Política Monetaria

Monetary Policy Report (IPOM)

Second Quarter

2022

This quarterly publication aims to analyze the national and international economic situation, assess the dynamics of inflation and its prospects, and explain in a transparent manner the fundamentals of monetary policy decisions.

Table of Contents

Chapters

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlook

2. International context

3. Economic Activity and Employment

4. External Sector

5. Public Finance

6. Pricing

7. Monetary Policy

Sections

1. Fiscal measures against the inflationary impact of raw materials

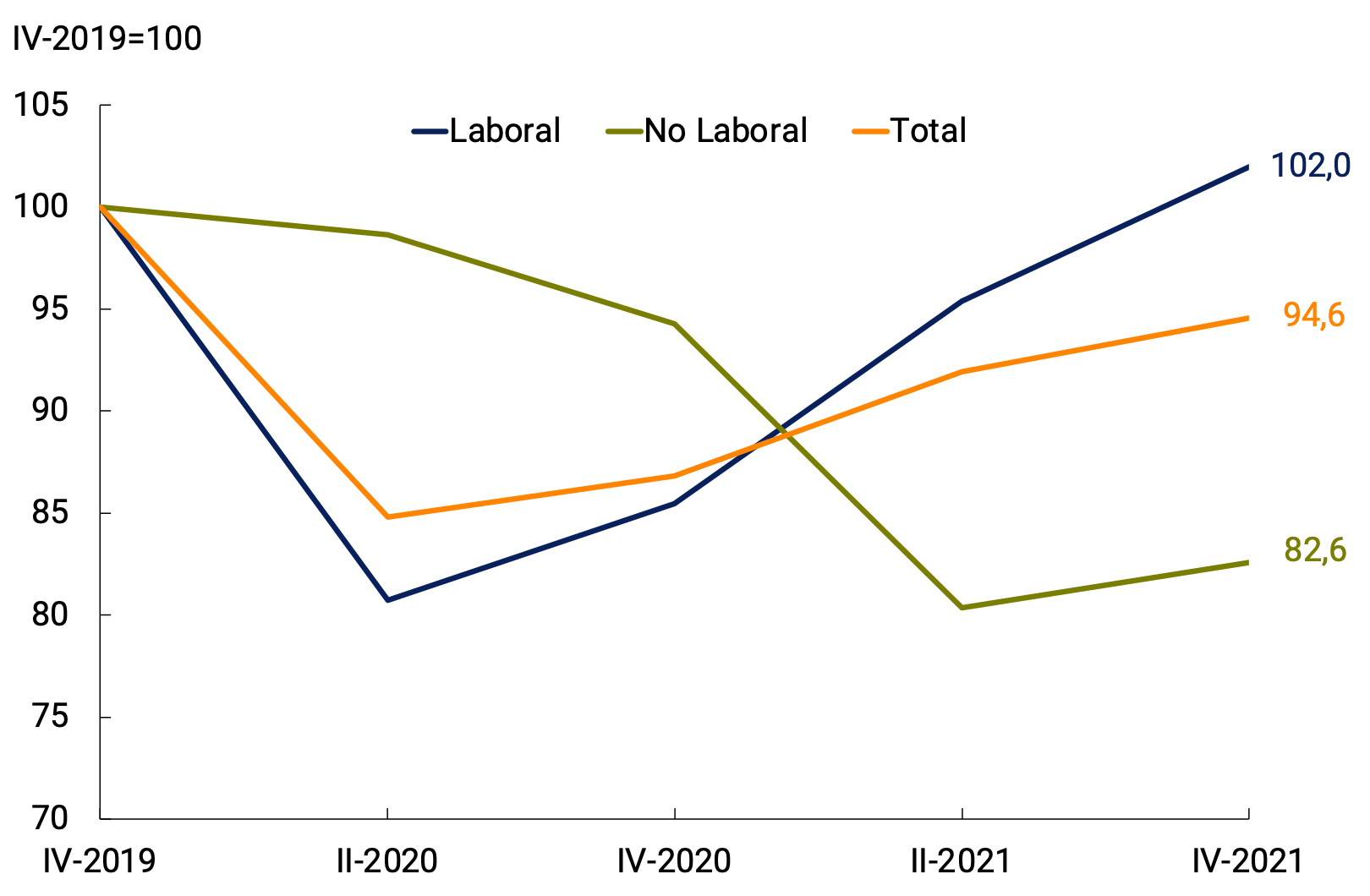

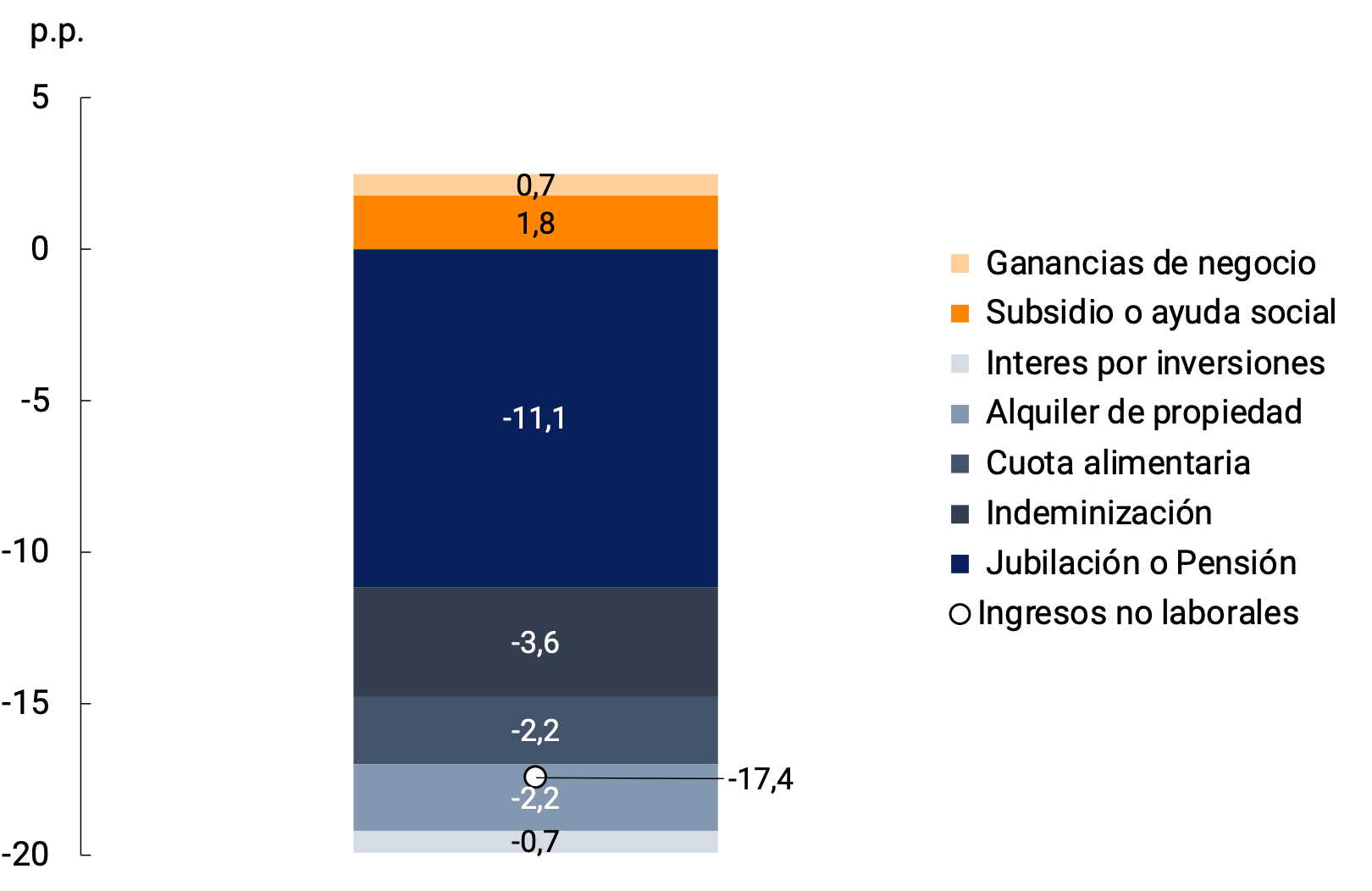

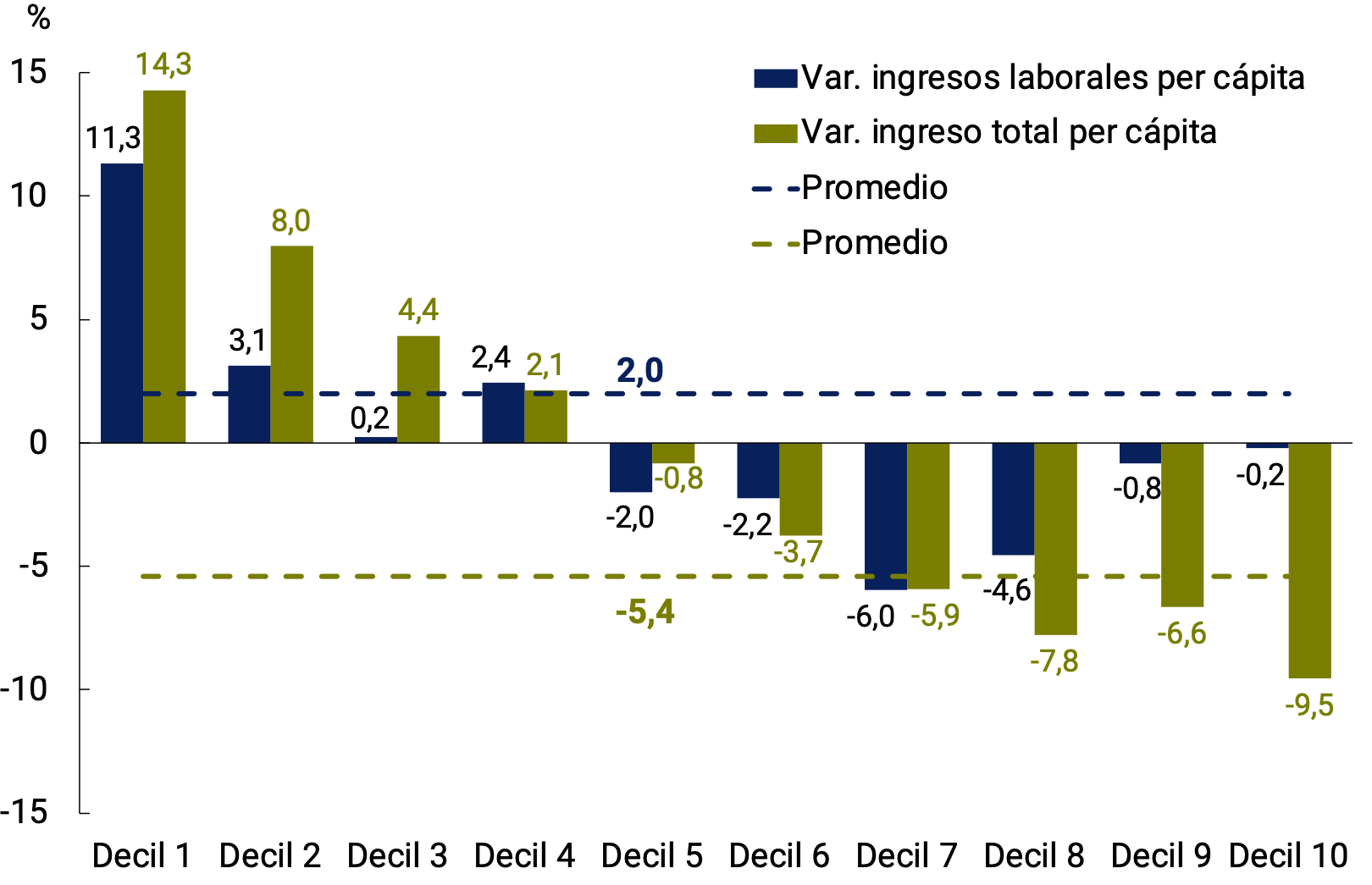

2. Employment and income: two years after the start of the pandemic

3. Measures taken to strengthen revenues

4. Recent developments in food prices

5. Financing Line for Productive Investment of MSMEs: renewal and compliance with the 2021/2022 quota

6. Transformations in payment infrastructure: the use of cash and the growing influence of digital means of payment in the region

Summary

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlook

The external context has become more complex in the last three months. The deepening of the war in Ukraine pushed up international food and energy prices and undermined the dynamism of global economic activity. Higher inflationary pressures led to a cycle of monetary tightening in advanced economies that was more pronounced than expected at the beginning of the year. The increase in global interest rates pressured the values of financial assets listed on the world’s main stock exchanges, generated a global appreciation of the dollar and increased the risk of capital outflows from emerging countries. For developing countries, and in particular those in Latin America, different perspectives for growth and inflation opened up depending on whether upward pressures on commodity prices and the consequent real appreciation of exchange rates continue; or, if the appreciation of the dollar results in lower commodity prices and more depreciated real exchange rates.

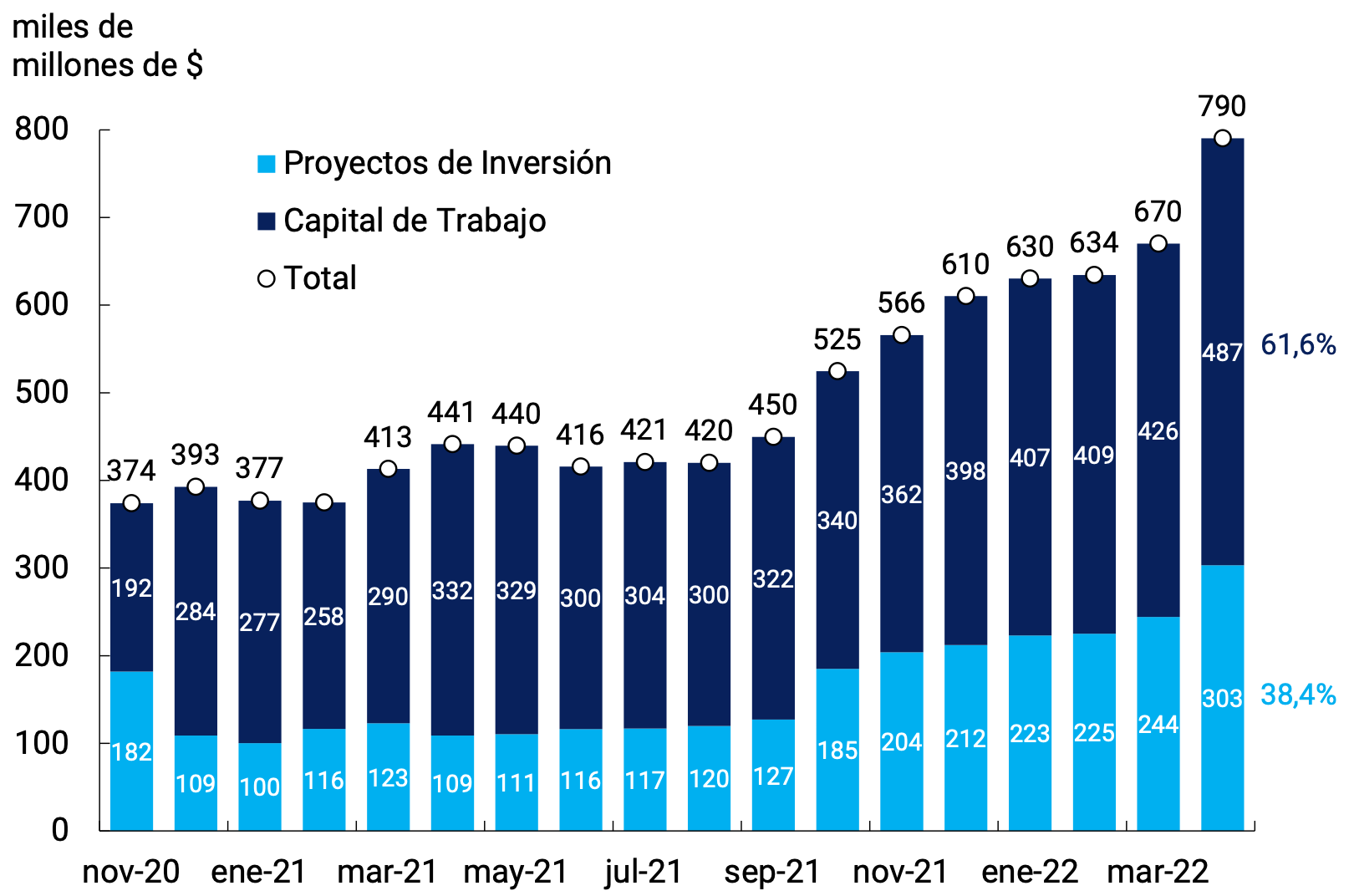

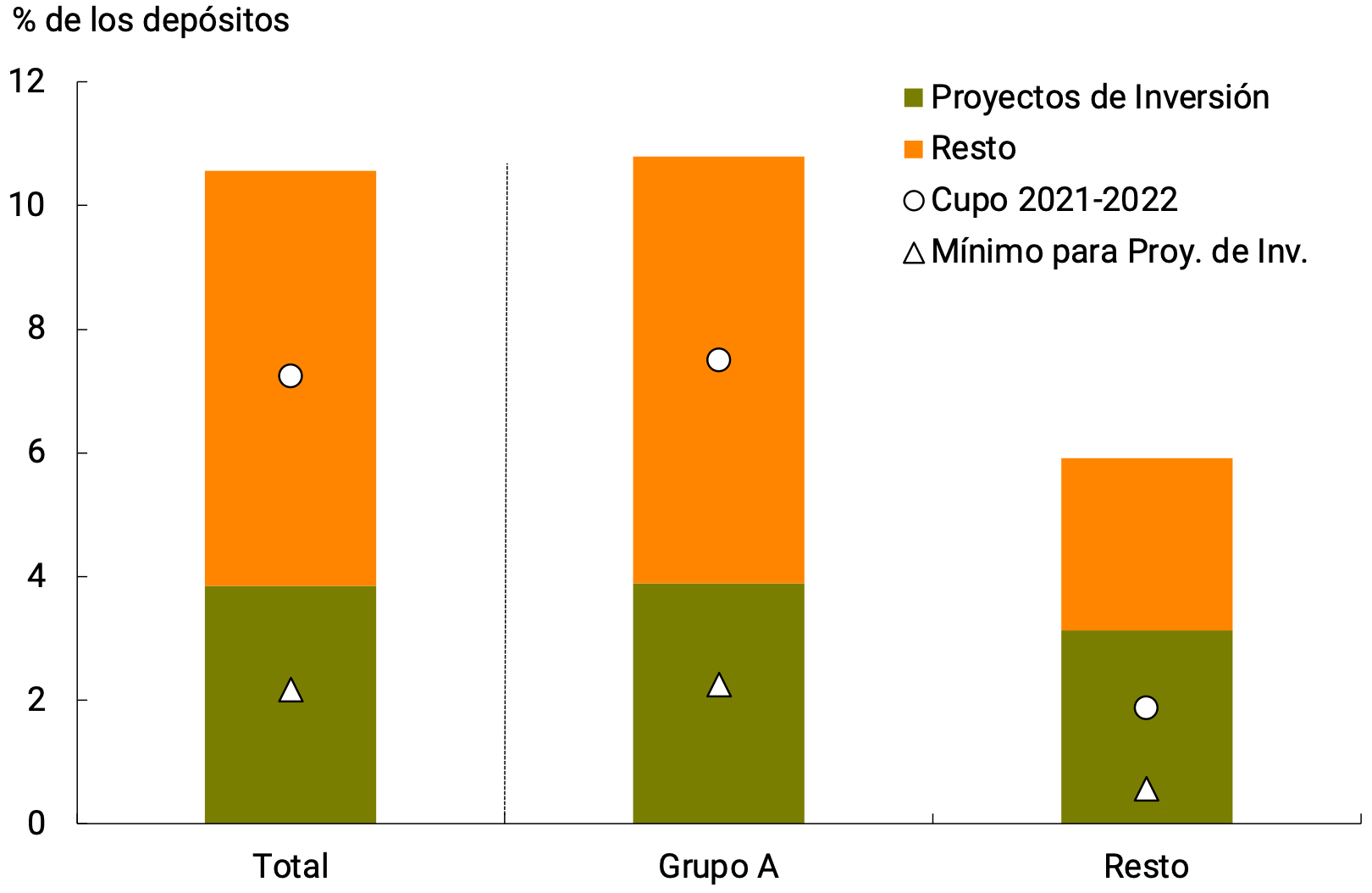

The Argentine economy continued to consolidate its recovery process that began in 2021 and continued to operate at levels higher than pre-pandemic levels, with increases in the investment rate. This improvement in economic activity was accompanied by a recovery in registered employment, which is at an all-time high. After a first quarter of growth, GDP is expected to contract slightly during the second quarter due to the impact of the drought conditions that affected the main soybean and corn producing areas during the summer and then resume its growth path in the second half of the year. to close 2022 with an expansion of around 4%. In this context of continuity in the process of recovery of economic activity, the BCRA focused its credit policy on the most lagging sectors and on the financing of productive development and structural change. The Productive Investment Financing Line (LFIP) continued to be the main tool used to channel productive credit to MSMEs under favorable conditions. The average balance of financing granted between October 1, 2021 and March 31, 2022 through the LFIP reached $670,000 million.

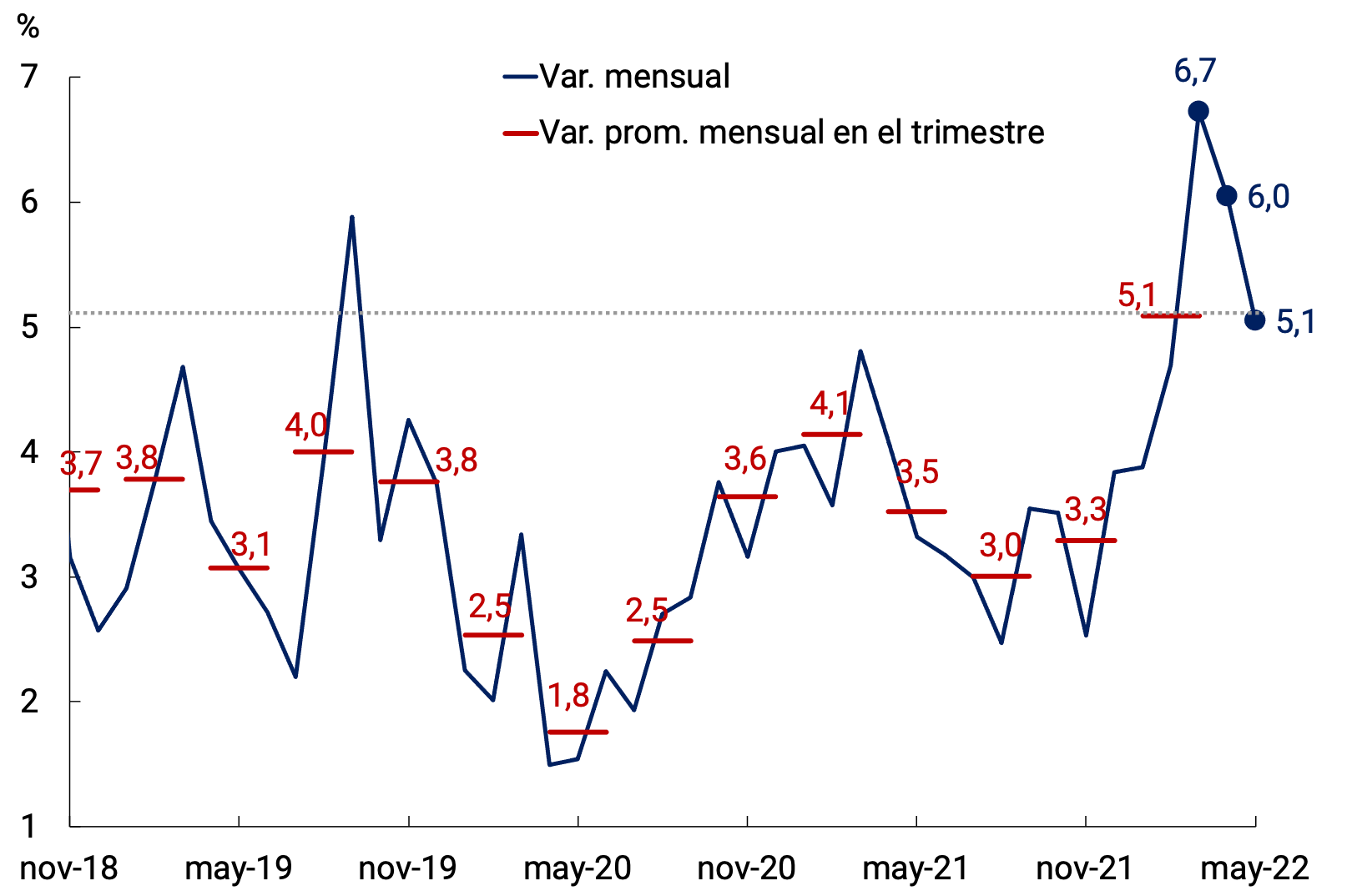

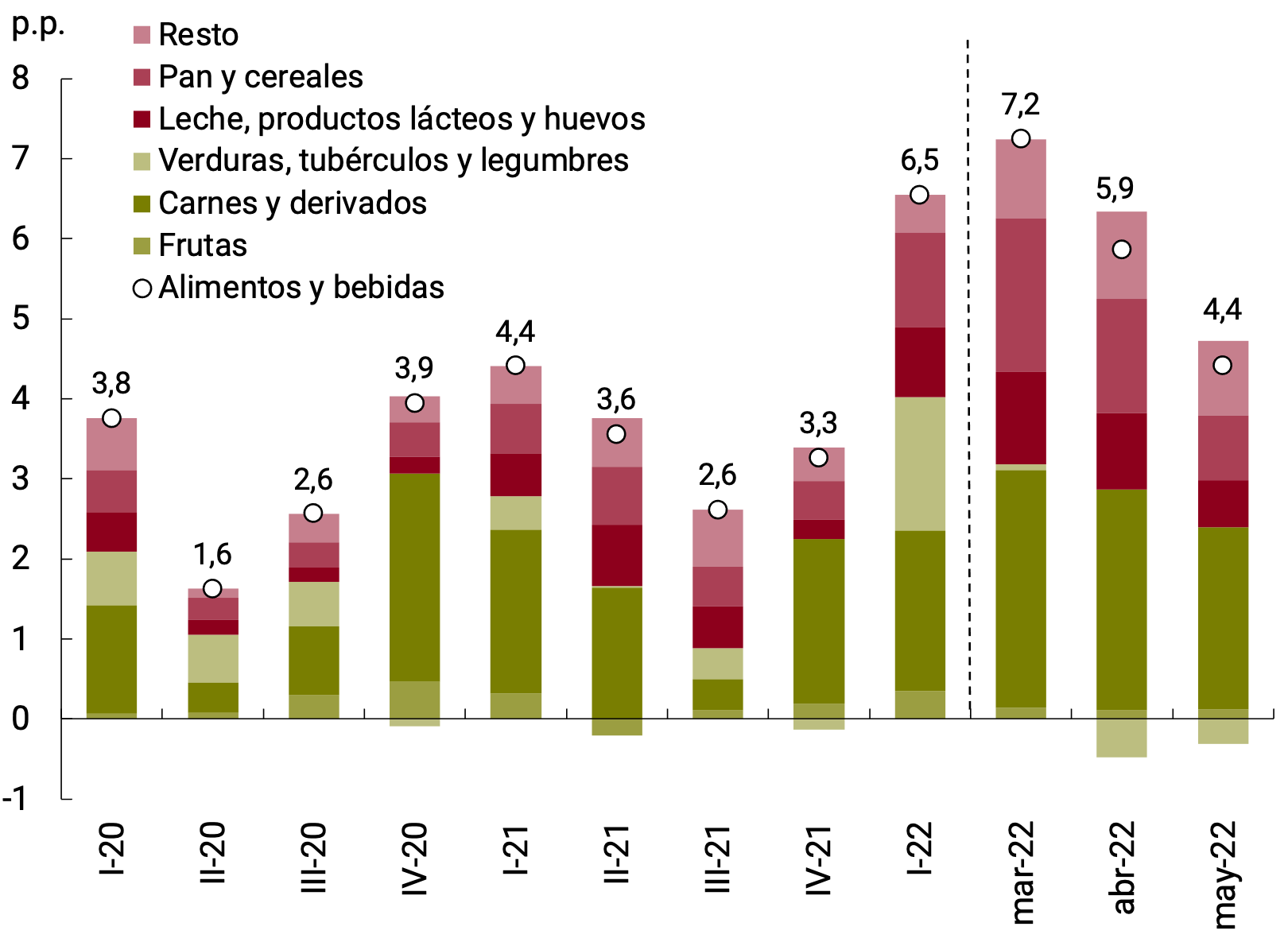

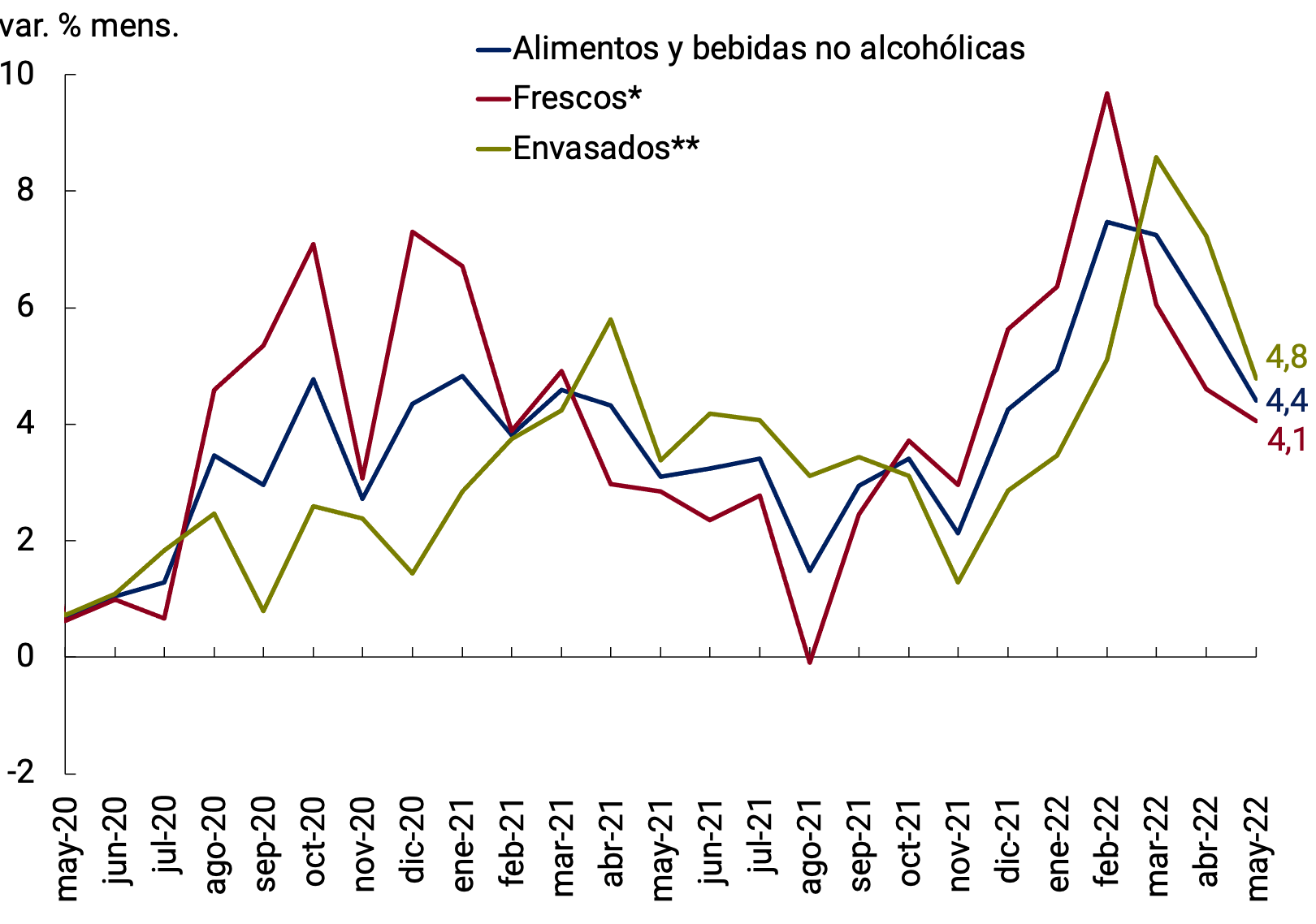

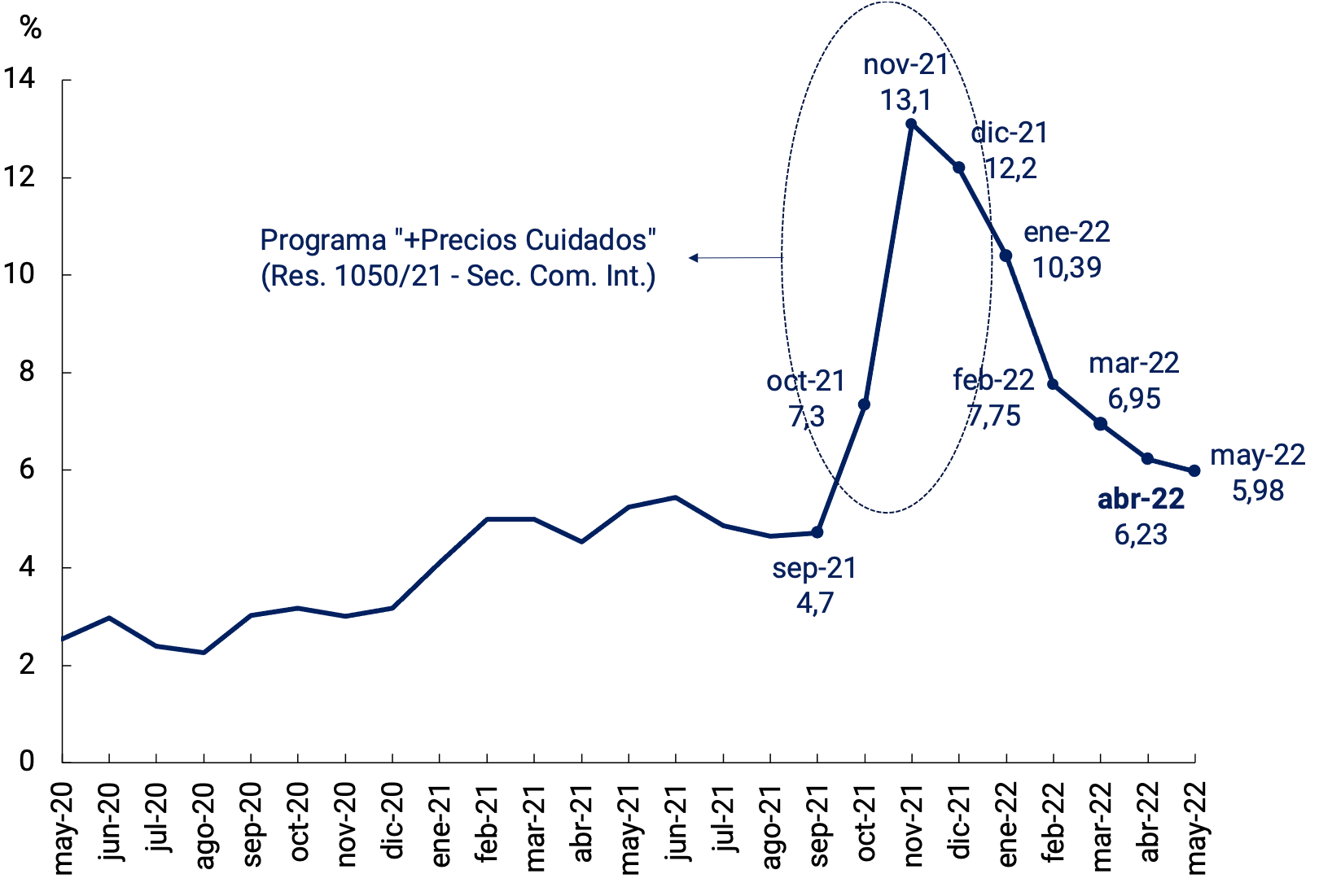

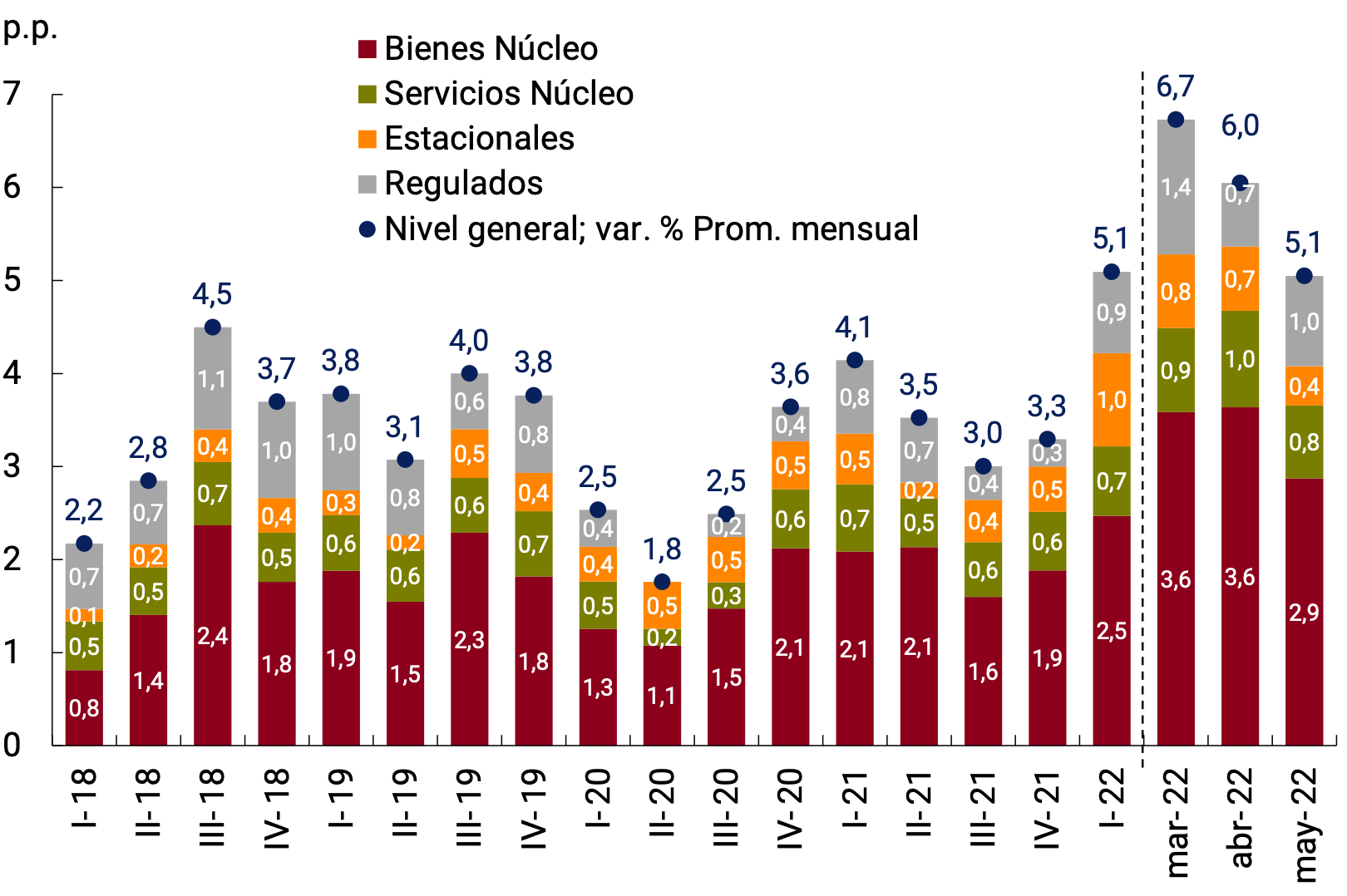

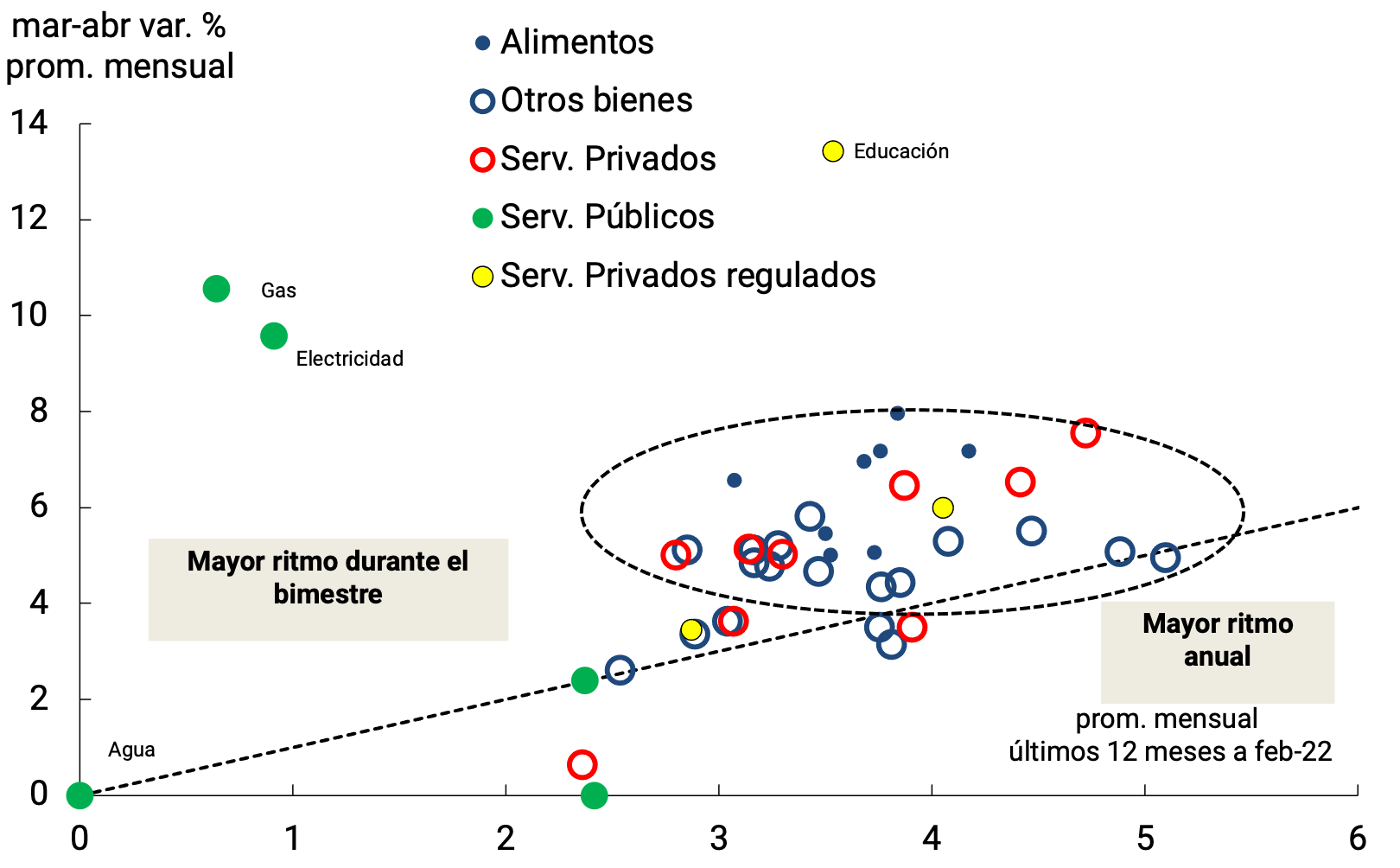

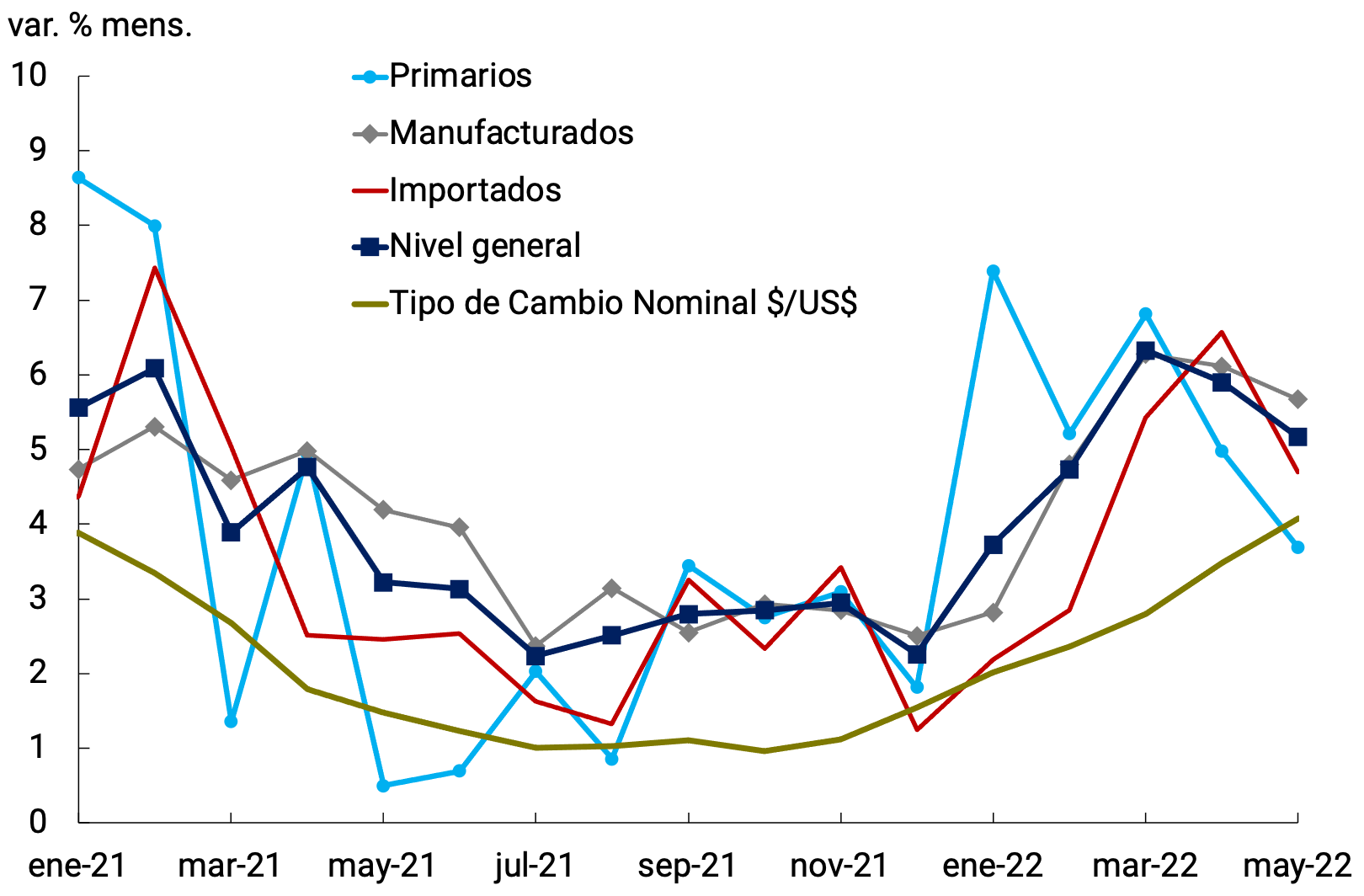

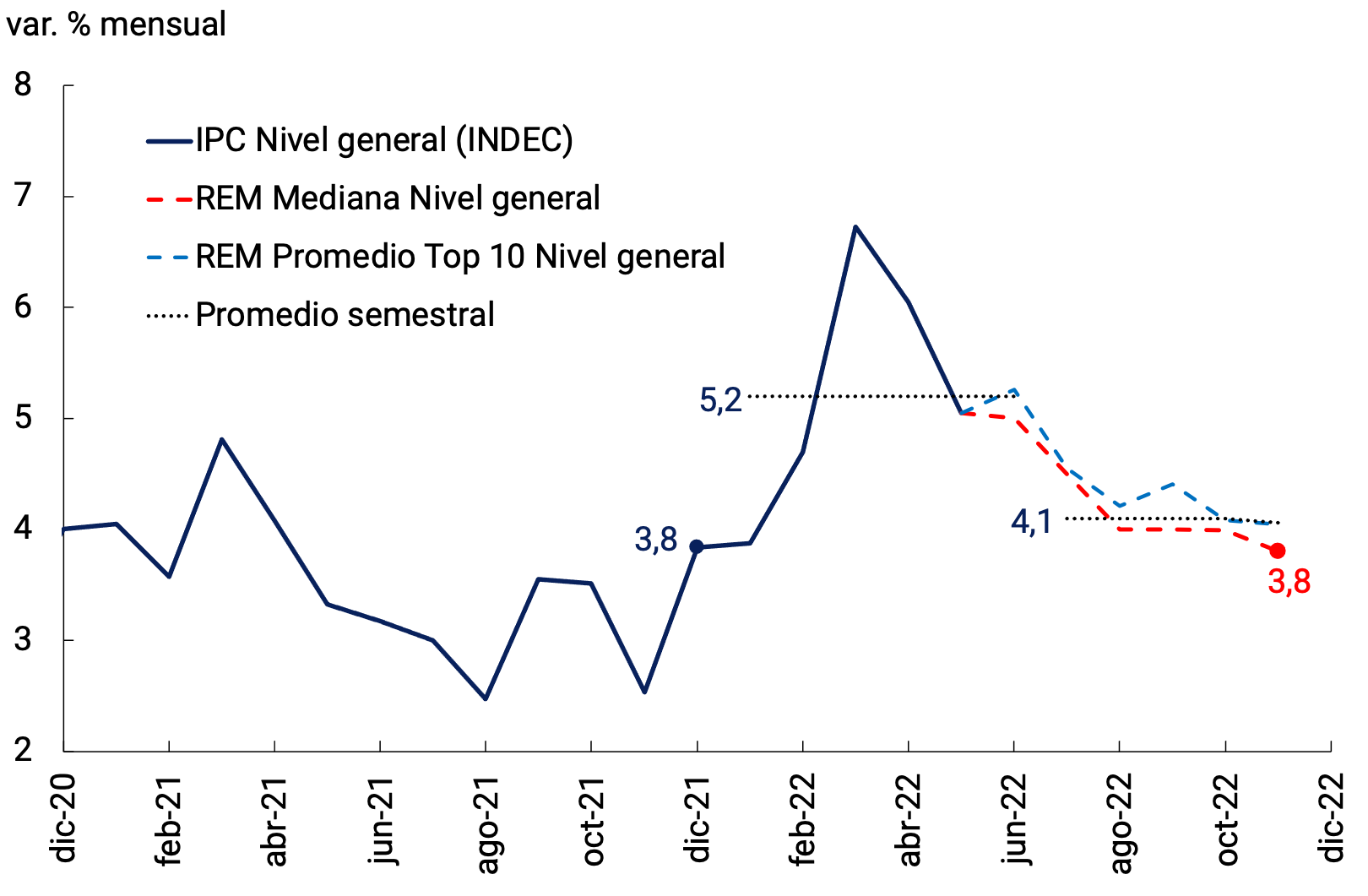

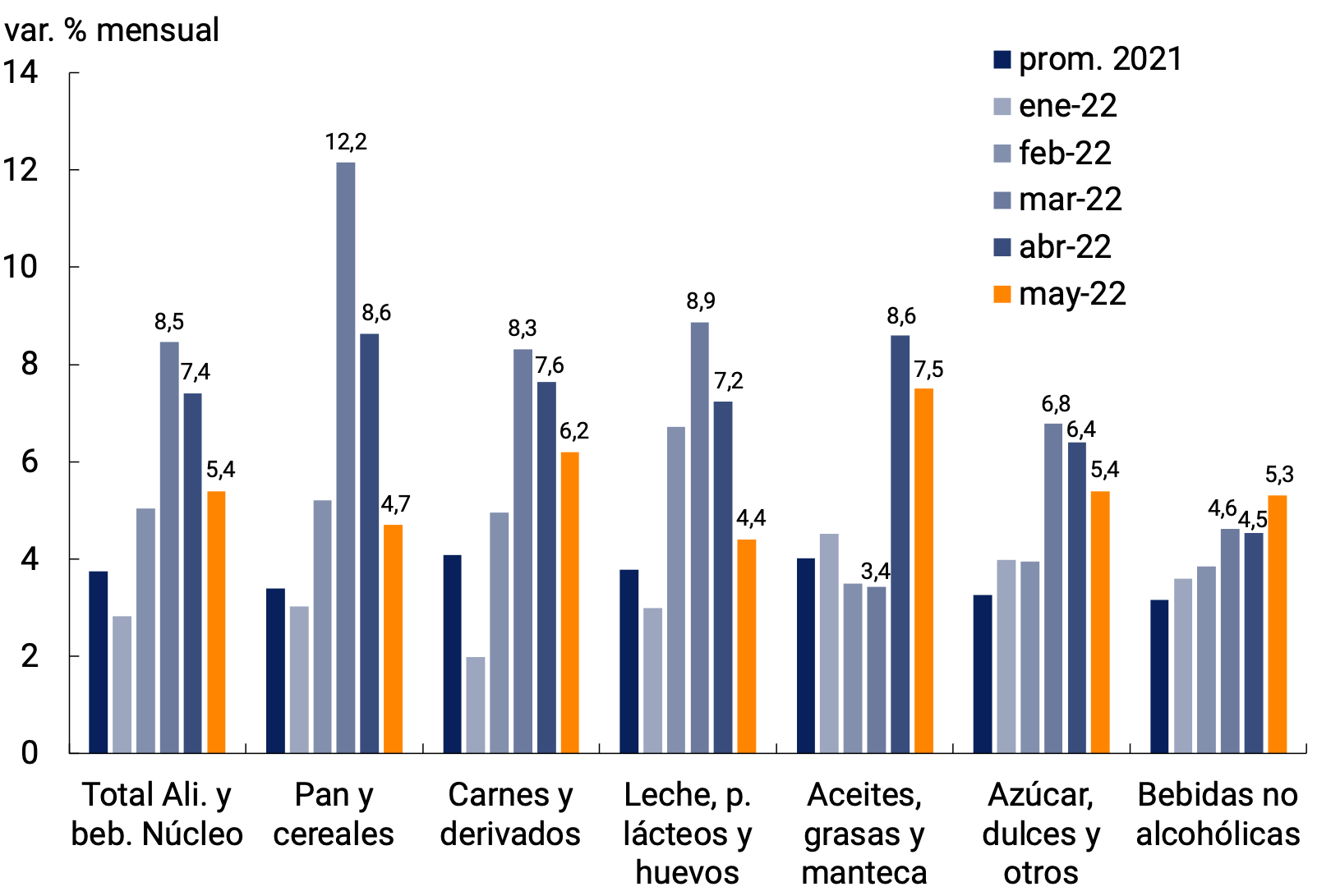

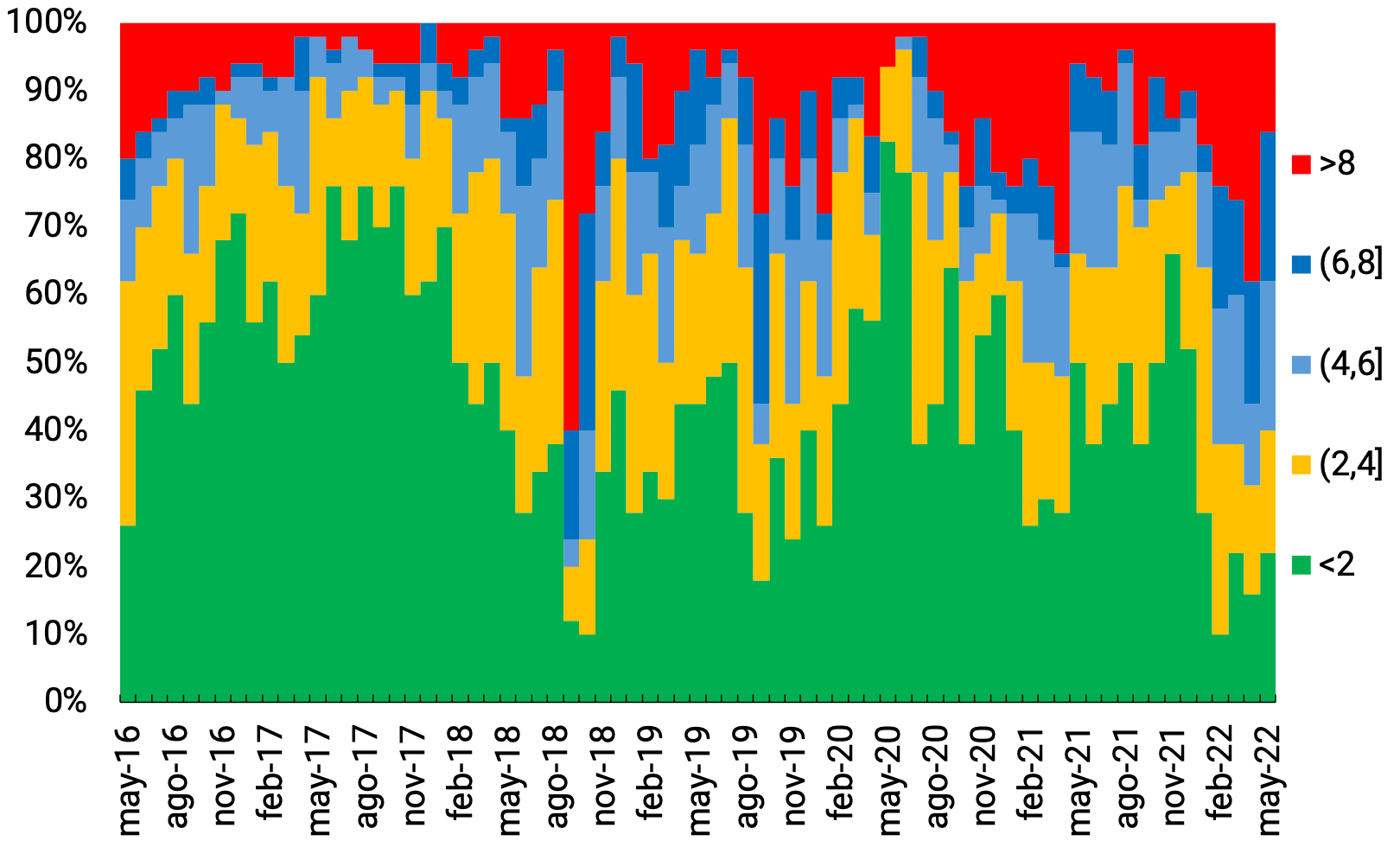

In March 2022, inflation accelerated significantly, reaching a monthly rate of 6.7%, a very high record in historical terms. This increase was mainly observed in the Core category, and within it, in the value of food, driven by the increases in international commodity prices as a result of the war in Ukraine. This external shock affected Argentina in the context of a recovering economic activity and with a previous high inflationary inertia. After the maximum reached in March for the General Level, the May data confirmed the slowdown in inflation that had begun in April, with a significant drop in the Core category. However, inflationary records remain at high levels, in part due to the existence of formal and informal indexation mechanisms that contribute to increasing the magnitude and persistence of the shock.

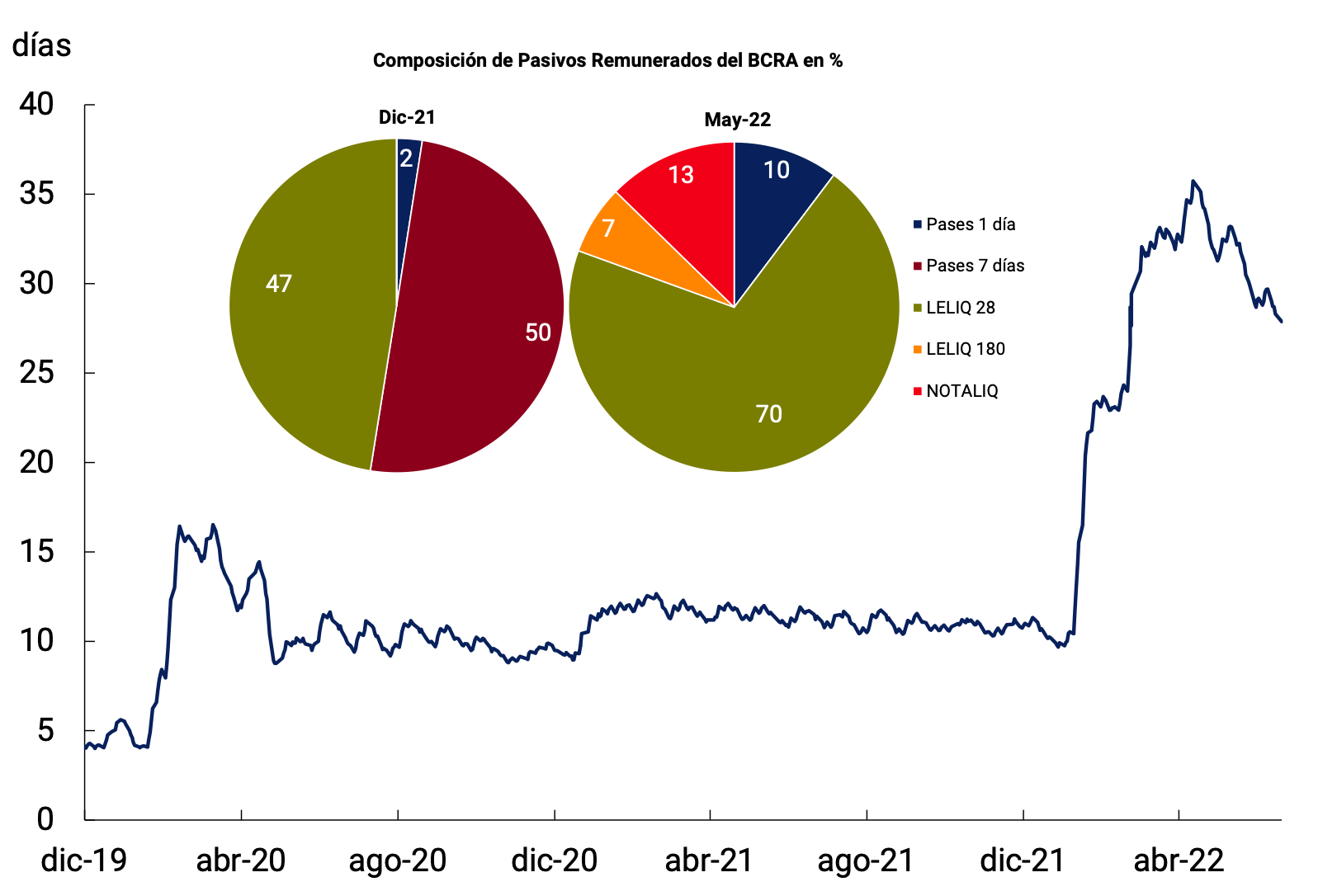

Faced with this scenario, the monetary authority continued its process of normalization of the policy interest rate and the rest of the economy’s interest rate structure, seeking to move towards an interest rate path that allows safeguarding the value of investments made in instruments denominated in domestic currency and avoiding pressures in the foreign exchange market. without affecting the economic recovery underway. At the close of this edition, the interest rate of the LELIQ with a 28-day term amounted to 52% n.a. (66.5% y.a.), with a total increase of 14 p.p. since the beginning of the year. Likewise, the floor for the interest rate of fixed terms of individuals accumulated an increase of 19 p.p. for the segment between $1 and $10 million and 16 p.p. for the segment of less than $1 million so far this year, currently standing at 53% n.a. for both types of placements (68% e.a.). For the rest of the private sector’s fixed-term deposits, the minimum guaranteed rate accumulated a rise of 16 p.p. to 50% n.a. (63.2% y.a.).

In order to contain the impact of the acceleration of prices, the National Government decided to mitigate the loss of purchasing power of income of people without formal income and/or in a situation of socioeconomic vulnerability. Likewise, the increase in energy prices had a negative impact on public finances. The increased financing needs were met using a multiplicity of sources, including monetary financing. Thus, so far this year, monetary assistance to the Treasury in terms of GDP was at a level similar to that of the years prior to the pandemic. On the other hand, during June, in the face of an increase in volatility in global and local financial markets, the BCRA intervened in the secondary market of public securities with the aim of recomposing the Treasury’s curve in pesos, in a context of excessive and unjustified price volatility that could compromise financial stability. The counterpart of these operations was an expansionary effect on the monetary base, offset by operations to sterilize excess liquidity. However, the seasonally adjusted monetary base at constant prices is at historically low levels and in terms of GDP reached a record low in April. The BCRA will maintain a prudent administration of monetary aggregates, sterilizing any surplus liquidity, to avoid imbalances that directly or indirectly threaten the disinflation process.

Going forward, the National Government and the BCRA will continue to adopt measures to lower inflation. In this sense, the current policy scheme within the framework of the agreement with the IMF will consolidate a framework of macroeconomic certainty, thus helping to limit expectations of an increase in the exchange rate and inflation. Recently, the IMF and the Argentine authorities reached an agreement at the technical level on the first review of the Extended Facilities Program. The review focused on evaluating the performance since the approval of the agreement, contemplating the impact of the war in Ukraine on the Argentine economy and identifying policies that allow its effects to be mitigated. With the aim of strengthening macroeconomic stability, it was agreed to keep the annual targets related to the primary fiscal deficit, monetary financing and net international reserves established in March unchanged, changing their quarterly trajectory. After meeting all the program’s quantitative targets for the first quarter of 2022, the agreement on the first review was approved by the IMF’s executive board.

The BCRA will continue to calibrate monetary policy based on the observed and prospective evolution of the general price level and will continue to carry out actions to align its monetary policy with the BCRA’s Objectives and Plans for 2022, in which the authorities established as a goal to set the path of the policy interest rate towards positive real returns on investments in local currency.

2. International context

The global economy continues to feel the impact of the war through higher food and energy prices and a slowdown in activity. Higher inflationary pressures have led to a cycle of monetary contraction that was more pronounced than expected a few months ago in advanced economies. And COVID-19 outbreaks, although localized, implied new restrictions in China, hampering trade flows.

This has led to a reduction in the global growth forecast for this year of 1 p.p. on average compared to what was expected before the war; only commodity exporting countries would grow somewhat more than expected at the close of the previous IPOM. Meanwhile, inflation is reaching levels not seen in decades in advanced countries, leading their central banks to bring forward and accentuate interest rate hikes, while contracting the money supply generated in response to the pandemic. Developing countries, which had already shown higher inflation since 2021, continued to raise interest rates. The combination of higher inflation and lower growth is more costly for these countries because: they had been recovering more slowly than the advanced countries; food has a greater weight in its consumption basket; and face more unfavorable financial conditions.

Higher international interest rates put pressure on stocks and bonds, and generate a global appreciation of the dollar. They also present the risk of capital outflows from emerging countries. For growth and inflation in developing countries, and in particular in Latin America, different perspectives open up depending on: whether commodity prices continue to rise, and this is associated with an appreciation of the real exchange rate (which compensates for inflationary pressures); or a more appreciated dollar puts downward pressure on commodity prices, while the real exchange rate depreciates. It will also be key whether monetary policy in the US and Europe can reduce inflation without hurting growth in larger economies too much or destabilizing global financial conditions.

2.1. COVID-19 cases continue to decline, but focus on China impacts international trade

COVID-19 cases continued to decline sharply from a record 24 million weekly at the end of January 2022 and stand at 3.4 million weekly cases at the end of June, with 9 thousand deaths. As a result, the death rate for cases 10 days ago reached a low of 0.27% (up from more than 2.5% in March 2021). Along with the increase in cases in January and then in early April, global mobility was reduced; it is currently recovering and is already on average above 80% of its pre-pandemic level (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 | New global confirmed cases and deaths from COVID-19 and the mobility normality

Source: BCRA based on data from WHO and The Economist.

During March and April, cases rose in Europe (mainly Germany and France) and Asia (Japan and Korea). Since mid-March and due to its COVID-0 policy, China carried out a strict quarantine in the city of Shanghai for 65 days, impacting international trade due to its importance as an Asian port (other cities such as Beijing had more limited restrictions).

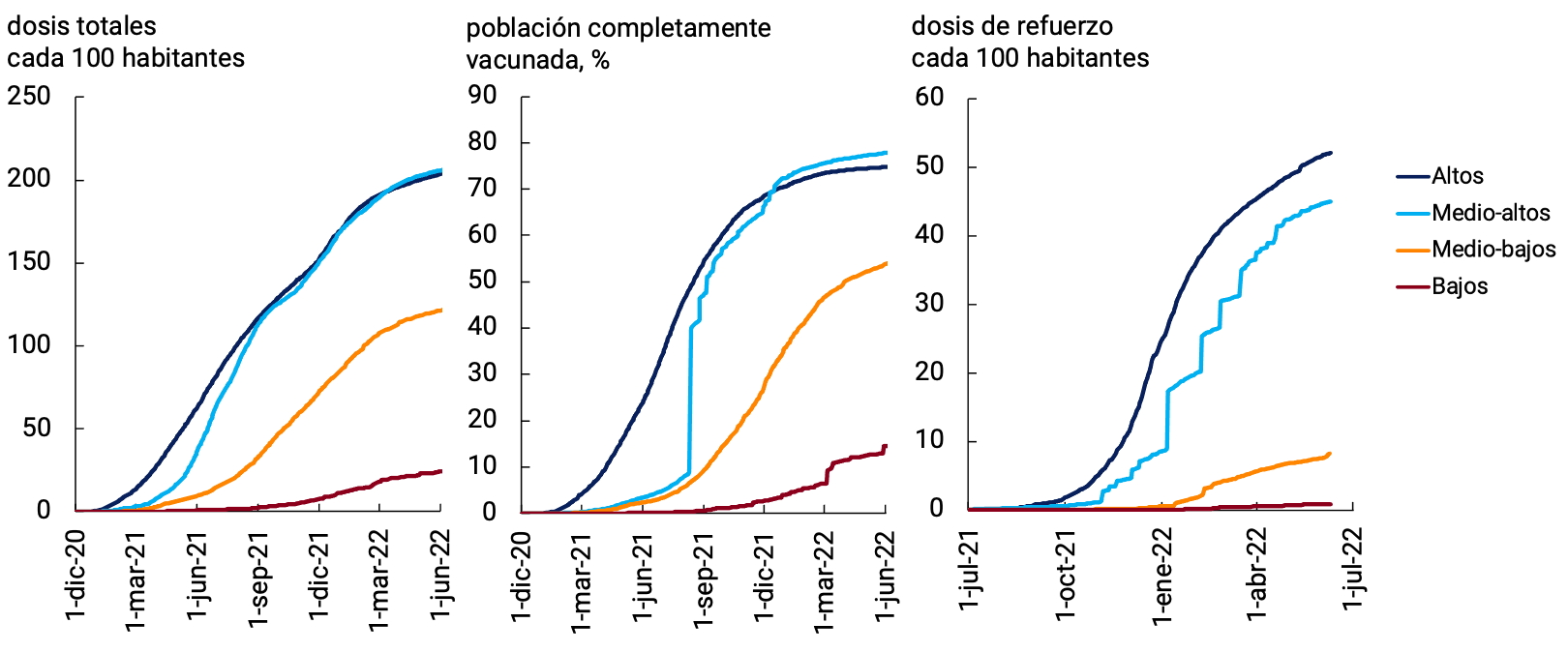

Vaccination campaigns continue: 65% of the world’s population has received at least one dose, although the gap between countries remains. The percentage of the population fully vaccinated in low-income countries is more than 8 times lower than in high-income countries; and while high-income countries have more than 45 booster doses per 100 inhabitants, low-income countries have applied less than 0.4 (see Figure 2.2).

2.2. The global economy slowed in the first quarter and growth forecasts for this year were lowered

The war generated uncertainty and a sharp rise in the price of raw materials, leading to prospects of higher inflation and lower global growth. The expectation and the subsequent start of a more aggressive contractionary cycle by the US Federal Reserve (Fed) tightened global financial conditions. Finally, restrictions in key cities in China impacted international trade and global supply chains.

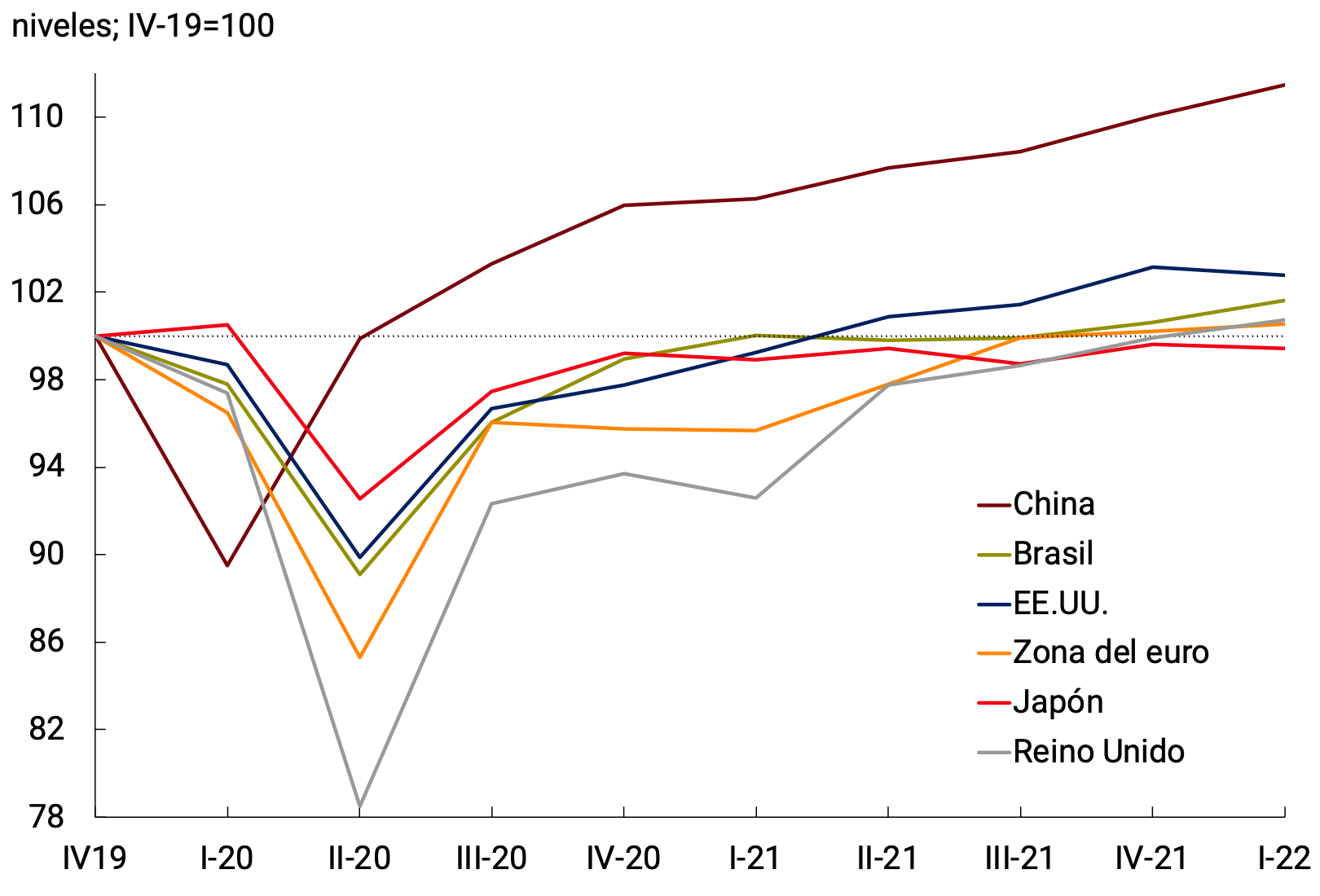

Thus, in the first quarter of the year, a slowdown in the main world economies is generally observed, with lower quarterly growth rates in China and the United Kingdom and falls in activity in the United States and Japan. On the other hand, activity in the euro area accelerated slightly, but with a poor performance of household consumption, government spending and fixed investment. The Brazilian economy showed a higher quarterly growth rate, driven by private consumption and exports (see Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 | Evolution of GDP in selected countries (real GDP without seasonality)

Source: BCRA based on data from national statistics institutes.

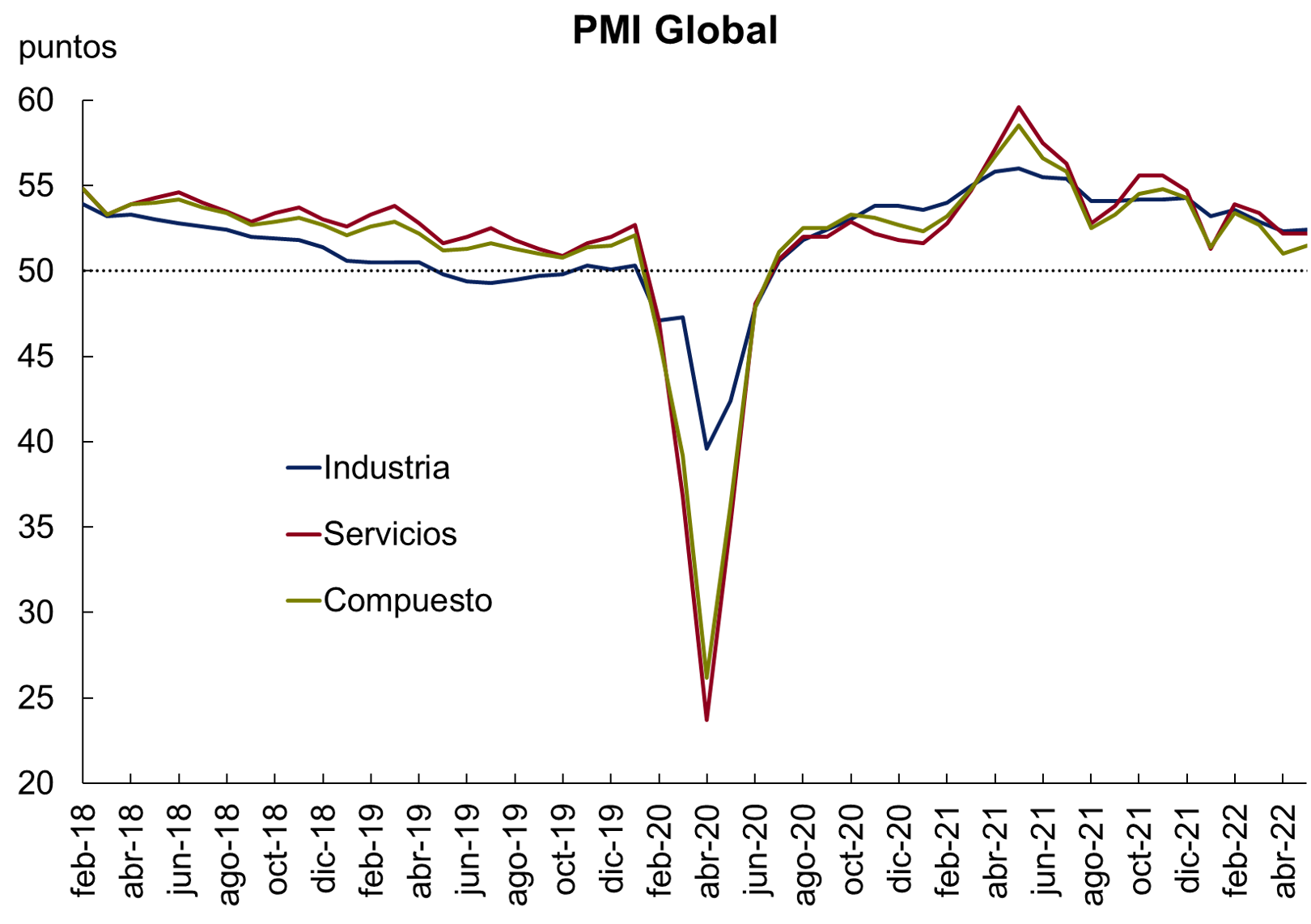

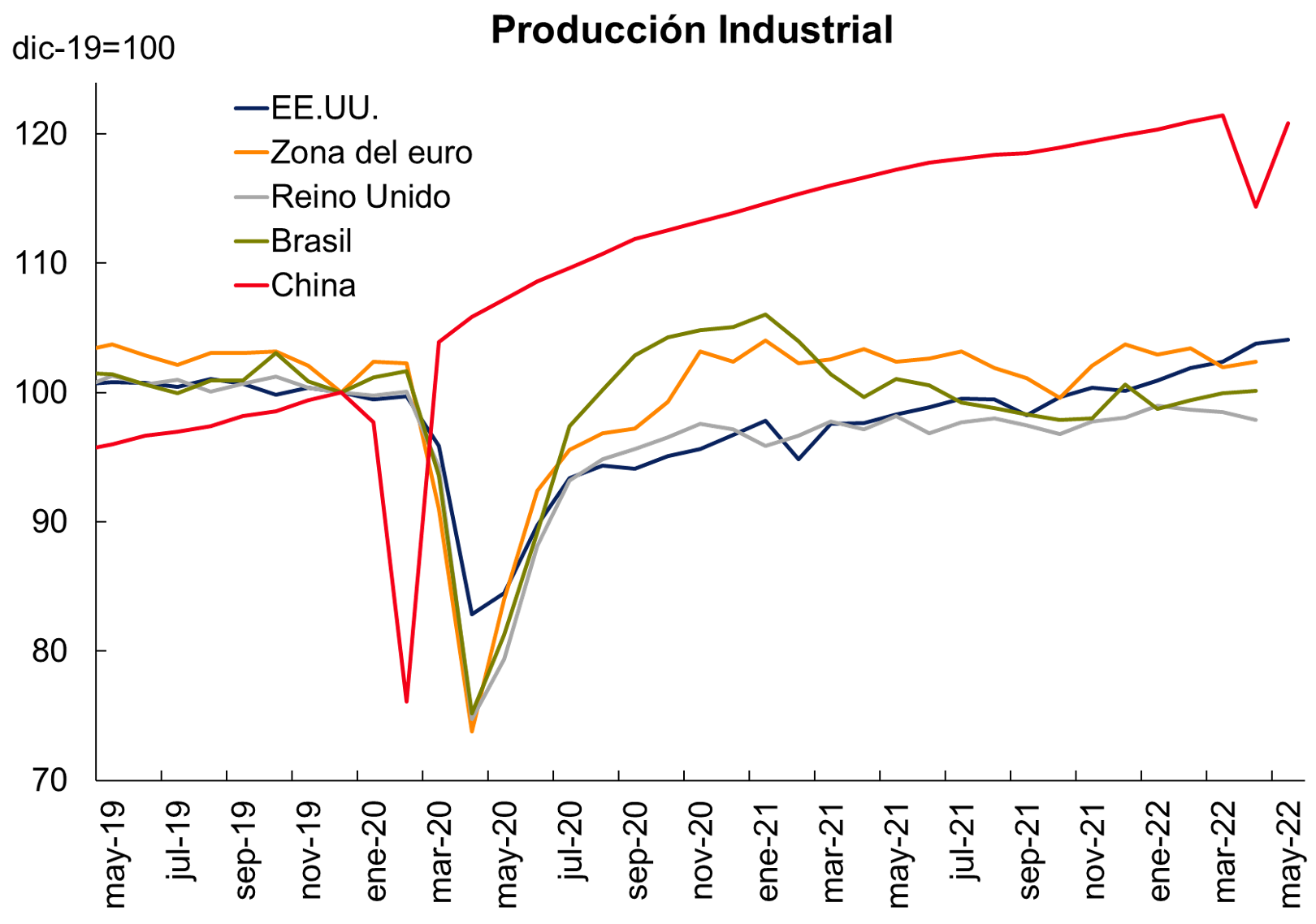

Monthly indicators suggest that the global slowdown continued at the start of the second quarter. From March onwards, consumer confidence, retail sales, the purchasing managers’ indicator (PMI) and industrial production in the euro area and the United Kingdom fell, reflecting uncertainty and rising energy prices (see Figure 2.4)1.

In China, mobility restrictions led to contractions in retail sales, industrial production and the PMI, only surpassed in recent months by those recorded when the pandemic broke out in early 2020. In May, the effects of a relaxation of restrictions began to be felt, with a partial recovery in activity indicators.

In the United States, the fall in GDP in the first three months of the year was due to a decrease in inventories, exports and public spending; but private consumption and private fixed investment accelerated. For the second quarter, activity is expected to grow again, although at a slower pace than that observed in 2021. Retail sales and industrial production were strong in April but weakened in May, the purchasing managers’ indicator trended down from March, and consumer confidence hit a multi-year low in June (see Figure 2.4).

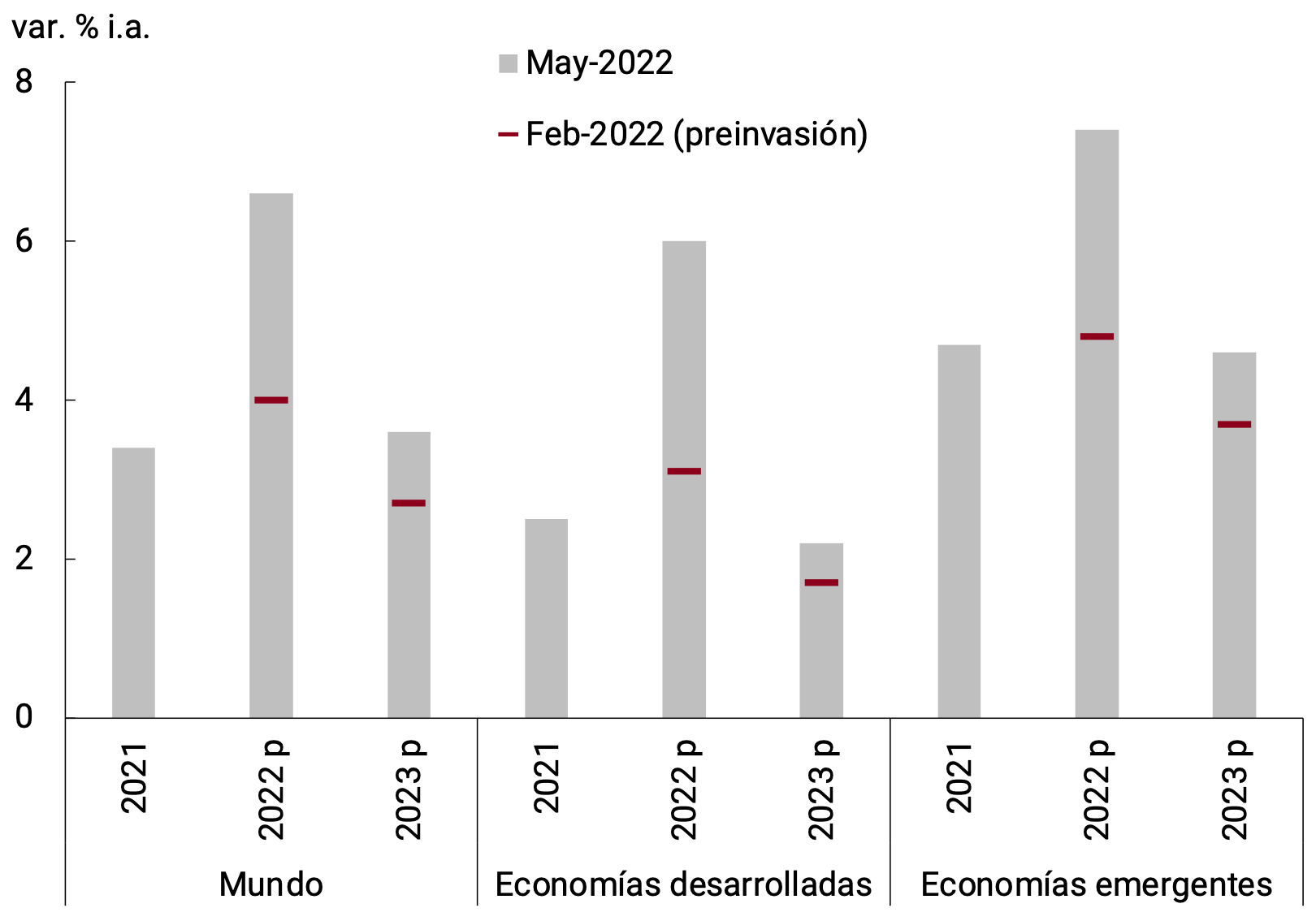

Global growth forecasts continued to be lowered, although they still point to growth for this year. The IMF and World Bank lowered the global growth projection by 1 percentage point on average for 2022 (to 3.6% and 2.9%, respectively) and by 0.2 p.p. for 2023. This reflected the direct impact of the war in Ukraine and economic sanctions on Russia, with sharp contractions expected for these economies this year. The second largest contributor to the reduction in global growth was the European Union due to the indirect impact of the conflict. Growth forecast for China and the United States this year is also lower, reflecting the impact of COVID-0 restrictions on mobility and tighter monetary policy, respectively, while forecasts for only some commodity-exporting emerging economies improved (see Table 2.1). In particular, the strong downward correction of the growth of the U.S. economy for this year that the Fed presented after its June meeting (1.7% for 2022, down 2.3 p.p. compared to the forecast at the end of last year) was highlighted. Other bodies, such as the European Central Bank and the OECD, and the market consensus also agree with the lower optimism expected for global economic activity this year.

Table 2.1 | Economic activity projections 2022-2023

Source: IMF (WEO), World Bank, Reuters (market consensus) and other sources: OECD (world and China), ECB (euro area), Fed (United States), BCB – Focus Survey (Brazil). (1) April 2022. (2) May 2022.

2.3. Central banks are taking contractionary measures at a pace unprecedented in recent decades, in the face of rising inflation

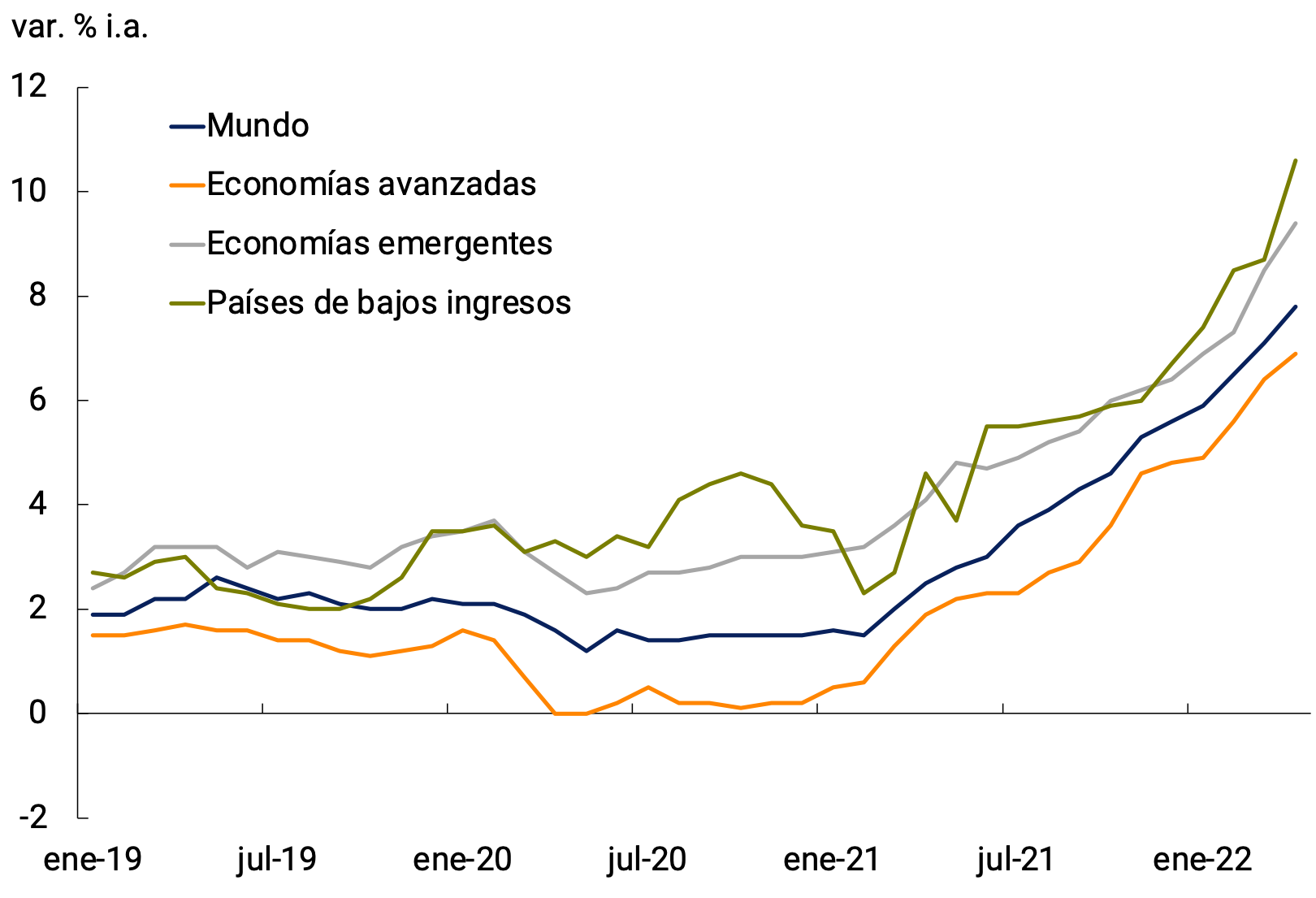

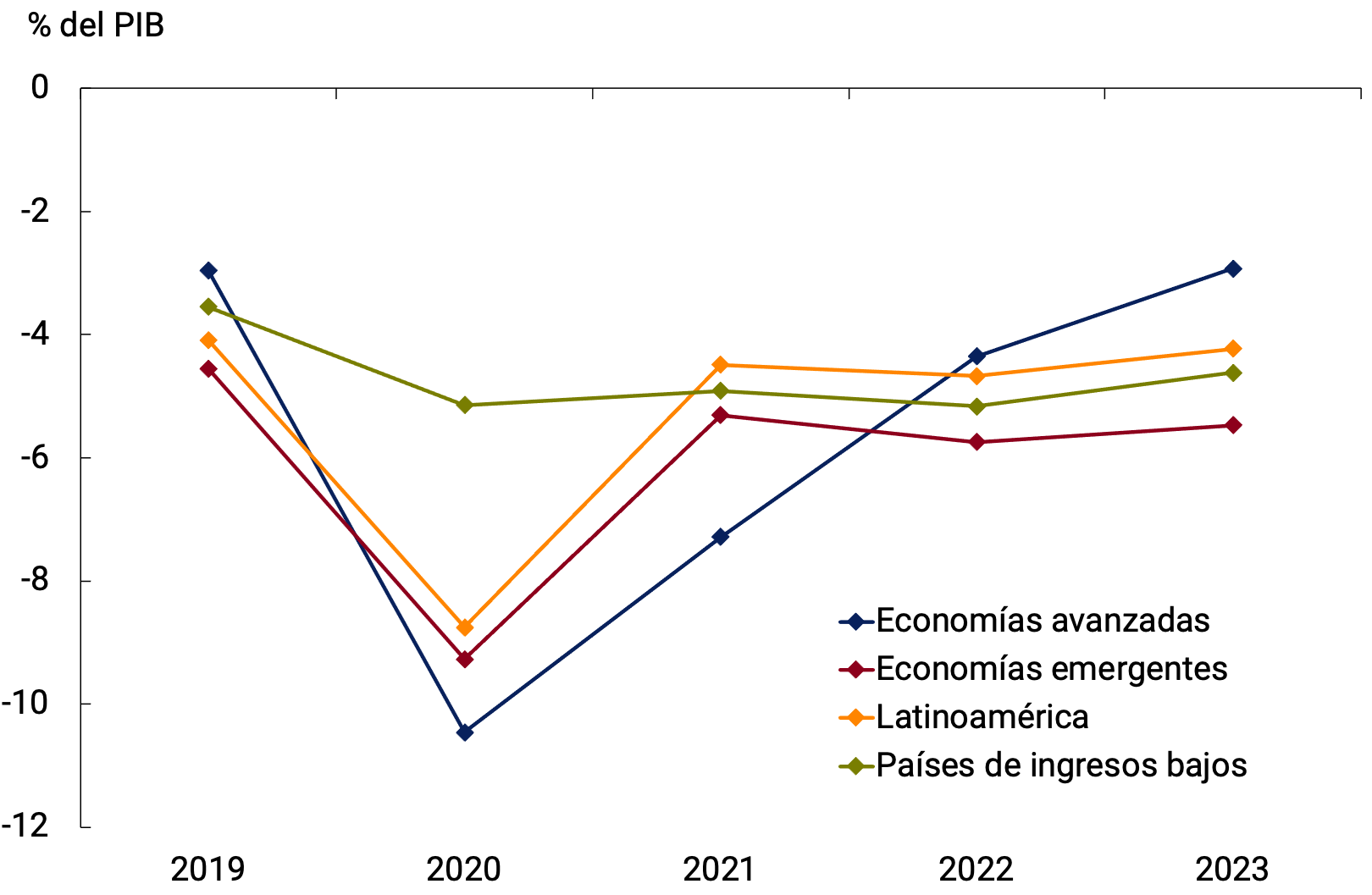

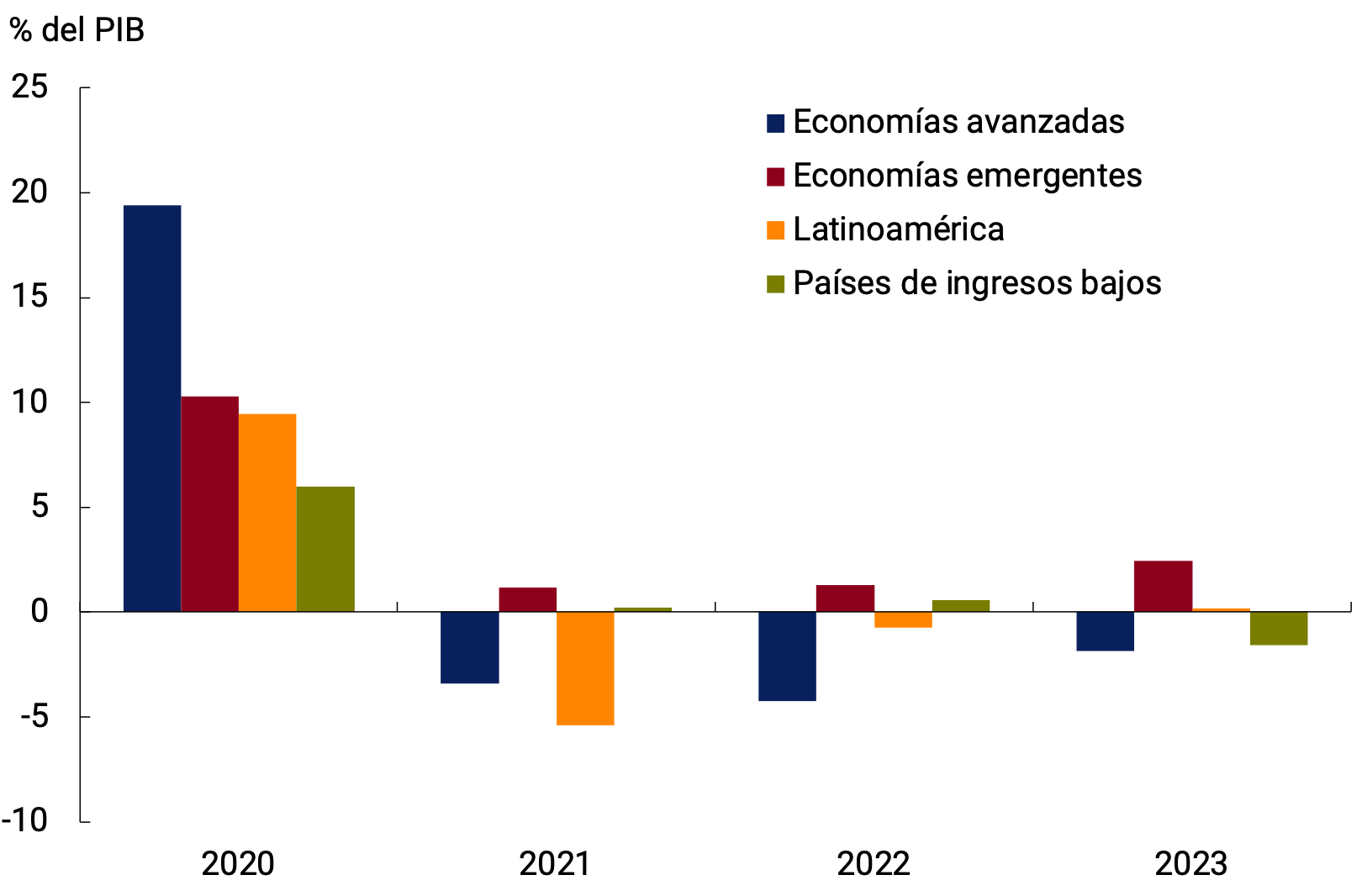

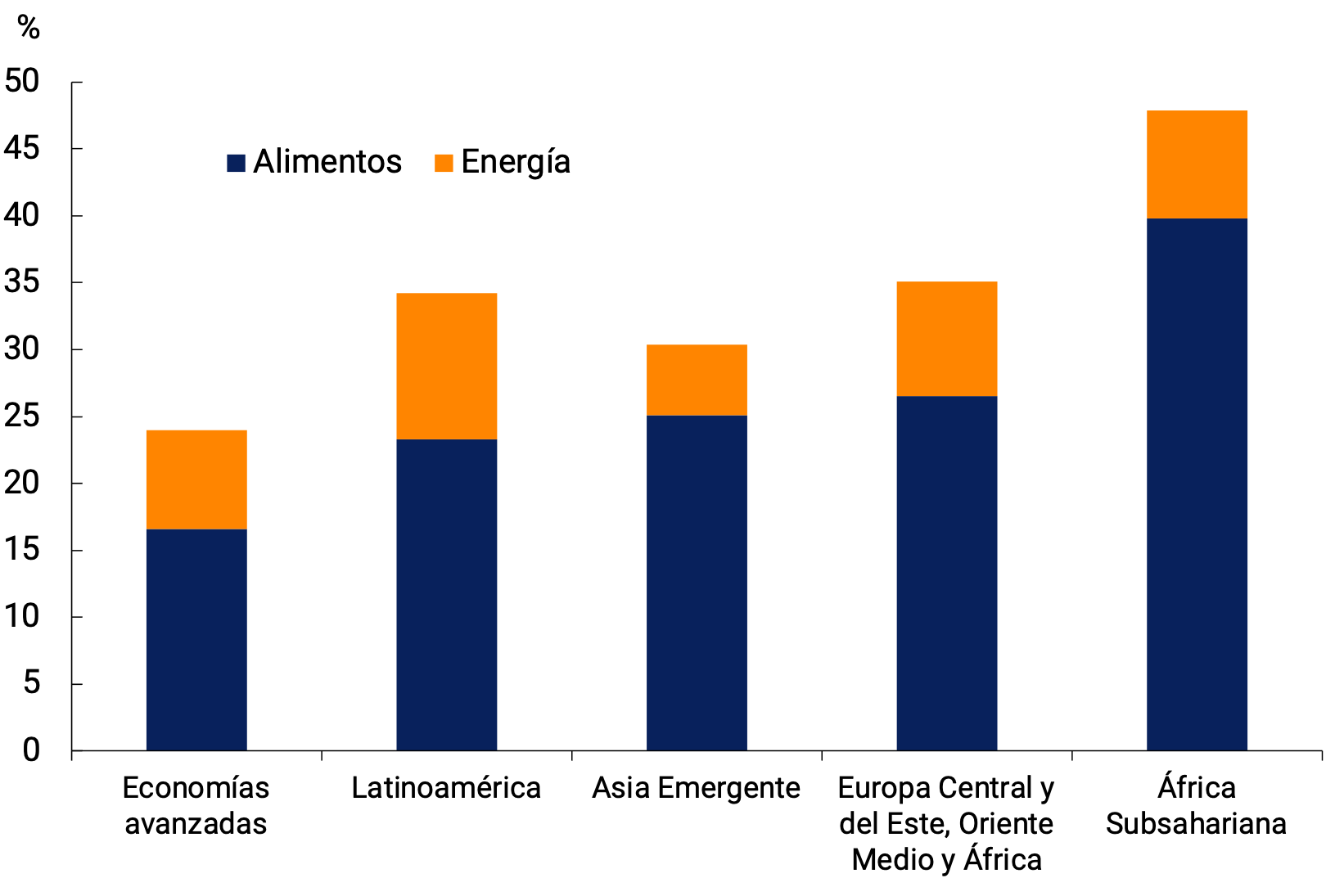

The war accentuated inflationary pressures, which have reached multi-decade records and in many cases several times above countries’ targets. Global inflation is estimated at 7.8% YoY in April; if it closed 2022 at that figure, it would be the highest value since 1996 (see Figure 2.5). In response, the most aggressive monetary policy rate hike (MPR) in recent decades was consolidated, first in developing economies, now in advanced economies. This impacts the whole world, but more so in developing countries because: 1) they are taking longer to recover; 2) food prices have a greater weight in their consumption baskets; 3) the rise in the MPR of developed countries presents the risk of capital outflows and depreciation of their currencies.

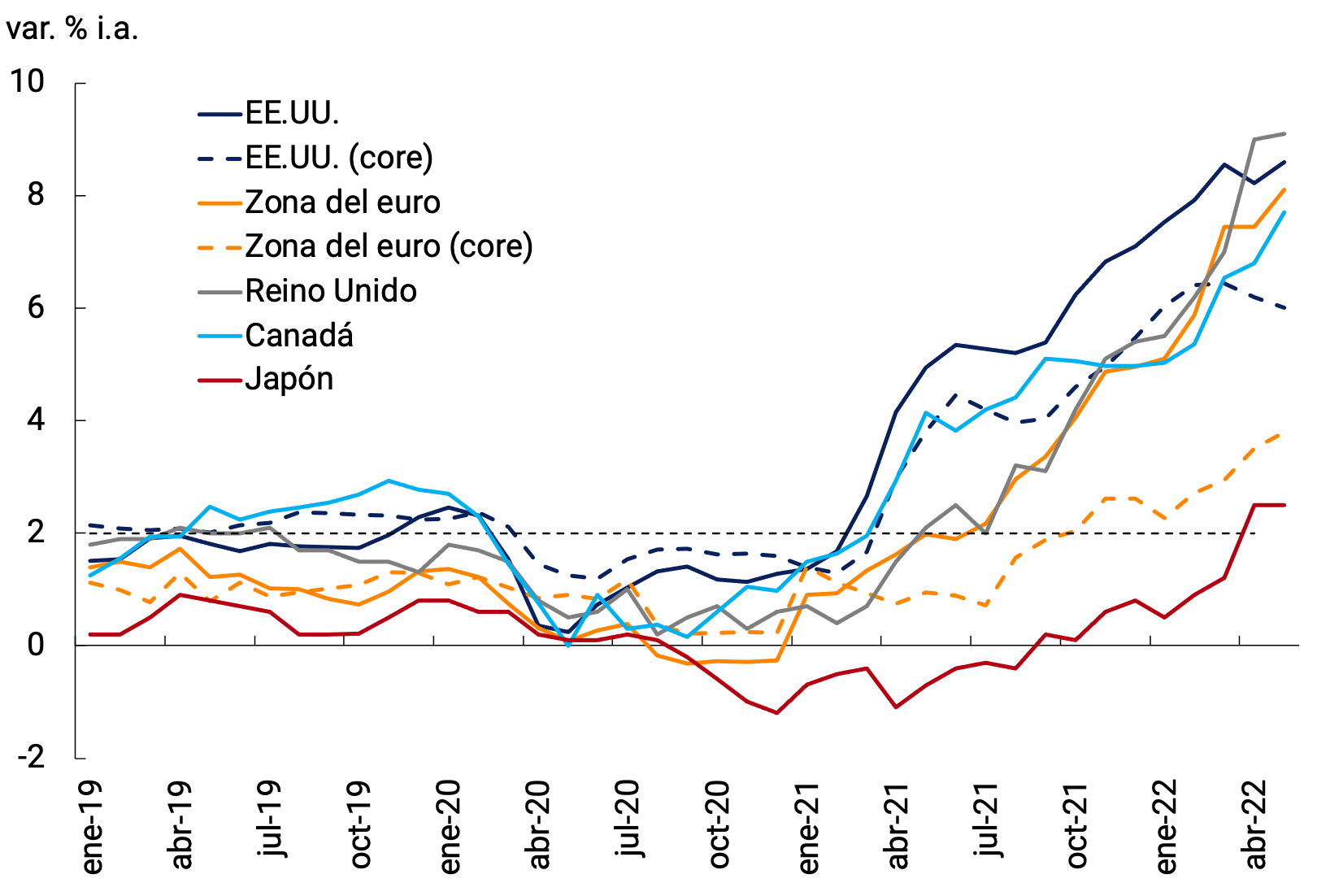

Figure 2.5 | Inflation rate by country group and inflation expectations

In the US, inflation rose to 8.6% in May (the highest rate since December 1981); in the euro area, to 8.1% (the highest rate since the emergence of the monetary union); in Canada, to 6.8% (the highest inflation since 1990) and 9.1% in England (an all-time high of the current measurement). Even Japan, with decades of low inflation, went from 1.1% deflation twelve months ago to 2.5% inflation in May (the highest since 2015). This dynamic is becoming more widespread beyond food and energy in the US and the euro area (see Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6 | Inflation rates and monetary policy interest rates

Source: BCRA based on data from the respective central banks.

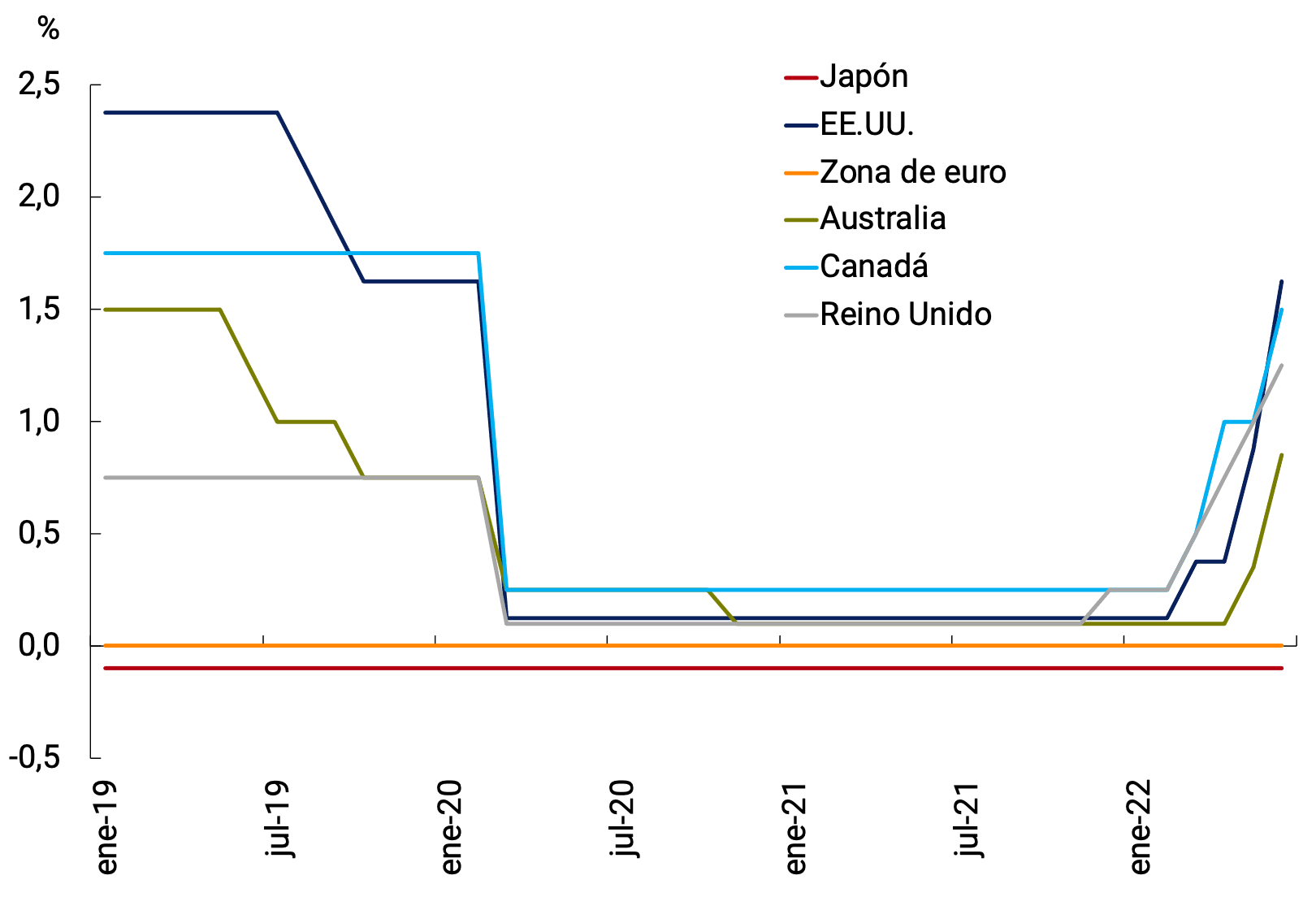

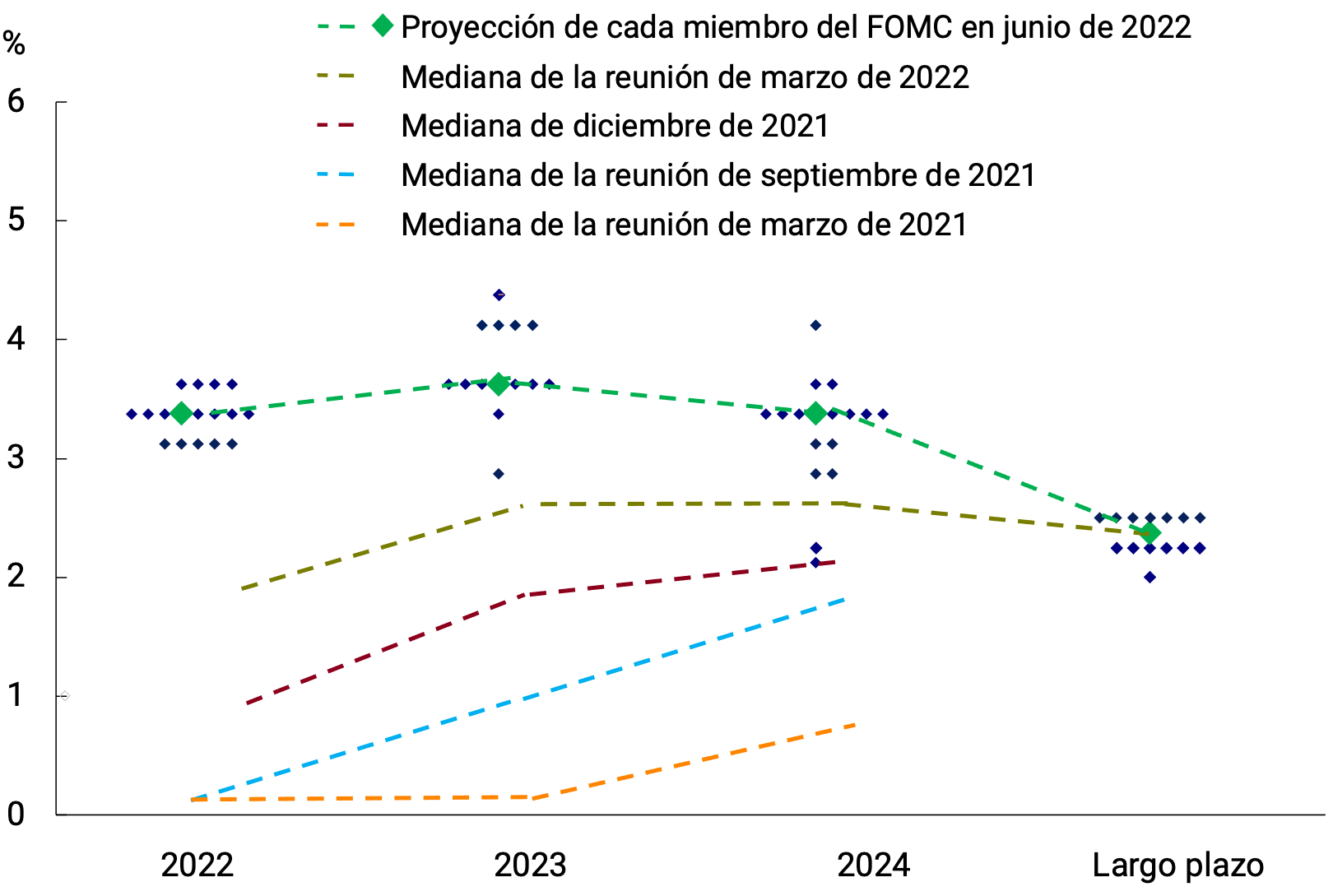

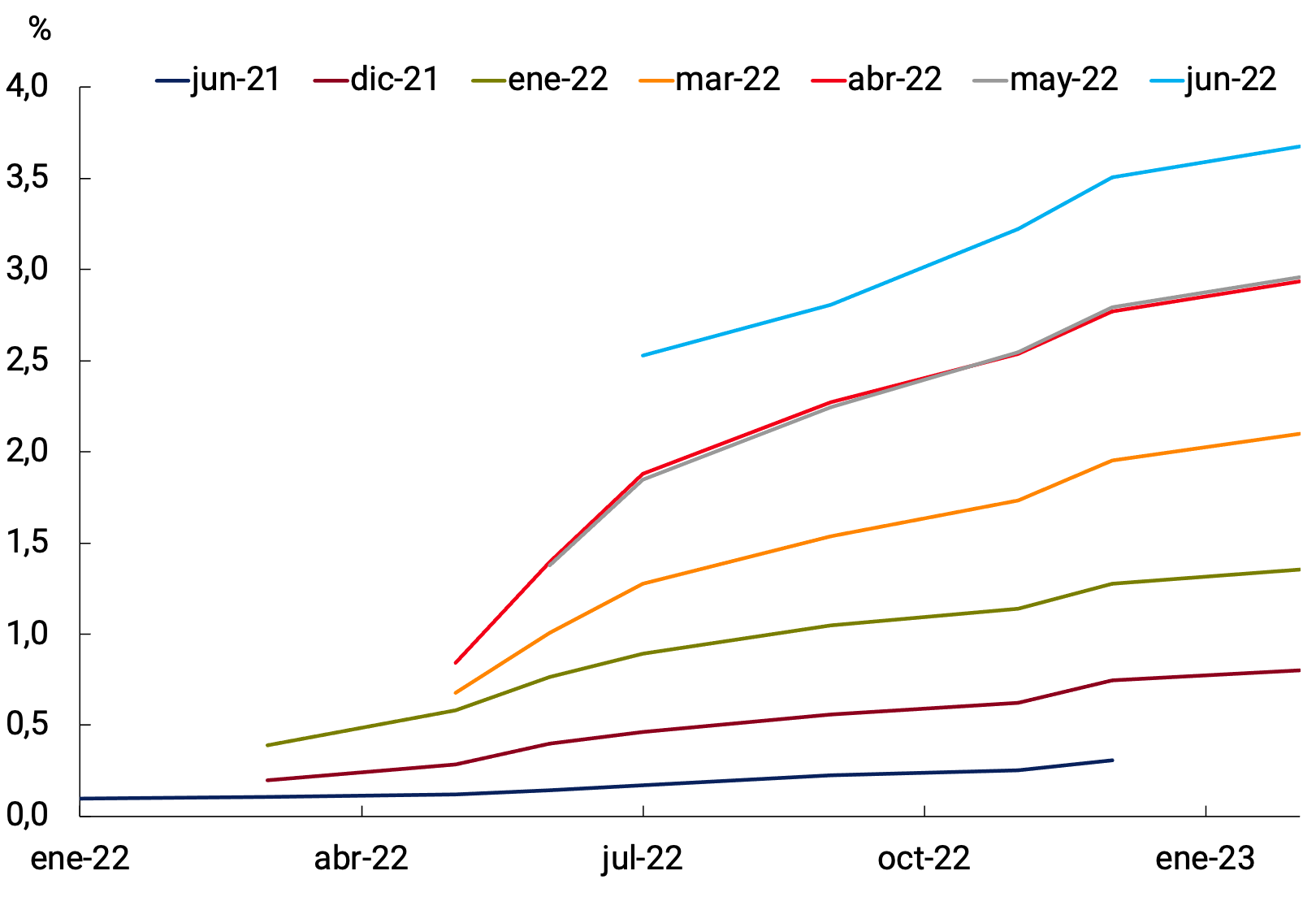

The monetary authorities of developed countries, which until a year ago had practically no increase in their policy interest rates (MPRs), changed their outlook in a very short time (see Figure 2.7a). The Fed increased its MPR by 1.5 p.p. so far in 2022; The last of these increases was 0.75 p.p., the first of such magnitude since the beginning of 1994. Moreover, according to the Fed’s own projections, increases of at least an additional 1.75 p.p. are expected (see Figure 2.7a). The latest market projections foresee an increase in the MPR of up to 3.2 p.p. in 2022, which, if materialized, would be the largest monetary contraction in ten months since 1989 (see Figure 2.7b).

Figure 2.7 | Fed Fed Funds Rate Target Projection

Source: BCRA based on data from the US Federal Reserve and Bloomberg.

In addition, since June of this year, the Fed has begun to reduce its assets on its balance sheet at a rate that will be at least three times higher than the previous reduction (since September, when the rate of reduction increases, see Figure 2.8). This would have repercussions on the liquidity of the U.S. Treasury bond market (and eventually the global one). Other developed countries also took (or will take) contractionary measures, in some cases well ahead of schedule until recently. The European Central Bank (ECB) will end its quantitative easing program in July and start raising rates in that month, it announced.

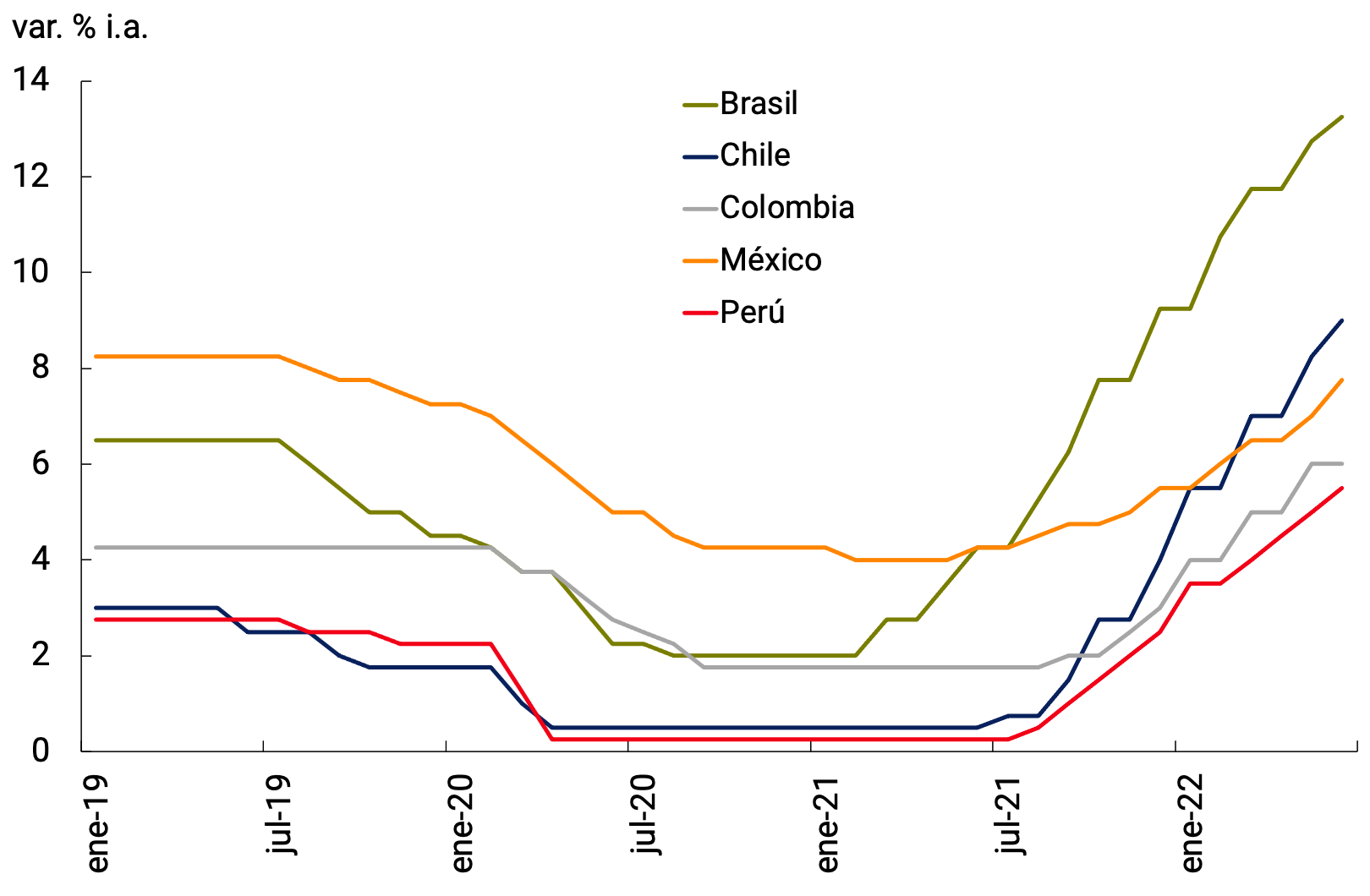

Developing countries have also been recording inflation rates several times above their pre-war targets. In fact, in Latin America it has been at higher levels than the rest of the emerging countries. And the greater weight of food in the CPI basket in the region gives this rise a greater regressive bias (see Figure 2.9).

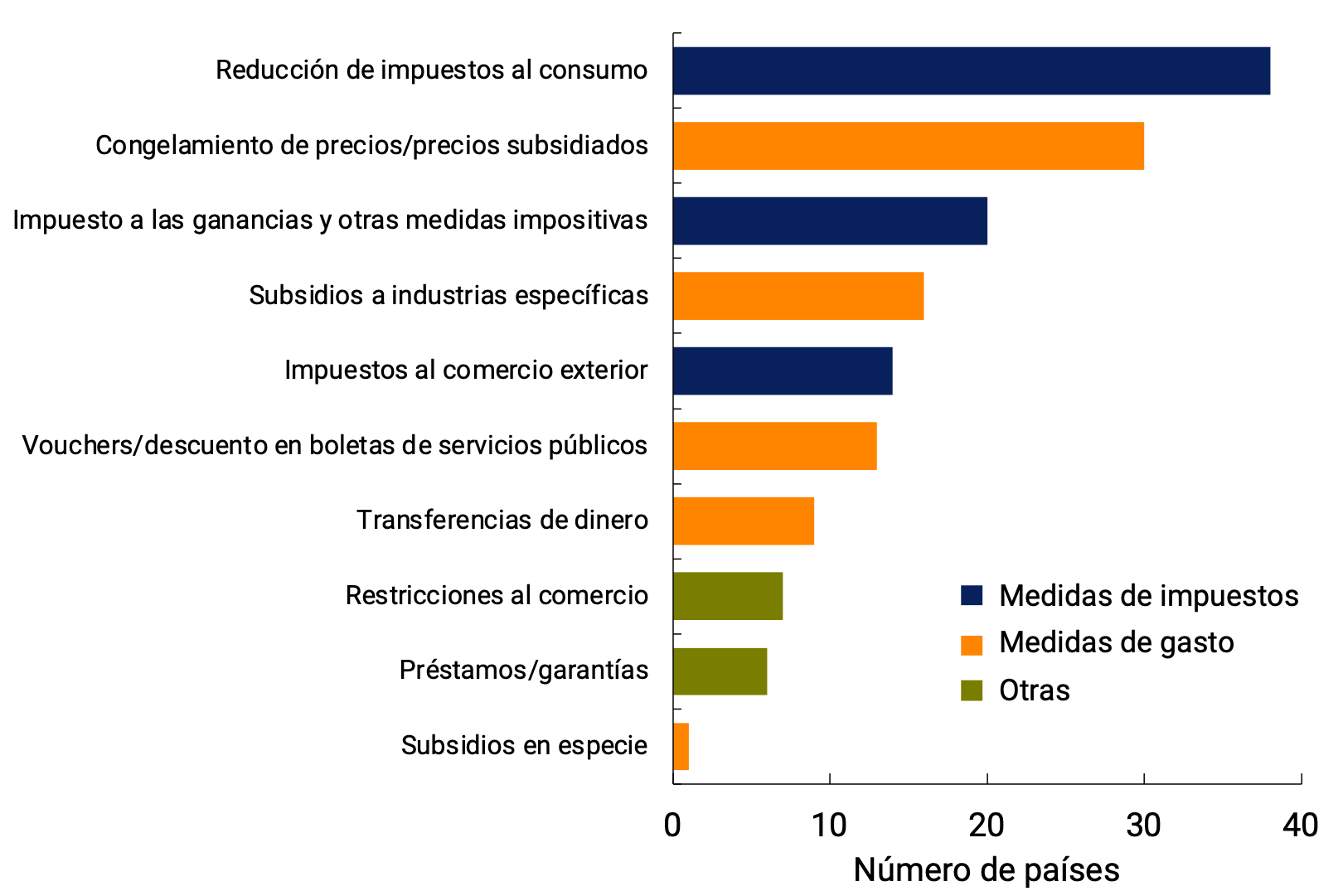

Against this backdrop, major central banks in the region and other developing countries continued to raise MPRs, with record levels of increases in Brazil and Chile (see Figure 2.10). So did those of some East Asian economies that had so far kept MPRs unchanged, including India, South Korea, Singapore, the Philippines and Malaysia. The responses also included fiscal and revenue policy measures (see Section 1 / Fiscal measures against the inflationary impact of raw materials).

Figure 2.10 | Inflation rates and monetary policy interest rate

Source: BCRA based on data from official national statistics institutes and the Central Bank of Brazil.

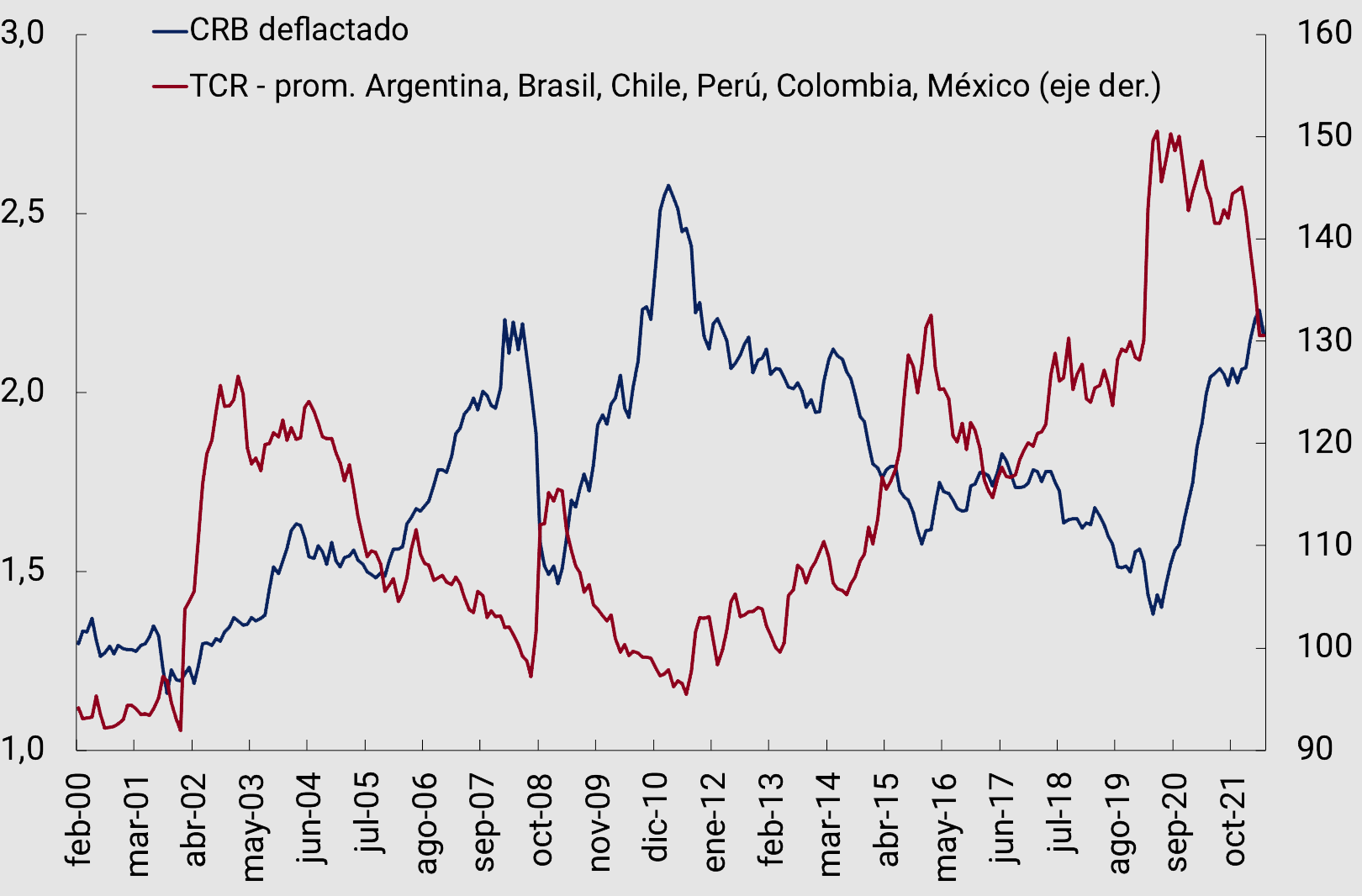

Box. Real Exchange Rate and Commodity Price in Latin America

A key element for the inflationary and activity dynamics in Latin America will be the relationship between the exchange rate and commodity prices. During the “commodity supercycle” in the 2000s, higher commodity prices tended to be accompanied by an appreciation of the real exchange rate, softening the impact on inflation. However, during the pandemic, the opposite happened: higher commodity prices along with exchange rate depreciation (see Figure 2.11). It is unclear which of these effects will prevail in the near future: whether the exchange rate will offset or amplify the impact; and whether commodity prices will continue to rise due to supply disruptions or decline in the face of a more appreciated U.S. dollar.

Figure 2.11 | Commodity prices and real exchange rate in selected

Source: official national statistics institutes and Bloomberg.

Indeed, evidence shows that the U.S. dollar is inversely correlated with commodity prices. In this way, commodity-exporting countries are simultaneously affected through trade and financial channels, through higher international interest rates, lower global liquidity, and appreciation of the U.S. dollar, all of which tend to increase the sovereign spreads of emerging economies, and weaken commodity prices at the same time (Bastourre, Carrera et al., 2012). This last effect must be weighed against the impact on commodity prices of the war.

2.4. Global financial conditions tighten

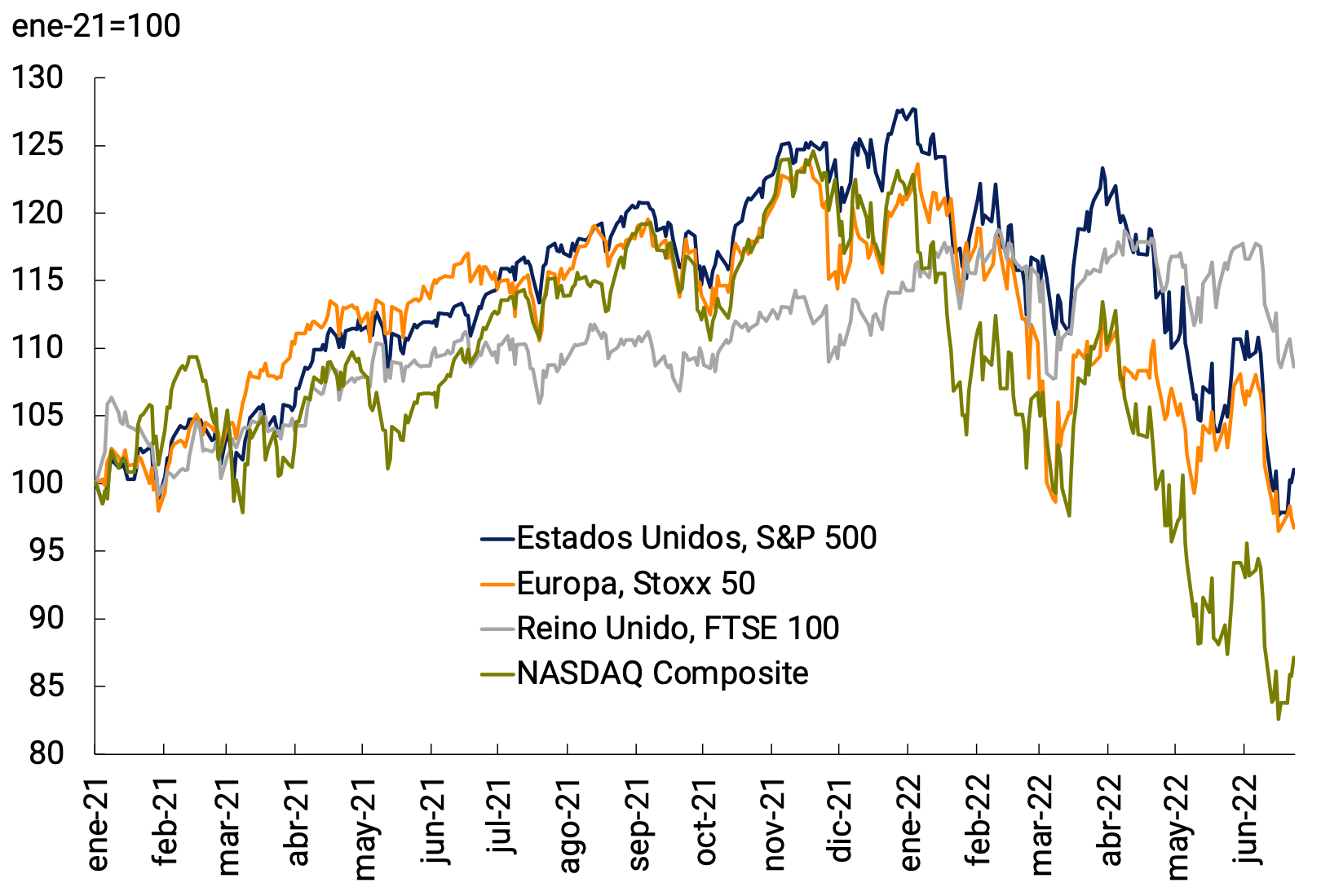

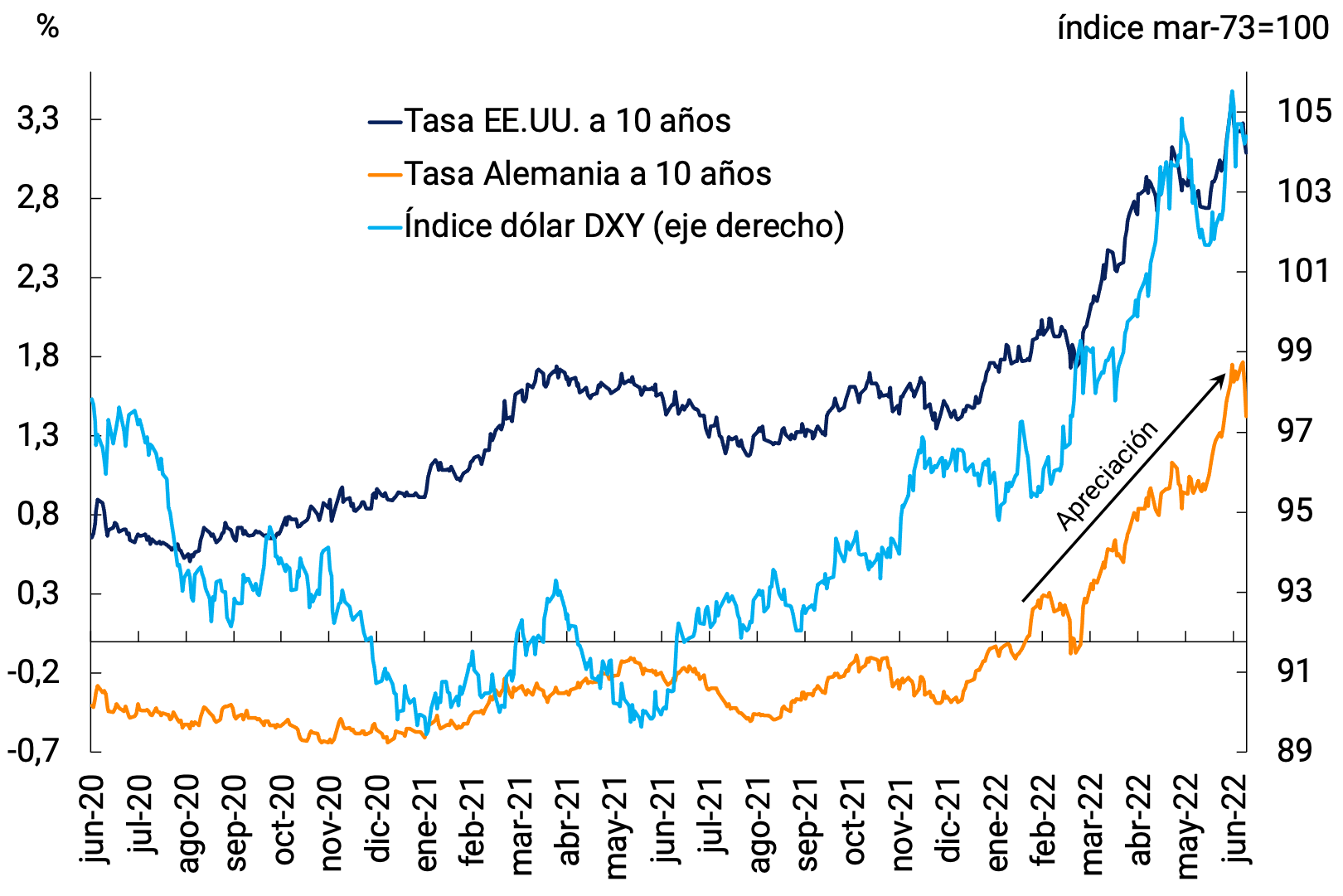

The aggressive increases in the MPR had an impact on bonds, stocks and currencies. On the one hand, the rates of government bonds of advanced countries rose. The 10-year U.S. Treasury bond rate rose sharply to more than 3 percent (see Figure 2.12b), up 158 basis points for the year. The German 10-year bond rate has also risen. Meanwhile, the prices of riskier assets such as stocks continued to fall and, particularly, those of technology companies, which had had more significant increases in recent years. Thus, the S&P 500 is 21% below the maximum and the Nasdaq, with a greater component of technology companies, is 30% below. In Europe, the Stoxx 50 loses 20% of its value for the year (see Figure 2.12a).

In addition, the positive policy rate differential between the United States and the other advanced countries favored the movement of funds to the United States. The multilateral dollar appreciated by about 6% from the previous IPOM (see Figure 2.12b), while the euro and, especially, the yen registered their lows in decades.

Source: BCRA based on Bloomberg data.

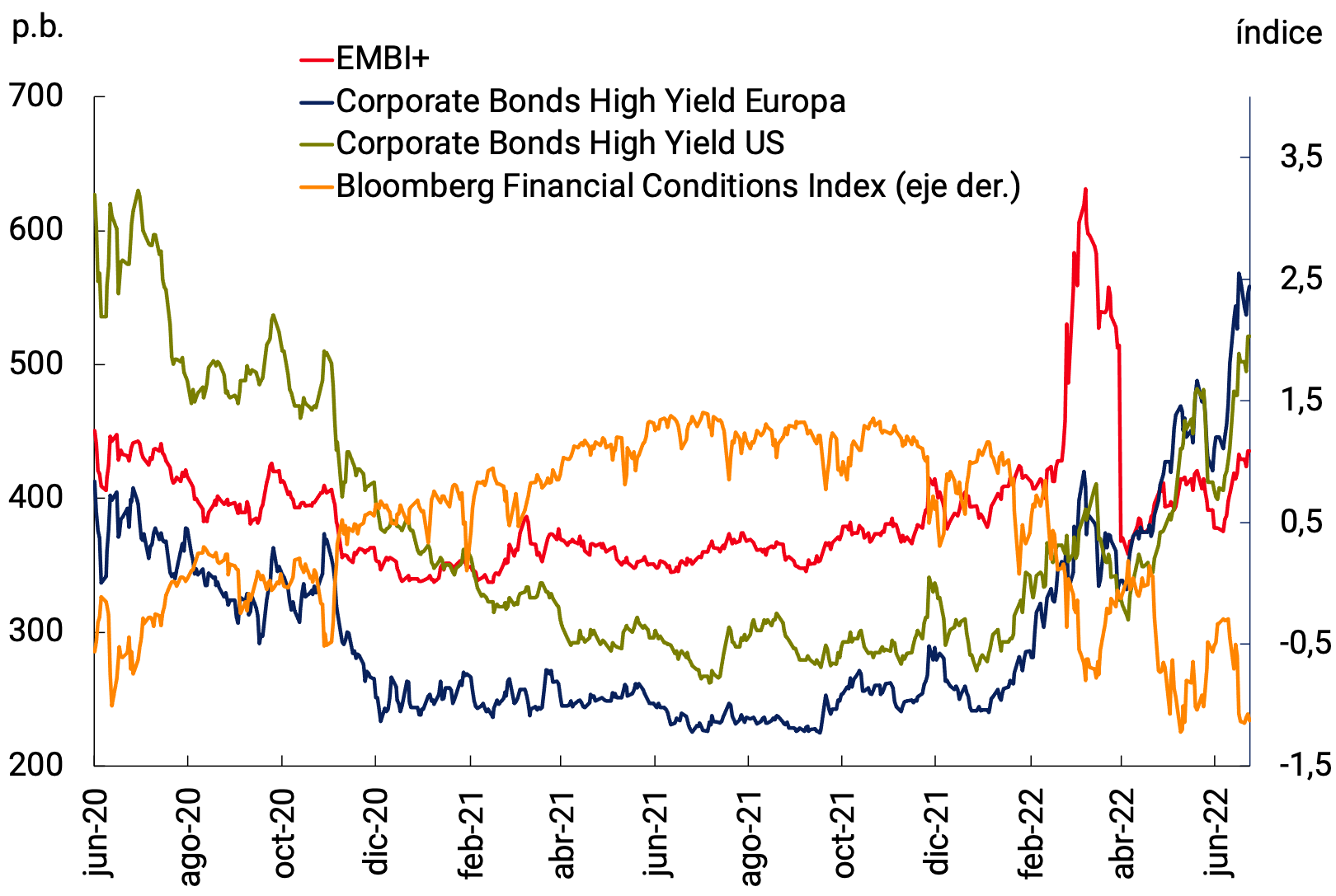

The effects of the war in Ukraine and mobility restrictions in China put further downward pressure on risk assets. Along with a sharp decline in the Financial Conditions Index in the United States (see Figure 2.13a), both interest rates on high-yield corporate bonds in advanced countries and spreads on sovereign bonds in emerging countries rose. Capital flows to emerging countries have suffered outflows since the beginning of the war (although with a period of inflows during mid-March and early April). All of this implies more unfavourable financial conditions for emerging and developing countries.

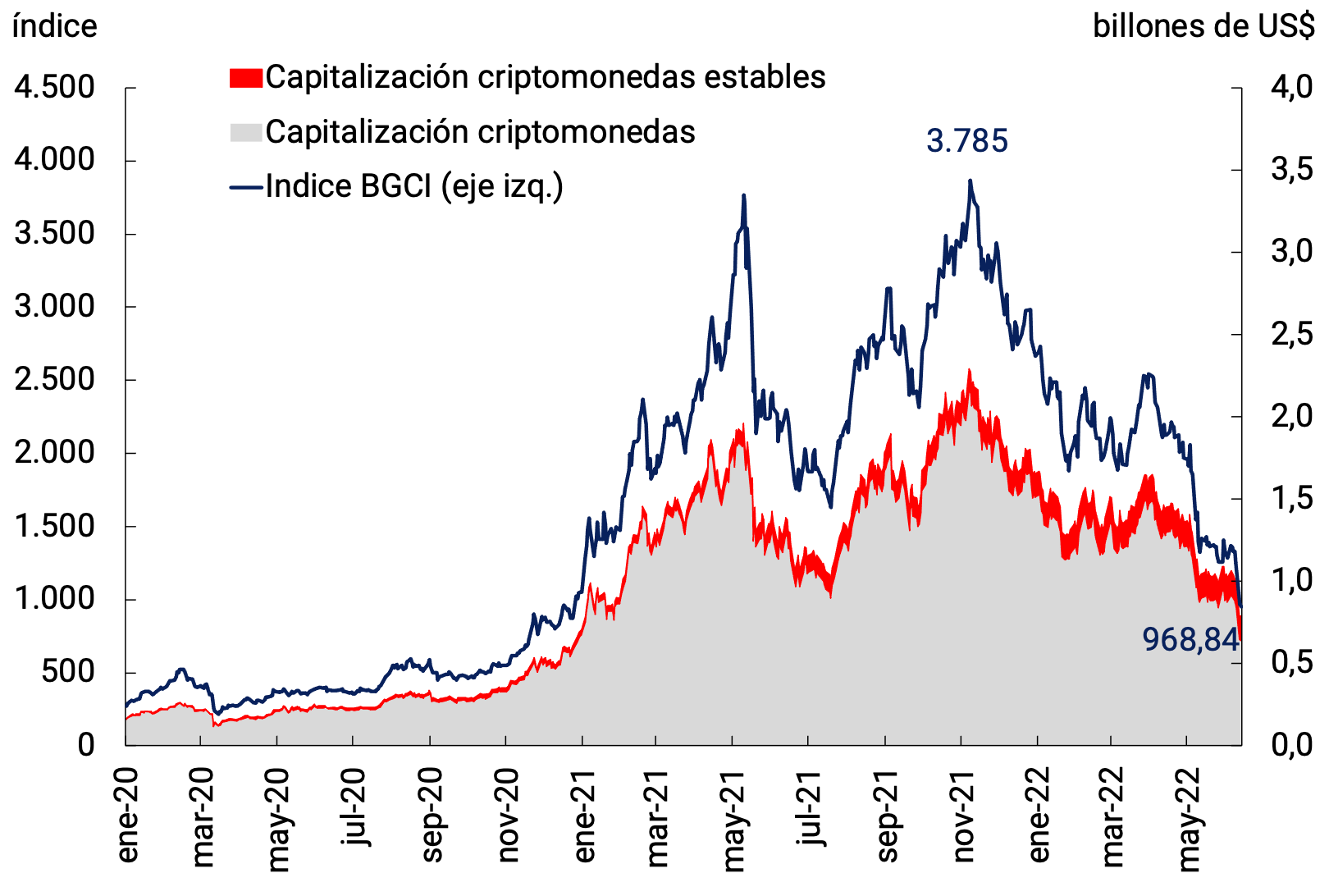

With the fall in risk assets, cryptocurrencies also suffered falls, showing that they are not “safe haven assets”. The market capitalization of eight cryptocurrencies and four “stablecoins” has shrunk by 70% since mid-November; while the prices of these assets are 75% lower (see Figure 2.13b)2.

Figure 2.13 | Asset Markets

2.5. Commodity prices continue to rise, impacting the currencies of their exporters

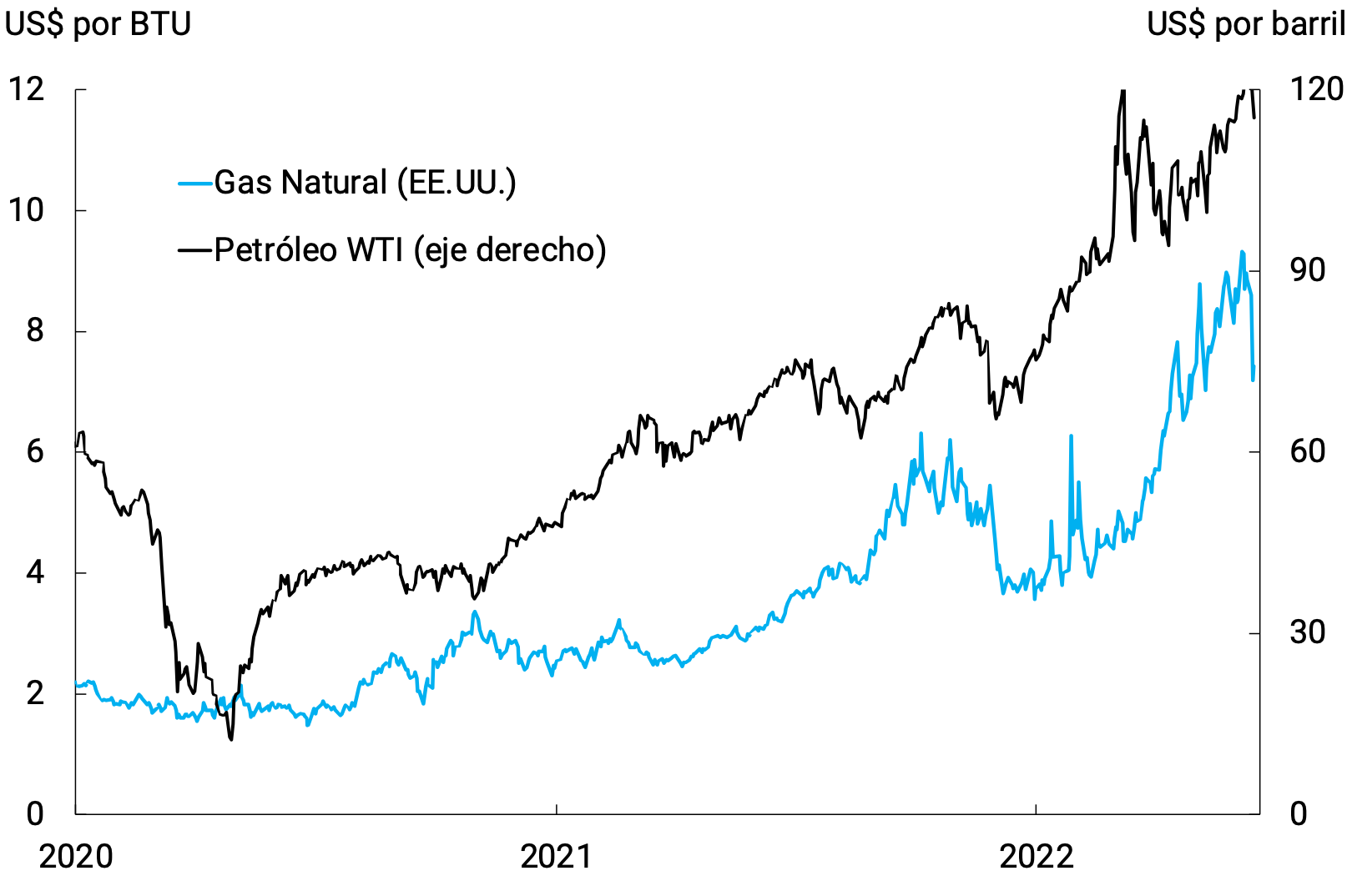

The sanctions imposed on Russia continued to have a strong impact on both the level and volatility of the price of oil, which reached US$119 per barrel on June 8 (WTI). At the end of May, the European Union agreed to ban the import of Russian oil, starting in December on crude oil and two months later on refined products: it bans all crude oil that arrives by ship and leaves out those that arrive by pipeline, thus reaching almost 90% of the oil imported from Russia. The price of gas was also affected after Russia imposed payment for gas in rubles instead of euros. Several European countries saw their supplies cut off during April and May as they did not meet the requirement. Thus, gas imports from the US grew, reaching a price of US$9.45 per BTU, the highest in 14 years (see Figure 2.14).

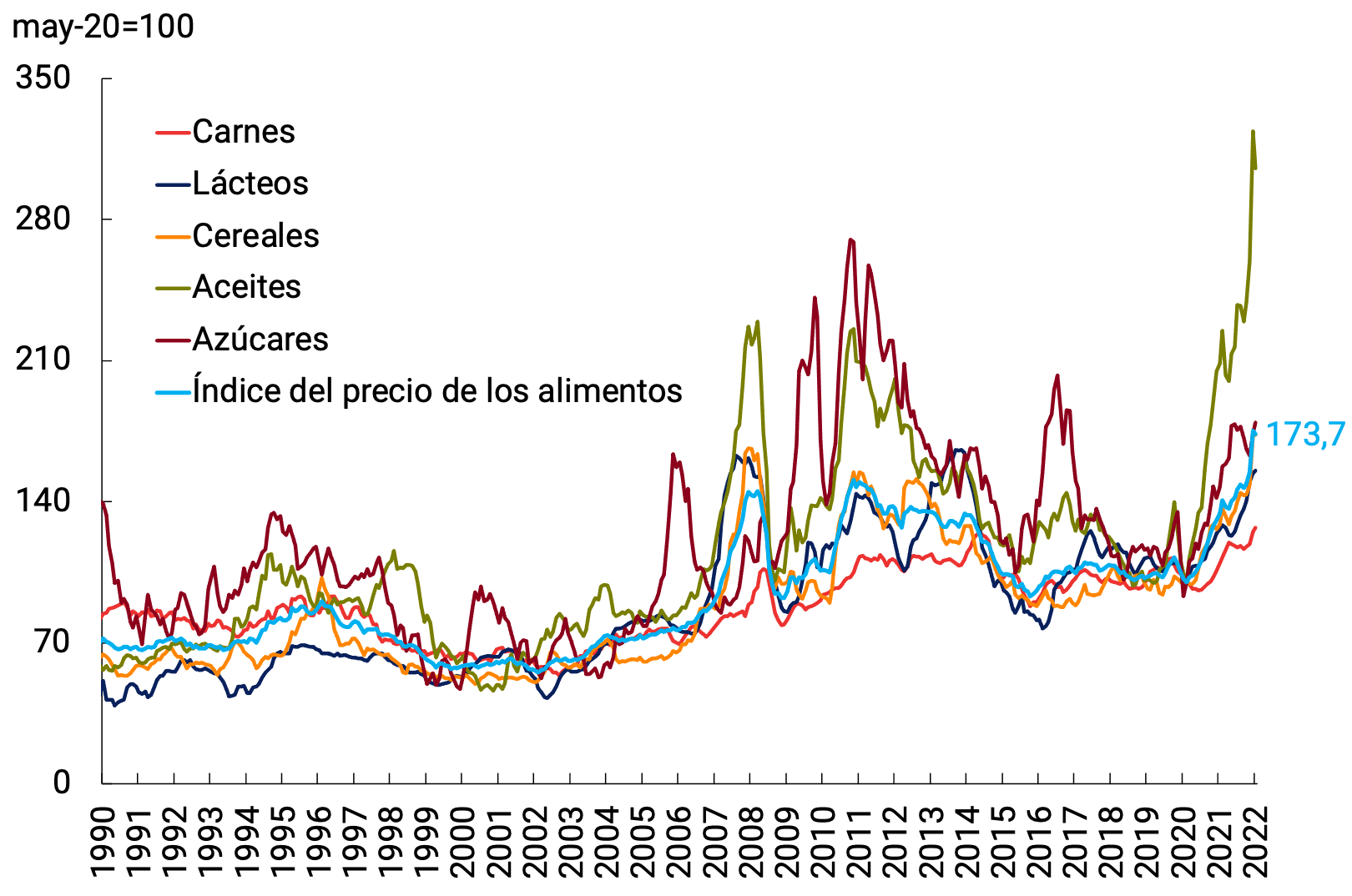

Wheat continued to feel the impact of the conflict: approximately 20 million tons of Ukrainian grain have accumulated in ports since shipping was halted. In addition, India vetoed wheat exports. Currently, it is trading at around US$370 per tonne, almost 20% above pre-conflict prices. Soybeans rose to US$649 per tonne on June 9, a 14-year high. Indonesia’s decision to ban the export of palm oil also affected the price of soybeans and currently stands at around US$600 per tonne (see Figure 2.14).

The currencies of emerging countries have faced differentiated situations according to their status or not as exporters of raw materials. Those of countries such as Brazil, Peru, Mexico, and Colombia (mainly commodity exporters) performed better than those of Eastern European nations and oil-importing countries in Asia.

The main Latin American currencies had been appreciating since the end of last year (gray bars in Figure 2.15). After the beginning of the conflict and depending on whether or not the country was an exporter of energy-related commodities, differentiated effects were noted compared to other emerging countries (blue bars). Subsequently, when a more aggressive view of the Fed’s rate hike was consolidated, most of the countries in the sample faced depreciating pressures.

Figure 2.15 | Evolution of the currencies of selected

Source: BCRA based on Bloomberg data.

2.6. In summary

The global economy is feeling the simultaneous impact of the war, the evolution of the pandemic and the more aggressive interest rate hike cycle. For emerging and developing economies, the latter implies more adverse global financial conditions and the risk of increased capital outflows. A key dilemma for Latin America is whether a combination of higher commodity prices coupled with pressures on the appreciation of its currencies will prevail; or the impact of the rate hike in central countries, with downward pressure on commodity prices and currency depreciation. The first case would imply a more favorable growth and inflation trajectory than the second. In any case, several of Argentina’s trading partners would show lower growth this year than expected a few months ago.

3. Economic Activity and Employment

In the first quarter of 2022, economic activity continued to strengthen the process of economic reactivation and growth that began in 2021, after the progressive normalization of social mobility, and continued to operate at levels higher than pre-pandemic levels. This growth took place even in the context of a third wave of COVID-19 in the country, with limited and transitory impacts on the level of activity given the progress of the vaccination process and in a context of accelerating inflation affected by adverse weather conditions in the country and by sharp increases in international prices. This improvement in economic activity was accompanied by a recovery in total registered employment which, although it continued to present some sectoral heterogeneity, its level is at an all-time high.

In this context, the National Government continued to implement policies aimed at economic growth, promoting strategic sectors to enhance production chains, the modernization of industry and the promotion of regional economies in order to increase exports. Likewise, in the face of higher inflation – particularly in food – the National Government temporarily implemented income reinforcement measures, mainly aimed at the most vulnerable sectors. For its part, the BCRA continued to contribute to the growth process through the extension of credit lines linked to productive development (LFIP), through which it seeks to stimulate production.

With data for the first quarter, economic activity has a statistical drag of 4.1 percentage points of growth for this year. The BCRA expects that the services that were most affected by the pandemic will continue to recompose their activity levels. However, in the second quarter the Product will show a fall compared to the first due to the impact of the drought conditions that affected the main soybean and corn producing areas during the summer, with indirect effects on other sectors associated with this activity. The evolution of GDP during the rest of the year will continue to be conditioned by the risks associated with a less favourable international scenario and tensions in the energy market, while new epidemiological threats at the global level cannot yet be ruled out.

3.1. In the first quarter of 2022, domestic demand continued to increase, mainly explained by greater dynamism in private consumption

In the first quarter of 2022, GDP increased 0.9% qoq s.e. (6% y.o.y.) and was 4.4% s.e. above its level in the last quarter of 2019 (see Figure 3.1). Domestic demand – total domestic expenditure on consumption and investment, measured at constant 2004 prices – exceeded its pre-pandemic level by 10.5% s.e. and increased 2.9% quarter-on-quarter s.e., mainly due to the performance of private consumption, which recovered 3.2% quarter-on-quarter (9.3% y.o.y.) and contributed 2.2 p.p. to the variation in output, while public consumption increased 0.7% s.e. (6.5% y.o.y.). Investment5 continued to show great dynamism and registered a 3.3% quarter-on-quarter increase (12.7% y.o.y.). For its part. External demand for goods and services, at constant prices, decreased by 2.3% quarter-on-quarter to 9.3% y.o.y., while imports increased by 7.6% qoq-o-y (28.1% y.o.y.; see Chart 3.2). Thus, the external sector had a negative contribution to the seasonally adjusted quarterly variation of GDP of 2.4 p.p. during the first quarter.

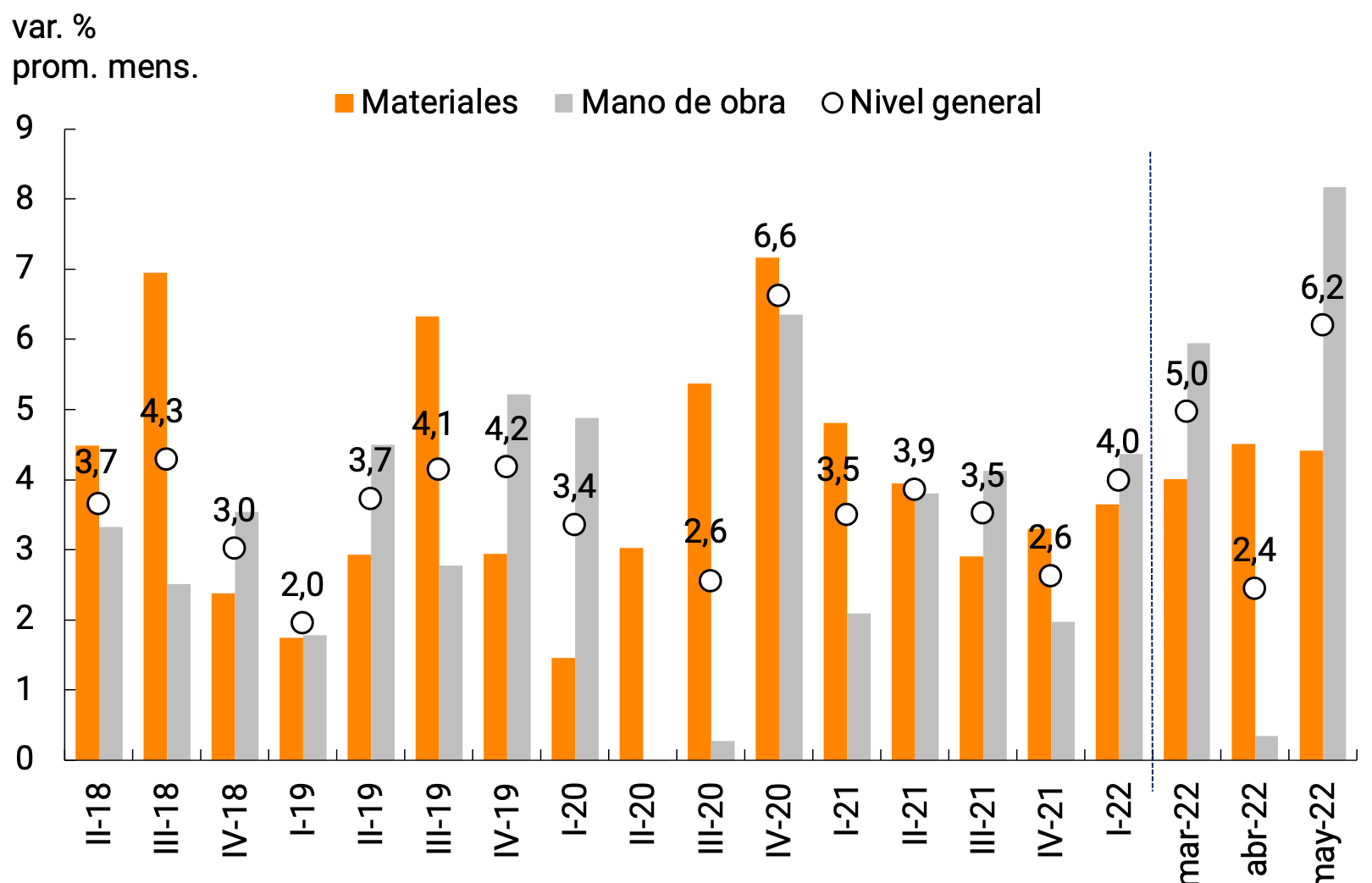

The Investment Rate (measured at constant prices and seasonally adjusted) stood at 20.9%, the highest level since II-18 and above the 17.2% average of 2019. The recovery of investment after the shock caused by Covid-19 was mainly explained by the increase in real expenditure on Durable Production Equipment, which accumulated a 60.5% increase since IV-19 in seasonally adjusted terms, representing 59% of total investment in I-22. Investment in construction, on the other hand, accumulated an increase of 16.8% s.e. in the same period (see Figure 3.2).

It is expected that, in line with the information on the commercial exchange of goods from INDEC available as of May, for the second quarter the negative impact of net exports of goods and services on the quarterly variation of the Product will be reduced. It should be noted that, with data up to May, the quantities exported of goods registered a monthly fall (-3.3% s.e.) while the imported volumes of goods increased 0.3% in seasonally adjusted terms (see Chapter 4. External Sector).

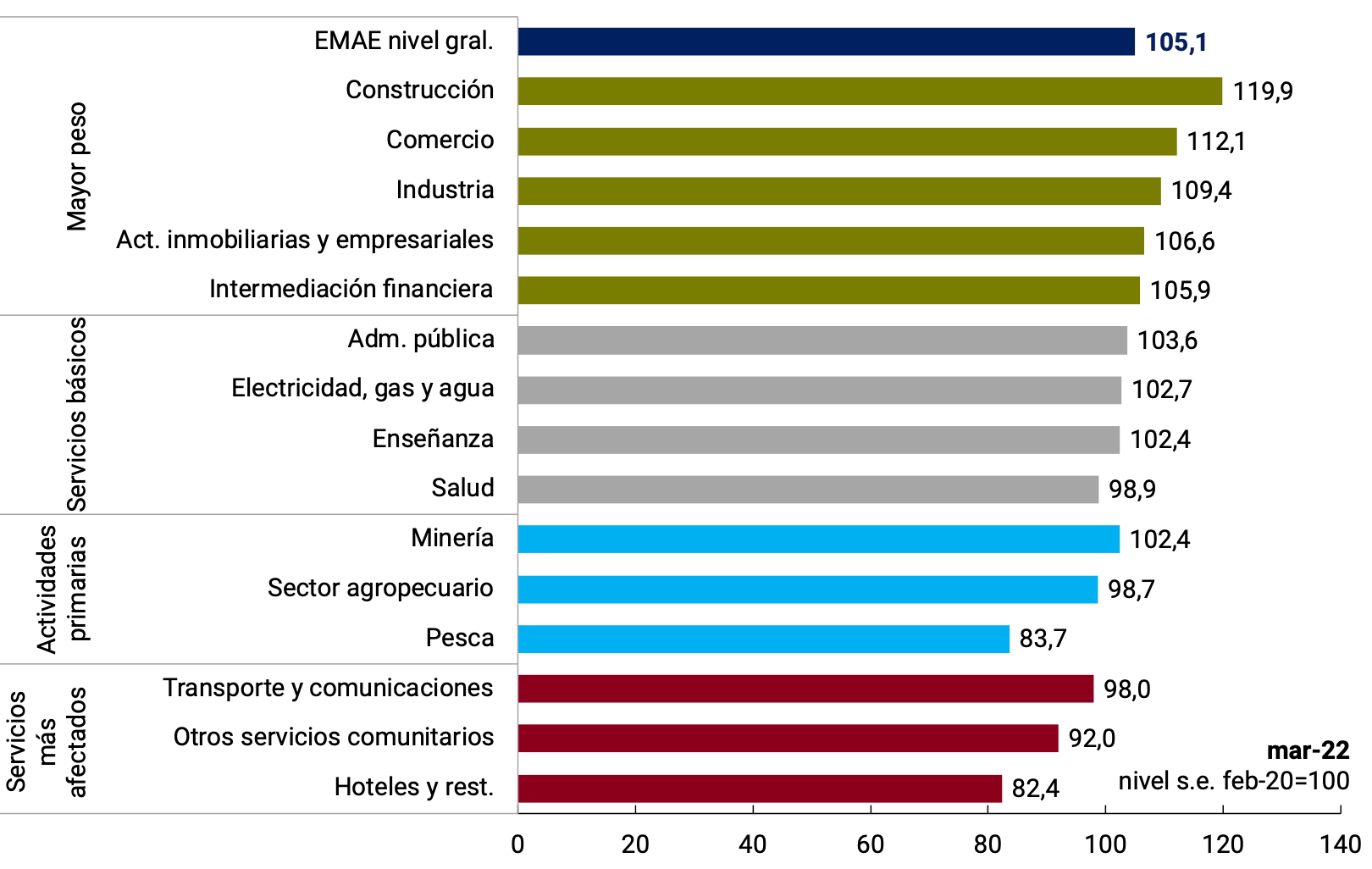

3.2. Among the productive sectors, services were the ones with the greatest contribution to growth so far in 2022

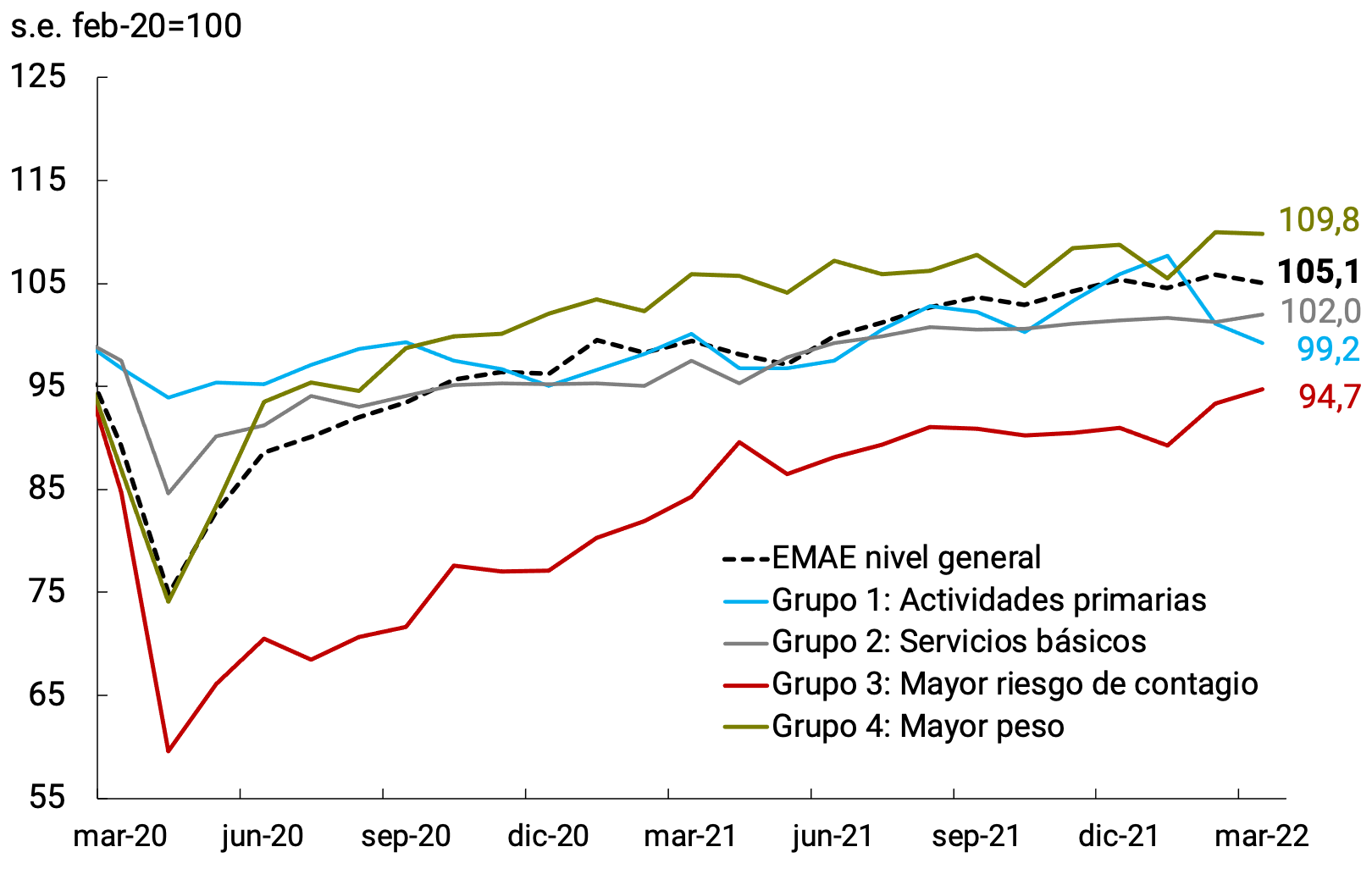

In line with what was anticipated in the previous IPOM, during the first quarter of this year services were the ones with the greatest contribution to the quarterly variation of GDP (1.3 p.p. on the var. % s.e. of GDP). Among them, those in the group of services with “Most risk of contagion” – made up of Hotels and restaurants, Transport and communications and Other community services – stand out, which are still lagging behind the rest of the sectors that make up the EMAE. In March, the value added by this set of services – which accounts for 13% of GDP – was still 5.3% s.e. below its pre-pandemic level (see Figure 3.3).

Although the post-pandemic recovery of the productive sectors has been widespread, there is still great heterogeneity regarding the level of activity at which each of them operates. Among the goods-producing sectors, Construction and Industry were the most dynamic, registering a cumulative increase of 19.9% and 9.4% s.e., respectively, between March 2020 and March 2022. In those two years, the joint contribution of these two sectors to the recovery of activity. was 2 p.p. Among services, Trade stands out, which rose 12.1% s.e. in the same period and contributed another 1.5 p.p. Hotels and restaurants are the services lagging behind: they would have to grow by 17.6% s.e. to recover the level of activity they recorded in February 2020 (see Figure 3.4).

3.3. During the second quarter, economic activity would contract temporarily mainly due to the impact of the drought on the coarse harvest

It is expected that in April and mainly in May, the Monthly Activity Estimator (EMAE) will account for the negative impact of the drought, when the negative results of the soybean and corn harvests are imputed to the Value Added by the Agricultural Sector (see Box below).

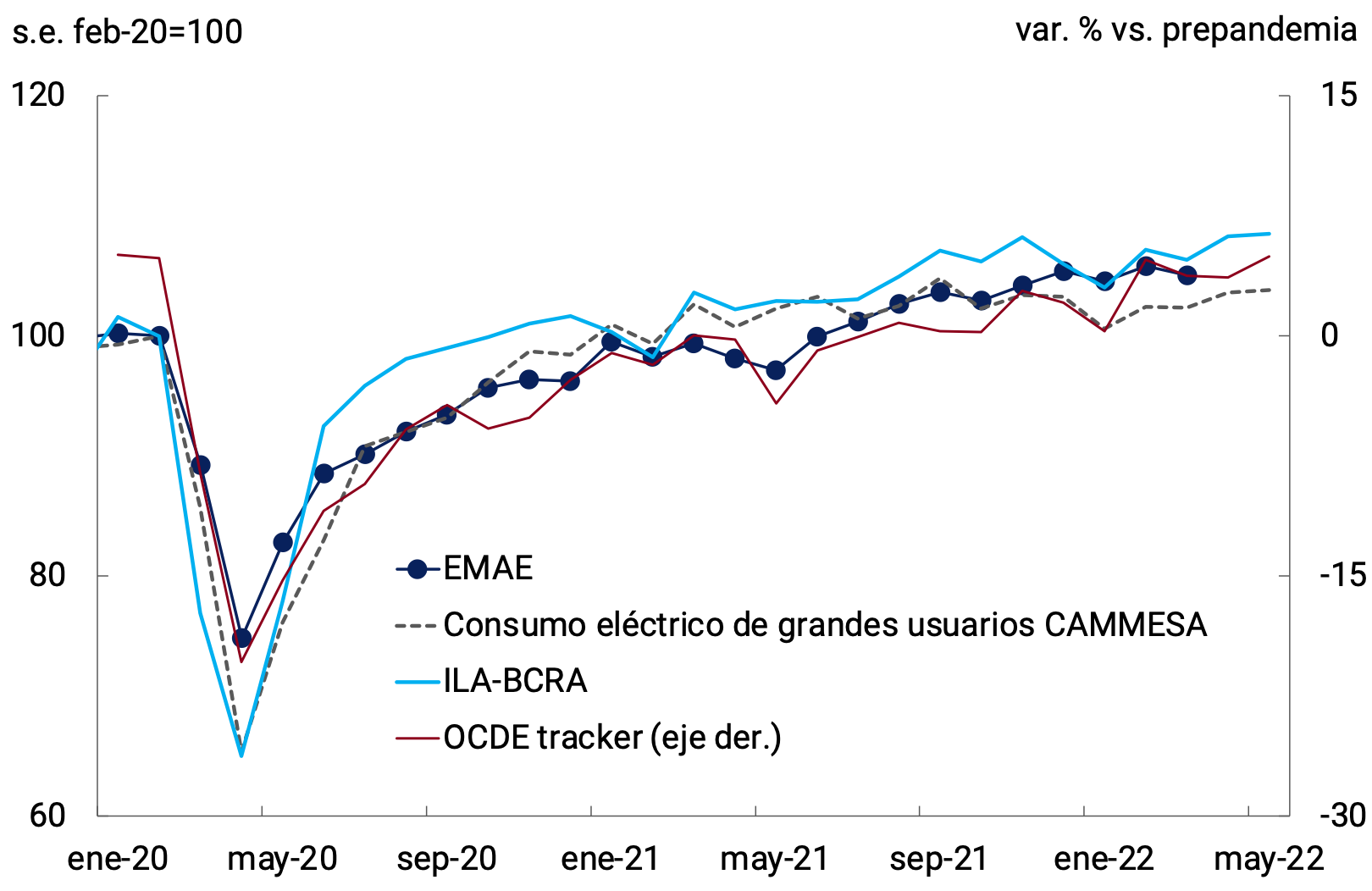

The set of leading indicators available for both April and May show that the activity of the rest of the productive sectors (excluding the agricultural sector) would have grown: the normalized and seasonally adjusted electricity demand of the large users of CAMMESA increased 1.2% monthly s.e. in April and 0.2% monthly s.e. in May, while the OECD indicator – based on Internet searches – widened its difference with respect to the pre-pandemic trajectory to 3.8% in April and 5.3% in May, after being 3.1% above the same trend in March. For its part, the ILA-BCRA6 showed a strong rise in April (1.9% monthly) and increased again in May (see Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5 | Monthly indicators of economic

Source: BCRA based on data from INDEC, CAMESA and OECD.

Box. The Value Added by the agricultural sector in 2022

Agricultural production would total 139.6 million tonnes in the current campaign, very similar to that recorded in the previous one (0.1%) but with falls in corn (-5.8% y.o.y.) and soybeans (-4.3% y.o.y.) offset by an increase in the production of wheat (25.6% y.o.y.) and the rest of the crops (7.3% y.o.y.). It should be noted that the joint production of soybeans, corn, wheat and sunflower accounted for 91.4% of total agricultural production in the 2020-2021 campaign.

These results respond to the drought conditions observed in the main productive areas during the summer, particularly in January – a significant month for determining the yields of prime soybeans, because it is the stage where most of the filling of the grains takes place and is when the crop critically needs water. The Useful Water map in the profiles of the entire country presented as of January 31, 2022 a relatively more deteriorated picture than the previous year in some areas of southern Santa Fe and Córdoba and in a large part of Corrientes, Formosa and Chaco; although better conditions in the north and center of the province of Buenos Aires. Conditions were much more favorable in the core zone compared to January 2018, when a severe drought was recorded with a strong impact on the coarse harvest7.

This year, the total planted area remained practically stable compared to the two previous seasons, with substitutions between the types of crops: less area planted with soybeans (-3% y.o.y.) and more area allocated to the rest of the crops, especially corn (6.2% y.o.y.). Soybean production has been showing a downward structural trend, with an uninterrupted reduction in the area planted since 2016. Since 2015, the only year in which soybean production registered an increase was in 2019, when it recovered from the extreme drought of 2018. Thus, compared to 2016, the area planted with soybeans lost 4.4 million hectares, of which 78% was used for corn (see Figure 3.6).

Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries.

Regarding the evolution of livestock, the indirect indicators corresponding to the first quarter show deteriorations in poultry and pork meat production along with improvements in both meat and beef milk production.

With the data available to date and considering the previously mentioned agricultural production assumptions, a determined evolution for animal husbandry (whose main proxy is beef production) and for the rest of agricultural production, it is estimated that the GDP of the agricultural sector would present a fall of 2.7% during 2022. This fall will be concentrated in the second quarter, when the result of the coarse harvest is imputed, so a contraction of agricultural GDP of around 5.1% y.o.y. is expected, with a direct impact of -0.8 p.p. on the year-on-year variation of GDP in the second quarter of 2022. In seasonally adjusted terms, the GDP of this sector will register a lower contraction than that observed in previous episodes of drought, although it will still have a high negative impact (close to -1.5 p.p.) on the variation in GDP during II-22, which would result in a fall in activity of between 0.3 and 0.9% s.e. compared to the first quarter. To this would be added the indirect effects on industry, transport, commerce and other services associated with agricultural activity.

3.3.1. The labour market continued on the growth path during the beginning of 2022

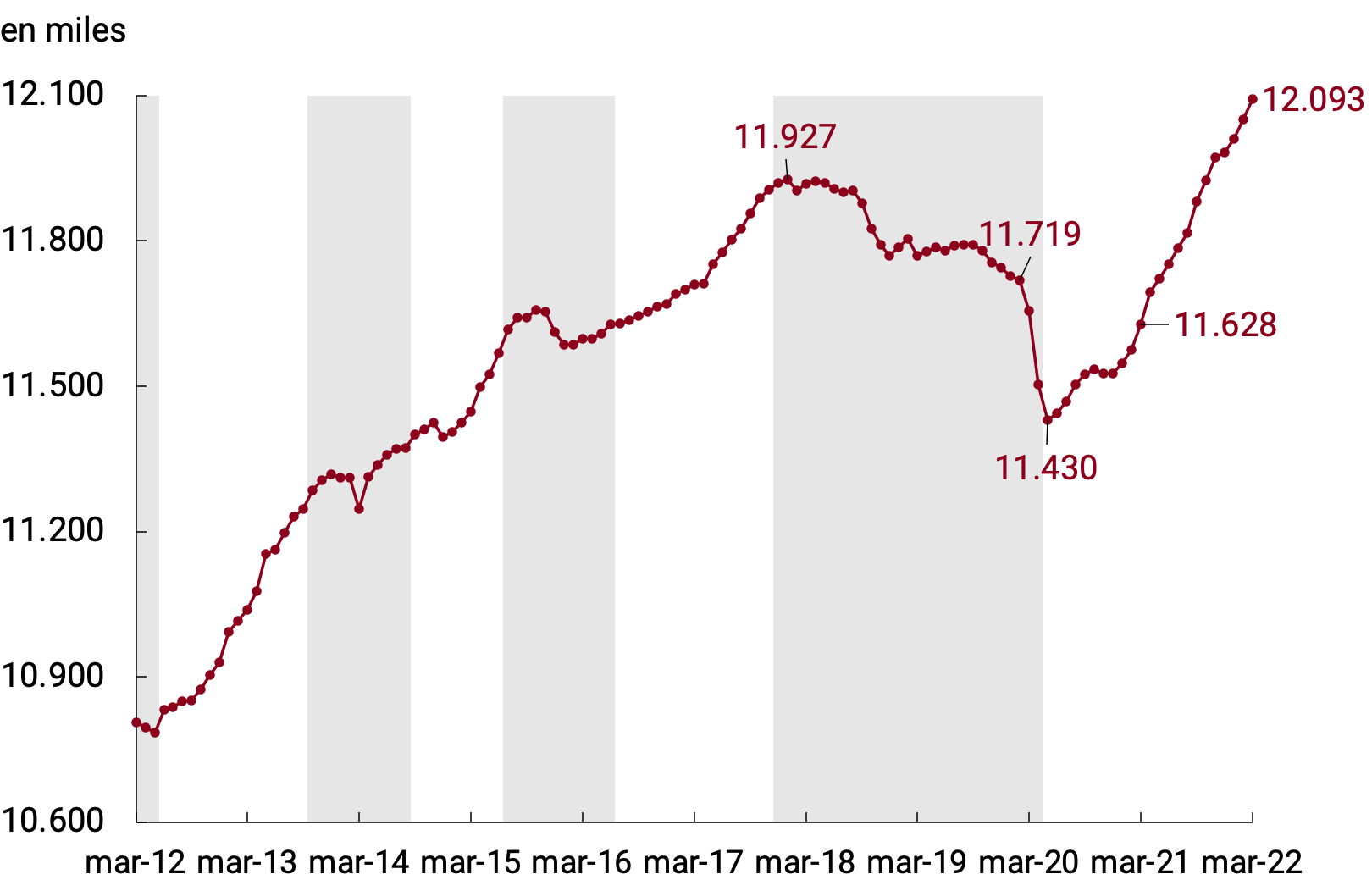

According to the Ministry of Labor, Employment and Social Security (MTEySS), registered employment continued, during the beginning of 2022, the growth path that began in June 2020. Thus, with data as of March 2022, total registered employment (without social monotax) continues at historic highs and chained 15 consecutive months of growth. The pace of expansion during the first quarter of 2022 maintained the dynamics evidenced since the beginning of 2021, growing at 0.3% per month on average (see Figure 3.7).

During the first quarter of 2022, the increase in total registered employment was mainly driven by self-employment (2.3% accumulated) and private registered salaried employment (1.0% accumulated). Public employment, on the other hand, moderated its growth rate, accumulating 0.1% in the first three months of 2022 (see Figure 3.8).

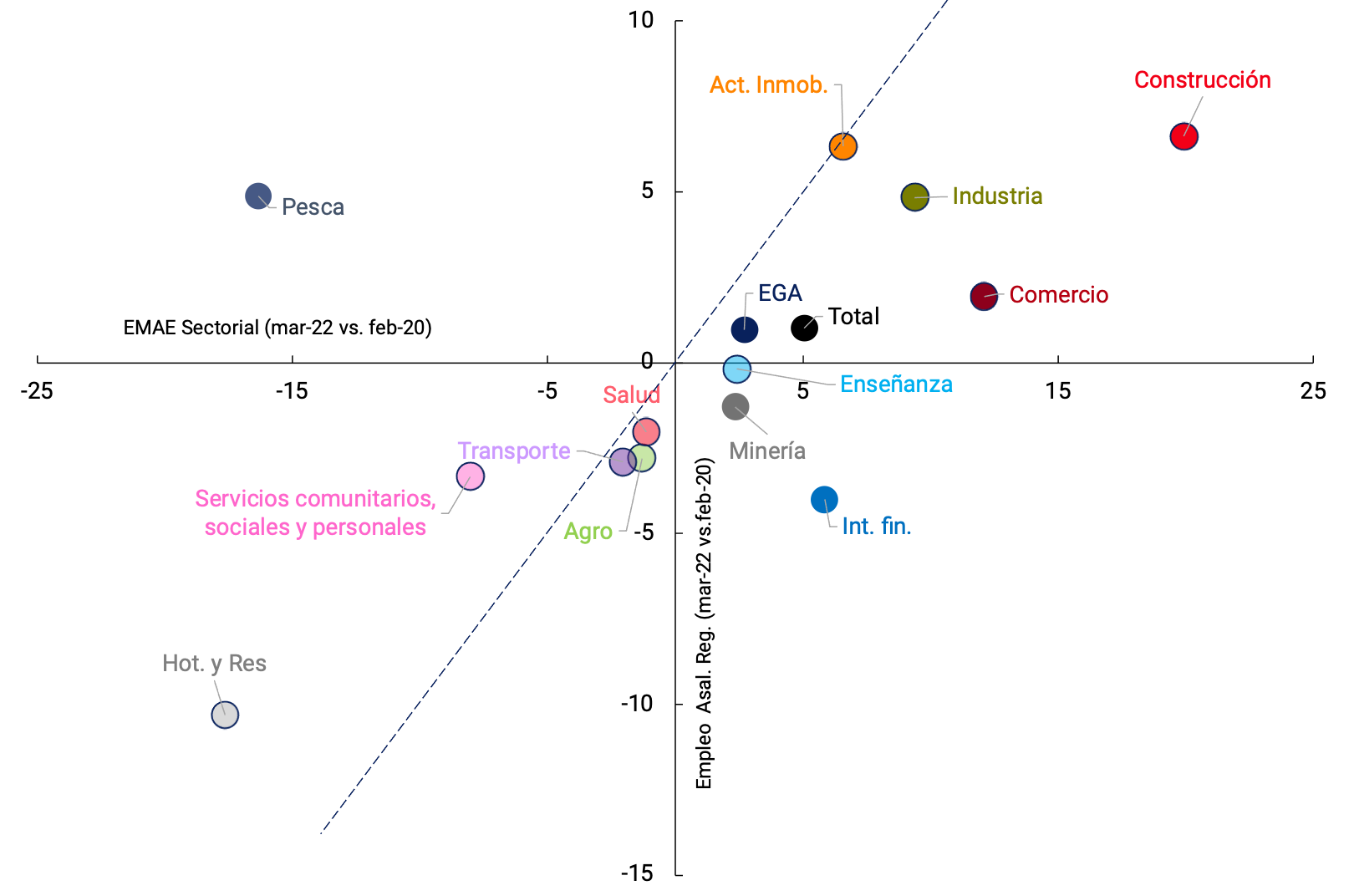

Figure 3.8 | Public, private, private and self-employed

Source: BCRA based on data from MTEySS.

The behavior of private salaried employment between December 2021 and March 2022 allows us to distinguish at the sectoral level, as in the previous quarter, a strong dynamism in branches such as Hotels and restaurants (3.8% s.e. acum.) and Construction (3.0% s.e. acum.). However, taking into account pre-pandemic levels, it can be seen that the Hotels and Restaurants sector, as well as Community, Social and Personal Services, still has potential for recovery both in terms of activity and staff hiring. On the other hand, in the sectors that experienced the greatest recovery in terms of activity (Trade and Construction and Industry), the growth in registered salaried employment has occurred in a smaller proportion (see Figure 3.9).

Figure 3.9 | Activity and Registered Employment. Percentage

Source: BCRA based on data from MTEySS and INDEC.

The Labor Indicators Survey (EIL) as of April 2022 ratified the positive trend in net hiring expectations that began in February 2021, chaining 15 consecutive months of positive values. On the other hand, suspensions after a sharp reduction during 2021 remained at levels within the historical average and the rate of layoffs remains in a limited range.

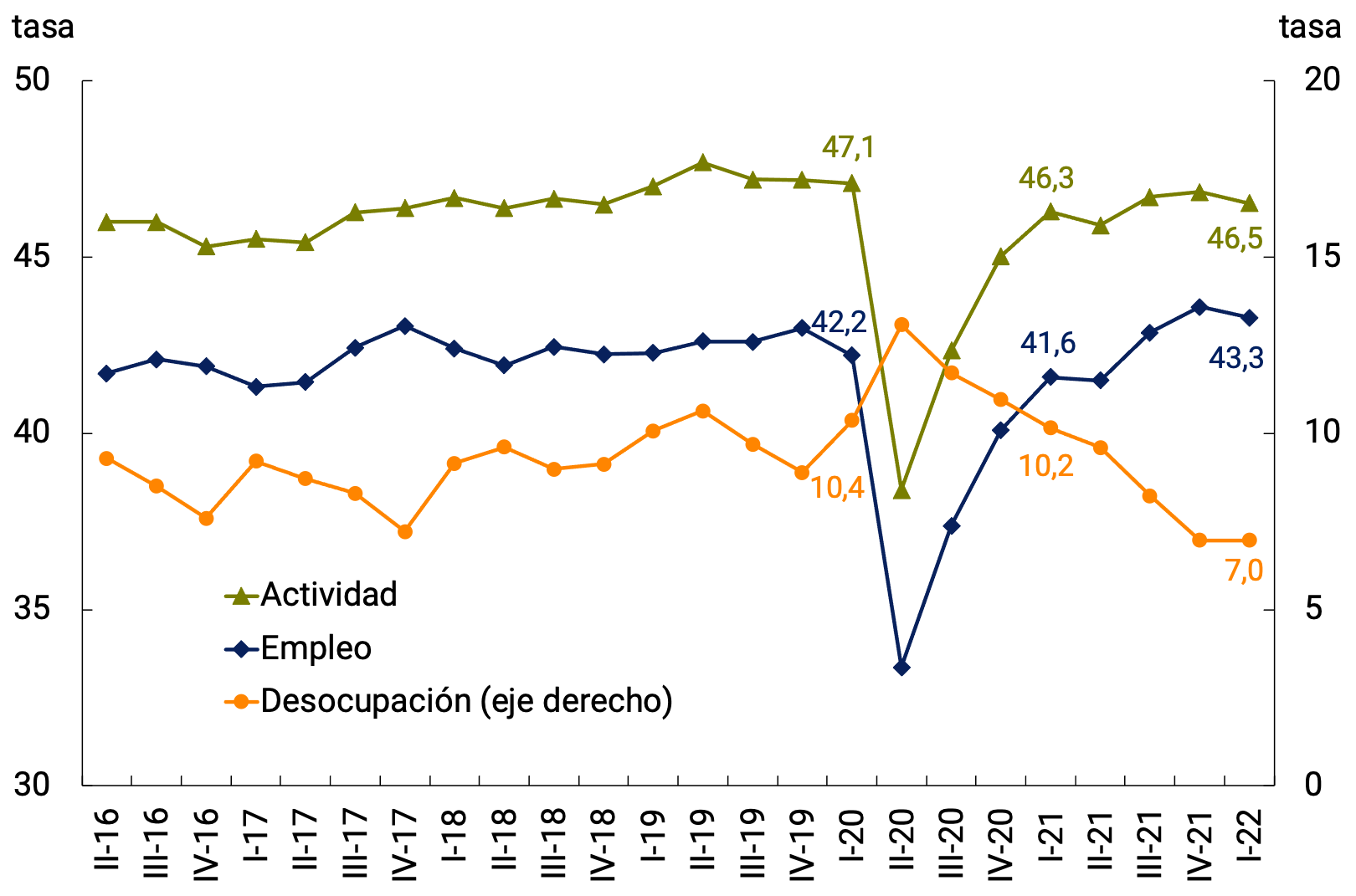

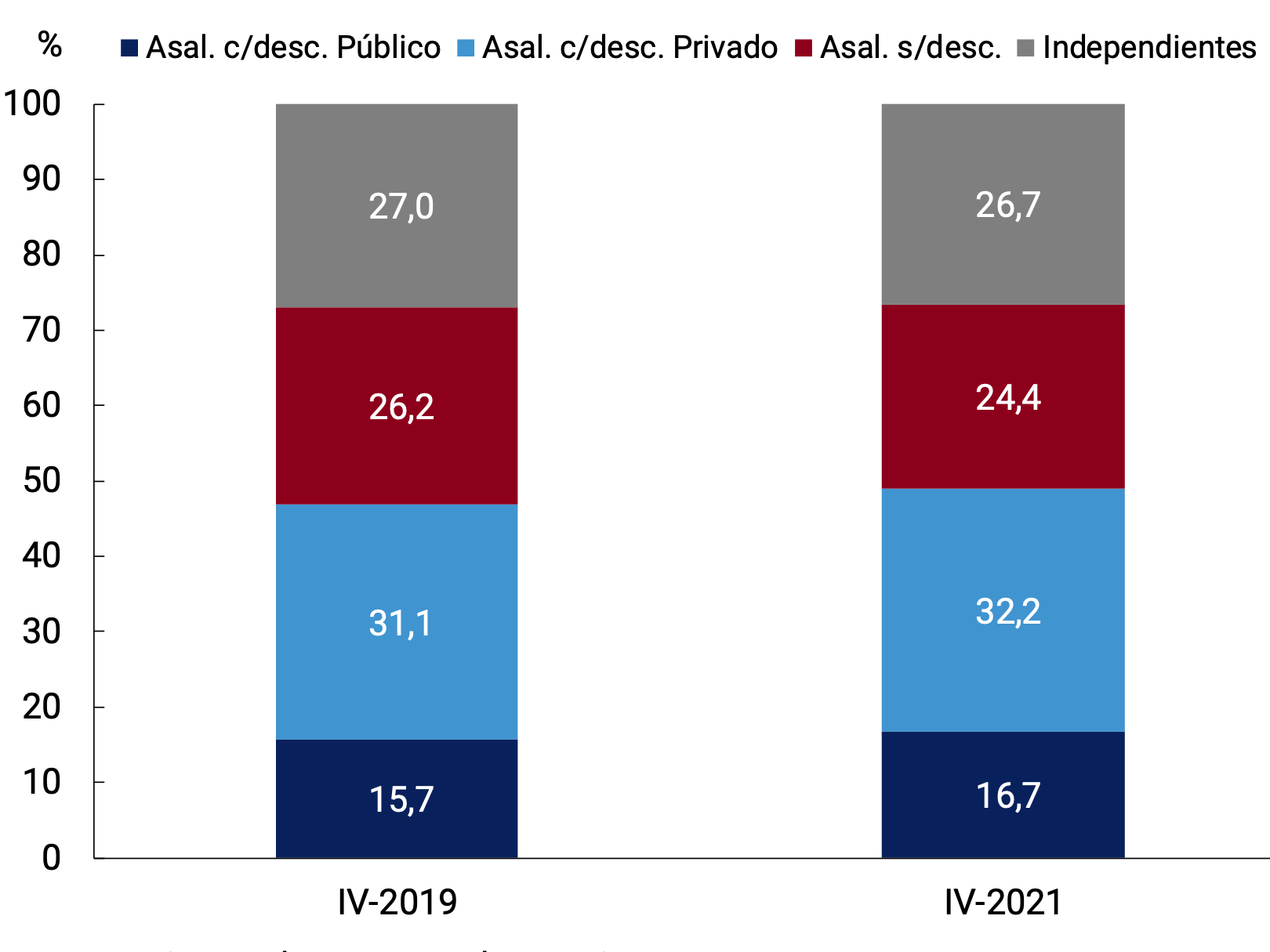

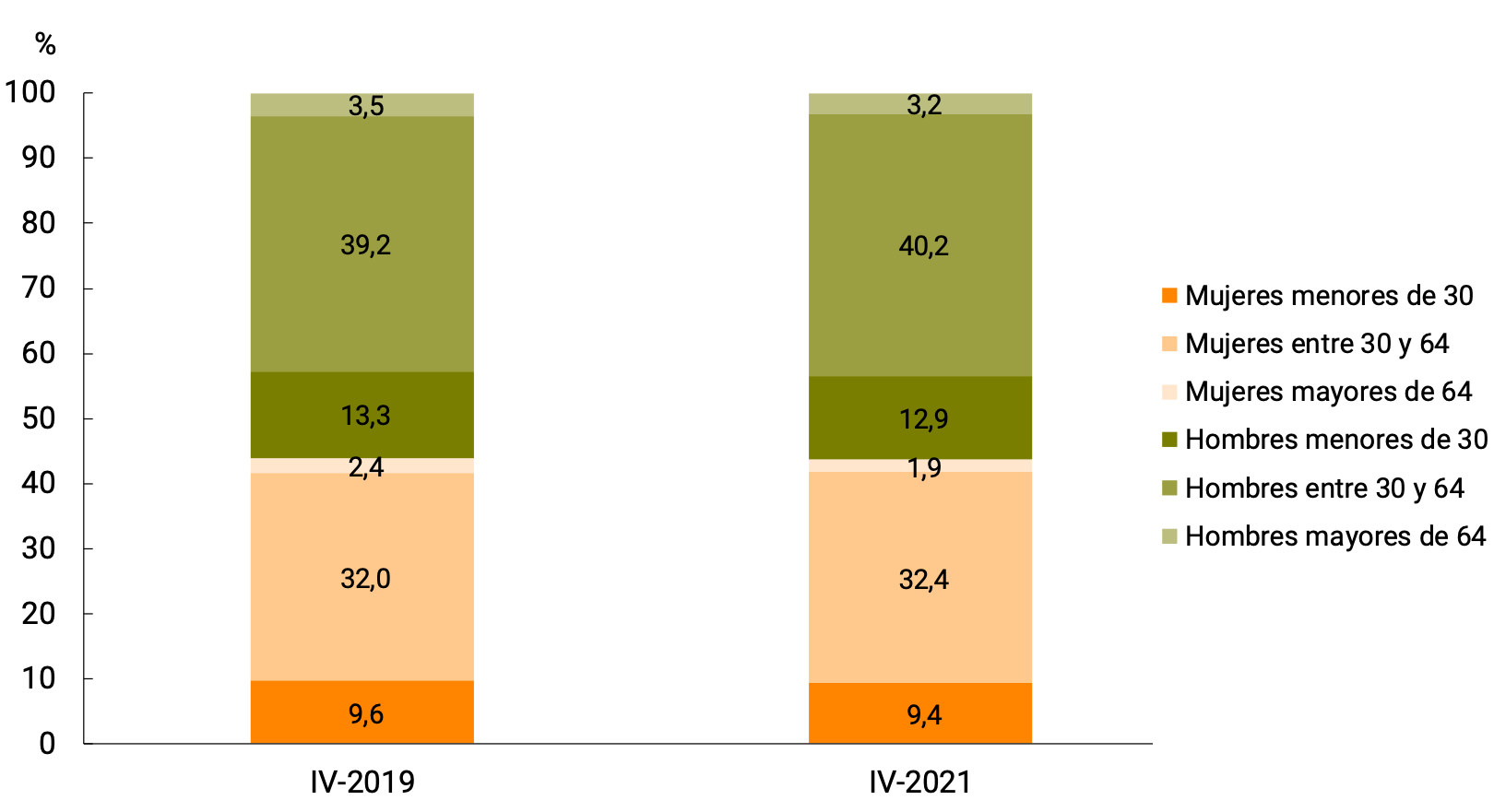

According to data from the Permanent Household Survey (EPH), in the first quarter of 2022 the employment rate stood at 43.3% (+1.7 p.p. y.o.y.), after reaching a maximum in the fourth quarter of 2021 in the new INDEC series (II-2016 / I-2022) standing at 43.6% (See Section 2 / Employment and Income: two years after the start of the pandemic). For its part, the EAP stood at 46.5% (+0.2 p.p. y.o.y.), slightly below pre-pandemic activity levels. Thus, the open unemployment rate stood at 7.0% (see Figure 3.10), as in the previous quarter, remaining at the lowest level since the beginning of the new INDEC series.

As for the evolution of the different occupational categories, self-employment remained relatively stable compared to the previous two quarters. The “employers” category showed, as in the fourth quarter of 2021, a significant drop that leaves them far from pre-pandemic levels. Formal wage earners fell compared to the previous quarter, but are still close to the average growth of employment. Finally, the number of informal salaried people increased again, thus exceeding the level of the first quarter of 2020.

With regard to the age range and gender, it was observed that, in both women and men, it is still the category of people over 65 years of age that has not yet managed to recover after the impact of the pandemic. In the case of young people (under 30 years of age), women have already exceeded the levels of the first quarter of 2020 while men are very close to achieving it. Both women and adults (between 30 and 64 years old) had already overcome it before.

3.4. Perspectives

So far this year, economic activity continued to strengthen the recovery and growth process that began in 2021. The wide coverage of the population against COVID-198 allowed the different sectors to operate in an environment of “normality”. In this context, it is expected that the services that are still lagging behind will recover their pre-pandemic levels, at the same time that the rest of the sectors – which mostly operate at levels much higher than those of the beginning of 2020 – will continue the growth process driven by the policies of the National Government and the BCRA9. With respect to the agricultural sector, the expected contraction in its level of activity in the second quarter as a result of the drought will be much lower than that observed in previous episodes.

This base scenario continues to present several risks. Among the main ones are the continuity of a more deteriorated international financial context in the face of the persistence of international inflation, greater pressure on international energy prices as a result of the prolongation of the armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine and, with a low probability of occurrence, the circulation of new variants of the Coronavirus that could emerge and truncate the health advances achieved so far (see Chapter 2. International Context).

The outlook for global growth contemplates a slowdown in the coming months, associated with the systematic reduction of monetary stimuli by advanced economies and the continuation of bottlenecks in certain supply chains, as a result of geopolitical conflicts and the health policies implemented in China in response to the increase in positive COVID-19 cases at the beginning of the year. This scenario continues to put pressure on external financing costs for emerging countries and on international prices of raw materials and energy, which remain at historically high levels.

After recovering 10.3% annually in 2021, the Argentine economy grew 6% YoY in the first quarter of the year. For the average of 2022, the statistical carryover is 4.1 p.p., the midpoint of the range of economic growth forecast contemplated in the IMF’s PFE for the year (3.5% – 4.5%). The market outlook is below this level: according to the estimates of the Market Expectations Survey (REM) at the end of May 2022, specialized analysts expect a growth of 3.3% for economic activity during this year.

The National Government continued to implement policies aimed at sustainable and inclusive economic growth within the framework of the “Argentina 2030” Development Plan10. Among them, the promotion of strategic sectors to enhance production chains, the modernization of industry and the promotion of regional economies in order to increase exports11. In addition, in the context of a recent acceleration in inflation, the National Government temporarily implemented income-boosting measures, mainly aimed at the most vulnerable sectors12. The calibration of public policies in a dynamic and uncertain context will contribute to strengthening greater macroeconomic stability.

4. External Sector

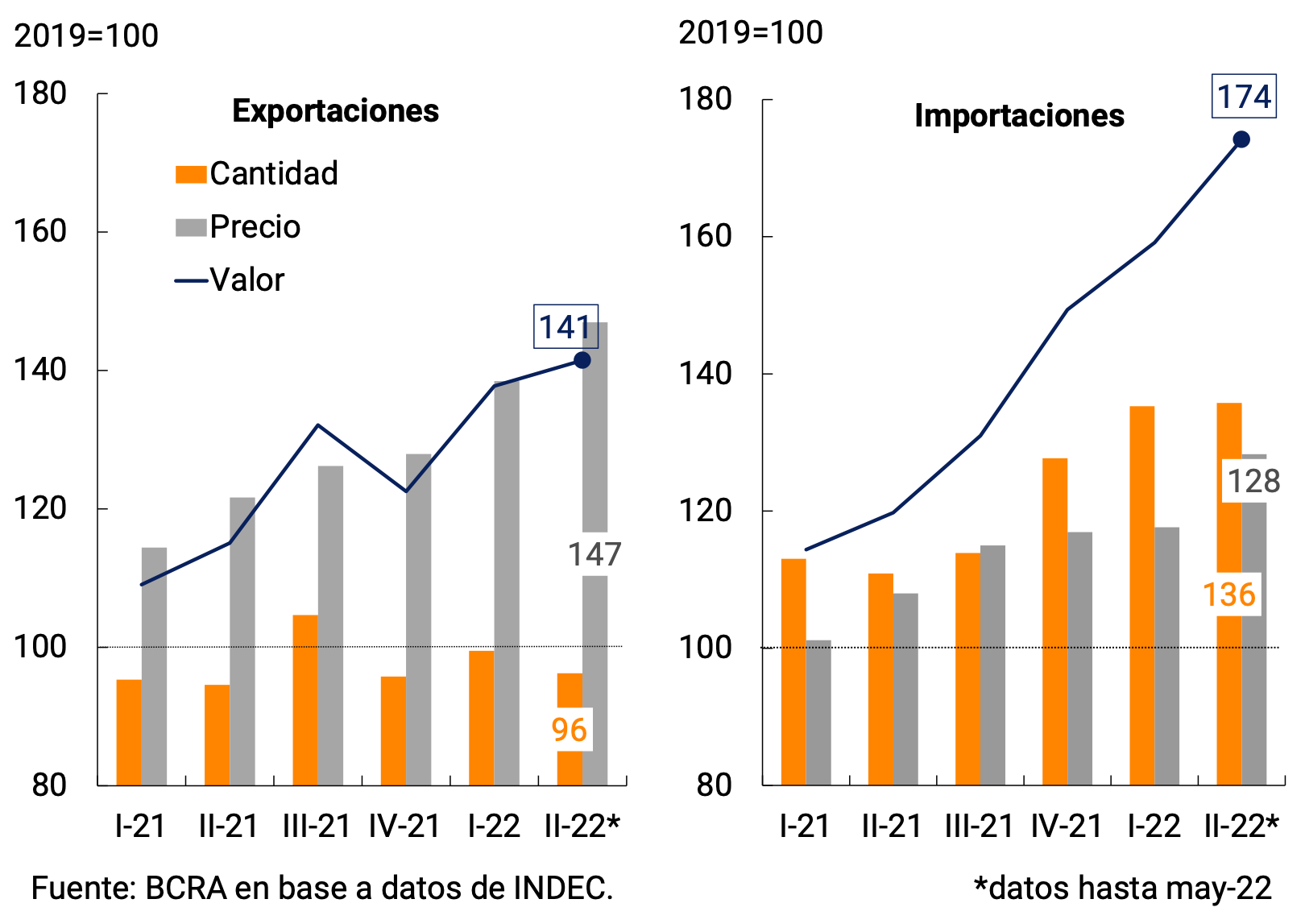

In the first quarter of 2022, in a context of trade flows at record levels (measured in current dollars), the trade surplus in goods was recovered, mainly due to an improvement in the terms of trade. In this context, the economy is expected to have sustained the seasonally adjusted current account surplus. In the April-May two-month period, due to the strong growth in imports of goods, driven by high fuel prices, the seasonally adjusted monthly average trade surplus was reduced by 40%.

In the foreign exchange market, the evolution of exports and imports of goods added to the dynamics of commercial debt for these concepts, resulted in a net result in the exchange market for goods of US$7,278 million in the first five months of 2022, significantly decreasing compared to what was observed in the same period of the previous year. Additionally, net outflows were recorded through the foreign exchange market for services, interest and other financial transactions for US$6,928 million, while entities made sales for US$154 million. For its part, the BCRA bought US$844 million net in the foreign exchange market, in addition to net payments through the Local Currency System (SML) for US$339 million.

These operations in the foreign exchange market by the BCRA together with the net income of financial debt of the General Government of about US$3,100 million, explained entirely by the income of the IMF, brought the level of international reserves to US$41,561 million at the end of May, which represented an increase of US$1,899 million above its value at the end of 2021.

Following the agreement reached with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that resulted in the current Extended Facilities Program (EPP), the goal for monitoring Net International Reserves was set at an increase of at least US$1,200 million for the first quarter of 2022, which was satisfactorily achieved given the increase of US$1,521 million for the period arising from using the methodology defined in program18.

After the first review of the PFE and after recognizing the importance of investing in economic stability and maintaining the objectives of the year-end program with some flexibility in quarterly trajectories to adapt to external shocks, the objective of accumulating Net International Reserves for the first half of 2022, according to the parameters established in said program, they were established in an increase of at least US$3,450 million.

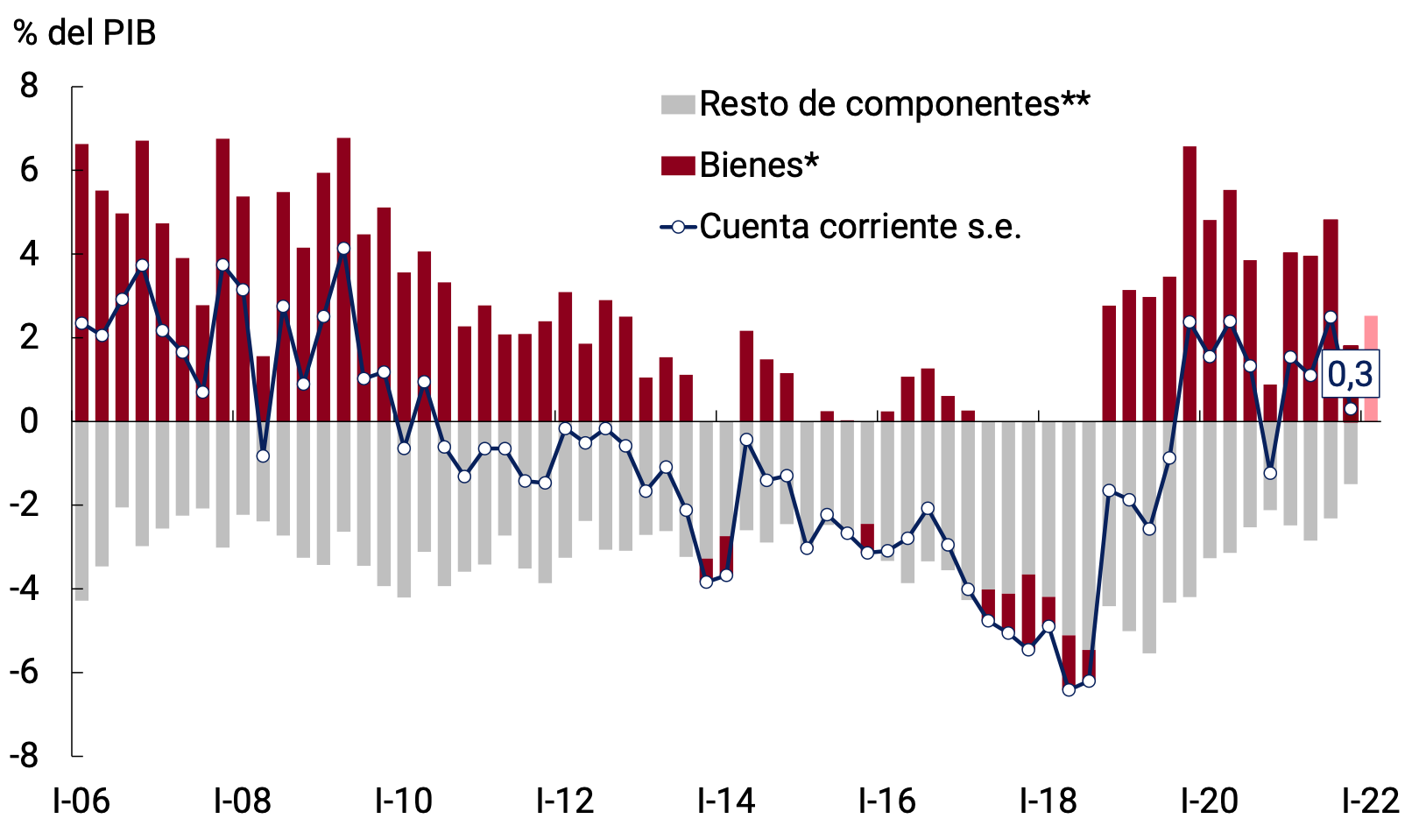

4.1. In the first quarter of 2022, the economy would have sustained the current account surplus

In the fourth quarter of 2021 (latest official data available) the Argentine economy had registered a current account surplus of US$373 million – equivalent to 0.3% of GDP in seasonally adjusted and annualized terms. The fall in the volumes of goods exported compared to the third quarter had been the main reason behind the temporary decline in the current account surplus.

In the first quarter of 2022, the trade surplus in goods was recovered, mainly due to an improvement in the terms of trade. In this context, the seasonally adjusted current account would have remained in positive territory (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 | Seasonally adjusted current account. Annualized

* IV-21: estimated.

** Includes the accounts: Services, Primary Income, and Secondary Income.

Source: BCRA based on INDEC data.

In that period, the exported values of seasonally adjusted goods reached US$22,425 million (Free on Board —FOB—) at current prices, which represented an increase of 12.4% compared to the level recorded in the fourth quarter of 2021. This evolution was mainly due to the performance of export prices, which grew 8% s.e. on average between January and March 2022 compared to the previous quarter. To a lesser extent, the quantities exported had a lesser impact, which expanded 4% in s.e. terms and were around 2019 levels. In the April-May two-month period, exported values rose again at a rate of 3% quarter-on-quarter s.e., again driven by prices that more than compensated for a fall in quantities.

For its part, between January and March 2022, seasonally adjusted imports of goods totaled US$19,543 million (CIF), which was a record for imported values at current prices. This performance of imported values was explained to a greater extent by the rise in volumes, which grew 6% quarter-on-quarter (see Figure 4.2). In the April-May two-month period, imported values accelerated at a rate of 9% quarter-on-quarter s.e., reflecting a rise in prices of the same magnitude, while imported quantities remained practically constant.

As a result of the recent evolution of exports and imports, the seasonally adjusted average monthly trade balance went from US$961 million in the first quarter of 2022 to US$546 million in the April-May two-month period.

Two of the four main export items had increases in exported volumes in the first quarter of 2022. In the case of Primary Products (PP, +5% qq. s.e.), 6 of the 10 categories that make up the category showed increases, with higher shipments of cereals (in the context of the record wheat harvest) and fishery products standing out for their incidence. The quantities exported from. Fuels and Energy (S) increased 11% QoQ. s.e., mainly due to higher crude oil exports. On the other hand, shipments of Manufactures of Industrial Origin (MOI) fell (-2% QoQ, s.e.), with a strong negative impact on land transport material. Finally, the exported quantities of Manufactures of Agricultural Origin (MOA) fell 5% s.e. in the quarter, affected by a weak performance of soybean derivatives, partially offset by an increase in shipments of dairy products. In the two months of Apr-May, almost all the dynamics of the first quarter of the year were reversed. There were increases in MOA and MOI (due to recoveries in the quantities exported of soybean derivatives and land transport material, respectively) and falls in PP and S, as a result of declines in shipments of oil and fishery products, and a deepening decline in oilseed exports (see Figure 4.3).

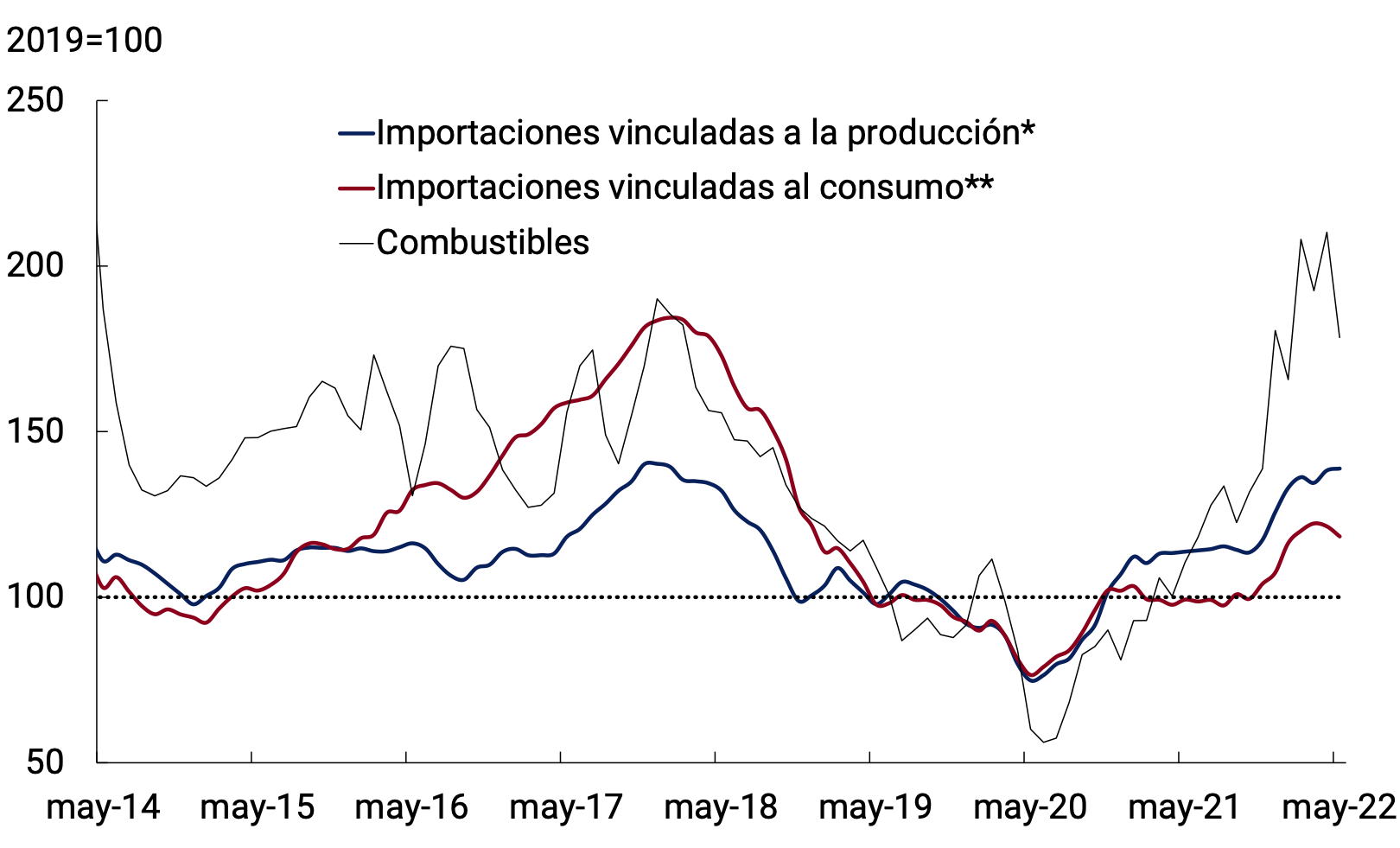

In the case of imported quantities of goods, the increase in the first quarter was publicized, fuel purchases grew 7% quarter. s.e., those associated with consumption 14% s.e. and those linked to production, 7% s.e. In the two months of April-May, this strong growth was interrupted. Imported volumes of fuels and consumer goods fell 8% and 6% respectively and imported quantities of goods closely associated with production slowed their growth to a 3% quarter-on-quarter pace. s.e. (see Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4 | Quantities imported. Seasonally adjusted seriesMoving average 3 months* Includes imports of capital goods and parts thereof and intermediate goods.

** Includes imports of consumer goods and vehicles.

Source: INDEC.

Box. Commodity prices

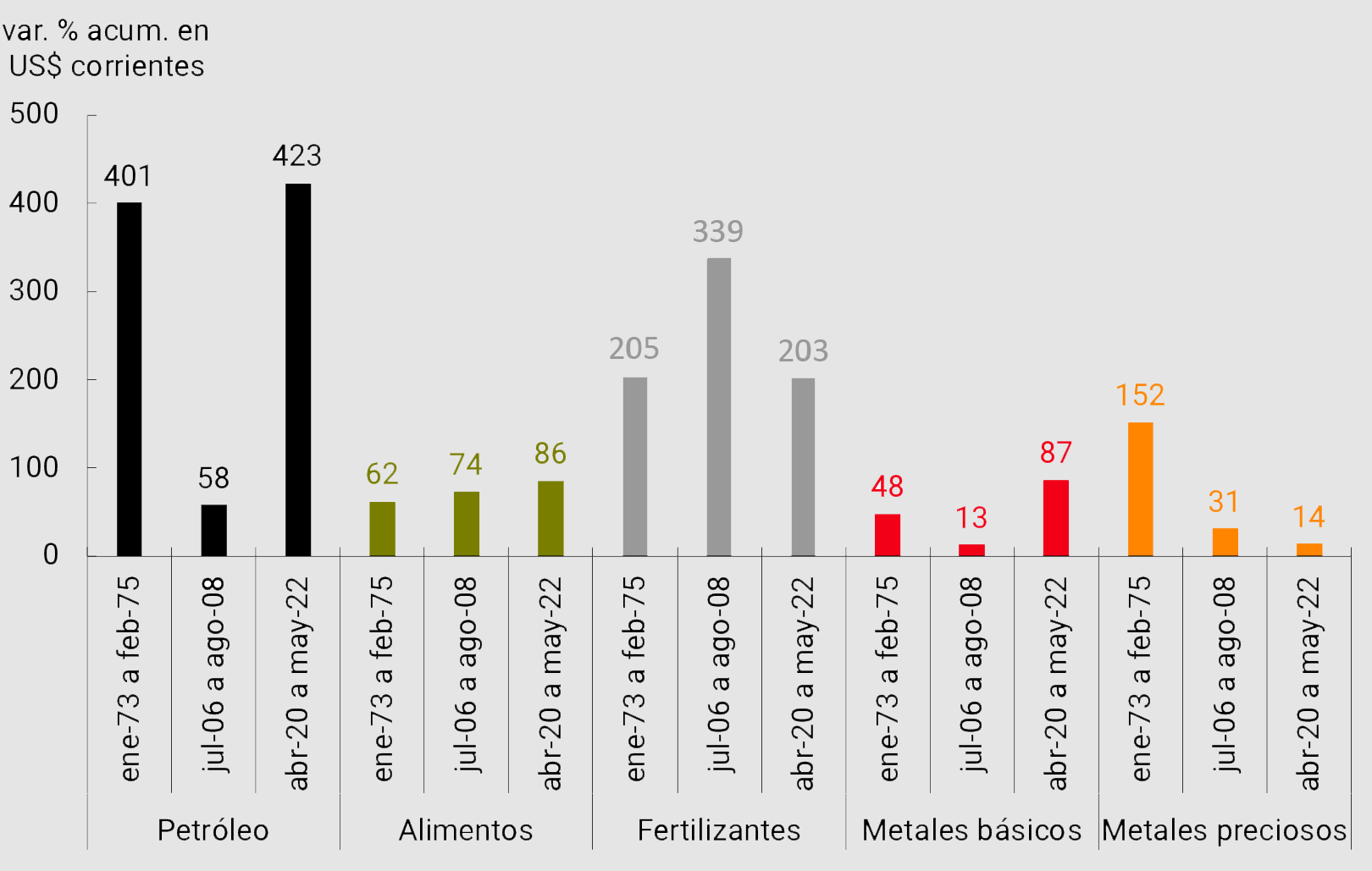

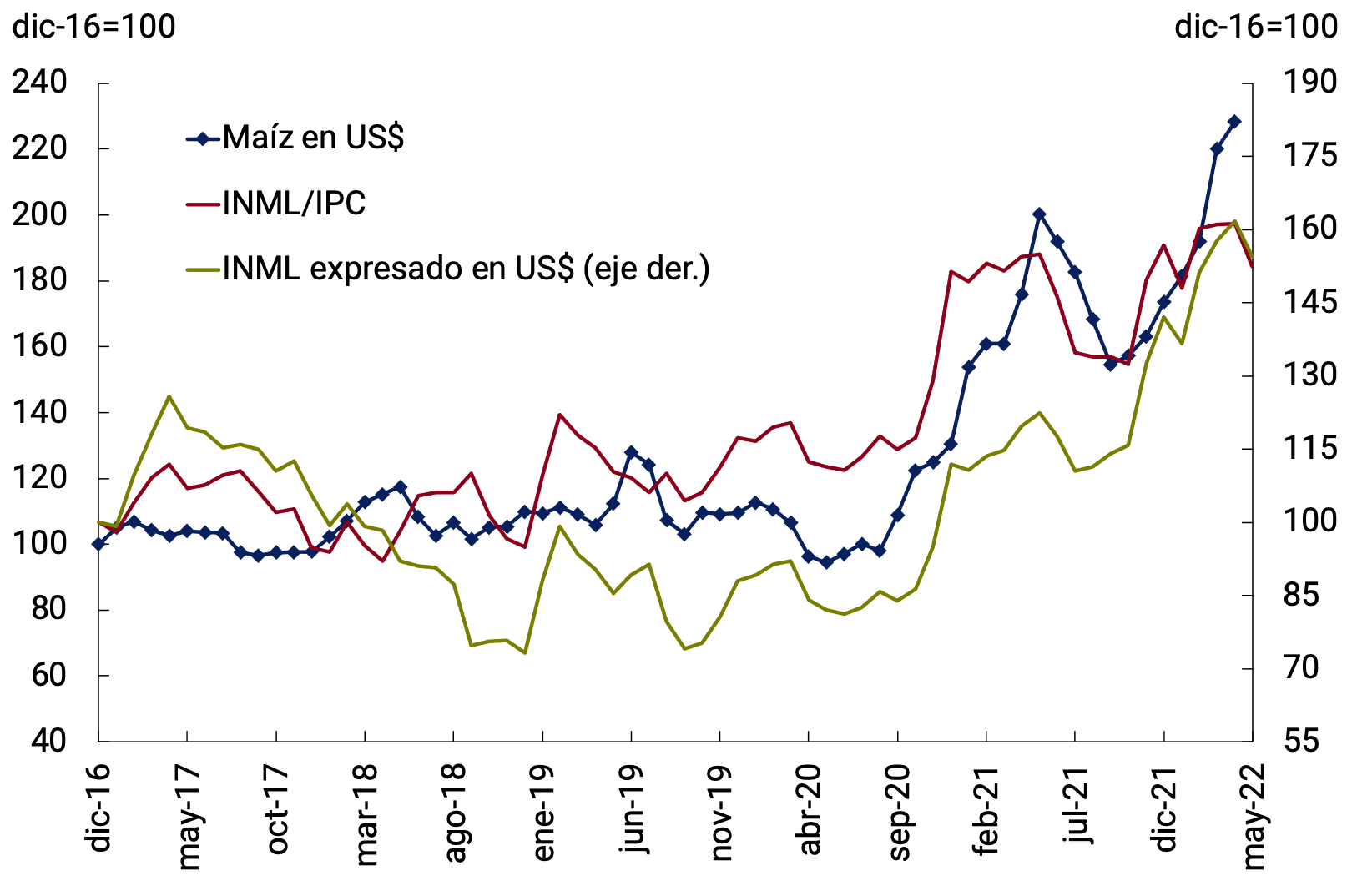

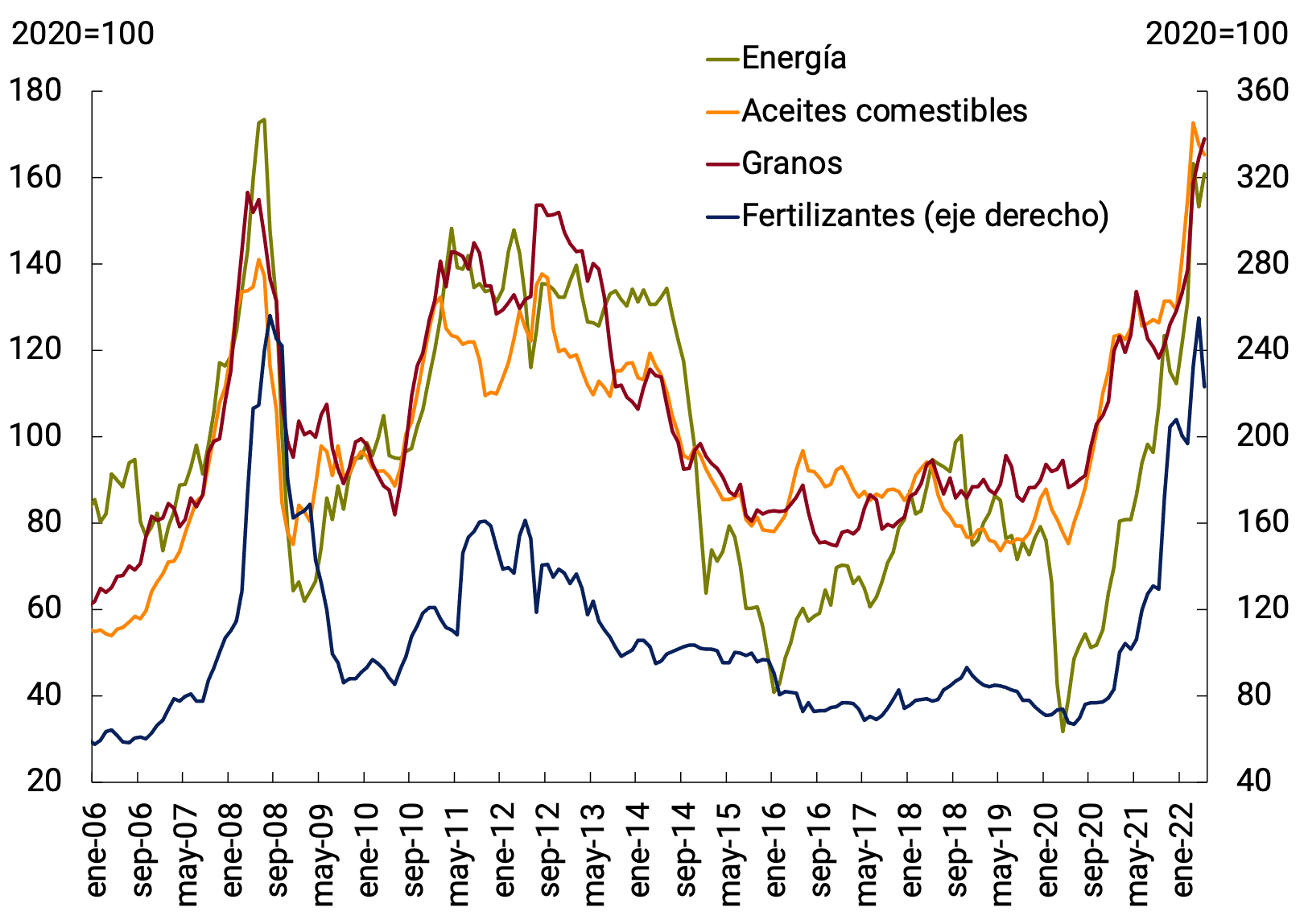

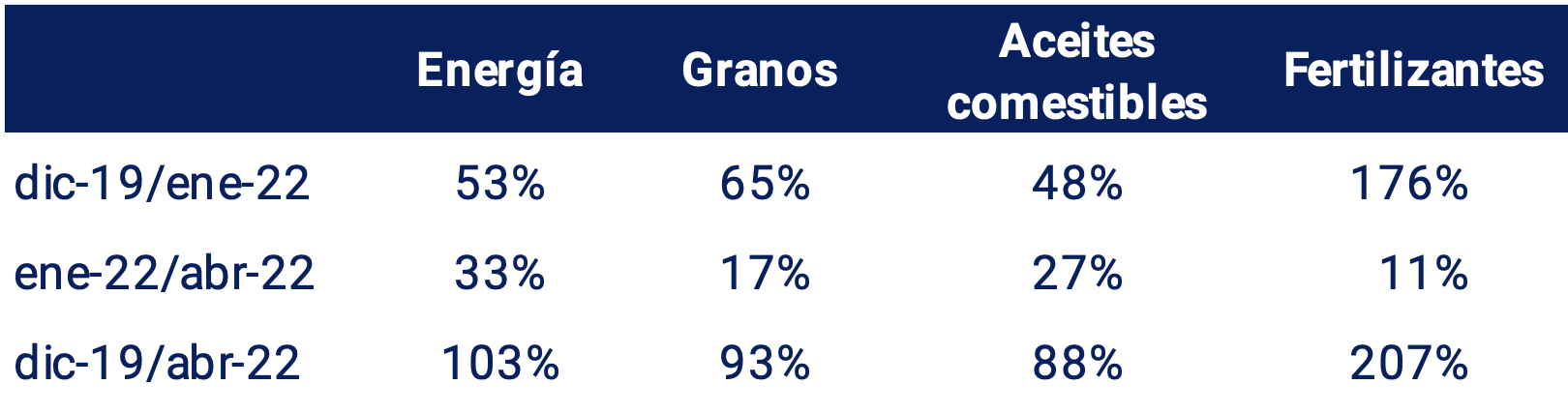

Global commodity markets were under pressure at the beginning of 2022, before the armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine broke out. The strong recovery in demand as the recessionary effects of the pandemic dissipated was not matched by a proportional increase in supply affected by some bottlenecks resulting from years of low investment and restrictive trade measures19. From April 2020 to December 2021, the Commodity Price Index prepared by the BCRA (IPMP) accumulated a 61% increase in current dollars.

In this context, the shock of the war in Ukraine occurred (see Chapter 2. International Context). Russia and Ukraine have a significant weight as exporters of a variety of raw materials, including wheat, gas, oil, sunflower oil, palladium, barley, corn, urea, phosphates and potassium chloride. Both the economic sanctions imposed on Russia and the material damage suffered in Ukraine put additional pressure on global commodity markets. So far this year, the main grains have accumulated increases of between 29% and 33%, oil grew 49% and the reference price of liquefied natural gas in Europe (TTF) increased 42%.

As a result of these events, the world economy is going through one of the three episodes of the most intense increases in commodity prices in the last 50 years. Taking a 25-month window, since April 2020 oil accumulated a rise of 423%, food 86%, fertilizers 203% and base metals 87%. In both oil and fertilizers, these increases are comparable to those observed in 1973/76, while in food and base metals the current increases far exceed those verified in the historical episodes indicated (see Figure 4.5).

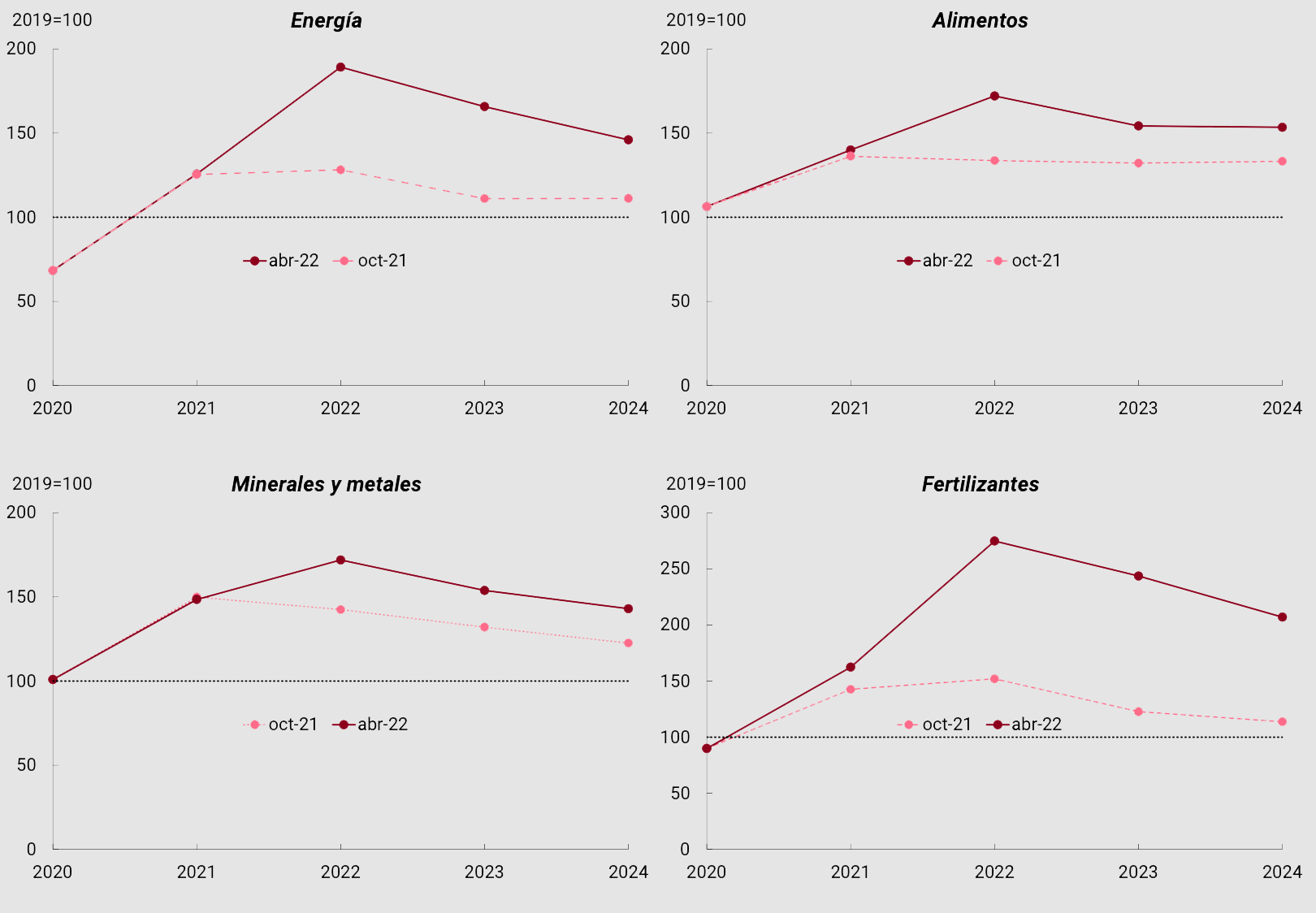

The effects of the shock of the war in Ukraine are expected to last in the medium term. While commodity prices are expected to peak in 2022, forecasts through 2024 suggest that prices would hold comfortably above pre-pandemic levels, a prospect that has sharpened in recent months (see Figure 4.6).

4.3. So far in 2022, the BCRA recorded an increase in international reserves

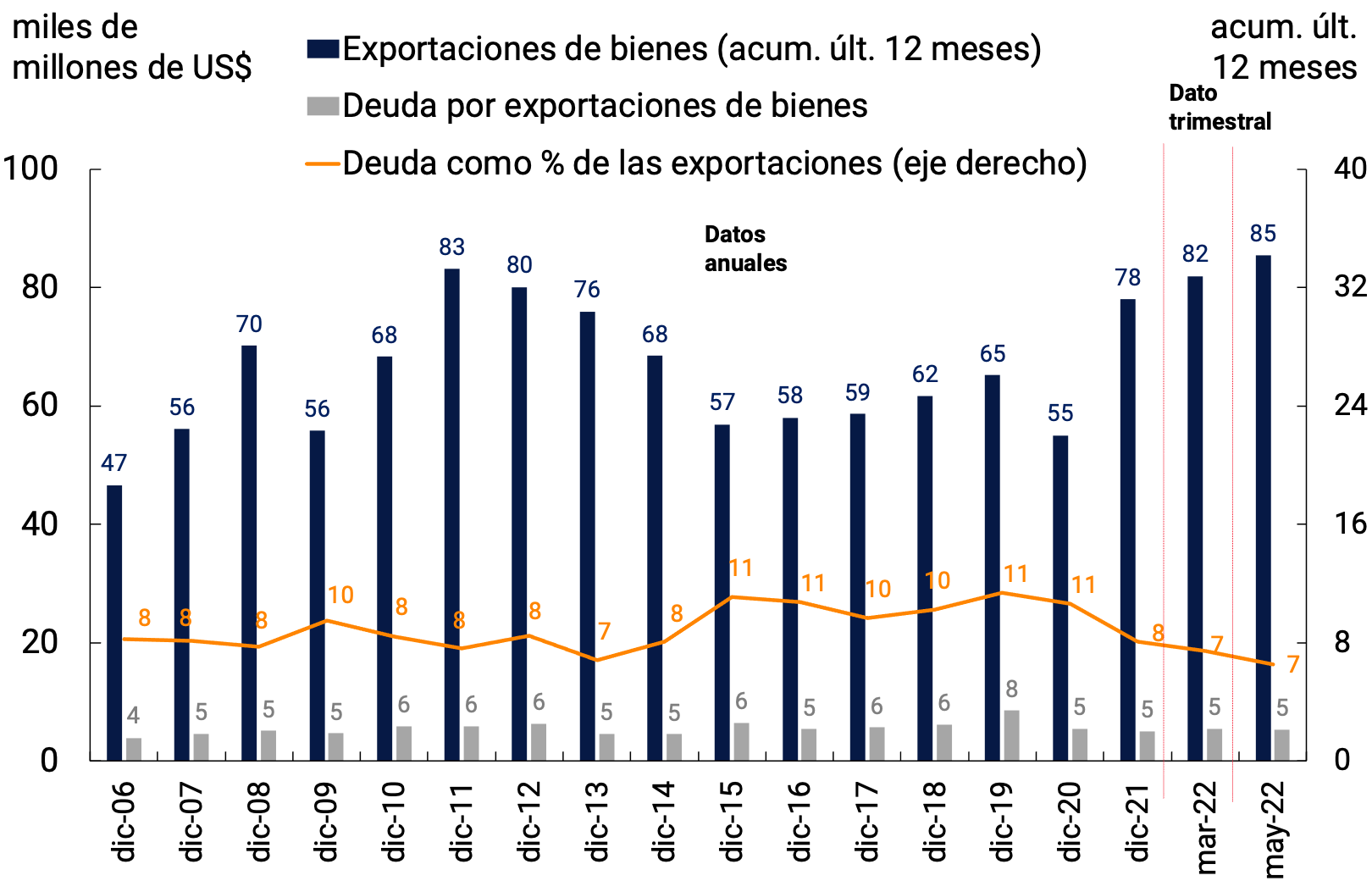

During the first five months of 2022, exporters recorded revenues from collections of exports of goods of about US$36,065 million. On the other hand, exports of goods totaled about US$35,827 million, which is why a slight increase in external debt for advances and pre-financing of about US$237 million is estimated. Despite this increase, the ratio of this type of debt to exported securities is reduced to 6.5% and represents the lowest ratio verified since December 2006 (see Figure 4.7).

Figure 4.7 | Assets. Exports and external debt for exports

Note: I-22 and May-22 debt estimated based on accrual data and cash.

Source: BCRA based on INDEC data and own data.

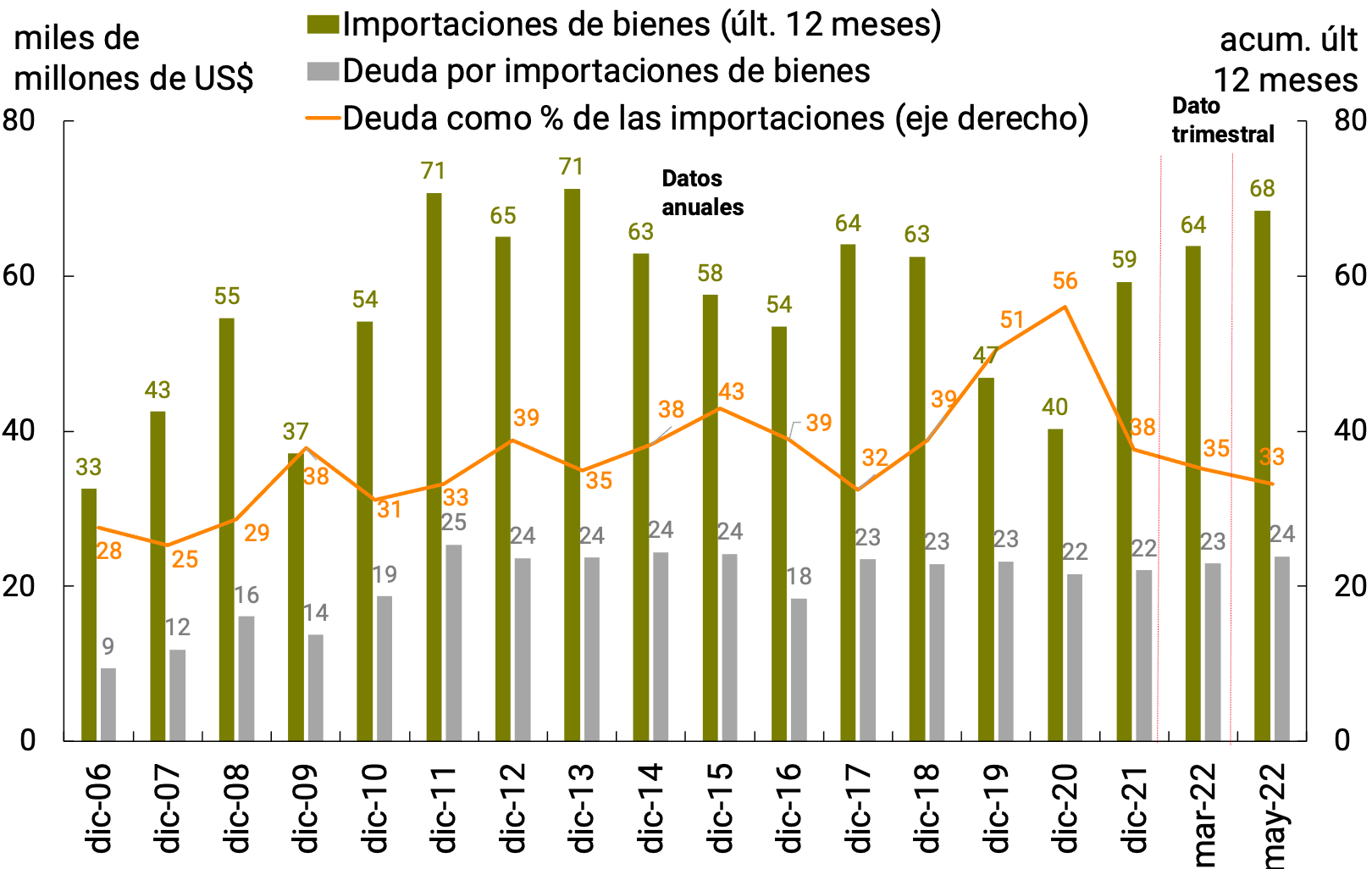

During 2020, the BCRA established a series of regulations that aim to promote the allocation of foreign currency more efficiently, with an impact on both the evolution of private commercial and financial debt. These rules were maintained throughout 2021 and continued to be refined throughout 202220. In this context, during the first five months of this year, payments for imports of goods through the foreign exchange market for around US$28,800 million were about US$1,800 million below FOB imports for the period, which would imply an increase in foreign debt for this concept. However, the relationship between external indebtedness and the level of imports registered a further fall in May 2022, which would imply about 23 p.p. less than at the end of 2020 (see Figure 4.8).

Figure 4.8 | Assets. Imports and external debt for imports

Note: I-22 and May-22 debt estimated based on accrual data and cash.

Source: BCRA based on INDEC data and own data.

With regard to financial debt and as part of the current regulatory framework mentioned above, in September 2020, Communication “A” 7106 established the guidelines under which private sector companies could initiate a process of refinancing their respective external liabilities, which would allow them to adapt their maturity profile to the guidelines required for the normal functioning of the foreign exchange market. This communication, which reached certain capital maturities between 15-Jan-20 and 31-Mar-21, was extended by Communication “A” 7230, covering maturities from then until the end of 2021. Likewise, Communication “A” 7422 extended the term of the maturities until 30-Jun-22 and Communication “A” 7466 did so until 31-Dec-22.

In this context, the renegotiations recorded during the first five months of 2022 had an impact on lower net purchases in the foreign exchange market of about US$550 million compared to the original maturities for that same period, accumulating lower net payments of about US$3,100 million since its inception. It should be noted that in the first five months of 2022, net cancellations represented only 26% of the maturities reached, with almost three-quarters of the maturities of securities and financial debts being refinanced.

The aforementioned evolution of trade in goods and commercial debt for exports and imports of goods, resulted in a net result for goods in the foreign exchange market of US$7,278 million in the year, about US$1,000 million higher than the result of the FOB trade balance of the same period and exhibiting a fall compared to the previous year (17% y.o.y.).

This result allowed the BCRA to accumulate net purchases in the foreign exchange market for US$844 million during the year (see Figure 4.9), while international reserves increased by US$1,899 million in the same period. This difference was mainly explained by the purchases detailed above, by the net income of debt in foreign currency of the National Government with a direct impact on international reserves of about US$3,100 million —of which about US$4,700 million corresponded to IMF revenues—, payments for operations carried out through the Local Currency Systems with Brazil, Uruguay and Paraguay and ALADI for about US$380 million and for the decrease in the prices of the assets that make up the international reserves in relation to the currency of account (US dollar), which resulted in a decrease of about US$1,100 million.

Figure 4.9 | Exchange market. Result

*Data as of May-22.

Note: joint cumulative result of the BCRA and the National Treasury in the foreign exchange market.

Source: BCRA.

4.4. Perspectives

For the year 2022, the economy is expected to register a trade surplus in goods for the fourth consecutive year, within the framework of a managed floating exchange rate policy.

Various factors in the international context make up the risk matrix of the external sector of the Argentine economy. The continuation and potential escalation of the war in Ukraine, a resurgence of the pandemic and an increase in volatility in financial markets could have a negative impact on the growth of our trading partners and on commodity prices, which are at historically high levels.

The BCRA will continue to prudently manage foreign exchange regulations in order to adapt them to the needs of the situation, favoring monetary and exchange rate stability. Along these lines, on June 27, 2022, Communication “A” 7532 was issued, which, in order to respond to the extraordinary needs for foreign currency to meet energy imports and in order to sustain economic growth and the development of SMEs, extends the import financing system to those made under a Non-Automatic License and to the import of services and will be in force for one quarter. to give time for the normalization of foreign trade. In the same sense, it was decided in coordination with the Ministry of Productive Development to expand the tariff positions of goods equivalent to those produced in the country that will have access to the market from 180 days and that of luxury goods that will be able to access from 360 days.

To the extent that macroeconomic conditions allow, regulations will be relaxed, with the aim of maintaining in the medium and long term a set of macroprudential regulations compatible with the dynamization of capital flows oriented to the real economy. Examples of this were the regime for the availability of foreign currency for exporters of services (Communication “A” 7518 of June 2, 2022)21 and the Regime for Access to Foreign Exchange for Incremental Oil Production (RADPIP), created by Decree 277/2022 of May 27, 2022, which makes access to the foreign exchange market more flexible depending on the increase observed in hydrocarbon production.

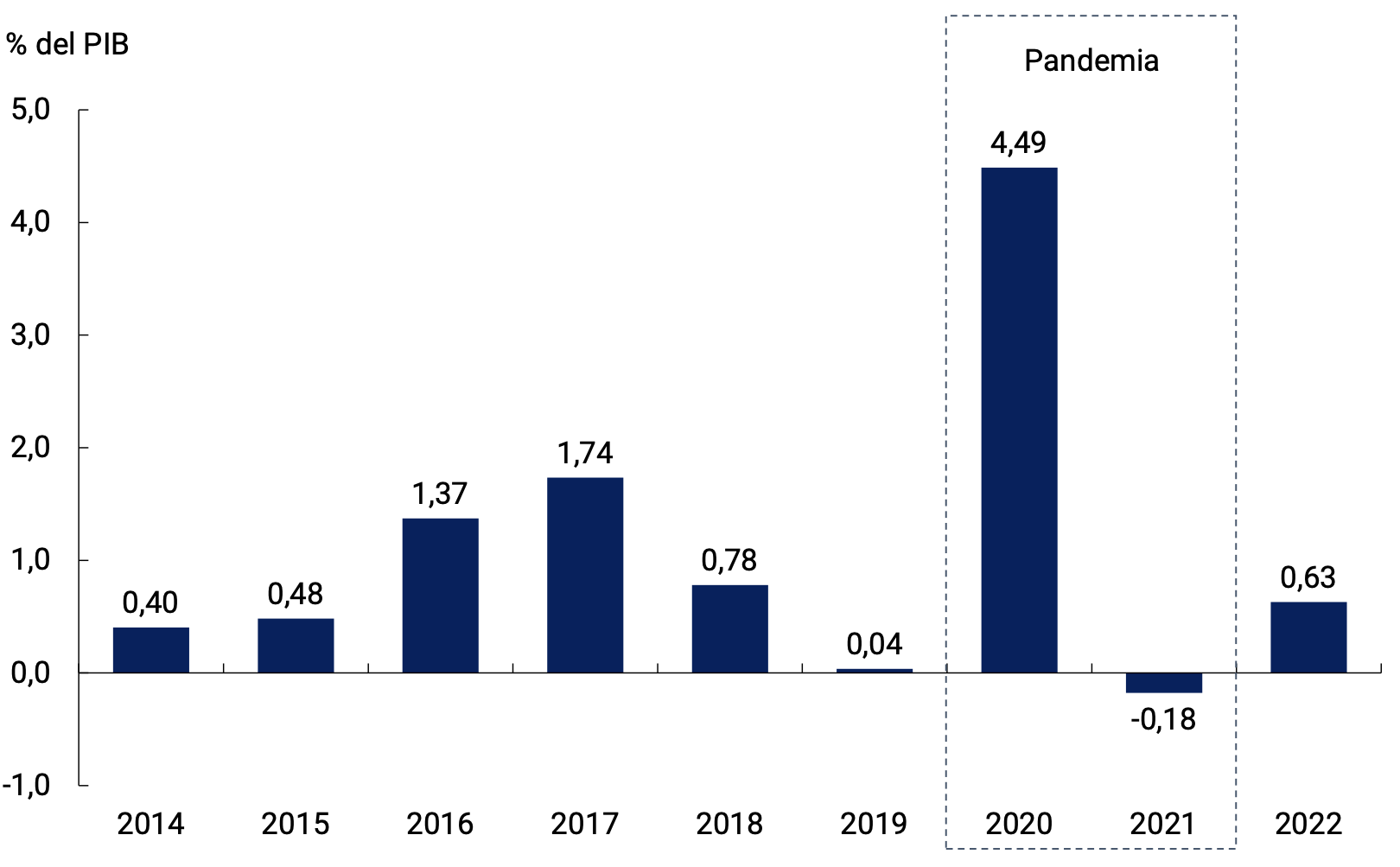

5. Public Finance

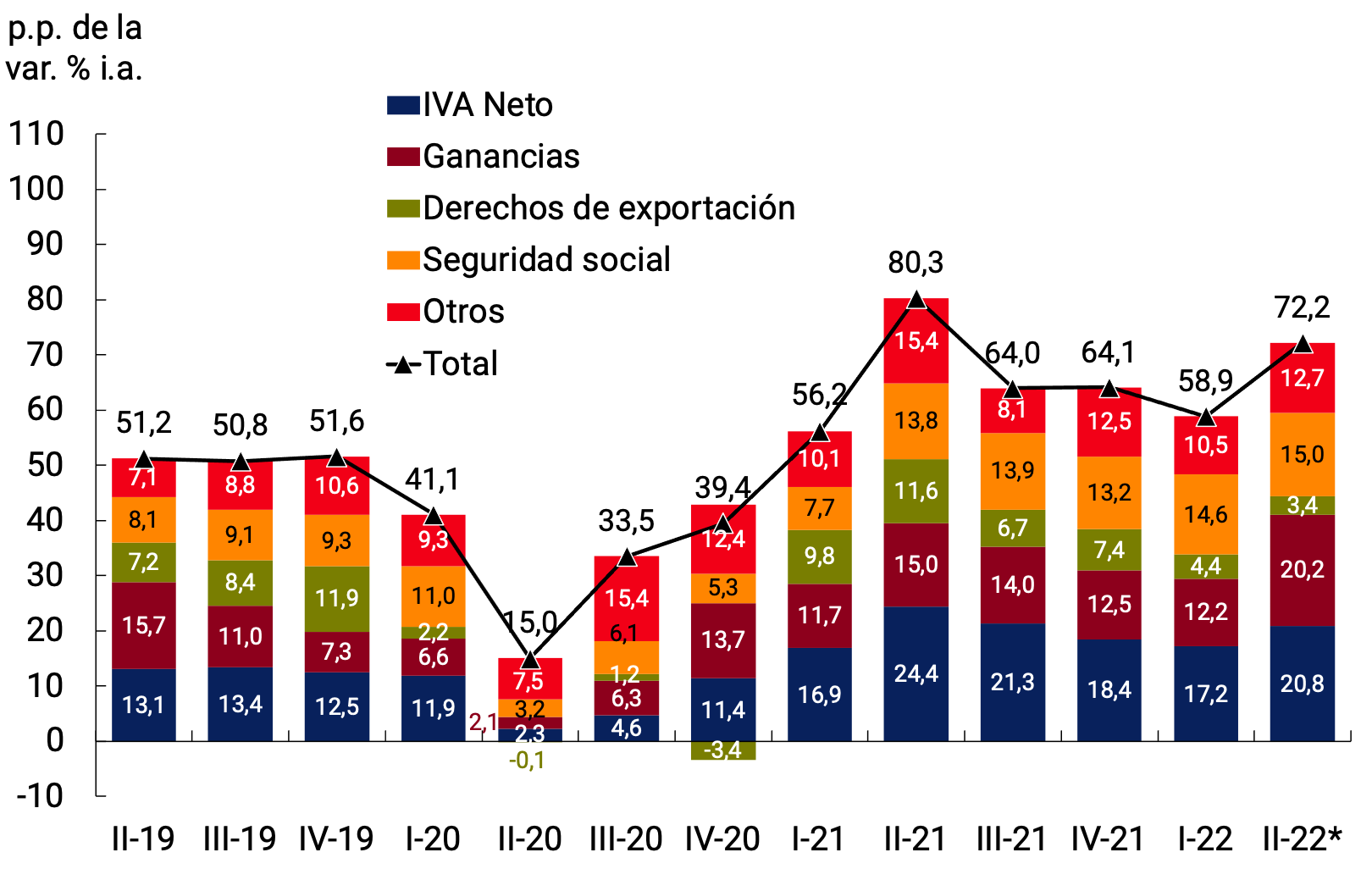

National tax collection grew in real terms during the first part of 2022, strengthening national tax revenues. The tax collection increased by 58.9% during the first quarter of 2022 compared to the previous year (see Figure 5.1), which meant a real growth of 4%. With data up to May, during the second quarter collection accelerated to 72.2% y.o.y. (+7.9% y.o.y. in real terms). The performance of taxes during the first five months responded to the consolidation of the economic recovery and the improvement in wages and employment. Taxes associated with foreign purchases maintained a high dynamism while export duties had a more limited advance.

During the first quarter of 2022, revenues of the National Non-Financial Public Sector (NFPS) grew 66.6% YoY (+8.7% YoY in real terms), while they increased to 67.6% YoY (+5.2% in real terms) in the second quarter with data as of May. Primary expenditure rose 71.0% YoY (+11.6% YoY in real terms) during the first three months of the year and expanded at a rate of 87.9% YoY (+17.9% YoY in real terms) between April and May. The increase in expenditures was widespread among the main items of expenditure, while those linked to social programs, economic subsidies and current transfers to the provinces stood out for their dynamism. This evolution reflected the impact of the external context on public finances: the sharp rise in international energy prices increased the magnitude of economic subsidies – given the proposed tariff update path – while the National Government implemented extraordinary reinforcements of household income in the face of the abrupt rise in food prices worldwide.

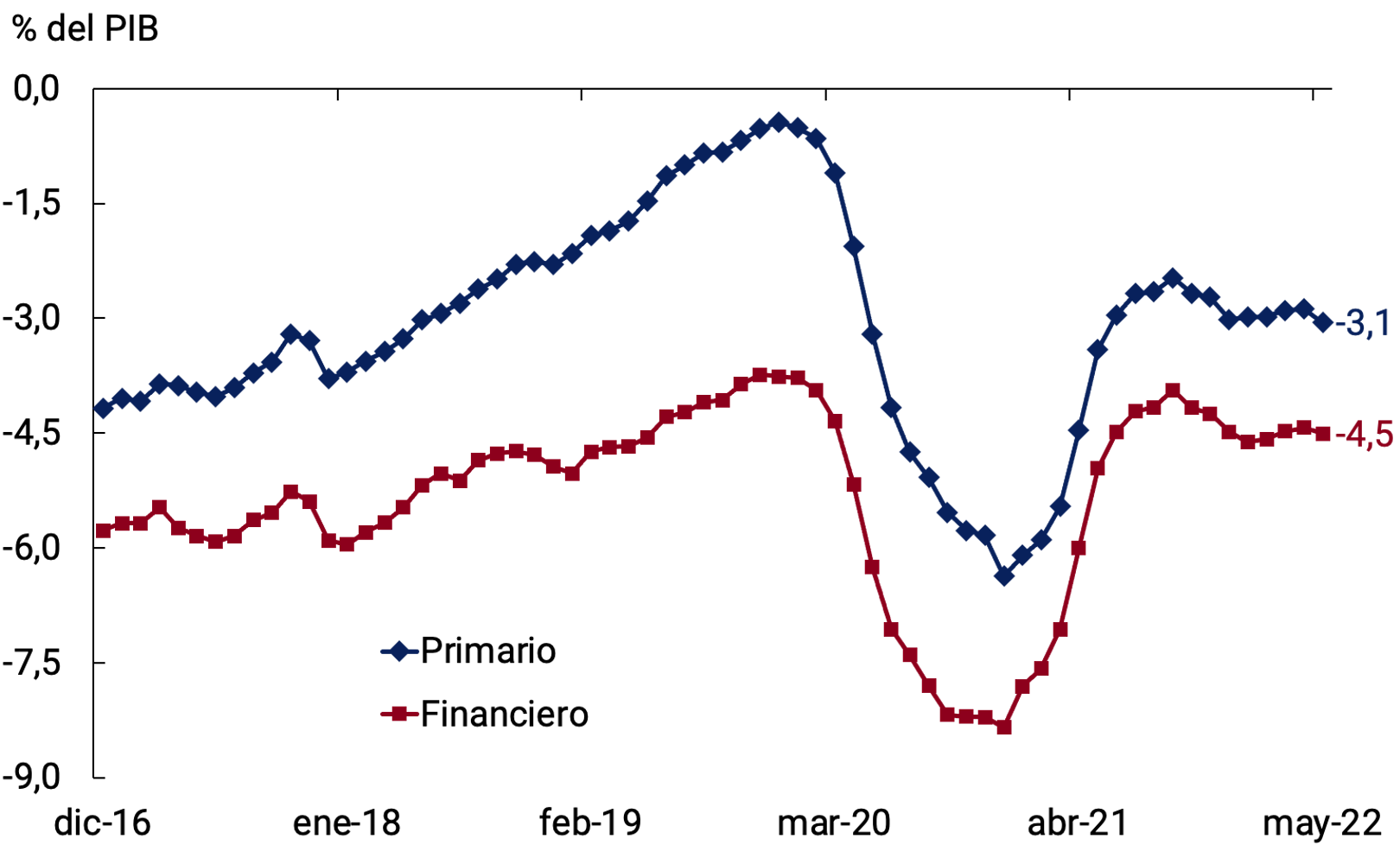

Thus, in the first five months of the year, primary expenditure grew above the increase in revenues, with a considerable impact on the primary deficit in the second quarter. However, the fiscal deficit on a cash basis of the NFPS in terms of GDP remained at levels similar to those of the end of 2021 for an amount equivalent to 3.1% of GDP, a deficit level significantly lower than that observed during 2020 (6.4% of GDP).

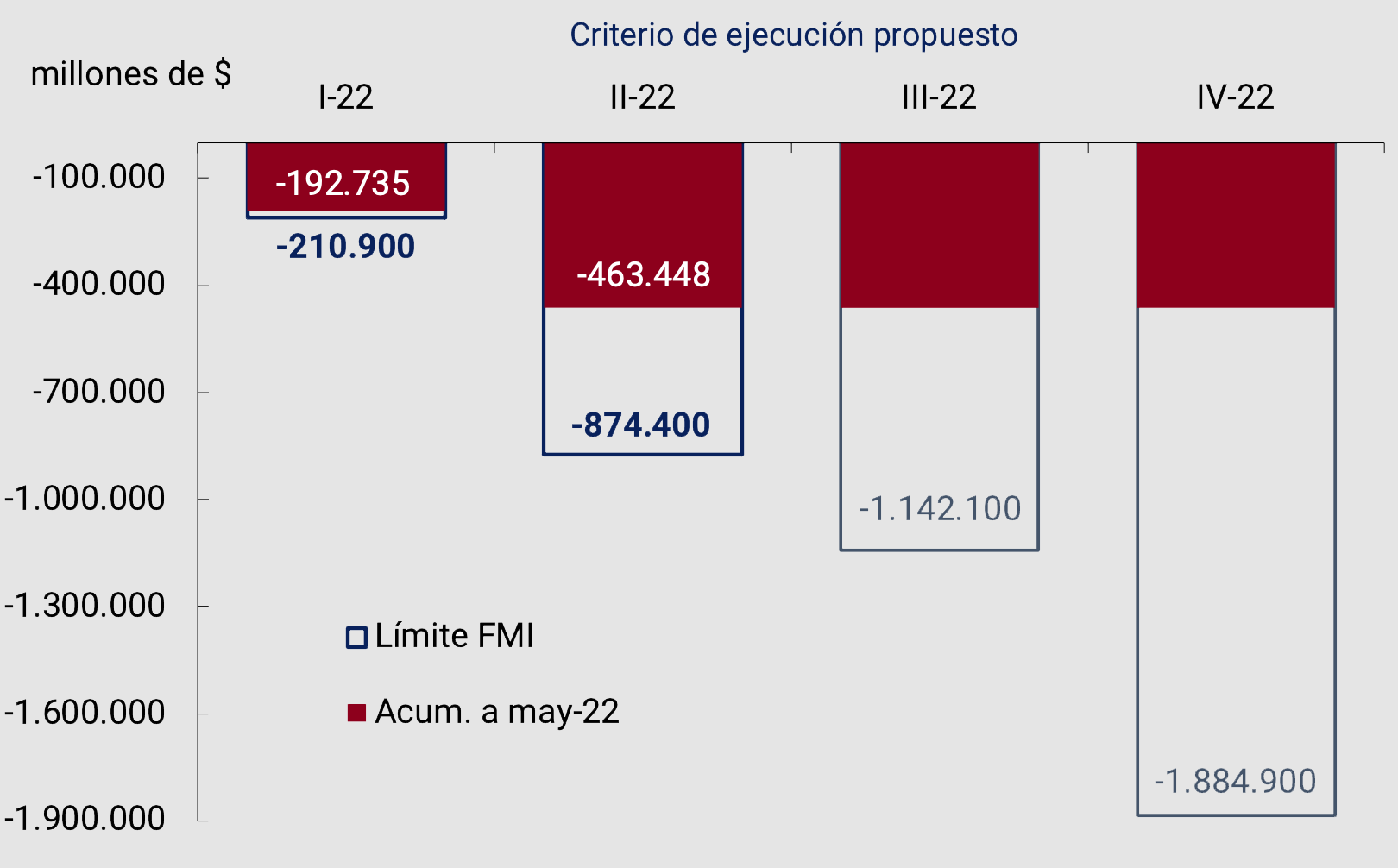

With respect to the Extended Facilities Program (PFE) with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the fiscal targets agreed upon for the first quarter of the year were met, while no modifications are expected for the annual primary deficit targets of the NFPS (2.5% of GDP) or financing by the BCRA to the National Treasury (1% of GDP). This implies the adoption of compensatory measures that reduce the magnitude of the deficit in the second half of the year. The National Government, through Decree 331/22, updated the National Budget, adapting it to the current conditions of the macroeconomic context. The Ministry of Economy has stated22 that the budgetary result derived from Decree 331/2022 is consistent with a projection of the primary deficit base cash of the National Public Sector (SPN) of 2.5% of GDP.

The stock of National Public Debt at the end of May23 , 2022 represented approximately 77% of GDP, exhibiting a reduction of about 12 p.p. compared to the end of 2019. The financing strategy made it possible to obtain net funding of about $660,000 million in the first five months of the year, while an extension of the terms of the instruments tendered in the market was sought, evidencing a growth in the share of debt adjustable by the Reference Stabilization Coefficient.

5.1. National tax collection grew in real terms during the first part of 2022, strengthening national tax revenues

National tax collection increased 58.9% during the first quarter of 2022 compared to the previous year (see Figure 5.1), which meant a real growth of 4%. With data up to May, during the second quarter collection accelerated to 72.2% y.o.y. (+7.9% y.o.y. in real terms). The performance of taxes during the first five months was mainly due to the consolidation of the economic recovery and the improvement in wages and employment. Taxes associated with foreign purchases maintained a high dynamism while export duties had a more limited advance, given the impact of the drought on the agricultural harvest, although sustained by higher international grain prices.

Figure 5.1 | Contribution to the growth of national tax

* Data as of May-22.

Source: BCRA based on AFIP data.

The vast majority of taxes related to the domestic market (Value Added Tax (VAT), Profits, among others) performed well at the beginning of the year, mainly due to the maintenance of the recovery of economic activity. Net VAT grew 55.9% YoY in the first quarter and 71.4% YoY with partial data in the second. On the other hand, the Tax on credits and debits in bank accounts advanced 64.3% YoY and 61.3% YoY in the first and second quarters to May, respectively. The exemption to the Health sector (which is maintained until June 2022) operates negatively on this tax. The income tax showed great dynamism: it grew 63.1% YoY between January and March and 94.2% between April and May. This is explained by improvements in the labour market, as well as by better results of companies with a balance sheet closure in December 2021 compared to the previous period.

Other taxes had a more irregular start to the year: Internal Taxes grew 39.2% YoY between January and March and 55.2% YoY between April and May, while Fuels advanced only 23.3% YoY and 29.7% YoY in the same periods, mainly due to the delay in updating the tax. On the other hand, Personal Assets advanced 33.6% YoY and 18% YoY in the first and second quarters respectively, affected by a high base of comparison: last year a payment on account for assets abroad had been paid in April, which did not occur this year.

Social security resources increased by 65% YoY between January and March and 74% between April and May, explained by improvements in the labor market (see Chapter 3. Activity and employment), both due to increases in registered employment and improvements in the real formal wage. It is worth adding that these resources continue to be negatively impacted by the measures taken by the National Government – which remain in place until June 2022 – which reduced employer contributions in the health sector, to the critical sectors contemplated in the REPRO program and to companies located in the provinces of the Norte Grande.

Import duties and the statistical tax showed a joint increase of 66.8% y.o.y. during the first quarter and 69.5% y.o.y. in the second. This behavior was explained by higher imported values (see Chapter 4. External Sector). Finally, export duties had a more limited performance: +46.4% YoY between January and March and +33% YoY between April and May, in a context of drought that affected agricultural production, which was partly offset by the favorable international context for international prices of the main export products and the recovery of external demand.

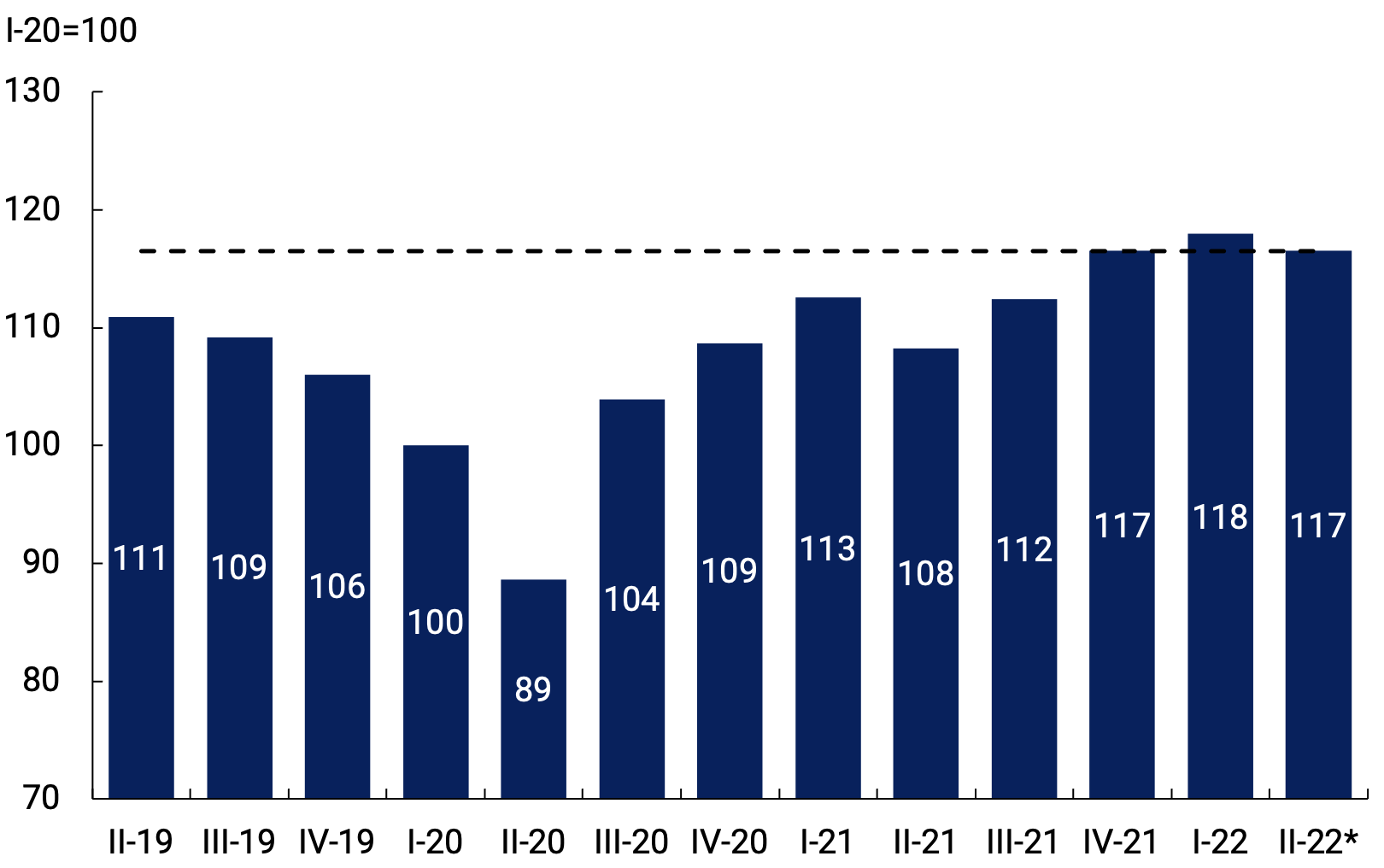

In real terms, seasonally adjusted national tax collection grew 1.2% in the first quarter of 2022 and fell by a similar magnitude during the second quarter with partial data as of May. In any case, this indicator was 16.6% above the pre-pandemic level between April and May (see Figure 5.2). This performance reflects the consolidation of the recovery in tax revenues after the harmful effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. In relation to 2019, the tax structure had been modified at the end of 2019, mainly from the creation of the PAIS Tax, the modification of the export duty rates, the changes on the Personal Property Tax, as well as the revision of the tax reform promoted during 2017 that affected social security resources.

Figure 5.2 | Real seasonally adjusted national

tax collection

Source: BCRA based on data from the Ministry of Economy and AFIP.

The evolution of tax revenues allowed the total revenues of the National Non-Financial Public Sector (NFPS) to increase in nominal terms by 66.6% YoY in the first quarter (+8.7% YoY in real terms) and 67.6% YoY in the second quarter (+5.2% YoY in real terms, with partial data as of May-22). The performance of resources was affected by the extraordinary registration of property income linked to the primary issuances of public securities24. For this reason, property rents increased 242% YoY between January and March and 325% YoY between April and May. Net of this effect, funds would have shown a nominal increase of 60% YoY in the first quarter and a similar figure in April. Tax and social security revenues increased by 58% YoY in the first quarter and 68.2% YoY in the second.

Meanwhile, the tax collection of the provinces as a whole exhibited a behavior consistent with what was observed at the national level. According to the partial information available for the main districts, in the first quarter of the year the nominal advance of own tax resources would have shown an increase of close to 55% YoY, while at the beginning of the second quarter it would have expanded by around 63% YoY.

5.2. NFPS primary expenditure expanded in real terms, with the boost of subsidies and social programs standing out in the face of the deterioration of the international context

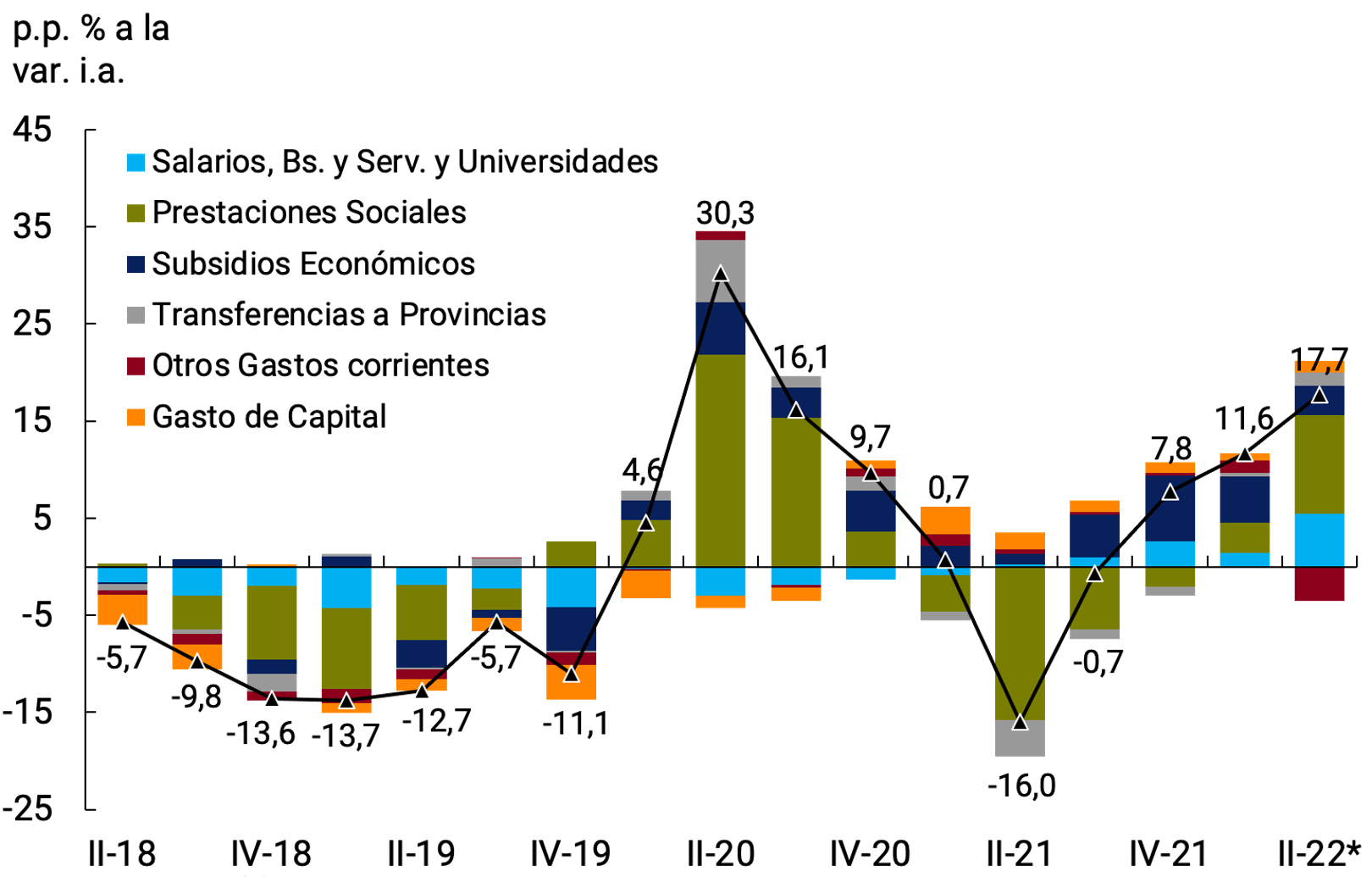

NFPS primary expenditure exhibited a nominal increase of 71.0% y.o.y. during the first quarter of 2022, slightly above the nominal advance of revenues in the same period. During the first quarter, real primary expenditures advanced 11.6% compared to the same quarter of 2021 (see Figure 5.3). However, the data for the months of April and May provide a growth in primary expenditure of 17.9% in real terms for the second quarter of the year compared to April and May 2021.

Figure 5.3 | NFPS

Real Primary Income and Expenditures

* Net of Special Drawing Rights (SDR) Allocation in Sep-21.

** Data as of May-22.

Source: BCRA based on data from the Ministry of Economy and INDEC.

Spending grew in a widespread manner among the main items, although the increases in social programs, economic subsidies and current transfers to the provinces stood out. This evolution reflected the impact of the external context on public finances: the sharp rise in international energy prices increased the magnitude of economic subsidies – given the proposed tariff update path – while the National Government implemented extraordinary reinforcements of household income in the face of the abrupt rise in food prices worldwide.

Figure 5.4 | NFPS

seasonally adjusted real primary expenditure

*Data as of May-22.

Source: BCRA based on data from the Ministry of Economy and INDEC.

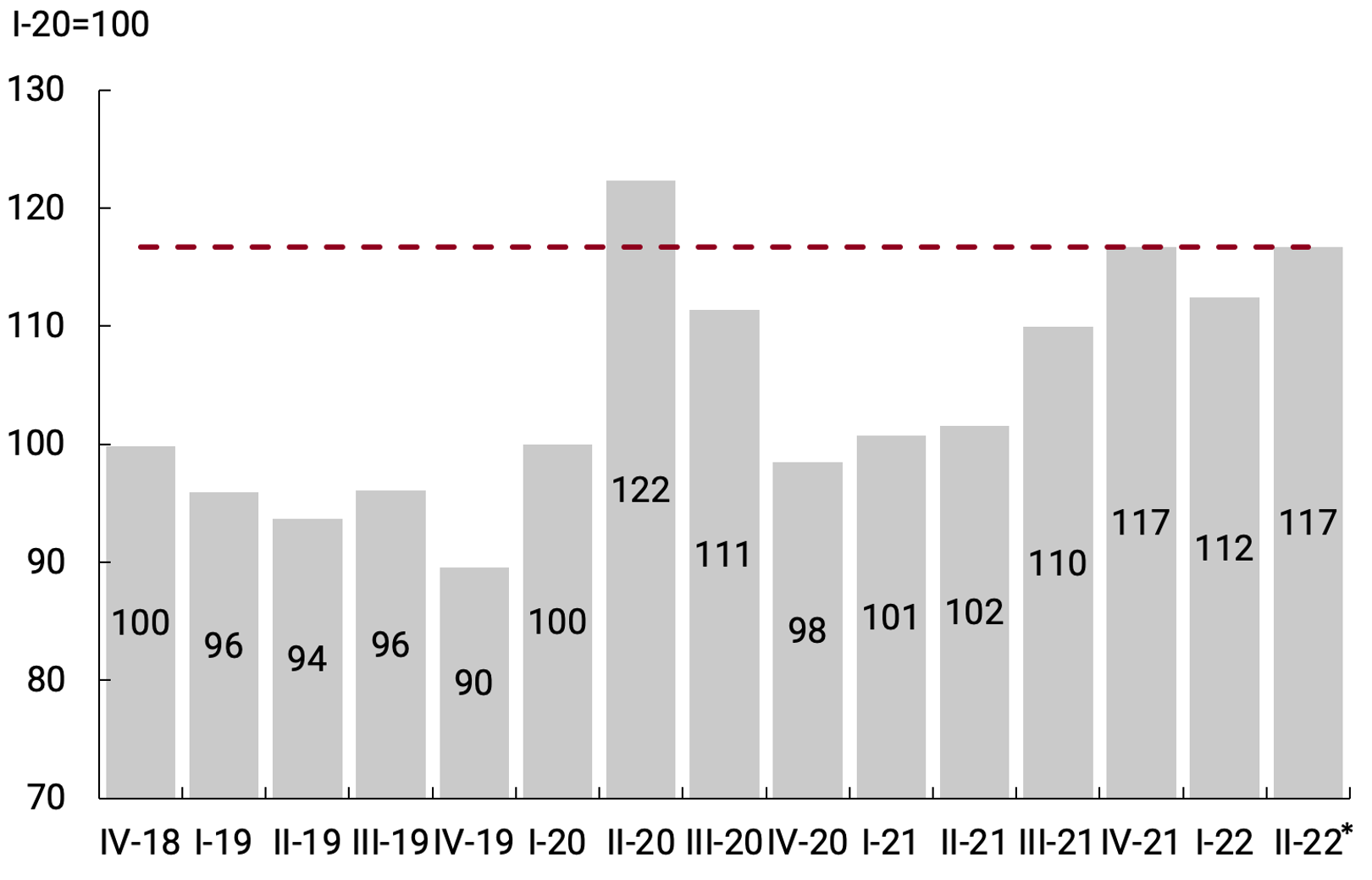

In this regard, seasonally adjusted real primary expenditure was 17% above the pre-pandemic level (I-20) and the fourth quarter of 2018 in the fourth quarter of 2021 (see Figure 5.4). In the first quarter of 2022, this level had fallen by 5 percentage points; however, considering the social containment measures adopted and the higher costs of subsidies in the face of the international shock of commodity prices, a real level similar to that of the end of 2021 was recovered.

Among the main items of expenditure that explain this evolution are social benefits and economic subsidies (see Figure 5.5). Expenditure on pension benefits (retirements and pensions) increased by 5.3% YoY in real terms in the first quarter of the year and by 3.6% YoY during the months of April and May. This behavior is influenced by the provisions of the salary adjustments in accordance with the Pension Mobility Law25, which established a variation of 58.62% y.o.y. in the salaries to March, 3.5 p.p. more than the accumulated inflation in the last 12 months to March 2022. In June, the more than 7 million people who are holders of retirements and pensions will automatically contemplate the half bonus together with their assets, while they will receive their pension benefits with the 15% increase corresponding to the second quarterly increase in the year provided for by the Pension Mobility Law. This improvement also includes family allowances, including the Universal Child Allowance (AUH) and Pregnancy Allowance, impacting the income received by almost 9 million children and adolescents.

Figure 5.5 | Contribution to the growth of primary expenditure of the NFPS

*Data as of May-22.

Source: BCRA based on data from the Ministry of Economy and INDECs.

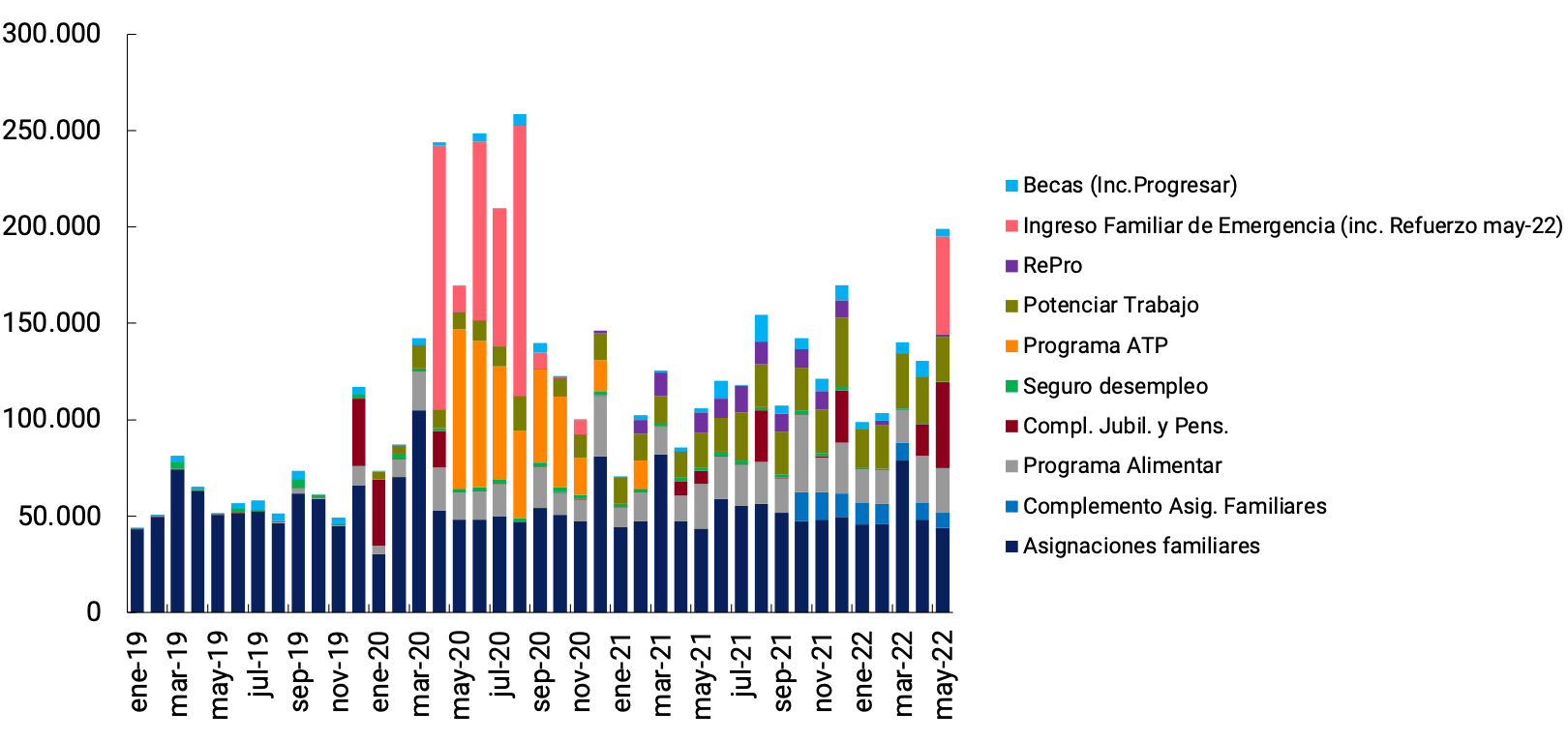

As for the remaining social benefits, these expenditures had a slight reduction in real terms during the first quarter, but a strong real boost from the months of April and May (51.3% YoY). This was due to the income reinforcement policies carried out by the National Government to protect and improve the purchasing power of households in the face of the sharp increase in food prices globally. In this way, some 7.5 million people with informal jobs, in private homes, social monotributistas and categories A and B received economic assistance during May and June of $9,000. On the other hand, around 6 million retired people and pensioners with monthly incomes of less than 2 minimum salaries, received together with their May salaries a sum of $12,000, which is in addition to the $6,000 bonus in April for those who receive a minimum pension.

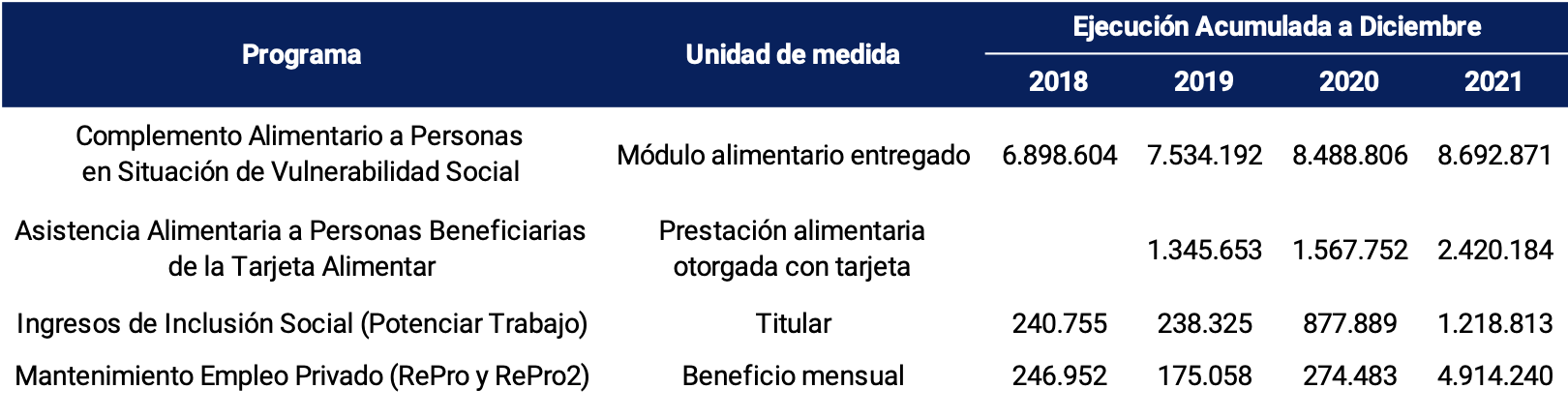

In this category of social benefits, a large part of the programs to sustain income have been incorporated since 2020 (such as the Emergency Family Income (IFE) and the Emergency Assistance Program for Work and Production (ATP). Once the stage of Mandatory Preventive Social Isolation (ASPO) due to the COVID-19 pandemic was over, these programs gave way to income and employment programs such as the Productive Recovery Program (REPRO)26 or the National Program for Socio-Productive Inclusion and Local Development “Empower Work”27, which provide assistance for up to a maximum of fifty percent 50% of the value of the Minimum Living and Mobile Wage28 (SMVyM; see Section 3 / Measures taken to reinforce income). In the second quarter, the disbursements of the Food Policies program are also highlighted, which had a 50% increase in the benefit, which 2.4 million beneficiaries receive and reaches 4 million people, bringing the new amounts since May to $9,000 for families with a child up to fourteen years of age or disabled or receive the pregnancy allowance. $13,500 in the case of families with two children and $18,000 in the case of families with three or more children under 14 years of age. For their part, for all workers who receive family allowances, since October 2021 a monthly supplement has been in force that doubled the family salary for those who received family incomes of up to $115,062 and that with the successive increases in the family salary was losing share.

On the other hand, the attention to the requirements to pay for the provision of public services until the end of May, in a context of rising energy and fuel costs – as a result of the war between Ukraine and Russia – and the higher domestic costs of electricity production due to the lower contribution of hydroelectric generation (in a context of low rivers due to drought), led to economic subsidies accounting for a growing portion of primary expenditure, growing 45.2% YoY in real terms in the first quarter of the year and 22.3% YoY in real terms in April and May. This increase in participation was mainly due to the increase in expenditure associated with energy subsidies and subsidies for public passenger transport.

In relation to electricity and gas tariffs, a segmentation of subsidies was formalized with an effective date as of June 202229. The new subsidy regime defines three segments of users, classified by the Ministry of Energy according to objective criteria of income and externalization of assets. Those with higher incomes will pay the full cost of electricity and natural gas services. There will be a harmonization process and the subsidy removal will be carried out gradually and in bimonthly thirds, so that people within this segment will be paying the full cost of energy by the end of 2022. Secondly, for the lower-income segment, energy increases may not exceed 40% of the increase in the Wage Variation Coefficient (CVS) of the previous year. Finally, for middle-income users, the tariff increases will be up to 80% of the CVS growth. The middle- and low-income segments will not have a new increase in bills for the year 2022.

Items associated with salaries (including transfers to National Universities) and operating expenditure grew 7.1% YoY in real terms in the first quarter of the year and 13% YoY in real terms in April and May. It should be noted that the latter item includes purchases of goods and services (including expenditures associated with the purchase of COVID-19 vaccines and expenses associated with the organization of the National Census). On the other hand, current transfers to provinces30 boosted their rate of increase (+10.6% real y.o.y. during the first quarter and 45.4% y.o.y. real between April and May).

Capital spending, in line with the definition of priorities set out to sustain the recovery of economic activity, grew 11.2% YoY in real terms during the first quarter and 16.2% YoY in April and May.

Considering that in the first five months of 2022 NFPS revenues grew 67% YoY (7.2% YoY in real terms), and that primary expenditures advanced 78.2% YoY (+14.1% YoY in real terms), the NFPS primary deficit stabilized at around 3.1% of GDP (see Figure 5.6). For its part, the financial deficit of the NFPS accumulated in the same period stood at 4.5% of GDP. The National Government updated the National Budget31 , adapting it to the current conditions of the macroeconomic context, in order to establish a framework of predictability for fiscal and financial management, determining a new calculation of resources and credits of the National Public Administration (APN), as well as a determination of the primary deficit on an accrual basis. The Ministry of Economy has stated that the result derived from the budget modification is consistent with a projection of the primary deficit base cash of the NFPS of 2.5% of GDP.

Figure 5.6 | Fiscal Result of the National Non-Financial

Public Sector Accumulated 12 months

Note: the allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) of the IMF for $427,400 million in Sep-21 are excluded among the Revenues.

Source: BCRA based on data from the Ministry of Economy and INDEC.

Box. Meeting the fiscal targets agreed with the IMF

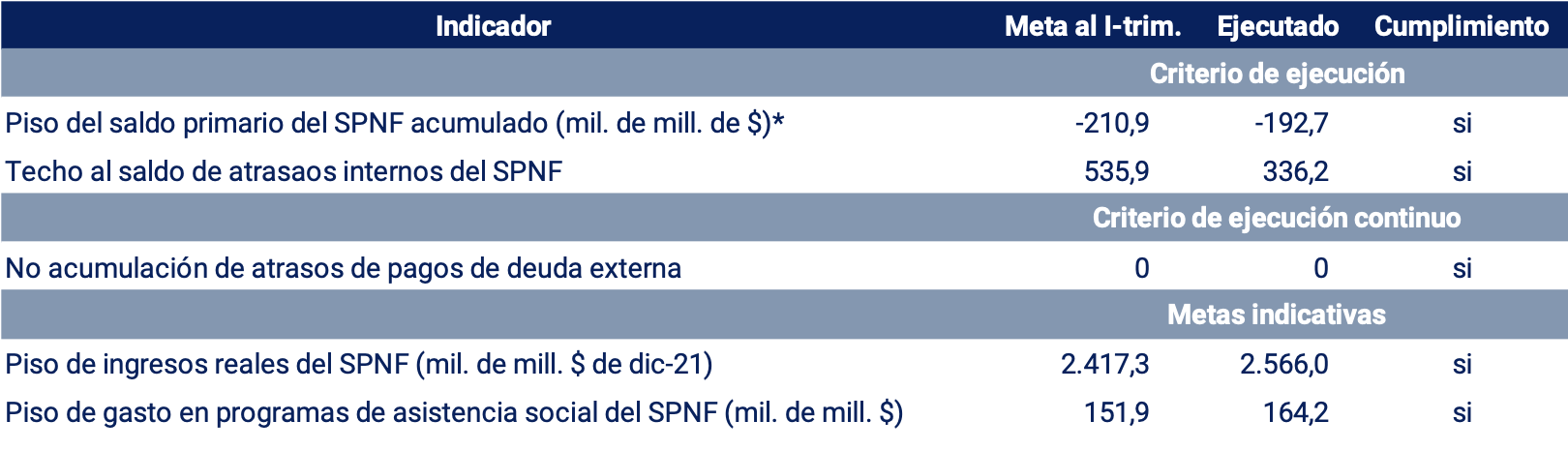

During the first quarter, the fiscal targets agreed upon under the Extended Facilities Program (PFE) were met, as detailed in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 | Fiscal targets under the Extended

*Adjusted according to adjustment factors defined in the Technical Memorandum of Understanding with the IMF.

Source: BCRA based on the First Review of the Extended Facilities Program (IMF).

On the one hand, the primary result of the NFPS cumulative to March 2022 was $192.7 billion, $18.2 billion below the quantitative target stipulated by the PFE. Second, the indicative target for the NFPS real income floor was comfortably met for the first three months of 2022. Real income was 6.2 per cent higher than the indicative target. Third, the agreement incorporated a target for a real social expenditure floor. Social spending included expenditures for the Universal Child Allowance, the Progresar plan and food programs. The sum of these expenditures resulted in the accumulated of the first three months of 2022 at around $164.2 billion, complying with the indicative floor of the agreement. Fourth, the financing of the National Treasury by the BCRA through Transitory Advances did not exceed the ceiling indicated in the PFE targets: $122 billion of this type of financing was accumulated, some $115 billion less than the ceiling provided for in the agreement (see Figure 5.7).

Figure 5.7 | Accumulated Primary Deficit and IMF

Note: Targets subject to adjustment factors defined in the Technical Memorandum of Understanding (IMF).

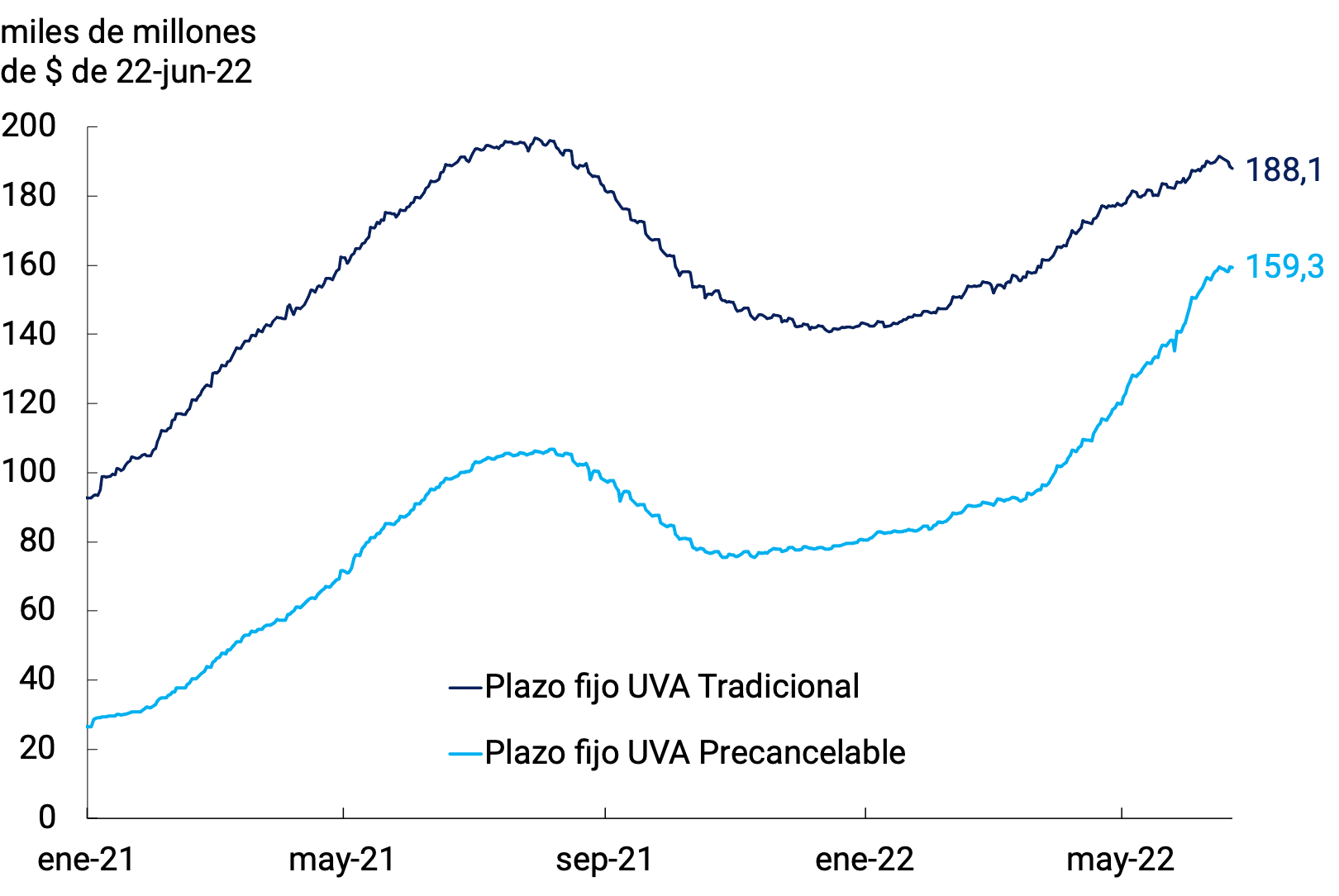

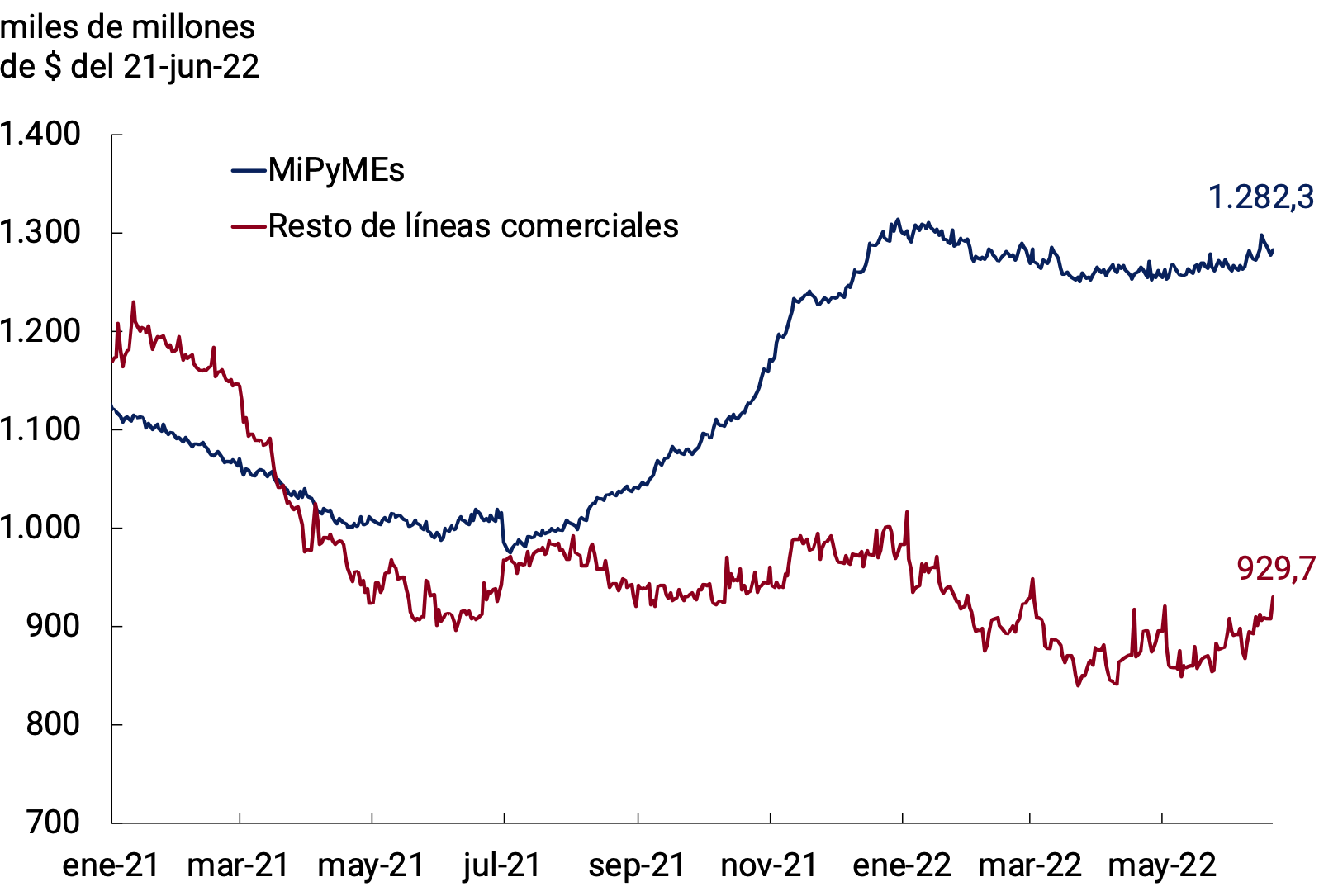

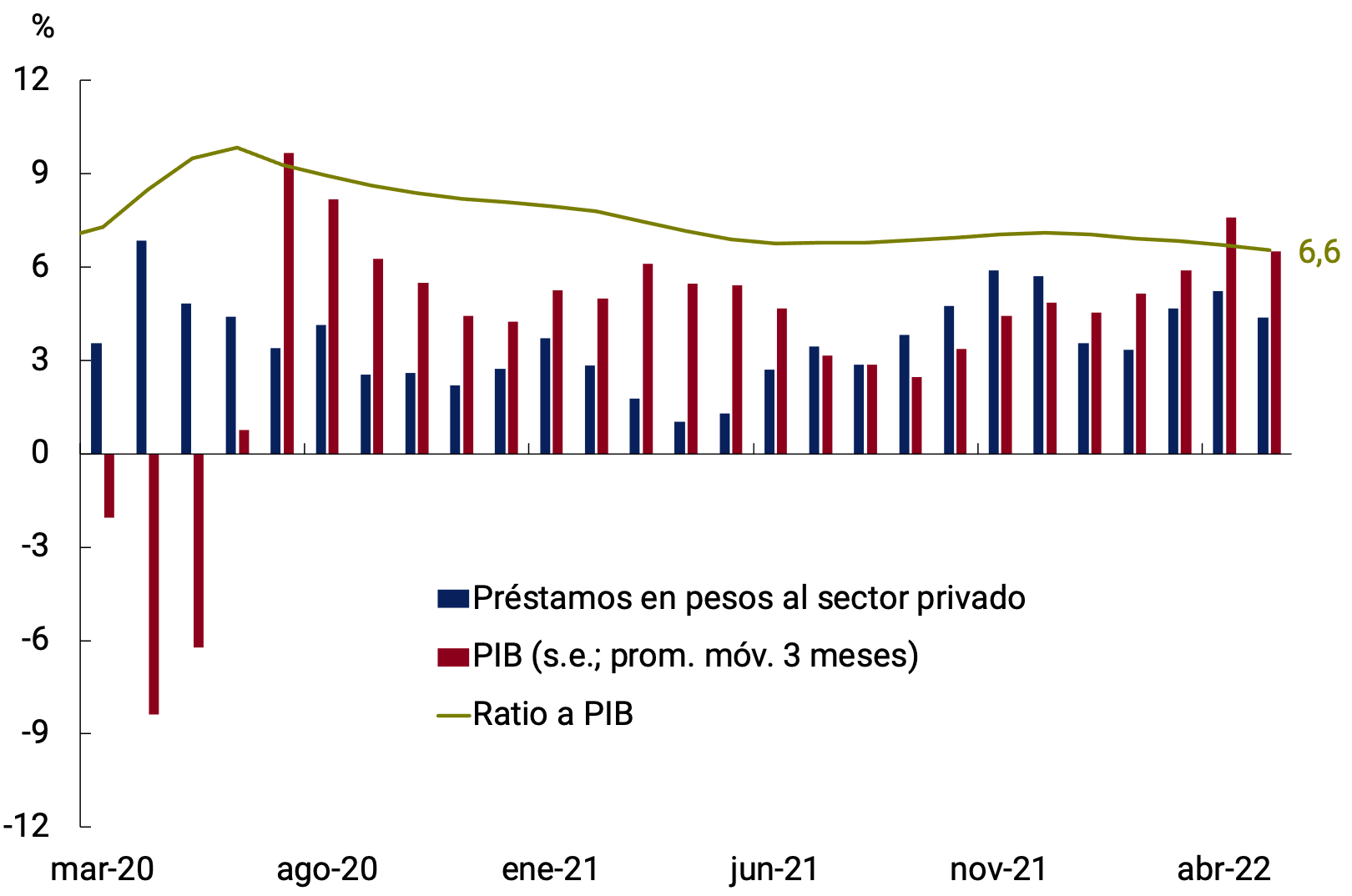

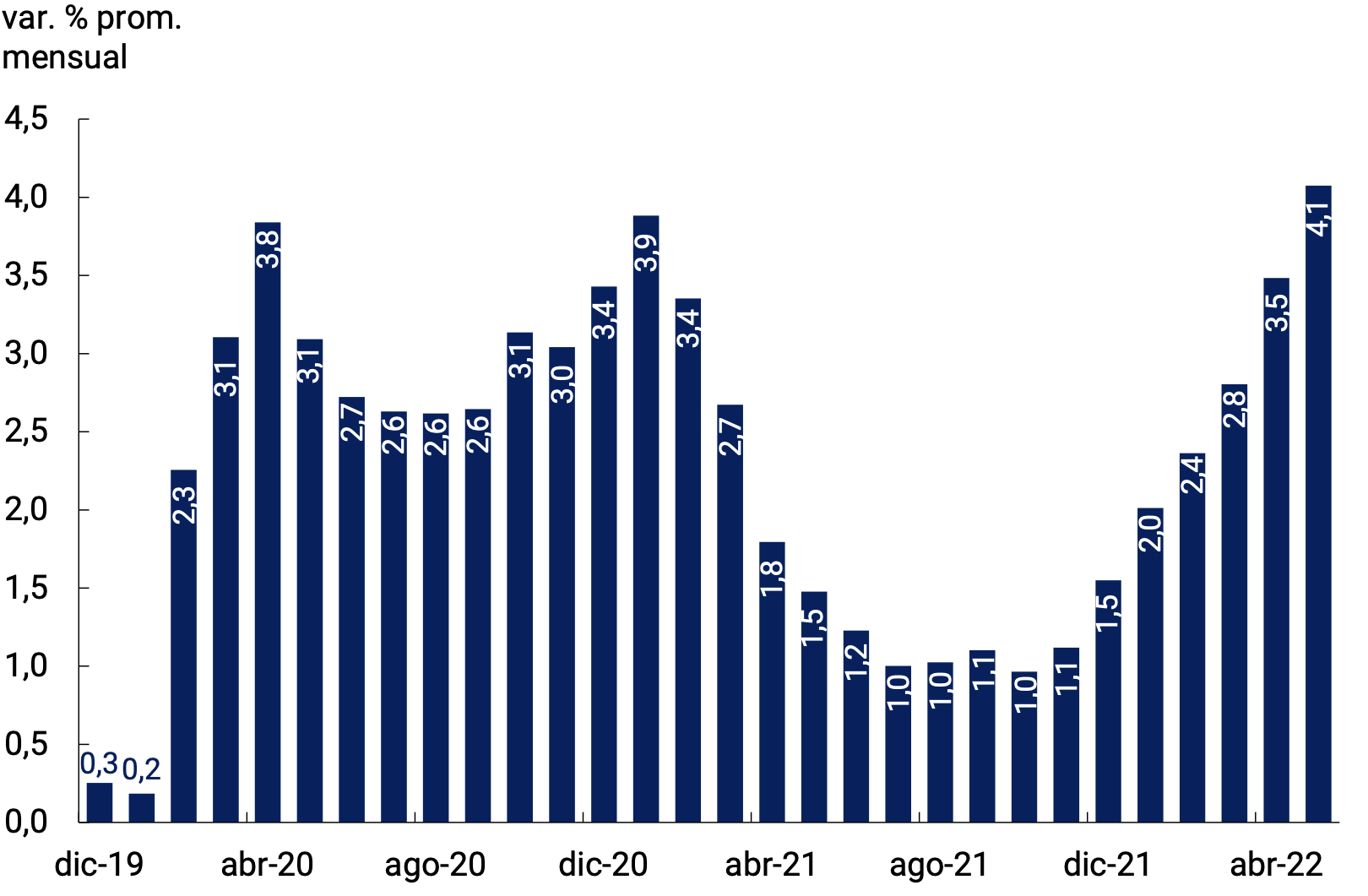

Source: BCRA based on data from the Ministry of Economy and IMF.