Federico Sturzenegger at the XXI Global Economics Symposium

Federico Sturzenegger, Governor of the Central Bank of Argentina (BCRA), opened the XXI Global Economics Symposium today organized by the Tel Aviv University under the heading “Economics and financial outlook: national and international perspectives”.

The full speech follows:

It is a pleasure to be here today at this Global Economics Symposium 2016. I remember that last year I had to cancel my presentation at the last minute given the hectic times of elections transition. Now that the Argentine society has cast votes, I can be here today being certain that we have already gone part of the way with an adequate insight so as to analyze the BCRA‘s main focus: the evolution and perspectives on inflation in our country.

This implies reviewing the strategy that is, and will be, followed in the future to reach the 5% annual inflation target in 2019.

At present, we need to clarify two relevant issues. As you may know, August will show a significant deceleration of inflation. When I say “significant deceleration”, I am not referring to the deflationary effect of tax reversal. On the contrary, this Central Bank has analyzed the likelihood of fixing monthly inflation target below 1.5% for the last quarter this year. We may, indeed, reach that target two months earlier, regardless the effect of taxes.

Given this situation, what can we expect from monetary policy? This is one of the topics I would like to address.

The second topic is about the relationship between monetary and fiscal policy, an issue which has not been fully discussed at the BCRA but has thoroughly been discussed among analysts involved in Argentine macroeconomics. The question is whether fiscal gradualism endangers the deflationary objectives of the BCRA or not.

I will now move ahead to the key conclusions in order to avoid holding these issues in abeyance for long. Regarding the first topic, I will conclude that the August slowdown does not suffice to believe that we should relax our monetary policy.

On the other hand, I will endeavor to support the idea that fiscal gradualism proposed by the government does neither threaten nor condition our monetary.

Fighting inflation

As we all know, Argentina has gone through chronic inflation for many years. This seems surprising today given that virtually most countries have learnt to consolidate a macroeconomic plan without inflation.

For this reason, I would like to start by depicting the way other countries have fought to achieve, and even keep, low inflation. In particular, I would like to share with you a comment Mario Draghi made in a meeting a few months ago.

Draghi quoted:

“In the last half century central banks have come a long way in how they approach their macro-stabilization functions. As recently as the late 1970s, views still diverged across advanced economy central banks as to the efficacy of monetary policy in delivering price stability. Some, such as the Bundesbank and the Swiss National Bank, were already committed to using monetary measures to control inflation. But others, such as the Federal Reserve and various European central banks, remained more pessimistic in their outlook, believing that monetary policy was an inefficient means to tame inflation and that other policies should be better employed.

Illustrating this view, Fed Chairman William Miller observed in his first FOMC meeting in March 1978 that “inflation is going to be left to the Federal Reserve and that’s going to be bad news. An effective program to reduce the rate of inflation has to extend beyond monetary policy and needs to be complemented by programs designed to enhance competition and to correct structural problems.

In this context of timidity about the effectiveness of policy, inflation expectations were allowed to de-anchor, opening the door to bouts of double-digit price rises. The outcome was a phase of so-called “stagflation”, where both inflation and unemployment rose in tandem.

The policy lesson that emerged from this period was that sustainable growth could not be separated from price stability, and that price stability in turn depended on a credible and committed monetary policy. From late 1979 onwards – with Volcker’s assumption of the Fed chairmanship – central banks converged towards this orientation and took ownership for fulfilling their inflation mandates. As their renewed commitment to control inflation became understood, inflation rates fell steeply in a context of improved anchoring of inflation expectations. Central banks abandoned the self-absolving notion that price stability depended on other, non-monetary authorities.”(1)

It is worth thinking about the former paragraphs to understand that inflation was overcome in the world because central banks committed themselves to its reduction by resorting to tools, which proved to be enough and produced convincing results.

We have learnt from such successful experience that the Central Bank’s autonomy is of vital importance. This autonomy is central because an important part of the agenda on low inflation rates requires that the commitment to reduce inflation will not be determined by political emergencies or short-term objectives. Even if the Central Bank’s objective is a low inflation rate or a dynamic economic growth, monetary policy should not be subject to the latter for it can produce a boomerang effect given that inflation rate will only be low should the Central Bank not surrender to short-term objectives.

Anyway, as we know, inflation is reduced by means of an adequate monetary policy, and deflation processes are not complexity free given the need to coordinate agents’ expectations among one another within a new schedule, on the one hand, and such expectations in light of the path towards inflation reduction sought by authorities, on the other. As regards this point, it is important to bear in mind that there is no particular feature in our deflation process. Rather we have faced the same problems as such countries that resorted to deflation.

For instance, during Canada’s deflationary process, Gordon Thiessen, Governor of the Bank of Canada, made reference to the following quotation:

“A distinction should be made between reducing inflation and keeping it at a low level. Reducing inflation requires adapting to low inflation expectations and may imply transition costs, which does not take place when the objective is merely keeping inflation low. It is generally accepted that, when inflation is high, the benefits achieved when inflation decreases are higher than transition costs.”2

In our new monetary regime, the Central Bank fixes inflation targets and resorts to all the tools within reach to achieve them even if that implies fixing the interest rate at 38% for several months. Likewise, monetary policy does not adjust to inflation expectations. Rather it causes agents’ expectations and actions to be coherent with the Central Bank’s objectives. That was exactly what Draghi referred to.

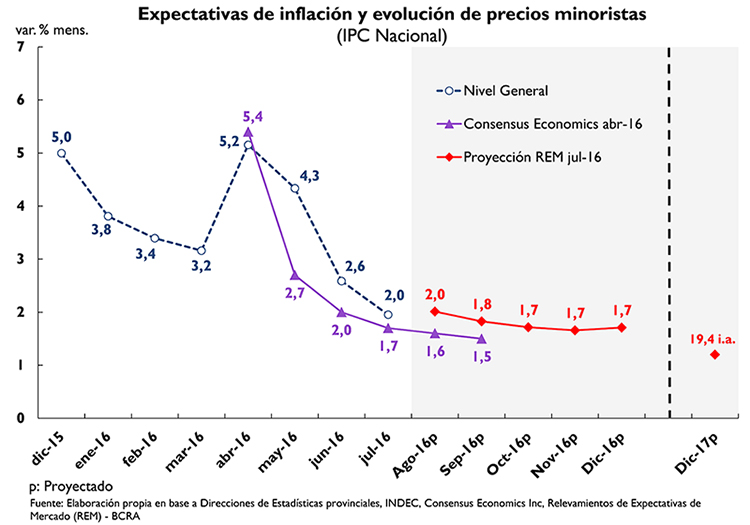

Therefore, it is central to start crystalizing these expectations and taking them as a benchmark for decision-making processes. Now, let’s consider the chart on the inflation expectations during April. As you can see, at that time, a sharp decline in inflation was assumed during the year.

We then claimed that our objective for this year was to set inflation target below those expectations and, a few months later, we set a 1.5% or lower monthly inflation target for the last quarter.

The chart also shows inflation expectations to date, from which we may conclude that these expectations were well anchored. In turn, the dotted line shows where we stood vis-à-vis our initial aim. Likewise, it shows inflation expectations for 2017, which stand above our hopes, seeking inflation rate even below 17%.

Why is it so important to internalize these expectations? Just for a simple reason. Many of the people here today are involved in price and wage formation. And the price and wage decision cannot be detached from any expectations about what would happen with prices in the future.

In other words, let´s imagine, for instance, that next year’s inflation rate would be 0%. In that case, if you negotiated wages so as to compensate for the year’s inflation so far, you would be fixing real wages much above the previous year. Why? Because the adjustment implemented would not be followed by future inflation. Hence, given that the initial value of last year’s wages lost purchasing power in the face of inflation along the year, average wages would be higher in 2017 compared to 2016.

You may want to move in that direction and it would be all right, but I would like to point out that the decisions about prices and wages should not be taken in the vacuum; rather the development of expected prices and wages should be taken into account.

An Inflation Target Regime becomes fruitful in defining and accomplishing such expectations, and helping to coordinate the expectations of all economic agents.

If this new regime is not clearly understood, i.e., expectations are detached from monetary authorities’ measures will make the following deflation process harder, as the Governor of the Bank of Canada said 20 years ago.

Now, let us suppose we understand the mechanism and inflation targets are clear: I would like to emphasize the 1.5% monthly inflation rate of the last quarter and place inflation expectations for next year below 17%. Anyway, someone may ask himself “why will it work?” “How could I learn that inflation targets will be accomplished?”

At this juncture it is important to go back to Draghi’s comments and to bear in mind that inflation is defeated in the monetary market. Price level is nothing but the representation of money price. If there is more money than the amount people need, money price will fall or, in other words, the price of goods will rise (relating to money). This phenomenon is called inflation. That is, whenever there is more money than people demand (either because of an offer increase or a demand decrease), there will be inflation.

Therefore, the road towards fighting inflation is to build a schedule in which both money offer and demand could strike a balance. Upon the consistent implementation of an institutional schedule aimed at balancing the domestic monetary market, the “engines” that give rise to inflation come to a halt. Thus, a schedule with these characteristics that matches monetary offer and demand will enable inflation rate to fall dramatically in Argentina.

>In turn, we have explicitly stated a clear operating rule: the Central Bank will keep positive real interest rates with a noninflationary bias until the final objective is reached. This requires that nominal interest rates decrease as inflation and inflationary expectations go down.

Anyway, let me stray for a while: the concept of a positive real interest rate, even if low, has mounted considerable resistance within the business community. However, it is worth noting that a positive real interest rate will not only ensure a path towards deflation but also provide depositors with a reasonable return. In my view, this is the way towards both a decline in inflation levels and growth deposits and, eventually, credit. This has been a ten-year, though poor, longing given we could never develop credit in the absence of deposits and we cannot have deposits if we do not protect and compensate depositors.

Reaction to the August inflation

Going back to inflation, we may ask, “What happens when we achieve inflation targets in a given month as it is likely to happen next August?”

If nothing goes wrong in the next few days, we estimate this month inflation will stand below the 1.5% expected for the end of the year.

In spite of this early success, the BCRA holds that reasonable conditions for monetary policy loosening are not yet in place for a number of reasons. Firstly, an inflation reduction in a given month does not flag a sustained decrease in inflation level because a persistent deflationary process needs several months for consolidation, even if the core inflation decreases, presumably exempt from seasonal effects or regulated prices. Secondly, inflation expectations for 2017 are still above BCRA’s expectations. Thirdly, the way towards reaching a 5% annual inflation target is still far away.

To sum up, the BCRA will go on acting with due caution to ensure the consolidation of a deflationary process.

Monetary and fiscal policy

Let us pass on to the second topic: the relationship between fiscal situation and inflation. Argentina has experienced both in theory and in practice that the issue of inflation is raised when the Central Bank ends up defining its monetary policy according to the Treasury’s financing needs. This is called “fiscal dominance of monetary policy”. Being aware of this problem, we have been working together with the Ministry of the Treasury to define a fixed amount in pesos ($160 billion—nominal value—for 2016), which clearly restrains fiscal dominance. In turn, that amount was assessed together with the Ministry of the Treasury to be consistent with inflation targets. This value will fall in real and nominal terms as long as inflation falls.

While analysts do not address this issue, many of them openly criticize the government for following a policy of excessive fiscal gradualism, and for doing little to lower the high inherited deficits and to ensure fiscal consistency.

Today, I would like to give you three reasons why the BCRA is not concerned about fiscal gradualism.

The first reason is that, at present, our public sector bears a low indebtedness level with the private sector, which—making allowances for the unprecedented conditions in terms of funds availability—implies that the government has a high level of financing at hand. This enables to lower the transfers from the BCRA to the Treasury and to analyze the fiscal issue from a long-term perspective.

The second one is related to the government’s significant efforts made in the fiscal field as proved by its will to assume the political cost of reducing the number of subsidies and to sustain energy policy. The key point here is that fiscal efforts have been focused on both reducing the deficit and lowering taxes.

The reduction of distortive taxation rates may imply a short-term fiscal resources’ loss. Tax pressure drop, which is at present one percentage point lower than last year in terms of the GDP, is probably the best news of 2016. And this tax drop is basically oriented towards improving real wages both indirectly—by improving return conditions of the domestic economic activity—and directly—by lowering the income tax or giving part of the VAT back to some beneficiaries. Above all, this gives rise to the right incentives for economy to grow.

Broadly, the third reason is not so much referred to, but it is very clear to all of us who have accompanied the current President in his former mandate in the City of Buenos Aires. This reason is not so much related to the fiscal situation; rather it is concerned with public expenditure quality as a whole. From a macroeconomic point of view, the improvement of expenditure quality is comparable to reducing deficit because resources are saved in the private sector.

Therefore, a review over statistics of public employment in the City of Buenos Aires during the current President’s mandate shows that the number of public employees grew 7%. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that there has been an underlying change in priorities as evidenced by the 19 % increase in the number of teachers, doctors and police officers who have been hired. Today, these improvements in the efficient management of expenditure—which can take place against a backdrop of increased expenditure and employment as experienced in the City—are replicated in all administrative areas. At present, tenders for public works are submitted for half the price than last year but, more importantly, public works are given priority according to their social profitability. These coordinated efforts are the prelude to improve our management of the national public expenditure that will be critical to boost our economy’s productivity. And I am sure this will happen.

Thus, the BCRA holds that the fiscal scenario does neither compromise nor entail risks to the government’s anti-inflationary policy given the government’s experience in administration and its efforts oriented towards lowering taxes.

In addition, the BCRA supports that this anti-inflationary policy does not involve any risks because the government is determined to set an agenda on the reconstruction of investments and formal employment in Argentina and, among these objectives, on the reduction of inflation rate.

Argentina should adopt a positive attitude to become a ‘real’ country, which means being predictable and reliable. It also implies telling the truth. Moreover, being ‘real’ stands for a country where people do not need to think about price increase every day, or to be interested in listening to the BCRA governor to learn about news on inflation. We dream of a country where macroeconomics is no longer a matter of concern but a strong and invisible support for everyone’s development. Finally, we do not seek to be original; we only commit ourselves to work consistently.

(1)Passage from a speech by Peter Praet, member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank, at the LUISS School of European Political Economy, April 4th, 2016, Rome (self-translation)

(2)In “Inflation Targeting: Lessons from the International Experience” by Ben Bernanke, Thomas Laubach, Frederic Mishkin and Adam Posen (1999, Princeton University Press). Self-translation.

August 30th, 2016