Financial Stability

Financial Stability Report

First half

2019

Half-yearly report presenting recent developments and prospects for financial stability.

Table of Contents

Chapters

- 1. Executive Summary

- 2. Risk factors for the financial system

- 3. Analysis of the stability of the financial system

Sections

- Section 1 / Financial situation of publicly offered companies

- Section 2 / Analysis of household indebtedness based on microdata from the Central Debtors’ Office

- Section 3 / Non-bank financing in Argentina

- Glossary of abbreviations and acronyms

1. Executive Summary

The financial system continues to show a significant degree of resilience in a challenging context. Since the publication of the last IEF, in November 2018, the Argentine economy continued to advance in the normalization process, with clear improvements in terms of the fiscal and current account situation. However, in recent months, exchange rate volatility and inflation records have been temporarily higher than expected. In this context, the BCRA reinforced the contractionary bias in its monetary policy, understanding that perseverance to resume the path of disinflation is its main contribution to the expected improvement in the level of economic activity and to the recovery of the dynamism of financial intermediation.

The relative levels of solvency and liquidity of banks have widened in recent months, showing historically comfortable margins, maintaining limited exposures to risks related to activity, structural and those related to the financial cycle. Together with a regulatory framework in line with international standards (Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and adequate macroprudential and microprudential monitoring, the position of banks continues to be solid in the face of the expected evolution of the economy. For their part, the main sources of potential risk that could eventually condition the proper functioning of the financial system would remain contained in the coming months. While those linked to the international context did not show significant changes in aggregate terms since the publication of the last IEF, local sources of risk grew at the margin (including the effects of the uncertainty of the election processes on the financial markets and the possibility that the economic recovery will be slower than expected). Given the strength of the Argentine financial system, very extreme adverse deviations should occur in order for financial stability conditions to be disturbed.

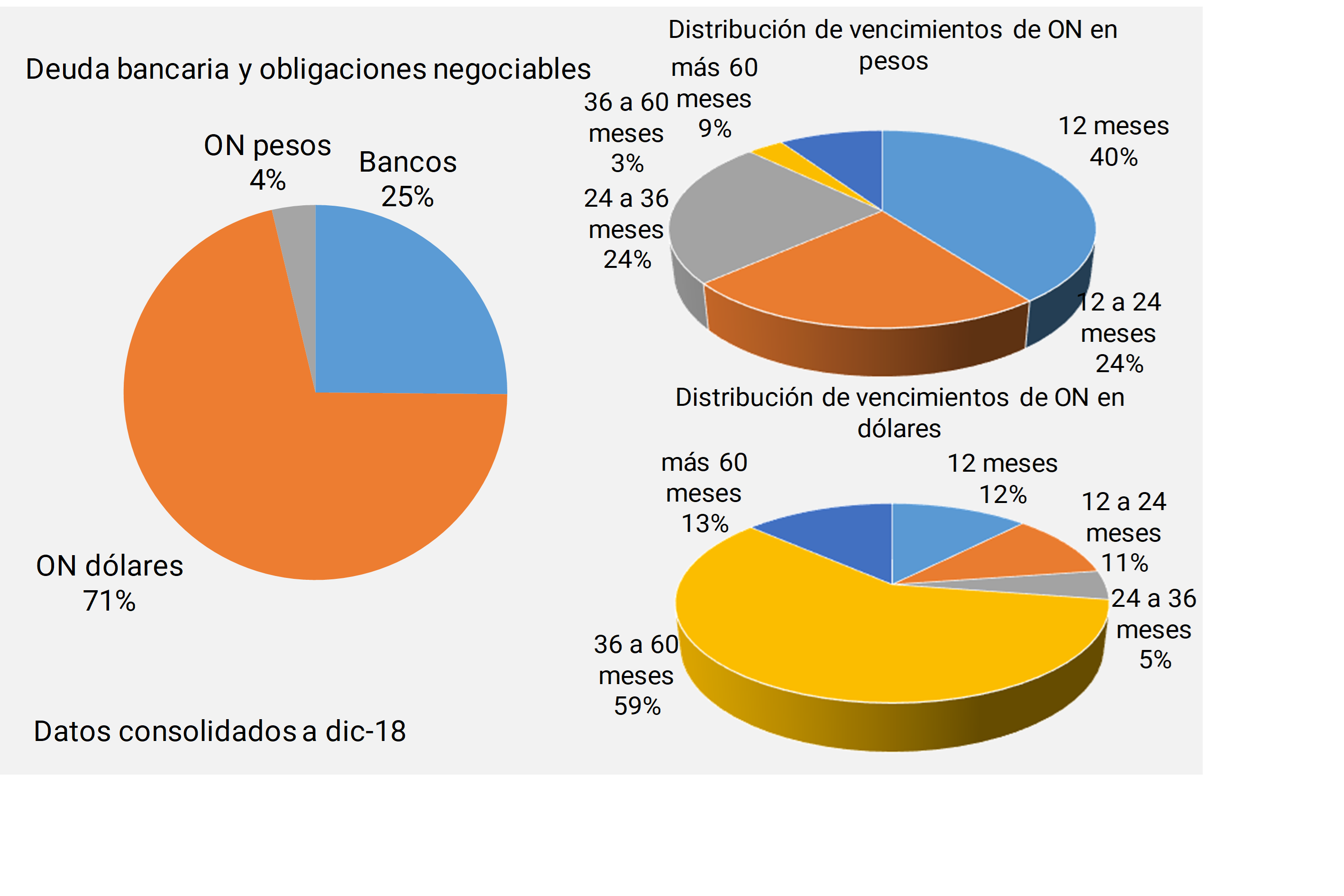

The dynamism of financial intermediation continued to attenuate in recent months, mainly explained by lower lending grants. Deposits performed positively in recent months, accompanying movements in passive interest rates, given increases in the monetary policy rate, incentives generated by reserve requirements and, more recently, by greater competition among banks for fixed terms in local currency. On the other hand, funding with negotiable obligations is relatively limited, and the expected maturities for the coming months are manageable and mostly in local currency.

Accompanying the evolution of economic activity, the quality of the banks’ loan portfolio has shown a deterioration in margin (largely explained by loans to companies), with an increase in non-performing loans from historically low levels. This trend is expected to continue in the coming months, given that sectoral revenues would recover gradually, which would add to certain lags in the adjustment in the classifications. In particular, it is noteworthy that irregularity remains at minimal levels in the case of the UVA segment (which accounted for much of the last phase of financing expansion), in line with the good practices applied at the time of credit generation. Another notable factor is the persistence of relatively low aggregate levels of leverage and corporate and household debt burdens. On the other hand, depending on the existing regulation in terms of portfolio forecasting, a relatively high level of coverage is observed with forecasts of the irregular portfolio for the financial system. Together with the low gross credit exposure and the aforementioned slack in capital integration, this situation contributes to providing resilience to all financial institutions. The regulatory framework also helps to keep both the equity mismatches of the banks, as well as their debtors, limited.

Within the framework of the macroprudential policy approach implemented, the BCRA will continue to monitor the sources of risks and the evolution of the financial sector situation, attentive to a possible growth of vulnerabilities that may have systemic implications.

2. Risk factors for the financial system

The process of normalization of the Argentine economy poses challenges in terms of the context in which the financial system operates. From the analysis of the most relevant risk factors – given their probability and possible impact – exogenous to the financial system, it emerges that those linked to the international scenario remained mostly unchanged in the aggregate, while those of local origin grew in the margin. These include the uncertainty linked to the electoral process and an eventual recovery of the economy slower than expected. These risk factors could have an impact on the intermediation process – through greater volatility of the exchange rate and local interest rates – and on the irregularity of the loan portfolio granted by banks. The financial system is expected to continue to show significant resilience, based on the observed levels of solvency and liquidity (see Chapter 3). The BCRA will continue to monitor these developments to mitigate possible systemic effects.

Background

As mentioned in the latest Monetary Policy Report, the Argentine economy is going through a process of correcting existing imbalances. There is a more accelerated convergence towards primary fiscal balance, without monetary financing from the Treasury and with regulated services prices already largely corrected. Added to this in recent months has been a more contractionary bias in monetary policy, which will continue throughout 2019. 1 These measures are expected to contribute to the gradual reduction of inflation and, consequently, of interest rates. The achievement of greater nominal certainty represents one of the BCRA’s main contributions to financial stability and the establishment of a growth environment. With a more competitive exchange rate and a reduction in the fiscal deficit, rapid progress is being made in reducing the current account deficit. The future recovery of the economy will then take place on a more sustainable basis than in the past.

In this context of transition, and given its macroprudential approach, the BCRA has been monitoring a series of risk factors that could potentially generate some degree of tension in the Argentine financial system. To this end, exogenous risk factors are identified with a certain possibility of occurrence (even if they imply extreme adverse behavior), which, if they materialize – given the pre-existing risk exposures – could test the conditions of financial stability. The rest of this chapter summarizes the main risk factors considered, while Chapter 3 will analyze the degree of resilience of the financial system in the face of these potential shocks.

2.1 Possibility of a more adverse international scenario

The eventuality of an external shock remains relevant, although in aggregate terms it is considered that its probability would not show significant changes since the last edition of the IEF. The main factors that could trigger a deterioration in the international context were mixed. On the one hand, fears about a slowdown in global growth have grown in recent months. With respect to Argentina’s main trading partners, the Brazilian economy has so far shown a more favorable dynamism than in previous years, although its growth prospects have worsened in recent months. 2 On the other hand, tensions deepened in the framework of the negotiations between the US and China, with announcements of new protectionist measures in May. The possibility of a disorderly exit of the United Kingdom from the European Union, greater uncertainty associated with the situation of certain economies in the euro area (such as Italy) or the materialization of geopolitical conflicts remains in force. Finally, the possibility of a more aggressive tightening of monetary policy in developed economies than expected was losing steam.

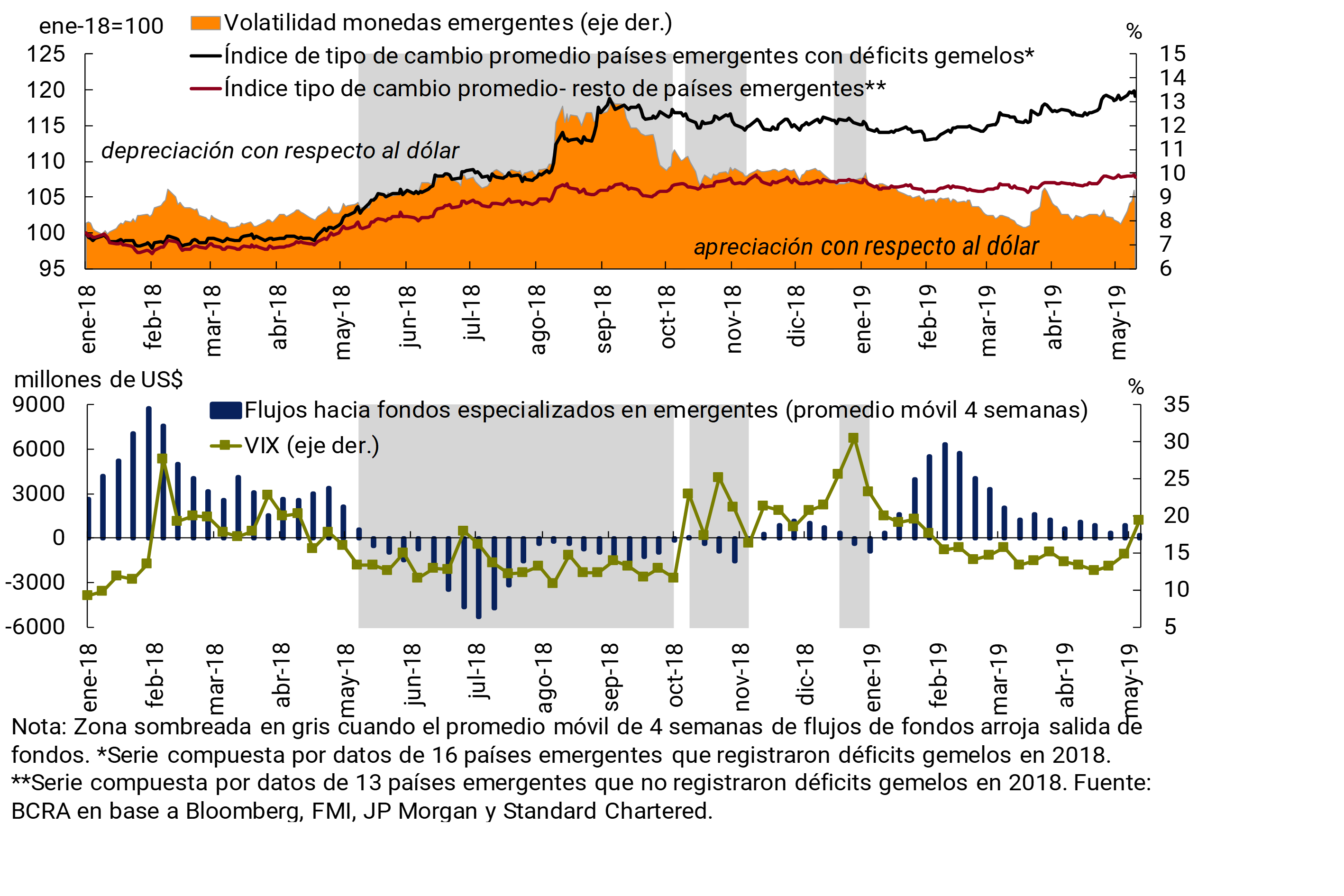

The impact of a possible more unfavorable international scenario will depend on the factor that generates it. An external shock mostly linked to the financial channel, with growing uncertainty at the global level, would initially imply negative portfolio flows for emerging economies and deterioration of their currencies (as was observed temporarily around December 2018). 3 In recent episodes of persistent negative portfolio flows and strong pressure on emerging currencies (such as the one that occurred towards the end of the second quarter and during the third quarter of 2018), exchange rate movements were more marked for economies with less solid macroeconomic fundamentals (see Figure 2.1). Greater volatility in the local exchange market, with an impact on interest rates, could condition banking operations. On the other hand, a shock linked to the trade channel would have a more direct impact on the level of activity, with a primary effect on the quality of the loan portfolio in the financial system.

Figure 2.1 | Emerging Currencies and Portfolio Flows

2.2 Growing uncertainty due to electoral cycle, with an effect on local financial markets

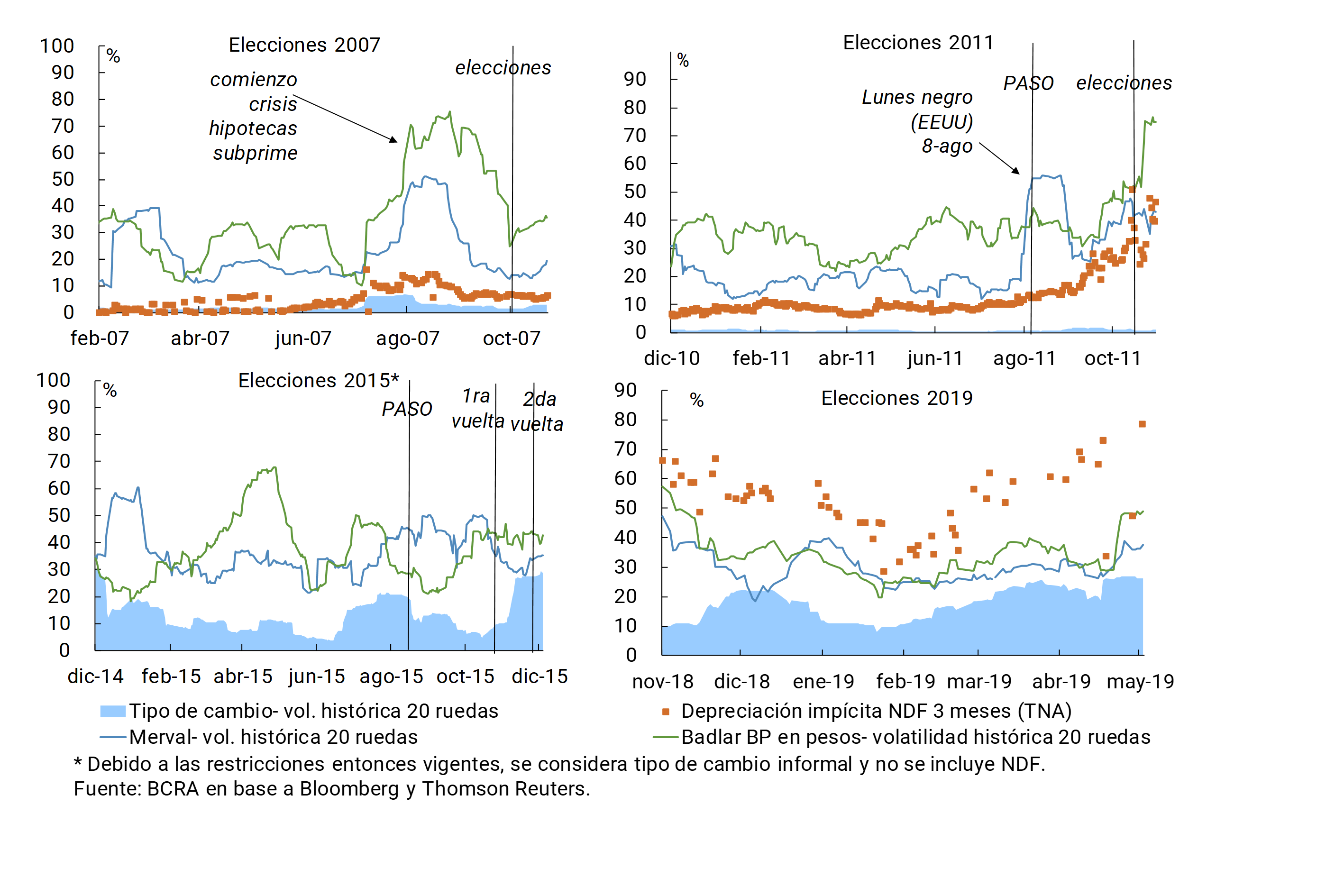

The proximity of the 2019 electoral process has meant that in recent months the uncertainty that usually occurs in this type of context has begun to become evident (see Figure 2.2). This means that there may be portfolio adjustments by economic agents, with an eventual impact on the exchange rate and local interest rates (as observed since the end of February) and, in more extreme cases, on the funding behavior of all the entities in the financial system.

Figure 2.2 | Elections, historical volatility of market variables, and implied depreciation in NDF contracts

Inflation is currently at levels higher than those desired by the BCRA. However, given the monetary policy measures applied and the progress made in reducing the fiscal and external imbalance, expectations suggest that in the coming months the trend towards greater stability of the currency will be resumed, although the disinflation process may not be linear. 4

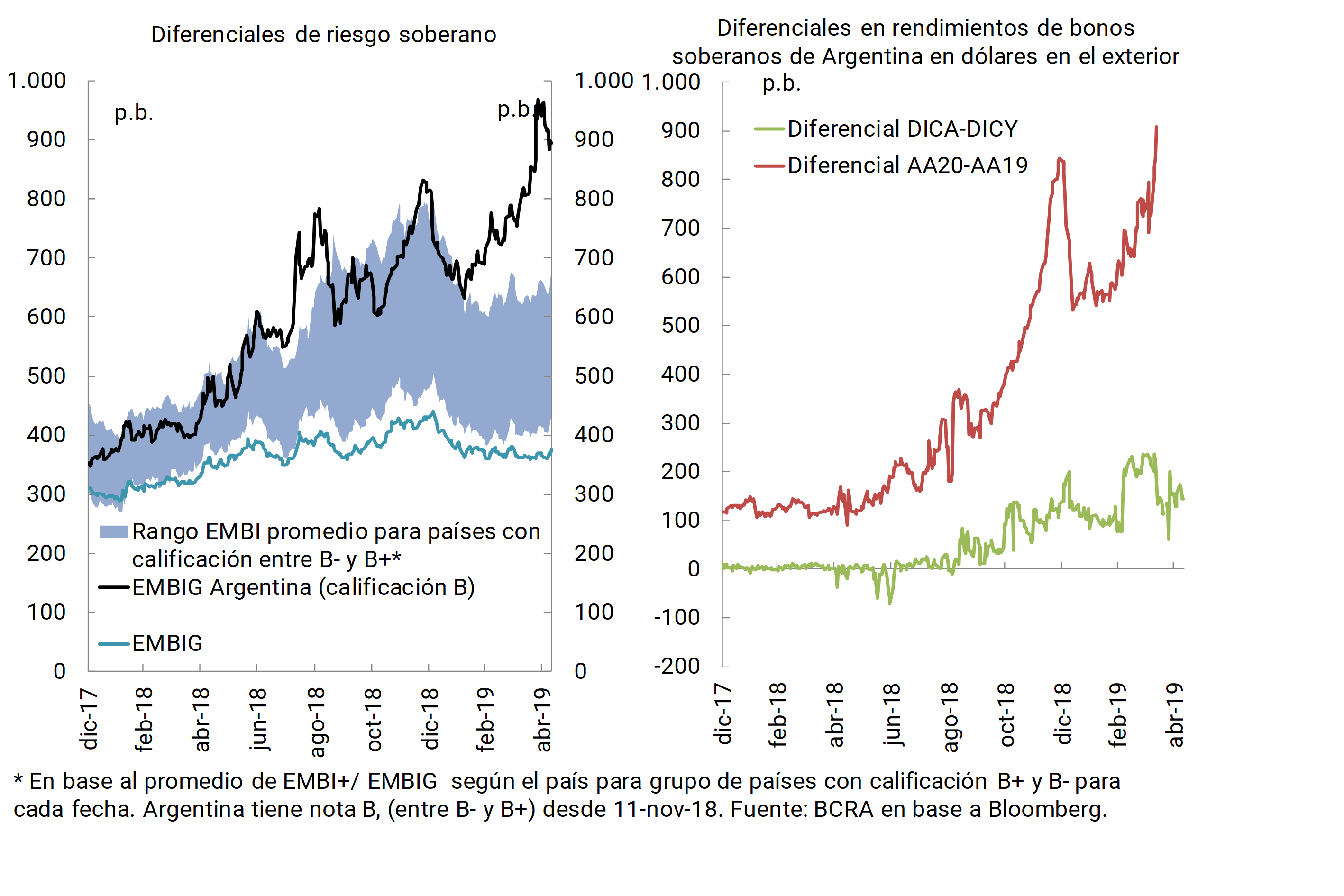

The heightened uncertainty also affects the perceived risk of foreign currency sovereign debt, with a more limited direct impact on banks. Although the agreement with the IMF allows the government not to have the need to access international markets until 20205, in recent months the surcharge required in the trading of Argentine bonds in dollars has increased (in April the Argentine EMBI spread exceeded 1,000 bps intraday). The difference in yields between bonds maturing during or after 2019 also increased (the dollar bond yield curve shows a negative slope from 2020 onwards) and a larger spread between bonds of equal financial conditions with international and local legislation (see Figure 2.3). In the case of companies, the maturities of bonds in dollars in the short term are limited, with repayments that become more demanding only from 2023 (see Section 1).

Figure 2.3 | Argentina’s sovereign risk spreads and bond curve spreads

2.3 Economic recovery eventually slower than expected

The level of activity, which had begun to contract during the first quarter of 2018, showed the first signs of recovery towards the end of last year. 6 In January and February 2019, the EMAE showed positive variations in line with the Contemporary GDP Prediction (PCP-BCRA), which anticipates GDP growth during the first quarter of 2019.

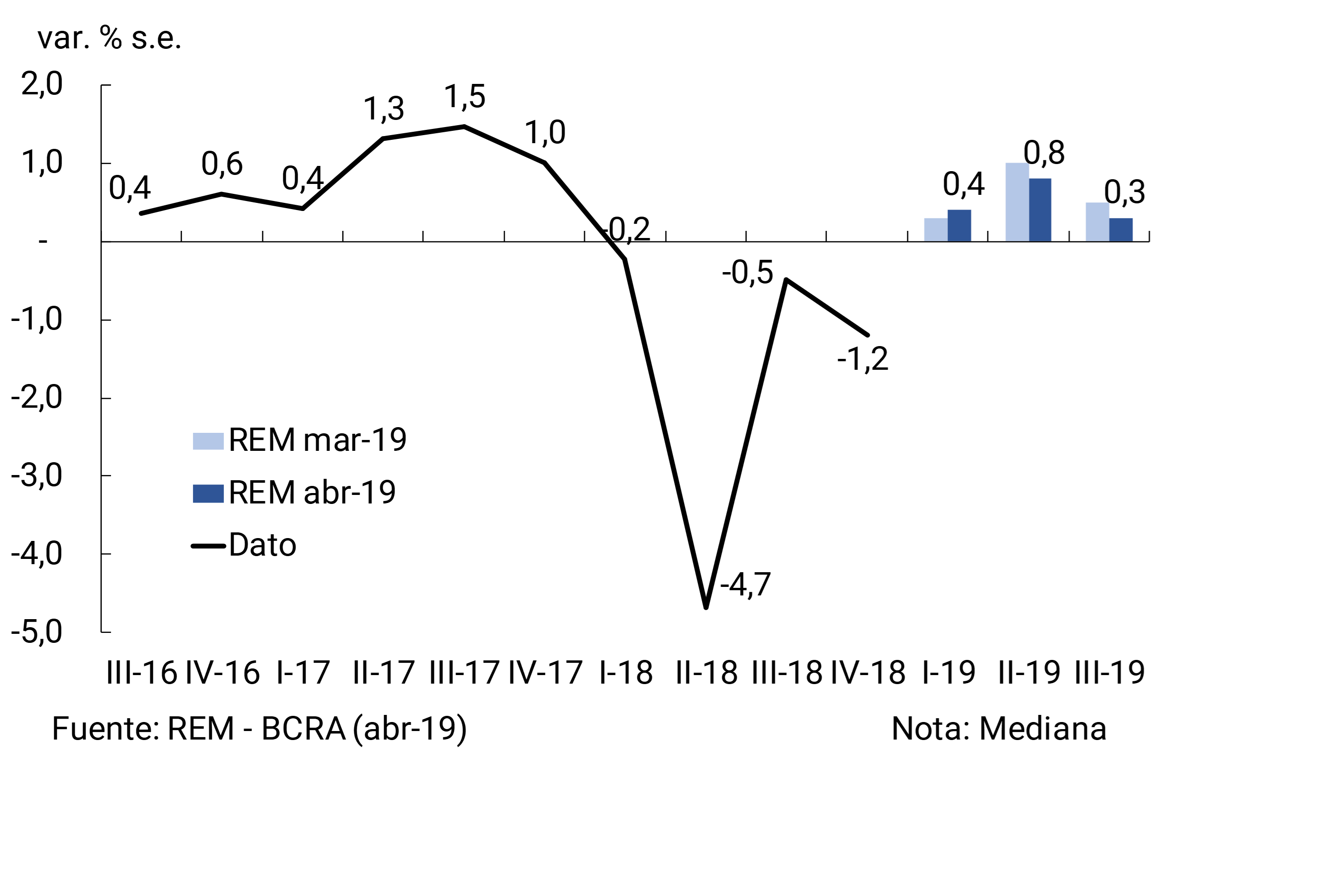

After the renewed exchange rate and financial tensions observed since the end of February, recovery expectations have so far shown marginal adjustments, according to REM analysts. 7. Indeed, the EMR forecasts that the cyclical phase of GDP recovery will begin in the first quarter of 2019 (see Figure 2.4). In this base scenario, the recovery would be underpinned by the positive contribution of agriculture, exports in general, and a gradual recovery in household incomes. An alternative scenario of a slower-than-expected economic recovery would have potential implications for the quality of banks’ loan portfolios. The pace of the recovery in activity would also have an impact on the dynamics of loan demand (and thus on the process of financial intermediation).

Figure 2.4 | Seasonally adjusted quarterly GDP growth and expectations

3. Analysis of the stability of the financial system

The sector’s solvency and liquidity indicators improved in recent months and remained at relatively comfortable levels, in a context in which deposit-to-loan intermediation remained weak (deposits performed positively, but loans fell in real terms). The quality of banks’ loan portfolios recently deteriorated, starting from relatively low levels and in a context of broad coverage with forecasts. Very extreme adverse deviations of the main variables should be observed for financial stability conditions to be significantly compromised. The degree of resilience that all financial institutions have been showing is reinforced by a micro and macroprudential policy approach in line with international standards.

Main strengths

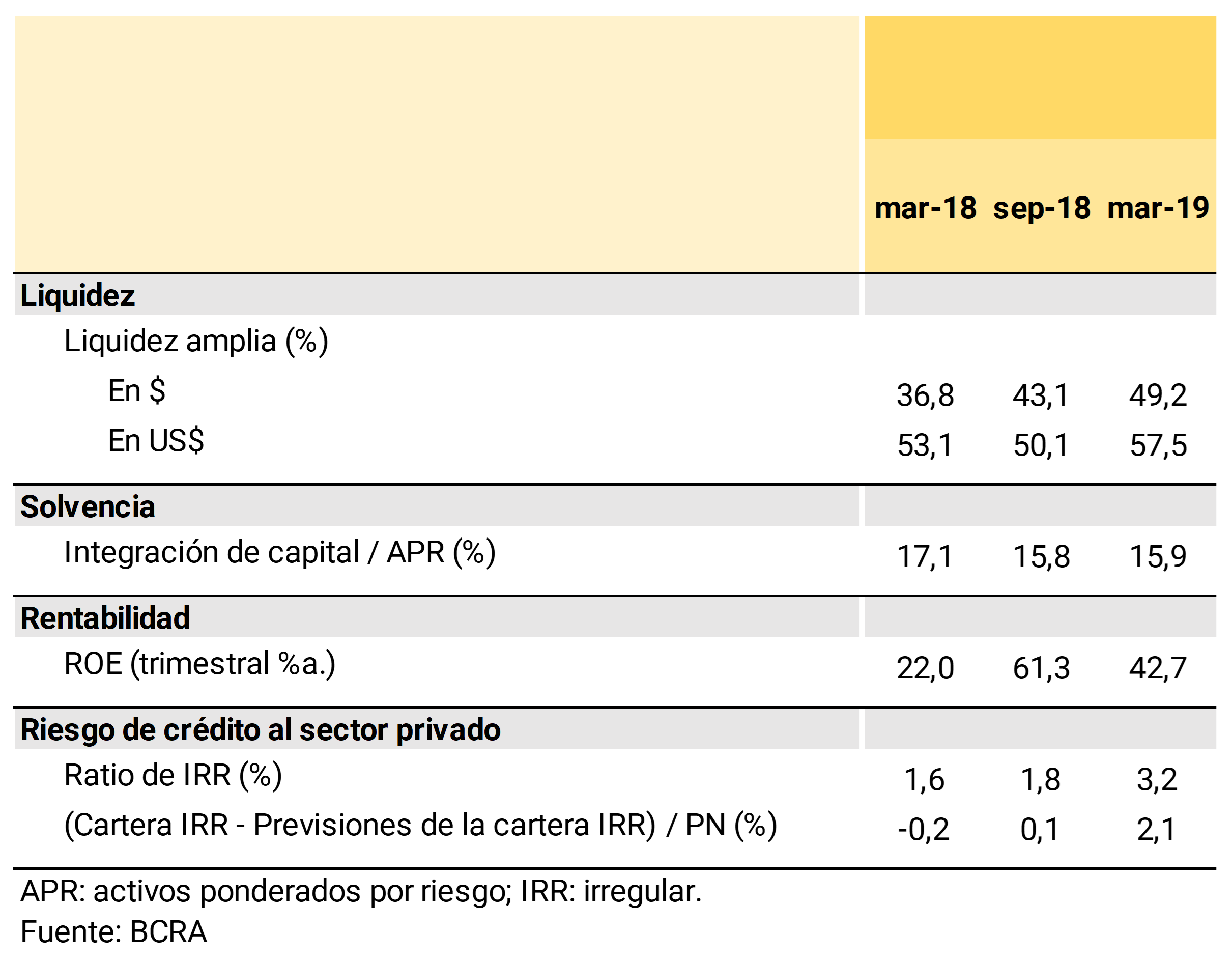

When analyzing the main factors influencing the stability conditions of the Argentine financial system, it is estimated that the sector has a significant degree of strength to face the challenges mentioned in Chapter 2, and thus continue to fulfill its characteristic functions (see Table 3.1). In line with the analyses provided in the IEF II-18 and in the Reports on Banks of the lastfew months 8, in a framework of low financial depth, unsophisticated traditional operations, scarce transformation of maturities and low sectoral levels of aggregate leverage, the set of local banks shows:

Table 3.1 | Main indicators of the soundness of the financial system

i. Total liquidity at high levels in historical terms, with gradual but widespread growth in recent months. There is broad compliance with the liquidity requirements designed and implemented according to international standards, both in terms of the liquidity coverage ratio and the stable net funding ratio. 9 In terms of the tools to manage liquidity risk, the local safety net has deposit insurance and the role of lender of last resort in national currency of the BCRA (windows for liquidity provision).

ii. Comfortable solvency levels, above those observed at the time of the last publication of the IEF (II-18). Given the sector’s nominal returns, some new capitalizations in medium/small banks, and risk-weighted assets (RWAs) with relatively limited growth, capital integration increased 1.3 p.p. from September to a level of 15.9% of RWAs in March this year. This trend was especially driven at the margin by private banks. In this context, there is a significant degree of compliance with the additional regulatory capital margins (both the capital conservation margin of 2.5% of the RWAs for all financial institutions – 90% of the total in the aggregate – and the corresponding additional 1% of the RWAs for the 5 locally systemic banks – 100% compliance). For its part, in terms of the definition recommended by the Basel Committee, the general leverage ratio – for the aggregate financial system – far exceeds both the local regulatory limit and the values observed at the international level.

iii. Broad levels of coverage with forecasts for the portfolio of irregular loans, in a context of historically low gross exposure to credit risk. The irregularity of the loan portfolio is increasing at the margin, accompanying the performance of the economy. However, the system’s irregularity ratio remains relatively low compared to its own history and does not deviate significantly from the average value for the region. Given the comfortable levels of forecasting and capital, and the moderate credit exposure to the private sector, the degree of solvency of the financial system would not be significantly affected by possible extreme increases in the levels of irregularity. This is in the context of local macroprudential regulations that limit debtors’ currency equity mismatches as well as those of banks (see Section 3.5). At the end of the first quarter of the year, the currency mismatch in the balance sheets of the financial system remained small, although the weighting of instruments denominated in foreign currency in both the assets and liabilities of the system’s balance sheet increased.

iv. A regulatory framework that is in line with the best international banking standards, without neglecting the characteristics of a developing financial system, such as the Argentine case. To this is added adequate macroprudential and microprudential monitoring. In this regard, within the framework of the BIS’s Regulatory Consistency Assessment Programme (RCAP) on the local application of Basel III standards, Argentina obtained the best possible score (“compliant”) in 2016. In addition, more recently, in March 2019, the European Commission indicated that Argentina’s financial regulatory framework has requirements equivalent to those of the European Union in terms of the prudential and supervisory framework. This type of recognition by the European Commission is reserved for third countries with the highest standards in regulatory matters.

The situation of relative solidity of the banks occurs in a context in which the BCRA continued to deepen its policies aimed at anchoring expectations. The continuous efforts of the BCRA’s monetary policy to reduce inflation and excessive exchange rate volatility (which are currently reflected in the system’s funding costs) represent the best contribution by this Institution to the sustained recovery of the level of economic activity and the process of intermediation of credit deposits in the medium term.

In the next subsections of this chapter, an assessment is made – identifying changes since the publication of the last IEF – of both the most relevant aspects in the analysis of the sources of vulnerability for the financial system, as well as the particular resilience elements in the hypothetical case of materialization of the risk factors indicated in Chapter 2. The last subsection mentions the main macroprudential measures in place and the most recently implemented changes.

3.1 Financial intermediation

Weak economic activity, together with higher-than-expected levels of inflation, continued to be conditioned by bank intermediation (between deposits and loans to the private sector), in line with what was observed in the previous IEF (II-18). The eventual materialization of a more adverse local economic scenario than expected, with a financial intermediation that fails to recover a path of growth in the short term, could affect the profitability of the sector.

At the beginning of 2019, and as has been observed since the second half of last year, the balance of credit in pesos to the private sector continued to fall in real terms. 10 This was reflected in a fall in the share of these lines in the total assets of the financial system (-4.3 p.p. in the last 6 months) (see Table 3.2), as well as in relation to the economy’s output. In this sense, bank credit in pesos went from representing 11% of GDP in September 2018 to 9.1% at the end of the first quarter of this year. When considering loans in foreign currency, the credit-to-GDP ratio reached 12.8% in the first quarter, 2.2 p.p. less than last September.

Table 3.2 | Equity situation – Financial system

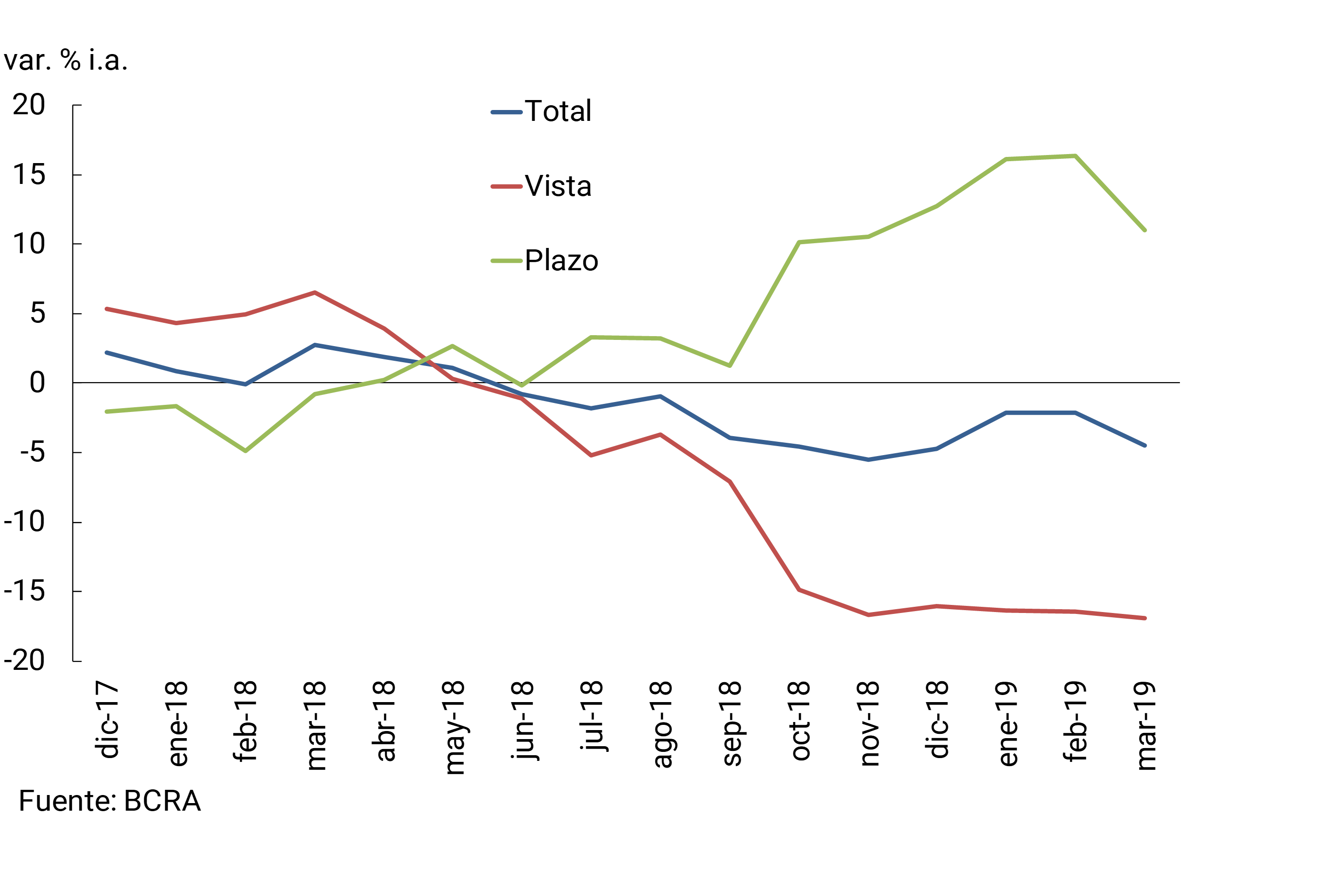

On the side of the funding structure of the financial system, since the last quarter of 2018 the growth of time deposits in pesos of the private sector accelerated. This trend mainly reflects the effect of the measures taken by the BCRA in terms of policy interest rates and changes in the reserve requirements required of banks11, thus improving the transmission mechanism between the policy interest rate and the economy’s passive interest rates. More recently, measures were implemented to promote greater competition in the market for fixed-term deposits in pesos. 12 Term placements gained participation in the total liabilities of the system in the last 6 months (increasing 4 p.p. to represent 20% of total funding). On the other hand, demand deposits from the private sector decreased slightly compared to the levels observed at the time of publication of the previous IEF (up to 17% of funding).

The relative evolution of loans versus deposits – both in pesos to the private sector – led to the ratio between them currently being at the lowest level in the last 10 years for the aggregate of the financial system (75% level), with a marked decline in recent months. On the other hand, the share of liquid assets in its broad definition (availabilities plus BCRA instruments) continued to grow.

Despite this lower intermediation between deposits and loans to the private sector, so far there have been no abrupt changes in the profitability of the system (see Table 3.3). In the last two quarters, there has been a certain drop in the results for services by banks compared to the cumulative figure for 2018, higher interest outflows linked to deposits and gradually increasing bad debt charges (due to the deterioration of the loan portfolio). However, these effects are partly offset by the increase in other sources of earnings (results from securities, especially from BCRA instruments) and the reduction in the weight of expenditures such as administrative expenses and taxes.

Table 3.3 | Profitability of the financial system

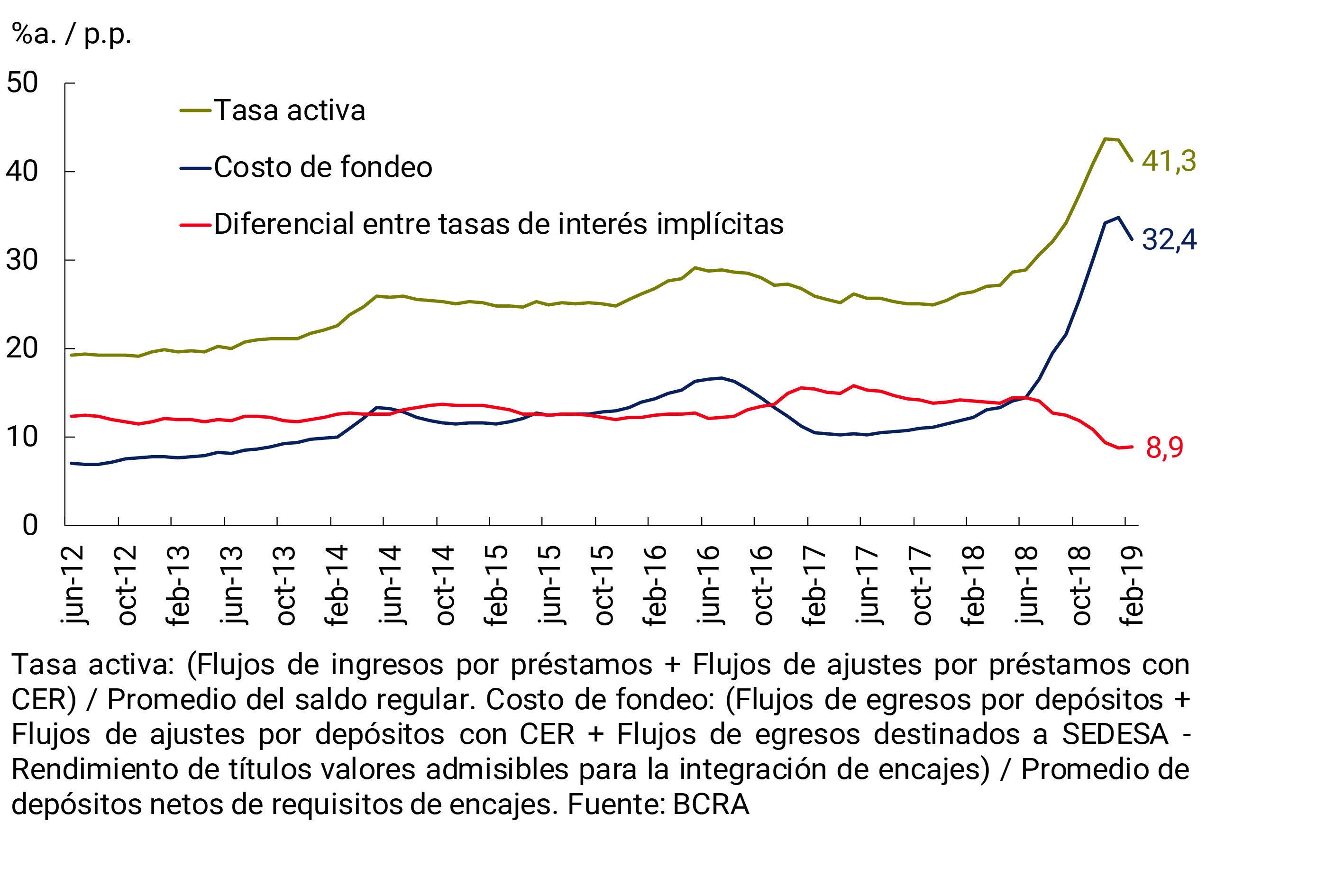

Focusing on the recent evolution of the sources of profitability associated with intermediation in the peso segment, it can be seen that in recent quarters, in addition to the lower weighting of credit in assets, there has been a certain decrease in the implied rate margin. Since mid-2018, the cost of funding for deposits in pesos has increased more markedly than implicit lending rates in the same currency, leading to a gradual reduction in the aforementioned differential (see Figure 3.1). As mentioned, these behaviors occur in the context of the measures taken by the BCRA in terms of interest rates and reserve requirements.

Figure 3.1 | Estimation of the Implicit Interest Rate and the Implicit Funding Cost for Deposits – Items in Pesos – Financial System – Cumulative 3 Months Moving Chart

Specific elements of resilience and policy actions taken

As detailed at the beginning of this chapter, the current configuration of the main indicators of the soundness of the financial system – particularly in terms of liquidity and solvency – shows a good relative position to face a possible scenario of lower intermediation between deposits and loans with the private sector. Additional aspects that help build resilience in the face of this potential adverse scenario are mentioned below.

The BCRA continues to take specific measures that seek to promote financial intermediation. Among the most recent are the expansion of preferred guarantees13, the increase in the maximum exposure limit for an MSME to be framed as a retail portfolio, the regulation of ECHEQ, the authorization of complementary agencies, the elimination of the collection of commissions for MSMEs’ over-the-counter deposits, the increase in the limits of immediate transfers and the implementation of online fixed terms in entities in which users they do not have a sight account, among other measures. 14

There is adequate monitoring at the microprudential level. Financial institutions are subject to a continuous supervisory process that is oriented to the risk profile they assume, a process that adopts best practices and international recommendations, as well as local experience in the field. Thus, the SEFyC carries out multiple monitoring actions (general and specific inspections, off-site supervision, etc.), adjusting their scope, intensity and frequency to the business model of the different entities.

3.2 Loan portfolio performance

In the event that any of the risk factors presented in Chapter 2 materialize, the financial system could face a further deterioration in the quality of the loan portfolio. This situation would put pressure on profitability and aggregate solvency indicators in the sector. In the hypothetical case of a further significant deterioration in asset quality, the dynamics of granting new financing15 could be further conditioned, with a possible impact on the generation of results. It should be noted that so far the impact of the materialization of credit risk on profitability and solvency margins at the aggregate level has been significantly limited, while the current slack both in terms of the level of capitalization and coverage with forecasts is giving a significant degree of resilience to the system in the face of this potential source of vulnerability.

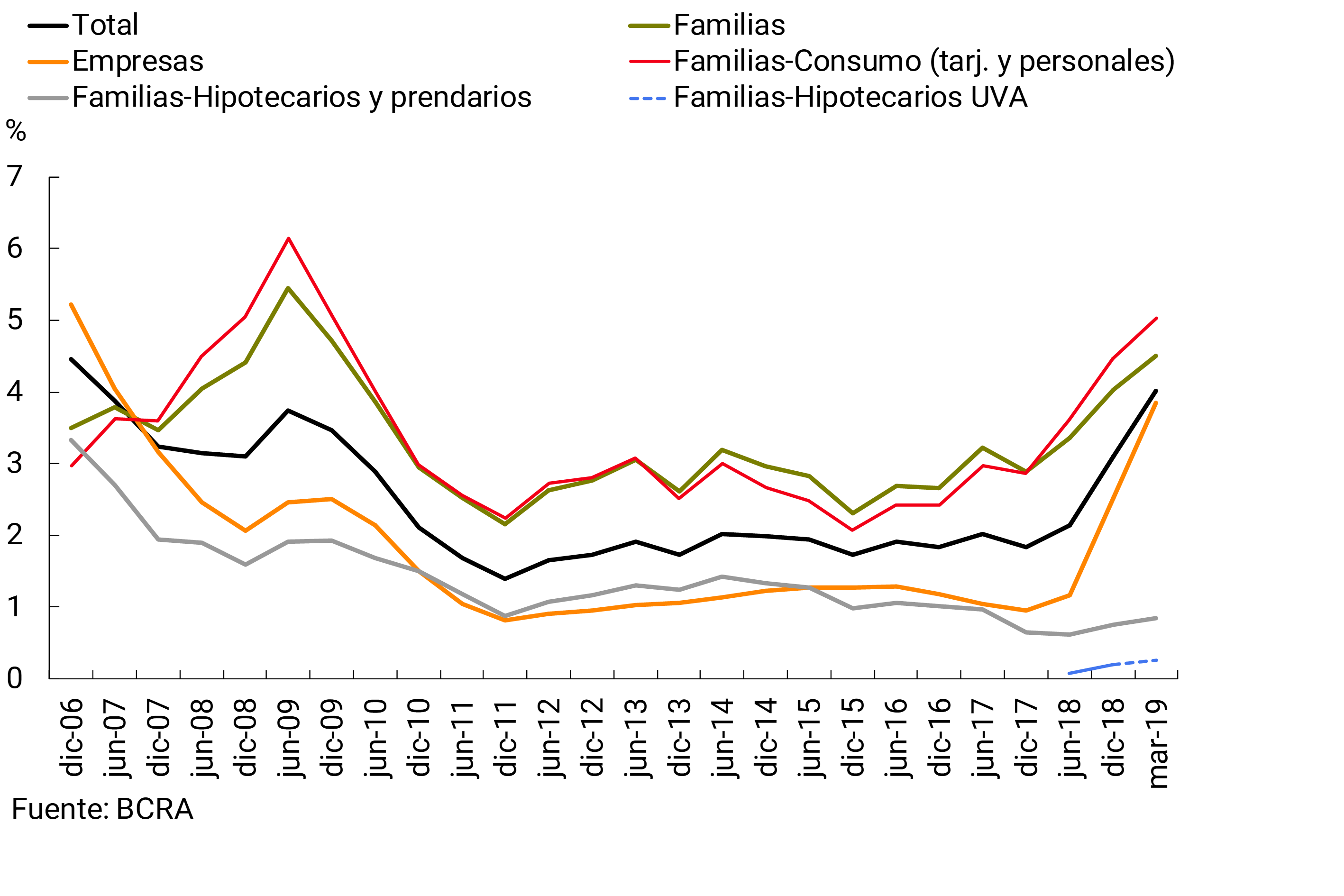

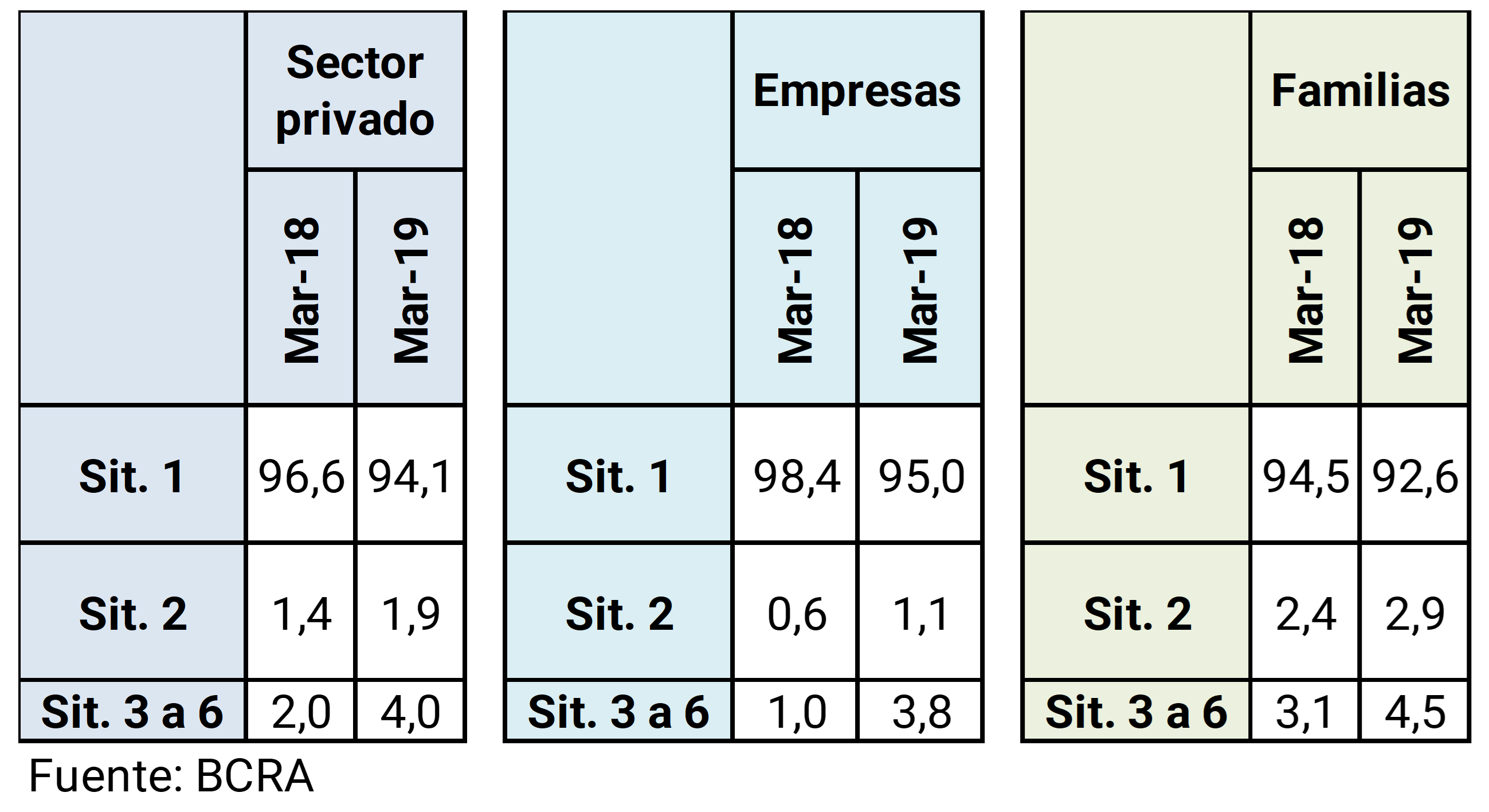

The quality of the system’s loan portfolio began to deteriorate (from historically low levels) since the end of 2017. This trend has been accentuated since mid-2018, in the context of the recessionary phase that the Argentine economy is going through and the significant real fall in credit to the private sector. The non-performing loan ratio for private sector loans reached 4% in March of this year, with a year-on-year increase of 2.1 p.p. (see Figure 3.2). This increase occurred almost entirely in the last 6 months, and was mainly explained by the behavior of irregularity in credit to companies (+2.8 p.p. y.o.y.). The increase in this ratio was mainly due to the behavior of debtors belonging to the industry and commerce sectors. The irregularity of loans to households, which shows a higher relative level, grew less markedly (+1.4 p.p. y.o.y.). Among the latter, the performance of mortgage lines denominated in UVA stands out (irregularity of 0.3% as of March 2019).

Figure 3.2 | Irregularity of credit to the private sector

In recent months, a drop in the weighting of financing granted to debtors in a better situation has been observed in the face of the risk of uncollectibility. Compared to March 2018, at the aggregate level, the proportion of debtors in situation 1 (normal) fell by 2.5 p.p., and the relevance of situation 2 (low risk or with special monitoring) increased by 0.5 p.p. (see Table 3.4). This change was mainly explained by the business credit segment.

Table 3.4 | Financing according to the situation of private sector debtors In % – According to debtor classification standard

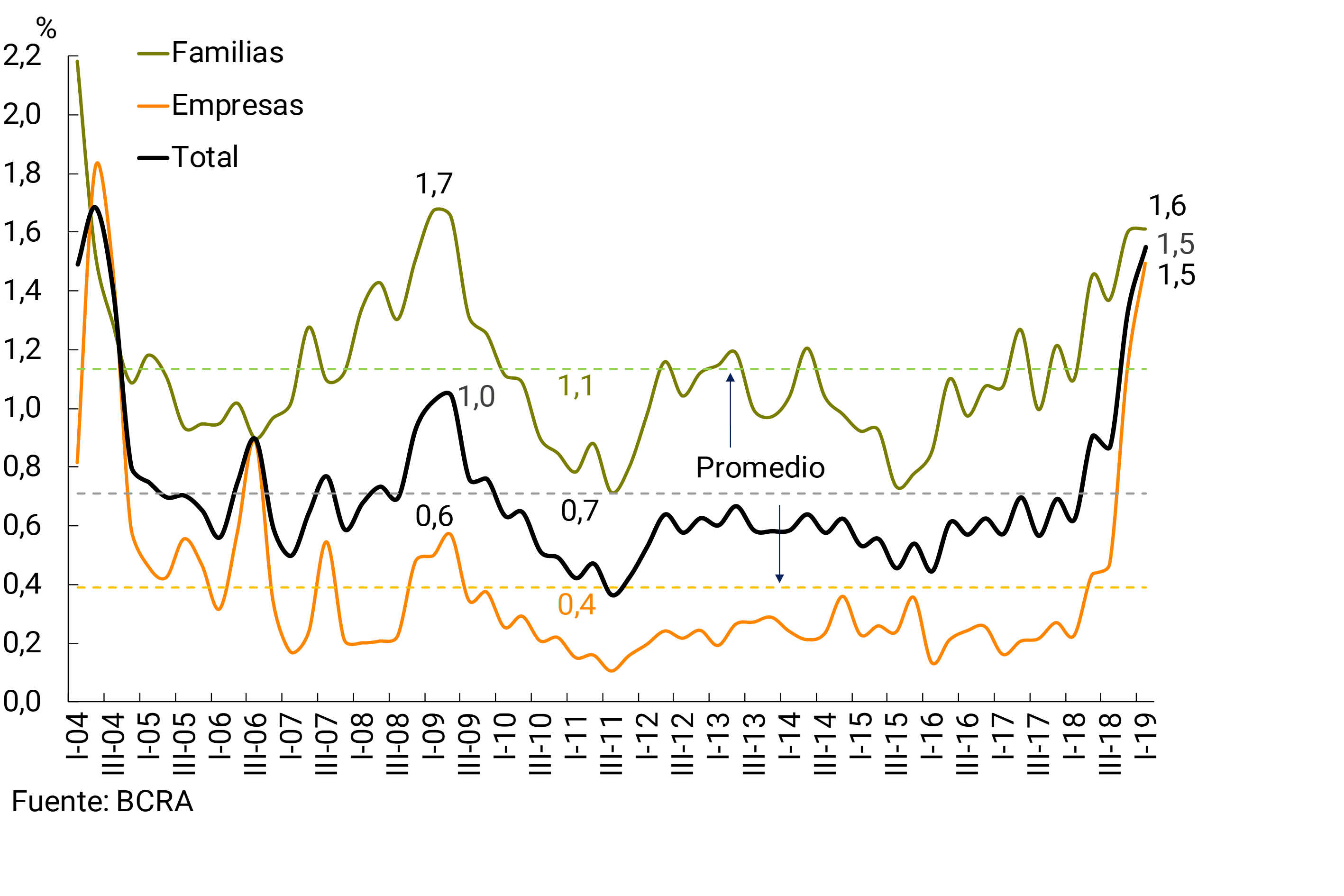

Indicators designed to capture the eventual transition of debtors at the individual level – according to risk of uncollectibility – and which therefore provide an estimate of the probability of default of credit subjects, continued to reflect the deterioration in credit quality (see Figure 3.3). High levels were observed in relation to the values of the last 15 years. 16

Figure 3.3 | Estimated Probability of Default (PDE) – Credit balance to the private sector

In terms of the observed fall in the level of economic activity, the percentage change in the irregularity ratio of credit to the private sector from March 2018 to the present was greater than that recorded in past recession experiences (especially 2008-2009). While the market expects a slight increase in economic activity for the first and second quarters of 2019, portfolio quality indicators are expected to continue to show some deterioration in the coming months. This would be explained both by the fact that the recomposition of the income of families and companies would be gradual, and by a certain temporary lag with which some financial institutions would adjust the classifications of their debtors. In addition, given that the contractionary bias of the monetary scheme will continue in 2019, it is expected that the reduction in interest rates will be gradual and will be verified only to the extent that inflation decreases.

Specific elements of resilience

In addition to the considerations made at the beginning of the section regarding the degree of resilience of the financial system to this source of vulnerability, some additional elements should be added that would act as mitigators of the possible impact that an additional materialization of credit risk could generate.

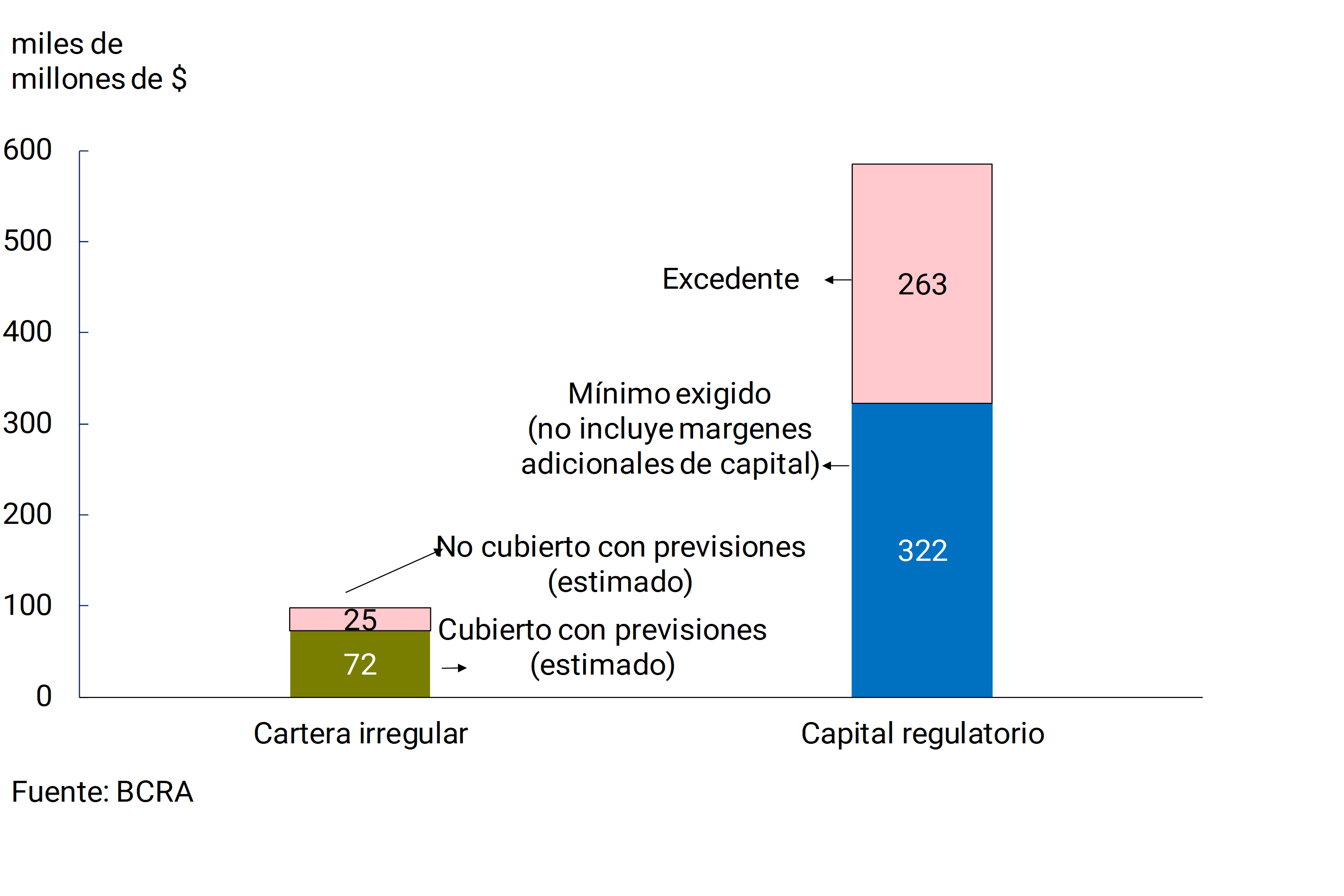

Very low equity exposure to credit risk. Given the current combination of historically low gross credit exposure (39.4% of assets), still limited irregularity and high levels of relative forecasts and solvency, the current level of regulatory capital slack at the level of the financial system would still be maintained in extreme hypothetical scenarios of credit risk materialization. In this regard, it is estimated that loans to the private sector in an irregular situation not covered by accounting forecasts would reach $25.3 billion in March 201917, which is equivalent to less than 10% of the excess regulatory capital (integration minus total requirements) (see Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4 | Irregular portfolio, pension and capital. Financial system. Mar-19

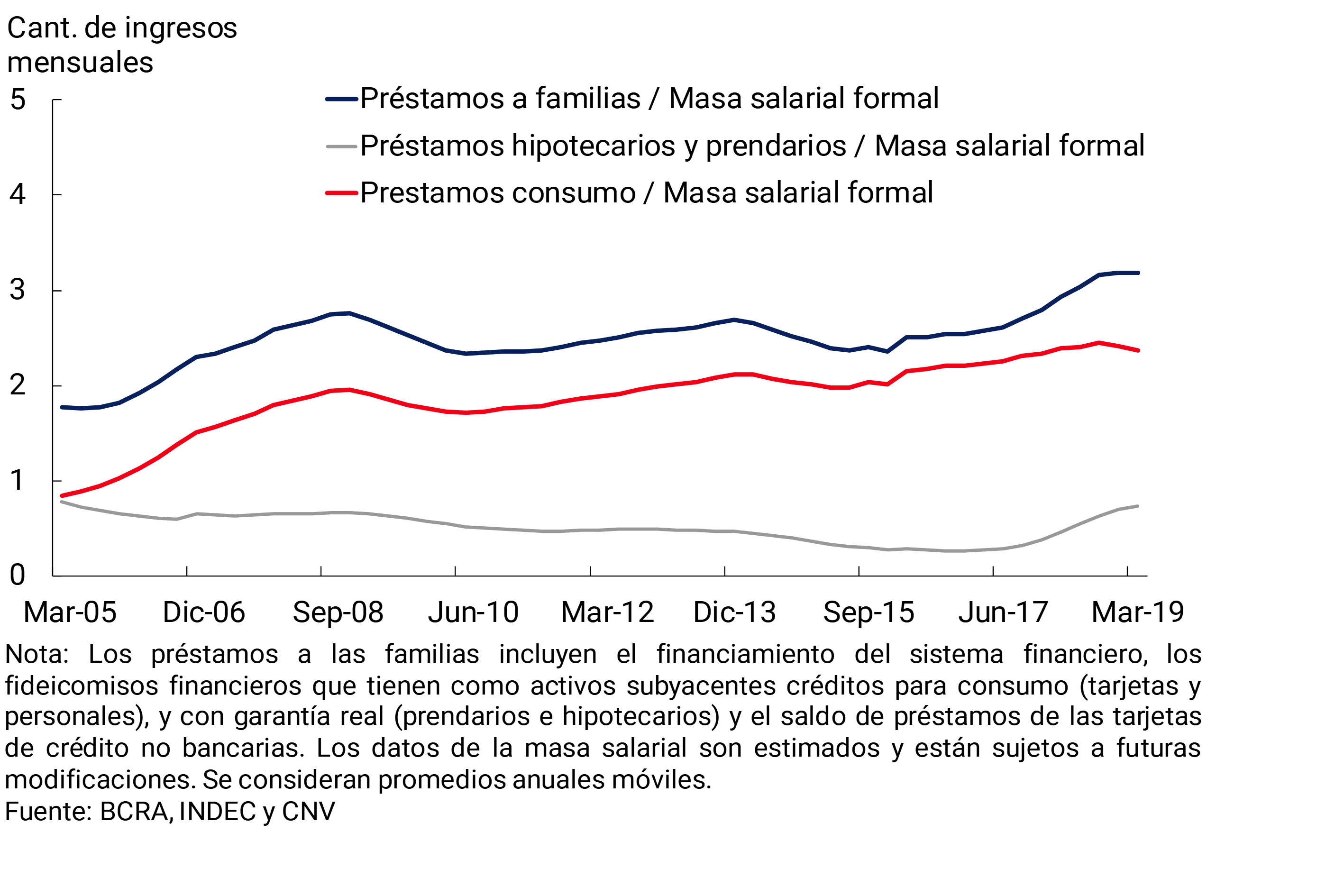

Moderate leverage and debt burden of private sector debtors. Households, both generally and by income strata (see Section 2), maintain a low relationship between their level of debt and their income (see Figure 3.5). It is worth noting the low level of estimated household indebtedness compared to what has been observed in the rest of the countries of the region: 7% of GDP in Argentina compared to a regional average of more than 20%. 18

Figure 3.5 | Household debt – In terms of the amount of monthly income Wage bill net of contributions and contributions

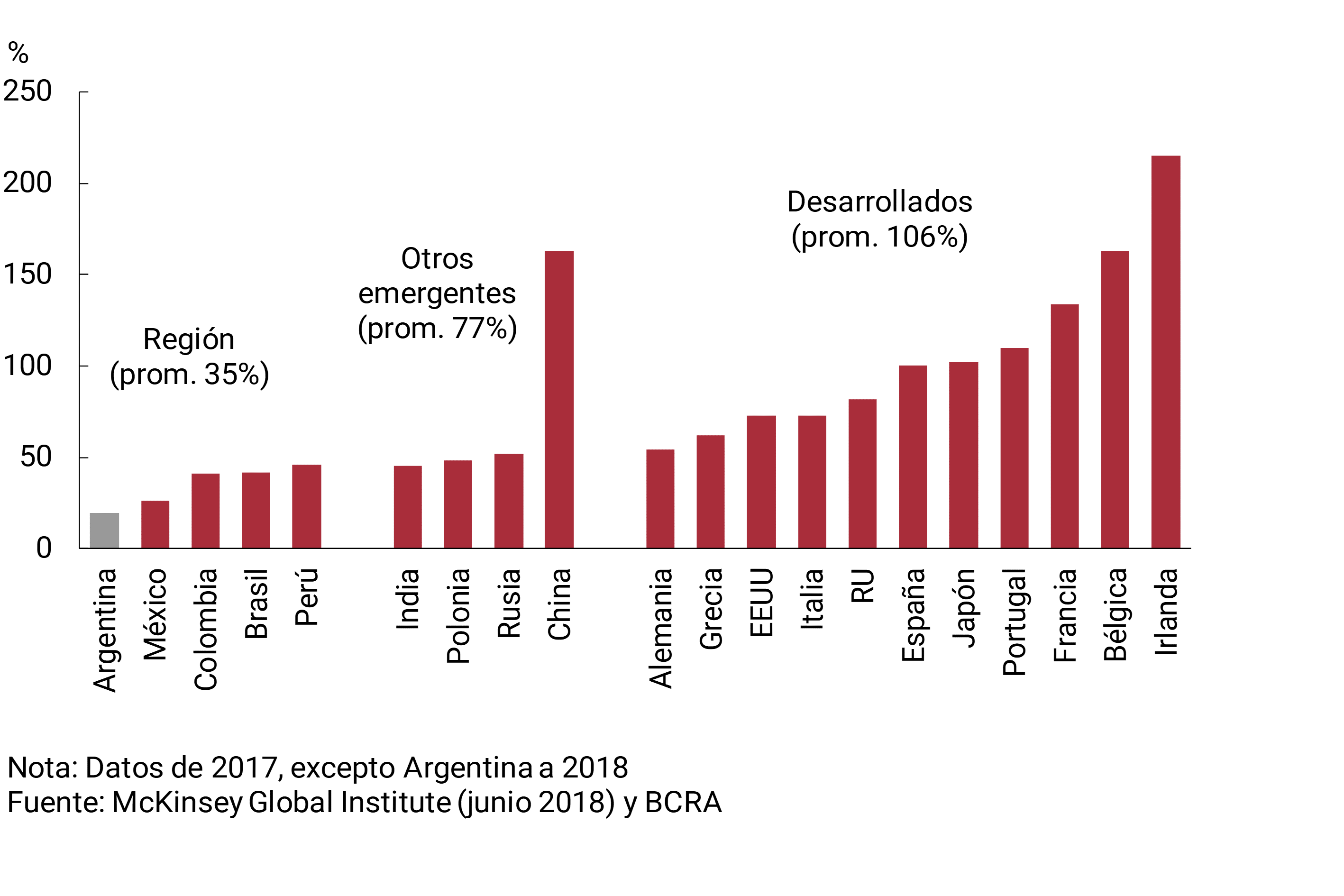

The corporate sector is also poorly leveraged at the aggregate level. Corporate debt accounts for about 20 percent of GDP, well below other economies (see Figure 3.6).

Figure 3.6 | Corporate Debt – International Comparison. % of GDP

Conservative credit origination standards. During the last expansionary phase of credit, between early 2017 and mid-2018, there was no significant relaxation of the credit origination standards, terms, and conditions applied by banks. 19 By way of example, the origination of mortgage loans in UVA was consistent with good banking practices: the ratio required by the entities between the down payment and the income of the borrower was around 30% and the quotient between the amount of the loan and the value of the property to be acquired was around 70%. 20 This is consistent with the relatively low level of delinquency shown by the different harvests of this type of credit.

Moderate currency mismatch of debtors. The risk associated with currency mismatches on debtors’ balance sheets is also low. Indebtedness (local and external) in foreign currency is limited and several of the sectors with the greatest exposure have income flows correlated with the evolution of the exchange rate. In the case of local bank credit, the BCRA’s macroprudential regulation limits the uses of the lending capacity of deposits in foreign currency to prevent banks from being exposed to currency mismatches of debtors (See Table 3.6).

Low exposure to the public sector. The credit exposure of the financial system to the different levels of government remained low. The gross exposure of banks as a whole to the non-financial public sector totaled 9.7% of assets as of March 2019 (See Table 3.2), with no significant changes in the last 5 years. If the total deposits of the public sector are considered, the financial system maintained a negative net exposure (debt position) to the public sector.

3.3 Bank funding

Deposits are the main source of funding for the local financial system (72% of the total at the end of the first quarter of 2019), with a greater weighting of those that come from the private sector (more than 80% of total deposits) (see Table 3.1). Net equity and, to a lesser extent, other instruments such as negotiable bonds, subordinated bonds and foreign lines constitute the remaining sources of funding for the entities. This funding structure, with a preponderance of sources considered relatively more stable, is generally a feature of the strength of the local financial system.

However, in the face of an election year and/or the materialization of a more adverse scenario at the international level – with local economic agents relatively adapted to operate in contexts of high volatility – certain portfolio changes could occur, with an eventual negative impact on the level and/or composition of banks’ funding. This situation could eventually translate into pressure on liquidity margins at a systemic level. A highly volatile exchange rate and interest rate context would also affect the ability of banks to refinance negotiable obligations in the local market.

As detailed in Section 3.1, private sector peso time deposits have performed positively in recent months (see Figure 3.7). As a result, at the end of the first quarter of 2019, time deposits accounted for just over 52.5% of the total deposits in pesos of the private sector, with a year-on-year increase of almost 7 p.p. in their participation compared to 6 months ago.

Figure 3.7 | Evolution of private sector deposits in pesos in real terms

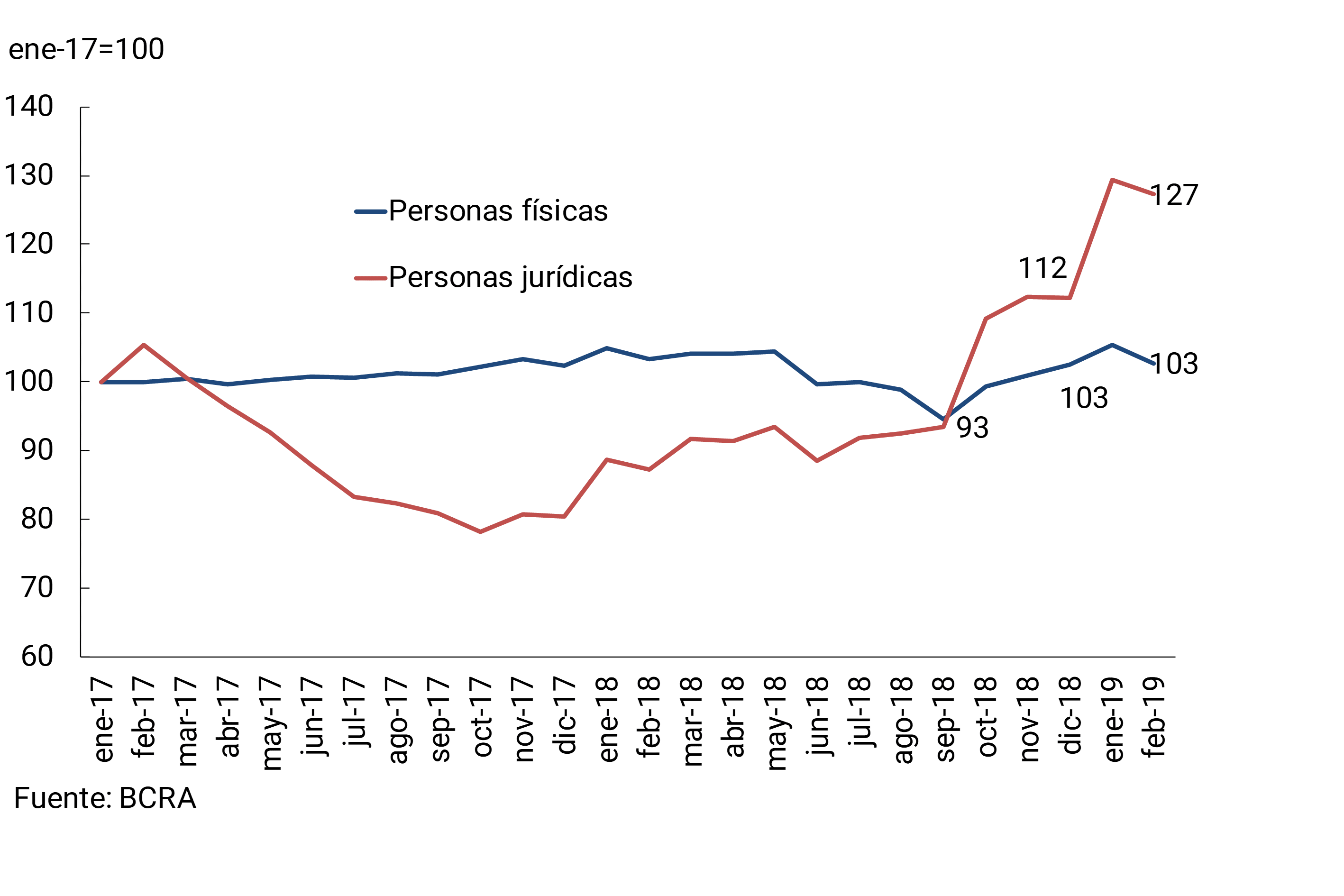

The evolution of fixed-term deposits in pesos was mainly led by the increase in placements by legal entities (see Figure 3.8), while the balance of the same type of deposits by individuals remained relatively stable in real terms. In recent months, both types of placements have had a contractual term of just under 2 months (in line with what has been observed in recent years). Although this source of funding is short-term, it has shown a positive performance in recent quarters, in a scenario of ample levels of liquidity in pesos in the system.

Figure 3.8 | Performance of fixed-term deposits in pesos in real terms

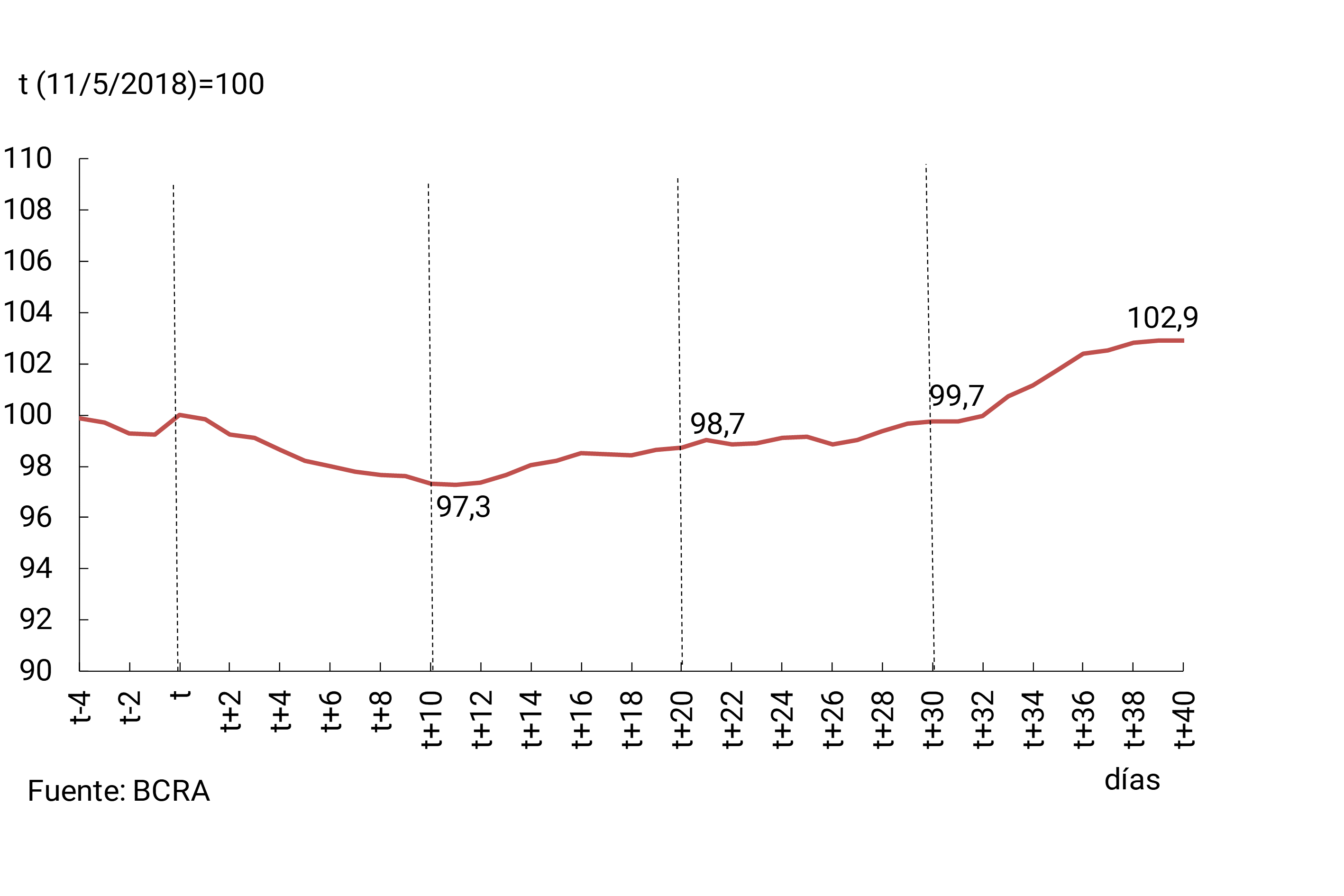

In recent quarters, the weighting of foreign currency deposits within total private sector placements has gradually increased. These deposits (mainly on demand) went from representing 26% of total private sector deposits in the first quarter of 2018 to almost 37% of the total at the end of the same period in 2019. This increase was explained both by the expansion of the total balance in currency of origin (15%) and by the increase in the nominal exchange rate in the period. This type of placement registered a transitory episode of reduction in the second quarter of 2018 (see Figure 3.9), coinciding with a moment of instability in the foreign exchange market. These placements quickly stabilized and recomposed their growth, in a context in which banks maintained ample levels of liquidity in foreign currency. As of March 2019, the balance of private sector deposits in foreign currency – in the currency of origin – is 150% higher than the level observed three years ago.

Figure 3.9 | Episode of temporary reduction in the balance of private sector dollar deposits

Specific elements of resilience

The effect on bank funding of greater volatility would be limited, mainly by:

Liquidity by currency at historically high levels. Liquidity represents 61% for placements in pesos and 57% in dollars. In addition, the requirements that are in line with the international Basel standards are currently widely exceeded, both in terms of the liquidity coverage ratio (2.2 for the largest banks in aggregateform 21, with a regulatory minimum of 1) and the stable net funding ratio (1.7 also for the same type of banks, with a regulatory minimum of 1). With respect to the tools to manage liquidity risk, the local safety net has deposit insurance (whose ceiling was recently increased to cover placements of up to $1 million) and the BCRA in its role as lender of last resort in national currency (windows for liquidity provision).

Limits on the lending capacity of foreign currency deposits. This macroprudential policy, in force since 2002 (see Section 3.5), ensures an adequate channeling of deposits in foreign currency to loans in the same denomination, specifically to debtors who have the capacity to generate income in that currency.

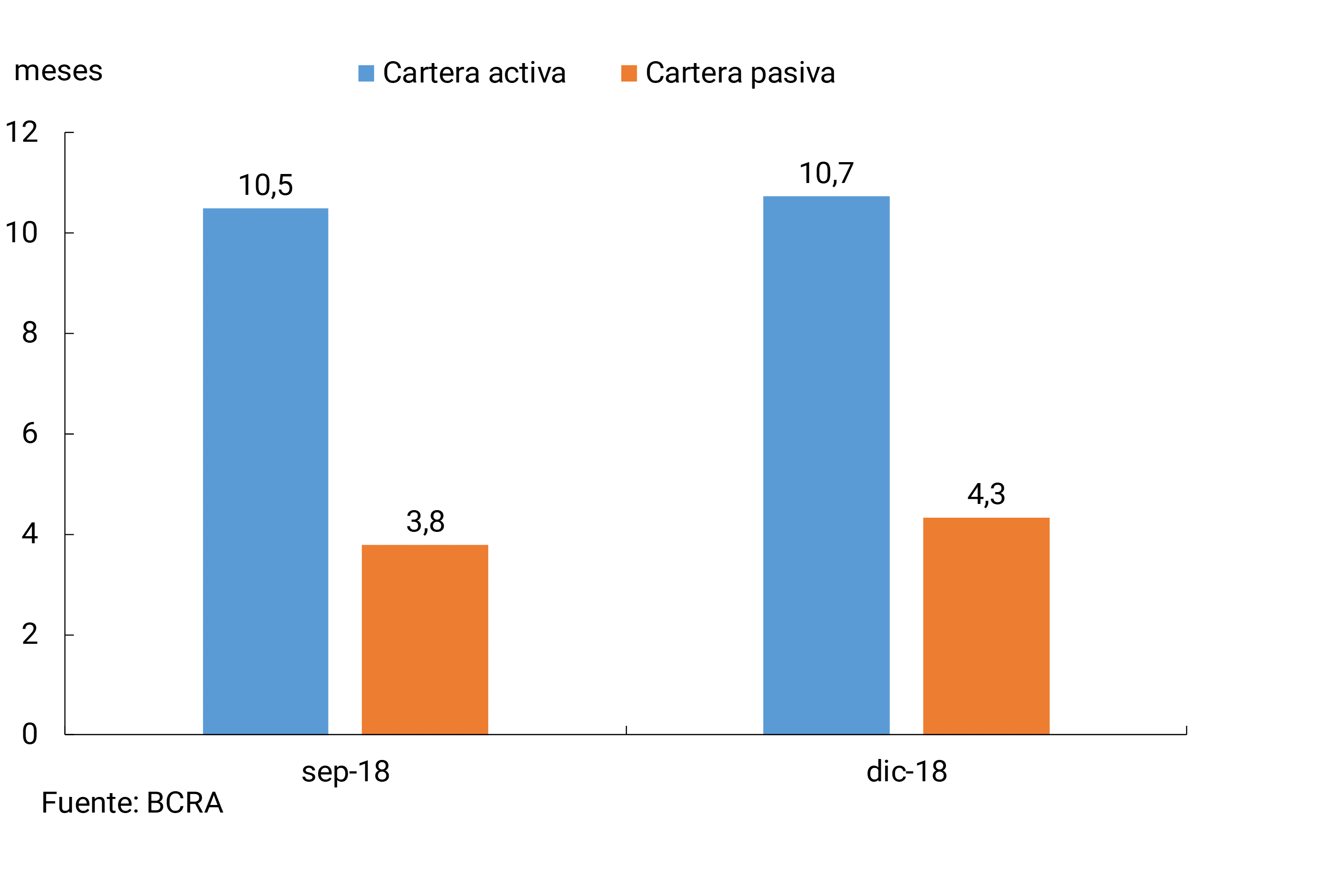

Limited transformation of deadlines. Although the emergence of the UVA denomination in loans and deposits made it possible to extend the weighted average term of credit lines to the private sector and placements, at a general level the transformation of terms in the financial system remains relatively limited. In particular, at the end of 2018, compared to an average duration of just over 4 months in liabilities, the average term of the system’s assets reached just under 11 months (see Figure 3.10). 22

Figure 3.10 | Duration of the portfolio in pesos of the financial system (includes CER). Financial system

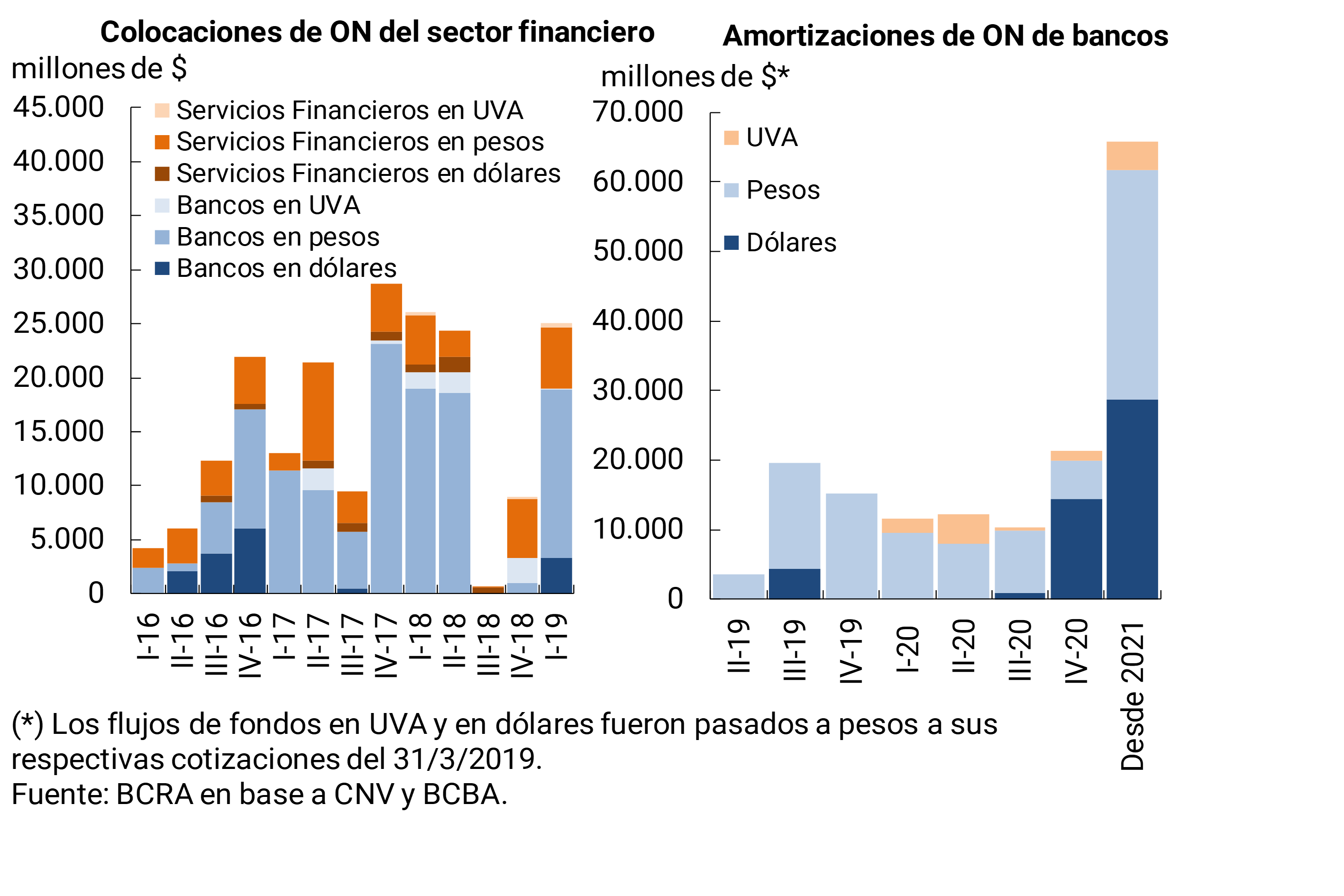

Low dependence on funding through market instruments. In general, banks have a very limited part of their funding through negotiable obligations (only 2.7% of the total23), and in the aggregate the capital maturities they face in the short term are manageable and mostly in pesos. In the last three quarters of 2019, less than a quarter of the total balance of bank negotiable obligations matures and almost 90% of these maturities are in pesos. For its part, in the local capital market, the placements of negotiable obligations began to recompose in recent months, although the pace was not sustained. Banks took advantage of times with more limited exchange rate and interest rate volatility in local financial markets to place new issues (see Figure 3.11). 24

Figure 3.11 | Negotiable obligations

3.4 Other topics of stability of the financial system

Interconnection in the financial system

The link between the degree of interconnectedness of the financial system and its stability has several edges (see Section 3 of the IEF for the second half of 2018). Understanding the financial system as a network, the more complete it is, the deeper the market it represents, collaborating with a better distribution of risks. However, greater interconnection may imply a relatively faster and more intense spread of an eventual materialization of risk factors.

In the Argentine financial system, a relatively important source of direct interconnection between entities is the interfinancial markets (repo and call markets). These markets are limited in size (conditioning the possibility of managing liquidity) and usually have limited direct interconnection between entities (which could eventually generate a lower risk of contagion). Although the call market has a smaller relative size than the repo market, as it is an unsecured transaction, its analysis is more relevant in terms of financial stability.

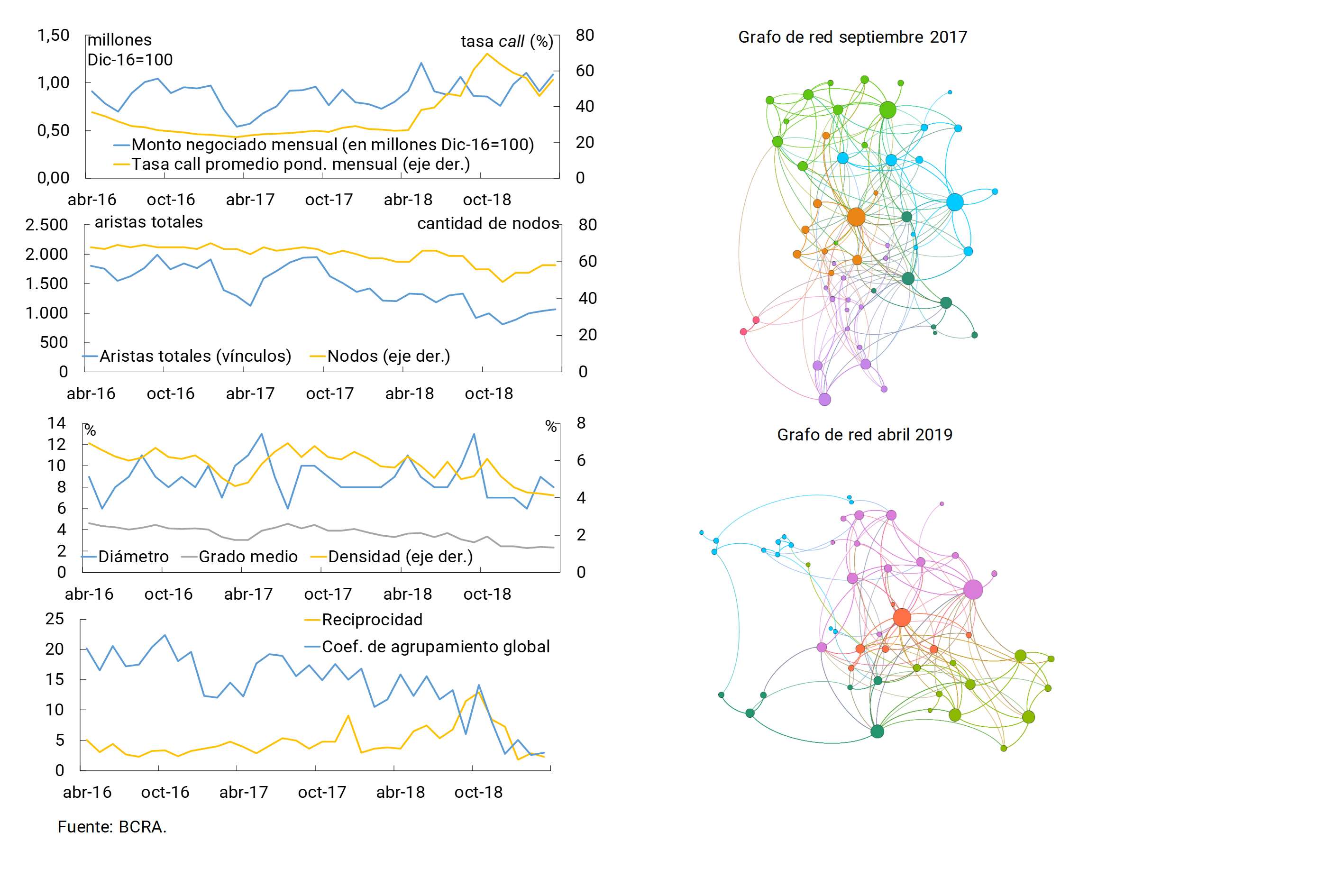

In a context of an increase in the weighted average rate and a marginal drop in the amounts traded in real terms, in recent months the different network analysis metrics applied to the call market show a relatively low degree of interconnection (see Figure 3.12). 25 These results are in line with what has been observed in other episodes of greater volatility in the markets.

Figure 3.12 | Network analysis metrics and graphs and amounts and rates traded for the call market

Direct links between banks and the rest of the financial sector are also limited, considering, for example, the connection through deposits and loans (see Section 3).

Soundness of local systemically important financial institutions (D-SIBs)

Potential problems in the soundness of local systemically important financial institutions (D-SIBs) could have unintended consequences for the financial sector and the economy as a whole due to their size, interconnectedness, complexity, and low substitutability. In line with international standards, the BCRA developed a methodology to identify these entities. 26

The banks considered D-SIBs in Argentina represent half of the assets of the Argentine financial system. In addition to fully complying with the capital conservation margin in force for all financial institutions, these banks currently verify the entire additional conservation margin because they are classified as systemically important. 27 Given the relative importance of this group of D-SIBs, their performance was largely reflected in the aggregate indicators for the financial system. In particular, liquidity and solvency indicators remained high, in a context in which there was evidence of some deterioration in the quality of their assets (see Table 3.5).

Table 3.5 | Strength indicators for DSIBS-rated entities

3.5 Main macroprudential policy measures

The BCRA has a wide range of macroprudential policy instruments at its disposal that helps mitigate possible systemic risks. This toolkit was designed in part to address the vulnerabilities observed during the 2001-2002 local financial crisis. This includes risks related to excessive exposure to the public sector at all levels and currency mismatches, both on banks’ balance sheets and in debtors’ equity (see Table 3.6). In addition to these measures, the strengthening of the already existing liquidity requirements (reserve requirements) according to the currency of origin of the deposits and improvements in the regulation of banks’ exposures to individual debtors were added.

Table 3.6 | Macroprudential policy instruments

Among the macroprudential regulations there are also several linked to Basel III (end of 2010). These measures include those linked to the new international capital standards (improvements in capital components, limits on leverage and introduction of additional capital margins, among others) and liquidity standards (new ratios to be met, among others), as well as better supervisory standards.

In recent months, two new regulations were added aimed at limiting the development of sources of vulnerability for the local financial system. On the one hand, and following the Basel recommendations, from the beginning of 2019 regulations on Large Exposures to Credit Risk were introduced, which aligned local regulations on this issue with international standards. On the other hand, in February 2019, a limit was added to the position of BCRA instruments (LELIQ) by financial institutions. Currently, the aforementioned limit is the lower between: i. the PRC of the entity and ii. 100% of the monthly average of daily balances of total deposits in pesos – excluding those of the financial sector – and of the residual value of its negotiable obligations in pesos – issued until 8/2/19. In practice, this meant a limit to the BCRA’s positioning in liabilities for very short-term foreign capital flows, which can lead to greater volatility in the foreign exchange market.

In line with what is detailed in IEF II-18 and in Section 3.2 of this Chapter, the current situation with respect to the economic and financial cycles is consistent with a reduction in the exposure of the financial system to credit risk, in a general framework of moderate levels of sectoral leverage (households and firms). These factors, together with other additional variables taken into account by the BCRA when assessing the vulnerabilities faced by the system as well as its degree of resilience, support the decision of this Institution to maintain the additional rate of the Countercyclical Capital Margin (Distribution of results) at 0% as of June 2019.

Section 1 / Financial situation of publicly offered companies

Monitoring the corporate sector and its interrelationship with the financial system is an important component of macroprudential analysis. Changes in the context (level of activity, exchange rate, interest rates) affect the situation of companies, including their ability to pay, with an eventual impact on their creditors (banks, bondholders, and others). They can also have an impact on variables such as investment and employment, with second-round effects on the level of activity. Hence the importance of surveying the trends observed in the corporate sector and identifying segments with potential vulnerabilities.

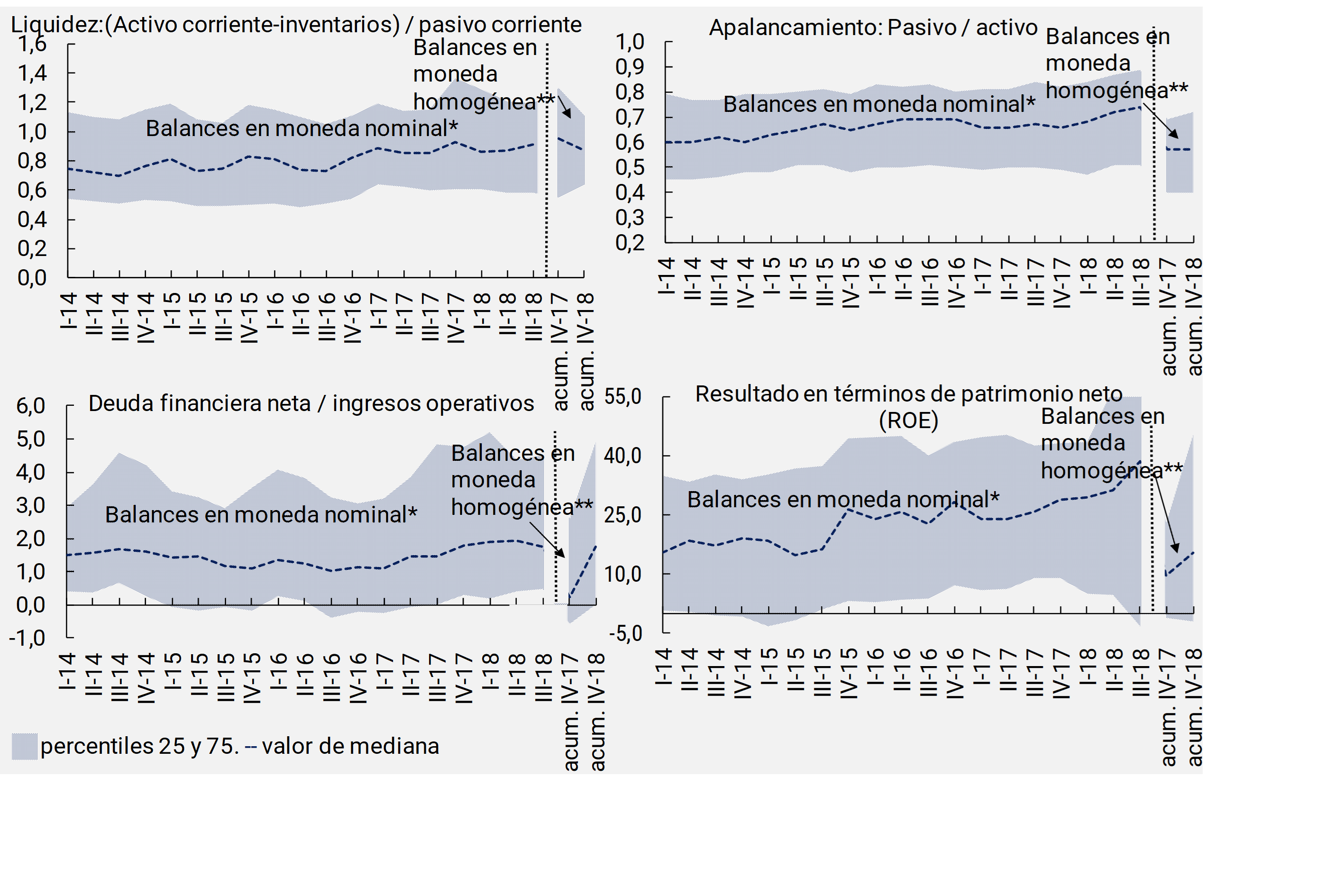

Working with the set of company balance sheets presented to CNV28 (see Chart A.1.1), an increase in median leverage, the weight of financial debt (total financial obligations, net of cash, as a percentage of operating income) and liquidity (measured as current assets net of inventories as a percentage of current liabilities) can be observed until IIIT-18. In particular, given the evolution of the $/US$ exchange rate, companies with negotiable obligations (ON) in dollars showed a more marked increase in all three measures. On the other hand, nominal profitability (in terms of equity) increased as a function of the performance of companies in the primary and service sectors, while it fell in industry due to a reduction in the profitability margin (result as a percentage of sales).

Figure A.1.1 | Financial ratios of publicly offered companies

Based on the enactment of Law 27,468 and General Resolution No. 777/18 of the CNV29, the balance sheets closed at the end of 2018 were prepared in homogeneous currency. Thus, the data for the end of 2018 in homogeneous currency show a certain stability in leverage (although the debt-to-earnings ratio increases), an increase in profitability (although with greater dispersion) and a fall in the liquidity ratio with respect to the data from twelve months ago in the same currency (presented for comparative purposes). 30

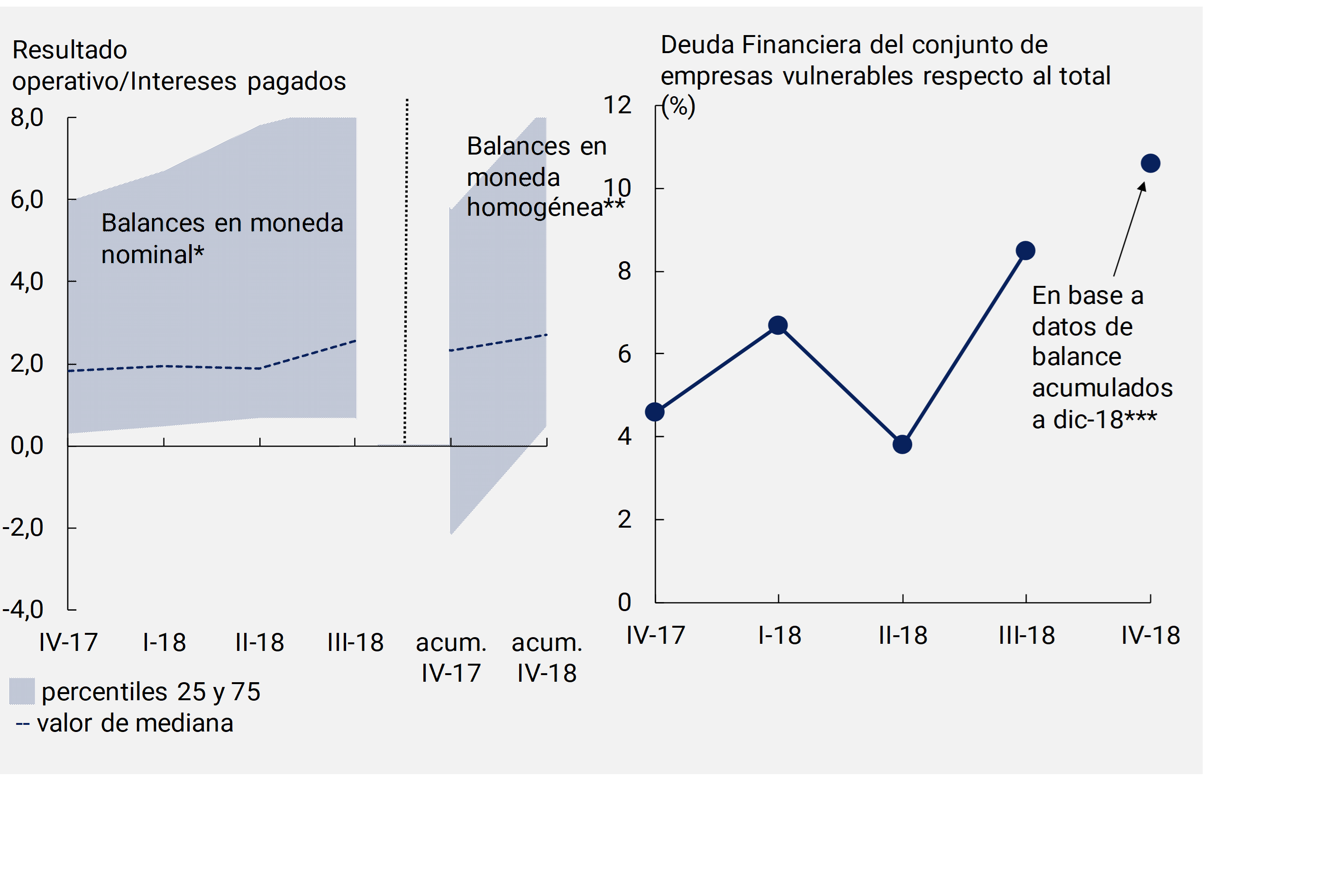

One of the usual indicators to measure the degree of financial vulnerability in terms of the repayment capacity of companies is the interest coverage ratio (operating results over interest paid). For the balance sheets analyzed, the median of this ratio had a slight decrease in the IIT-18, and then rose during the IIIT-18 – based on an improvement in revenues in sectors such as primary production – to a level of 2.6 (see Figure A.1.2 left panel). As a reference, based on an analysis of the balance sheet of companies at the global level, the IMF defines a threshold of 2 for this indicator, below which a company would show a significant level of financial vulnerability. 31 For the cumulative figure up to December 2018, based on balance sheets in homogeneous currency, this ratio also remains above 2 for the median of companies with a public offering (with a slight increase compared to 12 months ago).

Figure A.1.2 | Interest and financial debt coverage of vulnerable companies

In order to understand the possible systemic scope of the situation of companies in a more fragile situation in relative terms, a subset of firms that show vulnerability in at least two of the three most relevant financial ratios (interest coverage, leverage and liquidity) was determined. 3233 This group was made up of 28 companies from heterogeneous sectors, which represent about 10% of the total financial debt of the sample of publicly offered companies (see Figure A.1.2 right panel). 34 As of December 2018, the funding of this subset of firms would be mostly by ON, followed by bank financing (see Figure A.1.3). With respect to their ability to pay, the median liquidity of this subset of companies is lower than that of the total sample, as is their ROE.

Figure A.1.3 | Debt characterization of relatively vulnerable companies

The credit exposure of the financial system to the subset of firms identified as relatively more vulnerable is very limited. The total balance of bank debt of this group of companies represents less than 2% of the aggregate credit of the financial system to the corporate sector. As of March 2019 (latest available data), 97% of this debt was in situation 1 or 2 (portfolio in a regular situation), although there has been a deterioration in the margin (as of December 2017, almost 100% of these financings were in situation 1). 35 The remaining 3% is distributed in situations 3 and 4 (1.4% and 1.7%, respectively).

The bond debt of these potentially vulnerable companies represents 9% of the total balance of corporate sector bonds as of December 2018. The bonds of these companies are mostly in dollars (95% of their ON balance). The maturity profile of these bonds in dollars (both interest and amortization) is concentrated after 2022 (72% of the total), given the refinancing operations carried out in the last36 years, and corresponds to companies from different economic sectors (several of them with tradable assets or with operations abroad). With respect to its bonds in pesos (refinanceable in the domestic market), 40% mature in 2019 and 24% in 2020.

In summary, the corporate sector is monitored with a focus on the most vulnerable segments to assess their importance in systemic terms, which will be enriched as new balance sheets are presented in homogeneous currency (extending the history of comparable data). So far, it has been highlighted that those companies with public offerings that have relatively less solid financial ratios have a low weighting on the aggregate credit portfolio of banks, while their bonds in dollars (their main source of financing) imply relatively light repayment commitments in the short term.

Section 2 / Analysis of household indebtedness based on microdata from the Central Debtors’ Office

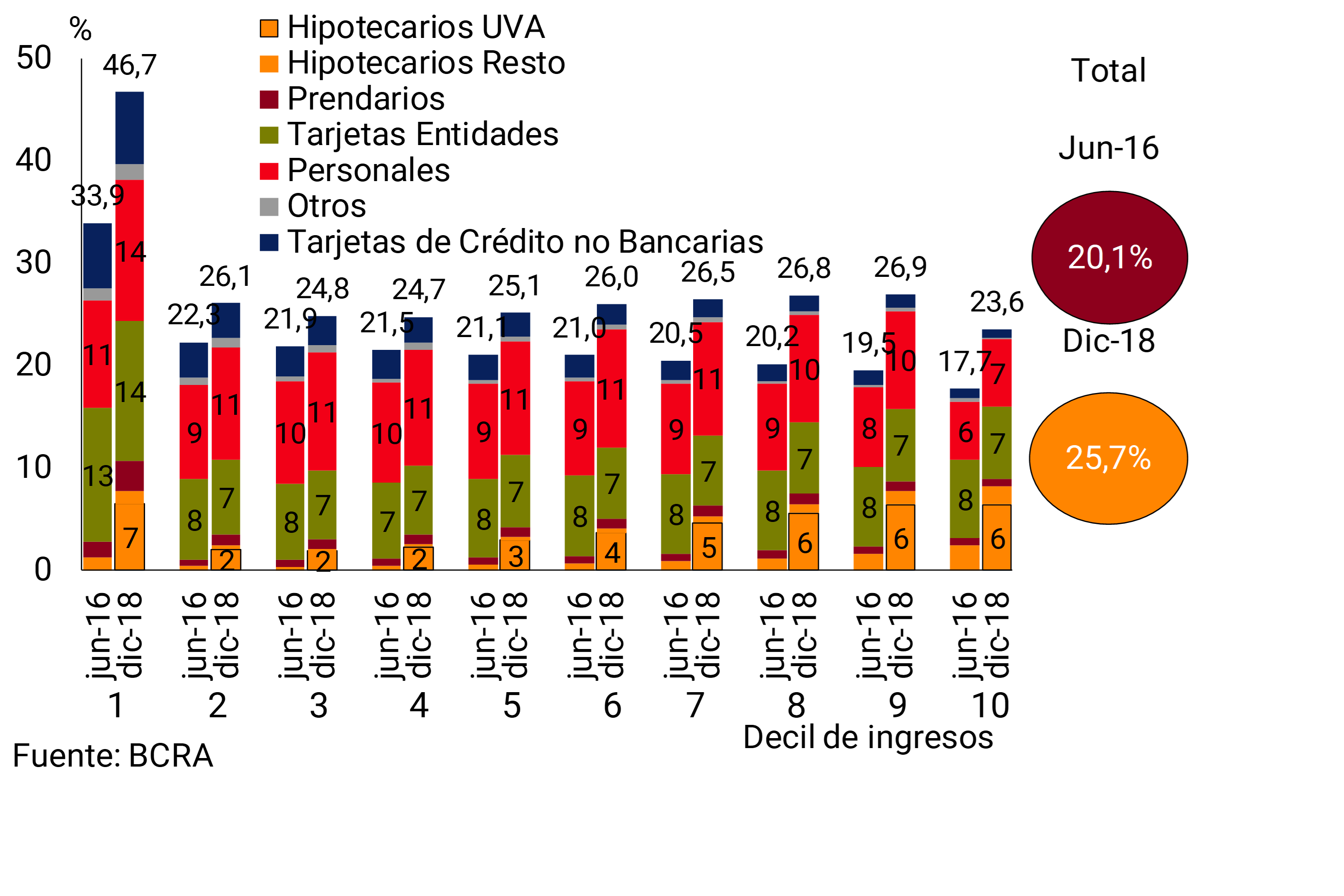

As mentioned in Chapter 3, the aggregate level of indebtedness37 of Argentine families is low (in the order of 8% of GDP), much lower both than the maximum values reached historically and the current records of other countries in the region (above 20% of GDP on average). This is despite the sustained growth in credit to this sector observed between the end of 2016 and mid-2018, a period in which the expansion of mortgage lines denominated in UVA was particularly noteworthy.

Although the aforementioned information allows us to have a perspective on the indebtedness of the household sector, it represents an average of Argentine households (including both those that have debt and those that do not). In order to carry out a detailed analysis of the level of sectoral leverage, which allows capturing potential differential behaviors and sources of risks not observable at the aggregate level, a monitoring of the relative level of household indebtedness according to the income strata (remunerations) in which they are located is updated. Estimates of these characteristics were presented in Section 3 of IEF II-16, as well as in a December 2017 note published in Ideas de Peso.

Using the same methodology38, the evolution of indebtedness by income strata between mid-2016 and the end of 201839 is analyzed, with the aim of measuring the impact of the last period of credit expansion on household leverage. It can be seen that between peaks in the aforementioned period, the level of indebtedness – in relation to annual income – increased for all deciles of remuneration (see Graph A.2.1). This ratio was in a range ranging from 24% to 27% in deciles 2 to 10, with a peak of 47% in decile 1. 40

Figure A.2.1 | Debt ratios according to annual remuneration strata

The increase in indebtedness between mid-2016 and the end of 2018 was proportionally more marked in the lowest income decile (variation of 12.8 p.p.) and in one of the deciles with the highest resources (9). In this growth process, the role of UVA-denominated mortgage loans was highlighted. Although these lines implied in 2018 a greater weight in the total indebtedness of middle- and high-income families (in the three highest deciles they have a weighting ranging between 21% and 27% of total indebtedness), it is observed that all strata of households accessed this type of credit.

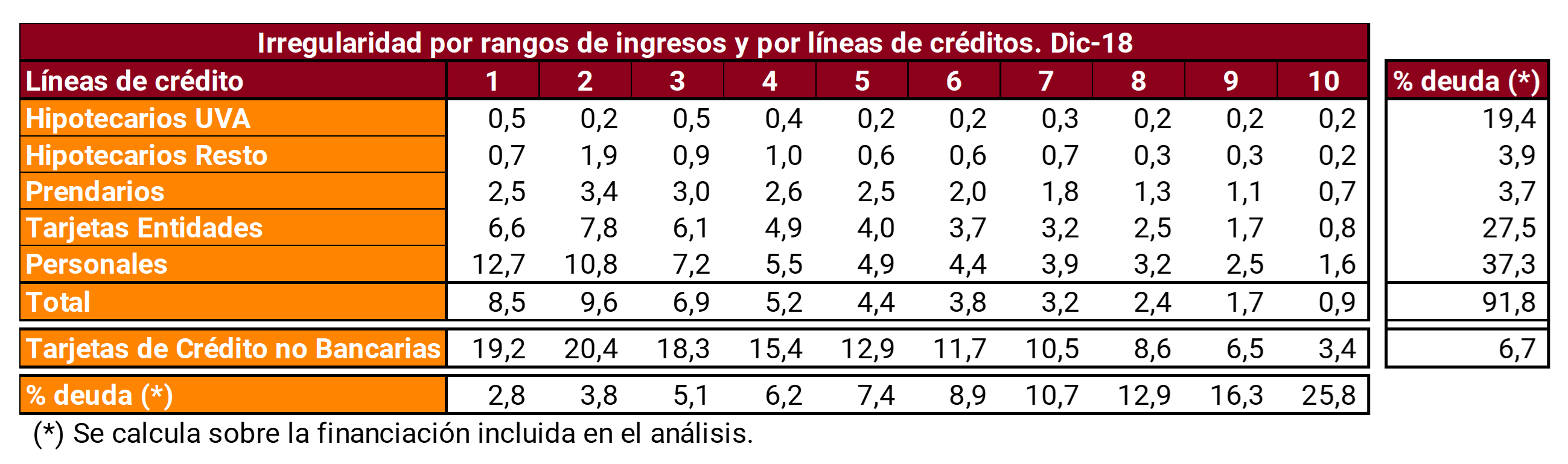

Debtors corresponding to the higher-income strata of the population tend to show lower levels of arrears (see Table A.2.1). Within the universe of debtors who have income in a relationship of dependency, the two deciles with the highest income (9 and 10) have total irregularity ratios of 1.7% and 0.9% respectively in 2018. Debtors in these income ranges accumulated 42% of the total financing involved in the analysis. On the other hand, non-performing loans in the two lowest wage strata reached 8.5% and 9.6% respectively (less than 7% of the financing analyzed). This behavior is similar in all credit lines, highlighting the low level of irregularity of UVA mortgages in all strata (with the maximum delinquency rate being 0.5%).

Table A.2.1 | Irregularity by income ranges and credit lines

The foregoing analysis shows that the indebtedness of Argentine households is relatively low, both from an aggregate point of view and by income strata. This implies that the degree of vulnerability of the family sector (and the financial sector) to the eventual materialization of risk factors or stress events such as those observed in 2018 would be limited.

Section 3 / Non-bank financing in Argentina

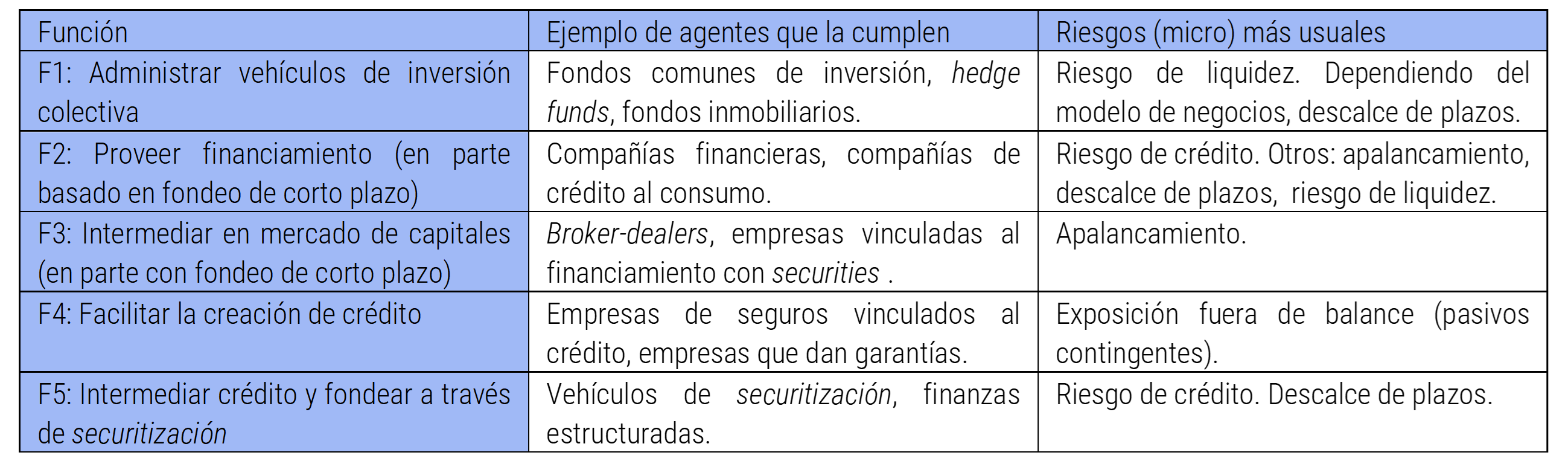

The activity of banks is complemented by that of agents who, without carrying out classic intermediation funded with deposits, grant financing (via loans or through financial instruments) or facilitate access to it by granting insurance or guarantees. In addition to expanding funding sources, these agents can generate competition and drive innovation and financial inclusion.

The activity of non-bank agents involves risks, in some cases similar to those of banks (leverage, credit and liquidity risk, mismatch of terms). These risks, usually considered in micro supervision, can become systemic depending on the volume of activity of these agents and their interconnection with banks, as evidenced in the international financial crisis that peaked in 2008-2009. One approach to address the analysis of non-bank agents is given by the annual mapping carried out since 2011 by the Financial Stability Board (FSB, created at the initiative of the G-20), with the participation of Argentina. 41 The FSB’s general mapping includes banks, pension funds, and insurance companies, but focuses on the rest of the non-bank financial agents (NBFAs), divided into five functions:

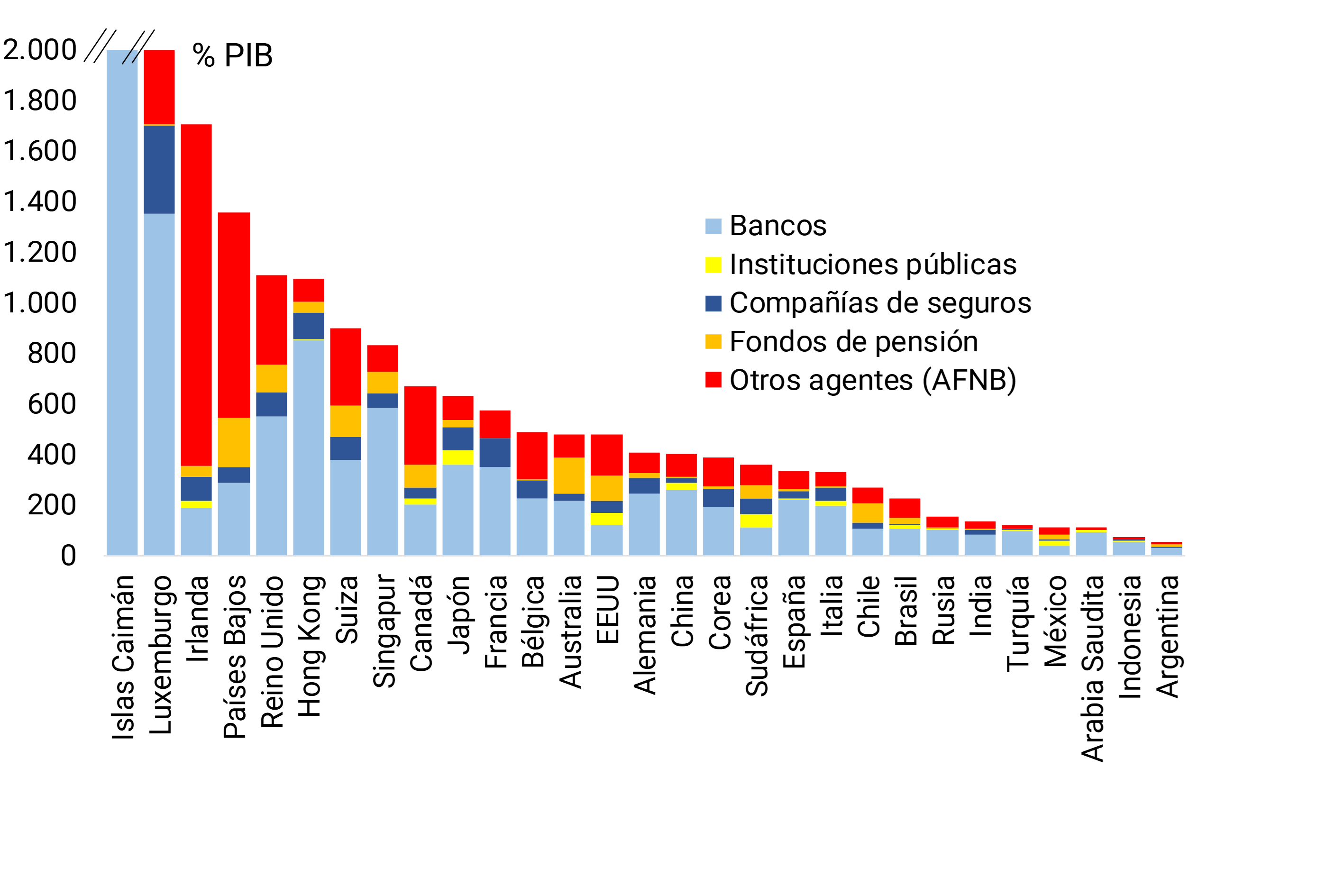

Following this methodology, in the case of Argentina, it can be seen that the financial sector in the broad sense is small in size in terms of GDP and is fundamentally banking (see Graph A.3.1). 42 The assets of the AFNBs represent 12% of the assets of the financial sector in Argentina, below the average of close to 30% observed for the rest of the countries. In the last 10 years, the assets of the AFNBs grew on average at a faster rate than that of banks, the FGS or insurance companies (in line with global trends), although in 2018 they slowed down their pace (differentiating themselves from the rest).

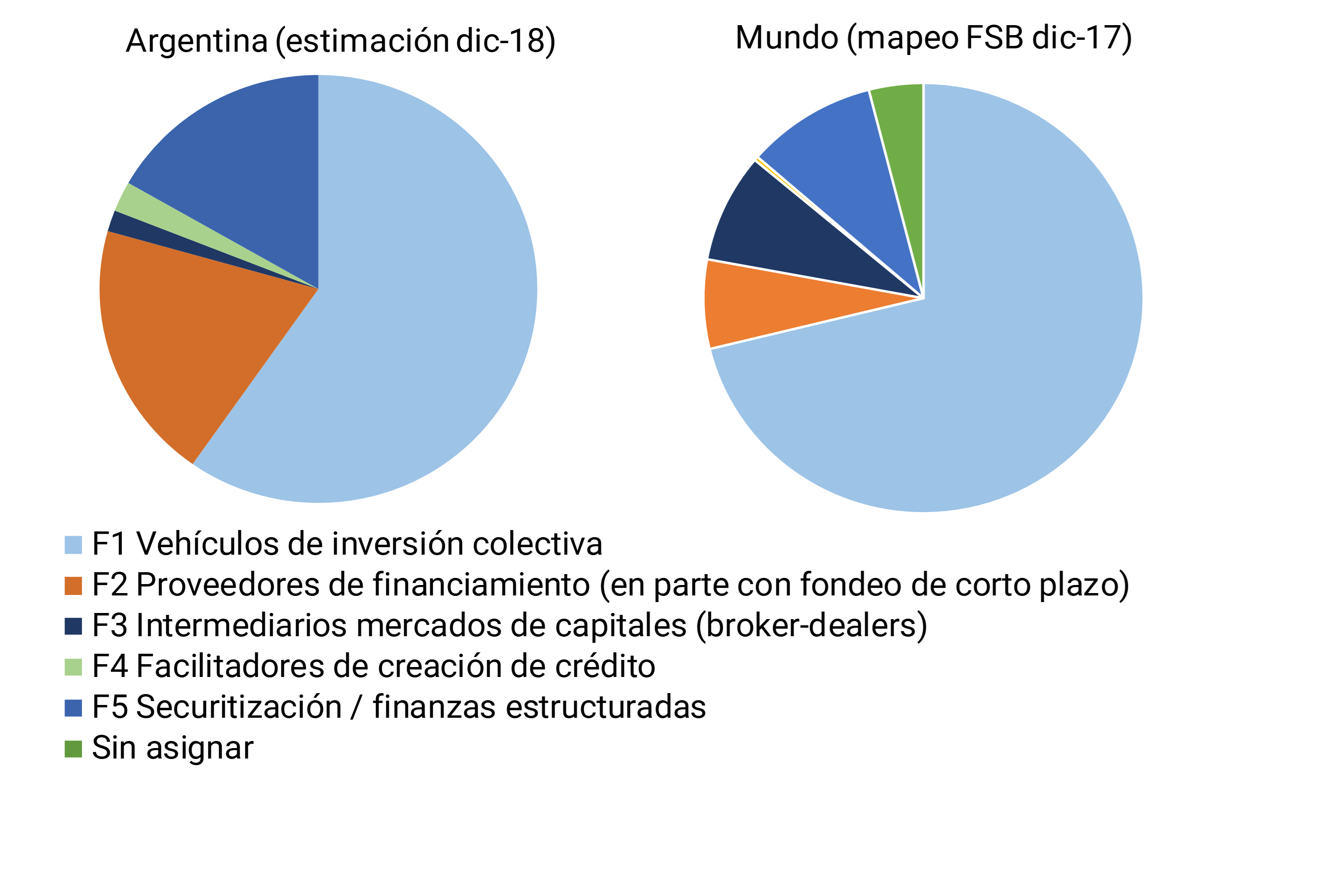

Figure A.3.1 | Mapping the financial sector by country

The composition of NBAs by function in Argentina does not show marked differences with what has been observed at the global level (see Figure A.3.2). As is the case at the global level, at the local level the greatest weighting is held by collective investment vehicles, which account for nearly 60% of the assets of the AFNBs (and a large part of their growth up to and including 2017, slowing down in 2018). 43 This category is basically represented by mutual funds (FCIs, with a strong weighting of fixed income and money markets funds) and does not include more complex figures such as hedge funds. The second most important function among AFNBs is the provision of financing (partly with short-term funding), which in Argentina includes credit card systems, mutuals and cooperatives, leasing/factoring companies and others. 44 This significant but not central role of non-bank credit providers is more common in emerging economies. The third function in terms of importance is given by structured finance vehicles. In Argentina, this corresponds mostly to classic securitizations carried out using financial trusts (FFs linked to infrastructure and, to a lesser extent, to consumer portfolios). More complex structures such as Collateralized Loan Obligations or Collateralized Debt Obligations are not observed. A more marginal weight is presented by the functions that involve capital market intermediaries (settlement and clearing agents, AlyC, which in some cases have their own relevant investment portfolios) and the facilitators of access to credit (mutual guarantee societies or SGRs).

Figure A.3.2 | Non-Banking Financial Agents (NBFAs): FSB-based functions

A large part of the AFNBs (FCI, FF and ALyC) are regulated by the National Securities Commission (CNV), with specific requirements for each type of agent. Starting with the Productive Financing Law (27,440), the CNV incorporated an objective linked to financial stability. For its part, the National Institute of Associativism and Social Economy (INAES) regulates mutuals and cooperatives (requiring compliance with technical ratios) and the Ministry of Production monitors the SGRs and their regulations. 45

The degree of interconnection between the different agents of the financial sector is relatively limited in Argentina. 46 For example, deposits from FGS, insurance companies, and several of the most important components among AFNBs (FCI, FF, mutuals, and cooperatives) represented less than 8% of total bank deposits at the end of 2018, with an increase of more than 1.p.p. compared to the average of the previous 5 years (in the case of loans, the weighting was marginal). 47

Coinciding with international trends, in Argentina the main innovations in recent years are linked to the fintech segment. 48 Added to this is the modernization of closed investment funds introduced by the Productive Financing Law. Although these are segments with development potential, the volume of financing they imply so far is very modest in comparative terms.

In summary, although non-bank financing in Argentina has been showing a certain relative dynamism, its volume remains small, its operation is generally simple, its interconnection is limited and its activity is largely framed within different regulatory schemes, which limits its implications as a source of risk for financial intermediation. In line with international recommendations, this segment of the financial sector is monitored with the aim of identifying and mitigating possible increases in risk factors and sources of vulnerability for the system. 49

References

1See monetary policy statements for March and April.

2In the coming months, the treatment of structural reforms could be a relevant source of uncertainty.

3In December, there was a new episode of dismantling of positions in emerging assets and greater volatility in currencies (linked to growing uncertainty regarding the US stock markets), although it was shorter and less intense compared to what was observed in previous situations of tension.

4Given the lags in monetary policy, inflationary inertia and the effects of increases in the exchange rate (such as the one observed since the end of February).

5At the local level, bills in dollars have been renewed with renewal levels above 60% so far in 2019 (83% on average).

6From the reduction of financial uncertainty. The implementation of a set of income policies aimed at households with a high propensity to consume and the reopening of several parity agreements also contributed positively to activity.

7The last REM published corresponds to the month of April.

8See editions from October 2018 to February 2019.

9In both cases, they are only payable to the largest banks in the system: A banks, which accounted for 88% of the total assets of the financial system as of March 2019. A banks are classified according to the BCRA’s Harmonized Text on “Authorities of Financial Institutions”.

10For more detail, see IEF II-18 as well as October 2018 to February 2019 editions of the Banking Report.

11To this were also added resources from the complete dismantling of the LEBAC balance during the second half of 2018.

12At the beginning of April, the BCRA allowed users to make online fixed terms in entities where they do not have a demand account. In this way, users will be able to compare the interest rates offered by different banks and choose the option that is most convenient for them, promoting competition between financial institutions.

13Including the pledge or assignment as a guarantee of the purchase and sale tickets on future functional units and the naval mortgage or pledge registered in the first degree on ships or naval artifacts.

14For more details, see Normative Annex.

15The results of the BCRA’s Credit Conditions Survey at the end of 2018 and the beginning of 2019 account for this situation.

16The Estimated Probability of Default (EDP) is considered, which is defined as the proportion of loans that were initially in credit situation 1 and 2 (regular) and become in situation 3, 4, 5 and 6 (irregular) at the end of the period under analysis (in this case a three-month comparison is taken). The Quarterly Frequency of Worsening of the Debt Situation is also used, which is an estimate of the probability that a debtor will worsen its credit situation in a period of three months.

17In the event that the irregular portfolio becomes uncollectible, this amount would have the potential to impact the capital.

18Source: International Monetary Fund – Financial Soundness Indicator.

19See, for example, the results of the Credit Conditions Survey.

20As it emerges from the information provided by the entities to the BCRA’s Transparency Regime. The balance of mortgage loans in UVA represented 8.5% of the balance of credit to the private sector.

21Banks classified as Group A according to the BCRA’s Consolidated Text on “Authorities of Financial Institutions”.

22 The limited activity of transforming the terms of the local financial system is reflected, among other dimensions, in the reduced weighting of mortgage credit in total credit to the private sector, standing at 13%. This weighting reaches, for example, almost 19% in Brazil, 24% in Bolivia, 38% in Spain and 50% in Portugal (Source: International Monetary Fund – Financial Soundness Indicator)

23This is almost 2% of the total for negotiable obligations denominated in pesos.

24Between May and the end of October 2018, in a context of greater exchange rate volatility and increases in local interest rates, banks did not place these instruments. From then on, new bank placements began to take place, although mostly in pesos and for terms of about 15 months on an average weighted by amount (almost half of that observed in the first four months of last year). The placements were concentrated between the end of October and the beginning of November 2018 and, more recently, in the second half of February.

25The number of nodes and links, the global clustering coefficient, reciprocity, and density decrease. Reciprocity refers to the proportion of times that there are links in both directions, considering the nodes taken in pairs. The global clustering coefficient is based on the nodes considered to be threes (triad). A triad consists of three nodes that are connected by either the other two (open triad) or three (closed triad) undirected loops. The global grouping coefficient is the number of closed triads over the total number of triads (both open and closed).

26The determination of local systemically important entities (D-SIBs) can be found HERE.

27Requirement equivalent to 1% of its risk-weighted assets, in addition to the conservation margin of 2.5% of the RWAs in force for all financial institutions.

28Balance sheets of 131 companies as of IIIT-18, with firms from various sectors (highlighting the presence of companies in industry, primary production and services). This base, in general, is more representative of the situation of large or medium-sized companies.

29In September 2018, the Argentine Federation of Professional Councils of Economic Sciences and the Professional Council of Economic Sciences of the City of Buenos Aires indicated that Argentina should be considered an inflationary economy in the terms of professional accounting standards as of 7/1/2018, and based on this the preparation of financial statements in homogeneous currency under IAS 29. In December 2018, Law No. 27,468 was published, which repealed, among others, Decree No. 664/03 (prevented official agencies from receiving financial statements adjusted for inflation), and then the CNV published General Resolution No. 777/18, establishing that financial statements closing on or after 12/31/2018 must be presented in homogeneous currency.

30The methodological change in the preparation of the financial statements does not allow for direct comparison between these new data and those that were being presented.

31See, for example , the “Global Financial Stability Report” of April 2014.

32Adapting a simplified version of the World Bank’s methodology presented in “Which Emerging Markets and Developing Economies Face Corporate Balance Sheet Vulnerabilities?: A Novel Monitoring Framework” of September 2017.

33Based on data from the end of 2018 and taking into account as thresholds a level of 2 for interest coverage (the benchmark considered by the IMF) and the location in the worst decile of the quarter for leverage and liquidity ratios. Given that these data in homogeneous currency have no history, firms that were also considered in a situation of potential vulnerability were added to this set (in the latter case, having a history of comparable data, the worst decile of leverage and liquidity is considered taking into account each sector in a period of 5 years).

34Although the data are not strictly comparable, based on this methodology, as of December 2017 there were 12 companies in a potentially vulnerable situation and represented 4.6% of the financial debt of companies with public offerings.

35According to the “Debtor Classification” regulations, financial institutions must classify their loan customers in descending order of quality (in 6 classification levels), according to the risk of uncollectibility they present.

37The definition of debt includes financing obtained in the local financial system, financial trusts that have consumer and collateralized loans as their underlying assets, and financing from non-bank credit cards.

38The Information Regime (IR) for Debtors of the Financial System (BCRA) and the RI on Payment of Remunerations (BCRA) are used. It should be noted that the latter IR is a subset of the population surveyed in the Permanent Household Survey, since it only incorporates information on the income from workers in a relationship of dependency. Given this, the individuals included in this IR are generally concentrated in the highest deciles of the income distribution at the population level according to the INDEC Permanent Household Survey.

39For the estimation exercise, the income received by employees in a relationship of dependency in twelve-month periods was considered: July 2015 to June 2016 and from January to December 2018. Within a universe of 8.7 and 9.2 million individuals who reported income during both periods of analysis, respectively, those who met three requirements were used: i. have at least six remunerations in the year, ii. that the annual remuneration is higher than the average of the Minimum Living and Mobile Wage for the period, and iii. that the maximum income does not exceed the median income by more than ten times. In this way, extreme observations were discarded, leaving a total of 7.0 and 7.4 million salaried workers in each period, respectively. For the observations used in the estimation exercise, the debt data as of June 2016 and December 2018, respectively, are considered.

40Other sources of income such as retirements, pensions, capital income and formal contractual relationships that are not dependent, as well as income from informal ties, are omitted. By not having these sources of income, it could be generating a bias in the estimation of higher levels of indebtedness than those that families actually face.

41The mapping covers 29 jurisdictions, which account for 80% of the world’s GDP. See the FSB’s latest annual report on non-bank financial intermediation, published earlier this year, with data up to the end of 2017.

42The data mentioned for Argentina are estimates as of December 2018. In Argentina, banks account for more than 60% of the total assets of the mapped set of agents, a value similar to that observed on average for the rest of the emerging countries at the end of 2017 (but above that computed for developed countries, with a value below 45% on average). Estimate based on mapping without considering central bank assets.

43Globally, the growth of AFNBs in recent years is mostly explained by collective investment vehicles. Prior to the global financial crisis, the dynamics were largely driven by structured finance products.

44Including consumer retail companies that provide financing to their customers, financial companies dedicated to consumer loans, online personal loan providers, micro-financing entities, etc.

45Non-bank credit cards must comply with the Credit Card Law (25.065) and the BCRA regulations for the protection of users of financial services, in addition to reporting information to the BCRA. Non-bank credit providers that obtain financing from banks must register with the BCRA and report information. To the extent that they issue instruments in the capital markets, these agents must also provide information to the CNV. Likewise, any activity that involves the granting of consumer credit is contemplated by the Consumer Defense Law (24.240).

46Measured as a percentage of banks’ assets, banks’ use of AFNB funding and banks’ exposure to AFNBs is rather low compared to other economies in the FSB sample. At the global level, the interconnection between banks and AFNBs has been showing marginal growth, remaining at levels similar to those observed in 2003-2006.

47The greatest interconnection via deposits is given by the placements of the FCIs in banks. In terms of direct interconnection between banks and AFNB, there are additional links. For example, through the holding of financial instruments (such as FFs) by banks or by AFNBs (e.g. holding by CRFs of ON or bank shares). There is also an indirect interconnection, for example, due to exposure to common factors.

48New platforms, including online credit firms that are financed with their own capital, P2P credit models and crowdfunding platforms.

49In 2017, the FSB determined that the aspects of global non-bank financing that contributed to the international financial crisis had diminished and no longer posed a risk to financial stability. The FSB recommends globally that monitoring be maintained (and improved), that policy recommendations continue to be implemented, and that the regulatory perimeter be updated based on what has been observed.

Glossary of abbreviations and acronyms

€: Euro

to.: Annualized

AFIP: Federal Administration of Public Revenues

ANSeS: National Social Security Administration

RWA: risk-weighted assets

ATM: Automated Teller Machine

BADLAR: Buenos Aires Deposits of Large Amount Rate (interest rate paid for 30 to 35-day fixed-term deposits, more than $1 million, average of entities)

ECB: European Central Bank

BCBA: Buenos Aires Stock Exchange

BCBS: Basel Committee on Banking Supervision

BCRA: Central Bank of the Argentine Republic

IDB: Inter-American Development Bank

BIS: Bank for International Settlements

BoE: Bank of England

BONAD: Argentine Nation Bond linked to the Dollar

BONUS: Argentine Nation Bond

BONCER: Treasury bonds in pesos adjusted for CER

BONUSES: Fixed-rate Treasury bonds in pesos

CABA: Autonomous City of Buenos Aires

CAFCI: Argentine Chamber of FCI

Call: Interest rate on unsecured financial market operations

CCP: Central Counterparty (Contraparte Central)

CDS: Credit Default Swaps

CEMBI+: Corporate Emerging Market Bond Index Plus

CER: Reference Stabilization Coefficient

NVC: National Securities Commission

MUST: Immediate Debit Payment Method

DPN: National Public Debt

DSIB: Domestic Systemically Important Banks

ECAI: External Credit Assessment Institution

ECB: European Central Bank

ECC: Credit Conditions Survey

USA: United States

EFNB: Non-Banking Financial Institutions

EMAE: Monthly Estimator of Economic Activity

EMBI+: Emerging Markets Bond Index

EPH: Permanent Household Survey

FCI: Mutual Funds

Fed: US Federal Reserve

Fed Founds: US Federal Reserve Benchmark Interest Rate

FGS: Sustainability Guarantee Fund

IMF: International Monetary Fund

FSB: Financial Stability Board

GBA: Greater Buenos Aires (includes all 24 matches)

A.I.: Year-on-year

IAMC: Argentine Institute of Capital Markets

IBIF: Gross Domestic Fixed Investment

IEF: Financial Stability Report

INDEC: National Index of Statistics and Censuses

CPI: Consumer Price Index

IPIM: Domestic Wholesale Price Index

IPMP: Commodity Price Index

IPOM: Monetary Policy Report

VAT: Value Added Tax

CSF: Liquidity Coverage Ratio

LEBAC: Central Bank Bills (Argentina)

LETES: U.S. dollar treasury bills

LFPIF: Financing line for production and financial inclusion

LR: Leverage Ratio

MAE: Electronic Open Market

MERCOSUR: Southern Common Market

Merval: Buenos Aires Stock Market (benchmark stock market index)

MF: Ministry of Finance

MH: Ministry of Finance

MSCI: Morgan Stanley Capital International

MULC: Single and Free Exchange Market

OECD: Organization for Cooperation and Development Ec.

ON: Negotiable obligations

OPEC: Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries

P.B.: The Basics

P.P.: Percentage points

PEN: National Executive Branch

PGNME: Global Net Foreign Exchange Position

GDP: Gross Domestic Product

PN: Net Worth

PPM: Mobile Payment Platform

SMEs: Small and Medium Enterprises

REM: Market Expectations Survey

ROA: Return on assets

SWEE: Return in terms of equity

ROFEX: Rosario Futures Exchange (Mercado a término de Rosario)

RPC: Computable Patrimonial Liability

S&P: Standard and Poor’s (Index of the main stocks in the US by market capitalization)

s.e.: Series without seasonality

SEFyC: Superintendence of Financial and Exchange Institutions

NFPS: National Non-Financial Public Sector

TCR: Real exchange rate

TN: National Treasure

TNA: Annual Nominal Rate

Trim.: Quarterly / Quarter

ICU: Utilization of Installed Capacity

EU: European Union

US$: US Dollars

UVA: Unit of Purchasing Value

ICU: Housing Unit

UVP: GDP-Linked Units

Var.: Variation

VIX: S&P 500 volatility

WTI: West Texas Intermediate