Política Monetaria

Monetary Policy Report (IPOM)

Third quarter

2018

Quarterly report presenting the macroeconomic analysis and monetary policy guidelines of the BCRA.

Table of Contents

Chapters

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlook

2. International context

3. Economic Activity and Employment

4. External Sector

5. Public Finance

6. Prices

7. Monetary Policy

Sections

1. Labor market and external

shocks 2. Fiscal consolidation and current account results

Glossary of abbreviations and acronyms

For inquiries, write to analisismacro@bcra.gob.ar

Summary

As indicated in its Organic Charter, the Central Bank of the Argentine Republic “aims to promote, to the extent of its powers and within the framework of the policies established by the National Government, monetary stability, financial stability, employment and economic development with social equity”.

Without prejudice to the use of other more specific instruments for the fulfillment of the other mandates — such as financial regulation and supervision, exchange rate regulation, and innovation in savings, credit, and means of payment instruments — the main contribution that monetary policy can make for the monetary authority to fulfill all its mandates is to focus on price stability.

With low and stable inflation, financial institutions can better estimate their risks, which ensures greater financial stability. With low and stable inflation, producers and employers have more predictability to invent, undertake, produce and hire, which promotes investment and employment. With low and stable inflation, families with lower purchasing power can preserve the value of their income and savings, which makes economic development with social equity possible.

The contribution of low and stable inflation to these objectives is never more evident than when it does not exist: the flight of the local currency can destabilize the financial system and lead to crises, the destruction of the price system complicates productivity and the generation of genuine employment, the inflationary tax hits the most vulnerable families and leads to redistributions of wealth in favor of the wealthiest. Low and stable inflation prevents all this.

In line with this vision, the BCRA formally adopted an Inflation Targeting regime that came into effect as of January 2017. As part of this new regime, the institution publishes its Monetary Policy Report on a quarterly basis. Its main objectives are to communicate to society how the Central Bank perceives recent inflationary dynamics and how it anticipates the evolution of prices, and to explain in a transparent manner the reasons for its monetary policy decisions.

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlook

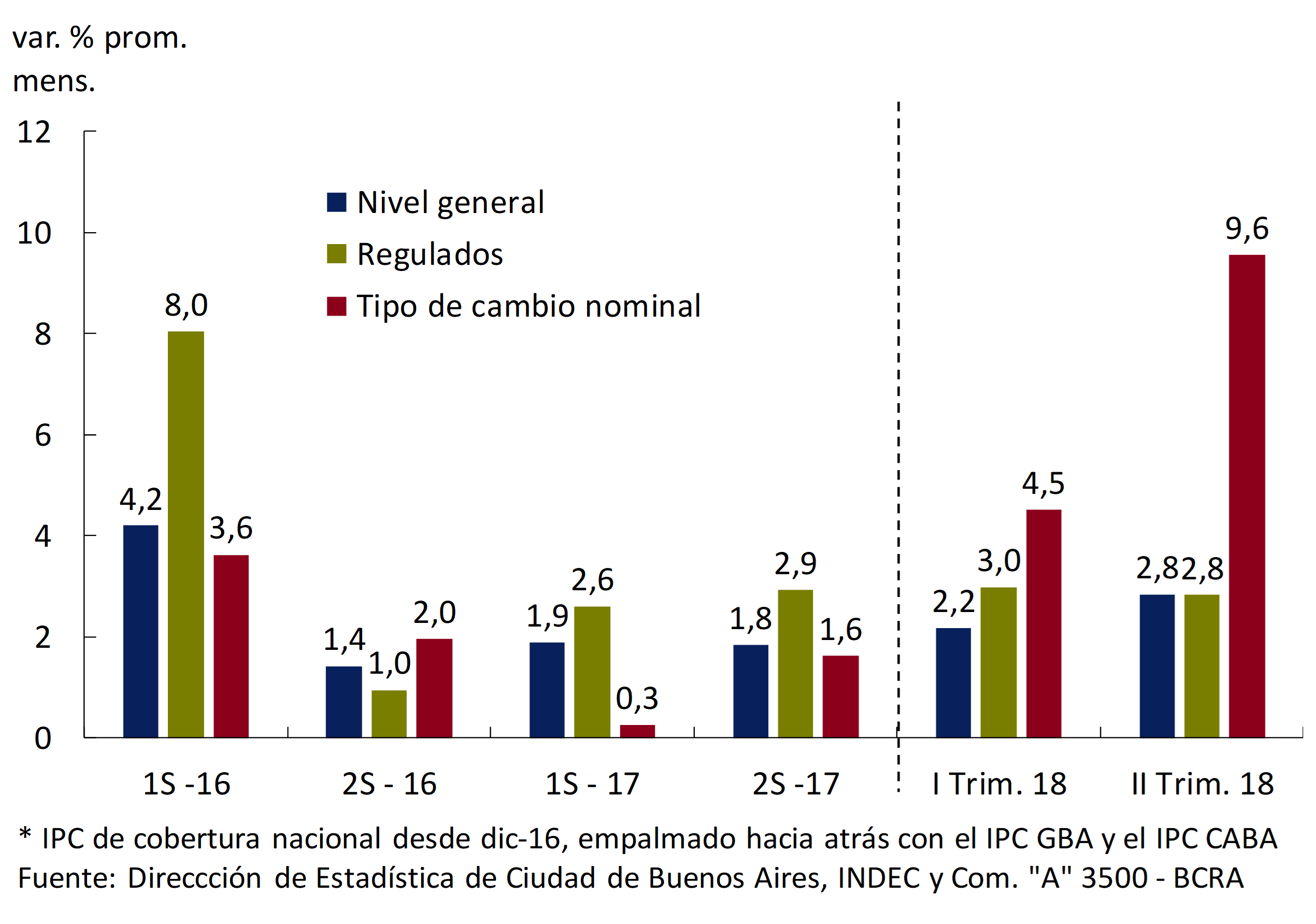

Inflation accelerated in the second quarter of 2018 compared to the first quarter, reaching a monthly average of 2.8%. This increase was mainly caused by the depreciation of the peso as of the end of April. In fact, the price of goods grew by 4.6% month-on-month while that of services grew by 2.2%, reflecting the more tradable nature of the former. Having achieved greater stability in the foreign exchange market from a decisive monetary policy reaction, the Central Bank of the Argentine Republic (BCRA) considers in its base scenario that inflation begins to moderate in July and the third quarter shows a value close to 2% per month on average. This scenario envisages a prolonged reduction in exchange rate volatility and a continuation of the contractionary bias of monetary policy.

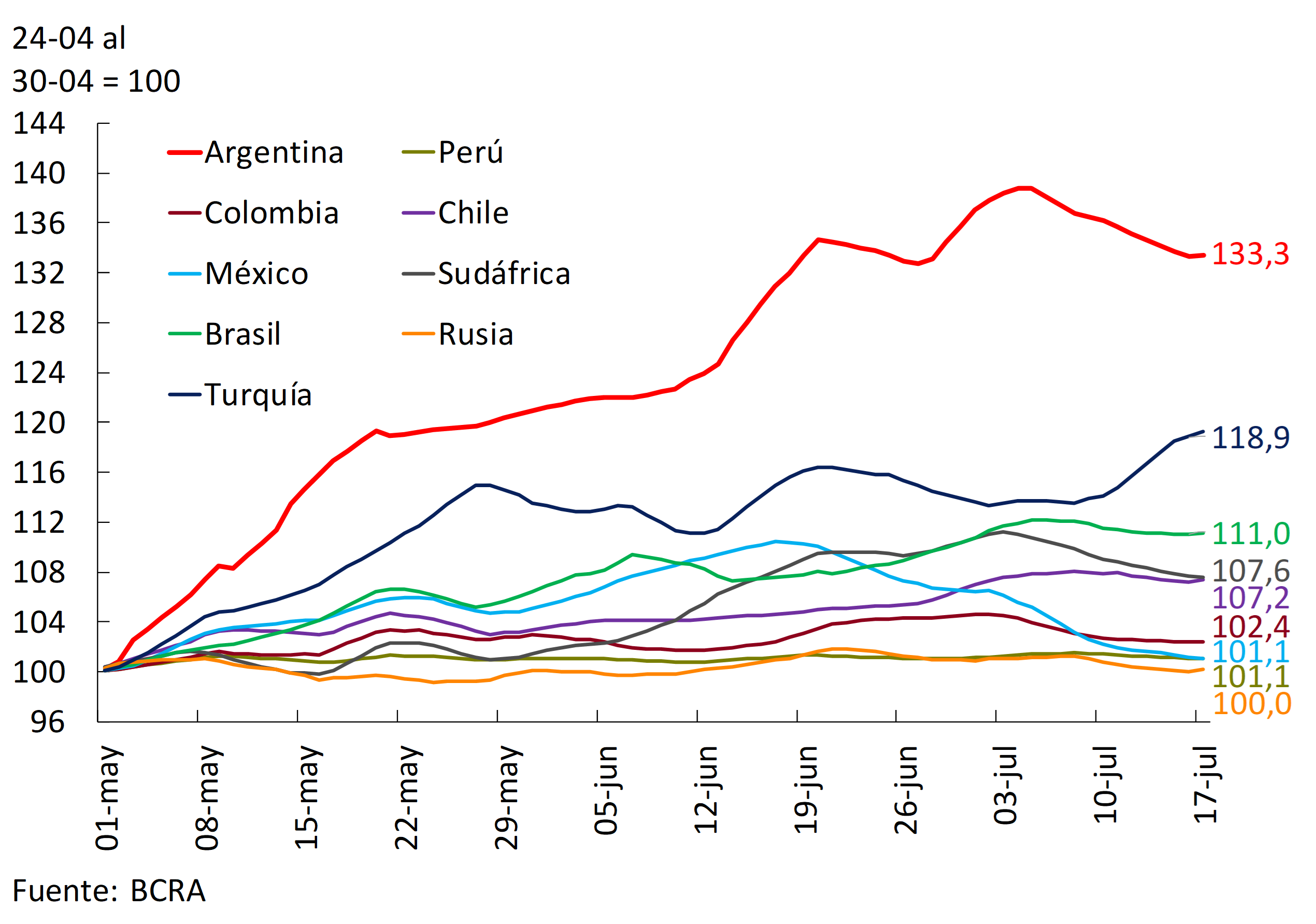

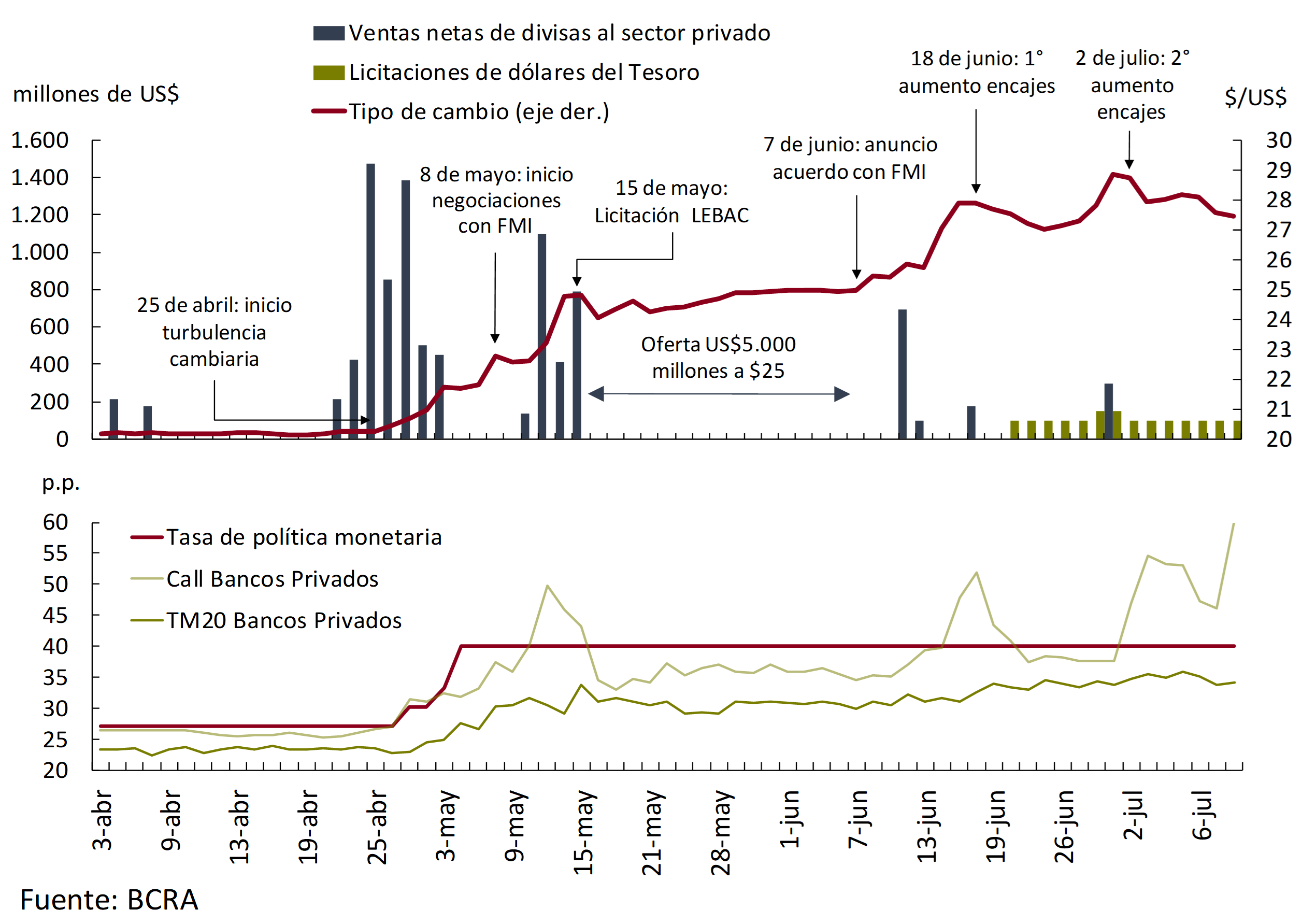

The depreciation of the peso in the second quarter occurred in the context of a withdrawal of capital from emerging countries, deepened in the case of our country by a situation of vulnerability based on existing current account and fiscal deficits, and by a severe drought that reduced exports of the soybean complex. Faced with this situation, the monetary authority initially increased the monetary policy rate and allowed an increase in the interest rate on Central Bank Bills (LEBAC). In addition, Argentina decided to accelerate the fiscal deficit reduction schedule and received US$55.6 billion in support from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other multilateral agencies, in the form of a Stand-By agreement. Starting in mid-June, a new leadership of the BCRA focused on achieving greater control of monetary aggregates, introducing increases in the minimum cash requirements of financial institutions to reduce the liquidity of the system. An accommodation of rates in the secondary LEBAC market consistent with the greater monetary tightening was also allowed. The combination of all these measures finally managed to bring greater calm to the foreign exchange market after several weeks of strong instability.

In terms of economic activity, the aforementioned drought has produced a very significant contraction of the agricultural sector in the second quarter, which would lead to a fall in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the second quarter. The pattern of previous droughts (2009 and 2012) suggests that in the third quarter the level of agricultural output should return to that of the first quarter of 2018, contributing positively to GDP. The BCRA’s base scenario has the non-agricultural sectors showing a contraction in the third quarter, as a result of the income effect of higher inflation, and the agricultural sector compensating for this fall.

The BCRA’s view, as mentioned above, is that in the base scenario, inflation will moderate from the third quarter onwards. In any case, it believes that the current contractionary bias should be maintained until the trajectory of inflation and expected inflation are aligned with the 17% target in December 2019. In addition, the BCRA considers that, in the transition to reach single-digit inflation rates, the inflation targeting scheme with the interest rate as the only monetary policy instrument should be complemented by a more attentive monitoring of monetary aggregates. Finally, the BCRA considers that monetary policy decisions should reflect the monetary authority’s perspective on the trend in inflation rather than the reaction to high-frequency events. Consequently, it decided to move to a monthly frequency of definition of the monetary policy rate, maintaining the possibility of operating in the secondary LEBAC market with the aim of reinforcing the monetary policy signal, when necessary, between policy rate decisions. The BCRA will operate with this new monetary policy scheme and the contractionary bias necessary to achieve its inflation target of 17% per year in December 2019.

2. International context

The conditions of access of emerging economies to international financial markets deteriorated in the second quarter of the year. Among the main factors that influenced are: the rise in interest rates in the United States and the expectation of less monetary stimulus from both the Federal Reserve (Fed) and the European Central Bank (ECB); new trade restrictions among the largest economies; and political and economic uncertainty in some European countries. All these elements led to an outflow of capital from emerging countries and a depreciation of their currencies.

However, a positive performance of global economic activity continued to be observed, including in Argentina’s main trading partners, although with a slowdown in Brazil. Thus, despite the deterioration in financial conditions, the external scenario as a whole still continues to be favorable in historical terms for Argentina.

Even more contractionary international financial conditions, together with a deepening of protectionist measures, are the main risks of the international scenario facing Argentina. If they materialize, they would imply a further deterioration in the situation of the global economy, particularly in emerging countries, which would have an impact on the level of activity of our main trading partners, and therefore on that of Argentina.

2.1 Global economic activity continues to grow

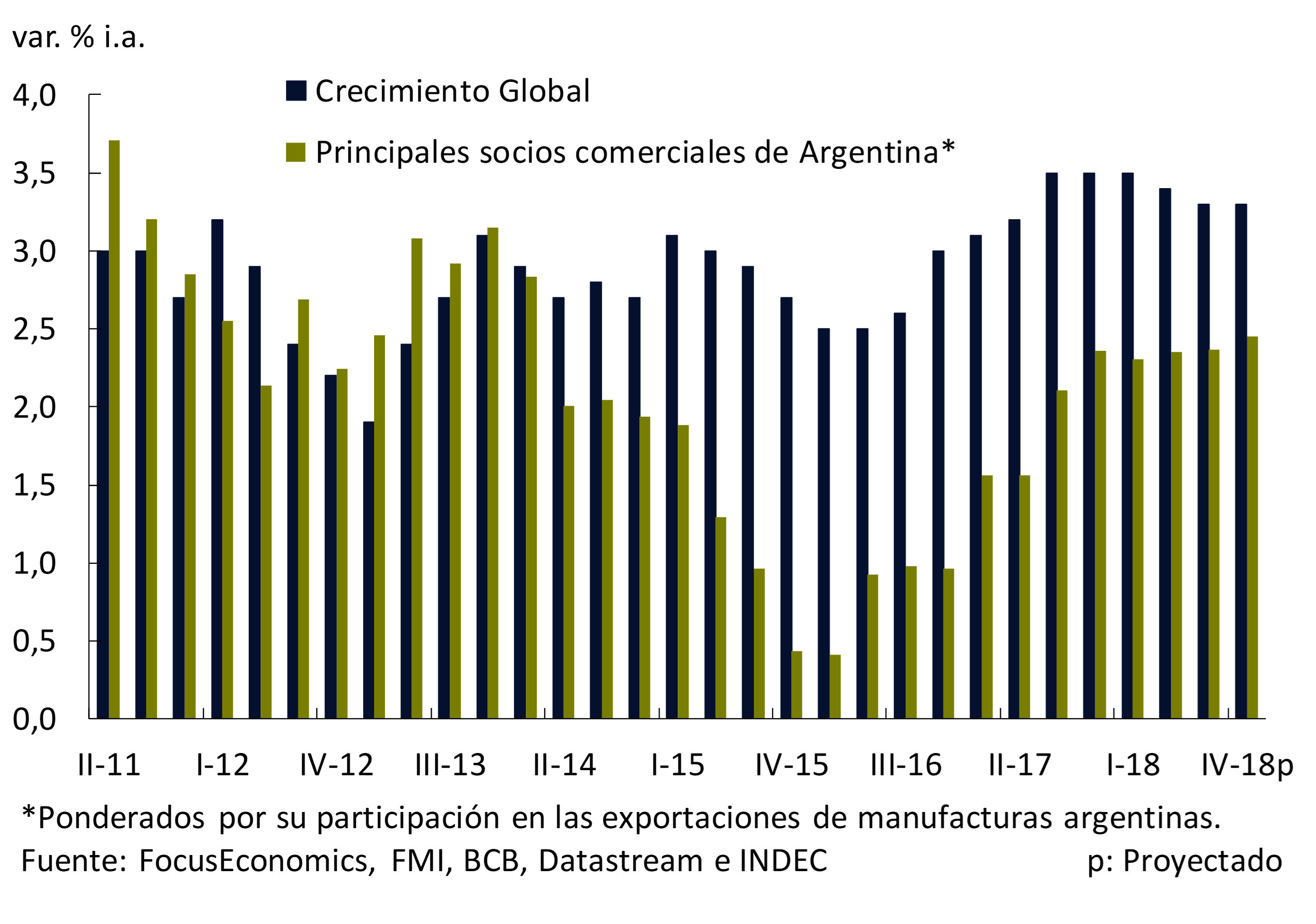

Argentina’s trading partners as a whole are expected to continue to grow at rates similar to those recorded in recent quarters (see Figure 2.1). However, the economic growth outlook for these countries fell in relation to what was forecast in the previous IPOM, basically due to the lower expansion forecast for Brazil.

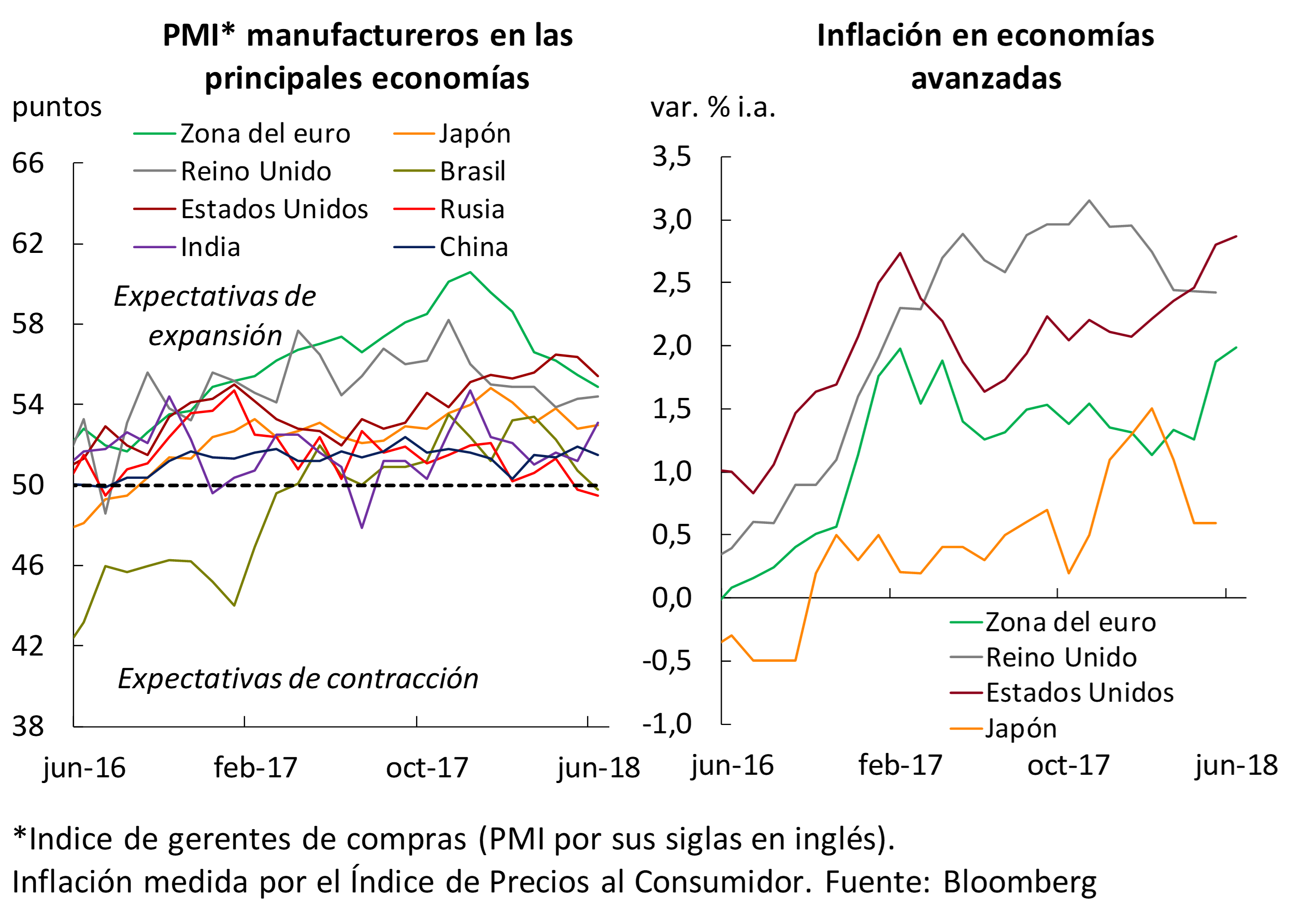

The leading indicators of activity in the main economies are in almost all cases in the expansion zone, with a certain slowdown in the margin. According to the most recent data, inflation continued to rise (except in Japan), making the scenario of a larger-than-expected tightening of monetary policy more likely. More specifically, inflation in the United States is 0.9 p.p. above target, UK inflation is 0.4 p.p. above target, and in the euro area it is above target (see Figure 2.2).

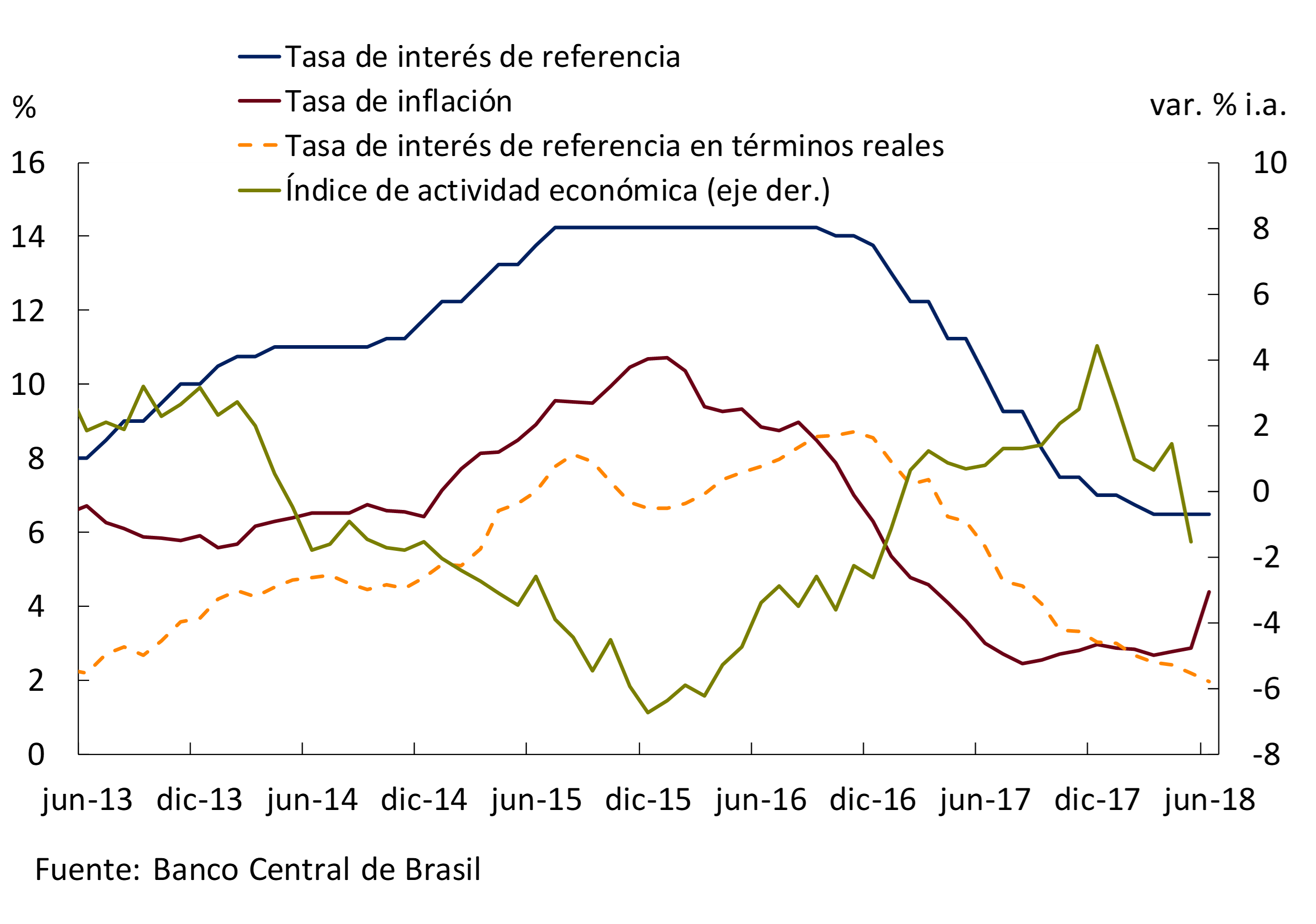

The most recent data confirm that Brazil, our main trading partner, will continue to grow during 2018, beyond the drop in the level of activity in May linked to a specific event, a measure of force that paralyzed transport. This was reflected in the growth rate of the Economic Activity Index prepared by the BCB, which was negative in May (see Figure 2.3). The most recent projections of the Focus survey – carried out by Brazil’s central bank (BCB) among market analysts – foresee GDP growth of 1.5% for 2018. Thus, the projected growth for this year is 1.1 p.p. lower than what was expected at the time of publication of the previous IPOM.

For its part, after having reduced the monetary policy interest rate (the target on the Selic rate) by 7.75 p.p. – in just under two years – the BCB kept it unchanged in the face of an inflation rate with an increase in the margin and the instability of the exchange rate. The most recent inflation projections foresee a price rate of change of 4.1% for 2018, that is, close to the average target range of 4.5% ± 1.5%. The analysts surveyed by Focus do not foresee a further reduction in the Selic rate for the rest of 2018 (unlike the previous IPOM, when a reduction of 0.25 p.p. was expected). The monetary policy rate in real terms continued to decline.

In the euro area, the second destination for Argentine exports, economic growth slowed in the first months of 2018, according to the European Central Bank (ECB), due to a series of temporary factors, including: adverse weather conditions; a series of union conflicts; and an outbreak of influenza with a marked impact on absenteeism from work. So the GDP growth rate fell in the first quarter of 2018 to 0.4% (compared to the previous quarter), after five quarters with growth of 0.7%. However, according to the latest projections, the level of activity in the euro area is expected to stabilise at around 0.5% quarterly growth for the remainder of 2018 and 2019. Finally, labor market data for May show an unemployment rate of 8.4%, the lowest value since December 2008.

As expected, the ECB did not modify its monetary policy interest rate, which it applies to Main Refinancing Operations, which remains at the historic low of 0%, nor did the rate broker, thus leaving the interest rate on the lending facility at 0.25% and the interest rate on the deposit facility at -0.4%. According to ECB staff projections , no changes in these interest rates are expected for the remainder of 2018, nor for most of 2019. In addition, the ECB increased the inflation estimate for 2018 by 0.3 p.p. to 1.7%, partly due to the increase in oil prices. Finally, the ECB maintains its decision to end its quantitative easing programme at the end of the year, which it will halve again in September this year (from €30,000 million per month to €15,000 million)1.

In the United States, Argentina’s third largest export destination, the growth rate slowed in the first quarter of 2018 to 2% (seasonally free and annualized) compared to 2.9% in the previous quarter. This was mainly due to lower growth in private consumption – from a contribution to growth of 2.8 per cent to 0.6 per cent – and exports. Regarding the labor market, the unemployment rate reached 4% in June.

As was widely expected by the market, the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) Monetary Policy Committee (FOMC) again increased the benchmark interest rate to the 1.75-2% range at its June meeting. The Fed projects further increases of 0.5 p.p. during 2018, 0.25 p.p. more than expected at the time of publication of the previous IPOM; while by the end of 2019 the FOMC projects a monetary policy rate 0.75 p.p. higher than the values with which it will end 2018. This had already been anticipated by the market, which impacted expectations regarding global liquidity conditions in mid-May, momentarily leading the yield rate on ten-year US treasury bonds above 3%, producing a global appreciation of the dollar. For its part, the Fed kept its growth projections for 2018 and 2019 almost unchanged, while slightly increasing expected inflation. Thus, it forecasts a price increase (measured by the core deflator of household spending) of 2.1% for this year (0.2 p.p. higher than the projection in force in the previous IPOM).

Finally, China, the main destination for Argentina’s exports of primary products, had GDP growth of 6.8% year-on-year during the first three months of the year, driven mainly by consumption, residential investment and exports. The most recent projections for 2018 show expected GDP growth of 6.6%, slightly below the increase in the level of activity in 2017. Finally, the Chinese yuan, which had not followed the trend of some emerging currencies until early June, depreciated sharply against the dollar in the last days prior to the publication of the IPOM (4.4%).

2.2 The external financial scenario became less favourable: reversal of capital flows to emerging countries and higher risk premiums

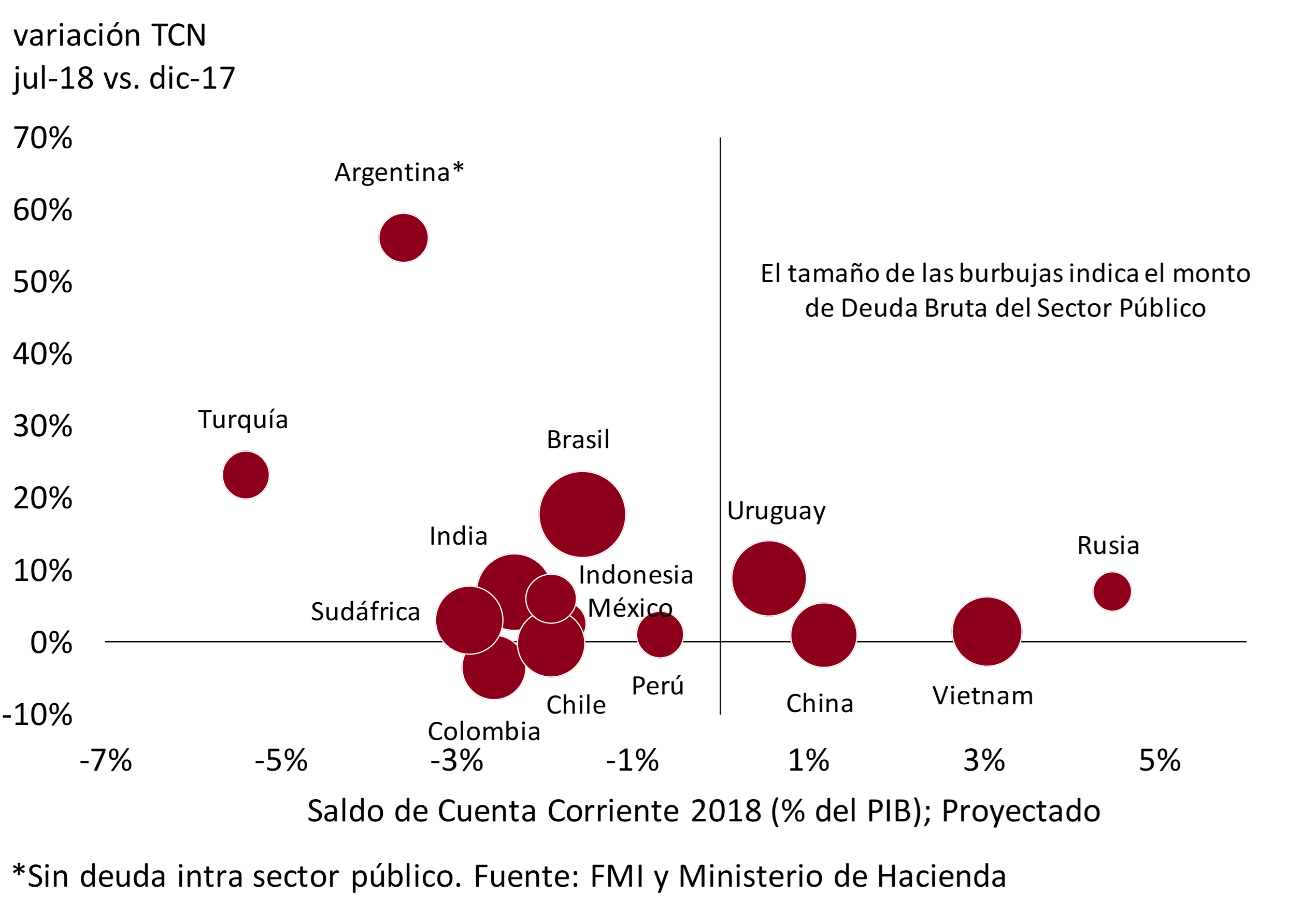

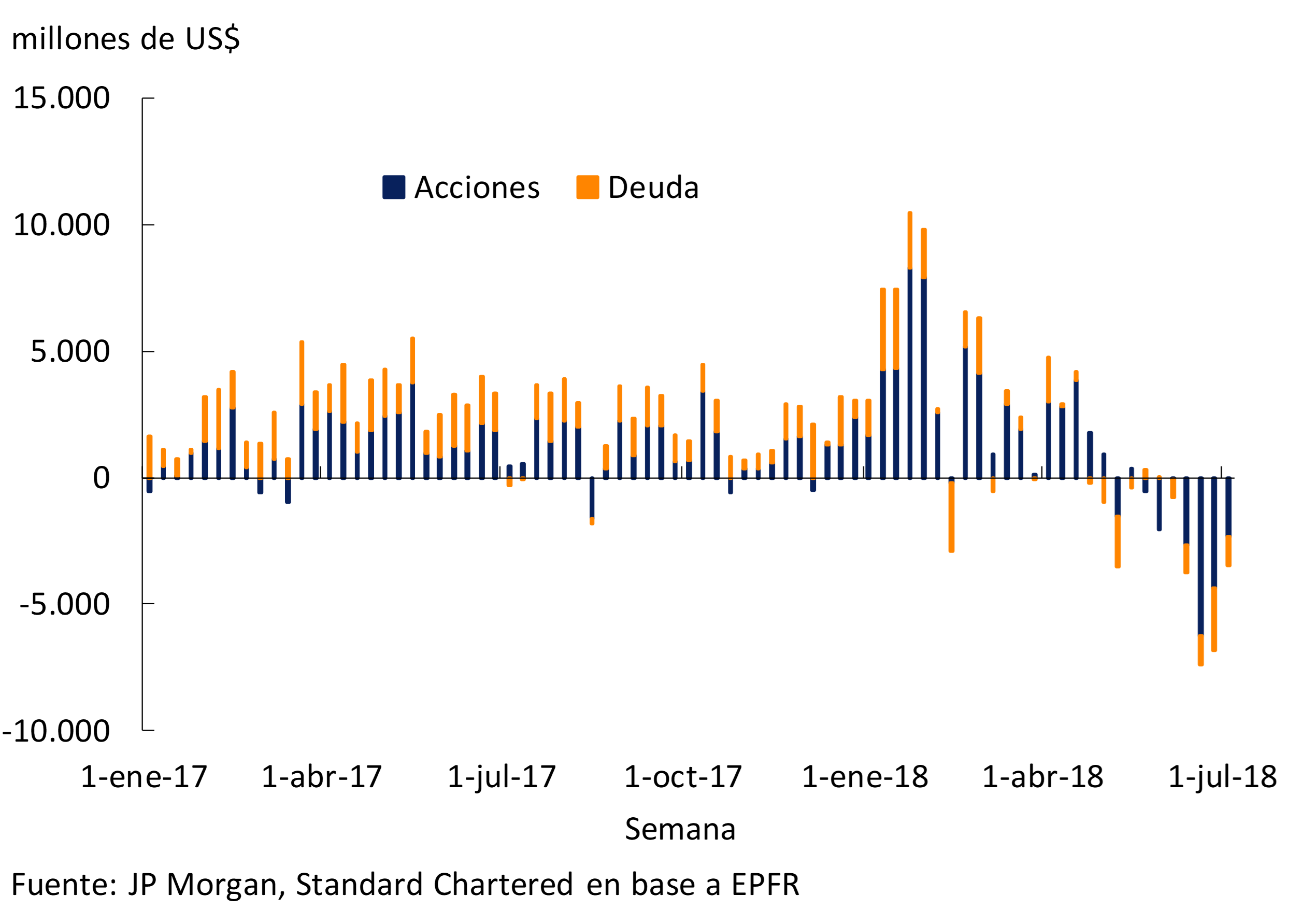

The risks identified in the previous report materialised, leading to a tightening of the external financial scenario. Although global liquidity conditions continue to be comfortable in historical terms, they worsened markedly for emerging countries, and for Argentina in particular. Economies with external imbalances and high levels of debt (see Figure 2.4) were particularly affected. Thus, capital flows to emerging economies reversed (see Figure 2.5), their currencies depreciated, and sovereign risk premiums rose.

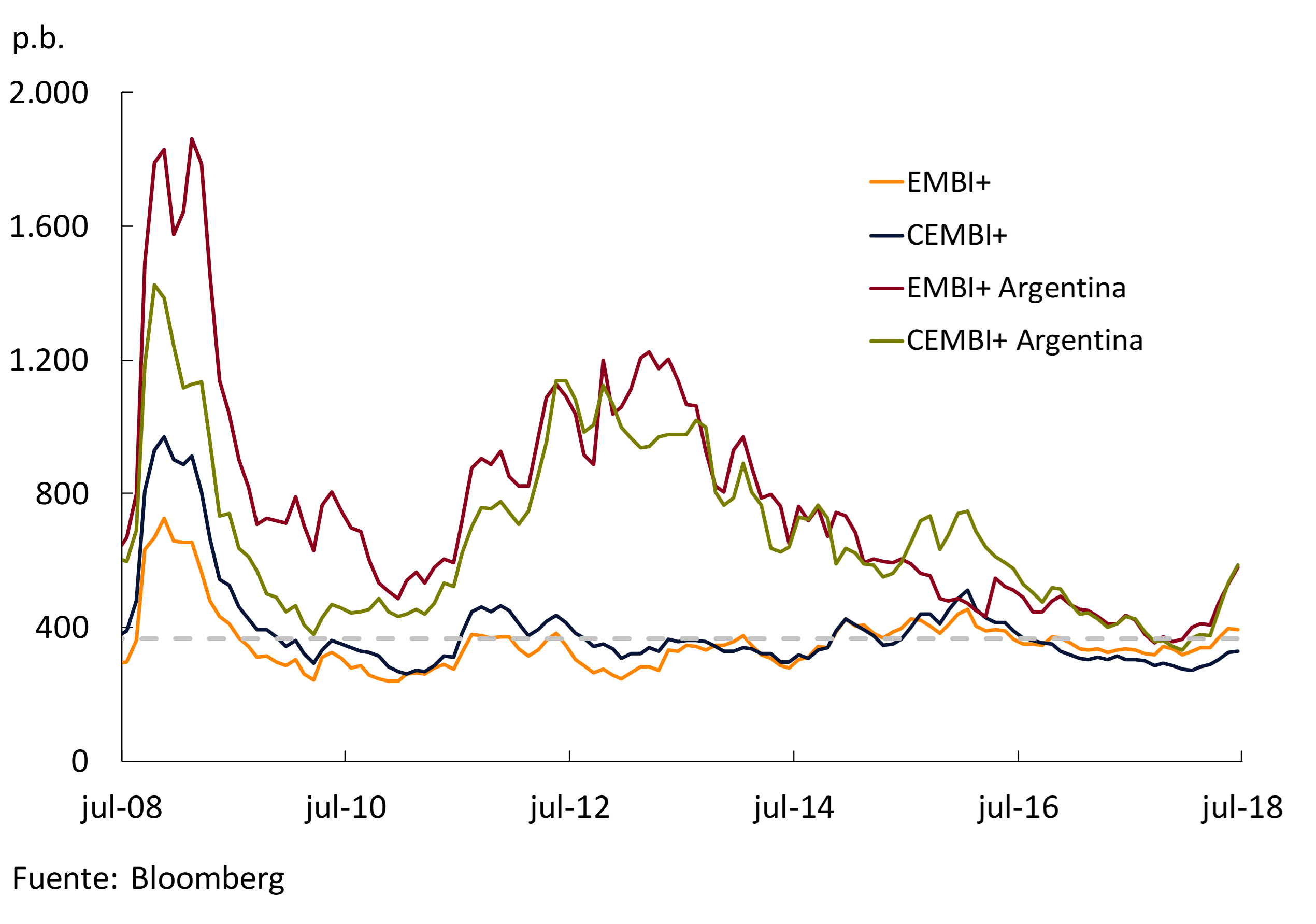

During the second quarter of 2018, emerging countries faced higher sovereign risk premiums than in recent years. Corporate risk premiums in these countries have also increased recently, although they are still around the lowest levels of recent years. Given the increase in the cost of external financing, the amount of gross debt issuances of emerging countries in international debt markets showed a contraction of 8% YoY in the second quarter. Corporate issuances were particularly affected (-20% YoY), as sovereign issuances registered a 23% YoY increase.

The external credit conditions of several countries deteriorated compared to the first quarter of the current year, and compared to the end of 2017 (see Figure 2.4). Argentina’s sovereign and corporate risk premiums rose, widening the relative gaps with respect to the rest of the emerging economies (see Figure 2.6). In this scenario, in the second quarter there were no sovereign issuances abroad, among other reasons because issuances were brought forward to the first quarter, with an issuance for US$9,000 million in January 2018. Meanwhile, corporate placements totaled US$500 million (compared to US$1,300 million in the second quarter of 2017), associated with a liability refinancing operation that took place before the start of the turbulence at the end of April.

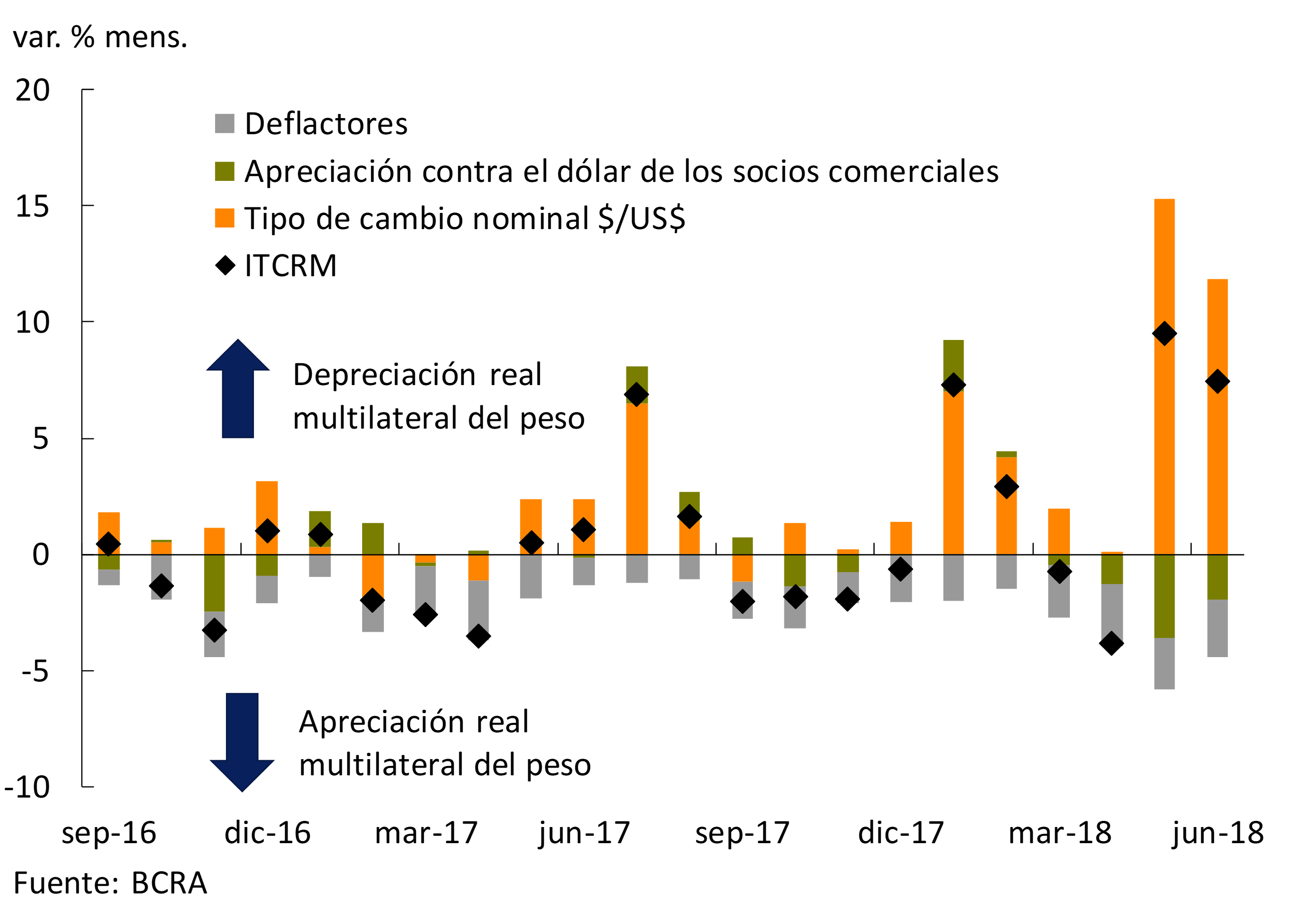

As with most emerging currencies, in the second quarter the Argentine peso depreciated against the dollar, although at a faster pace. As a result of this evolution of currencies and domestic inflation higher than that of our trading partners, the ITCRM rose by an average of 5.9% in that period (see Figure 2.7). Thus, at the end of June, the ITCRM was approximately 15% above the level immediately after the exchange rate reunification and at records similar to those of the end of 2011, when the country accumulated a trade surplus of 1.7% of GDP.

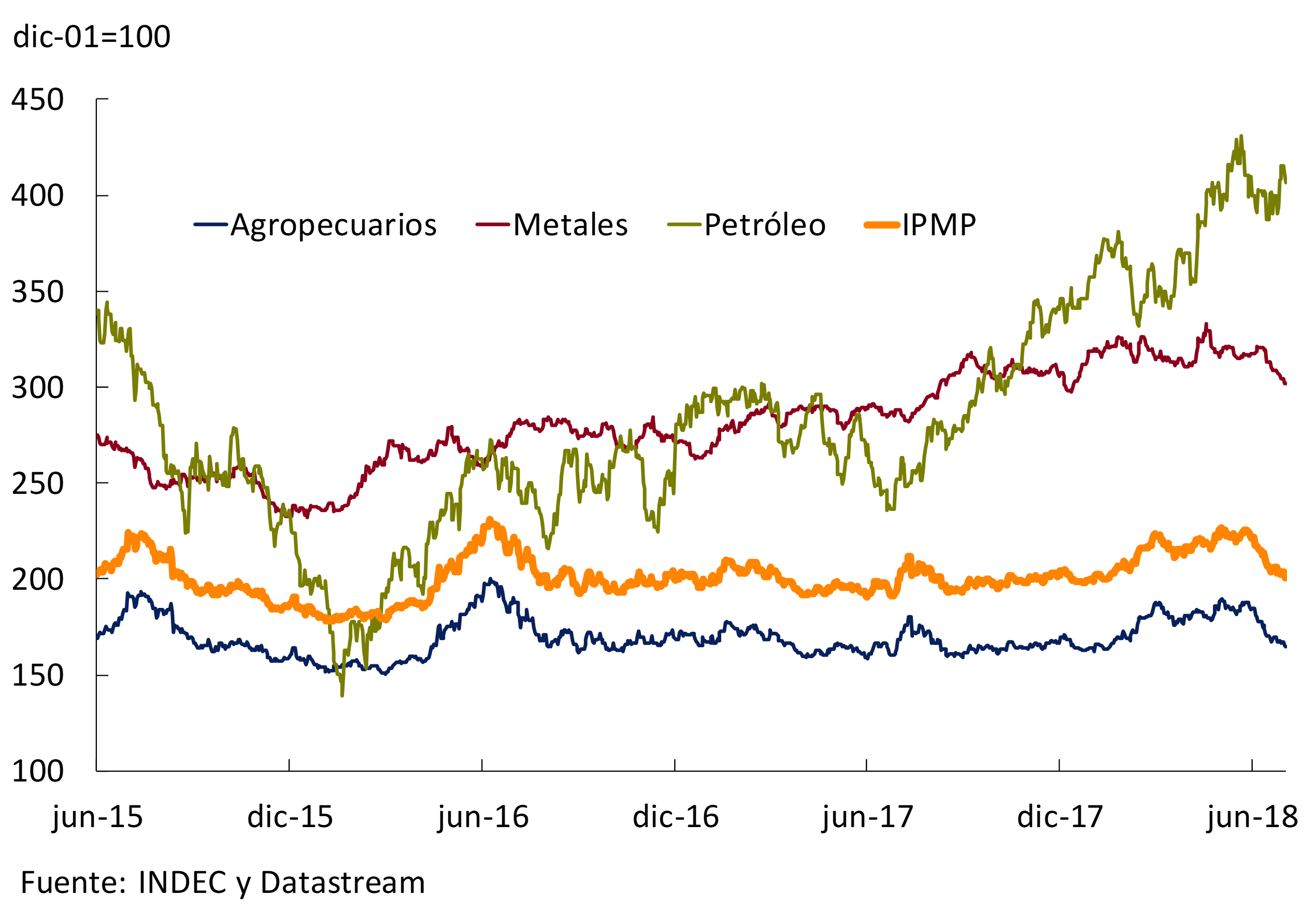

On the other hand, international commodity prices measured in dollars, which registered increases until the end of May, began to show a fall. Its values at the end of June 2018 are around 2% below the levels of the same period of the previous year. Prices of agricultural products and metals fell in June, unlike oil, which continued to hover around highs in recent years (see Figure 2.8).

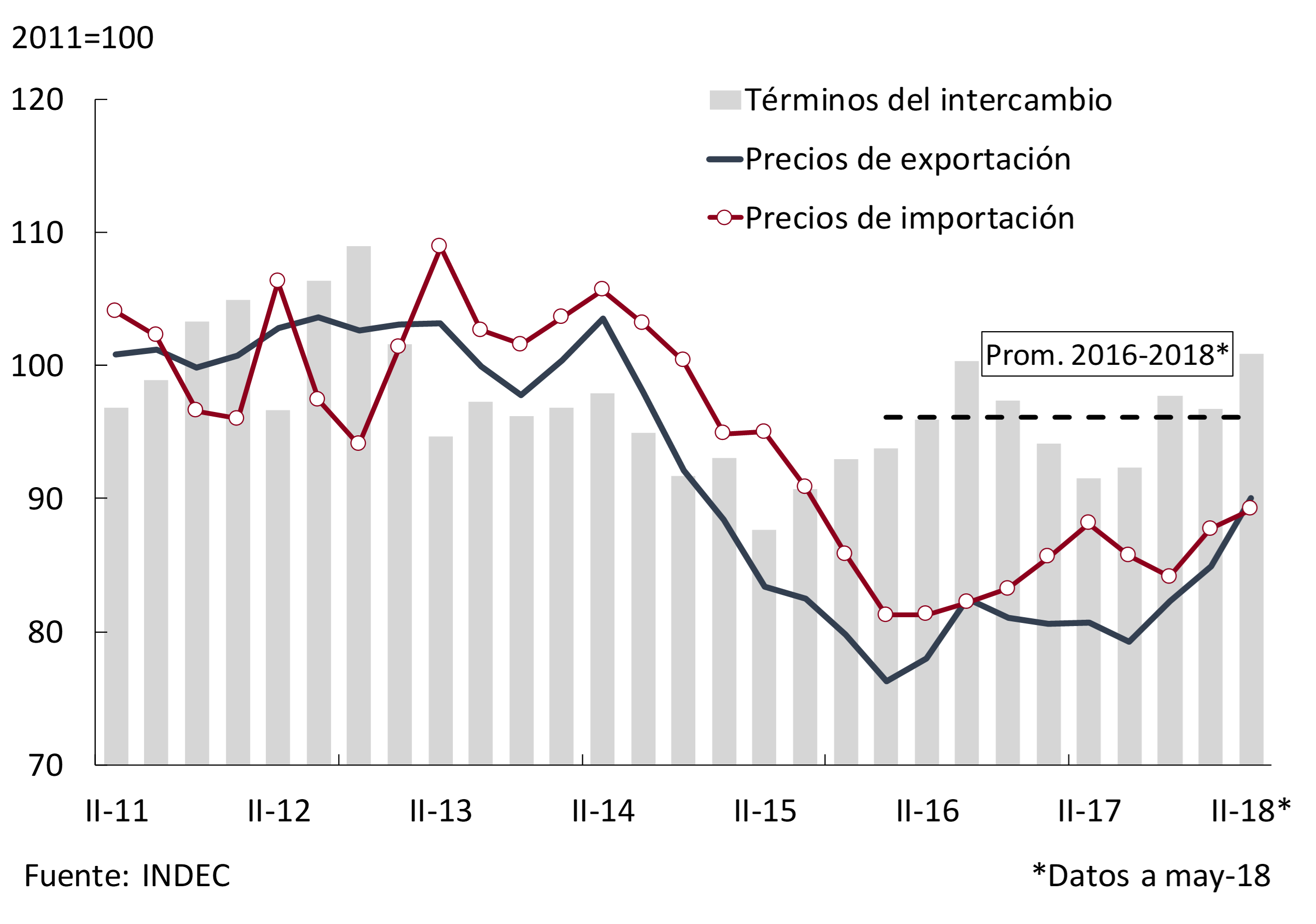

Finally, the terms of trade (quotient between the prices of Argentine exports and imports) rose 4.3% in the April-May two-month period, as a result of a greater rise in export prices than that of imports. This evolution was influenced by the reaction of international soybean and corn prices to the cut in the Argentine harvest. The terms of trade are currently at the highest level since the beginning of 2013 (see Figure 2.9). It is expected that the lower prices of agricultural raw materials that began to be observed since June 2, added to the sustained rise in the value of oil, will lead to a decrease in the terms of trade in the coming months.

In summary, this quarter was characterized by a deterioration in international financial conditions, in emerging countries in general and in Argentina in particular. However, the good moment of the level of activity of our main trading partners as a whole (despite the lower growth expected for Brazil), means that the external scenario as a whole still continues to be favorable for Argentina. The main risks of this scenario are a further tightening of international financial conditions and a possible deepening of protectionist measures; This would deteriorate the situation of the global economy, of emerging countries in particular, with an impact on the level of activity of our trading partners.

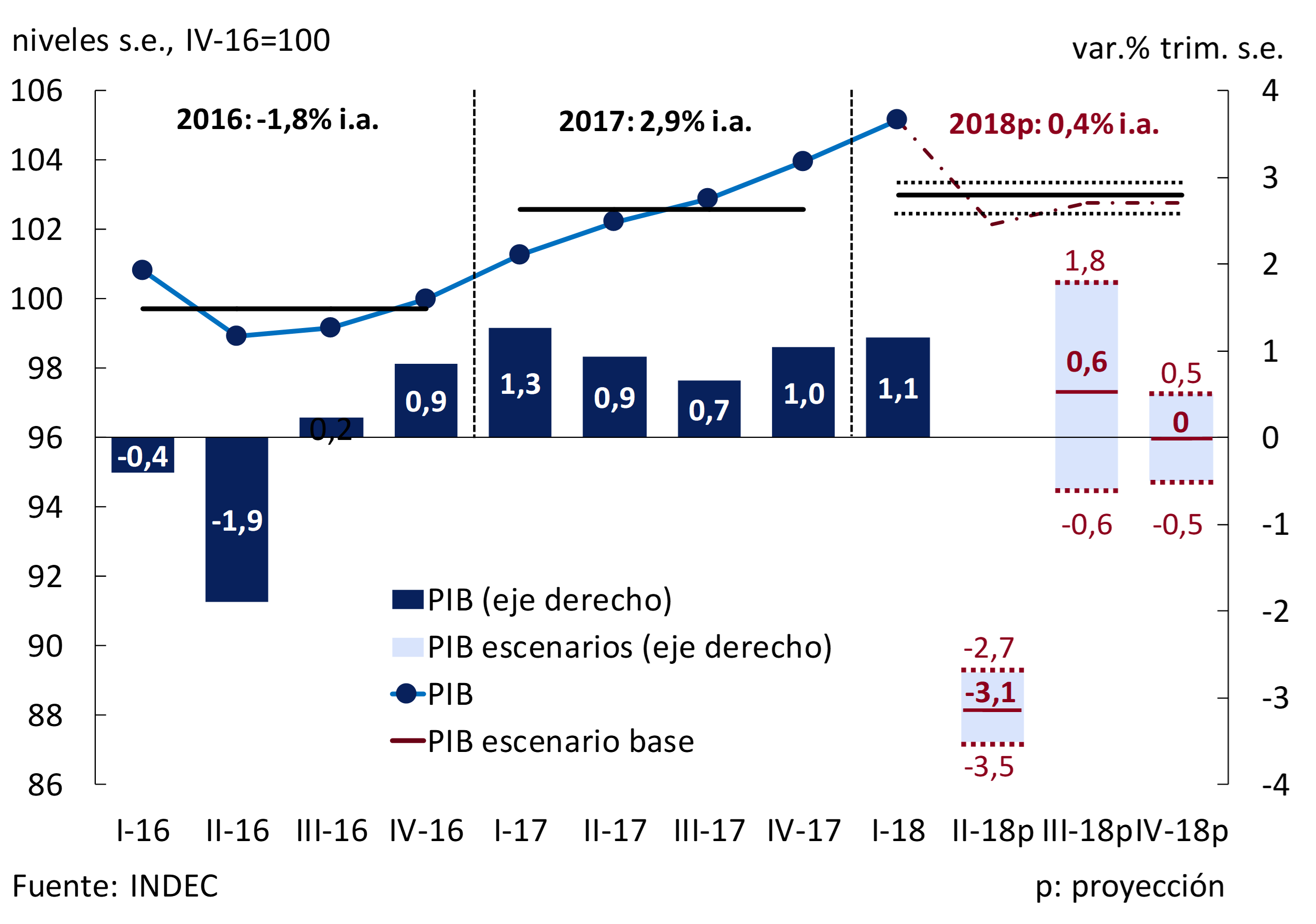

3. Economic activity

During the first quarter of 2018, activity showed widespread growth, while in the second quarter a marked drop was observed. In addition to the impact of the drought on agricultural production, which had been anticipated in the previous IPOM, there was the deterioration of international financial conditions for emerging economies and the income effect that the recent inflationary acceleration is generating. External demand was weaker than expected as a result of the change in the international scenario that also affected Brazil. In this more challenging context, the government reached an agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that supports the economic program. The measures taken under the agreement, together with the monetary policy response, will gradually begin to improve local financial conditions and the economic outlook for agents. The base scenario of the Central Bank of the Argentine Republic (BCRA) foresees a slight economic growth in 2018 to resume a greater expansion in 2019.

3.1 Growth forecasts were cut

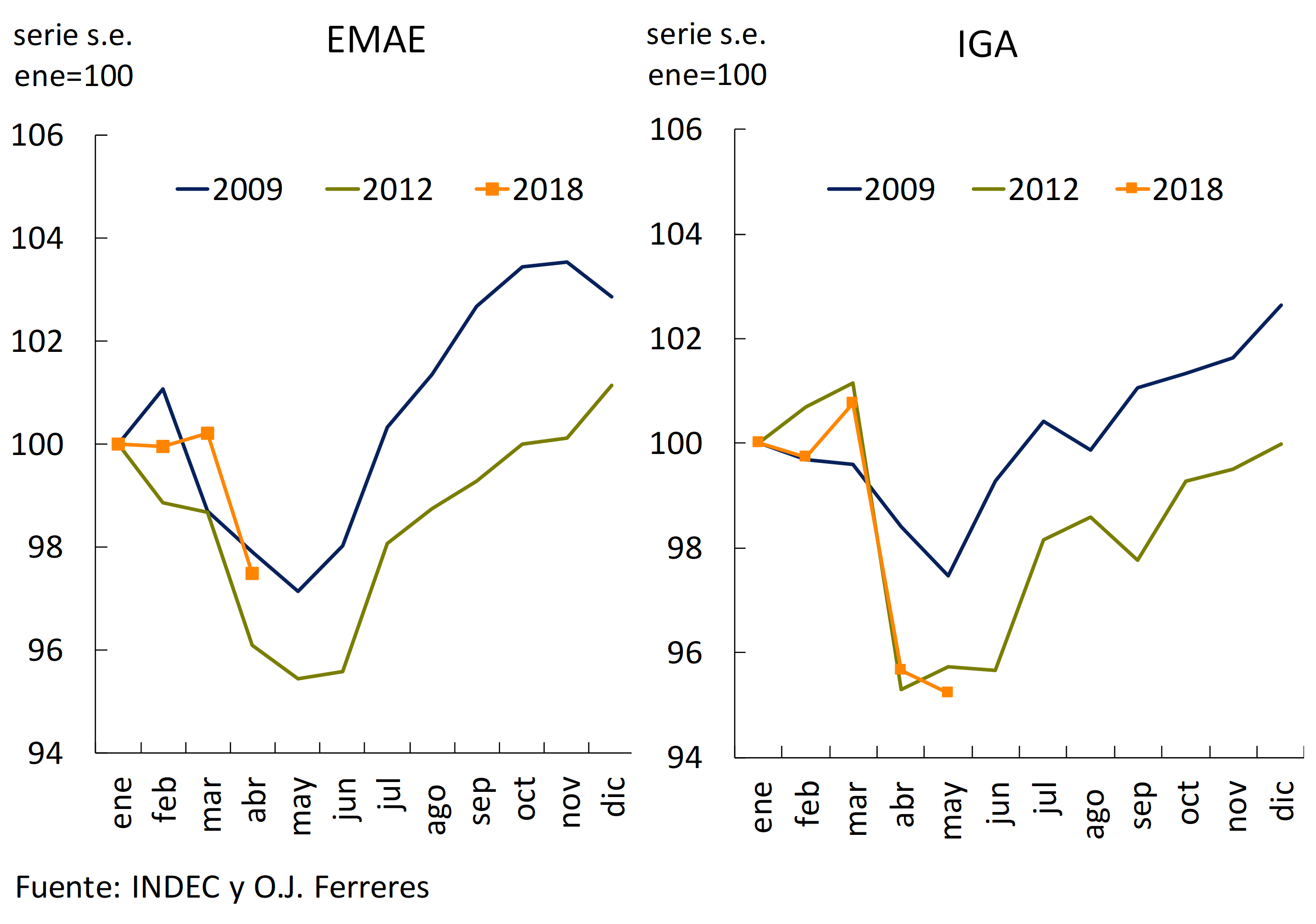

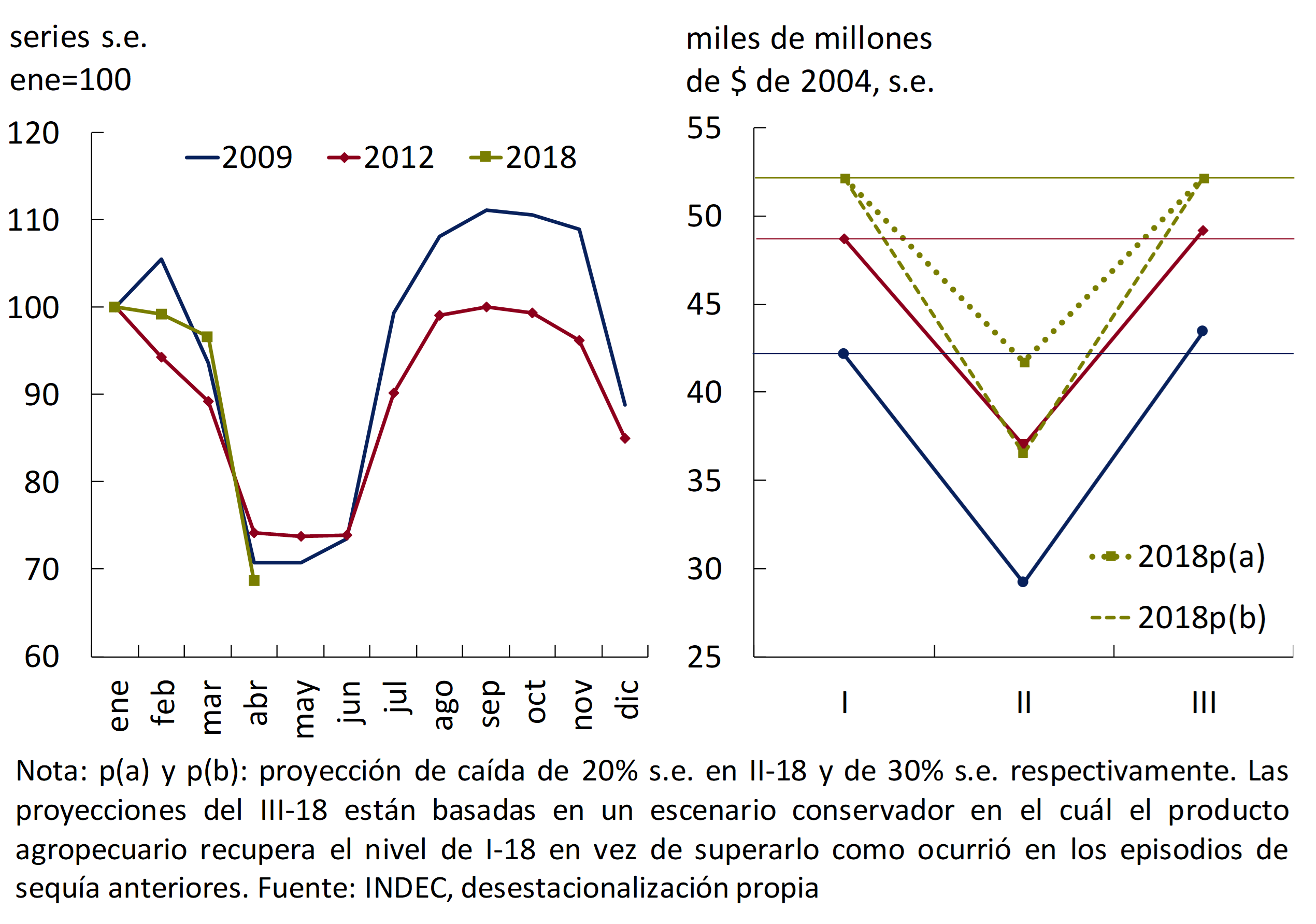

During the second quarter of 2018, there was a sharp drop in GDP, mainly explained by the impact of the drought on the agricultural sector. In addition to the direct effect of the drought on agricultural GDP, the lower industrial activity due to the reduction in soybean crushing and its impact on transport and trade services must be considered. In this context, economic activity performs similarly to that observed in 2009 and 2012 (see Figure 3.1). The first available indicators for the second quarter account for this performance. The General Activity Index (IGA) of O.J. Ferreres fell sharply in April (-5.1% s.e.) and fell again in May (-0.5% s.e.), while the Monthly Estimator of Economic Activity (EMAE) of INDEC decreased 2.7% s.e. in April.

For the third quarter, a relative improvement is expected in the agricultural sector due to the normalization of sowing tasks after drought3, while the “non-agricultural” productive sectors will be affected by lower domestic demand and the tightening of financial conditions (see Chapter 2. International context).

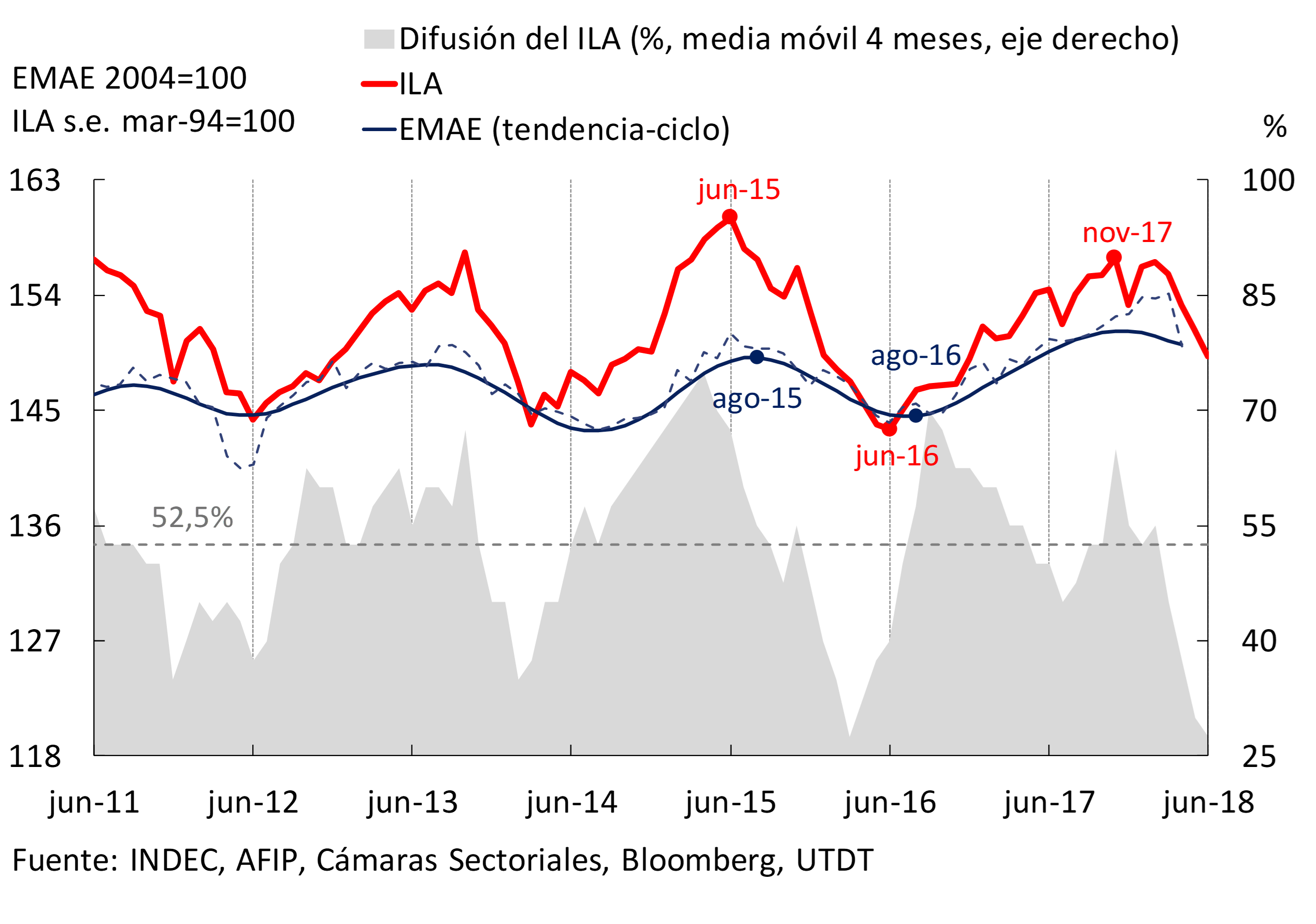

The three conditions that must be met to emit a strong signal of a change in the phase of the Leading Indicator of Activity (ILA-BCRA) towards a recessive phase are: duration (three months of consecutive fall of the ILA), diffusion (percentage of ILA components with falls is below 52.5%) and depth (cumulative fall of the ILA in the last six months below 4.8%). All three of these criteria were met in May, indicating that there will be at least two consecutive quarters of declines in activity (see Figure 3.2). On this occasion, and given that the agricultural sector suffered a transitory shock of magnitude (drought) that reverses in the third quarter, the ILA anticipates the evolution of the “non-agricultural” sectors and not that of total GDP 4.

3.1.1 Domestic demand was affected by the deterioration in financial conditions from the second quarter onwards

In the first quarter of 2018, GDP grew by 3.6% YoY, at a quarterly annualized rate of 4.7% in seasonally adjusted terms, above the rate of expansion of 2017 and the BCRA Contemporary GDP Prediction (PCP-BCRA) anticipated in the previous IPOM, completing seven quarters of uninterrupted growth for the first time since 2011. Domestic demand grew 2.2% quarter-on-quarter (5.9% y.o.y.), with the rise in investment standing out (3.3% s.e. and 18.3% y.o.y.). Private consumption increased 2.3% s.e. (4.1% y.o.y.) while public consumption fell 0.8% s.e. (grew 1.4% y.o.y.).

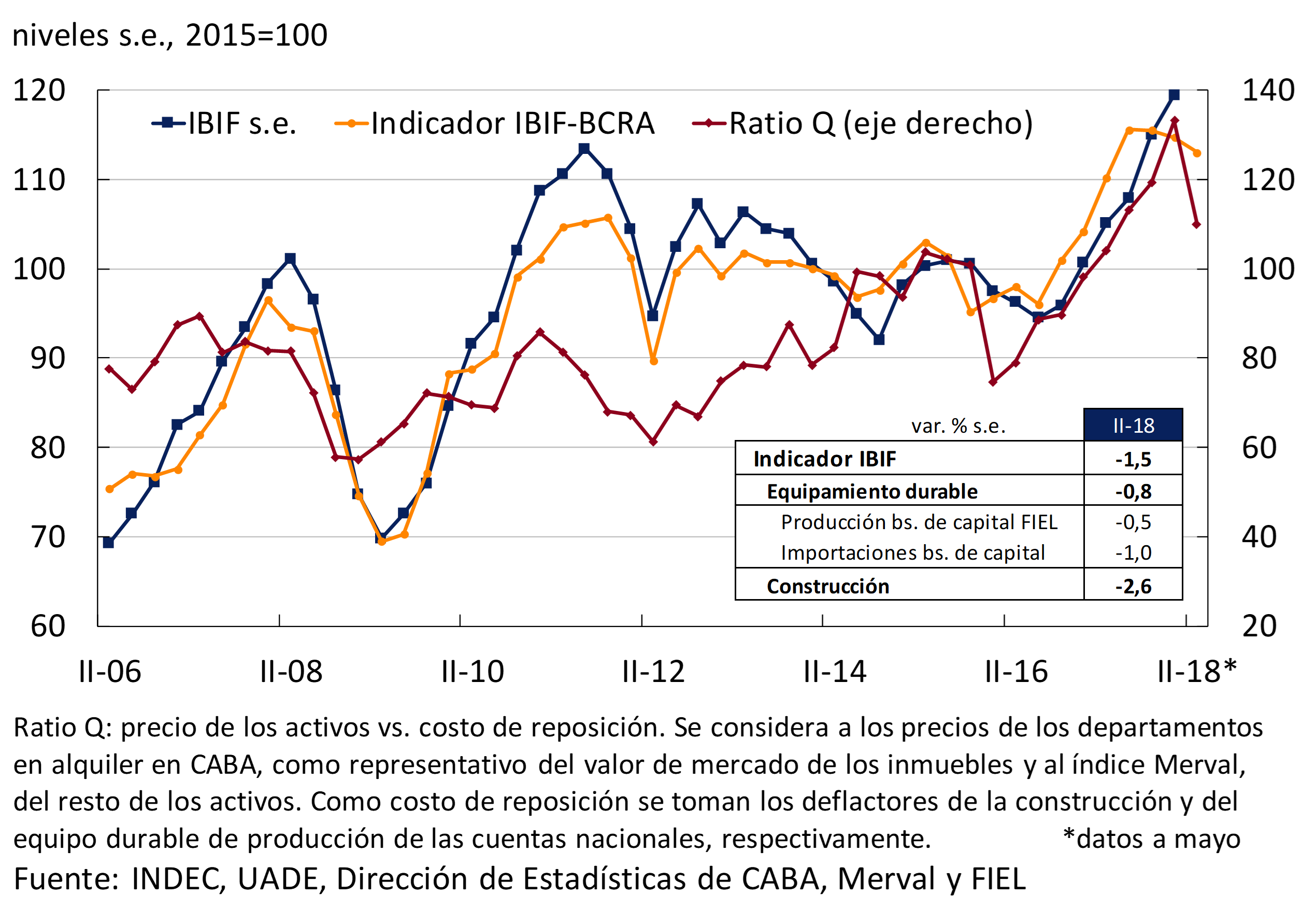

From the second quarter onwards, a contraction in private investment is expected due to the deterioration of financial conditions and the lower expected return on assets with respect to the replacement cost of capital raised in the Tobin Q. Private consumption will be negatively affected by the income effect of the inflationary acceleration and the increases in local interest rates.

The Q ratio, which relates the market value of assets linked to construction and durable equipment with their replacement cost, registered a sharp decline in the second quarter. The IBIF-BCRA5 indicator decreased 1.5% s.e. between April and May compared to the previous quarter (see Figure 3.3) and the Coincident Investment Index prepared by the Undersecretariat of Macroeconomic Programming of the Ministry of Finance showed a fall of 1.7% s.e. It should be noted that the investment rate had reached 22.1% of GDP in the first quarter of 2018, the maximum in the series that began in 2004 due to the increase in spending on durable equipment (14.2% of GDP), mainly of imported origin. 6

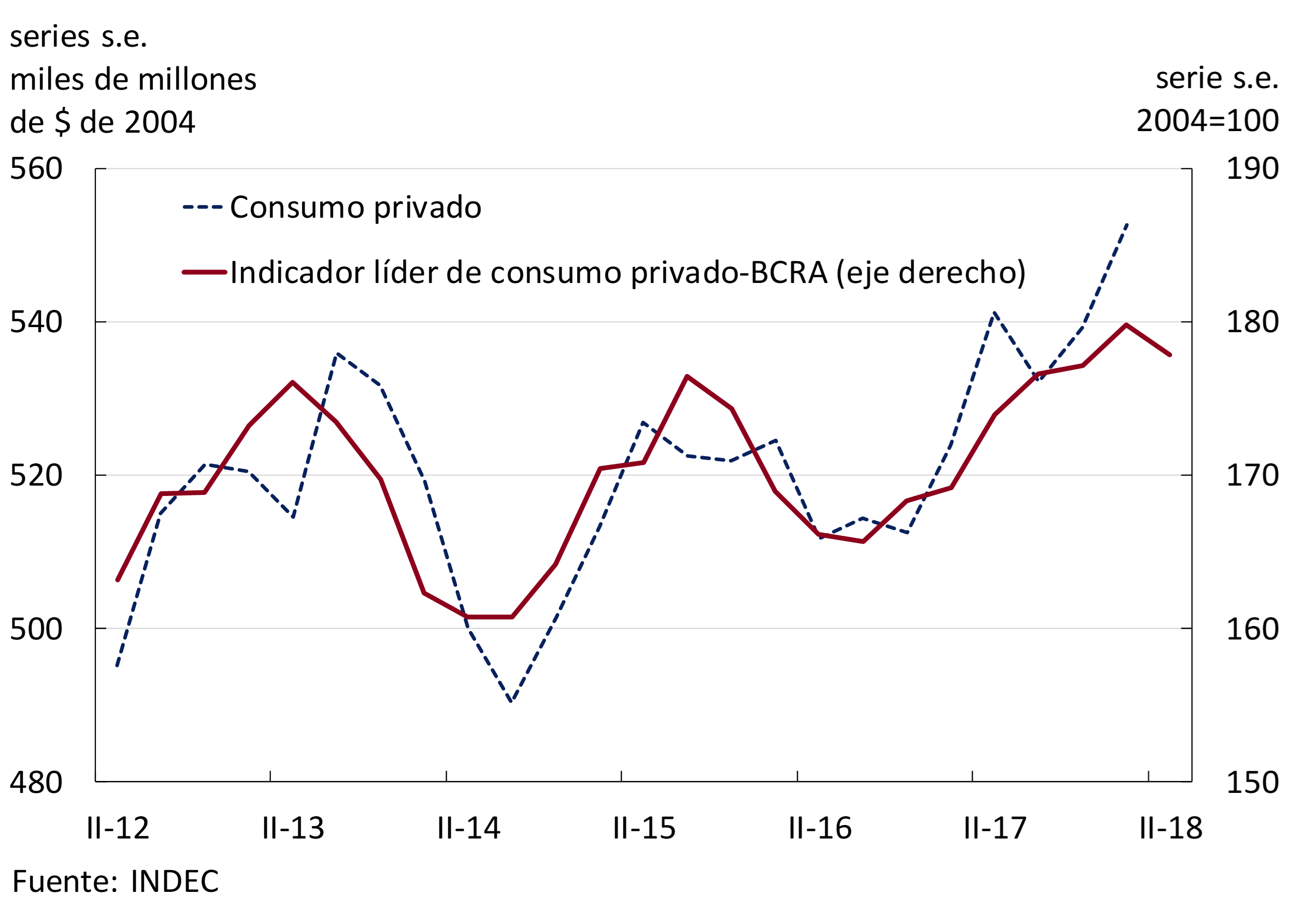

As for consumption, the Coincident Index of Private Consumption prepared by the Undersecretariat of Macroeconomic Programming shows a fall of 2.8% s.e. in the second quarter (with data as of May). The BCRA’s Leading Indicator of Private Consumption7 suggests that the contraction in consumption would continue in the coming months (see Figure 3.4).

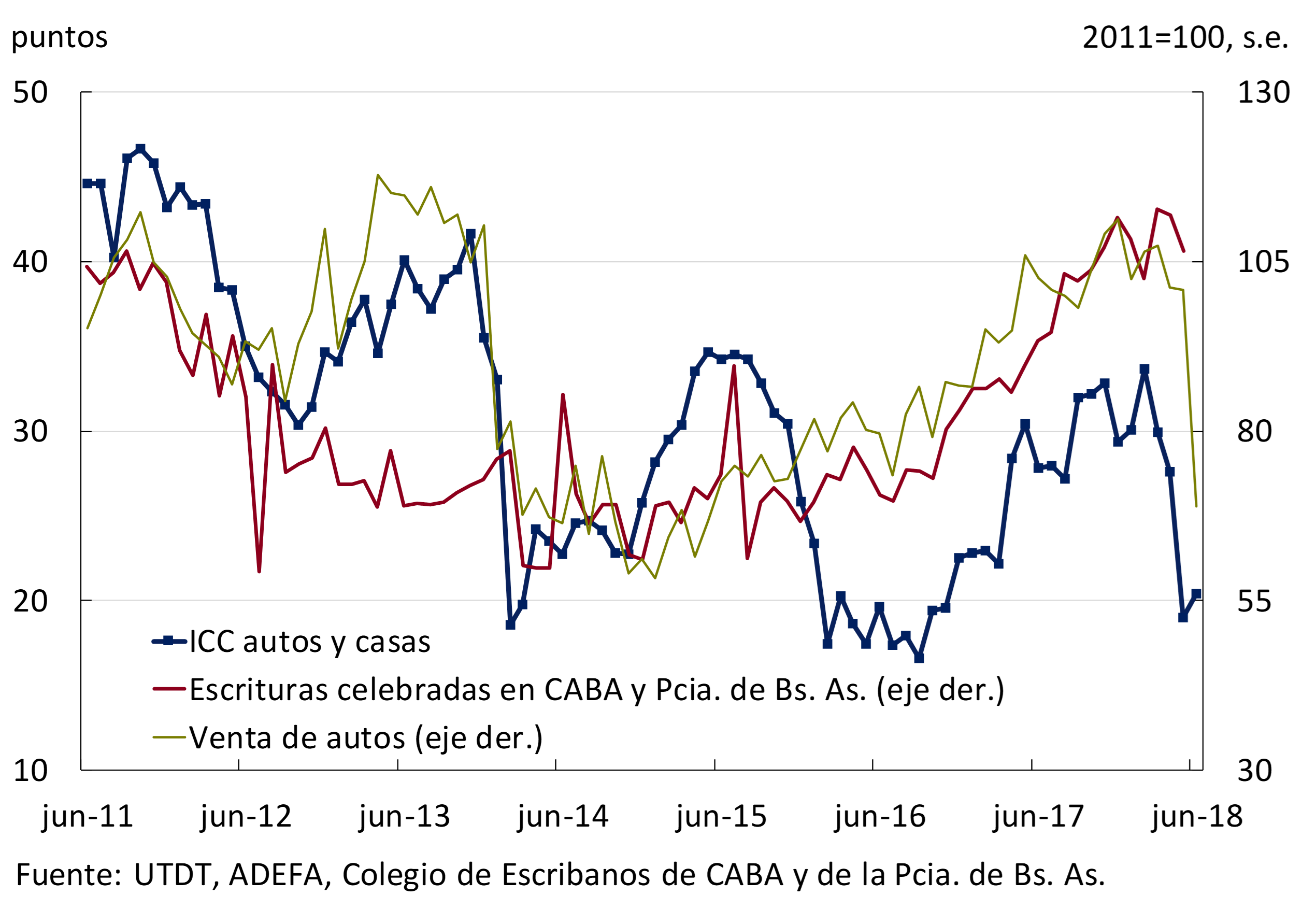

The Consumer Confidence Index revealed a lower predisposition to buy durable goods and real estate between April and June. This fall, similar to that observed in previous depreciations of the peso, anticipates a reduction in real estate activity and in the demand for durable goods in general (see Figure 3.5). Deeds executed in CABA and in the province of Buenos Aires already suffered in May (-4.7% s.e.) and car sales in the domestic market fell 4.1% s.e. on average for the second quarter.

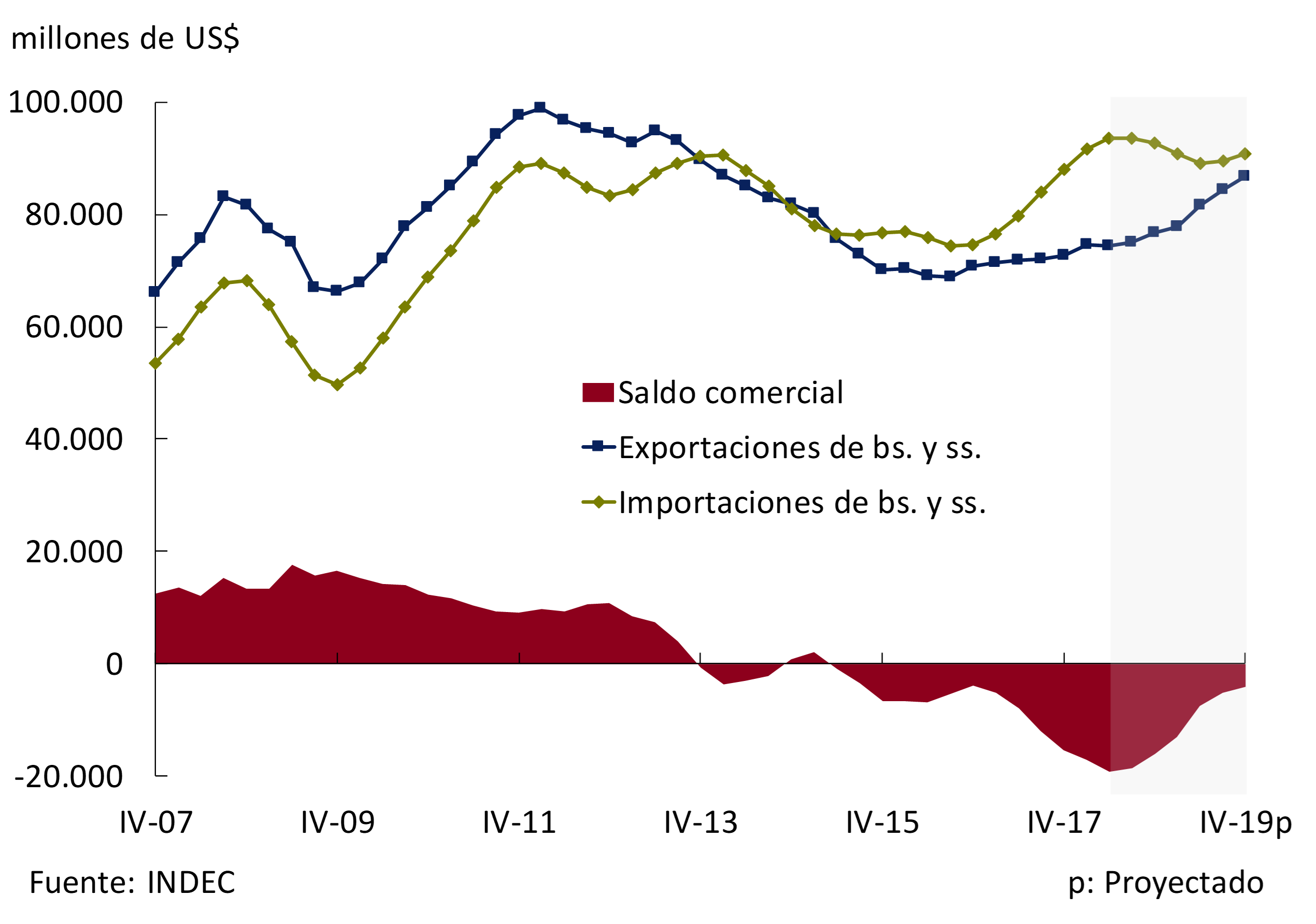

3.1.2 Exports fell from April onwards, affected by the drought, deteriorating the current account deficit in the second quarter

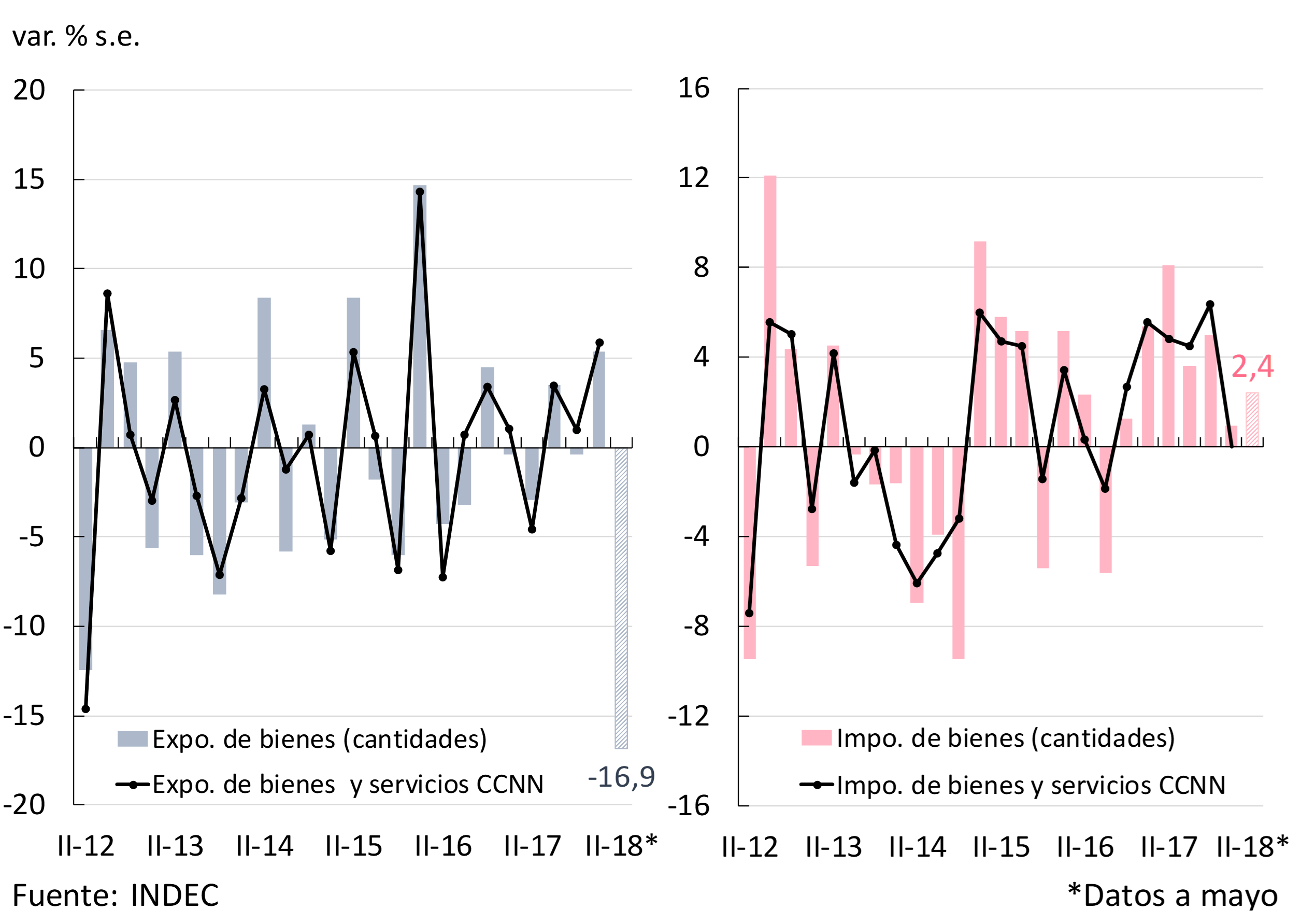

In the first quarter, the quantities exported of goods and services rose 5.8% s.e. but in the April-May period there was a sharp drop of 10.7% compared to the same period in 2017 and 19.8% s.e. compared to the first quarter of this year8. Although the contraction in the quantities exported was widespread at the level of items, the greatest depth was recorded in primary products (28.6% y.o.y. and -45.7% s.e.). The slowdown in Brazil’s growth was also a determining factor in the performance of non-agricultural exports (see Chapter 2. International context).

The quarterly changes in exports and imports of goods and services published in the National Accounts—in the demand-side breakdown of GDP—are similar to those arising from seasonally adjusting the AQI data (see Figure 3.6). The data show a strong negative contribution of net exports to economic growth in the second quarter from the point of view of demand, reflecting the transitory negative shock to agricultural supply.

Imported quantities of goods grew in the April-May period by 2.4% s.e. compared to the first quarter, reaching an increase of 12.5% compared to the same period in 2017. The only item that showed a decrease in year-on-year terms was Fuels and lubricants (-12.6%), partly explained by a high base of comparison. A contraction in total imported quantities is expected in the coming quarters as a result of the increase in the real exchange rate and the lower expected activity of the “non-agricultural” sectors.

Affected by the dynamics of exports and imports, the current account of the Balance of Payments would have exhibited a still high deficit in the second quarter. The recent change in relative prices – favourable to the tradable sector – and the expected lower demand for imports due to income will influence the future evolution of the external accounts. The BCRA forecasts as a base scenario that the trade deficit of goods and services will be reduced by around US$2,800 million by the end of 2018 compared to a year ago.

3.1.3 On the productive sector, agriculture is experiencing the transitory shock of the drought, while the rest of the sectors show a contraction that will extend beyond June

The drought that affected soybean and corn harvests had a direct impact on the output of the agricultural sector and indirectly on related sectors such as transport and trade. Soybean production in the current season fell 32% YoY to 37.2 million tons9, a drop greater than the previous IPOM forecast, and corn production by 14% YoY to 42.4 million tons. In terms of the direct impact of this transitory shock on activity so far this year, the value added by the agricultural sector fell 13.8% y.o.y. in the January-April period according to the EMAE, subtracting 1.2 percentage points (p.p.) from the growth of total product measured at basic prices (which was 1.8% y.o.y. in the period).

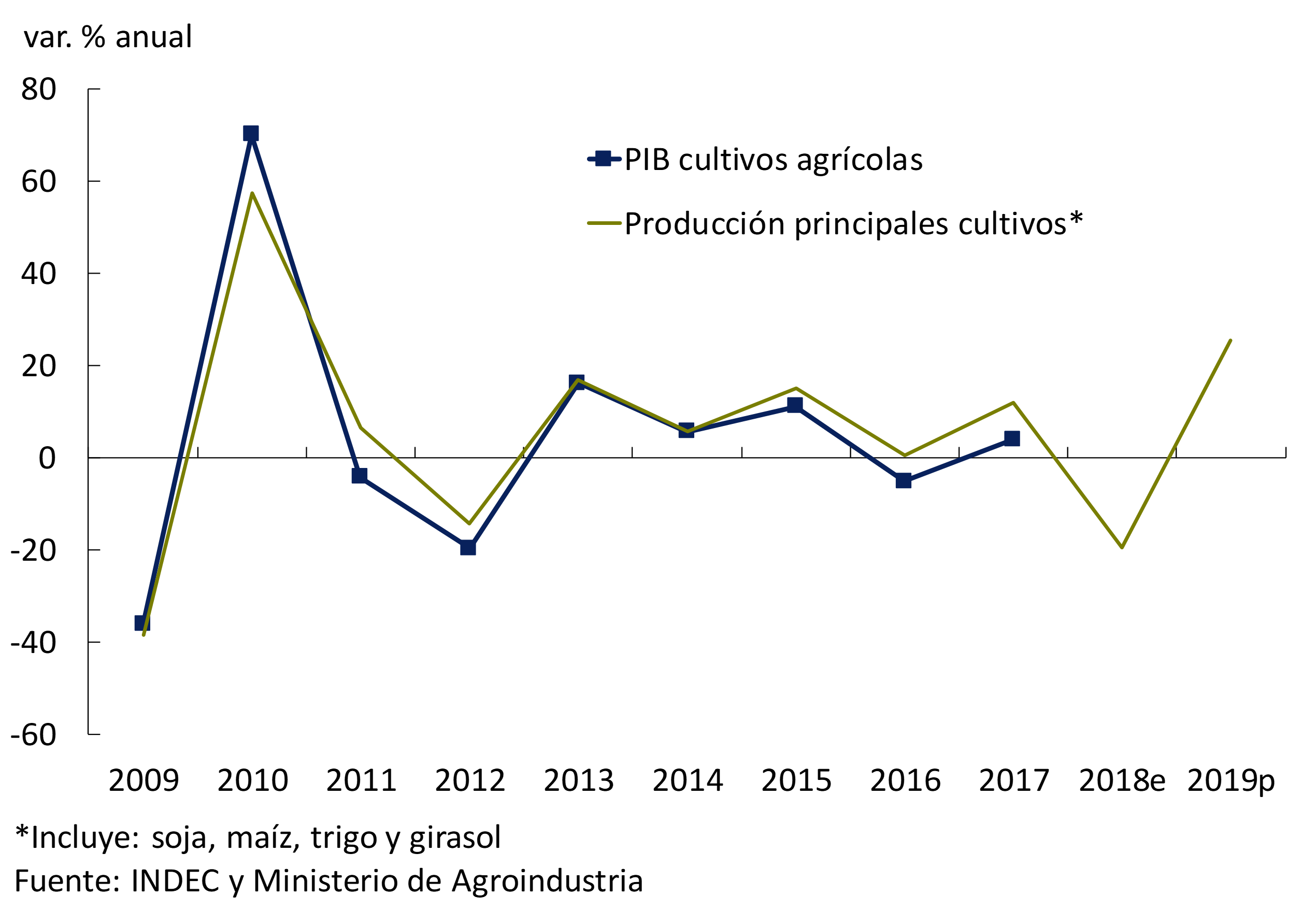

As happened in 2009 and 2012, the drought affected the production of soybeans and concentrated corn in the second quarter10. Based on harvest estimates, the base scenario is a seasonally adjusted contraction of 30% in agricultural GDP in the second quarter, in line with the April data from the EMAE. Taking into account that in the measurement of the output of this sector in the third quarters, the soybean and corn harvest no longer has weight and the planting tasks of other agricultural crops with good prospects are computed, the base scenario is that the output of the agricultural sector recovers in seasonally adjusted terms in the third quarter. it is estimated that it will return to the level of the first11 (see Figure 3.7).

Regarding the “non-agricultural” sectors, the partial leading indicators reflect a contraction during the second quarter. The Synthetic Indicator of Construction Activity (ISAC) fell 2.6% s.e. (with data as of May) and a decrease in cement shipments was evident (-6.3% s.e.). The Monthly Industrial Estimator (EMI) contracted 0.4% s.e., while the FIEL Industrial Production Index contracted by 1.4% s.e. Within the industry, the fall in automotive production (-6.3% s.e.) stands out after an excellent first quarter (13.2% s.e.). With regard to the main services activities, the EMAE’s April data show a contraction compared to the first quarter in Trade (-1.2% s.e.) and Transport (-1.6% s.e.).

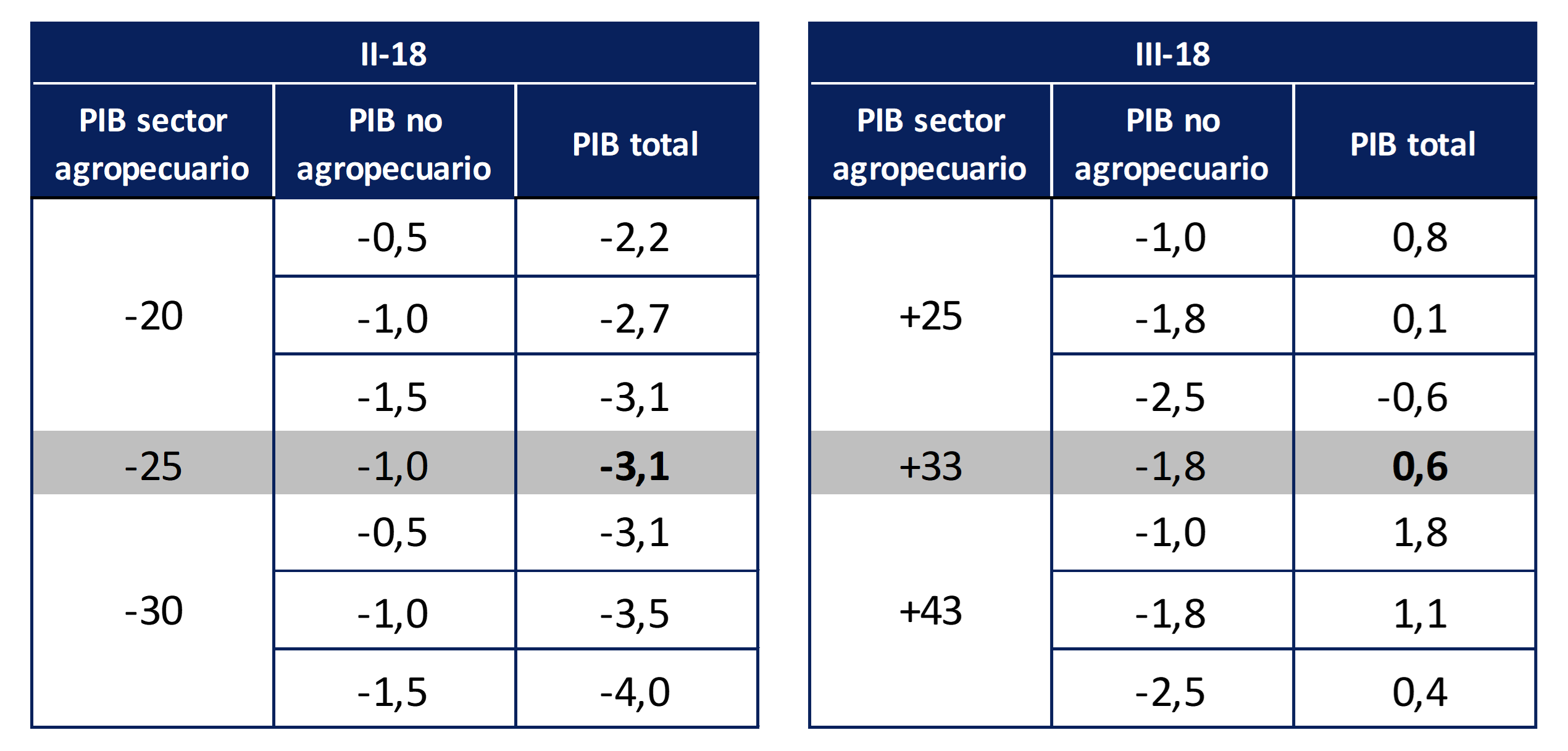

For the second quarter, the second-to-last BCRA Contemporary GDP Prediction (PCP-BCRA) indicated a quarterly fall of 0.85% s.e. which, on this occasion, better approximates the evolution of the “non-agricultural” sectors and not that of total GDP (due to the shock that affected the agricultural sector). The baseline scenario envisages a 3.1% s.e. drop in total GDP in the second quarter (see Table 3.1).

In the third quarter, the normalization of agricultural activity would compensate for the deterioration of the rest of the economy. The BCRA’s base scenario contemplates a strong recovery of agricultural output and a contraction of 1.8% s.e. in the “non-agricultural” sectors, resulting in a growth in total GDP of 0.6% s.e.

The following table shows possible scenarios of total GDP at basic prices for the second and third quarters of 2018 that arise as a result of expected trajectories of agricultural and “non-agricultural” products. The shaded area indicates what is considered to be the base scenario.

With this scenario – in a context of normalization of the financial markets, reduction in expected monthly inflation and greater agricultural activity from the third quarter onwards – the BCRA forecasts low but positive economic growth on average for 2018.

Box. Why the effect of the drought has a concentrated and transitory impact on the GDP of the agricultural sector of the National Accounts

The accounting of grain production in GDP/Gross Value Added (GVA) in real terms presents particularities linked to the concentration and aggregation of crops and the sowing/harvesting period (seasonal factors) that are typical of this activity. The Argentine System of National Accounts (SNA) uses internationally accepted and standardized concepts, definitions and classifications12.

GVA is defined as the value of output minus the value of intermediate consumption and represents the contribution of labor and capital to the production process13. The sum of the GVA of all resident units – remuneration for the factors of production – plus taxes minus subsidies on products, constitutes GDP.

For most goods, GVA is determined in each period, when their production ends. However, when it takes a long time to produce a unit, as is the case with agricultural products, the criterion of “work in progress” is used, recognizing that its production is generated continuously. In each period, there is an incomplete production that is not yet marketable and that continues in the next period. When the final product is obtained (end of the harvest), the gross value of the production is recorded, at the FAS prices reported by the Ministry of Agroindustry. Intermediate consumption – remuneration – is netted to this production value and taken to 2004 prices to obtain GVA in constant terms.

In our country, agricultural production is concentrated in four products: soybeans, corn, wheat and sunflower which, in the last 10 years, accounted for 90% of the total harvest. Thus, throughout each year, agricultural GVA varies in line with the production performance of these crops (see Figure 3.8).

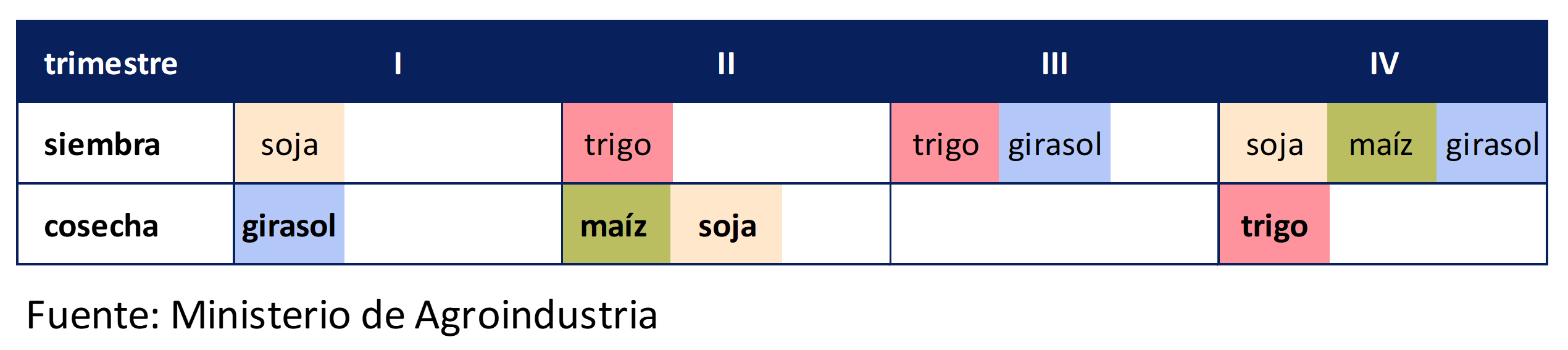

The distribution of agricultural production throughout the year is not homogeneous. Sunflower is harvested in the first quarter of each year, corn and soybeans in the second and wheat in the fourth. For each product, the accounting of GVA begins with sowing and includes the tasks of earthmoving, fertilizer application, seed implantation, among others, according to table 3.1. In the case of soybeans, these tasks begin in the fourth quarter, continue in the first and are harvested in the second, thus completing most of the GVA of this product. In the third quarter, the GVA corresponding to the sowing of wheat and sunflower is counted, and so on.

In all cases, estimates of planted and harvested area, yields and production from the Ministry of Agroindustry are used. The calculation of intermediate consumption to allocate GVA in each quarter is based on remuneration and technical coefficients/requirements that include the use of machinery, fertilizers and any other work carried out in relation to the conservation and care of natural resources (soil, water, etc.).

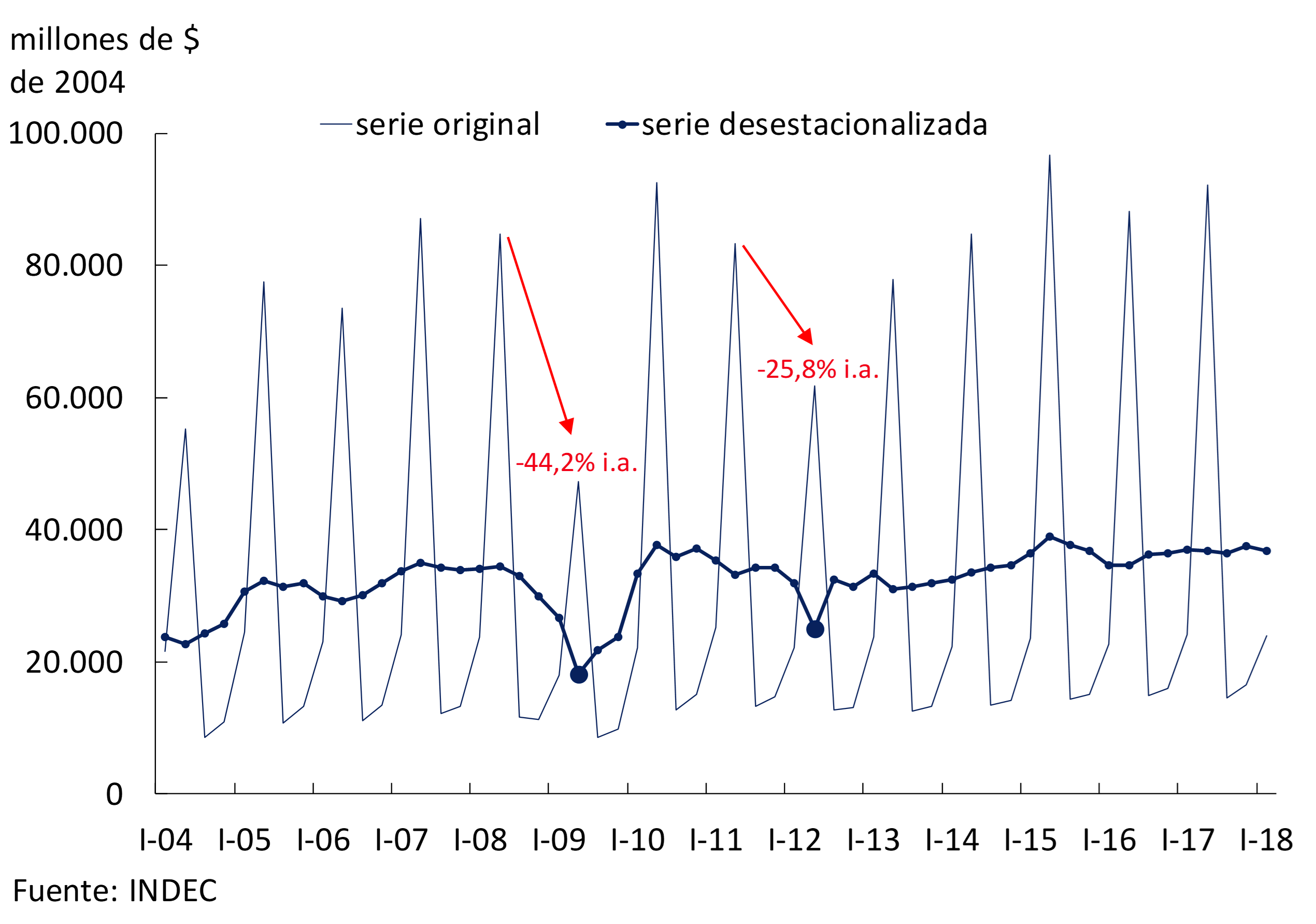

In this way, a harmonized series of GVA of agricultural crops is obtained, whose main characteristic is that it is highly concentrated in the second quarters, when the production of soybeans and corn (which represents 75% of agricultural production in the last 10 years) ends. The quarter-by-quarter comparison of this series is worthless if this seasonal effect is not eliminated, since the agricultural GVA of the second quarters is normally three times higher than that of the first quarter. The seasonally adjusted series allows us to clearly identify other components of the series, such as, for example, the great irregularity of the second quarters of 2009 and 2012, when soybean and corn productions affected by drought episodes were computed. Similar dynamics are expected in 201814 (see Figure 3.9).

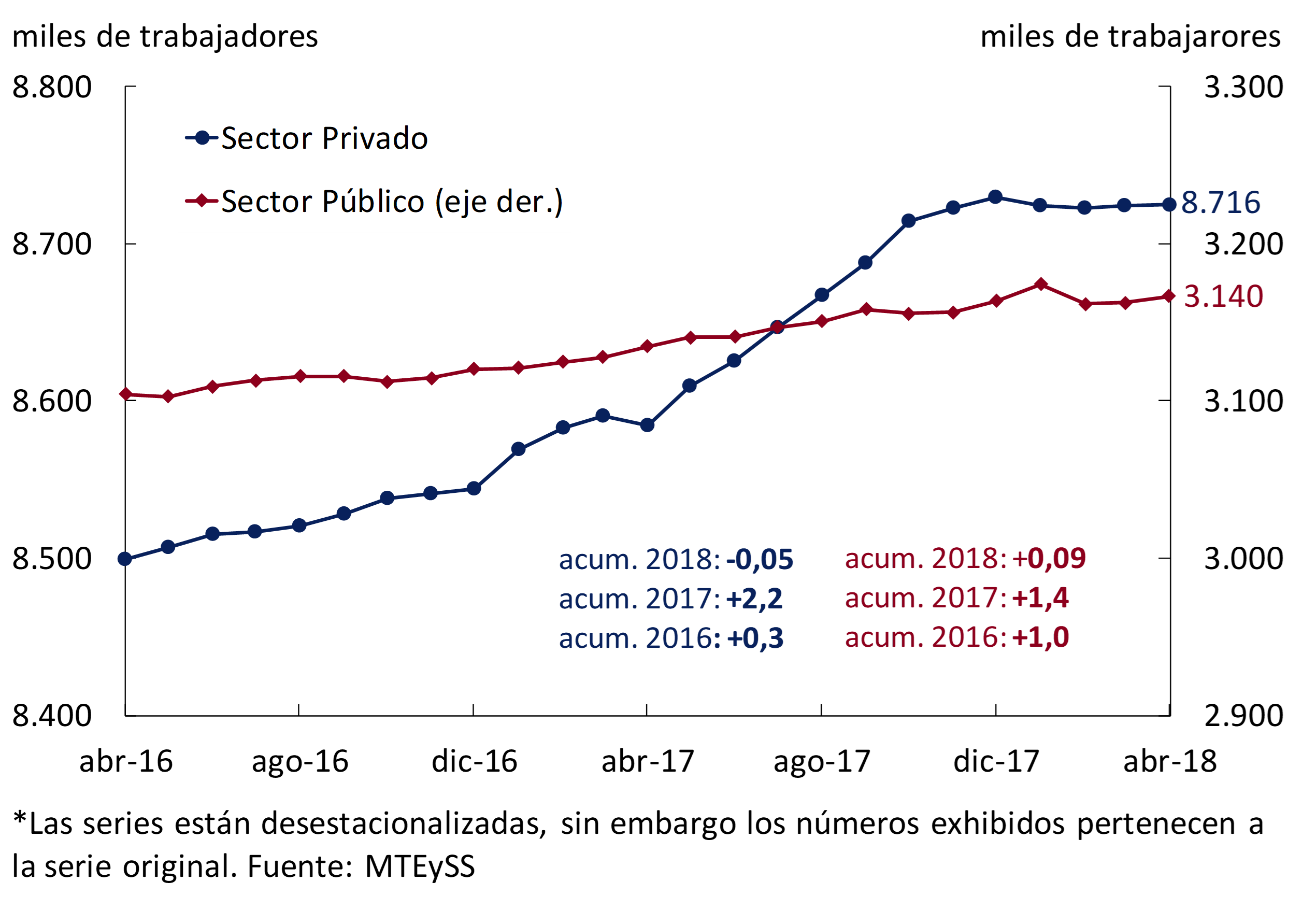

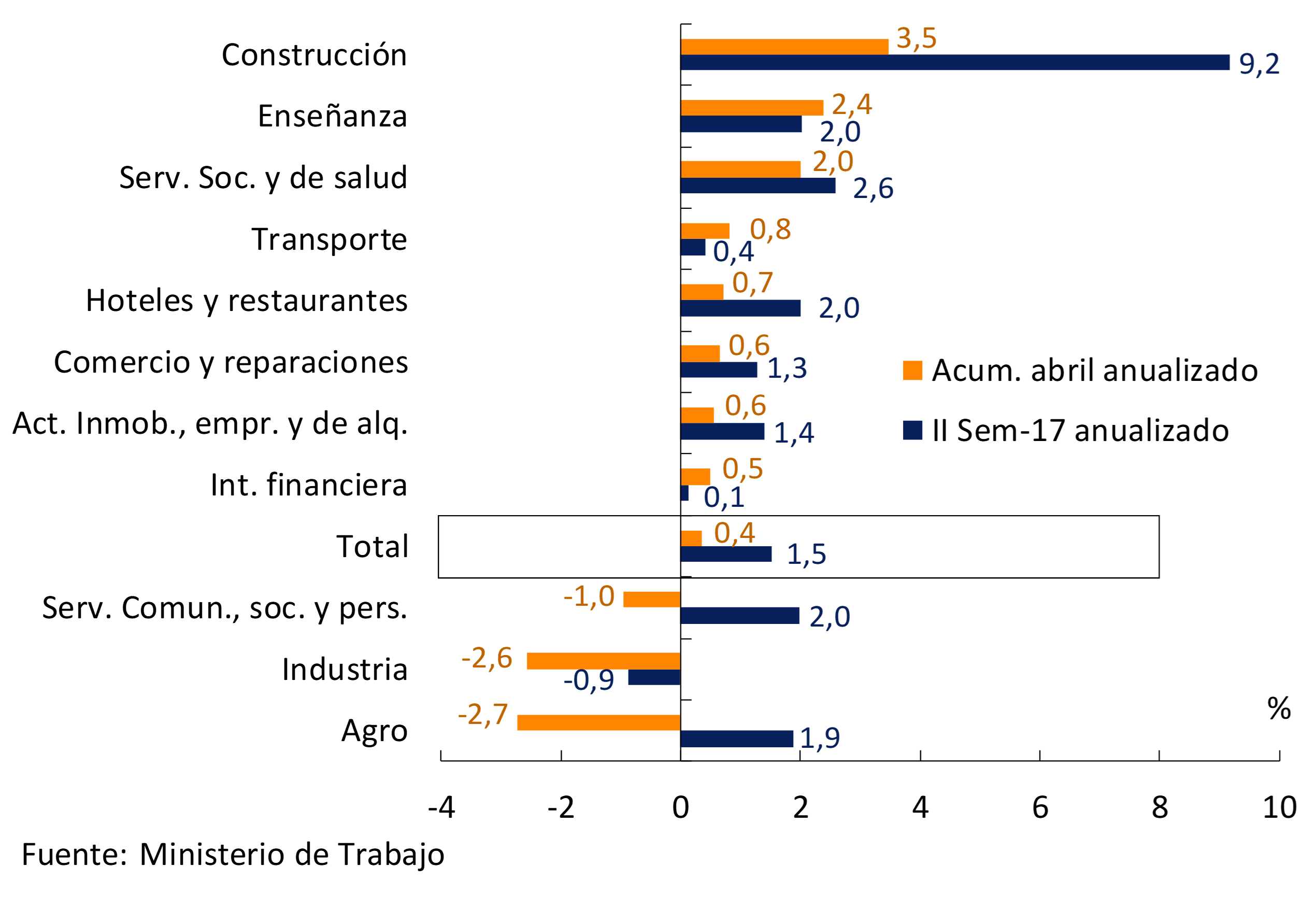

3.1.4 The rate of wage job creation slowed

In the first quarter of 2018, economic growth (3.6% YoY) was correlated with a significant year-on-year increase in total employed people (3.8% YoY) and in the labour supply (3.7% YoY), leaving the unemployment rate unchanged, according to EPH data. Compared to the previous quarter, the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate increased by around 0.4 p.p., reversing the fall in unemployment exhibited during 2017. This dynamic was explained by a rate of total job creation that was not able to meet the increase in the labor participation rate, especially for women. Employment growth showed an improvement in labor market conditions. The ratio of unregistered salaried employees fell by 0.5 p.p. compared to the previous quarter. In the same vein, within registered employment, there was a change in composition in favour of private salaried work, which grew since October without seasonality by 28,200 employed persons, while the number of non-salaried employed persons contracted by 26,300 (see Graph 3.10).

During the first four months of 2018, the pace of creation of registered private salaried employment slowed. This behavior was mainly explained by the lower expansion of employment in construction and by the contraction of employment in the agricultural sector – in the context of the deep drought that the sector went through – and in the industrial sector (see Figure 3.11).

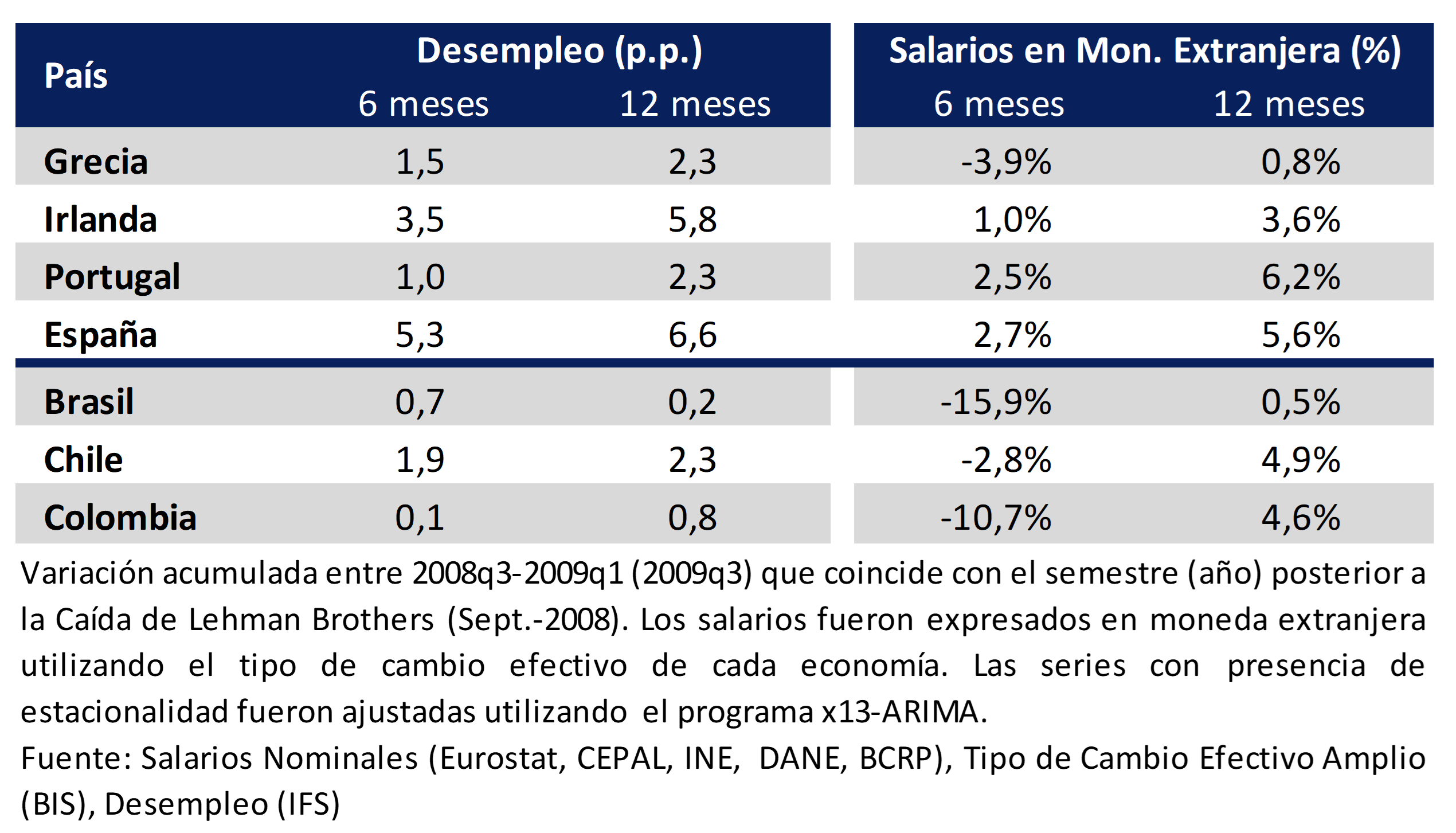

The outlook for job creation for the next three months deteriorated in line with the expected retraction of economic activity in the coming months. The May survey of the EIL-MTEySS showed a reduction in net expectations of job creation to 3.4% (-1.4 p.p. compared to the previous month). However, it is expected that the depreciation of the currency will limit the increase in unemployment (See Section 1 / Labor market and external shocks).

3.2 Outlook

After the contraction of activity in the second quarter, the BCRA’s base scenario foresees a gradual recovery of GDP from the third quarter of 2018 based on the expected performance of agricultural activity, the normalization of the functioning of financial markets and the rise in real incomes as a result of the lower monthly inflation expected for the second half of the year. In its base scenario, the BCRA forecasts growth of around 0.4% YoY for 2018 and a gradual strengthening of the economy for 2019 (see Figure 3.12).

There are good prospects for agricultural production and exports in general, given the expected growth of trading partners and with more favorable relative prices. Soybean and corn harvests will reach at least the levels of the 2016/2017 season, which means increases of approximately 60% and 20% y.o.y., respectively. In the baseline scenario, the BCRA estimates a sustained reduction in the external deficit (see Figure 3.13).

Within the framework of the agreement signed with the IMF, the government committed to move forward with the process of fiscal consolidation in order to reduce the financing needs of the national government and, consequently, correct the external imbalance (see Section 2. Fiscal consolidation and current account results). The broad set of measures included in the agreement contemplates an ambitious fiscal effort—with reductions in capital spending, subsidies for utility rates, and other expenditures—that will gradually lower the cost of financing and facilitate a rebalancing of domestic demand toward a greater share of private consumption and investment.

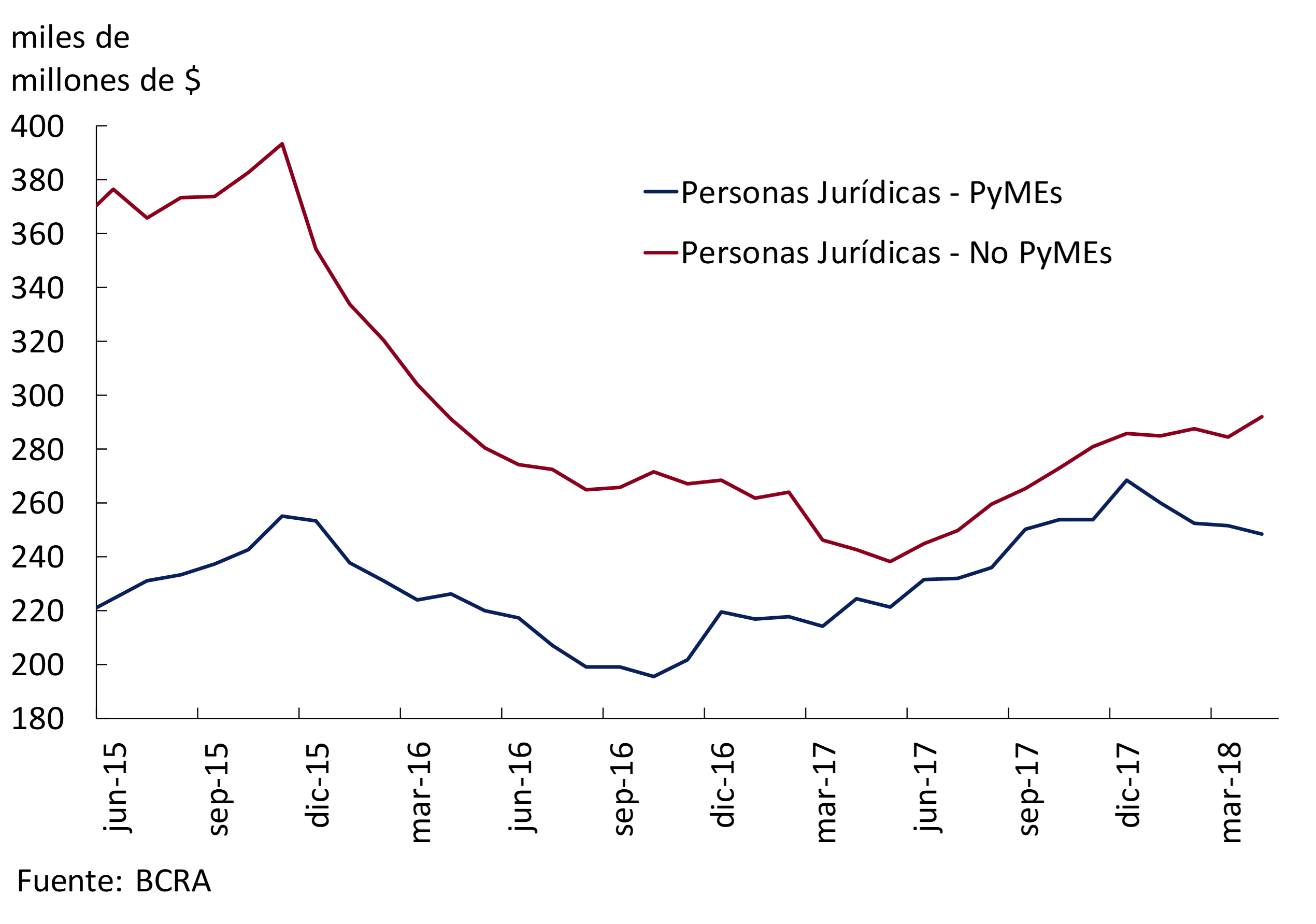

Finally, the enactment in May 2018 of the productive financing law15 will promote the development of the local capital market16 facilitating access for SMEs. Along the same lines, Argentina’s entry into the MSCI17 emerging economies index last June would expand the supply of external funds available to Argentine companies. The greater capture of these flows could mean a reduction in the cost of financing and at the same time, free up space for local financing of smaller companies.

4. Pricing

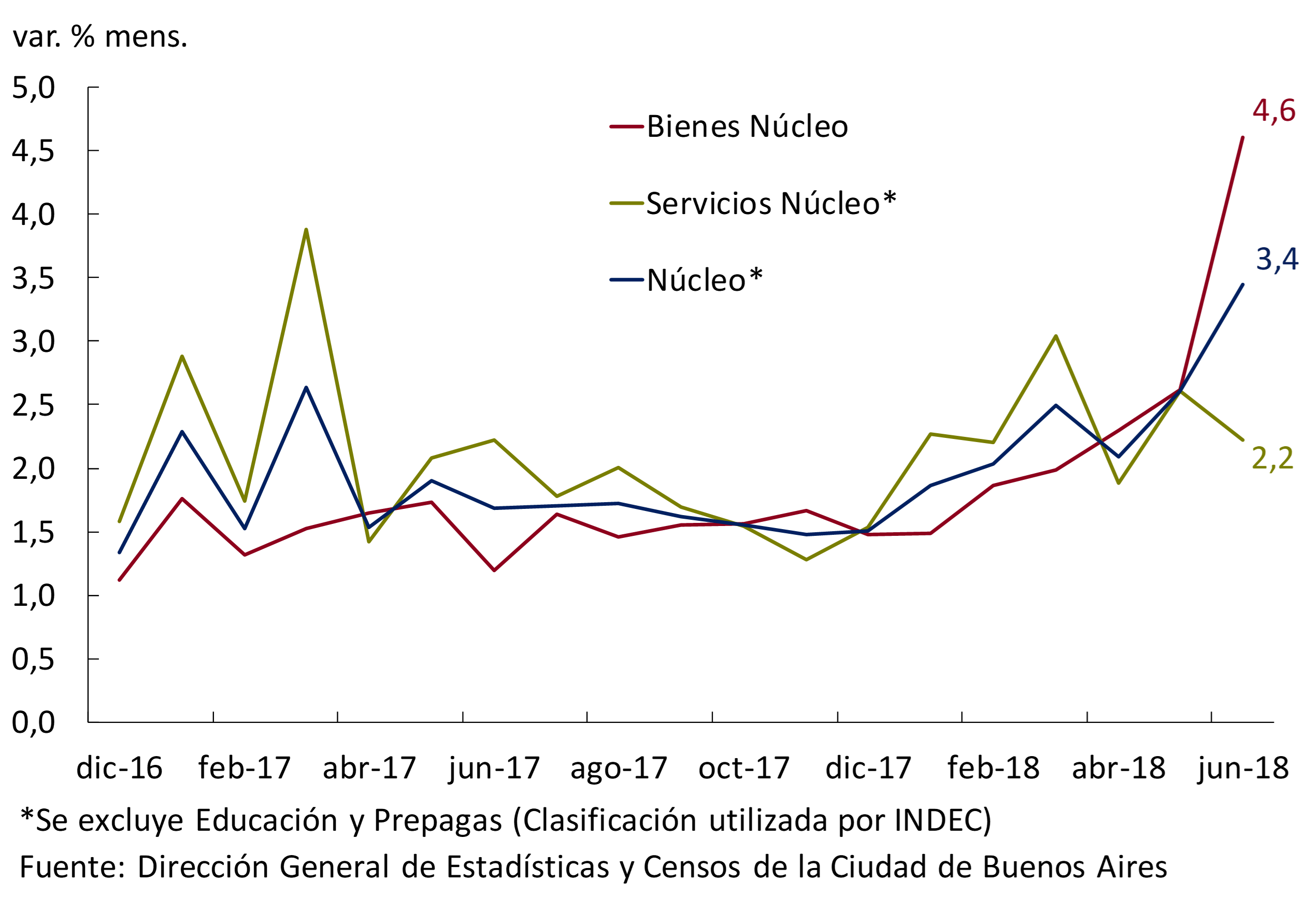

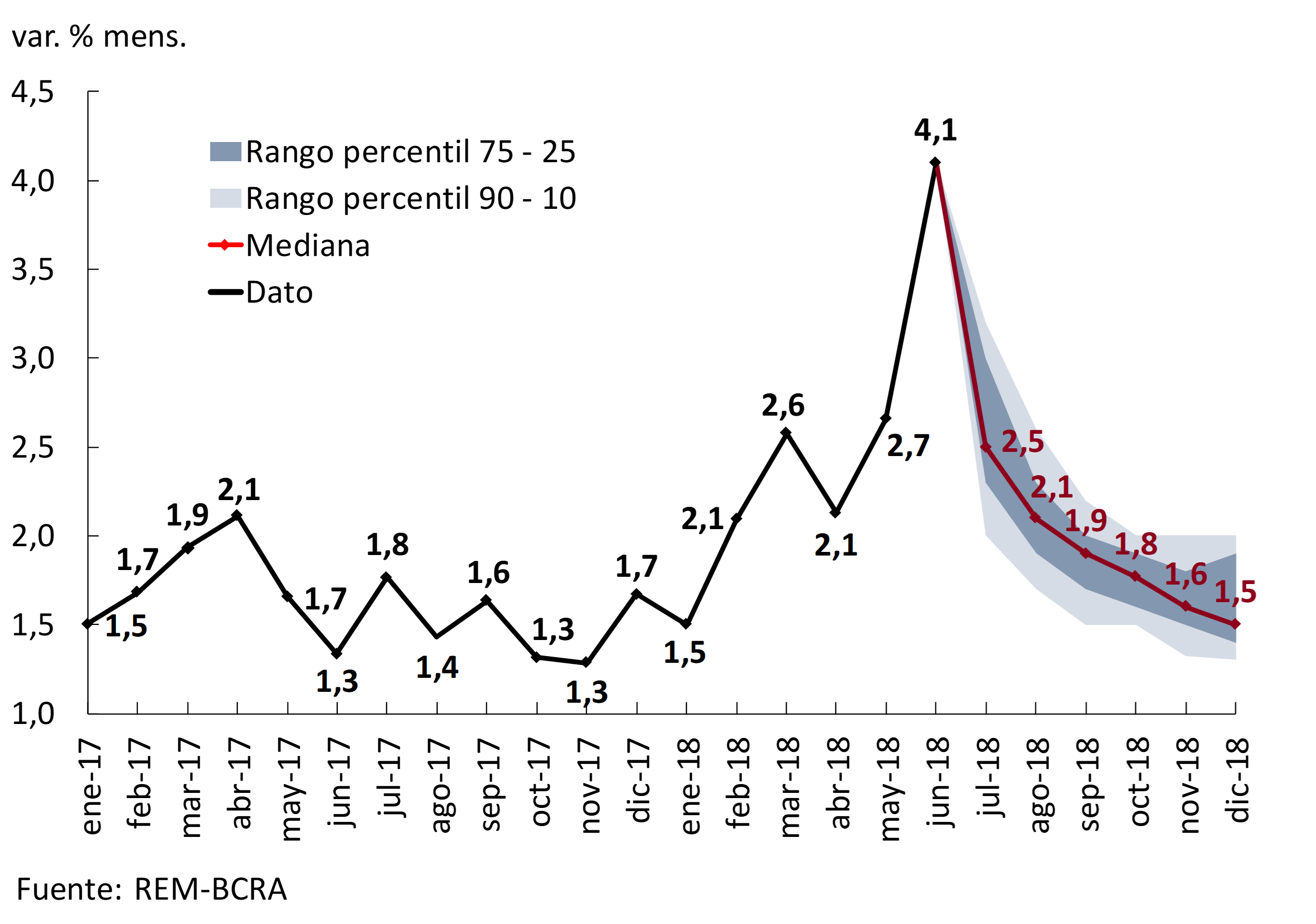

During the second quarter of the year, inflation averaged a monthly rate of 2.8%, according to the Consumer Price Index (CPI) of national coverage. The rise in the general price level was driven by the depreciation of the peso, particularly in May and June, and to a lesser extent by the direct and indirect impact of the increase in utility rates. On a year-on-year basis, retail prices rose at a rate of 29.5% at the end of the second quarter. Core inflation also gained dynamism compared to previous months, averaging a 2.9% monthly increase between March and June. The base scenario of the Central Bank of the Argentine Republic (BCRA) contemplates a reduction in monthly inflation starting in July and a significant inflationary slowdown for the next two years, a trend that is also reflected in the inflation expectations of the Market Expectations Survey (REM).

4.1 Prices accelerated in the second quarter

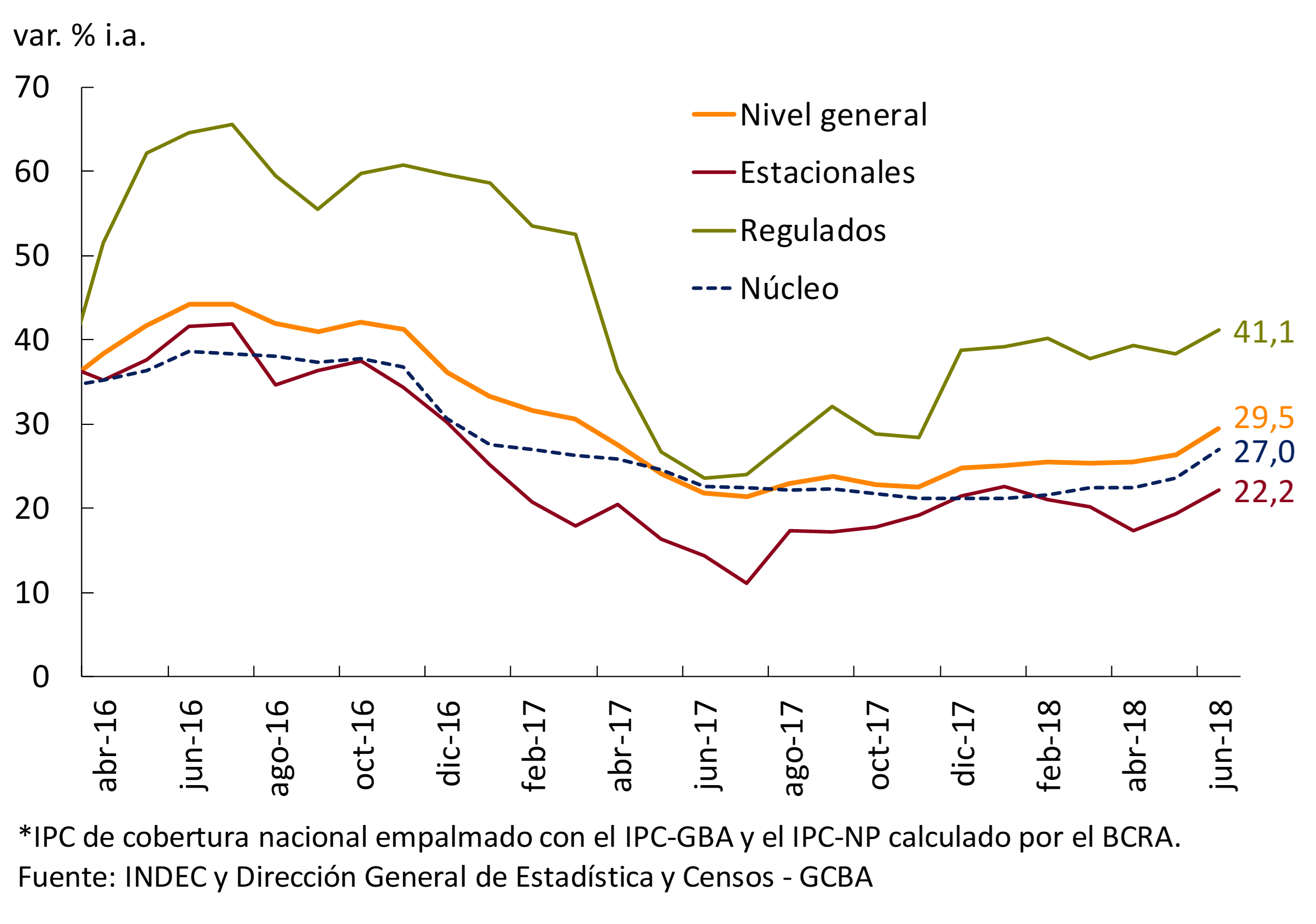

In the second quarter of the year, inflation gained dynamism, reaching rates close to 3% monthly average. In this way, prices accumulated a 16% increase so far this year. The recent evolution of inflation was directly associated with the depreciation of the local currency, which had a greater impact on goods and, to a lesser extent, with corrections in the relative prices of regulated services. Thus, in the second quarter, the dynamics observed in the first months of the year were accentuated (see Figure 4.1). The continued acceleration of prices during the first half of the year led to a rise in the year-on-year rate of change of the general level of the CPI to reach a rate of 29.5% in June.

Since the end of April, changes in the international scenario have led to a global appreciation of the dollar, driving a depreciation in the currencies of emerging countries (see Chapter 2. International context). In Argentina, some local factors contributed to exacerbate this behavior, leading to a depreciation of the peso greater than that of the currencies of other emerging countries (see Chapter 5. Monetary policy; see Figure 4.2).

Core inflation accelerated since the beginning of the year, driven by the depreciation of the exchange rate and the direct and indirect impact of the sharp adjustment in prices of regulated services since December 2017. Thus, core inflation averaged increases of 2.9% monthly, 0.9 p.p. above the average rate of the first quarter of 2018.

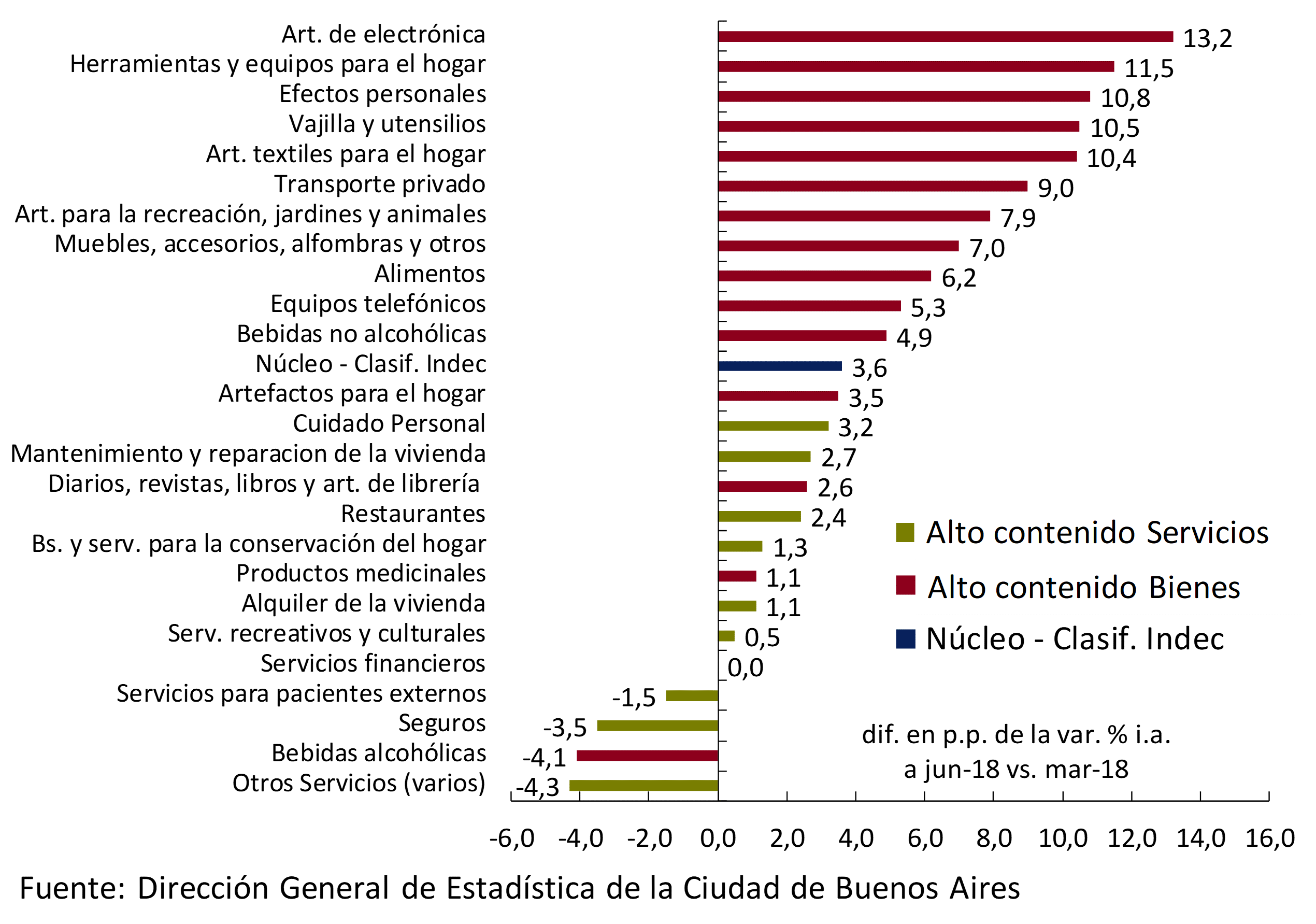

Goods included in core inflation, particularly food, were the biggest drivers of the recent acceleration in prices (see Figure 4.3). Because of their tradable nature, these products are more sensitive to currency depreciation. Meanwhile, the dynamics of private services were more closely linked to the evolution of wages. Services were also affected, although to a lesser extent, by the rise in public services18.

In year-on-year terms, after falling since mid-2016 and during 2017, core inflation rose to 26.9% YoY in June. The largest increase occurred in the second quarter of the year, gaining 4.6 p.p. above the year-on-year rate of March. At a more disaggregated level, with information from the Statistics Directorate of the City of Buenos Aires, it is also observed that the groups that accelerated the most in year-on-year terms compared to March 2018 were those with a high component of tradable goods (see Figure 4.4).

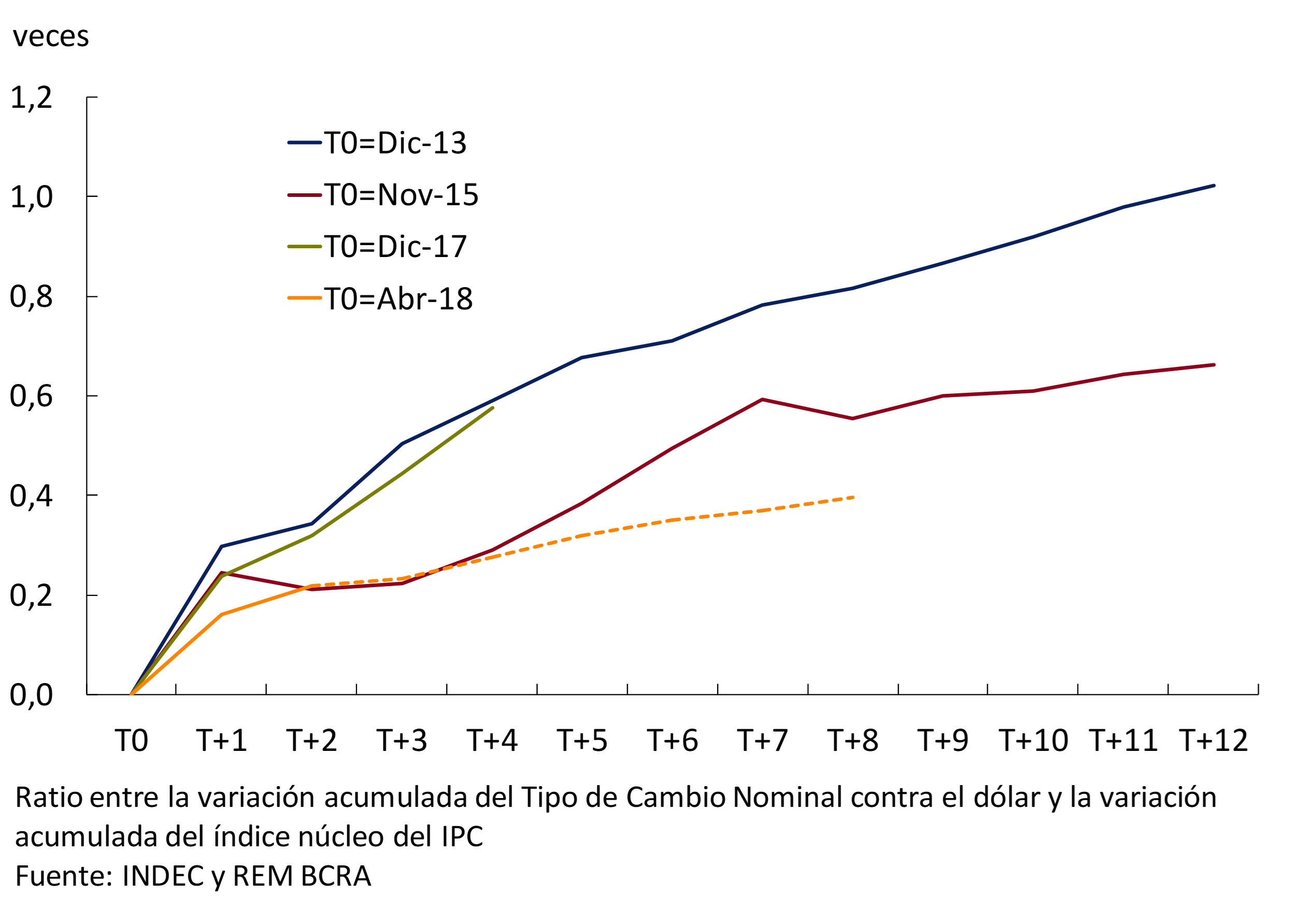

If we analyze the relationship between the exchange rate and core inflation, in the first four months of 2018 it can be seen that the nominal rise in the exchange rate was transferred to prices at a rate similar to that observed in the depreciation of early 2014 (blue line in Figure 4.5). On the other hand, since May, there has been less transfer of the depreciation of the currency to prices, presenting an even more moderate behavior than that observed after the normalization of the foreign exchange market at the end of 2015 (orange line in Figure 4.5).

According to the projections of the latest REM, in the coming months the lowest transfer would be maintained compared to previous episodes of similar characteristics.

The prices of regulated items also had a significant impact on inflation in the period, even considering some regulatory/tax changes that tended to attenuate the increases. In the second quarter of 2018, these goods and services adjusted at an average rate of 2.8%, reflecting increases in public passenger transport, gas by network, water and electricity19. In addition, there were increases in the prices of cigarettes, prepaid, telephony and fuel for the automobile. The exemption of some taxes on public service rates in some districts and the temporary reduction of the gas rate for users with Social Tariff20 operated in the opposite direction. In year-on-year terms, regulated goods and services maintained growth rates of close to 41% YoY (see Figure 4.6).

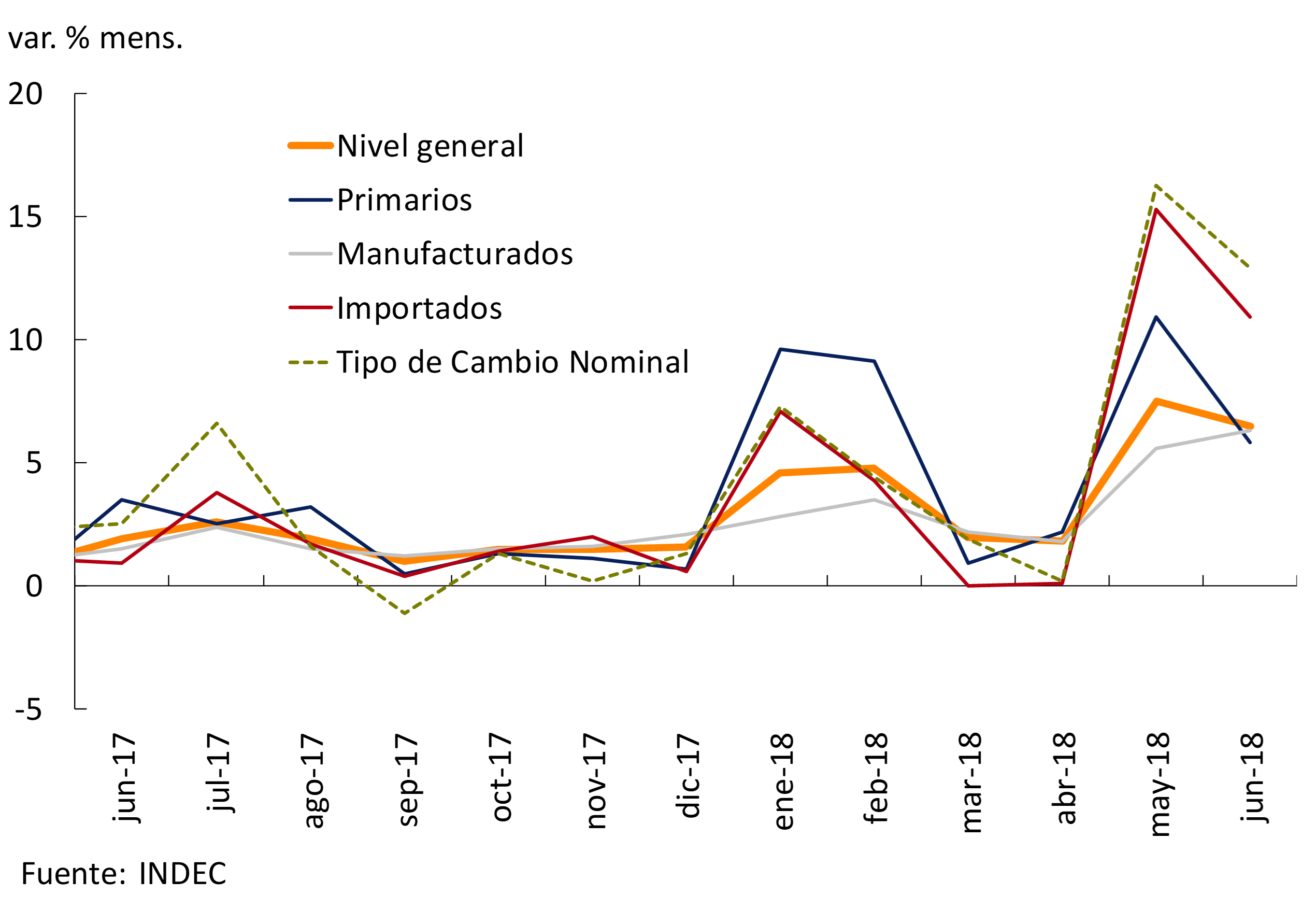

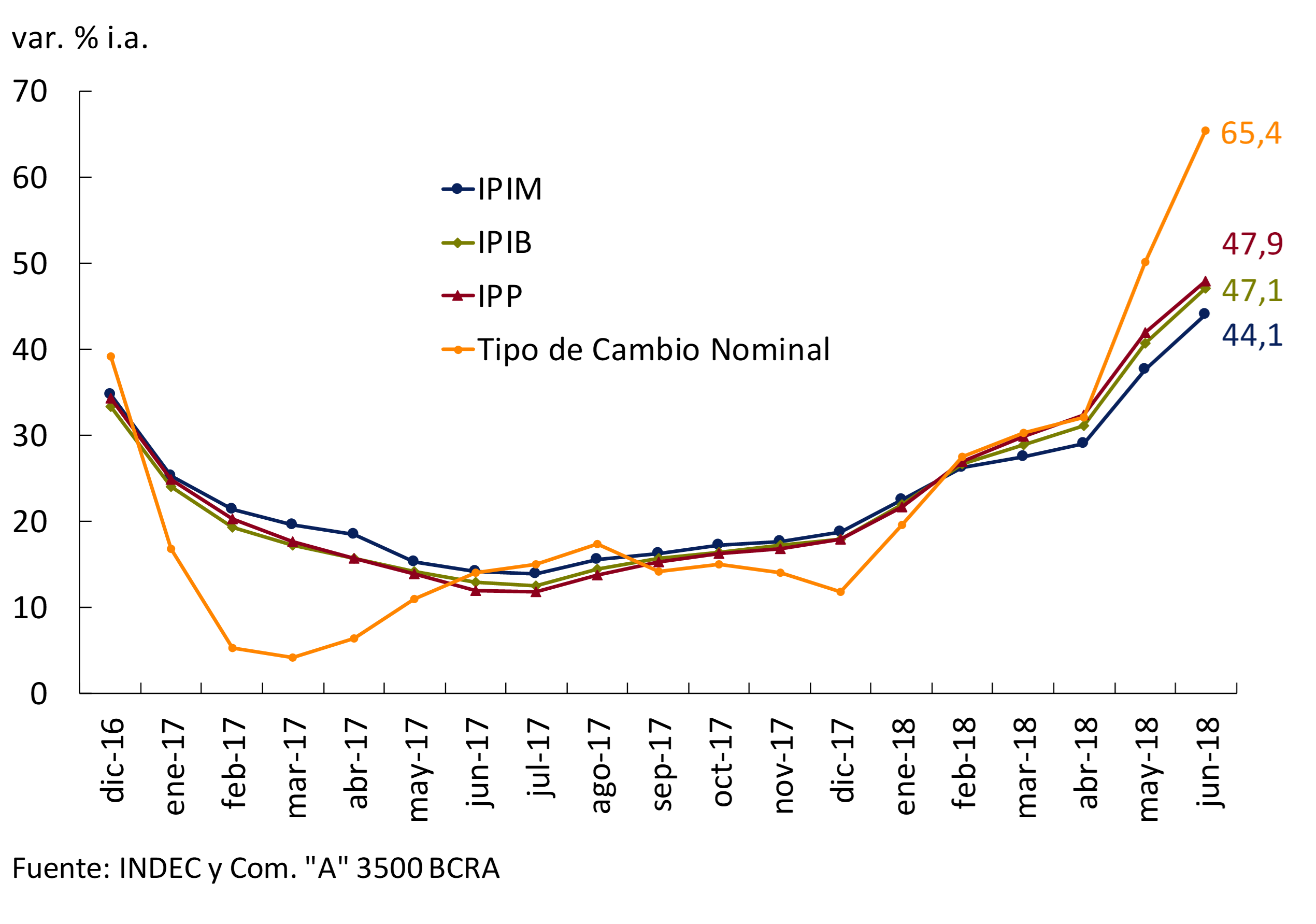

Wholesale prices saw increases higher than those of consumer prices and the records of the first months of the year, averaging a 5% monthly increase in the second quarter (+1.5 p.p. above the monthly increase of the first quarter of 2018). The pass-through of the depreciation of the peso to wholesale prices is greater than to retail prices due to the high tradable component that characterizes wholesale price indices. Wholesale price indices mainly reflect variations in the prices of goods, while services have a greater share in the CPI basket. The intrinsic characteristics in the construction of both indicators make the Domestic Wholesale Price Index (IPIM) an index more sensitive to exchange rate movements (see Figure 4.7).

The acceleration of the IPIM in the second quarter of the year was mainly due to the dynamics of the prices of Manufactured and Imported Products, while Primary Products averaged increases similar to those of the first quarter of the year. The increases that had the greatest impact on the rise in manufacturing prices were those of Food and beverages, Chemical substances and products, Refined petroleum products, Motor vehicles and Machinery and equipment. New increases were added to agricultural products in pesos, on which the depreciation of the local currency played a determining role. The crude oil and gas component also averaged high increases in the period basically due to the increase in crude oil (monthly average of 4% in dollars), which was boosted by the depreciation of the peso. The prices of imported products are the ones that increased the most, directly affected by the dynamics of the exchange rate, although their incidence is more limited in the IPIM due to the low weighting that this component has in the index. The monthly acceleration of wholesale prices during the second quarter of the year boosted the year-on-year rates of change, which rose to values close to 47% in June 2018 (see Figure 4.8).

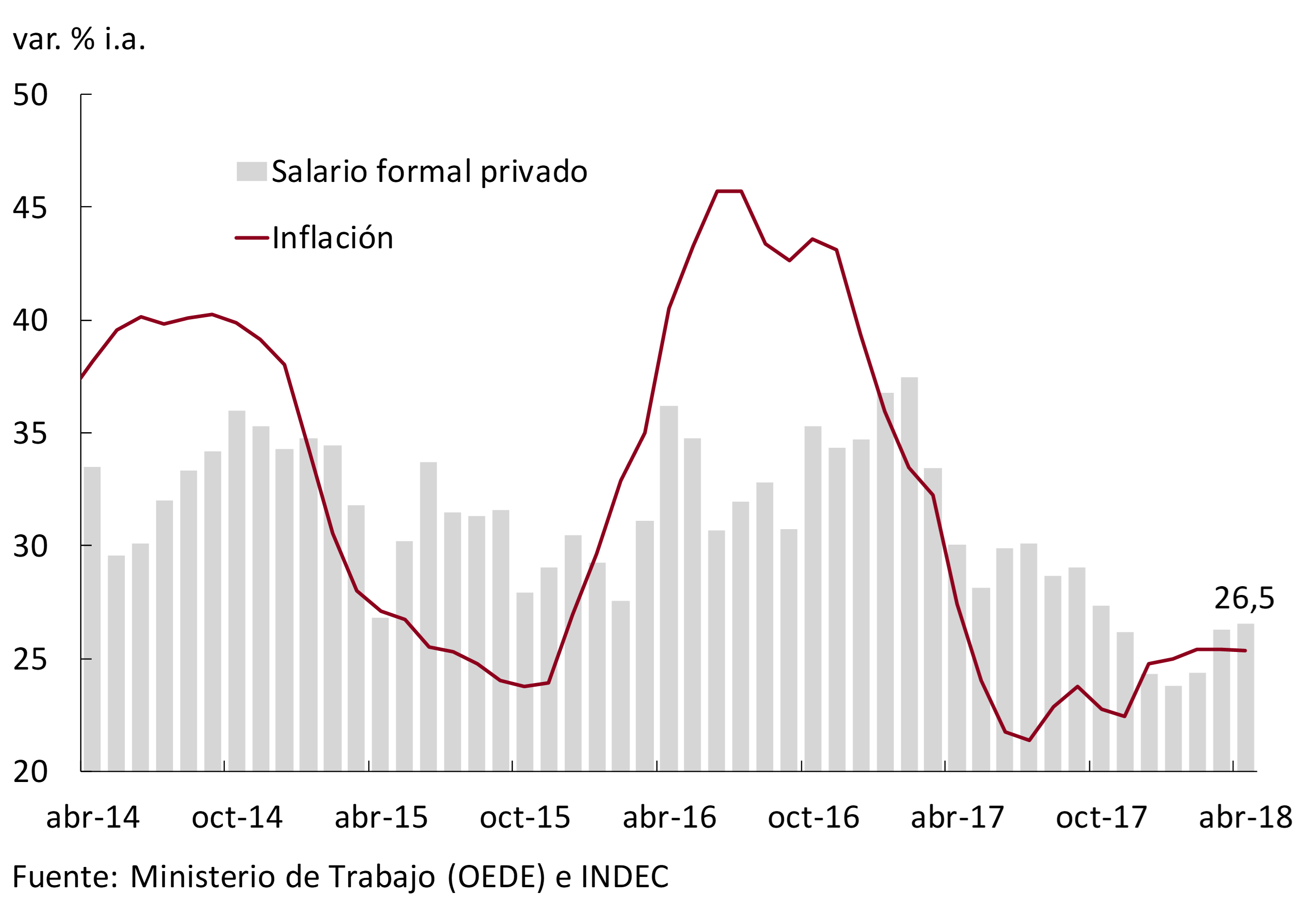

4.2 Wage patterns are being revised upwards

In the first part of the year, wages in the formal private sector showed an increase in the year-on-year growth rate, due to the payment of compensations linked to the collective bargaining agreements of the previous year. On the other hand, the first tranches of increase corresponding to a large part of the 2018 parity agreements came into force. Given that the annual inflation pattern at the beginning of the year was 15%, the collective bargaining agreements tended to close around that value and with the increases concentrated in the first months. However, these increases will prove insufficient to offset the accelerating inflation of the second quarter (see Figure 4.9).

In this framework, wage guidelines are being revised upwards in line with a higher annual inflation forecast. To the original guideline of 15%, new increases of around 7% would be added that would be calculated on the base salary of the paritaria, being paid in tranches during the second part of this year and the first months of 2019.

4.3 The BCRA’s baseline scenario foresees a reduction in inflation in the second half of the year

The depreciation of the currency in May and June of this year postponed the slowdown expected from the second quarter. Consequently, the inflation projections of the BCRA’s base scenario were corrected upwards. The expectations of market analysts were modified in the same sense. For December 2018, the REM estimates that inflation will stand at 30%, 10 p.p. above the forecasts that analysts had in March.

Based on the available information, the monetary policy bias adopted, and in the absence of new shocks, the BCRA forecasts a moderation in inflation for the coming months, with an average increase in consumer prices of close to 2% for the third quarter of the year. Market analysts’ expectations have a similar dynamic built in, predicting disinflation for the second half of the year (see Figure 4.10).

In the coming months, increases linked to vehicle fuels could be observed, due to the fact that their retail price is approximately 20% below the import parity with data as of July 1621 (price reference for the industry). On the other hand, and with a lesser impact on the CPI, the elimination of minimum prices for the sale of tourist tickets is being analyzed. This could lead to greater competition among the providers of these services that could help contain price increases in this item.

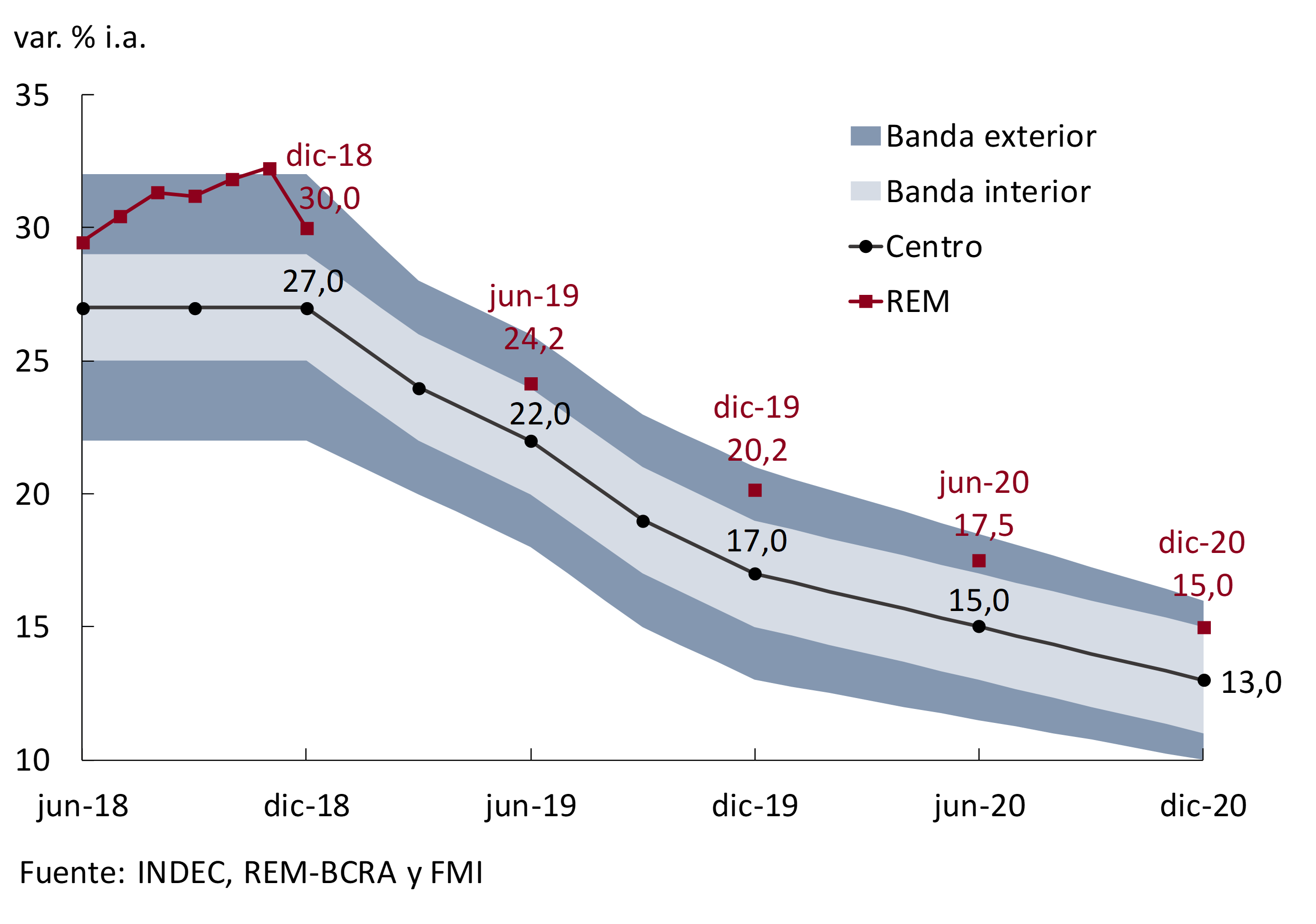

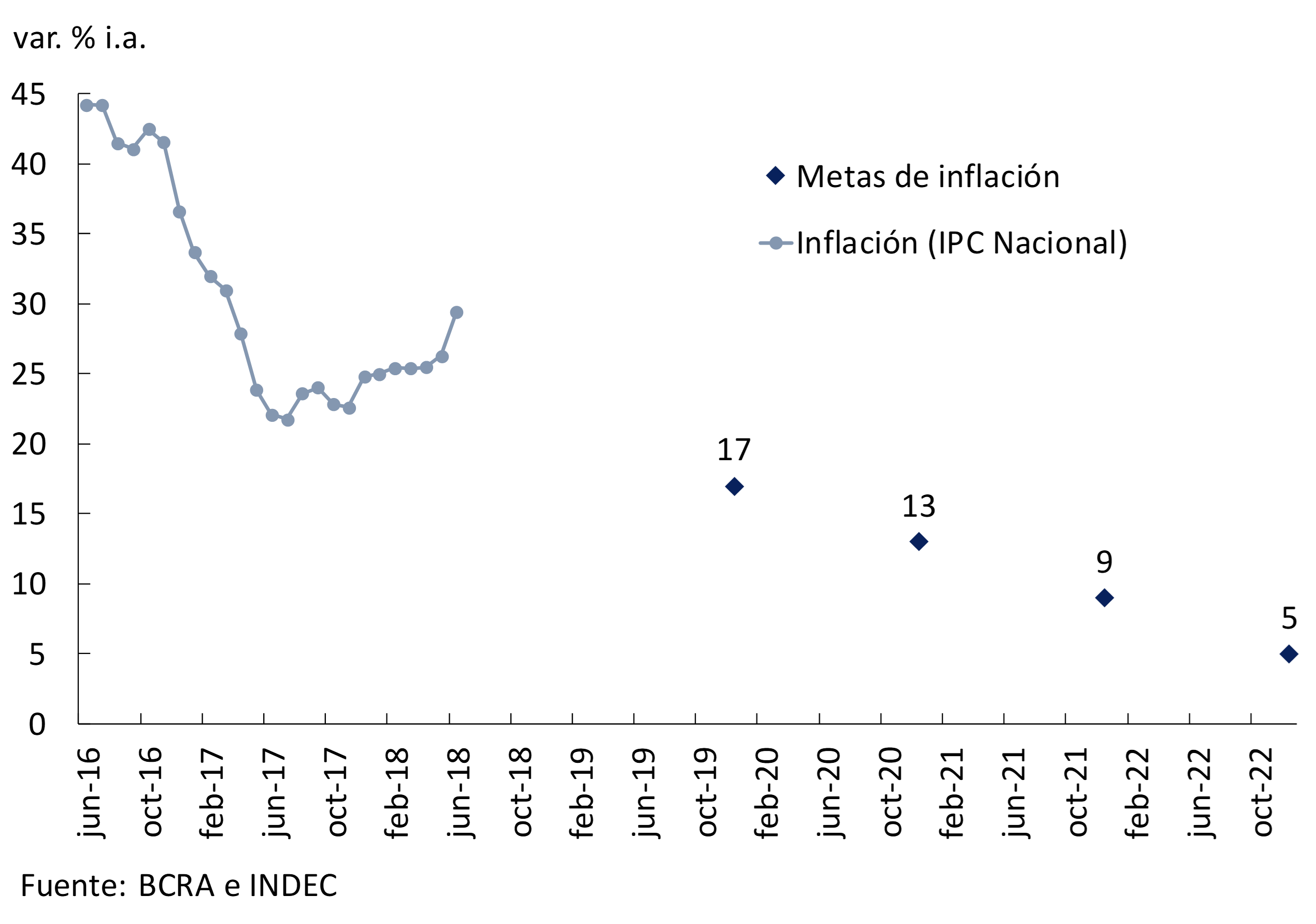

On June 7, 2018, the Argentine government announced an economic program aimed at strengthening the monetary policy framework with the aim of lowering inflation (see Chapter 5. Monetary policy). This program established new inflation targets, in coordination with the new fiscal program. The inflation targets for the coming years are: 17% for 2019, 13% for 2020, 9% for 2021 and 5% for 2022. In addition, the agreement of understanding with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) sets deviation bands with respect to the target. In the event that inflation is above or below some of these limits, potential corrective measures should be consulted with different IMF bodies.

The Central Bank’s base scenario anticipates that the disinflation process will continue over the next few years within the first consultation bands for 2019. The estimates of the REM market analysts anticipate a rise of 20.2% YoY for 2019 and 15% YoY for 2020, both within the outer consultation bands (see Figure 4.11).

5. Monetary policy

The exchange rate turbulence that began at the end of April was explained by a combination of external and internal factors. In response to the pressures on the foreign exchange market, the Central Bank acted progressively with all the tools available to deal with this type of episode: sale of international reserves, exchange rate flexibility and increases in monetary policy interest rates and Central Bank securities.

Likewise, negotiations began with the International Monetary Fund that culminated in early June with a three-year Stand-By program for US$50,000 million and with the commitment to deepen the economic reforms initiated in December 2015, accelerating the reduction of the imbalance in public accounts and redoubling efforts to reduce inflation.

In the program agreed with the multilateral organization, the inflation targeting regime is maintained, but new targets were defined for the coming years: 17% in 2019, 13% in 2020, 9% in 2021 and 5% year-on-year in 2022 (as of December of each year). Also, the flexible exchange rate scheme is maintained along with the possibility that the Central Bank will make limited interventions to moderate disruptive movements in the foreign exchange market that may affect financial stability or the path of disinflation.

To strengthen the inflation targeting regime, a series of measures were defined that aim to deepen the operational and financial autonomy of the Central Bank, to clean up its balance sheet and to promote greater transparency in the preparation of its financial statements. Among the most relevant changes are the end of financing to the Treasury by the Central Bank, the beginning of a program to reduce the stock of non-transferable bills (which will be used to, in turn, reduce the stock of LEBACs in circulation), and the draft reform of the Organic Charter to grant greater autonomy to the monetary authority. improve accountability and increase transparency.

Faced with the return of the exchange rate turbulence in mid-June, a new leadership of the Central Bank took additional measures to moderate the rise in the exchange rate, which consisted of absorbing liquidity in pesos (through increases in bank reserve requirements), allowing an increase in interest rates consistent with the new monetary tightening, and providing dollars to the market in situations of illiquidity or disruption (through the Central Bank’s auction of foreign currency). Simultaneously, the National Treasury announced a schedule of daily auctions of dollars from the agreement with the IMF to cover current expenses.

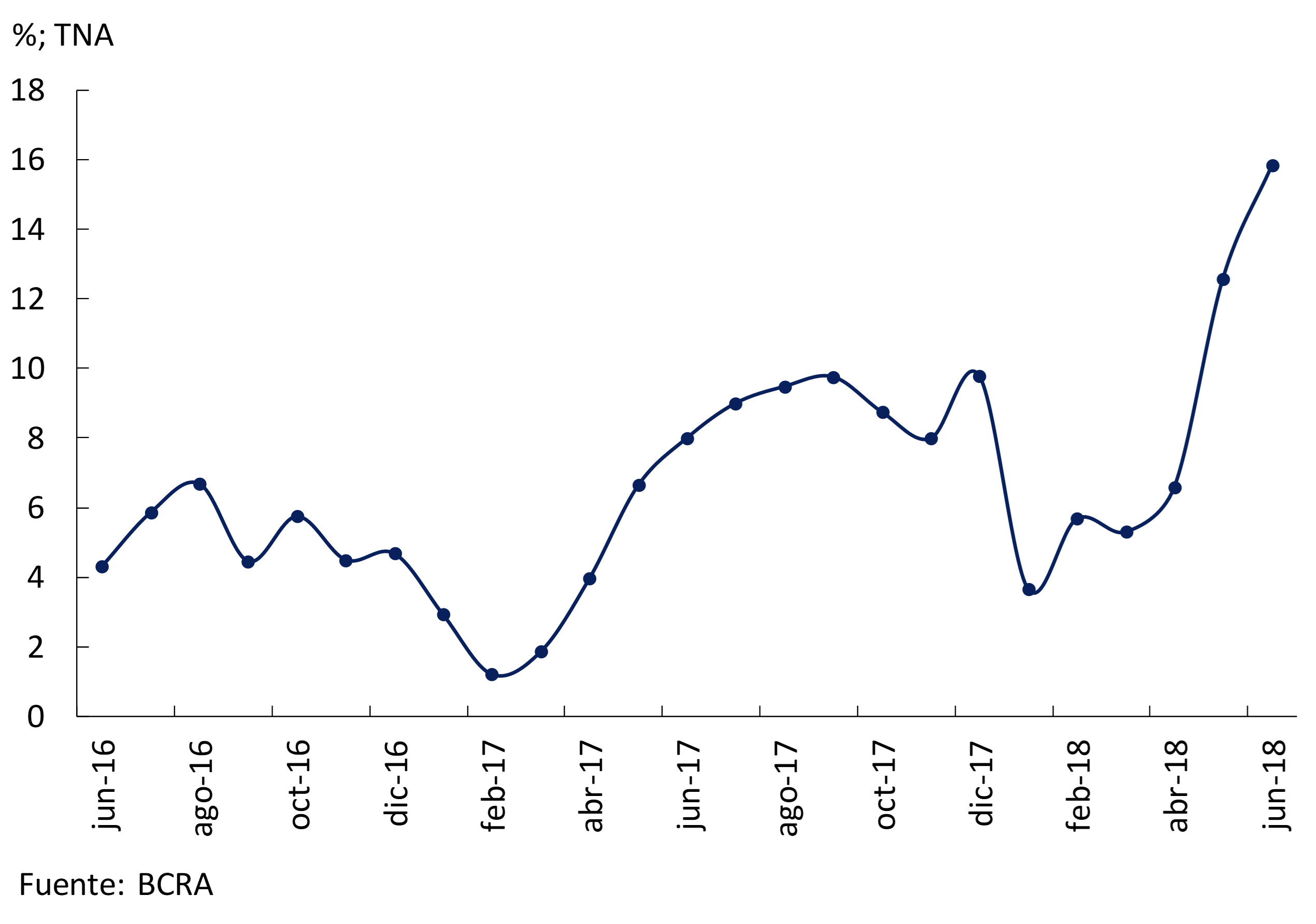

At the end of the exchange rate episode in early July, the multilateral real exchange rate was above the highest since the lifting of exchange restrictions in March 2016 and approached a level not recorded since November 2011. This facilitates the adjustment of external accounts, and has a smaller impact on the level of activity than a more rigid exchange rate policy would require. At the same time, the real interest rate (ex ante) reached maximum levels, more than doubling in June the level of March of this year, which marks the contractionary bias of monetary policy aimed at moderating the impact of the rise in the exchange rate on domestic inflation.

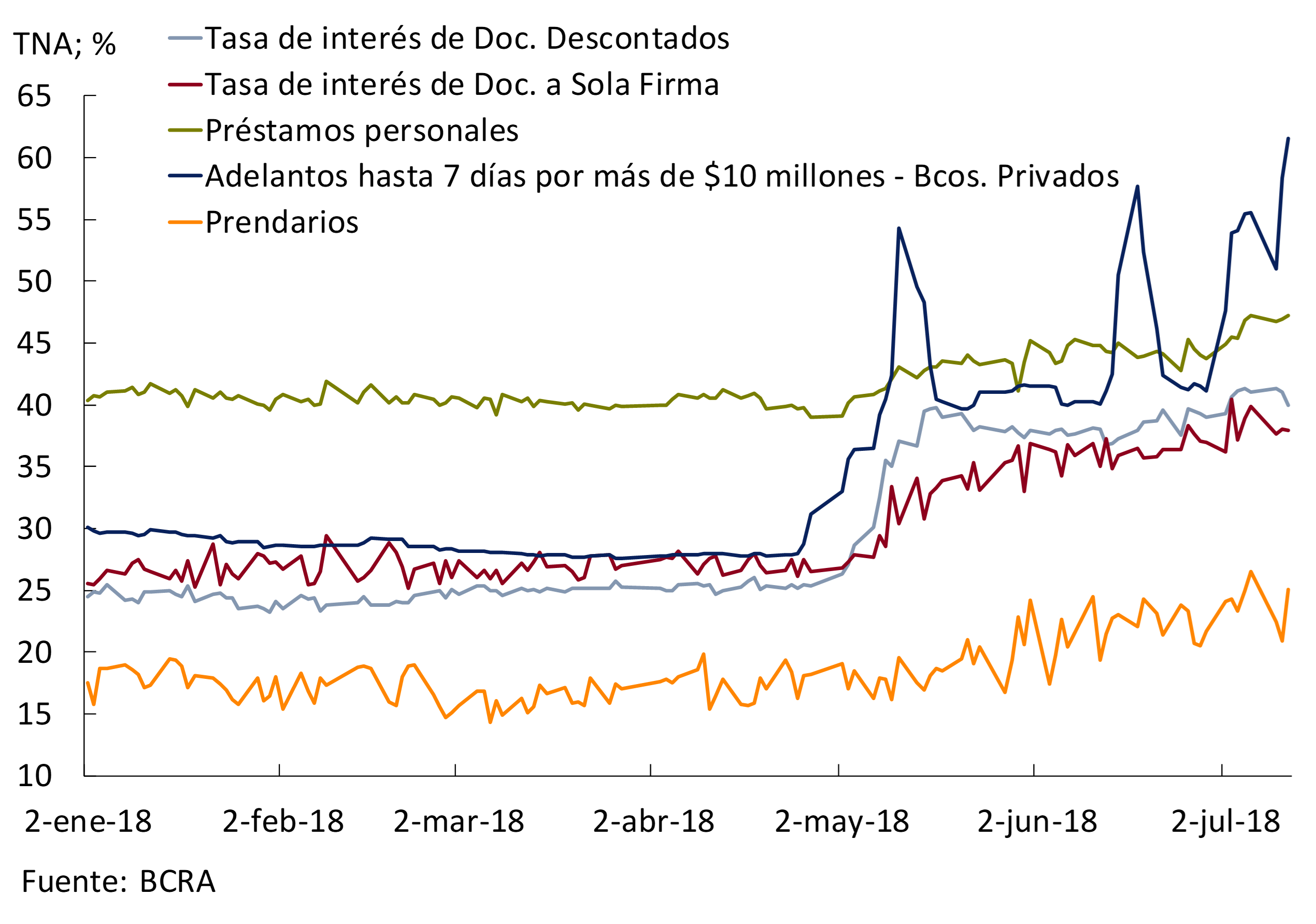

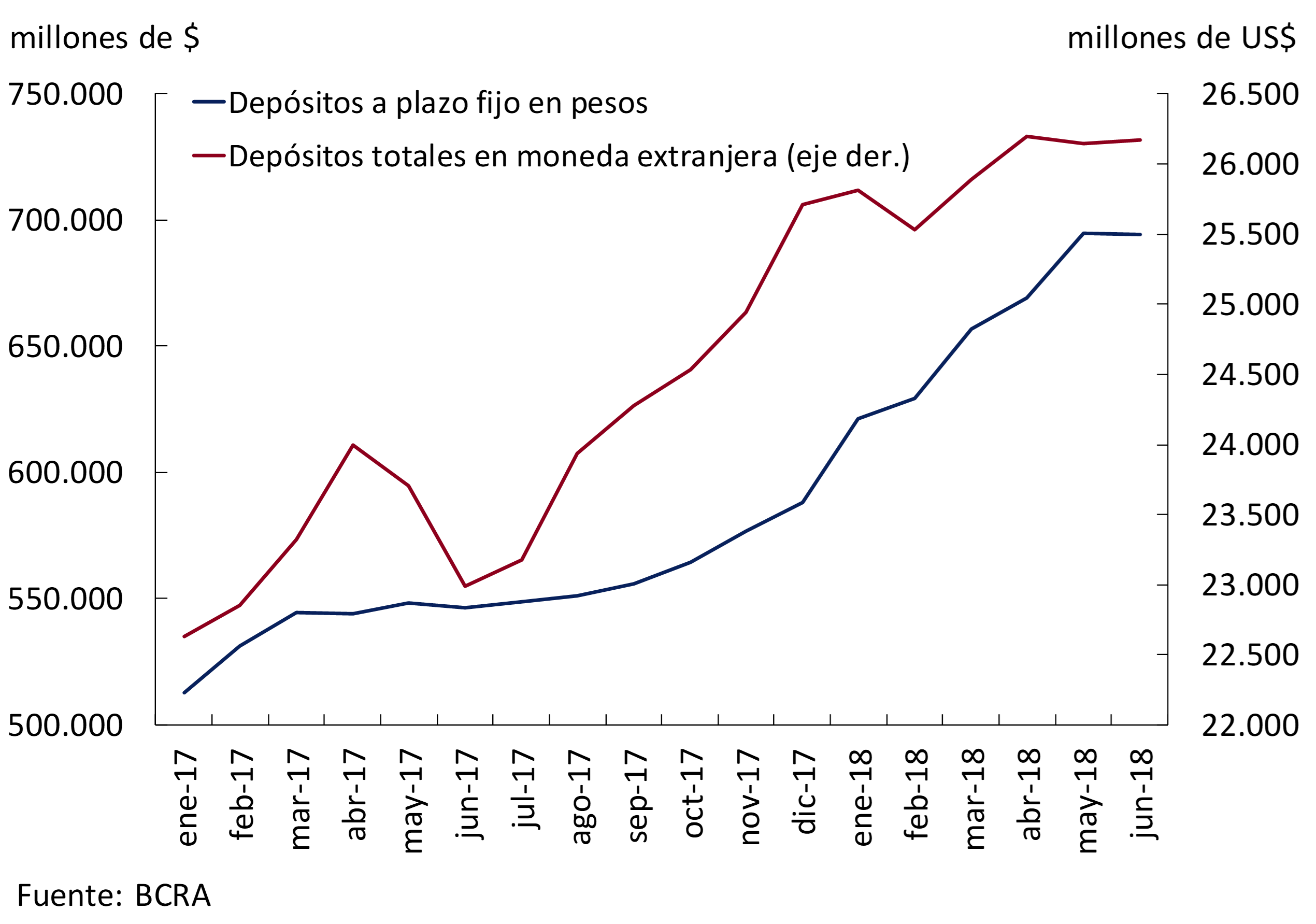

The passive and lending rates of the financial system accompanied the rise in reference interest rates to varying degrees. Bank deposits showed great resilience, reflecting the strength of the financial system, while bank lending began to decelerate, a trend that is expected to continue following the readjustment of aggregate demand.

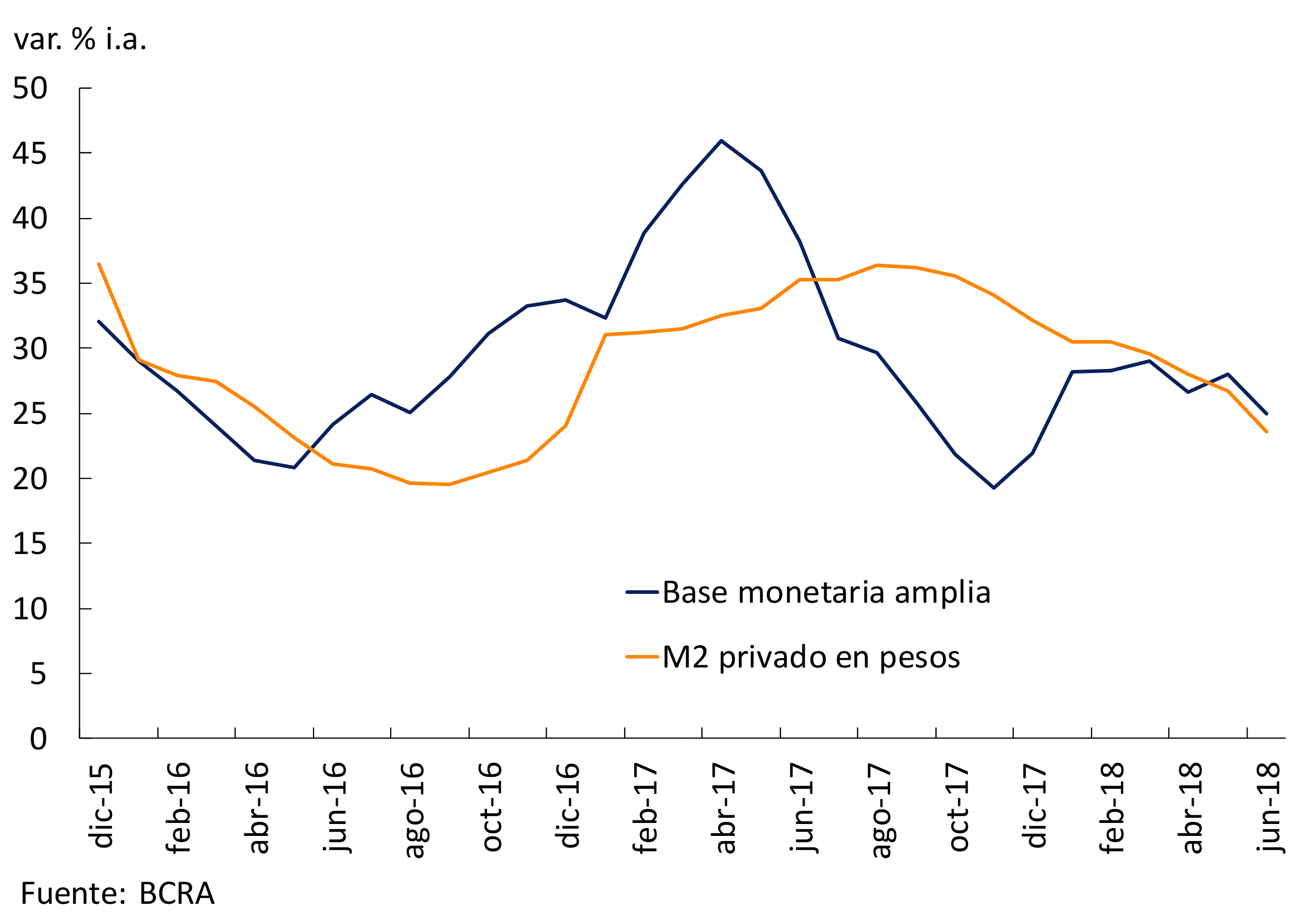

The new authorities of the Central Bank announced changes in the implementation of monetary policy, within the inflation targeting scheme with a flexible exchange rate. The most significant is that in the transition to reach single-digit inflation rates, the scheme with the interest rate as the only monetary policy instrument will be reinforced by a more attentive monitoring of monetary aggregates. In this sense, both the private M2 in pesos and a broad monetary base measure (which also considers the net passes, LELIQ and LEBAC held by banks) are showing signs of slowing down in terms of year-on-year variations.

The acceleration of inflation in June and the rise in inflation expectations in the latest REM survey reflected the direct and indirect effects of the increase in the exchange rate in recent months. While the latest available high-frequency data show a slowdown in inflation from July onwards, in line with the Central Bank’s projections, the current contractionary bias in monetary policy will continue to be maintained until tangible signs are seen that both inflation in the coming months and the inflation expected for 2019 will begin to decline.

The new declining inflation targets come in very different circumstances from those of the scheme originally launched in 2016, which improves the Central Bank’s ability to achieve compliance with the disinflation path. The bias of monetary policy is more contractionary; the level of international reserves of the Central Bank is higher; new transfers from the Central Bank to the Treasury are eliminated; the balance sheet of the monetary authority will be strengthened; the process of correcting public sector tariffs is much more advanced; and the fiscal deficit will be lower in terms of GDP, with a faster path of reduction in the coming years than initially expected.

5.1 April-May Exchange Turbulence

5.1.1 Triggers

The exchange rate turbulence that began on April 25 was explained by a combination of external and internal factors.

At the international level, the rise in the interest rate in the United States, due to the prospect of a stronger-than-expected recovery of the U.S. economy, unleashed an outflow of capital from emerging economies (see Chapter 2. International context). This increase in the international rate occurred in a context in which some fiscal indicators and the external sector of the Argentine economy showed a weaker situation compared to the rest of the emerging countries; this is due to the gradual correction of macroeconomic imbalances that began at the end of 2015.

As for internal factors, the drought stood out, which, according to estimates by the Ministry of Finance, contracted the supply of dollars by US$8,500 million. In addition, the entry into force of the financial income tax for non-residents and the discussion of public service rates in the National Congress, which questioned the feasibility of fiscal convergence proposed by the Executive Branch, were mentioned as factors that reduced investors’ appetite for Argentine assets.

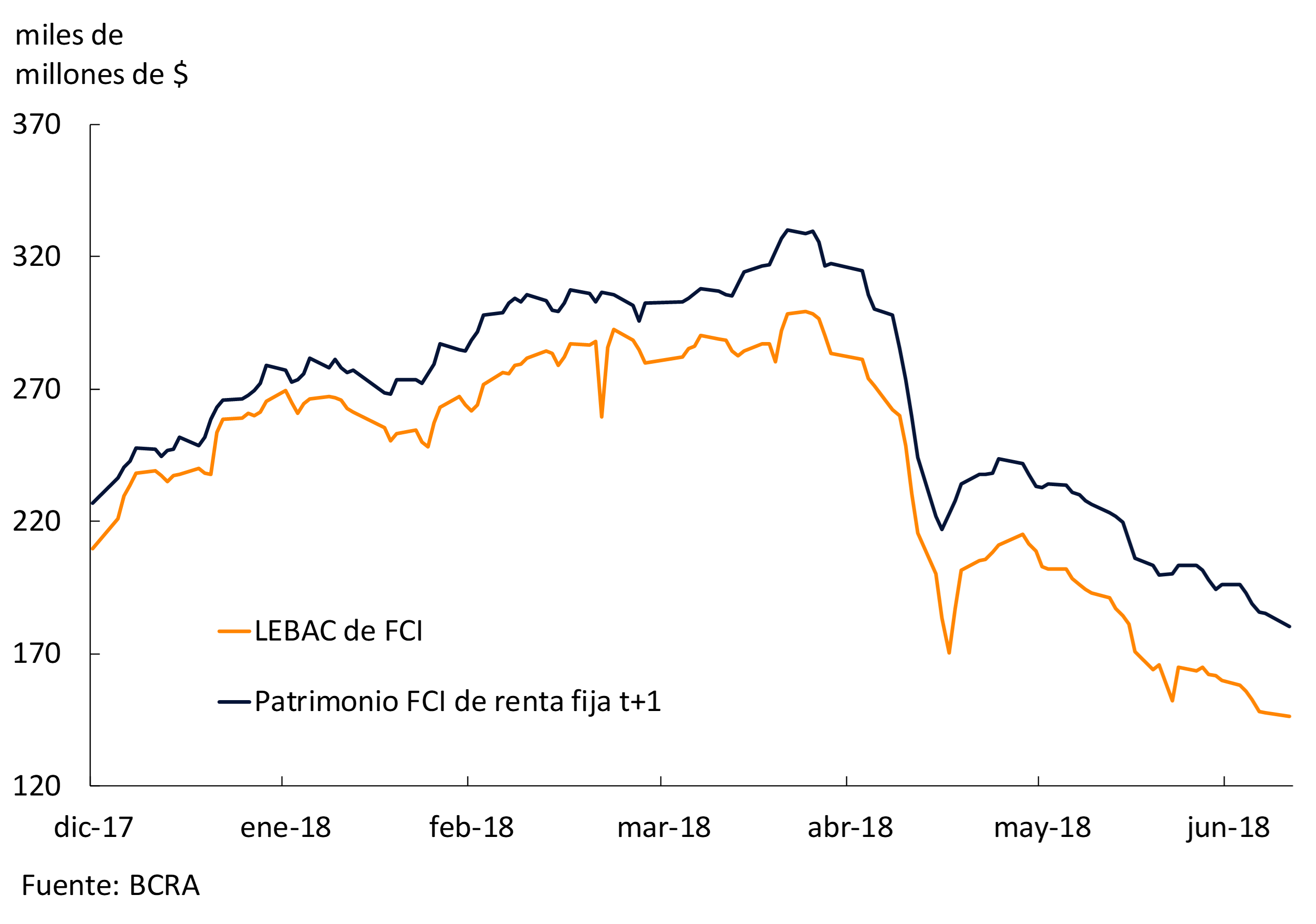

All of the above contributed to the greater impact of capital outflows in Argentina than in other emerging economies, which was reflected in an increase in the country risk premium and the expectation of depreciation of the peso. While investors’ portfolio shifts affected Argentine assets in both dollars and pesos, it was concentrated in Central Bank Bills (LEBACs), first through sales by non-residents and then, to a greater extent, through the liquidation of fixed-income mutual funds (T+1) (see Figure 5.1).

5.1.2 The Central Bank’s response

In response to the pressures on the foreign exchange market, the Central Bank acted progressively with all available tools to deal with this type of episode. At the beginning of the exchange rate tensions, the Central Bank decided to intervene in the foreign exchange market to contain the depreciation of the peso, with the aim of guaranteeing the disinflation process. As the days went by, and given the evidence that the movements observed reflected a deeper shock on the foreign exchange market and not an isolated episode of volatility, the Central Bank reduced the magnitude of its interventions and allowed a greater slide in the exchange rate. While in the first five days of the turbulence the intervention in the foreign exchange market accumulated US$4,663 million and the exchange rate increased 7.4%, in the rest of the episode, until May 15, the Central Bank used US$2,440 million of its reserves and the peso depreciated 14.0% (see Figure 5.2).

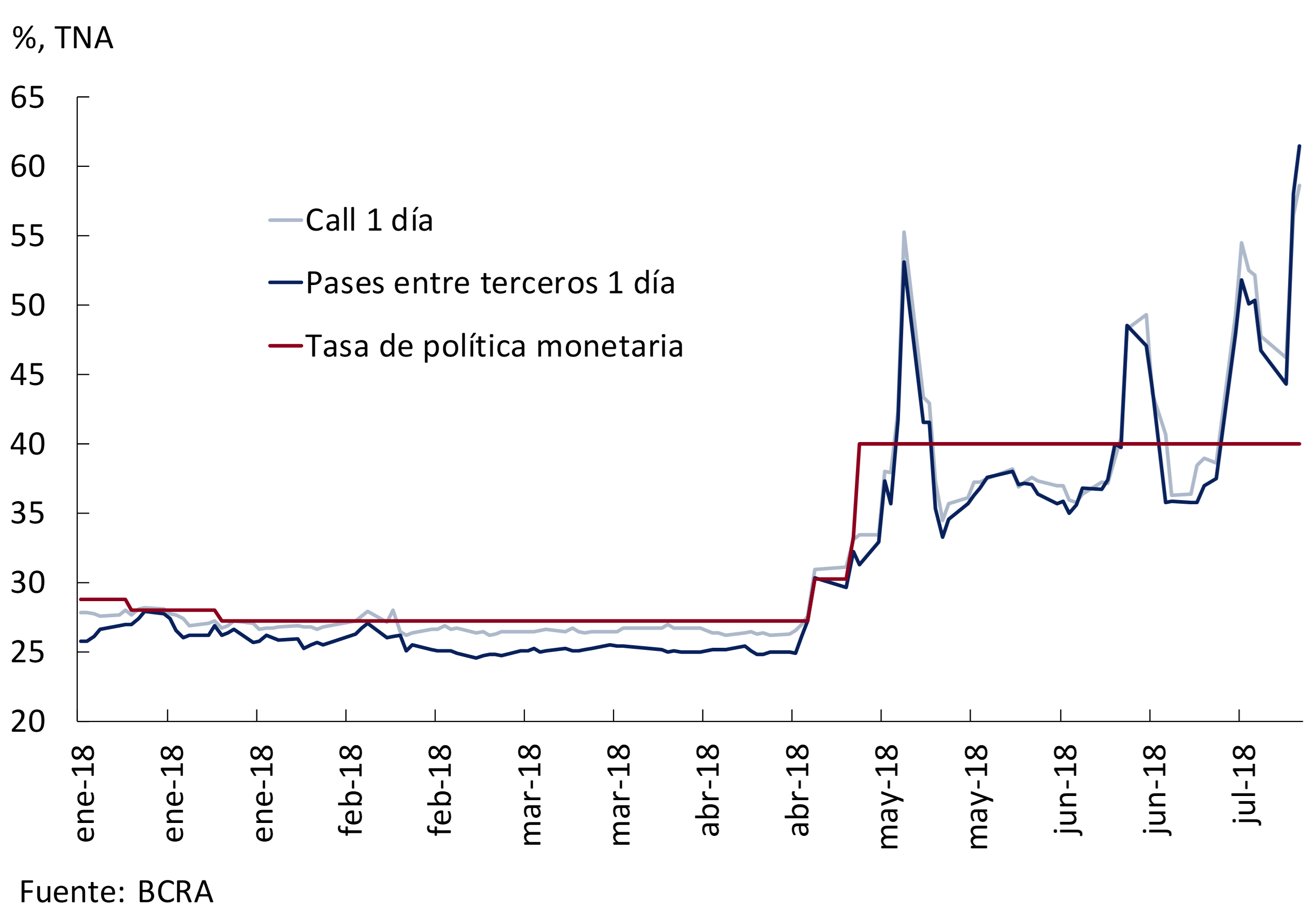

At the same time, the Central Bank increased the monetary policy rate (the center of the 7-day pass corridor) by 1,275 basis points on three occasions outside the meeting schedule, to 40% per year, in order to moderate the transfer of exchange rate movements to the rest of the economy’s prices. It also widened the rate corridor to allow domestic asset yields to respond more freely to high-frequency shocks. The first increase was on April 27, in which the policy rate was brought to 30.25% per annum. Then, on May 3, the Central Bank increased it to 33.25% annually, widening the distance between the monetary policy rate and the active pass rate by 500 basis points, so that the latter was set at 38.25%. Finally, on May 4, it decided to increase the monetary policy rate to 40%, expanding the corridor again (47% per year for the active pass and 33% per year for the passive pass), and defining the overnight trading rates at 57% per year for the active pass and 28% per year for the passive pass (see Figure 5.2).

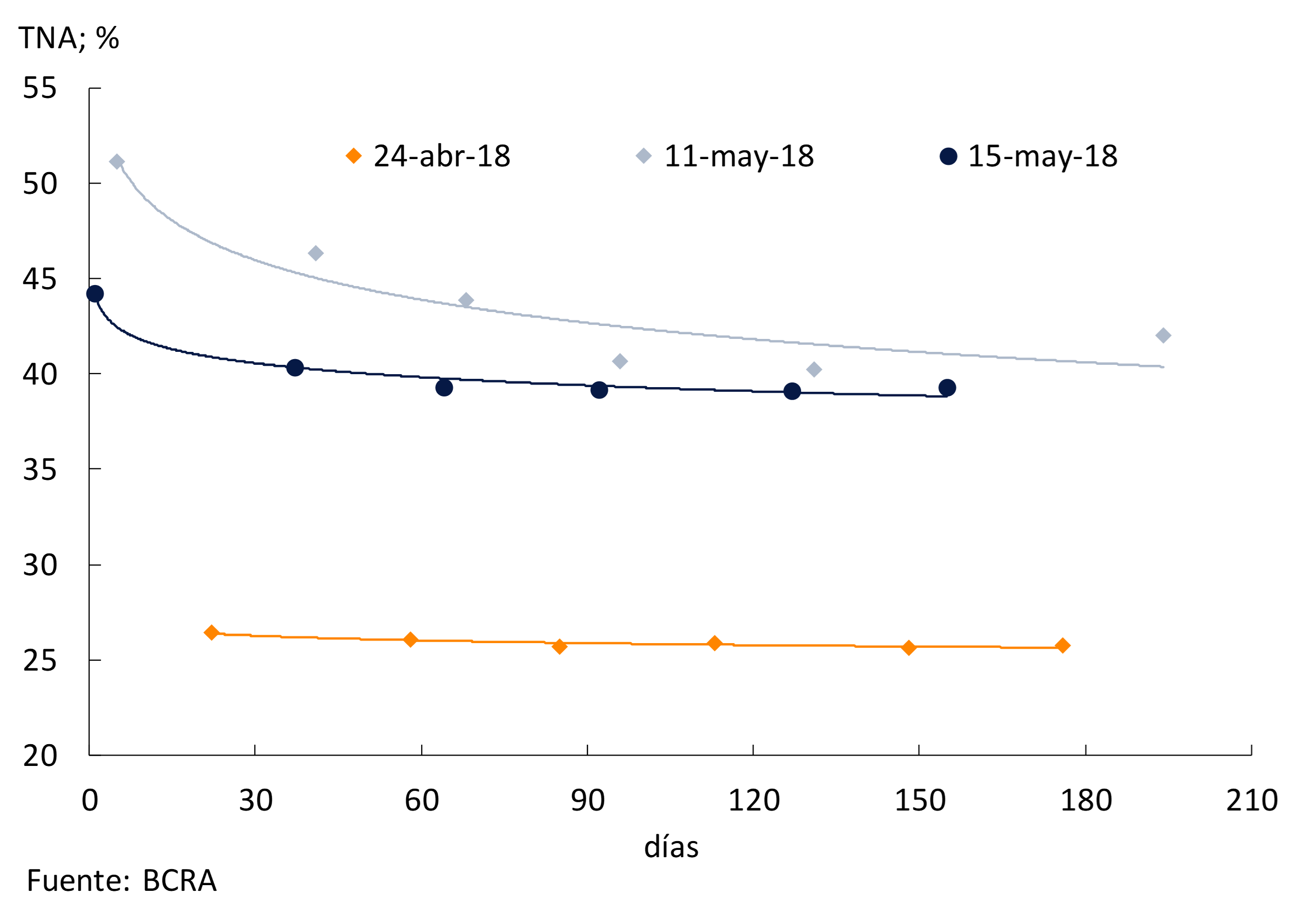

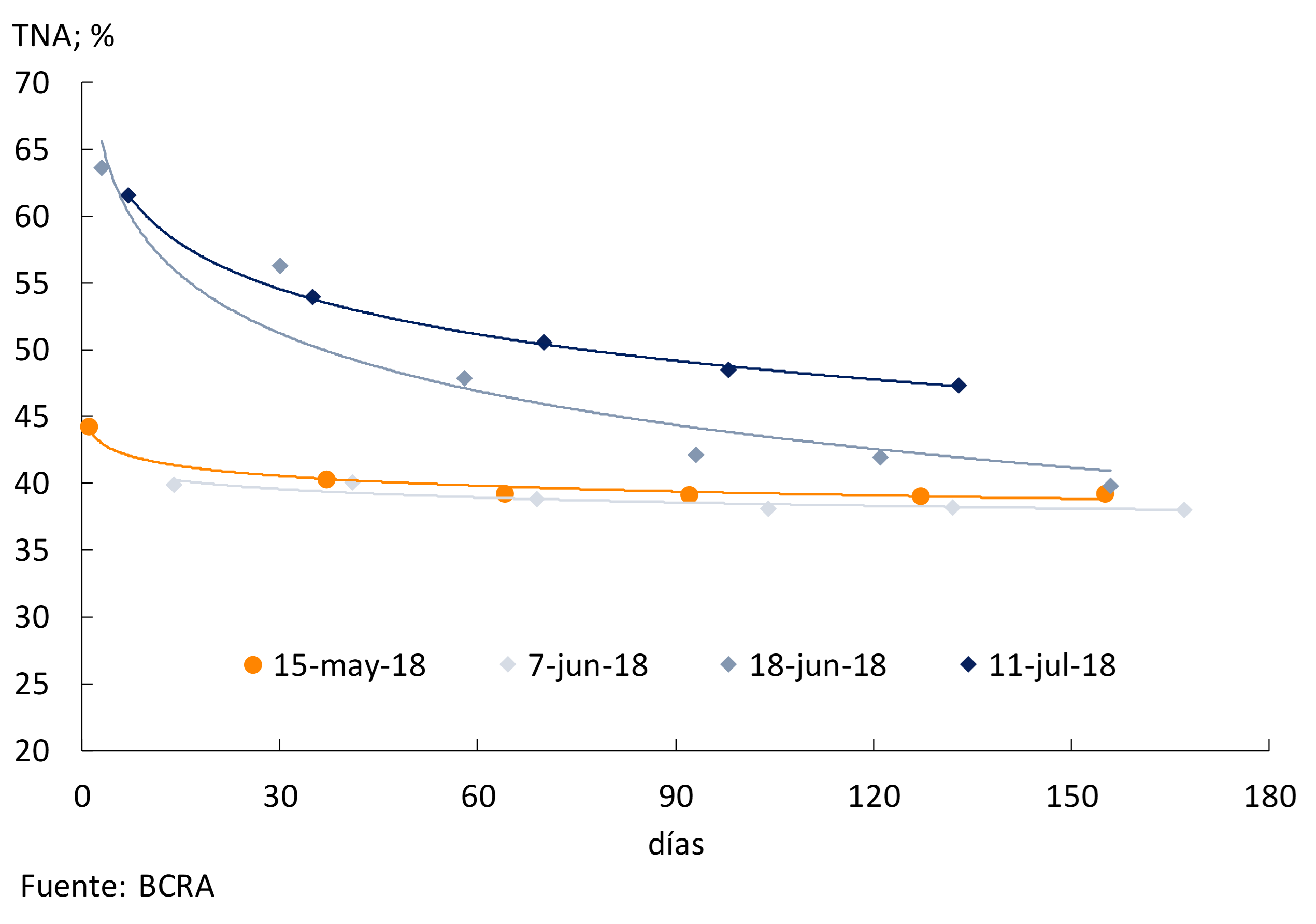

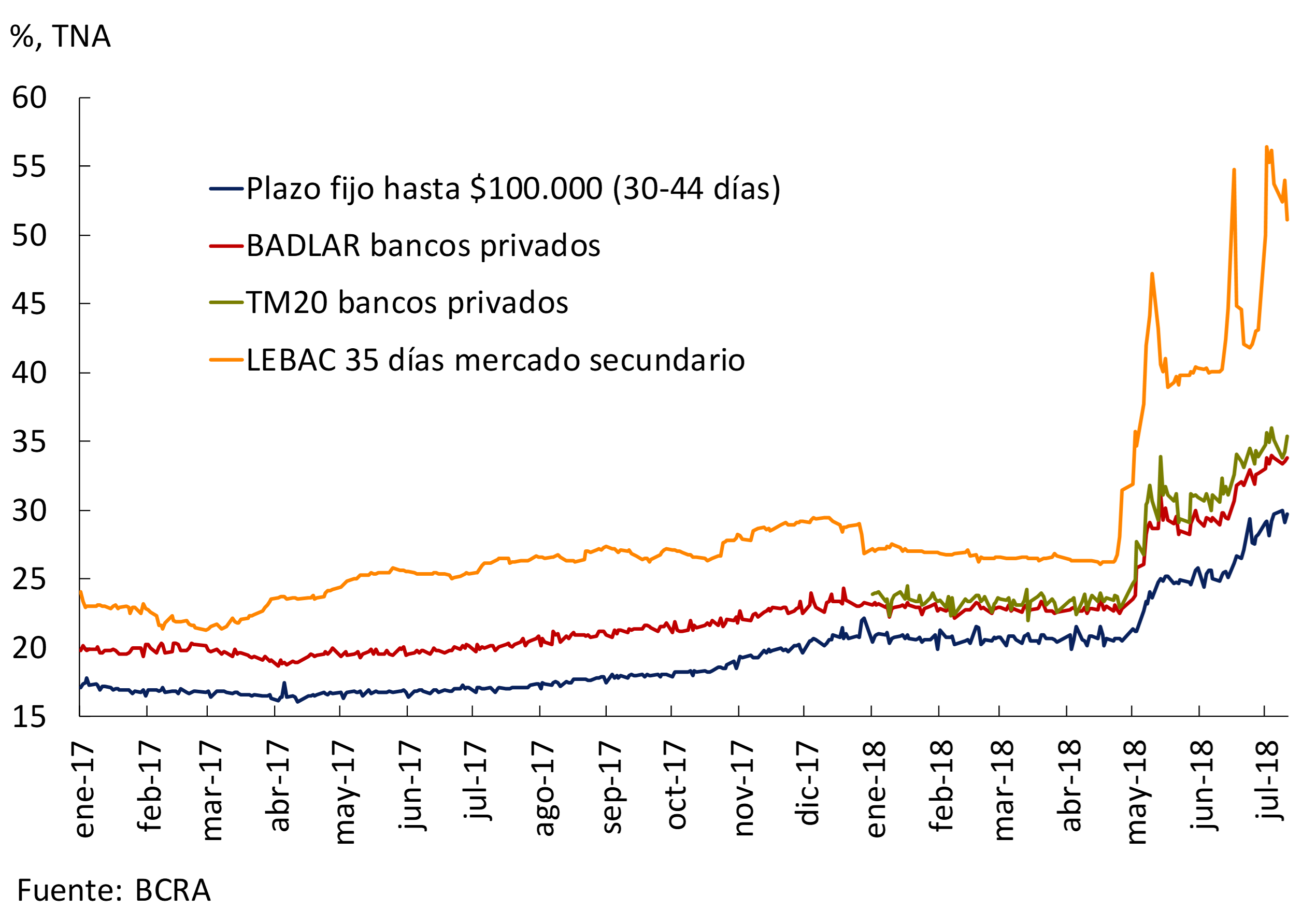

To ensure the transmission of the policy rate to the rest of the market rates, the Central Bank also operated in the LEBAC secondary market, carrying out purchase and sale operations of its securities (part of these operations also aimed to reduce the LEBAC maturities of mid-May). The yield curve on bills increased by 13 to 14 percentage points on average between late April and mid-May, peaking on May 11, especially in the short end of the curve, which saw increases of close to 20 basis points compared to the days prior to the onset of the exchange rate turbulence (see Figure 5.3).

In addition, the monetary authority restricted the positive net global position of foreign currency of financial institutions to a maximum of 10% of the computable equity liability in order to increase the supply of dollars (effective as of May 7); and began operating in the futures market, as of May 8, to reduce the interest rates implicit in this type of operation.

All this was complemented by an announcement by the Ministry of Finance of a reduction in the primary fiscal deficit in 2018 greater than originally planned (from 3.2% of GDP to 2.7% of GDP), made on May 4; and another from the Executive Branch to initiate negotiations with the IMF to ensure the financing of the national public sector in the coming years, held on May 8.

In this context, the market began to perceive with uncertainty the LEBAC auction of May 15, given the possibility of the non-renewal of a relevant portion of the maturity of bills, which was VN $615,877 million, equivalent to approximately half of the stock of said securities. The Central Bank’s strategy to address these doubts was to reach the day of the auction with the return of the shortest LEBACs at around 40% per year and the rates implied in the futures at consistent levels of arbitrage. It also presented the market with an offer of US$5,000 million to $25 million to contain the rise in the exchange rate, and relaxed the minimum cash requirement for May for financial institutions, taking the calculation from monthly to quarterly and eliminating the minimum daily integration in pesos during the same month in order to strengthen the renewal of LEBAC. In the tender, the total renewal of the maturities was finally achieved with cut-off rates in the secondary market levels.

This result, together with the monetary policy actions and the announcements of the previous days, restored calm to the foreign exchange market, which was maintained while negotiations with the IMF were underway. In that period, the Central Bank maintained the offer of US$5,000 million dollars at $25 without selling international reserves and, at the same time, kept the policy interest rate and the interest rate corridor unchanged. At the same time, it dedicated itself to taking pressure off the maturity of LEBAC on June 21, actively intervening in the LEBAC secondary market, mainly through the purchase of the shortest security, and to a lesser extent, carrying out bill swap operations.

5.2 Strengthening the inflation targeting regime

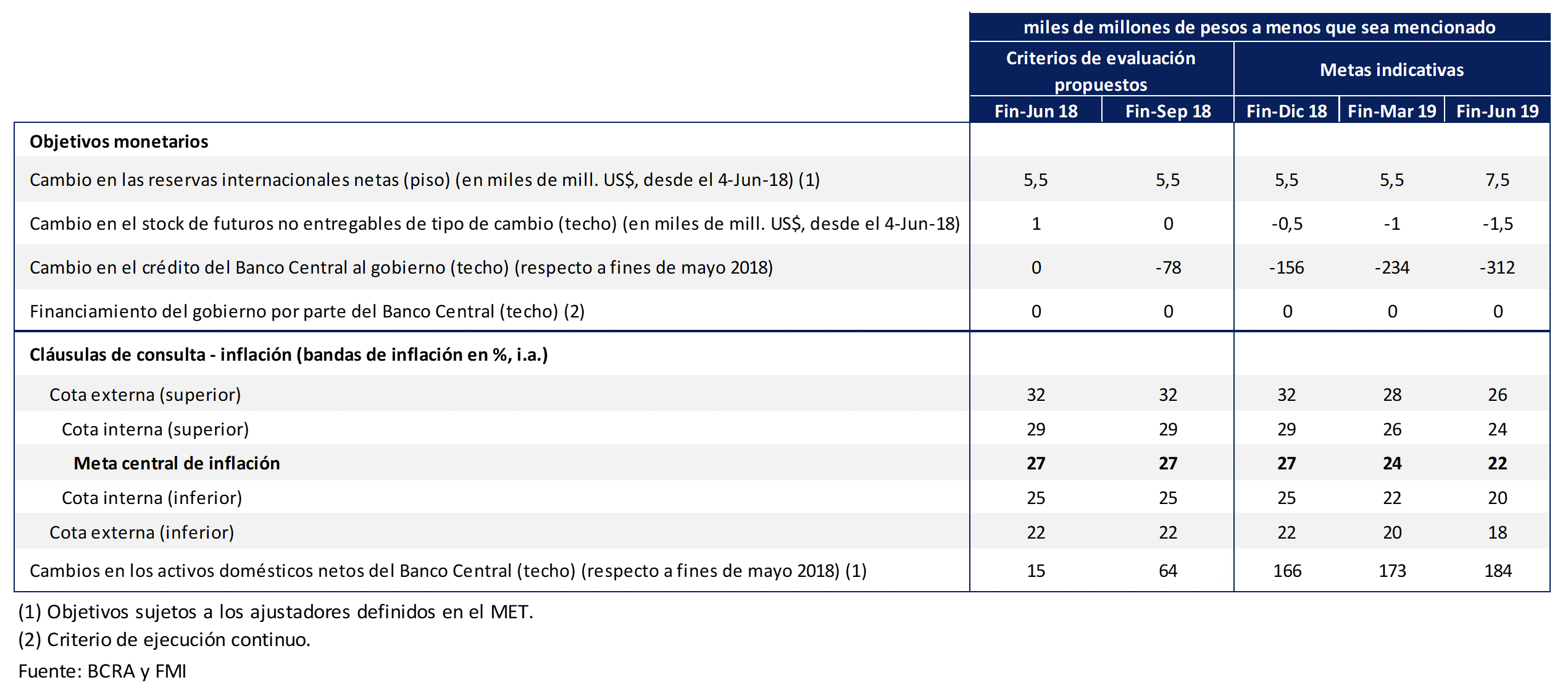

Negotiations with the International Monetary Fund that began in early May culminated on June 7 with a three-year Stand-By program for US$50 billion and with the commitment to deepen the economic reforms initiated in December 2015, accelerating the reduction of the imbalance in the public accounts and, in its monetary chapter, including a series of measures aimed at redoubling efforts to reduce inflation. Tables 5.1 and 5.2 show the quantitative and structural goals agreed with the multilateral organization, respectively.

5.2.1 The inflation targeting regime with a flexible exchange rate is maintained

In the new economic program, the inflation targeting regime with a flexible exchange rate is maintained, but new targets were defined for the coming years. The change in the international scenario, which led to a depreciation of the peso and an increase in the price of energy at the global level, prevented compliance with the current inflation target. This led to a redefinition of inflation targets for the coming years, which will be 17% in 2019, 13% in 2020, 9% in 2021, and 5% year-on-year in 2022 (as of December of each year) (see Figure 5.4). To ensure the consistency of the fiscal convergence program proposed in the agreement with the IMF with the disinflation path, the choice of the new targets was coordinated with the Ministry of Finance; This was due to the fact that some expenses are updated due to past inflation while revenues grow at the pace of current inflation.

For the period up to December 2019, bands were defined for the inflation target that may trigger different instances of consultation with the IMF (see Table 5.1). If the inflation rate is outside the inner band, the central bank should discuss with IMF staff the appropriate policy response, while if it were outside the outer band, consultation on the appropriate policy response should be conducted with the IMF board before the funds from the arrangement can be drawn. Likewise, to reinforce the commitment to the disinflation process, a ceiling was established for the change in net domestic assets (DNA), defined as the difference between the monetary base and the net international reserves (NIR) of the Central Bank, with respect to the level at the end of May 2018 ($432,900 million) (see Table 5.1). 22 If the ADNs exceed the established ceiling, the Central Bank must consult the IMF board regarding the economic policy response to be implemented before disposing of the funds of the agreement.

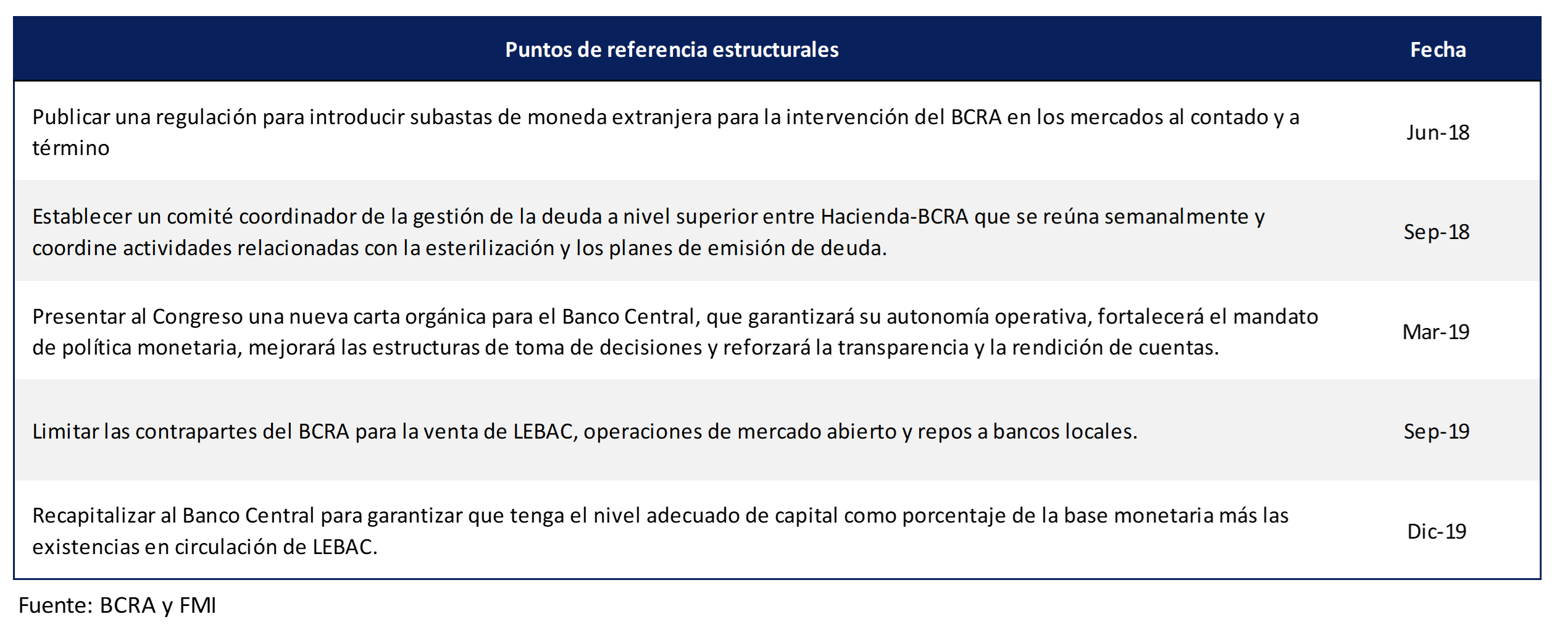

Table 5.1 | Quantitative Implementation Criteria and Monetary Consultation Clauses Agreed with the IMF

Table 5.2 | Argentina’s structural conditionalities associated with the Central Bank agreed with the IMF

With regard to exchange rate policy, the flexible exchange rate regime was maintained along with the possibility that the Central Bank may make limited interventions to moderate disruptive movements in the foreign exchange market that may affect financial stability or the path of disinflation.

Likewise, the medium-term objective of bringing international reserves to prudent levels given Argentina’s exposure to global current and capital account shocks is maintained, but with a different strategy than the previous one of reaching a level of international reserves of 15% of GDP. To this end, it was defined that net international reserves (NIR) do not fall below a certain floor, which in turn provides room for the decumulation of foreign currency in case of eventual periods of market volatility. Starting from a level of US$23,100 million as of June 4, the NIRs should show a cumulative increase of US$5,500 million until the first quarter of 2019 and US$7,500 million until the end of June 2019 (see Table 5.1), after incorporating the contribution to the BCRA from the International Monetary Fund. A ceiling was also defined for the evolution of the stock of non-delivery forwards from the level of June 4, which was at US$2,300 million (see Table 5.1). In the event that the required intervention in the foreign exchange market (spot and futures) is above what is consistent with this path, the appropriate economic policy response should be agreed with the IMF staff.

On the other hand, the Central Bank committed to introduce a foreign exchange auction mechanism to intervene in the spot and futures markets to be implemented in cases where clear signs of dysfunctionality are observed in terms of price differential, volume or volatility in the foreign exchange market (structural target for the program with the IMF; see Table 5.2). In addition, it was agreed that the Central Bank would be the executor of a program to sell in the market part of the IMF’s budgetary assistance to finance the Treasury’s obligations denominated in pesos, under the modality of previously announced daily foreign currency auctions.

At the same time, in order to strengthen the inflation targeting regime, a series of measures were defined that aim to deepen the operational and financial autonomy of the Central Bank, to clean up its balance sheet and to promote greater transparency in the preparation of its financial statements, which are detailed below.

5.2.2 Operational and financial independence of the Central Bank

It is essential that the monetary authority allows the population to trust that its decisions are credible and stable in the medium and long term. An important factor contributing to achieving such credibility is the institutional, functional and financial independence of the monetary authority. There is consensus about its relevance as one of the fundamental institutional characteristics for a good implementation of economic policy. In fact, in recent years, a significant number of countries have modified the regulations of their central banks in terms of their independence and the strengthening of it.

A very relevant point in this regard, and which has already begun to be implemented, is the elimination of all direct or indirect financing from the Central Bank to the Treasury (transitory advances, transfer of profits, purchase of government securities in the primary market or for purchases from public institutions), limiting the transfer of profits only to those that have been made and when the Central Bank has an adequate level of capitalization. This will be consolidated in the draft reform of the Central Bank’s Charter that the Executive Branch will send to Congress before March 2019 (it is a structural goal of the program with the IMF; see Table 5.2).

In addition, the reform project will include the following points: a) strengthening price stability as the main mandate of the Central Bank, b) setting inflation targets by the monetary authority three years in advance and prior consultation with the Ministry of Finance, c) establishing an instance of explanation of the authorities of the Central Bank before Congress and the President of the Nation through a public letter whenever there is a deviation from the objectives set, d) define strict limits on the reasons why the President, the Vice President and the Directors of the monetary authority can be removed from their posts, e) reestablish international accounting standards to ensure transparent reporting of the Central Bank’s balance sheet, and (f) establish that international reserves can only be used to implement exchange rate and monetary policies.

5.2.3 Strengthening the Central Bank’s balance sheet

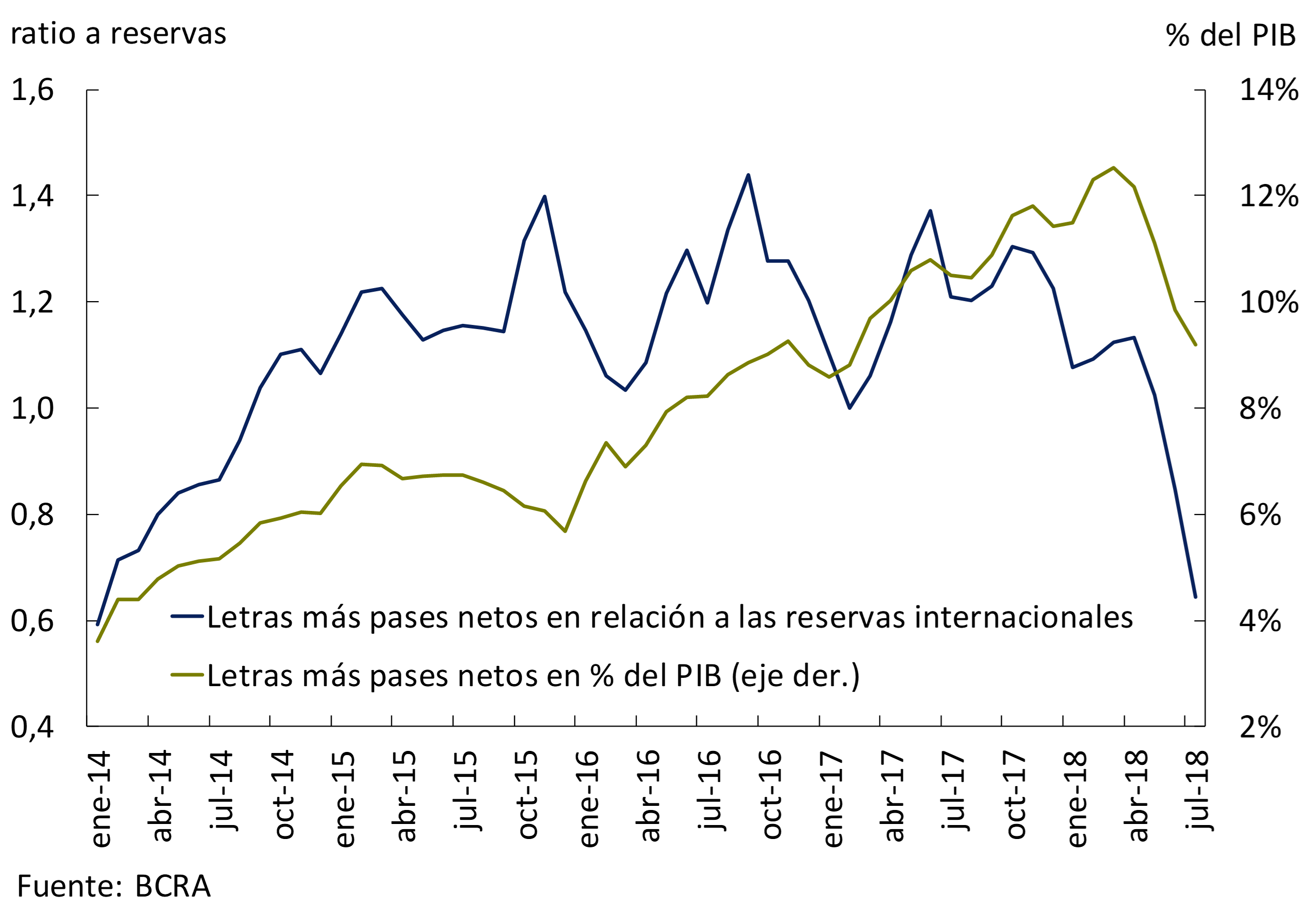

The Central Bank’s balance sheet includes a stock of interest-bearing liabilities (LEBAC, LELIQ and net passes) that at the end of May reached 10.8% of GDP. These liabilities arose as a result of the sterilization of fiscal deficits until December 10, 2015, the sterilization of monetary surpluses from exchange restrictions and losses from sales of dollar futures contracts prior to December 10, 2015, and the acquisition of reserves by the monetary authority as of December 10, 2015.

In the recent episode of exchange rate turbulence, this level of the stock of remunerated liabilities generated concern among economic agents regarding their risk of renewal, with which the Central Bank will seek to reduce the weight of these liabilities on its balance sheet, basically, through three measures: the end of the direct and indirect financing of the Central Bank to the Treasury, which will result in lower sterilization needs, the gradual cancellation of non-transferable bills by the Treasury, which will grant funds to the monetary authority to buy LEBACs, and the use of other genuine resources for this same purpose when they are available.

With regard to the first measure, for this year the transfers agreed with the Treasury in terms of transitory advances and transfers of profits amounted to $140,000 million (1.1% of GDP), in 2019 they were going to reach $70,000 million (0.5% of GDP) and, as of 2020, a figure equivalent to the real growth in the demand for money. which in practice amounted to a seigniorage rule based on multiplying economic growth by the monetary base (0.3% of GDP in 2020). In this context, on June 7, the end of transfers to the Treasury for transitory advances and remittance of profits was ordered (this is a criterion for the quantitative execution of the program with the IMF; see Table 5.1), which means that the $70,100 million that remained for this year will not be transferred. This will help to reduce the Central Bank’s sterilization needs and, consequently, to moderate the increase in the stock of interest-bearing liabilities.

By December 2019, the government committed to providing financial autonomy to the Central Bank, with an adequate level of capital (see Table 5.2). As part of this process, the Ministry of Finance intends to gradually repurchase, according to current financial conditions, a significant portion of non-transferable bills held by the Central Bank of up to US$25,000 million as of May 2021 (see Table 5.1). These bills are Treasury liabilities denominated in dollars, pay a low interest rate (the interest rate accrued by the BCRA’s international reserves for the same period and up to a maximum of the annual LIBOR rate minus one percentage point) and are illiquid, since they cannot be traded in the market. Its appearance on the Central Bank’s balance sheet was due to the transfer of international reserves to the Treasury through the successive Deleveraging Funds created between 2010 and 2015. They accumulated a maximum of US$65,000 million within the assets of the Central Bank in November 2015. In December of the same year, an exchange of US$16,000 million was made for BONAR 2022, BONAR 2025 and BONAR 2027 to strengthen the balance sheet (by incorporating instruments with better issuance conditions and that could be traded in the market), so that as of May of this year they totaled about US$49,000 million (7.8% of GDP).

To pay off part of these bills in advance, the Treasury will issue short- and medium-term debt in pesos. With the pesos obtained by the cancellation of these bills, the monetary authority will buy LEBAC in the market, with which the circulating stock of these securities will fall. Thus, the Treasury will become an important source of monetary absorption and the short-term debt of the Central Bank will be transformed into longer-term Treasury debt. To facilitate this process, a debt management coordinating committee will be established with senior officials from the Ministry of Finance and the Central Bank that will meet weekly and coordinate activities related to sterilization and debt issuance plans (this is a structural goal of the IMF program; See Table 5.2). In addition, the Central Bank will limit the counterparties of its debt securities with local banks only by the end of September 2019 (another structural goal of the program with the IMF; See Table 5.2).

In the agreement with the IMF, these measures were embodied in two quantitative execution criteria, one that reflects the end of net financing to the government (transitory advances, anticipated and unrealized profits, purchase of debt in the primary market or by purchases from other public institutions) and a desired path of reduction of the stock of credit from the Central Bank to the government. which includes government securities, non-transferable bills and transitory advances, for the equivalent in pesos of US$3,125 million per quarter until the end of June 2019 and then the same amount per semester until the end of April 2021, until accumulating US$25,000 million at the end of May 2021 (see Table 5.1).

5.3 Exchange rate turbulence continued in June-July

After the announcement of the agreement with the IMF, in early June, the Central Bank withdrew the offer of US$5,000 million at $25 from the foreign exchange market and maintained the monetary policy rate at 40% at the June 12 meeting (although it reduced the width of the 7-day pass corridor from 1,400 to 600 basis points and the 1-day trading corridor from 2,900 to 1,000 basis points). However, the return of the exchange rate turbulence in the following days led a new administration of the Central Bank to take additional measures to moderate the rise in the exchange rate, absorb liquidity in pesos through higher bank reserve requirements, allow consistent increases in LEBAC rates, and provide dollars to the market in the form of an auction in the event of episodes of illiquidity or obvious disruption.

First, the monetary authority allowed LEBAC rates to rise in the secondary market in order to make speculative financing more expensive, which was reflected in an increase in the yield curve of Central Bank securities, especially in the shortest tranche (see Figure 5.5). Thus, the yield of the 35-day LEBAC went from 40.0% to 51.1% annually between June 7 and July 12, accumulating a 25 p.p. increase since the beginning of the exchange rate volatility episode at the end of April (see Figure 5.12).

On the other hand, the monetary authority implemented the mechanism to carry out cash foreign currency purchase and sale operations through tenders that had been agreed with the IMF, and which began with the proposal of two daily auctions of US$400 million. 23 Likewise, it reduced the limit of the positive net global position of foreign currency from 10% to 5% of the computable equity liability of the entities (PGN), in order to increase the supply of dollars in the foreign exchange market, allowing the PGN to be increased up to 30% if the excess is integrated with National Treasury Bills in foreign currency. 24

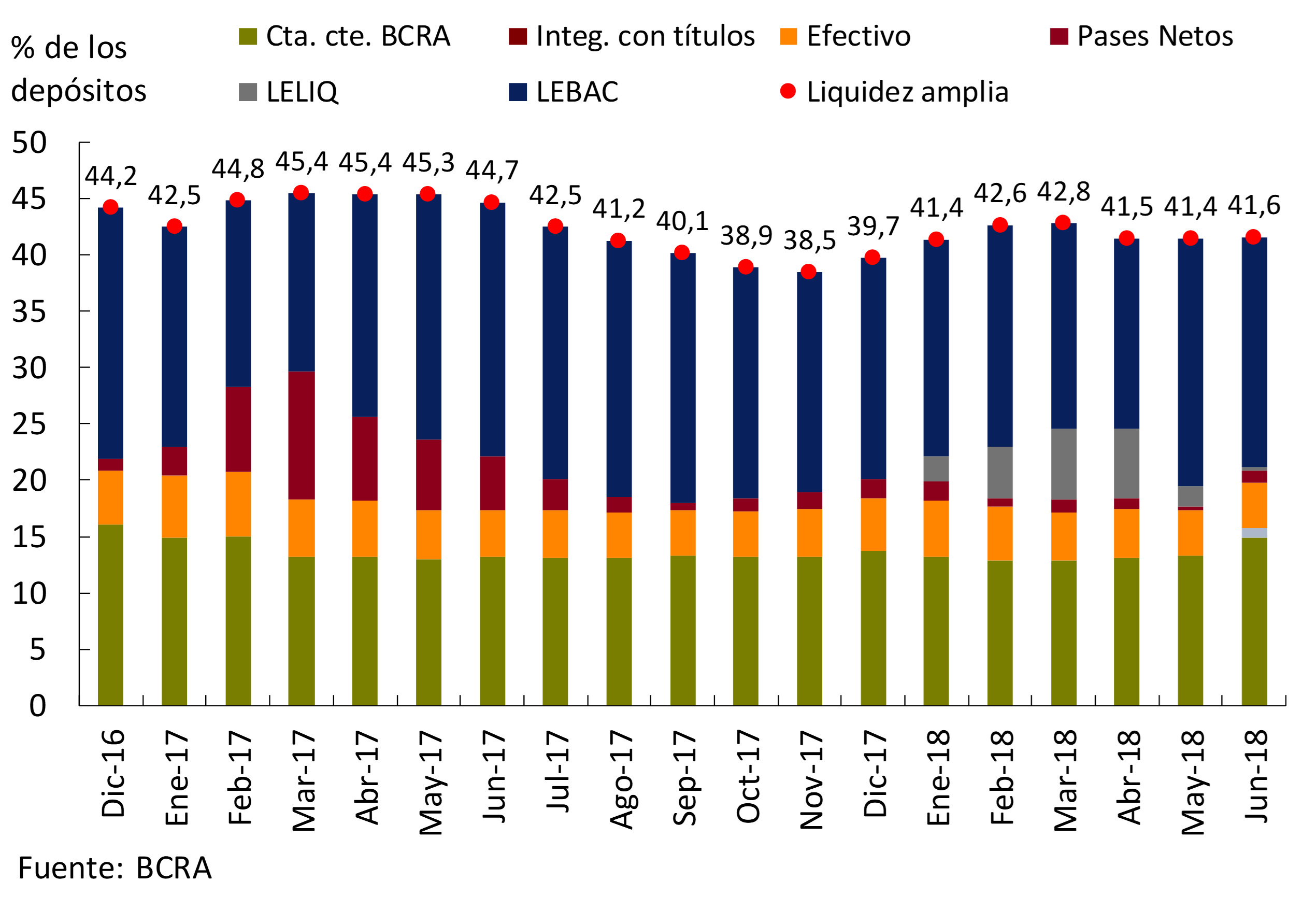

The Central Bank also decided to raise bank reserve requirements by 5 percentage points for demand and time deposits in pesos (3 p.p. on June 21 and 2 p.p. on July 18), in order to withdraw liquidity from the market, allowing financial institutions to integrate this increase with cash or through fixed-rate National Treasury Bonds in pesos maturing in November 2020. Then, at the beginning of July, it ordered an additional 3 p.p. increase in bank reserve requirements on the same types of deposits, but to be integrated only with current account funds. The total expected effect of liquidity absorption would be in the order of $160,000 million. 25

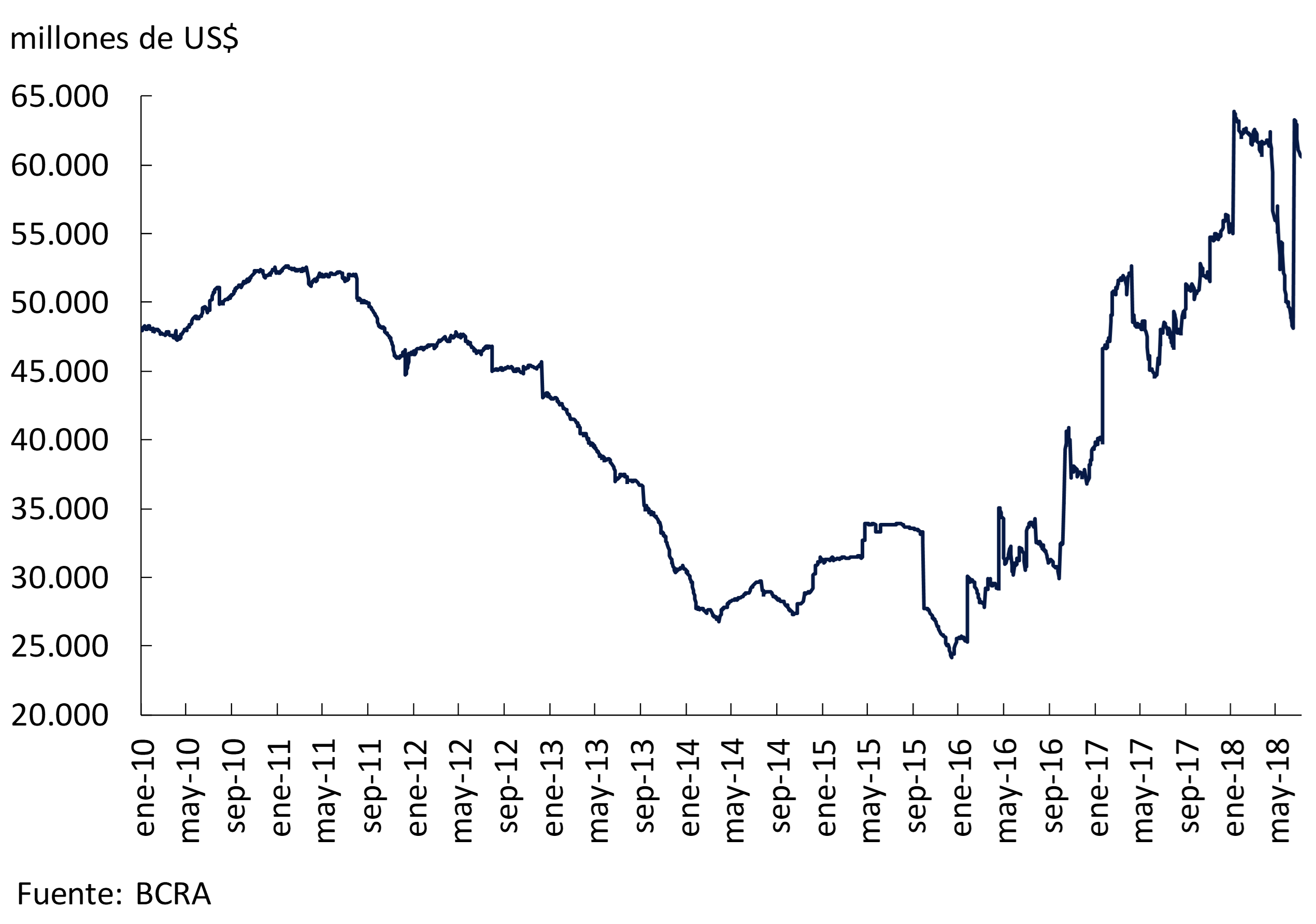

At the same time, on June 20, the IMF board approved the Stand-By arrangement, which enabled the disbursement of the first US$15 billion, of which US$7.5 billion was allocated to budget support and the rest to strengthen the Central Bank’s assets (the rest of the loan tranches are precautionary). Thus, the monetary authority’s international reserves, which had fallen by US$15.348 billion since the beginning of the year, mainly due to foreign exchange interventions (US$11.135 billion) and sales of foreign currency by the Treasury (US$4.171 billion), increased to US$63.274 billion on June 22 with the first tranche of multilateral loan funds (see Figure 5.6).

At the same time, the program of daily tenders, which had been agreed with the IMF, was implemented to sell the total of the US$7,500 million received by the Treasury while it obtained resources in domestic currency to meet its needs. The initial schedule called for the sale of US$100 million per day for 75 business days, which was increased to US$150 million on some occasions in strict reflection of the Treasury’s cash needs (see Figure 5.2).

This set of measures stabilized the foreign exchange market. Thus, since the beginning of the exchange rate turbulence at the end of April, the nominal exchange rate has increased 36%, accumulating a 47% increase so far this year. Thus, the level of the multilateral real exchange rate was above the highest since the lifting of exchange restrictions in March 2016 and approached a level not recorded since November 2011 (with the exception of the peak of the devaluation in early 2014, see Figure 5.7). This increase in the real exchange rate facilitates the adjustment of the external accounts, with a lesser impact on the level of activity than would be required by a scheme with a more rigid exchange rate policy.

For its part, the real interest rate (ex ante) reached maximum levels during the exchange rate episode (see Figure 5.8). 26 In June, it more than doubled the level of March this year and exceeded the peak of December last year, marking the contractionary bias of monetary policy aimed at moderating the impact of the rise in the exchange rate on domestic inflation.

5.4 Changes in the implementation of monetary policy

At the beginning of July, the new authorities of the Central Bank defined a series of changes in the implementation of monetary policy, within the inflation targeting scheme with a flexible exchange rate. In the transition to single-digit inflation rates, the inflation targeting scheme with the interest rate as the only monetary policy instrument will be reinforced by a more attentive monitoring of monetary aggregates. In this sense, the recent decisions to increase legal reserve requirements and to gradually reduce the weight of the Central Bank’s remunerated liabilities (net passes, LELIQ and LEBAC) aim precisely to generate greater control over liquidity in a broad sense.

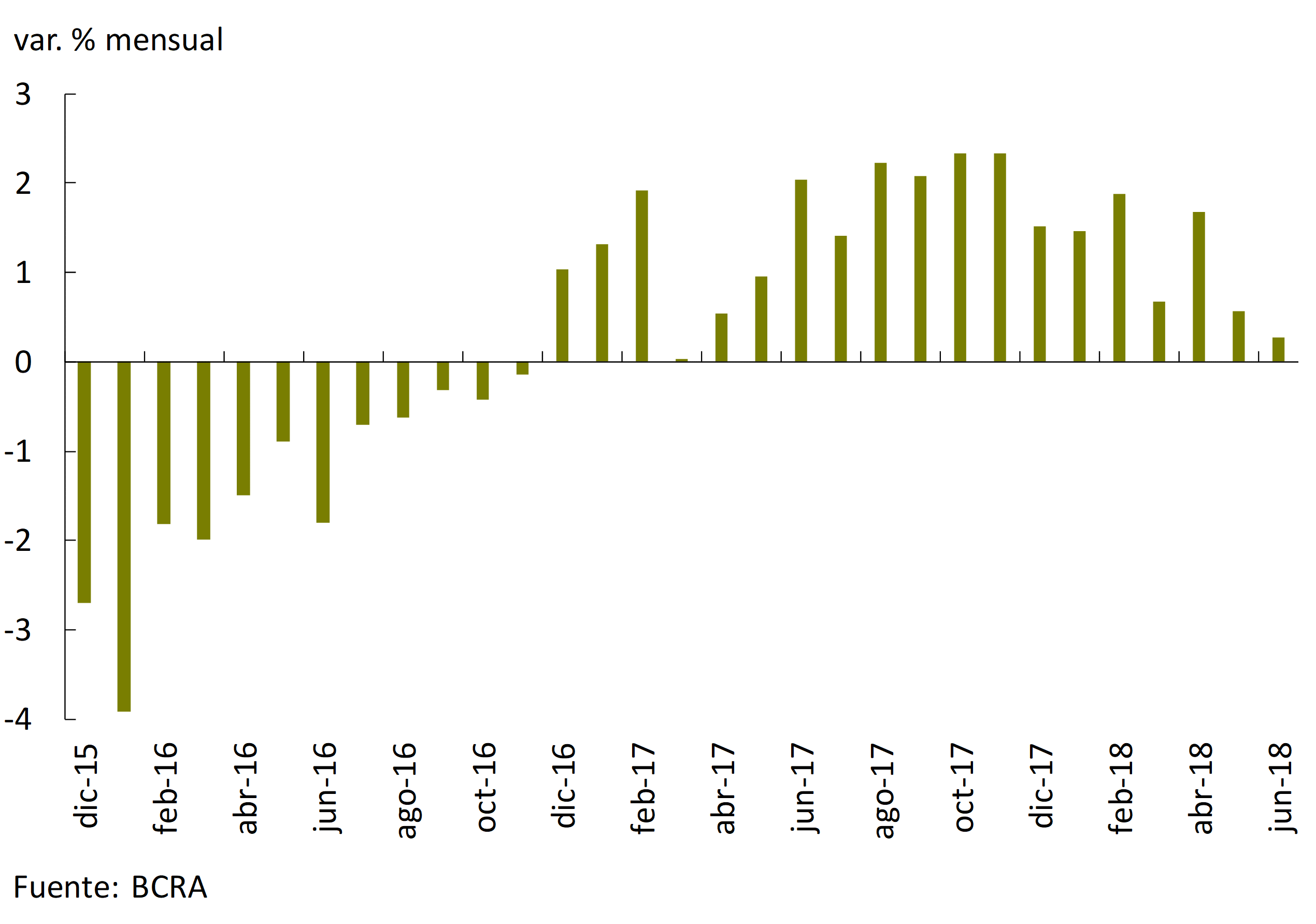

Thus, private M2 in pesos registered a year-on-year growth of 23.6% in June, below the inflation of the last twelve months, while in the same month last year it expanded to 35.3% y.o.y. (see Figure 5.9). Another relevant addition to monitor is the monetary base, since it is a measure of liquidity over which the Central Bank has the ability to exercise greater control. Although this aggregate showed a growth rate of 31.5% year-on-year in the same month, it should be taken into account that this dynamic was influenced by the reserve increases recently defined by the Central Bank. For this reason, the monetary authority began to monitor a broad monetary base, which includes all the monetary authority’s liabilities to banks (net passes, LELIQs, and LEBACs held by banks), which showed a sharp slowdown in recent months, going from a year-on-year growth of 38.3% in June 2017 to 25.0% in June of this year (see Figure 5.9).

With regard to the Central Bank’s remunerated liabilities, its stock began to shrink as a result, mainly, of the purchases made by the monetary authority in the secondary market and the latest LEBAC auctions. Thus, it fell by $323.446 billion in nominal terms between the end of March and the beginning of July, which in terms of international reserves resulted in a contraction from 1.15 to 0.64 and in terms of GDP from 12.5% to 9.2% (see Figure 5.10).

Figure 5.10 | Remunerated liabilities of the Central Bank in relation to international reserves and GDP