Financial Stability

Financial Stability Report

First half

2021

Half-yearly report presenting recent developments and prospects for financial stability.

Table of Contents

Chapters

- Executive summary

- 1. International and local context

- 2. Main strengths of the financial system in the face of the risks faced

- 3. Sources of vulnerability and specific resilience factors of the financial system

- 4. Other topics of stability of the financial system

- 5. Main macroprudential measures

Sections

- Section 1 / Global transition to new benchmark interest rates

- Section 2 / Guidelines for entities aimed at strengthening the cyber resilience of the financial system

- Section 3 / Risks faced by the financial system linked to climate change

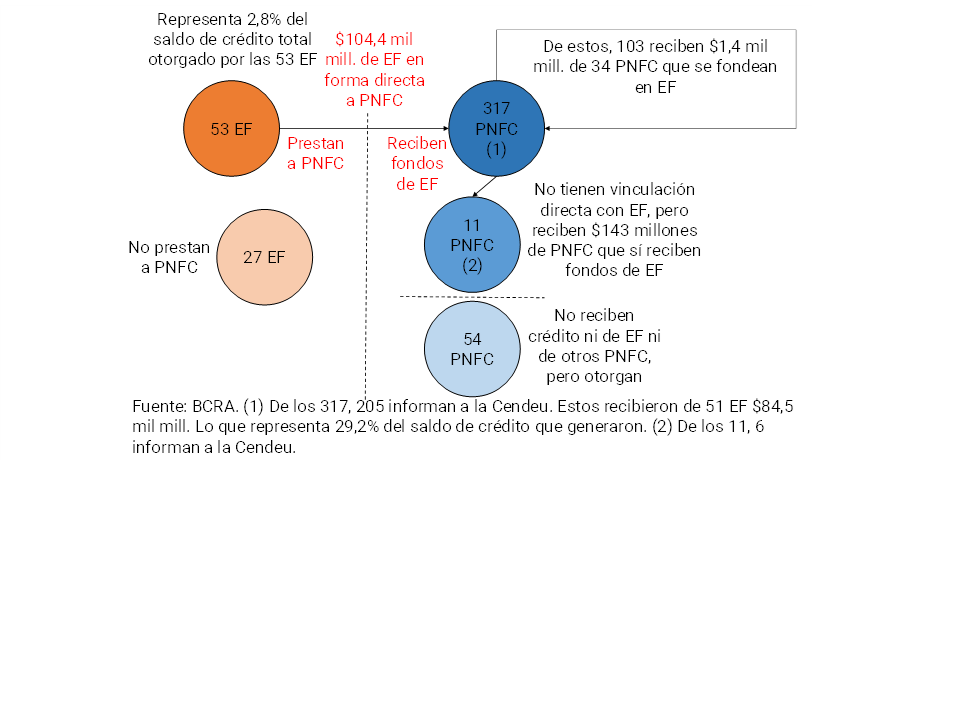

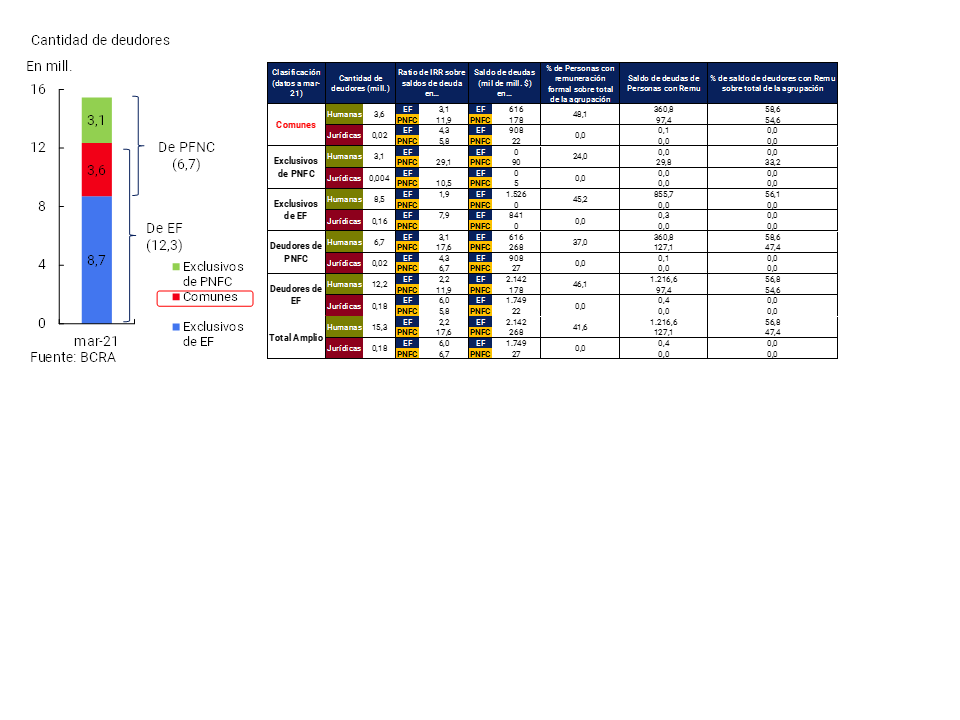

- Section 4 / Certain channels of interconnection between financial institutions and non-financial credit providers

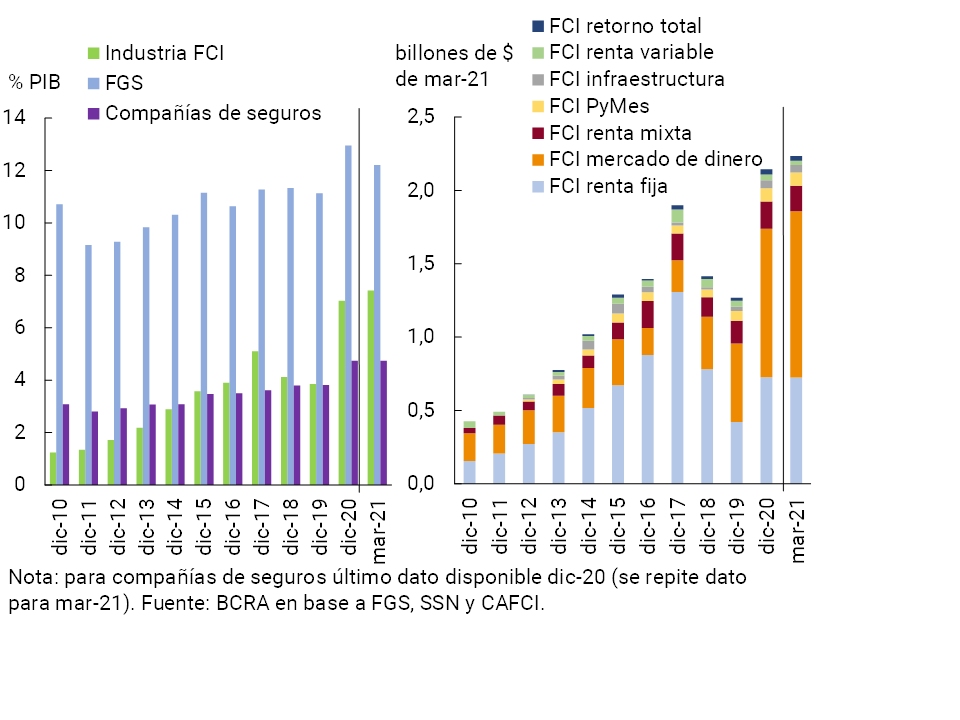

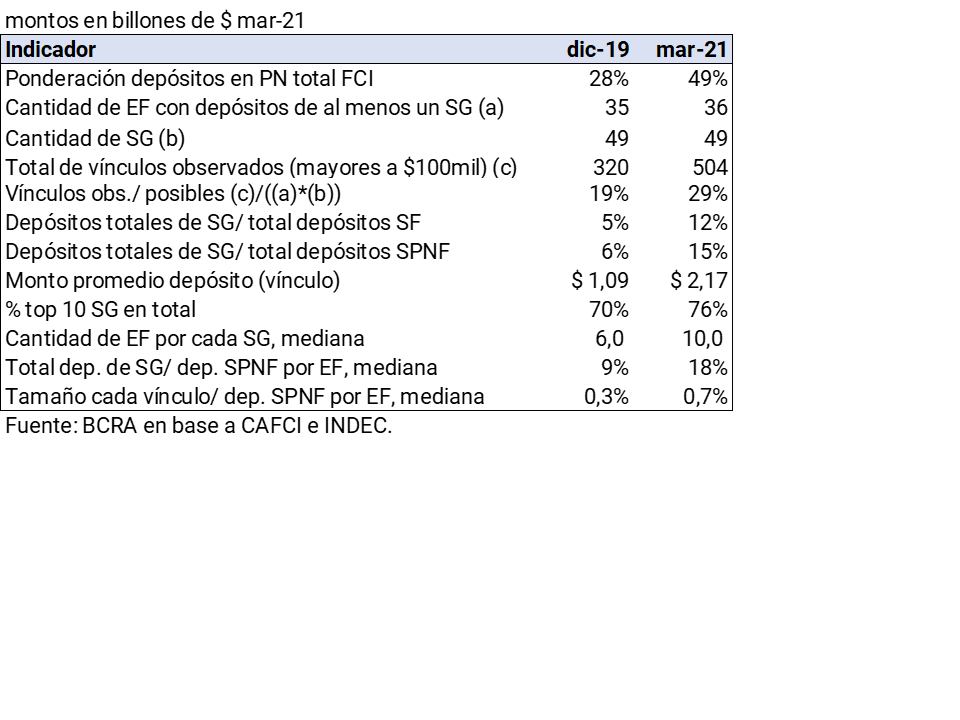

- Section 5 / Evolution of the Mutual Fund (FCI) industry and interconnection with the financial system

- Glossary of abbreviations and acronyms

Inquiries: analisis.financiero@bcra.gob.ar

About the use of inclusive language in this publication

The use of language that does not discriminate and that makes all gender identities visible is an institutional commitment of the Central Bank of the Argentine Republic. This publication recognizes the influence of language on ideas, feelings, ways of thinking and evaluation schemes.

This document has sought to avoid sexist and binary language. However, for ease of reading, resources such as “@” or “x” are not included.

Summary

Since the publication of the previous edition of the IEF (December 2020), the financial system continued to perform its functions without experiencing episodes of stress, preserving a set of strength traits that distinguish it and generate protection against its main sources of vulnerability given its intrinsic exposures to risks. This occurred within the framework of the policy measures applied in the face of the COVID-19 shock, which helped to consolidate the economic recovery at the local level in a framework of financial stability.

As is the case worldwide, local economic prospects continue to be conditioned by the evolution of the pandemic. The focus continues to be on the health situation – which in recent months led to the reintroduction of certain restrictions on mobility, although less intensely than a year ago – to which is added the progress in the application of vaccines that has been showing favorable results in line with a greater number of doses recently received. The achievements achieved, for their part, made it possible to advance in the targeting of the policy measures implemented. In this context, through its prudential actions, the BCRA continued to accompany the process of normalization of the functioning of the economy, seeking to mitigate a potential systemic impact of the shock on the private sector. Thus, the axes of the prudential policy implemented in the first part of 2020 were sustained, mainly aimed at: i. boosting credit to the private sector; ii. alleviating the financial situation of the private sector; iii. to promote bank savings in pesos in installments; iv. to maintain the slack in terms of solvency that the entities have; and V. Maintain and improve exchange regulations, preventing transitory imbalances between supply and demand from affecting the position of international reserves.

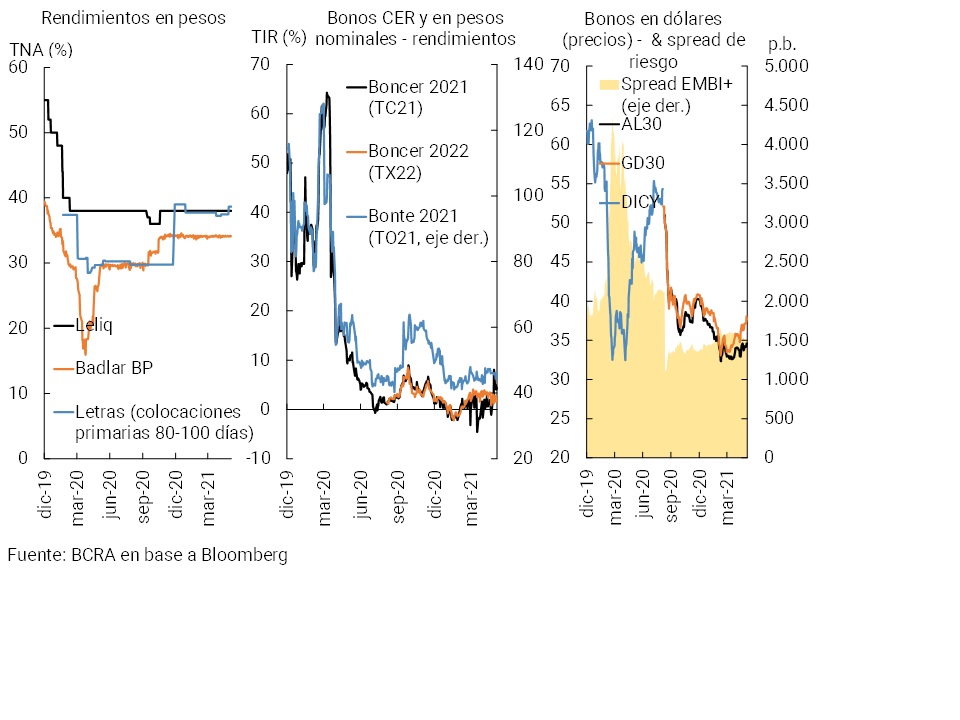

In the financial markets, on the other hand, mixed changes were observed in recent months, highlighting the lower exchange rate volatility, with accumulation of reserves by the BCRA. Also noteworthy is the progressive reconstruction of the domestic debt markets, a situation that allowed the Treasury to place debt above maturities, while the private sector evidenced a growth in real terms in its financing through the market.

For perspective, the situation remains challenging, given the presence of various potential risks in the near term. On the one hand, the external context continues to present a set of factors of uncertainty and vulnerabilities. With respect to the former, considerations prevail regarding the evolution of the pandemic and expectations regarding the effectiveness and sustainability of stimulus policies in developed countries. In terms of the sources of vulnerability, there are signs of over-appreciation in different market segments, growth in investment fund activity with pro-cyclical effects on the global financial cycle and increased leverage that raises doubts about debt sustainability, among others. In this context, a possible deterioration in the outlook and an increase in market volatility cannot be ruled out in the coming months. At the local level, expectations continue to be conditioned by the health situation, to which are added factors such as the open negotiation with international organizations (IMF, Paris Club) and the election process that will take place this year, among other factors. On the other hand, in view of an increase in the weighting of the operational risk factor related to the increase in teleworking and the greater use of digital channels to carry out transactions (as is the case globally), prevention and awareness actions are being developed focused on its mitigation, in addition to the regulatory framework and supervisory actions that the BCRA has in this area. While the aforementioned risk factors could have some impact on the financial system, an adequate degree of resilience in the sector is expected to continue to prevail, as observed so far.

Traditional financial intermediation with a low degree of sophistication and a high transactional component continued to be the main activity of the sector. In a context of relatively low credit depth in the economy, the financial system maintained high liquidity, solvency, and forecasting coverage, both with respect to recent history and compared to other countries in the region. Within the framework of the prudential regulations in force, mismatches in the system’s balance sheet (both currencies and maturities) remained limited, as did equity exposure to the public sector. The degree of direct interconnection of the institutions with each other and with the main institutional investors remained at relatively low levels, showing a decreasing path in the first case and a gradual increase in the second (role of the CRFs).

The balance between the potential vulnerabilities of the financial system and its strength traits showed some improvement in the margin (lower intensity in some vulnerabilities, in a context of higher risk coverage ratios). Compared to the previous IEF, there are some positive signs in terms of credit risk faced at the systemic level. During this period, there was a slight drop in the exposure of all institutions to the private sector, accompanied by signs of an improvement in the payment capacity of debtors. In this sense, within the framework of the actions implemented by the BCRA in conjunction with the PEN to temper the adverse effects of the pandemic context, since March 2020 both families and companies have benefited from a set of financial relief initiatives that gradually began to focus from the second quarter of this year. These contributed to limiting the deterioration of the financial situation of the private sector, avoiding a consequent adverse impact on the solvency of the aggregate of local financial institutions. Despite this improvement in the margin, for the rest of 2021 situations of tension in the payment capacity of debtors cannot be ruled out as long as any of the risk factors raised materialise – especially those concerning the level of economic activity – with this potential source of systemic vulnerability remaining the most important in relative terms.

A possible greater weakness in the financial intermediation process in the coming months constitutes another potential source of vulnerability for the system. If this scenario materializes, its sources of income could be affected and, eventually, its solvency – although starting from high levels. In this context, it should be mentioned that the system maintained positive levels of profitability in real terms, although decreasing. Over the next few months, the development of financial intermediation will be conditioned by the performance of economic activity, the latter influenced by developments regarding the second wave of COVID infections, public policies to address it and the vaccination process of the population.

A final relevant source of potential vulnerability for the financial system originates in the dynamics and composition of its funding sources. The real balance of private sector deposits in pesos decreased in real terms compared to the previous IEF. This performance occurred in the context of a lower monetary issuance by the BCRA based on the targeting of PEN assistance programs, the moderation of the process of multiplication of money given the aforementioned dynamics of credit and inflation levels above those of the previous semester. Beyond this performance at the margin, the total balance of private sector deposits in pesos accumulated a real year-on-year increase, highlighting the marked growth of the time deposit segment, which also increases so far in 2021. Faced with this potential source of vulnerability, the coverage of the financial system with liquidity margins remained high. Looking ahead to the short and medium term, in the event of a hypothetical scenario of greater volatility in the financial markets or a less dynamic than expected recovery in economic activity, they could have a certain impact on the demand for deposits (or their composition), with possible implications for the management of assets and liabilities in the financial system.

Going forward, the framework of uncertainty in terms of the development of the pandemic scenario – tempered by the recent acceleration in the vaccination process – continues to represent a challenge for the proper development of the economy in general and the financial system in particular. In a context in which the financial system has been showing a significant degree of resilience, the BCRA will continue its monitoring and evaluation of this scenario – in conjunction with the National Executive Branch – and, if necessary, will make use of the available tools in order to promote local conditions of financial stability.

1. International and local context

The international economic and financial scenario continues to be fundamentally conditioned by the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic, although significant progress has been made with respect to the situation observed a year ago. After the publication of the last IEF at the end of 2020, the focus shifted to the second wave of infections, the appearance of new strains and the pace observed in vaccination campaigns globally. Although there is a recovery in the level of activity on a global scale (accompanied by an improvement in commodity prices)1, its pace is heterogeneous and uncertain. There is still significant uncertainty about the economic outlook, in turn linked to the continuity and effectiveness of the stimulus measures implemented in the different countries.

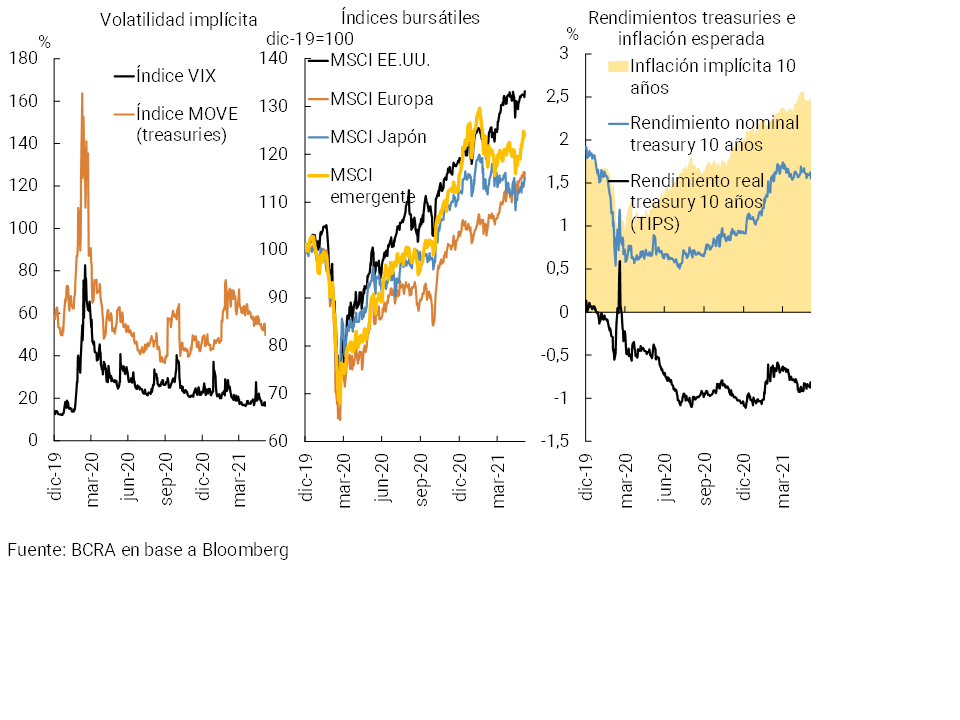

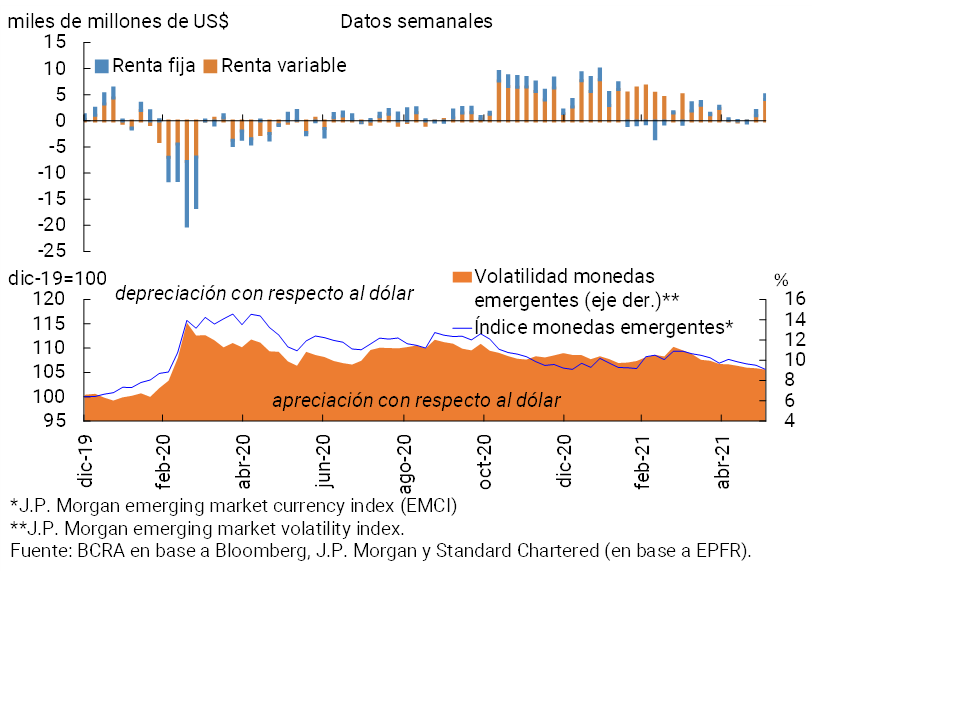

International financial markets have shown a favorable behavior so far this year (see Chart 1). However, due to the effect of the duration of the pandemic and the maintenance of a context of low interest rates in international markets, this positive trend is accompanied by the deepening of a series of vulnerabilities that have been commented on in recent editions of the IEFs. The existence of signs of over-appreciation in different markets (such as the stock markets of certain countries) is highlighted, with a certain disconnection between the prices of financial assets and the performance of the global economy. This generates the possibility of sudden corrections in prices due to changes in the perception of risk (such as the increase in volatility in the US stock market at the beginning of the year, an episode that finally had limited effects)2. On the other hand, with economic recovery and rising inflation expectations in certain developed economies, in a post-pandemic scenario, the markets’ attention would shift to the process of normalizing monetary policy and its impact on international interest rates. An indication of this already occurred in February and March, through the rise in the yields of 10-year US Treasury instruments3. More recently, at the Federal Reserve’s mid-June meeting, FOMC members’ forecasts showed for the first time a start of policy rate hikes (for the median) in 2023. A shift in expectations towards a faster-than-expected rise in interest rates in developed economies could have negative effects globally, in a context marked by over-appreciated assets, increased global leverage (and greater possibilities of rating downgrades or defaults) and increased non-bank financial intermediation. Although so far this year there have been inflows to investment funds specializing in emerging markets4 (see Chart 2), at the onset of the COVID-19 shock in 2020, they showed a strongly pro-cyclical behavior in a scenario of a run on liquidity that keeps the financial markets on alert —in particular equity funds specializing exclusively in LATAM that have exhibited net outflows since then—5

Since the last publication of the IEF, the process of economic and employment recovery in Argentina continued to consolidate, although with heterogeneity between sectors. This was a function of the evolution of the epidemiological situation6 and the battery of policies applied in the face of the COVID-19 shock (including unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimuli and, more recently, progress in vaccination). The improvements have allowed progress to be made in a greater focus of policies on critical sectors of the economy; in this regard, it is worth mentioning the launch of the Productive Recovery Program II by the State at the end of last year, aimed at sustaining employment levels in the productive sectors that are still facing economic difficulties. This initiative was supported by the BCRA through the maintenance of financial relief measures for the segment of firms eligible for this Program. Although local growth expectations for 2021 have been improving at the margin, as in international terms, sources of uncertainty persist linked in large part to the evolution of the pandemic itself, including the evolution of cases, changes in health measures and progress in the vaccination process. among other factors. Added to this is the transition implied by the policies applied to address the macroeconomic imbalances that existed prior to the pandemic, with advances in the fiscal, external, and monetary situation7. In this regard, the BCRA continues to contribute to the normalization of the functioning of the economy, in coordination with the fiscal strategy of the National Government, in order to lay the macroeconomic foundations for a path of economic development with social equity8. As will be seen in the next sections of this Report, it is expected that in the face of this local context the financial system will continue to show an adequate degree of resilience, in line with what has been observed so far.

So far this year, the different variables linked to local financial markets had a mixed behavior. The lower volatility in the foreign exchange market stands out, after the tensions observed in the second half of 2020, which led to the application of a series of measures to achieve better currency management and prevent temporary imbalances. Thus, so far this year the BCRA managed to maintain an increasing trend in the balance of international reserves. Despite this, and while negotiations with the IMF and the Paris Club remain open, the prices of public securities in dollars have fallen since the publication of the last IEF, despite the fact that in May they showed some recovery in the margin (see Graph 3). On the other hand, in the local markets, the prices of public securities in pesos have accumulated improvements so far this year in their different segments, in a context in which the Treasury continued to renew the maturities of local debt with amounts awarded above the needs of each month, through different types of instruments (highlighting the greater weighting of those with CER adjustment, especially for longer terms). In order to continue normalizing and seeking greater liquidity in the public securities market (thus promoting the capital market in local currency), in May the BCRA determined that financial institutions will have the option of integrating the portion of their reserve requirements that they currently hold in the form of BCRA Liquidity Bills (Leliq) in Treasury bonds. 9

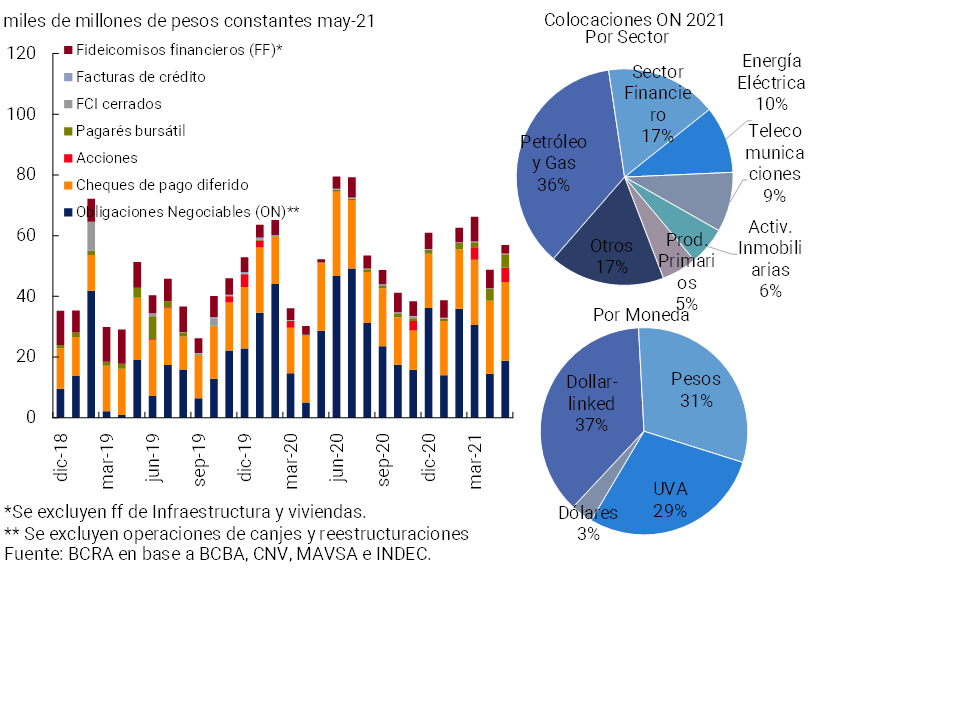

Placements of private sector instruments in the local capital market10 increased 10% in real terms year-on-year (January-May period, see Chart 4), while the cost of placement did not show major changes with respect to what was observed at the time of publication of the last IEF. By instrument, there was less dynamism for negotiable obligations (ON), which was offset by higher transactions of deferred payment checks (with an increasing weighting of E-CHEQs) and an improvement in the operations of stock market promissory notes and financial trusts. Among ON’s placements, those in areas such as oil and gas, the financial sector, electric power and telecommunications continued to stand out. In terms of placement currency, for the ON the weighting of operations in pesos and dollar-linked (with an average term of around 13 and 35 months, respectively), while those in UVA (average terms close to 43 months) gained ground. In line with the restructuring operations carried out by the public sector (national and provincial11), and following the guidelines established by the BCRA regulations (Com. “A” 7106 and amendments) with the aim of avoiding temporary imbalances in the foreign exchange market and prudently managing international reserves, foreign currency exchange operations continued to be carried out12. So far this year, operations in the oil and gas sector (the one with the highest weighting in the current balance of ONs) stand out, after the transactions observed in 2020 in sectors such as electric power, banks, real estate activities and agribusiness.

2. Main strengths of the financial system in the face of the risks faced

So far in 2021, the aggregate financial system continued to carry out its functions without experiencing situations of tension, maintaining high coverage against the intrinsic risks assumed. The operational context through which the financial system went through showed a process of recovery of economic activity evidenced until the beginning of the year, largely favored by the stimulus measures of the National Government in conjunction with the BCRA, as well as by the start of vaccination of the population against COVID 19. This recovery scenario was subsequently tempered, mainly as a result of the worsening of the health situation from the end of the first quarter. 13

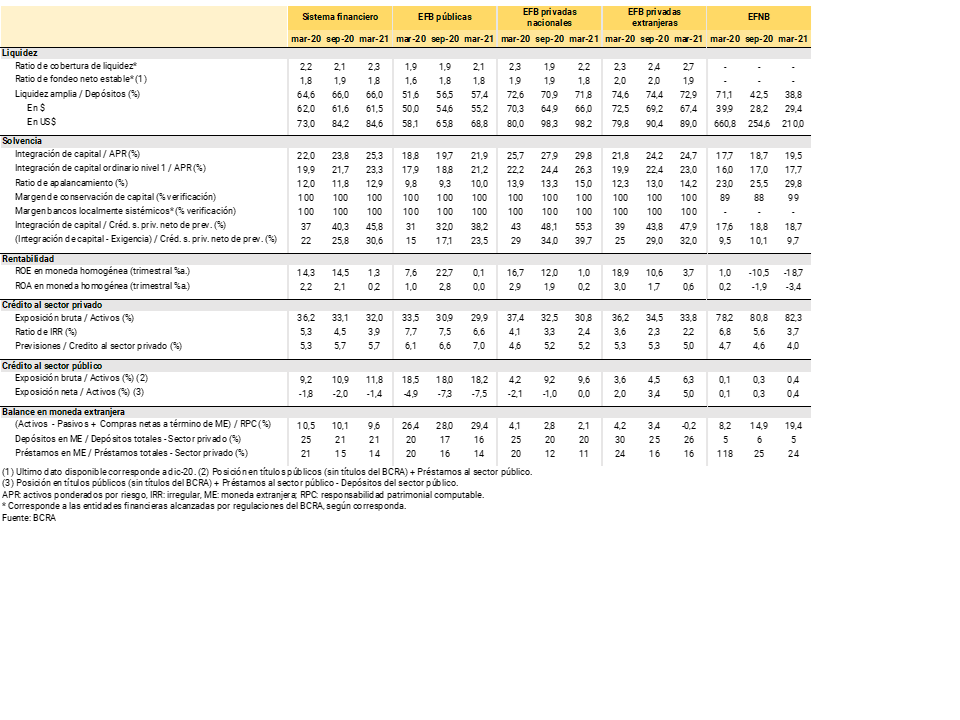

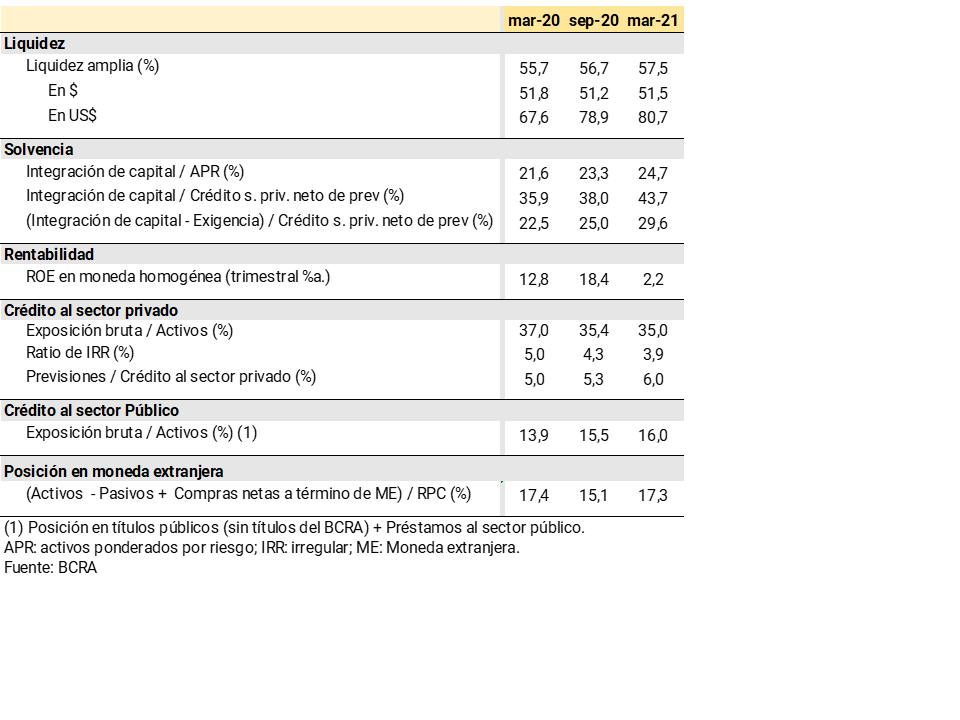

Similar to what was observed in the last publication of the IEF at the end of 2020, the set of financial institutions preserved high margins of liquidity, solvency and forecasting (see Table 1). The sector continues to develop traditional financial intermediation operations (not very complex), with a predominantly transactional bias, maintaining a low direct interconnection between institutions and a reduced depth of total credit in the economy. The equity mismatches (of currencies and maturities) assumed by the financial system as a whole remained at limited values, as did the equity exposure to the public sector, in line with the prudential regulations in force. It should be remembered that the activity of the sector was carried out within a scheme of regulation and supervision that is in line with the best practices recommended by international standards. Below are the main strengths of the sector in the face of the risks faced, which will be addressed in greater detail in the following sections.

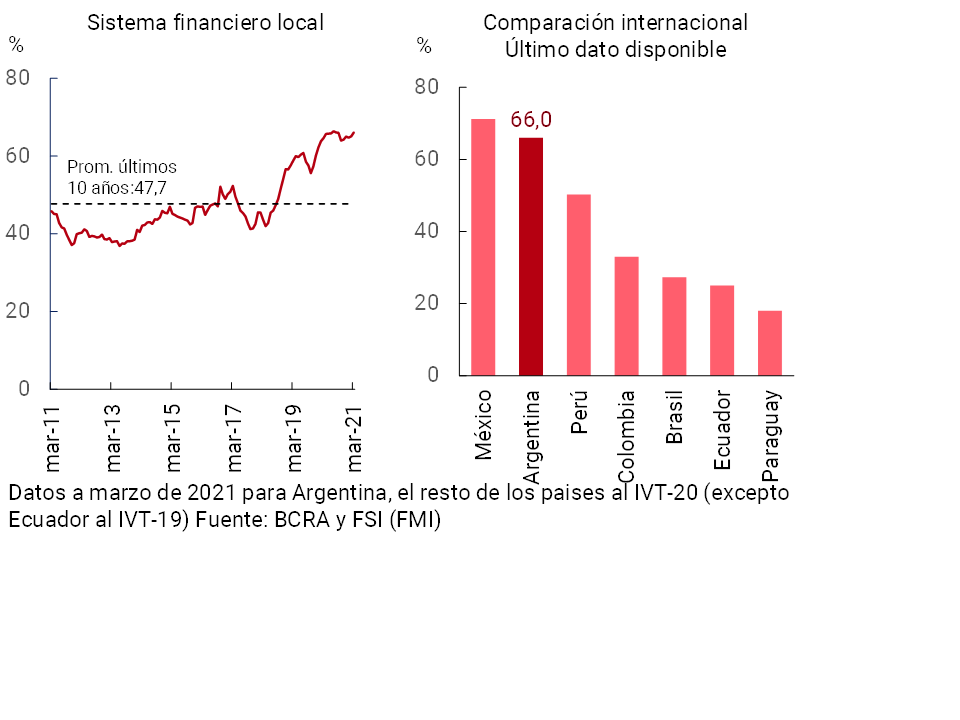

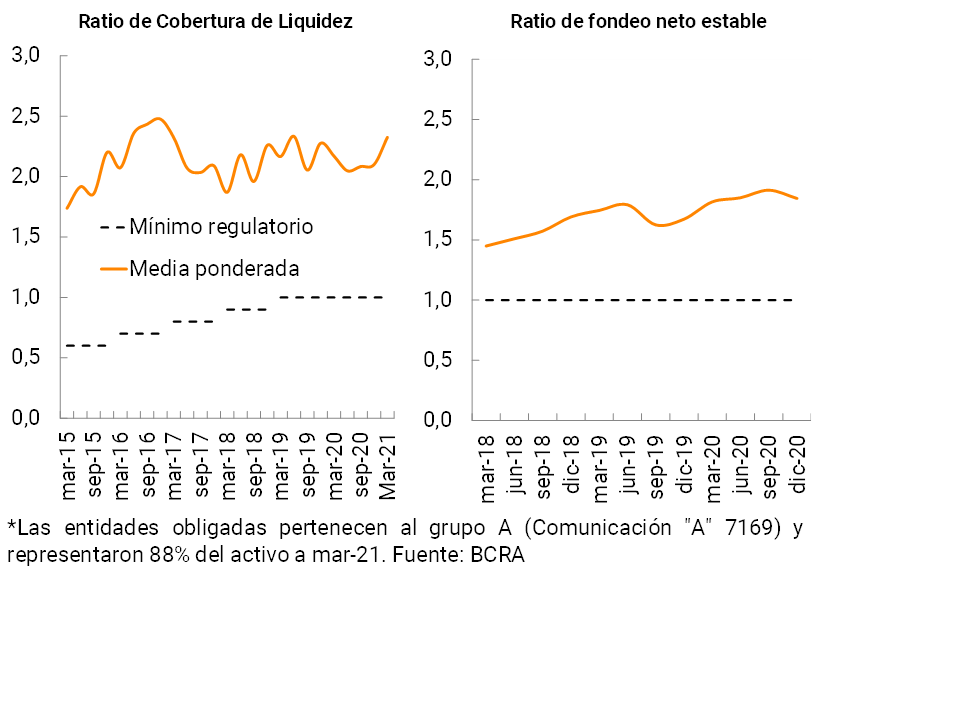

i. High levels of liquidity of all financial institutions. Since the last publication of the IEF, the financial system as a whole continued to preserve high liquidity margins. At the end of the first quarter of 2021, thesector’s broad sense liquidity 14 stood at 66% of total deposits, remaining without significant changes with respect to the previous edition of the IEF and slightly above the record for the first quarter of 2020. This level exceeds the average observed in the last 10 years and the values of other countries in the region (see Graph 5). Liquidity margins according to the currency of denomination of the liabilities also remain at relatively high levels and almost unchanged from what was observed six months ago (see Table 1).

In addition, the liquidity indicators that emerge from the internationally recommended standards remained high, above the minimum regulatory requirements at the local level and the values observed in other economies in the region. In particular, the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and the Stable Net Funding Ratio (NSFR)15 totaled 2.3 and 1.8 —for financial institutions belonging to group A, with information as of March 2021 and December 2020, respectively—, almost doubling the minimum levels required by regulation16.

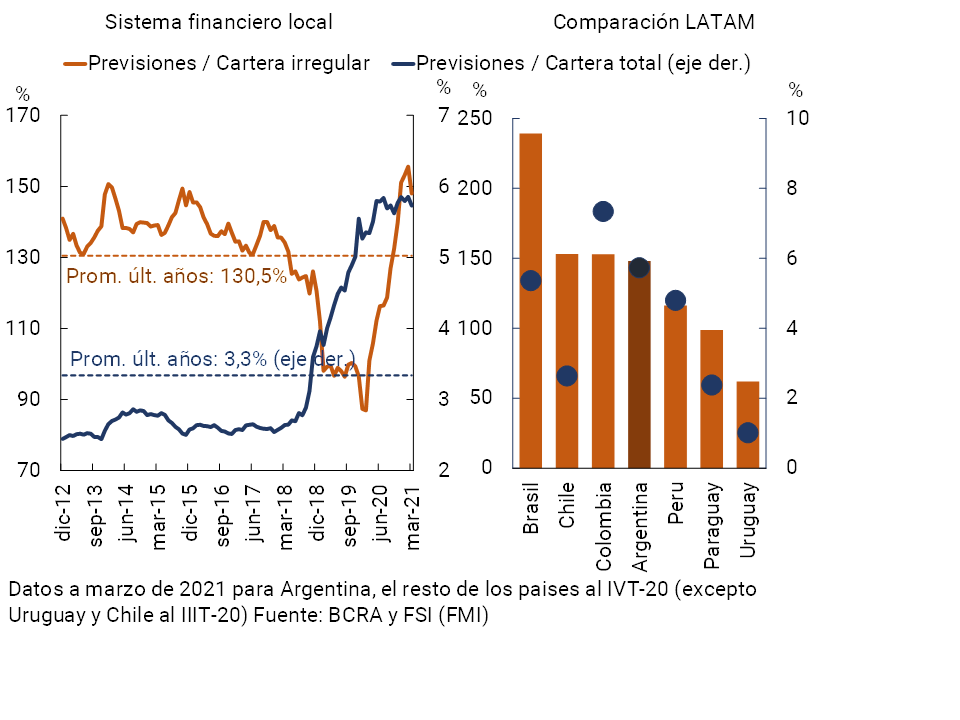

ii. High and growing levels of forecasting and solvency of the financial system. In the last six months, the aggregate of financial institutions continued to increase their forecasting, in a context of comfortable and growing levels of solvency. The financial system’s accounting forecasts totaled 148% of the balance of credit to the private sector in an irregular situation in March 2021, 21.1 p.p. above the level of September 2020. For its part, the level of forecasting in relation to total financing to the private sector (in a regular and irregular situation) reached 5.7%, remaining unchanged in magnitude with respect to last September and increasing slightly in year-on-year terms. The year-on-year increase in this ratio observed at the margin was driven by public and domestic private financial institutions, while it fell in foreign private institutions and EFNBs.

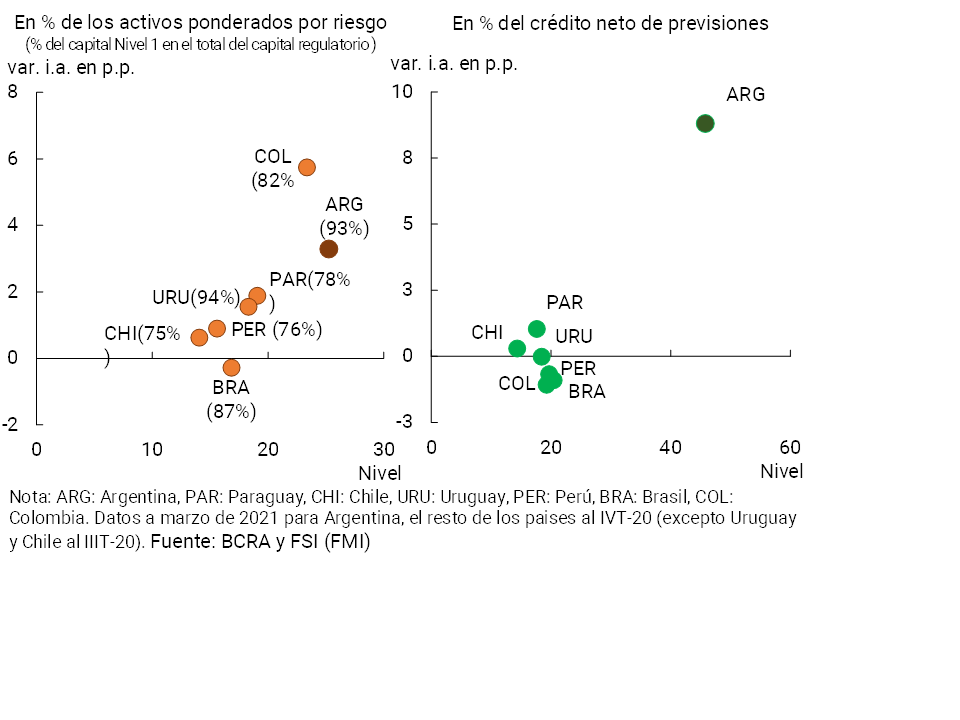

With regard to the sector’s solvency, in the last six months the aggregate financial system increased its level of capital integration (RPC) in terms of risk-weighted assets (RWA), totaling 25.3% in March (+1.5 p.p. compared to September 2020 and +3.3 p.p. y.o.y.). Tier 1 capital—the capital with the greatest capacity to face eventual losses—comprised almost 93% of the total capital integration. These levels are above those observed in other economies in the region (see Chart 6). The capital position (RPC net of regulatory requirements) of all entities totaled 202% of the requirement, growing almost 23 p.p. compared to last September. The sector also continued to preserve a high degree of compliance with additional regulatory capital margins. In addition, the leverage ratio of all financial institutions (in terms of the definition recommended by Basel) stood at 12.9% in March, far exceeding the minimum required of 3% and above the value of last September and March 2020. The maintenance of the sector’s high solvency indicators is taking place within the framework of the macroprudential policy that suspended the possibility of distributing dividends to banks in the face of the shock of the pandemic, the obtaining of positive results – decreasing in the margin – by all institutions and a certain slowdown in the performance of financial intermediation.

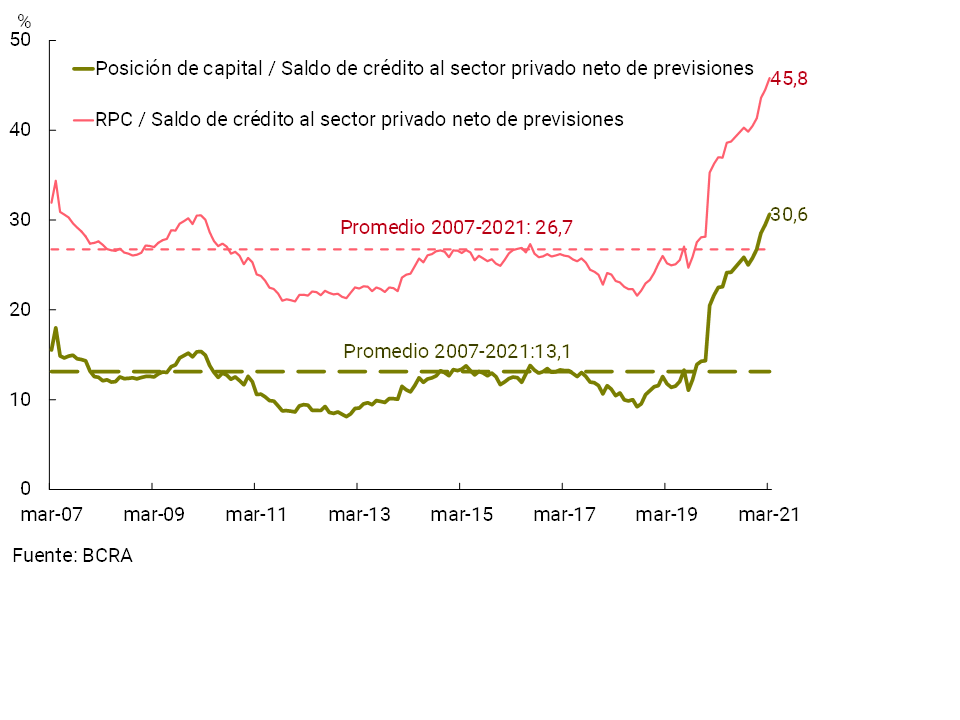

Graph 6 |Solvency and forecasting

indicators

Regulatory capital – Comparison of LATAM financial systems

One way to show the level of resilience of the financial system in the face of a possible materialization of credit risk from a historical and international perspective (isolating the effect of the transitional measures adopted by the BCRA to alleviate the financial burden of debtors in the pandemic scenario) is to study the relationship between regulatory capital and credit to the private sector net of forecasts. This ratio at the local level stood at 45.8% at the aggregate level in March, reaching the highest level in the last 15 years and surpassing the records of other economies in the region17. This value reflects the relatively low credit exposure and the high levels of capital and forecasting of the aggregate of the local financial system.

iii. Reduced exposure of the balance sheet to foreign currency items and limited mismatch of foreign currency. The weighting of foreign currency assets and liabilities on the balance sheet of the aggregate financial system continued to remain low from a historical perspective. The foreign currency assets of all financial institutions represented 19.2% of total assets in March, decreasing in a year-on-year comparison and 0.7 p.p. less than the average of the last 10 years. Liabilities in the same denomination totaled 17.4% of total funding (liabilities and equity), below the level observed a year ago and 1.2 p.p. less than the average of the last 10 years. When including the forward purchase and sale of foreign currency classified off-balance sheet, the difference between assets and liabilities in this denomination represented 9.6% of regulatory capital at the end of the first quarter of 2021, a level that remains well below the average of the last ten years within the framework of the regulatory limits that entities must verify.

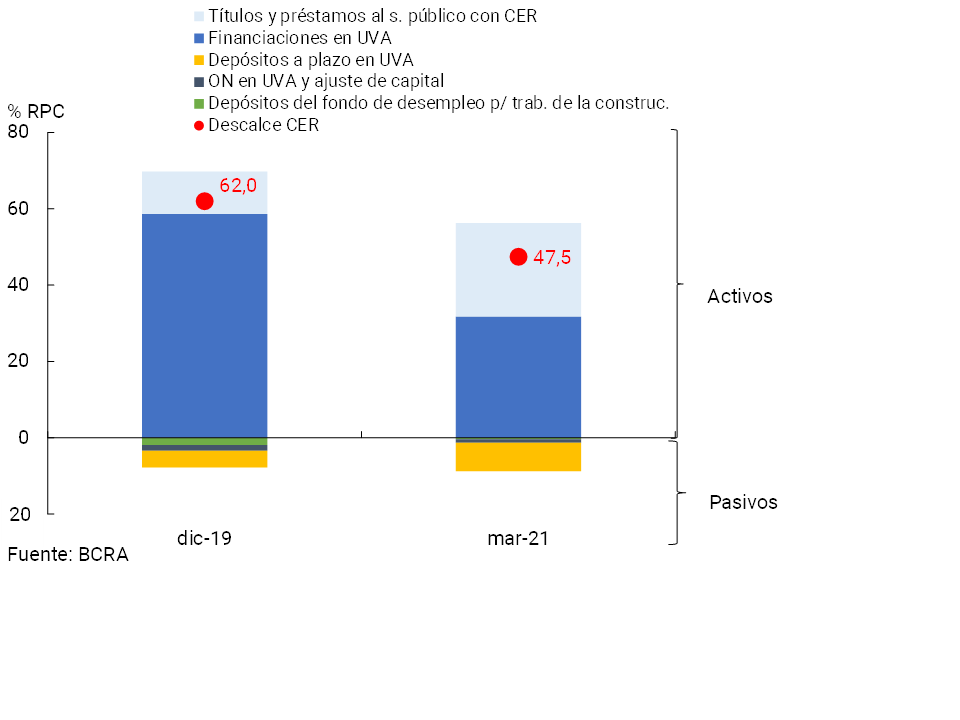

iv. Limited mismatch of items with CER adjustment in the balance sheets of the financial system. The aggregate of entities continued to show a moderate mismatch of items with CER adjustment in the last six months. Considering all assets and liabilities with capital adjustment by CER (including UVA adjustment), the aggregate financial system presented an active mismatch in this segment (greater assets than liabilities) estimated at 47.5% of the total regulatory capital integration at the beginning of 2021, falling almost 15 p.p. compared to the levels at the end of 2019 (see Chart 7).

v. Limited exposure of all financial institutions to the public sector. At the end of the first quarter of 2021, credit to the public sector represented 11.8% of total assets, increasing slightly in recent months. The limited exposure to the public sector occurs within the framework of current macroprudential regulations. The financial system at the aggregate level maintains a net debt position vis-à-vis the public sector (all levels), when considering deposits from this sector.

vi. Regulatory framework in line with international standards. The micro and macroprudential regulations in force on the Argentine financial system focus on the particularities of the local environment, without neglecting international best practices. In this context, the BCRA recently made progress in replacing references to the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) in local regulations, replacing them with references to the rates recommended at the international level (see Section 1). This came after warning entities last year about the legal, operational and financial risks associated with LIBOR operations that extend beyond the end of 2021, at which time its preparation and dissemination in the United Kingdom will no longer be mandatory.

The elements mentioned as strengths of the financial system would allow it to sustain its current degree of soundness, maintaining its resilience in the face of a context that continues to be challenging. In this sense, within the framework of the stability analysis, the main exogenous risk factors that the financial system could eventually face in the coming months are identified below:

i. Possible deterioration of the external context, given the existence of various fronts of uncertainty and vulnerabilities at the global level. The emergence of vaccines and the progress (albeit heterogeneous) in their application generates more favorable expectations worldwide compared to the last IEF, but in the short term the pandemic continues to be a source of uncertainty. Possible complications may have an impact on the level of global activity, international trade and commodity prices, with an effect on emerging countries, including Argentina. Likewise, different vulnerability factors have been accentuated in international financial markets, linked to the persistence of interest rates at historically low levels18. On the other hand, there are different types of factors that could eventually trigger a generalized contraction in risk appetite, including, for example, a change in expectations regarding the pandemic or stimulus policies in developed countries (premature withdrawal of support measures), or an increase in uncertainty due to a possible generalized increase in rating downgrades or defaults by governments and/or companies. A possible scenario of abrupt changes in prices and short-term capital flows cannot be ruled out for the short term, affecting the majority of emerging economies. In the medium term, a context of normalization (higher level) of interest rates in international markets could also imply a challenge for emerging markets. With respect to local transmission channels in the face of the different types of shocks mentioned, the one linked to the real channel would have a more direct impact on local economic activity and, in turn, on the repayment capacity of families and companies. While the one related to the financial channel could generate greater volatility on exchange rates and interest rates, affecting the environment in which financial intermediation is carried out.

ii. Possibility of a less dynamic recovery than expected or greater volatility in local financial markets. Although expectations point to an improvement in the level of activity in the remainder of 2021 and a gradual decrease in inflation rates, the situation is dynamic and changing, while elements of uncertainty remain. The evolution of the second wave of the pandemic (and the associated health measures) could condition economic activity to some extent, and may affect both the context in which financial intermediation is carried out and the ability of debtors to pay. On the other hand, it is not possible to rule out the possibility of a more volatile context in the local financial markets, depending on factors such as the negotiation processes opened with the IMF and the Paris Club, the dynamics of the election process scheduled for this year or seasonal issues in the foreign exchange market (with the incidence of variables such as the liquidation of the harvest and the international price of raw materials). Greater volatility in financial conditions – including interest rates and/or the exchange rate – could affect the context in which financial intermediation occurs.

iii. Operational risks, increased by the greater dependence on technological resources as a result of the pandemic. Based on social distancing measures, from 2020 onwards, teleworking became widespread and a greater use of digital channels for financial transactions was promoted, which implies greater exposure to operational risks, a situation verified at a global level (including, for example, those linked to fraud or cybersecurity attacks or disruption in the provision of intermediation and payment services). So far, no disruptive event has been verified in the local market. In this context, outreach and prevention efforts continue to be deepened. In this regard, the BCRA issued cybersecurity guidelines for response and recovery, in addition to carrying out an awareness campaign regarding fraud and having preventive regulations on the subject (see Section 2). While exposure to this risk increased with the deepening of restrictions as a preventive measure against the second wave of infections, it is expected to decrease in the coming months, to the extent that it can converge to a greater normalization of activity.

Another risk factor that is important to mention is the one linked to the economic and financial impact that climate change could have (related to the process of global warming), which is having an increasingly marked international recognition (see Section 3). In the medium term, in addition to the aforementioned challenge that emerging economies would face with respect to the dismantling of monetary stimulus policies by developed economies (in a context of greater public and private indebtedness), it is expected that in a post-pandemic world, changes will be seen in the business models of both the corporate sector in general (given the effects on consumption patterns and on production and marketing chains). and the financial sector in particular (e.g., regulatory changes), with an impact on both banks and non-bank financial intermediation.

The next section continues with the analysis of financial stability, analyzing the main sources of vulnerability identified for the local financial system, given its exposure in the balance sheet to the aforementioned risk factors. These vulnerabilities will be contrasted with the strengths of the financial system, to consider how it is in a position to deal with the eventual materialization of these risks.

3. Sources of vulnerability and specific resilience factors of the financial system

3.1 Credit risk to the private sector. Exposure, materialization and coverage

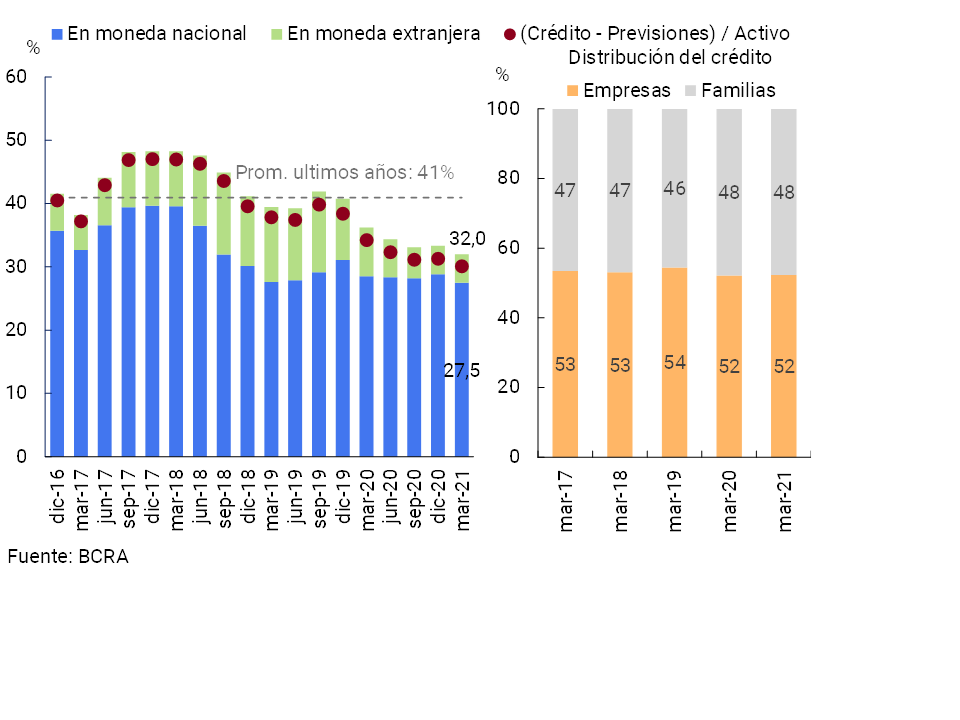

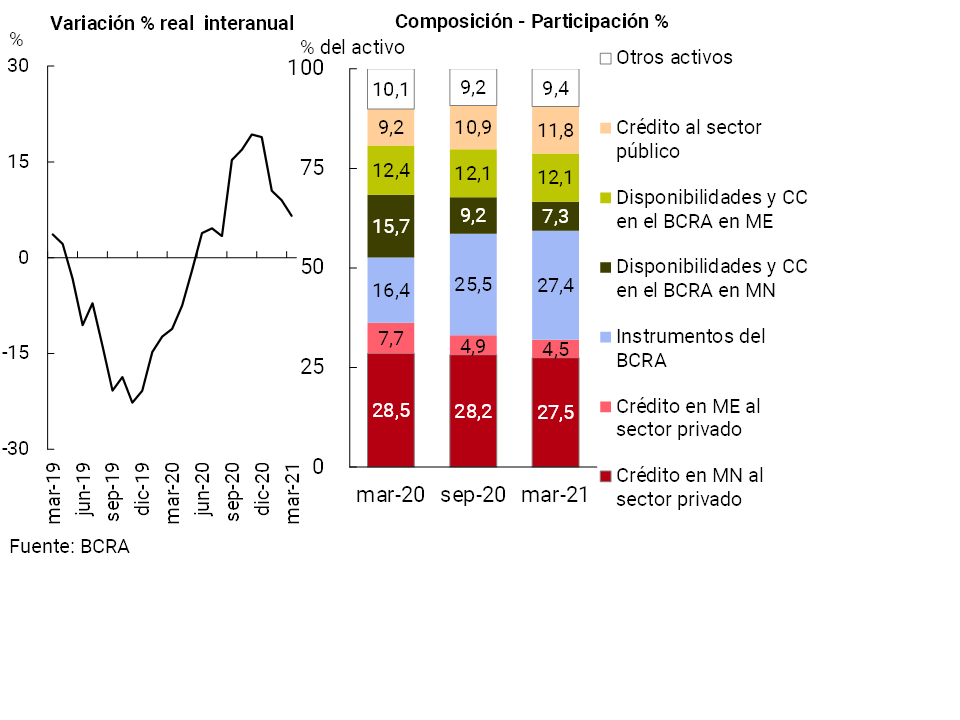

At the end of the first quarter of 2021, the financial system continued to have a low exposure to the private sector, lower than that recorded at the time of publication of the previous edition of the IEF. The credit balance to this sector stood at 32% of the assets of all financial institutions in March (27.5% for the segment in national currency), down 1.1 p.p. compared to the value of September 2020 (see Chart 8). Financing to the private sector net of forecasts in terms of the assets of the financial system also decreased in the period, totaling 30.1%.

Figure 8 | Gross exposure to the non-financial private sector

Financing to the private sector as a % of assets – Financial system

Within the framework of the actions implemented by the BCRA in conjunction with the PEN, aimed at mitigating the adverse effects on the private sector of the pandemic context, since March 2020 both families and companies have benefited from a set of financial relief measures. The measures sought to reduce potential episodes of financial stress to be faced by families and companies, and from the point of view of their debts with the financial system, the conditions of repayment were also facilitated, in order to limit the impact on the financial system, which also has low levels of exposure to the private sector. However, given the persistence of uncertainty factors associated with the pandemic and the need to reinforce confinement measures – with their consequent impact on the level of activity – situations of tension in the payment capacity of families and companies over the coming months cannot be ruled out, with potential spillover on the local financial system.

Until March 2021, a transitory modification was in force on the parameters for classifying debtors in the financial system, in addition to the possibility of transferring their unpaid installments at the end of the life of the loan, facing only the agreed compensatory interest. Regarding the parameters for the classification of debtors, the BCRA decided to establish a gradual transition schedule between April and May of this year, returning to the parameters existing prior to the pandemic as of June. At the same time, in order to mitigate the effect of the local situation derived from the second wave of the pandemic, while focusing efforts on those most affected, the BCRA recently allowed entities to incorporate the unpaid installments of assistance granted to employers reached by the Productive Recovery Program II —REPRO II— at the end of the life of the loan. considering only the accrual of compensatory interest.

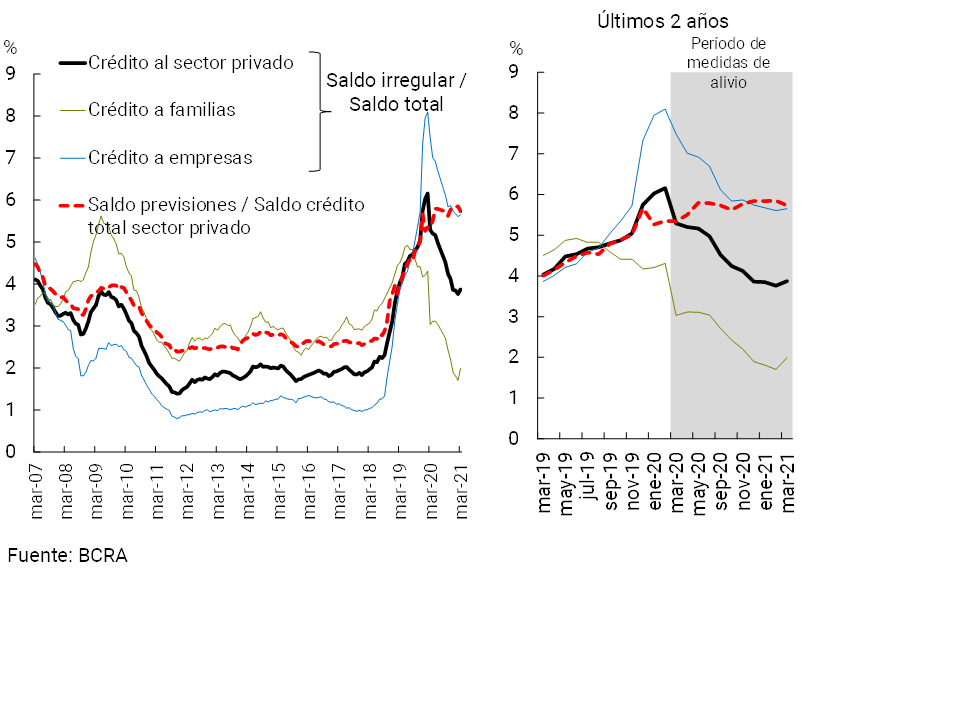

In this context, the non-performing loan ratio to the private sector stood at 3.9% in March 2021, reducing 0.6 p.p. compared to the value recorded in September 2020 (-1.4 p.p. y.o.y.) (see Graph 9), although growing slightly at the end of the first quarter of the year. Differentiating by credit segment, the indicator of delinquency of loans to households decreased 0.7 p.p. in the last 6 months to a total of 2% (-1 p.p. y.o.y.), mainly due to the performance of collateral and personal loans19. On the other hand, non-performing loans to companies stood at 5.6%, showing a fall of 0.5 p.p. compared to September 2020 (-1.8 p.p. y.o.y.). Within this sector, the irregularity of pledge and mortgage loans showed the largest relative drop. As mentioned in the last IEF, it should be noted that the level and variation of these indicators – commonly used to have a dimension of the materialisation of credit risk – must be interpreted within the framework of the aforementioned provisions on relief measures (see Box. Resilience of the financial system in the context of COVID-19: exposure and coverage to debt that is estimated to be in a relatively more vulnerable situation).

Box. Resilience of the financial system in the context of COVID-19: exposure and coverage to debt that is estimated to be in a relatively more vulnerable situation.

As detailed in the last two editions of the IEF, since the beginning of the pandemic, the BCRA in conjunction with the PEN began to implement financial relief measures to temper the effects of a significantly adverse context on companies and families. In particular, the parameters for classifying debtors in the financial system were modified (with convergence to pre-pandemic parameters as of next June), the transfer of unpaid installments at the end of the life of the credit was made possible (a tool that was in force until the end of the first quarter of this year) and the installments of mortgage and pledge loans that adjusted for UVA were frozen. among other measures20. Thus, the so-called irregularity ratio21 began to show some weakness in assessing the current evolution of the quality of the financial system’s loan portfolio. In this framework, and based on the information available, some complementary indicators are prepared and monitored on the degree of exposure of the financial system to financing granted to debtors who, under certain criteria, are considered to be in a situation of greater relative vulnerability at this juncture. Then, with this information, it is possible to generate additional estimates of the degree of resilience of the aggregate sector (relative impact on solvency) in the event of the materialization of credit risk.

In particular, here is presented the estimation of a complementary indicator called the Vulnerable Debtors Ratio, and for its construction the following additional criteria were used to characterize debtors with respect to their ability to repay: a) the activity to which they belong, b) whether they had the possibility (or not) of receiving subsidized credits within the framework of the Emergency Assistance Program for Work and Production (ATP), c) whether or not they used the relief measures promoted by the BCRA in conjunction with the National Executive Branch (whether these were debt refinancings, such as freezing mortgage and UVA loan installments), d) whether they observed a relatively high growth in their indebtedness with respect to the average variation in the income of their economic sector, and e) their eventual departure from the universe of formal jobs in the last year (in the case of individuals).

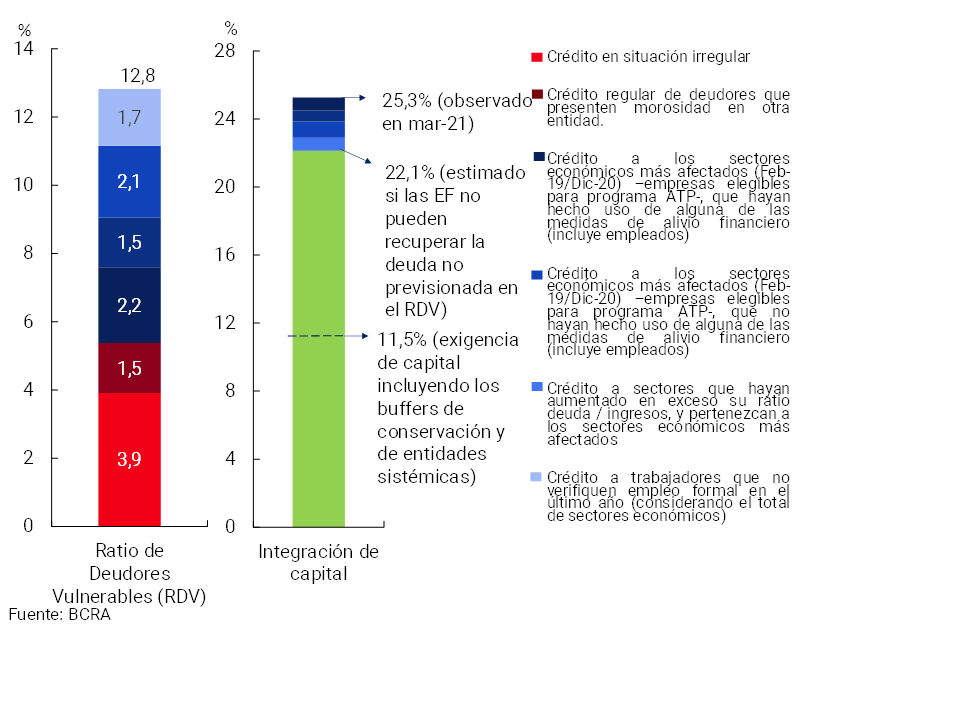

In this sense, the first part of the exercise consists of starting from the observed ratio of financing in an irregular situation and adding different credit blocks to the numerator according to the aforementioned categories of vulnerable debtors – who will not necessarily become debtors with effective problems in the repayment of their debts. We start from a level of irregularity of 3.9% at the end of the first quarter of the year for the entire financial system, which increases to 5.4% if we add the regular balance of debtors with some credit in an irregular situation (see left panel, Graph 10). When adding the balance of debtors eligible for the ATP program (and that of their employees, if any), belonging to economic activities that have performed relatively worse between February 2019 and December 2020, and that have taken some measure to relieve the financial system, the estimated debtor vulnerability ratio would reach 7.6%. If we do the same by also including ATP-eligible debtors who have not taken relief measures (and their employees), the ratio would rise to 9.1%. If we also incorporate those debtors whose debt increases much more than the average income of the economic sector – above the 90th percentile – of these activities with relatively more deteriorated performance (be it the sectoral GDP in the case of legal entities or the sectoral CVS for individuals), the aforementioned indicator reaches a level of 11.2%. Finally, if we add the debt of people who had formal remuneration on Mar-20 and stopped having it on Feb-21 for some reason, we reach a vulnerable debtor ratio of 12.8%. It should be noted that this percentage refers to credit to debtors who, due to the characteristics indicated, are estimated to be having a relatively lower capacity to repay, but that this would not necessarily translate into effective default on their obligations to meet their debt services.

As mentioned, once this set of debts has been calculated, which could potentially be in a situation of greater relative vulnerability, the degree of resilience of the system – given its current high levels of regulatory capital and forecasting – is analysed in the face of a possible scenario of tension. In this sense, if we assume a hypothetical exercise (extreme, with a low probability of occurrence) of non-payment of all the debt considered here (which does not constitute a projection), the integration of the system’s regulatory capital would be slightly reduced (see right panel, Graph 10), maintaining a significant capital gap with respect to the minimum regulatory requirement, thus configuring a situation of significant solidity of the financial system at the aggregate level.

After the peak of the first wave of COVID-19, around the end of 2020 onwards, as the level of economic activity and household income gradually recomposed (with some heterogeneity between economic sectors), the degree of use of the aforementioned financial relief measures began to moderate. In this framework, the BCRA promoted various programs already focused on the sectors most affected by the pandemic context. It is estimated that the scenario for the first quarter of 2021 would have presented itself with fewer relative difficulties for debtors compared to the second and third quarters of 2020, tempering to some extent the credit risk faced by the entities.

Although the last six months have seen a slight drop in the financial system’s exposure to the private sector, accompanied by certain indications of an improvement in the payment capacity of debtors, this potential source of vulnerability of the financial system is expected to remain the most important relatively (within the set of risk exposures in the financial system) for the rest of 2021. The evolution of this will depend on the possible degree of materialization of the risk factors mentioned in Section 2, especially on the possibility of a less dynamic economic recovery than expected.

3.1.1 Resilience elements and mitigating measures:

High levels of forecasts and regulatory capital in relation to credit exposure. In March, the accounting forecasts of all financial institutions totaled 148% of the irregular portfolio and 5.7% of the total balance of credit to the private sector, above the records of a year ago22. The year-on-year increase was mainly explained by the largest institutions (belonging to group A), in line with the requirements governing them to make forecasts based on expected loss models (within the framework of the adoption of the criteria included in International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). These levels are high compared to the records of the last 10 years and slightly above the average for the region (see Graph 11).

The level of resilience of financial institutions as a whole to credit risk can be illustrated, among other ways23, by the relationship between the regulatory capital position (regulatory capital – regulatory requirement) and credit to the private sector net of forecasts. This ratio stood at 30.6% at the aggregate level in March 2021 (45.8% when considering regulatory capital, rather than position), reaching the highest level in the last 15 years (see Chart 12) and surpassing the records of other economies in the region. This indicator reflects a first approximation (hypothetically, extremely) of how much the deterioration in the quality of the private sector credit portfolio (without recovery)24 would have to be in order to exhaust the excess capital of the financial system as a whole. The historically high levels of these indicators suggest a high degree of resilience of the aggregate financial system to an eventual materialization of credit risk. This result reflects the effects of limited exposure to the private sector and high relative levels of capital and forecasting.

Figure 12 | Regulatory capital (RPC) and capital position (RPC – Requirement), in terms of the balance of credit to the private sector net of forecasts.

Financial System

Credit origination standards have not changed significantly in recent years. According to recent surveys by the Credit Conditions Survey (ECC)25, since the end of 2020, participating financial institutions as a whole have not relaxed the credit standards associated with loans to companies (general level). On the side of loans to households, in the last survey a heterogeneous behavior was observed according to credit assistance: a moderate relaxation of the standards associated with other consumer loans, neutrality for pledges and mortgages, and a slight restriction for credit cards.

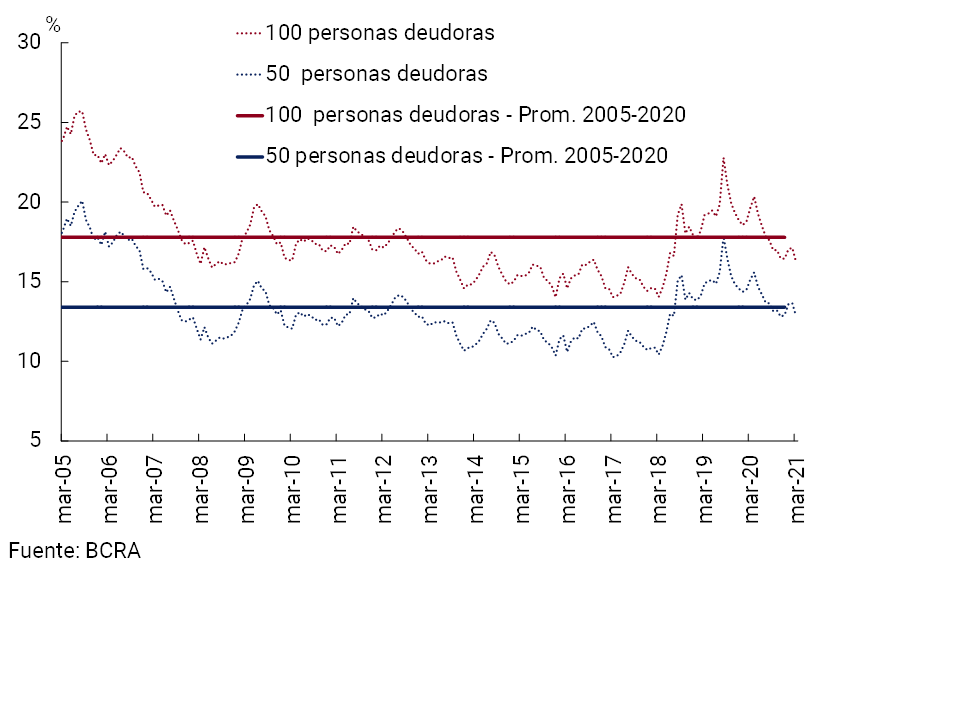

Moderate and decreasing concentration of private sector debtors in the financial system. Within the framework of the prudential regulation in force, the share of the main debtors (legal and human) in the total credit portfolio of all financial institutions remained limited at the beginning of 2021 (see Chart 13), showing a certain downward trend at the margin. In particular, the top 100 and 50 private sector debtors in the aggregate financial system accounted for 16.2% and 12.8% of the total credit balance at the end of the first quarter of the year, 3.4 p.p. and 2.3 p.p. below the levels of a year ago. To a certain extent, greater diversification of the debtors’ portfolio helps to temper the credit risk assumed.

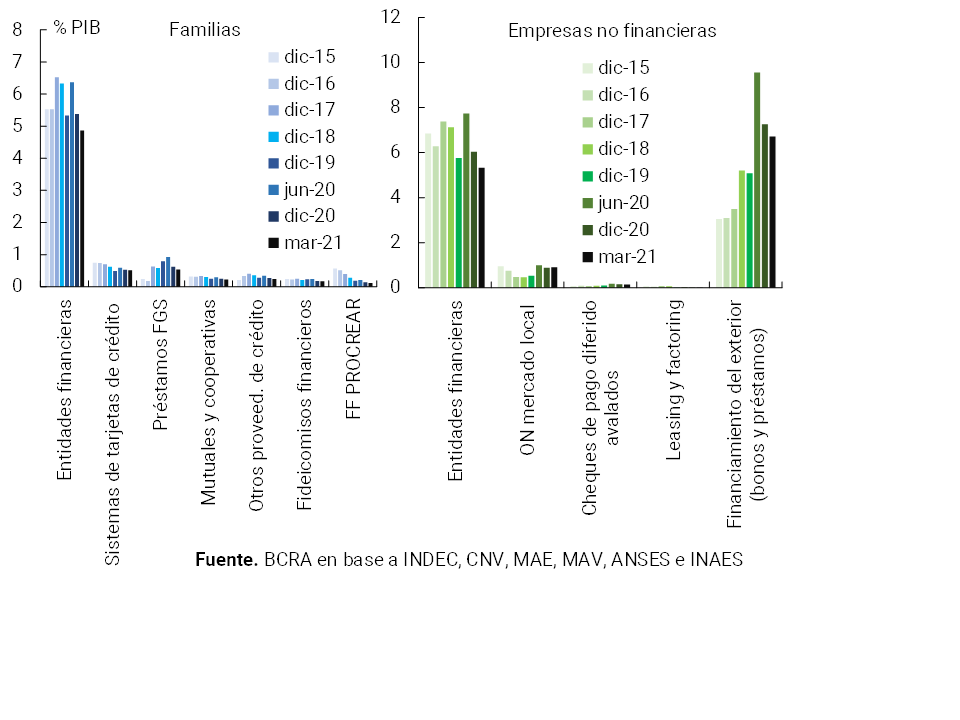

Figure 13 | Share of the total balance of credit to the private sector of the main debtors – Financial system

The balance of private debt fell in real terms and with respect to GDP in the first quarter, remaining at limited relative levels. As of March 2021, the estimated balance of financing in the broad sense was equivalent to 6.7% of GDP for households and 13.1% for companies (see Chart 14)26, levels that continue to be significantly limited, for example in an international comparison, particularly with respect to what has been observed for other emerging countries. These aggregate debt indicators show a decrease compared to the end of 2020, mainly explained by the recomposition of GDP, although debt balances fall in real terms. In the case of household debt, in the first quarter of 2021, both the loan balances of financial institutions, the main component of their debt, and the balances linked to non-bank financing fell in real terms – and at a similar rate27. In the case of companies (with debt mostly explained by two components, bank loans and foreign financing), all components fell in real terms in the quarter, except for the balance of bonds in the local market (due to the combined effect of net placements and restatement of balances in pesos). 28, 29 In the context of the evolution of financial stability conditions, the BCRA maintains periodic monitoring of the interconnection channels between the main credit providers in the economy (See Section 4).

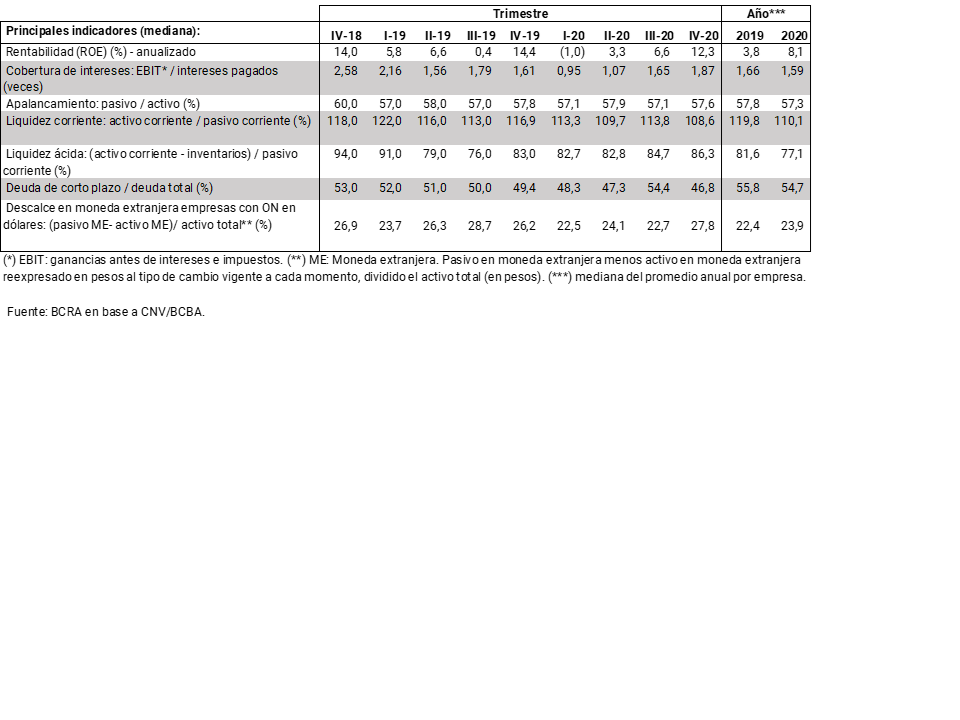

Box. Financial situation of publicly offered companies – 2020

The monitoring of the situation of the non-financial corporate sector based on analysis of companies with publicoffering30 shows for 2020 mixed changes in the main indicators compared to what was observed in 2019. It should be remembered that in 2019 there was already evidence of a certain negative trend depending on the local recessionary context prior to the initial impact of the COVID-19 shock and the measures adopted to mitigate its health effects. Taking into account the median (see Table 2), in 2020 the liquidity indicators and, to a lesser extent, the interest coverage with income indicators weakened, while profitability increased (measured by ROE) and leverage fell slightly31. Although during the first half of the year there was a generalized deterioration in the indicators, they later tended to recover, accompanying economic activity. It is noteworthy that, despite the deterioration in the indicators during the first half of 2020, there were relatively few cases of problems in meeting payments for services or bond capital, which represented a negligible portion of the outstanding note balance of non-financial companies (0.35% of the note balance at the end of 2019, prior to the initial impact of the COVID-19 shock)32.

The evolution of the main financial indicators resulted in a slight increase in the number of companies with public offerings in a relatively vulnerable position; defined here as those firms that show vulnerability in at least two of the three most relevant financial ratios (interest coverage, leverage, and acid liquidity)33. Based on this simple methodology, at the end of 2020 there were 19 companies in a relatively vulnerable situation: 3 more than a year ago. The indebtedness (financing of financial institutions and markets) of these companies represents 21% of the total indebtedness of companies with public offerings,34.10 p.p. more than what was observed at the end of 2019. In terms of the credit exposure of the financial system to companies in relatively more vulnerable situations, although it is increasing, it remains at relatively low levels: they went from 1% to 4% of total credit to companies from the end of 2019 to the end of 2020. With regard to the capital market, the bonds of relatively more vulnerable companies went from representing 8% of the total balance (end of 2019) to 14% (end of 2020). The maturities of dollar bonds in the most vulnerable position represent only 9% of the flows payable in dollars for the total non-financial sector bonds during the second half of 2021 and all of 202235.

Moderate burden of household and corporate debt services. It is estimated that the aggregate of the family sector continued to maintain a limited relationship between the financial services of its debt with the financial system and its income since the publication of the last edition of the IEF, with a certain increase in recent months. At the beginning of 2021, the burden of household debt services accounted for approximately 14.1% in terms of the wage bill, 0.5 p.p. above the level of September 2020. Within the framework of policies to stimulate credit to companies – mainly to MSMEs under favorable financial conditions – and low levels of aggregate indebtedness, it is estimated that the debt service burden of the business sector also remains at limited levels.

Reduced participation of financing in foreign currency in the aggregate of the financial system and limited mismatch of foreign currency of debtors. The balance of credit to the private sector in foreign currency represented only 14% of the total credit balance to this sector in March, reducing 0.7 p.p. compared to the September 2020 record and 7.2 p.p. in year-on-year terms. In other words, the exposure of the aggregate balance sheet of financial institutions to credit risk derived from possible exchange rate fluctuations remains relatively low. In addition, in accordance with the macroprudential regulations in force, the balance of credit in foreign currency is granted mainly to debtors whose income is in foreign currency – due to their export activity – or is positively related to the evolution of the exchange rate, reducing the possibility of credit risk situations arising from fluctuations in the latter.

Limited link between potentially vulnerable public offering companies and the financial system Although in 2020 the balance sheets of publicly offered companies showed an impact due to the Covid-19 shock (which affected the number of companies in potentially vulnerable situations), the link between potentially vulnerable companies within this universe of companies and the financial system remains limited (see Box “Financial situation of publicly offered companies – 2020”).

Moderate exposure of the financial system to the public sector within the framework of the macroprudential measures in force. The credit of the financial system to the public sector totaled 11.8% of total assets in March, increasing slightly in recent months, although it continued to be low from a historical perspective. When considering public sector deposits, all financial institutions maintain a net debt position vis-à-vis the public sector.

3.2 Weak performance of financial intermediation activity

Since the last publication of the IEF, the activity of intermediation of funds from the financial system with the private sector has been reduced. The balances of credit and deposits in national currency in this sector decreased in real terms in this period, although they continued to be above those observed a year ago. This occurred in a context in which the rate of change in the general price level of the economy increased, and in which the recovery of economic activity – favored by the measures adopted by the National Government and the BCRA in the face of the health emergency – was attenuated since mid-March due to the worsening of the epidemiological situation and the sanitary measures to contain the second wave of infections of COVID36. At the same time, financial intermediation in foreign currency fell slightly in the period.

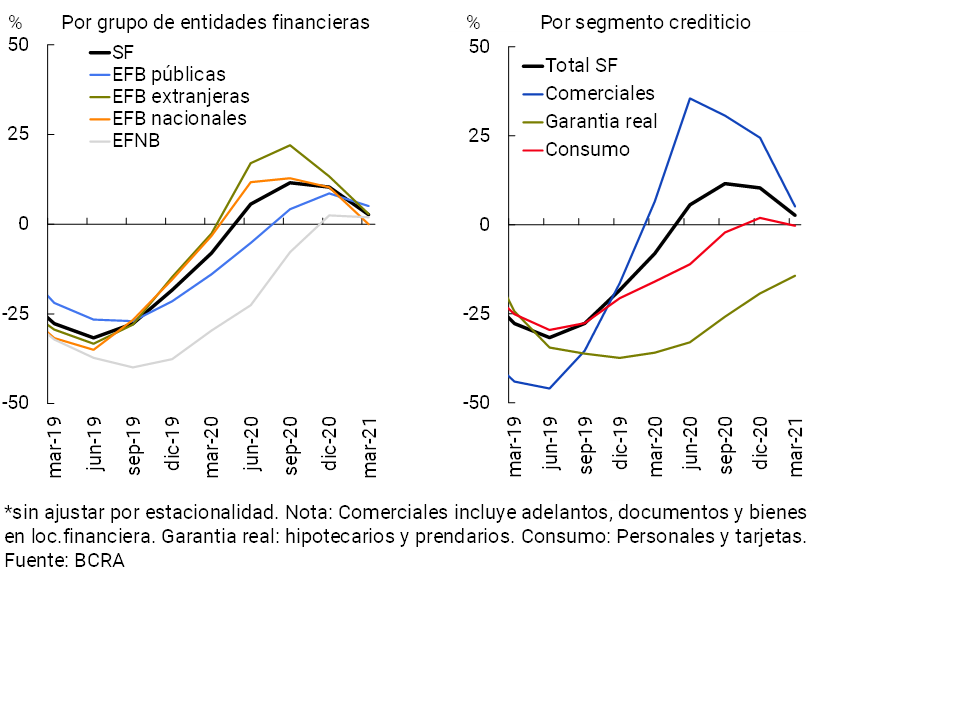

The real balance of credit to the private sector in national currency at the end of the first quarter of 2021 was 6.2% lower than at the end of the third quarter of 2020. This evolution was mainly explained by the performance of lines linked to companies (commercial), while the segment of loans to households (mainly those destined for consumption) remained without significant real variations in the last six months. However, receiving the effect of the credit stimulus programs promoted by the National Government and the BCRA, in year-on-year terms financing in pesos to the private sector accumulated an increase of 2.7% in real terms, exceeding the variations of the same month in previous years (see Chart 15). For their part, loans in foreign currency fell 8% – in source currency – when comparing March 2021 and September 2020 (with a year-on-year drop of 37.7%), although they are observing a recomposition in recent months.

In the context of the economic recovery process that has taken place since the middle of last year and the aforementioned performance of financial intermediation, as mentioned in the previous section, in the last six months the ratio between total credit to the private sector from the financial system and the GDP of the economy has fallen. This indicator stood at 9.8% in March (8.5% for the segment in national currency), almost 2 p.p. less than the level of September 2020 (-1.4 p.p. in pesos), below the levels observed locally years ago, as well as in other economies in the region.

Within the framework of this evolution of intermediation activity, the total assets of all financial institutions showed a certain decrease between September 2020 and March 2021, although it accumulated a year-on-year increase of 6.6% in real terms (see Chart 16). In terms of its composition, in the last six months the relative importance of the holding of BCRA instruments (LELIQ and passes) and, to a lesser extent, of credit to the public sector increased. On the other hand, financing (both in domestic and foreign currency) to the private sector and the remaining liquid assets (mainly the current accounts in national currency of the entities in the BCRA) reduced their relative weight in total assets. This occurred in a scenario where there was a limited variation in the factors of monetary expansion – sterilizing surplus liquidity – and a progressive focus of official credit assistance efforts on the sectors most affected by the pandemic.

In the coming months, developments regarding the development of the second wave of COVID infections and public policies to address this situation will take precedence, with a consequent effect on the activity of the financial sector. Recently, the National Government implemented restrictions on mobility to slow down the speed of infections and, in parallel, sought to focus its assistance programs on the most affected sectors to mitigate the economic and social effects, while advancing with the vaccination program. Going forward, if part of the risk factors set out in Section 2 materialize in terms of the development of economic activity, the financial intermediation process could be affected, especially the performance of credit to both companies and households. This situation could eventually translate into some impact on the sector’s sources of income, in a context in which lower levels of profitability were observed at the margin.

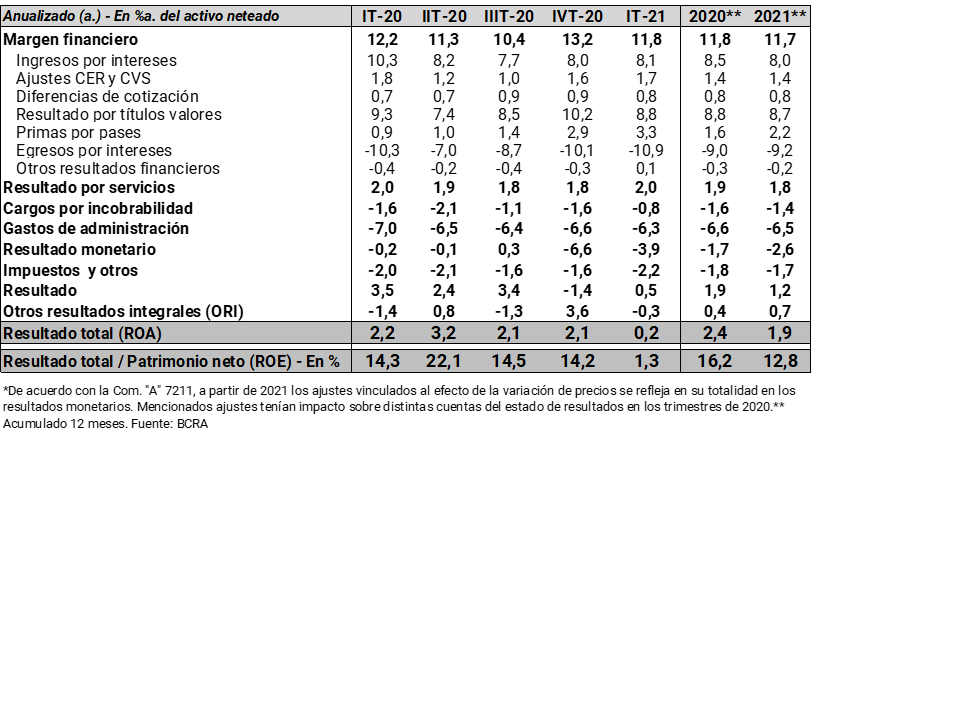

3.2.1 Specific elements of resilience

The profitability of the aggregate financial system, although declining, remains at positive levels. All financial institutions continued to register positive profitability indicators – considering comprehensive total results in constant currency – at the end of 2020 and at the beginning of 2021 (see Table 3). In the first quarter of 2021, these results represented 0.2% annualized (y.) of assets (ROA) and 1.3% y. of equity (ROE), being lower than those verified in 2019 and 2020. The lower levels for the profitability indicators recorded at the beginning of 2021, compared to the accumulated in 2020, are reflecting the effects of the dynamics of the items that reflect the adjustments linked to the evolution of the general price level, the higher interest outflows (in a context of an increase in the proportion of these placements in the funding of the financial system and minimum interest rates for deposits future) and a drop in the results of securities. These effects were tempered by a decrease in uncollectibility charges and administration expenses.

Risk-oriented supervision by the SEFyC. The Superintendence of Financial and Exchange Institutions (SEFyC) continues to monitor the performance of financial institutions through the identification of their individual risks and the development of appropriate supervision plans. It should be noted that systemically important institutions at the local level continue to have relatively high levels for their robustness indicators (see Section 3).

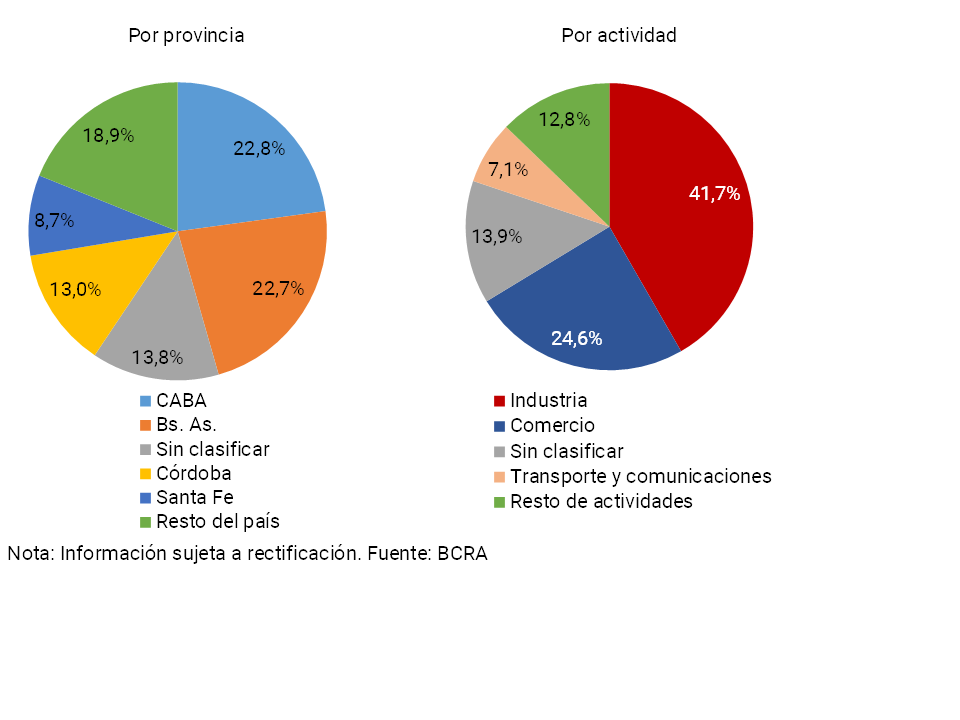

Credit assistance to small and medium-sized enterprises. Over the last six months, the BCRA continued to promote measures focused on the sectors most affected by the pandemic37. In order to continue expanding access to credit for MSMEs and contribute to economic reactivation, in March 2021 the BCRA established a new quota for the Financing Line for Productive Investment (LFIP), under financial conditions similar to those in force for the 2020 quota38. In the first month of the 2021 quota, the39 financial institutions granted disbursements for a total of $101,643 million (13% destined for investment projects), benefiting more than 22,100 companies. Through the 2020 quota, loans were granted that accumulated an average balance of almost $400,000 million between mid-October 2020 and the end of March 202140 . It is estimated that the LFIP had a positive impact in various areas of the country: 22.8% of the average balance corresponding to the 2020 quota was channeled to companies with tax domicile in CABA, followed by Buenos Aires (22.7%), Córdoba (13%) and Santa Fe (8.7%) (see Graph 17). The LFIP was channeled to various branches of activity41: it is estimated that almost 42% of the balance would have been allocated mainly to industrial companies and 24.6% to firms linked to commerce.

Moderate active mismatch of items with CER adjustment. The CER mismatch of all financial institutions continued to remain at limited values, standing at around 47.5% of the PRC (23% of the same when considering only the items denominated in UVA) at the end of the first quarter of 2021 (For more details see Section 2). When disaggregated by group of financial institutions, it can be seen that this mismatch was mainly explained by the set of public entities, and to a lesser extent, that of non-bank financial institutions.

3.3 Financial System Funding and Liquidity Performance

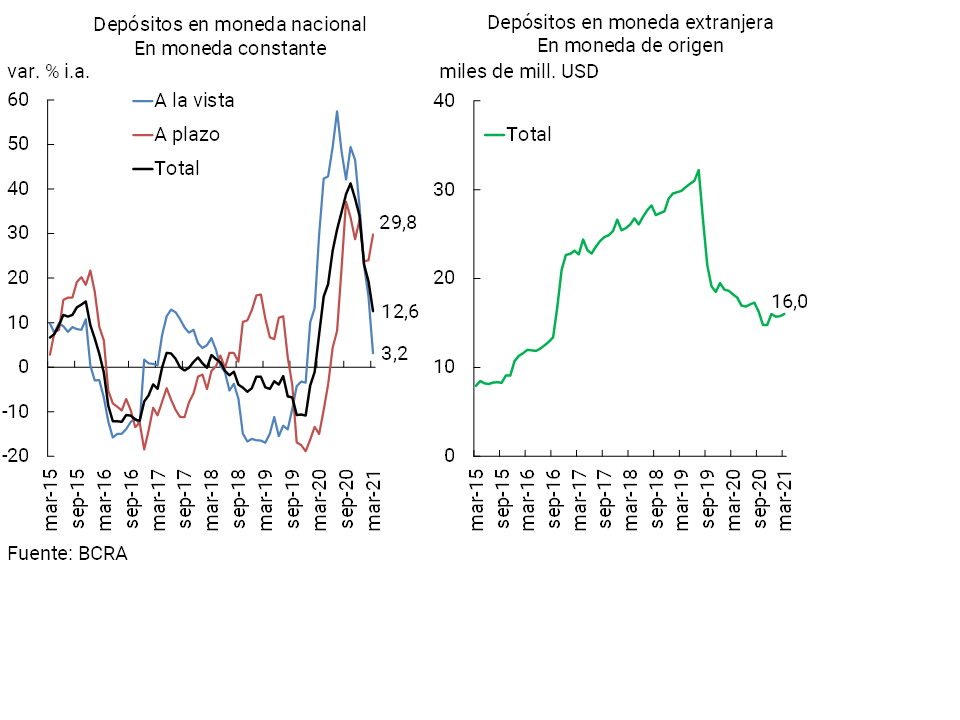

After the expansion of funding of the financial system through private sector deposits in pesos recorded in the first part of 202042, in the last quarter of last year and in the first quarter of 2021 the balance of these placements decreased in real terms. This performance occurred in the context of a lower monetary issuance by the BCRA based on the targeting of the National Government’s assistance programs and the moderation of the process of multiplication of money given the evolution of credit (see Section 1). Private sector deposits in national currency fell 4.7% in real terms in the last six months to March, a variation mainly explained by household deposits, and which is reflected to a greater extent in demand accounts. Time deposits in pesos in the private sector showed a better relative performance in the period, especially since the end of 2020 (-2.3% in real terms in the first half of the year and +6% in real terms in the first quarter of this year). Although still with little weighting, in line with the various savings instruments launched by the BCRA with inflation coverage, time deposits in UVA showed a significant relative increase in recent months.

Beyond the evolution in the margin, the total balance of private sector deposits in pesos accumulated an increase of 12.6% YoY in real terms over the end of the first quarter of 2021, with significant dynamism in the term segment (29.8% YoY). (see Graph 18). Public sector deposits in pesos also increased in a year-on-year comparison (+32.8% in real terms). In this context, distinguishing by stratum of amounts, larger placements in pesos (greater than $20 million) showed a greater relative increase in the last year43, reflected in a certain increase in the indicators of concentration of deposits44.

In recent months, the private sector’s foreign currency deposits have shown an incipient recovery, leaving behind the floor recorded at the end of last October (see Chart 18) as a result of an episode of some financial volatility.

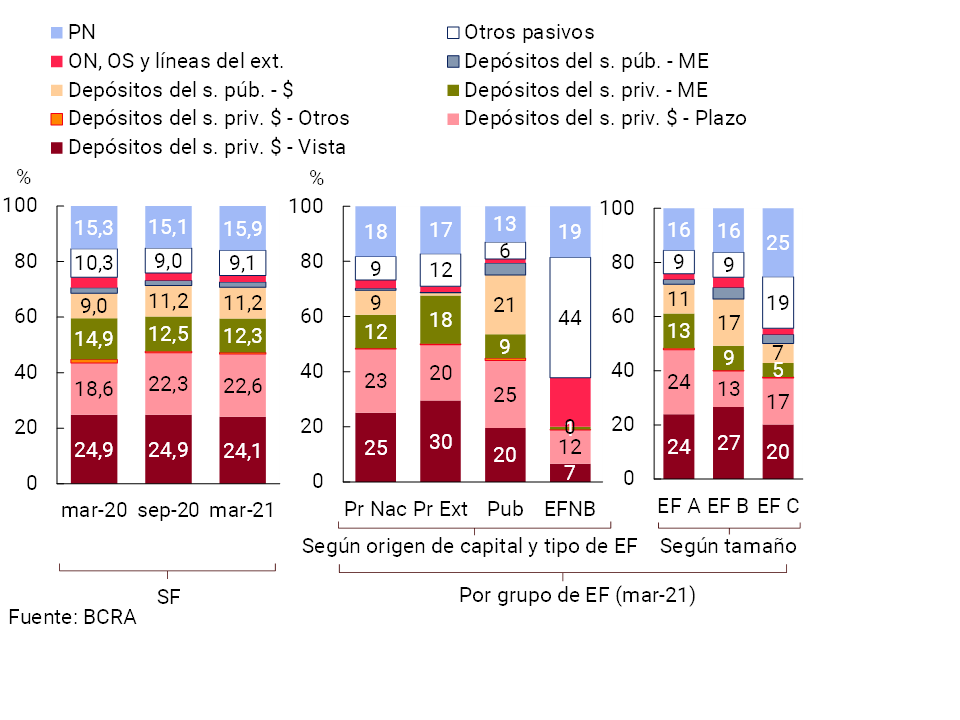

Despite the reduction in real balances compared to the last edition of the IEF, private sector deposits in national currency continued to be the main source of funding for the financial system (liabilities and equity), accounting for about 47% of the total (see Chart 19). Within these liabilities, private sector time deposits increased their relative weighting slightly in the last 6 months to total 22.6% at the system level, while demand accounts slightly reduced their relevance to cover 24.1% of total funding. Deposits in national currency of the public sector represented about 11.2% of the total, resulting in total deposits in pesos being around 58.5% of the total funding of the system in March.

The rest of the financial system’s funding (41.5%) is mainly made up of net worth (15.9%), foreign currency deposits of the private sector (12.3%) and other liabilities such as On, Os, foreign credit lines and miscellaneous obligations. Among these concepts, in the last six months the relative increase in equity stood out (see Chart 19), partly reflecting the effects of the macroprudential measure of suspension of the distribution of results of the entities, implemented by the BCRA to temper the potential economic and financial impacts of the pandemic.

Going forward, the level and composition of funding sources could be affected if any of the risk factors set out in Section 2 materialize. In particular, greater volatility in financial markets, as well as a less dynamic than expected recovery in economic activity, could have a certain impact on the demand for deposits (or their composition) by companies and households, as observed in previous years, with possible implications in terms of asset and liability management for the financial system.

3.3.1 Specific elements of resilience and mitigating measures

Broad liquidity risk hedging. The financial system has liquid assets in the broad sense that as of March 2021 represented 66% of total deposits, being practically the same level as that evidenced in the previous edition of the IEF. The liquidity ratio reached 61.5% for items in pesos and 84.6% for the foreign currency segment at the end of the first quarter of the year, observing records similar to those of September 2020 and higher than those of the average of the last 15 years (41% in national currency and 78.4% in foreign currency). In this context of high levels of liquidity, the BCRA recently provided that as of June 2021, financial institutions will have the option of integrating part of the minimum cash requirements in national currency with Treasury securities with a minimum duration of 180 days, replacing part of the integration with LELIQ —arising from the regulatory requirement for time deposits—45. This measure, which seeks to deepen the liquidity of the public securities market in pesos by promoting the development of the local capital market, is complemented by the implementation of a specific mechanism so that entities, if required, can sell these financial assets to the BCRA. In addition, it should be considered that the exposure of the financial system to the public sector is currently at limited levels (see Section 2), with the aggregate of financial institutions observing a net debt position vis-à-vis the public sector when considering their deposits —from all levels of government—. It should be noted that this new regulation is specific to operations in pesos.

In this context, the local financial system continued to exhibit high liquidity margins, well above international standards. In March 2021, the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR)46 stood at 2.3 for the group of entities obliged to verify it (Group A), comfortably exceeding the established minimum equivalent to “1”. This indicator increased slightly with respect to the record of the previous edition of the IEF and was above the average of the last 6 years (see Graph 20). The latter is mainly due to the growing impact on the numerator of the ratio (High Quality Liquid Asset Funds -FALAC-) of monetary regulation instruments and the current account balances of institutions, in a framework in which the denominator of the indicator (Total Net Cash Outflow -SENT-) presented relatively minor modifications.

The Stable Net Funding Ratio (NSFR)47 totaled 1.8 at the end of 2020 (latest available information) for group A of financial institutions, exceeding the minimum requirement of 1 and the average of the last 3 years (see Chart 20). The high relative level of this indicator reflects the relevance of more stable deposits and regulatory capital (they account for most of the available funds (numerator), while the weight of assets with restricted availability over a period of more than one year (they make up the main concept of the required funds (denominator) remains moderate.

Limited mismatch of deadlines. The activity of the financial system continues to be characterized by low complexity, with a preponderance in transactional items, maintaining a low transformation of terms. Despite the better performance of fixed-term deposits in relation to demand accounts in recent months, the maturity of liabilities did not change in magnitude in the last year. Given the performance in terms of credit and liquidity (see Section 3), the average maturity of assets fell slightly in the last year, in a context of a greater share of the balance of public securities and monetary regulation instruments in the balance sheet of the entities – with a shorter duration than that of the rest of the assets. As a result, the exposure of all institutions to the assumed term mismatch decreased slightly in the period, thus remaining at moderate levels.

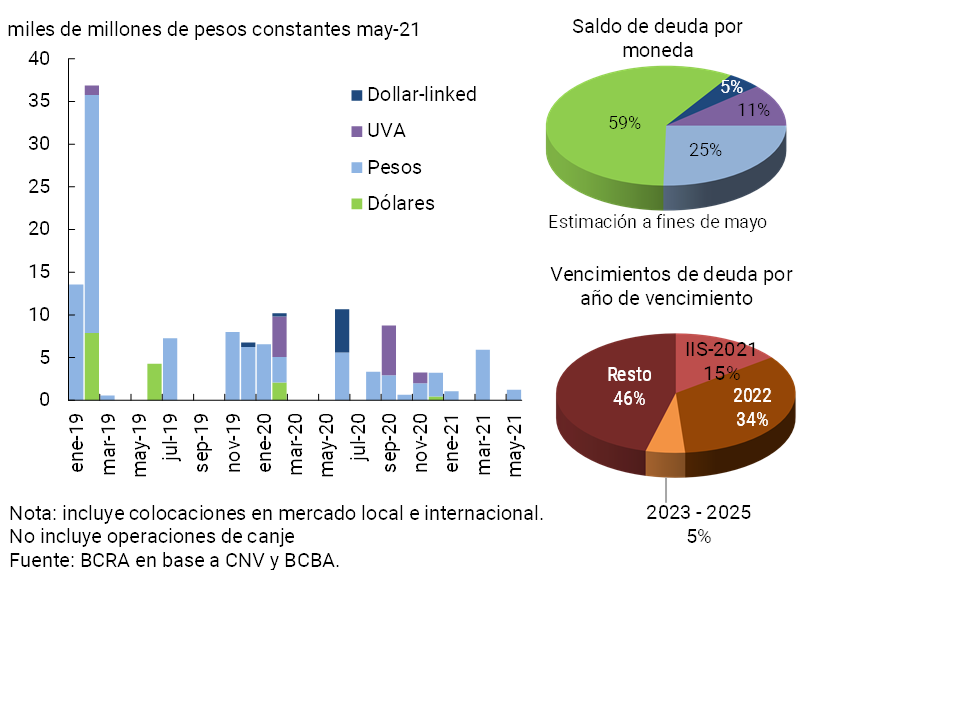

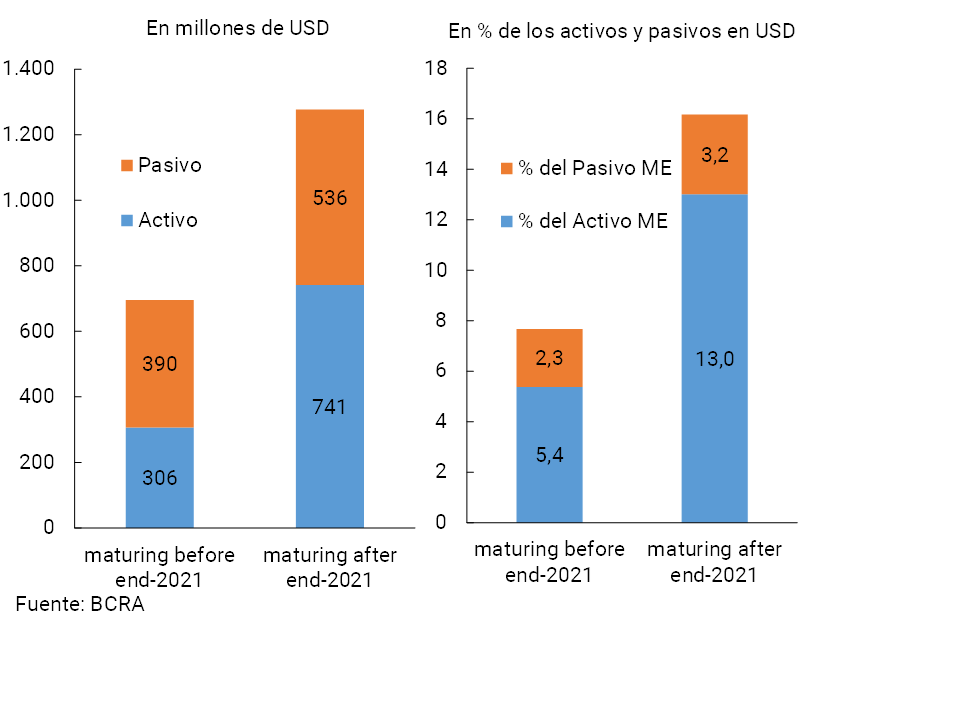

The funding of the financial system through the capital market continues at limited levels and with moderate amortizations in the coming months Currently, financing through the capital market represents a relatively small part of the total funding of financial institutions. For the aggregate of entities, outstanding bonds represent 0.7% of liabilities plus equity as of March of this year (1.7% if considered in aggregate terms only those entities that are funded with bonds)48. In turn, these bonds imply maturities for the second half of 2021 that represent 15% of the outstanding balance of these bonds in the financial system (the greatest weight of maturities occurs from 2023 onwards). In terms of currency, almost half of the maturities scheduled for 2021 are in pesos (including payments of ON in pesos, in UVA and dollar-linked) and the rest in dollars. Between January and May 2021, financial institutions made placements in the local market – not including swaps – for about $7,800 million (see Chart 21), which implies a year-on-year drop of 53% in real terms. These placements in 2021 were in nominal pesos and with a term between 12 and 15 months49. On the other hand, so far this year there has been only one ON buyback operation by financial institutions.

4. Other topics of stability of the financial system

4.1 Systemically Important Financial Institutions at Local Level (DSIBS)

The monitoring and differential approach of those financial institutions identified as systemically important at the local level (commonly referred to as DSIBS), seeks to prevent episodes of stress in an individual financial institution – which has certain characteristics – from causing adverse systemic effects. A hypothetical scenario of these characteristics could impact the economy as a whole, deteriorating the situation of families and companies.

This type of entity, which as of 2016 has received particular regulatory and supervisory treatment in Argentina50 – in line with what happens in other countries, in accordance with the standards recommended at the international level51 – can acquire systemic importance either because of their size, the level of their interconnections, the degree of complexity and the possibility of substitution they have. dimensions to consider regularly when monitoring their performance.

As of March 2021, the solvency and liquidity ratios of all local DSIBS (which represent approximately half of the assets of all institutions) were similar to those of the aggregate financial system and higher than those evidenced in the last edition of the IEF, with full compliance with the capital conservation margin52 (see Table 4). In line with the lower profitability in real terms that the sector has been showing in recent quarters, the ROE of DSIBS also decreased compared to 2020. Credit risk indicators remained in line with those recorded throughout the system, with an increase in margin forecasting and high capital coverage of credit net of forecasts. The exposure to the public sector and the mismatch of foreign currency of these entities presented levels above the average of the sector, and slightly higher than those of six months ago.

4.2 Interconnection in the financial system

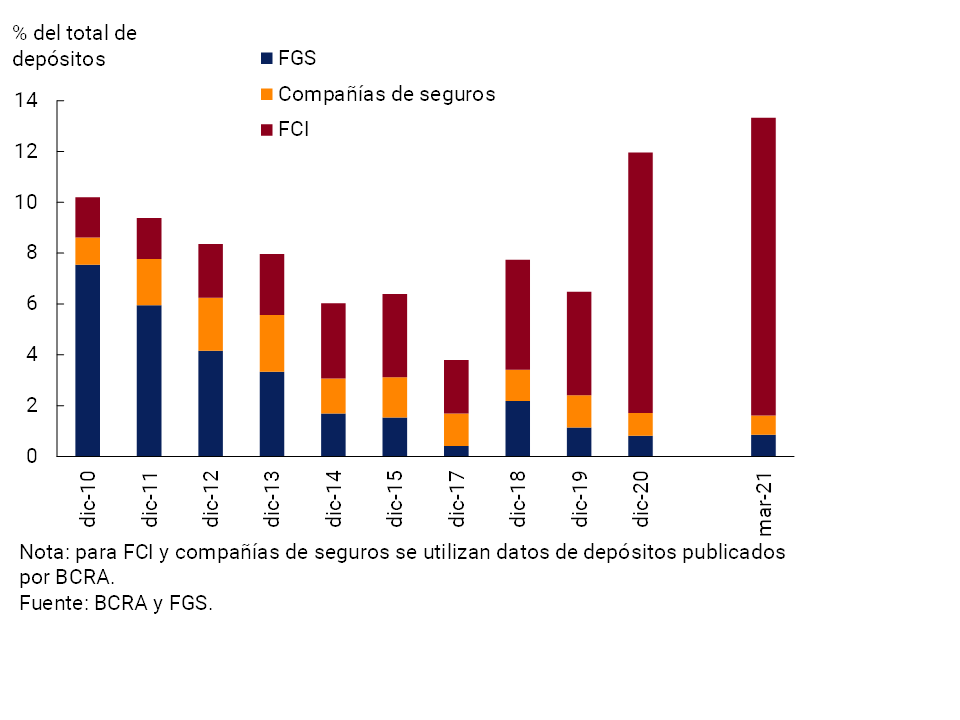

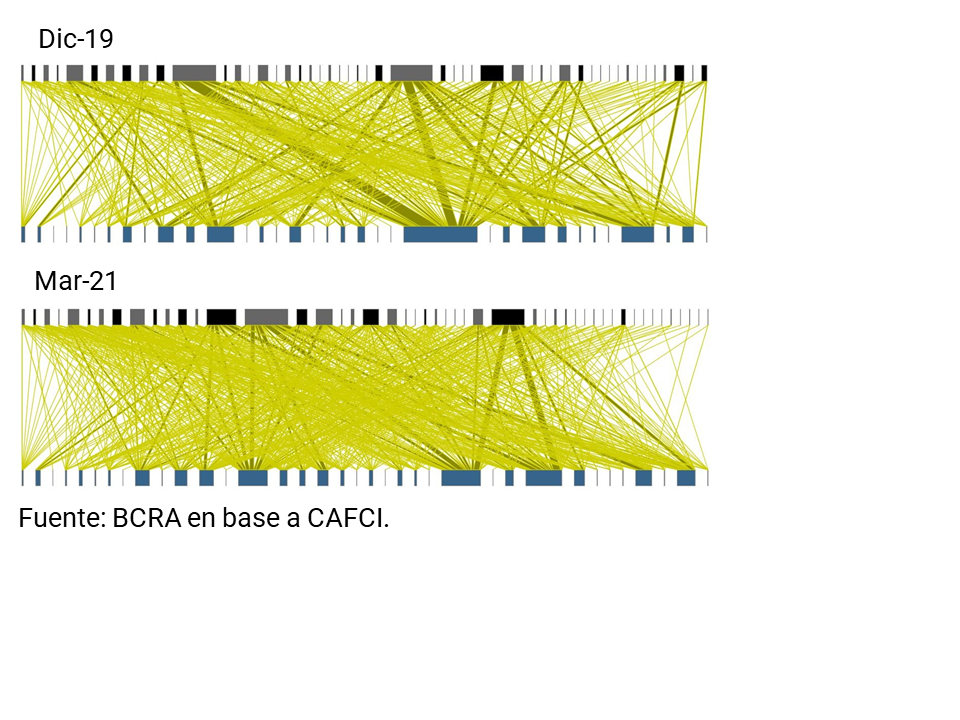

The main source of direct interconnection between institutional investors and the financial system (a group of entities regulated by the BCRA) is the deposits and time investments made by the former in the latter, with placements of Mutual Funds or FCIs standing out in this regard (see Chart 22)53. In recent months, there has been a new increase in the importance of funding provided by deposits from institutional investors for the total financial system, currently representing 13.3% of the total. This weighting exceeds by 3p.p. at the value observed 10 years ago and at 6p.p.al average of that period.

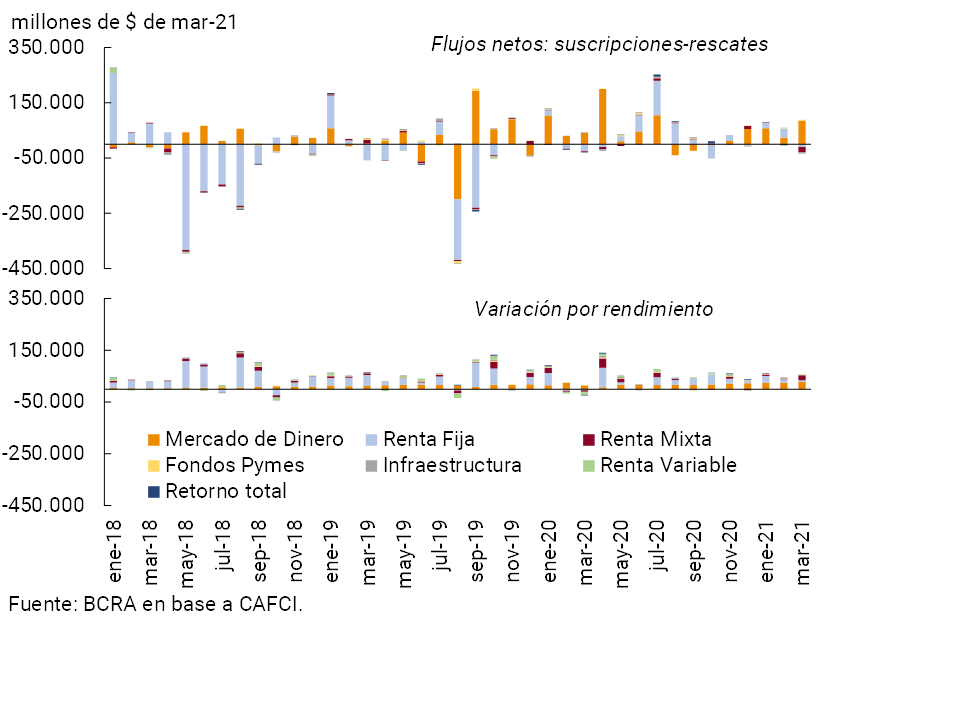

In particular, the increase in interconnection through deposits is largely explained by the performance of the FCIs, with assets that continued to grow in the first months of 2021, although at a slower pace than in the second half of 2020 (see Section 5). This dynamic is led by new subscriptions in money market FCIs (see Chart 23), which currently account for half of the assets of the FCIs.

Figure 23 | Evolution of net subscriptions and performance of the FCIs

Change in equity by FCI class

In terms of direct interconnection within the financial system, it is worth mentioning the recent performance of the market for unsecured interfinancial loans (call market)54. The intensity of this type of interconnection between the entities tended to decrease in recent months due to the decrease in the amounts negotiated in real terms. This was accompanied by a rise in the rates agreed in nominal terms, with a reduction in the differential with respect to other reference rates such as the BADLAR. Using the indicators of the network analysis methodology, a drop in the degree of interconnection in recent months with respect to longer-term values is also observed55, 56.

5. Main macroprudential measures

The BCRA’s prudential actions continued to be mainly focused on mitigating the systemic impact of the pandemic shock on the private sector of the economy, in a scenario in which the epidemiological situation remained challenging in recent months (see Section 1). At the end of 2020 and in the first part of this year, the axes of the prudential policy that was implemented in the first part of last year were maintained, in line with the initiatives taken by other developed and emerging economies to face the effects of the health situation. In this regard, the Financial Stability Board released a survey last April that indicates that, in the face of the still challenging scenario and uncertainty about the global macroeconomic outlook, most countries were still maintaining the measures taken to deal with the pandemic context57.

In the current macro-financial context, the BCRA maintained its regulatory approach in order to:

i. Boost credit to the private sector, especially through the Financing Line for Productive Investment in MSMEs (LFIP), expanding its available quota for 2021 and thus promoting favorable financial conditions for firms. This initiative was consolidated as the BCRA’s main credit promotion tool. More recently, measures were added to the same end, such as the implementation of regulatory incentives in terms of Minimum Cash, for those entities that generate loans to people who are not in the Debtors’ Central; 58

ii. Alleviate the financial situation of families and companies. Until the end of the first quarter of this year, a transitory modification was in force on the parameters for classifying debtors in the financial system, in addition to the possibility of transferring their unpaid installments at the end of the life of the credit (accruing only compensatory interest). Regarding the first of the measures, the BCRA decided to establish a gradual transition schedule between April and May, thus gradually returning to the parameters existing prior to the pandemic since the middle of the year. In terms of the possibility of transferring unpaid installments at the end of the life of the loan, in the face of the second wave of the pandemic, the BCRA decided to focus efforts on the most affected sectors, allowing employers covered by the Productive Recovery Program II (REPRO II) (accruing only compensatory interest) to use this tool.

iii. To support the measures that promote bank savings in pesos on a term basis, especially in terms of the availability of adjustable UVA pre-cancellable deposits that contribute to protecting depositors’ claims against variations in the general price level of the economy (even providing an additional return on the evolution of inflation);

iv. Maintain the current position of slack in terms of solvency that financial institutions have by temporarily extending the suspension of the possibility of distributing results. The aim is to protect the soundness of the system and its resilience in the event of stress events (possibility of materialization of private sector credit risk, see Section 3), while avoiding conditions that reinforce procyclical credit behavior;

v. Maintain and improve exchange regulations, preventing transitory imbalances between supply and demand from affecting the economy’s position of international reserves.

Finally, it should be mentioned that the BCRA recently issued a joint alert with the CNV with the aim of informing the public about the risks of operating with cryptoassets.

Section 1 / Global transition to new benchmark interest rates

A wide range of financial instruments available in the markets worldwide use the so-called reference interest rates. The use of these to set the price of financial contracts helps to reduce their complexity, while facilitating their standardization. This, in turn, helps reduce transaction costs and improve liquidity conditions.

Since 2007, when a set of facts of manipulation of reference interest rates59 was publicly disseminated, in particular of the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR), a process of deterioration of confidence in them began to be evident. First, in what turned out to be a design flaw, LIBOR is built from a survey of a small group of banks reporting non-binding quotes rather than actual quotes from agreed trades. This created a widemargin of 60 for banks to have the ability to manipulate LIBOR. Second, the lack of liquidity in the unsecured interbank credit markets after the international financial crisis of 2007-08 gradually reduced their depth and solidity due to the lack of underlying transactions, a situation that deepened over time.