Política Monetaria

Monthly Monetary Report

January

2022

Monthly report on the evolution of the monetary base, international reserves and foreign exchange market.

1. Executive Summary

The broad monetary aggregate, private M3, at constant prices would have registered a monthly expansion of 1.1% s.e. in January. This behavior was explained both by an expansion of means of payment and fixed-term deposits. The dynamics of savings instruments were partly explained by a change in monetary policy decisions.

In the first week of January, the BCRA reconfigured its monetary policy instruments. These changes aim to achieve better liquidity management for financial institutions, increase the average term of sterilization instruments, and refocus the policy interest rate signal on the LELIQ rate. Not only were policy instruments readjusted, but benchmark interest rates were also adjusted upwards. To guarantee the transmission of the new rates to depositors, the minimum guaranteed rates of savings instruments in pesos were also modified. This last measure also seeks to tend towards positive returns for savings in domestic currency.

On the other hand, the National Government announced an agreement in principle with the IMF for an extended facilitiesprogram 1, which allows the resolution of the large obligations of 2022 and 2023 set out in the Stand-By Agreement signed in 2018. The resolution of the negotiation with the IMF will help to improve the expectations of those agents who condition their vision of the sustainability of the external sector on the outcome of the negotiation, helping to contain exchange rate pressures and inflation expectations.

2. Payment methods

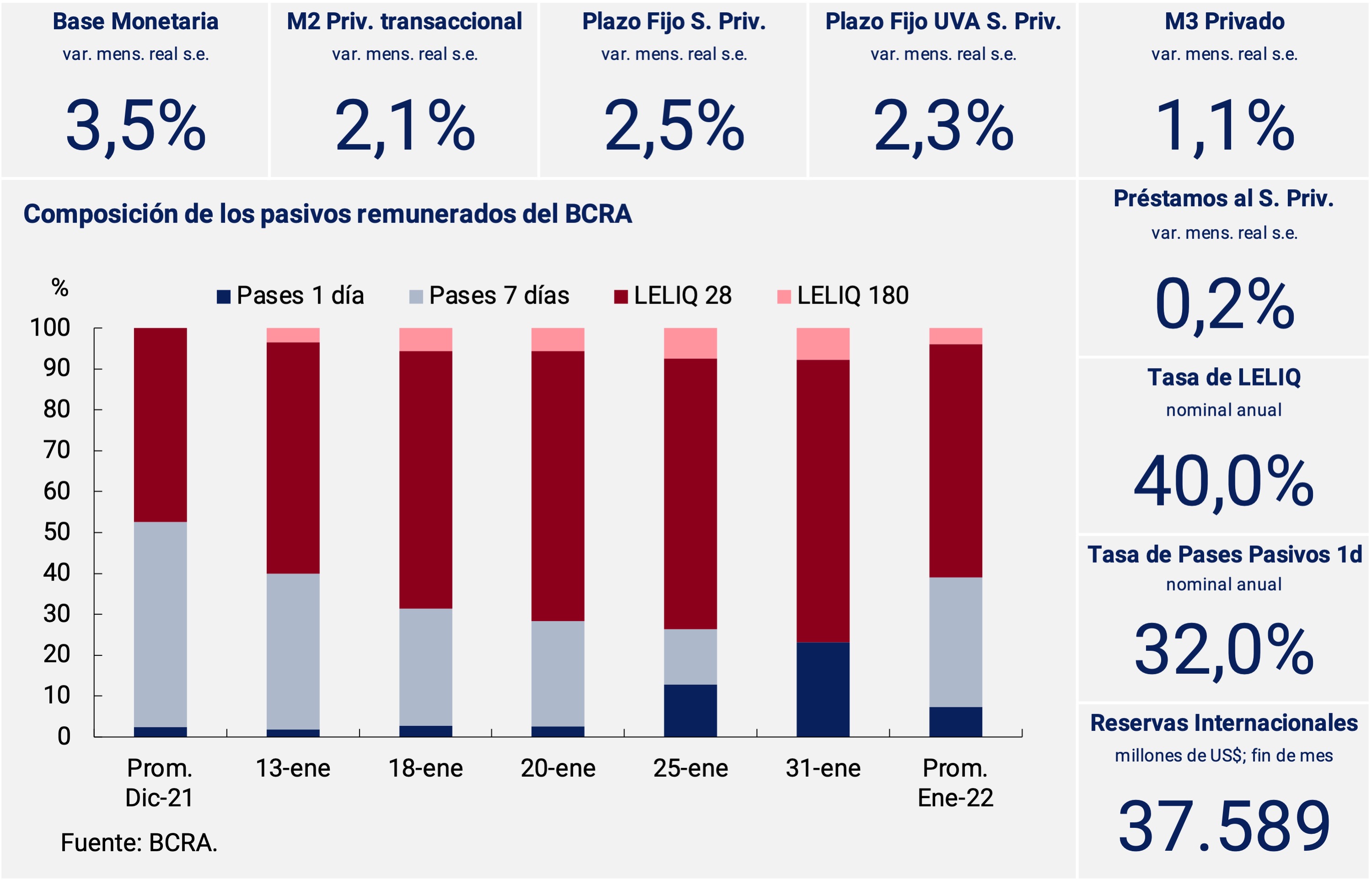

The means of payment (private transactional M22), in real terms3 and adjusted for seasonality (s.e.), would have registered an increase of 2.1% in January, mainly explained by the positive carry-over left in December as a result of the payment of the half bonus. Within its components, the largest contribution to growth came from non-interest-bearing demand deposits, although working capital held by the public also contributed positively to the variation for the month (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 | Private transactional M2 at constant

prices Contribution by component to the monthly vari. s.e.

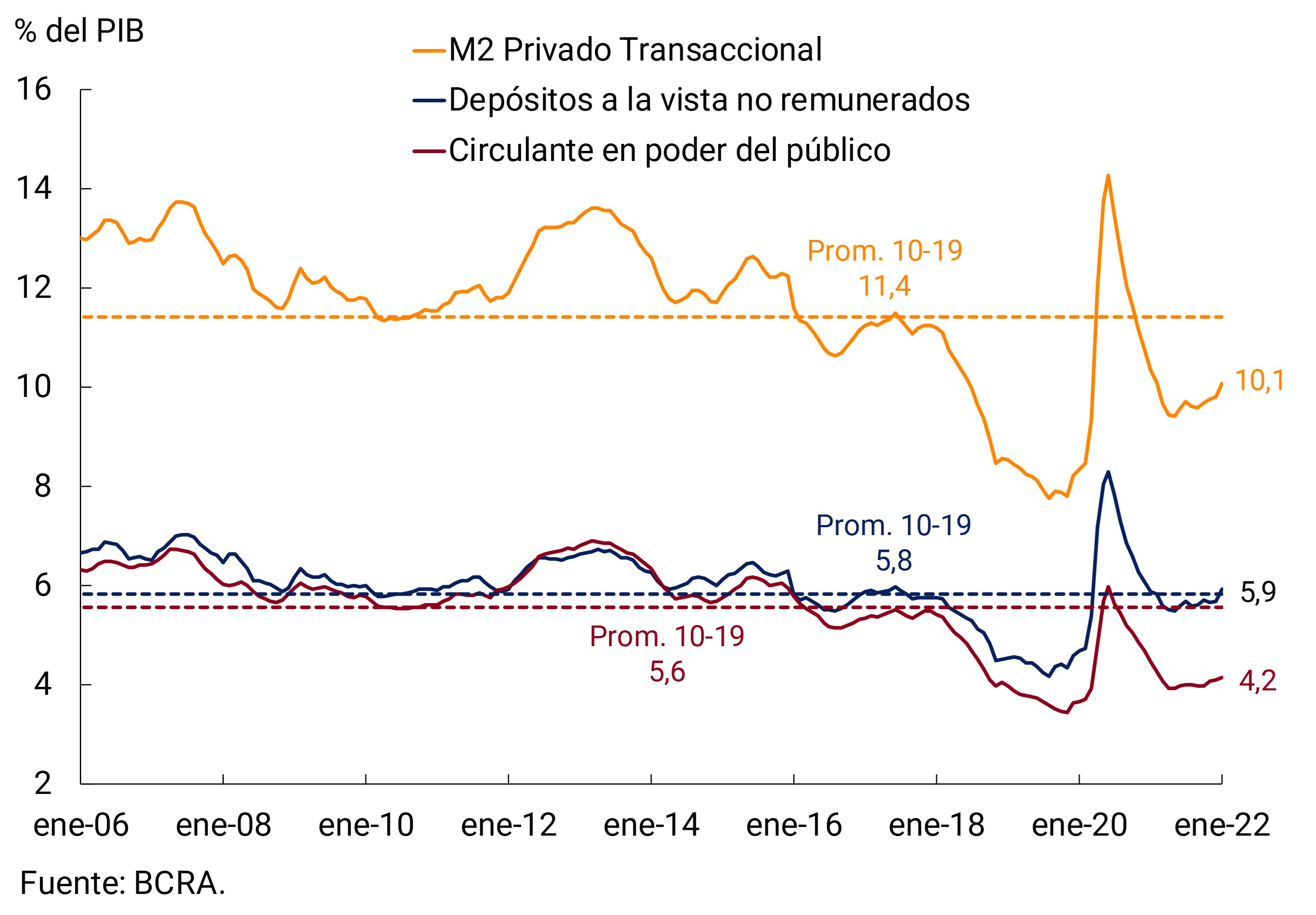

The transactional private M2 in terms of output continued to be below the average record for the 2010-2019 period. As already mentioned in previous editions, the low levels of money in the hands of the public are what explain this behavior. In fact, banknotes and coins in the hands of the public were positioned 1.4 p.p. below the average recorded between 2010 and 2019, and at a value close to the lowest of the last 15 years (see Figure 2.2). This evolution influenced the increasing use of electronic means of payment.

3. Savings instruments in pesos

In the first days of January, the Board of Directors of the BCRA decided to raise the minimum guaranteed interest rates on fixed-term deposits in order to underpin its demand4. Thus, a minimum guaranteed rate was set for placements of individuals for up to an amount of $10 million of 39% n.a. (46.80% e.a.), which implied an increase of 2 p.p. for depositors with investments of up to $1 million and 5 p.p. for those with placements between $1 and $10 million. For the rest of the depositors of the financial system5 the new floor was set at 37% n.a. (43.98% e.a.). The measure is part of the Objectives and Plans defined for 20226), among which is the establishment of an interest rate path that tends to Argentines obtain returns in line with the evolution of inflation and the exchange rate.

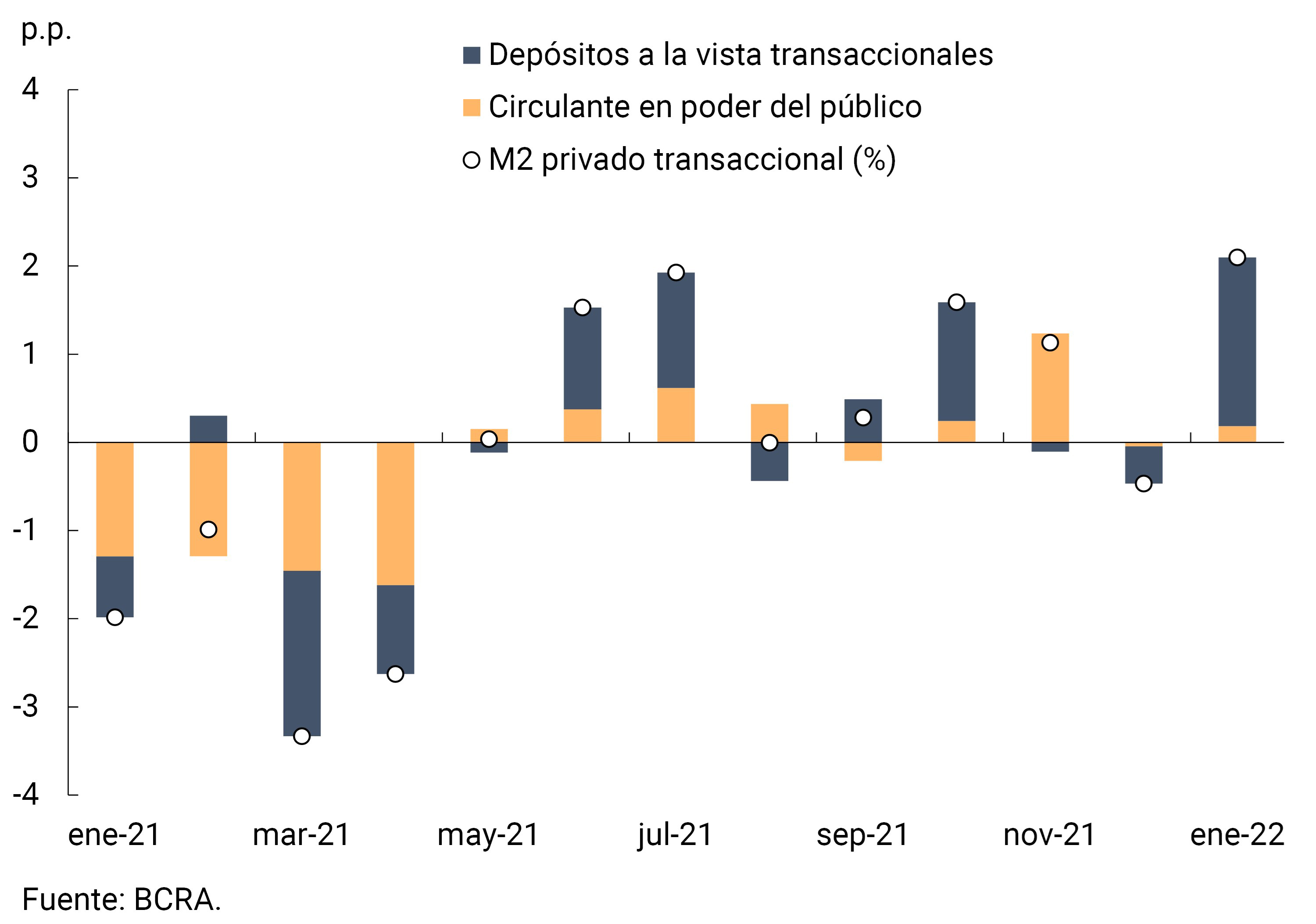

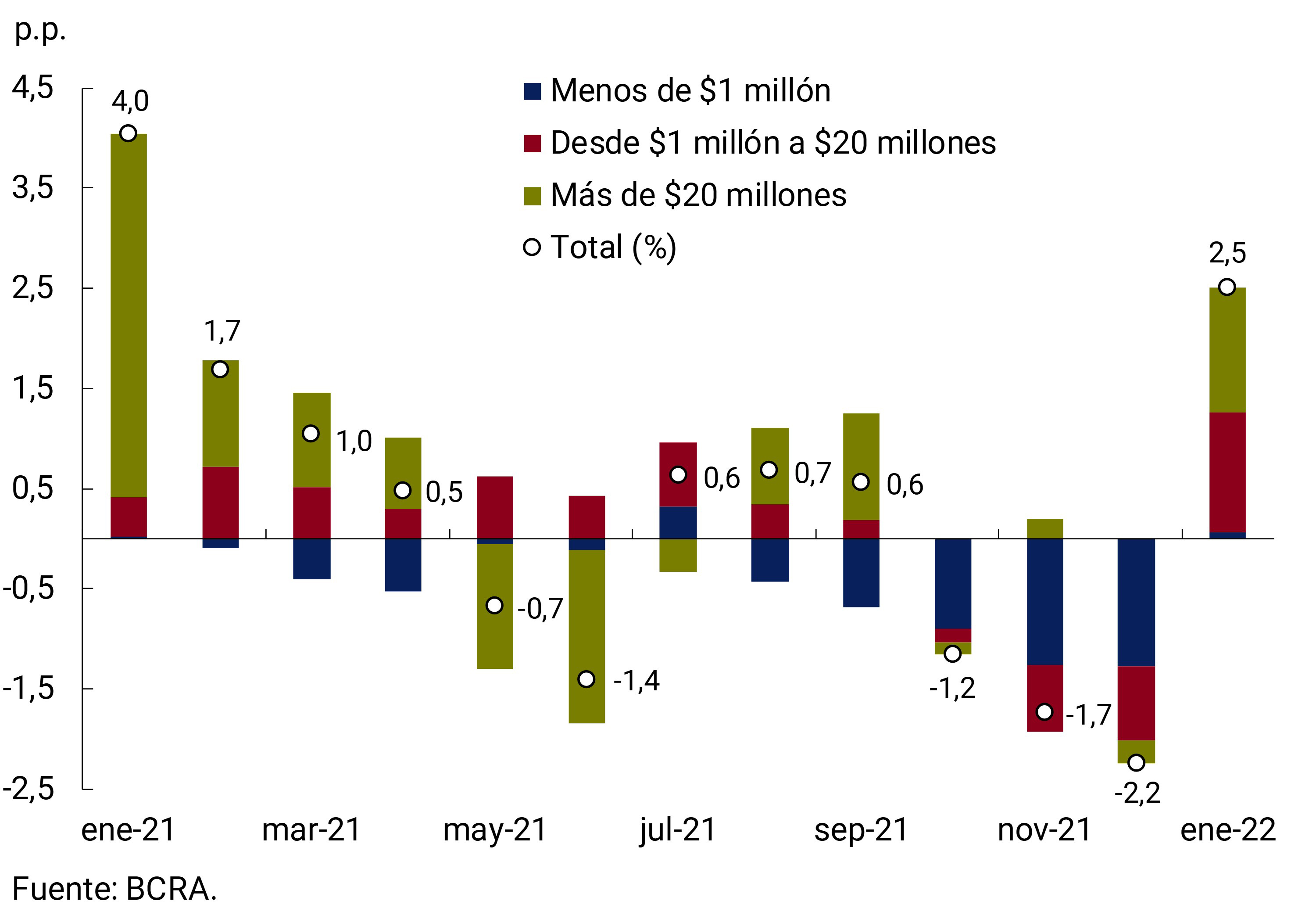

In a context of higher interest rates, and considering that January is a month that in recent years presented a greater demand for savings instruments in pesos7, fixed-term deposits in pesos in the private sector would have registered a monthly expansion in real terms of 2.5% s.e., breaking with a period of three consecutive months of declines. Thus, term placements expanded 0.2 p.p. in terms of GDP to 6.6%, placing 1.1 p.p. above the average record of 2010-2019 and 1.3 p.p. below the peak of mid-2020.

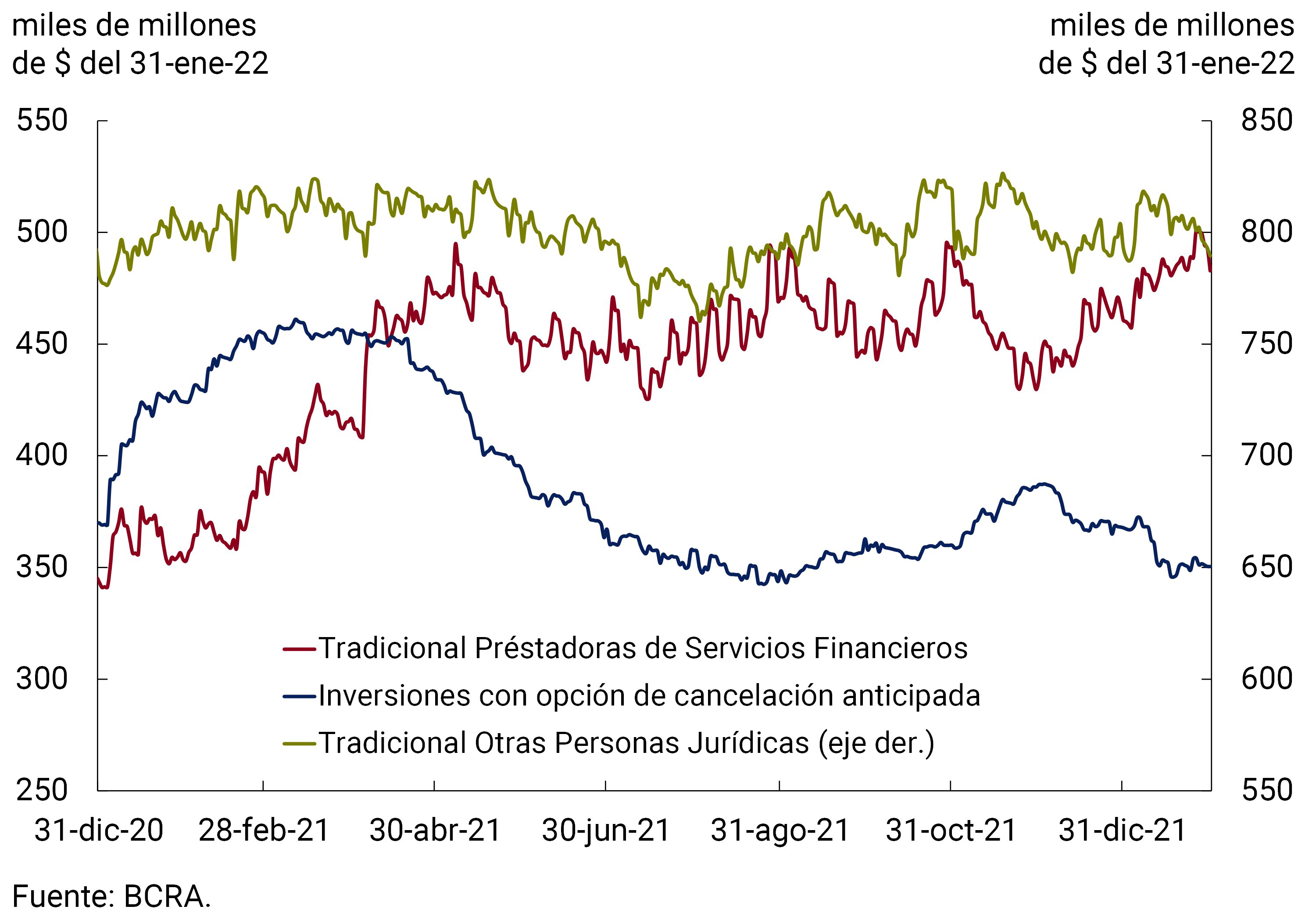

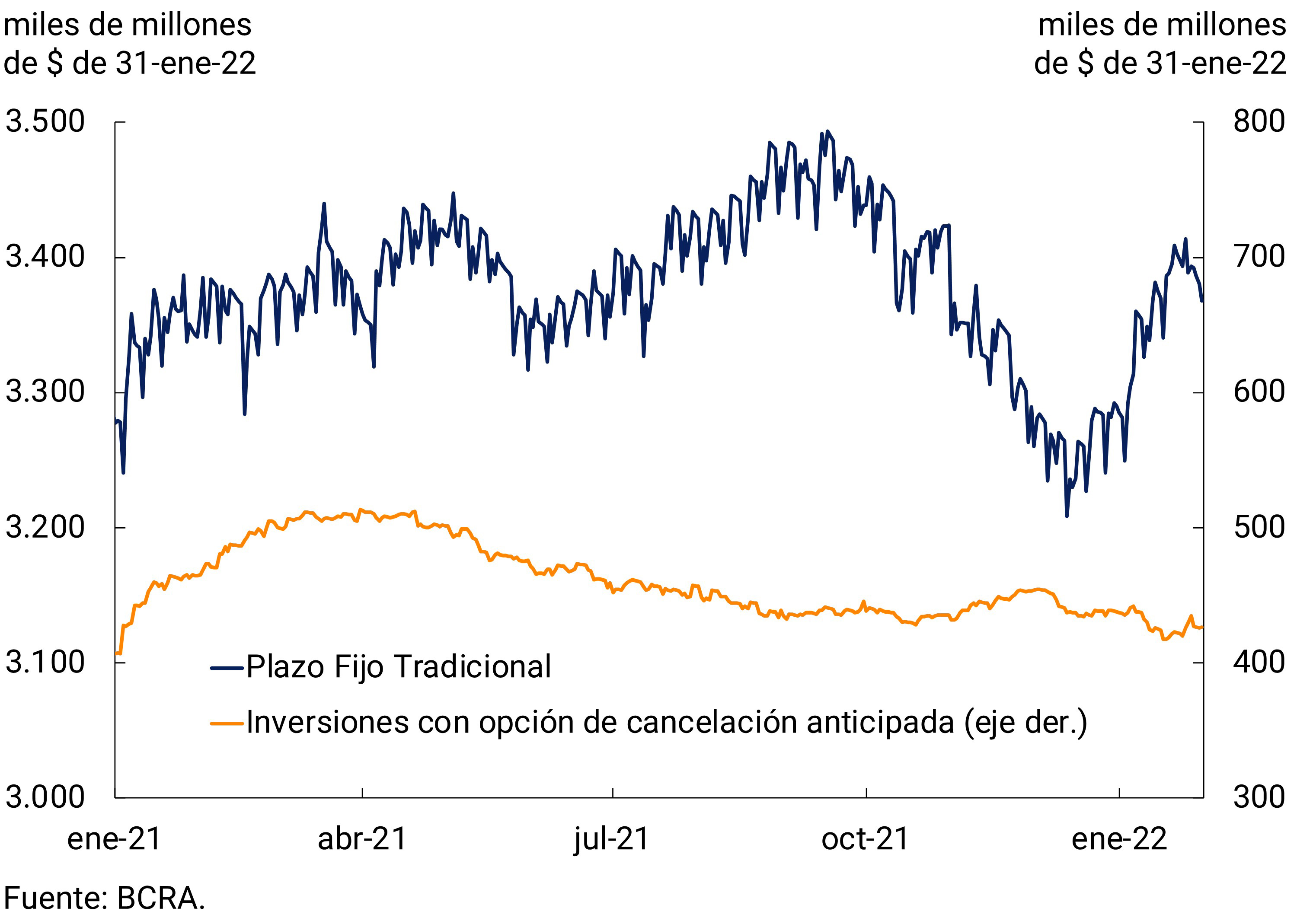

January’s growth was mainly driven by the impositions of human persons, which throughout the month showed a sustained increase, both in nominal and real terms. Distinguishing by strata of amount, growth was concentrated in placements of more than $1 million (see Figure 3.1). In fact, placements of between $1 and $20 million, whose main holders are individuals, registered an expansion at constant prices throughout the month. Deposits in the wholesale segment (more than $20 million) also grew in real terms in January. This dynamic was influenced by the behavior of the Money Market Mutual Funds (FCI MM), which are an important agent of this strata of amount. In a context in which its assets remained unchanged, part of its shorter-term assets (interest-bearing demand deposits and investments with early cancellation option) were replaced by traditional fixed-term placements (see Figure 3.2). Finally, deposits of up to $1 million grew in nominal terms at a rate similar to that of prices, which implied relative stability in the month at constant prices, interrupting the downward trend that began last August.

Figure 3.1 | Private sector fixed-term depositsContribution by layer of amount to real monthly change

At the instrument level, once again a preference was observed for longer-term assets. Thus, traditional fixed-term deposits continued the growing trend that began in mid-December, driven by placements denominated in pesos. On the other hand, traditional deposits adjustable by CER remained without significant variations at constant prices. Meanwhile, investments with an early cancellation option showed a decline in the same period (see Figure 3.3). In particular, CER adjustable pre-cancellable deposits stabilized from mid-January, after two months of showing a slight upward trend (see Figure 3.4).

All in all, the broad monetary aggregate, private M38, at constant prices would have registered a monthly expansion of 1.1% s.e. in January. In the year-on-year comparison, this aggregate would have experienced a slight increase (1.5%). As a percentage of GDP, it registered a slight acceleration to 18.5%, a record slightly higher than the average observed between 2010 and 2019.

4. Monetary base

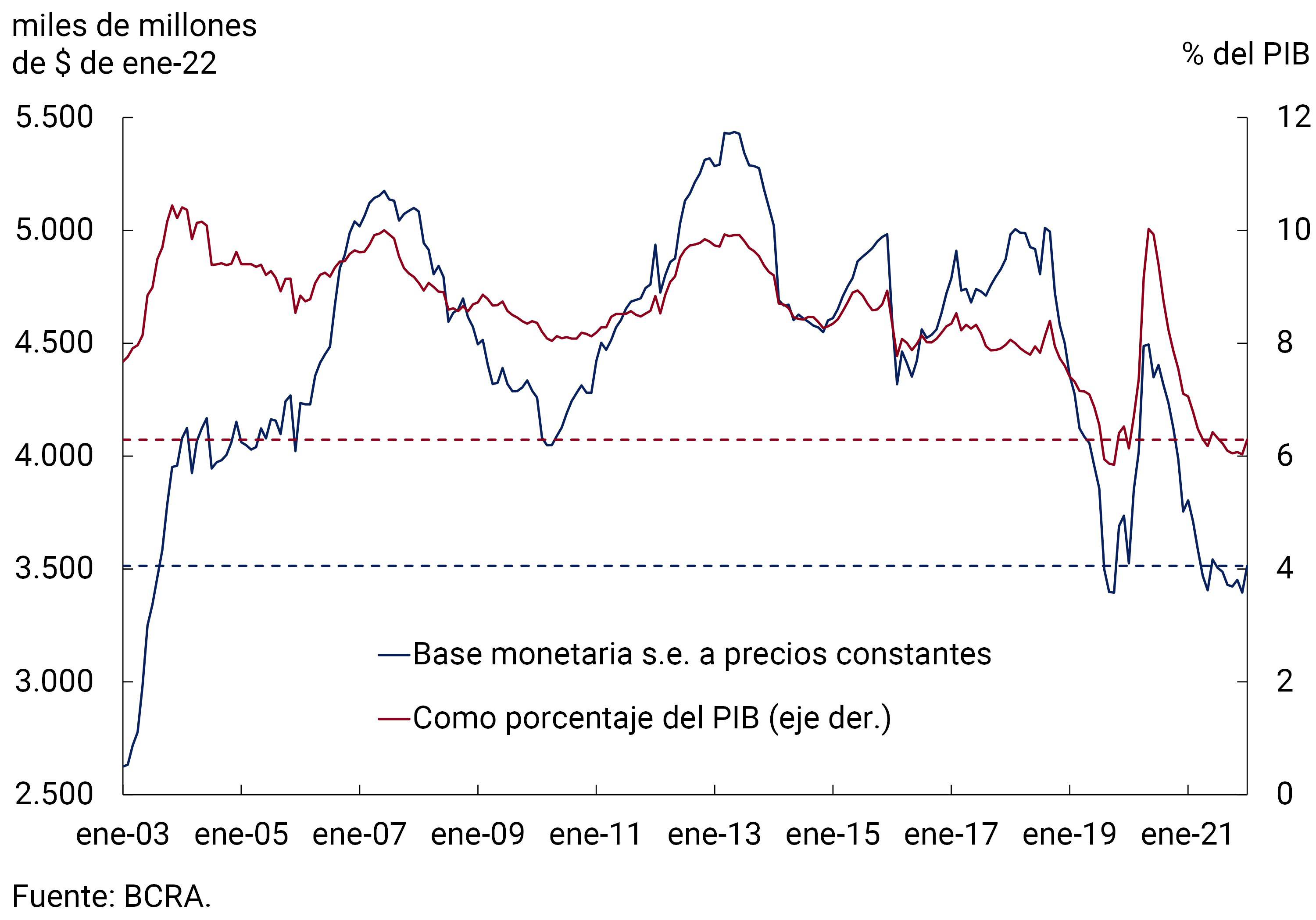

In January, the Monetary Base stood at $3,836 billion, which meant an average monthly nominal increase of 8.6% (+$291,153 million) in the original series. This rise was largely explained by the positive statistical carryover left by December, a month with strong seasonality. In fact, the peak variation – between December 31 and January 31 – was -0.6% (-$22,989 million). Adjusted for seasonality and inflation, the Monetary Base would have registered an increase of 3.5% and in year-on-year terms a contraction of around 8%. As a GDP ratio, the Monetary Base stood at 6.3%, a figure similar to that of the end of 2019 and around the lowest values since 2003 (see Figure 4.1).

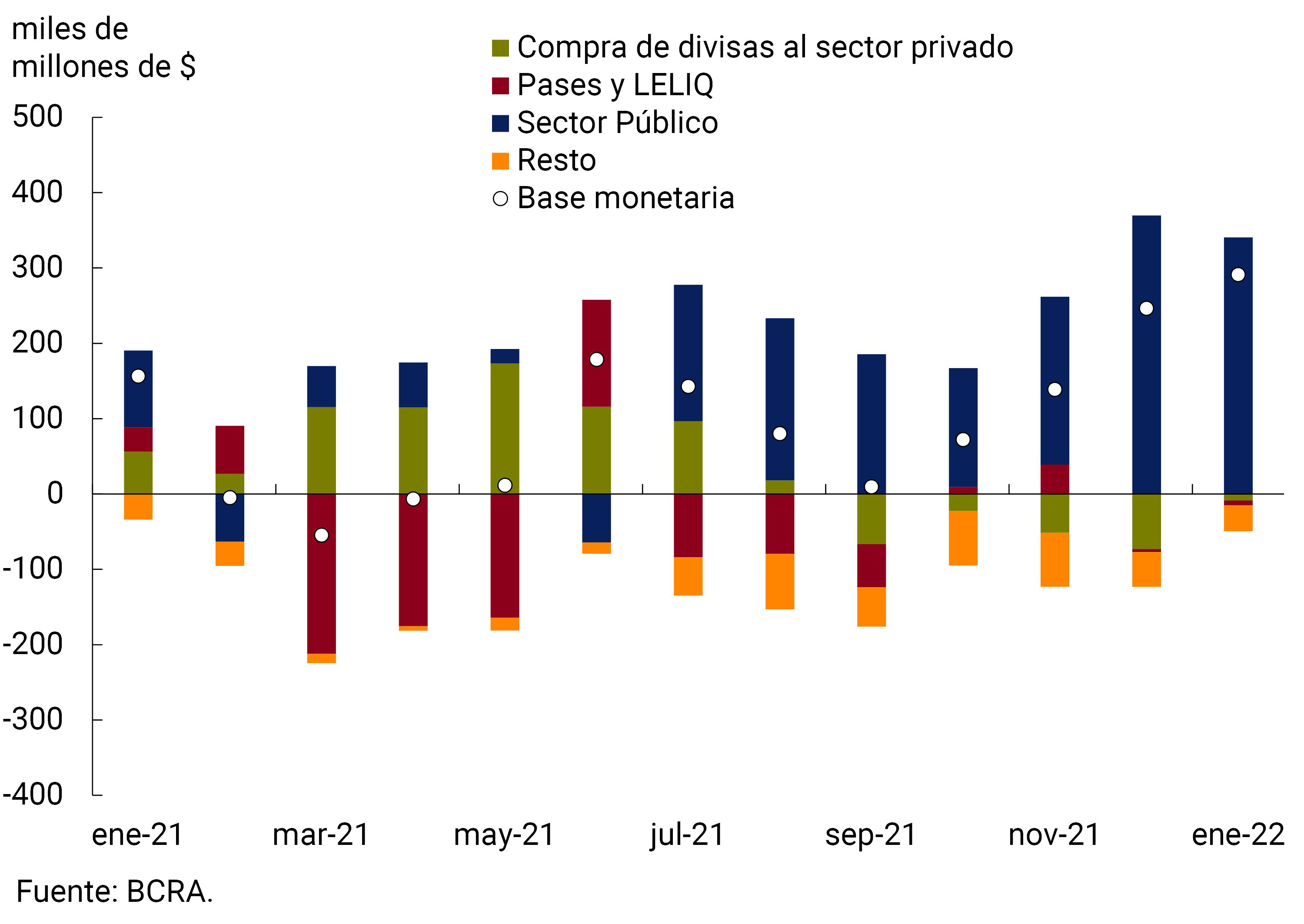

If we analyze the factors of variation on the supply side, the expansion of the monetary base in January was mainly explained by public sector operations, mainly due to the carry-over effect of monetary financing to the National Treasury last December (see Figure 4.2). On the other hand, monetary regulation instruments and foreign currency purchases from the private sector made a slight negative contribution in the month.

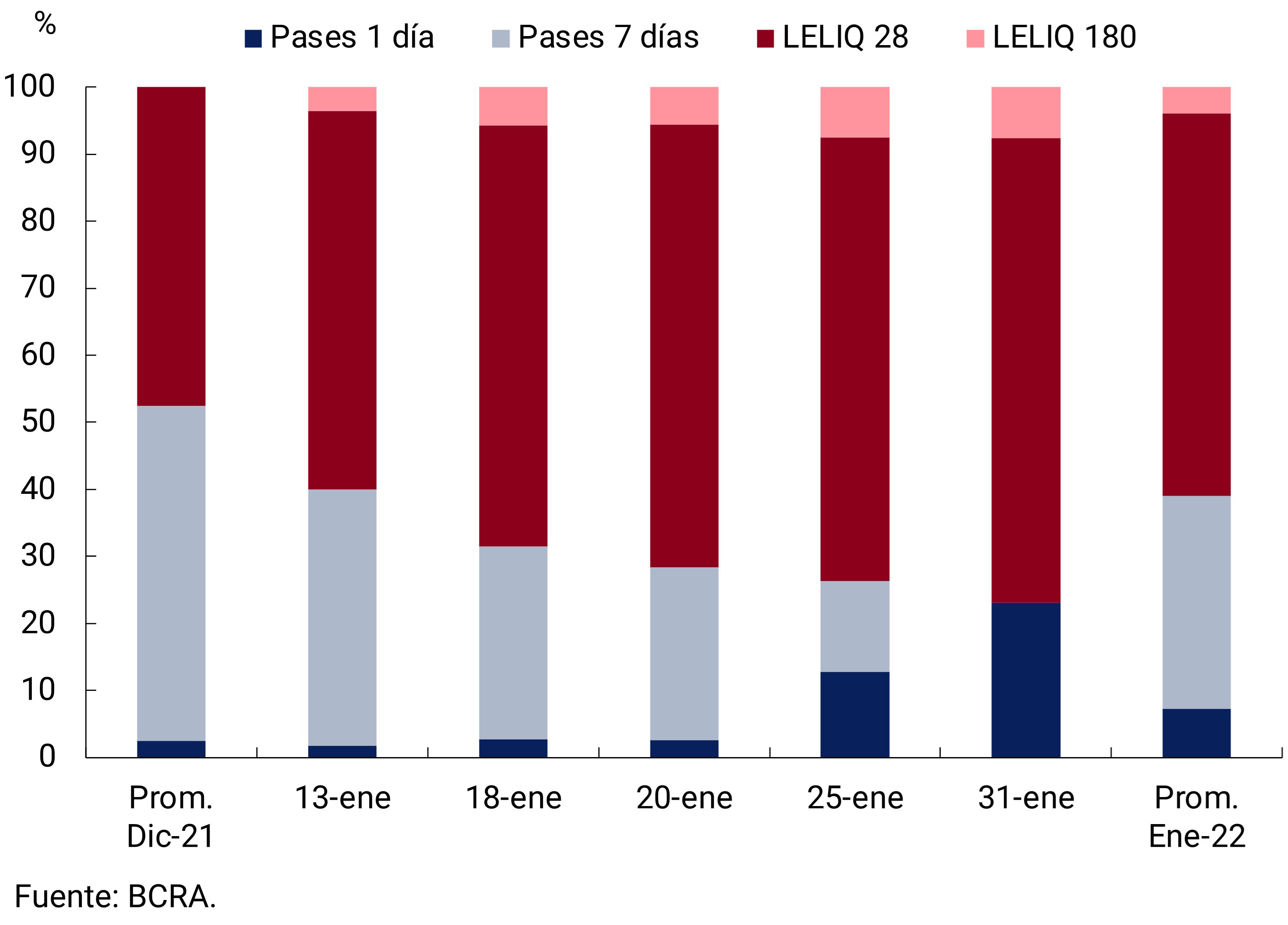

With regard to interest-bearing liabilities, and in line with the objectives and plans set for 2022, at the beginning of January the BCRA decided to carry out a reconfiguration of these9. The changes made are aimed at achieving better liquidity management for financial institutions, increasing the average term of sterilization instruments, and refocusing the policy interest rate signal on the LELIQ rate. In this sense, the elimination of the passive passes to 7 days and the creation of a new instrument, the LELIQ to 180 days, whose auctions will be held once a week10. The 1-day passive passes will absorb the short-term liquidity of the entities, while the long LELIQs will seek to channel structural liquidity. Meanwhile, the 28-day LELIQ will remain as the central reference instrument of monetary policy, so their access was made more flexible for up to the stock of time deposits of the private sector of each financial institution.

Not only were policy instruments readjusted, but interest rates were also adjusted upwards. Specifically, it was decided to raise the interest rate of the LELIQ to 28 days in 2 p.p., which stood at 40% n.a. (48.29% y.a.). Meanwhile, for LELIQs with a 180-day term, the interest rate was set at 44% n.a. (48.9% e.a.). Finally, with regard to shorter-term instruments, since January 17, the interest rate on 7-day passive passes has been progressively reduced, equaling that of 1-day passes, which maintain their interest rate at 32% n.a. (37.69% y.a.).

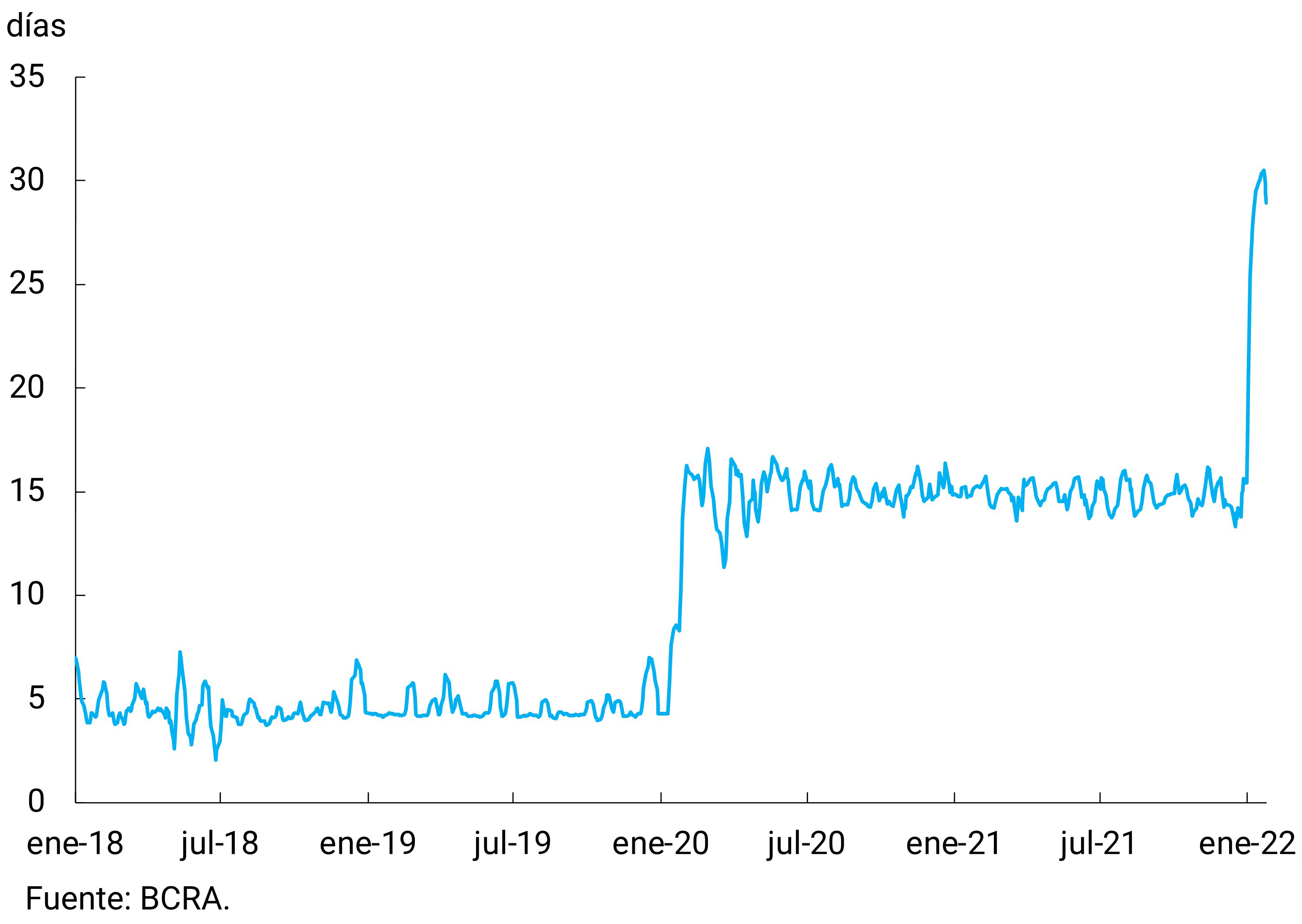

All these changes led to a change in the composition of the BCRA’s interest-bearing liabilities (see Figure 4.3). With regard to 7-day passes, the reduction in the interest rate led to entities not maintaining positions in this instrument by the end of the month. The funds were channelled towards the other remunerated liabilities. Thus, passive 1-day passes expanded to represent 23.1% of the total. Meanwhile, 180-day bills went on to account for 7.7% of the total as of January 31. Finally, the remaining 70% was explained by the 28-day LELIQ, which implied an expansion of just over 20 p.p. compared to the December average. These changes in the relative composition of interest-bearing liabilities made it possible to continue with the policy of extending the terms of the BCRA’s interest-bearing liabilities initiated at the beginning of the administration with the change of term of the shorter LELIQs from 7 to 28 days in February 2020. With the current instrument configuration, the average residual term of the total LELIQ stock almost doubled, from approximately 15 to 30 days (see Figure 4.4).

5. Loans to the private sector

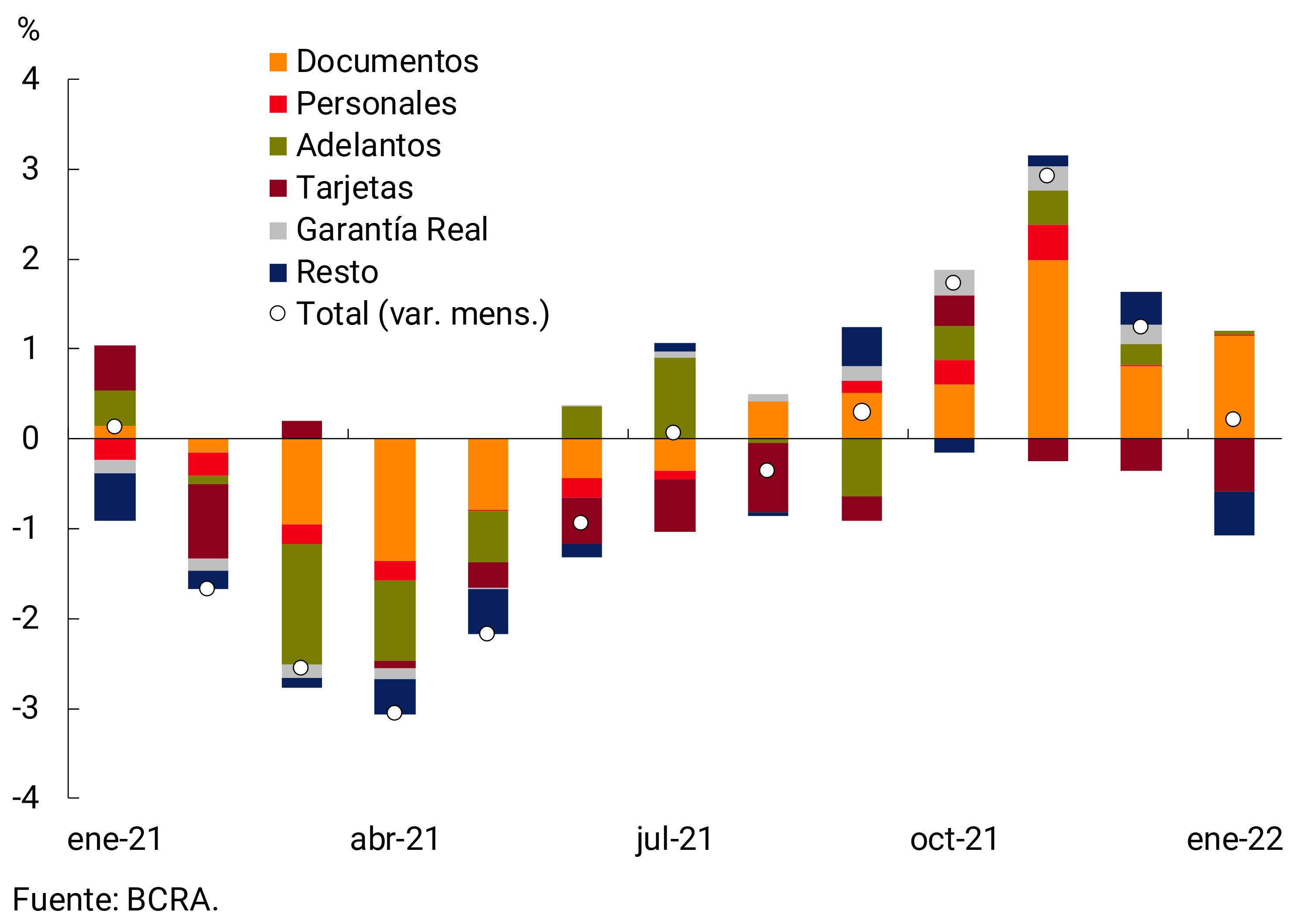

In real terms and without seasonality, loans in pesos to the private sector would have registered a slight increase in January (0.2%), recording five consecutive months of increase. Commercial lines continued to make a positive contribution to the month’s variation, which was partially offset by a drop in credit card financing (see Figure 5.1). Measured in terms of GDP, credit in pesos to the private sector remained slightly above 7%, at a level similar to that observed in December.

Figure 5.1 | Loans in pesos to the Real Private

Sector without seasonality; contrib. to monthly growth

Commercial lines would have grown 2.8% monthly at constant prices and adjusted for seasonality. These financings were again driven by the lines instrumented through documents, whose expansion rate at constant prices would have been 4.6% s.e. (see Figure 5.2). This increase was explained both by the dynamics of single-signature documents, which have a longer average term, and discounted documents (they would have grown at constant prices by 5.4% s.e. and 3% s.e., respectively).

However, it should be noted that practically all the growth in commercial lines was explained by the carry-over effect of the previous month. In fact, if we consider the peak growth in the month, no significant variations were observed and even in some lines they showed marked falls. This dynamic occurred in a month in which the demand for credit by companies tends to decrease in response to the lower activity during the summer recess.

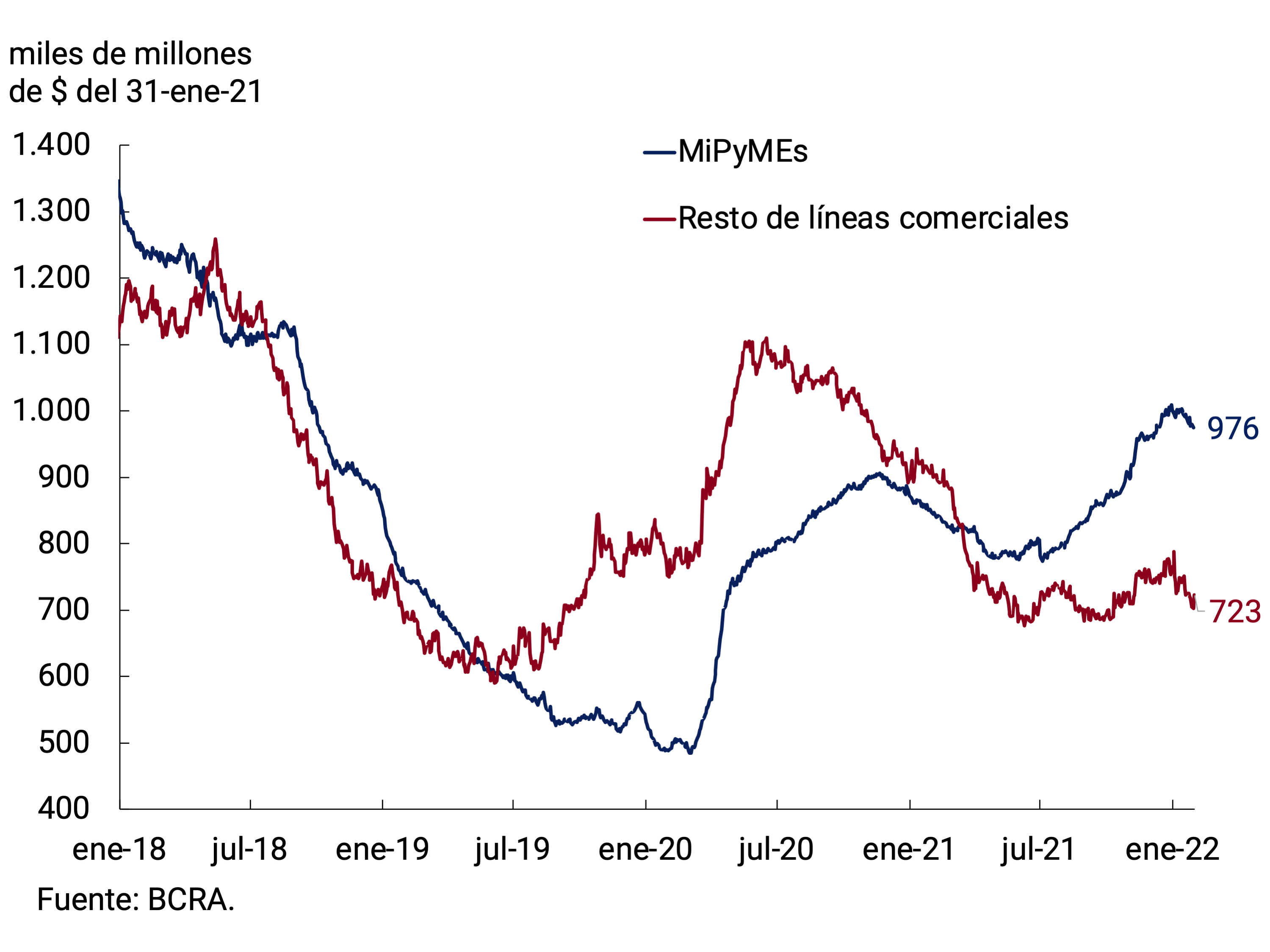

Despite the lower demand for commercial credit observed during the month, the Financing Line for Productive Investment (LFIP) continued to be the main channel through which loans were channeled to Micro, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (MSMEs). The preferential conditions of the line allowed the observed fall in the loan balances of MSMEs to be less than that recorded for the rest of the companies (see Figure 5.3). In fact, on average for the month, inflation-adjusted loans to MSMEs remained in positive territory, which was not the case with the rest of the companies.

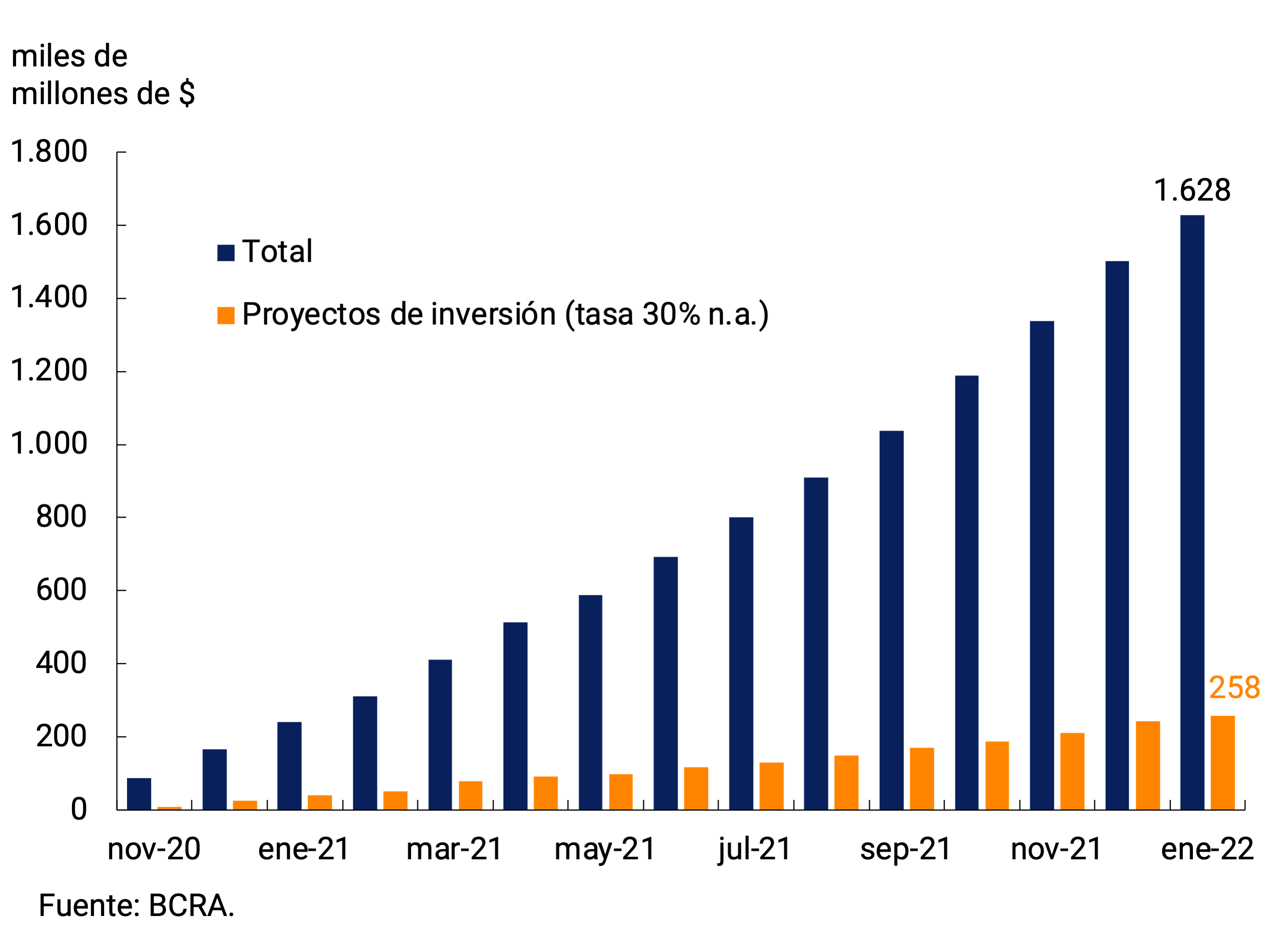

At the end of January, loans granted through the LFIP accumulated disbursements of approximately $1,628 billion since its inception, with an increase of 8.4% compared to the end of December. (see Figure 5.4). So far, more than 215 thousand companies have accessed loans within the framework of the LFIP. Approximately 84% of the total lent was used to finance working capital and the rest to investment projects. It should be noted that, in line with the increase in reference interest rates that was ordered at the beginning of 2022, the BCRA decided to increase the maximum interest rate for working capital financing by 6 p.p. to 41% n.a. and kept the interest rate for the financing of investment projects unchanged at 30% n.a.

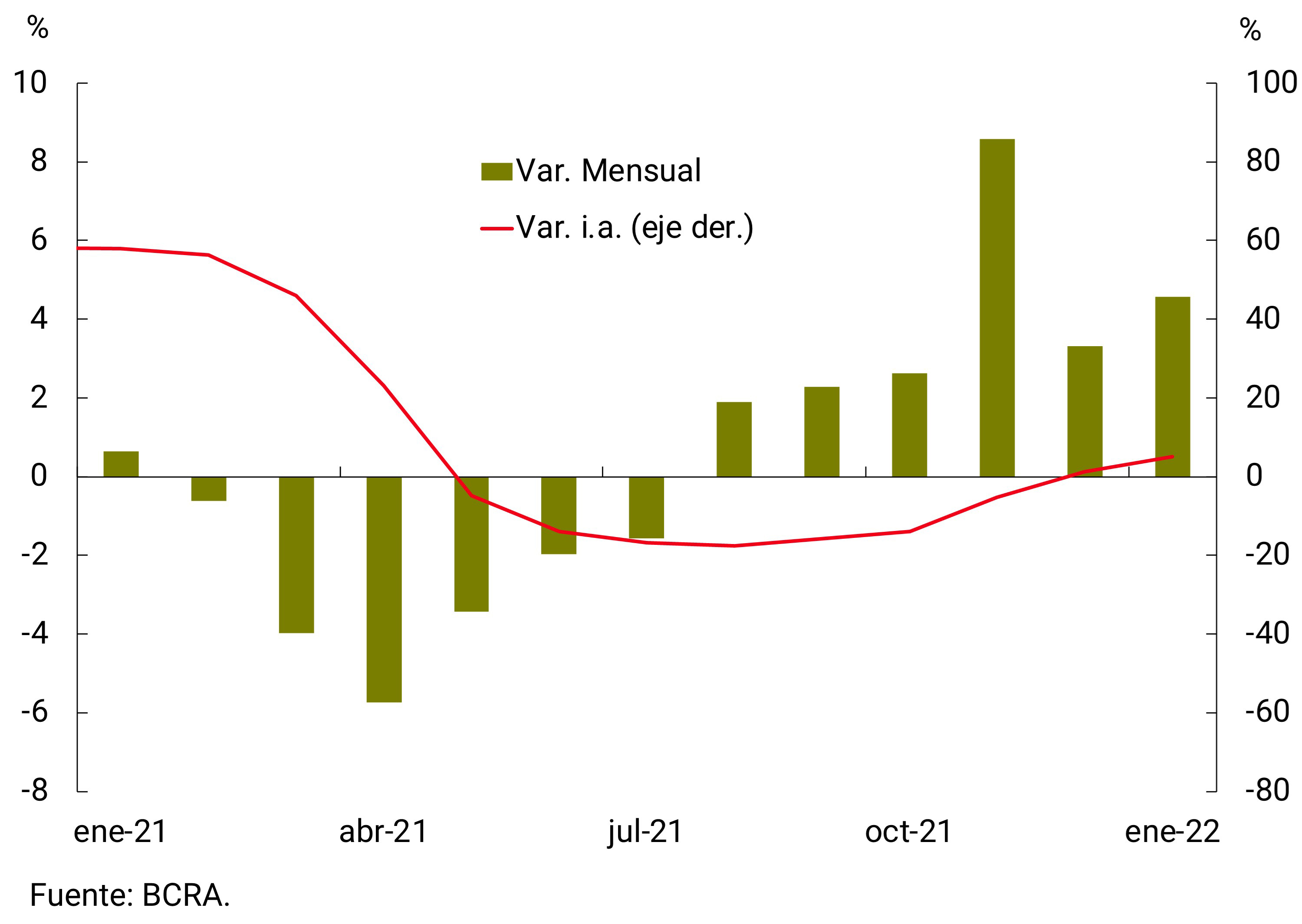

As for the lines with real collateral, collateral loans registered a monthly expansion rate of 2% s.e. at constant prices and, thus, completed nineteen consecutive months of growth. In the last twelve months they accumulated an expansion of 43.7% and together with loans instrumented through documents are the only lines that show a positive variation compared to January 2021. On the other hand, the balance of mortgage loans fell 0.5% in real terms and without seasonality, accumulating a fall of 13.7% in the last twelve months.

Finally, loans associated with consumption showed a contraction during January. Financing instrumented with credit cards would have exhibited a decrease of 2% s.e. in real terms during the first month of 2022 and were positioned 12% below the level of a year ago. Meanwhile, personal loans would have remained relatively stable at constant prices (0.1% s.e.), cutting the year-on-year decrease to 1.5%. The interest rate corresponding to personal loans rose 1.9 p.p. on average in January and stood at 54.9% n.a.

6. Liquidity in pesos of financial institutions

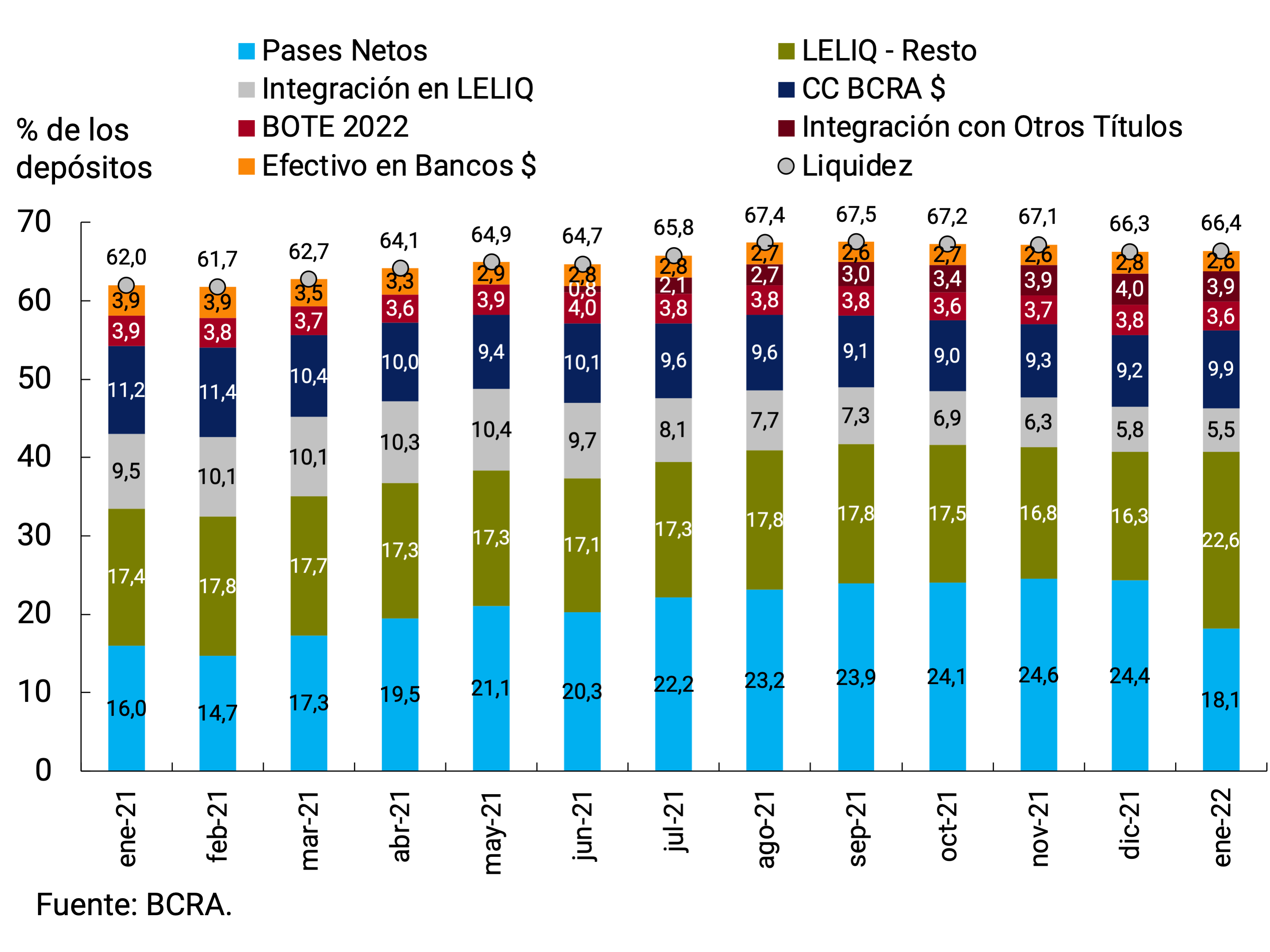

In January, ample bank liquidity in local currency11 averaged 66.4% of deposits, 0.1 p.p. above that observed in December, remaining at historically high levels.

The reformulation of monetary policy instruments at the beginning of the year (see Monetary Base Section) had an impact on the composition of bank liquidity. In fact, there was an increase in the unused LELIQ for minimum cash integration from 16.3 to 22.6% of deposits and a fall in passive passes from 24.4 to 18.1% of deposits. It should be noted that this trend would continue in February, given that at the end of the month there were no 7-day passes left (see Figure 6.1).

In addition, with regard to the reserve requirement regime, the scales of the minimum cash deduction associated with financing to MSMEs were modified, the percentage admitted to be deducted for new financing of investment projects within the framework of the “Financing Line for the productive investment of MSMEs” was increased, and a reserve rate of 100% was established for the balances of the deposit accounts of the Service Providers Payment Accounts (PSPs) that offer payment accounts in which their customers’ funds are deposited12. With all these changes, the current account increased by 0.7 p.p. of deposits on average in January. Finally, it should be noted that as of February, a reduction was established in the percentage of Ahora 12 financing admitted for minimum cash integration, becoming 40% of newfinancing13.

7. Foreign currency

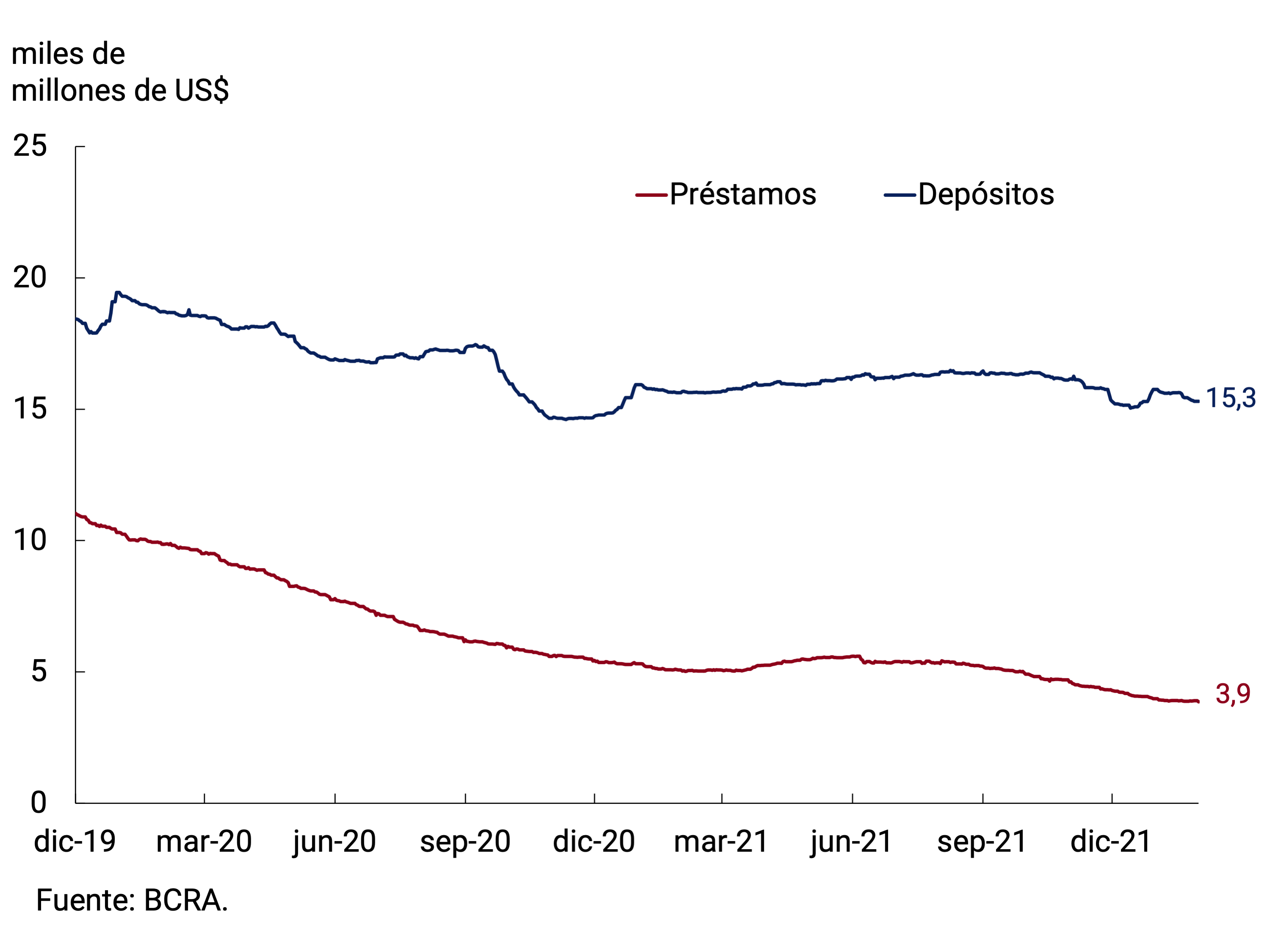

In the foreign currency segment, private sector deposits showed a slight increase compared to last December. However, this increase in deposits was explained by the statistical carryover from December, due to the increase in deposits associated with the exemption from the payment of personal assets tax on demand accounts. In fact, if we consider the peak variation in deposits – between December 31 and January 31 – a decrease of US$455 million is observed. Thus, they ended January with a balance of US$15,301 million (see Figure 7.1). On the other hand, loans to the private sector showed a contraction in both the monthly average variation and the peak, accumulating their eighth consecutive fall. The decrease in financing was concentrated in single-signature documents, which represent practically all loans in foreign currency.

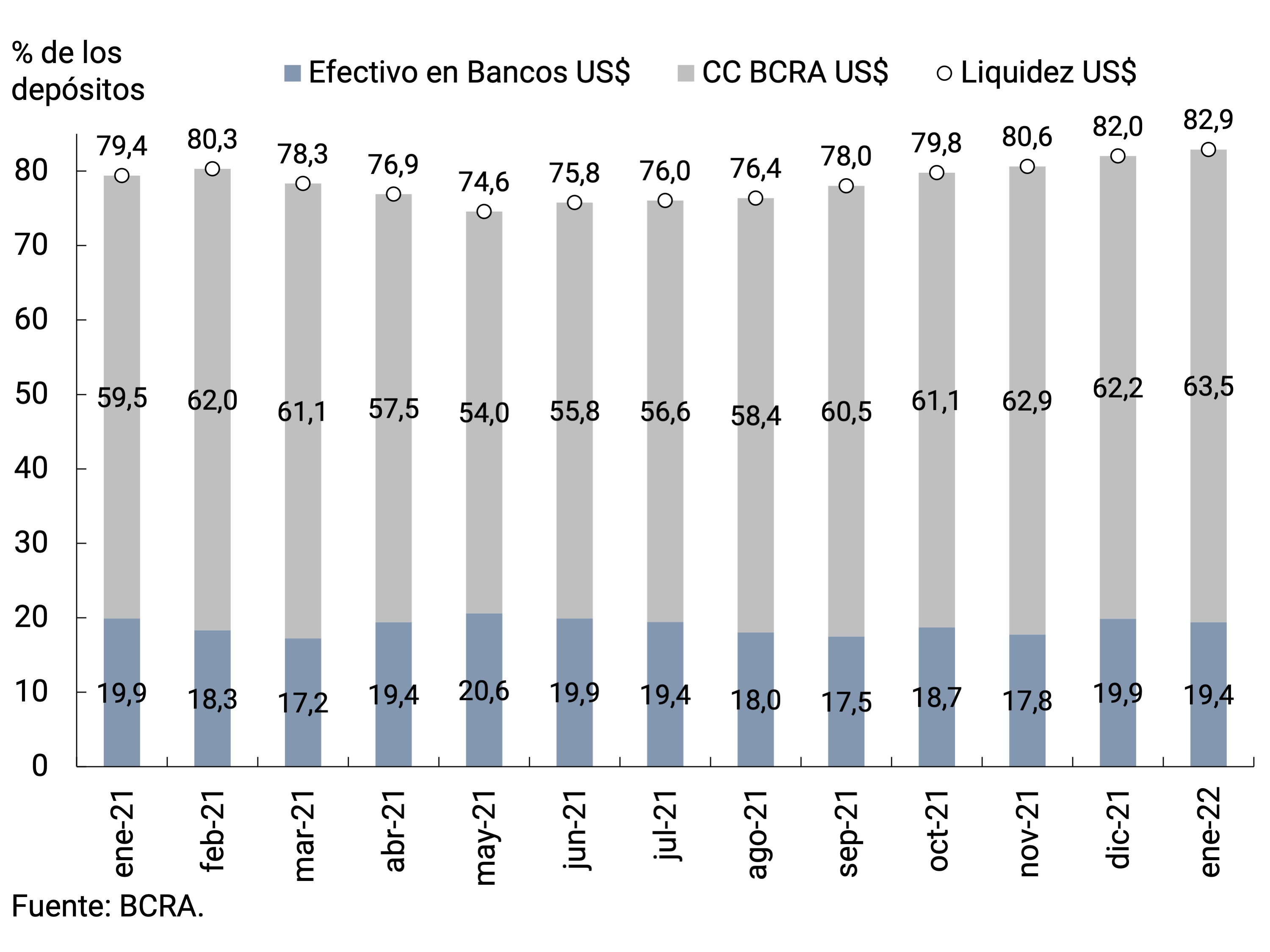

Bank liquidity in foreign currency registered an increase of 0.9 p.p., averaging 82.9% of deposits in January. This increase was explained by an increase in deposits of financial institutions in the Central Bank and was partially offset by a fall in cash in banks (see Figure 7.2).

During January, some regulatory changes took place in foreign exchange matters. On the one hand, it was exempted from requiring the prior approval of the BCRA to access the exchange market for demand payments or commercial debts without a customs entry record for the import of inputs that will be used for the manufacture of goods in the country, provided that the average amount of imports of inputs that have been registered in the last twelve months does not exceed that established in Rule14. On the other hand, after the Federal Administration of Public Revenues (AFIP) created the Comprehensive System for Monitoring Payments of Services Abroad (SIMPES) with which compliance with tax duties and the economic and financial capacity of taxpayers who intend to make a payment abroad for the services provided from abroad is analyzed, the Central Bank ordered financial institutions to verify that the customer has the endorsement of said system to transfer the funds abroad.

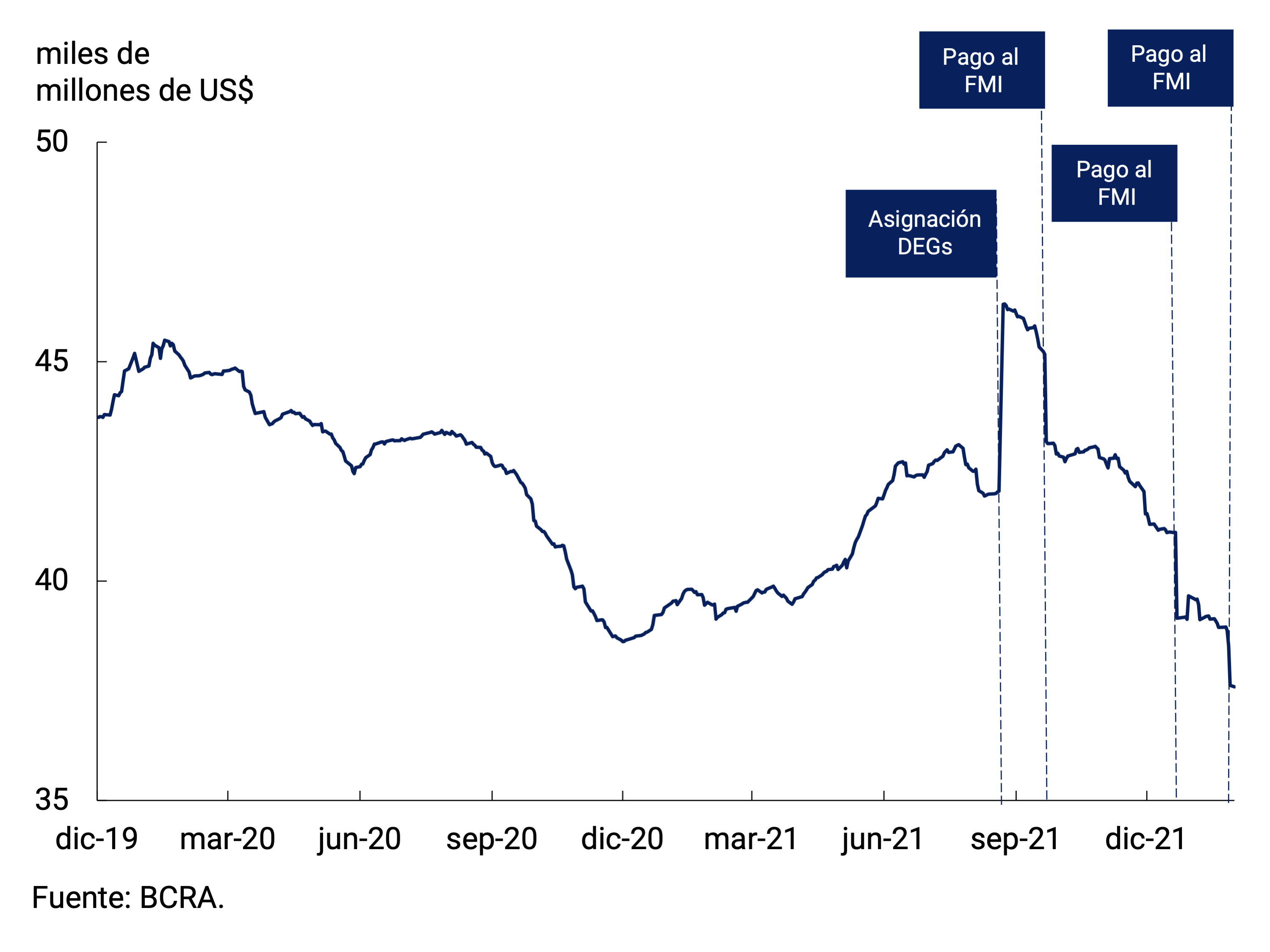

The BCRA’s International Reserves ended January with a balance of US$37,589 million, reflecting a fall of US$2,073 million compared to the end of December (see Figure 7.3). Among the factors that explained this drop is the payment to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for US$714 million towards the end of the month. The rest of the fall was basically explained by payments to other International Organizations, other payments of debt of the National Government in foreign currency and the net sale of foreign currency to the private sector.

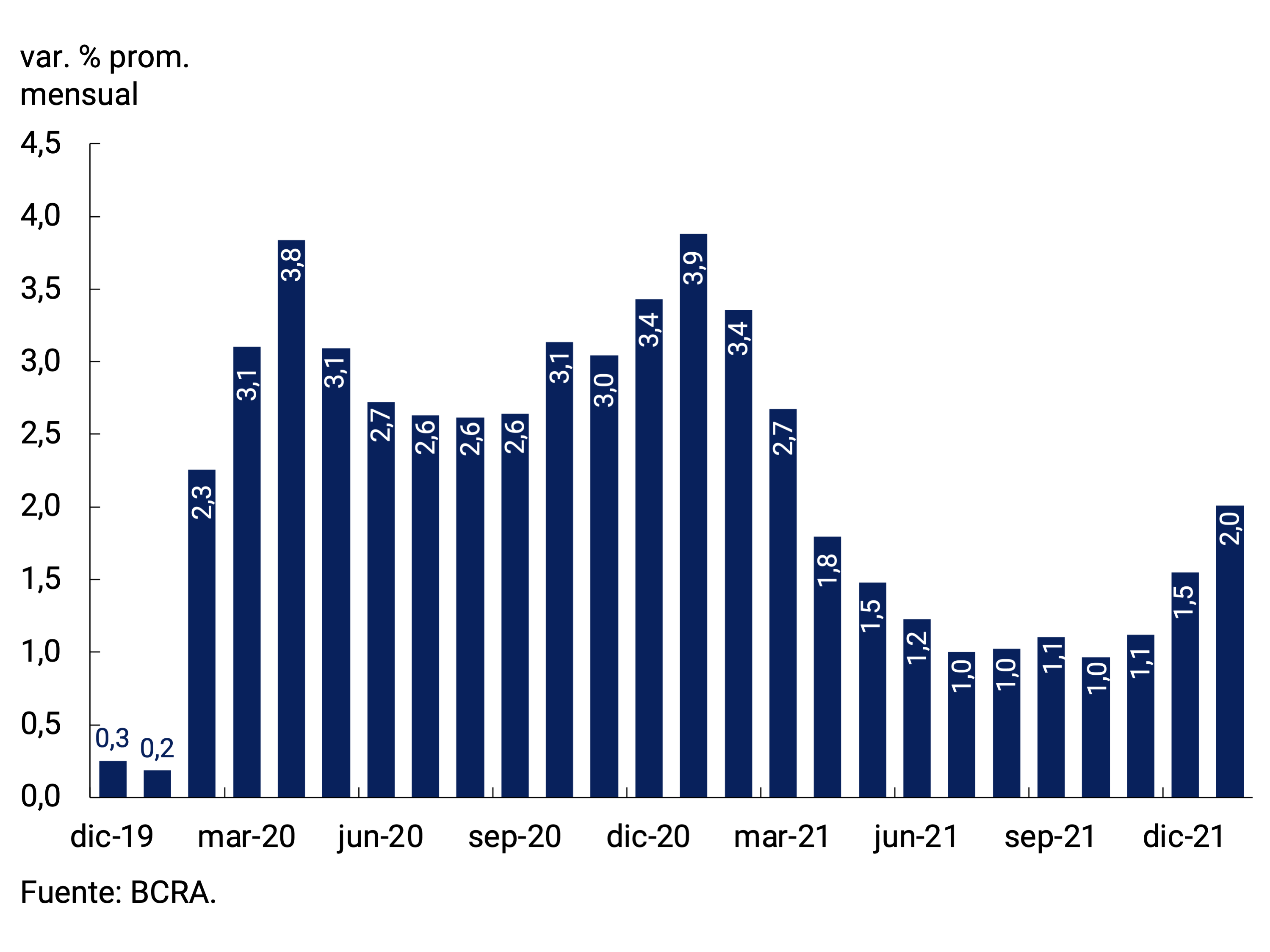

In line with the 2022 Objectives and Plans, the BCRA will seek to preserve the levels of external competitiveness by adjusting the rate of depreciation of the domestic currency to levels more compatible with the inflation rate. This policy also seeks to strengthen the position of International Reserves through the accumulation of the external surplus reflected in the foreign exchange market. Thus, the bilateral nominal exchange rate (TCN) against the US dollar increased 2.0% in January to settle, on average, at $103.93/US$ (see Figure 7.4). The greater dynamism of the TCN, added to the dynamics presented by the main trading partners, allowed the stabilization of the Multilateral Real Exchange Rate Index (ITCRM) during January.

Glossary

ANSES: National Social Security Administration.

BADLAR: Interest rate on fixed-term deposits for amounts greater than one million pesos and a term of 30 to 35 days.

BCRA: Central Bank of the Argentine Republic.

BM: Monetary Base, includes monetary circulation plus deposits in pesos in current account at the BCRA.

CC BCRA: Current account deposits at the BCRA.

CER: Reference Stabilization Coefficient.

NVC: National Securities Commission.

SDR: Special Drawing Rights.

EFNB: Non-Banking Financial Institutions.

EM: Minimum Cash.

FCI: Common Investment Fund.

A.I.: Year-on-year .

IAMC: Argentine Institute of Capital Markets

CPI: Consumer Price Index.

ITCNM: Multilateral Nominal Exchange Rate Index

ITCRM: Multilateral Real Exchange Rate Index

LEBAC: Central Bank bills.

LELIQ: Liquidity Bills of the BCRA.

LFIP: Financing Line for Productive Investment.

M2 Total: Means of payment, which includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and demand deposits in pesos from the public and non-financial private sector.

Private M2: Means of payment, includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and demand deposits in pesos from the non-financial private sector.

Private transactional M2: Means of payment, includes working capital held by the public, cancelling cheques in pesos and non-remunerated demand deposits in pesos from the non-financial private sector.

M3 Total: Broad aggregate in pesos, includes the current currency held by the public, cancelling checks in pesos and the total deposits in pesos of the public and non-financial private sector.

Private M3: Broad aggregate in pesos, includes the working capital held by the public, cancelling checks in pesos and the total deposits in pesos of the non-financial private sector.

MERVAL: Buenos Aires Stock Market.

MM: Money Market.

N.A.: Annual nominal

E.A.: Annual Effective

NOCOM: Cash Clearing Notes.

ON: Negotiable Obligation.

GDP: Gross Domestic Product.

P.B.: basis points.

p.p.: percentage points.

MSMEs: Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises.

ROFEX: Rosario Term Market.

S.E.: No seasonality

SISCEN: Centralized System of Information Requirements of the BCRA.

TCN: Nominal Exchange Rate

IRR: Internal Rate of Return.

TM20: Interest rate on fixed-term deposits for amounts greater than 20 million pesos and a term of 30 to 35 days.

TNA: Annual Nominal Rate.

UVA: Unit of Purchasing Value

References

1 https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/martin-guzman-este-acuerdo-con-el-fmi-abre-un-camino-transitable and https://www.imf.org/es/News/Articles/2022/01/28/pr2218-argentina-imf-staff-statement-on-argentina.

2 M2 private excluding interest-bearing demand deposits from companies and financial service providers. This component was excluded since it is more similar to a savings instrument than to a means of payment.

3 INDEC will release the inflation data for January on February 15.

4 Communication “A” 7432.

5 Financial Services Providers, Companies and Individuals with deposits of more than $10 million.

6 https://www.bcra.gob.ar/archivos/Pdfs/Institucional/ObjetivosBCRA_2022.pdf.

7 It should be noted that the series of fixed-term deposits in pesos in the private sector does not present identifiable seasonality. However, in recent years there has been a systematic growth in this series in the first month of the year.

8 Includes the working capital held by the public and the deposits in pesos of the non-financial private sector (sight, term and others).

9 See Com. “A”7432.

10 To access this bill, the entity must have a balance of fixed-term deposits greater than 20% of its deposits in pesos from the private sector.

11 Includes current accounts at the BCRA, cash in banks, balances of net passes arranged with the BCRA, holdings of LELIQ, and bonds eligible for reserve requirements.

12 Communication “A” 7429.

13 Communication “A” 7448.

14 Communication “A” 7433.