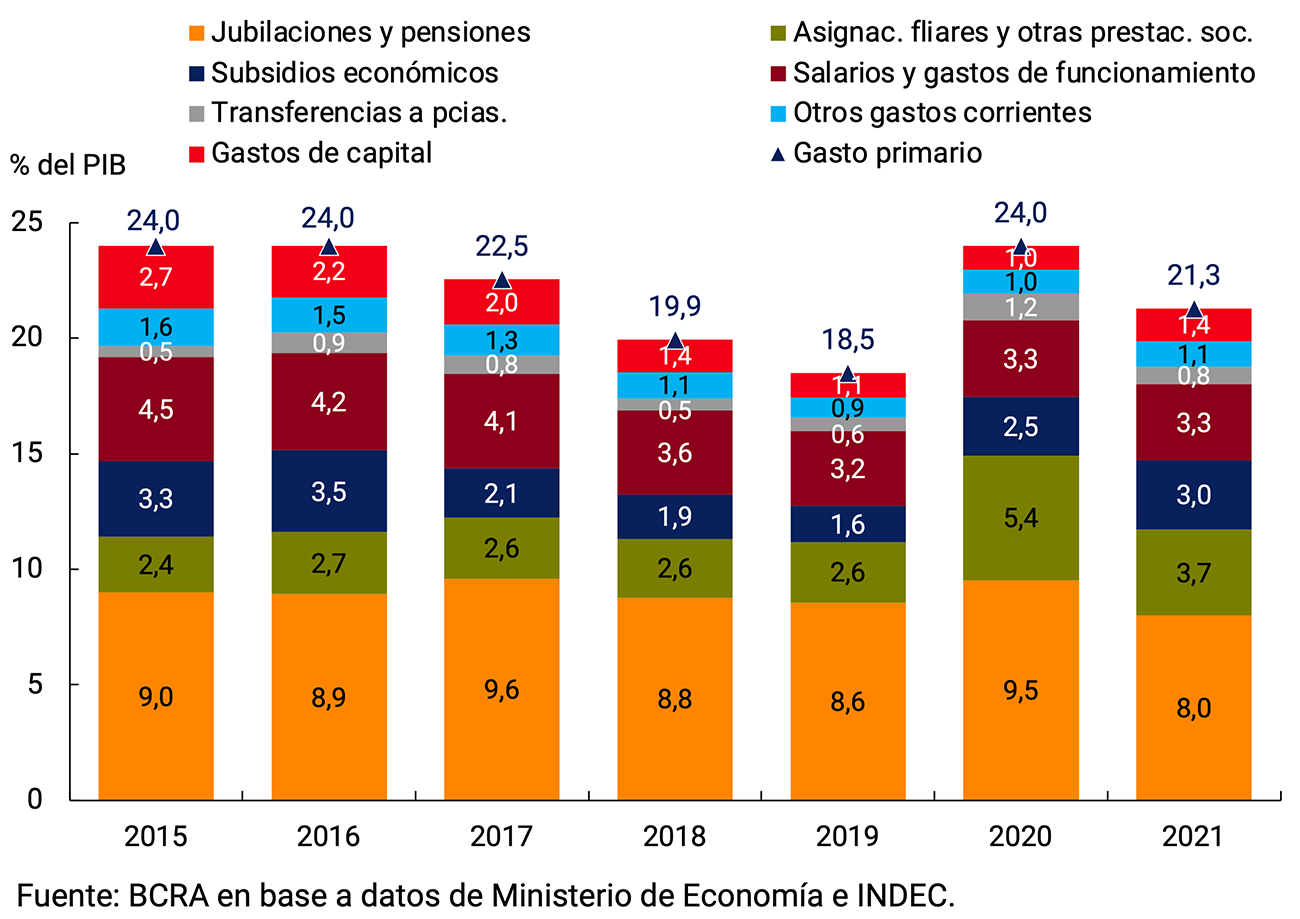

However, measured in relation to Output, primary expenditure reduced its participation, explained by economic growth. NFPS primary expenditure accounted for 21.3% of GDP in 2021 (-2.7 p.p. compared to the previous year). Expenditure on pension benefits (retirements and pensions) increased 41.9% in 2021 in accordance with the provisions of the Pension Mobility Law31. Thus, they reported an amount equivalent to approximately 8% of GDP in 2021 (-1.5 p.p. compared to the previous year). As of March 2022, the expected mobility of 12.28% has an impact, implying a variation of 58.62% y.o.y. in the salaries. This improvement will also include family allowances, including the Universal Child Allowance (AUH) and Pregnancy Allowance, impacting the income received by almost 9 million children and adolescents.

As for social benefits, these expenses had a nominal increase of only 16.1% during 2021 because this item had incorporated during 2020 a large part of the programs to sustain income during the most intense months of the pandemic (such as the Emergency Family Income (IFE) and the Emergency Assistance Program for Work and Production (ATP). In this way, they decreased their share in terms of GDP in primary spending: during 2021 they represented 3.7% of GDP, which implied a decrease of 1.7 p.p. compared to the previous year. In 2021, the expenditures of the Food Policy program were highlighted: since February, the allocation was increased by 50% while the universe of beneficiaries was expanded to 14 years of age. In turn, payments from the Employment Actions program – mainly REPRO II – as well as the Empower Work program, registered a significant increase aimed at assisting the productive sectors critically affected by the pandemic. For its part, the set of family allowances grew 49.4% in 2021.

In a context in which the National Government promoted a policy of containing the rates of public services – electricity, gas, water and public transport – economic subsidies accounted for a growing portion of primary spending: they grew 118.8% YoY in the year and came to represent 3% of GDP (+0.5 p.p. of GDP, see Figure 5.5). This increase in participation is mainly due to the increase in spending associated with energy subsidies in a context in which there were also significant increases in international fuel and energy prices and higher domestic costs of electricity production due to the lower contribution of hydroelectric generation (in a context of low water in rivers due to drought). On the other hand, subsidies for public passenger transport remained practically unchanged in relation to the Product.

Items associated with salaries and operating expenses grew 68.6% last year compared to 2020 and maintained their share at 3.3% of GDP. It should be noted that the latter item includes purchases of goods and services (including expenditures associated with the purchase of vaccines against COVID-19 and expenses associated with the organization of the national election). On the other hand, current transfers to the provinces moderated significantly (+15.2% nominal y.o.y. in 2021) compared to 2020, when the National Government had extraordinarily assisted the districts in the face of the abrupt decline in subnational collection. This performance was verified despite the fact that since the beginning of 2021, the transfers associated with the creation of the Fund for the Fiscal Strengthening of the Province of Buenos Aires32 began to be recorded in the budget. In this way, transfers to provinces reduced their share of expenditure in relation to GDP by 0.4 p.p., to stand at 0.8% of GDP in 2021 (see Figure 5.5.).

Capital expenditure showed great dynamism throughout last year, in line with the definition of priorities set out in the 2021 National Budget to promote the recovery of economic activity. In fact, this item grew 132.8%, with Real Direct Investment (IRD) being the sub-item that had the best performance (+177.5%)33. Thus, NFPS capital expenditure stood at 1.4% of GDP in 2021 (+0.4 p.p. vs. 2020).