Política Monetaria

Monthly Monetary Report

June

2021

Monthly report on the evolution of the monetary base, international reserves and foreign exchange market.

1. Executive Summary

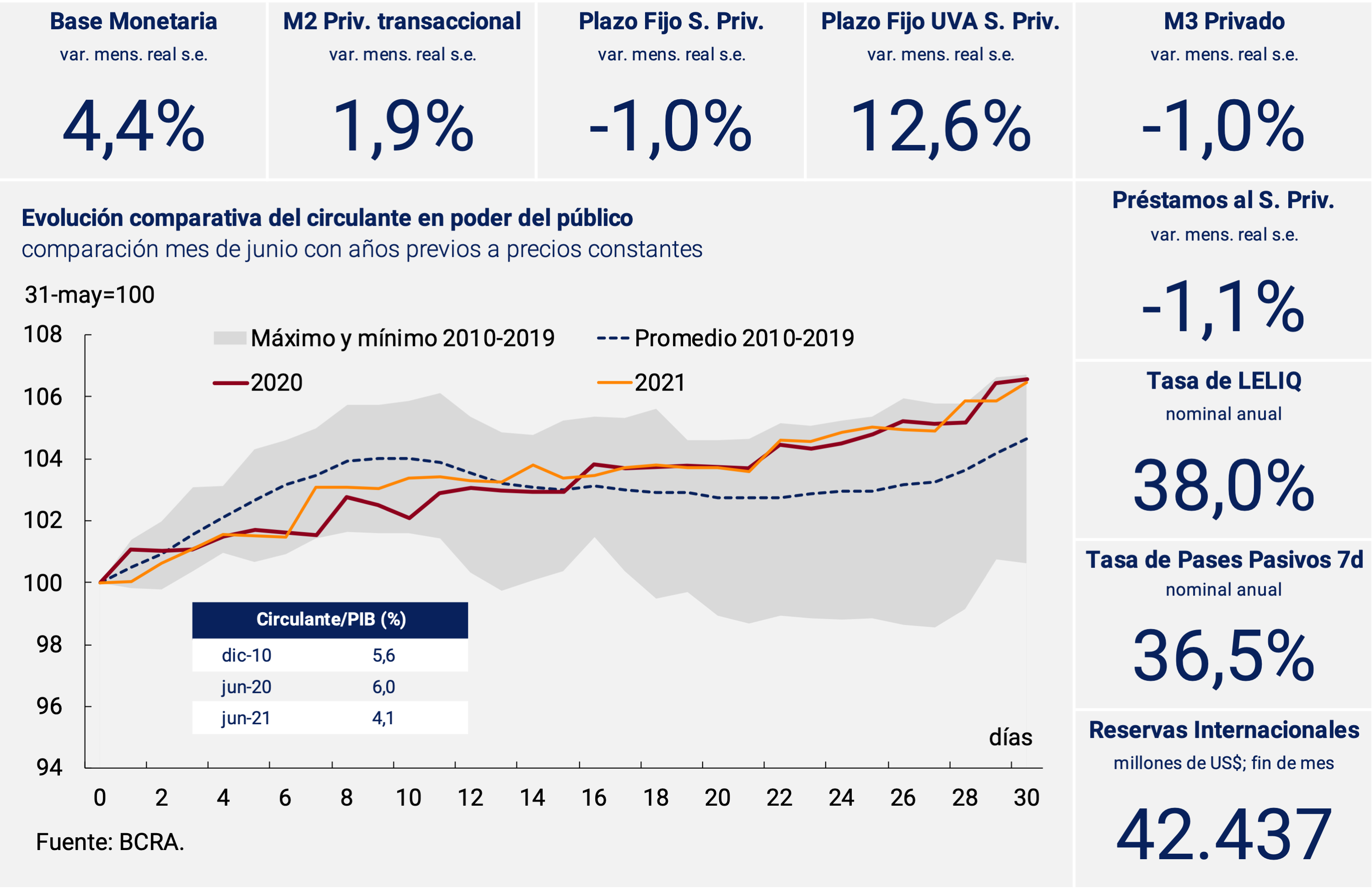

In real and seasonally adjusted terms, transactional means of payment increased in the month, due to various factors such as the transfer of resources to the most vulnerable sectors and higher salaries due to the entry of adjustment tranches of various collective bargaining agreements. In particular, transfers to the most vulnerable sectors, which are intensive cash demanders, led to a growing demand for working capital throughout the month (in a period whose intra-monthly seasonality is less marked by the payment of the half bonus).

Time deposits in pesos in the private sector registered a new monthly contraction at constant prices. However, the behavior was not homogeneous, highlighting the evolution of time deposits denominated in UVA, which partially offset the negative contribution of placements in pesos. All in all, the broad monetary aggregate (private M3) at constant prices would have registered a decrease of 1.0% s.e. in June and would have been 7.5% below the same month of the previous year.

Loans in pesos to the non-financial private sector fell again in the month at constant prices (-1.1% s.e.). Within the commercial lines, advances and discounted documents stood out, the latter promoted by the Productive Investment Financing Line (LFIP).

In the foreign currency segment, no significant changes were observed in either the assets or liabilities of financial institutions. Meanwhile, the BCRA continued for the seventh consecutive month to increase its international reserve position, with the net purchase of foreign currency being the component with the greatest positive contribution.

2. Payment methods

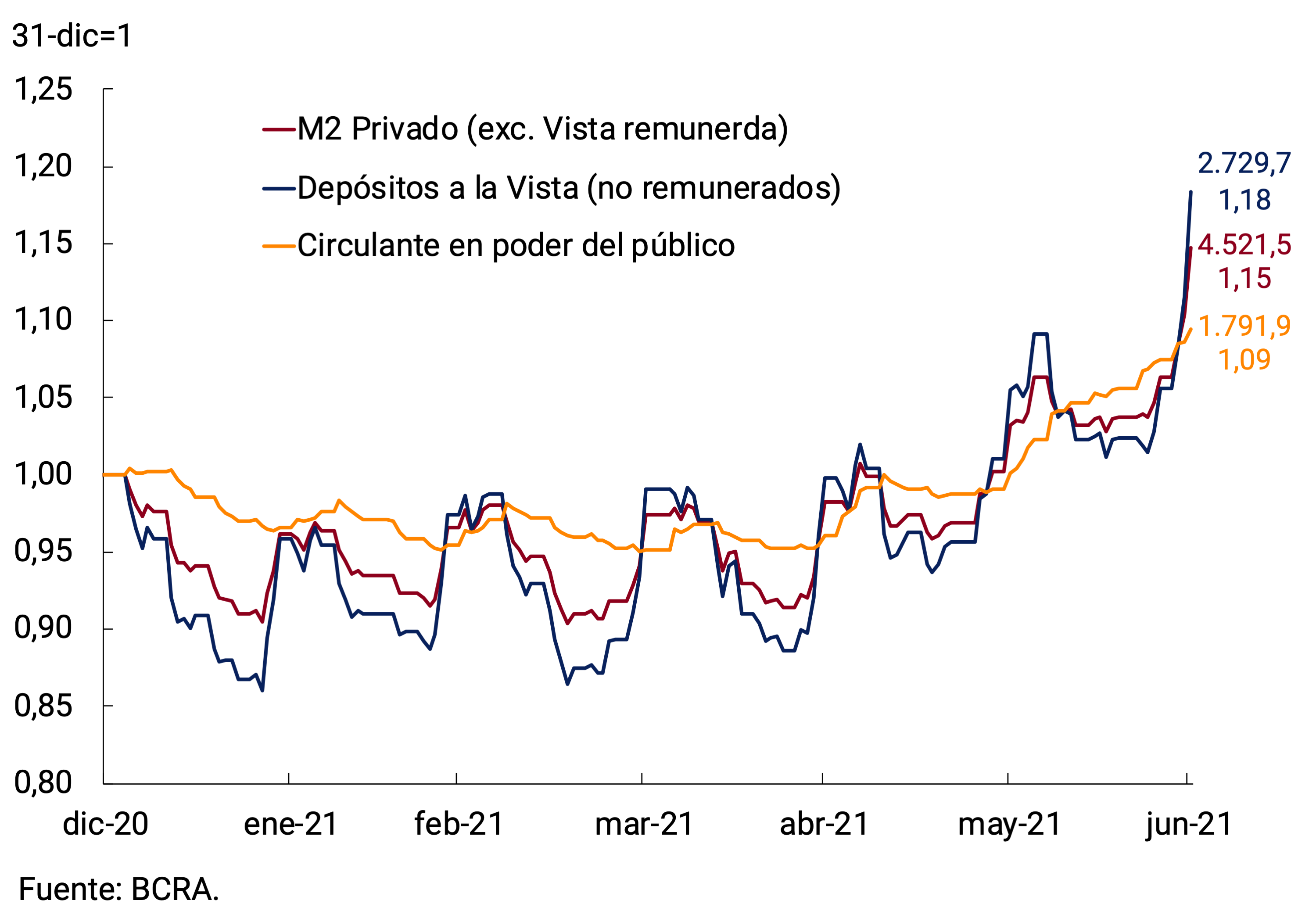

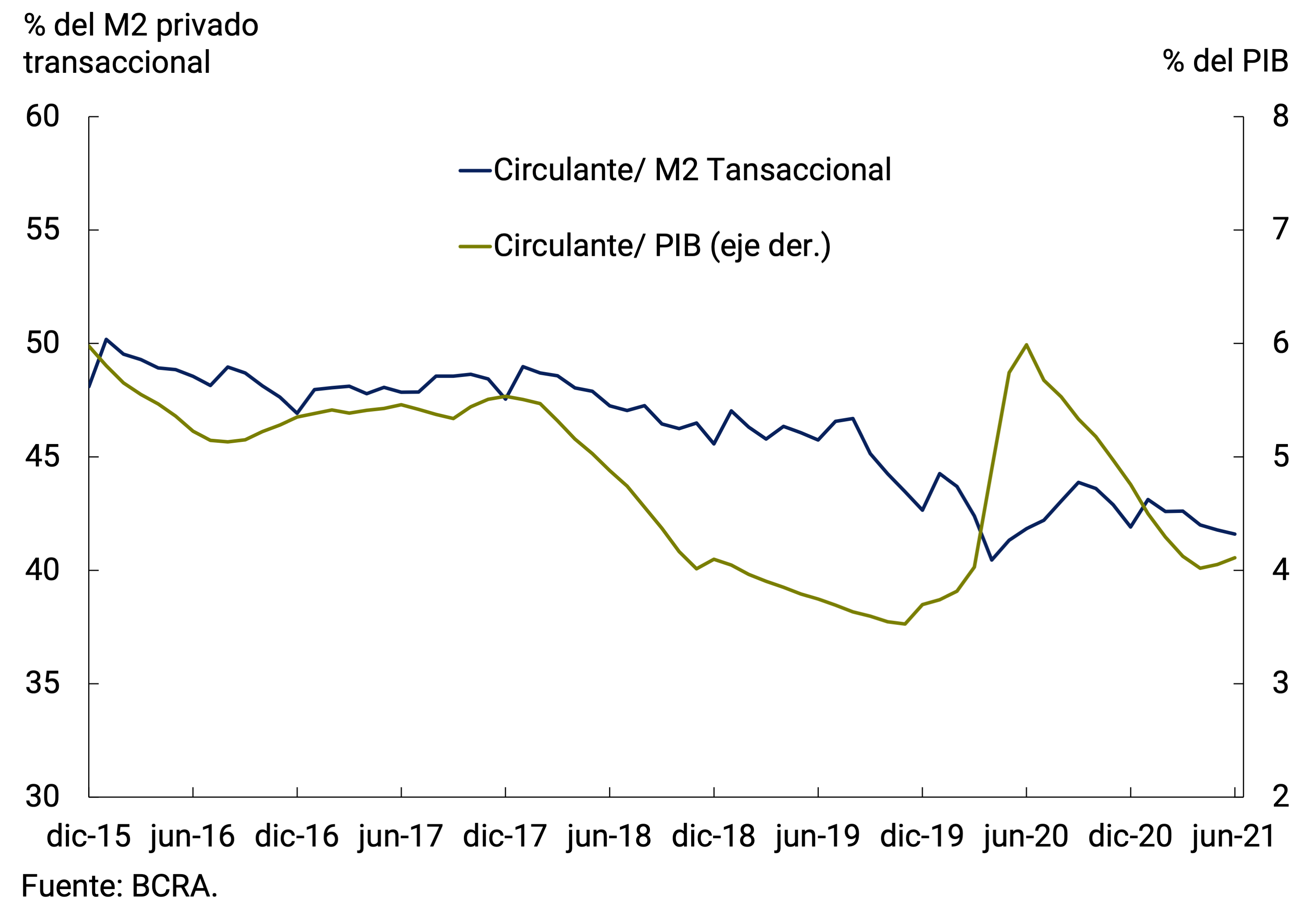

In real terms1 and seasonally adjusted (s.e.), transactional means of payment (measured through private transactional M22) showed an increase (1.9%), breaking with 10 consecutive months of contractions. In terms of GDP, private transactional M2 has remained in the order of 10% since March and has accumulated a fall of 4.5 p.p. since June last year, when it reached a maximum of 14.3%. The upward trend observed in the month was due to both the behavior of transactional demand deposits and the current deposits held by the public (see Figure 2.1).

Several factors impacted the evolution of non-interest-bearing demand deposits in June. On the one hand, additional resources were transferred to the most vulnerable sectors of the population. In particular, in that month the ANSES advanced the payment of 20% of the supplement per child of the Universal Allowance for Daughter (AUH) that is usually made on December3. This had an impact on the dynamics of deposits in savings banks of individuals of lower strata (up to $50 thousand), which notoriously softened their intra-monthly seasonal fall, given that the payment was extended between June 8 and 22. On the other hand, in the sixth month of the year, there were salary adjustment tranches of several collective agreements, which was reflected, in particular, in the growth of deposits in savings banks of between $50,000 and $250,000 (see Figure 2.2). Finally, the law establishes the obligation to integrate the payment of the half bonus for June before the 30th of that month; however, many companies and/or organizations usually pay it before the deadline4. All in all, non-interest-bearing demand deposits registered a monthly increase of 2.4% s.e. at constant prices in the sixth month of the year.

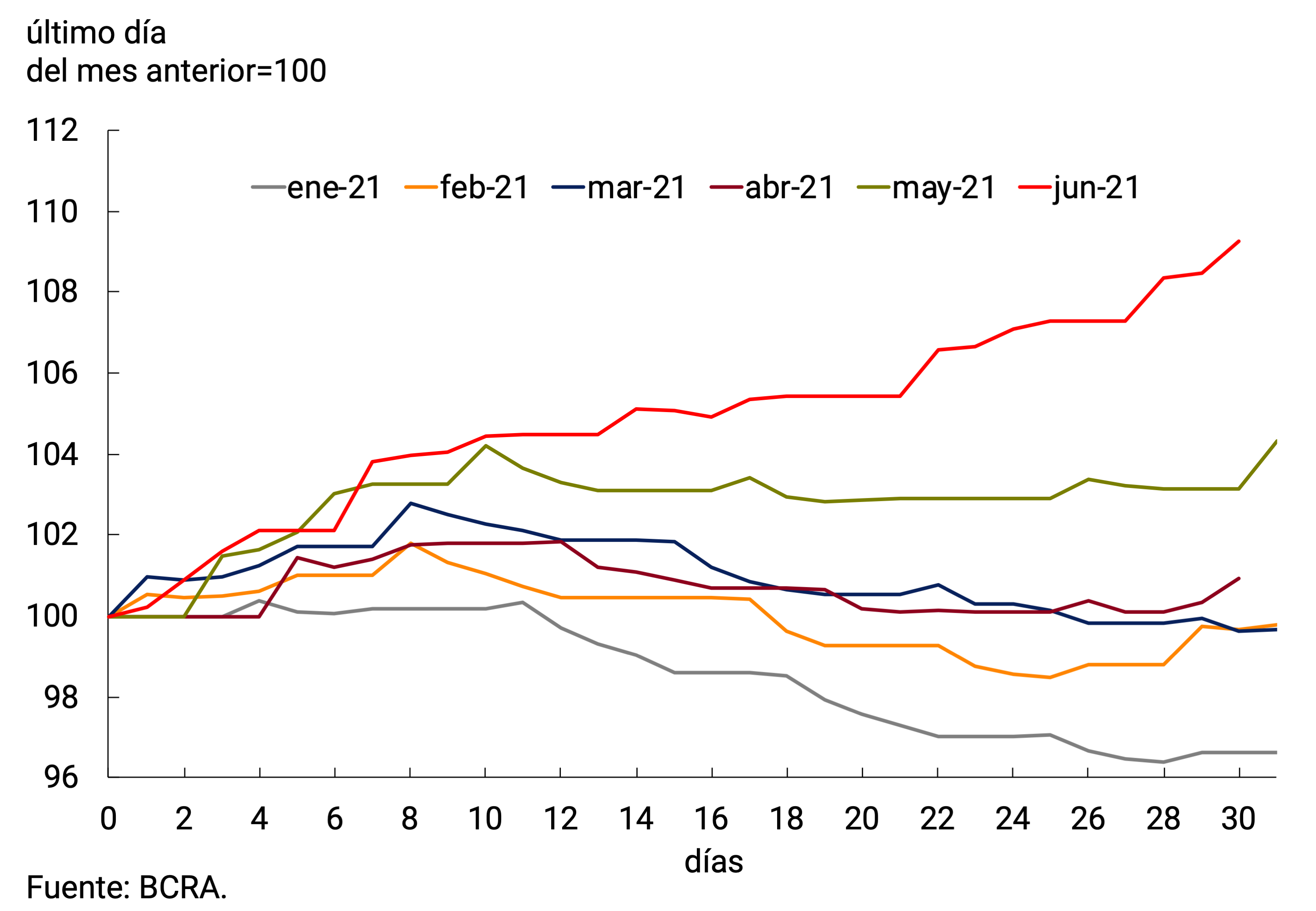

The lower-income sectors are intensive demanders of cash5, so the greater availability of resources of these agents explained the growth of the working capital held by the public. Another factor that could also have contributed to this dynamic is the greater demand for cash for purchases in nearby stores, given the restrictions on the mobility of people who operated in most of the country until the first week of the month. Added to this is the seasonal growth linked to the payment of the half bonus in June. Thus, the circulating currency held by the public showed a sustained upward trend throughout June, differing from its intra-month seasonal behavior and with a dynamic very similar to that of the same month of the previous year (see Chart 2.3 and Executive Summary). Thus, at constant prices, it exhibited a monthly increase of 1.4% s.e. and closed the first half of the year with a cumulative real contraction of around 11%. Unlike what happened in April 2020, the expansion of the use of cash did not manage to break the downward trend experienced by banknotes and coins within transactional money, due to the rise of new means of payment such as QR payment codes (see Figure 2.4). Recently, and with the aim of continuing to promote a greater use of electronic means of payment, the BCRA agreed with financial institutions to shorten to 1 business day the deadline for depositing the payment of sales made with debit cards6 in the accounts of businesses.

3. Savings instruments in pesos

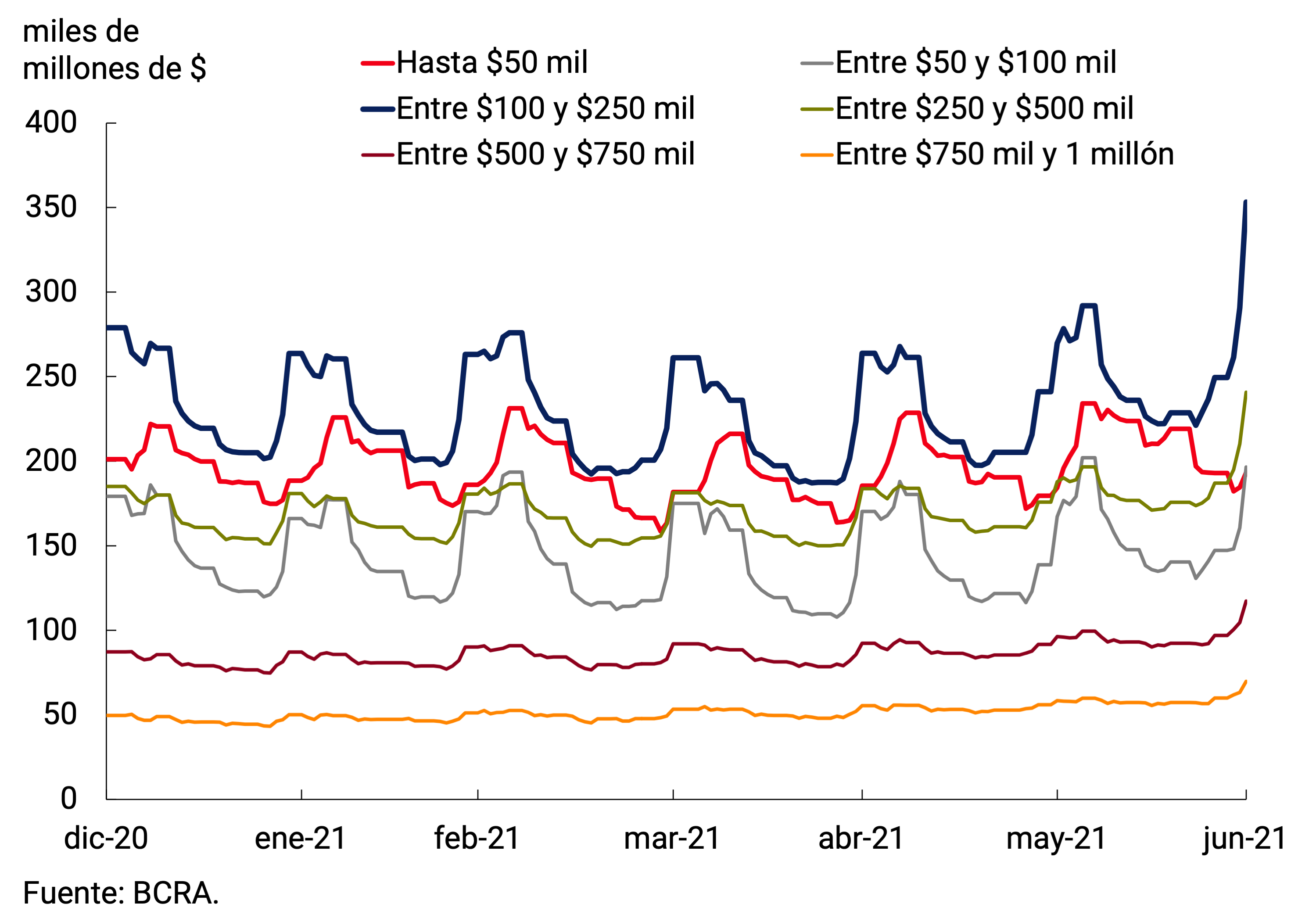

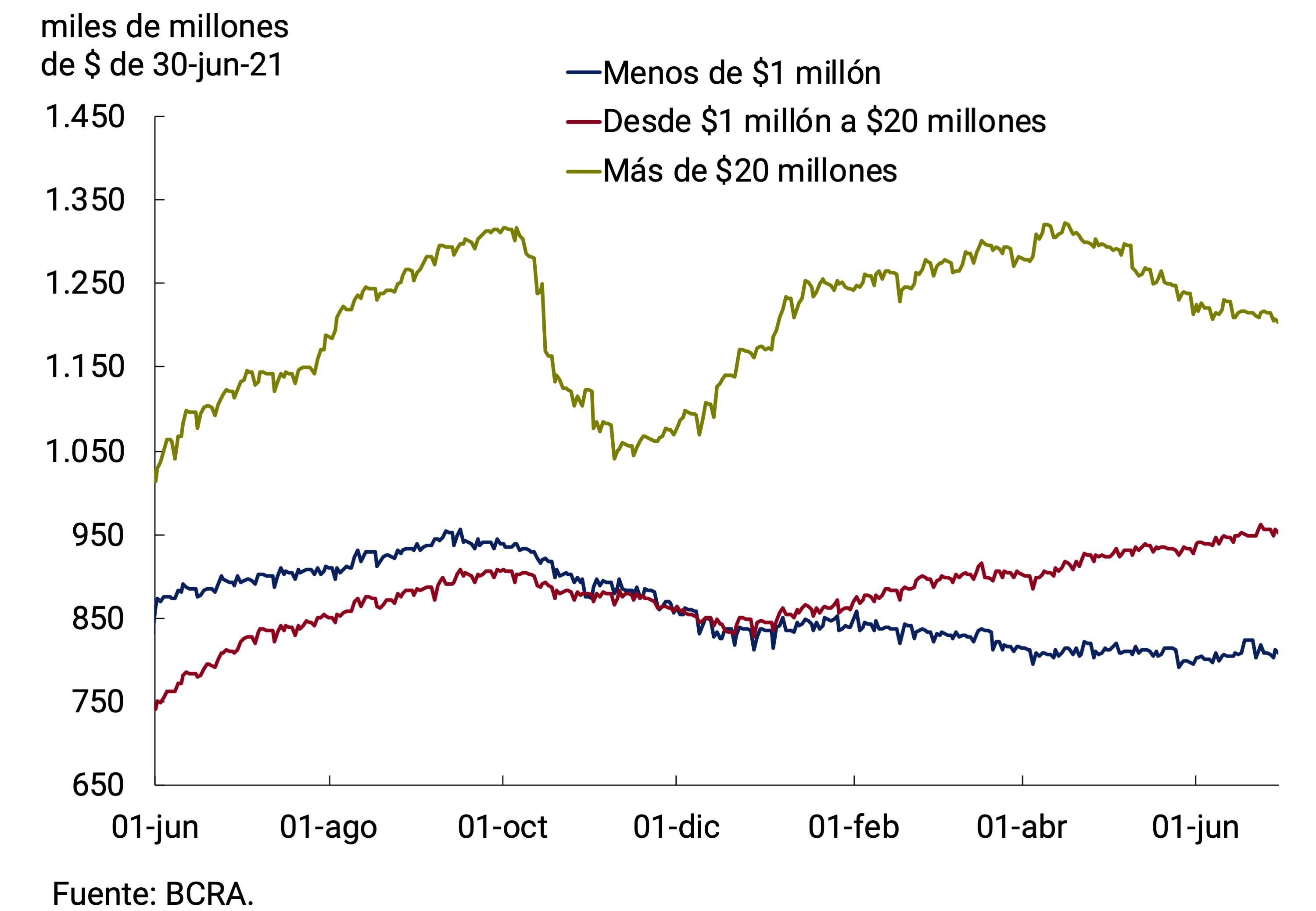

The fixed-term deposits in pesos7 of the private sector continued to moderate their monthly expansion rate, which implied that at constant prices they registered a contraction of close to 1.0% s.e. By strata of amount, we observe that the fall was concentrated in deposits in the wholesale segment (more than $20 million) and was mainly explained by the negative “statistical carryover” left by the previous month (-2.3 p.p.). These placements stopped falling in real terms as of the first days of June and stabilized.

Within the wholesale segment of time deposits, there are two major players: financial service providers (FSPs) and companies. So far this year, it is the PSFs and, in particular, the Money Market Mutual Funds (FCI MM), that explain the dynamics of these deposits. Given that in the last month the assets of the FCI MM remained practically unchanged and that they did not register changes in the composition of their portfolio due to the stability of interest rates, their time and interest-bearing demand deposits remained practically unchanged. In fact, the TM20 interest rate of private banks stood at 33.9% n.a. (39.7% y.a.) in June, while the interest rate on the remunerated sight stood at 29.9% n.a. (34.3% y.a.).

Deposits between $1 million and $20 million registered an increasing trend at constant prices throughout the month. Within this stratum, the growth was explained by the instrumentation of human persons, which represent just over 75% of the total deposits in the segment. Finally, placements of up to $1 million remained relatively stable by maintaining nominal growth similar to that of inflation (see Figure 3.1). It should be noted that the most dynamic stratum is between $750,000 and $1 million, so considering the capitalization of interest, many deposits over time cross stratum to between $1 and $20 million. The interest rate on time deposits of less than $1 million stood at 36.1% n.a. (42.8% y.a.).

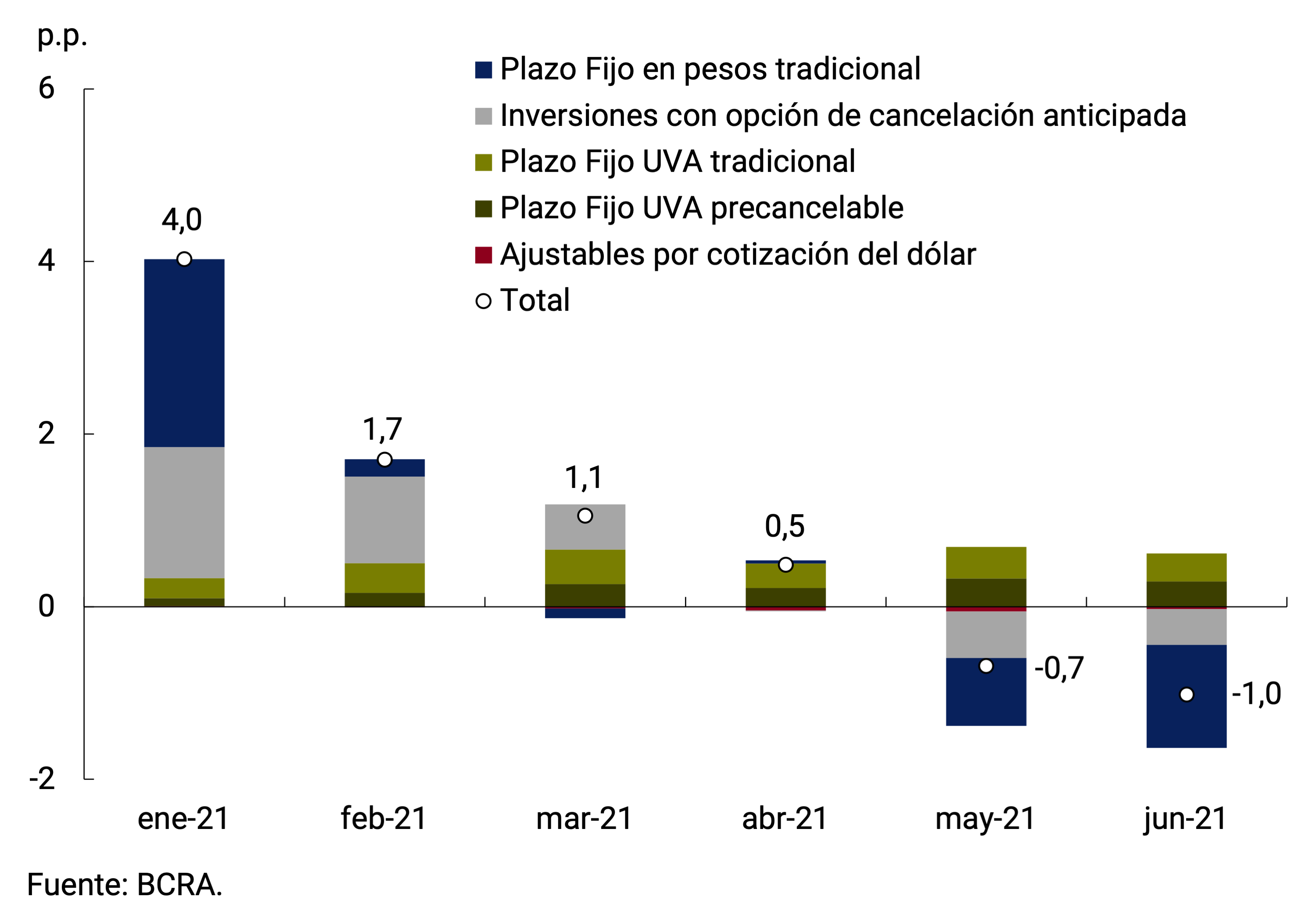

Within fixed-term deposits in pesos, a heterogeneous behavior was observed by type of instrument. Placements in pesos, both traditional and pre-cancellable, contributed negatively to the monthly variation and were partially offset by the positive contribution of fixed-term deposits denominated in UVA (see Figure 3.2).

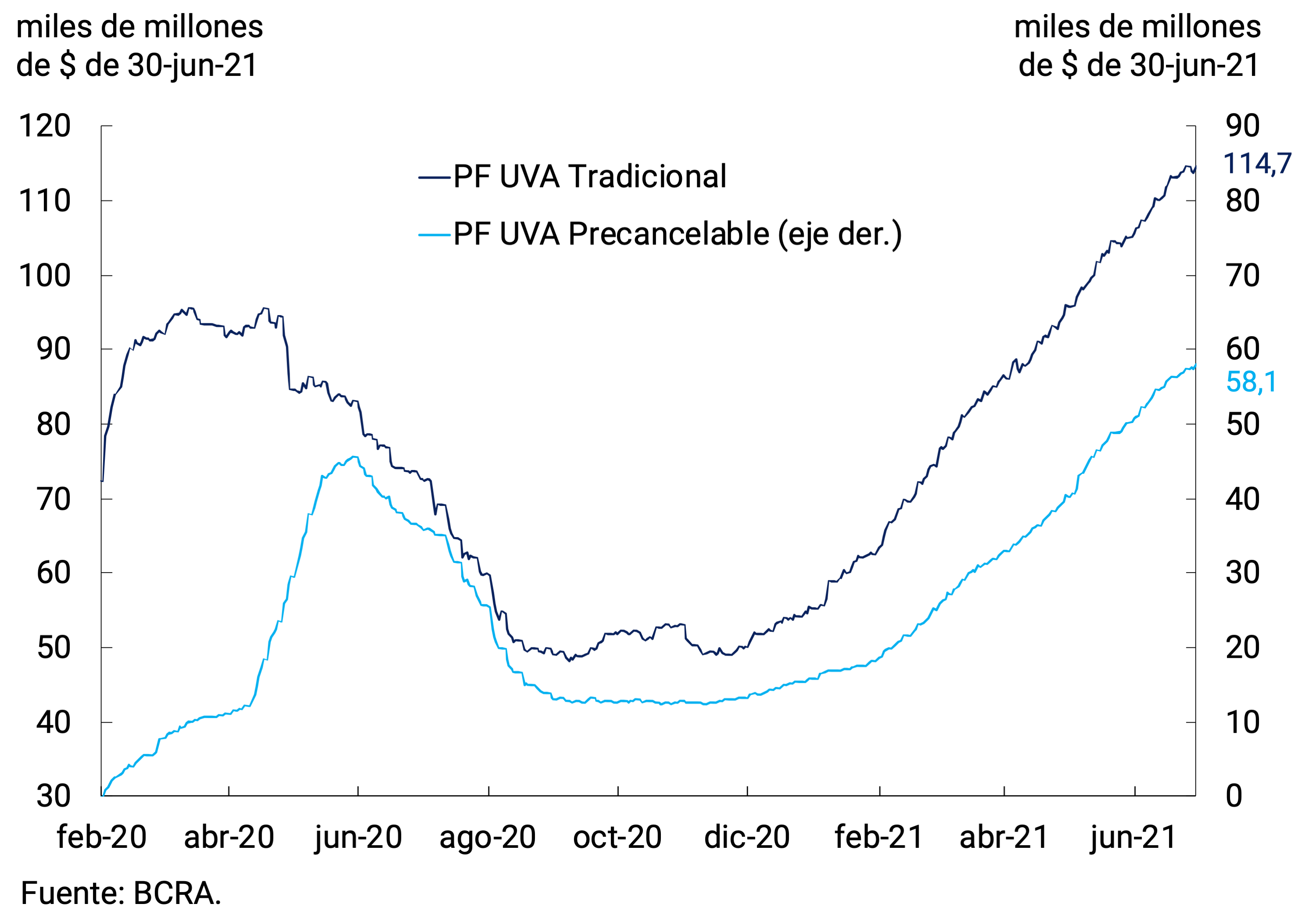

In fact, deposits expressed in UVA continued with the dynamism they have been showing since the end of last year. In June, they reached an average monthly balance of $164,076 million, which meant an increase of 12.6% s.e. in real terms compared to May. The boost came from both traditional UVA placements and those with a pre-payment option after 30 days, whose monthly expansion rate at constant prices was 9.7% and 19.0%, respectively (see Figure 3.3). The growing demand for this type of ERC adjustable instruments took place in a context in which the BCRA kept the reference interest rates unchanged, in line with the need to accompany the process of normalization of economic activity. Thus, the existence of inflation-hedged instruments made it possible to channel savings to ensure positive returns in real terms.

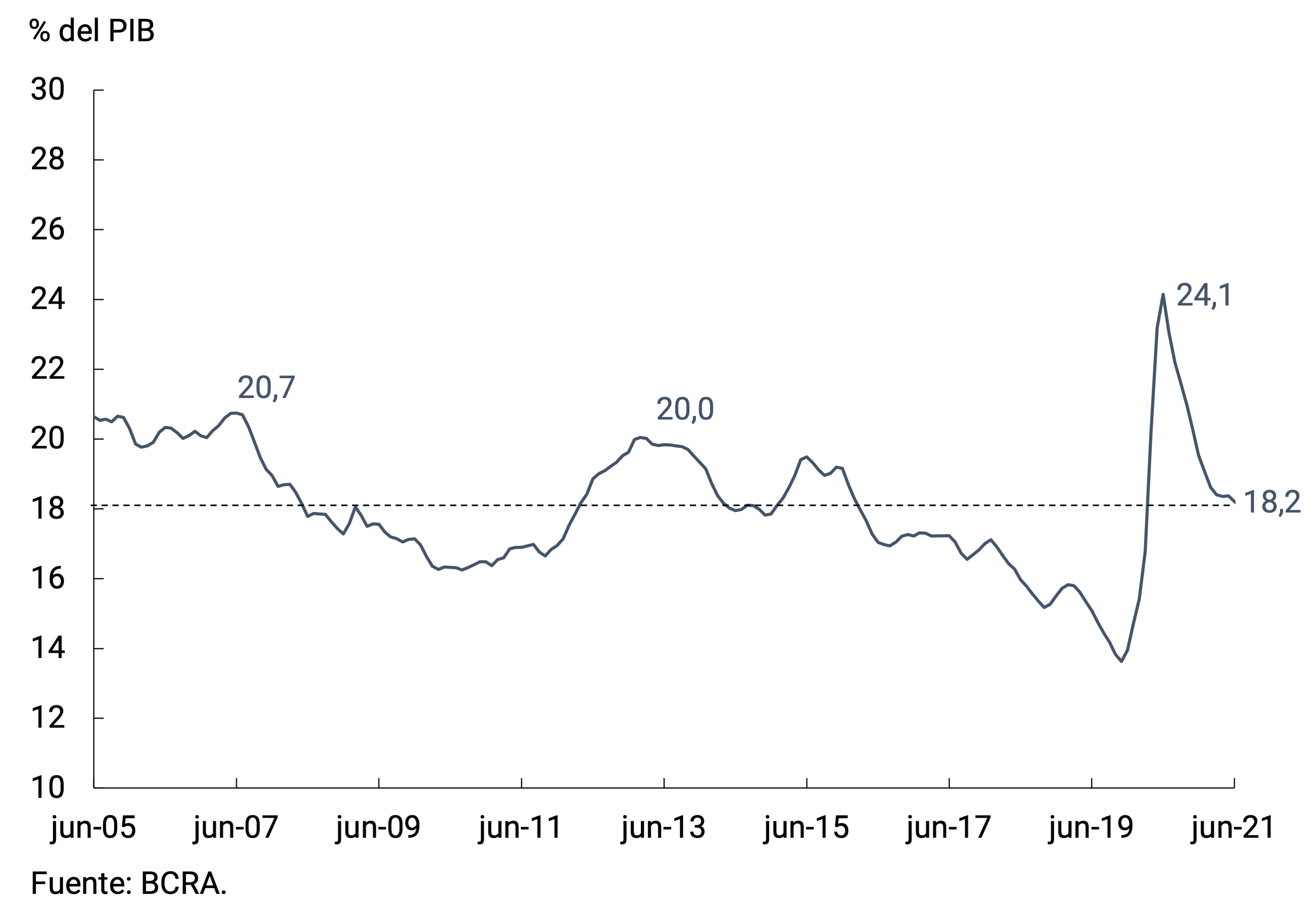

The broad monetary aggregate (private M3)8 at constant prices would have registered a decrease of 1.0% s.e. in June and would have been 7.5% below the same month of the previous year. In terms of Output, it remained practically unchanged in the month, standing at 18.2%, a figure similar to the historical average (see Figure 3.4).

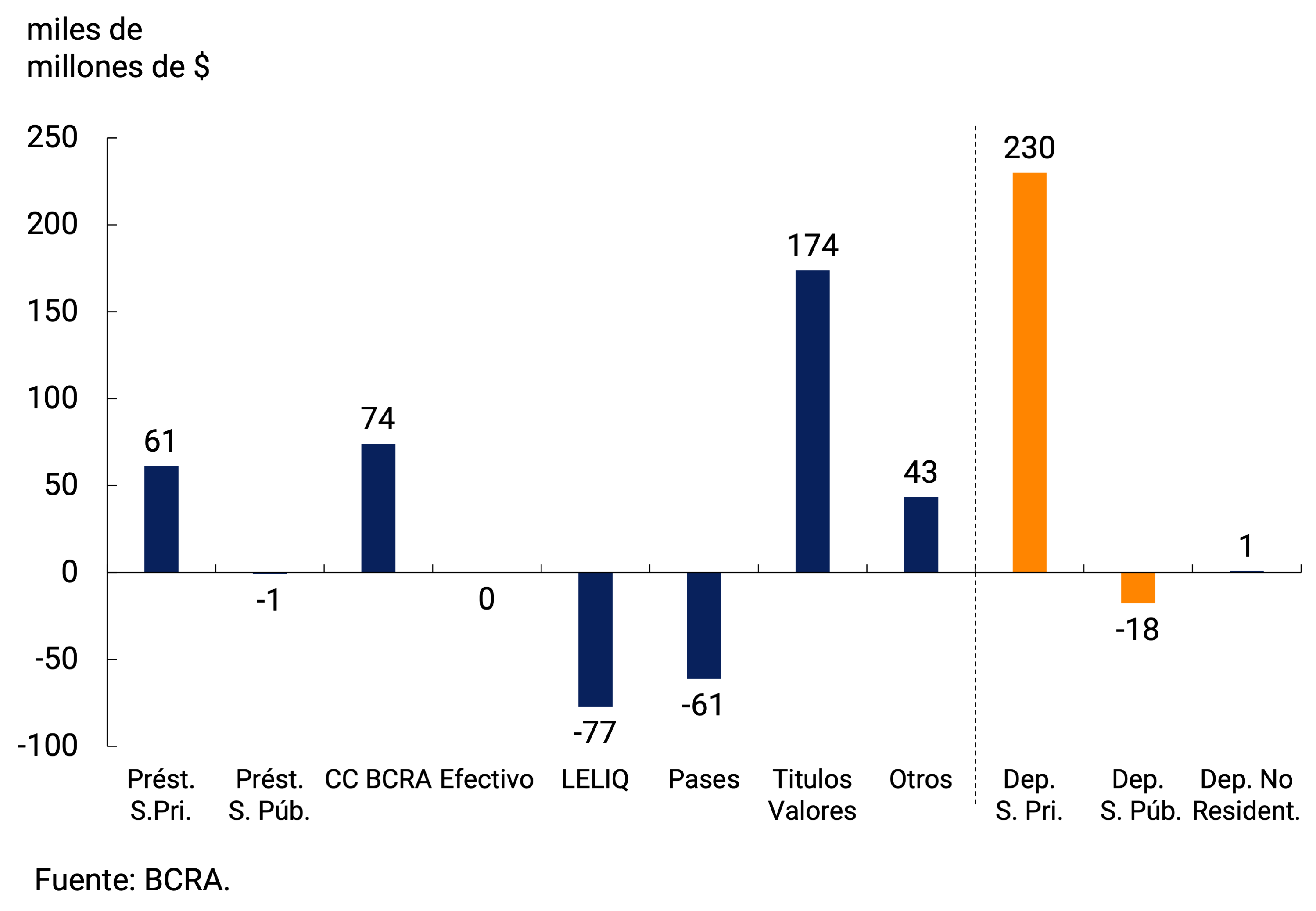

4. Monetary base

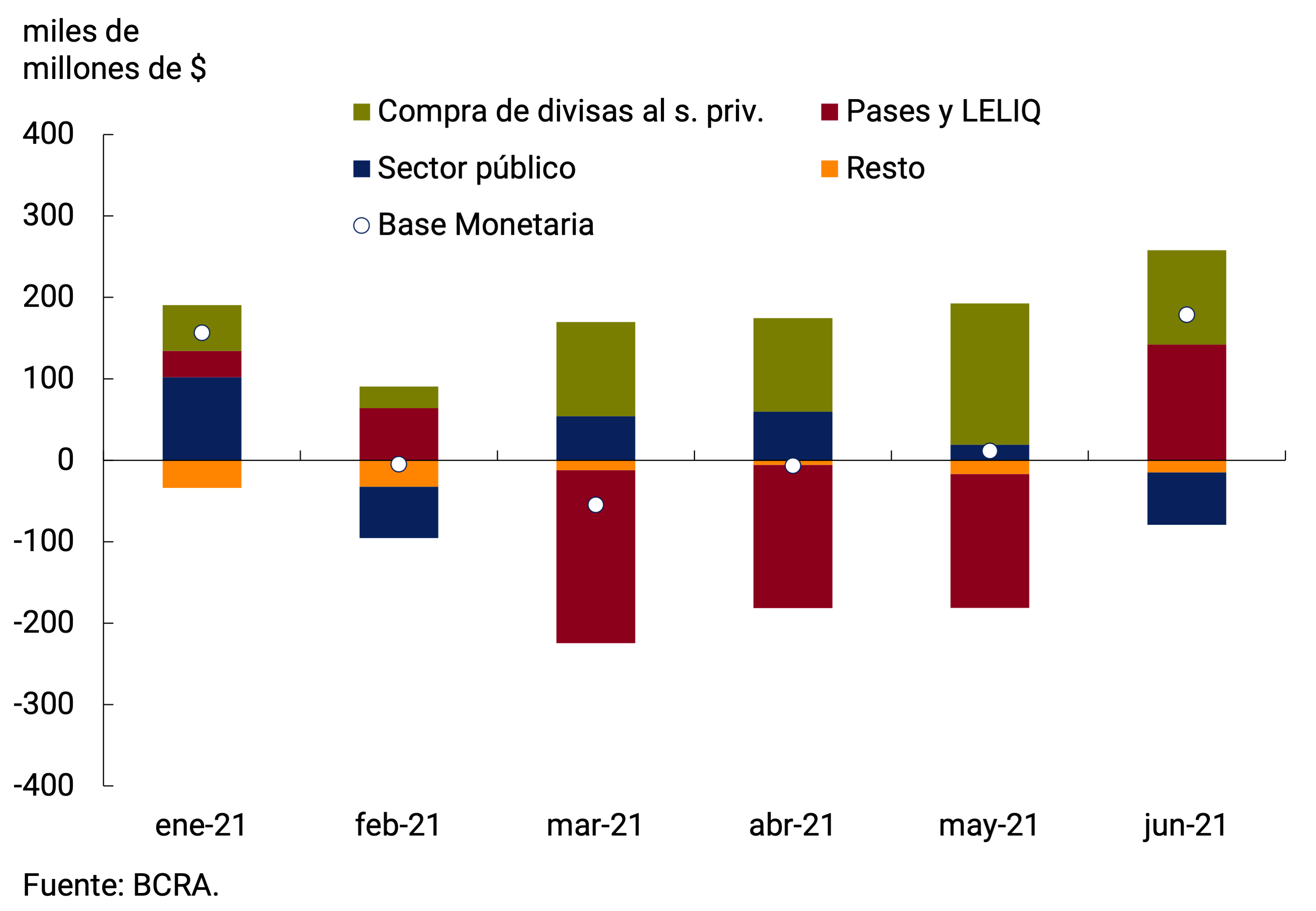

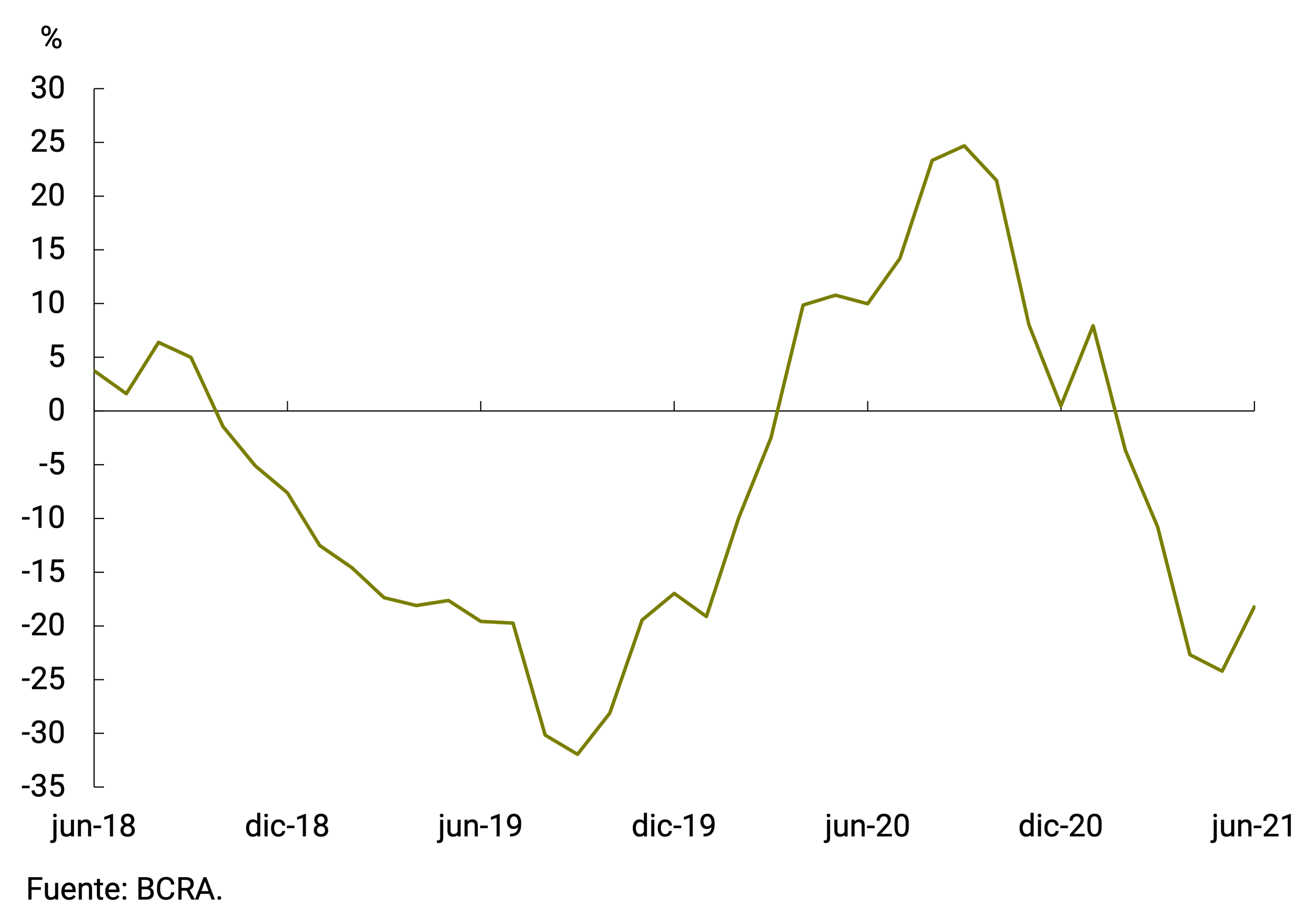

In June, the Monetary Base stood at $2,705 billion, presenting an average monthly nominal increase of 7.1% ($178.6 billion; +4.4% real s.e.). The monetary expansion responded to the net purchase of foreign currency from the private sector and the operations of passes and LELIQ. The latter coincided with an increase in the number of public securities in pesos in the portfolio of financial institutions, in a month in which entities had the possibility of integrating the fraction of reserve requirements, which until May were integrable into LELIQ, using Treasury bonds in pesos acquired by primary subscription (see Section “Liquidity in pesos of financial institutions”). For their part, public sector operations and the rest contributed negatively in the month (see Figure 4.1). However, in year-on-year terms and at constant prices, the Monetary Base continued to contract, with a decrease of around 18% (see Figure 4.2).

5. Loans to the private sector

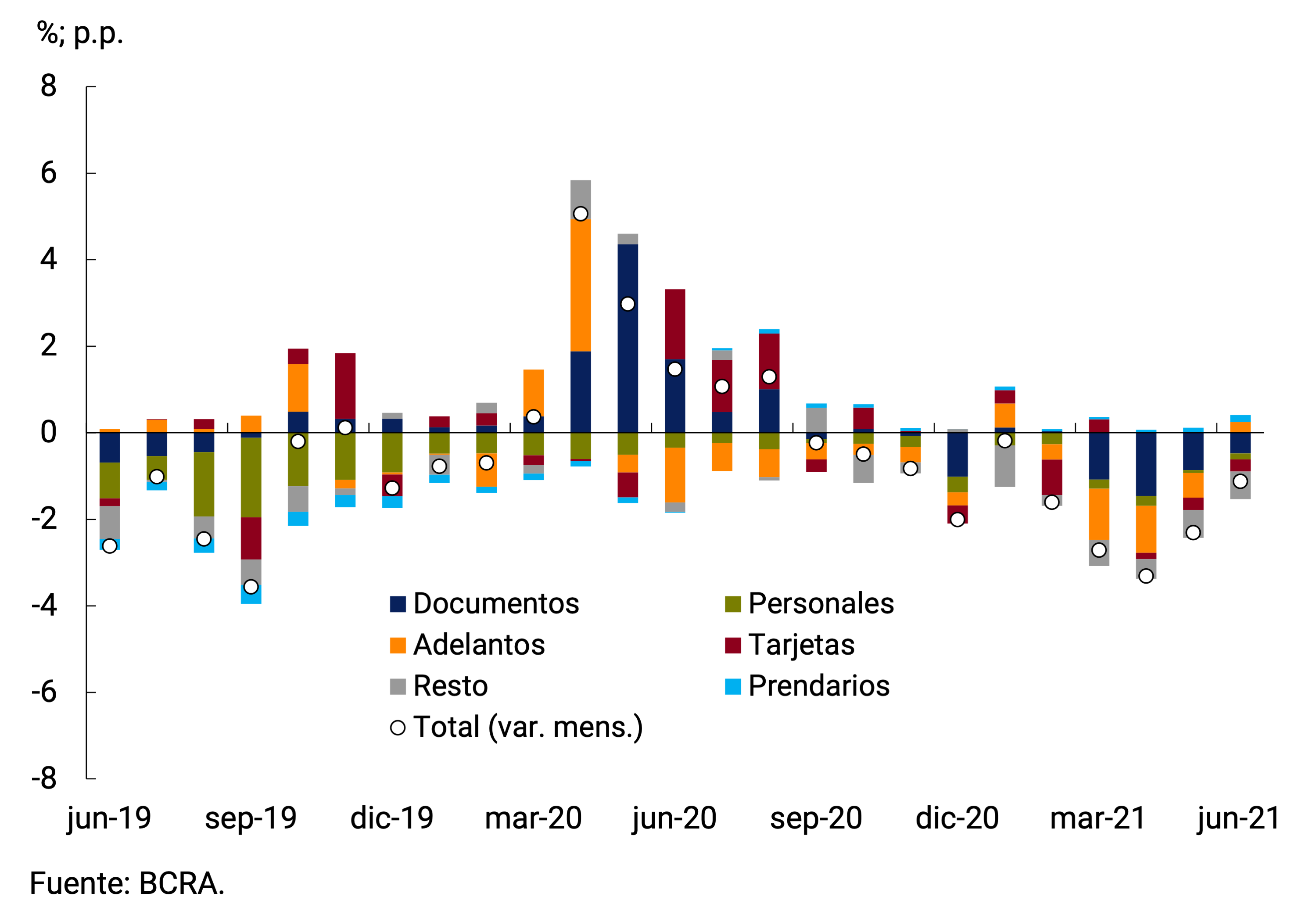

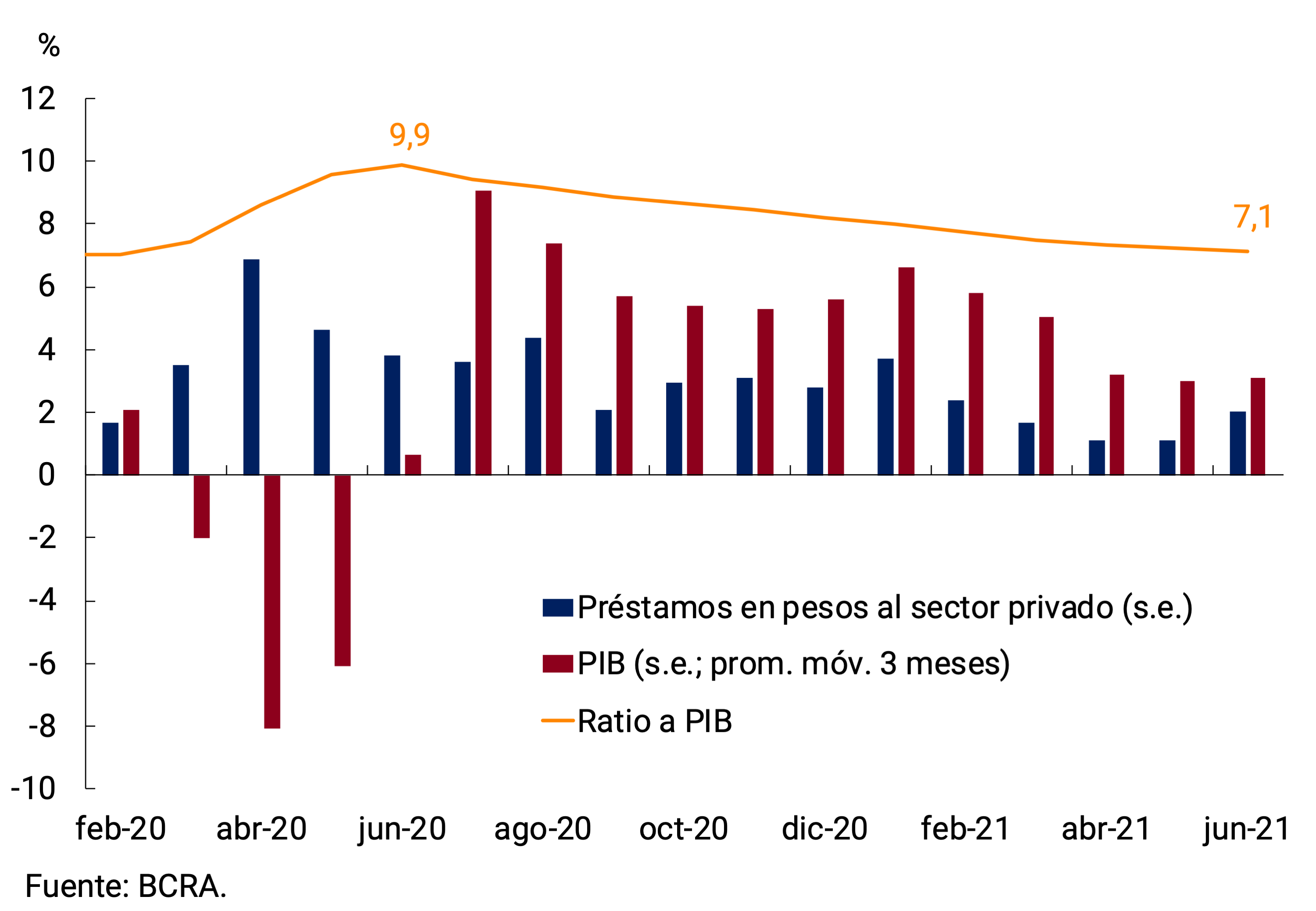

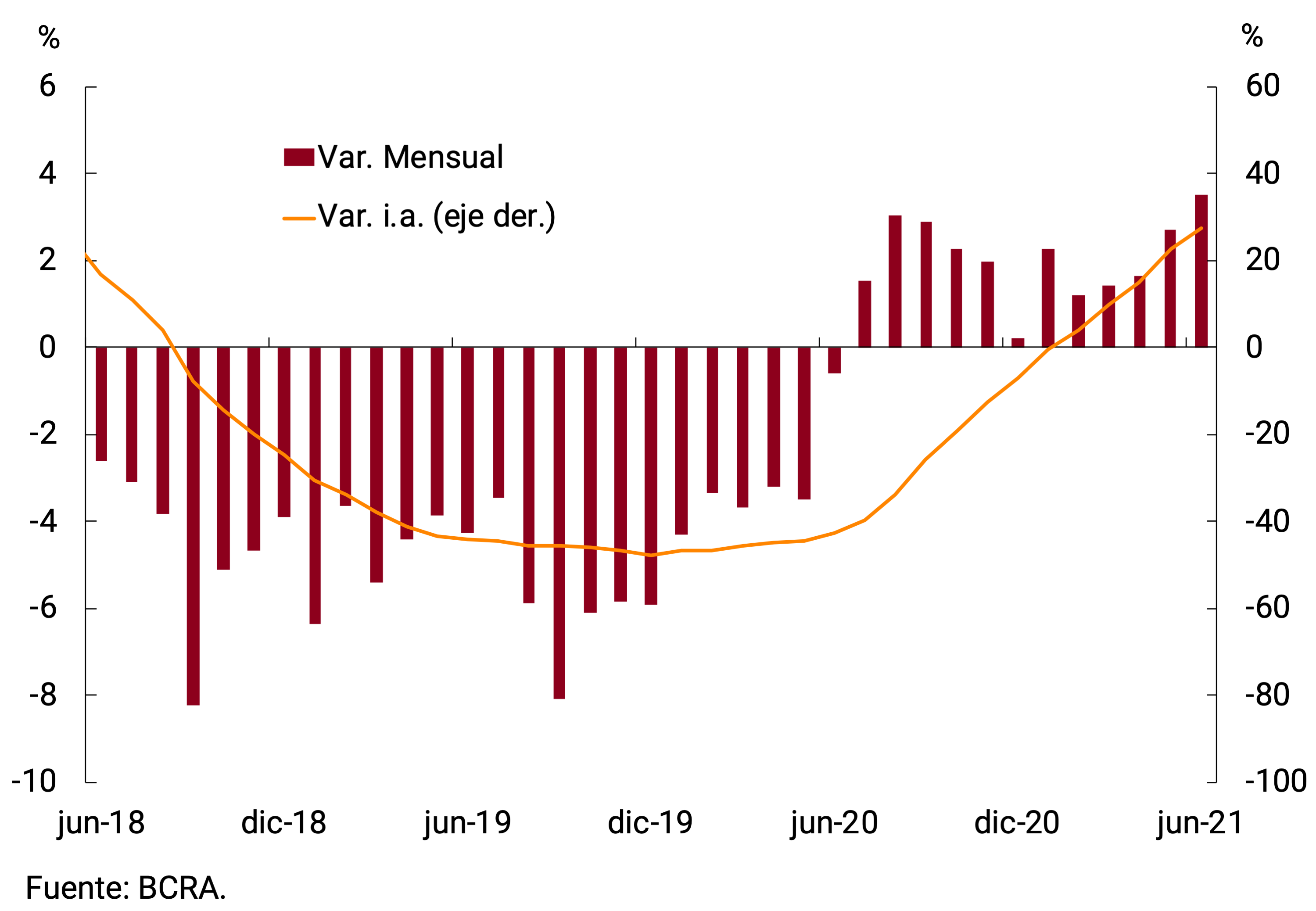

Loans in pesos to the private sector, in real terms and without seasonality, would have registered a monthly contraction of 1.1% in June, cutting the rate of decline in relation to previous months (see Figure 5.1). In year-on-year terms, they accumulated a fall of 11.8% at constant prices, once again influencing the calculation both the contraction of the month and the high base of comparison of June of the previous year. Most of the monthly decline was explained by the behavior of credit card financing and those instrumented through documents, while advances and collateral loans were the only lines with a positive impact on the variation of the month. The ratio of loans in pesos to the private sector to GDP stood at 7.1% in June, a figure similar to that observed prior to the beginning of the pandemic. The reversal in the ratio to GDP was explained both by the moderation in the nominal expansion rate of financing lines and by the recovery in economic activity (see Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.1 | Loans in Pesos to the Real Private Sector

without seasonality; contribution to monthly growth

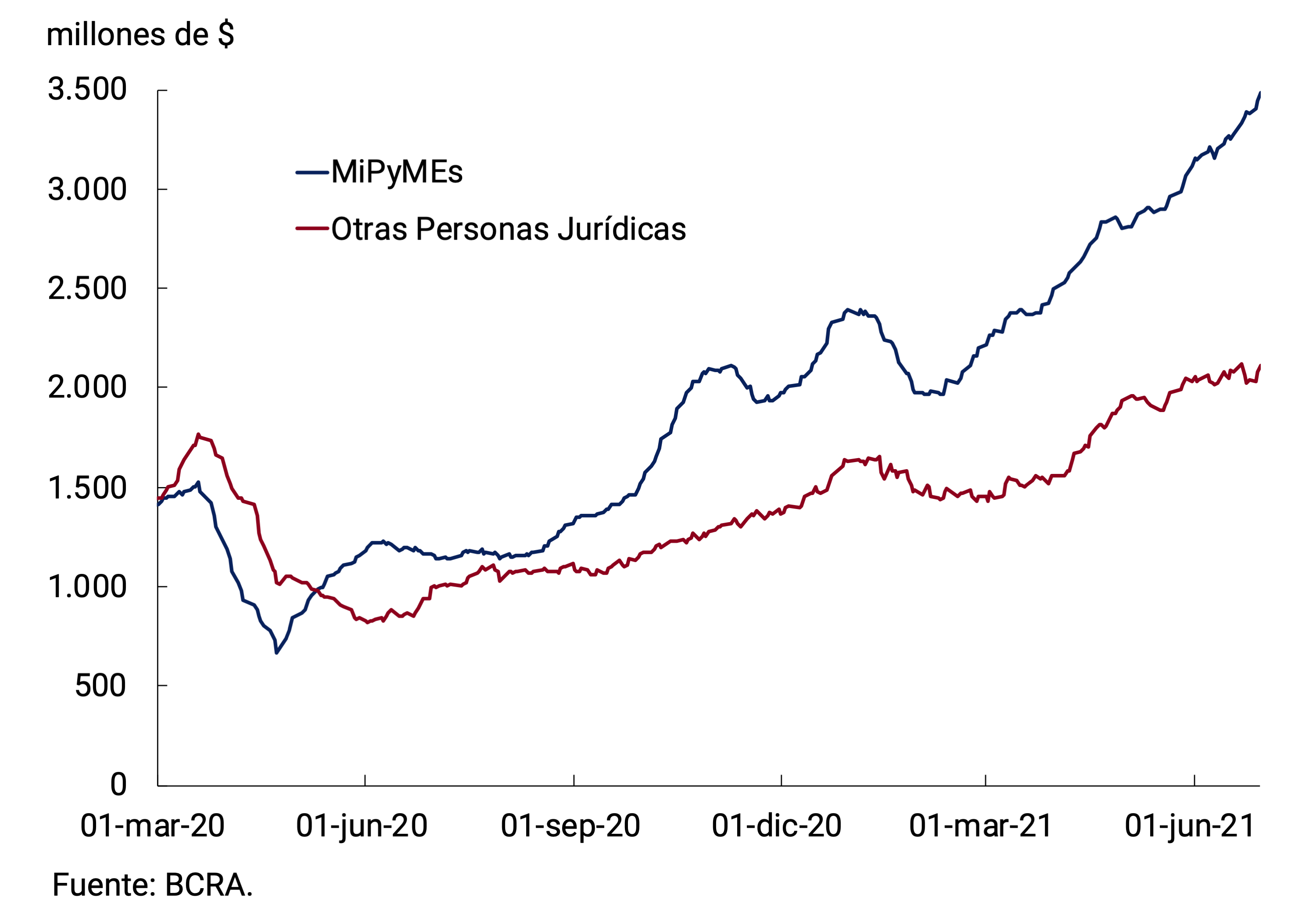

Commercial loans registered, as a whole, a monthly contraction of 1.0% s.e. at constant prices, with a year-on-year fall of 20.7%. Within these financings, a heterogeneous behavior was observed. While single-signed documents showed a monthly fall at constant prices of 4.4% s.e., advances and discounted documents showed real increases of 2.9% and 3.3% s.e., respectively. The growth in discounted documents is linked to the Financing Line for Productive Investment (LFIP), due to the fact that the largest granting was concentrated in MSMEs and at rates in line with the LFIP (see Figure 5.3). It should be noted that the LFIP contemplates a maximum interest rate of 30% n.a. for the financing of investment projects and 35% n.a. for working capital.

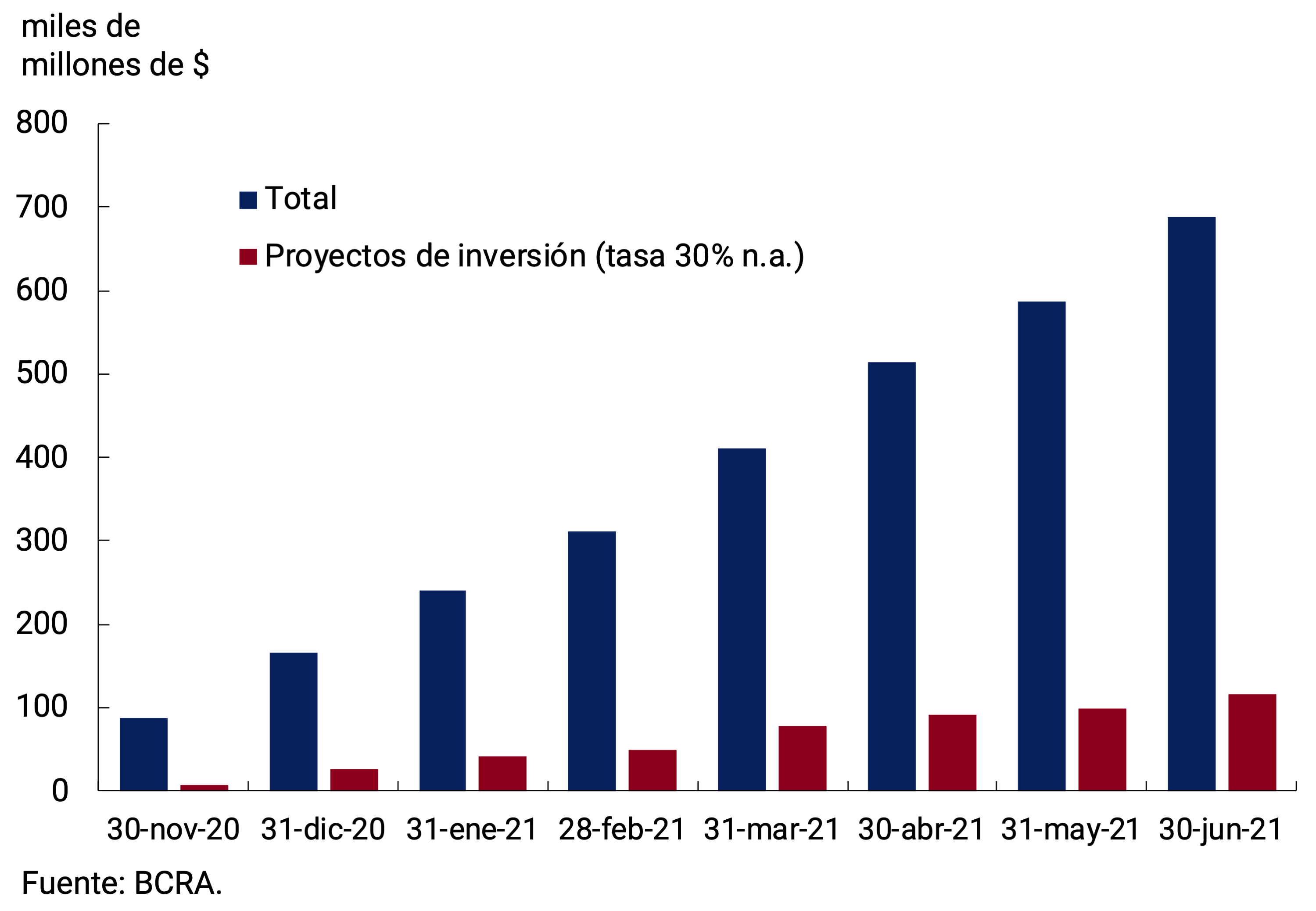

In June, within the framework of the LFIP, loans for $100,375 million were granted and the line accumulates disbursements for approximately a total of $687,400 million. As for the uses of these funds, about 83% of the total disbursed corresponds to the financing of working capital and the rest to the line that finances investment projects (see Figure 5.4). Finally, it is worth noting that at the time of this publication the number of companies that accessed the LFIP amounted to around 147,000.

As for consumer loans, credit card financing would have presented a monthly contraction at constant prices of 0.9% s.e., although in year-on-year terms they would still be 5 p.p. above the previous year’s record (see Chart 5.5). Recently, and in order to guarantee the fluidity of the payment system, the BCRA decided to reduce the maximum settlement period for payments made by financial institutions to businesses for sales made with credit cards in a single payment. The measure, which will come into force in July, will reduce collection times for 1.5 million micro and small enterprises9. Until this measure, the maximum settlement period was 10 working days. With the new provision, micro or small enterprises and individuals will receive the collection of sales made by credit card 8 business days after they have been made. In the case of medium-sized companies, the deadline will remain at 10 business days and for large companies the term will be extended to 18 business days. For health, gastronomic and hotel companies, the reduction to 8 days will also apply if they are micro or small businesses and remains at 10 business days for the rest.

Meanwhile, personal loans showed a fall in the month of 0.8% in real and seasonally adjusted terms. It is worth noting that the interest rate charged for personal loans gradually decreased from the middle of the month and with greater force in recent days. The latter was linked to a special line of credit created by a bank. All in all, the average rate in June stood at 52.7% n.a., which implied a reduction of 1.9 p.p. compared to May.

With respect to lines with real collateral, collateral loans would have registered an average monthly increase of 3.5% s.e. in real terms in June, accumulating 12 consecutive months of positive variations at constant prices. Thus, the real year-on-year rate of expansion would be around 27.5% (see Figure 5.6). Finally, the balance of mortgage loans showed a decrease of 1.5% in real terms without seasonality, standing 27.8% below the figure for the same month of the previous year.

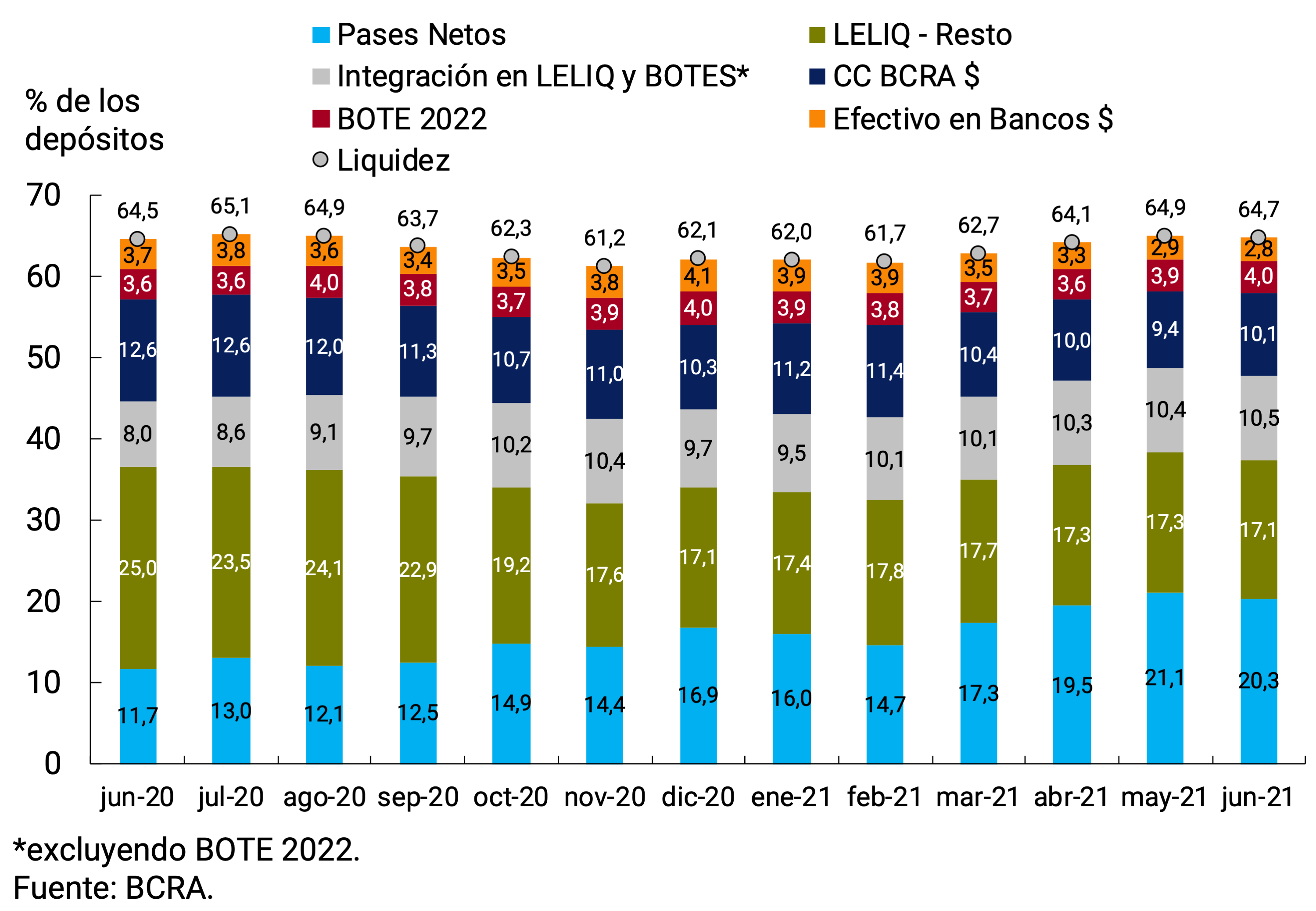

6. Liquidity in pesos of financial institutions

Ample bank liquidity in local currency10 continued to be at historically high levels. During the month of June, it experienced a slight drop of 0.2 p.p., averaging 64.7% of deposits (see Figure 6.1). In terms of its components, the share of net passes and LELIQ was reduced, with the increase in the balance of national treasury bonds for integration as a counterpart (see Figure 6.2). This is explained by the regulatory change that came into force in June and that allows financial institutions to integrate the percentage of reserve requirements that can be integrated into LELIQ in national public securities in pesos (excluding those linked to the price of the dollar) and a residual term of at least 180 days11. On the other hand, there was an increase in current accounts at the BCRA, mainly explained by the greater increase in demand deposits in the previous month compared to time deposits (it should be remembered that reserve requirements lag behind). On the other hand, cash in banks represented, on average, 2.8% of deposits.

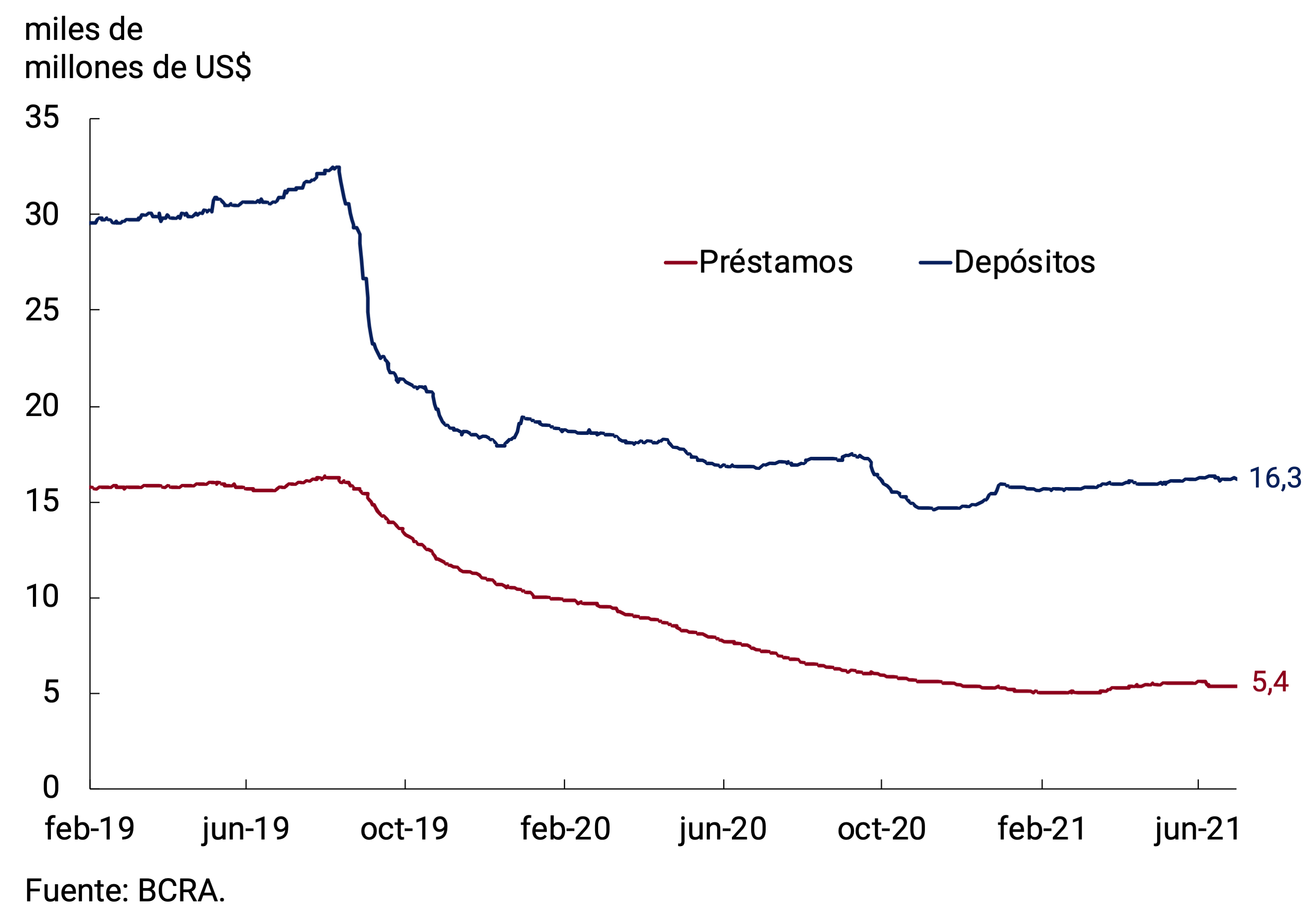

7. Foreign currency

Deposits and loans in foreign currency to the private sector showed little significant variation in the month. The average monthly balance of the former stood at US$16,242 million (+US$158 million compared to May), while loans averaged US$5,416 million in June, registering a decrease in the month (-US$124 million; see Figure 7.1).

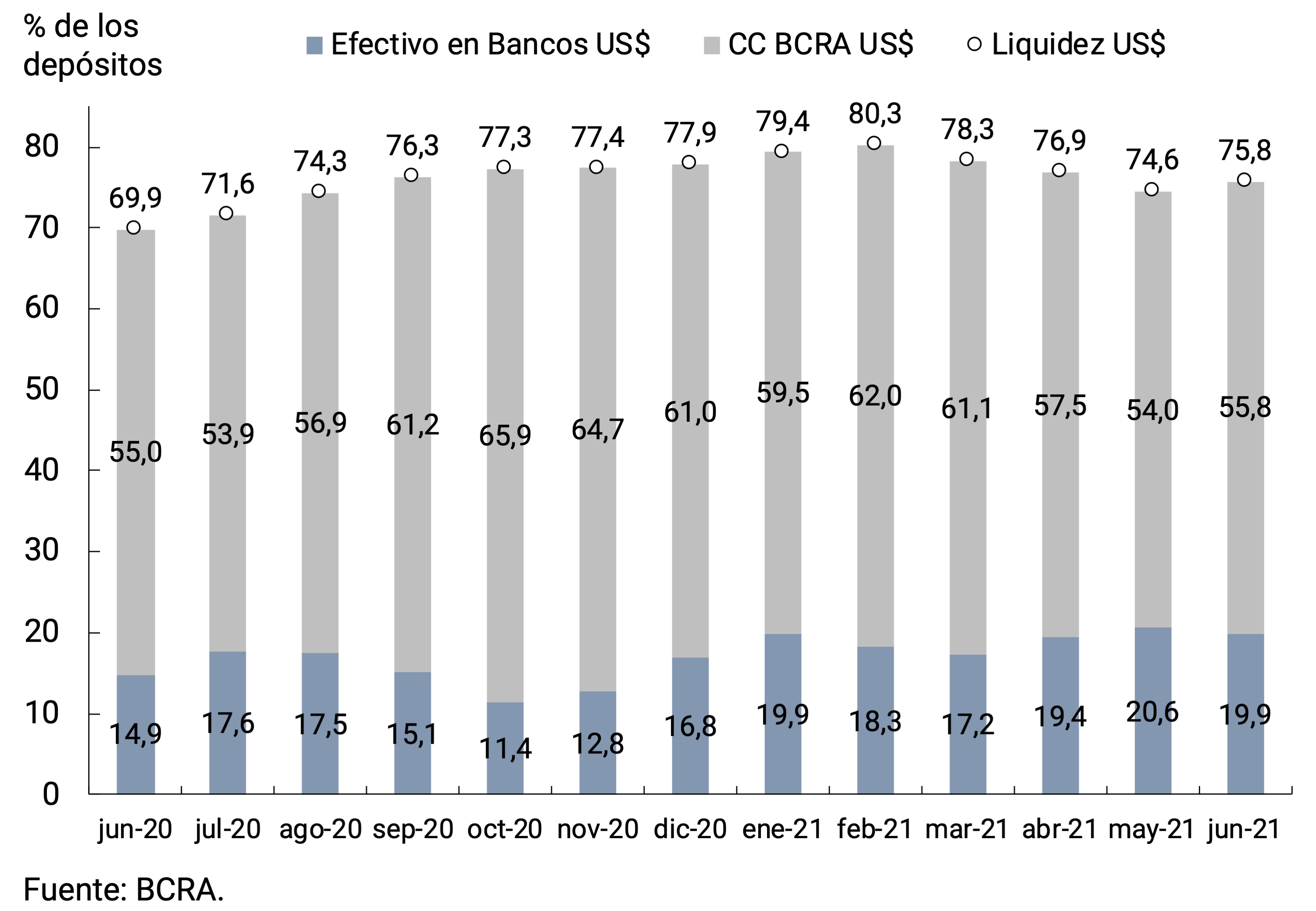

Bank liquidity in foreign currency averaged 75.8% of deposits, registering an increase of 1.2 p.p. compared to May. In this way, it is at historically high levels. This increase in liquidity during the month of June was explained by the 1.8 p.p. increase in current accounts at the BCRA, partially offset by a 0.7 p.p. drop in cash in banks (see Chart 7.2).

With regard to regulatory modifications, the BCRA extended until the end of the year the requirement of prior conformity to access the foreign exchange market for the payment of imports of goods (in the case of operations for which this requirement is contemplated) and to make payments of financial debts abroad for those companies with scheduled capital maturities that operate between April 1, 2021 and December 31, 2021 and exceeding US$2 million per month12. The requirement of prior conformity to access the foreign exchange market will also not apply to those companies that have a “Certification of increase in exports of goods in the year 2021”13.

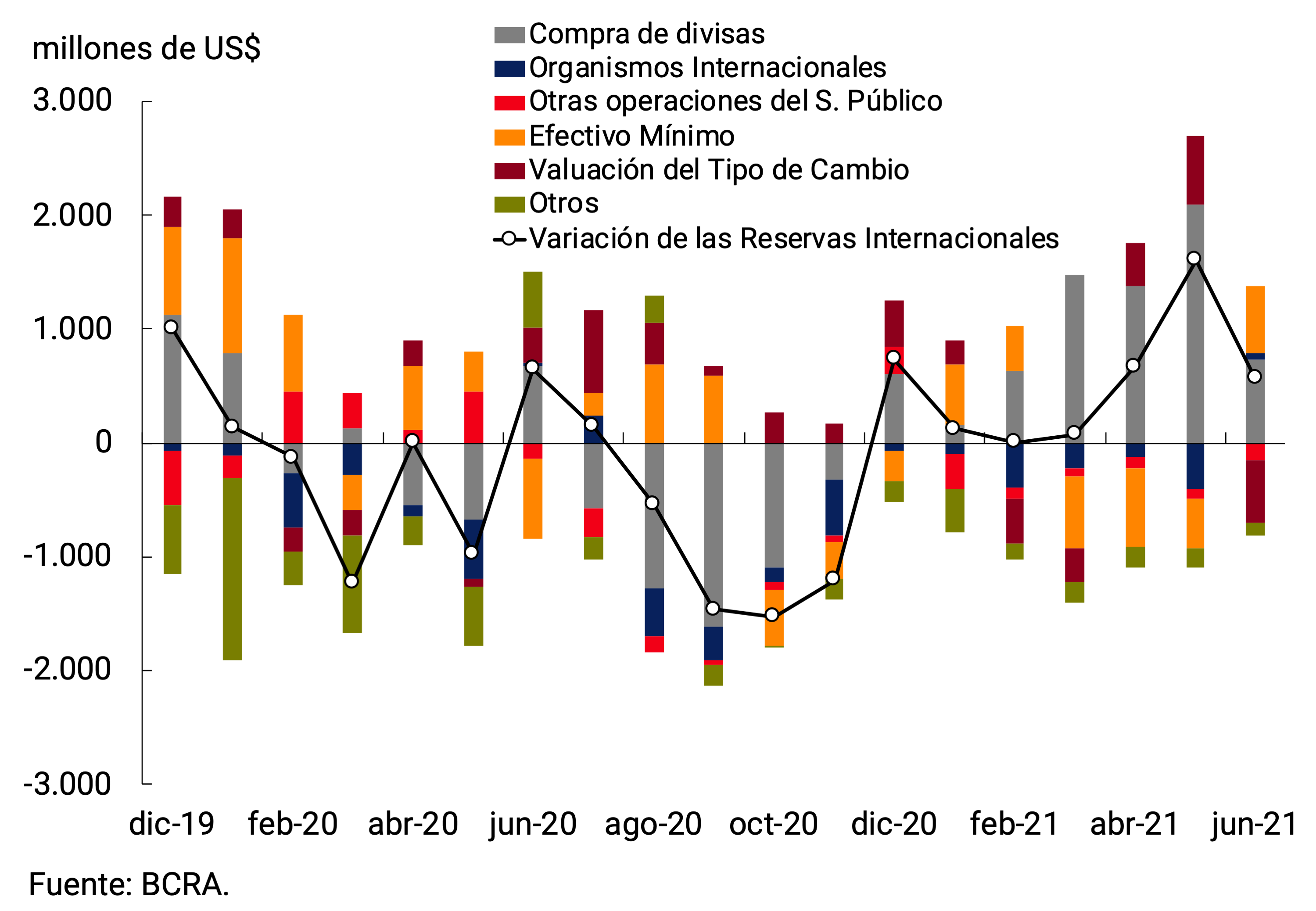

The BCRA’s International Reserves registered an expansion of US$565 million compared to May 31, ending the month with a balance of US$42,437 million, accumulating 7 consecutive months of increases. In terms of the factors of change, the net purchase of foreign currency and the increase in the minimum cash position of financial institutions explained the expansion of the month, although these factors were partially offset by changes in exchange rate valuation and, to a lesser extent, by net payments by the public sector (see Figure 7.3).

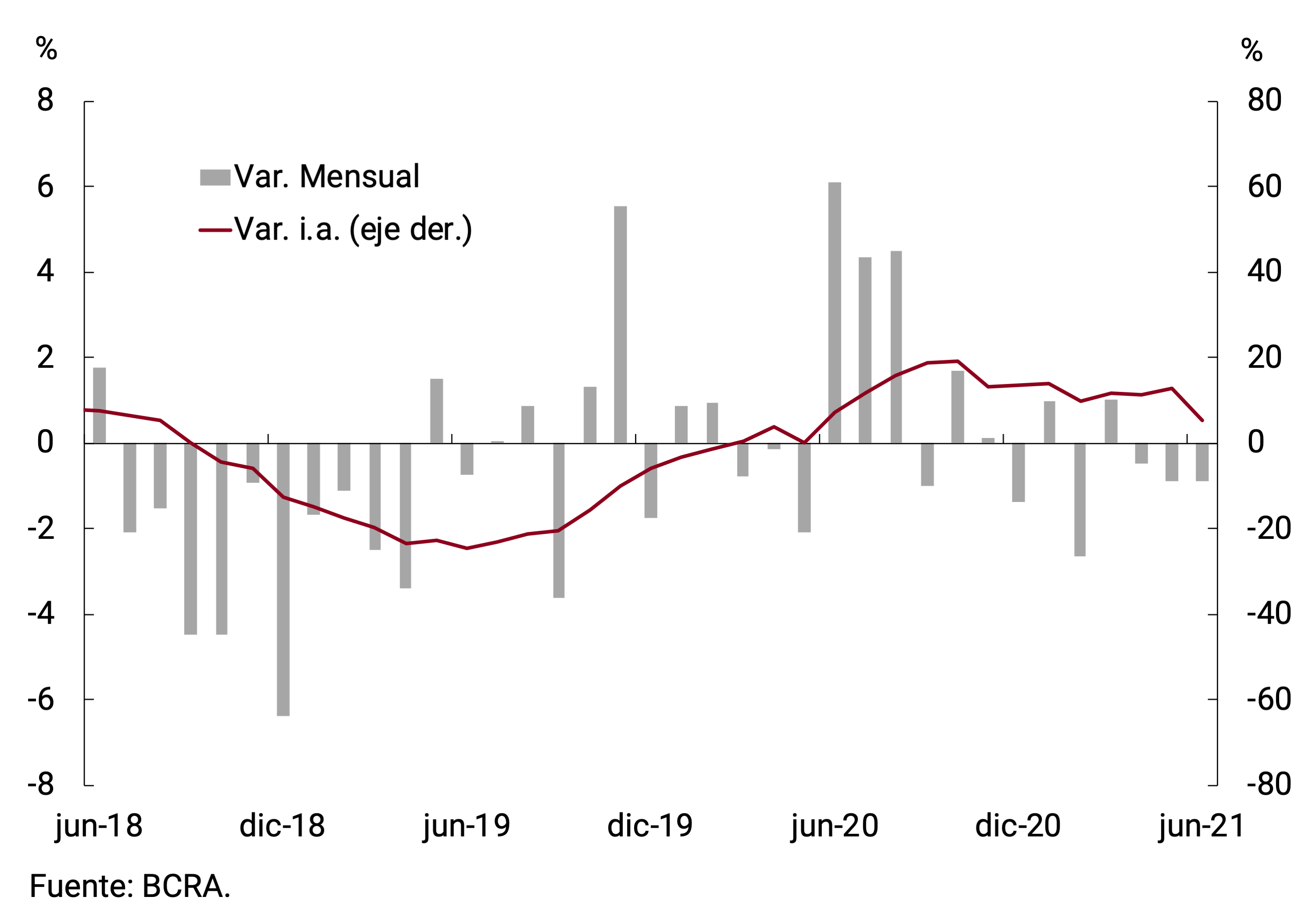

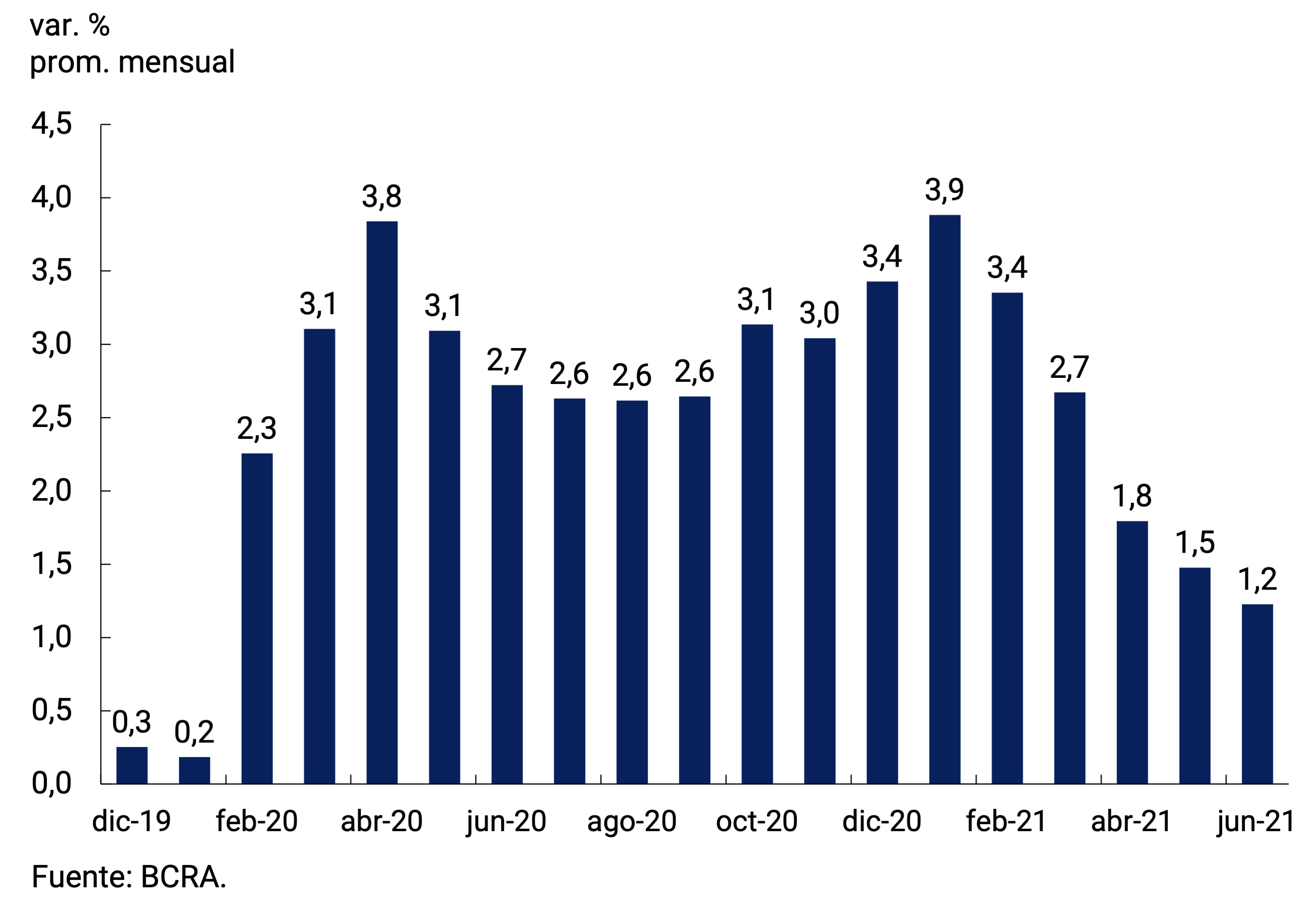

The nominal bilateral exchange rate against the U.S. dollar stood at $95.26/US$, on average for the month. This implied a variation in the nominal exchange rate of 1.2% in June, 0.3 p.p. lower than in May. This responds to the moderation in the rate of depreciation of the domestic currency with which it seeks to contribute to the disinflation process (see Figure 7.4). Even so, the average Multilateral Real Exchange Rate (ITCRM) for the month remains in line with its historical average.

Glossary

ANSES: National Social Security Administration.

BADLAR: Interest rate on fixed-term deposits for amounts greater than one million pesos and a term of 30 to 35 days.

BCRA: Central Bank of the Argentine Republic.

BM: Monetary Base, includes monetary circulation plus deposits in pesos in current account at the BCRA.

CC BCRA: Current account deposits at the BCRA.

CER: Reference Stabilization Coefficient.

NVC: National Securities Commission.

SDR: Special Drawing Rights.

EFNB: Non-Banking Financial Institutions.

EM: Minimum Cash.

FCI: Common Investment Fund.

A.I.: Year-on-year .

IAMC: Argentine Institute of Capital Markets

CPI: Consumer Price Index.

ITCNM: Multilateral Nominal Exchange Rate Index

ITCRM: Multilateral Real Exchange Rate Index

LEBAC: Central Bank bills.

LELIQ: Liquidity Bills of the BCRA.

LFIP: Financing Line for Productive Investment.

M2 Total: Means of payment, which includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and demand deposits in pesos from the public and non-financial private sector.

Private M2: Means of payment, includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and demand deposits in pesos from the non-financial private sector.

Private transactional M2: Means of payment, includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and non-remunerated demand deposits in pesos from the non-financial private sector.

M3 Total: Broad aggregate in pesos, includes the current currency held by the public, cancelling checks in pesos and the total deposits in pesos of the public and non-financial private sector.

Private M3: Broad aggregate in pesos, includes the working capital held by the public, cancelling checks in pesos and the total deposits in pesos of the non-financial private sector.

MERVAL: Buenos Aires Stock Market.

MM: Money Market.

N.A.: Annual nominal

E.A.: Annual Effective

NOCOM: Cash Clearing Notes.

ON: Negotiable Obligation.

GDP: Gross Domestic Product.

P.B.: Basic points.

P.P.: Percentage points.

MSMEs: Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises.

ROFEX: Rosario Term Market.

S.E.: No seasonality

SISCEN: Centralized System of Information Requirements of the BCRA.

TCN: Nominal Exchange Rate

IRR: Internal Rate of Return.

TM20: Interest rate on fixed-term deposits for amounts greater than 20 million pesos and a term of 30 to 35 days.

TNA: Annual Nominal Rate.

UVA: Unit of Purchasing Value

References

1 INDEC will release the inflation data for May on July 15.

2 M2 private excluding interest-bearing demand deposits from companies and financial service providers. This component was excluded since it does not represent a transactional means of payment.

3 Every year, the ANSES withholds 20% of the AUH that is paid at the end of the year to beneficiaries who have increased their schooling status and have complied with the vaccination schedule. This time the amount is $7,083.4 per child.

4 This effect is corrected with monthly seasonalization.

5 According to data from the latest National Household Expenditure Survey (ENGHo 2018), the first decile of income makes practically 90% of their expenditures with cash payment.

6 Law 25065 on Credit Cards set a maximum period of 3 business days and, by an agreement with the regulator, the banks had agreed to do so within 2 business days. Now that period is reduced to 1 day according to the agreement reached between the BCRA and the financial institutions.

7 These include UVA-denominated deposits.

8 Includes the working capital held by the public and the deposits in pesos of the non-financial private sector (sight, term and others).

9 See Communication A7305.

10 Includes current accounts at the BCRA, cash in banks, balances of passes arranged with the BCRA, holdings of LELIQ, and bonds eligible for reserve requirements.

11 See Communication A7290.