Política Monetaria

Monthly Monetary Report

March

2022

Monthly report on the evolution of the monetary base, international reserves and foreign exchange market.

1. Executive Summary

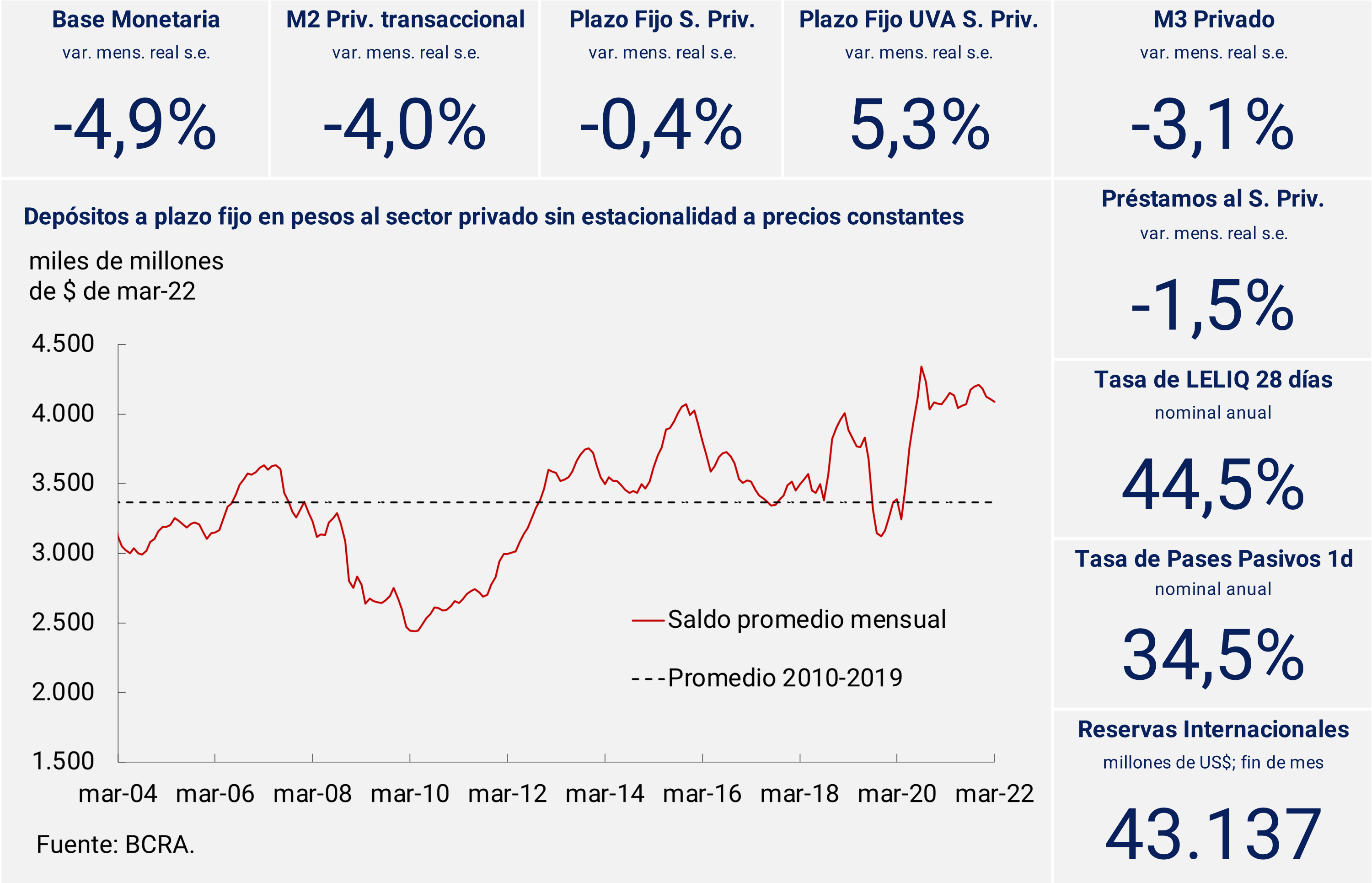

The broad monetary aggregate, private M3, at constant prices would have registered a monthly decrease of 3.1% s.e. in March. This dynamic was explained by the behavior of the means of payment, while fixed-term deposits in the private sector remained relatively stable, remaining around the highest levels in recent decades. Within the different savings instruments in pesos, the growth of placements adjustable by CER stood out.

In March, the BCRA decided to raise the benchmark interest rates for the third time this year. Likewise, to guarantee the transmission of the new rates to depositors and to tend towards positive returns for savings in domestic currency, the minimum guaranteed interest rates of savings instruments in pesos were also modified. Likewise, in March the BCRA decided to extend until September 30 the Financing Line for Productive Investment. In this way, a new stage begins where, once the central objective of protecting the productive apparatus during the pandemic has been fulfilled, the LFIP is now aimed at stimulating productive development as a way to contribute to expanding the aggregate supply. Both the increase in reference interest rates and the measures that tend to promote productive credit are intended to contribute to the process of controlling inflation.

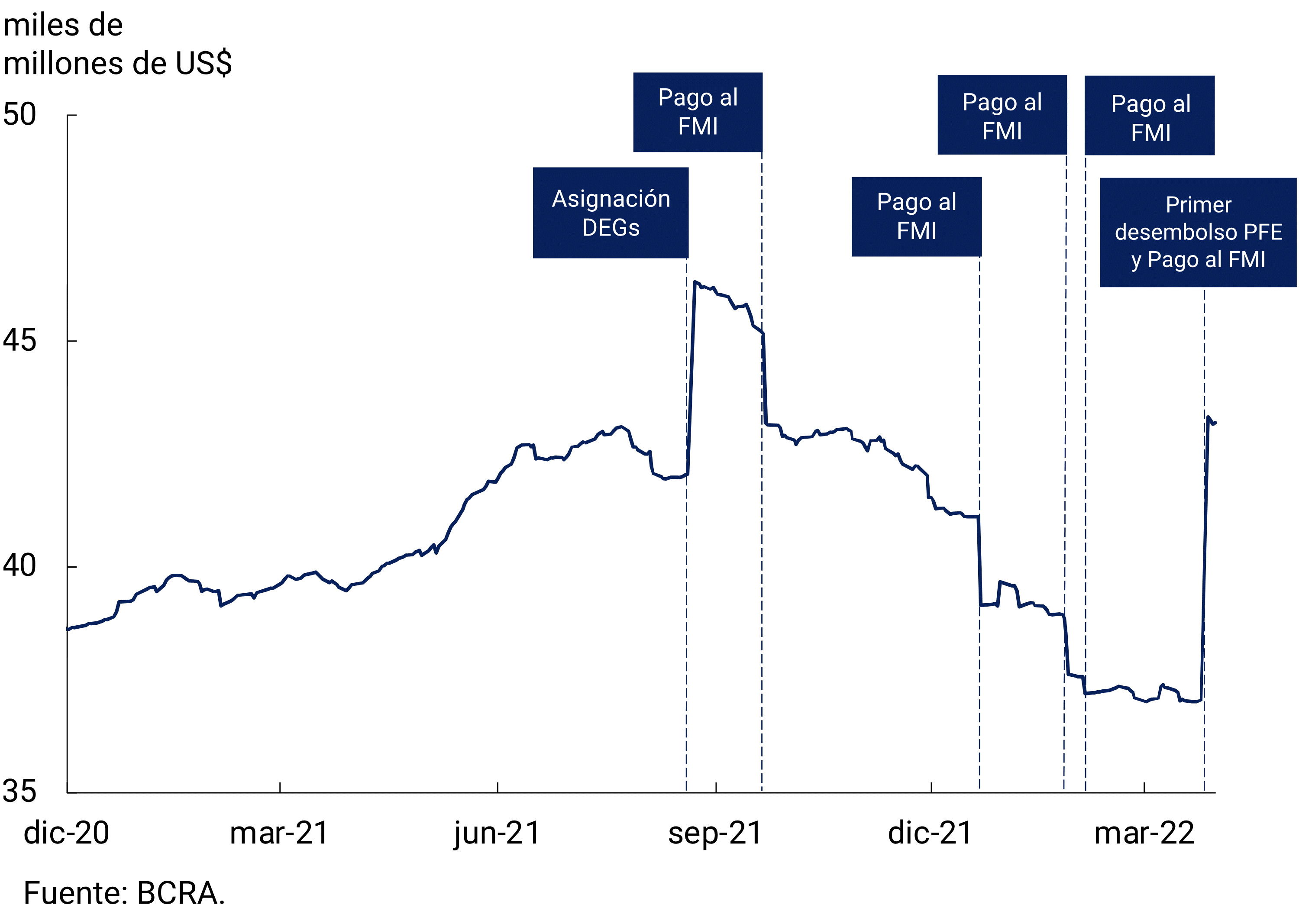

On the other hand, the National Government recently reached an agreement with the IMF for an extended facilitiesprogram 1, which allows the refinancing of the large obligations of 2022 and 2023 set out in the Stand-By Agreement signed in 2018. In this context, the first disbursement of the new program was made during March. These funds made it possible to meet the payment of capital scheduled for the month of about US$2,800 million, while contributing to strengthen the level of International Reserves. The level of the latter, during March, was also positively influenced by the net purchase of foreign currency by the BCRA.

2. Payment methods

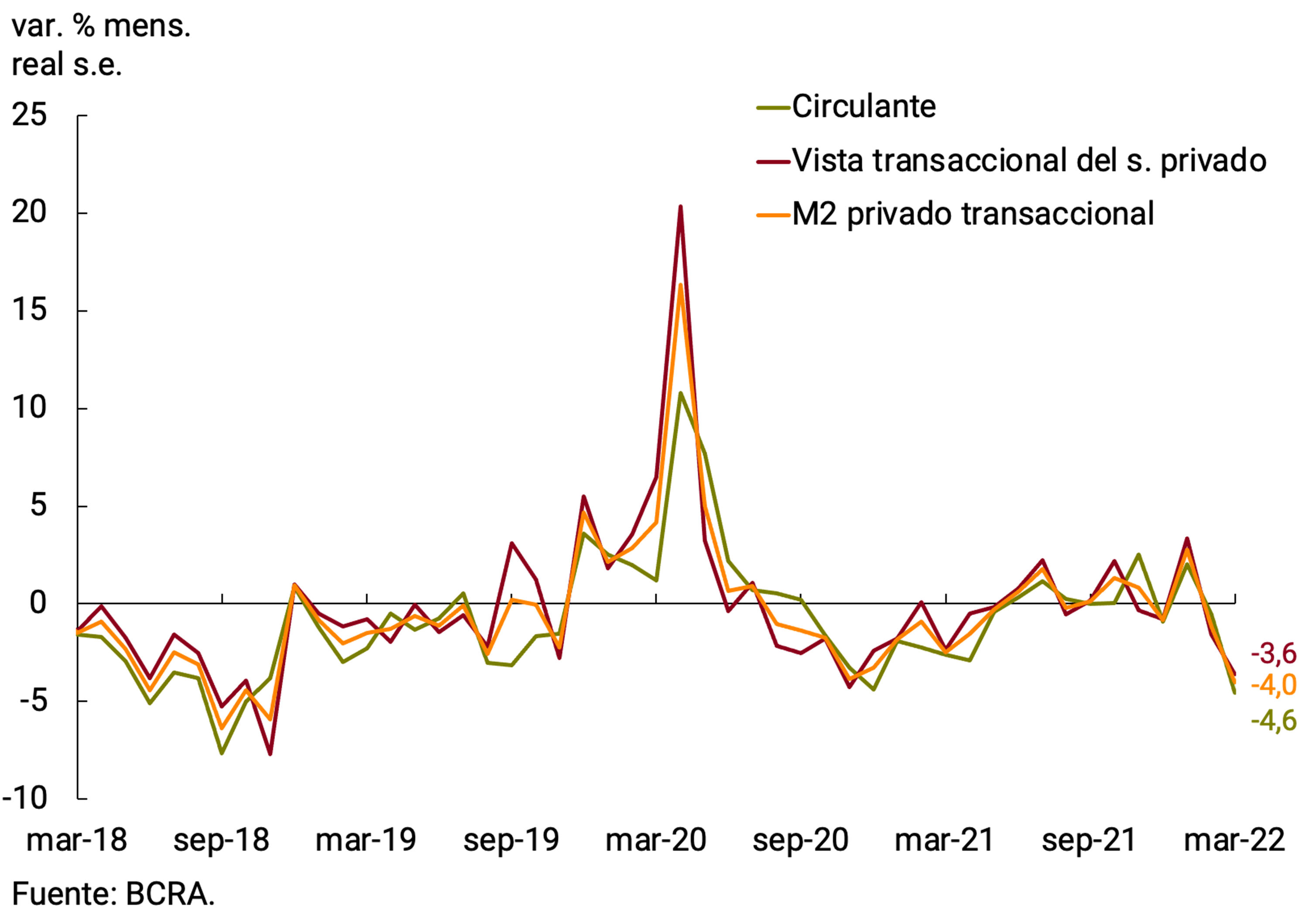

Means of payment (private transactional M22), in real terms3 and seasonally adjusted (s.e.), would have registered a decrease of 4.0% in March, the largest contraction since the end of 2018 (see Figure 2.1). This fall was due to the behavior of both non-interest-bearing demand deposits and working capital held by the public. In the year-on-year comparison, and at constant prices, the transactional private M2 would be just 0.7% below the level of the same month last year.

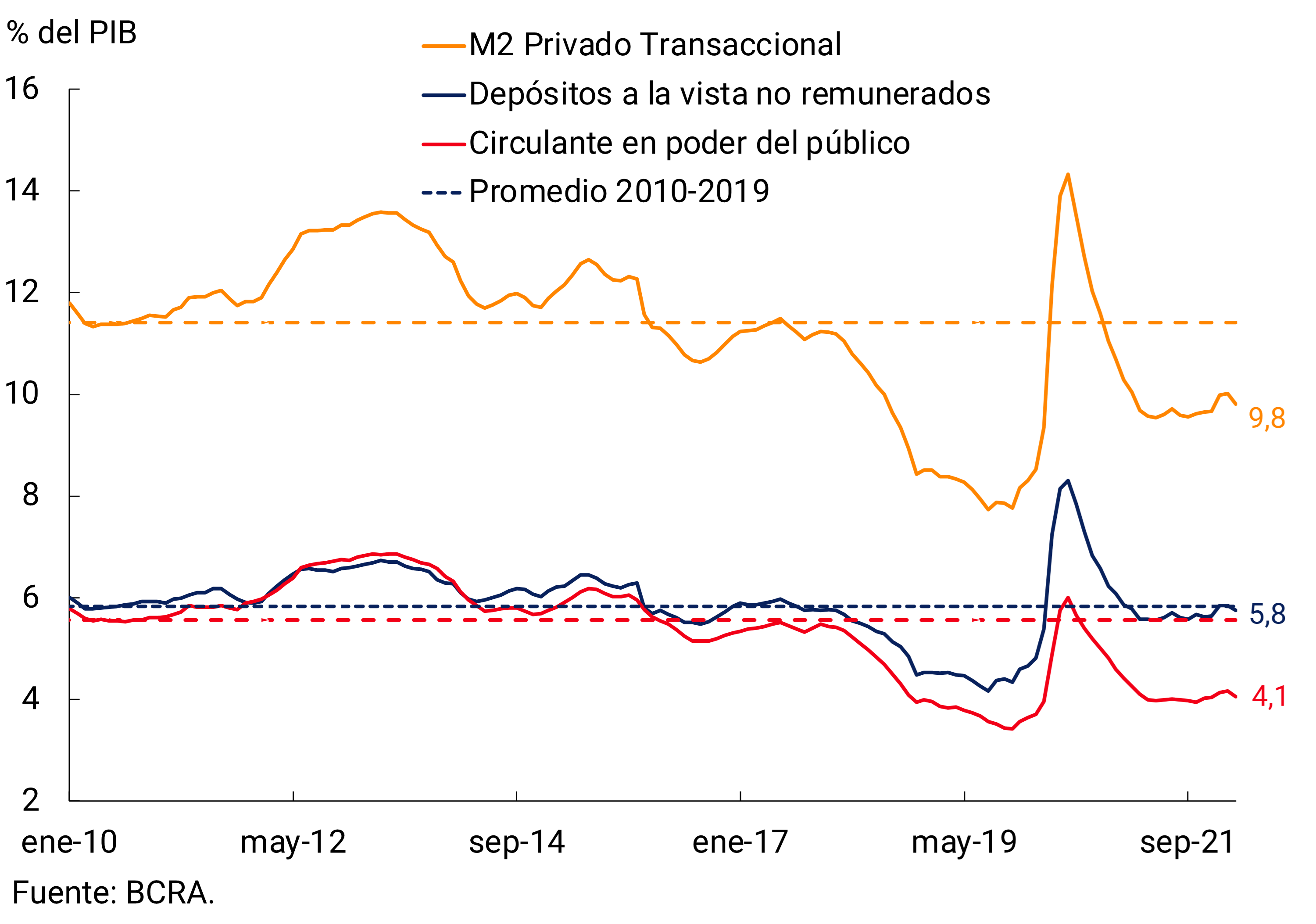

In terms of Output, the transactional private M2 would have registered a decrease (0.2 p.p.) compared to February and, thus, would continue to be below the average record for the period 2010-2019 (see Chart 2.2). In terms of its components, as already commented in previous editions, the circulating currency held by the public remained around its lowest records of the last 15 years and 1.5 p.p. below the average verified between 2010 and 2019. The low level of demand for banknotes and coins is partly linked to a higher relative demand for demand deposits, given the growing use of electronic means of payment in recent years. As a result of the latter, private sector transactional demand deposits were positioned around the average recorded between 2010 and 2019.

3. Savings instruments in pesos

At the end of March, the Board of Directors of the BCRA decided to raise the minimum guaranteed interest rates on fixed-term deposits for the third time this year4. The measure is in line with its strategy of establishing a path of interest rates that tend to achieve returns in line with the evolution of inflation. Thus, the minimum guaranteed rate for placements of individuals for up to an amount of $10 million was increased from 41.5% n.a. to 43.5% n.a. (53.3% y.a.). For the rest of the depositors in the financial system, the interest rate also rose by 2.0 p.p. to 41.5% (50.4% y.a.).

In March, the private sector’s fixed-term deposits in pesos remained unchanged in real and seasonally adjusted terms (-0.4%). Thus, term placements persisted around the highest levels in recent decades. As a percentage of GDP, they stood at 6.9%, 1.4 p.p. above the average record of 2010-2019 and 0.9 p.p. below the peak of mid-2020.

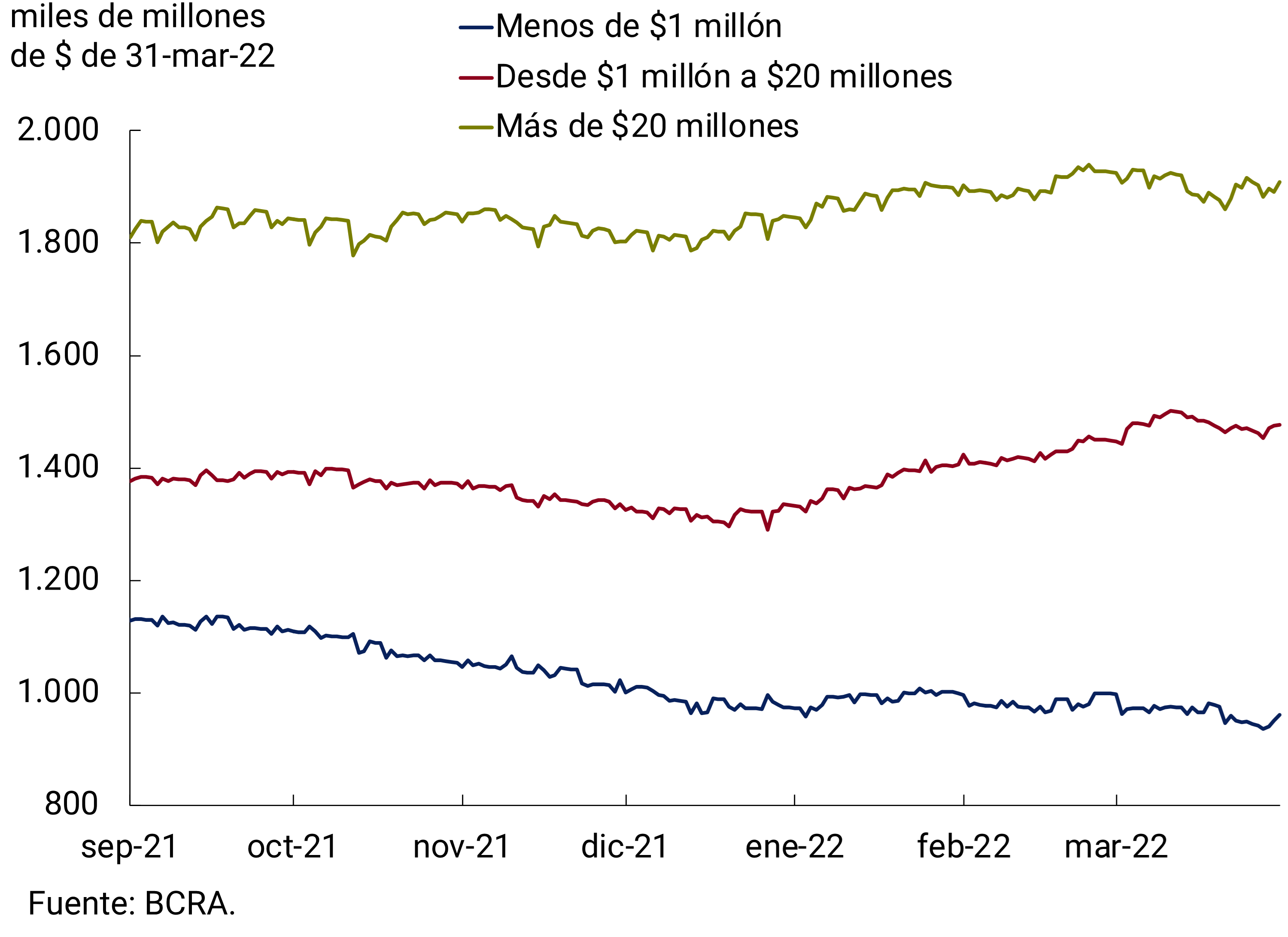

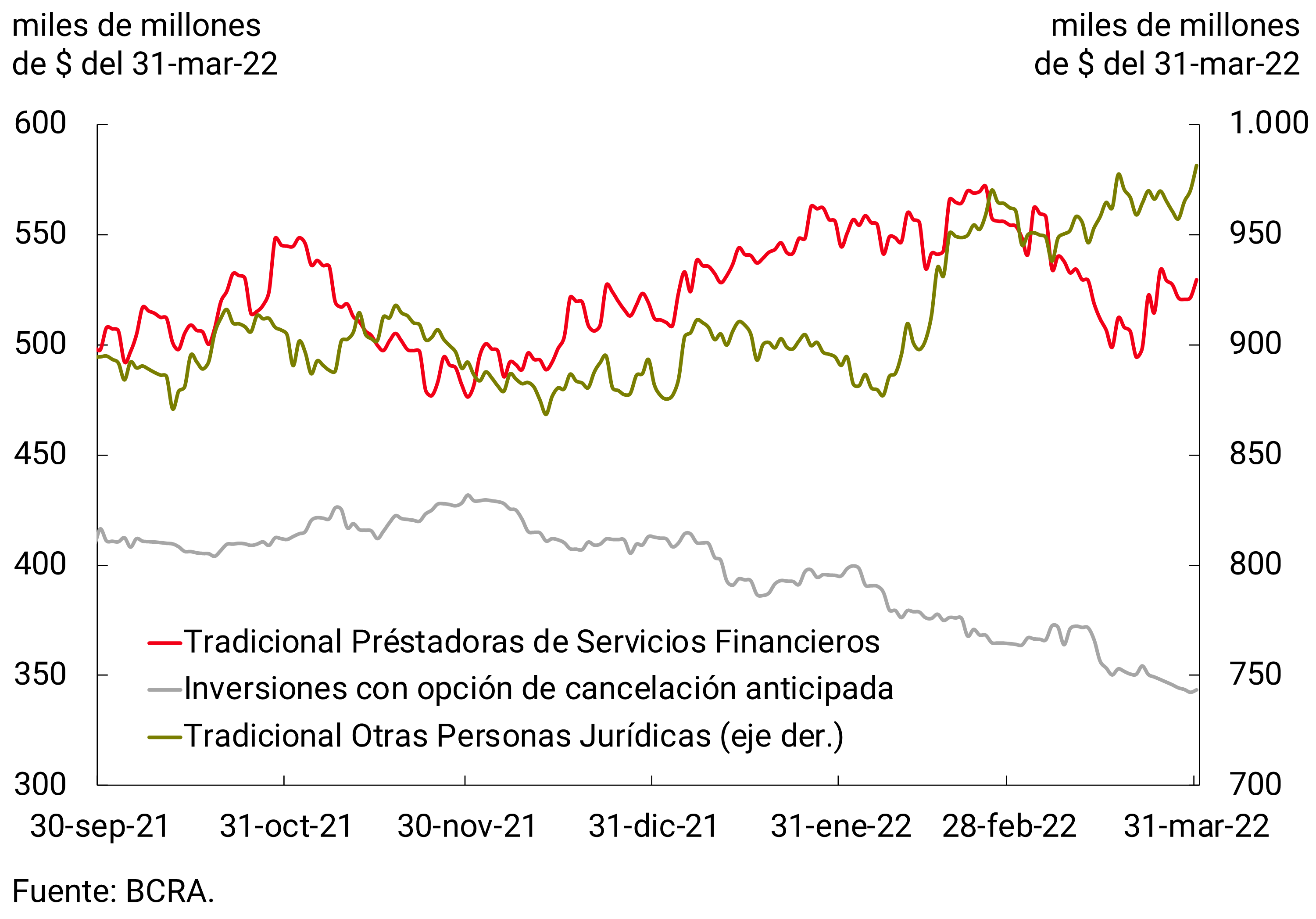

Analysing the evolution of term placements by strata of amount, a heterogeneous behaviour can be observed. In this sense, deposits of less than $1 million at constant prices presented a monthly contraction of practically -3% in real terms s.e. Deposits of more than $20 million also contracted in the month, although in a more limited magnitude. Meanwhile, deposits of $1 to $20 million, whose main holders are individuals, registered an increase on average in the month, partially offsetting the dynamics of the rest of the strata (see Figure 3.1).

The fall, in real terms, of the wholesale segment was concentrated in the placements of Financial Services Providers (FSPs), in a period in which the assets of the Money Market Mutual Funds (FCI MM), which are the main agents within the PSFs, decreased. Meanwhile, the rest of the legal entities increased, for the second consecutive month, their holdings of fixed-term instruments (see Figure 3.2). The latter could be linked to the lower relative performance of other investment options such as interest-bearing view and FCIs. Finally, Investments with early cancellation option, which cannot be classified by type of holder, continued to show a drop in the month.

Figure 3.1 | Fixed-term deposits in pesos of the private

sector Balance at constant prices by amount stratum

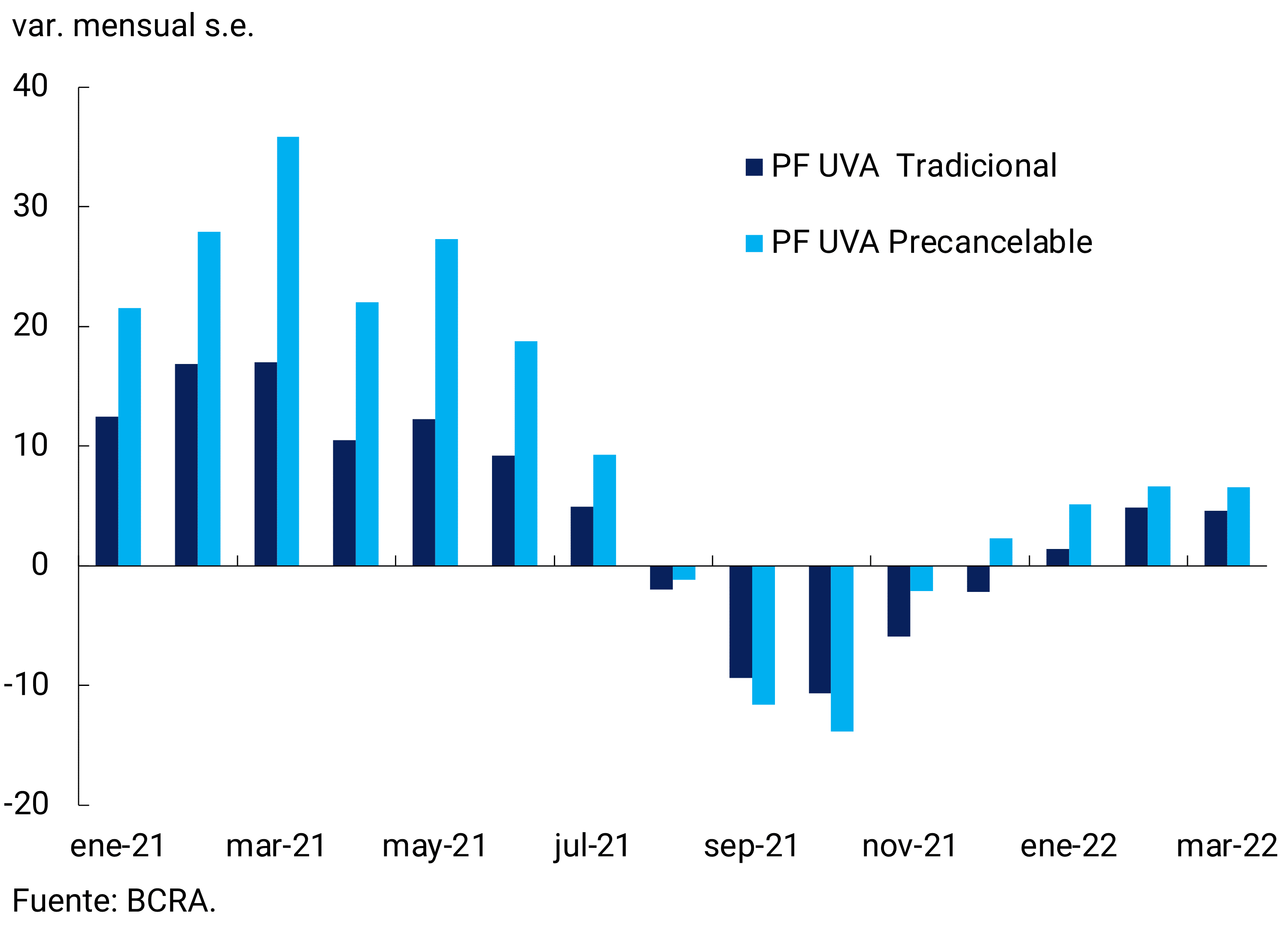

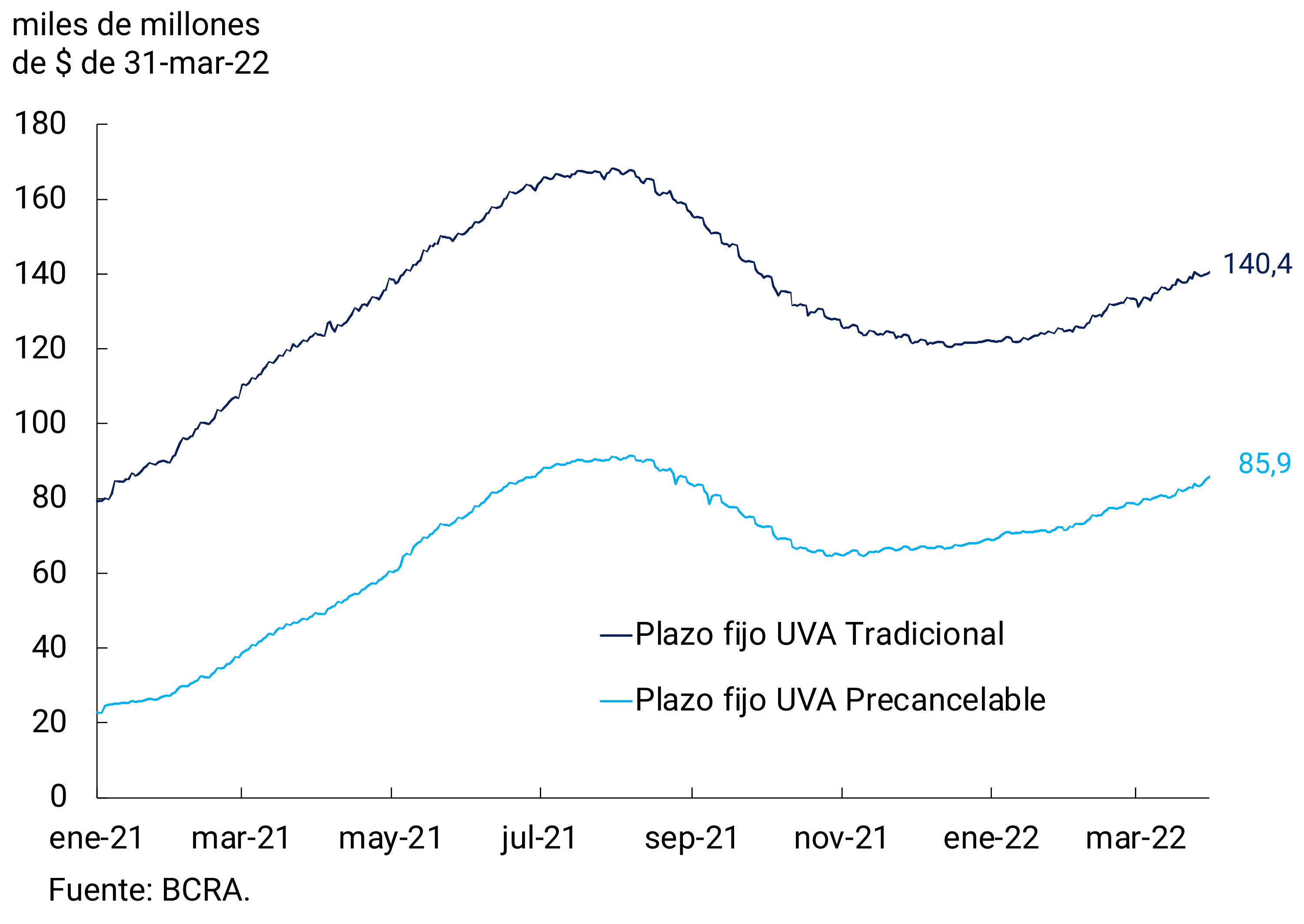

The relative stability of savings instruments in pesos hides a heterogeneous behavior at the instrument level. In fact, fixed-term deposits in traditional pesos made a negative contribution to the variation of the month, which was partially offset by the expansion of deposits adjustable by CER. At constant and seasonally adjusted prices, these placements maintained a growth rate similar to that of the previous month (5.3%). This growth was verified in the case of both traditional and pre-cancellable UVA placements, whose monthly expansion rates stood at 4.7% s.e. and 6.5% s.e. respectively in real terms (see Figures 3.3 and 3.4).

Figure 3.3 | Fixed-term deposits in UVA of the private

sector Var. monthly s.e by type of instrument

However, the broad monetary aggregate, private M36, at constant prices would have registered a monthly decrease of 3.1% s.e. in March, the largest contraction since the end of 2019. Meanwhile, in year-on-year terms, this aggregate would have remained practically unchanged. As a percentage of GDP, it would have stood at 18.2%, 0.3 p.p. below the value of February. However, it remains slightly above the average observed between 2010 and 2019.

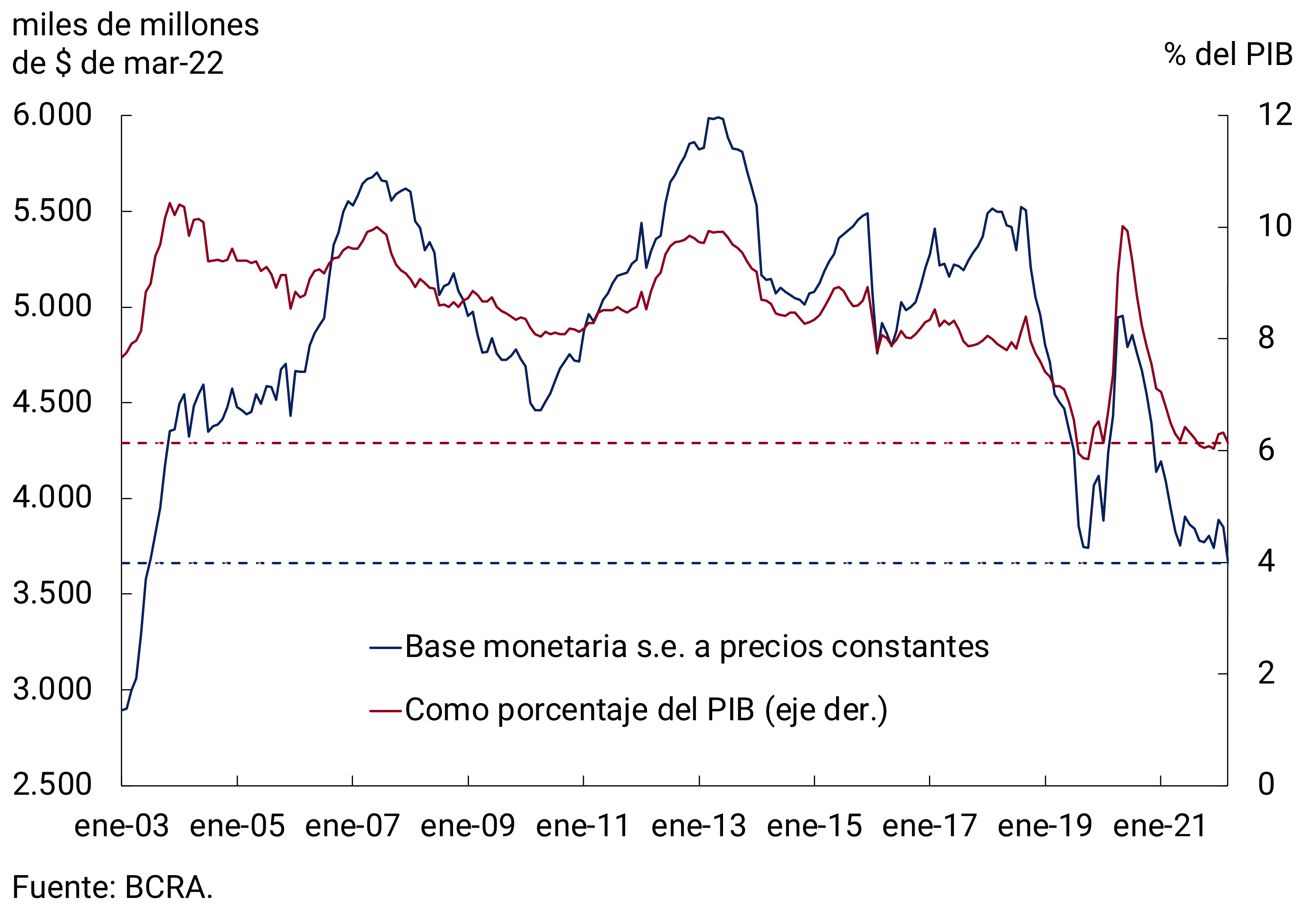

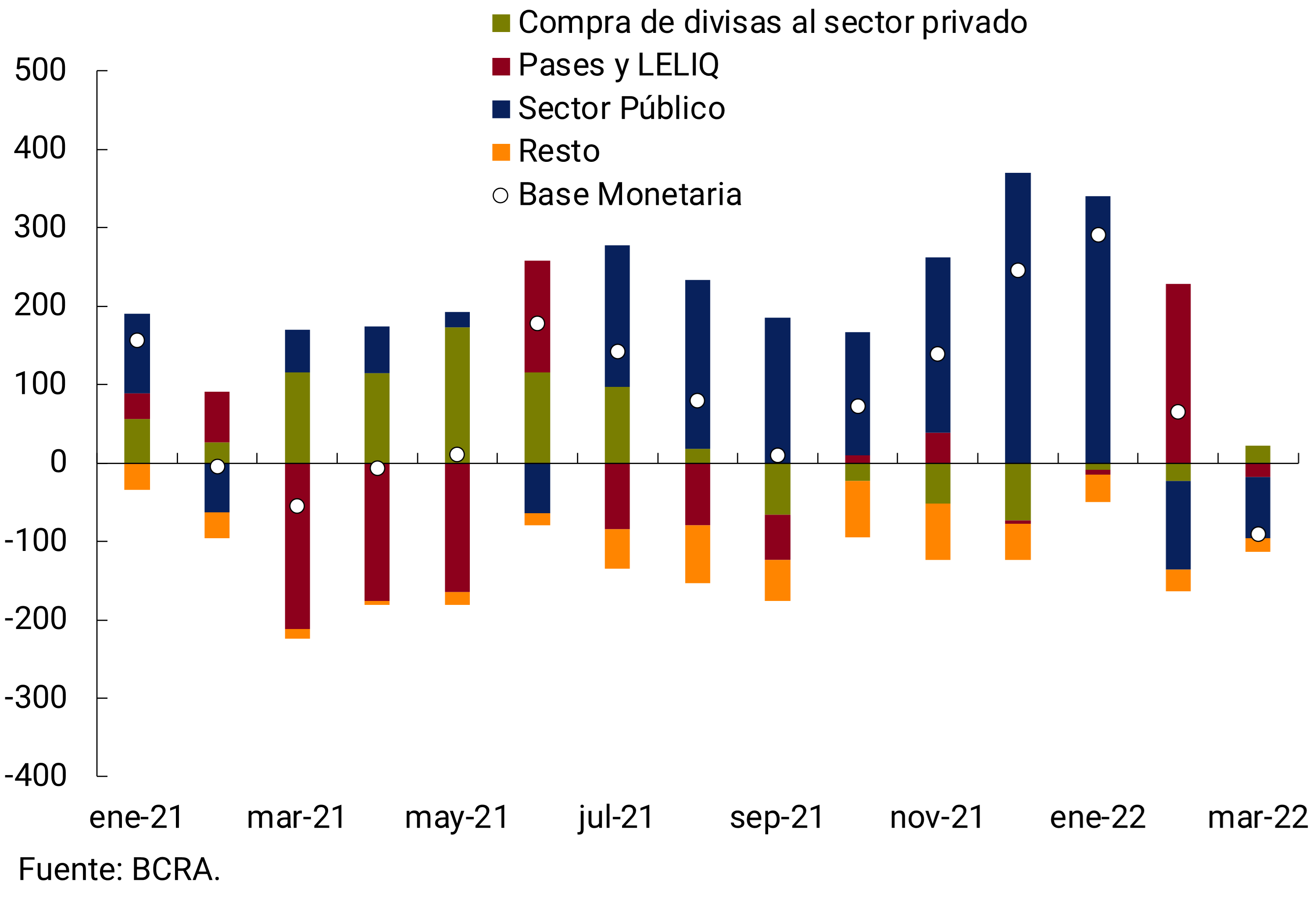

4. Monetary base

In March, the Monetary Base stood at an average of $3,660.3 billion, registering a monthly fall of 2.4% (-$90,677 million) in the original series at current prices. This contraction is the first since April 2021. Adjusted for seasonality and expected inflation for the month, the Monetary Base would have presented a monthly contraction of 4.9%, registering a 7.3% fall in year-on-year terms. As a GDP ratio, the Monetary Base would stand at 6.1%, a figure similar to that of early 2020 and around the lowest values since 2003 (see Figure 4.1).

On the supply side, the monthly contraction of the monetary base was mainly explained by public sector operations, together with the absorption of liquidity through monetary regulation instruments, although the latter had a lesser impact. It should be noted that the only factor of expansion in the month was the purchase of foreign currency from the private sector (see Figure 4.2).

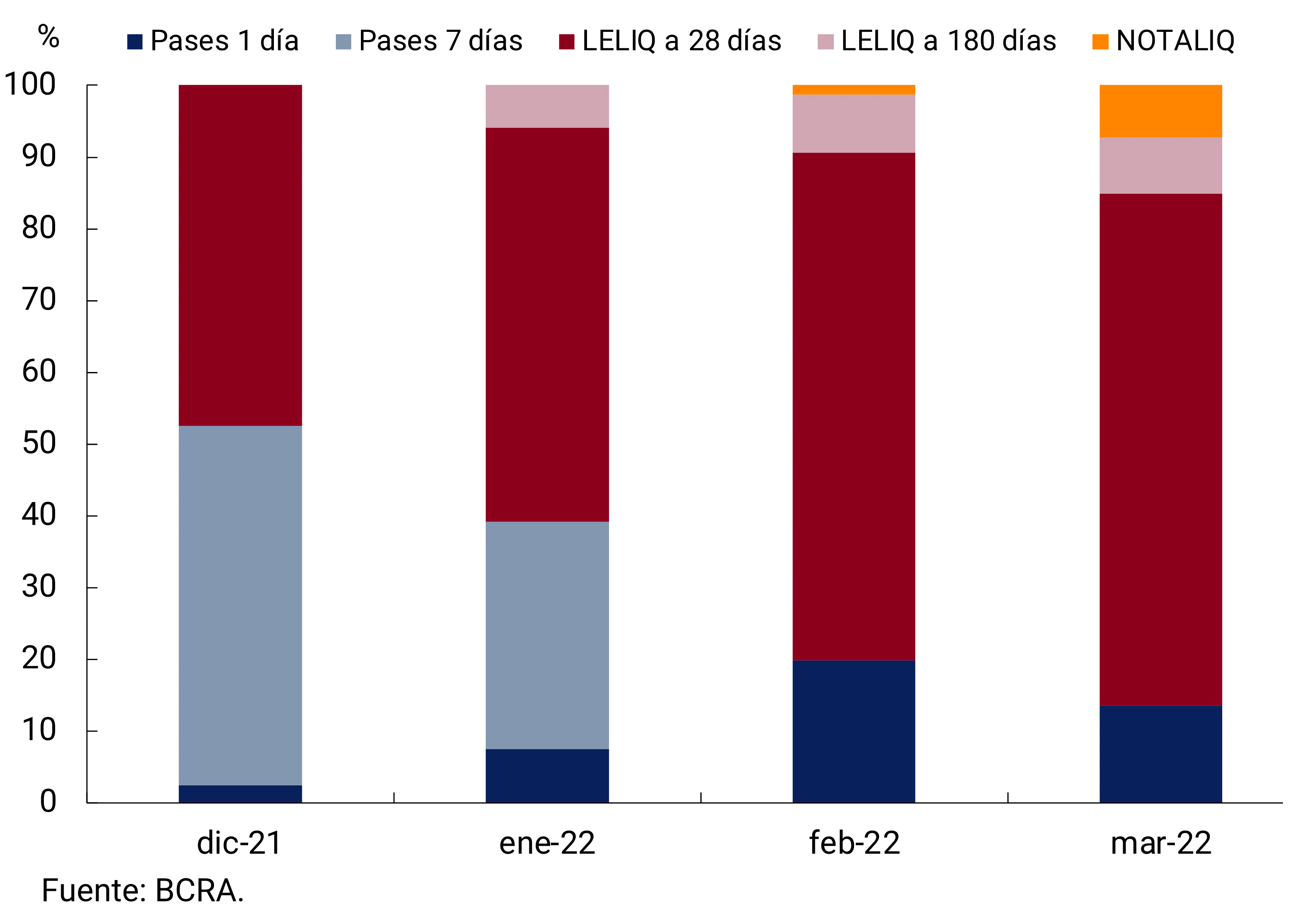

At the end of March, the Board of Directors of the BCRA decided to raise interest rates on monetary policy instruments again, in line with the objectives of establishing a path for the policy interest rate in order to tend towards positive real returns on investments in local currency and to preserve monetary and exchange rate stability. In effect, an increase of 2.0 p.p. in the interest rate of the LELIQ for 28 days and 2.5 p.p. for the 180-day term was ordered. Thus, the monetary policy interest rate stood at 44.5% (54.89% y.a.), while that corresponding to the longer-term LELIQs stood at 49.5% n.a. (55.72% y.a.). On the other hand, with regard to short-term instruments, the interest rate on 1-day pass-through increases by 1.0 p.p. to 34.5% n.a. (41.18% y.a.); while the 1-day active passes stood at 46.5% n.a. (59.15% y.a.). Finally, the fixed spread of the NOTALIQ in the last auction of the month stood at 5.0 p.p., increasing 0.5 p.p. compared to the previous auction.

With the current configuration of instruments, in March the remunerated liabilities were made up of around 80% of LELIQ (considering both types), highlighting the shortest term that represented approximately 70% of the total. The rest corresponded to 1-day pass-by-passes and NOTALIQ, with the latter accounting for a higher share in the month to the detriment of the former (see Figure 4.3).

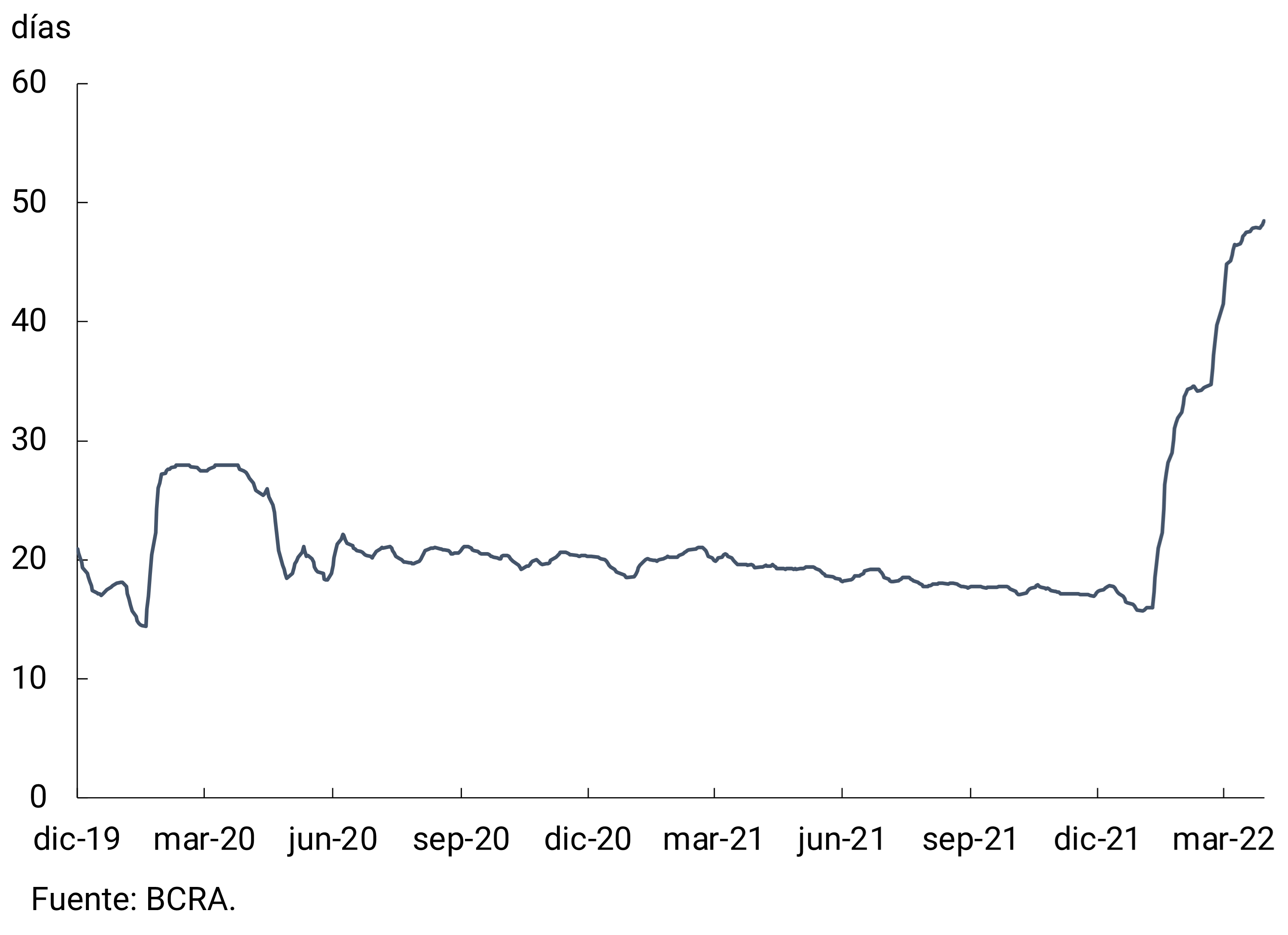

These changes in the relative composition of the monetary regulation instruments made it possible to continue with the policy of extending the terms of interest-bearing liabilities initiated by the BCRA since the beginning of the administration. In fact, the average term of the monetary regulation instruments (LELIQ, Pases and NOTALIQ) was approximately 50 days, more than triple the one in force at the beginning of this year (see Figure 4.4).

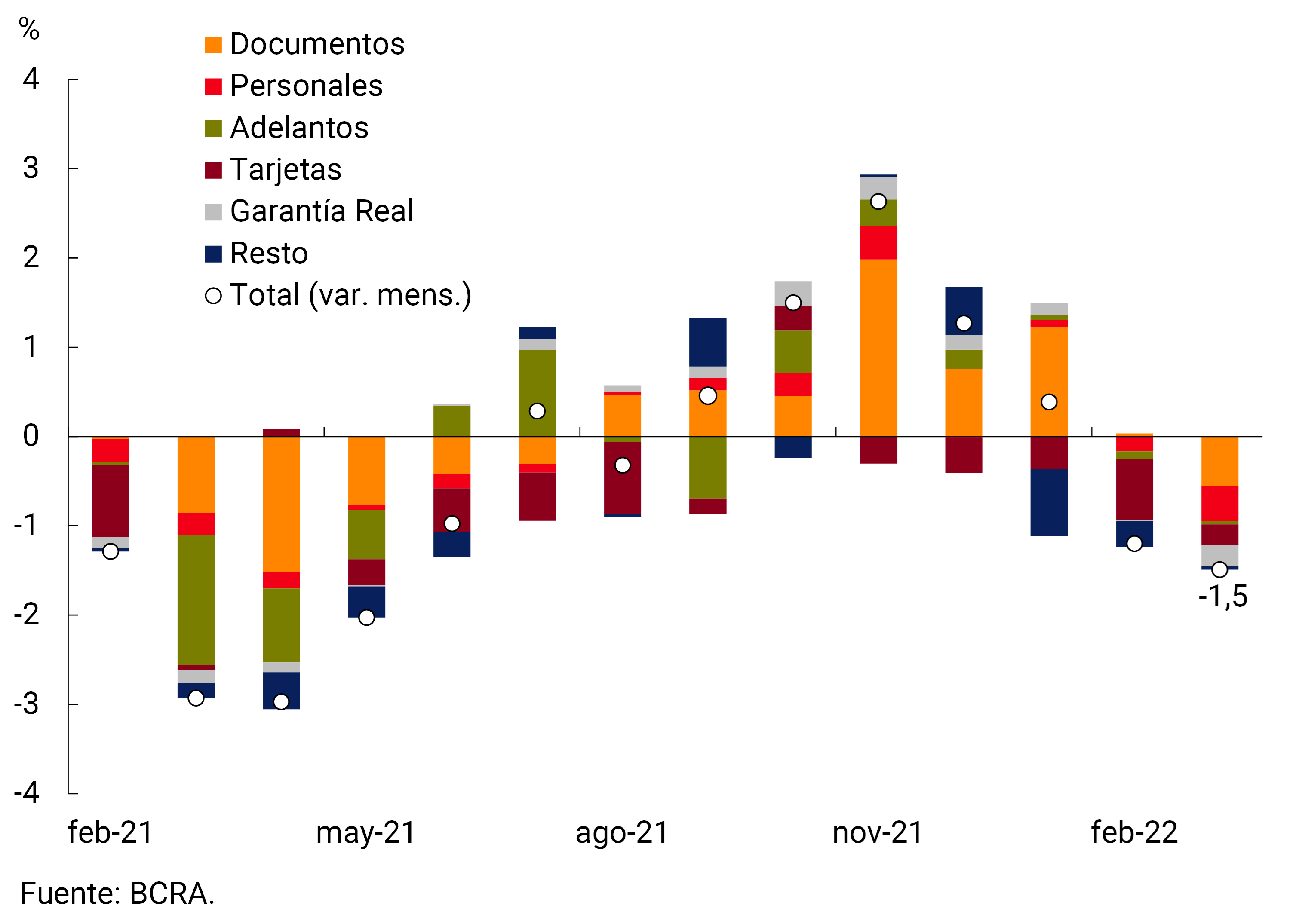

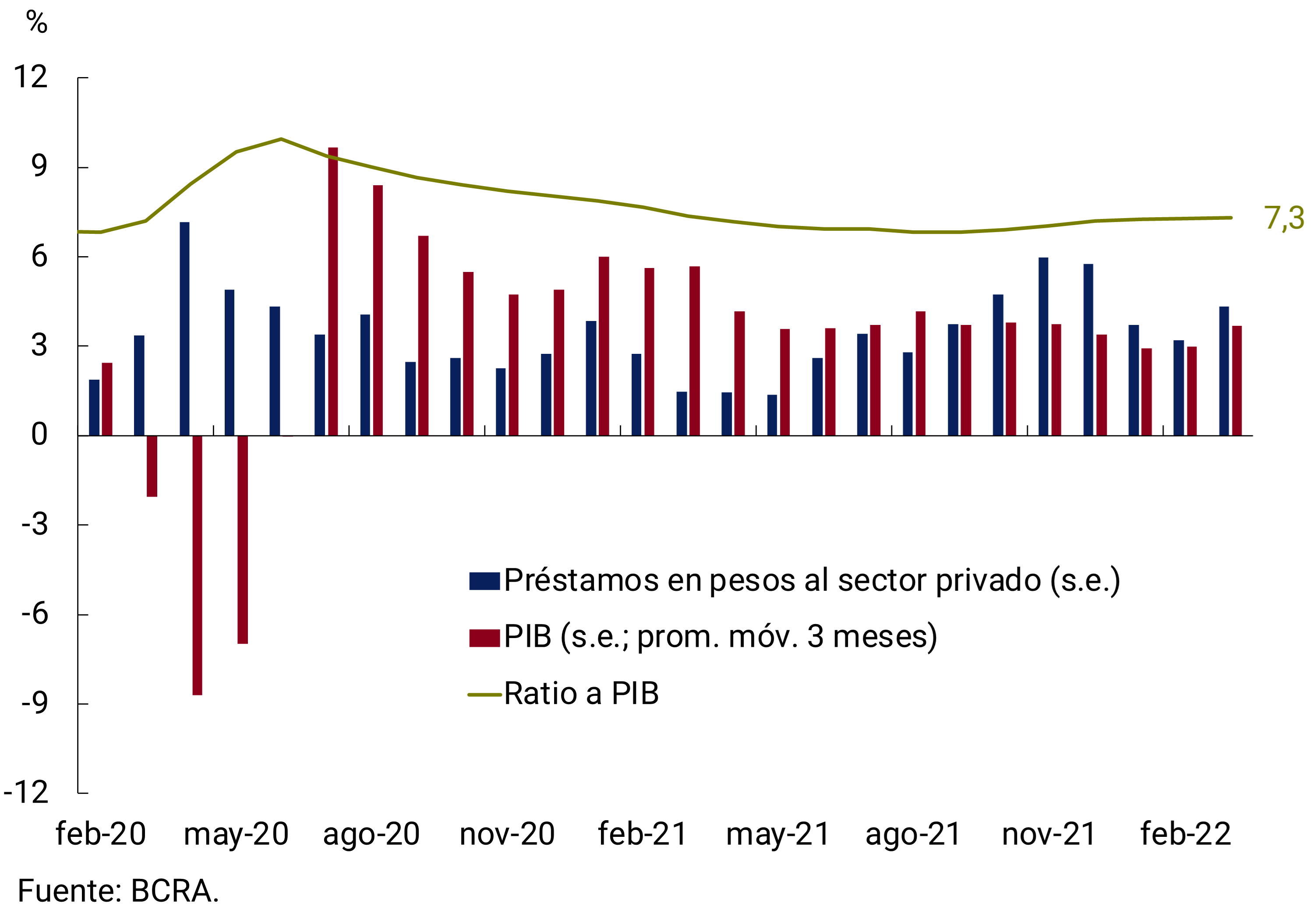

5. Loans to the private sector

Loans in pesos to the private sector, adjusted for seasonality, would have grown in March at a slower pace than prices. In fact, in the country they would have registered a contraction of 1.5% s.e. per month at constant prices. In this way, they have accumulated two consecutive months of decline. All lines of financing contributed negatively to the variation of the month (see Figure 5.1). The ratio of loans in pesos to the private sector to GDP was slightly above 7%, similar to that of previous months (see Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.1 | Loans in pesos to the private

sector Real without seasonality; contribution to monthly growth

Lines with essentially commercial destinations would have exhibited a decrease of 1.7% s.e. at constant prices in March, although they are 2.1% above the record of a year ago. This drop was mainly the result of a decrease in financing instrumented through documents, which was explained both by the behavior of single-signature documents (-1.6% real s.e.) and discounted documents (-1.4% real s.e.), which have a shorter average term (around 2 months). Meanwhile, financing granted through current account advances would have contracted 0.4% s.e. in the month.

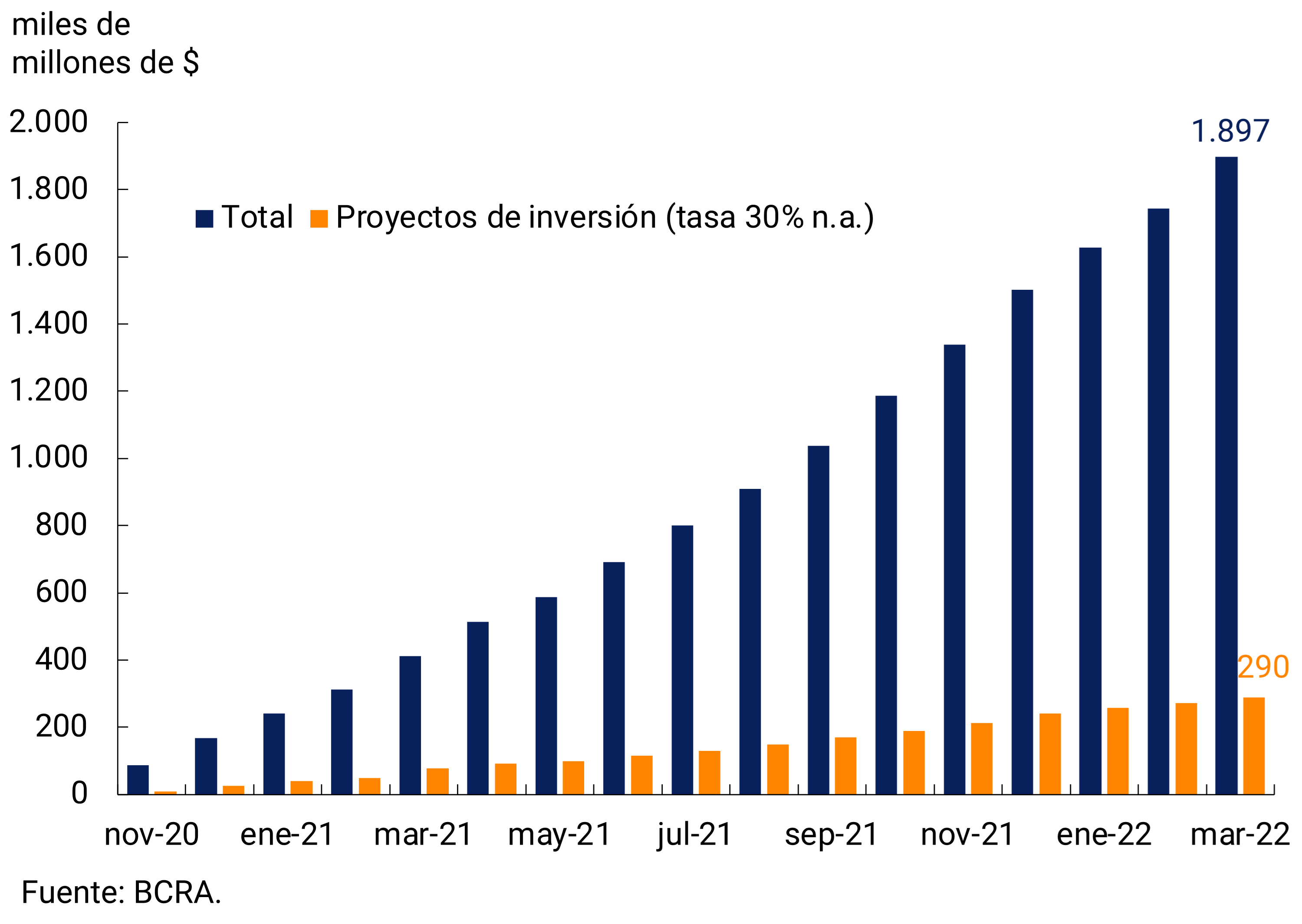

Recently, the BCRA extended the Financing Line for Productive Investment (LFIP) until September. Thus, group A financial institutions must maintain a balance of financing within this line that is equivalent to at least 7.5% of their non-financial private sector deposits in pesos, calculated based on the monthly average of daily balances as of March 20227. In line with the increase in the monetary policy interest rate, an increase in the maximum interest rates applicable to loans granted under the LFIP was ordered. Thus, the interest rate corresponding to investment projects went from 30% to 35% n.a., while that of working capital increased by 2 p.p., standing at 43% n.a.

The LFIP has been the main vehicle through which loans to Micro, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (MSMEs) have been channeled. At the end of March, loans granted under the LFIP accumulated disbursements of approximately $1.897 billion since its inception, an increase of 8.8% compared to last month (see Figure 5.3). As for the destinations of these funds, around 85% of the total disbursed corresponds to the financing of working capital and the rest to the line that finances investment projects. At the time of publication, the number of companies that accessed the LFIP amounted to 230,631.

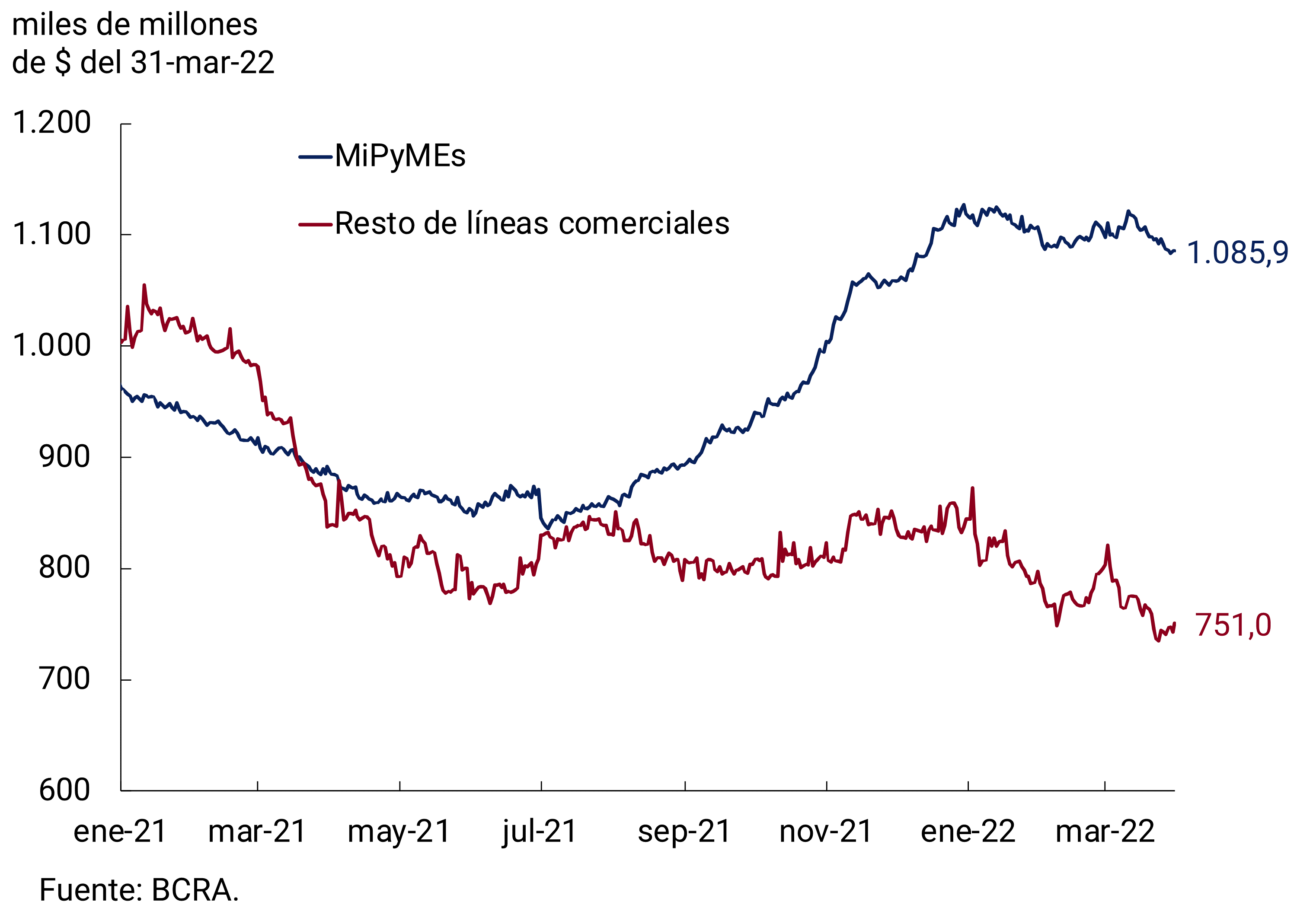

When we analyze the composition of commercial loans by type of debtor, it can be seen that while financing to MSMEs would have remained relatively stable in real terms, financing for large companies would have continued to decrease, the latter accounting for practically all trade financing (see Figure 5.4). In year-on-year terms, credit to MSMEs exhibited an expansion rate at constant prices of 22.4%, while large companies showed a contraction (-16.2%).

Figure 5.3 | Financing granted through the Productive Investment Financing Line (LFIP)

Accumulated disbursed amounts; data at the end of the month

Among loans associated with consumption, financing instrumented with credit cards would have fallen in real terms 0.8% s.e. during March, standing 12.0% below the level of a year ago. Meanwhile, personal loans would have exhibited a 2.3% monthly drop at constant prices and are 1.2% below the level of March 2021. The interest rate corresponding to personal loans stood at 55.9% n.a. in March (72.7% y.a.), a value similar to that of the previous month.

As for the lines with real collateral, the balance of collateral loans would have remained practically unchanged in real terms and without seasonality (-0.3%), accumulating a growth of 43.1% y.o.y. in March (the highest among all loan lines). For its part, the balance of mortgage financing fell 3.2% s.e. in real terms in the month, which would imply a contraction of 13.6% in the last 12 months.

6. Liquidity in pesos of financial institutions

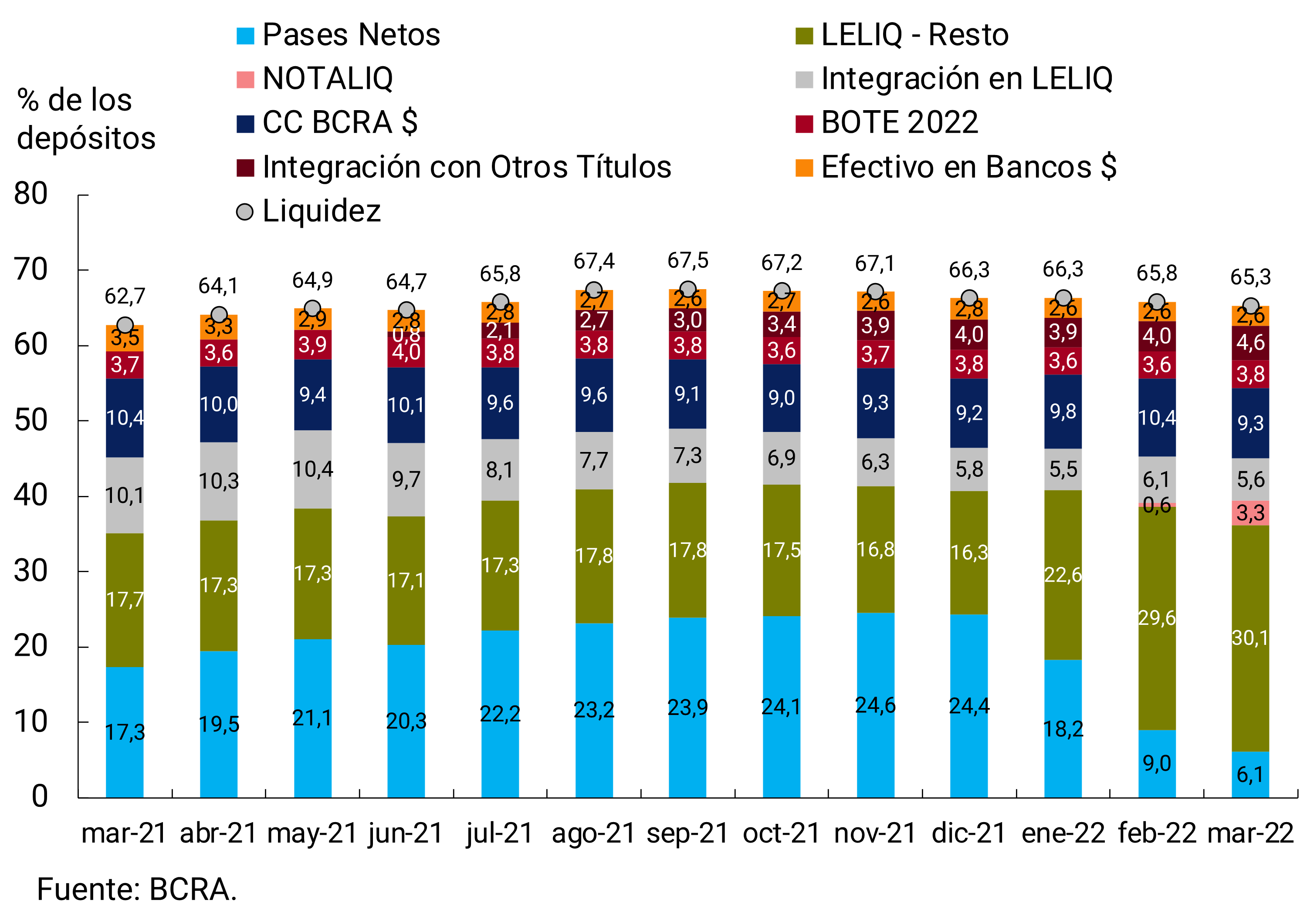

In March, ample bank liquidity in local currency8 averaged 65.3% of deposits, slightly below the previous month. In this way, it remained at historically high levels.

The composition of bank liquidity continued to change in line with regulatory changes introduced in January. Financial institutions continued to dismantle their stock of passive passes, highlighting this month the growth of public securities admitted for minimum cash integration and NOTALIQ. For its part, LELIQ’s stock remained constant in terms of deposits. However, a change in composition was observed, with a lower relative share of integrable LELIQs and an increase in the rest of the holdings of these securities (see Figure 6.1).

7. Foreign currency

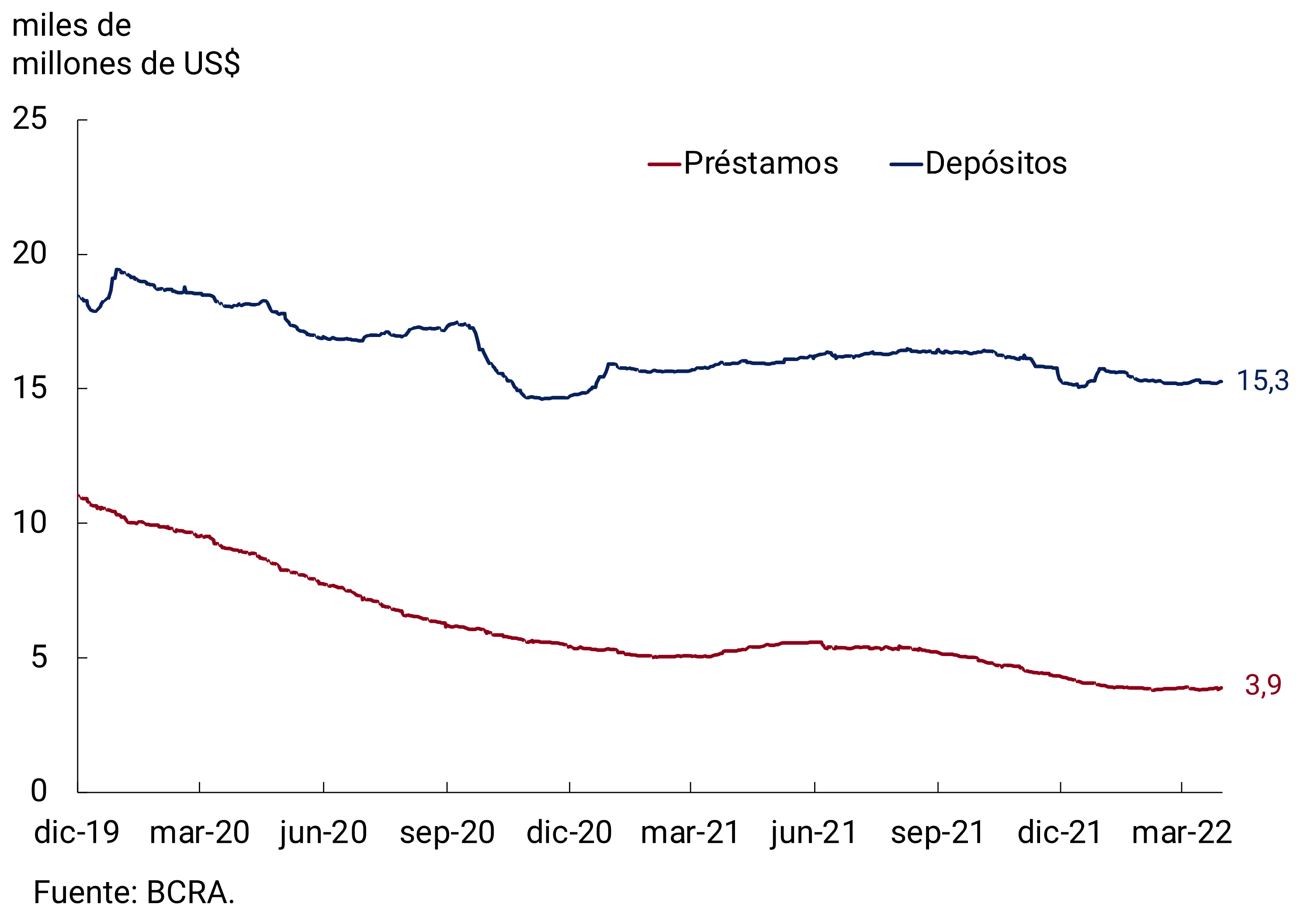

In the foreign currency segment, the main assets and liabilities of financial institutions presented, on average, little significant variations. In fact, the average monthly balance of private sector deposits remained at around US$15,241 million in March. Considering the peak variation, these placements registered a slight increase (US$83 million), which was explained by demand deposits of individuals of less than US$250,000 and fixed-term deposits of legal entities of more than US$1 million. On the other hand, loans to the private sector stopped the downward trend observed since the middle of last year, stabilizing since mid-February. All in all, they verified an average monthly balance of US$3,855 million in March (see Figure 7.1).

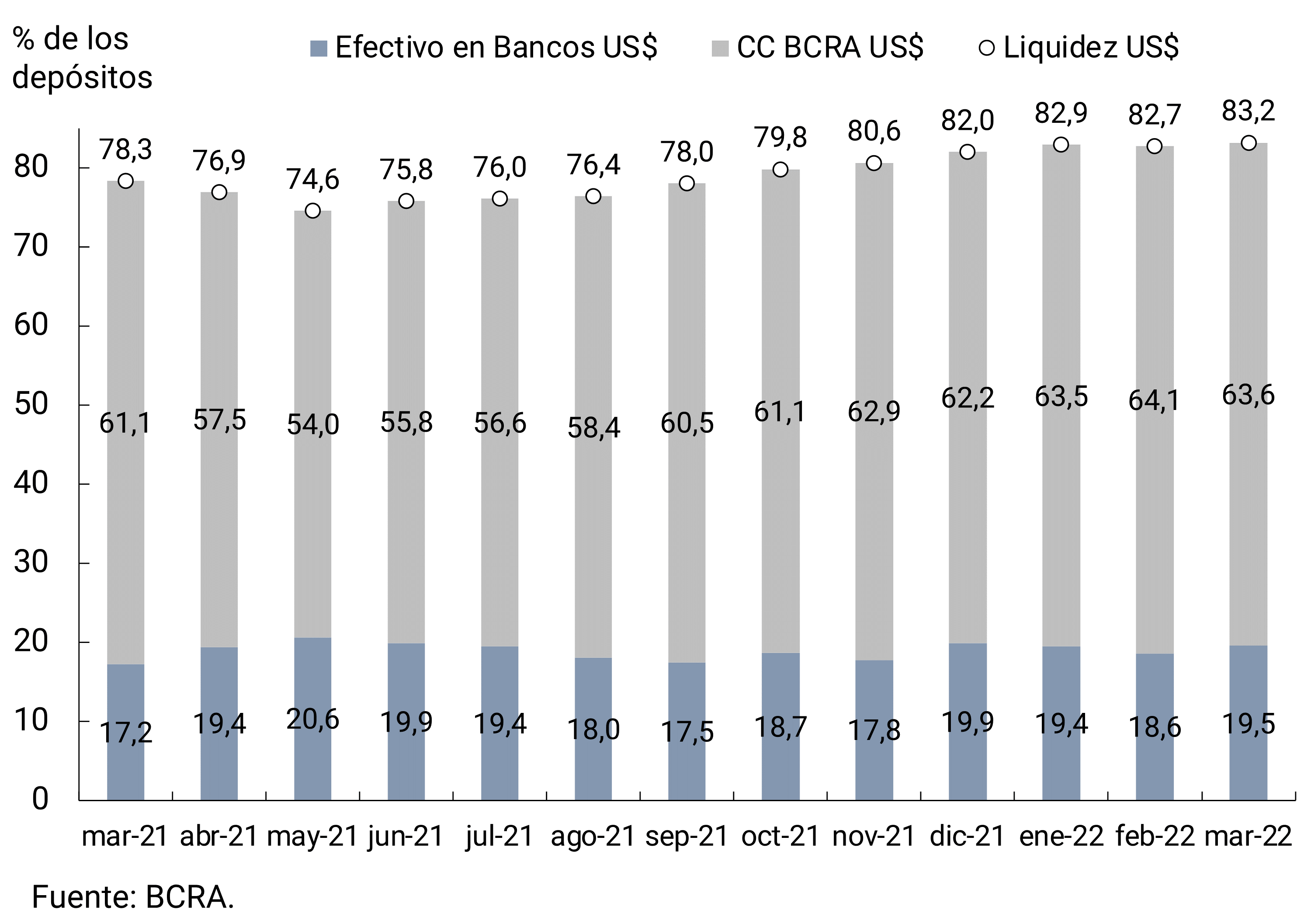

Bank liquidity in foreign currency averaged 83.2% of deposits in March, experiencing an increase of 0.5 p.p. compared to February. This increase was explained by cash in banks, which was partially offset by a reduction in current account balances at the BCRA in terms of deposits (see Figure 7.2).

In foreign exchange matters, the conditions of access to the foreign exchange market applicable to import payments, prior approval to make payments for foreign financial debts with related creditors and the rules on the refinancing of external liabilities were extended until the end of the year. In addition, in the case of imported goods for which it is required to have the declaration in the Comprehensive Import Monitoring System (SIMI) and are not included in the deadlines provided for in the exchange regulations, it was decided to classify importers according to certain parameters of demand for foreign currency, to determine if they will have rapid access to the foreign exchange market or if they must have financing from abroad with a term Minimum of 180 calendar days from the registration of the customs entry of the goods into the country9. Finally, it was established that agricultural companies will be able to finance part of the annual increase in their imports of fertilizers and phytosanitary products, at least, for 90 calendar days from the registration of customs entry, instead of the 180 days that would have corresponded when the SIMI assigned to them is category B10. This difference with respect to the rest of the activities to which this category is assigned has to do with the usual cycle of trade in agricultural activity11.

The BCRA’s International Reserves ended March with a balance of US$43,137 million, reflecting an increase of US$6,120 million compared to the end of February (see Figure 7.3). This increase was mainly explained by the first disbursement by the IMF towards the end of the month for US$9,650 million, within the framework of the Extended Facilities Program (PFE) signed with our country. This increase was partially offset by the payment of capital for US$2,780 million to the organization. For its part, the purchase of foreign currency from the private sector was another factor in the expansion of international reserves in the month.

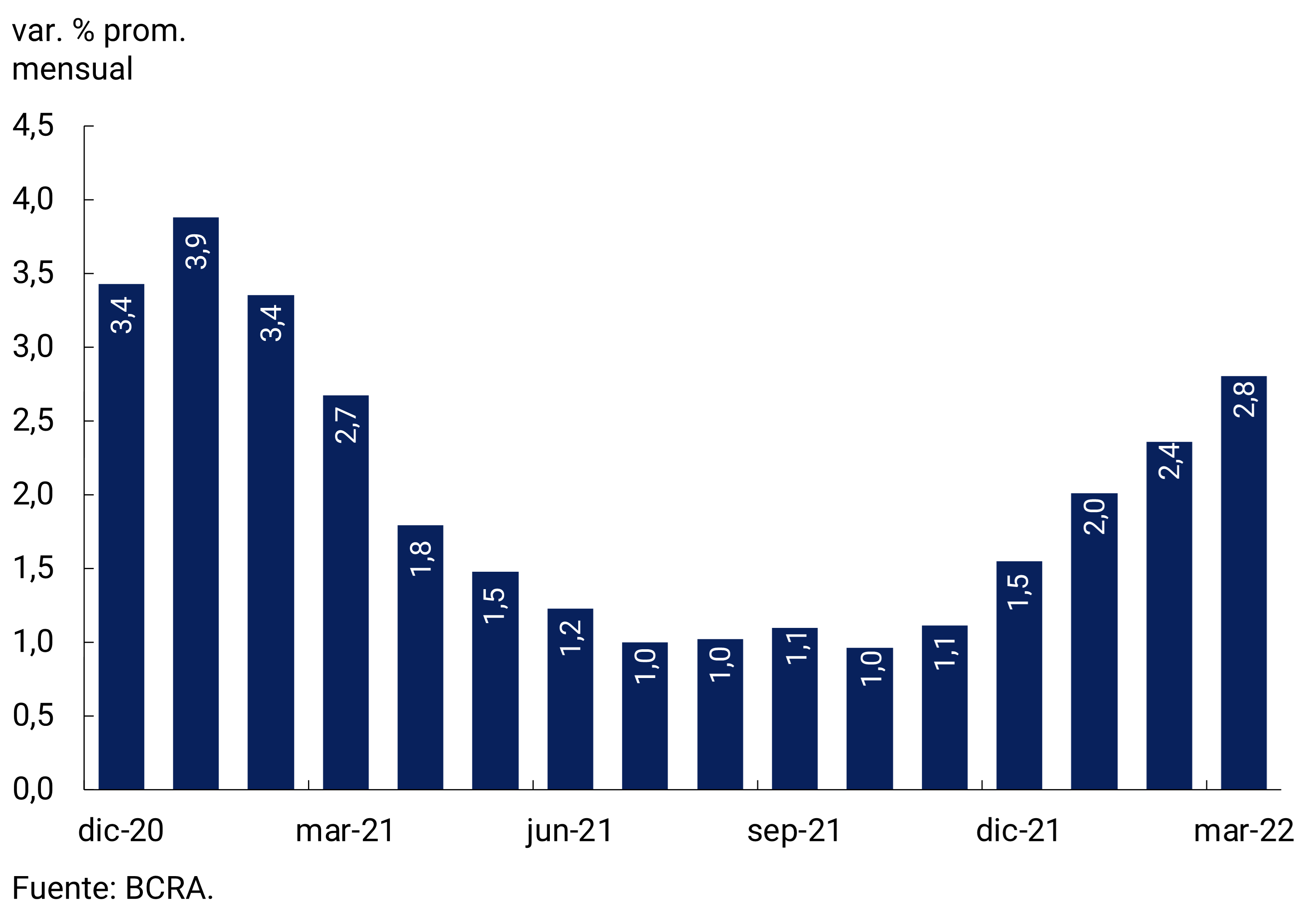

Finally, the bilateral nominal exchange rate (TCN) against the U.S. dollar increased 2.8% in March to settle, on average, at $109.37/US$ (see Figure 7.4). In this way, the rate of depreciation of the domestic currency gradually converges to levels more compatible with the inflation rate. The greater dynamism of the TCN, added to the dynamics presented by the quotations of the main trading partners, allowed the Multilateral Real Exchange Rate Index (ITCRM) to remain relatively stable and around competitive levels. Thus, it seeks to strengthen the position of International Reserves, based on the genuine income of foreign currency from the external sector.

Glossary

ANSES: National Social Security Administration.

BADLAR: Interest rate on fixed-term deposits for amounts greater than one million pesos and a term of 30 to 35 days.

BCRA: Central Bank of the Argentine Republic.

BM: Monetary Base, includes monetary circulation plus deposits in pesos in current account at the BCRA.

CC BCRA: Current account deposits at the BCRA.

CER: Reference Stabilization Coefficient.

NVC: National Securities Commission.

SDR: Special Drawing Rights.

EFNB: Non-Banking Financial Institutions.

EM: Minimum Cash.

FCI: Common Investment Fund.

A.I.: Year-on-year .

IAMC: Argentine Institute of Capital Markets

CPI: Consumer Price Index.

ITCNM: Multilateral Nominal Exchange Rate Index

ITCRM: Multilateral Real Exchange Rate Index

LEBAC: Central Bank bills.

LELIQ: Liquidity Bills of the BCRA.

LFIP: Financing Line for Productive Investment.

M2 Total: Means of payment, which includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and demand deposits in pesos from the public and non-financial private sector.

Private M2: Means of payment, includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and demand deposits in pesos from the non-financial private sector.

Private transactional M2: Means of payment, includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and non-remunerated demand deposits in pesos from the non-financial private sector.

M3 Total: Broad aggregate in pesos, includes the current currency held by the public, cancelling checks in pesos and the total deposits in pesos of the public and non-financial private sector.

Private M3: Broad aggregate in pesos, includes the working capital held by the public, cancelling checks in pesos and the total deposits in pesos of the non-financial private sector.

MERVAL: Buenos Aires Stock Market.

MM: Money Market.

N.A.: Annual nominal

E.A.: Annual Effective

NOCOM: Cash Clearing Notes.

ON: Negotiable Obligation.

GDP: Gross Domestic Product.

P.B.: basis points.

p.p.: percentage points.

MSMEs: Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises.

ROFEX: Rosario Term Market.

S.E.: No seasonality

SISCEN: Centralized System of Information Requirements of the BCRA.

TCN: Nominal Exchange Rate

IRR: Internal Rate of Return.

TM20: Interest rate on fixed-term deposits for amounts greater than 20 million pesos and a term of 30 to 35 days.

TNA: Annual Nominal Rate.

UVA: Unit of Purchasing Value

References

1 https://www.hcdn.gob.ar/institucional/infGestion/balances-gestion/archivos/0001-PE-2022.pdf

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2022/03/25/Argentina-Staff-Report-for-2022-Article-IV-Consultation-and-request-for-an-Extended-515742.

2 M2 private excluding interest-bearing demand deposits from companies and financial service providers. This component was excluded since it is more similar to a savings instrument than to a means of payment.

3 INDEC will release the inflation data for March on April 13.

5 Financial Services Providers, Companies and Individuals with deposits of more than $10 million.

6 Includes working capital held by the public and deposits in pesos of the non-financial private sector (sight, term and others).

8 Includes current accounts at the BCRA, cash in banks, balances of net passes arranged with the BCRA, holdings of LELIQ, and bonds eligible for reserve requirements.

9 Communications “A” 7466, “A” 7469 and “A” 7471.

10 A category B implies that imports of associated goods must be financed at least 180 calendar days from the registration of the customs entry of the goods into the Argentine Republic.