Financial Stability

Financial Stability Report

First half

2022

This semi-annual report presents recent developments and prospects for financial stability in Argentina.

Table of Contents

Chapters

- Executive summary

- 1. International and local context

- 2. Main strengths of the financial system in the face of the risks faced

- 3. Sources of vulnerability and specific resilience factors of the financial system

- 4. Other topics of stability of the financial system

- 5. Main macroprudential measures

Sections

-

- Section 1 / Russia-Ukraine conflict and challenges to global financial stability

- Section 2 / Credit risk assumed by financial institutions due to their exposure to common debtors with non-financial credit providers

- Section 3 / Cryptoassets. Some recent developments and main implications

- Glossary of abbreviations and acronyms

Inquiries: analisis.financiero@bcra.gob.ar

Summary

In the first part of 2022, the aggregate of local financial institutions continued to show comfortable levels of capital, liquidity and provisioning, as well as moderate NPL ratios in their loan portfolio, a situation that contributes positively to shaping a framework with a significant degree of resilience in the face of possible situations of stress. The operational scenario for the sector was favored by the maintenance of the local economic recovery process initiated in 2021, supported both by the improvements observed in the health situation and by the stimulus policies implemented by the National Government in conjunction with the BCRA. In this context, the Argentine financial system continued to carry out its activities of intermediation of funds and provision of payment services to families and companies.

At the beginning of 2022, the Argentine economy continued to strengthen the aforementioned reactivation process, after the effects of the COVID-19 shock. Positive prospects remain for the coming months, led by the recovery of the sectors that were most affected by the pandemic, although they are subject to somewhat increasing risks. The international context became less favorable after the publication of the latest IEF at the end of last year: the war between Russia and Ukraine generated a shock on the price of raw materials, aggravating concerns about inflationary pressures in developed economies, among other aspects. This resulted in a more restrictive monetary policy implementation faster than initially expected in these countries, generating fears in recent months regarding the possibility of stagflation scenarios and lower risk appetite.

Increases in commodity prices also had an impact on local inflation, in a context of recovering economic activity. The BCRA continued with the process of normalization of monetary policy interest rates, seeking to tend towards a path of interest rates that allows positive real returns for investments in pesos and avoid pressures in the foreign exchange market, without affecting the economic recovery process underway. To this were added, among others, the credit policy focused on productive development with an emphasis on MSMEs (Productive Investment Financing Line -LFIP-), as well as measures aimed at achieving a more efficient use of international reserves.

Local financial markets showed a mixed performance in recent months. Accompanying the policies to promote its growth, the Treasury refinanced debt maturities, while the private sector maintained the amounts of financing through markets, in a context of increases in nominal interest rates. The upward trend in yields in the secondary markets of Treasury bonds in pesos accelerated in June, so the BCRA intervened in order to recompose the curve in pesos and avoid excessive volatility that compromises financial stability. It is expected that the current policy scheme, in the context of the agreement with the IMF, will consolidate a framework of macroeconomic certainty, helping to limit expectations about the evolution of the exchange rate and inflation.

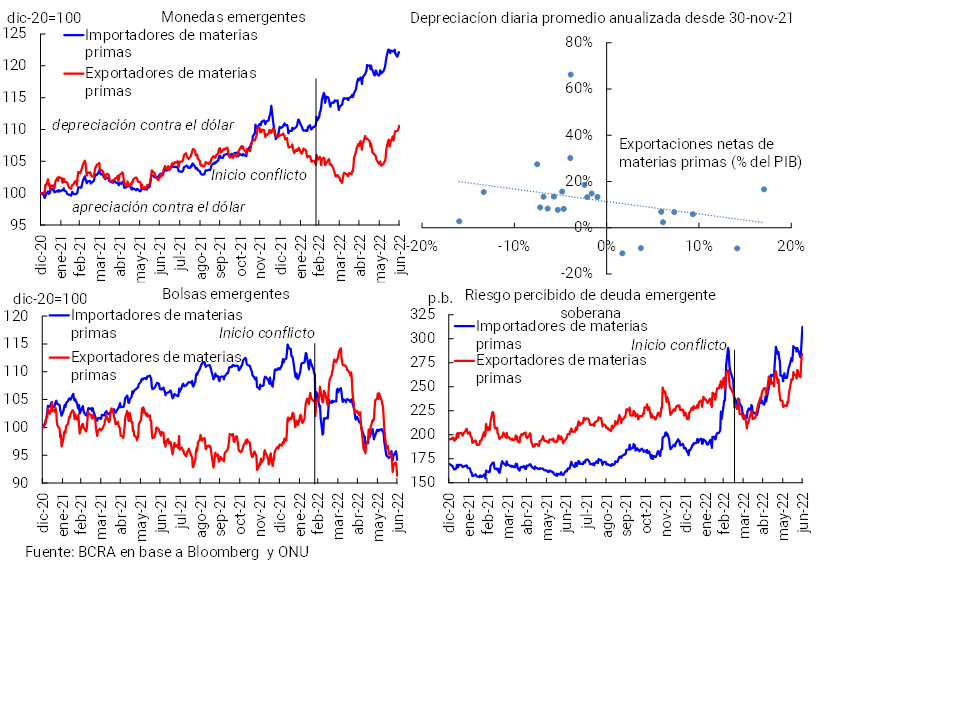

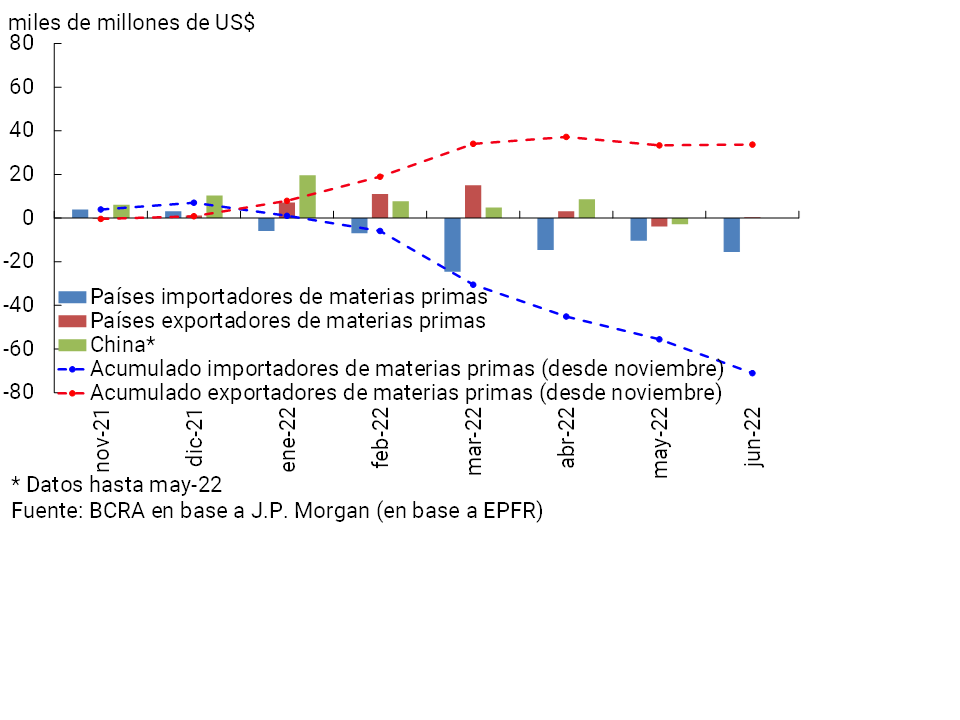

The Argentine financial system retains adequate features of soundness, although it faces the possibility of the materialization of different exogenous risk factors that could potentially condition its normal functioning. The deterioration of the external context stands out in recent months, with tighter global growth prospects and greater uncertainty, volatility in commodity prices, falls in the prices of instruments with greater relative risk and outflows from investment funds specialising in emerging markets. Given the presence of different types of vulnerabilities at the global level, this could trigger more marked negative dynamics with abrupt changes in international markets, implying challenges for emerging economies. At the local level, idiosyncratic factors must be taken into account, such as the effect of drought in the summer and the possibility of energy market tensions. Although significant progress has been made, possible negative effects of new strains of COVID-19 cannot be ruled out. Depending on the type of shock, this type of scenario could condition the evolution of the local economy or generate volatility in the local financial market.

The balance between sources of vulnerability and strengths of the financial system shows little change compared to the IEF at the end of 2021. There was a slight increase in certain exposures to risks, although these are low to moderate, with hedging remaining relatively high. In addition, the system preserves structural features that limit potential sources of systemic risk: (i) low credit depth in the economy, (ii) traditional financial intermediation biased towards the short term and with low relevance of complex operations, and (iii) reduced interconnection between entities in the sector.

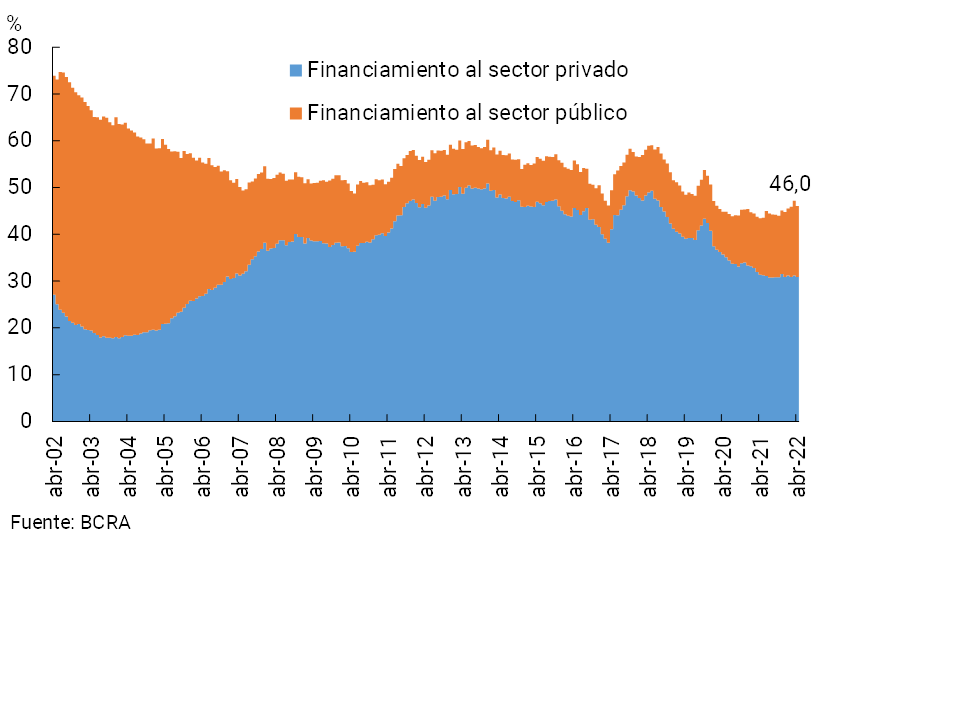

In the first part of the year, there was a slight increase in the financial system’s equity exposure to aggregate credit risk, although it remains at low levels from a historical perspective. Total financing to the private and public sectors reached 46% of the system’s assets, increasing slightly in recent months, mainly due to the last component. The slight increase in exposure to the private sector (to approximately 30.9% of total assets) occurred in conjunction with a gradual reduction in irregularity levels, which reached 3.6% of the portfolio in April. The irregularity indicator is practically no longer influenced by the regulatory modifications implemented in 2020, aimed at alleviating the financial burden of debtors in the context of the pandemic. Looking ahead to the coming quarters, this source of vulnerability for the system – derived from its credit exposure – would remain one of the most important in relative terms. To weigh these potential effects (subject to the materialization of exogenous factors that have an impact on the repayment capacity of debtors), the system sustains high and growing levels of forecasts and capital, in a context in which indebtedness and the financial burden of the private sector are limited.

The performance of financial intermediation could also be a source of potential vulnerabilities for all institutions. Compared to the previous IEF, intermediation activity remained at moderate levels, with a slight increase in the real balance of credit to the private sector in pesos, with greater relative dynamism in public banks and commercial lines. The latter occurred within the framework of the LFIP, a stimulus program that resulted in a positive performance of loans to SMEs. In the coming months, the process of gradual recovery of economic activity is expected to continue, with a positive impact on intermediation, both in the supply and demand of financing and deposit funding. However, it should be considered that potential scenarios for the materialization of risk factors could generate challenges for the financial system. In contrast, the institutions as a whole maintain high and growing solvency indicators, with positive internal capital generation.

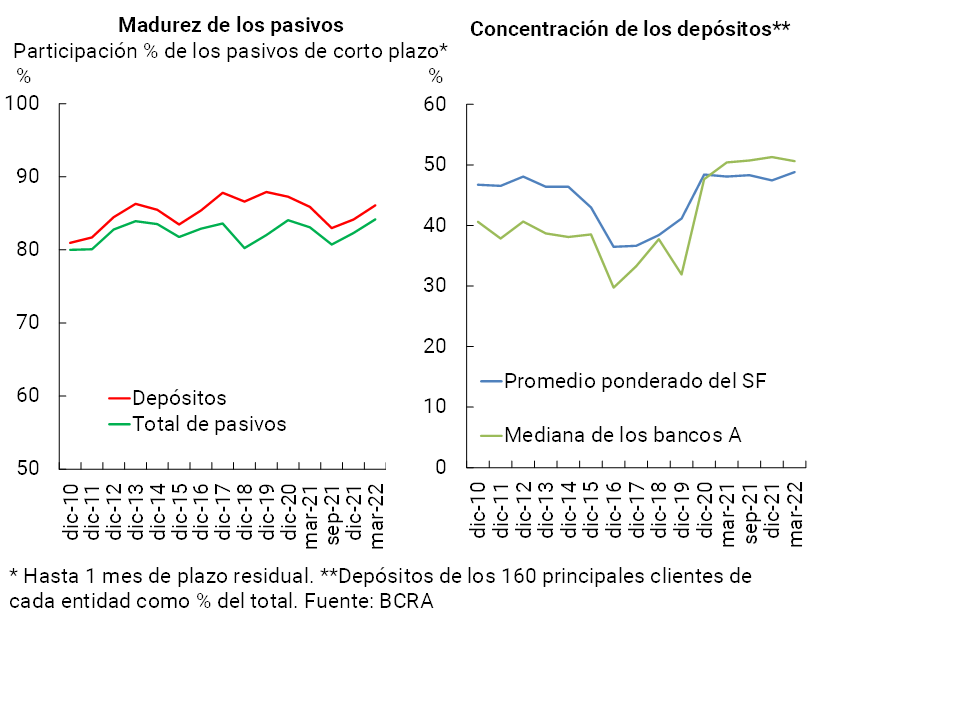

A third source of potential vulnerability for financial systems in general originates in the evolution, composition and conditions of funding. Compared to the IEF at the end of 2021, the real balance of deposits in pesos decreased slightly due to the performance of demand accounts, as time deposits increased. The latter were boosted by minimum interest rate hikes during 2022, as well as increased demand for UVA time deposits, instruments that offer positive real returns. Compared to the previous IEF, there was a slight increase in some indicators of exposure to liquidity risk, such as in terms of funding maturity. The indicators of depositor concentration did not show significant changes, although they remain at levels higher than those observed in the recent past. Going forward, changes in the system’s funding cannot be ruled out in the event of an eventual materialization of some of the risk factors raised. Faced with situations of this type, the institutions as a whole maintain high coverage with liquid assets, which comfortably exceed the minimum regulatory requirements that are in line with international recommendations.

In the remainder of 2022, the aggregate of financial institutions would maintain an adequate degree of resilience, with adequate margins to overcome potential scenarios for the materialization of any of the risks considered above. The ongoing economic recovery process will continue to contribute, in addition to the active actions of the BCRA with its policies that promote a context of financial stability.

1. International and local context

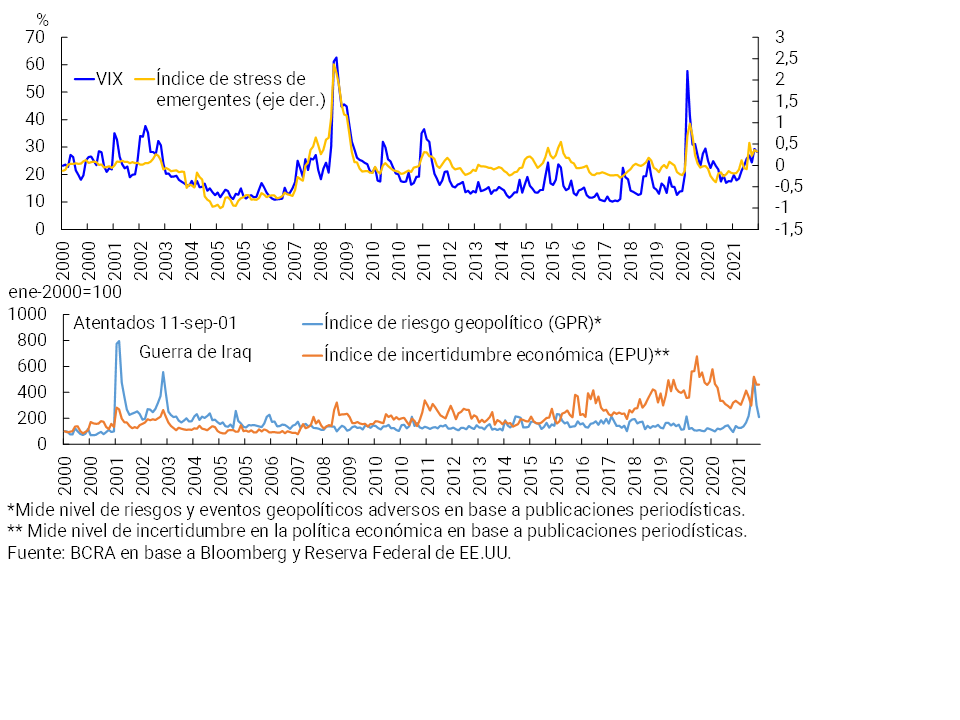

Since the publication of the last IEF, and continuing with the trends observed until then, the sources of risk from the external context have intensified. The concern that had already been observed regarding the increase in inflationary pressures worldwide was accentuated by the effects of the war between Russia and Ukraine (including sanctions on the Russian economy), with a particular impact on commodity prices. This situation contributed to the persistence of problems in international supply chains that arose in the context of COVID-191. Although so far this conflict has not generated a systemic event worldwide, it has configured a scenario of greater volatility (see Section 1), with a peak in early March according to the VIX index. This growing uncertainty conditions the heterogeneous recovery process of the global economy that has been taking place based on the improvements observed with respect to the Covid-19 pandemic. Since the end of April and the beginning of May, there has been a new outbreak of volatility, this time focused on concerns about the possibility of stagflation scenarios in developed economies. Both the evolution of the war and the macro fundamentals in developed economies and expectations regarding the normalization process of their monetary policies will be elements that will condition the behavior of volatility levels in the coming months (with a potential effect on financial stability at the global level).

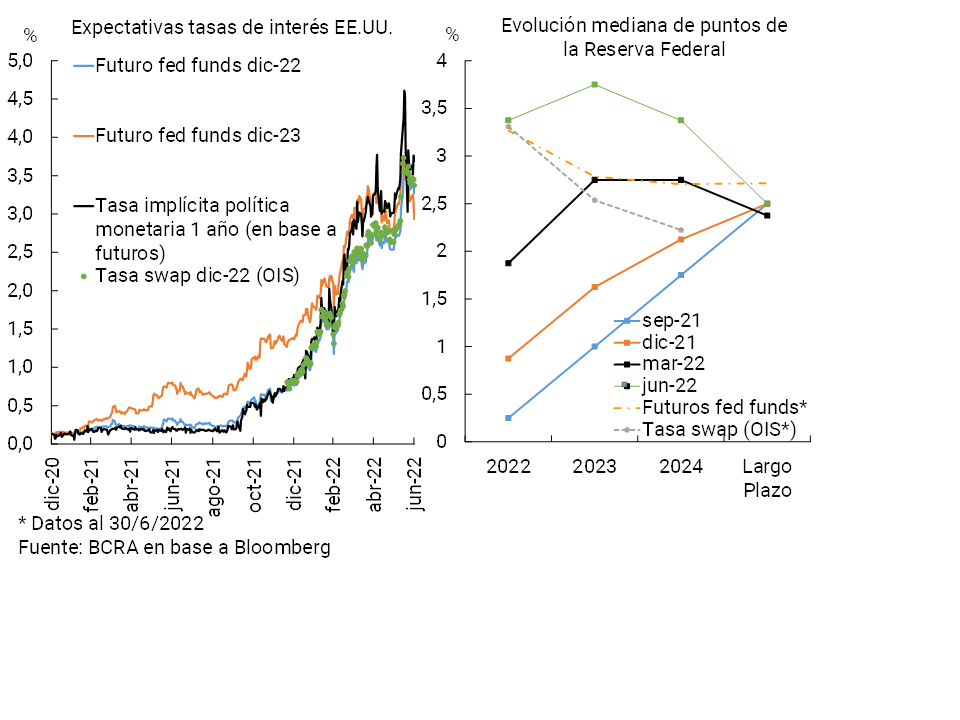

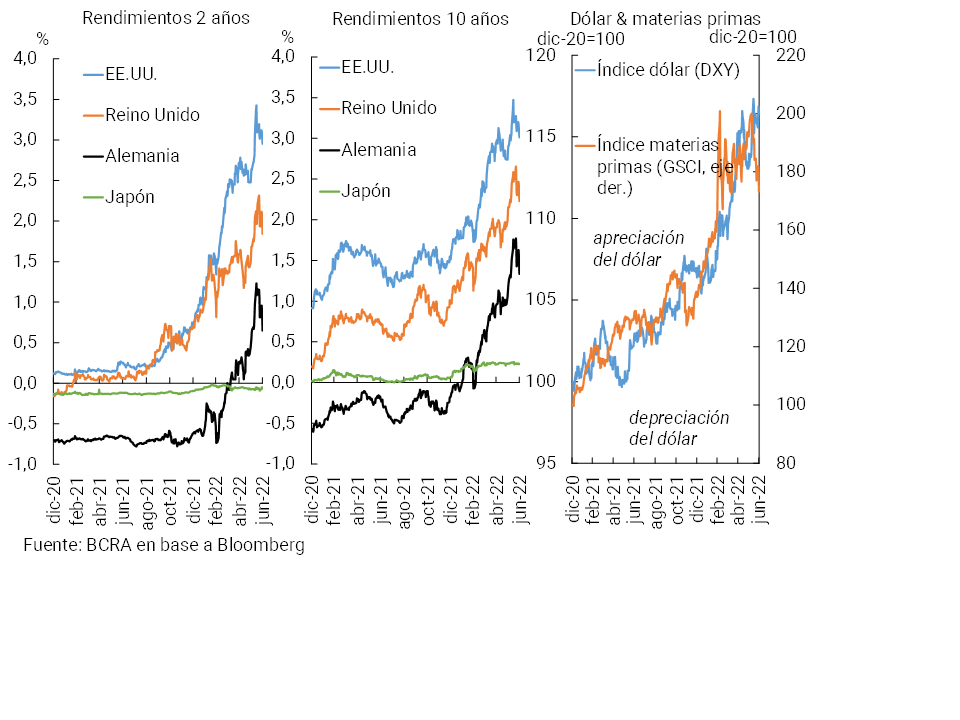

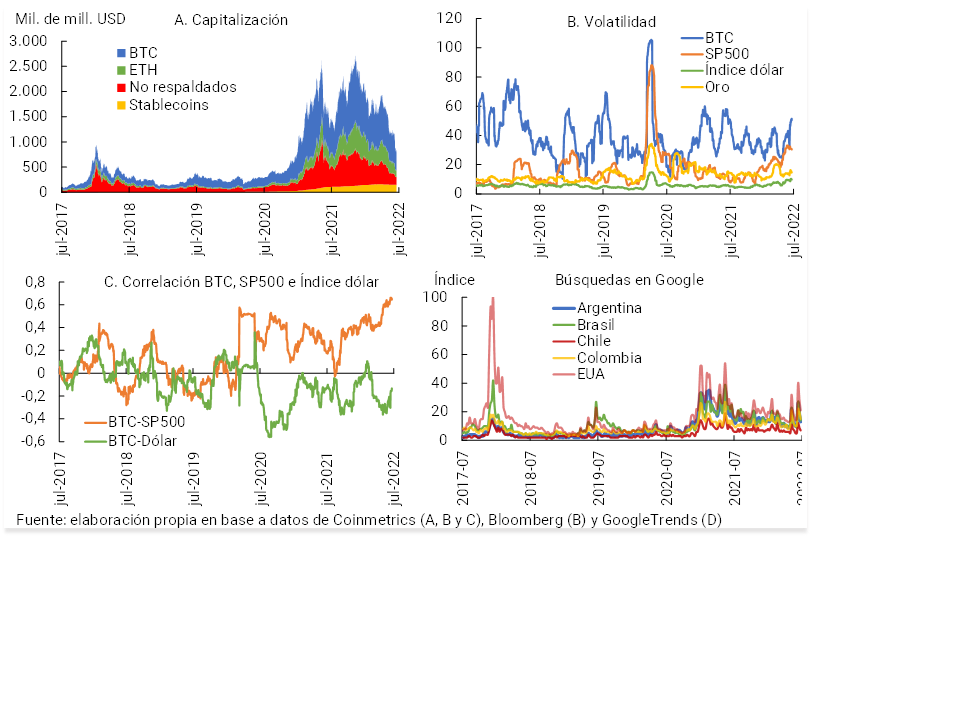

In the specific case of the US, the Federal Reserve began a cycle of interest rate hikes in March (with additional hikes in May and June), which was added to the end of net purchases of debt instruments2. There was then an increase in the yields of US Treasury instruments (more marked for two-year instruments, with a greater correlation with monetary policy rates), accompanying different indicators – such as the expectations implied in the derivatives markets and the forecasts of participants of the Federal Reserve’s FOMC – which were evidencing expectations of more aggressive interest rate hikes in 2022-2023 (see Chart 1)3. With greater volatility and expectations of increasingly high interest rates, the dollar continued to appreciate against the rest of the major currencies, accumulating a revaluation of 9% so far this year (see Chart 2). With regard to assets of greater relative risk, which had been the subject of concern given the existence of segments with historically high prices, the stock indices of the US and Europe accumulate losses in dollars in a range of 10-25% so far in 2022, while the main cryptocurrencies accumulate sharp falls (in a range of 60-75%).

Graph 1 | Implied Interest Rate Expectations in Derivatives Markets and Federal Reserve FOMC Member Projections

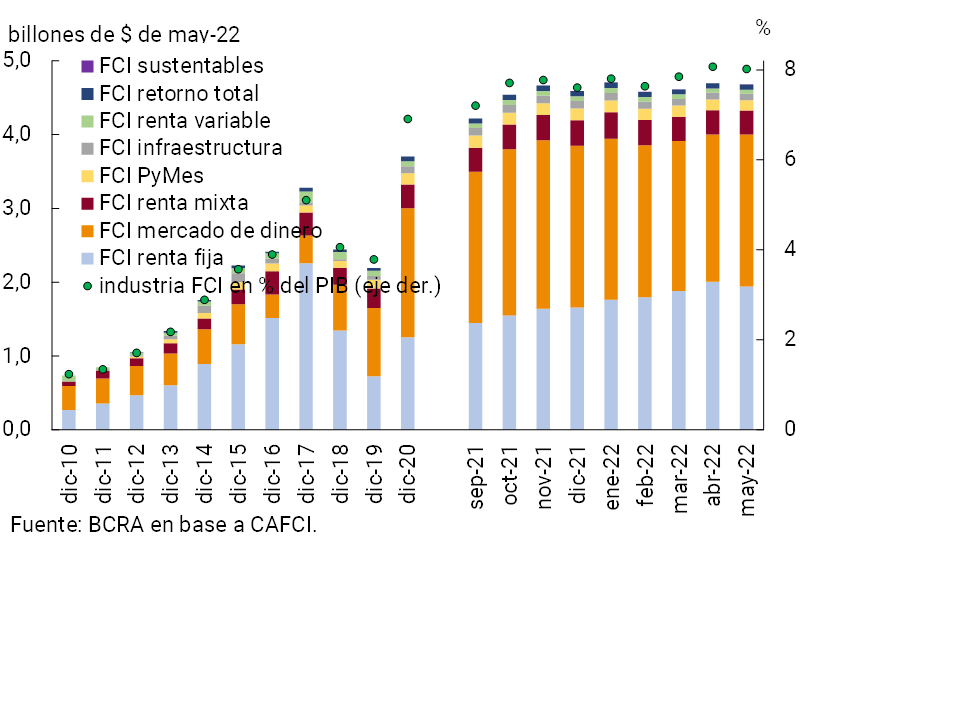

These factors influence a more challenging context for emerging economies, given that there are still important sources of vulnerabilities at the global level that could eventually contribute to the amplification of situations of tension in the face of an external shock (see Box 1). An example is the growing global weighting of investment funds, with a bias towards procyclical behaviour and very sensitive to changes in the international context. In the face of an external shock, the performance of these funds could amplify the impact on capital flows and significantly increase pressures on foreign exchange markets in emerging economies4.

Box 1 / Main vulnerabilities present in the global economy

As mentioned in previous editions of this IEF, in a context of abundant liquidity and low interest rates in international markets, a series of vulnerabilities have crystallized in recent years. This is challenging for financial stability globally, as these vulnerabilities mean that in an environment of perceived greater risk, abrupt negative dynamics can be unleashed across different markets and jurisdictions. The main vulnerabilities include:

• Over-appreciation in different market segments, including instruments of greater relative risk (stocks, cryptocurrencies or emerging market instruments considered as an asset class), more susceptible to sudden price corrections, for example, due to abrupt changes in portfolio flows). This situation was partly corrected (in some segments) by the price declines observed in recent months.

• Sustained global trend towards an increasing debt burden of both the public and private sectors. Greater risk of repayment perceived in a context still marked by the COVID-19 shock (with more limited fiscal space, more limited corporate profitability) and greater vulnerability in the face of a context of interest rate hikes. In the case of emerging economies, there is also the impact of greater fluctuations in the value of currencies, given the existence of relevant currency mismatches in many countries. Given the greater leverage observed at the global level (among both developed and emerging economies), efforts are being made at the international level to monitor the evolution of the corporate sector more closely.

• Growth of non-bank financial intermediation or NBFIs (led by investment funds) worldwide. In addition to increasing the interconnection between market segments and jurisdictions, the NBFI exhibits a pro-cyclical behavior, depending on the use of passive strategies, liquidity mismatches and, in the specific case of hedge funds, the presence of leverage. This implies that it may end up intensifying the effects of situations of tension, with a particular impact on emerging economies, with possible negative effects on both the dollar debt markets and the foreign exchange markets and the local currency debt markets (particularly in those markets that are relatively less liquid and deep). Given this issue, policies implemented to improve the resilience of NBFI are being reviewed at the global level (e.g. by revising recommendations to mitigate liquidity mismatches in open-ended investment funds) and move towards a systemic risk approach for this sector5.

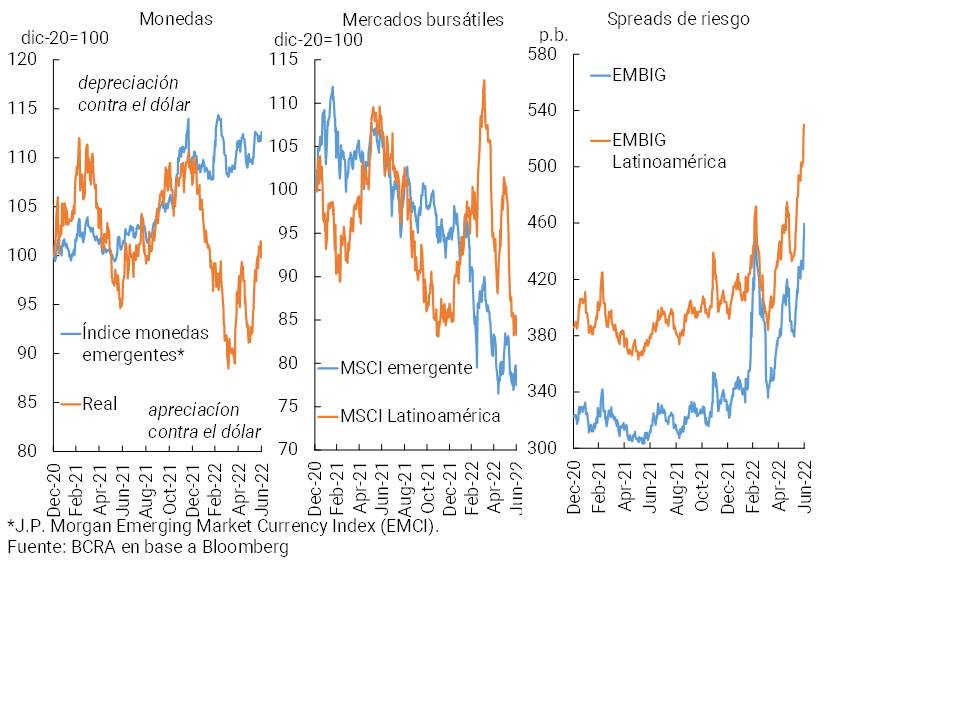

In 2022, the currencies of emerging economies tended to depreciate against the dollar on average, although with heterogeneous behaviors at the individual level and by region (depending on the link of each economy with commodities and the evolution of the monetary policy rate itself)6. The depreciation of emerging currencies was most marked in early March, between late April and mid-May, and in the second half of June (see Chart 3), mostly in line with periods of stronger outflows from investment funds specializing in emerging markets (although net inflows to this type of fund have accumulated since the last IEF). In this context, emerging market stocks measured in dollars have accumulated a decline so far this year according to the MSCI index (19%), although for Latin America it is much more limited (4%). In the sovereign debt market, yields in dollars tended to increase, accompanying the increases observed for US Treasury instruments. However, the EMBI margin, which accumulates an expansion of about 75 bps in 2022 for the aggregate of emerging economies, remains close to its historical average. In international markets, governments and companies in emerging economies continued to issue debt during the first 5 months of the year, although for amounts almost 40% below the record records observed on average, for the same period, in the last 5 years.

At the local level, economic activity continued to improve since the last edition of the IEF. This recovery process is expected to continue in the coming months (led by the sectors that were most affected by the pandemic at the time, such as the services sector), although partly conditioned by factors such as the impact of drought conditions during the summer and less favourable external conditions. The agreement reached with the IMF would also contribute to the consolidation of a framework of macroeconomic certainty, based on its expected effect on different variables, including, among others, the accumulation of international reserves, the reduction of monetary assistance to the Treasury in terms of GDP, and the gradual impact on the primary deficit. The EMBI margin for Argentina, which before the aforementioned agreement was confirmed reached levels close to 2,000 bp, reached levels below 1,700 bps in April. 7, although it subsequently rose again (to over 2,400 bps at the end of June) in a context of greater uncertainty regarding the possibility of stagflation in developed economies and expectations of a more restrictive bias in its monetary policies.

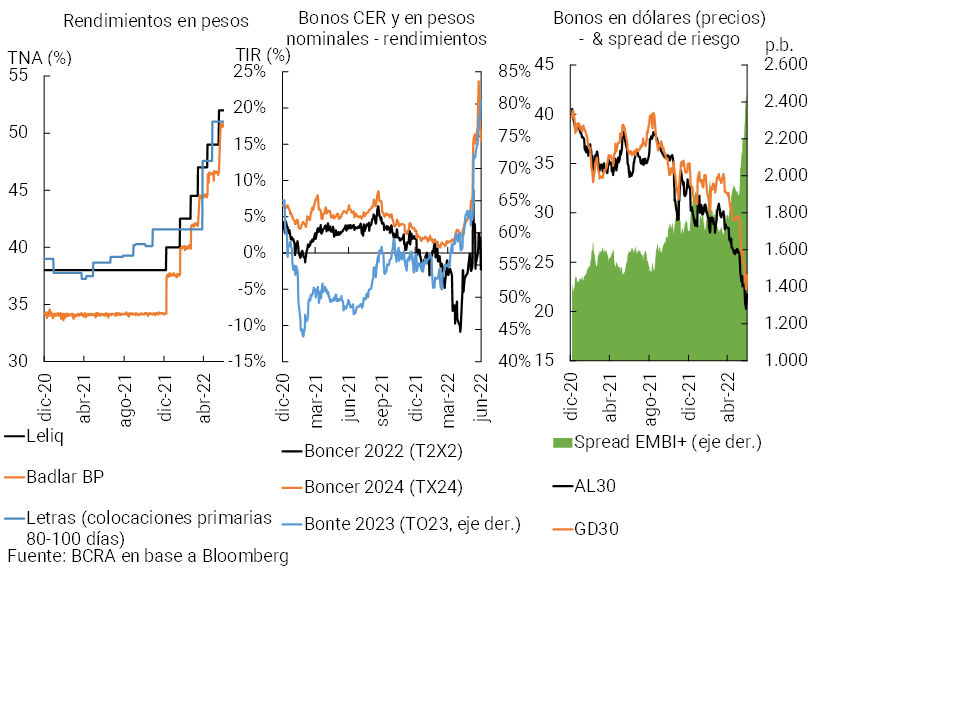

Progress in the process of normalizing the activities of the productive sectors allowed the BCRA to continue with its credit policy focused on the most backward sectors and on promoting productive development (see Box 6). In a more dynamic macroeconomic environment, coupled with higher international commodity prices and unfavorable weather conditions, inflation rose significantly. Faced with this scenario, and in line with the objective of beginning to leave behind the period of exceptional policies generated by the pandemic, the BCRA increased the monetary policy interest rate six times since January in order to set the path of the policy interest rate towards positive real returns on investments in local currency and avoid pressures in the foreign exchange market. without affecting the economic recovery underway (see June Monetary Policy Report). On the other hand, the rate of depreciation gradually readjusted to levels more compatible with the domestic inflation rate. Certain relaxations were also introduced in the regulations for the operation of negotiable securities with settlement in foreign currency.

The Treasury continued to manage to refinance debt maturities in the local market (ratio of placements against maturities on average above 100% so far this year), in addition to implementing several asset conversion operations. In this sense, the policy of rebuilding and promoting greater development of the local marketis maintained 8. The placements were mostly explained by bills – LEDES in nominal pesos and LECER adjustable for inflation – and bonds that adjust for CER (BONCER). Instruments with CERs were used to extend placement terms. Accompanying the rise in other reference rates in pesos, in the primary market the yields of Treasury debt were increasing for fixed-rate instruments. In the secondary market, yields also tended to rise, both for fixed-rate instruments and for instruments adjusted for CER (see Chart 4). Yield increases were strongest in June. To avoid excessive and unjustified price volatility that could compromise financial stability, the BCRA then intervened in the secondary market of public securities with the aim of recomposing the curve in pesos.

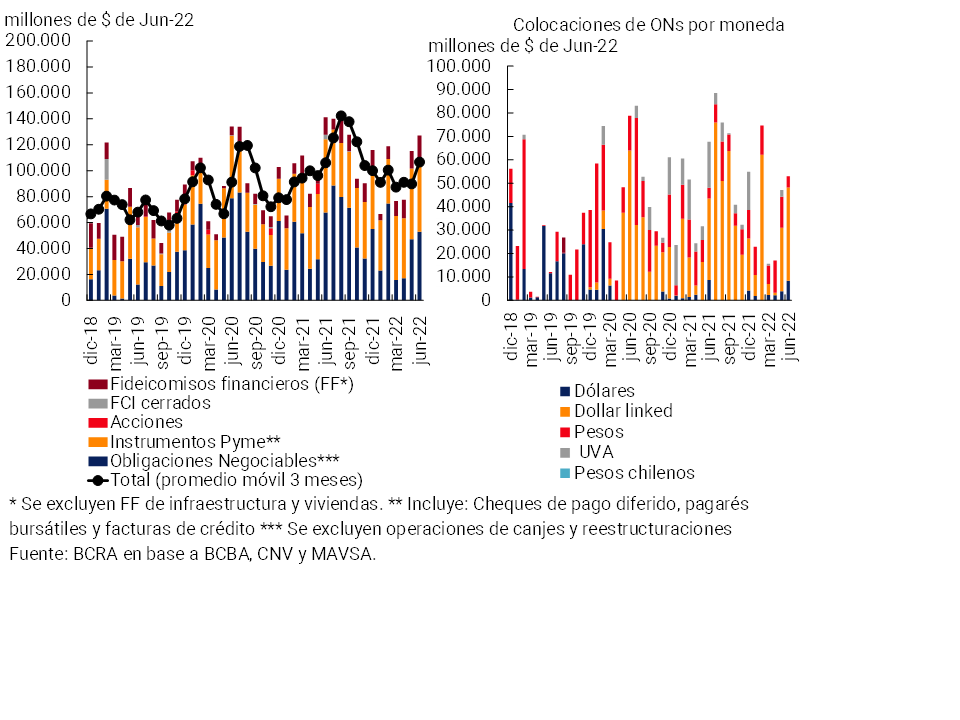

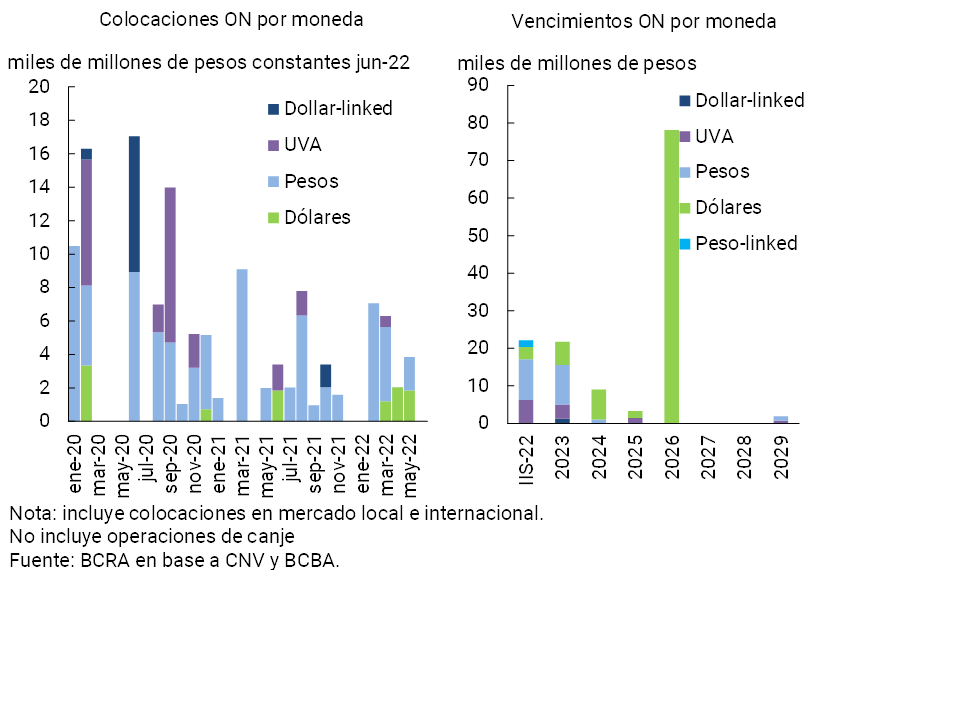

With respect to financing to the private sector through the local market during the first half of 2022 and considering the different instruments (negotiable obligations or ON, financial trusts, deferred payment checks, shares, promissory notes and others), the total amounts presented a practically neutral variation in year-on-year terms (see Chart 5)9. The local market continues to be limited compared to that of other emerging economies, with room to continue deepening its development. Among the non-bonded segments, the dollar-linked segment continues to stand out, which maintained its dynamism in year-on-year terms, while placements in pesos fell sharply in the case of placements in UVA. A large part of the amounts placed in dollar-linked ON were made by the energy and oil and gas sectors. Dollar-linked transactions have longer maturities than placements in nominal pesos10. In terms of cost, while the placement yields of dollar-linked bonds fell slightly, for bonds in pesos they tended to rise, keeping pace with the evolution of the different reference rates. With respect to sustainable finance, so far this year 7 companies have carried out 9 placements framed in the “Guidelines for the issuance of green, social and sustainable Negotiable Securities in Argentina” of the CNV11. Finally, in recent months there were a few ON operations in dollars linked to restructuring processes (Com. “A” 7106)12, after the dynamism observed during the fourth quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of 2021. These restructurings have allowed for a more efficient use of available international reserves and avoided a generalized default crisis13. The period proposed by Com. “A”7106 to restructure external liabilities was extended until the end of 2022.

2. Main strengths of the financial system in the face of the risks faced

Since the last edition of the IEF, the financial system has continued to operate without disruption and to perform its functions of intermediation and provision of payment services, while at the same time being able to preserve the aspects that are characteristic of it in terms of strength. In particular, low exposures to the risks faced and relatively high liquidity and solvency coverage remained moderate.

In addition, certain structural features of the set of institutions that reinforce the perception of facing moderate systemic risk are preserved: limited depth of credit in the economy, fundamentally traditional financial intermediation – with low relevance of complex operations and a short-term bias – and reduced interconnection between entities in the sector. In addition, the financial system is operating within a framework of regulation and supervision that includes the best practices recommended at the international level, adapting them to the local reality.

Throughout this section, the main features of the strength of the local financial system in the face of an eventual materialization of risks are reviewed. The following sections will address in greater detail these and other aspects that provide robustness to the sector when assessing potential vulnerabilities from the perspective of macroprudential monitoring.

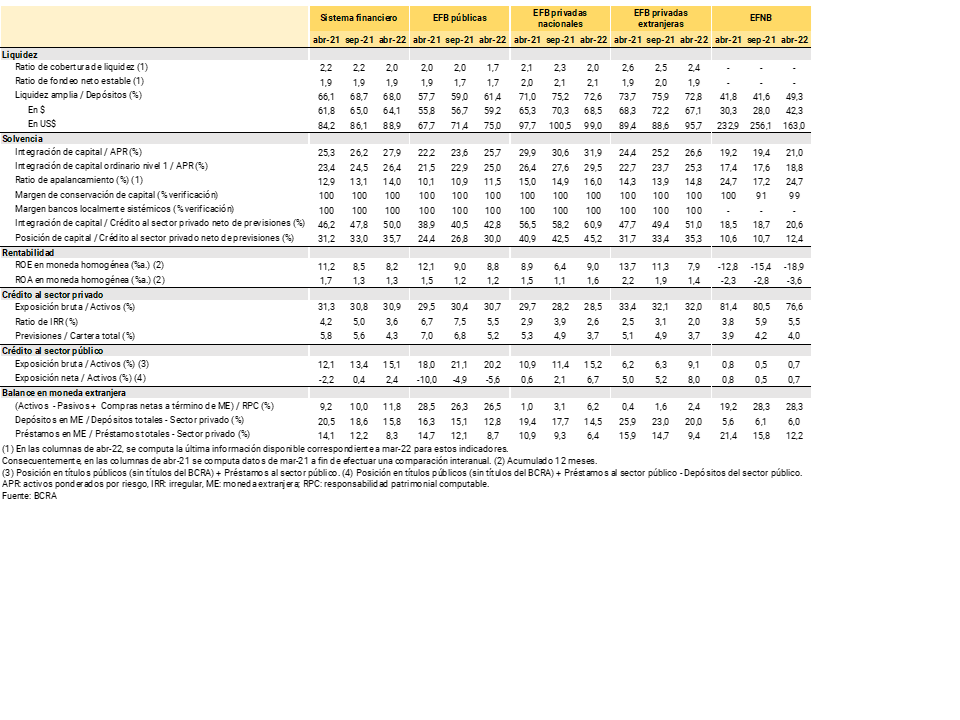

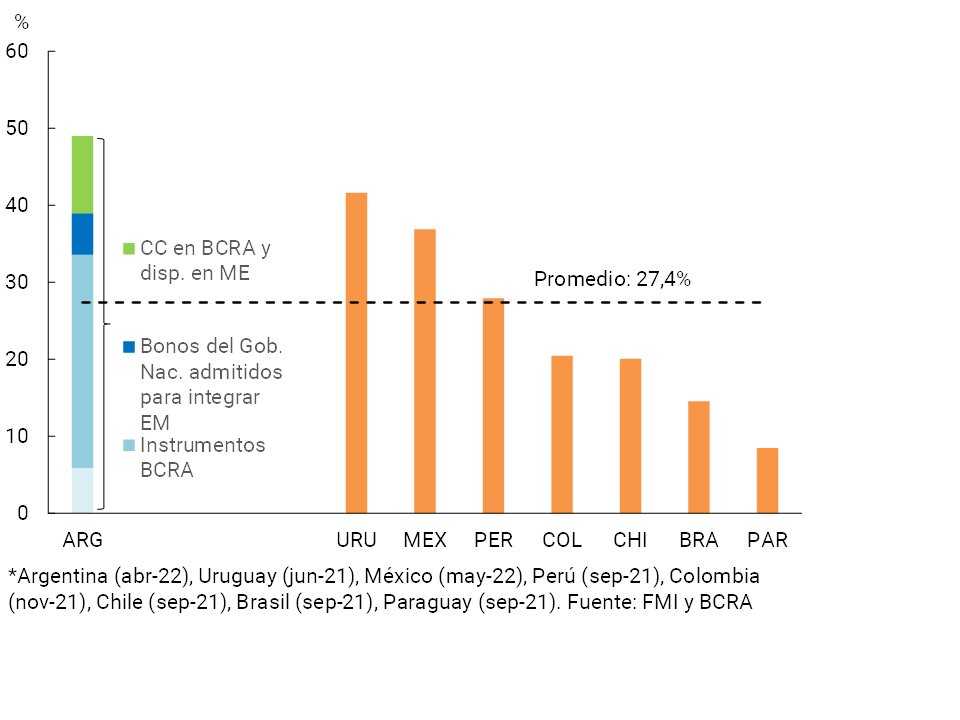

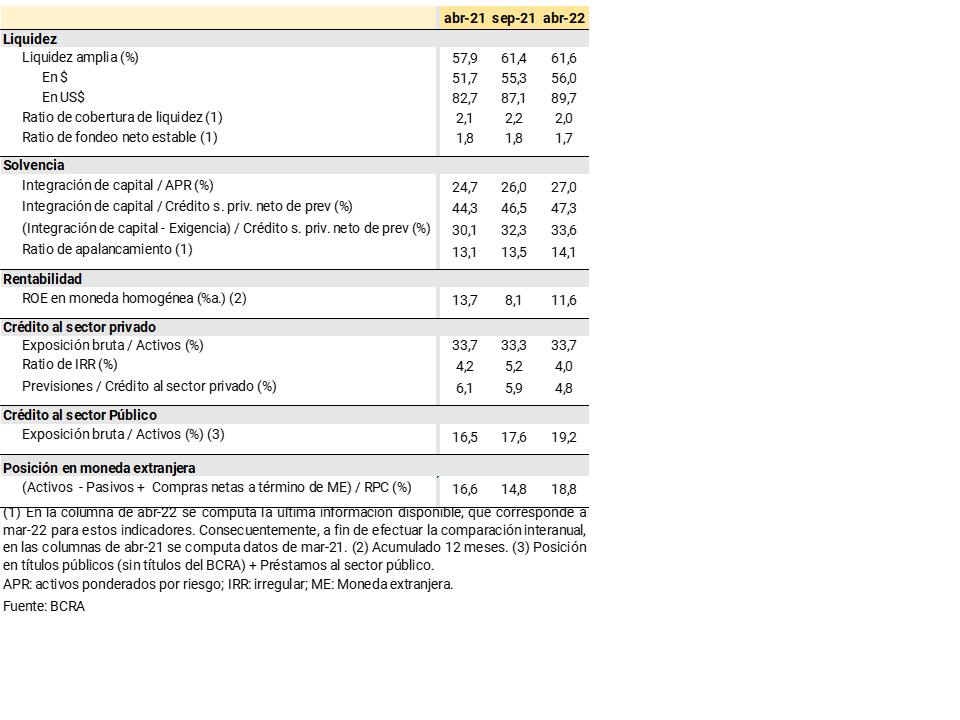

i. High relative levels of liquidity. The financial system maintains relatively high liquidity coverage when compared to its own records in recent years, as well as to the average of the values currently observed in the region’s financial systems (see Table 1). In April 2022, the14th broad sense liquidity of all financial institutions stood at 68% of deposits (64.1% in the segment in pesos and 88.9% in foreign currency). Although this figure was slightly lower than that observed at the time of publication of the previous IEF (-0.8 p.p.), it exceeded that verified in a year-on-year comparison (+1.9 p.p.), and far above the average of the last 10 years (+17.4 p.p.).

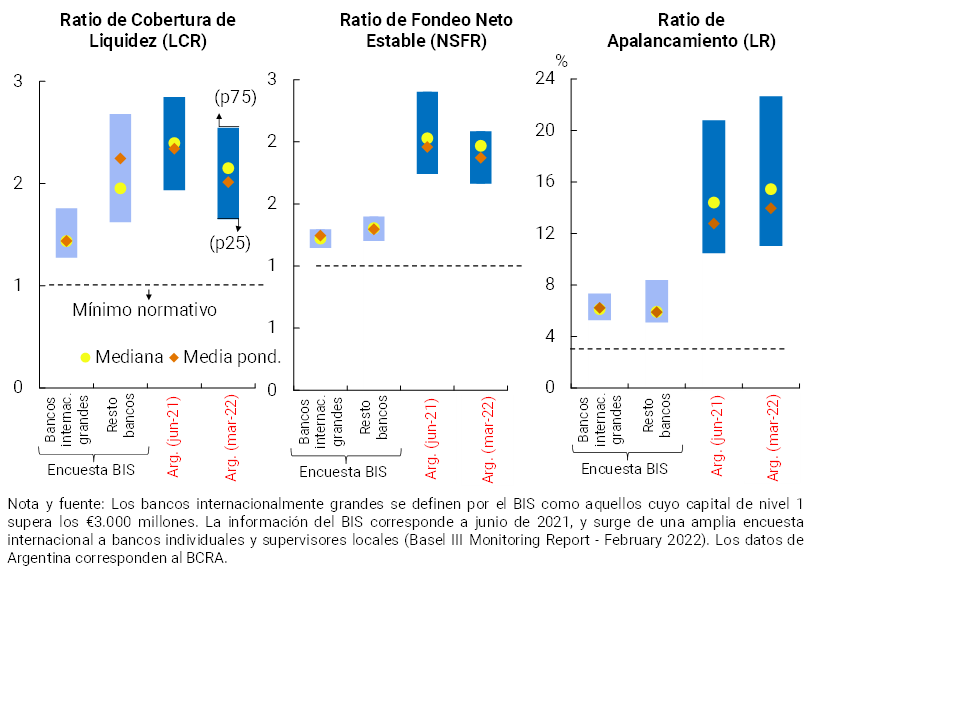

The liquidity indicators arising from the recommendations of the Basel Committee (BCBS) continued to exceed the regulatory minimums for all local entities required to verify them (Group A)15. The local level of the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR)16 was in line with that of a sample of medium-sized banks in othercountries17 (and is higher than that of large banks), while the local Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR)18 remained relatively high when compared to what was observed in other economies (see Chart 6).

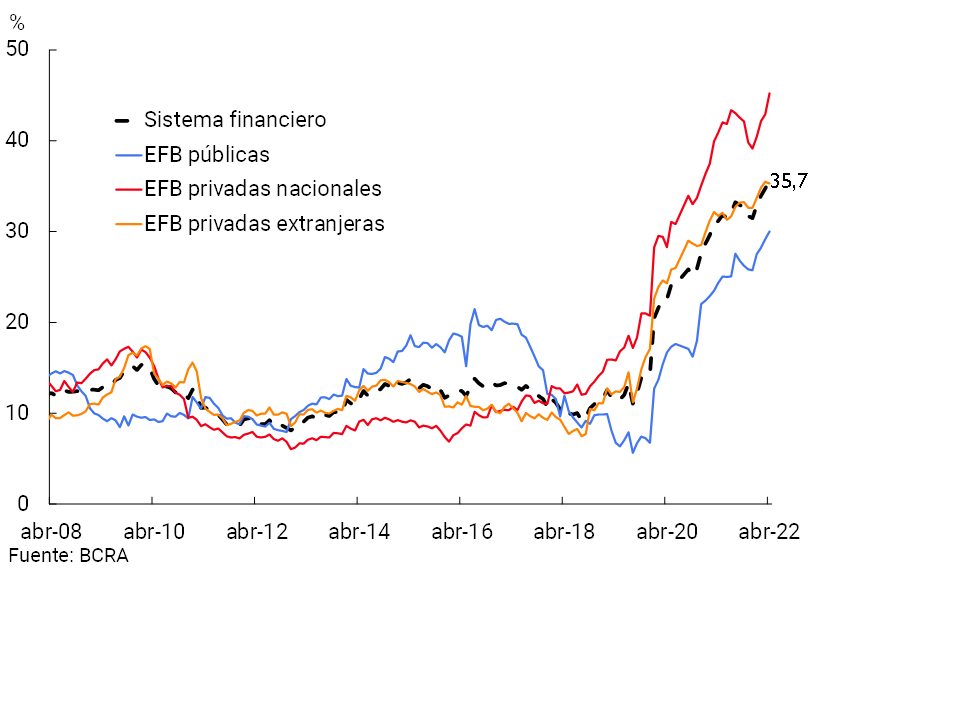

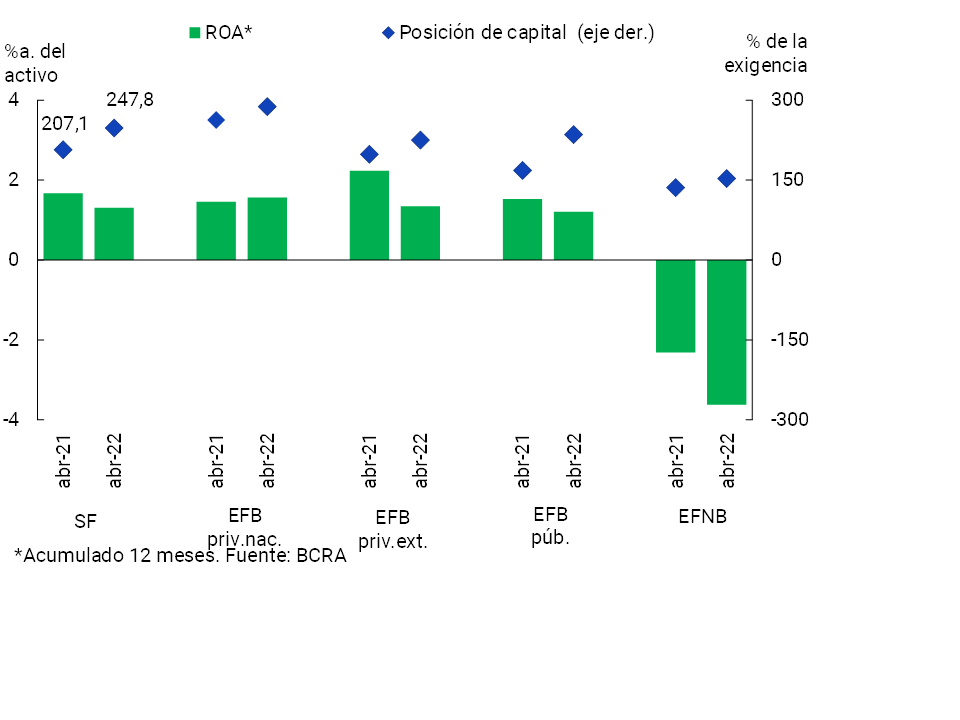

ii. Relatively high levels of solvency. Regulatory capital integration (RPC) for the aggregate financial system accounted for 27.9% of risk-weighted assets (RWA) in April 2022, up from the previous IEF and on a year-on-year basis. The year-on-year increase in the indicator (+2.6 p.p.) was due to both the growth in real terms of the PRC (+5.1% YoY) and the decrease in real terms of RWAs (-4.7% YoY), both of which were similar in size. The excess regulatory capital (above the minimum required) of all entities increased to 248% of the regulatory requirement. In addition, local financial institutions maintain extensive complementary verification of the additional capital margins established in local regulations.

To complement the minimum capital requirements, institutions should also verify a minimum level for the leverage ratio (as defined by the Basel Committee). This indicator stood at 14% over the beginning of 2022, comfortably exceeding the minimum required of 3% and the records of other economies (see Chart 6).

In a context of record solvency levels, the BCRA adopted changes in prudential rules allowing the distribution of up to 20% of distributable results in 12 monthly installments.

iii. Low relative importance of foreign currency items in the aggregate balance sheet of the sector and limited differential between assets and liabilities in this denomination. The total foreign currency assets of the financial system accounted for 15.2% of total assets in April 2022, decreasing compared to the last IEF and in a year-on-year comparison (being values lower than the average of the last 10 years, of 18.5%). Within assets, the balance of credit to the private sector in foreign currency (mainly granted to companies whose revenues are correlated with the exchange rate) accounted for only 8.3% of total credit to the private sector in April 2022, also falling with respect to the last IEF and year-on-year. For its part, at the beginning of the second quarter, the balance of total liabilities in foreign currency represented 13.4% of total funding (liabilities and equity), falling compared to last September and compared to April 2021 (moderate levels when compared to the average of the last 10 years, of 16.3%). Within funding, deposits in foreign currency totaled 15.8% of private sector deposits, below the level of the previous IEF and the one observed a year ago. Considering all assets and liabilities in foreign currency, as well as forward purchase and sale transactions of foreign currency classified off-balance sheet, the spread in this denomination for the financial system was equivalent to 11.8% of regulatory capital in April 2022, remaining at a range of values limited in the last year within the framework of the macroprudential measures in force.

iv. Moderate exposure to the private sector, with a decrease in the irregularity ratio to levels below pre-pandemic levels. The financial system’s exposure to the private sector stood at 30.9% of total assets in April 2022, slightly above the September 2021 record, although 0.4 p.p. below the April 2021 level. These levels of exposure are moderate when compared to the local average of the last 10 years (42.7% for the group of entities) and with the median of a sample of countries in the region (63% for the latest available information).

In this context, the irregularity ratio of credit to the private sector, which is less and less influenced by the effect of financial relief measures, reached 3.6% in April, lower than the level recorded prior to the beginning of the pandemic (this indicator reached 6.2% in February 2020 and 4.9% for the 12-month average up to that point).

Given the strengths of the Argentine financial system, it is expected that it will continue to show resilience in the event of adverse scenarios, which should be very extreme (low-probability events) to impact financial stability conditions. In this regard, as part of the stability analysis, the main potential risk factors (exogenous to the financial system) to be considered in the coming months are explained below.

Risk of further deterioration in the external context, given the uncertainty factors and existing vulnerabilities. Although an environment of growth in economic activity continues to be observed globally, and financial markets still show relatively favorable conditions in historical terms, the outlook is increasingly uncertain and subject to increasing volatility (as observed in June). The investor base remains focused on the processes of monetary policy normalization in developed economies and their impact on global growth. The Russia-Ukraine conflict also remains ongoing, with the potential to continue to affect commodity prices and help with the persistence of supply chain bottlenecks. Despite the considerable progress made in the normalization process, the pandemic context remains in force, with the possibility of complications in the face of new strains, although with high levels of vaccination. These uncertainty factors could have a stronger impact on the level of activity at the global and regional levels (with effects on international trade) or be combined with existing vulnerabilities at the global level (relatively high prices in certain market segments, greater gravitation of investment funds – with procyclical dynamics – increase in the debt burden of governments and companies – and greater implicit risk). to trigger new episodes of sudden revaluation of perceived risk that imply abrupt changes in financial conditions and capital flows. Thus, different types of shocks will have a greater impact on the commercial channel (with a more direct effect on the level of local activity) or on the financial channel (with a more direct effect on the exchange rate and interest rates), in turn affecting the local context in which financial intermediation is carried out and the credit risk faced by the financial system. Given the characteristics of the domestic financial system, and the existence of restrictions in the foreign exchange market, it is estimated that these shocks should be abrupt and of very high intensity to condition local financial stability significantly.

Risk of a lower-than-expected recovery of the local economy or greater volatility in the financial market. At the local level, the economic outlook remains positive, due to a lower incidence of COVID (which would allow an improvement in sectors that have not yet recovered to pre-pandemic levels, such as services), the achievement of an agreement with the IMF (enabling a reduction in perceived risk) and the maintenance of policies aimed at sustainable growth and the promotion of financial stability. However, risks linked to the evolution of the pandemic persist, in addition to idiosyncratic factors such as the effect of low rainfall scenarios on crops and exports, in addition to the local impact of the conflict in Ukraine (for example, generating potential tensions on the energy market or due to its impact on inflationary dynamics). This could eventually condition both the evolution of economic activity and the behaviour of the foreign exchange market (as observed in July) and of financial markets in general, with an impact – to the extent that they are major shocks – on the environment in which financial intermediation is carried out (demand and supply of credit, evolution of deposits) and/or on the credit risk faced by the banking sector.

Increasing operational risk, due to the increased reliance on technology. After growing during the pandemic, the use of teleworking and digital channels for financial transactions is expected to maintain its dynamism, while other technological innovations are being added. Although so far there have been no events of this nature with systemic incidences in Argentina, the rise of digital modalities implies by definition a greater exposure to operational risks, including disruptions in operations as well as fraud and cyber-attacks. In this regard, the BCRA continues to make continuous efforts in the areas of disclosure, prevention, and supervision (see Box 2).

Box 2 / BCRA’s Progress in Fraud Risk Management

The growth in the quantity and diversity of digital financial services arising from the evolution of technology and innovation – a process accelerated by the pandemic scenario – added to the promotion of new digital payment tools designed by the Central Bank (in particular with transfers), brought with them a wide range of benefits for users. with a consequent increase in risk exposure.

In that order. the document “BIS CPMI Fast payments – Enhancing the speed and availability of retail payments”19, points out that these new operations are presented as an alternative to cash, due to the focus they place on immediacy and interoperability, facilitating the flow of transactions between consumers/issuers and beneficiaries/receivers from any provider, interconnecting new and numerous participants to the payment system. However, this greater number of participants and their interconnection and the new ease of use supported by new technologies, although they facilitate the implementation of new services and generate benefits, also produce new risks to consider.

As mentioned in this document, there are risks that must be taken into account such as fraud and security risk. For the latter, it recommends that actions be implemented to address the cyber resilience of the business and critical services, that is, to promote the ability of organizations to recover quickly in the event of a cyber incident, maintaining redundancy and continuity. In relation to the risk of fraud, it highlights that immediate payment systems present challenges to traditional fraud prevention given the number of participants involved in the processing of the transaction, added to the immediacy and irrevocable nature of these payments. In this sense, it is recommended to define dispute and error resolution processes, establish clear responsibilities among participants, improve monitoring capacities, among others.

Local financial institutions have been developing their operations within a framework of minimum security measures that they must implement. There, it is worth highlighting the relevance of the analysis of parameters extracted from the systems that allow the identification of suspicious patterns of customer behavior that help prevent fraud incidents, among others.

This monitoring process is part of a comprehensive security scheme that financial institutions must have today for their electronic channels that is made up of 5 interrelated security processes: Awareness and Training, access control, Integrity and Registration, monitoring and control of events and incident management

In relation to customer protection, a financial institution should implement the aforementioned processes in order to:

• Keep customers informed and trained, through an awareness program with content according to the risks of the situation.

• Require customer identification and authentication for the use of electronic channels.

• Have records that allow determining the traceability of the activities carried out by the client.

• Have transactional monitoring mechanisms that can warn of suspicious situations based on characteristics of the customer’s profile and transactional pattern, verifying with the customer through alternative channels, in the event of certain alarms or alerts that occur.

• Have the capabilities to deal with detected incidents.

In order to strengthen actions against cyberattacks and improve cybersecurity and cyber resilience levels, in April 2021 the BCRA issued Com.”A” 7266 on “Guidelines for Response and Recovery in the event of cyber incidents”. This regulation covers Financial Institutions, and extends to Financial Market Infrastructures and Payment Service Providers and payment accounts.

In relation to the local transfer payment system, it is made up of various participants: initiating Payment Service Providers, payment service providers that offer payment accounts, digital wallets, administrators of transfer schemes, financial institutions, customers, among others. Given the diverse technological infrastructure that supports the scheme and the large interconnection resulting from the number of participants, frauds could occur in any member of the aforementioned payment chain. Therefore, it was necessary to require comprehensive fraud prevention, so that all participants in the scheme could provide information that would serve to monitor transactions and the scheme from start to finish.

Therefore, to mitigate the risks of fraud related to payment transactions through transfers (Transfers 3.020), in the first quarter of 2022 the BCRA issued a new regulation21. There, a set of guidelines was defined to reduce the potential occurrence of fraud and/or ignorance of payments and transfers, events that can occur in this type of operation, requiring that:

• The different instant transfer schemes and their participants implement technical and organizational measures for fraud management, as well as circuits, resolution procedures and information available to all members;

• Customer complaints are handled by the provider of the affected account;

• The schemes define internally with their participants and among them roles and responsibilities for fraud management, documenting the procedures to be followed in the event of complaints;

• The schemes and their participants define the information and infrastructure that will allow them to record the transactions and follow their traceability22 from end to end, with the data they deem sufficient, accurate and complete so that all participants can analyze the circuit that followed an operation and thus detect where the fraud may have originated;

• Transfer schemes exchange information on vulnerabilities and threats that affect their processes and infrastructures, contributing to the prevention of the ecosystem.

This regulation was extended to Payment Service Providers that provide digital wallet services, who must arbitrate the mechanisms to mitigate fraud23, thus covering all participants of payment systems with transfers, and their interconnections. This will allow, among others, to improve the information bases necessary to detect fraud when more than one actor is involved in a payment scheme, and consequently to focus and attend more efficiently to user complaints.

The BCRA continues to work on measures aimed at comprehensively addressing and preventing fraud risks that may affect the normal functioning of the financial system, in awareness campaigns for the development of a resilient financial system.

In addition to these risks, other factors can be mentioned that, it is considered, could be relevant in the medium and long term. On the one hand, the risks involved in the rapid growth of crypto-asset operations globally (although they are not yet in widespread use). This includes, in addition to its high volatility – which implies risks for both users and the financial system in aggregate terms – the challenges they generate in terms of monetary and exchange rate policy for emerging economies with less developed markets. In this regard, in May the BCRA determined that financial institutions will not be able to carry out or facilitate their customers to carry out operations with digital assets. Another front of risks to be taken into account, with greater monitoring at the international level, is those linked to climate change (see Box 3). Finally, beyond the normalization of the policies implemented during the pandemic (in particular with regard to the monetary policies of developed economies), in a post-pandemic scenario it remains to be seen what will be the structural scope of various changes observed in the framework of the COVID shock (including modifications in business models with differential impact between sectors, countries and regions).

Box 3 / Environmental, Social and Governance Factors: Actions of Financial Regulators in Latin America

In the last decade, there has been an awareness that Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) aspects, and especially those related to climate change, must begin to be considered as emerging sources of financial risk. This is so given that they have the potential to eventually destabilize the provision of financial services at the level of an individual entity and even in the aggregate of the financial system24

Within the framework of the Paris Agreement and the United Nations 2030 Agenda, progress was made at the international level in addressing the effects of climate change and its interrelations with the financial system, in order to promote sustainable economic development at the global level. International Organizations25 and financial regulators have begun to focus their efforts on designing strategies that promote better management of the financial risks associated with ESG factors and in this way, among other objectives, achieve a transition to a low-carbon economy that is resilient to the impacts of climate change.

Latin America is no stranger to this trend and some of its financial regulators have begun to adopt different policy actions related to these risks, within the framework of their respective national strategies linked to sustainable development. In general terms, these strategies move around three axes: generation of information, development of green instruments and strengthening of understanding and capacities on this subject. Most Latin American banking regulators are at an early stage indicating to the banks in their jurisdiction their expectations about managing these risks. The tasks of these regulators consist of: (i) analyzing the state of affairs, (ii) improving their knowledge on the subject to generate the necessary capacities to evaluate and design the best possible policy, and (iii) designing future plans taking into account the best practices that emerge at the international level and the voluntary public-private agreements that usually precede other actions.

Within a second group of regulators are those that have already begun to require banks to incorporate the risk associated with climate change for large loans. Finally, Brazil is the jurisdiction that has fully incorporated the regulatory treatment of climate change risk. These are regulations that took into account a concept of proportionality for their design – with certain criteria of segmentation, materiality and under a gradual implementation.

The development of the capacities of the different market actors, i.e. regulators, government, investors and companies, as well as potential issuers of “green” products, is one of the points to advance in sustainable finance. In turn, the developments carried out by other central banks/supervisors in the region are of utmost relevance to advance in harmonized approaches.

A more detailed analysis of financial stability will be developed in the next section. To this end, the main sources of vulnerability identified for the local financial system will be considered, given their exposure to the aforementioned risk factors. These sources of vulnerability will be analyzed in contrast to the strengths of the financial system itself, with the aim of evaluating the present conditions to face the eventual materialization of the risk factors already indicated.

3. Sources of vulnerability and specific resilience factors of the financial system

3.1 Equity exposure to credit risk

In April 2022, the financial system’s gross exposure to credit, both to the private sector and to the public sector26, was moderate from a historical perspective, verifying an increase compared to 2021 records. Total financing reached 46% of aggregate financial system assets, 1.8 p.p. and 2.6 p.p. above the level of September and April 2021, respectively (see Chart 7). However, the level of this indicator remained below the average of the last 20 years (55%).

The recent increase in the weighting of credit in the assets of the financial system was mainly explained by financing to the public sector. The exposure of all entities to the public sector totaled 15.1% of total assets in April, 1.8 p.p. more than 7 months ago (previous IEF) and 3 p.p. y.o.y. It should be considered that this level of exposure is below the average of the last 20 years (approximately 18%). When taking into account public sector deposits, in April the financial system maintained a net credit position (net deposit financing) vis-à-vis this sector, in the order of 2.4% of its total assets.

The financial system’s exposure to the private sector remained at moderate levels (see Chart 8). The balance of credit to the private sector stood at 30.9% of the total assets of all financial institutions, slightly above the September 2021 figure, although 0.4 p.p. below the level of April 2021 (the average of the last 20 years reaches 37%)27. The slight increase in the exposure of the financial system to the private sector compared to the previous IEF was driven by the segment in pesos (it accounted for 28.3 p.p. of assets, 1.3 p.p. more than in September 2021).

Figure 8 | Credit to the private sector as a percentage of assets

In terms of the composition of the financial system’s exposure to the private sector by type of debtor, as of April 2022, 47.4% corresponded to loans to households and 52.6% to loans to companies – the one aimed at SMEs with relatively more dynamism at the margin.

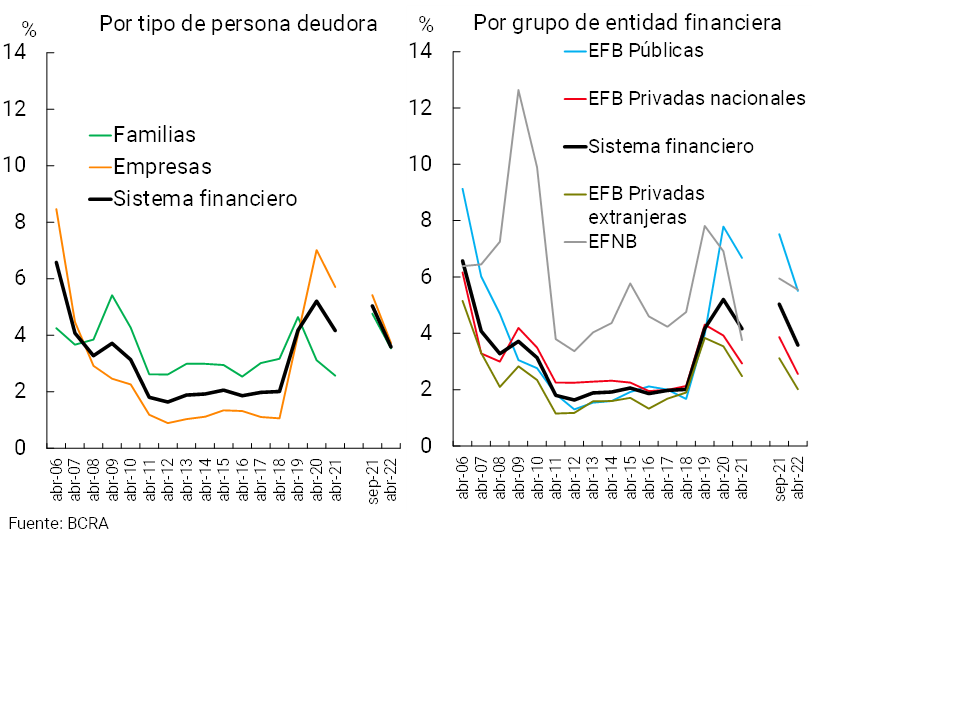

In relation to the degree of materialization of credit risk, the non-compliance ratio of financing to the private sector for institutions as a whole totaled 3.6% in April 2022, 1.5 p.p. less than in the previous IEF28 and 0.6 p.p. below April 2021. The regulatory modifications opportunely implemented in the context of the pandemic that alleviated the financial burden of debtors practically no longer have an impact on this indicator, allowing a more accurate comparison with pre-pandemic levels. The decrease in the irregularity ratio compared to September 2021 was verified in both the segment of credit to households and companies, and in all groups of financial institutions (see Chart 9).

Equity exposure to household credit risk

Credit to households accounted for almost 15% of the financial system’s assets in April 2022, slightly lower than the previous IEF record (-0.2 p.p.) and in a year-on-year comparison (-0.6 p.p.). As of April 2022, it is estimated that 64% of the financial system’s exposure to households was made up of loans whose debtor had a job in a dependent relationship (a ratio that increased approximately 4 p.p. compared to the situation 2 years ago and 3.6 p.p. compared to the average of the last 8 years).

Non-performing loans to households stood at 3.5% of this portfolio in April, 1.2 p.p. below the level of September 2021 (+1 p.p. y.o.y.), mainly due to the performance in the margin of consumer loans (personal and credit cards). The current levels of irregularity of credit to households are lower than those recorded prior to the beginning of the pandemic (-0.8 p.p. compared to the 6-month average to February 2020). Within the household credit segment, there was a low dispersion in the irregularity ratio between geographical areas of the country, being slightly higher than the weighted average in the Cuyo region and slightly lower in the Central zone. In turn, the fall in the irregularity ratio of credit to households compared to the level of September 2021 was relatively greater in this Central area (-1.4 p.p.), while it was more moderate in the NOA region (-0.6 p.p.).

Equity exposure to corporate credit risk

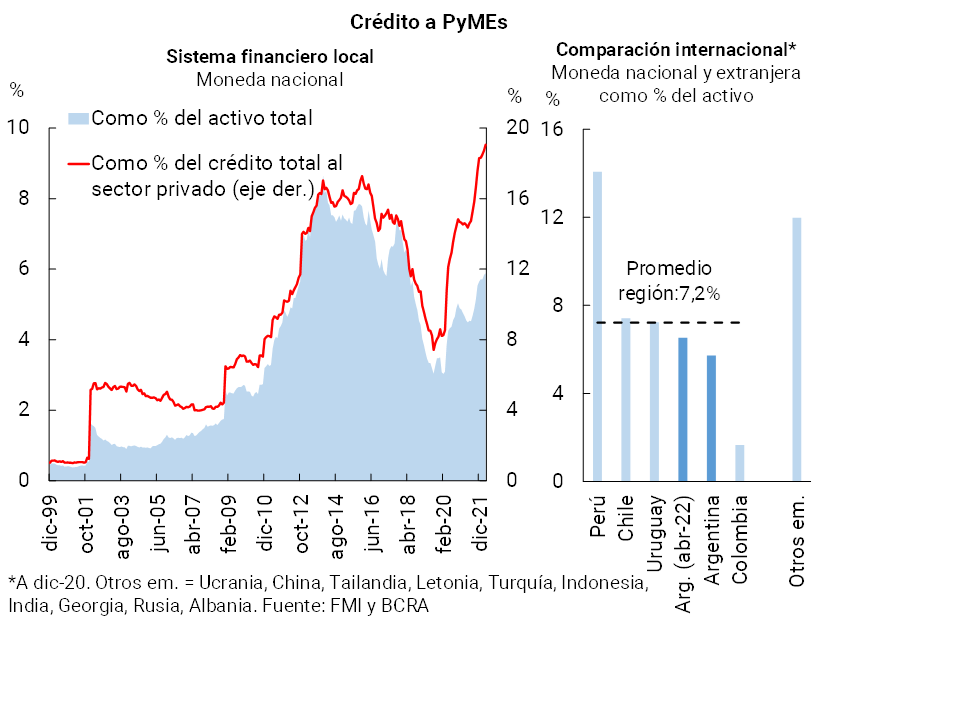

Financing to companies represented just over 16% of the assets of the financial system in April 2022, without significant changes compared to the previous IEF and in a year-on-year comparison. Within this segment, financing to SMEs (see Chart 8 and Box 4) represented 6.5% of the assets of the group of entities, evidencing an expansion in margin (+0.7 p.p. and +0.9 p.p. compared to September 2021 and a year ago, respectively), to the detriment of the rest, mainly associated with large companies.

Box 4 / Bank financing to SMEs: recent increase, exposure on the balance sheet of the financial system and hedging

Within the framework of the credit policy promoted by the BCRA since the end of 2019 that contributes to focusing resources on the promotion of productive development, in the last two years bank credit for SMEs29 grew significantly30. The real balance of financing in national currency for this sector expanded 26.4% year-on-year as of April of this year, more than doubling when considering the performance since the beginning of 202031.

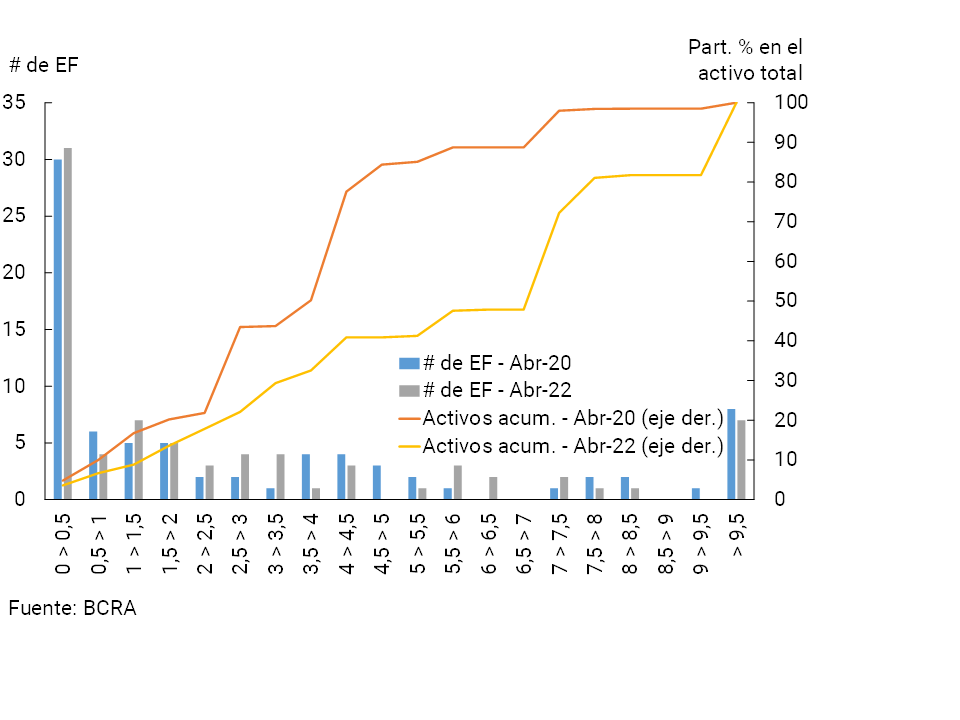

Based on this marked dynamism, at the beginning of the second quarter of 2022, credit in national currency to SMEs reached 5.9% of the total assets of the financial system, 1.3 p.p. and 2 p.p. above the levels evidenced one and two years ago, respectively, an increase that amounts to 1.9 p.p. compared to the average of the last 20 years (see Graph R.4.1). This performance occurred in a context of gradual reduction in the exposure of all financial institutions to the private sector, which in turn caused credit in pesos to SMEs to reach a peak of participation close to 20% in total credit to the private sector at the beginning of 2022. Despite the increase observed in the last two years, when compared with other economies, it can be seen that the exposure of the local financial system to this segment of debtors is slightly below the average of the countries of the region (see Chart R.4.1)32.

Figure R.4.2 | Credit balance to SMEs in pesos as a % of assets – Distribution among financial institutions

The increase in the exposure of the balance sheet of the financial system to SME credit in the last two years occurred together with an increase in the concentration indicators of the offering entities. In total, 27 of the 50 SME credit providers showed an increase in exposure to this segment in assets in the last two years (see Figure R. 4.2), while 23 reduced it. With regard to the indicators of concentration of supply, as of April 2022 the main 5 entities accounted for 72% of the balance of credit to SMEs, 11 p.p. more than in April 202033. It should be considered that financing to SMEs contributes to the diversification of the credit portfolio of entities, tempering to a certain extent their exposure to credit risk. This occurs in a context in which this type of debtor would present relatively lower levels of irregularity.

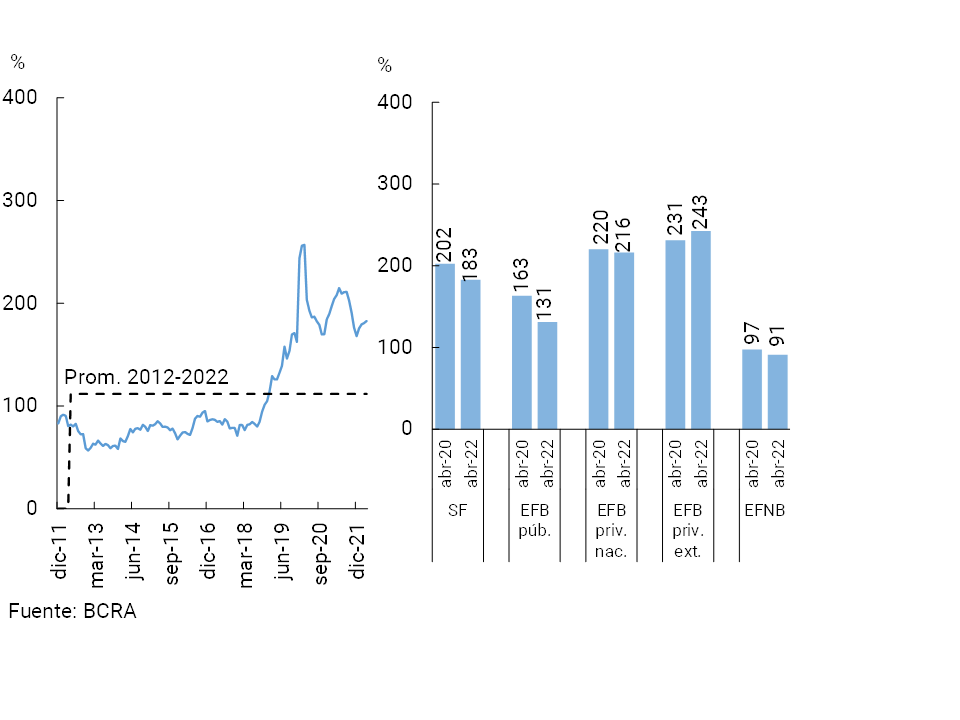

To measure the relative size of the hedges constituted by the financial system in the face of possible scenarios of materialization of the counterparty risk of this credit segment, the relationship between the surplus regulatory capital and the balance of financing to SMEs can be considered. This ratio, although it fell in the last two years in the context of the strong dynamism of SME credit, remained in a range of high values when compared to the average of recent years: at the systemic level, this ratio rose to 183% in April 2022, 71 p.p. above the average of the last 10 years (see Graph R.4.3)34.

The non-performing ratio of loans to companies totaled 3.7% in the period, 1.7 p.p. below the level of September 2021 (-2 p.p. y.o.y.). In the same way as what was observed in households, the current records of irregularity in credit to companies are lower than those evidenced before the beginning of the pandemic (-2.9 p.p. compared to the 6-month average to February 2020).

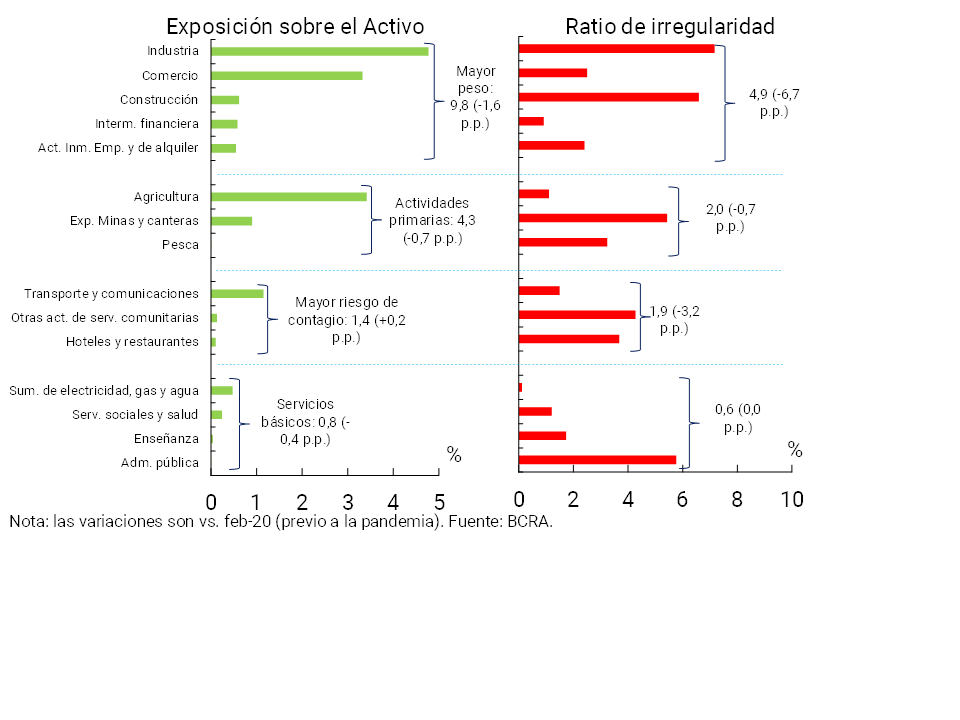

When considering the composition of financing to firms by sector, the group of companies whose activities have the greatest weight in the economy35 maintained a debt balance equivalent to 9.8% of the assets of the financial system in April 2022, 1.6 p.p. less than the pre-pandemic situation (see Chart 10). Companies belonging to primary activities were financed for an equivalent of 4.3% of the assets of all entities (-0.7 p.p. compared to February 2020). For its part, the exposure of the financial system to activities considered to be at greater risk of contagion (in the context of the effects of the pandemic) and to basic services was 1.4% of assets (slightly higher than the pre-pandemic level) and 0.8% (-0.4 p.p. compared to February 2020), respectively.

The credit irregularity ratio as of April 2022 was relatively higher in the set of companies with the greatest weight in the economy (4.9%) compared to the rest of the groupings, although it presented the largest decrease compared to the pre-pandemic situation (-6.7 p.p., see Graph 10).

As mentioned above, the financial system maintains a low exposure to debtors associated with activities considered to be at greater risk of contagion36. However, given the impact on companies in these sectors in 2020 and 2021, coupled with the potential risk of new occasional and repeated shocks from the pandemic on their performance, sensitivity exercises are carried out for all institutions to assess the degree of coverage against a hypothetical and unlikely shock (see Box 5).

Box 5 / Credit Risk Sensitivity Exercises

The results of the sensitivity exercises carried out with data as of April 2022 provide evidence that the Argentine financial system, in aggregate, maintains a significant degree of resilience to the eventual materialization of the credit risk assumed37. In these exercises, the impact on the solvency of the financial system is analysed (without assuming additional changes), in the event of a hypothetical total impossibility of recovering a certain set of loans (extreme assumption of very low probability of occurrence). These exercises are part of the BCRA’s set of monitoring tools to assess the stability of the financial system.

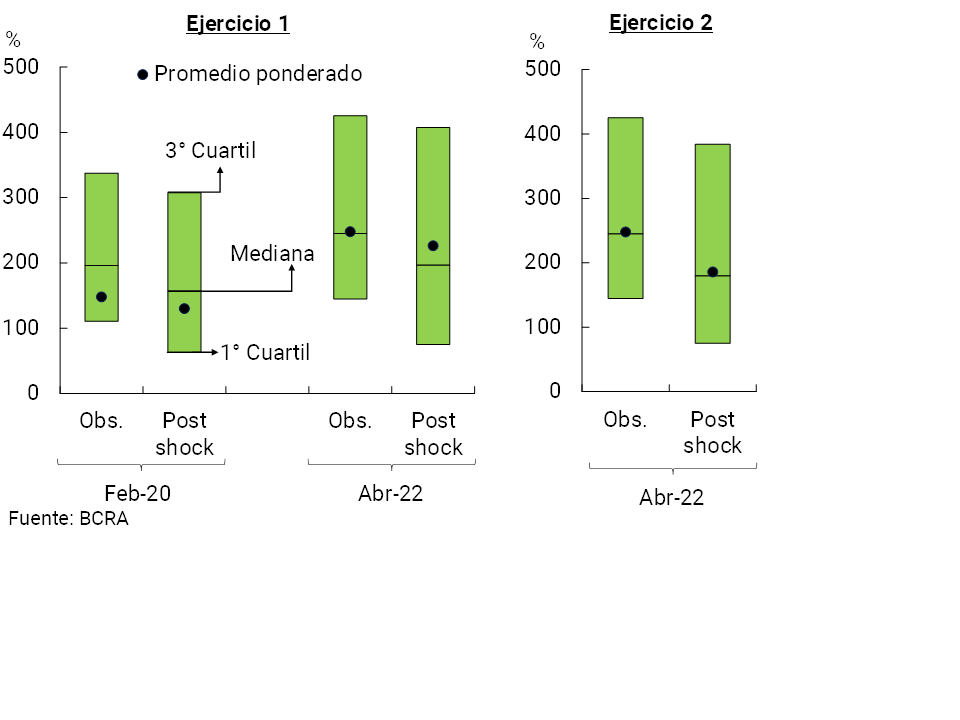

Exercise 1: it is assumed that in each financial institution the ratio of irregularity of loans to the private sector increases to the highest level reached at the individual level in the last 15 years (April 2007-April 2022)38. These assets are derecognized from the balance sheet, net of the estimated forecasts for them39. The resulting regulatory capital position is estimated as of April 2022 (latest available information) and February 2020 (prior to the start of the pandemic).

In this year, the median capital position40 of the institutions as a whole would decrease from 245% (weighted average of 248%) to 197% (226%) (see Chart R.5.1). Based on a high aggregate capital position, it is estimated that at present (April 2022) there would be greater slack once a possible shock occurred with respect to the pre-pandemic situation (February 2020).

Exercise 2: it is assumed that companies (and their employees) that have debts in the financial system and that belong to the sectors of activity “with the highest risk of contagion” due to the COVID41 Pandemic scenario, present a situation of impossibility of repayment of their loans42.

The estimated impact based on this exercise lowers the median capital position of the group of entities as of April 2022 by 65 p.p., to 180% (the weighted average would fall by 62 p.p., to 186%). Here too, the system would maintain, in aggregate, an appreciable capital slack.

Within the framework of the changes that have been registered in the credit exposures assumed by the financial system (both with the private and public sectors), and despite the recent improvement in the quality of the portfolio, in relative terms this source of vulnerability would remain the most relevant for the remainder of 2022 for the aggregate of financial institutions. The eventual materialization of the risk factors mentioned above (especially a less dynamic performance of economic activity than expected) would condition the payment capacity of debtors and, given the exposure of the financial system, there could be some impact on the sector’s balance sheet.

3.1.1 Resilience elements and mitigating measures:

The levels of forecasting and solvency of the aggregate financial system remained high. In April 2022, the forecasts accounted for dealing with bad debt situations represented 4.3% of total financing to the private sector. These forecasts continued to exceed the portfolio in an irregular situation (118.9% of it), above the September 2021 record and above the average in the 6 months prior to the pandemic (95%). The excess regulatory capital of the institutions as a whole, measured in terms of the loan portfolio net of provisions, remains high in a historical comparison (see Chart 11)43. The evolution of this ratio is reflected both at the level of the financial system and in all groups of banking institutions.

Figure 11 | Capital regulatory position (PRC-requirement) in terms of the balance of credit to the private sector net of forecasts

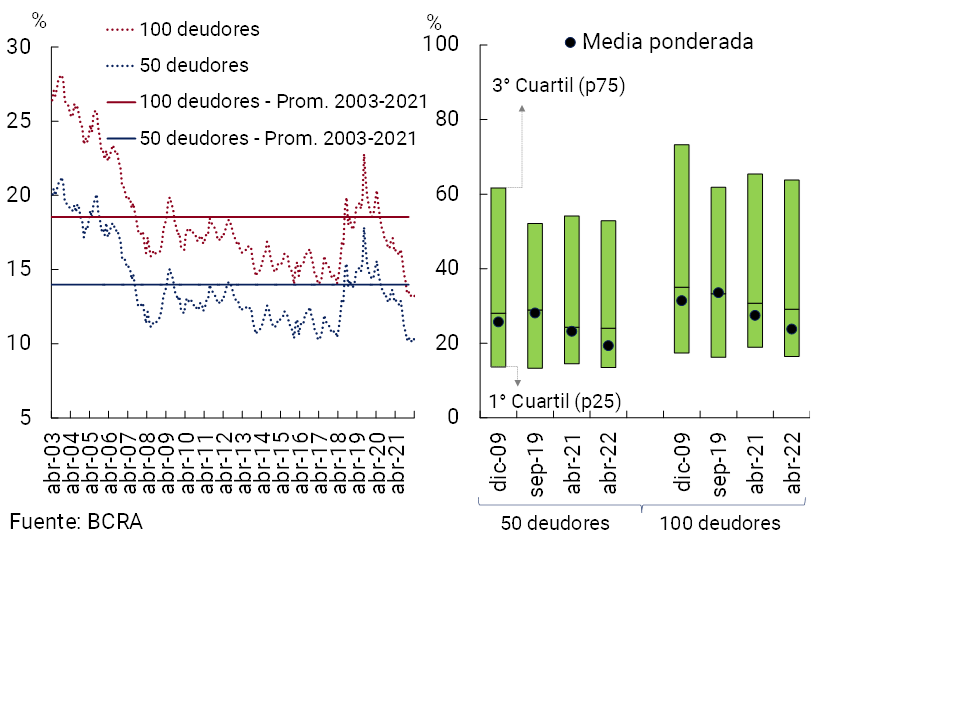

The concentration of private sector debtors in the financial system remains low. In April, the share of the top 100 and 50 debtors accounted for 13.2% and 10.2% of credit to the private sector, respectively (see Chart 12). These levels were lower than those recorded in the previous IEF (1.5 p.p. and 1 p.p., respectively), and remain at historically low values. Part of this performance is associated with the various credit stimulus programs promoted by the BCRA that made it possible to focus resources on the most backward sectors and promote productive development, such as the “Financing Line for Productive Investment of MSMEs” (LFIP, for more details see Box 6).

Box 6 / Financing Line for Productive Investment (LFIP)

Throughout 2021 and so far in 2022, the Financing Line for Productive Investment (LFIP) was an important tool to boost credit to the productive sector, especially to MSMEs44. In March 2022, the BCRA extended the LFIP until the end of September, maintaining relatively favorable financial conditions for companies and benefits for participating financial institutions45. The 2022 quota – in a context of increases in the monetary policy interest rate – has an interest rate (TNA) of 42% for investment projects, and 52.5% for the rest of the financing reached46.

The LFIP credit balance is estimated at $790,400 million as of April 2022, equivalent to 27% of the total credit balance to companies (+8.7 p.p. compared to the level of September 2021) and 13.3% of the total balance to the private sector (+3.7 p.p.).47. Of the total balance, approximately 38.5% was used to finance investment projects.

The irregularity ratio of the total loans of the companies taking the LFIP stood at 0.7% as of April 2022 (-0.8 p.p. compared to September 2021), in a context in which this indicator for the total financing of the financial system stands at 3.6% (-1.5 p.p.).

It is estimated that since the last publication of the IEF, some 223 companies that did not have bank financing48, accessed this line of credit. Since the beginning of the LFIP, some 12,151 companies have been included in the financial system. As of April 2022, a total of almost 93,700 companies had a balance of financing channeled through the LFIP throughout the financial system. Most LFIP policyholders are relatively small in size: 94% (87%) of these companies have a staff of less than 100 (50) workers49. It is estimated that the number of people employed by companies with LFIP financing is equivalent to 19.5% of the total number of salaried people in the private sector50.

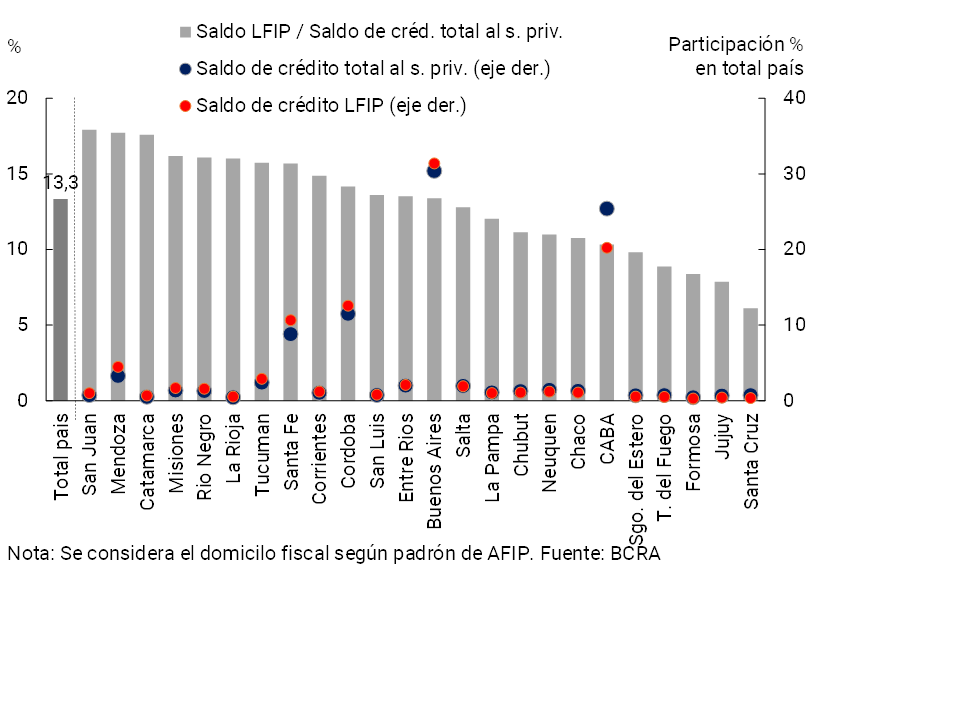

In terms of the distribution of LFIP resources among the different jurisdictions of the country, this tool continues to show a wide scope. Thirteen provinces have a weighting of the credit balance instrumented through the LFIP in total credit to the private sector that exceeds the average observed at the country level (see Figure R.6.1).

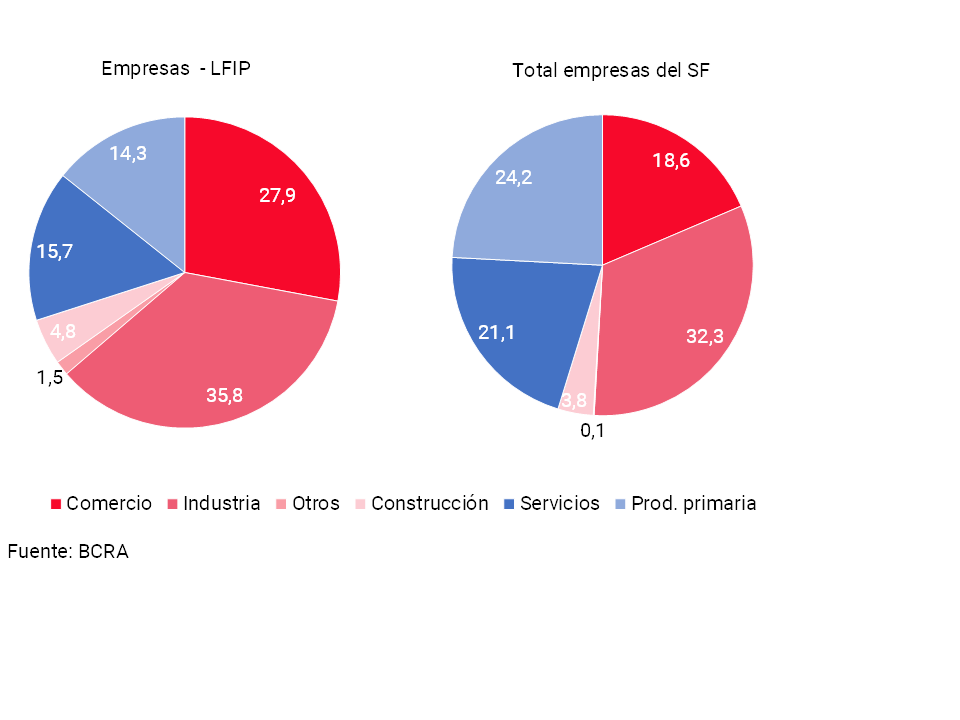

As for the sectors of activity of the companies taking the LFIP, about 36% of the balance would have been channeled to industry (see Graph R.6.2). In particular, companies engaged in the manufacture of food and beverage products accounted for approximately one-third of the total in this area. Meanwhile, it is estimated that almost 28% of the LFIP balance was granted to firms linked to trade (mainly wholesale trade companies). When comparing the distribution of the LFIP balance with the distribution of total bank credit to companies, it emerges that companies in industry, commerce and construction used this instrument relatively more than the rest of the sectors.

Figure R.6.2 | LFIP – Estimate by economic activity –

Share % in total balance – Latest available data

Credit origination standards remained unchanged over the past51 quarters. In the case of loans to households, according to the CCP, during the first quarter of the year there were no relevant modifications in credit standards. For its part, in the aforementioned survey, neutrality was observed in the case of credit origination standards for companies, both for large and SMEs.

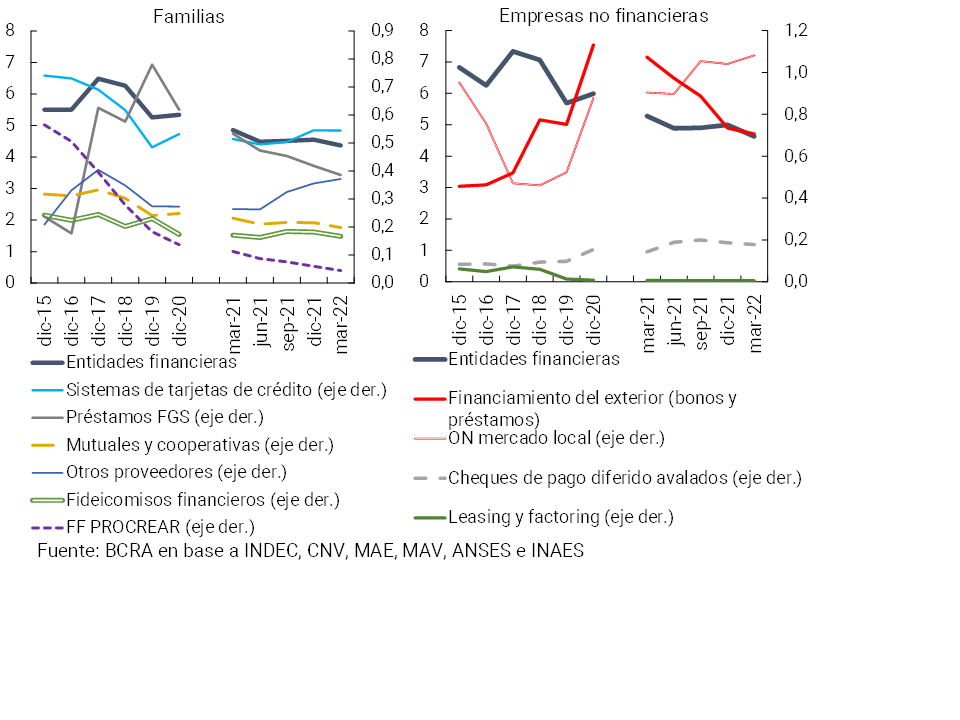

In aggregate terms and as a percentage of GDP, the levels of indebtedness of both companies and households remain limited. The broad credit ratio as a percentage of GDP represented a level of 6.1% for households and 10.6% for companiesin March 52, with decreases in both cases compared to their level six months ago (milder in the case of families). Data from publicly offered companies also show a downward trend in corporate leverage in the second half of 2021 (see Box 7). The six-month change occurs in a context of rising GDP and declining credit amounts (in real terms) in the broad sense for households (1% semi-annually) and companies (10% semi-annually). For both households and companies, the balances as a percentage of GDP are below the average of the last five years (about 8% of GDP for families and 12% for companies). Considering credit to households, the main component continues to be bank credit, the amount of which fell slightly in real terms between September 2021 and March 2022, with additional losses for FGS loans and loans in the FF PRO.CRE.AR, loans from mutuals and cooperatives and those in the portfolio of financial trusts not linked to infrastructure. On the other hand, the amounts associated with other credit providers registered with the BCRA53 and non-bank credit cards increased in real terms (see Graph 13). With respect to the corporate sector, the main components are bank credit and the balance of financial financing from abroad, both with six-month decreases in real terms as of March. The balance of local ON54, with a lower weight (6%) in total financing of companies, showed real growth, in contrast to what was observed for other local capital market instruments, such as deferred payment checks (with a more marginal weight on financing to companies).

Box 7 / Financial situation of publicly offered companies

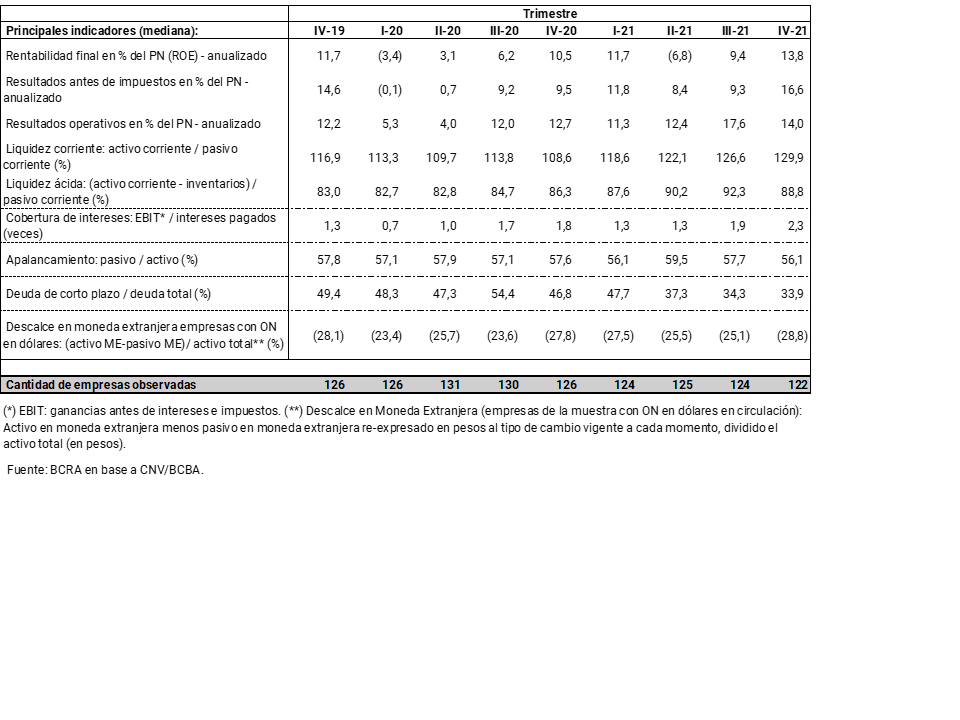

One of the ways to monitor the situation of the corporate sector is through the analysis of the balance sheets of companies with public offerings in the non-financial private sector55. Measured in terms of their median, the financial indicators of these companies tended to recompose themselves in 2021, after the deterioration implied by the COVID-19 shock in 2020.

Final profitability in terms of equity, in homogeneous currency, improved in 2021 (see Table R.7.1), in a context of recomposition of operating results. This had a favorable impact on both liquidity indicators and payment capacity (interest coverage ratio with results)56. The leverage ratio ended 2021 with a decrease compared to 2020, which was accompanied by a trend towards a lower weight of short-term liabilities over total liabilities (consistent with a context of liability refinancing operations). On the other hand, in absolute value, the currency mismatch for companies that have ON in dollars ended the year slightly above the level observed a year ago.

Given the evolution of the financial indicators of publicly offered companies, following a simple methodology57, at the end of 2021 it is observed that the proportion of companies in a relatively more vulnerable situation decreased. The financial system has a very limited exposure to these relatively more vulnerable companies (less than 1% of its total portfolio of loans to the corporate sector).

It is estimated that households maintained a moderate burden of servicing their bank debt, increasing slightly after the minimum evidenced in September 202158.

Reduced importance of financing to the private sector in foreign currency in the aggregate balance sheet of the financial system, with low foreign currency mismatch of debtors based on current macroprudential regulations. For more details, see the section on Main strengths of the financial system.

3.2 Performance of the financial intermediation activity

Financial intermediation activity has remained at moderate levels since the last publication of the IEF, in a scenario of gradual recovery of the different economic sectors. Despite the local and international context of higher inflation levels at the beginning of 2022 compared to previous periods59, the real balance of financing in pesos to the private sector increased slightly both in the last seven months, as well as in a year-on-year comparison.

For its part, the balance of deposits in national currency in this sector fell slightly in the period, accumulating a slight increase compared to the level of a year ago (see Section 3.3). On the foreign currency items, private sector credit and deposits continued to decline gradually when compared to the previous IEF.

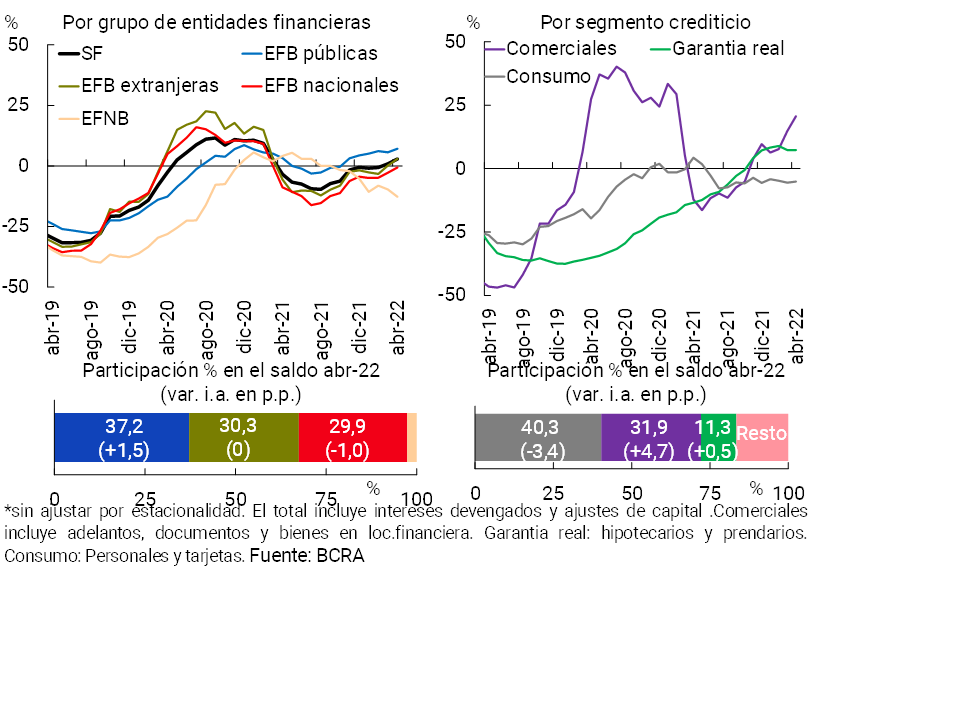

The balance of credit in pesos to the private sector increased 1.2% in real terms in the last seven months, and 2.8% y.o.y. in real terms, with a higher relative contribution from the group of public financial institutions (see Chart 14). Commercial loans (mainly documents) had the highest relative growth in the period and increased their share of total credit within the framework of the stimulus programs implemented by the BCRA, followed by lines with real collateral (mainly pledges). Given the reduction in the balance of financing in foreign currency, the total credit balance to the private sector (in domestic and foreign currency) accumulated a fall of 3% in real terms in the last seven months (-3.7% real y.o.y.).

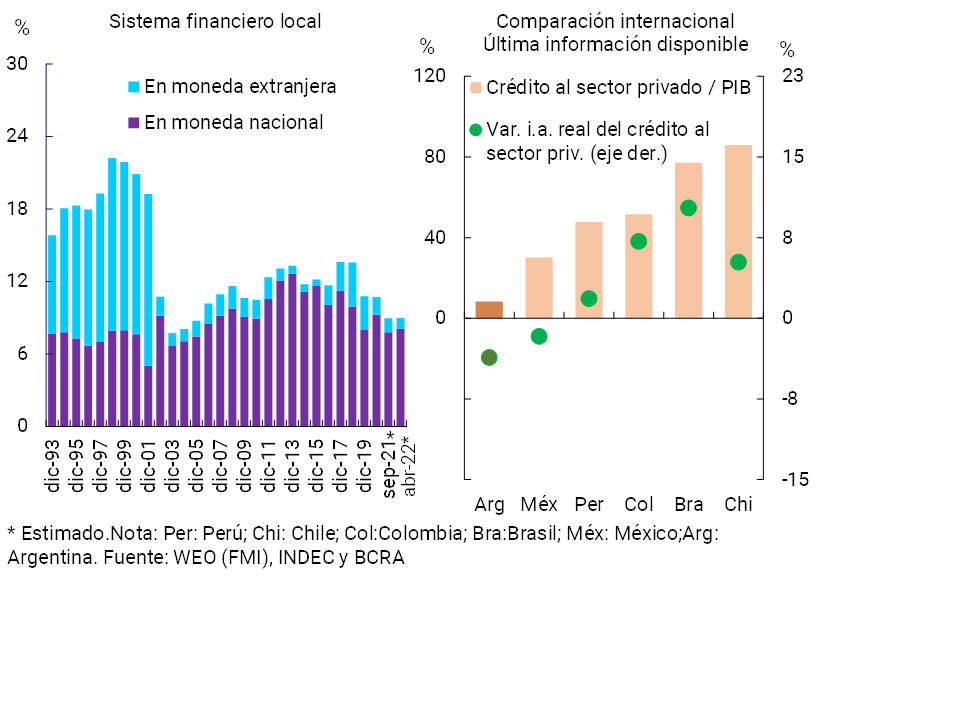

The local financial system continued to maintain a low degree of depth in the economy (see Graph 15). As has been commented in recent editions of the IEF, the ratio between bank credit to the private sector and output is at levels that are relatively low when compared to the local average of the last thirty years (13.5%) – already moderate – and with the records of other countries in the region (median of 49.7%).

The performance in financial intermediation took place in the context of the redesign of monetary policy instruments that began in January 2022, including the increase in the economy’s nominal interest rates. In this context, the aim was to ensure that lending rates were maintained at levels compatible with the promotion of credit to small and medium-sized enterprises, so that the development of tools such as the “Financing Line for Productive Investment in MSMEs” (See Box 6) can be deepened. It is estimated that for the first four months of 2022, the average nominal lending rates agreed for loans in pesos to individuals and legal entities increased less than the fixed-term interest rate, registering increases that are more in line with what was verified in the average nominal passive interest rate – operated by total deposits in pesos, both at sight and in the term.

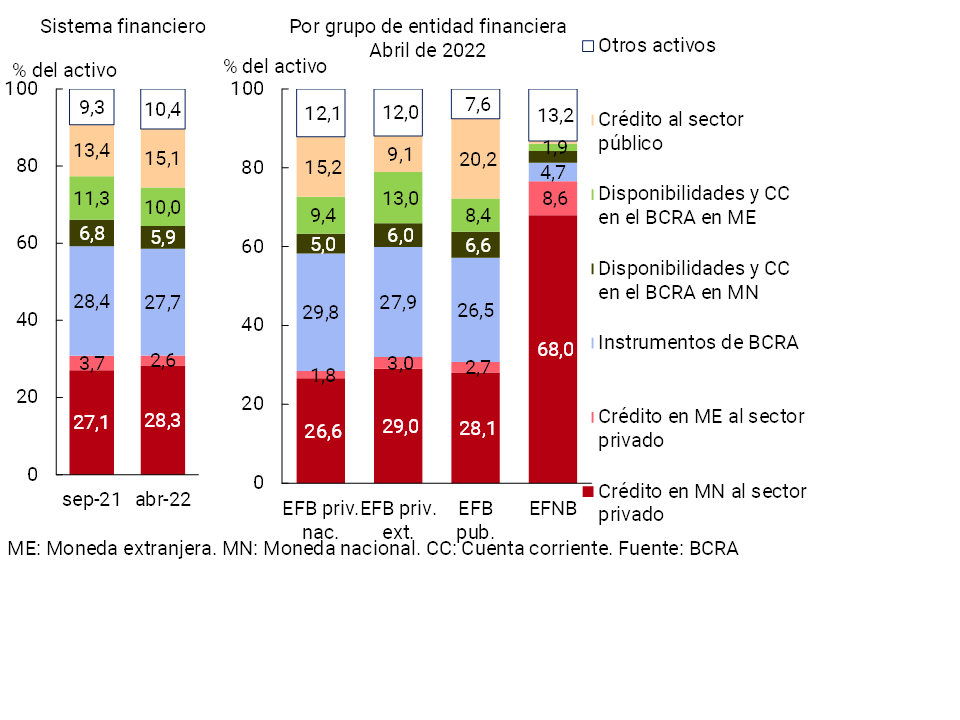

In the context of the aforementioned performance of financial intermediation, the assets of the institutions as a whole, measured in homogeneous currency, fell slightly compared to the level of the last IEF and in a year-on-year comparison (-3.3% real and -2.3% y.o.y., respectively), also reflecting certain changes in their composition. In particular, in the last seven months, the relative weight of financing to the public sector increased (to represent 15.1% of total assets) and credit in pesos to the private sector (up to 28.3% of the total); while the weighting of the balance of current accounts in the BCRA, of the BCRA’s instruments (mainly by passes) and of foreign currency loans to the private sector was reduced (see Graph 16). In the period, the financial institutions as a whole slightly increased the relevance of assets in national currency with CER adjustment (to 11.7% of total assets) and the share of those denominated in foreign currency decreased (to 15.2% of assets).

In the coming months, the process of gradual recovery of economic activity is expected to continue, a scenario that would have a positive impact on financial intermediation (supply and demand of credit and deposits, as well as financial services). However, this expected evolution could be affected by the eventual materialization of the risk factors mentioned in the previous section, generating a challenging context for all financial institutions.

3.2.1 Resilience elements and mitigating measures:

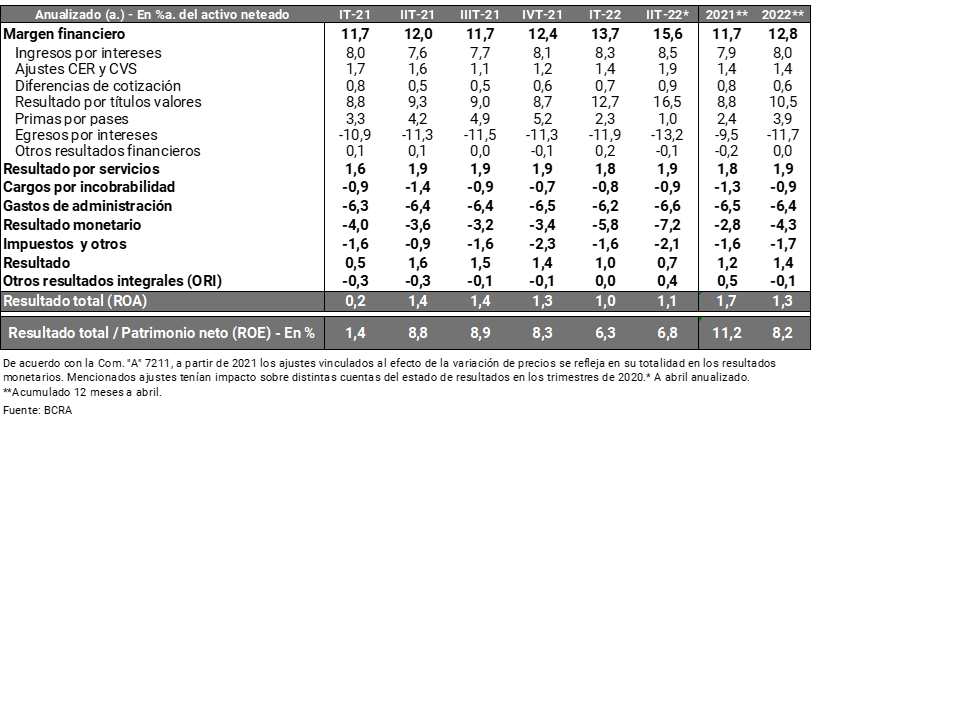

Internal capital generation. The aggregate of financial institutions continued to exhibit positive profitability at the beginning of 2022, although with indicators at slightly lower levels than those observed in the last quarters of 2021 (see Table 2). Considering the accumulated results in the last 12 months, the year-on-year decrease in the sector’s profitability levels is explained by the increase in interest outflows (increase in nominal interest rates and greater relevance of time deposits in funding) and by higher outflows due to exposure to monetary items (influenced by higher inflation). These changes were partly offset by higher premiums for passes and positive results for securities and lower charges for uncollectibility. Administrative expenses did not show significant variations compared to the previous year, maintaining an important relative weight in the aggregate financial system’s results table (see Box 8).

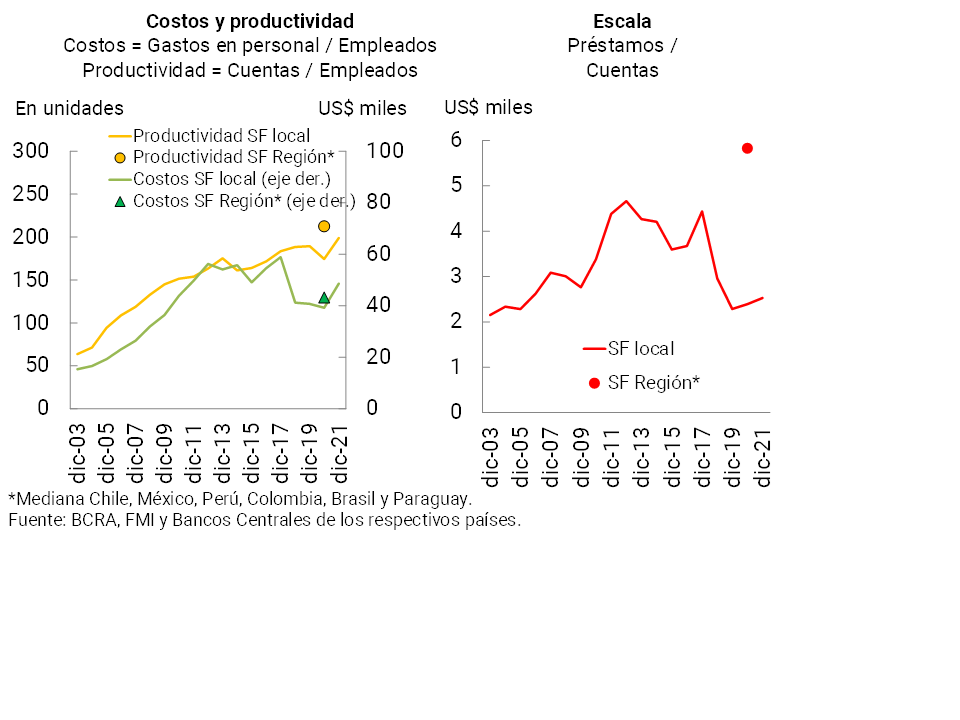

Box 8 / Measures of productivity and scale of the financial system. A regional comparison

Compared to the financial systems of other countries in the region, the Argentine financial system has similar levels both in terms of the unit cost of personnel employed (personnel expenditure per employee) and certain indicators of employment productivity (for example, based on the number of active account holders per employee60— (see Figure R.8.1, left panel). Notwithstanding the value of these indicators, the levels of sectoral operational efficiency – for example, approximate in terms of the ratio between personnel expenditure and the balance of loans to the private sector61 – are comparatively lower for the aggregate of local banks.

Figure R.8.1 |Indicators of scale and productivity of financial

systems

Annual data – Local evolution and latest available data for countries in the region* (2020)

The differences in the observed levels of operational efficiency of the Argentine financial system would be reflecting, in large part, the effects of a relatively low scale of the sector —approximated here by the balance of loans to the private sector per account holder— (see Figure R.8.1, right panel)62. The local financial system would thus maintain a wide margin to benefit from the expansion of its size, generating economies of scale through the growth of credit (greater extensive and intensive use), thus resulting in potential benefits for the sector and for the economy as a whole. In this regard, the active credit promotion policy that the BCRA has been developing in recent years (see Box 4) is relevant, in addition to the gradual introduction of new technological tools and innovations in business models that would eventually be reflected in improvements in all sectoral indicators

Within the framework of the rise in monetary policy interest rates and the rest of the interest rates operated, it is estimated that in the first part of 2022 there were gradual increases in nominal implicit interest rates for the segment in pesos63. Compared to the end of 2021, the magnitude of the changes in implied rates was similar in assets (for loans to the private sector) and in liabilities (cost of funding for deposits), so that the differential between these implied rates did not present significant changes in the period. When estimating real implied interest rates (isolating the effect of inflation), the differential between the two concepts verified a reduction in the period.

The profitability indicators maintained some heterogeneity among the groups of financial institutions, although it should be noted that all these groups presented high (and growing) solvency indicators (see Graph 17).

Regulation and supervision scheme in line with international recommendations on the matter. Within the framework of the risk-oriented supervision plan, the Superintendence of Financial and Exchange Institutions (SEFyC) continues to permanently monitor the performance of financial institutions. In particular, financial institutions defined as systemically important at the local level (DSIBS) maintained high levels of liquidity and solvency and limited risk exposures in the period (see Section 4.1).

Credit policies aimed at productive development. Throughout 2021 and so far in 2022, the BCRA continued to promote various policies to accompany the economic recovery process in a sustainable manner. With the aim of continuing to stimulate the production of certain productive sectors, at the end of the first quarter of 2022 the BCRA decided to extend the “Financing Line for the productive investment of MSMEs” until the end of September 2022, maintaining favorable financial conditions for debtors.

Low mismatch of foreign currency. In the context of the macroprudential regulations in force, the foreign currency mismatch faced by the aggregate financial system continued to remain at limited levels at the beginning of 2022 (see Section 2).

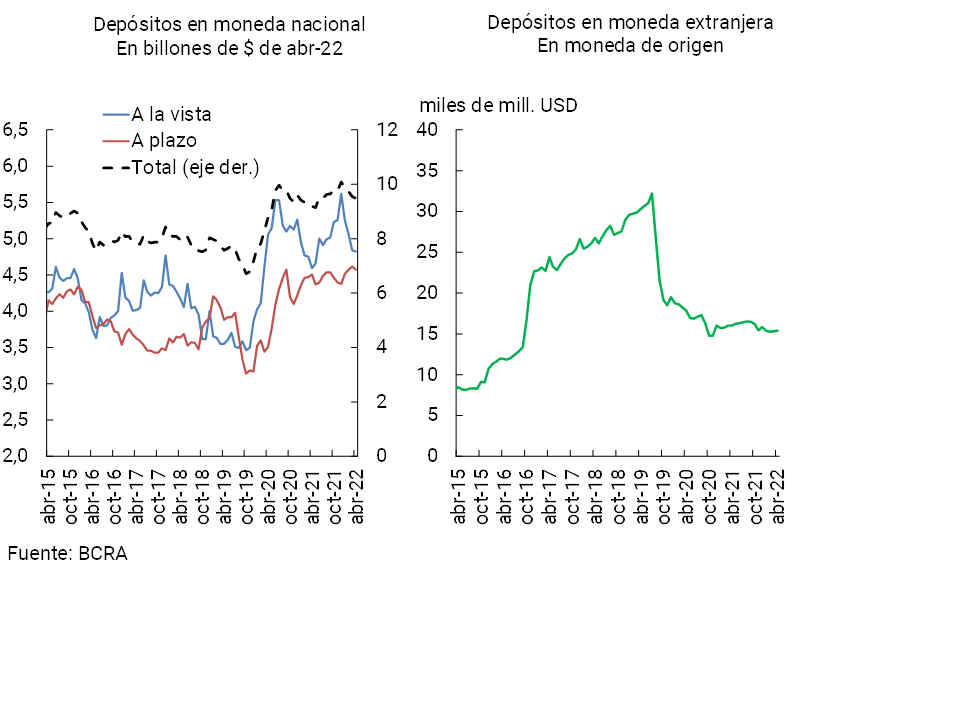

3.3 Funding and liquidity of the financial system

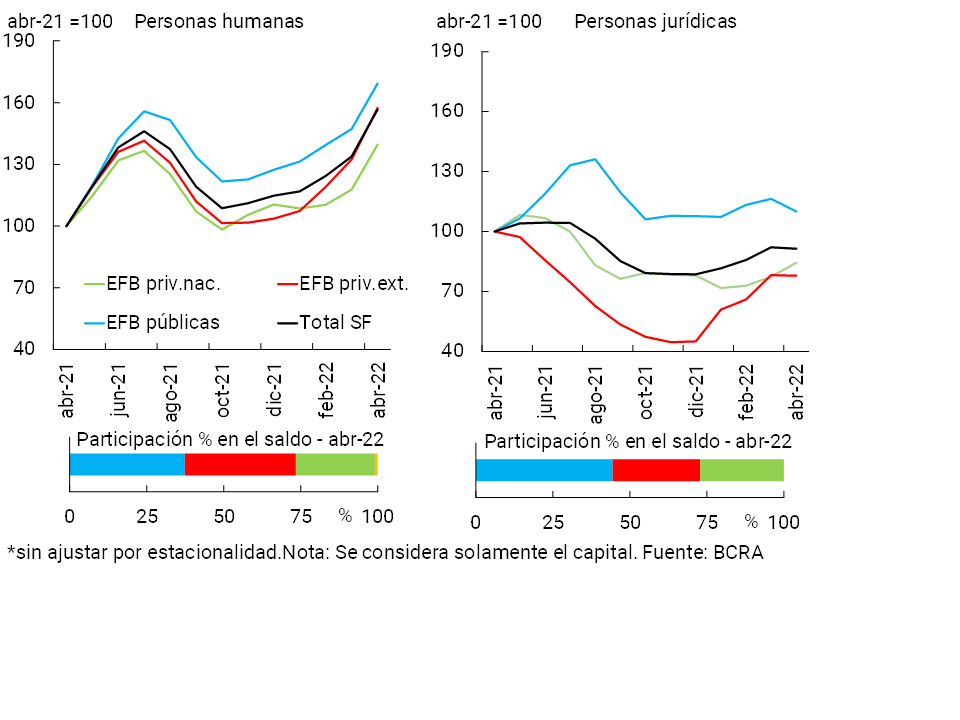

As mentioned in the previous section, the real balance of private sector deposits in national currency decreased slightly compared to the previous IEF (-1.7% in real terms, a variation explained by the performance of demand accounts, see Chart 18). For their part, the private sector’s time deposits in national currency increased in the period, mainly due to the performance so far in 2022 (see Box 9). The greater dynamism in this segment reflected the effect of the BCRA’s decision to increase the minimum limits of interest rates on fixed terms on several occasions. Private sector deposits in foreign currency were reduced compared to the level of last September (in currency of origin).

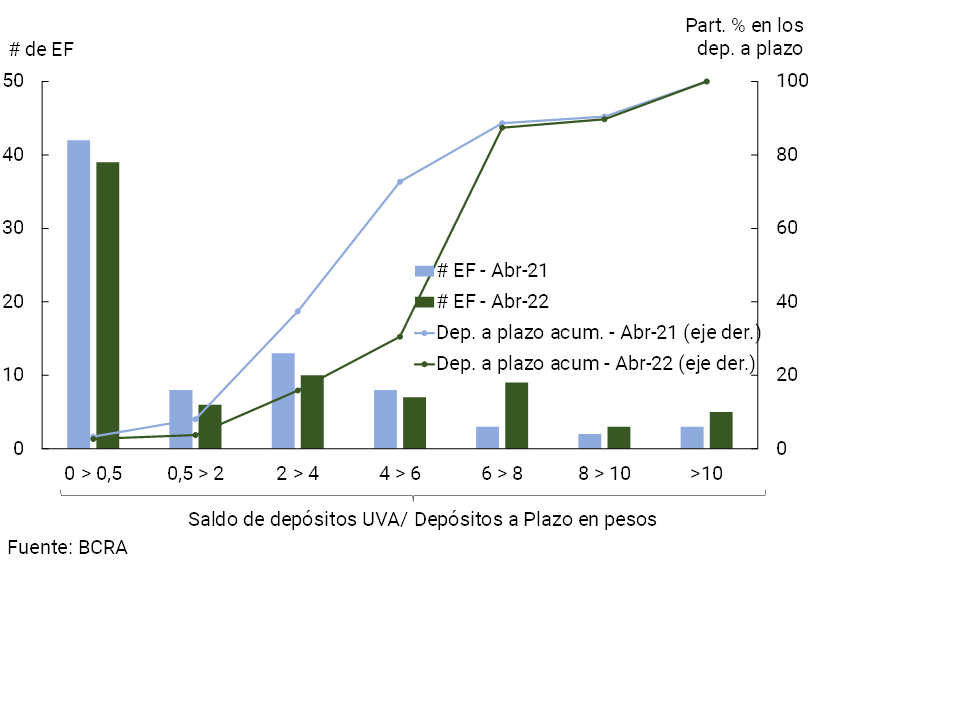

Box 9 / Recent performance of UVA time deposits in the private sector

Since the end of 2021, there has been a significant growth in UVA time deposits, which offer positive real returns to the depositor. The balance of this type of private sector deposits increased 36.4% in real terms in the first four months of the year, thus reaching a level similar to that observed in mid-2021, and gaining share in total time deposits in pesos. In particular, those instruments with early cancellation64 —representing 39% of the total— verified a higher relative growth: an increase of almost 53% in real terms between December 2021 and April of this year (72.4% real y.a.). The balance of placements in traditional UVAs – 61% of the total65 – accumulated an increase of 27.6% in the last four months (14.7% real y.a.).

The performance of total UVA time deposits was driven by individuals: they represent almost 72% of these deposits and explain 83% of the growth in the last four months (see Graph R.9.1)66. Within the segment of individuals, this type of placements received by public financial institutions presented the greatest relative dynamism in recent months, followed by foreign private financial institutions. In the case of legal entities, UVA deposits from foreign private entities verified the largest relative increase since the end of 2021.

Figure R.9.1 |Estimation of the balance of private sector UVA time deposits by holder

In real terms*

As a result of the outstanding growth, UVA time deposits, considering traditional and pre-cancellable deposits, accounted for about 6.4% of the total balance of time deposits in pesos in the private sector as of April, increasing 1.5 p.p. in year-on-year terms. This increase in weighting was widespread among financial institutions (see Figure R.9.2).

Figure R.9.2 |Time deposits in UVA as % of time deposits in pesos–Distribution among financial institutions

Private sector

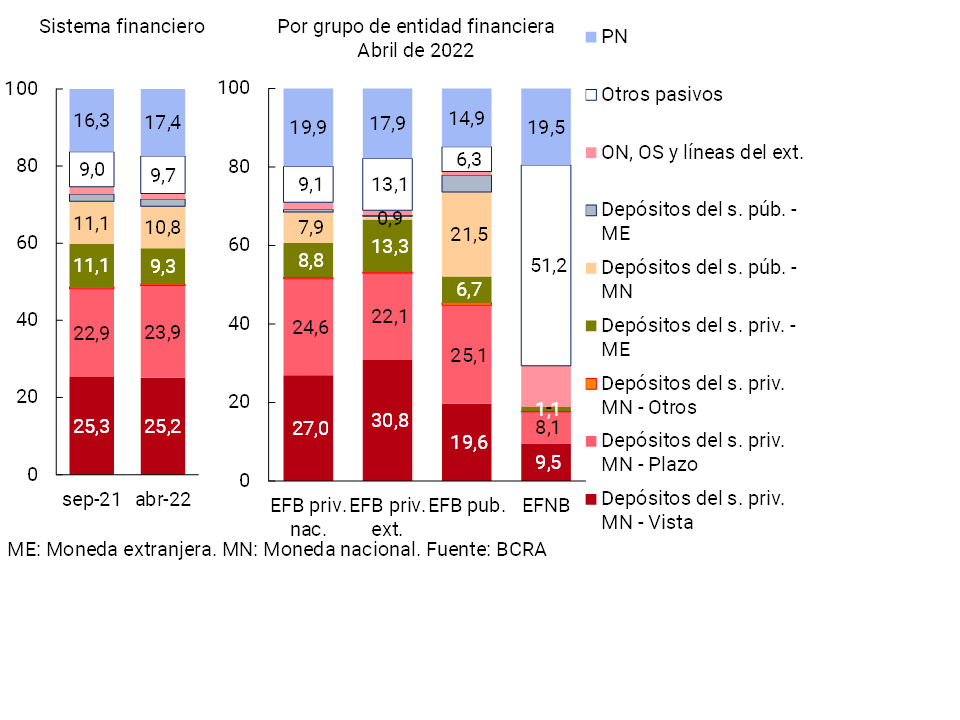

Private sector deposits in national currency continued to represent most of the funding (liabilities and net worth) of the financial system, reaching 49.5% of the total. This level was slightly higher than that evidenced in the last IEF, a dynamic driven by time deposits (23.9% of funding, +1 p.p. compared to September 2021, see Chart 19). The net worth of the financial system totaled 17.4% of total funding as of April, 1.1 p.p. above what was observed in the last edition of the IEF. On the other hand, compared to the end of September 2021, the foreign currency deposits of households and companies reduced their relative weight in total funding by 1.9 p.p., to 9.3% at the aggregate level.

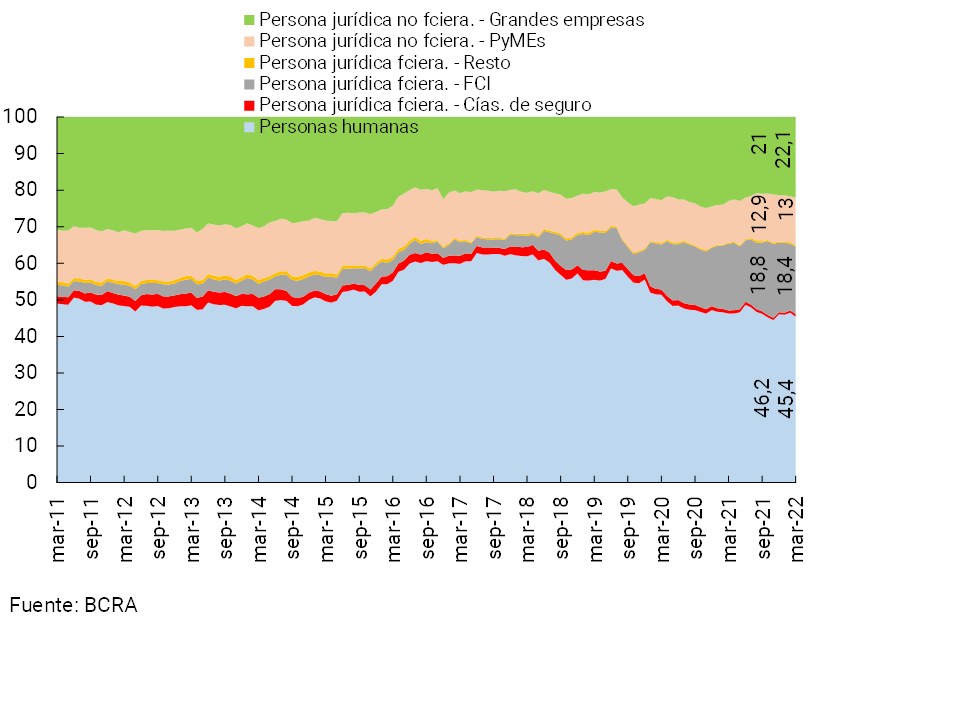

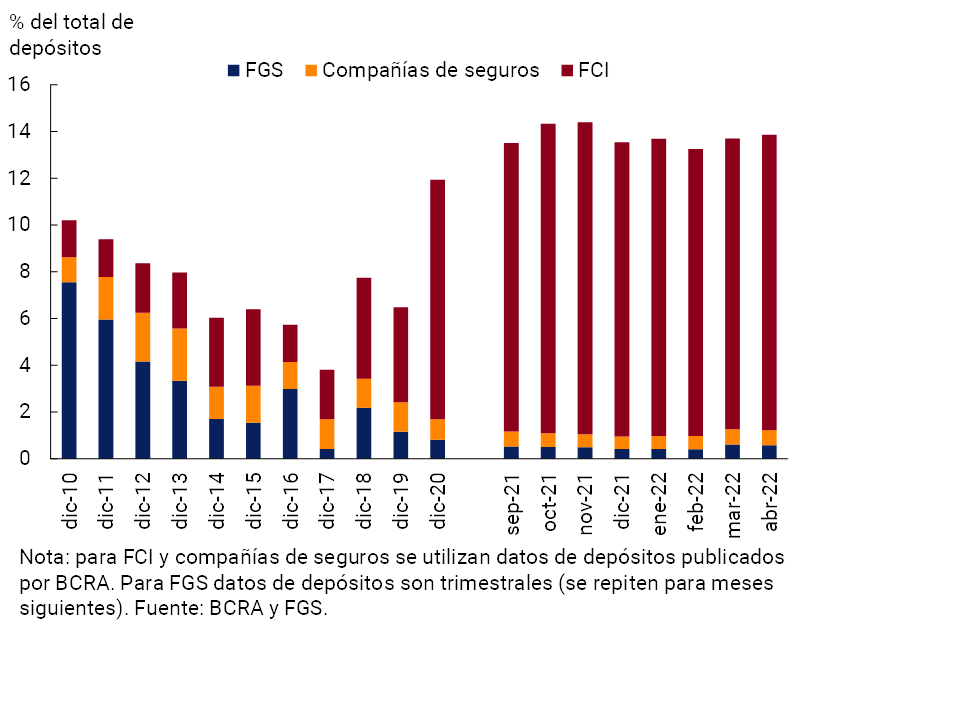

In terms of distinguishing potential changes in the exposure assumed by institutions to liquidity risk, it is relevant to monitor certain characteristics of aggregate bank funding, such as the profile of depositors as well as the relative maturity and degree of concentration of the main liabilities.