Financial Stability

Financial Stability Report

First half

2020

This semi-annual report presents recent developments and prospects for financial stability in Argentina.

Table of Contents

Chapters

Sections

- Section 1 / Prudential approach to the COVID-19 shock by Central Banks and Supervisory Bodies

- Section 2 / COVID-19 and challenges to global financial stability

- Section 3 / Policy actions to restore public debt sustainability in Argentina

- Section 4 / Main measures taken by the BCRA to mitigate the economic impact of COVID-19 on companies and families

- Section 5 / Progress in the financial reporting criteria applied to Argentine banks

- Section 6 / Technology and security challenges and risks faced by financial institutions in the context of COVID-19

Summary

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the sanitary measures taken to contain it, since February 2020 an unprecedented and particularly challenging operational context for the Argentine financial system has been materializing. In this adverse context, the set of financial institutions continued to show a significant degree of resilience which, together with the policy actions implemented, made it possible to preserve the conditions of financial stability. In particular, the financial system continued to operate without disruption both in terms of financial intermediation and the provision of means of payment, maintaining large liquidity and solvency margins, above the requirements set by local regulation, with a prudential regulatory framework in line with international standards.

The shock of the pandemic occurred in a scenario in which the Argentine economy was already conditioned by a recessionary process that began in mid-2018, high inflation levels and unsustainable public debt. As of December 2019, a set of policies with new priorities was implemented, seeking to stabilize the economy, including fiscal, debt, foreign exchange market and monetary policy dimensions, among others. The BCRA sharply reduced monetary policy interest rates and introduced incentives to improve access to financing for companies (especially MSMEs) and households. Starting in March, it was complemented with specific actions to mitigate the economic and financial effects of the pandemic, aimed at stimulating savings in national currency, alleviating the financial situation of the private sector, shoring up the payment chain and avoiding a pro-cyclical credit dynamic, always seeking to maintain the soundness of the financial system. Progress was made with different lines of action to recover the sustainability of the debt and new modifications were introduced for access to the foreign exchange market.

Accompanying the dynamics of economic activity, financial intermediation continued to show a relatively weak performance since the last IEF. In response to the measures implemented more recently, there is a certain rebound in credit, especially in commercial lines in pesos. The indicator of irregularity of the loan portfolio continued to increase at the end of 2019 and the beginning of this year. This dynamic is explained by the business segment, as households were observing better credit performance. This occurs in a context of limited exposure to credit risk in the financial system, diversified portfolios and high coverage with forecasts. In this context, at the end of the first quarter, it is estimated that the possible capital impact on the financial system of a hypothetical and unlikely scenario of non-recovery of debtors in an irregular situation would be shallow/significant.

The funding of the financial system, mainly composed of deposits, has shown less pressure in recent months. Private sector deposits in pesos increased their relevance in funding – led by demand accounts – while those in foreign currency continued to decline, but at a much slower rate than that evidenced in the last months of 2019. Depending on the dynamics of deposits and credit, the liquidity ratios of the financial system increased. This was accompanied by an increase in the regulatory indicators of solvency of the financial system, which are complemented by reduced leverage. In the current context, the financial system posted positive results in homogeneous currency in the first quarter of 2020.

The sources of vulnerability of the aggregate of financial institutions remain relatively limited. It is a shallow financial system, which still carries out traditional intermediation, largely of a transactional type, and with a moderate degree of interconnection between entities. In a context where households and companies show low levels of debt in aggregate terms, the financial system maintains a low equity exposure to credit risk. Existing macroprudential regulations limit both the possibility of currency mismatches and exposure to the public sector. With respect to this last factor, and within the framework of the different types of actions implemented to recover debt sustainability, it should be noted that the limited exposure to the public sector is largely made up of instruments in local currency, a segment where exchanges have been carried out with good acceptance. The implementation of social isolation measures, including the use of teleworking and greater use of virtual banking, leads to the financial system being more exposed to certain types of disruptive events, although of low probability. Based on the relative strength factors shown by the aggregate of financial institutions, the eventual materialization of risks such as those mentioned should take extreme values so that the conditions of local financial stability are affected.

It is estimated that the context would remain challenging for the financial system in the coming months, as the pandemic is still an ongoing phenomenon. Although health measures are expected to be gradually relaxed, it remains to be seen how long, intense and widespread the effect of COVID-19 will be on the evolution of the Argentine economy, while the possibility of a resurgence of tensions in international markets (which could generate greater volatility in local markets) is not ruled out. In this context, the BCRA has been strengthening monitoring processes, while continuing to implement measures if necessary within the current macroprudential policy approach in order to promote the stability of the financial system.

Financial System Stability Analysis

1. Context

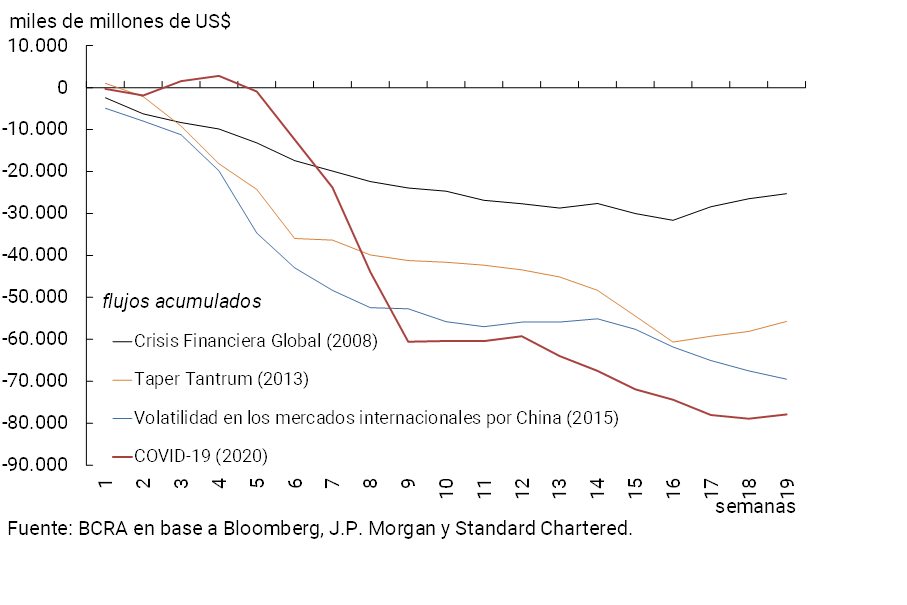

The COVID-19 pandemic, together with the health prevention measures that had to be applied, have shaped an unprecedented shock since February, with a strong impact on global growth expectations and on commodity prices. The growing uncertainty had a rapid and marked impact on financial markets, with volatility peaks not seen since the global crisis of 2008-2009 (see Chart 1). Significant portfolio reallocations were verified, with a particularly adverse effect on emerging economy instruments (equities, debt instruments, and currencies). Given the policy responses implemented so far to mitigate the effects of the pandemic (see Section 1), since April the global financial markets tended to limit their deterioration and no episodes of systemic disruption were observed, although the context remains challenging (see Section 2).

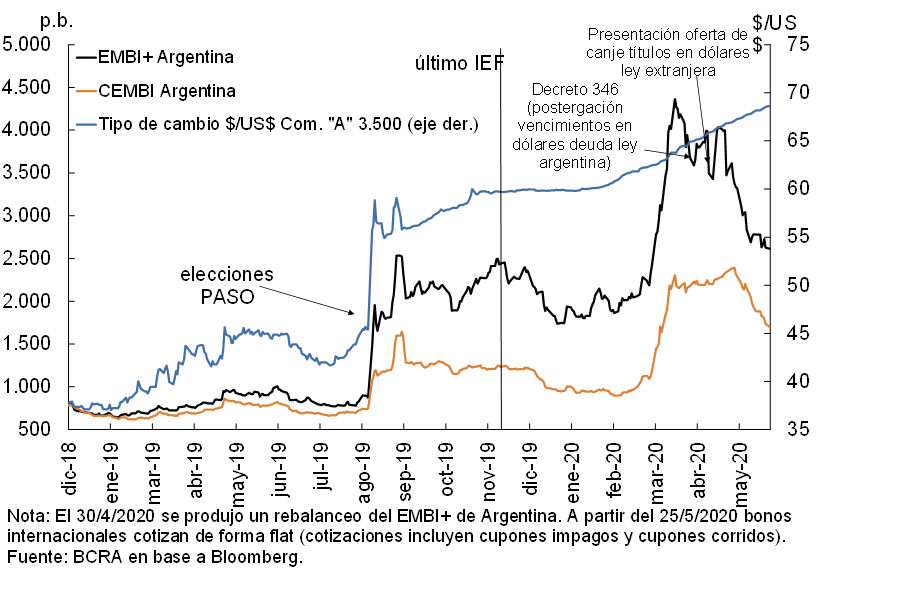

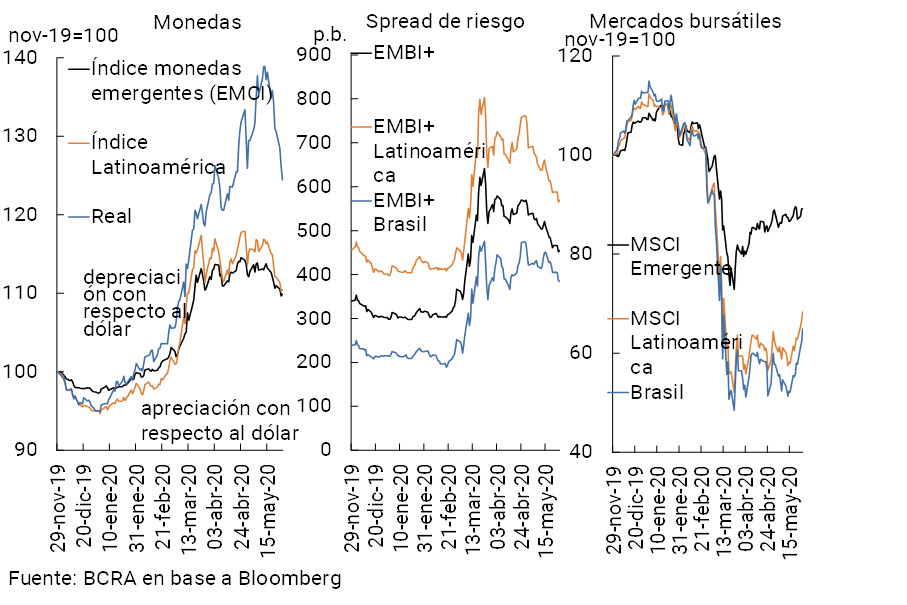

In Argentina, this scenario of tension implied the aggravation of an already vulnerable economic and social situation, given the presence of a recessionary process that began in 2018, still high inflationary records, a shortage of foreign currency and public debt at unsustainable levels, among other factors1. This deterioration of the macroeconomic scenario had already been configuring a volatile behavior in certain variables of the financial markets (see Chart 2). As will be seen throughout this report, despite this adverse context, the financial system continued to show an adequate degree of resilience, maintaining the conditions of financial stability.

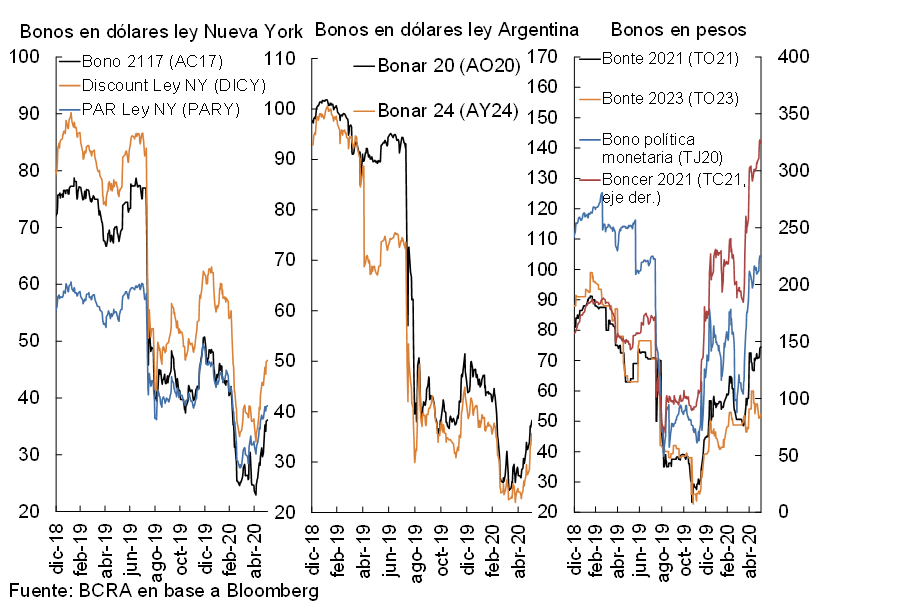

After the publication of the last IEF (Nov-19), since the end of last year this situation of local vulnerability was addressed with a new set of economic policy priorities. In this context, at the end of 2019, the Law of Social Solidarity and Productive Reactivation was sanctioned, which included, among others, measures on the exchange market, the fiscal front and on public debt. This was complemented by new monetary policy guidelines from the BCRA, including a sustained reduction in reference interest rates and new incentives to improve the conditions of access to financing for companies, with emphasis on MSMEs. Since mid-March, additional actions have been implemented to temper the effects of the adverse shock implied by COVID-19. On the other hand, progress was made in a comprehensive strategy to recover the sustainability of public debt, including the launch of an exchange for public securities issued under foreign law2 and the implementation of various swaps in the local market (see Section 3), which influenced the evolution of prices and yields in the debt markets (see Graph 3). More recently, modifications were implemented in the regulatory framework applicable to the foreign exchange market3.

2. Main strengths of the financial system in the face of the risks faced

The financial system continued to perform its intermediation and payment service provision functions in a particularly challenging operational context. Faced with this scenario, the BCRA sought to mitigate the adverse effects by adapting the operation of the sector to social, preventive and mandatory isolation (ASPO), designing and implementing a broad set of measures aimed at stimulating savings in national currency, boosting credit and alleviating the financial situation of companies and families (see Section 4).

The group of financial institutions maintained signs of strength in the first quarter of the year, within a prudential regulatory framework in line with international standards. High margins of liquidity, capital and forecasts were preserved, with moderate exposures to the risks inherent to banking operations, in a context of reduced credit depth in the economy. Financial institutions continue to carry out mainly unsophisticated traditional intermediation operations, with limited transformation of terms and low direct interconnection between them. Equity mismatches in the financial system remain at low levels. The main strengths of the sector are presented in an overview below, which will be addressed in greater detail in the following sections when assessing potential vulnerabilities.

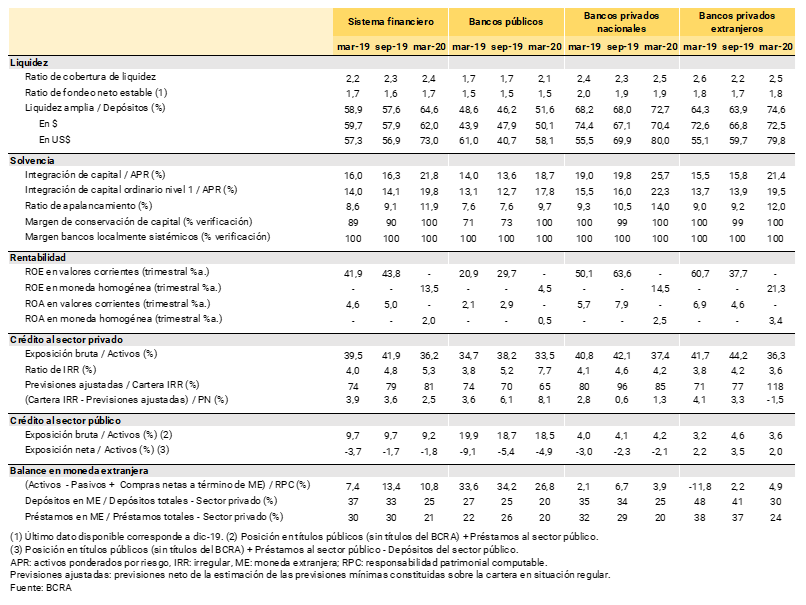

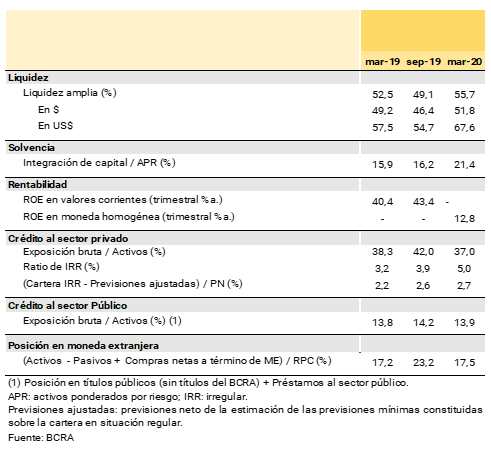

i. Large aggregate liquidity and solvency margins. The set of financial institutions maintains high levels of liquidity when compared to their own history. At the end of the first quarter of 2020, liquidity in the broad sense (considering items in domestic and foreign currency) reached 64.6% of total deposits, increasing compared to the last IEF and in a year-on-year comparison (see Table 1). Moreover, in terms of internationally recommended regulatory standards, the liquidity ratios of the financial system far exceed local requirements, as well as the values observed in other economies (see Chart 4).

Aggregate capital integration (RPC) represented 21.8% of risk-weighted assets (RWA) in March 2020, expanding in the last six months and compared to March 2019. Local financial institutions observe low levels of relative leverage, while, in aggregate, they fully verify the additional capital margins established in local regulations. Moreover, despite the relatively adverse operating framework, in the first quarter of the year the financial system recorded positive results measured in homogeneous currency.

ii. Progress in the implementation of international accounting and financial reporting standards. The local financial system remains in line with the best internationally recommended standards in this area. Since 2020, financial institutions must present financial statements in homogeneous currency in accordance with International Accounting Standard (IAS) 29 and consider the provisions on impairment of financial assets contained in International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) 9 (see Section 5).

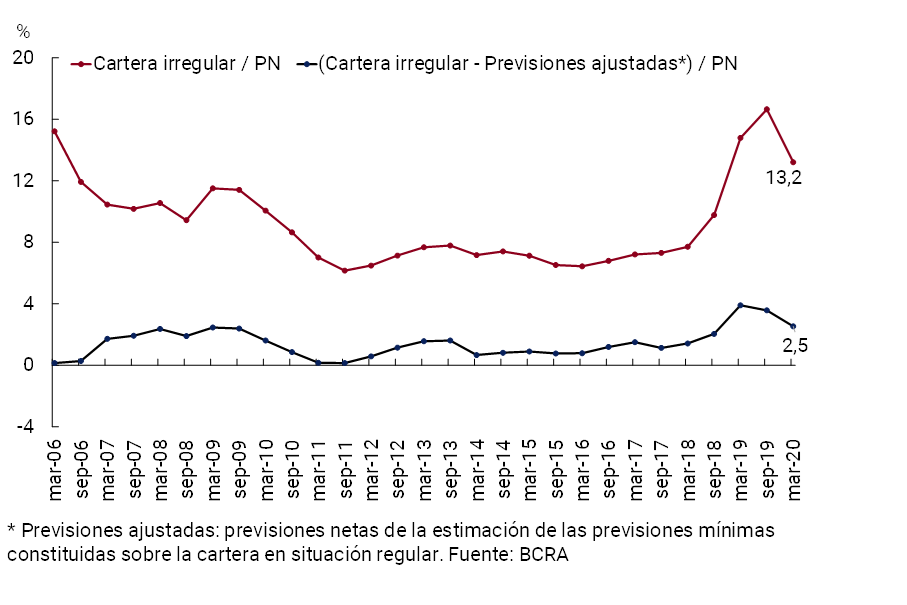

iii. High forecasting of the portfolio in an irregular situation, combined with moderate and decreasing exposure to credit risk. Although there is a growth in non-performing loans, it is estimated that the level of coverage with forecasts of the portfolio of financing in an irregular situation of the financial system remained high, in the order of 81% as of March 2020 (see Table 1). In this context, the equity exposure of all financial institutions to credit risk (irregular portfolio net of forecasts attributable to this portfolio) remained relatively low, at around 2.5% of equity. Moreover, at the beginning of 2020, the system’s private sector loan portfolio maintained relatively low levels of concentration, similar to the average of recent years4.

iv. Low exposure to the consolidated public sector. At the end of the first quarter of the year, financing to the public sector represented 9.2% of the total assets of the financial system. The balance of deposits in the public sector continues to exceed the financing of the aggregate of financial institutions to the public sector.

v. Moderate term and currency mismatches, and low weighting of assets and liabilities in foreign currency. Assets in foreign currency represented 22.7% of the total assets of the financial system in March 2020, while liabilities in the same denomination totaled 21.4% of total funding (liabilities and equity). All financial institutions and their debtors maintained low foreign currency mismatches on their balance sheets, reflecting the effects of local macroprudential regulations. On the other hand, the financial system preserves a limited transformation of terms, concentrating mainly on transactional operations. In a context of lower financial intermediation with the private sector, the estimated duration of the financial system’s investment portfolio in national currency fell in the latter part of 2019 (December last available information), reducing the difference between the durations of the active and passive portfolios.

vi. Local financial institutions have not requested financial assistance from the BCRA to face the shock of COVID-19. In the context of the outbreak of the pandemic, the BCRA and the SEFyC have reinforced their monitoring of the performance of financial institutions (both on their main financial indicators and on their operational activities), anticipating possible measures to deal with situations of greater tension.

The characteristics mentioned above would provide an adequate degree of solidity to the balance sheet of all financial institutions. In a challenging operational context, the system is expected to remain resilient in the face of the eventual materialization of stress factors in the coming months. In the context of the financial stability assessment, the main risk factors (exogenous to the system) to be taken into account are:

i. Possibility of a greater deterioration in economic activity than currently expected. While the recession that the Argentine economy is going through was exacerbated by the pandemic, according to the latest measurement of the REM, the impact of COVID-19 is expected to be transitory and mostly concentrated in the second quarter of the year, with a gradual recovery starting in the third quarter5. However, it is not yet clear what the duration and intensity of the shock will be, both in terms of the trade channel (depending on the effect of the pandemic at the global level) and the financial channel (the possibility of aggravation of tensions in international financial markets, influencing exchange rates and interest rates)6. Added to this is the direct impact of social isolation measures on the level of local economic activity. It is expected that these measures will continue to be relaxed progressively and with different speeds between regions and economic segments, although there is a risk that a resurgence of COVID-19 infections will be observed that will slow down the planned process of gradual opening. Another important effect, linked to the pandemic, is given by the precautionary behavior of families and companies in their consumption and investment decisions. Thus, although various financial stimulus and relief policies have been implemented at the local level (and the launch of new initiatives is not ruled out), to the extent that economic activity takes longer to recover, this could directly condition the financial intermediation process (which had already been showing a weak dynamic), potentially reflecting both the supply and demand of credit and the sources of income of financial institutions. Although special emphasis is being placed on alleviating the financial situation of the private sector and shoring up the payment chain, an eventual economic deterioration greater than expected could affect its ability to pay, which had already been showing a weakening since mid-2018 (see Section 3.2).

ii. Possible resurgence of volatility in local financial markets. In line with what was mentioned in the previous point, although the conditions of the international financial markets tended to recover from April onwards, vulnerability factors persist and doubts about a potential decoupling with respect to the latent conditions in the real economy, so the possibility of new episodes of financial stress at the global level could not be ruled out (second-round effects, with adjustments in the appetite for risk assets). In addition, there could eventually be greater volatility in the markets linked to local factors. Although foreign exchange market regulations have made it possible to limit its volatility, new episodes of tension could influence the exchange rate and local interest rates, affecting the environment in which financial intermediation takes place and the credit risk faced by financial institutions.

iii. Potential impact of the increase in operational risk in the context of the pandemic. Given the preventive measures implemented to address the pandemic (restrictions on mobility, teleworking with remote access to information, greater use of digital channels, etc.), the financial system faces significant challenges in terms of increased exposure to operational risks (disruptive events with a low probability of occurrence that could affect the continuity in the provision of intermediation and payment services). Exposure to these risks, in particular, those associated with fraud or cybersecurity attacks, has grown in recent times mainly due to the system’s greater dependence on technological infrastructure. The current context defined by the pandemic has accentuated this phenomenon. The actions carried out by the BCRA are highlighted, as well as the internal policies of the entities that aim to address and mitigate the aforementioned risk (see Section 6).

With regard to the medium-term challenges, once the tensions generated by the pandemic have been overcome, it remains to be seen what the lasting effects of the pandemic (and of the government measures taken so far) will be on economic and financial activity worldwide, and on emerging countries in particular. The subsequent effects of the stimuli implemented in recent months (extension of the scenario of low interest rates in international markets) and, depending on the challenges observed, the possible existence of additional changes in business models, risk management and regulatory frameworks should be evaluated.

The next section provides an analysis of the sources of vulnerability identified for the Argentine financial system, given its exposure to the risk factors mentioned above. In each case, those more specific elements of strengths that the financial system possesses will be identified, which would allow it to deal with an eventual materialization of adverse scenarios. Finally, the macroprudential policy actions implemented in recent months will be detailed, with a focus on strengthening financial stability conditions in the current situation.

3. Vulnerabilities and specific resilience factors of the financial system

3.1 Performance of financial intermediation.

In line with the dynamics of economic activity (see Section 1)7, the financial intermediation of all financial institutions with the private sector has been showing a relatively weak performance. Since the end of 2019, and in particular since COVID-19, the BCRA has implemented a set of policy actions aimed at stimulating savings and credit in pesos by companies and households (see Section 4). As a result, there was a rebound in the real balance of credit since the end of March and the beginning of April, mainly in commercial lines. This behavior is highlighted at the margin, while the measures implemented by the BCRA seek to avoid the deepening of a procyclical credit dynamic that would eventually impact debtors and aggregate economic activity, with an impact on financial stability conditions.

The balance of credit to the private sector in national currency increased 1.9% in real terms between the end of the first quarter of 2020 and last September – the time of publication of the last IEF – (-8.1% YoY), while loans in foreign currency fell 32.5% in the same period (-42.6% YoY) – in the currency of origin. However, from mid-March – the beginning of the BCRA’s measures within the framework of the ASPO – and until the end of May, total credit to the private sector in pesos increased by about 17% nominally, especially for commercial lines that expanded 40% in the same period.

In this context, total credit to the private sector – both in domestic and foreign currency – measured in terms of GDP, remained at historically low relative levels (see Chart 5), declining slightly in the first quarter of 2020 compared to the third and first quarters of the previous year. In this scenario, it is estimated that the level of this indicator accumulates a reduction of close to 3 p.p. since the end of 2018. It should be considered that this evolution does not yet incorporate the full effect of the measures taken by the BCRA in the face of the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

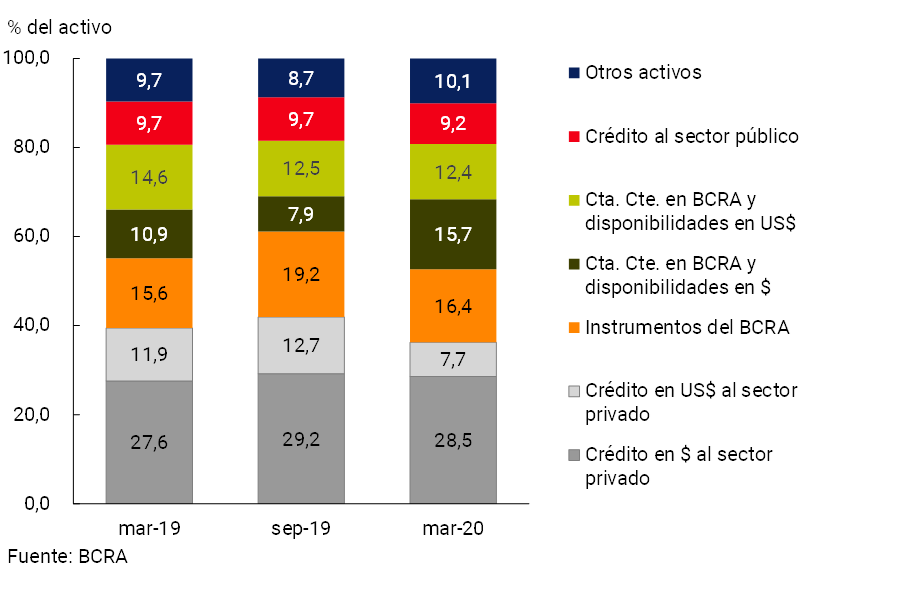

An analysis of the balance sheet of the financial system shows that credit to the private sector has reduced its weighting in total assets in recent quarters (see Chart 6), reaching a 12-year low (15 p.p. less than the recent peak at the end of 2017). Given the performance of the private sector’s deposits in pesos (see Section 3.3), the real increase observed in the sector’s assets in the last six months (+4.1%) was mainly based on the increase in the most liquid items in national currency (current account at the BCRA and other availabilities). As a result, the more liquid components increased their relevance in total assets compared to IEF II-19. In addition, monetary regulation instruments decreased their participation in the assets of the financial system in the same period.

In the context of the possible materialisation of the exogenous risks set out in the previous section, a relatively weaker behaviour of the financial intermediation process could have some impact on the sector’s traditional sources of profitability, such as net interest income and service results. It should be noted that the profitability in real terms of the financial system was at positive levels in the first quarter of the year, while relatively comfortable levels of solvency are maintained, as detailed below.

3.1.1 Specific elements of resilience

Reduced leverage of the financial system and high levels of regulatory solvency ratios. The leverage of all financial institutions continued to be limited in the first quarter of 2020, ranking among the lowest when compared to the countries of the region, and to other emerging and developed economies (see Chart 7). As of March, the ratio of total assets to net worth in the local financial system fell 1.4 and 2.4 times from the level recorded in the previous IEF and in a year-on-year comparison, respectively.

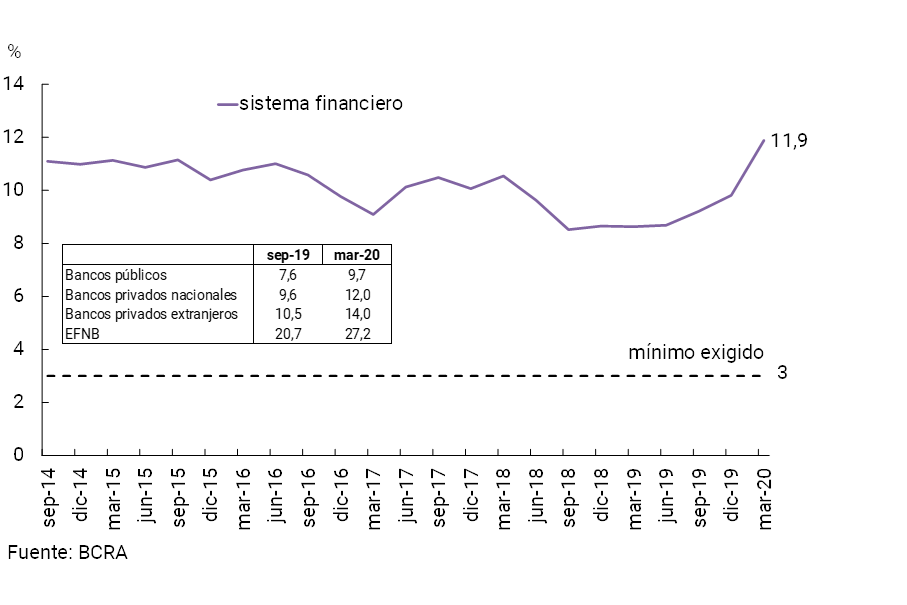

When considering the leverage ratio recommended by the Basel Committee—defined as the ratio between the highest quality regulatory capital and a broad measure of exposures—the local financial system sees increasing levels of slack with respect to the minimum threshold required (see Chart 8), positioning it appropriately in an international comparison (see Chart 4). This is an indicator of the strength of the sector, as well as the absence of limitations in terms of capital availability to resume a process of expansion of financing for investment and consumption in the face of a scenario of economic recovery.

Figure 8 | Basel leverage ratio

The capital integration of all financial institutions stood at 21.8% of risk-weighted assets (RWA) at the end of the first quarter, growing 5.5 p.p. compared to last September. In March, a large excess of regulatory capital continued to be observed above what was required by regulations, which reached 153% of the requirement (66 p.p. higher than the record of 6 months ago). Moreover, Tier 1 capital comprises more than 90% of total capital integration8. For their part, as of March, financial institutions observed a 100% verification of capital conservation margins (including the additional for systemic entities at the local level)

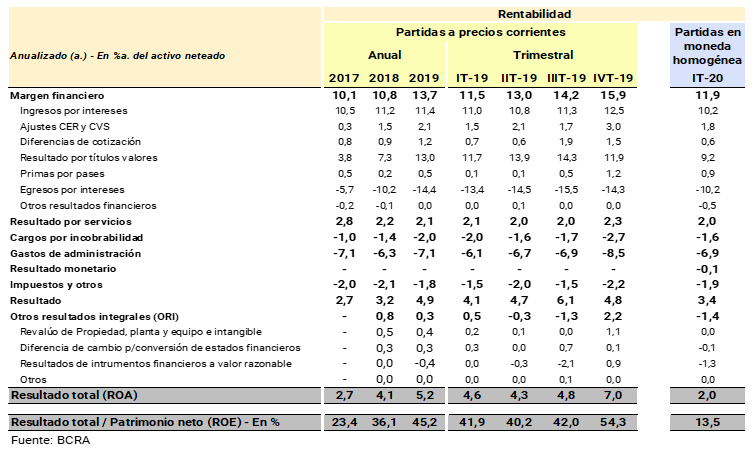

Positive aggregate real profitability indicators in the first quarter of 2020. The financial system closed the first quarter of the year with annualized accounting profits (a.) – measured in homogeneous currency – equivalent to 2% of assets (ROA) and 13.5% of equity (ROE) (see Table 2). Within the framework of the improvements introduced in the financial reporting criteria, certain indicators, such as profitability, are not directly comparable with those of previous periods (which were not expressed in homogeneous currency, see Section 5).

In this regard, the financial margin of all financial institutions reached 11.9% of assets in the first quarter of the year. Interest income from loans was the concept that contributed the most to the financial margin in this period, followed by those from securities, while interest expenses on deposits explained the main expenditures of this segment of the income statement. Services results were another positive component for the financial system, totaling 2% of assets in the first 3 months of the year. Among expenses, bad charges stood at 1.6% of assets in the first quarter, while administrative expenses reached 6.9%. The financial system recorded quarterly losses in “Other Comprehensive Income” (ORI) in the order of 1.4% y/y of assets, and monetary results —which include the effect of the adjustment for inflation— negative for the equivalent of 0.1% y/y of assets in the same period.

Given the performance of economic activity anticipated by the REM for the remainder of the year, a scenario that is partly tempered by the policy actions taken by the PEN in conjunction with the BCRA – which are beginning to be reflected in greater financial intermediation – no negative profitability levels are expected for the sector in the cumulative 2020.

Risk-oriented supervision. The SEFyC continues to carry out specific monitoring focused on identifying and addressing the eventual occurrence of special situations of vulnerability in the current most challenging context. From a macroprudential perspective, the appropriate indicators of the soundness of systemically important institutions should be highlighted (see Section 4 for more detail).

3.2 Loan portfolio performance

The quality of the financial system’s loan portfolio has deteriorated moderately since the publication of the last IEF, mainly due to the corporate financing segment, as loans to households showed a reduction in their non-performing loans (see Chart 9). The non-performing ratio of credit to the private sector reached 5.3% as of March, increasing 0.5 p.p. compared to September 2019 and 1.3 p.p. y.o.y. The performance of the irregularity was tempered in part by the modification in the debtor classification parameters ordered by the BCRA at the end of March, a measure that is part of a broader set of instruments implemented to mitigate the economic and financial impact of the pandemic on families and companies. 9

Figure 9 | Irregularity of credit to the private

sector

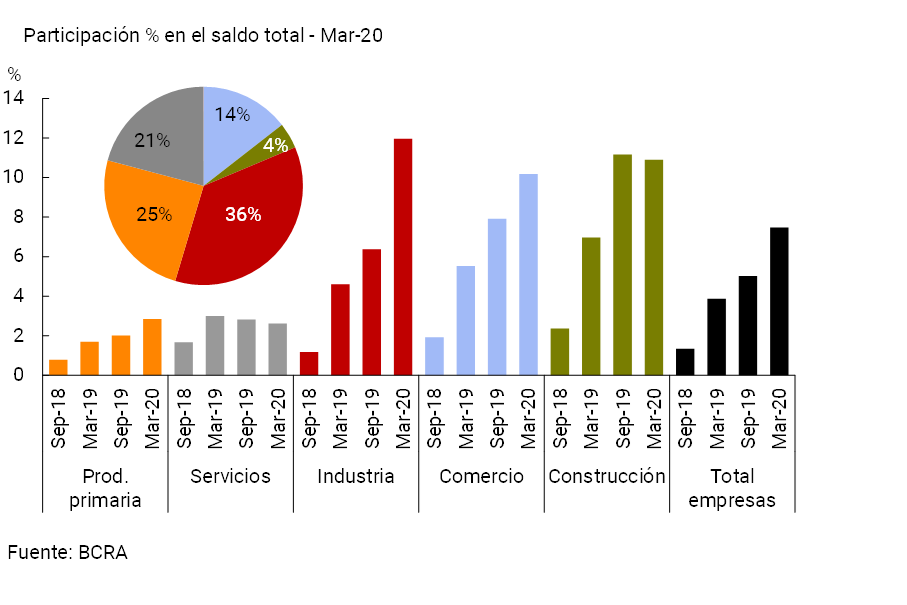

Irregular financing / Total financing (%) – Sistema Financiero

The increase in the irregularity ratio of credit to companies between September 2019 and March 2020 was mainly explained by the financing segment for industry10, and to a lesser extent, by credit to the commercial sector and primary production (see Chart 10). On the other hand, the decrease in the non-performing ratio of loans to households recorded in the last six months – a path of reduction that was observed before the modification in the parameters for the classification of debtors – was mainly due to the performance of the consumption lines. Among loans to households, mortgage loans continue to have a low delinquency rate (irregularity ratio of 0.49% for the UVA segment and 0.63% for the rest).

Figure 10 | Irregularity of credit to companies by activity

Irregular financing / Total financing – Financial system

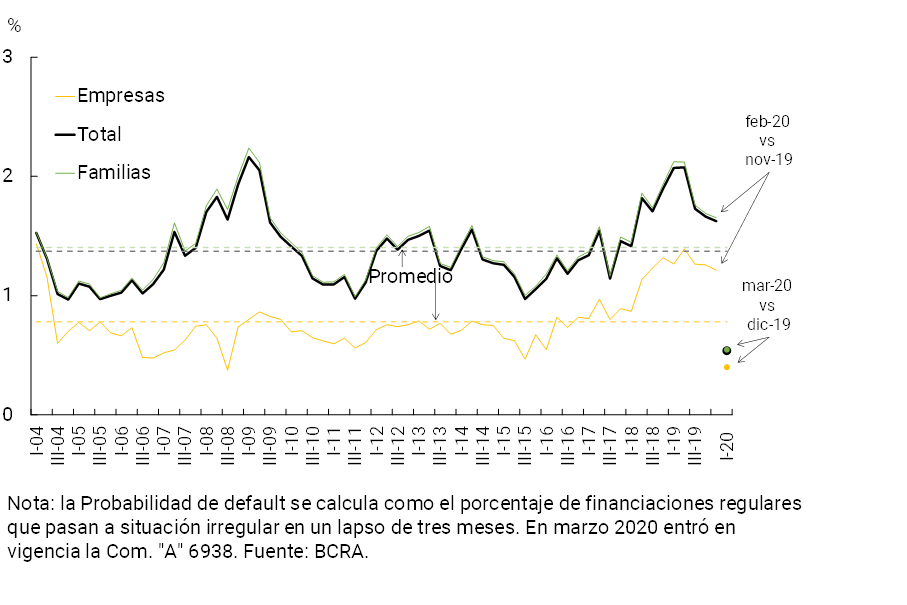

The indicators designed to capture the movement of debtors towards worse credit situations11 were reduced in March of this year, within the framework of the entry into force of the modification in the debtor classification parameters (see Graph 11). Prior to such modification, at the beginning of 2020 this indicator was at high levels, although lower than the peaks of the end of 2018.

Figure 11 | Estimated probability of default (EDP) – Amount of financing

Credit to the private sector

Going forward, some path of increase in credit delinquencies could be expected, as aggregate economic activity gradually transitions to normal after the shock. Although the persistence of this situation could eventually affect some profitability indicators, the financial system presents the following pillars of resilience that would allow it to address this scenario.

3.2.1 Specific elements of resilience

Low equity exposure to credit risk to the private sector. Credit to the private sector reduced its share of the total assets of the financial system compared to the previous IEF (see Section 3.1). In this context, the forecast remained high12, reaching almost 100% of the portfolio in an irregular situation in March. This level totaled 81% if the minimum regulatory forecasts for the portfolio in a regular situation are not computed13. The net irregular portfolio of the forecasts attributable to this portfolio in terms of the net worth of the financial system (an indicator of equity exposure to credit risk) stood at 2.5% in the first quarter of 2020, being a moderate level both from a historical point of view (see Chart 12), and with respect to other economies. The possible capital impact in the event of non-payment by debtors of the irregular portfolio remains low for the aggregate of financial institutions.

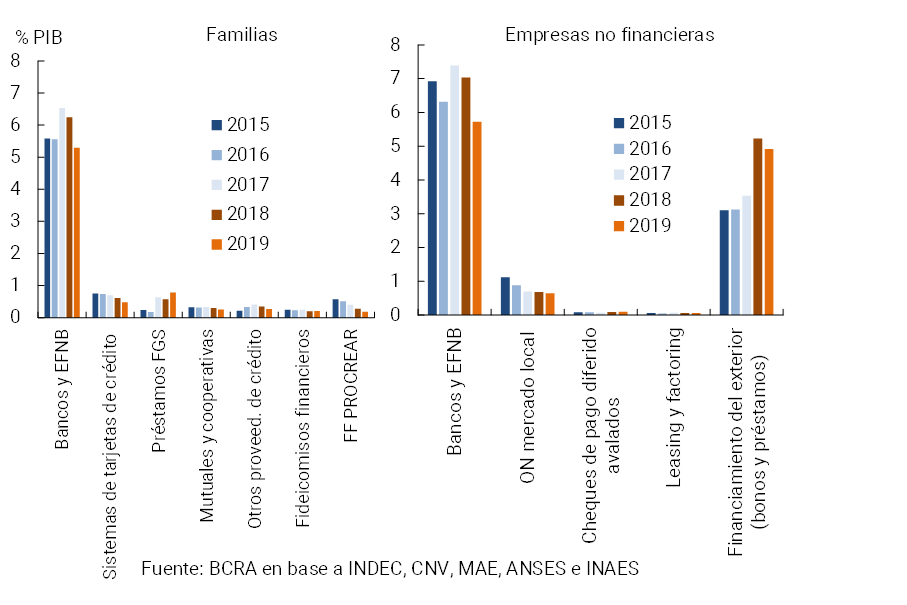

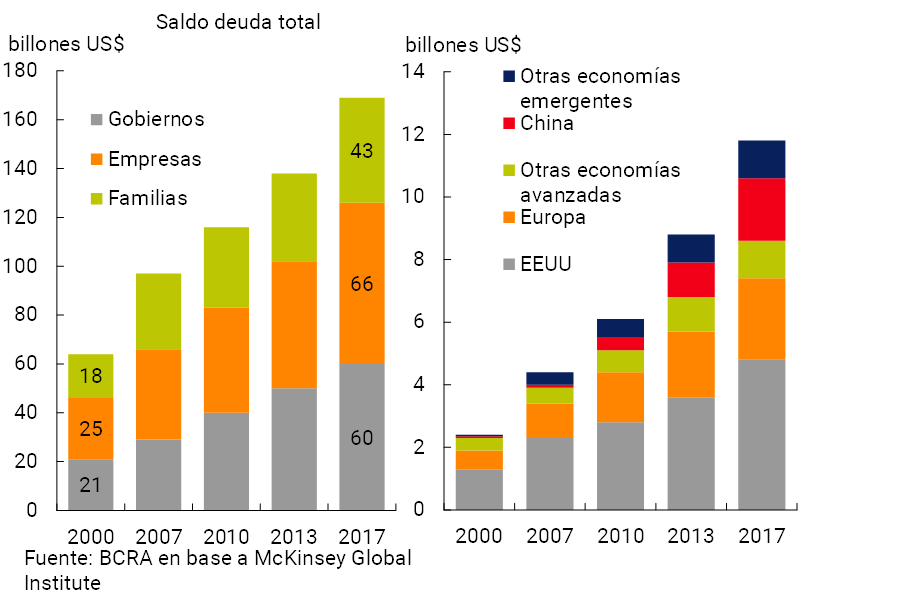

Limited levels of indebtedness and financial burden of the private sector. It is estimated that the balance of financing in the broadsense14 reached 7.5% of GDP for households and 11.5% of GDP for companies at the end of 2019 (see Figure 13)15. These levels are relatively low compared to what has been observed in other economies. In particular, it is estimated that the median household debt for some emerging economies was around 16.5% of GDP and for developed economies at 62.9% of GDP (see Chart 14).

In the case of financing to households in terms of GDP, there has been a downward trend in recent years in Argentina, while for companies there is no defined trend (balances linked to local sources tend to decrease as a percentage of GDP, while those from external sources increase as a function of the evolution of the exchange rate). The financial system is the main source of household financing (more than 70% of total estimated household debt), followed by FGS (10% of the total), non-bank credit card systems (6%), and other providers – large retail chains, financial companies – registered with the BCRA (4%)16. In line with what was recorded in the previous IEF, at the aggregate level the financial burden of household debt is in a range of moderate values.

On the other hand, of the financing of the aggregate of companies in the non-financial private sector, 57% comes basically from loans from all financial institutions (with a limited complementary role of capital market instruments17), while 43% is from foreign sources (bonds or loans). With respect to this last factor, the balance of ON in dollars (mostly with international legislation) is estimated as of March 2020 at approximately US$17,000 million (4% of GDP)18. This balance shows a significant concentration in a few companies (70% of the total is explained by 10 firms). Almost half of the balance of ON in dollars originates from companies in the oil and gas sector (with part of their revenues in foreign currency, although now impacted by the decline in commodity prices), followed by firms in the electricity sector. The rest are diversified into different sectors19.

In this context, it should be mentioned that the corporate sector has been facing an adverse economic context since 2018, with an impact on its financial situation. For example, considering the balance sheets filed with CNV of companies with a public offering20, in 2019 some deterioration was observed in the profitability, liquidity and interest coverage indicators with income in the median of the same, with no change in the level of leverage. Given the worsening of the recessionary scenario in 2020 due to the pandemic (see Section 1), some impact on the sector’s ability to pay would be expected21.

Diversification of the debtor portfolio of financial institutions. The concentration of the portfolio of private sector debtors in the financial system remains at moderate levels, even lower than those observed six months ago (the last IEF). In particular, the top 100 and 50 private sector debtors in the financial system aggregate represent 19.6% and 15.1% of the total credit balance, 1.5 p.p. and 1.3 p.p. below Sep-19 values. In line with international recommendations, the local regulatory framework has prudential rules that encourage this diversification of debtors22.

Limited currency mismatch in the balance sheets of the financial system (see Table 1) and of debtors. Both results reflect the effect of the macroprudential regulations in force. The foreign currency mismatch for the financial system stood at 10.8% of the PRC in the first quarter of 2020, below the average of the last 10 years.

Reduced exposure of the financial system to the public sector. Financial system financing to the public sector (including all levels of government) remained low. The gross exposure of all financial institutions to the public sector totaled 9.2% of total assets as of March 2020, falling slightly compared to the last IEF and in a year-on-year comparison (see Table 1). Considering total public sector deposits, the system maintained a negative net exposure (debt position) to the public sector.

3.3 Funding and liquidity of financial institutions in the face of a framework of financial volatility

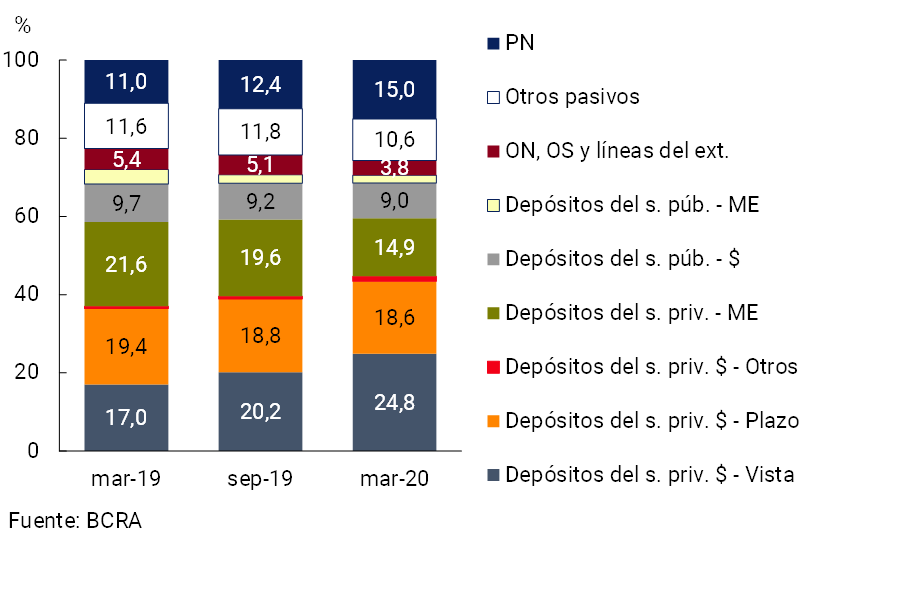

The funding structure of the aggregate of financial institutions is characterized by being mostly composed of deposits from the private and public sectors (about 70%, see Graph 15). Capital (around 15%) and, to a lesser extent, other instruments such as non-depository bonds, subordinated bonds (SOs), foreign credit lines and other liabilities, complete the rest of the total funding of the financial system. The weighting of total deposits in total funding did not change significantly with respect to the time of publication of the previous edition of the IEF, although its composition was modified. Private sector deposits in national currency increased their relative weight in total funding by 5.1 p.p. (to 44.7% in March), mainly due to the demand account segment. Private sector deposits arranged in foreign currency decreased their relative importance in total funding by 4.8 p.p. in the last six months (to 14.9% in March). The rest of the concepts presented minor changes. Looking ahead to the coming months, if a scenario of greater financial volatility is verified, it could lead to certain modifications in the level and/or composition of funding in the financial system.

The balance of total deposits in the private sector increased 4.7% in real terms in the last six months to March (accumulating a reduction of 9.7% YoY). In particular, private sector deposits in local currency gained momentum since the beginning of the year, totaling an increase of 17.4% in real terms in the last six months. Within this segment, demand accounts mainly explained this performance by growing 28.3% in real terms compared to the last IEF, while time deposits increased 3.3% in real terms in the same period (see Chart 16). In particular, at the end of this year’s quarter, the dynamics of deposits began to be influenced by a greater precautionary demand for liquidity by households and companies based on the new COVID-19 pandemic scenario23. On the other hand, although the foreign currency deposits of families and companies continued to show a certain downward path, the monthly rate of reduction is much lower than that evidenced between November and July 2019, when a drop of almost 43% was recorded in the same24.

3.3.1 Specific elements of resilience and mitigating measures

High and growing levels of liquidity. The financial system as a whole operates with high levels of liquidity, both for the segment in domestic and foreign currency. As of March, the coverage of deposits in pesos with liquid assets in the same denomination reached 62% for all financial institutions, 4.2 p.p. more than the level observed in the last IEF25. This dynamic was reflected in all groups of financial institutions. On the other hand, liquid assets in foreign currency totaled 73% of deposits in that denomination at the end of the first quarter, 16 p.p. more than in September 2019 (evolution that was evident in all groups of entities.

Moreover, liquidity indicators that follow the international standards of the Basel Committee continue to comfortably exceed the minimum requirements in all financial institutions26. In this regard, in March the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) stood at around 2.4 for all institutions, well above the minimum regulatory threshold (set at 1 as of 2019)27. For its part, the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) of all financial institutions totaled 1.7 by the end of 2019 —the latest information available—, well above the regulatory minimum (equivalent to 1 since its implementation)28. The local financial system shows a high level of both ratios – LCR and NSFR – when compared at the international level (see Graph 4)29.

A moderate concentration of deposits is maintained. One of the indicators used to characterize the exposure to liquidity risk assumed by financial institutions is the degree of concentration of funding. In this regard, the participation of the main depositors in the total balance of deposits did not change in magnitude in recent months.

Recent measures to stimulate savings in national currency. Within the framework of the measures implemented by the BCRA to face the effects of the pandemic, it sought to stimulate the performance of private sector deposits in pesos, especially those with time deposits. In particular, it was established that financial institutions must grant a minimum interest rate for all time deposits in pesos made by the private sector. This minimum interest rate was equivalent to 70% of the interest rate of the LELIQs, being focused on a segment of the deposits of individuals, to later reach all depositors with a level of 79% of the LELIQrate 30. This measure is in addition to the introduction, at the beginning of the year, of fixed terms in UVA with the possibility of pre-cancellation before 90 days.

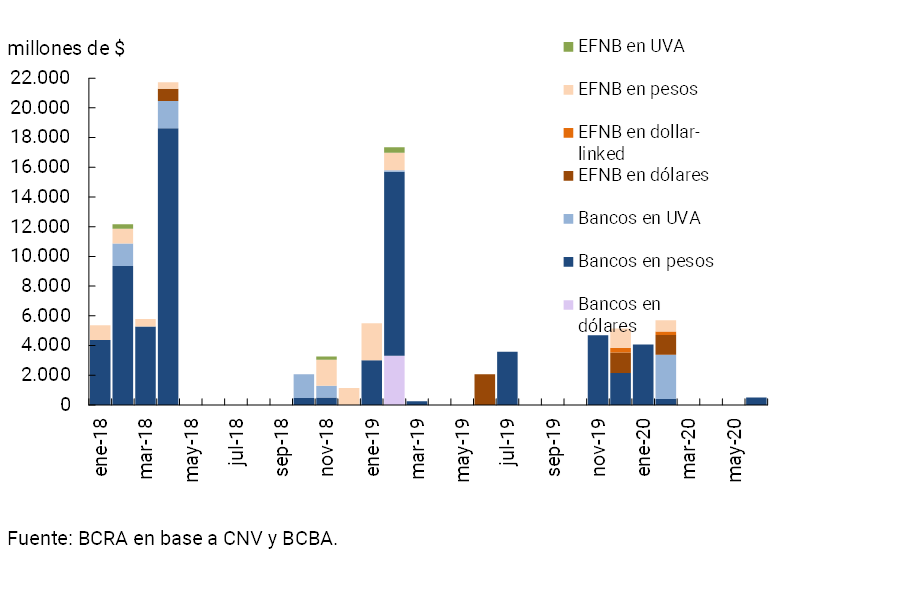

Anchoring with ON. As previously mentioned, the funding of the financial system is mainly made up of deposits. Capital market instruments, such as ON and OS, represent a very limited part of total funding (2.3% of liabilities plus net worth in the system as of March). In particular, of the bonds issued by financial institutions, almost half of the balance payable in pesos and a third of the balance payable in dollars matures between June and until the end of December, and which are the equivalent of only 1% and 1.3% of the total deposits in each currency as of March31. Although private sector bond placements in the domestic market have shown a decline in recent months, operations continue to be recorded. The bank placements that were made since the last IEF were all in pesos (with a weighted average term of 7 months), including a placement in UVA (24 months) (see Chart 17).

Availability of the banking safety net.

In special situations of need, financial institutions can access the different liquidity windows in pesos provided by the BCRA32.

Deposit Guarantee Insurance System. In addition, to safeguard the savings of families and companies in the face of potential adverse financial situations in a financial institution, there is deposit insurance that guarantees the return of up to $1,500,000 of those deposits that verify certain requirements with respect to the agreed interest rate33. Currently, the entities contribute the equivalent of 0.015% of their deposits to this fund, which accumulated an available balance totaling 3.4% of deposits in the financial system as of March. This level is similar to the records of recent months and higher than those evidenced years ago.

4. Other topics of stability of the financial system

4.1 Systemically Important Financial Institutions at Local Level (DSIBS)

Given the relative importance of certain entities within the local financial system, special monitoring is carried out from a systemic risk perspective. Following international guidelines, indicators are used to determine this set of systemically important entities (DSIBs), reflecting different features of them, such as their size, degree of interconnection, complexity, and degree of substitution of their activities34. In addition to having a differential treatment for compliance with certain financial regulations, these entities are subject to closer monitoring by the BCRA, while having to verify in particular a greater margin of capital conservation.

The group of local SIBs represents approximately half of the assets of the total financial system. As of March 2020, all DSIBS verified 100% of the current capital conservation margin. Considered as a whole, the DSIBS increased solvency and liquidity ratios in the last six months and recorded positive quarterly profitability indicators considering items in homogeneous currency (see Table 3). With respect to the last IEF, this grouping of financial institutions showed an increase in the irregularity ratio of credit to the private sector (up to 5% as of March, in line with the indicator for the aggregate of financial institutions), maintaining a moderate equity exposure to credit risk (2.7%). In addition, these entities verified a reduction compared to last September in the exposure to the public sector in terms of assets in aggregate form, and in the ratio between the spread of assets and liabilities in foreign currency and regulatory capital.

4.2 Interconnection in the financial system

With respect to the last IEF, there is a growing but limited interconnection between the financial system and institutional investors, mainly due to the dynamism in the subscriptions of money market mutual funds. The relatively most important institutional investor in the local market is the FGS (with a portfolio of funds equivalent to 10% of GDP), followed by mutual funds (FCIs) and insurance companies (with portfolios representing 4% and 3% of GDP, respectively)35. The most relevant direct interconnection between institutional investors and the financial system occurs through the latter’s funding. In recent months, institutional investors’ deposits have shown an increasing trend over total deposits in the financial system, but their weighting remains low (11% of the total as of March 2020, compared to 6% six months ago). This increase is mainly explained by the FCIs, given the prominence of the FCIs in money markets36. The latter, used to channel surplus liquidity, have been growing strongly since September37, largely due to new subscriptions. In addition to the increase in deposits due to the new subscriptions of money market FCIs, at the beginning of the year, there was the effect of the transfer to deposits of the balance of passes of these FCIs with the BCRA38.

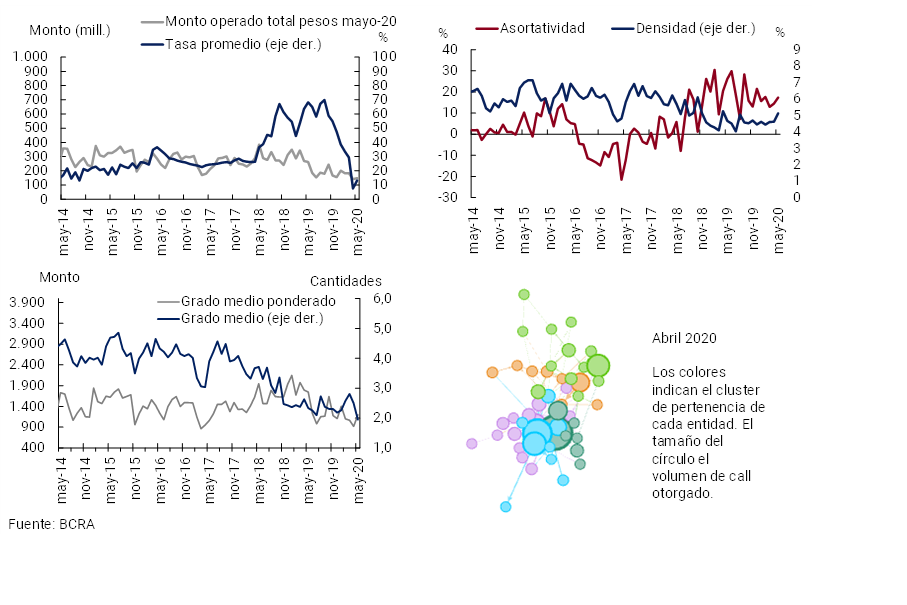

On the other hand, the market for unsecured interfinancial loans is analysed as another source of direct interconnection39. Thus, in a context of sharp declines in the LELIQ interest rate in recent months, interest rates in the call market also verified a downward trend. In this context, both a widening of the nominal spread with respect to the LELIQ rate and a fall in the amount traded in this market (in real terms) were observed. Based on the monitoring of the call market through the network analysis methodology, it is observed that there were slight changes in the main metrics with a bias of the network to a decrease in the degree of interconnection, following the trend observed in the previous period (see Graph 18). Likewise, both the network density, the weighted average degree and the assortativity have a lower volatility40.

5. Main macroprudential policy measures

As highlighted throughout the different Sections of this Chapter, the emergence of COVID-19 led the BCRA to reorient a large part of its prudential policies, seeking to mitigate the economic and financial impact of the pandemic. Thus, it was ensured that families and companies do not have to face extremely acute financial situations. In terms of the macroprudential approach, this scenario could jeopardize their ability to pay, generating a direct adverse effect on the economy in general and on the financial system in particular.

As a result, the BCRA implemented a set of measures whose objectives are to avoid a situation in which a pro-cyclical credit dynamic deepens. As described in detail in Section 4 of this report (as well as in the Regulatory Annex), the pillars of this strategy, so far, have been:

i. Promotion of credit to the private sector, through the introduction of lines of financing under favorable conditions (measures that were implemented in conjunction with different public sector agencies), as well as through the strengthening of the incentives of the Ahora 12 Program.

ii. Relief of the financial situation of families and companies, mainly with a redesign of the criteria for classifying debtors, flexibility in the conditions of payments of loan installments already in force, limits on card interest rates, flexibility of check operations, among others.

iii. Strengthening bank savings in pesos, through the introduction of tools such as the pre-cancellable UVA fixed term, and minimum interest rates that protect the debts of private sector depositors41.

iv. To ensure the solvency of the entities, by suspending the distribution of dividends.

In addition, regulations on the foreign exchange market were readjusted, making the conditions more flexible for those individuals who were abroad at the time of the emergence of COVID-19, and incorporating additional conditions for those agents who want to access the MULC and carry out, at the same time, operations in securities with settlement in foreign currency.

Finally, the financial reporting criteria that financial institutions must meet were improved (see Section 5).

Section 1 / Prudential approach to the COVID-19 shock by Central Banks and Supervisory Bodies

In response to the strong economic impact generated by the emergence of the pandemic, a wide range of Central Banks and Supervisory Bodies of emerging and developed countries began to design, and implement, mitigating policy actions. In general, these actions are aimed at sustaining the process of financial intermediation – especially in terms of credit to the real sector – alleviating the excessive levels of financial burden to which the different members of the economy may be exposed, as well as reducing tensions in the financial markets. In this way, it seeks to preserve the conditions of financial stability at the global level. Argentina is no stranger to this new scenario, having implemented in the last three months an extensive program of public policies that, without losing sight of the particular features of the local economy, is in line with the tools used at the international level (see Section 4).

Initially, the measures taken globally in the face of COVID-19 sought to ensure the continuity of the business of financial institutions, basically in operational terms42. Subsequently, progress was made towards the implementation of financial relief and economic stimulus tools for the private sector. With respect to this last segment of initiatives, without attempting to carry out an exhaustive analysis at the level of individual countries, it is generally observed that they share a set of axes and strategic guidelines that are described below43.

First, in a scenario of monetary stimulus measures with an aggregate impact44, several governments and central banks promoted the introduction of new lines of credit, under advantageous financial conditions for private sector debtors (both firms and households). In many cases, these initiatives were complemented by efforts to provide government guarantees—partial or total—to loans obtained by the privatesector.45

The sovereign authorities also promoted the restructuring of financial conditions of part of the current obligations to the financial system prior to the shock, as well as the implementation of additional fiscal assistance to companies (for example, via tax deferrals, channeling resources for the payment of salaries, among others). On the other hand, some sovereign agencies relaxed their regulatory classifications and definitions of loans restructured in the context of COVID-19, taking them as having normal performance46. Moreover, in certain countries, it was chosen—or is being evaluated—to make capital injections into certain non-financial companies in the economy, which are strategic from the sovereign point of view. Although in general all these measures have a broad scope on the corporate sector, in many countries they were especially channeled to firms of relatively smaller size, a segment that generally suffers the impact of the shock of the pandemic more intensely47.

In addition, another set of actions were taken from the point of view of international regulatory frameworks, which tended to ensure that financial institutions maintain their levels of credit to the productive sector and to households. In jurisdictions where counter-cyclical capital margins were activated prior to COVID-19, in the face of the new context, their authorities were reducing and even deactivating them completely. Regulators also reduced other existing capital margin requirements (such as those used on financial institutions classified as domestically systemic)48. Likewise, some regulators began to recommend and encourage financial institutions to use the aforementioned capital margins, as well as those of liquidity, to sustain credit to the private sector. These initiatives were in line with the recommendations of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) and other international organizations, which encourage the use of the capital and liquidity margins originated in Basel III in the face of a shock such as the current49, as well as the different degrees of flexibility currently in force in international standards.

Finally, in order for financial institutions to preserve levels of capital necessary to maintain credit to the private sector, several economies established temporary restrictions for financial institutions to distribute dividends, carry out share buybacks and pay bonuses to part of their authorities.

Section 2 / COVID-19 and challenges to global financial stability

The COVID-19 pandemic forced the implementation of a series of health measures worldwide, generating a context of strong uncertainty regarding the evolution of global economic activity that worsened over time, given the difficulties in determining the duration and scope of the shock50. As far as financial markets are concerned, the pandemic acted as a trigger for an abrupt and significant change in investors’ perception of risk, exacerbating the scenario of uncertainty.

As mentioned in previous editions of the IEF, in recent years a series of vulnerabilities have accumulated in global financial markets that made them susceptible to an eventual sudden stop in response to a change in the risk version51. These include:

• Extended period of international interest rates at historically low levels and search for higher yields. With funding available and risk perceived at unusually limited levels, investors’ positioning in segments of higher relative risk became widespread, including the stock market and the riskier debt market (high yield) in both developed and emerging economies. In recent years, the possibility that in certain segments there were already signs of overvaluation and, eventually, a potential price correction, increased the market risk faced by investors, began to be considered. The search for higher yields also implied a growing positioning in less liquid and/or more complex segments, with strong growth in recent years52, whose performance under stressful situations has not yet been properly tested.

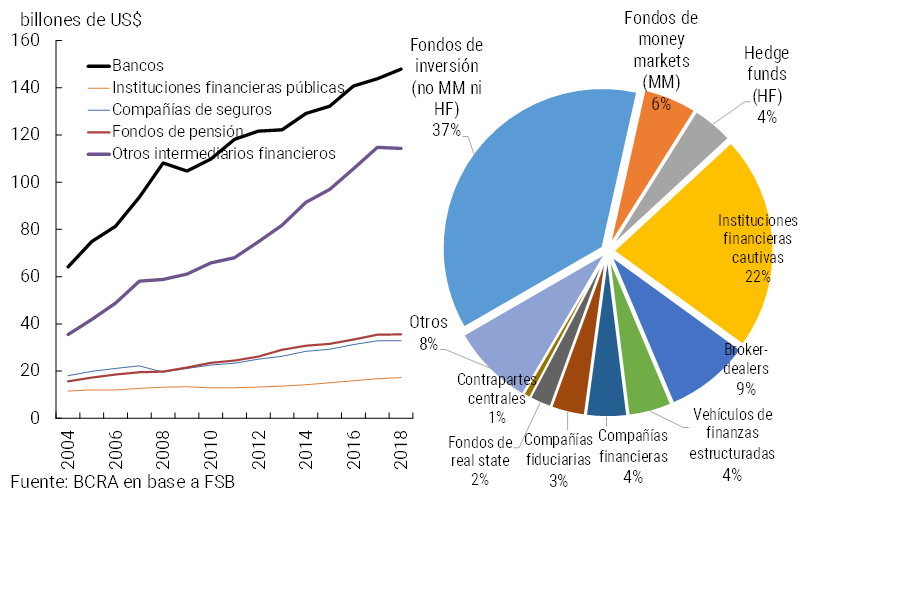

• Growth in non-bank financial intermediation worldwide, led by investment fund activity. The search for higher returns had as a counterpart a growing weighting of “other financial intermediaries”, as the FSB calls them in the global monitoring it carries out annually on the subject (see Graph A.2.1)53. Almost half of this non-bank financing occurred through a growing positioning in different types of investment funds: classic open-ended investment funds (including money market funds) and the so-called exchange-traded funds (ETFs), as well as hedge funds, among other alternatives54. Given that many of these funds contemplate the possibility of carrying out bailouts relatively quickly, their positioning in segments of lower relative liquidity generates the possibility of amplifying tensions in an adverse situation. The greater interconnectedness between different market segments generated by the growth of mutual funds55 is also evident in portfolio flows between countries (e.g., through funds that invest in emerging economy assets).

Figure A.2.1 | Evolution of global financial intermediation and composition of Other Financial Intermediaries

• A general increase in leverage in both the public and private sectors (although with heterogeneity between countries). With investors looking for higher yields, there was a boom in both public and private debt placements in international markets (a phenomenon that in certain countries was accompanied by a growth in domestic financial markets). This growing leverage at the global level (see Figure A.2.2) translates into a rise in credit risk, with greater vulnerability of debtors to more adverse contexts in terms of economic growth and the availability of alternatives to refinance.

Given these vulnerabilities, once volatility in financial markets began to increase globally in February due to the spread of COVID-19, it went on to show levels not seen since the international financial crisis of 2008-2009 in a few weeks. The VIX index went from an average of less than 14% in January to peaks above 80% in mid-March (it would then tend to contract to levels below 30% in mid-May)56. This was accompanied by a significant decline in stock prices (for example, the US S&P500 contracted by almost 30% between mid-February and mid-March), while signs of a repositioning in liquid and short-term assets considered to be of lower relative riskwere observed 57.

This behavior had a clear impact on the markets of emerging economies, with outflows of investment funds specialized in these economies that were stronger than those observed in previous crises (see Figure A.2.3)58 and greater pressure on currency markets. Emerging currencies depreciated by an average of 12% against the dollar between mid-February and the end of April59 (see Chart A.2.4), although in specific cases such as the Brazilian real, the Mexican peso or the South African rand they came to show depreciations close to or greater than 30%. This implied significant declines in emerging market stock indices (the MSCI EM measured in dollars fell by more than 30%) and a jump in the spreads of sovereign and corporate debt in dollars (the EMBI spread doubled from almost 300 bps to more than 600 bps in the second half of March, with CEMBI showing a similar behavior).

Figure A.2.3 | Weekly outflows from funds specializing in emerging assets compared to previous periods of turbulence

While this is evidence of the presence of tensions in global financial markets (with an impact on the real economy) in a context of pre-COVID-19 vulnerabilities, it is noteworthy that so far no situations of disruption have been observed at the systemic level. Since mid-March, market volatility has been attenuating60, partly in response to policy actions implemented in developed and emerging economies (although the VIX remains above its historical average). On the other hand, it should be taken into account that after the peak international financial crisis in 2008-2009, an effort was made to achieve greater coordination at the global level to implement new standards of prudential regulation and supervision in the financial sector, which resulted in a greater degree of resilience61.

This is an episode that is still ongoing and, given the aforementioned vulnerabilities, different areas are monitoring a series of factors considered key to understanding the evolution of tensions, the impact on financial stability at the global level (given that a disruption in the financial markets would imply second-round effects, compounding the initial shock) and the eventual need for further policy measures. Among the main variables monitored are: a) the fluid availability of financing for the corporate sector and households through financial institutions and markets (in response to the measures implemented by the different central banks to inject liquidity and boost credit); b) the evolution of the credit risk of different economic agents and the impact of the same on different counterparties, in an interconnected system; c) the evolution of open-ended investment funds at a global level as well as potential tensions in specific market segments in the event of greater redemptions, including effects on emerging economies; and d) the existence of currency mismatches between different agents (particularly in dollars, given the boom in debt placements in this currency in recent years) and the possibility of refinancing in this currency62.

Section 3 / Policy actions to restore public debt sustainability in Argentina

In the second half of 2019, without access to international markets and faced with the impossibility of refinancing short-term debt maturities in foreign currency, the National Executive Branch decided to reschedule short-term Treasury Bills in dollars (LETES) and announced the intention to advance in a voluntary extension of the maturities of public securities63. In December, after the change of government and through Law No. 27,541aon “Social Solidarity and Productive Reactivation”, the National Executive Branch was empowered to carry out the necessary acts to recover the sustainability of the national public debt. At the end of last year, channels of dialogue began to be established with creditors and financial institutions with the aim of reaching a new maturity profile.

At the end of January, a schedule of actions was determined to manage the process of restoring the sustainability of the external public debt and in February Law 27,544on “Restoration of the sustainability of the public debt issued under foreign law” was enacted. This Law authorized the Ministry of Economy of the Nation to carry out a series of operations to achieve this objective under the terms of Article 65 of Law No. 24,156 on Financial Administration and Control Systems of the National Public Sector. At the beginning of March, the perimeter of the restructuring of the debt in foreign currency with the private sector was decreed (Decree 250/2020). In order to guide a constructive and good-faith interaction with Argentine debt holders, the debt sustainability framework was released through two presentations made in March by the National Authorities, including general criteria and underlying macroeconomic assumptions64. In these presentations, the guidelines of a comprehensive strategy to face payments to the different creditors were made explicit, for a total debt balance of US$323,000 million at the end of 2019, which includes:

• Debt with the public sector (including the Central Bank, the BNA and the ANSES). This debt, which represented 40% of the total at the end of 2019, will be refinanced in the future taking into account the objective of safeguarding monetary and financial stability;

• Debt with official creditors. Talks began with the IMF to seek a new program to refinance the line already granted by this institution in 2018 and 2019 (14% of the total debt as of December 2019). In the same sense, progress will be made in the dialogue with other international organizations and official bilateral creditors to agree on a refinancing;

• Debt with the private sector. With respect to these obligations (37% of the total), a strategy was proposed for instruments in local currency and in foreign currency.

With respect to this last group of creditors, the main guidelines and progress for the different existing segments are detailed below.

1. Debt to the private sector: public securities in local currency>

Since the end of 2019, measures began to be implemented to reconstruct a yield curve in pesos, refinance debt at sustainable rates and extend maturities. The placement of new short-term peso bills with a Badlar Private Banks plus a margin (LEBAD) coupon began. Since March, mostly peso bills began to be placed at a discount in auctions for refinancing. In addition, bonds and bills in pesos were placed at a discount with capital adjustment by CER (BONCER and LECER). In this way, it was possible to extend the term of the placements while reducing the cost of financing. This line of work will be maintained through new tenders for instruments in pesos, based on a schedule set month by month.

In parallel, constructive discussions were made with holders of pre-existing bonds to renew debt service obligations, while ensuring overall debt sustainability. The latter implied the holding of various auctions of new short-term bills and bonds through the subscription in kind and exchanges of pre-existing instruments65. In general terms, in the latest exchange and conversion operations of assets, a fixed basket of instruments was offered, which included discount bills and new BONCER. The new BONCERs were placed with terms of 1 to 4 years and coupons in a range of 1% to 1.5% (on the capital adjusted by CER). As a result of the exchange operations, about half of the principal and interest maturities of public securities in pesos in 2020 have been rescheduled so far.

With regard to the secondary market for the new instruments, liquidity is still very limited in the case of LEBAD and discounted bills in pesos. For its part, the operation with the new BONCER and, to a lesser extent, the Badlar+100bp Bond maturing in August 2021 was gaining momentum.

2. Debt with the private sector: public securities in foreign currency with local legislation

For this segment, which includes both the bonds of the 2005 and 2010 exchanges issued under Argentine law (US$3,500 million) as well as the BONAR (US$10,200 million) and LETES (US$3,900 million) subsequently issued under the same legislation, on April 5, Decree 346/2020 provided for the deferral of interest service payments and principal amortizations until the end of 2020 or until an earlier date. that the Ministry of Economy would determine, considering the degree of progress and execution of the process of restoring the sustainability of the public debt. Likewise, the Ministry of Economy was authorized to carry out the necessary exchanges and/or restructurings linked to these public securities. In this regard, two asset conversion operations were carried out during May, for which BONCER was offered to LETES holders. As a result of the operations, approximately half of the LETES held by the private sectorwere exchanged 66. A fixed portfolio of BONCER maturing in 2022, 2023 and 2024 and interest coupons with a range of 1.2% to 1.5% were delivered.

3. Debt with the private sector: public securities in foreign currency with foreign legislation

These securities include both bonds from the 2005 and 2010 exchanges issued under foreign law, as well as global bonds issued from 2016 onwards (BIRAD bonds). In this case, on April 17, an exchange proposal was formally presented for 21 pre-existing bonds with a balance of US$66,238 million67 (of which US$41,548 million were issued between 2016 and 2019), with a deadline for acceptance on May 8, later extended three times, to May 2268, to June 2 and June 12. Dialogue with creditors continued in early June, with proposals for agreement being discussed69.

The proposal for exchange for new bonds contemplates eligible bonds that were issued in 3 different currencies (dollars, euros and Swiss francs) and two legislations (see Table A.3.1). For each eligible bond, alternative bonds are offered in exchange (at least two, depending on the eligible bond), with different financial conditions both in terms of the nominal haircut that is applied (ranging from 0% to 12% in the dollar series, and from 0% to 18% in the euro series and in the Swiss franc series). The bonds issued in the 2005 and 2010 international swaps have 3 alternative swap options, two of which are without nominal haircut. The new bonds have a grace period of 3 years in which no interest is accrued, and will subsequently pay a coupon that rises in stages from a level of 0.5% to a maximum of 4.875%. On the other hand, there is a maximum limit to be placed on the shortest new species (maturing in 2030 and 2036 in both dollars and euros) which proposes a cascade scheme for the allocation of the exchange (not applicable in certain cases).

Table A.3.1 | Example for Eligible Dollar Bonds: Summary of Financial Conditions of New Bonds and Exchange Options

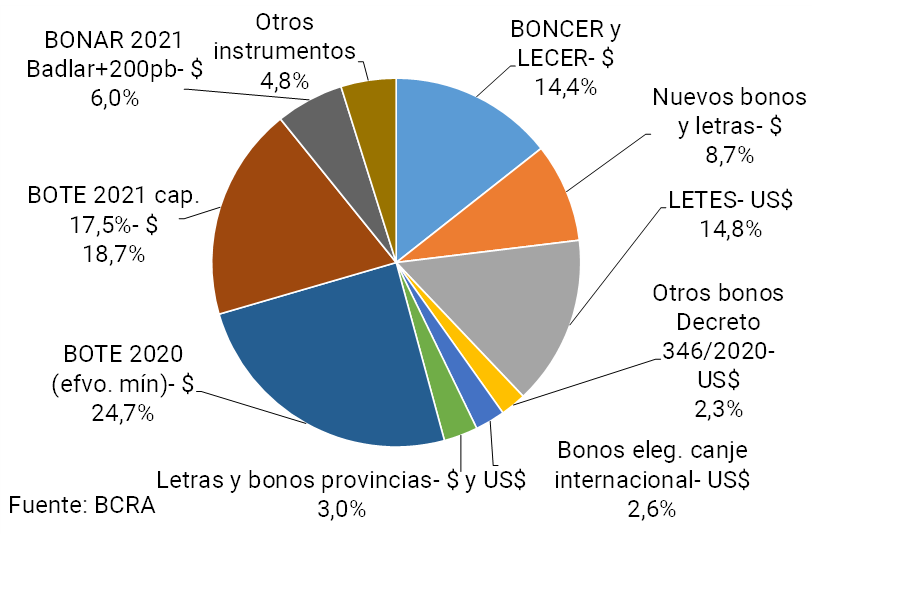

With respect to the possible implications of these measures for the financial system, first, it is important to bear in mind that the exposure of financial institutions to the public sector is limited70. With information as of April 2020, it can be seen that the portfolio of public securities of the financial system (for a total of $671 billion at book value)71 has a higher weighting of the set of instruments in pesos ($533 billion at book value and approximately $835 billion at residual value). The holding of securities resulting from the aforementioned refinancing operations and exchanges of instruments in pesos represents around 19% of the total book value of the securities portfolio. For its part, the holding of bonds in dollars under domestic legislation included in the reprofiling of Decree 346/2020 amounted to $115 billion in book value (17% of the total book value and US$2.3 billion in residual value), which was comprised of almost all of LETES at the end of April (87%). As mentioned, these LETES began to be exchanged in May through asset conversion operations for BONCER72. Finally, the financial system has a very limited position in bonds eligible for the exchange of public securities with foreign legislation ($18 billion in book value or US$275 million in residual value), equivalent to only 2.6% of the total book value of the securities portfolio (see Figure A.3.1).

Figure A.3.1 | Composition of the portfolio of public securities in the financial system Book value as of April 2020

Section 4 / Main measures taken by the BCRA to mitigate the economic impact of COVID-19 on companies and families

Anticipating the economic impact that the pandemic would unleash, in parallel to the beginning of the social isolation ordered by the Government, the BCRA designed a set of tools that sought to temper its effects on both companies – especially MSMEs – and on families. These initiatives, which complement the fiscal efforts introduced by the National Executive Branch (PEN), were implemented on the basis of the strengths that the financial system has been developing in recent years, especially in terms of ample sectoral liquidity (see Section 2). Thus, in the last three months, this Institution implemented a program that includes tools both to address financing conditions for all components of the private sector, and to strengthen bank funding, especially through the channeling of savings in pesos.

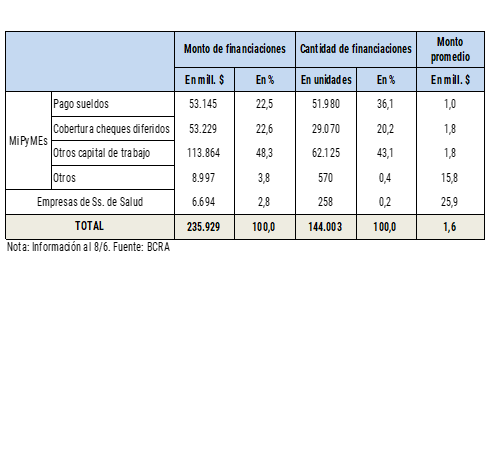

I. Tools for relieving the financial situation of companies

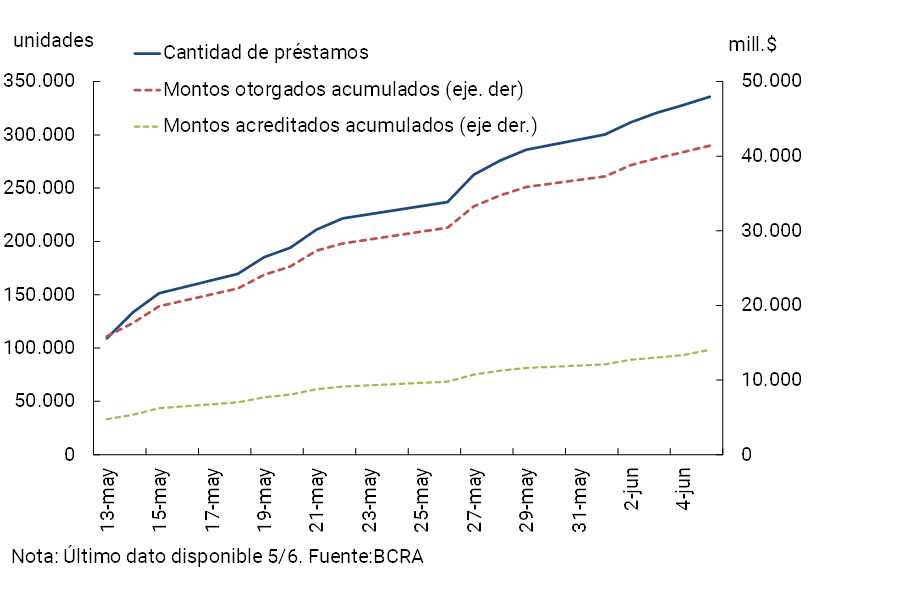

I.I. Line of loans for MSMEs. This line was designed to finance the working capital needs of MSMEs, especially for the payment of salaries, as well as for the acquisition of supplies from firms providing health services73. It was implemented as of March 20 with an annual nominal interest rate of up to 24%, below market rates. The BCRA included a regulatory incentive for it, given that the entities that offer it obtain a reduction in their minimum cash requirements for the equivalent of 40% of the loans. At the time of publication of this IEF, the financial system accumulates disbursements of almost $236 billion (equivalent to 12% of the total financing in local currency at the beginning of the ASPO —3/20—), with direct benefit to an estimated total of 144 thousand firms74. The resources were mainly channeled to finance the payment of salaries, the coverage of checks and other working capital needs of MSMEs (see Table A.4.1). To give greater impetus to this initiative, the Government promoted the granting of guarantees through the Argentine Guarantee Fund (FOGAR)75.

I.ii. Line of loans for MSMEs without financing. In May, this line of loans was extended at an interest rate of up to 24%76, making it possible for MSMEs that did not have bank credit (almost 200,000 in the country) to have access. In those cases in which companies have guarantees from FOGAR, the entities must grant such credits (accessing the aforementioned regulatory benefits).

Both measures should be considered to contribute to reinforcing the efforts that the BCRA had already begun to implement in early 2020, at which time greater regulatory incentives were introduced for entities to channel resources to MSMEs with lower interest rates than market rates77.

II. Tools for Easing the Financial Situation of Families

II.i Promotion of NOW 12. Also in parallel to the start of the ASPO, the BCRA sought to encourage the growth of credit card financing within the framework of the AHORA 1278 Program. Thus, the regulatory benefits were strengthened for those entities that promote the use of this tool that improves financial conditions for household consumption, an initiative on which the BCRA had already been contributing since the beginning of1979. In this sense, bank financing through this Program grew in the first months of the year, totaling more than 30% of total credit in pesos through cards in March.

II.ii Caps on credit card interest rates. Also with the aim of improving the financial conditions of families, this Institution promoted a significant reduction in credit card financing rates, establishing a limit that currently stands at 43% nominal annual80, below the market rates observed at the end of 2019 (almost 70%)81. In addition, in the case of unpaid credit card debts as of April 30, they were automatically refinanced with a one-year term

II.iii Line of credit at zero interest rate for single-tax and self-employed workers. To underpin the financial capacity of those households whose income is closely linked to the independent activities of their members (affected by the ASPO), in April the PEN and the BCRA implemented a line of loans without costs for single-payers and the self-employed82. Through it, each individual can access resources for up to $150,000, with 7 months before starting to make the 12 stipulated interest-free payments. Banks are obliged to credit this line to those who request it – who meet certain requirements – thus obtaining a significant regulatory incentive: a reduction in the minimum cash requirement by 60% of these loans. For its part, the National Fund for Productive Development bears all the financial costs. This line of credit has increased rapidly (see Graph A.4.1), currently reaching a volume of more than $41 billion ($14 billion credited) to 336,000 individuals (equivalent to almost 3% of the total number of individuals taking bank financing on Mar-20).

III. Instruments with impact on the entire private sector

III.i. Flexibility of the parameters for the classification of bank debtors. This measure seeks to ensure that the effects of the pandemic do not exacerbate the deterioration of the economic and financial capacity of debtors83.

III.ii. Reduction of the burden of maturities of current loans. The BCRA determined the elimination of punitive interest on unpaid installments of loans until mid-year, as well as the possibility of requesting the entity to defer payment of the same84.

III.iii. Flexibility of check operations. A set of measures were taken to decompress the financial situation of the private sector that frequently uses this payment instrument85.

IV. Measures to strengthen savings in pesos and sources of funding to boost financing

IV.i. Suspension of the distribution of dividends by entities. In order to ensure that the sector has adequate resources to provide credit to the private sector, in a challenging economic scenario, the BCRA decided to suspend the distribution of dividends by entities until the end of the year86.

IV.ii. Strengthening bank savings in pesos. In order to strengthen bank savings in pesos, a minimum interest rate was established in mid-April to benefit depositors, a tool that was later increased and expanded in scope87. Thus, the minimum interest rate is currently 30% for the fixed terms of families and companies, above the rates observed before its entry into force (20% for retail fixed terms and for 15% for wholesalers, in mid-April)88. These measures are in addition to the introduction of the fixed term in pre-cancelable UVA in February89.

Section 5 / Progress in the financial reporting criteria applicable to financial institutions

The BCRA promotes a path of constant modernization of the regulatory and accounting framework that local financial institutions must implement, contributing to its alignment with the best practices and international recommendations in the matter. In this context, as of January 2020, financial institutions must consider the provisions on impairment of financial assets contained in point 5.5 of International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) No. 990, when presenting their financial statements expressed in homogeneous currency in accordance with International Accounting Standard (IAS) No. 2991. Both advances represent a relevant milestone in the process of continuous improvement in financial information that must be provided by financial institutions that act locally.

As of January of this year, the calculation of provisions for uncollectibility risk of the largest local financial institutions (belonging to Group “A”, i.e., those whose assets reach at least 1% of the total assets of the system) began to be calculated according to the estimate of expected credit losses in accordance with IFRS No. 992. On the other hand, it had originally been provided that the smallest entities (belonging to Group “B”) would have the option of prorating the impact of the estimate of expected credit losses over 5 years93. However, given the tenor of the local effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the BCRA recently decided – among other measures taken to face this new scenario – to postpone until 2021 the application of the calculation of expected credit losses for smaller institutions94.

According to this new forecasting regulation, the expected credit loss is calculated as the difference between the contractual cash flows that a customer owes to an entity and the cash flows that the entity expects to receive from the same95. In cases where the credit risk of a financial instrument has not increased significantly since the time of its incorporation (initial recognition), institutions must record losses on that instrument in an amount equivalent to the expected credit impairment in the following 12 months (value adjustment). On the other hand, in those instruments in which the risk has increased significantly, the value adjustment must be estimated based on the expected credit losses over the life of the asset.

The initial impact on the entities that applied this new methodology (Group “A”), was reflected in accounting terms in the form of adjustments to previous years’ results, i.e., in the accumulated results that had not been allocated until January 2020. Since then, the effects of this new methodology have been materialized periodically in the forecasts of financial assets, being incorporated monthly in results for uncollectibility charges. The impairment provisions of IFRS No. 9 should be considered to apply mainly to those instruments measured at amortized cost, at fair value through other comprehensive income, accounts receivable from leases and loan agreements.