Política Monetaria

Monthly Monetary Report

May

2022

Monthly report on the evolution of the monetary base, international reserves and foreign exchange market.

Table of Contents

Contents

1. Executive Summary

2. Payment Methods

3. Savings instruments in pesos

4. Monetary base

5. Loans in pesos to the private sector

6. Liquidity in pesos of financial institutions

7. Foreign currency

The statistical closing of this report was January 8, 2024. All figures are provisional and subject to revision.

Inquiries and/or comments should be directed to analisis.monetario@bcra.gob.ar

The content of this report may be freely cited as long as the source is clarified: Monetary Report – BCRA.

1. Executive Summary

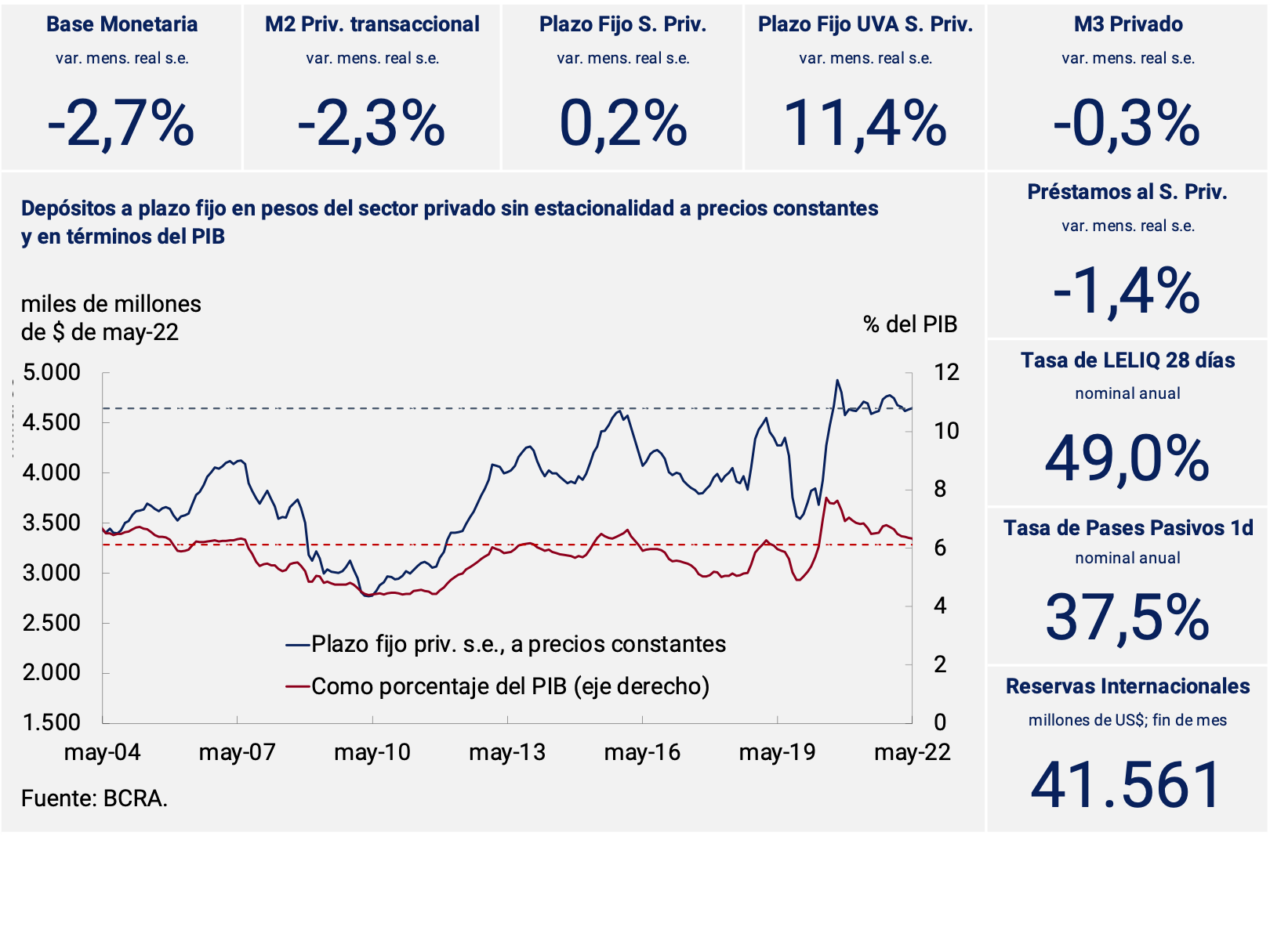

In the fifth month of the year, the broad monetary aggregate (private M3) would have registered a slight monthly contraction at constant prices (-0.3% s.e.), moderating the rate of decline for the second consecutive month. This contraction was mainly explained by what happened with transactional means of payment, given that fixed-term deposits remained practically unchanged in the month.

The balances of fixed-term deposits in pesos of the private sector remained around the highest levels of recent decades, both at constant prices and as a percentage of GDP. In terms of instruments, the behavior was heterogeneous. In particular, the growth of deposits denominated in UVA was highlighted, reaching a balance of $312,700 million at the end of May. In this way, they exceeded the historical maximum they had registered in the middle of last year, although they still maintain a limited participation in the total (6.5%).

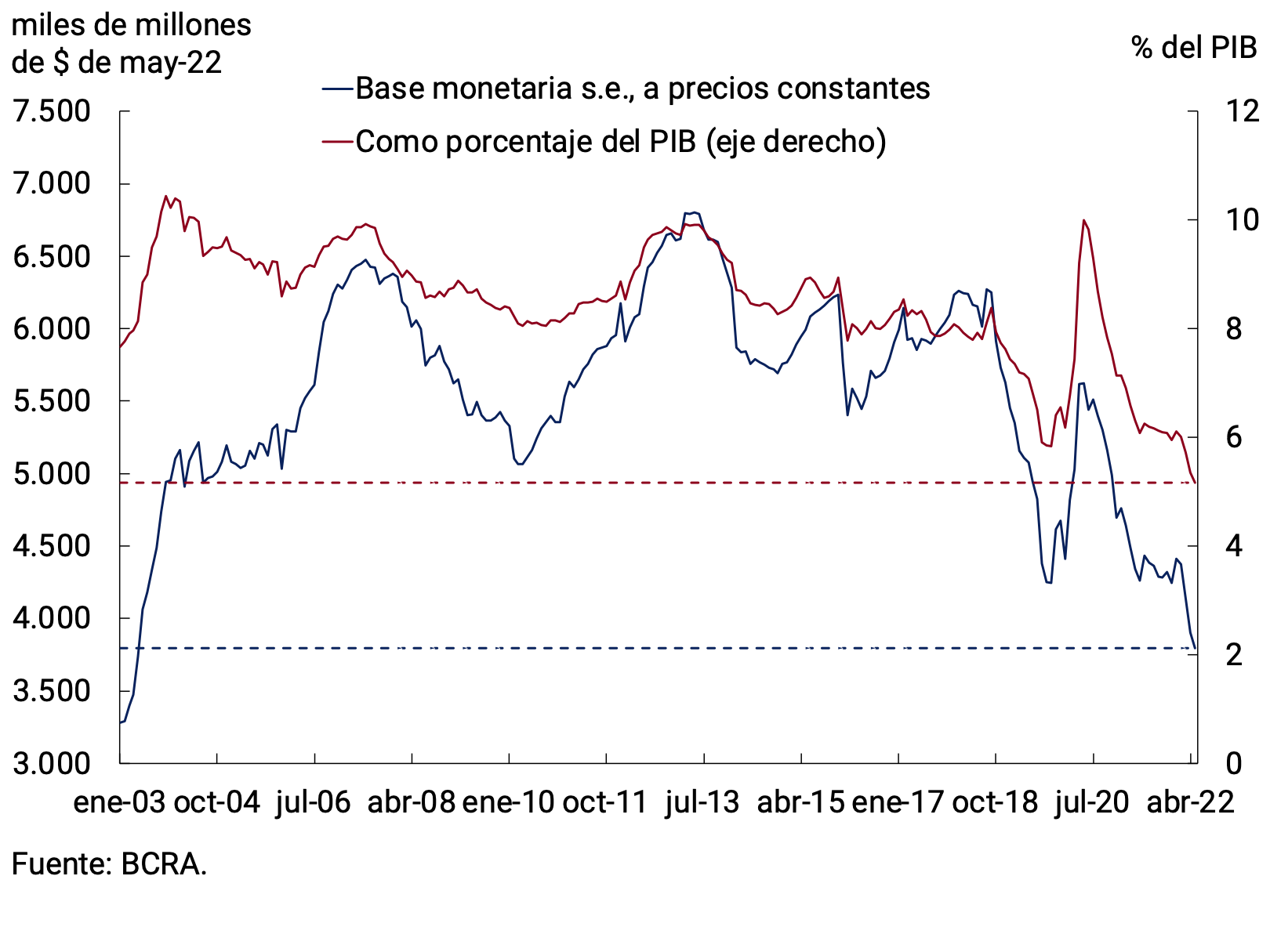

The Monetary Base adjusted for seasonality and inflation, on average in May, would have exhibited a fall of 2.7% (-10.9% y.o.y.). As a GDP ratio, the Monetary Base would stand at 5.2%, at its lowest value since 2003.

Finally, loans to the private sector at constant prices contracted again in the month, accumulating four consecutive months of declines. Most of the lines contributed negatively to the variation of the month, with the exception of loans with collateral and discounted documents.

2. Payment methods

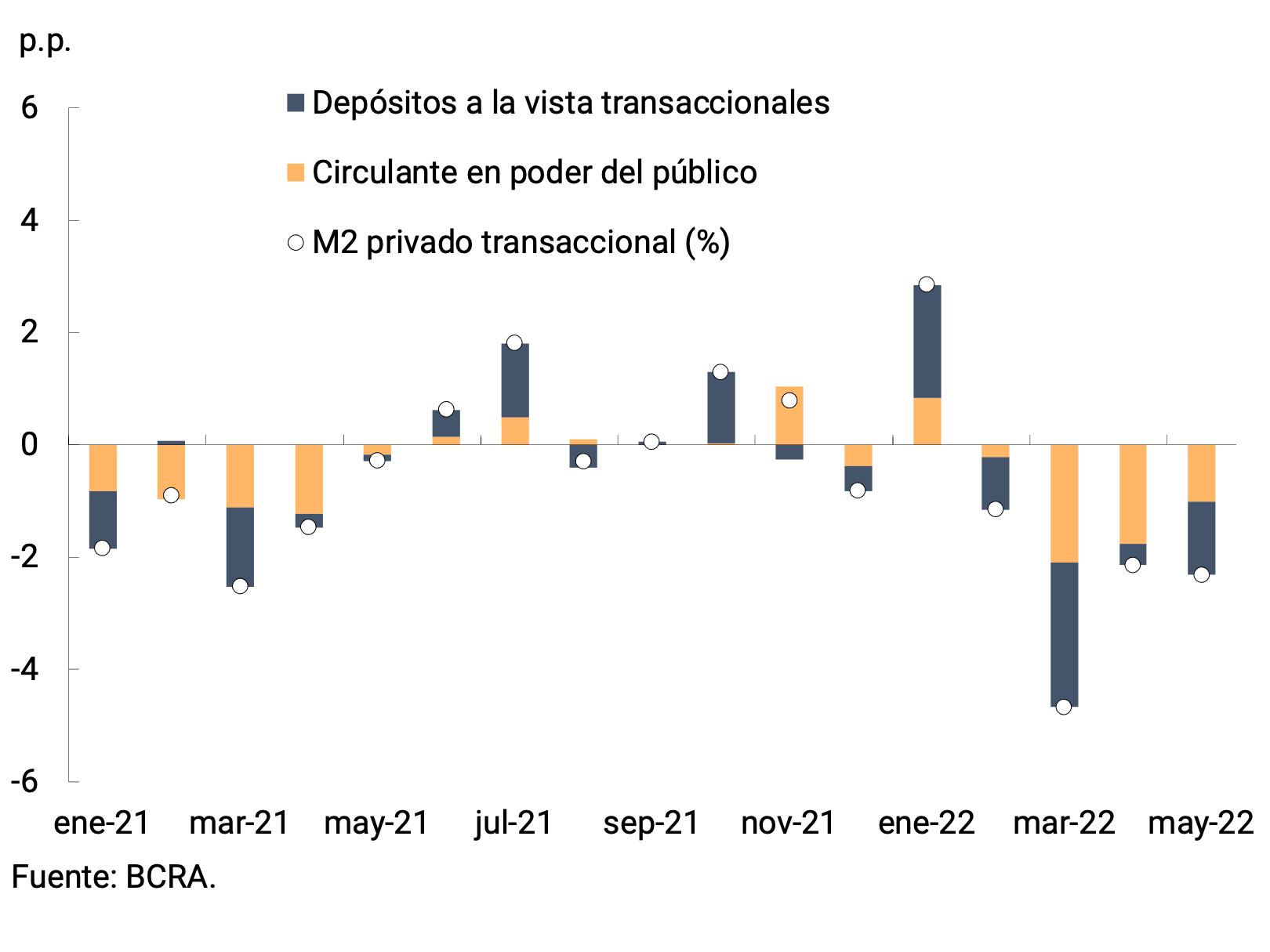

In real and seasonally adjusted terms (s.e.), means of payment (private transactional M21) would have registered a contraction of 2.3% in May, recording four consecutive months of decline (see Figure 2.1). At the level of its components, the decrease was explained both by the behavior of non-interest-bearing demand deposits and working capital deposits in the hands of the public. Thus, in year-on-year terms, private M2 would have contracted by around 4.6% at constant prices.

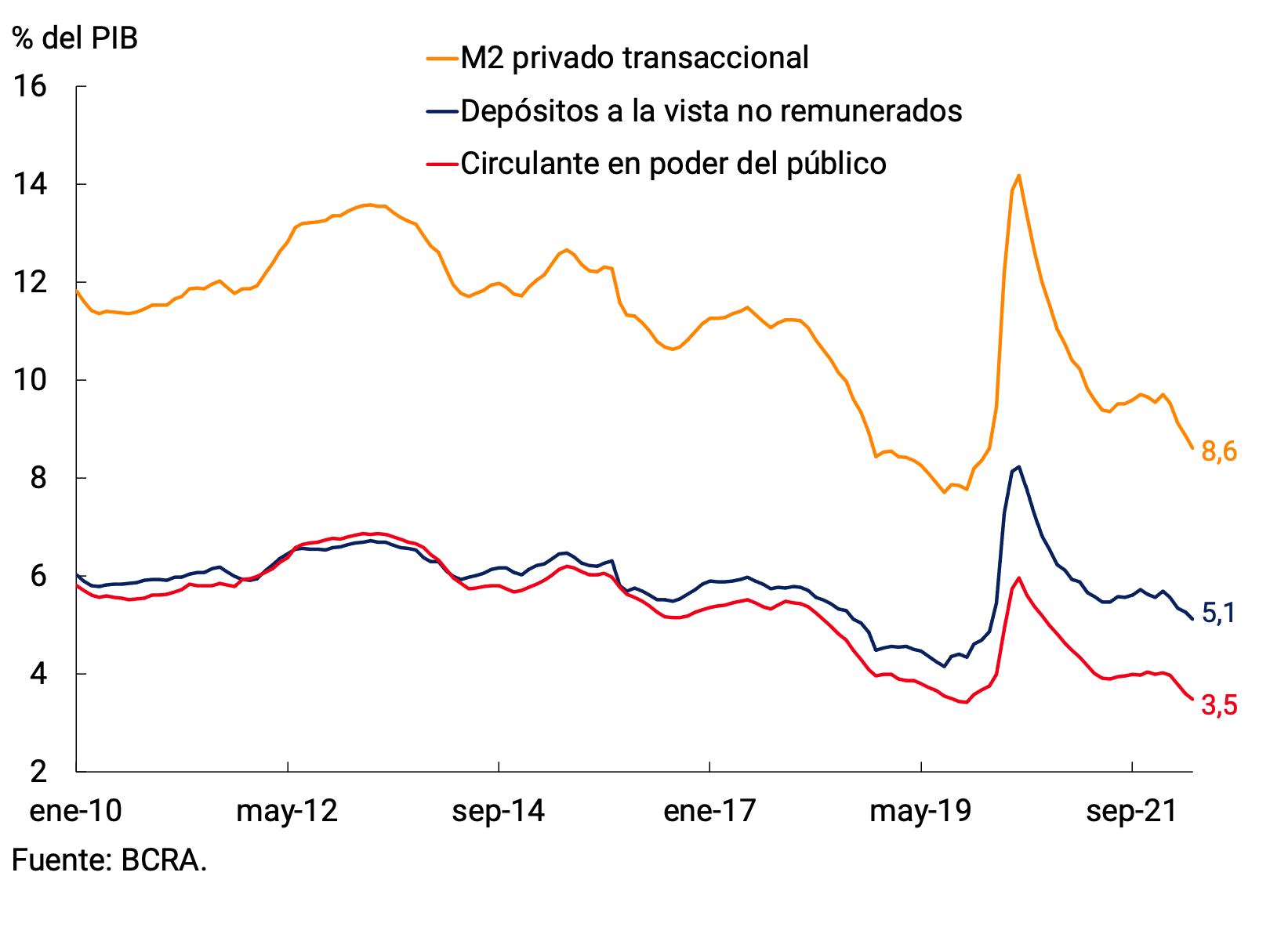

In May, private transactional M2 would have stood at 8.6% of GDP, showing a decrease (0.3 p.p.) compared to last month (see Chart 2.2). As mentioned in previous editions, the circulating currency held by the public remained around its lowest records of the last 15 years. The low level of demand for banknotes and coins is partly linked to a higher relative demand for demand deposits, given the growing use of electronic means of payment in recent years.

Figure 2.1 | Private transactional M2 at constant

prices Contribution by component to the monthly vari. s.e.

3. Savings instruments in pesos

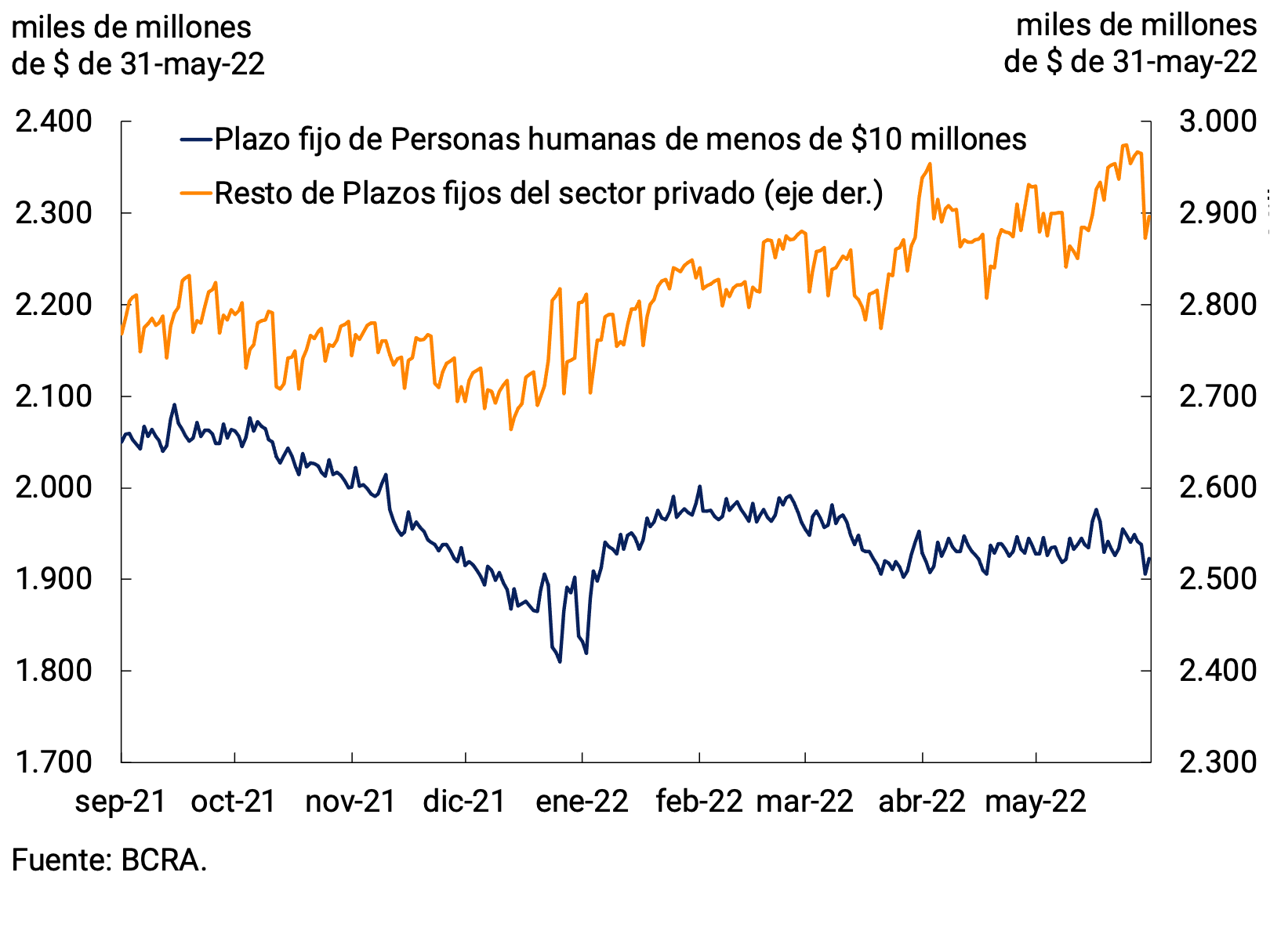

In mid-May, the Board of Directors of the BCRA decided to raise the minimum guaranteed interest rates on fixed-term deposits, marking the fifth consecutive increase so far this year. The measure is in line with its strategy of establishing an interest rate path that tends to achieve yields in line with the evolution of inflation. Thus, the minimum guaranteed rate for placements of individuals for up to $10 million was increased from 46% n.a. to 48% n.a. (60.1% y.a.). For the rest of the depositors in the financial system3, the interest rate also rose by 2 p.p. to 46% (57.1% y.a.).

In May, fixed-term deposits in pesos of the private sector at constant prices would have remained practically unchanged (0.2% s.e.), and in this way, they are still maintained around the highest records of recent decades. As a percentage of GDP, these deposits would have been positioned in the fifth month of the year at a value of 6.3%, a figure that is also among the highs of recent years.

Analyzing the evolution of time deposits, segmenting according to minimum guaranteed rate strata, it can be seen that placements by individuals of less than $10 million in real terms would have remained relatively stable throughout the month, as in April. On the other hand, the rest of the deposits of the non-financial private sector (those constituted by legal entities, regardless of the amount, and by individuals with placements of more than $10 million) would have registered, adjusted for seasonality, a slight increase in the average for the month, which was explained by an increasing trend from the second week of May (see Chart 3.1).

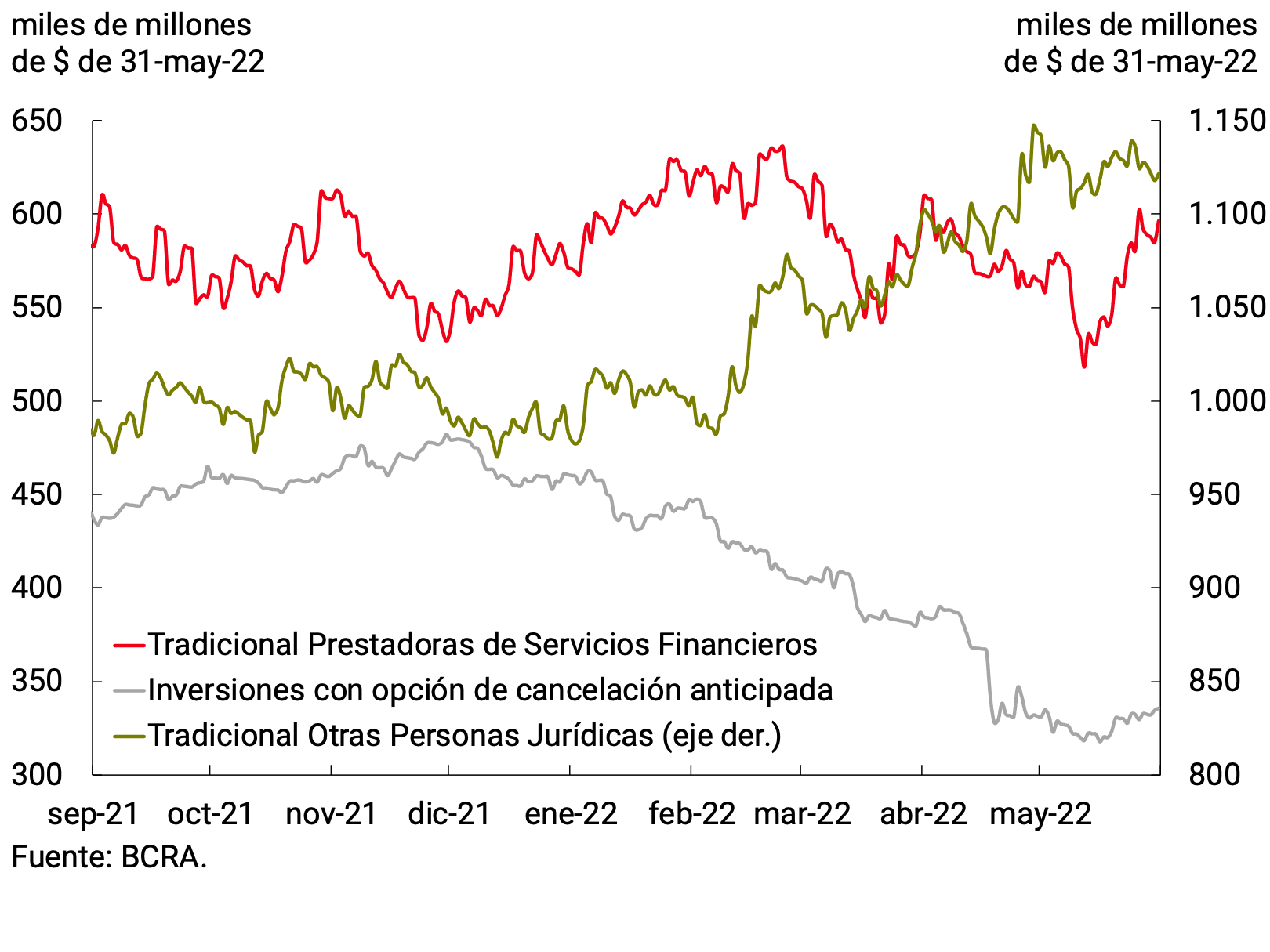

As for time deposits of legal entities, companies (excluding Financial Services Providers (PSF) registered an increase on average in the month, which was mainly explained by the carry-over effect in April. Meanwhile, the PSF slightly reduced their holdings in May, although in the peak variation they verified an expansion of approximately 2% at constant prices. The behavior of these agents within the month was heterogeneous. In the first part of the month, they showed a portfolio rebalancing, with an increase in interest-bearing demand placements to the detriment of term holdings, in a context of a fall in the assets of the Money Market Mutual Funds (FCI MM), which are the main agents within the PSFs. From the second week onwards, the trend in equity was reversed, leading to a relative recomposition in the holdings of fixed-term deposits of FSPs (see Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.1 | Fixed-term deposits in pesos from the private

sector At constant prices by rate segment of the original series

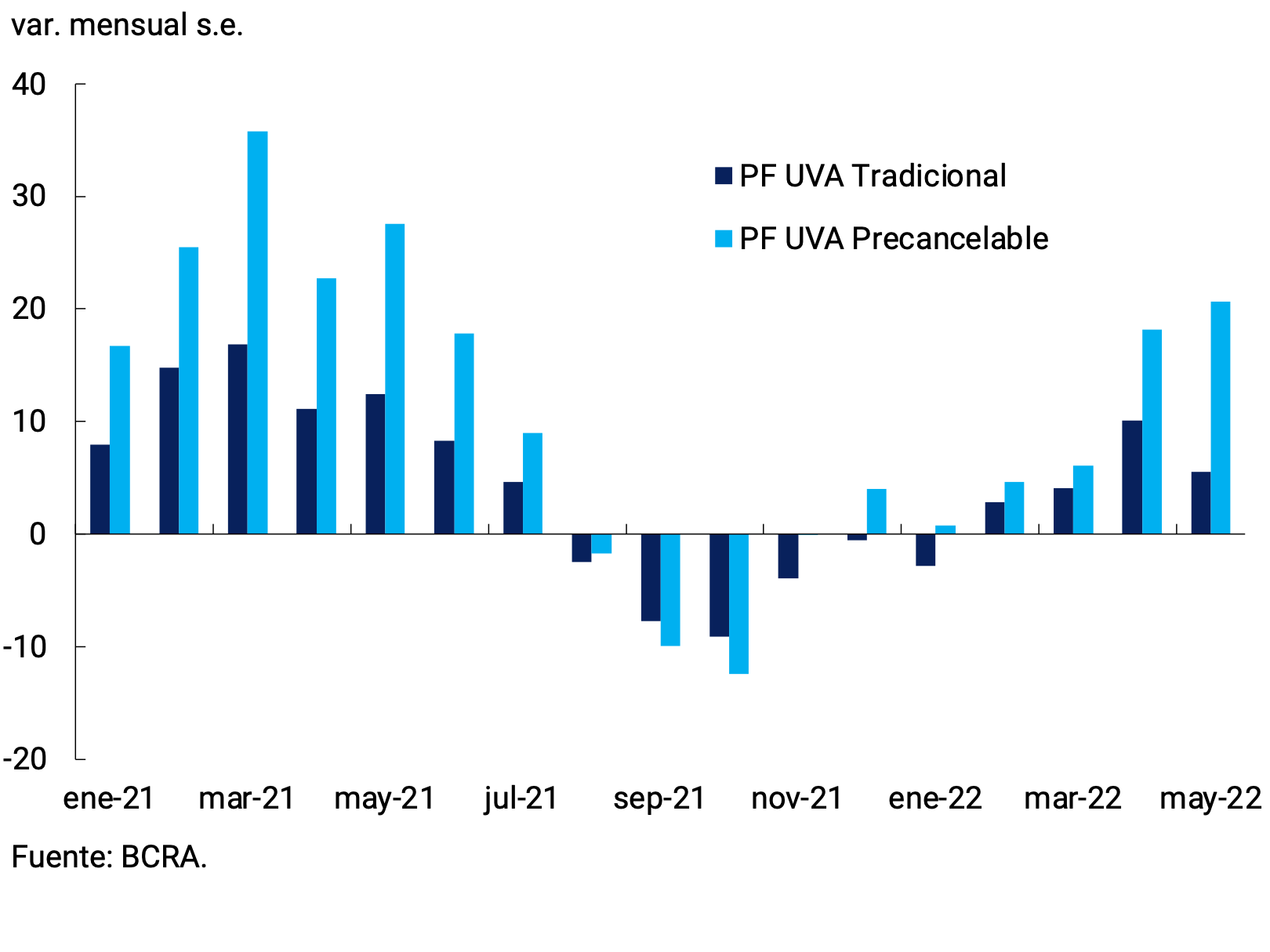

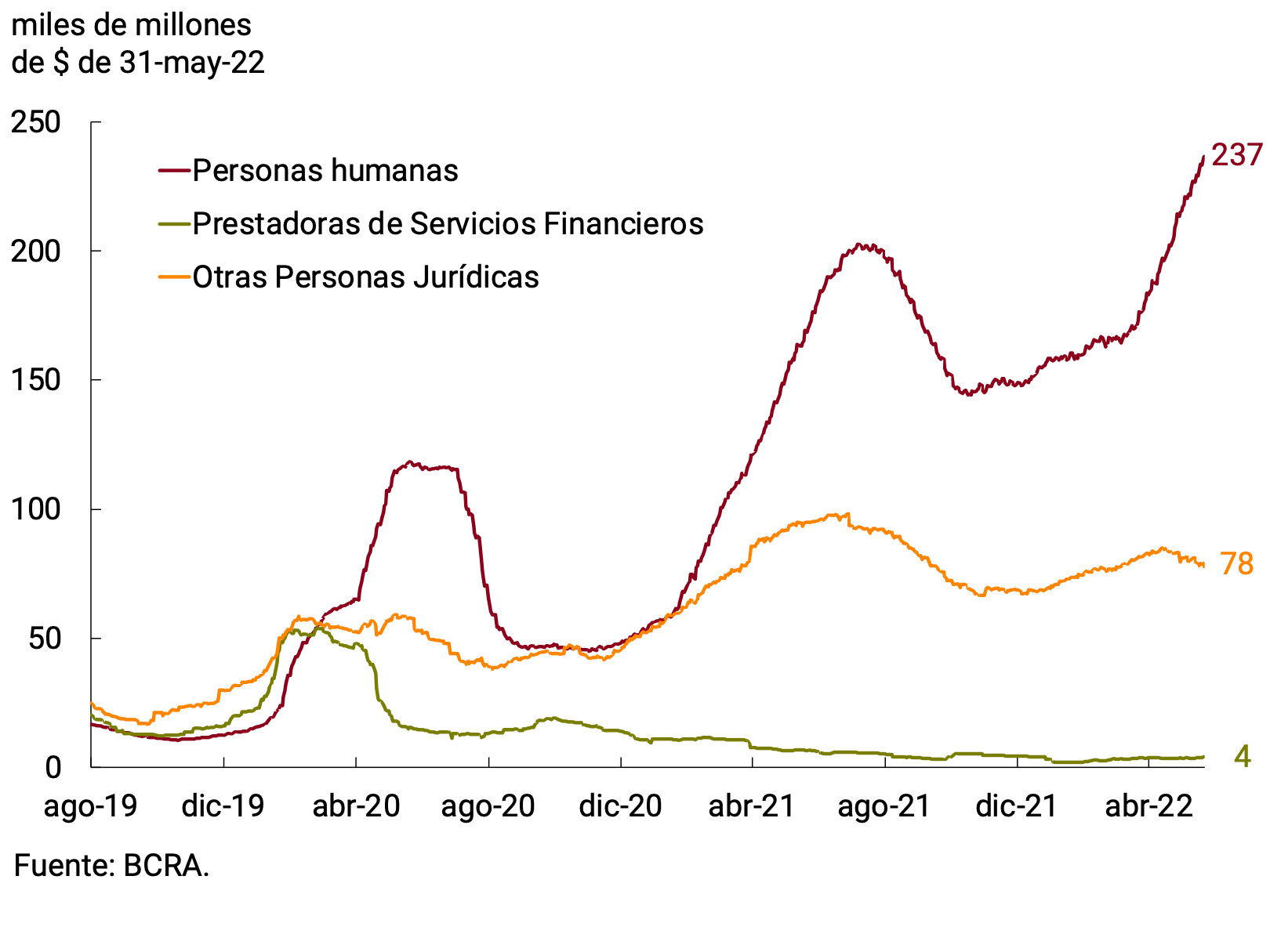

The relative stability of savings instruments in pesos hides a heterogeneous behavior at the instrument level. In fact, investments with early cancellation options made a negative contribution to the monthly variation in total term placements, which was offset by the expansion of CER adjustable deposits and traditional fixed-term deposits in pesos. Thus, UVA deposits continued the upward trend that began at the beginning of the year and their relative share continued to grow in the month, reaching 6.5% of total private sector time deposits by the end of the month. At constant and seasonally adjusted prices, these placements exhibited an average monthly growth of 11.4%, reaching a balance of $312,700 million at the end of May, surpassing the historical maximum reached in the middle of last year. This growth was verified in the case of both traditional and pre-cancellable UVA placements, whose monthly expansion rates stood at 5.5% s.e. and 20.7% s.e. in real terms, respectively (see Figure 3.3). Discriminating the balance by type of holder, it can be seen that the boost came from the placements of individuals, given that companies (excluding FSPs) slightly decreased their holdings (see Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.3 | Fixed-term deposits in UVA of the private

sector Var. monthly s.e by type of instrument

All in all, the broad monetary aggregate, private M34, at constant prices would have registered a monthly decrease of 0.3% s.e. in May, moderating the rate of decline for the second consecutive month. In year-on-year terms, this aggregate would have experienced a decrease of 1.4%. As a percentage of GDP, it stood at 16.4%, 0.1 p.p. below the value of April.

4. Monetary base

The Monetary Base on average in May stood at $3,696.4 billion, registering a monthly increase of 1.9% in the original series at current prices. Adjusted for seasonality and inflation, it would have exhibited a fall of 2.7% (-10.9% y.o.y.). As a GDP ratio, the Monetary Base would stand at 5.2%, 0.1 p.p. below the value recorded in the previous month and at its lowest value since 2003 (see Figure 4.1).

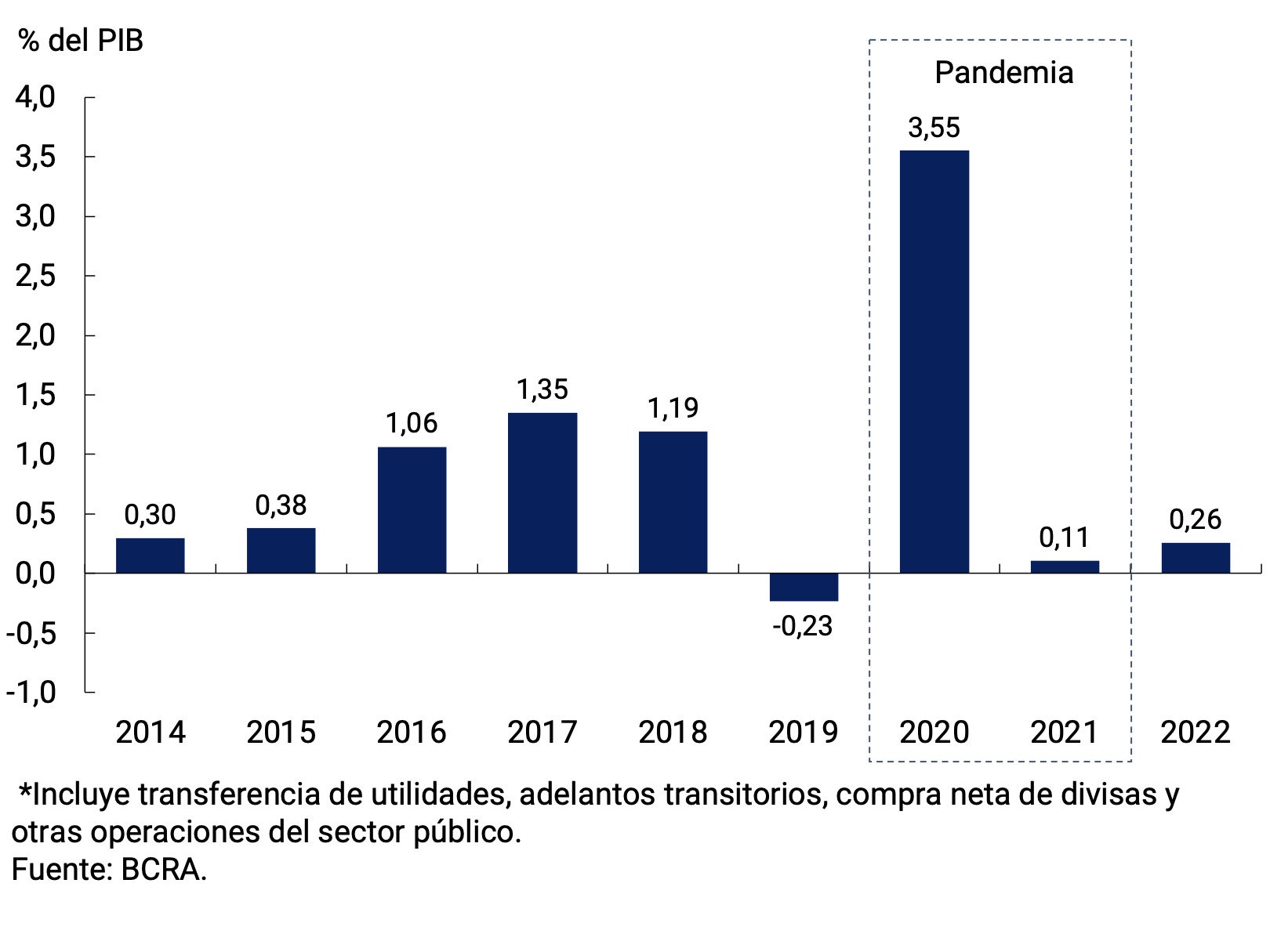

On the supply side, the monthly expansion of the monetary base was mainly explained by public sector operations. However, public sector primary issuance in terms of GDP remained, in the first five months of 2022, among the lowest levels in recent years (see Figure 4.2). The net purchase of foreign currency from the private sector was another expansionary factor of liquidity in May, although it had a lesser impact. These effects were partially offset by the absorption of liquidity through the BCRA’s monetary regulation instruments.

In mid-May, the BCRA again adjusted the interest rates of monetary policy instruments upwards. Specifically, the interest rate of the LELIQ with a 28-day term was raised by 2 p.p., which stood at 49% n.a. (61.8% y.a.). Meanwhile, the interest rate on the LELIQ with a 180-day term increased by 2.5 p.p. and was set at 54.5% n.a. (62% y.a.). As for shorter-term instruments, the interest rate on 1-day pass-by-passes increased 1.5 p.p. to 37.5% n.a. (45.5% y.a.); Meanwhile, the interest rate on 1-day active passes stood at 53% n.a. (69.8% e.a.). Finally, the fixed spread of the NOTALIQ in the last auction of the month remained at 5.0 p.p.

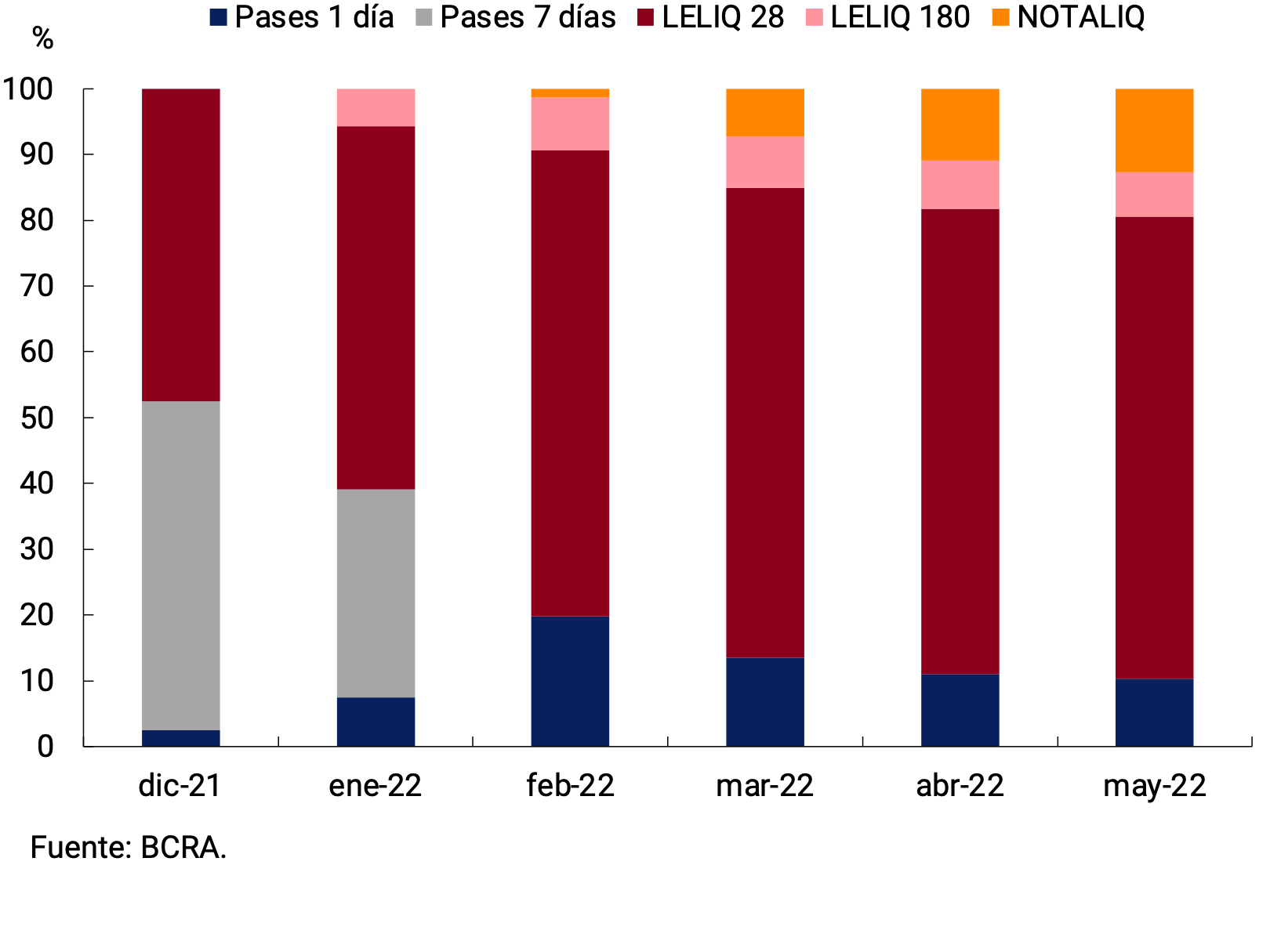

With the current configuration of instruments, in May the remunerated liabilities were made up of around 70% by LELIQ with a 28-day term. As for the longer-term species, the 180-day LELIQs reduced their participation to 6.8% of the total, unlike what happened with the NOTALIQs, whose participation continued to increase in the month (12.7% of the total). The rest corresponded to 1-day passes, which again reduced their relative weight (see Figure 4.3).

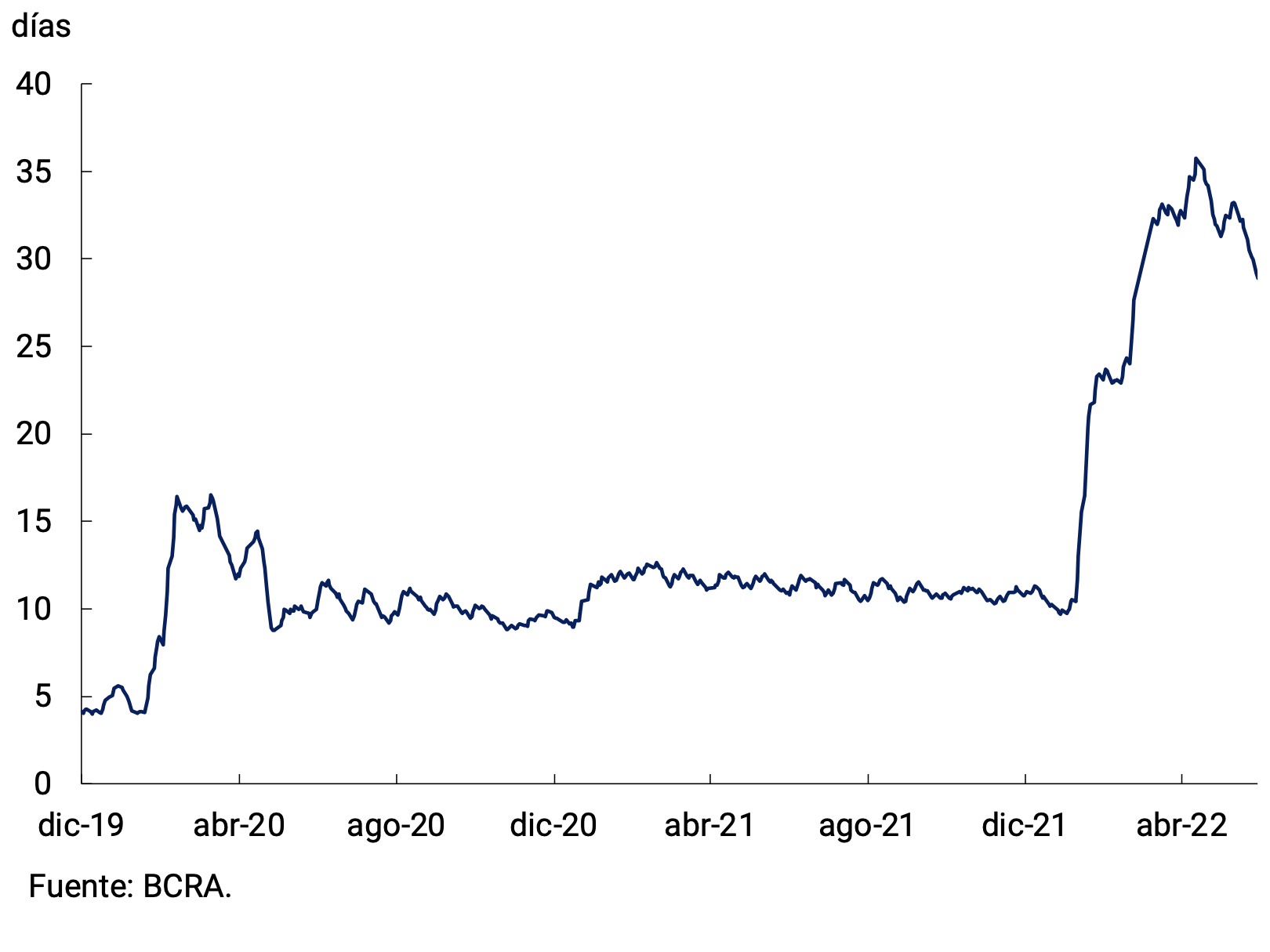

These changes in the relative composition of the monetary regulation instruments made it possible to continue with the policy of extending the terms of interest-bearing liabilities initiated by the BCRA since the beginning of the current administration. In fact, the average residual term of the monetary regulation instruments (LELIQ, Pases and NOTALIQ) stood at almost 30 days, tripling the one in force at the beginning of this year (see Figure 4.4).

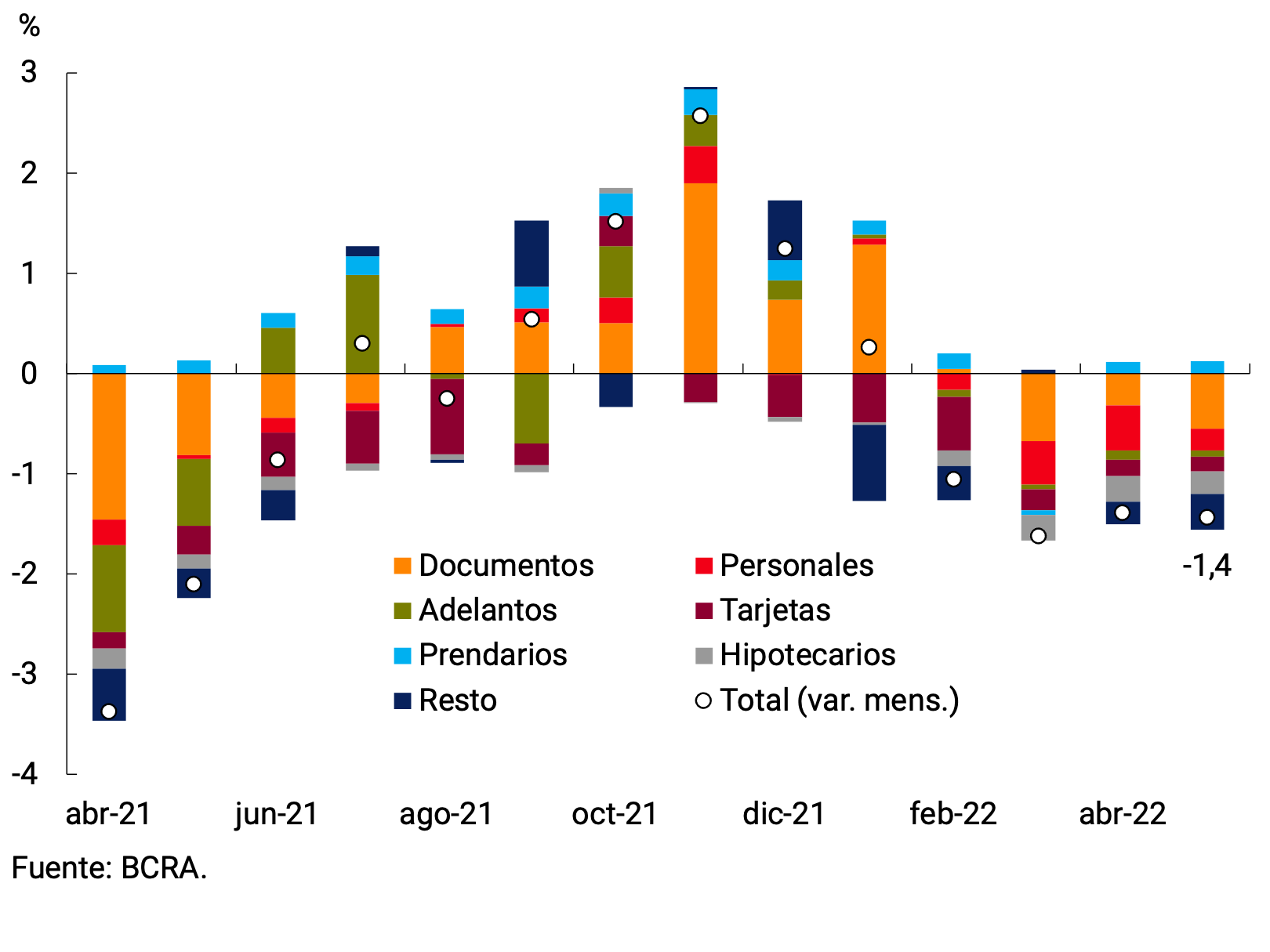

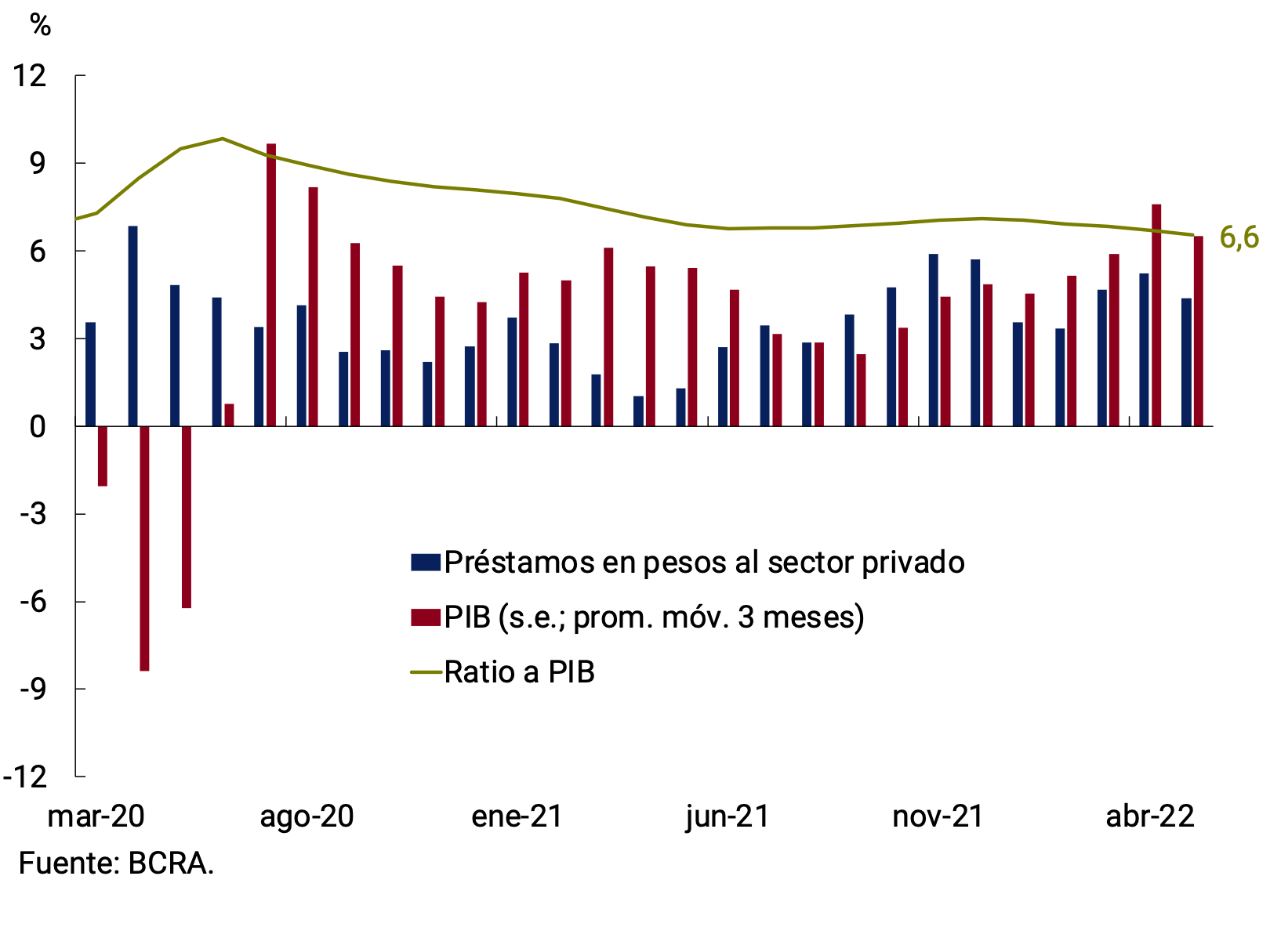

5. Loans to the private sector

In May, loans in pesos to the private sector measured in real terms and without seasonality, would have registered a monthly contraction of 1.4%, its fourth consecutive monthly fall. All loan lines, with the exception of pledges and discounted documents, contributed negatively to the variation for the month (see Figure 5.1). Thus, in the last twelve months, loans in pesos accumulated a contraction at constant prices of 0.3%. The ratio of loans in pesos to the private sector to GDP fell slightly in the month (0.1 p.p.) and stood at 6.6% (see Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.1 | Loans in pesos to the private

sector Real without seasonality; contribution to monthly growth

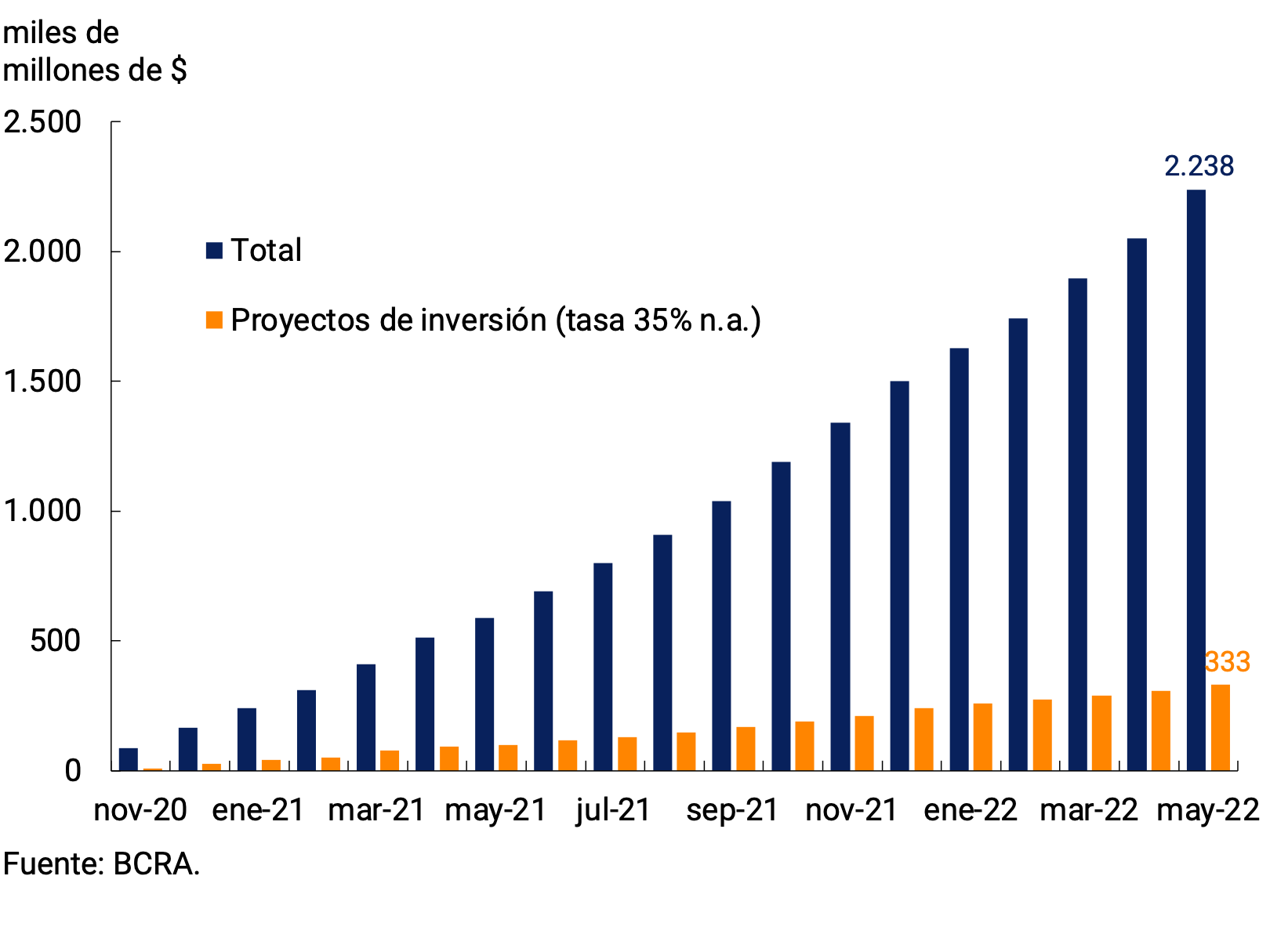

The Financing Line for Productive Investment (LFIP) remained the main vehicle through which loans to Micro, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (MSMEs) were channeled. At the end of May, loans granted under the LFIP accumulated disbursements of approximately $2.238 billion since its inception, an increase of 9.2% compared to last month (see Figure 5.3). As for the destinations of these funds, about 85% of the total disbursed corresponds to working capital financing and the rest to the line that finances investment projects. At the time of publication, the number of companies that accessed the LFIP amounted to 269,308.

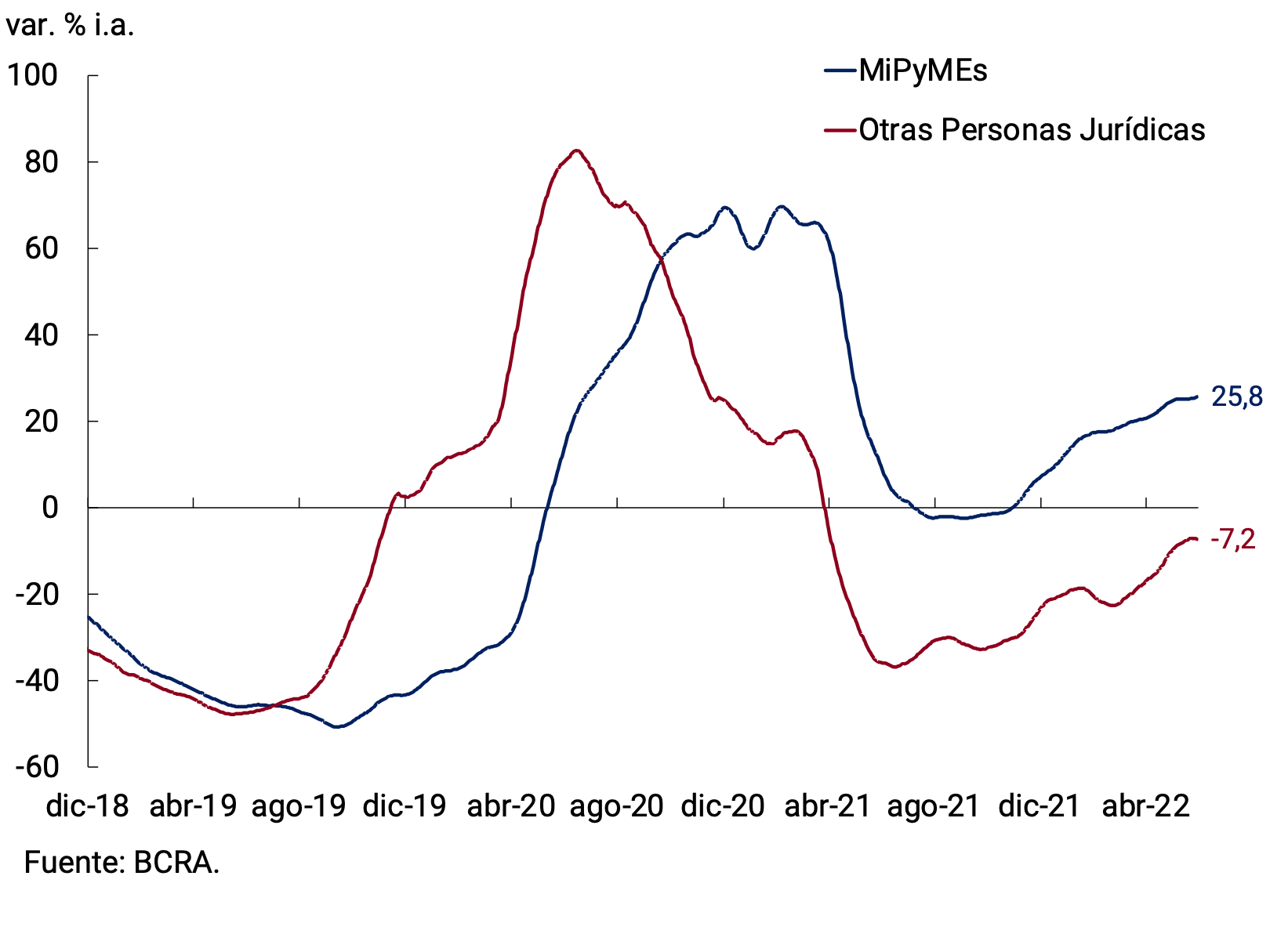

In this way, the LFIP has contributed to sustaining financing for relatively smaller companies. In fact, distinguishing trade credit by type of debtor, it can be seen that at constant prices and in year-on-year terms, credit to MSMEs would have grown by just over 25.8%, while credit to large companies showed a contraction of about 7.2% compared to a year ago (see Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.3 | Financing granted through the Productive Investment Financing Line (LFIP)

Accumulated disbursed amounts; data at the end of the month

However, mainly commercial lines would have exhibited a fall of 2.1% s.e. at constant prices in May, standing 9.9% above the record of a year ago. This dynamic was homogeneous by type of financing. In fact, financing granted through current account advances would have registered a monthly contraction of 0.6% s.e. at constant prices (+16.9% y.o.y.), while the documents would have shown a decrease of 2.1% s.e. in real terms (+14.1% y.o.y.). The evolution of documents was explained by the fall in those instrumented with a single signature, which was partially offset by the growth of discounted documents.

Among loans associated with consumption, financing instrumented with credit cards would have fallen 0.5% s.e. in real terms, standing 12.1% below the level of a year ago. Meanwhile, personal loans would also have exhibited a contraction of 1.3% per month at constant prices and are 3.9% below the level of May 2021. The interest rate on personal loans rose in May to 59.0% n.a. (77.8% y.a.), increasing by almost 1.0 p.p. compared to April.

As for lines with real collateral, collateral loans would have registered an increase in real terms (1.9% s.e.) and in year-on-year terms they would have accumulated a growth of 40.3%. On the other hand, the balance of mortgage loans would have registered a fall of 3.3% s.e. at constant prices in the month, accumulating a contraction of around 16% in the last twelve months.

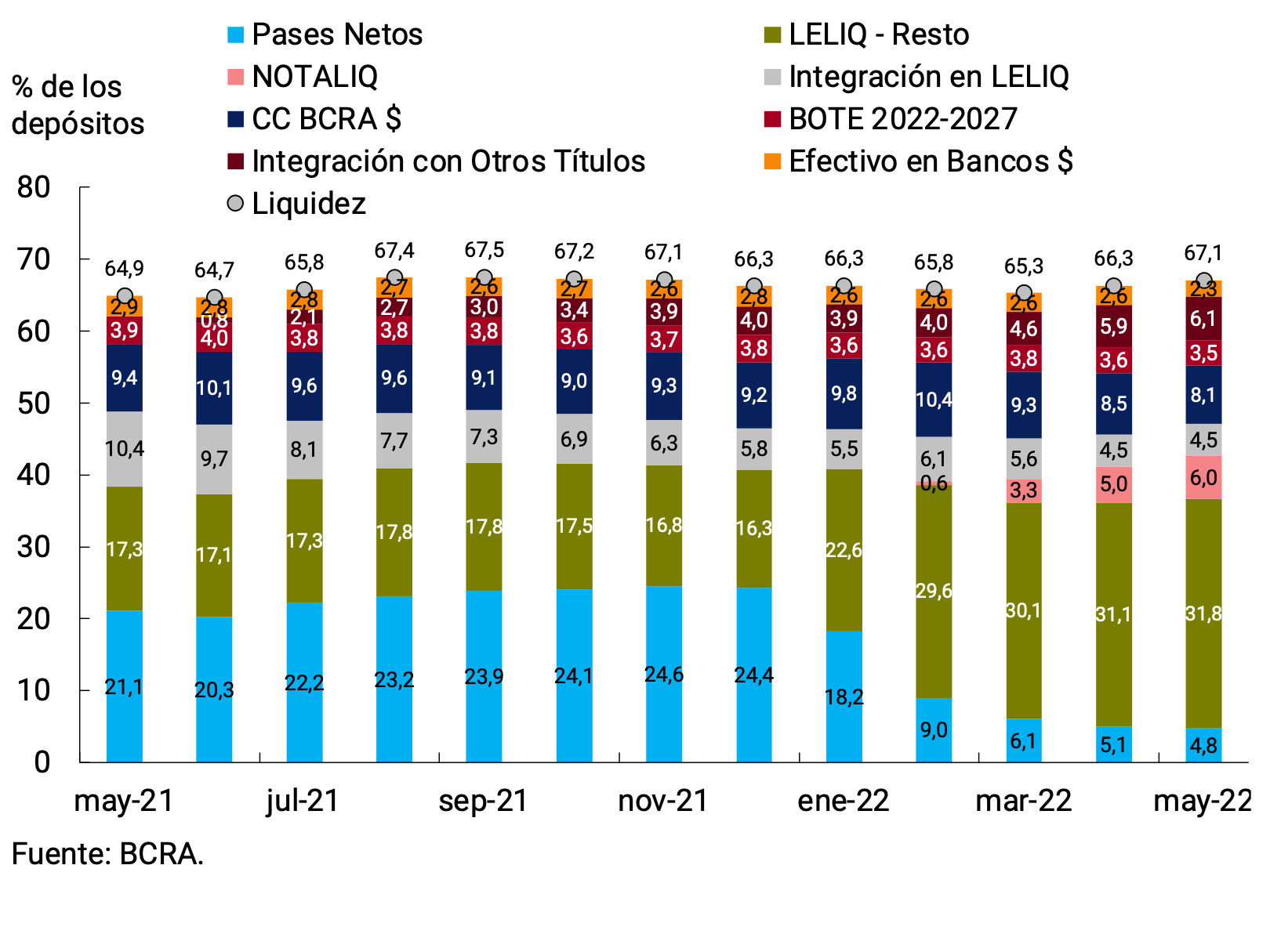

6. Liquidity in pesos of financial institutions

In May, ample bank liquidity in local currency5 averaged 67.1% of deposits, standing 0.8 p.p. above the April level. Thus, it remains at historically high levels.

In terms of the composition of bank liquidity, there was an increase in the holding of LELIQ (in particular, those that are not used for the integration of minimum cash), NOTALIQ and public securities admitted for integration. On the other hand, the balance of passive passes fell again, as did current accounts at the BCRA (see Figure 6.1).

Regarding regulatory changes with minimal cash impact, it was provided that the requirement associated with deposits in pesos in accounts of payment service providers that offer payment accounts (PSPOCP) in which their customers’ funds are deposited will be determined based on the average of daily balances recorded at the end of each day during each calendar month6.

In turn, it is worth mentioning that on May 23, the settlement of the first auction of the new National Treasury Bond in Pesos maturing May 23, 2027 (BOTE 2027) admitted for the integration of minimumcash 7 to replace the BOTE 2022 that matured on May 21, was carried out. Thus, it is expected that in June there will be an increase in integration with this bond, when the new balance fully impacts the average of the month.

7. Foreign currency

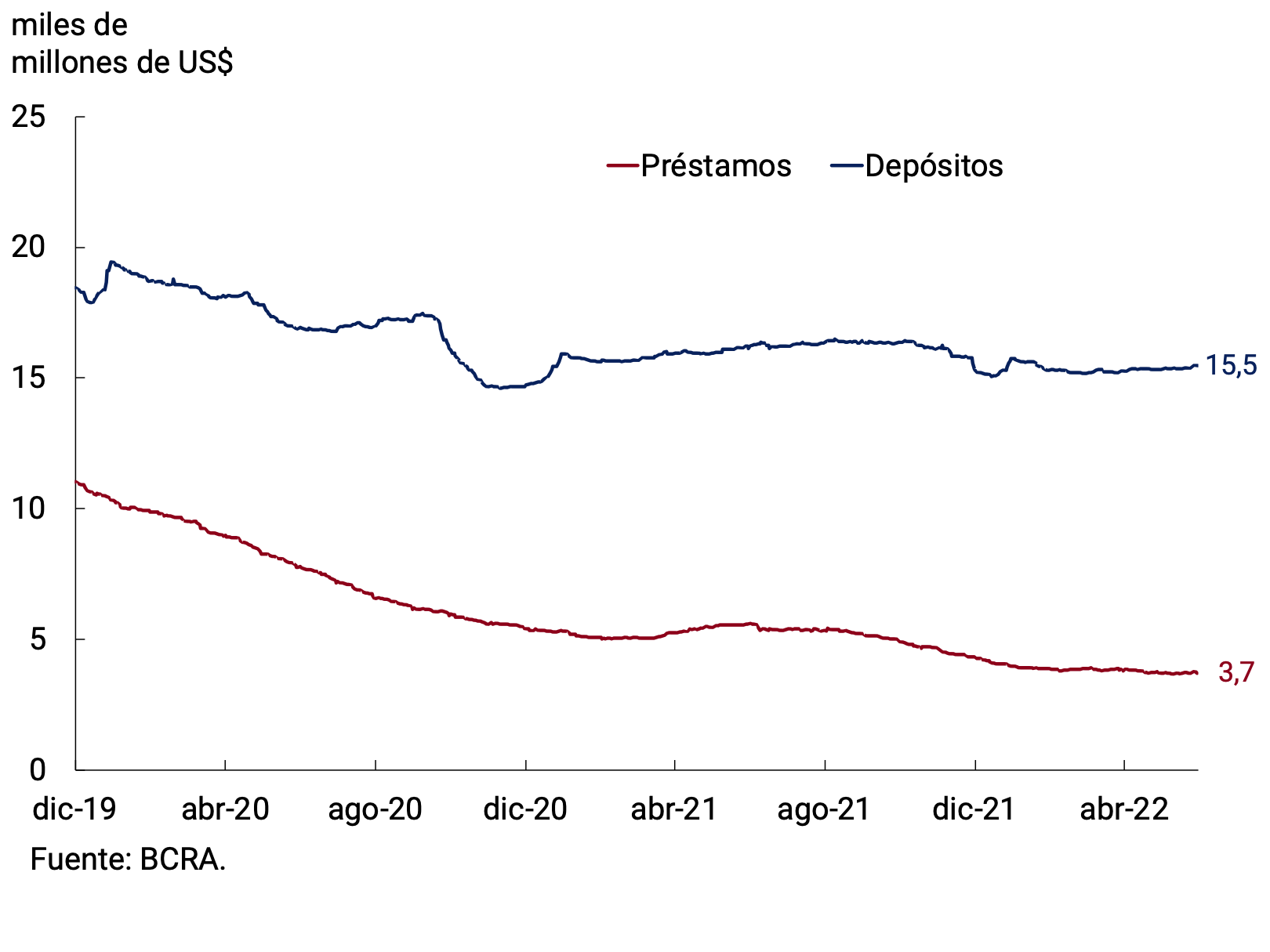

In the foreign currency segment, in May, the main assets and liabilities of financial institutions presented limited variations. In fact, the average monthly balance of private sector deposits stood at US$15,386 million, which meant an increase of US$52 million compared to April. This slight increase was driven by demand deposits and, to a lesser extent, by time deposits of individuals. On the other hand, the average monthly balance of loans to the private sector was US$3,713 million, which implied a drop of US$65 million compared to the previous month (see Figure 7.1).

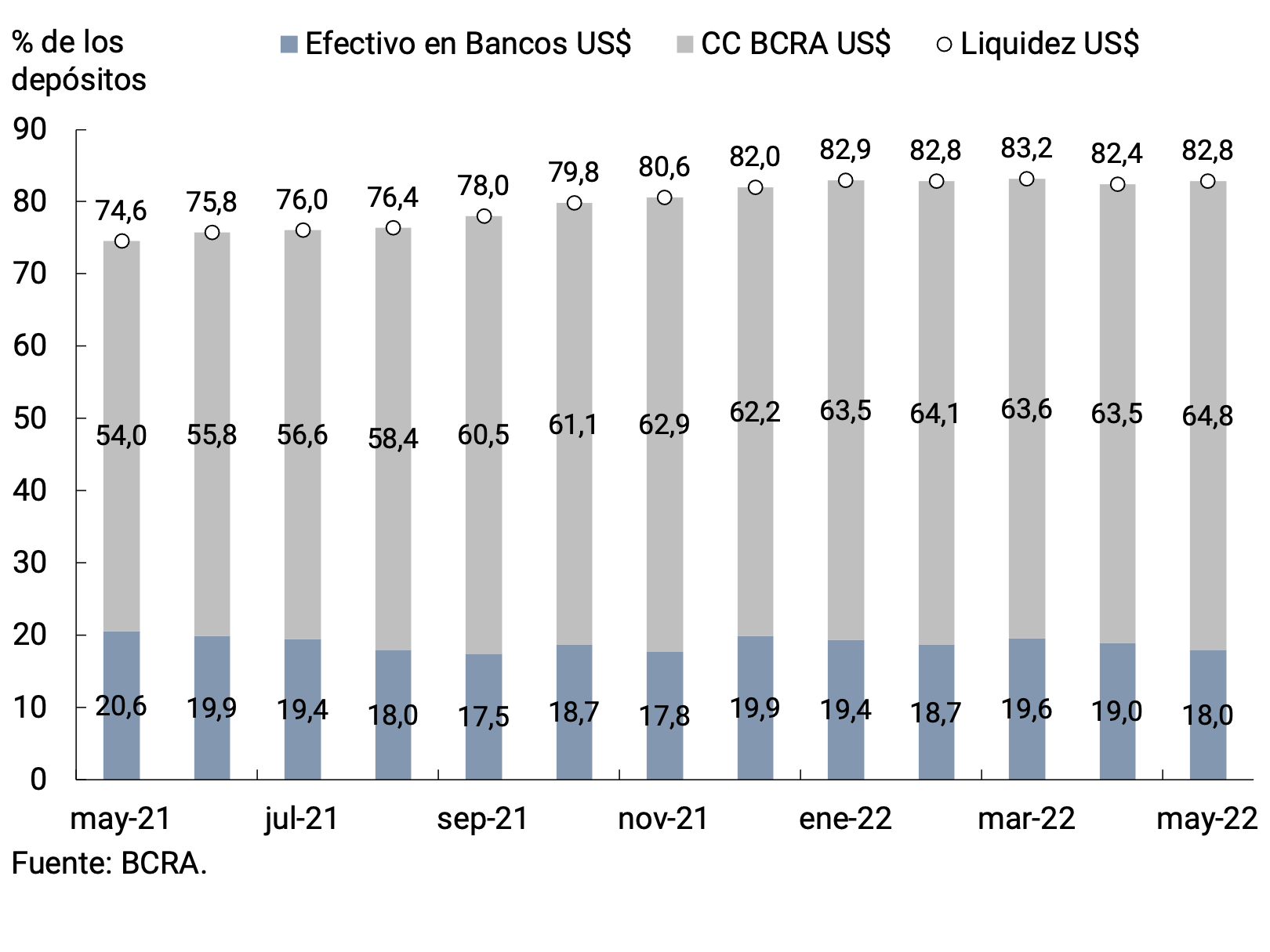

The liquidity of financial institutions in the foreign currency segment stood at 82.8% of deposits in May, registering an increase (0.3 p.p.) compared to April. Among its components, the observed increase was linked to the variation in current accounts at the BCRA, which was partially offset by a fall in cash in banks (see Figure 7.2).

During May, some regulatory changes took place in foreign exchange matters. First, the creation of foreign exchange access regimes for the incremental production of oil and natural gas was determined. They aim to generate certainty and incentives to promote investments and increase production in the hydrocarbon sector. Access to foreign currency may be used to pay principal and interest on commercial or financial liabilities abroad, including liabilities with non-resident related companies, and/or profits and dividends, and/or repatriation of direct investments by non-residents. This right may be transferred in whole or in part to direct suppliers of the beneficiary for the same purposes available to the operator8.

Likewise, in the first days of June, the BCRA approved the regime for the availability of foreign currency for exporters of services9. Thus, individuals who export services linked to the knowledge economy will be able to have up to US$12,000 per year in accounts in local financial institutions without the requirement of settlement in pesos. The benefit extends to companies in the sector, which will have foreign currency available for salary payment for a percentage of the increase in foreign sales they make this year compared to 2021.

On the other hand, the conditions under which access to the foreign exchange market is given to make payments for imports of goods to those that have a SIMI category B or C declaration in force were made more flexible, provided that the goods paid correspond to pharmaceutical products and/or their production inputs and inputs that are used for the local manufacture of goods necessary for the construction of infrastructure works contracted by the National Public Sector. Finally, access to the foreign exchange market was enabled, with certification of the entry of new financial indebtedness abroad, in the case of capital payments prior to the maturity of commercial debts for the importation of goods and services, under certain conditions detailed in regulation10.

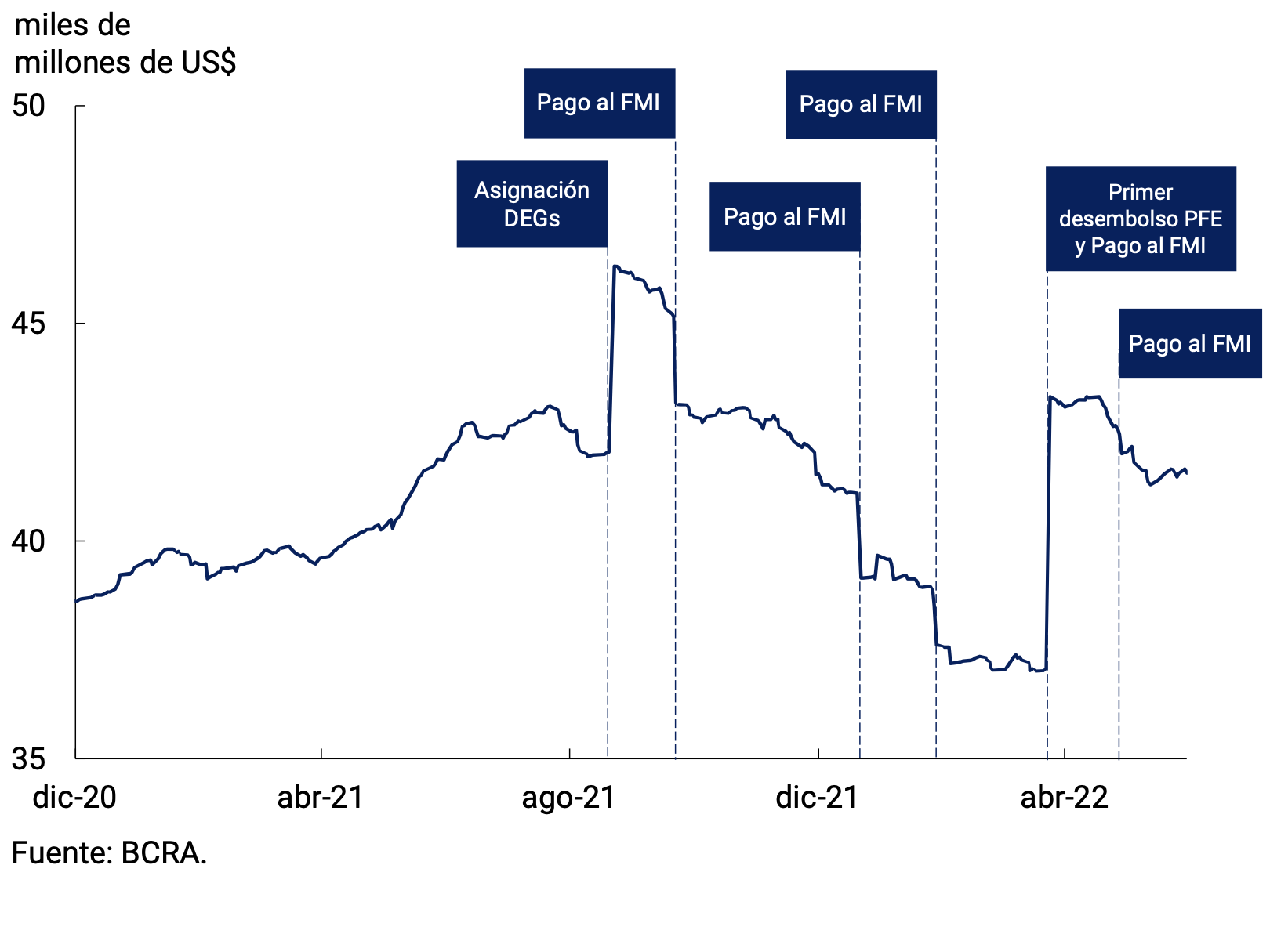

The BCRA’s International Reserves ended May with a balance of US$41,561 million, reflecting a decrease of US$446 million compared to the end of April (see Figure 7.3). The decrease was explained by several factors. In the month, the interest payment made to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for US$364 million had a negative impact, as well as the loss on valuation of net foreign assets and the variation in dollar balances in current account at the BCRA. These effects were partially offset by the net purchase of foreign currency from the private sector, which contributed positively in the month (US$784 million).

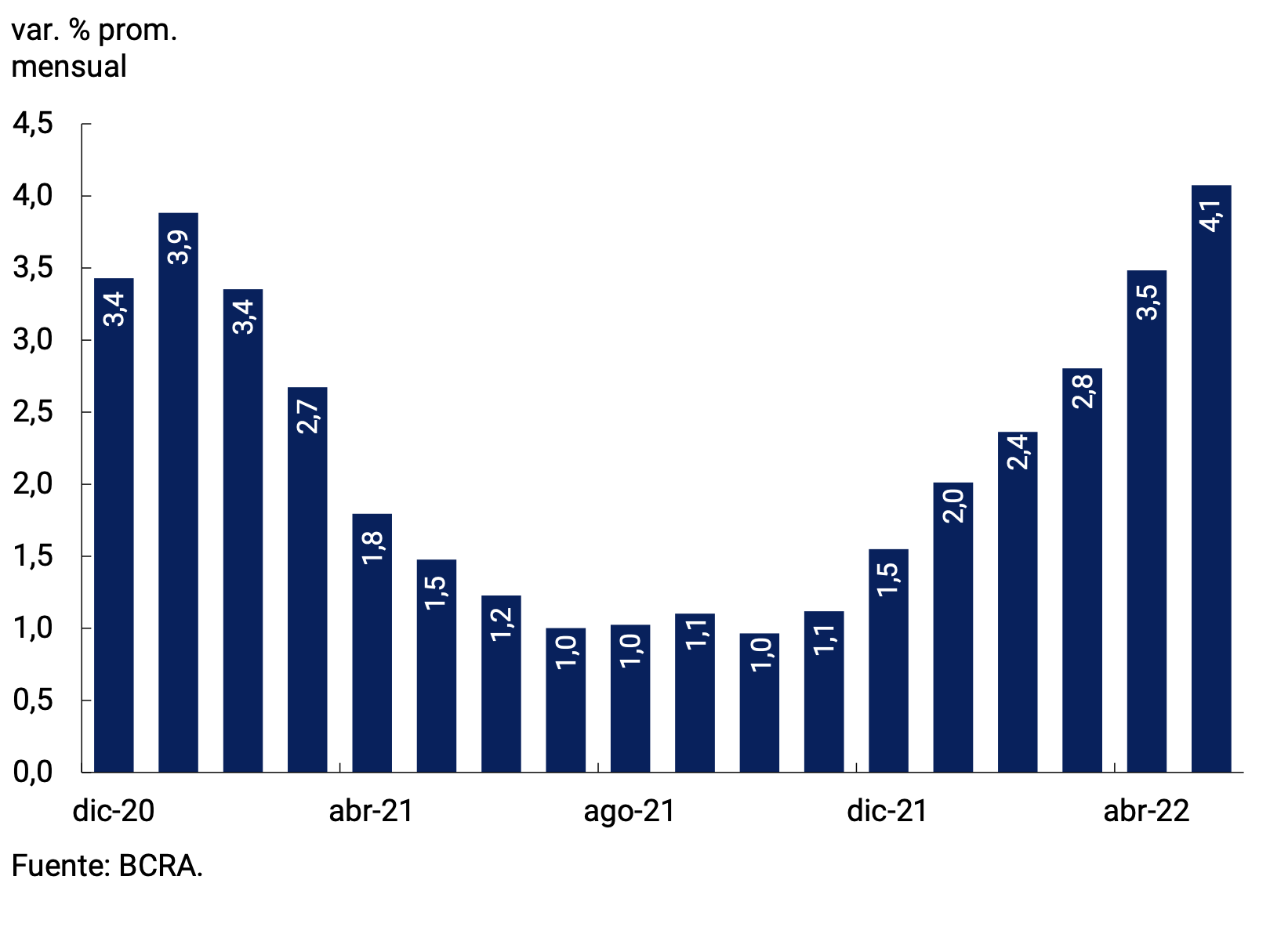

Finally, the bilateral nominal exchange rate (TCN) against the U.S. dollar increased 4.1% in May to settle, on average, at $117.79/US$ (see Figure 7.4). Given that the rate of depreciation of the domestic currency accelerated throughout the month, the peak variation in April was higher (4.2%). In this way, the rate of depreciation of the domestic currency is gradually converging to levels more compatible with the inflation rate, with the aim of preserving the Multilateral Real Exchange Rate Index (ITCRM) around competitive levels.

Glossary

ANSES: National Social Security Administration.

BADLAR: Interest rate on fixed-term deposits for amounts greater than one million pesos and a term of 30 to 35 days.

BCRA: Central Bank of the Argentine Republic.

BM: Monetary Base, includes monetary circulation plus deposits in pesos in current account at the BCRA.

CC BCRA: Current account deposits at the BCRA.

CER: Reference Stabilization Coefficient.

NVC: National Securities Commission.

SDR: Special Drawing Rights.

EFNB: Non-Banking Financial Institutions.

EM: Minimum Cash.

FCI: Common Investment Fund.

A.I.: Year-on-year .

IAMC: Argentine Institute of Capital Markets

CPI: Consumer Price Index.

ITCNM: Multilateral Nominal Exchange Rate Index

ITCRM: Multilateral Real Exchange Rate Index

LEBAC: Central Bank bills.

LELIQ: Liquidity Bills of the BCRA.

LFIP: Financing Line for Productive Investment.

M2 Total: Means of payment, which includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and demand deposits in pesos from the public and non-financial private sector.

Private M2: Means of payment, includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and demand deposits in pesos from the non-financial private sector.

Private transactional M2: Means of payment, includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and non-remunerated demand deposits in pesos from the non-financial private sector.

M3 Total: Broad aggregate in pesos, includes the current currency held by the public, cancelling checks in pesos and the total deposits in pesos of the public and non-financial private sector.

Private M3: Broad aggregate in pesos, includes the working capital held by the public, cancelling checks in pesos and the total deposits in pesos of the non-financial private sector.

MERVAL: Buenos Aires Stock Market.

MM: Money Market.

N.A.: Annual nominal

E.A.: Annual Effective

NOCOM: Cash Clearing Notes.

ON: Negotiable Obligation.

GDP: Gross Domestic Product.

P.B.: basis points.

p.p.: percentage points.

MSMEs: Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises.

ROFEX: Rosario Term Market.

S.E.: No seasonality

SISCEN: Centralized System of Information Requirements of the BCRA.

TCN: Nominal Exchange Rate

IRR: Internal Rate of Return.

TM20: Interest rate on fixed-term deposits for amounts greater than 20 million pesos and a term of 30 to 35 days.

TNA: Annual Nominal Rate.

UVA: Unit of Purchasing Value

References

1 Corresponds to private M2 excluding interest-bearing demand deposits from companies and financial service providers. This component was excluded since it is more similar to a savings instrument than to a means of payment.

3 Financial Services Providers, Companies and Individuals with deposits of more than $10 million.

4 Includes the working capital held by the public and the deposits in pesos of the non-financial private sector (demand, time and others).

5 Includes current accounts at the BCRA, cash in banks, balances of net passes arranged with the BCRA, holdings of LELIQ, and bonds eligible for reserve requirements.

8 Decree 277/2022 of the National Executive Branch.