Financial Stability

Financial Stability Report

Second half

2019

Half-yearly report presenting recent developments and prospects for financial stability.

Table of Contents

Chapters

- Executive summary

- Financial System Stability Analysis

Sections

- Paragraph 1 / Reduced exposure of the financial system to public sector risk

- Section 2 / Second cyber exercise carried out in the financial system

- Section 3 / Stablecoins. Progress and implications for financial stability

- Section 4 / Macroprudential regulations in Argentina that promote the resilience of the system in situations of uncertainty

- Section 5 / Evolution of the concentration of debtors in the local banking market

- Glossary of abbreviations and acronyms

Summary

In recent months, the Argentine financial system has demonstrated a significant degree of resilience in the face of a challenging context, operating without disruption in the provision of intermediation services and means of payment, while maintaining significant prudential liquidity and solvency margins, within a prudential regulatory framework in line with international standards. The set of financial institutions operated in a framework of greater uncertainty – inherent to the recent electoral process – where there was greater volatility in the exchange rate, outflow of deposits in foreign currency and growing pressures on the prices of public securities.

The Ministry of Finance and the BCRA implemented a set of measures that sought to temper the effects of volatility on the performance of prices and economic activity. At the end of August, given limited access to the debt market, the amortizations of Treasury Bills were rescheduled and the intention to advance in a voluntary extension of the terms of part of public securities was announced. The BCRA limited the formation of foreign assets without a specific purpose and adjusted the terms for the settlement of export collections, without altering the normal functioning of foreign trade or the ability to use the credits available in bank accounts. These regulations had to necessarily consider their impact on both the foreign exchange market and international reserves, as well as on depositors’ confidence in the Argentine financial system. The BCRA continued to implement a contractionary monetary policy, along with interventions in the foreign exchange market.

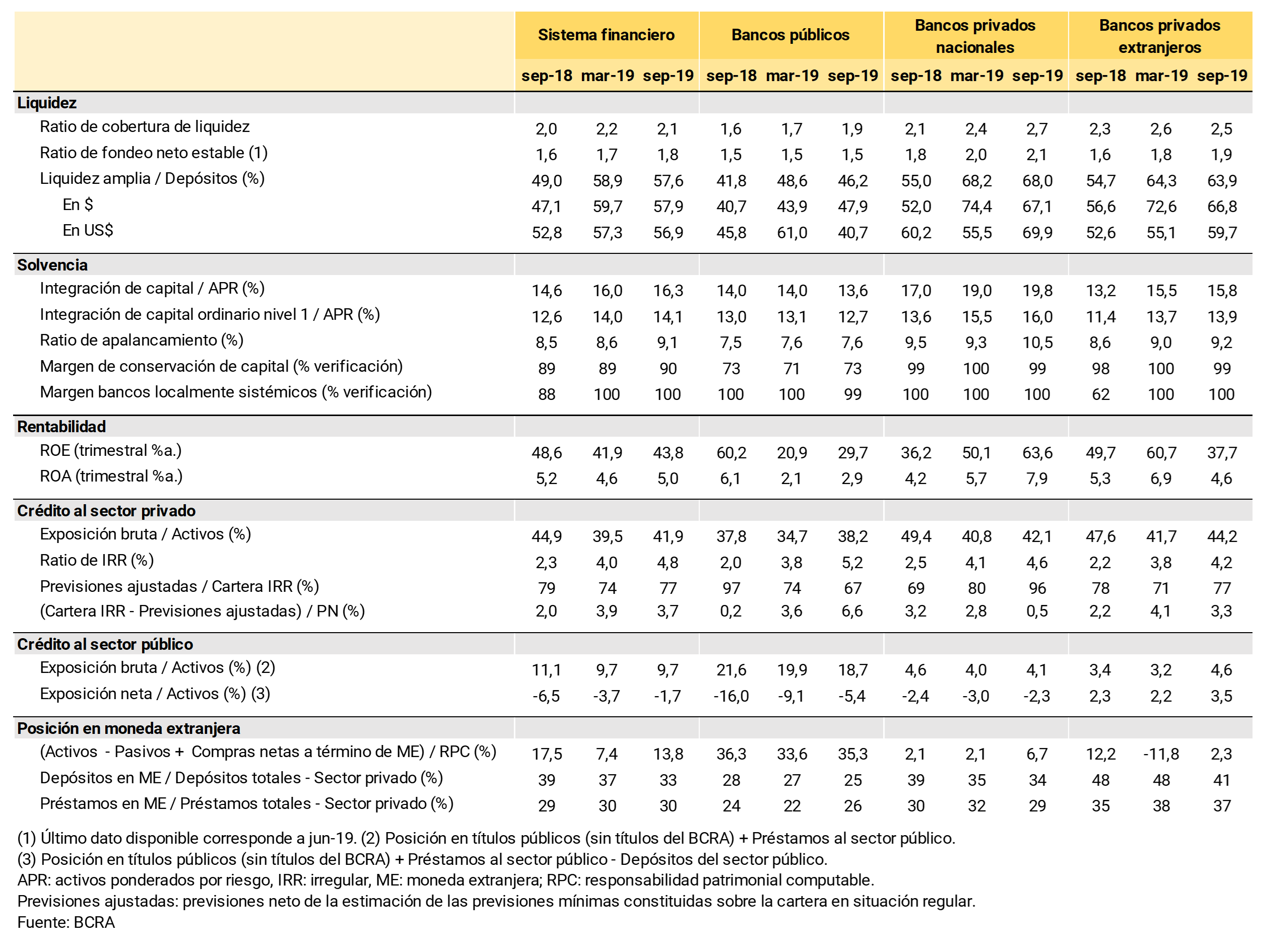

Despite the pressures observed on funding conditions and composition, including a decline of approximately 40% in the balance of private sector foreign currency deposits from mid-August to the end of October, liquidity levels in the financial system remained in line with historical highs, with no significant changes from the IEF I-19. It should be considered that, based on the macroprudential rules in force, deposits in foreign currency are mainly offset by loans in foreign currency to exporting companies and liquid assets in this denomination. For its part, the system’s solvency indicators increased compared to last March, placing them above the local minimum prudential requirements – with leverage levels well below those recommended internationally – and showing adequate verification of additional capital margins.

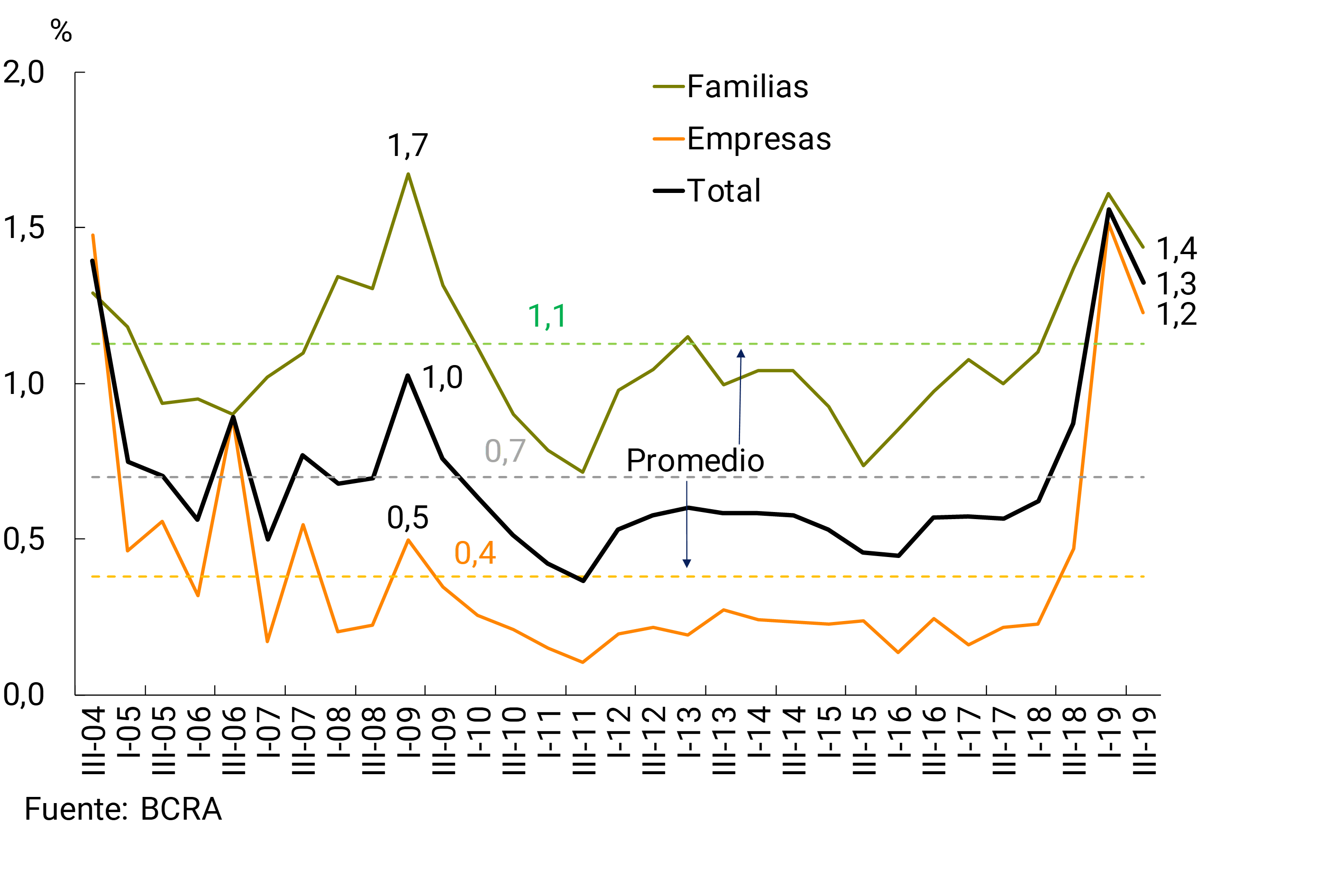

In the face of the economic weakness observed, financial intermediation activity fell compared to the last IEF. With a declining level of financing to the private sector, the loan portfolio irregularity ratio continued to grow – mainly in loans to companies – but moderated compared to the performance of the previous semester. Given the limited gross exposure of banks as a whole to credit risk and the high levels of provisioning, the proportion of the capital in the financial system that could be affected by a higher degree of bad debt in the non-performing portfolio is very low.

At the structural level, the intrinsic sources of vulnerability of the financial system remain limited. The aggregate of banks shows very low levels of credit depth – associated with low-leveraged debtors – an operation based on traditional intermediation with little transformation of terms, in a framework of low degree of direct interconnection between entities. Added to this are the positive effects of the aforementioned Argentine macroprudential regulatory framework, which contributes, among other aspects, to the fact that the process of financial intermediation in pesos is carried out practically independently of that carried out in foreign currency, and to the fact that banks’ exposure to public sector credit risk remains low.

By the end of 2019 and the beginning of 2020 – given the recent evolution of the main financial variables and the real sector of the economy – a challenging operating scenario is expected for the financial system. In terms of exogenous risks, local uncertainty factors could lead to new periods of stress on financial markets and on the level of aggregate activity, with an eventual effect on the intermediation process of the financial system. However, given the factors of relative strength currently shown by the Argentine financial system, there would have to be very extreme episodes of risk materialization for the conditions of local financial stability to be significantly affected.

The BCRA will continue to act within the framework of its macroprudential policy approach, reinforcing the process of monitoring the financial system with a view to early identification of sources of risks and vulnerabilities that may eventually have an adverse impact on the economy as a whole.

Financial System Stability Analysis

1. Context

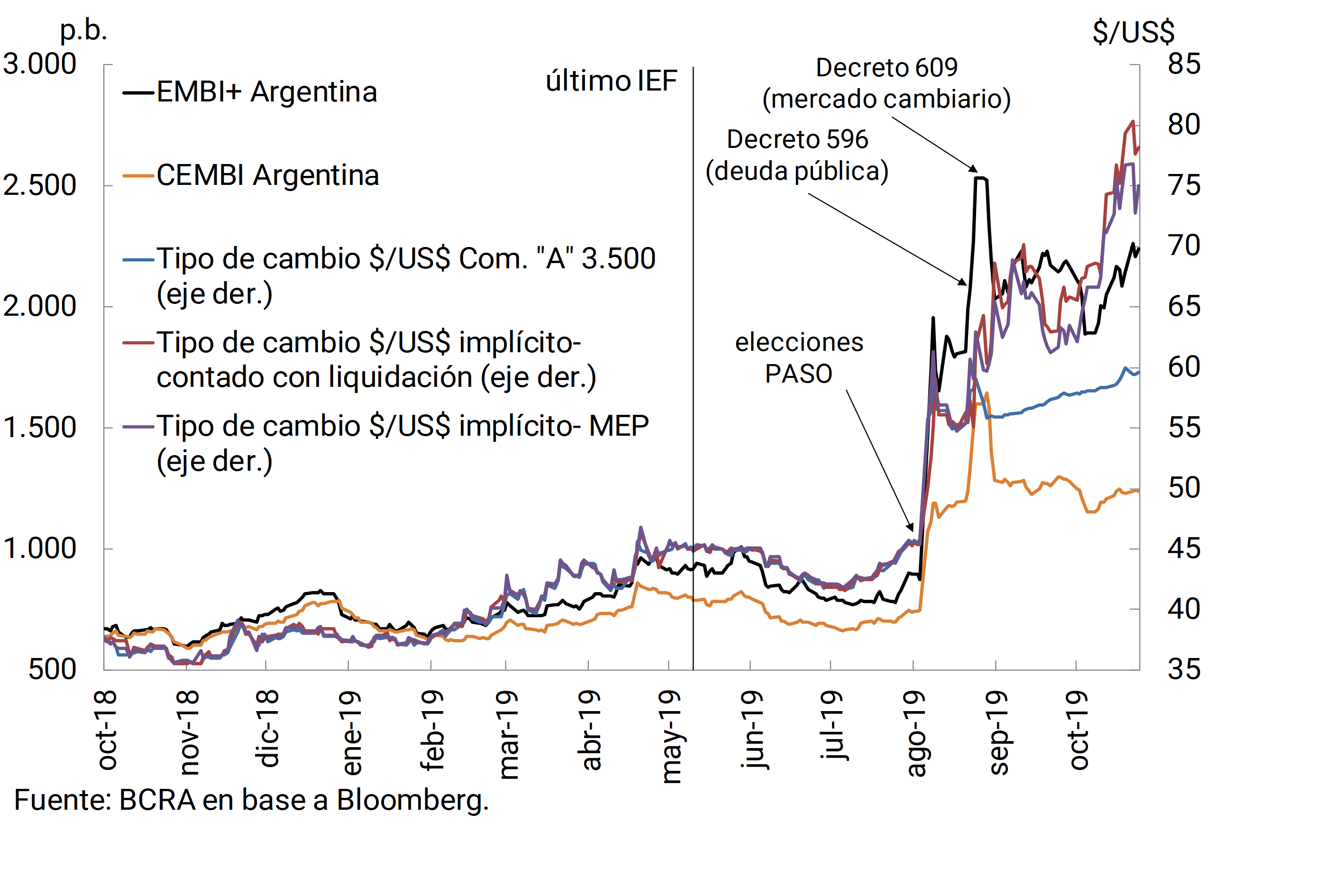

The uncertainty inherent in the electoral process led to a deterioration in financial market conditions in recent months (see Chart 1). In particular, after the Simultaneous and Mandatory Open Primary (PASO) elections, there was a significant increase in the volatility of Argentine asset prices and the exchange rate, and a fall in foreign currency deposits. As will be analysed in the following sections, all financial institutions showed a significant degree of resilience in the face of this adverse context, preserving the conditions of financial stability.

Given the increasingly restricted access to short-term financing for the Treasury, pressures on the exchange rate, and the fall in foreign currency deposits, several measures were implemented to preserve nominal and financial stability (mitigating the effects of financial volatility on the real economy)1. At the end of August, the amortizations of Treasury Bills2 were rescheduled and the intention to move towards a voluntary extension of the maturities of medium- and long-term public securities3 was announced. At the beginning of September4, this was complemented by modifications in the regulation of the foreign exchange market, with controls that were deepened at the end of October.

Likewise, a contractionary monetary policy continued to be implemented, based on the fulfillment of monetary targets and the consolidation of positive real interest rates, together with exchange rate interventions, to moderate nominal volatility5. In addition, on August 30, the BCRA decided to temporarily hold auctions of active passes and purchases of Treasury Bills in the portfolio of mutual funds (of these two instruments only the second has been used so far), helping to stabilize this market6.

2. Main strengths of the financial system in the face of the risks faced

Although the developments of recent months implied the materialization of certain risk factors considered in the previous edition of the IEF (May 2019), the financial system has continued to carry out its functions with a significant degree of solidity, acting within a regulatory framework in line with international standards. On the one hand, the financial system’s exposures to risks inherent to its operations remain limited. In this sense, the depth of bank credit to the private sector in the economy is small and decreasing, exposure to the public sector is relatively low, unsophisticated traditional banking operations predominate, the transformation of terms on banks’ balance sheets is limited, the degree of direct interconnection between entities is low, and financial intermediation in pesos is carried out practically independently of that carried out in foreign currency. On the other hand, the financial system maintains significant prudential margins of liquidity and solvency. These aspects, which provide resilience to the aggregate financial system, are addressed in general below and, in greater detail, in the following sections.

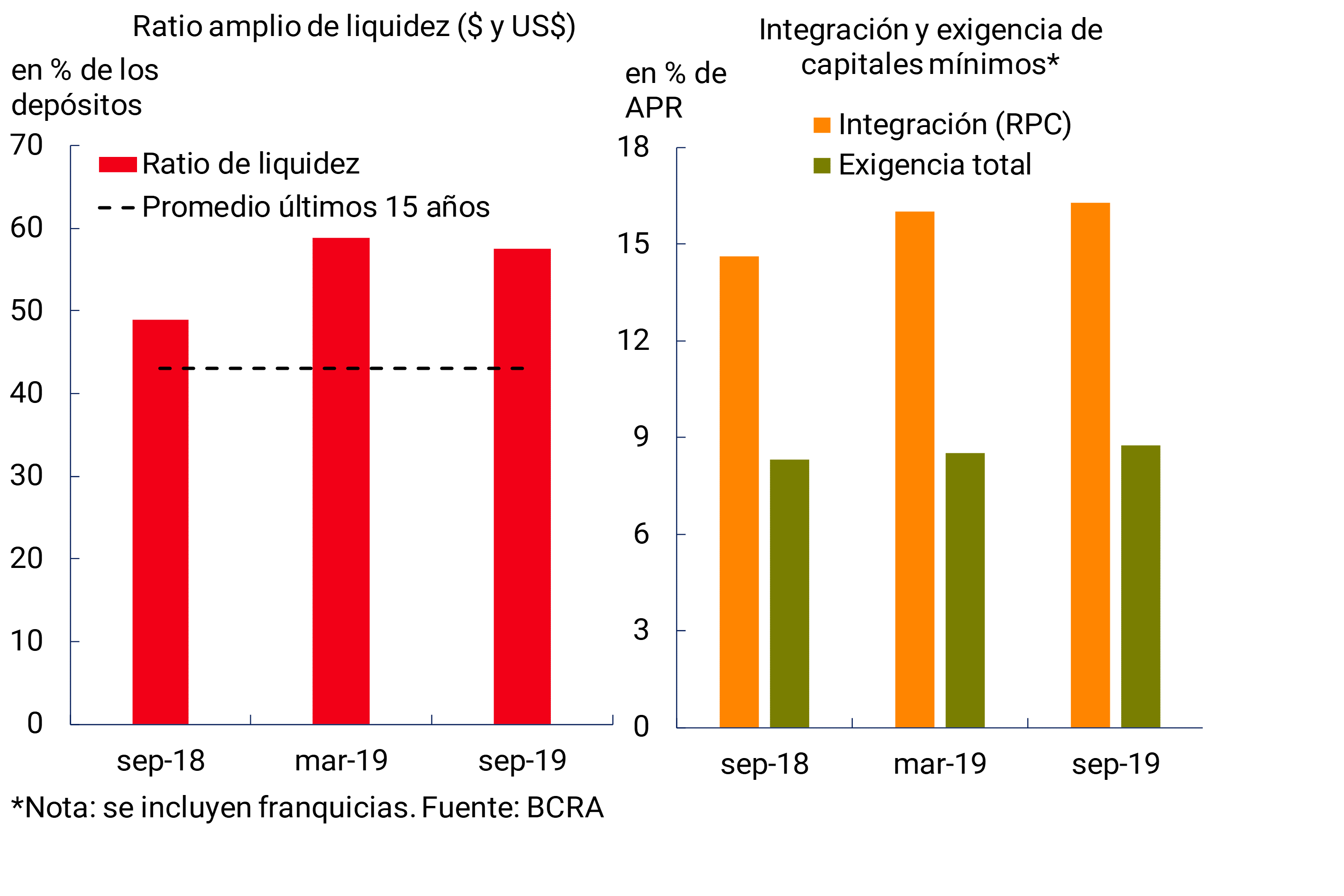

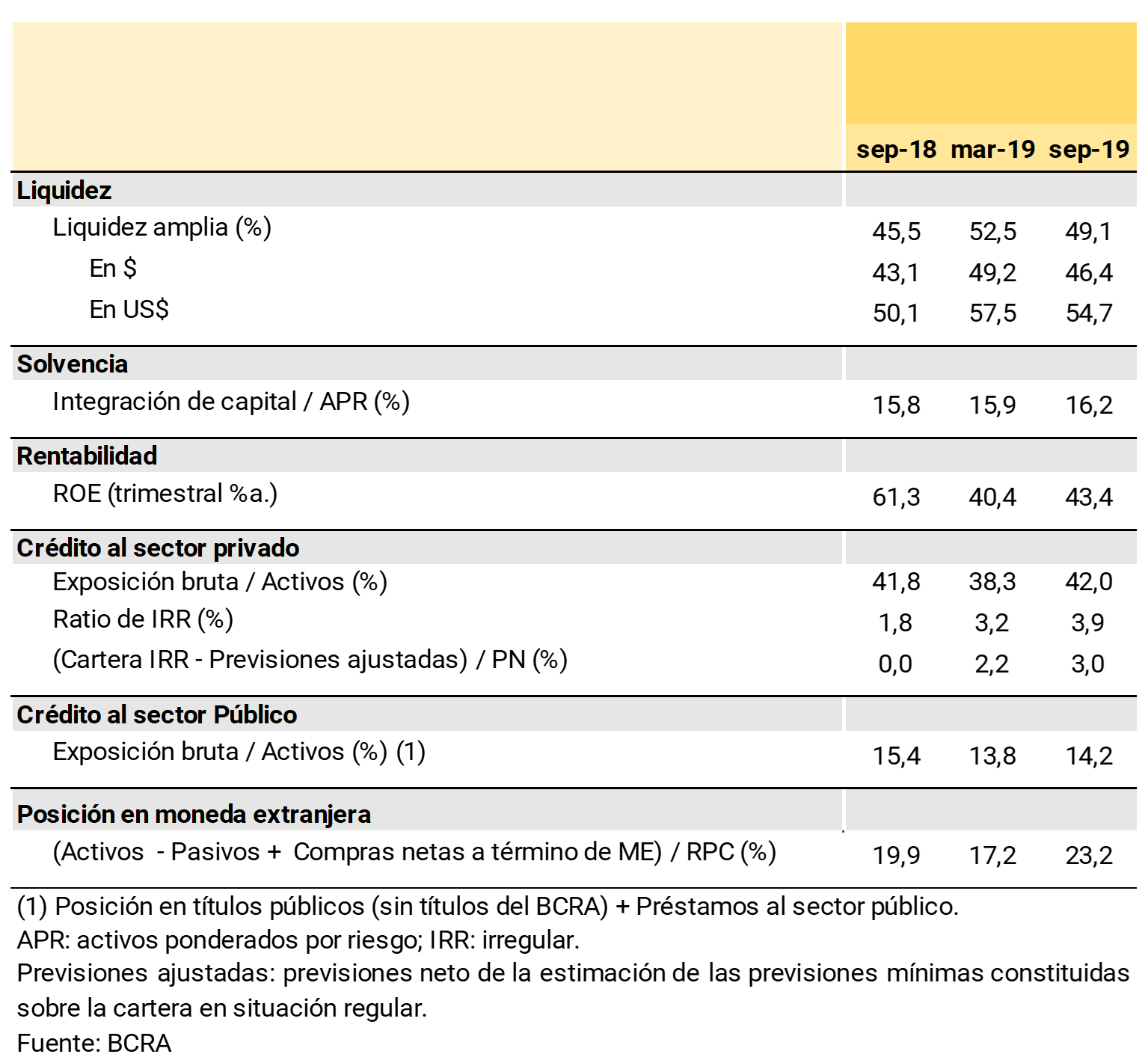

i. High liquidity and comfortable aggregate solvency. At the end of the third quarter of the year, the ample liquidity of the financial system in terms of its deposits remained in line with historical highs, around 58% (see Chart 2). With respect to the last IEF, there were no significant changes in the liquidity ratios in pesos or foreign currency (see Table 1). It should be noted that foreign currency coverage remained high despite the outflow of just over 40% of private sector deposits in foreign currency from mid-August to the end of October (see Section 4). In addition, local liquidity indicators arising from international recommendations remained high, exceeding the minimum regulatory requirements.

The solvency ratios of the financial system continued to be comfortably above the minimum prudential requirements. Capital integration (RPC) totaled 16.3% of risk-weighted assets (RWA) in September. In addition, the set of financial institutions showed an almost complete verification of the additional capital margins. In addition, the degree of leverage in the sector remains well below the maximum allowed by local regulation, prudential regulations in line with international recommendations (for more details see Section 3.3.1).

ii. Moderate direct equity exposure to nominal exchange rate volatility. The exposure of the financial system’s balance sheet to foreign currency items remained at limited levels at the end of the third quarter, with 30% of credit and 33% of private sector deposits in that denomination, in a context of greater volatility in the nominal exchange rate since mid-August 2019 (see Chart 1). Foreign currency mismatches on the balance sheet of local banks remained low, reflecting the effect of the macroprudential regulations in force (see Section 4).

iii. Limited exposure of the financial system to the public sector. Banks’ exposure to the public sector is low, mainly as a result of the set of prudential rules in place to limit this source of credit risk (see Section 1). In addition, considering all government jurisdictions, the balance of public sector deposits exceeds the financing obtained (loans and position in public securities). The aggregate public sector retains its net creditor position vis-à-vis the financial system.

iv. High forecasting of the portfolio in an irregular situation, combined with a moderate gross exposure to credit risk. In the last six months, the bank credit irregularity ratio continued to increase, although at a slower pace than in the previous semester. Thus, at the end of September, the balance of financing to the private sector in an irregular situation reached 4.8% of the total. This is in a context of moderate gross exposure of banks as a whole to credit risk: financing to the private sector reached 41.9% of total assets in the third quarter of the year (4.3 p.p. less than the average for 2018)7. In addition, the levels of provision are comfortable, and it is estimated that the capital of the system that would be affected in the event that the irregular portfolio becomes uncollectible would be only 3.7% of the total8.

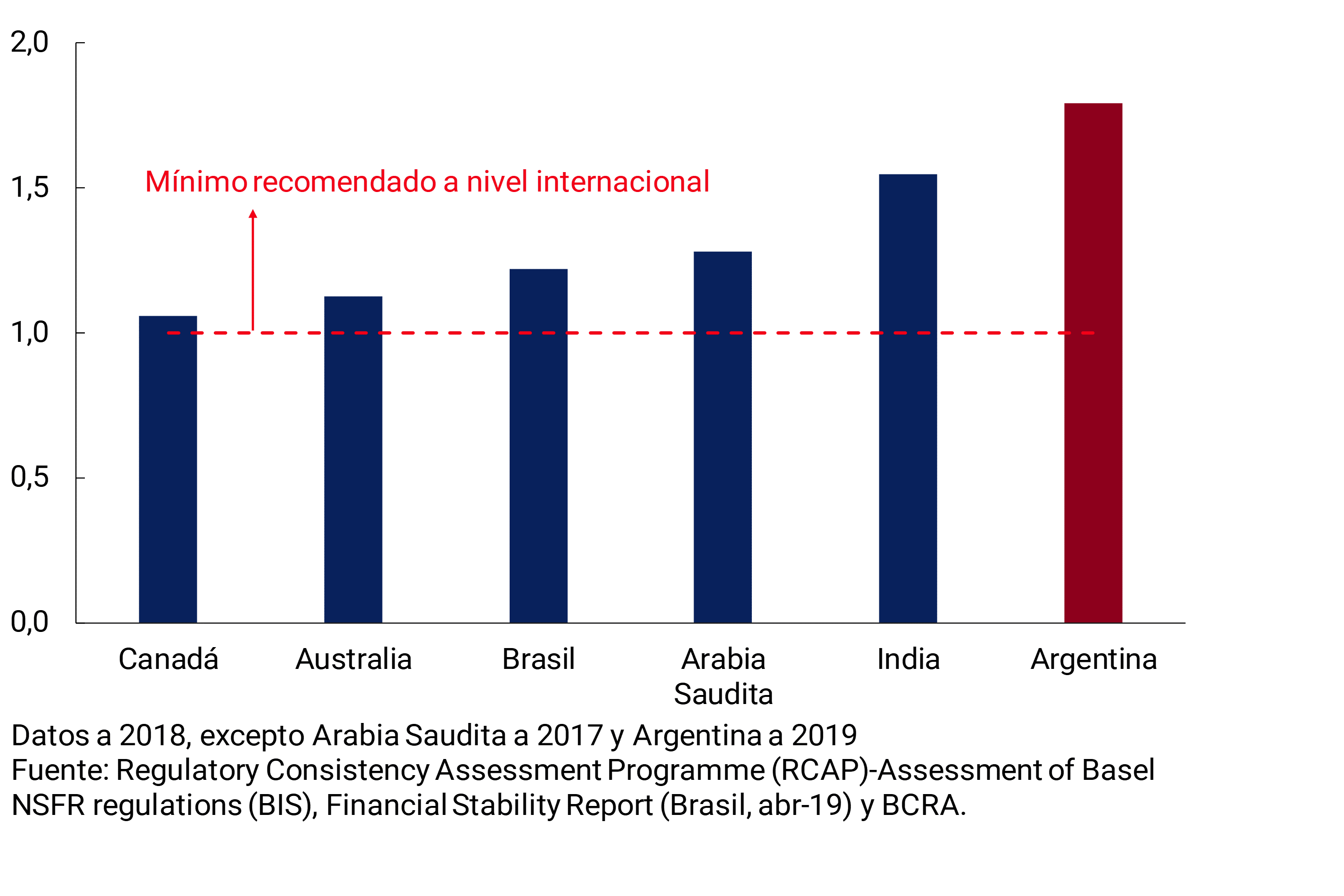

v. Regulatory framework in line with international standards. The micro and macroprudential regulations in force on the Argentine financial system focus on the particularities of the local environment, without losing sight of international best practices. In particular, the Basel Committee, within the framework of its Regulatory Consistency Assessment Programme (RCAP), and reinforcing the positive opinion it had issued in 20169, in 2019 evaluated Argentina’s regulations on Large Exposures (LEX) and the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR). In both cases, Argentina once again obtained the best possible score (“Compliant”), in terms of its compliance with international recommendations regarding the diversification of debtors (see Section 5) and the composition of medium- and long-term bank funding10.

The degree of resilience observed by the aggregate of banks in the context of greater exchange rate and financial volatility in recent months also reflected the effect of the above-mentioned measures, adopted by both the BCRA and the Ministry of Finance. In this scenario, the BCRA continued to develop a restrictive monetary policy combined with interventions in the foreign exchange market to moderate nominal volatility.

The aforementioned aspects should allow the financial system to face the challenging context expected for the coming months with relative strength. In this sense, and following a macroprudential approach, the main risk factors (exogenous to the system) that could be mentioned for the short and medium term are:

i. Possibility of new episodes of volatility in the fixed income market and the foreign exchange market. The measures implemented so far have made it possible to limit financial and exchange rate volatility11. However, the possibility of new episodes of volatility in local financial markets cannot be ruled out. Greater stress in the sovereign debt market would have a direct but limited impact on banks’ balance sheets, given their low exposure to the public sector (see Section 1). Renewed tensions could also be observed in the foreign exchange market, although in a limited way given the existence of exchange controls. These stresses could affect agents’ portfolio decisions. Although the banks as a whole have liquidity ratios similar to those observed prior to the PASO and do not show significant mismatches in foreign currency, this risk factor could put pressure on the conditions and channels through which financial intermediation occurs, particularly on the side of the sector’s funding sources.

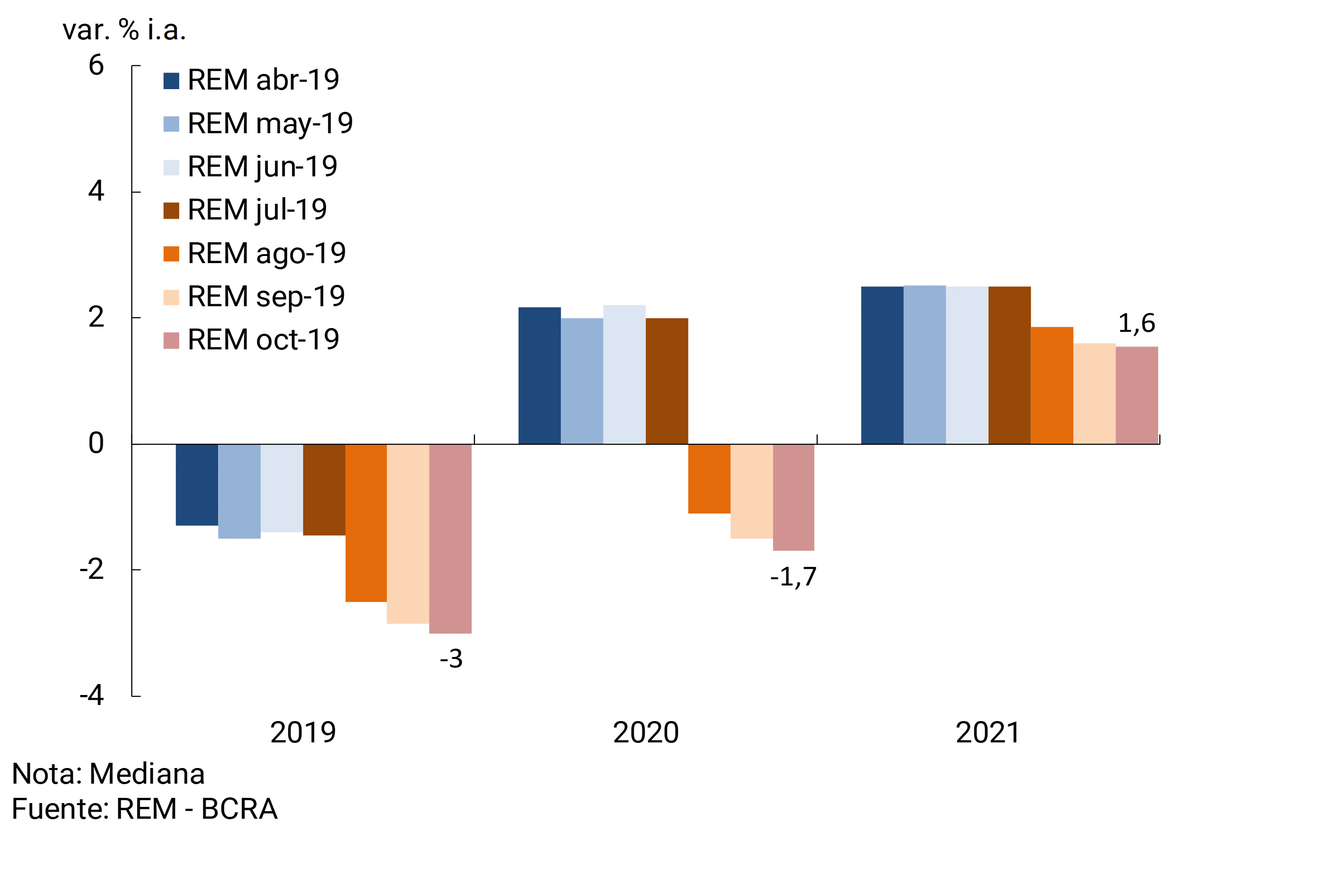

ii. Possible greater than expected deterioration in economic activity. Although by July there were signs of an exit from the recession that began in the last months of 201712, this trend was truncated as of August, in a context of greater volatility in financial variables. According to the REM, expectations about the evolution of the economy were adjusted downwards in the measurements made as of August, with an impact on what was expected for 2019-2020 (see Graph 3). REM analysts expect a recovery to begin in 2020, although slower than expected. In this context, a macroeconomic scenario with greater materialization of private sector credit risk, with an effect on the quality of banks’ portfolios, cannot be ruled out13. Nor can we rule out a lower dynamism in the demand and supply of credit to the private sector. As will be discussed below, the financial system retains significant relative levels of capital and forecasts that would mitigate the impact of a possible materialization of this risk factor.

iii. Possibly more adverse international context. At the global level, there are still several sources of risk14, which could generate tensions through the financial channel (greater risk aversion and portfolio readjustment, with an impact on the prices of assets in emerging economies, including their currencies and interest rates) and/or the trade channel (putting pressure on the level of activity in emerging economies). In turn, these tensions – with different impacts on interest rates, exchange rates and activity, depending on their nature – could affect the behavior of the financial system, mainly due to their possible repercussions on the dynamics of the local financial intermediation process and the credit risk assumed by banks.

iv. Potential impact of financial innovations on the financial system at the global level in the medium term. Financial innovations (fintech, techfin/bigtech) are monitored based on potential associated risk factors. On the one hand, they generate competition for banks, with eventual pressures on their sources of profitability. On the other hand, these innovations imply a greater weighting of specific risks related to the use of new technologies, such as those linked to cyberattacks (see Section 2). More recently, at the international level, the potential implications that a scenario of rapid expansion of the use of digital currencies by the private sector – in particular, the so-called stablecoins – could have for the traditional financial system, as well as for the global conditions of financial stability (see Section 3), have begun to be monitored.

The following section presents an assessment of the main sources of vulnerability for the financial system (based on its exposures to intrinsic risks), identifying those particular characteristics of strength that the sector has to face eventual materialization of adverse scenarios. Other topics of financial stability are addressed below, and at the end the macroprudential policy actions adopted recently are analyzed.

3. Vulnerabilities and specific resilience factors of the financial system

3.1 Bank funding

A certain materialization of the risk factors raised in the last IEF tested the conditions and funding structure of the local banks as a whole. In this context, and given the current prudential regulatory framework, the sector’s specific resilience elements acted as expected. The possibility that new episodes of tension in anchoring in the short term cannot be ruled out.

In a context of weak economic activity, depreciation of the exchange rate and outflow of deposits in foreign currency after the PASO, the size of the balance sheet of the financial system was reduced in relation to six months ago and in a year-on-year comparison. The sources of funding (liabilities plus net worth) of the aggregate of banks decreased 14.6% in real terms in the last six months, mainly due to the outflow of foreign currency deposits from the private sector and, to a lesser extent, due to the performance of deposits in national currency from the public and private sectors.

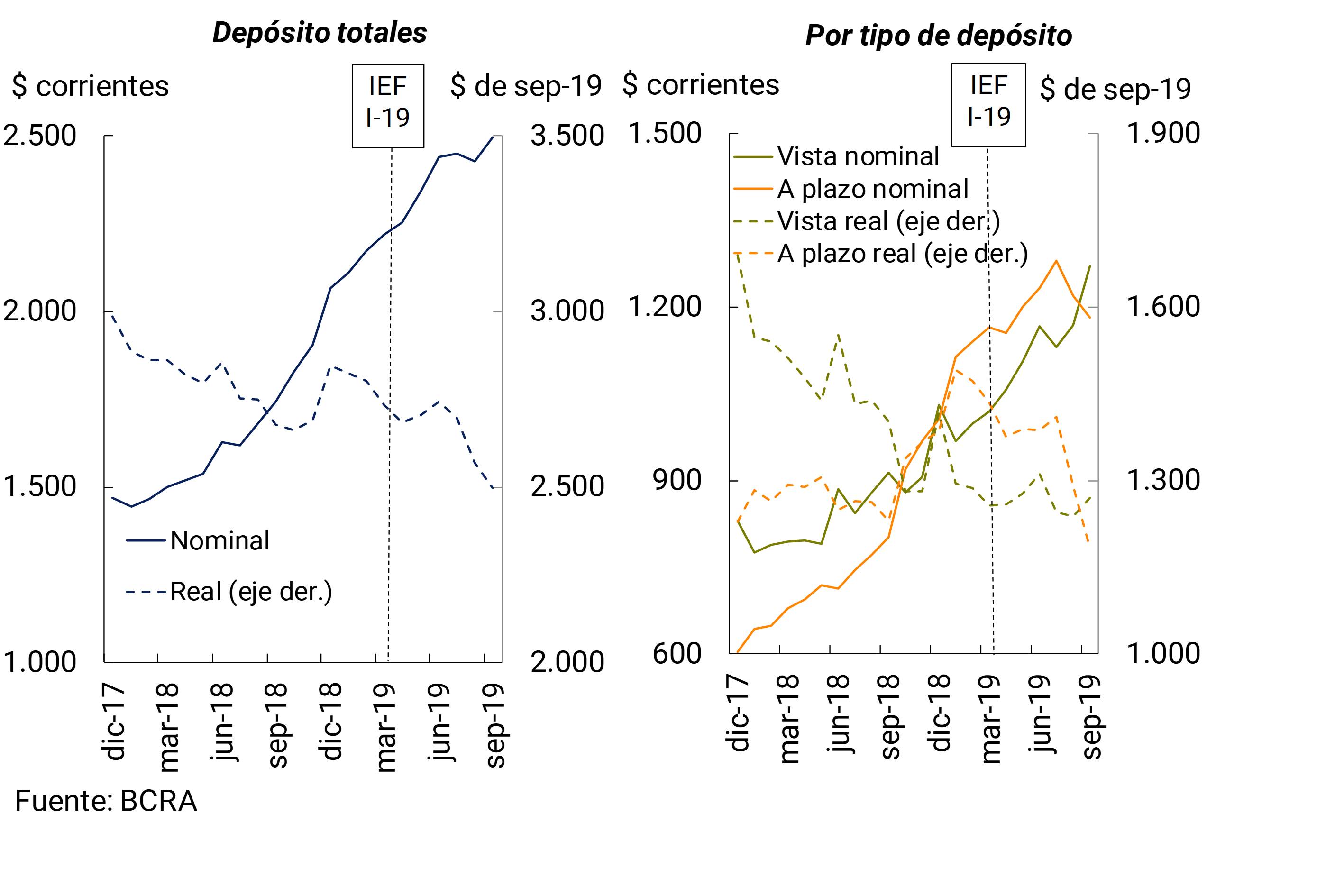

The reduction of foreign currency deposits in the private sector began in mid-August – after the PASO – (see Section 4). The balance of deposits of households and companies arranged in foreign currency accumulated a fall of approximately a third of the total observed prior to the PASO until the end of September15, after increasing 11% in the first 7 months of the year – both values in currency of origin. For its part, the nominal balance of deposits in national currency of the private sector increased 12.5% in the last six months (-8.7% in real terms) (see Chart 4), mainly due to the performance of demand accounts.

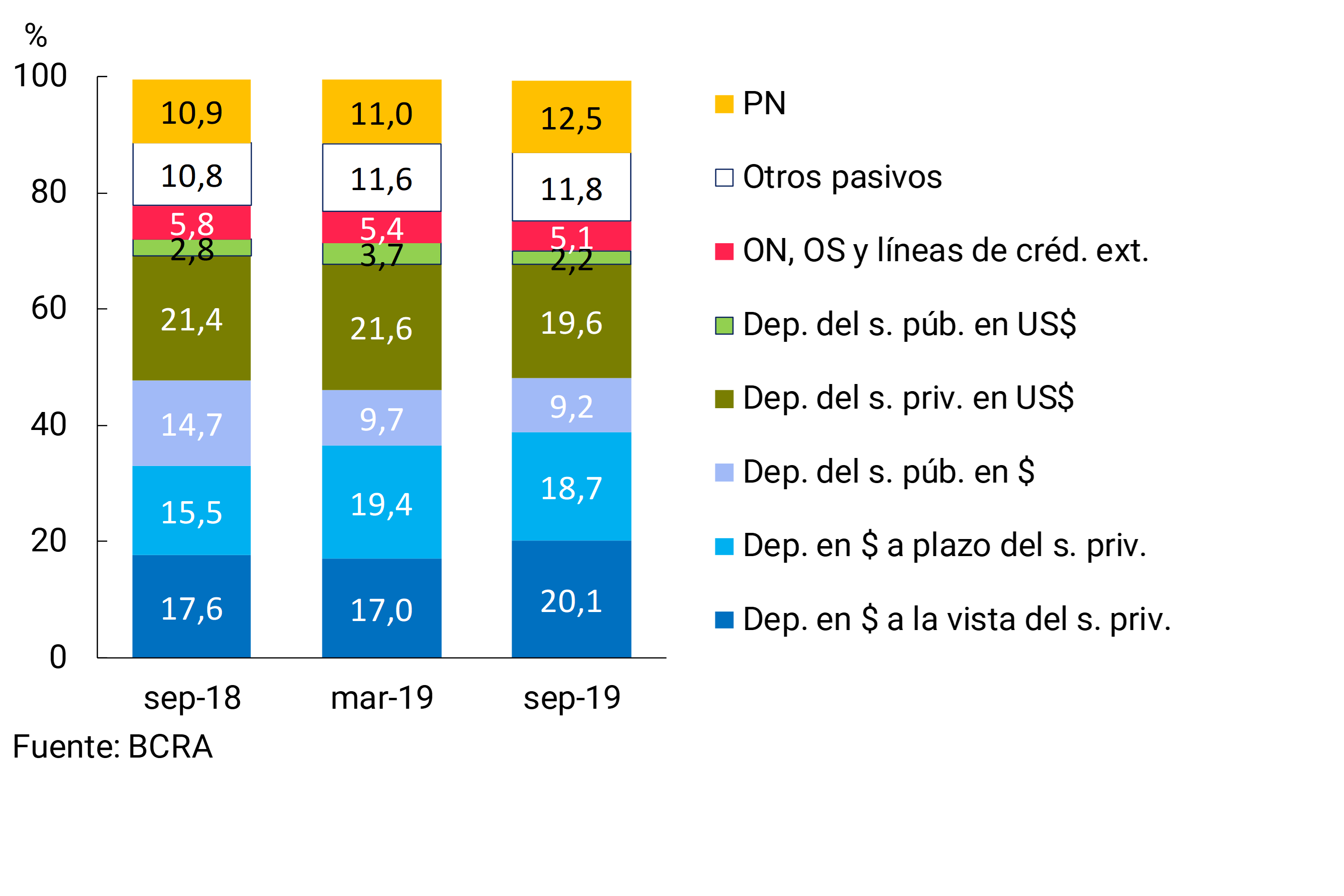

The changes detailed above in the main sources of funds of the banks modified part of their funding structure, although more traditional instruments such as deposits and equity continue to predominate (see Chart 5). With respect to IEF I-19, deposits in foreign currency lost weight in total funding (-2 p.p. in those originating in the private sector, and -1.5 p.p. in those of the public sector). On the other hand, as of September, private sector demand deposits in national currency and net worth gained weighting in total funding compared to March, growing 3.1 p.p. and 1.4 p.p., respectively.

3.1.1 Specific elements of resilience

Historically high levels of liquidity. As detailed at the beginning of this Chapter, bank liquidity is at historically high levels. Liquid assets in the broad sense in national currency stood at 57.9% of deposits in the same denomination as of September, far exceeding the average of the last 15 years (38.3%), and only 1.8 p.p. lower than the level of the first quarter of this year. The liquidity ratio reached 56.9% of deposits in the foreign currency segment, similar to the level of the IEF I-19. All groups of banks increased year-on-year in their ample liquidity indicators (considering national and foreign currency), reaching 46.2% in public entities, 68% in domestic private entities and 63.9% in foreign private entities.

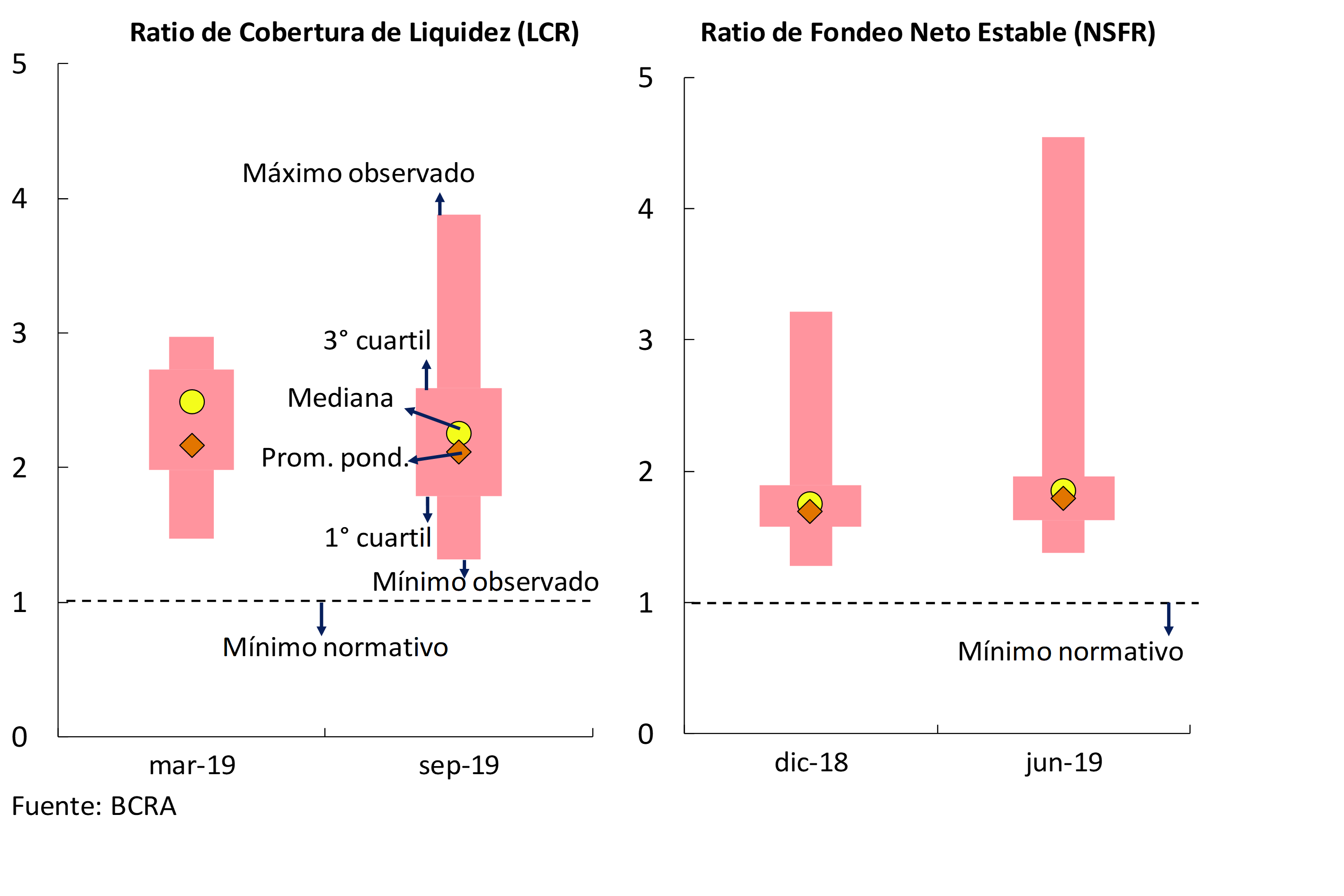

The liquidity indicators derived from the international recommendations of the Basel Committee comfortably exceed the established regulatory minimums. The Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), which assesses the liquidity available to face a potential outflow of funds in a possible stress scenario, totaled 2.1 at the aggregate level in September, well above the regulatorily-mandated minimum (equal to 1 as of 2019) (see Chart 6). The level of this indicator showed no change from last March’s record. All financial institutions that must comply with this requirement (belonging to Group A)16 presented values above the regulatory minimum. Similarly, in the middle of the year, the Stable Net Funding Ratio (NSFR) of the aggregate of banks – aimed at assessing whether entities have a funding structure in line with the business they are engaged in – was above the local regulatory minimum (equivalent to 1 since its implementation in 2018), and the value recorded at the end of 2018. The NSFR level for the aggregate of local banks is one of the highest values when compared to other emerging and developed economies (see Chart 7).

Graph 6 | Basel liquidity ratios

Distribution of obligated banks (Group A according to

Com. “A” 6608)

Figure 7 | Stable Net Funding Ratio – International Comparison

Segmentation of operations in national and foreign currency. Since 2002, the framework of macroprudential policies has been in force, which, on the one hand, establish that funds raised in foreign currency can only be used for applications in foreign currency to debtors with income from foreign trade operations and related activities. On the other hand, it determines that, in the event of surplus resources in foreign currency, they must be kept liquid. These regulations help the financial system to better manage the risks associated with episodes of stress that include high exchange rate volatility (see Section 4).

Limited exposure to the risk of term mismatch. The financial system continues to exhibit a reduced transformation of terms, focusing mainly on transactional activities. In a context of lower financial intermediation with the private sector, it is estimated that in the first part of 2019 – June latest information available – the average maturity of the active investment portfolio in national currency of the banks as a whole fell by about 2.5 months to just over 8 months, while the duration of liabilities in the same denomination that do not have market value went from 4.3 months to 3.6 months months.

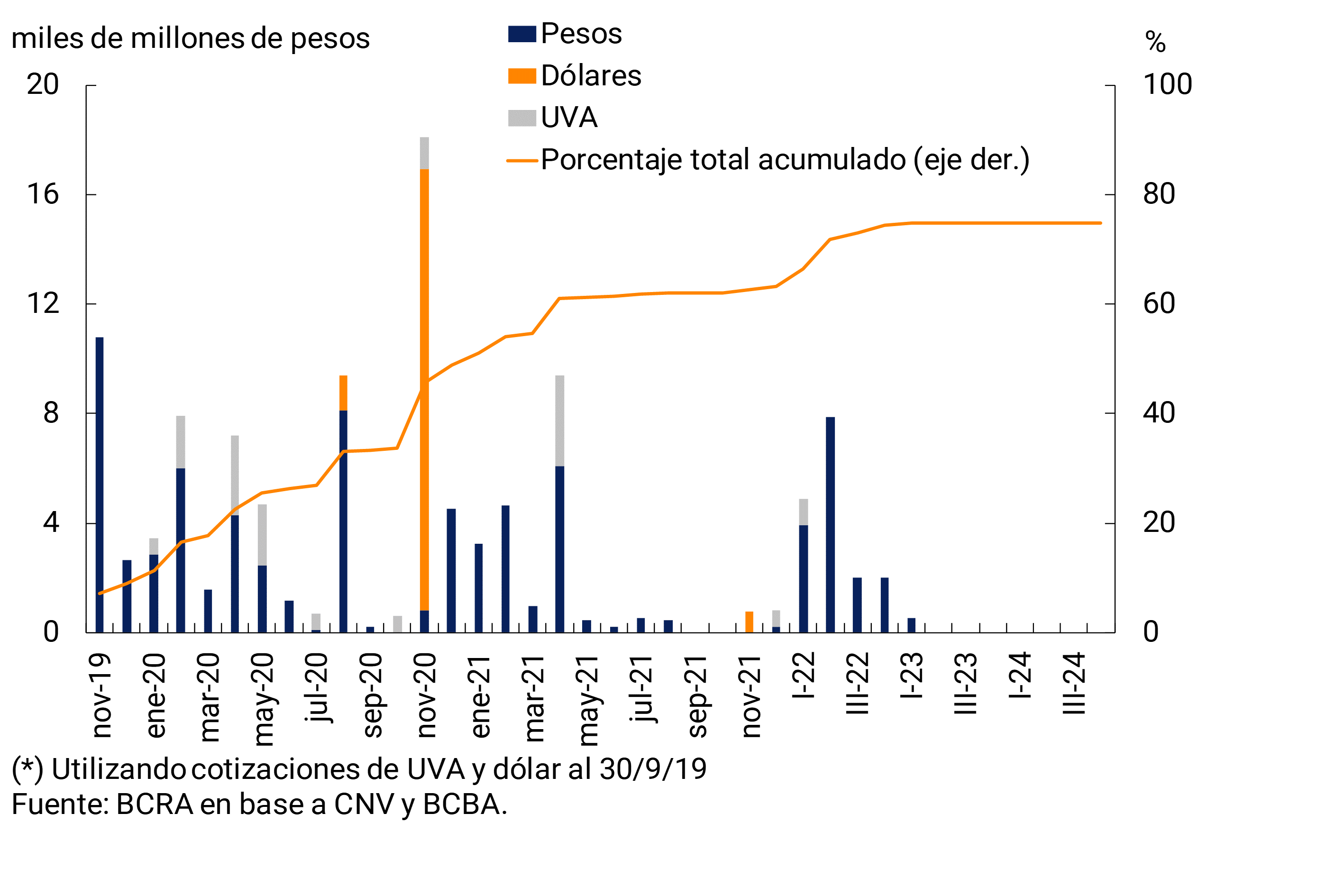

Low risk of funding refinancing through negotiable obligations (ON). The maturities of ON during the next few months are moderate for the aggregate of the financial system. Between November 2019 and March 2020, about $26,400 million in principal payments of these instruments denominated in pesos from bank funding mature, representing almost 18% of the total balance of ON in the sector at the end of October, and being equivalent to only 0.6% of total deposits at the same date (see Graph 8). The outstanding balance of these payments, as of the second quarter of 2020, is also mainly denominated in domestic currency (55% of the total). Among the outstanding commitments in foreign currency, the one corresponding to the end of 2020 stands out. It should be considered that since the publication of the last IEF, banks have repurchased ON in the markets for a total of $7,300 million. 82% of this amount was verified from the primary elections in a context of greater volatility, falling prices of species and increase in the cost of future payments committed by the conditions of issuance.

Banking safety net. The local financial system has had deposit insurance for more than two decades17, a tool that seeks to protect private sector savings in the financial system. The maximum guarantee per customer is $1 million, with the exception of those deposits that do not meet certain conditions in terms of agreed interest rates18. Banks allocate 0.015% of the monthly average daily balance of these deposits to the Deposit Guarantee Fund (FGD) on a monthly basis. As a result, as of September 2019, the balance of the DGF’s available resources amounted to 3.6% of total deposits, almost 3 times higher than the 2010 record. In addition, the BCRA is the lender of last resort in national currency – windows for liquidity provision – a tool that has not been necessary to use in recent years.

3.2 Loan portfolio performance

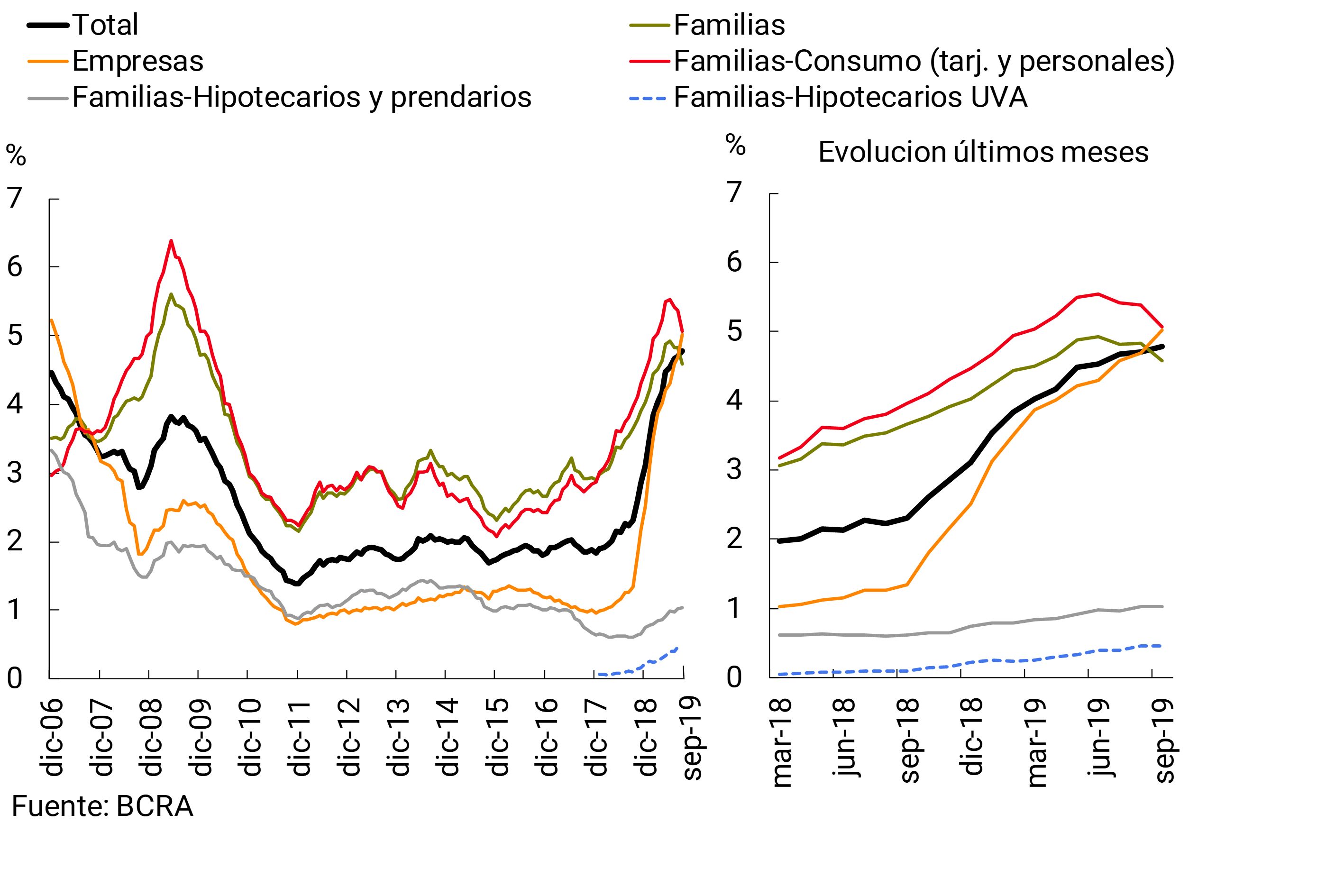

Until the third quarter of 2019, the degree of materialization of credit risk had a limited effect on the solvency of the financial system, while maintaining aggregate coverage levels with forecasts providing additional systemic resilience. In recent months, the rate of increase in the non-performing loan ratio of total credit to the private sector has moderated (see Chart 9), reaching 4.8% as of September. This performance occurred in a context of weakness in economic activity (and some acceleration of the inflationary records of August and September), with a real fall in the balance of credit to the private sector and a real increase in the balance in an irregular situation.

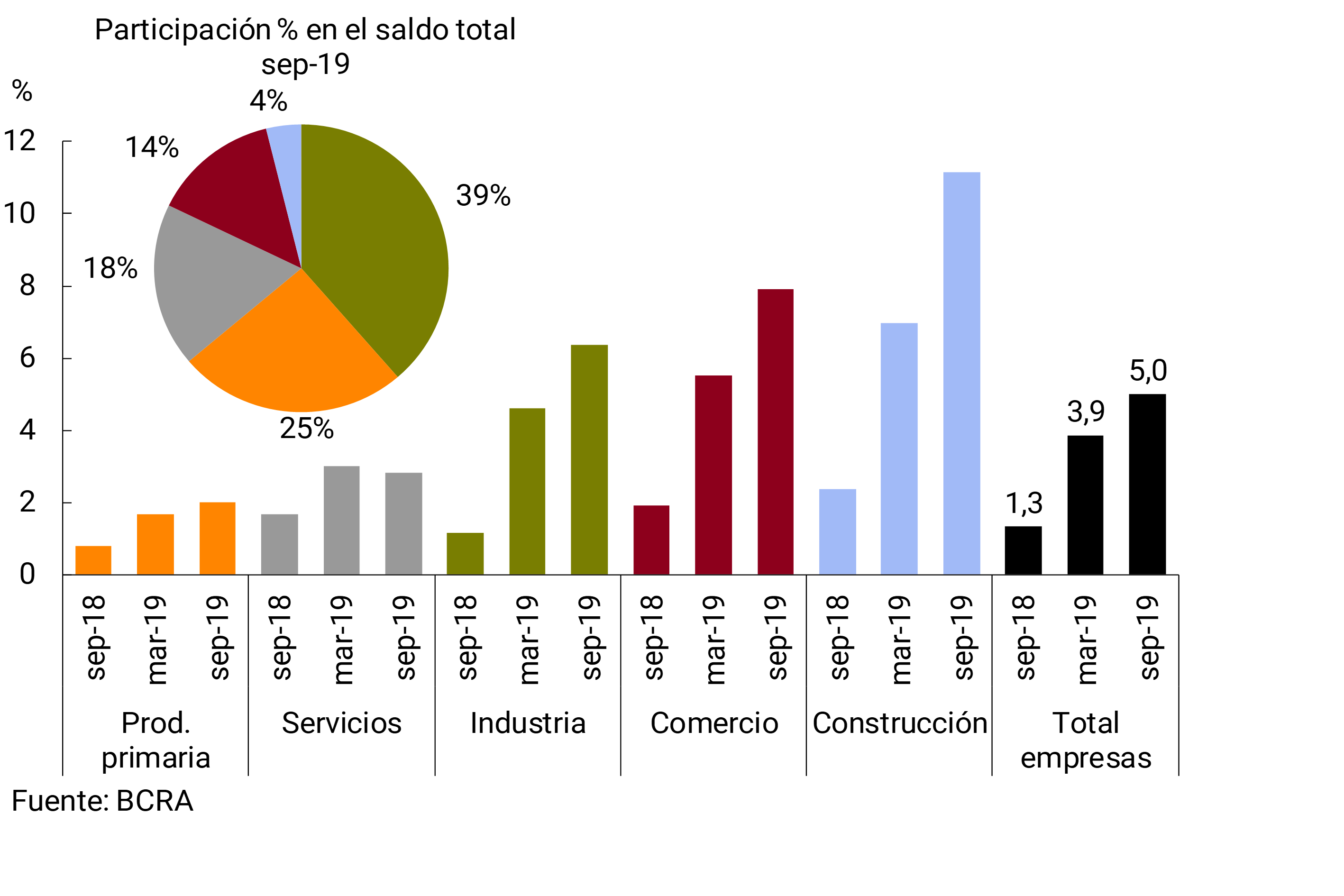

The increase in the irregularity ratio was mainly due to the behavior recorded in the corporate financing segment, particularly in the construction and commercial sectors, although these are segments with a relatively small share of the total balance (see Chart 10). For its part, the increase in non-performing loans to households was more moderate and with a slight reduction in the last three months. Within this set of loans, mortgage loan lines maintain a lower delinquency rate (irregularity ratio of 0.46% for those granted in UVA and 0.83% for the rest as of September 2019).

Figure 10 | Irregularity of lending to companies by activity

Irregular financing / Total financing (%) – Financial system

On the other hand, the indicators that seek to capture the magnitude of the migration of debtors to worse credit situations continued at high levels, although lower than those recorded during the previous IEF. In particular, the ratio for estimating the probability of default of private sector credit subjects exceeded the average of recent years at the end of the quarter, although it fell when compared to six months ago, both in companies and in households (see Chart 11)19.

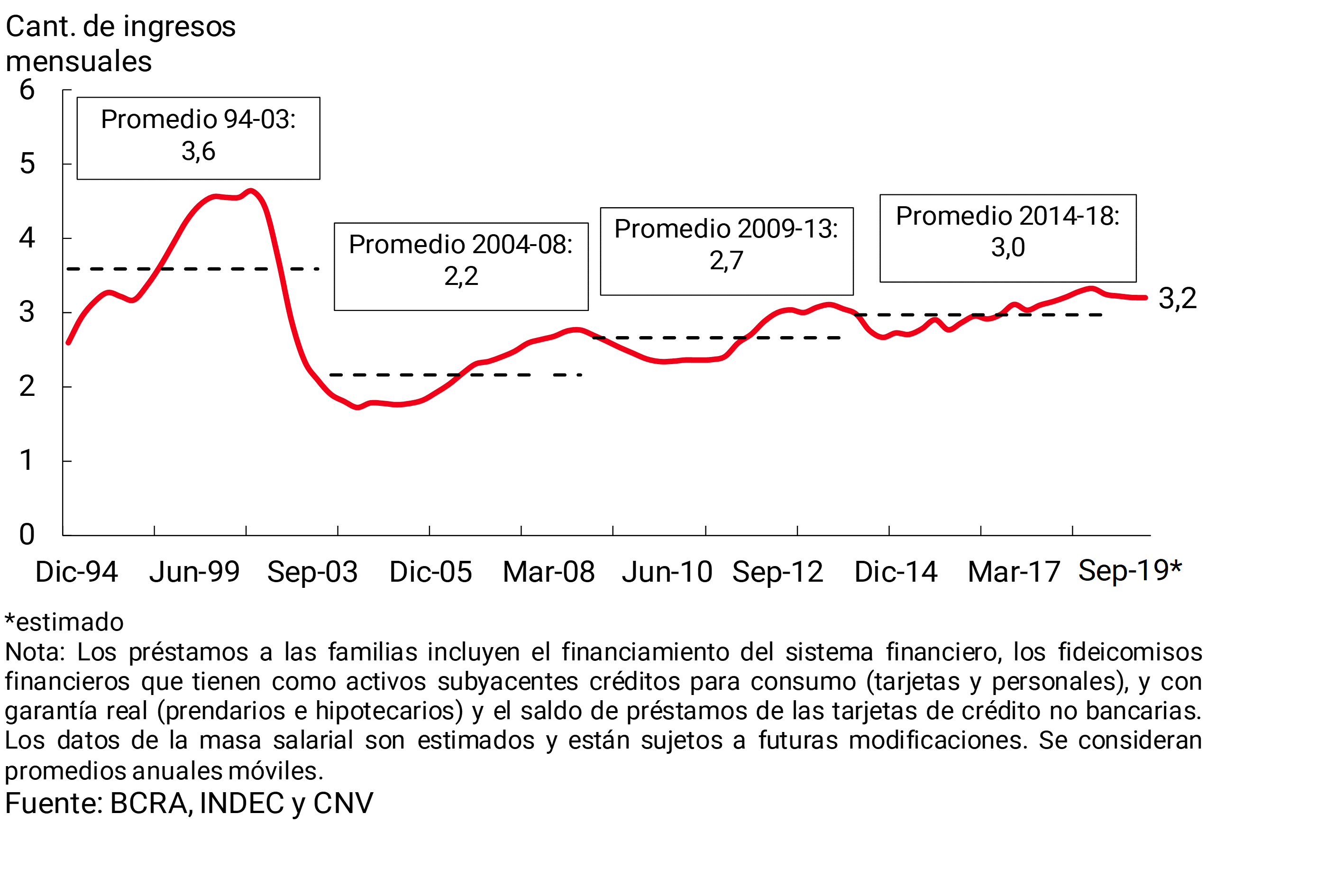

It should be noted that the performance of the credit portfolio of the financial system occurs in a general framework of limited levels of indebtedness and financial burden of the private sector. It is estimated that household debt represented approximately three monthly incomes from this sector as of September 2019, with a reduction in recent quarters (see Graph 12). This value was in line with the average of the previous five years (2014-2018). Households also maintained a very low level of indebtedness from an international perspective: it totaled 6.6% of GDP in the third quarter of 2019, below the average for the region (21%) and other developed economies (81%)20. At the aggregate level, the financial burden of household debt remains moderate in an international comparison21.

Figure 12 | Household debt – In terms of the amount of monthly income (Wage bill net of contributions and contributions)

With respect to the corporate sector, the aggregate debt burden is also relatively low in terms of GDP. Although the proportion of those with some signs of vulnerability increased among publicly offered companies22 in the second quarter of 201923, the links between this segment of the corporate sector and banks are limited. Bank loans to firms considered to be more relatively vulnerable – within the group with public offerings – represent less than 2% of total bank loans to companies in the middle of the year. Depending on the evolution of the exchange rate and interest rates so far in the second part of the year, some deterioration in the financial indicators for this sample of companies could be expected, which would eventually put pressure on their ability to pay. However, at the end of the third quarter, banks maintained a comfortable level of forecasting of the total portfolio in an irregular situation, combined with a moderate gross exposure to credit risk.

3.2.1 Specific elements of resilience

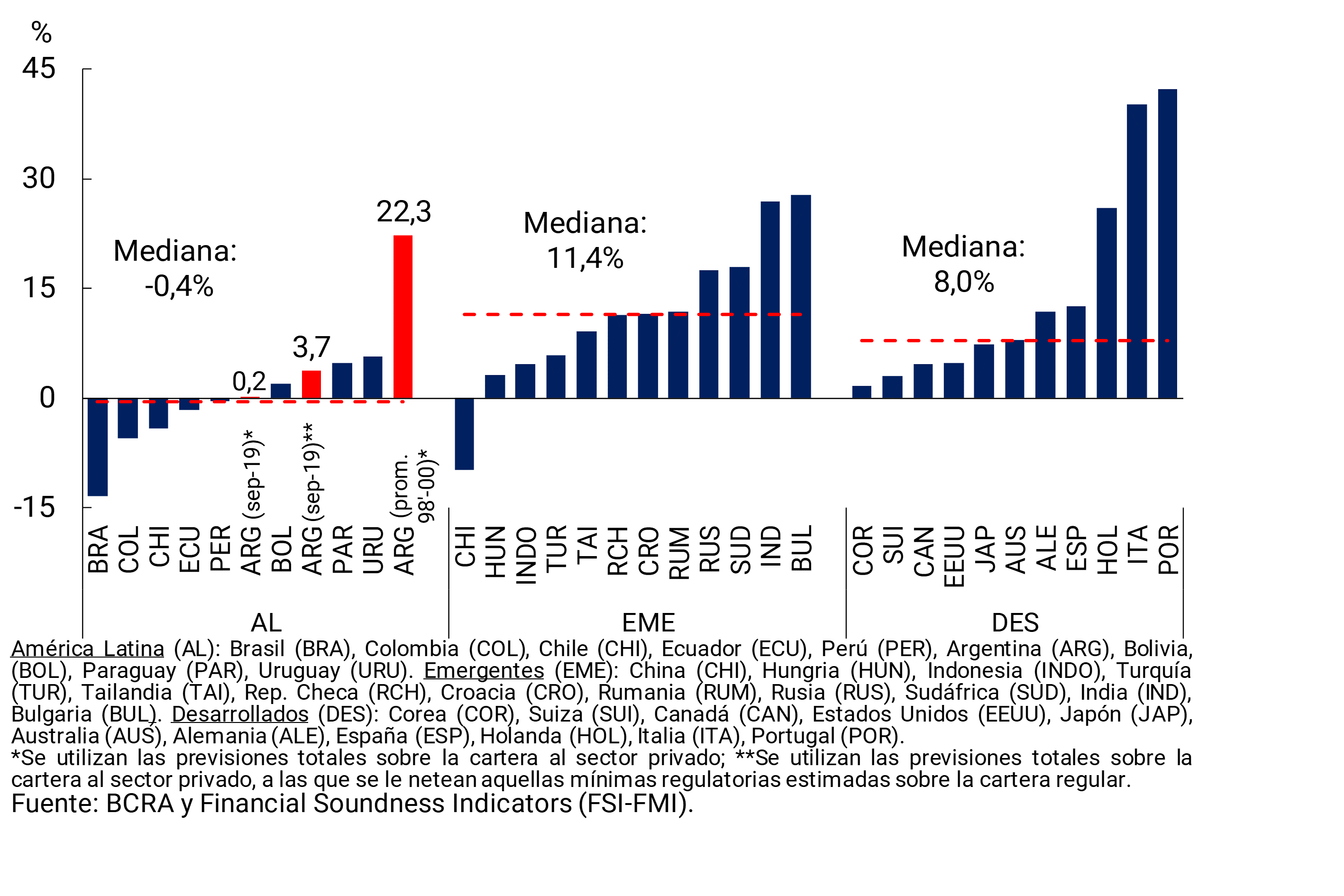

Moderate equity exposure to credit risk to the private sector. The financial system’s gross credit exposure to the private sector remained moderate at the end of the third quarter (see section on the main strengths of the financial system). In addition, the total forecast continued to be high and reached 99% of the portfolio in an irregular situation in September. This level stands at 77% if the estimation of the minimum forecasts constituted for the portfolio in a regular situation is excluded, far exceeding the minimum regulatory requirement (49%)24. Given the capital levels of the Argentine financial system detailed above, the private sector’s equity exposure to credit risk – an irregular portfolio net of capital forecasts – remained limited in the aggregate of banks, with ratios that are in line with those of the region and below those of other emerging and developed economies (see Chart 13).

Diversification of the debtor portfolio of financial institutions. The concentration of the portfolio of debtors in the aggregate financial system is moderate and similar to that verified 10 years ago, although it registered a slight increase in recent months. In this regard, the Argentine regulatory framework has a set of rules that seek to promote the diversification of the banks’ debtor portfolio, while the BCRA periodically monitors the levels of debtor concentration from a systemic perspective (see Section 5).

In the last stage of higher credit growth (2017 to mid-2018), prudent credit origination standards were maintained25. Financial institutions maintained a precautionary bias during the last stage of financing growth, partly reflecting the BCRA’s prudential regulations and its commercial practices.

Limited exposure to the public sector of the financial system and limited foreign currency mismatches of banks and their debtors. The macroprudential regulation in force on these aspects contributed to the resilience of the aggregate of banks in the face of a challenging local scenario (see Sections 1 and 4).

3.3 Financial intermediation

The financial intermediation of the banks as a whole with the private sector has been reduced since the publication of the IEF I-19, accompanying the local context of weakness in economic activity that, according to REM analysts, would begin to recover next year (although more slowly than previously expected). In this context, the nominal profitability of the aggregate of banks remained at positive values26 and limited leverage and comfortable levels of solvency were maintained.

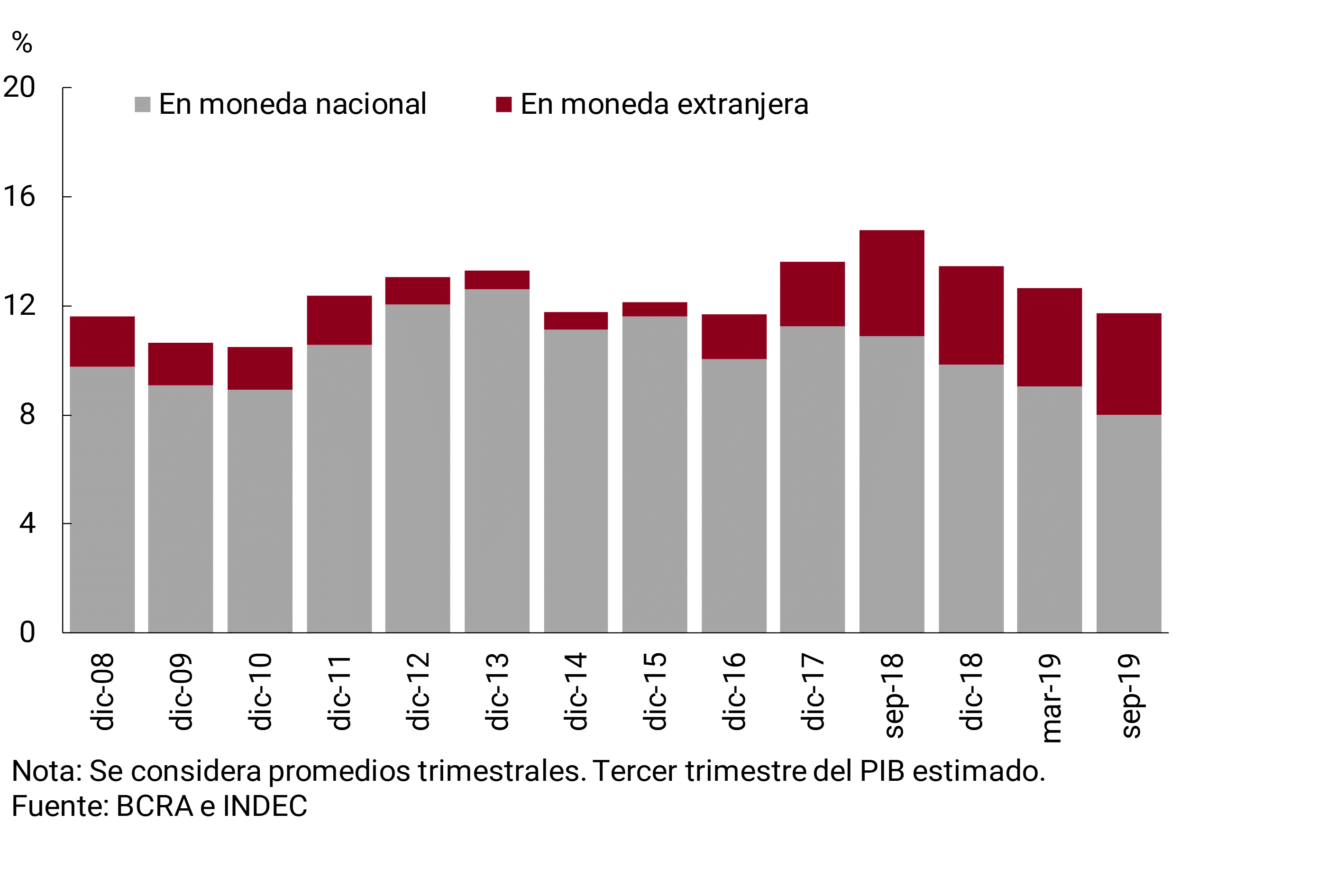

The balance of credit in national currency channeled to companies and households decreased in real terms since the release of the IEF I-19 (-9.8% between the end of March and September 2019 and -27.7% y.o.y.). Meanwhile, the balance of loans in foreign currency to the private sector also contracted, mainly since the PASO (-17.6% in the last two months and -15.1% y.o.y. —in source currency—). As a result, total financing to the private sector – including domestic and foreign currency – fell to 11.7% of GDP at the end of September 2019 (-0.9 p.p. compared to the level of the first quarter of the year), mainly due to the behavior observed in the segment in pesos (see Chart 14).

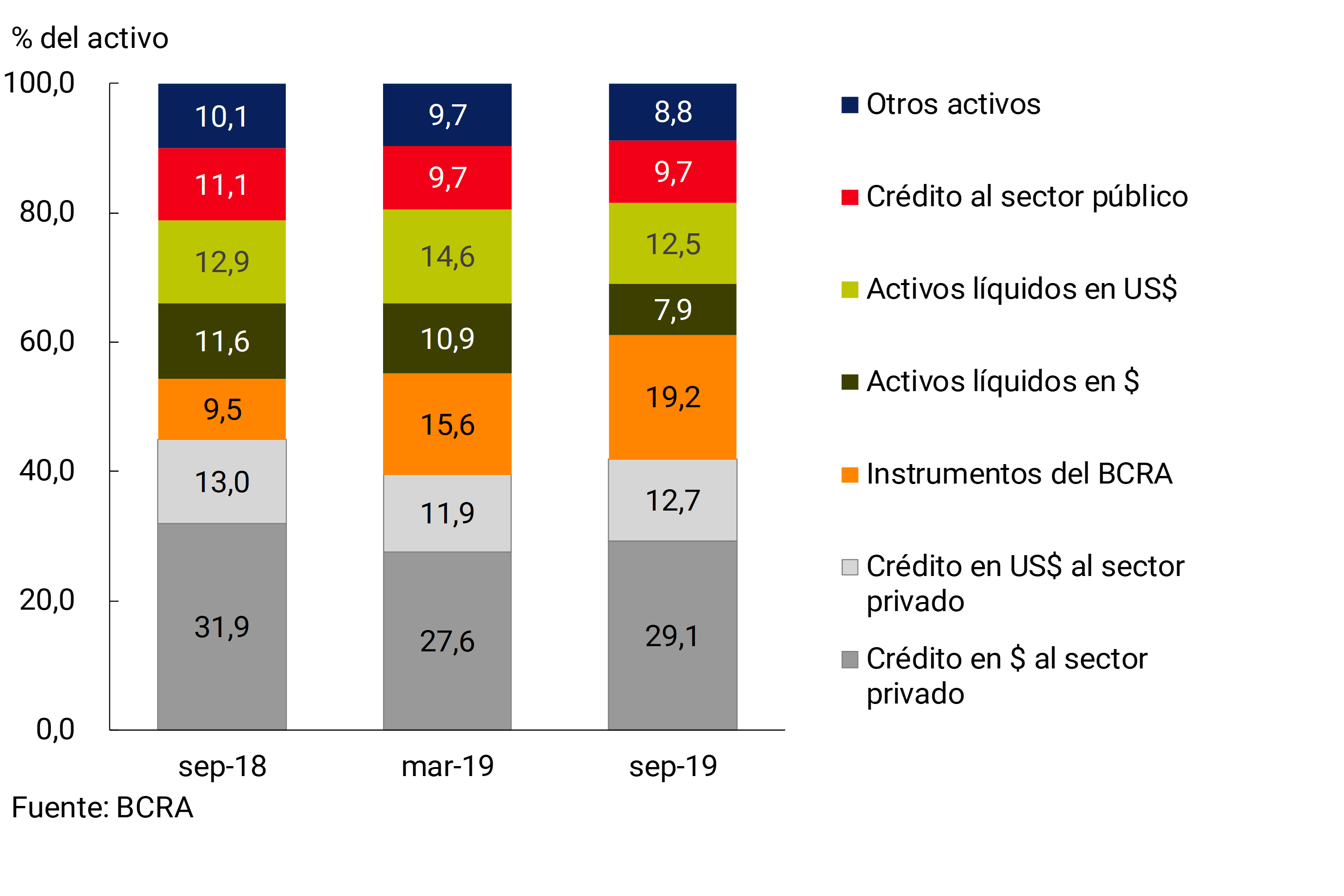

In this context of a real fall in credit to the private sector, in the last six months the total assets of the financial system fell even more (-14.3% in real terms)27. This led to a slight increase in the weighting of credit to the private sector in total assets with respect to IEF I-19. On the other hand, liquid assets (availabilities and current account) in foreign currency reduced their relative importance in total assets (see Chart 15). With respect to liquid assets in pesos, the current accounts at the BCRA and the other availabilities of the entities verified a lower weighting, an evolution that was offset by the increase in the holding of monetary regulation instruments. This evolution reflected, in part, the effect of the regulatory changes implemented by the BCRA in terms of the Minimum Cash regulations (see Regulatory Annex). Credit to the public sector in relation to the assets of the aggregate of banks remained at low levels, without significant changes compared to the first quarter of the year (see Section 1).

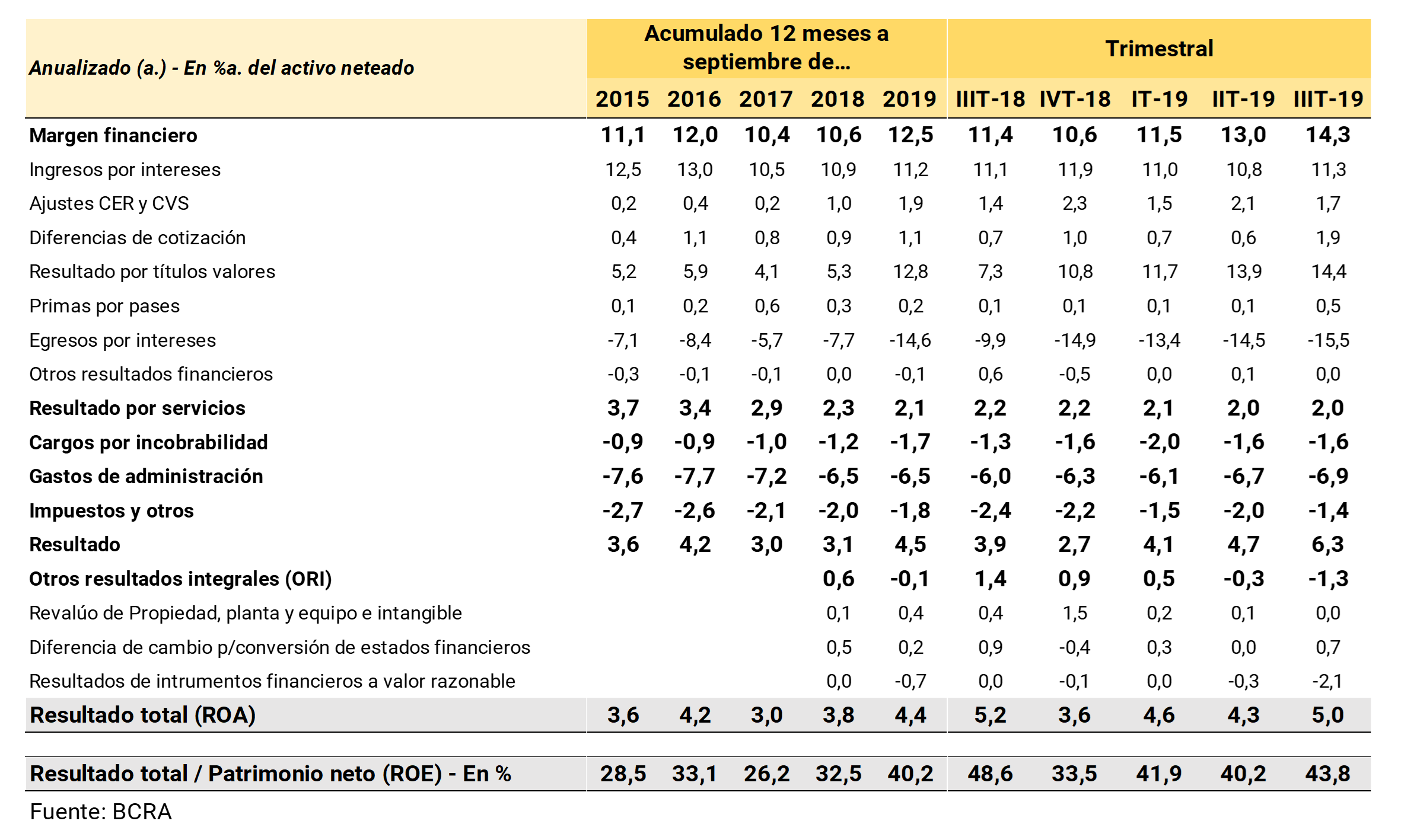

The nominal profitability of the financial system remained positive since the publication of the last IEF (see Table 2). In particular, in the third quarter of 2019, the nominal results of the banks as a whole stood at 5% annualized (y.) of assets or 43.8% y. of equity, slightly above the levels of the first quarters of the year. This performance was mainly reflected in domestic private banks and public banks, while in foreign private banks nominal profitability declined compared to the first quarters.

When comparing the nominal return of the third quarter of the year with that of the first two quarters of 2019, higher results were verified by securities (mainly due to the flows accrued on the portfolio in local currency, within the framework of increases in the interest rate of the LELIQ) and increases in gains due to exchange rate differences (from the effect of the increase in the peso-dollar exchange rate on the aggregate positive differential between assets and liabilities in foreign currency), while interest income did not show any changes in magnitude (in a context of an increase in implied interest rates and a fall in the share of credit in total assets). These variations were partly offset by an increase in interest outflows, mostly linked to a rise in the cost of funding in the segment in pesos28, and by a reduction in results for services in a context of lower activity. In addition, the fall in the prices of financial assets – affected by the turbulence of recent months – was mainly reflected in the accrual of losses in other comprehensive income (ORI) on the portfolio accounted for at market price.

Bad debt charges were down slightly from the peak recorded in the first quarter of the year, although they remained at high levels compared to previous years. Meanwhile, administrative expenses increased in the period, mainly due to expenditures not related to personnel29.

3.3.1 Specific elements of resilience

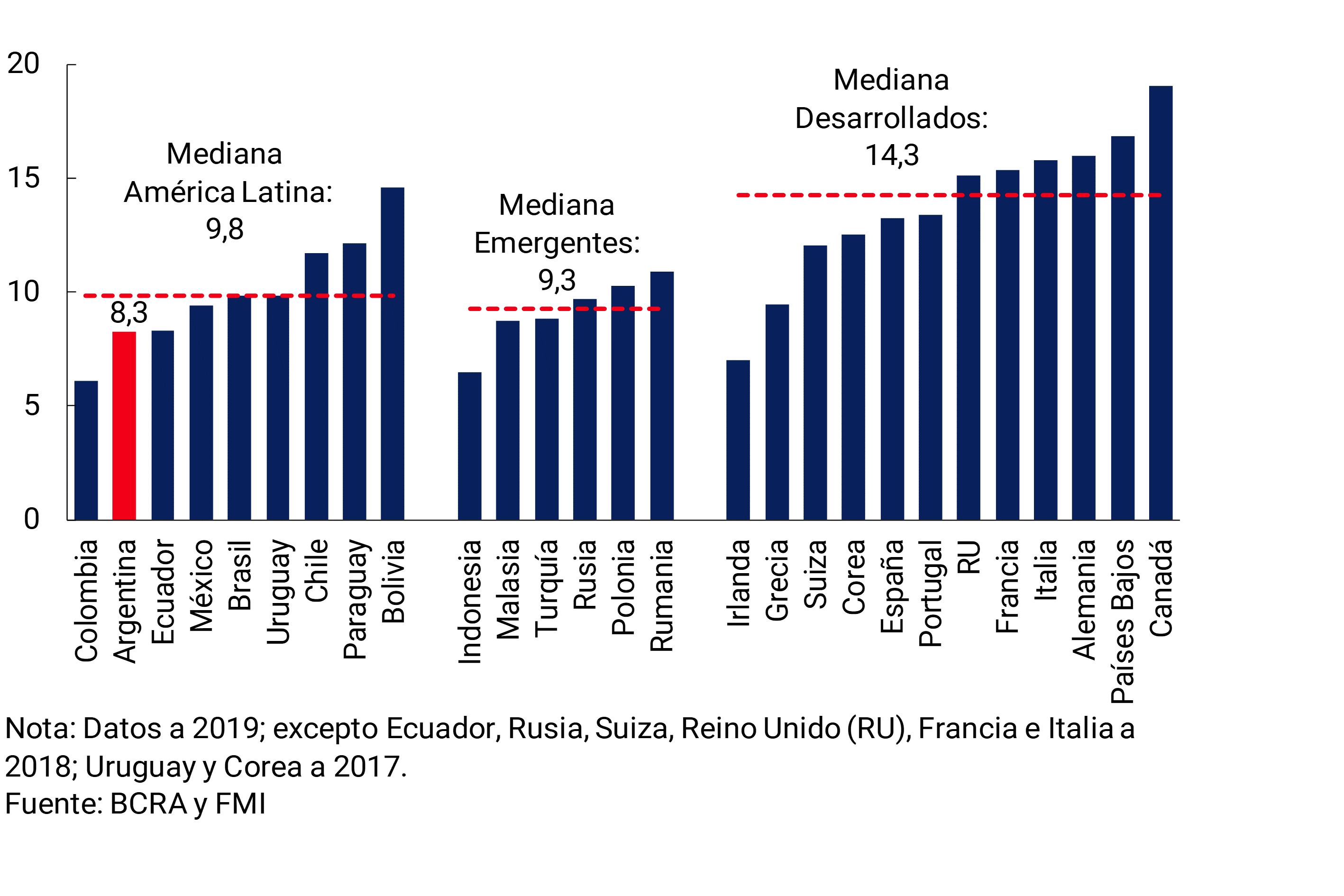

Limited level of leverage and comfortable levels of solvency of the banks as a whole. The local financial system has a low (and decreasing) level of leverage – total assets in terms of net worth – placing it below other countries in the region, and other emerging and developed economies (see Chart 16). This ratio stood at 8.3 in September, 1 and 1.2 times lower than the records of March and a year ago, respectively. In terms of the international standards recommended by the Basel Committee, the Leverage Ratio (ratio between capital with the greatest capacity to absorb losses and a large measure of exposures) reached 9.1% as of September, comfortably exceeding the local regulatory minimum of 3% (a requirement in line with international recommendations). These indicators reflect both the strength of the sector and its ability to resume the process of financing investment and consumption, in the event of a possible reversal of the economic cycle and adjustment in expectations.

The financial institutions as a whole maintained a high level of solvency, verifying large margins of capital conservation and systemic banks30. The PRC of the financial system stood at 16.3% RWAs in September, slightly increasing compared to the March level (+0.3 p.p.).31, with a nominal increase in the PRC greater than the nominal increase in RWAs32. The PRC in terms of the minimum prudential capital requirement accounted for 184% for the financial system in September. Tier 1 common equity, which reflects the greater capacity to absorb losses, accounted for 88% of the total PRC. The aggregate amount of Tier 1 common capital that each entity allocated to cover the capital conservation margin represented 90% of the level required for the capital conservation margin.

4. Other topics of stability of the financial system

4.1 Systemically important banks at the local level

The macroprudential risk monitoring approach recommends special monitoring of certain local entities with systemic characteristics, taking into account the importance of their size, their degree of interconnection, complexity, and degree of substitution of their activities33. If any of these entities eventually had difficulties in fulfilling their functions, it could generate an impact of systemic dimensions for the economy.

As of September, the entities that make up the group of D-SIBs together represented just over half of the assets of the local financial sector. They verified the totality of the specific additional capital margin defined since 201634, while observing soundness indicators in line with those of the system’s aggregate. In particular, the integration of capital in terms of RWAs of this group of banks was similar to that of the financial system, while liquidity levels were also high. The irregularity ratio increased with respect to the last IEF, as did the equity exposure to credit risk, although these indicators are lower than those recorded by the aggregate system (see Table 3).

4.2 Interconnection in the financial system

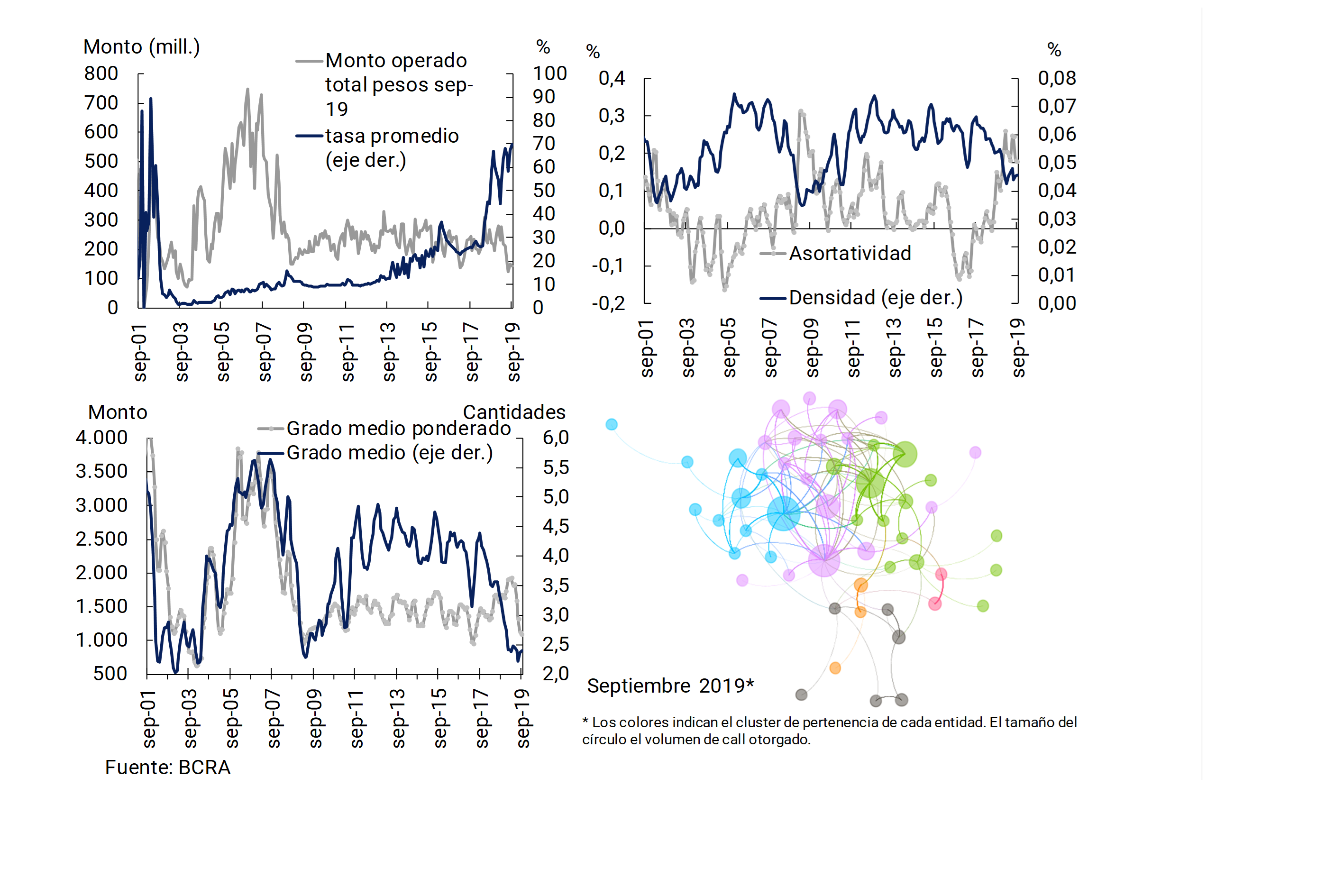

In the context of recent financial volatility, there was an increase in interest rates in the call market, a widening of the spread with respect to the LELIQ interest rate and a reduction in the (real) amounts traded in this market.

Analysis of a broad set of network metrics suggests that the degree of interconnection through the35 call market decreased over the past six months. From a systemic risk perspective, in the face of an eventual materialization of risks, a lower interconnection between financial institutions could be associated with a relatively less rapid, more limited situation of the spread of the shock.

In particular, for the call network, both the density and the average grade decreased with respect to what was observed in the IEF I-19 (see Graph 17)36. In the same sense, the37th assortativity of the network was located in positive values and higher than what was recorded six months ago, suggesting that the entities connect with those of a similar degree. Compared to other periods of volatility, the decline in interconnection is more moderate up to September 2019 (e.g., compared to the period associated with the global financial crisis of 2008-2009)

5. Main macroprudential policy measures

As detailed in IEF I-19, in recent years a broad set of macroprudential policy tools has been implemented to prevent different sources of systemic risk that could adversely affect the Argentine financial system. In recent months, modifications were made to part of the existing macroprudential regulations and new ones were incorporated.

On the one hand, it was established that since 2020 Group “A” banks whose parent company is a holding company (not a financial institution), must comply with the rules on “Minimum capital of financial institutions”, “Large exposures to credit risk”, “Liquidity coverage ratio” (LCR) and “Stable net funding ratio” (NSFR) on a consolidated basis (including the holding company and all subsidiaries engaged in financial activities, excluding insurance companies)38.

On the other hand, in order to maintain exchange rate stability and protect savers, the National Executive Branch (PEN) and the BCRA recently took a set of measures. A limit was set on banks’ foreign currency cash position (4% of the previous month’s PRC or the amount of US$2.5 million, whichever is greater). In addition, modifications were introduced in the rules governing the foreign exchange market, establishing a set of parameters for income and expenditure in this market, maintaining full freedom to withdraw dollars from bank accounts and without affecting the normal functioning of foreign trade. In addition, the deadlines for settling the collections of exports of goods were modified and resident legal entities were authorized to buy foreign currency without restrictions for the import or payment of debts when due and, with the agreement of the BCRA, to acquire foreign currency for the formation of foreign assets, to transfer profits and dividends abroad and to make transfers abroad. Meanwhile, it was provided that individuals do not have any limitation to buy up to US$10,000 per month by debit from a bank account, a limit that was reduced to US$200 per month at the end of October.

In line with the above, and continuing with the assessment made explicit in the previous edition of the IEF, the BCRA decided to maintain the required level of the Countercyclical Capital Margin39 unchanged (currently the coefficient is 0%). Among the main considerations underlying this decision, it is worth highlighting the validity of the current period of contraction of credit to the private sector (with a trajectory below its long-term trend) in a context of weakness in the level of economic activity, the general framework of low structural levels of indebtedness of companies and households, the evolution of the terms and conditions used by financial institutions in the generation of new financing in recent periods, and the low exposure to credit risk and current high levels of solvency of the financial system.

Paragraph 1 / Reduced exposure of the financial system to public sector risk

The exposure of all financial institutions to the public sector – at all levels – has remained at historically low values for more than ten years. This characteristic of the aggregate balance sheet of the financial system forms an element of relative strength for the sector. The low level of exposure to the public sector is partly due to a set of macroprudential regulations adopted since 2002, in particular, by those measures that seek to mitigate the vulnerabilities faced by institutions by concentrating exposure to a specific sector of the economy40. In this context, the recent liquidity tensions faced by the National Public Sector, which led the PEN to reschedule amortizations of Treasury Bills (and to advance in the coming months in the longer term obligations), did not significantly affect the liquidity or solvency of the local banks as a whole.

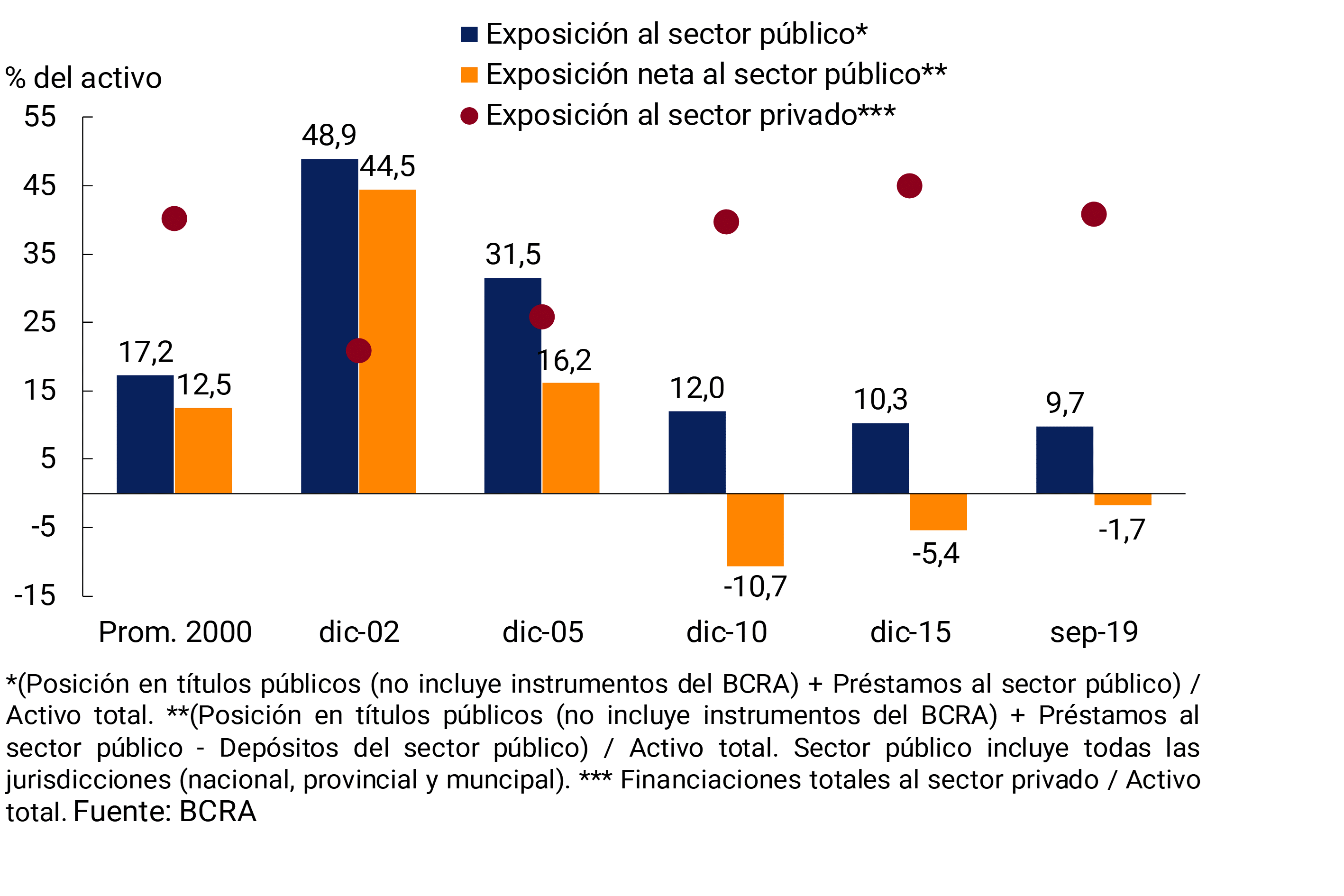

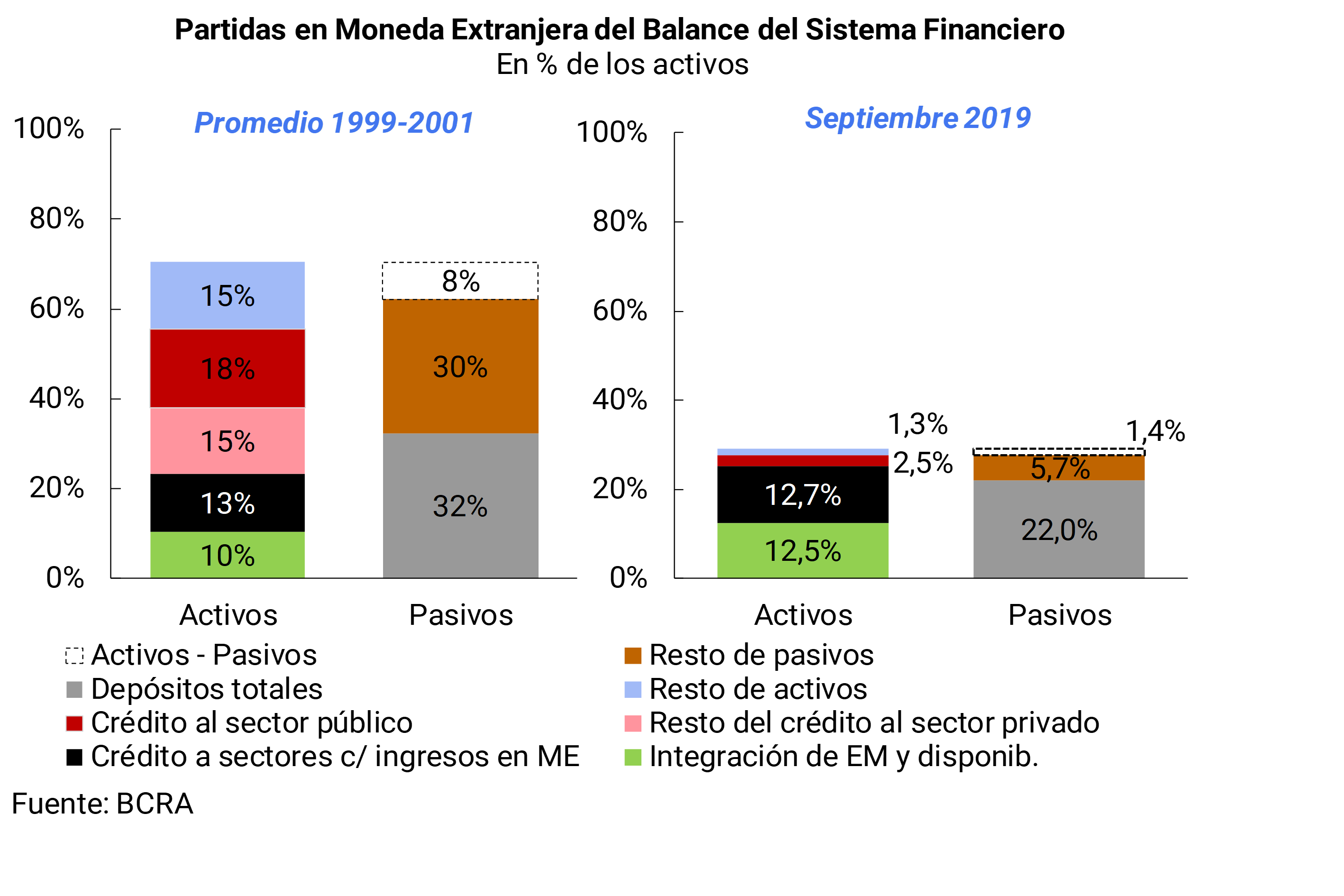

Until the beginning of the last decade, the local banking regulatory framework did not have maximum limits on financing to the public sector41. While this situation was in line with international recommendations on the matter, it left aside the unique characteristics and challenges that developing economies generally face. In the case of Argentina, partially due to the impact of an adverse international scenario during the second part of the 1990s, the exposure of the financial system to the public sector began to increase steadily. At the beginning of the last decade, and partly as a result of the measures taken after the exit from the convertibility regime42, almost half of bank assets were accounted for by securities and loans to the public sector (see Figure A.1.1), almost tripling the share of financing channeled to firms and households.

In order to reactivate the process of intermediation of the economy’s savings towards the financing of household production and consumption, as well as to avoid new episodes of over-exposure of the balance sheet to a specific type of debtor, as of 2003 the BCRA incorporated limits on the exposure of financial institutions to public sector risk. The explicit requirement of authorization by the BCRA for some types of financing was even implemented. The aforementioned limits considered both the aggregate financing to the public sector in terms of the assets and capital of financial institutions, as well as their composition by level of government jurisdiction43.

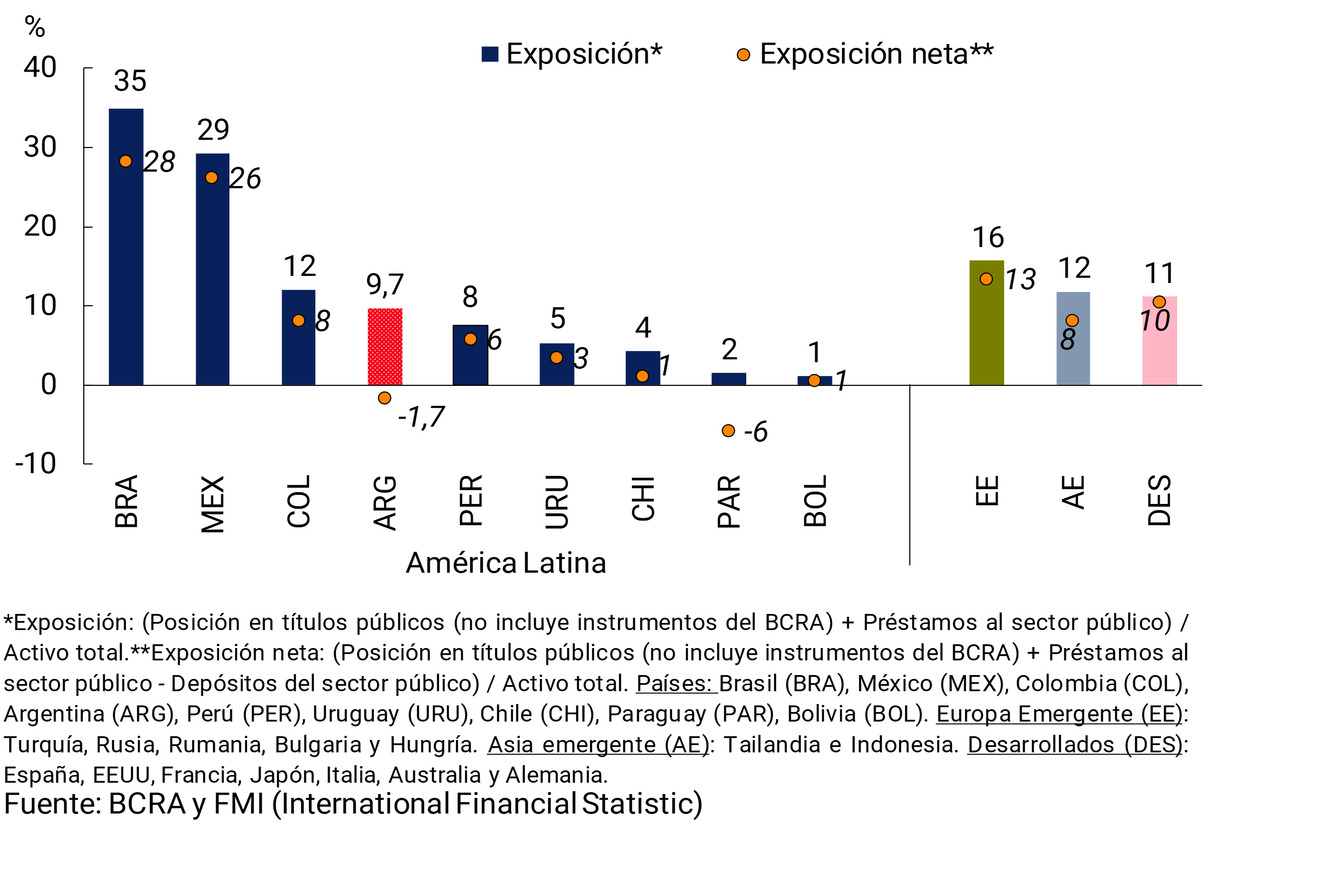

As a result, in the middle of the last decade the financial system began a path of reducing its exposure to the public sector, a behavior that was registered in all groups of banks (national, foreign and public private). Thus, Argentina’s macroprudential regulations made it possible to achieve a financial system with a low dependence on the public sector, below that observed in other emerging and developed economies (see Figure A.1.2)44.

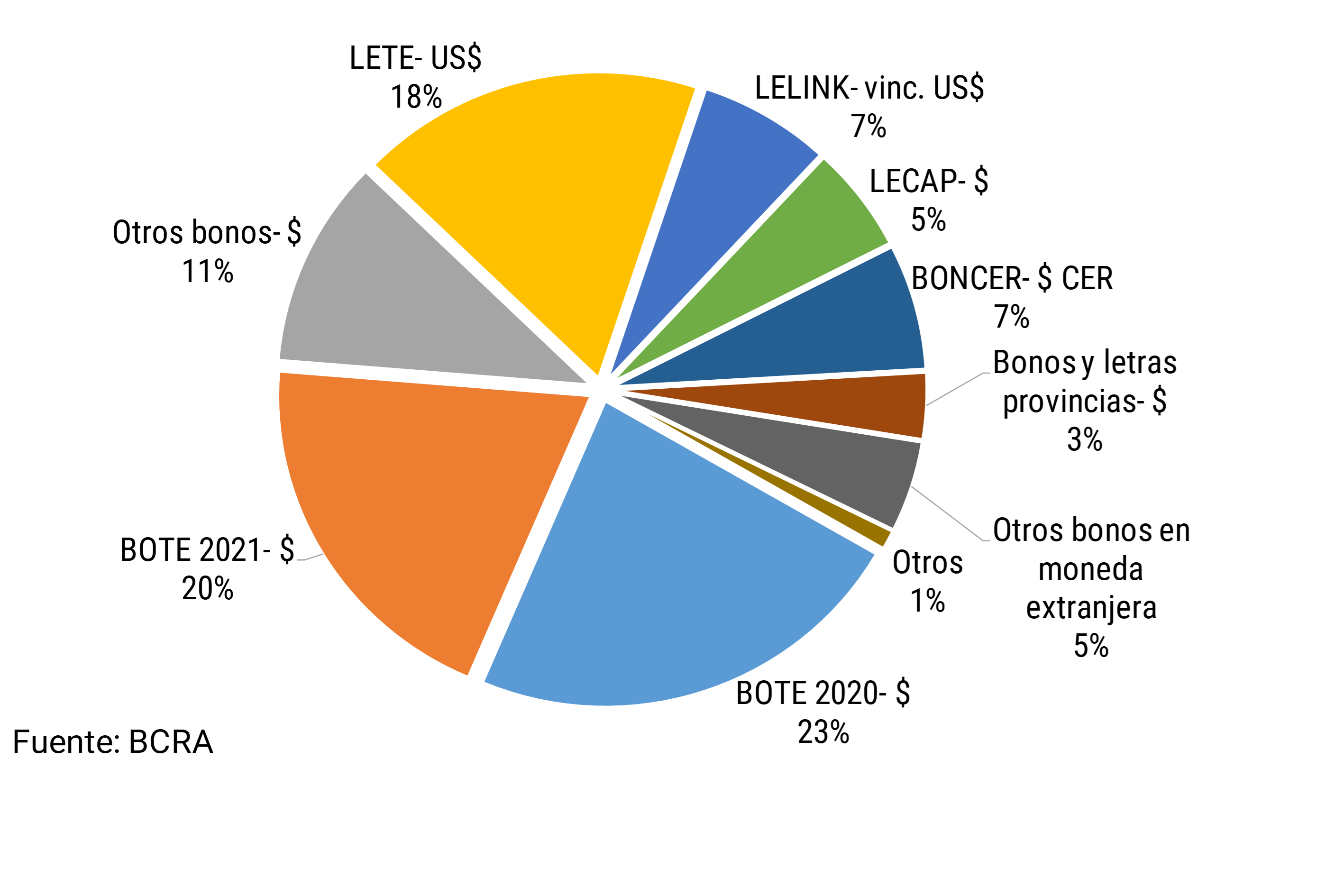

When analyzing the exposure of the aggregate financial system to the public sector, it is observed that just over 90% is made up of the portfolio of public securities, with the rest being loans channeled to different government jurisdictions. It should be noted that more than two-thirds of the securities portfolio—book value—is made up of local currency specie (see Chart A.1.3). Among the securities in pesos, those payable in the next three years stand out, with special participation of the National Treasury Bond maturing in November 2020 (commonly called BOTE 2020), a species that financial institutions can use in their integration of the Minimum Cash45 requirements. Treasury Bills – both in dollars and pesos – whose payment profiles were rescheduled at the end of August, extending them throughout the first three quarters of 2020 (Decree 596/19) – identified in Graph A.1.3 as LETE in the case of dollar instruments, LELINK in those in pesos linked to the dollar and LECAP in those capitalizable in pesos, they represent approximately 30% of the book value of the total portfolio of securities of the aggregate of banks (equivalent to 2.6% of net assets)46. Given the characteristics of the bonds and bills in the portfolio, before the aforementioned rescheduling, almost a quarter of the value of the total portfolio (residual value) was amortized in the last four months of 2019, while in 2020 and 2021 it was about a third in each year. After the rescheduling, part of the payments from 2019 are redistributed to 2020, causing amortizations to decrease to 10% of the total by the last months of 2019 and rise to about 50% in 2020, modifying to a lesser extent the relatively comfortable liquidity position of the aggregate of financial institutions47 (see Section on main strengths of the financial system).

Figure A.1.3 | Composition of the portfolio of public securities in the financial system

Book value as of August 2019

In perspective, the sound macroprudential policies implemented by the BCRA in terms of financing the financial system to the public sector in the last seventeen years have contributed to the maintenance of relatively adequate patterns of diversification in their loan portfolio, helping to limit potential sources of systemic risk and increasing the degree of resilience in the face of a more challenging local scenario.

Section 2 / Second cyber exercise carried out in the financial system

Digital transformation promotes the use and adoption of innovative financial services and products, which provide a positive perception in the user experience. However, these services can bring with them new security risks that could become, under certain circumstances, incidents that can unexpectedly and suddenly affect the stability conditions of a financial system, with an impact on the real sector of the economy.

As detailed in IEF II-18 (Section 4), a large number of digital incidents have been known in recent years, which caused both direct and indirect economic damage to financial institutions. In this context, international organizations began to promote, on the one hand, the adoption of good practices regarding the prevention, detection and monitoring of security incidents, promoting the attention and early detection of problems of this origin. On the other hand, and in view of the increasingly likely occurrence of incidents of these characteristics and origin, progress was also made in the implementation of actions to prepare financial regulators and supervisors so that, in the future, they can respond quickly to a possible incident and have adequate recovery mechanisms in place.

Within the framework of these last actions, one of the most recommended activities at an international level is the performance of tests or trials, also known as cyber exercises, to test the levels of preparedness of the existing processes aimed at responding to and achieving recovery from cybersecurity incidents. The findings detected during these exercises serve as lessons to drive the updating and improvement of existing procedures, allowing the level of maturity of incident management processes to be raised, adapting them to current risks.

Along these lines, and as part of the strategy of awareness and continuous improvement of cybersecurity processes, at the end of 2018 the BCRA carried out the first cyber exercise in Argentina – of a voluntary nature – in order to obtain an overview of the local problems of cybersecurity in the field of the financial system. This allowed for a first approach to the communication, coordination and incident response capabilities of local banks. In this scenario, it should be mentioned that cybersecurity problems are not limited to technological issues, but also cross the processes of organizations and even States. In our country, during 2019, some regulations that contribute to the protection of the financial system have been sanctioned, such as Resolution No. 1523 of the Government Secretariat of Modernization, which identifies the financial sector as Critical Infrastructure. The National Cybersecurity Strategy published by Resolution No. 829, establishes in its central objectives the protection of critical infrastructures that enable the provision of essential services for society and the economy.

Continuing with the awareness and continuous improvement plan undertaken, in September 2019 the BCRA carried out a second exercise where a crisis scenario generated from a cybersecurity incident in one of the digital services provided by the system was simulated. The purpose of the proposed scenario was to obtain a preliminary diagnosis regarding the level of preparation, communication, and coordination existing in the financial system in the event of a cybersecurity incident that had the potential to affect local financial stability conditions.

In this second cyber exercise, a set of financial institutions participated that were selected based on their systemic importance from the point of view of the local financial market. Each bank was represented by a team of technicians – from different internal areas – whose purpose was to emulate the actions that would happen in the event of having to face a real incident. In part, the aim was to raise awareness among the participants that this practice is not merely an issue linked to computer aspects, but that several areas of the entities would be involved. On this occasion, members of the National Cybersecurity Committee were invited to participate as observers.

The design of the exercise allowed all participants to share their reflections after each of the stages, self-assess their own incident response and recovery processes. Likewise, the event enabled the regulator to identify specific needs for improvement regarding the coordination and communication circuit in the event of incidents, aiming at its effectiveness and efficiency. In this sense, the exercise has been useful to identify and propose the definition of formal processes aimed at providing timely attention and preventive action in the face of cybersecurity incidents.

As part of the BCRA’s strategy, it is proposed to continue organizing activities that help raise awareness, identify and advance cybersecurity risks that may pose a risk to local financial stability conditions.

Section 3 / Stablecoins. Progress and implications for financial stability

The rapid development and incorporation of new technologies, coupled with changes in consumer preferences, are a challenge for traditional financial and payment service providers. Among the most recent technological advances are digital assets, instruments that are beginning to be driven by both Central Banks and the private sector. In particular, among the recent developments in the private sector are so-called stable cryptoassets or stablecoins.

While there is no commonly accepted definition of a stablecoin, it is typically characterized as a type of cryptoasset of private origin48, designed to maintain a stable value relative to another asset, typically a fiat currency, a commodity (such as a commodity), or a basket of assets49,50. The issuance of a stablecoin would be in the hands of centralized private actors. Thus, it would resemble commercial banks (secondary creators of money), and would be distinguished from first-generation cryptoassets (e.g., bitcoin and ether) and a central bank digital currency (CBDC) whose issuance is carried out in a decentralized manner and by central banks, respectively.

Under certain circumstances, these stablecoins could reach a global scale (GSCs)51. These innovations give rise to various questions about their implications for the traditional monetary-financial system. Among others: how do traditional means of payment evolve, compete and coordinate with respect to these new instruments, and what are the potential implications from the point of view of financial stability? This Section seeks to begin to outline some considerations on this last point52.

International forums began to monitor the implications and risks of cryptoassets in general and stablecoins in particular. In general terms, these organizations tend to indicate that although stablecoins do not yet represent a source of financial risk at a global level, they may reach it in the not too distant future53. Given that some of the stablecoin initiatives are being carried out by technology companies with massive international reach (BigTech)54, they present a considerable probability of scaling globally suddenly, making it necessary to monitor them adequately and in a timelymanner55. Recently, the Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors of the G20 countries asked the IMF, together with other international organizations, to continue advancing in the monitoring and analysis of the potential risks that stablecoins can entail at the global level56.

The current discussion on stablecoins identifies several dimensions that are still in the process of being defined. Its design could include details regarding the type of backup, the form of validation of operations, the degree of anonymity, the type and scope of access to users, among some relevant aspects.

In relation to backing, stablecoin initiatives could make explicit whether the total issuance or only part of it is covered. If they are not fully backed, they could resemble bank deposits in a fractional reserve scheme. Regarding the mode of validation of transactions, like cash or CBDCs57, with a stablecoin it could be transferred between parties (peer-to-peer) without the need for a third party to act as an intermediary. In this sense, the scheme for validating transactions is not yet clear, which could be centralized or decentralized. If a decentralized process is chosen, distributed network technologies (DLT), initially linked to the first generation of digital assets, could be used. In this case, the direct participation of a clearing house would not be necessary. If the validation is centralized, it would be similar to the traditional process carried out by banks or payment processors in transactions using debit or credit cards, for example. In terms of the type of user access, a stablecoin could be available for both local and cross-border transactions. This characteristic becomes especially relevant when projecting the potential scale that this instrument could reach. Finally, stablecoins could be anonymous or traceable, with implications for the type of operations to be carried out.

A similar situation arises on the side of potential demand for a stablecoin. In principle, the main determinants of this are identified as the value of the services provided in terms of speed and ease (usability) to make payments and/or transfer money, the degree of acceptance for the purchase of goods and services and the payment of taxes, the possibility of maintaining anonymity in operations, the economic return net of transaction costs (in cases where remuneration for their possession is contemplated) and the risk perception of the instrument, which will depend on the structure of its offer.

The characteristics that a stablecoin finally assumes will affect the demand for current means of payment and, consequently, the financial and monetary conditions of both emerging and developed economies. Under certain supply characteristics, an increase in the relative demand for stablecoins could decrease the demand for traditional means of payment such as cash or bank deposits. In addition, in the event of a possible loss of confidence regarding a stablecoin whose backing in fiat currency or assets does not correspond to the total issued, sudden outflows of deposits of these stable assets could take place. This situation could generate stress events with characteristics similar to those that occur during an outflow of bank deposits.

Stablecoins may involve additional risks, especially for emerging economies. For example, under a certain macro-financial context, in a developing economy the existence of a stablecoin pegged to a foreign currency could result in relatively more volatile demand for local-currency-denominated assets, particularly banknotes and bank deposits. This circumstance could have a certain impact on the country’s monetary and financial stabilityconditions 58. In particular, certain vulnerabilities to episodes of nominal and external account stress could be aggravated, constituting an additional channel for capital outflows.

In this scenario, in October 2019 global leaders agreed that the challenges and risks of global stablecoin initiatives should be properly assessed and addressed before they go live. In this sense, it is essential to advance in the analysis of appropriate designs, as well as in the examination and eventual implementation of a regulation that is clear and proportional to the risks they represent. Thus, the regulatory response is expected to consider cross-border issues taking into account the perspective of emerging and developing economies (G7, 2019; G20, 2019)59.

Section 4 / Macroprudential regulations in Argentina that promote the resilience of the system in situations of uncertainty

Since 2002, local authorities have made progress in modifying the existing regulatory framework on the financial system, seeking to encourage a modality of intermediation of resources in which exchange rate fluctuations have the least possible adverse effect on the assets of its participants (depositors, debtors and banks) and on the economy as a whole. The spirit of the regulatory changes was based on the separation of foreign currency transactions from those in domestic currency. This contributed to the system adequately going through the recent events of greater uncertainty.

In order to address possible vulnerabilities associated with situations of exchange rate stress, since mid-2002 it was established that deposits in foreign currency could only be used by banks to finance debtors with income from foreign trade operations and related activities60. This macroprudential measure sought to limit banks’ exposure to the credit risk component related to the impact that eventual fluctuations in the exchange rate would have on the debtor’s balance sheet.

Although local prudential regulation already had reserve requirements on deposits, measures were promoted to strengthen liquidity risk coverage based on the experience of the 2001 crisis. In particular, it was mandatory for banks to keep available (liquid) all those resources from deposits in foreign currency that were not applied to loans in the same denomination61.

In addition to limiting the financial system’s exposure to mismatches in the debtor’s balance sheet and consolidating liquidity in foreign currency, local rules also limited mismatches in bank balance sheets. The prudential regulation on the Net Global Foreign Currency Position implemented in May 2003 is a simple measure of net exposure on banks’ balance sheets, on which minimum and maximum limits (in terms of capital level) were imposed62.

In addition, the BCRA included the risk of exchange rate fluctuations in the minimum capital regulations for financial institutions as one of the categories of Market Risk63. Thus, the risk of foreign currency positions is addressed throughout the banking business, not only trading operations, and it is required to cover with capital the eventual losses due to variations in the exchange rate according to a Value at Risk methodology with high levels of confidence.

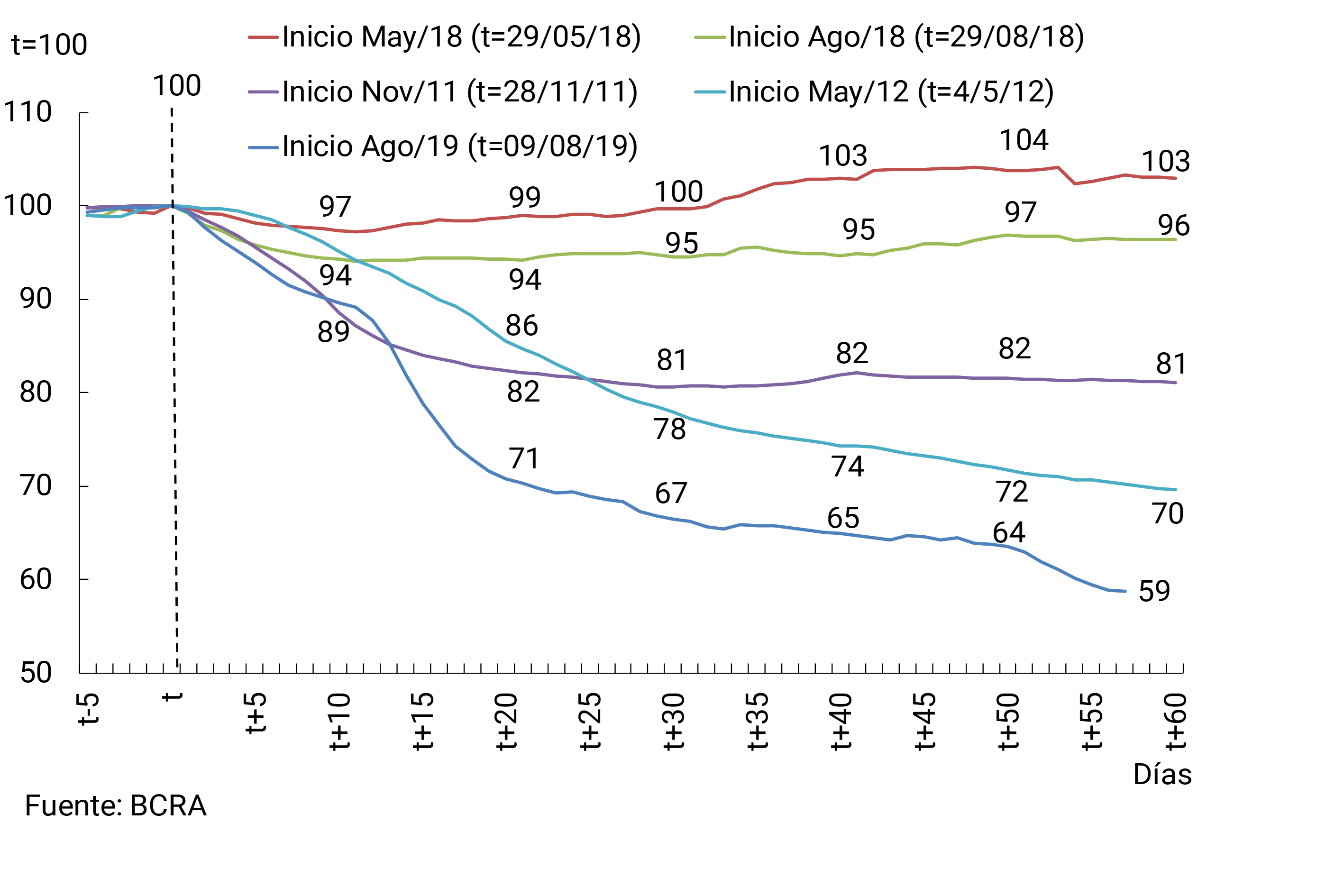

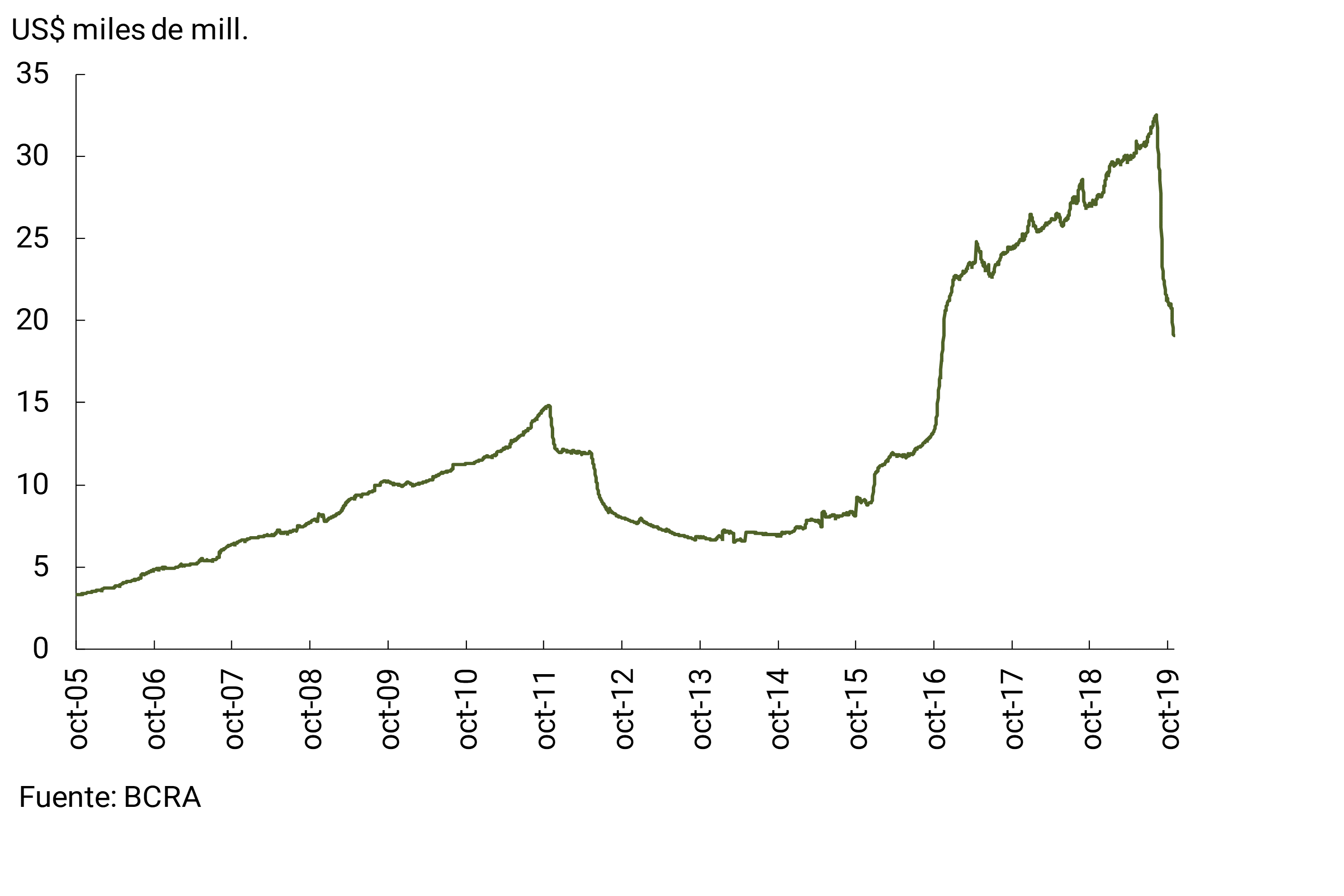

This combination of measures helped the financial system to go through periods of significant decrease in foreign currency deposits with resilience. In particular, in a context of rising exchange rates since the primary elections (08/11/2019) and greater financial volatility, the balance of foreign currency deposits of the private sector fell (see Chart A.4.1). Although this episode turned out to be one of the most acute in relation to the experience of previous years, the current balance of private sector deposits in foreign currency remains relatively high compared to the last 15 years (see Figure A.4.2).

Figure A.4.1 | Episodes of fall in the balance of private sector deposits in foreign currency – In source currency

Figure A.4.2 | Balance of private sector deposits in foreign currency

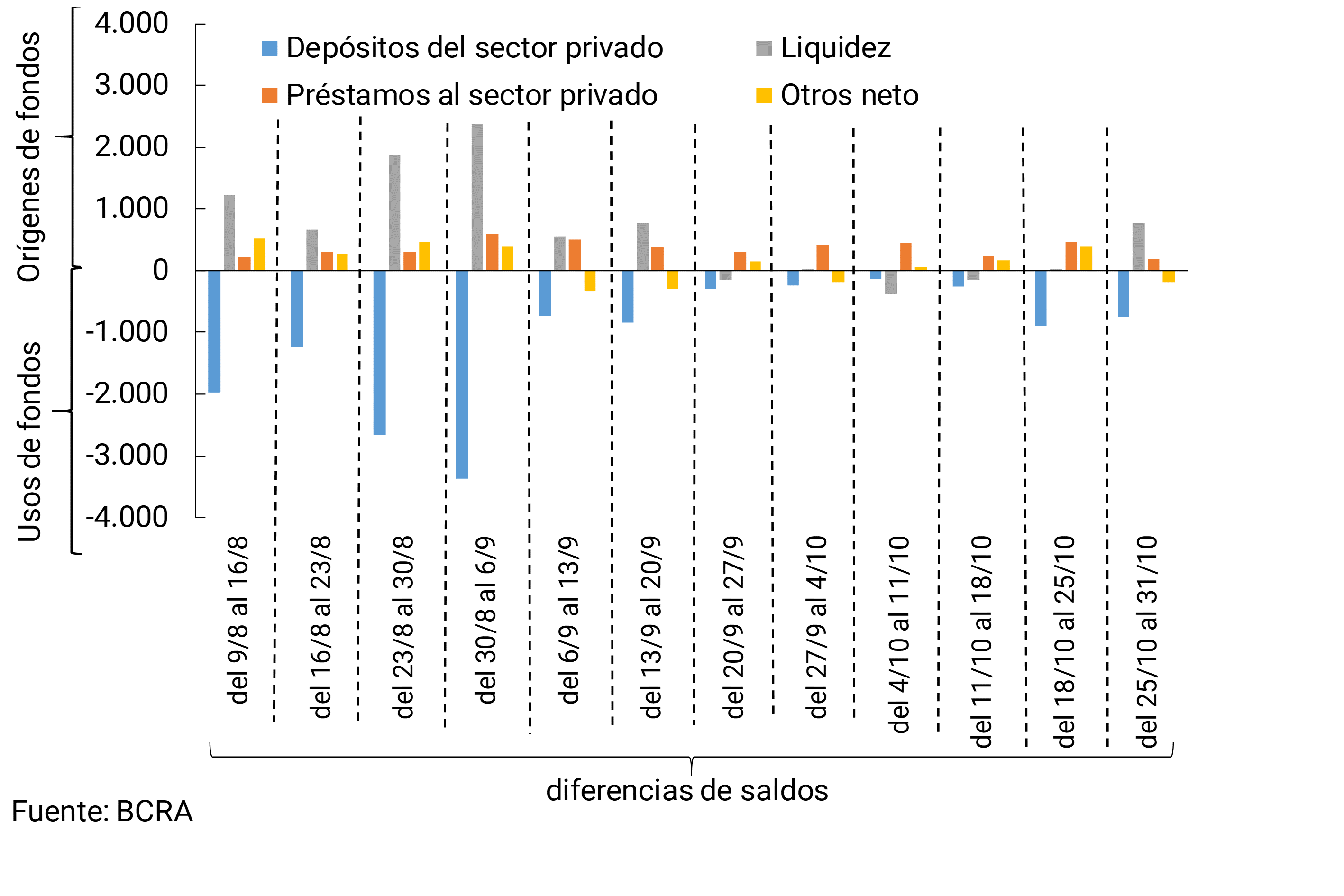

The aforementioned fall in deposits in foreign currency slowed down as the weeks went by, within the framework of the measures adopted by the Ministry of Finance and the BCRA. From the point of view of the flow of funds to the financial system, in the first four weeks the withdrawal of funds was mainly supplied with liquidity (current account resources of the entities in the BCRA and cash), while as the days went by, the funds from the collection of part of the loans in dollars to the private sector —mainly to exporters— became relevant (see Graph A.4.3)64.

Figure A.4.3 | Fall in private sector deposits in foreign currency and estimation of sources for funding it

Financial system – In millions of USD – Per week

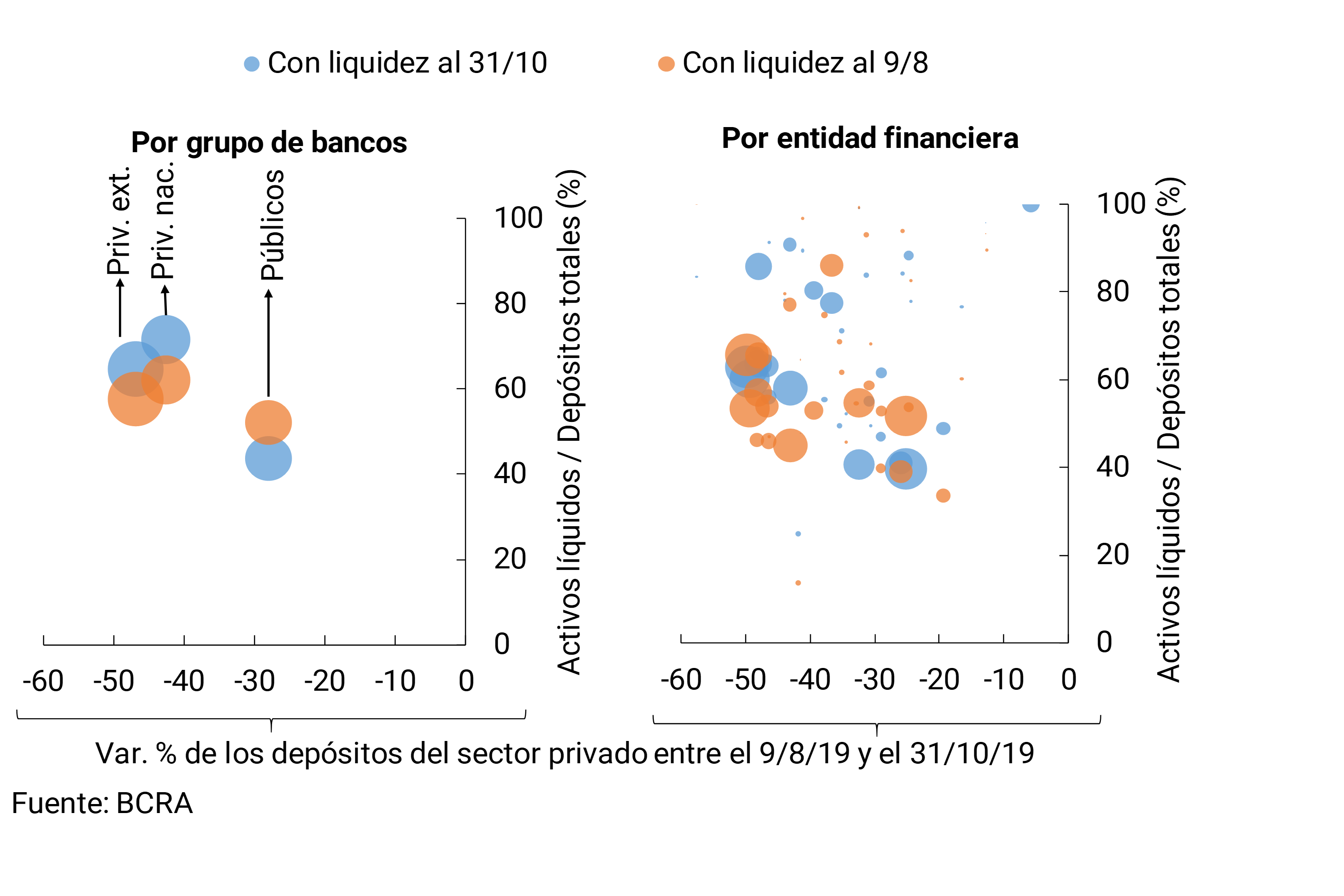

While the group of private banks (both domestic and foreign) faced a greater relative decline in private sector deposits in foreign currency since the primary elections, this group maintained a high level of liquidity coverage (higher than the weighted average of the financial system and slightly higher than that recorded the day before the elections, see Figure A.4.4). This is a reflection of the behavior observed in private banks of relative size.

In short, the current macroprudential framework for the financial system considers the risk of exchange rate fluctuations among its central aspects. This was reflected in the transformation of the sector’s balance sheet, with a great contrast between the situation prior to 2002 and the current one. Currently, 71% of total bank assets are denominated in domestic currency, a value that only reached 30% in 2001 (see Chart A.4.5), while credit in foreign currency is granted to sectors with incomes in this denomination. In addition, as of September 2019, funding in foreign currency comes mainly from deposits, in a framework in which the resources not applied to credit must be kept liquid. In turn, the spread between foreign currency assets and liabilities is relatively low. All these characteristics make the financial system better prepared to go through stressful events.

Section 5 / Evolution of the concentration of debtors in the local banking market

For almost three decades now, the Argentine regulatory framework has had a set of rules that seek to promote the diversification of the debtor portfolio of financial institutions. Its objective is to avoid situations of excessive exposure of a bank to individual customers – considering both the case of families and companies – which could markedly increase the levels of credit risk assumed and, potentially, adversely affect its capital. In this framework, the maximum limits applicable to customer financing were established in terms of the banks’ regulatory capital, while ceilings were also implemented for the addition of those debtors most representative in the equity of each entity65. These limits are part of a broader set of regulations implemented by the BCRA that encourage banks to carry out a healthy management of the credit risk faced66.

More recently, and following the international recommendations of the Basel Committee on the matter, at the end of 2018 the BCRA made a set of changes in the regulations on debtor diversification67. The new international recommendations focus on the protection of banks’ capital against possible losses due to exposures to large debtors, a dimension that Argentina already contemplated in its regulations. Likewise, some nuances were added that improved local regulations, among which the following stand out: i. the limits on individual customers are now measured according to the Tier 1 capital of the entities (instead of the total capital), which has a greater capacity to absorb eventual losses; and ii. definitions were incorporated relating to groups of connected counterparts, when the criterion of control relationship or economic interdependence is met between two or more natural or legal persons68. To monitor adequate compliance with this regulation by individual financial institutions, in 2019 the BCRA implemented a specific Reporting Regime on Large Exposures to Credit Risk69.

In addition to the microprudential supervision mentioned above, the BCRA carries out macroprudential monitoring of exposure to this risk. In this sense, the relative evolution of the financial system’s exposure at the aggregate level to the credit risk assumed with respect to a group of large debtors (an aspect related to the degree of concentration of credit risk) is analyzed. To this end, a set of indicators is periodically prepared based on the micro data available in the Debtors’ Center, which allows for a historical perspective given the extension of this source of information. On the one hand, the share of the main debtors in the portfolio of each financial institution in the last 15 years is calculated, considering the total balance of individual financing at each moment of time70. With this information at the level of individual entities, distributions are calculated and prepared for the entire financial system.

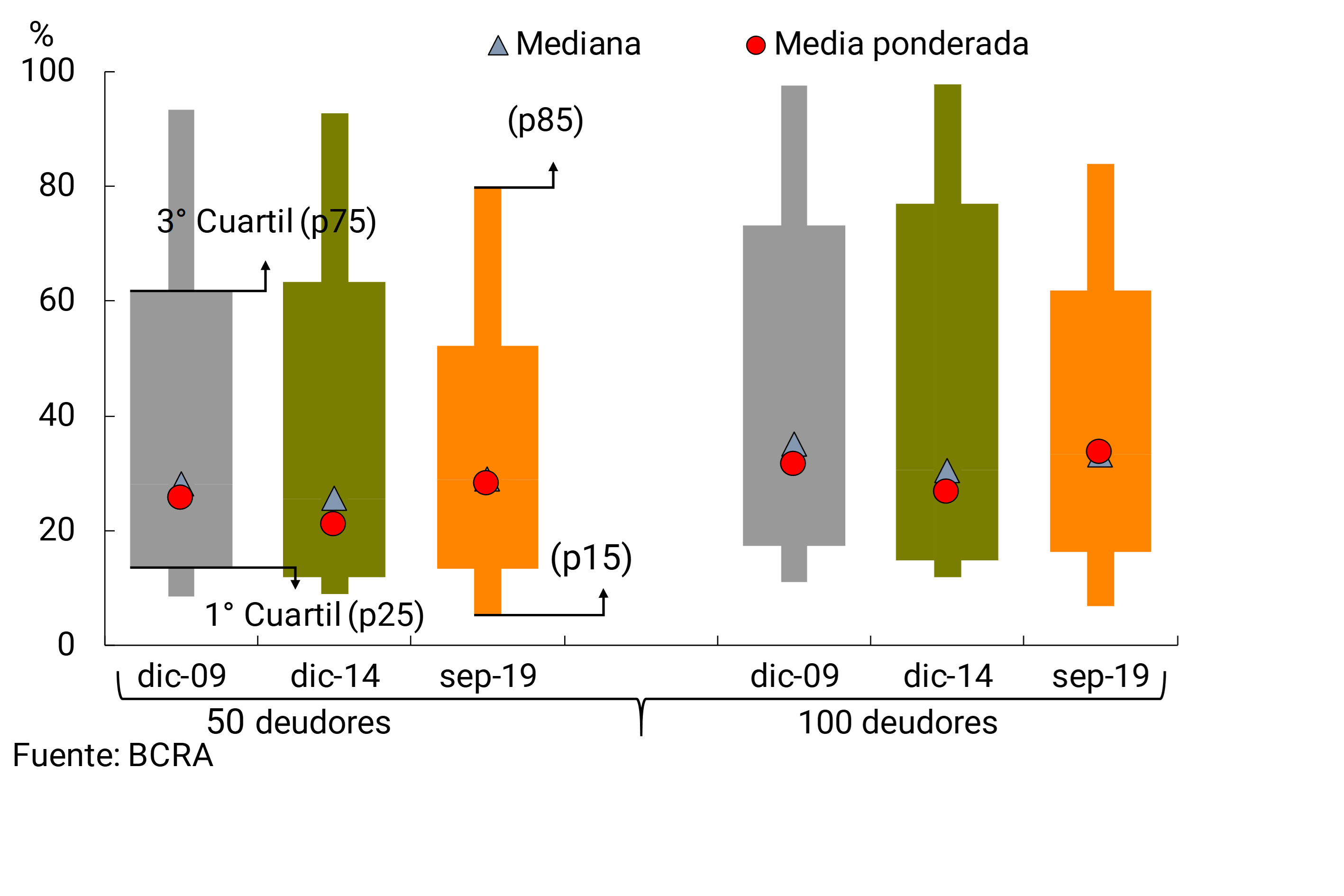

As can be seen in Figure A.5.1, in September 2019 the distribution by entity of the top 50 debtors had a median of 29% of the portfolio and a weighted average of 28%71. These indicators grew compared to those of the end of 2014 (+3 p.p. and +7 p.p. respectively), although they are in line with those verified 10 years ago (28% and 26% in December 2009). Moreover, in September of this year, three-quarters of the entities active in the system had concentration levels of their top 50 debtors below 52% of the portfolio, an indicator that implied a decrease in recent years. When analysing the case of the top 100 debtors by bank, it can be seen that the concentration indicators are only slightly higher than those verified for the first 50 debtors, indicating that the relative weight of additional debtors in the portfolio of all banks falls sharply.

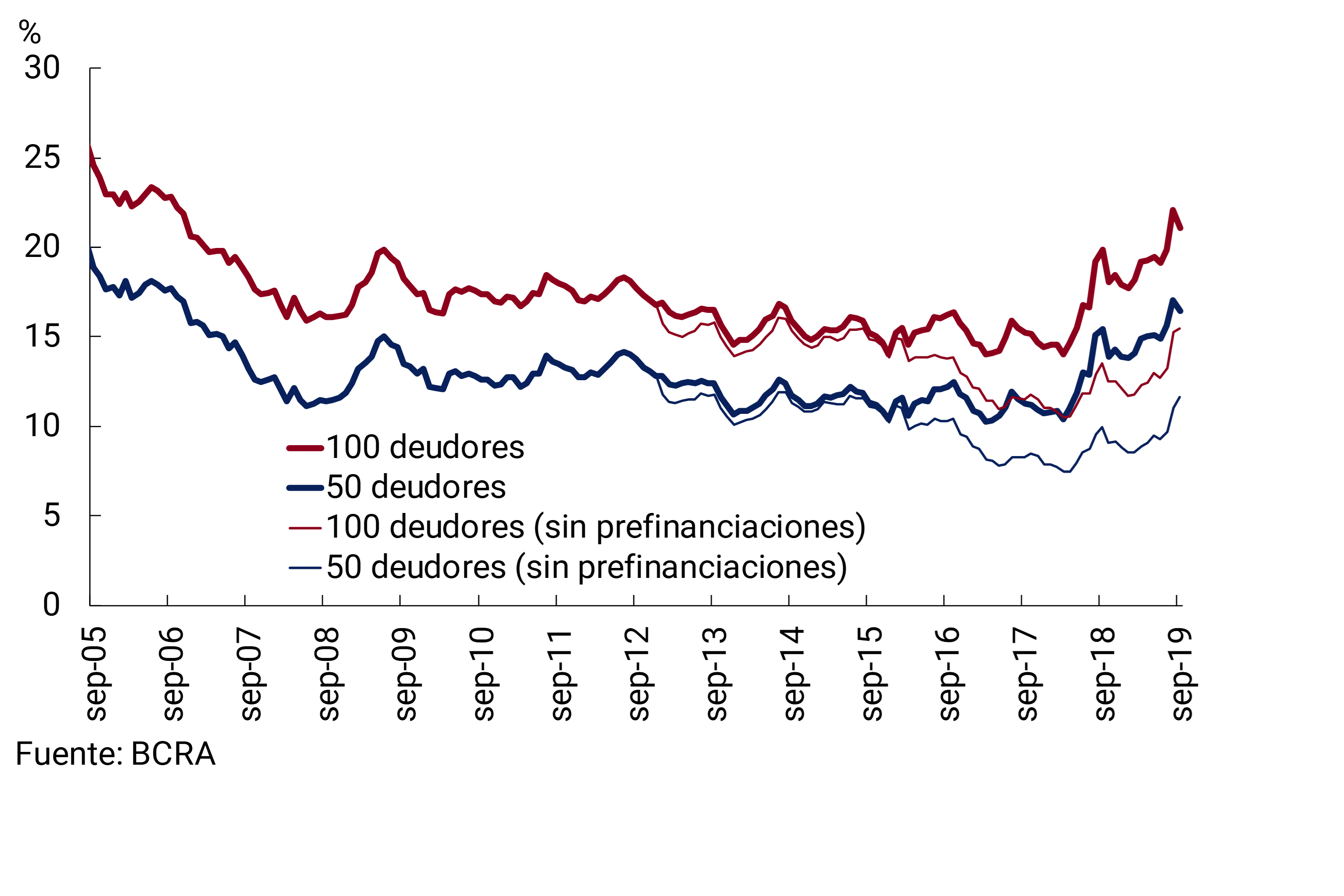

From a systemic perspective, potential sources of vulnerability are also monitored, which, for the aggregate of banks, may be generated by exposure to a relatively small set of debtors. Thus, the relative weight of financing granted to the main debtors throughout the financial system is evaluated, in relation to the financing portfolio of the sector as a whole. Figure A.5.2 shows the evolution of the holdings of the top 50 and 100 private sector debtors from a systemic point of view. Although these indicators show an increase since the last quarter of 2018, partly due to the impact of the nominal exchange rate on lines taken in foreign currency (e.g., pre-financing, lines used to finance foreign trade activities)72, the current levels of concentration are at values similar to those of 10 years ago. In particular, as of September 2019, the participation of the top 50 and 100 debtors was in the order of 16.4% and 21.1% of the portfolio, representing 7% and 9% of the total assets of the system, respectively73.

An additional exercise in the analysis of credit risk concentration—assuming an extreme assumption of linkage in terms of repayment capacity—consists of considering together both the amounts of bank debt of the companies and the financing taken by the personnel in a relationship of dependency employed by those companies. In this exercise, the aforementioned concentration indicators only grow marginally, reaching 17.1% in the case of the top 50 debtors in the system and 22% when taking the first 100.

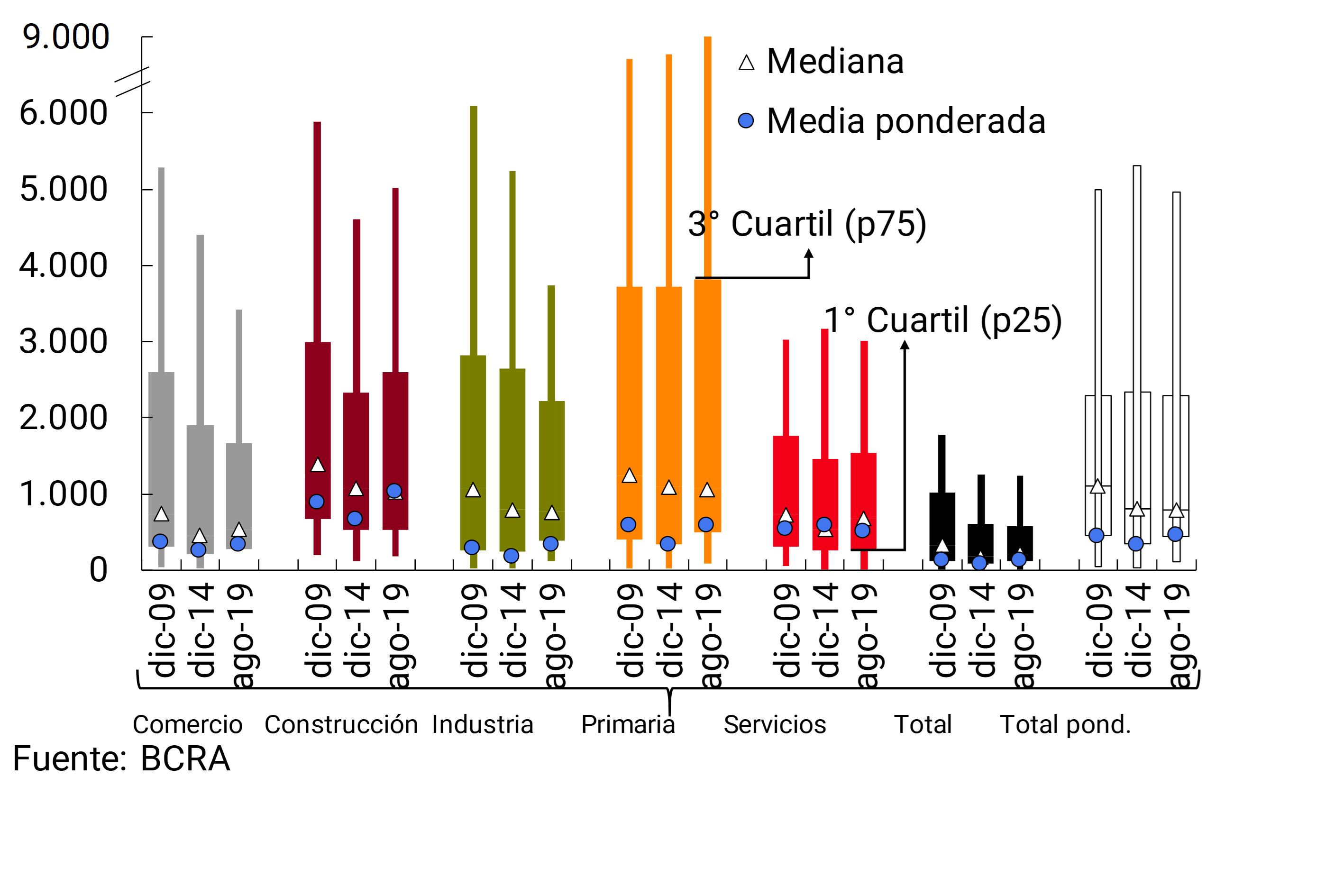

It is also appropriate to analyse the degree of concentration of debtors considering those customer segments that have similar characteristics, such as belonging to the same activity in the economy. Thus, the debtors of the main branches of productive activity (primary production of goods, industry, services, trade and construction) are considered, and the degree of diversification/concentration of existing debtors in each of these segments is evaluated. Figure A.5.3 calculates the Herfindahl and Hirschman Index74 (IHH) for the aforementioned groups of debtors, at the level of each financial institution. As can be seen, the financing portfolios for primary production of goods and construction registered the indicators with the highest concentration at the level of debtors as of September 201975 (with medians of 1,020 and 960 in their respective IHH, with a fall in both cases in recent years), followed by industry and services (medians of 780 and 660, values similar to those of previous periods)76. The portfolio of financing to debtors in the trade sector would be the most decentralized at the level of financial institutions, with a median of 480 in the calculation of IHH77. For the total number of debtors in the business segment, a median of IHH of 200 is observed, which reaches 720 when weighted by the financing portfolio78 (with a decline in recent years).

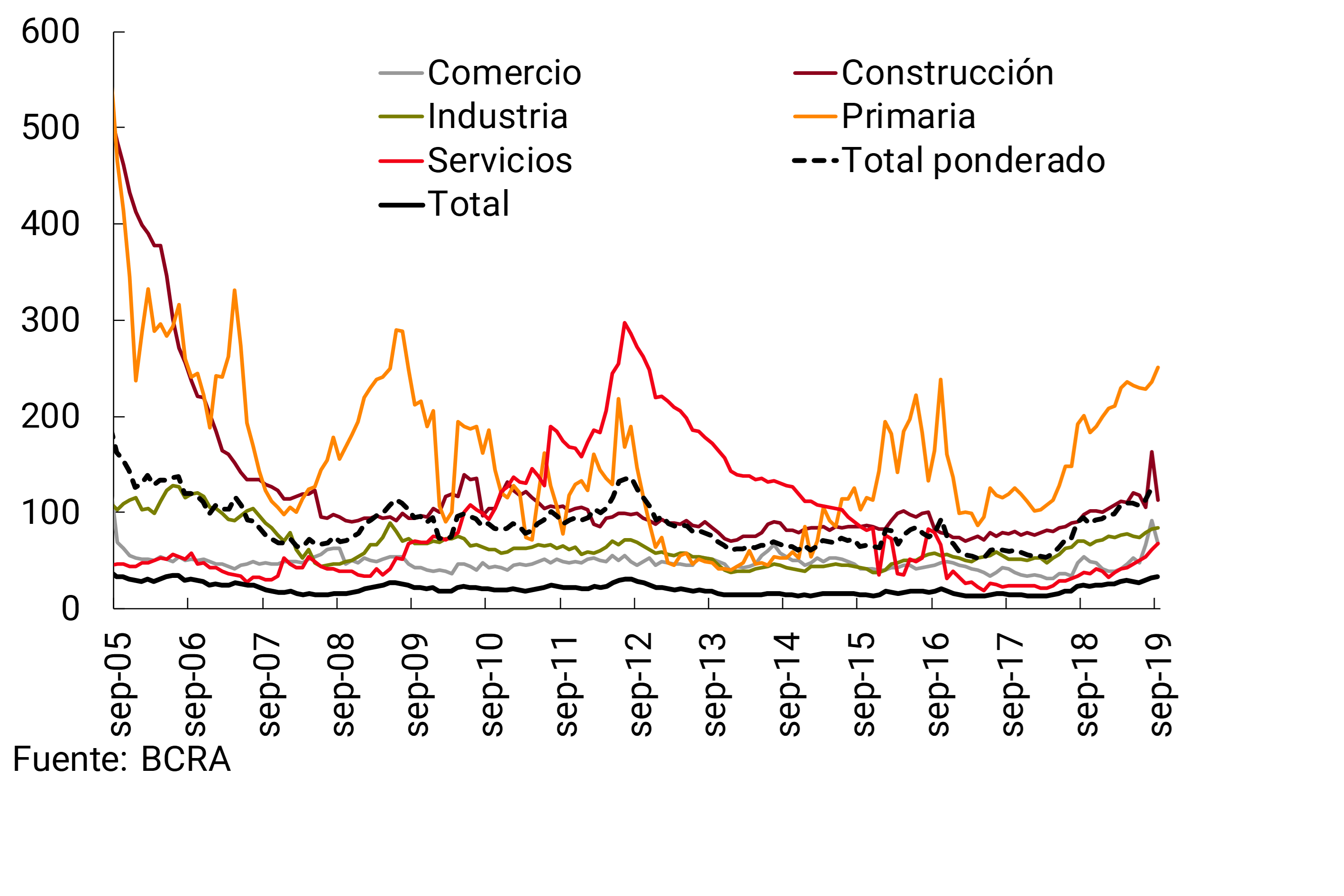

When analyzing the sectoral concentration of debtors from a systemic perspective – no longer by individual financial institutions – it is also verified that the aggregate portfolios of financing to debtors whose main activities are both primary production – with some growth in the margin – and construction are the most concentrated within the different productive activities (see Graph A.5.4). By including all companies that receive bank financing – regardless of the sector to which they belong – the IHH is significantly reduced to just over 30, a value that is in line with recent years. When taking an IHH weighting the different sectors mentioned above (based on the participation of each productive segment in the portfolio of bank financing to companies), the concentration indicator would total about 125, in values similar to those observed 10 years ago.

In general, from a historical perspective, moderate levels of concentration of bank debtors in the Argentine financial system are observed.

References

1For more detail, see Monetary Policy Report.

3In the second week of September, a Bill was sent to Congress to incorporate Collective Action Clauses into public securities with local legislation.

4 Decree 609/19 and related regulations of the BCRA and the CNV. See Monetary Policy Report and Regulatory Annex of this IEF.

5 After the PASO, the absorption of pesos intensified (which resulted in a rise in the interest rate of the LELIQ) and the foreign exchange market was intervened by selling dollars (non-sterilized sales). Faced with an acceleration in inflation, in the second half of September the Monetary Policy Committee (COPOM) announced new targets for the monetary base and increased the lower limit for the interest rate of the LELIQ (see Monthly Monetary Report). The LELIQ rate peaked at 86 percent annually on September 10 and then gradually declined (to a level of 68 percent at the end of October). At the end of October, the COPOM decided to modify the lower limit of the interest rate of the LELIQ (reducing it to a level of 63%).

6 FCI redemptions increased due to the deterioration in the prices of public debt instruments and the rescheduling of bills (see section “The BCRA’s response to the impact of financial volatility on mutual funds” in the latest edition of the Monetary Policy Report).

7 Thus, financing to the private sector in an irregular situation represented a balance equivalent to only 2.1% of total assets.

8 The indicator used corresponds to the private sector portfolio net of the total forecasts (minus the estimate of the regulatory minimums for the regular portfolio), all in terms of equity.

9 In the framework of the RCAP, in 2016 Argentina obtained the best possible score in terms of the application of the capital standards and the Basel III LCR (see IEF II-16).

10 For more details on the results of the RCAP, see HERE.

11 In addition to the volatility in the foreign exchange market, after the PASO, the yield differentials required in the secondary market for sovereign debt grew strongly (the Argentine EMBI surcharge went from a range of 900-1,000 bps in May to an average of over 2,000 bps after the primary elections, while the slope of the yield curve became more negative). This occurred in a context of a decrease in the amounts traded in the fixed income market and a fall in market financing to the private sector (in a context of rising funding rates).

12 For example, with respect to the EMAE and the ILA-BCRA Leading Indicator of Activity.

13 A weak evolution of the economy would have a more marked impact on the most leveraged companies, putting pressure on their ability to repay and/or on their level of investment and employment (which could generate second-round effects that would feed back into a recessionary context).

14 Since the publication of the IEF I-19, the external context has become more adverse in aggregate terms. Concerns intensified regarding the conflict between the United States and China, the possibility of a disorderly Brexit, and conflicts in the Middle East, among other geopolitical factors, putting pressure on global growth expectations. This ratified the trend towards more expansive monetary policies in developed economies. In this context, concern persists about the high valuations of risk assets, which are susceptible to price corrections – and portfolio adjustments – if there were to be a change in risk appetite, after several years with interest rates at historically low levels. A substantial change in risk appetite (with an effect in terms of flows and rates) would also impact the public and corporate sector of several economies, given the significant increase observed in debt in recent years. Regarding the regional situation, growth expectations in 2019 for Brazil were corrected upwards in recent months, while activity is expected to continue improving in 2020-21.

15 A drop that reaches just over 40% in the accumulated from mid-August to the end of October.

16 For the Liquidity Coverage Ratio and for the Stable Net Funding Ratio, a minimum is required for the group of largest banks called Group A (they account for 89% of the total assets of the financial system), according to the Consolidated Text “Authorities of Financial Institutions”.

17Law 24.485 and Regulatory Decree 540/1995.

18 For more details, see IEF I-18 (Box 3) and ordered text of “Application of the deposit guarantee insurance system”.

19 The Estimated Probability of Default (EDP) was used, defined as the proportion of loans that were initially in credit situation 1 and 2 (regular) and go to situation 3, 4, 5 or 6 (irregular) at the end of the period under analysis (in this case a three-month comparison is taken). Estimates prepared based on micro data from the Central Debtors (BCRA).

20 If an estimate of credit granted by other providers (e.g., FGS loans, mutuals and cooperatives, etc.) is also considered, the level of financing to the private sector would increase by approximately 1.7 p.p. of GDP. This definition of “broad” private sector credit in terms of GDP was slightly reduced from the estimate for the end of 2018.

21 It is estimated that the financial burden (principal and interest) of household debt represents less than 3% of GDP (while the median for a sample of 8 countries reached 6%, according to the latest information available for each case in the IMF).

22 See methodology in Section 1 of IEF I-19. A vulnerable company, from a financial perspective, is defined as those companies whose values for at least two of the three most relevant financial indicators (interest coverage with operating income, leverage and liquidity) exceed predetermined thresholds.

23 Although the evolution of this subset of companies – with public offerings – can be considered as one of the indicative references of the situation of all local firms, caution should be exercised given that this sample is biased towards relatively large firms. Towards the second half of 2019 (latest available data) companies with public offerings showed some deterioration in terms of their liquidity levels and cash mismatches, as well as increases in their leverage and a higher debt interest burden on revenues.

24 According to the estimate made by weighting the different types of portfolios and their credit situations.

25 See, for example, the results of the BCRA’s Credit Conditions Survey for the aforementioned periods.

26 In accordance with the provisions of Communication A6651, as of January 2020, financial institutions and exchange houses subject to the control of the BCRA must apply the accounting inflation adjustment to their balance sheets.

27 This is mainly due to the fall in liquidity in foreign currency (associated with the outflow of deposits in this post-PASO denomination).

28 With respect to the last IEF, it is estimated that the increase in the nominal cost of funding was similar to that of implied lending rates. In a year-on-year comparison, the estimated funding cost exceeded that recorded in implied lending rates.