Política Monetaria

Monetary Policy Report (IPOM)

Fourth quarter

2021

Publication that aims to explain in a transparent manner the reasons of the BCRA for its monetary policy decisions.

Table of Contents

Chapters

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlook

2. International context

3. Economic Activity and Employment

4. External Sector

5. Public Finance

6. Prices

7. Monetary Policy

Sections

1. The rise in international

inflation 2. Vaccination as a key determinant of the evolution of economic

activity 3. Exports of goods ten years after the record

4. Restructuring of provincial public debts

5. Seasonal Prices and Their Influence on Monthly

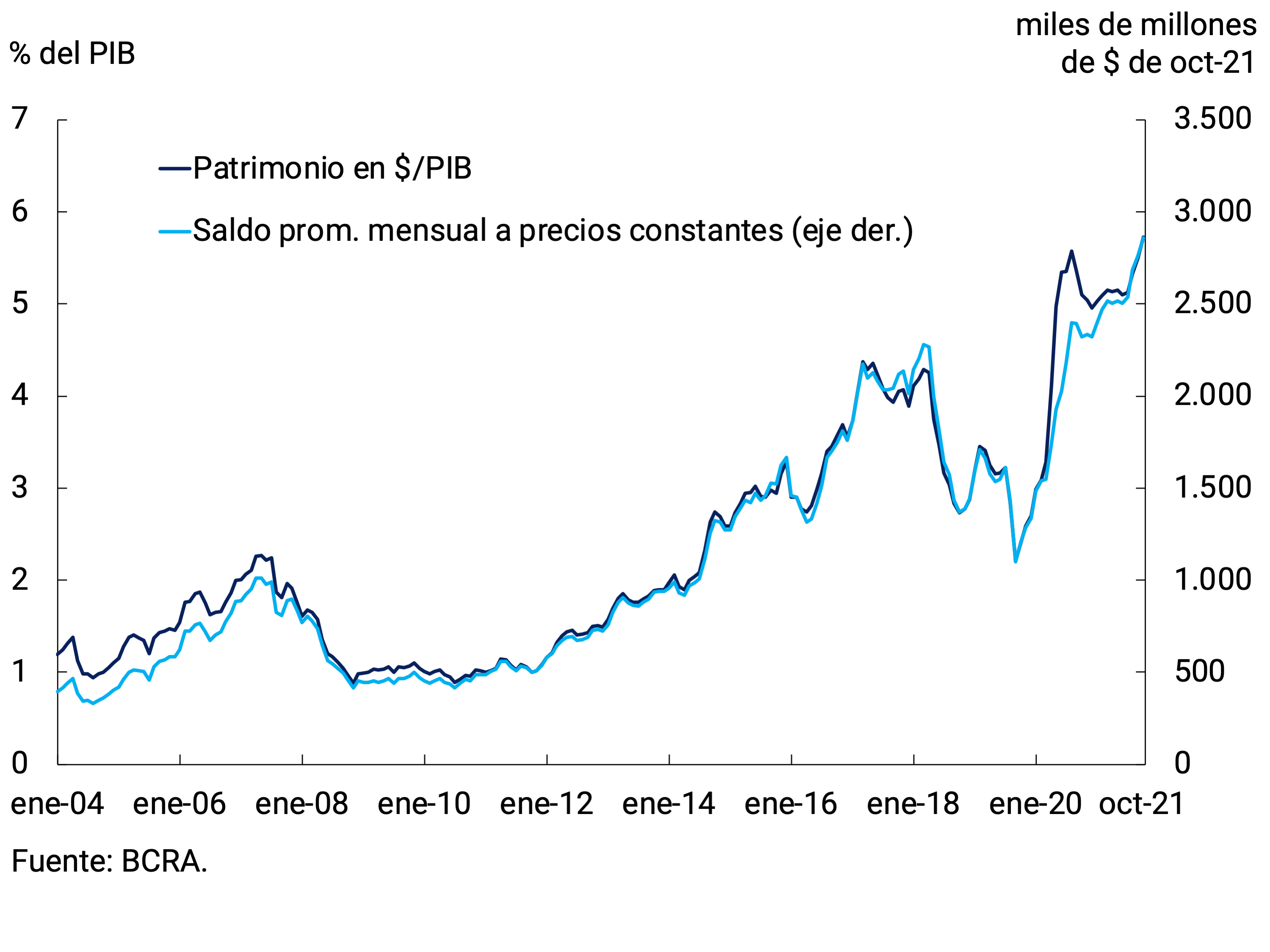

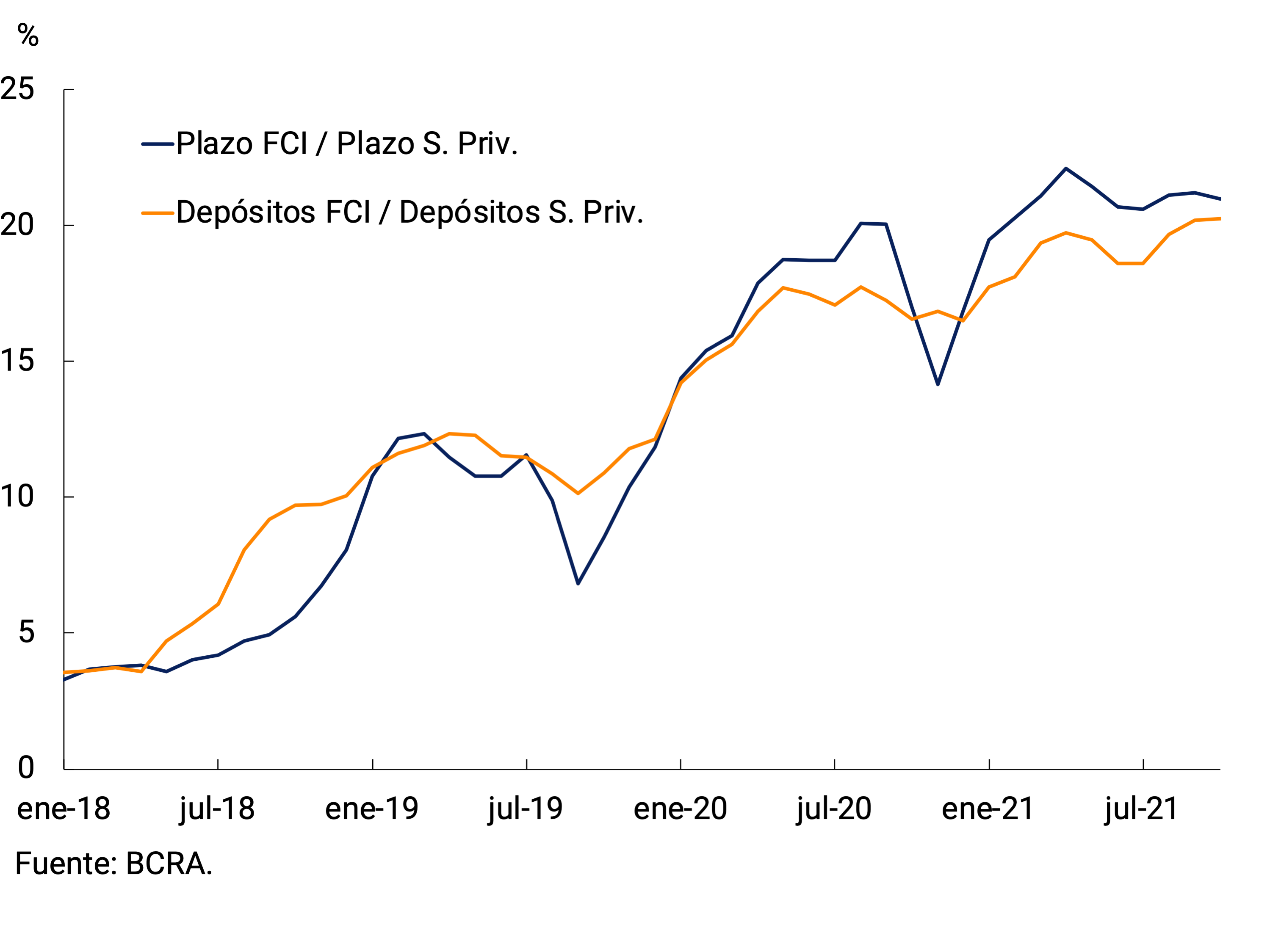

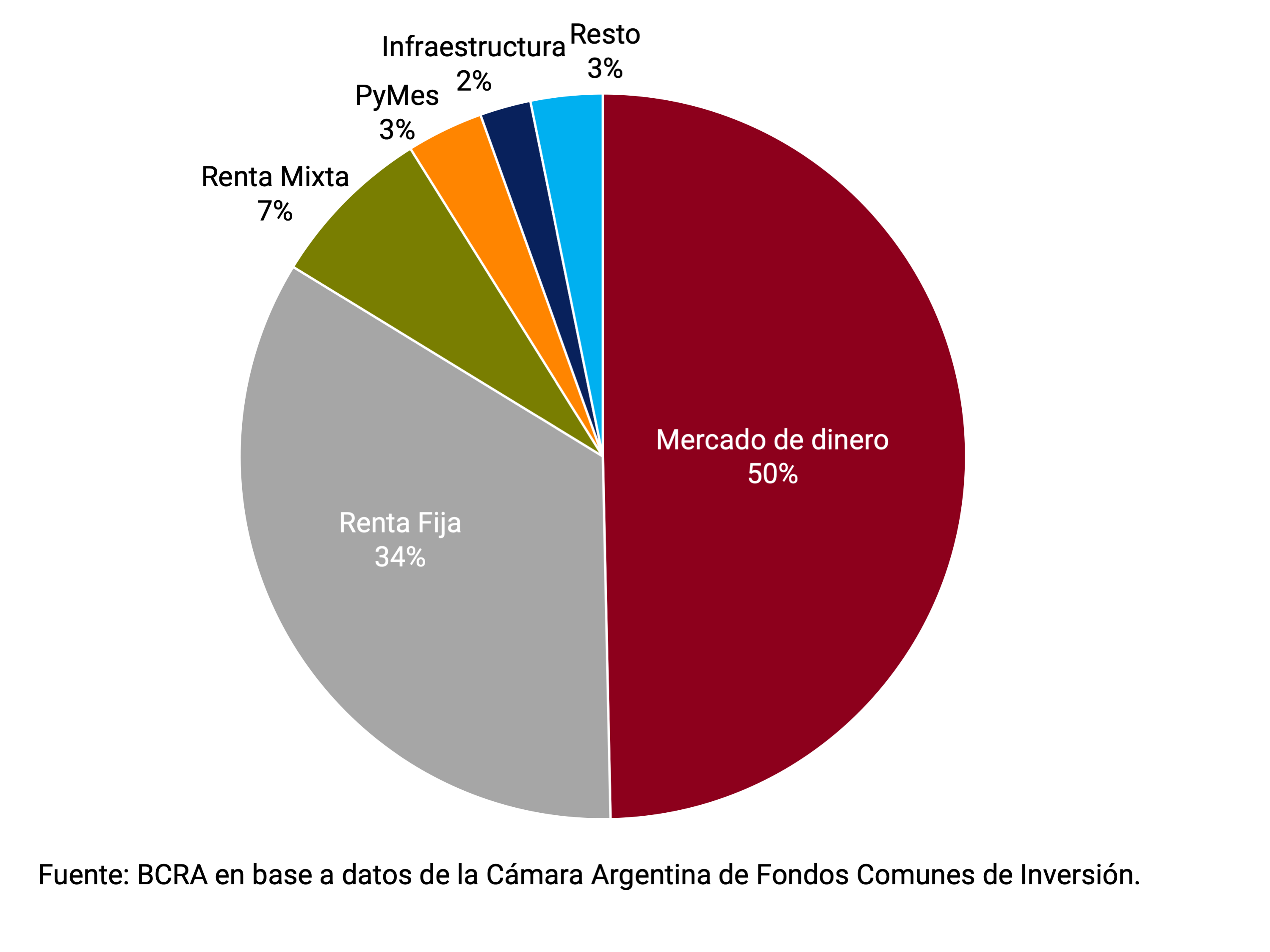

Inflation Volatility 6. The Mutual Fund Industry and Its Participation in the Money

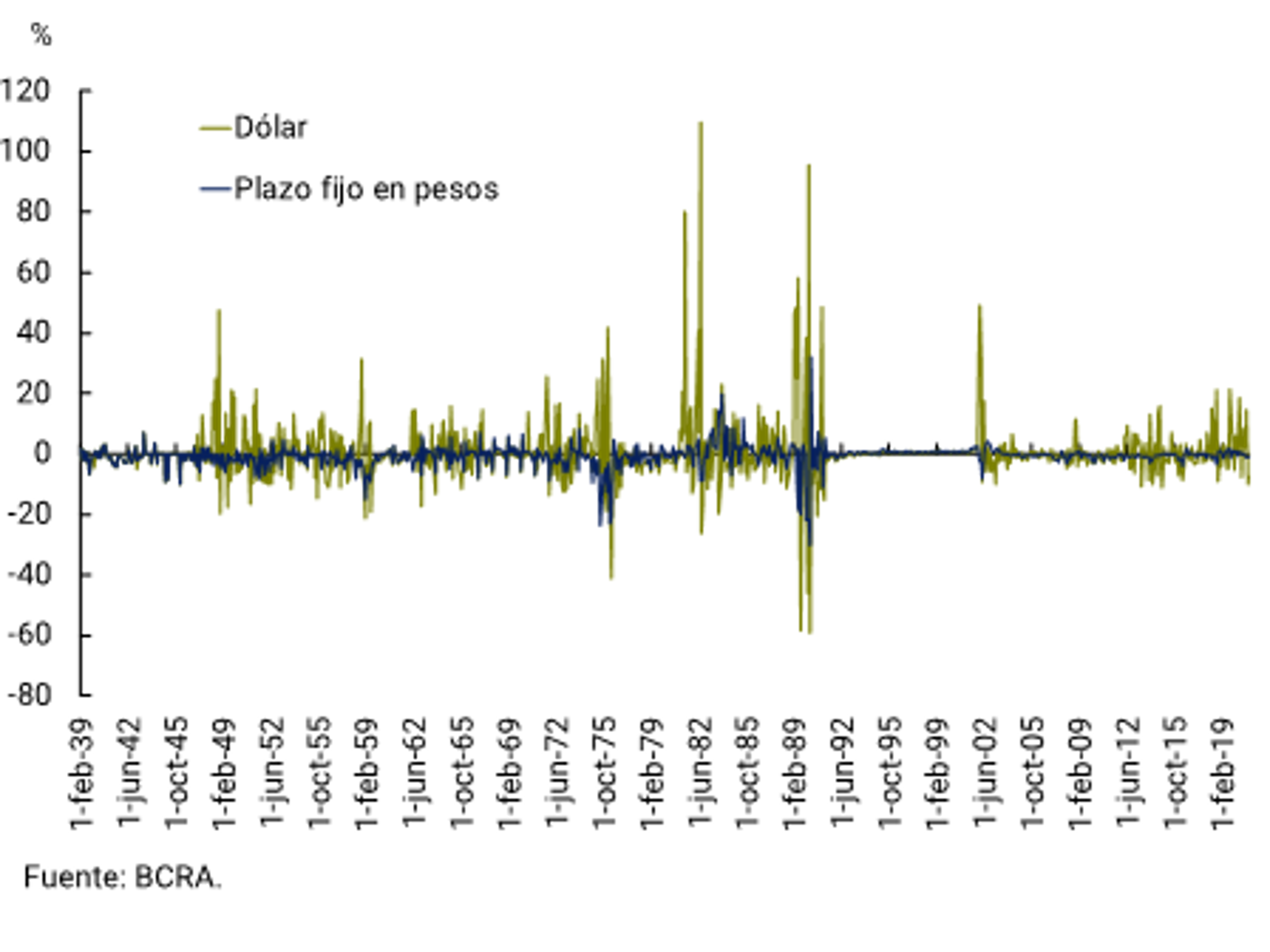

Market 7. Financial de-dollarization. Reflections based on the Argentine experience

For inquiries, write to analisismacro@bcra.gob.ar

Summary

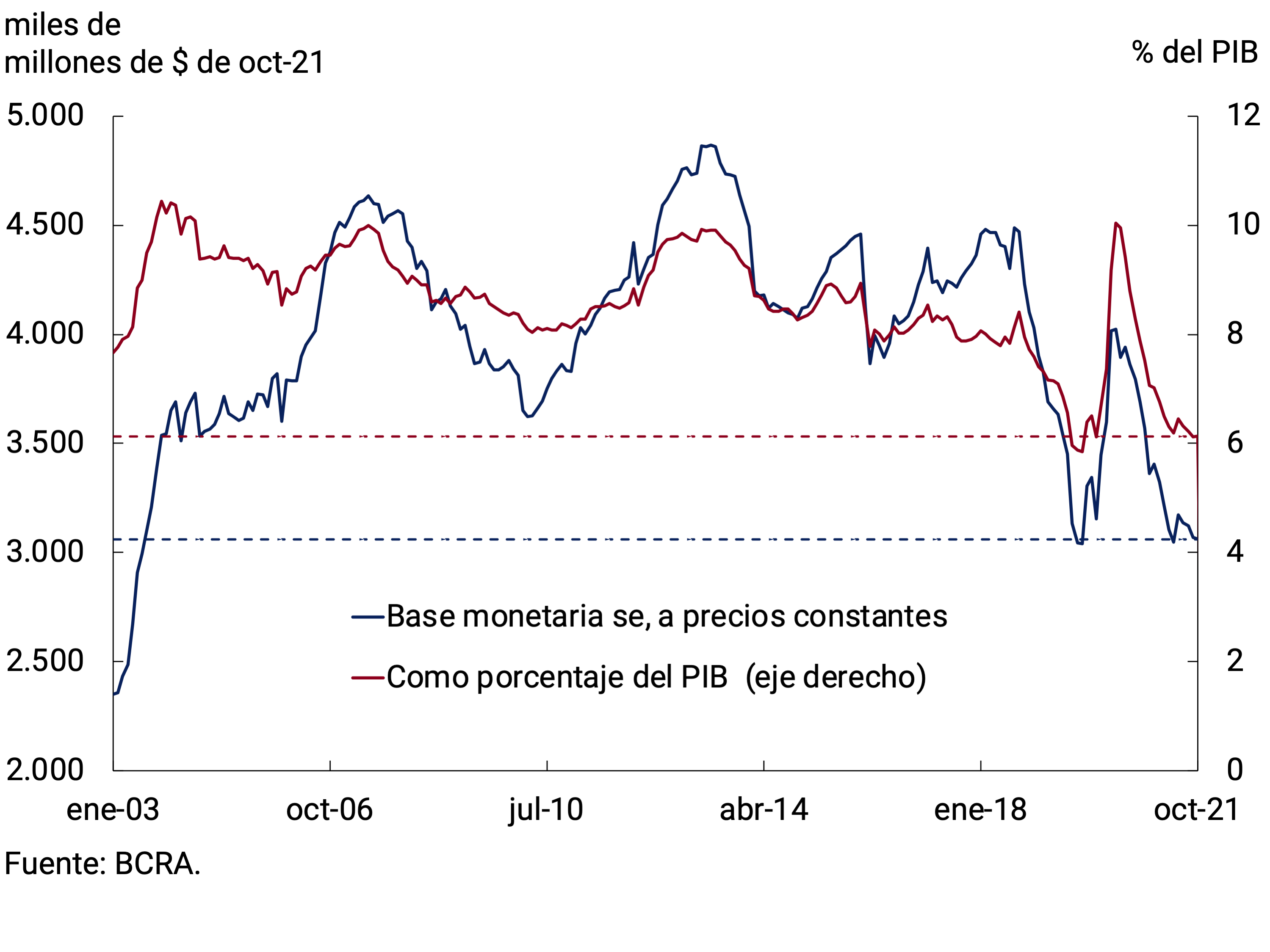

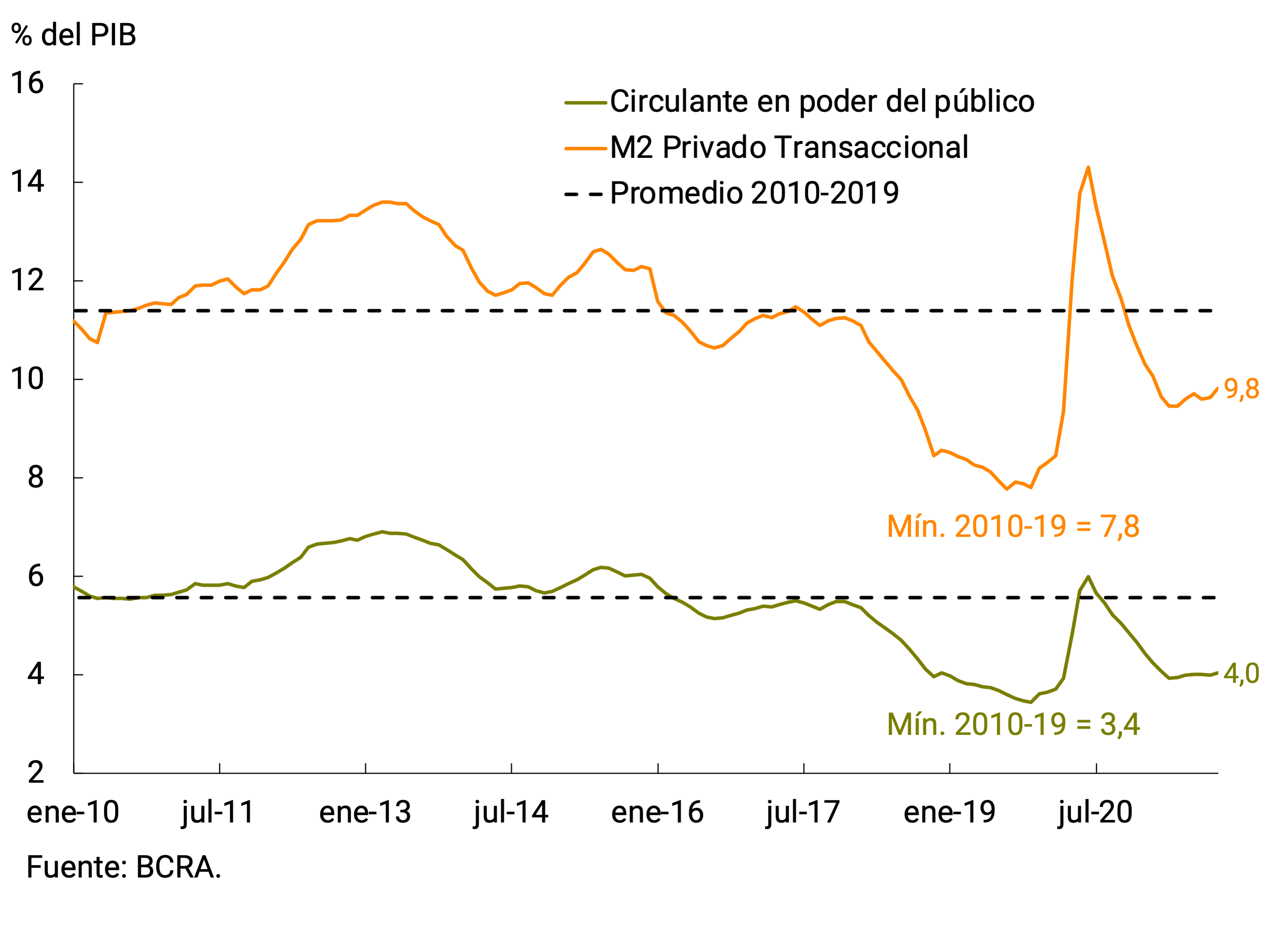

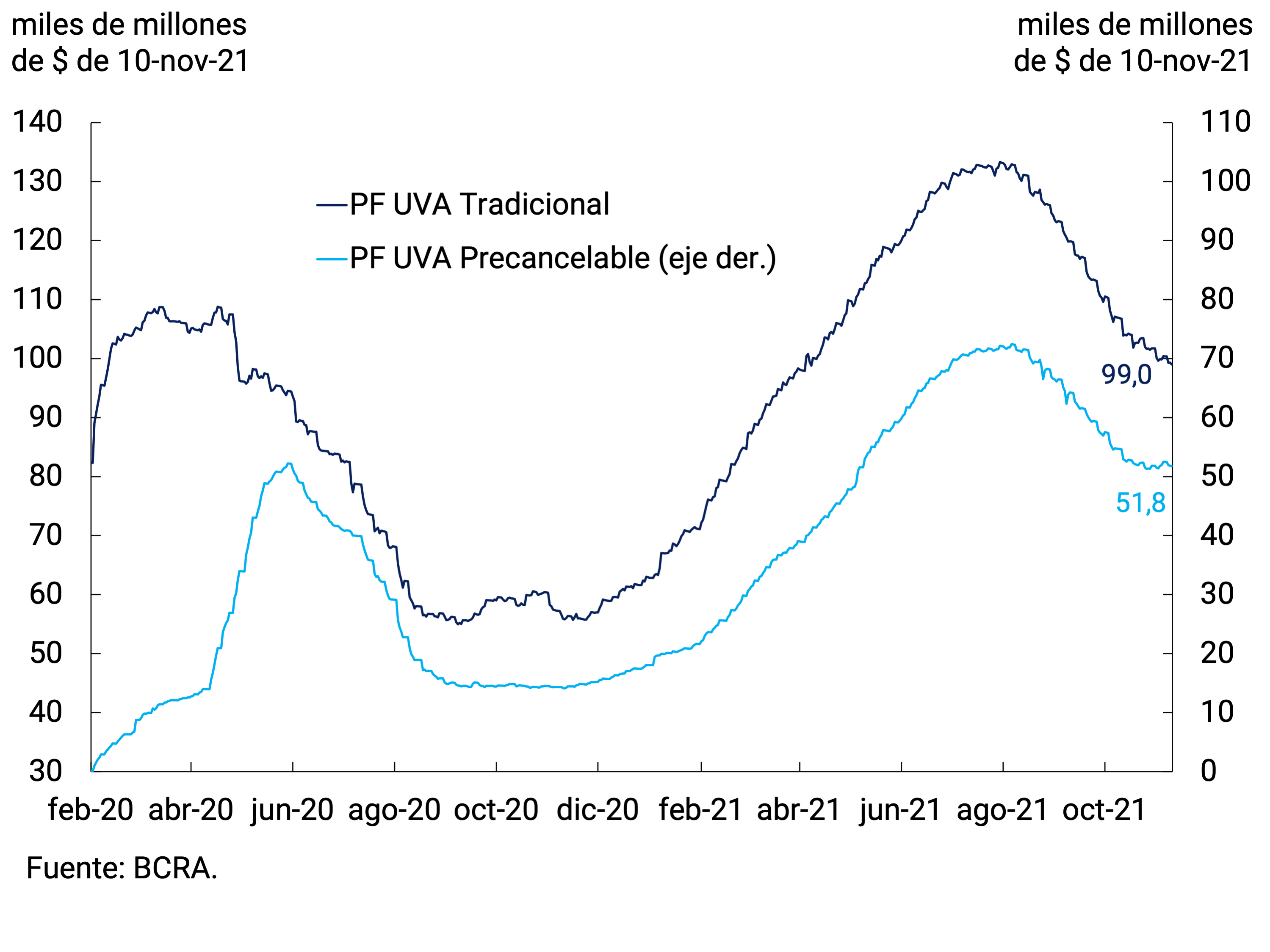

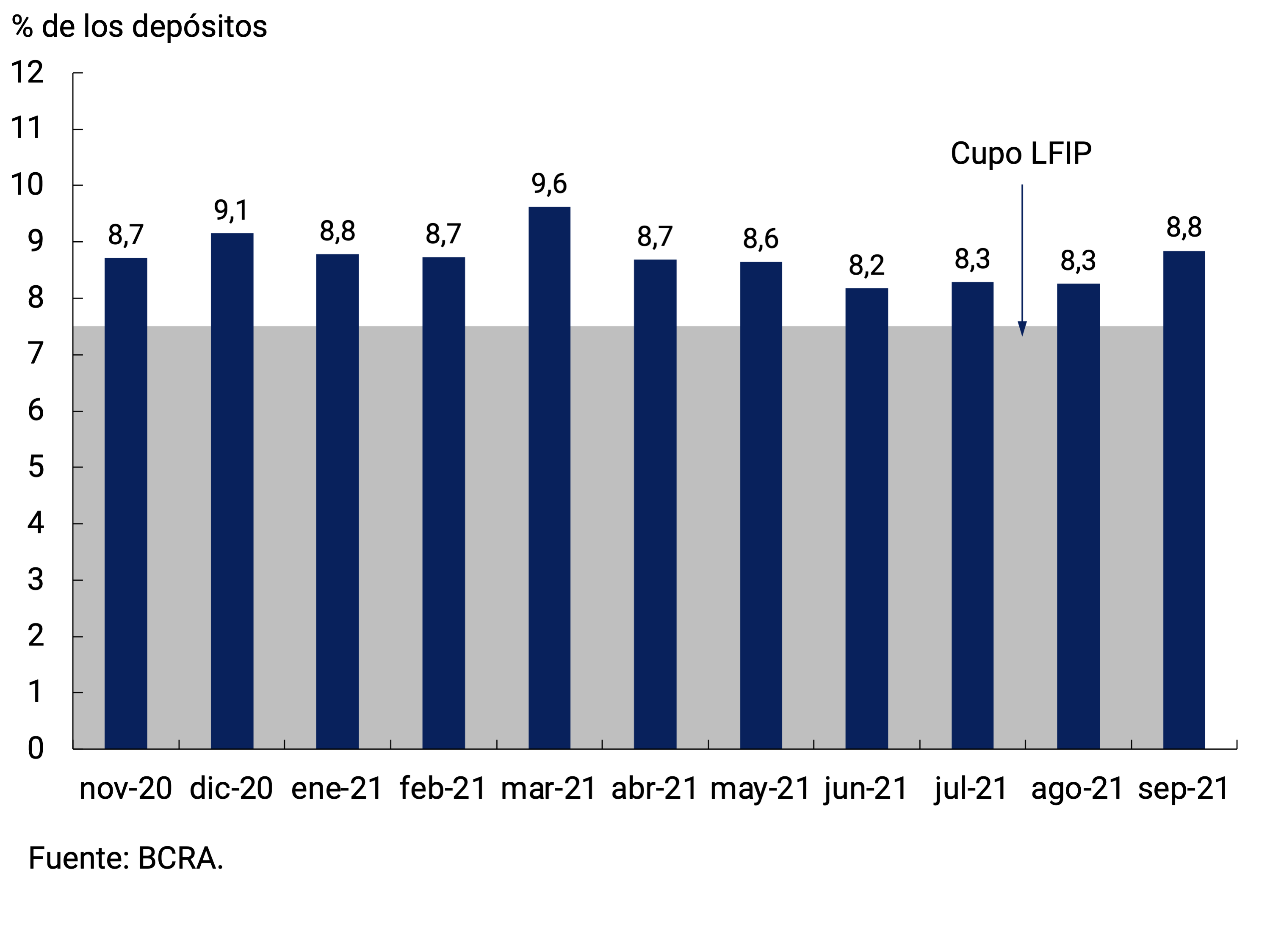

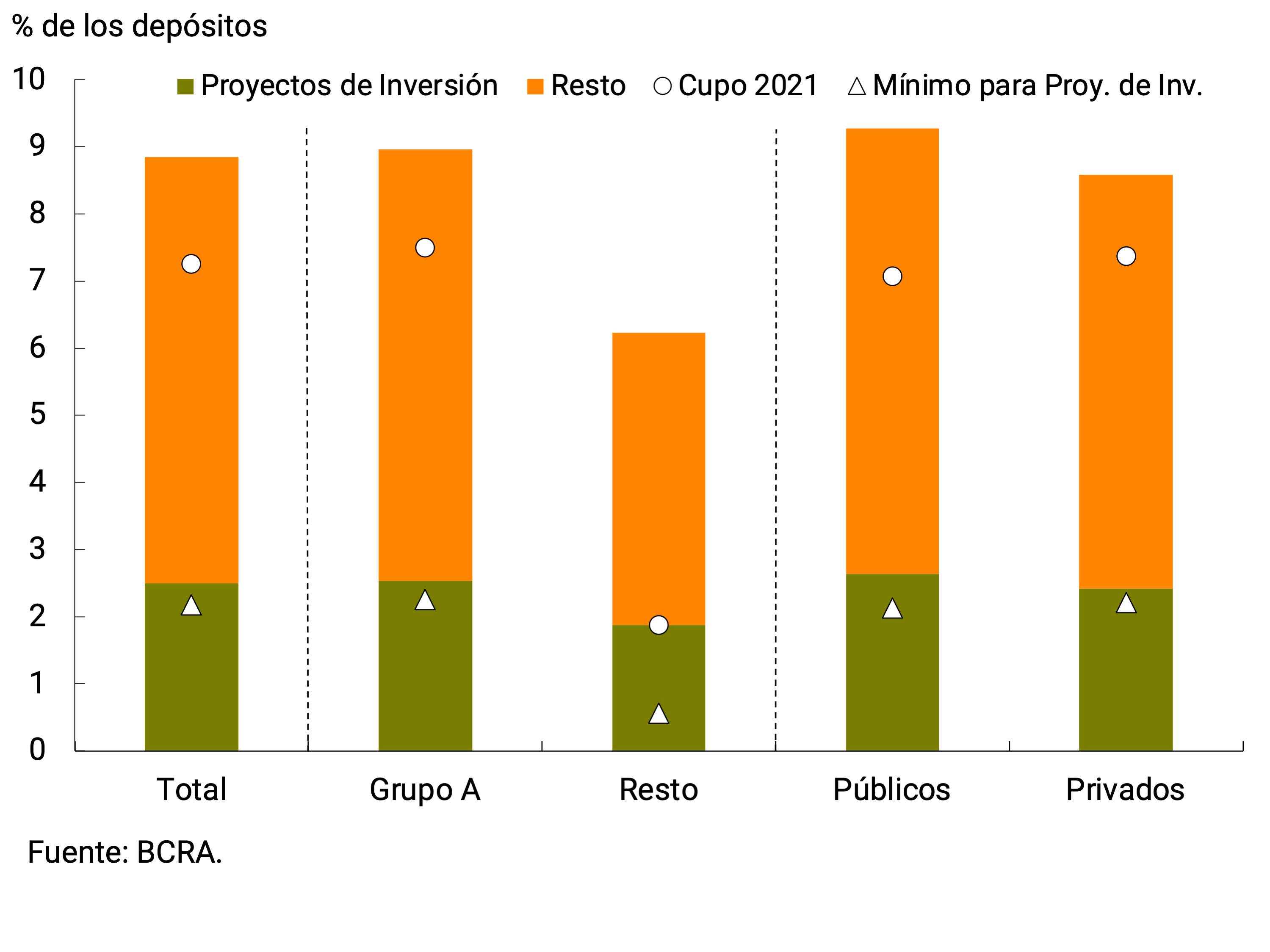

1. Monetary policy: assessment and outlookThe international context continues to be favorable for Argentina. The global economy continued to recover during the third quarter of the year, although at a slower pace than in previous months. The latest forecasts kept the growth projections for the global economy for this year and next practically unchanged (5.8% and 4.8%, respectively). On the other hand, although with a reduction in the margin, the prices of raw materials exported by the country remained at high levels in historical terms. Going forward, external risks are mainly linked to the implications of the rise in international energy prices, which, in a context of rising inflationary expectations in advanced countries, could accelerate the reduction of the monetary stimuli deployed during the crisis and slow down global growth. In the same sense, possible outbreaks of the Delta variant or the expansion of new strains of COVID-19 could have an impact that force the reimposition of sanitary measures that restrict circulation. In Argentina, since June, a systematic drop in the rate of COVID-19 infections has been observed, which reached minimum levels in October. This improvement in the epidemiological situation was possible thanks to the significant progress made in the vaccination campaign. The lower economic impact of the second wave and the subsequent rapid recovery made it possible to achieve continuity in the process of reopening and revitalizing the local economy, although with still heterogeneous sectoral performances. It is estimated that activity will continue to recover in the remainder of the year, driven by the flexibilities of both activities and capacity, supported by greater vaccination coverage with complete schemes of the population, and by the stimulus policies implemented by the National Government and the BCRA. All in all, GDP would grow by about 9% in 2021, also translating into improvements in employment. In this more dynamic macroeconomic environment, retail inflation in September and October stood at 3.5%, above the monthly average observed during the third quarter of 3%. Core inflation, essentially less volatile, also remained at a high value since July, close to 3.2%. On top of an inflationary inertia that remains at high values in recent months, transitory factors anticipated in previous versions of the IPOM were added, with greater intensity than expected. These include the impact of international prices, which have lately been more closely linked to energy prices and the cost of global manufacturing, the observed recomposition of marketing margins in certain sectors and the readjustment of relative prices of private services in the face of the reopening of activities within the framework of the improvement in the epidemiological situation, and, to a lesser extent, to the updates of the salary parity agreements. This occurred in a context where the electoral process gave greater volatility to exchange rate expectations. The BCRA faced these weeks of greater financial volatility, calibrating its intervention in the spot and forward exchange markets and adapting the exchange regulation in order to preserve exchange rate stability. It should be noted that, between January and October, the monetary authority accumulated purchases in the foreign exchange market for US$6,421 million, constituting the highest value since 2012 for the first 10 months of the year, while international reserves increased by US$3,430 million in the same period, mainly considering the net cancellations of principal and interest on debt in foreign currency of the National Government and the open market operations of the BCRA. At the close of this edition, also counting on the income of the allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) by the IMF to mitigate the effects of the pandemic, international reserves stood at around US$42.6 billion and, despite the lower dynamism of the nominal exchange rate in recent months, the ITCRM remained at competitive levels and around the average of the last 24 years. The BCRA calibrates the liquidity of the economy, sterilizing any surpluses, to help preserve monetary balance. In this regard, so far this year, primary expansion linked to the public sector was at levels significantly lower than those of the previous year of the pandemic, reflecting values with respect to GDP similar to those of previous years. In this sense, in the third quarter of the year the growth of the monetary base was 8.6%, maintaining in October an expansion rate similar to that of the previous three months. In year-on-year terms and at constant prices, the base continued to contract, reaching a variation of -17.1% in October, which placed it in GDP terms at figures similar to those of mid-2003.In support of the economic recovery, the BCRA continued with its credit policy focused on the most backward sectors and on the promotion of productive development. The Productive Investment Financing Line (LFIP) continued to be the main vehicle for channeling productive credit to MSMEs under favorable financial conditions. Since its implementation, and with data as of October 31, the LFIP has accumulated disbursements for a total of $1,187,780 million. Recently, the BCRA decided to extend the validity of the LFIP until the end of March 2022, extending it to some specific sectors. With the boost of the LFIP, the balance of credit to relatively smaller companies showed a sustained increase in real terms since the beginning of August, registering an average monthly increase in the third quarter of 2% and accelerating to 4.9% in real terms s.e. in October. Among consumer-related loans, credit card financing has recovered since the end of September, mainly due to the relaunch of zero-rate loans for single-tax individuals. In the coming months, it is expected that as the transitory factors that pressured the general price level subside, inflation will resume a path of gradual deceleration. In this regard, the BCRA will focus its efforts on promoting a macroeconomic environment with lower inflation levels than those currently observed, without damaging the economic recovery underway. For its part, the temporary setting of maximum prices for sale to the final consumer recently established by the National Government, aimed at bringing the prices of a set of products back to their values of early October and keeping them unchanged until next January, will also contribute to moderating inflation in the last months of the year. Looking ahead to 2022, an upcoming agreement with the IMF will help improve the expectations of those actors who condition their vision of the sustainability of the external sector on the outcome of such negotiations, helping to contain exchange rate pressures and inflation expectations. In this sense, the sustained growth of economic activity and a moderation in the inflation rate will lead to a greater demand for real monetary balances, which would be around the average value recorded during the previous decade (2010-2019). In this new stage, it is expected that the lower financing needs of the National Treasury and the greater role of the peso debt market will contribute to reducing the monetary sterilization effort. This will favor the demand for the monetary base to be provided by the interest associated with the BCRA’s interest-bearing liabilities and, potentially, by a reduction in its stock.

2. International context

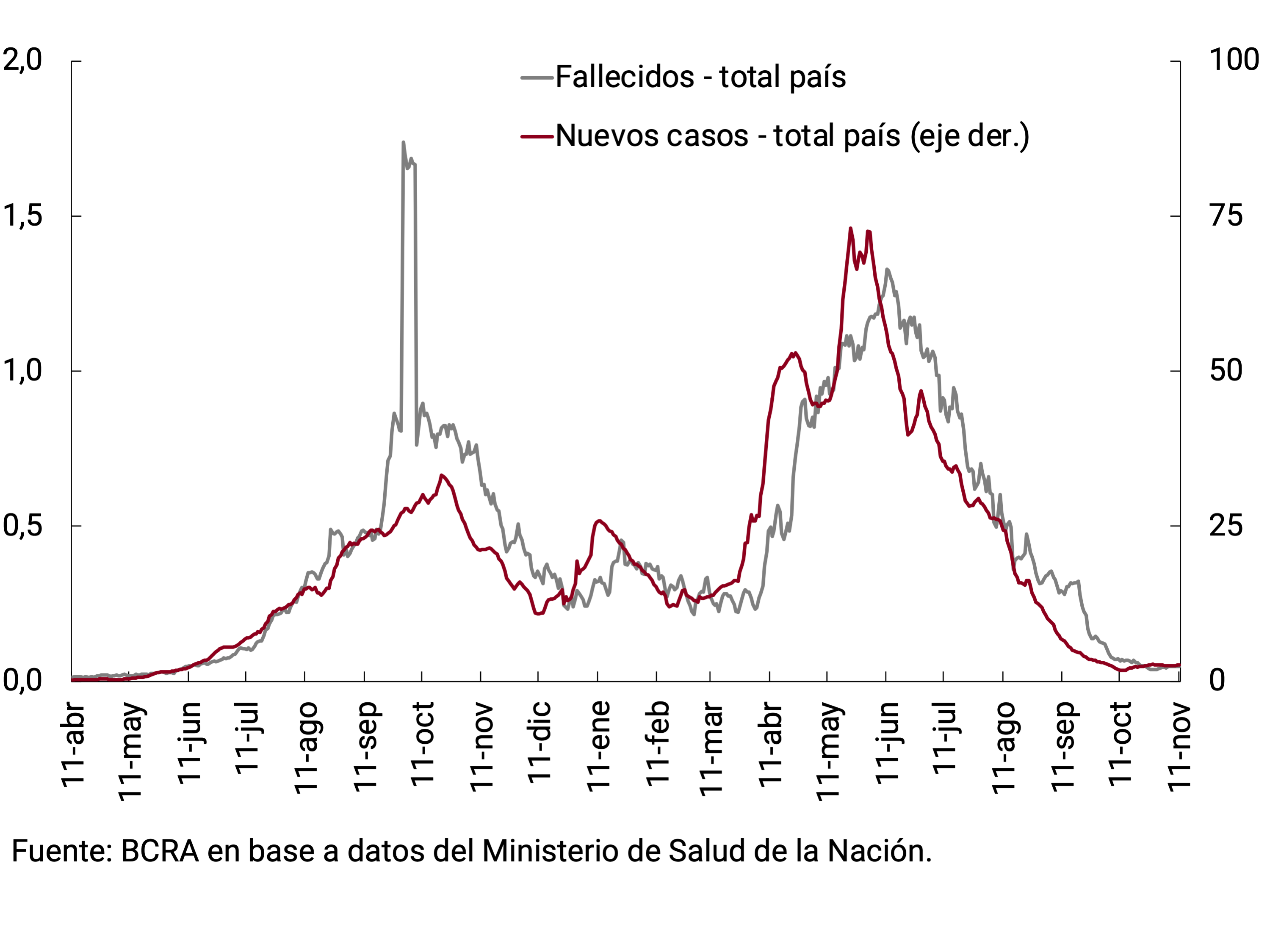

During the third quarter of the year, new global COVID-19 cases continued to rise to a peak of 4.2 million per week towards the end of August, and have since dropped to 2.8 million by the end of October. Although at the date of publication of this report cases were increasing again, standing at 3.4 million per week, the lethality rate is lower than in previous phases of the pandemic. Vaccination also accelerated in Latin America and Asia, although significant divergences remain between high- and low-income countries. The global economy continued to recover during the third quarter of the year, albeit at a slower pace, given the disruption of global supply chains and the continuation of the pandemic. The latest forecasts kept the growth projections for the global economy for this year and next practically unchanged (5.8% and 4.8% on average, respectively), while a divergent evolution between advanced and developing countries is still expected. Global inflation accelerated, and it did so most markedly in developing countries. The central banks of the latter have reacted with sharp interest rate hikes, while those of advanced countries have begun to withdraw their quantitative monetary stimulus. Going forward, the global economic recovery remains subject to high uncertainty. The disparity of vaccination campaigns and the continuity (or not) of support policies give rise to a scenario in which developing economies will take several more years to reach pre-pandemic levels of activity. The advanced countries’ response to inflation could lead to tighter financial conditions for the rest of the world. Similarly, the boom in the stock market and cryptocurrencies presents the risk of a “sudden correction”, with a potentially adverse impact on capital flows to emerging countries.2.1. Daily cases rose with lower lethality than in previous phases and booster doses of vaccines began to be appliedDuring the third quarter of the year, new global cases of COVID-19 continued to rise to a peak of 4.2 million per week at the end of August, and since then they fell to 2.8 million by the end of October. First cases fell in Southeast Asia, and then in the United States. In contrast, in Europe they remained relatively stable, and from the end of September they began a marked rise, particularly in Germany, Russia and the United Kingdom. South America, so far, has not registered a strong rise in cases again, although in the days prior to the publication of this report, increases were observed in some countries. At the time of publication, global cases were at 3.4 per week and rising again, with an epicentre in Europe (see Figure 2.1). Deaths followed the evolution of cases, but increased less than in previous phases: the global fatality rate fell from 2.5% in June (during the peak of deaths in India) to 1.40%, and in mid-November it stood at 1.66%.

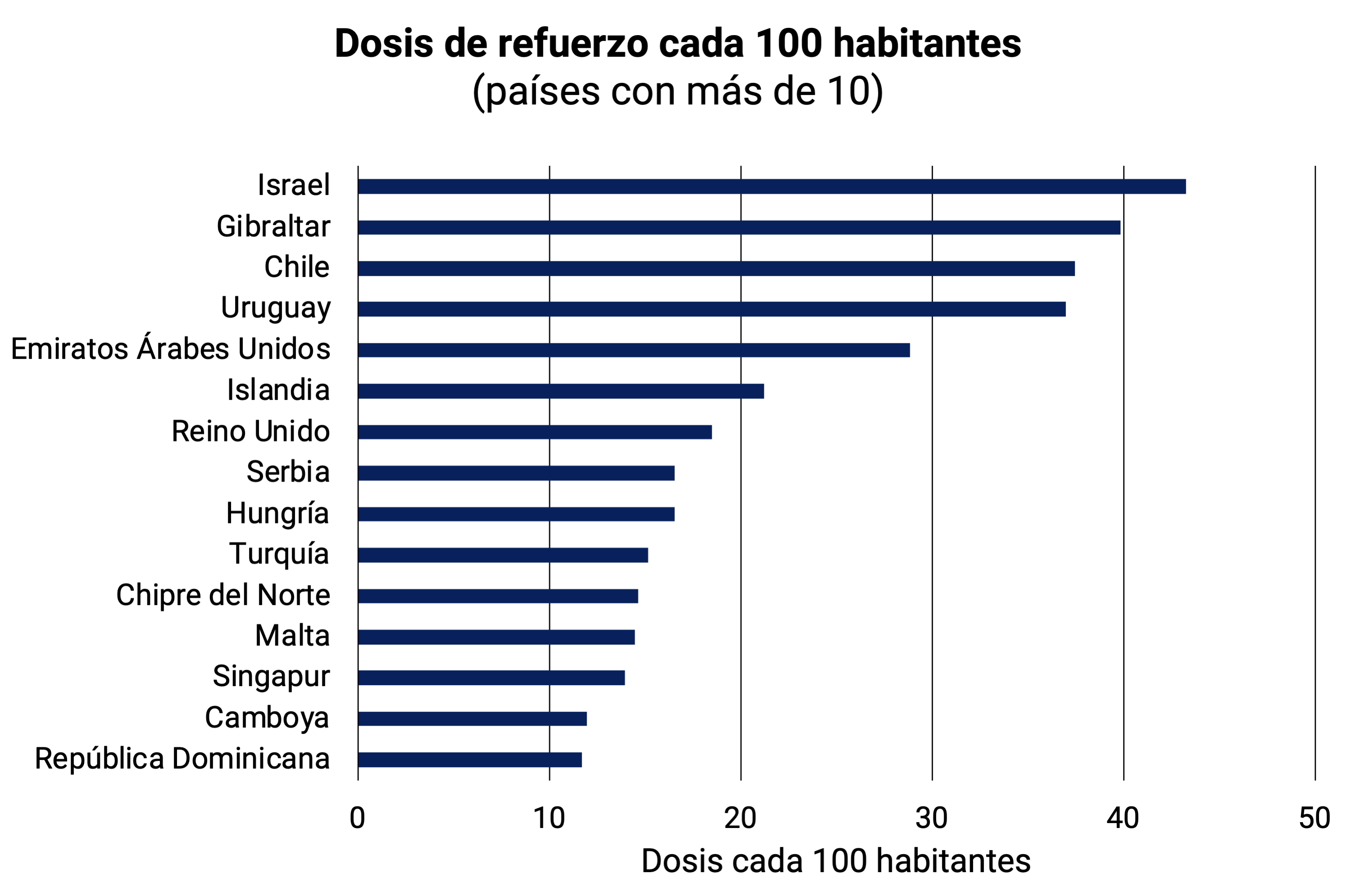

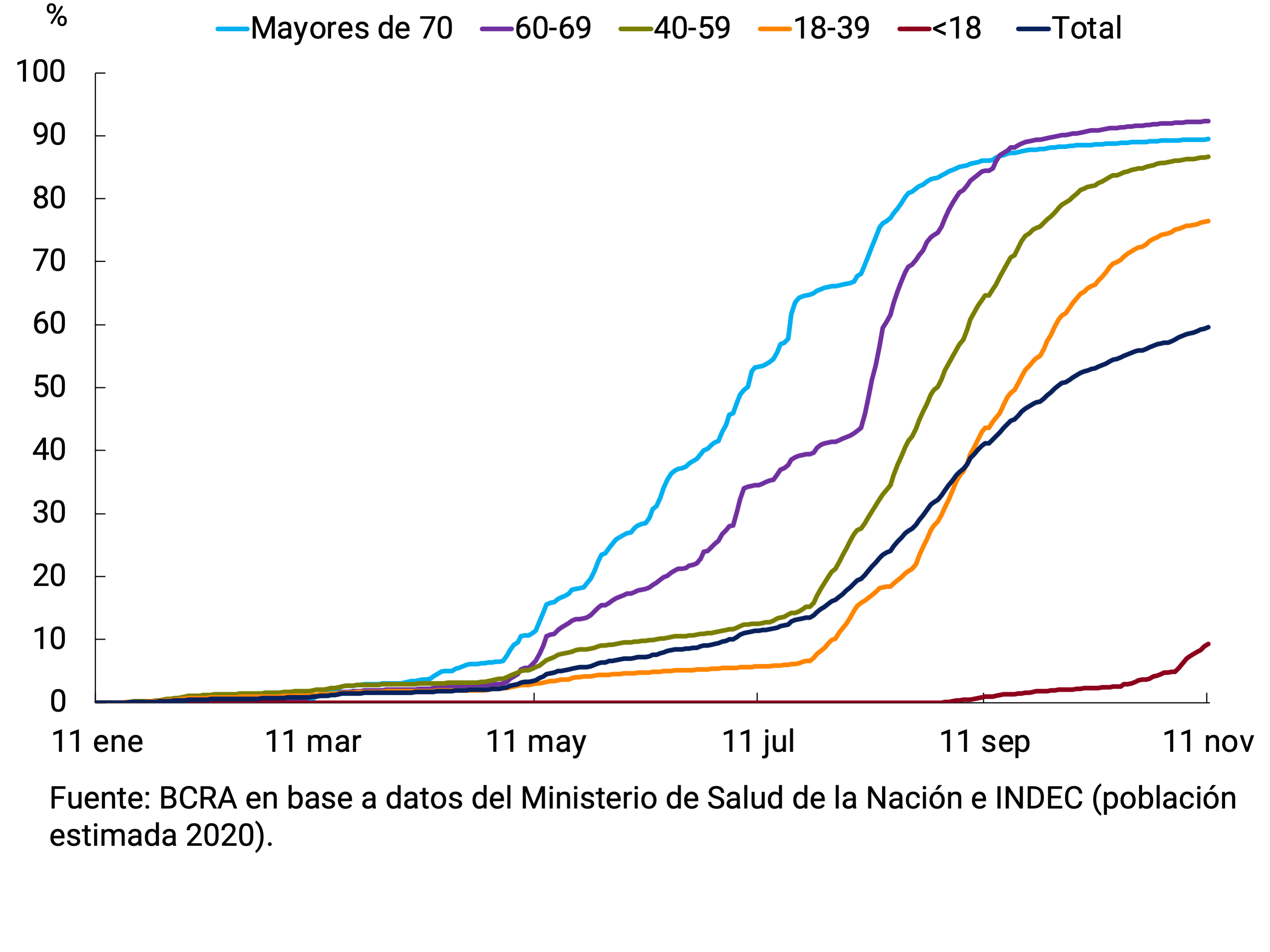

Vaccination accelerated notably in South America, Oceania and Asia, which converge towards the levels of percentage of the population with a complete scheme in Europe and North America. Meanwhile, vaccination in Africa is lagging markedly behind (see Figure 2.2). Thus, while more than 65% of the population in high-income countries is fully vaccinated, less than 4% completed the scheme in low-income countries. Given the greater contagiousness of the Delta variant and the evidence of the fading effectiveness of vaccines over time, more than 50 countries have already begun to apply booster doses. Israel has already applied them to 43% of its population, Uruguay and Chile to 37%.

In countries where cases increased, the growing trend in mobility that had been observed slowed down, or even fell. Some (such as Germany and France) reintroduced restrictions that, except for Japan, generally did not reach last year’s levels (see Figure 2.3).

2.2. Global economic recovery continues, but slows in the third quarter

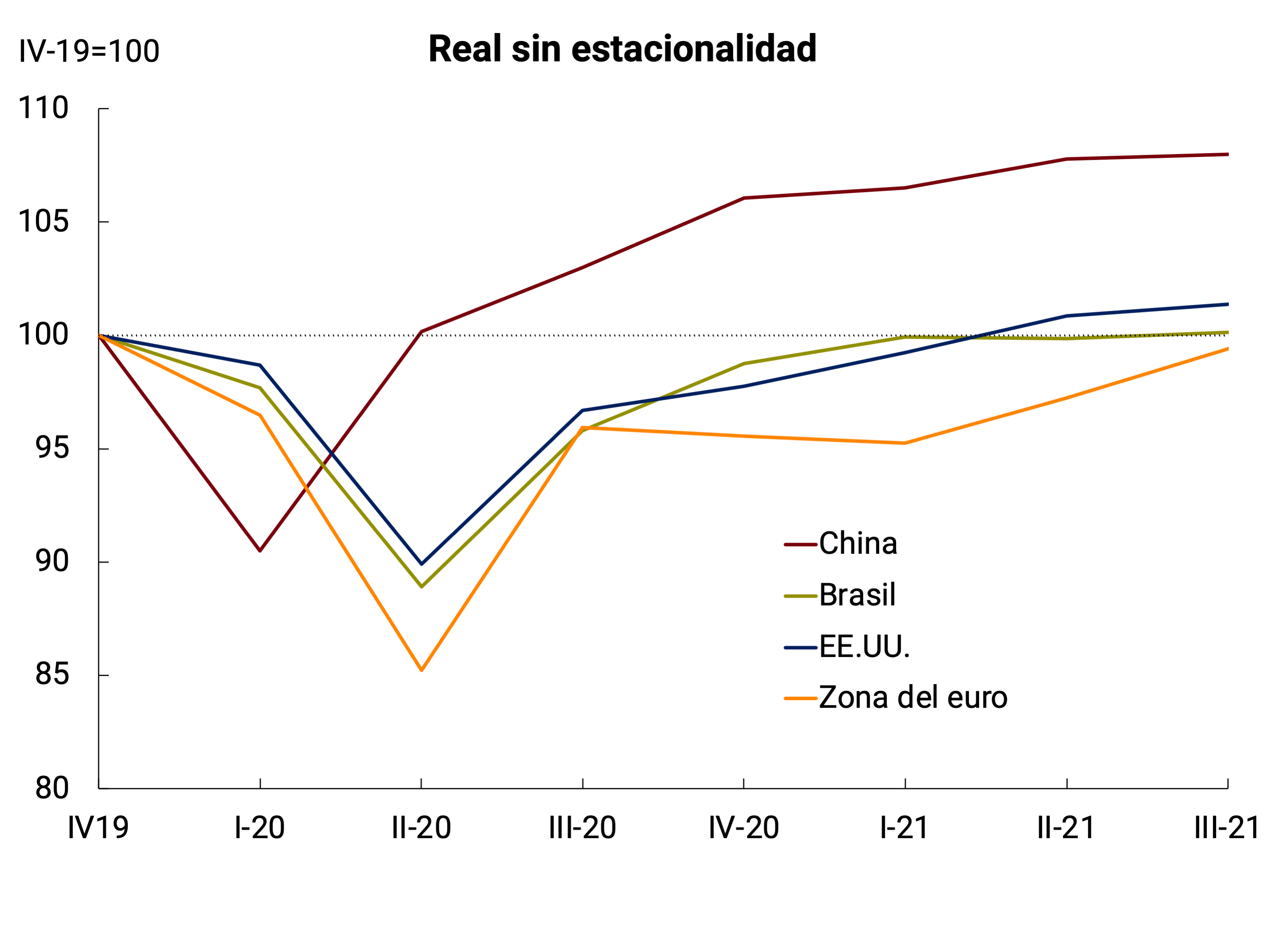

The global economy continued to grow in the third quarter of the year, albeit at a slower pace than in previous quarters (see Figure 2.4). This was due to the interruption of global supply chains and the continuity of the pandemic in some countries. Among Argentina’s main trading partners, the slowdowns in the expansion of economic activity in the United States and, especially, in China, and the low growth in Brazil stand out. In the euro area, economic activity picked up again at a high rate, similar to that of the second quarter. Thus, in the third quarter of 2021, the activity levels of Argentina’s main trading partners were above or close to pre-pandemic levels (see Figure 2.4).

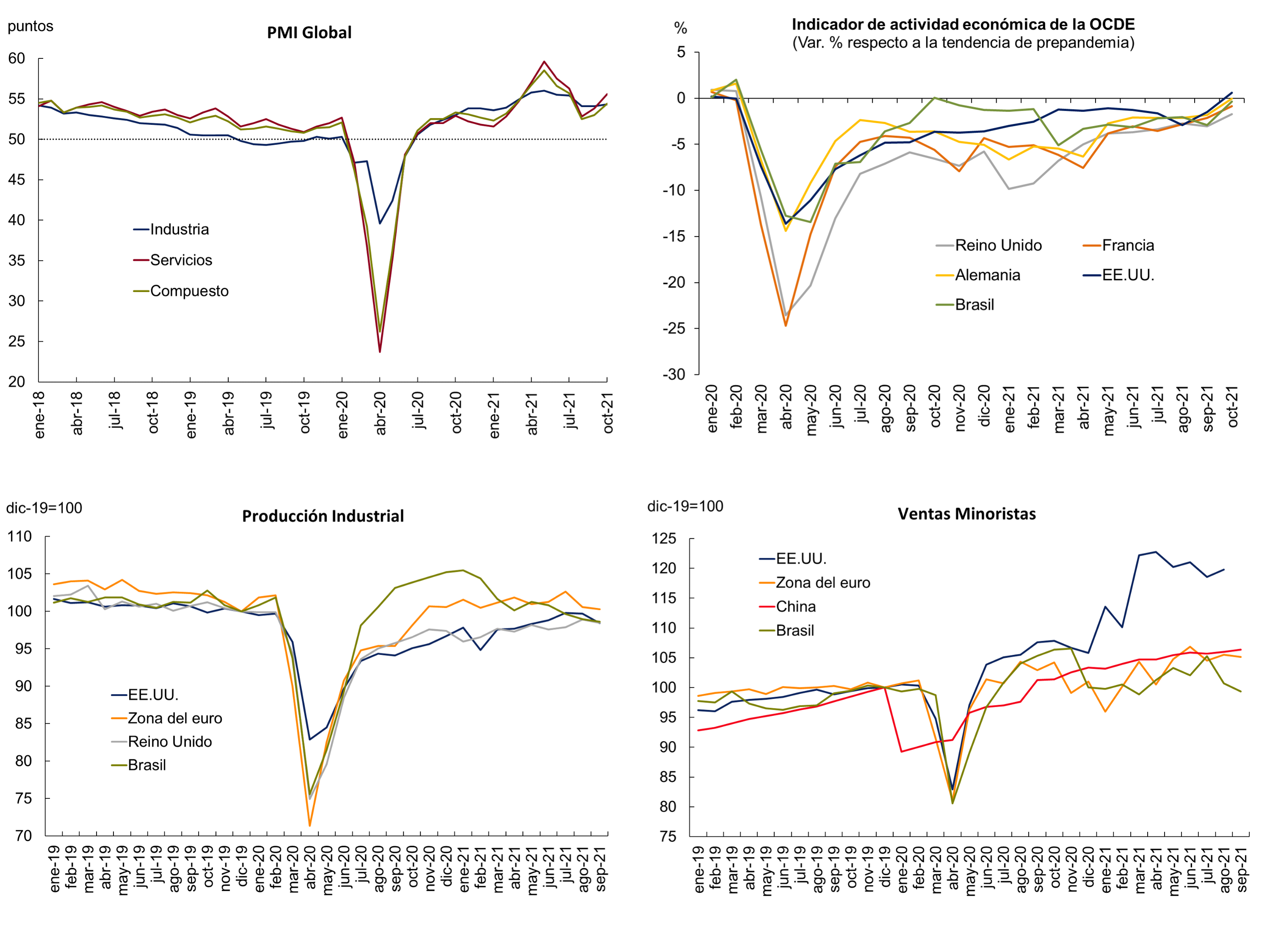

The high-frequency data also reflect lower growth in the global economy in the third quarter of the year. The global purchasing managers’ indicator (PMI) shows a downward trend from the 15-year high recorded in May, with a more marked fall in the services sector, although it remained in expansionary territory (above 50)1. On the other hand, industrial production indicators stagnated in the third quarter, mainly due to global “bottlenecks” in raw materials, semiconductors and maritime transport; while retail sales showed a lower growth rate than previous quarters (see Figure 2.5). Between September and October, there is a recovery in the PMI in the United States and China. The OECD economic activity indicator also shows better performance in October in the United States, the major euro area countries, and Brazil (see Figure 2.5).2

Internacional slightly lowered its growth forecast for 2021 from 6% to 5.9% and maintained its growth forecast for 2022 at 4.9%. The latest forecasts kept the growth projections for the global economy for this year and next largely unchanged (see Table 2.1). The IMF’s downward correction this year focused on advanced economies (from 5.6% to 5.2%), particularly in the United States (from 7.0% to 6.0%) due to the impact of bottlenecks in some inputs and a moderation in consumption in the third quarter. The growth forecast for emerging and developing economies improved slightly (from 6.3 percent to 6.4 percent), based in part on the recent performance of commodity prices. Other sources of forecasts, such as those of the OECD (global economy and China), the Federal Reserve (United States) and the European Central Bank (euro area) show a similar picture for 2021 and 2022 (see Table 2.1). Meanwhile, Brazil’s expected growth for next year fell significantly (from 2.0% to 1.5%, for the average forecast), due to the expectation of a more contractionary monetary policy to deal with inflation and the greater fiscal uncertainty linked to the relaxation of the public spending rule and the election year.

Table 2.1 | Economic

Source: IMF (WEO) and other sources: OECD (world and China), ECB (euro area), Fed (United States), Bacen – Focus Survey (Brazil). (1) Corresponds to October 2021. (2) Corresponds to May 2021. (3) Corresponds to June 2021.

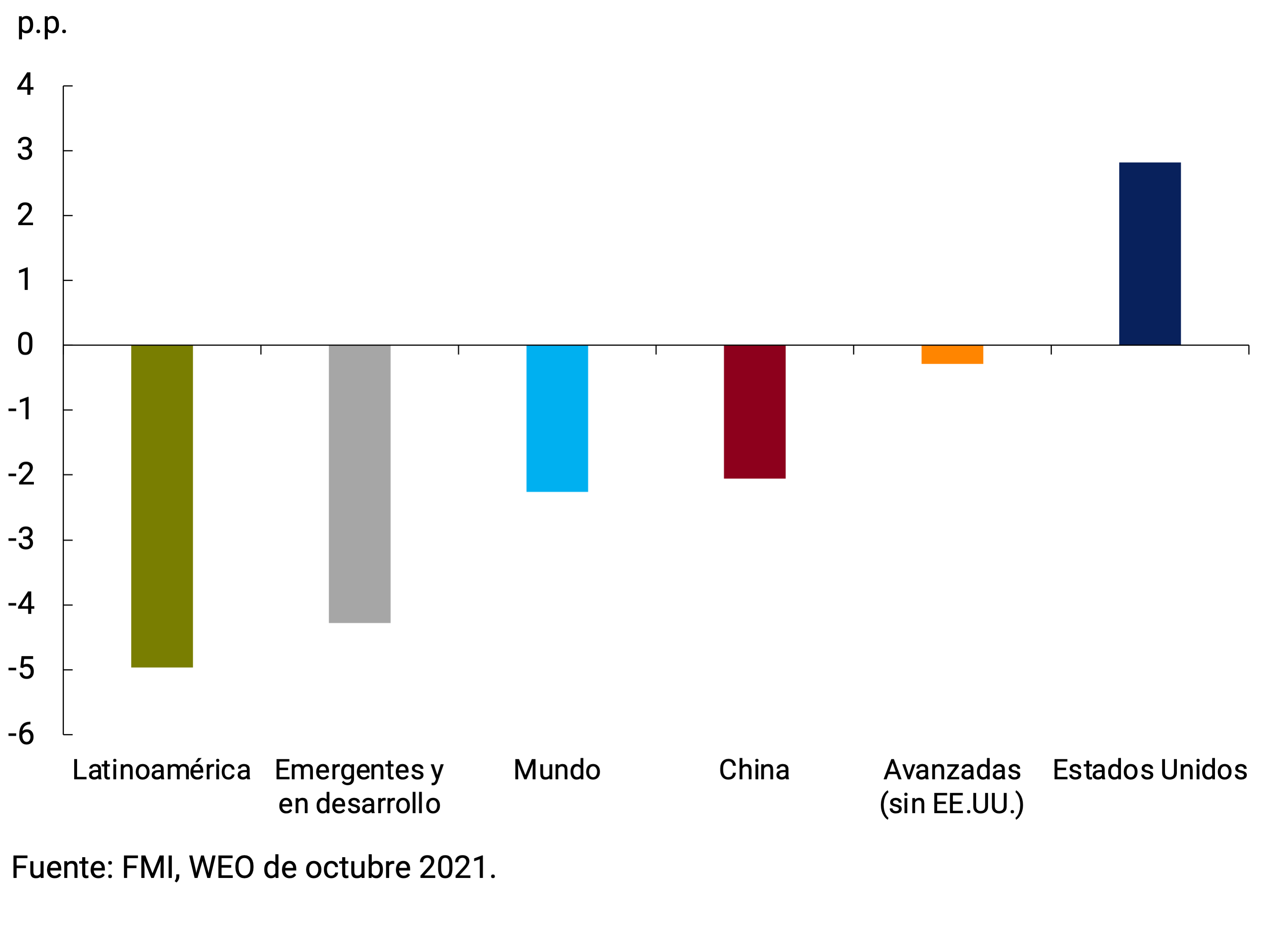

For the medium term, the prospects for a divergent recovery between advanced economies and emerging and developing countries remain in the face of differences in access to vaccines and in the policy space for the implementation of stimulus measures. Considering the IMF’s growth forecasts through 2024, economic activity in advanced economies would exceed the pre-pandemic forecast trajectory by 0.9 p.p., while that of emerging and developing economies would remain 4.3 p.p. below the pre-pandemic trend (see Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6 | Evolution of GDP compared to pre-pandemic

trends

Loss of GDP in 2024 compared to pre-pandemic trends

The labor market continues to show less dynamism in most of the world’s economies. Employment rates have increased since the trough of the second and third quarters of 2020 but generally remain below pre-pandemic levels, even in countries where activity has returned or is close to reaching pre-pandemic levels (see Figure 2.7). This phenomenon is even more prevalent in developing countries. And it is affecting low-skilled workers, young people and women to a greater extent, resulting in growing inequality and making it difficult to reverse the increase in poverty generated by the pandemic. The IMF estimates that around 65 to 75 million more people will be in extreme poverty in 2021 compared to pre-pandemic projections.

2.3. Central banks began to reduce stimulus in the face of rising inflation

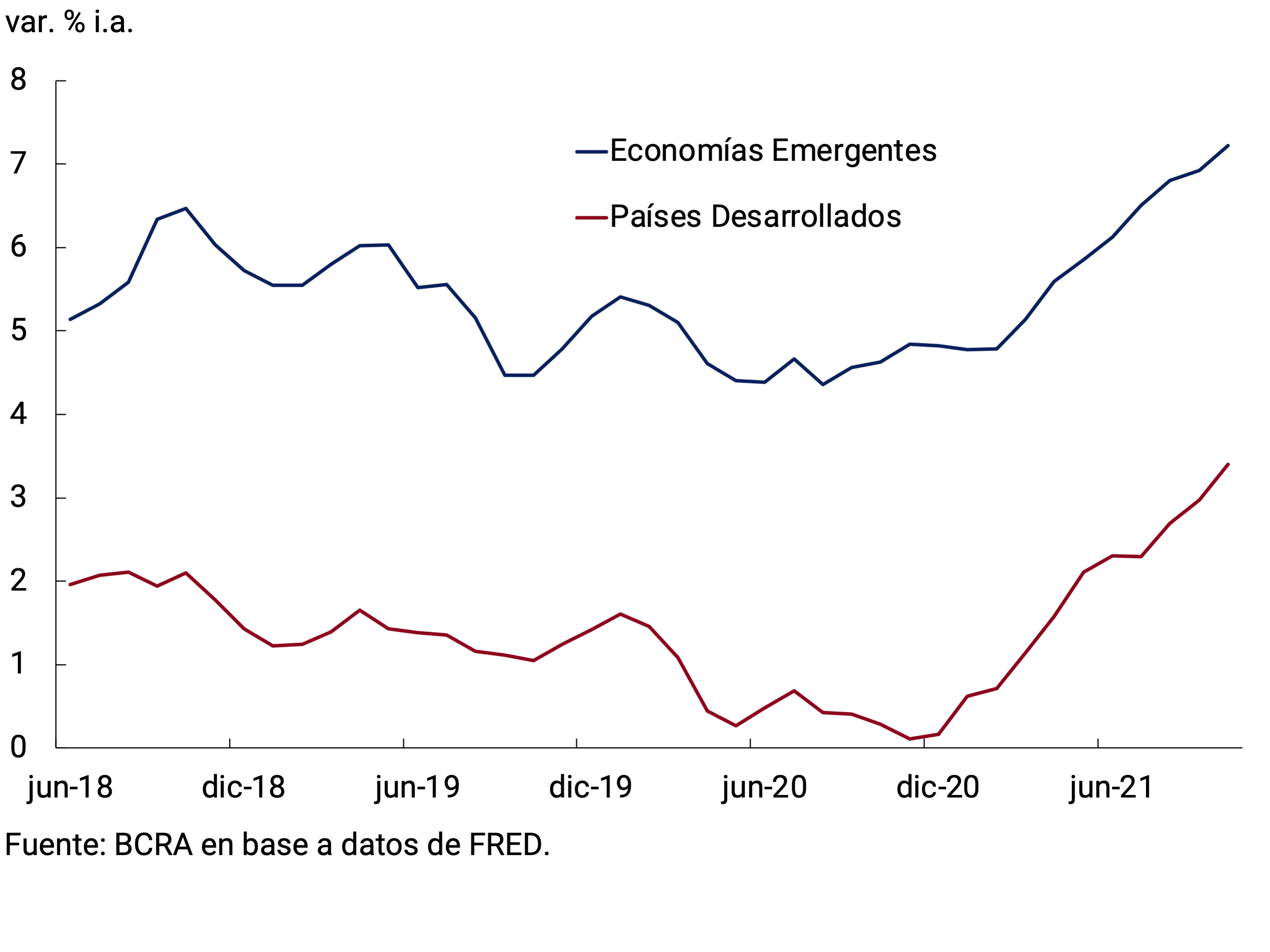

Central banks in emerging countries continued to take monetary policy measures with a contractionary bias. Meanwhile, central banks in developed countries have largely maintained expansionary monetary measures, but have begun to withdraw part of the quantitative stimulus; This creates the risk of negative spillovers to developing countries.

The average interest rate of the emerging countries surveyed went from 3% in October 2020 to 4.5% a year later (see Figure 2.8). In some cases, the contractionary measures accelerated. At its meeting last October, the Central Bank of Chile decided on the largest increase in its monetary policy interest rate in the last two decades (+1.25 p.p.). Similarly, the Monetary Policy Committee of the Central Bank of Brazil increased the target on the SELIC rate by 1.5 p.p. at the end of October; It was also a record increase in more than two decades, and 50 bps above market surveys.

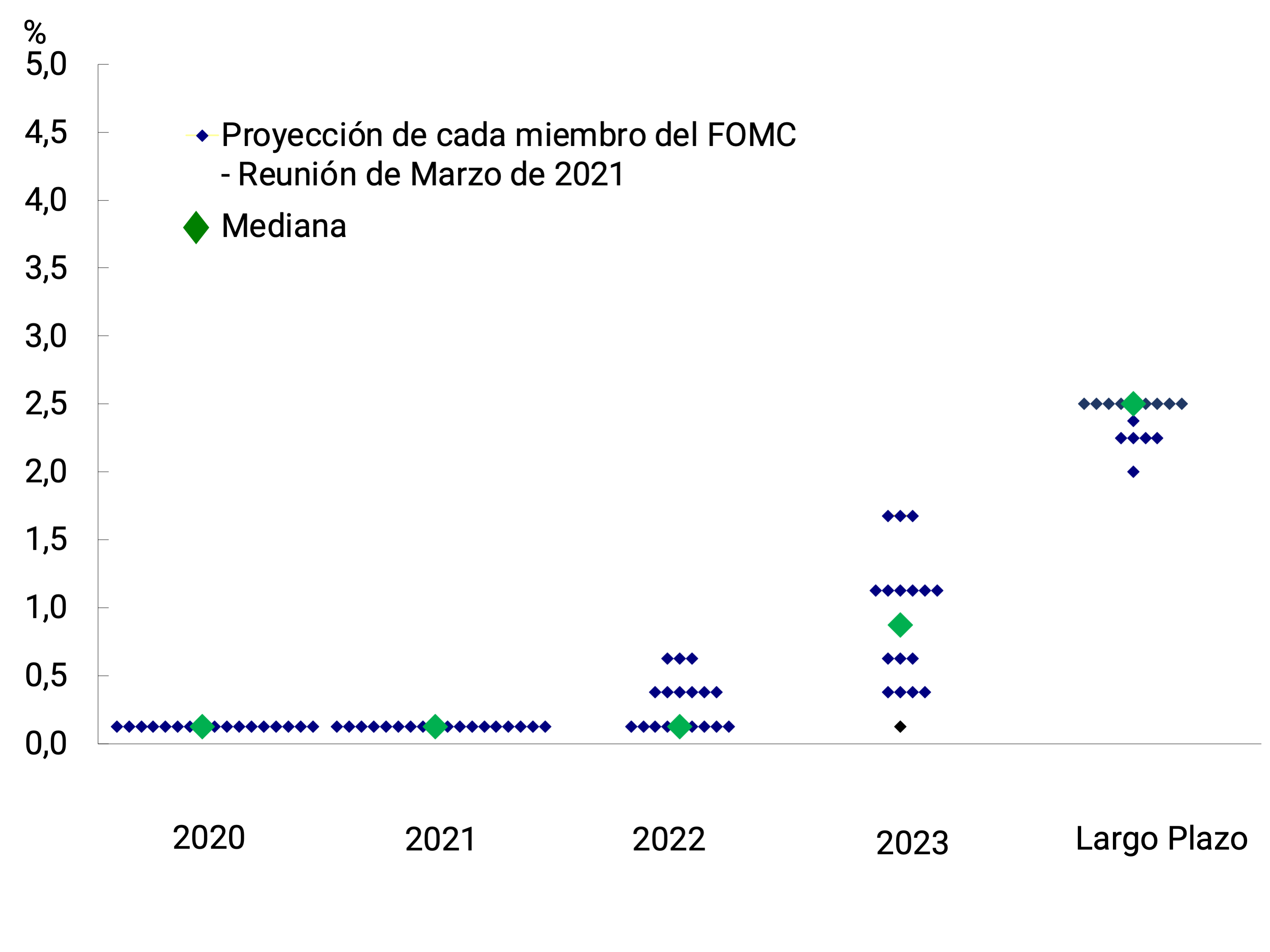

On the other hand, for developed countries in the same period, the policy interest rate remained unchanged. Central banks in the US, Australia and Canada have begun to withdraw unconventional monetary policies, reducing net asset purchases to zero at the end of October in the latter case. This contractionary bias could become widespread to most central banks in developed countries in the coming months. Thus, the Federal Reserve (Fed) gave clear signals that before the end of the year it would announce the reduction of its asset purchase program. In turn, it would also bring forward the first increase in the target on the federal funds rate. This is based on projections by members of the Fed’s Open Market Committee (see Figure 2.9). In addition, the Bank of England could raise the Bank rate, perhaps even at the end of 2021. On the other hand, the European Central Bank would maintain its expansionary policy without major changes.

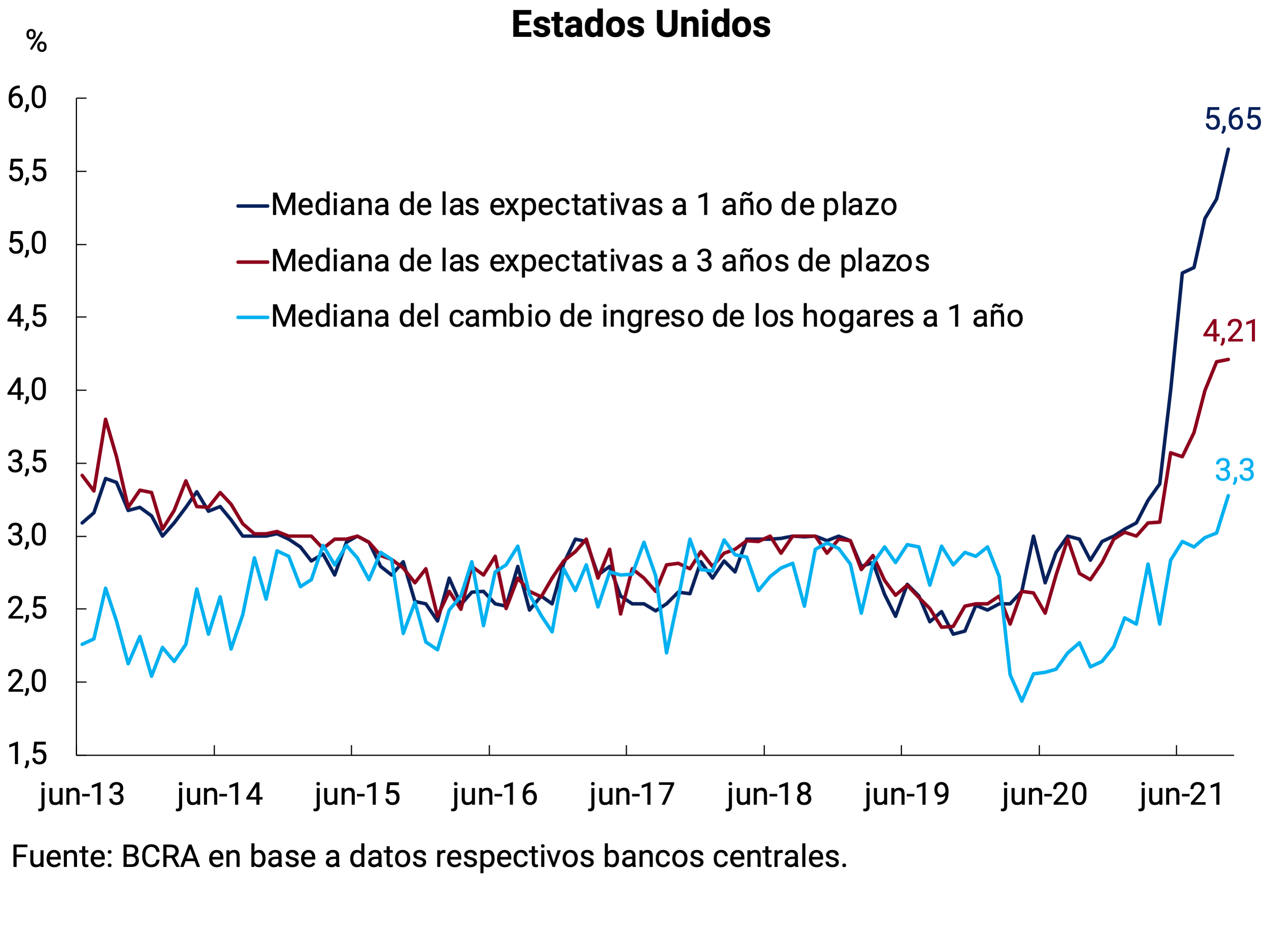

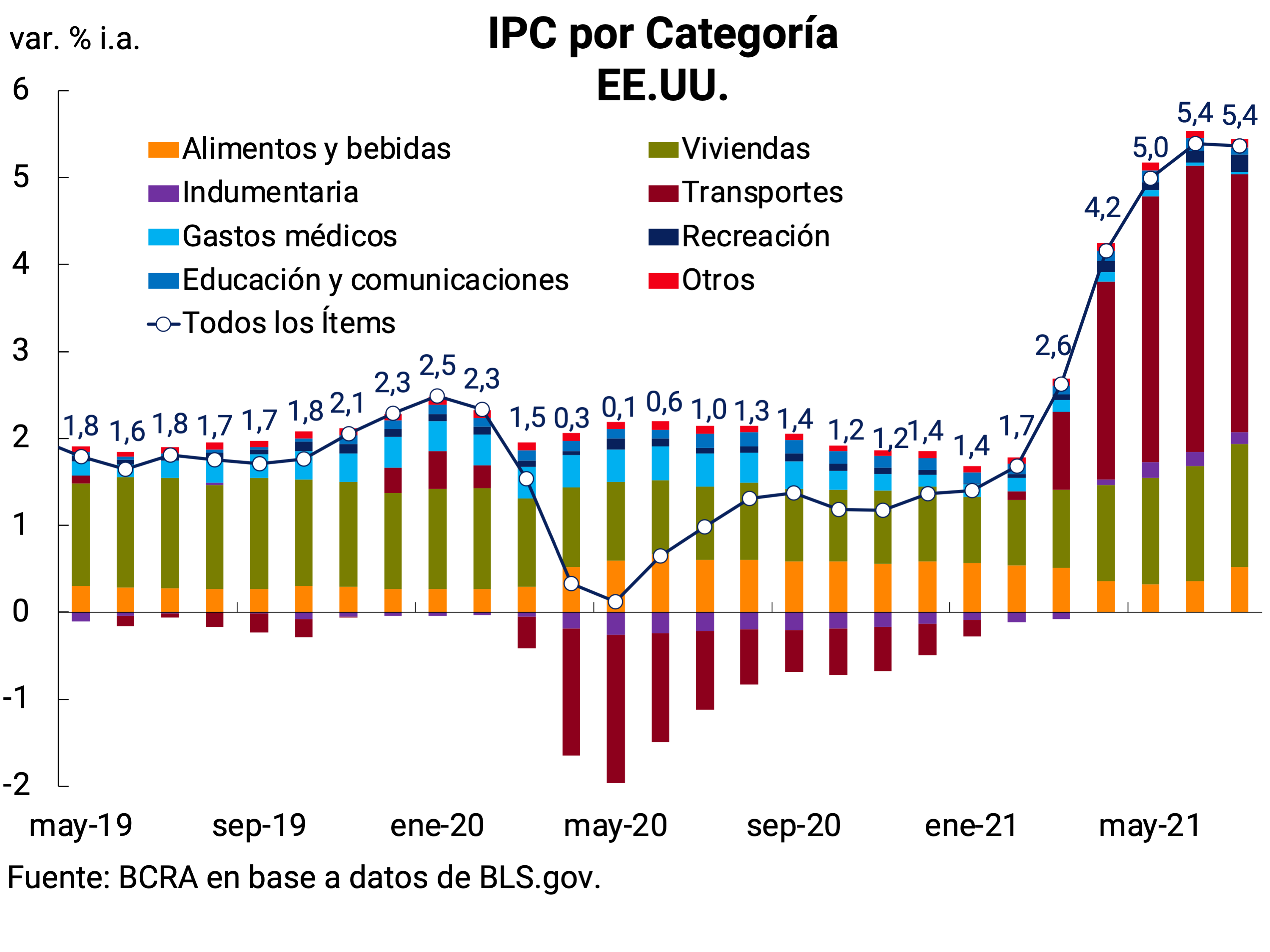

Changes in global monetary policy are in response to rising inflation. It is explained by supply mismatches, the base effect of comparison, the increase in the price of raw materials, mainly energy; all this in the context of monetary support measures taken since March last year (see Section 1). In emerging economies, the impact of higher commodity prices was enhanced by exchange rate depreciation; This is the opposite of what happened during the commodity boom (2003-2008), when higher prices were offset by exchange rate appreciations. Central banks in emerging countries have responded more quickly to a further acceleration in inflation (see Figure 2.10 and Figure 2 in paragraph 1), and to the risk of price expectations becoming unanchored. Meanwhile, inflation expectations in developed countries have increased, but remain in most cases anchored in the medium term. In the United States, indicators of expected inflation by the market show a slight increase in the margin, but a greater rebound in expected inflation is observed in consumer surveys. Expected inflation in the euro area is anchored (see Figure 2.11).

In many advanced economies, fiscal policy remained expansionary and is shifting towards spending more closely related to infrastructure, human capital accumulation, climate change, and digital transformation. The Employment Plan and the Family Plan in the United States and the “New Generation” plan in the European Union are the most relevant examples. By contrast, in emerging and developing economies, the fiscal impulse is more constrained by the challenges of financing large deficits, given reduced market access and limited scope for tax collection in the short term.

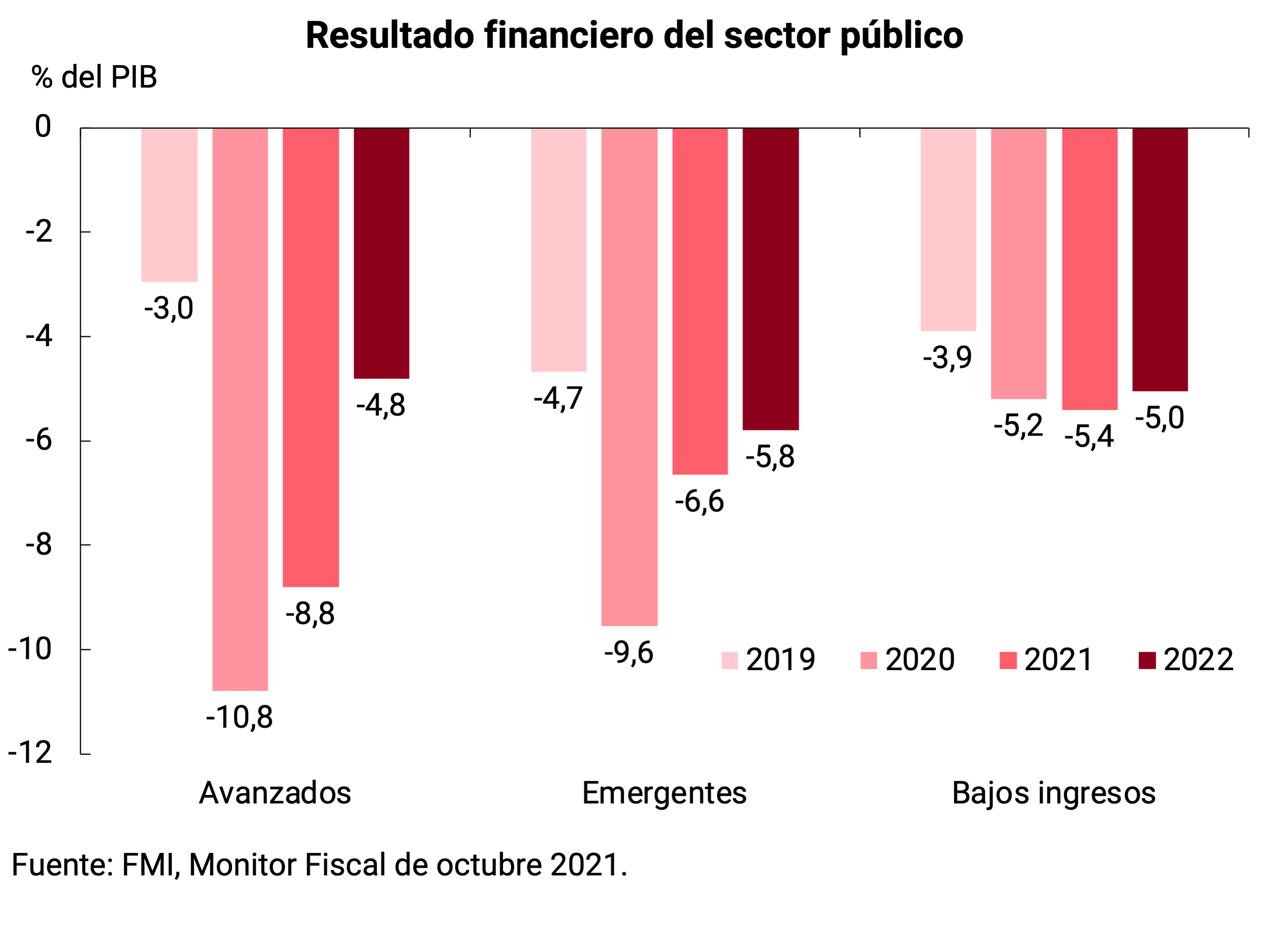

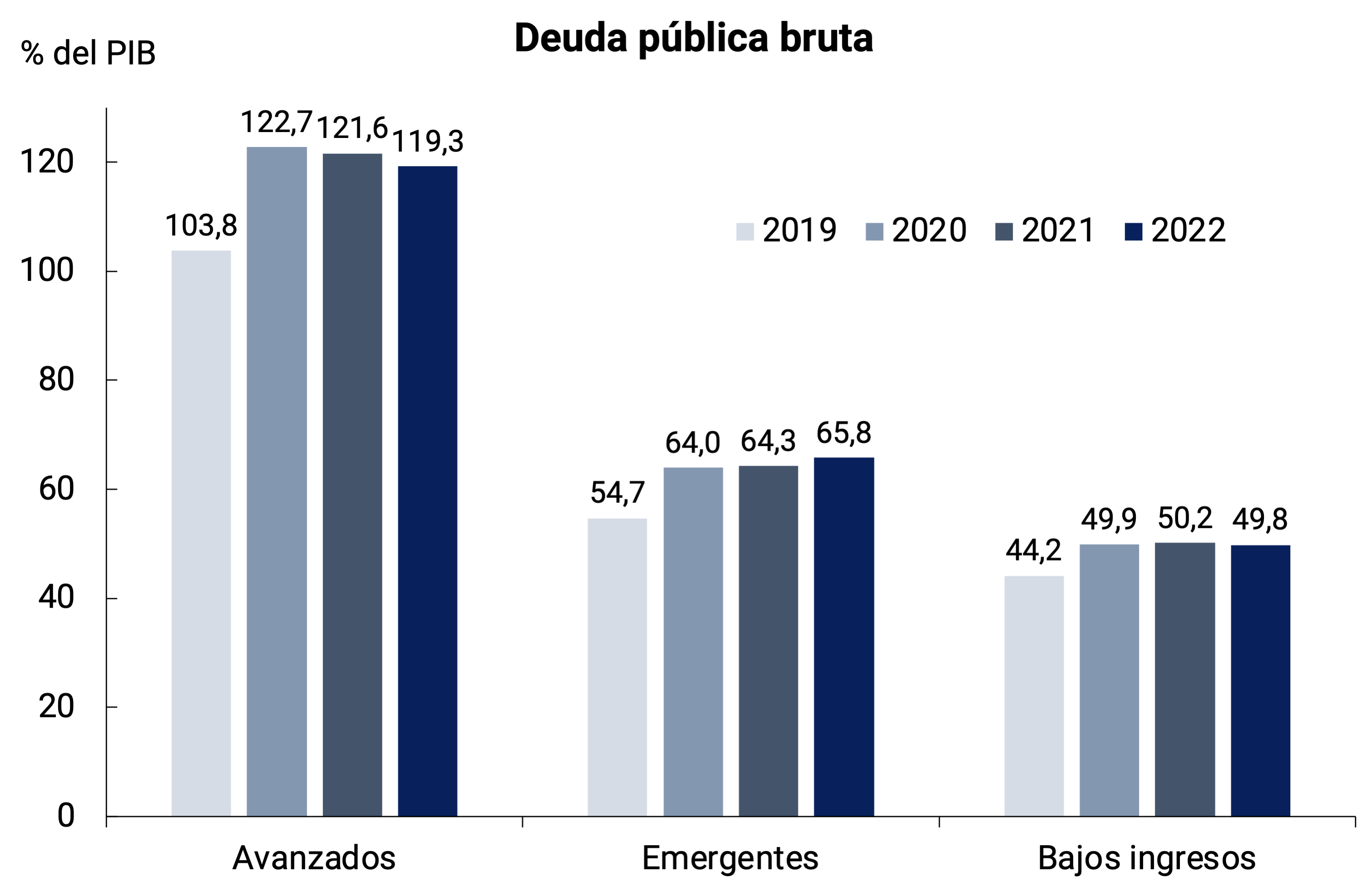

According to IMF estimates, most countries would register smaller deficits in their public accounts in the year than in 2020, a trend that would continue in 2022. For this year, the largest imbalances would be registered in advanced countries, which would close the year with an average fiscal deficit of 8.8% of GDP, while emerging economies and lower-income economies would end up with imbalances of -6.6% of GDP and -5.4% of GDP, respectively (see Figure 2.12). This fiscal dynamic, together with the expected recovery in economic activity, would lead to a moderation in the evolution of debt-to-GDP ratios at the global level during this year and 2022, even with slight declines in advanced countries (see Figure 2.12).

Figure 2.12 | Financial performance and public debt

2.4. Markets: Hikes in global interest rates and stock market increases continue

Since the close of the previous IPOM, there has been a tightening of the margin of financial conditions for emerging countries. Interest rates on advanced-country government bonds have continued to rise since August. In the United States, expectations of an earlier hike in the policy rate in the face of higher expected inflation (see Figure 2.13) drove shorter rates. The 10-year rate, which peaked at 1.70% in May, then fell to a low of 1.20% in early August, continued to rise and stands at 1.56%, up 32 bps since the close of the previous IPOM. For the moment, these are not sudden movements or movements of magnitude that could generate turbulence, especially in emerging countries. Despite the rise in the 10-year rate, the 30-year rate barely rose in the last three months, so the yield curve has flattened (see Figure 2.13), an indication that markets are expecting a slowdown in global growth. This phenomenon of 10-year rate hikes and flattening of yield curves is also being observed in Europe and Great Britain (see Figure 2.13). Meanwhile, the U.S. dollar, which hit a low in late May, continued to appreciate against a basket of currencies.

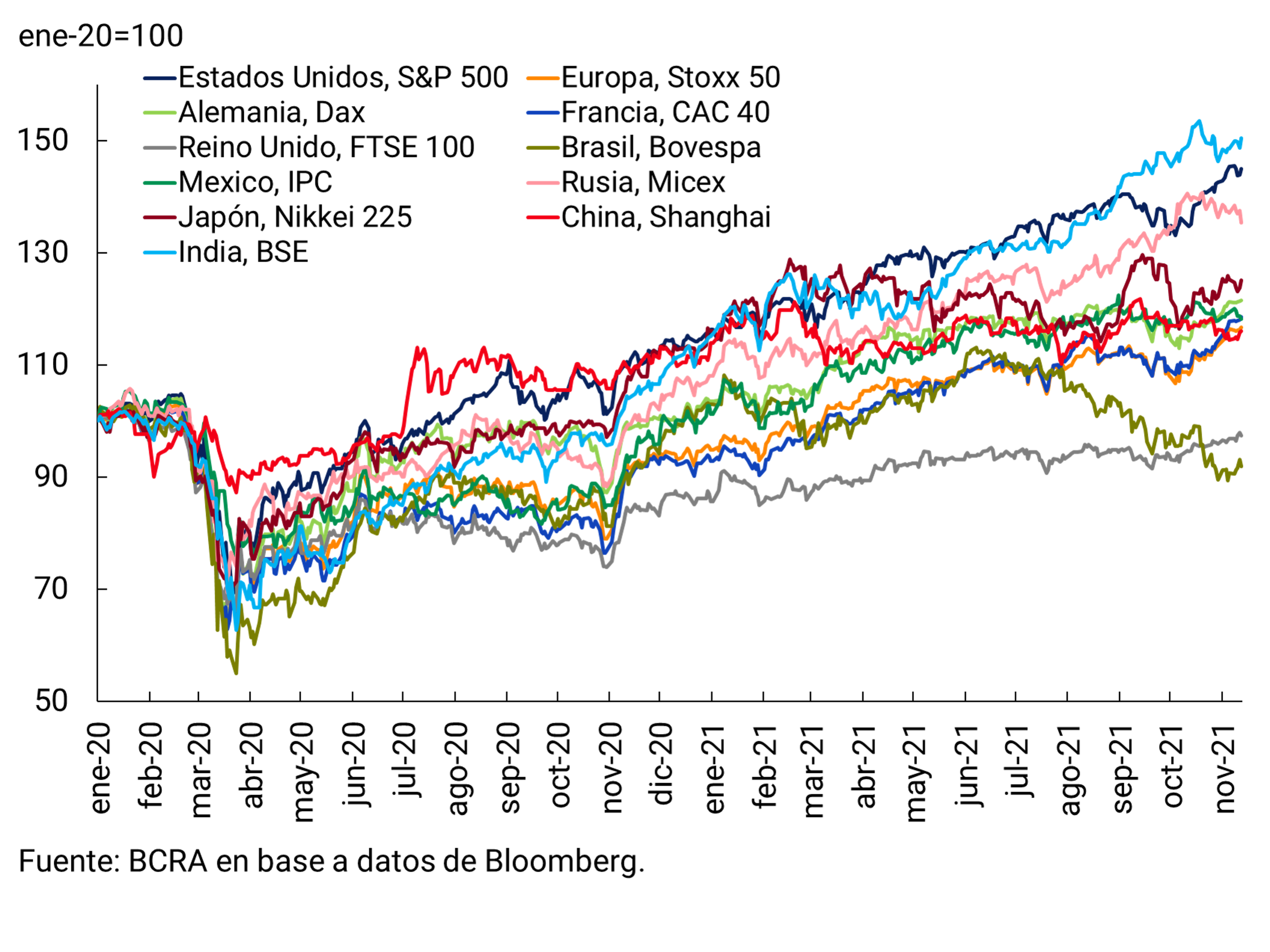

While bond prices may suggest lower expected growth, global equities remain elevated (see Figure 2.14). The S&P500 is 6% above the previous IPOM close and up 25% for the year. European stocks, as measured by the Stoxx 50 index, are also up 6% since the close of the previous IPOM and are up 23% for the year. This dynamic continues to present the risk of a sudden correction in equity markets.

Figure 2.14 |

In September, there were a few days of turbulence in the stock markets due to fears of what the global impact of the problems to face debt maturities by Evergrande and other Chinese real estate developers could be; Although the fear of financial contagion has been diluted, it is estimated that the impact on the real sector may be considerable. The cryptoasset markets continued with euphoria and high volatility. The market capitalization tripled in 2021 to an all-time high of $2.6 trillion today, although before peaking at $2.4 trillion in May to fall to $1.2 trillion in July, showing the high volatility.

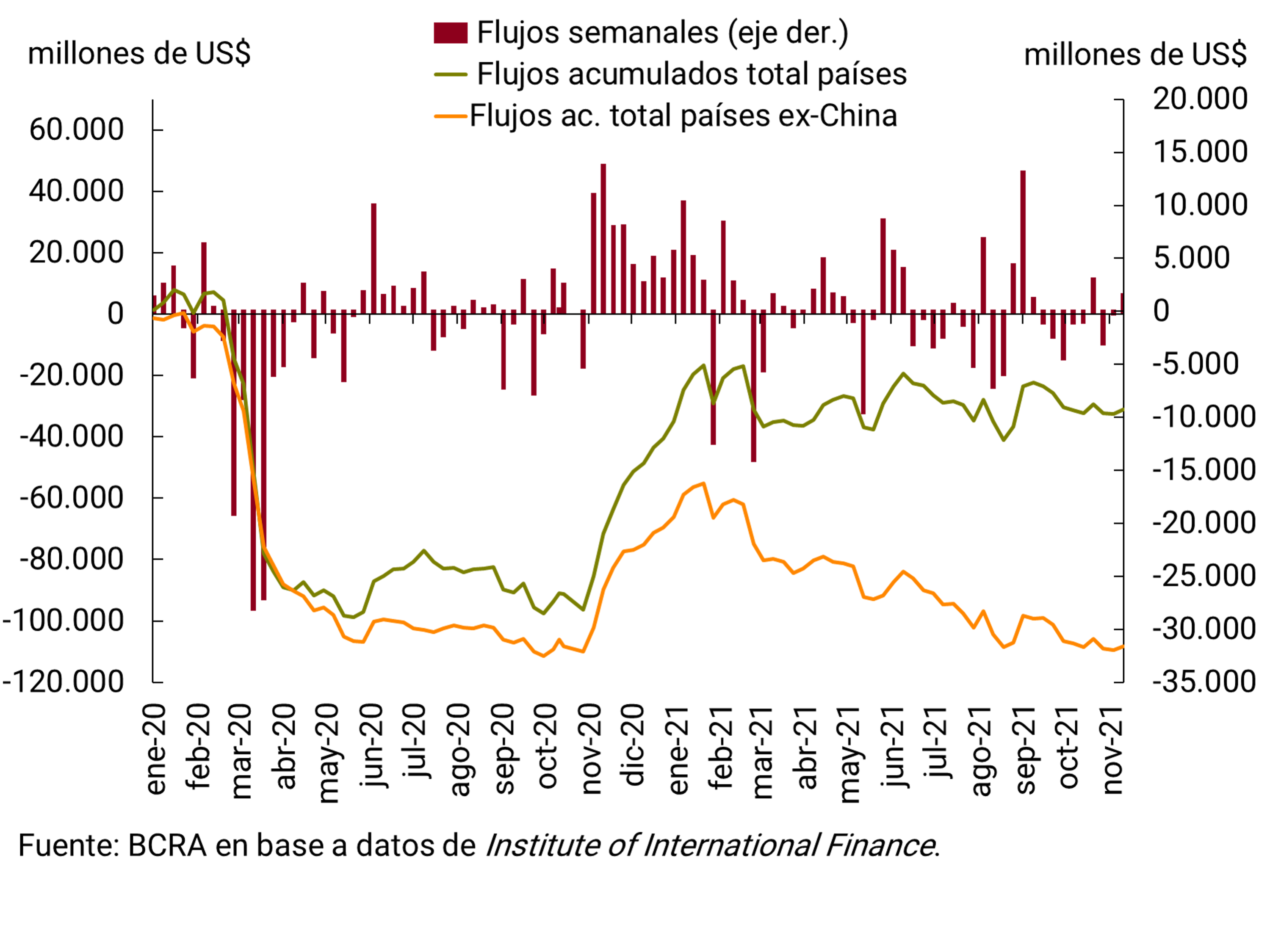

Capital flows to emerging countries have not changed much in recent months, accumulating a net inflow of US$9.9 billion since the previous IPOM and a similar number since the beginning of the year (see Figure 2.14). In any case, it should be noted that a large part of them went to China and are negative towards the rest of the countries. Since the beginning of the pandemic, emerging countries (excluding China) have accumulated capital outflows of US$31 billion, while China has registered inflows of US$77 billion. Finally, commodity prices did not show major movements (a 2% drop since the close of the previous IPOM according to the BCRA’s IPMP), with the exception of the price of oil, which rose by 25% in the same period.

2.5. In summary

The global economy is recovering, but in a disparate way between advanced and developing countries, and with rising inflation. On the one hand, this reduces the monetary and fiscal policy space available to the latter countries to continue to boost the recovery. On the other hand, the monetary policy reaction of advanced countries could negatively “spill over” to the rest of the world through less favorable financial conditions: higher interest rates, global appreciation of the dollar and its eventual impact on capital flows and commodity prices. Financial markets carry additional risks: a collapse in crypto-asset prices, which could have unknown ramifications at this time; a possible contagion of the real estate crisis in China to other assets. The balance of risks of the global economy can be summarized as follows: positive expected growth, but with downside risks; expected inflation stable or falling, but with upside risks.

3. Economic Activity and Employment

Economic activity resumed the path of recovery in the third quarter of the year, after temporarily receding as a result of the impact of the second wave of COVID-19, in line with what was anticipated in the previous IPOM. The data available from the EMAE for August showed that the sectoral performance is still heterogeneous, in which activities that managed to operate and remain at relatively high levels coexist with others that recently began to gain greater momentum. According to the evolution of various leading indicators, economic activity would continue to improve in the remainder of the year, driven mainly by the performance of services.

As anticipated in the previous IPOM, the measures implemented by the National Government aimed at delaying the entry of new variants of the virus in a context of greater availability of vaccines made it possible to accelerate the vaccination process and thus significantly improve the local health context. The lower probability of a new outbreak of COVID-19 made it possible to advance on a plan for greater opening of activities, in a progressive and sustained manner, accelerating the economic recovery process.

The National Government established new policies during the third quarter aimed at sustainable and inclusive economic growth based on technological innovation and the recovery of employment and income, while implementing measures to support sectors still postponed by the COVID-19 crisis. For its part, the BCRA continued to contribute to the process of economic normalization through lines of credit for productive purposes aimed at promoting a balanced and sustained recovery and the continuity of measures to promote private consumption, such as the “Ahora 12” Program.

The BCRA expects activity to continue to recover in the remainder of the year, driven by the flexibilities of both activities and capacity, with greater vaccination coverage with complete schemes of the population and by the policies to support the activity of strategic sectors implemented by the National Government and the BCRA. All in all, GDP would grow by about 9% in 2021, also translating into improvements in employment. Although less likely, the risk associated with the circulation of the Delta variant of the virus in the country persists, as well as other strains that could eventually compromise the favorable epidemiological evolution.

3.1. Activity recovered within the framework of a great advance in the vaccination process that allowed the health situation to be controlled

The accelerated progress of the vaccination process since June made it possible to significantly improve the epidemiological situation and implement a process of progressive and sustained reopenings, simultaneously with the gradual expansion – and in some cases elimination – of the capacities in various activities (See Section 2 / Vaccination as a key determinant of the evolution of economic activity). In this context of progress towards a new normality, the National Government established various policies aimed at strategic sectors for the increase of exports and the recovery of employment and income, sustaining policies focused on the sectors in which the speed of recovery has been slower. For its part, the BCRA continued to contribute to the process of economic normalization through new lines of credit aimed at promoting a balanced and sustained recovery and the continuity of policies to promote private consumption (See Chapter 7. Monetary Policy).

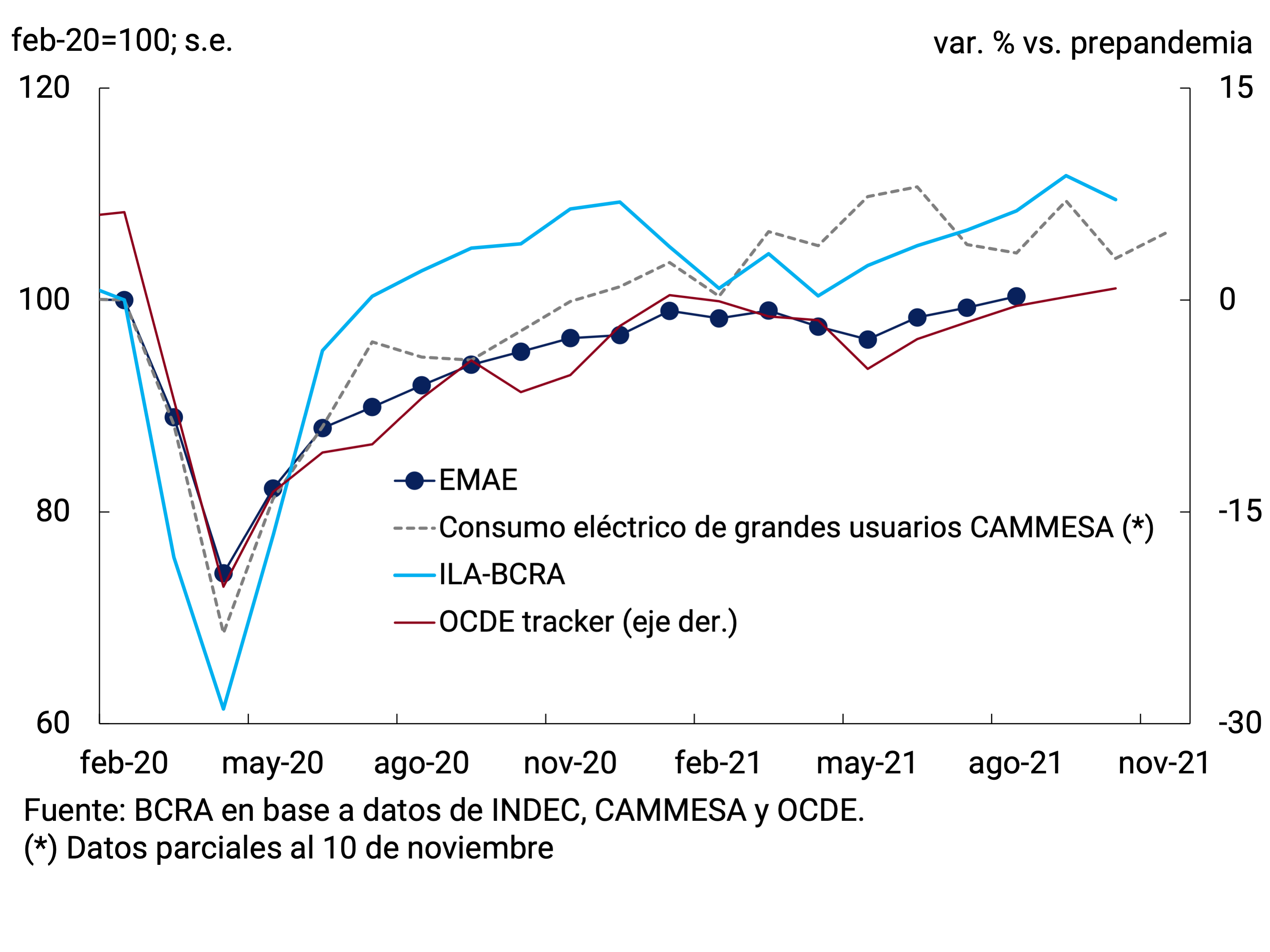

The Monthly Estimator of Economic Activity (EMAE) adjusted for seasonal factors (s.e.) recovered quickly after the impact of the second wave of infections in April-May. Thus, after registering a fall of 1.4% s.e. in the second quarter – reflecting the impact of the second wave of infections – the Product would register an improvement of close to 3% quarterly s.e. in the third, higher than initially forecast by market analysts3.

The high-frequency data available for the fourth quarter anticipate the continuation of the recovery in economic activity, with an accelerated progress in the vaccination process and, consequently, a favorable epidemiological situation. The Leading Indicator of Economic Activity (ILA-BCRA) remained in the recovery phase4 while the OECD’s weekly indicator of activity continued to increase in October (see Figure 3.1).

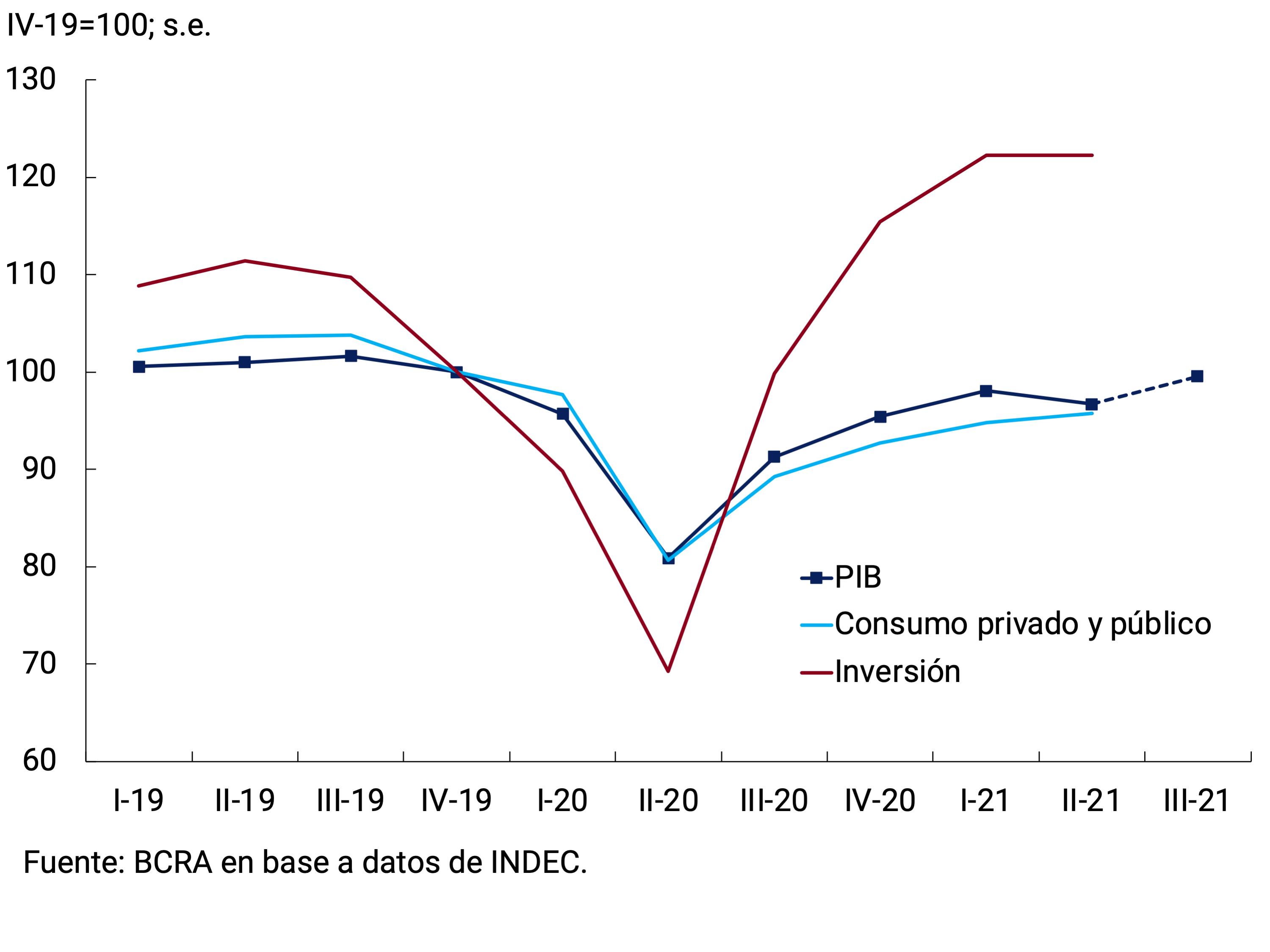

3.1.1. Domestic demand continued to recover and greater dynamism in private consumption stood out

In the second quarter of 2021, GDP contracted 1.4% quarter-on-quarter (+17.9% y.o.y.) and was 3.3% below its level in the last quarter of 2019, while domestic demand – total domestic expenditure on consumption and investment – recovered 0.8% quarter-on-quarter s.e., reaching its pre-pandemic level. Private consumption recovered 1.1% qoq s.e. (21.9% y.o.y.) and public consumption increased 0.5% s.e. (8.2% y.o.y.) and investment5 remained stable in relation to the previous quarter (76.6% y.o.y.). Exports of goods and services increased 5.7% qoq s.e. (6.3% y.o.y.) and imports, 5.4% qoq s.e. (36.6% y.o.y.)6. Available data for the third quarter7 anticipate increases in both private consumption and investment (see Figure 3.2).

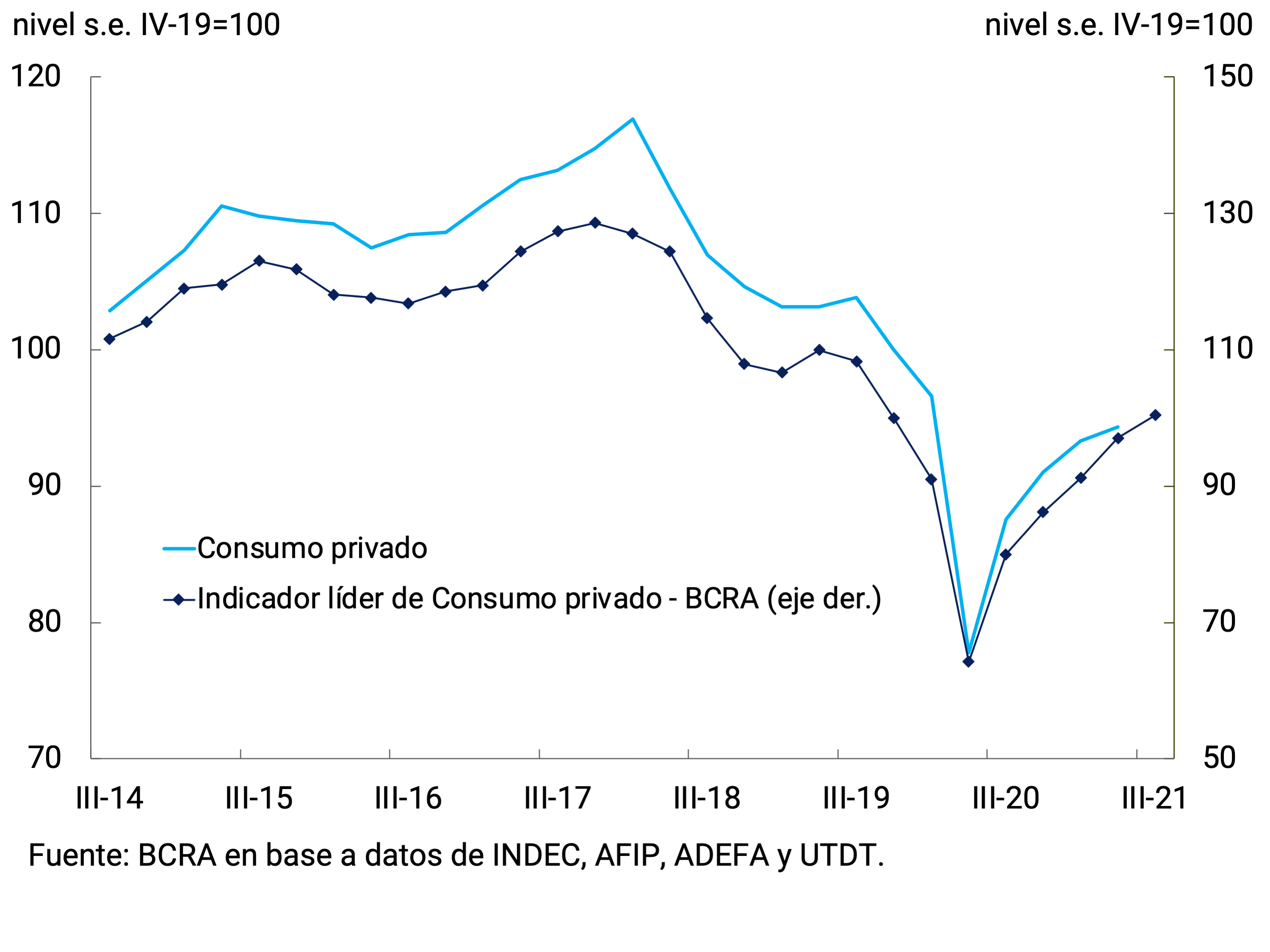

As for Private Consumption, the BCRA Leading Indicator8 shows an increase in the third quarter, recovering the level of the last quarter of 2019 (see Chart 3.3). The gradual recomposition of the level of private consumption is associated with the evolution of the mass of household income, which includes improvements in both employment levels and real wages, and was favored by the income policies of the National Government. In this context, the gradual normalization of social mobility was mainly reflected in an increase in the consumption of services.

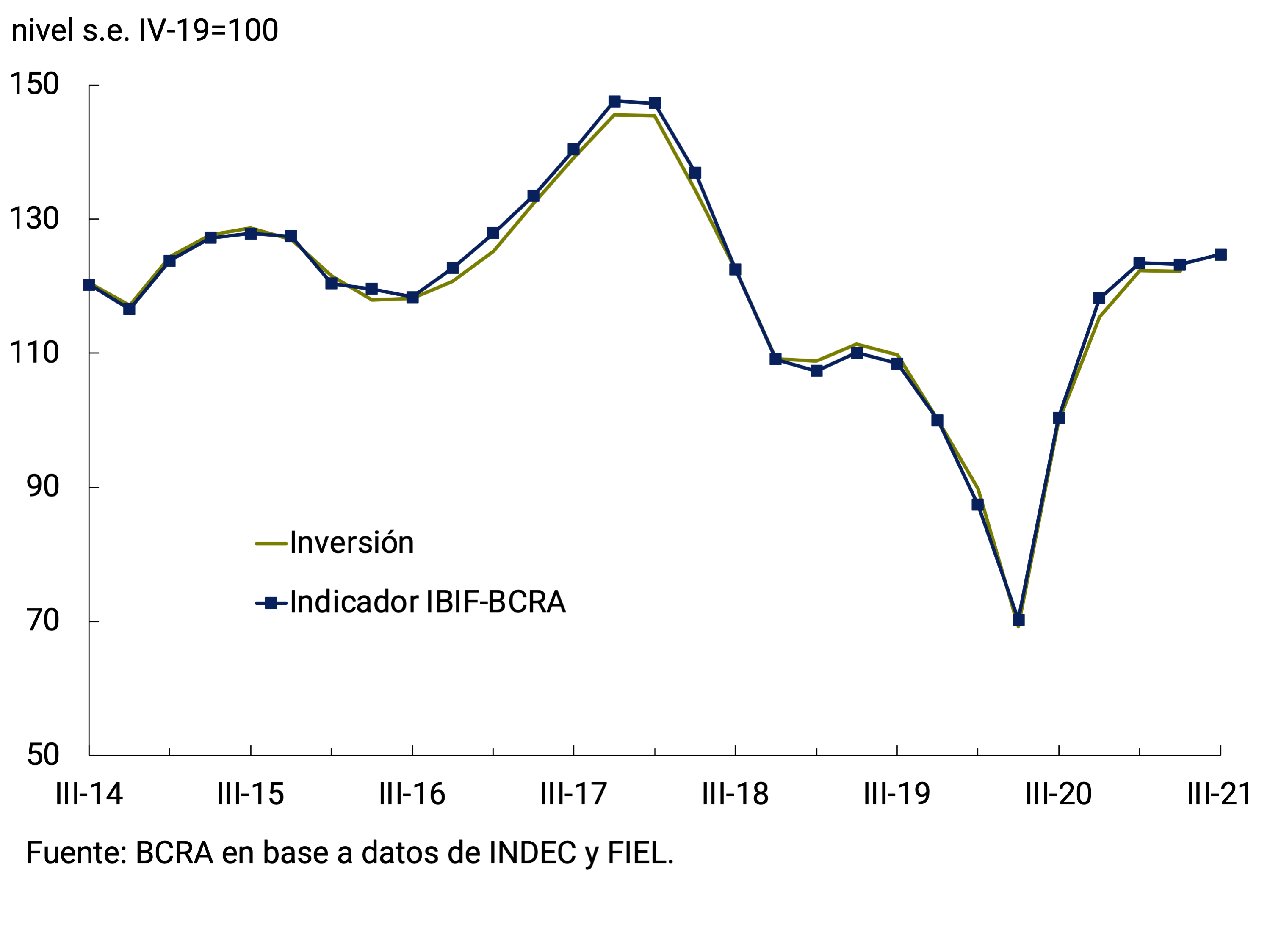

For its part, the IBIF-BCRA indicator continued to increase and showed a quarterly improvement of 1.3% s.e. in the third quarter of 2021 (see Chart 3.4). This increase was due to increases in investment in durable equipment of national origin and construction, partially offset by a fall in imported equipment9. With respect to the external sector and according to the information referring to the Commercial Exchange of Goods of INDEC, in the third quarter the contribution of net exports of goods and services to the quarterly variation of the Product would have been positive. Exported quantities of goods registered a strong quarterly increase (7.6% s.e.), while imported volumes of goods remained at levels very similar to those of the previous quarter in seasonally adjusted terms (see Chapter 4. External Sector).

3.1.2. The services that suffered the most from the impact of the pandemic in 2020 are those that are contributing the most to the growth of economic activity at the margin

During the third quarter of 2021, in which activity managed to recompose the level observed at the beginning of 2020, services would have explained almost two-thirds of the seasonally adjusted quarterly variation of Output. As can be seen from EMAE10, the sectors with the greatest contribution to the quarterly variation of the general level were: Other social and community services and Hotels and Restaurants. These two service categories had been the ones that suffered the greatest impact of the pandemic, having registered cumulative falls of 65.6% s.e. and 81.7% s.e. between March and April 2020, respectively.

By way of synthesis, the following graph shows the seasonally adjusted levels of activity of the different productive sectors at the worst moment of the COVID-19 crisis (April 2020) and the latest available data (August 2021), always in relation to the level at which each sector operated at the time prior to the outbreak of the pandemic (February 2020), when a value of 100 was assigned. in order to facilitate comparisons.

In the upper left quadrant are the blocks that have reached or exceeded their pre-pandemic level, led by construction and commerce. These sectors were hit hard by the pandemic in 2020, but recovered quickly and are more than 10% higher than the level observed in February 2020. In the lower left quadrant are the branches with the worst relative performance, with the Hotels and Restaurants segment showing the weakest recovery and still far from its pre-pandemic levels (-28.5% s.e.). The “Other social and community services” sector, which includes, among others, the activity of cinemas, theaters, hairdressers, cultural and sports activities, managed to recover more quickly and operate practically at pre-pandemic levels (-0.9% s.e.).

Other sectors that until August 2021 were unable to recompose the level of activity they had at the time prior to the start of the COVID-19 crisis are Fishing (-11.7% s.e.), Transport and communications (-9.2% s.e.) and Mining (-3% s.e.). Financial intermediation was the only sector of activity that continued to increase during the pandemic, unlike in previous recessions, this time driven by an active credit policy of the BCRA and the National Government (see Figure 3.5).

The health situation allowed the implementation of new flexibilizations starting in the third quarter, with gradual reductions in capacity —up to zero in some cases—, enabling group travel, opening of land, air and foreign tourism borders without quota, expansion of capacity for recreational activities and social events and the return to face-to-face in the Public Administration. These measures began to be reflected in the most recent activity indicators. The reactivation of activities that were severely restricted by the health situation is expected to intensify and drive the growth of activity in the last quarter and throughout the summer period, favoured by measures to boost tourism11.

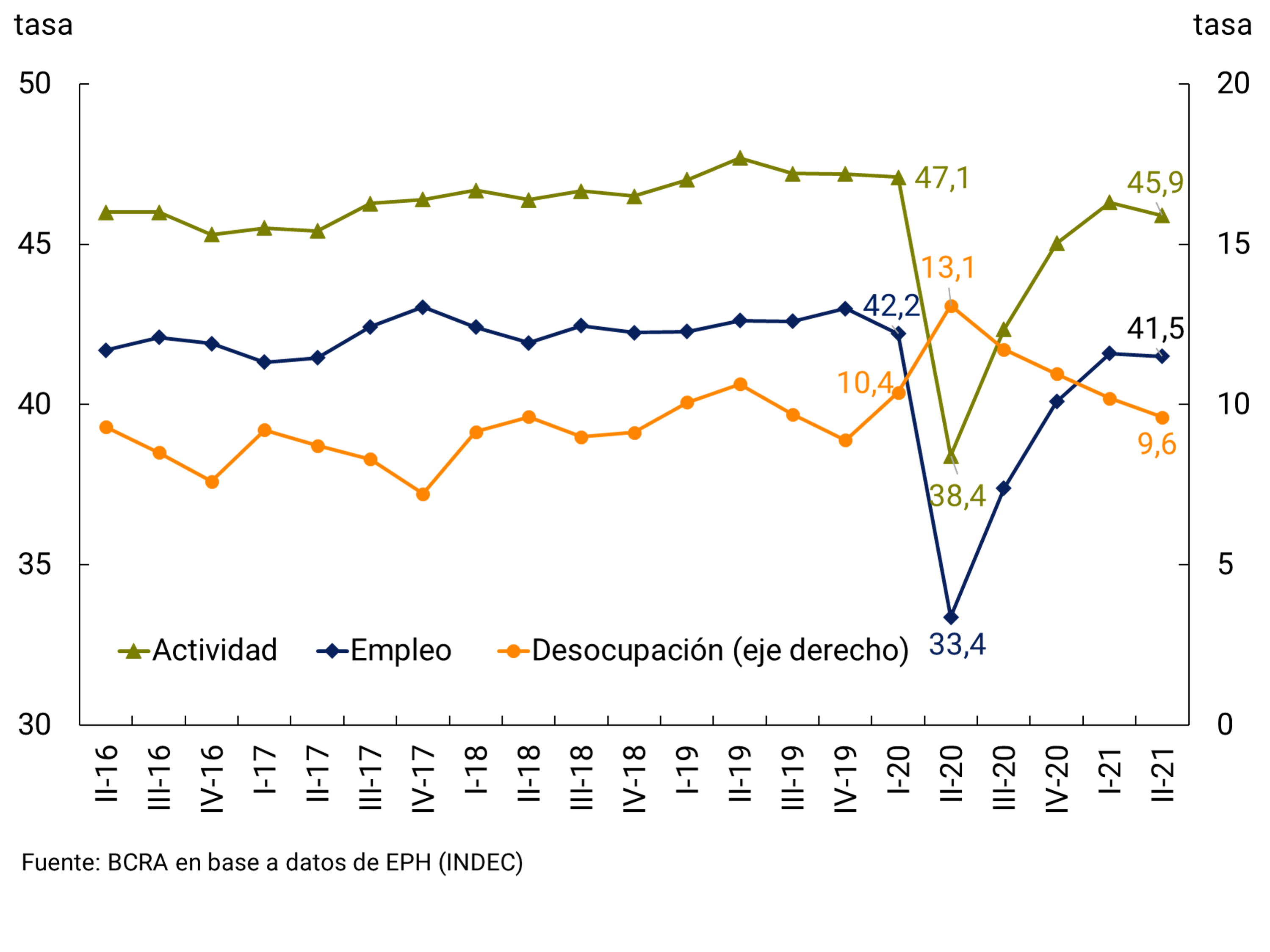

3.1.3. The labor market would show a gradual and sustained recovery after the slower pace of growth in the second quarter

During the first quarter of 2021, the labour market extended the recovery seen in the previous two quarters. The Employment and Economically Active Population (EAP) rates were slightly below the levels in force in the first quarter of 2020 (-0.6 p.p. and -0.8 p.p. respectively). The open unemployment rate stood at 10.2% and showed a reduction of 0.2 p.p. compared to that of the first quarter of 2020 (see Figure 3.6).

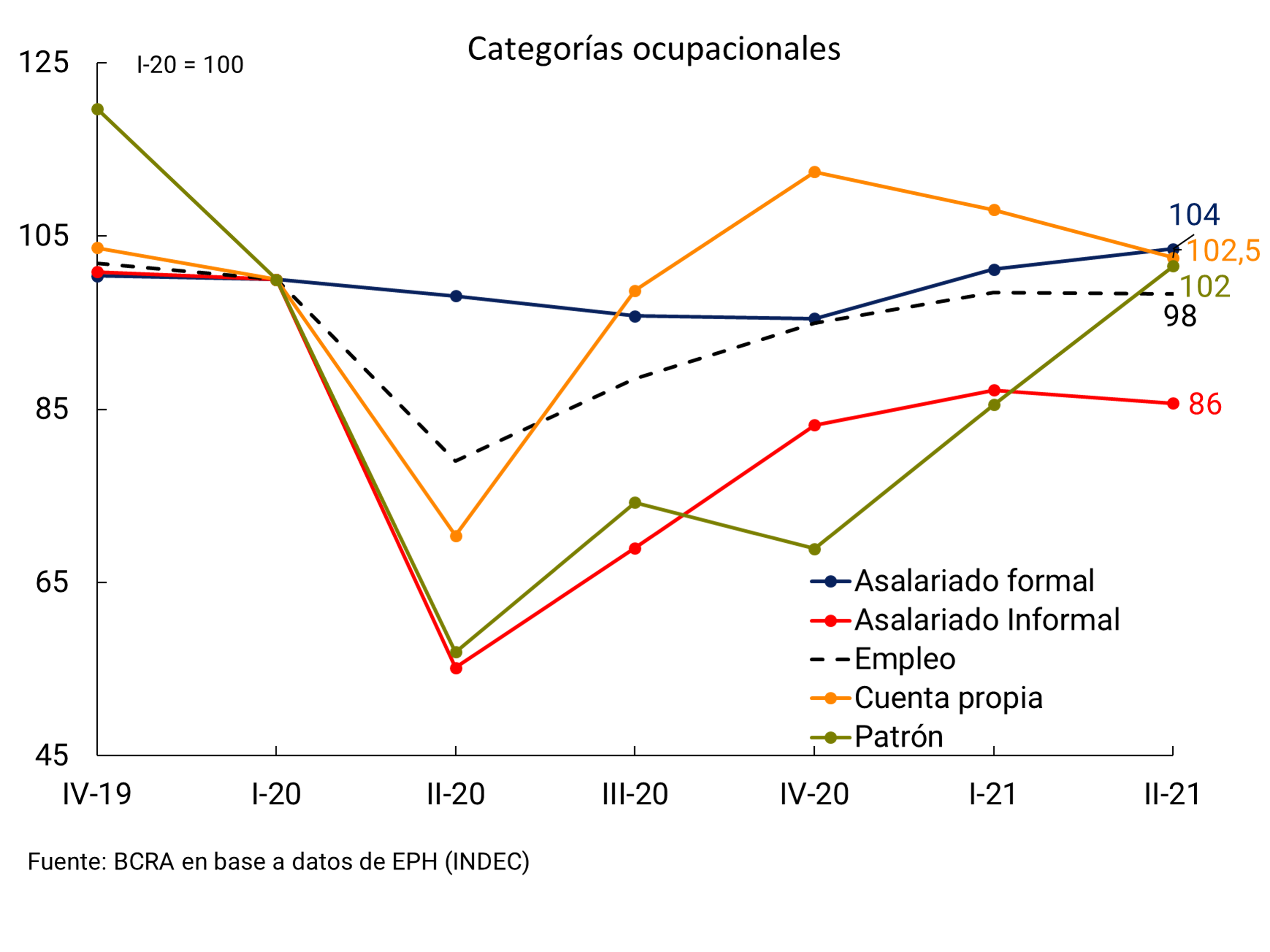

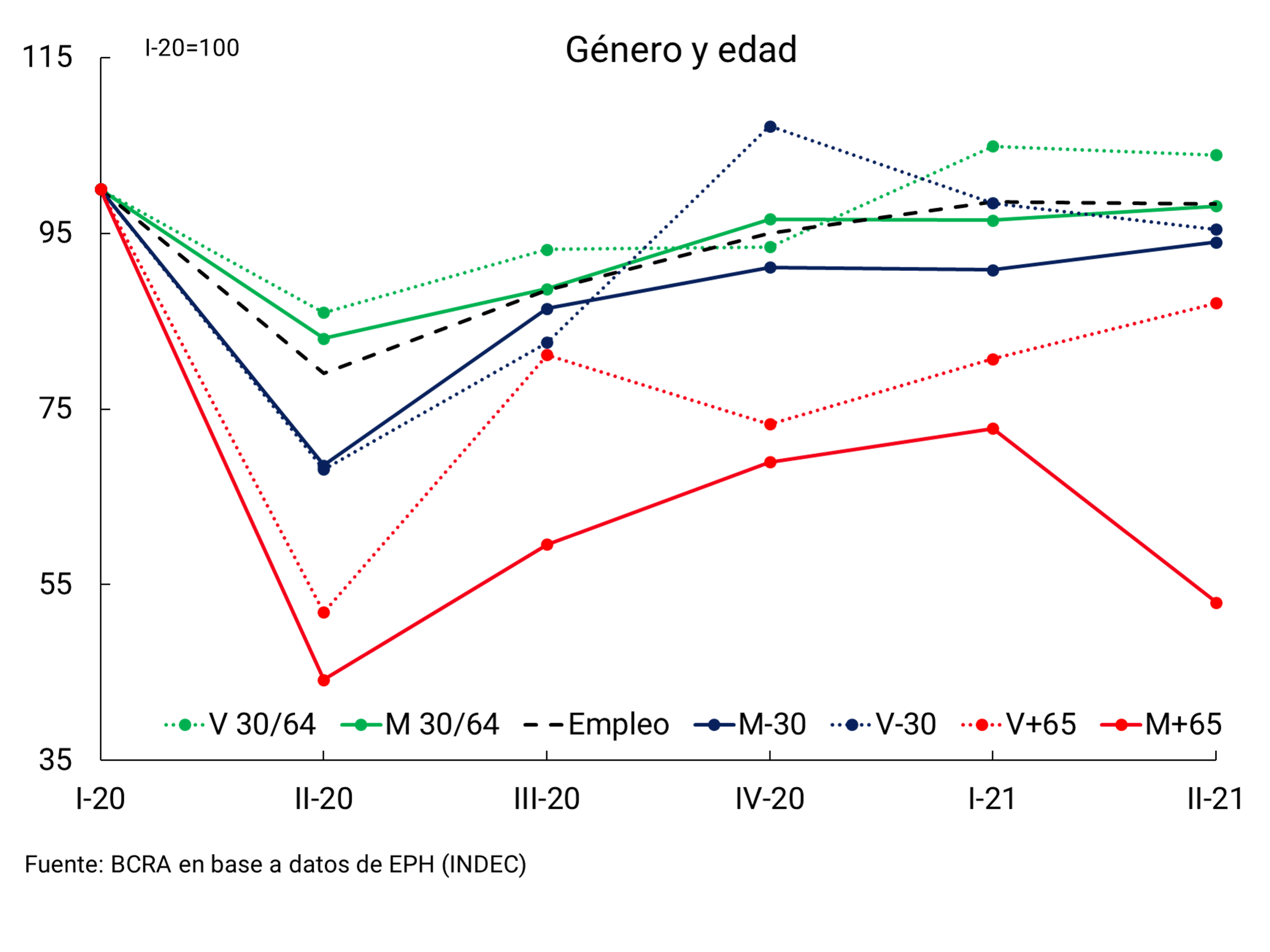

According to data from the Permanent Household Survey (EPH), in II-21, the labor market stopped the pace of recovery verified in the previous three quarters. This phenomenon is associated with the temporary decrease in the level of activity as a result of the restrictions implemented during the second wave of infections. The employment and economically active population (EAP) rates were slightly below the levels in force in the first quarter (45.9% and 41.5%, respectively), while the open unemployment rate stood at 9.6%, showing a reduction compared to the first quarter (10.2%; see Figure 3.6)12. Regarding the evolution of the different occupational categories, it can be observed that during II-21 self-employment fell again (although it is still above the pre-pandemic levels of I-20) and that employers have maintained sustained growth since IV-20. This dynamic could be due to a continuity of the substitution effect between the two categories (self-employed who incorporate employees into their tasks and become employers). On the other hand, the growth of informal wage earners stagnated still far from pre-pandemic levels. Likewise, the most outstanding data was the growth for the second consecutive period of salaried workers with a retirement discount that, with a significant increase, exceeded the I-20 level13. Finally, the most affected age range continued to be those over 65 years of age, and women in general were the ones who lagged behind in terms of employment recovery (see Figure 3.7).

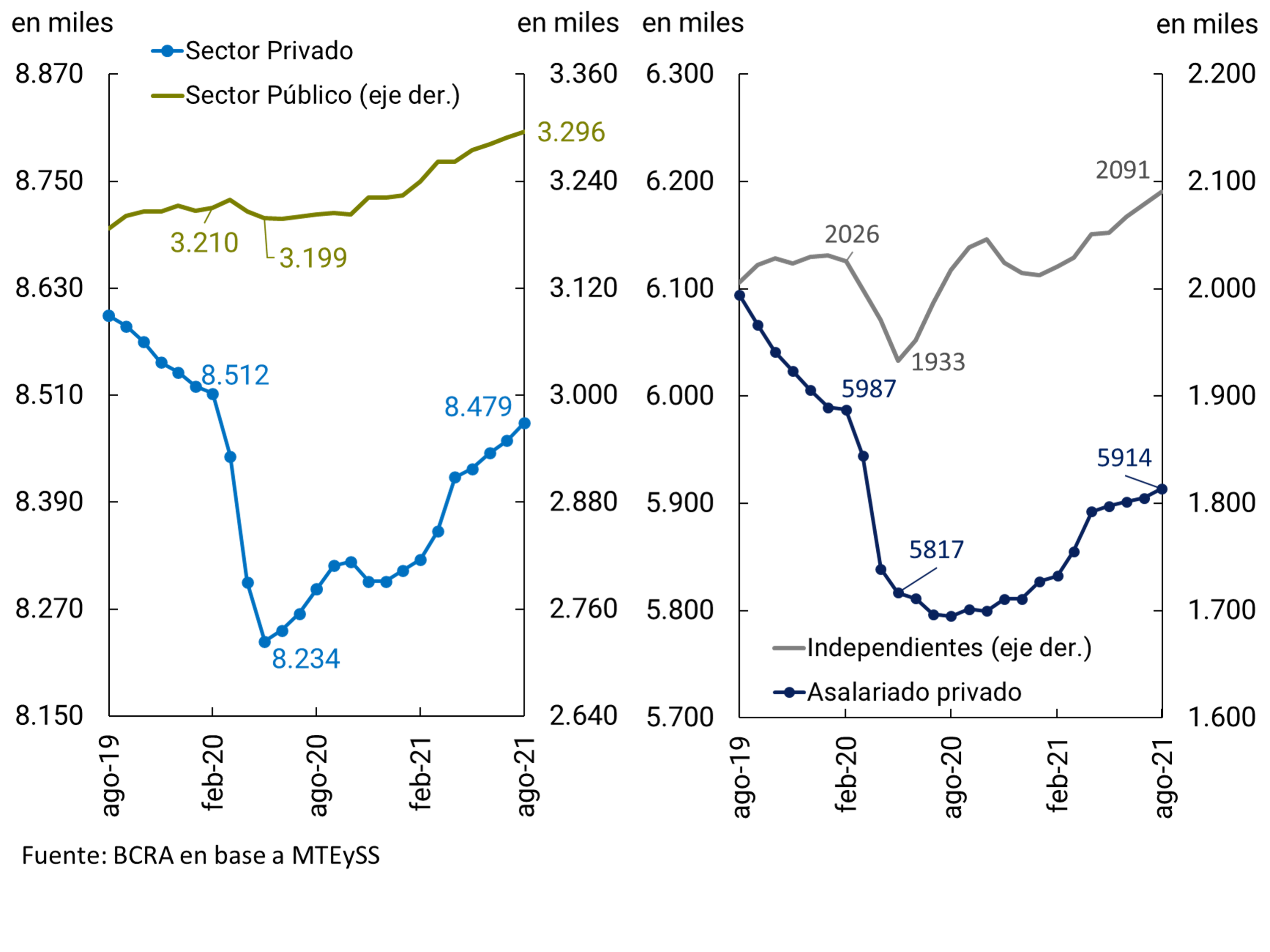

With data as of August for registered employment, the pace of expansion during the third quarter would maintain the dynamics evidenced since April. According to the Ministry of Labor, Employment and Social Security (MTEySS), total registered employment maintained the positive trend that began at the beginning of the year, accumulating a rise of 0.6% between June and August. Thus, this indicator showed an improvement of 0.4% s.e. compared to February 2020, the level prior to the outbreak of the pandemic (see Figure 3.8).

This recovery in total registered employment is related to a positive dynamic of both self-employment and registered public sector wage earners. In particular, since June, the sustained increase in registered self-employment (single-tax and self-employed people) was 1.9% s.e. (38.2 thousand people) while that of public wage earners was 0.6% s.e. (21.1 thousand people), maintaining the trend observed since October 2020. For its part, the private salaried sector maintained the pace of growth, accumulating 0.3% s.e. (16.4 thousand people) for the same period without yet reaching pre-pandemic levels (-1.2% s.e. vs. Feb-20; see Figure 3.9).

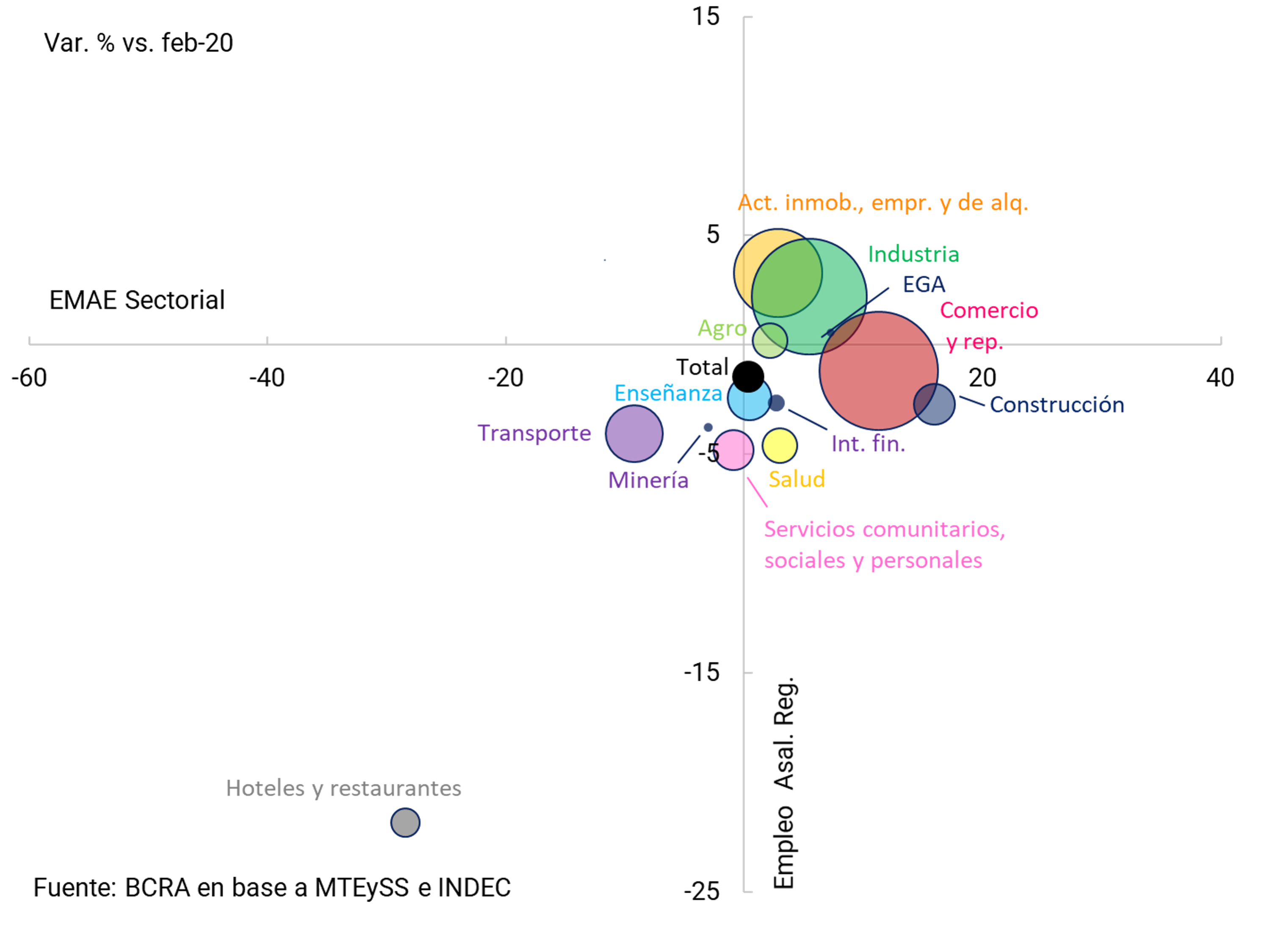

The behavior of private salaried employment between June and August allows us to distinguish at the sectoral level a greater dynamism in branches such as Construction (3.7% s.e.), Fishing (1.5% s.e.) and Mining (1.4% s.e.). On the other hand, the most affected sectors in terms of employment are Social and Health Services (-0.5% s.e.) and Transport (-0.4% s.e.). Compared to pre-pandemic levels, there are some sectors lagging behind, both in terms of activity and employment (taking both data as of Aug-21), such as Hotels and restaurants, Community, social and personal services and Transport, which retained a significant margin for recovery, supported by the favourable conditions generated by the easing of restrictions in the context of a significant improvement in the health situation and the measures to stimulate tourism (see Figure 3.10).

Figure 3.10 | Private registered salaried employment and activity by sector up to August 2021

Seasonally adjusted data

The Labor Indicators Survey (EIL) as of September 2021 showed a positive trend in net hiring expectations, in addition to the sustained drop in suspensions and the stability of the dismissal rate. Net expectations for hiring personnel over three months remained in positive territory between July and September, with values that grew from 2.7 p.p. to 5.1 p.p. Suspensions fell to 12.5 per thousand workers, a figure close to pre-pandemic levels. For its part, despite the validity of decree 413/2021, the rate of dismissals remained stable since June.

3.2. Perspectives

After the advances in the vaccination scheme of the population that allowed the epidemiological situation to be controlled, it is expected that all productive sectors will strengthen the process of “normalization” of their levels of activity. During the third quarter, the National Government announced a series of additional measures aimed at favoring those sectors that are lagging behind and families that were left behind in the recovery process, which included credit stimulus policies. Technological innovation, the creation of formal employment, the increase in productive investment and the export capacity of some sectors considered strategic were favored14.

The scenario of “normalized” activity is beginning to be glimpsed progressively, expressed in a favorable evolution of employment and real wages. However, the health risk has not yet disappeared and is associated with an eventual and uncertain impact of the circulation of the Delta variant in the country or of new strains that could emerge globally.

Meanwhile, the prospects for global growth account for an international context that still drives domestic dynamics. The external risks are mainly linked to the recent rise in the international price of oil which, in addition to increasing production costs, in a context of rising inflation expectations in advanced countries, could anticipate the reduction of monetary stimuli in those countries. This situation would generate incentives for capital outflows from emerging countries, slowing down the global recovery, including that of our main trading partners. Also threatening global growth are global problems associated with the resurgence of the Delta variant in some core countries, bottlenecks in supply chains – such as microchips – and a slowdown in activity in China (see Chapter 2. International Context and Section 1 / The rise in international inflation).

The terms of trade would continue to be favorable in historical terms for our exports. Climatic and water factors in the region could generate a decrease in agricultural production, although this effect could be partially offset by eventual increases in the international prices of these products.

Regarding the magnitude of Argentina’s economic recovery, the seasonally adjusted data from the EMAE for August left a high statistical drag of 2.7 p.p. of growth for the third quarter and 8.4 p.p. for 2021. The high-frequency indicators available as of November point to the continuity of the recovery, mainly explained by the performance of services, so the average variation in GDP in 2021 is expected to be close to 9%, leaving a growth floor of 2.5 p.p. for next year. This figure would exceed the growth forecasts of the REM (8.3%), the IMF (7.5%) and also those released on the occasion of the presentation of the 2022 National Budget Bill last September (8%).

4. External Sector

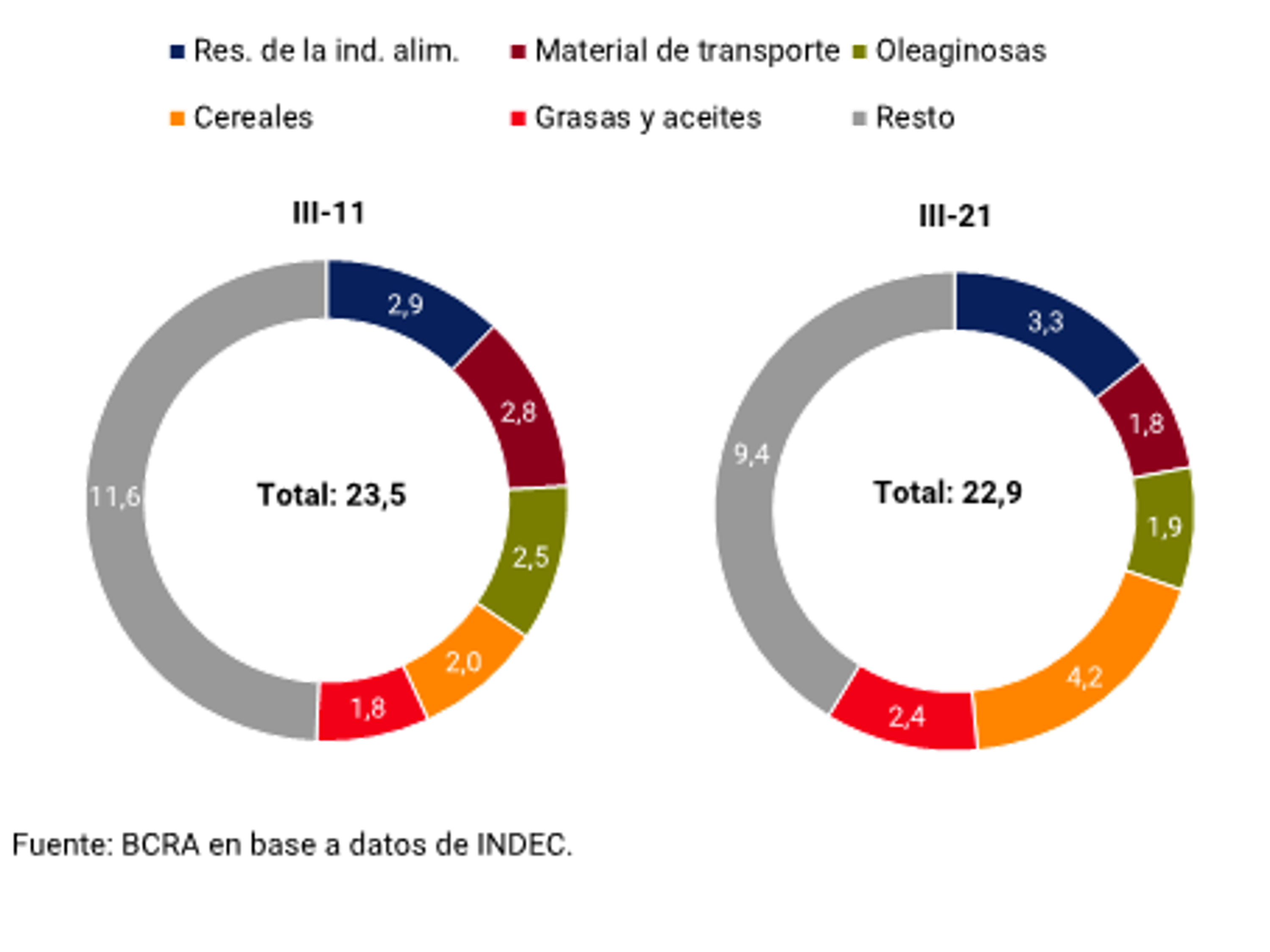

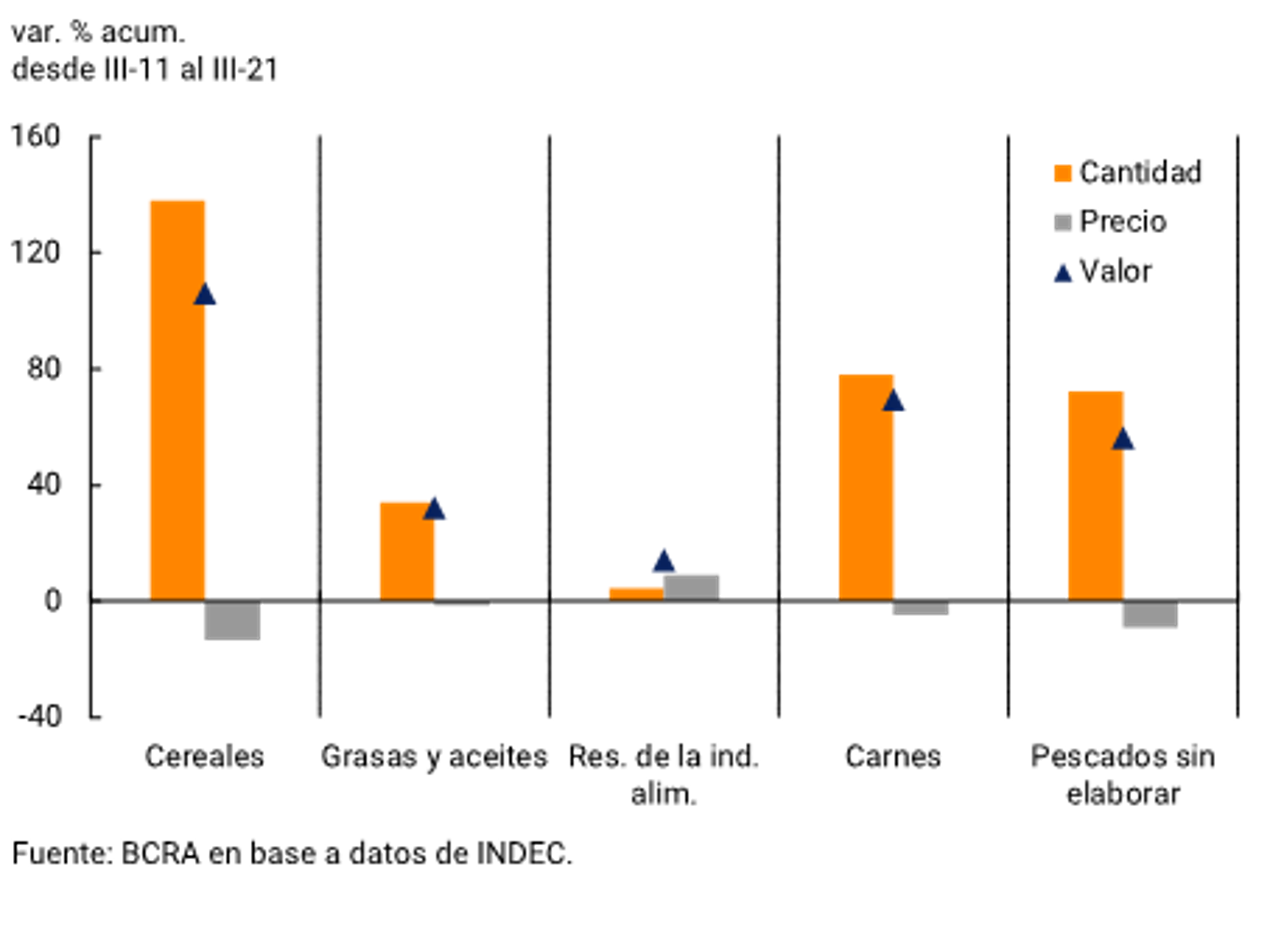

As a result of a high trade balance of goods, the Argentine economy would have sustained the current account surplus during the third quarter of 2021. Exports of goods at current prices were around the all-time high of 2011, driven at the margin by a sharp rise in export volumes. On the other hand, the imported values of goods grew for the fifth consecutive quarter, reflecting the increase in international prices of manufactured goods.

In the foreign exchange market, the evolution of exports and imports of goods, added to the evolution of commercial debt for exports and imports of goods, resulted in a net result for goods of US$2,402 million in the third quarter, decreasing by about US$3,700 million compared to the previous quarter. This prompted the BCRA to sell US$396 million in the foreign exchange market, which, together with the net income of financial debt of the public sector and the BCRA for about US$900 million, brought the level of international reserves to US$42,911 million at the end of the quarter.

From an annual perspective, the year is expected to close with a current account surplus, supported by the goods trade surplus. The main risk factors for the external sector of the Argentine economy going forward are a possible resurgence of the COVID-19 pandemic due to the expansion of new strains, or that the change in the monetary policy bias of most of the world’s central banks leads to a slowdown in the global economy. in addition to the potential impact that a deterioration in international financial conditions could have on the trajectory of commodity prices.

4.1. In the third quarter of 2021, the economy would have sustained the current account surplus

In the second quarter of 2021 (latest official data available) the Argentine economy recorded a current account surplus of US$2,763 million – equivalent to 1.4% of GDP in seasonally adjusted and annualized terms. The improvement in international prices of the main agricultural commodities exported by Argentina was the main factor behind this result.

In the third quarter of 2021, the increase in the quantities exported allowed the trade balance of goods to increase. In this context, the current account is expected to return to a positive balance of around 1.5% of GDP (see Figure 4.1).

In that period, the export values of seasonally adjusted goods reached US$21,461 million (Free on Board (FOB)) at current prices, just US$2 million below the record of the third quarter of 2011 (see Section 3 / Exports of goods ten years after the record). This favorable evolution of exports of goods was mainly due to the performance of the quantities exported, which grew 11% quarter-on-quarter s.e. and exceeded pre-pandemic records for the first time. To a lesser extent, export prices also contributed positively, growing 3% compared to the previous quarter.

Three of the four main export items had increases in exported volumes in the third quarter of the year. There was only a decrease in shipments of Manufactures of Agricultural Origin (MOA; -2% qoq, s.e.), affected by lower meat sales. Fuel exports grew 64% compared to the previous quarter, driven mainly by electricity shipments to Brazil, while those of Primary Products (PP) increased 31% s.e., highlighting corn shipments that set a quarterly record reaching 14.0 million tons. On the other hand, the exported quantities of Manufactures of Industrial Origin (MOI) had a more moderate growth (7% quarterly s.e.), driven by foreign sales of land transport material.

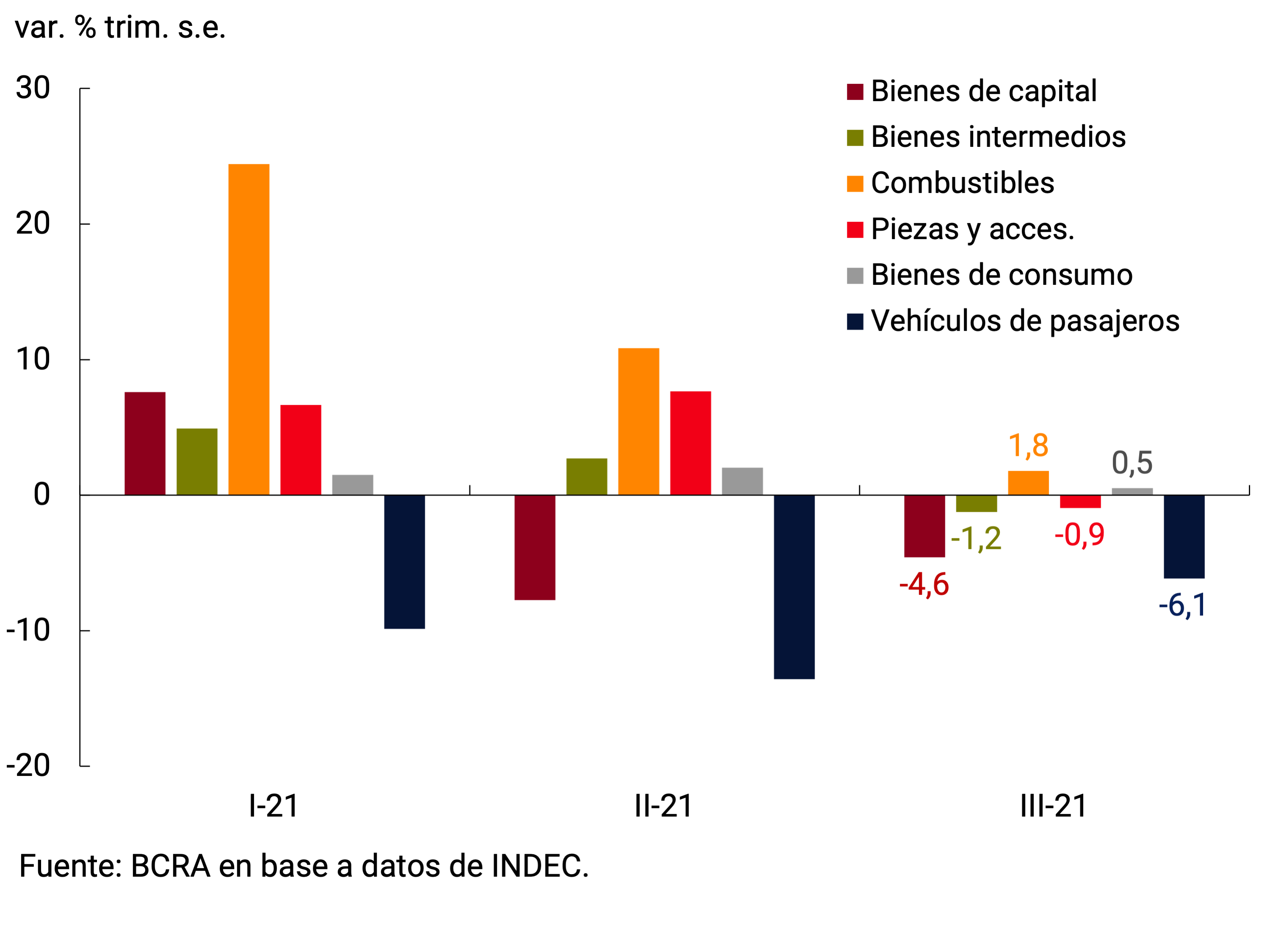

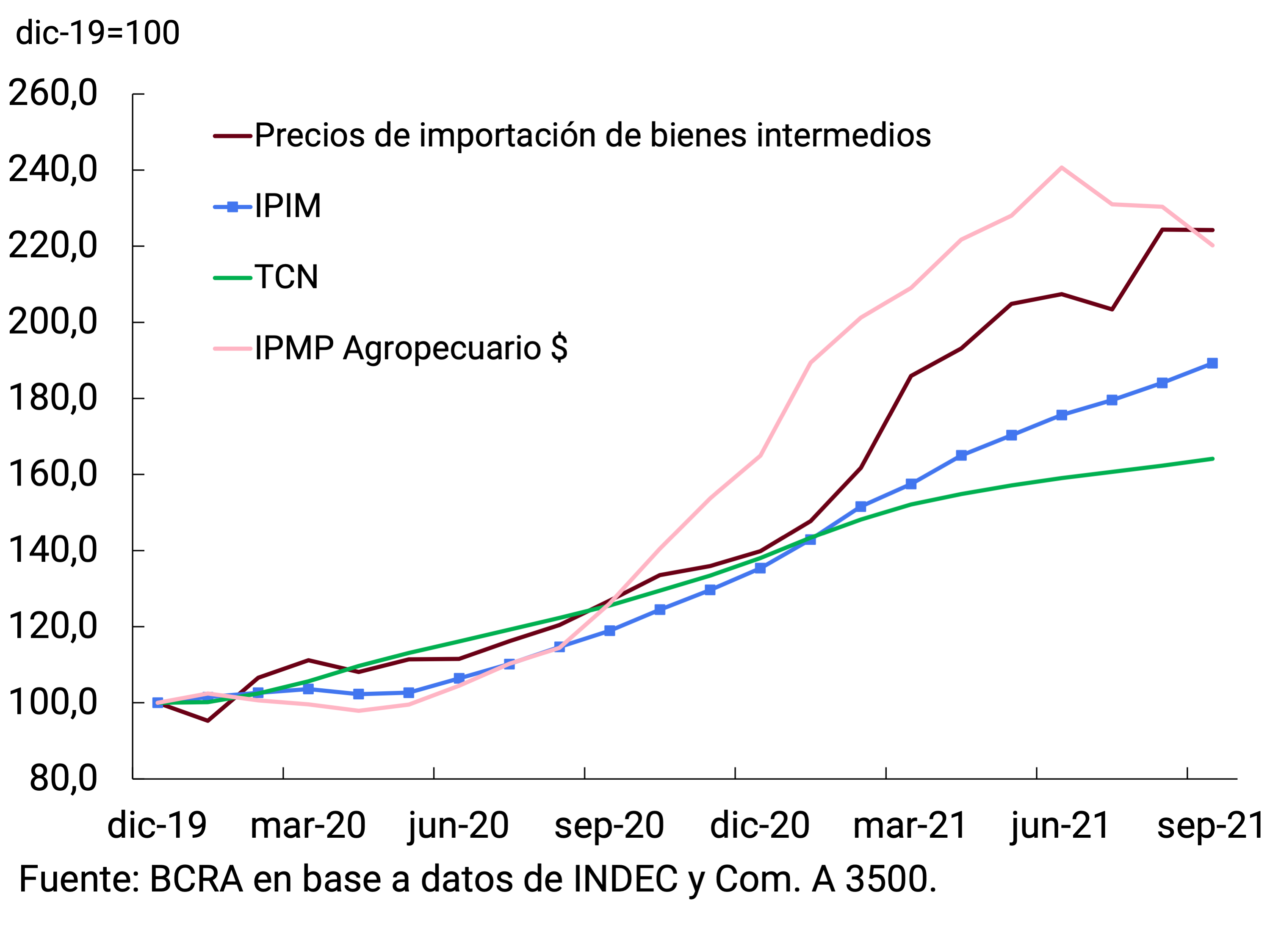

For its part, between July and September 2021, seasonally adjusted imports of goods totaled US$15,994 million (CIF), 51% above the quarterly average recorded in 2020 and 30% higher than the average for 2019. In the case of foreign purchases, it was import prices that explained this new rise (they grew 10% in the quarter), while the volumes purchased showed a slight drop (1% quarter-on-quarter s.e.) and seem to have stagnated since the beginning of the year (see Chart 4.2).

At the level of economic use, the quantities imported showed mixed behaviors. Compared to the previous quarter, there were increases in the volumes purchased of fuels (2% quarter-on-quarter) and consumer goods (1% quarter-on-quarter), while the rest showed declines, the most notable being passenger vehicles (6% quarter-on-quarter) and final capital goods (5% quarter-on-quarter; see Figure 4.3).

Box. Import prices in global perspective

One of the characteristic features of the Argentine economy is its status as a net importer of manufactured goods. In the period 2016-2020, manufactures of industrial origin accounted for more than 80% of total imports of goods. Given this pattern of trade, import prices measured in dollars are expected to be closely linked to overall manufacturing prices. With a few exceptions23, this has been the case over the past 15 years (see Figure 4.4).

In recent months, there has been a resurgence of inflationary pressures at the global level, with price variations that had not been observed in more than a decade (see Section 1 / The rise in international inflation). In this context, manufacturing was no exception. The Manufacturing Export Price Index prepared by the World Trade Organization (WTO) marked a year-on-year increase of 9% in dollars in July 2021 (latest available data). Records of the August and September producer price indices of manufactured goods from the major industrial powers suggest that the upward trend remained firm throughout the third quarter. In this context, import prices in dollars of the Argentine economy had a year-on-year increase of 19% in September.

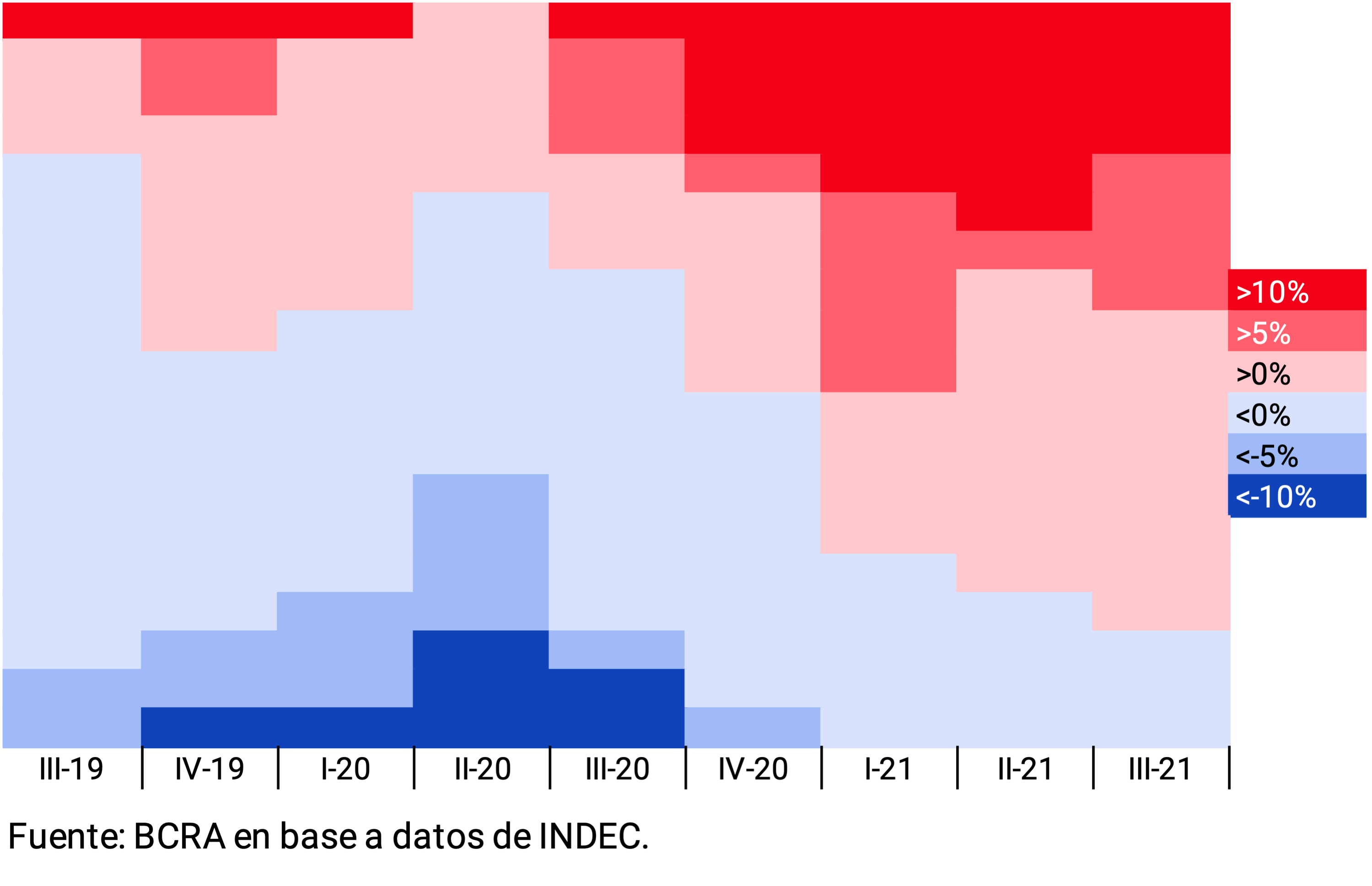

This dynamism of import prices was very widespread. For the third consecutive quarter, 16 of the 19 grouped showed increases compared to the previous period (see Figure 4.5). In the July-September period, the increases in the prices in dollars of mineral inputs (33% quarterly), basic fuels (19%), textile fibers (17%) and processed fuels (13%) stood out for their intensity. In year-on-year terms, some of these categories became significantly more expensive: mineral inputs (+106% YoY), processed fuels (+97% YoY), plastic and rubber (+59% YoY) and chemical inputs (+41% YoY).

For their part, the prices of exports of goods grew 3% in the third quarter, which constituted a slowdown compared to the pace of the first half of the year. Thus, as a result of the faster growth in import prices, the terms of trade – the ratio between export and import prices – deteriorated by 1% in the third quarter of 2021. However, they continue to be favorable in historical terms.

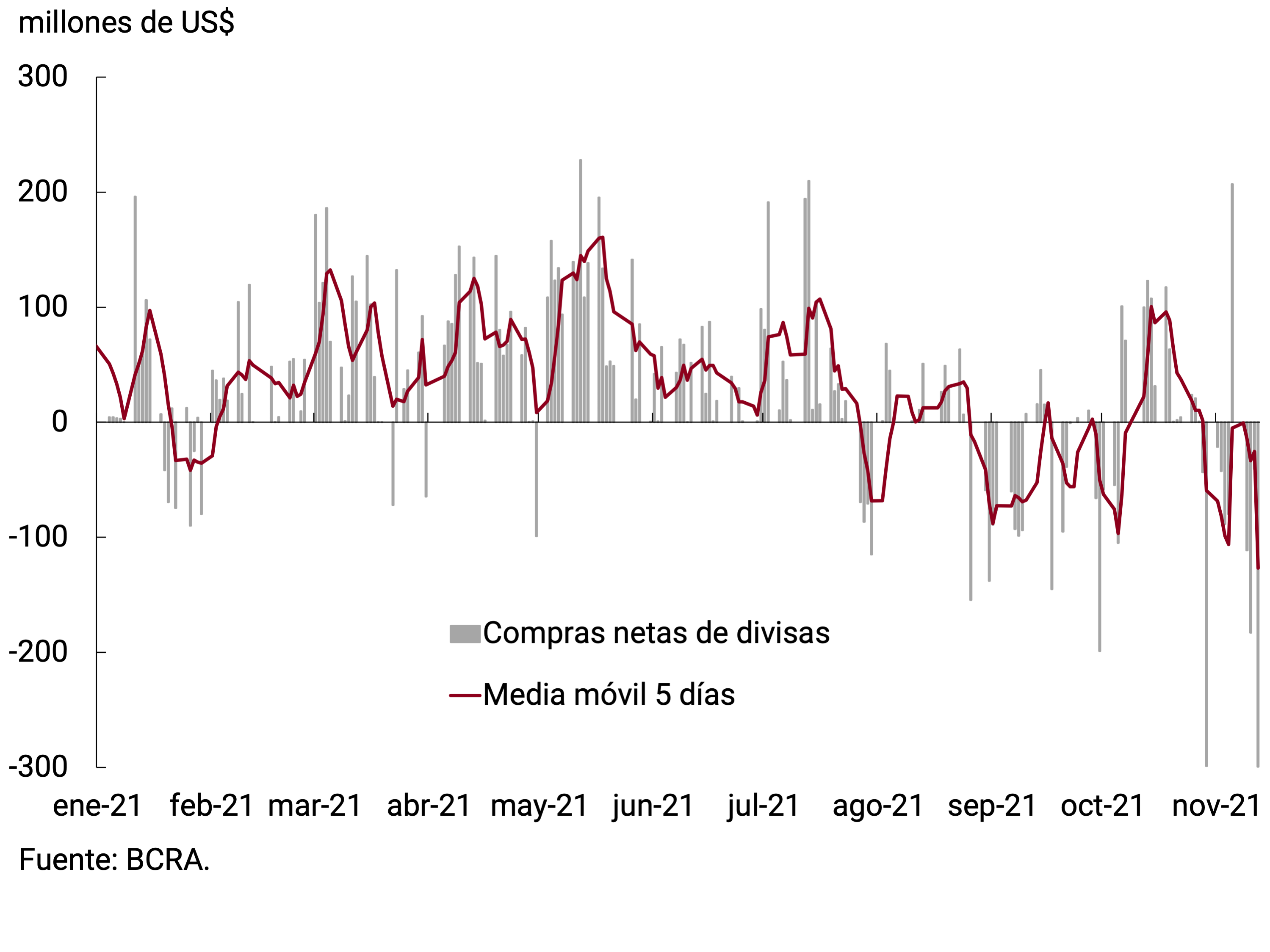

4.3. In the first nine months of the year, the BCRA recorded the largest net purchases of foreign currency in the foreign exchange market since 2012

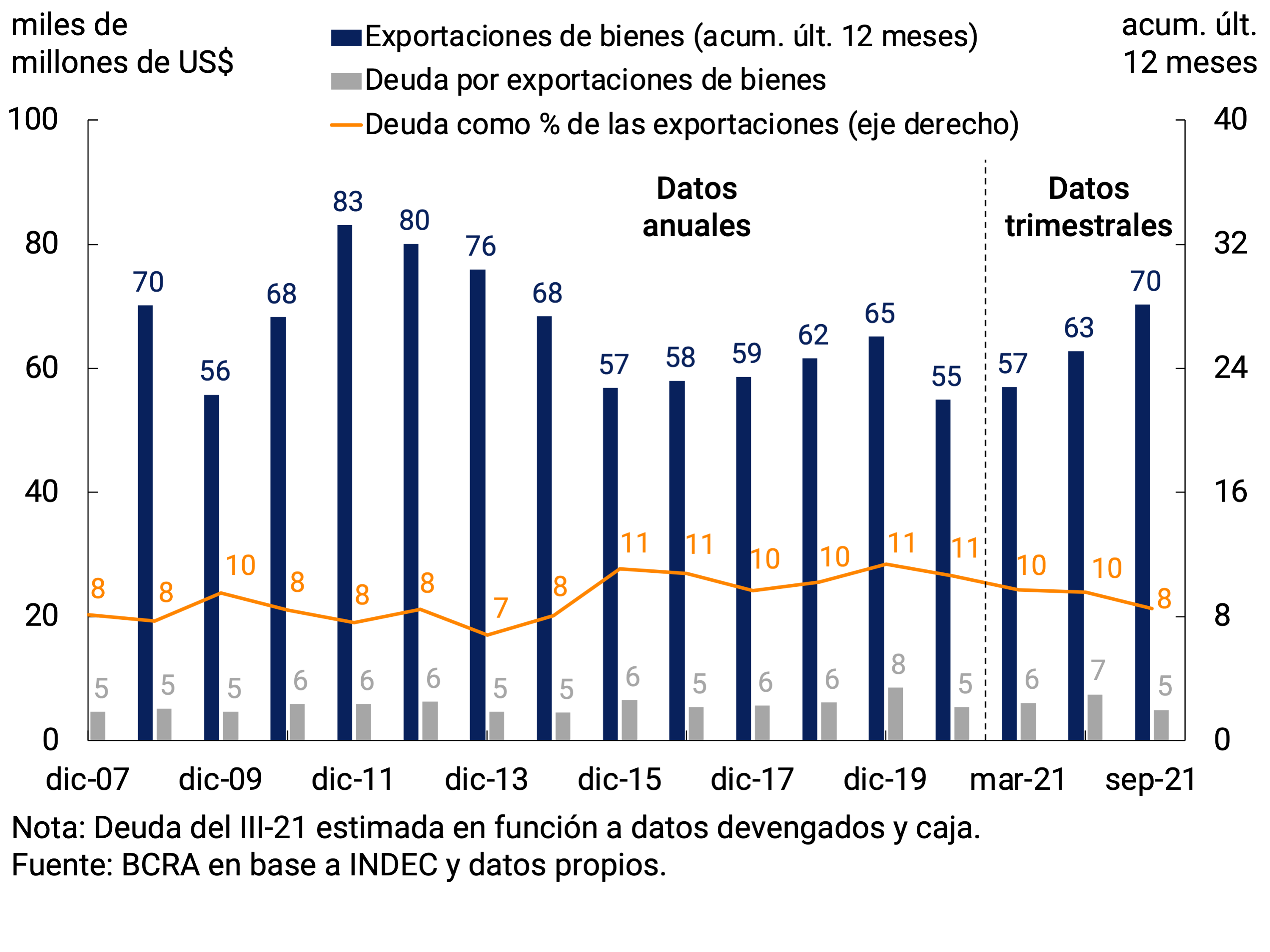

During the third quarter of 2021, exporters recorded revenues from exports of goods of about US$20,350 million. Given that exports of goods stood at about US$22,850 million, it is estimated that the external debt will be reduced by advances and pre-financing of about US$2,500 million. Thus, the ratio of this type of indebtedness to exported values is reduced to 8%, with respect to the values observed in recent years, a level that has not been verified since March 2015 (see Figure 4.6).

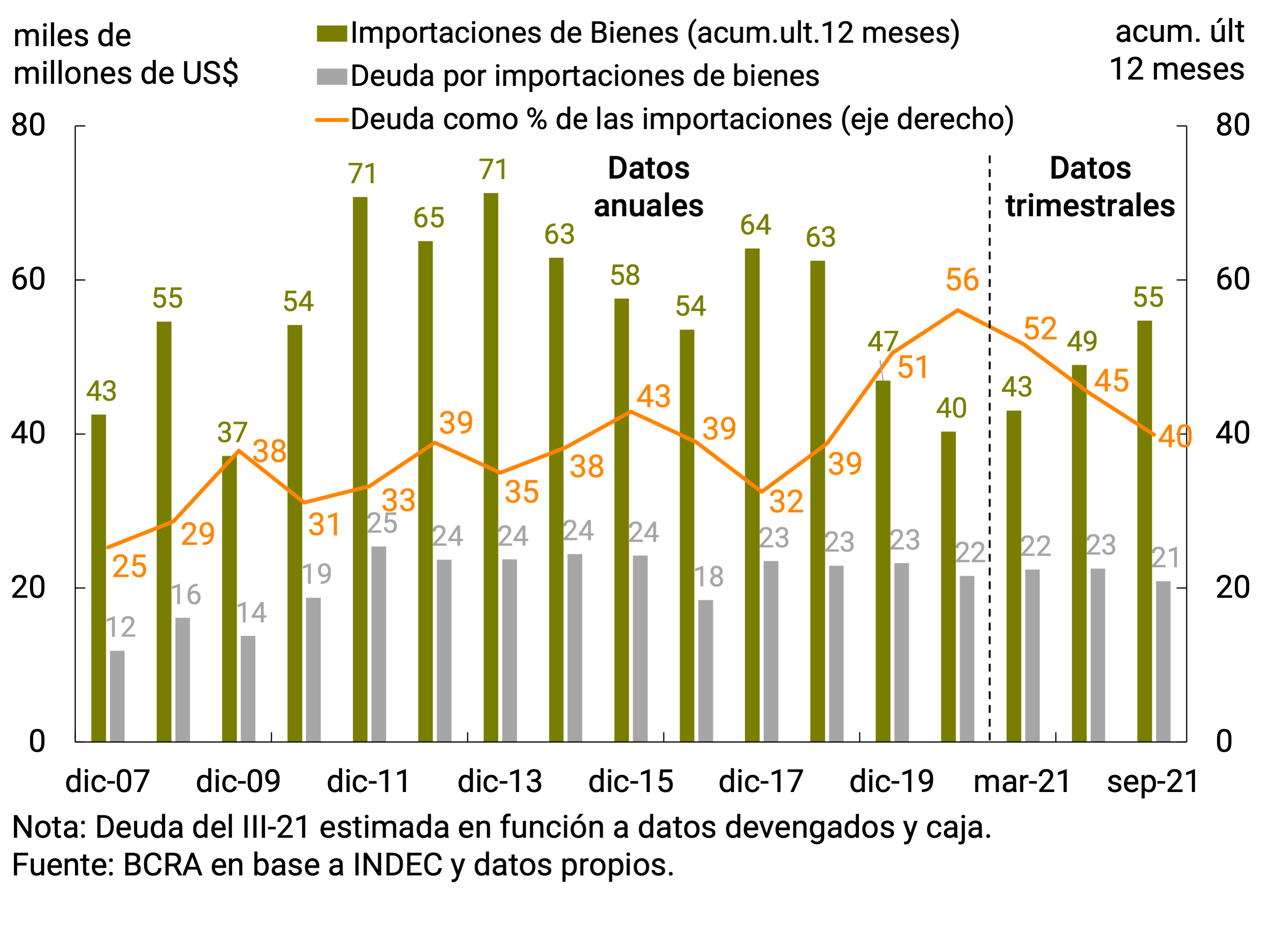

During 2020, the BCRA established a series of regulations aimed at promoting a more efficient allocation of foreign currency, which affected both the evolution of private commercial and financial debt, and which remain in force for the year 202124. In this context, during the third quarter of 2021, payments for imports of goods through the foreign exchange market for US$18,000 million were about US$1,650 million above FOB imports for the period, which would imply a fall in foreign indebtedness for this concept (or an increase in foreign assets due to early payments). In addition, due to the increase in the value of shipments to the market in recent months, the relationship between external debt and the level of imports registered a new fall, which implied 5 percentage points compared to the previous quarter and 16 p.p. compared to the end of 2020 (see Chart 4.7).

Finally, with regard to financial debt, and as part of the current regulatory framework mentioned above, in September 2020, through Communication “A” 7106, the guidelines were established under which private sector companies could initiate a process of refinancing their respective external liabilities, which would allow their maturity profile to be adapted to the guidelines required for the normal functioning of the foreign exchange market. This communication, which reached certain capital maturities between October 15, 2020 and March 31, 2021, was extended by Communication “A” 7230, covering maturities from then until the end of 2021.

In this context, the renegotiations registered during the third quarter of 2021 of some 25 companies had an impact on lower net purchases in the foreign exchange market of about US$600 million compared to the original maturities for that same period. In this way, lower net payments of more than US$1,900 million were accumulated in the year.

Finally, with regard to financial debt, and as part of the current regulatory framework mentioned above, in September 2020, through Communication “A” 7106, the guidelines were established under which private sector companies could initiate a process of refinancing their respective external liabilities, which would allow their maturity profile to be adapted to the guidelines required for the normal functioning of the foreign exchange market. This communication, which reached certain capital maturities between October 15, 2020 and March 31, 2021, was extended by Communication “A” 7230, covering maturities from then until the end of 2021.

The aforementioned recovery of exports, added to the evolution of the commercial debt for exports and imports of goods, resulted in a net result for goods in the foreign exchange market of US$12,964 million in the first 9 months of the year, about US$2,000 million lower than the result of the FOB trade balance for the same period. implying a significant improvement compared to the same period of the previous year (83%).

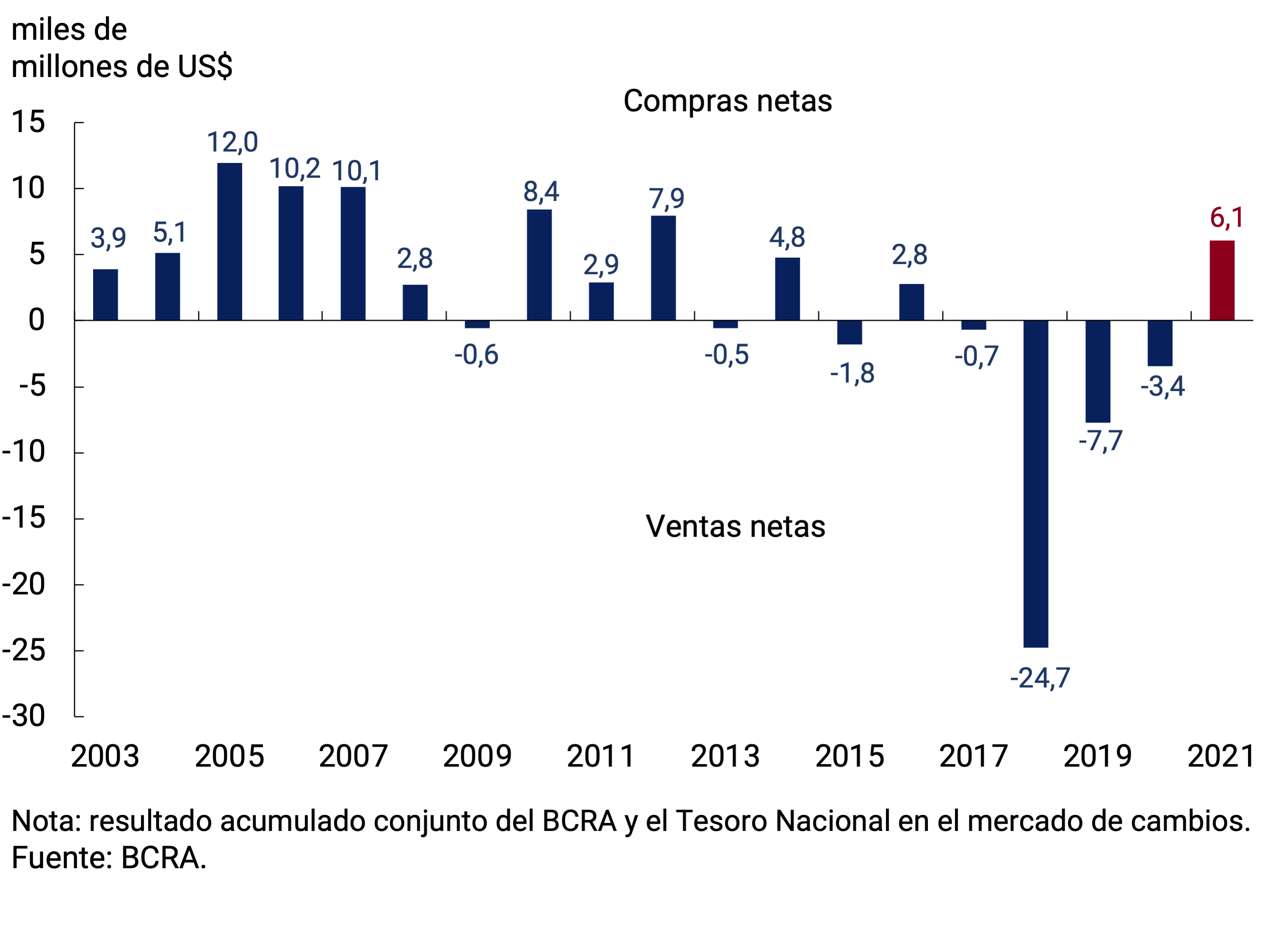

Thus, the BCRA accumulated purchases in the foreign exchange market until September by US$6,062 million, constituting a record value for the first 9 months of the year since 2012 (see Chart 4.8), while international reserves increased by US$3,523 million in the same period. This difference is mainly explained by the net cancellations of principal and interest on debt in foreign currency by the BCRA and the National Government with a direct impact on international reserves of about US$2,800 million and payments for operations carried out through the Local Currency Systems with Brazil, Uruguay and Paraguay and ALADI for about US$500 million. partly offset by the increase in the holdings of entities in foreign currency accounts at the BCRA by about US$800 million.

4.4. Perspectives

For the last quarter of 2021, the economy is expected to incur a slight current account deficit, due to the seasonal decline in the goods surplus typical of the last months of the year. In any case, the year would close with a surplus, as a result of the high positive balance of goods. A resurgence of the pandemic due to the expansion of new strains of COVID-19 and/or a slowdown in the global economy as a result of the change in the bias of the monetary policy of most of the world’s central banks, added to the potential impact that a deterioration in international financial conditions could have on the trajectory of commodity prices, are the main risk factors for the external sector of the Argentine economy.

The regulatory framework in force in the Foreign Exchange Market will allow the BCRA to continue to efficiently manage foreign currency originating in commercial and financial transactions, in order to preserve monetary and exchange rate stability.

5. Public Finance

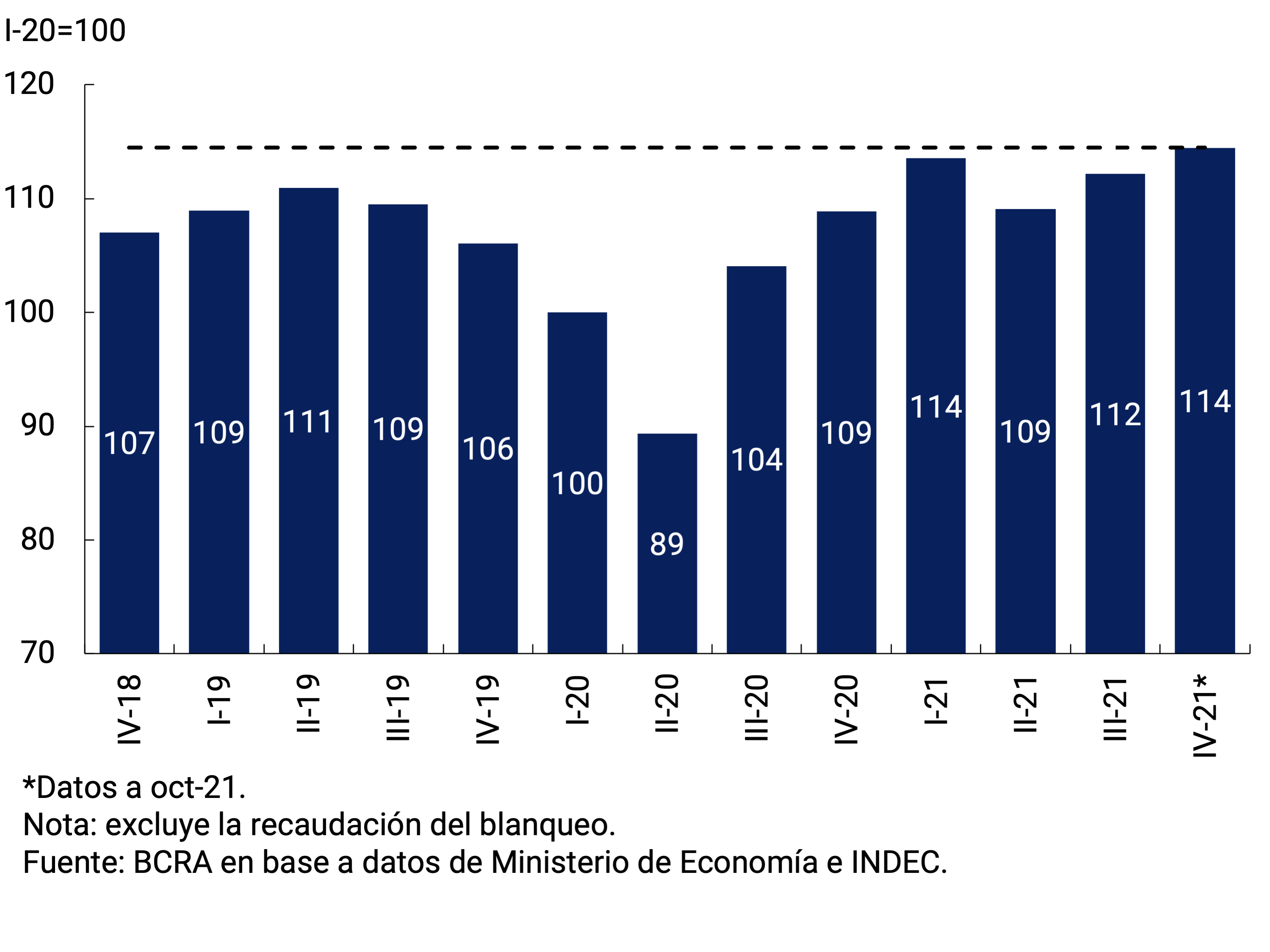

During the third quarter of 2021, national public finances continued to strengthen due to higher public revenues. National tax collection was 12.2% above the pre-pandemic value (first quarter of 2020) in seasonally adjusted real terms. This revenue dynamic made it possible to develop an expansive fiscal policy with a view to economic growth with social inclusion. The recovery in domestic demand and taxes related to foreign trade—in a context of higher international commodity prices—determined this favorable evolution. Likewise, the regulatory modifications on taxes provided for in the Social Solidarity and Productive Reactivation Law of the end of 2019 and in the National Budget Law 2021 continued to have a positive impact. On the other hand, non-tax resources (driven by the solidarity and extraordinary contribution of large fortunes) also contributed to improving the situation of the public accounts.

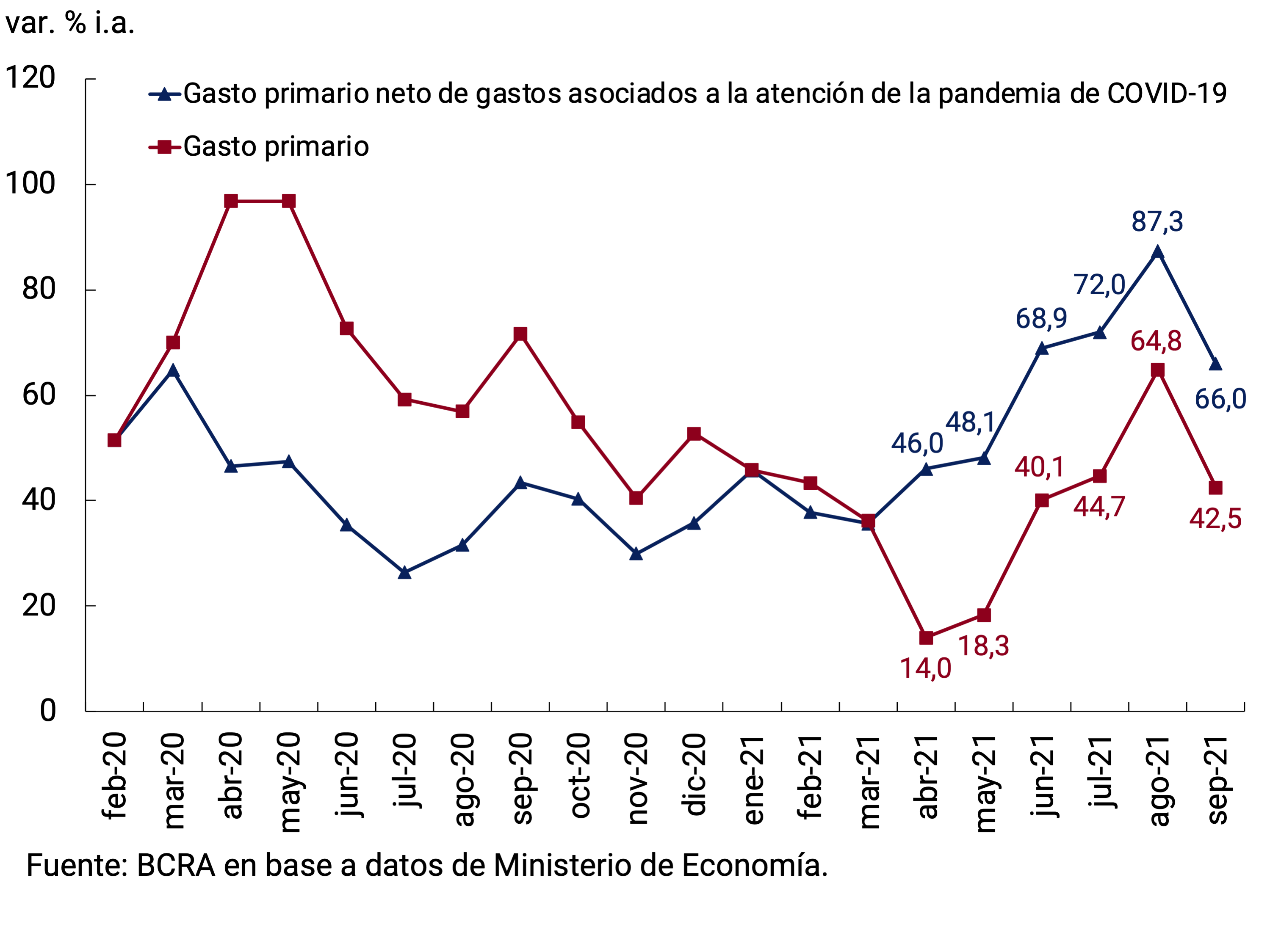

Social spending was sustained – within the framework of the social and economic emergency that has been in force since the end of 2019 – and an increase in capital spending was promoted in line with the provisions of the 2021 National Budget, with the aim of supporting the recovery process of economic activity. In the opposite direction, there was a more limited trajectory of extraordinary expenditures associated with the evolution of the pandemic. However, excluding extraordinary expenditures in 2020 and 2021 aimed at mitigating the effects of the pandemic and accompanying the most affected sectors, real primary expenditure expanded by 15% YoY in the third quarter of 2021.

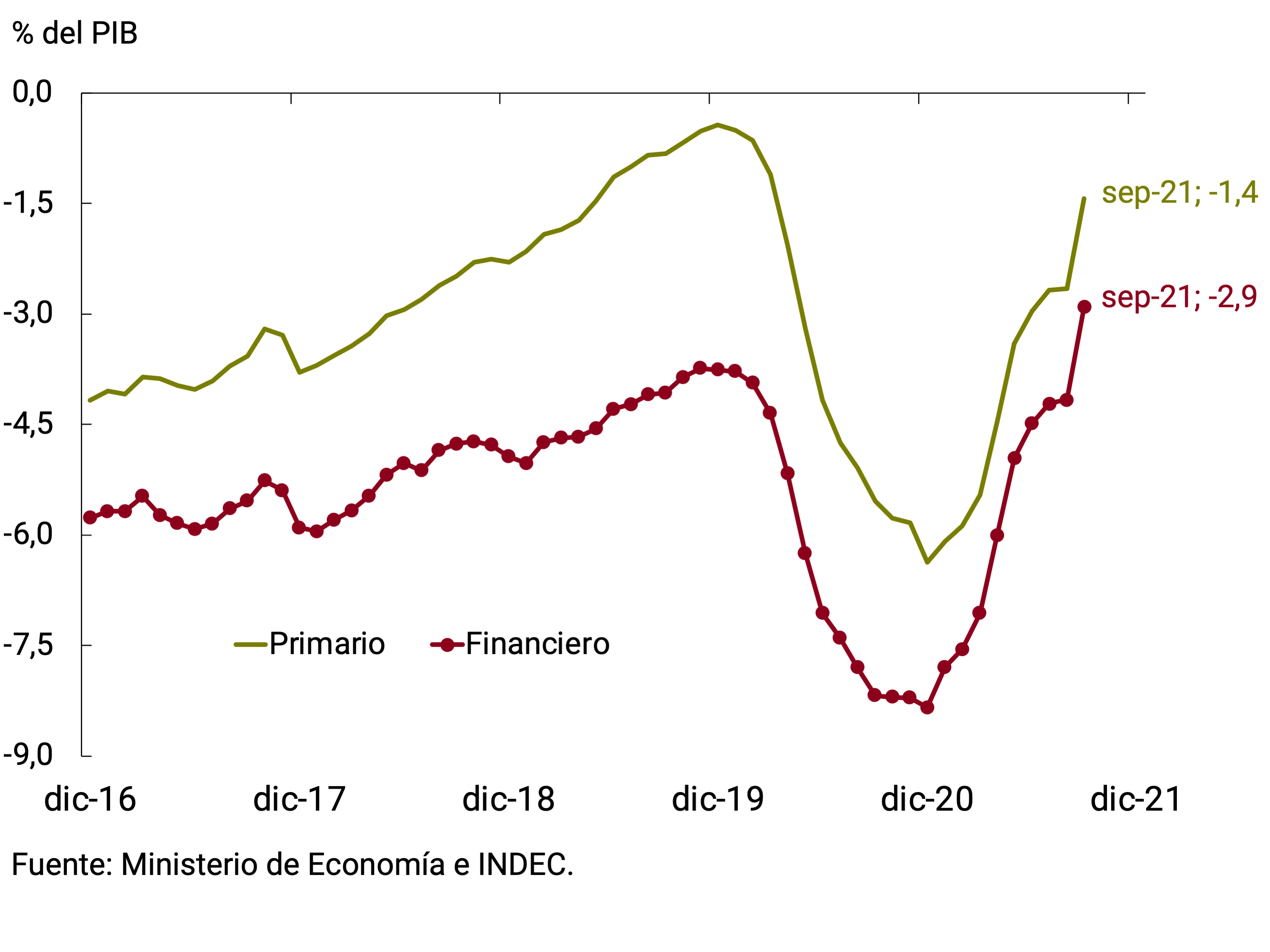

Given the trajectory of revenues and expenditures, the fiscal deficit continued to be reduced. In the last 12 months to September 2021, the primary deficit on a cash basis accumulated a balance equivalent to 1.4% of GDP, significantly lower than that observed during 2020 (-6.4% of GDP). It should be noted that this value incorporates the resources from the allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) made extraordinarily for approximately 1% of GDP. In mid-September, the National Government presented the 2022 National Budget Bill that foresees a primary deficit of NFPS of 4.0% of GDP during the current year (not including the extraordinary resources for the SDR allocation that impacted resources towards the end of September) and a reduction of this to 3.3% of GDP for 2022.

So far in 2021, in line with budget forecasts and in contrast to the same period last year, lower monetary financing of the needs of the National Treasury (NT) continued to be observed, even taking into account the greater assistance observed in recent months. The National Government is negotiating an agreement with the IMF to meet the large obligations that are concentrated in 2022 and 2023 (amortizations of about US$17,900 million and US$19,000 million, respectively) derived from the stand-by loan taken by the previous administration. Among the risks faced in the fiscal scenario, an eventual resurgence of the pandemic stands out, which could require intensifying policies to assist vulnerable people and companies and negatively affect tax revenues. Likewise, challenges persist in continuing to implement a financing policy that prioritizes the development of the local debt market.

5.1. Tax revenues remained highly dynamic, contributing to the strengthening of public accounts

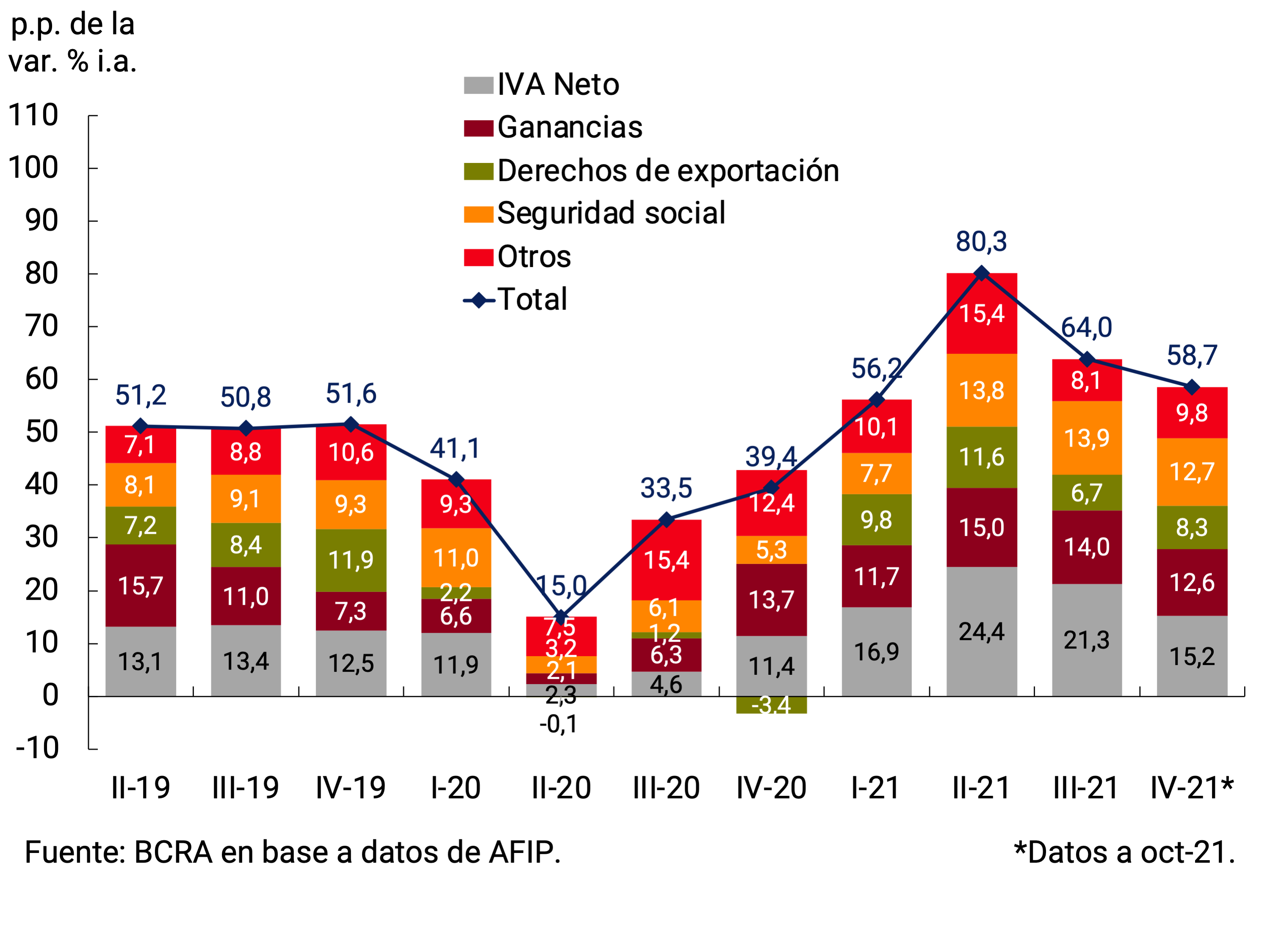

National tax collection increased 64% YoY in the third quarter of 2021 (see Figure 5.1). This increase is explained by the consolidation of the economic recovery and the low base of comparison due to the impact of the pandemic during the third quarter of 2020. In addition, the higher values of international trade flows that are taxed continued to contribute positively. In real terms, tax collection expanded 8% YoY between July and September. In October, the nominal increase was 58.7% YoY (+4.7% YoY in real terms).

Taxes associated with foreign trade sustained a good performance. Export duties grew 135% in October and 103% in the third quarter. The rise responds both to the maintenance of the favorable international context for the prices of the main export products and to the progressive recovery of external demand. Taxes linked to foreign purchases28 also showed a strong increase during the period: 66% YoY in October and 90% YoY in the third quarter. This behavior continues to be explained basically by the increase in imported values (see Chapter 4. External Sector).

Taxes related to the domestic market (Value Added Tax (VAT), Profits, Fuels, among others) maintained the dynamism observed in the previous quarter due to the recovery of economic activity and the low base of comparison (the pandemic had still had a negative impact in the third quarter of 2020). Income Tax rose 57.7% YoY in October and 67.3% between July and September in line with what was observed in the second quarter. The regulatory change of September 2020 associated with the withholding on purchases of dollars and expenses in foreign currency through credit cards continues to have an upward effect on this tax. In addition, it is negatively impacted by the increase in personal deductions on the income of employees and by refunds for differences owed from past months to these taxpayers29. For the coming months, the modification that incorporates new rates in a staggered manner for companies, setting the maximum rate at 35% and maintaining the tax on dividends at 7%30, will have an upward impact on the collection of profits30. Net VAT remained highly dynamic, growing 79.9% YoY between July and September after having increased 88.5% YoY in the previous quarter.

Between July and September, social security resources continued to show the dynamism observed in the second quarter, basically explained by the recovery of wages and employment: they grew 63.2% YoY in the third quarter (a figure similar to that observed between April and June) and 65.0% YoY in October. This set of taxes is still negatively impacted by the measures taken by the National Government, with reductions in employer contributions in the health sector, the critical sectors contemplated in the REPRO program and in the provinces of the Norte Grande.

In real terms, seasonally adjusted national tax revenue grew 2.9% in the third quarter and 2.0% at the beginning of the fourth quarter (with data as of October; see Figure 5.2). The set of real national taxes, discounting seasonal effects, are 12.2% above the pre-pandemic level (first quarter 2020) in the third quarter and 14.4% in the fourth (with data as of October). This performance shows the recovery of tax revenues after the harmful effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The evolution of tax revenues allowed the total revenues of the National Non-Financial Public Sector (NFPS) to increase in nominal terms by 102.2% y.o.y. (33% y.o.y. in real terms) between July and September, after having increased 99.4% y.o.y. during the second quarter of the year. The year-on-year comparison of the third quarter was impacted by the calculation in current transfers of the extraordinary allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) that the IMF made in the context of the global crisis due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Net of this effect, funds would have shown a nominal increase of 69.7% in the quarter. Non-tax revenues increased by 1,209% y.o.y. in the third quarter due to the allocation of resources associated with the Solidarity and Extraordinary Contribution to Help Mitigate the Impact of the pandemic (between July and August, $61,641 million were recorded for this concept and accumulating $231,609 million in the year; Law 27605) and the allocation of SDRs (for about $427,400 million). Property rents increased 118% y.o.y. between July and September, from the collection of services of loans granted by the National Social Security Administration (ANSeS) – which was suspended during the same period last year. Meanwhile, capital resources continued to decrease in year-on-year terms in the third quarter, affected by the provisions of Law 27574 on the defense of the assets of the Sustainability Guarantee Fund (FGS), which stipulates the suspension of financing to the ANSES by the FGS to meet the disbursements of the Historical Reparation program.

Meanwhile, the tax collection of the provinces as a whole exhibited a behavior consistent with what was observed at the national level. According to the partial information available for the main districts, in the third quarter of the year the nominal advance of own tax resources would have shown an increase of more than 65% y.o.y., still impacted by the low base of comparison of the same quarter of 2020.

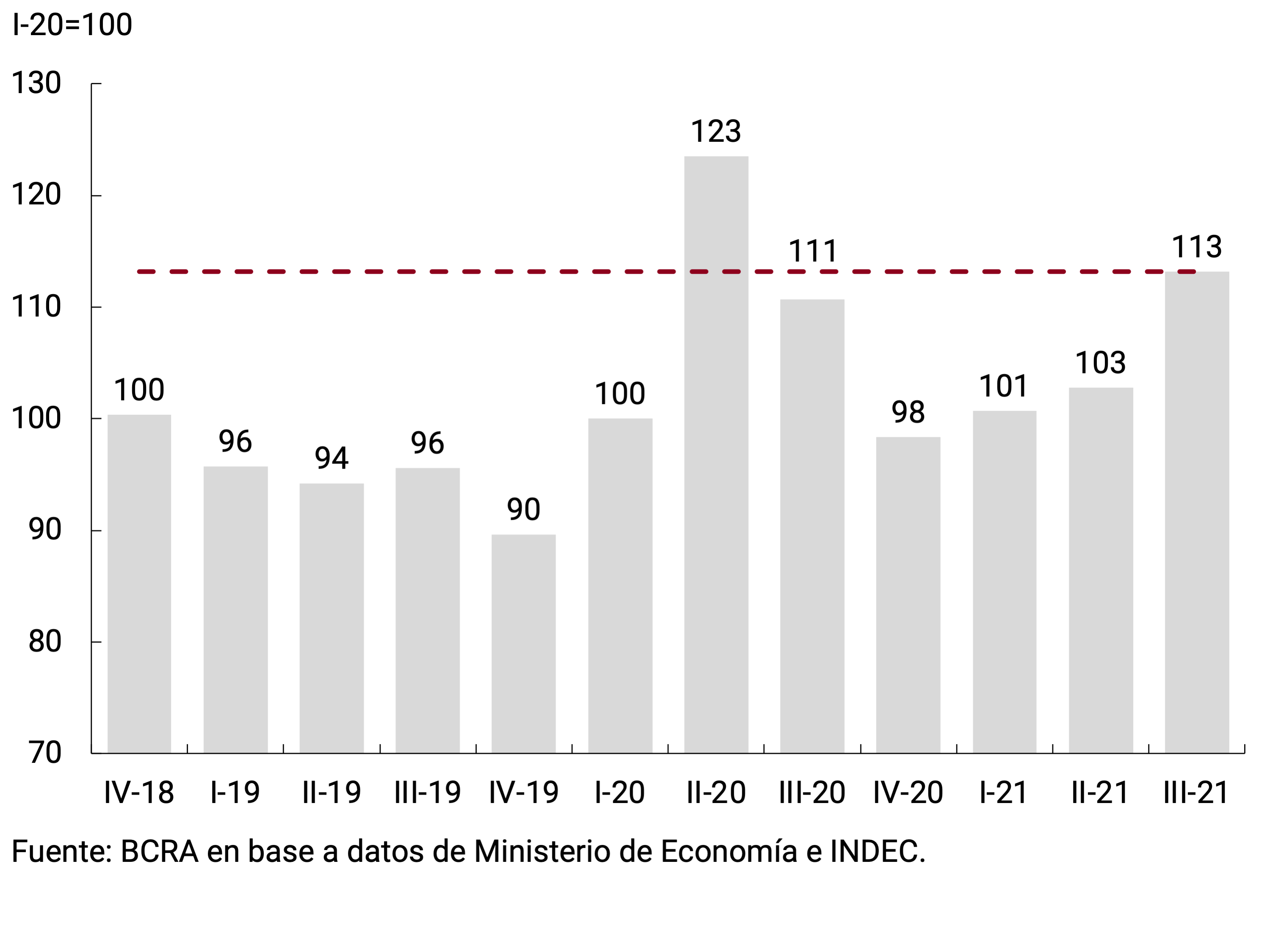

5.2. Seasonally adjusted NFPS primary expenditure showed a year-on-year increase in real terms in the third quarter, remaining above pre-pandemic levels

NFPS primary expenditure exhibited a nominal increase of 50.0% YoY in the third quarter and 38.4% YoY in the year to date, below the nominal increase in revenues in the nine months of 2021. In real terms, expenses decreased 1.2% YoY in the quarter and 6.3% YoY in the nine months of the year accumulated. Meanwhile, revenues31 at constant prices increased 11.8% and 25.6% y.o.y. in the third quarter and so far this year, respectively (see Figure 5.3).

It should be taken into account that during most of the current year the public accounts were affected by a basis of comparison that includes the effects of the pandemic, whose greatest deployment was concentrated in the second and third quarters of 2020. Indeed, excluding extraordinary expenditures in 2020 and 2021 aimed at mitigating the effects of the pandemic and accompanying the most affected sectors, since April 2021 primary expenditure has expanded at a nominal rate approximately 25 p.p. higher than that of primary expenditure without deductions for COVID-19 expenditure (see Figure 5.4).

In this sense, if real seasonally adjusted primary expenditure is observed, it was 13% above the pre-pandemic level (I-20) in the third quarter of 2021 and exhibited an increase of 15% year-on-year (see Figure 5.5).

During the third quarter of 2021, social security benefits accounted for most of the increase in primary spending: they grew 45.5% YoY (vs. +32.2% YoY in the first half of the year)32, within the framework of the provisions of the Pension Mobility Law33. Regarding social programs, the expenditures of the Food Policies program were highlighted due to the increase in the allocation of 50% and the expansion of the universe of beneficiaries up to 14 years of age, as of February 2021, and of the Empower Work program due to the increase in both the number of people and the Minimum Living and Mobile Wage since September. In turn, payments from the Employment Actions program – mainly REPRO II – registered a significant increase in order to assist the productive sectors critically affected by the pandemic. On the other hand, the growth of the Universal Child Allowances for Social Protection (AUH) and the Universal Pregnancy Allowance (AUE) (+88.0% in the quarter, +56.3% in the year) is explained by the advance of the supplement corresponding to the submission of Affidavits for schooling34. In order to sustain the purchasing power of the most vulnerable older adults, ANSES also ordered the granting in August of a $5,000 bonus to retirees and pensioners who receive up to two minimum salaries.

In a context in which the National Government promoted a policy of containing the rates of public services – electricity, gas, water and public transport – economic subsidies explained a significant portion of the year-on-year increase in spending: they grew 118.8% YoY in the third quarter and 89.5% YoY during the first nine months of the year. The increase was disseminated among the main destinations associated with energy and public passenger transport.

Items associated with salaries (including transfers to universities) grew 56.1% YoY in the third quarter and 44% YoY between January and September, while other current expenditures grew by 163.5% YoY and 111.6% YoY, respectively. It should be noted that in this last item the purchases of goods and services are recorded (including the expenditures associated with the purchase of vaccines and the expenses associated with the organization of the national electoral act) and the deficit of public companies, among others. On the other hand, current transfers to the provinces moderated significantly (28.8% y.o.y. in the third quarter) compared to 2020, when the National Government had extraordinarily assisted the districts in the face of the abrupt decrease in collection. This performance was verified despite the fact that since the beginning of 2021, the transfers associated with the creation of the Fund for the Fiscal Strengthening of the Province of Buenos Aires began to be budgeted35.

Capital expenditure continued to show dynamism, in line with the definition of priorities set out in the 2021 National Budget to boost the recovery of economic activity. In fact, Real Direct Investment (IRD) grew 193% YoY during the third quarter, while transfers for capital expenditures increased 37% YoY in the36th quarter. In the first nine months of the year, capital expenditure increased 113.6% YoY.

Thus, the primary deficit of NFPS accumulated in the last 12 months to September represented approximately 1.4% of GDP (see Figure 5.6). Net of the $427.4 billion from the extraordinary allocation of Special Drawing Rights that the IMF made in the context of the global crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the primary deficit accumulated in the last 12 months to September represented approximately 2.5% of GDP, below the annual forecast contained in the 2022 National Budget Bill —see Box. 2022 National Budget Bill (PPN-22)—. For its part, the financial deficit of the NFPS accumulated in the same period stood at 2.9% of GDP (3.9% net of SDRs).

Box. National Budget Bill 2022 (PPN-22)

On September 15, the National Government presented the 2022 National Budget Bill.

With a revenue forecast similar to that estimated for 2021 as a proportion of GDP, the PPN-22 projects an increase in tax collection that compensates for the reduction in non-tax revenues (which in 2021 include the resources that were collected only once associated with the Extraordinary Solidarity Contribution).

On the expenditure side, the official document forecasts stable primary expenditure in real terms, although implying a reduction of 0.7 p.p. of GDP in 2022. The reduction is concentrated in current transfers, consumption expenditures and other current expenditures. For its part, the PPN-22 foresees a significant dynamism of the capital expenditure item to reach 2.6% of GDP in 2022 after estimating an execution of an amount equivalent to 2.3% of GDP in 2021.

Given the stable trajectory of resources and the decline in primary expenditures, the project foresees a reduction in the NFPS primary deficit from 4% of GDP in 2021 to 3.3% of GDP in 2022.

The financial result would fall from -5.4% of GDP to -4.9% of GDP in 2022. The budget document does not contemplate the transfer of profits from the BCRA for 2022. Regarding the financing of the BCRA to the National Treasury (TN), an amount of $1.08 billion associated with net financial assistance from Transitory Advances is foreseen and provides for the full refinancing of the debt maturities in the BCRA’s portfolio.

5.3. In contrast to the previous year, so far in 2021 the National Government has met its needs with less monetary financing despite the increased recent assistance

During the third quarter of 2021, the TN achieved a refinancing of 108% of principal and interest services (around 106% refinancing in October), which implied a net financing of approximately $57,300 million (to which was added about $29,700 million in October)37, accumulating a net financing in the year of about $443,300 million (around the 117% refinancing rate). Issuances of public debt instruments during the quarter were mainly with fixed-rate securities and adjustable by CER, and to a lesser extent with securities adjusted to the evolution of the dollar and at a variable rate.

The extension of the maturities of the instruments issued remained relatively stable during the quarter, while there was an increase in the cost of financing in pesos. For its part, during the month of June and July 2021, voluntary debt conversion operations were carried out, which made it possible to significantly decompress the profile of short-term maturities. With the aim of developing the local peso debt market, the participation of the 2021 Aspiring Market Makers continued to be strengthened, and the menu of investments available to Mutual Funds (FCI) was expanded from the auctions of Treasury Liquidity Bills (LELITES), while the Central Bank continued to operate in the public securities futures market.

So far in 2021, in contrast to the same period last year, lower monetary financing of the needs of the NT continued to be observed, even despite the greater assistance observed in recent months. In line with budget forecasts, so far this year $787,700 million have been transferred as a transfer of profits from the BCRA to the TN. Likewise, until mid-November, there was a net granting of net Transitory Advances from the BCRA to the TN for $147,600 million. It is worth highlighting the decision of the National Treasury to cancel Transitory Advances with the $422,174 million received as a counterpart to the sale of SDRs assigned by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to the Central Bank of the Argentine Republic38. In addition, the National Executive Branch ordered the placement to the BCRA of SDR bills for an amount equivalent to US$4,334 million to the BCRA, the proceeds of which may only be applied to the payment of obligations to the IMF39.

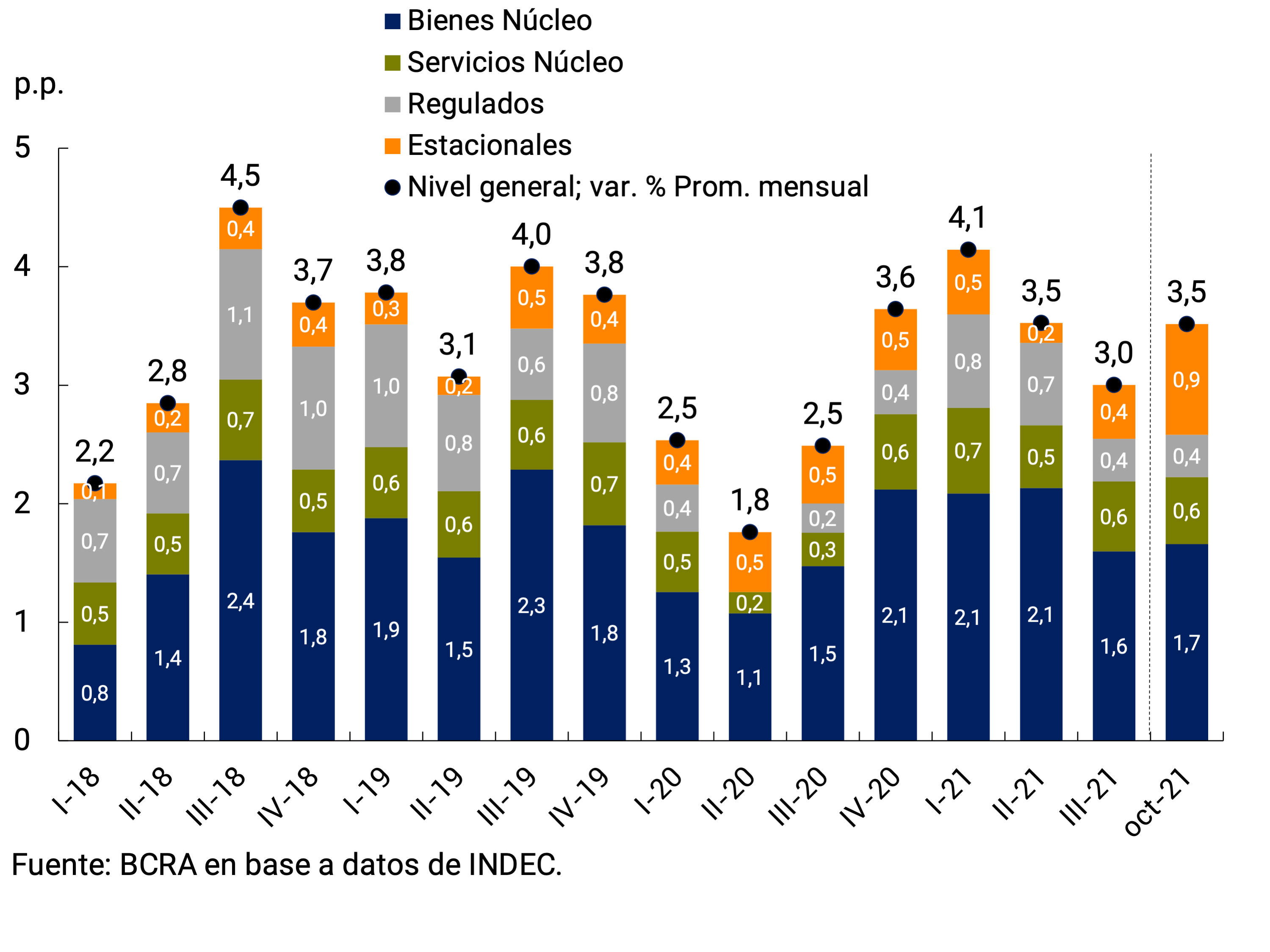

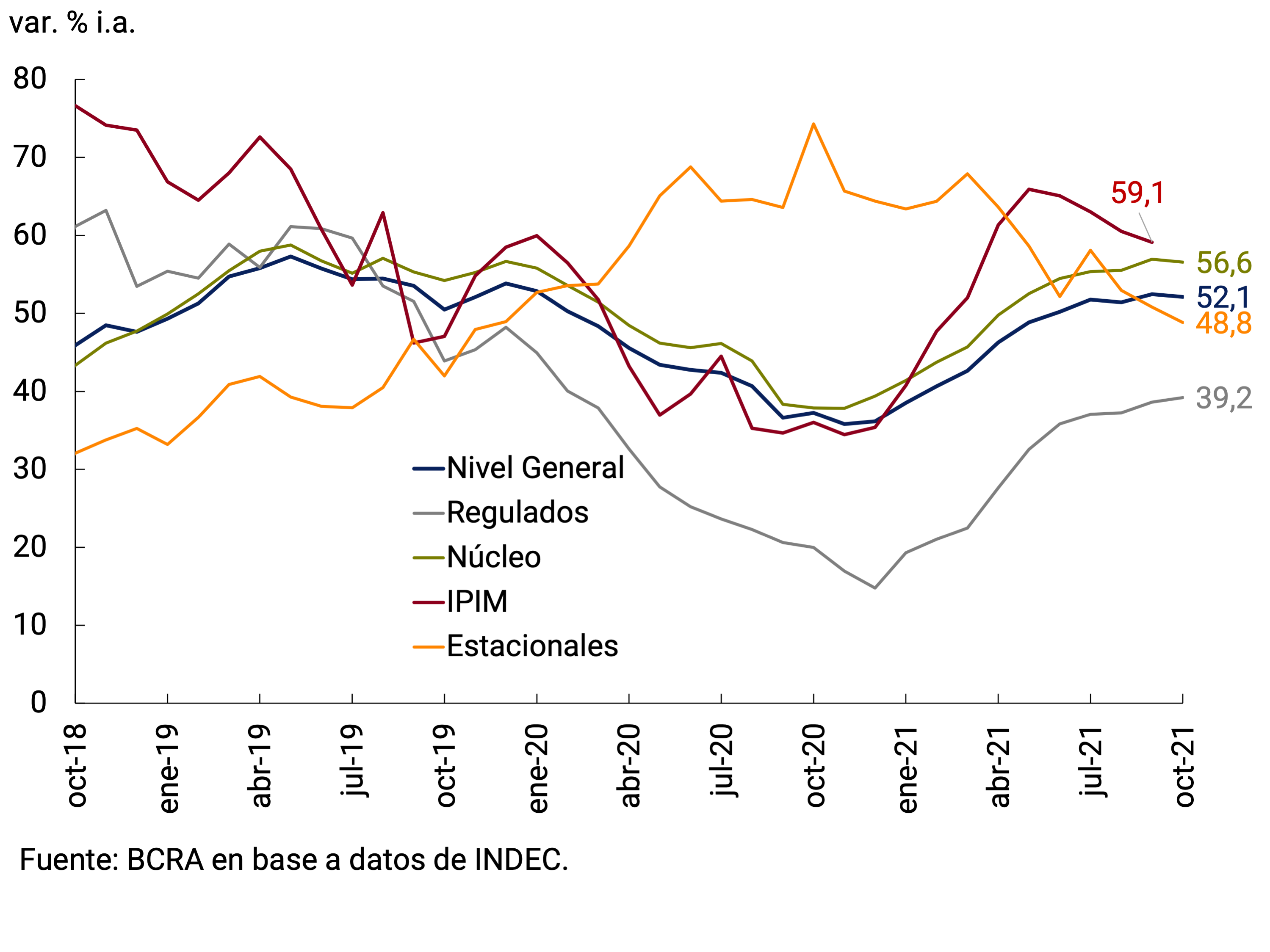

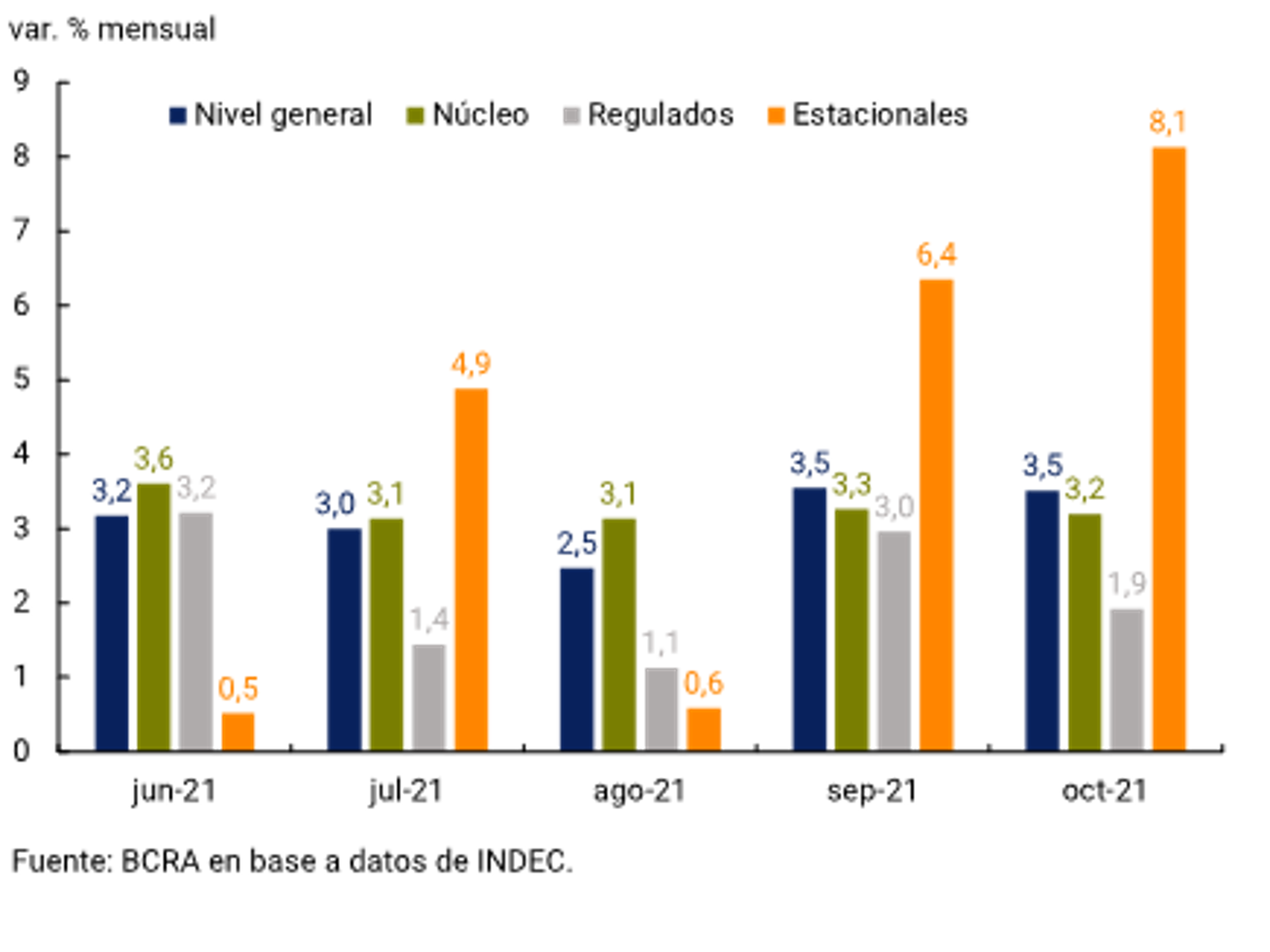

6. Pricing

Average monthly retail inflation in the third quarter was 3%, reducing in relation to the previous quarter, in a period with limited variations in the nominal exchange rate and a policy of containment of public service rates by the National Government. However, after the gradual deceleration of inflation that was evident from April to August, the records for September and October amounted to 3.5% and accumulated 52.1% in 12 months. Core inflation, that is, that which discounts the effects of seasonal and regulated prices, remained close to 3.2% since July, manifesting an inertia that still remains at high levels.

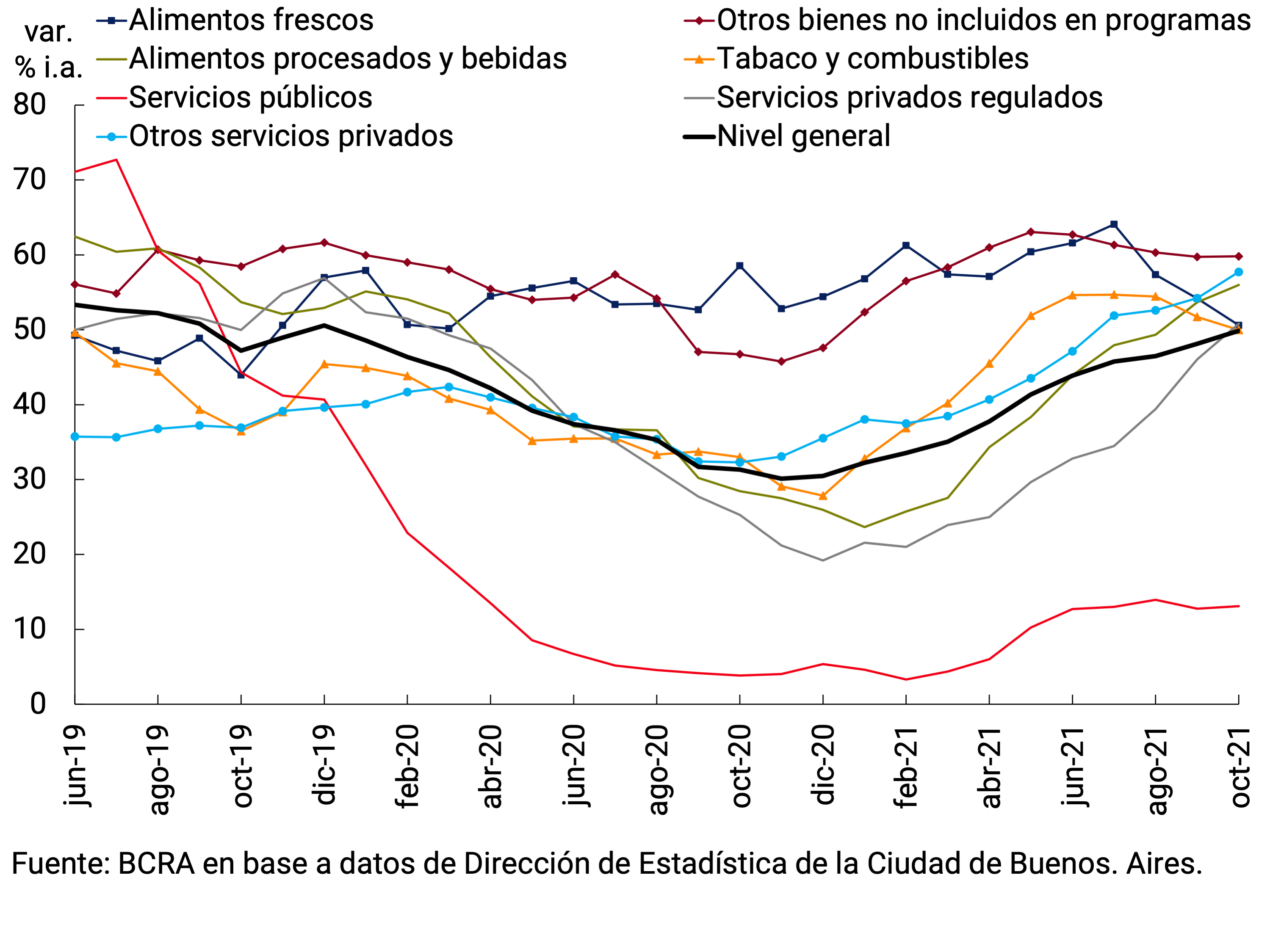

In recent months, transitory factors qualitatively anticipated in previous versions of the IPOM have had a greater impact than expected. Within core inflation, the prices of services increased at a faster rate than those of goods, after their relative price deteriorated steadily since the first quarter of 2019. In line with what was anticipated in the previous IPOM, this performance was due to the recovery of the demand for private services in the face of the reopening of activities within the framework of the improvement in the epidemiological situation and, to a lesser extent, to the updates of the wage parity agreements. In the same vein, international prices had an impact – based on the higher costs of global manufacturing and lately on energy prices – supply restrictions on some products, the observed recomposition of marketing margins in certain sectors and higher inflation expectations in a context of greater financial volatility.

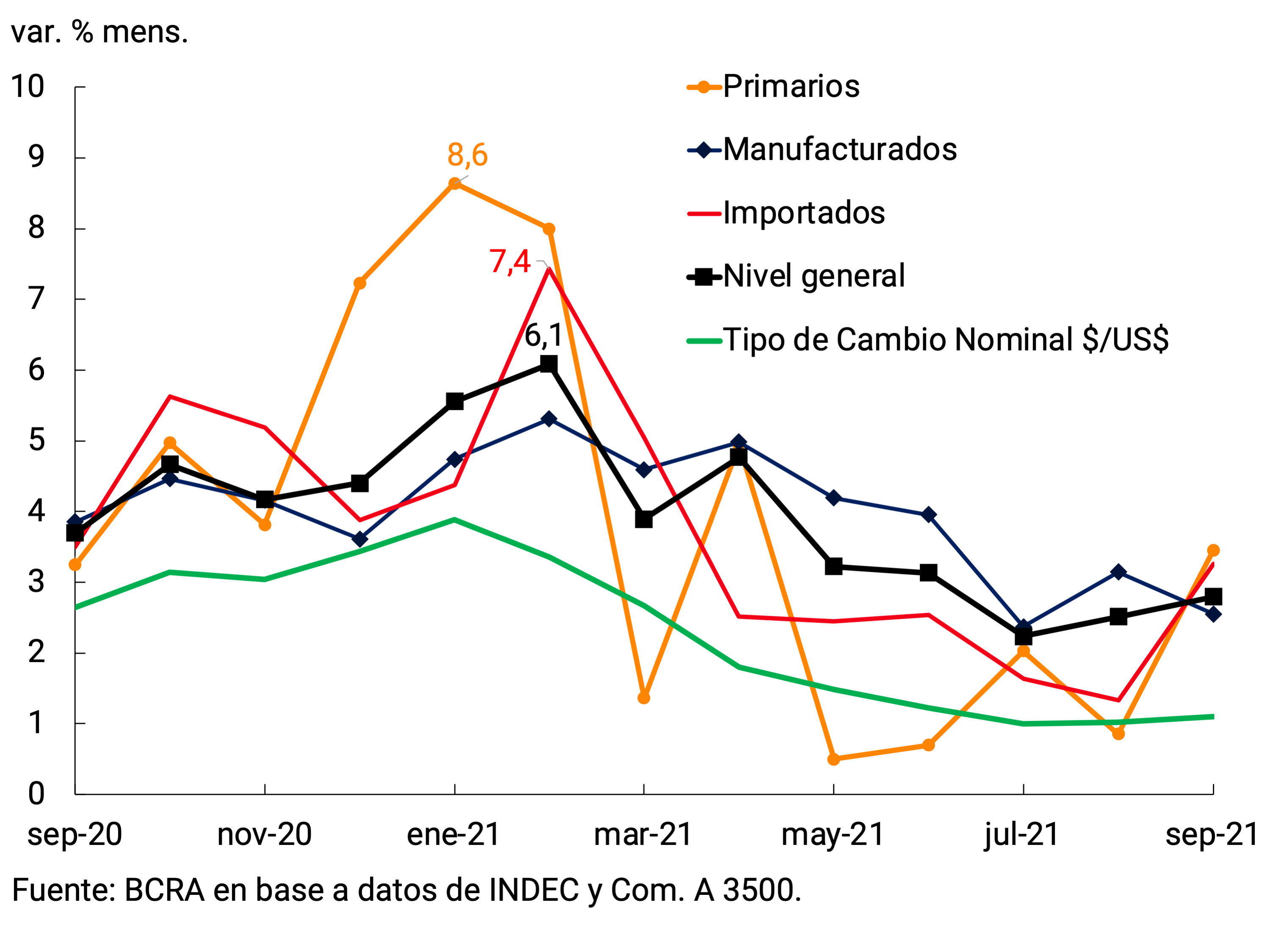

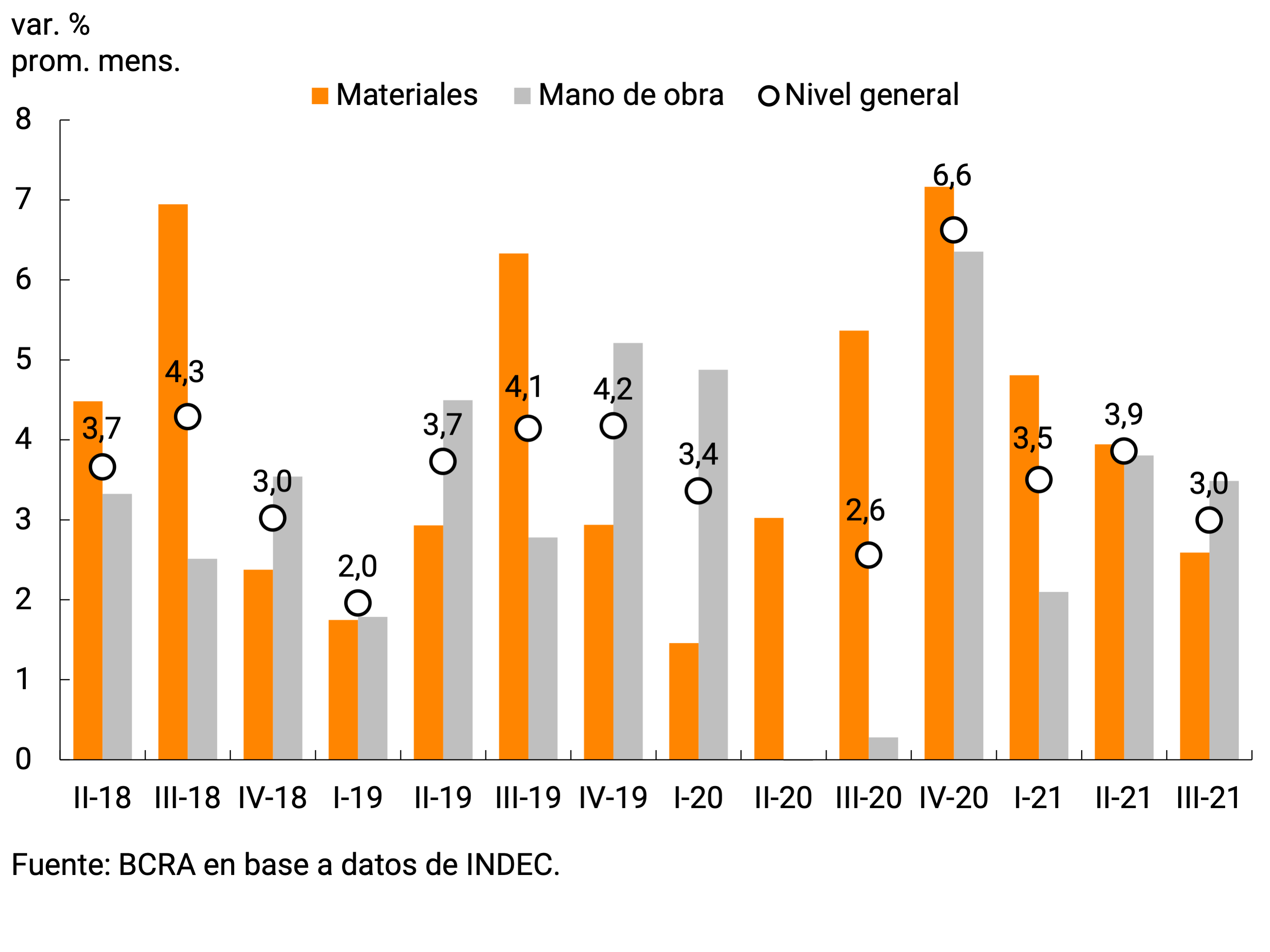

Wholesale prices reversed their slowdown trend in August, although monthly variations during the third quarter remained on average at lower levels than those of the previous quarter, especially in manufactured goods. The Domestic Wholesale Price Index (IPIM) and the materials that make up the Construction Cost Index (CCI) increased at a slower rate than that of retail goods, although higher than that evidenced by the exchange rate, partly influenced by international prices.

Going forward, the BCRA will direct its efforts to promote a macroeconomic environment with lower inflation levels than those currently observed, without damaging the economic recovery underway. The maximum price setting program, for a representative set of mass consumption products launched in mid-October by the National Government, would contribute in the same sense during the last months of the year. In the remainder of 2021, monthly inflation rates are expected to oscillate around the average recorded in the third quarter while, due to the base effect of comparison, year-on-year rates would begin to decline only towards the end of the year.

6.1. Inflation fell in the third quarter and increased since September

During the third quarter of 2021, retail prices registered an average monthly increase of 3.0%, slowing down 0.5 p.p. compared to the previous period (see Figure 6.1). Quarterly inflation was the lowest since the third quarter of 2020, being one of the lowest records in the last three years. After the trend of gradual reduction in inflation that was evident from April to August, the records for September and October rose and stood at 3.5%.

The slower rate of increase in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in the third quarter was mainly explained by the slowdown in the Core category (3.2% monthly average, -0.7 p.p. compared to II-21) and, to a lesser extent, by the Regulated category (1.8%, -1.7 p.p.), favored by the containment of public service rates. The Seasonal category (3.9%, +2.5 p.p.) accelerated, as is usually the case in the same period each year, mainly due to the higher rate of increase in the prices of tourism-related services and also of fruit and vegetables (see Graph 6.2, see Section 5/ Seasonal prices and their influence on the volatility of monthly inflation).

The reduction in inflation in the third quarter was a consequence of the slowdown in goods (3.0% monthly average, -0.9 p.p. compared to II-21), in a context of limited variations in the exchange rate. At the divisional level, Food and non-alcoholic beverages (2.6% monthly average, -0.9 p.p. compared to II-21) was the one with the greatest contribution to the reduction in the rate of increase in goods. The slowdown in Clothing and footwear also had a lesser impact (3.5% monthly average, -0.3 p.p. compared to II-21). On the other hand, the Alcoholic Beverages and Tobacco division (3.7%, +0.1 p.p. compared to II-21) accelerated slightly.

The slowdown in Food and beverages was seen in both packaged and fresh products, although the recovery in the relative prices of processed products continued after the update of the price agreement programmes. The more limited rate of increase in fresh foods was explained by the evolution of meats and their derivatives, which offset the higher records of vegetables and fruits. In fact, retail beef prices sharply cut their rate of expansion for the third consecutive quarter, averaging a monthly variation of 1% in the quarter (-3.3 p.p. compared to II-21), contributing significantly to the reduction of core inflation. In September and early October, the prices of packaged foods accelerated and, in this context, the National Government launched the maximum price program on a set of 1,432 products of mass consumption41.

On the other hand, the prices of services (3.0% monthly average, +0.4 p.p. compared to II-21) accelerated during the third quarter and grew at a slightly faster rate than that of goods. This performance, in line with what was anticipated in the previous IPOM, was mainly due to the recovery of demand for private services, which are mainly part of the Core category of the CPI, driven by the reopening of activities in the face of the improvement in the epidemiological situation. To a lesser extent, the updates of the wage parity agreements that took place in the third quarter would also have helped to explain the higher rate of increase in services. The divisions that contributed the most to the acceleration were Restaurants and hotels (3.9% monthly average, +0.3 p.p. compared to II-21) and Recreation and culture (3.5%, +1.2 p.p.; see Figure 6.3).

Figure 6.3 | CPI Core disaggregated. Average monthly change by quarter and contributions by selected components

The prices of tourist services that make up the Seasonal category – accommodation, transportation, packages and excursions – generally increase their rate of increase in the third quarter of each year due to the winter recess. In 2021, the acceleration would have been greater due to the recovery in demand driven by the reduction of restrictions and by the stimulus plan for the sector launched by the National Government (Previaje).