Política Monetaria

Monthly Monetary Report

July

2022

Monthly report on the evolution of the monetary base, international reserves and foreign exchange market.

Table of Contents

Contents

1. Executive Summary

2. Payment Methods

3. Savings instruments in pesos

4. Monetary base

5. Loans in pesos to the private sector

6. Liquidity in pesos of financial institutions

7. Foreign currency

The statistical closing of this report was January 8, 2024. All figures are provisional and subject to revision.

Inquiries and/or comments should be directed to analisis.monetario@bcra.gob.ar

The content of this report may be freely cited as long as the source is clarified: Monetary Report – BCRA.

1. Executive Summary

The BCRA set in its objectives and plans to establish a path for the policy interest rate in order to tend towards positive real returns on investments in local currency, to preserve monetary and exchange rate stability. To this end, the BCRA currently conducts its monetary policy through changes in the interest rates of the 28-day Liquidity Bills (LELIQ), an instrument on which it defines the reference interest rate of monetary policy. Asimismo, para que las entidades financieras puedan calibrar su liquidez de corto plazo tienen a disposición una ventanilla de pases pasivos y activos, que se regula tomando como referencia la tasa de las LELIQ. También, en el entorno actual de elevados niveles de ahorro en el sistema financiero y reducida profundidad del crédito, el BCRA administra la liquidez bancaria estructural mediante la licitación periódica de sus instrumentos (LELIQ y NOTALIQ).

In the medium term, the BCRA seeks to gradually converge towards managing the economy’s liquidity through open market operations (OMA) with Treasury bills and other short-term securities denominated in local currency, as is the case in other countries and in line with what is expressed in the Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies within the framework of the current program with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). where such reform is considered a convenient alternative to reduce the quasi-fiscal cost of monetary policy. Pursuing this objective requires greater liquidity, depth and transparency of sovereign debt markets.

In this regard, the BCRA has on several occasions used its capacity to intervene through open market operations. In particular, in the last two months, the monetary authority sought to reduce volatility in the prices of Treasury instruments. This action is complemented by a deepening of coordination efforts with the Ministry of Economy of the Nation so that the BCRA’s interest rate structure presents reasonable spreads with National Treasury bills.

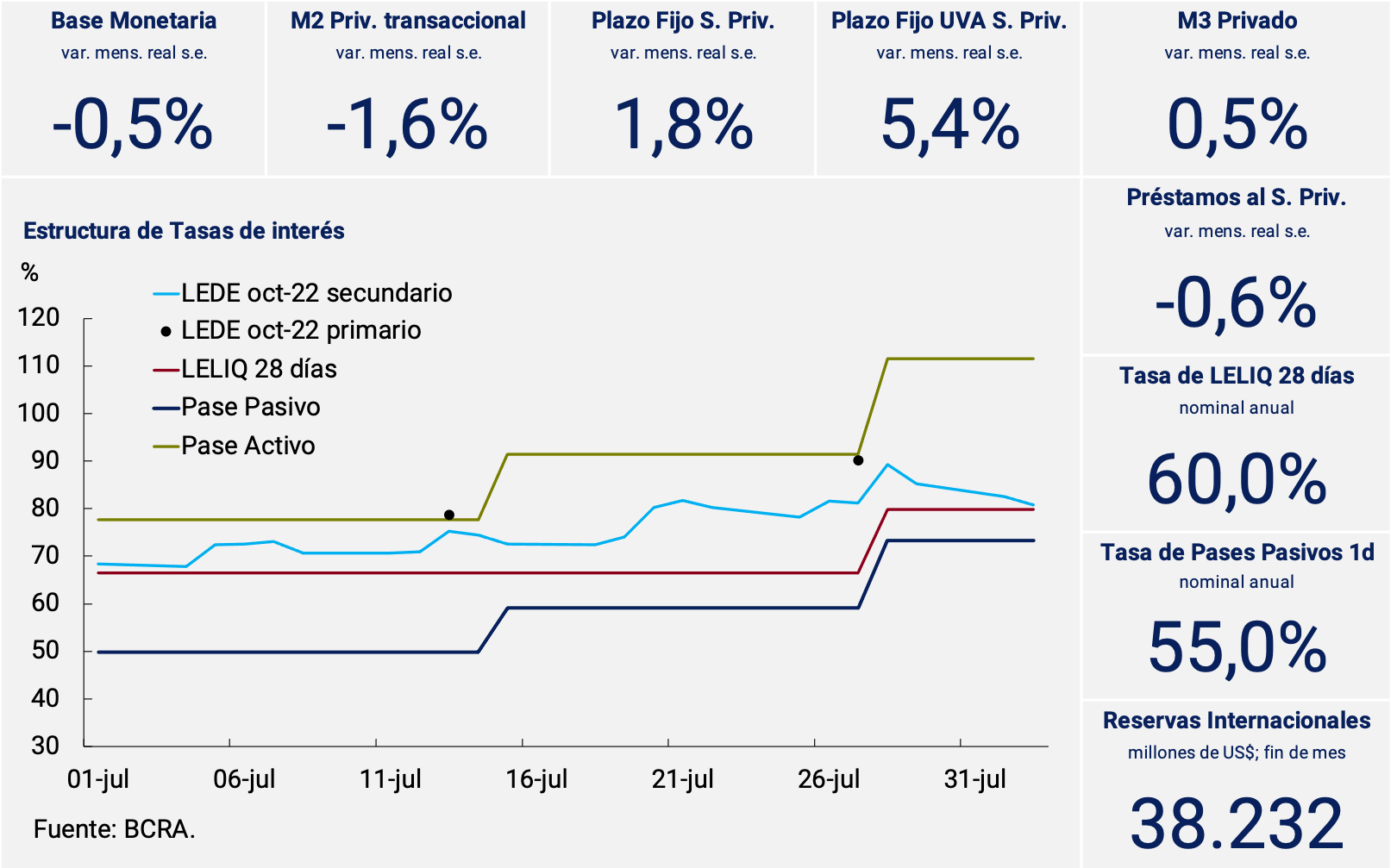

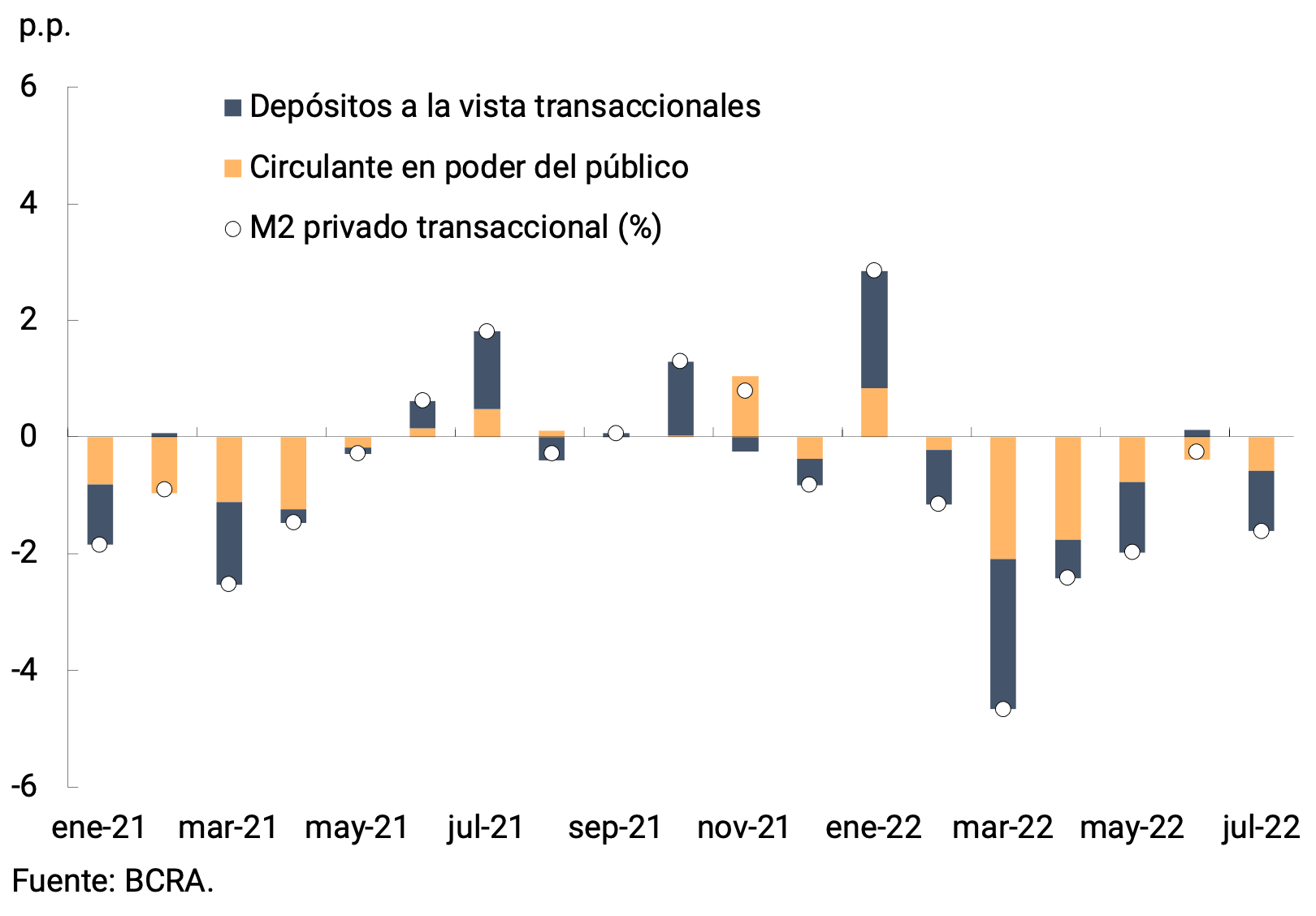

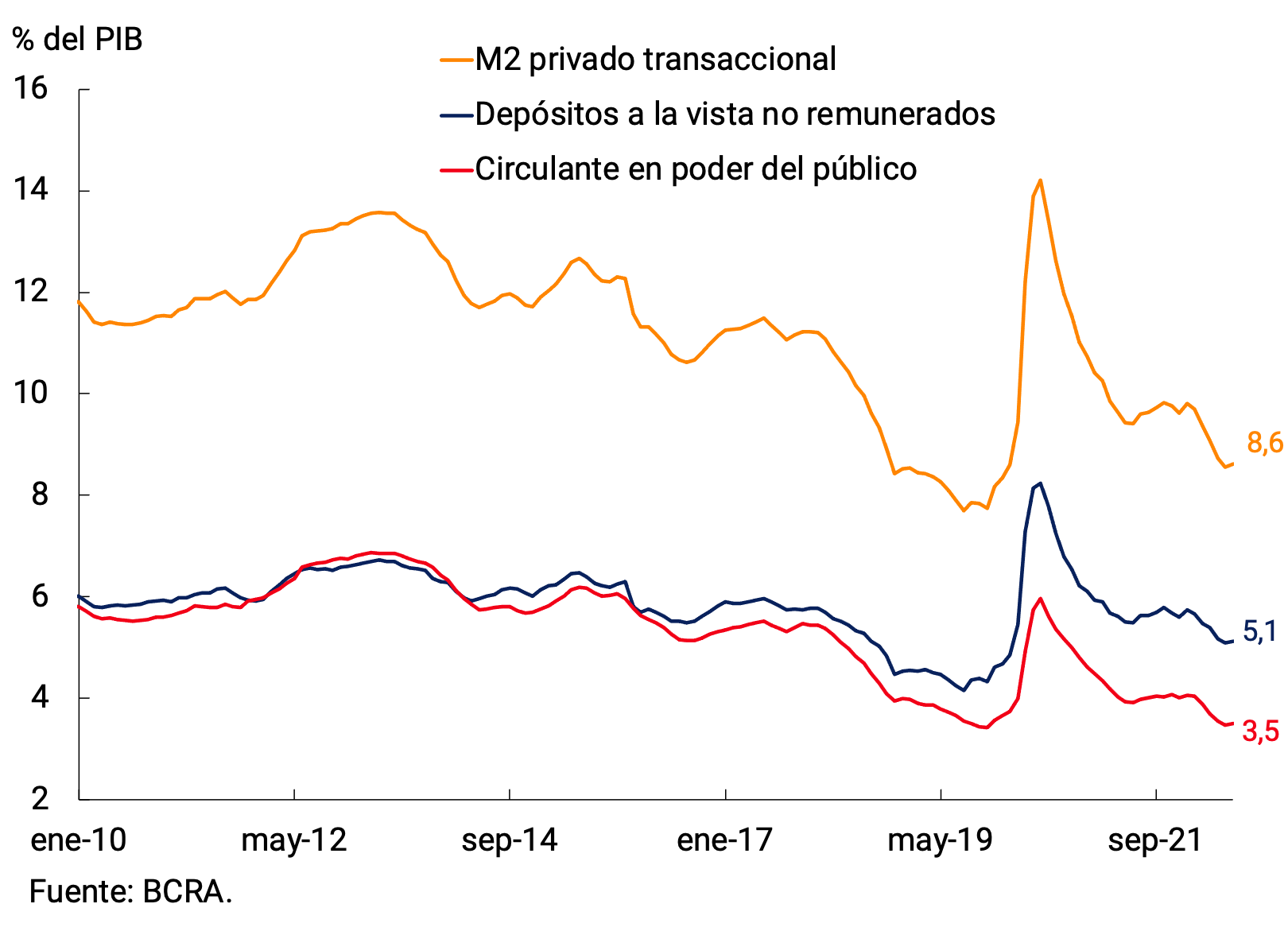

2. Payment methods

Means of payment (private transactional M21), at constant and seasonally adjusted prices (s.e.), would have registered a contraction of 1.6% in July, accumulating six consecutive months of declines (see Chart 2.1). The dynamics of the month responded both to the behavior of working capital held by the public and of non-interest-bearing demand deposits. In the year-on-year comparison, and at constant prices, the transactional private M2 would be around 7.6% below the level of July 2021. In terms of Output, private transactional M2 would have stood at 8.6%, approaching the lowest levels in the last 15 years (see Figure 2.2). In particular, the working capital held by the public reached a minimum, while demand deposits are at values similar to those of the average of recent years.

Figure 2.1 | Private transactional M2 at constant

prices Contribution by component to the monthly vari. s.e.

3. Savings instruments in pesos

At the end of the month, the Board of Directors of the BCRA decided to raise the minimum guaranteed interest rates on fixed-term deposits for the seventh time this year2. On this occasion, it increased by 8 p.p. the minimum guaranteed rate for placements of individuals for up to an amount of $10 million, which went from 53% n.a. to 61% (81.3% e.a.). For the rest of the depositors of the financial system3 , the interest rate rose by 4 p.p. to 54% (69.6% y.a.). This measure is aimed at tending towards positive real returns on investments in local currency and preserving monetary and exchange rate stability.

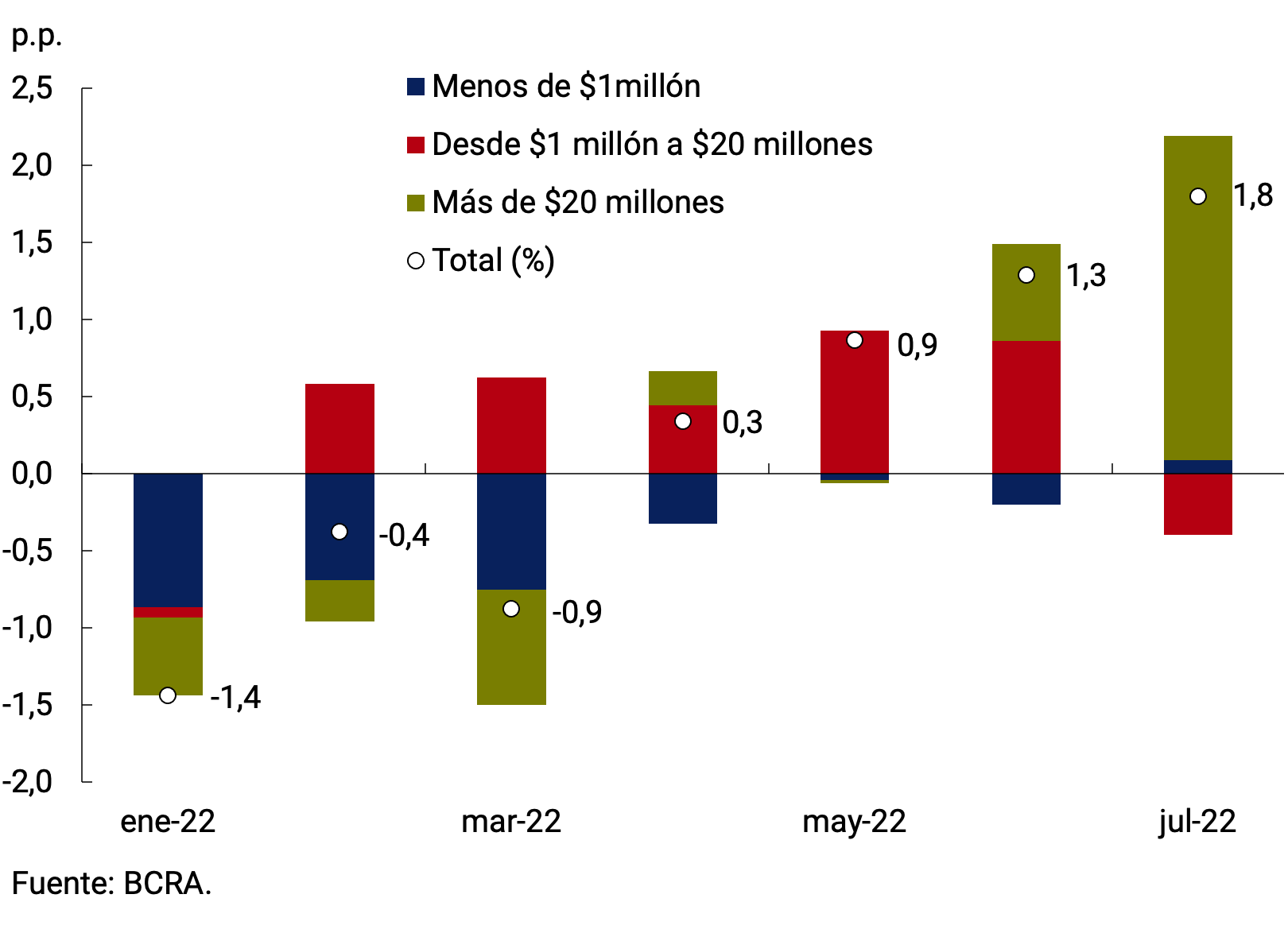

In real and seasonally adjusted terms, fixed-term deposits in pesos in the private sector would have registered a monthly growth of 1.8% s.e., completing four consecutive months of expansion. In this way, term placements persist around the highest levels in recent decades. As a GDP ratio, they would have registered an increase compared to June (0.3 p.p.) and would reach 6.7%, a record that continues to be among the highs of recent years.

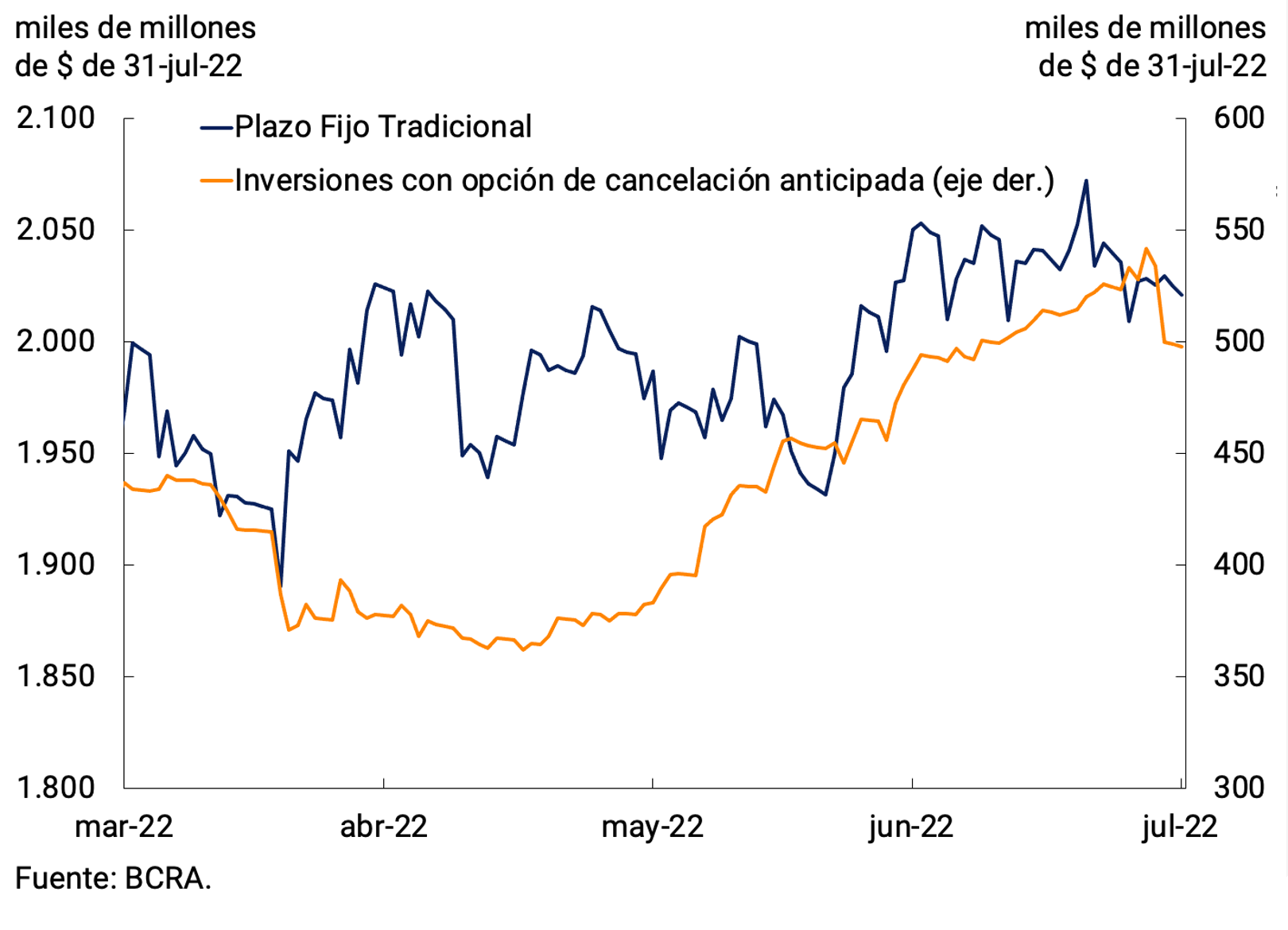

The growth of the month was concentrated in the wholesale segment (more than $20 million; see Figure 3.1) and was explained by investments with an early cancellation option. Meanwhile, traditional deposits remained largely unchanged throughout the month (see Figure 3.2). Within this type of placement, an increase in the holdings of Financial Services Providers (FSPs) was observed, offset by a fall in the holdings of other companies. The main agents within the PSFs are the Mutual Funds, whose assets continued to increase in the month. The dynamism evidenced by the wholesale segment was partially offset by the fall in deposits from $1 million to $20 million, while placements of less than $1 million remained relatively stable at constant prices.

Figure 3.1 | Fixed-term deposits in pesos of the private

sector Var. real monthly and without seasonality by amount stratum

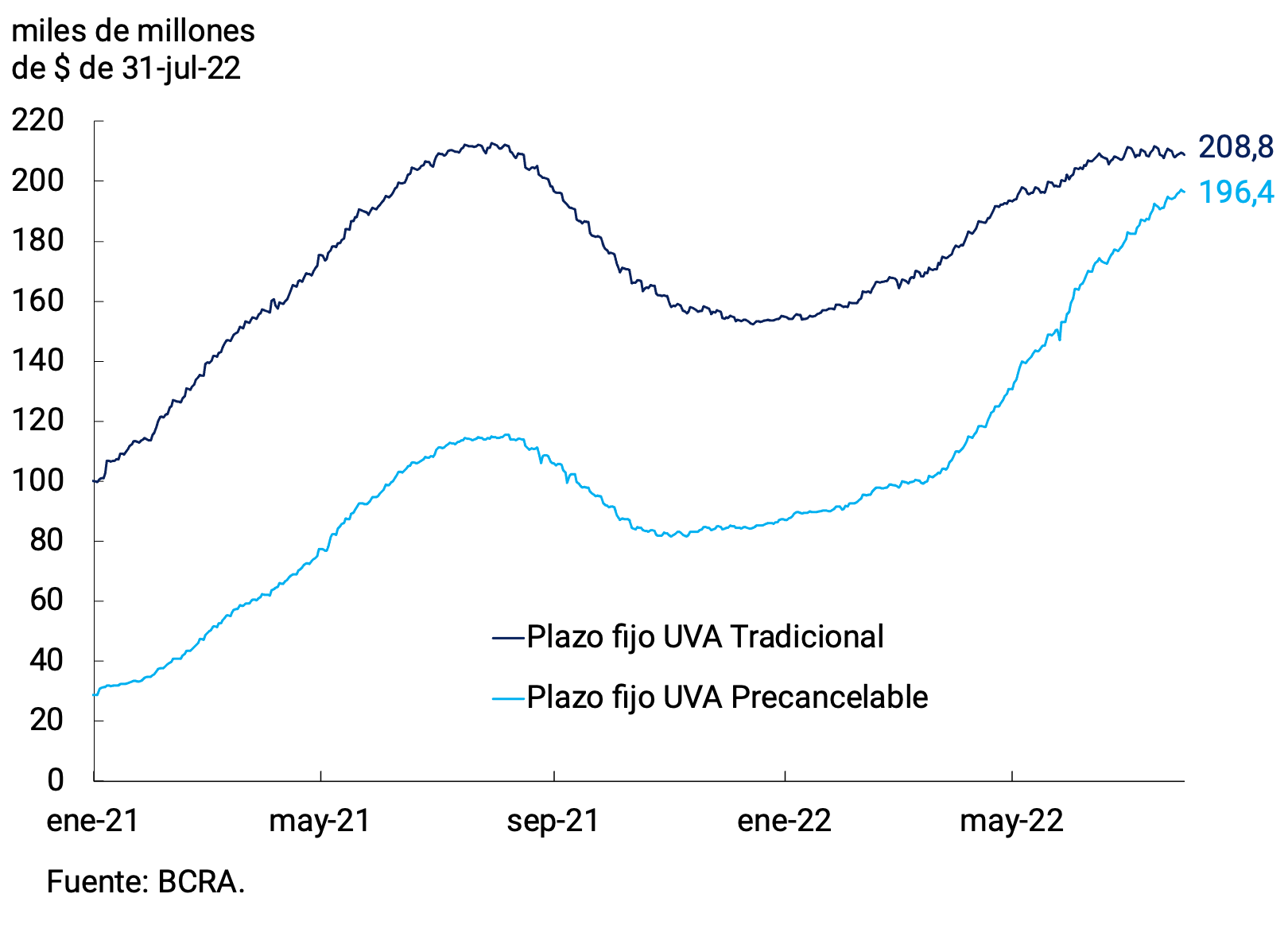

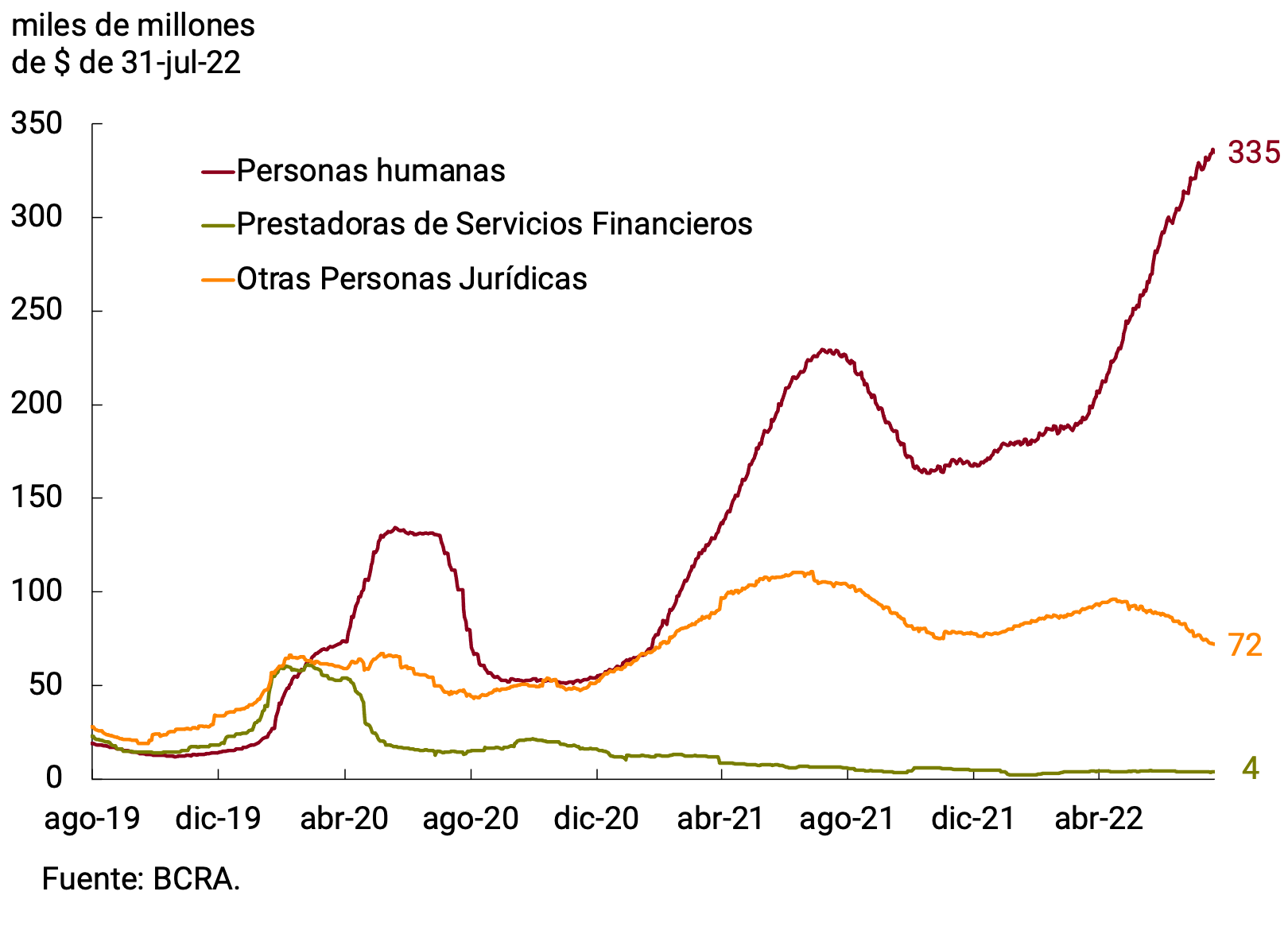

At the instrument level, in a context of greater financial volatility, the preference for shorter-term assets was accentuated. In fact, deposits with early cancellation options continued with the upward trend they have been showing since the beginning of June, driven mainly by placements in the wholesale segment. In particular, a similar behavior was also observed in the segment of CER adjustable deposits. While pre-cancelable placements continued the upward trend of previous months, traditional placements stabilized throughout July (see Figure 3.3). Thus, the monthly expansion rate of UVA placements with early cancellation option would have been 10.5% s.e. at constant prices, compared to 1.1% s.e. in the case of traditional UVA deposits. Distinguishing by type of holder, it can be seen that the impulse came mainly from the holdings of individuals (see Figure 3.4). All in all, UVA deposits reached a balance of $405,215 million at the end of July. However, its relative share of total term instruments remained limited (around 7% of total term deposits).

Figure 3.3 | Fixed-term deposits in UVA from the private

sector Balance at constant prices by type of instrument

Original series

However, the broad monetary aggregate, private M34, at constant prices would have registered a slight monthly expansion in July (0.5% s.e.). In the year-on-year comparison, this aggregate would have exhibited a slight contraction (-0.2%) and as a percentage of GDP it would have stood at 17%, 0.4 p.p. above the previous month’s record.

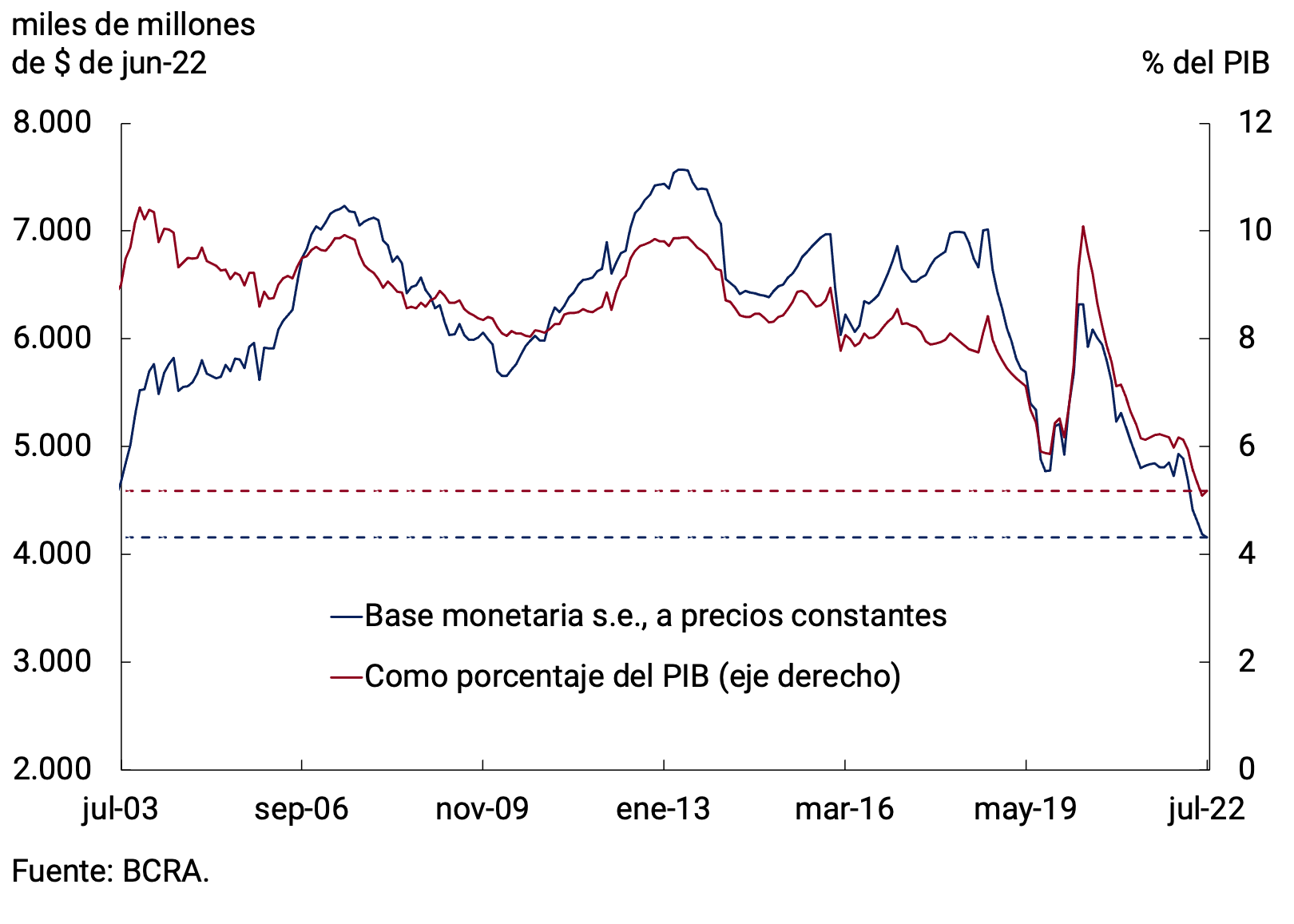

4. Monetary base

The Monetary Base on average in July stood at $4,212.0 billion, which implied a monthly increase of 8.2% (+$320,850 million) in the original series at current prices. Adjusted for seasonality and at constant prices, it would have exhibited a contraction of 0.5% and in the last twelve months it would accumulate a fall of the order of 13.9%. In terms of GDP, the Monetary Base would stand at 5.2%, a figure around the lowest values since 2003 (see Figure 4.1).

On the supply side, among the factors of monthly expansion of the monetary base can be mentioned the intervention of the BCRA in the secondary market of public securities with the aim of stabilizing the curve in pesos of these bonds and, to a lesser extent, the net purchase of foreign currency from the private sector. These effects were partially offset by the absorption of liquidity through the BCRA’s monetary regulation instruments.

The BCRA set in its objectives and plans to establish a path for the policy interest rate in order to tend towards positive real returns on investments in local currency, to preserve monetary and exchange rate stability. To this end, the BCRA currently conducts its monetary policy through changes in the interest rates of the 28-day Liquidity Bills (LELIQ), an instrument on which it defines the reference interest rate of monetary policy.

The BCRA also manages liquidity to avoid imbalances that directly or indirectly translate into additional inflationary pressures. In order for financial institutions to calibrate their short-term liquidity, they have at their disposal a window for passive and active passes, which is regulated by reference to the LELIQ rate. Likewise, in the current environment of high levels of savings in the financial system and reduced credit depth, the BCRA manages structural bank liquidity through the periodic auction of its instruments (LELIQ and NOTALIQ).

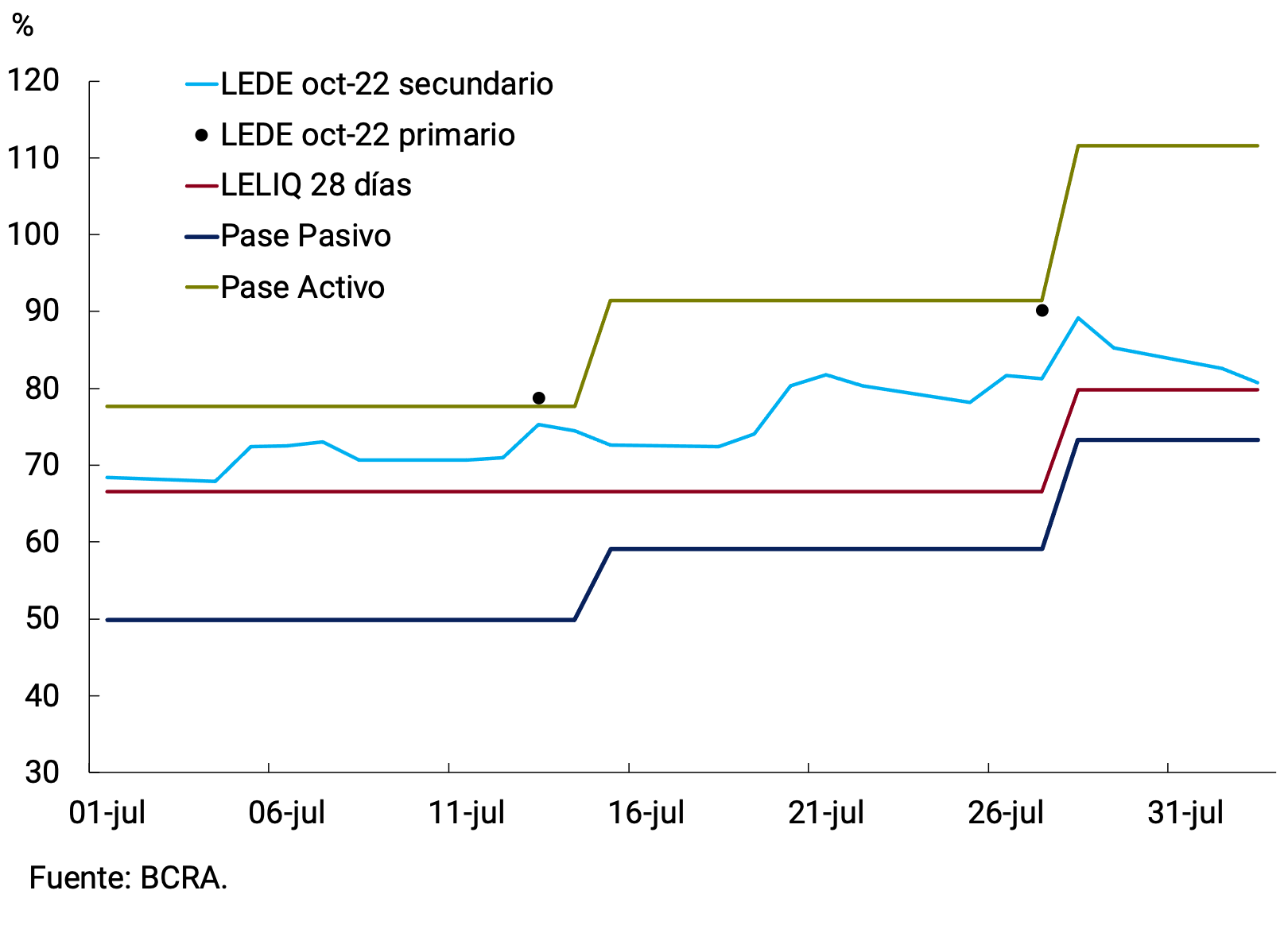

In this context, towards the end of the month, the BCRA raised the interest rates of its instruments so that the structure of its rates presents as a floor that of its 1-day passive passes with 55% n.a. (73.3% e.a.) and as a ceiling that of its active passes with 75% n.a. (111.5% e.a.). establishing the monetary policy interest rate within these limits, so that the 28-day LELIQ remained at 60% n.a. (79.8% e.a.). For its part, the interest rate of the LELIQ with a 180-day term was set at 68.1% n.a. (79.9% y.a.). Finally, the fixed spread of the NOTALIQ in the last auction of the month remained at 5.0 p.p.

In the medium term, the BCRA seeks to gradually converge towards managing the economy’s liquidity through open market operations (OMA) with Treasury bills and other short-term securities denominated in local currency, as is the case in other countries and in line with what is expressed in the Memorandum on Economic and Financial Policies within the framework of the current program with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). where such reform is considered a convenient alternative to reduce the quasi-fiscal cost of monetary policy. The pursuit of this objective requires that the local capital market assume an increasing importance for the financing of economic actors, both in the public and private sectors.

In this regard, the BCRA has on several occasions used its capacity to intervene through open market operations, in order to promote greater liquidity, depth and transparency in the sovereign debt markets. In particular, in the last two months, the monetary authority sought to reduce volatility in the prices of Treasury instruments, reaffirming its commitment to operate on the yield curve of public debt in local currency, ensuring that yields in the secondary market remain in a reasonable relationship with those determined in the framework of the Treasury’s primary auctions5.

To this end, the Board of Directors of the Central Bank decided to incorporate as a reference for the design and decisions of monetary policy the interest rate of short-term Treasury Bills (currently Discount Bills -LEDES- with maturities of 60-90 days). This decision is part of the strategy to (i) tend to a structure of positive interest rates in real terms, taking as a reference the main financial assets of the economy, (ii) strengthen the public debt market in pesos so that it achieves depth and liquidity and (iii) gradually advance in the use of Treasury instruments as monetary policy instruments.

This action is complemented by a deepening of coordination efforts with the Ministry of Economy of the Nation so that the BCRA’s interest rate structure presents reasonable spreads with National Treasury bills (see Figure 4.2). In this sense, the interest rate of the shortest instrument of the last auction, the Discount Bill maturing on October 31, was placed in the primary market with a 70% n.a. (90.1% e.a.).

Going forward, the BCRA will continue to monitor the secondary market for public securities and the evolution of their prices in relation to primary auctions, participating to limit their volatility, consistent with the current interest rate structure. In this way, it aims to prevent the yield of these securities from being located outside their macroeconomic fundamentals, which could alter the normal mechanisms of monetary policy transmission. In the near future, the Board of Directors will determine the monetary policy rate in such a way as to maintain an appropriate rate structure on these grounds, generating conditions conducive to the proper functioning of the local capital market, while complying with the objectives set in terms of monetary, financial and exchange rate stability.

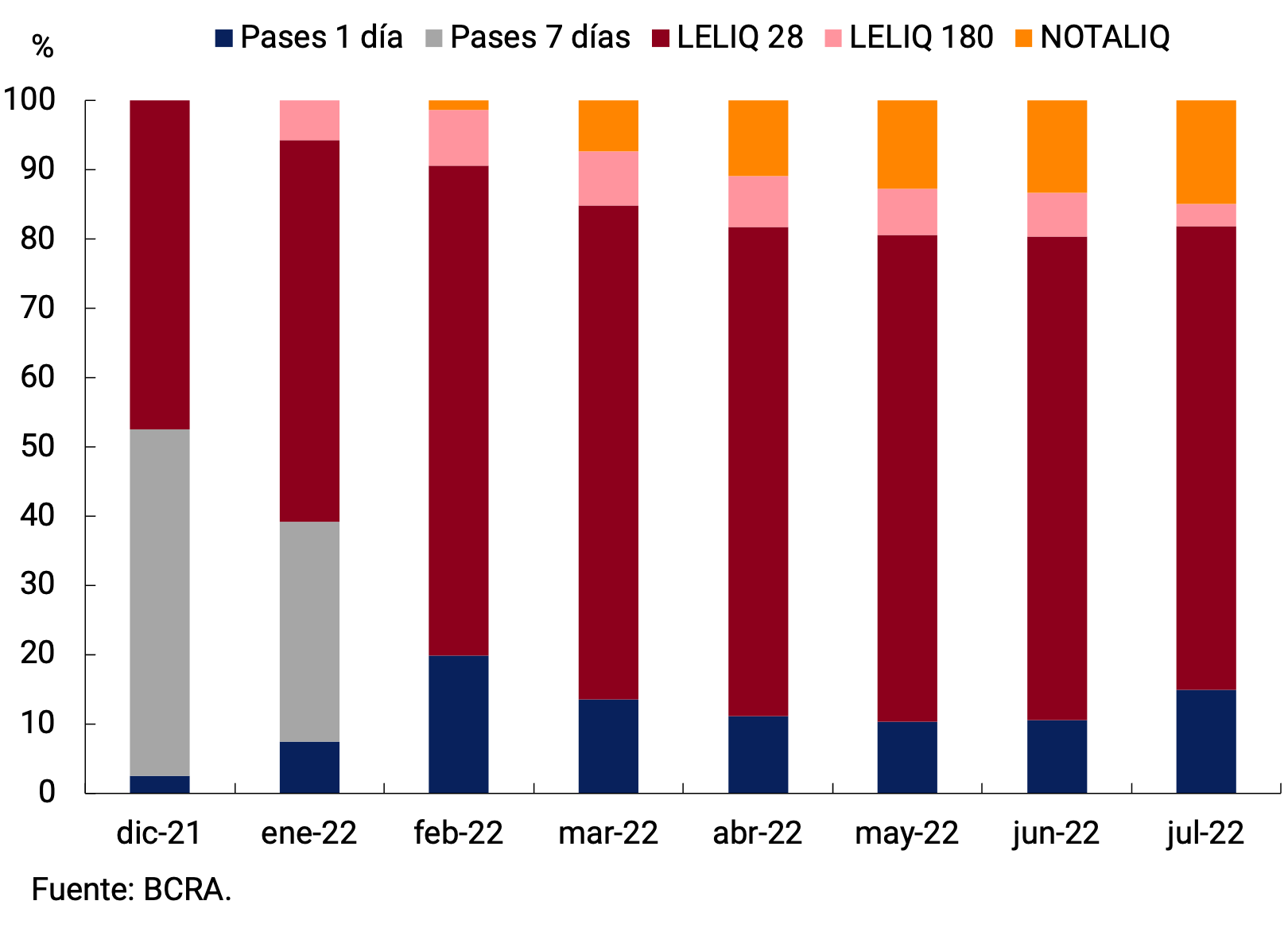

With the current configuration of instruments, in July the remunerated liabilities were made up of around 67% by LELIQ with a 28-day term. With respect to the species with a longer term, the 180-day LELIQ decreased its share to 3.2% of the total, unlike what happened with the NOTALIQ, whose share continued to increase in the month (14.9% of the total). The rest corresponded to 1-day passes, which increased their relative weight to 14.9% of the total (see Figure 4.3).

5. Loans to the private sector

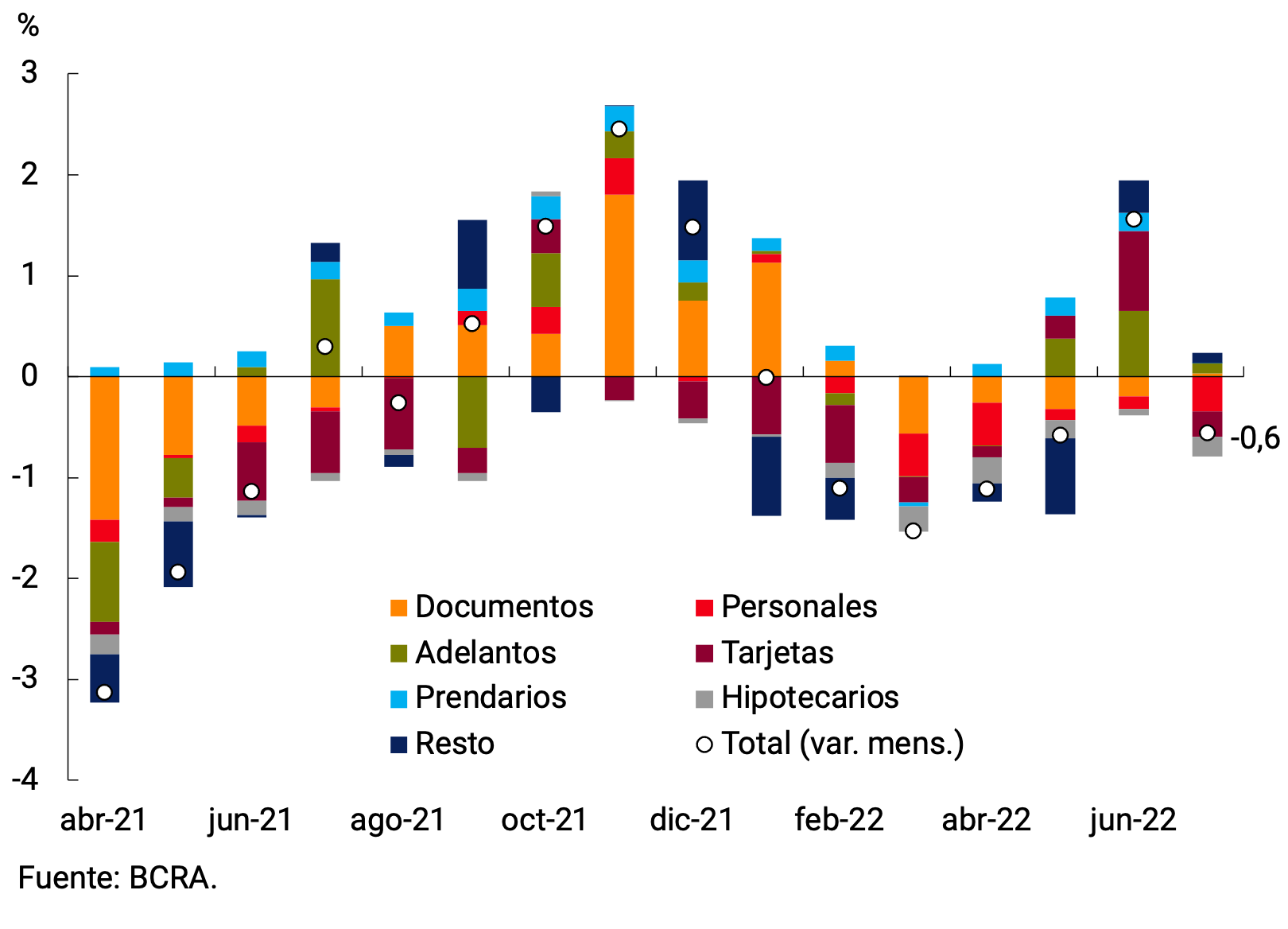

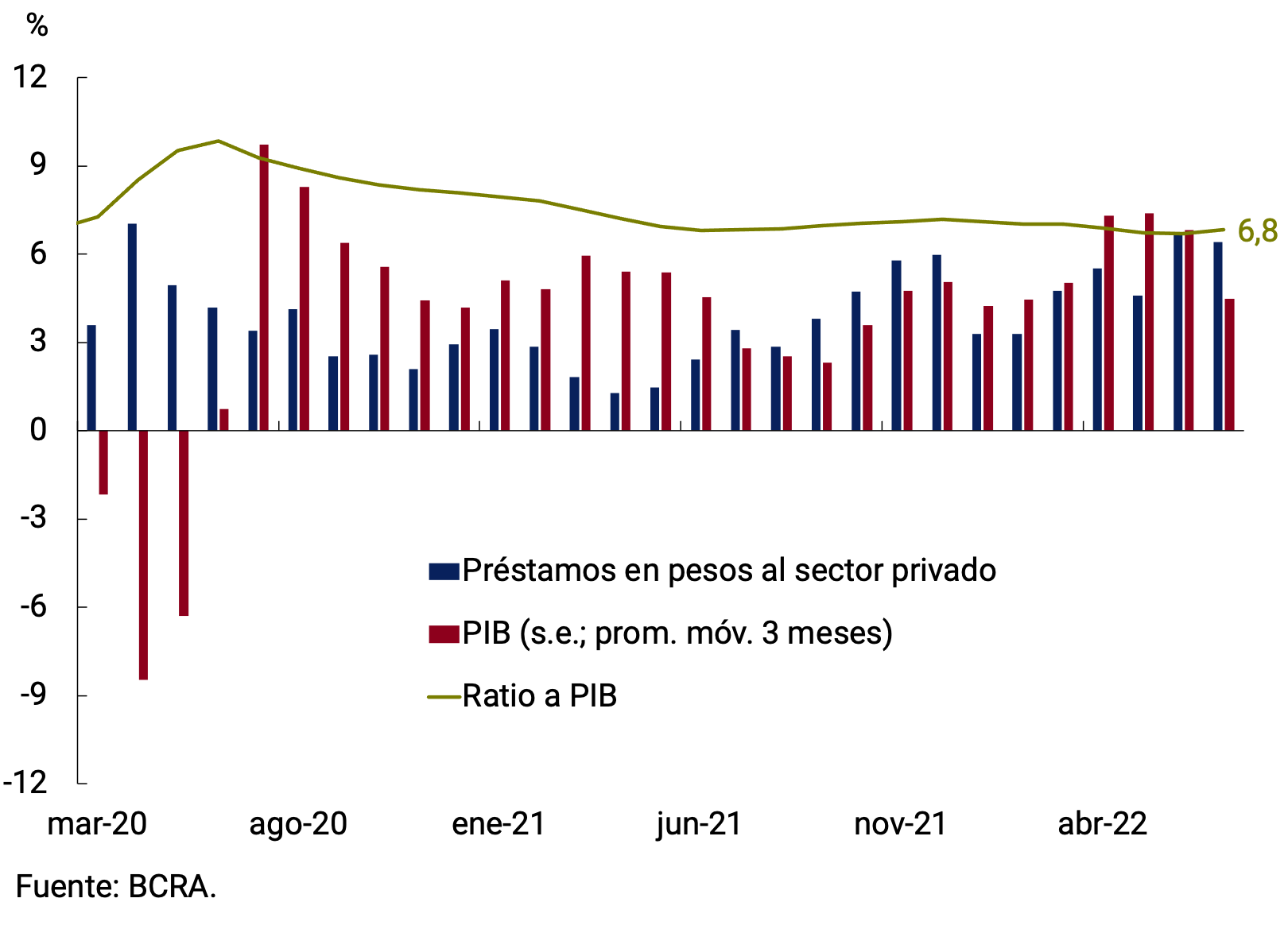

Loans to the private sector, adjusted for seasonality, would have registered a contraction of 0.6% s.e. per month at constant prices. However, in the last twelve months they would have accumulated an increase of 2.2% in real terms. Among the different lines of credit, the fall was mainly explained by the behavior of consumer financing (see Figure 5.1). The ratio of loans in pesos to the private sector to GDP would have stood at 6.8%, remaining at the levels of the last 12 months (See Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.1 | Loans in pesos to the private

sector Real without seasonality; contribution to monthly growth

Analysing the evolution of loans by type of financing, lines with an essentially commercial purpose would have remained relatively stable in real terms. In the year-on-year comparison and at constant prices, they are 12.0% above the level of the same month of the previous year. Within these lines, documents would have grown 0.1% s.e. in real terms (+18.4% y.o.y.). This relative stability hides a heterogeneous behavior by document type, with an increase in those instrumented with a single signature and a decrease in discounted documents. On the other hand, financing granted through current account advances would have expanded at constant prices of 0.9% s.e. (+13.1% y.o.y.).

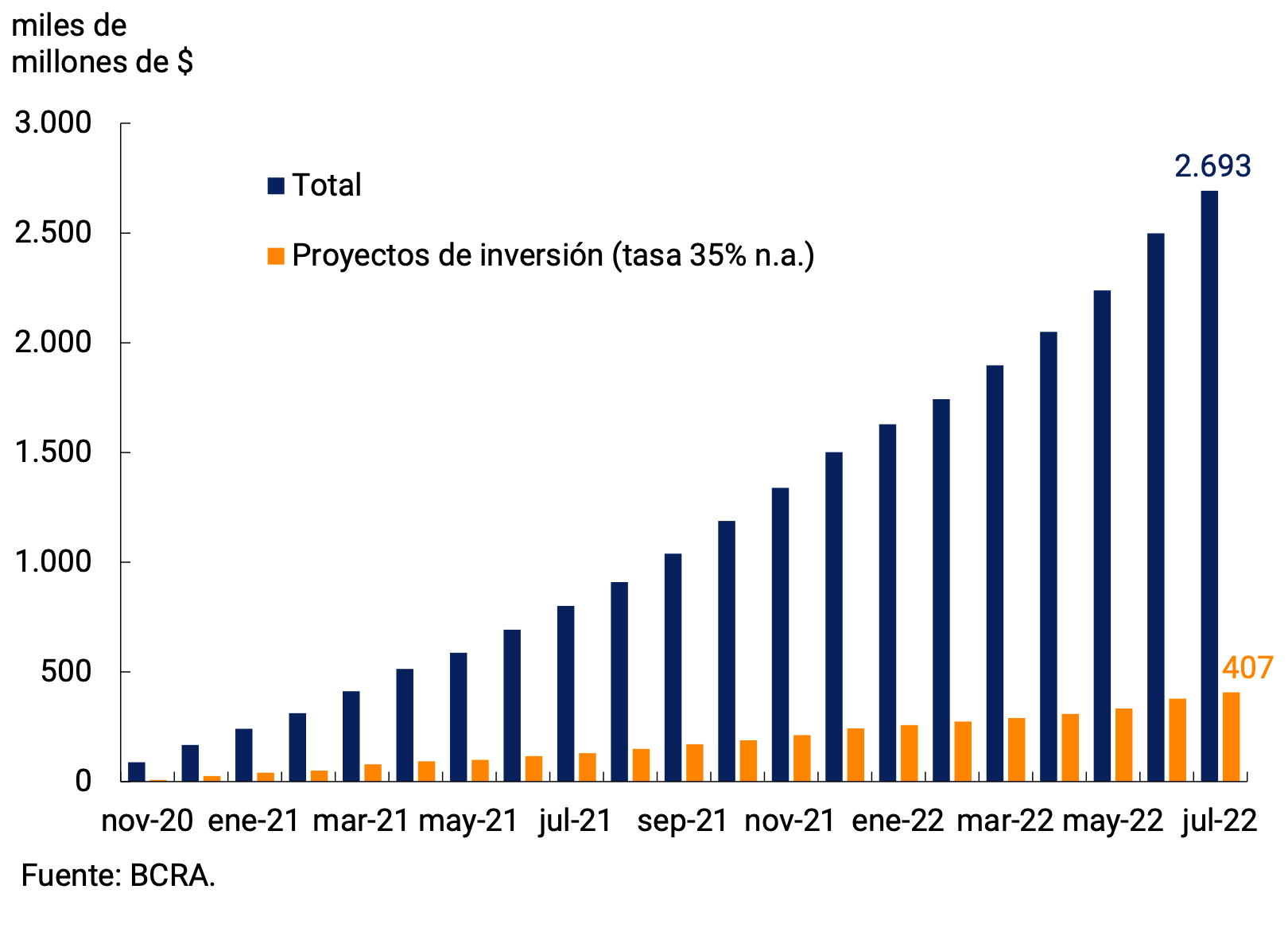

The Financing Line for Productive Investment (LFIP) continued to be the main tool used to channel productive credit to Micro, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (MSMEs). At the end of July, loans granted under the LFIP accumulated disbursements of approximately $2.693 billion since its launch, an increase of 8% compared to last month (see Figure 5.3). As for the destinations of these funds, about 85% of the total disbursed corresponds to working capital financing and the rest to the line that finances investment projects. At the time of publication, the number of companies that accessed the LFIP amounted to 291,314. It should be noted that, in line with the increase in the BCRA’s reference interest rates, the maximum rate of the line to finance working capital was raised from 52.5% to 58% n.a.; and that corresponding to investment projects went from 42% to 50% n.a.

Figure 5.3 | Financing granted through the Productive Investment Financing Line (LFIP)

Accumulated disbursed amounts; data at the end of the month

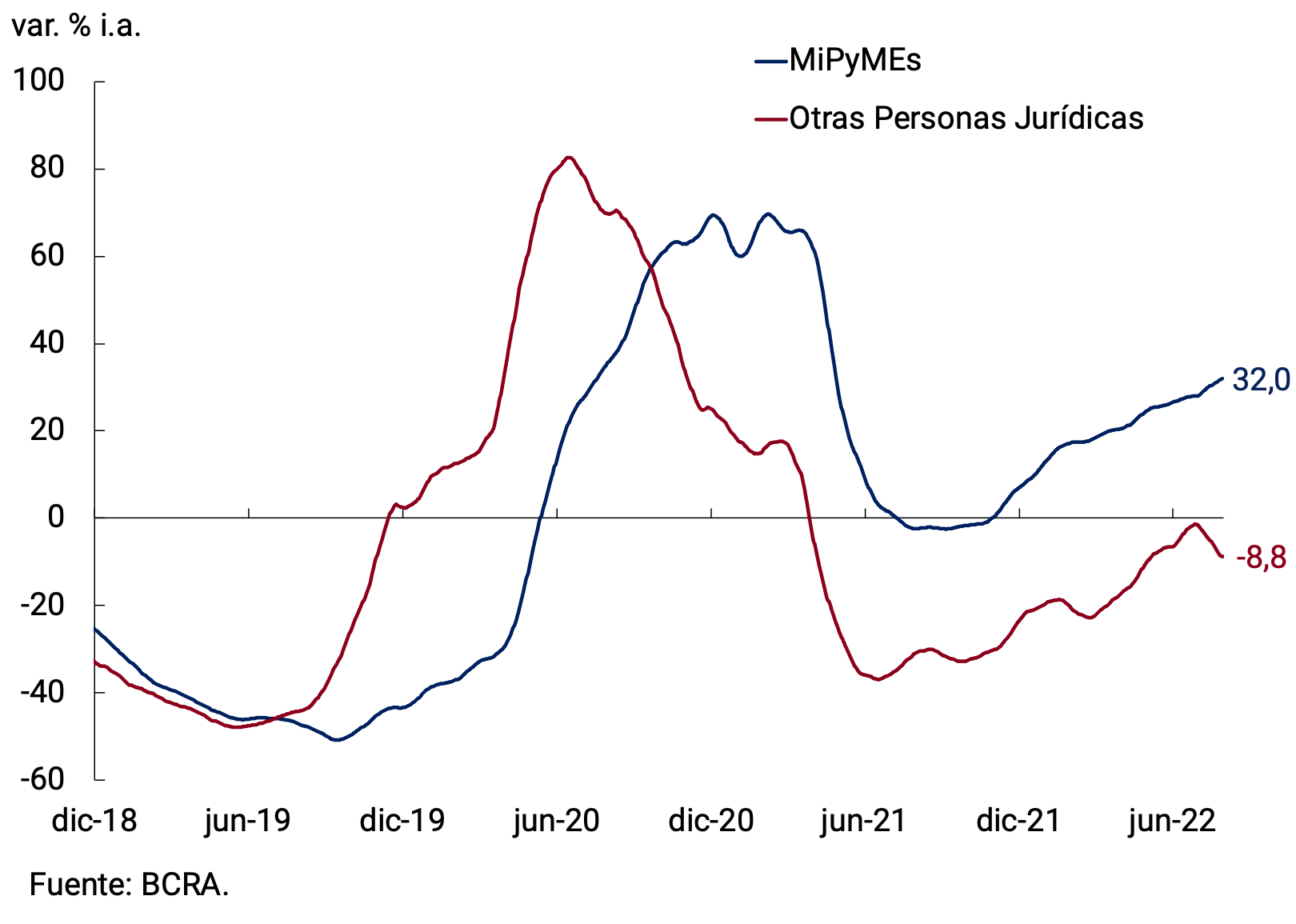

In this way, the favorable conditions of the LFIP contributed to sustaining the growth of financing to relatively smaller companies. In fact, differentiating commercial credit by type of debtor, it can be seen that in July credit to MSMEs would have expanded in year-on-year terms at a rate of around 32%, while credit to large companies showed a contraction of around 8.8% at constant prices in the last twelve months (see Figure 5.4).

Among loans associated with consumption, credit card financing would have shown a decrease of 0.9% s.e. in real terms, with the average balance for the month being 6.4% below the level of a year ago. Meanwhile, personal loans would have exhibited a contraction of 2.1% per month at constant prices and would be 5.0% below the level of July 2021. It should be noted that the interest rate corresponding to personal loans amounted in July to 65.6% n.a. (89.5% y.a.), increasing 5.4 p.p. compared to the previous month.

With regard to lines with real guarantees, collateral loans would have registered an increase in real terms (0.1% s.e.), and, thus, completed 4 consecutive months of growth. In year-on-year terms, they would have accumulated a growth of 35.7%. For its part, the balance of mortgage loans would have presented a fall of 3.1% s.e. at constant prices in the month, accumulating a contraction of around 17% in the last twelve months.

6. Liquidity in pesos of financial institutions

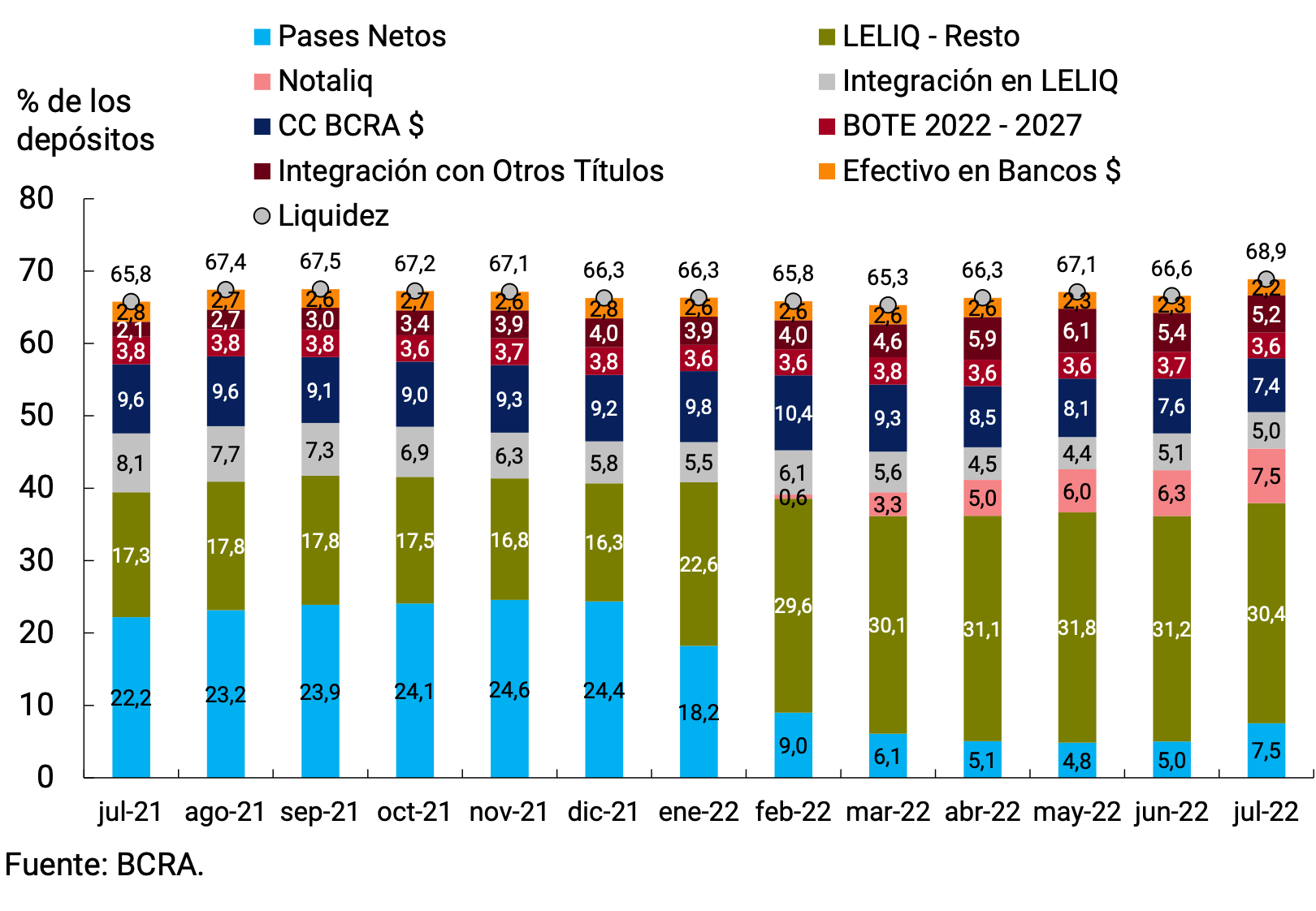

In July, ample bank liquidity in local currency6 averaged 68.9% of deposits, 2.3 p.p. above the June level. Thus, it remains at historically high levels. This increase is mainly explained by the behavior of the BCRA’s interest-bearing liabilities, which increased by 2.9 p.p. during the month.

With regard to the composition of bank liquidity, there was a change in the structure of interest-bearing liabilities, with passive passes and NOTALIQs gaining weight over LELIQs. This is partly explained by the maturity of the first LELIQ species at 180 days, and the placement of NOTALIQ at a variable rate in its replacement. On the other hand, a fall of 0.2 p.p. was observed in current accounts at the BCRA and in integration with public securities (see Chart 6.1).

Regarding the regulatory modifications with a potential impact on bank liquidity, it is worth mentioning that the minimum term of national public securities in pesos acquired by primary subscription accepted to integrate minimum cash was reduced from 120 to 90 calendar days7. At the same time, the new “special accounts for holders with agricultural activity” (in pesos adjustable by the quotation of the reference exchange rate Com. “A” 3500) were created, which will not be subject to a minimum cash requirement. Financial institutions may apply these resources to the acquisition of the new non-transferable internal bills of the BCRA in pesos liquidable by the Reference Exchange Rate Com. “A” 3500 (LEDIV) at a zero rate8. Finally, the percentage of financing within the framework of the “Financing Line for Productive Investment of MSMEs” admitted as a minimum cash reductionwas increased from 34 to 40% 9.

7. Foreign currency

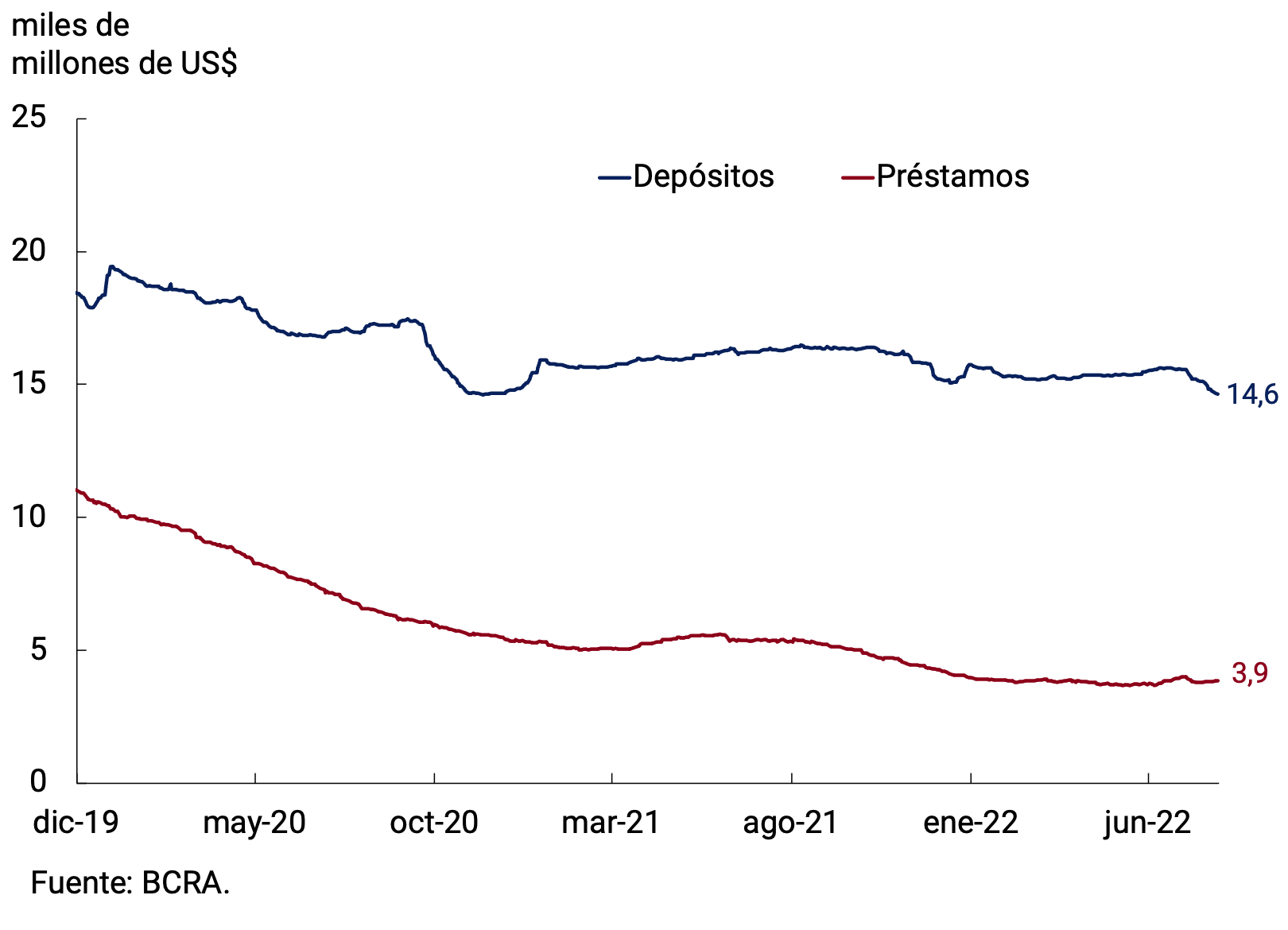

In the foreign currency segment, the main assets and liabilities of financial institutions had a heterogeneous behavior. On the one hand, private sector deposits registered an average drop of around US$500 million compared to June. Thus, the average monthly balance stood at US$15,074 million. This decrease was mainly driven by demand deposits of human persons. On the other hand, the average monthly balance of loans to the private sector was US$3,850 million, remaining largely unchanged from the previous month (see Figure 7.1).

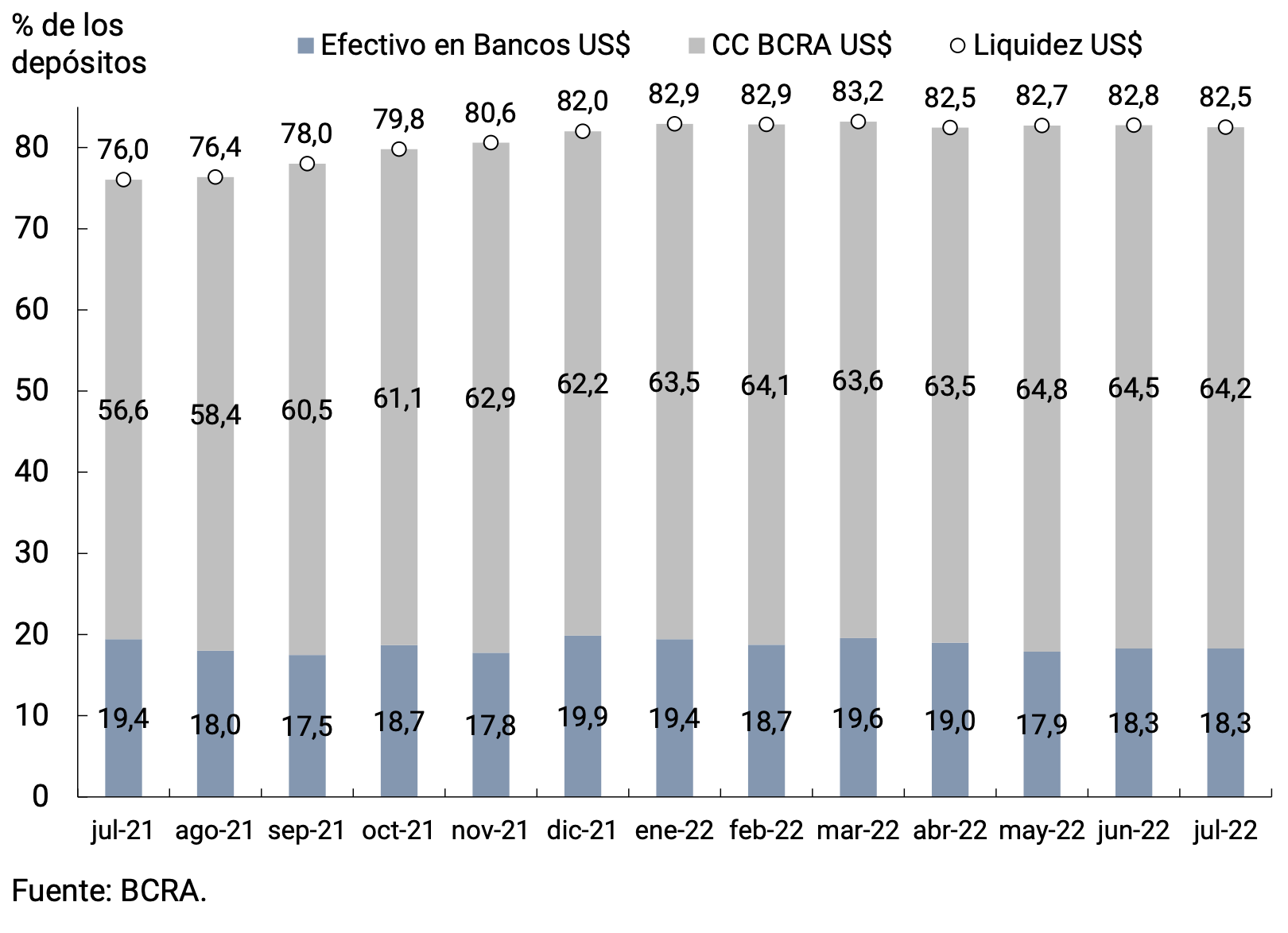

The liquidity of financial institutions in the foreign currency segment stood at 82.5% of deposits in July, remaining stable compared to June. This fall was explained by the decrease in current accounts at the BCRA (see Figure 7.2).

During July, a series of regulatory changes took place in foreign exchange matters. First, financing conditions for imports of fertilizers, plant protection products and inputs needed for their production in the country were improved, and market access to automotive terminals for the production of units for export was simplified10. At the same time, access to the foreign exchange market was freed for the payment of imports of inputs that will be used for the manufacture of goods in the country and that were shipped at origin until June 27, 202211. In addition, financial institutions were allowed to apply foreign financial lines to foreign trade financing operations in foreign currency12. For its part, the possibility of paying in installments with cards for consumption in duty-free stores was restricted, extending the prohibition that governs tourist tickets and services abroad and products from abroad that are received through the door-to-door system13. In the same sense, the maximum rate to finance unpaid balances of credit cards was increased when the account summary for the month records consumption for an amount greater than 200 dollars in foreign currency14.

Likewise, it was decided to include the holding of CEDEAR in the US$100,000 availability limit that companies that access the official foreign exchange market may have, and it was prevented from operating these instruments in the 90 days before and after access to the official market15. Finally, measures were taken regarding the value of the exchange rate to which customers have access. Thus, on the one hand, it was provided that non-resident tourists can sell foreign currency at the reference value of the dollar in the financial market for a maximum amount of US$5,000 (or its equivalent in other currencies)per month 16 and, on the other hand, the collection on account of income tax or personal property tax (as appropriate) was raised from 35% to 45% for payments registered with foreign currency abroadQuestion 17.

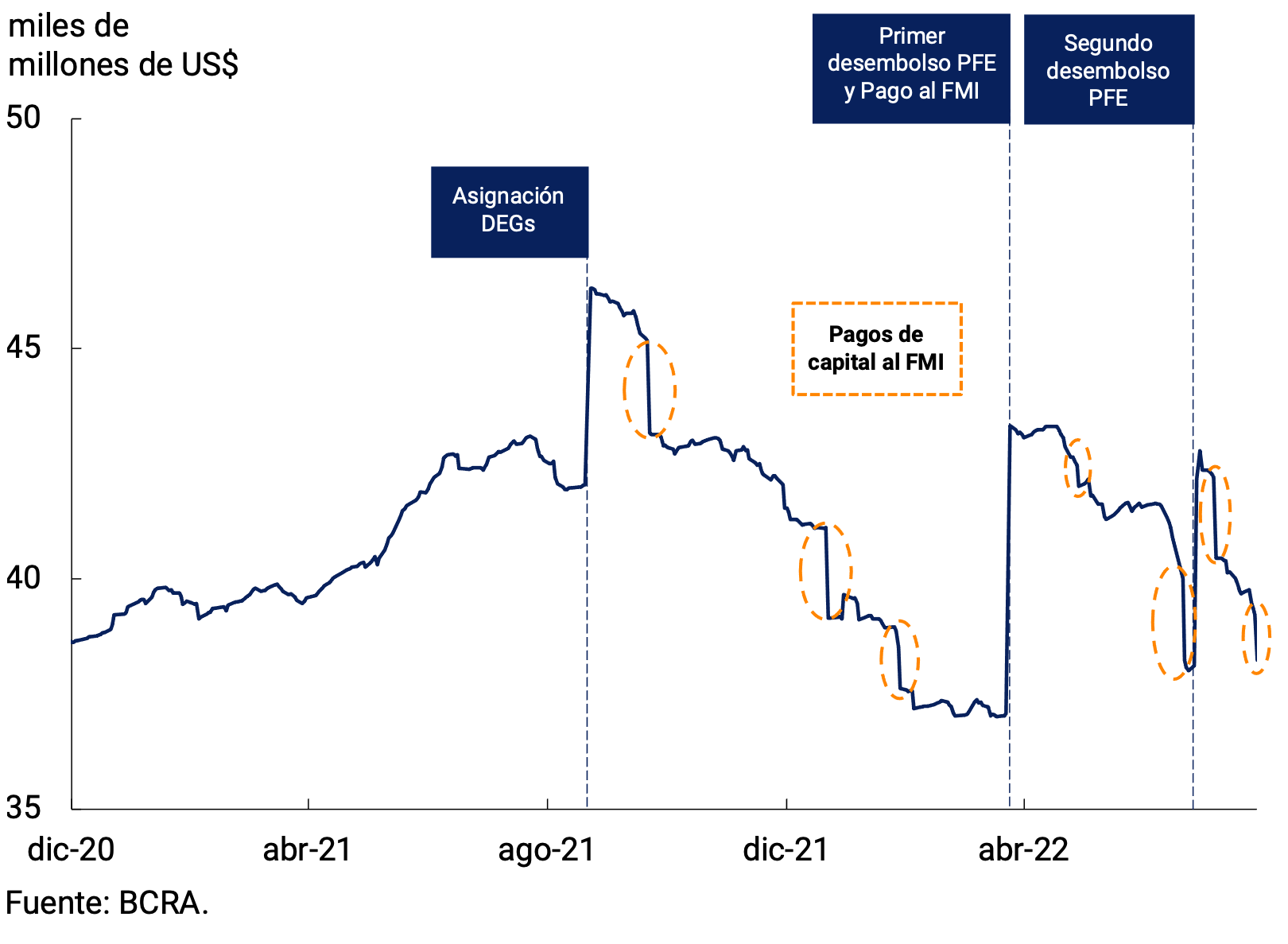

In this context, the BCRA’s International Reserves ended July with a balance of US$38,232 million, reflecting a decrease of US$4,555 million compared to the end of June (see Figure 7.3). The dynamics of the month were impacted by the capital maturity payments to the International Monetary Fund for a total of US$1,961 million, commitments that were assumed with the Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) that were received within the framework of the Extended Facilities Program (PFE) in force. Other debt payments of the National Government also had a negative impact, including the payment of interest for holders of global bonds (foreign legislation); the net sale of foreign currency to the private sector and, to a lesser extent, the losses on the valuation of net foreign assets.

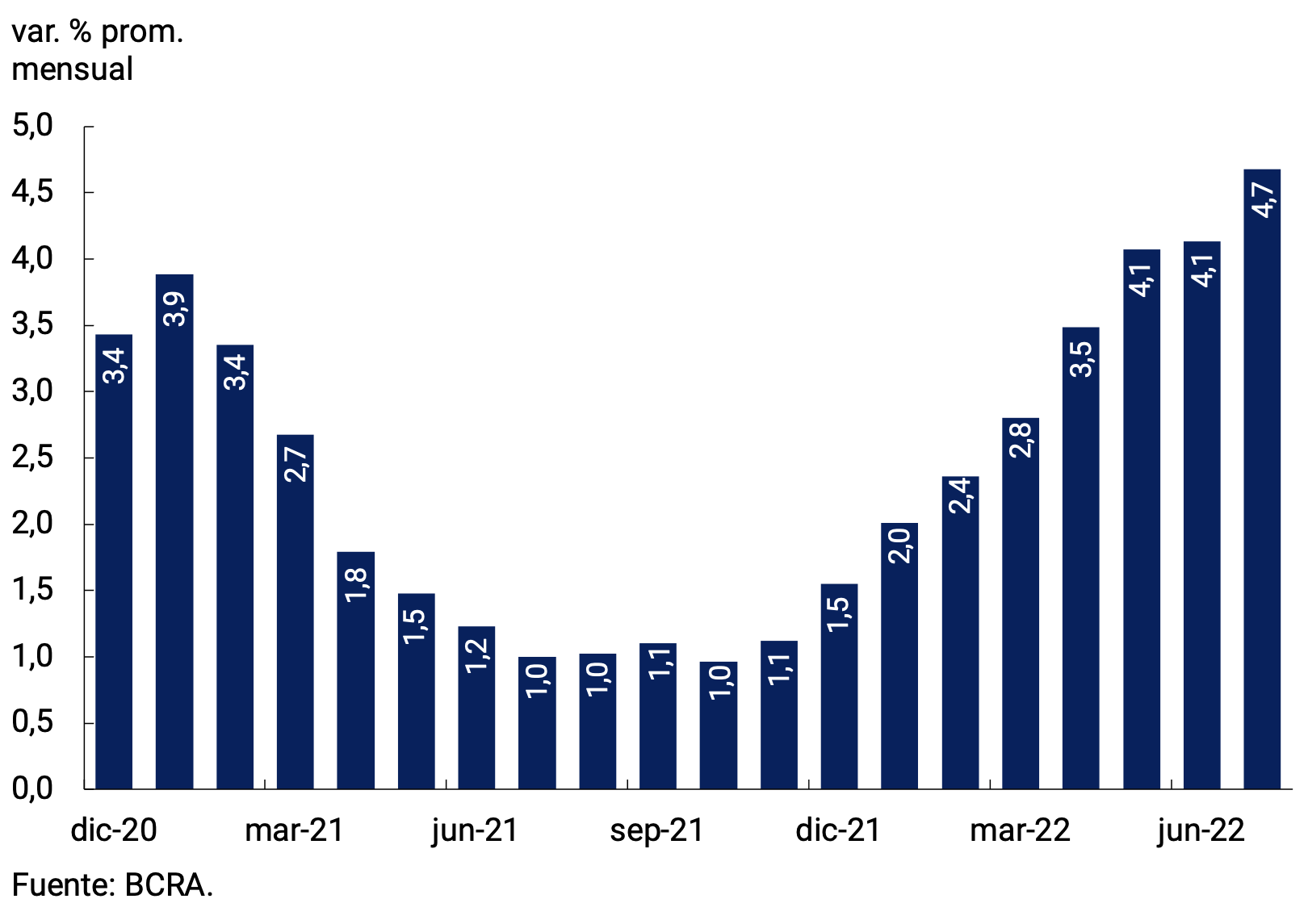

Finally, the bilateral nominal exchange rate (TCN) against the U.S. dollar increased 4.7% in July to stand, on average, at $128.39/US$ (see Figure 7.4).

Glossary

ANSES: National Social Security Administration.

BADLAR: Interest rate on fixed-term deposits for amounts greater than one million pesos and a term of 30 to 35 days.

BCRA: Central Bank of the Argentine Republic.

BM: Monetary Base, includes monetary circulation plus deposits in pesos in current account at the BCRA.

CC BCRA: Current account deposits at the BCRA.

CER: Reference Stabilization Coefficient.

NVC: National Securities Commission.

SDR: Special Drawing Rights.

EFNB: Non-Banking Financial Institutions.

EM: Minimum Cash.

FCI: Common Investment Fund.

A.I.: Year-on-year .

IAMC: Argentine Institute of Capital Markets

CPI: Consumer Price Index.

ITCNM: Multilateral Nominal Exchange Rate Index

ITCRM: Multilateral Real Exchange Rate Index

LEBAC: Central Bank bills.

LELIQ: Liquidity Bills of the BCRA.

LFIP: Financing Line for Productive Investment.

M2 Total: Means of payment, which includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and demand deposits in pesos from the public and non-financial private sector.

Private M2: Means of payment, includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and demand deposits in pesos from the non-financial private sector.

Private transactional M2: Means of payment, includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and non-remunerated demand deposits in pesos from the non-financial private sector.

M3 Total: Broad aggregate in pesos, includes the current currency held by the public, cancelling checks in pesos and the total deposits in pesos of the public and non-financial private sector.

Private M3: Broad aggregate in pesos, includes the working capital held by the public, cancelling checks in pesos and the total deposits in pesos of the non-financial private sector.

MERVAL: Buenos Aires Stock Market.

MM: Money Market.

N.A.: Annual nominal

E.A.: Annual Effective

NOCOM: Cash Clearing Notes.

ON: Negotiable Obligation.

GDP: Gross Domestic Product.

P.B.: basis points.

p.p.: percentage points.

MSMEs: Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises.

ROFEX: Rosario Term Market.

S.E.: No seasonality

SISCEN: Centralized System of Information Requirements of the BCRA.

TCN: Nominal Exchange Rate

IRR: Internal Rate of Return.

TM20: Interest rate on fixed-term deposits for amounts greater than 20 million pesos and a term of 30 to 35 days.

TNA: Annual Nominal Rate.

UVA: Unit of Purchasing Value

References

1 Corresponds to private M2 excluding interest-bearing demand deposits from companies and financial service providers. This component was excluded since it is more similar to a savings instrument than to a means of payment.

3 Financial Services Providers, Companies and Individuals with deposits of more than $10 million.

4 Includes the working capital held by the public and the deposits in pesos of the non-financial private sector (demand, time and others).

5 The BCRA ordered its participation in the secondary market of securities issued by the National Government as of July with a residual term of more than 15 days, buying at rates similar to those of the last auctions, plus a maximum spread of 2%.

6 Includes current accounts at the BCRA, cash in banks, balances of net passes arranged with the BCRA, holdings of LELIQ and NOTALIQ, and public bonds eligible for reserve requirements.

10 Communication “A” 7542 and Communication “A” 7547.

17 General Resolution 5232/2022 of the Federal Administration of Public Revenues (AFIP).