Financial Stability

Financial Stability Report

Second half

2020

Half-yearly report presenting recent developments and prospects for financial stability.

Table of Contents

Chapters

- Executive summary

- 1. International and local context

- 2. Main strengths of the financial system in the face of the risks faced

- 3. Sources of vulnerability and specific resilience factors of the financial system

- 4. Other topics of stability of the financial system

- 5. Main macroprudential policy measures

Sections

- Section 1 / COVID-19 and risks to financial stability in emerging economies

- Section 2 / Measures adopted by the BCRA to sustain the flow of financing to the private sector

- Section 3 / Investment funds and financial stability at a global level

- Section 4 / COVID-19. Using regulatory flexibility

- Glossary of abbreviations and acronyms

Summary

Since the publication of the last IEF in June, the financial system continued to carry out its activities relatively normally and without disruptions, despite going through an economic scenario marked by an extraordinary event. The pandemic led to a combination of unprecedented external and internal shocks to an economy that had previously been in a recession of almost two years, with high inflation and unsustainable levels of public debt. In this challenging context, all financial institutions continued to show an adequate degree of resilience1. This performance was sustained both by the combination of previously constituted hedges to address situations of tension – high and growing levels of liquidity, forecasting and capital – the benefits of having a regulatory framework and supervision in line with international standards, as well as by the specific actions promoted by the BCRA in order to mitigate a procyclical credit dynamic. protect the neediest families and companies and preserve the conditions of financial stability.

Recently, some positive signs have been reflected about the operational framework in which the financial system operates. On the one hand, various economic sectors began to gradually recover their activity, a situation that is allowing the BCRA to adjust the set of measures taken in the face of the shock, as well as to move towards the harmonization of policy interest rates. The improvement in activity was partly favored by the monetary, credit boost (with subsidized rates) and fiscal measures taken to prevent the shock from having permanent consequences on the economic fabric, and by the gradual easing of health restrictions. On the other hand, progress was made in the normalization of public debt markets. In addition to the measures being taken to reconstruct the yield curve in pesos and enhance the role of capital markets, there was the successful closing of bond restructurings – both international and local – and debt swaps to improve the composition and sustainability of public debt. In this context, since the publication of the last IEF, financial intermediation activity in national currency with the private sector showed increases, reflected both in the real balances of credit and in that of deposits (with a certain slowdown in the margin). This performance was driven by the actions of the BCRA, aimed at promoting financing, as well as promoting savings alternatives in national currency. In this regard, the BCRA continues to make efforts to develop savings and investment instruments that allow positive returns to be obtained with respect to inflation and the exchange rate.

Despite the recent dynamism, the system continues to maintain a low depth in the economy (partly on the opposite side of the low leverage of the private sector) and a limited transformation of maturities. In addition, a considerable part of the operations continue to focus on low-complexity products, mostly transactional, while the institutions as a whole show a low degree of direct interconnection. In the current challenging context, these features limit the sources of vulnerability derived from the usual risk exposures of this activity, while highlighting the important potential for future development of the sector.

In this scenario, it is expected that the financial system will continue to perform its functions relatively normally in the coming months, going through the challenges still caused by the pandemic without any surprises and thus maintaining its conditions of strength. For the coming months, it is considered that there are at least three exogenous risk factors for the financial system, given the exposures derived from its operations, which need to be monitored. First, the risk of a weaker-than-expected local economic recovery. The eventual materialization of this situation will depend on the development of a range of factors, including the evolution of the pandemic, as well as external determinants associated with the growth of the world economy, the evolution of international trade and the course of commodity prices. Secondly, the risk of new episodes of volatility in the financial markets could not be completely ruled out, although less so in a context where negotiations with the IMF are taking place and the transitory decoupling between supply and demand factors in the foreign exchange market continues to be channelled. Third, the financial system is exposed to an operational risk factor that grows at the margin (due to structural and short-term issues), based on a greater dependence on technological resources, which will continue to be addressed with prudential actions appropriate to the new reality.

In the event of a materialization of the aforementioned risk factors, it should be noted that the system shows limited sources of vulnerability and important elements of coverage, which should give it a significant degree of resilience. In this sense, one aspect to monitor in the sector would be the development of the quality of the loan portfolio. Although the irregularity ratio remained at low levels within the framework of the financial relief measures promoted by the BCRA, it should be considered that the current shock is of unprecedented characteristics, and that in the short or medium term it could have a certain impact on the payment capacity of debtors. This could eventually be reflected in the profitability of the entities, thus influencing, at least to some extent, the dynamism of credit. In this context, the aggregate of institutions has increased their relative levels of forecasting in recent months, a performance that, added to the comfortable and growing levels of solvency, have reduced equity exposure to credit risk to minimum levels in a historical comparison.

Another potential source of vulnerability for the system in the face of the aforementioned risks is associated with a deterioration in the dynamics of the intermediation activity. The eventual materialization of a lower-than-expected economic growth scenario could affect the supply and demand of credit, as well as the provision of other services, which could have an impact on the sector’s sources of net income, with a possible effect on the dynamics of domestic capital generation. Again, it should be considered that the solvency indicators of the system are at high levels, both in terms of recent history and in an international comparison. Here it is relevant to highlight the set of policy actions of the BCRA that has been aimed at sustaining the flow of financing to the private sector. Finally, it should be noted that funding in pesos through deposits grew significantly since the last IEF, thus increasing its participation in the system’s liabilities. Foreign currency deposits showed a mixed performance throughout the semester, with slight growth until mid-September, and then a transitory decrease. If new episodes of volatility materialize in the coming months, the funding of the entities as a whole could receive some impact, both in terms of level and composition, although the aggregate maintains liquidity coverage above the average of the last 10 years, accounting for the margin of capacity available to cope with these eventualities.

The coordination of the BCRA’s actions with the National Government will continue to help the economy recover its normal functioning in the coming months, in a context that is still challenging. At the same time, the BCRA will continue to monitor possible deviations from the expected path and, eventually, may implement the measures that are necessary to maintain the conditions of financial stability, thus protecting families and companies and seeking to avoid potential adverse effects that are long-lasting, while establishing the foundations for a sustainable process of growth and greater inclusion of the Argentine financial system.

1. International and local context

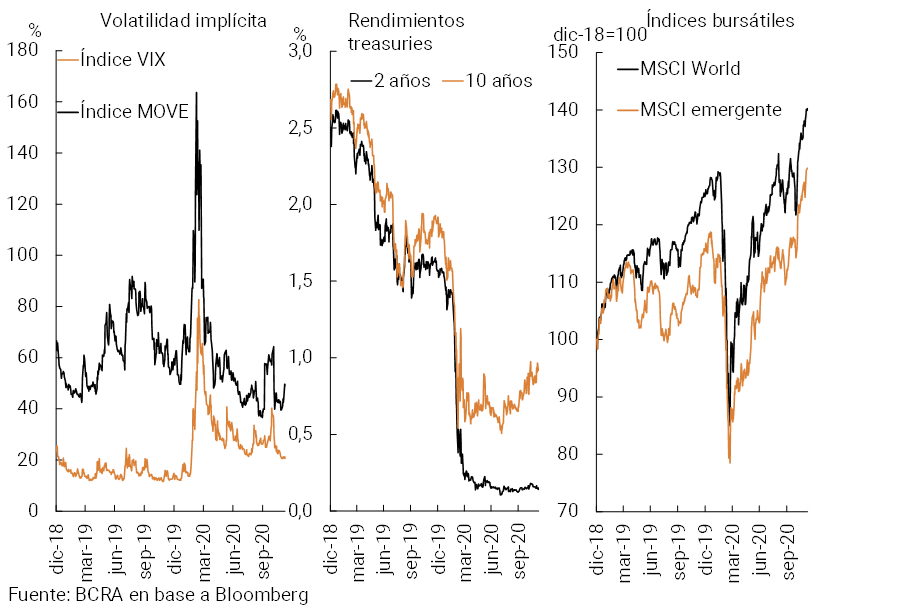

The COVID-19 pandemic continued to create a challenging global context in the second half of 2020. The health situation showed some improvements, the stricter distancing measures were relaxed (with differences by region and country) and the expected volatility in the markets is more contained compared to the worst moment of the pandemic2, although the situation is dynamic and several risk fronts remain. While the strongest global impact was seen in the first half of the year – heterogeneously across regions and sectors – expectations for global economic growth remain weak and with downside risks3. Despite this, the rapid and forceful stimulus measures applied by governments, together with the absence of episodes of disruption in international financial markets, allowed a trend towards market recovery from May onwards, including those in emerging economies (see Section 1).

More recently, in the face of outbreaks of COVID-19 in the northern hemisphere and some doubts regarding the continuity and effectiveness of economic policy stimuli, in September-October some signs of greater caution began to be seen in the financial markets. However, there was no evidence of a generalized increase in risk aversion or the search for refuge in assets considered safer as in the mid-first half of the year (see Chart 1). As early as November, announcements linked to advances in vaccine testing (which led to the approval of different versions of the vaccine in the United Kingdom and the US) began to generate optimism, although it remains to be confirmed when doses will be widely available.

Given this scenario, for Argentina the pandemic implied a combination of unprecedented external and internal shocks on an economy that had already come from almost two years of recession, with high inflation and public debt at unsustainable levels. However, as will be seen in the next sections of this Report, the financial system continued to show an adequate degree of resilience over the course of 2020, a situation that is expected to continue in the coming months. This is taking place in a local context that is gradually showing signs of recomposition, a situation that continues to be dynamic. In this regard, given the battery of policy measures (monetary, financial, fiscal and income) aimed at preventing these transitory shocks from leaving permanent consequences on the economy, to which was added the gradual progress in the relaxation of health policies, since the last publication of the IEF there have been signs of greater dynamism in domestic demand and of an incipient economic recovery that is gaining strength in the second half of the year of the year (although with disparity between sectors). This trend could accelerate if the possibility of vaccines being available on a massive scale is confirmed in the coming months.

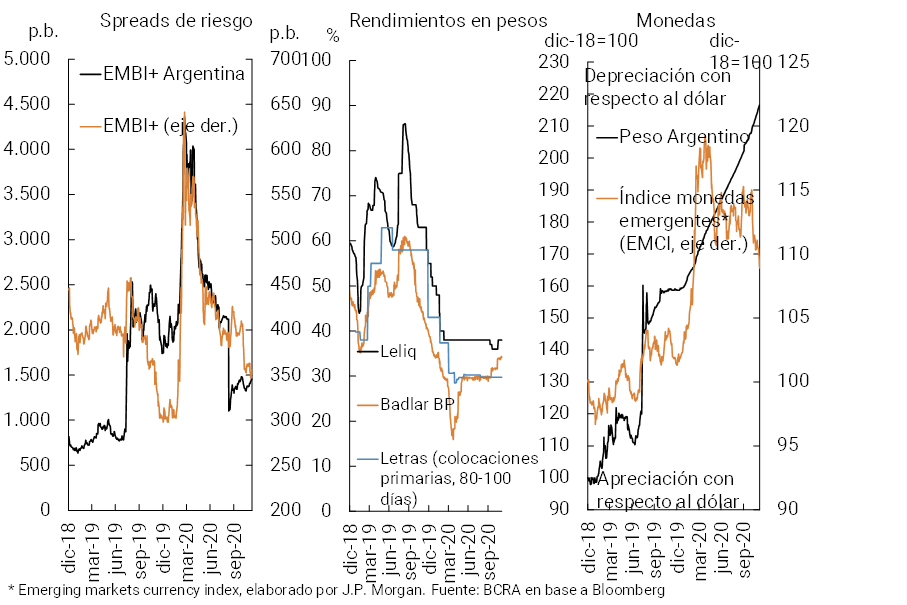

In turn, in recent months, progress has been made locally in the normalization of public debt markets. In addition to the measures being taken to reconstruct the yield curve in pesos, significant achievements were made in restoring debt sustainability: the successful closing of foreign currency bond restructurings with international and local legislation (in August and September), various swaps and conversion operations of local instruments (expanding the menu of Treasury financing instruments), the beginning of talks to readjust financial commitments with the IMF and the sending to Congress of a multi-year fiscal path. Based on this, some improvement was observed in the markets in the prices of different assets, although not without volatility (see Chart 2).

In mid-September, a series of measures were announced to promote better administration of foreign currency and to establish the guidelines for a renegotiation of private external debt compatible with the normal functioning of the foreign exchange market4. In October, the BCRA updated its monetary policy guidelines, including measures to harmonize monetary policy interest rates (initiating a process of increases in different interest rates), develop savings and investment instruments in pesos that allow positive returns to be obtained with respect to inflation and the exchange rate, and adjust regulations linked to the foreign exchange market to avoid temporary imbalances that could affect the position International Currency5. More recently, in November and December, the Ministry of Economy carried out two auctions to convert peso securities into dollar securities (each for an amount of US$750 million), to continue advancing in the normalization of the peso debt market.

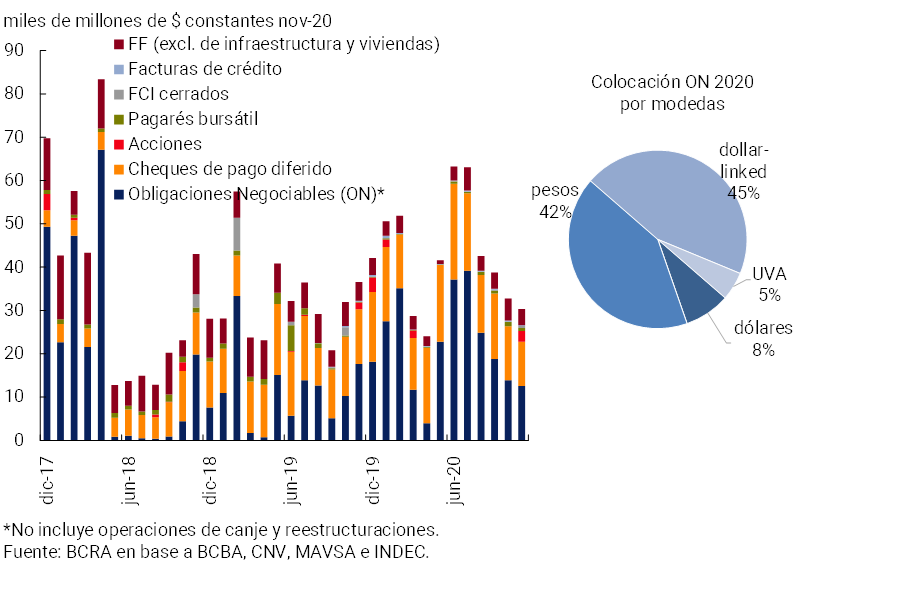

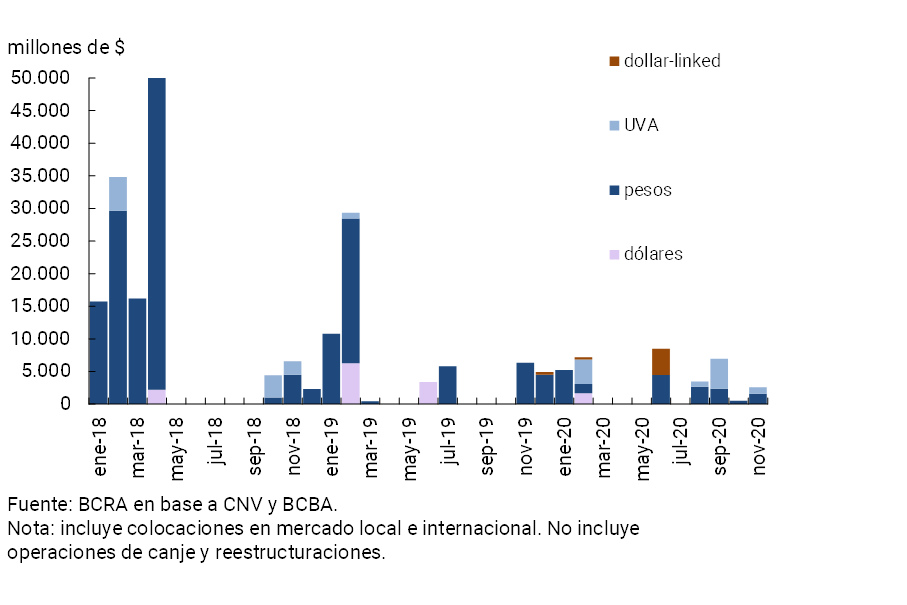

Once the situation of a large part of the debt has been regularized and with the economy in the process of recovery, it is expected to continue advancing in the improvement of the fiscal, external and monetary situation6. In this context, the conditions would be in place to continue promoting the development of the capital market, so that it assumes an increasing importance in the financing of the public and private sectors. In this sense, while the public sector shows a sustained and growing level of refinancing of its debt in local markets, financing to the private sector in the local market increased by about 30% in real terms so far this year compared to the same period in 2019 (see Graph 3). This was mainly due to the increase observed in negotiable obligations (with a lower weighting of placements in dollars and greater dynamism of dollar-linked and peso-linked operations -nominal and UVA-) and in deferred payment checks (a segment in which the relevance of the E-CHEQ stands out).

2. Main strengths of the financial system in the face of the risks faced

The financial system as a whole continued to operate with high solvency and liquidity margins since the publication of the last IEF. These characteristics helped to sustain without disruption the process of financial intermediation with companies and families, as well as an adequate provision of payment services to the economy. In recent months, financial intermediation activity in pesos grew in real terms (with a certain slowdown in the margin), a performance that mainly reflected the effect of the measures implemented by the National Government in conjunction with the BCRA to mitigate the economic-financial effects of the pandemic and the health and social isolation policies taken at the beginning of it. The measures that were adopted contributed to providing liquidity to companies and families, avoiding exacerbating a situation of tension with a possible impact on the conditions of financial stability.

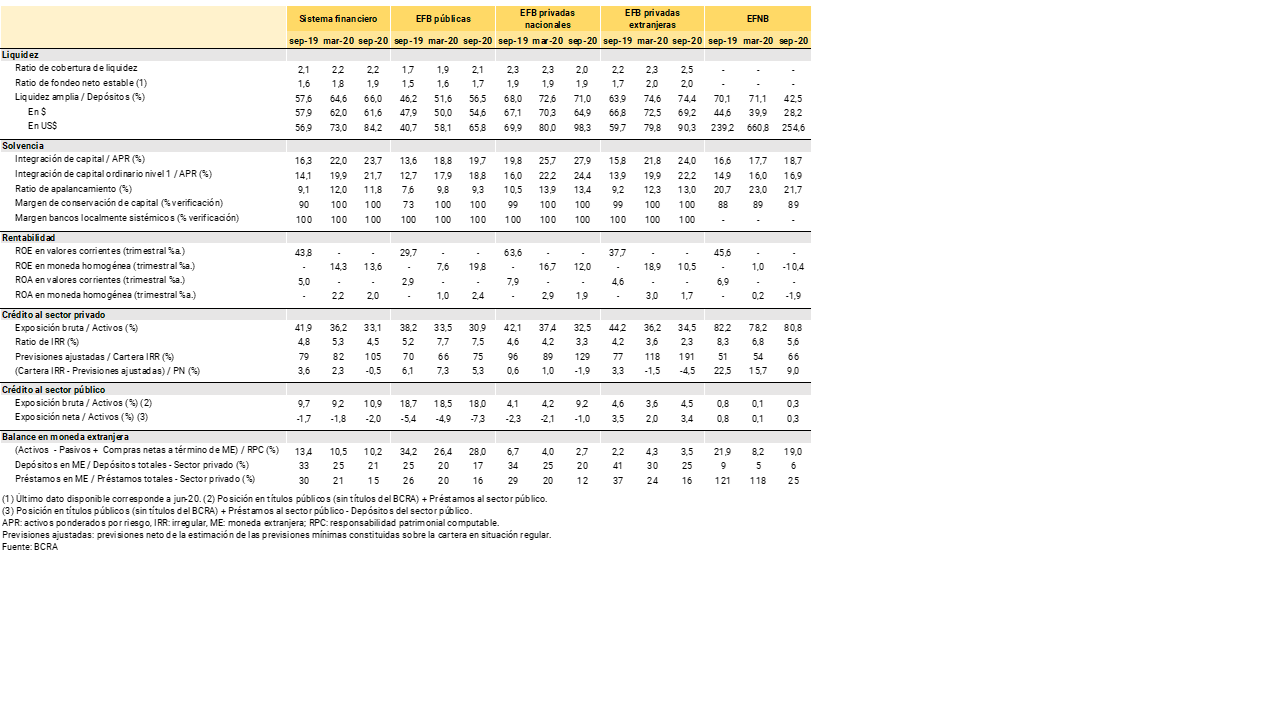

The financial system continues to maintain a set of structural characteristics that contribute to generating a limited exposure to risks from a systemic perspective. Among them, there is still a very low depth of bank financing in the economy (both in historical and international comparison), the predominance of traditional financial intermediation operations that are not very complex, reduced term transformation, and low direct interconnection between financial institutions. In the analysis of the strengths of the sector, the existence of a prudential regulatory framework in line with the international standards proposed by the Basel Committee must be weighed. The main features that make the financial system resilient are presented below (see Table 1). More detail is included in the subsequent sections.

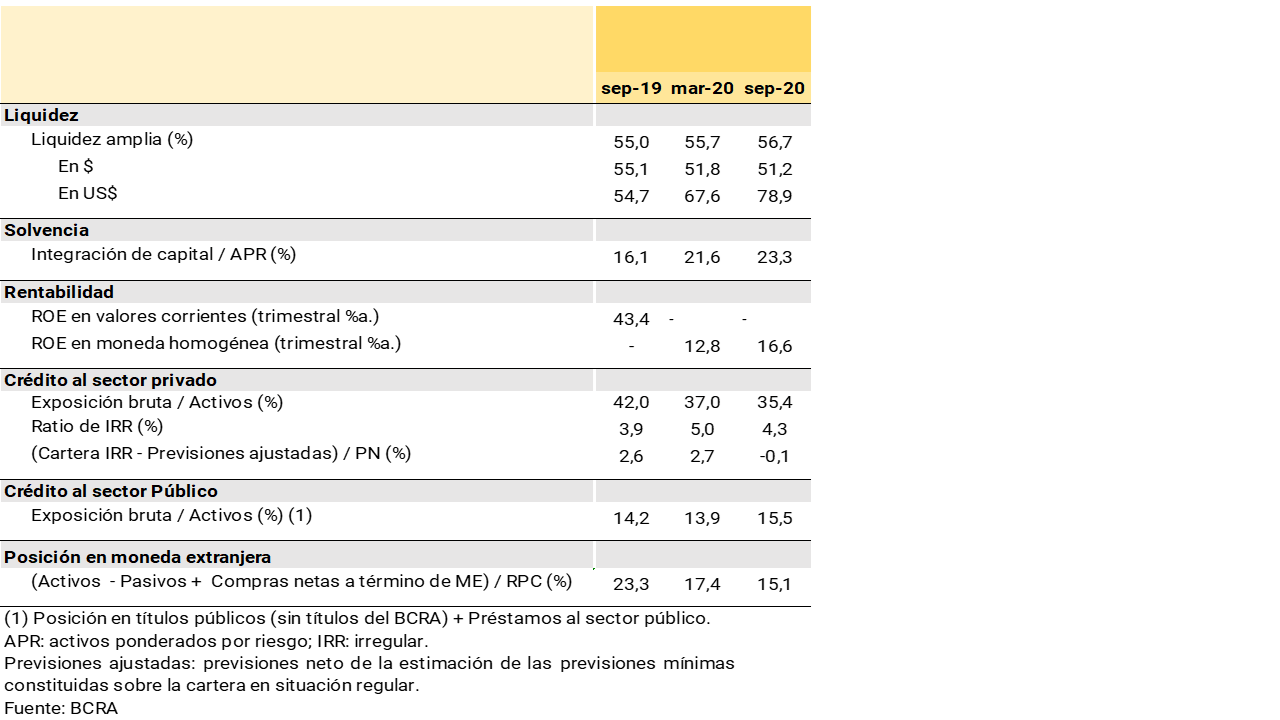

i. Adequate liquidity margins at the aggregate level. So far in 2020, the system’s liquidity ratios, both for total and by currency, continued to be at relatively high levels compared to what has been observed in recent years. At the end of the third quarter, total liquidity in the broad sense7 represented 66% of total deposits, increasing slightly compared to March (cut-off date of the previous IEF).

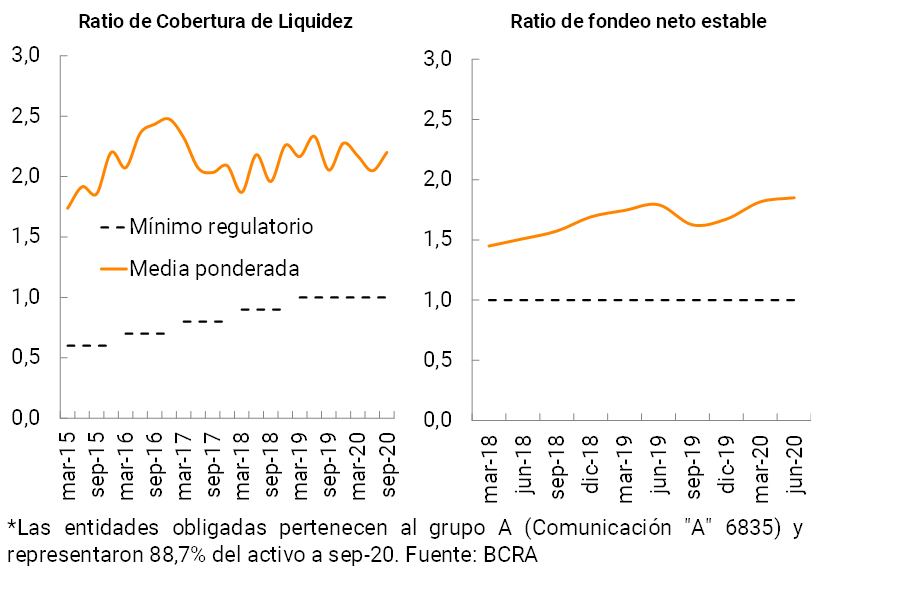

The levels observed for the liquidity ratios that emerged within the framework of the Basel Committee’s recommendations – Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and Stable Net Funding Ratio (NSFR)8 – also remained high at the aggregate level, above the minimums required in local regulation and those included in international standards.

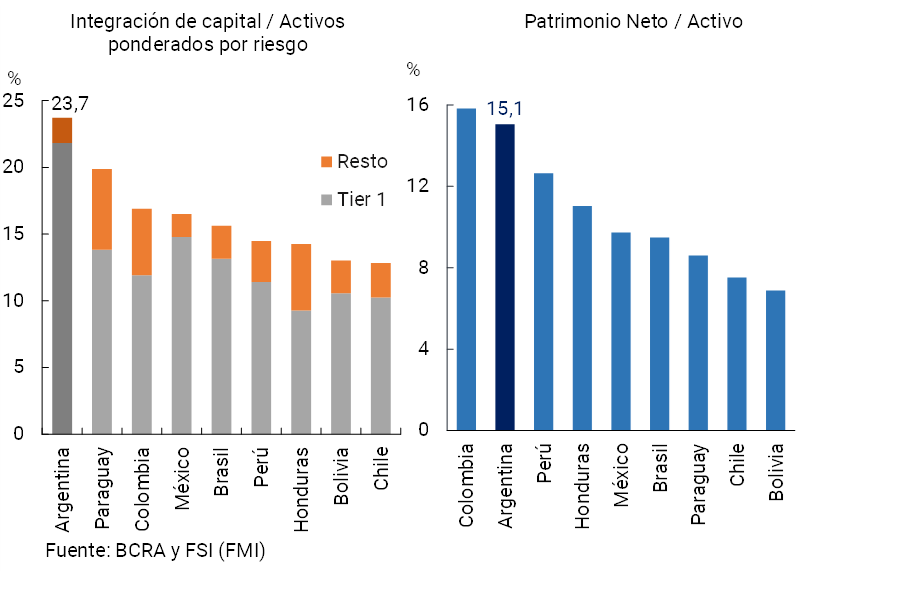

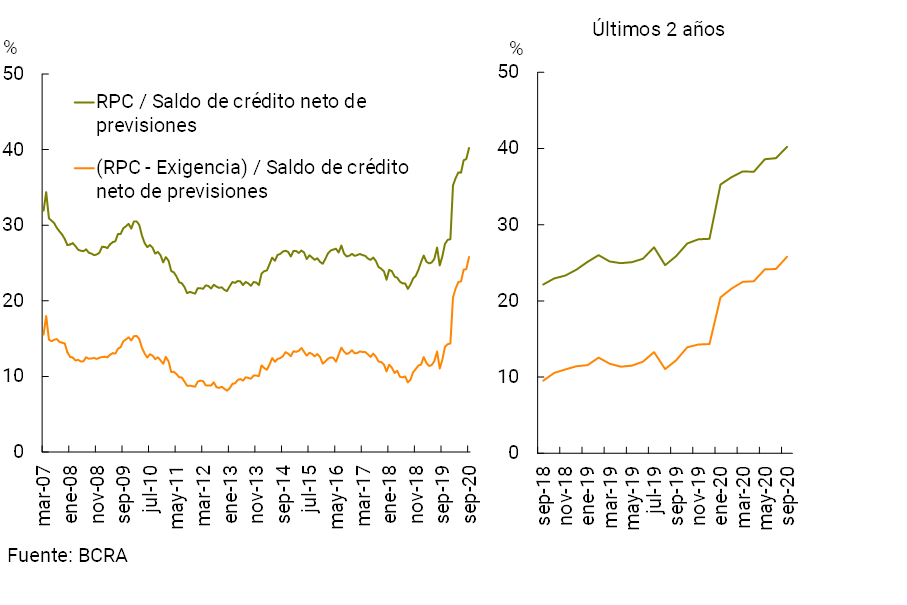

ii. High solvency levels. The regulatory capital indicators of the financial system, both at the aggregate level and by group of entities, have increased since the last publication of the IEF. The system’s capital integration (RPC) totaled 23.7% of risk-weighted assets (RWA) in September, ranking above other countries in the region. The level of this solvency ratio increased by 1.8 p.p. compared to the value recorded in March and by 7.4 p.p. y.o.y. (see Graph 4). Tier 1 capital – the capital with the greatest capacity to face eventual losses – of local entities in aggregate accounted for 92% of capital integration. The capital position (RPC net of the minimum regulatory requirement, in terms of that requirement) of the aggregate of financial institutions stood at 179% in September. In this context, it should be noted that practically all financial institutions continued to verify 100% of the additional capital margins9.

The system continued to present a moderate level of leverage both from a historical and regional comparison. In terms of the international standards recommended by the Basel Committee, the leverage ratio – the ratio between the best quality capital and a broad measure of exposures – reached 11.8% in September, well above the minimum threshold required by law of 3% (in line with the international recommendation).

While the momentum in terms of domestic capital generation was maintained during the period, the performance of the sector’s soundness indicators was also reflected in the impetus of the macroprudential policies adopted by this Institution in a timely manner. In particular, the possibility of distributing results to entities in the face of the pandemic scenario was suspended, in line with the initiatives of other Central Banks in emerging and developed economies10.

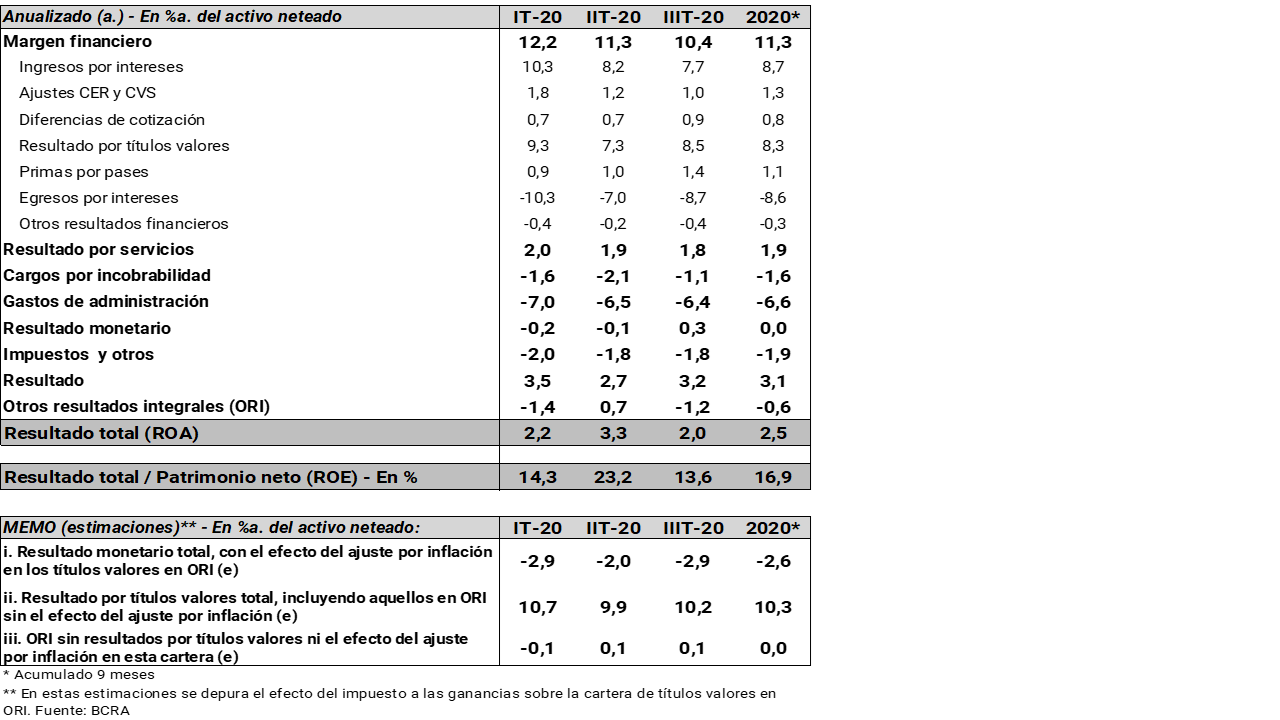

iii. The financial system continued with positive results, although declining (in homogeneous currency). In the first nine months of the year, the entities as a whole accrued comprehensive total results, in homogeneous currency, equivalent to 2.5% annualized (a) of assets (ROA) and 16.9% y. of equity (ROE). However, there has been a decrease in profitability so far in 2020 and compared to that recorded in 2019 (see Section 3.2 and Box. Year-on-year evolution of the profitability in homogeneous currency of the financial system), which deepens as of August 2020.

Box. Year-on-year evolution of the financial system’s profitability in homogeneous currency

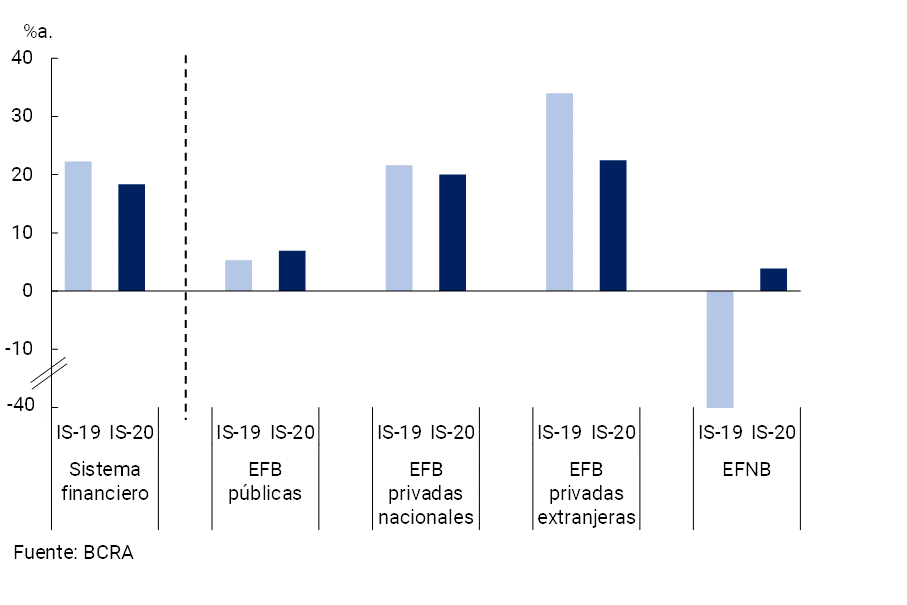

In order to have a better appreciation of the recent dynamics of the sector in terms of endogenous generation of solvency11, profitability indicators are constructed and compared here using data from the Quarterly/Annual Reporting Regime12. Based on the information available, it is estimated that the ROE in homogeneous currency of the aggregate system registered a year-on-year reduction of 3.9 p.p. (maintaining a positive level) during the first half of 2020 (see Chart 5)13. This aggregate performance mainly reflected the behavior of relatively larger private entities14. Although their relative participation in the financial system is small15, the year-on-year increase in the ROE of non-bank financial institutions stands out. The distribution of ROE by entity shows a lower dispersion in 2020 compared to the previous year.

In relation to the factors that explained the year-on-year reduction in ROE in the system’s aggregate, the decreases in the financial margin16 and net income from services stand out. These were partially offset by a reduction in non-financial expenditures.

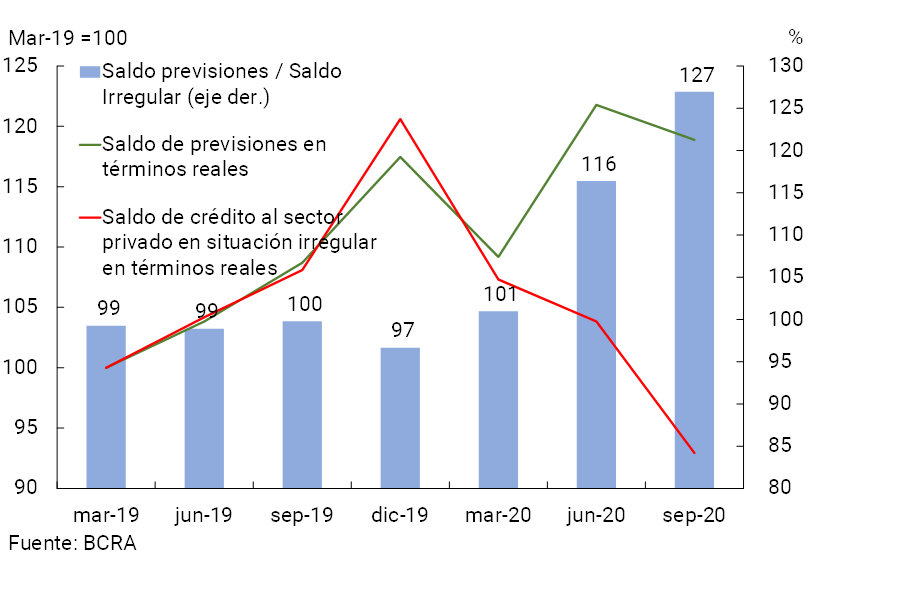

iv. High and growing pension ratios. The balance of forecasts accounted for by all institutions increased throughout 2020, both in absolute terms and in relation to total and irregular loans. The level of forecasts for the financial system reached 127% of the irregular portfolio in September. It should be considered that in view of the transitional financial relief measures for debtors taken by the BCRA, the traditional indicators used to measure the degree of exposure and coverage against credit risk (for example, the estimated ratio for the portfolio in an unforeseen irregular situation in terms of regulatory capital) may not be fully comparable with those verified in the pre-COVID-19 period. However, in terms of illustrating the relatively moderate exposure and current high coverage against credit risk, it should be considered that the ratio between regulatory capital and credit to the private sector (net of total forecasts) at the aggregate level is currently at the highest level in the last 15 years (see Chart 10).

v. Low weighting of foreign currency items and reduced currency mismatch in the balance sheet of the financial system. In a scenario of a decrease in financial intermediation in foreign currency throughout 2020, and in view of the current regulatory framework, the share of assets and liabilities in that denomination in the system’s balance sheet continued to decline. Assets in foreign currency accounted for 19.1% of total assets in September (3.6 p.p. below the value of March), while liabilities in this denomination reached 17.9% of total funding (-3.5 p.p.). The difference between assets and liabilities in foreign currency (including net off-balance sheet purchases) of the sector remains at low levels, in the order of 10% of the PRC.

vi. Limited exposure to the risk of term mismatches. The operations of financial institutions continue to focus on transactional activities, evidencing a limited mismatch of terms. For more detail see Section 3.3.

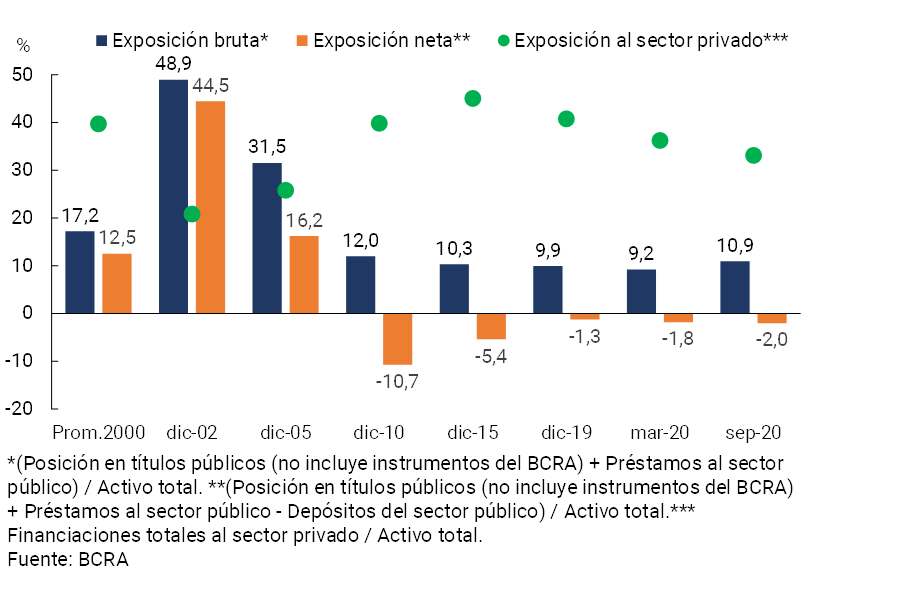

vii. Between low and moderate exposure of the system to the public sector. Credit to the public sector totaled 10.9% of total assets at the end of the third quarter of the year, a value that continues to be low from a historical perspective and when compared to other emerging and developed economies (see Chart 6). When considering the total deposits of the public sector, the financial system preserves a negative net exposure (debt position) with respect to that sector.

viii. Credit assistance programs were implemented to promote better financial conditions for companies and families. The BCRA, together with the National Government, implemented measures that provided liquidity to the non-financial private sector (see Section 2), avoiding exacerbating a situation of tension that would translate into generalized solvency problems, with an eventual impact on financial stability conditions and the real economy. It should be noted that the normalization of activity that is gradually beginning to be observed will allow the efforts of these credit assistance to continue to be reduced and focused on the most affected sectors, adapting to the needs of each moment.

Based on the aforementioned strengths, the system is expected to show resilience in the face of short- and medium-term challenges. Among the main risks exogenous to the system that could eventually be faced, the following stand out:

i. Risk of a weaker-than-expected recovery of the economy. In the face of the pandemic, the evolution of the local economy has been showing a pattern of strong initial deterioration that would be followed by a rebound from the third quarter, although with a certain slowdown over time. The dynamics of economic activity will therefore depend on several factors, including the evolution of the pandemic (pace of progressive opening of activities, access to vaccines, impact of the context on private consumption) and the effectiveness of the measures implemented (for example, those to protect household income and support businesses, which would be increasingly targeted).

A more conditioned evolution of the economy could be due to external factors (worsening of the second wave of infections in the northern hemisphere and more extreme isolation measures), with an impact on global growth expectations, international trade and commodity prices (directly impacting the level of local activity through the trade channel). There could be greater volatility in external markets, as a result of changes in risk aversion (for example, due to the generalization of sovereign and/or corporate debt defaults at the global level), with an impact on portfolio flows to emerging markets and on the prices of different assets (with an effect on the exchange rate and interest rates through the financial channel, which currently has less weight due to the existence of capital controls in Argentina). Economic growth could also be conditioned by changes in some local issues, such as the evolution of the epidemiological situation, the degree of progress in the relaxation of sanitary isolation measures or an increase in the uncertainty that still remains. A relatively more deteriorated economy would have a direct impact on financial intermediation (mainly on the supply and demand of credit, with a correlation in the sources of income of the institutions) and on the payment capacity of the debtors of the financial system (although the relief measures implemented would weigh part of these effects).

ii. Risk of new episodes of volatility in local financial markets. In addition to the period of greater volatility in March-April (the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic), tensions in the debt markets were later added (within the framework of the renegotiation process completed in August and September) and, more recently, temporary imbalances in the supply and demand of foreign currency with an effect on the foreign exchange market (with a downward trend in the differential between the exchange rate implicit in securities purchase and sale operations and the official exchange rate). The eventual reappearance of some volatility in the markets could not be ruled out. This could be due to external factors, taking into account that at the international level there are still several components of vulnerability that have been aggravated by the spread of the pandemic17, or to elements of a local nature. Greater volatility in interest rates and the exchange rate would affect both the context in which financial intermediation is carried out (including the evolution and composition of bank funding) and the credit risk faced by the system.

iii. Operational risks linked to greater dependence on technological resources, for example, greater use of digital channels and teleworking. Although so far there have been no high-impact disruptive events, the dynamics imposed by the pandemic imply greater exposure to operational risks, such as those associated with scams or fraud linked to social engineering (“phishing” or “ransomware”), the possibility of suffering other types of information security attacks, or problems in the provision of intermediation and payment services. as a result of the need for new users to join the use of remote services. In this sense, it should be considered that being able to provide services in this modality implied a great effort for the private and public sectors, which also addressed, among other challenges, that of reinforcing the dissemination of preventive aspects related to information security18.

With a medium-term perspective, as discussed in the previous IEF, the need to address a set of challenges linked to the post-pandemic at the global level is identified. On the one hand, it remains to be seen what situation certain pre-existing vulnerabilities (for example, debt sustainability) will remain. On the other hand, stimulus measures at the global level will have to be gradually dismantled, a process that, if not carried out in an orderly and coordinated manner, could to some extent have negative implications for financial markets (including those of emerging economies). Added to this is the impact of more permanent changes in the business models of the financial sector in particular (including the impact of changes in the sector’s regulations and the agenda related to the non-banking financial sector (see Section 3)) and the corporate sector in general (permanent impacts on productive capacity).

The next section analyzes the sources of vulnerability identified for the Argentine financial system, given its exposure to the risk factors mentioned so far. In each case, the strengths of the financial system will be listed to allow it to deal with these risks if they materialize. Finally, a series of issues related to financial stability that are relevant in the current situation will be developed in greater detail.

3. Sources of vulnerability and specific resilience factors of the financial system

3.1 Performance of credit quality to the private sector

The situation of economic recession that has been accumulating for more than two years, deepened by the shock of COVID-19 and the health measures taken to protect the population, have had a heterogeneous impact on the income of the different economic sectors and regions of the country19. This could create a framework of significant tension on the payment capacity of debtors in the Argentine financial system, becoming one of the sources of vulnerability to the solvency of the sector given its credit exposures.

This aspect increased its relevance within the map of vulnerabilities of the financial system compared to the previous IEF , although its weighting is moderated by the relief measures promoted by the BCRA in conjunction with the National Government since the end of March20. These transitional measures, aimed at mitigating the adverse financial effects of the shock scenario on households and firms, have generally been in line with actions taken in other emerging and developed economies (see Section 4).

A possible materialisation of the risk factors detailed in Section 2, especially in terms of the evolution of economic activity or episodes of volatility in the financial markets, could further alter the ability to service payments to debtors, implying a certain deterioration in the quality of assets, profitability and the solvency of the aggregate system.

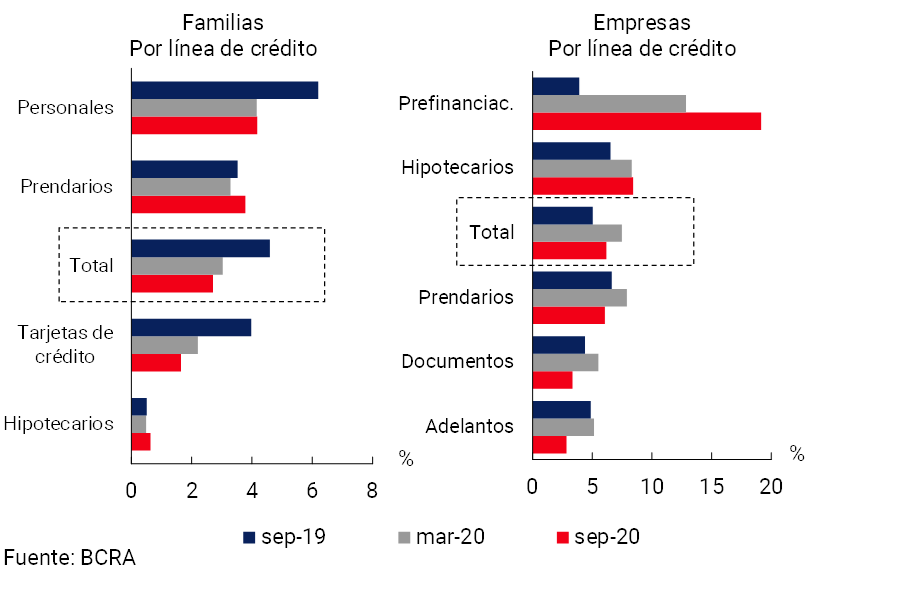

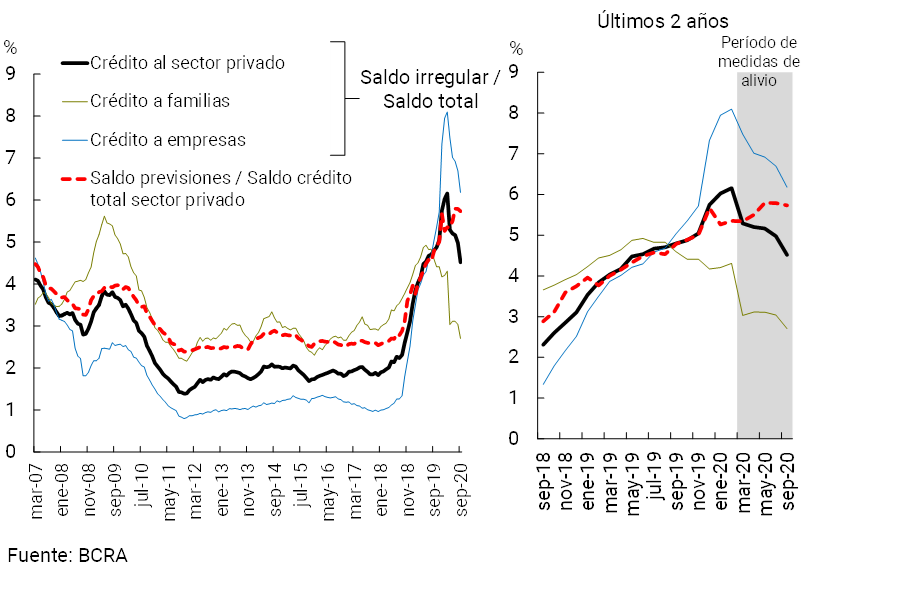

Under the effect of the aforementioned measures, and in a scenario in which the real balance of financing to the private sector stopped falling as a result of the credit stimulus measures at subsidized rates promoted by the BCRA, the irregularity ratio of credit to the private sector stood at 4.5% in September (0.8 p.p. below that observed at the time of publication of the previous IEF) (see Chart 7). In this context, the non-performing loan indicator for loans to companies totaled 6.2% at the end of the third quarter of21, and that of loans to families 2.7%. While the non-performing ratio of credit to companies fell by 1.3 p.p. compared to March 2020 (see Chart 8), mainly driven by the performance of documents and advances, the ratio corresponding to the household segment remained without significant changes (with some heterogeneous behavior when analyzing by credit lines).

Figure 7 | Irregularity of credit to the private sector

Irregular financing / Total financing (%) – Financial system

Figure 8 | Credit to the private sector, situation and forecasting

Financial system

Indicators that include information on the classification of debtors must be interpreted taking into account the impact of regulatory actions taken to mitigate the consequences of the shock. These effects could gradually begin to temper over the course of 2021, as the BCRA assesses the convenience of advancing in the recalibration in stages of the regulatory measures taken to temper the effects of the pandemic scenario.

In view of the aforementioned limitations on the informative content of traditional indicators, it is also relevant to monitor the evolution of the forecasts accounted for by financial institutions in order to specify their reaction in the current context and in the face of regulatory changes. This type of variable is an approximation of the expected losses due to credit risk, an indicator that is even more sensitive in entities belonging to Group A22.

In this regard, prior to the first quarter of 2020, there was a positive correlation between the forecast balance and the irregular balance in the aggregate of the financial system, a situation that changed from that moment on. Thus, in the last six months, the balance of total forecasts in real terms grew at an annualized rate of 18.5%, while the balance in an irregular situation fell at an annualized rate of 25% in the same period (see Graph 9)23. Based on this evolution, in September the balance of accounting forecasts represented 127% of credit to the private sector in an irregular situation of the financial system, 26 p.p. more than six months ago. With this performance, the ratio between the balance of forecasts and total credit to the private sector continued to show an upward trend (see Chart 8), even within the framework of regulatory changes.

Subject to the continued presence of the risk factors detailed above, especially those relating to the evolution of economic activity and possible episodes of financial stress, this potential source of vulnerability for the aggregate of institutions would remain in force in the coming quarters. However, the financial system has elements of resilience that would help mitigate its possible effects.

3.1.1 Specific elements of resilience

Moderate gross exposure of the financial system to the private sector. The total credit balance to the private sector – in domestic and foreign currency – represented only 33.1% of the assets of the financial system in September, down from the previous IEF and in a year-on-year comparison mainly due to the performance of the segment in foreign currency.

Limited concentration of the debtor portfolio. From moderate levels, and within the framework of current prudential regulations, the degree of concentration of debtors has been decreasing in recent months. For example, in September the 100 most important debtors (in terms of balance) of the private sector in the financial system accounted for 17% of the total balance of credit to the sector, 4 p.p. less than the record a year ago.

In recent years, banks have not shown a significant bias towards the relaxation of credit standards. In particular, the results of the third quarter 2020 of the Credit Conditions Survey (ECC) show that a slightly restrictive bias of the credit standards associated with loans to companies was maintained. Regarding loans to families in the same period, the aggregate of the entities showed a bias towards a certain flexibility of credit standards in cards and other consumer loans, while there were no significant changes for pledges and they were moderately restricted for mortgages.

High degree of resistance to the materialization of credit risk. The possible equity impact for the aggregate set of entities would remain relatively low in the face of a scenario of non-payment of debtors of financing in an irregular situation. This is inferred by estimating that the balance of regulatory forecasts attributable to the private sector’s irregular portfolio (following the criteria of the minimum forecasts for bad debt risk) exceeded these loans as of September 2020 (the ratio between the two concepts stood at 105% in the third quarter, increasing compared to the last IEF). However, as already mentioned, the level of irregularity is influenced by the relief measures adopted (which would be recalibrated in the coming months without neglecting a close monitoring of their potential impacts on the situation of families and businesses).

An alternative way to provide a first-order approximation of the financial system’s resistance position at the aggregate level to an eventual materialization of credit risk is to show how much regulatory capital (or regulatory capital position) is equivalent to in terms of total credit net of forecasts. This indicator, without the limitations mentioned above, could be read as a simple stress exercise (sensitivity analysis) that shows in a hypothetical and extreme way (unlikely to be realized) how much the quality of the system’s credit portfolio would have to deteriorate in order for a significant impact on its capital level to be observed. This proportion is estimated to have reached the highest level in recent years in September 2020 (see Chart 10), reflecting the combination of low gross exposure to the private sector, high forecasting, and high capital levels.

Figure 10 | Regulatory capital (RPC) and capital position (RPC – Requirement), in terms of the balance of credit to the private sector net of forecasts

Financial system

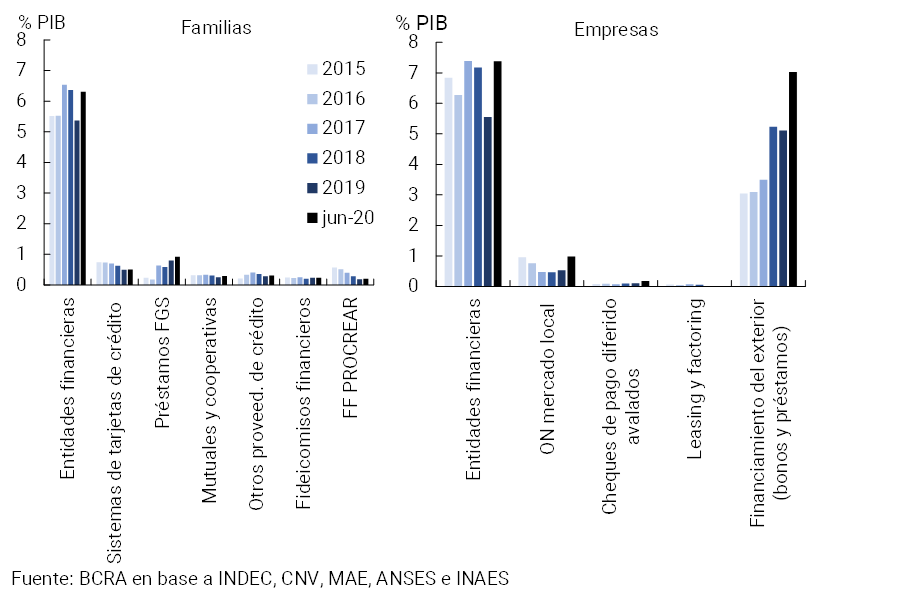

Although they have increased so far in 2020, debt levels in the private sector remain limited. As of June 2020, it is estimated that the balance of financing in the broad sense was equivalent to 8.8% and 15.6% of GDP for households and companies in the non-financial private sector, respectively (see Chart 11)24. This implies an increase compared to the end of 2019 of 1.2 p.p. in terms of GDP for households and 4.3 p.p. for companies25, although in general these levels are still low in aggregate terms compared to what has been observed in other emerging countries.

For both families and companies, the increase in 2020 is partly explained by the policies applied by the BCRA in the current context of the pandemic. In fact, in the case of households, the main dynamism in the year is in the credit segment of financial institutions (followed, with much lower weighting, by FGS loans and those from mutuals and cooperatives), while nominal amounts fall for the rest of the monitored sources (credit card systems, financial trusts, other credit provider institutions that submit information to the BCRA26). In the case of the corporate sector, the main growth is in the credit provided by financial institutions (due to the policies applied) and in that obtained by financing from abroad27. In the latter case (loans and bonds from abroad), although the amounts in dollars show a certain increase, it is influenced by the evolution of the exchange rate. The amount of financing through local capital markets (local negotiable obligations and deferred payment checks) also grew strongly28, in a context in which greater growth in capital markets is being promoted, accompanying the normalization of public debt markets (although the weighting of local market instruments over total financing is still more limited).

The financing of the financial system to companies with public offerings in a relatively more vulnerable situation continues to account for a marginal percentage of the total financing of the sector. The corporate sector (with a focus on the set of publicly offered companies) continues to show signs of deterioration (see Box. Financial situation of publicly offered companies), with weakening in liquidity and profitability indicators in year-on-year terms and increasing leverage. However, this sample of companies maintains a low representativeness in the total credit balance.

Box. Financial situation of publicly offered companies

Based on the balance sheets presented quarterly by companies with a public offering to the CNV, a series of indicators are monitored to have a first approximation of the financial situation of the Argentine corporate sector, considering its link with the financial system and the local capital market. It should be clarified that the companies with a public offering considered constitute a segment of relatively large/medium-sized firms within the entire non-financial corporate sector with activity at the local level29.

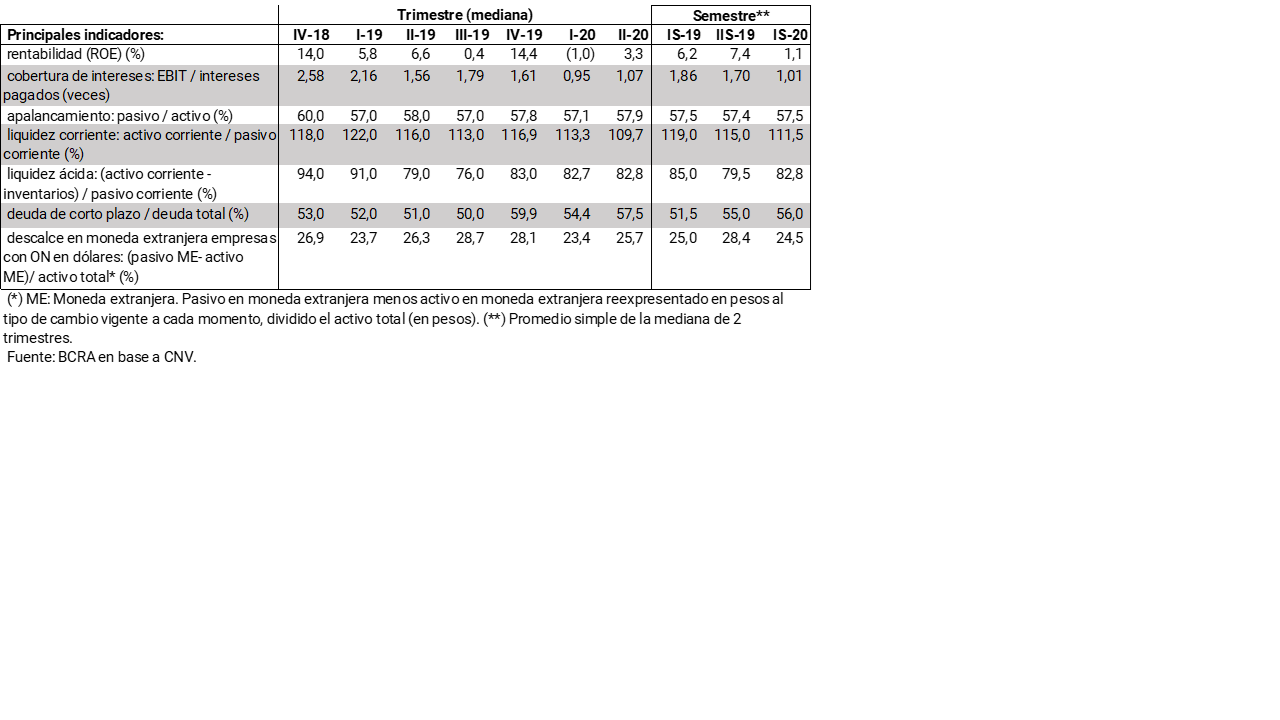

With the latest available information (balance sheets in homogeneous currency up to the IIT-20 of 131 firms), the main indicators of (non-financial) companies with public offerings, in terms of the median, show a weakening in the first half of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019, extending the deterioration observed since 2018 (in a recessionary context). In the first half of 2020, the main impact of the pandemic, the year-on-year decline in profitability and interest coverage stands out, while liquidity shows a more limited drop (see Table 2)30. Leverage trended slightly upwards, although short-term debt shows an increasing weighting in the first half of 202031.

Table 2 |Summary of indicators on the financial situation of the non-financial corporate sector based on analysis of the financial statements of publicly offered companies

In this context, the number of publicly offered companies that could be identified as being in a relatively vulnerable position (using a simple methodology based on the main financialindicators32), reached 16 at IIT-20 (12% of the total, 4 companies more than a year ago). The indebtedness of these companies represents almost 17% of the total financing (banks and markets) of companies with public offerings (against almost 6% in the IIT-19). However, at the aggregate level, the weight of these relatively more vulnerable companies is diluted. With respect to the financial system, the weighting of financing to these most vulnerable companies with public offerings over total financing to companies is limited, although increasing (by IIT-20 they represented 3.5% of the total financing of the financial system to companies, compared to 1.4% in IIT-19). For its part, the balance of ON of the relatively most vulnerable companies represents 9% of the total balance of NO as of June 2020 (being 6% a year ago). In the case of these companies, 84% of their debt in bond format was denominated in dollars as of June. However, the weighting of their maturities on the total maturities of corporate sector bonds in dollars in 2021 is limited (less than 6% of almost US$1,800 million)33.

Households continue to have moderate levels of debt servicing burden, which even the relief measures implemented by the BCRA in conjunction with the PEN sought to temper in part.

Low currency mismatch of the financial system and its debtors (macroprudential regulations). The difference between assets and liabilities – including net off-balance sheet purchases – denominated in foreign currency stood at a value equivalent to 10.2% of the Computable Patrimonial Liability (CPR) for the financial system in September 2020, 0.4 p.p. and 3.3 p.p. less than in March 2020 and September 2019. respectively.

With respect to the debtors of the financial system, in line with the low debt burden of the corporate sector in aggregate form, the balance of ON issued by these firms in foreign currency represents a reduced value (and mostly explained by a few cases, with a predominance of the energy sector). Despite its low relevance, the monitoring of the corporate sector with debt in ON format is maintained.

3.2 Moderation in the growth of financial intermediation

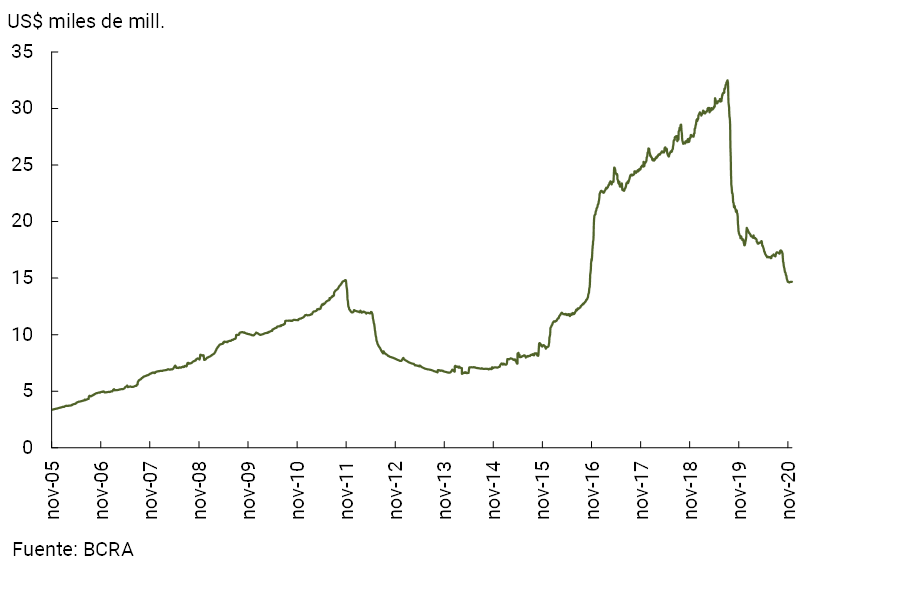

In the months since the publication of the last IEF, the intermediation activity of all financial institutions with the private sector showed a significant dynamism in the segment in national currency, with increases in both the real balance of credit and deposits (mainly time). This performance has largely reflected the actions of the BCRA based on the various measures implemented to provide liquidity to the private sector in the face of the shock, as well as to promote savings alternatives in national currency in the financial system. For its part, financial intermediation in foreign currency continued to decline in recent months, an evolution that was partly accentuated in mid-September, and then stabilized from November onwards. However, the rates of decline in deposits in this denomination are significantly lower than those observed in the second half of 2019.

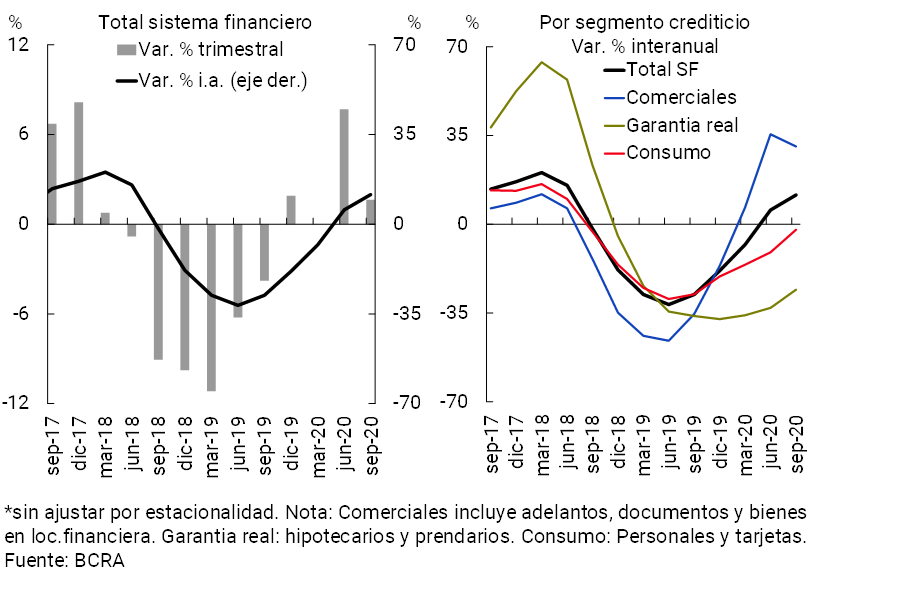

The real balance of credit in pesos channeled to the private sector accumulated an increase of 9.5% between the end of the first and third quarters of the year (+11.6% YoY, see Graph 12). Commercial lines (mainly documents) had a greater relative real increase in the last six months, followed by card financing. On the other hand, loans in foreign currency fell 32.4% compared to March in the currency of origin (-54.3% YoY).

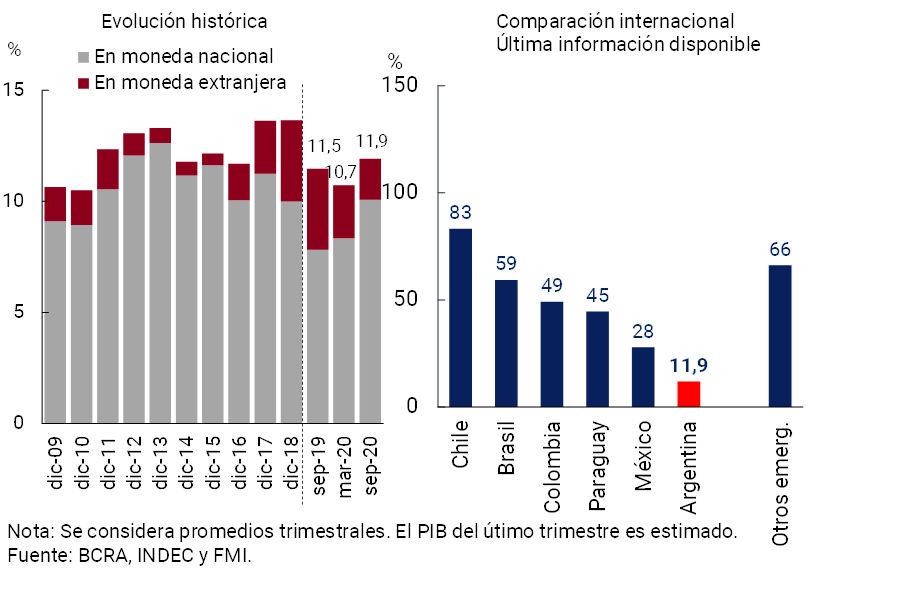

As a result of this credit dynamic, given the scenario of a fall in economic activity, total financing (in domestic and foreign currency) to the private sector in terms of gross domestic product increased by 1.2 p.p. compared to March (+1.7 p.p. in pesos), to represent 11.9% in September (10.1% in pesos) (see Chart 13). These figures continue to be significantly low when compared to history itself and to the values observed in other economies in the region, this being an indicator of the wide margin of growth that the sector has over the next few years34.

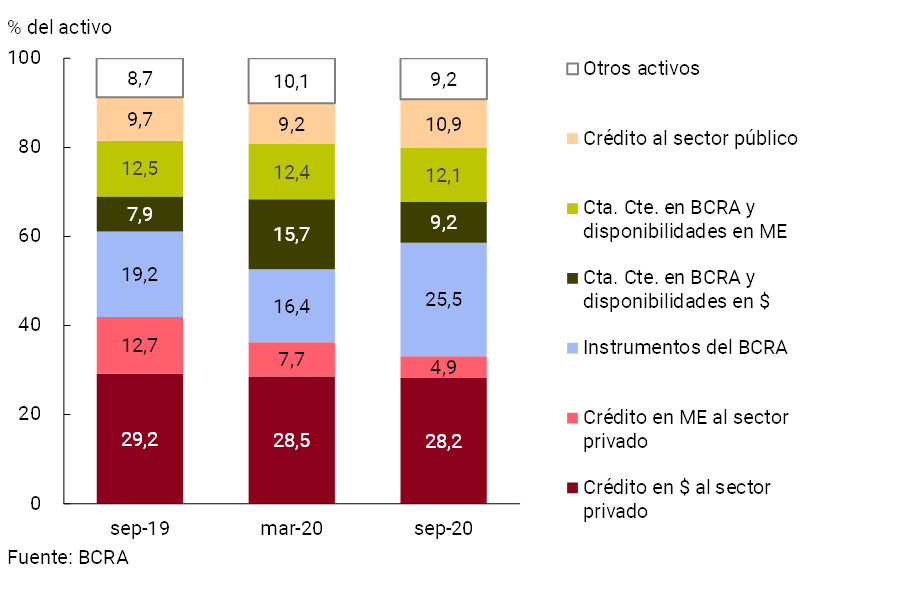

The total assets of the financial system increased by 10.7% in real terms between March and September (15.3% real YoY), with changes in its composition. In a context of monetary expansion to face the pandemic scenario, in recent months the holding of BCRA instruments (LELIQ and passes) in the aggregate balance sheet of the entities increased, to represent 25.5% of assets in September (see Chart 14). Total financing to the private sector lost some share of assets between March and September, mainly due to the performance of the segment in foreign currency. From limited values, financing to the public sector increased slightly in its importance in assets, to 10.9% in September.

Going forward, if economic activity were to evolve more moderately than expected (see Section 1) – in a scenario of gradual readjustment and targeting of official stimulus measures – the intermediation activity of institutions as a whole could be relatively affected (reflected on the supply and demand of credit, and the provision of other services) with a possible impact on the sector’s net income flows. In turn, less channeling of financing to the private sector, or in more demanding financial conditions, could lead to some tension on the payment capacity of debtors, which may affect to some extent the capital slack position of the financial system.

The development of this vulnerability in the coming year will depend largely on the evolution of the aforementioned risk factors, the materialization of which will be conditioned by the health situation (potential effects of a new wave of infections, advances in the massification of a vaccine, effect on the pace of opening of activities, etc.) and the effectiveness of the measures implemented (which would be increasingly focused). among other elements.

3.2.1 Specific elements of resilience

The profitability of the system remains at positive levels in homogeneous currency, although in decline. In the third quarter, the aggregate of financial institutions as a whole presented comprehensive accounting profits in homogeneous currency equivalent to 2% annualized (a) of assets (ROA) or 13.6% y. of equity (ROE). These indicators were lower than those observed in the first two quarters of the year (see Table 3).

The financial margin of the entities stood at 10.4% of assets in the third quarter of 2020, reducing compared to the first and second quarters of the year. This performance was mainly explained by higher interest outflows on deposits on the margin, in part due to the effect of the various measures promoted by the BCRA to stimulate savings in national currency. In addition, there was a reduction in interest income in the aggregate of the financial system. These variations were tempered by the increase in the results for securities and in the premiums for passes. On the other hand, the results by services showed a certain downward trend in recent quarters and greater adjustments for inflation, effects partly offset by the gradual reduction in administrative expenses35.

Compared to 2019, there was also a decrease in the comprehensive profitability in homogeneous currency of all financial institutions (for more details, see Box. Year-on-year evolution of the profitability in homogeneous currency of the financial system).

Risk-oriented supervision of entities. In the face of the pandemic scenario, the Superintendence of Financial and Exchange Institutions (SEFyC) continues, within the framework of its functions, to monitor the performance of entities in order to foresee and address possible situations of vulnerability, aiming to maintain adequate levels of liquidity and solvency in all entities. In this regard, it should be noted that the entities identified as systemically important domestically observe adequate indicators of financial soundness (see Section 4).

Credit assistance focused on MSMEs. Since March, the BCRA has been implementing a set of credit assistance programs for small and medium-sized enterprises. In mid-October, the BCRA approved a new financing scheme in order to continue improving access conditions for those companies affected by the consequences of the pandemic, including MSMEs that wish to expand their production processes (see Section 2). The normalization of activity that is beginning to be observed (albeit with some heterogeneity at the sectoral level) will help to reduce and focus credit assistance efforts, depending on the needs of this stage.

Progress in terms of regulatory proportionality. In September, the classification of financial institutions was modified according to their size of assets. In particular, it was provided that Group “B” will be made up of those financial institutions that have assets of less than 1% and greater than or equal to 0.25% of the total assets of the financial system, and a new Group “C” was created, made up of entities that have assets of less than 0.25% of the total assets of the financial system36. In this way, the BCRA continues to adapt local prudential regulation in accordance with the intrinsic characteristics of the Argentine financial system.

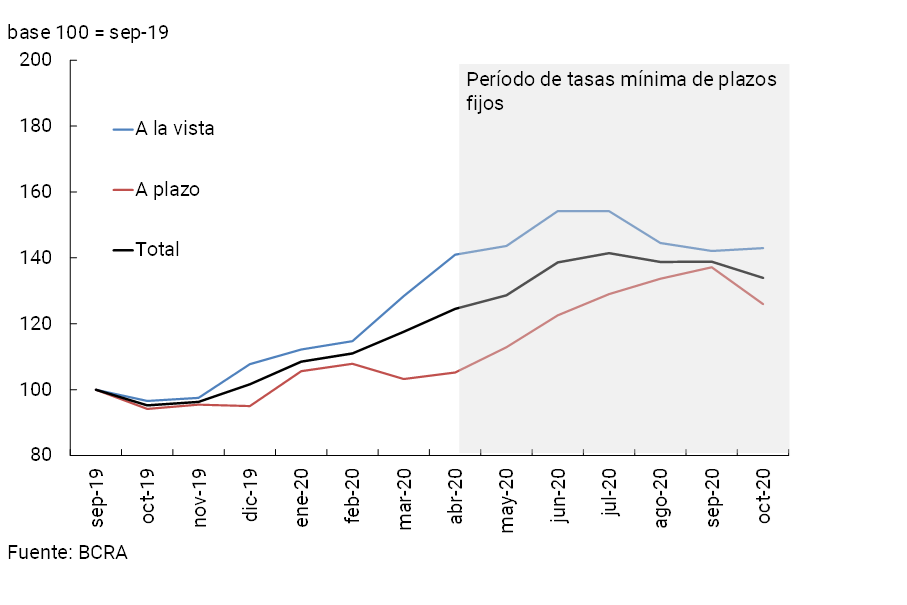

3.3 Funding and liquidity performance of entities

In recent months, certain changes have been observed in the composition of the total funding of the financial system, in a context in which private sector deposits continue to be its main component. On the one hand, private sector deposits in pesos showed a significant increase in real terms of 18.1% between March and September (see Chart 15), tempering to some extent this performance more at the margin. Within this segment, time deposits increased 32.8% in real terms and demand accounts grew 10.7% in real terms in the six months to September, a behavior that reflects the effect of the measures that were taken jointly by this Institution and the National Government, with the aim of promoting savings in national currency and facing the beginning of the pandemic. In this regard, minimum interest rates were established for time deposits in national currency since mid-April (with successive modifications in their scope and level) and collections were established in demand accounts for certain social assistance programs, such as the Emergency Family Income (IFE) and extraordinary subsidies for the most vulnerable strata of the population37.

Figure 15 |Private sector deposits in local currency

Financial system – Constant currency developments

On the margin, in October time deposits in pesos showed a certain slowdown, mainly due to the investment decisions of medium and large market participants (for example, to channel resources to different tenders carried out by the Ministry of Economy in recent months).

On the other hand, after growing gradually since the publication of the last IEF until mid-September, the balance of private sector deposits in foreign currency showed a new decline, and then stabilized in November (see Chart 16). This performance reflected some materialization of the risk factors raised in the last IEF. However, in this scenario, the current prudential regulatory framework (minimum liquidity requirements per currency, limits on mismatching, among others), added to the specific elements of resilience of the sector, acted as expected, avoiding adverse effects on the participants of the financial system.

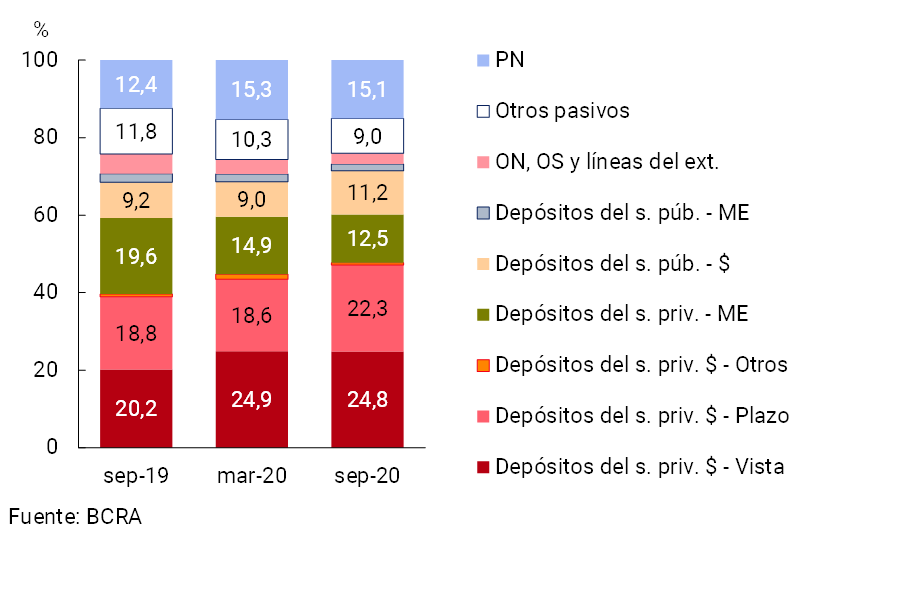

As a result of the above-mentioned performances, the balance of deposits in pesos in the private sector reached about 47.7% of the total funding (liabilities and net worth) of the system as of September, increasing its weighting by 3 p.p. compared to March (see Chart 17), mainly due to term placements. Thus, the weighting of time deposits verified a significant increase of almost 5 p.p. between March and September, reaching almost 47% of the total placements of the private sector in pesos.

Total deposits in pesos accounted for 58.9% of total funding when including public sector placements in the same denomination, which also increased their weighting in the period (+5.2 p.p. compared to last March). On the other hand, deposits in dollars reduced their weight in total funding, especially due to placements from the private sector. Of the remaining 27% of funding, 15 p.p. is made up of the entities’ own capital and the rest is made up of other liabilities, such as negotiable obligations, subordinated debt, foreign credit lines, among others.

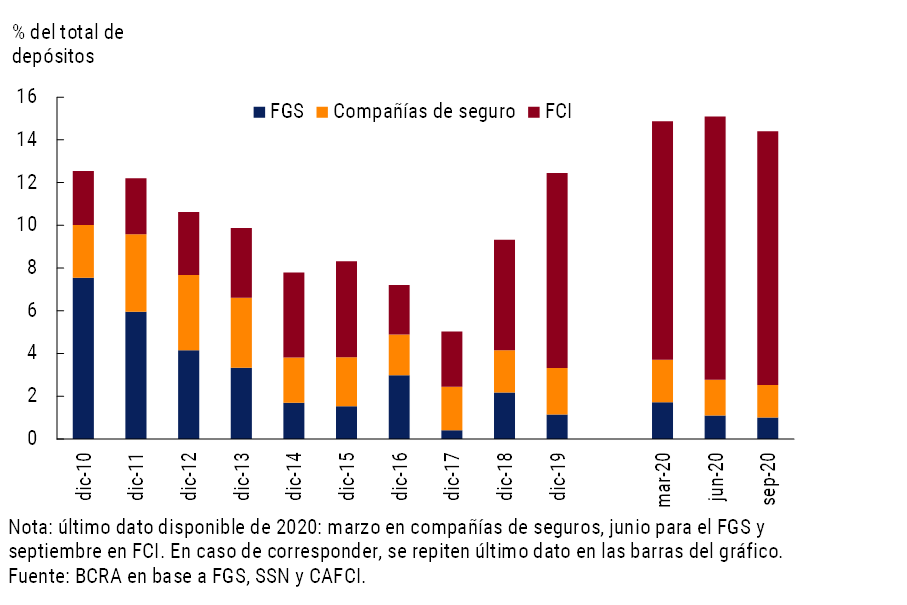

On the other hand, it can be seen that the expansion of the balance of deposits so far this year occurred together with a greater share of deposits from the main customers of each institution in their total deposits, an effect partly explained by placements from large institutional investors (such as mutual funds -FCI-)38.

If a scenario of greater financial volatility materializes in the coming months (see Section 1), further changes in the funding of the entities could not be ruled out, both in terms of level and composition.

3.3.1 Specific elements of resilience and mitigating measures

Adequate levels of liquidity. The financial system continued to develop its activity maintaining liquidity levels above the average of the last 10 years. Compared to the last IEF, the coverage of deposits with liquid assets remained stable in the peso segment (around 62%) and grew in foreign currency items (+11.4 p.p. to 84.3%)39.

It should be considered that the aggregate of financial institutions comfortably meets the regulatory liquidity requirements derived from the international standards recommended by the Basel Committee (see Chart 18). In September, the value observed for the so-called Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) was around 2.2 for the group of banks with the largest relative size (obliged to comply with this requirement), similar to the record evidenced at the time of publication of the IEF immediately above, and well above the minimum regulatory threshold at the local level (set at 1 as of 2019). For its part, the Stable Net Funding Ratio (NSFR) totaled 1.9 in the middle of the year (latest available information) for the same group of entities mentioned above. This value was 0.2 times higher than that recorded at the end of 2019 and also comfortably exceeded the minimum requirement.

A low transformation of terms is maintained. The financial system is characterized by having a high weight of transactional activities in its usual operations. Given the greater relevance of the BCRA’s instruments and short/medium-term financing lines in the assets of the entities, in the last semester the average maturity of the active portfolio in national currency was reduced. For its part, the estimated duration of liabilities increased slightly compared to last March, in line with the aforementioned relative better performance of time deposits in national currency. From low levels, the spread between the duration of assets and that of liabilities decreased slightly compared to the last IEF.

The funding of the financial system through the capital market remains limited. Financing through NO in the capital market continued to be a small part of the total funding of the entities (approximately 2% of the sum of liabilities and equity). Although greater diversification of funding allows for better risk management by the system, in more challenging situations, the refinancing of funding through markets can constitute a vulnerability. Thus, in 2021 these NOTES imply maturities that represent only a quarter of the total outstanding stock of NOTES in the system’s portfolio, most of which are in40 pesos. In perspective, since 2018 it has been verified that the dynamism of the placement of ON by entities decreased. After the publication of the latest IEF, the amount placed between May and October fell 18% in real terms compared to the previous 6 months41. Placements in recent months were mostly carried out in pesos, followed by UVA and dollar-linked (see Chart 19). Placements in pesos went from an average term of 7 months to 17 months (there was also a lengthening in UVA and dollar-linked placements)42.

4. Other topics of stability of the financial system

4.1 Systemically Important Financial Institutions at Local Level (DSIBS)

From a systemic risk perspective and in line with international recommendations on the matter, since 2014 the BCRA has been using and publishing a methodology to identify systemically important financial institutions at the local level43. Given the relevance of these entities in the sector, a hypothetical scenario of tension in any of them (regardless of the origin that causes it) could spread and impact a considerable part of the Argentine financial system. That is, it could eventually manifest itself systemically, and have a significant impact on the real sector of the economy. That is why this type of entity is subject at the local level, in line with international recommendations on the matter, to special regulatory treatment (they have to verify a greater margin of capital conservation compared to the rest of the institutions44), as well as closer supervision.

It should be considered that, at the local level, this group of entities continues to represent approximately half of the assets of the financial system. As at the time of publication of the previous IEF, at the end of the third quarter it was observed that all the systemically important entities at the local level verified the entire capital conservation margin. Its liquidity and solvency ratios showed increasing performances in the last two quarters, in line with the evolution observed in the system, while its profitability indicators were slightly higher than those recorded at the aggregate level, although with a downward trend compared to 2019 (see Table 4). The indicators related to the exposure to credit risk of the private sector and currency mismatch evolved in the same direction as those recorded for the aggregate of entities (slight decrease compared to what was observed at the time of publication of the previous IEF).

4.2 Interconnection in the financial system

The interconnection between the financial system and the institutional investor base (Sustainability Guarantee Fund (FGS), mutual funds (FCI) and insurance companies) maintained the growing trend that began in 2018, although it remains relatively small compared to the levels observed in other economies. The most important institutional investor continues to be the FGS (its investment portfolio is equivalent to 12% of GDP), followed by FCIs (with assets under management equivalent to 7% of GDP) and insurance companies (with a portfolio that represents 4% of GDP)45,46. FCIs are the main source of direct interconnection with the financial system based on funding (their time deposits and availabilities represent 12% of the total deposits in the financial system), while the main indirect source is the holding of public securities (due to the risk that overlapping portfolios in the same types of assets eventually imply). Considering the three main categories of institutional investors, the weighting of total deposits in the financial system is around 14%47 (it was 12% at the end of 2019). As in the previous period, the increase in direct interconnection was driven by the performance of money market funds (see Chart 20)48.

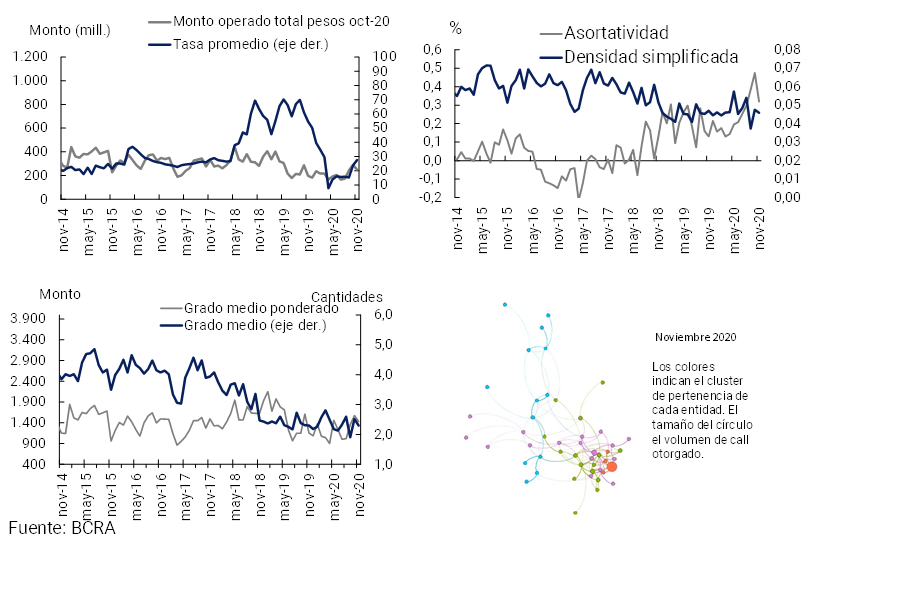

With respect to other sources of direct interconnection and in terms of an intra-financial system analysis, the market for unsecured interfinancial loans is monitored using the network analysis methodology49. In a context of an increase in the amounts traded in real terms (accompanied by higher nominal interest rates) in recent months, interconnection through the call market was increased after the historical lows of April, although this market continues to be relatively limited in size in Argentina (in this particular, an increase in the weighted mean degree and network density was observed)50. In turn, it is verified that the entities begin to connect with others with characteristics different from their own (decrease in assortativity) (see Graph 21). In a long-term comparison, a lower level of relative interconnection is observed, with a medium degree and density that are below the 5-year average.

5. Main macroprudential policy measures

Since the publication of the last IEF in June, the BCRA maintained its prudential policy scheme focused on tempering the economic and financial impact of the shock, promoting the provision of liquidity to households and the productive sector, as well as tools that allow financial relief to the aforementioned sectors. These measures, which were in line with what was observed in other developed and emerging economies in the face of the pandemic, continue to seek to avoid a scenario of lasting damage to the Argentine economy, which could have a correlation in the levels of activity and employment, with the consequent impact on local financial stability conditions.

In this regard, the measures continued to be aimed at:

i. To promote financing to the private sector under favorable financial conditions, thus tempering the procyclical dynamics of credit commonly observed in other contractionary periods. This was done through the strengthening of flexible credit lines for companies and self-employed personnel and single-tax payers (see Section 2), initiatives taken in conjunction with the PEN. In addition, family consumption continued to be encouraged by strengthening existing benefits under the Ahora 12 Programme;

ii. Sustain the measures to alleviate the financial situation of families and companies, extending until the end of the year the modifications in the criteria for classifying debtors, as well as the flexibility in the conditions of payments of current loan installments (including credit cards), among other elements;

iii. To promote bank savings in pesos at the time of the calibration, on successive occasions, of the minimum interest rates that protect the debts of private sector depositors in the face of price variations in the economy, the launch of deposits adjustable by UVA and pre-cancelable at market rates, as well as the implementation of savings alternatives in term investments with variable remuneration for certain sectors of the economy;

iv. Contribute to strengthening the solvency levels of the entities, extending the suspension of the distribution of dividends;

v. Maintain regulations on the foreign exchange market that seek to prevent transitory imbalances from affecting the position of the economy’s international reserves. Likewise, in the medium term, it seeks to maintain macroprudential regulations compatible with the dynamization of capital flows oriented to the real economy.

Section 1 / COVID-19 and risks to financial stability in emerging economies

After the publication of the latest IEF last June, the financial assets of emerging economies continued to follow the recovery trend observed until the end of August in the markets of developed economies. However, several of the leading indicators for emerging markets did not return to pre-pandemic values51. The EMBI+ surcharge for emerging sovereign bonds was about 90 bps above its average levels in January at the beginning of September, while currencies depreciated by close to 10% against the dollar in the same period. Volatility in emerging currencies remained double what it was at the beginning of the year.

Accompanying the signs of a resurgence of COVID-19 in the northern hemisphere, at the end of October there was an increase in risk aversion in markets globally. The persistent uncertainty (added to a certain disconnect between the improvement in financial markets and the downside risks linked to global growth expectations) means that – although the approval of vaccines generates a more optimistic view – the possibility of new events of this nature cannot be ruled out, with the consequent impact on emerging economies

The pandemic has had a direct effect on the prices of emerging market assets, in part due to the characteristics of these economies. On the one hand, in several of the emerging countries, the importance of the production of raw materials (establishing an important correlation with global growth) and other sectors directly affected by the COVID-19 crisis (such as tourism) is highlighted. Although policy responses in this group of economies were swift and forceful, in line with actions in developed countries, their room for maneuver is more restricted, given the lower availability of resources as a percentage of GDP and greater informality. On the other hand, the financial markets of these economies tend to show less depth and liquidity than in developed countries.

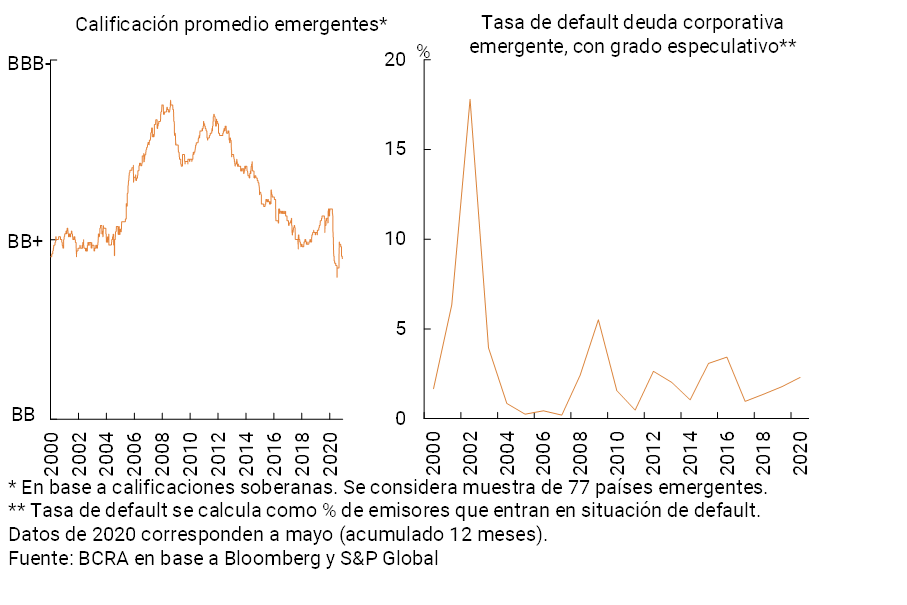

With economic activity weakened globally, a further downward adjustment in growth expectations would put greater pressure on the credit risk associated with agents in emerging economies. While for sovereigns this is partly linked to the fiscal effort made in the context of the pandemic, for companies it is particularly due to a context of relatively high and growing indebtedness and increased currency mismatches, as well as lower revenues and sectoral profitability. With a certain heterogeneity between countries, a situation of fragility was then configured in the face of possible scenarios of renewed increase in refinancing costs in international markets and greater volatility in foreign exchange markets.

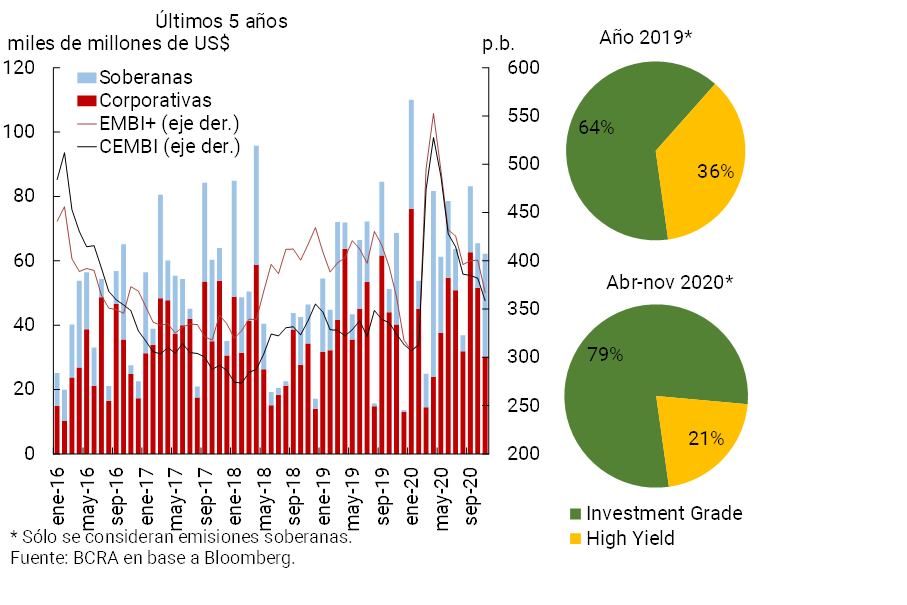

Although the placement of emerging market debt quickly revived as a result of the implementation of forceful policy measures52 (see Figure A.1.1), operations show greater relative dynamism in the sovereign segment than in the corporate segment, with a bias towards countries with better debt ratings53. However, with economic activity conditioned by the existing uncertainty, the trend of increasing the downgrades of emerging market debt ratings could accelerate (see Figure A.1.2), with potential procyclical effects54. Going forward, it will be necessary to monitor the final impact on the sustainability situation of the higher level of indebtedness of each country.

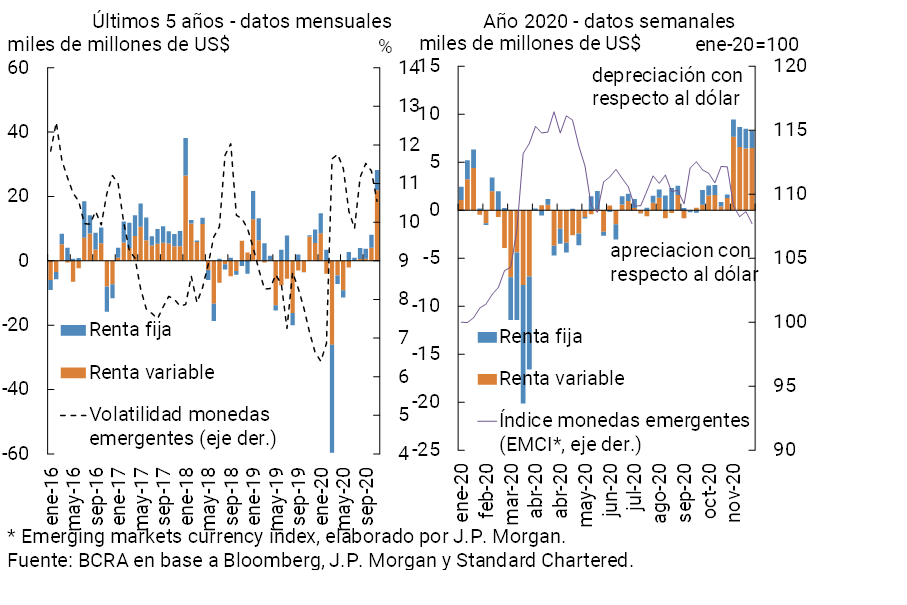

The growth in emerging market debt placements is also linked to the increase observed in recent years in non-bank financial intermediation (NBFI) worldwide55, particularly given the growth of investment funds that relatively increased their positioning in emerging economy assets (see Section 3). In contexts of strong risk aversion and generalized search for liquidity, as happened in March of this year, these funds can generate abrupt portfolio outflows from emerging countries (see Figure A.1.3), implying contagion effects that can be disruptive for the prices of financial assets and exchange rates, putting pressure on the evolution of the rest of the macroeconomic variables of relevance of these economies (international reserves and inflation, etc.). for example).

With respect to banks in emerging economies, their resilience has generally improved as a result of the regulatory changes implemented after the global crisis that peaked in 2008-2009. This does not imply that there are no specific countries (or specific banks in certain countries) in a situation of greater relative weakness, which could find themselves in trouble if the context worsens, especially with regard to credit risk (the possibility that liquidity problems for the private sector will lead to solvency problems).

Through different international forums and forums (FSB, BIS, IMF), the different factors of fragility of emerging economies and their interrelation with the trends observed in international markets are being closely monitored. The possibility of contagion effects with an impact on emerging markets would generate space for coordinated policy actions at the global level. Thus, an agenda56 is taking shape that aims to achieve a better understanding of the role of NBFIs and its link with variables such as liquidity, agent leverage and the interconnection between different markets and different countries (including emerging countries). This agenda could eventually lead to future policy actions and adjustments in macroprudential regulation with the aim of improving the resilience of the broader financial sector globally.

Section 2 / Measures adopted by the BCRA to sustain the flow of financing to the private sector

Since last June, when the IEF I-20 was published, the BCRA has continued to make progress in its objective of making improvements in the set of measures implemented to strengthen the channeling of credit to families and companies given the evolution of the pandemic scenario that began in March57. The tools designed for this purpose, which in all cases took into account the initial liquidity and solvency conditions of the financial system, gradually began to be recalibrated at the margin. These changes reflect the developments observed in the economic and financial situation of the local private sector, which largely reflect the modifications in the health measures in force in the different jurisdictions of the country.

Among the different credit assistance initiatives implemented by the BCRA throughout 2020, the special line for MSMEs and Health Service Providers at a nominal interest rate of 24% (MSMEs 24%)58 stood out, both for its magnitude and for its broad scope. This initiative was implemented before the beginning of the sanitary restrictions, seeking to contribute to the financing of working capital needs as well as the acquisition of capital goods by MSMEs and health service provider companies, with costs that were significantly lower than those in force in the market. In order to promote the granting of these loans in a scenario of high uncertainty caused by the shock of unprecedented magnitude, the Minimum Cash requirements that institutions must comply with were reduced. As of May, this line of credit was extended by the so-called MSME 24% Plus59, aimed at assisting companies that did not have access to credit from the financial system (i.e., very small companies with greater difficulties in accessing formal credit). Both initiatives accumulated disbursements, in aggregate, of just over $540 billion until the beginning of November (counting just over 10% of the total guaranteed by FoGar).

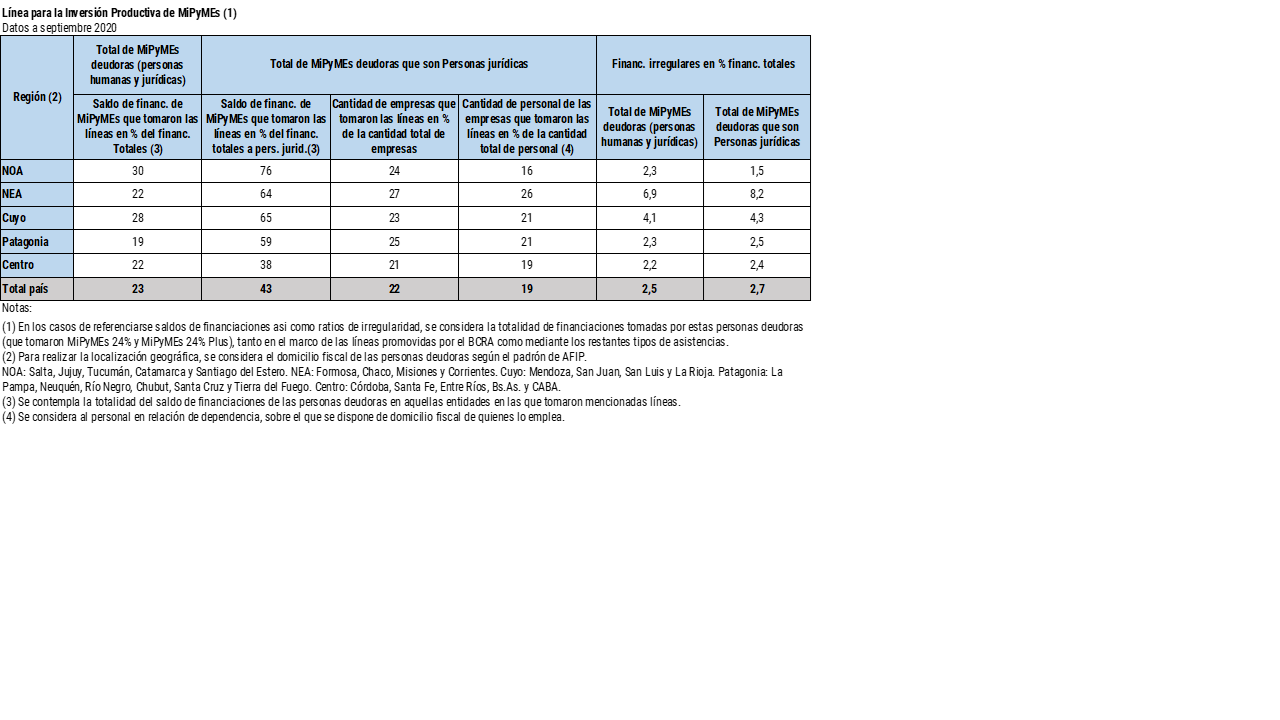

As a result, MSMEs 24% and MSMEs 24% Plus benefited approximately 114,000 MSMEs until the end of the third quarter of the year, companies that employed almost 1.6 million people60 and that, for the most part, were incorporated as legal entities. It should be noted that these lines allowed access to financing on favorable terms for MSMEs in all regions of the country (see Table A.2.1). Thus, these debtors in aggregate came to register a credit balance equivalent to almost 24% of the total balance of financing at the level of the financial system as of September61 (with relative maximums in the NEA and NOA regions), verifying irregularity ratios below those observed in the financial system as a whole. The scope of these debtors grows to 43% of the total financing in the specific case of legal entities, representing almost a third of this type of debtors in the aggregate of the system. Moreover, approximately 15% of the total number of companies reached by MSMEs 24% and MSMEs 24% Plus taken together, were not present as recipients of credit in the financial system at the beginning of the pandemic, a proportion that increases to 21% if the segment of legal entities is specifically considered. This is an example of the ability of these credit assistance policies to drive greater inclusion.

In order to deepen the financing channels for the companies that saw their activity most affected as a result of the shock, and thus focus the action of public policies, two relevant modifications were subsequently implemented. First, in August, the BCRA, in conjunction with the PEN, implemented a new line of financing at subsidized interest rates channeled to firms that verified a relatively weaker performance in their sales —in real terms—, thus providing them with an additional tool to pay the salaries of their workers62. These credits are available to all those companies enrolled in the “Emergency Assistance Program for Work and Production” (ATP), providing interest rates significantly lower than market rates, while granting regulatory benefits in terms of Minimum Cash for the entities that originate them. Since its launch until the first days of December, more than 11,000 loans have been granted for a total of $7,100 million under this program, benefiting approximately 340 thousand working people.

Second, and also with the aim of adapting public credit stimulus measures to the progress in the economic scenario of gradual recovery63, in mid-October the BCRA implemented a new scheme called the Financing Line for Productive Investment of MSMEs64. It is intended both for companies affected by the consequences of the pandemic, as well as for the rest of the MSMEs that wish to expand their production processes for the next65 years. It consists mainly of a line for the financing of investment projects of MSMEs with a maximum APR of 30% and an average term equal to or greater than 24 months, and another aimed at financing working capital, checks and electronic invoices of the same segment of companies with a maximum APR of 35%. From mid-October to the present, loans for around $104 billion have been disbursed through this new scheme (approximately 9% corresponds to investment projects), channeled to almost 30,000 companies.

It should be considered that the BCRA’s actions also focused on addressing the situation of households whose main sources of income were linked to self-employed activities. Since April, a line of loans at a 0% rate has been promoted in conjunction with the PEN, aimed at alleviating part of the economic effects of the shock on people who make up the category of Monotributistas and Self-Employed66, which was later expanded in August to include those people who carry out activities related to culture67. In all cases the interest rate is 0%, the financing is credited to the applicant’s credit card and there is a grace period to start making your payment (which must be made in 12 equal and consecutive installments). Through them, about $67 billion have been granted until the beginning of December (almost all of which has already been disbursed) through some 565 thousand loans. The implementation of this credit assistance led to the issuance of 250 thousand new credit cards in the population.

This wide range of credit initiatives promoted by the BCRA in the face of the shock, added to the measures specially designed to temper the financial burden of the private sector in the same scenario, have sought to promote a framework of financial sustainability for the complex productive framework of the local economy. These initiatives drove much of the recovery in the real balance of credit in pesos observed since last March, after almost 2 years of sustained decline in the flow of financing to the private sector (see Section 3.2). In this way, it contributed to mitigating the procyclical behavior of credit that the financial system generally presents, thus reducing potential long-lasting adverse effects that have a correlation in the conditions of local financial stability and, consequently, on the country’s growth possibilities in the coming years.

Section 3 / Investment funds and financial stability at a global level

In recent decades, non-bank financial intermediation (NBFI) has grown relatively more than banking at a global level. The FSB’s mapping of the financial sector in broad terms68 shows that, while NBFI manifests itself in a variety of ways, globally almost half of it is explained by investment funds.

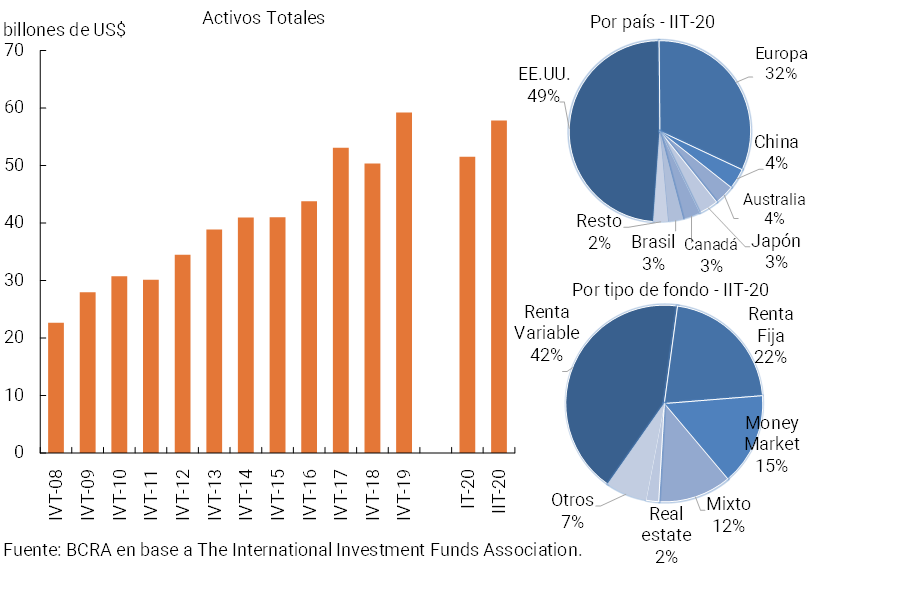

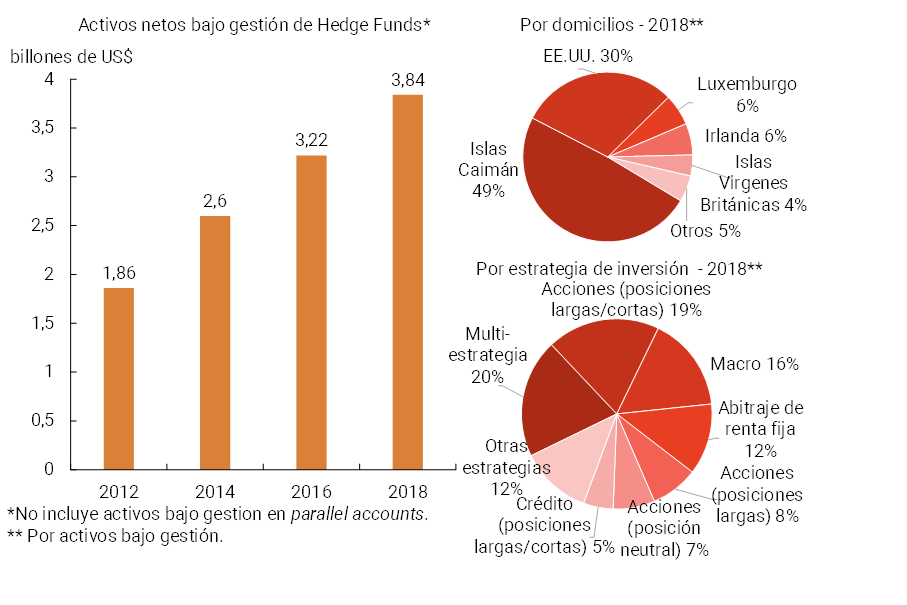

The main component of the fund industry is the so-called open-ended funds, their simplest version. According to IIFA69, globally these funds reached a balance of over US$59 trillion at the end of 2019, more than double the figure a decade ago (see Figure A.3.1). The composition by type shows that as of June 2020, stocks account for 42% of total assets, followed by bonds (22%), money market (15%) and mixed (12%), among70 others. Another segment of the fund industry, more complex and riskier to operate, is that of hedge funds (HF). These funds have much more flexibility than open-ended funds: they have fewer restrictions on borrowing, they can build short positions, they can use derivatives for speculative purposes, and they can follow more complex strategies71. According to IOSCO, HFs reached a balance of almost US$4 trillion at the end of 2018 (to which would be added almost US$0.6 trillion in assets under management in parallel accounts), more than double the amounts observed in 2012 (see Figure A.3.2)72. The HF industry shows a strong concentration in a few jurisdictions: almost 80% of the managed funds that IOSCO follows are in the US and the Cayman Islands. These funds follow various strategies and have a large presence in the financial markets73.

The actions of investment funds, even the simplest and most regulated (such as open exchanges), entail a series of vulnerabilities for both advanced and emerging economies:

Term and liquidity mismatch. This is due to the difference between the liquidity of the investments and the redemption conditions. This vulnerability is more noticeable in the case of open-ended funds, which can be rescued in the short term. In stressful situations, there may be incentives for investors to redeem their holdings before the rest, especially in funds that invest in riskier or less liquid assets (exacerbating procyclical behaviour).