Política Monetaria

Monetary Policy Report (IPOM)

Third quarter

2019

Quarterly report presenting the macroeconomic analysis and monetary policy guidelines of the BCRA.

Table of Contents

Chapters

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlook

2. International context

3. Economic Activity and Employment

4. External Sector

5. Public Finance

6. Prices

7. Monetary Policy

Sections

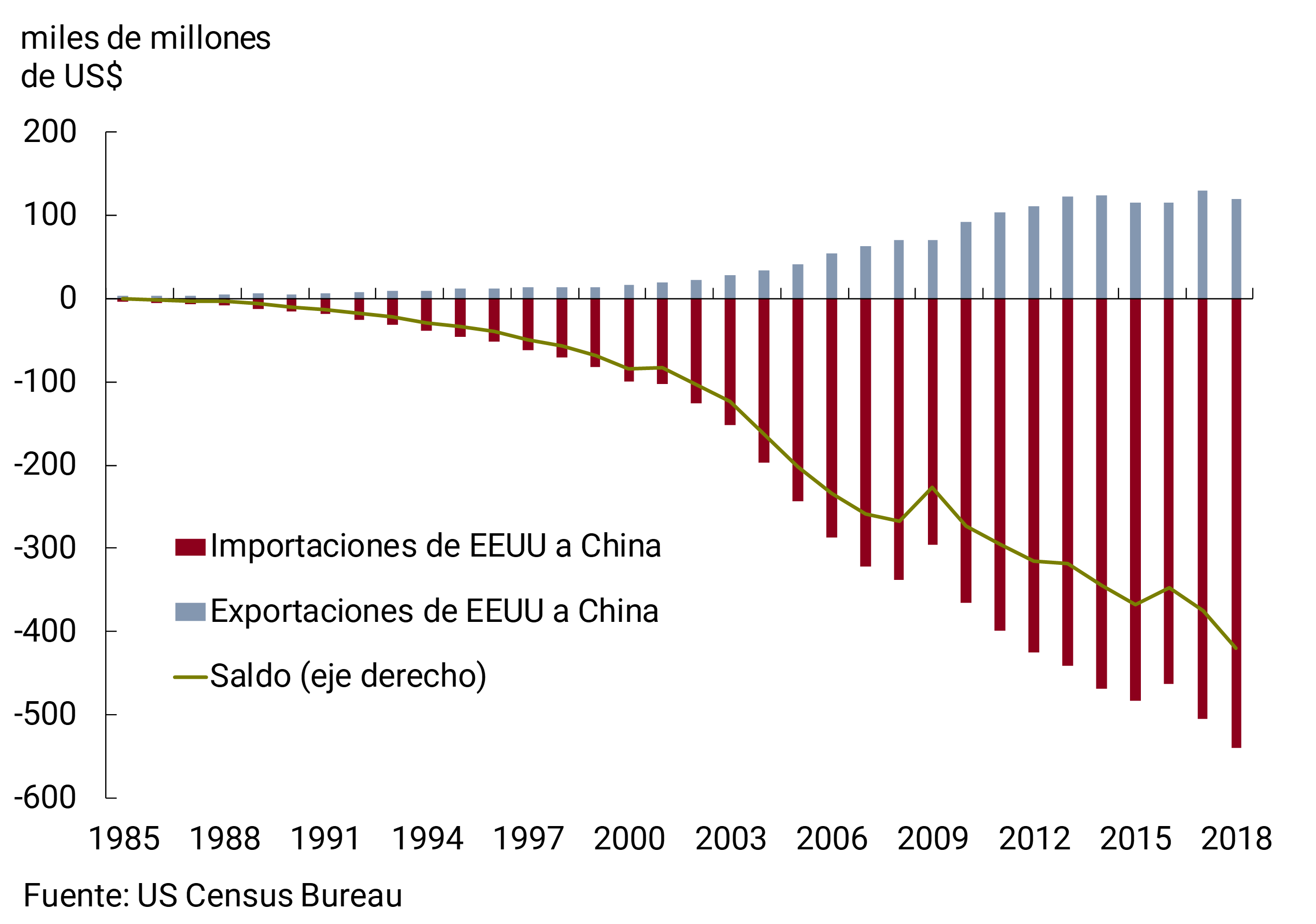

1. The trade war between the United States and China

2. Section 2 / Agricultural Harvest 2018/19

3. Nine months of operation of the monetary

aggregate scheme 4. The goal of zero growth of the monetary base and the seasonal behavior of demand

5. Effects of the new online fixed-term operation for non-customers

Glossary of abbreviations and acronyms

For inquiries, write to analisismacro@bcra.gob.ar

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlook

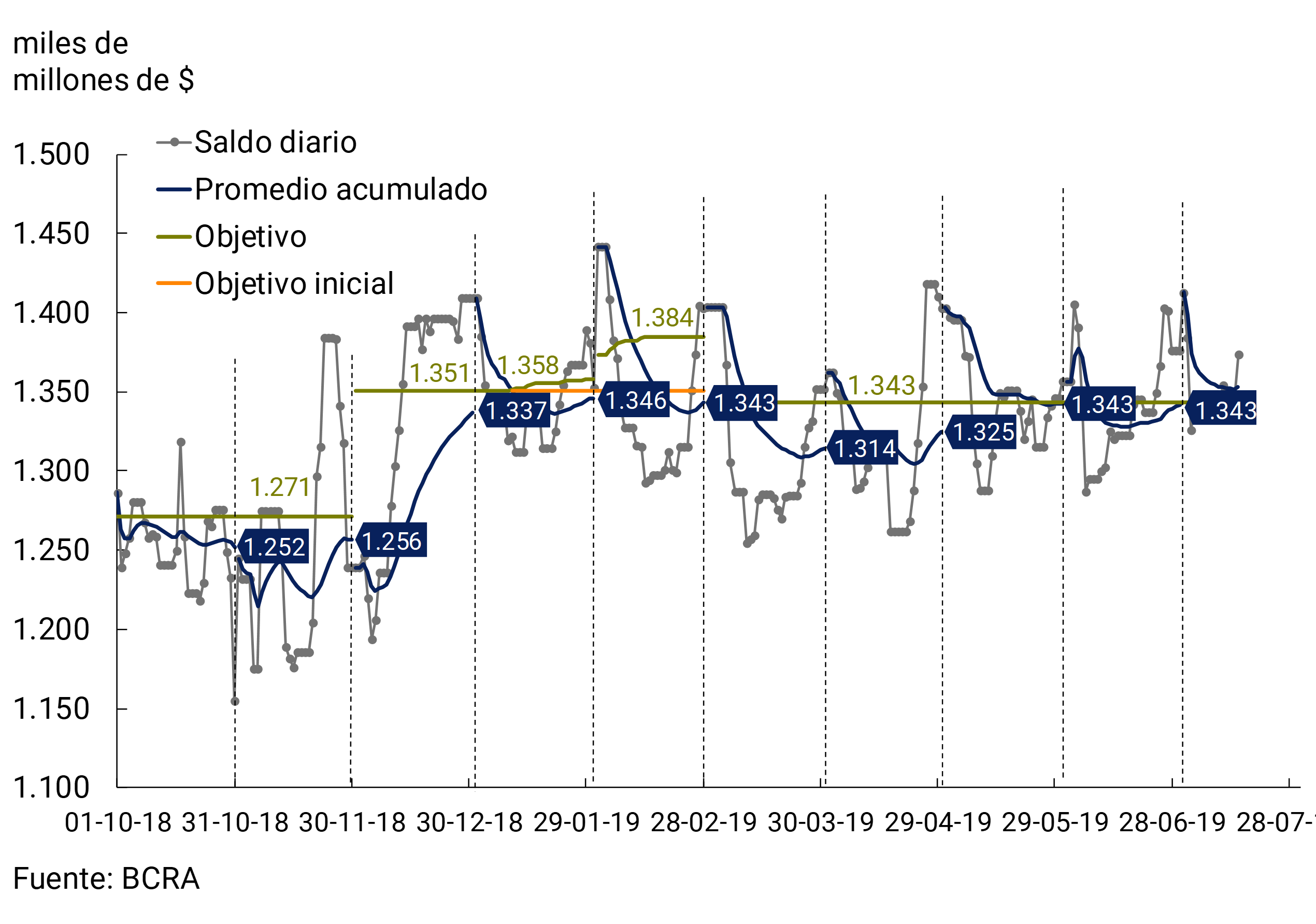

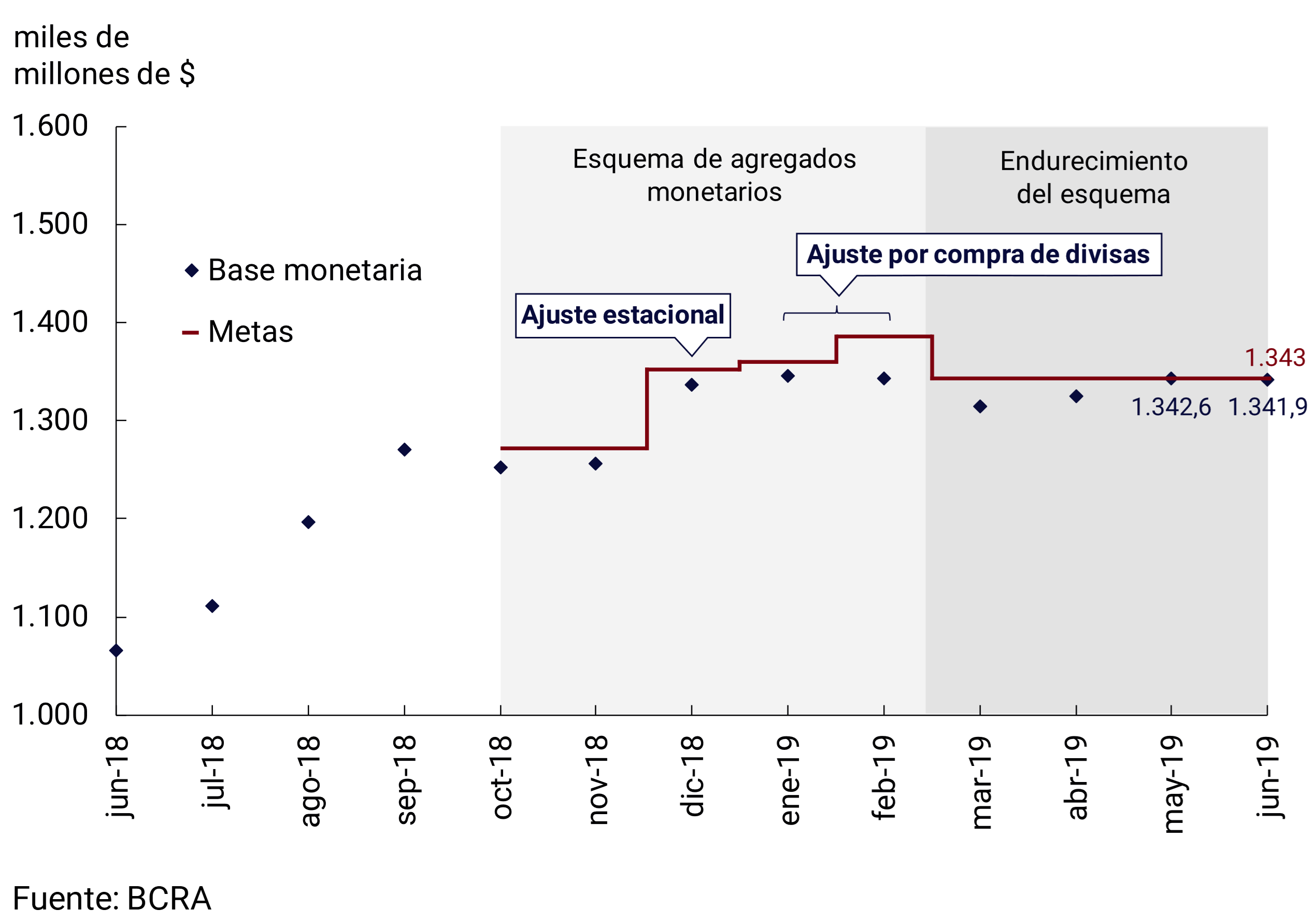

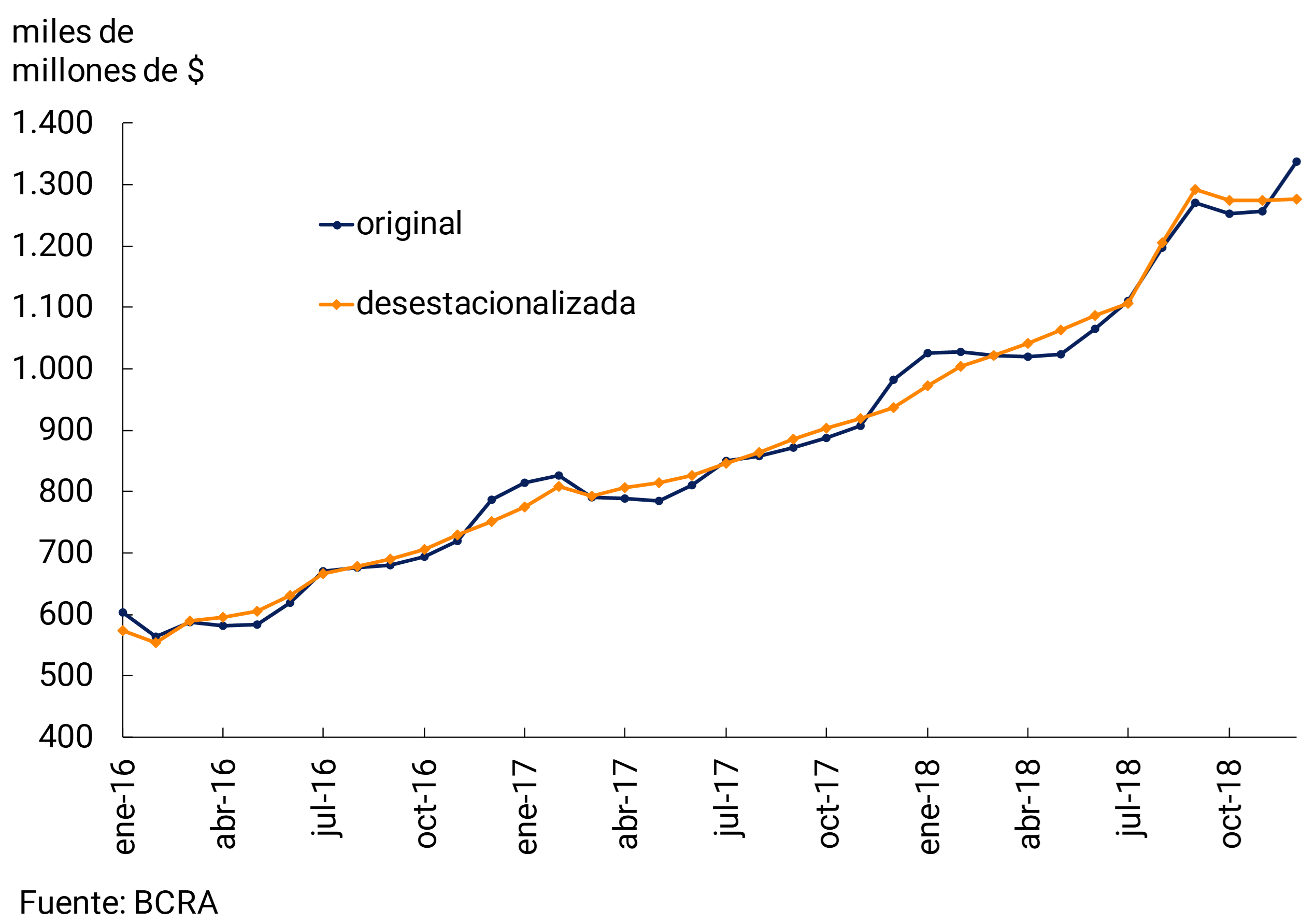

Since October 2018, the Central Bank of the Argentine Republic has been carrying out a scheme based on strict control of the monetary base and the definition of an exchange rate reference zone (formerly called the foreign exchange non-intervention zone). During the second quarter of the year, the Central Bank continued to meet its goal of zero growth of the monetary base (WB) every month, which remained at $ 1,343.2 billion.

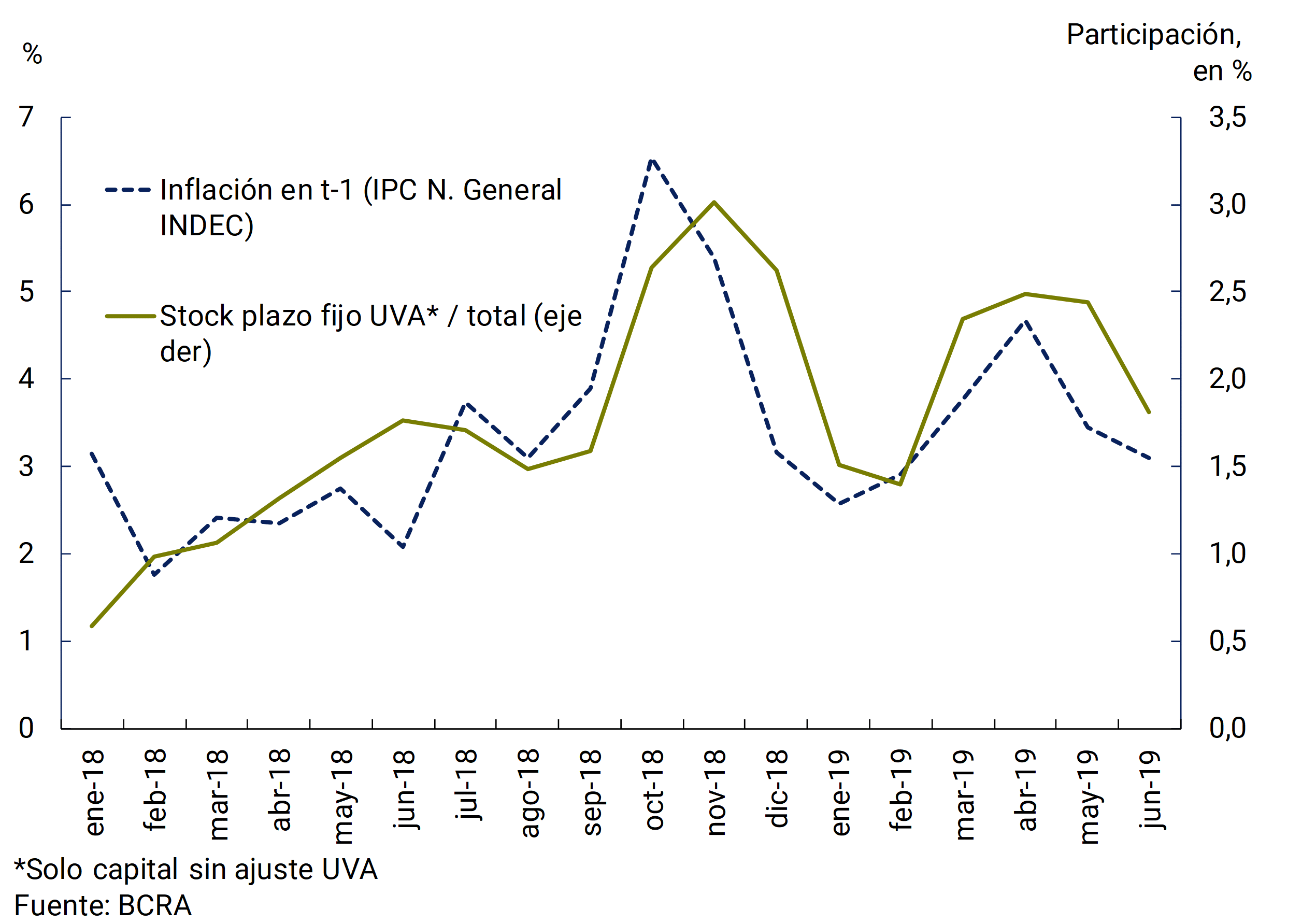

The monetary aggregate scheme reduced the nominal volatility recorded until the third quarter of last year, and inflation began to decline from the peak of 6.5% per month recorded in September 2018. However, during the first quarter of 2019, the concentration of increases in regulated prices, to which were added the lagged effects of the exchange rate depreciation of 2018 and a new episode of exchange rate volatility, caused inflation to rise again.

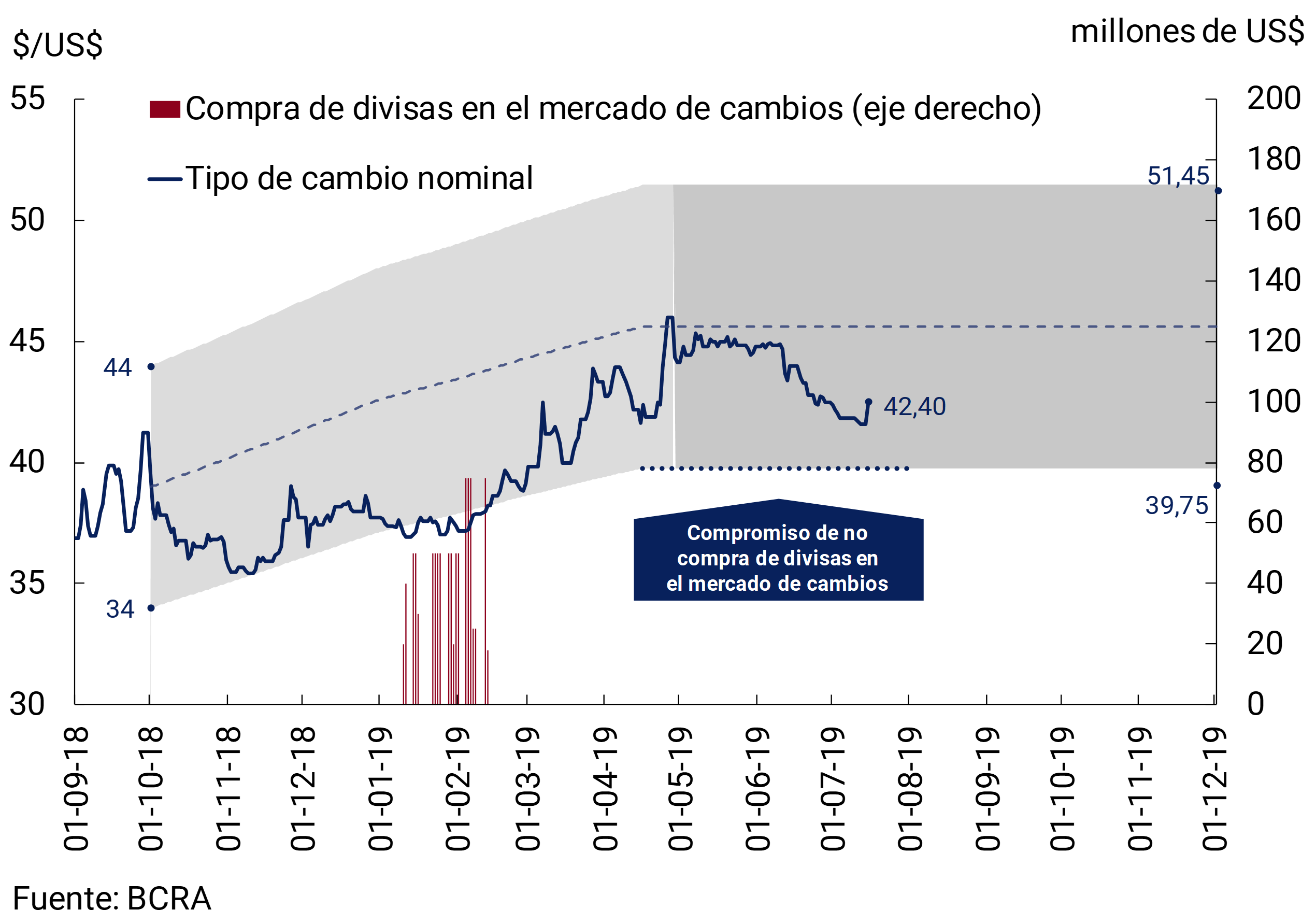

Faced with this situation, the Monetary Policy Committee (COPOM) took a series of additional measures during March and April 2019 to strengthen the monetary-exchange rate scheme: 1) it reduced the monetary base target by $43 billion, eliminated the seasonal adjustment of the target set for June and extended the commitment to zero growth of the monetary base to all of 2019, initially planned until June 2019; 2) established a minimum reference interest rate; (3) set the growth of the limits of the exchange reference zone at zero, leaving the upper limit constant at 51.448 pesos per dollar and the lower limit at 39.755 pesos per dollar until the end of the year, and decided to refrain from buying foreign currency if the exchange rate was below the reference zone; and 4) it provided that foreign currency sales may be made in the foreign exchange market in the event of episodes of excessive volatility, even if the exchange rate is within the reference zone (see section 3).

The measures adopted and the maintenance of a contractionary monetary policy, in a context of better international conditions, stabilized the foreign exchange market and inflation expectations, allowing inflation to resume its downward path since April. This in turn led, together with a series of measures implemented by the Executive Branch to shore up household spending, that economic activity continued with the recovery that began in December.

In an environment of lower nominal volatility and falling inflation expectations, the nominal interest rate of the LELIQ showed a downward trend since the beginning of May, reaching the minimum level of 62.5% that had been established since April and until the end of June. To guarantee the contractionary bias of its monetary policy, and in a cautious attitude in the face of possible episodes of uncertainty, the COPOM reduced the floor of the benchmark interest rate to 58% during July. This reduction recognizes that there has been a drop in inflation and inflation expectations in recent months, but at the same time recognizes that the economy is still going through a period of uncertainty. This ensures that the real interest rate remains at positive high levels.

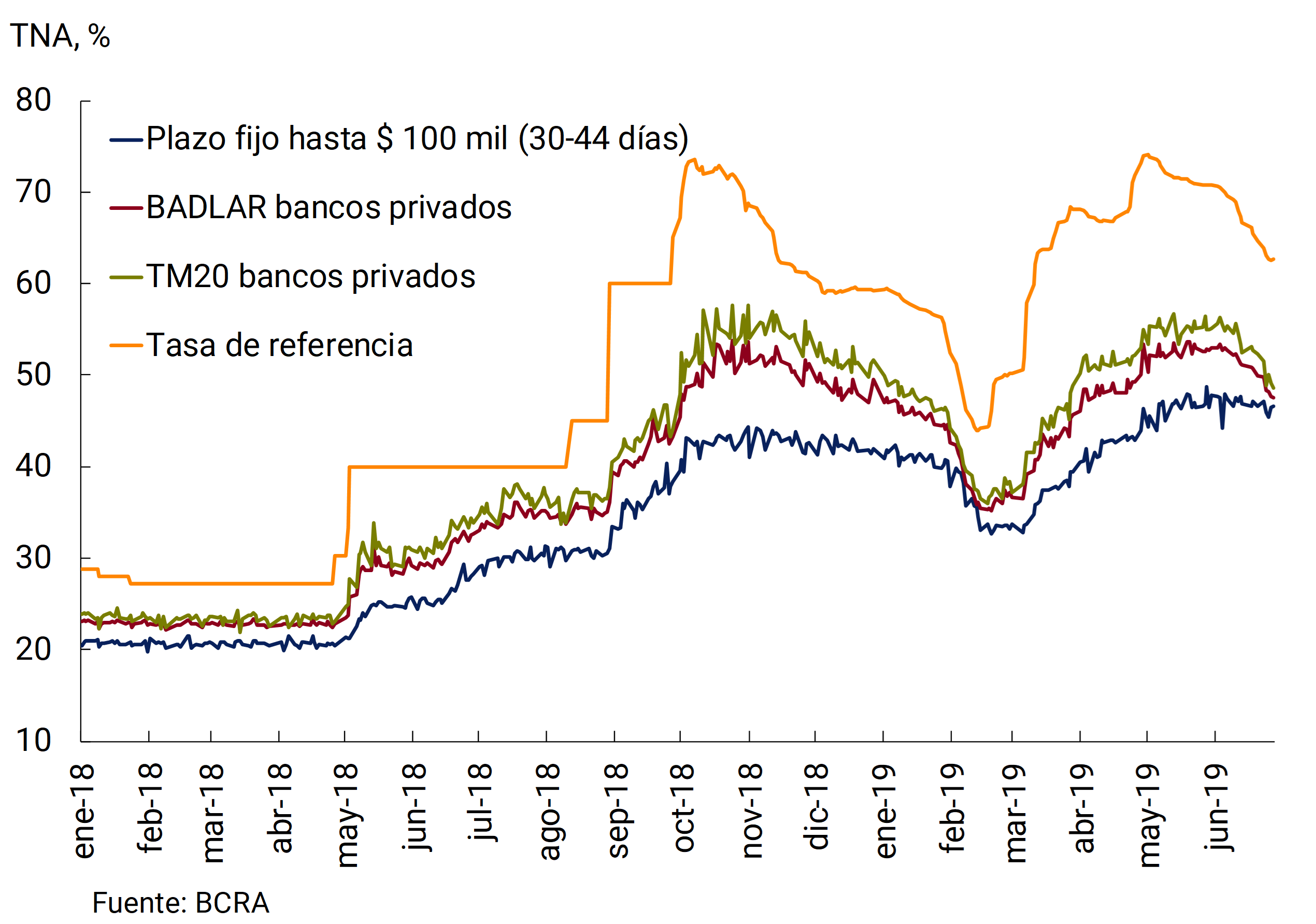

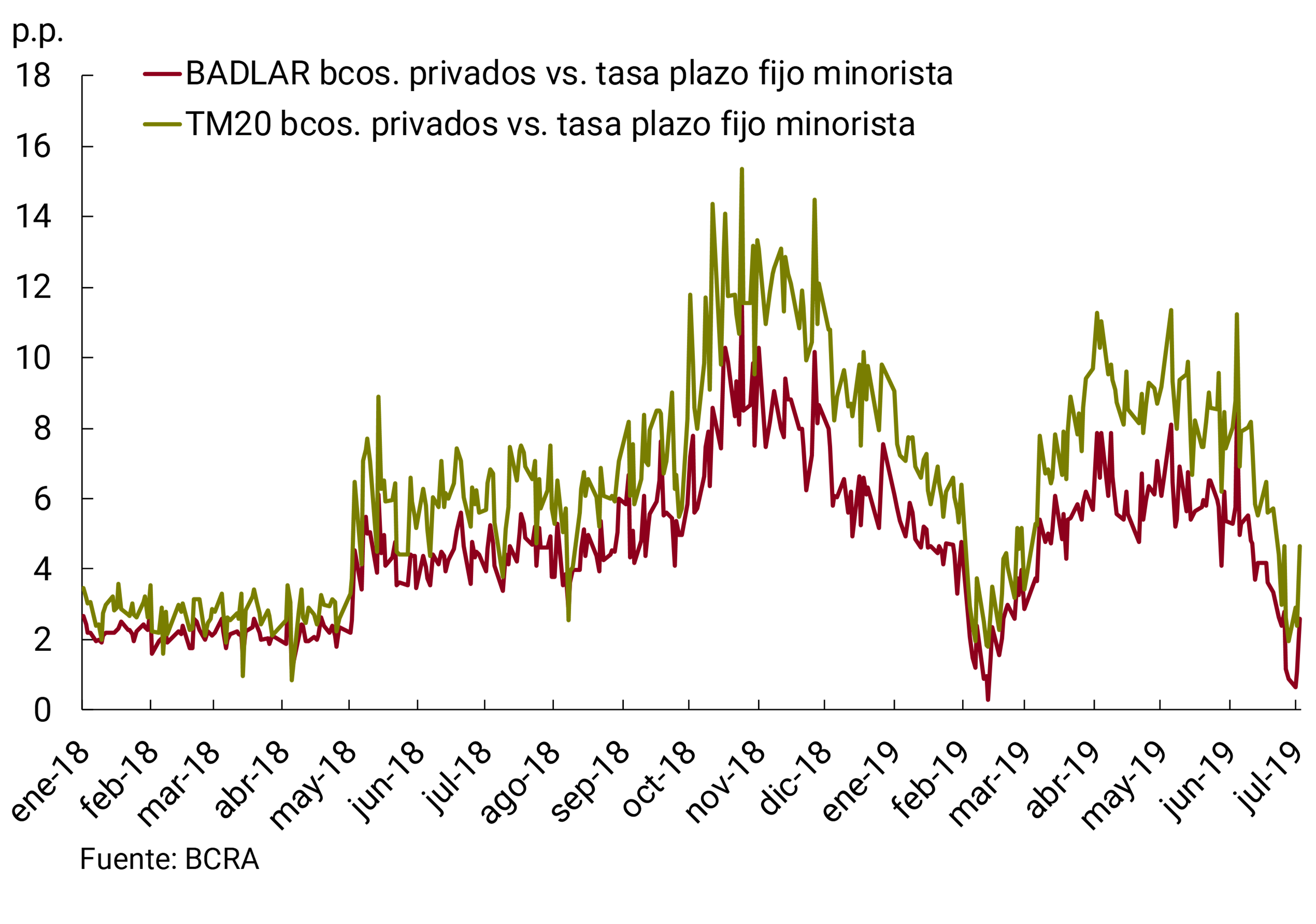

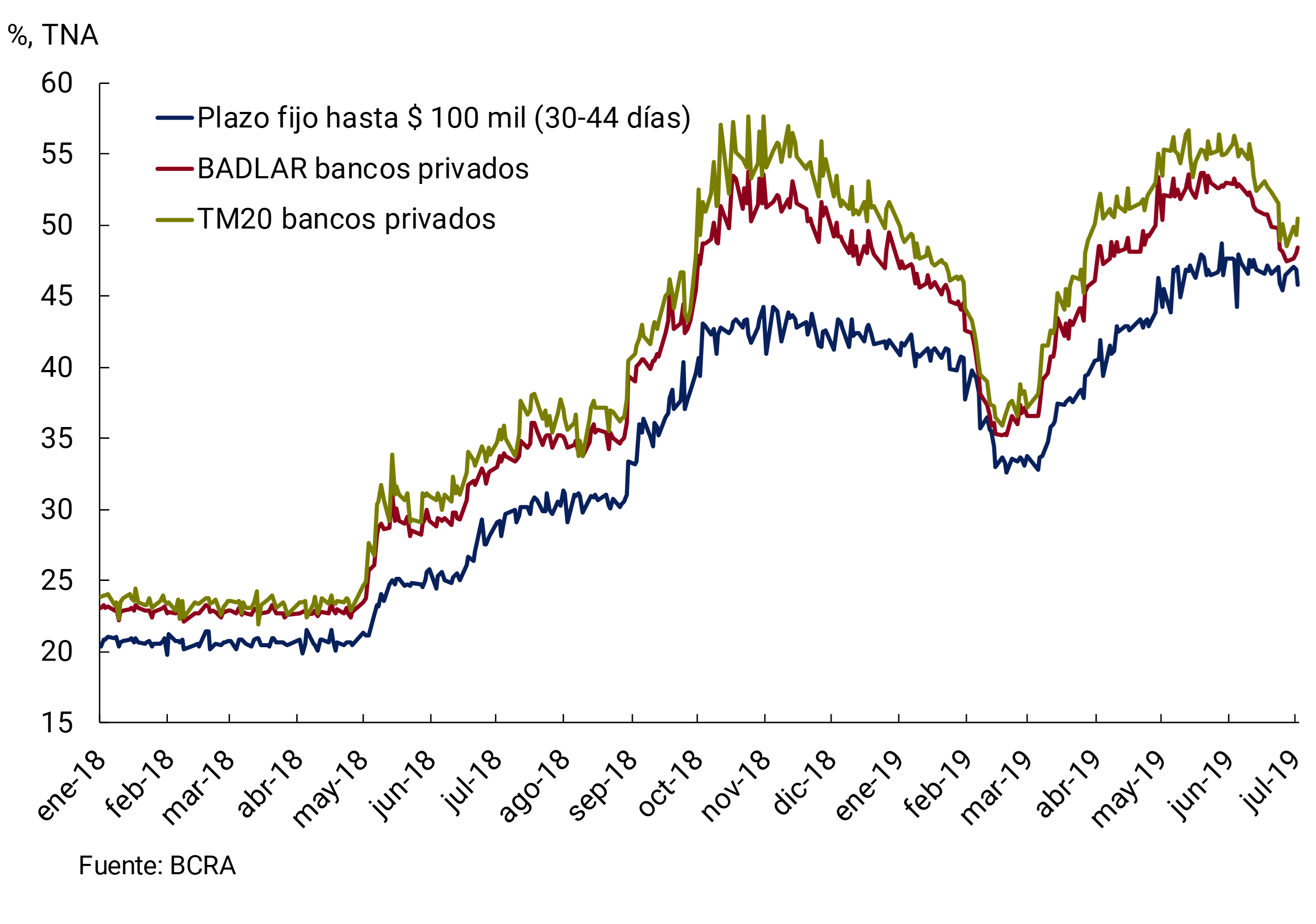

Additionally, to promote competition among financial institutions and improve the mechanism for transmitting the reference rate to the interest rates received by savers, the Central Bank allowed bank customers to make fixed-term deposits in pesos online at any financial institution without the need to be a customer or carry out additional procedures. In this way, retail fixed-term interest rates grew and approached those of larger transactions (see section 5).

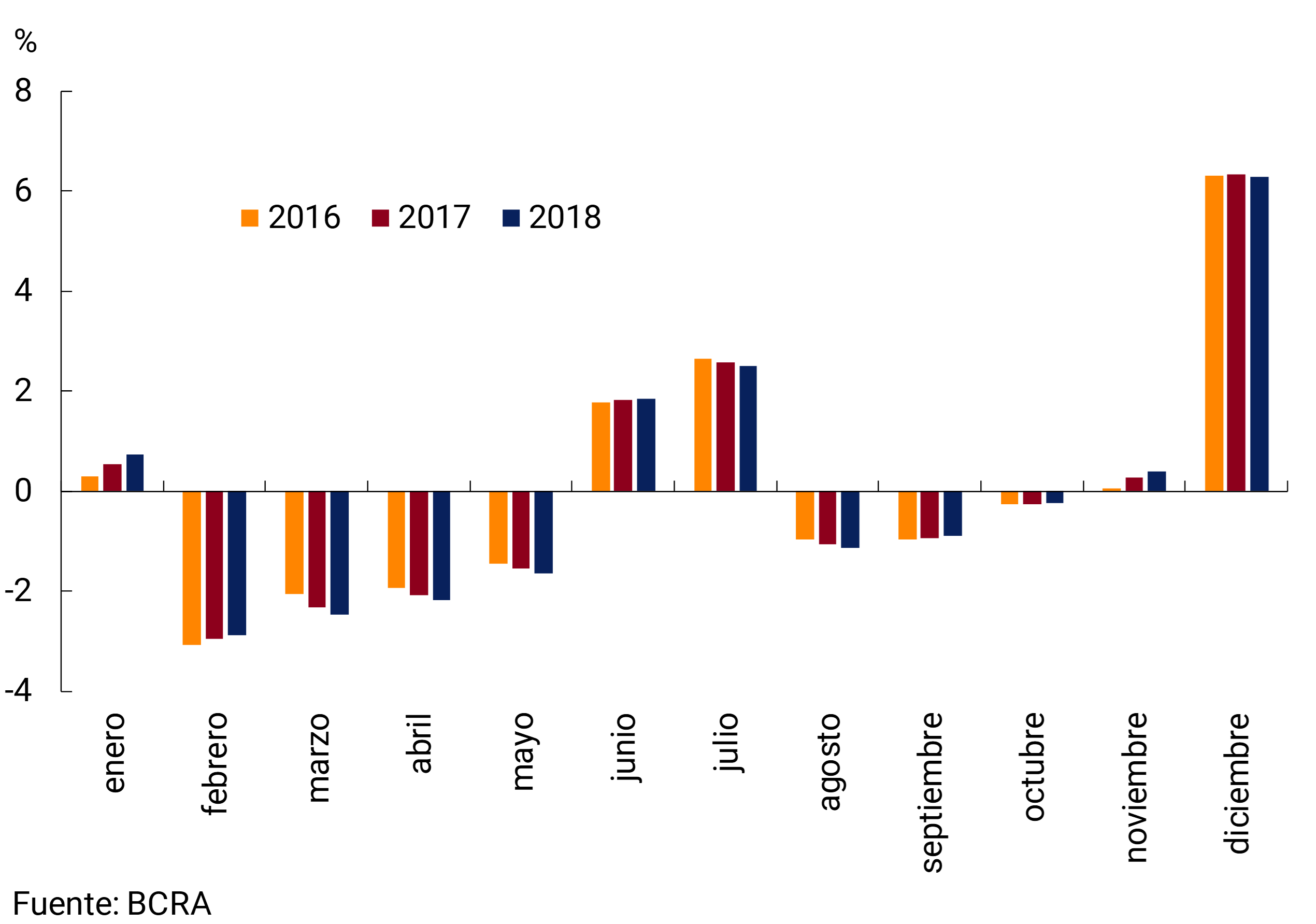

The fulfillment of the goal is particularly demanding in the months of June and July, due to the seasonal behavior of the demand for BM, which increases due to the payment of the half bonus and the higher expenses of the winter recess. In order to allow for better management of liquidity conditions during this period, the BCRA decided to establish a joint reserve position for the months of July-August, and for the months of December-January, where a similar phenomenon is repeated (see section 4).

In addition, and to also contribute to strengthening the transmission of the interest rate of the LELIQ, it was decided to reduce by 3 p.p. the minimum cash requirement on fixed-term deposits as of July. This represents a reduction in the demand for the monetary base due to reserve requirements of approximately $45 billion that compensates for the seasonal increase in demand per working capital. In order not to relax monetary policy, once this seasonal phenomenon has been overcome, the monetary base target will be reduced as of August to reach $1,298.2 billion in October, fully offsetting the effect of the reduction in reserve requirements.

The BCRA’s view is that the macroeconomic conditions are in place to achieve sustainable disinflation, given that basic macroeconomic balances have been restored. Fiscal balance is being achieved and monetary financing from the Treasury has ceased. The exchange rate today is competitive, with a level in June that is around 50% higher than the value recorded prior to the exchange rate unification of December 2015, which has made it possible to correct the imbalance of the external sector. In addition, distortions generated by energy price arrears have been virtually eliminated. In turn, the BCRA has a strengthened balance sheet, with a sustainable level of interest-bearing liabilities and an adequate stock of international reserves, along with greater degrees of freedom to intervene in the foreign exchange market.

However, disinflation processes tend to be gradual and not linear, given that monetary policy operates with lags, and inflation also has an inertial component. This inertial component is reinforced after more than a decade of high inflation. Thus, the contractionary bias of the monetary scheme will remain throughout 2019, and the benchmark interest rate is expected to fall gradually and only as inflation falls. However, this medium-term trend could be temporarily disrupted in the event that some of the risks to which the economy is exposed materialize, such as a new episode of volatility in global financial conditions, or the usual uncertainty of electoral processes. In the current scheme, the endogenous interest rate allows us to respond immediately to any unforeseen shock.

Therefore, the BCRA must be persevering in its policy of strict control of the quantity of money and thus achieve a lasting reduction in inflation, providing an environment of stability conducive to economic growth.

2. International context

So far in 2019, the slowdown in the level of global activity that had begun to be observed at the end of 2018 continued, now extended to the main developed and emerging economies. As a result, the expected growth for Argentina’s main trading partners went from being the highest in the last six years in January of this year (2.2% average expected for 2019), to being the lowest in the last four years (1.2% average expected for the same period) according to the most recent projections. This is mainly due to the sharp decline in growth projections for Brazil.

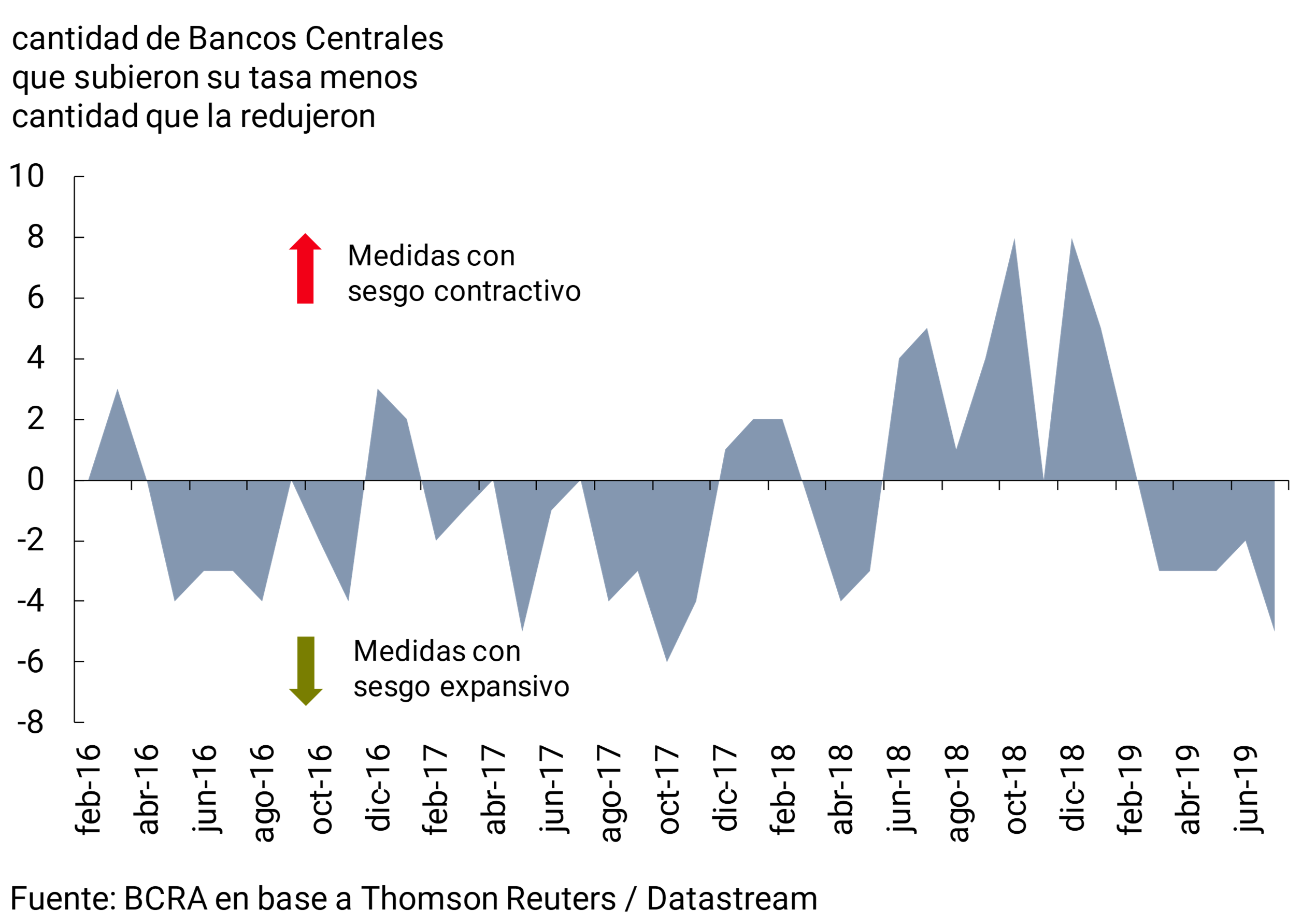

Monetary authorities in advanced economies are responding to this scenario with a more expansionary policy path. Something similar is observed in most emerging countries. In this context, it is feasible that global liquidity conditions for emerging markets will continue to improve, as long as the effect of uncertainty related to trade and geopolitical tensions is not greater, and that this leads to a flight to quality.

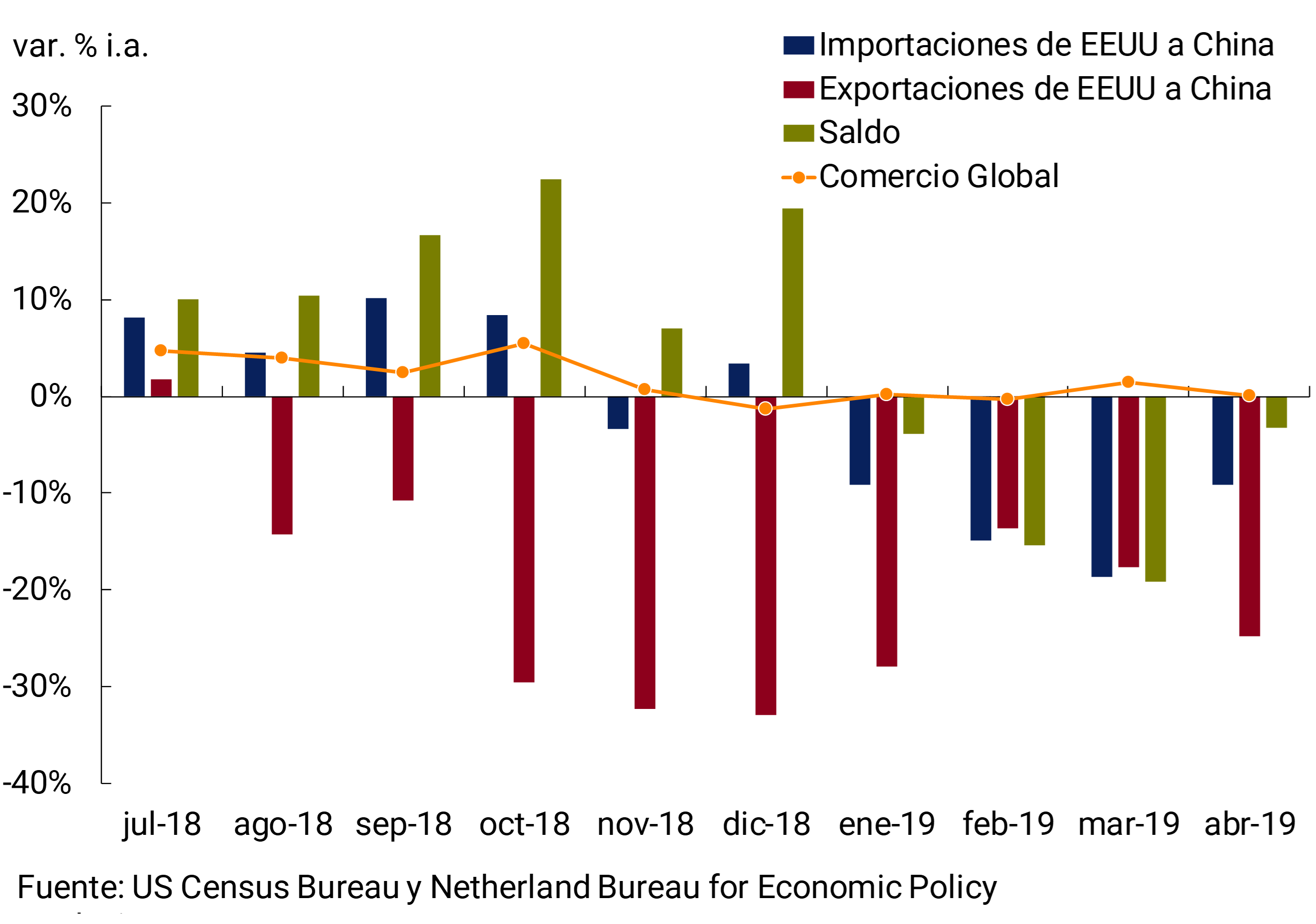

Therefore, a mixed international scenario continues to be observed for Argentina. On the one hand, lower global growth prospects in general, and in particular, for the country’s main trading partners. On the other hand, the conditions are in place for a better external financial scenario, as long as the current stress factors are not strengthened, and therefore a capital outflow from emerging countries to the main advanced countries is triggered. Precisely, the main risk factor in the international context would be that trade disputes between the United States and China deepen (see Section 1).

2.1 There was a deterioration in the level of global activity that had a negative impact on the main trading partners, which would lead to expansionary monetary policies in some of these countries

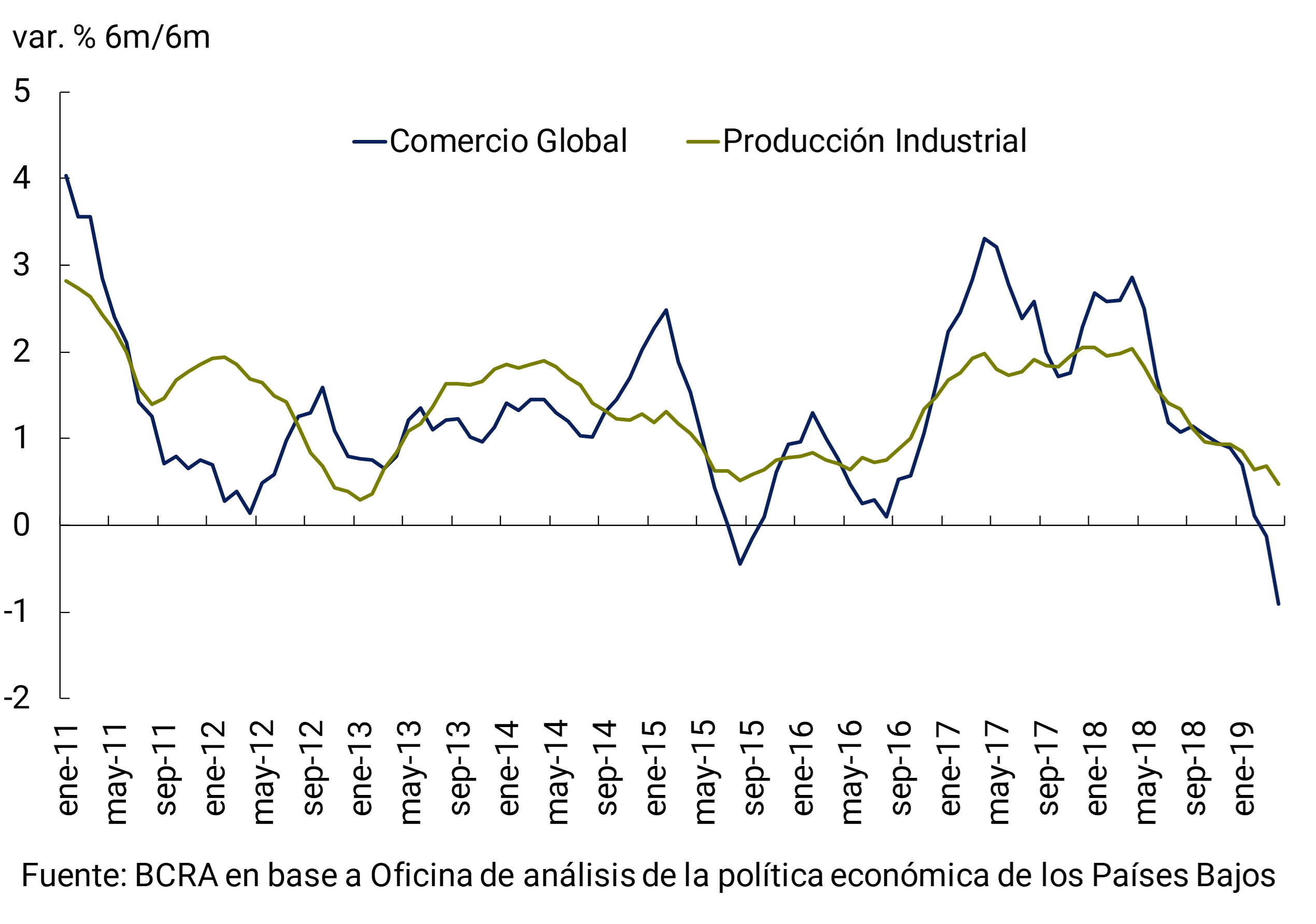

Signs of slowdown in global economic activity continued in recent months. 1 The most recent global trade data evolved in this regard, falling by 2.3% s.e. from the peak of October 2018, while industrial production fell by 0.2% s.e. in the same period (see Figure 2.1).

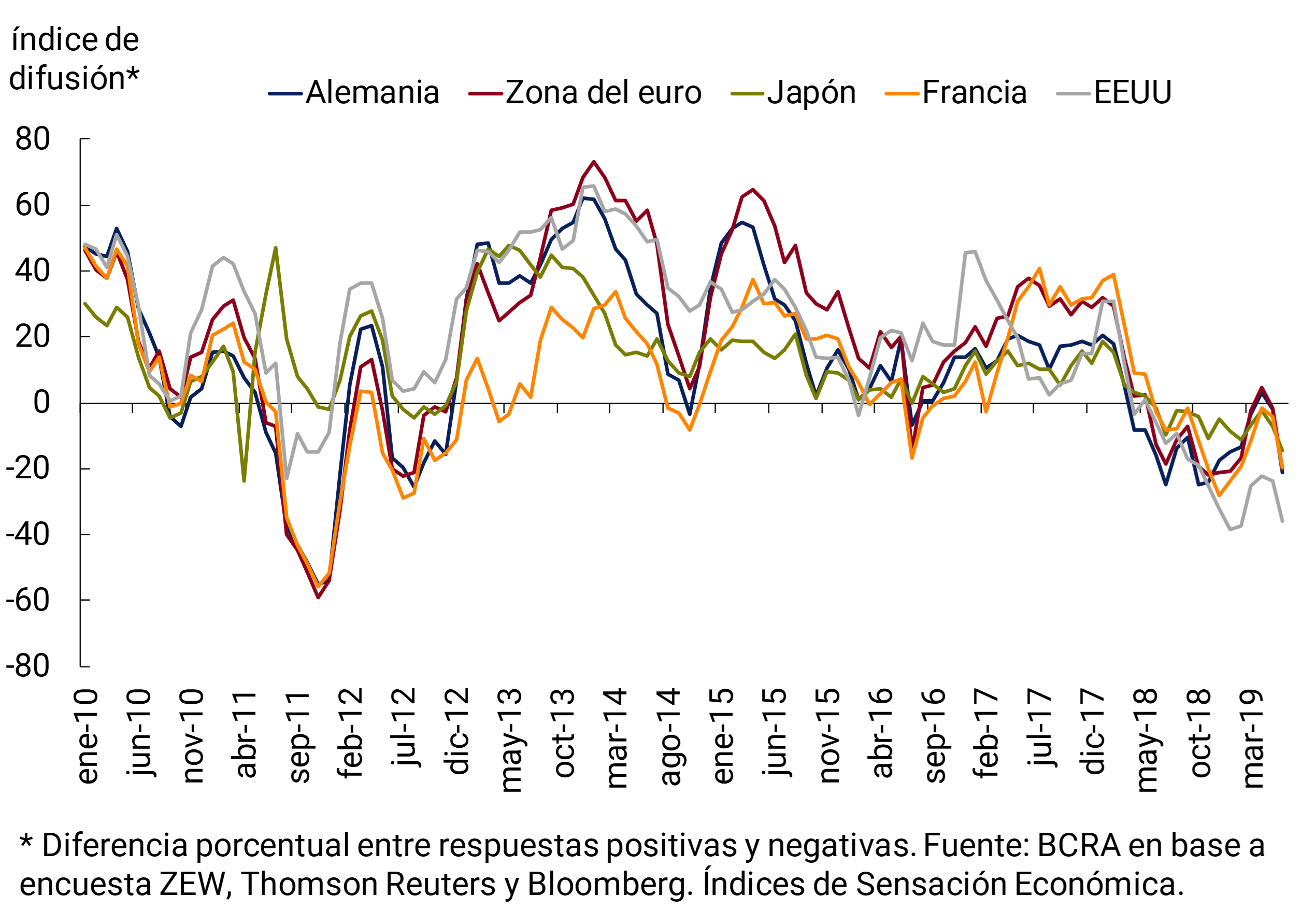

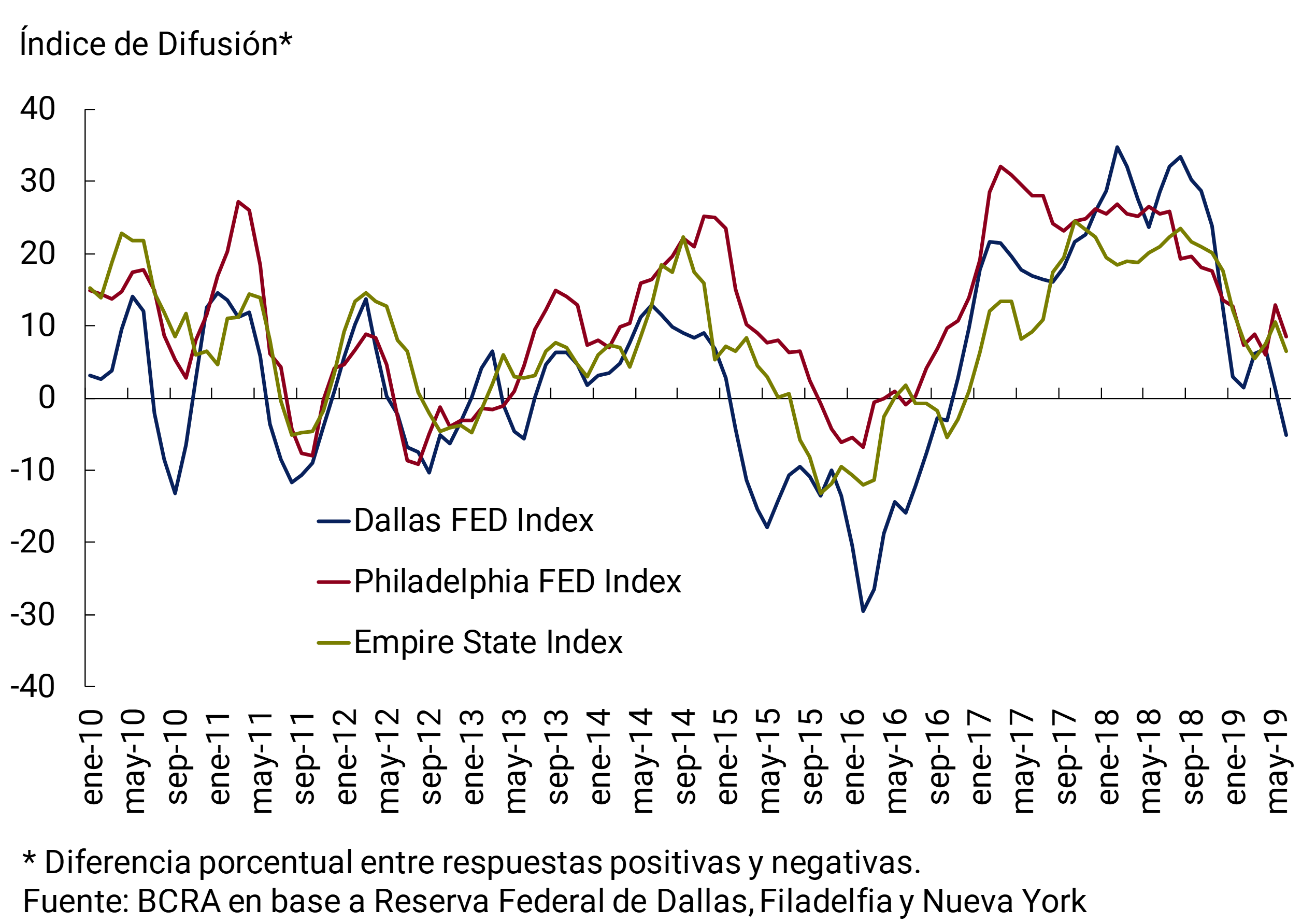

As mentioned in the previous IPOM, a considerable part of the decline in the pace of global growth would appear to be linked to a marked reduction in capital goods investment. This lower investment could be explained by the uncertainty generated by trade tensions and their impact on business confidence (see Figure 2.2).

This is reflected in most of the manufacturing PMI indices that in the previous IPOM were in the expansion zone, and became in the contraction zone. Something similar happens with the global PMI of the industry (see Figure 2.3). The overall PMI for the services sector, although still in the expansion zone, has a clear trend towards the contraction zone, the same is true for the composite PMI. On the other hand, inflation rates in the main advanced economies (the United States, the euro area, Japan and the United Kingdom) remain low in all cases, which gives the monetary authorities room to take measures with an expansionary bias.

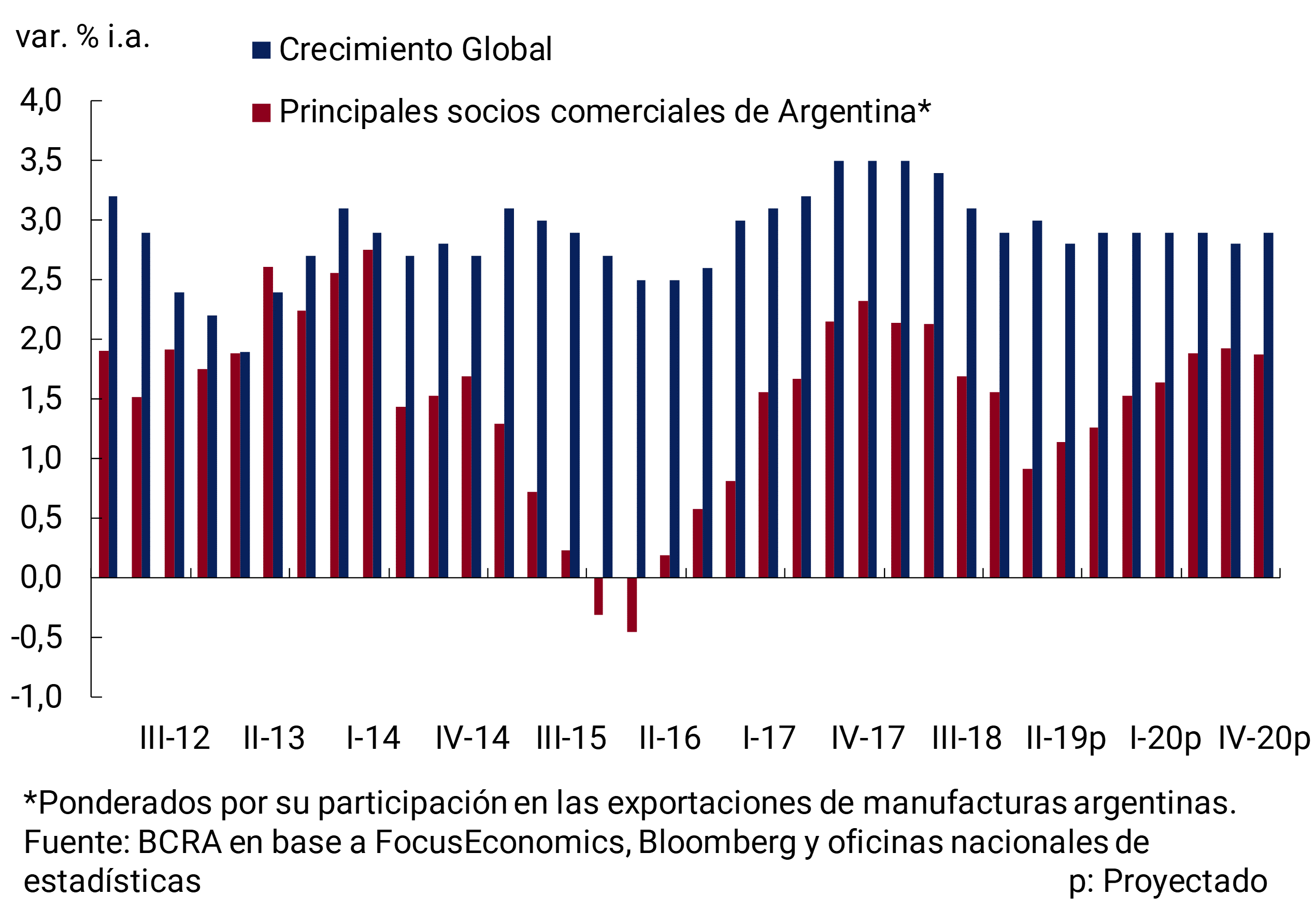

This panorama of lower global growth is also observed in the level of activity of Argentina’s main trading partners. For these countries, the expected growth for 2019, which until the IPOM of January of this year was the highest in the last six years, became the lowest in the last four years (see Figure 2.4). However, the negative impact on Argentina of Brazil’s expected lower growth could be partially offset by more competitive levels of real exchange rates.

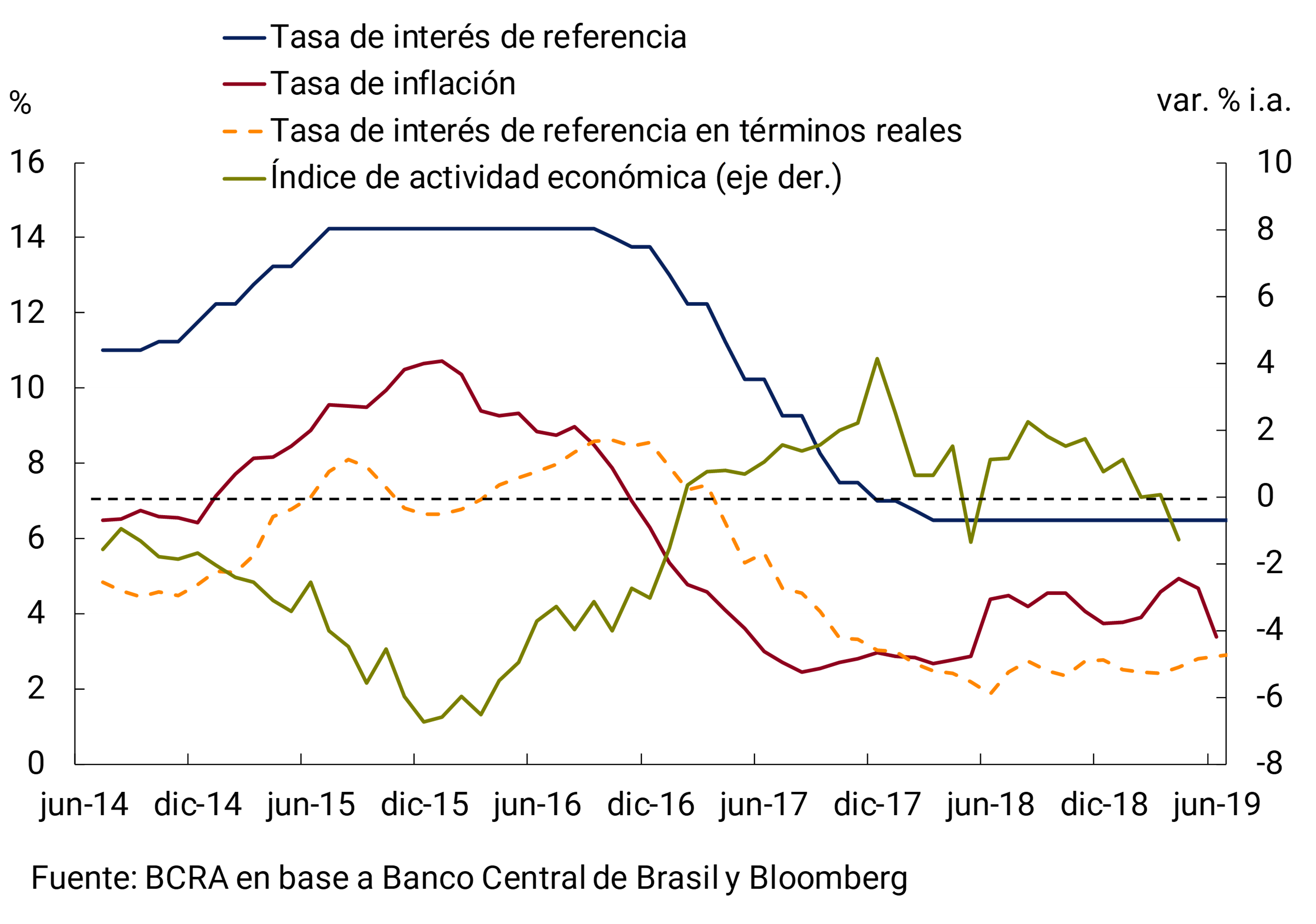

Much of the decline in growth expectations for our trading partners is linked to Brazil’s expected poorer performance. Growth in this country was negative in the first quarter by 0.2% s.e. (compared to the previous quarter) mainly due to the performance of investment and exports. In the same sense, the monthly activity data measured by the IBC-Br estimator of the Central Bank of Brazil (BCB) showed negative rates of variation in the first four months of the year. On the other hand, the most recent estimates of the BCB’s Focus survey foresee growth for 2019 of 0.8% YoY, 1.2 p.p. lower than the growth forecast in April. Lower external demand due to the expected lower level of global activity, local political uncertainties, and fiscal reforms are factors that negatively impact Brazilian growth in 2019.

In this regard, and as in the previous IPOM, an unfavorable change in investors’ perception of the structural reform process continues to be a potential destabilizing risk factor for the Brazilian economy. Thus, the BCB in its latest Inflation Report highlights the importance that progress in the structural reform agenda would have in Brazil’s economic performance for this year. Therefore, the BCB forecasts GDP growth in 2019 of 0.8% YoY, but conditional on progress being made in this regard.

The most recent inflation data in Brazil (June) was 3.4% year-on-year, below the center of the target (4.25% ± 1.5). Inflation in the first months of the year was driven by specific factors that have lost strength since mid-2019. In turn, analysts surveyed by Focus predict that the inflation rate will end 2019 at 3.8%. The BCB recently left the monetary policy interest rate (SELIC) unchanged, which has been at 6.5% since the end of March 2018 (see Figure 2.5). Unlike the previous IPOM, where no changes were expected, in the latest Focus analysts project a reduction of 1 p.p. by the end of the year. The main reasons that would lead to reducing the target on the SELIC rate would be inflation below the target, lower growth prospects in Brazil and in the world, together with the increasingly likely expansionary monetary policy measures of the main central banks.

The most recent data on activity in the United States show that GDP grew in the first quarter by 3.1% (compared to the previous quarter, seasonally and annualized), more than 0.2 p.p. above the market consensus, and 0.9 p.p. more than the previous quarter. In a context where GDP grew in the last year at a rate of 3.2% on average, the indications that the United States Federal Reserve (Fed) would reduce its benchmark interest rate in 2019 are explained by several factors. Among these: 1) the aforementioned deterioration in the level of world activity; (2) the slowdown in the rate of increase in hourly pay; 3) the inflation rate (measured by the core deflator of household spending) has been below or around the target since mid-2012; and 4) the evolution of different indicators that in other economic cycles functioned as predictors of recession (see Figures 2.6, 2.7 and 2.8).

The Fed lowered its policy interest rate projections. In December 2018, an increase of 0.5 p.p. was expected during 2019, while in the latest projections it is expected to remain unchanged during the year. But, as mentioned, there are indications (including statements by Fed authorities) about the growing possibility of a reduction in the same in the coming months. This change in such a short term could also be understood because, given the proximity to the effective lower bound (elb2) that reduces the margin for action of monetary policy, it would be advisable, in order to increase its effectiveness, to overreact to the first indications of the need for monetary stimulus (for more details see this conference). Finally, the projections for the rest of the economic variables released by the Fed at its June meeting remained almost unchanged, except for inflation, which decreased slightly compared to March.

In the euro area, economic activity performed better than expected by the market consensus (0.3%) in the first quarter, with growth of 0.4% s.e. This would have been due to one-off factors, such as the UK’s exceptional demand for euro area goods (linked to possible Brexit). In addition, after the implementation of the Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicle Test Procedures (WLTP)3 , an increase in vehicle procurement was observed – especially in Germany. On the other hand, there was higher private consumption in the quarter due to fiscal stimulus measures that came into force at the beginning of the year, and whose greatest impact would be concentrated in the first quarter. Finally, better weather conditions than in the previous quarter allowed an increase in construction activity in some countries.

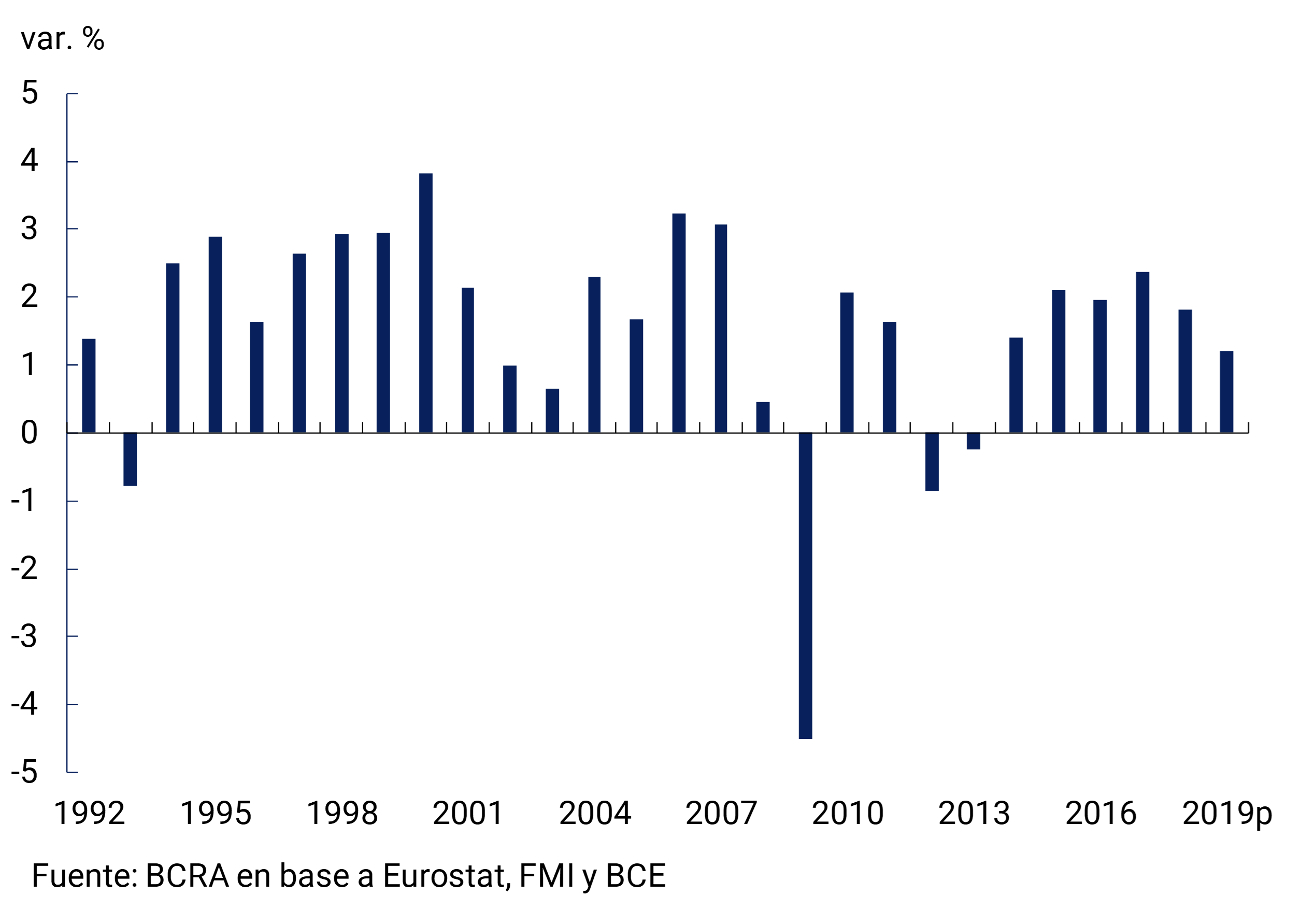

However, similar to the case of the United States monetary authority, the European Central Bank (ECB) also went from giving signals that it would be ready to increase its benchmark interest rate in 2019, to taking expansionary measures in April 2019 (see the IPOM of April 2019). and to signal in early June that it is ready to resort to new expansionary measures (probably a new quantitative easing program). Also, the ECB at its last meeting mentioned global factors with a direct impact on business confidence that would be markedly affecting the growth prospects of the euro area, which is being sustained mainly by private consumption. As a result, the growth rate projected by the ECB for this year (1.2% YoY) is the lowest in the last six years (see Figure 2.9).

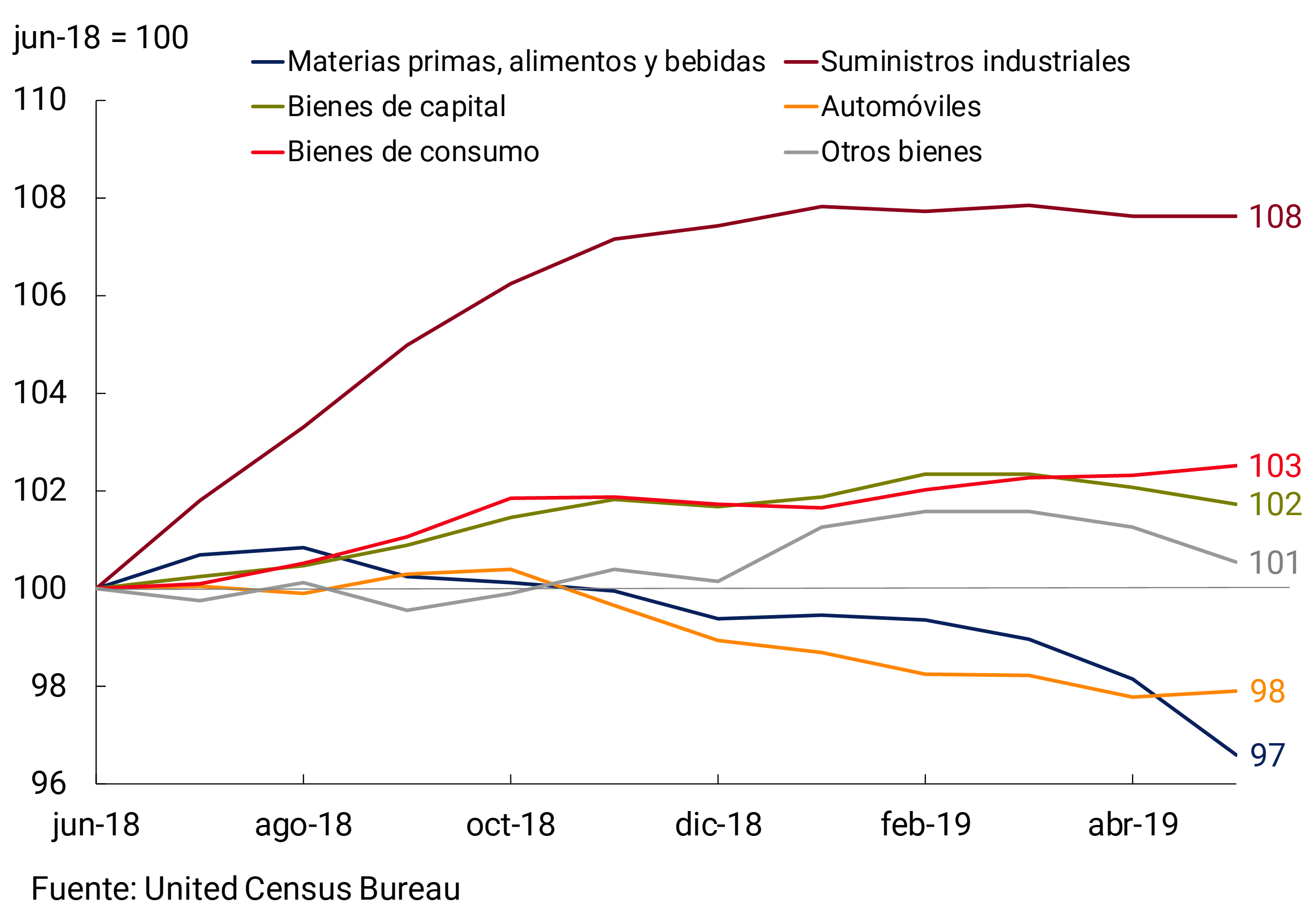

China’s economy continues to slow. After growing in 2018 at 6.6%, the lowest rate of expansion since 1990, in the first quarter4 of the year it registered a growth of 6.4% year-on-year. Moreover, according to the Focus Economics survey, analysts expect the growth rate to continue to slow until it stabilizes at around 6% by the end of 2020. Several factors converge to explain this slowdown: the effects of the imposition of mutual tariffs with the United States (see Section 1), the still failed attempt by the authorities to boost private consumption to the detriment of investment, and the credit deleveraging policies carried out until recently by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC, the monetary authority). Industrial production in general has been affected, with growth rates that are around seventeen year lows.

The Chinese authorities implemented some stimulus measures based on tax cuts and increased spending on public infrastructure, and put on hold the policies of deleveraging the financial system. In this regard, they have recently reduced the requirements for reserve requirements. At the end of May, in the face of serious credit risks, the PBOC and China’s bank and insurance regulatory commission took control of Baoshang Bank, announcing a restructuring aimed at cleaning up its balance sheet. The last time the Chinese authorities took such a measure was in 1998. In this context, the monetary authority has been injecting liquidity through open market operations, and could again reduce reserve requirements, in order to avoid problems in other financial institutions.

2.2 Global liquidity conditions for emerging markets are likely to improve

As mentioned, the monetary authorities of the largest economies would be about to implement monetary policies with an expansionary bias again. Something similar is observed in the case of emerging countries, where the bias of monetary policy would be leaning towards expansionary (see Figure 2.10). In this context, it is feasible that global liquidity conditions for emerging markets will improve, as long as the effect of uncertainty related to trade and geopolitical tensions that leads to a flight to quality process is not greater.

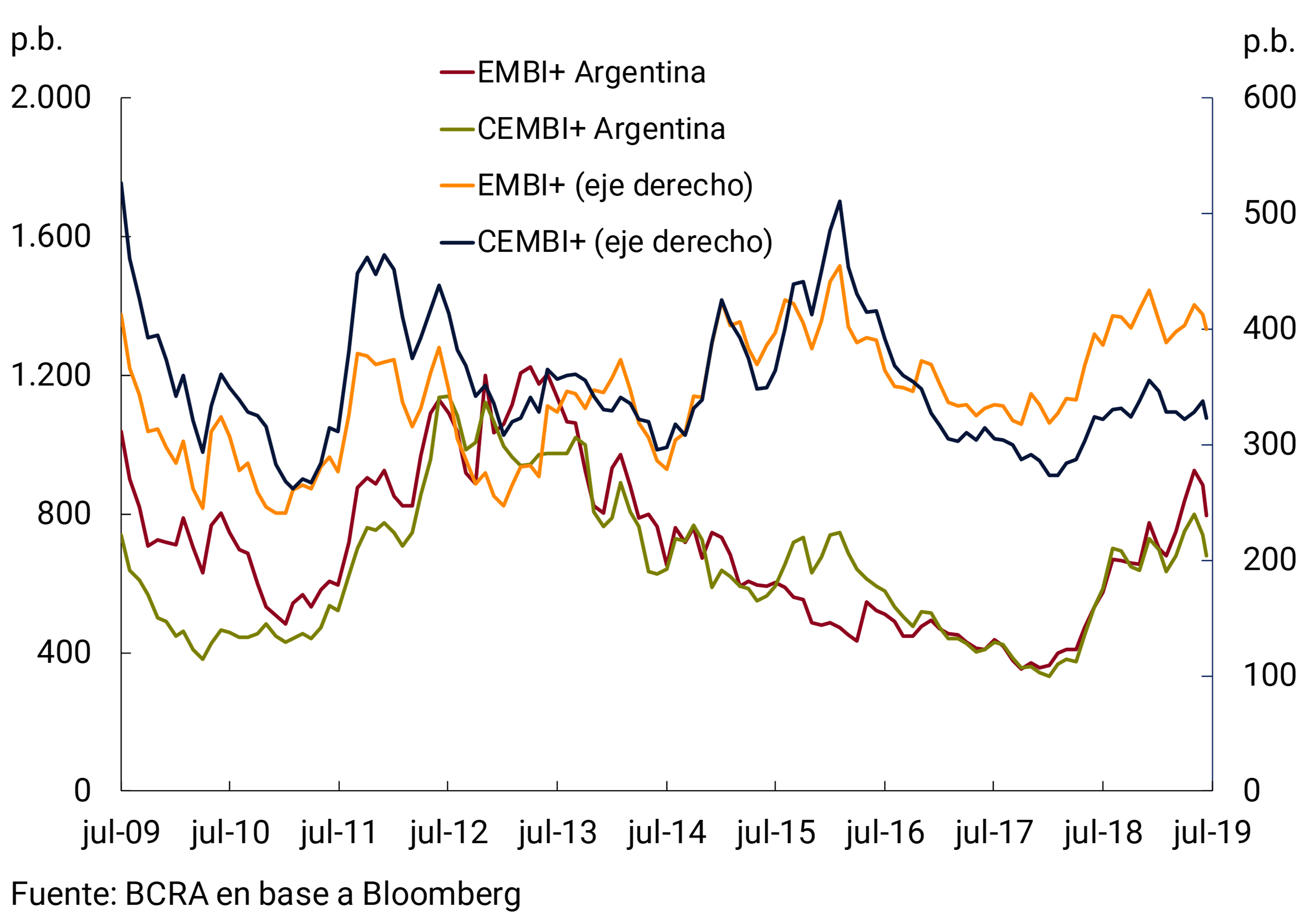

Sovereign and corporate risk premiums in emerging economies rose towards the end of the second quarter of 2019, after the decline experienced in the first quarter of the year, and remain at high levels compared to recent years. However, emerging market debt placements in international markets showed the first year-on-year increase in the second quarter of 2019 after four consecutive quarters of declines. The amount of gross placements (sovereign and corporate) increased 8% YoY in the second quarter (compared to a 7% YoY drop in the previous quarter). This was explained by the performance of the corporate segment (with an expansion of 35% YoY), while sovereign issuances contracted 40% YoY.

In this context, the yield differential required in the secondary markets for Argentine sovereign debt between peaks remained almost unchanged from the previous IPOM, at around 800 bps, having momentarily exceeded 1,000 points in early June, and then fell by more than 200 bps (see Figure 2.11). In the quarter there were no new international placements of the sovereign, because given the agreement with the International Monetary Fund and as it emerges from the Financial Program, the National Government has no need to access these markets in the remainder of 2019 and 2020.

For its part, despite the fact that Argentina’s CEMBI behaved in a similar way to the sovereign index, there were some one-off placements of Argentine corporate debt in foreign markets by companies in the metallurgical and energy sectors. Placements by publicly offered companies in international markets in the second quarter of 2019 totaled US$650 million (one of which was made with a guarantee of export collections), while in the same period of 2018 there was a single placement at the end of April for US$500 million.

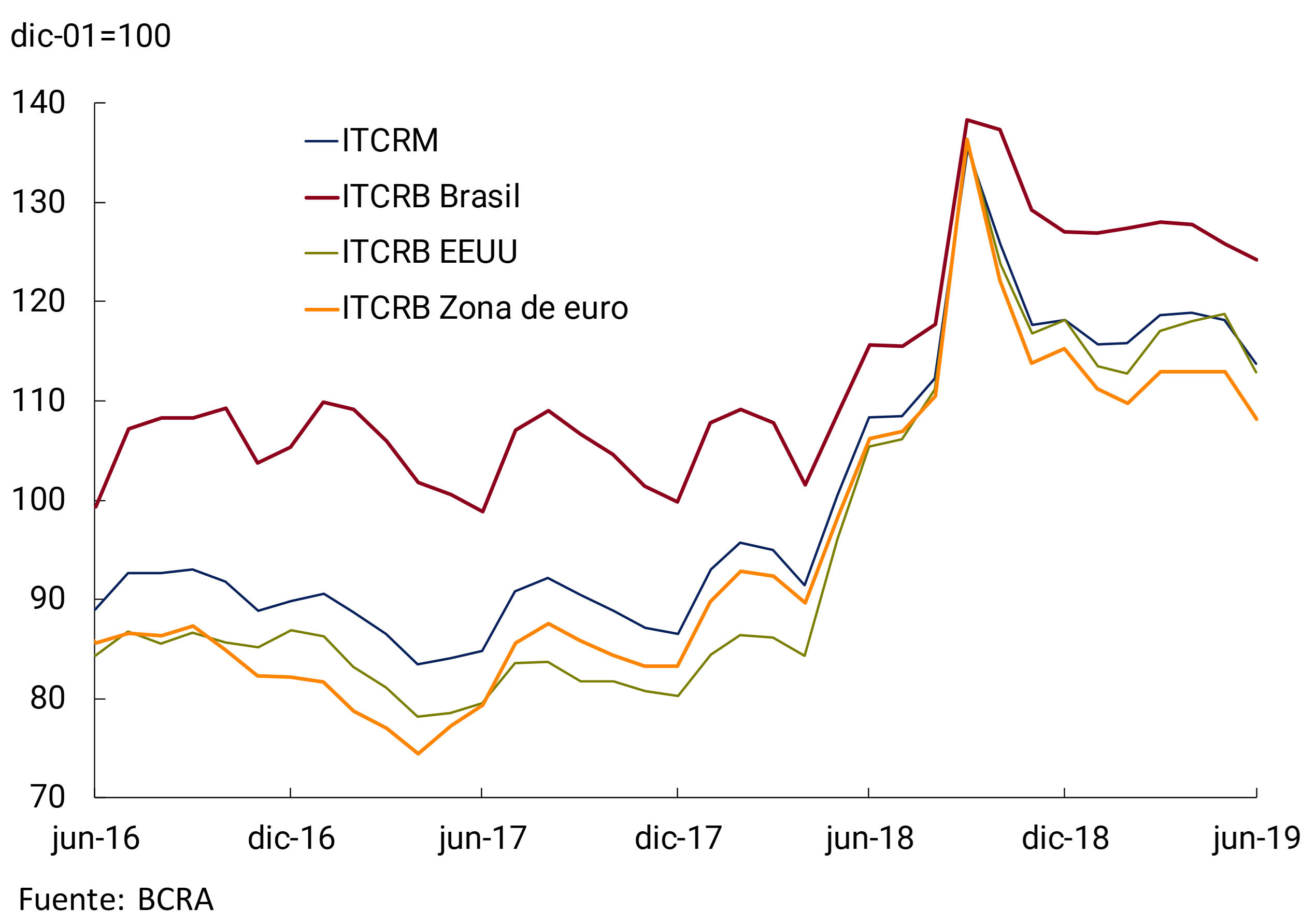

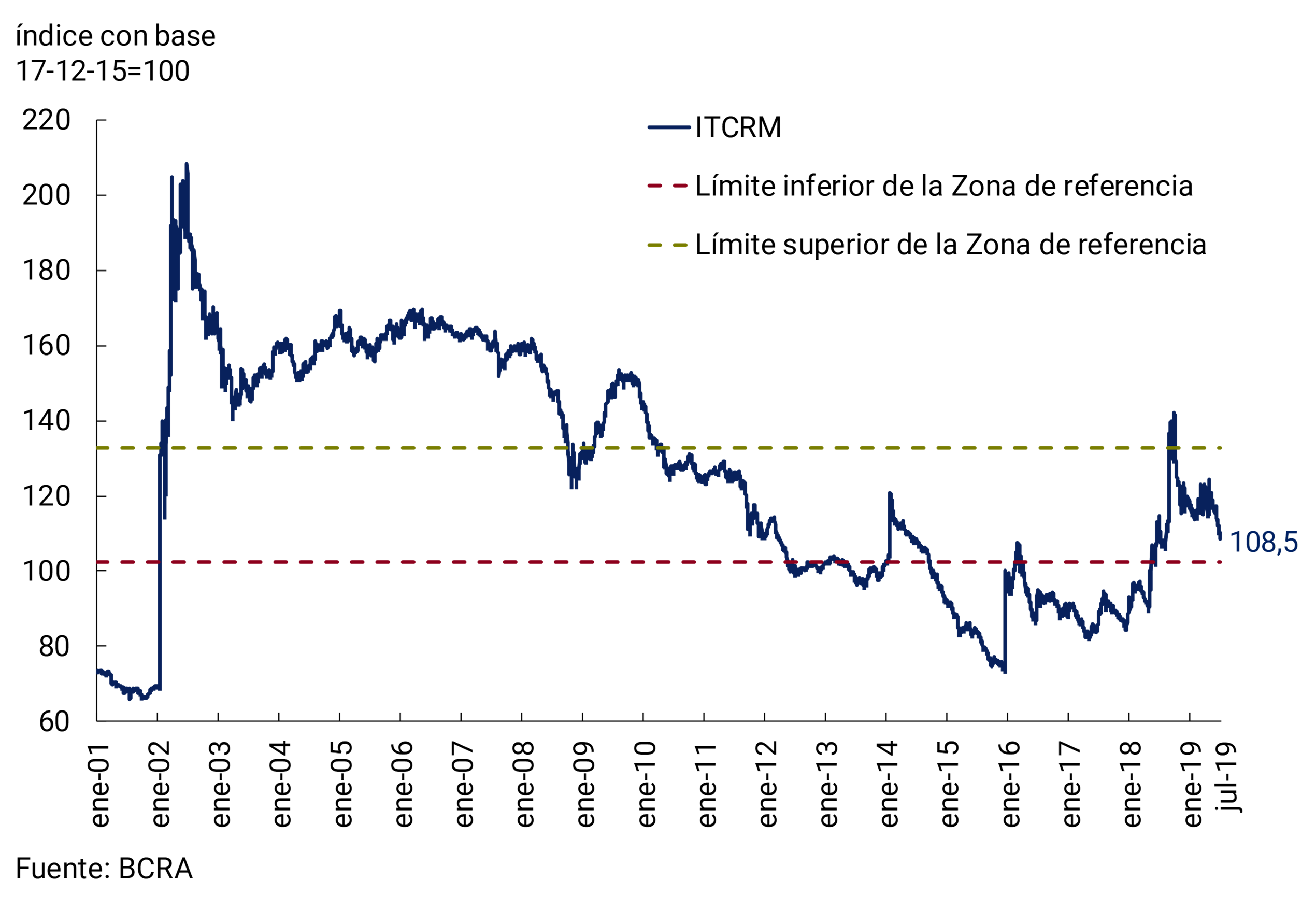

After registering a relatively stable evolution throughout the second quarter, the Multilateral Real Exchange Rate Index (ITCRM) fell in the last days of June. Thus, at the end of June it was around 8% below the level recorded at the beginning of April, and returned to levels close to those of August 2018. However, it is 51% above the value of November 2015 (see Figure 2.12). The evolution of the bilateral nominal exchange rate of the Argentine peso with the dollar accompanied the movement of the main Latin American currencies.

2.3 At the margin, the prices of Argentine agricultural exports improved slightly

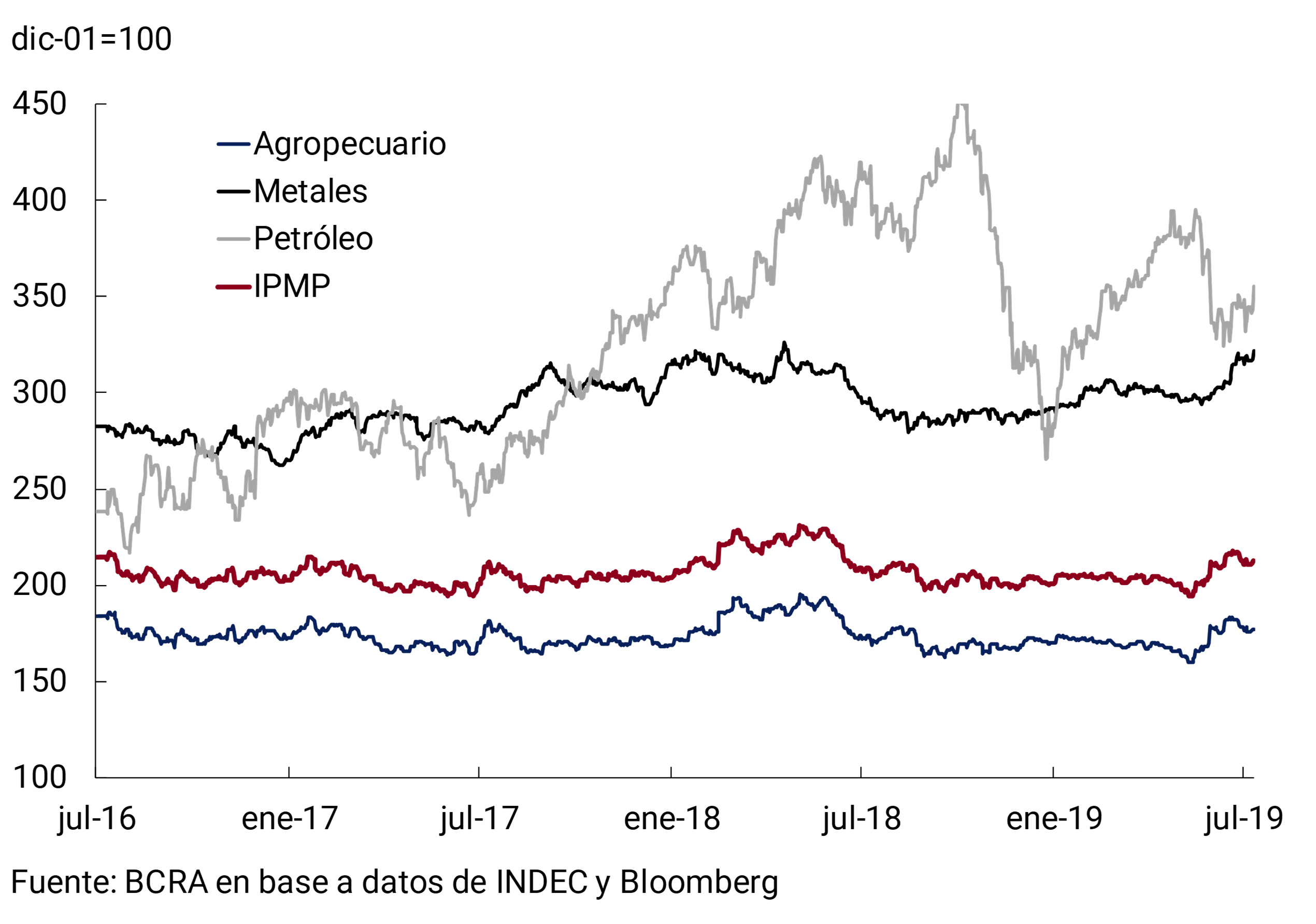

In the second quarter of the year, international commodity prices measured in dollar5 increased slightly compared to the previous quarter – mainly since the end of May – mainly due to the evolution of the grouping of agricultural raw materials and metals, while crude oil values fell at the margin. Since the end of May, international agricultural commodity values have been boosted by delayed U.S. corn and soybean planting due to excess soil moisture. In any case, during the second quarter, the prices of the main commodity groups remained on average below the levels they had in the same period of 2018, implying a 9% YoY drop in the Commodity Price Index (CPI), which reflects the evolution of Argentina’s main export commodities (see Figure 2.13).

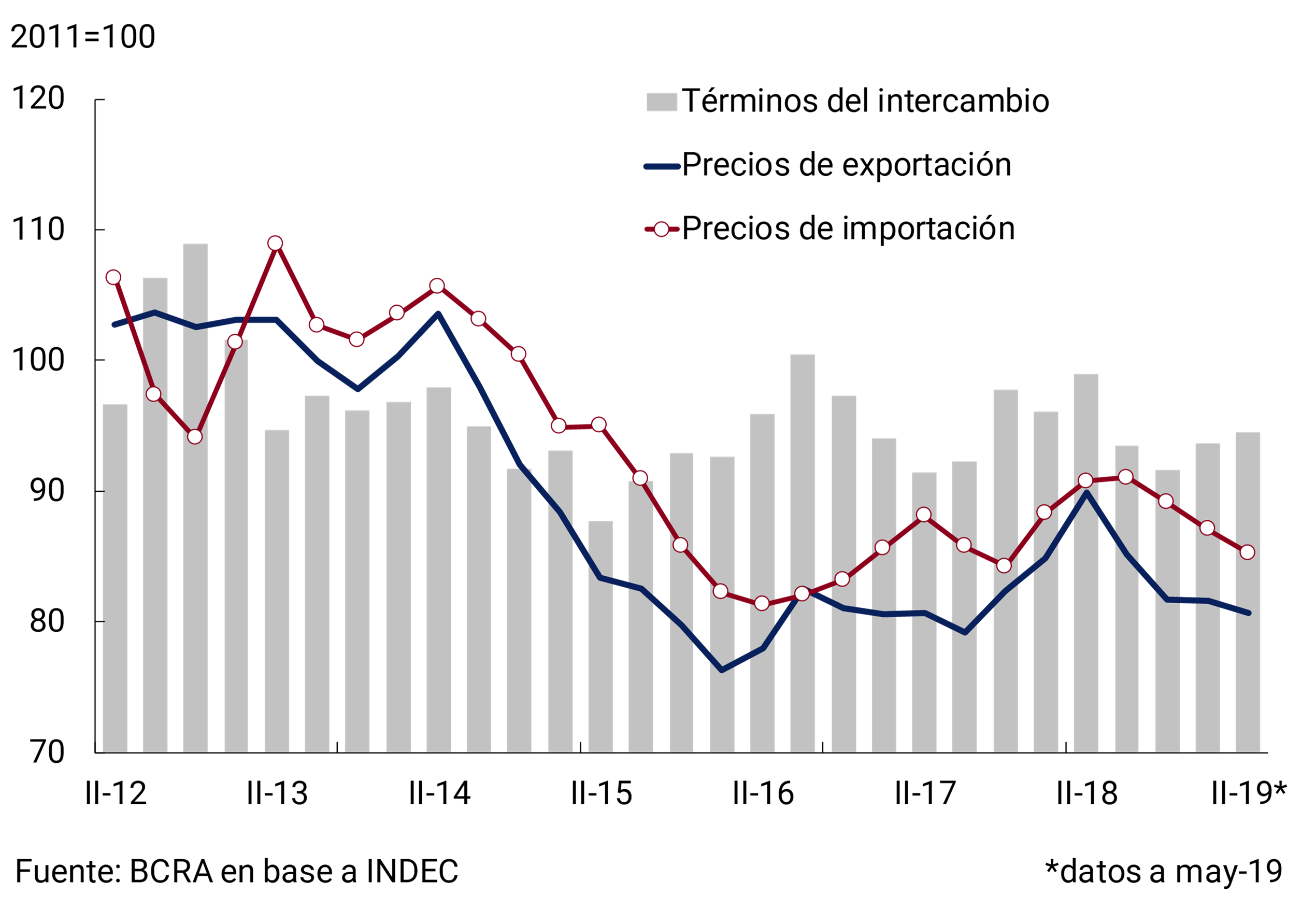

The data available for the April-May two-month period indicate that there was a 1.2% drop in Argentina’s export prices compared to the previous quarter, mainly due to the decrease in the quotations in dollars of primary products in that period (-6%). Meanwhile, import prices showed a 2.1% drop in the same period, with a strong incidence of reductions in the dollar prices of imported capital goods and their parts. As a result, the terms of trade rose slightly (0.9%) and remained around the average level of the last 3 years (see Figure 2.14). It is estimated that as of June, export prices would have begun to reflect higher international quotations for the main agricultural products.

In summary, the recent slowdown in the level of global activity was generalized to the major developed and emerging economies. In this context, both advanced and emerging economies are returning to a path of more expansionary monetary policies. This makes it feasible that global liquidity conditions for emerging markets will continue to improve, as long as the effect of uncertainty related to trade and geopolitical tensions is not greater, ending in a flight to quality. That is why the main risk factor in the international context continues to be the deepening of trade disputes between the United States and China.

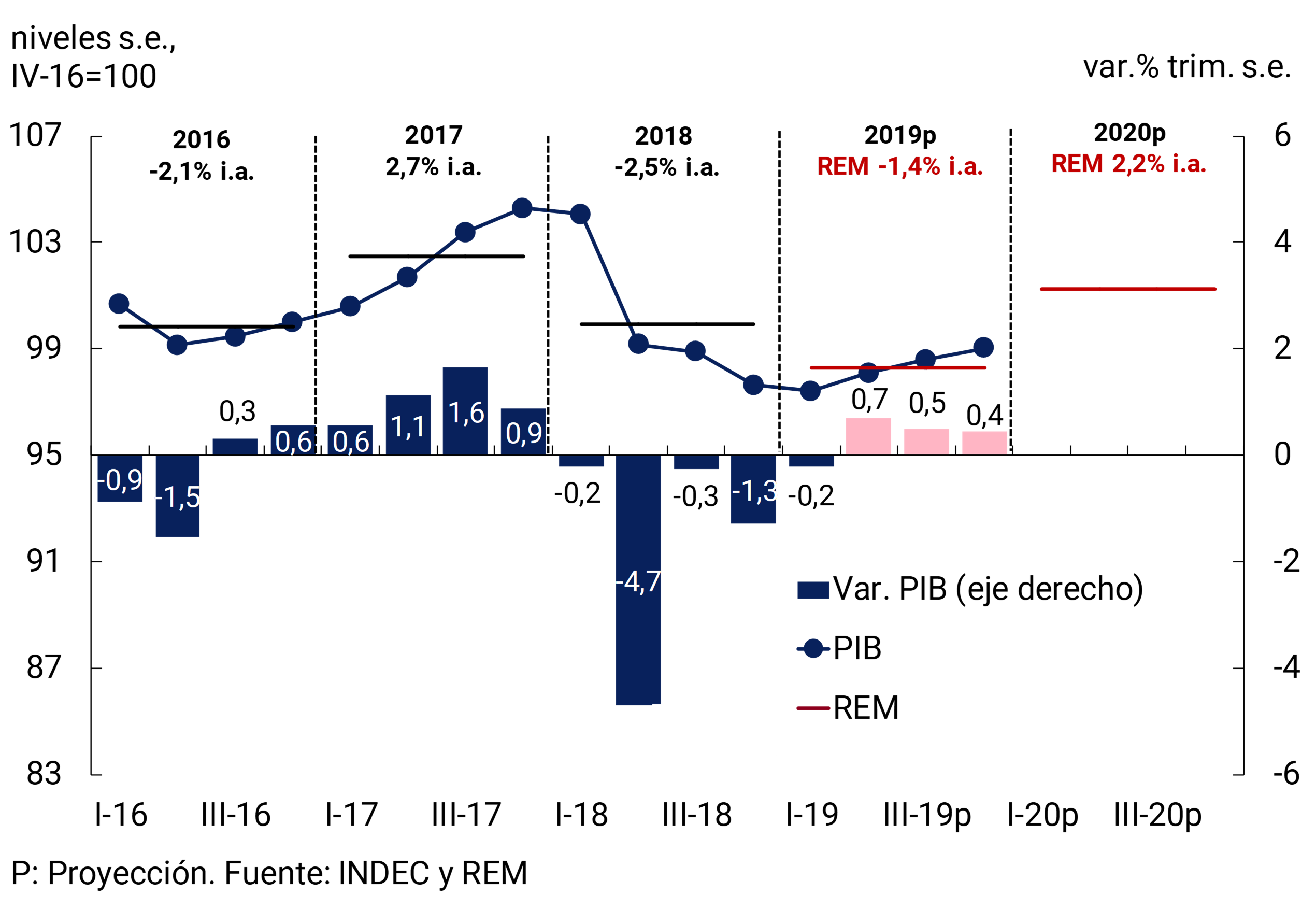

3. Economic activity

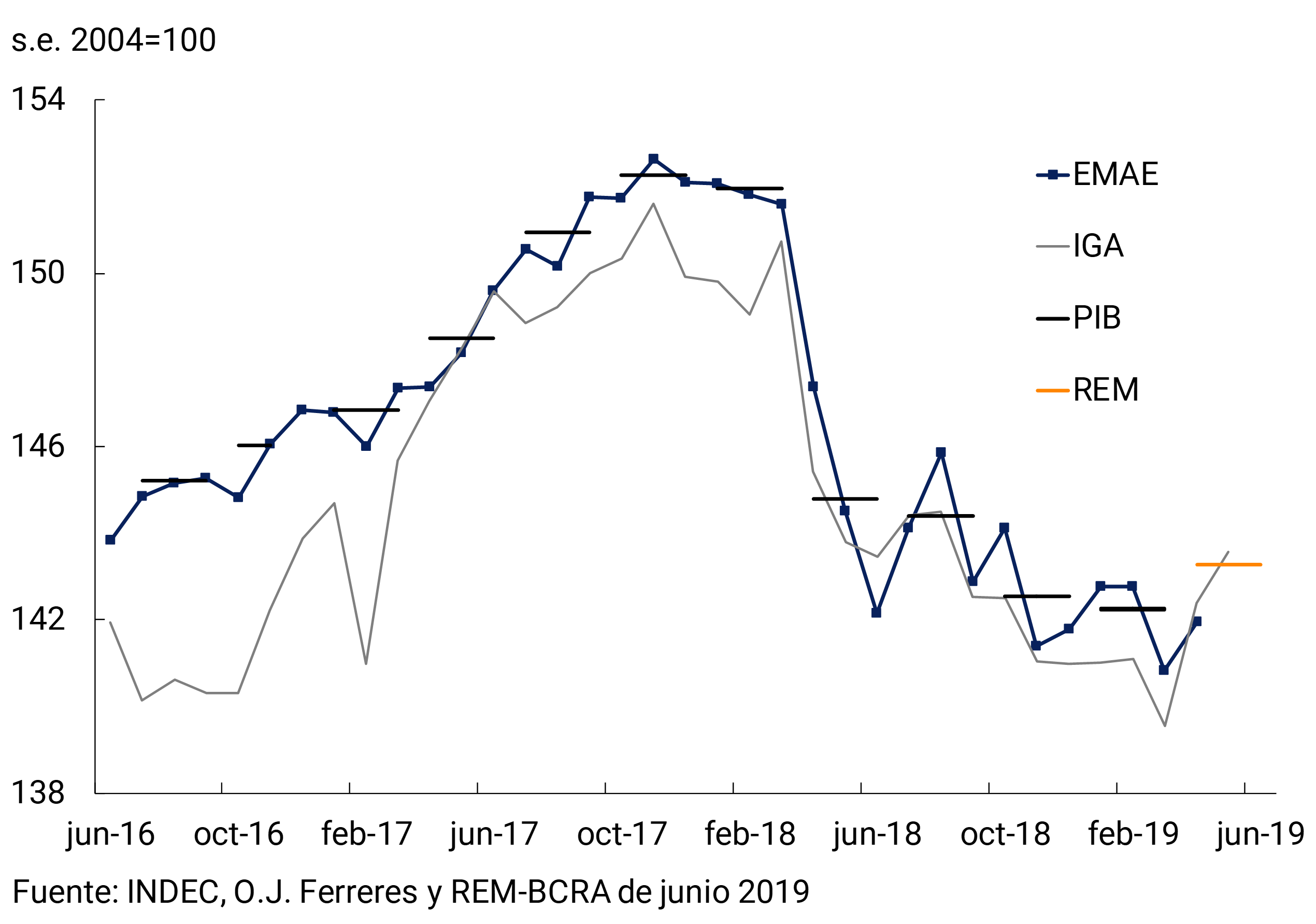

During the second quarter, economic activity resumed the recovery that began in December, which had been temporarily interrupted in March. In addition to the positive impact on activity of the record agricultural harvest and the mobilization of resources associated with Vaca Muerta, there was an increase in consumer confidence. Domestic demand recovered in a context of better international financial conditions and lower exchange rate volatility. The REM estimates a 0.7% s.e. quarterly increase for the second quarter of 2019. The Leading Activity Index (ILA-BCRA) for May met all the necessary criteria to confirm that activity would enter an expansionary phase.

For the remainder of the year, private consumption will recover from the improvement in household incomes in combination with the programs implemented by the National Government that will tend to boost spending. At the sectoral level, the favorable performance of agriculture and gas and oil production is compounded by growth prospects in other activities that produce tradable goods and services based on a higher real exchange rate and the opening of new markets. The vision of a recovery of the economy is shared by REM analysts who project the beginning of an expansive phase during 2019 and growth for 2020.

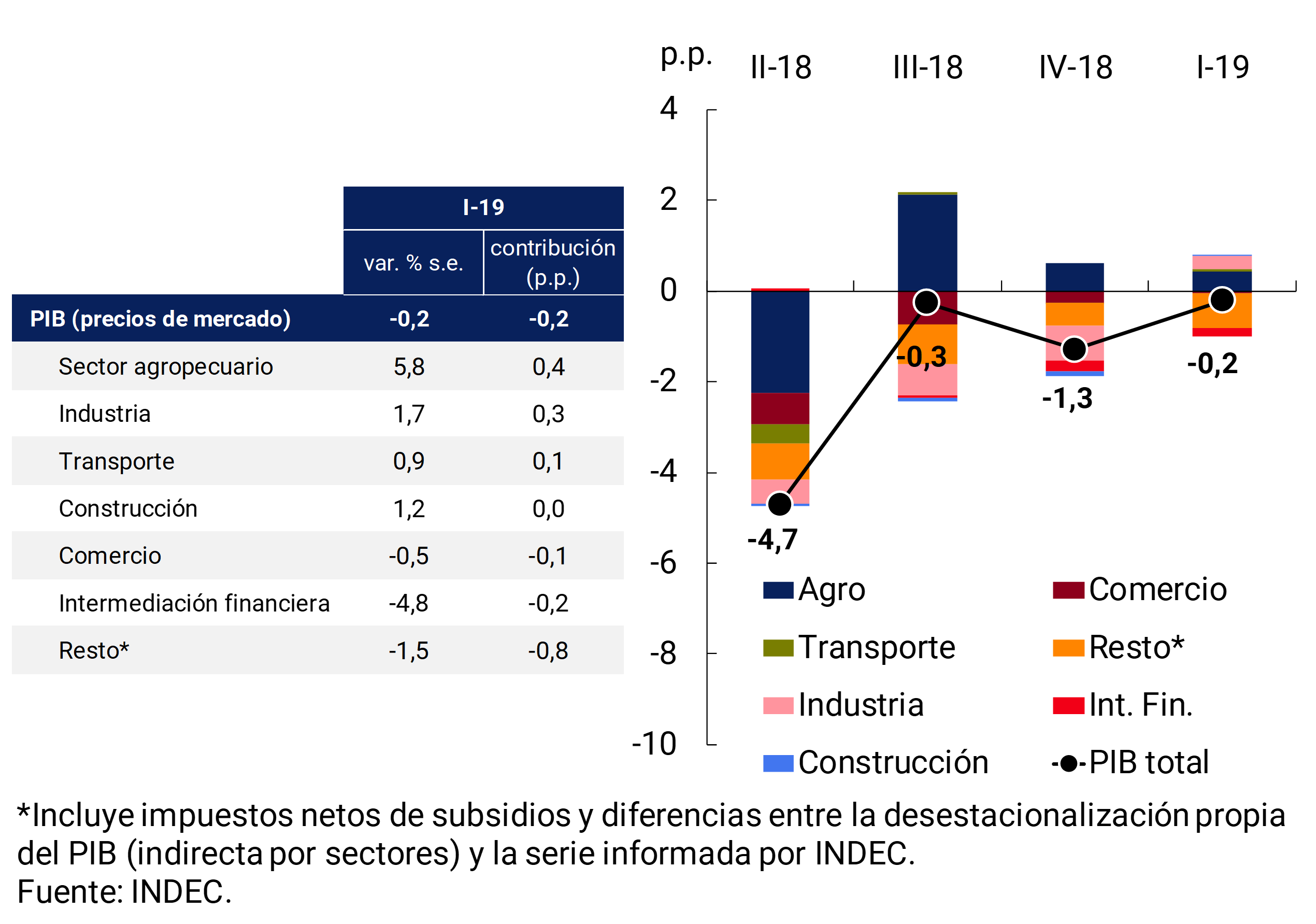

3.1 During the second quarter, signs of recovery in the economy were evident

In the first quarter of 2019, GDP contracted 0.2% quarter-on-quarter and 5.8% compared to the same period of the previous year. The result was in line with what was forecast by market analysts at the REM in May and below what was expected in the latest Contemporary GDP Prediction (0.5% s.e; PCP-BCRA). The slight contraction in the first quarter was explained by a sharp temporary drop in activity in March, associated with greater exchange rate volatility, which interrupted the recovery that had begun in December.

During the second quarter, the BCRA introduced some modifications to the monetary-exchange regime (see Monetary Policy Chapter) that contributed to reducing exchange rate volatility and improving financial conditions. In this context of less uncertainty, the Executive Branch implemented a series of measures towards the end of April that underpinned household spending, the impact of which will last beyond the second quarter (see box).

The Monthly Estimator of Economic Activity (EMAE) showed a recovery in April (0.8% s.e.), cutting the year-on-year contraction to 1.3% and leaving a statistical drag close to zero for the second quarter. The first available indicators for May and June allow us to affirm that activity would have grown during the second quarter. In the same vein, the median of the REM estimates for June stood at 0.7% seasonally adjusted quarterly growth. Although the latest Contemporary GDP Prediction (PCP-BCRA) still shows a fall of 0.56% quarter-on-quarter s.e. (see Figure 3.1), the incorporation of new data is expected to change the sign of the projection.

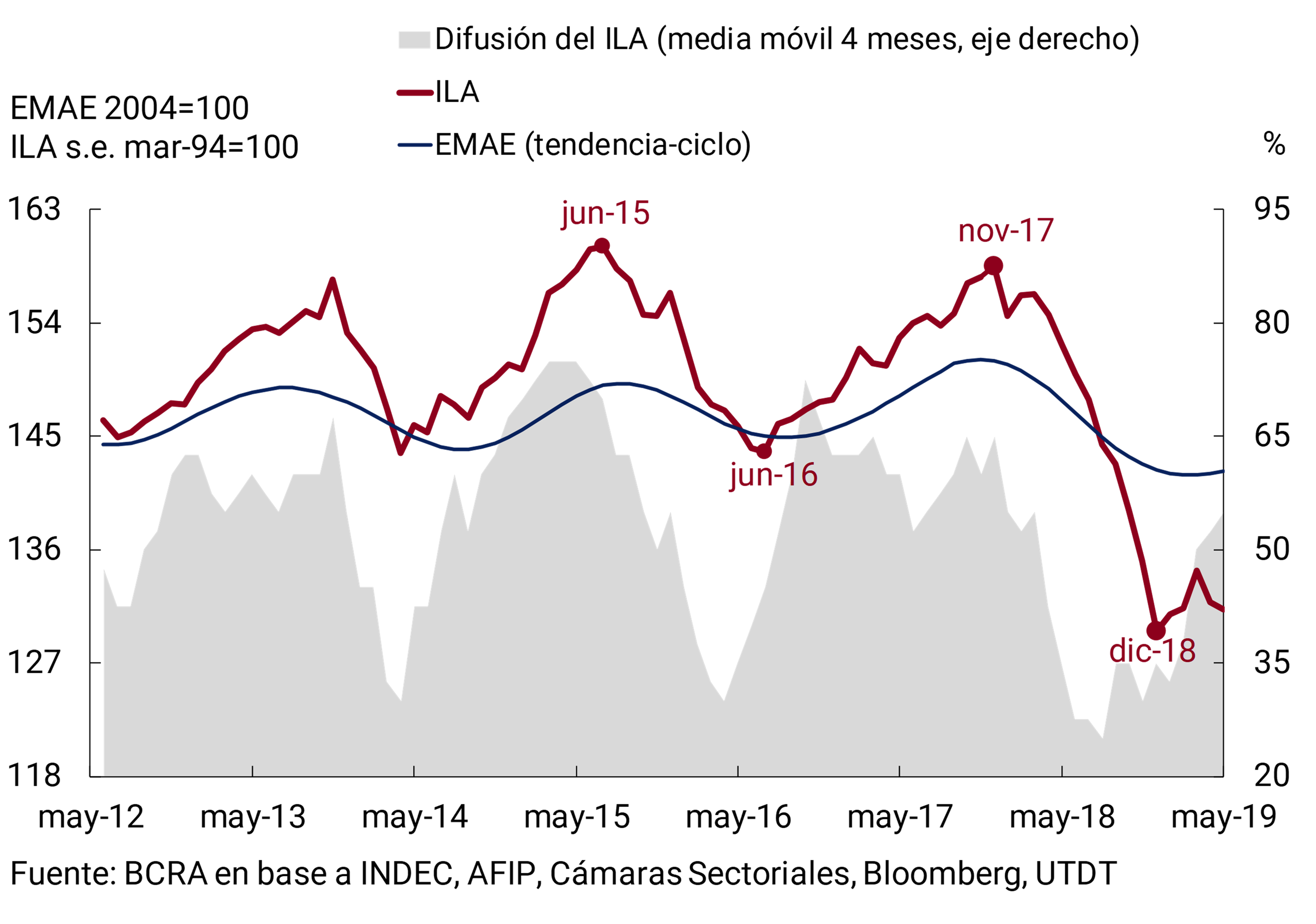

According to the Leading Activity Indicator (ILA), in May all the necessary criteria were met to confirm that the activity had entered an expansionary phase. Diffusion and depth exceeded the thresholds required to ensure the existence of a pivot point in the ILA in November 2018. In this way, the ILA anticipated the EMAE valley, which would probably be in March 2019 (see Figure 3.2).

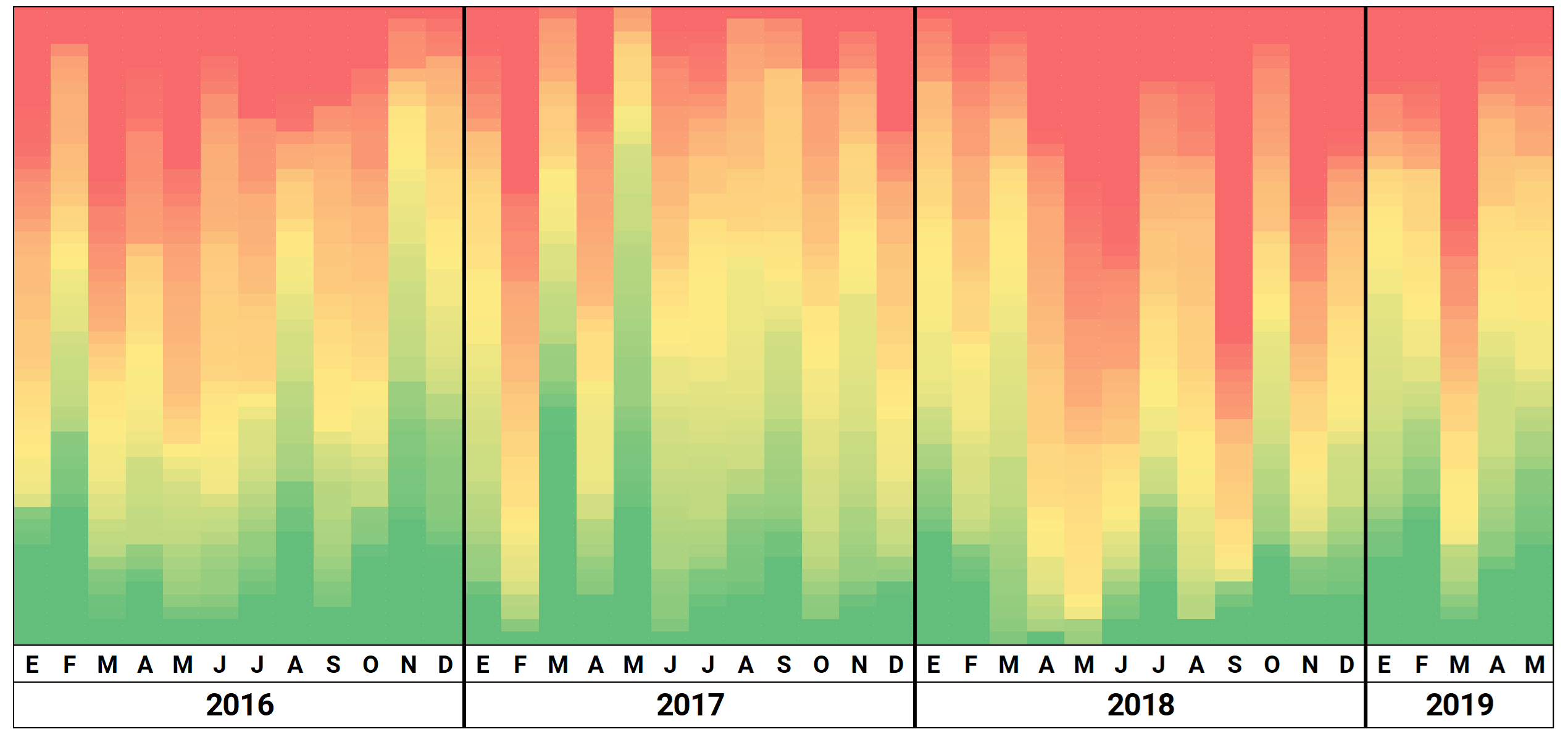

The diffusion and intensity of the growth of a broad set of activity indicators provides evidence in the same sense as the ILA-BCRA 6. As can be seen in the following graph, since December – with the exception of March – the growth of this group of variables has been more widespread and intense (the red areas have been reduced and the green areas have intensified; see Figure 3.3.).

Box: Corrections in seasonally adjusted series

The incorporation of new data to the original series modifies the series without seasonality as a result of the characteristics of the methods used to discard the seasonal component. These corrections are usually more important at the turning points of the series, affecting even the sign of the variation of the series without seasonality. This phenomenon was present in the EMAE series during the third quarter of 2016 and the first quarter of 2018, which are the last two turning points recorded so far (see Figure 3.4). The first EMAE publications for the third quarter of 2016 indicated that the economy continued to go through a recessionary phase. With the incorporation of new data, the variation of the EMAE without seasonality went from a fall of 0.9% to a rise of 0.3% in that period. In contrast, during the first quarter of 2018, the variation of the EMAE without seasonality went from an increase of 1.1% (first publication) to a fall of 0.2% (last publication).

Various consumption and activity indicators analyzed in this IPOM have been showing a recovery since December 2018. It is expected that the EMAE’s non-seasonality series for the first quarter of 2019 may be revised upwards with the incorporation of new observations to the original series.

3.1.1 Domestic demand began to recover

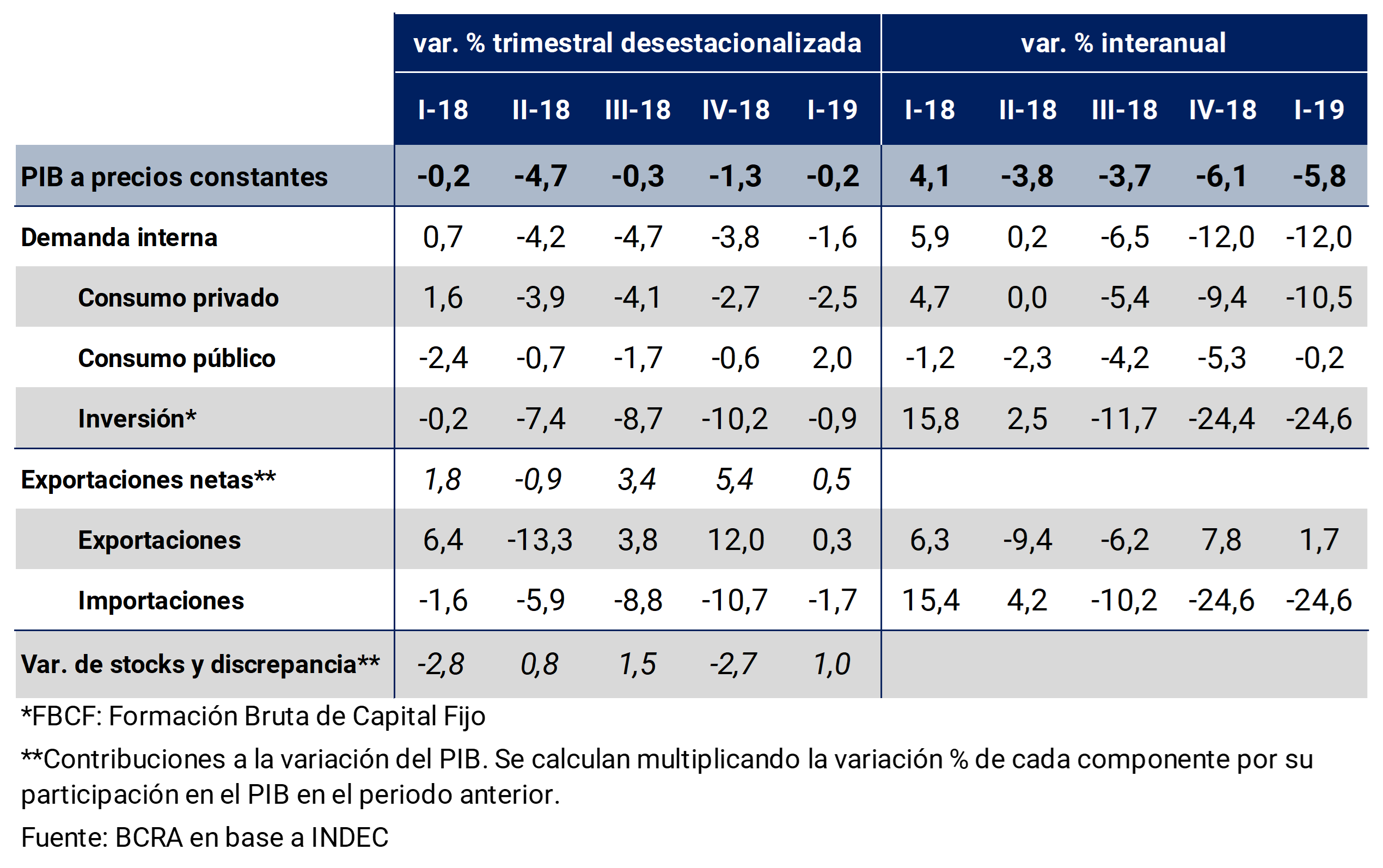

During the first quarter of 2019, domestic demand continued to deteriorate, although it slowed its decline (-1.6% quarter-on-quarter) due to the rise in public consumption (2.0% s.e.) and the sharp cut in the contraction of investment7 (-0.9% s.e.). Private consumption had another significant drop (-2.5% s.e.).

Net exports made a slightly positive contribution to the seasonally adjusted quarterly variation of GDP in the first quarter (0.5 percentage points (p.p.), as a result of the reduction in imports (-1.7% s.e.) – explained by the performance of domestic demand – and a slight increase in exports (0.3% s.e.). Finally, the change in stocks and the discrepancy had a positive contribution to the seasonally adjusted quarterly variation of GDP (1 p.p.; see Table 3.1).

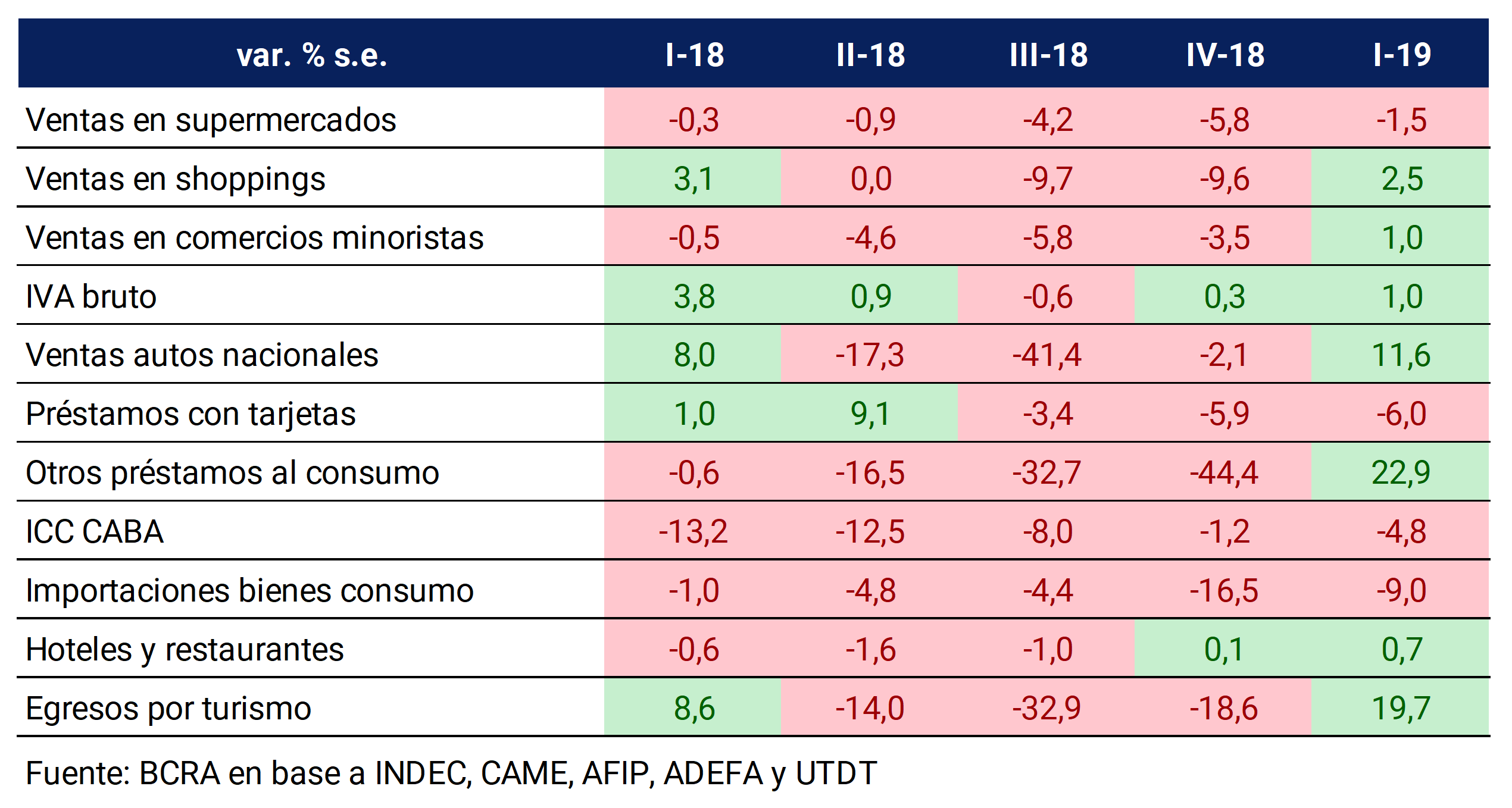

Private consumption registered a new fall during the first quarter of 2019 despite the fact that several partial indicators showed an improvement. Among them, the growth in sales volumes in shopping malls (2.5% s.e.), sales of domestic cars (11.6% s.e.) and the net granting of consumer loans (22.6%) (see Table 3.2) stand out.

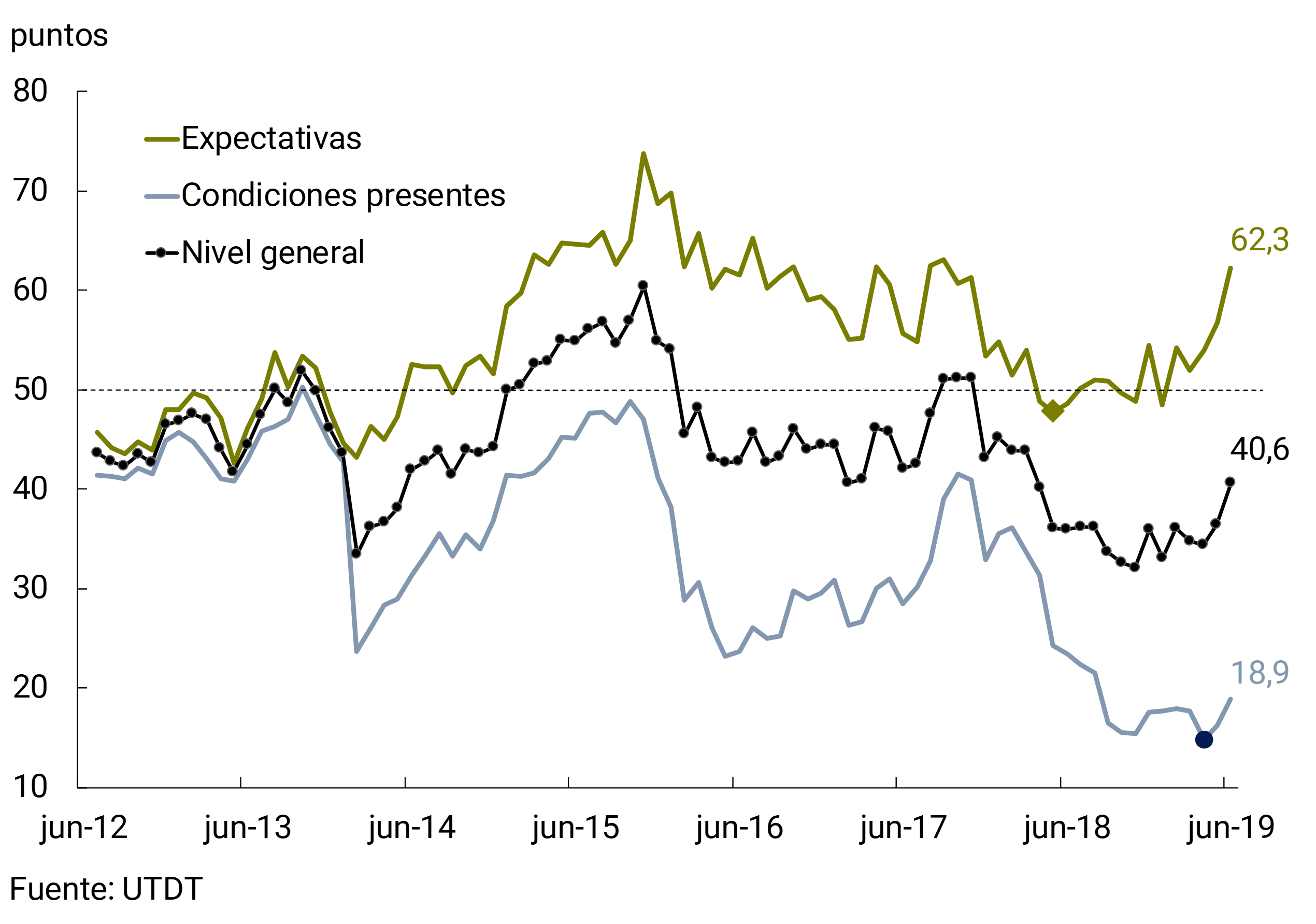

The BCRA’s Leading Indicator of consumption rose in the first quarter. This indicator usually anticipates the turning points of INDEC’s private consumption, so it allows us to expect a recovery in the second quarter (see Figure 3.5). For the remainder of the year, the expected recovery in income, together with the measures announced by the government (see box Measures to promote consumption), foresee good prospects for consumption. Some data related to household consumption in the second quarter showed a better performance. The Consumer Confidence Index of the Di Tella University at the national level (ICC-UTDT) rose 5.8 p.p. between March and June (2.5 p.p. quarterly on average), gross VAT collection (DGI + DGA) increased 4.5% s.e.8 and the quantities imported of consumer goods during the April-May two-month period increased on average 0.8% s.e. compared to the first quarter.

The expected recovery in revenues together with the measures announced by the national government (see Box: Measures to promote consumption) will boost consumption during the remainder of the year.

Box: Measures to promote consumption

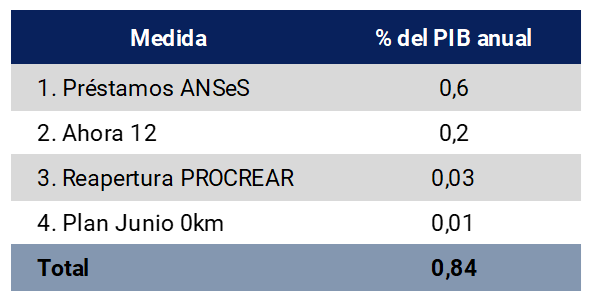

During the second quarter of 2019, the National Government carried out different measures to promote private consumption for an approximate amount of 0.8% of GDP. The full impact of these measures will be recorded between the third and fourth quarters of 2019.

The plans have different purposes such as the purchase of homes (PROCREAR), cars (June 0KM), household appliances (Ahora12) and personal expenses (ANSES) the main objective of these programs is to improve household consumption.

The line of credit granted by ANSeS9 is a program of personal loans for retirees, pensioners and those who receive Child Allowances. The amounts range from $5,000 to $200,000 in the first two cases, while those designated for AUH beneficiaries are in a range of $1,000 to $12,000. ANSES estimates that it will grant loans for $124,000 million until the end of the year, that is, 0.6% of GDP.

With the aim of “promoting consumption and national production of goods and services,” the quota purchase programs called Ahora 3, Ahora 6, Ahora 12 and Ahora 18 were launched. The rates for all cards issued by banks are 20%, which represents a decrease of 25 percentage points compared to the previous rate of the program (45%) effective from June 1 to December 3110. The financing granted could reach 0.2% of GDP in the second half of the year.

The launch of a new phase of the Procrear Plan allows access to credit for the purchase of housing, new or used, for family use and permanent occupation11. This line of credit is key in segments of the population that have housing needs or significant improvements in their homes.

To encourage car sales, the June 0km12 plan has bonuses that are around $50,000 and $90,000, according to the price of the chosen car. In addition, the City of Buenos Aires and the Province of Buenos Aires will reduce the stamp tax (to units of less than $750,000) that is charged with the patenting13. The fiscal cost of this program would be partially offset by the tax revenue derived from the sale of a greater number of cars. The different measures mentioned could together reach around 0.8 p.p. of GDP (see Table 3.3).

Table 3.3 | Estimation of the maximum amounts involved in the different programs as a percentage of GDP in 2019

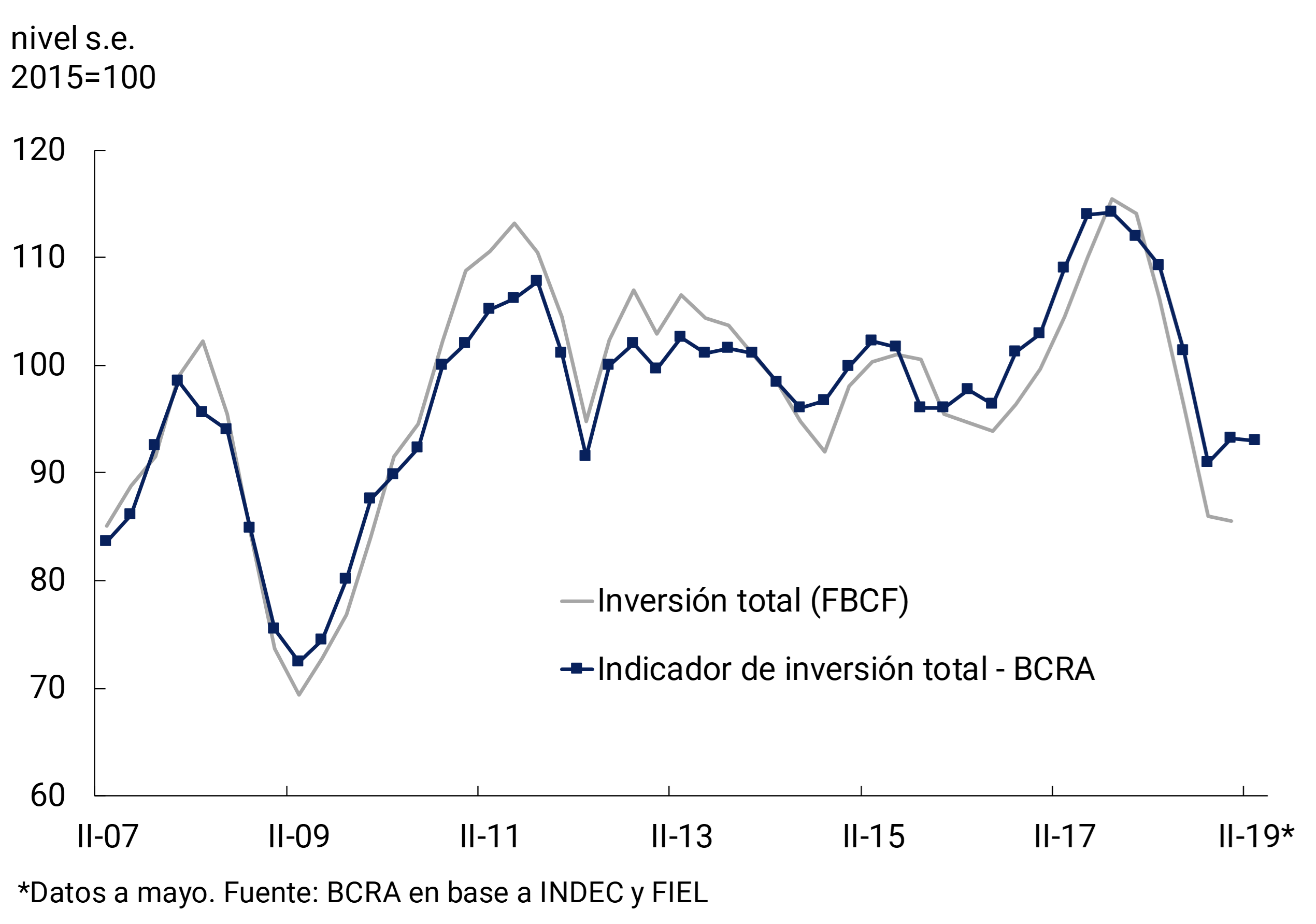

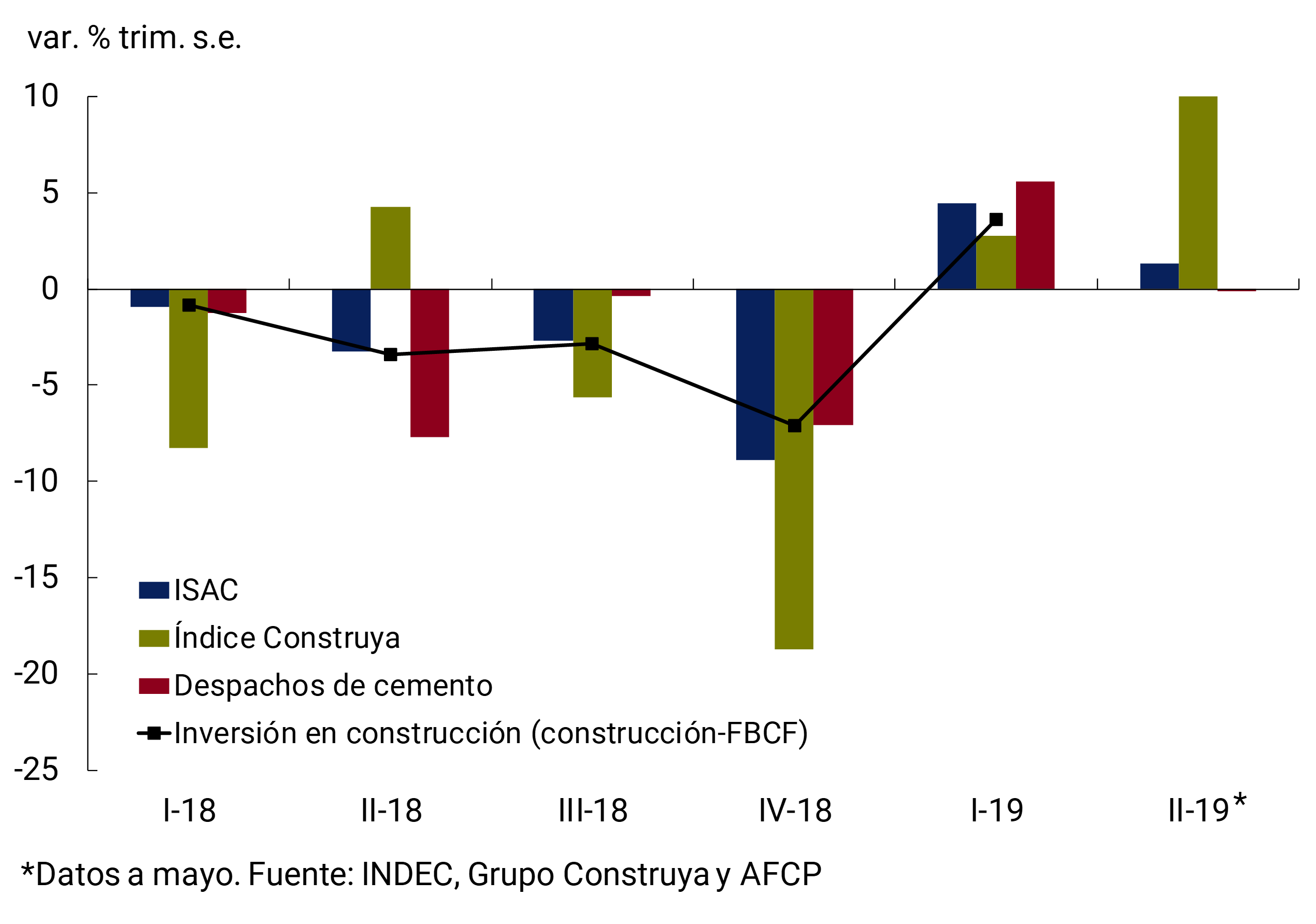

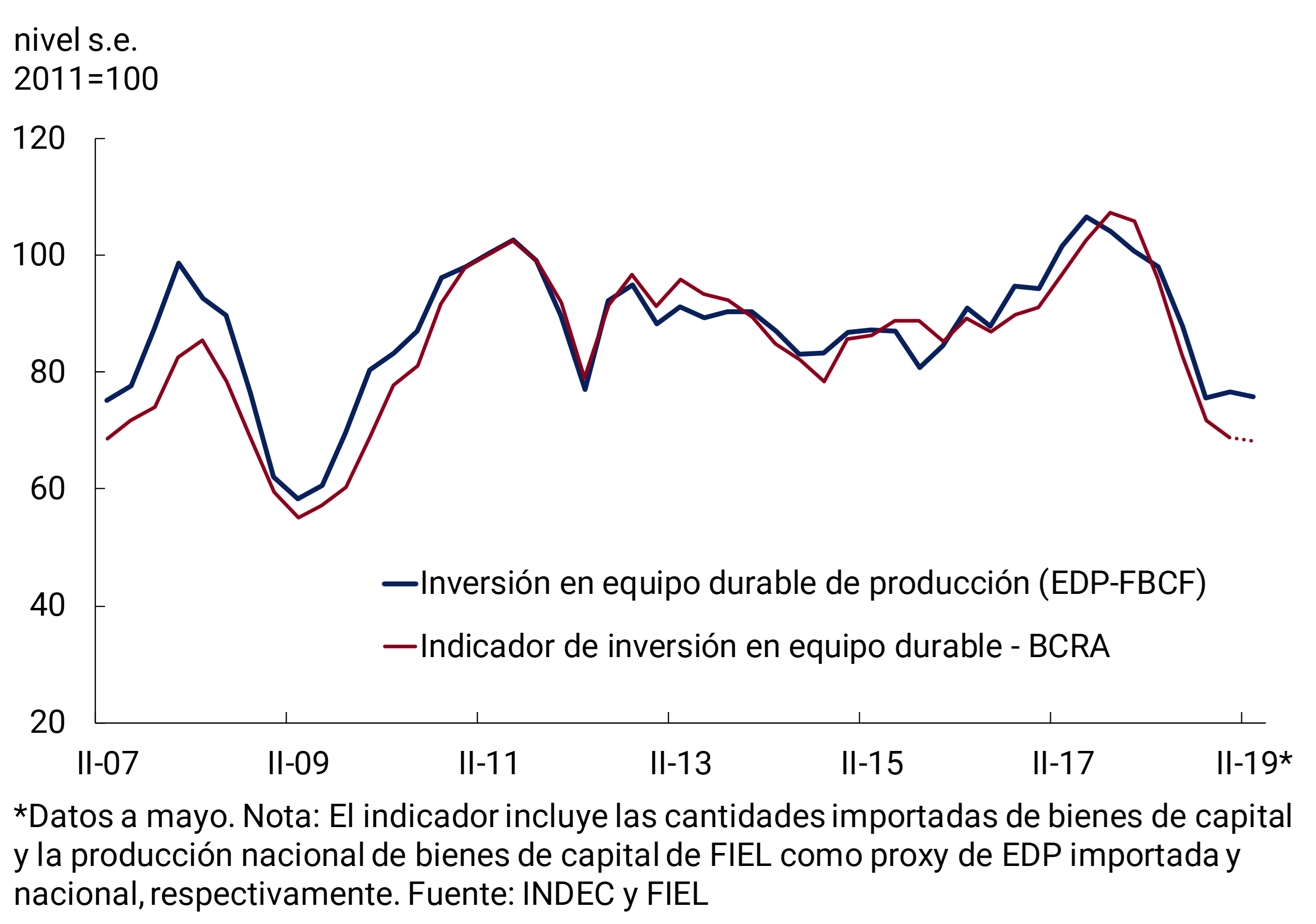

With respect to investment, the fall observed in the last quarter of 2018 (-10.2% s.e.) was considerably reduced. The contraction of 0.9% s.e. in the first quarter was explained by a sharp decrease in expenditure on Durable Production Equipment (-5.8% s.e.), which was attenuated by an increase in Construction (3.6% s.e.). With partial data from the second quarter, the BCRA-investment indicator—which had recovered slightly in the first quarter—remained stable (see Figure 3.6).

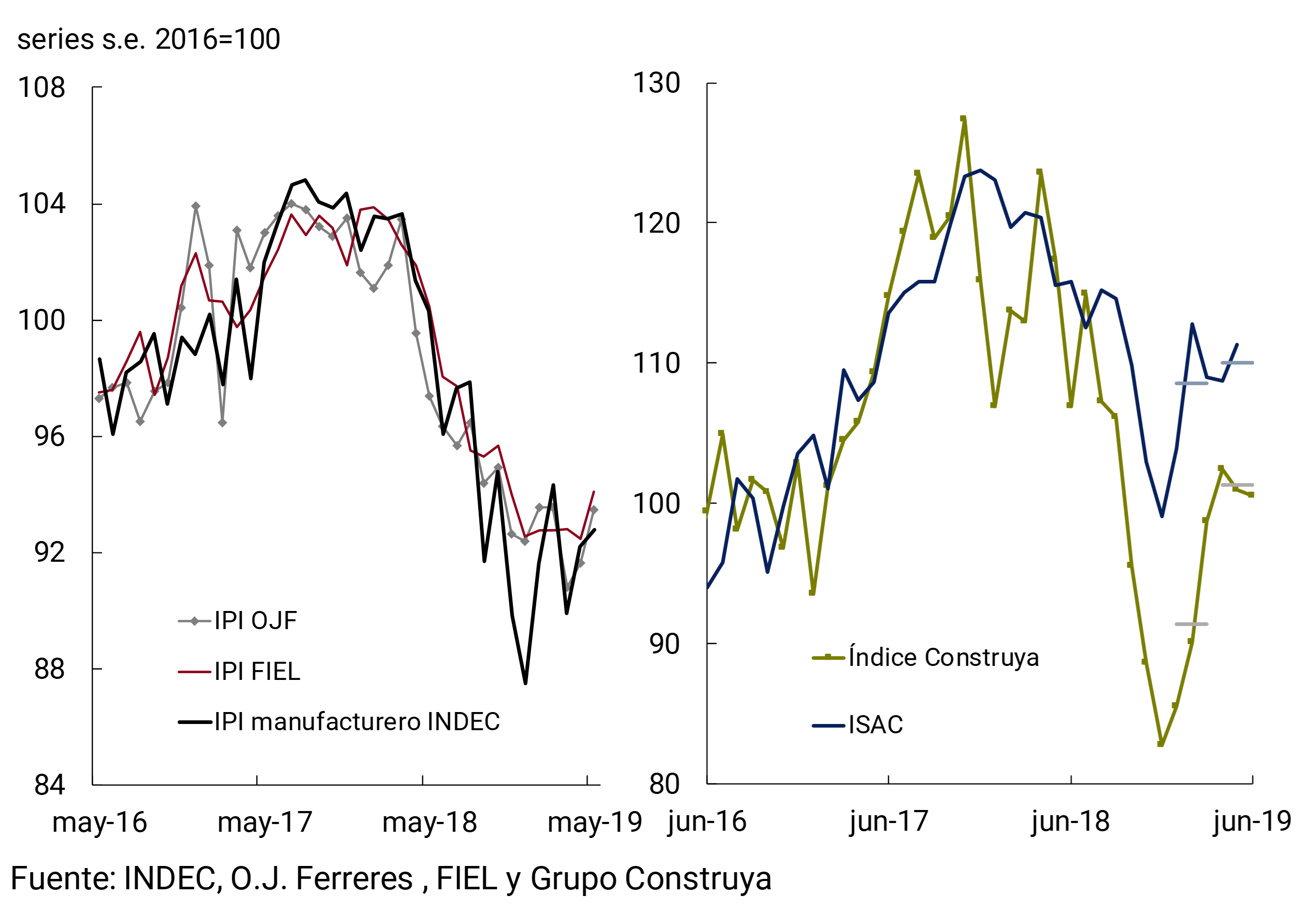

The Construction component of the Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) of INDEC would show a new increase during the second quarter of 2019. The Construya Index, which measures sales of the main construction inputs, increased 9.4% between April and May compared to the first quarter of 2019, while the Construction sector of the EMAE – an indicator that weights the demand for the main construction materials and the labor involved – 14 grew 0.8% s.e. in April compared to the first quarter of 2019 (see Chart 3.7).

The good performance of construction was explained both by the reactivation of private works and by the faster pace of execution of public works. The greater dynamism of private works can be seen from the evolution of the inputs typically used in this type of construction, such as ceramic floors and coatings (+9.5% s.e. between April and May compared to the first quarter) and gypsum (+5.3% s.e. in the same period). As for public works, according to data from Construar15, the amounts involved in the calls for public tenders (from the national, provincial and municipal states) rose 61% y.o.y. in nominal terms in the first quarter of 2019, a figure that, deflated by the INDEC Construction Cost Index, meant an increase of 11.1% y.o.y. in real terms.

The BCRA’s Durable Equipment Investment Indicator remained stable during April and May compared to the previous quarter. The improvement in demand for imported equipment was offset by the fall in domestic production of capital goods surveyed by FIEL, which has a high correlation with investment in domestic equipment (see Figure 3.8).

3.1.2 In the second quarter, exports of goods were driven by the agricultural sector

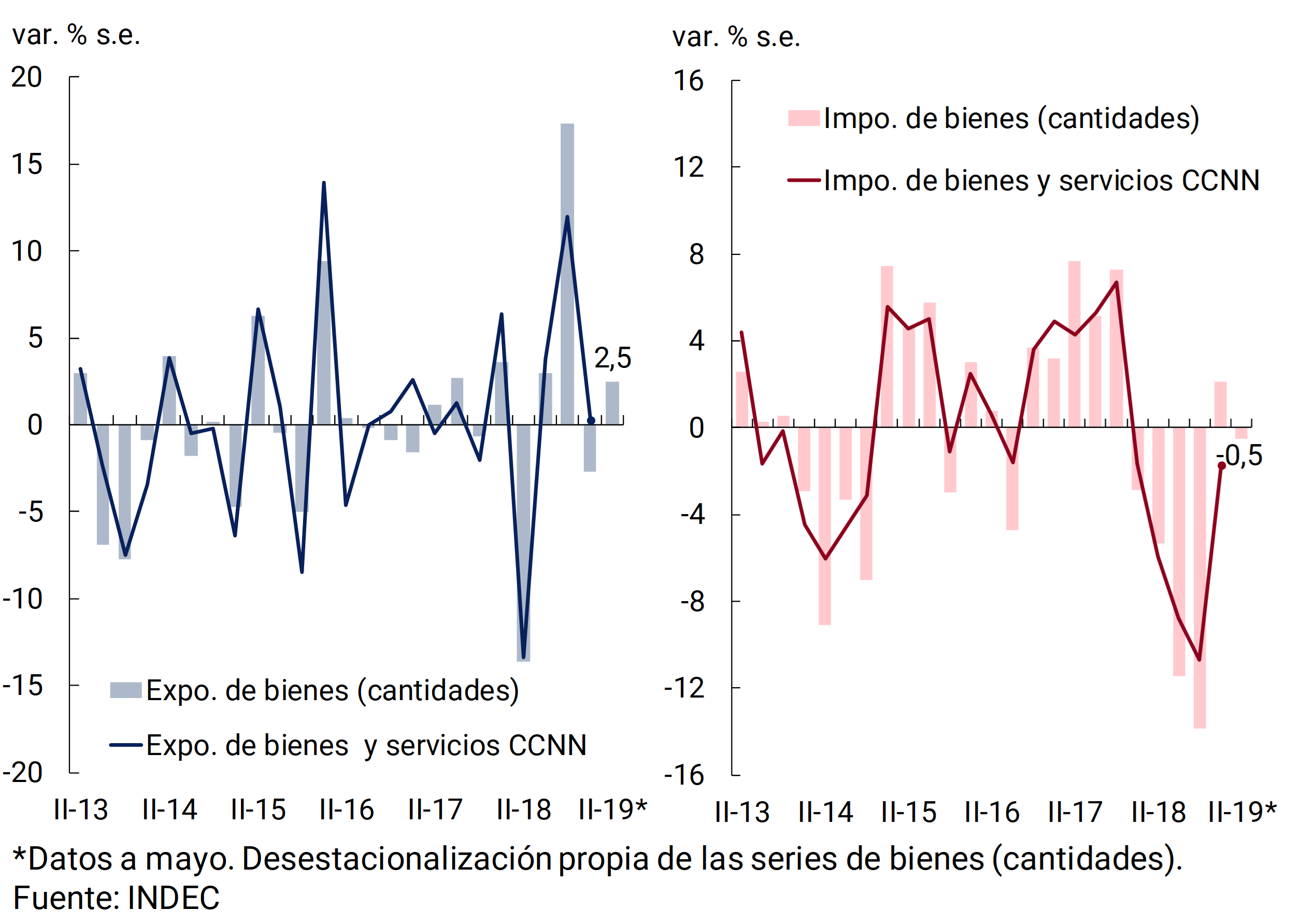

In the first quarter of 2019, real exports of goods and services showed slight growth (0.3% qoq s.e. and 1.7% y.o.y.), while imports fell again (-1.7% s.e. and -24.6% y.o.y.), partially offsetting the contraction in domestic demand. The slight improvement in total exports was explained by higher exports of services, particularly travel, which more than offset the decline in exports of goods in the quarter (see Figure 3.9).

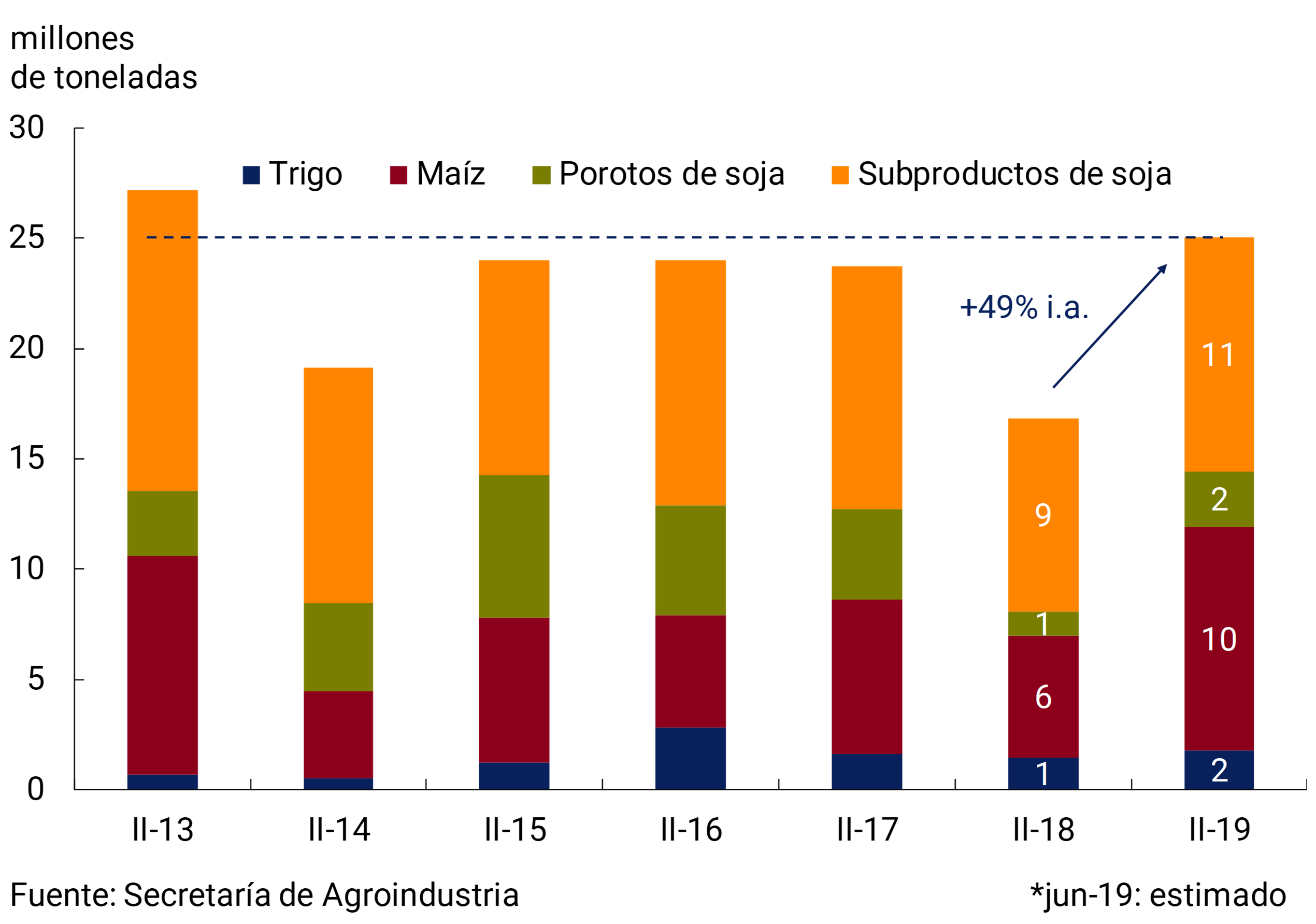

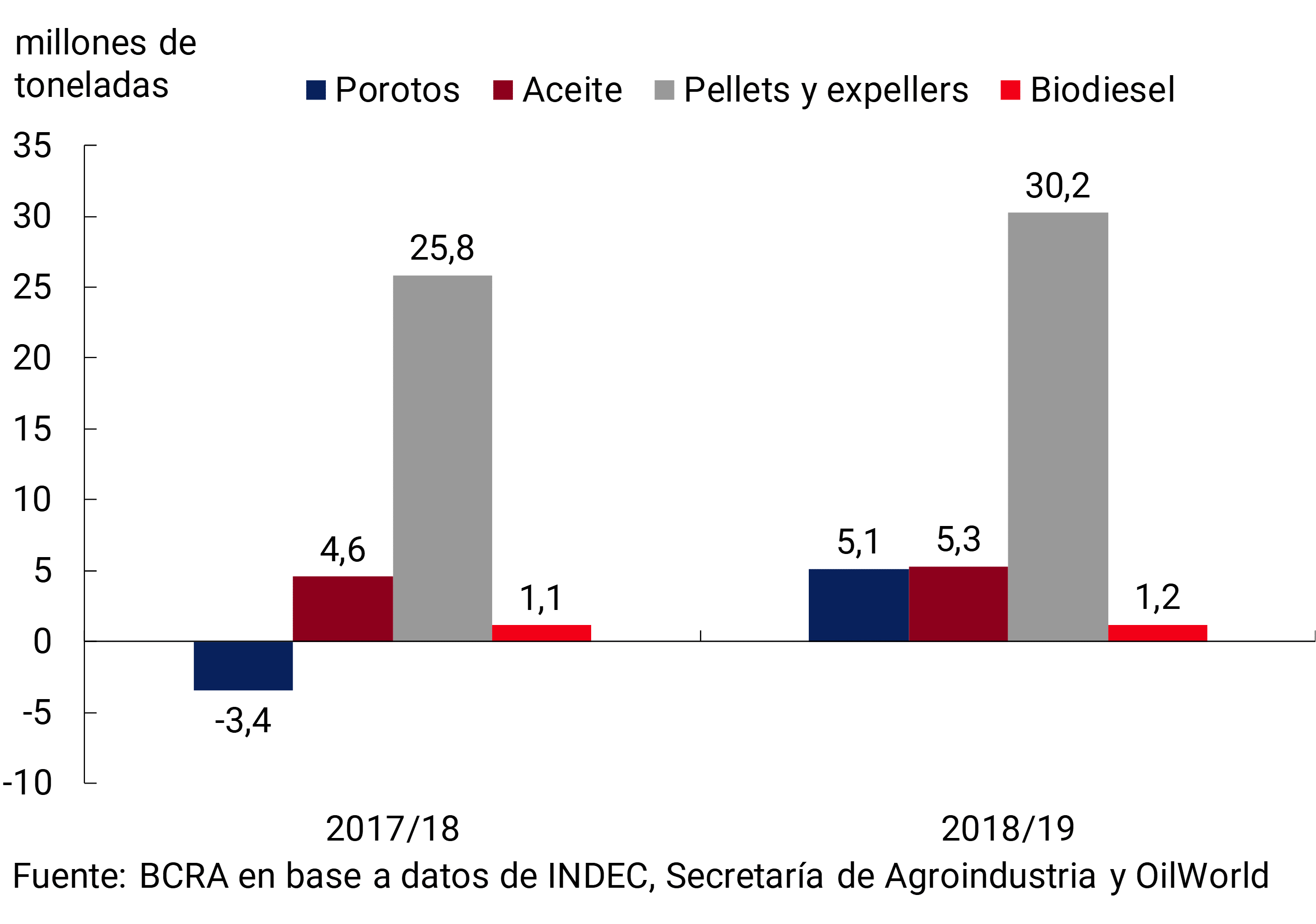

In the two months of April-May 2019, exports of goods rose 2.5% s.e. compared to the previous quarter. This performance was more influenced by shipments of cereals (22% s.e.) and soybean by-products (6% s.e.). Advance shipment data suggest that the good performance of products linked to the record harvest was sustained in June. The total shipped of the main grains and their derivatives increased 47% YoY in the second quarter, reaching the highest cumulative since II-13 (see Figure 3.10).

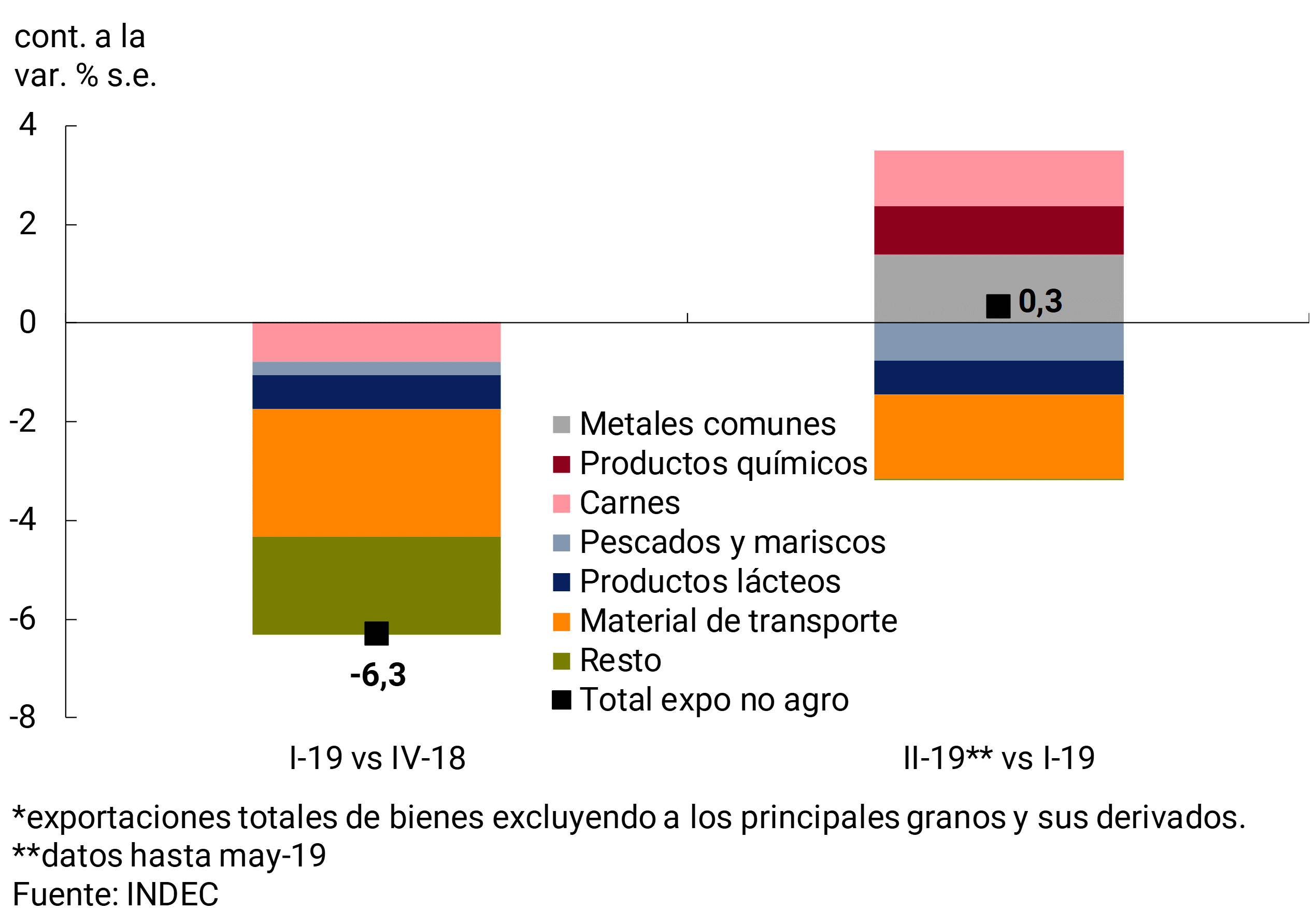

In the April-May period of this year, non-agricultural exports rose by just 0.3% s.e. after a negative first quarter in which they fell widely. In any case, they were 1.7% above last year and accumulate a seasonally adjusted increase of 27% compared to the minimum of Dec-15. The sectors that showed a recovery in exports during the second quarter compared to the previous quarter were: base metals (22% s.e.; 27% y.o.y.), meat (19% s.e.; 33% y.o.y.) and chemical products (10% s.e., 2% y.o.y.). On the other hand, external sales of land transport material, dairy products, and fish and seafood fell for the second consecutive quarter and were lower than those of the same period in 2018 (see Figure 3.11).

On the other hand, in the April-May two-month period, imported quantities registered a slight drop (-0.5% s.e. compared to the first quarter), explained by the negative carry-over left by the March data (-6.5% s.e.). Both April and May saw monthly increases (5.3% s.e. and 2.1% s.e., respectively). At the disaggregated level, the purchases of parts and accessories for capital goods (12% s.e.) and chemical inputs (8% s.e.) stood out for their incidence. Despite this recent increase, in May the volumes acquired were 31% s.e. below the previous maximum reached in Nov-17.

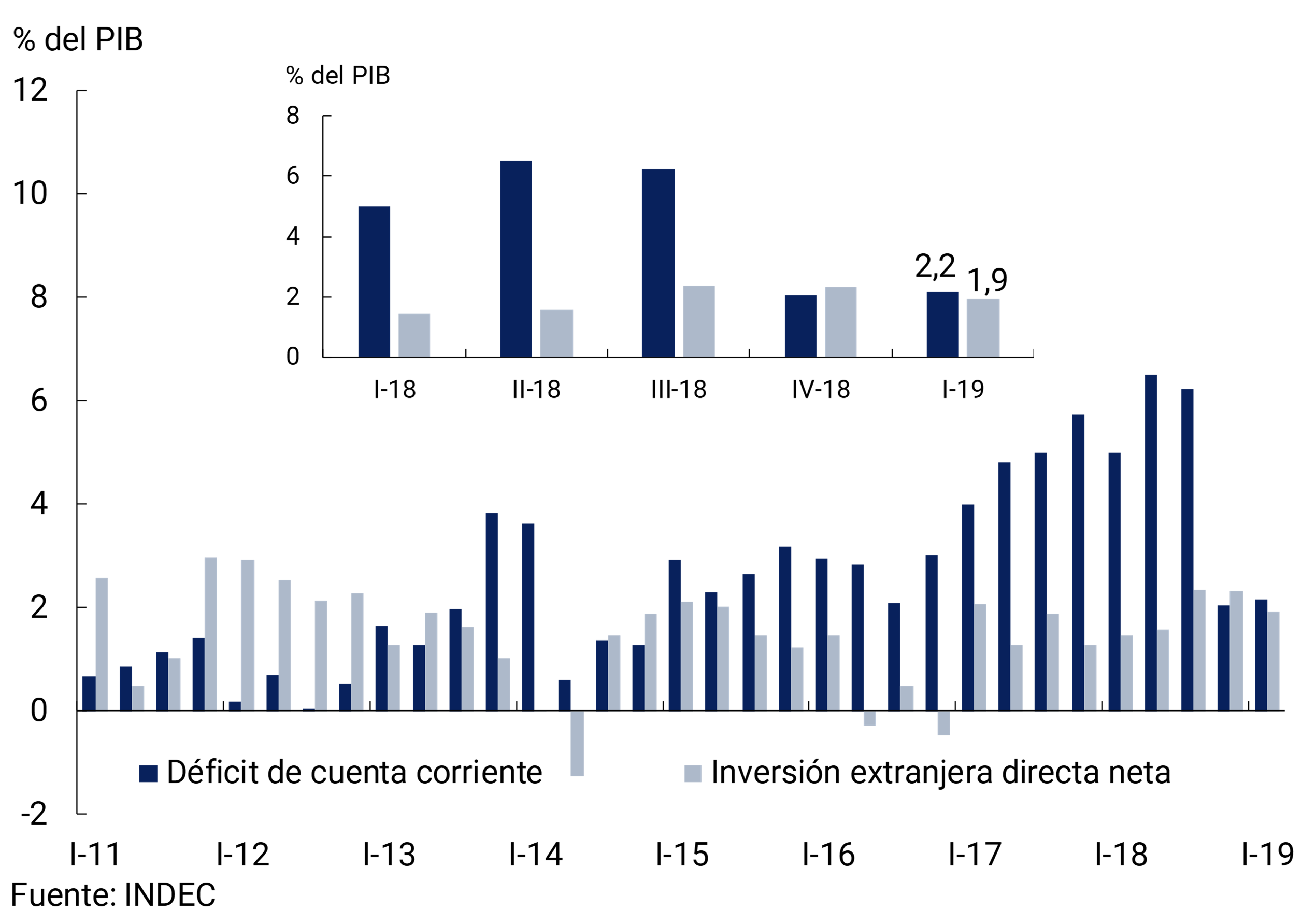

This evolution of trade flows of goods in the second quarter shows the continuity of the process of correction of the external accounts of the Argentine economy that began in the second half of 2018. The rise in the real exchange rate during 2018 allowed the Argentine economy to start the year with a seasonally adjusted and annualized current account deficit of around 2% for the first time since 2014, a level similar to the annual net income from foreign direct investment that Argentina receives (see Figure 3.12).

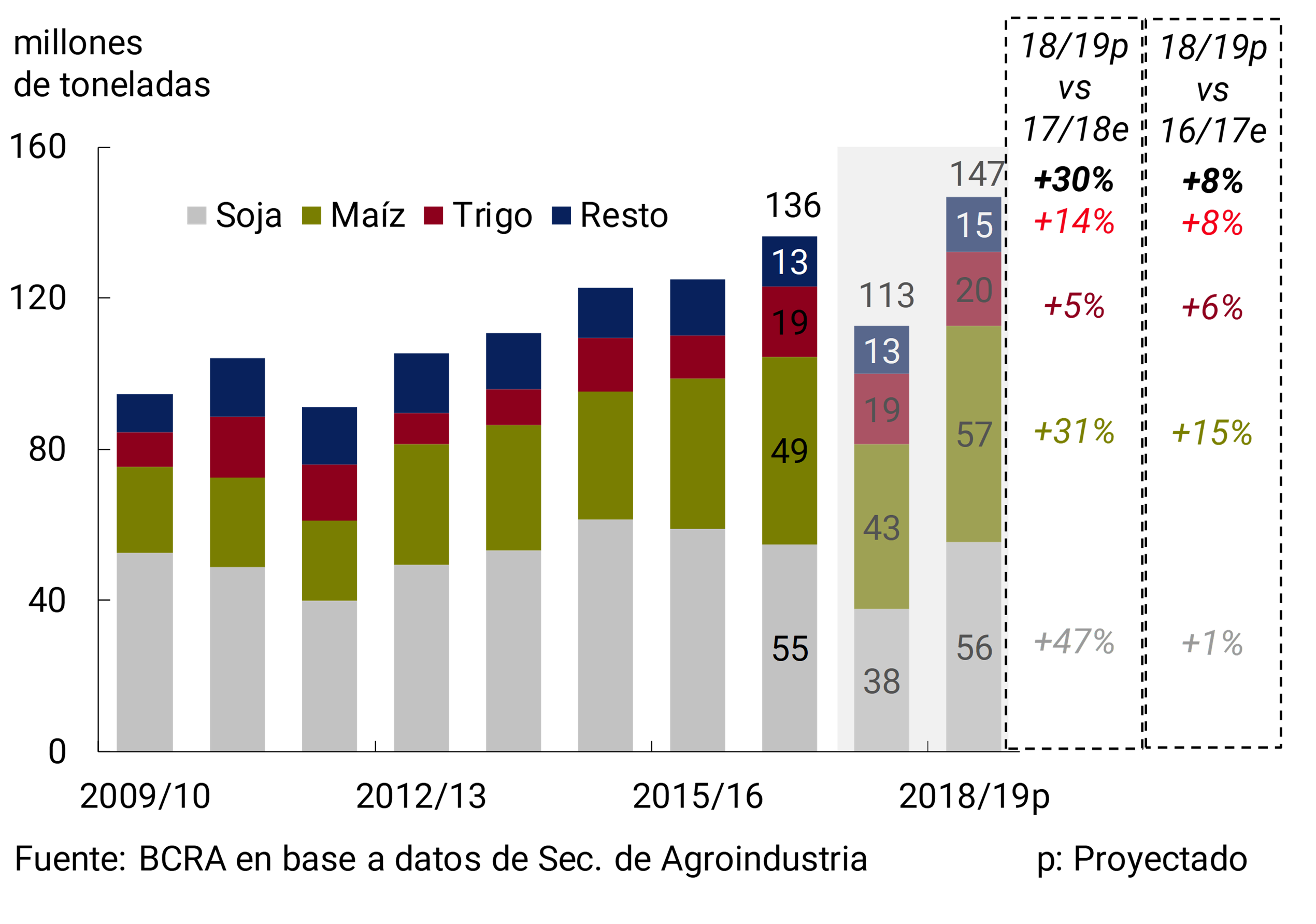

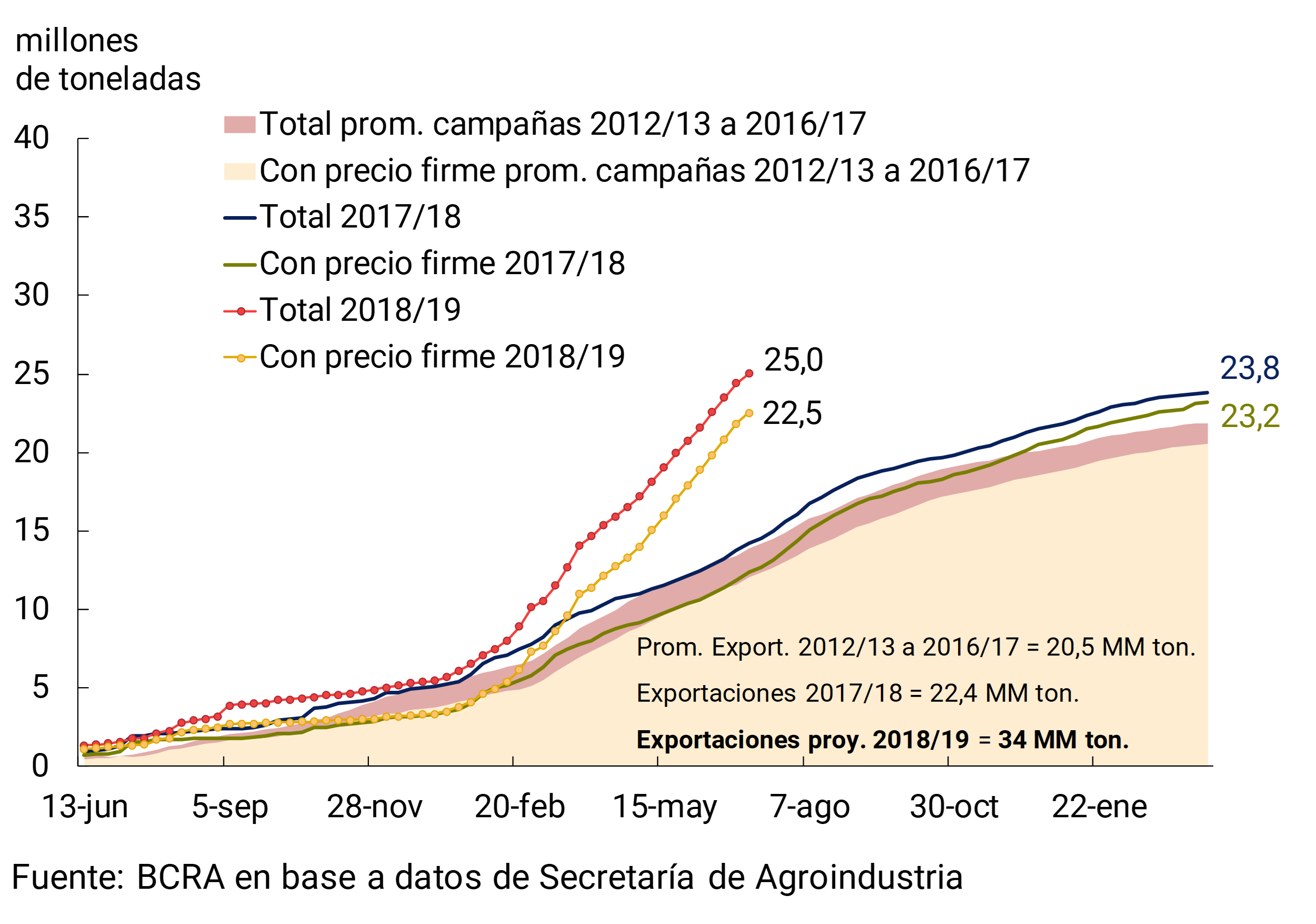

For the remainder of the year, exports are expected to continue to be driven mainly by the agricultural sector. After a record harvest, 73% of soybean exports, 60% of by-product sales and 44% of corn shipments estimated for 2019 would be completed in the second half of the year (see Agricultural Harvest). For its part, it is estimated that, after having found a floor in March, imports will consolidate a reactivation, to the extent that economic activity demands it.

3.1.3 Major sectors of the economy continue to recover

The slight fall in the economy during the first quarter (-0.2% s.e.) was explained by the transitory fall in activity in March and was concentrated in only four of the sixteen sectors of GDP. A number of important activities – Agriculture, Industry, Construction, Mining and Quarrying, and Transport – grew compared to the previous quarter.

The contractions with the greatest incidences were registered in Financial Intermediation and Commerce, affected by the reduction in private consumption and exchange rate instability in March. Electricity, Gas and Water, Other Community Service Activities and the tax component net of subsidies accounted for the rest of the fall in GDP measured at market prices (see Figure 3.13).

The level of activity improved again in April, reaching above the level of December 2018 in eleven of the fifteen sectors that make up the EMAE. According to different available indicators, relevant sectors such as industry and construction would have grown during the second quarter compared to the first quarter (see Figure 3.14).

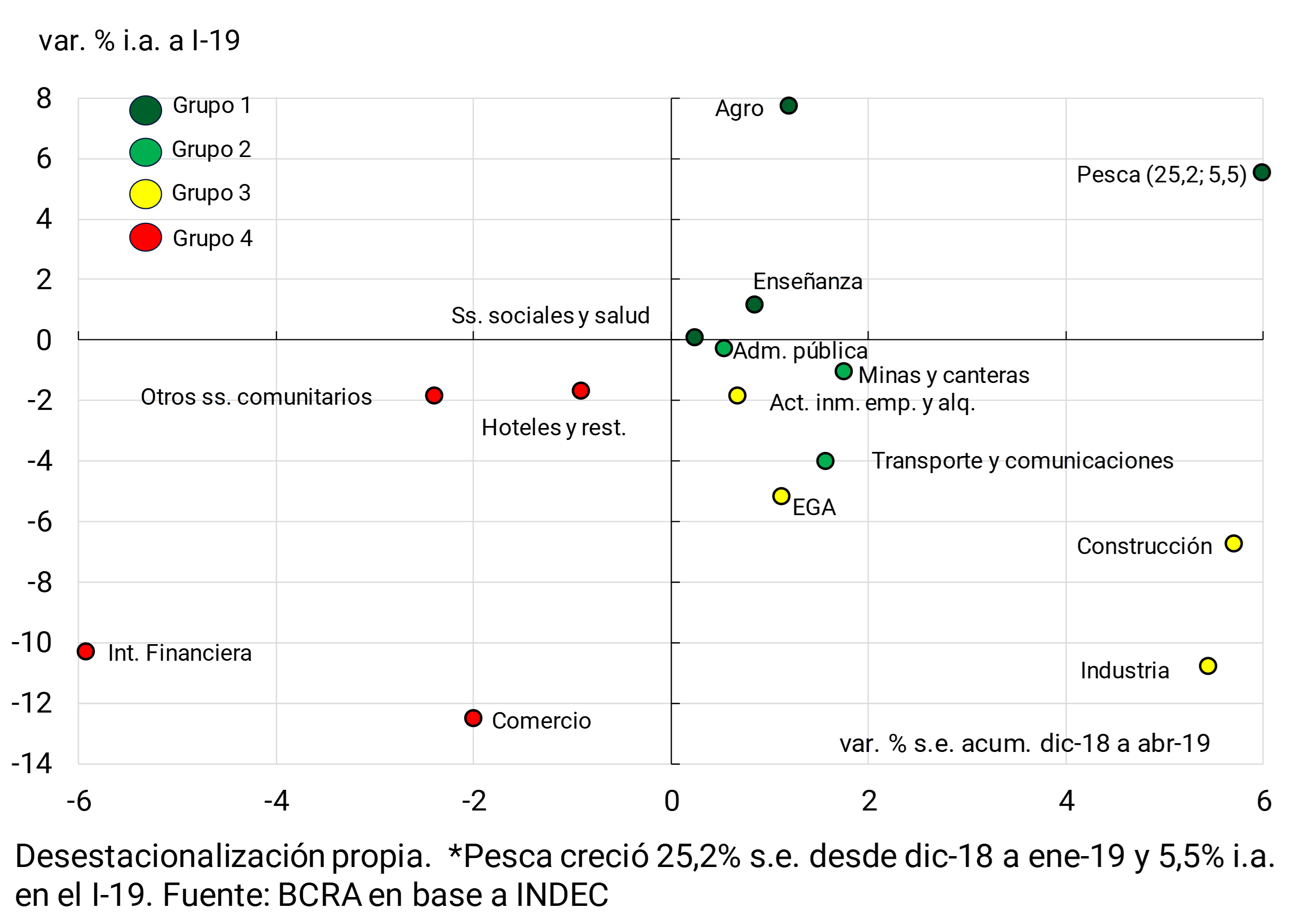

The performance of economic activity since the end of 2018 has not been homogeneous among the different productive sectors. In line with the classification made in the last IPOM of April 2019, the sectors can be separated into four groups according to their recent evolution.

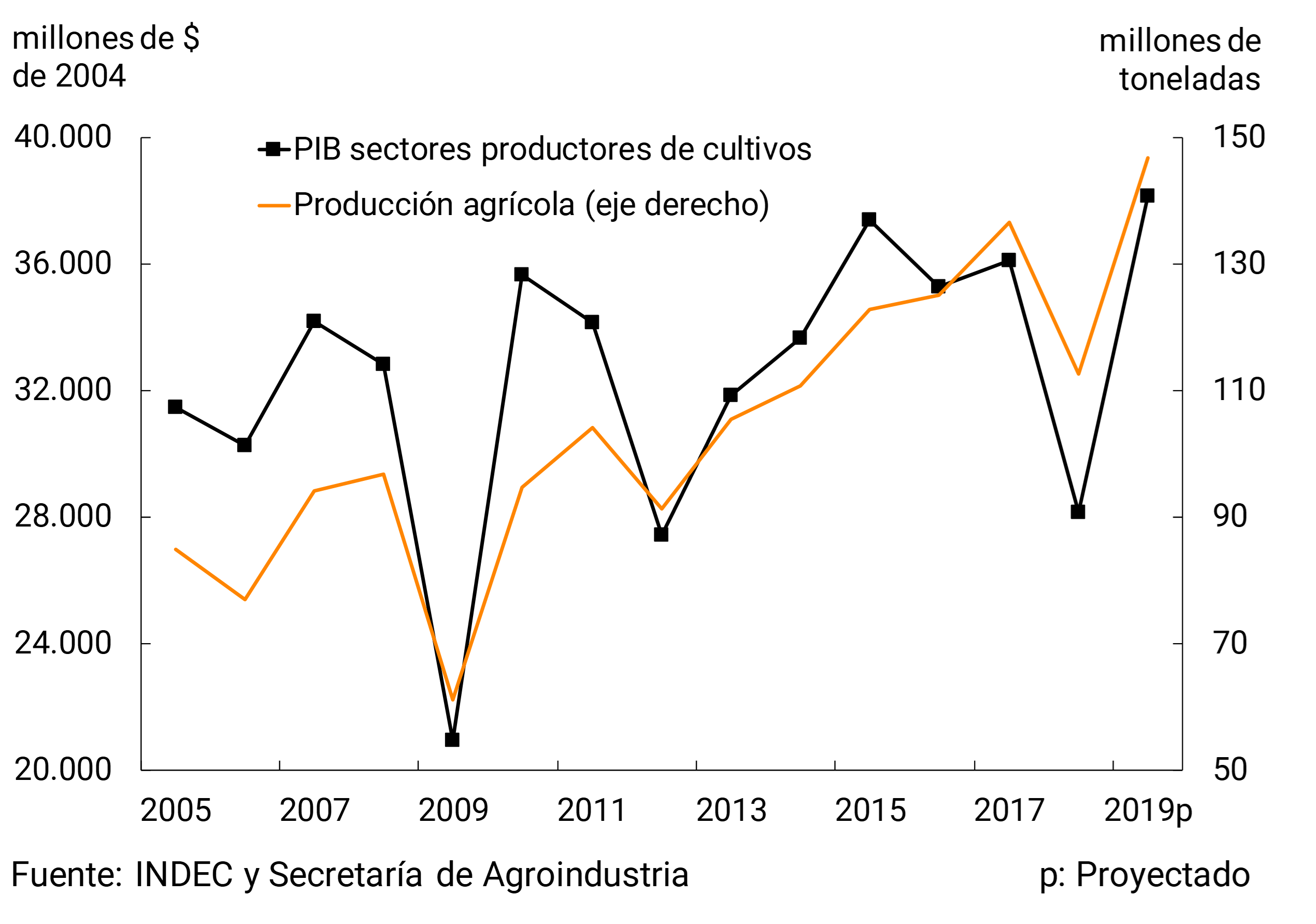

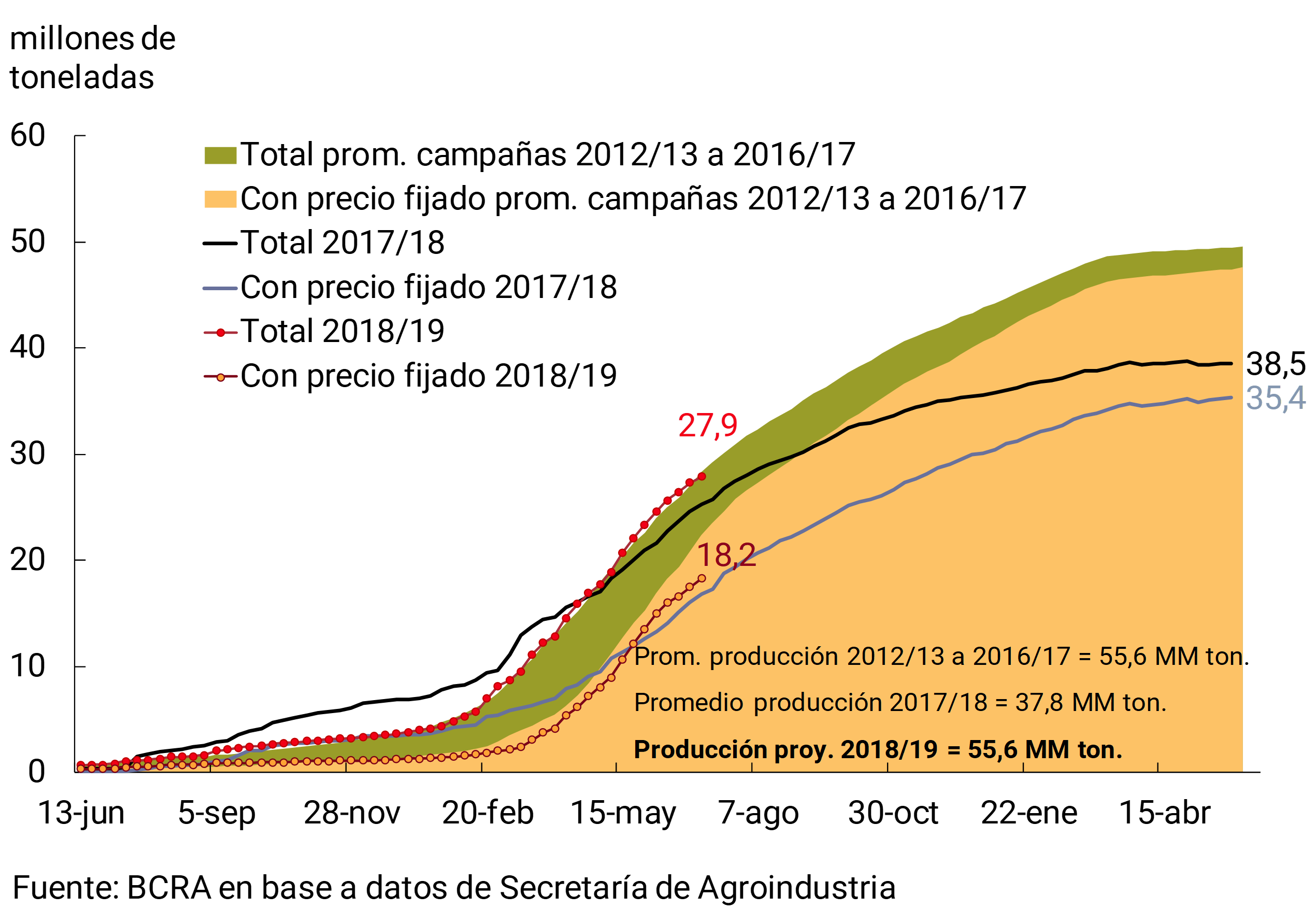

Group 1 – Agriculture, Fisheries, Education and Social and Health Services – is made up of the activities that have been improving since mid-2018 and that during the first quarter of 2019 reached or exceeded the level of the same period of the previous year. The most relevant sector of this group is Agriculture, which rebounded in the third quarter of 2018 (in seasonally adjusted terms) after the fall caused by the drought, and since then it has continued to grow thanks to the good harvest of the main crops (see Agricultural Harvest Section). According to EMAE data, agricultural produce grew 40.2% year-on-year in April. On the other hand, the Fisheries product was not affected by the recession and performed well in 2018 (5.4% YoY). The growth continued during the first months of 2019, registering a year-on-year increase of 35% in April. Meanwhile, Education and Health services slowed down during 2018 without entering a recessionary phase16.

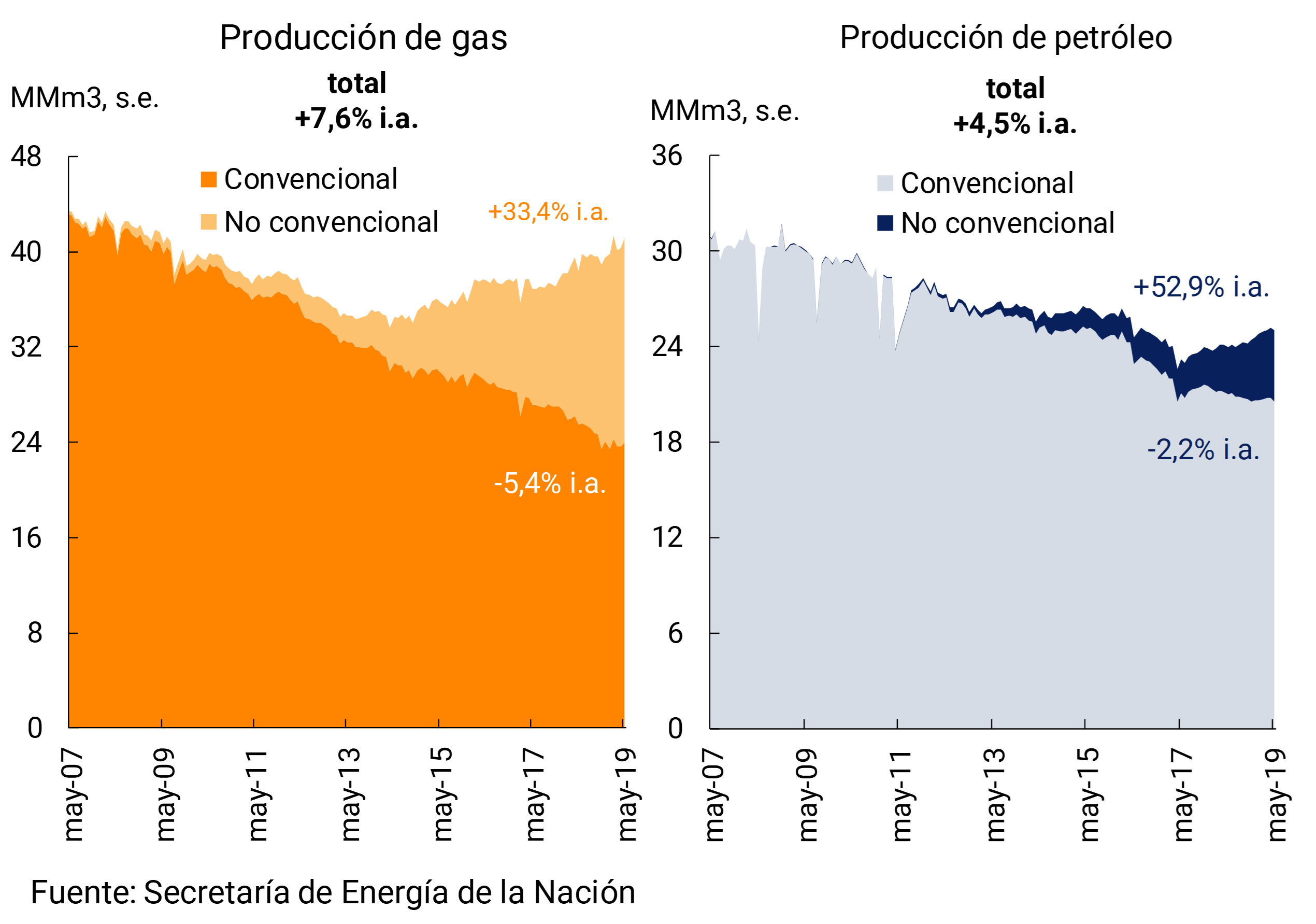

Group 2 – Mining and quarrying, Public Administration and Transport – is made up of sectors that recovered since the end of last year and that, if the recent trend continues, could grow in year-on-year terms during the second quarter of 2019. Oil (+4.5% YoY in May) and Gas (+7.6% YoY in May) production leads the Mining and Quarrying sector with a multiplier effect on other economic sectors. The extraction of unconventional oil and gas from the Vaca Muerta field grew by 52.9% YoY and 33.4% YoY, respectively, outpacing the decline in production from conventional wells (see Figure 3.15). The Transport sector has been recovering, driven by the growth of agriculture and tourism, and is expected to reach a positive year-on-year growth rate of between 1% and 2% in May. Within the framework of a process of fiscal consolidation, the public administration sector has registered a structural breakdown since 2016, growing at a low rate in historical terms17. Between December 2017 and August 2018 it accumulated a contraction of 1% and then began to recover, reaching a slight growth of 0.2% y.o.y. in April.

Group 3 includes sectors that have begun to reactivate since the end of 2018 but, due to the depth of the previous decline, it will take longer for them to reach pre-recession levels. This group – Industry, Construction, Real Estate Activities and Production of Electricity, Gas and Water – is the one with the greatest weight in the economy (35%). The EMAE of April 2019 and the data available as of June18 indicate that this group of activities would have grown in the second quarter of the year compared to the first. The improvement was mainly explained by the recovery of domestic demand, in a context of greater exchange rate stability, which was added to the aforementioned indirect impulses from agriculture and the hydrocarbon production sector.

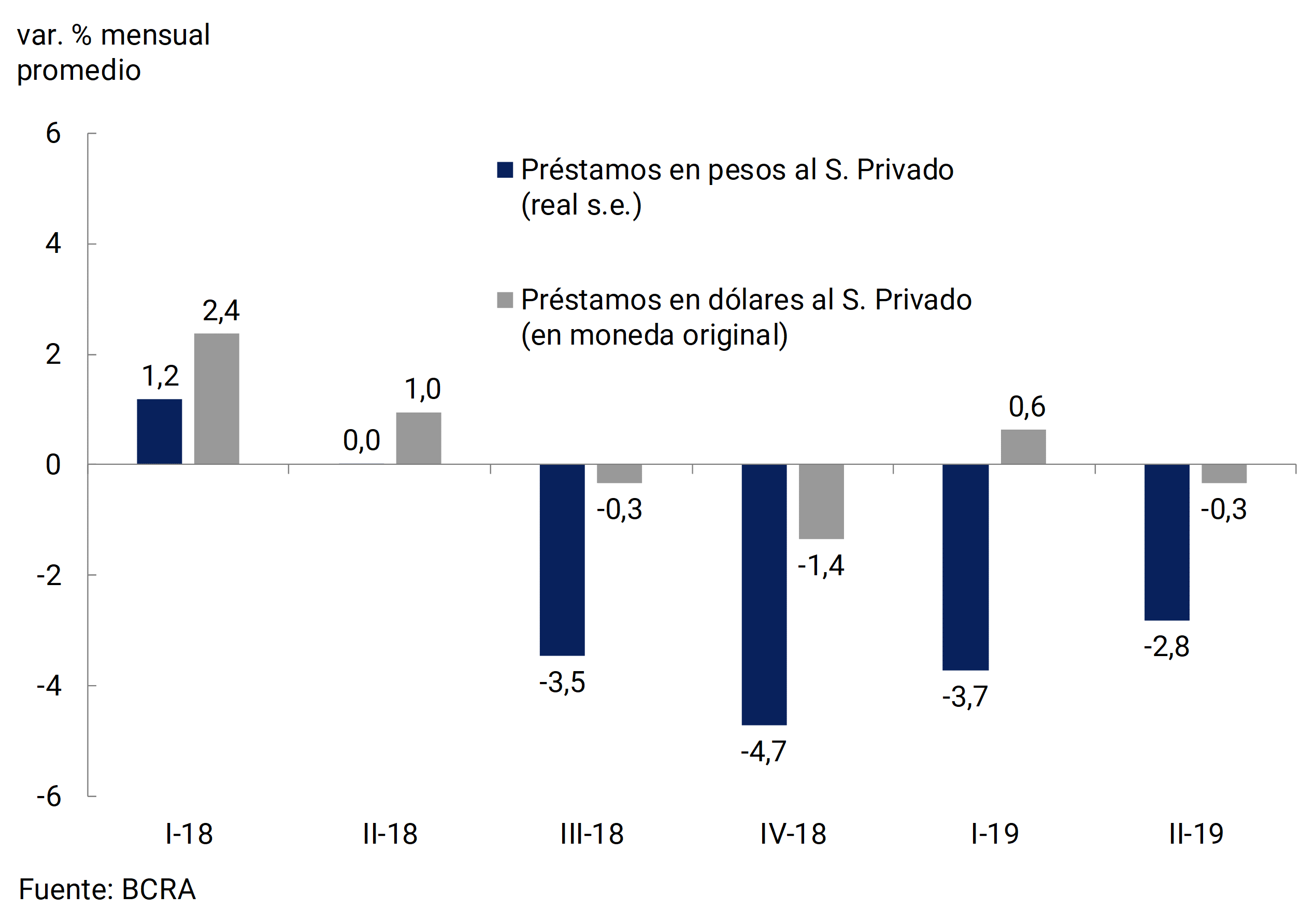

Group 4 – Trade, Financial Intermediation, Hotels and Restaurants, and Other Community Services – is made up of the activities of the EMAE that have not yet managed to reverse the declining trajectory. Trade, which had begun to recover in December 2018, fell sharply in March and, unlike the rest of the main sectors, did not recover in April. Financial intermediation continued to be affected by the tightening of financial conditions that increased the cost and reduced the demand for bank loans. The favorable boost from higher inbound tourism in the Hotels and Restaurants sector has so far not been able to offset the contraction in domestic demand, resulting in a level of activity for April 2019 similar to that of the third quarter of 2018. This group of sectors is expected to begin a recovery as the improvement in the rest of the economic activities is consolidated during the coming quarters of 2019 (see Figure 3.16).

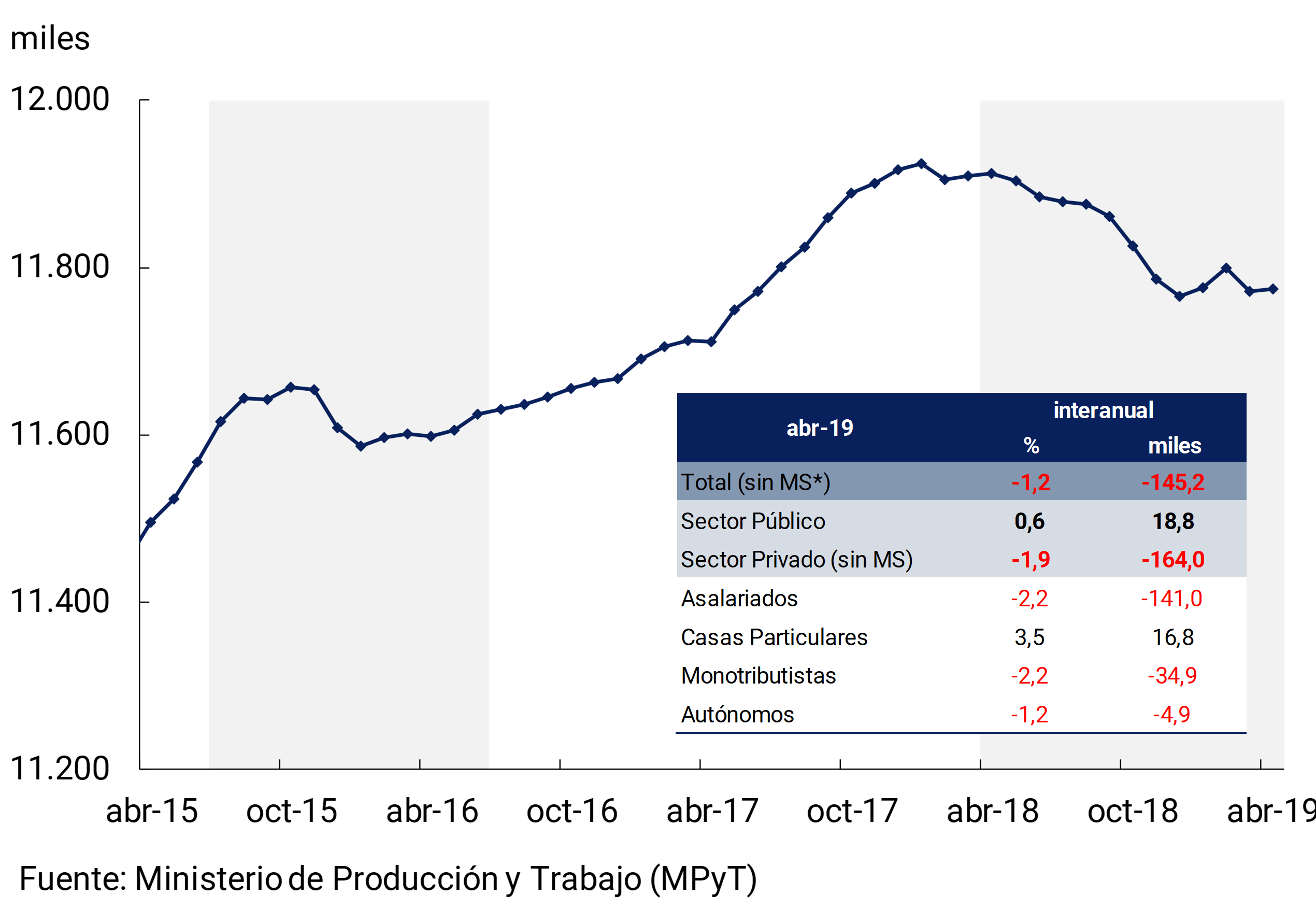

3.1.4 Registered employment was sustained so far this year

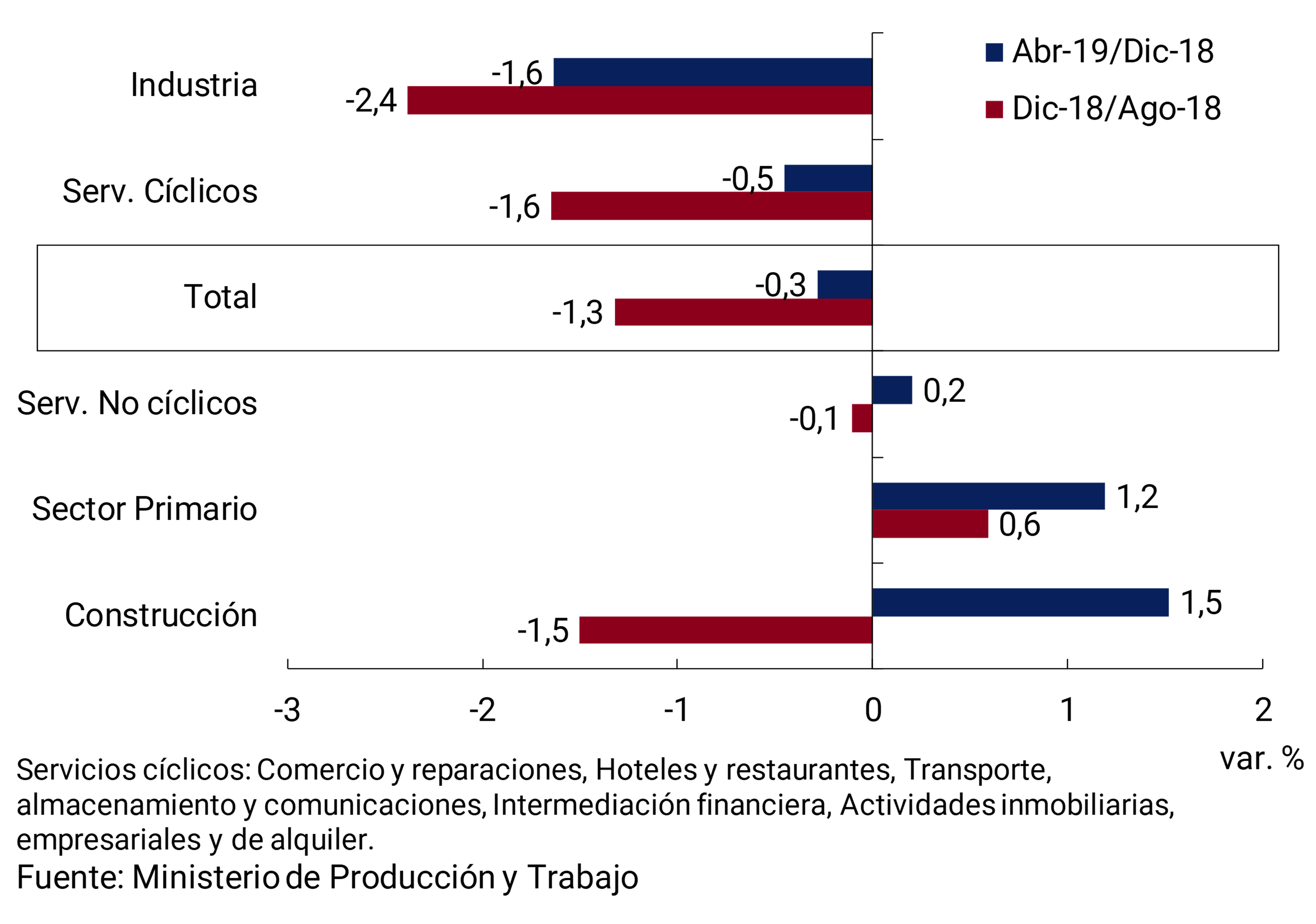

Total registered employment maintained its level in the first four months of the year after 11 months of downward trend, in line with signs of improving economic activity. After a slight rebound at the beginning of the year, interrupted in March by exchange rate instability, it returned to marginal growth in April (see Figure 3.17).

During the first four months, registered employment was sustained by the increase in public salaried employment (0.7% s.e.) and private households (1.2% s.e.), while self-employed and private salaried employment exhibited falls (-0.1 s.e. and -0.3% s.e., respectively). Private salaried employment attenuated its fall during the period due to the good performance of the primary sector and the recovery of construction, in a context in which jobs in industry and cyclical services continued to fall. (see Figure 3.18).

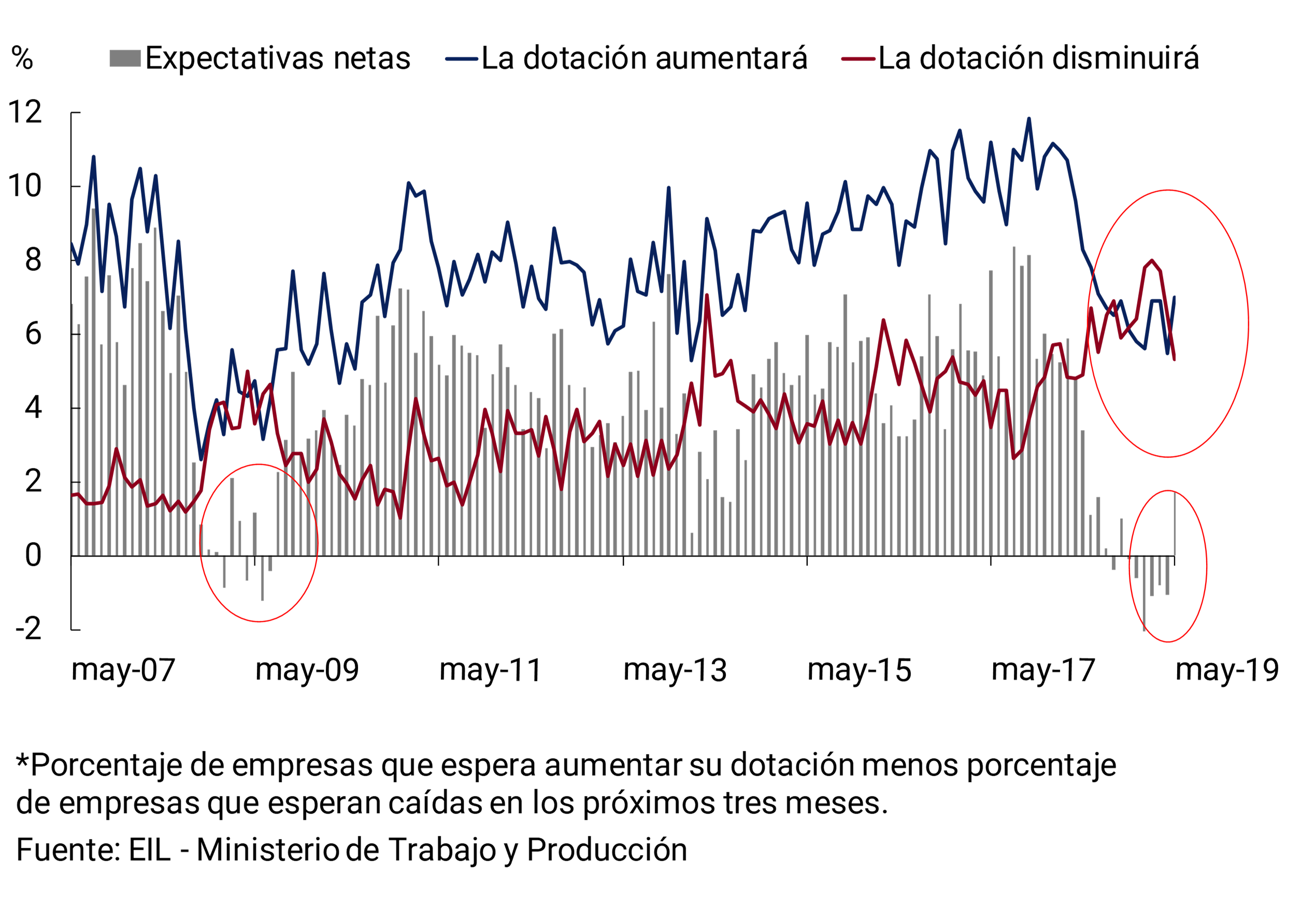

Companies expect a recovery in formal employment starting in June. According to the May survey of the Labor Indicators Survey (EIL), job creation expectations for the next 3 months were positive, after 6 months with negative records. This result was mainly due to a significant drop in staff reduction expectations and an expected increase in staffing (see Figure 3.19).

According to EPH figures, during the first quarter the informal sector and self-employment continued to offset the impact of the fall in registered employment. This made it possible for the employment rate to exhibit relative stability in the last year19. This growth in employment failed to cover that of the labor supply, leading the unemployment rate to reach 10.1% y.o.y. (1 p.p. year-on-year).

This change in composition in favor of jobs with lower labor intensity and/or lower remuneration, intensified pressures on the labor market. As usually happens in recessions, more people went out to look for work and/or more hours to complement their working day. As a result, in the first quarter the number of people with employment problems (work pressure) increased from 29.9% of the population to 33.9% (4.0 p.p. year-on-year; see Figure 3.20).

It is expected that the expected recovery of formal work from June, in a context of growth in economic activity, together with the improvement in family incomes will begin to reverse the pressure on the labor market.

3.2 Outlook

The favorable outlook in several sectors allows us to foresee a good performance of economic activity for the remainder of 2019. In addition to the direct and indirect impact of the record agricultural harvest and the continued development of gas and oil production from the Vaca Muerta field, there was a boost from activities producing tradable goods and services favored by a higher real exchange rate and greater market opening. This view is shared by REM analysts who project a stage of recovery and growth during 2019 and 2020 (see Figure 3.21).

The record agricultural harvest, still in process, will continue to boost various economic activities directly or indirectly linked to production, such as the marketing and transport of agricultural products (see box Agricultural Campaign).

The energy sector will continue to show a good performance because its investment plans remained unchanged. The expected increase in oil and gas production in the coming years will reduce the external deficit20.

The domestic market will be strengthened by the expected improvement in household incomes in a context of falling inflation. Along the same lines, households find themselves with a debt-to-income ratio eased after several months of falling consumer loans with respect to output21. This will allow them to carry out a certain level of consumption previously postponed through the recovery of credit and the implementation of different consumption financing programs such as Ahora 12, Argenta, Junio/Julio 0Km (see box measures to promote consumption). Along these lines, the improvement in consumer confidence (ICC-DiTella) since January 2019 allows us to anticipate a recovery in the sale of durable goods and real estate for the current year (see Figure 3.22). Finally, investment in the construction sector will be driven by the fall in construction costs in relation to housing prices in a context of improved economic expectations.

Since December 2015 and within a framework of openness to international trade, new markets have been opened for Argentine products and pre-existing trade agreements have been deepened22. After a negotiation that lasted more than two decades, an agreement was signed with the EU with the aim of expanding and diversifying our exports, as well as stimulating investment and competitiveness through a better insertion of our economy in global production chains. Although the agreement is broad and the details of it are still under study, a high impact is expected in the coming years on FDI23, the export of agro-industrial goods24 and knowledge services25, a sector in which Argentina is beginning to stand out (see IPOM of April 2019).

Although the international context in which emerging economies operate has improved, some risk factors could condition this scenario of progressive recovery of activity (See Chapter 2. International Context). At the local level, the economic recovery scenario could be affected by some risks, mainly linked to a new episode of volatility in global financial conditions or to the usual uncertainty of electoral processes. In any case, in the context of the reduction of fiscal and external imbalances, a stronger balance sheet of the BCRA and a monetary regime in which the policy interest rate reacts immediately to developments, the space for local financial volatility events to occur is more limited (see Chapter 5. Monetary Policy).

4. Pricing

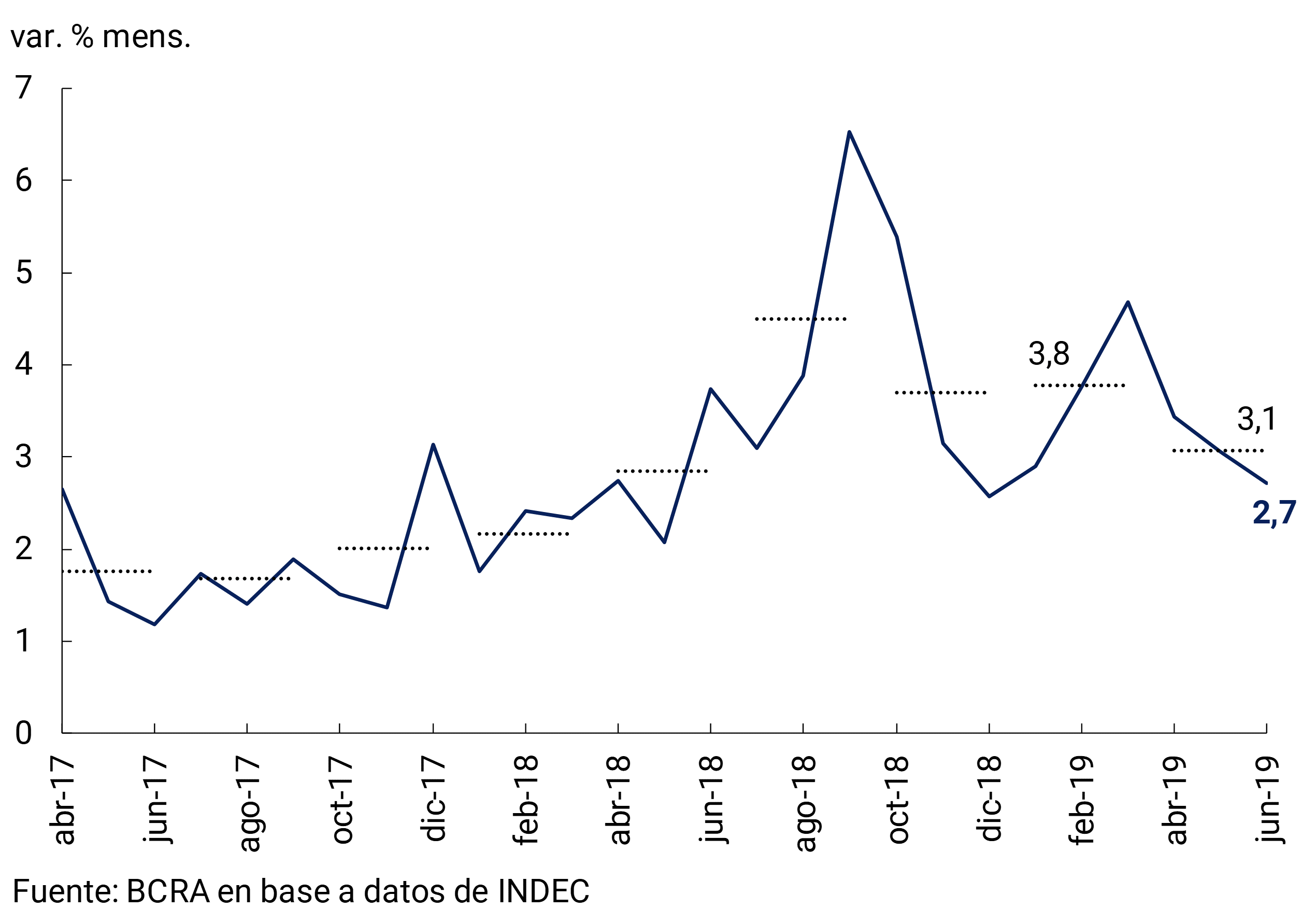

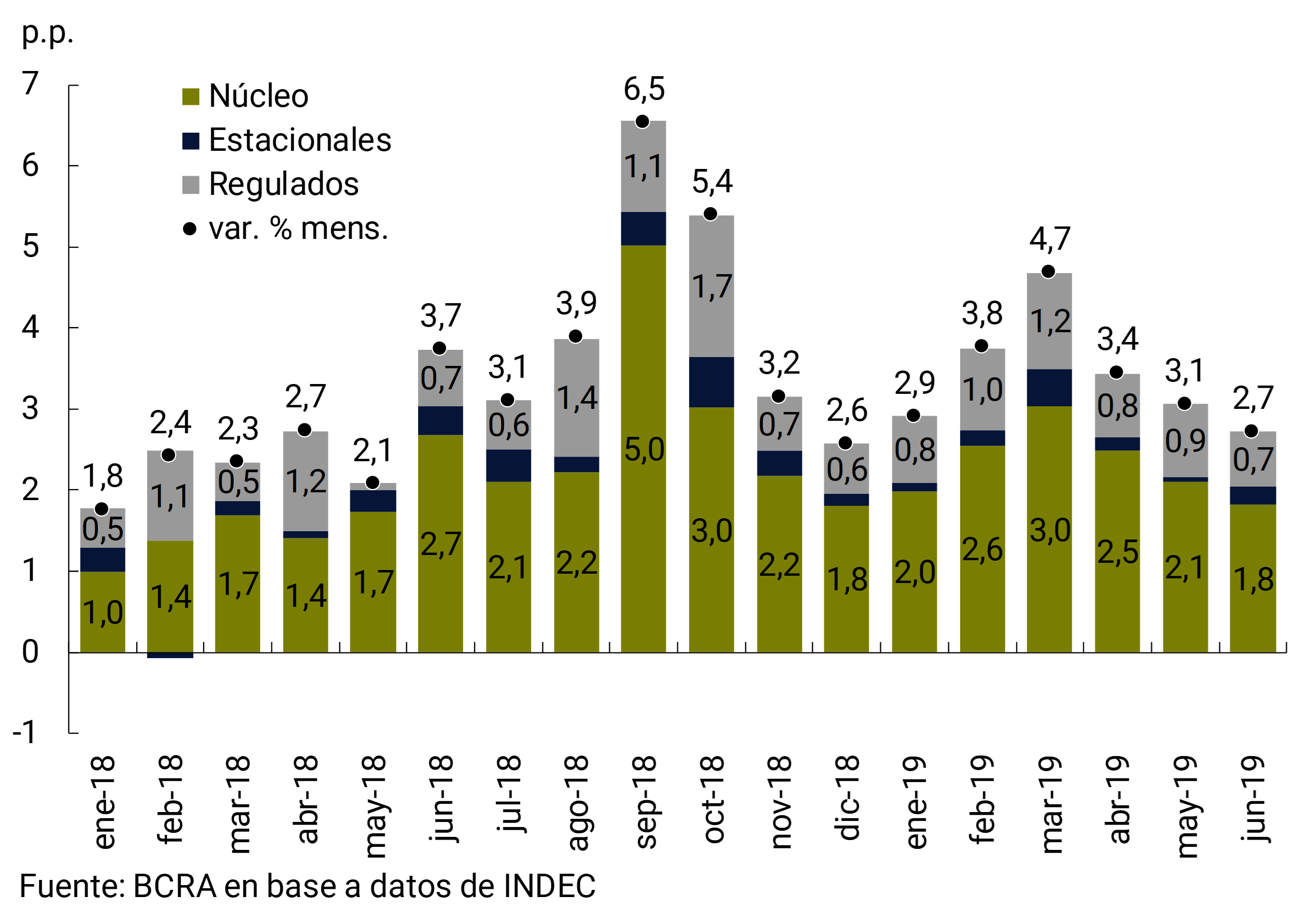

In the second quarter of the year, inflation showed some moderation, reversing the acceleration of the first quarter. This behavior in prices was generalized at the level of categories (Seasonal, Regulated and Core). In June, inflation stood at 2.7%, the lowest value of the year. However, it remained at high levels, with an annualized rate of around 38%.

The factors that had explained the acceleration of inflation during the previous quarter were attenuated in the second quarter. Corrections in utility rates continued, but to a lesser extent than in the first quarter of the year. Likewise, the supply shocks that had affected the price of meat were diluted. The tightening of monetary policy and the possibility of intervening within Exchange Reference Zone26 by the BCRA contributed to reducing exchange rate volatility and moderating inflation.

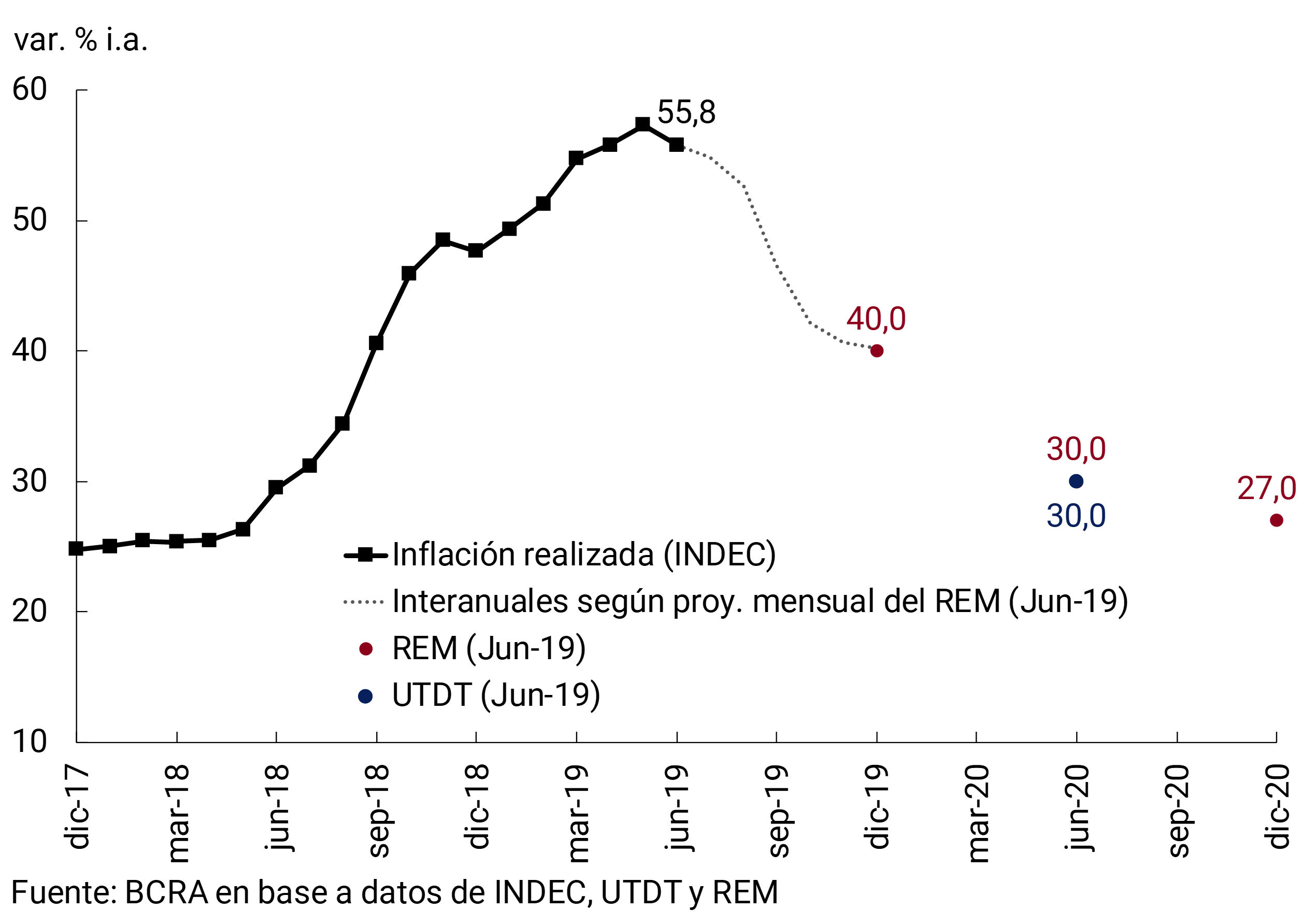

The contractionary bias of monetary policy, coupled with the fact that most of the correction in utility tariffs has already taken place, suggests that inflation would continue to fall in the coming months. This view is shared by market analysts who anticipate a downward path in inflation for the second half of the year. The Market Expectations Survey (REM) expects an average monthly increase in inflation of 2.3% for the period between July and December 2019 (30.8% annualized), reaching an inflation of 40% y.o.y. at the end of the year. Likewise, expectations indicate that the disinflation process would continue throughout next year, consistent with a more sustainable monetary policy framework.

4.1 In the second quarter, inflation figures were lower than those observed in the first months of the year

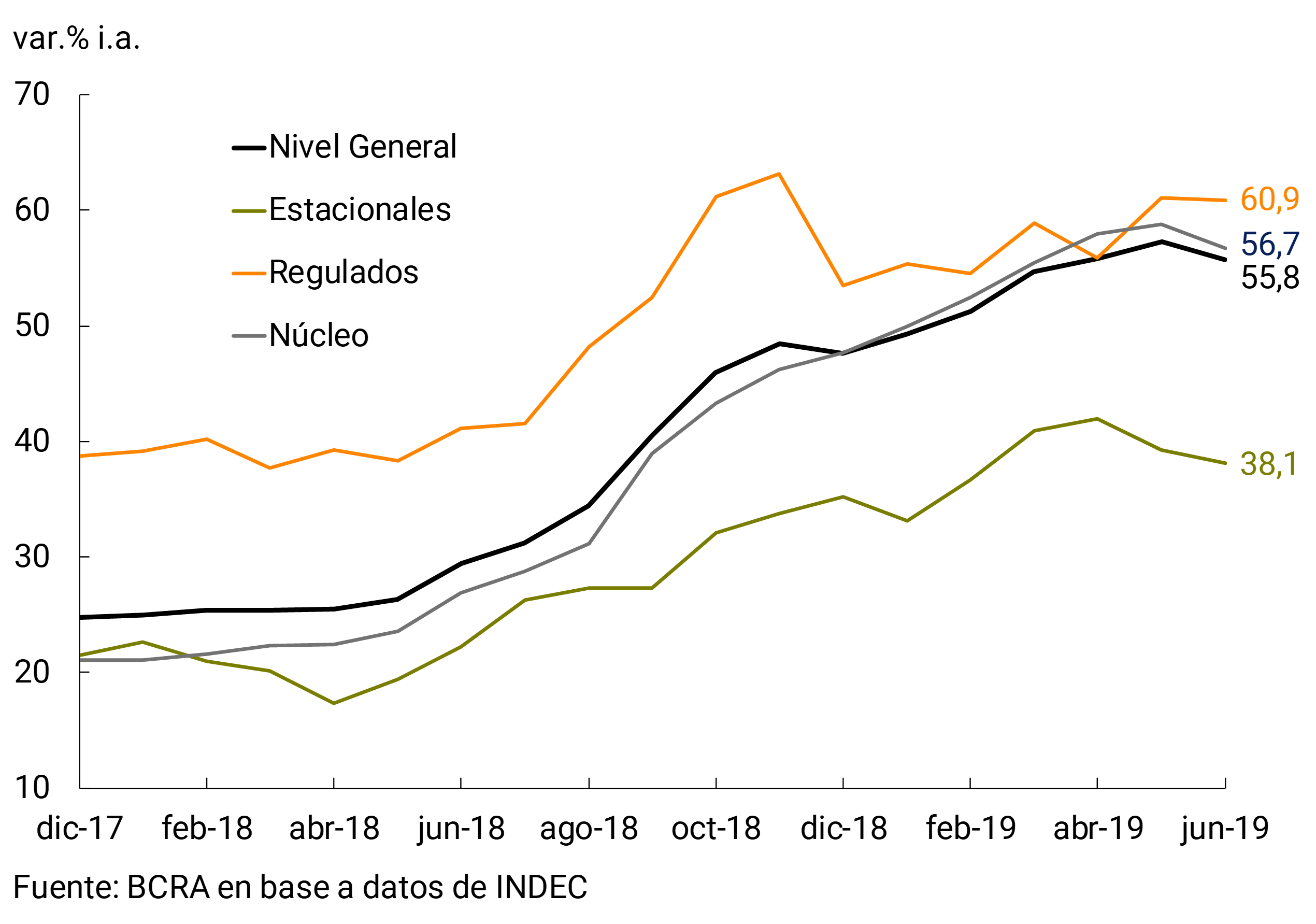

During the second quarter of the year, retail inflation moderated, reversing the upward trend of the first three months. The average monthly increase in the National CPI was 3.1%, 0.7 percentage points (p.p.) below the increases in the first months of 2019. The slowdown was generalized at the level of categories (Seasonal, Regulated and Core). In any case, inflation remains at high levels, reaching a monthly rate of 2.7% in June, equivalent to an annualized rate of around 38% (see Figure 4.1).

The moderation in the inflation rate in the second quarter of the year was anticipated by the REM. The survey in March of this year predicted a rise in prices for the second quarter of 8.8%. In that period, the cumulative variation of the National CPI was 9.5%, only 0.7 p.p. above the data forecast by market analysts.

The factors that had driven inflation during the previous quarter were attenuated in recent months. After inflation hit 4.7% in March, it fell to an average of 2.7% in June, the lowest record so far this year. Lower inflation was basically due to the greater contractionary bias of monetary policy and the absence of new supply shocks. The tightening of monetary policy and the possibility of interventions within the exchange rate reference zone contributed to reducing the volatility of the exchange rate (see Chapter on Monetary Policy). The latter allowed to mitigate the upward pressures on the prices of the goods included in the index.

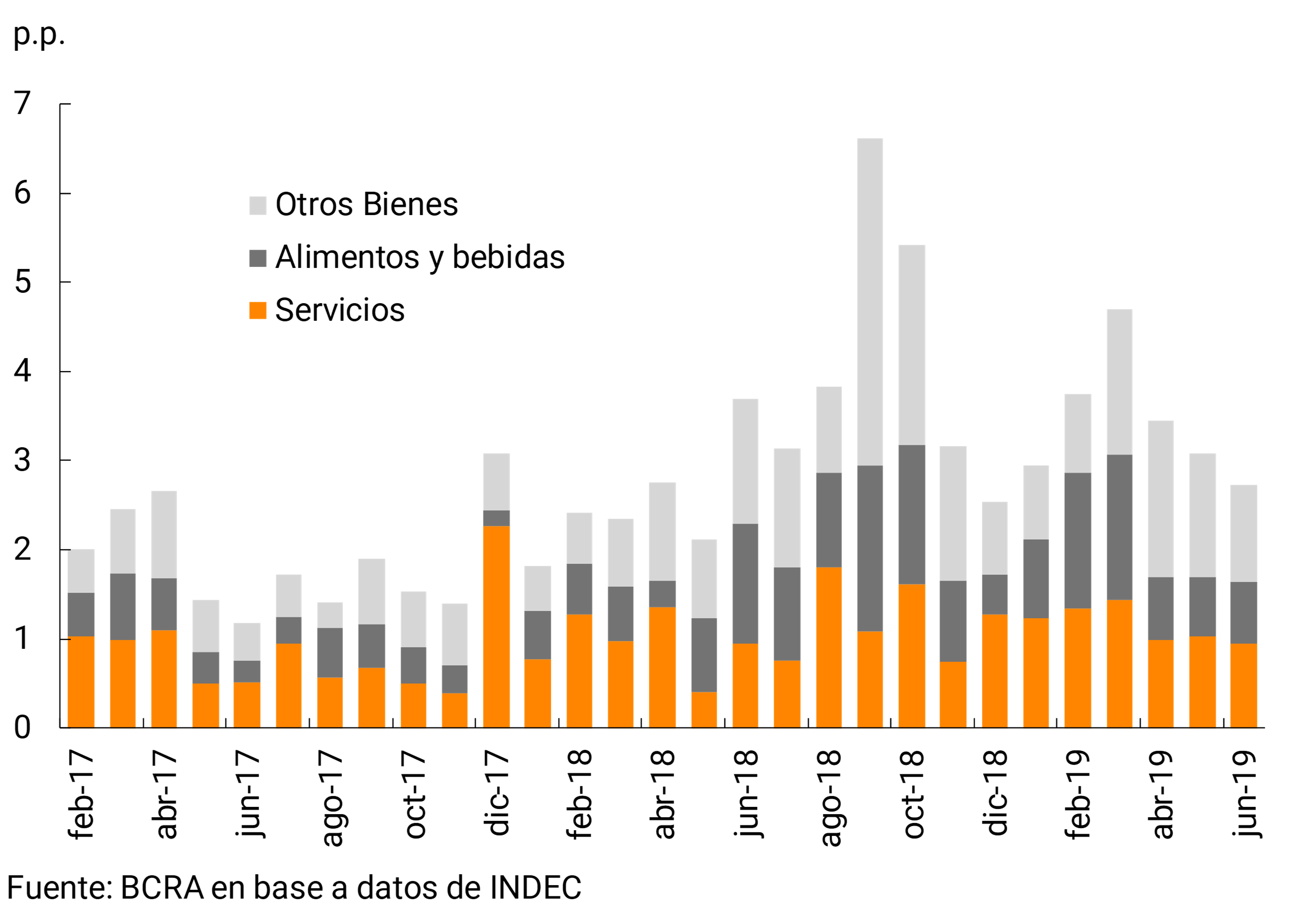

During the second quarter, the performance of the General Price Level reflected to a greater extent the evolution of core inflation, which represents approximately 70% of the CPI basket. The average monthly increase in prices in this category was 3.2%, 0.6 points p.p. lower than that recorded during the first quarter of the year (see Chart 4.2).

Both the acceleration of core inflation in the first months of the year and the lower increases recorded in the second quarter were mainly due to the behavior of the prices of goods. During the first quarter, the rise in the prices of goods, which are more tradable, responded to the lagged effect of the exchange rate jump in August and September 2018 and the contemporaneous effect of the depreciation of the peso at the end of the first quarter. The modifications introduced by the BCRA to the monetary-exchange regime in April 2019 reduced the volatility of the exchange rate. Thus, goods went from an average monthly increase of 3.8% in the first quarter of the year to 3.2% in the second quarter.

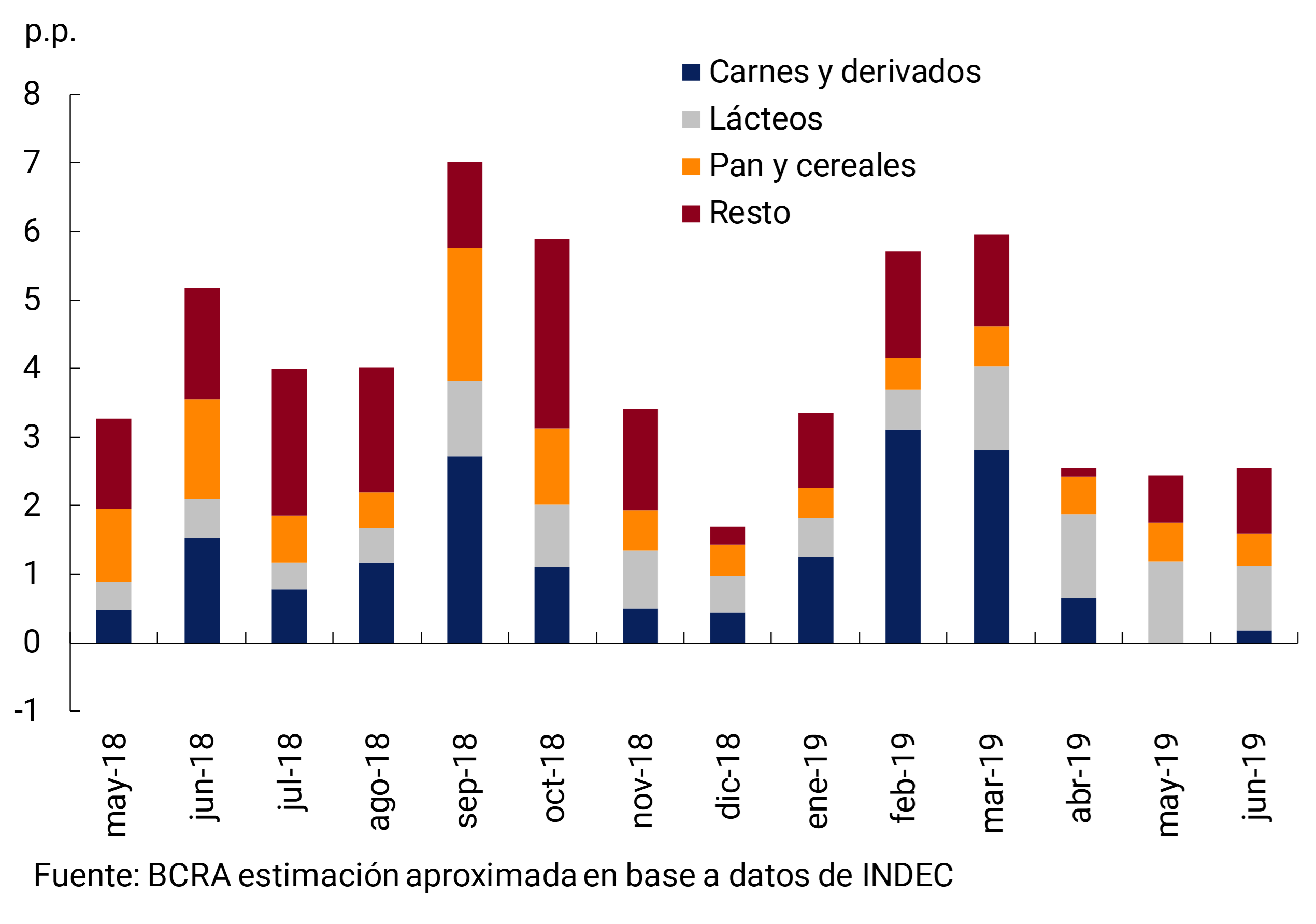

The slowdown in the prices of goods was largely due to the behavior of food and beverages. This category reduced its pace of increase to 2.5% monthly in the second quarter, from 5% recorded between January and March. Within this division, the supply shock that boosted beef prices in the first quarter ceased to operate, taking pressure off food prices. On the contrary, the dairy sector continued to be affected by the supply restrictions verified since the middle of last quarter. The prices of these products continued to grow at higher rates than other foods, with increases of close to 7% per month since March. Dairy price dynamics only partially offset the slowdown in meat prices. Finally, prices of other goods (i.e., goods excluding food and beverages) have gradually slowed since May, in line with lower nominal exchange rate volatility (see Figure 4.3 and Figure 4.4).

As anticipated in the previous IPOM, the increases in the prices of regulated products were strongly concentrated in the first part of the year. In the second quarter of the year, the prices of regulated products at the national level reduced their average monthly rate of change to 3.3%, 0.9 p.p. below the figure for the first quarter. However, the behavior was not homogeneous at the regional level, with greater increases in the rates of regulated vehicles in the Northwest compared to those registered in the first quarter. The impetus came from the elimination of the social tariff on electricity in some provinces of the region and from provincial increases in the water tariff.

In mid-April, the National Government announced that there would be no new increases in the rates of public services (electricity, gas and public transport) beyond what was already announced. This measure only reaches those rates that are under the orbit of the national executive power, so the components subject to provincial/municipal regulation could be modified in the coming months. Still, the utility rate corrections have been largely completed.

The rest of the regulated goods and services, i.e. excluding public services, continued to adjust in the second quarter. Fuels for vehicles averaged increases of around 4%, influenced by lagged effects of the increase in the exchange rate and tax corrections. The quotas of prepaid medicine evolved in line with the parity of the sector. Educational services continued to increase after March, although they averaged more limited increases. Fixed and mobile telephony services also had updates in their rates between April and June.

Finally, seasonal goods and services also showed a slowdown in their prices in the second quarter, with lower rates of increase than the rest of the components. In fact, the average monthly rate for the second quarter was 1.6% (-1.0 p.p. compared to the first quarter), practically half the rate of increase of the General Level (3.1%). Thus, the set of these items continued to lose relative share in the CPI basket.

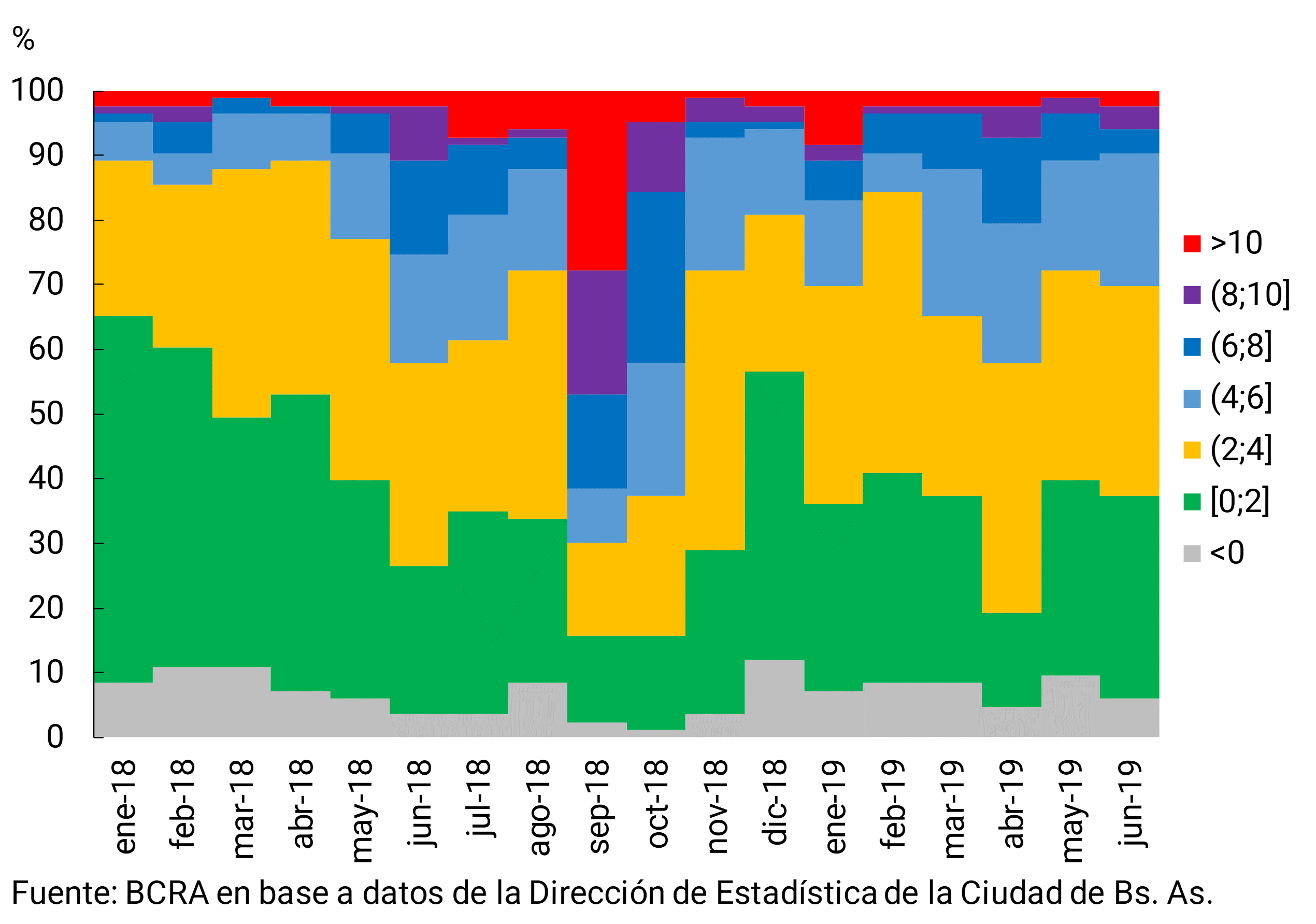

The CPI of the City of Buenos Aires showed a relatively similar behavior to that of INDEC in the accumulated between the end of last year27 , although with some differences in the monthly variations. These responded in general terms to questions related to the composition of the basket, assigning the City’s a greater weight to Services. The similarities in the cumulative behavior allow the data from the City of Buenos Aires to be used to analyze the diffusion and magnitude of price increases. Using the classification by purpose of expenditure, at the maximum level of disaggregation available28, it was observed that as of May the proportion of classes with monthly variations of less than 2% increased. Meanwhile, the proportion of classes with increases of more than 6% decreased. Despite this improvement, price increases are widely disseminated and the distribution of variations still continues to concentrate a high density in values higher than those of the beginning of 2018 (see Figure 4.5).

In the second quarter of the year, retail prices continued to grow in year-on-year terms until May, and then exhibited a moderation in the pace of increase. The National CPI registered a 55.8% YoY increase in June, 1.5 p.p. below the peak of May. The year-on-year trajectory of the core component marked an increase of 56.7% y.o.y. in the same period (-2.1 p.p. less than in May). Meanwhile, regulated goods and services grew in year-on-year terms above the rest of prices (60.9% YoY), continuing the process of adjustment of relative prices (see Figure 4.6).

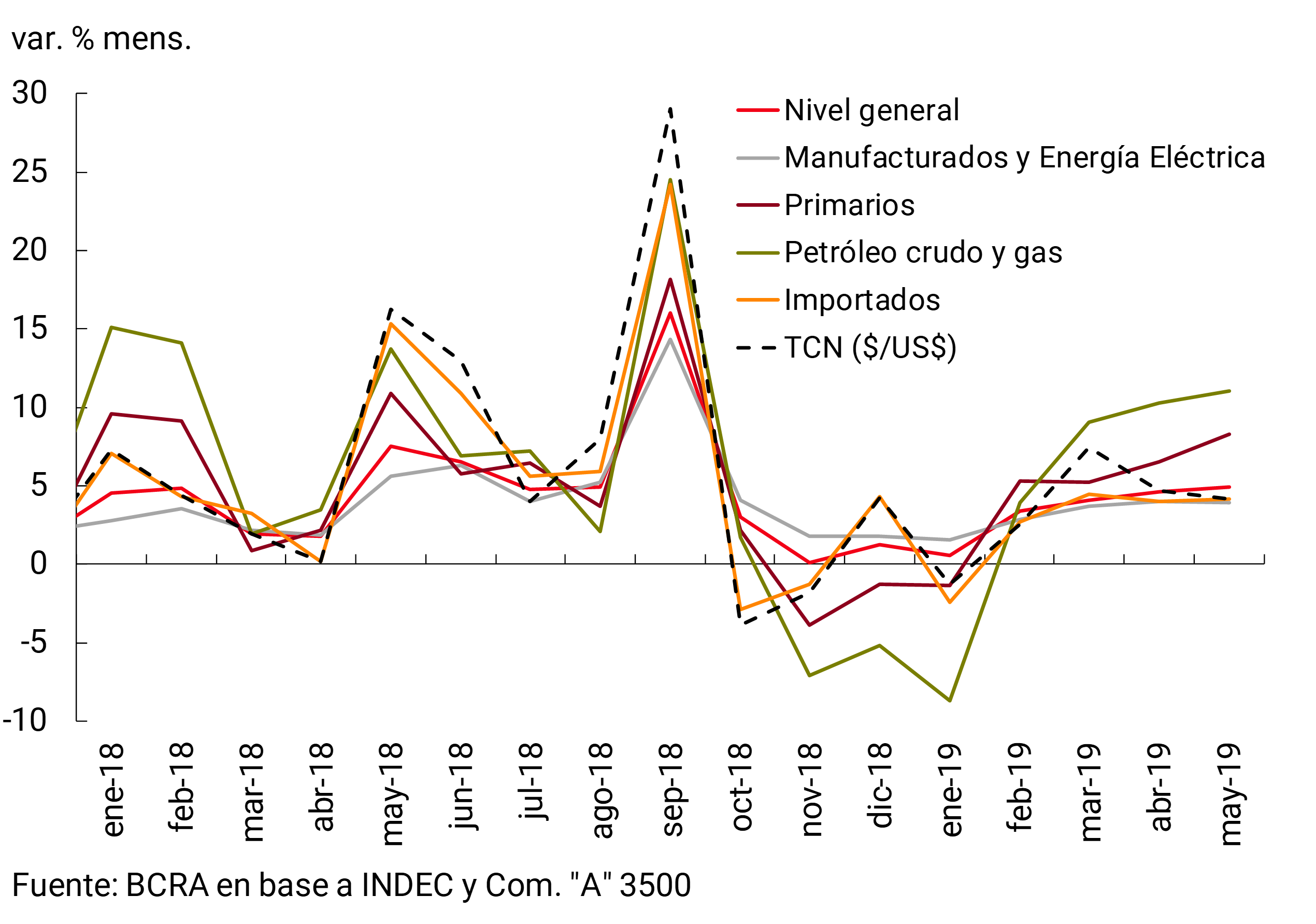

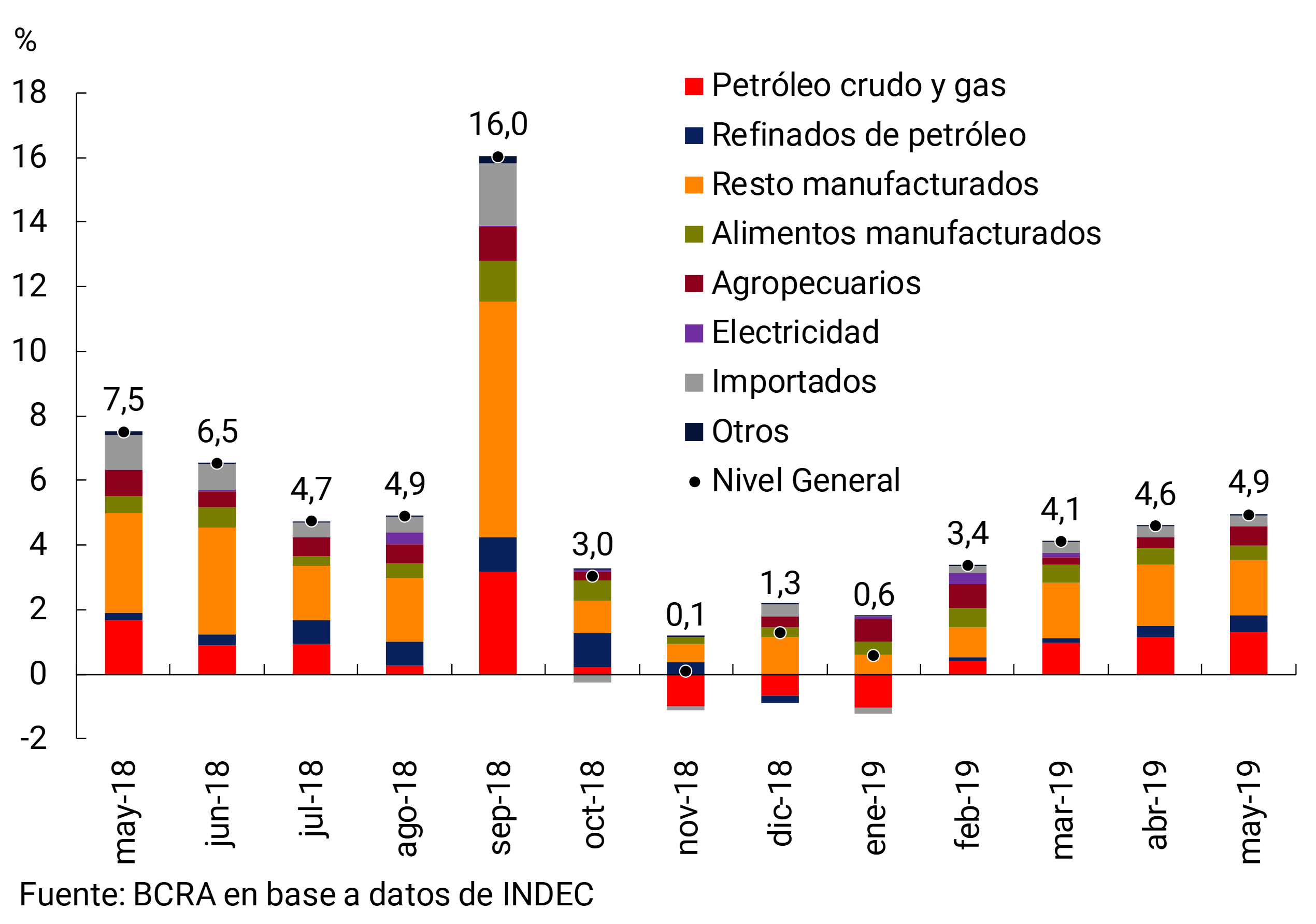

Wholesale prices continued to accelerate in monthly terms from March to May in line with the significant increases in the exchange rate between mid-March and the end of April. In June, the fall in the nominal exchange rate anticipates a significant slowdown in wholesale prices, in line with what has happened with consumer prices (see Figure 4.7).

Between April and May, wholesale prices were also affected by increases in international prices of primary products. In the two months, the IPIM averaged a 4.8% monthly increase, 2.1 p.p. above that of the first quarter of the year. In terms of contributions, the largest contribution to the acceleration came from the Crude Oil and Gas component, which averaged increases of around 10% in the two months. This component synthesized the rise in the international price of oil, the depreciation of the exchange rate and the rise in the domestic price of gas at the wellhead. This dynamic was also reflected in refined petroleum products, which, together with chemical substances, contributed to the monthly acceleration of the general level of wholesale prices. To a lesser extent, the rise in international prices of agricultural commodities (cereals and oilseeds) contributed in the same way (see Figure 4.8).

Wholesale food prices moderated compared to the first quarter of the year, but continued to make a significant contribution to the increase in the general level. Producer food prices showed a similar evolution to that of consumer prices. The quotations of live cattle showed more limited variations in April and May, after the shocks that affected these prices in the first months of the year. Meanwhile, vegetable prices fell 17% in the April-May two-month period, helping to take pressure off agricultural prices. Within manufactured products, the prices of meat products remained stable between April and May, after a cumulative increase of 19% in the first quarter. Dairy products averaged monthly increases of 7.3% between April and May, 1.7 p.p. above the average rate of the first quarter. The dynamics of dairy prices partially offset the slowdown in meats, postponing the slowdown in wholesale food and beverage prices until May.

Between April and May, wholesale prices, both primary and manufactured, showed rates of increase that were above those of retail prices, unlike what happened during the first quarter of the year. In this context, the evolution of retail marketing margins29 stabilized, which had been recovering since the last quarter of the previous year after having been compressed after the exchange rate depreciation of August and September 2018 (see Figure 4.9).

In year-on-year terms, wholesale prices accelerated in March and April and then cut their rates of increase in May, showing a similar trajectory to that of the nominal exchange rate. The IPIM marked an average increase of 70.5% in April and May, standing 4 p.p. above the year-on-year rate of change of the first quarter of the year. The appreciation of the nominal exchange rate in June anticipates a slowdown in wholesale prices, given their high sensitivity to the price of the dollar due to its high component of “tradables” (see Figure 4.10).

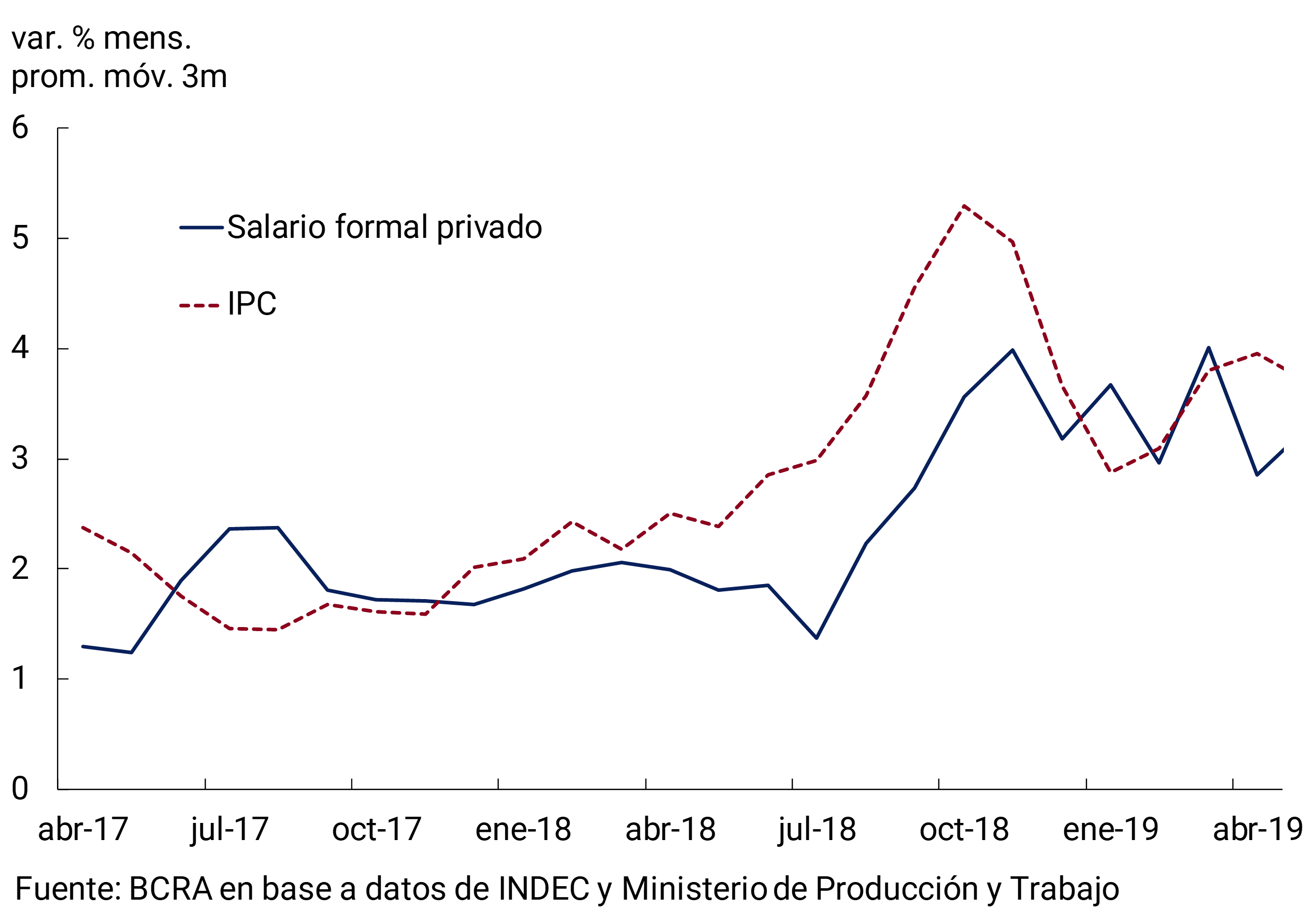

4.2 The temporal distribution of wage increases was more uniform than in previous years

In the second quarter of the year, according to data from the Ministry of Production and Labor (MPyT), nominal wages in the formal private sector continued to accelerate in year-on-year terms. Wages in real terms stabilized in the first part of the year and would begin to show a recomposition starting in May (see Figure 4.11).

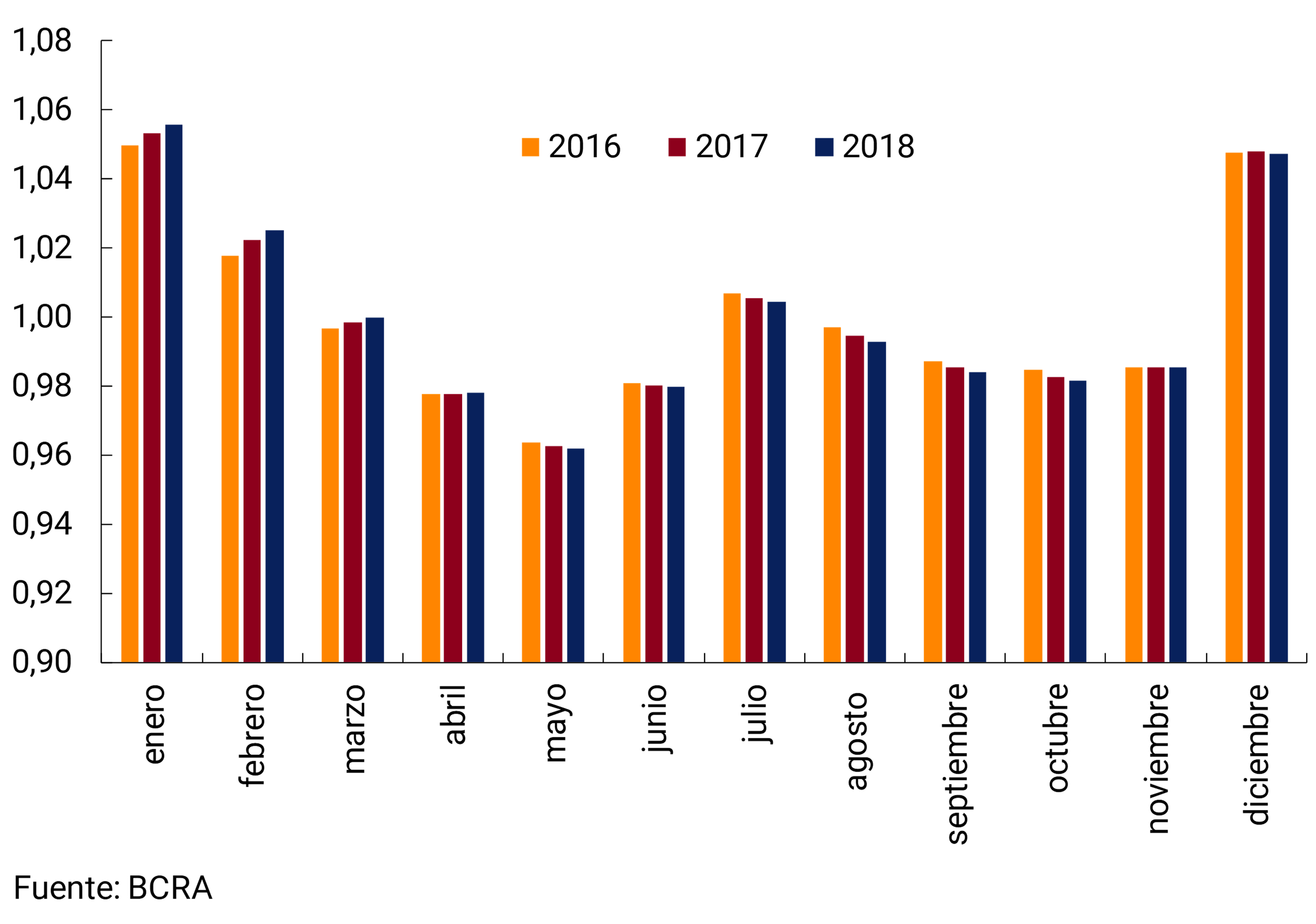

In 2019, the parity negotiations showed greater diversity compared to other years. The agreements contemplated a greater number of tranches, adjustments for inflation and eventual instances of revision of the contracts. Most of the unions negotiated an annual guideline of around 30%, to be integrated into several quotas (between 2 and 6 tranches). Other agreements were structured on the basis of quarterly adjustments, conditional on the evolution of the CPI30. This diversity in the way wages were negotiated resulted in a relatively more heterogeneous distribution (between unions) of wage increase brackets. This behavior was also contributed by the payment, in some cases, of compensatory sums corresponding to 2018. As a result of this heterogeneity, the temporal distribution of wage increases at the aggregate level was more uniform than in previous years in which there was a high concentration of increases in a few months.

Considering the structure of increases agreed in the collective bargaining agreements and if the market’s expectations of a moderation in inflation are met, real wages would improve throughout the second half of the year.

Outlook: The market continues to anticipate a slowdown in monthly inflation rates for the coming months.

As a result of the inflationary acceleration in the first quarter, and in order to prevent it from feeding back into future inflationary expectations, the COPOM decided to reinforce the bias of its monetary policy as of April (see Chapter 5. Monetary Policy). The measures adopted by the BCRA were effective in reducing exchange rate volatility. This, added to the fact that most of the correction in public service rates has already taken place, suggests that inflation would continue to fall in the coming months.

The REM for June anticipates that inflation, both general and core, would register a moderation in the second half of the year as it would be below the average for the second quarter. The REM expects an average monthly variation of 2.3% for the general level and 2.5% for core inflation for the period from June to December (see Figure 4.12).

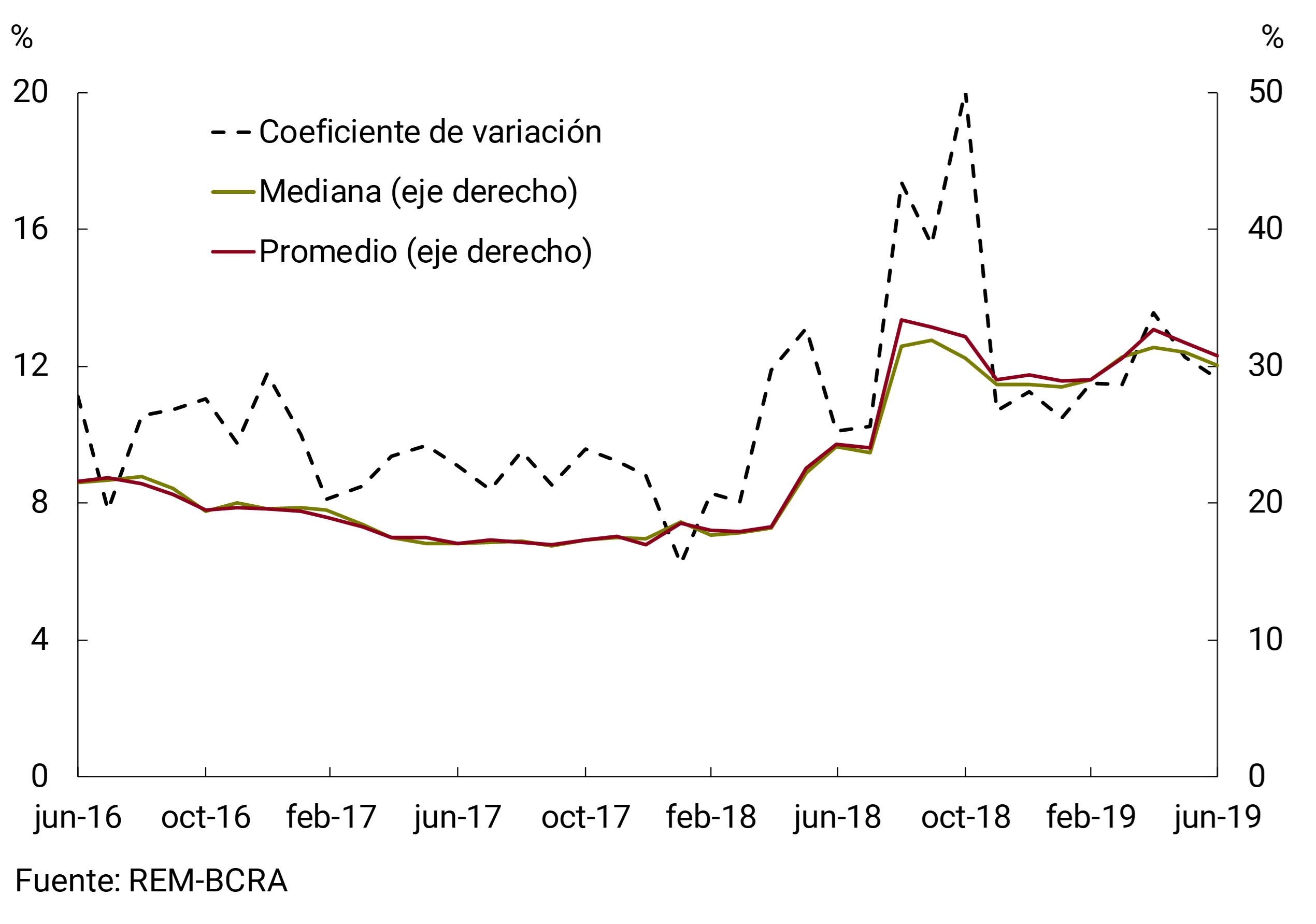

Given the inflation observed in the first six months of the year, market analysts project a rate of increase in prices of 40% y.o.y. as of December 2019. If this scenario is fulfilled, this year’s inflation would be almost 7 p.p. below last year. REM analysts predict a year-on-year growth in prices of 30% for July 2020 and 27% for December of the same year. Thus, according to the REM, the disinflation process would continue both throughout the current year and the next. Along the same lines, the median of the UTDT Inflation Expectations survey, which reflects household inflation expectations twelve months ahead, fell 10 p.p. in May and remained at 30% y.o.y. in June. Meanwhile, the average value of inflation twelve months ago went from 40.8% to 34.5% (see Figure 4.13).

On the other hand, the dispersion of the REM’s inflation forecasts remained around the values of recent months, although it continues to be higher than that recorded during periods of lower inflation. Specifically, the coefficient of variation of the responses for general inflation over the next twelve months stabilized at values close to 12%, almost 8 p.p. below the October peak and approximately 4 p.p. above the 2017 average (see Figure 4.14).

5. Monetary policy

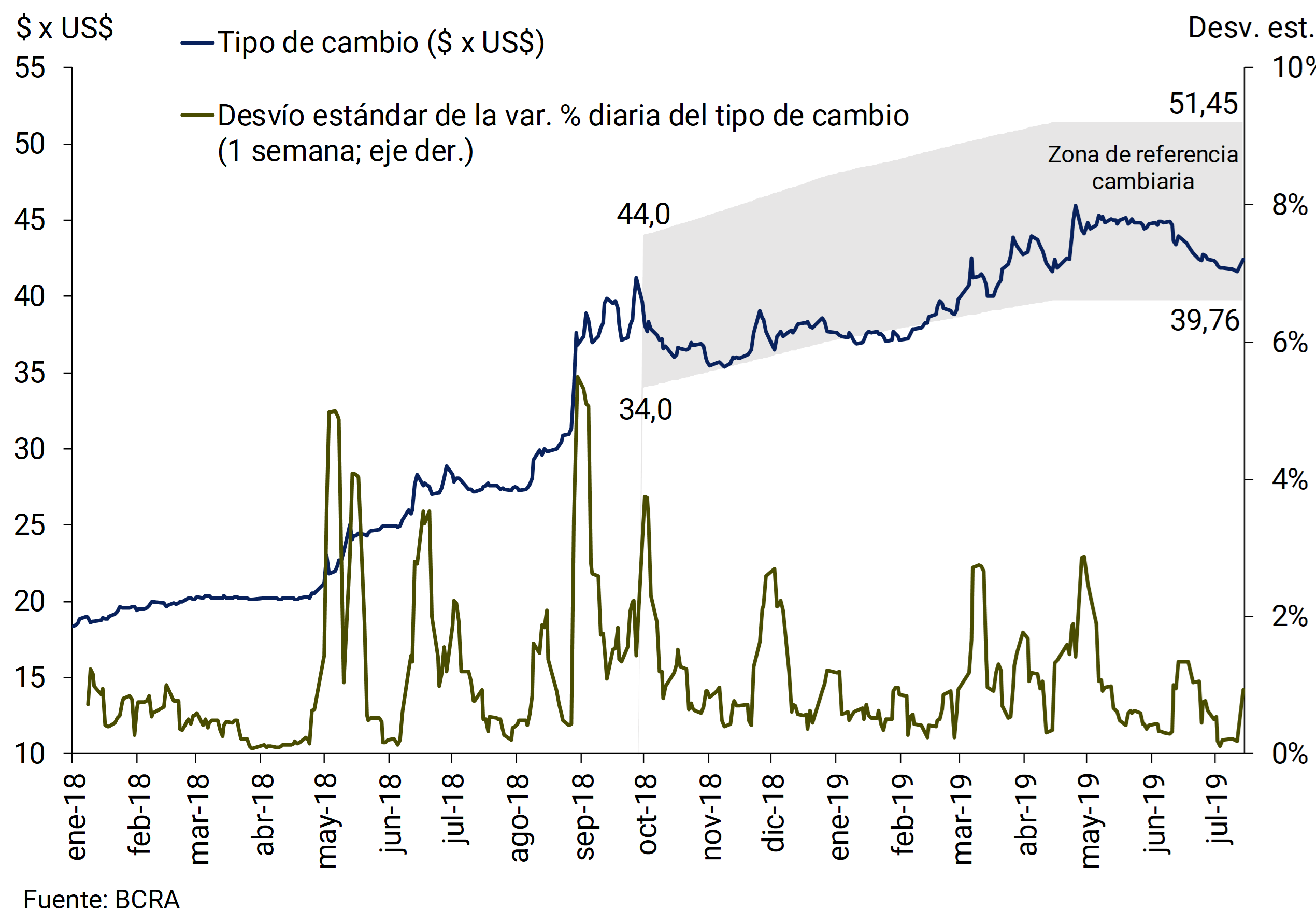

Given the reappearance of exchange rate instability in March and its disruptive effect on the ongoing disinflation process, the Monetary Policy Committee (COPOM) announced in April modifications to its foreign exchange intervention scheme: it set the growth of the limits of the exchange reference zone (formerly called the non-intervention zone) at zero until the end of the year and provided for the possibility of selling foreign currency even when the exchange rate is above the lower limit of the exchange rate reference zone. In the same sense, the COPOM reestablished the floor of the reference interest rate (LELIQ rate). In the current monetary scheme, the reference rate is endogenous, that is, it is the one that ensures that the demand for LELIQ is consistent with the monetary base objective. But by guaranteeing a floor, the COPOM gives greater predictability to its evolution. Finally, with the launch of fixed-term operations for non-customers, the BCRA stimulated competition among financial institutions and improved the mechanism for transmitting the reference interest rate to the rest of the interest rates in the economy.

The measures adopted and the maintenance of a restrictive monetary policy, in a context of better international conditions, allowed inflation to decrease as of April and stabilized inflation expectations and the foreign exchange market. In an environment of lower nominal volatility and low inflation expectations, the nominal interest rate of the LELIQ showed a downward trend since the beginning of May, with the real interest rate remaining at high levels in historical terms.

The electoral process usually entails greater financial uncertainty. With these tools, the BCRA will be better equipped to mitigate its impact on nominal variables and thus give greater predictability to price makers.

5.1 Monetary policy in the second quarter of the year

5.1.1 The Central Bank took further steps to reinforce the contractionary bias of monetary policy

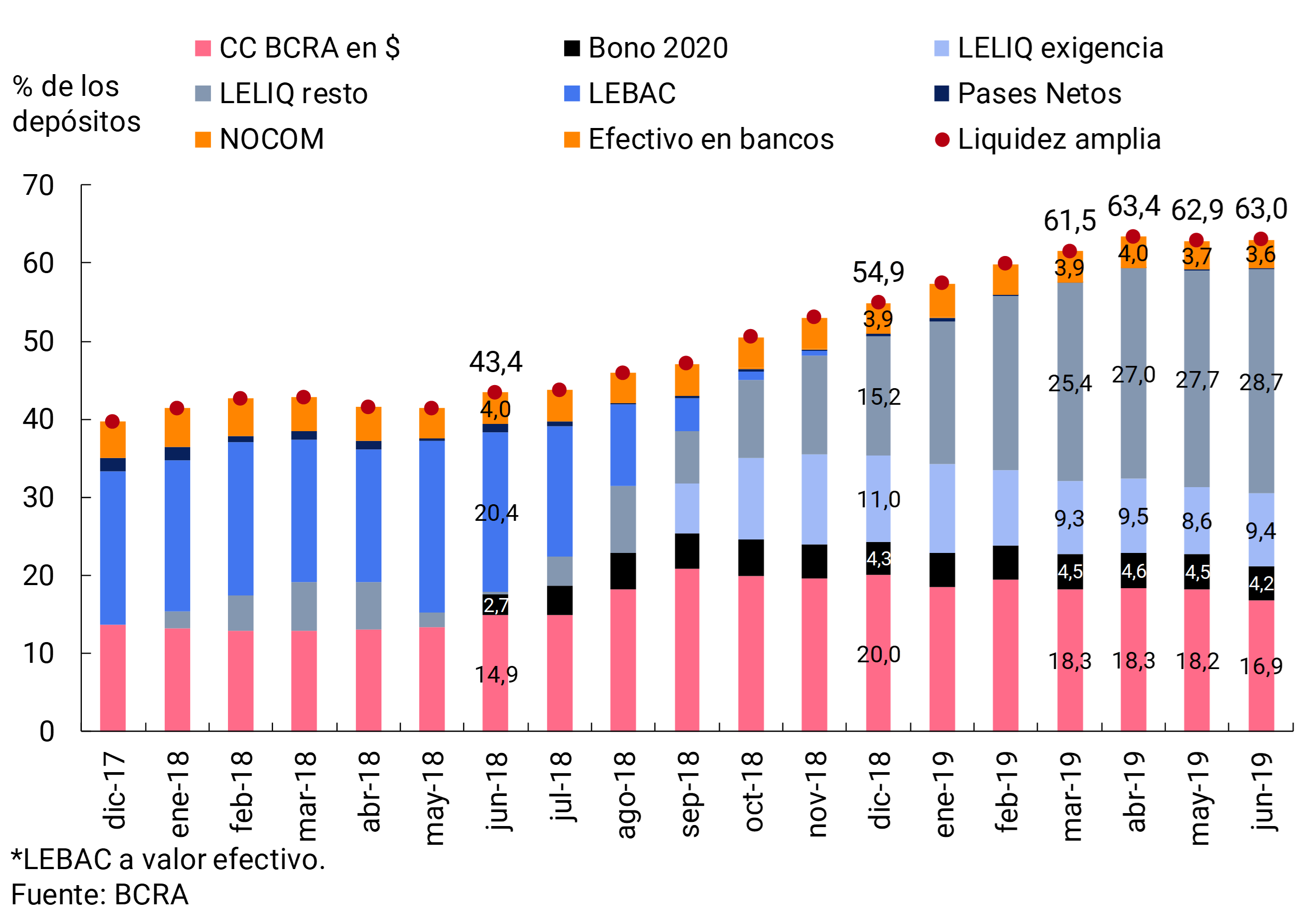

The high levels of inflation in February and March and the increase in exchange rate volatility from February onwards had led the Monetary Policy Committee (COPOM) to take measures in mid-March to strengthen the monetary scheme (see Section 3 for a description of how the scheme operated in its first nine months). Thus, it extended the objective of zero growth of the monetary base until the end of the year, eliminating the seasonality adjustment planned for June (maintaining the 6.3% adjustment of December), and set the target at the level reached during February ($1,343.2 billion), making permanent the overfulfillment of the target reached in that month. 31

Given the persistence of exchange rate volatility, the COPOM took additional measures in April to reinforce the restrictive bias of monetary policy and prevent further shifts from the exchange rate to the inflation rate.

Thus, the COPOM decided to leave the limits of the non-intervention zone (ZNI) constant at $39,755 and $51,448 for the rest of the year (see Figure 5.4). 32 It also established that no foreign exchange purchases would be made in the event that the exchange rate was below the lower limit of the ZNI until June 30, which guaranteed that the monetary base target would not increase for this reason (later, this was extended until July 31). In the event that the exchange rate is above the upper limit of the ZNI, the Central Bank would maintain its intervention mechanism of selling up to US$150 million per day through auctions and the monetary base target would be reduced with such sales.

Later, the COPOM decided that the Central Bank could make sales of foreign currency even when the exchange rate was within the ZNI, which was renamed the exchange reference zone (ZRC). The amount and frequency of these interventions became dependent on market dynamics. 33 It also defined that the daily sale of foreign currency will increase from US$150 to US$250 million if the exchange rate is above $51,448, although additional sales may also be made to counteract episodes of excessive volatility. In all cases, the amount of pesos resulting from these sales will be discounted from the monetary base target, reinforcing the contractionary bias of monetary policy in these scenarios.

Additionally, with the aim of maintaining a restrictive monetary policy and showing caution in the face of possible episodes of uncertainty, the COPOM announced a floor of 62.5% per year for the reference interest rate, which was in force during the April-June quarter and was reduced to 58% annually in July.

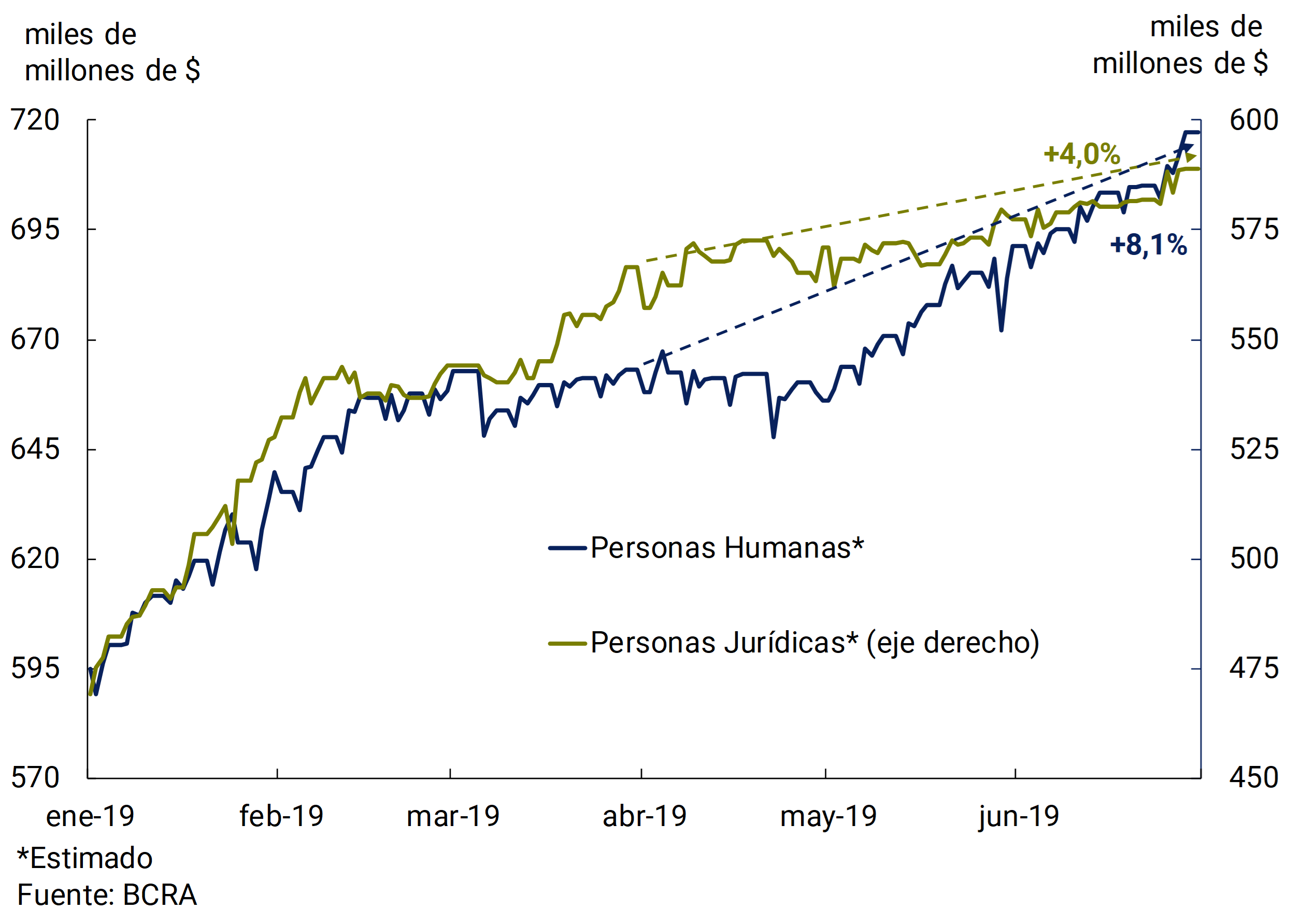

To promote competition among financial institutions and improve the mechanism for transmitting the reference rate to the passive rates of financial institutions, the Central Bank allowed bank customers to make fixed-term deposits in pesos online at any financial institution without having to be customers or carry out additional procedures (see Section 5).34

Finally, in mid-April, the Ministry of Finance began to hold daily auctions for US$ 60 million to cover needs in pesos. These tenders will be carried out to reach a cumulative amount of US$9,600 million in November of this year. 35

5.1.2 The Central Bank met the monetary targets

In the second quarter of the year, the Central Bank met its goal of zero growth of the monetary base (WB), accumulating nine consecutive months of compliance (see Figure 5.1). 36 The target throughout the quarter remained at $1,343.2 billion, due to the fact that there were no interventions by the monetary authority in the foreign exchange market. 37

In April, the Central Bank exceeded the target by $18 billion (1.4%), while in May and June compliance was tighter, $591 million (0.04%) and $1,300 million (0.1%), respectively. During May, the increase in the WB was mainly explained by the higher reserve requirements generated by the increase in public sector deposits. To moderate its monetary impact, part of these deposits were transferred by the National Treasury to the Central Bank. At the end of May, a transfer of profits from the BCRA to the National Treasury was made for $77,245 million, an amount equivalent to the interest payment that the latter will have to make to the monetary authority for its holdings of public securities during the rest of the year. This operation had no monetary effect, not even temporarily, since these funds are deposited in the Treasury account at the Central Bank until they are used to make the payment. 39 In June, the fulfillment of the goal was particularly demanding due to the seasonal behavior of the demand for BM, which is increased by the payment of the half bonus and the higher expenses of the winter recess (see Section 4).

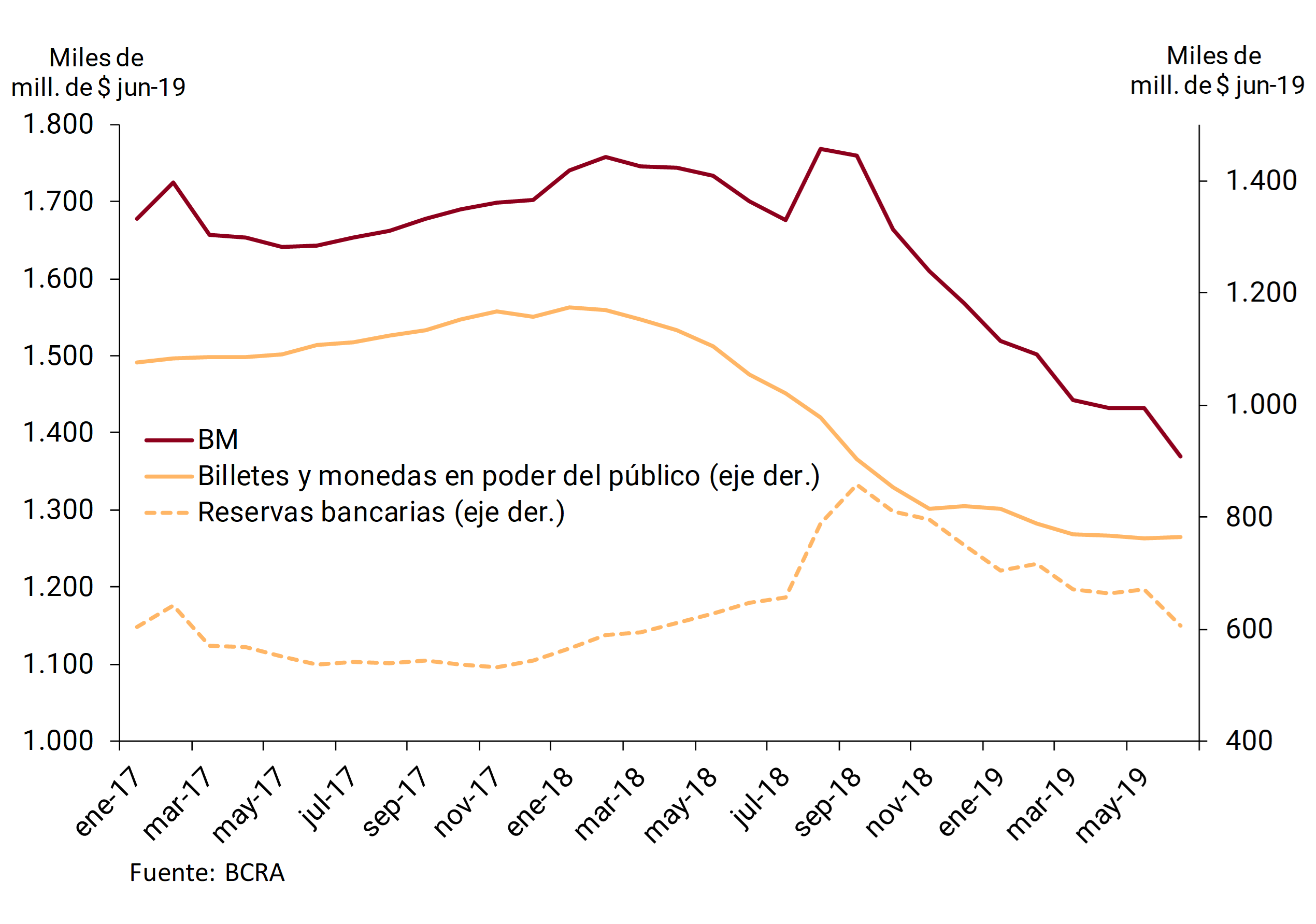

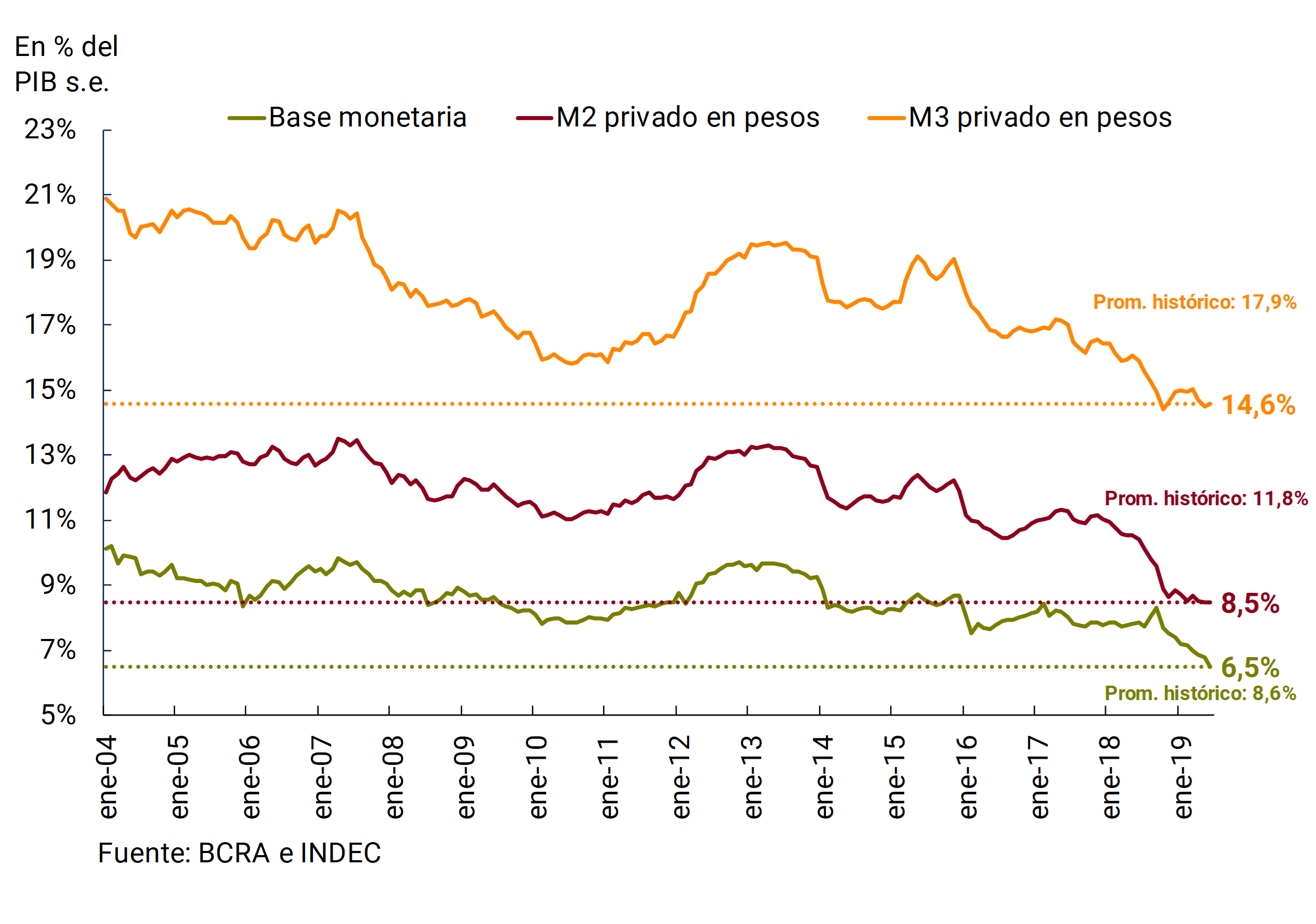

Given the dynamics of inflation in the second quarter of the year, meeting the monetary target continued to imply a significant reduction in the quantity of money in real terms, reflecting the contractionary bias of monetary policy. The World Bank fell 5.0% in real terms without seasonality between March and June of this year and accumulated a real fall without seasonality of 22.2% since the beginning of the monetary scheme in October last year (see Figure 5.2). Currency held by the public contracted 0.8% in the quarter (in real terms without seasonality), moderating its rate of contraction compared to what was observed in previous quarters, while bank reserves showed a greater contraction (-9.9% in the quarter in real terms without seasonality).

In July, the monetary base target remained at $1,343.2 billion. During this month, the high seasonality of the demand for working capital continues. In order to allow for better management of liquidity conditions in this period and to help strengthen the transmission of the interest rate of the LELIQ to the rate received by savers, the BCRA decided to reduce the minimum cash requirement on fixed-term deposits by 3 p.p. This represents a reduction in the demand for the monetary base due to reserve requirements of approximately $45 billion that compensates for the seasonal increase in the demand for working capital. In order to maintain the contractionary bias of monetary policy, once this seasonal phenomenon has been overcome, the monetary base target will be reduced as of August to reach $1,298.2 billion in October; this will fully offset the effect of the reduction of reserve requirements. 40

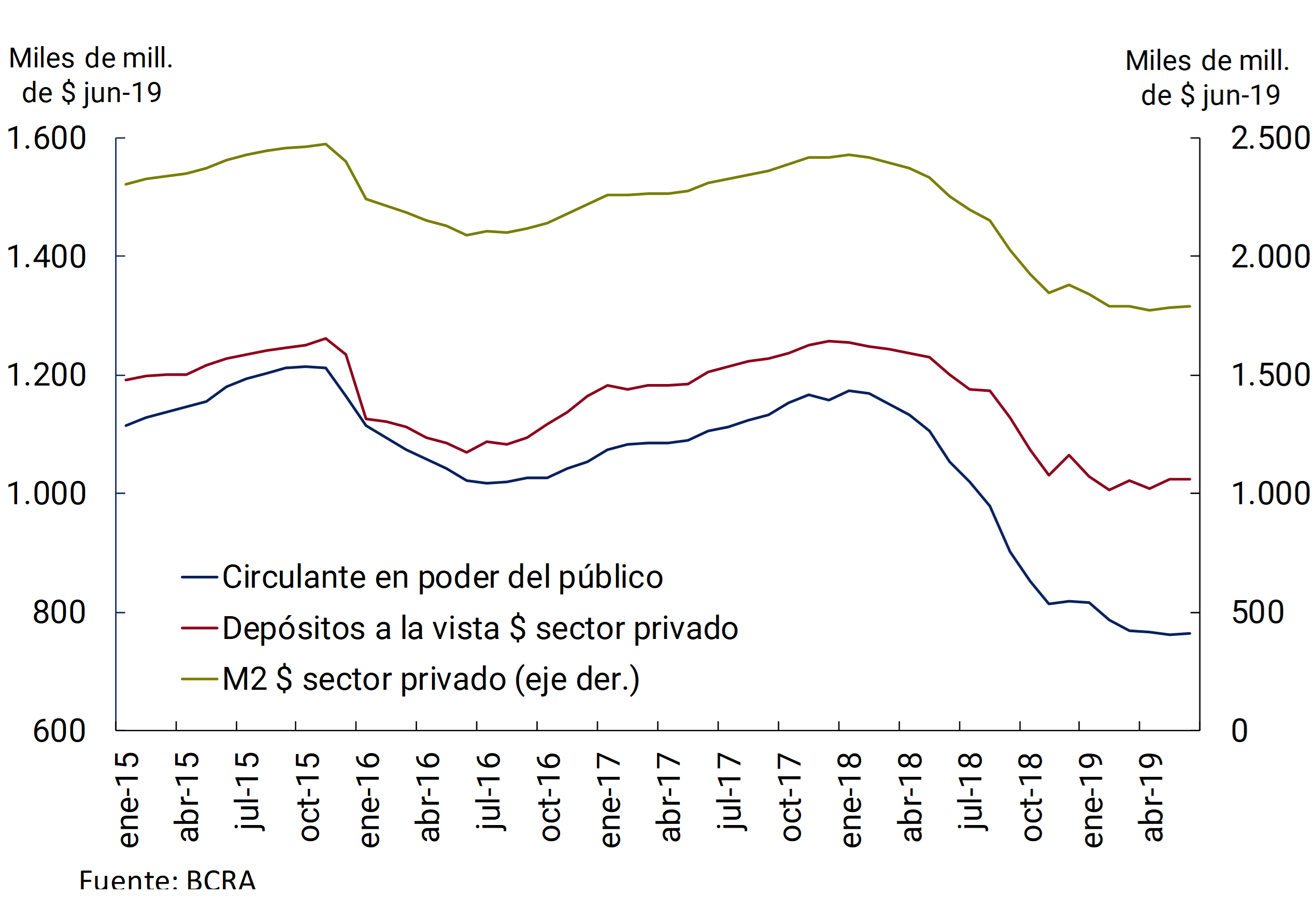

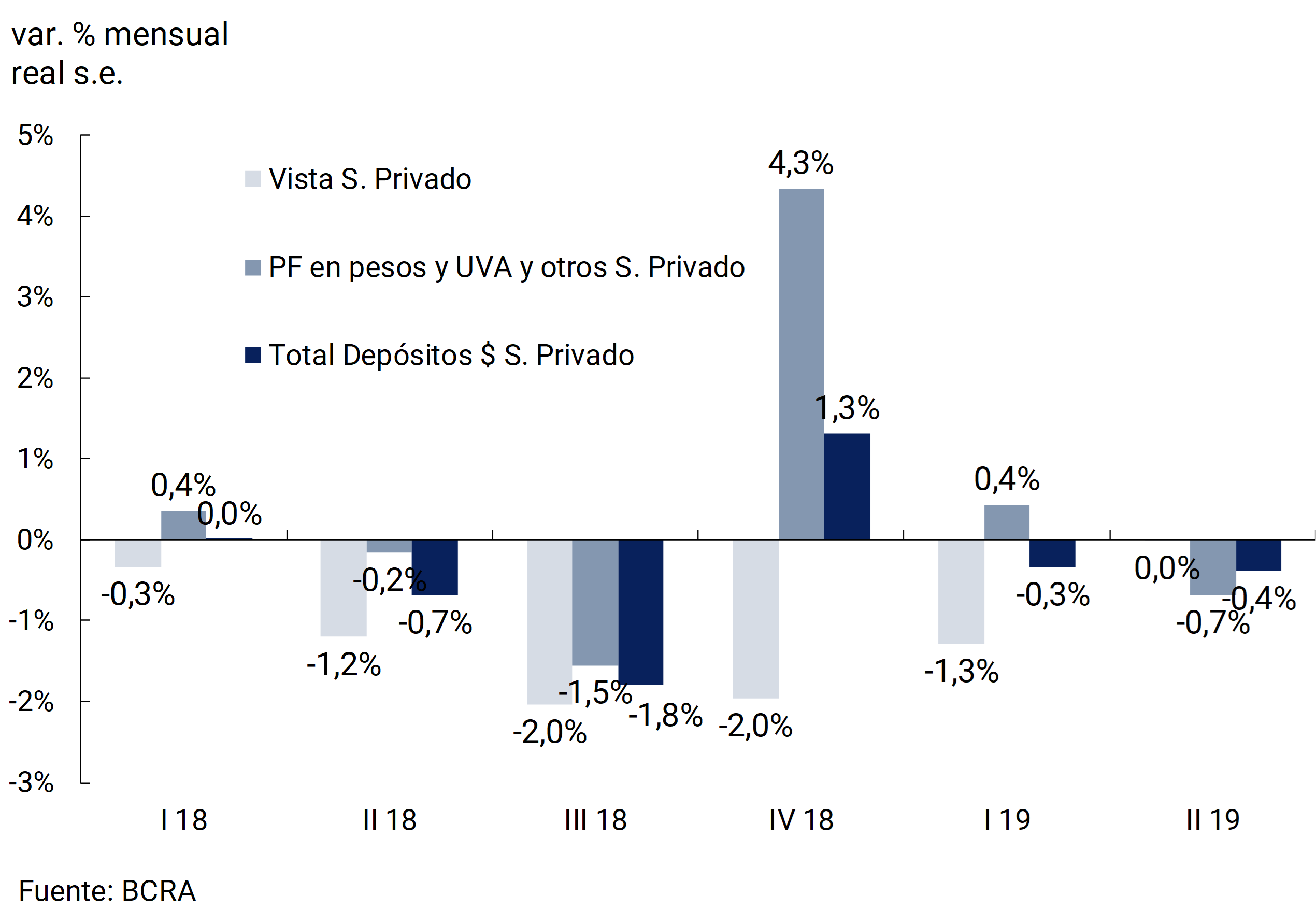

The private M2 monetary aggregate in pesos was stable during the second quarter in real seasonally adjusted terms (reduction of 0.1% per month on average), after the contractionary trend recorded during most of last year (see Figure 5.3). 41 This behavior was mainly a consequence of the stability of demand deposits in pesos in the private sector (current account and savings banks), which did not vary in the period in seasonally adjusted real terms.

5.1.3 Exchange rate volatility was reduced, inflation expectations stabilized, and the interest rate began to fall

The measures adopted and the maintenance of a restrictive monetary policy, in a context of better international conditions, contributed to the stabilization of exchange rate dynamics. After rising 19 percent between early February and late April, the U.S. currency fell 4 percent through mid-July, while weekly volatility in daily exchange rate changes declined sharply from its peak in late April (see Figure 5.4). At the same time, inflation began to show a downward trajectory since April and inflation expectations stabilized in the May and June surveys (see Chapter 4). 42

When setting a target on the quantity of money, the benchmark interest rate is determined by the demand for liquidity in LELIQ’s daily auctions. If there are increases in inflation expectations or a greater perception of risk, financial institutions demand a higher interest rate to maintain their positions in pesos, which is quickly reflected in the interest rate that arises from LELIQ’s tenders. This reaction of the benchmark interest rate helps to reduce exchange rate volatility and increase the contractionary bias in the face of inflationary surprises.

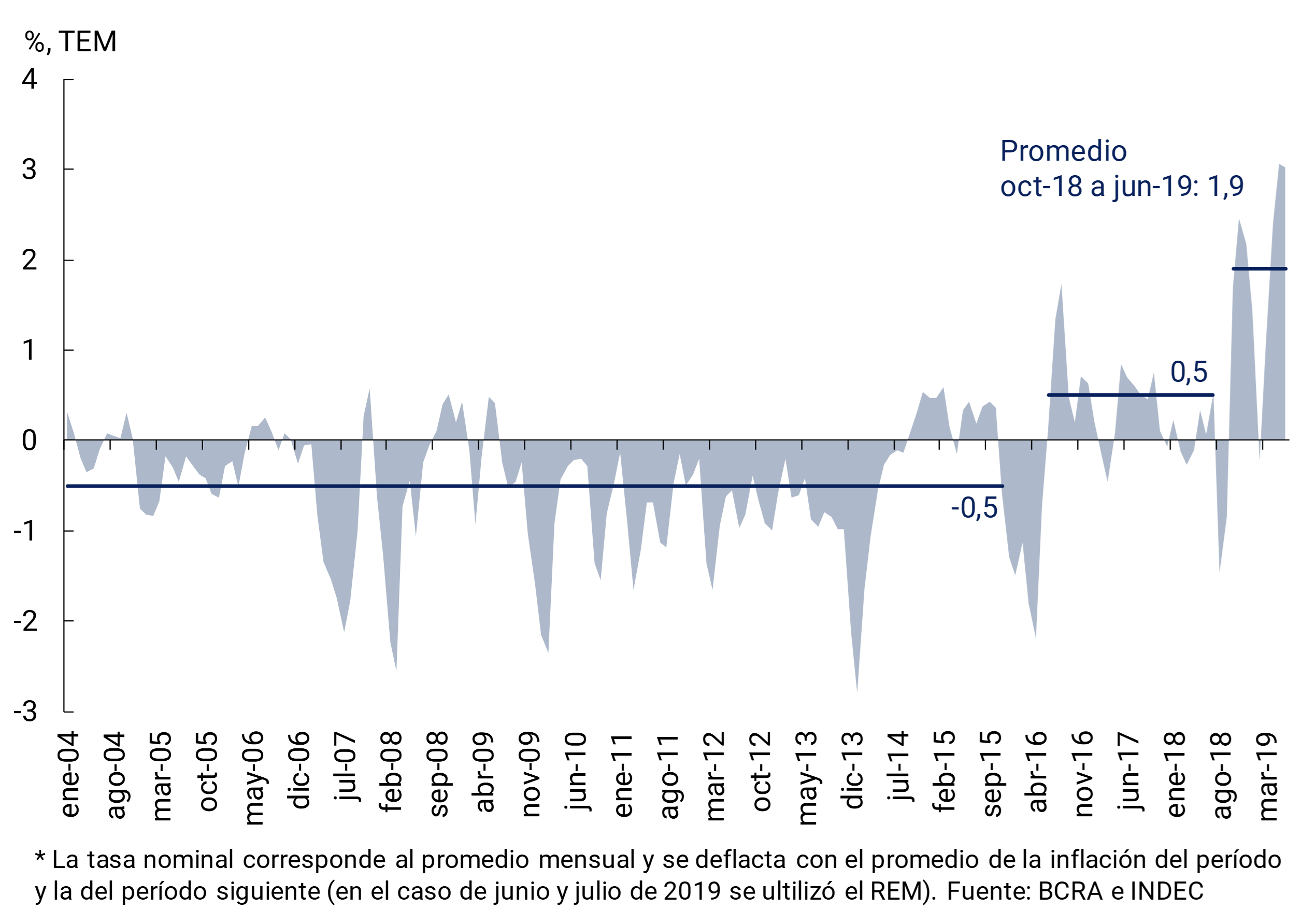

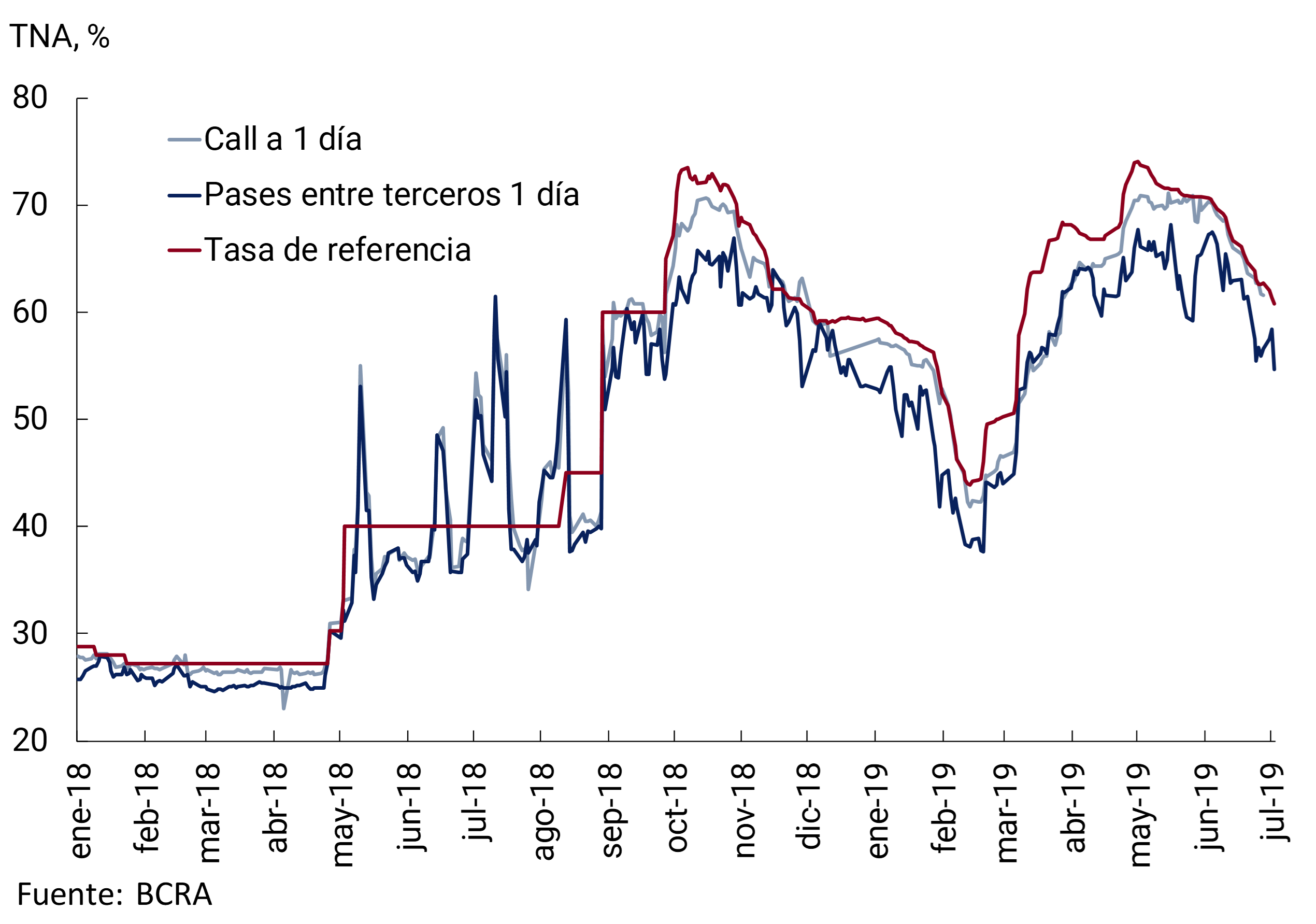

Thus, in the face of the greater exchange rate volatility in April, the benchmark interest rate increased by 7.2 p.p. to reach 74.1% annually on May 2 (see Figure 5.5). This dynamic of the nominal reference rate implied that the real interest rate has reached a high level in historical terms, which reinforces the contractionary bias of monetary policy (see Figure 5.6). 43 Then, in a context of lower nominal volatility and falling inflation expectations, the nominal interest rate of the LELIQ showed a downward trend until it reached the minimum of 62.5% per annum set by the COPOM for that month in the last days of June. For July, the COPOM decided to reduce the minimum rate of LELIQ auctions to 58% per annum, in line with the drop in inflation observed and that expected by the REM for this month. 44 The interest rate on the LELIQ continued to be gradually reduced until it reached 58.8% per annum on the 15th.

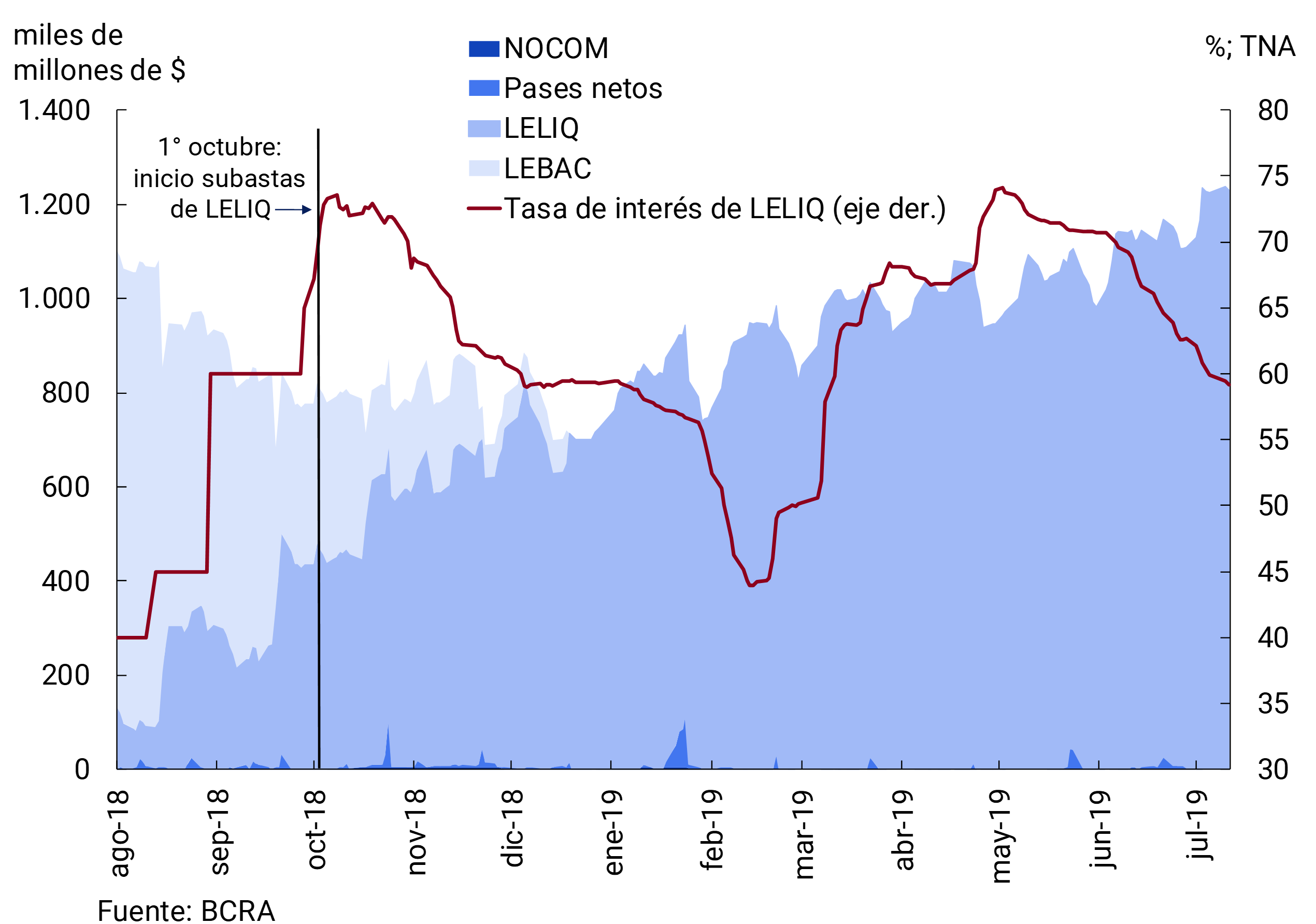

Figure 5.5 | LELIQ interest rate and stock of interest-bearing liabilities in pesos (LEBAC, LELIQ, NOCOM and net passes)

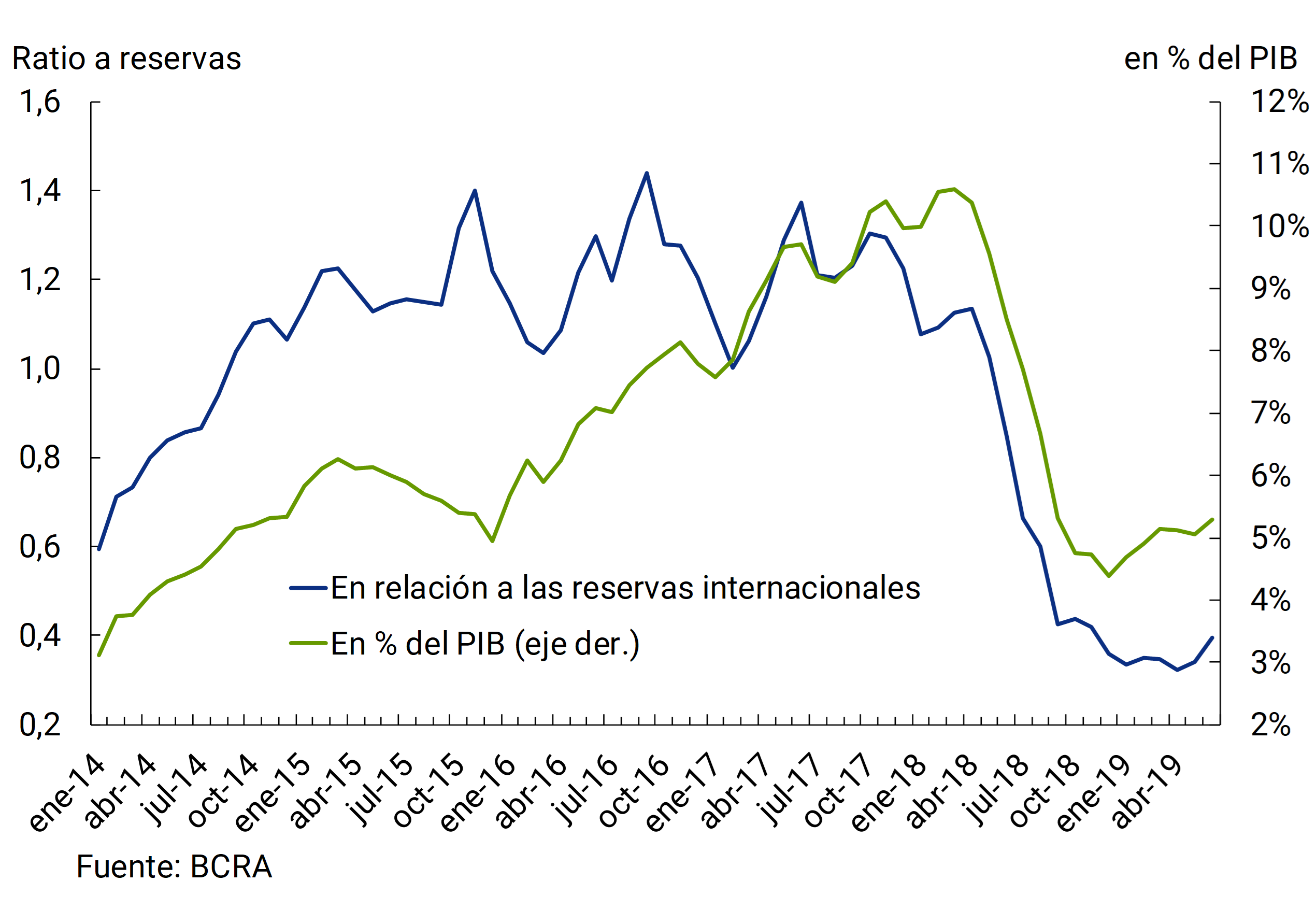

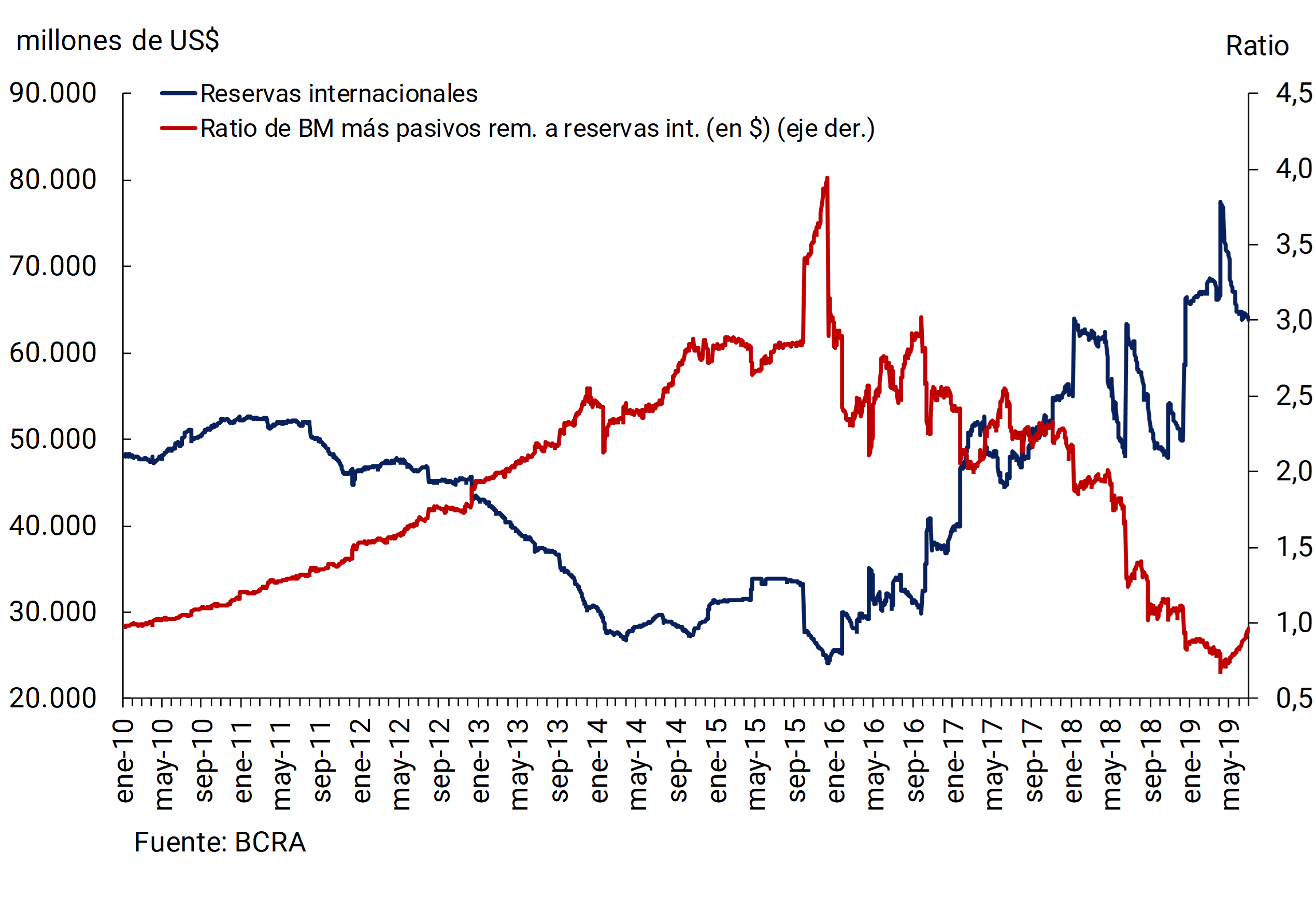

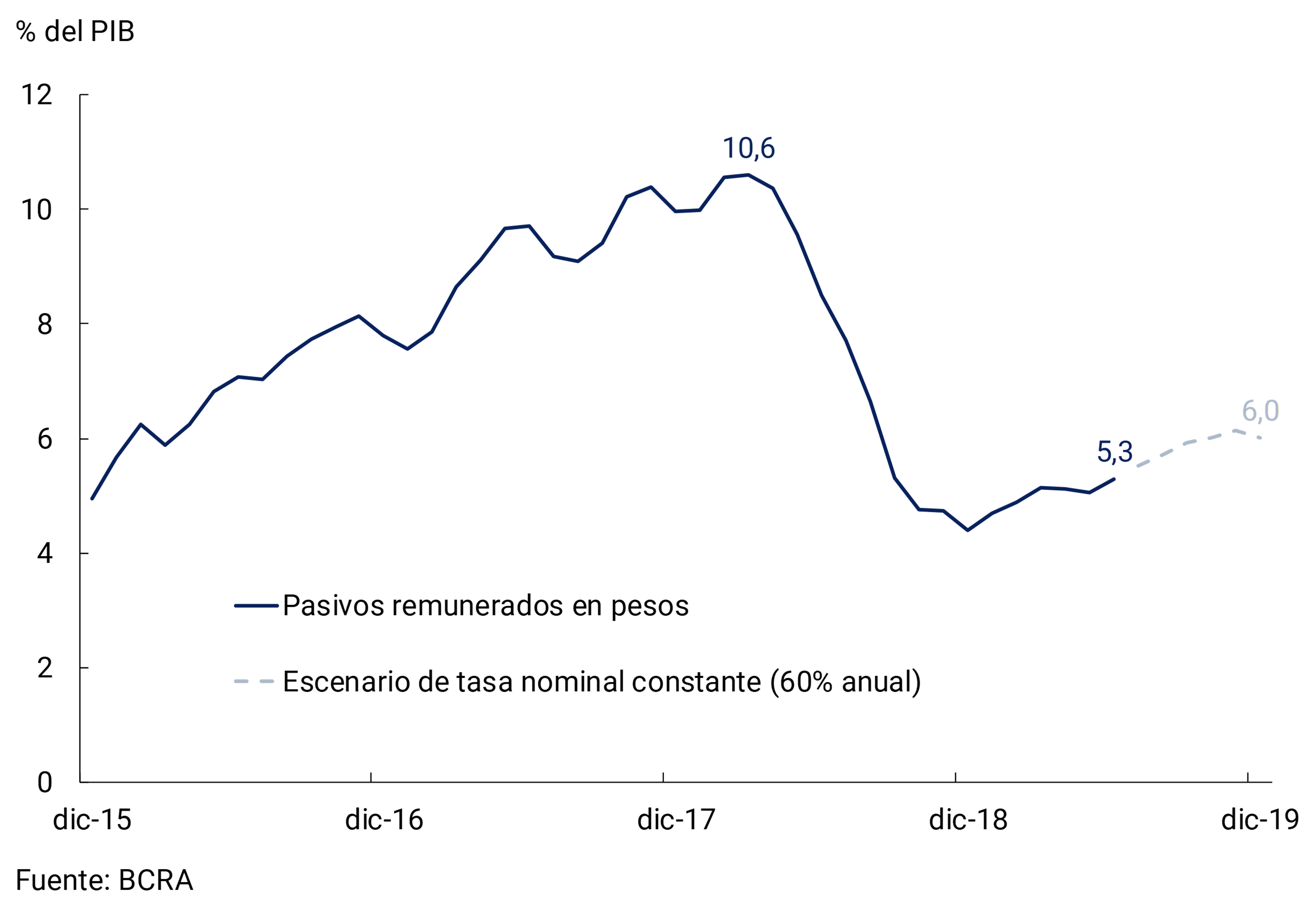

The Central Bank’s interest-bearing liabilities in pesos (LELIQ, NOCOM and net passes) showed an upward trajectory in nominal terms in the second quarter, going from $955.3 billion at the end of March to $1,232.3 billion at the beginning of July (see Figure 5.5). This increase was mainly associated with the accrual of interest and, to a lesser extent, with some foreign currency purchase operations from the National Treasury at the end of June and beginning of July. 45 However, the stock of interest-bearing liabilities was 16% below the peak of $1,459.0 billion reached on March 20 of last year (when LEBACs were included). At the same time, in terms of GDP, these liabilities represented 5.3% in June, compared to 10.6% in March last year, and as a ratio of international reserves they reached 0.40 in June, compared to 1.12 in March 2018 (see Figure 5.7).

Figure 5.7 | Central Bank’s interest-bearing liabilities in pesos (LEBAC, LELIQ, net passes and NOCOM) (in terms of GDP and international reserves)

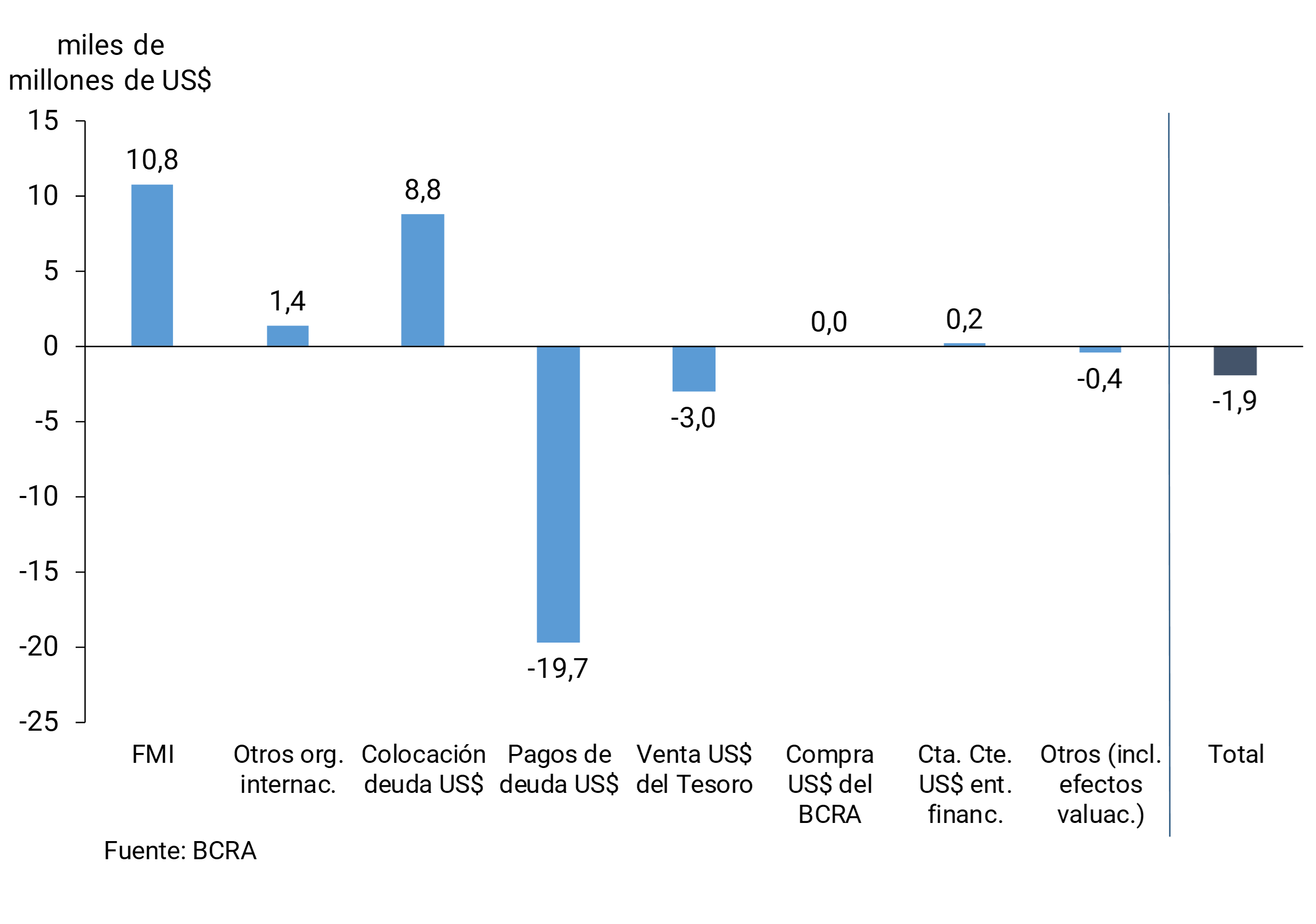

The evolution of international reserves in the second quarter was mainly explained by the debt operations of the National Treasury and was not related to the Central Bank’s exchange rate policy, since it did not intervene in the foreign exchange market (see Figure 5.8). These Treasury operations included foreign exchange inflows of US$21,997 million as a counterpart to borrowing operations in foreign currency (US$10,830 million from the income from the fourth tranche of the Stand-by arrangement with the IMF, US$1,383 million from disbursements from other international organizations – mainly the IDB and the World Bank – and US$8,785 million for other debt placements). in the face of foreign currency outflows due to payments of debt maturities in foreign currency of US$19,710 million and daily auctions of foreign currency in the market for US$3,000 million. 46 In net terms, these operations accounted for US$1,713 million of the US$1,909 million that fell in reserves in the quarter, which reached US$64,278 million at the end of June. Thus, the ratio of monetary base plus interest-bearing liabilities in pesos to international reserves valued in pesos remained at the lowest levels in recent years, at an average of 0.87 in June compared to 1.94 in March 2018 (see Figure 5.9).

Figure 5.8 | Explanatory factors for the change in international reserves in the second quarter of 2019

5.1.4 Outlook

The contractionary bias of the monetary scheme will continue throughout 2019 with the fundamental purpose of consolidating the downward trajectory evidenced by the inflation rate in recent months. At the same time, this monetary policy stance allows the Central Bank to be prepared to face possible sources of uncertainty. The disinflation process is expected to be non-linear and gradual, due to inflationary inertia. In this context, the benchmark interest rate is expected to fall gradually, only to the extent that expected inflation decreases and no new volatility events arise.