Política Monetaria

Monetary Policy Report (IPOM)

Second Quarter

2021

Publication that aims to explain in a transparent manner the reasons of the BCRA for its monetary policy decisions.

Table of Contents

Chapters

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlook

2. International context

3. Economic Activity and Employment

4. External Sector

5. Public Finance

6. Prices

7. Monetary Policy

Sections

1. The new allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs): what it is and what it means for developing

countries 2. The challenge of central banks in the face of climate

change 3. Changes in work modalities: Telework in Argentina

4. The change in the external debt of the private sector during 2020

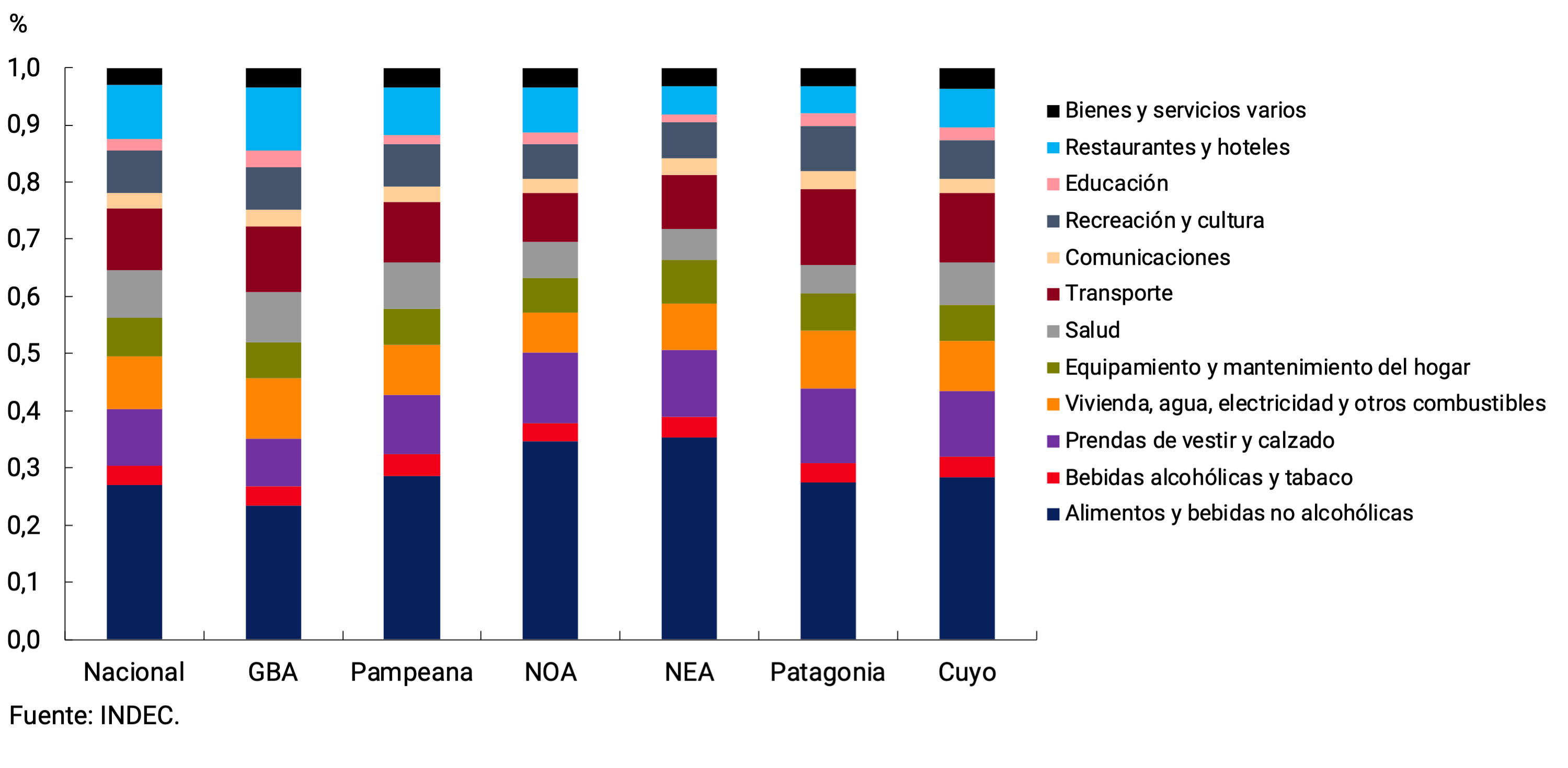

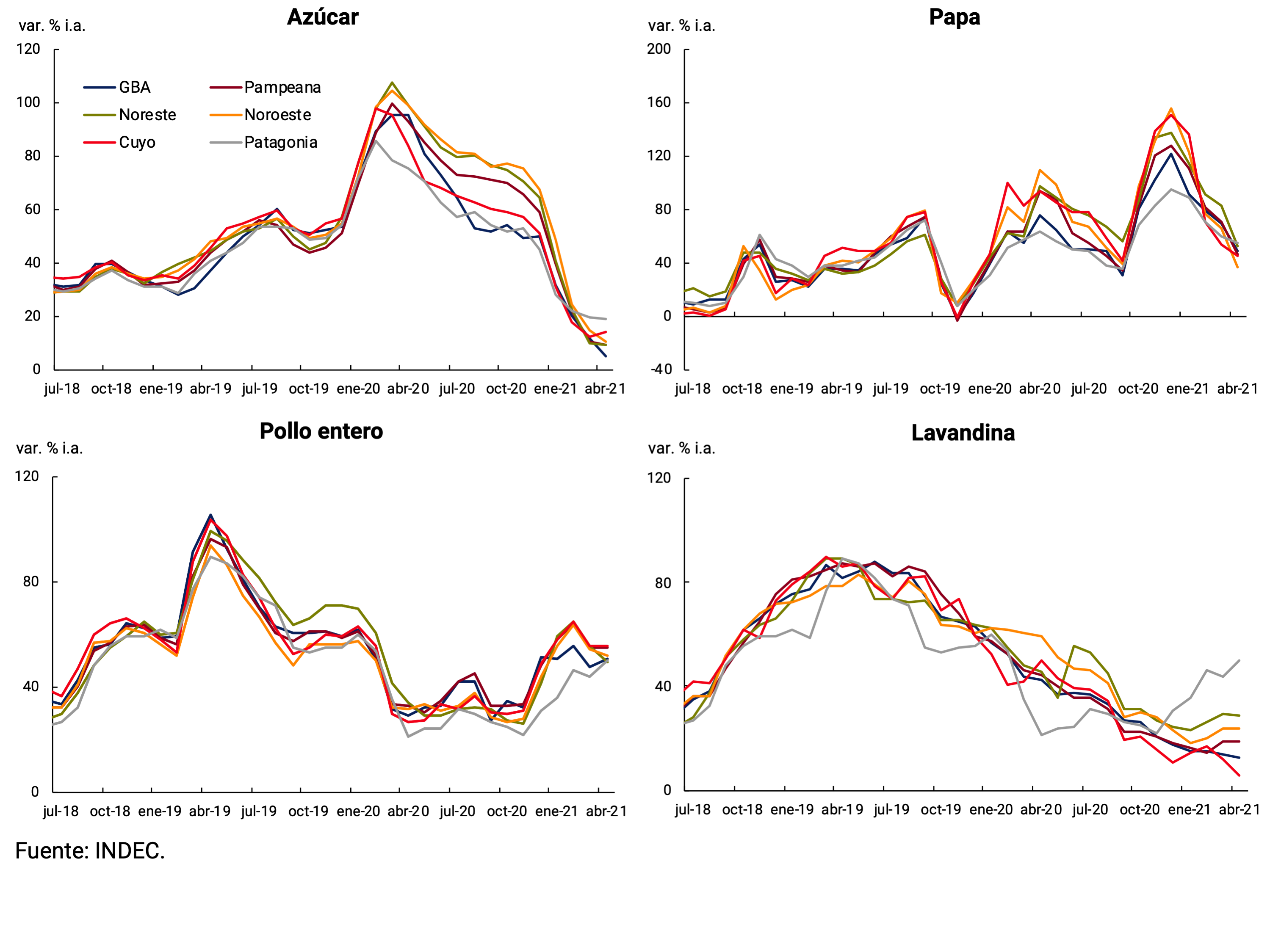

5. Regional opening of retail

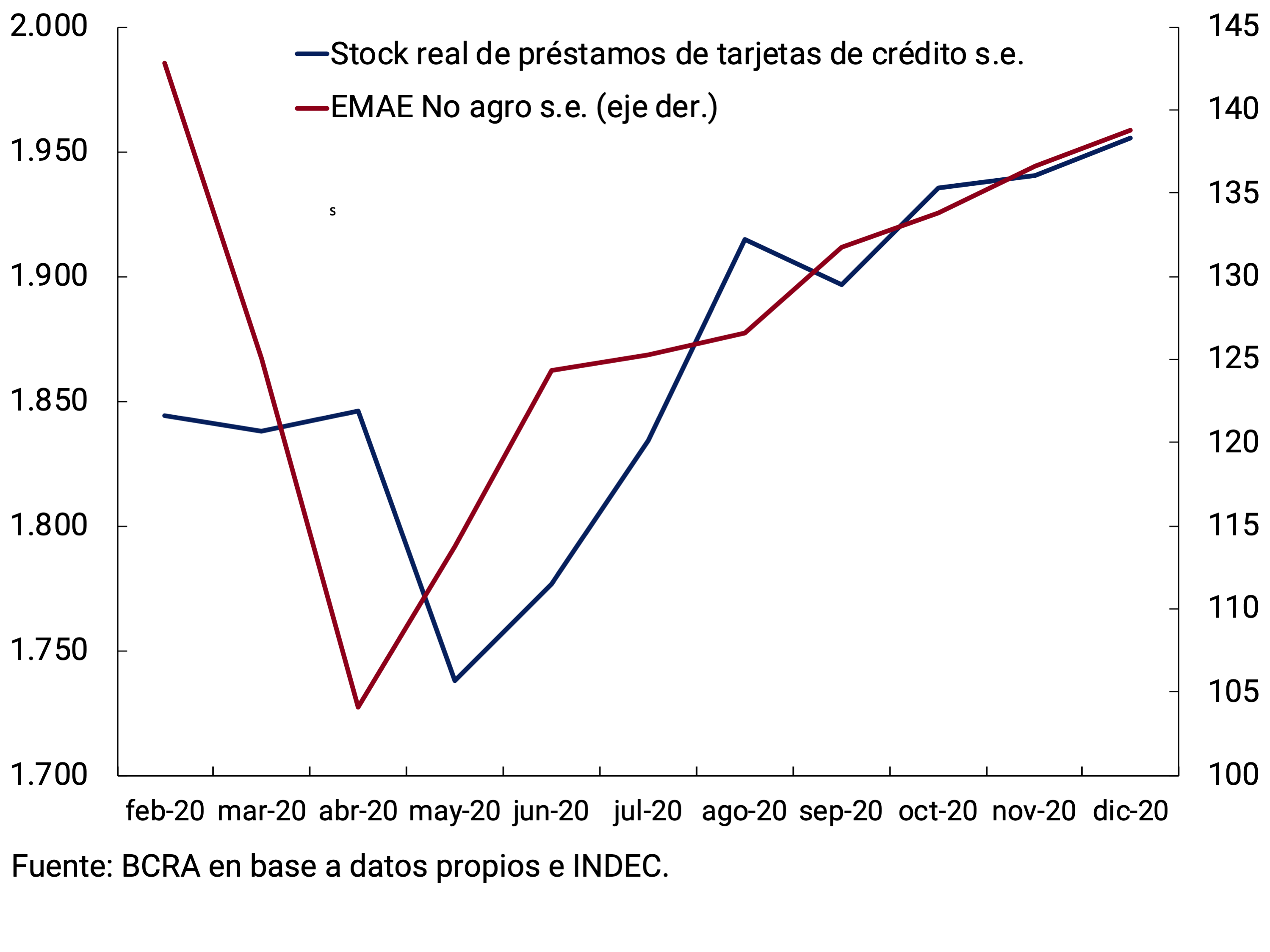

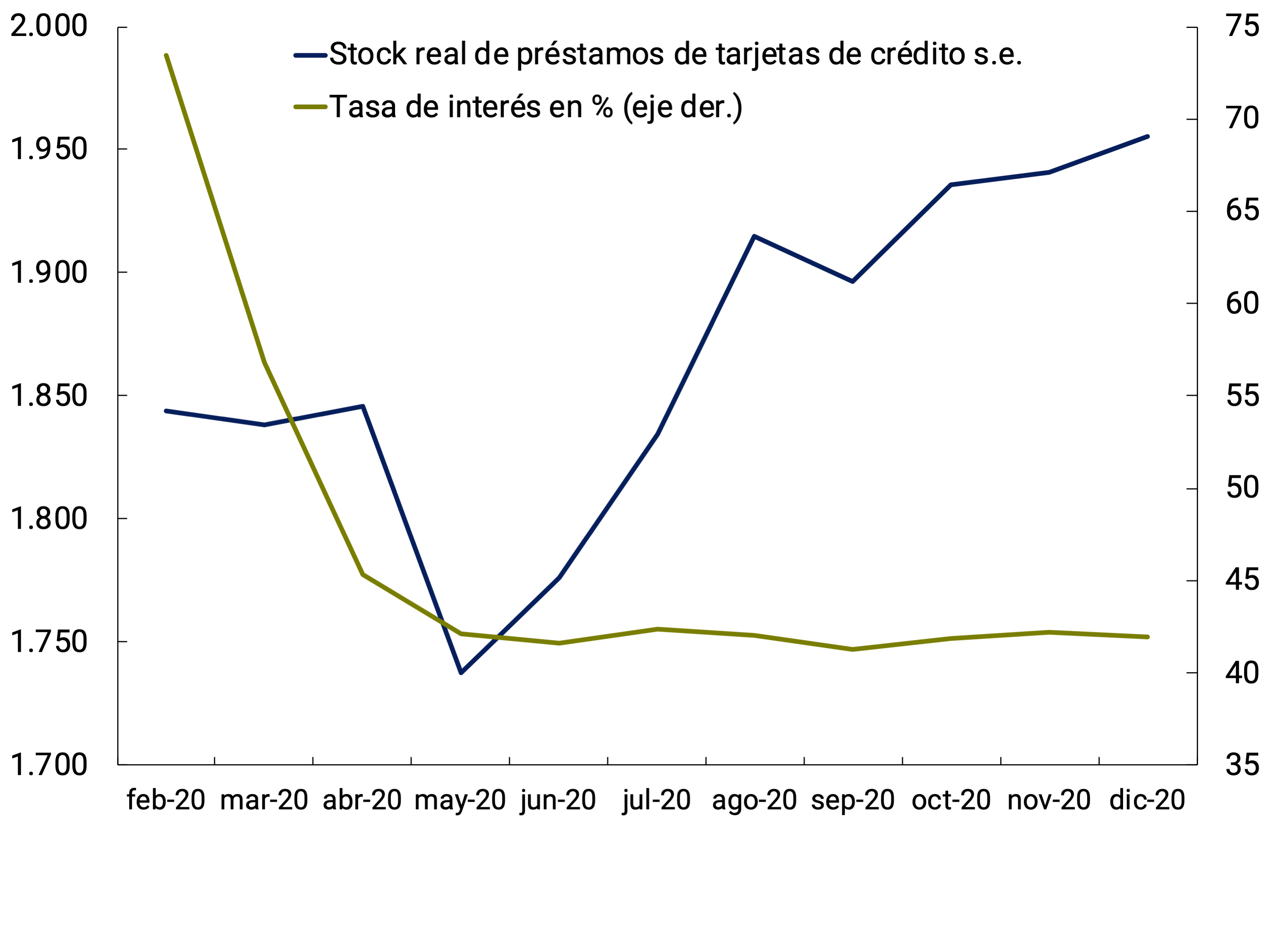

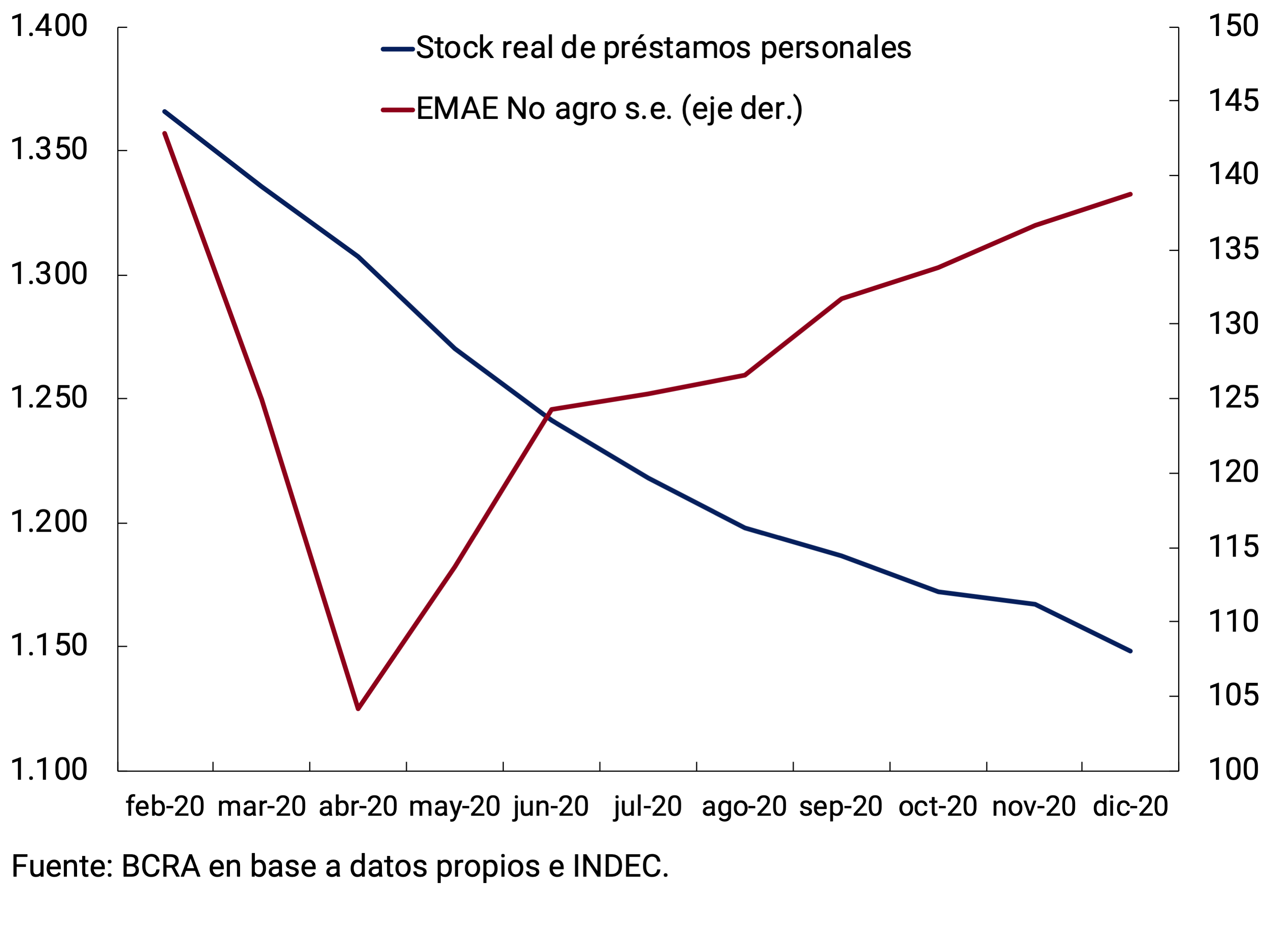

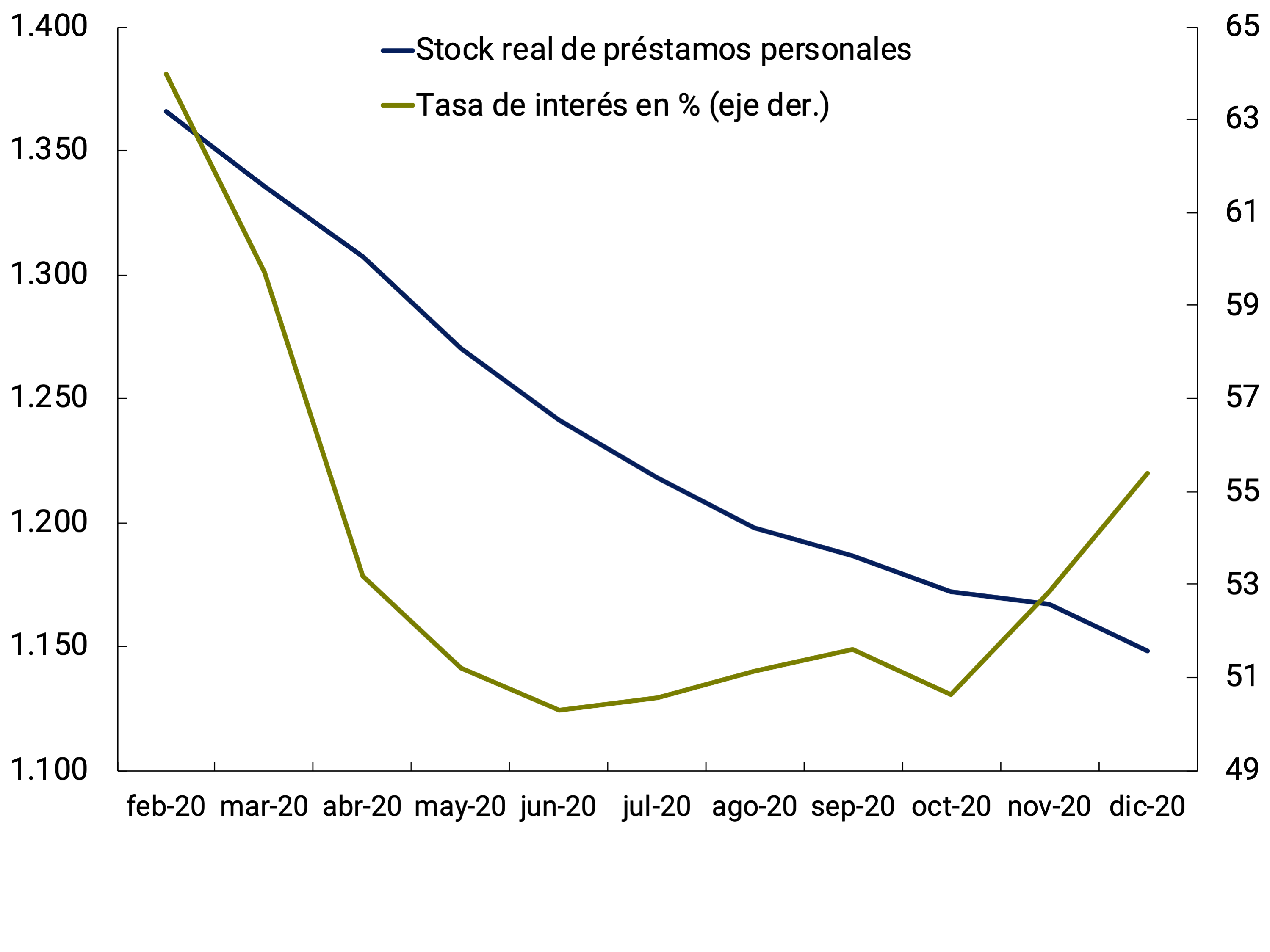

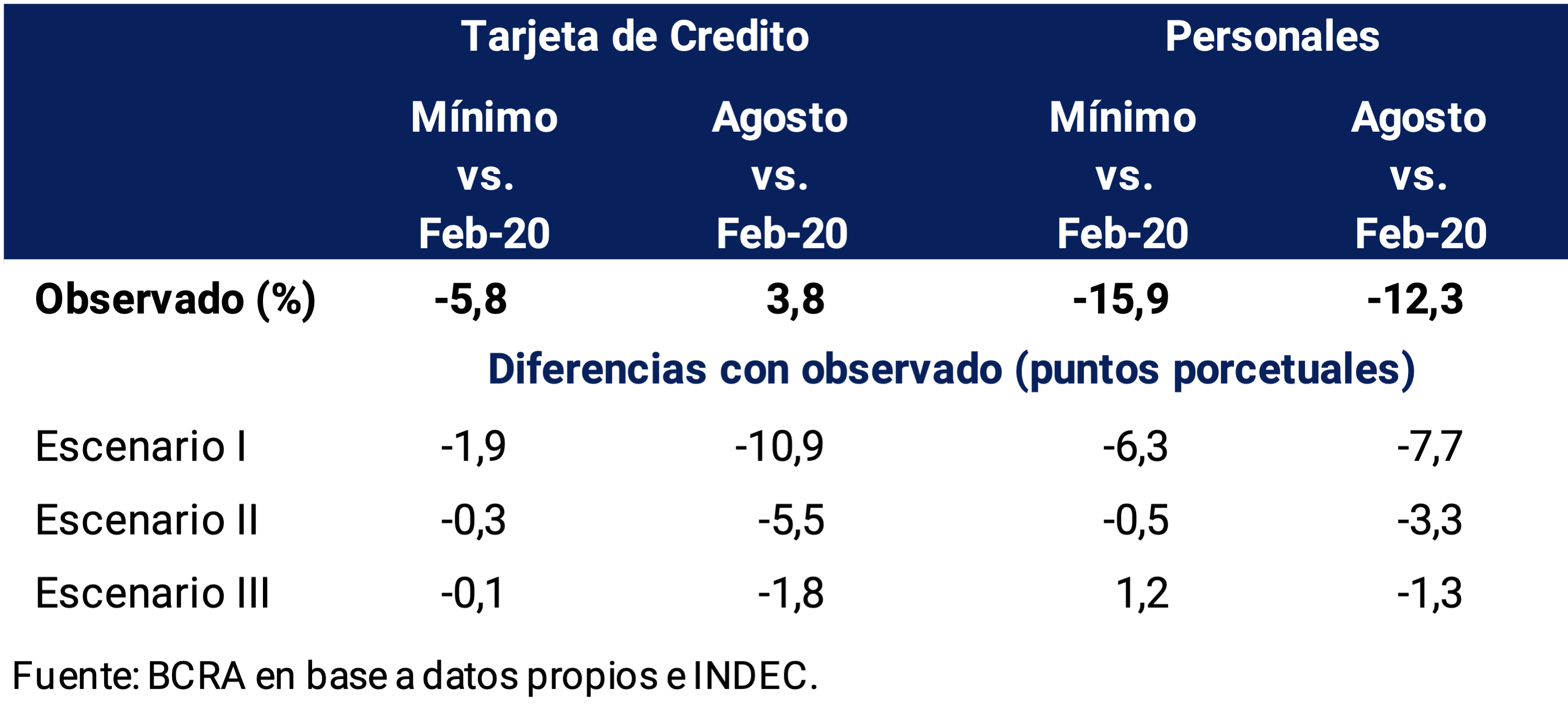

price developments 6. Consumer-linked loans during 2020

For inquiries, write to politica.monetaria@bcra.gob.ar

Summary

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlook

Despite significant progress in the fight against COVID-19, the global rate of infections and deaths has intensified since the publication of the last IPOM. Under this scenario, the world economy continued to recover, but at a heterogeneous pace and with several factors of uncertainty ahead. The outlook for the coming months is conditioned by the progress in the vaccination process and the effect of monetary and fiscal stimulus policies, especially those driven by the central economies.

Argentina registered a worsening of the epidemiological picture in mid-March. With the arrival of the second wave of COVID-19, the National Government implemented new restrictions on mobility to slow down the speed of infections. These measures were, so far, of less intensity than those implemented a year ago, specific to each jurisdiction and calibrated taking into account the progress of vaccination and the strengthening achieved in the health system. To contain the economic and social effects of this second wave, the National Government focused its assistance programs on the most vulnerable social strata and on helping companies in the affected jurisdictions.

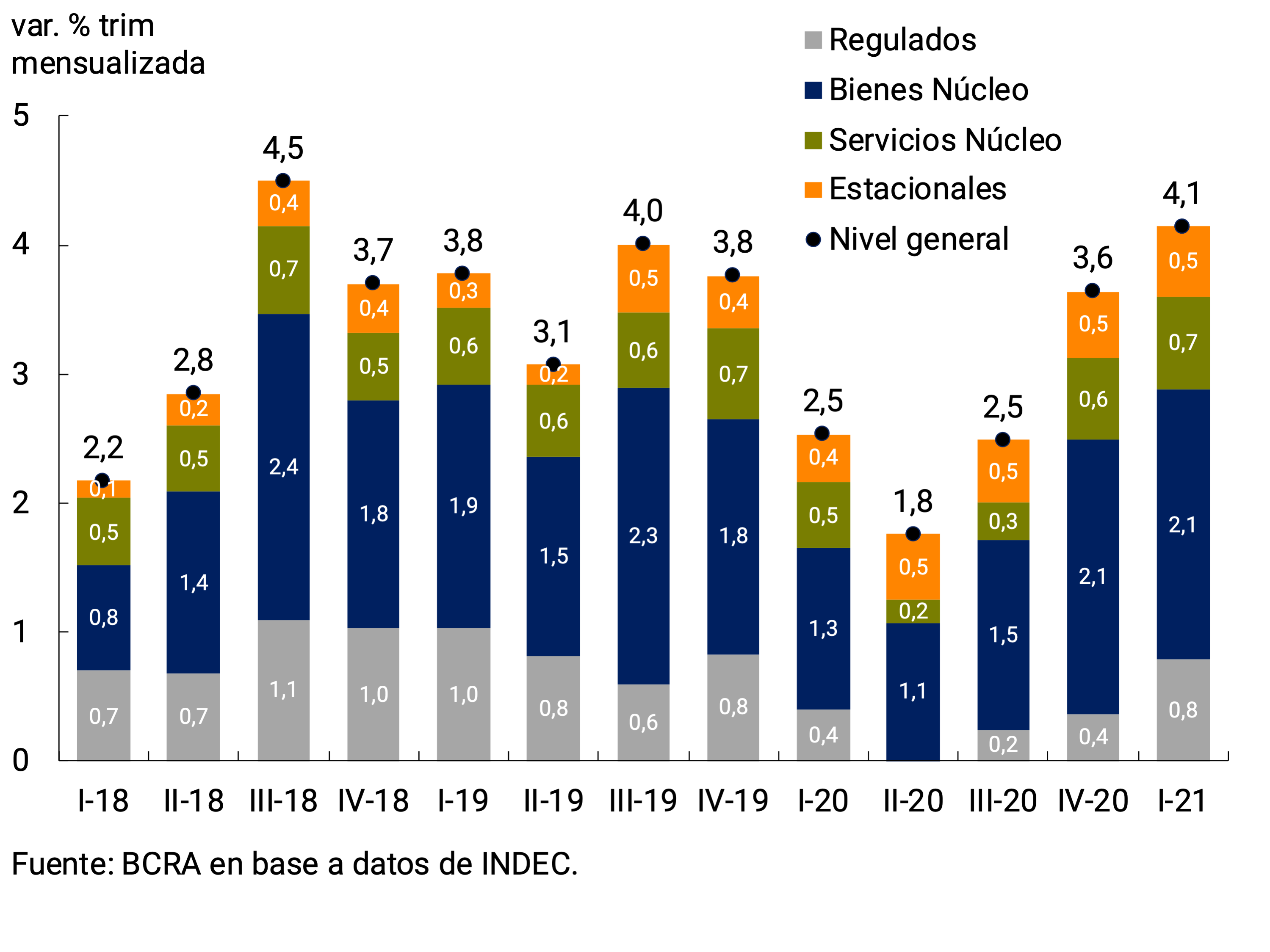

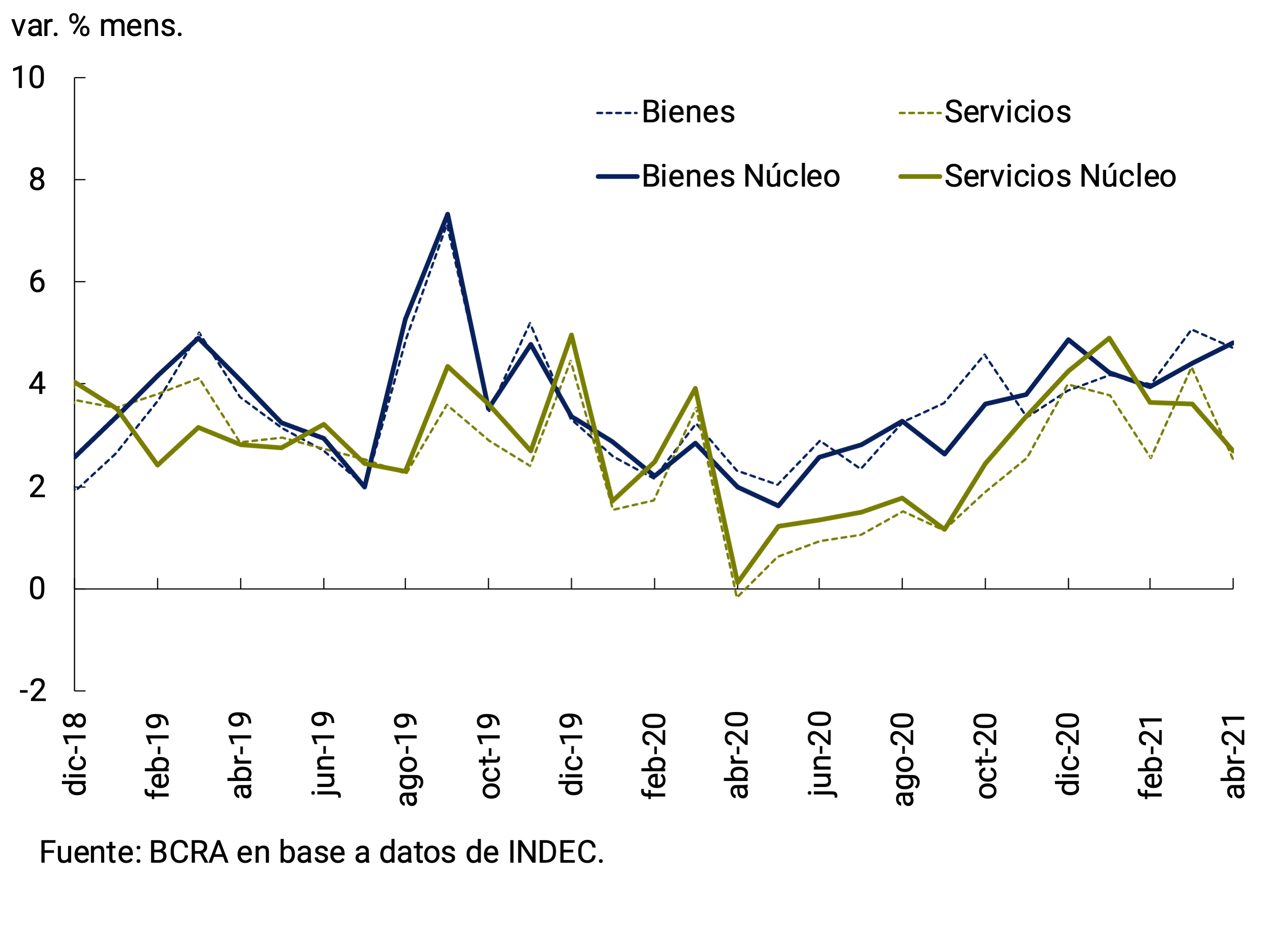

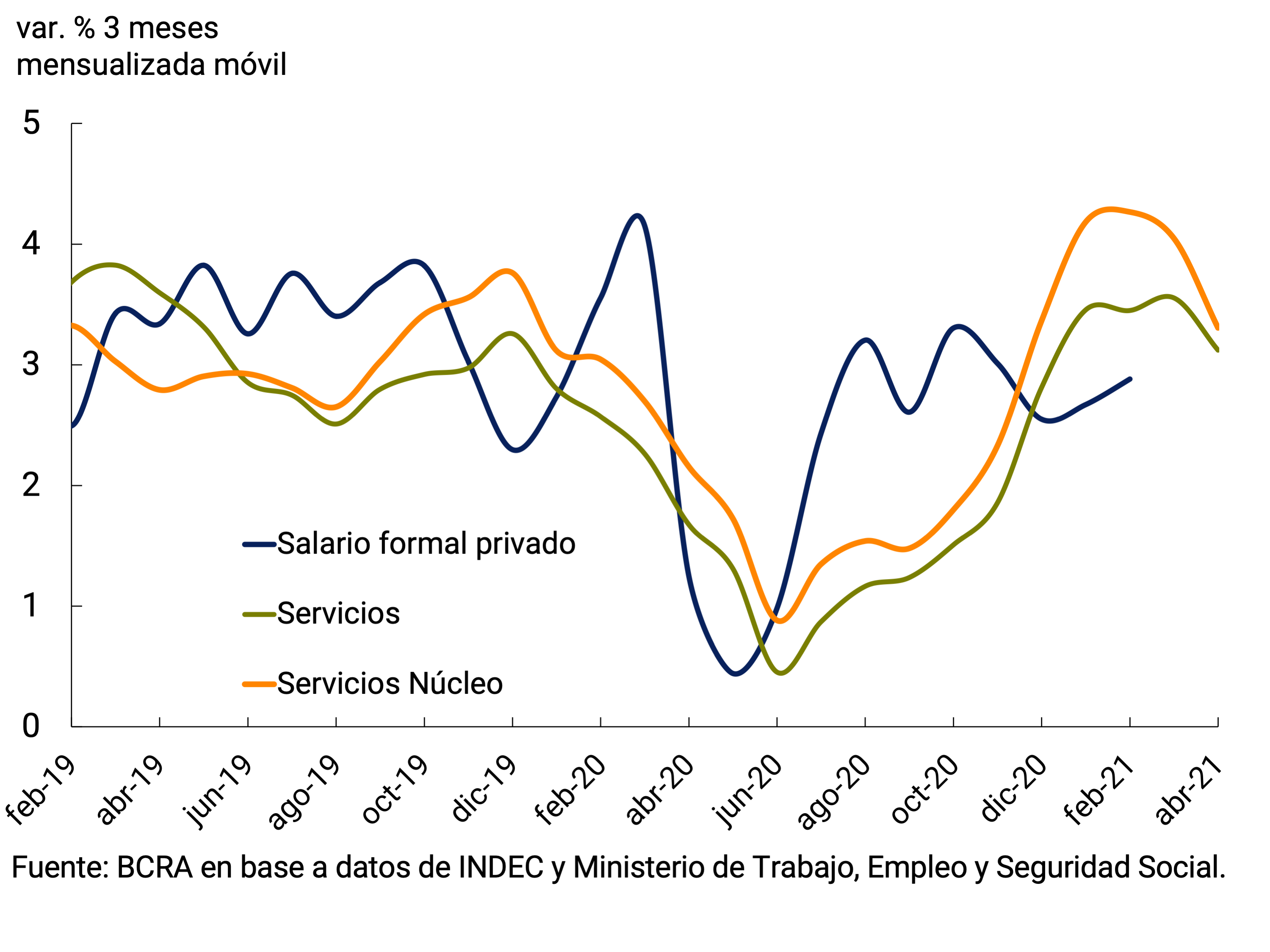

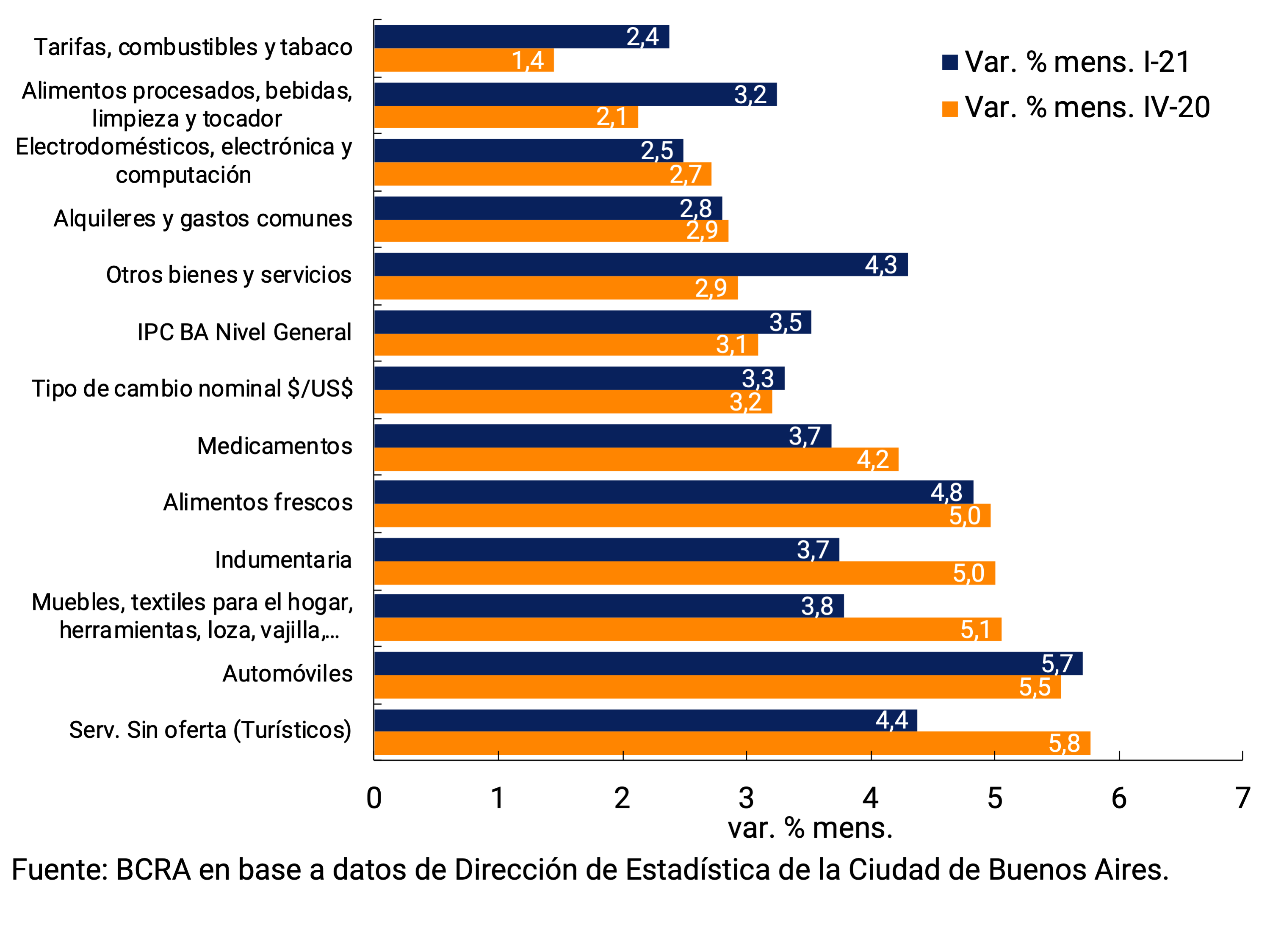

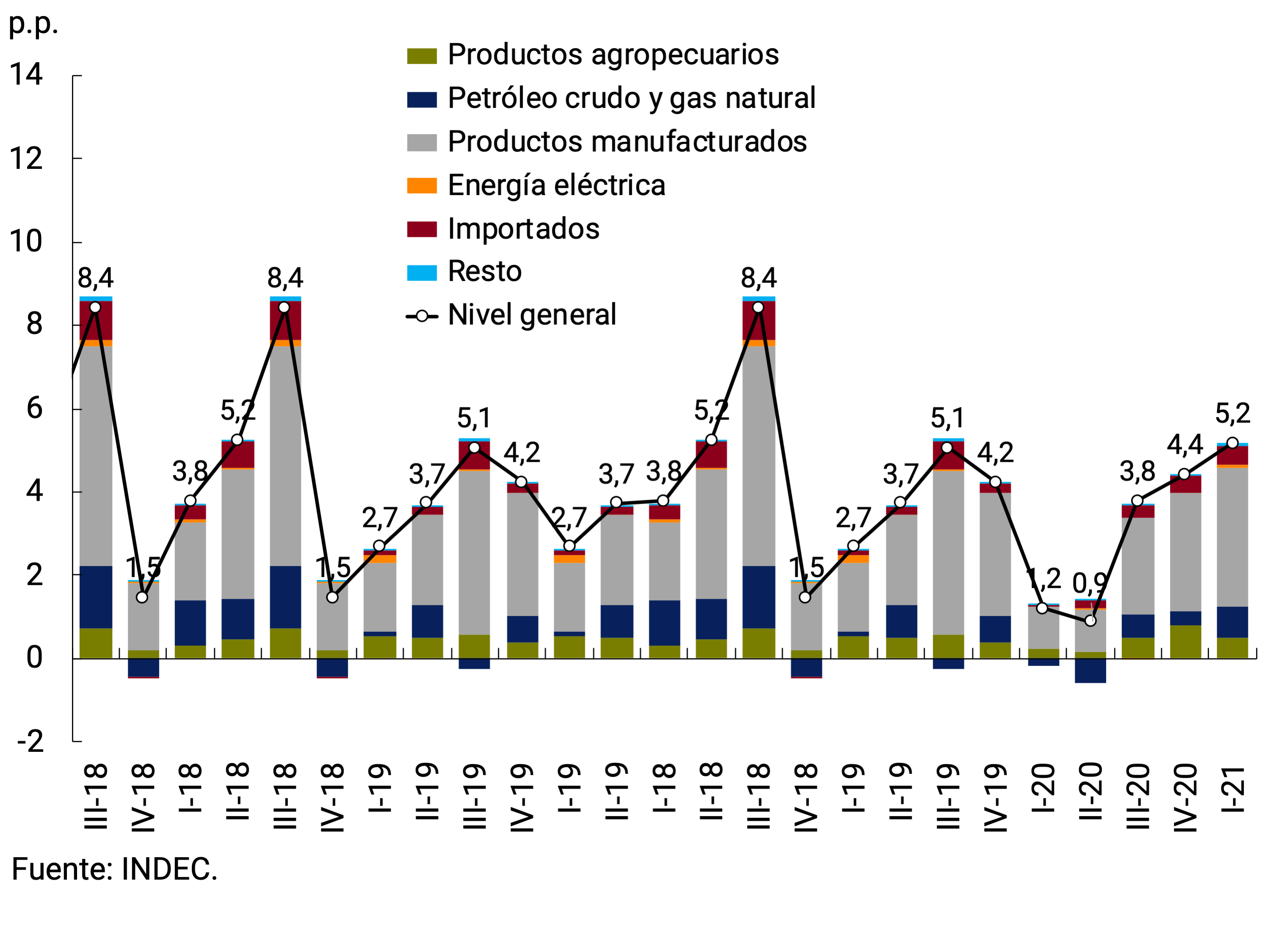

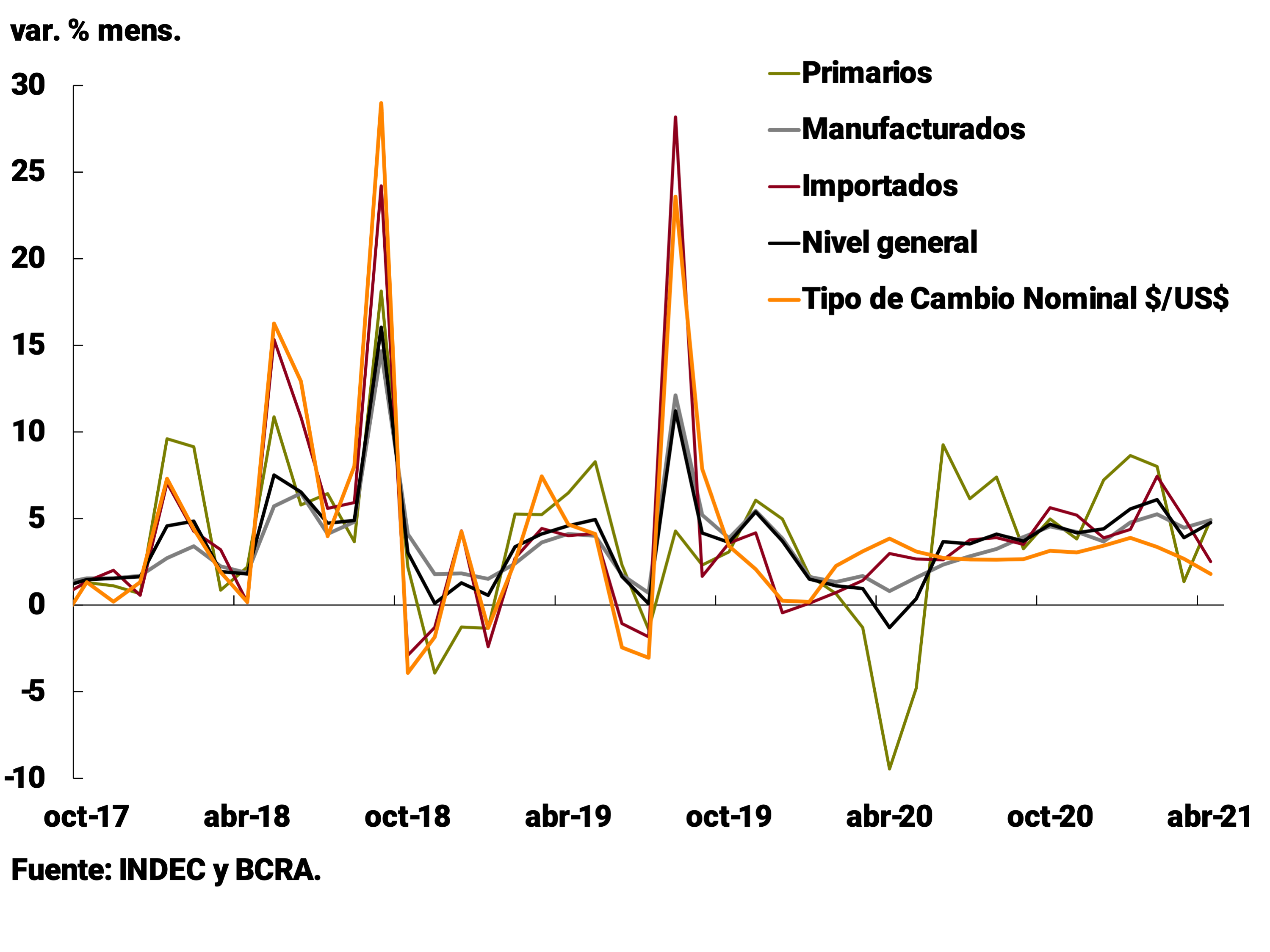

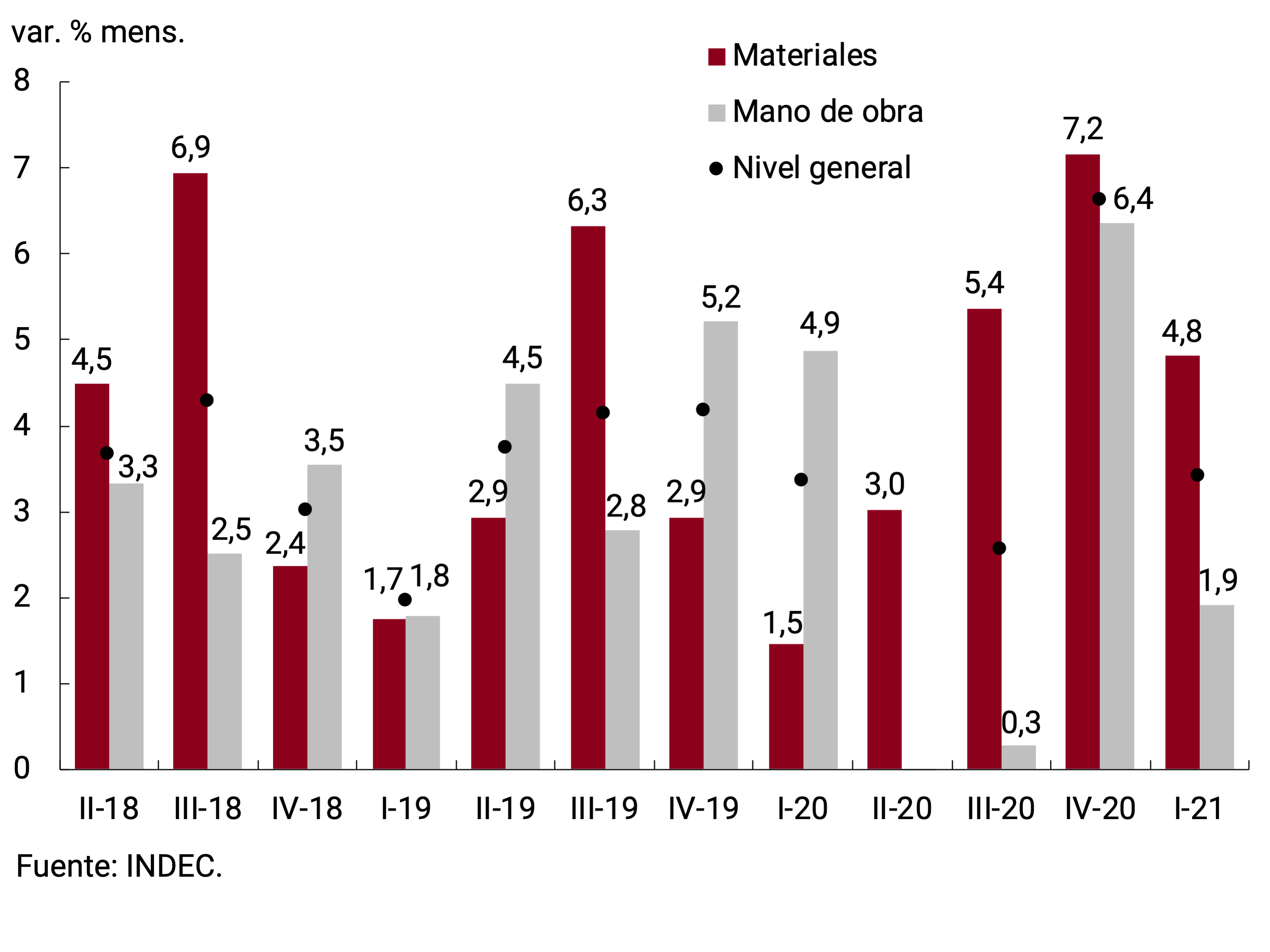

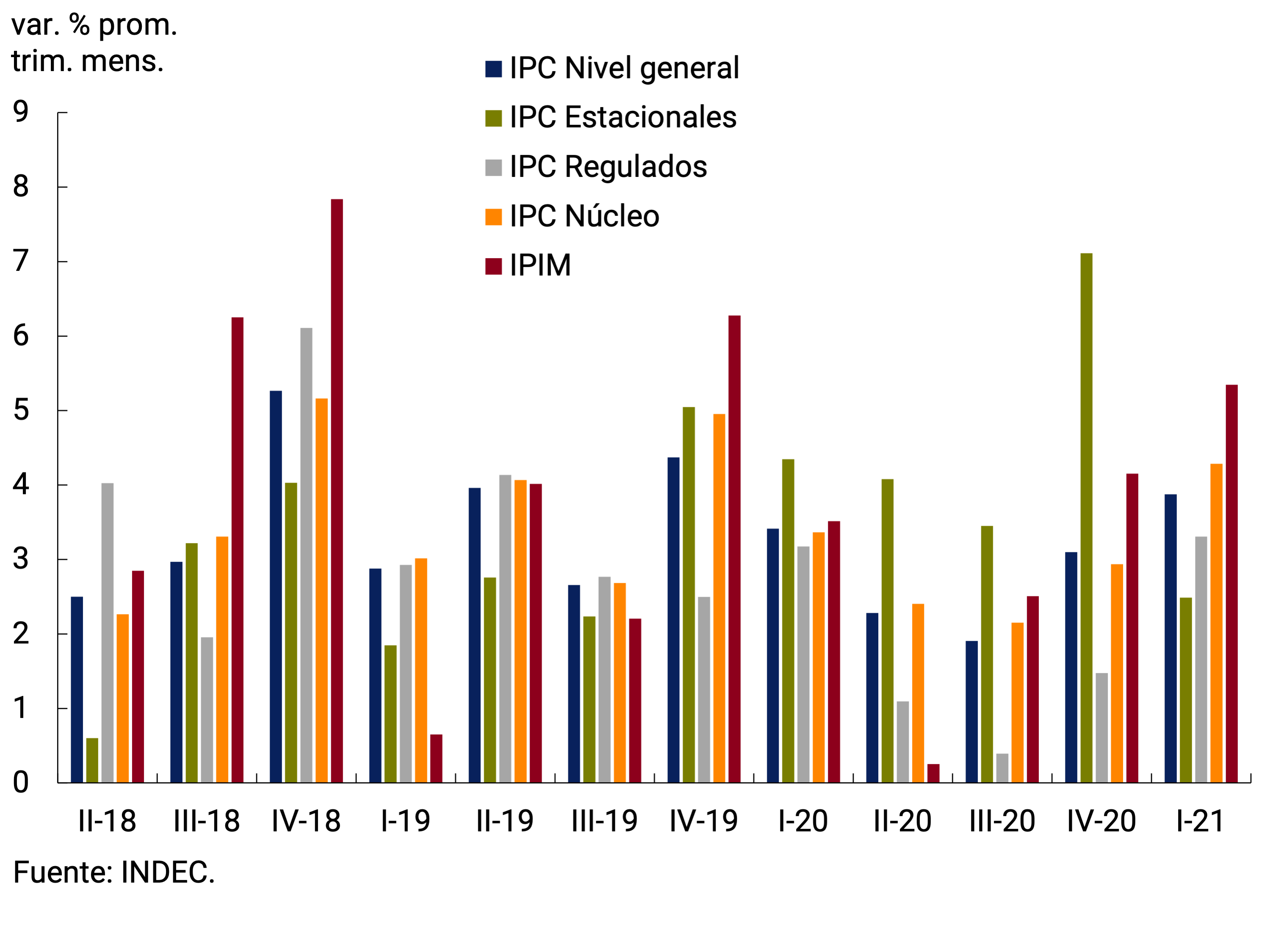

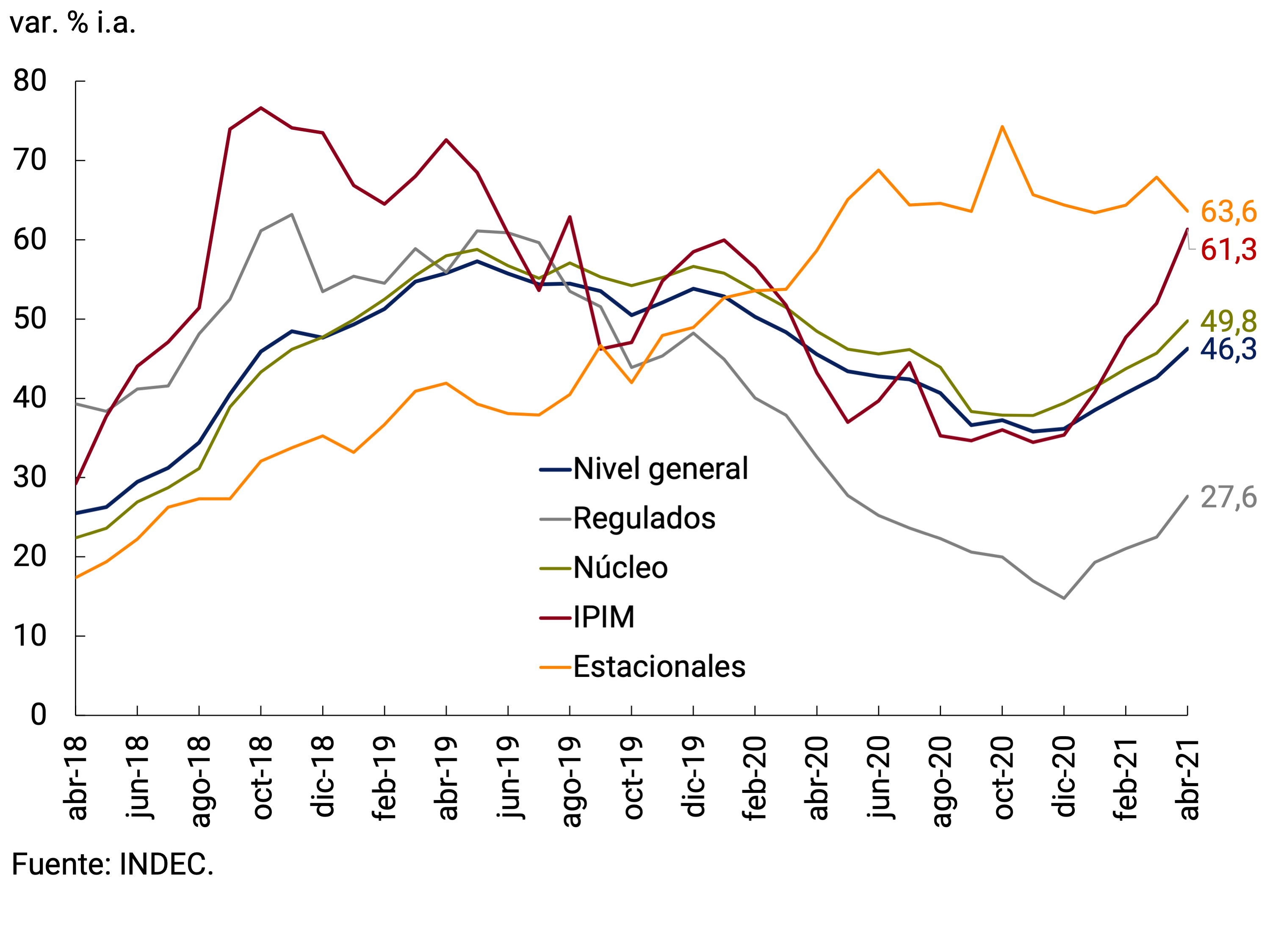

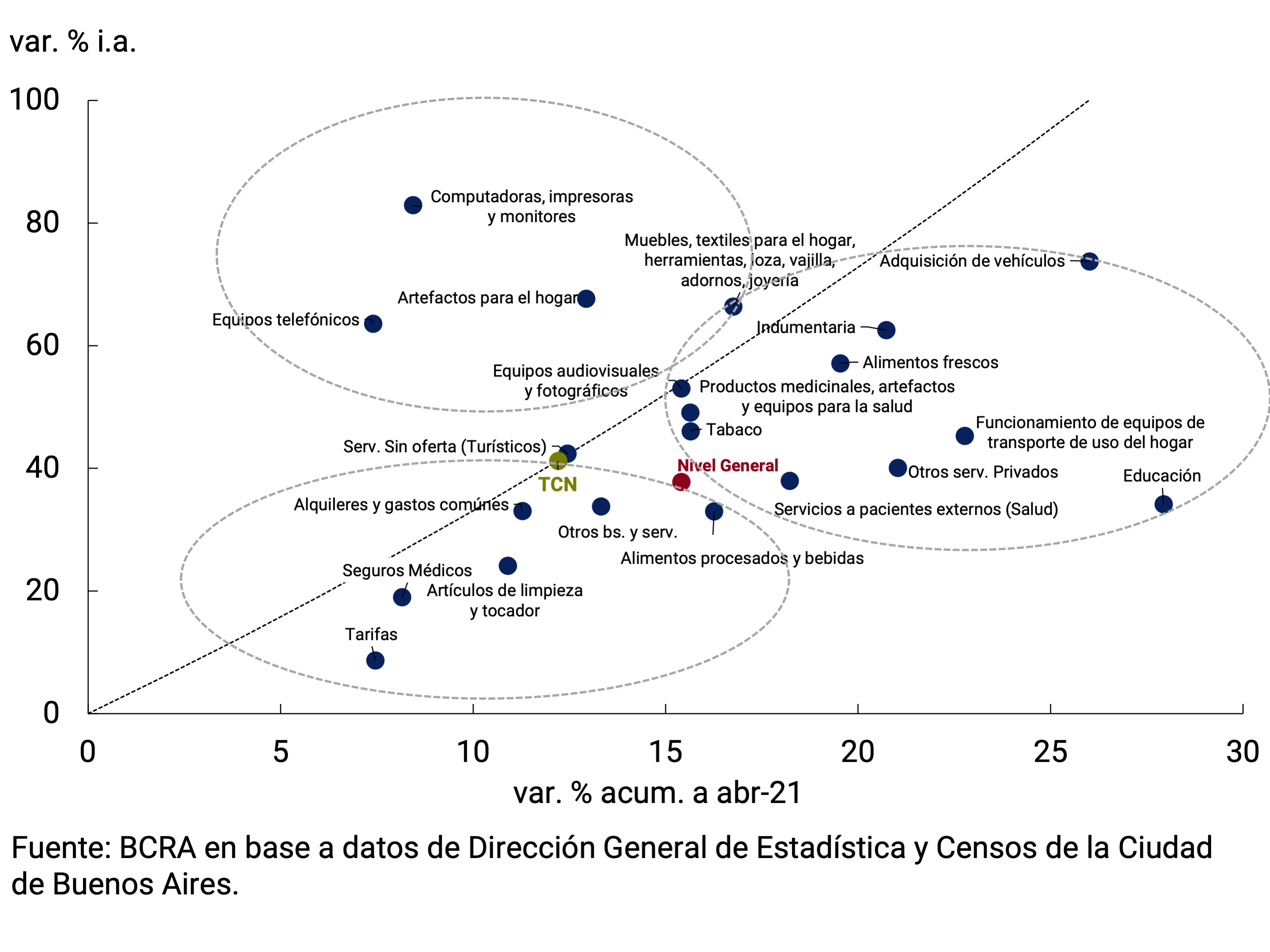

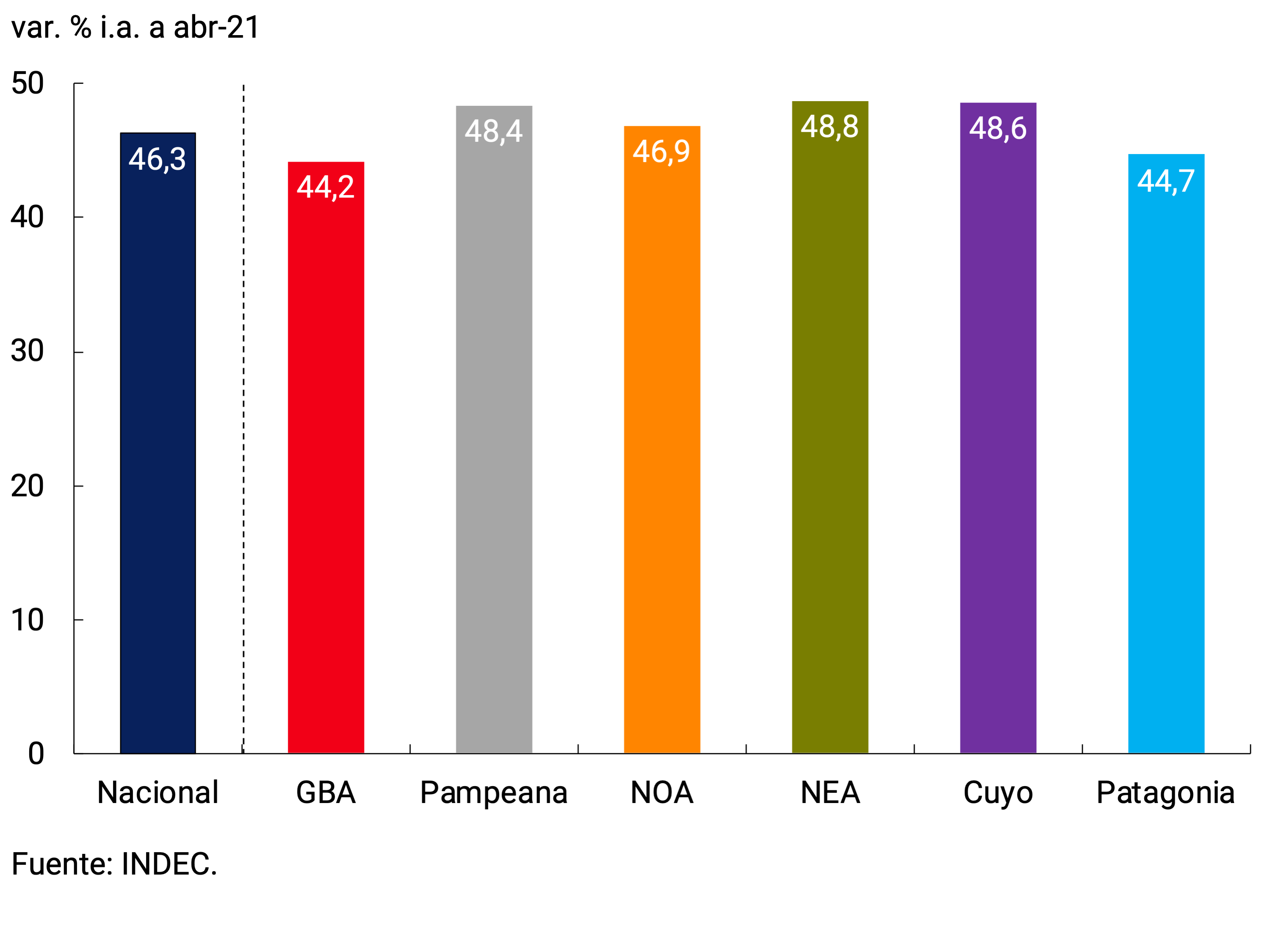

In recent months, as we have been anticipating in previous editions of the IPOM, various factors such as the recovery of the relative price of services, the recomposition of retail marketing margins in some sectors, and the progress of parity agreements, exerted pressure on the price formation process. Added to this was the significant increase in international commodity prices and their pass-through on the domestic price of food. Thus, during the first four months of the year, the year-on-year inflation rate accelerated by 10.2 p.p., to 46.3%. Given the transitory nature of several of these shocks, inflation is expected to begin a gradual and sustained decline in the coming months.

In this context, the BCRA continues with the policy of managing the exchange rate, encouraging the exchange rate dynamics to contribute to consolidating the gradual process of lowering the inflation rate. Indeed, in a favorable external context marked by the rise in the price of raw materials, the monetary authority adapts the pace of exchange rate sliding in order to contain the price rises of tradable goods and influence inflationary expectations. With respect to its monetary policy, the BCRA maintains a prudent administration of monetary aggregates, sterilizing any surplus liquidity that may arise and ensuring the existence of savings instruments in pesos that exhibit positive returns with respect to inflation and the exchange rate. Finally, the BCRA has focused on access to productive lines of credit at subsidized rates, with the aim of promoting a rapid recovery of aggregate supply.

For its part, the National Government intensified its efforts to break the inflationary inertia by moderating the distributive bid, through dialogue between business chambers and unions within the framework of the Economic and Social Council.

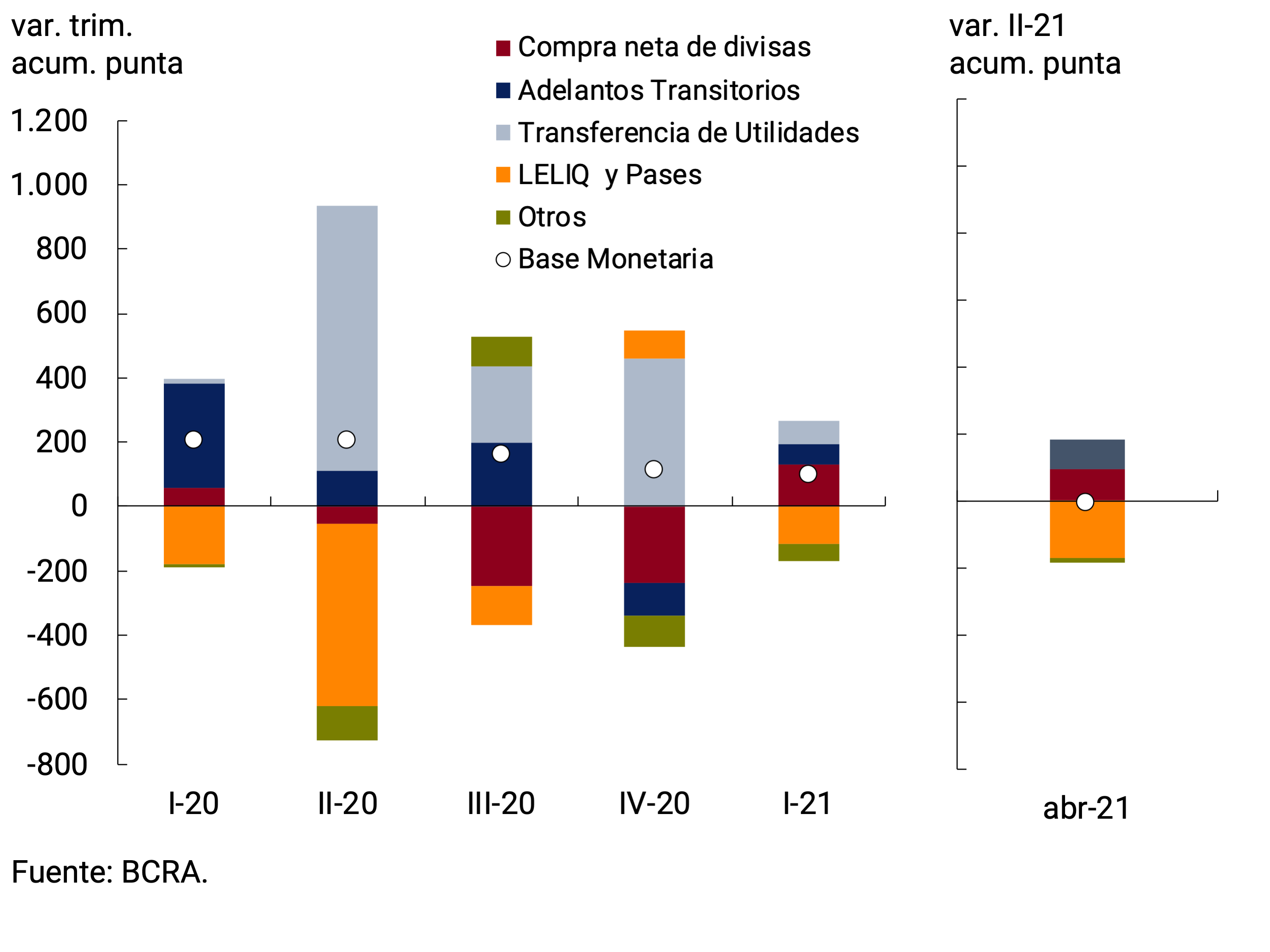

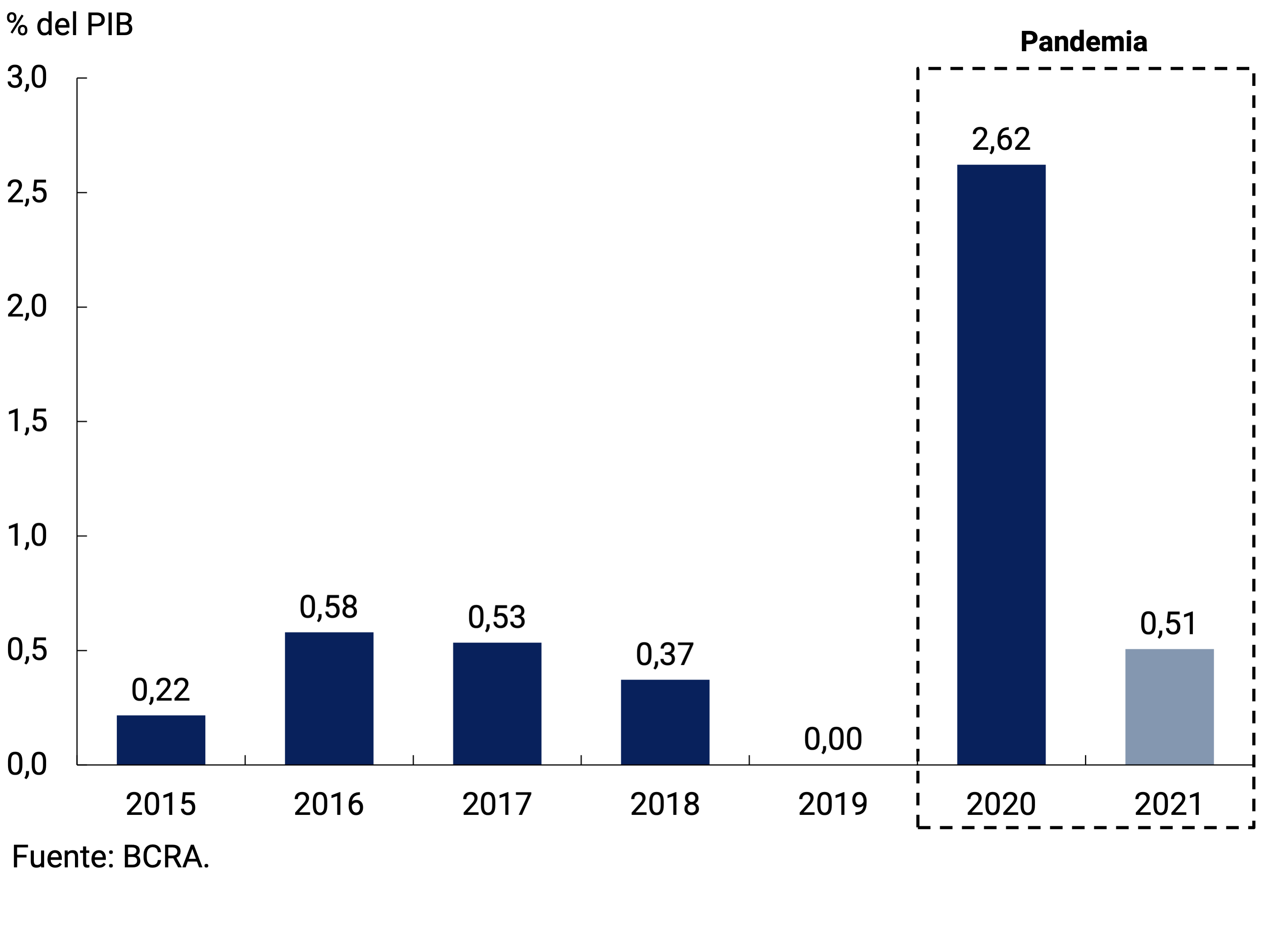

Tax collection continued to strengthen during the first four months of the year, based on the contribution of taxes related to foreign trade – in a context of increases in international commodity prices – and the sustained recovery of taxes linked to domestic economic activity, favored by a faster recovery than initially expected. Likewise, the regulatory modifications on taxes provided for in the Social Solidarity and Productive Reactivation Law of the end of 2019 and in the National Budget Law 2021 continued to have a positive impact on public revenues. This, added to the efforts deployed by the National Government to rebuild the peso debt market, made it possible to reduce the Central Bank’s financial assistance to the National Treasury. Thus, so far in 2021 there has been a limited and balanced variation in the factors of expansion of the monetary base. Specifically, with regard to financial assistance to the Treasury, it is in line with the records of previous years in terms of GDP, excluding the first year of the pandemic.

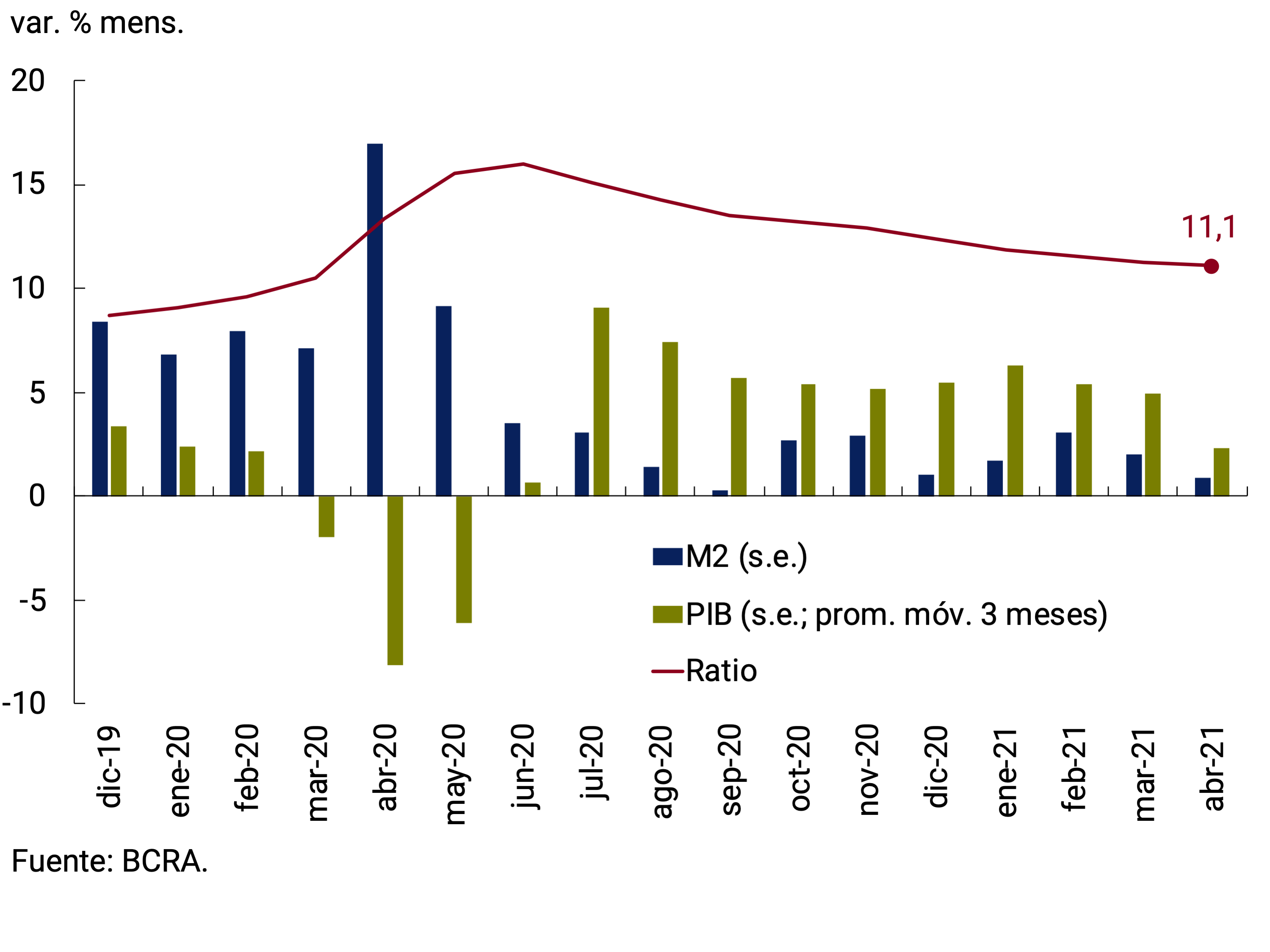

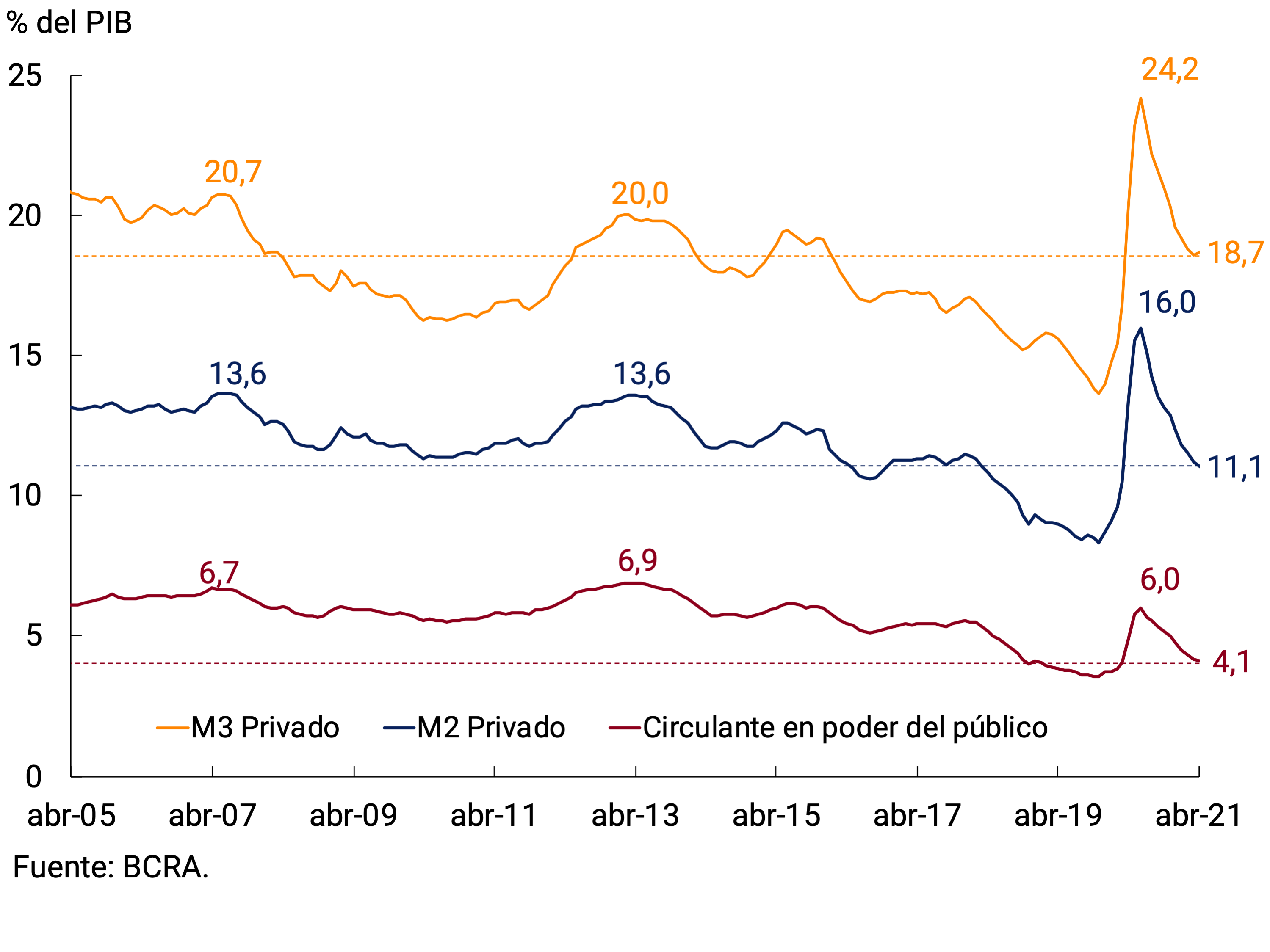

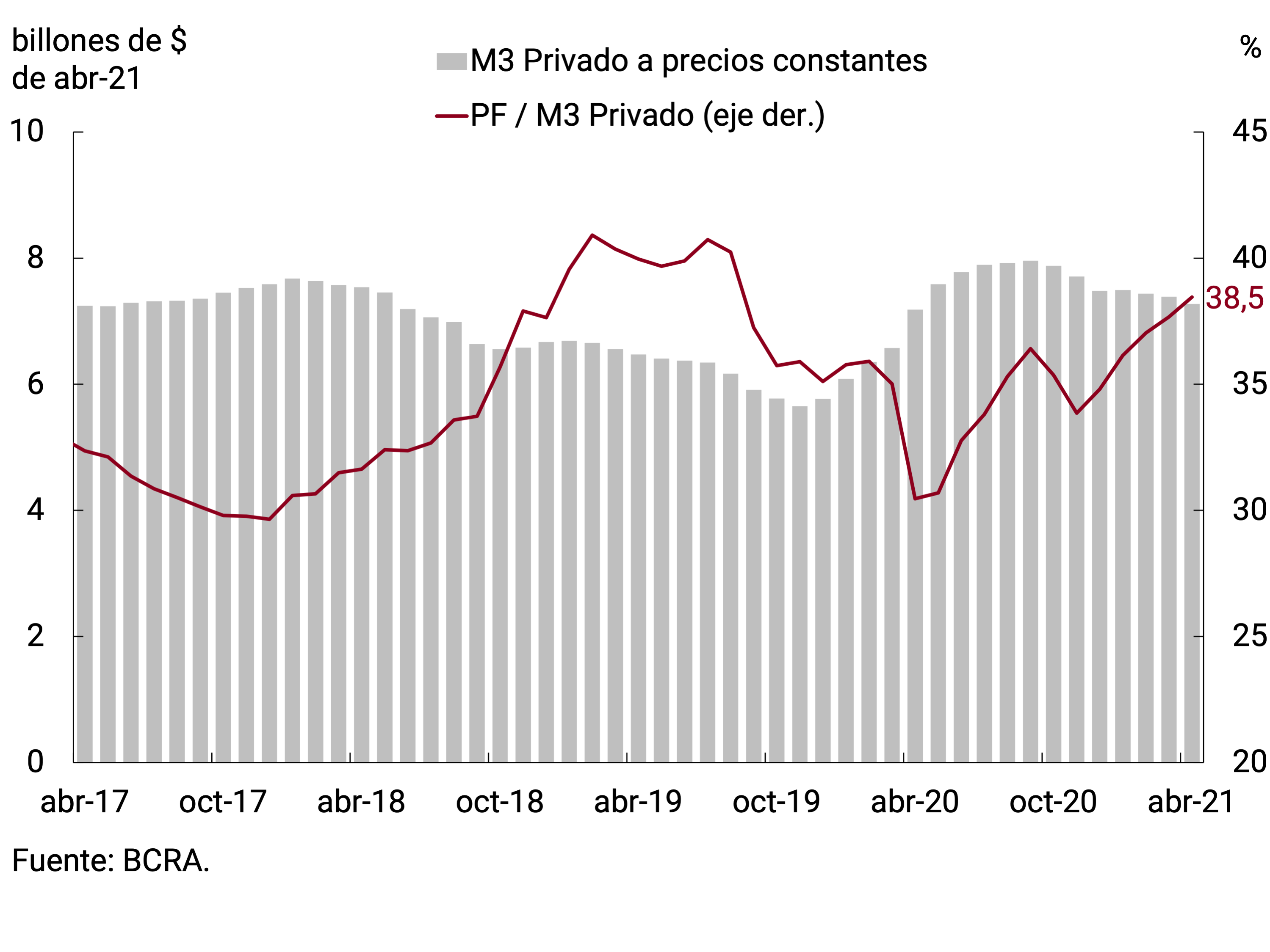

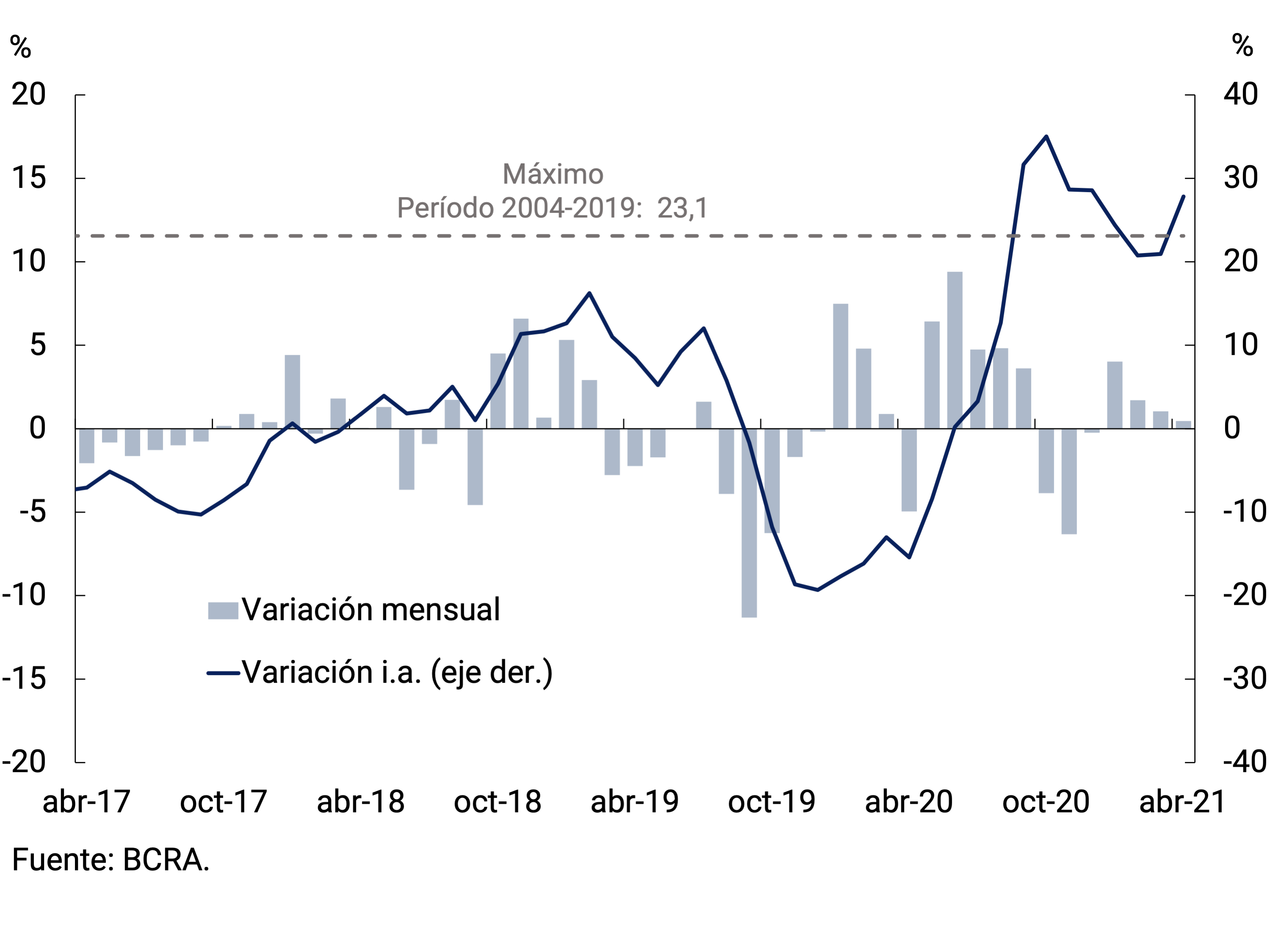

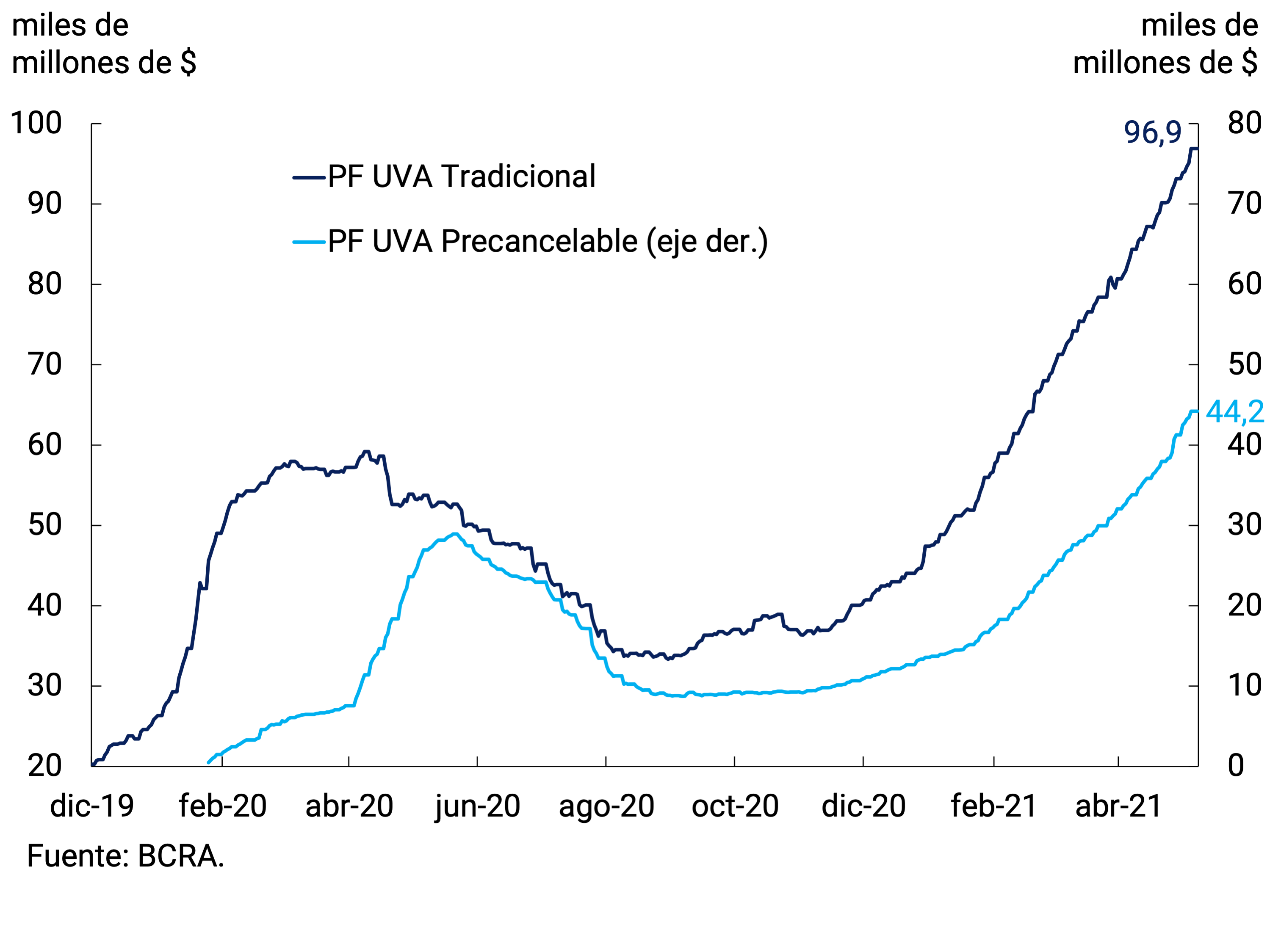

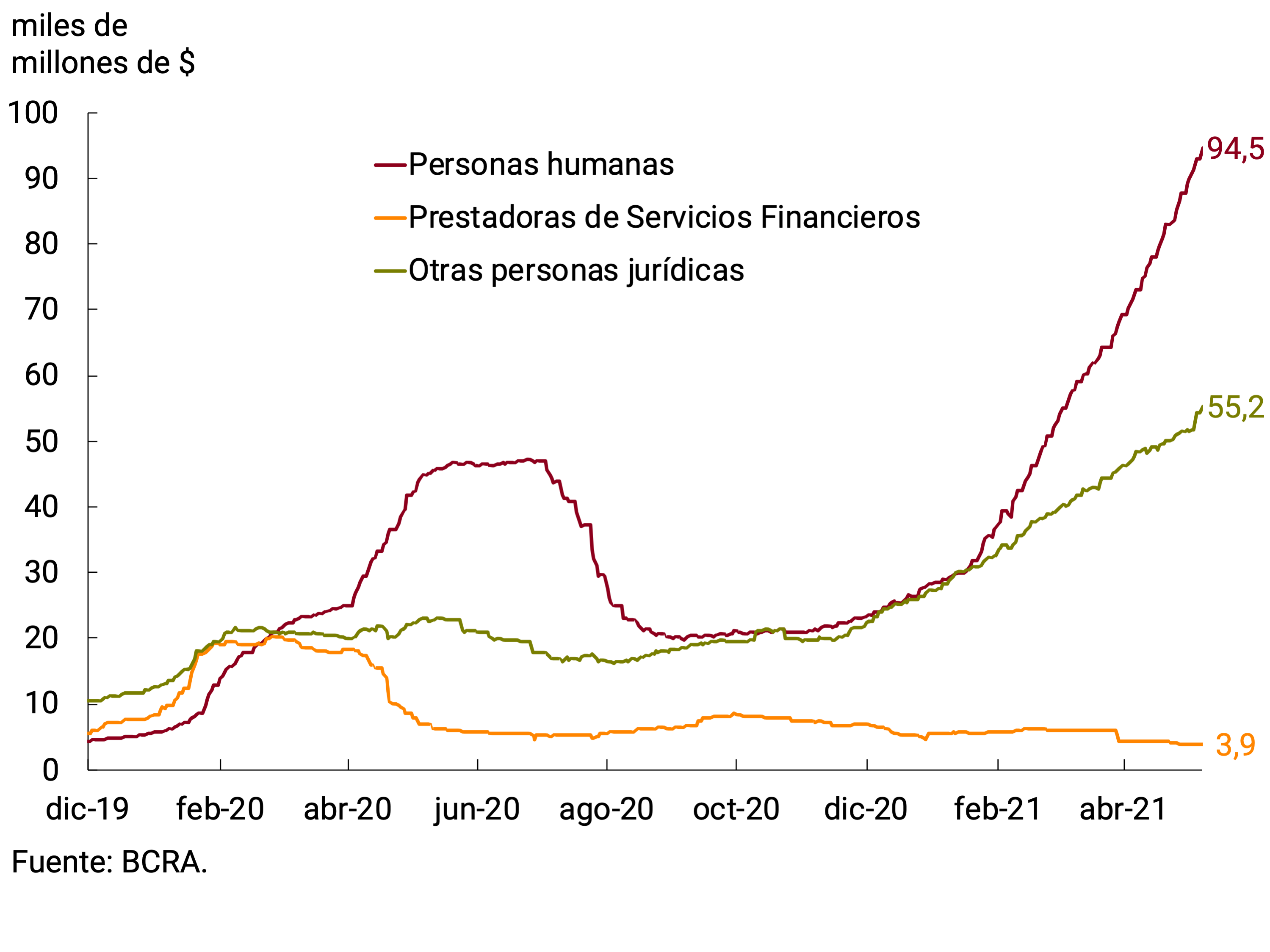

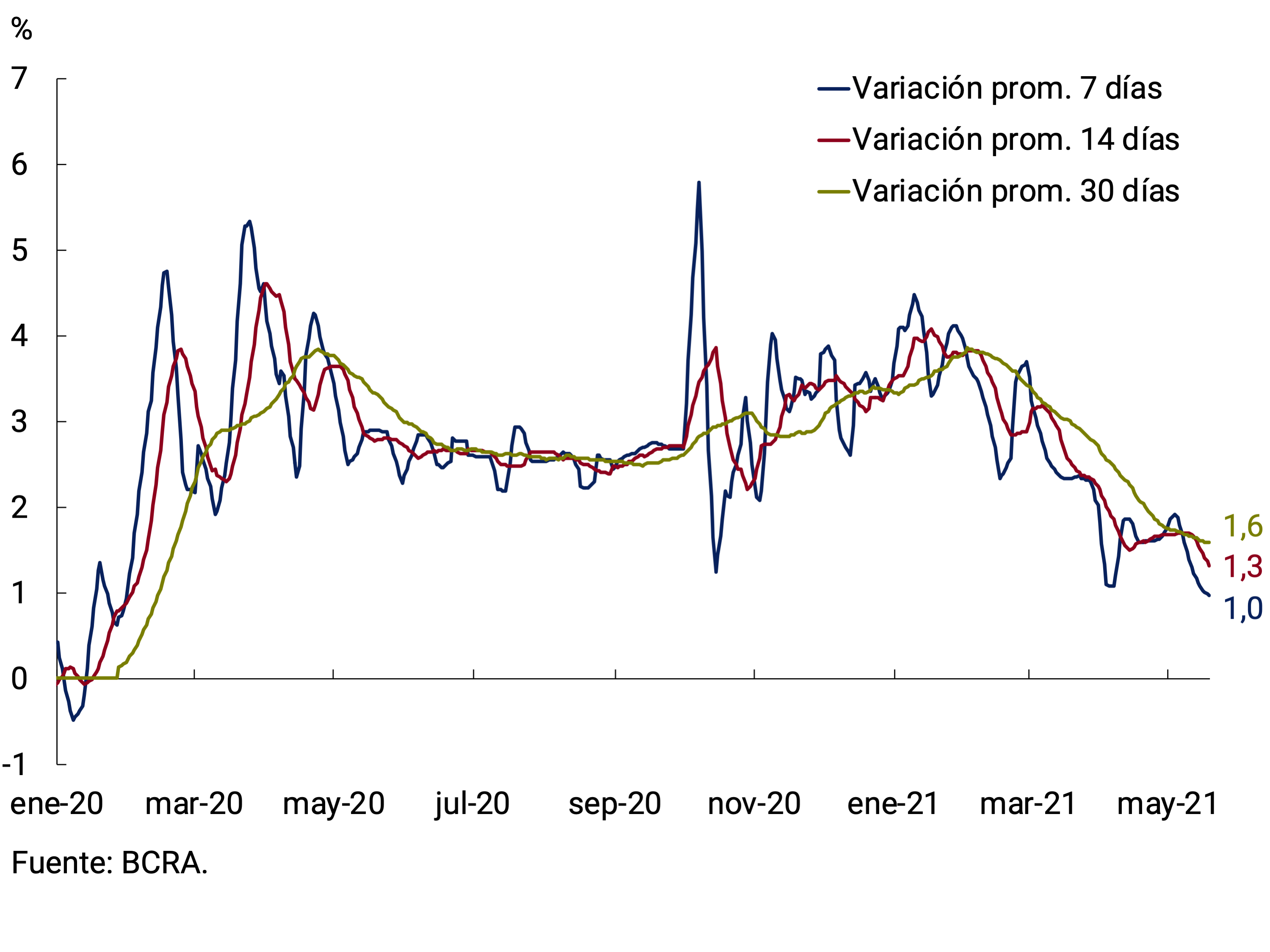

Monetary aggregates continued with the moderation process initiated in the last quarter of 2020. So far in 2021, the means of payment presented a continuous fall in real terms, which was explained both by demand deposits and by the circulating deposits held by the public. In terms of GDP, these aggregates were around their historical average. A factor that contributed to the low dynamism of the means of payment was the demand for savings instruments denominated in pesos. Time deposits grew at an average monthly rate of 1.9% in real terms without seasonality during the first four months of the year. A segment that stood out especially is the one denominated in UVA, whose traditional placements grew at a monthly average of 14.2% in real terms, while pre-cancelable placements, which have a real guaranteed rate of 1%, expanded to a monthly average of 25.4% in real terms.

The improvement in the fiscal and monetary position, together with the growth of traditional fixed terms and the existence of savings alternatives with inflation and exchange rate hedging, allowed the BCRA to face the new stage while maintaining the minimum fixed-term interest rates and monetary policy unchanged. This is in line with the importance of accompanying the process of normalization of economic activity.

The moderation of the monthly depreciation rate of the peso took place in a context where the real exchange rate is above its historical average, and in which a current account surplus is registered. The BCRA maintains its structural objective of accumulating international reserves by maintaining a competitive and stable real exchange rate. So far this year, the BCRA managed to maintain an increasing trend in the balance of International Reserves, which accumulated an increase of US$2,130 million since the beginning of the year and stood at US$41,517 million as of May 20.

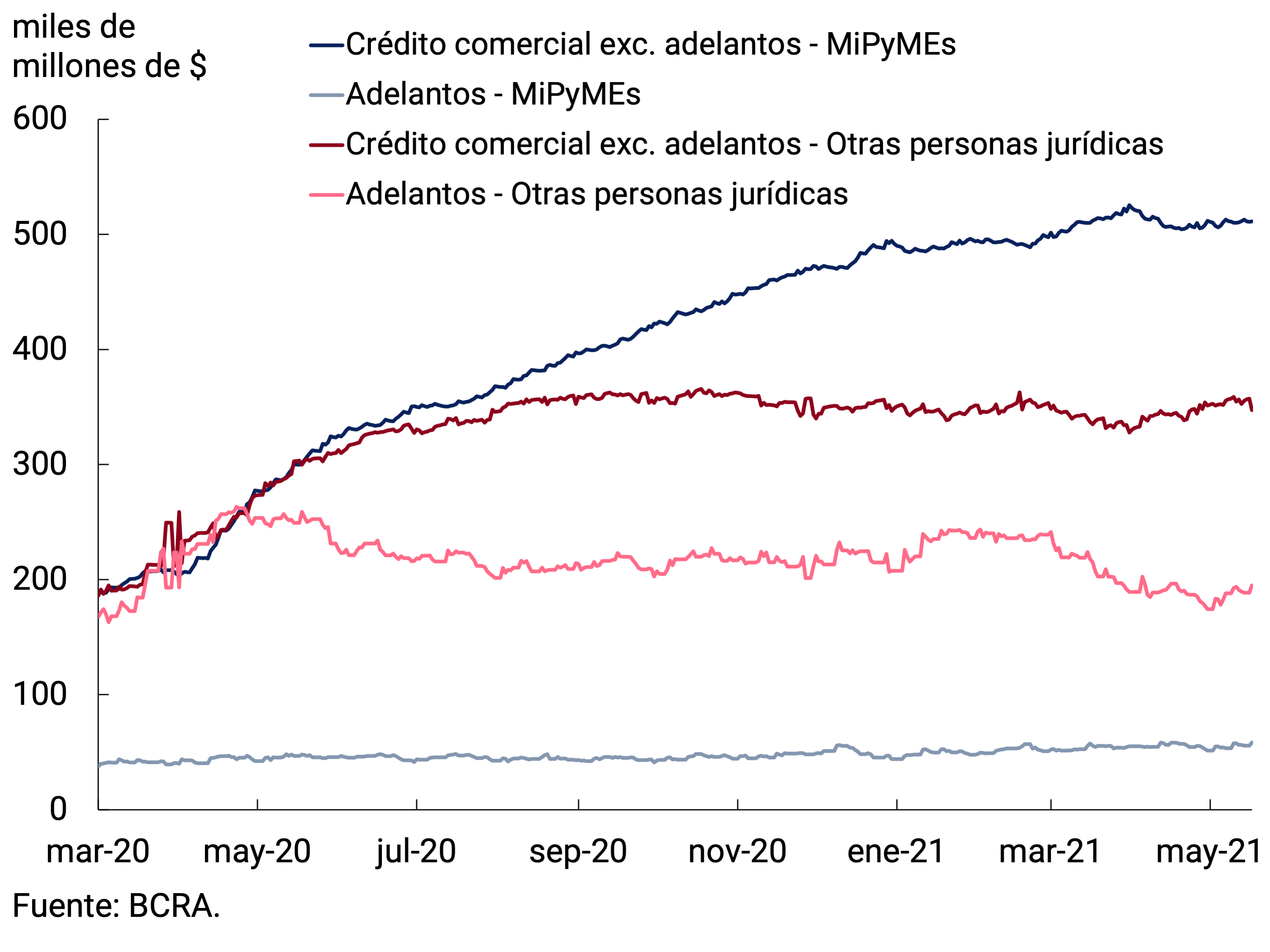

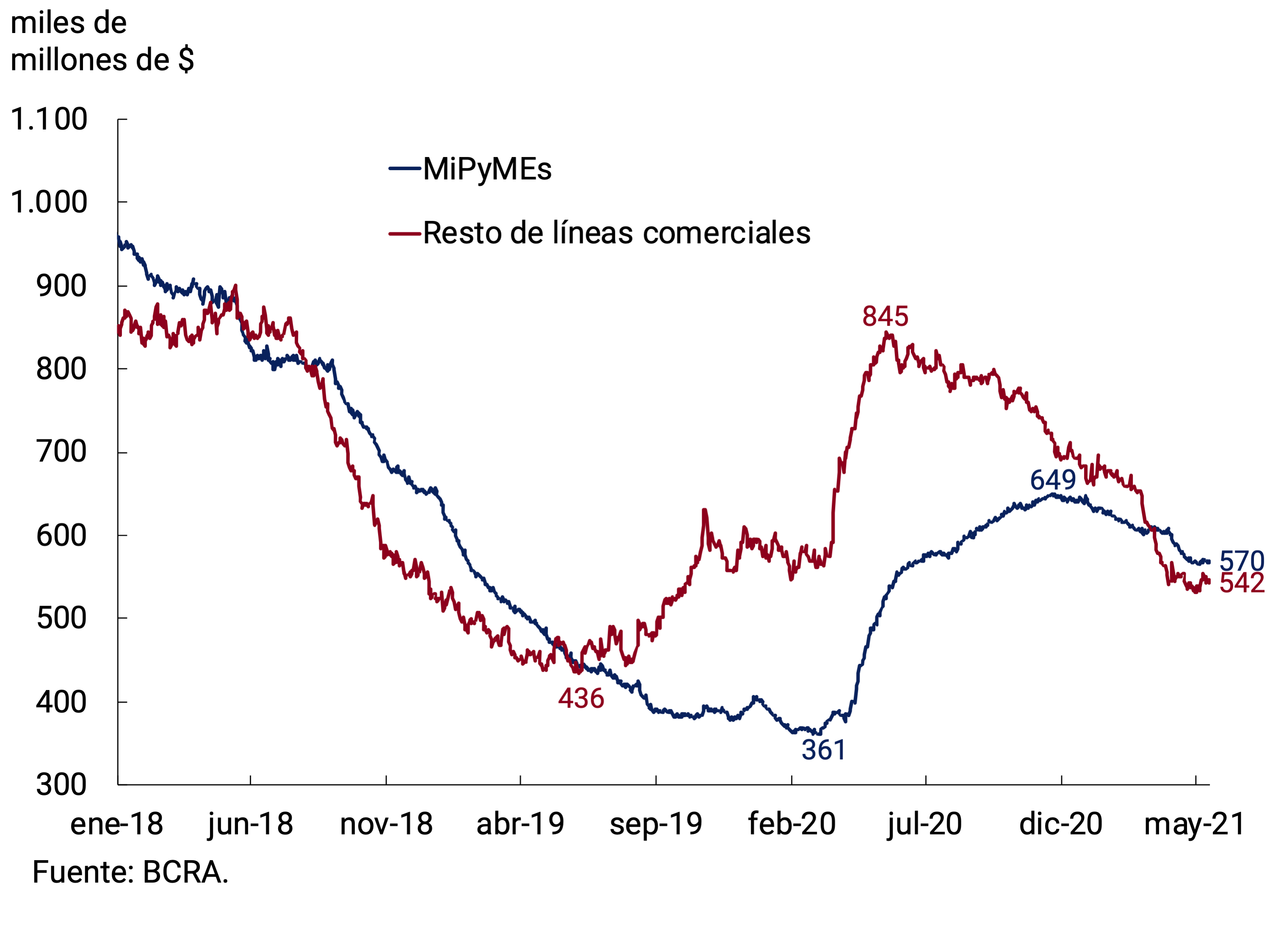

The BCRA seeks to promote economic recovery and generate the conditions for a process of sustained economic growth by promoting adequate credit conditions and financing levels for companies and families. Currently, the productive credit policy is channeled through the Productive Investment Financing Line (LFIP), whose interest rates are at levels consistent with those of the monetary policy rate. Since its implementation, and with data as of April 30, the LFIP accumulated disbursements for a total of $513,321 million, which implied an average monthly nominal growth of 32.4% in the first four months. At the time of publication, some 120,180 companies had accessed a loan granted within the framework of the LFIP.

In a context still marked by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the BCRA will carry out a monetary policy that, in addition to preserving monetary and financial stability, will lay the foundations for a path of economic development with social equity. To this end, it will continue to sterilize any monetary surpluses and manage the exchange rate in order to contain inflationary pressures and preserve external balance. At the same time, it will continue to promote productive development and structural change through its financial and credit policies.

2. International context

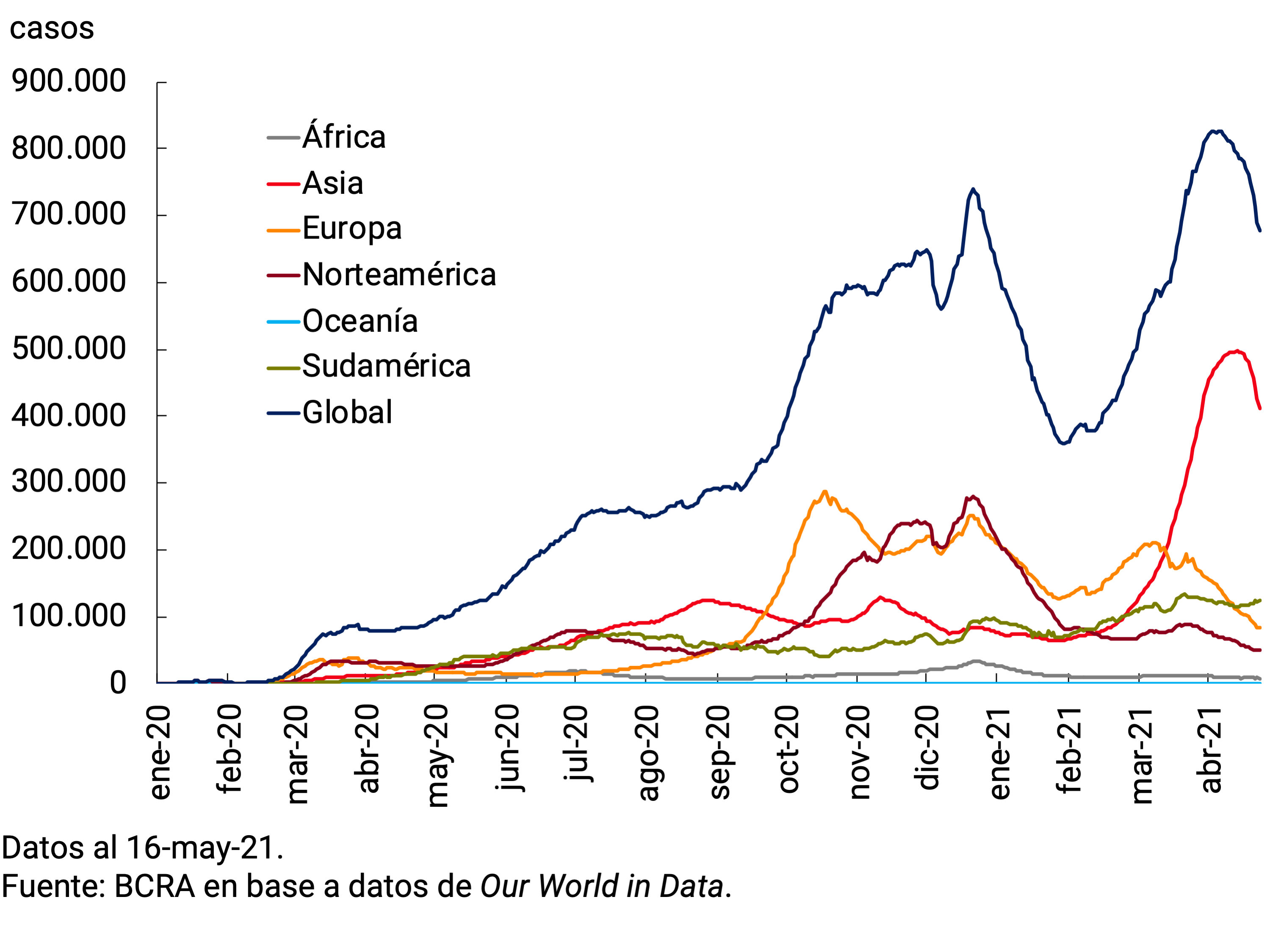

Since the previous IPOM, the global rate of COVID-19 infections has intensified again, with the focus of the pandemic shifting first to Latin America (mainly Brazil) and then to India. At the beginning of May 2021, the cases registered reached their highest since the beginning of the health crisis (plus 5.7 million per week). Vaccination is progressing at a slow pace and with marked differences between high- and low-income countries.

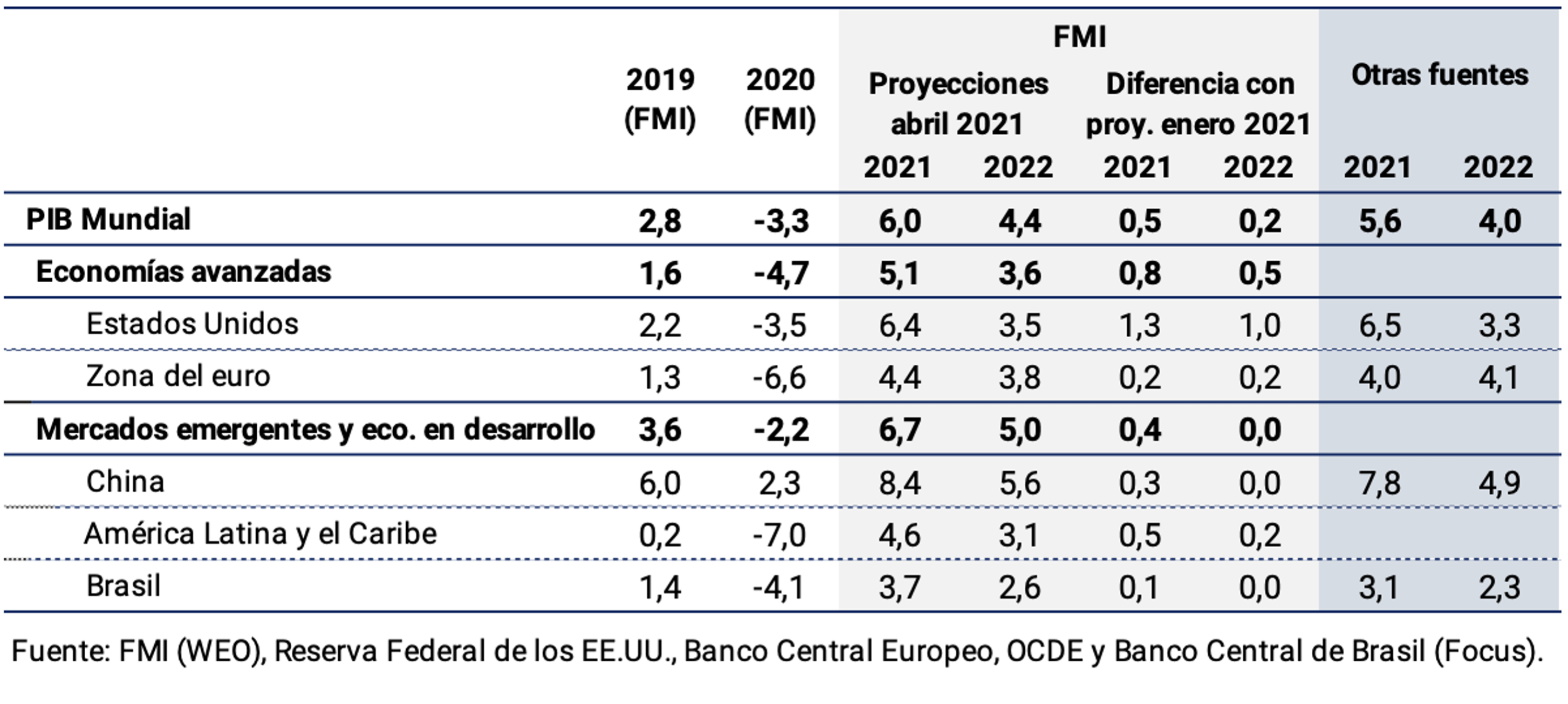

The global economic recovery continues, but at an uncertain and heterogeneous pace. During the first quarter of 2021, activity still showed the impact of outbreaks in many countries: growth accelerated in the United States, slowed in China, and GDP contracted in the euro area and Brazil (to mention Argentina’s main trading partners). As vaccination progresses and expansionary monetary and fiscal policies are implemented—such as those recently announced in the United States—the recovery will gain new momentum. This is reflected in expectations and upward revisions to growth forecasts, with the IMF forecasting global growth of 6% this year.

Global risks persist: vaccination and the ability to implement supportive policies are very disparate between countries. Developing economies may take longer than advanced economies to reach pre-pandemic levels of output, creating wider gaps in living standards between these countries. The increase in long-term interest rates in advanced economies could induce greater volatility in capital flows to emerging countries, as observed in recent months. Thus, the pace and extent of vaccination campaigns, the continuity of support policies and the effective provision of global liquidity will determine the intensity of the recovery.

2.1. Pandemic: daily cases at peak levels and uneven vaccination progress

The decline in global cases that had begun at the close of the previous IPOM stopped towards the end of February, at a floor of 2.5 million per week. By that time, cases began to fall in the United States, but increased exponentially in Brazil (and the rest of Latin America) and then in India. They also resurfaced in several European countries. In early May, recorded cases reached their highest since the beginning of the pandemic (more than 5.7 million per week; see Figure 2.1). The resurgence paralleled the spread of more contagious variants. The UK variant was dominant in Europe and spread in North America; and the Manaus variant in Brazil. As of the date of publication of this report, cases were declining from their peaks on all continents except South America.

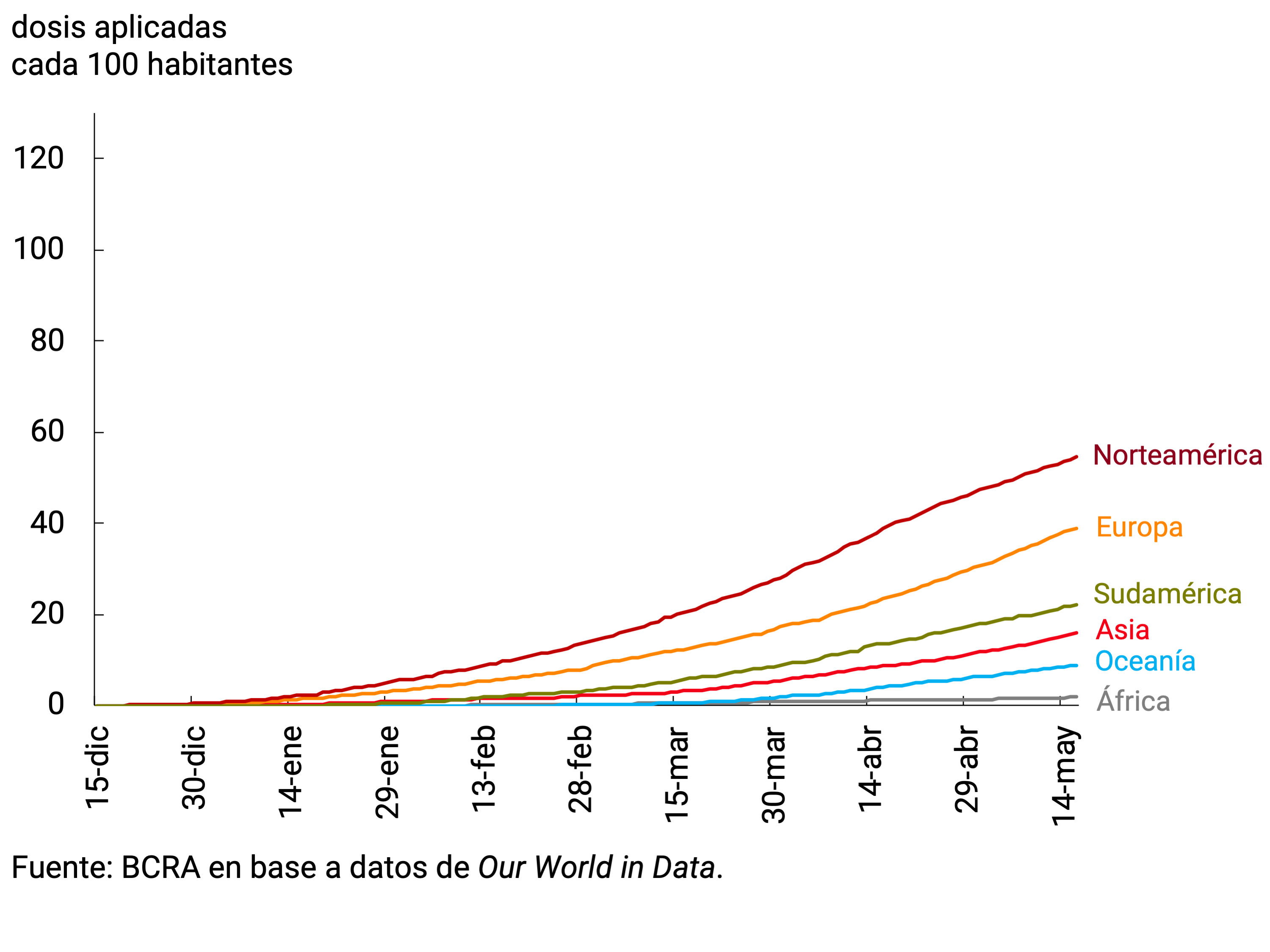

The new wave found most countries in the early stages of vaccination campaigns (see Figure 2.2). In recent months, the pace of vaccination has increased: at the beginning of March, 1 dose was applied per thousand inhabitants on average per day in the world, and by the end of April, just over 2. Studies suggest that vaccines are effective in preventing, above all, hospitalizations and deaths. While new variants might be more adept at evading the immune system, available evidence also indicates that some vaccines remain effective against the U.K. and Manaus variants.

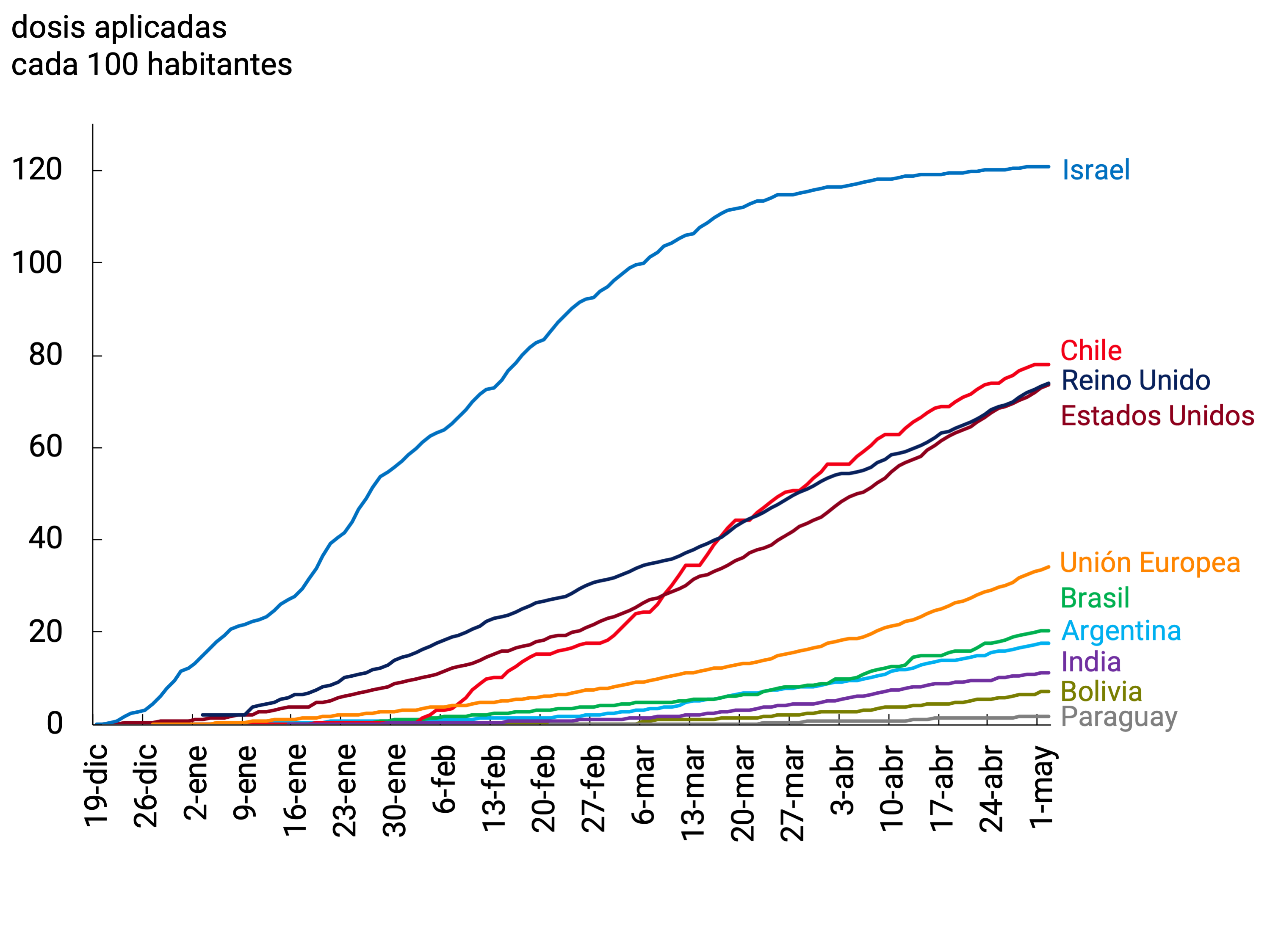

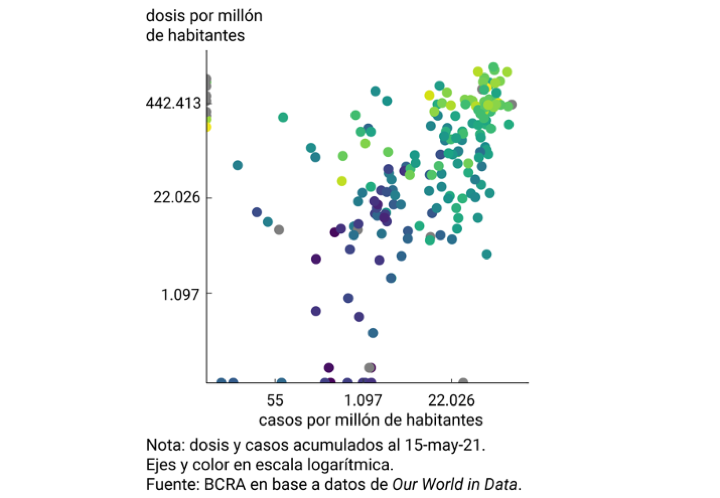

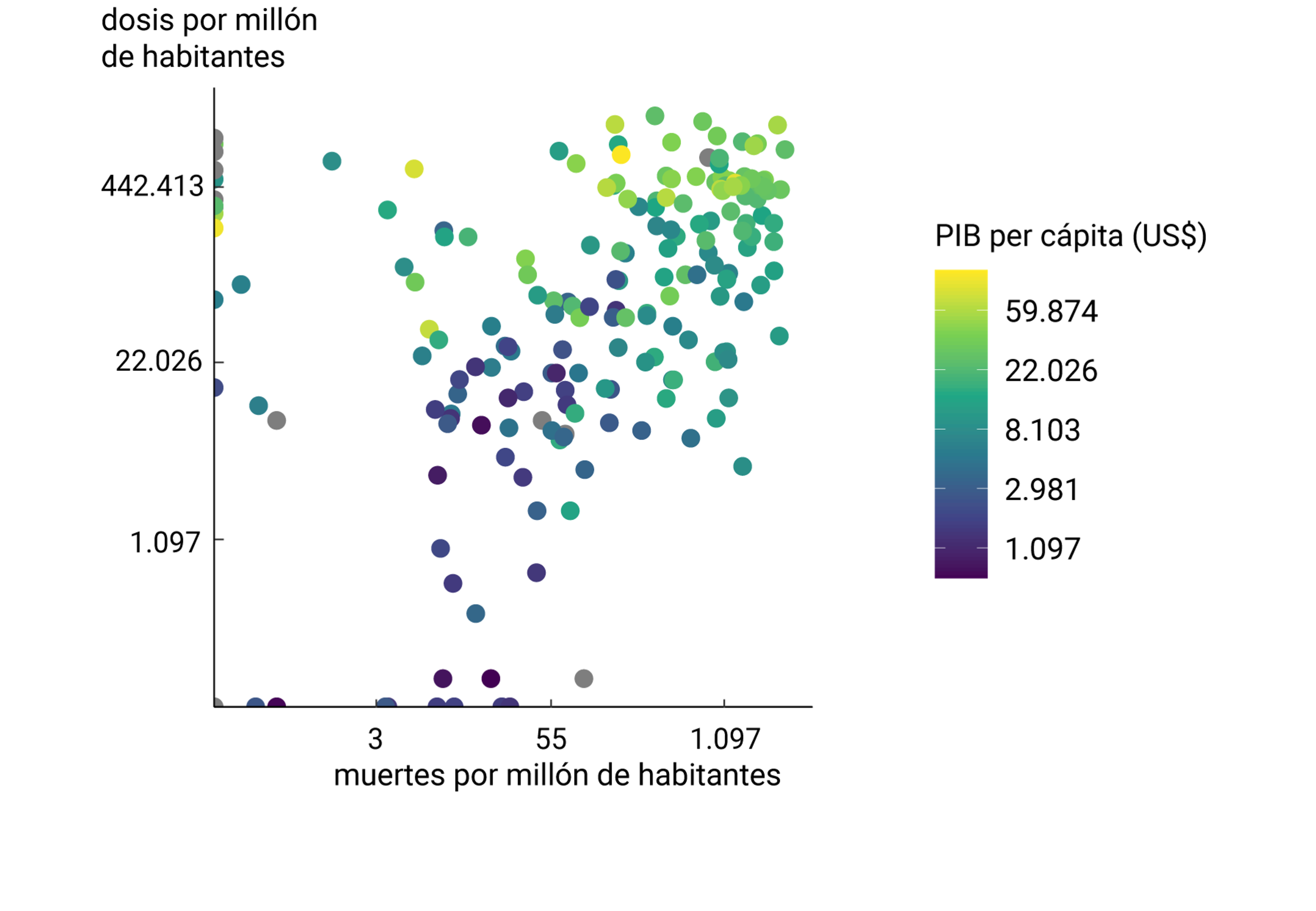

For the same level of cumulative cases, higher-income countries have applied the most doses (see Figure 2.3). In North America and Europe, campaigns have started earlier and have more than 54 and 38 doses applied per 100 inhabitants, respectively (data as of May 16). In contrast, South America has more than 21 doses per 100 inhabitants, with large differences between countries. The leaders are Chile (with more than 47% of the population with at least one dose), Uruguay (more than 38%), Argentina (more than 17%), Brazil (more than 16%). In the rest of South American countries, more than 90% of the population has not even received the first dose.

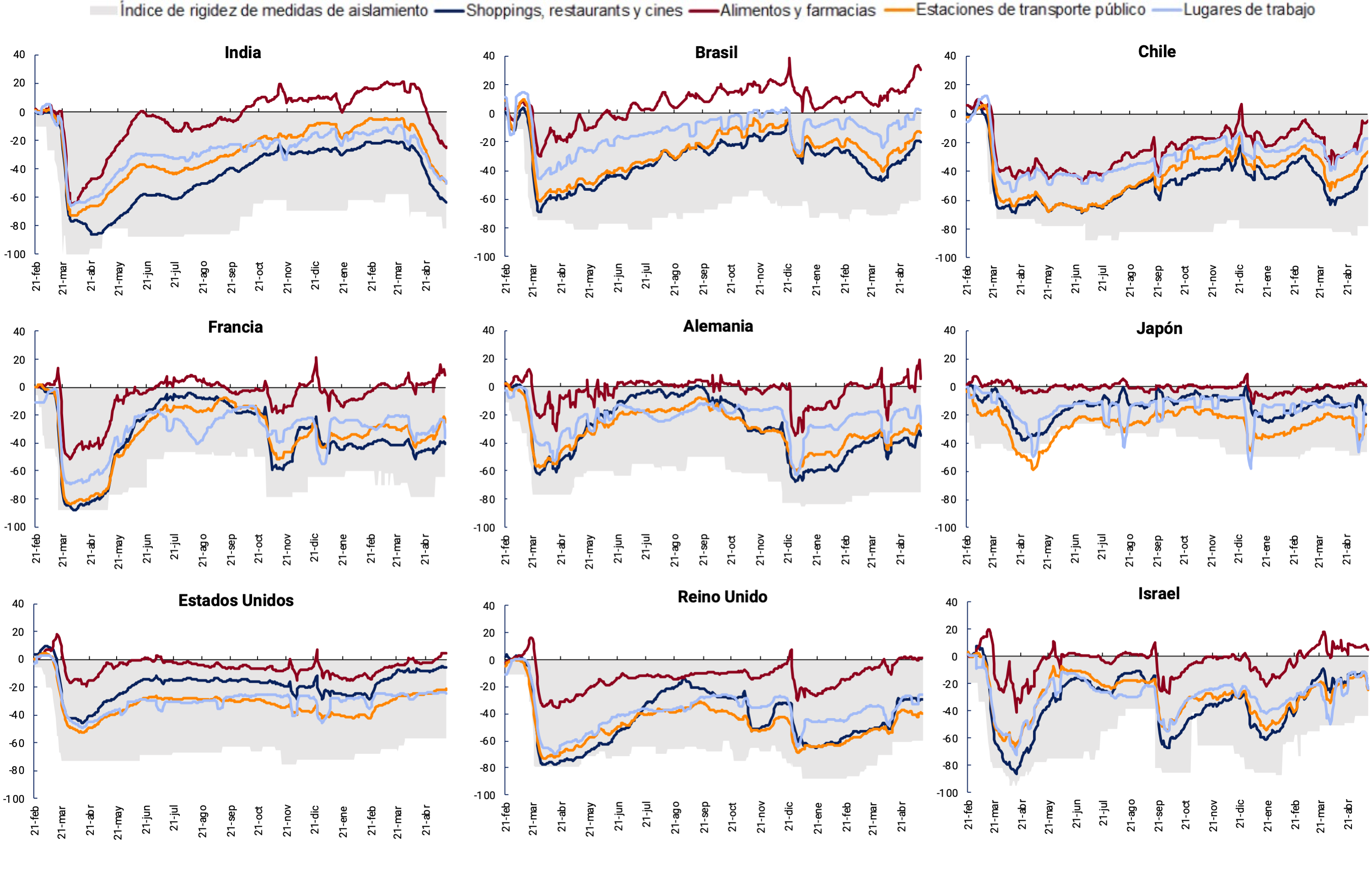

The uneven dynamics of vaccination and the shift in the epicenter of the pandemic translate into divergent trends in mobility rates between countries. Israel, the United Kingdom and the United States significantly reduced restrictions thanks to the progress of vaccination campaigns and the drop in cases. In contrast, in India, restrictions were tightened as a result of the exponential rise in cases (see Figure 2.4), and the same happened in Brazil, Chile, and some European countries; although in the latter mobility rose again in recent weeks.

Figure 2.4 | Mobility index (7-day moving average) and social distancing measures stiffness index (-100 = maximum rigidity) of selected countries

2.2. Global economic recovery continues, but divergence between countries is accentuated

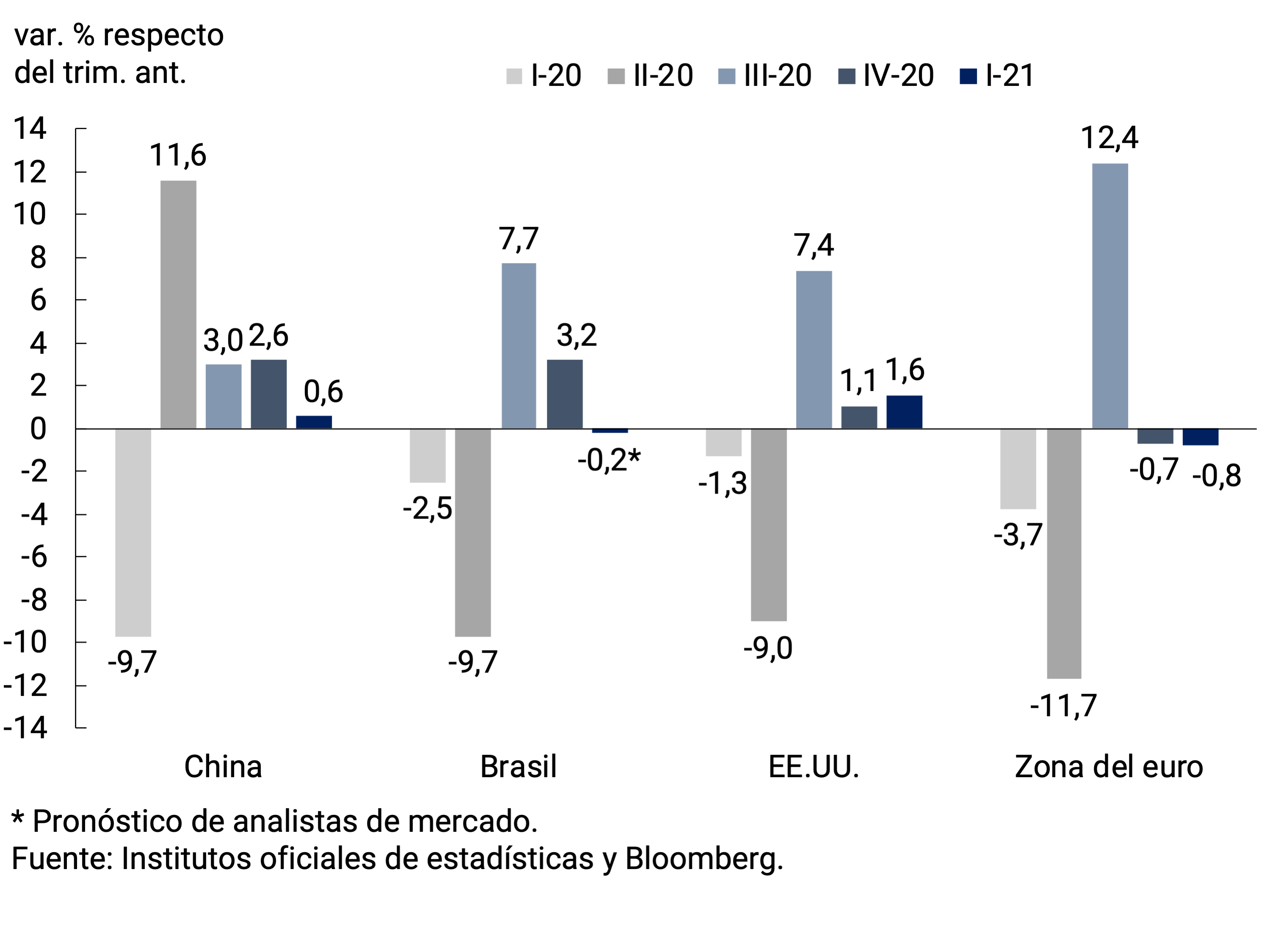

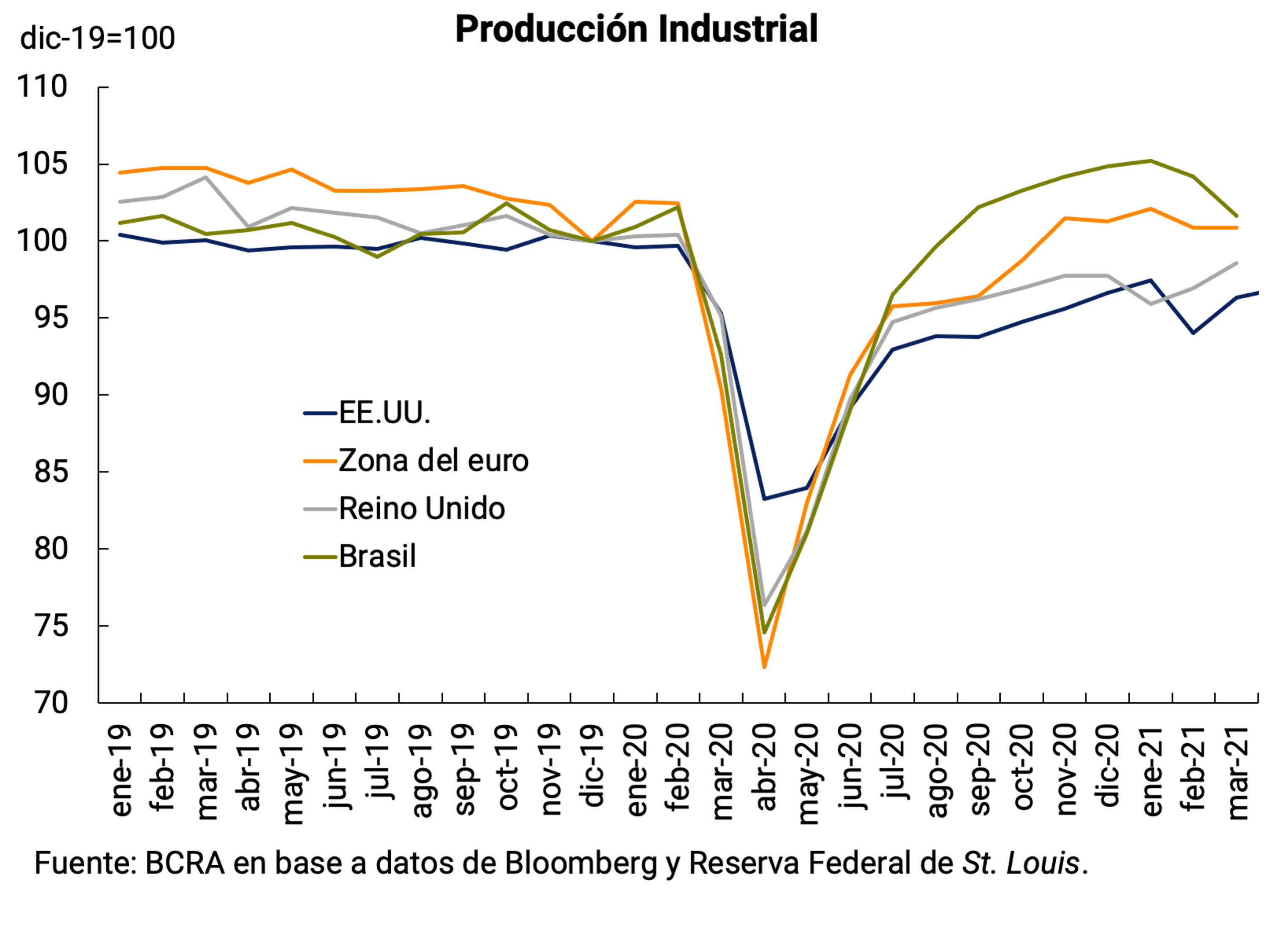

After the strong recovery in the level of activity in the third quarter of 2020 and the slowdown in the following quarter, activity still showed the uneven impact of outbreaks in many countries during the first quarter of 2021. In the first quarter of the year, there was a slight increase in the growth rate in the United States according to the advance estimate of GDP. On the other hand, China’s output went from growing 2.6% (quarterly, s.e.) in the fourth quarter of 2020, to 0.6% (quarterly, s.e.) in the first quarter of this year. As a result of the new wave of COVID-19 cases, the eurozone’s GDP fell by 0.8% (quarterly, s.e.), and Brazil’s would fall by 0.2% (quarterly, s.e., see Figure 2.5) in the first quarter of 2021.

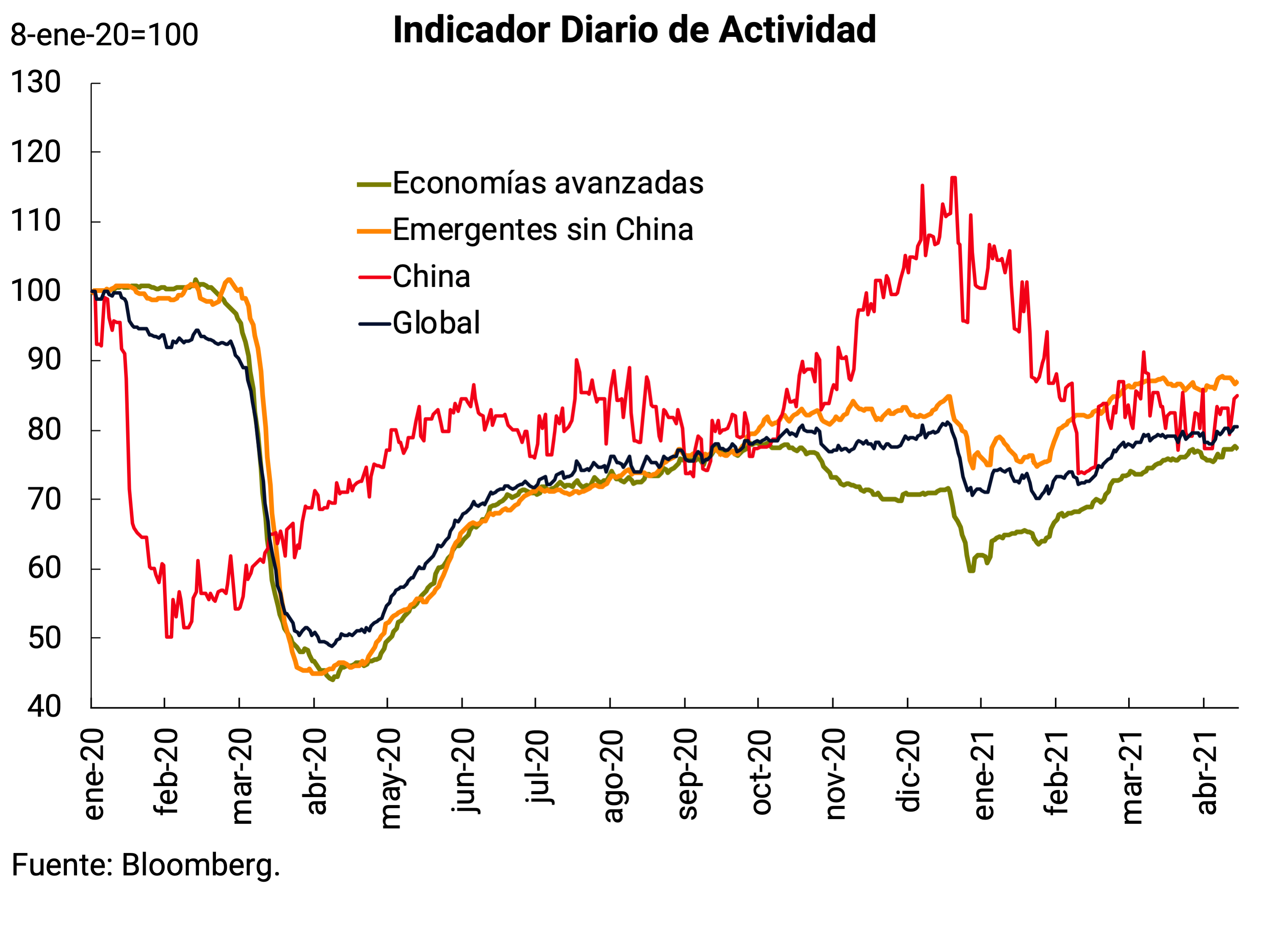

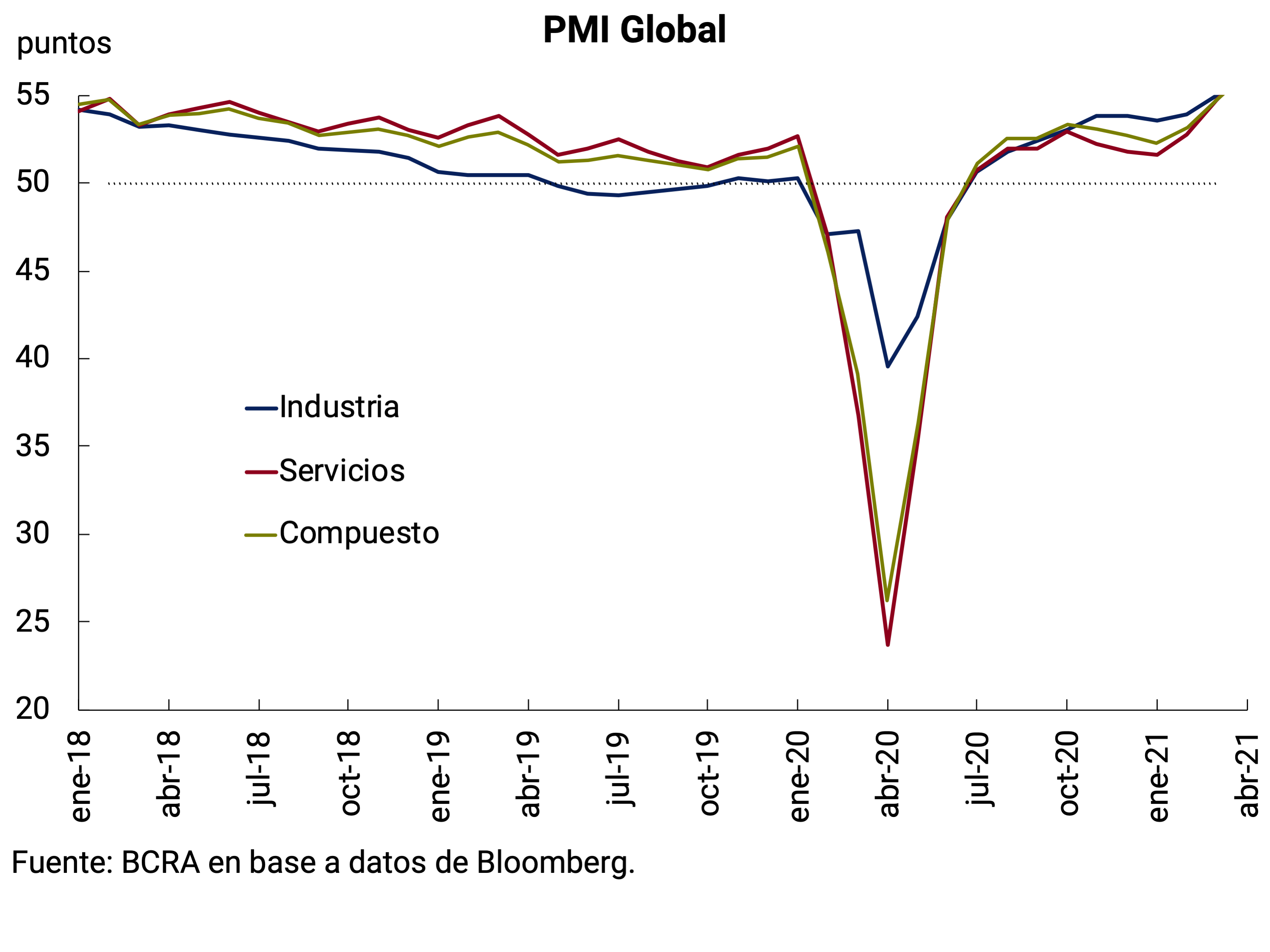

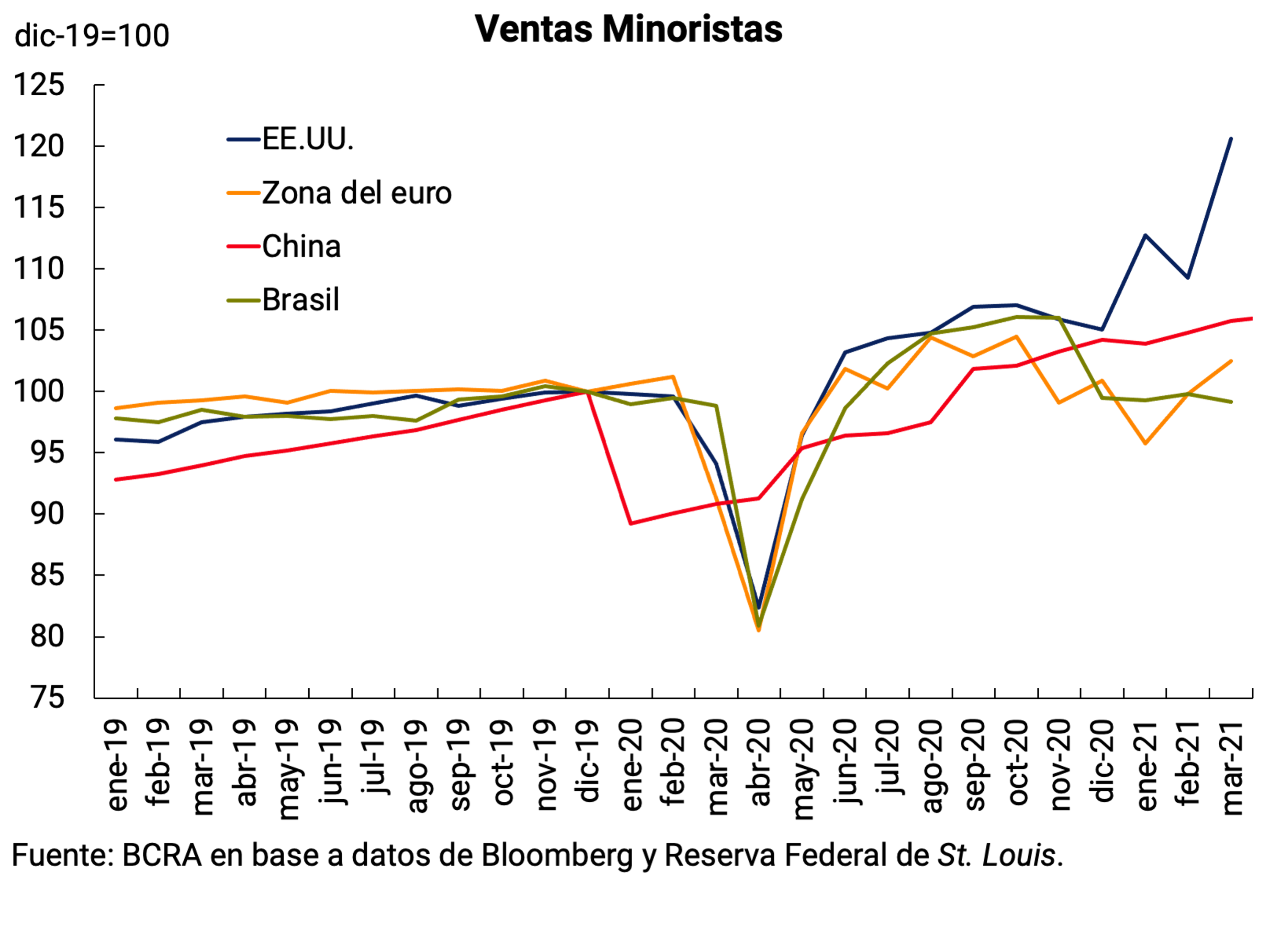

Based on high-frequency data and some forward-looking indicators, the level of global activity has accelerated slightly since February (see Figure 2.6). Bloomberg’s daily activity gauge resumed growth earlier that month. The global purchasing managers’ survey index (PMI), which also registered a slowdown in the fourth quarter, resumed a higher pace of growth since February, especially the services PMI, the most relegated due to the greater impact of the pandemic on this sector of the economy. In the euro area it has a similar performance, with a recovery in industry since February and to a lesser extent in services (whose index entered the “expansion zone” in April). Retail sales have also begun to recover in this region since February. In the United States, the PMI also shows a similar behavior, but with a more homogeneous recovery between industry and services.

Two trading partners of Argentina with a different dynamic compared to the rest are Brazil and China. In Brazil (see Box. Brazil), there were lower values of the PMI indices from November 2020 onwards, along with a fall in retail sales, (which seems to have stopped since January of this year). In China, there has been a fall in the PMI since December, but with a slight rebound in March for services and in April for industry. In contrast, China’s retail sales continue to grow from the lows recorded in January 2020.

Growth forecasts for the world economy have been revised upwards in view of the progress of vaccination campaigns and the continuity of monetary and fiscal support policies, (among which the fiscal package recently approved in the United States stands out; see Table 2.1); and in line with world trade, which has exceeded the pre-pandemic volume. The IMF now forecasts a growth of the world economy of 6% in 2021, 0.5 p.p. above what was projected in January. GDP growth projections for advanced economies were also improved to 5.1% (+0.8 p.p.), and for emerging economies to 6.7% (+0.4 p.p.). The recovery is also divergent across groups of countries. Developing economies, in general, would take longer than advanced economies to reach pre-pandemic GDP levels, due to less policy space and greater difficulties in accessing vaccines, which would create wider gaps between these countries’ living standards (see Figure 2.7). A risk linked to faster growth in advanced economies is that it will lead to higher interest rates in advanced economies, which will end up affecting the recovery of developing countries.

Box. Brazil

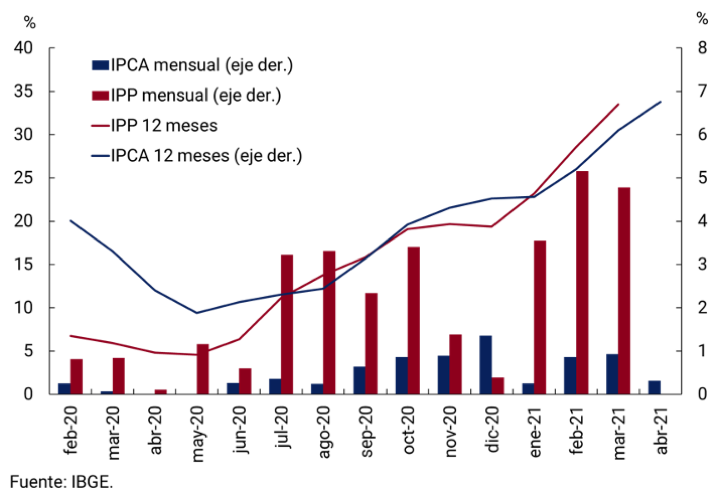

In Argentina’s main trading partner, there are signs that would limit the space for fiscal and monetary policies to sustain the recovery. Inflation accelerated in recent months: in April, consumer prices (HICP) increased 6.8% year-on-year, above the central bank’s target of 3.75% ± 1.5, and with significant food increases. Although it is the second consecutive measurement to exceed the upper limit, inflation is above the average value of 3.75% since October last year. Wholesale prices, driven by increases in commodity prices and exchange rate depreciation, are rising well above inflation. The headline producer price index (PPI) stood at 33.52% year-on-year in March and has been in double digits since July last year (see Figure 2.8a). These increases in wholesale prices have largely not yet been passed on to retailers. Although long-term inflation expectations are in line with the target, the monetary policy committee reacted with two hikes, of 75 basis points (bps) each, in its policy rate (Selic), leaving it at 3.50%, and announcing that it expects a new adjustment of the same magnitude for the next meeting.

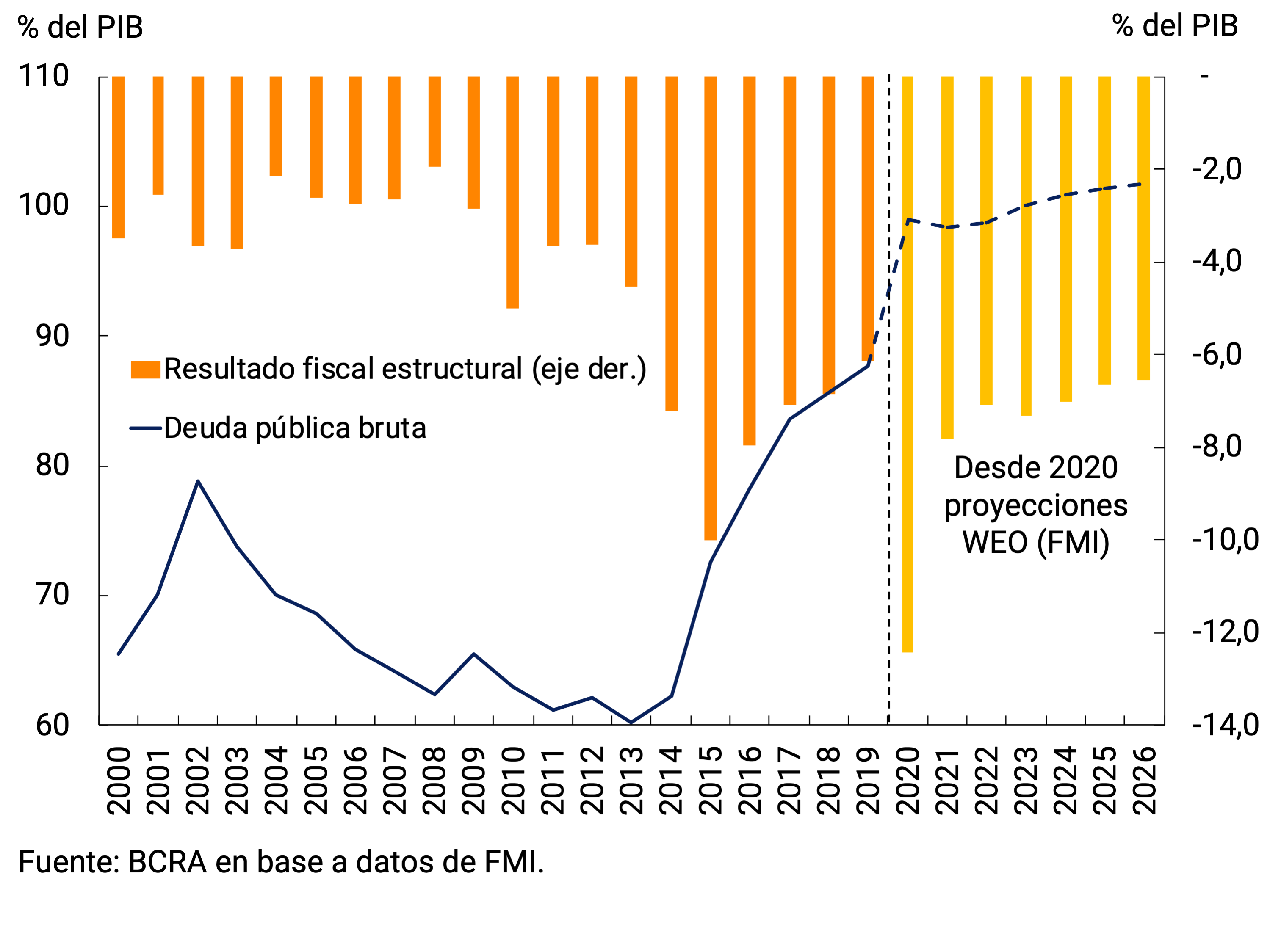

The process of structural reforms and fiscal consolidation initiated in Brazil before the pandemic also presupposes a contractionary fiscal policy. The structural fiscal deficit (according to IMF calculations) reached 12.4% of GDP this year in the face of the stimulus measures implemented to deal with the pandemic, interrupting a decline that had taken it from 10% in 2015 to 6.1% in 2019. Public debt to GDP reached 99% this year. The IMF expects the fiscal deficit to remain above 7% through 2024, with debt exceeding 101% of GDP (see Figure 2.8b). The need to reduce the fiscal deficit is difficult in the face of the serious economic and social situation due to the impact of the pandemic. In addition, with 46% of the debt indexed to the Selic rate, attempts to control inflation would worsen the fiscal result; interest expenditure increases by approximately 0.4% of GDP for each percentage point increase in the interest rate. The lower fiscal and monetary stimulus and the possibility of reduced investor appetite for the fiscal situation represent risks to the strength of the economic recovery.

2.3. Financial markets: higher long-term interest rates

One of the risks to international financial conditions is the increase in interest rates in advanced countries. Since the middle of last year, medium- and long-term interest rates in the United States have increased, and they are expected to continue to do so in the coming months. This is mainly due to an improving economic outlook for that country, but also to a higher expected inflation rate and more uncertainty about the economic and political outlook. For the time being, the steepening of the yield curve (higher increase in long interest rates than in short ones) seems to have stopped and partially reversed. Although rates are still low by historical averages, surprise hikes can generate volatility in financial markets. An example of this was the increase at the end of March, which generated turbulence and uncertainty, and in which the 10-year rate reached a peak of 1.74%. In the following weeks, rates fell, although they were 26 and 72 bps above the previous IPOM close and at the end of 2020, respectively. Just as the process of raising rates had occurred together with an appreciation of the dollar, when rates fell, the U.S. currency also depreciated (see Figure 2.9a).

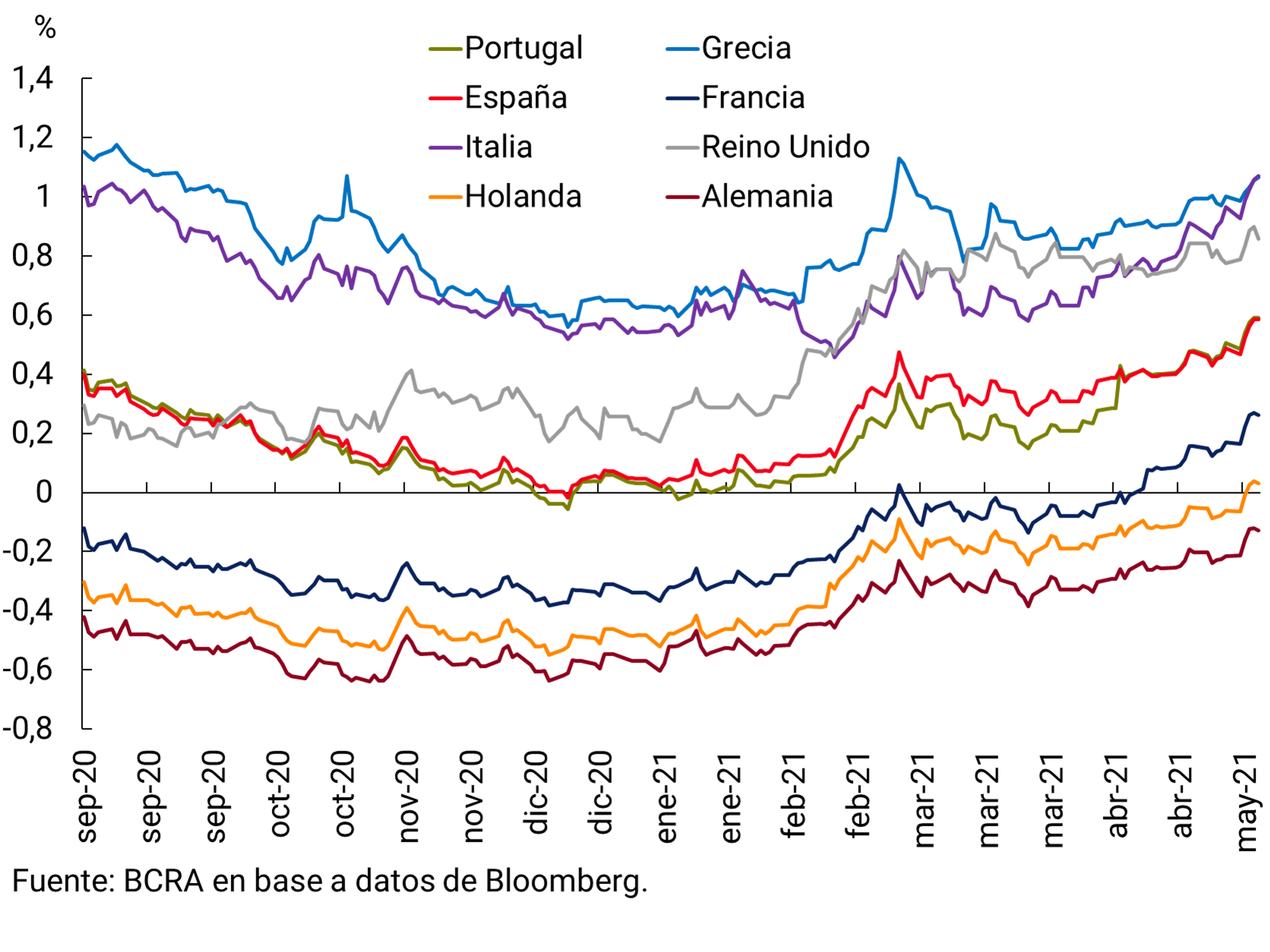

The yields on government bonds of European countries partially reversed the increase at the beginning of the year in March, among other reasons due to the clear signs of continuity of the asset purchase program by the European Central Bank. In recent weeks, European bond rates have risen again, although they have accumulated a lower rise than US bonds this year. Thus, rates have risen by an average of 52 bps since the beginning of the year and 30 bps since the close of the last IPOM (see Figure 2.9b).

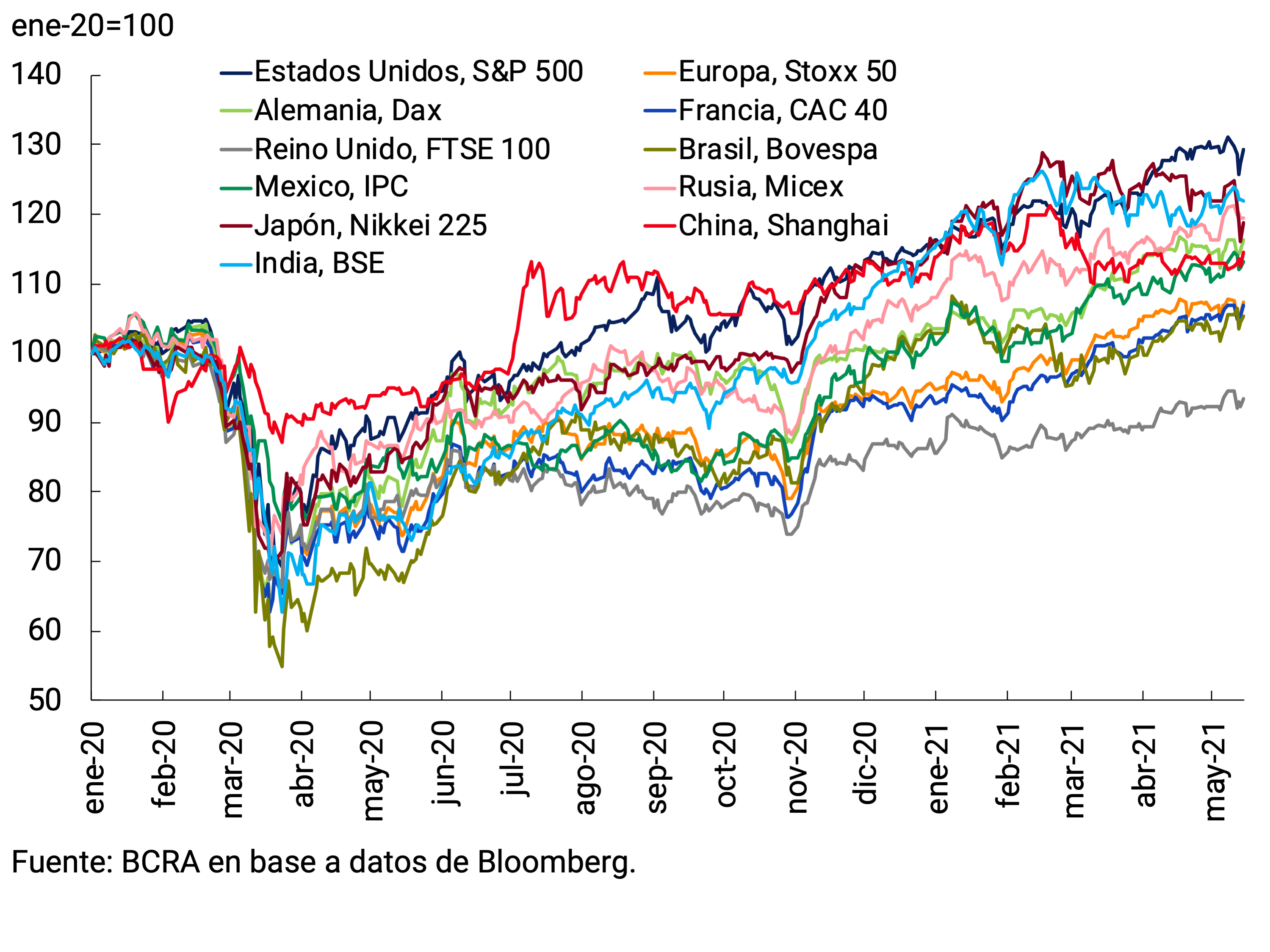

Equity markets continued to perform well. Although the increases in the last quarter were not excessive (both the S&P 500 in the United States and the European Stoxx 50 increased by about 8% since the close of the previous IPOM, see Figure 2.10a), when we take into account the last year and so far this year, the strength in prices is still surprising given the context of economic activity. For example, the S&P 500 is up 29% since the end of 2019, a significant rise considering the economic effects of the pandemic. The disconnect between the boom in the financial markets and the performance of the economy is still present.

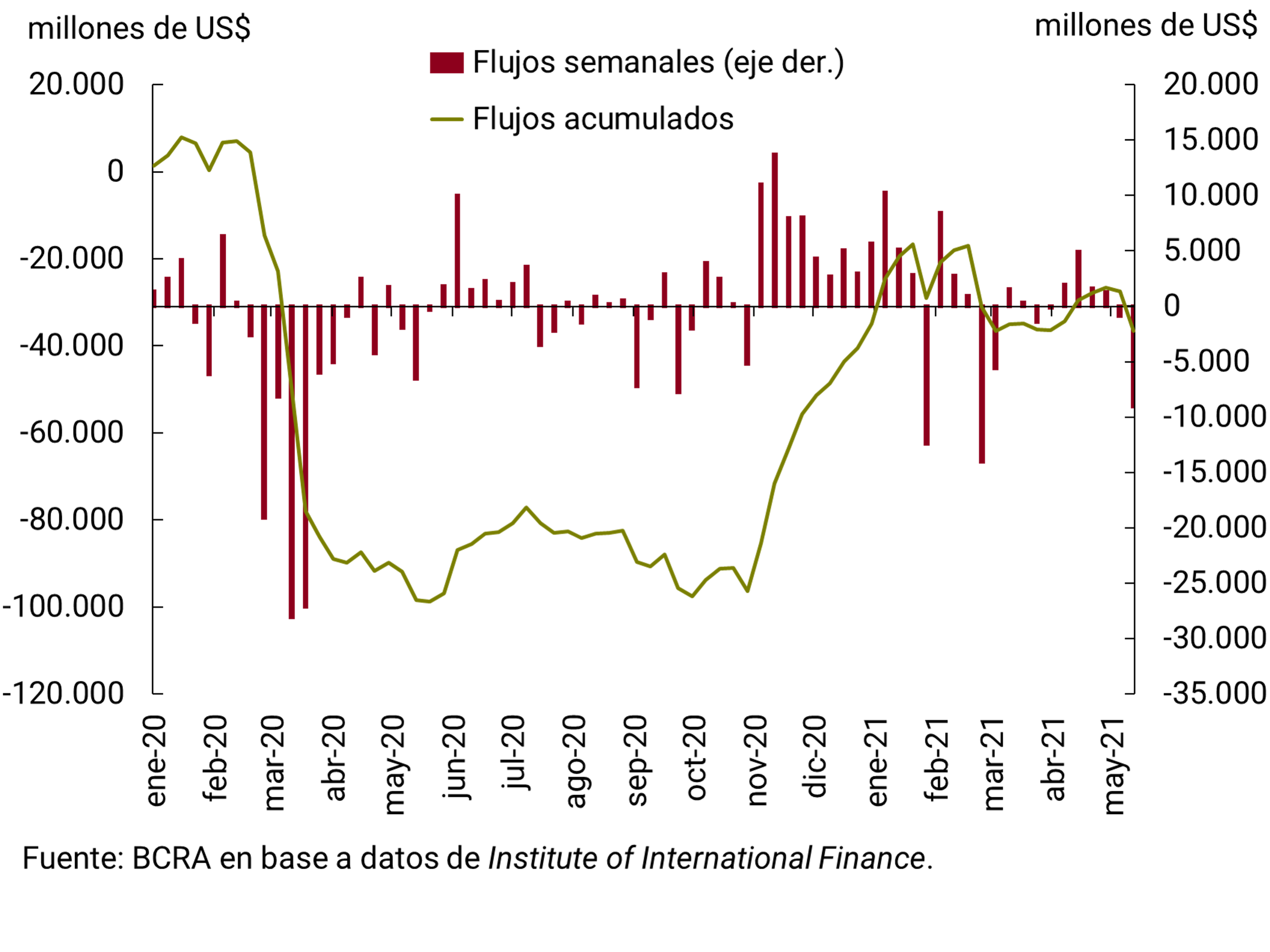

Capital flows to emerging countries have been negative by US$18 billion since the close of the previous IPOM, although they have accumulated a net inflow of US$4 billion in the year, not having fully recovered since the strong outflow at the beginning of the pandemic (see Figure 2.10b). The episodes of capital outflows at the end of February and the end of March of this year occurred at the same time as rate hikes in the United States. These events particularly affect developing countries.

Commodity prices continued to rise, especially agricultural commodity prices, which are already at their highest since 2012 (see Box. Recent developments in international prices of Chapter 4 raw materials. External Sector).

2.4. Fiscal and monetary support measures continue, but some are already beginning to be reduced

Monetary and fiscal policy continues to be expansionary in the world, but with significant differences between advanced and developing countries.

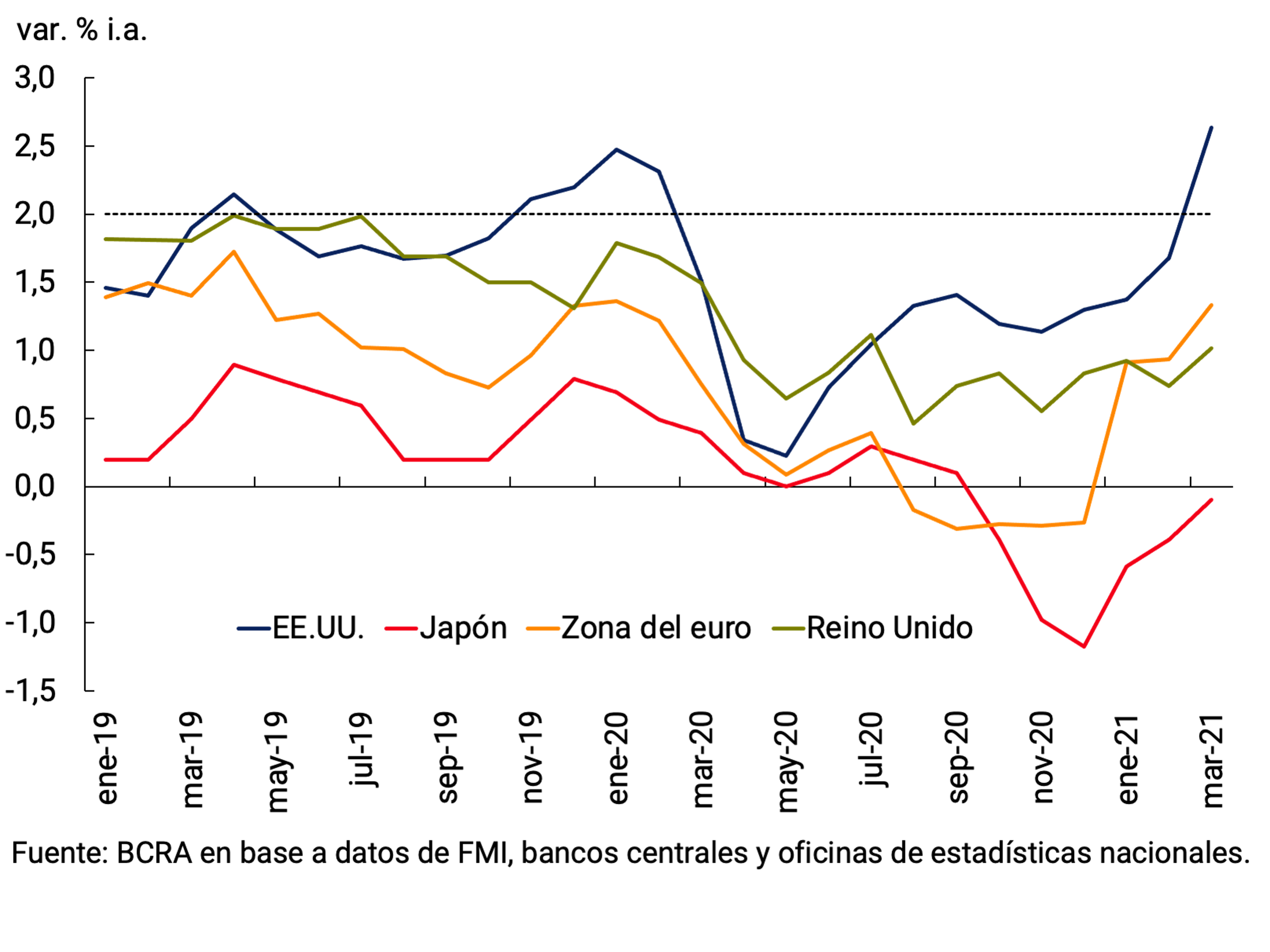

Central banks in advanced countries maintained their pace of asset purchases, with inflation remaining within their tolerance range (see Figure 2.11). Some exceptions were the European Central Bank, the Central Bank of Canada, and the Bank of Sweden. The former has increased the weekly pace of its asset purchases since mid-March to avoid a steepening of the yield curve of the region’s sovereign bonds, which could affect the level of activity. For its part, the Central Bank of Canada announced a reduction in weekly asset purchases after improving the growth projection of the Canadian economy in 2021 by 2.5 p.p. (from 4% to 6.5%), thus being the first G7 country to begin to reverse its unconventional monetary policies. Sweden’s monetary authority also decided to reduce its asset purchase program from the third quarter of 2021, due to a higher-than-expected recovery in the level of activity.

For their part, the authorities of the Federal Reserve of the United States (Fed) indicated on several occasions that they will maintain the expansionary bias of their monetary policy, not foreseeing an interest rate hike until 2024; however, some analysts expect such action in 2023. The reason for this analysts’ projection is that the improvement of the U.S. economy is being faster than expected, in part due to the recently approved fiscal stimulus package. The Fed upgraded its own projections for the economy, forecasting growth for this year at 6.5 percent (compared with 4.2 percent in its previous projection in December), the biggest increase in GDP since 1984. Unemployment projections are 4.5% by the end of the year (compared to the previous projection of 5%). Regarding inflation, the Fed predicts an increase for 2021 for the core household spending deflator of 2.2% (against 1.8% projected last December; 2.4% for the general level) and above the 2% target.

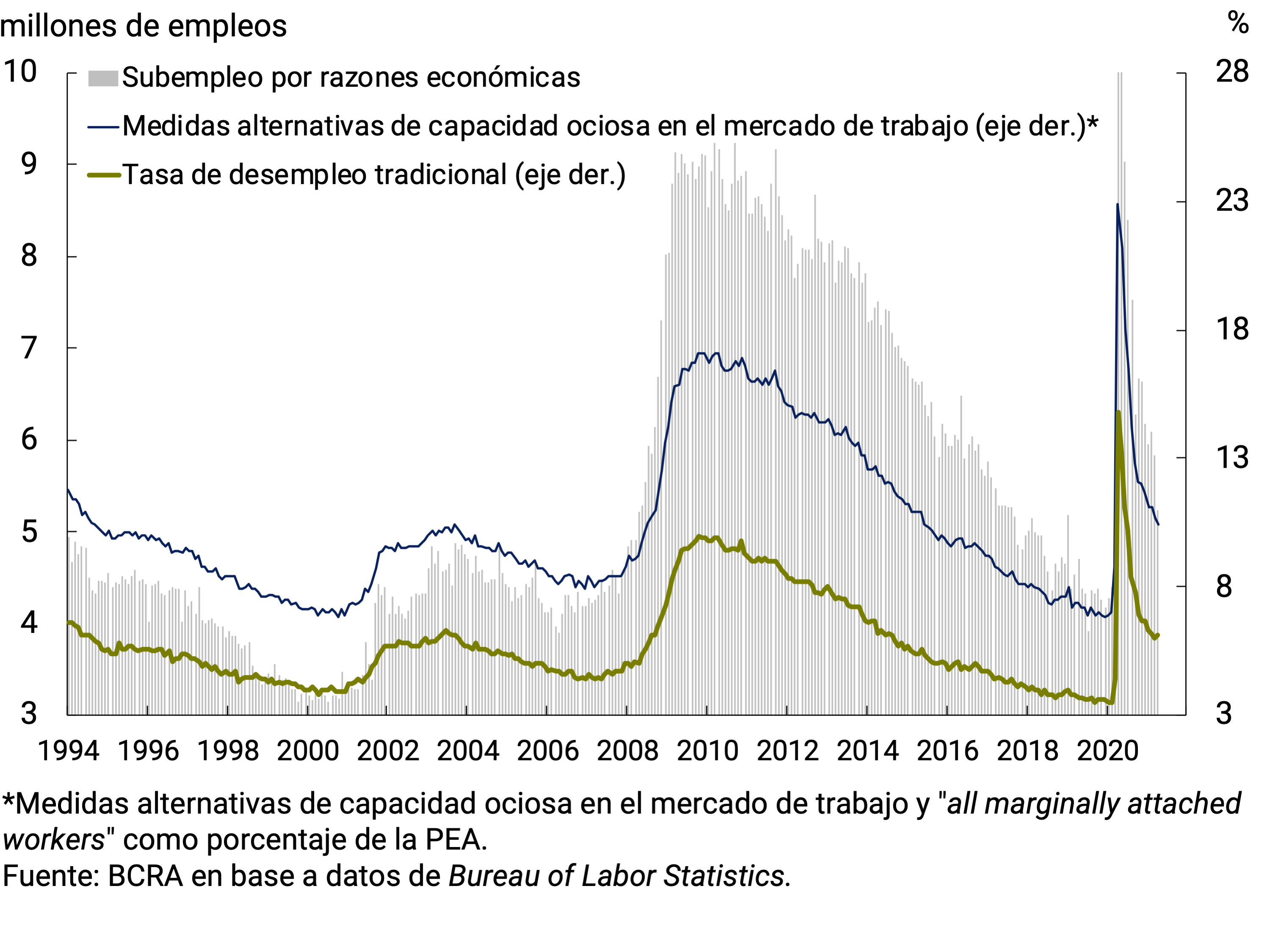

Several factors would explain why, despite these better projections, the Fed does not raise the target on the federal funds rate. First, it emerges from their own projections that they expect higher inflation to be only temporary, since they project inflation of 2% for 2022 and 2.1% for 2023. In addition, the Fed has a dual mandate: stability and maximum employment. In this regard, labour market indicators, especially broader measures of unemployment and underemployment, are still far from pre-pandemic values (see Figure 2.12).

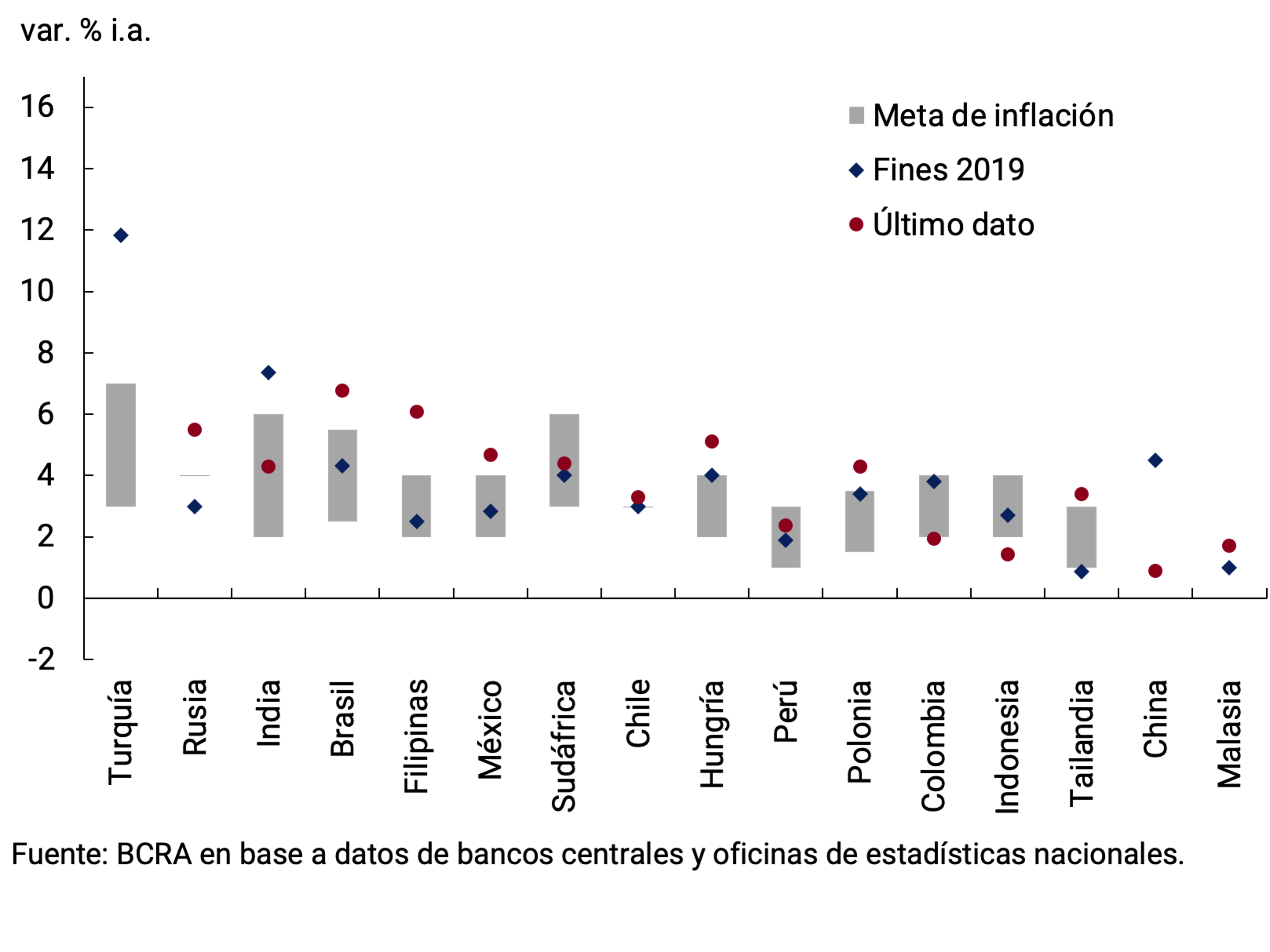

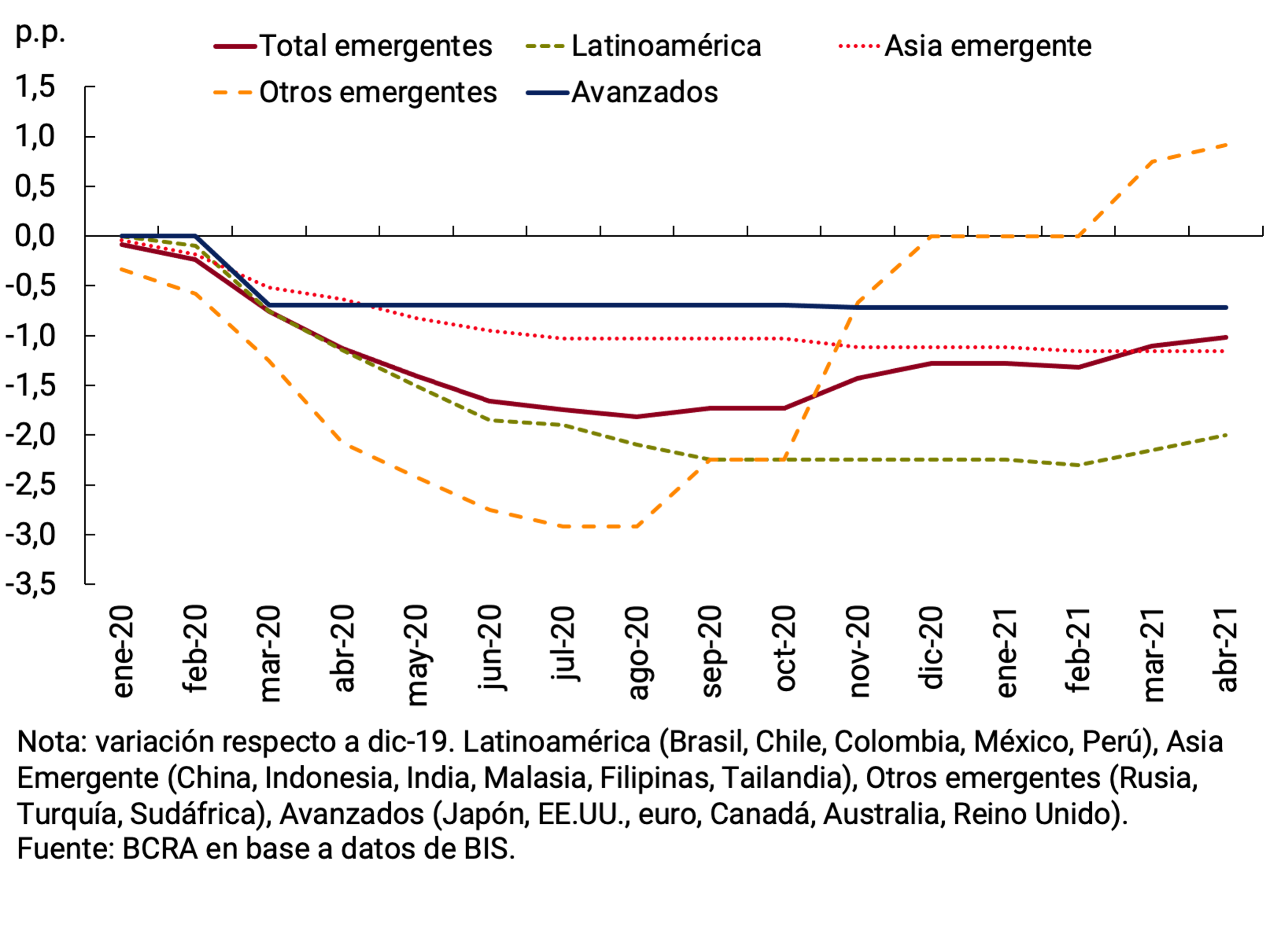

Some emerging countries are beginning to face more limited monetary policy space: they are experiencing higher inflation (see Figure 2.13a), suffering from the impact of sharp depreciations of their currencies and/or higher commodity prices. Thus, policy interest rates rose in Turkey, Russia, and Brazil (see Figure 2.13b). In turn, private sector analysts foresee contractionary measures from Chile’s monetary authority by the end of the year.

In the first quarter of the year, the global fiscal policy response to the pandemic increased by US$2.2 trillion, to US$16 trillion (15.3% of global GDP), according to IMF data. Most of this increase was explained by the US$1.9 trillion fiscal package recently approved in the United States (about 9% of GDP) which, in turn, led analysts and international organizations to revise upwards the growth forecasts of the US economy and the global economy (together with greater optimism about vaccination campaigns)1.

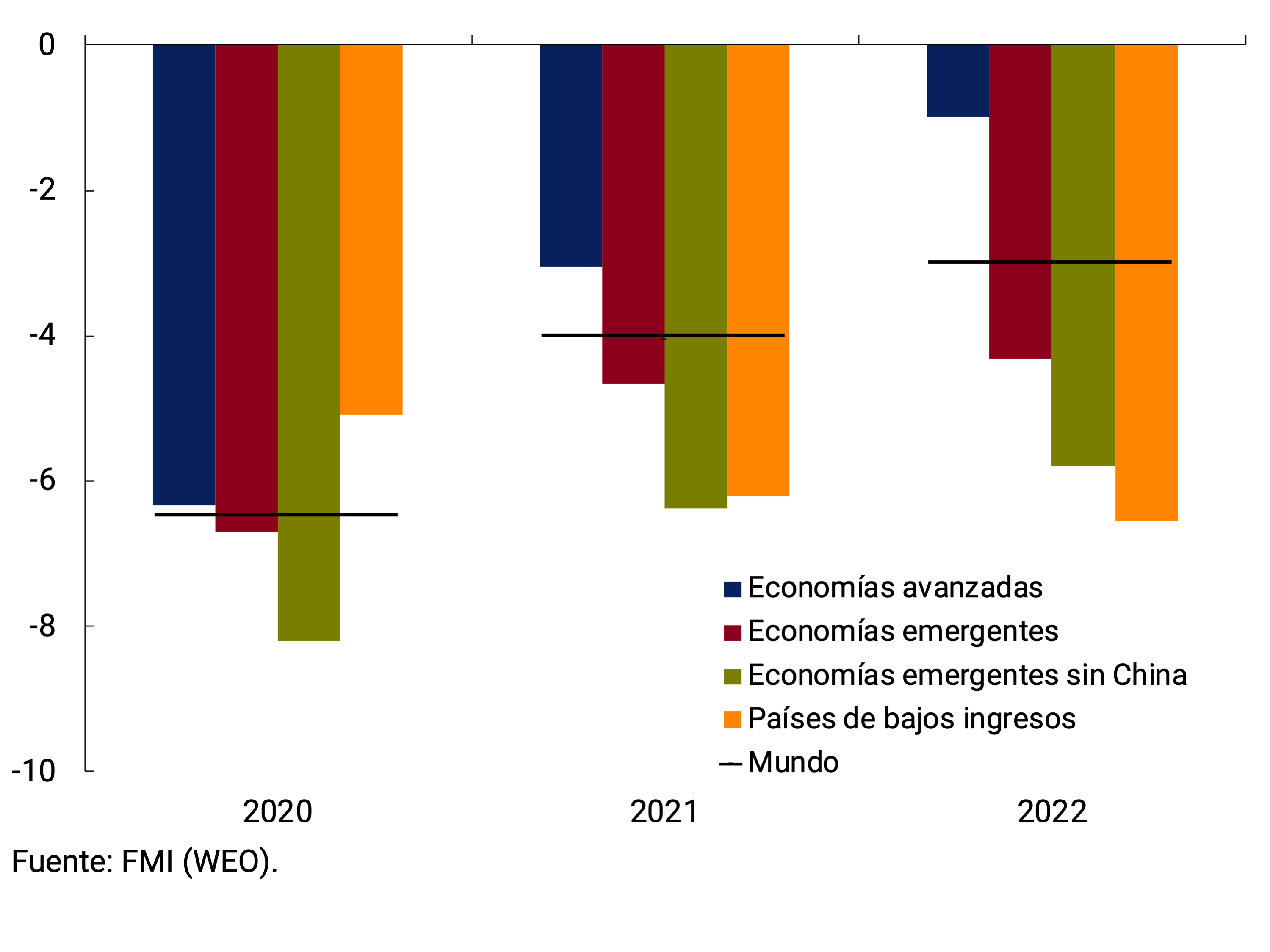

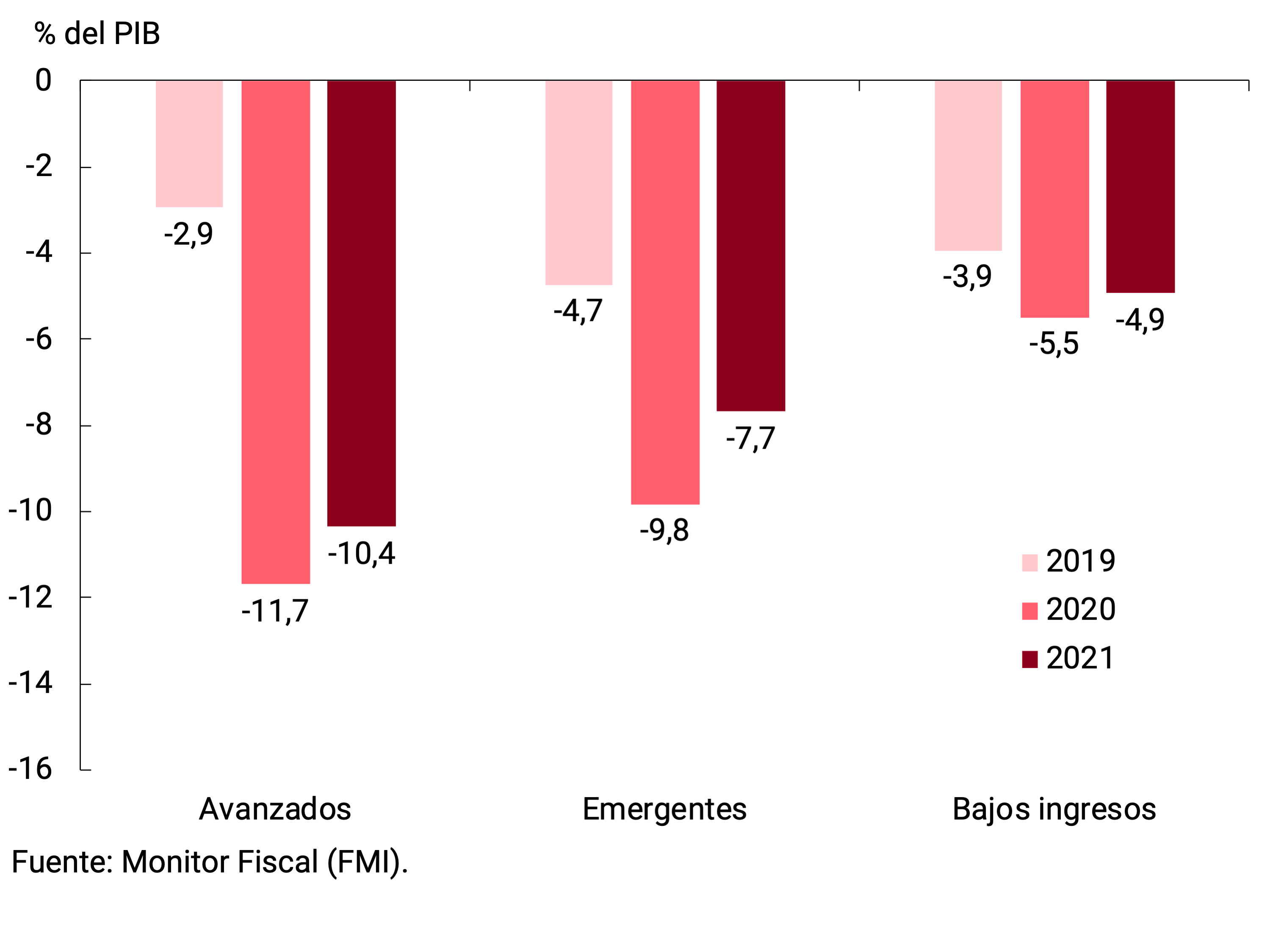

After the sharp increases in fiscal deficits recorded during 2020 as a result of the response to the pandemic, for this year the international organization expects most countries to experience smaller imbalances in their public accounts as tax revenues increase and some expenditures automatically decrease with the recovery and pandemic-related measures expire (see Figure 2.14a).

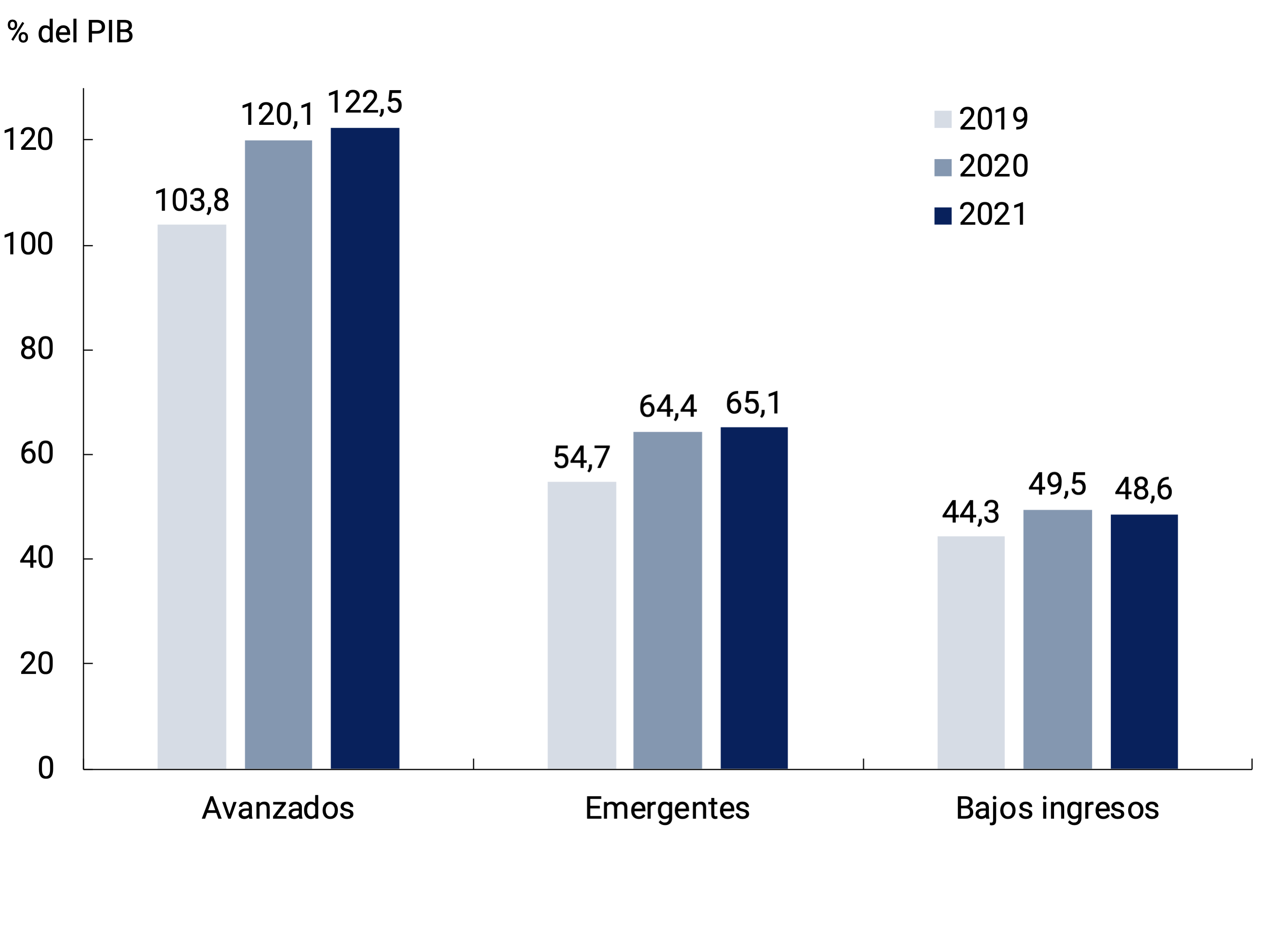

The fiscal bias measures estimated by the IMF, which try to “clean up” the effects of the business cycle on public accounts, show that for this year advanced economies would maintain the expansionary bias, while emerging economies would reduce it. Thus, the fiscal deficit adjusted for the economic cycle would remain stable in the former (from -9.0% in 2020 to -8.8% of GDP in 2021) and fall more significantly in the latter (from -8.1% to -7.3% of GDP). This fiscal dynamic, together with the expected recovery in economic activity, would lead to a more moderate increase in debt-to-GDP ratios at the global level this year compared to what was observed in 2020 (see Figure 2.14b).

Despite the increase in the debt burden, interest payments have remained limited, in general, given the low levels of interest rates driven by the expansive monetary policies of advanced countries and many emerging countries. However, for some middle-income and low-income countries, financing large deficits remains a challenge, given limited market access and limited scope for tax collection in the short term. In this context, higher interest rates, particularly in advanced countries, would put pressure on the dynamics of public accounts, especially on the possibilities of access to financing for emerging and developing countries.

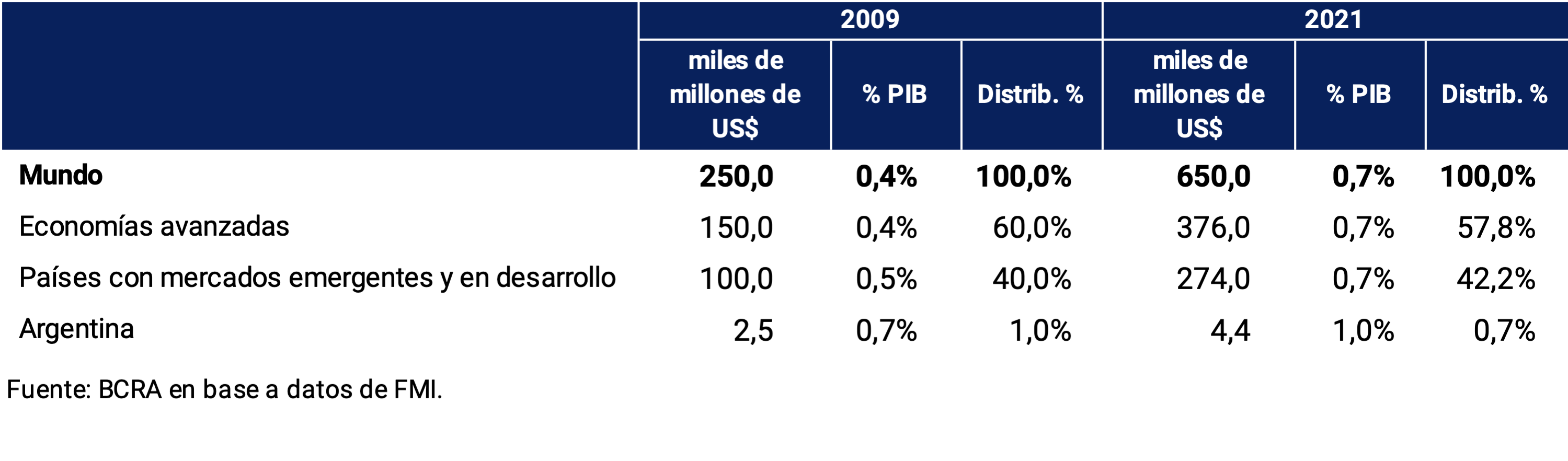

Along with national responses, multilateral economic measures have been taken to address the crisis (see Section 2 / The need for a coordinated international approach to the IPOM crisis of May 2020). These include: currency swaps between central banks; the suspension of official public debt services for low-income countries by the G20, together with a common framework to deal with debt problems beyond this suspension; special financing lines from the IMF, the World Bank and multilateral development banks; and the relaxation of financial system rules by the Financial Stability Board (FSB).

The measures have been effective, but they cover a limited range of countries: the amount allocated to high- and low-income countries is estimated to account for 70% of multilateral financial assistance. Many developing economies have been left out of this coverage. The measures taken so far also revealed the limitations of the current tools of international organizations in terms of middle-income countries; or countries that do not qualify as either solid or low-income. That is why the G20’s decision to push for a new allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), and to explore the recirculation of surplus SDRs, is essential (see Section 1 / The New Allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs): What It Is and What It Means for Developing Countries).

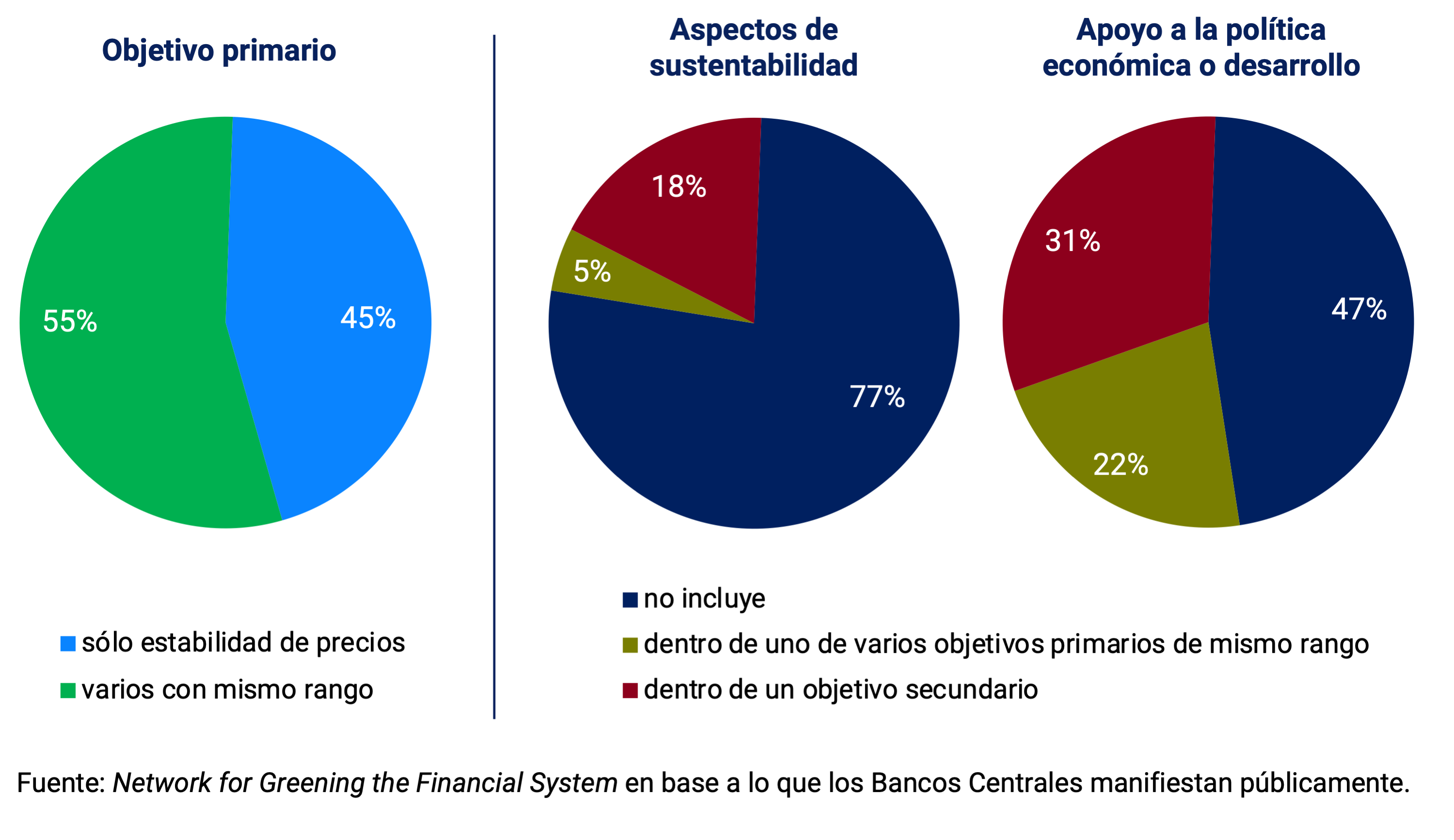

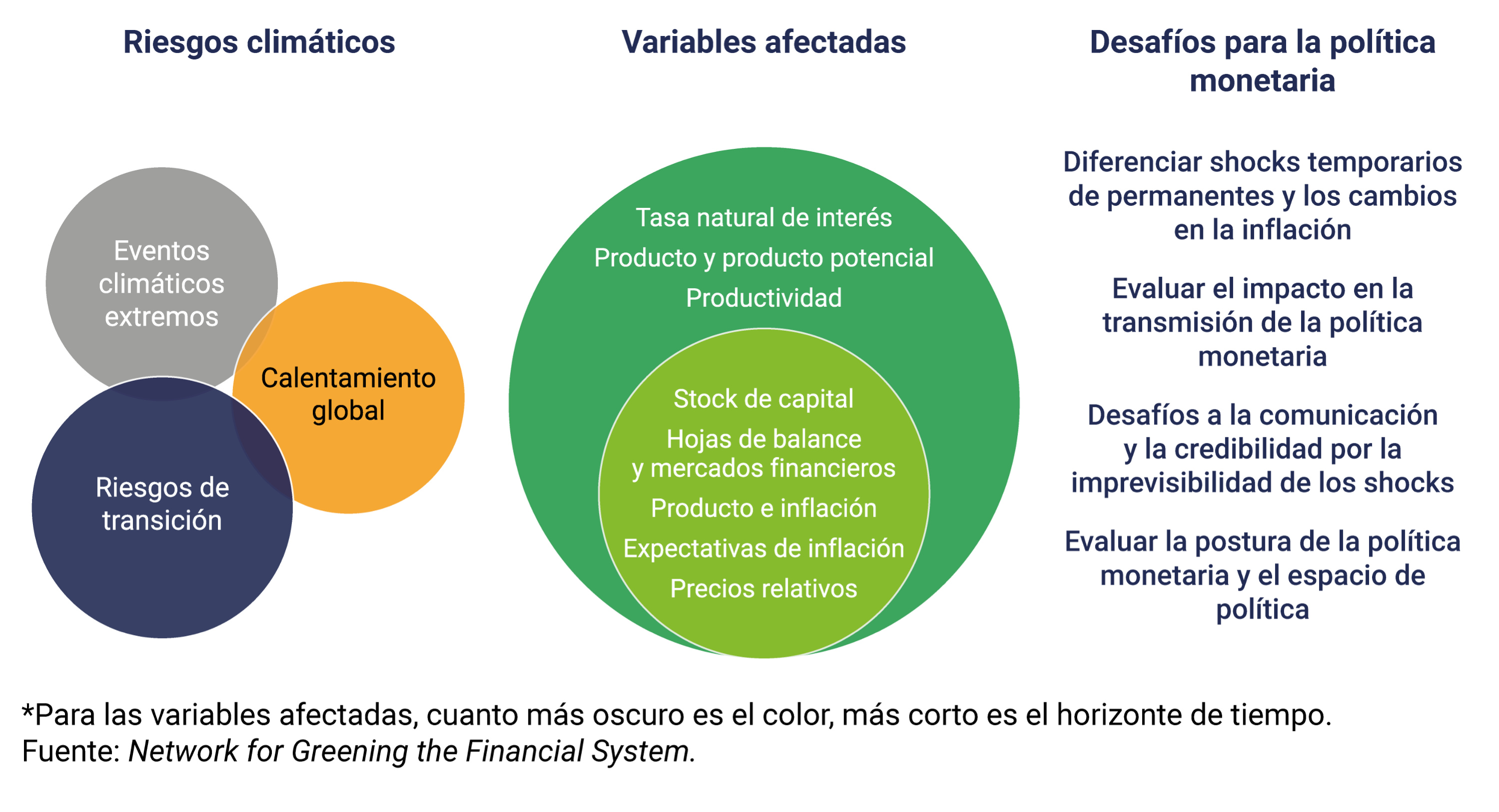

Likewise, and as part of the policies to promote inclusive and resilient growth beyond the recovery, the Italian presidency of the G20 has placed special emphasis on environmental issues, so that the growth pattern that emerges beyond the recovery fundamentally incorporates sustainability. Its treatment from the point of view of central banks is discussed in Section 2 / The challenge of central banks in the face of climate change.

2.5. In summary

The recovery of the global economy continues, but it is mixed across countries and subject to a variety of risks. Outbreaks and new variants of the virus, together with vaccination campaigns disparate in scope and speed between countries, are today the main limit to the continuity of the recovery. The greater intensity of fiscal support in advanced economies justifies the upward revision of growth forecasts; But there is still a risk of premature withdrawal of support measures in many countries, including those with less policy space. Divergence in health and support responses would deepen inequality between countries, and even within them. Some of the risks marked in the previous IPOM, such as the rise in medium- and long-term interest rates in the United States, have partially materialized: the risk is that the next hikes will be more abrupt and surprise the market, driving new capital outflows. Overall, the disconnect between the booming financial markets and the performance of the economy remains, along with the risks of private and public sector insolvency, which could lead to sharp corrections in asset prices.

3. Economic Activity and Employment

Economic activity continued to improve in the first quarter of 2021, favored by the measures taken by the National Government and the BCRA in the face of the health emergency, the authorization of economic activities under protocol rules and the implementation of the vaccination process against COVID-19. This recovery partially attenuated the sectoral heterogeneity, based on the progress in the activities most sensitive to the pandemic.

The sharp rise in COVID-19 cases observed since March led the National Government, in coordination with provincial authorities, to take measures to contain infections. Partial and specific mobility restrictions were implemented in each jurisdiction, considering the improvement of the health system in the last year and the progress of vaccination, which was added to the validity of sanitary protocols in the various productive activities. Based on the deterioration of the epidemiological situation, the Government recently temporarily reinforced the restrictions, complementing them with policies to support the affected sectors and households, in order to limit the impact on the social and productive fabric.

Economic activity could slow down due to the impact of the second wave of infections during the second quarter. The health measures adopted that temporarily restrict activity in some sectors, lower consumption due to the reduction in mobility, the fear of contagion and the consequent increase in economic uncertainty affect the normal development of production.

Going forward, the main risk factor is associated with greater difficulty in containing the pandemic from the appearance and circulation of new variants of the virus, which could be more contagious, and could lead to closures of activities and isolations for a longer time than expected. On the other hand, the ongoing vaccination process and a positive effect of the measures recently adopted could limit the duration and intensity of this second wave, allowing the impact on the economy to be less. Thus, the improvement in the health situation would allow economic activity to resume the pace of expansion.

3.1. The second wave of infections would temporarily impact an economy that was approaching its pre-pandemic levels of activity

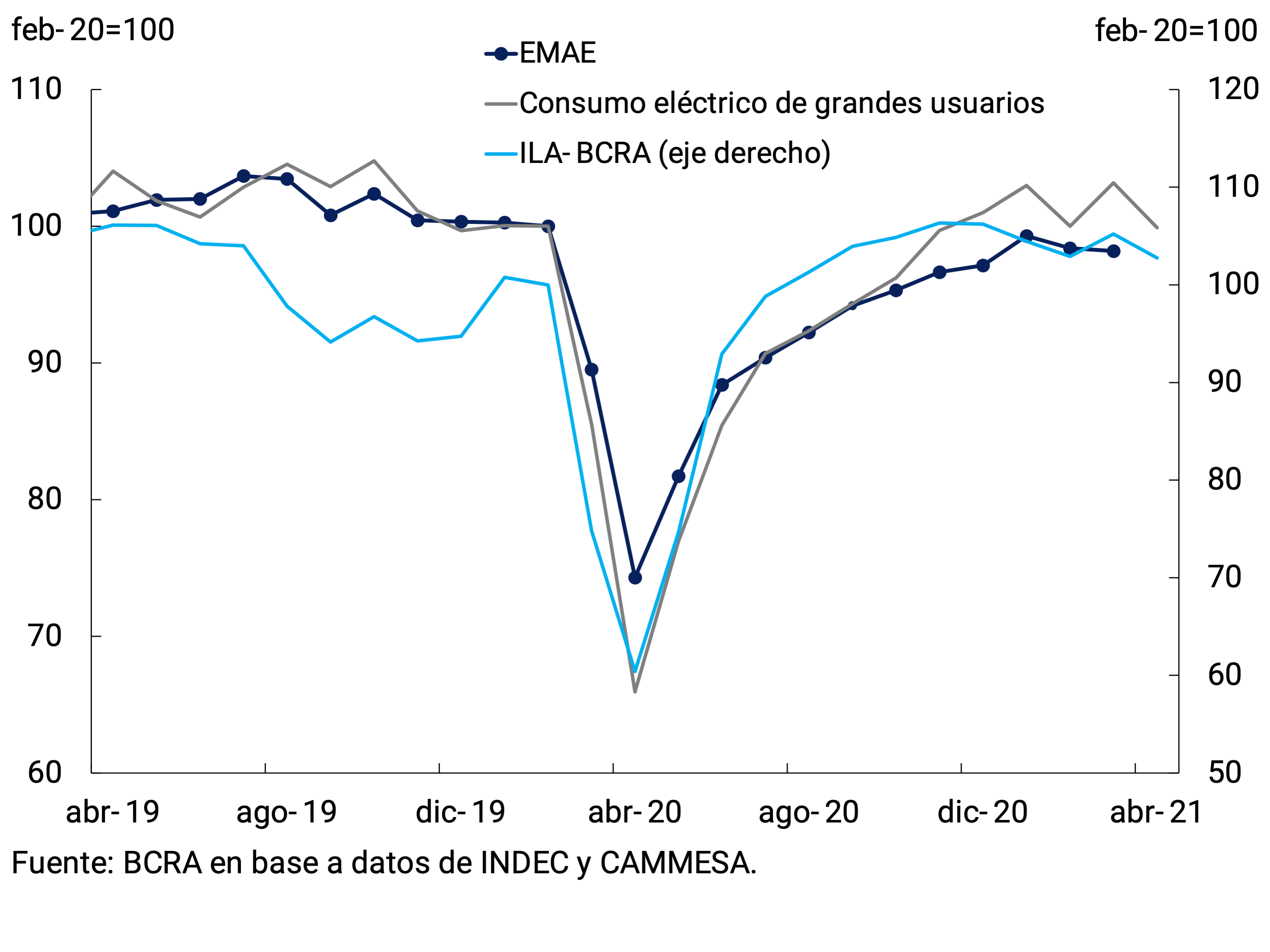

At the beginning of the year, economic activity continued to recover. The Monthly Estimator of Economic Activity (EMAE) adjusted for seasonal factors (s.e.) was 11.4% above the level of March 2020 in March 2021 and just 1.8% below the seasonally adjusted level of February 2020, the month prior to the spread of COVID-19 in the country. In the first quarter of the year, activity showed a growth of 2.3% s.e. compared to the previous period.

At the beginning of the second quarter, the materialization of a second wave of infections and the rapid deterioration of the health situation led to the implementation of restrictions on mobility – although of less intensity and duration than those in force a year ago – and revived uncertainty regarding the normal development of activity over the coming months.

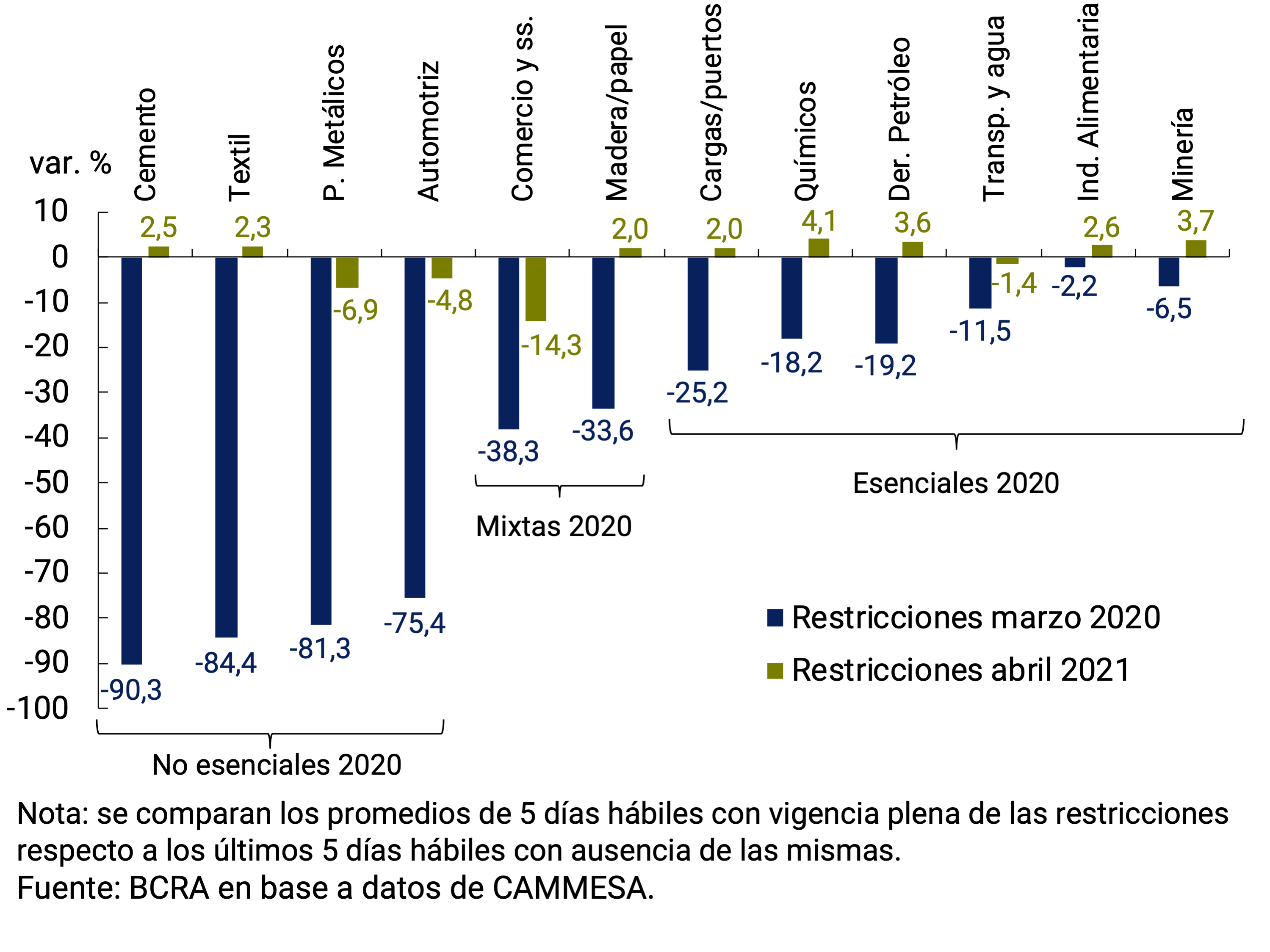

The first high-frequency data for the month of April anticipate a limited contraction in activity. The electricity consumption of large users of CAMMESA3 adjusted for seasonal factors fell to reach the level of last February, which is very similar to those of the pre-pandemic (February 2020). This performance of electricity demand reflected the reduction in the mobility of people at night, the closure of shopping malls and gastronomic establishments, and also the lower activity in Vaca Muerta and the surrounding region as a result of the road blockades that took place during most of the month due to the union conflict of health workers (see Figure 3.1).

The level of activity would register transitory falls during the second quarter, although for the rest of the year there are factors that play in favor of a good economic performance. In this scenario, once the epidemiological situation is controlled, the economy would resume the path of expansion in the third quarter and the year would show a recovery compared to the previous year, although sectoral heterogeneity will persist.

Among the factors that operate in favor compared to last year are, in the first place, greater knowledge about the contagiousness of the coronavirus, learning about the management of the pandemic, the progress of the vaccination campaign and the adaptability of individuals and economic sectors to the operation with health protocols and virtuality. In the same vein, global growth, greater international liquidity and high commodity prices compared to a year ago (see Chapter 2. International Context).

3.1.1. The recovery in demand continued to be led by the great dynamism of Investment

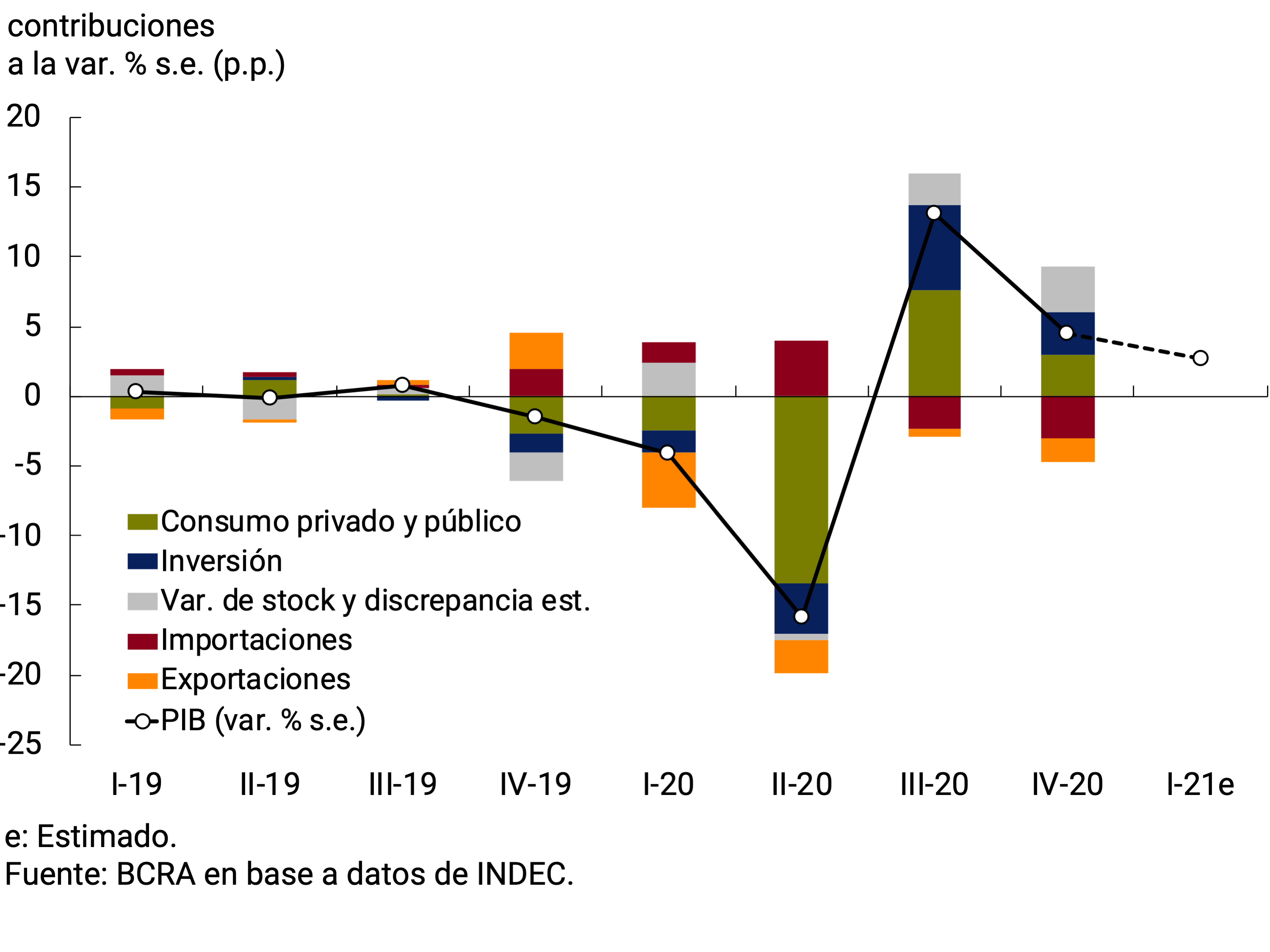

In the last quarter of 2020, GDP recovered 4.5% quarter-on-quarter (-4.3% y.o.y.) but domestic demand – total domestic expenditure on consumption and investment – in seasonally adjusted terms expanded again at a faster pace. Private consumption grew 4.2% qoq s.e. (-8.1% y.o.y.), public consumption increased 1.3% s.e. (-2.6% y.o.y.) and Investment4 again experienced a strong rebound, of 17.3% qoq s.e. (15.9% y.o.y.).

In terms of the contribution5 to quarterly GDP growth of each of the components of aggregate demand, Total Consumption and Investment both contributed 3 percentage points (p.p.) while the accumulation of stocks6 set a historical record of 3.3 p.p. of positive impact. On the other hand, the net external sector subtracted 4.8 p.p. from the quarterly variation in GDP, due to the increase in imports (-3 p.p.) and the fall in external demand (-1.8 p.p.; see Chart 3.2).

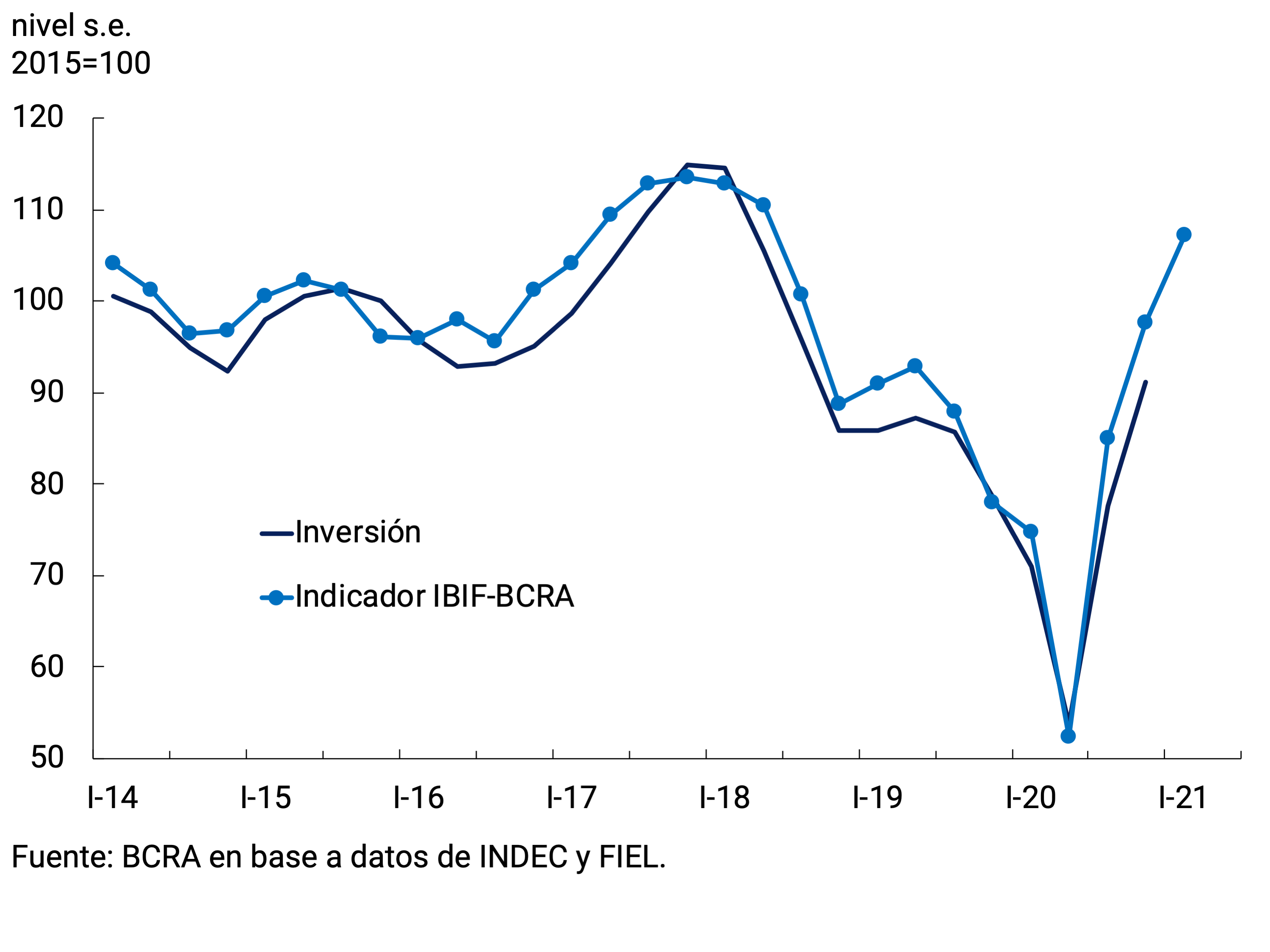

Advance data for the first quarter of 2021 allow us to anticipate a new rebound in investment that would place it at seasonally adjusted levels similar to those of 2018 (see Figure 3.3). The IBIF-BCRA indicator showed a quarterly increase of 9.8% s.e. with increases in both construction and spending on durable production equipment7. Investment is expected to grow by around 40% compared to a year ago, led both by the dynamism of the construction sector and by purchases of agricultural machinery and capital goods by the industrial sector.

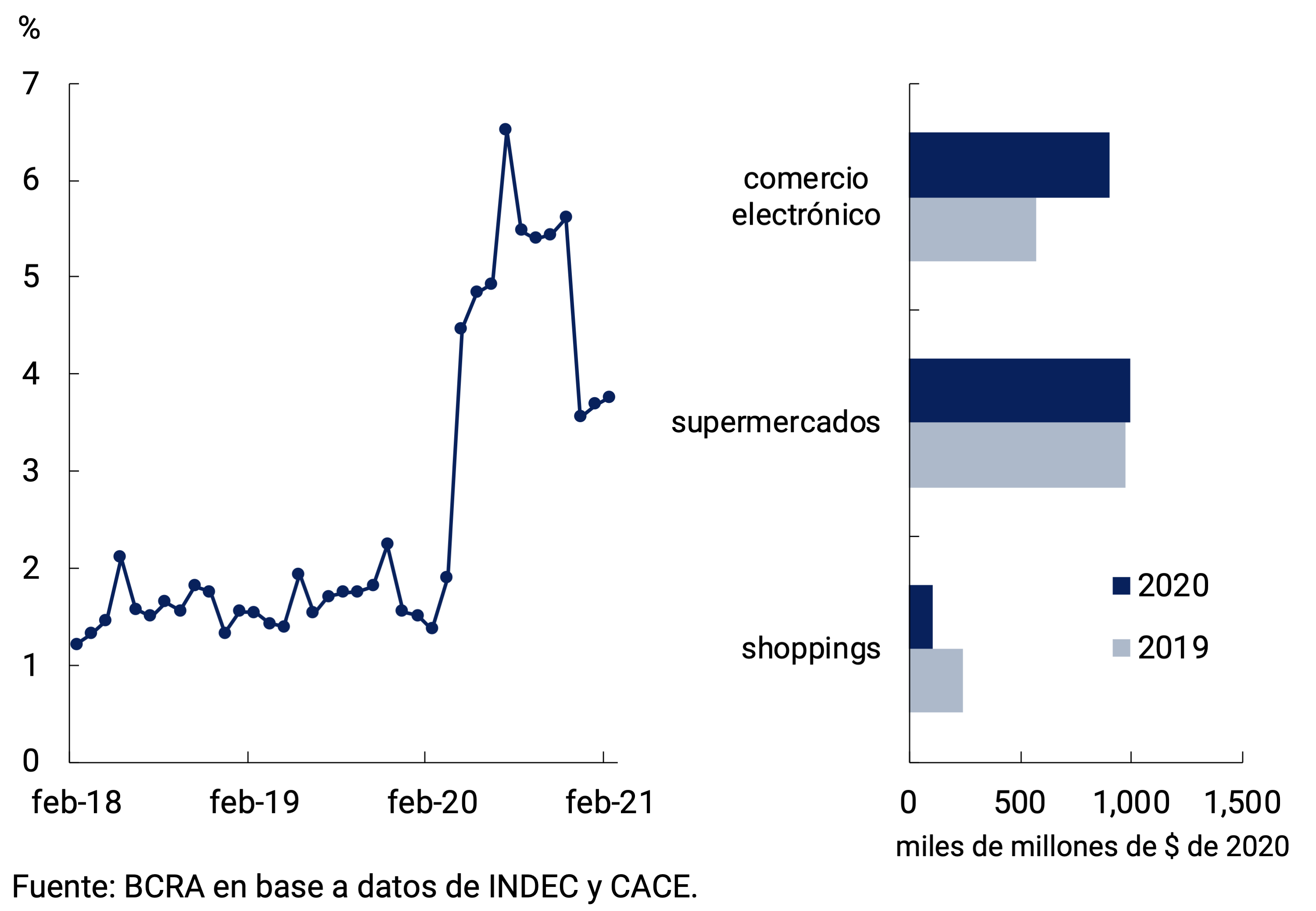

Private consumption had moderate growth during the fourth quarter of 2020, standing 8.3 p.p. below the pre-pandemic level. The recovery in household incomes was driven by independent and informal employment, while the formal wage bill was more stable throughout that year (see Employment Section). With partial data from the first quarter of 2021, the BCRA’s Private Consumption Indicator showed an improvement of 3% s.e. compared to the previous quarter. An important factor in the evolution of household spending during the rest of the year is the greater supply of services available and the strong redirection of spending in favor of consumption through electronic channels, compared to a year ago, when the pandemic broke out. The second quarter of 2020 was the period of greatest impact of this unusual shock that motivated the development of new digital platforms to which both consumers and firms gradually adapted.

According to the survey of the Argentine Chamber of Electronic Commerce8 in 2020, e-commerce turnover grew in 2020 by 124% compared to 2019 and the number of products sold increased 84%, with more than 1.2 million new buyers. The same survey reveals that 67% of companies in the sector are very optimistic for 20219. In supermarkets, the increase in online purchases from March 2020 was also noticeable and the participation of this modality in total turnover is still much higher than in the pre-pandemic period. In this way, total turnover via e-commerce, measured at 2020 retail prices, increased by 58% in 2020 and was close in magnitude to that of supermarkets as a whole (see Figure 3.4).

Net exports would contribute positively to aggregate demand during the first quarter of 2021. According to the information referring to the Commercial Exchange of Goods of INDEC, a partial reversal of the behavior observed during the previous quarter is expected, with a positive contribution of net exports close to 2 p.p. Quantities traded abroad registered a quarterly increase of 19.1% s.e., while imports measured at constant prices slowed down sharply, to 3.2% quarterly s.e. (see Chapter 4. External Sector).

3.1.2. The arrival of the second wave of COVID-19 would accentuate the heterogeneity of sectoral performance in the second quarter

During the fourth quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of 2021, the good performance of sectors that are very relevant to the economy was maintained, which continued to grow above their pre-pandemic levels. Services activities most affected by the crisis accelerated their recovery during that period, although they remained far from their previous levels. The second wave of COVID-19 has interrupted since April the improvement of those services that involve greater social contact. The necessary partial restrictions on movement were deepened in the last week of May and their impact could be directly or indirectly spread to other sectors. Health protocols, the strengthening of the health system and the ongoing vaccination process have allowed these restrictive measures to be, so far, less intense than those applied in March and April 2020. As a result, most productive activities will register strongly positive year-on-year growth rates in the second quarter of 2021, in some cases in double digits.

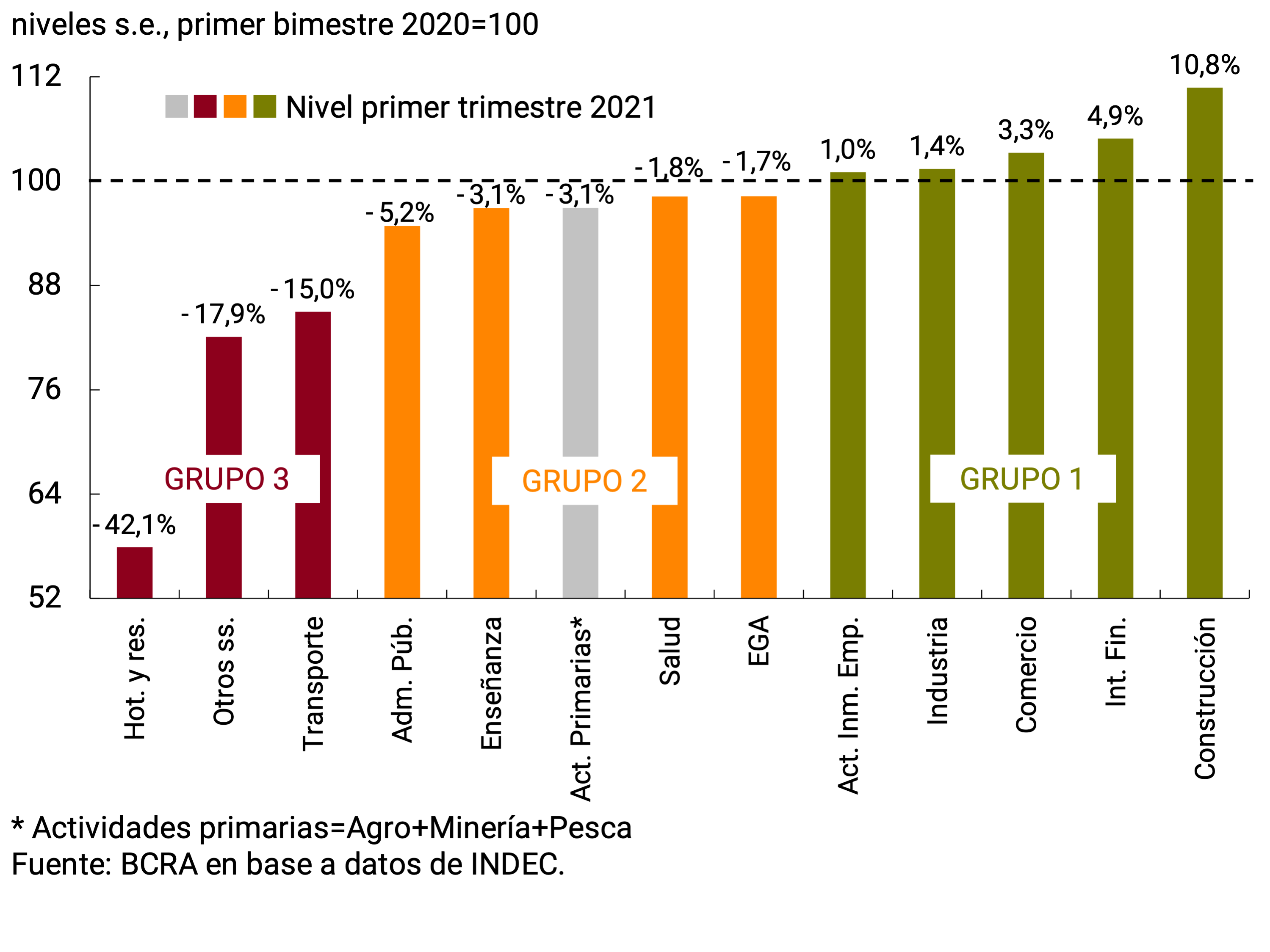

Regarding the performance since the beginning of the recovery, three groups can be identified based on the cumulative rates of change between the first two months of 2020 and the first quarter of 2021. In this way, the first available data from the EMAE in 2021 are compared with the months immediately prior to the arrival of COVID-19 in the country, following a classification similar to that used in the previous IPOM (see Figure 3.5).

The first group is made up of several of the main economic sectors that operated in conditions close to normal during the first months of 2021 and have managed to exceed the production levels recorded in the first two months of 2020: Construction (10.8%), Financial intermediation (4.9%), Commerce (3.3%), Industry (1.4%) and Real estate and business activities (1%)10. The relaxation of social isolation measures since May 2020, added to the policies adopted by the National Government and the BCRA to strengthen aggregate demand and domestic credit, allowed the rapid recovery of these sectors, which together represent 67% of GDP11. The second wave of COVID-19, the associated higher absenteeism and the necessary restrictions adopted to deal with it could have affected these sectors from April 2021 onwards, although to a lesser extent compared to other activities that involve greater social contact. In the event of monthly falls, adjusted for seasonality, they would be significantly lower than those evidenced in March and April 2020. This would allow high growth rates to be recorded in year-on-year terms during the second quarter of 2021, especially in Construction, Industry, Commerce, and Real Estate and Business Activities (see Chart 3.6).

Figure 3.6 | Variation in the demand for electricity from productive activities after the adoption of restrictions on social interaction

A second group is made up of sectors that cut much of the fall generated by the pandemic, but failed to reach previous levels and, therefore, registered limited falls in the first quarter of 2021 compared to the first two months of 2020: Public administration (-5.2%), Education (-3.1%), Electricity, gas and water (EGA, -1.7%) and Health (-1.8%). These sectors evolved heterogeneously since May 2020, while Public Administration and Education slowly improved as their functions and activities were enabled, the Health and EGA sectors recovered rapidly, oscillating at levels close to normal. The impact of the second wave of COVID and the measures adopted since the second half of April would also be uneven among the sectors that make up this second group. Some activities will depend on the possibility of continuing to provide services with less “face-to-face” (Public Administration and Education); others, such as EGA and Health, would be affected by the restrictions in a mixed way, with upward and downward factors.

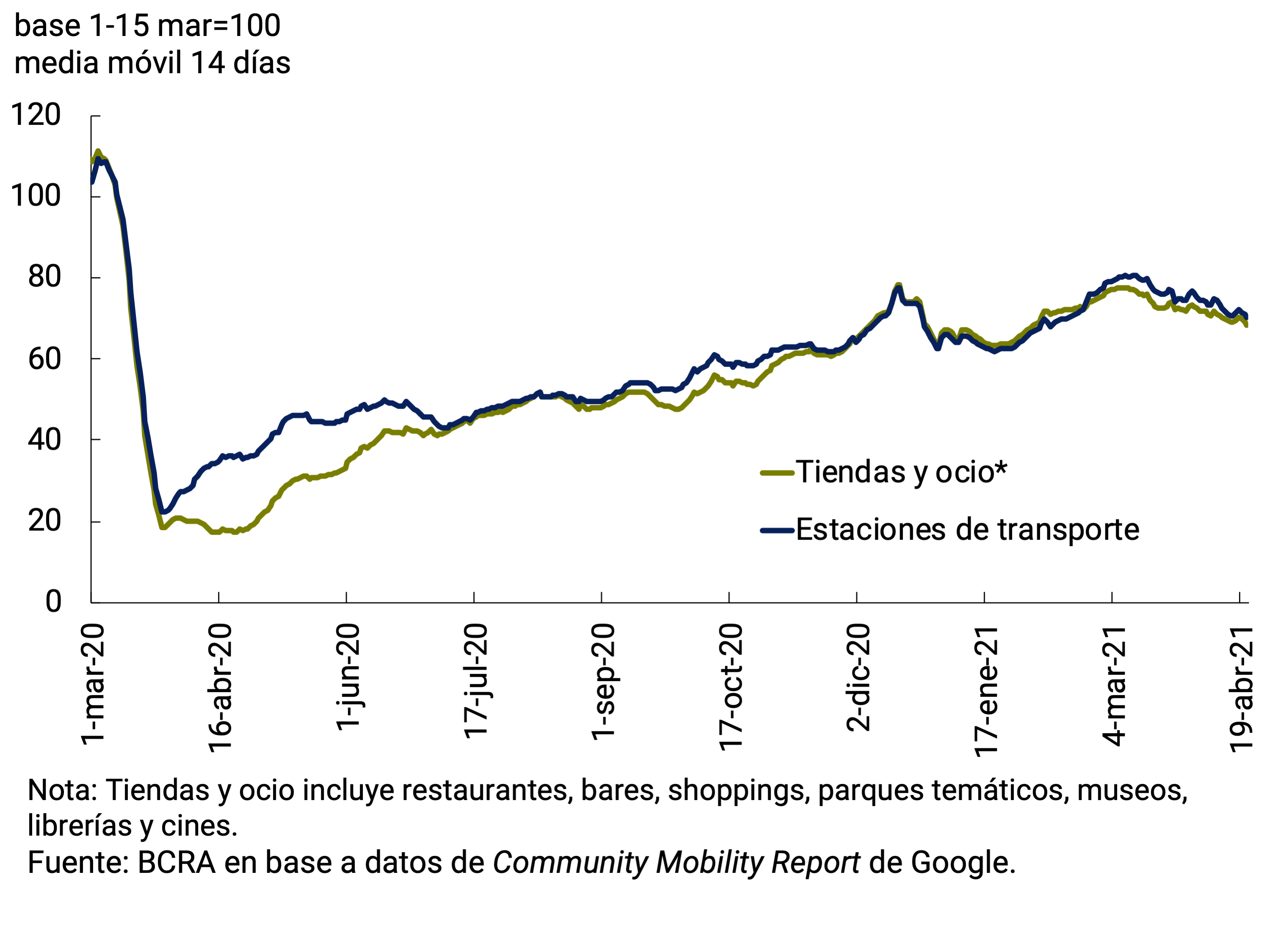

A third group is made up of some service sectors that, as they imply a greater health risk, were the most affected by the pandemic, accumulating strong contractions until the first quarter of 2021: Hotels and restaurants (-42.1%), Other services (-17.9%) and Transport (-15%). In the fourth quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of 2021, the restrictions affecting these activities were partially relaxed, allowing an acceleration in their recovery. The increase in circulation, the authorization of domestic tourism, the reactivation of flights, and the permission to operate cinemas and theaters gave impetus to these sectors which, however, were still far from normal levels, in the context of a preemptively contained demand. As noted in the previous IPOM, the speed of recovery of this group of activities depends directly on the evolution of the pandemic. In this sense, the arrival of the second wave and the implementation of restrictions to face it would have negatively affected these sectors as of April and a deepening is expected at the end of May. The mobility data associated with transport and recreation show declines compared to March, although of a reduced magnitude compared to those observed during the period of strict isolation during March and April 2020 (see Figure 3.7). The National Government reinforced assistance plans for these most sensitive sectors with the aim of cushioning the contraction in their incomes during the period of greatest severity of the health situation.

Finally, the primary activities, Fishing (-0.4%), Agriculture (-1.3%) and Mining (-7.6%) have not been included in these three groups as their evolution depends on idiosyncratic factors of both supply and demand, which are less linked to the pandemic. The output of the agricultural sector recovered since May 2020 as a result of better-than-expected weather conditions and soil moisture, also favored by the increase in international prices. Fishery output continued to be highly volatile depending on the level of catches. Finally, in Mining, which includes oil and gas extraction, the recovery from the minimum in April 2020 has been slow. Plan Gas.Ar12 is expected to gradually boost production, after generating a sharp increase in the number of fracturing stages in the Vaca Muerta hydrocarbon wells during the first quarter of 2021. Specifically, in the month of April, there would have been a severe transitory retraction attributable to the union conflicts that interrupted activity in the area for much of the month. As happened in 2020, the second wave of COVID-19 would not significantly affect these three sectors and its evolution would continue to depend on idiosyncratic factors.

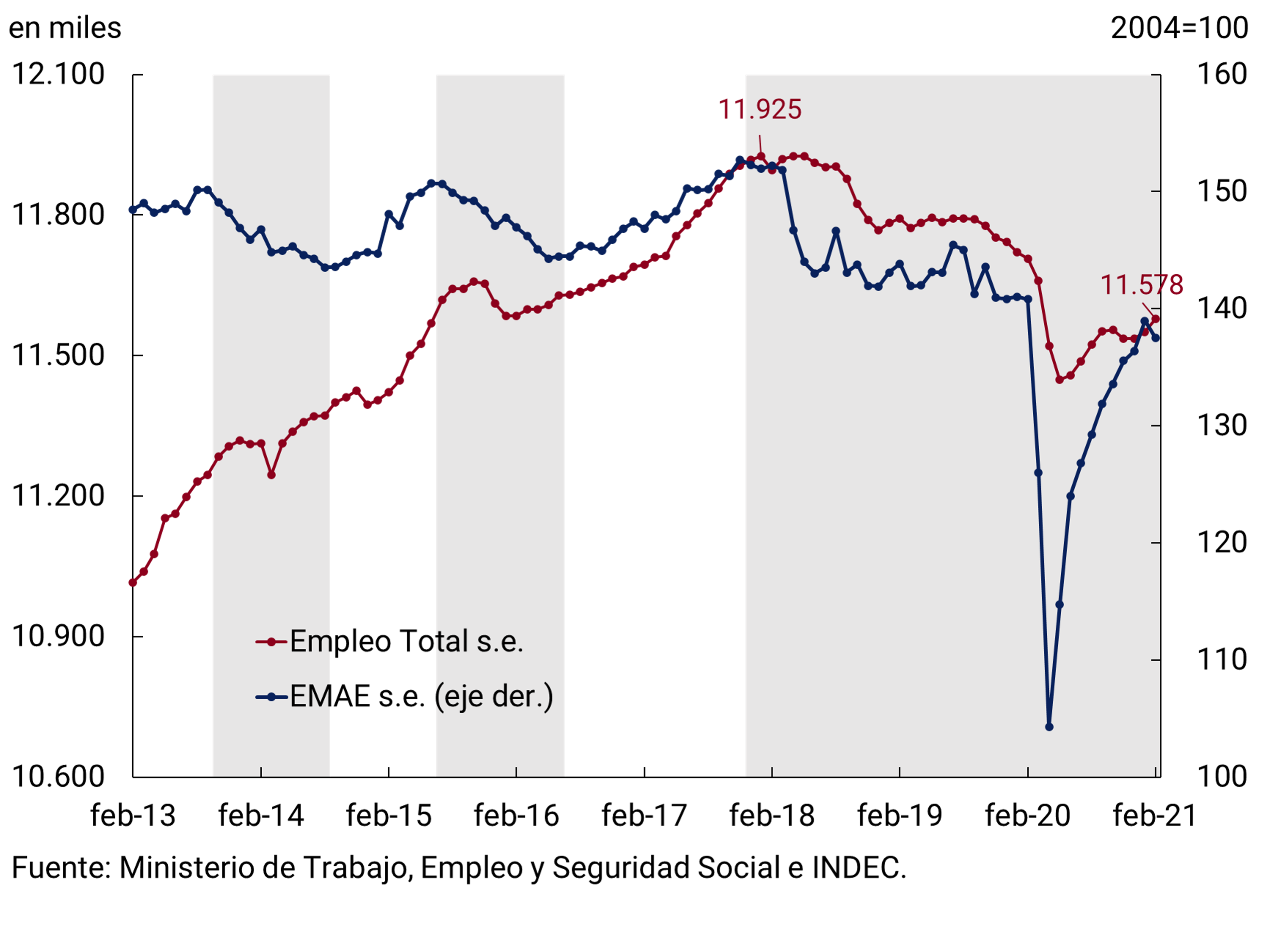

3.1.3. Employment indicators accompanied the economic recovery, although most have not yet returned to their pre-pandemic level

In a context of economic recovery prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, which implied the relaunch of health, labor, and income policies of the population, the labor market showed mixed trends. Registered salaried employment showed limited variations at the end of 2020 and the beginning of 2021, while within the informal market (both salaried and non-salaried) positive dynamics stood out that drove a gradual recovery in employment.

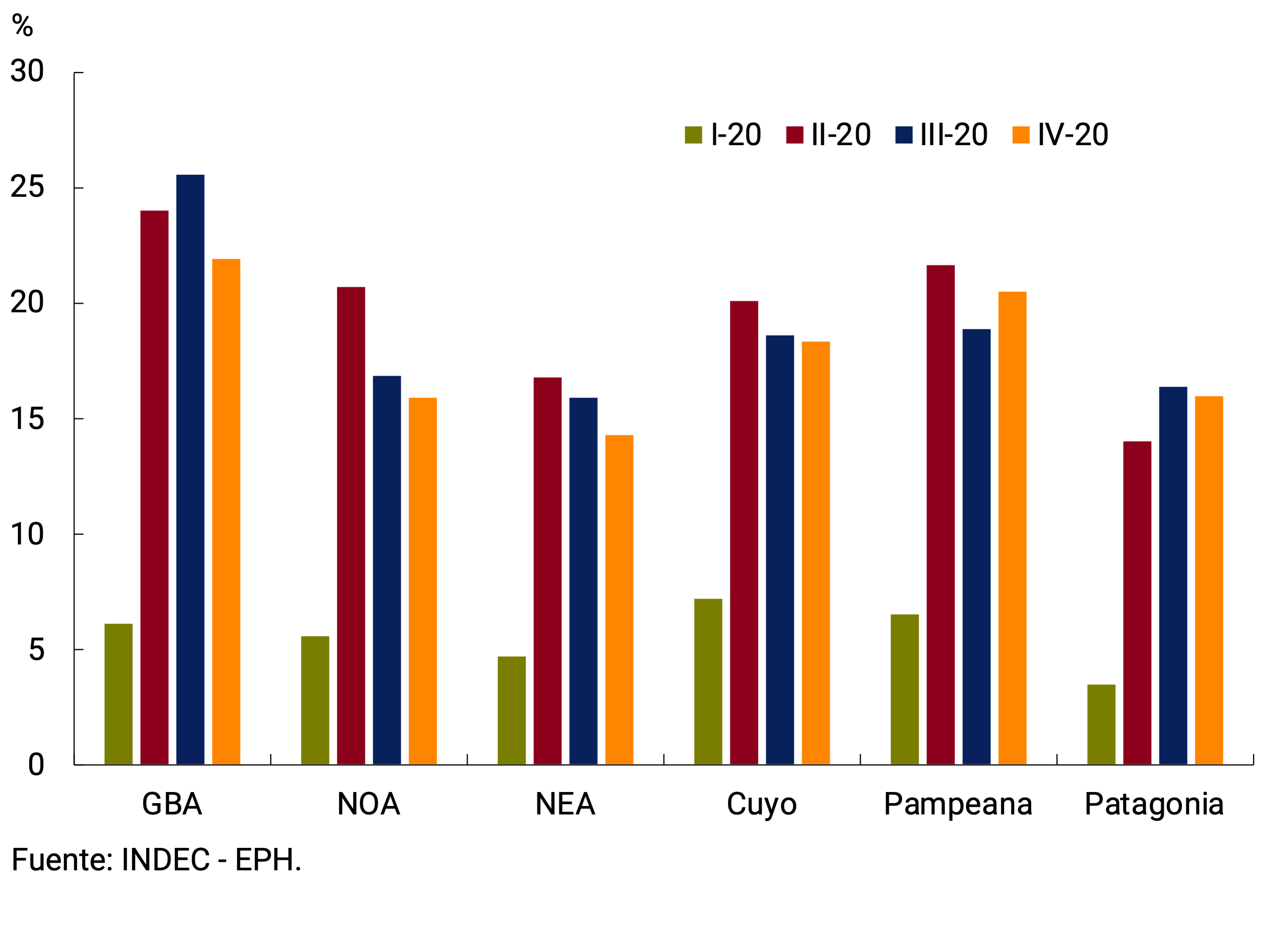

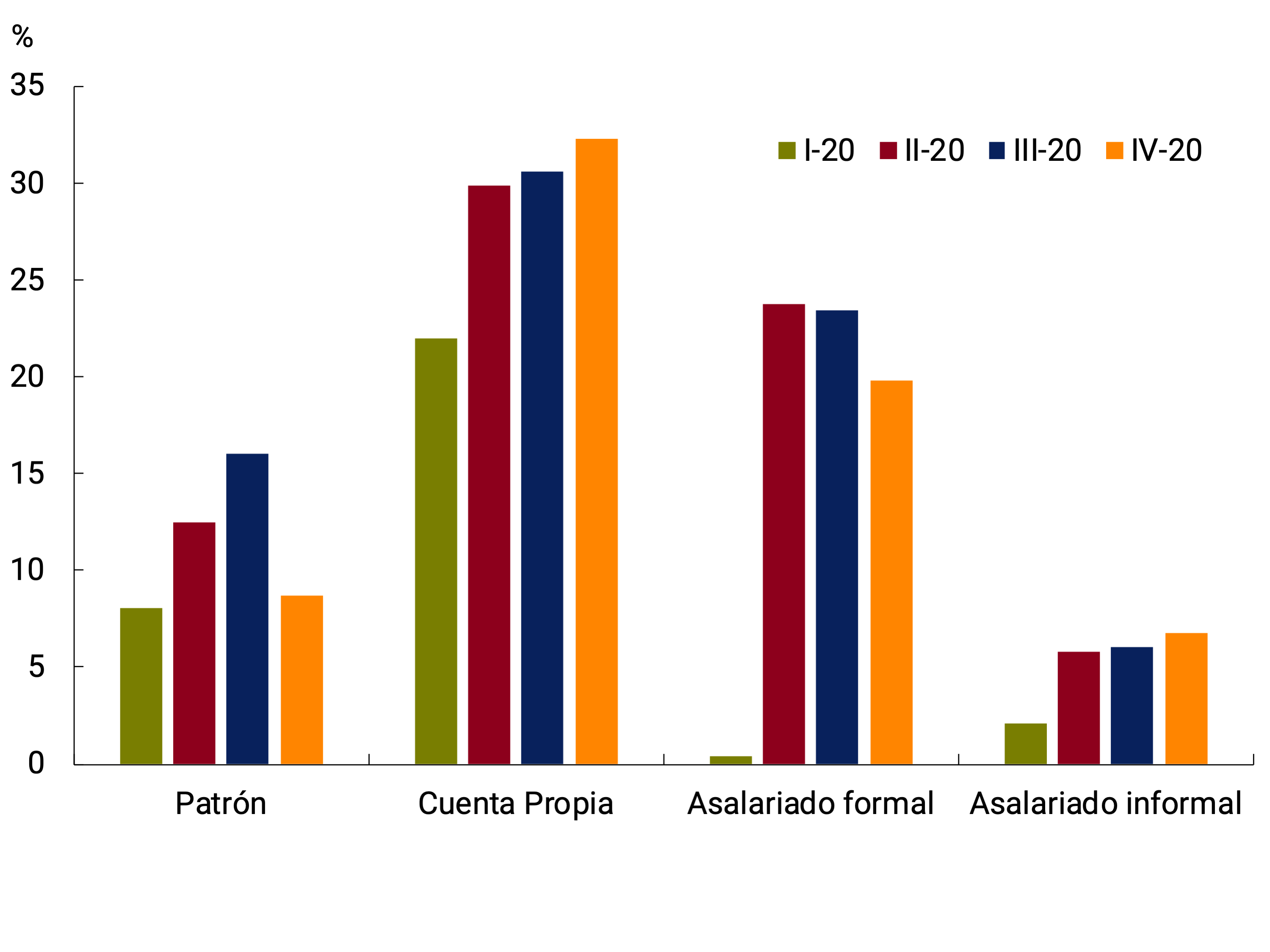

Employment indicators accompanied the economic recovery, although most have not yet returned to their pre-pandemic level. In the fourth quarter of 2020, the employment rate showed an improvement simultaneously with the normalization process of the activity rate13. The economically active population grew by up to 45%, 2.7 p.p. compared to the previous quarter, but with a decrease of 2.2 p.p. in year-on-year terms. In the fourth quarter of 2020, 3.1 million people re-entered a job, thus recovering 79% of the jobs lost during the second quarter of 2020. The employment modalities that were most affected during 2020 were the most dynamic: 1.4 million unregistered salaried workers and 1.9 million non-salaried workers (self-employed and employers) rejoined the labour market. The adaptation of the labour market to the pandemic also implied new trends in the way of working (see Section 3. Changes in work methodologies: Telework in Argentina). Finally, the unemployment rate stood at 11.0%, 2.1 p.p. lower than the rate of the second quarter and 2.1 p.p. higher than that of the fourth quarter of 2019, both due to the year-on-year increase in the unemployed and the effect of the reduction of the Economically Active Population (EAP).

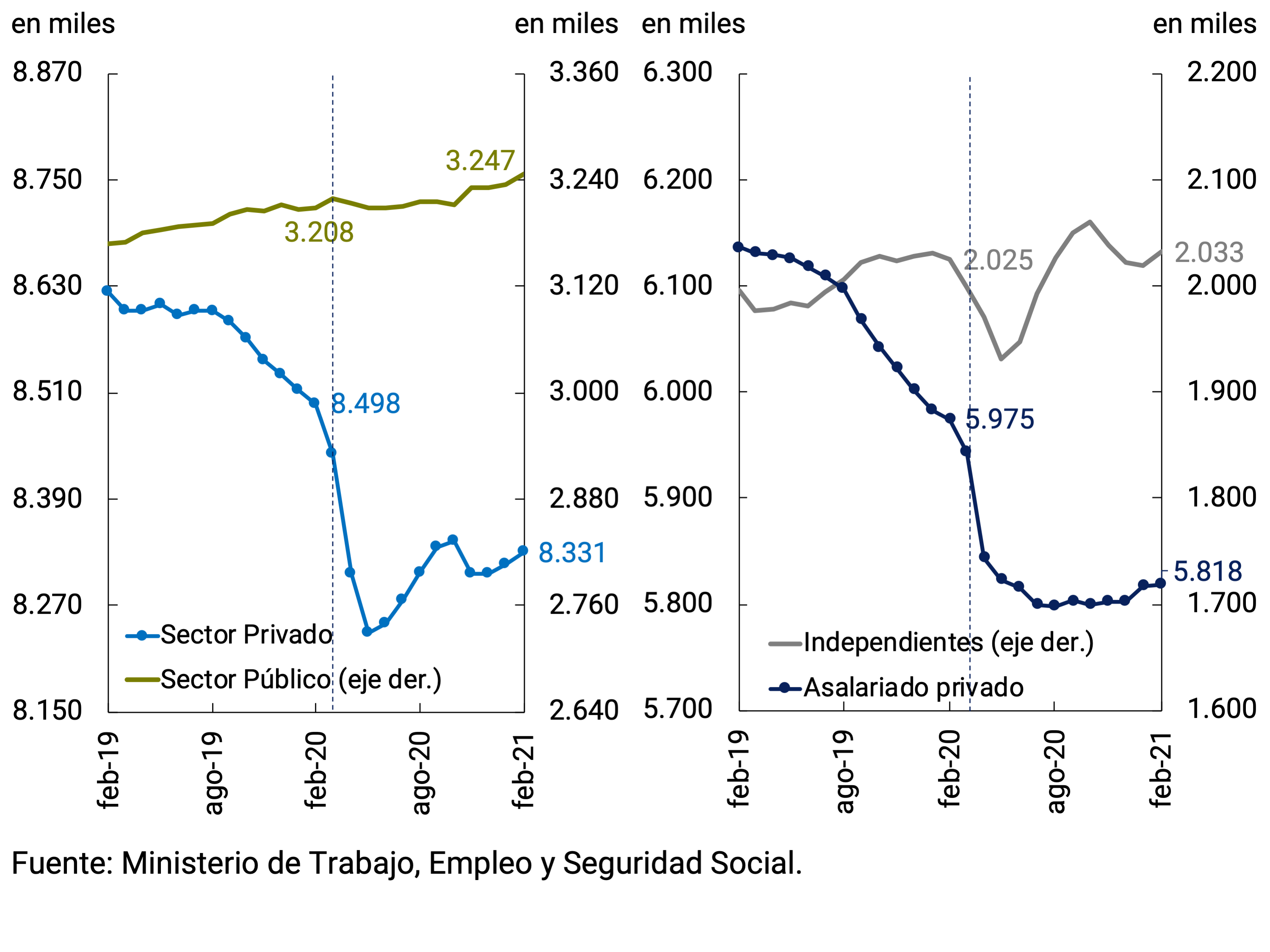

Total registered employment resumed the positive trend between November 2020 and February 2021 (+0.3% s.e.), reaching an improvement of 1.2% s.e. since the pandemic floor (May 2020), according to data from the Ministry of Labor, Employment and Social Security (MTEySS14; see Figure 3.8).

This recovery in total registered employment is related to an incipient positive dynamic of registered wage earners. In particular, public wage earners grew 0.5% s.e. while private wage earners showed an increase of 0.2 s.e. since Nov-20. This growth offset the 0.3% drop s.e. in registered self-employment (single-tax and self-employed persons; see Figure 3.9). The aggregate behavior of private salaried employment hides at the sectoral level, a significant increase in employment in sectors such as Real Estate, Business and Rental Activity, Manufacturing Industry and Construction since Jun-20. On the other hand, the less economically dynamic branches (Transport, Hotels and restaurants and Other services) continued in a process of job destruction in the period Jun-20/Feb-21.

The Labor Indicators Survey (EIL) as of February 2021 shows a recovery in net hiring expectations, coupled with low rates of layoffs and stability in suspensions. 3 months ahead, the trend towards hiring personnel expanded in net terms (0.5 p.p. in February) for the second consecutive month. Suspensions, after a persistent drop from their peak in May 2020, stabilized at around 18.2 per thousand workers. For its part, the dismissal rate has remained at low levels since May (2.9 per thousand workers in February) due to decree 266/2021, an extension that prohibits layoffs and extends the obligation of double severance pay until May 2021. In this regard, both the improvement in net expectations in the increase in staffing and the suspensions and layoffs could be affected by the resurgence of COVID-19 cases evidenced at the beginning of March.

In addition, it is also worth mentioning the policies recently implemented by the National Government to deal with the effects of the second wave of the pandemic. The nationwide assistance involved a $6,500 bonus for three months for 740,000 health workers and the launch of the second edition of the Productive Recovery Program15 (REPRO II) aimed at sustaining employment in sectors with economic difficulties. In April, the Emergency Assistance Program for the Independent Gastronomic Sector was also implemented, a measure that aims to assist independent workers in the Gastronomic Sector with $18,000, both for single-payers and self-employed. Likewise, policies were implemented to sustain income in the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires (AMBA)16. A bonus of $15,000 was granted for beneficiaries of AUH and AUE as well as for low-category single-payers (A and B) – which are estimated at 960,000 beneficiaries – with a total expenditure of $13,900 million. In addition to the latter, in May the expansion of the scope of the Food Card was announced, both in amount and in the universe of children reached17.

3.2. Perspectives

At the beginning of 2021, with a large part of economic activities having been enabled to operate under protocol rules and with the vaccination process against COVID-19 underway, economic activity continued to improve, partially attenuating sectoral heterogeneity, based on the improvement in the activities most sensitive to the pandemic.

In this context of normalization of the economy, the BCRA continued to contribute to the economic recovery process by sustaining lines of credit both for productive purposes and for promoting private consumption18 (see Chapter 7. Monetary Policy). In the same sense, the recent measures implemented by the National Government aimed at the promotion of strategic sectors19 contributed.

However, the materialisation of downside risks contemplated in the central activity scenario generated a greater degree of uncertainty regarding their evolution for the rest of the year. Towards the beginning of March, the speed of infections in the AMBA increased simultaneously with the appearance of new strains in the country. This deterioration of the epidemiological situation implied new restrictions on mobility and the normal functioning of activities in April, which were deepened on May20. These measures, which are less intense and far-reaching than those of April and March 2020, will be reflected in aggregate economic activity over the coming months. In this new scenario, the BCRA expects a temporary interruption of the recovery process of activity in the second quarter, associated with both direct and indirect effects of the new health context. For the rest of the year, activity is expected to resume the path of recovery, in a framework of a high degree of adaptation of families and companies to operate in a pandemic, at the same time as the vaccination process advances.

Although the international context is favorable, with improvements in global growth prospects21 and high prices of raw materials exported by Argentina, the degree of uncertainty is still high and is fundamentally associated with the control of the speed of contagion vis-à-vis the progress of the effective vaccination of the population. given the asymmetric global availability of vaccines and the emergence of new strains of the virus. Other risk factors must be monitored, such as the persistence of the damage caused by the pandemic on productive capacity in each economy, greater financial volatility, and a larger-than-expected increase in the U.S. Federal Reserve’s (Fed) benchmark interest rate in response to inflationary pressures in the U.S. economy (see Chapter 2. International Context).

Among the factors that would improve growth prospects in Argentina is the faster-than-expected progress of the vaccination process, which would allow the supply of services to be normalized more quickly, based on a greater opening of activities with a risk of contact. This would contribute to an improvement in activity and allow the normalisation of consumer behaviour to be completed more quickly.

The recovery of GDP at a faster pace than expected in the second half of last year and the beginning of this year left a high growth floor for this year. The market’s projections for the economic recovery from May 2020 onwards were successively revised upwards. Thus, while at the end of June the median REM anticipated a 12% drop in GDP in 2020 and a 5% recovery in 2021, GDP finally showed a 9.9% drop last year. The seasonally adjusted EMAE data for the first quarter left a statistical drag of 7.6 percentage points of growth for 2021. In the April REM, a GDP recovery of 6.4% is forecast for 2021, above the projections of the International Monetary Fund (IMF; 5.8%).

4. External Sector

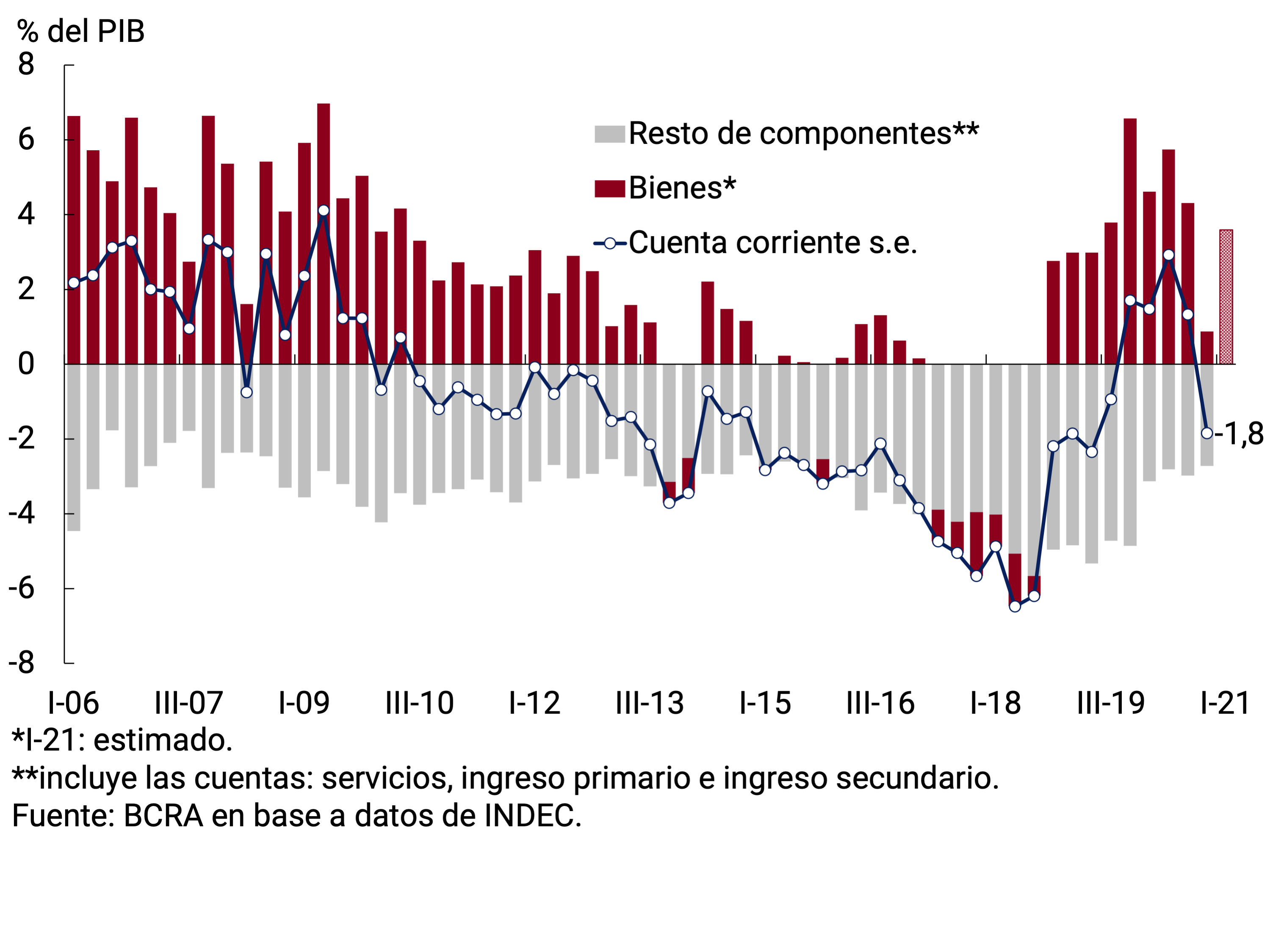

After a limited performance in the fourth quarter of 2020, exports of goods recovered thanks to the normalization of shipments of agricultural products and the increase in international prices of raw materials. Imports rose again, particularly those closely linked to investment spending. Thus, in the first quarter of 2021, in a context in which the terms of trade were close to the highest in the last 25 years, the economy would have recovered a current account surplus, a trend that continued in April.

This improvement in the trade surplus of goods, added to the renegotiation of financial debt maturities, allowed the BCRA to buy US$5,432 million in the Foreign Exchange Market so far this year.

Going forward, with the risk of a severe drought on the coarse harvest cleared, the current account surplus is expected to be maintained, supported by a comfortable trade balance of goods, in a context of high international commodity prices. The current regulatory framework will allow the BCRA to continue to efficiently manage the foreign currency originated in commercial operations, in order to preserve monetary, financial and exchange rate stability.

4.1. In the first quarter of 2021, the economy would have resumed the current account surplus

In the fourth quarter of 2020 (latest official data available) the Argentine economy recorded a current account deficit of US$1,372 million – equivalent to 1.8 p.p. of GDP in seasonally adjusted and annualized terms – linked to a marked contraction in the trade surplus in goods compared to previous quarters. In particular, the abrupt drop in exports of goods in December, temporarily affected by a union conflict that paralyzed grain shipments for almost the entire month, played a role.

In the first quarter of 2021, the normalization of port operations, coupled with the improvement in international prices of the main agricultural commodities exported by Argentina, were reflected in an increase in the trade balance of goods, which would push the quarterly current account balance back into surplus territory (see Figure 4.1).

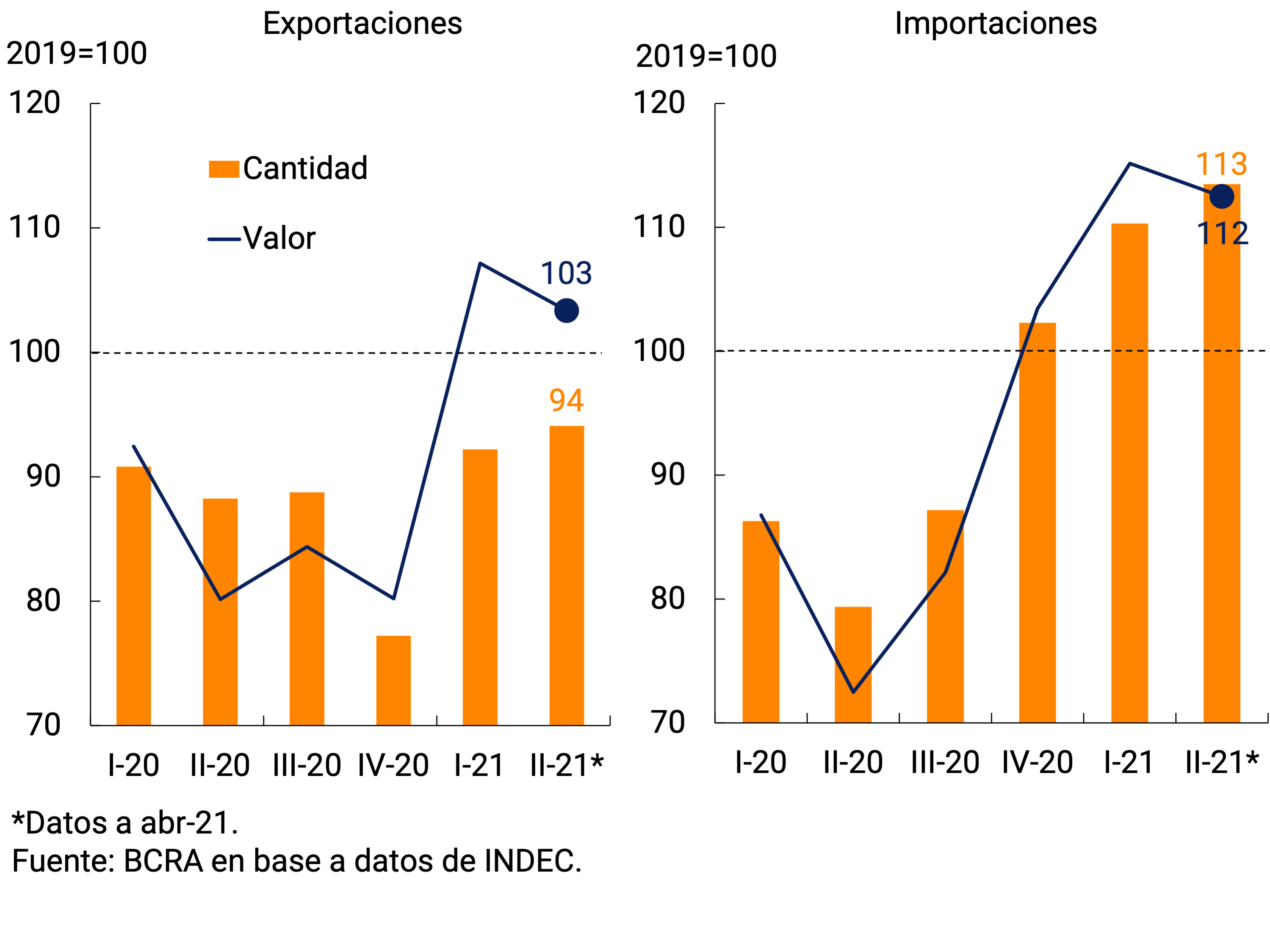

In the first three months of 2021, the export values of seasonally adjusted goods reached US$17,443 million (FOB), 27% above the quarterly average of 2020 and 7% higher than the average of 2019. This favorable evolution of exports of goods was due to the performance of export prices, which between May 2020 and March 2021 accumulated a rise of 27% and were comfortably above pre-pandemic levels, in a period in which the international quotations of raw materials exported by Argentina measured from the Commodity Price Index prepared and published by the BCRA (IPMP) grew 54%.

In April, exported values fell 4% month-on-month compared to March levels as a result of a decrease in the exported volumes of Manufactures of Industrial Origin (MOI) and Fuels and Energy. However, seasonally adjusted exports of goods remained above US$ 5,600 million in April, a level significantly higher than that recorded pre-pandemic.

For its part, between January and March 2021, seasonally adjusted imports of goods totaled US$14,141 million, 34% above the quarterly average recorded in 2020 and 15% higher than the average for 2019. In the case of external purchases, both prices and volumes contributed to the increase in imported values (see Figure 4.2).

Specifically, in March there was a sharp increase in imported quantities (+15% s.e. monthly compared to Feb-21). This increase was widespread among the different import uses. The case of the acquired volumes of intermediate goods (reached an all-time high) and capital goods and their parts, which returned to mid-2018 levels, stood out. These data suggest that private investment spending, which had already stood out in the fourth quarter of 2020, continues to strengthen (see Chapter 3. Economic Activity and Employment). In April, import volumes fell partially on a widespread basis, with the exception of purchases of parts and accessories for capital goods and vehicles, which continued to increase. Despite this slight correction in the margin, the level of imported quantities in April leaves a positive carry-over of 3 p.p. for II-21 (see Figure 4.3).

For its part, in recent months there was also a marked rebound in import prices, which have accumulated an increase of 11% since December 2020.

Box. Volumes exported one year into the pandemic

The four main items of export of goods (Primary Products (PP), Manufactures of Agricultural Origin (MOA), Manufactures of Industrial Origin (MOI) and Fuels and Energy (S)) can be subdivided into 38 groups of products23. The information available at this degree of disaggregation allows us to understand the performance of foreign sales from a more granular perspective, linked to the export sectors. Overall, all sectors were severely affected by the pandemic in 2020. During the second quarter of 2020, only 7 of the 38 grouped exhibited export volumes above the pre-pandemic level (fourth quarter of 2019). As of the first quarter of 2021, most sectors have not yet been able to recover those levels.

Depending on the recent evolution of shipments abroad, at least four stages can be distinguished in which the export sectors are (see Figure 4.4). The abscissa axis measures the change in the margin (var. % s.e. trim. between IV-20 and I-21), while the ordinate axis assesses the current level with respect to the level at which the sectors were before global trade was affected by the pandemic (var. % s.e. acum. between IV-19 and I-21).

The set of five products located in quadrant I is in a growth phase: their non-seasonal export quantities currently exceed those recorded at the end of 2020 (floor of total exported volumes) and are also higher than those of the fourth quarter of 2019, i.e. those of the pre-pandemic global context. All the groupings that are located in this quadrant (vegetable fats and oils, dairy products, land transport material, chemical products, and machines and electrical material) stand out for their weight in the values exported: in sum, they represented 25% of total exports in 2020. In the specific case of foreign sales of vegetable fats and oils (where soybean oil is registered), not only was there a growth in quantities, but also in export prices, as a result of a manifest shortage in the global market for vegetable oils, which boosted the demand for soybean oil from our country. Foreign sales of land transport equipment and machinery and electrical equipment were boosted by a recovery in external demand (mainly from Brazil), while chemicals were boosted by the resumption of biodiesel shipments to the European Union. For its part, the increase in exports of dairy products was linked to a rise in primary milk production.

A larger group of products (quadrant II) is in a recovery phase, with improvements in the margin, but still far from pre-pandemic levels. In this segment, grains (cereals and oilseeds) and residues from the food industry (where soybean pellets are registered) stand out, affected in December by the strike in the ports where the bulk of the production is shipped.

A large number of grouped members (18) exhibit a negative dynamic. They are below the levels of the end of 2019 and continue to fall at the margin. In this group (quadrant III), precious metals stand out, whose domestic production continues to be affected by the sanitary measures put in place to mitigate the effects of the pandemic.

Finally, three categories of goods can be counted whose exported volumes exhibited a different dynamic from that of most sectors. They had their best moment during 2020 (tobacco in the IV-20, beverages in the III-20 and oil in the II-20), and in the margin they show signs of weakness (quadrant IV).

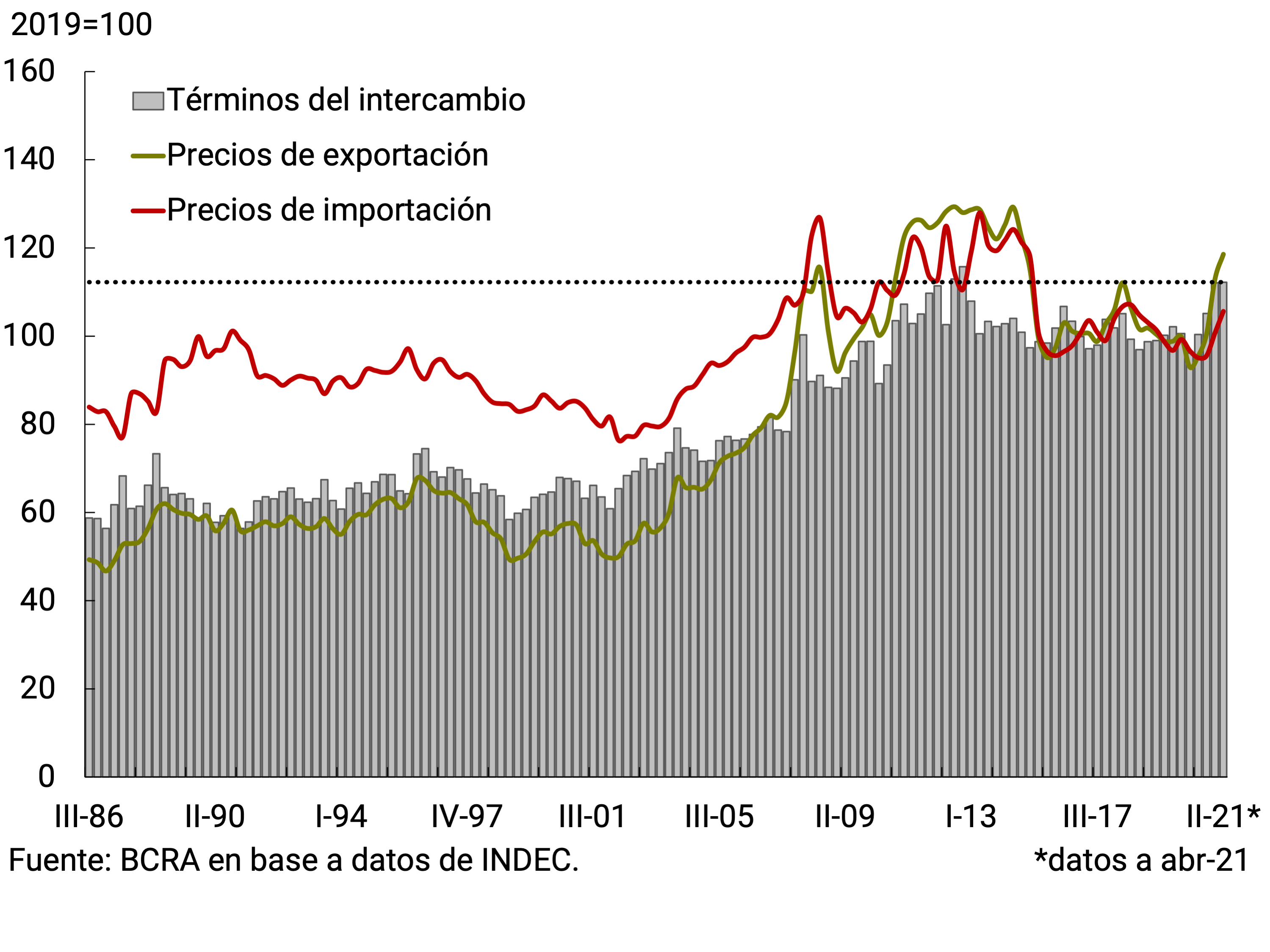

In the first quarter of 2021, the evolution of foreign trade prices in goods resulted in a 7.5% improvement in the terms of trade compared to the fourth quarter of 2020. The sustained rise in export prices allowed Argentina to have the most favorable terms of trade in the last 9 years, standing just 2.4% below the peak recorded in the third quarter of 2012 (see Figure 4.5). With partial data up to April, the terms of trade remained constant so far in the second quarter as a result of similar increases in export and import prices compared to the average for the first quarter of 2021.

Box. Recent developments in international commodity prices

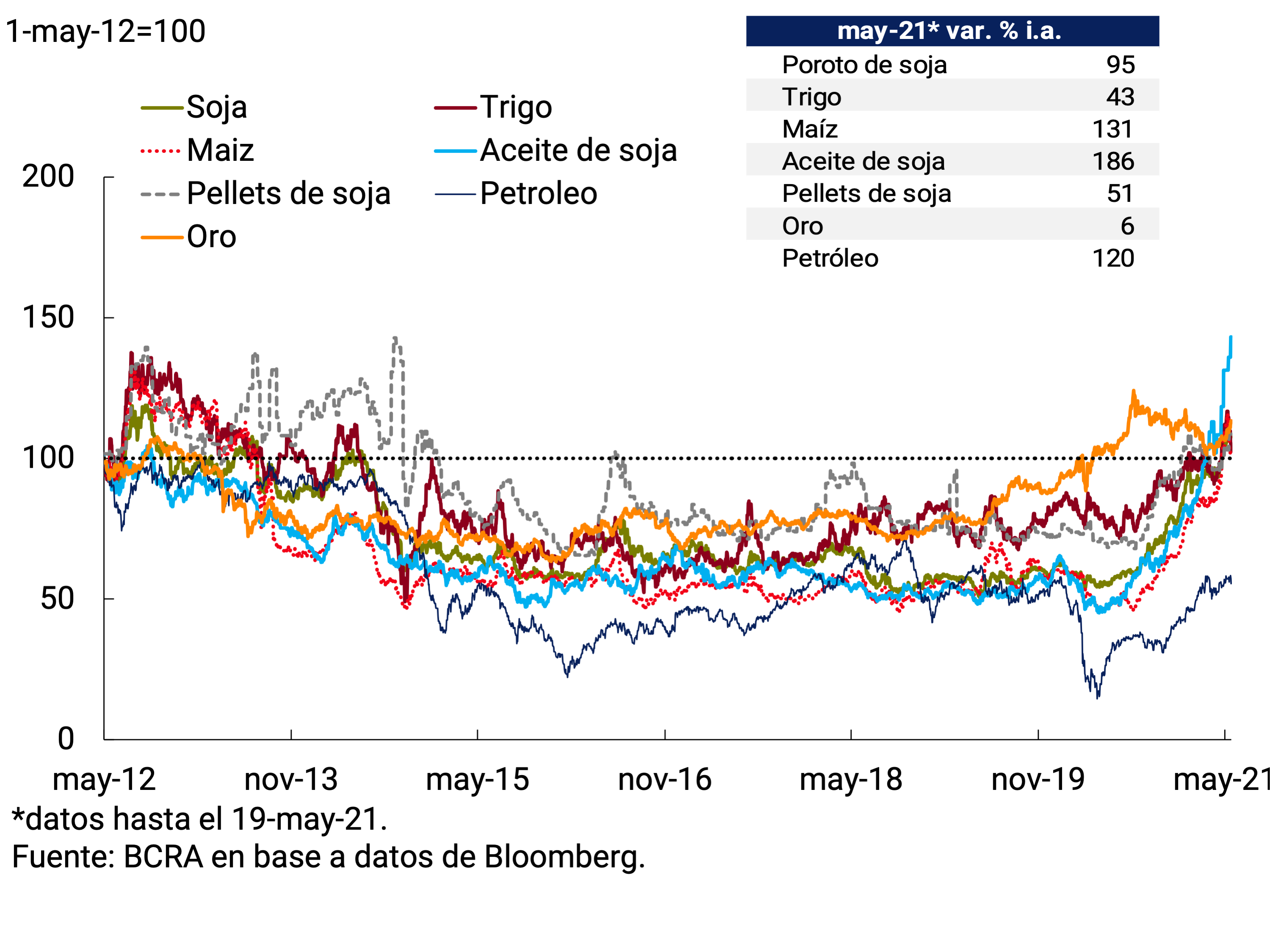

Since the publication of the IPOM in February 2021, international commodity prices continued their upward trend. Among those that have a significant weight in Argentina’s export basket, since the beginning of March, the increases in the reference prices of soybean oil (+46%), corn (+21%) and soybeans (+14%) stood out. Thus, international prices of agricultural commodities in current dollars recently reached levels similar to those of the second quarter of 2012. On May 19, 2021 (latest available data) soybeans were close to US$590/tn. tonne, and both wheat and corn exceeded US$250/tn. The case of soybean oil stood out, which in the Chicago spot market reached an all-time high on May 18, 2021: US$1,701 per ton.

The price of crude oil also registered a significant increase (almost tripling in value compared to the minimum records of April 2020). However, in historical terms, the recently reached level (around US$66 a barrel in the Brent variety) is still a long way from the figures for the second quarter of 2012 (approx. US$109 a barrel; see Figure 4.6).

This combination of prices (food near the highs of 2012 and lagging oil) implies that the relative soybean/oil price will remain comfortably above the average of the last 20 years, a favorable level for the Argentine economy.

4.2. The BCRA bought US$5.432 billion in the foreign exchange market so far this year

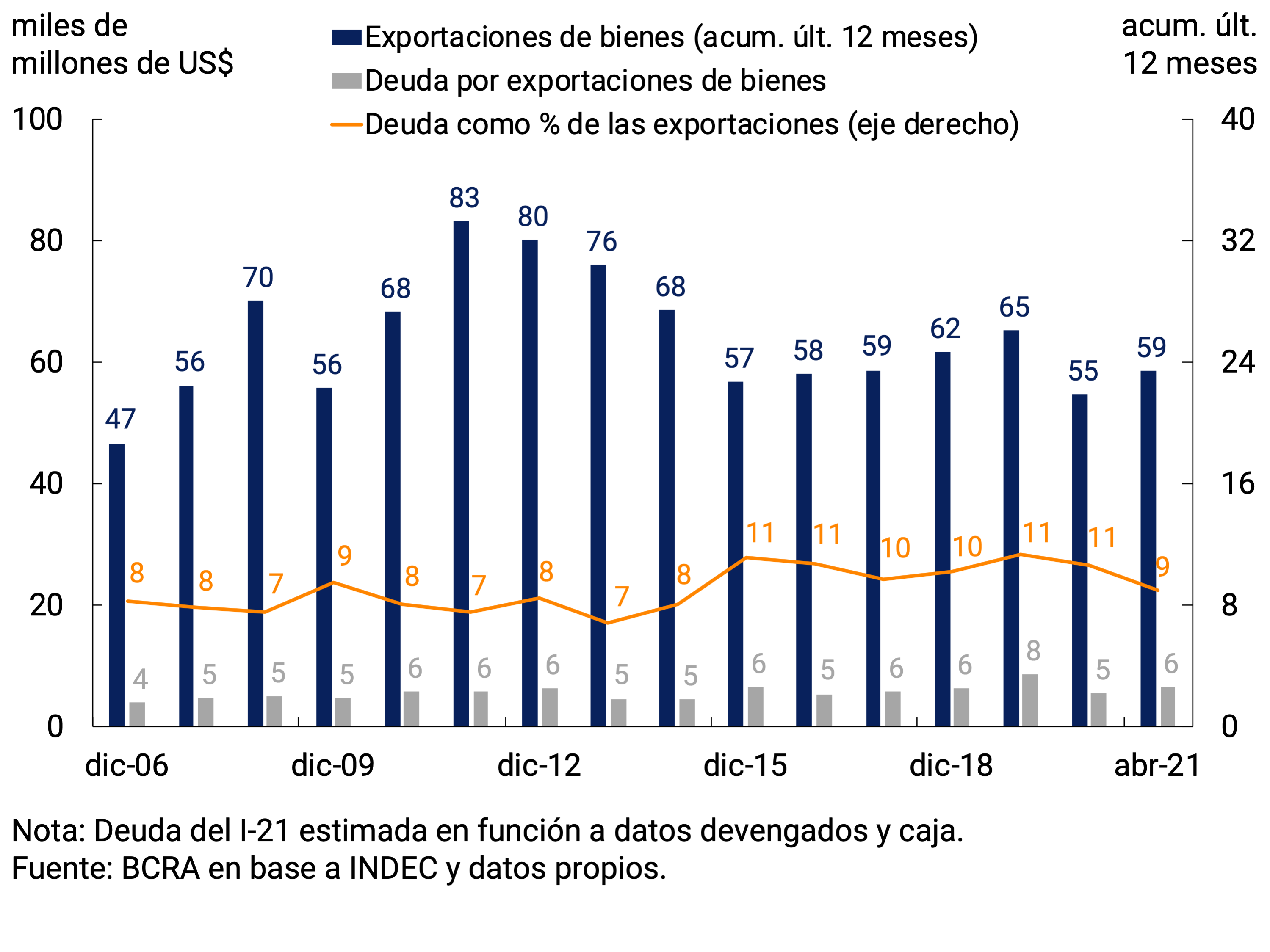

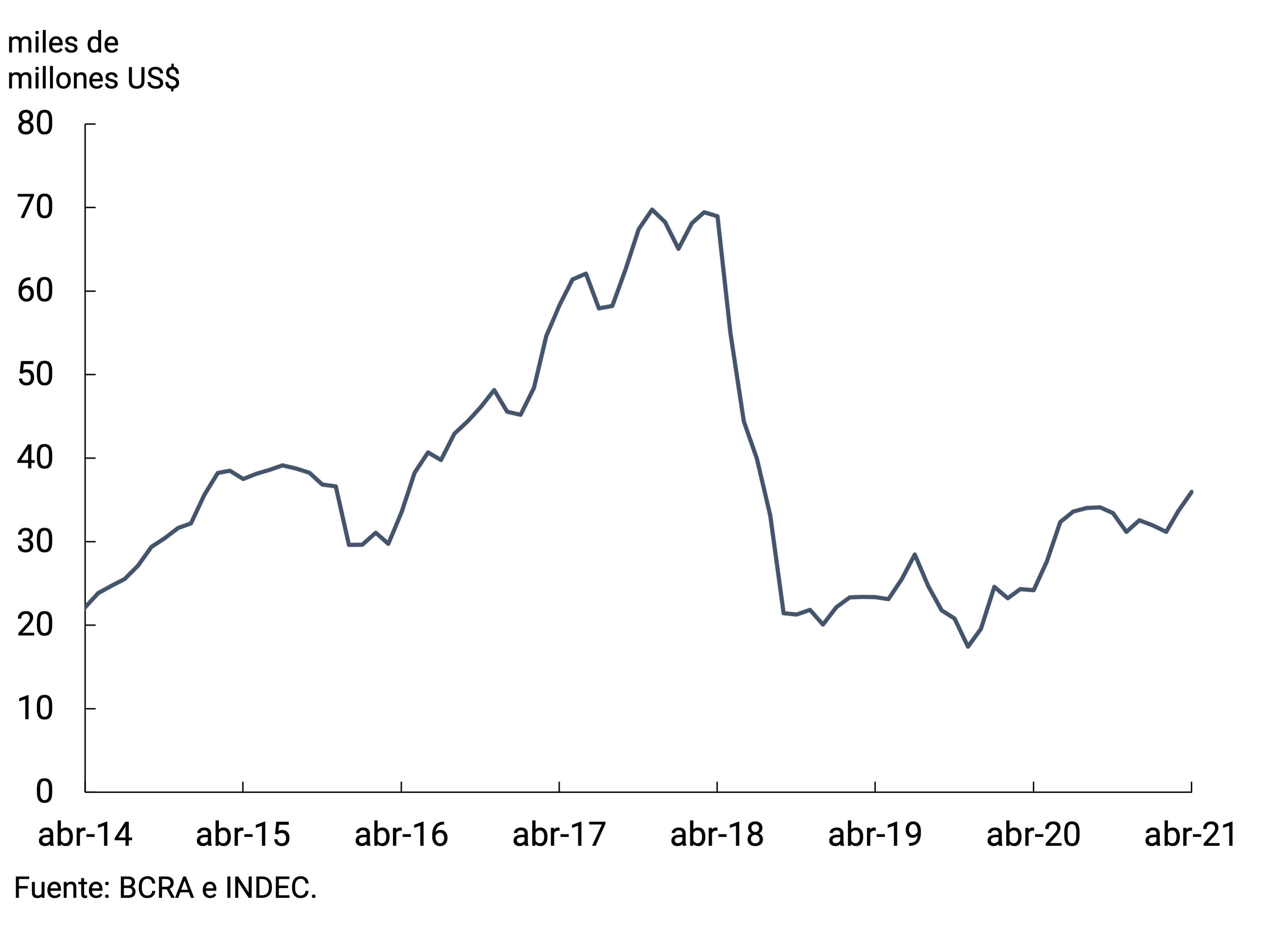

During the first 4 months of 2021, exporters recorded revenues from collections of exports of goods through the foreign exchange market of US$22,900 million, surpassing exports of goods by about US$1,300 million in the period. Considering that most of this differential was explained by an increase in external debt through advances and pre-financing24, the ratio of this type of debt to exported securities stood at 9%, a level lower than in recent years (see Figure 4.7).

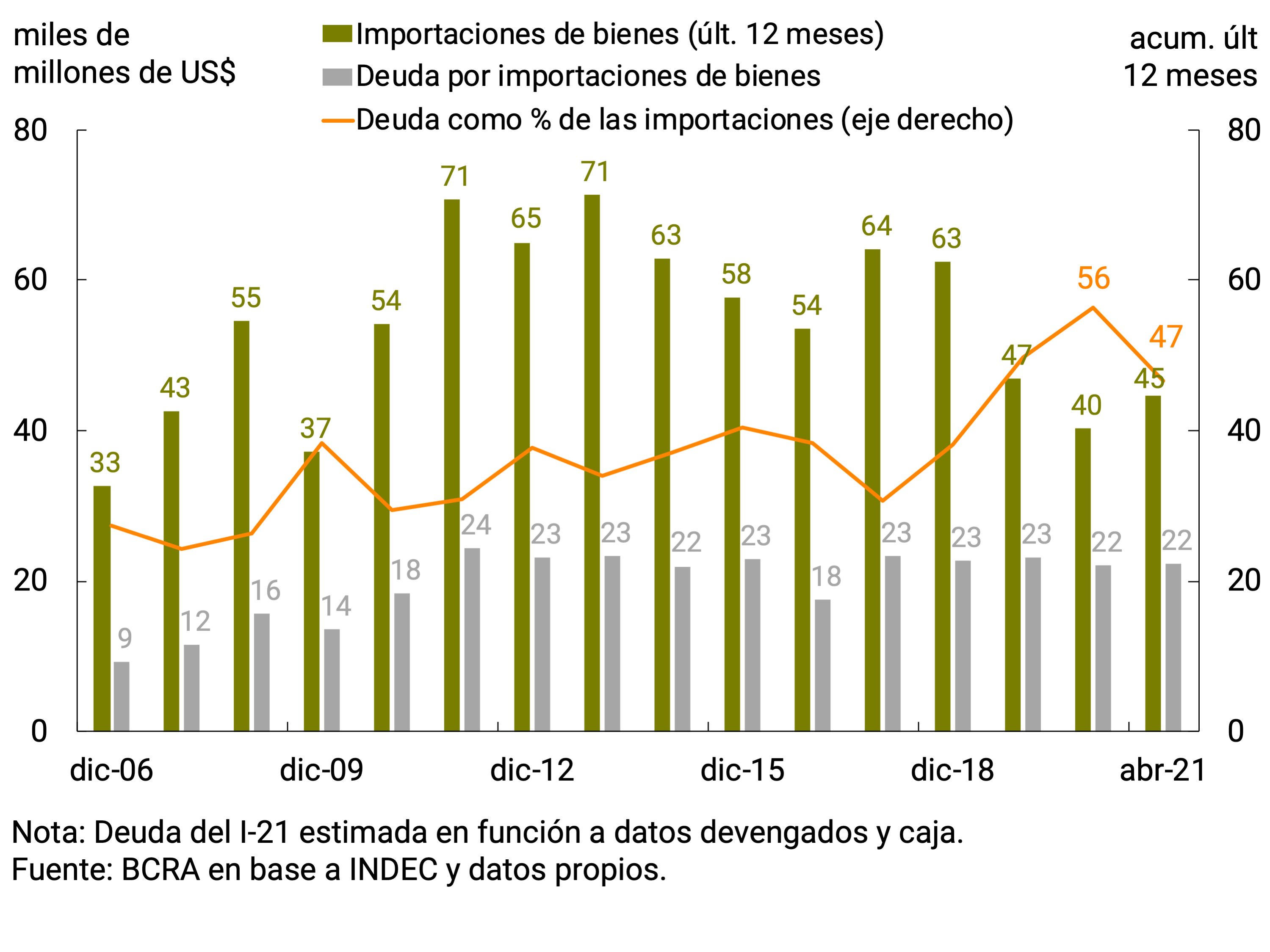

During 2020, the BCRA established a series of regulations aimed at promoting a more efficient allocation of foreign currency, which affected both the evolution of private commercial and financial debt, and which remain in force for the year 202125. In this context, payments for imports of goods through the foreign exchange market in the first four months, for US$16,400 million, were about US$140 million below imports in FOB value for the period, which would imply an increase in foreign indebtedness for this concept (or a reduction in foreign assets due to advances). Thus, the relationship between external debt and the level of imports, which reached the highest level in the last 15 years in 2020, registered a fall of 9 percentage points compared to the previous quarter, based on the increase recorded in the level of external purchases (see Figure 4.8).

Finally, with regard to financial debt, and as part of the current regulatory framework mentioned above, in September 2020, through Communication A7106, the guidelines were established under which private sector companies could initiate a process of refinancing their respective external liabilities, which would allow their maturity profile to be adapted to the guidelines required for the normal functioning of the foreign exchange market.

In this context, the renegotiations registered during the first four months of 2021 of some 40 companies had an impact on lower net purchases in the foreign exchange market of about US$500 million compared to the original maturities for the same period. For this same reason, in the fourth quarter of 2020, private financial debt service payments were reduced by US$500 million.

The aforementioned recovery in exports, added to the increase in commercial debt for exports and imports of goods, resulted in a net result for goods in the foreign exchange market of US$6,427 million in the first four months, about US$1,500 million higher than the result of the FOB trade balance in the same period, and exhibiting a strong improvement compared to the same period of the previous year (90%)26.

Thus, until May 20, the BCRA bought US$5,432 million in the foreign exchange market, while international reserves increased by US$2,130 million in the same period. This difference is mainly explained by the cancellations of principal and interest on foreign currency debt of the National Government, which directly affected international reserves of about US$1,876 million, and the fall in the holdings of entities in foreign currency accounts at the BCRA, which generated a decrease in the BCRA’s International Reserves of US$678 million in the period.

4.3. Perspectives

Going forward, the economy is expected to sustain the current account surplus. The probability of a severe drought scenario on the coarse crop was substantially reduced thanks to the rainfall of the last few weeks. Likewise, the international prices of the main grains exported by Argentina remained at high levels, which allows us to foresee higher income from agricultural exports than those of the last 5 years. On the other hand, imports of goods, which experienced a strong rebound from the second half of 2020, would resume a more moderate growth trend, linked to the trajectory of economic activity, which is close to the pre-pandemic level.

The regulatory framework in force in the Foreign Exchange Market will allow the BCRA to continue to efficiently manage the foreign currency originated in commercial transactions, in order to preserve monetary, financial and exchange stability.

5. Public Finance

During the first four months of 2021, the public accounts continued to strengthen due to higher tax collection associated with the economic recovery and a more limited trajectory of extraordinary expenditures, compared to the massive financial assistance deployed during 2020 to alleviate the critical situation faced by families and businesses at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Tax collection continued to boost during the first four months of the year from the contribution of taxes related to foreign trade – in a context of increases in international commodity prices – and the sustained recovery of taxes linked to domestic demand. Likewise, the regulatory modifications on taxes provided for in the Social Solidarity and Productive Reactivation Law of the end of 2019 and in the National Budget Law 2021 continued to have a positive impact on public revenues.

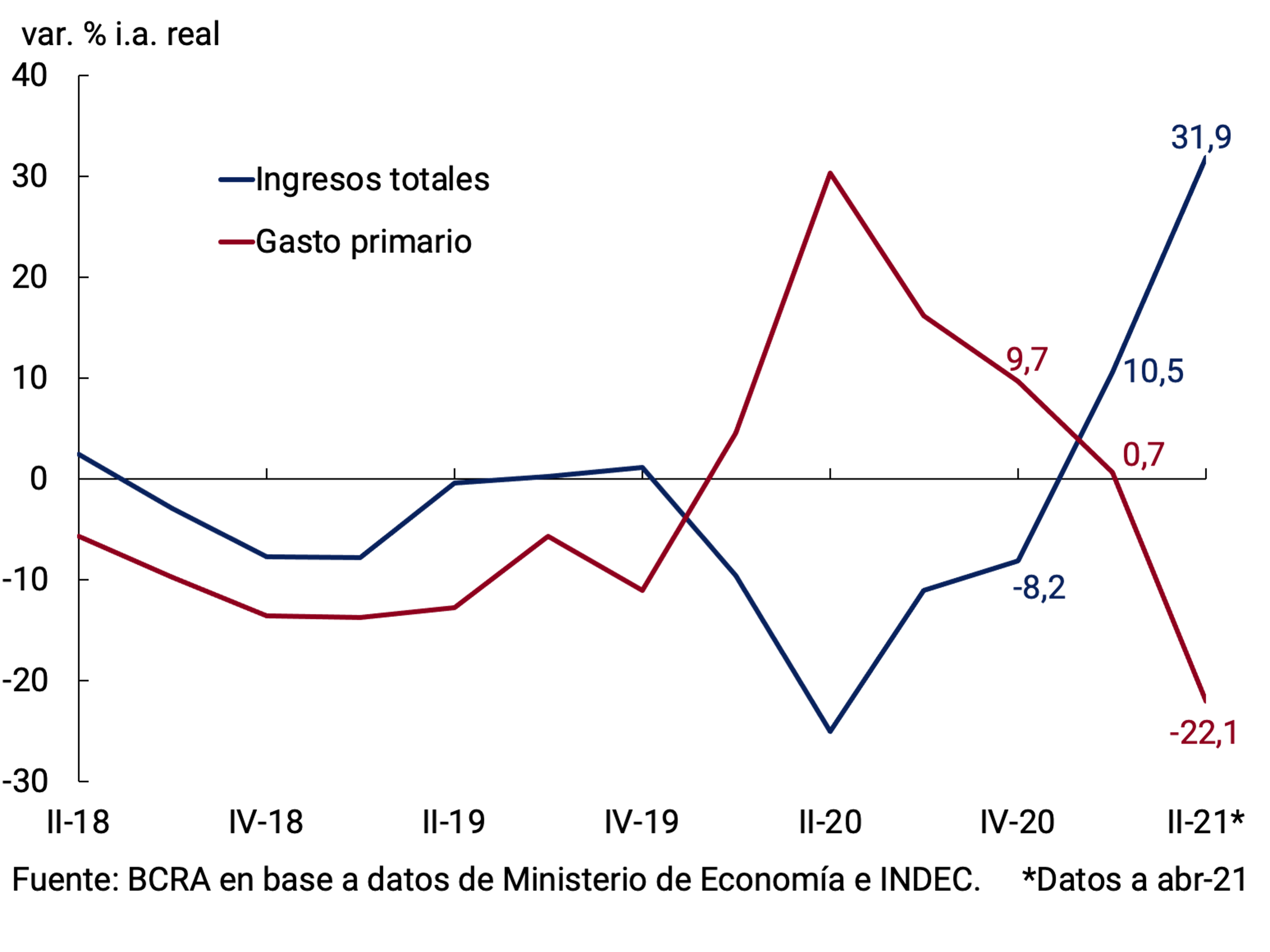

For its part, during the first quarter of the year, expenditures continued to grow in real terms compared to the same period of the previous year. In April, they exhibited a retraction due to the high base of comparison of 2020, when massive assistance to families and companies had been made. Taking care of the critical situations derived from the economic and social emergency, primary spending was also driven by a significant dynamism of capital expenditure with the aim of supporting the recovery process of economic activity, in accordance with the provisions of the 2021 National Budget.

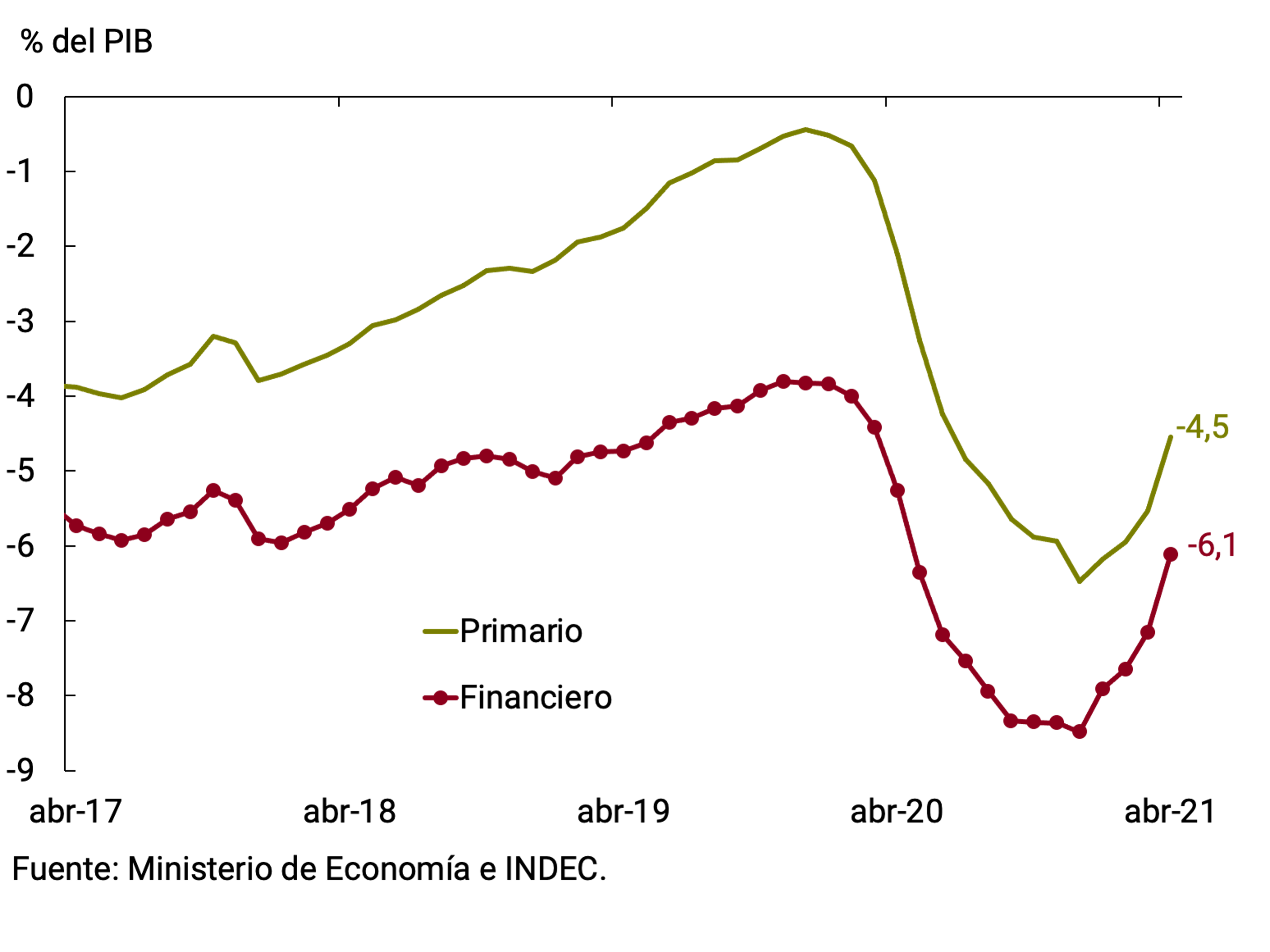

The nominal growth rate of expenditure showed a lower year-on-year growth than that of revenues, which allowed the primary deficit to continue to be progressively reduced. In the last 12 months to April 2021, the primary deficit on a cash basis accumulated a balance equivalent to 4.5% of GDP, significantly lower than that observed during 2020 (-6.5% of GDP). This trajectory is consistent with what was established in the 2021 National Budget, which foresees a primary deficit of NFPS of 4.2% of GDP during this year. Going forward, revenues that were not originally budgeted are expected, basically from the Solidarity and Extraordinary Contribution of large fortunes (Law 27605), while new assistance to families and companies was also provided that will involve additional expenses in the context of the pandemic.

Regarding financing from the National Treasury, during the first four months of 2021, the local market continued to play a greater role compared to the same period of the previous year, allowing less financial assistance from the BCRA. The National Government continues negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and with the bilateral creditors grouped in the Paris Club. For its part, expectations of an extraordinary allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) by the IMF that would benefit Argentina are consolidated. Among the risks faced in the fiscal scenario, the resurgence of the pandemic stands out, resulting in the need to intensify assistance policies and negatively affecting tax revenues.

5.1. Tax revenue performance improved at the start of 2021

The consolidation of a heterogeneous but sustained economic recovery during the beginning of the year contributed to a 56% YoY increase in national tax collection in the first quarter of 2021, accelerating the pace of increase compared to the previous quarter (see Figure 5.1). In real terms, this performance implied an increase of 9 percentage points (p.p.) compared to the variation recorded during the fourth quarter (+2.2% y.o.y.). In April, the nominal increase was 105% YoY (+40.3% YoY in real terms), due in part to a low base of comparison due to the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020.

The high dynamism of taxes associated with foreign trade was highlighted. In a context of high international commodity prices, export duties registered significant year-on-year growth (+190.4% YoY between January and March, compared to -30% YoY between October and December 2020, a performance that was maintained in April). Taxes linked to foreign purchases29 also showed a strong increase in the first quarter that was sustained during the fourth month of the year, basically explained by the dynamism of imports (see Chapter 4. External Sector).

Taxes related to the domestic market (Value Added Tax (VAT), Profits, Fuels, among others) showed a better year-on-year performance at the beginning of 2021 in relation to previous quarters, in line with the heterogeneous but sustained recovery of economic activity. Income tax rose 63% y.o.y. between January and March, slightly lower than that which had been verified in the previous quarter. It continued to be affected upwards by the regulatory change of September 2020 on the withholding of purchases of dollars and expenses in foreign currency through credit cards30. Net VAT grew 54% YoY in the first quarter of 2021 compared to the 38% YoY increase recorded in the previous quarter. For its part, a set of taxes that were modified by the Law of Social Solidarity and Productive Reactivation (such as Personal Property, Internal, PAIS) and those modified from the 2021 National Budget Law, maintained a good performance.

Finally, social security resources continued to grow more limitedly, influenced by the evolution of wages and employment: they grew 28.3% YoY between January and March, 4 p.p. above the increase observed between October and December31 and continued to recover year-on-year dynamism in April, given the low base of comparison of the same period in 2020. This set of taxes is still negatively impacted by the measures taken by the National Government to address situations in sectors critically affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The evolution of tax revenues allowed the total revenues of the National Non-Financial Public Sector (NFPS) to increase in nominal terms by 60.9% y.o.y. between January and March, after having increased 28.6% y.o.y. during the previous quarter32. In April, NFPS revenues advanced 92.9% YoY due in part to the low base of comparison due to the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020. Going forward, it is expected that non-tax revenues will include the resources associated with the Solidarity and Extraordinary Contribution to Help Mitigate the Impact of the pandemic (Law 27605).

Meanwhile, the tax collection of the provinces as a whole exhibited a behavior consistent with what was observed at the national level. According to the partial information available for the main districts, in the first quarter of the year the nominal increase in equity would have accelerated to about 52% YoY after growth of around 35% YoY and 27% YoY in the fourth and third quarters of 2020, respectively. In April, this figure would be around 100% YoY due to the low base of comparison of the same month in 2020.

5.2. The improvement in revenues strengthened the public accounts and, without neglecting the vulnerable sectors, capital spending was prioritized to contribute to the economic recovery

NFPS primary expenditure showed a nominal increase of 41.5% YoY in the first quarter of the year, 13.9 p.p. below the nominal increase in revenues. In real terms, expenditures grew by 0.7% YoY between January and March, while revenues grew by 10.5% YoY in the period (see Figure 5.2). In April, primary expenditure increased by 14% YoY, which implied a real drop of 22.1% YoY, explained by the high base of comparison in April 2020, when massive assistance to families and companies had been made.

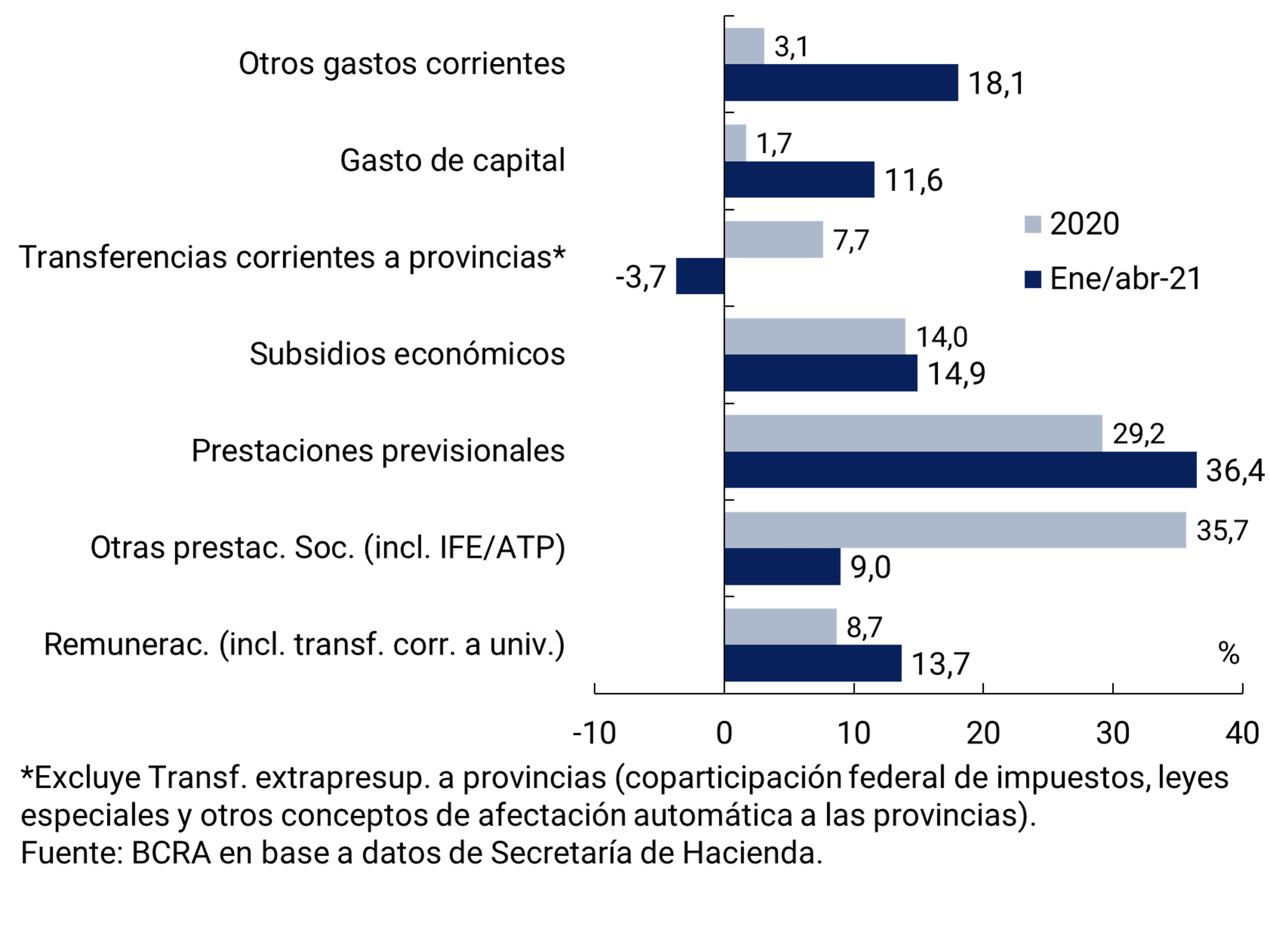

During the first four months of 2021, the increase in primary expenditure continued to be allocated mainly to expenditure on pension benefits, within the framework of the provisions of the new Pension Mobility Law. The contribution of pension benefits to the year-on-year increase in primary expenditure was 36%, a figure somewhat higher than that recorded for this item in 2020 (29%; see Figure 5.3). Likewise, the incidence of other social benefits decreased between January and April 2021 compared to 2020 (9% vs. 36% in both cases), given that this item had included during the past year the massive extraordinary disbursements of assistance to families and companies (such as the Emergency Family Income (IFE) and the Emergency Assistance Program for Work and Production (ATP). among other social programs. In the first four months of 2021, the efforts associated with the Empower Work program, the Food Card and the reinforcements of the Universal Child Allowance for social protection in the area of Greater Buenos Aires were highlighted. Extraordinary bonuses to strengthen the income of beneficiaries of the lower brackets of pension benefits were also highlighted.

For the coming months, it should be taken into account that the public accounts will be affected by a basis of comparison that includes the effects of the pandemic. In any case, the need to address the harmful effects of the new wave of COVID-19 will have an impact. Likewise, a large part of the expenditure (pension benefits and family allowances) will have an expected increase of 12.12% as of June, as a result of the application of pension mobility33.

Economic subsidies also accounted for a significant portion of the year-on-year increase in spending (14.9%): they grew 54% YoY in the first four months of the year. The increase was disseminated among the main destinations associated with energy and public passenger transport.

Likewise, capital expenditure gained relevance (+138% YoY between January and April, contributing 11.6% to the advance of primary expenditure), due in part to a low base of comparison and in line with the guidelines stipulated in the 2021 National Budget. Items associated with salaries (including transfers to universities) and other current expenses increased their participation in the increase in primary spending, going from 8.7% and 3.1% in 2020 to 13.7% and 18.1% respectively. It should be noted that in this last item, purchases of goods and services (including expenditures associated with the purchase of vaccines) and the deficit of public companies, among others, are recorded. For their part, current transfers to the provinces moderated significantly compared to the same period in 2020, when the National Government had extraordinarily assisted the districts in the face of the significant decrease in subnational tax collection.

The primary deficit of the NFPS accumulated in the last 12 months to April 2021 represented approximately 4.5% of GDP, 1.9 p.p. less than in December 2020 (see Figure 5.4). This evolution is in line with the 2021 National Budget, which forecasts that the primary deficit result will be reduced to 4.2% of GDP for the accumulated to December.

After the restructuring of the National Public Debt carried out in 2020 and the reconstruction of the local debt market, it was possible to reduce the interest burden faced by the National Government. Services with private, multilateral, bilateral creditors and with the public financial sector went from representing 3.4% of GDP in 2019 to around 2% of GDP in 2020 (see Figure 5.5) and around 1.6% of GDP in the accumulated of the last 12 months to April 2021. Thus, the financial deficit of the NFPS accumulated in the same period stood at 6.1% of GDP, 2.4 p.p. below the total deficit of 2020.

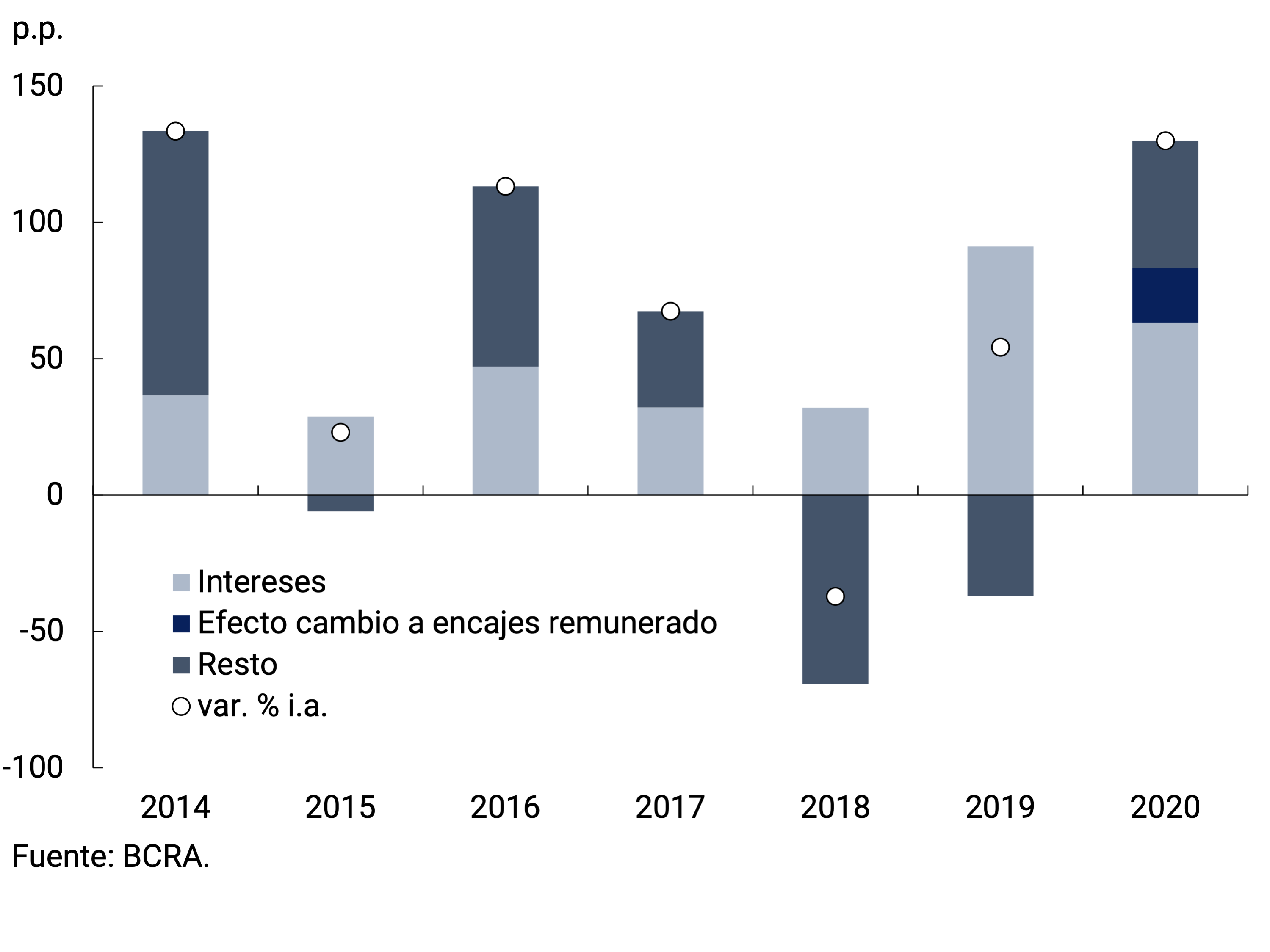

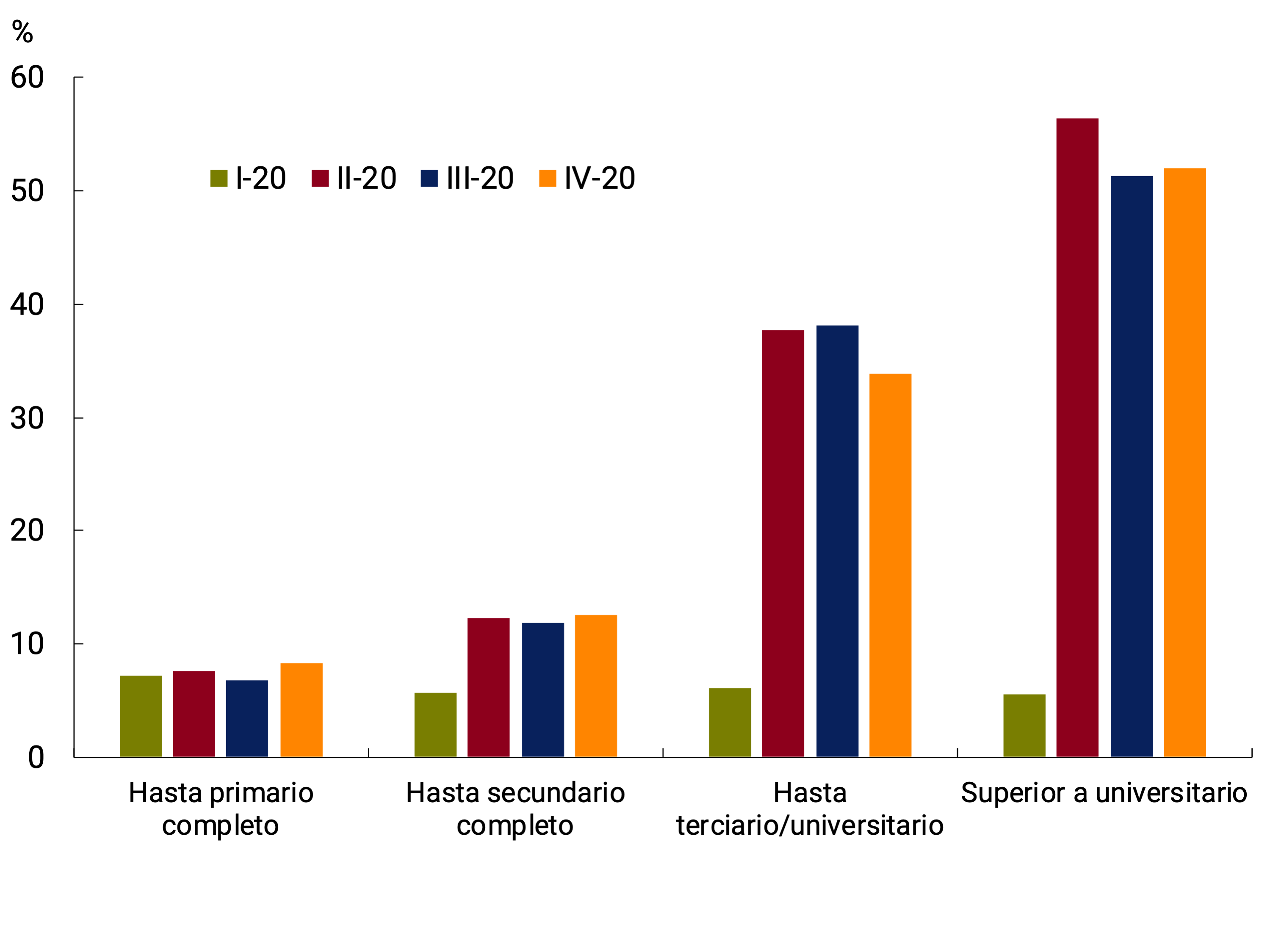

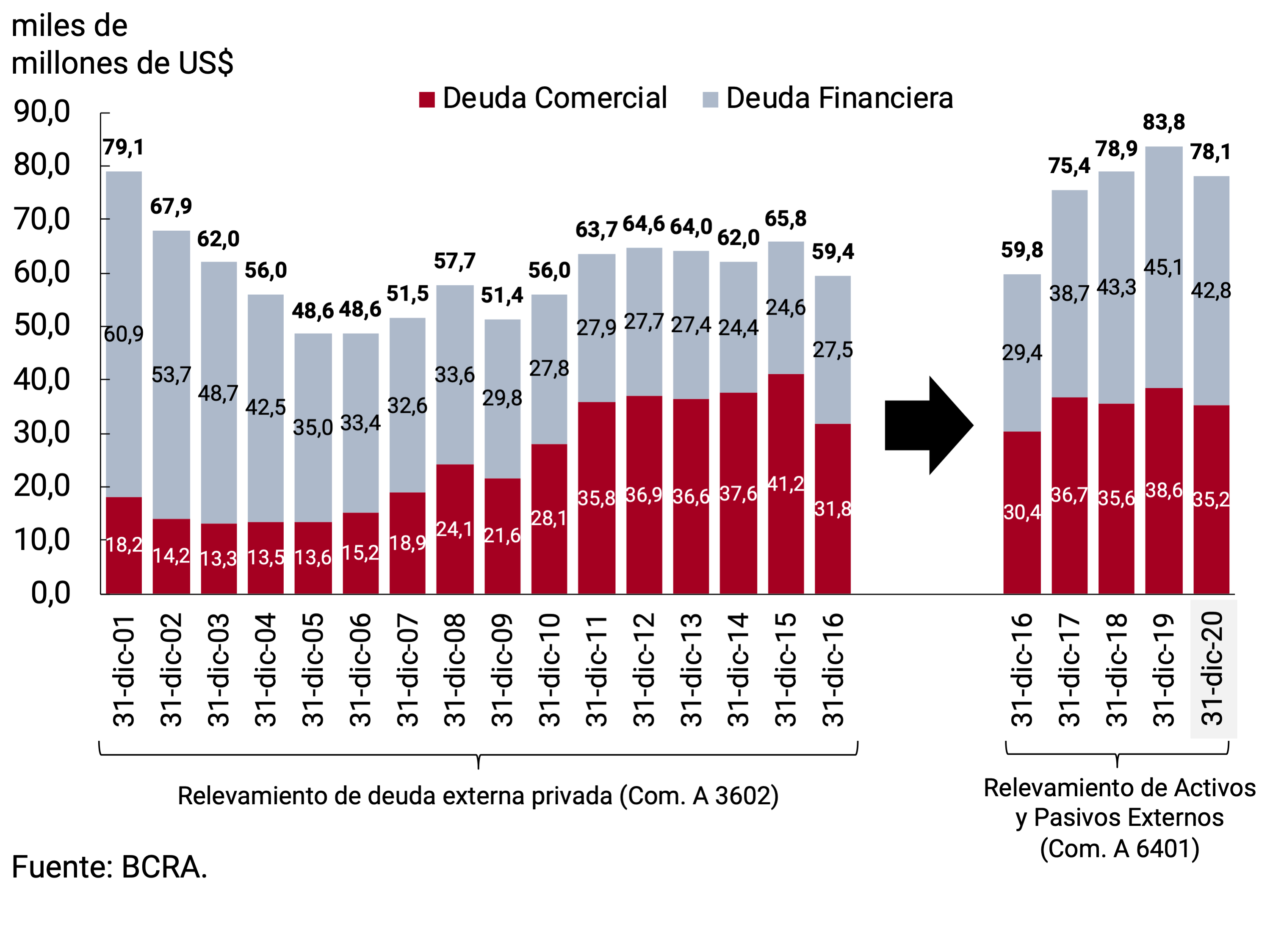

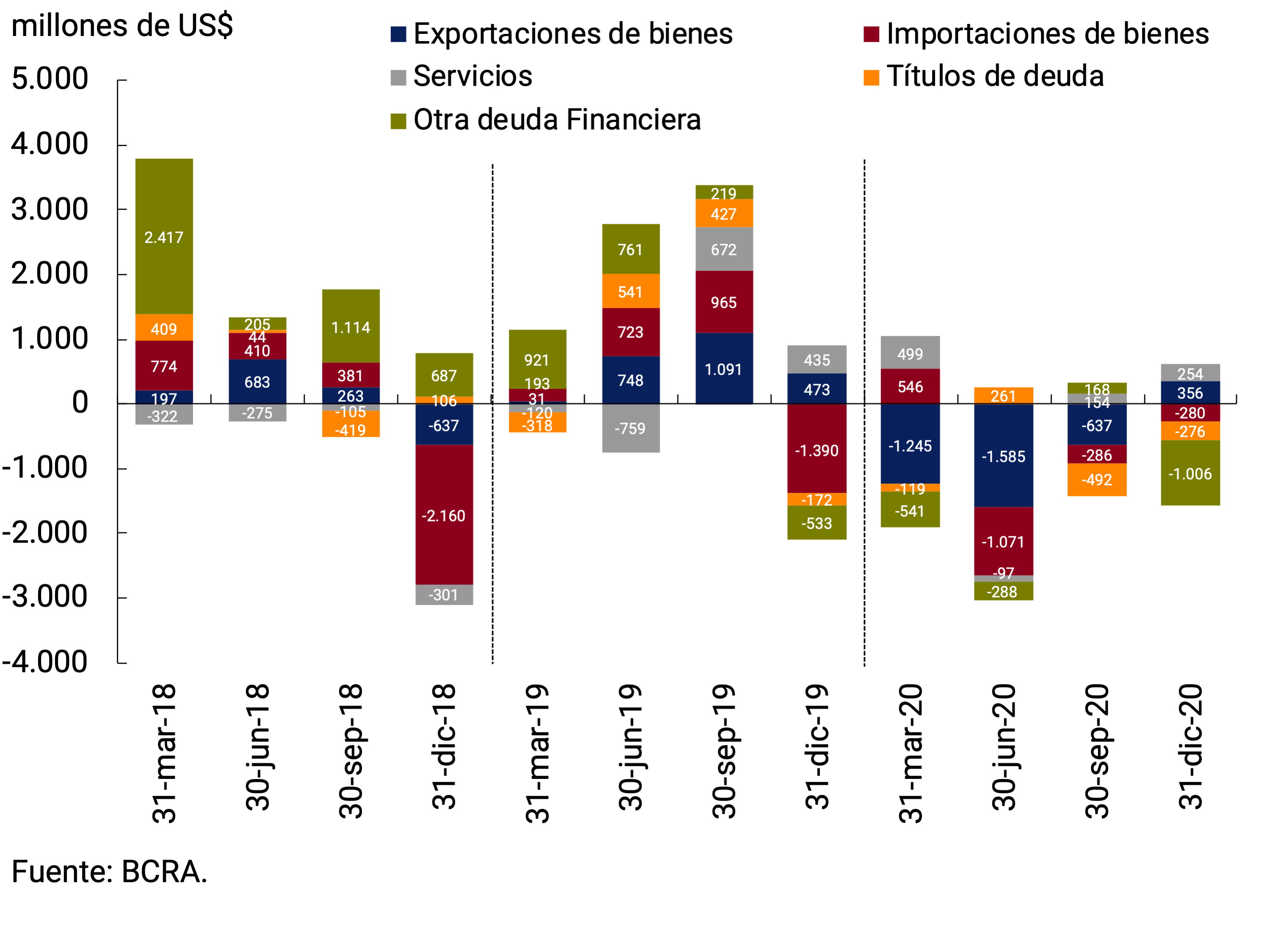

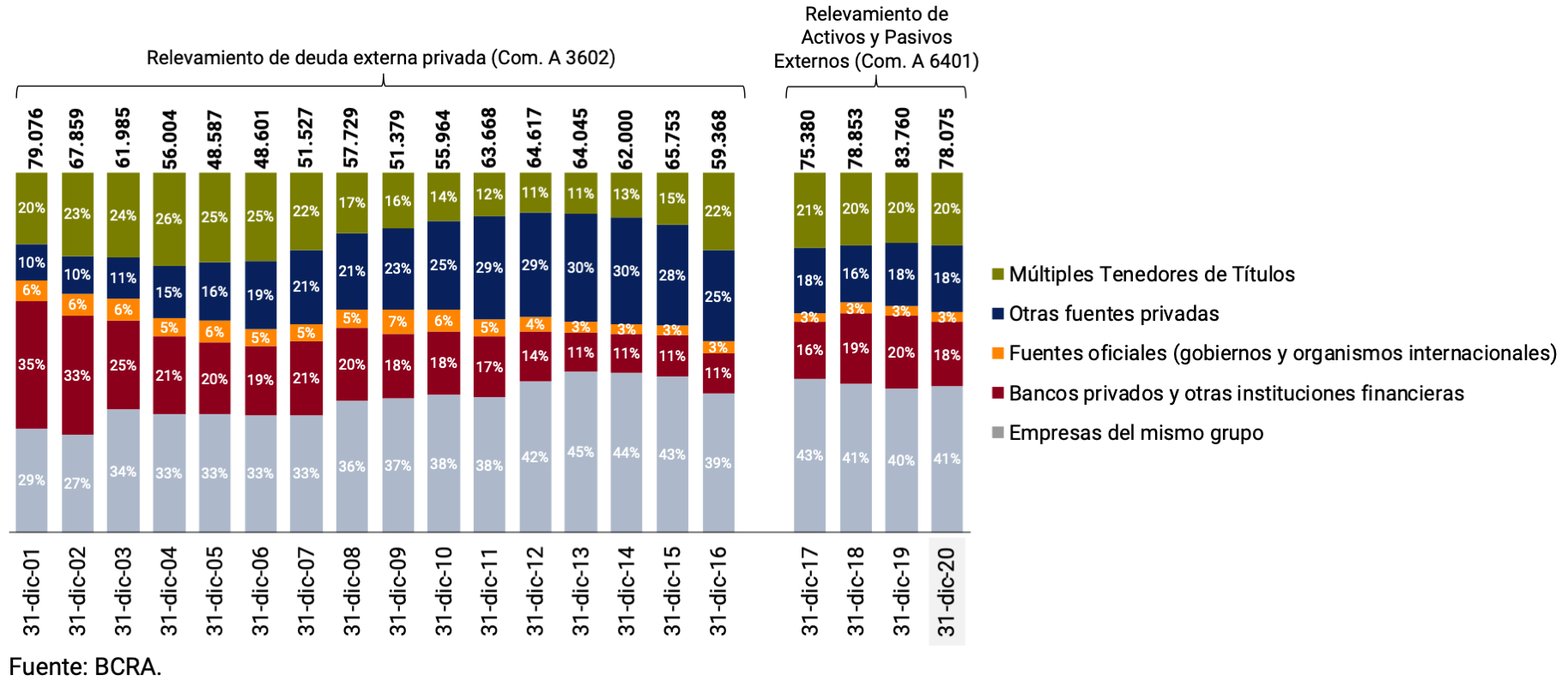

5.3. The National Government met its needs basically by placing debt instruments in the local market